Spiritual Science and Medicine

GA 312

21 March 1920, Dornach

Lecture I

We may take it as obvious that only a very small proportion of what my present hearers probably expect for the future of their professional life can be indicated in this series of lectures; for you will all agree that any confidence in the future among medical workers depends on the reform of the actual medical curriculum. It is impossible to give any direct impetus to such reform by means of a course of lectures. The most that may possibly result is that certain individuals will feel the urge to help and participate in such reform. Any medical subject under discussion today has, as its background, those initial studies in anatomy, physiology and general biology, which are the preliminaries to medicine proper. These preliminaries bias the medical mind in a certain direction from the first; and it is absolutely essential that such bias should be rectified.

In this series of lectures I should like, in the first place, to submit to you some facts bearing on the obstacles in the customary curriculum to any really objective recognition of the nature of disease per se. Secondly, I would suggest the direction in which we should seek that knowledge of human nature which can afford a real foundation for medical work. Thirdly, I would indicate the possibilities of a rational therapy based on the knowledge of the relationship between man and the surrounding world. In this section I would include the question whether actual healing were possible and practicable.

Today I shall restrict myself to introductory remarks, and to a kind of orientation. My principal aim will be to collect for consideration from Spiritual Science all that can be of value to physicians. It is my wish that this attempt should not be confused with an actual medical course, which it nevertheless will be in a sense. But I shall give special attention to everything that may be of value to the medical worker. A true medical science, or art, if I may call it so, can only be attained by consideration of the factors to which I have referred.

Probably you have all, in thinking over the task of the physician, been baffled by the question: “What does sickness mean and what is a sick human being?” The most usual definition or explanation of sickness in general and of sick people, is that the morbid process is a deviation from the normal life process; that certain facts which affect human beings, and for which normal human functions are not in the first place adapted, cause certain changes in the normal life process and in the organisation; and that sickness consists in the functional deficiency of the organs caused by such changes. But you must admit that this is a merely negative definition. It offers no help when we are dealing with actual diseases. It is just this practical help that I shall aim at here, help in dealing with actual diseases. In order to make things clear it seems advisable to refer to certain views, which have developed in the course of time, as to the nature of disease; not as indispensable for the present interpretation of morbid symptoms, but as signposts showing the way. For it is easier to recognise where we are now if we appreciate former points of view which led up to those now current.

The accepted version of the origin of medicine derives it from the Greece of the fifth and fourth centuries before the Christian era, when the influence of Hippocrates was supreme. Thus an impression is produced that the system of Hippocrates—which developed into the Humoral pathology accepted until well into the nineteenth century—was the first attempt at medicine in the Occident. But this is a fundamental error, and is still harmful as a hindrance to an unprejudiced view of sickness. We must, to begin with, clear this error away. For an unbiased view the conceptions of Hippocrates which even survived until the time of Rokitansky, that is until the last century—are not a beginning only, but to a very significant degree are a conclusion and summary of older medical conceptions. In the ideas which have come down to us from Hippocrates we meet a final filtered remainder of ancient medical conceptions. These were not reached by contemporary methods, i.e., through anatomy, but by the paths of ancient atavistic vision. The most accurate abstract definition of Hippocratic medicine would be: the conclusion of archaic medicine based on atavistic clairvoyance. From an external point of view, we may say that the followers of Hippocrates attributed all forms of sickness to an incorrect blending of the various humours or fluids which co-operate in the human organism. They pointed out that these fluids bore a certain ratio to one another in a normal organism, and that this ratio was disturbed in the sick human body. They termed the healthy mixture or balance Krasis, the improper mixture Dyskrasis. The latter had to be influenced so that the proper blend might be restored. In the external world, they beheld four substances which constituted all physical existence: Earth, Water, Air and Fire—Fire meaning what we describe simply as warmth. They held that these four elements were specialised in the bodies of man and the animals, as black bile, yellow bile, (gall) mucus (slime), and blood, and that the human organism must therefore function by means of the correct blending of these four fluids.

The contemporary man with some kind of scientific grounding, who considers this theory, argues as follows: the blending and interaction of blood, mucus, bile and gall, in due proportion, must produce an effect according to their inherent qualities known to chemistry. And this restricted view is thought to be the essence of Humoral pathology; but erroneously. Only one of the four “humours,” the most Hippocratic of all—as it appears to us today—namely “black bile” was believed to work through its actual chemical attributes on the other “humours.” In the case of the remaining three fluids, it was believed that besides the chemical properties there were certain intrinsic qualities of extra-telluric origin. (I am referring to the human organism for the moment, excluding animals from consideration.) Just as water, air and fire were believed to be dependent on extra-telluric forces, so also these ingredients of the organism were believed to be inter-penetrated with forces emanating from beyond the earth.

In the course of evolution, western science has completely lost this reference to extra-terrestrial forces. For the scientist of today, there is something absolutely grotesque in the suggestion that water possesses not only the qualities verifiable by chemical tests, but also, in its action within the human organism, qualities appertaining to it as a part of the extra-terrestrial universe. Thus the Ancients held that the fluids of the human body carried into the organism forces derived from the cosmos itself. Such cosmic forces were regarded less and less as the centuries went on; but nevertheless medical thought was built up on the remains of the fading conceptions of Hippocrates until the fifteenth century. Contemporary scientists therefore have great difficulty in understanding pre-fifteenth century treatises on medical subjects; and we must admit that the writers of these treatises did not, as a rule, themselves fully comprehend what they wrote. They talked of the four elements of the human organism, but their special description of these elements was derived from a body of wisdom that had really perished with Hippocrates. Nevertheless, the qualities of these fluids were still matters of discussion and dispute. In fact, from the time of Galen till the fifteenth century, we find a collection of inherited maxims that become continuously less and less intelligible. Yet there were always isolated individuals able to perceive that there was something beyond what could be physically or chemically verified, or included in the merely terrestrial. Such individuals were opponents of what “humoral pathology” had become in current thought and practice. And chief among them were Paracelsus and Van Helmont, who lived and worked from the end of the fifteenth century into the seventeenth, and contributed something new to medical thought, by their attempts to formulate something their contemporaries no longer troubled to define. But the formulation they gave could only be fully understood with some remainder of clairvoyance, which Paracelsus and Van Helmont certainly possessed. If we ignore these facts, we cannot arrive at any conclusion concerning peculiarities of medical terminology whose origin is no longer recognisable.

Paracelsus assumed the existence of the Archaeus, as the foundation for the activity of the organic “humours” in man; and his followers accepted it. He assumed the Archaeus, as we today speak of the “Etheric” body of man.

Whether we use the term Archaeus, as Paracelsus did, or our term, the etheric body, we refer to an entity which exists but whose origin we do not trace. If we were to do this, our argument would be as follows: Man possesses a physical organism (see Diagram No. 1) mainly constructed by forces acting out of the sphere of the earth; and also an etheric organism (Diagram No. 1 in Red) mainly constructed by forces acting from the cosmic periphery. Our physical body is a portion as it were of the whole organism of our Earth. Our etheric body—like the Archaeus of Paracelsus—is a portion of that which does not belong to the earth, but which acts on and affects the earth from all parts of the cosmos. Thus Paracelsus viewed what was formerly designated the cosmic element in man—of which the knowledge had perished with Hippocratic medicine—in the form of an etheric body, which is the basis of the physical. But he did not investigate further—though he gave some hints—the extra-terrestrial forces associated with the Archaeus and acting in it.

The exact significance of such facts grew more and more obscure, especially with the advent of Stahl's medical school in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Stahl's school has wholly ceased to comprehend this working of cosmic forces into terrestrial occurrences; it grasps instead at vague concepts such as “vital force” and “spirits of life.” Paracelsus and Van Helmont were consciously aware of the reality at work between the soul and spirit of man and his physical organisation. Stahl and his followers talk as though the conscious soul-element was at work, though in another form, upon the structure of man's body. This naturally provoked a vehement reaction. For if one proceeds like this and founds a sort of hypothetic vitalism one comes to purely arbitrary assertions, and the nineteenth century opposed these assertions. Only a very great mind, like Johannes Müller (the teacher of Ernst Haeckel), who died in 1858, was able to overcome the noxious effects of this confusion, a confusion of soul forces with “vital forces” which were supposed to work in the human organism, although how they operated was not very clear.

Meanwhile a quite new current made its appearance. We have followed up the other current which faded out; the new current in the nineteenth century had a rather different bearing upon medical thought. It was set in motion by one extremely influential piece of work dating from the preceding century: the De sedibus et causis morborum per anatomen indugatis by Morgagni. Morgagni was a physician of Padua, who introduced an essentially materialistic trend into medicine; the term materialism is used here, of course, as an objective description, without sympathies and antipathies. The new trend initiated by Morgagni's work consisted in turning the interest to the after-effect of disease upon the organism. Post-mortem dissections were regarded as decisive; they revealed that whatever the disease may have been, typical effects could be studied in certain organs, and the changes of the organs by disease were studied from the autopsy. With Morgagni, pathological anatomy begins, whereas the former content of medicine still retained some traces of the ancient element of clairvoyance.

