On the Dimensions of Space

GA 213

24 June 1922, Dornach

Translator Unknown

My dear Friends,

The things I shall have to explain to-day may be apparently a little far removed from our more concrete studies of Anthroposophy. They are however a necessary foundation for many other perceptions which we need—a foundation on which we shall afterwards have to build in our more intimate considerations.

There is a certain inherent difficulty for our human power of knowledge and understanding when we speak of the physical bodily nature of man on the one hand, and the soul-and-spirit on the other. Man can gain ideas about the physical and bodily with comparative ease, for it is given to him through the senses. It comes out to meet him, as it were, from his environment on all sides, without his having to do very much for it himself—at any rate so far as his consciousness is concerned. But it is very different when we come to speak of the soul-and-spirit. True, if he is open-minded enough, man is distinctly aware of the fact that such a thing exists. Men have always received into their language designations, words and phrases referring to the soul-and-spirit. The very existence of such words and phrases shews after all, for an open-minded consciousness, that something does exist to draw man's attention to the reality of soul-and-spirit.

But the difficulties begin at once when man endeavours to relate the world of things physical and bodily with the world of soul and spirit. Indeed for those who try to grapple with such questions philosophically, shall we say, the search for this relationship gives rise to the greatest imaginable difficulties. They know that the physical and bodily is extended in space. They can even represent it spatially. Man forms his ideas of it comparatively easily. He can use all that space with its three dimensions gives to him, in forming his ideas about things physical and bodily. But the spiritual as such is nowhere to be found in space.

Some people, who imagine they are not materialistically minded—though in reality they are all the more so—try to conceive the things of the soul and spirit in the world of space. Thus they are led to the well-known spiritualistic aberrations. These aberrations are in reality materialistic, for they are an effort to bring the soul and spirit perforce into space.

But quite apart from all that, the fact is that man is conscious of his own soul-and-spirit. He is well aware of how it works, for he is aware that when he resolves to move about in space his thought is translated into movement through his will. The movement is in space, but of the thought no open-minded, unbiased thinking person can assert that it is in space. In this way the greatest difficulties have arisen, especially for philosophic thinking.

People ask: How can the soul-and-spirit in man—to which the Ego itself belongs—work upon the physical and bodily which is in space? How can something essentially unspatial work upon something spatial?

Diverse theories have arisen on this point, but they all of them labour more or less under the difficulty of bringing the soul-and-spirit, which is unspatial, into relation with the physical and bodily, which is spatial. Some people say: In the will, the soul-and-spirit works upon the bodily nature. But in the first place, with ordinary consciousness, no one can say how the thought flows into the will, or how it can be that the will, which is itself a kind of spiritual essence, manifests itself in outer forms of movement, in outer activities.

On the other hand the processes which are called forth by the physical world in our senses—i.e., in the bodily nature—are also processes extended in space. Yet inasmuch as they become an experience in soul and spirit, they are transformed into something non-spatial. Man cannot say out of his ordinary consciousness, how the physical and spatial process which takes place in sense-perception can influence the non-spatial, the soul-and-spirit.

In recent times, it is true, men have sought refuge in the conception, to which I have often referred, of ‘psychophysical parallelism.’ It really amounts to a confession that we can say nothing of the relation of the physical and bodily to the soul-and-spirit. It says, for example: The human being walks, he moves his legs, he changes his position in external space. This is a spatial, a physical-bodily process. Simultaneously, while this is taking place in his body, a process of soul-and-spirit is enacted—a process of thought, feeling and will. All that we know is that when the physical and bodily process takes place in space and time, the process of soul and spirit also takes place. But we have no concrete idea of how the one works upon the other. We have psycho-physical parallelism: a psychical process takes its course simultaneously with the bodily process. But we still do not get behind the secret—whose existence is thus expressed—that the two processes run parallel to one another. We gain no notion of how they work on one another. And so it is invariably, when men try to form a conception of the existence of the soul-and-spirit.

In the 19th Century, when the ideas of men were so thoroughly saturated with materialism, even this question could arise:—Where do the souls sojourn in universal space when they have left the body? There were even men who tried to refute spiritualism by proving that when so and so many men are dying and so and so many are already dead, there can be no room in the whole world of space for all these souls to find a place of abode! This absurd line of thought actually arose more than once during the 19th Century. People said, Man cannot be immortal, for all the spaces of the world would already have been filled with their immortal souls.

All these things indicate what difficulties arise when we seek the relation between the bodily and physical, clearly spread out as it is in space, and the soul and spirit which we cannot in the first place assign to the spatial universe.

Things have gradually come to this pass; our purely intellectualistic thinking has placed the bodily-physical and the soul-and-spirit sharply and crudely side by side. For the modern consciousness they stand side by side, without any intermediary. Nor is there any possibility of finding a relation on the lines along which people think of them to-day. The man of to-day conceives the spatial and physical in such a way that the soul has no conceivable place in it. Again, he is driven to conceive the soul-qualities so sharply separated from the physical and bodily, that the absolutely unspatial soul-and-spirit, as he conceives it, cannot possibly impinge at any point upon the physical. ...

This sharp contrast and division was however only developed in the course of time. We must now begin again from an altogether different angle of approach, which is only made possible once more by taking our start from what anthroposophical spiritual science has to say.

In the first place, anthroposophical science must consider the nature of the will. To begin with, straightforward observation shews undoubtedly that the will of man follows his movements everywhere. Moreover, the movements man accomplishes externally in space when he moves about, and those too which take place within him in the fulfilment of his everyday functions of life, in a word, all the activities of man in the physical world-are in the three dimensions of space. Hence the will must also go everywhere, wherever the three dimensions extend. Of this there can be no doubt.

Thus if we are speaking of the will as of an element of soul-and-spirit, there can be no question but that the will—albeit a thing of soul and spirit—is three-dimensional. It has a three-dimensional configuration.

We cannot but think of it in this way:—When we carry out a movement through our will, the will adapts itself and enters into all the spatial positions which are traced, for example, by the arm and hand. The will goes with it everywhere, wherever the movement of a limb takes place. Thus after all we must speak of the will as of a quality of soul which can assume a three-dimensional configuration.

Now the question is, do all the soul-qualities assume this three-dimensional configuration? Let us pass from the Will to the world of Feeling. To begin with, we can make the same kind of observation. Considering the matter with the ordinary everyday consciousness, man will say to himself, for example: ‘If I am pricked by a needle on the right-hand side of my head, I feel it; if I am pricked on the left-hand side I feel it also.’ In the everyday consciousness he can, therefore, be of opinion that his Feeling is spread out over his whole body. He will then speak of Feeling as having a three-dimensional configuration in the same sense as the Will. But in so doing he gives himself up to an illusion. It is not really so. The fact is, at this point there are certain experiences which every man can have in his own nature, and from these we must take our start today. Our considerations will have to be somewhat subtle, but spiritual science cannot really be understood without subtlety of thought.

Consider for a moment what it is like when you touch your own left hand with your right. You have a perception of yourself thereby. Just as in other cases you perceive an outer object, so do you perceive yourself when you touch your right hand with your left hand-say with the several fingers one by one.

The fact to which I am referring appears still more distinctly when you consider that you have two eyes. To focus an object with both eyes you have to exert your will to some extent. We often do not think of this exertion of the will. It comes out more strongly when you try to focus a very near object. You then endeavour to turn your left eye towards the right and your right eye towards the left. You focus an object by bringing the lines of vision into contact, just as you bring your right and left hands into contact when you touch yourself. From these examples you can see that it is of some importance for man, with respect to his orientation in the world, to bring his left and right into a certain mutual relation. By the contact of the hands or the crossing of the lines of vision we can thus become aware of an underlying fact which is of deep significance. Though the everyday consciousness does not generally go farther than this, it is possible to continue very much farther along this line of study.

Suppose we are pricked by a needle on the right-hand side of our body. We feel the prick. But we cannot really say so simply ‘where’ we feel the prick-meaning by ‘where’ some portion of the surface of our body. For unless the several members of our organism stood in a living mutual relationship to one-another,—unless they were working one upon the other—our human nature, body and soul together, would not be what it is. Even when our body is pricked, let us say, on the right-hand side, there is always a connection established from the right-hand side to the central plane of symmetry. For any feeling or sensation to be brought about, the left half of the body must always enter into relation with the right.

It is comparatively easy to realise—if this be the plane of symmetry, seen from in front—that when the right hand touches the left the mutual feeling of the two hands is brought about in the plane of symmetry. It is comparatively easy to speak of the crossing of the lines of vision from the two eyes. But there is always a connecting line in every case—whenever we are pricked, for example, on the right-hand side;—the left half of the body crosses with the connecting line from the right. Without this process, the sensation would never come about. In all the surging waves of feeling and sensation, the fact that we have a right and a left half of the body—the fact that we are built symmetrically—plays an immense part. We always relate to the left-hand side what happens to us on the right. In a vague groping way something reaches over in us from the left, to cross with what is flowing from the right.

Only so does Feeling come about. Feeling never comes about in space, but only in the plane. Thus the world of Feeling is in reality spread out, not three-dimensionally, but two-dimensionally. Man experiences it only in the plane which as a plane of section would divide him into two symmetrical halves.

The life of Feeling is really like a painting on a canvas—but we are painting it not only from the one side but from both. Imagine that I here erect a canvas, which I paint from right to left and from left to right, and observe the interweaving of what I have painted from the one side and the other. The picture is only in two dimensions. Everything three-dimensional is projected, so to speak, into the two dimensions.

You can arrive at the same idea in a somewhat different way. Suppose you were able to project on to a flat surface shadow-pictures of objects on the right-hand side and on the left. On the flat expanded wall you then have shadows of left- and right-hand objects. So it is with our world of Feeling. It is two-dimensional, not three-dimensional. Man is a painter working from two sides. He does not simply feel his way into space. Through his three-dimensional will he projects on to a plane in shadow-forms, in pictures, the influences of feeling which meet him in the world of space. In his life of feeling, man lives in a picture drawn two-dimensionally through his body-only it is for ever being painted from both sides. Thus if we would seek the transition from Will to Feeling in ourselves—as human beings in the life of soul—we must pass from the three-dimensional into the two-dimensional.

But this will already give you a different spatial relationship of the soul-quality which is expressed in feeling, than if you merely say of the soul-life that it is unspatial. The plane has two dimensions, but it has no ‘space.’ Take any plane in the outer world—the blackboard for example. In reality it is a solid body, it has a certain thickness. But an actual plane, though it is in space, is not in itself spatial. ‘Space’ must always be of three dimensions; and only our Will enters into this three-dimensional space. Feeling does not enter into the three dimensions of space. Feeling is two-dimensional. Nevertheless it has its own relations to space, just as a shadow-picture has. In saying this, I am drawing your attention at the same time to a fact of very great importance, which is not at all easy to penetrate with clear perception, because with his everyday consciousness man has little inclination as a rule to perceive the peculiar nature of his world of Feeling.

