Health and Illness I

GA 348

16 December 1922, Dornach

VI. The Nose, Smell, and Taste

As you recall, gentlemen, last time we talked about the eye, and we were particularly impressed with its marvellous configuration. Even in regard to its external form, the eye reproduces a whole world. When we become acquainted with the interior of the eye, the way we did the last time, we discover that there is indeed a miniature world within. That I have explained to you, and thus we have become familiar with two senses of man, sight and hearing.

Now, in connection with other questions you have recently posed, we shall see that a particularly fascinating and interesting human sense is that of smell. This sense appears to be of minor importance in man but, as you know, it is of great significance in the dog. You could say that all the intelligence of the dog is, in fact, transferred to the sense of smell. You need only consider how much the animal can accomplish by smell. A dog recognizes people by smell long after it has been with them. Anyone who observes dogs knows that they recognize and identify somebody with whom they have been acquainted, not by the sense of sight, but by that of smell. If you have heard recently how dogs can become excellent detectives and search for lawbreakers or for people in general, you will say to yourselves that here the sense of smell accomplishes rare things that naturally appear simple but are in actuality not so simple at all. You need only consider these matters to realize that they are not so simple.

“Well,” you may say casually, “the dog merely follows the scent.” Yes, gentlemen, that is true, the dog does indeed follow the scent. But think about it. Police dogs are used to follow, say, first the track of thief X and then the track of thief Y, one right after the other. The two scents are completely different from each other; if they were alike the dog could naturally never be able to follow them. Imagine now that you had to point out the difference between these tracks that the dogs distinguish by smell; you would discover no significant difference. The dog, however, does detect differences. The point is not that the dog follows the tracks back and forth in general but that it is capable of distinguishing between the various traces of scent. That, indeed, indicates intelligence.

There is yet another extremely important consideration. Civilized men use their sense of smell for foods and other external things, but it doesn't inform them of much else. In contrast, primitive tribes in Africa can smell out their enemies at far range, just as a dog can detect a scent. They are warned of their foes by smell. Thus, the intelligence that is found in such great measure in the dog is also found to a certain degree among primitive people. The member of a primitive tribe in Africa can tell long before he has seen his adversary that he is approaching; he distinguishes him from other people with his nose. Imagine how delicate one's sense of discernment in the nose must be if by that one can know that an enemy is nearby. Also, Africans know how to utter a certain warning sound that Europeans cannot make at all. It is a clicking sound, somewhat like the cracking of a whip.

It can be said that the more civilized a man becomes, the more diminished is the importance of his sense of smell. We can use this sense to ascertain whether we are dealing with a less developed species like the canine family—and they are a lower species—or one more developed. If we were to follow up on this, we would probably make some priceless discoveries about hogs, which, of course, have an exceptionally strong sense of smell.

There is something else in regard to this that will interest you. The elephant is reputed to be one of the most intelligent animals, and it certainly is; the elephant is a highly intelligent animal. Well, what feature is particularly well-developed in the elephant? Look at the area above the teeth in the dog and the pig, the area that in man forms itself into the nose. When you picture an especially strong and pronounced development of this part, you arrive at the elephant's trunk. The elephant possesses what is nose in us to a particularly pronounced degree, and therefore it is the most intelligent animal. The extreme intelligence of the elephant does not depend on the size of the brain but on its extension straight into the nose.

All these facts challenge us to ask how matters stand in respect to the human nose, an organ that civilized man today does not really know too much about. Of course, he is familiar with its anatomy and structure, but basically, he does not know much more than the fact that it sits in the middle of his face. Yet, the nose, with its continuation into the brain, is actually a most interesting organ. If you will recall my descriptions of the ear and the eye, you will say to yourselves that they are complicated. The nose, however, is not so complicated, but it is quite ingenious.

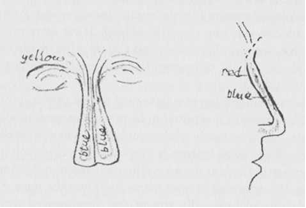

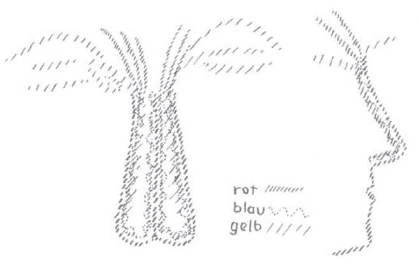

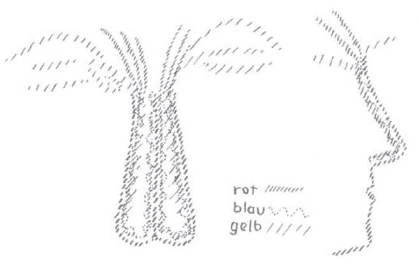

Seen from the front, the nose has a wall in the middle, the septum. This can be felt when you hold your nose. The septum divides the nose into a left and a right side, and to the left and the right are the actual parts of this organ. From the front it looks like this (sketching). The cribriform plate is located in the skull bone up where the nose sits between the eyes. It is like a little sieve. In other words, it is a bone with many holes. It is intricate but in my drawing I shall simplify it. On the exterior, the nose has skin like the skin on the rest of the body; inside, it is completely lined and filled out with a mucous membrane. This is everywhere in the nose, a fact that you can readily confirm. This membrane secretes mucus; if you did not have it, you would not have to blow your nose. So, inside the nose is a membrane that secretes mucus, but the matter is more complicated. You will have noticed that children who cry secrete a lot of nasal mucus. A canal in the upper part of the nose leads to the tear glands, which are located on both sides in the interior. There the secretion, the tears, enters the nose and mixes with the nasal mucus. Thus, the nose has a kind of “fluidic connection” with the eyes. The secretion of the eyes flows into the mucous membrane and combines with the secretion of the nose. This connection shows us again that no organ in the body is isolated. The eyes are not only for seeing; they can also cry, and what they then discharge mixes with what is primarily secreted in the membrane of the nose.

The olfactory nerve, the actual nerve used for smelling, passes through the cribriform plate, which is located at the roof of the nose. This nerve has two fibres that pass from the brain through the sieve-like bone and spread out within the nose. The mucous membrane, which we can touch with our finger, is interlaced by the olfactory nerve, which reaches into the brain. We can easily discern that because the nose is constructed quite simply.

Now we come to something that can reveal much to one who thinks sensibly. You see, a thorough examination will show that no one has eyes of equally strong vision, and when we examine the two hands we readily discover that they are not of equal strength. The organs of the human being are never completely equal in strength on both the left and right side. So it is also with the nose. Generally, we simply do not smell as well with the left nostril as with the right, but it is the same here as it is with the hand; some individuals are better at smelling with the left nostril than with the right, just as some people are left-handed. As you know, some people in the world are screwed together the wrong way. I am not referring to those people whose heads are screwed on wrong [(A play on words. In German, a “Querkopf' is a person who is odd. Rudolf Steiner then uses the term “Querherz” to indicate the anatomical oddity of the heart.)] but to those whose hearts are screwed on the wrong way. In the average person, the heart is located slightly off-centre to the left, as are the rest of the internal organs. Now, in a person whose heart is screwed on the wrong way, as it were, whose heart is off-centre a bit to the right, the stomach is also pushed over slightly to the right. Such a person is all “screwed up,” but this phenomenon is indeed less noticeable than when one is screwed up in the head. The fact becomes apparent when a person has fallen ill or has been dissected. Autopsies first led to the discovery that there are such odd people whose hearts and stomachs are shifted to the right. Of course, since not everyone who is queer in the head is dissected after death, one often doesn't even know that there are many more such “odd people” than is normally assumed whose hearts are off-centre to the right.

A truly effective pedagogy must take this into consideration. When dealing with a child who does not have its heart in the right place, speaking strictly anatomically, this must be taken into account; otherwise, it can have awkward consequences for the youngster. Because man is not just a physical apparatus, he does not necessarily have to be educated in such a way that abnormalities like this have to become an obstacle. Taking such aspects into consideration is what truly makes pedagogy an art.

A Professor Benedikt has examined the brains of many criminals. In Austria this was frowned upon because the people there are Catholics and they see to it that such things are not done. Benedikt was a professor in Vienna. He got in touch with officials in Hungary, where at one time there were more Calvinists, and he was given permission to transport the heads of executed criminals to Vienna. Several things then happened to him. There was a really ruthless killer who had I don't know how many murders on his conscience and who also had religious faith. He was a devout Catholic. When a rumour broke out that the brains of criminals were being sent to Professor Benedikt in Vienna, this criminal who was a cold-blooded murderer protested. He did not want his head sent to the professor because he didn't know where he would look for it to piece it together with the rest of his body when the dead arise on Judgment Day. Even though he was a hardened criminal, he did believe in Judgment Day.

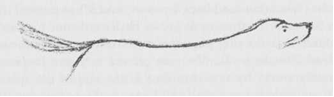

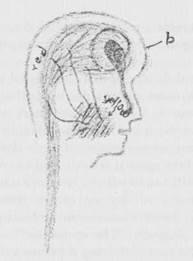

So what did Professor Benedikt find in the brains of criminals? In the back of our heads we have a “little brain,” the cerebellum, which I shall speak about later on. It is covered by a lobe of the “large brain,” the cerebrum. It looks like a small tree (drawing). On top it is covered by the cerebrum and the occipital lobe. Now, Professor Benedikt discovered that in people who have never committed murder or a theft—and there are such people—the occipital lobe extends down to here (drawing), whereas in those who had been murderers or other criminals the lobe did not extend so far; it did not cover the cerebellum below.