It is of interest to observe the suddenness with which this great change finally occurred. The volte-face took place within two decades. The ancient inheritance was abandoned and the atomistic-materialistic conception in modern medicine was founded. Rokitansky's Pathological Anatomy (published in 1842) still contains some traces of the “Humoral” tradition; of the conception that illnesses are due to the abnormal interaction of the fluids. Rokitansky achieved a brilliant combination of the study of organic change, with a belief in the importance of the fluid (humours); but it is impossible to consider these bodily fluids adequately without some recognition of their extra-terrestrial qualities. Rokitansky referred the degenerative changes revealed in autopsies to the effect of the abnormal mixture of the bodily fluids. Thus the last visible trace of the ancient tradition of “Humoral pathology” was in the year 1842. The interlocking of this perishing heritage of the past with attempts such as Hahnemann's—attempts forecasting future trends of dealing with more comprehensive concepts of disease—we shall consider in the next few days, for this subject is far too important to be relegated to an introduction. Similar experiments must be discussed in their general connection and then in detail.

The two decades immediately following the appearance of Rokitansky's book were decisive for the growth of the atomistic-materialistic conception in medicine. In the first half of the nineteenth century there were curious echoes of the ancient conceptions. Thus, for example, Schwann may be termed the discoverer of the vegetable cell; and he believed that cells were formed out of a formless fluid substance to which he gave the name Blastem, by a process of solidification, so that the nucleus emerges together with the surrounding protoplasm. Schwann derived cells from a fluid with the special property of differentiation, and believed that the cell was the result of such differentiation. Later on the view gradually develops that the human frame is “built up” of cells; this view is still held today; the cell is the “elementary organism,” and from the combination of cells, the body of man is built up.

This conception of Schwann's, which can be read “between the lines” and even quite obviously, is the last remainder of ancient medical thought, because it is not concerned with atomism. It regards the atomistic element, the cell, as the product of a fluid which can never properly be considered as being atomistic—a fluid which contains forces and only differentiates the atomistic from itself. Thus in these two decades, the forties and fifties of the nineteenth century, the older, more universal view approaches its final end, and the atomistic medical view shows its faint beginnings. And it has fully arrived when, in 1858, appeared the Zellular Pathologie (Cellular Pathology) of Virchow. Between Pathologischen Anatomie, 1842, by Rokitansky and Zellular Pathologie, 1858, by Virchow one must actually see an immense revolution—proceeding in leaps and bounds—in the newer medical thinking. Cellular Pathology derives all the manifestations of the human organism from cellular changes. The official ideal henceforth consists in tracing every phenomenon to changes in the cells. From the change in the cell the disease is supposed to be understood. The appeal of this atomism is its simplicity. It makes everything so easy, so evident. In spite of all the progress of modern science, the aim is to make everything quickly and easily understood, regardless of the fact that nature and the universe are essentially extremely complex.

For example: It is easy to demonstrate through a microscope that an Amoeba, in a drop of water, changes form continuously, extending and retracting its limb-like projections. It is easy to raise the temperature of the water, and to observe the greater rapidity with which the pseudo-podia protrude and retract, until the temperature reaches a certain point. The amoeba contracts and becomes immobile, unable to meet the change in its environment. Now, an electric current can be sent through the water, the amoeba swells like a balloon, and finally bursts if the voltage becomes too high. Thus it is possible to observe and record the changes of a single cell, under the influence of its environment; and it is possible to construct a theory of the origin and causation of disease, through cumulative cellular change.

What is the essential result of this revolution which took place in two decades? It lives on in everything that permeates the acknowledged medical science of today. It is the general tendency to interpret the world atomistically which has gradually arisen in the age of materialistic thought.

As I stated at the beginning of this address, the medical worker today must of necessity inquire: What sort of processes are those we term diseased? What is the essential difference between the diseased and the so-called normal processes in the human organism? Only a positive representation of this deviation is practicable, not the official and generally accepted definitions, which are merely negative. These deviations from normality are stated to exist, and then there are attempts to find how they may be removed. But there is no penetrating conception of the nature of the human being. And from the lack of such a conception our whole medical science is suffering. For what, indeed, are morbid processes? It cannot be denied that they are natural processes, for you cannot make an abstract distinction between any external natural process, whose stages can be observed, and a morbid process within the body. The natural process is called normal, the morbid one abnormal, without showing why the process in the human organism differs from normality. No practical treatment can be attained without finding out. Only then can we investigate how to counter-balance it. Only then can we find out from what angle of universal existence the removal of such a process is possible. Moreover, the term “abnormal” is an obstacle to understanding; why should such-and-such a process in man be termed abnormal? Even a lesion, such as a wound or deep cut with a knife, in the finger, is only relatively “abnormal,” for to cut a piece of wood is “normal.” That we are accustomed to other processes than the cutting of a finger says nothing; it is only playing with words. For what happens through the cutting of my finger is, when viewed from a certain angle, as normal as any other natural process. The task before us is to investigate the actual difference between the so-called diseased processes, which are after all quite normal processes of nature, but must be occasioned by definite causes, and the other processes, which we call healthy and which occur every day. We must ascertain this essential difference; it cannot, however, be ascertained without a knowledge of man which leads to his essential being. I shall give you, in this introduction, the first elements; we shall later on proceed to the details.

As these lectures are limited in number, you will understand that I am principally giving things which you cannot find in books or lectures and am assuming the knowledge presented in those sources. It would not seem to me worth while to put a theory before you, which you could find stated and illustrated elsewhere.

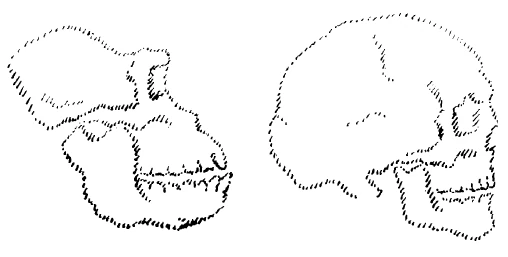

Let us therefore begin here with a simple visual comparison which you can all make: the difference between a human skeleton and that of a gorilla, an ape of so-called high grade. Compare the visible outlines and proportions of these two bony frameworks. The most conspicuous feature of the gorilla, in point of size, is the development of the lower jaw and its appurtenances. This enormous jaw seems to weight down, to overload, the whole bony structure of the head (see Diagram 2), so that the gorilla appears to stand upright only with an effort. But there is the same weightiness in comparison with the human skeleton, if you examine the forearms and hands and fingers. They are heavy and clumsy in the gorilla; whereas in man they are delicate and frail; there the mass is less obvious. Just in these parts, the system of the lower jaws and forearms with the fingers, the mass recedes in man, whereas it is very obvious in the gorilla. The same comparative peculiarities of structure can be traced in the lower limbs and feet of the two skeletons. There, too, we find a certain weight pressing in a definite direction. I should like to denote the force which one can see in the systems of underjaw, arm, leg, foot—by means of this [e.Ed: down and left slanting arrow.] line in the diagram. (See Diagram 3).

These differences in structure suggest to the observer that in human beings, where the weight of the jaws recede and the arms and finger bones are delicate, the downward pressing forces are countered everywhere by a force directed upwards and away from the earth. The formative forces in man must be represented in a certain parallelogram of forces which results from the same force which is directed upwards and which the gorilla appropriates externally only, standing upright with difficulty. I then arrive at a parallelogram of forces that is formed by this line and by this one. (See Diagram 4).

As a rule nowadays we are content to compare the bones and muscles of the higher animals with our own, but to ignore the changes in form and posture. Yet the contemplation of the formative changes is of essential significance. There must be certain forces acting against those other forces which mould the typical gorilla frame. They must exist. They must operate. In seeking them we shall find that which has been lost inasmuch as the ancient medical wisdom has been filtered from the system of Hippocrates. The first set of forces in the parallelogram are of a terrestrial nature, while the other set of forces which unite with the terrestrial forces so as to form a resultant which is not of terrestrial origin, must be sought outside the terrestrial sphere. We must search for tractive forces which bring man into the upright posture, not merely on occasion, as among the higher mammals, but so that these forces are at the same time formative. The difference is obvious: the ape if he walks upright has to counteract forces which oppose the erection with their mass; whereas man forms his very skeleton in accordance with forces of a non-terrestrial nature. If one not only compares the particular bones of the man with those of the animal, but examines the dynamic principle in the human skeleton, one finds that there is something unique and not to be found in the other kingdoms of nature. Forces emerge that we have to combine with the others to make the parallelogram. We find resultants not to be found among the forces of extra-human nature. Our task will be to follow up systematically this “jump” leading from animal to man. Then we can find the origin and essence of “sickness” in animals as well as in man. I can only indicate little by little these lines of inquiry; we shall find much of importance from these elements as we continue further.

Now let me mention another fact, which concerns the muscular system. There is a remarkable difference in muscular reactions; when in repose, the chemical reactions of the muscles are alkaline, though very slightly so in comparison with most other alkaline reactions. When in action, the muscular reactions are acid, though also faint. Now consider that from the point of view of metabolism the muscle is formed out of assimilated material, that is, it is a result of the forces present in terrestrial substances. But when man passes to action the normal properties of the muscle, as a substance affected by ordinary metabolism, are overcome. This is quite evident. Changes take place in the muscle itself, which are different from ordinary metabolic processes, and can only be compared with the forces active in the human bone-system. Just as these formative forces in man transcend what he has from outside, inter-penetrating terrestrial forces and uniting with them so that a resultant arises, so we must recognise the force that is manifested through the altered metabolism of muscles in action, as something working chemically from outside the earth into terrestrial chemistry. Here we have something of an extra-terrestrial nature, which works into earthly mechanics and dynamics. In metabolism there is something active beyond terrestrial chemistry, and capable of other results than those caused by terrestrial chemistry alone.

