Man as Symphony of the Creative Word

Part Two. The Inner Connection of World-Phenomena and World-Being

GA 230

Cosmic activity is indeed the greatest of artists. The cosmos fashions everything according to laws which bring the deepest satisfaction to the artistic sense.

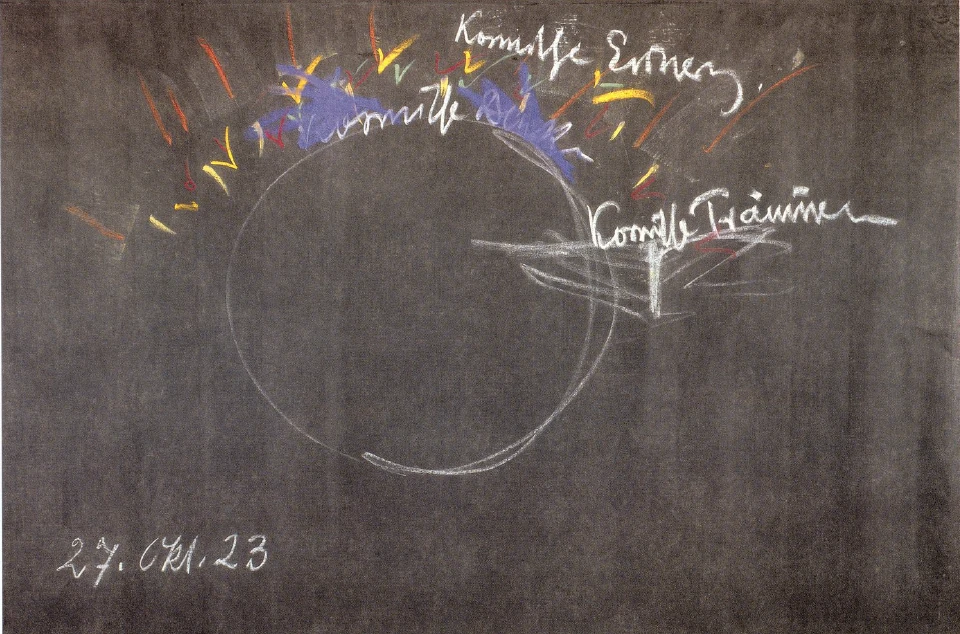

27 October 1923, Dornach

Lecture V

These lectures deal with the inner connection between appearance and reality in the world, and you have already seen that there are many things of which those whose vision is limited to the world of appearance have no idea. We have seen how every species of being—this was shown by a number of examples—has its task in the whole nexus of cosmic existence. Now today, as a kind of recapitulation, we will again consider what I said recently about the nature of several beings and in the first place of the butterfly. In my description of this butterfly nature, as contrasted with that of the plants, we found that the butterfly is essentially a being belonging to the light—to the light in so far as it is modified by the forces of the outer planets, of Mars, of Jupiter, and of Saturn. Hence, if we wish to understand the butterfly in its true nature, we must in fact look up into the higher regions of the cosmos, and must say to ourselves: These higher cosmic regions endow and bless the earth, with the world of the butterflies.

The bestowal of this blessing upon the earth has an even deeper significance. Let us recall how we had to say that the butterfly does not participate in what is directly connected with earthly existence, but only indirectly, in so far as the sun, with its power of warmth and light, is active in this earthly existence. Actually a butterfly lays its eggs only where they do not become separated from sun activity, so that the butterfly does not entrust its egg to the earth, but only to the sun. Then out creeps the caterpillar, which is under the influence of Mars-activity, though naturally the sun influence always remains present. Then the chrysalis is formed, and this is under the influence of Jupiter-activity. Out of the chrysalis emerges the butterfly, which can now in its iridescent colours reproduce in the earth's environment the luminous Sun-power of the earth united with the power of Saturn.

Thus in the manifold colours of the butterfly world we see, in the environment of earth-existence, the direct working of Saturn-activity within the sphere of the earthly. But let us bear in mind that the substances necessary for earth-existence are in fact of two kinds. We have the purely material substances of the earth, and we have the spiritual substances; and I told you that the remarkable thing about this is that in the case of man the underlying substance of his metabolic and limb system is spiritual whereas that of the head is physical. Moreover in man's lower nature spiritual substance is permeated with the activity of physical forces, with the action of gravity, with the action of the other earthly forces. In the head, the earthly substance, conjured up into it by the whole digestive process, the circulation, nerve-activity and the like, is permeated by super-sensible spiritual forces, which are reflected in our thinking, in our power of forming mental pictures. Thus in the human head we have spiritualized physical matter, and in the metabolic-limb-system we have earthized—if I may coin a word—earthized spiritual substantiality.

Now it is this spiritualized matter that we find to the greatest degree in the butterfly. Because a butterfly always remains in the sphere of sun-existence, it only takes to itself earthly matter—naturally I am still speaking pictorially—as though in the form of the finest dust. It also derives its nourishment from those earthly substances which are worked upon by the sun. It unites with its own being only what is sun-imbued; and it takes from earthly substance only what is finest, and works on it until it is entirely spiritualized. When we look at a butterfly's wing we actually have before us earthly matter in its most spiritualized form. Through the fact that the matter of the butterfly's wing is imbued with colour, it is the most spiritualized of all earthly substances.

The butterfly is the creature which lives entirely in spiritualized earth-matter. And one can even see spiritually how in a certain way a butterfly despises the body which it carries between its coloured wings, because its whole attention, its whole group-soul being, is centred on its joyous delight in the colours of its wings.

And just as we marvel at its shimmering colours as we follow it, so also can we marvel at its own fluttering joy in these colours. This is something which it is of fundamental importance to cultivate in children, this joy in the spirituality fluttering about in the air, which is in fact fluttering joy, joy in the play of colours. The nuances of butterfly-nature reflect all this in a wonderful way: and something else lies in the background as well.

