Third Scientific Lecture-Course:

Astronomy

GA 323

10 January 1921, Stuttgart

Lecture X

Taking my start yesterday from certain considerations in the realm of form, I showed how the connections should be thought of between the processes of the human metabolic system and the processes of the head, the nervous system, or whatever you wish to call it in the sense of the indications given in my book Riddles of the Soul (Von Seelenrätseln).

It would be regarded as quite out of the question to study the movements of a magnet-needle on the Earth's surface in such a way as to try to explain these movements solely out of what can be observed within the space occupied by the needle. The movements of the magnet-needle are, as you know, brought into connection with the magnetism of the Earth. We connect the momentary direction of the needle with the direction of the Earth's magnetism, that is, with the line of direction which can be drawn between the north and south magnetic poles of the Earth. When it is a question of explaining the phenomena presented by the magnetic needle, we go out of the region of the needle itself and try to enter, with the facts that have been collected towards an explanation, into the totality which alone affords the opportunity to explain phenomena, the manifestations of which belong to this totality. This rule of method is certainly observed in regard to some phenomena,—to those, I should say, the significance of which is fairly obvious. But it is not observed when it is a question of explaining and understanding more complicated phenomena.

Just as it is impossible to explain the phenomena of the magnetic needle from the needle itself, it is equally and fundamentally impossible to explain the phenomena relating to the organism from out of the organism itself, or from connections which do not belong to a totality, to a whole. And just for this reason, because there is so little inclination to reach the realm of totalities in order to find explanations, we arrive at those results put forward by the modern scientific method in which the wider connections are almost entirely left out of the picture. This method encloses the phenomena, whatever they may be, within the field of vision of the microscope; while the celestial phenomena are restricted to what is observable externally, with the help of instruments. In seeking for explanations, no attempt is made to consider the necessity of reaching out to the surrounding totality within which a phenomenon is localised. Only when we become familiar with this quite indispensable principle of method, are we in a position to bring our judgment to bear upon such things as I was describing to you yesterday. Only in this way shall we grow able to estimate how such realms of phenomena as are met within the human organism will appear, when truly recognised in the totality to which they properly belong.

Remember what I described at the very beginning of this course of lectures. I drew your attention to the fact that the principle of metamorphosis as it appeared first in the work of Goethe and Oken must be modified if it is truly to be applied to man. The attempt was made—and it was made with genius on the part of Goethe—to derive the formation of the bones of the skull from that of the vertebrae. These investigations were continued by others in a way more akin to 19th-century method, and the progress of the method of investigation (I will not now decide whether it was a step forward or not) can be studied by comparing how this problem of the metamorphosis of one form of bone into another was conceived on the one hand by Goethe and Oken and on the other, for example, by the anatomist Gegenbauer.

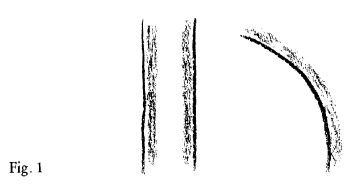

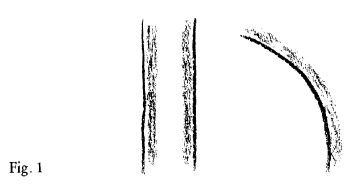

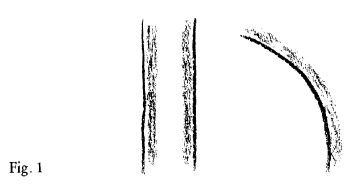

These things are only to be set on a real basis, if one knows (as I said, I have already mentioned this in the course of these lectures, but we will now link on to it again) how two types of bone in the human organism (not the animal, but the human organism), most widely separated from the point of view of their morphology, are actually related to one another. Bones far removed from one another in the aspect of their form would be a tubular or long bone—femur or humerus, for example,—and a skull-bone. To make a superficial comparison, without really entering into the inner nature of the form and bringing a whole range of phenomena into connection with it, is not enough to reveal the morphological relationship between two polar opposite bones—polar opposite, once more, in regard to their form. We only begin to perceive it if we compare the inner surface of a tubular bone with the outer surface of a skull-bone. Only thus do we get the true correspondence (Fig. 1) which we must have in order to establish the morphological relation. The inner surface of the tubular bone corresponds morphologically to the outer surface of the skull-bone. The skull-bone can be derived from the tubular bone if we picture it as being reversed, to begin with, according to the principle of the turning-inside-out of a glove. In the glove, however, when I turn the outer surface to the inside and the inner to the outside, I get a form similar to the original one. But if in the moment of turning the inside of the tubular bone to the outside, certain forces of tension come into play and mutual relationships of the forces change in such a way that the form which was inside and has now been turned outward alters the shape and distribution of its surface, then we obtain, through inversion on the principle of the turning-inside-out of a glove, the outer surface of the skull bone as derived from the inner surface of the tubular bone. From this you can conclude as follows. The inner space of the tubular bone, this compressed inner space, corresponds in regard to the human skull to the entire outer world. You must consider as related in their influence upon the human being: The outer universe, forming the outside of his head, and what works within, tending from within toward the inner surface of the tubular bone. These you must see to belong together. You must regard the world in the inside of the tubular bone as a kind of inversion of the world surrounding us outside.

There, for the bones in the first place, you have the true principle of metamorphosis! The other bones are intermediary forms; morphologically, they mediate between the two opposite extremes, which represent a complete inversion, accompanied by a change in the forces determining the surface. The idea must however be extended to the entire human organism. In one way, it comes to expression most clearly in the bones; but in all the human organs we must distinguish between two opposing factors,—that which works outward from an unknown interior, as we will call it for the moment, and that which works inward from without. The latter corresponds to all that surrounds us human beings on the planet Earth.

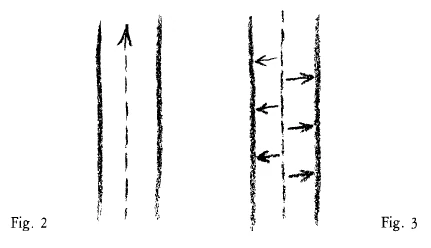

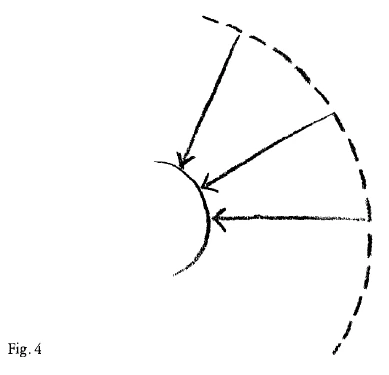

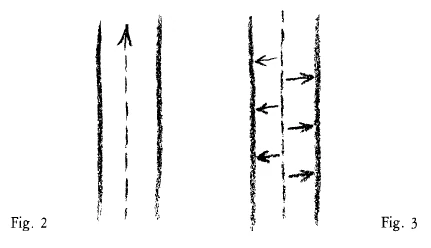

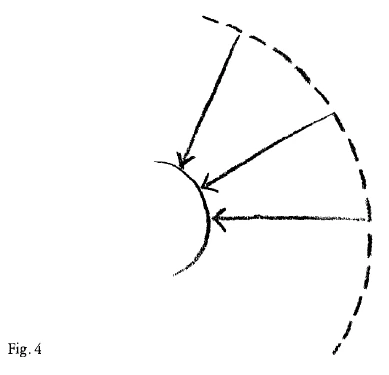

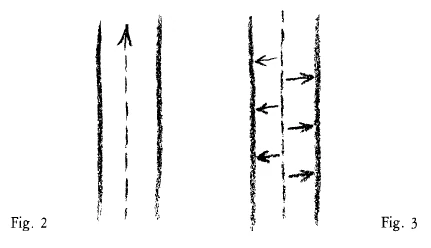

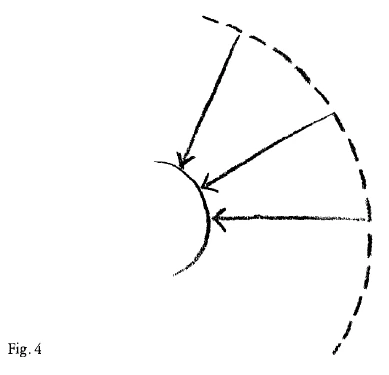

The tubular bone and the skull-bone represent indeed a remarkable polarity. Take the tubular bone and think of this centre-line (Fig. 2). This line is in a way the place of origin of what works outward, in a direction perpendicular to the inner surface of the bone (Fig. 3). If you now think of what envelops the human skull, you have what corresponds to the central line of the tubular bone. But how must you draw the counterpart of this line? You must draw it somewhere as a circle, or more exactly, as a spherical surface, far way at some indeterminate distance (Fig. 4). All the lines which can be drawn from the centre-line of the tubular bone towards it inner surface (Fig. 3). correspond, in regard to the skull-bone, to all the lines which can be drawn from a spherical surface as though to meet in the centre of the Earth (Fig. 4). In this way you find a connection—approximate, needless to say—between a straight line, or a system of straight lines, passing through a tubular bone and bearing a certain relation to the vertical axis of the body, the direction of which coincides, in fact, with that of the Earth's radius and a sphere surrounding the Earth at an indeterminate distance. In other words, the connection is as follows. The radius of the Earth has the same cosmic value in regard to the vertical posture of the human organism, perpendicular to the surface of the Earth, as a spherical surface, a cosmic spherical surface has in regard to the skull organisation. This, however, is the same contrast which you experience within yourself if you make yourself aware of the feeling of being inside your own organism and experiencing of the outer world at the same time. This is the polarity you reach if you compare your feeling of self—that feeling of self which is really based on the fact that in normal life you can depend upon your bodily organisation, that you do not become giddy, but keeping a right relation to the force of gravity—with all that is present in your consciousness in connection with what you see around you through the senses, even as far away as the stars.

