The Foundations of Esotericism

GA 93a

28 September 1905, Berlin

Lecture III

There are three elements in evolution which must be differentiated: form, life and consciousness. Today we will speak about the different kinds of consciousness.

We can regard plants and lower animals as the means whereby higher beings extend their senses into the world in order to behold this world through them. Let us take our start from the sense organs of the plants. When we speak of these we must be clear that we are not only dealing with the sense organs of the single plants, but with beings in higher worlds. The plants are, as it were, only the feelers which are extended by the higher beings; they gain information through the plants.

All plants have cells, more especially at the root-tip but also in other places, in which granules of starch are to be found. Even in otherwise non-starch-containing plants, these starch granules appear at the root-tips. Members of the lily family, for instance, which otherwise contain no starch, possess these starch granules in the cells attached to the roots. These starch granules are loose and movable, and the important point is whether they are situated in one place or another.

Whenever a plant turns even slightly, one starch granule falls towards the other side. This the plant cannot stand. It then turns again in such a way that the granules come back to their right position. And these starch granules actually lie in a symmetrical relationship to the direction of the gravity of the earth. The plant grows upwards because it senses the direction of gravity. By observing the starch granules at the root-tips, we learn to recognise a kind of sense organ. This is for a plant the sense of gravity. This sense belongs not only to the plant, but to the soul of the whole earth, which orders the growth of the plant in accordance with this sense.

This is of primary importance. The plant takes its direction in accordance with gravity. Now if one takes a wheel, for instance a water-wheel, into which plants can be inserted, and turns the wheel together with the plants, another force is added to the force of gravity: a revolving force. This is now in every part of the plant, and its roots and stalks grow in the direction of the tangent of the wheel, in the direction of the tangential force, not the force of gravity. In accordance with this, the starch granules adjust their position.

Let us now consider the human ear. At first we have the outer auditory passage, then the tympanum, and in the inner ear the little auditory bones: hammer, anvil and stirrup—quite minute bones. Hearing depends upon these little bones bringing the other organs into vibration. Further in we find three semicircular membranous canals arranged according to the three dimensions. These are filled with fluid. Then we find, further within the ear, the labyrinth, a structure in the form of a snail shell, filled with very fine little hairs. Each of these is tuned, like the strings of a piano, to a particular pitch. The labyrinth is connected with the auditory nerve that goes to the brain.

The three semicircular canals are especially interesting. They stand in relation to one another in the three directions of space. They are filled with little otoliths, similar to the starch granules of the plant. When these are disturbed a person cannot hold himself erect or walk in an upright position. In the case of fainting the rush of blood to the head can cause a disturbance in the three canals. The sense of direction in man depends on these three semicircular canals. This is the same sense which in the plant, as sense of balance, is localised in the root-tips. What occurs in the root-tips is, in the human being, developed up above in the head.

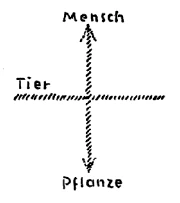

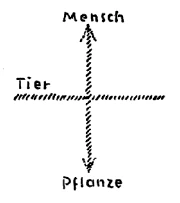

In surveying the whole evolution: plant, animal, man, one discovers definite relationships between them. The plant is reversed in man. The direction of the animal lies midway between them. The plant has sunk its roots into the earth and directs its sexual organs upward towards the sun. If we turn the plant halfway round we have the animal. If we turn it right round we have man. That is the original significance of the cross;11This is described in more detail in a lecture 22.11.1907. ‘The plant is drawn with its direction vertically towards the earth, the human being also vertically directed away from the earth, the animal horizontal.’ St. John, Notes on 8 lectures. Lecture 7. (Typescript). plant kingdom, animal kingdom, human kingdom. The plant sinks its roots into the earth. The animal is the half-reversed plant. Man is the completely reversed plant. This is why Plato says: ‘The World Soul is stretched on the Cross of the World Body.’12Plato, Timaeus Chapter 8.

In the plant the organ of direction lies in the root-tips. In man it is in the head. What in man is the head, is the root in the case of the plant. The reason, why in man the sense of direction is connected with the sense of hearing, is that hearing is the sense which raises man into a higher kingdom. The last faculty to be attained by man is the faculty of speech. Again, speech is connected with the upright carriage, which without the sense of direction or balance would not be possible. The sound which man produces through speech is the active complement to the passive sense of hearing. What in the plant is simply a sense of orientation has become in man the sense of hearing, which bears within itself the old sense of orientation in the three semicircular canals, which are arranged in accordance with the three dimensions of space.