We were able to say of the bird—which we regarded as represented by the eagle—that at its death it can carry spiritualized earth-substance into the spiritual world, and that thereby, as bird, it has the task in cosmic existence of spiritualizing earthly matter, thus being able to accomplish what cannot be done by man. The human being also possesses in his head earth-matter which has been to a certain degree spiritualized, but he cannot take this earthly matter into the world in which he lives between death and a new birth, for he would continually have to endure unspeakable, unbearable, devastating pain, if he were to carry this spiritualized earth-matter of his head into the spiritual world.

The bird-world, represented by the eagle, can do this, so that thereby a connection is actually created between what is earthly and what is extra-earthly. Earthly matter is, as it were, gradually converted into spirit, and the bird-creation has the task of giving over this spiritualized earthly matter to the universe. One can actually say that, when the earth has reached the end of its existence, this earth-matter will have been spiritualized, and that the bird-creation had its place in the whole economy of earthly existence for the purpose of carrying back this spiritualized earth-matter into spirit-land.

It is somewhat different with butterflies. The butterfly spiritualizes earthly matter to an even greater degree than the bird. The bird after all comes into much closer contact with the earth than does the butterfly. I will explain this in detail later. Because the butterfly never actually leaves the region of the sun, it is in a position to spiritualize its matter to such a degree that it does not, like the bird, have to await its death, but already during its life it is continually restoring spiritualized matter to the environment of the earth, to the cosmic environment of the earth.

Only think of the magnificence of all this in the whole cosmic economy! Only picture the earth with the world of the butterflies fluttering around it in its infinite variety, continually sending out into world-space the spiritualized earthly matter which this butterfly-world yields up to the cosmos! Then, with such knowledge, we can contemplate the region of the world, of the butterflies encircling the earth with totally different feelings.

We can look into this fluttering world and say: From you, O fluttering creatures, there streams out something still better than sunlight; you radiate spirit-light into the cosmos! Our materialistic science pays but little heed to things of the spirit. And so this materialistic science is absolutely unequipped with any means of grasping at these things, which are, nevertheless, part of the whole cosmic economy. They are there, just as the effects of physical activities are there, and they are even more real. For what thus streams out into spirit-land will work on further when the earth has long passed away, whereas what is taught by the modern chemist and physicist will reach its end with the conclusion of the earth's existence. So that if some observer or other were to sit outside in the cosmos, with a long period of time for observation, he would see something like a continual outstreaming into spirit-land of matter which has become spiritualized, as the earth radiates its own being out into cosmic space; and he would see—like scintillating sparks, sparks which ever and again flash up into light—what the bird-kingdom, what every bird after its death sends forth as glittering light, streaming out into the universe in the form of rays: a shimmering of the spirit-light of the butterflies, and a sparkling of the spirit-light of the birds.

Such things as these should also make us realize that, when we look up to the rest of the starry world, we should not think that from there, too, there only streams down what is shown by the spectroscope, or rather what is conjured into the spectroscope by the fantasy of the expert in optics. What streams down to earth from other worlds of the stars is just as much the product of living beings in other worlds, as what streams out from the earth into world-space is the product of living beings. People look at a star, and with the modern physicist picture it as something in the nature of a kindled inorganic flame—or the like. This, of course, is absolute nonsense. For what we behold there is entirely the product of something imbued with life, imbued with soul, imbued with spirit.