Putting all this together, you will be able to say: There is the same relation between this feeling of being in yourself and the feeling of consciousness you have in perceiving the outer world as there is between the structure of your body and of your skull. We are thus led to the relationship between what we might call: Earthly influence upon man, of such a character that it works in the direction of the Earth's radius, and what we might call: The influence which makes itself felt in the entire circumference of our life of consciousness, and which we must look for in the sphere, in what really is for us the inner wall, the inner surface, of a hollow sphere. This polarity prevails in our normal day-waking conscious life. It is this polarity which, roughly speaking—if we leave out of account what is in our consciousness as a result of observating our earthly environment—we may look upon as the contrast between the starry sphere and earthly consciousness, earthly feeling of ourselves,—Earth-impulse living in us. If we compare this impulse of Earth, this radial Earth-impulse, to our consciousness of the vast sphere,—if we observe how this polarity, prevails in normal waking consciousness, we shall perceive that it is always there, living in us, playing its part in our conscious life. We live far more in this polarity than we are wont to think. It is always present and we live within it. The connection between the forming of mental images and the life of will can be really studied in no other way than by considering the contrast between ‘sphere’ and ‘radius’. In psychology, too, we should come to truer results with regard to the connection of our world of ideas and mental pictures, manifold and extensive as it is, with the more unified world of our will, if a similar relationship were sought between them as is symbolised in the relation of the surface-area of a sphere with the corresponding radius.

Now, my dear friends, let us look at all this which is at work in our day-waking consciousness, forming the content of our soul-life, let us now consider how it takes its course when we are in quite a different situation. In effect, how does it work upon us during the time of the embryonic life? We can well imagine, indeed we must imagine that the same polarity will be at work here too, only in another way. During the embryonic period, we do not direct towards the outer world the same activity which afterwards dims down this polarity to a pictorial one; at this time, the polarity affects all that is formative in our organisation, in a much more real way than when, in picture form, it becomes active in our life of mind and soul. If therefore we project the activity of consciousness back in time to the embryonic period, then one might say that in the embryonic life we have what we otherwise have in the activity of consciousness, but we have it at a more intensive, more realistic stage. Just as we clearly see the relation of sphere and radius in our consciousness, so to reach any real result, we must look for this same polarity of heavenly sphere and earthly activity in what happens in the embryonic life. In other words, we must look for the genesis of human embryonic life by finding a resultant between what takes place out in the starry world—an activity in the ‘sphere’—and what takes place in man as a result of the radial Earth-activity.

What I have just described must be taken into account with the same inner necessity of method as the Earth's magnetism is in connection with the magnetic needle. There may be much that is hypothetical even in this, but I will not go into it now. I only wish to point out: We have no right to restrict our considerations to the embryo alone,—to explain the processes taking place within it simply out of the embryo itself. In just the same way as we have no right too explain the phenomenon of the magnet out of itself alone, so too, we have no right to explain the form and development of the embryo purely on the basis of the embryo itself. In attempting to explain the embryo we must take these two opposites into account. As we take the Earth's magnetism into account in connection with the magnet, so must we observe the polarity of sphere and radial activity, in order to understand what is developing in the embryo,—which, when the embryo is born, fades into the pictorial quality of the experience of consciousness. The point is, we must learn to see the relationship which exists in man between tubular or long bone and skull-bone in the other systems too—in muscle and nerve, and so on;—and when we do study this polarity, we are led out into the life of the Cosmos. Consider how closely related (as described in my book “Riddles of the Soul”) is the whole essence and content of the human metabolic system with what I have now characterised as being under the influence of the ‘radial’ element, and how closely related is the head system to what I have just described as being under the influence of the ‘sphere’. Then you will say: We must distinguish in the human being what conditions his sensory nature and what conditions his metabolic life; moreover, these two elements are related to one another as heavenly sphere to earthly activity.

We must therefore look for the product of the celestial activity in what we bear in our head organisation and for what unites to a resultant with this, the activity belonging to the Earth—tending, as it were, towards the centre of the Earth—in our metabolism. These two realms of activity and influence fall apart in man; it is as thought they represent two Ice Ages, and the middle realm, the rhythmic realm, mediates between them. In the rhythmic system we actually have something,—if I may so express myself,—which is a realm of mutual interplay between Earth and Heaven.

And now if we wish to go further, we must consider various other relationships which reveal themselves to us in the realm of reality. I will now draw your attention to something very intimately connected with what I have just been describing.

There is the familiar membering of the outer world which surrounds us and to which we as physical man belong; we divide it into mineral kingdom, plant kingdom, animal kingdom, and regard man as the culmination of this external world of Nature. Now, if we would obtain a clearer view of what we have described in connection with the working of the celestial phenomena, we must turn our attention to yet another thing.

It is not to be denied—it is indeed quite obvious to any prejudiced observer—that with our human organisation as it is now, in the present phase of the cosmic evolution of humanity, we are, in regard to our capacities of knowledge, entirely adapted to the mineral kingdom. Take the kind of laws we seek in Nature; and you will agree that we are certainly not adapted to all aspects of our environment. To put it curtly, all that we really understand is the mineral kingdom. Hence all the efforts to refer the other kingdoms of Nature back to the laws of the mineral domain. After all, it is because of this that such confusion has arisen with regard to mechanism and vitalism. To the ordinary view which is ours toady, life remains either a vague hypothesis, as it was in earlier times, or else its manifestations are explained in terms of the mechanical, the mineral. The ideal, to reach an understanding of life, is unaccompanied by any recognition of the fact that life must be understood as life; on the contrary, the fundamental aim is to refer life back to the laws of the mineral realm. Precisely this betrays a vague awareness of the fact that man's faculties of knowledge are only adapted to understand the mineral kingdom and not the plant nor animal.

Now when we study on the one hand the mineral kingdom itself and on the other hand its counterpart, namely, our own knowledge of the mineral kingdom, in that these two correspond to one another, we shall be compelled,—since as explained just now we must relate all our life of knowledge to the heavenly sphere, also to bring into connection with the heavenly sphere, in some way, that to which our knowledge is related, namely the mineral kingdom. We must admit: In regard to our head organisation, we are organised from the celestial sphere; therefore what underlies the forces of the mineral kingdom must also be organised from the celestial sphere in some way. Compare then what you have to your sphere of understanding—the whole compass of your knowledge of the mineral kingdom—with what is actually there in the mineral kingdom in the outer world, and you will be led to say: What is thus within you relates to what is in the mineral kingdom outside you, as picture to reality.

Now we must think of this relationship more concretely than in the form of picture and reality, and we are helped to do so by what I said before. Our attention is drawn to what underlies the human metabolic system and to the forces active there, forces which are connected with the pole of earthly activity, typified by the radius. In seeking for the polar opposite, within ourselves, to that part of our organisation which forms the basis for our life of knowledge, we are directed from the encompassing Sphere to the Earth. The radii converge to the middle point of the Earth. In the radial element we have something by which we feel ourselves, which gives us the feeling of being real. This is not what fills us with pictures in which we are merely conscious; this is what gives us the experience of ourselves as a reality. When we really experience this contrast, we come into the sphere of the mineral kingdom. We are led from what is organised only for the picture to what is organised for the reality. In other words: In connection with the cause and origin of our life of knowledge, we are led to the wide, encompassing sphere,—we concave it in the first place as a sphere,—whereas, in following the radii of the sphere towards the middle of the Earth, we are led to the middle point of the Earth as the other pole.

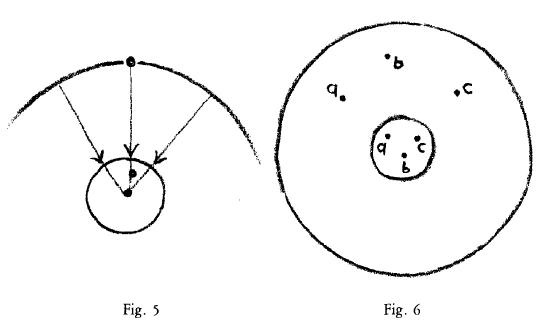

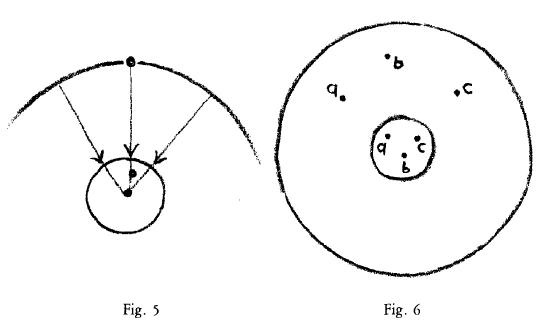

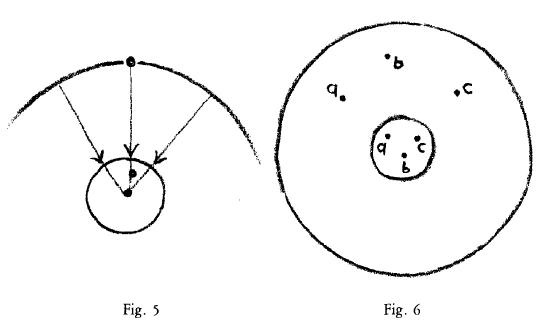

Thinking this out in more detail, we might say: Well, according to the Ptolemaic conception for example, out there is the blue sphere, on it a point (Fig. 5)—we should have to think of a polar point in the centre of the Earth. Every point of the sphere would have its reflected point in the Earth's centre. But, or course, it is not to be understood like that. (I shall speak more in detail later on; to what extent these things correspond exactly is not the question for the moment.) The stars, in effect, would be here (Fig. 6). So that in thinking of the sphere concentrated in the centre of the Earth, we should have to think of it in the following way: The pole of this star is here, of this one here, and so on (Fig. 6). We come, then, to a complete mirroring of what is outside in the interior of the Earth.