The fact is that the world of Feeling is always permeated by the Will. Think only for a moment of this: If you really receive on the right-hand side of your body the prick or sting of which we spoke just now, you do not immediately sever the Feeling from the Will. You will certainly not patiently receive the sting. Quite apart from the fact that you will probably reach out in a very tangible way, striking out pretty intensely with your Will into the three dimensions of space ; inwardly too there will be a defensive movement which does not appear externally but shews itself in all manner of delicate disturbances of the blood and the breathing. The defensive movement which we make, when, stung by a gnat, we reach out with our hand, is only the crudest and most external aspect. Of the finer aspect—the inner defensive movement which we perform in the motion of the blood and breathing and many another inward process—we are generally unaware. Hence we do not distinguish what the Will contributes from the content of Feeling as such.

The real content of Feeling is in fact far too shy, far too elusive. We can only get at it by very careful meditation. If however you can exclude, from the Feeling as such, all that belongs to the Will, then as it were you shrink together from the right and left and you become the plane in the middle. And when you are the central plane, and like a conscious painter you record your inner experiences on this plane, then you begin to understand why the real world of Feeling is so very different from our ordinary, everyday experience.

We can indeed experience this plane-quality, this surface-quality of Feeling. But it needs to be experienced meditatively. We must feel all the shadow-likeness of our feelings as against the robust outer experiences in three-dimensional space. We must first prepare ourselves for this experience, but if we do so we can really have it, and then we gradually come near the truth that Feeling takes its course in two dimensions.

How shall we characterise Thinking? To begin with we must admit with open and unbiased mind how impossible it is to speak of a thought as if it were in space. A thought is really nowhere there in space. Nevertheless the thought must have some relation to space, for undoubtedly the brain—if not the instrument—is at least the foundation of our Thinking. Without the brain we cannot think. Thus our Thinking takes its course in connection with the activity of the brain. If Thinking had nothing to do with space, we should get the following curious result: If you were able to think well as a child of 12, your head having now grown beyond the position in which it was when you were 12 years old, you would have grown out of your Thinking. But that is not the case. As we grow up, we do not leave our Thinking behind. The very fact of growth will serve to indicate that even with our Thinking we are somehow in the world of Space.

The fact is this. Just as we can separate out the world of Feeling—the world of inner experience of our Feelings—by learning gradually to perceive our plane of symmetry, so too we can learn to experience our Thinking meditatively, as something that only has extension upward and downward. Thinking is one-dimensional. It takes its course in man in the line.

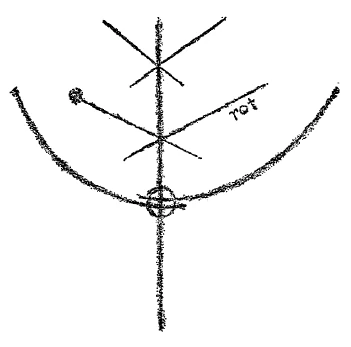

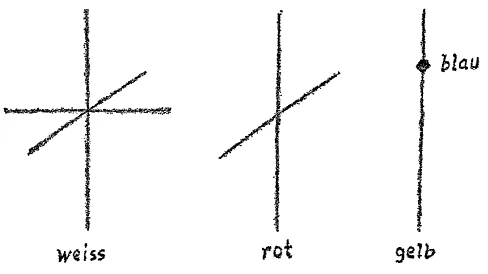

In a word, we must say: The Will takes on a three-dimensional configuration, the Feeling a two-dimensional and the Thinking a one-dimensional configuration.

When we make these inner differentiations of space, we do not arrive at the same hard-and-fast transition as the mere intellect. We are led to perceive a gradual transition. The mere intellect says : The physical is three-dimensional, spatially extended. The soul-and-Spirit has no extension at all. From this point of view no relationship can be discovered between them. For it goes without saying, there is no relationship between that which has extension and that which has none. But when once we perceive that the Will has a three-dimensional configuration, then indeed we find that the Will pours itself out everywhere into the three-dimensional world. And again, when once we know that Feeling has a two-dimensional configuration, then we must pass from the three dimensions to the two, and as we do so we are led to something which still has a relationship to space, though it is no longer spatial in itself. For the mere plane—the two-dimensional—is not spatial, but the two dimensions are there in space; they are not entirely apart from space. Lastly, when we pass from Feeling to Thinking we pass from the two dimensions to the one. Thus we still do not go right out of space. We pass over gradually from the spatial to the unspatial.

As I have often said, it is the tragedy of materialism that it fails to understand the material-the material even in its three-dimensional extension. Materialism imagines that it understands the material, substantial world, but that is precisely what it does not understand. Many things of real historic importance emerged in the 19th century, which still present an unsolved riddle to the ordinary consciousness. Think only of the great impression which Schopenhauer's philosophic system, The World as Will and Idea, made on so many thinking people. There is something unreal in the Idea, says Schopenhauer. The Will alone has reality. Why did Schopenhauer arrive at the idea that the world only consists of Will? Because even he was infected with materialism. Into the world in which matter is extended three-dimensionally, only the Will pours itself out. To place the Feelings too into this world, we must look for the relationship which obtains between the three-dimensional object and the two-dimensional image on the screen. Whatever we experience in our Feelings is a shadow-picture of something in which our Will too is living in its three-dimensional configuration. And what we experience in our Thinking consists of one-dimensional configurations. Only when we go right out of the dimensions—that is to say, when we pass to the dimensionless point,—only then do we arrive at our I or Ego. Our Ego has no extension at all. It is purely point-like, ‘punctual.’

So we may say, we pass from the three-dimensional to the two-dimensional, to the one-dimensional and to the ‘punctual.’ So long as we remain within the three-dimensional, there is our Will in the three dimensions. Our Feeling and our Thinking are also there within them, only they are not extended three-dimensionally. If we leave out the third dimension and come down to the two dimensions, we only have the shadow of outward existence, but in the shadow is extended that element of soul-and-spirit which lives in our Feeling. We are already getting more away from space. Then, when we go on to Thinking, we come away from space still more. And lastly when we pass on to the Ego, we go right out of space.

Thus we are led out of space, as it were piece by piece. Now we see that it is meaningless merely to speak of the contrast between the soul-and-spirit, and the physical and bodily. It is meaningless, for if we wish to discover the relation between the soul-and-spirit and the physical and bodily, we must ask: How are things which are extended in three-dimensional space (our own body, for example) related to the soul as a being of Will? How is the bodily and physical in man related to the soul as a being of Feeling? The bodily and physical is related to the soul as a being of Will in such a way that one would say, it is saturated by the Will on all sides, in all dimensions, just like the sponge is saturated by water. Again, the bodily and physical is related to the Feeling, like objects whose shadows are thrown upon the screen. And when we pass from Feeling to the quality of Thought, then we must indeed become strange painters—for we must paint on to a line what is otherwise existing in the two dimensions of the picture.

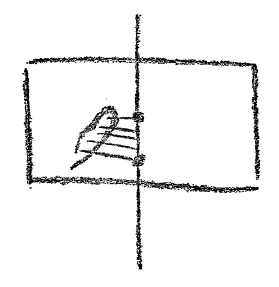

Ask yourselves the following question. (It will indeed make some demands on your imagination.) Suppose that you are standing face to face with the ‘Last Supper’ by Leonardo da Vinci. You have it before you in the surface. The whole thing is two-dimensional—for we need not take into account the thickness of the colours. The picture which you have before you is essentially two-dimensional.

But now imagine to yourselves a line, drawn through the middle from top to bottom of the picture. This line shall represent a one-dimensional being. Imagine that this one-dimensional being has the peculiar quality that Judas, let us say, is not indifferent to him. He feels Judas in a certain way. He feels him more where Judas inclines his head in that direction, and where Judas turns away he feels him less. Likewise this one-dimensional being feels all the other figures. He senses them differently according as the one figure is in blue and the other in a yellow colour. He feels all that is there, to the left and to the right of him. All that is present in the picture is livingly felt by this one-dimensional being.

Such in reality is our Thinking within us. Our Thinking is a one-dimensional being of this kind, and only partakes in the life of the remainder of our human being inasmuch as it is related to the picture which divides us into the left- and right-hand man. Via this two-dimensional picture, our Thinking stands in relation to the world of Will with its threefold configuration.

If we wish to gain an idea of our being of soul-and-spirit (to begin with without the Ego; only in so far as it is willing, feeling and thinking) we must conceive it not as a mere nebulous cloud. We must regard the soul and spirit, as it were diagramatically. There it appears, to begin with, as a cloud, but that is only the being of Will. It has the constant tendency to become pressed together; thereby it becomes a being of Feeling. First we see a cloud of light. Then we see the cloud of light creating itself in the centre as a plane, whereby it feels itself. And the plane in turn strives to become a line. We must conceive this constant process—cloud, plane and line as an inwardly living form. It constantly tends to be a cloud, and then to squeeze together from the cloud into the plane, and then to elongate into the line. Imagine the plane that becomes a line and then a plane again and then again a cloud in three dimensions. Cloud, plane line; line, plane, cloud, and so on. Only so can you imagine graphically what your soul is in its inner being, its inner nature and essence. An idea that remains at rest will not suffice. No idea that remains at rest within itself can reproduce the essence of the soul. You need an idea with an inner activity of its own. The soul itself, as it conceives itself, plays with the dimension of space. Letting the third dimension vanish, it loses the Will. Letting the second dimension vanish, it loses the Feeling. And the Thinking is only lost when we let the first dimension vanish. Then we arrive at the point, and then only do we pass over to the Ego.

Hence all the difficulty in gaining a knowledge of the soul. People are accustomed only to form spatial ideas. Hence they would like to have spatial ideas—however diluted—of the soul's nature. But in this form they only have the element of Will.

Unless we make our thinking inwardly alive and mobile we can reach no conception of the soul-and-spirit. If we wish to conceive a quality of soul-and-spirit, and our conception is the same in two successive instants, we shall at most have conceived a quality of Will. We must not conceive the soul-and-spirit in the same form in two successive moments. We must become alive and mobile-not by moving from one point in space to another, but rather by passing from one dimension to another. This is difficult for the modern consciousness. Hence even the most well-meaning people—well-meaning for the conception of spiritual things—have tried to escape from Space by transcending the three dimensions. They come to a fourth dimension. They pass from the three-dimensional to the four-dimensional. So long as we remain within the mathematical domain, the thoughts which we arrive at in this way are quite in order. It is all perfectly correct. But it is no longer correct when we relate it to the reality. For the peculiar thing is, that when we think the fourth dimension in its reality, it eliminates the third. Through the fourth dimension the third dimension vanishes. Moreover, through the fifth dimension the second vanishes, and through the sixth the first vanishes, and we arrive at length at the point.

When we pass in reality from the third to the fourth dimension, we come into the Spiritual. We eliminate the dimensions one by one, we do not add them, and in this way we enter more and more into the Spiritual.