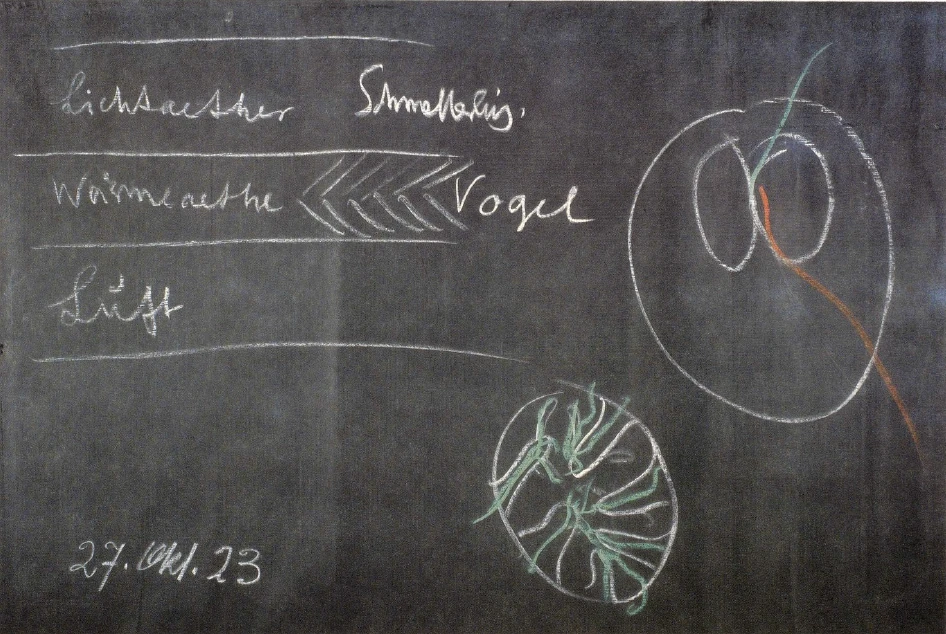

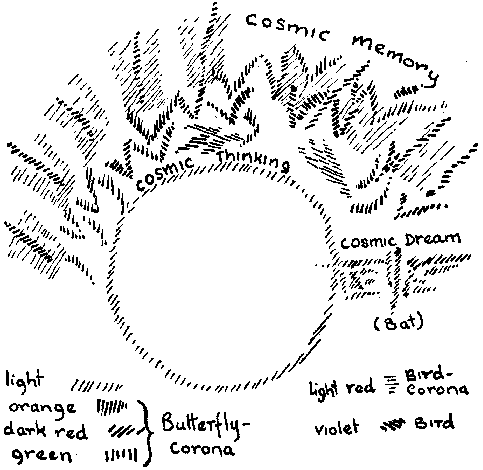

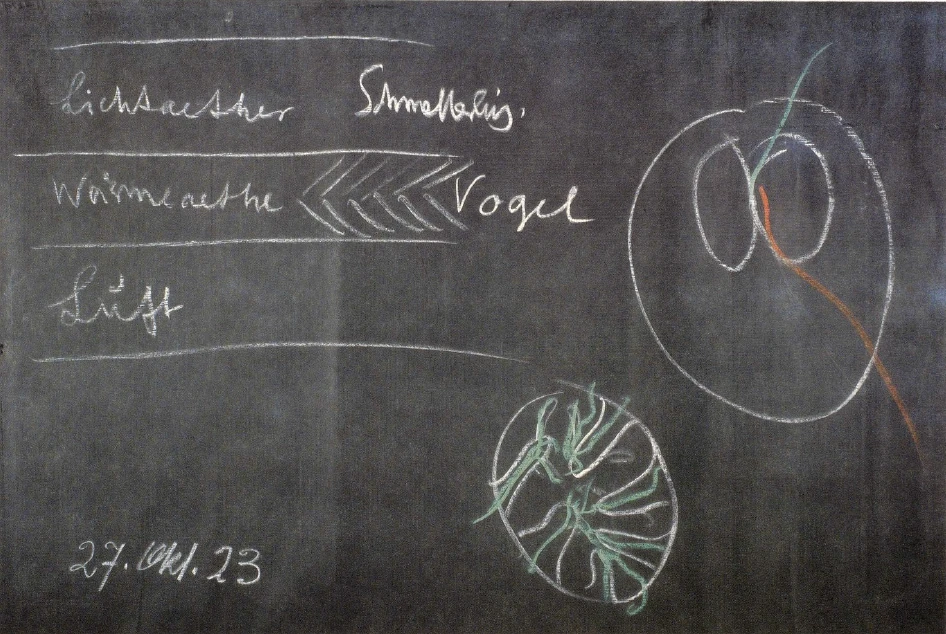

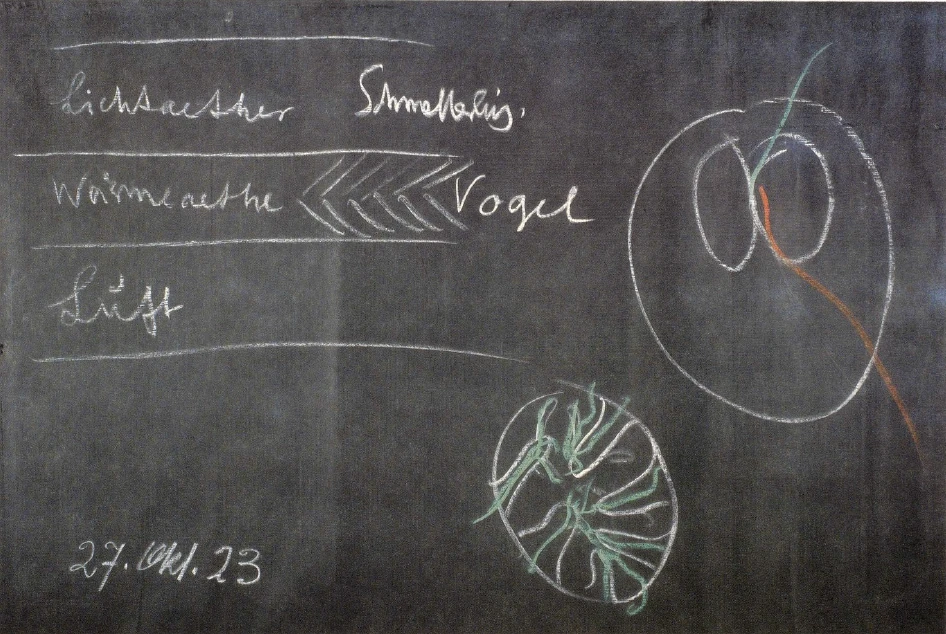

And now let us pass inwards from this girdle of butterflies—if I may call it so—which encircles the earth, and return to the kingdom of the birds. If we call to mind something which is already known to us, we must picture three regions adjoining each other. There are other regions above these, and again other regions below them. We have the light-ether and we have the warmth-ether, which, however, actually consists of two parts, of two layers, the one being the layer of earthly warmth, the other that of cosmic warmth, and these continually play one into the other. Thus we have not only one, but two kinds of warmth, the one which is of earthly, tellurian origin, and the other of a kind which is of cosmic origin. These are always playing one into the other. Then, bordering on the warmth-ether, there is the air. Below this would come water and earth, and above would come chemical ether and light-ether.

The world of the butterflies belongs more particularly to the light-ether; it is the light-ether itself which is the means whereby the power of the light draws forth the caterpillar from the butterfly's egg. Essentially it is the power of the light which draws the caterpillar forth.

This is not the case with the bird-kingdom. The birds lay their eggs. These must now be hatched out by warmth. The butterfly's egg is simply given over to what is of the nature of the sun; the bird's egg comes into the region of warmth. It is in the region of the warmth-ether that the bird has its being, and it overcomes what is purely of the air.