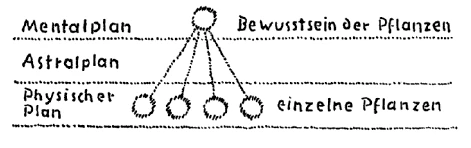

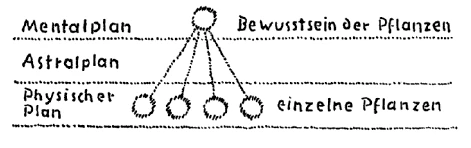

Every being possesses consciousness. This is also true of the plant, but its consciousness lies on the devachanic plane, on the mental plane. A diagram of the consciousness of the plant would have to be done in the following way:

The plants can also speak and answer us, only we must learn to observe them on the mental plane. There they tell us their own names.

Man's consciousness reaches down to the physical plane. Here his consciousness depends upon the same organ with which the plant is made fast to the earth. We first learn to know man in a true sense when we see how he produces speech and in speech the word ‘Ich’ (I). This ‘I’ has its roots in the mental plane. Without the faculty of uttering the little word ‘I’ we might regard the human form also as that of an animal.

The plant has its roots in the mental plane and man by means of his organ of hearing is an inhabitant of the mental plane. This is why we connect the ‘Es denkt’ (‘it thinks’) with speech. The ear is a higher development of the sense of direction. Because man in relation to the plant has reversed his position and turned again to the spirit, he has in the organ of hearing the old residue of the sense of direction. He gives himself his direction. These are therefore two opposite kinds of consciousness: the plant's consciousness on the mental plane and here the consciousness of man, who carries his being down from the mental world into the physical world. This earthly consciousness of man is called Kama-manas.

Each of the sense organs has a consciousness of its own. These different forms of consciousness, the consciousness of the visible, the audible, the sense of smell and so on, are brought together in the soul. The consciousness only becomes ‘manasic’ when its separate forms are gathered together in the centre of the soul. Without this integration man would fall apart into the consciousness of his organs. These were originally fashioned through the solar plexus, through the sympathetic nervous system. When man himself was a sort of plant, he too was not yet conscious on the physical plane. At that time the higher consciousness first developed the organs.

In a condition of deep trance the central consciousness is silenced. Then the separate organs are conscious and the person begins to see with the pit of the stomach and the solar plexus. Such a consciousness was possessed by the Seeress of Prevost.13Notes published by Justinus Kerner. Stuttgart 1828. She describes correctly light forms which are however only to be observed by the consciousness of the organs. The lowest consciousness is that of the minerals. A somewhat more centralised consciousness, one more like the consciousness of present day man, is the astral consciousness. The development of consciousness in the whole astral body finds its expression in the spinal cord. Then a person perceives the world in pictures. Only those people whose physical brain does not operate have such a consciousness. Idiots, for instance, see the world in pictures; their soul life is analogous to dream life. They can only say that they know nothing of what is going on around them. Other beings in the world have a similar consciousness.

When someone develops astral consciousness, so that he experiences dreams consciously, he can undertake the following: Let us assume that we are in a position to develop this consciousness and imagine ourselves standing before the flower called Venus Fly Trap. If we gaze at it long enough and let it work upon us quite exclusively there comes the moment when we have the feeling that the centre of consciousness sinks down from the head and creeps into the plant.14This is more clearly dealt with in lecture 4. One is then conscious in the plant and sees the world through it. One must transfer one's consciousness, into the plant. Then one becomes aware of how things appear to the astral perception of this being. One then experiences this soul. A sensitive plant's consciousness is quite similar to that of an idiot; not a purely mental consciousness. Such a plant has brought consciousness down to the astral plane. Thus there are two kinds of plants; those which only have their consciousness on the mental plane, and those which have it also on the astral plane.

Certain kinds of animals also have a consciousness on the astral plane, which is likewise the plane of idiot consciousness. Helena Petrovna Blavatsky mentions especially certain Indian night insects, nocturnal moths. Spiders also have an astral consciousness;15Described by H.P. Blavatsky in The Secret Doctrine, Vol. 3. the delicate spider webs are actually spun out of the astral plane. The spiders are merely the instruments of astral activity. The ants too, like the spiders have a consciousness on the astral plane. There the ant heaps have their soul. This is why the behaviour of the ants is so precisely regulated.16See further in lecture 4.

The minerals also have consciousness. This lies on the higher mental plane, in higher regions than that of the plant. Blavatsky calls it Kama-prana consciousness. Man too can later achieve this consciousness while retaining his present state of consciousness undisturbed. He then no longer needs to enter into a physical body, no longer needs to be incarnated. The stones are below on the physical plane and their consciousness is in the higher regions of the mental plane. The crystals are ordered from above. When a man is able to raise his consciousness to this level he then forms his physical body for himself out of the minerals of the world.