A malformation like that is naturally congenital; a person is born with it. And, gentlemen, there are a great many people born with an occipital lobe that is too small to properly cover the cerebellum! It can be made up for by education, however. Nobody has to become a killer because he has a shorter occipital lobe; he becomes a criminal only if he is not properly educated. From this you can see that if the body is not correctly developed one can compensate for it with the forces of the soul. Therefore, it is nonsense to say that a person cannot help becoming a criminal—which is what the otherwise brilliant professor stated—because as an embryo he was incorrectly positioned in the mother's womb and thus did not properly develop the occipital lobe. He might be quite well-educated by accepted standards, but he is not properly educated in regard to such an abnormality. Of course, he cannot help the inadequacies of education, but society can help it; society must see to it that the matter is handled correctly in education. I mention this so you may realize the great significance of the whole organization of man.

Let us return again to the subject of the dog. We must admit that in the dog the nose is especially well-developed. Now, gentlemen, what do we actually smell? What does a dog really smell? If you take a bit of substance like this piece of chalk, you will not smell it. You will be able to smell it only if the substance is set on fire, and the ingredients evaporate to be received into the nose as vapor. You cannot even smell liquid substances unless they first evaporate. We smell only what has first evaporated. Also, there must be air around us with which the vapours from substances can mix. Only when substances have become vaporous can we smell them; we cannot smell anything else. Of course, we do smell an apple or a lily, but it is nonsense to say that we smell the solid lily. We smell the fragrance arising from the lily. When the vapor-like scent of the lily wafts in our direction, then the nerve in the nose is able to experience it.

What a primitive tribesman smells of his enemy are his evaporations. You can conclude from this that a man's presence makes itself felt much farther than his hands can reach. If we were primitive people and one of us were down in Arlesheim, he would know if an adversary of his were up here among us. This would mean that his foe would have to make his being felt all the way down to Arlesheim! (Arlesheim is about 154 miles from Dornach.) Indeed, all of you extend to Arlesheim by virtue of what you evaporate. On account of a man's perspirations, something of himself extends a good distance around himself, and through that he is present to a greater degree than through what one can see externally.

Now, the dog does something interesting that man cannot do. All of you are quite familiar with it. If somewhere you meet a dog you know well and that is equally well-acquainted with you, the animal will wag its tail because it is glad to see you. Yes, gentlemen, why does it wag its tail? Because it experiences joy? A man cannot wag his tail when he is happy, because he does not have one anymore. In this regard man has become stunted, insofar as he has no way to immediately lend expression to his joy. The dog, however, smells the person and wags its tail. On account of the scent, the dog's whole body reaches a state of excitement that is expressed by the tail muscles receiving the experience of gladness. In this respect man has reached the stage where he lacks such an organ with which he could express his joy in this way.

We see that while man is more cultivated than dogs, he lacks the ability to drive the sensation of smell down his spinal cord. The dog can do this; the scent enters its nose and is transmitted down the spinal cord, and then the dog wags its tail. What enters its nose as scent travels down the spinal cord. The end of the spine is the tail, and so it wags it. Man cannot do that and I shall tell you why he cannot. Man also possesses a spinal cord, but he cannot transmit a scent through it. Now, I shall draw the whole head of the human being in profile (diagram). The spinal cord continues down on the left. In the case of the dog it becomes the tail, which the animal can wag. Man, however, turns the force of his spinal cord in the other direction. Indeed, he has the capacity to change many things around, something that the animals cannot do. Thus, animals walk on all fours, or if they do not, as in the case of some monkeys, it is all the worse for them. They are actually organized to walk on all fours. But the human being raises himself up. At first man too walks on all fours, but then he stands erect. The force through which he accomplishes this and that passes through the spinal cord is the same force that pushes the whole brain forward. It is actually quite interesting to see a dog wag its tail. If a human being compared himself to the dog, he can exclaim, “Isn't that something; it can wag its tail, and I cannot!”

The whole force that is contained in this wagging tail, however, has been dammed back by man, and it has pushed the brain forward. In the dog it grows backward, not forward. The force that the dog possesses in its tail we turn around and lead into the brain. You can picture to yourselves how this really works by realizing that at the end of the spine, where we have the so-called tail bone, is the coccyx, which consists of several atrophied vertebrae. In the dog they are well-formed and developed; in us they are a fused and completely stunted protrusion that we can no longer wag. It ends here and is covered by skin. Now, we are able to turn this whole “wagging ability” around, and if in fact the top of the skull were not up here (b), upon smelling a pleasant odour we could wag with our brain, as it were. If our skull bones did not hold it together, we would actually wag with our brain toward the front when we are glad to see somebody.

You see, this is what marks the human organization; it reverses that function found in the animals. This tail wagging ability is still developed but it is reversed. In reality, we too wag something, and some people have a sensitivity for perceiving it. Isn't it true that court officials fawn and cringe in the royal presence? Of course, theirs is not a wagging like that of a dog, but some people still get the feeling that they are really wagging their tails. This is because their wagging is on the soul level and indeed looks like tail wagging. If one has acquired clairvoyance—something that is easily misunderstood but that merely consists of being able to see some things better than others—then, gentlemen, one does not just have the feeling that a courtier is wagging his tail in front of a personage of high rank; one actually sees it. He does not wag something in the back, but he does indeed wag something in the front. Of course, the solid substances within the brain are held together by the skull bones, but what is developed there in the form of delicate substantiality, as warmth, wags when a courtier is standing before royalty. It fluctuates. Now it is warm, now a little cooler, warmer, cooler. Someone with a delicate sensitivity for this fluctuating warmth, who is standing in the presence of courtiers surrounding the Lords, sees something that looks like a fool's cap wagging back and forth in front. It is correct to say that the etheric body, the more delicate organization of man, is wagging in front. It is absolutely true that the etheric body wags.

In the dog or the elephant all this is utilized to form the spinal cord. What remains stunted in both these animals is reversed and pushed forward in man. How is that? In the brain two things meet: The “wagging organ,” which has been pushed forward and is present only in man, and the olfactory nerve, which is also present in man. In the case of the dog, the olfactory nerve enlarges considerably because nothing counteracts it; what would restrain it is wagging in the back. The human being turns this around. The whole “wagging force” comes forward to the nose, and thus the olfactory nerve is made as small as possible; as it penetrates into the brain it is compressed from all sides by what comes to meet it there. You see, man has within the head an organ that, on the one hand, forces back his faculty of smell but, on the other, makes him into a human being. This organ results from the forces that are pushed up and forward.

In the case of the dog and the elephant, much of the olfactory nerve is located in the forward part of the brain; a large olfactory nerve is present there. In man, this nerve is somewhat stunted. The nerves that were pushed upward from below spread out instead. As a result, in this spot where in the dog sensations of smell spread out much further, in the human being the noblest part of the brain is located. There, located in the forward part of the brain, is the sense for compassion, the sense for understanding other human beings, and that is something noble. What the dog expends in its tail wagging, man transforms into something noble. There, in the forward part of the brain, just at the spot where the lowly nose would otherwise transmit its olfactory nerve, man possesses an extraordinarily noble organ.

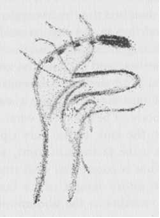

I have mentioned that we do not smell equally well with the left and the right nostrils. Now, try to recall someone who is in the habit of making pronounced gestures. What does he do when he is pondering something? I am sure you have seen it. He reaches up with his finger or his hand and touches his nose; his index finger comes to rest directly over the septum, the inner wall dividing the nasal passages. For right here, behind the nose and within the brain, the capacity for discrimination has its physical expression.

The septum of the dog enables it not only to follow a lead exactingly but also to distinguish carefully with the left and the right nostrils how the scents appear to either one or the other. The dog always has in its right nostril the scent of what it is pursuing at the moment, while in the left it has the scents of everything it has already pursued. The dog therefore becomes increasingly skilful in pursuit, just as we men become more and more intelligent when we learn more and commit facts to our memory. The dog has a particularly good memory for scents, and that is why he becomes such a keen tracker.

A trace of that still exists in human life. Man's sense of smell has become dulled, but Mozart, for example, was sometimes inspired with his best melodies when he smelled a flower in a garden. When he pondered the reason for this, he realized that it happened because he had already smelled this flower somewhere else and that he had especially liked it. Mozart would never have gone so far as to say, “Well, I was once in this beautiful garden in such and such a place, and there was this flower with a wonderful fragrance that pleased me immensely; now, here is the fragrance again, and it makes me almost want to, well—wag my tail.” Mozart would not have said that, but a beautiful melody entered his mind when he smelled this flower the second time. You can tell from this how closely linked are the senses of smell and memory.

This is caused not by what we human beings absorb as scents but rather by what we push forward in the brain and against it. Our power of discrimination is developed there. If a person can think especially logically, if he has the proper thought relationships, then we can say that he has pushed his brain forward against his olfactory nerve, that he has actually adjusted the brain to what otherwise would have also been the olfactory nerve. We can say, too, that the more intelligent a man is, the more he has overcome the dog nature in himself. If a person were born with a dog-like capability to smell especially well, and he was educated to learn to distinguish things other than smells, he would become an unusually clever person because he would be able to discriminate among these other things by virtue of what he had pushed up against the olfactory nerve.