Through such ideas we gain a deeper insight too into the human form and figure. For a more artistic way of feeling is it not rather crude how we generally observe a human being, as he places himself with his three dimensions into the world? That after all is not the only thing. Even in ordinary life we have a feeling for the essential symmetry between the left and right halves of the body. And when we thus comprise the human being in his central plane, we are already led beyond the three dimensions. We pass into the plane itself. And only thereafter do we gain a clear conception of the one dimension in which he grows. Artistically we do already make use of this transition, from three to two and on to one dimension. If we cultivated more intensely this artistic perception of the human form, we should find more easily the transition to the soul's life. For you would never be able to feel a being, unsymmetrically formed, as a being of united and harmonious Feeling.

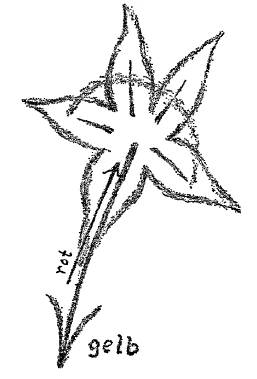

Look at the star-fish. It has not this symmetrical form. It has five rays. Of course you can pass it by without any inner feeling. But if you perceive it feelingly, you could never say that the star-fish has a united feeling-life. The star-fish cannot possibly relate a right-hand to a left-hand side, or grasp a right-hand with a left-hand member. The star-fish must continually relate the one ray to one or two or three, or even to all four remaining rays. What we know as Feeling cannot live in the star-fish at all.

I beg you to follow me along this intimate line of thought. What we know as Feeling comes from the right and from the left, and finds itself at rest in the middle. We go through the world by placing ourselves with our Feeling restfully into the world. The star-fish cannot do so. Whatever the star-fish has, as influence of the world upon itself, it cannot relate it symmetrically to another side. It can only relate it to one, or two, or to the third or fourth ray. But the first influence will always be more powerful. Thus the star-fish has no Feeling-life at rest within itself. When, as it were, it turns its attention to the one side, then by the whole arrangement of its form it will experience: ‘You are raying out in that direction, thither you are sending forth a ray.’ The star-fish has no restfulness in feeling. It has the feeling of shooting forth out of itself. It feels itself as raying forth in the world.

If you develop your feelings in a more intimate way, you will be able to experience this even as you contemplate the star-fish. Observing the end-point of any one ray and relating it to the creature as a whole, in your imagination the star-fish will begin to move in the direction of this ray, as it were a streaming, wandering light. And so it is with all the other animals which are not symmetrically built, which have no real access of symmetry.

If man would only enter into this more intimate way of Feeling—instead of giving himself up entirely to the intellectual, merely because in the course of time he had to become an intellectual being,—then indeed he would find his way far more intimately into the world.

It is so also in a certain sense for the plant world, and for all things that surround us. True self-knowledge takes us ever farther and farther into the inwardness of things.

Erster Vortrag

[ 1 ] Ich werde heute einiges auseinanderzusetzen haben, das scheinbar etwas abliegt von den konkreteren Betrachtungen unserer Anthroposophie, das aber dennoch die Grundlage von vielen Anschauungen bilden muß, und auf das dann in intimeren Betrachtungen manches gebaut werden kann.

[ 2 ] Wenn wir sprechen von dem Physisch-Leiblichen des Menschen auf der einen Seite und dem Geistig-Seelischen auf der anderen Seite, dann liegt ja für die Erkenntnis, für das Auffassungsvermögen des Menschen eine Schwierigkeit vor. Der Mensch kann verhältnismäßig leicht Vorstellungen gewinnen über das Physisch-Leibliche. Dieses Physisch-Leibliche ist ihm ja durch die Sinne gegeben. Es gehört sozusagen zu demjenigen, was von allen Seiten seiner Umgebung ihm entgegentritt, ohne daß er dazu selbst Wesentliches tut, wenigstens insofern sein Bewußtsein in Betracht kommt. Anders liegt die Sache, wenn von dem Geistig-Seelischen gesprochen wird. Das Geistig-Seelische ist ja von der Art, daß der Mensch, wenn er unbefangen genug ist, ein deutliches Bewußtsein davon hat, daß es vorhanden ist. Die Menschheit hat ja auch immer in ihre Sprachen Bezeichnungen, Worte, Satzwendungen aufgenommen für das Geistig-Seelische, und schon die Tatsache, daß solche Worte, Wendungen, Bezeichnungen innerhalb der Sprache sich befinden, zeigt, daß für das unbefangene Bewußtsein immerhin doch etwas da ist, was den Menschen hinweist auf das Geistig-Seelische.

[ 3 ] Die Schwierigkeit entsteht aber sofort, wenn der Mensch die Welt des Physisch-Leiblichen und die Welt des Geistig-Seelischen in eine Beziehung bringen will. Und dieses Aufsuchen einer Beziehung bietet gerade für diejenigen, die sich, sagen wir, in philosophischer Weise mit solchen Fragen beschäftigen, die denkbar größten Schwierigkeiten. Sie wissen, daß das Leiblich-Physische im Raume ausgedehnt ist. Sie können sogar dieses Leiblich-Physische im Raume darstellen. Und der Mensch bekommt verhältnismäßig leicht Vorstellungen davon, weil er eben dasjenige, was ihm der Raum darbietet mit seinen drei Dimensionen, verwenden kann zu den Vorstellungen über das Leiblich-Physische. Aber der Mensch findet schließlich nirgends im Raume das Geistige als solches.

[ 4 ] Menschen, die da glauben, nicht materialistisch gesinnt zu sein, die es aber erst recht sind, die möchten sich allerdings auch das Geistig-Seelische im Raume vorstellen und kommen dadurch zu den bekannten spiritistischen Verirrungen. Die spiritistischen Verirrungen sind ja materialistische Verirrungen; sie sind ein Bestreben, das Geistig-Seelische in den Raum hereinzubringen. Aber ganz abgesehen davon ist es ja so, daß der Mensch sich seines eigenen Geistig-Seelischen bewußt ist. Er weiß, wie das Geistig-Seelische wirkt, denn er sagt sich, daß sein Gedanke, den er hegt, wenn er zum Beispiel sich vornimmt, im Raume eine Bewegung zu machen, sich umsetzt in die Bewegung vermittelst des Willens. Die Bewegung ist im Raume; aber von dem Gedanken kann der unbefangene Mensch nicht sagen, daß er im Raume ist. Und so haben sich gerade für das philosophische Denken die größten Schwierigkeiten ergeben. Man frägt: Wie kann das Seelisch-Geistige im Menschen, zu dem auch das Ich gehört, auf das Physisch-Leibliche, das im Raume ist, wirken? Wie kann ein Unräumliches auf ein Räumliches wirken?

[ 5 ] Es sind die verschiedensten 'Theorien entstanden, welche mehr oder weniger alle an der Schwierigkeit leiden, das unräumliche GeistigSeelische in eine Beziehung zu bringen zu dem räumlichen Leiblich-Physischen. Man sagt, im Willen wirke das Geistig-Seelische auf das Leibliche. Aber zunächst kann mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein niemand sagen, wie der Gedanke in den Willen hineinfließt, und wie der Wille, der selber eine Art Geistiges ist, nun dazu kommt, in äußeren Bewegungsformen, in äußerer Betätigung zum Vorschein zu kommen.

[ 6 ] Auf der anderen Seite wiederum sind die Vorgänge, die zum Beispiel durch die physische Welt in den Sinnen, also im Leiblichen hervorgerufen werden, im Raume ausgedehnt. Sie verwandeln sich, indem sie ein Geistig-Seelisches werden, in ein Unräumliches. Der Mensch kann aus seinem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein heraus nicht sagen, wie das Räumlich-Physische, das geschieht in der Sinneswahrnehmung, eine Wirkung ausübt auf das Nichträumliche, auf das Geistig-Seelische.

[ 7 ] Man ist ja in der neuesten Zeit zu dem Auskunftsmittel gekommen, das ich schon öfter erwähnt habe: man redet von «psychophysischem Parallelismus». Das ist eigentlich das Eingeständnis, daß man nichts zu sagen weiß über die Beziehung des Leiblich-Physischen und des Geistig-Seelischen. Man sagt zum Beispiel: Der Mensch geht, seine Beine bewegen sich, er verändert den Ort im äußeren Raume. Das alles stellt ein Räumliches, ein Physisch-Leibliches dar.

[ 8 ] Gleichzeitig damit, wenn in seinem Leibe etwas vorgeht, wickelt sich ein Geistig-Seelisches ab, ein Gedanklich-Gefühlsmäßig-Willensmäßiges. Man weiß nur, so sagt man, daß wenn sich das LeiblichPhysische räumlich abspielt und zeitlich, daß sich dann das GeistigSeelische auch abspielt. Aber wie das eine auf das andere wirkt, davon kann man sich keine Vorstellung machen. Psychophysischer Parallelismus heißt: es läuft ein psychischer, ein seelischer Prozeß ab, während ein leiblicher abläuft. Aber über dieses, möchte man sagen, also ausgesprochene Geheimnis, daß die beiden Vorgänge parallel ablaufen, kommt man nicht hinaus. Man kommt nicht zu einer Vorstellung, wie die beiden aufeinander wirken. So ist es dann, wenn die Menschen sich eine Vorstellung machen wollen über das Vorhandensein, das Dasein des Geistig-Seelischen überhaupt.

[ 9 ] Im 19. Jahrhundert, in dem die Menschen in ihren Anschauungen so sehr durchsetzt worden sind vom Materialismus, entstand ja bei Materialisten auch die Frage: Wo im Weltenraume halten sich denn die Seelen eigentlich auf, wenn sie den Leib verlassen haben? Und es hat sogar Leute gegeben, die den Spiritualismus dadurch widerlegen wollten, daß sie versuchten, die Unmöglichkeit ins Auge zu fassen, die darin gegeben ist, daß, da so viele Menschen sterben und so viele Menschen schon gestorben sind, in der ganzen Raumeswelt eigentlich kein Platz sei, um all den Seelen, die von gestorbenen Menschen herrühren, einen Aufenthaltsort zu geben. Diese absurde Anschauungsweise ist ja tatsächlich gerade im 19. Jahrhundert oftmals aufgetreten. Man hat gesagt: Der Mensch kann nicht unsterblich sein, denn es müßten schon alle Räume der Welt mit den unsterblichen Seelen erfüllt sein. Alle diese Dinge weisen darauf hin, welche Schwierigkeiten auftauchen, wenn in Frage kommt die Beziehung zwischen dem deutlich im Raume ausgedehnten Leiblich-Physischen und demjenigen, was man zunächst nicht in den Raum versetzen kann, dem GeistigSeelischen.

