Education

GA 307

13 August 1923, Ilkley

VIII. Reading, Writing and Nature Study

In the previous lectures I have shown that when the child reaches the usual school age (after the change of teeth) all teaching should be given in an artistic, pictorial form. To-day, I propose to carry further the ideas already put before you and to show how this method appeals directly to the child's sentient life, the foundation from which all teaching must now proceed.

Let us take a few characteristic examples to show how writing can be derived from the artistic element of painting and drawing. I have already said that if a system of education is to harmonize with the natural development of the human organism, the child must be taught to write before he learns to read. The reason for this is that in writing the whole being is more active than is the case in reading. You will say: Yes, but writing entails the movement of only one particular member. That is quite true, but fundamentally speaking, the forces of the whole being must lend themselves to this movement. In reading only the head and the intellect are engaged, and in a truly organic system of education we must draw that which is to develop from the whole being of the child.

We will assume that we have been able to give the child some idea of flowing water; he has learnt to form a mental picture of waves and flowing water. We now call the child's attention to the initial sound, the initial letter of the word ‘wave.’

We indicate that the surface of water rising into waves follows this line:

Then we lead the child from the drawing of this line over to the sign W derived from it. The child is thus introduced to the form of the letter ‘W’ in writing. The W has arisen from the picture of a wave. In the first place the child is given a mental picture which can lead over to the letter which he then learns to write. Or we may let the child draw the form of the mouth:—

and then we introduce to him the first letter of the word “Mouth.” In one of our evening talks [Between the lectures there were meetings for discussion and questions at which Rudolf Steiner was often present.] I gave you another example. The child draws the form of a fish; when the fundamental form is firmly in his mind, we pass on to the initial letter of the word “fish.”

A great many letters can be treated in this way; others will have to be derived somewhat differently. Suppose, for instance, we give the child an imaginative idea of the sound of the wind. Obviously the possibilities are many, but this particular way is the best for very young children. We picture to the child the raging of the wind and then we allow the child to imitate and to arrive at this form:—

By drawing the child's attention to definite contours, to movements, or even to actual activities, all of which can be expressed in drawing or painting, we can develop nearly all the consonants. In the case of the vowels we must turn rather to gesture, for the vowels are an expression of man's inner being. ‘A’ (ah), for example, inevitably contains an element of wonder, of astonishment. Eurhythmy will prove to be of great assistance here for there we have gestures that truly correspond to feeling. The ‘I’ the ‘A’ and all the other vowels can be drawn from the corresponding gesture in Eurhythmy, for the vowels must be derived from movements that are an expression of the inner life of the human soul.

In this way we can approach the abstract nature of writing by way of the more concrete elements contained in painting and drawing. We succeed in making the child start from the feeling called up by a picture; he then becomes able to relate to the actual letters the quality of soul contained in the feeling. The principle underlying writing thus arises from the sentient life of the soul.

When we come to reading, our efforts must simply be in the direction of making the child aware, and this time in his head, of what has already been elaborated by the bodily forces as a whole. Reading is then grasped mentally, because it is recognized in the child's mind as an activity in which he has already been employed. This is of the very greatest significance. The whole process of development is hindered if the child is led straight away to what is abstract, if he is taught, that is, from the beginning to carry out any special activity by means of a purely mental concept. On the other hand, a healthy growth will always ensue if the activity is first of all undertaken, and then the mental idea afterwards unfolded as a result of the activity. Reading is essentially a mental act. Therefore if reading is taught before, and not after writing the child is prematurely involved in a process of development exclusively concerned with the head instead of with the forces of his whole being.

By such methods as these all instruction can be guided into a sphere that embraces the whole man, into the realm of art. This must indeed be the aim of all our teaching up to the age of about nine-and-a-half; picture, rhythm, measure, these qualities must pervade all our teaching. Everything else is premature.

It is for this reason utterly impossible before this age to convey anything to the child in which definite distinction is made between himself and the outer world. The child only begins to realize himself as a being apart from the outer world between the ninth and tenth years. Hence when he first comes to school, we must make all outer things appear living. We should speak of the plants as holding converse with us and with each other in such a way that the child's outlook on Nature and man is filled with imagination. The plants, the trees, the clouds all speak to him, and at this age he must feel no separation between himself and this living outer world. We must give him the feeling that just as he himself can speak, so everything that surrounds him also speaks.

The more we enable the child thus to flow out into his whole environment, the more vividly we describe plant, animal and stone, so that weaving, articulate spirituality seems to be wafted towards him, the more adequately do we respond to the demands of his innermost being in these early years. They are years when the sentient life of the soul must flow into the processes of breathing and of the circulation of the blood and into the whole vascular system, indeed into the whole human organism. If we educate in this sense, the child's life of feeling will unfold itself organically and naturally in a form suited to the requirements of our times.

It is of incalculable benefit to the child if we develop this element of feeling in writing and then allow a faint echo of the intellect to enter as he re-discovers in reading what he has already experienced in writing. This is the very best way of leading the child on towards his ninth year.

Between the ages of seven and nine-and-a-half, it is therefore essential that all the teaching shall make a direct appeal to the element of feeling. The child must learn to feel the forms of the various letters. This is very important. We harden the child's nature unduly, we over-strengthen the forces of bones and cartilage and sinew in relation to the rest of the organism, if we teach him to write mechanically, making him trace arbitrary curves and lines for the letters, making use only of his bodily mechanism without calling upon the eye as well.

If we also call upon the eye—and the eye is of course connected with the movements of the hand—by developing the letters in an artistic way, so that the letter does not spring from merely mechanical movements of the hand, it will then have an individual character in which the eye itself will take pleasure. Qualities of the soul are thus brought into play and the life of feeling develops at an age when it can best flow into the physical organism with health-giving power.

I wonder what you would say if you were to see someone with a plate of fish in front of him, carefully cutting away the flesh and consuming the bones! You would certainly be afraid the bones might choke him and that in any case he would not be able to digest them. On another level, the level of the soul, exactly the same thing happens when we give the child dry, abstract ideas instead of living pictures, instead of something that engages the activities of his whole being. These dry, abstract concepts must only be there as a kind of support for the pictures that are to arise in the soul.

When we make use of this imaginative, pictorial method in education in the way I have described, we so orientate the child's nature that his concepts will always be living and vital. We shall find that when he has passed the age of nine or nine-and-a-half, we can lead him on to a really vital understanding of an outer world in which he must of necessity learn to distinguish himself from his environment.

When we have given sufficient time to speaking of the plant world in living pictures, we can then introduce something he can learn in the best possible way between the ninth and tenth years, gradually carrying it further during the eleventh and twelfth.

The child is now ready to form ideas about the plant world. But naturally, in any system of education aiming at the living development of the human being, the way in which the plants are described must be very different from such methods as are used for no other reason than that they were usual in our own school days. To give the child a plant or flower and then make him learn its name, the number of its stamens, the petals and so forth, has absolutely no meaning for human life, or at most only a conventional one.

Whatever is taught the child in this way remains quite foreign to him. He is merely aware of being forced to learn it, and those who teach botany to a child of eleven or twelve in this way have no true knowledge of the real connections of Nature. To study some particular plant by itself, to have it in the specimen box at home for study is just as though we were to pull out a single hair and observe it as it lay there before us. The hair by itself is nothing; it cannot grow of itself and has no meaning apart from the human head. Its meaning lies simply and solely in the fact that it grows on the head of a man, or on the skin of an animal. Only in its connections has it any living import. Similarly, the plant only has meaning in its relation to the earth, to the forces of the sun and, as I shall presently show, to other forces also. In teaching children about a plant therefore, we must always begin by showing how it is related to the earth and to the sun.

I can only make a rough sketch here of something that can be illustrated in pictures in a number of lessons. Here (drawing on the blackboard) is the earth; the roots of the plant are intimately bound up with the earth and belong to it. The chief thought to awaken in the child is that the earth and the root belong to one another and that the blossom is drawn forth from the plant by the rays of the sun. The child is thus led out into the Cosmos in a living way.

If the teacher has sufficient inner vitality it is easy to give the child at this particular age a living conception of the plant in its cosmic existence. To begin with, we can awaken a feeling of how the earth-substances permeate the root; the root then tears itself away from the earth and sends a shoot upwards; this shoot is born of the earth and unfolds into leaf and flower by the light and warmth of the sun. The sun draws out the blossoms and the earth retains the root.

Then we call the child's attention to the fact that a moist earth, earth inwardly watery in nature, works quite differently upon the root from what a dry earth does; that the roots become shrivelled up in a dry soil and are filled with living sap in a moist, watery earth.

Again, we explain how the rays of the sun, falling perpendicularly to the earth, call forth flowers of plants like yellow dandelions, buttercups and roses. When the rays of the sun fall obliquely, we have plants like the mauve autumn crocus, and so on. Everywhere we can point to living connections between root and earth, between blossom and sun.

Having given the child a mental picture of the plant in its cosmic setting, we pass on to describe how the whole of its growth is finally concentrated in the seed vessels from which the new plant is to grow.