Cleverness, the power of discrimination, is basically the result of man's overcoming his sense of smell. The elephant and the dog have their intelligence in their noses; in other words, it is quite outside themselves. Man has this cleverness inside himself, and that is what distinguishes him. Hence it is not enough just to check and see whether the human being possesses the same organs as the animals. Certainly, both dog and man have a nose, but what matters is how each nose is organized. You can see from this that something is at work in man that is not active in the dog, and if you perceive this you gradually work yourself up from the physical level to the soul level. In the dog the nose and the bushy end of the spine, which is only covered by skin permeated with bony matter, have no inclination to grow toward each other. This tendency originates only from the soul, which the dog does not have in the way a man does. So, then, I have described the nose and everything that belongs to it in such a way that you see its continuation into the brain and find that man's intelligence is connected with this organ.

There is another sense that is quite similar to the sense of smell but in other respects totally different: the sense of taste. It is so closely related that the people in the region where I was born never say “smell”; the word is not used there at all. They say instead, “It tastes good,” or “It tastes bad,” when they smell something. Where I was born they do not talk of smelling but only of tasting. (Someone in the audience calls out, “Here, too, in Switzerland!”) Yes, also here in Switzerland you don't talk of smelling; smelling and tasting appear so closely related to people that they don't distinguish between the two.

If we now investigate the sense of taste, we will find that here there is something strange. Again, it is somewhat like it was with the sense of smell. So, if you take the cavity of the mouth, here in the back is the so-called soft palate, in the front is the hard palate, and there are the teeth with the gums. If you examine all this you will find something strange. Just as a nerve runs down into the nose, so here, too, nerves run from the brain down into the mouth. But these nerves do not penetrate into the gums, nor do they extend into the hard palate in front. They reach only into the soft palate in the back, and they go only into the back part of the tongue, not its front part. So if you see how the nerves are distributed that lead to the sense of taste, you will find only a few in front, practically none. The tip of the tongue is not really an organ of taste but rather one of touch. Only the back part of the tongue and the soft palate can taste. The mouth is soft in the back and hard in the front; only the soft parts are capable of tasting. The gums also have no sensation of taste.

The peculiar thing is that these nerves that convey the sense of taste in man are also connected primarily with everything that makes up the intestinal organization. It is indeed true that first and foremost a food must taste good, although its chemical composition is also important. In his taste man has a regulator for the intake of his food. We should study much more carefully what a small child likes or does not like rather than examine the chemical ingredients of its food. If the child always rejects a food, we shall find that something is amiss with its lower abdominal organs, and then one must intervene there.

I have already sketched the “tail wagging ability” that is reversed in man and that in the dog extends all the way into the back. If we now move forward from the tail, we reach the abdomen, the intestines, and to these the taste nerves correspond. It is like this: When a dog abandons itself to smelling, it wags its tail, which signifies that it drives everything through its entire body. The effects of what it smells pass all the way through to the end, to the very tip end of the tail. The tip of the nose is the farthest in front, and the tail is the farthest behind. What is connected with smelling in the dog passes through the entire length of its body, but what it tastes does not; it remains in the abdominal area and does not go as far. We can see from this that the farther something related with the nerves is located within the organism, the less far-reaching is its effect in the body. This will teach us to understand even better than we know already that the whole form of man depends on his nerves. Man is formed after his nerves. In the case of the dog, its tail is formed after the nose. What are its intestines formed after? They are formed after the nerves of the muzzle. The nerves are situated on one end, and they bring about the form on the other end. This is something that you must take as a basis for further consideration. You will gain much from realizing that the dog owes its whole tail wagging ability to its nose, and that when it feels good in the abdominal area, this is due to the nerves of the mouth. We shall learn more about this later.

It is extraordinarily interesting how the nerves are related to form. This is why I said the other day that even a blind person benefits from his eyes; even though the eyes are useless for sight, their nerves still help shape the body. The way a person appears is caused by the nerves of his head and in part by the nerves of his eyes, as well as by many other nerves. Therefore, if we want to understand why the human being differs in form from the dog, we have to think of the nose! The nose plays an important part in the shape of a dog, but in the human being it is overcome and somewhat subdued in its functions. In the dog, the nose occupies a higher rung on the ladder; it is the head-master, so to speak. In man, the function of the nose is forced back. The eye and the ear are certainly more important for his formation than is the nose.

Sechster Vortrag

Meine Herren, haben Sie noch etwas zum letzten Vortrag zu fragen? Oder haben Sie sonst noch etwas, was Sie wissen möchten?

Nicht wahr, wir haben das letzte Mal über das Auge gesprochen, und was uns besonders aufgefallen ist, das ist, ich möchte schon wirklich sagen, die ganze Wunderbarkeit des Auges. Denn im Auge ist ja wirklich schon der äußeren Gestalt nach eine ganze Welt nachgebildet. Und wenn man so, wie wir es das letzte Mal getan haben, das Innere des Auges kennenlernt, so kommt man eben darauf, daß wirklich da eine kleine Welt im Auge enthalten ist. Nun, das habe ich Ihnen ja auseinandergesetzt.

So haben wir also jetzt zwei Sinne des Menschen kennengelernt: das Ohr und das Auge.

Nun, ein besonders interessanter Sinn beim Menschen, der Sie auch interessieren kann im Zusammenhang mit Fragen, die Sie in der letzten Zeit gestellt haben, ist, wie ich Ihnen noch zeigen werde, der Geruchssinn. Der Geruchssinn hat scheinbar beim Menschen eine geringe Bedeutung, aber er hat eine große Bedeutung, wie Sie wissen, beim Hund zum Beispiel; beim Hund ist wirklich, man möchte sagen, die ganze Intelligenz des Tieres in den Geruchssinn verlegt. Denn Sie brauchen sich nur einmal zu überlegen, was der Hund alles durch den Geruch erreicht. Der Hund erkennt durch den Geruch die Leute, mit denen er einmal zusammengewesen ist, noch lange. Wer Hunde beobachtet, der weiß, daß es nicht etwa der Gesichtssinn des Hundes ist, durch den er jemanden, den er kennengelernt hat, wiedererkennt, sondern es ist der Geruchssinn des Hundes. Und wenn Sie in der letzten Zeit viel davon gehört haben, welche ausgezeichneten Detektive die Hunde werden, indem sie die Spuren von Verbrechern und so weiter, überhaupt von Menschen suchen, so werden Sie sich sagen: Der Geruchssinn vollbringt da seltene Leistungen, die natürlich eigentlich sehr einfach aussehen, aber die so einfach nicht sind. Sie brauchen sich nur zu überlegen, wie die Geschichte ist, dann werden Sie schon sehen, daß das nicht so einfach ist.

Wenn man so in der Sprache redet: Nun ja, der Hund, der verfolgt eben die Spur — ja, meine Herren, das ist schon richtig, daß der Hund die Spur verfolgt. Er verfolgt sie auch. Aber denken Sie sich nur einmal, der Hund soll hintereinander verfolgen - die Polizeihunde werden ja dazu verwendet — die Spur von dem Dieb, dem Einbrecher Lehmann und gleich darauf die Spur vom Einbrecher Schmidt. Die zwei Spuren sind ja ganz verschieden voneinander. Wenn sie gleich wären, könnte der Hund ja natürlich überhaupt nicht dazu kommen, die Spuren zu verfolgen. Nur dadurch, daß sie verschieden sind, kommt er dazu, den Einzelnen wirklich verfolgen zu können. Aber nun denken Sie sich doch, wenn Sie angeben sollten die Unterschiede, die in den Spuren von Menschen sind, die man durch den Geruch unterscheiden kann, dann werden Sie keine großen Unterschiede finden. Der Hund findet die Unterschiede. Es kommt ja nicht darauf an, daß der Hund so hin und her die Spuren verfolgt, sondern daß er unterscheiden kann die verschiedenen Geruchsspuren. Da kommen Sie eben schon auf die Intelligenz.

Dazu kommt ein anderes, das außerordentlich wichtig ist. Sehen Sie, die Europäer können sich ja des Geruches noch in bezug auf die Speisen und auch in bezug auf einige äußere Dinge bedienen. Aber dieser Geruch zeigt ihnen nicht viel. Dagegen wittern zum Beispiel gerade in Afrika wilde Volksstämme, geradeso wie der Hund wittert, den Feind, der noch sehr weit entfernt ist. Die wittern diesen Feind und machen sich aus dem Staub. Also die Intelligenz, die man in so hohem Maße beim Hunde antrifft, die findet man noch in gewissem Sinne bei wilden Völkern, so daß ein wilder Mensch in Afrika bei gewissen Stämmen lange, bevor er den Feind sieht, weiß: da ist der Feind — denn er unterscheidet ihn mit der Nase von anderen Menschen. Nun denken Sie sich, wie fein man unterscheiden muß mit der Nase, wenn man wissen soll: das ist der Feind! Dann kommt noch ein Schnalzton dazu, ein Schnalzton, den man in Europa gar nicht machen kann, ein Schnalzen, wie Peitschenschnalzen.

Also kann man sagen: Je kultivierter, zivilisierter ein Mensch wird, desto mehr tritt die Bedeutung seines Geruchssinnes zurück. Und wir können an dem Geruchssinn so ein bißchen studieren, ob wir ein unzivilisiertes Geschlecht unter uns haben, wie zum Beispiel die Hunde — es ist ein unzivilisiertes Geschlecht — oder ein mehr zivilisiertes. Wahrscheinlich würden wir, wenn wir uns nach dieser Richtung etwas mehr abgeben würden mit dem Schwein, ganz kostbare Entdeckungen machen, denn die Schweine haben natürlich einen ausgesprochen starken Geruchssinn.