[ 10 ] Nun aber ist es allmählich dahin gekommen, daß das rein intellektualistische menschliche Denken schroff nebeneinandergestellt hat Leiblich-Physisches auf der einen Seite und Geistig-Seelisches auf der anderen Seite. Die beiden stehen für das heutige Bewußtsein ohne alle Vermittelung nebeneinander. Ja, so wie die Menschen allmählich dazu gekommen sind, zu denken über das Leiblich-Physische auf der einen und das Geistig-Seelische auf der anderen Seite, so gibt es überhaupt keine Möglichkeit, eine Beziehung aufzufinden. Der Mensch denkt sich eben heute einfach das Räumlich-Physische so, daß das Seelische darinnen nirgends unterzubringen ist, und wiederum das Seelische so schroff geschieden von dem Physisch-Räumlichen, daß das ganz unräumliche Geistig-Seelische nirgends dazu kommen kann, das Physische zu stoßen oder dergleichen. Man hat aber erst nach und nach diesen schroffen Gegensatz herausgebildet. Man muß eine ganz andere Betrachtungsweise zugrunde legen, eine Betrachtungsweise, die erst wiederum heraufkommen kann dadurch, daß angeknüpft wird an dasjenige, was anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft zu sagen hat. Anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft muß zunächst den Willen betrachten. Zunächst liefert eine unbefangene Anschauung zweifellos den Beweis, daß der Wille des Menschen seinen Bewegungen überallhin folgt, und daß die Bewegungen des Menschen, die er äußerlich im Raume vollführt, indem er sich selber bewegt, aber auch die Bewegungen, die in ihm vorgehen, indem seine alltäglichen Funktionen sich vollziehen, daß überhaupt alle Betätigung des Menschen hier in der physischen Welt räumlich dreidimensional ist. Darüber kann ja der unbefangene Mensch in keinem Zweifel sein. Alle diese Bewegungen werden begleitet vom Willen, der Wille muß also überall hinkommen, wo die drei Dimensionen ausgedehnt sind. Darüber kann auch kein Zweifel sein.

[ 11 ] Wenn also vom Willen als von einem Geistig-Seelischen gesprochen wird, kann gar keine Frage sein darüber, daß dieser Wille, trotzdem er ein Geistig-Seelisches ist, ein Dreidimensionales ist, dreidimensionale Gestaltung hat. Wir müssen einfach so denken: Wenn wir durch unseren Willen, sagen wir eine Bewegung ausführen mit der Hand, so schmiegt sich der Wille in alle die Lagen hinein, welche im Raume von Arm und Hand ausgeführt werden. Der Wille geht überall mit, wo irgendeine Bewegung eines Gliedes sich vollzieht. So daß wir vom Willen selber als von demjenigen Seelischen sprechen müssen, das eine dreidimensionale Gestaltung annehmen kann.

[ 12 ] Eine weitere Frage ist aber diese, ob alles Seelische eine dreidimensionale Gestaltung annimmt. Und gehen wir da über vom Willen auf die Welt des Fühlens, auf die Welt des Gefühles, so wird der Mensch zunächst, wenn er einfach mit seinem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein über diese Dinge nachdenkt, sich ja allerdings sagen: Wenn ich, sagen wir, hier auf der rechten Seite des Gesichtes, des Kopfes, von einer Nadel gestochen werde, so fühle ich das; wenn ich auf der linken Seite gestochen werde, fühle ich es auch. Er kann also mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein die Meinung haben, sein Gefühl ist in seinem ganzen Leibe ausgedehnt. Und dann wird er auch vom Fühlen im selben Sinne als dreidimensional gestaltet sprechen, wie er vom Willen als dreidimensional gestaltet spricht.

[ 13 ] Aber da gibt er sich doch einer Täuschung hin. Es ist nicht so. Es ist vielmehr so, daß da berücksichtigt werden muß, wie der Mensch zunächst gewisse Erfahrungen an sich selber machen kann, und von diesen Erfahrungen wollen wir ausgehen. Die heutige Betrachtung wird etwas subtil sein, aber ohne solche subtilen Betrachtungen kann ganz gründlich doch das Geisteswissenschaftliche nicht verstanden werden.

[ 14 ] Fassen Sie nur einmal ins Auge, ich meine ins Seelenauge, wie das ist, wenn Sie Ihre linke Hand mit der rechten Hand selber berühren. Dadurch haben Sie die Wahrnehmung von sich selbst. Wie Sie einen äußeren Gegenstand sonst empfinden, so empfinden Sie sich selbst, wenn Sie die rechte Hand mit der linken berühren, sagen wir durch Vermittelung der einzelnen Finger.

[ 15 ] Noch viel deutlicher haben Sie aber das Faktum, das da vorliegt, wenn Sie daran denken, daß Sie zwei Augen haben, und daß, wenn Sie einen Gegenstand fixieren mit beiden Augen, Sie ja den Willen zunächst anstrengen müssen. Man denkt oftmals an diese Willensanstrengung nicht. Sie müssen, um zum Beispiel einen sehr nahen Gegenstand zu fixieren, wobei es eben stärker hervortritt als sonst, das linke Auge nach rechts wenden, das rechte Auge nach links, und Sie fixieren den Gegenstand dadurch, daß Sie die Sehlinien in einer ähnlichen Weise miteinander in Berührung bringen, wie Sie die rechte Hand mit der linken in Berührung bringen, wenn Sie sich sozusagen selber angreifen.

[ 16 ] Sie können auf diese Weise sehen, wie es einfach eine gewisse Bedeutung für den Menschen hat in bezug auf seine Weltorientierung, das Linke auf das Rechte zu beziehen, das Linke mit dem Rechten in eine gewisse Beziehung zu bringen.

[ 17 ] Nun, viel weiter, als sich das hier zugrunde liegende ganz bedeutungsvolle Faktum durch die Berührung der Hände, durch die Kreuzung der Sehvisierlinie zum Bewußtsein zu bringen, kommt das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein meistens nicht; aber man kann diese Betrachtung weiter fortsetzen.

[ 18 ] Nehmen wir an, daß wir auf unserer rechten Körperhälfte mit einer Nadel gestochen werden: Wir empfinden, wir fühlen den Stich. Aber wir dürfen nicht ohne weiteres sagen, wo wir den Stich fühlen, indem wir etwa bei diesem Wo hinweisen auf unsere Körperoberfläche. Denn ohne daß alle einzelnen Glieder unseres Organismus miteinander in einem Verhältnisse, und zwar in einem lebendigen Wechselverhältnisse stehen, so daß sie aufeinander wirken, ohne das würde unser leiblich-seelisch-menschliches Wesen überhaupt nicht dasjenige sein, was es ist. Und es ist immer, auch wenn wir nicht die linke Hand durch die rechte angreifen, um so die linke Hand durch die rechte Hand zu fühlen, und auch wenn unser Organismus, sagen wir, auf seiner rechten Seite gestochen wird, eine Leitung vorhanden von der rechten Seite nach der Symmetrieebene in der Mitte, und die linke Körperhälfte muß in eine Beziehung treten zu der rechten Körperhälfte, damit die Empfindung, das Gefühl zustande kommen kann.

[ 19 ] Es ist verhältnismäßig leicht, sich zu sagen: Wenn ich hier, von vorne nach rückwärts angesehen, die Symmetrieebene habe, dann berührt die rechte Hand die linke Hand, und das Gefühl der beiden Hände, jeder Hand durch die andere, kommt in der Symmetrieebene zustande. Das wird offenbar so gesehen, und es ist verhältnismäßig leicht, von der Kreuzung der Visierlinie des Auges zu sprechen. Aber es ist immer, wenn wir zum Beispiel rechts gestochen werden, eine Leitung vorhanden (rot), und die linke Körperhälfte kreuzt sich in diesen Leitungen mit der rechten Körperhälfte, sonst würde die Empfindung nicht zustande kommen. Bei allen Empfindungs- und Gefühlswegen spielt die Tatsache, daß wir eine rechte und eine linke Körperhälfte haben, daß wir symmetrisch gebaut sind, eine ungeheuer bedeutsame Rolle. Wir beziehen dadurch immer dasjenige, was uns rechts geschieht, auf das Linke, indem immer, gewissermaßen unsichtbar vom Linken etwas herübergreift, um sich mit dem, was vom Rechten herüberströmt, zu kreuzen.

[ 20 ] Dadurch allein kommt das Fühlen zustande. Das Fühlen kommt niemals im dreidimensionalen Raume zustande, das Fühlen kommt immer in der Ebene zustande. Die Gefühlswelt ist in Wirklichkeit gar nicht dreidimensional ausgebreitet, die Gefühlswelt ist in Wahrheit nur zweidimensional ausgebreitet. Die Gefühlswelt erlebt der Mensch nur in derjenigen Ebene, die, wenn man sie als eine Schnittebene vollziehen würde, den Menschen in zwei symmetrische Hälften spalten würde.

[ 21 ] Das Gefühlsleben ist nämlich eigentlich so wie ein Gemälde, das auf einer Leinwand gemalt ist, wobei man aber nicht bloß von der einen Seite malt, sondern von beiden Seiten malt. Denken Sie sich, ich spanne mir eine Leinwand auf, bemale sie von rechts nach links und von links nach rechts, und ich lasse in der Anschauung durcheinanderwirken dasjenige, was ich von vorne und von rückwärts, das heißt, von rechts nach links und von links nach rechts bemalt habe. Und das Gemälde, das da ist, das ist durchaus nur zweidimensional. Alles, was dreidimensional ist, ist, wenn ich so sagen darf, auf die zwei Dimensionen projiziert.

[ 22 ] Sie könnten sich die Vorstellung auch noch anders bilden. Denken Sie sich, Sie wären imstande, auf einer Fläche Gegenstände, welche rechts sind, und Gegenstände, welche links sind, in Schattenbilder zu werfen. Dann würden Sie Schatten von rechten Gegenständen, von linken Gegenständen auf der aufgespannten Wand haben. So ist es mit unserer Gefühlswelt. Sie ist nicht dreidimensional, sie ist zweidimensional. Der Mensch ist im Grunde genommen ein von zwei Seiten her arbeitender Maler, indem er sich nicht einfach in den Raum fühlend hineinlebt, sondern indem er durch seinen dreidimensionalen Willen alles dasjenige, was ihm im Raume als Gefühlswirkung begegnet, indem er durch den Willen, der allerdings dreidimensional ist — der ist der Maler, der Wille —, alles auf eine von vorne nach rückwärts durchgehende Ebene in Schattenbildungen, in Gemälden entwirft. Der Mensch lebt fühlend in einem Gemälde, das durch seinen Leib zweidimensional gezogen ist, das nur eben von beiden Seiten bemalt wird. So daß wir, wenn wir für uns selbst, für die Menschen, im Seelischen den Übergang suchen wollen vom Willen zum Gefühl, aus dem Dreidimensionalen in das Zweidimensionale übergehen müssen.

[ 23 ] Damit aber haben Sie ein anderes Verhältnis zunächst desjenigen Seelischen, das sich im Fühlen ausspricht, zu dem Räumlichen, als wenn Sie einfach vom Seelischen sagen, es sei unräumlich. Die Ebene hat zwei Dimensionen, aber sie ist nicht räumlich. Sie können die Tafel eine Ebene nennen, aber sie ist in Wirklichkeit ein Körper, denn sie hat eine Dicke. Eine Ebene ist zwar im Raume drinnen, aber sie ist nicht selber räumlich; der Raum muß immer drei Dimensionen haben. Und in diesen dreidimensionalen Raum geht nur der Wille hinein. Aber das Gefühl, das geht nicht in die drei Dimensionen des Raumes hinein. Es ist zweidimensional. Aber es hat dennoch Beziehungen zum Raume, geradeso wie das Schattenbild Beziehungen zum Raume hat.