The three parts of the brain (thinking, feeling, willing) must later become completely separated. Then man's consciousness must be master of his brain, as in an ant heap a higher consciousness rules. But as in the ant heap, one can separate the workers, the males and females from one another, so, later, a complete separation into three parts can also take place in the brain. Then man becomes a planetary spirit, a creator who brings things into being. As the Earth Spirit builds the crust of the earth, so at that stage man also will build a planet. For this he must have a Kama-pranasic consciousness. Today he has only a Kama-manasic consciousness. This consists in the consciousness of the organs being saturated, impregnated with understanding (Manas). The consciousness becomes, as Blavatsky says, rationalised. The process of rationalisation is brought about during the ascent from animal to man. Organ-consciousness by itself can recognise the objective, but does not know the means whereby it can be achieved. Rationalised consciousness can direct the means. Blavatsky says quite rightly: ‘A dog, for instance, which is shut into a room has the instinct to get out, but he cannot do this because his instinct is not as yet sufficiently imbued with understanding to enable him to take the necessary steps; whereas man immediately grasps the situation and frees himself.’ We therefore differentiate with Blavatsky:

- The organic consciousness possessed by the organs.

- The astral consciousness possessed by animals, certain plants and idiots.

- The kama-pranasic consciousness of the stones, also to be achieved later by man.

- The kama-manasic consciousness, dependent on understanding.

In this way one must differentiate the members of the cross of world-existence.

The real meaning of the cross is infinitely deep. The old sagas also are pictures, drawn out of such depths. A great service was bestowed on the human soul by the sagas, as long as man in earlier times could understand their truths in his feeling life. An example of this is the old saga of the sphinx.17The Sphinx (daughter of Chimaera and her son the hound Orthus)—a monster with the body of a hound, a woman's head, lion's claws, dragon's tail and wings—was sent to Thebes where she dealt out death and destruction by means of a riddle. She asked the unfortunate ones who confronted her: What creature goes on four legs in the morning, on two at midday and on three in the evening? Oedipus was the fortunate one who found the answer—man. Upon which she threw herself down from her rock. In the painting in the large cupola of the first Goetheanum the motif representing Greece also includes this Sphinx-Oedipus theme. The sphinx propounded the riddle: In the morning it goes on four, at mid-day on two and in the evening on three. What is that? It is man. To begin with, in the morning of the earth, man in his animal state went on fours. The front limbs were at that time organs of movement. He then raised himself to the upright position. The limb system separated off into two categories and the organs divided into the physical-sensible and the spiritual organs. He then went on two. In the distant future the lower organs will fall away and also the right hand. Only the left hand and the two petalled lotus flower will remain. Then he goes on three. That is why the Vulcan human being limps.18(In Latin Vulcanus, in Greek Hephaistos.) The god of fire and the forger of metals. He limped because twice Zeus, in anger, threw him out of Olympus. According to the original myth his smithy was in Olympus, but in later versions in volcanic regions. His legs are in retrogression; they cease to have significance. At the end of evolution, in the Vulcan metamorphosis of the Earth, man will be the three-membered being that the saga indicates as the ideal.

III

Es gibt in der Entwickelung drei Dinge, die man unterscheiden muß: Form, Leben und Bewußtsein. Heute wollen wir über die Bewußtseinsformen sprechen.

Wir können Pflanzen und niedere Tiere so ansehen, als ob höhere Wesen durch sie ihre Sinne in die Welt hinausstreckten, um die Welt durch sie anzuschauen. Gehen wir zunächst aus von den Sinnesorganen der Pflanzen. Wenn man von Sinnesorganen der Pflanzen spricht, so muß man sich darüber klar sein, daß man es nicht nur mit den Sinnesorganen der einzelnen Pflanzen zu tun hat, sondern mit Wesenheiten in höheren Welten. Die Pflanzen sind gleichsam nur die Fühlhörner, die die höheren Wesen ausstrecken. Das höhere Wesen informiert sich durch die Pflanzen.

Alle Pflanzen haben, namentlich an den Wurzelspitzen, doch auch an anderen Stellen, Zellen, in denen sich Stärkekörner befinden. Auch bei sonst nicht stärkehaltigen Pflanzen sind diese Stärkekörner an der Wurzelspitze. Die Liliengewächse zum Beispiel, die sonst keine Stärke haben, besitzen in den Zellen an der Wurzelspitze diese Stärkekörner. Diese Stärkekörner sind lose, beweglich, und es kommt darauf an, ob die Körner an der einen oder der anderen Stelle liegen.

Sobald sich die Pflanze ein bißchen wendet, fällt das eine Stärkekorn nach der anderen Seite. Das kann die Pflanze nicht vertragen. Sie wendet sich dann wieder so, daß die Stärkekörner an die richtige Stelle zu liegen kommen. Und zwar liegen diese Stärkekörner symmetrisch zur Schwerkraftlinie der Erde. Die Pflanze wächst aufrecht, weil sie die Richtung der Schwerkraft spürt. Die Stärkekörner spüren die Schwerkraft. Bei der Beobachtung der Stärkekörner an den Wurzelspitzen lernen wir eine Art von Sinnesorgan kennen. Es ist für die Pflanze der Sinn für die Schwerkraft. Dieser Sinn gehört nicht nur zur Pflanze, sondern zur Seele der ganzen Erde, die nach diesem Sinn die ganze Pflanze wachsen läßt.