Aber jetzt will ich Ihnen noch etwas anderes sagen, was Sie sehr interessieren wird nach dieser Richtung. Als eines der intelligentesten Tiere gilt nämlich der Elefant. Er ist es auch. Denn der Elefant ist ein außerordentlich intelligentes Tier. Ja, was ist denn beim Elefanten ganz besonders ausgebildet? Wenn Sie sich alles, was zum Beispiel beim Hund oder beim Schwein über den Zähnen liegt, was also bei uns zur Nase wird, wenn Sie sich das alles besonders hervorragend ausgebildet denken, so kriegen Sie den Elefantenrüssel. Also ein Elefant hat schon das, was bei uns die Nase ist, ganz besonders ausgebildet, und daher ist er eigentlich das intelligenteste Tier, denn er ist sehr intelligent. Das hängt nicht ab von der Größe seines Gehirns; das hängt davon ab, daß sein Gehirn gerade in die Nase geht.

Das alles fordert uns auf, einmal nachzudenken, wie denn das eigentlich beim Menschen ist mit der Nase, von der der heutige zivilisierte Mensch eigentlich nicht viel weiß — er weiß zwar, wie die Nase gebaut ist und so weiter, aber er weiß eigentlich denn doch nicht viel mehr von der Nase, als daß sie mitten im Gesicht ist. Aber die Nase mit ihrer Fortsetzung ins Gehirn hinein ist tatsächlich ein furchtbar interessantes Organ. Und wenn Sie zurückdenken, wie ich Ihnen das Ohr, das Auge beschrieben habe, werden Sie sich sagen: das ist außerordentlich kompliziert. Bei der Nase kann ich nicht einmal sagen, daß sie außerordentlich kompliziert ist, aber außerordentlich geistreich ist sie.

Wenn Sie die Nase nehmen, von vorne angesehen, dann ist in der Mitte eine Wand - die werden Sie ja schon angegriffen haben. Die teilt nach rechts und links die Nase, und rechts und links sind dann die Nasenflügel (siehe Zeichnung). Da oben, wo die Nase zwischen den Augen ist, da sitzt in dem Schädelknochen drinnen das sogenannte Siebbein. Das ist ein kleines Sieb. Also da oben müßte ich in die Schädelknochen hinein — es ist sehr kompliziert, ich will es aber einfach zeichnen — ein Sieb, ein Knochensieb zeichnen, also einen Knochen, der lauter Löcher hat. Und diese Nase — außen haben Sie ja auch Haut, wie die übrige Körperhaut ist —, diese Nase ist innerlich ausgekleidet, ausgefüllt mit einer Schleimhaut. Da überall ist die Schleimhaut (Zeichnung). Die können Sie ja konstatieren: Es ist eine Haut, die Schleim absondert. Wenn Sie die Schleimhaut nicht hätten, brauchten Sie sich nicht zu schneuzen. Also wenn Sie sich schneuzen müssen, sehen Sie, daß man da eine Haut drinnen hat in der Nase, die Schleim absondert.

Aber die Geschichte ist noch komplizierter. Sie werden schon bei Kindern, die weinen, gesehen haben, daß sie auch viel Nasenschleim absondern. Wenigstens auf dem Lande draußen, wo man weniger auf die Nase achtgibt, da findet man: wenn ein Kind weint, so muß es oft geschneuzt werden; oder aber es rinnt eben herunter durch die Nase, weil nämlich da oben ein Kanal zu den sogenannten 'Tränendrüsen geht. Da oben (Zeichnung) sind ja die beiden Augen, und da kommt von den Tränendrüsen, die am äußeren oberen Rand der Augenhöhle sitzen, fortwährend auch der Tränensaft hinein. Der vermischt sich mit dem Nasenschleim, so daß also die Nase in Verbindung steht, ich möchte sagen, in flüssiger Verbindung steht mit den Augen, weil die Tränen eben in die Nasenschleimhaut hineinfließen, weil eigentlich der Augenschleim sich vermischt mit dem Nasenschleim. So daß wir also auch da sehen, daß gar kein Organ im Körper allein für sich ist. Die Nase ist verbunden mit den Augen. Und die Augen können ja nicht nur sehen, sondern sie können auch weinen. Und das, was sie dann absondern, wenn sie weinen, das vermischt sich mit dem, was eben einfach in der Nase, in der Schleimhaut der Nase abgesondert wird.

Durch dieses Siebbein, das da oben ist an der Nasenwurzel, wie man sagt, da geht nun der eigentliche Riechnerv. Der Riechnerv geht nun zum Gehirn hin, hat zwei Stränge, geht da (Zeichnung) durch das Siebbein und breitet sich da drinnen in der Nase aus. So daß wir also, wenn wir in die Nase — was unartig ist - mit unserem kleinen Finger hineingreifen, wir auf dieNasenschleimhaut greifen; aber diese Nasenschleimhaut ist durchzogen mit dem Riechnerv, der ins Gehirn hineinführt. Das ist dasjenige, was man an der Nase selber sehen kann, denn sie ist eigentlich furchtbar einfach gestalter.

Aber da kommt schon etwas, was einem viel verraten kann, wenn man vernünftig denkt. Wer zum Beispiel die Augen des Menschen ordentlich untersucht, der findet bei keinem Menschen, daß die beiden Augen vollständig gleich stark sehen. Wer die beiden Hände untersucht, der wird schon finden, daß sie nicht gleich stark sind. Der Mensch ist niemals an der linken und rechten Seite in seinen Organen vollständig gleich stark. Und so ist es auch bei der Nase. Man riecht einfach mit dem linken Nasenloch, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, weniger stark als mit dem rechten Nasenloch. Geradeso aber wie es mit den Händen ist, so ist es mit den Nasenlöchern: es gibt einzelne Menschen, die riechen stärker mit dem linken Nasenloch als mit dem rechten, geradeso wie es auch Linkshänder gibt. Es gibt ja überhaupt solche verkehrten Menschen in der Welt. Ich meine jetzt nicht nur die Querköpfe, sondern es gibt schon auch Querherzen!

Beim gewöhnlichen Menschen, da liegt das Herz - nicht viel, aber ein klein bißchen — nach der linken Seite verschoben, und danach sind die ganzen Eingeweide gebildet. Nun gibt es solche Quermenschen, die haben das Herz ein bißchen nach der rechten Seite geschoben, den Magen auch ein bißchen nach rechts, sind ganz verdreht. Das bemerkt man nämlich viel weniger, als wenn die Menschen im Kopf verdreht sind. Wenn die Menschen im Herz oder im Magen verdreht sind, da tritt die Geschichte erst auf, wenn der Mensch irgendwie krank geworden ist oder wenn er seziert wird. Und man ist da erst durch die Sektion darauf gekommen, daß es solche sonderbaren Quermenschen gibt, welche Herz und Magen nach rechts dirigiert haben. Und da nicht jeder Querkopf im Leben seziert wird nicht wahr, es geschieht ja nicht immer —, so weiß man manchmal gar nicht, daß es viel mehr solche Quermenschen gibt, als man glaubt, die das Herz zu stark nach der rechten Seite getrieben haben.

Aber sehen Sie einmal, bei einer ordentlichen Pädagogik muß man darauf Rücksicht nehmen, denn wenn man ein Kind hat, das das Herz nicht auf dem rechten Fleck hat — jetzt nur im anatomischen Sinne gemeint —, so muß man wirklich darauf Rücksicht nehmen, sonst kann eine ganz dumme Geschichte für das Kind daraus werden. Aber der Mensch muß nicht, weil er eben nicht bloß ein physikalischer Apparat ist, so aufgezogen werden, daß ihm solche Dinge ein Hindernis werden. Das ist eben gerade die große Kunst der Erziehung, daß man auf solche Dinge Rücksicht nimmt. Sehen Sie, der Professor Benedikt, der hat eine ganze Menge von Verbrechergehirnen untersucht. In Österreich hat man ihm das nicht gerne zugelassen, weil ja in Österreich die Leute Katholiken sind, und da halten sie darauf, daß man solche Sachen nicht macht. Er war in Wien Professor. Da hat er sich mit den Ungarn in Verbindung gesetzt, die sind in einer gewissen Zeit mehr Calvinisten gewesen, und da hat man ihm gestattet, die Verbrecherschädel nach Wien zu transportieren. Da ist ihm verschiedenes passiert. Da war ein hartgesottener Mörder - ich habe vergessen, wie viele Morde er auf dem Gewissen hatte - und der war nämlich fromm. Der war ein frommer Katholik. Und es ist einmal das Gerücht ausgebrochen, daß der Professor Benedikt in Wien die Verbrecherschädel geschickt kriege und dort untersuche. Da hat sich dieser eine Verbrecher, der ein hartgesottener Mörder war, dagegen aufgelehnt: das wolle er nicht, er wolle nicht seinen Schädel an den Professor Benedikt geschickt haben, denn wo solle er am Jüngsten Tag, wenn alle Leute auferstehen, dann seinen Kopf zusammensuchen mit seinem andern Leib!—Also an den Jüngsten Tag hat er schon geglaubt, trotzdem er ein hartgesottener Verbrecher war.