Picturing this in regard to each individual planet, we have, say, Jupiter and then a polar Jupiter’ within the Earth. We come to something which works outward from within the Earth in the way that Jupiter works in the Earth's environment. We arrive at a mirroring (in reality it is the opposite way round, but I will now describe it like this), a mirroring of what is outside the Earth into the interior of the Earth. And if we see the effect of this reflection in the forms of the minerals then we must also see the effect of what works in the cosmic sphere itself in forming our faculty of understanding the minerals. In other words: We can think of the whole celestial sphere as being mirrored in the Earth: We conceive the mineral kingdom of the Earth as an outcome of this reflection, and we conceive that what lives within us, enabling us to understand the mineral kingdom, comes from what surrounds us out in the celestial space. Meanwhile the realities we grasp by means of this faculty of understanding come from within the Earth.

You need only follow up this idea and then cast a glance at man, at the human countenance, and, if you really look at this human countenance, you will hardly be able to doubt that in it something is expressed of the celestial sphere, and that there also appears in it what is present as pictorial experience in the soul, namely the forces which rise up into the realm of soul activity from the realm of bodily activity, after having been at work more intensively in this bodily realm during embryonic life. Thus we find a connection between what is out side us in outer reality, and our own organisation for the understanding of this outer reality. We can say: The cosmos produces the outer reality, and our power to understand this outer reality is organised physically by virtue of the fact that the cosmic sphere is only active in us now for our faculty of knowledge. Therefore we must distinguish, in the genesis of the Earth as well, between two phases: One in which active forces work in such a way that the real Earth itself is created, and then a later phase of evolution, in which the forces work so as to create the human faculty for understanding the realities of the Earth.

Only in this way, my dear friends, do we really come near to an understanding of the Universe.

You may say: Well and good, but this method of understanding is less secure than the method used today with the aid of microscope and telescope. It may be that to some people it appears less secure. But if things are so constituted that we cannot reach the realities with the methods in favour today, then we are faced with the absolute necessity of comprehending the reality with other modes of understanding and we shall have to get used to developing those other methods. It is of no avail to say, you will have nothing to do with such lines of thought, since they appear too uncertain. What if this degree of certainty alone were possible! However, if you really follow up this line of thought, you will see that the degree of certainty is just as great as in your conception of a real triangle in the outer world when you take hold of it in thought with the inner idea of construction of a triangle. It is the same principle, the same manner of comprehending outer reality in the one case as in the other. This should be borne in mind.

Certainly, the question arises: Taking these thoughts, as I have here developed them, it is possible to become clear in a general way about such connections, but how can one reach a more definite comprehension of these things? For only in a much more definite form can they be of use in helping us to grasp the realm of reality. In order to go into this, I must draw your attention to something else.

Let us return to what I aid yesterday, for example, in regard to the Cassini curve. We know that this curve has three, or, if you like, four forms. You remember, the Cassini curve is determined as follows. Given two points \(A\) and \(B\), I will call the distance between them \(2a\); then any point of the curve will be such that \(AM \cdot MB=b2\), that is, a constant. And I obtain the various forms of the Cassini Curve according to whether \(a\), that is, half the distance between the foci, is greater than, equal to, or less than \(b\). I obtain the lemniscate when \(a=b\), and the discontinuous curve when a is greater than \(b\).

Imagine now that I wanted not only to solve this geometrical problem, assuming two constant magnitudes a and b and then setting up equations to determine the distances of \(M\) from \(A\) and \(B\). Suppose I wanted to do more than this, namely, to move in the plane from one form of line or curve to another by treating as variable magnitudes those magnitudes which remain constant for a particular curve. In the image (Lecture IX, Fig. 3) after all, we only envisaged certain limiting positions with a greater or smaller than b. Between these there are an infinite number of possibilities. I can pass over quite continuously to the construction of one form of the Cassini curve after another. And I shall obtain these different forms if, let us say, to the variability of the first order, say between \(y\) and \(x\). I add a variability of the second order; that is, if I allow my construction of the curves as they pass over from one to the other continuously, to take its course in such a way that a remains a function of \(b\).

What am I doing when I do this? I am constructing curves in such a way that I create a continuous, moving system of Cassini curves passing over via the lemniscate into the discontinuous forms, not at random, but by basing it on a variability of the second order, in that I bring the constants of the curves themselves into relationship with one another so that a is a function of \(b\), \(a=φ(b)\). Mathematically, it is of course perfectly feasible. But what do we obtain by it? Just think, by means of it I obtain the condition for the character of a surface such that there is a qualitative difference even mathematically speaking, in all its points. At every point another quality is present. I cannot comprehend the surface obtained like this in the same way as I comprehend some abstract Euclidean plane. I must look upon it as a surface which is differentiated within itself. And if by rotation I create three-dimensional forms then I should obtain bodies differentiated within themselves.

If you think of what I said yesterday, namely, that the Cassini Curve is also the curve in which a point must move in space if, illuminated from a point \(B\), it reflects the light to a point \(A\) with constant intensity; and if you also bear in mind that the constancy underlying the curve here brings about a relation between the effects of light at different points; then, just as in this instance certain light-effects result from the relation of the constants, so one can also imagine that a system of light-effects would follow if a variability of the second order were added to the variability of the first. In this way you can create, even in mathematics itself, a process of transition from the quantitative to the qualitative aspect.

These attempts must indeed be made in order to find a way of transition from quantity to quality,—and this endeavour we must not abandon. For a start can be made from what it is that we are really doing when we form an inner connection between the function within the variability of the second order and the function within variability of the first order. (It has nothing to do with the expression “order”, as it is familiarly used; but you will understand me, as I have explained the whole thing from the beginning.) By turning our attention to this relationship between what I have called first and second order, we shall gradually come to see that our equations must be formed differently, according to whether we are taking into account, for example, what in an ordinary bodily surface lies between the surface and our eye, or what lies behind the surface of the body. For a relationship not unlike this between the variability's of the first order and of the second order, exists between what I must consider as being between myself and the surface of a quite ordinary body and what lies behind the surface of the body. For example, suppose we are trying to understand the so-called reflection of the rays of light,—what we observe when there is a reflecting surface. It is a process taking place, to begin with, between the observer and the surface of the body. Suppose that I conceive this as a confluence of equations taking their course between me and the surface of the body in a variability of the first order, and then, in this connection consider what is at work behind the surface so as to bring about the reflection as an equation in the variability of the second order. I shall arrive at quite other formulae than are now applied according to purely mechanical laws,—omitting phases of vibration and so on—when dealing with reflection and refraction.

In this way the possibility would be reached of creating a form of mathematics capable of dealing with realities; and it is essential for this to happen, if we would find explanations particularly in the realm of astronomical phenomena. In regard to the external world, we have before us what takes place between the surface of the Earth-body and ourselves. When, however, we contemplate the celestial phenomena—say, a loop of Venus—trivially speaking we also have before us something which takes place between us and some other thing; yet the reality confronting us in this case is in fact like the realm beyond the sphere in its relation to what is within the central point. However we look to the phenomena of the heavens, we must recognise that we cannot study them simply according to the laws of centric forces, but that we must regard them in the light of laws which are related to the laws of centric forces as is the sphere to the radius.

If, then, we would reach an interpretation at all of the celestial phenomena, we must not arrange the calculations in such a way that they are a picture of the kind of calculations used in mechanics in the development of the laws of centric forces; but we must formulate the calculations, and also the geometrical forms involved, so that they relate to mechanics as sphere relates to radius. It will then become apparent (and we will speak about this next time) that we need: In the first place, the manner of thinking of mechanics and phoronomy, which has essentially to do with centric forces, and secondly, in addition to this system, another, which has to do with rotating movements, with shearing movements and with deforming movements. Only then, when we apply the meta-mechanical, meta-phoronomical system for the rotating, shearing and deforming movements, just as we now apply the familiar system of mechanics and phoronomy to the centric forces and centric phenomena of movement, only then shall we arrive at an explanation of the celestial phenomena, taking our start from what lies empirically before us.

Zehnter Vortrag

Ich habe gestern, ausgehend von gewissen formalen Betrachtungen, darauf hingewiesen, wie die Zusammenhänge gedacht werden sollen zwischen dem, was man nennen kann die Vorgänge im menschlichen Stoffwechselsystem, und den Vorgängen im menschlichen Kopfsystem, im Nerven-Sinnessystem, oder wie Sie es nennen wollen im Sinne der Andeutungen, die ich in meinem Buche «Von Seelenrätseln» gegeben habe.

Wenn man eine Magnetnadel so betrachten würde in ihren Schwankungen auf der Erdoberfläche, daß man versuchen wollte, diese Schwankungen lediglich zu erklären durch dasjenige, was man beobachten kann innerhalb des Raumes, in dem die Magnetnadel sich befindet, so würde man das selbstverständlich als etwas Unmögliches bezeichnen. Sie wissen ja, daß diese Schwankungen der Magnetnadel zusammengebracht werden mit dem Erdmagnetismus. Sie wissen, daß man die jeweilige Richtung der Magnetnadel zusammenbringt mit der Richtung des Erdmagnetismus, beziehungsweise mit jener Richtungslinie, die zwischen dem nördlichen und südlichen Magnetpol der Erde gezogen werden kann, daß man also, wenn es sich darum handelt, die Erscheinungen, die uns die Magnetnadel darbietet, zu erklären, aus dem Bereich der Magnetnadel selbst herausgeht und versucht, einzutreten mit den Elementen, die man zur Erklärung heranzieht, in jene Totalität, die erst die Möglichkeit bietet, die Erscheinungen von etwas, das zu dieser Totalität im Tatsachenablauf dazugehört, zu erklären. Diese methodische Regel wird ja zwar für gewisse Erscheinungen, man kann sagen, für diejenigen Erscheinungen, für die die Sache ganz an der Oberfläche liegt, durchaus beobachtet. Allein sie wird nicht beobachtet, wenn es sich darum handelt, kompliziertere Erscheinungen zu erklären, zu verstehen.