Das hat zunächst eine elementare Bedeutung. Die Pflanze richtet sich nach der Schwerkraft. Nimmt man nun ein Rad, zum Beispiel ein Wasserrad, in das man Pflanzen hineinsetzen kann, und dreht das Rad mitsamt den Pflanzen, so kommt zur Schwerkraft eine andere Kraft hinzu: die Kraft der Umdrehung. Die ist dann in jedem Punkt der Pflanzen, und es wachsen die Wurzeln der Pflanze und die Stengel in der Richtung der Tangente des Rades, in der Richtung der Tangentialkraft, und nicht der Schwerkraft. Darnach richten sich dann auch die Stärkekörner in ihrer Lage.

Betrachten wir nun das menschliche Ohr. Da haben wir zunächst den äußeren Gehörgang, dann das Trommelfell, und im inneren Ohr die Gehörknöchelchen: Hammer, Amboß und Steigbügel - ganz winzig kleine Knöchelchen. Das Hören beruht darauf, daß durch diese kleinen Knöchelchen die anderen Organe in Schwingung geraten. Innen finden wir weiter drei halbkreisförmige, häutige Kanäle in den Richtungen der drei Dimensionen angeordnet. Diese sind mit einer Flüssigkeit angefüllt. Dann finden wir weiter im Ohr das Labyrinth, ein schneckenförmiges Gebilde, angefüllt mit ganz feinen Härchen. Jedes ist wie die Saite in einem Klavier auf einen bestimmten Ton gestimmt. Das Labyrinth steht in Verbindung mit dem Hörnerv, der nach dem Gehirn geht.

Uns interessieren hauptsächlich die drei halbkreisförmigen Kanäle. Sie stehen zueinander in den drei Richtungen des Raumes. Sie sind angefüllt mit ähnlichen Dingen wie die Stärkekörner der Pflanze, mit Hörsteinchen. Wenn diese zerstört sind, kann der Mensch sich nicht aufrechthalten oder aufrechtgehen. Bei einer Ohnmacht kann durch Andrang des Blutes nach dem Kopfe der Organismus in den drei Kanälen gestört werden. Auf den drei halbkreisförmigen Kanälen beruht der Orientierungssinn des Menschen. Das ist derselbe Sinn, der sich bei der Pflanze als Gleichgewichtssinn an der Wurzelspitze befindet. Was dort an der Wurzelspitze sich befindet, ist beim Menschen oben am Kopfe ausgebildet.

Wenn man die ganze Evolution überschaut, Pflanze, Tier, Mensch, so findet man bestimmte Beziehungen zwischen ihnen. Die Pflanze ist der umgekehrte Mensch. Das Tier steht mitten drinnen. Die Pflanze hat ihre Wurzeln in den Boden gesenkt und richtet die Organe der Sexualität zur Sonne empor. Kehrt man die Pflanze halb um, so hat man das Tier. Kehrt man sie ganz um, so hat man den Menschen. Das ist die ursprüngliche Bedeutung des Kreuzzeichens: Pflanzenreich, Tierreich, Menschenreich. Die Pflanze senkt ihre Wurzeln in den Boden. Das Tier ist die halb umgekehrte Pflanze. Der Mensch ist die ganz umgekehrte Pflanze. Darum sagt Plato: Die Weltenseele ist an das Kreuz des Weltenleibes gespannt.

Bei der Pflanze liegt das Richtungsorgan in der Wurzelspitze, beim Menschen im Kopf. Was bei dem Menschen der Kopf ist, ist bei der Pflanze die Wurzel. Warum nun beim Menschen der Richtungssinn zusammenhängt mit dem Gehörsinn, hängt damit zusammen, daß der Gehörsinn derjenige Sinn ist, der den Menschen in ein höheres Reich erhebt. Die letzte Fähigkeit, die der Mensch errungen hat, ist die Fähigkeit des Sprechens. Das Sprechen hängt wiederum zusammen mit dem aufrechten Gang, der ohne den Richtungs- oder Gleichgewichtssinn nicht möglich wäre. Der Ton, den der Mensch durch das Sprechen hervorbringt, ist die aktive Ergänzung zu dem passiven Hören. Was bei der Pflanze bloßer Orientierungssinn ist, ist bei dem Menschen Gehörsinn geworden, der den alten Orientierungssinn in sich trägt in den drei halbkreisförmigen Kanälen, die sich nach den drei Raumesdimensionen richten.

Jedes Wesen hat ein Bewußtsein. Auch die Pflanze hat ein solches; aber dieses Bewußtsein liegt auf dem Devachanplan, auf dem mentalen Plan. Wenn man das Bewußtsein der Pflanze aufzeichnen wollte, müßte man es in folgender Weise zeichnen:

Die Pflanze kann uns auch Rede und Antwort stehen, nur muß man lernen, sie auf dem Mentalplan zu beobachten. Da sagt die Pflanze uns ihren eigenen Namen.