Then—and here I must to some extent anticipate the future—in a form suited to the age of the child we must begin to disclose a truth of which it is difficult as yet to speak openly, because modern science regards it as pure superstition or so much fantastic mysticism. Nevertheless it is indeed a fact that just as the sun draws the coloured blossom out of the plant, so is it the forces of the moon which develop the seed-vessels. Seed is brought forth by the forces of the moon. In this way we place the plant in a living setting of the forces of the sun, moon and earth. True, one cannot enter deeply into this working of the moon forces, for if the children were to say at home that they had been taught about the connection between seeds and the moon, their parents might easily be prevailed upon by scientific friends to remove them from such a school—even if the parents themselves were willing to accept such things! We shall have to be somewhat reticent on this subject and on many others too, in these materialistic days.

By this radical example I wished, however, to show you how necessary it is to develop living ideas, ideas that are drawn from actual reality and not from something that has no existence in itself. For in itself, without the sun and the earth, the plant has no existence.

We must now show the child something further. Here (drawing on the blackboard) is the earth; the earth sprouts forth, as it were, produces a hillock (swelling); this hillock is penetrated by the forces of air and sun. It remains earth substance no longer; it changes into something that lies between the sappy leaf and the root in the dry soil—into the trunk of a tree. On this plant that has grown out of the earth, other plants grow—the branches. The child thus realizes that the trunk of the tree is really earth-substance carried upwards. This also gives an idea of the inner kinship between the earth and all that finally becomes earthy. In order to bring this fully home to the child, we show him how the wood decays, becoming more and more earthy till it finally falls into dust. In this condition the wood becomes earth once more. Then we can explain how sand and stone have their origin in what was once really destined for the plants, how the earth is like one huge plant, a giant tree out of which the various plants grow like branches.

Here we develop an idea intelligible to the child; the whole earth as a living being of which the plants are an integral part.

It is all important that the child should not get into his head the false ideas suggested by modern geology—that the earth consists merely of mineral substances and mineral forces. For the plants belong to the earth as much as do the minerals. And now another point of great significance. To begin with, we avoid speaking of the mineral as such. The child is curious about many things but we shall find that he is no longer anxious to know what the stones are if we have conveyed to him a living idea of the plants as an integral part of the earth, drawn forth from the earth by the sun.

The child has no real interest in the mineral as such. And it is very much to the good if up to the eleventh or twelfth years he is not introduced to the dead mineral substances but can think of the earth as a living being, as a tree that has already crumbled to dust, from which the plants grow like branches.

From this point of view it is easy to pass on to the different plants. For instance, I say to the child: The root of such and such a plant is trying to find soil; its blossoms, remember, are drawn forth by the sun. Suppose that some roots cannot find any soil but only decaying earth, then the result will be that the sun cannot draw out the blossoms. Then we have a plant with no real root in the soil and no flower—a fungus, or mushroom-like growth. We now explain how a plant like a fungus, having found no proper soil in the earth, is able to take root in something partly earth, partly plant, that is, in the trunk of a tree. Thus it becomes a tree-lichen, that greyish-green lichen which one finds on the bark of a tree, a parasite.

From a study of the living, weaving forces of the earth itself, we can lead on to a characterization of all the different plants. And when the child has been given living ideas of the growth of the plants, we can pass on from this study of the living plant to a conception of the whole surface of the earth.

In some regions yellow flowers abound; in others the plants are stunted in their growth, and in each case the face of the earth is different. Thus we reach geography, which can play a great part in the child's development if we lead up to it from the plants.

We should try to give an idea of the face of the earth by connecting the forces at work on its surface with the varied plant-life we find in the different regions. Then we unfold a living instead of a dead intellectual faculty in the child. The very best age for this is the time between the ninth or tenth and the eleventh or twelfth years. If we can give the child this conception of the weaving activity of the earth whose inner life brings forth the different forms of the plants, we give him living and not dead ideas, ideas which have the same characteristics as a limb of the human body. A limb has to develop in earliest youth. If we enclosed a hand for instance in an iron glove, it could not grow. Yet it is constantly being said that the ideas we give to children should be as definite as possible, they should be definitions and the children ought always to be learning them. But nothing is more hurtful to the child than definitions and rigid ideas, for these have no quality of growth. Now the human being must grow as his organism grows. The child must be given mobile concepts, concepts whose form is constantly changing as he becomes more mature. If we have a certain idea when we are forty years of age, it should not be a mere repetition of something we learnt at ten years of age. It ought to have changed its form, just as our limbs and the whole of our organism have changed.

Living ideas cannot be roused if we only give the child what is nowadays called “science,” the dead knowledge which we so often find teaches us nothing! Rather must we give the child an idea of what is living in Nature. Then he will develop in a body which grows as Nature herself grows. We shall not then be guilty, as educational systems so often are, of implanting in a body engaged in a process of natural development, elements of soul-life that are dead and incapable of growth. We shall foster a living growing soul in harmony with a living, growing physical organism and this alone can lead to a true development.

This true development can best be induced by studying the life of plants in intimate connection with the configuration of the earth. The child should feel the life of the earth and the life of the plants as a unity: knowledge of the earth should be at the same time a knowledge of the world of the plants.

The child should first of all be shown how the lifeless mineral is a residue of life, for the tree decays and falls into dust. At the particular age of which I am now speaking, nothing in the way of mineralogy should be taught the child. He must first be given ideas and concepts of what is living. That is an essential thing.

Just as the world of the plants should be related to the earth and the child should learn to think of it as the offspring of a living earth-organism, so should the animal-world as a whole be related to man. The child is thus enabled in a living way to find his own place in Nature and in the world. He begins to understand that the plant-tapestry belongs to the living earth. On the other hand, however, we teach him to realize that the various animals spread over the world represent, in a certain sense, stages of a path to the human state. That the plants have kinship to the earth, the animals to man—this should be the basis from which we start. I can only justify it here as a principle; the actual details of what is taught to a child of ten, eleven or twelve years concerning the animal world must be worked out with true artistic feeling.

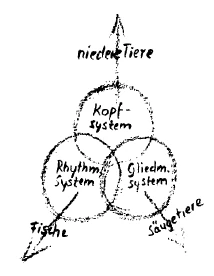

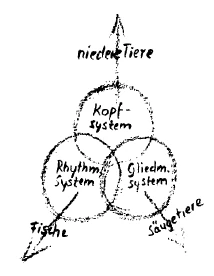

In a very simple, very elementary way, we begin by calling the child's attention to the nature of man. This is quite possible if the preliminary artistic foundations have already been laid. The child will learn to understand, in however simple a sense, that man has a threefold organization. First, there is the head. A hard shell encloses the system of nerves and the softer parts that lie within it. The head may thus be compared with the round earth within the Cosmos. We shall do our utmost to give the child a concrete, artistic understanding of the head-system and then lead on to the second member, the rhythmic system which includes the organs of breathing and circulation of the blood. Having spoken of the artistic modelling of the cup-like formation of the skull which encloses the soft parts of the brain, we pass on to consider the series of bones in the spinal column and the branching ribs. We shall study the characteristics of the chest, with its breathing and circulatory systems, that is, the human rhythmic system in its essential nature. Then we reach the third member, the system of metabolism and limbs. As organs of movement, the limbs really maintain and support the metabolism of the body, for the processes of combustion are regulated by their activities. The limbs are connected with metabolism. Limbs and metabolism must be taken together; they constitute the third member of man's being.

To begin with, then, we make this threefold division of man. If our teaching is pervaded with the necessary artistic feeling and is given in the form of pictures, it is quite possible to convey to the child this conception of man as a threefold being.

We now draw the child's attention to the different animal species spread over the earth. We begin with the lowest forms of animal life, with creatures whose inner parts are soft and are surrounded by shell-like formations. Certain members of the lower animal species consist, strictly speaking, merely of a sheath surrounding the protoplasm. We show the child how these lower creatures image in a primitive way the form of the human head.

Our head is the lower animal raised to the very highest degree of development. The head, and more particularly the nervous system, must not be correlated with the mammals or the apes, but with the lowest forms of animal life. We must go far, far back in the earth's history, to the most ancient forms of animal life, and there we find creatures which are wholly a kind of elementary head. Thus we try to make the lower animal world intelligible to the child as a primitive head-organization.

We then take the animals somewhat higher in the scale, the fishes and their allied species. Here the spinal column is especially developed and we explain that these “half-way” animals are beings in whom the human rhythmic system has developed, the other members being stunted. In the lowest animals, then, we find at an elementary stage, the organization corresponding to the human head. In the animal species grouped round the fishes, we find a one-sided development of the human chest-organization, and the system comprising the limbs and metabolism brings us finally to the higher animals.

The organs of movement are developed in great diversity of form in the higher animals. The mechanism of a horse's foot, a lion's pad, or the feet of the wading animals, all these give us a golden opportunity for artistic description. Or again, we can compare the limbs of man with the one-sided development we find in the limbs of the ape. In short, we begin to understand the higher animals by studying the plastic structure of the organs of movement, or the digestive organs.