Ja, was hat denn der Professor Benedikt an den Verbrecherschädeln gefunden? Wir haben da hinten im Gehirn das kleine Gehirn — ich werde davon noch sprechen -, und über dieses kleine Gehirn ist ein Lappen vom großen Gehirn gelegt. Das schaut so aus (siehe Zeichnung). Das kleine Gehirn, das schaut so aus wie ein kleiner Baum, und da drüber ist dann das große Gehirn gelegt, solch ein Lappen. Nun hat der Professor Benedikt gefunden, daß bei Menschen, die niemals gemordet haben, die niemals gestohlen haben—es gibt ja auch solche —, der Gehirnlappen sehr weit heruntergeht, und bei denen, die Mörder oder andere Verbrecher waren, da geht er nicht so weit herunter, da bedeckt er das Untere nicht.

Nun ist natürlich ein Mensch mit einem solchen Fehler geboren. Aber, meine Herren, Menschen, die mit einem zu kleinen Gehirnlappen geboren sind, der nicht richtig das kleine Gehirn zudeckt, die gibt es viele! Und da kann man durch die Erziehung schon nachhelfen. Es muß einer nicht ein Mörder werden, wenn er einen zu kleinen Hinterhauptslappen hat; er wird es nur, wenn er nicht richtig erzogen wird. Daraus sehen Sie wiederum, daß man dem Körper, wenn er nicht richtig ausgebildet ist, durch das Seelische nachhelfen kann. Also es ist ein Unsinn, zu sagen, wie der sonst geistreiche Professor Benedikt gesagt hat: Es kann einer nichts dafür, wenn er ein Verbrecher ist; ja, es kann einer nichts dafür. - Weil er als Keim, als Embryo im Mutterleibe nicht ordentlich gelegen hat, deshalb hat er einen zu kleinen Hinterhauptslappen gekriegt. Er mag ja nach dem, wie man erzieht, recht gut erzogen sein, aber er ist nicht richtig erzogen worden für so etwas. Da kann er natürlich nichts dafür. Aber die Gesellschaft kann dafür, die dafür zu sorgen hat, daß die Sache richtig gemacht wird in der Erziehung.

Alles das sage ich Ihnen, damit Sie sehen, welch große Bedeutung die Gesamtorganisation des Menschen eigentlich hat.

Und nun müssen wir sagen, es ist beim Hund — gehen wir noch einmal zurück auf den Hund -, es ist ja beim Hund eben dieses ganz Einfache der Nase besonders gut und stark ausgebildet. Meine Herren, was riechen wir denn eigentlich? Was riecht denn eigentlich der Hund?

Wenn irgendwo einfach ein Stück Stoff liegt, zum Beispiel die Kreide, dann riechen Sie sie nicht. Bloß wenn Sie den Stoff anzünden, und die Stoffe verdunsten, in Dunst übergehen, so daß sie in der Nase als Luft aufgenommen werden, dann riechen Sie sie. Sie riechen nicht einmal flüssige Stoffe, wenn sie nicht zuerst verdunsten. Also riechen wir nur dasjenige, was zuerst verdunstet. Wir können also sagen: Die Luft muß um uns herum sein, und mit dieser Luft müssen sich die Dünste der Stoffe verbinden. Dann riechen wir die Stoffe dadurch, daß sie dunstförmig geworden sind. Etwas anderes riechen wir nicht. Natürlich, wir riechen den Apfel oder die Lilie. Aber es ist Unsinn, zu glauben, daß wir die feste Lilie riechen. Wir riechen die Dünste, die aus der Lilie aufsteigen und die in unsere Nase kommen. Dann, wenn dieser Lilienduft, der also dunstförmig ist, heranweht, dann ist der Nerv der Nase dazu angetan, geeignet, den Geruch zu erleben.

Also es sind natürlich auch, wenn der Wilde seinen Feind riecht, die Ausdünstungen dabei. Sie können daraus entnehmen, daß der Mensch viel weiter sich geltend macht, als seine Hände reichen. Denn wenn wir Wilde wären, und einer von uns käme da unten in Arlesheim, dann würde er wissen, ob da hier unter uns ein Feind ist von ihm. Also müßte doch dieser Feind von ihm da sein ganzes Wesen bis nach Arlesheim hin geltend machen! Sie sind also auch noch in Arlesheim drunten durch dasjenige, was Sie ausdünsten. Überall ist weit um sich herum der Mensch durch seinen Dunst noch da. Er ist viel mehr durch seinen Dunst noch da, als durch das, was man äußerlich sieht.

Nun gibt es beim Hund etwas, was der Mensch nicht kann, und was außerordentlich interessant ist; Sie kennen es alle recht gut. Wenn Sie einen Hund haben oder nur einen Hund sehen, den Sie gut kennen und der Sie gut kennt und Sie treffen ihn wiederum, so wedelt er mit dem Schwanz. Ja, meine Herren, warum wedelt er mit dem Schwanz? Weil er Freude hat! Der Mensch kann nicht mit dem Schwanz wedeln, wenn er Freude hat, weil er ihn überhaupt nicht mehr hat. Soweit ist der Mensch verkümmert in bezug darauf, daß er seine Freude überhaupt zunächst gar nicht ausdrücken kann. Also der Hund, der riecht den Menschen und wedelt mit dem Schwanz. Durch den Geruch kommt nämlich sein ganzer Körper in Aufregung, und das drückt sich dadurch aus, daß er in seine Schwanzmuskeln dasjenige bekommt, was das Erlebnis der Freude ist, und er wedelt mit dem Schwanz. Beim Menschen ist es soweit gekommen, daß er überhaupt ein solches Organ gar nicht mehr hat, mit dem er seine Freude auf diese Weise ausdrücken könnte.

Wir sehen, der Mensch ist zwar kultivierter als das Hundegeschlecht, aber es fehlt ihm die Möglichkeit, durch sein Rückenmark seinen Geruch herunterzutreiben; denn so ist es ja beim Hund. Er bekommt durch die Nase den Geruch herein, treibt ihn dann durch sein Rückenmark hinunter, und nachher wedelt er mit dem Schwanz.

Also das, was er da als Geruch in die Nase hineinbekommt, das geht da in sein Rückenmark hinein. Und das Ende vom Rückenmark ist eben der Schwanz, und da wedelt er. Das kann der Mensch nicht. Warum? Ich will Ihnen sagen, warum das der Mensch nicht kann. Der Mensch hat auch dieses Rückenmark, aber er ist nicht imstande, den Geruch durch dieses Rückenmark hindurchzuleiten.

Jetzt will ich Ihnen von der Seite gesehen den ganzen Kopf des Menschen aufzeichnen. Da würde dann das Rückenmark weitergehen; das geht dann da hinunter. Beim Hund geht das also in den Schwanz hinein, und dadurch kann der Hund wedeln. Beim Menschen aber ist es so, daß er die Kraft dieses Rückenmarkes umkehrt. Der Mensch hat ja die Kraft, überhaupt manches umzukehren, was die Tiere nicht können. Die Tiere gehen daher auf allen vieren, oder wenn sie, wie manche Affen, nicht auf allen vieren gehen, dann ist das um so schlimmer für sie, weil sie eigentlich dazu organisiert sind, auf allen vieren zu gehen.

Der Mensch richtet sich aber auf während seines Lebens. Er geht auch zuerst auf allen vieren; dann richtet er sich auf. Das ist diese Kraft, die da durch das Rückenmark geht, und diese Kraft schoppt, möchte ich sagen, das ganze Gehirn hier nach vorne. Man kann wirklich sagen, wenn man einen Hund anschaut: das ist furchtbar interessant, besonders wenn man ihn wedeln sieht. Wenn man sich mit ihm vergleicht als Mensch, so muß man eigentlich sagen: Donnerwetter, der kann wedeln; ich kann das nicht! — Aber die ganze Kraft, die da in diesem Wedelschwanz liegt, die hat der Mensch zurückgeschoppt und hat das ins Gehirn hier heraufgeschoppt. Die da hier (beim Hund) wächst nach unten, nicht nach oben. Also diese Kraft, die der Hund da in seinem Schwanz rückwärts hat, die kehren wir um und führen sie nun zum Gehirn hinein. Und so können Sie sich vorstellen, daß die Geschichte so ist: Wenn Sie sich denken würden, da wäre das Ende Ihres eigenen Rückgrates, wo wir das sogenannte Steißbein haben, das aus verkümmerten Knochen besteht, während es beim Hund aus sehr gut ausgebildeten Knochen besteht; das ist bei uns schon zusammengewachsen und so ein ganz verkümmertes Bein, das nicht mehr wedeln kann, geht da herunter, wird von der Haut bedeckt. Nun, diese ganze Wedelkraft, die kehren wir um, und eigentlich, wenn da nicht die Schädeldecke wäre, dann könnten wir mit diesem Gehirn, wenn wir einen angenehmen Geruch wahrnehmen würden, da oben wedeln. Wir würden also eigentlich — was sehr interessant ist -, wenn wir uns freuen, wenn wir jemanden sehen, wenn unsere Gehirnknochen da nicht unser Gehirn zusammenhielten, mit dem Gehirn nach vorne wedeln.