Those considerations, which are concerned both with forms and qualities, must be the starting point in our quest for what really lies in the nature of man. Thus we may also find the way back to what we have lost, yet sorely need if we are not to stop at formal definitions of disease that cannot be of much use in actual practice. An important question arises here. Our materia medica contains only terrestrial substances taken from man's environment, for the treatment of the human organism which has suffered changes. But there are non-terrestrial processes active in him—or at least forces which cause his processes to become non-terrestrial—and so the question arises: how can we provoke an interaction leading from sickness to health, by methods affecting the sick organism through its physical earthly environment? How can we initiate an interaction which shall include those other forces, which work in the human organism, yet are not limited to the scope of the processes from which we take our remedies, even when they take effect through certain forms of diet, etc.?

You will realise the close connection between a correct conception of human nature and the methods that may lead to a certain therapy. I have intentionally chosen these first elements which are to lead us to an answer, from the differences between animals and men, although well aware of the objection that animals, like men, are subject to diseases, that even plants may become diseased, and that morbid states have recently been spoken of even among minerals; and that there should therefore be no distinction between sickness in animals and in the human race. The difference will become obvious when it will be apparent how little value in the long run, adheres to the results of animal experimentation undertaken solely to gain knowledge for use in human medicine. We shall consider why it is undoubtedly possible to attain some help for mankind through experiments on animals, but only if and when we understand the radical differences, even to the smallest detail, between animal and human organisms.

I want to emphasise that in referring to cosmic forces, far greater demands are made on man's personality than if we merely refer to so-called objective rules and laws of nature. The aim must be set before us to make medical diagnosis more and more a practice of intuition; the gift of basing conclusions on the formative phenomena of the individual human organism (which may be healthy or sick) can show how this training in intuitive observation of form will play an ever-increasing part in the future development of medicine.

These suggestions are only intended to serve as a sort of introductory orientation. Our concern today was to show that medicine must once more turn its attention to realms not accessible through chemistry or Comparative Anatomy as usually understood, realms only to be reached by consideration of the facts in the light of Spiritual Science. There are still many errors on this subject. Some hold the main essential for the spiritualising of medicine to be the substitution of spiritual means for material. This is quite justifiable in certain departments, but absolutely wrong in general. For there is a spiritual method of knowing the therapeutic properties of material remedies; spiritual science can be applied to evaluate material remedies. This will be the theme of that portion of our subject matter which I have termed the possibilities of healing through recognition of the inter-relationships between mankind and the external world.

I shall hope to base what I have to say about special methods of healing on as firm a foundation as possible, and to indicate that in every individual case of sickness it is possible to form a picture of the connection between the so-called “abnormal” process, which must also be a process of nature, and those “normal” processes which again are nothing else than nature processes. This primary problem of how the disease process can be regarded as a natural process has often cropped up. But the issue has been evaded again and again. I find certain facts about Troxler of great interest in this connection. Troxler taught medicine at the University of Berne and in the first half of the last century he devoted much energy to maintaining that the “normality of disease” should be investigated; that such investigation would finally lead to the recognition of a certain world connected with our own, and impinging on our world, as it were, through illegitimate gaps; and that this would be the key to something bearing on morbid phenomena. Please imagine such a diagrammatic picture; a world in the background whose laws, in themselves justified, could cause morbid phenomena amongst the human race. Then, if this world meets and interpenetrates our own, through certain “gaps,” its laws, which are adapted to another world, could do mischief here. Troxler wanted to work in this direction. And however obscure and difficult his expressions on many subjects may be, one notes that he had struck out a path for himself in medicine, with the purpose of working towards a certain restoration of medical science.

A friend and I once had the opportunity of inquiry into Troxler's standing amongst his Bernese colleagues and into the results of his initiative. The detailed History of the University had only one thing to say about Troxler: that he had caused much disturbance in the university! That had been remembered and recorded, but we could find nothing about his significance for science.

Erster Vortrag

[ 1 ] Es ist ja ziemlich selbstverständlich, daß von dem, was Sie wahrscheinlich alle erwarten von der Zukunft des medizinischen Lebens, nur ein sehr geringer Teil in diesem Kursus wird angedeutet werden können, denn Sie alle werden ja mit mir darinnen übereinstimmen, daß ein wirkliches, zukunftssicheres Arbeiten auf dem medizinischen Felde von einer Reform des medizinischen Studiums als solchem abhängt. Man kann nicht mit dem, was man in einem Kursus mitteilen kann, eine solche Reform des medizinischen Studiums auch nur im entferntesten anregen, höchstens in der Weise, daß in einer Anzahl von Menschen der Drang entsteht, mitzutun bei einer solchen Reform. Allein, was man auch heute auf medizinischem Felde bespricht, es hat ja immer zu seinem anderen Pol, zu seinem Hintergrunde die Art und Weise, wie die medizinische Arbeit vorbereitet wird durch Betrachtungen der Anatomie, Physiologie, der ganzen Biologie, und durch diese Vorbereitungen werden die Gedanken der Mediziner von vorneherein in eine bestimmte Richtung gebracht, und diese Richtung ist es vor allen Dingen, von der abgekommen werden muß.

[ 2 ] Dasjenige, was in diesen Vorträgen beigebracht werden soll, das möchte ich erreichen dadurch, daß ich in einer Art von Programm verteile das zu Betrachtende in der folgenden Weise: Erstens möchte ich Ihnen einiges geben, das hinweist auf die Hindernisse, die im heutigen gebräuchlichen Studium bestehen gegen eine wirklich sachgemäße Erfassung des Krankheitswesens als solchen. Zweitens möchte ich dann andeuten, in welcher Richtung eine Erkenntnis des Menschen zu suchen ist, die eine wirkliche Grundlage für das medizinische Arbeiten abgeben kann. Drittens möchte ich auf die Möglichkeiten eines rationellen Heilwesens hinweisen durch die Erkenntnis der Beziehungen des Menschen zur übrigen ‘Welt. Ich möchte dann in diesem Teil die Frage beantworten, ob Heilung überhaupt möglich und zu denken ist. Viertens — und ich denke, das wird vielleicht das wichtigste Glied der Betrachtungen sein, das sich aber mit den anderen drei Gesichtspunkten wird verschlingen müssen — möchte ich, daß jeder von den Teilnehmern mir bis morgen oder übermorgen auf einem Zettel seine besonderen Wünsche aufschreibt, das heißt aufschreibt, was er gern hören möchte, worüber er wünscht, daß in diesem Kursus gesprochen werden soll. Diese Wünsche können sich auf alles mögliche erstrecken. Ich möchte durch diesen vierten Teil des Programms, der aber, wie gesagt, hineingearbeitet werden soll dann in die anderen drei Teile, erreichen, daß Sie von diesem Kursus nicht hinwegzugehen brauchen mit dem Gefühl, Sie hätten vielleicht gerade dasjenige nicht gehört, was Sie zu hören wünschten. Deshalb werde ich den Kursus so gestalten, daß all das, was Sie als Fragen, als Wünsche aufzeichnen, in dem Kurse verarbeitet wird. Ich bitte Sie also, womöglich bis morgen oder, wenn das nicht sein kann, bis übermorgen bis zu dieser Stunde hier Ihre Aufzeichnungen über das von Ihnen Gewünschte zu machen. So werden wir, denke ich, am besten eine Art von Vollständigkeit, wie sie im Rahmen dieser Veranstaltungen liegt, erreichen können.

[ 3 ] Heute möchte ich nur eine Art von Einleitung geben, eine Art von orientierender Betrachtung. Ausgehen möchte ich davon, daß ja hauptsächlich von mir angestrebt wird, alles dasjenige zusammenzutragen, was gewissermaßen aus geisteswissenschaftlichen Betrachtungen heraus für Ärzte gegeben werden kann. Ich möchte nicht, daß verwechselt werde das, was ich versuchen werde, mit einem medizinischen Kursus, der es ja sein wird; aber es soll alles dasjenige, was von überallher für Ärzte wichtig sein kann, hauptsächlich berücksichtigt werden. Denn eine wirkliche ärztliche Wissenschaft oder Kunst, wenn ich so sagen darf, wird ja doch nur dadurch erreicht, daß alle die Dinge, die in dem angedeuteten Sinne in Betracht kommen, für den Aufbau einer solchen ärztlichen Wissenschaft oder Kunst wirklich berücksichtigt werden.

[ 4 ] Nur von einigen orientierenden Betrachtungen möchte ich heute ausgehen. Sie werden wahrscheinlich, wenn Sie nachgedacht haben über dasjenige, was Ihnen als Arzt zur Aufgabe gestellt ist, wohl des öfteren gestolpert sein über die Frage: Was ist denn Krankheit und was ist denn der kranke Mensch überhaupt? Selten findet man eigentlich eine andere Erklärung über Krankheit und den kranken Menschen als die — wenn sie auch maskiert ist durch diese oder jene scheinbar sachlichen Einschiebsel —, daß der Krankheitsprozeß eine Abweichung ist vom normalen Lebensprozeß, daß durch gewisse Tatsachen, die auf den Menschen wirken und für die der Mensch in seinem normalen Lebensprozeß zunächst nicht angepaßt ist, Veränderungen in dem normalen Lebensprozeß und in der Organisation hervorgerufen werden und daß die Krankheit in diesen mit den Veränderungen verbundenen, funktionellen Beeinträchtigungen der Körperteile besteht. Nun werden Sie sich aber zugestehen müssen, daß dies nichts weiter ist als eine negative Bestimmung der Krankheit. Es ist ja nicht irgend etwas, was einem helfen kann, wenn man es mit Krankheiten zu tun hat, und auf dieses Praktische möchte ich hier vor allen Dingen hinarbeiten, was einem helfen kann, wenn man es mit Krankheiten zu tun hat. Um auf das auf diesem Gebiete Maßgebliche zu kommen, scheint es mir doch gut zu sein, auf gewisse Ansichten hinzuweisen, welche im Laufe der Zeit über das Kranksein entstanden sind, nicht so sehr deshalb, weil ich das unbedingt für nötig halte für die gegenwärtige Erfassung der Krankheitserscheinungen, sondern weil es möglich ist, sich leichter zu orientieren, wenn man ältere Anschauungen, die ja doch zu den gegenwärtigen geführt haben, über das Kranksein berücksichtigen kann.