Ebenso untunlich, wie es wäre, die Erscheinungen an der Magnetnadel aus dieser selbst zu erklären, ebenso untunlich ist es im Grunde, die Erscheinungen, die am Organismus vor sich gehen, aus diesem Organismus oder aus gewissen, keiner Totalität angehörigen Zusammenhängen zu erklären. Und gerade aus diesem Grunde, weil das Bestreben so wenig vorliegt, zu Totalitäten vorzuschreiten, wenn man Erklärungen haben will, kommen wir zu dem, was die Betrachtungsweise unserer Wissenschaft darstellt, insofern man größere Zusammenhänge heute fast ganz unberücksichtigt läßt. Sie schließt irgendwelche Erscheinungen, möchte ich sagen, in das Blickfeld des Mikroskops ein und dergleichen; sie schließt Sternenerscheinungen ein in dasjenige, was wir zunächst äußerlich wahrnehmen können, vielleicht auch wahrnehmen können durch die Instrumente, die wir dazu verwenden, aber es liegt nicht das Bestreben vor, daß in erster Linie zu berücksichtigen ist, wo es sich um Erklärungen handelt, zu dem totalen Umkreis vorzuschreiten, innerhalb dessen irgendeine Erscheinung liegt. Nur wenn man mit diesem ganz unerläßlichen methodischen Prinzip sich bekanntmacht, ist man in der Lage, solche Dinge richtig zu beurteilen, wie diejenigen sind, auf die ich gestern aufmerksam gemacht habe. Denn nur dadurch wird man darauf kommen, in der richtigen Weise zu würdigen, wie sich in einem abgeschlossenen Totalzusammenhange solche Erscheinungsgebiete ausnehmen wie diejenigen, die uns am menschlichen Organismus entgegentreten.

Erinnern wir uns noch einmal an die Ausführungen, die ich ganz im Anfang dieser Betrachtungen gemacht habe. Ich habe Sie darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß das Prinzip der Metamorphose eigentlich modifiziert werden muß, wenn es sich darum handelt, diese Metamorphose, wie sie zuerst bei Goethe, bei Oken zutage getreten ist, wirklich verständlich auf die Morphologie des Menschen anzuwenden. Nicht wahr, man hat ja versucht - und es war ein genialischer Versuch, der bei Goethe aufgetreten ist -, die Formation der Schädelknochen auf die Formation der Wirbelknochen zurückzuführen. Diese Untersuchungen sind dann in einer der Methode des 19. Jahrhunderts mehr entsprechenden Weise von anderen fortgesetzt worden, und den ganzen Fortgang - ob es ein Fortschritt war oder nicht, will ich jetzt nicht entscheiden - in der Untersuchungsweise kann man studieren, wenn man vergleicht, wie dieses Problem der metamorphosischen Umgestaltung der Knochen aufgefaßt wurde auf der einen Seite von Goethe und Oken, auf der anderen Seite zum Beispiel von dem Anatomen Gegenbaur. Diese Dinge sind erst auf eine reale Basis zu bringen, wenn man weiß - wie gesagt, ich habe das ja im Verlauf dieser Vorträge schon erwähnt, aber wir wollen jetzt an diesen Punkt anknüpfen -, wie zwei in ihrer Morphologie am weitesten entfernt liegende Knochen des menschlichen Skeletts - also nicht des tierischen, sondern des menschlichen Skeletts - eigentlich zusammenhängen. Da liegen eben am weitesten entfernt voneinander ein Röhrenknochen, zum Beispiel ein Oberschenkel- oder Oberarmknochen, und ein Schädelknochen. Wenn man äußerlich einfach vergleicht, ohne auf das Innere einzugehen und ohne eine totale Erscheinungssphäre heranzuziehen, kann man nicht auf den morphologischen Zusammenhang kommen zwischen zwei polarisch einander entgegengesetzten Knochen, polarisch einander entgegengesetzt in bezug auf die Form. Man kommt nur darauf, wenn man die Innenfläche eines Röhrenknochens vergleicht mit der Außenfläche eines Schädelknochens. Denn dann bekommt man die entsprechende Fläche, um die es sich handelt (Fig.1) und die man braucht, um den morphologischen Zusammenhang konstatieren zu können. Man kommt dann darauf, daß die Innenfläche des Röhrenknochens der Außenfläche des Schädelknochens entspricht — das ist morphologisch -— und daß das ganze darauf beruht, daß der Schädelknochen aus dem Röhrenknochen hergeleitet werden kann, wenn man sich ihn gewendet denkt nach dem Prinzip zunächst der Umwendung eines Handschuhs. Wenn ich die Außenfläche des Handschuhs zur inneren, die innere Fläche zur äußeren mache, so bekomme ich allerdings beim Handschuh eine ähnliche Form, aber wenn außerdem noch in dem Augenblick sich geltend machen verschiedene Spannungskräfte, wenn gewissermaßen in dem Augenblick, wo ich das Innere des Röhrenknochens nach außen wende, die Spannungsverhältnisse sich so verändern, daß dadurch die nach außen gewendete innere Form sich anders verteilt in der Fläche, dann bekommt man durch Umwendung nach dem Prinzip des Handschuhumdrehens die Außenfläche des Schädelknochens, hergeleitet von der Innenfläche des Röhrenknochens. Daraus aber geht Ihnen hervor: Dem Innenraum des Röhrenknochens, diesem zusammengedrängten Innenraum des Röhrenknochens entspricht in bezug auf den menschlichen Schädel die ganze Außenwelt. Sie müssen also als zusammengehörig betrachten in der Wirkung auf den Menschen: die Außenwelt, formierend das Äußere seines Hauptes, und dasjenige, was im Innern wirkt, gewissermaßen hintendierend nach der Innenfläche der Röhrenknochen. Das müssen Sie als zusammengehörig betrachten. Sie müssen gewissermaßen die Welt im Innern der Röhrenknochen als eine Art inverser Welt zu derjenigen ansehen, die uns äußerlich umgibt.

Da haben Sie zunächst für den Knochenbau das wahre Prinzip der Metamorphose. Denn die anderen Knochen, sie sind im wesentlichen Zwischengebilde, morphologische Zwischengebilde zwischen den polarischen Gegensätzen, die völliger Umwendung entsprechen mit Änderung der die Fläche bedingenden Kräfte. Das aber muß ausgedehnt werden auf die gesamte menschliche Organisation. Bei den Knochen tritt es uns in einem gewissen Sinn besonders deutlich zutage. Es ist für alle Organe des Menschen zu beachten, daß wir, wenn wir von der Organisation sprechen, zu unterscheiden haben zwischen zwei polarischen Gegensätzen, zwischen dem, was von einem, wir wollen jetzt zunächst sagen, unbekannten Innern gewissermaßen nach außen wirkt, und demjenigen, was von außen nach innen wirkt. Demjenigen aber, was von außen nach innen wirkt, entspricht im Grunde alles dasjenige, was uns Menschen von außerhalb der Erde umgibt. Und Sie bekommen ja tatsächlich zwei außerordentliche Gegensätze, wenn Sie, sagen wir, den Röhrenknochen ins Auge fassen und sich diese Linie darin denken (Fig. 2). Sie bekommen gewissermaßen eine Linie, welche die Ursprungsstelle desjenigen enthält, was da wirkt senkrecht auf die betreffende Fläche

Und Sie bekommen, wenn Sie sich die menschliche Schädelumhüllung denken, auch dasjenige, was dieser Linie entspricht (Fig. 2, gestrichelt). Aber wie müssen Sie das zeichnen, was dieser Linie entspricht? Sie müssen es sich zeichnen irgendwo als einen Kreis, respektive sogar eine Kugelfläche, eine in irgendeiner unbestimmten Entfernung gelegene Kugelfläche (Fig. 4). Und all die Linien, die Sie sich zeichnen von der Geraden gegen die Fläche des Röhrenknochens hin (Fig. 3), die entsprechen in bezug auf den Schädelknochen all den Linien, die Sie sich ziehen gewissermaßen als im Mittelpunkt der Erde sich treffend von irgendeiner Sphäre her (Fig. 4). Dadurch bekommen Sie einen Zusammenhang - natürlich sind die Dinge approximativ -— zwischen einer Geraden oder zwischen einem System von Geraden, die durch einen Röhrenknochen gehen und die alle in einer gewissen Beziehung stehen zu der Vertikalachse der Organisation, zwischen dieser Richtung, die eigentlich zusammenfällt mit der Richtung des Erdradius, und einer Sphäre, die die Erde in einer unbestimmten Entfernung umgibt. Sie bekommen den Zusammenhang, daß Sie sagen können: Mit Bezug auf den senkrecht zur Erdoberfläche gerichteten Bau des Menschen hat der Radius der Erde denselben kosmischen Wert, wie eine Kugelfläche, eine kosmische Kugelfläche mit Bezug auf die Schädelorganisation.