Bei dem Menschen reicht das Bewußtsein bis auf den physischen Plan herunter. Das Bewußtsein des Menschen hier hängt mit demselben Organ zusammen, mit dem die Pflanze in der Erde befestigt ist. Den Menschen lernen wir erst wahrhaft kennen, wenn wir sehen, wie er die Sprache hervorbringt und in ihr das Wort «Ich» ausspricht. Dieses Ich wurzelt auf dem Mentalplan. Ohne die Fähigkeit, das Wörtchen «Ich» zu sprechen, würden wir die Gestalt des Menschen auch für ein Tier halten können.

Die Pflanze wurzelt im Mentalplan, und der Mensch wird gerade durch das Gehörorgan ein Bewohner des Mentalplanes. Daher verbinden wir das «Es denkt» mit der Sprache. Das Ohr ist eine höhere Ausbildung des Richtungssinnes. Weil der Mensch sich im Verhältnis zur Pflanze umgewendet und dann wiederum dem Geist zugewendet hat, hat er im Gehörorgan das alte Überbleibsel des Richtungssinnes. Er gibt sich selbst die Richtung. Es sind also zwei entgegengesetzte Bewußtseinsarten: Das Bewußtsein der Pflanze auf dem Mentalplan und das Bewußtsein des Menschen hier, der sein Wesen von der Mentalwelt in die physische Welt hinunterträgt. Dieses irdische Bewußtsein des Menschen nennt man das kama-manasische.

Unsere Sinnesorgane haben nun auch alle für sich ein Bewußtsein. Diese verschiedenen Bewußtseine: das Bewußtsein des Sichtbaren, Hörbaren, Riechbaren und so weiter werden in der Seele zusammengefaßt. Manasisch wird das Bewußtsein erst dadurch, daß die einzelnen Bewußtseine zusammengefaßt werden in dem Seelenzentrum. Ohne dieses Zusammenfassen würde der Mensch zerfallen in seine Organbewußtseine. Diese sind ursprünglich ausgebildet worden durch das Sonnengeflecht, durch das sympathische Nervensystem. Als der Mensch selbst noch eine Art Pflanze war, da hatte er auch noch nicht das Bewußtsein auf dem physischen Plan. Da bildete das höhere Bewußtsein erst die Organe aus.

Im tiefen Trancezustand schweigt das zentrale Bewußtsein. Dann sind die einzelnen Organe bewußt und der Mensch fängt an, mit der Magengrube, mit dem Sonnengeflecht zu sehen. Solch ein Bewußtsein hatte die Seherin von Prevorst. Sie beschreibt richtige Lichtgestalten, die aber nur von dem Organbewußtsein beobachtet werden. Das unterste Bewußtsein ist dasjenige des Minerals. Ein etwas zenttierteres Bewußtsein, etwas mehr dem Bewußtsein des jetzigen Menschen ähnlich, ist das astrale Bewußtsein. Daß sich das Bewußtwerden im ganzen Astralkörper gebildet hat, hat seinen Ausdruck im Rückenmark. Da nimmt der Mensch die Welt analog den Traumbildern wahr. Solch ein Bewußtsein haben nur Menschen, deren physisches Gehirn nicht zur Tätigkeit kommt. Idioten zum Beispiel sehen die Welt in Bildern; ihr Seelenleben ist analog dem Traumleben. Sie können nur sagen, daß sie nichts wissen von dem, was um sie her vorgeht. Auch andere Wesen in der Welt haben ein ähnliches Bewußtsein.

Wenn der Mensch das astrale Bewußtsein entwickelt, so daß er die Träume bewußt erlebt, dann kann er folgendes vornehmen: Wir nehmen an, wir sind imstande, dieses Bewußtsein auszubilden und stellen uns dann der Blume «Venusfliegenfalle» gegenüber. Wenn wir sie lange genug anschauen und sie ganz allein auf uns wirken lassen, dann bekommt man in einem bestimmten Moment das Gefühl, daß der Mittelpunkt des Bewußtseins sich vom Kopf herabsenkt und in die Pflanze hineinkriecht. Man ist dann bewußt in der Pflanze und sieht durch die Pflanze die Welt. Man muß sein Bewußtsein in die Pflanze hineinverlegen. Dann wird man sich klar darüber, wie es in diesem Wesen seelisch aussieht. Man erlebt dann diese Seele. Bei einer sensitiven Pflanze ist das Bewußtsein ganz ähnlich dem Bewußtsein eines Idioten; nicht ein bloß mentales Bewußtsein. Sie hat das Bewußtsein bis zum astralen Plan heruntergebracht. Es gibt demnach zweierlei Arten von Pflanzen: solche, die nur auf dem mentalen Plan bewußt sind, und solche, die es auch auf dem astralen Plan sind.