Sehen Sie, das ist eigentümlich in der menschlichen Organisation: Sie kehren die Geschichten um, die bei den Tieren sind. Also diese Wedelkraft, die wird zwar entwickelt, aber sie wird umgekehrt. Wir wedeln nämlich in Wirklichkeit auch, und manche Menschen haben dafür sogar ein feines Gefühl. Nicht wahr, Hofräte, die um die Herzöge herum sind, die wedeln, wenn die Herzöge in der Nähe sind — nun, so wie der Hund wedeln sie nicht, aber manche Menschen haben das Gefühl: die wedeln wirklich. Die wedeln nämlich seelisch. Das ist so etwas, das wie Wedeln ausschaut. Aber sehen Sie, wenn man sich die Empfindung angeeignet hat, die man manchmal, was leicht mißverstanden wird, Hellsehen nennt — das besteht ja darinnen, daß man eben manche Dinge besser sieht als andere Menschen -, ja, meine Herren, dann hat man nicht nur das Gefühl, daß der Hofrat vor dem Herzog wedelt, sondern dann sieht man es sozusagen; nur wedelt er nicht da hinten (wie der Hund), sondern er wedelt da vorne. Er wedelt wirklich! Nicht wahr, das, was da in Ihrem Gehirn drinnen an festen Stoffen ist, das wird ja durch Ihre Knochen zusammengehalten. Aber was da sich entwickelt als feine Stofflichkeit, als Wärme, das wedelt, wenn der Hofrat vor dem Herzog steht. Es ist so, daß es abwechselt, ein bißchen warm, kälter, wärmer, kälter. Und es ist tatsächlich so: Wenn die Hofräte den Herzog umgeben, und wenn Sie eine feine Empfindung für die wackelnde Wärme haben, dann können Sie schon so etwas sehen, wie man es macht, wenn man jemandem ein Eselsohr umhängt: da wedelt vorne, wir sagen dann, da wedelt vorne der Ätherkörper, der feinere Körper, weil das auch richtig ist. Das ist wahr: der Ätherkörper wedelt.

Nun aber, durch das Ganze wird ja beim Hund, oder beim Elefanten, eben das Rückenmark ausgebildet. Beim Menschen wird das, was beim Hund oder beim Elefanten verkümmert bleibt, nach vorne geschoben. Wie ist das? Jetzt will ich den Nerv, den ich da (siehe Zeichnung S. 115) rot hineingezeichnet habe, hier gelb hineinzeichnen, und der geht jetzt ins Gehirn hinein. Im Gehirn drinnen begegnen sich jetzt zwei Sachen: dasjenige, was da als Wedelorgan nach vorne geschoppt ist, was nur beim Menschen da ist, und dasjenige, was der Riechnerv ist, der auch beim Menschen vorhanden ist. Aber dieser Riechnerv, der schiebt sich beim Hund zu einer riesigen Größe ins Gehirn hinein, weil ihm nichts entgegenwirkt, denn das, was ihm entgegenwirken könnte, wedelt ja hinten heraus. Der Mensch aber kehrt das um. Diese ganze Wedelkraft kommt der Nase entgegen. Daher wird beim Menschen das, was da als Riechnerv hineingeht, so klein als möglich gemacht, weil es zusammengeschoppt wird von dem, was ihm entgegenkommt. Und so hat der Mensch da drinnen ein Organ, das erstens seinen Geruch zurückdrängt, aber das ihn eigentlich in gewisser Beziehung zum Menschen macht. Das sind die heraufgeschoppten Kräfte.

Daher kann man sagen, daß da im Vordergehirn drinnen beim Hund und beim Elefanten viel vom Riechnerv liegt, ein riesig großer Riechnerv liegt da drinnen. Beim Menschen ist der Riechnery etwas verkümmert; dagegen lagern sich vor die Nerven, die von unten heraufgeschoppt werden. So daß an der Stelle hier, wo beim Hund noch lange das liegt, was von der Nase hineinwedelt, beim Menschen da gerade das Edelste vom Gehirn liegt. Und die Folge davon ist, daß da im Vorderhirn eigentlich beim Menschen der Sinn vorhanden ist für Mitgefühl, für Verständnis der Menschen überhaupt. Etwas sehr Edles ist da. Das, was der Hund auswedelt, das ist beim Menschen in etwas sehr Edles umgestaltet. Und der Mensch hat da im Vorderhirn, gerade an der Stelle, wo die sehr verachtete Nase sonst ihren Riechnerv hineinschickt, eigentlich ein außerordentlich edles Organ.

Ich habe Ihnen gesagt, daß wir nicht mit dem linken und rechten Nasenloch gleich stark riechen. Nun denken Sie einmal daran, wenn einer, der gewohnt ist, recht starke Gebärden zu machen, nachdenkt — was tut er denn da? Das haben Sie sicher schon gesehen: Er fährt mit dem Finger oder mit der Hand da herauf, gerade so, daß der Zeigefinger über seiner Nasenscheidewand liegt — weil nämlich da hinter der Nase im Gehirn drinnen das Unterscheidungsvermögen seinen körperlichen Ausdruck hat.

Die Nasenscheidewand, die macht es beim Hund so, daß er sehr fein nicht nur die Spur verfolgen kann, sondern er kann mit seinem linken und rechten Nasenloch sehr fein unterscheiden, wie bei dem einen und bei dem andern die Gerüche sind, und er hat nämlich - das ist jetzt sehr interessant — in seinem rechten Nasenloch immer die Spur von demjenigen, den er gerade verfolgt, während er im linken Nasenloch drinnen die Spuren von all denen hat, die er schon verfolgt hat. Dadurch wird er immer gescheiter im Verfolgen, wie wir Menschen auch immer gescheiter werden, wenn wir mehr lernen und mehr in unserem Gedächtnis drinnen haben. Der Hund hat nämlich ein gutes Gedächtnis für Gerüche. Dadurch wird er ein so guter Spurverfolger.

Und da geht aber noch eine Spur ins Menschenleben herein. Man kann nämlich folgendes beobachten. Sehen Sie, der Mensch ist schon abgestumpft fürs Riechen; aber zum Beispiel dem Mozart sind manchmal seine schönsten Melodien eingefallen, wenn er in irgendeinem Garten eine Blume gerochen hat. Wenn er nachgedacht hat, warum das ist, so ist das deshalb gewesen, weil er diese Blume schon irgendwoanders gerochen hatte, wo es ihm gerade recht gut gefallen hatte. Er hätte sich niemals aufgeschwungen etwa, dieser Mozart, zu der Aussage: Nun ja, da war ich einmal in dem wunderschönen Garten von dort und dort, da war so eine Blume, die hat einen Duft gehabt, der mir besonders gefallen hat; jetzt ist wiederum so ein Duft da, das bringt mich ja - ja, fast zum Wedeln. Das hätte der Mozart nicht gesagt; aber eine schöne Melodie ist ihm eingefallen, wenn er die Blume wieder gerochen hat. Daraus sehen Sie, wie das Riechen mit unserem Gedächtnis zusammenhängt.

Das rührt aber nicht von dem her, was wir Menschen an Riechen hineinschicken, sondern von dem, was wir da drinnen entgegenschoppen. Da wird unser Unterscheidungsvermögen als Menschen entwickelt. Wenn also einer besonders logisch denken kann, richtig die Gedankenverbindungen hat, dann müssen wir sagen: Der hat gegen seinen Riechnerv sein Gehirn vorgeschoben und eigentlich angepaßt dem, was sonst der Riechnery wäre. - Man könnte schon sagen, ein besonders gescheiter Mensch ist eigentlich ein solcher, der die Hundenatur in sich möglichst groß überwunden hat.

Wenn also einer so geboren wird, daß er ein halber Hund ist, daß ei besonders gut riechen könnte, und man würde ihn dann so aufziehen, daß er andere Dinge, die nicht Gerüche sind, unterscheiden kann — denn die unterscheidet er durch das, was er dem Geruchsnerv entgegenschoppt —, dann würde er ein besonders gescheiter Mensch werden.

Die Gescheitheit, das Unterscheidungsvermögen, das rührt überhaupt davon her, daß der Mensch den Geruchssinn überwindet. Der Elefant und der Hund haben ihre Gescheitheit in der Nase, also ziemlich außerhalb von sich selbst; der Mensch hat seine Gescheitheit in sich. Das ist eben eigentlich der Unterschied. So daß man eben nicht bloß darauf schauen darf, ob der Mensch und die Tiere dieselben Organe haben. Gewiß, der Hund und der Mensch haben eine Nase, aber es kommt darauf an, wie die Nasen angeordnet sind. Und daraus sieht man eben, daß am Menschen etwas arbeitet, was am Hunde nicht arbeitet. Und so arbeitet man sich allmählich, wenn man so etwas erkennt, von dem Körperlichen zum Seelischen herauf. Denn weder die Nase, noch auch jenes besenförmige Ende des Rückenmarks, das der Hund zum Wedeln hat, was ja nur von Häuten überzogen ist, von etwas Knochen durchzogen ist, die haben keinen Drang, einander entgegenzuwachsen. Dieser Drang kommt dann erst vom Seelischen, das der Hund nicht in derselben Weise hat wie der Mensch.

Nun sehen Sie, ich habe Ihnen also die Nase mit allem, was dazu gehört, so beschreiben können, daß wir sie in ihrer Fortsetzung ins Gehirn hinein finden, und daß wir daran eigentlich die Gescheitheit des Menschen geknüpft finden.