The butterfly, too, flies in the air, but fundamentally it is entirely a creature of the light. And in that the air is permeated with light, in this light-air existence, the butterfly chooses not air existence but light existence. For the butterfly the air is only what sustains it—the waves, as it were, upon which it floats; but the butterfly's element is the light. The bird flies in the air, but its element is the warmth, the various differentiations of warmth in the air, and to a certain degree it overcomes the air. Certainly the bird is also an air-being inwardly and to a high degree. The bones of the mammals, the bones of the human being are filled with marrow. (We shall speak later as to why this is the case.) The bones of a bird are hollow and are filled only with air. We consist, in so far as the content of our bones is concerned, of what is of the nature of marrow; a bird consists of air. And what is of the nature of marrow in us for the bird is simply air. If you take the lungs of a bird, you will find a whole quantity of pockets which project from the lungs; these are air-pockets. When the bird inhales it does not only breathe air into its lungs, but it breathes the air into these air-pockets, and from thence it passes into the hollow bones. So that, if one could remove from the bird all its flesh and all its feathers and also take away the bones, one would still get a creature composed of air, having the form of what inwardly fills out the lungs, and what inwardly fills out all the bones. Picturing this in accordance with its form, you would really get the form of the bird. Within the eagle of flesh and bone dwells an eagle of air. This is not only because within the eagle there is also an eagle of air. The bird breathes and through its breathing it produces warmth. This warmth the bird imparts to the air, and draws it into its entire limb system. Thus arises the difference of temperature as compared to its outer environment. The bird has its inner warmth, as against the outer warmth. In this difference of degree between the warmth of the outer air and the warmth which the bird imparts to its own air within itself—it is really in this that the bird lives and has its being. And if you were to ask a bird how matters are with its body—supposing you understood bird language—the bird's reply would make you realize that it regards its solid material bones, and other material adjuncts, rather as you would luggage if you were loaded, left and right, on the back and on the head. You would not call this luggage your body. In the same way the bird, in speaking of itself, would only speak of the warmth-imbued air, and of everything else as the luggage which it bears about with it in earthly existence. These bones, which envelop the real body of the bird, these are its luggage. We are therefore, speaking in an absolute sense when we say that fundamentally the bird lives only and entirely in the element of warmth, and the butterfly in the element of light. For the butterfly everything of the nature of physical substance, which it spiritualizes, is, before this spiritualizing, not even personal luggage but more like furniture. It is even more remote from its real being.

When we thus ascend to the creatures of these regions, we come to something which cannot be judged in a physical way. If we do so, it is rather as if we were to draw a person with his hair growing out of the bundle on his head, boxes growing together with his arms, and a rucksack growing out of his back, making him appear a perfect hunch-back. If one were to draw a person in this way, it would actually correspond to the materialist's view of the bird. That is not the bird; it is the bird's luggage. The bird really feels encumbered by having to drag his luggage about, for it would like best to pursue its way through the world, free and unencumbered, as a creature of warm air. For the bird all else is a burden. And the bird pays tribute to world-existence by spiritualizing this burden for it, sending it out when it dies into spirit-land; a tribute which the butterfly already pays during its lifetime.

You see, the bird breathes, and makes use of the air in the way I told you. It is otherwise with the butterfly. The butterfly does not in any way breathe by means of an apparatus such as the so-called higher animals possess—though these in fact are only the more bulky, not in reality the higher animals. The butterfly breathes in fact only through tubes which proceed inwards from its outer casing, and, these being somewhat dilated, it can accumulate air during flight, so that it is not inconvenienced by always needing to breathe.

The butterfly always breathes through tubes which pass into its interior. Because this is so, it can take up into its whole body, together with the air which it inhales, the light which is in the air. Here, too, a great difference is to be found.

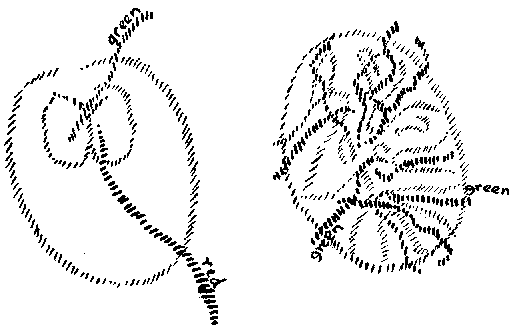

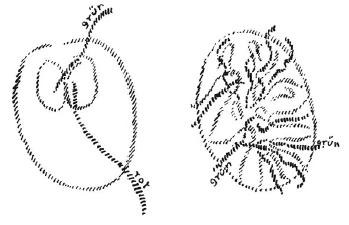

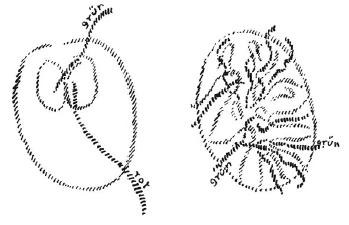

Let us represent this in a diagram. Picture to yourselves one of the higher animals, one with lungs. Into the lungs comes oxygen, and there it unites with the blood in its course through the heart. In the case of these bulky animals, and also with man, the blood must flow into the heart and lungs in order to come into contact with oxygen.

In the case of the butterfly I must draw the diagram quite differently. Here I must draw it in this way: If this is the butterfly, the tubes everywhere pass inwards; they then branch out more widely. And now the oxygen enters in everywhere, and spreads itself out through the tubes; so that the air penetrates into the whole body.