[ 24 ] Ich weise Sie damit aber auch hin auf eine außerordentlich bedeutungsvolle Tatsache, die gar nicht so leicht durchschaut werden kann, aus dem Grunde, weil der Mensch mit seinem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein in der Regel gar nicht geneigt ist, das Eigentümliche seiner Gefühlswelt aufzufassen. Diese Gefühlswelt ist ja immer von der Willenswelt durchsetzt. Denken Sie doch nur einmal, wenn Sie wirklich den Stich, von dem ich gesprochen habe, auf Ihre rechte Körperseite bekommen, da trennen Sie ja nicht gleich das Gefühl vom Willen. Sie werden ganz zweifellos diesen Stich nicht sehr geduldig empfangen, sondern abgesehen davon, daß Sie vielleicht äußerlich dahin greifen werden, also mit Ihrem Willen sehr in den dreidimensionalen Raum hineinfahren werden, wenn Sie gestochen werden, abgesehen davon haben Sie eine nach außen nicht hervortretende Abwehrbewegung, die sich nur in allerlei kleinen, intimen Strömungen des Blutes und des Atems zeigt. Dasjenige, was man als Abwehrbewegung macht, wenn man von einer Mücke gestochen wird und man greift hin, das ist ja eben auch nur das Grobklotzigste. Das Feinere, die Abwehrbewegung, die man eigentlich nur mit der Blutbewegung, mit der Atembewegung, mit allerlei anderem im Inneren macht, die beachtet man gewöhnlich nicht. Und so trennt man nicht dasjenige, was da der Wille tut, von demjenigen, was eigentlich Gefüblsinhalt ist. Dasjenige, was Gefühlsinhalt ist, ist auch zu scheu. Dazu kann man es nur bringen in sehr, sehr sorgfältiger Meditation. Wenn Sie aber einmal alles, was zum Willen gehört, ausschließen können von dem Fühlen, dann schrumpfen Sie allerdings zusammen von rechts und links, und Sie werden in der Mitte die Ebene. Und dann, wenn Sie in der Mitte die Ebene sind und gewissermaßen nun bewußt als Maler Ihre Erlebnisse auf dieser Ebene abmalen, dann fangen Sie an zu begreifen, warum sich die Gefühlswelt so außerordentlich unterscheidet von dem gewöhnlichen Erleben.

[ 25 ] Man kann schon dieses Flächenhafte, dieses Ebenenhafte des Fühlens erleben; aber man muß es meditativ erleben. Man muß das ganze Schattendasein der Gefühle gegenüber den robusten Erlebnissen im dreidimensionalen Raum haben. Man muß sich erst vorbereiten dazu, es zu haben. Dann aber kann man es auch haben. Und dann wird man allmählich sich dieser Wahrheit nähern, daß das Fühlen zweidimensional verläuft. Und das Denken, das läßt sich ja einfach dadurch charakterisieren, daß man mit unbefangenem Gemüte sich gesteht, wie wenig man doch sagen kann, daß ein Gedanke im Raume drinnen ist. Er ist doch nirgends eigentlich im Raume drinnen, der Gedanke. Aber eine Beziehung zum Raume muß er doch haben. Denn zweifellos ist ja das Gehirn, wenn auch nicht das Werkzeug, so doch die Unterlage des Denkens. Ohne Gehirn kann man nicht denken. Wenn aber das Denken, das also im Zusammenhange mit der Gehirntätigkeit verläuft, gar nichts mit dem Raum zu tun hätte, dann würde sich die kuriose Tatsache ergeben, daß, wenn man mit zwölf Jahren gut denken kann und man dann mit seinem Kopfe herausgewachsen ist über die Lage, in der man war mit zwölf Jahren, man dann aus seinem Denken herausgewachsen wäre. Das ist nicht der Fall. Indem man wächst, verläßt man das Denken nicht. Und schon das weist darauf hin, daß man mit dem Wachsen doch auch mit dem Denken im Raume drinnen ist.

[ 26 ] Nun, geradeso wie man die Welt des Fühlens, die Welt des Erlebens der Gefühle für sich selbst fühlen kann, indem man auf seine Symmetrieebene allmählich kommt, läßt sich wiederum meditativ das Denken erleben als dasjenige, das eigentlich nur die Ausdehnung oben und unten hat. Das Denken ist durchaus eindimensional, verläuft im Menschen in der Linie. Man muß also sagen: Der Wille gestaltet sich dreidimensional, das Gefühl zweidimensional und das Denken eindimensional.

[ 27 ] Sie sehen, wenn wir im Raume differenzieren, dann kommen wir nicht zu einem so schroffen Übergang, wie es der bloße Intellekt tut. Wir kommen zu einem allmählichen Übergang. Der bloße Intellekt sagt: Das Physische ist dreidimensional räumlich ausgedehnt; das Geistig-Seelische ist gar nicht ausgedehnt, also kann man keine Beziehung finden, denn man kann zwischen dem Ausdehnungslosen und dem Ausgedehnten selbstverständlich keine Beziehungen finden. Wird man aber aufmerksam, daß der Wille dreidimensional gestaltet ist, so findet man, daß der Wille überall sich hinergießt in die dreidimensionale Welt. Weiß man, daß das Gefühl zweidimensional gestaltet ist, dann muß man, indem man von den drei Dimensionen auf die zwei übergeht, zu etwas kommen, was zwar noch Beziehungen darstellt, was aber nur nicht mehr räumlich ist, denn die bloße Ebene, die bloßen zwei Dimensionen sind eben nicht räumlich. Aber sie sind im Raume drinnen, sie sind nicht völlig aus dem Raume draußen.