Beasts of prey differ from the ruminants in that the latter have a very long intestinal track, whereas in the former, while the intestinal coil is short, all that connects the heart and blood circulation with the digestive processes is strongly and powerfully developed. A study of the organization of the higher animals shows at once how one-sided is its development in comparison with the system of limbs and metabolism in man. We can give a concrete picture of how the front part of the spine in the animal is really nothing but head. The whole digestive system is continued right on into the head. The animal's head belongs essentially to the digestive organs, to the stomach and intestines. In man, on the other hand, that which has remained, as it were, in the virginal state—the soft parts of the brain with their enclosing, protecting shell of bone—is placed above the limb and metabolic system. The head organization in man is thus raised a stage higher than in the animal, in which, as we have seen, it is merely a continuation of the metabolism. Yet man, in so far as his head organization is concerned, preserves the simplest, most fundamental principles of form, namely, soft substance within surrounded by a cup-like bony formation.

One can show too how in certain animals the structure of the jaw can best be understood if the upper and under jaw are regarded as the foremost limbs. This best explains the animal head. In this way, the human being emerges as a synthesis of three systems—head system, chest system, system of limbs and metabolism. In the animal world there is a one-sided development of the one or other system. Thus we have first, the lower animals, the crustaceans, for example, but also others; then the mammals, birds and so on, where the chest system is predominantly developed; and finally the species of fishes, reptiles and so on.

We see, as it were, the animal kingdom as a human being spread out in diversity over the earth. We relate the world of the plants to the earth, and the diverse animal species to man who is, in fact, the synthesis of the entire animal world. Taking our start from man's physical organization, we give the child, in a simple way, an idea of the threefold nature of his being. Passing to the animals, we explain how in the different species there is always a one-sided development of certain organs, whereas in man these organs are united into one harmonious whole. This one-sided specialized development is manifested by the chest organs in certain animals; in others by the lower intestines, and in others again, by the upper organs of digestion. In many forms of animal life, birds for instance, we find metamorphoses of certain organs; the organs of digestion become the crop, and so forth.

We can characterize each animal species as representing a one-sided development of an organic system in man, so that the whole animal world appears as the being of man spread over the earth in diversity of forms, man himself being the synthesis of the animal kingdom.

When it has been made clear to the child that the animal world is the one-sided expression of the bodily organs of man, that one system of organs comes to expression as one species, another as a different species, then we can pass on to study man himself. This should be when the child is approaching his twelfth year, for he can then understand that because man bears the spirit within him, he is an artistic synthesis of the separate parts of his being, which are mirrored in the various species of animals. Only because man bears the spirit within him can he thus unite the lower forms of animal life in a harmonious unity. The human head and chest organizations arise as complex metamorphosis of animal forms, all of which have evolved in such a way that they fit in with the other parts of his body.

Thus he bears within himself that which is manifested in the fishes and that which is manifested in the higher animals but harmonized into a limb. The separate fragments of man's being scattered over the world in the realm of the animals are in man gathered together by the spirit into unity; man is their synthesis. Thus we relate man with the animal world, but he is at the same time raised above the animals because he is the bearer of the spirit.

Botany, taught in the way I have indicated, brings life into the child's world of ideas so that he stands rightly in the world through wisdom. A living intelligence will then enable him to become efficient in life and to find his place in the world.

His will is strengthened if he has acquired an equally living conception of his own relation to the animal world.

You will naturally realize that what I have had to discuss here in some twenty minutes or so must be developed stage by stage for a long period of time; the child must gradually unite these ideas with his inmost nature. Then they will play no small part in the position a man may take in the world by virtue of his strength of will. The will grows inwardly strong if a man realizes that by the grace of the living spirit he himself is the perfecting and the synthesis of the animal kingdom.

And so the aim of educational work must be net merely to teach facts about the plants and animals, but also to develop character, to develop the whole nature of the child. A true understanding of the life of plants brings wisdom, and a living conception of his relation to the animals strengthens the will of the child. If we have succeeded in this, the child has entered between the ninth and tenth years, into a relationship with the other living creatures of the earth such that he will be able to find his own way and place in the world through wisdom on the one hand and on the other through a purposeful strength of will.

The one great object of education is to enable the human being to find his way through life by his intelligence and will. These two will develop from the life of feeling that has unfolded in the child between the ages of seven and nine-and-a-half. Thinking, feeling and willing are then brought into a right relationship instead of developing in a chaotic way. Everything is rooted in feeling. We must therefore begin with the child's sentient life and from feeling engender the faculty of thought through a comprehension of the kingdom of the plants. For the life of the plants will never admit of dead conceptions. The will is developed if we lead the child to a knowledge of his connection with the animals and of the human spirit that lifts man above them.

Thus we strive to impart sound wisdom and strength of will; to the human being. This indeed is our task in education, for this alone will make him fully man and the evolution of the full manhood is the goal of all education.

Neunter Vortrag

Daß man, wenn das Kind in das schulpflichtige Alter kommt, also beim Übergang zum Zahnwechsel, mit einem künstlerisch-bildnerischen Unterrichten und Erziehen das Richtige trifft, habe ich in den letzten Vorträgen auseinandergesetzt. Ich will heute nur noch zu den dort gemachten prinzipiellen Bemerkungen einige ergänzend hinzufügen, um namentlich zu zeigen, wie durch einen solchen Unterricht, wie er vorgestern charakterisiert worden ist, gerade das Gefühl, das Gemütsleben des Kindes in Anspruch genommen wird, so daß man durch einen solchen Unterricht vor allen Dingen auf das Gefühlsleben des Kindes wirkt und alles aus dem Gefühlsleben heraus entwickelt.

Vergegenwärtigen wir uns einmal durch einige charakteristische Beispiele, wie man aus dem Malerischen, aus dem Künstlerisch-Zeichnerischen das Schreiben heraus entwickeln kann. Ich habe schon gesagt, daß das Schreiben bei einem organisch-naturgemäßen Unterrichte vorangehen müsse dem Lesenlernen aus dem Grunde, weil das Schreiben mehr von dem ganzen Menschen in Anspruch nimmt als das Lesen.

Das Schreiben wird ausgeübt in einer Bewegung eines Organes, zu dem sich aber im Grunde genommen der ganze Mensch anschicken muß. Das Lesen nimmt nur den Kopf, den Intellekt in Anspruch, und man soll bei einem organischen Unterricht immer aus dem ganzen Menschen heraus dasjenige holen, was zu entwickeln ist. Man nehme also an, man habe die Kinder dahin gebracht, eine Anschauung zu gewinnen von fließendem Wasser. Fließendes Wasser hat das Kind nun gelernt ins Bild zu bringen. Wir nehmen an, wir seien so weit gekommen, daß wir dem Kinde etwas beigebracht haben von der Verbildlichung des fließenden Wassers, das Wellen wirft (es wird farbig gezeichnet). Wir wollen darauf hinarbeiten, daß das Kind nun achten lernt auf den Anfangslaut, den Anfangsbuchstaben des Wortes «Welle». Wir versuchen gerade das Anlauten, das Aussprechen des Anfangsbuchstabens charakteristischer Worte ins Auge zu fassen. Wir bringen dem Kinde bei, wie gewissermaßen an der Oberfläche des wellen werfenden Wassers sich diese Linie ergibt. Und wir bringen das Kind herüber vom Ziehen dieser Linie, den Wellen des fließenden Wassers entlang, zum zeichnerischen Formen dessen, was sich daraus ergibt: W.

Und man hat das Kind auf diese Weise dazu gebracht, daß es beginnt, aus dem Bilde heraus das W dem Spiel, der Linie der Welle nach schriftlich zu fixieren. — So holt man aus der Anschauung desjenigen, was das Kind ins Bild bringt, den zu schreibenden Buchstaben heraus.

Oder sagen wir, man bringt das Kind dahin, daß es etwa folgende Zeichnung macht, daß es den menschlichen Mund in dieser Weise zur Aufzeichnung bringt. Man hält es an, diesen Zug des Mundes festzuhalten und herauszuheben, und läßt es von da an herüberkommen zu dem Verspüren des Anfangsbuchstabens des Wortes «Mund». — Ich habe bereits in einer Abendstunde angedeutet, wie man nun das Kind dazu bringen kann, einen Fisch aufzuzeichnen. Man bringt das Kind nun dahin, die Grundform festzuhalten und läßt es von da aus zum Erfühlen des Anfangslautes des Wortes kommen: «Fisch». Man wird auf diese Weise eine Anzahl von Buchstaben gewinnen können; andere wird man auf eine andere Weise aus dem Zeichnerischen hervorholen müssen. Sagen wir zum Beispiel, man bringt dem Kinde auf irgendeine anschauliche Weise bei, wie der dahinbrausende Wind sich bewegt. Bei kleinen Kindern wird dies besser sein als eine andere Art; die Dinge können natürlich in der verschiedensten Weise gemacht werden. Man bringt dem Kinde das Hinstürmen des Windes bei. Nun läßt man das Kind das Sausen des Windes nachmachen und bekommt auf diese Weise diese Form. Kurz, es ist möglich dadurch, daß man in dem Malerischen entweder scharf konturierte Gegenstände oder Bewegungen oder auch Tätigkeiten festzuhalten versucht, auf diese Weise fast alle Konsonanten zu entwickeln.

Bei den Vokalen wird man zu der Gebärde gehen müssen, denn die Vokale entstammen der Offenbarung des menschlichen Inneren. Im Grunde genommen ist das A zum Beispiel immer eine Art von Verwunderung und Staunen.