With us, and with the so-called higher animals, the air comes as far as the lungs as air only; in the case of the butterfly the outer air, with its content of light, is dispersed into the whole interior of the body. The bird diffuses the air right into its hollow bones; the butterfly is not only a creature of light outwardly, but it diffuses the light which is carried by the air into every part of its entire body, so that inwardly too the butterfly is composed of light. Just as I could characterize the bird as warmed air, so in fact is the butterfly composed entirely of light. Its body also consists of light; and for the butterfly warmth is actually a burden, is luggage. It flutters about only and entirely in the light, and it is light only that it builds into its body. When we see the butterflies fluttering in the air, what we must really see is only fluttering beings of light, beings of light rejoicing in their play of colours. All else is garment, is luggage. We must gain an understanding of what the beings around earth really consist, for outward appearance is deceptive.

Those who today have learned, in some superficial manner, this or that out of oriental wisdom speak about the world as Maya. But to say that the world is Maya really implies nothing. One must have insight into the details of why it is Maya. We understand Maya when we know that the real nature of the bird in no way accords with what is to be seen outwardly, but that it is a being of warm air. The butterfly is not at all what it appears to be, but what is seen fluttering about is a being of light, a being which actually consists of joy in the play of colours, in that play of colours which arises on the butterfly's wings through the earthly dust-substance being imbued with the element of colour, and thus entering on the first stage of its spiritualisation on the way out into the spiritual universe, into the spiritual cosmos.

You see, we have here, as it were, two levels: the butterfly, the inhabitant of the light-ether in an earth environment, and the bird, the inhabitant of the warmth-ether. And now comes the third level. When we descend into the air, we arrive at those beings which, at a certain period of our earth-evolution, could not yet have been there at all; for instance at the time when the moon had not yet separated from the earth but was still with it. Here we come to beings which are certainly also air-beings, living in the air, but which are in fact already strongly influenced by what is peculiar to the earth, gravity. The butterfly is completely untouched by earth-gravity. It flutters joyfully in the light-ether, and feels itself to be a creation of that ether. The bird overcomes gravity by imbuing the air within it with warmth, thereby becoming a being of warm air—and warm air is upborne by cold air. Earth-gravity is also overcome by the bird.

Those creatures which by reason of their origin must still live in the air but which are unable to overcome earth-gravity, because they have not hollow bones but bones filled with marrow, and also because they have not air-sacs like the birds—these creatures are the bats.

The bats are a quite remarkable order of animal-life. In no way do they overcome the gravity of earth through what is inside their bodies. They do not, like the butterflies, possess the lightness of light, or, like the bird, the lightness of warmth; they are subject to earth-gravity, and they experience themselves in their flesh and bone. Hence that element of which the butterfly consists, which is its whole sphere of life—the element of light—this is disagreeable to bats. They like the dusk. Bats have to make use of the air, but they like the air best when it is not the bearer of light. They yield themselves up to the dusk. They are veritable creatures of the dusk. And bats can only maintain themselves in the air because they possess their somewhat caricature-like bat-wings, which are not wings at all in the true sense, but stretched membrane, membrane stretched between their elongated fingers, a kind of parachute. By means of these they maintain themselves in the air. They overcome gravity—as a counter-weight—by opposing it with something which itself is related to gravity. Through this, however, they are completely yoked into the domain of earth-forces. One could never construct the flight of a butterfly solely according to physical, mechanical laws, neither could one the flight of a bird. Things would never come out absolutely right. In their case we must introduce something containing other laws of construction. But the bat's flight, that you can certainly construct according to earthly dynamics and mechanics.

The bat does not like the light, the light-imbued air, but at the most only twilight air. And the bat also differs from the bird through the fact that the bird, when it looks about it, always has in view what is in the air. Even the vulture, when it steals a lamb, perceives it as it sees it from above, as though it were at the end of the light sphere, like something painted onto the earth. And quite apart from this, it is no mere act of seeing; it is a craving. What you would perceive if you actually saw the flight of the vulture towards the lamb is a veritable dynamic of intention, of volition, of craving.

A butterfly sees what is on the earth as though in a mirror; for the butterfly the earth is a mirror. It sees what is in the cosmos. When you see a butterfly fluttering about, you must picture to yourselves that it disregards the earth, that for it the earth is just a mirror for what is in the cosmos. A bird does not see what belongs to the earth, but it sees what is in the air. The bat only perceives what it flies through, or flies past. And because it does not like the light, it is unpleasantly affected by everything it sees. It can certainly be said that the butterfly and the bird see in a very spiritual way. The first creature—descending from above downwards—which must see in an earthly way, is disagreeably affected by this seeing. A bat dislikes seeing, and in consequence it has a kind of embodied fear of what it sees, but does not want to see. And so it would like to slip past everything. It is obliged to see, yet is unwilling to do so—and thus it everywhere tries just to skirt past. And it is because it desires just to slip past everything, that it is so wonderfully intent on listening. The bat is actually a creature which is continually listening to its own flight, lest this flight should be in any way endangered.

Only look at the bat's ears. You can see from them that they are attuned to world-fear. So they are—these bats' ears. They are quite remarkable structures, attuned to evading the world, to world-fear. All this, you see, is only to be understood when the bat is studied in the framework into which we have just placed it.