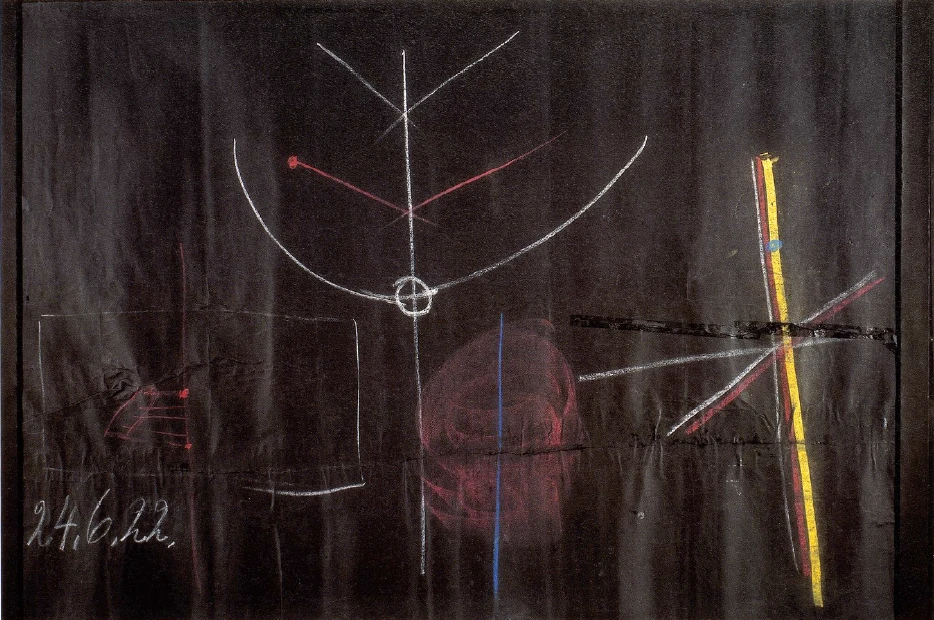

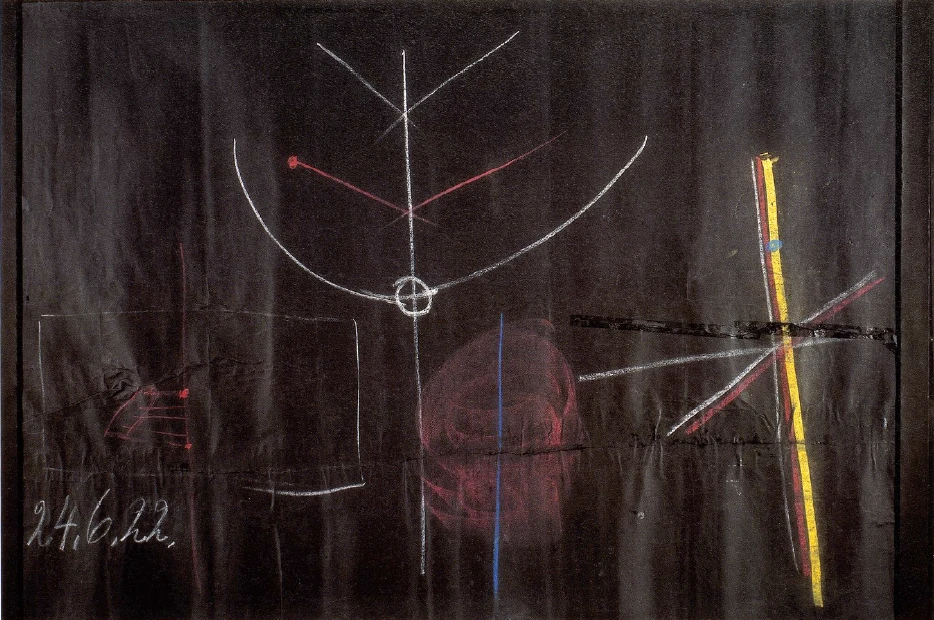

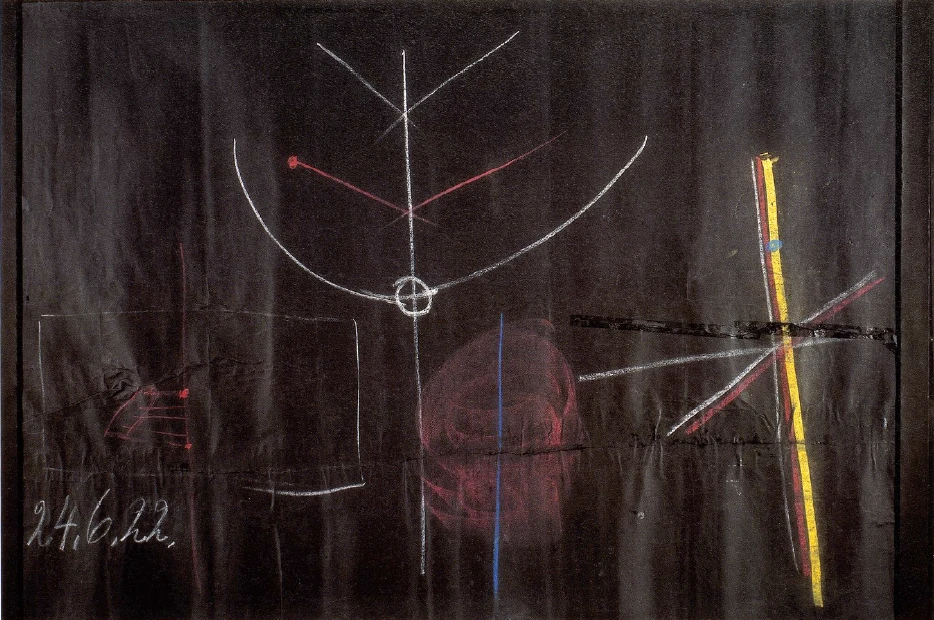

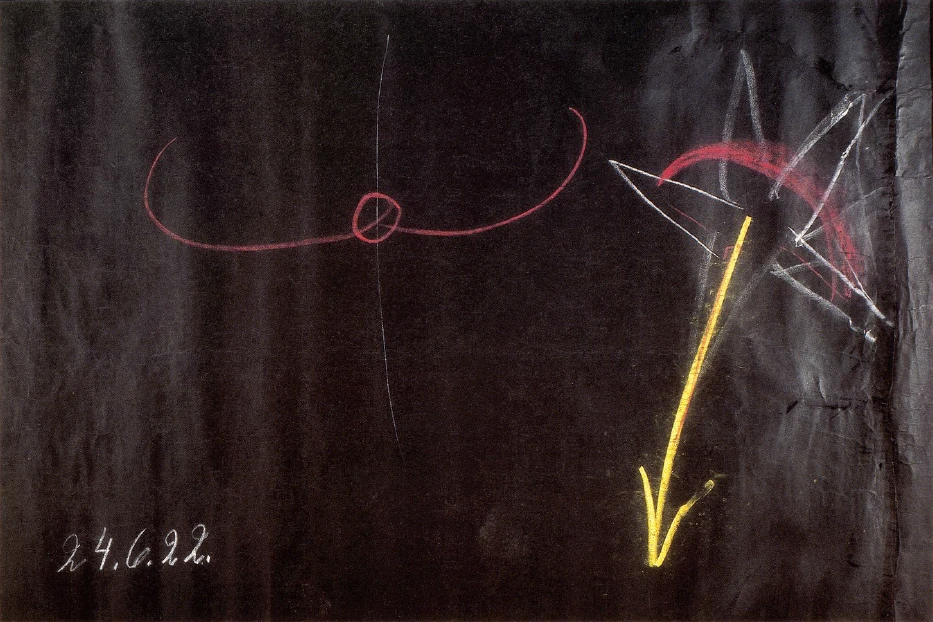

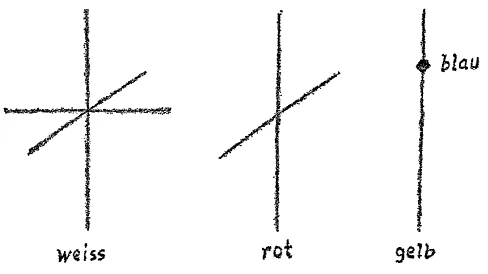

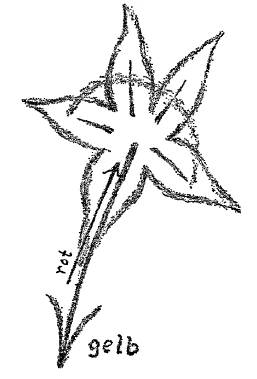

[ 28 ] Und wiederum, wenn wir vom Fühlen zum Denken übergehen, so gehen wir von den zwei Dimensionen zu der einen Dimension über, also noch immer nicht ganz aus dem Raume heraus. Wir gehen allmählich von dem Räumlichen in das Unräumliche hinein. Ich habe es ja öfter ausgesprochen, daß das Tragische des Materialismus darinnen besteht, daß er gerade das Materielle, das Stoflliche in seiner dreidimensionalen Ausdehnung nicht versteht. Er glaubt es zu verstehen, aber er versteht gerade das Stoffliche nicht. Und im 19. Jahrhundert sind historisch mancherlei bedeutsame Erscheinungen hervorgetreten, die mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein heute doch nicht in ordentlicher Weise enträtselt werden können. Denken Sie doch nur an das große Aufsehen, das bei vielen denkenden Menschen das Schopenhauersche philosophische System gemacht hat: «Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung.» Danach hat nur die Vorstellung etwas Unwirkliches, der Wille allein ist das Wirkliche. Ja, warum ist denn Schopenhauer za der Vorstellung gekommen, daß die Welt nur Wille ist? Weil er doch auch vom Materialismus angefressen war! Denn in die Welt, in der die Materie sich dreidimensional ausdehnt, da ist eben nur der Wille ergossen. Wer auch die Gefühle in diese Welt hineinstellen will, der muß die Beziehung aufsuchen, die besteht zwischen einem dreidimensionalen Ding und einem zweidimensionalen Schattenbilde. Was wir erleben in den Gefühlen, sind Schattenbilder desjenigen, worinnen auch unser Wille als dreidimensionale Gestaltung lebt. Und was wir erleben im Denken, das sind Gestaltungen in einer einzigen Dimension. Und erst wenn wir ganz aus den Dimensionen herausgehen, wenn wir übergehen zu dem dimensionslosen Punkte, dann sind wir bei unserem Ich angekommen. Das hat nun wirklich gar keine Ausdehnung, das ist ganz punktuell. So daß wir sagen können: Wir gehen über von dem Dreidimensionalen (weiß) zu dem Zweidimensionalen (rot), zu dem Eindimensionalen (gelb) und zu dem Punktuellen (blau).

[ 29 ] Aber indem wir beim Dreidimensionalen noch bleiben, haben wir in den drei Dimensionen unseren Willen drinnen. Es steckt auch das Fühlen, es steckt auch das Denken drinnen, aber nicht dreidimensional ausgedehnt. Indem wir die dritte Dimension weglassen und nur zu zwei Dimensionen kommen, haben wir den Schatten des äußeren Daseins, in dem sich aber dasjenige Geistig-Seelische ausdehnt, das im Fühlen lebt. Wir kommen schon mehr aus dem Raume heraus. Gehen wir zum Denken, dann kommen wir noch mehr aus dem Raume heraus, und indem wir zum Ich übergehen, kommen wir noch mehr aus dem Raume heraus. Da werden wir gewissermaßen Stück für Stück aus dem Raume herausgeführt. Und wir sehen, daß es einfach keinen Sinn hat, bloß zu sprechen von dem Gegensatz des Geistig-Seelischen und des Physisch-Leiblichen. Es hat keinen Sinn, denn man muß fragen, wenn man die Beziehung entdecken will zwischen dem Geistig-Seelischen und dem Physisch-Leiblichen: Wie verhalten sich Dinge, die im dreidimensionalen Raum ausgedehnt sind, zum Beispiel unser eigener Körper, zu dem Seelischen als Willenswesen? Wie verhält sich das Körperlich-Leibliche beim Menschen zu der Seele als einem Gefühlswesen? Zu der Seele als Willenswesen verhält sich das Leiblich-Physische als ein Körperliches so, daß eben einfach das Leiblich-Physische, wie ein Schwamm vom Wasser, vom Willen nach allen Seiten, nach allen Dimensionen durchtränkt wird.

[ 30 ] Zum Gefühl verhält sich aber das Leiblich-Physische so, wie Gegenstände sich verhalten, die ihre Schatten werfen auf eine Wand. Und wiederum, wenn wir von dem Gefühlsmäßigen zu dem Gedankenhaften übergehen wollen, dann müssen wir gar ein eigentümlicher Maler werden. Da müssen wir auf einer Linie dasjenige wiederum extra aufmalen, was sonst in den zwei Dimensionen des Gemäldes ist.

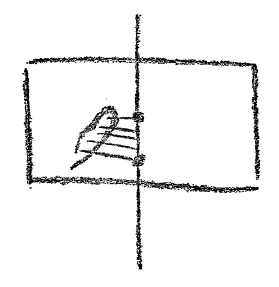

[ 31 ] Legen Sie sich einmal die folgende Frage vor. Das ist natürlich etwas, was einige Ansprüche stellt an das innere Anschauen, aber stellen Sie sich vor, Sie stünden, sagen wir, vor dem «Abendmahl» des Leonardo da Vinci. Sie haben es zunächst in der Fläche vor sich. Dasjenige, was in Betracht kommt, ist zweidimensional. Wir können ja natürlich von der Dicke der Farbflecken absehen, nicht wahr; aber das, was Sie vor sich haben als Gemälde, ist zweidimensional. Nun aber denke ich mir eine Linie gezogen in der Mitte von oben nach unten, und diese Linie stelle dar ein eindimensionales Wesen. Dieses eindimensionale Wesen hätte die Eigentümlichkeit, daß, sagen wir, der Judas hier (S.22) ihm nicht gleichgültig wäre; sondern daß der Judas da ist, das empfindet dieses Wesen in einer gewissen Beziehung. Das empfindet dieses Wesen so: Da, wo der Judas den Kopf hinüberneigt, da empfindet es mehr, wo der Judas sich abneigt, da empfindet es weniger; und von allen übrigen Gestalten empfindet dieses eindimensionale Wesen, je nachdem diese Gestalt in einer blauen, in einer gelben Farbe ist, anders. Alles dasjenige, was da links und rechts ist, das empfindet dieses eindimensionale Wesen. Dann ist alles das, was auf diesem Gemälde ist, lebendig von diesem eindimensionalen Wesen gefühlt.

[ 32 ] So ist aber wirklich unser Denken in uns. Unser Denken ist ein solches eindimensionales Wesen und lebt das übrige unseres menschlichen Wesens nur dadurch mit, daß es erstens in Beziehung steht zu dem Gemälde, das uns entzweischneidet als einen rechten und als einen linken Menschen, und daß es auf dem Umwege durch dieses Gemälde dann in Beziehung steht zu der dreifach gestalteten Willenswelt.