Da wird einem dann die Eurythmie besonders helfen. Denn in der Eurythmie sind genau die dem Empfinden entsprechenden Gebärden gegeben. Und man wird das I, das A und so weiter aus den entsprechenden Eurythmiegebärden durchaus herausentwickeln können. Vokale müssen aus den Gebärden, die ja aus der menschlichen Lebendigkeit die Gefühle begleiten, herausentwickelt werden. |

So kann man zu der Abstraktheit des Schreibens hingelangen aus dem ganz Konkreten des zeichnerischen Malens, des malenden Zeichnens, und man erlangt dadurch eben, daß das Kind immer von einem Gefühl im Bilde ausgegangen ist und den Buchstaben mit dem Seelischen des Gefühles in Verbindung hat bringen können, so daß das ganze Prinzip des Schreibens aus dem Gefühlsleben der menschlichen Seele hervorgeht.

Geht man dann über zum Lesen, so hat man ja im Grunde genommen nichts anderes zu tun, als darauf hinzuwirken, daß das Kind dasjenige durch den Kopf wiedererkennt, was es durch den ganzen Körper erarbeiten gelernt hat. So daß das Lesen ein Wiedererkennen einer Tätigkeit ist, die man selbst ausgeführt hat. Das ist von einer ungeheuren Wichtigkeit. Es verdirbt die ganze menschliche Entwickelung, wenn der Mensch zu einem Abstrakten direkt geführt wird, wenn er irgendeine Tätigkeit durch einen Begriff ausführen lernt. Dagegen führt es immer zu einer gesunden menschlichen Entwickelung, wenn zuerst die Tätigkeit angeregt wird und dann aus der Tätigkeit heraus der Begriff entwickelt wird.

Das Lesen ist durchaus in Begriffen lebend; daher hat man es als das zweite, nicht als das erste zu entwickeln. Sonst bringt man das Kind viel zu früh in eine Art von Kopfentwickelung hinein statt in eine vollmenschliche Entwickelung.

So sehen Sie ja, wie aller Unterricht im Grunde genommen in die Sphäre des ganzen Menschen, in die Sphäre des Künstlerischen dadurch gelenkt werden kann. Und dahin muß auch aller übrige Unterricht bis etwa zum Lebensalter von neuneinhalb Jahren zielen. Da muß alles auf das Bild, auf den Rhythmus, auf den Takt gehen. Alles andere ist verfrüht.

Daher ist es auch völlig unmöglich, einem Kinde irgendwie schon etwas vor diesem Lebensalter beizubringen, das einen starken Unterschied macht zwischen dem Menschen selber und zwischen der Außenwelt. Das Kind lernt sich selber von der Außenwelt erst zwischen dem neunten und zehnten Jahr unterscheiden. Daher handelt es sich darum, daß man alle Außendinge für das Kind, wenn es in die Schule hereinkommt, in eine Art lebendiger Wesen verwandelt, daß man nicht von Pflanzen spricht, sondern daß man spricht von den Pflanzen als lebenden Wesen, die einem selber etwas sagen, die einander etwas sagen, daß alle Naturbetrachtung, alle Menschheitsbetrachtung im Grunde genommen in Phantasie gegossen wird. Die Pflanzen sprechen, die Bäume sprechen, die Wolken sprechen. Und das Kind darf eigentlich in diesem Lebensalter einen Unterschied zwischen sich und der Welt gar nicht fühlen. Es muß in ihm künstlerisch das Gefühl erzeugt werden, daß es selber sprechen kann, daß die Gegenstände um es herum auch sprechen können.

Je mehr wir dieses Aufgehen des Kindes in der ganzen Umgebung erreichen, je mehr wir in der Lage sind, von allem, von Pflanze, Tier, Stein so zu reden, daß überall darinnen ein Sprechend-Webend-Geistiges an das Kind heranweht, desto mehr kommen wir dem entgegen, was das Kind in diesem Lebensalter aus dem Inneren seines Wesens heraus eigentlich von uns fordert, und wir erziehen dann das Kind in der Art, daß gerade in den Jahren, in denen das Gefühlsleben übergehen soll in Atmung und Blutkreislauf, in die Bildung der Gefäße, übergehen soll in den ganzen menschlichen Organismus, tatsächlich auch das Gefühlsleben für unsere Zeit richtig angesprochen wird, so daß das Kind in naturgemäßer Weise sich auch innerlich organisch gefühlsmäßig stark entwickelt.

Es ist eine ungeheure Wohltat, wenn wir so gefühlsmäßig das Schreiben entwickeln und dann leise nur den Intellekt anklingen lassen, indem wir das Geschriebene wiedererkennen lassen im Lesen. Da klingt leise der Intellekt an. Wir führen so das Kind am besten gegen das neunte Lebensjahr heran.

So daß wir sagen müssen: zwischen dem siebenten und neunten oder neuneinhalbten Lebensjahr ist vor allen Dingen aller Unterricht so zu geben, daß er an das Gefühlsleben appelliert, daß das Kind wirklich alle Formen der Buchstaben in das Gefühl hineinbekommt. Man tut damit ungeheuer Bedeutsames für das Leben des Kindes. Denn es verfestigt das Kind zu stark, macht es gewissermaßen zu stark in seinem Knochen- und Sehnen- und Knorpelsystem gegenüber dem übrigen Organismus, wenn wir ihm das Schreiben mechanisch beibringen, wenn wir ihm eine gewisse Linienführung für die Buchstaben beibringen, um dadurch an den Körpermechanismus zu appellieren, statt an das Auge mitzuappellieren.

Wenn man an das Auge mitappelliert, das in Verbindung steht mit der sich bewegenden Hand, dadurch daß man aus dem Künstlerischen die Buchstaben herausarbeitet, wird der Buchstabe nicht bloß mechanisch durch eine Handführung erzeugt, sondern er wird so erzeugt, daß das Auge mit Wohlgefallen auf dem Ergebnis der eigenen Tätigkeit ruht. Dadurch wird eben das Seelische in der richtigen Weise für den Menschen in Anspruch genommen; dadurch wird in der richtigen Weise in dem Lebensalter das Gefühlsleben entwickelt, in dem es gerade am allerbesten in den physischen Organismus gesundend hineinströmen kann.

Was würden Sie sagen, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, wenn jemand, dem ein Fisch auf den Teller gelegt worden ist, sorgfältig das Fischfleisch weglegen würde, sich die Gräten aussondern und diese verzehren würde! Sie würden wohl wahrscheinlich eine furchtbare Angst bekommen, daß ein solcher Mensch an den Fischgräten ersticken könnte. Außerdem würde er diese Fischgräten nicht in der richtigen Weise seinem Organismus einverleiben können.

Aber so ist es, ganz genau so, nur auf einem anderen Niveau, auf dem Niveau der seelischen Unterweisung, wenn wir einem Kinde statt der lebensvollen Bilder, statt desjenigen, was den ganzen Menschen beansprucht, trockene, abstrakte, nüchterne Begriffe beibringen. Diese trockenen, abstrakten, nüchternen Begriffe müssen bloß da sein, damit sie gewissermaßen stützen, was bildhaft in der menschlichen Seele wird.

Nun richten wir tatsächlich, wenn wir so erziehen, wie ich es eben angeführt habe, dadurch, daß wir alles aus dem Bildhaften heraus entwickeln, das Kind so zurecht, daß es in die Lage kommt, immer bewegliche Begriffe zu haben, nicht starre Begriffe. Und dadurch werden wir bemerken können, daß, wenn das Kind das neunte oder neuneinhalbte Lebensjahr überschritten hat, es nun in schön organischer Weise hineingeführt werden kann in das Begreifen der Welt, wobei es sich selber schon von den Dingen und Ereignissen der Welt unterscheiden muß. Wir können dem Kind, nachdem wir ihm von den Pflanzen wie von sprechenden Wesen genügend lange erzählt haben, so daß es in Bildern gelebt hat, indem es auf die Pflanzenwelt hinschaute, wir können ihm dann dasjenige beibringen, was der Mensch am allerbesten von der Pflanzenwelt lernt, wenn er damit anfängt zwischen dem neunten und zehnten Jahre und allmählich im zehnten, elften Jahre dazu geführt wird.

Da ist wiederum gerade der menschliche Organismus dazu bereit, mit der Pflanzenwelt sich innerlich ideenhaft auseinanderzusetzen. Allerdings muß die Pflanzenkunde eine ganz andere Form annehmen für einen lebendigen, die Menschenentwickelung wirklich fördernden Kindesunterricht als dasjenige, was wir heute oftmals als Pflanzenkunde in die Schule hineintragen, weil wir es selber als Pflanzenkunde gelernt haben. Es hat gar keine Bedeutung für das Menschenleben seiner Wirklichkeit nach, höchstens eine konventionelle, ob man vorgelegt bekommen hat diese Pflanzen und jene Pflanzen und so weiter und einem dann Namen und Staubgefäßezahl, Farbe der Blumenblätter für diese Pflanzen beigebracht worden sind.