Merkwürdig kommt es uns vor, wenn wir nun mit dem Geruchssinn einen Sinn vergleichen, der ganz ähnlich dem Geruchssinn ist, und doch wiederum kolossal verschieden ist: das ist der Geschmackssinn. Er ist so verwandt, daß zum Beispiel in der Gegend, wo ich geboren bin, die Leute überhaupt niemals sagen: riechen — das Wort «riechen» kommt da gar nicht vor. Die sagen: es schmeckt gut oder es schmeckt schlecht, wenn sie riechen; die reden dort, wo ich geboren bin, gar nicht vom Riechen. (Es wird eingeworfen: Hier auch!) Also auch hier in der Schweiz, auch hierzulande redet man nicht vom Riechen, sondern vom Schmecken, weil es den Leuten so verwandt vorkommt, was Riechen und Schmecken ist, daß sie es gar nicht unterscheiden.

Wenn wir nun aber den Geschmackssinn untersuchen, da ist es sehr merkwürdig. Da ist es wiederum so ähnlich wie beim Geruchssinn. Wenn Sie dahier die Rachenhöhle nehmen - ich kann das heute nur andeuten, werde es später weiter ausführen —, dahier hinten ist der sogenannte weiche Gaumen, da vorne ist der harte Gaumen, da sind die Zähne mit dem Zahnfleisch, wenn Sie das nehmen, dann haben Sie etwas sehr Merkwürdiges. Geradeso wie in die Nase hinein ein Nerv geht, den ich da rot gezeichnet habe, so gehen auch vom Gehirn aus überall hier hinein Nerven. Aber diese Nerven, die gehen zum Beispiel nicht ins Zahnfleisch hinein, die gehen auch nicht in den vorderen Gaumen hinein, sondern nur in den hinteren, gehen gar nicht einmal in die vordere Zunge hinein, sondern nur in die hintere Zunge. Also wenn Sie das anschauen, wie die Nerven verteilt sind, die zum Geschmack gehören, so werden Sie vorne wenige finden, fast gar keine. Die Zungenspitze ist eigentlich nicht ein Geschmacksorgan, sondern die Zungenspitze ist mehr zum Fühlen vorhanden. Nur der hintere Teil der Zunge, der kann schmecken, ebenso der weiche Gaumen. Wenn Sie in den Mund hineingreifen, werden Sie es hinten weich, vorne hart finden. Dieses Weiche ist zum Geschmack geeignet. An dem Zahnfleisch schmecken Sie gar nichts.

Nun ist es eigentümlich, daß diese Nerven, die dem Geschmack dienen, auch beim Menschen noch besonders zusammenhängen mit alledem, was Eingeweide ist. Und es ist schon wahr, es kommt nicht nur darauf an, daß man ein Nahrungsmittel chemisch untersucht, sondern es muß ein Nahrungsmittel zuerst schmecken. Und der Mensch hat schon im Geschmack einen Regulator für seine Nahrung. Wir sollten zum Beispiel beim kleinen Kinde viel mehr studieren, was es mag oder nicht mag, als daß wir die chemische Zusammensetzung studieren. Wenn wir darauf achtgeben, daß vom Kinde etwas immer zurückgewiesen wird, dann finden wir, daß in seinen Unterleibsorganen etwas nicht in Ordnung ist. Da muß man eingreifen. Ja, aber, meine Herren, das ist ja höchst eigentümlich. Sehen Sie, da habe ich Ihnen den Riechnerv da ganz vorne gezeichnet (siehe Zeichnung. 109); jetzt müßte ich die Nerven, die zu derZunge und zum Gaumen gehen, hier so zeichnen (siehe Zeichnung S. 120); und hier habe ich das gezeichnet, was beim Menschen, nun ja, die zurückgegangene Wedelkraft ist, was ganz hinten eigentlich ist beim Hund. Gehen wir jetzt allmählich nach vorne, so kommen wir beim Menschen in den Bauch, in die Eingeweide — beim Hund auch -, und dem entsprechen die Geschmacksnerven. Und es ist in der Tat so: Wenn der Hund sich seinem Riechen hingibt, dann wedelt er, das heißt, er treibt alles durch den ganzen Körper. Es geht da bis ins Ende. Der Schwanz ist ja das letzte Ende; die Nasenspitze ist ganz vorn, das Schwanzende ganz hinten. Was also beim Hund mit dem Riechen zusammenhängt, geht durch den ganzen Körper. Was der Hund frißt, wenn es ihm schmeckt, geht nicht durch den ganzen Körper, sondern bleibt in den Eingeweiden weiter zurück. Das ist sehr interessant.

So daß wir also daraus sehen können: Je mehr nach innen gelegen etwas ist, was mit den Nerven zusammenhängt, desto weniger weit wirkt es wiederum im Körper. Und das wird uns das nächstemal dazu führen, daß wir noch besser, als wir es schon begriffen haben, begreifen lernen, daß von den Nerven die ganze Gestalt des Menschen abhängt. Der Mensch ist nach den Nerven gestaltet. Wenn wir nämlich beim Hund fragen: Wonach ist denn sein Schwanz gestaltet? Nach der Nase. —- Wonach ist sein Eingeweide gestaltet? Nach den Nerven des Maules. — Die Nerven sind an einem Ende und machen die Gestalt am andern Ende. Das ist etwas, was Sie, bitte, weiteren Betrachtungen zugrunde legen wollen. Sie werden sehr viel davon haben, wenn Sie darauf kommen, daß der Hund seine ganze Schwanzwedelei von der Nase hat; daß er, wenn er zum Beispiel sich wohl fühlt in seinen Eingeweiden, das von den Nerven seines Mundes hat und so weiter. Das Weitere werden wir noch sehen.

Also es ist außerordentlich interessant, wie die Nerven mit der Gestalt zusammenhängen. Deshalb habe ich Ihnen neulich gesagt: Auch ein Blinder hat von seinen Augen etwas, weil die Augennerven, die zwar beim Blinden nicht zum Sehen da sind, noch immer seinen Körper gestalten. Wie er ausschaut, das rührt von seinen Kopfnerven, und zum Teil von seinen Augennerven her, aber auch viel von seinen anderen Nerven. Und wenn wir daher studieren wollen, warum der Mensch in der Gestalt unterschieden vom Hund ist, da müssen wir an die Nase denken! (Finger auf den Nasenrücken.) Beim Hund nimmt die Nase einen großen Anteil an der Gestalt. Beim Menschen ist ja das überwunden; da ist die Nase ein wenig zurückgedrängt in ihren Funktionen. Beim Hund hat eben die Nase einen höheren Grad in der Stufenleiter. Beim Hund ist die Nase sozusagen der allererste Meister; beim Menschen ist sie in ihrer Tätigkeit zurückgedrängt. Da werden wir sehen, was dann anderes eintritt zu seiner Gestaltung. Da ist schon das Auge und das Ohr wichtiger zu seiner Gestaltung als seine Nase.

Sixth Lecture

Gentlemen, do you have any questions about the last lecture? Or is there anything else you would like to know?

Last time, we talked about the eye, and what particularly struck us was, I would really say, the sheer wonder of the eye. For the eye truly replicates an entire world in its external form. And when you get to know the inside of the eye, as we did last time, you realize that there really is a small world contained within the eye. Well, I have explained that to you.

So now we have learned about two of the human senses: the ear and the eye.

Now, a particularly interesting sense in humans, which may also be of interest to you in connection with questions you have asked recently, is, as I will show you, the sense of smell. The sense of smell seems to be of little importance in humans, but it is very important, as you know, in dogs, for example; in dogs, one might say that the animal's entire intelligence is transferred to the sense of smell. Just think about everything a dog can do through smell. Dogs can recognize people they have been with before for a long time through smell. Anyone who observes dogs knows that it is not the dog's sense of sight that enables it to recognize someone it has met before, but its sense of smell. And if you have heard a lot lately about what excellent detectives dogs make, searching for the traces of criminals and so on, of people in general, you will say to yourself: The sense of smell accomplishes rare feats that, of course, look very simple, but are not so simple. You only need to consider how the story goes, and you will see that it is not so simple.

When people say: Well, the dog follows the trail — yes, gentlemen, it is true that the dog follows the trail. It does follow it. But just imagine, the dog has to follow one trail after another — police dogs are used for this — the trail of the thief, the burglar Lehmann, and immediately afterwards the trail of the burglar Schmidt. The two trails are completely different from each other. If they were the same, the dog would of course not be able to follow the trails at all. It is only because they are different that he is able to really follow the individual trails. But now think about it: if you were to identify the differences in the traces left by humans, which can be distinguished by smell, you would not find any major differences. The dog finds the differences. It is not important that the dog follows the trails back and forth, but that it can distinguish between the different scent trails. This is where intelligence comes in.

There is another factor that is extremely important. You see, Europeans can still use smell in relation to food and also in relation to some external things. But this smell does not tell them much. In contrast, wild tribes in Africa, for example, smell the enemy who is still very far away, just as a dog smells him. They smell this enemy and take off. So the intelligence that we find to such a high degree in dogs can also be found in a certain sense in wild peoples, so that a wild man in Africa, in certain tribes, knows long before he sees the enemy: there is the enemy — because he distinguishes him from other people with his nose. Now imagine how finely one must distinguish with one's nose in order to know: that is the enemy! Then there is a clicking sound, a clicking sound that cannot be made in Europe, a clicking like the crack of a whip.

So you could say that the more cultured and civilized a person becomes, the less important their sense of smell becomes. And we can use the sense of smell to study a little bit whether we have an uncivilized species among us, such as dogs — which are an uncivilized species — or a more civilized one. If we were to devote ourselves a little more to this area, we would probably make some very valuable discoveries with pigs, because pigs naturally have a very strong sense of smell.