Gewisse Tierarten haben auch ein Bewußtsein auf dem astralen Plan, der auch der Plan des Idiotenbewußtseins ist. Helena Petrowna Blavatsky weist besonders auf indische Nachtinsekten, Nachtfalter hin. Zum Beispiel haben auch die Spinnen ein astrales Bewußtsein; die feinen Spinnennetze werden eigentlich vom Astralplan herein gesponnen. Die Spinnen sind bloß die Werkzeuge für die astrale Tätigkeit. Die Fäden werden vom Astralplan herein gesponnen. Auch die Ameisen haben, ähnlich wie die Spinnen, ein Bewußtsein auf dem Astralplan. Dort hat der Ameisenhaufen seine Seele. Daher sind die Handlungen der Ameisen so geordnet.

Ein Bewußtsein haben auch die Mineralien. Das liegt auf dem höheren Mentalplan, auf höheren Partien als dasjenige der Pflanzen. Blavatsky nennt es kama-pranisches Bewußtsein. Der Mensch kann später auch dieses Bewußtsein erlangen mit Aufrechterhaltung seines jetzigen Bewußtseinszustandes. Er braucht dann nicht mehr in einen physischen Körper hineinzukommen, nicht mehr inkarniert zu werden. Die Steine sind unten auf dem physischen Plan und ihr Bewußtsein ist in den oberen Partien des Mentalplanes. Von oben ordnet es die Kristalle an. Wenn der Mensch sein Bewußtsein einmal da hinauftragen kann, dann bildet er sich aus den Mineralien der Welt selbst seinen physischen Leib.

Die drei Teile des Gehirns müssen später ganz getrennt werden (Denken, Fühlen, Wollen). Da muß das Bewußtsein des Menschen über sein Gehirn herrschen, wie beim Ameisenhaufen das höhere Bewußtsein herrscht. Wie man da Arbeiter, Männchen und Weibchen unterscheiden kann, so findet später auch im Gehirn eine genaue Unterscheidung in drei Teile statt. Dann ist der Mensch planetarischer Geist, ein Schöpfer, der die Dinge selbst schafft. Wie der Erdengeist die Erdkruste baut, so wird dann der Mensch auch einen Planeten bauen. Dazu muß er ein kama-pranisches Bewußtsein haben. Heute hat er nur ein kama-manasisches Bewußtsein. Das besteht darin, daß das Organbewußtsein mit dem Verstand (Manas) durchtränkt, durchsetzt wird. Das Bewußtsein wird, wie Blavatsky sagt, rationalisiert. Der Prozeß der Rationalisierung vollzieht sich vom Tier bis zum Menschen. Das bloße Organbewußtsein kann die Ziele erkennen, kennt aber nicht die Mittel zur Erreichung der Ziele. Das rationalisierte Bewußtsein kann die Mittel dirigieren. Blavatsky sagt ganz richtig: «Zum Beispiel hat ein in einem Zimmer eingeschlossener Hund den Instinkt, herauszukommen, aber er kann nicht, weil sein Instinkt nicht genügend vernünftig geworden ist, um die notwendigen Mittel zu ergreifen, während der Mensch sofort die Situation erfaßt und sich frei macht.»

Wir unterscheiden also mit Blavatsky:

1. Das Organbewußtsein, das unsere Organe haben.

2. Das astrale Bewußtsein der Tiere und gewisser Pflanzen und auch der Idioten.

3. Das kama-pranische Bewußtsein der Steine, das sich auch der Mensch später erwirbt.

4. Das kama-manasische Bewußtsein, das Verstandesmäßige.

Auf diese Weise muß man das Kreuz des Weltendaseins auseinandergliedern.

Der eigentliche Sinn des Kreuzes liegt unendlich tief. Auch die alten Sagen sind aus solchen Tiefen heraufgeholte Bilder. Der Menschenseele wurde ein großer Dienst erwiesen durch die Sagen, solange der Mensch früher die Wahrheiten der Sagen gefühlsmäßig verstehen konnte. Zum Beispiel ist da die alte Sphinxsage. Die Sphinx gab das Rätsel auf: Am Morgen geht es auf vieren, am Mittag auf zweien und am Abend auf dreien? Was ist das? - Es ist der Mensch! Zuerst, am Morgen der Erde, ging der Mensch auf vieren, in seinem tierischen Zustand. Die vorderen Gliedmaßen waren damals auch noch Bewegungsorgane. Dann hat er sich aufgerichtet. Die Gliedmaßen traten in zweierlei Arten auseinander und die Organe teilten sich in die physisch-sinnlichen und die geistigen Organe. Er ging dann auf zweien. In ferner Zukunft werden die unteren Organe abfallen und die rechte Hand. Nur die linke Hand und die zweiblättrige Lotusblume bleiben. Dann geht er auf dreien. Darum hinkt auch der Vulkan. Seine Beine sind in der Rückbildung begriffen, sie hören auf, etwas zu sein. Am Ende der Evolution, in der Vulkanmetamorphose der Erde, wird der Mensch das dreigliedrige Wesen sein, das die Sage als Ideal andeutet.

III

There are three things in evolution that must be distinguished: form, life, and consciousness. Today we want to talk about the forms of consciousness.