Dadurch aber bekommen Sie ja denselben Gegensatz heraus, den Sie eigentlich, wenn Sie achtgeben auf das In-sich-Fühlen Ihres Organismus und zu gleicher Zeit auf die äußere Erfahrung, als in sich tragend empfinden. Diesen Gegensatz bekommen Sie heraus, wenn Sie Ihr Eigengefühl nehmen, dasjenige Eigengefühl, das ja im wesentlichen dadurch begründet ist, daß Sie sich ruhig im normalen Leben Ihrer Körperlichkeit überlassen können, daß Sie nicht schwindlig werden, sondern in einem Verhältnis zur Schwerkraft stehen, und wenn Sie dann dieses, was in einem gewissen Sinn Ihr Eigengefühl ist, vergleichen mit all dem, was in Ihrem Bewußtsein präsent ist mit Bezug auf dasjenige, was Sie durch die Sinne rundherum sehen bis zu den Sternen hinauf.

Wenn Sie das zusammennehmen, so können Sie sagen: Es ist dasselbe Verhältnis zwischen diesem Innengefühl und dem Bewußtseinsgefühl im Wahrnehmen der äußeren Welt, wie zwischen Ihrem Körperbau und Ihrem Schädelbau. Und damit sind wir hingewiesen auf die Beziehung dessen, was man nennen könnte zunächst: Erdenwirkung auf den Menschen mit dem Charakter, daß sie im Sinne des Radius der Erde wirkt, zu demjenigen, was man nennen könnte Wirkung, die sich äußert in dem Umfange unseres Bewußtseins, die wir suchen müssen in der Sphäre, in demjenigen, was eigentlich einem die innere Wandung, die innere Fläche einer Kugelschale ist. Und für unser normales Tagesbewußtsein ist es dieser Gegensatz, den wir, wenn wir auslassen dasjenige, was in unserem Bewußtsein ist von den Beobachtungsergebnissen unserer irdischen Umgebung, grob angesehen auffassen können als den Gegensatz desjenigen, was Sternensphäfre ist, zum Erdenbewußtsein, zum Als-erden-sich-Erfühlen, zum Erdenimpuls, der in uns lebt. Wenn wir diesen Erdenimpuls, den radialen Erdenimpuls ins Verhältnis bringen zu unserem Bewußtsein von der Sphäre, so ist dieser Gegensatz, wenn wir uns ihn anschauen in unserem gewöhnlichen Tagesbewußtsein, im wesentlichen etwas, was in uns, eben in unserem Bewußtsein, vor sich geht. Wir leben in diesem Gegensatz drinnen mehr, als wir gewöhnlich meinen. Es ist eigentlich immer dieser Gegensatz da, in dem wir drinnen leben. Und wir können eigentlich nicht anders studieren das Verhältnis der Vorstellung zum Wollen, als indem wir diesen Gegensatz zwischen der Sphäre und dem Radius betrachten. Man würde auch in der Psychologie zu realeren Resultaten kommen über das Verhältnis unserer doch jedenfalls außerordentlich ausgedehnten Vorstellungswelt zur einförmigeren Willenswelt, wenn man diese mannigfaltige, ausgedehntere Vorstellungswelt in ein ähnliches Verhältnis zur Willenswelt bringen würde, wie man ces sich versinnlichen kann durch das Verhältnis des Flächeninhaltes einer Sphäre zu dem entsprechenden Radius dieser Sphäre.

Was nun so in unserem Tagesbewußtsein wirkt, daß es gewissermaßen die Erfüllung unseres Seelenlebens ist, betrachten wir das doch jetzt einmal dann, wenn wir in einer anderen Lage sind als in der, in der wir dieses Tagesbewußtsein ausbilden. Betrachten wir dasjenige, was so auf uns wirkt, einmal in derjenigen Zeit, in der wir unser Embryonalleben durchmachen, und wir können uns gut vorstellen, müssen es sogar, daß da ja derselbe Gegensatz wirkt, nur sich in einer anderen Weise auslebt. Da tragen wir nicht der Welt entgegen dieselbe Aktivität, die dann abschwächt diesen ganzen Gegensatz zu einem Bildgegensatz, sondern da ist dieser Gegensatz auf unsere formbare Organisation in einer realeren Weise wirksam, als er als Bildgegensatz wirksam ist, wenn wir ihn in unserem Seelenleben haben. Projizieren wir zeitlich zurück die Bewußtseinswirkungen auf das Embryonalleben, dann haben wir im Embryonalleben, man kann sagen, um einen Grad intensiver, realer dasjenige, was wir sonst in den Bewußtseinswirkungen haben. Und so, wie wir deutlich sehen die Beziehungen von Sphäre zu Radius in unserem Bewußtsein, müssen wir auch suchen, wenn wir überhaupt irgendwie zu einem Resultat kommen wollen, diesen Gegensatz von Himmelssphäre und Erdenwirkung in demjenigen, was in der Embryonalwirkung vor sich geht. Wir müssen, mit anderen Worten, die Genesis des menschlichen Embryonallebens suchen dadurch, daß wir eine Resultierende bilden zwischen demjenigen, was außen in den Sternen vorgeht als Sphärenwirkung und demjenigen, was im Menschen vorgeht infolge der radialen Erdenwirkung.

Wir müssen mit derselben methodologischen Notwendigkeit das ins Auge fassen, was ich jetzt gesagt habe, wie wir bei der Magnetnadel den Erdmagnetismus ins Auge fassen. Gewiß, es mag viel Hypothetisches dabei sein, das will ich jetzt nicht in Anschlag bringen, ich will nur darauf hinweisen, daß wir kein Recht dazu haben, bloß den Embryo zu betrachten und seine Vorgänge aus ihm selbst zu erklären. Wie wir kein Recht haben, die Vorgänge der Magnetnadel aus ihr selbst zu erklären, so haben wir kein Recht, die Formung des Embryos aus ihm selbst zu erklären, sondern wir müssen ihn erklären, indem wir die beiden charakterisierten Gegensätze ins Auge fassen. Wie wir bei der Magnetnadel den Erdmagnetismus ins Auge fassen, so müssen wir den Gegensatz ins Auge fassen Sphäre - Radialwirkung, um dasjenige, was sich formt im Embryo, zu erklären, was sich dann, wenn der Embryo geboren ist, eben ins Bildhafte des Bewußtseinserlebens abschwächt. Sie sehen also, es handelt sich eben darum, daß wir die Beziehung betrachten, welche im Menschen so besteht zwischen Röhrenknochen und Kopfknochen, auch zwischen den anderen Systemen, dem Muskelsystem, dem Nervensystem und so weiter, und daß, wenn wir diesen Gegensatz betrachten, wir hinausgeführt werden in das kosmische Leben. Und wenn Sie ins Auge fassen, in welch enger Beziehung zu dem, was ich angedeutet habe als den Inhalt des Stoffwechselsystems des Menschen in meinem Buche «Von Seelenrätseln», dasjenige steht, was ich jetzt charakterisiert habe als unter dem Einfluß der Radialität stehend, und in welch enger Beziehung dasjenige steht, was das Kopfsystem ist, zu dem, was ich jetzt charakterisiert habe als unter dem Einfluß der Sphäre stehend, so werden Sie sich sagen: Wir haben im Menschen zu unterscheiden dasjenige, was Bedingungen seines Sinneswesens sind und dasjenige, was Bedingungen seines Stoffwechsellebens sind, und diese beiden verhalten sich zueinander wie Himmelssphäre und Erdenradius.

Wir haben also in all dem, was wir in unserer Hauptesorganisation tragen, das Ergebnis der Himmelswirkung zu suchen, und wir haben, zu einer Resultierenden damit sich vereinigend, zu suchen in den Wirkungen in unserem Stoffwechsel dasjenige, was zur Erde gehört, was nach dem Erdenmittelpunkt gewissermaßen tendiert. Diese zwei Wirkungsgebiete, sie treten auseinander im Menschen, sie konstituieren gewissermaßen zwei Einseitigkeiten, und es ist die Vermittelung das mittlere Gebiet, das rhythmische Glied, so daß wir im rhythmischen Glied in der Tat etwas haben, was uns eine Wechselwirkung des Irdischen und des Himmlischen, wenn ich mich das Ausdrucks bedienen darf, darstellt.

Wenn wir nun weiterkommen wollen, so müssen wir einige andere Verhältnisse, die sich in der Wirklichkeit uns offenbaren, noch ins Auge fassen. Ich mache auf etwas aufmerksam, was sehr innig mit dem zusammenhängt, das ich eben jetzt charakterisiert habe. Sehen Sie, wir haben ja gewöhnlich die Gliederung der uns umgebenden Außenwelt, zu der wir selbst als physischer Mensch gehören, so, daß wir einteilen in Mineralreich, Pflanzenreich, Tierreich, und daß wir dann den Menschen als die höchste Spitze dieser Außenwelt, dieser Reiche der Natur, ansehen. Nun, wenn wir aber uns eine Vorstellung machen wollen, wie eigentlich dasjenige näher beschaffen ist, was wir jetzt zugeordnet haben in bezug auf die Wirkungen den himmlischen Erscheinungen, so müssen wir noch auf etwas anderes schauen.