[ 5 ] Sie alle wissen, daß man gewöhnlich, wenn man die Geschichte der Medizin betrachtet, hinweist auf die Entstehung der Medizin im alten Griechenland im fünften und vierten Jahrhundert, daß man auf Hippokrates hinweist, und man kann sagen, wenigstens das Gefühl wird dann hervorgerufen, als ob mit demjenigen, was bei Hippokrates als Anschauung auftritt und dann zur sogenannten Humoralpathologie geführt hat, die im Grunde genommen bis ins neunzehnte Jahrhundert herein noch eine Rolle gespielt hat, ein Erstes für die Entwickelung des medizinischen Wesens im Abendlande gegeben sei. Das ist aber schon der erste Fundamentalirrtum, den man begeht und der eigentlich im Grunde genommen nachwirkt so, daß er verhindert, heute noch zu einer unbefangenen Anschauung über das Krankheitswesen zu kommen. Mit diesem Fundamentalirrtum sollte zunächst aufgeräumt werden. Für den, der unbefangen gerade auf die Anschauungen des Hippokrates hinschaut, die, wie Sie ja vielleicht schon bemerkt haben werden, bis zu Rokitansky herauf, also ins neunzehnte Jahrhundert hinein, eine Rolle spielen, sind diese Anschauungen nicht ein bloßer Anfang, sondern sie sind zugleich, und zwar in einem sehr bedeutenden Maße, ein Ende alter medizinischer Anschauungen. Es tritt uns in dem, was von Hippokrates ausgeht, ich möchte sagen, ein letzter filtrierter Rest von uralten medizinischen Anschauungen entgegen, von Anschauungen, die nicht gewonnen worden sind auf den Wegen, auf denen man heute sucht, auf dem Wege der Anatomie, sondern die gewonnen worden sind auf dem Wege des alten atavistischen Schauens. Und man würde, wenn man zunächst abstrakt charakterisieren sollte die Stellung der Hippokratischen Medizin, eigentlich am besten sagen: mit ihr vollzieht sich das Aufhören der alten, auf einem atavistischen Schauen beruhenden Medizin. Äußerlich gesprochen — aber es ist eben nur äußerlich gesprochen —, kann man sagen: die Hippokraten suchten alles Kranksein in einer nicht gehörigen Mischung derjenigen Flüssigkeitskörper, die im menschlichen Organismus zusammenwirken. Sie wiesen darauf hin, daß in einem normalen Organismus die Flüssigkeitskörper in einem bestimmten Verhältnisse stehen müssen, daß sie in dem kranken Körper eine Abweichung von diesen ihren Mischungsverhältnissen erleiden. Als Krasis bezeichnete man die richtige Mischung, als Dyskrasis die unrichtige Mischung. Nun suchte man selbstverständlich dann einzuwirken auf die unrichtige Mischung, um sie wieder zurückzuführen in die richtige Mischung. Die vier Bestandteile, die man in der Außenwelt sah als konstituierend alles physische Sein, das waren ja Erde, Wasser, Luft und Feuer — Feuer aber war dasselbe, was wir heute einfach Wärme nennen. Für den menschlichen Organismus — auch für den tierischen — sah man spezialisiert diese vier Elemente als schwarze Galle, gelbe Galle, Schleim und Blut. Und man dachte sich, daß aus Blut, Schleim, schwarzer und gelber Galle in der richtigen Mischung der menschliche Organismus funktionieren müsse.

[ 6 ] Nun, wenn der heutige Mensch, so, wie man es sein kann, wissenschaftlich vorbereitet an so etwas herantritt, so denkt er sich zunächst: indem sich Blut, Schleim, gelbe und schwarze Galle mischen, mischen sie sich in Gemäßheit desjenigen, was ihnen als Eigenschaft innewohnt und was man so angeordnet als ihre Eigenschaft durch eine mehr oder weniger niedere oder höhere Chemie feststellen kann. Und eigentlich in diesem Lichte, als wenn die Hippokraten auch gesehen hätten Blut, Schleim und so weiter nur in dieser Weise, stellt man sich eigentlich vor, daß diese Humoralpathologie ihren Ausgangspunkt genommen hat. Das ist aber eben nicht der Fall, sondern bloß von einem einzigen Bestandteile, von der schwarzen Galle, die eigentlich als das Hippokratischeste erscheint für den heutigen Betrachter, dachte man sich, daß die gewöhnlichen chemischen Eigenschaften das sind, was auf das andere wirkt. Von allem übrigen, von weißer oder gelber Galle, von Schleim, von Blut, dachte man nicht etwa bloß an die Eigenschaften, die man durch chemische Reaktionen feststellen kann, sondern man dachte bei diesen flüssigen Bestandteilen des menschlichen Organismus — und ich werde mich immer auf diesen beschränken, auf den tierischen Organismus zunächst keine Rücksicht nehmen —, daß diese Flüssigkeiten gewisse ihnen innewohnenden Eigenschaften von Kräften haben, die außerhalb unseres irdischen Bestandes liegen. So daß also, wie man sich das Wasser, die Luft, die Wärme als abhängig dachte von den Kräften des außerirdischen Kosmos, man sich auch diese Bestandteile des menschlichen Organismus als durchdrungen von Kräften, die von außerhalb der Erde kommen, dachte.

[ 7 ] Dieses Hinschauen auf Kräfte, die von außerhalb der Erde kommen, das hat man ja im Laufe der Entwickelung der abendländischen Wissenschaft ganz verloren. Und für den heutigen Wissenschafter erscheint es geradezu kurios, wenn man ihm zumutet, zu denken, das Wasser solle nicht nur diejenigen Eigenschaften haben, welche ihm zukommen als chemisch nachweisbar, sondern es soll auch, indem es in den menschlichen Organismus hineinwirkt, Eigenschaften haben, die es hat als Angehöriger des außerirdischen Kosmos. Es werden also durch die Flüssigkeitsbestandteile, die in dem menschlichen Organismus sind, in diesen Organismus, nach der Ansicht der Alten, Kräftewirkungen hineingetragen, die aus dem Kosmos selber stammen. Auf diese Kräftewirkungen, die aus dem Kosmos selber stammen, wurde eben nach und nach nicht mehr die geringste Rücksicht genommen. Dennoch hat man aufgebaut das medizinische Denken bis ins fünfzehnte Jahrhundert hinein auf dasjenige, was gewissermaßen übriggeblieben war von der filtrierten Anschauung, die bei Hippokrates uns entgegentritt. Und daher ist es so schwierig für den heutigen Wissenschafter, überhaupt zu verstehen ältere Werke der Medizin, die vor dem fünfzehnten Jahrhundert liegen, denn es muß schon gesagt werden: die meisten der Menschen, die da geschrieben haben, haben selbst gar nicht einmal ordentlich verstanden, was sie geschrieben haben. Sie haben geredet über die vier Grundbestandteile des menschlichen Organismus, aber warum sie sie in dieser oder jener Weise charakterisierten, das führte zurück auf ein Wissen, das eigentlich mit Hippokrates schon untergegangen war. Man sprach noch über die Nachwirkungen dieses Wissens, über die Eigenschaften der Flüssigkeiten, die den menschlichen Organismus zusammengesetzt haben. Daher ist im Grunde genommen dasjenige, was entstanden ist durch Galer und dann bis ins fünfzehnte Jahrhundert nachgewirkt hat, ein Zusammenstellen von alten Erbschaften, die unverständlicher und unverständlicher geworden sind. Aber einzelne Menschen gab es immer, welche eben einfach aus dem, was da war, noch erkennen konnten: da ist auf irgend etwas hinzuweisen, was nicht sich erschöpft in dem chemisch Feststellbaren oder in dem physisch Feststellbaren, in dem rein Irdischen. Und zu diesen Menschen, die wußten: da ist auf etwas hinzuweisen im menschlichen Organismus, wodurch die flüssigen Substanzen in ihm anders wirken, als man es chemisch konstatieren kann, zu diesen Bekämpfern also der landläufigen Humoralpathologie gehören vorzugsweise — ich könnte auch andere Namen nennen — Paracelsus und van Helmont, die gerade um die Wende des fünfzehnten, sechzehnten Jahrhunderts ins siebzehnte Jahrhundert hinein einen neuen Zug gebracht haben in das medizinische Denken, indem sie einfach, könnte man sagen, etwas versuchten zu formulieren, was die anderen schon nicht mehr formuliert haben. Aber in der Formulierung war etwas enthalten, was man eigentlich nur noch verfolgen konnte, wenn man etwas hellseherisch war, wie es ja Paracelsus und van Helmont ganz entschieden waren. Wir müssen uns schon alle diese Dinge klarmachen, sonst werden wir uns nicht verständigen können über dasjenige, was auch heute noch der medizinischen Terminologie anhaftet, was aber gar nicht mehr seinem Ursprung nach erkennbar ist. So haben denn Paracelsus und später unter seinem Einfluß andere angenommen als die Grundlage für das Wirken der Flüssigkeiten im Organismus den Archäus. Den Archäus hat er angenommen, so wie wir etwa sprechen von dem Ätherleib des Menschen.