[ 33 ] Wenn wir von unserem geistig-seelischen Wesen, nur insoferne es wollend, fühlend, denkend ist, zunächst sogar ohne das Ich eine Vorstellung bekommen wollen, müssen wir es eigentlich nicht vorstellen als eine Nebelwolke, sondern indem wir innerlich-seelisch etwas vollziehen. Wir wollen uns also das Geistig-Seelische schematisch vorstellen. Wir müssen gewissermaßen hinschauen: Da stellt es sich uns zunächst als eine Wolke dar. Aber das ist zunächst nur ein Willenswesen. Das hat immerfort die Tendenz, sich zusammenzuquetschen; da wird es Gefühlswesen. Wir sehen als erstes eine Lichtwolke, dann aber eine solche Lichtwolke, die in der Mitte sich selber als eine Ebene erzeugt und sich dadurch fühlt. Und diese Ebene wiederum hat das Bestreben, zur Linie zu werden. Wir müssen also fortwährend uns vorstellen: Wolke, Ebene, Linie, als ein in sich lebendes Gebilde: etwas, was fortwährend Wolke sein will, von der Wolke aber zur Ebene sich zusammenquetschen will, zur Linie sich verlängern will. Wenn Sie sich eine Linie vorstellen, die Ebene wird, die Ebene wird wiederum dreidimensionale Wolke, wenn Sie sich also vorstellen: Wolke, Ebene, Linie — Linie, Ebene, Wolke und so weiter, dann haben Sie dasjenige, was Ihnen nun schematisch veranschaulichen kann, was Ihre Seele in ihrem innerlichen Wesen, in ihrer innerlichen Wesenhaftigkeit eigentlich ist. Sie kommen nicht aus mit einer Vorstellung, die nur in sich ruhig bleibt. Keine Vorstellung, die in sich ruhig bleibt, gibt dasjenige, was das Seelische ist, wieder. Sie müssen eine solche Vorstellung haben, die selber eine innerliche Tätigkeit ausführt, und zwar eine solche innerliche Tätigkeit, daß die Seele, indem sie sich vorstellt, spielt mit den Dimensionen des Raumes: Sie läßt verschwinden die dritte Dimension, verliert dadurch den Willen, läßt verschwinden die zweite Dimension, verliert dadurch das Gefühl; und das Denken verliert man erst, wenn man auch die erste Dimension verschwinden läßt. Dann kommt man bei dem Punktuellen an. Dann geht es erst zu dem Ich über.

[ 34 ] Deshalb kommt ja diese Schwierigkeit zustande. Die Menschen möchten das Seelische erkennen, sie sind aber gewöhnt, nur räumliche Vorstellungen sich zu machen. Nun machen sie sich auch, wenn auch noch so verdünnte, räumliche Vorstellungen vom Seelischen. Aber da hat man ja nur das Willenshafte. Man müßte sich das Seelische stets so vorstellen, daß man, indem man sich etwa eine Wolke vorstellt, diese Wolke gleichzeitig fortwährend zusammengepreßt und wiederum auch eindimensional vorstellen würde. Ohne daß man das Denken innerlich beweglich macht, bekommt man überhaupt keine Vorstellung von dem Geistig-Seelischen. Einer, der ein Geistig-Seelisches sich vorstellen will und in zwei aufeinanderfolgenden Augenblicken sich das Gleiche vorstellt, der hat sich nur ein Willenshaftes vorgestellt. Man darf sich einfach das Geistig-Seelische in zwei aufeinanderfolgenden Augenblicken nicht gleichgestaltet vorstellen. Man muß innerlich beweglich werden, und zwar nicht nur so, daß man von einem Raumpunkte zum anderen übergeht, sondern daß man von einer Dimension in die andere übergeht. Das ist dasjenige, was gewöhnlich dem heutigen Bewußtsein schwer wird. Das hat ja sogar dazu geführt, daß nun die gutmütigsten Menschen — gutmütig in bezug auf die Vorstellung des Geistigen — aus dem Raume schon heraus möchten, die drei Dimensionen überwinden möchten. Dann kommen sie zu einer vierten Dimension. Das ist ja ganz nett, vom Dreidimensionalen zu einem Vierdimensionalen überzugehen. Solange man im Mathematischen bleibt, sind auch alle die Gedanken, die man sich darüber macht, ganz zutreffend, es stimmt alles. Nur wenn man übergeht zur Realität, stimmt es nicht mehr, denn das Eigentümliche ist, daß wenn man real die vierte Dimension denkt, dann hebt sie einem die dritte auf. Durch die vierte Dimension verschwindet die dritte Dimension, und durch die fünfte Dimension verschwindet die zweite, und durch die sechste verschwindet die erste; dann ist man beim Punkt angekommen.

[ 35 ] In Wirklichkeit kommt man nämlich beim Übergang von der dritten in die vierte Dimension in das Geistige hinein, und man kommt, indem man Dimensionen wegläßt, nicht indem man sie hinzufügt, immer mehr und mehr in das Geistige hinein. Man bekommt: aber durch solche Vorstellungen auch Einblicke in die menschliche Gestalt.

[ 36 ] Ist es denn nicht für ein künstlerisches Empfinden so, daß man eigentlich, ich möchte sagen, brutal den Menschen anschaut, wenn man ihn anschaut, wie er sich mit seinen drei Dimensionen nach allen Seiten hin in die Welt hineinstellt? Gewiß, so tut man es; aber das ist doch nicht das einzige. Man hat doch im allgemeinen ein Gefühl dafür, daß die linke und die rechte Körperhälfte im wesentlichen symmetrisch sind. Und das führt einen über die drei Dimensionen hinaus, indem man den Menschen zusammenfaßt in seiner Mittelebene. Man geht da schon über zu dieser Mittelebene; und von der einen Dimension, in der der Mensch wächst, da hat man erst dann eine recht deutliche Vorstellung. Künstlerisch verwendet man schon diesen Übergang von drei zu zwei zu einer Dimension. Und würde man mehr pflegen dieses künstlerische Anschauen des Menschen, dann würde man auch leichter den Übergang finden zu dem Seelischen. Sie würden niemals ein Wesen als ein einheitlich fühlendes Wesen empfinden können, das nicht symmetrisch gestaltet ist.

[ 37 ] Wenn Sie einen Seestern anschauen, der nicht symmetrisch gestaltet, sondern fünfstrahlig ist, so können Sie ja selbstverständlich gefühllos an ihm vorübergehen, aber Sie können niemals, wenn Sie sich gefühlsmäßig fragen, sich sagen, der hat ein einheitliches Gefühl. Der Seestern kann unmöglich ein Rechtes auf ein Linkes beziehen, ein Rechtes mit einem Linken umgreifen, sondern er muß fortwährend den einen Strahl mit einem oder mit zweien oder mit dreien oder mit allen vier anderen in eine Beziehung bringen. Dadurch lebt dasjenige, was wir als Fühlen kennen, überhaupt nicht im Seestern.

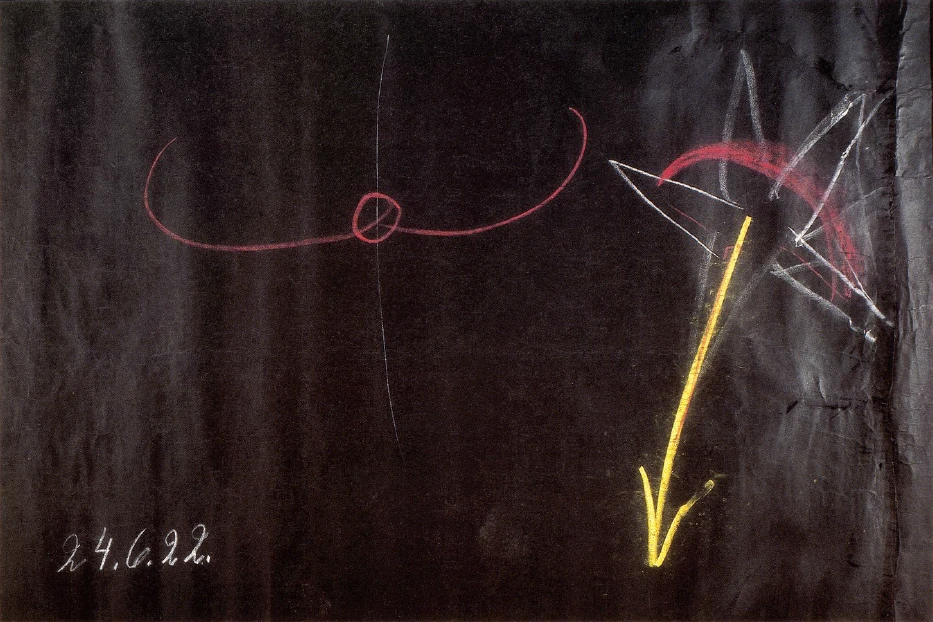

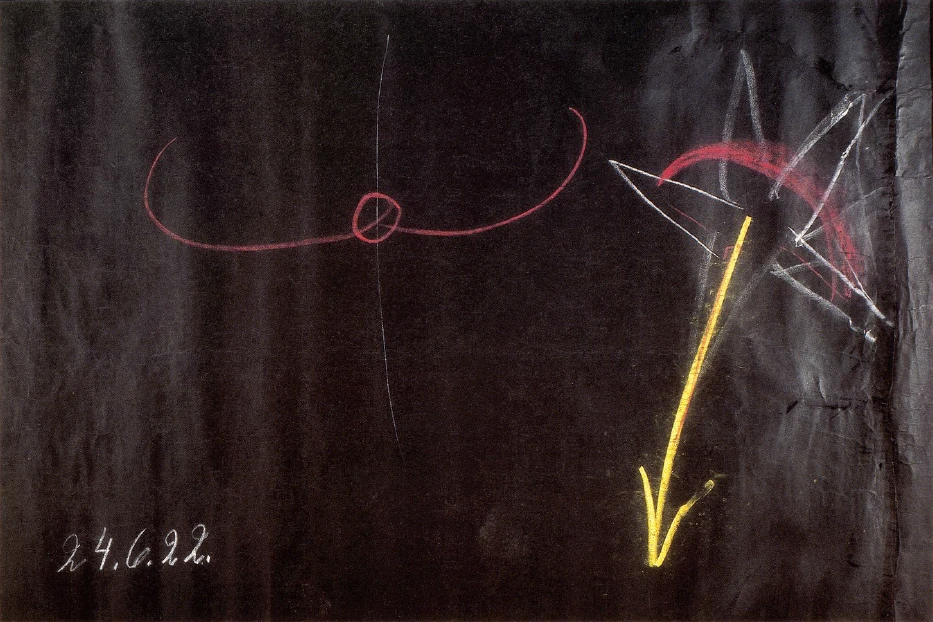

[ 38 ] Wie ist es mit demjenigen — ich bitte Sie, bei diesem intimen Gedankengang mir zu folgen -, was wir als Gefühl kennen? Was wir als Gefühl kennen, kommt von rechts, kommt von links und hält in der Mitte die Ruhe. Wir gehen durch die Welt, indem wir uns mit unserem Gefühl ruhend in die Welt hineinstellen. Der Seestern kann das nicht. Er kann dasjenige, was er von hier aus auf sich als Wirkung der Welt hat (roter Pfeil), nicht symmetrisch auf etwas anderes beziehen. Er kann es beziehen auf (rot) eins oder zwei oder auf den dritten oder vierten anderen Strahl, er wird aber immer hier ein Mächtigeres haben (gelb). Daher hat der Seestern nicht innerlich das ruhende Fühlen, sondern wenn er gewissermaßen die Aufmerksamkeit nach der einen Seite hinwendet, dann wird durch seine Anordnung in ihm das Erlebnis entstehen: Du strahlst dahin, du schickst dahin einen Strahl (gelber Pfeil). Wenn er von dort empfindet, so fühlt er, als ob es schießen würde aus ihm. Er hat kein ruhendes Gefühl. Er hat das Gefühl, aus sich herauszuschießen. Er fühlt sich als hinstrahlend in der Welt.