Alles, was auf diese Weise an das Kind herangebracht wird, bleibt dem Kinde fremd. Das Kind fühlt nur den Zwang, das erlernen zu müssen. Und derjenige, der auf diese Weise Pflanzenkunde im zehnten, elften Jahre an das Kind heranbringt, weiß eigentlich nichts von dem wirklichen Naturzusammenhange. Eine Pflanze für sich abgesondert zu betrachten, sie in die Botanisiertrommel einzupacken und dann zu Hause herauszulegen und für sich abgesondert zu betrachten, das heißt nichts anderes, als ein Haar sich auszupfen und dieses Haar auf ein Papier legen und das Haar für sich betrachten. Das Haar für sich ist nichts, das Haar für sich kann nicht entstehen, das Haar für sich hat keine Bedeutung - es hat nur eine Bedeutung, indem es lebendig am Kopfe des Menschen oder auf der Haut des Tieres wächst. Es hat nur einen lebendigen Sinn in seinem Zusammenhange. So aber hat auch die Pflanze nur einen lebendigen Sinn im Zusammenhange mit der Erde und mit den Sonnenkräften und - wie ich gleich nachher auseinandersetzen werde — mit noch anderen Kräften. So daß wir niemals eine Pflanze für das kindliche Alter anders betrachten sollen als im Zusammenhange mit der Erde und im Zusammenhange mit den Sonnenkräften.

Ich kann hier nur skizzieren, was man in einer anschaulichen, bildlichen Weise in einer Anzahl von Stunden dem Kinde beibringen kann. Da muß es sich darum handeln, dem Kinde das Folgende beizubringen: Hier ist die Erde (siehe Zeichnung). Mit der Erde in inniger Verbindung, zur Erde gehörig, ist die Wurzel der Pflanze. Niemals sollte eine andere Vorstellung erweckt werden als die einzig lebendige, daß Erde und Wurzel zusammengehören. Und dann sollte niemals eine andere Vorstellung erweckt werden als diese, daß die Blüte von der Sonne und ihren Strahlen an der Pflanze hervorgerufen wird. So wird das Kind lebendig ins Weltenall hineinversetzt.

Wer als Lehrer innere Lebendigkeit genug hat, der kann dieses lebendig in das Weltenall Hineinversetztsein der Pflanze durchaus gerade in diesem Lebensalter, von dem ich jetzt spreche, am besten an das Kind heranbringen. Er kann in dem Kinde zunächst förmlich das Gefühl hervorrufen, wie die Erde mit ihren Stoffen die Wurzel durchdringt, wie die Wurzel sich der Erde entringt, und wie dann, wenn die Wurzel nach oben den Sproß getrieben hat, der Sproß von der Erde geboren wird, wie von der Sonne Licht und Wärme zum Blatt und zur Blüte entfaltet wird, wie die Sonne die Blüte sich heranerzieht, wie die Erde die Wurzel in Anspruch nimmt.

Dann macht man das Kind in lebendiger Art darauf aufmerksam, wie eine feuchtliche Erde, eine Erde, die also innerlich wässerig ist, in anderer Weise auf die Wurzel wirkt als eine trockene Erde; wie durch eine trockene Erde die Wurzel verkümmert wird, durch eine wässerige Erde die Wurzel selber saftig und lebensvoll gemacht wird.

Man macht das Kind darauf aufmerksam, wie die senkrecht auf die Erde auffallenden Sonnenstrahlen die gelben Löwenzahnblüten aus der Pflanze herausholen oder die Blüten der Ranunkeln oder dergleichen, oder auch die Rosenblüten; wie aber der schief einfallende Sonnenstrahl, der über die Pflanzen gewissermaßen hinwegstreicht, die dunkle, violette Herbstzeitlose hervorruft. Und man bringt so überall in lebendigen Zusammenhang die Wurzel mit der Erde, Blatt und Blüte mit der Sonne.

Und dann wird man auch, wenn man in dieser Weise lebendig das Ideenbild des Kindes in den Kosmos hineinstellt, ihm beibringen können, wiesich wiederum oben das ganze Pflanzenwachstum zum Fruchtknoten zusammenzieht, wie daraus die neue Pflanze wird.

Und jetzt wird man - ich darf da schon die Zukunft etwas vorausnehmen — einmal eine Wahrheit, ganz zugerichtet für das kindliche Lebensalter, entwickeln müssen, die auszusprechen man sich heute im öffentlichen Leben eigentlich noch etwas genieren muß, weil es als ein Aberglaube, als eine Phantasterei, als etwas mystisch Nebuloses angesehen wird. Aber geradeso wie die Sonne herausholt die Blüte in ihrer Farbigkeit, so holen die Mondenkräfte den wiederum sich zusammenziehenden Fruchtknoten aus der Pflanze heraus. Die Mondenkraft ist es, die den Fruchtknoten aus der Pflanze wiederum herausholt.

Und so stellt man die Pflanze lebendig hinein in Erdenwirkung, Sonnenwirkung, Mondenwirkung. Nur, die Mondenwirkung muß man heute noch weglassen; denn wenn die Kinder dann nach Hause kommen würden und würden erzählen, daß sie gelernt haben, der Fruchtknoten hätte etwas mit dem Mond zu tun, so würde vielleicht - selbst wenn die Eltern schon geneigt wären, bei den Kindern das entgegenzunehmen -, wenn gerade ein Naturforscher als Besuch da wäre, dieser sofort die Möglichkeit haben, die Eltern zu veranlassen, das Kind doch ja aus dieser Schule gleich wegzunehmen! Also damit muß man heute noch zurückhalten, wie man überhaupt in bezug auf wichtige Dinge selbstverständlich heute, unserer ganz veräußerlichten Zivilisation Rechnung tragend, mit manchem zurückhalten muß. Aber ich möchte gerade in dieser radikalen Weise zeigen, wie man die lebendigen Begriffe entwickeln muß, die nun nicht aus irgend etwas, was im Grunde genommen für sich gar nicht existiert, herausgeholt sind — denn die Pflanze existiert für sich nicht, ohne Sonne, ohne Erde ist sie nichts —, sondern wie man diesen Begriff von der wahren Wirklichkeit nehmen muß. Darum handelt es sich.

Nun muß man dem Kinde beibringen — und da wird man schon eher so vorgehen können -, wie, wenn hier die Erde ist (siehe Zeichnung), die Erde nun etwas auswächst, einen Hügel erzeugt. Aber der Hügel, der wird von den Kräften der Luft und schon von den Kräften der Sonne durchsetzt. Er bleibt nicht mehr Erde. Er wird etwas, was zwischen dem saftigen Pflanzenblatt und auch schließlich der Pflanzenwurzel und der trockenen Erde mitten drinnen steht: er wird Baumstamm. Und auf der also ausgewachsenen Pflanze wachsen nun erst die einzelnen Pflanzen, die die Äste des Baumes sind. So daß man kennenlernt, wie eigentlich der Baumstamm eine aufsprossende Erde ist.

Man bekommt dadurch nun auch den Begriff davon, wie innig verwandt dasjenige, was ins Holz übergeht, mit dem eigentlichen Erdreiche ist. Und damit das Kind das recht gut begreift, weist man es hin, wie das Holz vermodert, immer erdiger und erdiger wird und schließlich in Staub auseinanderfällt, schon ganz ähnlich der Erde ist, und wie im Grunde genommen aller Erdensand, alles Erdengestein auf diese Weise aus dem, was eigentlich hat Pflanze werden sollen, hervorgegangen ist, wie die Erde im Grunde genommen eine große Pflanze ist, ein Riesenbaum, und alle einzelnen Pflanzen als Äste darauf wachsen. Man bekommt nun für das Kind den möglichen Begriff, daß die Erde eigentlich im ganzen ein lebendes Wesen ist, und daß die Pflanzen zur Erde hinzugehören.

Das ist außerordentlich bedeutsam, daß das Kind in dieser Weise nicht den vertrackten Begriff unserer Geologie und Geognosie bekommt, als ob die Erde nur aus Gestein bestehen würde, und nur die Gesteinskräfte zur Erde gehörten, während doch die Pflanzenwachstumskräfte geradeso zur Erde gehören wie die Gesteinskräfte. Und was das Wichtigste ist: man redet gar nicht von Gestein für sich zunächst. Und man wird merken, daß das Kind in mancher Beziehung sehr neugierig ist. Aber wenn man ihm in dieser Beziehung lebendig, wie aus der Erde hervorgehend, durch die Sonne hervorgezogen, die ganze Pflanzendecke als etwas zur Erde Gehöriges beibringt, dann wird es nicht neugierig dem gegenüber, was die Steine für sich sind. Es interessiert sich noch nicht für das Mineralische. Und es ist das größte Glück, wenn das Kind sich bis zum elften, zwölften Jahre nicht für das tote Mineralische interessiert, sondern wenn es die Vorstellung aufnimmt, daß die Erde ein ganzes lebendes Wesen ist, gewissermaßen nur ein schon im Verbröckeln begriffener Baum, der alle Pflanzen als Äste hervorbringt. Und Sie sehen, man bekommt auf diese Weise außerordentlich gut die Möglichkeit, auch zu den einzelnen Pflanzen überzugehen.