[ 8 ] Wenn man so wie Paracelsus von dem Archäus spricht, wenn man so spricht, wie wir sprechen von dem Ätherleib des Menschen, so faßt man eigentlich etwas zusammen, das da ist, das man aber seinem eigentlichen Ursprunge nach nicht verfolgt. Denn würde man es seinem eigentlichen Ursprunge nach verfolgen, so müßte man in der folgenden Art vorgehen. Man müßte sagen: Der Mensch hat einen physischen Organismus (siehe Zeichnung Seite 20), der ist im wesentlichen aus Kräften konstituiert, die aus dem Irdischen wirken, und er hat einen ätherischen Organismus (siehe Zeichnung Seite 20 rot), der ist im wesentlichen aus Kräften konstituiert, die aus dem Umkreise des Kosmos wirken. Unser physischer Organismus ist gewissermaßen ein Ausschnitt der ganzen Organisation der Erde. Unser Ätherleib und auch der Paracelsussche Archäus ist ein Ausschnitt aus demjenigen, was nicht zur Erde gehört, was also von allen Seiten des Kosmos ins Irdische hereinwirkt. So daß also Paracelsus dasjenige, was man früher einfach als das Kosmische im Menschen bezeichnete und was mit der hippokratischen Medizin untergegangen ist, zusammengefaßt sah in seiner Anschauung eines ätherischen Organismus, der dem physischen zugrunde liegt. Er hat dann nicht weiter untersucht — er hat ja im einzelnen zwar hingedeutet, aber eben nicht weiter untersucht —, mit welchen außerirdischen Kräften das im Zusammenhang steht, was in diesem Archäus eigentlich wirkt.

[ 9 ] Nun kann man sagen: Immer weniger und weniger ist verständlich geblieben dasjenige, was da eigentlich gemeint ist. Das zeigt sich ja ganz besonders, wenn wir dann vorrücken bis ins siebzehnte, achtzehnte Jahrhundert und uns entgegentritt die Stahlsche Medizin, welche nichts mehr versteht von diesem Hereinwirken des Kosmischen in das Terrestrische. Die Stahlsche Medizin nimmt alle möglichen Begriffe zu Hilfe, die rein in der Luft schweben, Begriffe von Lebenskraft, Begriffe von Lebensgeistern. Während noch Paracelsus und van Helmont mit einer gewissen Bewußtheit sprachen von etwas, was zwischen dem eigentlich Geistig-Seelischen des Menschen und der physischen Organisation liegt, reden Stahl und seine Anhänger so, als ob das Bewußt-Seelische nur in einer anderen Form hineinspiele in die Strukturgebung des menschlichen Leibes. Dadurch riefen sie natürlich eine starke Reaktion hervor. Denn wenn man in dieser Weise vorgeht und eine Art von hypothetischem Vitalismus begründet, dann kommt man eigentlich in rein willkürliche Aufstellungen hinein. Gegen diese willkürlichen Aufstellungen ist namentlich das neunzehnte Jahrhundert dann angegangen. Man kann sagen: Nur so große Geister wie zum Beispiel Johannes Müller, der 1858 gestorben ist, der Lehrer von Ernst Haeckel, kamen darüber hinaus, all die Schädlichkeiten einigermaßen zu überwinden, die von dieser unklaren Sprechweise über den menschlichen Organismus herrührten, die darin bestand, daß man einfach wie von seelischen Kräften von Lebenskräften gesprochen hat, die wirken sollen im menschlichen Organismus, ohne daß man sich deutlich vorzustellen hätte, wie sie wirken sollen.

[ 10 ] Nun kam aber, während all das geschah, eine ganz andere Strömung herauf. Wir haben gewissermaßen jetzt die auslaufende Strömung verfolgt bis in ihre letzten Ausläufer hinein. Aber mit der neueren Zeit kam eben dasjenige herauf, was nun in einer anderen Weise ausschlaggebend geworden ist für die medizinische Begriffsbildung namentlich des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts. Das fällt im Grunde zurück auf ein einziges ungemein stark ausschlaggebendes Werk des achtzehnten Jahrhunderts erst, das «De sedibus et causis morborum per anatomen indagatis» von Morgagni, dem Arzt in Padua, mit dem etwas ganz Neues heraufgekommen ist, etwas, das im wesentlichen den materialistischen Zug in der Medizin eingeleitet hat. Man muß diese Dinge ganz objektiv charakterisieren, nicht mit Sympathien und Antipathien. Denn dasjenige, was mit diesem Werk heraufkam, das ist die Hinlenkung des Blickes auf die Folgen des Krankseins im menschlichen Organismus. Der Leichenbefund wurde ausschlaggebend. Eigentlich erst von dieser Zeit an kann man sagen: Der Leichenbefund wurde ausschlaggebend. Man sah an der Leiche, daß wenn diese oder jene Krankheit, gleichgültig, wie man sie benannte, gewirkt hat, so muß dieses oder jenes Organ diese oder jene Veränderung erfahren. Man fing nun an, diese oder jene Veränderung eben aus dem Leichenbefund heraus zu studieren. Eigentlich beginnt da erst die pathologische Anatomie, während alles dasjenige, was früher in der Medizin da war, auf einem gewissen Fortwirken noch des alten hellseherischen Elementes beruhte.

[ 11 ] Interessant ist es nun, wie mit einem Ruck, möchte ich sagen, sich der große Umschwung dann endgültig vollzogen hat. Man kann ja geradezu auf zwei Jahrzehnte hinweisen — und das ist interessant —, in denen sich der große Umschwung vollzogen hat, durch den verlassen wurde alles das, was noch als Erbschaft vom alten da war, und dutch den begründet wurde auch die atomistisch-materialistische Anschauung im modernen Medizinwesen. Wenn Sie sich einmal die Mühe nehmen und die im Jahre 1842 erschienene «Pathologische Anatomie» von Rokitansky durchnehmen, dann werden Sie finden: Bei Rokitansky ist noch immer vorhanden ein Rest der alten Humoralpathologie, noch ein Rest von der Anschauung, daß auf einem nicht normalen Zusammenwirken der Säfte das Kranksein beruht. Diese Anschauung, daß man hinwenden müsse den Blick auf diese Säftemischung — das kann man aber nur, wenn man noch Erbschaften hat der Anschauung über die außerirdischen Eigenschaften der Säfte —, wurde sehr geistreich zusammen verarbeitet durch Rokitansky mit dem Beobachten der Veränderungen der Organe. So daß eigentlich in dem Buch von Rokitansky immer zugrunde liegt die Beobachtung der Organveränderung durch den Leichenbefund, aber verbunden damit ein Hinweis darauf, daß diese spezielle Organveränderung unter dem Einfluß einer abnormen Säftemischung zustande gekommen ist. Da haben Sie 1842, ich möchte sagen, das letzte, was auftritt von der Erbschaft der alten Humoralpathologie. Wie sich hineinstellten in dieses Untergehen der alten Humoralpathologie die nach der Zukunft hinweisenden Versuche, mit umfassenderen Krankheitsvorstellungen zu rechnen, wie zum Beispiel der Versuch von Hahnemann, davon wollen wir dann in den nächsten Tagen sprechen, denn das ist zu wichtig, um es bloß in einer Einleitung darzustellen. Ähnliche Versuche müssen im Zusammenhang besprochen werden, dann in den Einzelheiten.

[ 12 ] Jetzt will ich aber darauf aufmerksam machen, daß nun die zwei nächsten Jahrzehnte nach dem Erscheinen der «Pathologischen Anatomie» von Rokitansky die eigentlich grundlegenden Jahrzehnte geworden sind für die atomistisch-materialistische Betrachtung des medizinischen Wesens. Es spielt das Alte noch ganz merkwürdig in die Vorstellungen, die in der ersten Hälfte des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts sich gebildet haben, hinein. Da ist es interessant, zu beobachten, wie zum Beispiel Schwann, der ja, man könnte sagen, der Entdecker der Pflanzenzelle ist, noch die Ansicht hat, daß zugrunde liegt der Zellbildung eine Art ungeformter Flüssigkeitsbildung, was er als Blastem bezeichnet, wie sich da aus dieser Flüssigkeitsbildung heraus verhärtet der Zellkern und herumgliedert das Zellprotoplasma. Es ist interessant zu beobachten, wie Schwann noch zugrunde legt ein flüssiges Element, das in sich Eigenschaften hat, die darauf hinauslaufen, sich zu differenzieren, und wie durch dieses Differenzieren dann das Zellige entsteht. Es ist interessant, zu verfolgen, wie später dann die Anschauung sich nach und nach allmählich herausbildet, die man zusammenfassen kann in die Worte: Der menschliche Organismus baut sich aus Zellen auf. Das ist ja eine Anschauung, die heute ungefähr gang und gäbe ist, daß die Zelle eine Art Elementarorganismus ist und daß sich der menschliche Organismus aus Zellen aufbaut.