We can view plants and lower animals as if higher beings were extending their senses into the world through them in order to observe the world through them. Let us start with the sensory organs of plants. When we speak of the sensory organs of plants, we must be clear that we are not only dealing with the sensory organs of individual plants, but with beings in higher worlds. Plants are, as it were, only the antennae that higher beings extend. The higher being informs itself through the plants.

All plants have cells containing starch grains, particularly at the tips of their roots, but also in other places. Even plants that do not otherwise contain starch have these starch grains at the tips of their roots. Lilies, for example, which do not otherwise contain starch, have these starch grains in the cells at the tips of their roots. These starch grains are loose and mobile, and it depends on whether the grains are located in one place or another.

As soon as the plant turns slightly, the starch granules fall to the other side. The plant cannot tolerate this. It then turns back so that the starch granules are in the right place. These starch granules are symmetrical to the Earth's gravitational line. The plant grows upright because it senses the direction of gravity. The starch grains sense gravity. By observing the starch grains at the root tips, we learn about a kind of sensory organ. For the plant, it is the sense of gravity. This sense belongs not only to the plant, but to the soul of the whole earth, which allows the whole plant to grow according to this sense.

This has a fundamental significance. The plant aligns itself with gravity. If we take a wheel, for example a water wheel, into which we can place plants, and turn the wheel together with the plants, another force is added to gravity: the force of rotation. This force is then present at every point of the plants, and the roots and stems of the plants grow in the direction of the tangent of the wheel, in the direction of the tangential force, and not in the direction of gravity. The starch grains then also align themselves in their position.

Let us now consider the human ear. First we have the external auditory canal, then the eardrum, and in the inner ear the ossicles: the malleus, incus, and stapes—tiny little bones. Hearing is based on these small bones causing the other organs to vibrate. Inside, we find three semicircular, membranous canals arranged in the directions of the three dimensions. These are filled with fluid. Then we find the labyrinth in the ear, a snail-shaped structure filled with very fine hairs. Each one is tuned to a specific tone, like the strings of a piano. The labyrinth is connected to the auditory nerve, which goes to the brain.

We are mainly interested in the three semicircular canals. They are arranged in relation to each other in the three directions of space. They are filled with substances similar to the starch grains in plants, with otoliths. If these are destroyed, a person cannot stand upright or walk upright. When a person faints, the rush of blood to the head can disrupt the organism in the three canals. The human sense of orientation is based on the three semicircular canals. This is the same sense that is located at the tip of the root in plants as the sense of balance. What is located at the tip of the root in plants is formed at the top of the head in humans.

If you look at the whole of evolution, plants, animals, humans, you will find certain relationships between them. The plant is the reverse of the human being. The animal stands in the middle. The plant has its roots in the ground and directs its sexual organs towards the sun. If you turn the plant halfway around, you have the animal. If you turn it completely upside down, you have the human being. This is the original meaning of the sign of the cross: the plant kingdom, the animal kingdom, the human kingdom. The plant sinks its roots into the ground. The animal is the half-reversed plant. The human being is the completely reversed plant. That is why Plato says: The world soul is stretched across the cross of the world body.

In plants, the organ of direction is located in the tip of the root; in humans, it is located in the head. What is the head in humans is the root in plants. The reason why the sense of direction in humans is connected with the sense of hearing is that the sense of hearing is the sense that elevates humans to a higher realm. The last ability that humans have acquired is the ability to speak. Speaking, in turn, is connected with upright walking, which would not be possible without the sense of direction or balance. The sound that humans produce through speech is the active complement to passive hearing. What is merely a sense of orientation in plants has become a sense of hearing in humans, which carries the old sense of orientation within itself in the three semicircular canals that are oriented toward the three spatial dimensions.

Every being has consciousness. Plants also have consciousness, but this consciousness lies on the devachanic plane, the mental plane. If one wanted to record the consciousness of a plant, one would have to draw it in the following way:

Plants can also answer our questions, but we must learn to observe them on the mental plane. There, the plant tells us its own name.

In humans, consciousness extends down to the physical plane. Human consciousness here is connected to the same organ that anchors the plant in the earth. We only truly get to know a person when we see how they produce speech and utter the word “I.” This “I” is rooted in the mental plane. Without the ability to speak the word “I,” we could mistake the human form for that of an animal.

The plant is rooted in the mental plane, and it is through the organ of hearing that the human being becomes an inhabitant of the mental plane. That is why we associate “it thinks” with language. The ear is a higher development of the sense of direction. Because the human being has turned away from the plant and then turned toward the spirit, he has the old remnant of the sense of direction in his hearing organ. He gives himself direction. So there are two opposite types of consciousness: the consciousness of the plant on the mental plane and the consciousness of the human being here, who carries his being down from the mental world into the physical world. This earthly consciousness of the human being is called the kama-manasic consciousness.