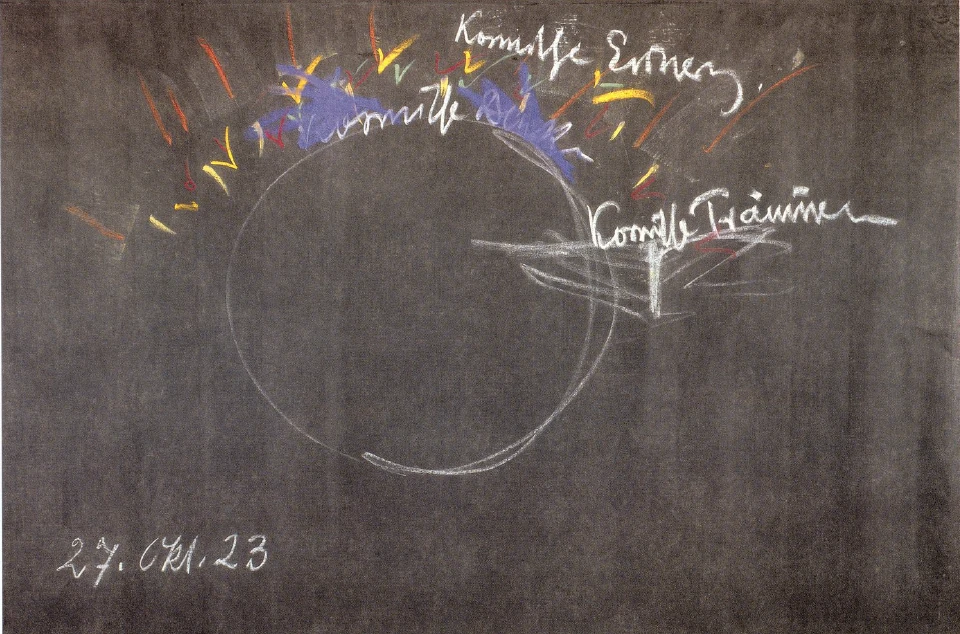

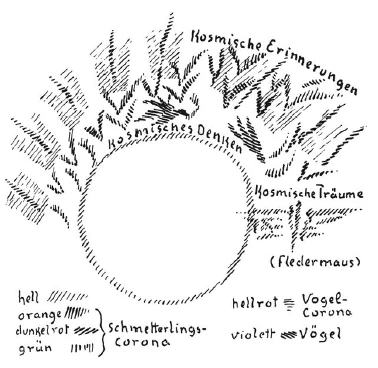

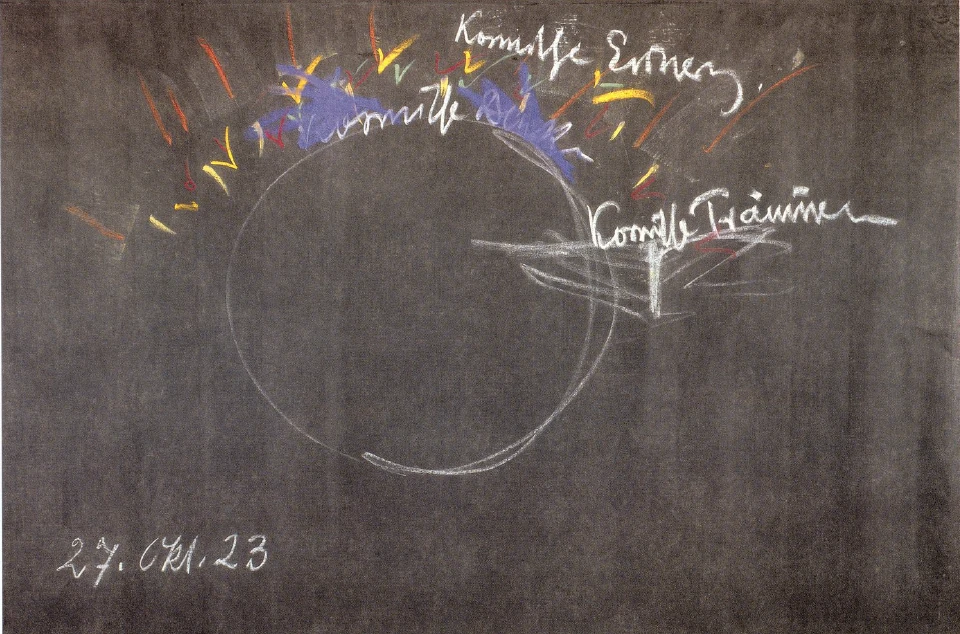

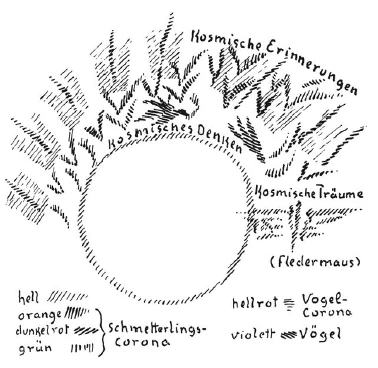

Here we must add something further. The butterfly continually imparts spiritualized matter to the cosmos. It is the darling of the Saturn influences. Now call to mind how I described Saturn as the great bearer of the memory of our planetary system. The butterfly is closely connected with what makes provision for memory in our planet. It is memory-thoughts which live in the butterfly. The bird—this, too, I have already described—is entirely a head, and as it flies through the warmth-imbued air in world-space it is actually the living, flying thought. What we have within us as thoughts—and this also is connected with the warmth-ether—is bird-nature, eagle-nature, in us. The bird is the flying thought. But the bat is the flying dream; the flying dream-picture of the cosmos. So we can say: The earth is surrounded by a web of butterflies—this is cosmic memory; and by the kingdom of the birds—this is cosmic thinking; and by the bats—they are the cosmic dream, cosmic dreaming. It is actually the flying dreams of the cosmos which sough through space as the bats. And as dreams love the twilight, so, too, does the cosmos love the twilight when it sends the bat through space. The enduring thoughts of memory, these we see embodied in the girdle of butterflies encircling the earth; thoughts of the moment we see in the bird-girdle of the earth; and dreams in the environment of the earth fly about embodied as bats. And you will surely feel, if we penetrate deeply into their form, how much affinity there is between this appearance of the bat and dreaming! One simply cannot look at a bat without the thought arising: I must be dreaming; that is really something which should not be there, something which is as much outside the other creations of nature as dreams are outside ordinary physical reality.