[ 13 ] Nun, diese Anschauung, die noch Schwann, ich möchte sagen, ganz gut zwischen den Zeilen hat, sogar mehr als zwischen den Zeilen, ist im Grunde genommen der letzte Rest des alten medizinischen Wesens, denn sie geht nicht auf das Atomistische. Sie betrachtet dasjenige, was atomistisch auftritt, das Zellenwesen, als hervorgehend aus etwas, das man niemals, wenn man es ordentlich betrachtet, atomistisch betrachten kann, aus einem flüssigen Wesen, das Kräfte in sich hat und das Atomistische erst aus sich heraus differenziert. Also in diesen zwei Jahrzehnten, in den vierziger und fünfziger Jahren des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts, geht die alte Anschauung, die universeller ist, ihrem letzten Ende entgegen und dämmert dasjenige auf, was atomistische medizinische Anschauung ist. Und das ist voll da, als 1858 erscheint die «Zellularpathologie» von Virchow. Zwischen diesen zwei Werken muß man eigentlich einen ungeheuer sprunghaften Umschwung in dem neueren medizinischen Denken sehen, zwischen der «Pathologischen Anatomie» 1842 von Rokitansky und der «Zellularpathologie» 1858 von Virchow. Durch diese Zellularpathologie wird im Grunde genommen alles, was auftritt im Menschen, abgeleitet von Veränderungen der Zellenwirkung. Im Grunde genommen betrachtet man es dann in der offiziellen Anschauungsweise als ein Ideal, alles aufzubauen auf die Veränderungen der Zelle. Man sieht geradezu darin das Ideal, die Veränderung der Zelle im Gewebe eines Organs zu studieren und aus der Veränderung der Zelle heraus die Krankheit begreifen zu wollen. Man hat es ja leicht mit dieser atomistischen Betrachtung, denn nicht wahr, sie liegt im Grunde, ich möchte sagen, auf der flachen Hand. Man kann alles so hinstellen, leicht begreiflich. Und trotz allen Fortschritten der neueren Wissenschaft geht diese neuere Wissenschaft eigentlich immer darauf aus, möglichst alles leicht zu begreifen und nicht zu bedenken, daß das Naturwesen und das Weltenwesen überhaupt etwas außerordentlich Kompliziertes ist.

[ 14 ] Nicht wahr, man kann so leicht experimentell zeigen, daß zum Beispiel eine Amöbe im Wasser ihre Form verändert, die armartigen Gebilde, Fortsätze, ausstreckt, wieder einzieht. Man kann dann die Flüssigkeit, in der die Amöbe schwimmt, erwärmen. Man wird dann sehen, daß das Ausstrecken und ebenso das Einziehen der Fortsätze lebhafter wird, bis man die Temperatur zu einem gewissen Punkt bringt. Dann zieht sich die Amöbe zusammen und kann nicht mehr weiter mitgehen mit diesen Veränderungen, die in dem umgebenden Medium vorgehen. Man kann dann in die Flüssigkeit hineinleiten einen Strom: man beobachtet dann die Amöbe, sie bildet ihren Körper kugelartig aus und platzt zum Schluß, wenn der Strom zu stark hineingeleitet wird. Also man kann studieren selbst wie die einzelne Zelle sich verändert unter dem Einfluß der Umgebung, und man kann dann daraus eine Theorie bilden, wie durch Veränderung des Zellwesens sich nach und nach das Krankheitswesen aufbaut.

[ 15 ] Was ist das Wesentliche all dessen, was da heraufgekommen ist durch den Umschwung, der sich in zwei Jahrzehnten vollzogen hat? Was da heraufgezogen ist, es lebt eigentlich fort in allem, was heute die offizielle medizinische Wissenschaft durchdringt. In dem, was da heraufgezogen ist, lebt eben doch nichts anderes als der allgemeine Zug, die Welt atomistisch zu begreifen, wie er sich eben im materialistischen Zeitalter herausgebildet hat.

[ 16 ] Nun bitte ich Sie, doch das Folgende zu beachten. Ich ging aus davon, daß ich Sie aufmerksam machte, daß derjenige, der es heute mit dem Arbeiten in der Medizin zu tun hat, sich ganz notwendigerweise doch die Frage vorlegen muß: Was sind denn eigentlich die Krankheiten für Prozesse? Wie unterscheiden sie sich denn von den sogenannten Normalprozessen des menschlichen Organismus? Denn nur mit einer positiven Vorstellung über diese Abweichung kann man doch arbeiten, während die Darstellungen, die man gewöhnlich findet und die gegeben werden in der offiziellen Wissenschaft, eigentlich nur negativ sind. Es wird nur darauf hingewiesen, daß eben solche Abweichungen da sind. Und dann probiert man, wie man etwa die Abweichungen beseitigen könne. Aber eine durchgreifende Anschauung über das Menschenwesen ist ja eigentlich nicht vorhanden. Und an dem Mangel einer solchen durchgreifenden Anschauung über das Menschenwesen krankt im Grunde genommen unsere ganze medizinische Anschauung. Denn was sind denn die Krankheitsprozesse? Sie werden doch nicht umhin können, sich zu sagen, daß es Naturprozesse sind. Sie können doch nicht einen abstrakten Unterschied konstruieren ohne weiteres zwischen irgendeinem Naturprozeß, der draußen verläuft und dessen Folgen Sie verfolgen, und zwischen einem Krankheitsprozesse. Den Naturprozeß, Sie nennen ihn normal, den Krankheitsprozeß nennen Sie abnorm, ohne eigentlich darauf hinzuweisen, warum nun dieser Prozeß im menschlichen Organismus ein abnormer ist. Man kann ja zu keiner Praxis kommen, wenn man nicht wenigstens sich Aufschluß darüber geben kann, warum der Prozeß abnorm ist. Dann erst kann man irgendwie nachforschen danach, wie man ihn aufheben kann. Denn man kann dadurch erst darauf kommen, aus welcher Ecke des Weltendaseins das Hinwegschaffen eines solchen Prozesses möglich ist. Schließlich ist sogar das Bezeichnen als abnorm ein Hindernis. Denn warum sollte denn mancher Prozeß im Menschen abnorm genannt werden? Selbst wenn ich mich in den Finger schneide, so ist das nur relativ abnorm für den Menschen, denn wenn ich mich nicht in den Finger schneide, sondern ein Stück Holz schneide zu irgendeiner Form, so ist das ein normaler Prozeß. Just, wenn ich mich in den Finger schneide, so nenne ich das einen abnormen Prozeß. Damit, nicht wahr, daß man gewöhnt ist, just andere Prozesse zu verfolgen, als sich in den Finger zu schneiden, ist ja gar nichts gesagt, es sind bloß Wortspiele eigentlich in die Welt gesetzt. Denn dasjenige, was geschieht, wenn ich mich in den Finger schneide, ist von einer gewissen Seite her ähnlich in seinem Verlauf, ganz ebenso normal wie irgendein anderer Naturprozeß.

[ 17 ] Die Aufgabe ist, nun wirklich darauf zu kommen, welcher Unterschied besteht zwischen den Prozessen im menschlichen Organismus, die wir als Krankheitsprozesse bezeichnen und die doch im Grunde genommen ganz normale Naturprozesse sind, nur eben durch bestimmte Ursachen hervorgerufen sein müssen, und denjenigen Prozessen, die wir gewöhnlich als die gesunden bezeichnen und die die alltäglichen sind. Dieser durchgreifende Unterschied muß gefunden werden. Er wird nicht gefunden werden, wenn man nicht eingehen kann auf eine Betrachtungsweise des Menschen, die zum menschlichen Wesen wirklich führt. Dazu möchte ich Ihnen in dieser Einleitung wenigstens die ersten Elemente aufzeichnen, die wir dann im einzelnen im Detail weiter ausführen wollen.

[ 18 ] Sie werden es begreifen, daß ich hier in diesen Vorträgen, die ja nur in einer beschränkten Anzahl gehalten werden können, hauptsächlich dasjenige gebe, was Sie sonst in Büchern oder Vorträgen eben nicht finden, und dasjenige voraussetze, was man eben sonst finden kann. Ich glaube nicht, daß es besonders wertvoll wäre, wenn ich Ihnen irgendeine Theorie geben würde in Aufstellungen, die Sie sonst auch finden könnten. Daher verweise ich Sie an diesem Punkt an dasjenige, was sich Ihnen ergeben kann, wenn Sie einfach miteinander vergleichen das, was Sie sehen, wenn Sie vor sich stellen ein Menschenskelett und das Skelett, sagen wir eines Gorillas, eines sogenannt hochstehenden Affen. Wenn Sie diese zwei Skelette rein äußerlich miteinander vergleichen, so werden Sie bemerken als Wesentliches, daß beim Gorilla vorhanden ist einfach der Masse nach eine besondere Ausbildung des ganzen Unterkiefersystems. Das Unterkiefersystem steht gewissermaßen als Lastendes im ganzen Kopfskelett drinnen, und man hat das Gefühl, wenn man den Gorillakopf ansieht (siehe Zeichnung Seite 27, links) mit seinem mächtigen Unterkiefer, daß dieses Unterkiefersystem in irgendeiner Weise lastet, nach vorne drückt das ganze Skelett, daß der Gorilla, ich möchte sagen, mit einer gewissen Anstrengung sich aufrecht erhält gegen dieses Lastende, das da wirkt, namentlich im Unterkiefer.