Our sense organs now also all have a consciousness of their own. These different consciousnesses: the consciousness of the visible, the audible, the olfactory, and so on, are summarized in the soul. Consciousness only becomes manasic when the individual consciousnesses are summarized in the soul center. Without this summarization, the human being would disintegrate into his organ consciousnesses. These were originally formed by the solar plexus, by the sympathetic nervous system. When humans themselves were still a kind of plant, they did not yet have consciousness on the physical plane. It was the higher consciousness that first formed the organs.

In a deep trance state, the central consciousness is silent. Then the individual organs become conscious and the human being begins to see with the pit of the stomach, with the solar plexus. The seer of Prevorst had such consciousness. She describes real figures of light, but they are only observed by the organ consciousness. The lowest consciousness is that of the mineral. A somewhat more centered consciousness, somewhat more similar to the consciousness of the present human being, is the astral consciousness. The fact that consciousness has formed in the entire astral body is expressed in the spinal cord. There, the human being perceives the world analogously to dream images. Only people whose physical brain is not active have such consciousness. Idiots, for example, see the world in images; their soul life is analogous to dream life. They can only say that they know nothing of what is going on around them. Other beings in the world also have a similar consciousness.

When a person develops astral consciousness so that they consciously experience dreams, they can do the following: Let us assume that we are able to develop this consciousness and then stand in front of the Venus flytrap flower. If we look at it long enough and let it work on us all by itself, then at a certain moment we get the feeling that the center of consciousness descends from the head and creeps into the plant. One is then consciously in the plant and sees the world through the plant. One must transfer one's consciousness into the plant. Then one becomes clear about what the soul of this being is like. One then experiences this soul. In a sensitive plant, consciousness is very similar to the consciousness of an idiot; it is not merely mental consciousness. It has brought consciousness down to the astral plane. There are therefore two kinds of plants: those that are conscious only on the mental plane, and those that are also conscious on the astral plane.

Certain animal species also have consciousness on the astral plane, which is also the plane of idiot consciousness. Helena Petrovna Blavatsky points in particular to Indian night insects, moths. Spiders, for example, also have astral consciousness; the fine spider webs are actually spun from the astral plane. The spiders are merely the tools for astral activity. The threads are spun from the astral plane. Ants, like spiders, also have consciousness on the astral plane. That is where the anthill has its soul. That is why the actions of ants are so orderly.

Minerals also have consciousness. This lies on the higher mental plane, on higher levels than that of plants. Blavatsky calls it kama-pranic consciousness. Humans can also attain this consciousness later on while maintaining their current state of consciousness. They then no longer need to enter a physical body, no longer need to be incarnated. Stones are on the lower physical plane and their consciousness is in the higher parts of the mental plane. From above, it arranges the crystals. Once humans can carry their consciousness up there, they form their own physical body from the minerals of the world.

The three parts of the brain must later be completely separated (thinking, feeling, willing). Human consciousness must rule over the brain, just as higher consciousness rules over the anthill. Just as one can distinguish between workers, males, and females in the anthill, so too will a precise distinction into three parts take place later in the brain. Then the human being will be a planetary spirit, a creator who creates things himself. Just as the Earth spirit builds the Earth's crust, so too will humans build a planet. To do this, they must have kama-pranic consciousness. Today, they only have kama-manasic consciousness. This consists of the organ consciousness being saturated and permeated by the mind (manas). Consciousness becomes rationalized, as Blavatsky says. The process of rationalization takes place from animals to humans. Mere organ consciousness can recognize goals, but does not know the means to achieve them. Rationalized consciousness can direct the means. Blavatsky says quite correctly: “For example, a dog locked in a room has the instinct to get out, but it cannot because its instinct has not become rational enough to take the necessary means, while humans immediately grasp the situation and free themselves.”

We therefore distinguish with Blavatsky:

1. The organ consciousness that our organs have.

2. The astral consciousness of animals and certain plants, and also of idiots.

3. The kama-pranic consciousness of stones, which humans also acquire later.

4. The kama-manasic consciousness, the intellectual.

In this way, one must dissect the cross of worldly existence.

The true meaning of the cross lies infinitely deep. Even the ancient legends are images drawn from such depths. The legends rendered a great service to the human soul as long as humans were able to understand the truths of the legends emotionally. Take, for example, the ancient legend of the Sphinx. The Sphinx posed the riddle: In the morning it walks on four legs, at noon on two, and in the evening on three. What is it? It is man! At first, in the morning of the earth, man walked on four legs, in his animal state. At that time, the front limbs were still organs of movement. Then he stood upright. The limbs diverged in two ways and the organs divided into the physical-sensory and the spiritual organs. He then walked on two legs. In the distant future, the lower organs will fall off, as will the right hand. Only the left hand and the two-petaled lotus flower will remain. Then he will walk on three. That is why Vulcan limps. His legs are in the process of regression; they are ceasing to be. At the end of evolution, in the Vulcan metamorphosis of the Earth, man will be the three-part being that legend suggests as the ideal.