Es ist ja nicht zu leugnen, denn es ist eigentlich für jeden klar, der die Sache unbefangen beobachtet, daß wir mit unserer menschlichen Organisation, so wie wir jetzt, in der jetzigen Phase unserer Weltentwickelung sind als Menschheit, angepaßt sind mit Bezug auf unser Erkenntnisvermögen lediglich an das Mineralreich. Nehmen Sie diejenige Art von Gesetzmäßigkeit, die wir aufsuchen in der Natur, dann kommen Sie dazu, sich zu sagen: Für dasjenige, was uns umgibt, sind wir durchaus nicht nach allen Seiten angepaßt. Wir verstehen eigentlich, trocken gesagt, nur das mineralische Reich. Deshalb bemühen sich die Leute so stark, auch die anderen Reiche zurückzuführen auf die Gesetze des mineralischen Reiches. Und schließlich ist ja aus diesem Grunde die Verwirrung in bezug auf Mechanismus und Vitalismus entstanden. Entweder bleibt der Vitalismus, wie er in älteren Zeiten war, für die gewöhnliche Anschauung, die einmal die heutige ist, eine vage Hypothese, oder aber man löst dasjenige, was im Vitalismus zutage tritt, in mechanische, mineralische Wirkungen auf. In dem Ideal, einmal das Leben zu verstehen, liegt ja durchaus nicht die Anerkennung, daß man das Leben als Leben verstehen will, sondern es liegt das Bestreben zugrunde, das Leben auf Mineralisches zurückzuführen. Gerade auch darin drückt sich das unbestimmte Bewußtsein aus, daß der Mensch eigentlich angepaßt ist in bezug auf sein Erkenntnisvermögen nur an das Mineralreich, nicht an das Pflanzenreich, nicht an das Tierreich.

Wenn wir nun verfolgen auf der einen Seite das Mineralreich, auf der anderen Seite sein Gegenbild, unsere Erkenntnis des Mineralreiches, dann werden wir, indem sich diese beiden entsprechen, nach den eben vorausgegangenen Auseinandersetzungen genötigt sein, weil wir unsere Erkenntnis beziehen müssen auf die Himmelssphäre, auch dasjenige in irgendeiner Weise mit der Himmelssphäre in Zusammenhang zu bringen, an das diese Erkenntnissphäre angepaßt ist, nämlich das Mineralreich. Wir sagen uns: Wir sind gewissermaßßen mit Bezug auf unsere Hauptesorganisation aus der Himmelssphäre heraus organisiert. Es muß also auch herausorganisiert sein aus der Himmelssphäre in irgendeiner Weise dasjenige, was den Kräften des Mineralreiches zugrunde liegt. Und vergleichen Sie dasjenige, was Sie haben in Ihrer Erkenntnissphäre als den ganzen Umfang Ihrer Erkenntnis vom Mineralreich, mit demjenigen, was draußen im Mineralreich ist, so werden Sie sich sagen: Zu dem, was in Ihnen ist, verhält sich das, was draußen im Mineralreich ist, wie Bild zu Realität.

Aber wir haben doch nötig, diese Beziehung uns konkreter vorzustellen als zwischen Bild und Realität, und da nehmen wir zu Hilfe dasjenige, was wir eben ausgesprochen haben. Wir werden hingewiesen auf dasjenige, was unserem Stoffwechselsystem zugrunde liegt, und auf die Wirkungskräfte, die drinnen sind, die mit dem Erdenwirken zusammenhängen, mit der Radiialität, mit dem Radius auch. Wir werden also, indem wir uns umsehen nach dem, was in uns selber der Gegensatz ist gegenüber derjenigen Organisation, die uns unsere Erkenntnis bringt, von der Sphäre in die Erde verwiesen. Die Radien gehen alle nach dem Erdmittelpunkt. Da haben wir dasjenige in dem Radialen, was wir erfühlen, wodurch wir uns real fühlen. Da haben wir nicht dasjenige, was uns in den Bildwirkungen erfüllt, wo wir bloß bewußt sind, sondern da haben wir dasjenige, was in unserem Erleben uns selbst als eine Realität erscheinen läßt. Wir kommen immer, wenn wir diesen Gegensatz wirklich erleben, in das hinein, was uns das Mineralreich darstellt. Wir werden gewissermaßen von dem, was nur organisiert ist für das Bild, zu dem geführt, was organisiert ist für die Realität. Das heißt mit anderen Worten: Wir werden geführt in bezug auf dasjenige, was als Ursache zugrunde liegt für unsere Erkenntnis, auf den ganzen Umfang der Sphäre, die wir zunächst also als Sphäre auffassen; und wir werden auf der anderen Seite gewiesen, indem wir da alle diejenigen Radien, die von der Sphäre ausgehen, verfolgen, wie sie nach dem Mittelpunkt der Erde hingehen, wir werden gewiesen nach dem Mittelpunkt der Erde als dem polarischen Gegensatz. Wenn wir uns das im einzelnen, im speziellen denken, so könnten wir geradezu so denken, wie das ptolemäische Weltensystem gedacht hat: da draußen die blaue Sphäre, hier (auf der Sphäre) einen Punkt (Fig. 5). Dazu müßten wir uns in einem gewissen Sinne einen Gegenpunkt im Mittelpunkt der Erde denken. So einfach gedacht, würde für jeden Punkt ein Gegenpunkt im Mittelpunkt der Erde sein. Aber Sie wissen ja - ich werde darauf noch näher zu sprechen kommen; das kommt für uns Jetzt nicht in Frage, inwieweit die Dinge genau der Realität entsprechen -, wir haben es nicht so aufzufassen, sondern wir haben zum Beispiel hier die Sterne (Fig.6, äußere Punkte \(a\), \(b\), \(c\)). Wenn wir uns die Sphäre selbst im Mittelpunkt der Erde konzentriert denken müssen, so müssen wir uns natürlich die Gegenpole so konstruieren, daß wir sagen: Der Gegenpol dieses Sternes ist hier, der Gegenpol dieses Sternes ist da und so weiter. Wir kommen dadurch zu einem vollständigen Gegenbild desjenigen, was draußen ist, im Erdinnern selber.

Wir kommen gewissermaßen nun, wenn wir das für irgendeinen Planeten auffassen, zum Jupiter und zu einem Gegenjupiter im Innern der Erde. Wir kommen zu etwas, was vom Innern der Erde nach außen so wirkt, wie der Jupiter draußen wirkt. Wir kommen zu einer Spiegelung - in Wirklichkeit ist die Sache umgekehrt, aber ich will jetzt so sagen -, zu einer Spiegelung desjenigen, was draußen ist, im Innern der Erde. Und wenn wir uns nun die Wirksamkeit denken dieser Spiegelung in den Gestalten unserer Mineralien, dann müssen wir uns denken die Wirksamkeit desjenigen, was in der Sphäre draußen wirkt, in der Gestaltung unseres Erkenntnisvermögens für das Mineralische. Mit anderen Worten: Wir können uns denken die ganze Himmelssphäre in der Erde gespiegelt; wir können uns denken das Mineralreich der Erde als ein Ergebnis dieser Spiegelung, und wir können uns denken, daß dasjenige, was in uns lebt zur Auffassung dieses Mineralreiches, von dem, was draußen im Raume uns umgibt, herrührt. Und die Realien, die wir begreifen dadurch, die rühren vom Innern der Erde her.

Sie brauchen diese Vorstellung nur zu verfolgen und brauchen dann bloß einen Blick auf den Menschen zu werfen, auf das menschliche Antlitz, und Sie werden, wenn Sie sich dieses menschliche Antlitz anschauen, kaum gar so stark zweifeln können, daß da irgend etwas von einem Abdruck der äußeren Himmelssphäre in diesem menschlichen Antlitz enthalten ist, und daß da in dem, was als BildErleben der Himmelssphäre präsent ist in der Seele, eben wiederum dasjenige zutage tritt, was, nachdem die Kräfte intensiver gewirkt haben während des Embryonallebens, aus dem Gebiete der körperlichen Wirksamkeit gewissermaßen herauforganisiert wird in das Gebiet der seelischen Wirksamkeit. Und so bekommen wir zunächst einen Zusammenhang zwischen demjenigen, was draußen in der Realität ist und unserer Organisation für diese äußere Realität. Wir sagen uns gewissermaßen: Dasjenige, was in der äußeren Realität draußen ist, das produziert der Kosmos, und unser Erkenntnisvermögen für diese Realität wird dadurch physisch organisiert, daß die Sphäre bloß auf unser Erkenntnisvermögen noch wirkt. Daher haben wir zu unterscheiden, selbstverständlich auch in der Genesis der Erde, eine Phase, in der starke Wirkungen so auftreten, daß aus dem Kosmos heraus konstituiert wird die Erde selbst, und eine spätere Phase der Erdenentwickelung, wo die Kräfte so wirken, daß konstituiert wird das Erkenntnisvermögen für diese realen Dinge.

Nur auf diese Weise kommt man wirklich heran an die Welt. Sie können nun sagen: Ja, das ist eine Erkenntnismethode, die weniger sicher ist als diejenige, die heute mit dem Mikroskop und dem Teleskop befolgt wird. Mag sein, daß sie dem Menschen weniger sicher vorkommt, aber wenn die Dinge so beschaffen wären, daß man eben mit denjenigen Methoden, die heute beliebt sind, nicht an die Realität herankommen könnte, wenn eben die absolute Notwendigkeit vorläge, daß man mit anderen Arten des Erkennens die Wirklichkeit umfassen muß, dann muß man sich eben bequemen, diese anderen Arten des Erkennens auszubilden. Damit ist es ja nicht getan, daß jemand sagt: Solche Gedankengänge, wie sie hier entwickelt werden, die wolle er nicht mitmachen, weil sie ihm zu unsicher erschienen. Ja, aber wenn nur dieser Grad eben der Sicherheit möglich wäre! Sie werden jedoch sehen, wenn Sie wirklich diesen Gedankengang verfolgen, daß dieser Grad von Sicherheit eben in derselben Weise intensiv ist, wie dasjenige, was lebt in Ihrer Auffassung eines äußeren realen Dreiecks, wenn Sie es mit der inneren Konstruktion des Dreiecks umfassen. Es ist schon dasselbe Prinzip, dieselbe Art und Weise der Erfassung der äußeren Wirklichkeit in dem einen wie in dem anderen wirksam. Das ist dasjenige, was ins Auge gefaßt werden muß.