[ 19 ] Aber dasselbe Lastsystem finden Sie gegenüber dem menschlichen Skelett, wenn Sie das Skelett der Vorderarme mit den daranhängenden Vorderhänden ins Auge fassen. Die wirken schwer, da ist alles massig beim Gorilla, während beim Menschen alles fein und zart gegliedert ist. Die Masse tritt da zurück. Gerade in diesem Teil, im Unterkiefersystem und im Vorderarmsystem mit dem Fingersystem, da tritt das Massige beim Menschen zurück, während es beim Gorilla auftritt. Der, der sich dann den Blick geschärft hat für diese Verhältnisse, der wird dasselbe auch noch verfolgen können beim Fuß- und Untergliedmaßenskelett. Auch da ist gewissermaßen noch ein Lastendes vorhanden, das nach einer bestimmten Richtung hin drückt. Ich möchte schematisch diese Kraft, die man sehen kann — man kann sie sehen im Unterkiefersystem, im Armsystem und im Bein-, im Fußsystem —, durch diese Linie bezeichnen (siehe Zeichnung Seite 28: Pfeile).

[ 1 ] Wenn Sie dies ins Auge fassen, was sich als Unterschied ergibt rein aus der Anschauung zwischen dem Gorillaskelett und dem Menschenskelett, wo zurücktritt, nicht mehr lastet das Unterkieferskelett, wo fein ausgebildet ist das Arm- und Fingerskelett, so werden Sie nicht umhin können, sich zu sagen: beim Menschen tritt diesen Kräften überall ein Aufwärtsstrebendes entgegen (Pfeile). Sie werden dasjenige konstruieren müssen, was beim Menschen formbildend ist aus einem gewissen Kräfteparallelogramm, das sich Ihnen ergibt aus derselben Kraft, die nach aufwärts geht und die der Gorilla sich nur äußerlich aneignet — man sieht es an der Mühe, mit der er sich aufrecht hält, mit der er sich aufrecht halten will. Dann bekomme ich ein Kräfteparallelogramm, das in diesen Linien verläuft (siehe Zeichnung Seite 29).

[ 20 ] Nun ist das höchst Eigentümliche dieses, daß wir uns ja gewöhnlich heute darauf beschränken, zu vergleichen die Knochen oder die Muskeln der höheren Tiere mit den Knochen und Muskeln der Menschen, aber dabei nicht das nötige Gewicht legen auf diese Formumwandelung. In der Anschauung dieser Formumwandelung muß man ein Wesentliches und Wichtiges suchen. Denn sehen Sie, diese Kräfte, die müssen ja dasein, die entgegenwirken den Kräften, die beim Gorilla die Gestalt bilden. Diese Kräfte müssen ja dasein, diese Kräfte müssen ja wirken. Wenn wir diese Kräfte suchen werden, werden wir wieder finden dasjenige, was verlassen worden ist, indem die alte Medizin filtriert worden ist vom hippokratischen System. Wir werden wiederum finden, daß diese Kräfte im Kräfteparallelogramm irdischer Natur sind und diejenigen Kräfte, die sich mit diesen irdischen Kräften im Kräfteparallelogramm vereinigen, so daß eine Resultierende entsteht, die nun nicht irdischen Kräften ihren Ursprung verdankt, sondern außerirdischen, außerterrestrischen Kräften, diese Kräfte müssen wir außerhalb des Irdischen suchen. Wir müssen Zugkräfte suchen, die den Menschen zur Aufrichtestellung bringen, aber nicht nur zur Aufrichtestellung bringen, wie sie beim höheren Tier vorhanden ist zuweilen, sondern so zur Aufrichtestellung bringen, daß die in der Aufrichtestellung wirkenden Kräfte zugleich Bildekräfte sind. Es ist ja ein Unterschied, ob der Affe, der aufrecht geht, dennoch Kräfte hat, die massig entgegenwirken, oder ob der Mensch sein Knochensystem schon so ausbildet, daß diese Ausbildung in der Richtung von Kräften wirkt, die nichtirdischen Ursprungs sind. Man kann einfach, wenn man richtig anschaut die Form des menschlichen Skeletts, sich nicht darauf beschränken, den einzelnen Knochen zu beschreiben und ihn zu vergleichen mit dem Tierknochen, sondern wenn man das Dynamische im Aufbau des menschlichen Skeletts verfolgt, dann kann man sich sagen: das findet man in den übrigen Reichen der Erde nicht, da treten uns Kräfte auf, die wir mit den übrigen zu dem Kräfteparallelogramm vereinigen müssen. Es entstehen Resultierende, die wir nicht finden können, wenn wir bloß auf die Kräfte Rücksicht nehmen, die außerhalb des Menschen vorhanden sind. Es wird sich also darum handeln, einmal diesen Sprung vom Tier zum Menschen ordentlich zu verfolgen. Dann wird man nicht nur beim Menschen, sondern auch beim Tier den Ursprung des Krankheitswesens finden können. Ich kann Sie nur nach und nach auf diese Elemente hinweisen, wir werden aber aus ihnen, weitergehend, sehr vieles finden können.

[ 21 ] Nun, im Zusammenhange mit dem, was ich Ihnen eben dargelegt habe, möchte ich Ihnen jetzt das Folgende erwähnen. Gehen wir über vom Kinochensystem zum Muskelsystem, so finden wir ja diesen bedeutsamen Unterschied im Wesen des Muskels, daß der ruhende Muskel alkalisch reagiert, wenn wir auf seine gewöhnliche chemische Wirkung Rücksicht nehmen; aber man kann doch nur sagen: ähnlich wie alkalisch, denn die alkalische Reaktion ist nicht eine absolut so klar ausgesprochene beim ruhenden Muskel, wie sonst alkalische Reaktionen sind. Beim tätigen Muskel tritt ebenso eine nicht ganz klare saure Reaktion in Tätigkeit. Nun bedenken Sie, daß ja selbstverständlich zunächst stoffwechselgemäß der Muskel zusammengesetzt ist aus dem, was der Mensch aufnimmt, daß er also in gewisser Weise ein Ergebnis ist der Kräfte, die in den irdischen Stoffen vorhanden sind. Aber indem der Mensch zur Tätigkeit übergeht, wird ja klarer und klarer dasjenige überwunden, was der Muskel in sich dadurch hat, daß er bloß dem gewöhnlichen Stoffwechsel unterliegt. Es treten im Muskel eben Veränderungen ein, die man zuletzt mit nichts anderem vergleichen kann gegenüber den gewöhnlichen stoffwechselgemäßen Veränderungen, als mit den Kräften, die die Bildung des Knochensystems beim Menschen bewirken. Wie diese Kräfte beim Menschen hinausgehen über dasjenige, was er von außen hat, wie sie sich terrestrisch durchdringen und sich mit ihnen zu einer bloßen Resultierenden vereinigen, so muß man auch mit dem, was im Muskel als wirkend im Stoffwechsel auftritt, etwas sehen, was nun hineinwirkt auch chemisch in die irdische Chemie. Hier haben wir, könnte man sagen, in die irdische Mechanik und Dynamik etwas hineinwirkend, was wir nicht mehr im Irdischen finden. Beim Stoffwechsel haben wir in die irdische Chemie etwas hineinwirkend, was nicht-irdische Chemie ist, was andere Wirkungen hervorbringt, als sie nur unter dem Einfluß der irdischen Chemie auftreten können.

[ 22 ] Von diesen Betrachtungen, die auf der einen Seite Formbetrachtungen, auf der anderen Seite Qualitätsbetrachtungen sind, werden wir auszugehen haben, wenn wir finden wollen dasjenige, was eigentlich im Menschenwesen liegt. Da wird man wiederum einen Rückweg sich eröffnen können zu dem, was verloren worden ist und was man ganz offenbar braucht, wenn man nicht stehenbleiben will bei einem bloßen formalen Definieren des Krankheitswesens, mit dem man dann in der Praxis eigentlich nicht viel anfangen kann. Denn denken Sie, daß ja eine sehr wichtige Frage auftaucht. Wir haben ja im Grunde genommen nur irdische Mittel, aus der Umgebung des Menschen, mit denen wir wirken können auf den menschlichen Organismus, wenn er Veränderungen erfährt. Aber im Menschen wirken nicht-irdische Prozesse oder wenigstens Kräfte, die seine Prozesse zu nicht-irdischen Prozessen machen. Und es entsteht also die Frage: Wie können wir eine Wechselwirkung, die hinführt vom Kranksein zum Gesundsein, hervorrufen zwischen dem, was wir als Wechselverhältnis bewirken zwischen dem kranken Organismus und seiner physischen Erdenumgebung? Wie können wir ein solches Wechselverhältnis hervorrufen, so daß nun wirklich durch dieses Wechselverhältnis beeinflußt werden können auch diejenigen Kräfte, die im menschlichen Organismus tätig sind und die nicht aufgehen in dem, worinnen die Prozesse aufgehen, aus denen heraus wir unsere Arzneimittel wählen können, selbst wenn diese Prozesse Anordnungen zur Diät sind und so weiter.

[ 23 ] Sie sehen, wie innig zusammenhängt mit einer richtigen Auffassung des Wesens des Menschen dasjenige, was schließlich zu einer gewissen Therapie führen kann. Und ich habe gerade die ersten Elemente, die uns befähigen sollen, zu einer Lösung dieser Frage aufzusteigen, hergenommen von Unterscheidungen des Menschen vom Tiere, mit vollem Bewußtsein, trotzdem der Einwand sehr leicht sein kann — wir werden ihn später beheben —, daß ja auch die Tiere erkranken, sogar Pflanzen eventuell erkranken — neuerdings hat man ja auch von Erkrankungen der Mineralien gesprochen — und daß daher gerade für das Kranksein der Unterschied des Menschen von dem Tiere nicht gemacht werden sollte. Man wird diesen Unterschied schon bemerken, wenn man sehen wird, wie wenig der Arzt auf die Dauer doch haben wird von der bloßen Untersuchung des Tierwesens mit dem Ziele, in der menschlichen Medizin weiterzukommen. Man kann — und das wird sich uns ergeben, warum das ist — ganz gewiß einiges erreichen für menschliche Heilung aus dem Tierversuch, aber nur dann, wenn man sich gründlich klar darüber ist, welch ein durchgreifender Unterschied bis in die einzelnsten Details hinein doch zwischen der tierischen und der menschlichen Organisation ist. Daher wird es sich darum handeln, gerade die Bedeutung des Tierversuches in der entsprechenden Weise immer mehr und mehr für die Entwickelung der Medizin klarlegen zu können.