To sum up we can say: The butterfly sends spiritualized substance into spirit-land during its lifetime; the bird sends it out after its death. Now what does the bat do? During its lifetime the bat gives off spiritualized substance, especially that spiritualized substance which exists in the stretched membrane between its separate fingers. But it does not give this over to the cosmos; it sheds it into the atmosphere of the earth. Thereby beads of spirit, so to say, are continually arising in the atmosphere.

Thus we find the earth to be surrounded by the continual glimmer of out-streaming spirit-matter from the butterflies and sparkling into this what comes from the dying birds; but also, streaming back towards the earth, we find peculiar segregations of air where the bats give off what they spiritualize. Those are the spiritual formations which are always to be observed when one sees a bat in flight. In fact a bat always has a kind of tail behind it, like a comet. The bat gives off spirit-matter; but instead of sending it outwards, it thrusts it back into the physical substance of the earth. It thrusts it back into the air. And just as one sees with the physical eye physical bats fluttering about, one can also see these corresponding spirit-formations which emanate from the bats fluttering through the air; they sough through the spaces of the air. We know that air consists of oxygen, nitrogen and other constituents, but this is not all; it also consists of the spirit-emanations of bats.

Strange and paradoxical as it may sound, this dream-order of the bats sends little spectres out into the air, which then unite into a general mass. In geology the matter below the earth, which is a rock-mass of a soft consistency like porridge, is called magma. We might also speak of a spirit-magma in the air, which comes from the emanations of bats.

In ancient times when an instinctive clairvoyance prevailed, people were very susceptible to this spirit magma, just as today many people are very susceptible to what is of a material nature, for instance, bad smelling air. This might certainly be regarded as somewhat vulgar, whereas in the ancient instinctive time of clairvoyance people were susceptible to the bat-residue which is present in the air.

They protected themselves against this. And in many Mysteries there were special formulas whereby people could inwardly arm themselves, so that this bat-residue might have no power over them. For as human beings we do not only inhale oxygen and nitrogen with the air, we also inhale these emanations of the bats. Modern people, however, are not interested in letting themselves be protected against these bat-remains, but whereas in certain conditions they are highly sensitive, let us say, to bad smells, they are highly insensitive to the emanations of the bats. It can really be said that they swallow them down without feeling the least trace of repulsion. It is quite extraordinary that people who are otherwise really prudish just swallow down what contains the stuff of which I have spoken. Nevertheless this too enters into the human being. Certainly it does not enter into the physical or etheric body, but it enters into the astral body.

Yes, you see, we here find remarkable connections. Initiation science everywhere leads into the inner aspect of relationships; this bat-residue is the most craved-for nutriment of what I have described in lectures here as the Dragon. But this bat-residue must first be breathed into the human being. The Dragon finds his surest foothold in human nature when man allows his instincts to be imbued with these emanations of the bats. There they seethe. And the dragon feeds on them and grows—in a spiritual sense, of course—gaining power over people, gaining power in the most manifold ways. This is something against which modern man must again protect himself: and the protection should come from what has been described here as the new form of Michael's fight with the Dragon. The increase in inner strength which man gains when he takes up into himself the Michael impulse as it has been described here, this is his safeguard against the nutriment which the Dragon desires; this is his protection against the unjustified bat-emanations in the atmosphere.

If one has the will to penetrate into these inner world-connections, one must not shrink back from facing the truths contained in them. For today the generally accepted form of the search for truth does not in any way lead to actuality, but at most to something even less actual than a dream, to Maya. Reality must of necessity be sought in the domain where all physical existence is regarded as interwoven with spiritual existence. We can only find our way to reality, when this reality is studied and observed, as has been done here in the present lectures.

In everything good and in everything evil, in some way or other beings are present. Everything in world-connections is so ordered that its relation to other beings can be recognized. For the materialistically minded, butterflies flutter, birds fly, bats flit. But this can really be compared to what often happens with a not very artistic person, who adorns the walls of his room with all manner of pictures which do not belong to each other, which have no inner connection. Thus for the ordinary observer of nature, what flies through the world also has no inner connection; because he sees none. But everything in the cosmos has its own place, because just from this very place it has a relation to the cosmos in its totality. Be it butterfly, bird, or bat, everything has its own meaning within the world-order.

As to those who today wish to scoff, let them scoff. People already have other things to their credit in the sphere of ridicule. Celebrated scholars have declared that meteor-stones cannot exist, because iron cannot fall from heaven, and so on. Why then should people not also scoff at the functions of the bats, about which I have spoken today? Such things, however, should not divert us from the task of imbuing our civilization with a knowledge of spiritual truths.

Fünfter Vortrag

Diese Vorträge handeln von dem inneren Zusammenhang der Welterscheinungen und Weltwesen, und Sie haben schon gesehen, daß sich mancherlei ergibt, von dem derjenige, der nur die äußere Erscheinungswelt ins Auge faßt, zunächst keine Ahnung haben kann. Wir haben gesehen, wie im Grunde genommen eine jede Wesensart - wir haben es an ein paar Beispielen gezeigt — ihre Aufgabe hat im ganzen Zusammenhange des kosmischen Daseins. Nun wollen wir heute gewissermaßen rekapitulierend noch einmal hinschauen auf Wesensarten, von denen wir schon gesprochen haben, wollen ins Auge fassen dasjenige, was ich in den letzten Tagen über die Schmetterlingsnatur gesagt habe. Ich habe gerade im Gegensatz zur Pflanzenwesenheit diese Schmetterlingsnatur entwickelt, und wir haben uns sagen können, wie der Schmetterling eigentlich ein Wesen ist, welches dem Lichte angehört, dem Lichte, insofern es modifiziert wird von der Kraft der äußeren Planeten, des Mars, des Jupiter, des Saturn. So daß wir eigentlich, wenn wir den Schmetterling in seiner Wesenheit verstehen wollen, hinaufschauen müssen in die höheren Regionen des Kosmos und uns sagen müssen: diese höheren Regionen des Kosmos beschenken die Erde, begnaden die Erde mit der Schmetterlingswesenheit.