Ich sage zum Beispiel dem Kinde: Nun ja, bei solch einer Pflanze (siehe Zeichnung) sucht die Wurzel den Boden, die Blüte wird von der Sonne herausgezogen. - Man nehme nun an, die Wurzel, die an der Pflanze wachsen will, finde nicht recht den Boden, sie findet nur verkümmerten Boden, und dadurch gibt sich auch die Sonne keine Mühe, die Blüte hervorzubringen. Dann hat man eine Pflanze, welche nicht recht den Boden findet, keine richtige Wurzel treibt, aber auch keine richtige Blüte hervorbringt: man hat einen Pilz.

Und man führt dann das Kind dazu, zu verstehen, wie es nun ist, wenn sich dasjenige, was, wenn es die Erde nicht recht findet, zum Pilz entwickelt, wenn das sich einpflanzen kann in etwas, wo die Erde schon ein wenig Pflanze geworden ist, wenn es sich also, statt sich in den Erdboden einpflanzen zu müssen, einpflanzen kann in den pflanzlich gewordenen Hügel, in den Baumstamm: da wird es Baumflechte, da wird es jene graugrüne Flechte, welche man an der Oberfläche der Bäume findet, ein Parasit.

Man bekommt auf diese Weise die Möglichkeit, aus dem lebendigen Wirken und Weben der Erde heraus selber dasjenige zu ziehen, was sich in allen einzelnen Pflanzen ausdrückt. Dadurch entwickelt man in dem Kinde, wenn man es so lebendig in das Pflanzenwachstum einführt, aus dem Botanischen, aus der Pflanzenkunde heraus die Anschauung von dem Antlitz der Erde.

Das Antlitz der Erde ist anders, wo gelbe, sprossende Pflanzen sind, das Antlitz der Erde ist anders, wo verkümmerte Pflanzen sind. Und man findet von der Pflanzenkunde den Übergang zu etwas anderem, was außerordentlich bedeutsam für die Entwickelung des Kindes wird, wenn es gerade aus der Pflanzenkunde herausgeholt wird: die Geographie. Das Antlitz der Erde den Kindern beizubringen, soll auf diese Weise geschehen, daß man hervorholt die Art und Weise, wie die Erde an ihrer Oberfläche wirken will, aus der Art und Weise, wie sie die Pflanzen an einer bestimmten Oberfläche hervorbringt.

Auf diese Weise entwickelt man in dem Kinde einen lebendigen Intellekt statt eines toten. Und für die Entwickelung dieses lebendigen Intellektes ist die Lebenszeit zwischen dem neunten, zehnten und dem elften, zwölften Lebensjahr die allerbeste. Dadurch, daß man in dieser Weise das Kind hineinführt in das lebendige Weben und Leben der Erde, die aus ihrer inneren Vitalkraft die verschieden gestalteten Pflanzen hervorbringt, bringt man dem Kinde statt toter Begriffe lebendige Begriffe bei, Begriffe, die dieselbe Eigenschaft haben wie ein menschliches Glied. Wenn man noch ein ganz kleines Kind ist, dann muß ein menschliches Glied wachsen. Wir dürfen die Hand nicht in einen eisernen Handschuh einspannen, sie würde nicht wachsen können. Aber die Begriffe, die wir den Kindern beibringen, die sollen möglichst scharfe Konturen haben, sollen Definitionen sein, und das Kind soll immer definieren. Das Schlimmste, was wir dem Kinde beibringen können, sind Definitionen, sind scharf konturierte Begriffe, denn die wachsen nicht; der Mensch aber wächst mit seinem organischen Wesen. Das Kind muß bewegliche Begriffe haben, die, wenn das Kind reifer und reifer wird, ihre Form fortwährend ändern. Wir dürfen uns nicht, wenn wir vierzig Jahre alt geworden sind, bei irgendeinem Begriff, der auftaucht, an das erinnern müssen, was wir mit zehn Jahren gelernt haben, sondern der Begriff muß sich in uns verändert haben, so wie unsere Glieder, unser ganzer Organismus sich organisch auch verändert haben.

Lebendige Begriffe bekommt man aber nur, indem man nicht dasjenige an das Kind heranträgt, was man Wissenschaft nennt, und was heute sich zumeist dadurch auszeichnet, daß man dadurch nichts weiß, diese tote Wissenschaft, die man nun einmal lernen muß, sondern indem man das Kind gerade einführt in das Lebendige im Natürlichen in der Welt. Dadurch bekommt es seine beweglichen Begriffe, und es wird seine Seele wachsen können in einem Körper, der wie die Natur wächst. Dann wird man nicht dasjenige, was so oft die Erziehung bietet, auch bieten: daß man in einen Körper, der naturgemäß wächst, ein Seelisches hineinverpflanzt, das nicht wachsen kann, sondern das tot ist. Für die menschliche Entwickelung taugt es nur, wenn in dem lebendig wachsenden physischen Organismus auch eine lebendig wachsende Seele, ein lebendig wachsendes Seelenleben ist.

Das muß aber auf diese Weise erzeugt werden und kann am besten erzeugt werden, wenn alles Pflanzenleben in innigem Zusammenhang mit der Erdengestaltung angeschaut wird, wenn also Erdenleben und Pflanzenleben dem Kinde als Einheit vorgeführt werden, wenn Erdenerkenntnis Pflanzenerkenntnis ist, und wenn das Kind das Leblose zunächst daran erkennt, daß der Baum vermodert und zu Staub wird, wenn es also das Leblose zunächst als den Überrest des Lebendigen kennenlernt. Wir sollen dem Kinde nur ja nicht Mineralkenntnis beibringen in diesem Lebensalter, von dem ich jetzt spreche, sondern Begriffe, Ideen von dem Lebendigen. Darauf kommt es an.

Wie man die Pflanzenwelt bei dem Unterweisen des Kindes in Zusammenhang bringen soll mit der Erde, so daß gewissermaßen die Pflanzenwelt als etwas erscheint, was aus dem lebendigen Erdenorganismus als dessen letztes Ergebnis nach außen herauswächst, so soll man die gesamte Tierwelt als eine Einheit wiederum heranbringen an den Menschen. Und so stellt man das Kind lebendig in die Natur, in die Welt hinein. Es lernt verstehen, wie der Pflanzenteppich der Erde zu dem Organismus Erde gehört. Es lernt aber auf der anderen Seite auch verstehen, wie alle Tierarten, die über die Erde ausgebreitet sind, in einer gewissen Weise der Weg zum Menschenwachstum sind. Die Pflanzen zur Erde, die Tiere an den Menschen herangeführt, das muß Unterrichtsprinzip werden. Ich kann dies nur prinzipiell rechtfertigen. Es handelt sich darum, daß dann mit wirklich künstlerischem Sinn für die Einzelheiten des Unterrichtes für das zehn-, elf-, zwölfjährige Kind die Unterweisung über die Tierwelt im Detail durchgeführt wird.

Sehen wir uns den Menschen an. Wir wollen, wenn auch in ganz einfacher, vielleicht primitiver Weise schon dem Kinde die Menschenwesenheit vor das Seelenauge führen, und man kann es, wenn man es in der Weise künstlerisch vorbereitet hat, wie es geschildert worden ist. Da wird das Kind, wenn auch in primitiver Weise, unterscheiden lernen, wie der Mensch zu gliedern ist in eine dreifache Organisation. Wir betrachten die Kopforganisation, bei der im wesentlichen die weichen Teile im Inneren sind, wie eine harte Schale insbesondere um das Nervensystem herumwächst, wie also die Kopforganisation in einer gewissen Weise nachbildet die kugelförmige Erde, wie sie im Kosmos drinnen steht, wie diese Kopforganisation im wesentlichen den weichen Innenteil, insbesondere nach dem Gehirn zu, und die harte äußere Schale umfaßt. Man wird möglichst anschaulich künstlerisch das Kind durch alle möglichen Mittel an ein Verstehen der Kopforganisation heranführen, und man wird dann versuchen, ebenso das Kind heranzuführen an das zweite Glied der menschlichen Wesenheit, an alles dasjenige, was zusammenhängt mit dem rhythmischen System des Menschen, was die Atmungsorgane, was die Blutzirkulationsorgane mit dem Herzen umfaßt. Man wird, grob gesprochen, das Kind heranführen an die Brustorganisation, wird — ebenso wie man plastisch-künstlerisch die schalenförmigen Kopfknochen, welche die Weichteile des Gehirnes umschließen, betrachtet - jetzt die sich Glied an Glied heranreihenden Rückgratknochen der Wirbelsäule künstlerisch betrachten, an die sich die Rippen anschließen. Man wird die ganze Brustorganisation mit Einschluß des Atmungs-, des Zirkulationssystems, kurz, der rhythmischen Wesenheit des Menschen in ihrer Eigenart betrachten und wird dann zum dritten Glied der menschlichen Organisation, zur Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganisation übergehen. Die Gliedmaßen als Bewegungsorgane unterhalten im wesentlichen den Stoffwechsel, indem sie durch ihre Bewegung eigentlich die Verbrennung regulieren. Sie hängen zusammen mit dem Stoffwechsel. Die Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganisation ist eine einheitliche.

So gliedern wir den Menschen zunächst in diese drei Glieder. Und wenn man den nötigen künstlerischen Sinn als Lehrer hat und dabei bildhaft vorgeht, so kann man durchaus diese Anschauung von dem dreigliedrigen Menschen schon dem Kinde beibringen.