[ 24 ] Weitergehend möchte ich Sie dann noch darauf aufmerksam machen, daß ja allerdings dann, wenn man auf solche außerirdischen Kräfte hinweisen muß, die Persönlichkeit des Menschen viel mehr in Anspruch genommen wird, als wenn man auf sogenannte objektive Regeln, objektive Naturgesetze immer hinweisen kann. Es wird sich allerdings darum handeln, daß man das medizinische Wesen viel mehr nach dem Intuitiven hin arbeitet und daß man darauf kommt, daß von dem Talent, aus Formerscheinungen heraus auf das Wesen des menschlichen Organismus, des individuellen menschlichen Organismus, der in einer gewissen Beziehung krank oder gesund sein kann, Schlüsse zu ziehen, daß dieses intuitive Eingeschultsein auf Formbeobachtung eine immer größere Rolle spieJen muß in der Entwickelung der Medizin und nach der Zukunft hin.

[ 25 ] Diese Dinge sollten, wie gesagt, nur zu einer Art von Einleitung, von orientierender Einleitung dienen. Denn das, worauf es hier ankam heute, das war, zu zeigen, daß die Medizin wiederum hinwenden müsse ihren Blick auf dasjenige, was sich durch Chemie oder auch durch die gewöhnliche vergleichende Anatomie nicht erreichen läßt, was nur erreicht werden kann, wenn man zu einer geisteswissenschaftlichen Betrachtung der Tatsachen übergeht. In bezug darauf gibt man sich ja heute noch mancherlei Irrtümern hin. Man denkt, daß es sich hauptsächlich darum handeln müsse, für eine Vergeistigung der Medizin an die Stelle der materiellen Mittel geistige zu setzen. Aber so berechtigt das auf gewissen Gebieten ist, so unberechtigt ist es in seiner Gänze. Denn es handelt sich vor allen Dingen auch darum, auf geistige Art zu erkennen, welcher Heilwert in einem materiellen Mittel stecken könnte, Geisteswissenschaft also schon anzuwenden auf die Bewertung der materiellen Mittel. Das wird namentlich die Aufgabe sein desjenigen Teiles, den ich bezeichnet habe: die Möglichkeiten der Heilung durch die Erkenntnis der Beziehung des Menschen zu der übrigen Welt aufzusuchen.

[ 26 ] Ich möchte ja, daß die Dinge, die ich werde zu sagen haben über spezielle Heilprozesse, möglichst gut fundiert seien und möglichst alle darauf hintendieren, daß bei jeder einzelnen Krankheit eigentlich eine Anschauung gewonnen werden kann über den Zusammenhang des sogenannten abnormen Prozesses, der auch ein Naturprozeß sein muß, mit den sogenannten normalen Prozessen, die ja auch wiederum nichts anderes sind als Naturprozesse. Wo immer diese Frage, diese Fundamentalfrage aufgetaucht ist — das möchte ich nur gleichsam als einen kleinen Anhang bemerken —: Wie kommt man eigentlich damit zurecht, daß die Krankheitsprozesse doch auch Naturprozesse sind? — da sucht man sich so bald wie möglich immer wiederum um die Sache zu drücken. Interessant war mir zum Beispiel ja, daß Troxler, der in Bern gelehrt hat, sehr intensiv schon in der ersten Hälfte des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts darauf hingewiesen hat, daß man gewissermaßen die Normalität der Krankheit untersuchen müsse und daß man dadurch in einer Richtung geführt wird, die zuletzt landet in der Anerkennung einer gewissen Welt, die mit der unseren verbunden ist und die nur wie durch unberechtigte Löcher sich hereinschiebt in unsere Welt und daß man dadurch auf irgend etwas in bezug auf die Krankheitserscheinungen kommen könne. Denken Sie sich — ich will das jetzt nur gewissermaßen grob schematisch andeuten -, es gäbe so irgendeine Welt im Hintergrunde, die zu ihren Gesetzen die ganz berechtigten Dinge hätte, die bei uns die Krankheitserscheinungen bewirken, dann könnten durch gewisse Löcher, durch die diese Welt hereindringt in unsere, diese Gesetze, die in einer anderen Welt ganz berechtigt sind, bei uns Unheil anrichten. Auf dieses wollte Troxler hinarbeiten. Und so unklar und undeutlich er sich auch in mancher Beziehung ausgesprochen hat, so merkt man doch, wie er auf einem Wege in der Medizin war, der hinarbeiter gerade auf eine gewisse Gesundung der medizinischen Wissenschaft.

[ 27 ] Ich habe dann mit einem Freunde einmal nachgesucht, da der Troxler doch in Bern gelehrt hat, wie er angesehen war unter seinen Kollegen, was man aus seiner Anregung gemacht hat, und wir konnten in dem Lexikon, das viele Dinge verzeichnet aus der Geschichte der Universität, bei Troxler nur herausfinden, daß er sehr viele Krache an der Universität gemacht hat! Das war dasjenige, was behalten worden ist. Und über seine wissenschaftliche Bedeutung konnte man gar nichts Besonderes herausfinden.

[ 28 ] Nun, ich wollte, wie gesagt, heute nur auf die Dinge hinweisen, und ich bitte Sie recht sehr, damit ich durchschießen kann dasjenige, was ich darstellen will aus meinen Absichten heraus mit dem, was in Ihren Wünschen liegt, mir bis morgen oder übermorgen alle Ihre Wünsche aufzuschreiben. Dann werde ich erst aus diesen Wünschen heraus dem Vortragszyklus die nötige Form geben. Ich glaube, so kommen wir dann am allerbesten zurecht. Ich bitte, das nur ganz ausgiebig zu machen.

First Lecture

[ 1 ] It goes without saying that only a very small part of what you all probably expect from the future of medical life can be touched upon in this course, for you will all agree with me that real, future-proof work in the medical field depends on a reform of medical studies as such. What can be communicated in a course cannot even remotely stimulate such a reform of medical studies, except perhaps in the sense that it may inspire a number of people to participate in such a reform. However, whatever is discussed in the medical field today always has its opposite pole, its background, in the way medical work is prepared through considerations of anatomy, physiology, and biology as a whole, and through these preparations, the thoughts of medical professionals are steered in a certain direction from the outset, and it is this direction above all that must be abandoned.

[ 2 ] I would like to achieve what is to be taught in these lectures by distributing what is to be considered in the following way in a kind of program: First, I would like to give you some pointers to the obstacles that exist in today's common studies to a truly appropriate understanding of disease as such. Secondly, I would like to suggest the direction in which to seek an understanding of human beings that can provide a real basis for medical work. Thirdly, I would like to point out the possibilities of a rational system of healing through an understanding of the relationship between human beings and the rest of the world. In this part, I would then like to answer the question of whether healing is even possible and conceivable. Fourthly—and I think this will perhaps be the most important part of the considerations, but it will have to be intertwined with the other three points of view—I would like each of the participants to write down their specific wishes on a piece of paper by tomorrow or the day after tomorrow, that is, to write down what they would like to hear, what they would like to be discussed in this course. These wishes can cover anything. Through this fourth part of the program, which, as I said, will be incorporated into the other three parts, I want to ensure that you do not leave this course with the feeling that you may not have heard what you wanted to hear. Therefore, I will structure the course in such a way that everything you write down as questions or wishes will be addressed in the course. So I ask you to make your notes about what you would like to hear, if possible by tomorrow, or if that is not possible, by the day after tomorrow, by this time. I think this is the best way to achieve a kind of completeness within the framework of these events.

[ 3 ] Today I would just like to give a kind of introduction, a kind of orientational overview. I would like to start from the premise that my main aim is to bring together everything that can be given to physicians from a spiritual scientific perspective, so to speak. I do not want what I am attempting to be confused with a medical course, which it will be; but everything that may be important for physicians from all areas should be taken into account. For true medical science or art, if I may say so, can only be achieved by truly taking into account all the things that are relevant in the sense indicated for the development of such medical science or art.

[ 4 ] Today, I would like to start with just a few preliminary observations. If you have thought about what your task as a physician is, you have probably often stumbled over the question: What is illness and what is a sick person anyway? It is rare to find any other explanation of illness and the sick person than the one — even if it is masked by this or that seemingly factual insertion — that the process of illness is a deviation from the normal process of life, that certain facts that affect the human being and to which the human being is not initially adapted in his normal life process changes in the normal life process and in the organization, and that illness consists of the functional impairments of the body parts associated with these changes. Now, you will have to admit that this is nothing more than a negative definition of illness. It is not something that can help you when you are dealing with illness, and I would like to work toward this practical aspect above all else, something that can help you when you are dealing with illness. In order to get to the heart of the matter in this area, it seems to me that it would be good to to point out certain views that have arisen over time about illness, not so much because I consider this absolutely necessary for the current understanding of disease symptoms, but because it is easier to orient oneself if one can take into account older views about illness, which have led to the current ones.