Nun frägt es sich allerdings: Wenn wir diese Gedanken nehmen, wie ich sie jetzt entwickelt habe, dann kann man in einer gewissen allgemeinen Weise solche Zusammenhänge sich vergegenwärtigen, aber wie kommen wit dann dazu, vielleicht noch in einer bestimmteren Art diese Dinge aufzufassen? Denn erst in einer bestimmteren Art können sie uns dazu dienen, daß wir von uns aus das Gebiet der Wirklichkeit begreifen. Und um das hier verfolgen zu können, muß ich noch auf etwas anderes aufmerksam machen. Gehen wir noch einmal zurück auf dasjenige, was ich gestern zum Beispiel gesagt habe mit Bezug auf die Cassinische Kurve (siehe Fig. 3-7). Wir wissen, daß die Cassinische Kurve drei, sogar, wenn wir wollen, vier Formen hat. Es beruht, wie Sie wissen, die Cassinische Kurve darauf, daß, wenn ich den Abstand von \(A\) zu \(B\) mit \(2a\) benenne, irgendein Punkt \(M\) so liegt, daß \(AM \cdot MB = b^2\), also konstant ist. Ich bekomme die verschiedenen Formen der Cassinischen Kurve heraus, je nachdem \(a\), also die halbe Entfernung der beiden Brennpunkte, größer ist als \(b\) oder gleich oder kleiner. Ich bekomme die Lemniskate, wenn \(a\) gleich \(b\) ist, und ich bekomme die diskontinuierliche Kurve, wenn z größer ist als \(b\).

Nun denken Sie sich, ich würde nicht bloß diese geometrische Aufgabe lösen wollen, unter der Voraussetzung von zwei konstanten Größen \(a\) und \(b\) durch die entsprechenden Gleichungen die Entfernung von \(M\) zu \(A\) und \(B\) zu bestimmen, sondern ich würde noch etwas anderes machen. Ich würde die Aufgabe lösen, aus einer Linienform in die andere in der Fläche überzugehen, indem ich diejenigen Größen, die für eine besondere Linie konstant bleiben, als veränderliche Größen behandle. Nicht wahr, ich habe hier nur Einzelfälle ins Auge gefaßt, einmal wenn \(a\) größer ist als \(b\), dann wenn \(a\) kleiner ist als \(b\). Zwischen diesen Einzelfällen sind unzählige andere möglich. Ich kann, wenn ich unzählige mache, dazu übergehen, ganz kontinuierlich verschiedene Formen der Cassinischen Kurve zu konstruieren. Ich werde diese verschiedenen Formen dann bekommen, wenn ich, sagen wir, der Variabilität der ersten Ordnung, die ich jetzt zwischen \(y\) und \(x\) hingestellt habe, eine Variabilität der zweiten Ordnung zufüge; wenn ich meine Konstruktion der kontinuierlich ineinander übergehenden Linien in der Fläche so verlaufen lasse, daß ich \(a\) eine Funktion von \(b\) sein lasse.

Also, was mache ich dann? Ich konstruiere dann so, daß ich ein System, aber ein kontinuserliches, fortlaufendes System von Cassinischen Kurven, in die Lemniskate übergehend, in das Diskontinuierliche übergehend, konstruiere, aber nicht beliebig, sondern so, daß ich zugrunde lege eine Variabilität der zweiten Ordnung, indem ich die Konstanten für die eine Kurve erst selber in den Zusammenhang einer Gleichung bringe, so daß \(a\) eine Funktion von \(b\) ist, \(a = φ(b)\). Es ist durchaus eine mathematisch vollziehbare Sache, selbstverständlich. Was aber bekommen wir dadurch? Denken Sie, dadurch bekomme ich das Gesetz für den Inhalt einer Fläche, die in sich selber aber in all ihren Punkten schon in der mathematischen Auffassung qualitativ verschieden ist. An jedem Punkte ist eine andere Qualität vorhanden. Ich kann die Fläche, die ich dadurch herausbekomme, nicht so auffassen, wie eine abstrakte euklidische Ebene etwa, sondern wie eine in sich differenzierte Fläche. Und wenn ich daraus durch Rotieren Körper bilde, so würde ich bekommen in sich differenzierte Körper.

Wenn Sie dasjenige bedenken, was ich gestern gesagt habe, daß die Cassinische Kurve zu gleicher Zeit die Kurve noch anzeigt, in der sich ein Punkt bewegen muß im Raume, damit er, wenn er von Punkt A beleuchtet ist, in Punkt B stets denselben Glanz zeigt (Fig. 10); wenn Sie also bedenken, daß in der Tat von der Konstanz, die dieser Kurve zugrunde liegt, hier ein Zusammenhang in der Lichtwirkung hervorgeht, so können Sie sich denken, daß geradeso, wie hier aus dem Zusammenhang der Konstanten eine gewisse Lichtwirkung hervorgeht, man sich auch denken kann, daß ein System von Lichtwirkungen folgt, wenn ich zur Variabilität der ersten Ordnung eine Variabilität der zweiten Ordnung hinzufüge. Sie können sich also tatsächlich hier einen Übergang vom Quantitativen ins Qualitative aus der Mathematik heraus selber bilden.

Diese Erwägungen muß man eben anstellen, wenn man, was doch nicht aufgegeben werden darf, einen Übergang finden will vom Quantitativen ins Qualitative. Denn man kann jetzt ausgehen von dem, was man da eigentlich tut, indem man eine Funktion bildet innerhalb der Variabilität der zweiten Ordnung in Abhängigkeit von einer Funktion innerhalb einer Variabilität erster Ordnung - der Ausdruck hat nichts zu tun mit dem Ausdruck «Ordnung», wie man ihn sonst vielfach gebraucht; wir verstehen uns ja wohl, da ich die Sache vom Ursprung aus erläutert habe. - Wenn man diesen Zusammenhang zwischen dem, was ich da erste und zweite Ordnung genannt habe, ins Auge faßt, dann wird man nach und nach dazu kommen, einzusehen, daß unsere Gleichungen anders gebildet werden müssen, je nachdem man ins Auge faßt, was zum Beispiel bei einer gewöhnlichen Körperoberfläche zwischen der Körperoberfläche und unserem Auge liegt, und demjenigen, was hinter der Körperoberfläche liegt. Denn ein ähnliches Verhältnis wie das hier zwischen der Variabilität der ersten Ordnung und der Variabilität der zweiten Ordnung besteht zwischen dem, was ich zu berücksichtigen habe zwischen mir und der Oberfläche eines ganz gewöhnlichen Körpers, und demjenigen, was hinter der Körperoberfläche liegt. So zum Beispiel, wenn einmal der Versuch gemacht werden muß, die sogenannte Reflexion des Lichtstrahles zu durchschauen, die einfach dadurch beobachtet wird, daß ich eine spiegelnde Fläche habe, also ein Vorgang, der sich zunächst abspielt zwischen mir und der Körperoberfläche. Wenn ich das so durchschaue, daß ich es fasse als einen Zusammenfluß von Gleichungen, die zwischen mir und der Oberfläche eines Körpers in einer Variabilität erster Ordnung abfließen, und jetzt in diesem Zusammenhang das, was hinter der Oberfläche wirkt, damit die Reflexion zustande kommt, als Gleichung der Variabilität der zweiten Ordnung betrachte, dann werde ich ganz andere Formeln herausbekommen, als diejenigen sind, die man gegenwärtig nach rein mechanischen Gesetzen durch Weglassung von Schwingungsphasen und so weiter für die Reflexions- und Brechungsgesetze anwendet.

Dadurch wird man in die Möglichkeit kommen, eine Mathematik zu schaffen, die mit den Realitäten wirklich rechnen kann. Und das muß im Grunde geschehen, wenn man gerade auf dem Gebiet der astronomischen Erscheinungen wiederum zu Erklärungen kommen will. Denn in bezug auf die äußere Welt haben wir vor uns dasjenige, was gewissermaßen zwischen der Oberfläche der Erdenkörper und uns sich abspielt. Wenn wir die Himmelserscheinungen betrachten, irgendeine Venusschleife oder so was, so haben wir vor uns, wenn wir den gewöhnlichen Tatbestand betrachten, auch etwas, was zwischen uns und irgend etwas anderem sich abspielt. Nur haben wir vor uns dasjenige, was sich so verhält, wie sich dasjenige verhält, was hinter der Sphäre liegt, zu dem, was im Mittelpunkt liegt. Wir müssen also immer, wenn wir auf Himmelserscheinungen hinsehen, uns klarmachen, daß wir sie nicht bloß nach dem System der Zentralkräfte betrachten können, sondern daß wir sie betrachten müssen nach dem System, welches zu dem System der Zentralkräfte sich so verhält, wie die Kugelsphäre zum Radius sich verhält.

Also, wollen wir überhaupt zu einer Erklärung der Himmelserscheinungen kommen, so müssen wir nicht die Berechnungen so anstellen, daß wir sie zum Abbild derjenigen Berechnungen machen, die die Mechanik anwendet, indem sie die Zentralkräfte ausbildet, sondern wir müssen sie so machen, daß diese Berechnungen, das ganze Figurale auch, sich zur Mechanik verhalten wie die Sphäre zum Radius. Dann wird sich schon ergeben, und darüber wollen wir das nächste Mal sprechen, daß wir nötig haben erstens die Denkweise der Mechanik und der Phoronomie, die es im wesentlichen mit Zentralkräften zu tun hat, und daß wir zweitens hinzufügen müssen zu dem ein anderes System, dasjenige System, das es zu tun hat mit rotierenden Bewegungen, mit scherenden Bewegungen und mit deformierenden Bewegungen. Erst dann, wenn wir ebenso berücksichtigen das meta-mechanische, das meta-phoronomische System für die rotierenden, für die scherenden, für die deformierenden Bewegungen, wie wir heute berücksichtigen das System der Mechanik und der Phoronomie für die Zentralkräfte, für die zentralen Bewegungserscheinungen, dann werden wir zu einer Möglichkeit kommen, aus demjenigen, was uns empirisch vorliegt, eine Erklärung der Himmelserscheinungen gewinnen zu können.