Jetzt führt man die Aufmerksamkeit des Kindes auf die in dem Erdendasein ausgebreiteten verschiedenen Tierarten. Man führt das Kind zunächst zu den niederen Tieren, zu denjenigen Tieren besonders, welche Weichteile im Inneren haben, Schalenförmiges nach außen, zu den Schalentieren, zu den niederen Tieren, die eigentlich nur aus einer das Protoplasma umhüllenden Haut bestehen; und man wird dem Kinde beibringen können, daß gerade diese niederen Tiere primitiv die Gestalt der menschlichen Hauptesorganisation an sich tragen.

Unser Haupt ist das aufs höchste ausgestaltete niedere Tier. Wir müssen — wenn wir das menschliche Haupt, namentlich die Nervenorganisation ins Auge fassen — nicht auf die Säugetiere schauen, nicht auf die Affen, sondern wir müssen zurückgehen gerade bis zu den niedersten Tieren. Wir müssen auch in der Erdengeschichte zurückgehen bis in älteste Formationen, wo wir Tiere finden, die gewissermaßen nur ein einfacher Kopf sind. Und so müssen wir die niedere Tierwelt dem Kinde als eine primitive Kopforganisation begreiflich machen. Wir müssen dann die etwas höheren Tiere, die um die Fischklasse herumgruppiert sind, die besonders die Wirbelsäule ausgebildet haben, die «mittleren Tiere» den Kindern begreiflich machen als solche Wesen, die eigentlich nur den rhythmischen Teil des Menschen stark ausgebildet und das andere verkümmert haben. Indem wir das Haupt des Menschen betrachten, finden wir also in der Tierwelt auf primitiver Stufe die entsprechende Organisation bei den niedersten Tieren; wenn wir die menschliche Brustorganisation betrachten, finden wir die Tierart, die um die Fischklasse herum ist als diejenige, welche in einseitiger Weise die rhythmische Organisation äußerlich offenbart. Und gehen wir zu der Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganisation, dann kommen wir herauf zu den höheren Tieren. Die höheren Tiere bilden besonders die Bewegungsorgane in der mannigfaltigsten Weise aus. Wie schön hat man Gelegenheit, mit künstlerischem Sinn den Bewegungsmechanismus im Pferdefuß zu betrachten, in dem Krallenfuß des Löwen, in dem Fuß, der mehr ausgebildet ist zum Waten beim Sumpftier. Welche Gelegenheiten hat man, von den menschlichen Gliedmaßen aus die einseitige Ausbildung des Affenfußes zu betrachten. Kurz, kommt man zu den höheren Tieren herauf, so fängt man an, das ganze Tier durch besondere Gliederung, durch plastische Ausgestaltung der Bewegungsorgane oder auch der Stoffwechselorgane zu begreifen. Die Raubtierarten unterscheiden sich von den Wiederkäuerarten dadurch, daß bei den Wiederkäuerarten ganz besonders das Darmsystem zu einer starken Länge ausgebildet ist, während bei den Raubtierarten der Darm kurz ist, dafür aber alles dasjenige, was das Herz und die Blutzirkulation zur Verdauung beitragen, besonders stark und kräftig ausgebildet ist.

Und indem man gerade die höheren Tiere betrachtet, erkennt man, wie einseitig diese höhere Tierorganisation dasjenige gibt, was im Menschen in der Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganisation ausgebildet ist. Anschaulich kann man da schildern, wie beim Tiere die Kopforganisation eigentlich nur der Vorderteil des Rückgrates ist. Da geht ja das ganze Verdauungssystem beim Tiere in die Kopforganisation hinein. Beim Tier gehört der Kopf wesentlich zu den Verdauungsorganen, zum Magen und Darm. Man kann beim Tiere eigentlich den Kopf nur im Zusammenhange mit Magen und Darm betrachten. Der Mensch setzt gerade dasjenige, was, man möchte sagen, jungfräulich geblieben ist, bloß als Weichteile von Schale umgeben ist, auf diese StoffwechselGliedmaßenorganisation, die das Tier noch im Kopfe trägt, darauf und erhebt dadurch die menschliche Kopforganisation eben über die Kopforganisation des Tieres, die nur eine Fortsetzung des Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßensystems ist; während der Mensch mit seiner Kopforganisation zurückgeht zu demjenigen, was in der einfachsten Weise die Organisation selber gibt: Weichteile, umschlossen von schaligen Organen, von schaligen Knochen. Man kann anschaulich entwickeln, wie die Kieferorganisation gewisser Tiere im Grunde genommen am besten betrachtet wird, wenn man den Kiefer, Unterkiefer, Oberkiefer als die vordersten Gliedmaßen betrachtet. So versteht man plastisch am allerbesten den Tierkopf.

Auf diese Weise bekommt man den Menschen als eine Zusammenfassung dreier Systeme: Kopfsystem, Brustsystem, Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselsystem; die Tierwelt als einseitige Ausbildung entweder des einen oder des anderen Systems. Niedere Tiere, zum Beispiel Schalentiere, entsprechen also dem Kopfsystem; die anderen lassen sich aber auch in einer gewissen Weise dadurch betrachten. Dann Gliedmaßentiere: Säugetiere, Vögel und so weiter. Brusttiere, die also das Brustsystem vorzugsweise ausgebildet haben: Fische, und was ähnlich noch den Fischen ist, die Reptilien und so weiter. Man bekommt das Tierreich als den auseinandergelegten Menschen, als den in fächerförmige Glieder über die Erde ausgebreiteten Menschen. Wie man die Pflanzen mit der Erde zusammenbringt, bringt man die fächerförmig ausgebreiteten Tierarten der Welt mit dem Menschen zusammen, der in der Tat die Zusammenfassung der ganzen Tierwelt ist.

Geht man also zuerst von der physischen Organisation des Menschen aus, bringt man dem Kinde so die dreifache Gliederung des Menschen in einfacher Weise bei, und geht man die Tiere durch, zeigt man, wie die Tiere einseitig nach irgendeiner Richtung dasjenige entwickeln, was beim Menschen in ein Ganzes harmonisch eingegliedert ist: dann kann man finden, wie gewisse Tiere die Brustorgane einseitig entwickeln, andere die Darmorgane einseitig entwickeln, andere die oberen Verdauungsorgane einseitig entwickeln und so weiter; wie bei manchen Tieren, etwa bei den Vögeln, Umgestaltungen gewisser Organe da sind, sogar der Verdauungsorgane in der Kropfbildung der Vögel und dergleichen. Man kann jede Tierart als die einseitige Ausbildung eines menschlichen Organsystems auf diese Weise hinstellen; die ganze Tierwelt als die fächerartige Ausbreitung des Menschenwesens über die Erde; den Menschen als die Zusammenfassung der ganzen Tierwelt.

Bringt man das zustande, versteht das Kind die Tierwelt als den Menschen, der seine einzelnen Organsysteme einseitig ausgebildet hat — das eine Organsystem lebt als diese Tierart, das andere Organsystem als die andere Tierart —, dann kann man, wenn sich das zwölfte Lebensjahr naht, wieder heraufkommen zum Menschen. Denn dann wird das Kind wie selbstverständlich begreifen, wie der Mensch gerade dadurch, daß er seinen Geist in sich trägt, eine symptomatische Einheit, eine künstlerische Zusammenfassung, eine künstlerische Ausgestaltung der einzelnen Menschenfragmente ist, welche die Tiere, die in der Welt verbreitet sind, darstellen. Eine solche künstlerische Zusammenfassung ist der Mensch dadurch, daß er seinen Geist in sich trägt. Dadurch harmonisiert er gegenseitig zu einem Ganzen die niedere Tierorganisation, die erkompliziert umbildet zur Kopforganisation, entsprechend eingliedert in die Brustorganisation, die er entsprechend ausbildet, damit sie zu den anderen Teilen der Organe paßt; er trägt also auch dasjenige, was in der Fischorganisation ist, in sich, und er trägt dasjenige in sich, was in der höheren Tierorganisation ist, aber harmonisch einem Ganzen eingeordnet. Der Mensch stellt sich heraus als die durch den Geist aus einzelnen Fragmenten, die als Tiere über die Welt zerstreut sind, zusammengefaßte totale Wesenheit. Dadurch wird die Tierwelt an den Menschen herangebracht, der Mensch aber zu gleicher Zeit als Geistträger über die Tierwelt erhöht.

Gibt man einen solchen Unterricht, dann wird man sehen, wenn man unbefangene Menschenerkenntnis hat, daß geradeso wie ein solcher Pflanzenkunde-Unterricht auf die lebendige Begriffswelt wirkt und den Menschen in der rechten Weise durch Klugheit in die Welt hineinstellt, durch Klugheit ihn tüchtig macht, so daß er sich mit seinen Begriffen lebendig durch das Leben findet; daß er dadurch, daß er aufnimmt eine solche belebte Anschauung über seine Stellung zur gesamten Tierwelt, besonders seinen Willen kräftigt.