But now I want to tell you something else that will be of great interest to you in this regard. The elephant is considered one of the most intelligent animals. And it is. Because the elephant is an extraordinarily intelligent animal. So what is particularly well developed in elephants? If you imagine everything that lies above the teeth in dogs or pigs, for example, which in humans becomes the nose, and if you imagine all of that being particularly well developed, you get the elephant's trunk. So an elephant has something that is very specially developed, which is what we call the nose, and that is why it is actually the most intelligent animal, because it is very intelligent. This does not depend on the size of its brain; it depends on the fact that its brain goes straight into its nose.

All of this prompts us to think about how this actually works in humans with the nose, about which today's civilized human beings don't really know much — they know how the nose is constructed and so on, but they don't really know much more about the nose than that it is in the middle of the face. But the nose, with its continuation into the brain, is actually a terribly interesting organ. And if you think back to how I described the ear and the eye, you will say to yourself: that is extremely complicated. I cannot even say that the nose is extremely complicated, but it is extremely ingenious.

If you look at the nose from the front, there is a wall in the middle—you will have already touched it. It divides the nose into right and left, and on the right and left are the nostrils (see drawing). Up there, where the nose is between the eyes, the so-called ethmoid bone sits inside the skull bone. It is a small sieve. So up there, I would have to draw a sieve, a bone sieve, into the skull bones—it's very complicated, but I'll just draw it—a bone with lots of holes. And this nose—on the outside, you also have skin, like the rest of your body—this nose is lined on the inside, filled with a mucous membrane. The mucous membrane is everywhere (drawing). You can see that for yourself: it is skin that secretes mucus. If you didn't have the mucous membrane, you wouldn't need to blow your nose. So when you need to blow your nose, you see that there is skin inside the nose that secretes mucus.

But the story is even more complicated. You will have noticed that children who cry also secrete a lot of nasal mucus. At least in the countryside, where people pay less attention to their noses, you find that when a child cries, they often have to blow their nose; or else it just runs down their nose because there is a channel up there to the so-called ‘lacrimal glands’. Up there (drawing) are the two eyes, and the tear ducts, which are located at the outer upper edge of the eye socket, continuously supply tear fluid. This mixes with the nasal mucus, so that the nose is connected, I would say, in a fluid connection with the eyes, because the tears flow into the nasal mucosa, because the eye mucus actually mixes with the nasal mucus. So we see here, too, that no organ in the body is alone. The nose is connected to the eyes. And the eyes can not only see, but they can also cry. And what they secrete when they cry mixes with what is secreted in the nose, in the mucous membrane of the nose.

The actual olfactory nerve passes through the ethmoid bone, which is located at the root of the nose, as they say. The olfactory nerve goes to the brain, has two strands, passes through the ethmoid bone (drawing) and spreads out inside the nose. So when we put our little finger into our nose—which is naughty—we are touching the nasal mucosa; but this nasal mucosa is permeated by the olfactory nerve, which leads into the brain. This is what you can see in the nose itself, because it is actually very simple in structure.

But there is something that can reveal a lot if you think about it sensibly. For example, if you examine a person's eyes closely, you will find that no one has eyes that are completely equal in strength. If you examine both hands, you will find that they are not equally strong. The human body is never completely equal in strength on the left and right sides. And so it is with the nose. One simply smells less strongly with the left nostril than with the right nostril, if I may express it that way. But just as it is with the hands, so it is with the nostrils: there are some people who smell more strongly with the left nostril than with the right, just as there are left-handed people. There are all kinds of unusual people in the world. I don't just mean stubborn people, there are also people with unusual hearts!

In ordinary people, the heart is shifted slightly to the left, and all the internal organs are formed accordingly. Now there are such cross-minded people who have their heart shifted a little to the right, their stomach also a little to the right, they are completely twisted. This is much less noticeable than when people are twisted in their heads. When people are twisted in their heart or stomach, the story only comes to light when the person has somehow fallen ill or when they are dissected. And it was only through dissection that it was discovered that there are such strange people who have their heart and stomach directed to the right. And since not every stubborn person is dissected in life, it doesn't always happen —, we sometimes don't even know that there are many more such cross-minded people than we think who have driven their hearts too far to the right.

But you see, in proper pedagogy, one must take this into account, because if you have a child whose heart is not in the right place — now meant only in the anatomical sense — then you really have to take this into account, otherwise it can turn into a very stupid story for the child. But because humans are not merely physical apparatuses, they must not be raised in such a way that such things become an obstacle for them. It is precisely the great art of education to take such things into consideration. You see, Professor Benedikt examined a whole lot of criminal brains. In Austria, they didn't like to allow him to do that, because in Austria people are Catholic, and they insist that such things should not be done. He was a professor in Vienna. There he got in touch with the Hungarians, who at that time were more Calvinist, and they allowed him to transport the criminals' skulls to Vienna. Various things happened to him there. There was a hardened murderer—I've forgotten how many murders he had on his conscience—and he was devout. He was a devout Catholic. And once a rumor broke out that Professor Benedikt in Vienna was receiving the criminals' skulls and examining them there. This one criminal, who was a hardened murderer, rebelled against it: he didn't want that, he didn't want his skull sent to Professor Benedikt, because where would he find his head on Judgment Day, when all people are resurrected, to put it back together with the rest of his body! So he did believe in Judgment Day, even though he was a hardened criminal.

So what did Professor Benedikt find in the criminals' skulls? At the back of the brain, we have the cerebellum—I'll talk about that later—and above this small brain is a lobe of the cerebrum. It looks like this (see drawing). The cerebellum looks like a small tree, and above it is the cerebrum, a lobe of this kind. Now Professor Benedikt found that in people who have never murdered, who have never stolen—there are such people—the lobe of the brain extends very far down, and in those who were murderers or other criminals, it does not extend so far down, so it does not cover the lower part.

Now, of course, a person is born with such a defect. But, gentlemen, there are many people who are born with a cerebral lobe that is too small and does not properly cover the cerebellum! And education can help here. A person does not have to become a murderer if he has a too small occipital lobe; he only becomes one if he is not properly educated. From this you can see that if the body is not properly developed, the soul can help. So it is nonsense to say, as the otherwise witty Professor Benedikt said: A person cannot help being a criminal; yes, a person cannot help it. Because he was not positioned properly as a germ, as an embryo in the womb, he ended up with an occipital lobe that is too small. He may well have been brought up quite well, depending on how he was educated, but he was not brought up properly for something like this. Of course, he cannot help that. But society can help, because it is responsible for ensuring that things are done properly in education.

I am telling you all this so that you can see how important the overall organization of the human being actually is.

And now we must say that in dogs — let's go back to dogs — it is precisely this very simple sense of smell that is particularly well and strongly developed. Gentlemen, what do we actually smell? What does a dog actually smell?

If there is simply a piece of fabric lying somewhere, for example chalk, then you cannot smell it. Only when you light the fabric and the substances evaporate, turning into vapor, so that they are absorbed into the nose as air, can you smell them. You cannot even smell liquid substances unless they evaporate first. So we only smell what evaporates first. We can therefore say: the air must be around us, and the vapors of the substances must combine with this air. Then we smell the substances because they have become vaporous. We don't smell anything else. Of course, we smell the apple or the lily. But it is nonsense to believe that we smell the solid lily. We smell the vapors that rise from the lily and enter our nose. Then, when this lily scent, which is vaporous, wafts toward us, the nerve in our nose is able to experience the smell.

So, of course, when the savage smells his enemy, the vapors are also present. You can conclude from this that human beings assert themselves much further than their hands can reach. For if we were savages, and one of us came down to Arlesheim, he would know if there was an enemy of his here among us. So this enemy of his would have to assert his entire being all the way to Arlesheim! So you are also still down in Arlesheim through what you exude. Everywhere, far and wide, man is still there through his vapor. He is much more present through his vapor than through what can be seen externally.

Now there is something about dogs that humans cannot do, and which is extremely interesting; you all know it very well. If you have a dog, or even just see a dog that you know well and that knows you well, and you meet it again, it wags its tail. Yes, gentlemen, why does it wag its tail? Because it is happy! Humans cannot wag their tails when they are happy because they no longer have tails. Humans have degenerated to such an extent that they cannot even express their joy in the first place. So the dog smells the human and wags its tail. The smell excites his whole body, and this is expressed by the experience of joy reaching his tail muscles, causing him to wag his tail. Humans have reached the point where they no longer have an organ with which they can express their joy in this way.

We see that humans are more cultured than dogs, but they lack the ability to transmit their scent through their spinal cord, as dogs do. Dogs take in the scent through their nose, transmit it down their spinal cord, and then wag their tail.

So what he takes in as a smell through his nose goes into his spinal cord. And the end of the spinal cord is the tail, and that's where he wags it. Humans cannot do that. Why? I will tell you why humans cannot do that. Humans also have this spinal cord, but they are not able to conduct the smell through it.

Now I want to draw the entire human head as seen from the side. The spinal cord would then continue; it goes down there. In dogs, it goes into the tail, which is why dogs can wag their tails. In humans, however, the power of the spinal cord is reversed. Humans have the power to reverse many things that animals cannot do. Animals therefore walk on all fours, or if, like some monkeys, they do not walk on all fours, it is all the worse for them because they are actually organized to walk on all fours.