Tenth Lecture

Yesterday, based on certain formal considerations, I pointed out how the connections between what can be called the processes in the human metabolic system and the processes in the human head system, in the nervous-sensory system, or whatever you want to call it in the sense of the hints I gave in my book “Von Seelenrätseln” (Mysteries of the Soul).

If one were to observe a magnetic needle in its fluctuations on the earth's surface and attempt to explain these fluctuations solely by what can be observed within the space in which the magnetic needle is located, one would naturally consider this impossible. You know that these fluctuations of the magnetic needle are associated with the Earth's magnetism. You know that the respective direction of the magnetic needle is associated with the direction of the Earth's magnetism, or rather with the line of direction that can be drawn between the northern and southern magnetic poles of the Earth, so that when it comes to explaining the phenomena presented to us by the magnetic needle, one leaves the realm of the magnetic needle itself and attempts to enter, with the elements used for explanation, into that totality which alone offers the possibility of explaining the phenomena of something that belongs to this totality in the course of events. This methodological rule is certainly observed for certain phenomena, namely those phenomena for which the matter lies entirely on the surface. However, it is not observed when it comes to explaining and understanding more complicated phenomena.

Just as it would be impractical to explain the phenomena of the magnetic needle from the needle itself, it is equally impractical to explain the phenomena that occur in the organism from this organism or from certain contexts that do not belong to a totality. And precisely for this reason, because there is so little effort to advance toward totalities when explanations are sought, we arrive at what constitutes the approach of our science, insofar as larger contexts are almost completely disregarded today. It includes certain phenomena, I would say, in the field of view of the microscope and the like; it includes stellar phenomena in what we can initially perceive externally, perhaps also perceive through the instruments we use for this purpose, but there is no endeavour to advance to the total context within which any phenomenon lies, which is to be taken into account first and foremost when it comes to explanations. Only when one becomes familiar with this absolutely indispensable methodological principle is one in a position to judge correctly such things as those to which I drew attention yesterday. For only in this way will one come to appreciate in the right way how, in a closed total context, such areas of phenomena as those we encounter in the human organism stand out.

Let us recall once more the remarks I made at the very beginning of these considerations. I drew your attention to the fact that the principle of metamorphosis actually has to be modified if this metamorphosis, as first revealed by Goethe and Oken, is to be applied in a truly comprehensible way to human morphology. It is true that attempts were made — and Goethe's attempt was a brilliant one — to trace the formation of the skull bones back to the formation of the vertebrae. These investigations were then continued by others in a manner more in keeping with 19th-century methods, and the entire progress – whether it was progress or not, I will not decide now – in the method of investigation can be studied by comparing how this problem of the metamorphic transformation of the bones was understood on the one hand by Goethe and Oken, and on the other hand, for example, by the anatomist Gegenbaur. These things can only be brought to a realistic basis when one knows—as I have already mentioned in the course of these lectures, but we will now pick up on this point—how two bones in the human skeleton that are furthest apart in their morphology—that is, not in the animal skeleton, but in the human skeleton—are actually connected. The two bones that are furthest apart are a long bone, for example a thigh bone or upper arm bone, and a skull bone. If one simply compares them externally, without going into the interior and without considering their overall appearance, one cannot arrive at the morphological connection between two bones that are polar opposites in terms of shape. One can only arrive at this conclusion by comparing the inner surface of a long bone with the outer surface of a skull bone. This provides the corresponding surface area in question (Fig. 1), which is needed to establish the morphological connection. One then realizes that the inner surface of the long bone corresponds to the outer surface of the skull bone—that is morphological—and that the whole thing is based on the fact that the skull bone can be derived from the long bone if one thinks of it as being turned inside out, following the principle of turning a glove inside out. If I turn the outer surface of the glove into the inner surface and the inner surface into the outer surface, I do indeed obtain a similar shape to the glove, but if, in addition, various tensile forces come into play at that moment, if, so to speak, at the moment when I turn the inside of the tubular bone outward, the tension ratios change in such a way that the inner form turned outward is distributed differently across the surface, then by turning it inside out according to the principle of turning a glove inside out, you get the outer surface of the skull bone, derived from the inner surface of the tubular bone. From this, however, it becomes clear to you that the interior of the tubular bone, this compressed interior of the tubular bone, corresponds to the entire outside world in relation to the human skull. You must therefore consider the following as belonging together in their effect on human beings: the external world, which forms the exterior of the head, and that which acts internally, in a sense mirroring the inner surface of the long bones. You must consider these as belonging together. You must, in a sense, regard the world inside the long bones as a kind of inverse world to the one that surrounds us externally.

First of all, you have the true principle of metamorphosis for bone structure. For the other bones are essentially intermediate structures, morphological intermediate structures between the polar opposites, which correspond to a complete reversal with a change in the forces that determine the surface area. But this must be extended to the entire human organization. In the case of bones, it becomes particularly clear to us in a certain sense. It should be noted for all human organs that when we speak of the organism, we must distinguish between two polar opposites: between what, let us say for now, has an effect from an unknown interior, so to speak, and what has an effect from the outside to the inside. But what has an effect from the outside to the inside basically corresponds to everything that surrounds us humans from outside the earth. And you actually get two extraordinary opposites when you look at, say, the tubular bone and imagine this line in it (Fig. 2). You get, as it were, a line that contains the point of origin of what acts vertically on the surface in question.

And if you think of the human skull, you also get what corresponds to this line (Fig. 2, dashed). But how should you draw what corresponds to this line? You have to draw it somewhere as a circle, or even a spherical surface, a spherical surface located at some indeterminate distance (Fig. 4). And all the lines that you draw from the straight line towards the surface of the tubular bone (Fig. 3) correspond, in relation to the skull bone, to all the lines that you draw, as it were, from some sphere meeting at the center of the earth (Fig. 4). This gives you a connection—of course, things are approximate—between a straight line or a system of straight lines that pass through a tubular bone and are all related in some way to the vertical axis of the organization, between this direction, which actually coincides with the direction of the Earth's radius, and a sphere that surrounds the Earth at an indeterminate distance. You get the connection that allows you to say: With regard to the structure of the human being, which is perpendicular to the Earth's surface, the radius of the Earth has the same cosmic value as a spherical surface, a cosmic spherical surface with regard to the skull organization.

But this brings out the same contrast that you actually feel within yourself when you pay attention to the inner feeling of your organism and at the same time to your outer experience. You get this contrast when you take your sense of self, the sense of self that is essentially based on the fact that you can calmly surrender to your physicality in normal life, that you do not become dizzy, but are in a relationship with gravity, and when you then compare this, which in a certain sense is your sense of self, with everything that is present in your consciousness in relation to what you see around you through your senses, up to the stars.

When you take all this together, you can say: the relationship between this inner feeling and the feeling of consciousness in perceiving the outer world is the same as that between your physique and the structure of your skull. And this points us to the relationship between what we might initially call the effect of the earth on human beings, which acts in the sense of the radius of the earth, and what we might call the effect that manifests itself in the scope of our consciousness, which we must seek in the sphere, in what is actually the inner wall, the inner surface of a spherical shell. And for our normal everyday consciousness, it is this contrast that we can roughly perceive, if we leave out what is in our consciousness from the observations of our earthly environment, as the contrast between what is the sphere of the stars and earthly consciousness, the feeling of being earthly, the earthly impulse that lives within us. When we relate this earthly impulse, the radial earthly impulse, to our consciousness of the sphere, this contrast, when we look at it in our ordinary everyday consciousness, is essentially something that takes place within us, precisely in our consciousness. We live within this contrast more than we usually think. This contrast is actually always there, within which we live. And we cannot really study the relationship between mental image and will in any other way than by considering this contrast between the sphere and the radius. In psychology, too, we would arrive at more realistic results concerning the relationship between our extraordinarily expansive world of ideas and the more uniform world of will if we were to place this diverse, more expansive world of ideas in a similar relationship to the world of will, as can be visualized by the relationship between the surface area of a sphere and the corresponding radius of that sphere.

Let us now consider what has such an effect on our daily consciousness that it is, in a sense, the fulfillment of our spiritual life, when we are in a different situation than the one in which we develop this daily consciousness. Let us consider what has such an effect on us during the time when we are going through our embryonic life, and we can well form a mental image, indeed we must form a mental image, that the same opposition is at work there, only it is lived out in a different way. There we do not carry the same activity toward the world, which then weakens this whole opposition to an opposition of images, but there this opposition is effective on our malleable organization in a more real way than it is effective as an opposition of images when we have it in our soul life. If we project the effects of consciousness back in time to embryonic life, then we have in embryonic life, one might say, a degree more intense, more real, what we otherwise have in the effects of consciousness. And just as we clearly see the relationships between sphere and radius in our consciousness, we must also seek, if we want to arrive at any kind of result, this contrast between the sphere of the heavens and the effect of the earth in what is happening in the embryonic effect. In other words, we must seek the genesis of human embryonic life by forming a resultant between what goes on outside in the stars as sphere effect and what goes on inside the human being as a result of the radial earth effect.