[ 39 ] Wenn Sie Ihre Gefühle fein entwickeln, dann werden Sie auch beim Anschauen des Seesternes das erleben können. Gucken Sie an irgendeinen Endpunkt eines Strahles und beziehen Sie das dann auf den ganzen Seestern, dann beginnt in Ihrer Vorstellung der Seestern nach diesem einen Strahl hin sich in Bewegung zu setzen, wie wenn er dahinwanderndes, strömendes Licht wäre. Und so ist es bei anderen Tieren, die nicht symmetrisch gebaut sind, die nicht eine wirkliche Symmetrieachse haben.

[ 40 ] Der Mensch könnte, wenn er auf dieses feinere Fühlen nur einmal einginge, wenn er nur nicht im Laufe der Zeit dadurch, daß er ein intellektuelles Wesen geworden ist, sich bloß dem Intellektuellen übergeben würde, er könnte viel feiner sich hineinfühlen in die Welt.

[ 41 ] So ist es auch in einem gewissen Sinne der Pflanzenwelt gegenüber. So ist es all dem gegenüber, was uns umgibt. Und wirkliche Selbsterkenntnis trägt uns auch immer weiter und weiter in das Innere der Dinge hinein.

[ 42 ] Auf das, was ich heute in einer abgelegeneren Weise, möchte ich sagen, entwickelt habe, möchte ich dann morgen und in der kommenden Zeit einiges aufbauen.

First Lecture

[ 1 ] Today I will have to deal with a number of things that seem to be somewhat removed from the more concrete considerations of our anthroposophy, but which nevertheless must form the basis of many views, and on which many things can then be built in more intimate considerations.

[ 2 ] When we speak of the physical-bodily aspect of the human being on the one hand and the spiritual-soul aspect on the other, we encounter a difficulty for human cognition and understanding. Human beings can relatively easily form ideas about the physical-corporeal. This physical-corporeal is given to them through the senses. It belongs, so to speak, to what confronts them from all sides of their environment without them themselves doing anything essential, at least insofar as their consciousness is concerned. The situation is different when we speak of the spiritual-soul. The spiritual-soul realm is such that, if a person is sufficiently uninhibited, they have a clear awareness of its existence. Humanity has always incorporated terms, words, and phrases into its languages to describe the spiritual-soul realm, and the very fact that such words, phrases, and terms exist within language shows that there is something there for the unbiased consciousness that points to the spiritual-soul realm.

[ 3 ] However, the difficulty arises immediately when human beings want to relate the physical world to the spiritual world. And this search for a relationship presents the greatest possible difficulties, especially for those who deal with such questions in a philosophical way. You know that the physical world is extended in space. You can even represent this physical body in space. And human beings can form ideas about it relatively easily because they can use what space offers them with its three dimensions to form ideas about the physical body. But ultimately, human beings cannot find the spiritual as such anywhere in space.

[ 4 ] People who believe that they are not materialistic, but who are in fact materialistic, want to imagine the spiritual and soul aspects in space and thus arrive at the well-known spiritualistic aberrations. Spiritualistic aberrations are materialistic aberrations; they are an attempt to bring the spiritual and soul into space. But quite apart from that, it is true that human beings are conscious of their own spiritual and soul life. He knows how the spiritual-soul element works, for he tells himself that the thought he harbors, when he decides, for example, to make a movement in space, is translated into movement by means of the will. The movement is in space; but the unprejudiced person cannot say that the thought is in space. And so the greatest difficulties have arisen precisely for philosophical thinking. One asks: How can the spiritual-soul element in human beings, to which the I also belongs, have an effect on the physical-bodily element that is in space? How can something non-spatial have an effect on something spatial?

[ 5 ] A wide variety of theories have arisen, all of which suffer to a greater or lesser extent from the difficulty of relating the non-spatial spiritual-soul to the spatial physical body. It is said that in the will, the spiritual-soul acts upon the physical body. But initially, with ordinary consciousness, no one can say how thought flows into the will, and how the will, which is itself a kind of spiritual entity, comes to manifest itself in external forms of movement, in external activity.

[ 6 ] On the other hand, the processes that are brought about, for example, by the physical world in the senses, that is, in the physical body, are extended in space. They are transformed into something non-spatial by becoming spiritual-soul. From their ordinary consciousness, human beings cannot say how the spatial-physical, which occurs in sensory perception, exerts an effect on the non-spatial, on the spiritual-soul.

[ 7 ] In recent times, we have arrived at the means of explanation that I have mentioned several times before: we speak of “psychophysical parallelism.” This is actually an admission that we have no idea about the relationship between the physical and the spiritual. For example, we say: A person walks, his legs move, he changes his location in outer space. All of this represents something spatial, something physical and corporeal.

[ 8 ] At the same time, when something happens in his body, something spiritual and mental unfolds, something intellectual, emotional, and volitional. One only knows, so they say, that when the physical-bodily takes place spatially and temporally, then the spiritual-soul also takes place. But how one affects the other, one cannot imagine. Psychophysical parallelism means that a psychological, a soul process takes place while a physical one takes place. But one cannot get beyond this, one might say, utter mystery that the two processes occur in parallel. One cannot form any idea of how the two interact. This is the case when people want to form an idea about the existence of the spiritual-soul realm in general.

[ 9 ] In the 19th century, when people's views were so deeply imbued with materialism, materialists also asked the question: Where in the universe do souls actually reside when they have left the body? There were even people who wanted to refute spiritualism by trying to grasp the impossibility inherent in the fact that, since so many people die and so many people have already died, there is actually no place in the entire universe to accommodate all the souls that originate from deceased human beings. This absurd view was indeed common in the 19th century. People said: Man cannot be immortal, because all the spaces in the world would have to be filled with immortal souls. All these things point to the difficulties that arise when we consider the relationship between the physical body, which is clearly extended in space, and that which cannot initially be placed in space, the spiritual soul.

[ 10 ] Now, however, it has gradually come about that purely intellectual human thinking has sharply juxtaposed the physical on the one hand and the spiritual on the other. In today's consciousness, the two stand side by side without any mediation. Yes, just as people have gradually come to think about the physical on the one hand and the spiritual on the other, there is absolutely no way of finding a relationship between them. Today, people simply think of the spatial-physical in such a way that the soul cannot be accommodated anywhere within it, and in turn, they think of the soul as so sharply separated from the physical-spatial that the completely non-spatial spiritual-soul cannot come into contact with the physical or anything like that. But this sharp contrast has only developed gradually. We must take a completely different approach, one that can only emerge by connecting with what anthroposophical spiritual science has to say. Anthroposophical spiritual science must first consider the will. At first glance, an unbiased observation undoubtedly proves that the human will follows its movements everywhere, and that the movements that humans perform externally in space by moving themselves, but also the movements that take place within them as their everyday functions are carried out, that all human activity here in the physical world is three-dimensional in space. The unbiased person can have no doubt about this. All these movements are accompanied by the will, so the will must be everywhere where the three dimensions are extended. There can be no doubt about this either.

[ 11 ] So when we speak of the will as something spiritual and soul-like, there can be no question that this will, even though it is spiritual and soul-like, is three-dimensional and has a three-dimensional form. We must simply think in this way: When we carry out a movement with our hand through our will, the will nestles into all the positions that are carried out in the space of the arm and hand. The will goes everywhere where any movement of a limb takes place. So we must speak of the will itself as that part of the soul that can take on a three-dimensional form.

[ 12 ] But another question is whether everything spiritual takes on a three-dimensional form. And if we move from the will to the world of feeling, to the world of emotion, then the human being, when thinking about these things with his ordinary consciousness, will initially say: If, say, I am pricked by a needle on the right side of my face, on my head, I feel it; if I am pricked on the left side, I feel it too. With his ordinary consciousness, he can therefore believe that his feeling is spread throughout his whole body. And then he will also speak of feeling in the same sense as three-dimensional, just as he speaks of the will as three-dimensional.

[ 13 ] But here he is deceiving himself. That is not the case. Rather, we must take into account how human beings can initially have certain experiences of themselves, and we want to start from these experiences. Today's consideration will be somewhat subtle, but without such subtle considerations, spiritual science cannot be thoroughly understood.

[ 14 ] Just consider, with your mind's eye, what it is like when you touch your left hand with your right hand. This gives you a perception of yourself. You perceive yourself in the same way as you perceive an external object when you touch your right hand with your left, say through the mediation of the individual fingers.

[ 15 ] But you have an even clearer understanding of this fact when you think about the fact that you have two eyes and that when you fix your gaze on an object with both eyes, you first have to exert your will. We often do not think about this exertion of will. For example, in order to fix your gaze on an object that is very close to you, which is more noticeable than usual, you have to turn your left eye to the right and your right eye to the left, and you fix your gaze on the object by bringing the lines of sight into contact with each other in a similar way to how you bring your right hand into contact with your left hand when you touch yourself, so to speak.

[ 16 ] In this way, you can see how it simply has a certain significance for humans in relation to their orientation in the world to relate the left to the right, to bring the left into a certain relationship with the right.

[ 17 ] Now, ordinary consciousness does not usually go much further than bringing this very significant fact to consciousness through the touching of the hands, through the crossing of the lines of sight; but we can continue this observation further.

[ 18 ] Let us assume that we are pricked with a needle on the right side of our body: we perceive, we feel the prick. But we cannot simply say where we feel the prick by pointing to a particular place on the surface of our body. For without all the individual members of our organism being in a relationship with each other, and indeed in a living interrelationship, so that they act upon each other, our physical, mental, and human nature would not be what it is. And even if we do not touch our left hand with our right hand in order to feel the left hand through the right hand, and even if our organism is pricked on its right side, there is always a connection from the right side to the plane of symmetry in the middle, and the left half of the body must enter into a relationship with the right half of the body so that the sensation, the feeling, can come about.

[ 19 ] It is relatively easy to say: if I have the plane of symmetry here, looking from front to back, then the right hand touches the left hand, and the feeling of the two hands, each hand through the other, comes about in the plane of symmetry. This is obviously how it is seen, and it is relatively easy to talk about the intersection of the line of sight. But whenever we are stabbed on the right, for example, there is a line (red), and the left half of the body crosses the right half of the body in these lines, otherwise the sensation would not occur. In all pathways of sensation and feeling, the fact that we have a right and a left half of the body, that we are symmetrically constructed, plays an enormously important role. As a result, we always relate what happens on the right to the left, because something from the left always crosses over, invisibly so to speak, to intersect with what flows over from the right.

[ 20 ] This alone is what makes feeling possible. Feeling never arises in three-dimensional space; feeling always arises in the plane. The world of feelings is not actually spread out in three dimensions; in reality, the world of feelings is only spread out in two dimensions. Human beings experience the world of feelings only in that plane which, if it were to be realized as a sectional plane, would divide human beings into two symmetrical halves.