Man muß nur bedenken, daß man ja das, was ich jetzt in zwanzig Minuten zu erörtern habe, durch längere Zeit erörtern wird, daß das von Stufe zu Stufe geht, daß man das Kind allmählich gewöhnt, seine ganze Wesenheit zu vereinigen mit solchen Vorstellungen. Und dadurch saugen sich diese Vorstellungen hinein in die willensgemäße Stellung, die sich der Mensch auf Erden gibt. Der Mensch wird innerlich dem Willen nach stark, wenn er in dieser Weise in seiner eigenen Erkenntnis sich hervorwachsen sieht aus dem Zusammenfließen aller tierischen Fragmente durch den lebendigen Geist, der diese Synthese bewirkt. Das geht über in die Willensbildung der Seele.

Und so wirken wir in einem Unterrichte nicht nur dahin, daß wir dem Menschen Kenntnisse beibringen über die Pflanzen, Kenntnisse beibringen über die Tiere, sondern wir wirken durch unseren Unterricht auf die Charakterbildung, auf die Bildung des ganzen Menschen: indem wir den Menschen heranführen an die Pflanzen und so seine Klugheit in gerechter Weise ausbilden, indem wir den Menschen heranbringen an die Tierwelt und dadurch seinen Willen in gerechter Weise ausbilden.

Dann haben wir es erreicht zwischen dem neunten und zwölften Jahre, daß wir den Menschen mit den anderen Geschöpfen, den Pflanzen und den Tieren der Erde, so in Zusammenhang gebracht haben, daß er in der richtigen Weise durch Klugheit, durch eine gerechte Klugheit, und auf der anderen Seite durch eine entsprechende, ihm seine Stellung in der Welt für sein eigenes Bewußtsein sichernde Willensstärke seinen Weg durch die Welt findet.

Und das sollen wir vor allem durch die Erziehung bewirken: den jungen Menschen sich so entwickeln zu lassen, daß er nach diesen beiden Seiten hin seinen Weg durch die Welt findet. Aus dem Fühlen, das wir entwickelt haben vom siebenten bis zum neunten oder neuneinhalbten Jahre, haben wir herausentwickelt Klugheit und Willensstärke. Und so kommen in der richtigen Weise, was sonst oftmals in ganz unorganischer Weise im Menschen entwickelt wird, Denken, Fühlen und Wollen in das richtige Verhältnis. Im Fühlen wurzelt alles andere. Das muß auch beim Kinde zuerst ergriffen werden, und aus dem Fühlen entwickeln wir im Zusammenhange mit der Welt das Denken an dem, was das Denken niemals tot sein läßt: an der Pflanzenwelt; den Willen an dem, was den Menschen, wenn er richtig betrachtet wird, mit dem Tiere richtig zusammenbringt, aber ihn auch über das Tier erhöht: durch die Tierkunde die Ausbildung des Willens.

So geben wir dem Menschen die richtige Klugheit und den starken Willen ins Leben mit. Und das sollen wir; denn dadurch wird er ein ganzer Mensch, und darauf hat es vor allen Dingen die Erziehung anzulegen.

Ninth Lecture

In my previous lectures, I have discussed how, when children reach school age, i.e., when they are transitioning to permanent teeth, artistic and creative teaching and education are the right approach. Today, I would like to add a few supplementary remarks to the fundamental observations made there, in order to show how such teaching, as characterized the day before yesterday, appeals to the child's feelings and emotional life, so that such teaching primarily affects the child's emotional life and develops everything out of the emotional life.

Let us consider a few characteristic examples of how writing can be developed from painting and artistic drawing. I have already said that in organic, natural teaching, writing must precede learning to read, because writing engages the whole person more than reading does.

Writing is practiced in a movement of one organ, but in essence the whole person must engage in it. Reading only engages the head, the intellect, and in organic teaching one should always draw from the whole person that which is to be developed. Let us assume, then, that we have led the children to gain an understanding of flowing water. The child has now learned to visualize flowing water. Let us assume that we have reached the point where we have taught the child something about visualizing flowing water that makes waves (it is drawn in color). We want to work toward the child learning to pay attention to the initial sound, the initial letter of the word “wave.” We are trying to focus on the initial sound, the pronunciation of the initial letter of characteristic words. We teach the child how this line is formed, as it were, on the surface of the water throwing waves. And we lead the child from drawing this line, along the waves of the flowing water, to drawing the shape that results from it: W.

And in this way, the child has been led to begin to fix the W in writing from the picture, following the line of the wave. — In this way, the letter to be written is extracted from the child's perception of what it brings into the picture.

Or let's say you get the child to make the following drawing, for example, so that it records the human mouth in this way. You encourage it to hold on to this feature of the mouth and highlight it, and from there you move on to feeling the first letter of the word “mouth.” — I have already indicated in an evening lesson how the child can be led to draw a fish. The child is now led to capture the basic form and from there to feel the initial sound of the word: “fish.” In this way, a number of letters can be obtained; others will have to be brought out of the drawing in a different way. Let us say, for example, that you teach the child in some vivid way how the rushing wind moves. With small children, this will be better than any other method; of course, things can be done in many different ways. You teach the child about the rushing of the wind. Now you let the child imitate the whistling of the wind and in this way you obtain this form. In short, it is possible to develop almost all consonants in this way by trying to capture either sharply contoured objects or movements or even activities in the pictures.

For the vowels, we will have to resort to gestures, because vowels originate from the revelation of the human inner self. Basically, the A, for example, is always a kind of wonder and amazement.

Eurythmy will be particularly helpful here. This is because eurythmy provides gestures that correspond precisely to feelings. And it will be possible to develop the I, the A, and so on from the corresponding eurythmy gestures. Vowels must be developed from gestures that accompany feelings arising from human vitality.

In this way, one can arrive at the abstract nature of writing from the very concrete nature of drawing, of painting, and one achieves this precisely because the child has always started from a feeling in the picture and has been able to connect the letter with the soul of the feeling, so that the whole principle of writing emerges from the feeling life of the human soul. p>

When moving on to reading, there is basically nothing else to do but to work toward the child recognizing with their mind what they have learned to do with their whole body. Reading is thus a recognition of an activity that one has performed oneself. This is of tremendous importance. It spoils the whole of human development if the human being is led directly to the abstract, if he learns to carry out some activity through a concept. On the other hand, it always leads to healthy human development if the activity is stimulated first and then the concept is developed out of the activity.

Reading is entirely alive in concepts; therefore, it should be developed as the second, not the first. Otherwise, the child is brought into a kind of intellectual development far too early instead of a fully human development.

So you see how all teaching can basically be directed into the sphere of the whole human being, into the sphere of the artistic. And all other teaching up to the age of about nine and a half must also aim at this. Everything must be directed toward the image, toward rhythm, toward beat. Everything else is premature.

Therefore, it is completely impossible to teach a child anything before this age that makes a strong distinction between the human being itself and the outside world. The child only learns to distinguish itself from the outside world between the ages of nine and ten. Therefore, when the child enters school, it is important to transform all external things into a kind of living being, not to speak of plants, but to speak of plants as living beings that say something to oneself, that say something to each other, that all observation of nature, all observation of humanity is basically cast in imagination. Plants speak, trees speak, clouds speak. And at this age, the child should not feel any difference between itself and the world. An artistic feeling must be created within it that it can speak itself, that the objects around it can also speak.

The more we achieve this merging of the child with its entire environment, the more we are able to talk about everything, about plants, animals, stones, in such a way that a speaking, weaving, spiritual essence wafts toward the child from everywhere, the more we meet what the child at this age actually demands of us from the depths of its being, and we then educate the child in such a way that, precisely in the years when the emotional life is to pass into breathing and blood circulation, into the formation of the vessels, into the whole human organism, the emotional life is actually addressed correctly for our time, so that the child also develops strongly in an inner, organic, emotional way in a natural way.

It is an enormous benefit when we develop writing in this emotional way and then only gently touch on the intellect by allowing the child to recognize what has been written in reading. This gently touches on the intellect. This is the best way to introduce the child to this around the age of nine.

So we must say: between the ages of seven and nine or nine and a half, all teaching must above all appeal to the emotional life, so that the child really internalizes all the forms of the letters. This is tremendously important for the child's life. For it strengthens the child too much, makes it too strong in its bone, tendon, and cartilage system in relation to the rest of the organism, if we teach it to write mechanically, if we teach it a certain line for the letters in order to appeal to the body mechanism instead of appealing to the eye as well.

If we appeal to the eye, which is connected to the moving hand, by working out the letters artistically, the letter is not merely produced mechanically by guiding the hand, but is produced in such a way that the eye rests with pleasure on the result of its own activity. In this way, the soul is engaged in the right way for the human being; in this way, the emotional life is developed in the right way at the age when it can flow most healthily into the physical organism.

What would you say, dear audience, if someone who had been served a fish carefully removed the flesh, picked out the bones, and ate them? You would probably be terribly afraid that such a person might choke on the fish bones. Moreover, he would not be able to incorporate these fish bones into his organism in the right way.

But that is exactly how it is, only on a different level, on the level of spiritual instruction, when we teach a child dry, abstract, sober concepts instead of lively images, instead of what engages the whole person. These dry, abstract, sober concepts must simply be there to support, as it were, what becomes pictorial in the human soul.