Nun geht aber, ich möchte sagen, diese Begnadung der Erde eigentlich noch viel tiefer. Erinnern wir uns, wie wir sagen mußten, der Schmetterling beteilige sich eigentlich nicht an dem unmittelbar irdischen Dasein, sondern nur mittelbar, insofern die Sonne mit ihrer Wärme undLeuchtekraft eben im irdischen Dasein tätig ist. Der Schmetterling legt sogar seine Eier dahin, wo sie aus der Region der Sonnenwirksamkeit nicht herauskommen, wo sie in der Region der Sonnenwirksamkeit bleiben, so daß der Schmetterling sein Ei nicht der Erde, sondern eigentlich nur der Sonne übergibt. Dann kriecht die Raupe aus, die unter dem Einfluß der Marswirkung steht; natürlich, die Sonnenwirkung bleibt immer vorhanden. Es bildet sich die Puppe, die unter der Jupitereinwirkung steht. Es kriecht aus der Puppe der Schmetterling aus, der dann in seinem Farbenschillern das in der Umgebung der Erde wiedergibt, was die mit der Saturnkraft vereinigte Sonnenleuchtekraft der Erde sein kann.

So sehen wir eigentlich unmittelbar wirksam innerhalb des irdischen Daseins, in der Umgebung des irdischen Daseins, die Saturnwirksamkeit in den mannigfaltigen Farben des Schmerterlingsdaseins. Aber erinnern wir uns daran, daß ja die Substanzen, die in Betracht kommen für das Weltendasein, zweierlei sind. Wir haben es zu tun mit den rein stofflichen Substanzen der Erde, und wir haben es zu tun mit den geistigen Substanzen, und ich habe Ihnen gesagt, daß das Merkwürdige darinnen besteht, daß der Mensch in bezug auf seinen StoffwechselGliedmaßenorganismus die geistige Substanz zugrundeliegend hat, während seinem Haupte, seinem Kopfe die physische Substanz zugrunde liegt. In der unteren Natur des Menschen wird die geistige Substanz durchdrungen mit physischer Kraftwirkung, mit Schwerewirkung, mit den anderen irdischen Kraftwirkungen. Im Haupte wird die irdische Substanz, die durch den ganzen Stoffwechsel, die Zirkulation, die Nerventätigkeit und so weiter hinaufgeschafft wird in das Haupt des Menschen, durchdrungen von übersinnlichen geistigen Kräften, die sich widerspiegeln in unserem Denken, in unserem Vorstellen. So daß wir also im Haupte des Menschen vergeistigte physische Materie haben, und daß wir im Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßensystem verirdischte - wenn ich das Wort bilden darf -, verirdischte geistig-spirituelle Substantialität haben.

Nun, diese vergeistigte Materie haben wir vor allen Dingen beim Schmetterlingswesen. Indem das Schmetterlingswesen überhaupt im Bereich des Sonnendaseins bleibt, bemächtigt es sich der irdischen Materie, ich möchte sagen - es ist natürlich noch bildlich gesprochen - nur wie im feinsten Staub. Der Schmetterling eignet sich die irdische Materie an nur wie im feinsten Staub. Er verschafft sich auch seine Nahrung aus denjenigen Substanzen der Erde, welche sonnendurcharbeitet sind. Er vereinigt mit seiner eigenen Wesenheit nur, was sonnendurcharbeitet ist; er entnimmt schon allem Irdischen das Feinste sozusagen und treibt es bis zur vollständigsten Vergeistigung. In der Tat hat man, wenn man den Schmetterlingsflügel ins Auge faßt, im Grunde die vergeistigteste Erdenmaterie vor sich. Dadurch, daß die Materie des Schmetterlingsflügels farbdurchdrungen ist, ist sie die vergeistigteste Erdenmaterie.

Der Schmetterling ist eigentlich diejenige Wesenheit, die ganz in vergeistigter Erdenmaterie lebt. Man kann es sogar geistig sehen, wie der Schmetterling seinen Körper, den er inmitten seiner Farbflügel hat, in einer gewissen Weise verachtet, weil seine ganze Aufmerksamkeit, sein ganzes Gruppenseelentum eigentlich im freudigen Genießen seiner Flügelfarben ruht.

Ebenso wie man dem Schmetterling folgen kann in der Bewunderung seiner schillernden Farben, kann man ihm folgen in der Bewunderung der flatternden Freude über diese Farben. Das ist etwas, was im Grunde genommen bei den Kindern schon kultiviert werden sollte, diese Freude an der Geistigkeit, die herumflattert in der Luft, und die eigentlich flatternde Freude ist, Freude am Farbenspiel. In dieser Beziehung nuanciert sich das Schmerterlingsmäßige in einer ganz wunderbaren Weise. Und dem allem liegt dann etwas anderes zugrunde.

Wir konnten vom Vogel, den wir im Adler repräsentiert fanden, sagen, daß er bei seinem Tode die vergeistigte Erdensubstanz in die geistige Welt hineintragen kann, daß er dadurch seine Aufgabe im kosmischen Dasein hat, daß er als Vogel die Erdenmaterie vergeistigt und dasjenige tun kann, was der Mensch nicht tun kann. Der Mensch hat in seinem Kopfe auch die Erdenmaterie bis zu einem gewissen Grade vergeistigt, aber er kann diese Erdenmaterie nicht hineinnehmen in die Welt, die er durchlebt zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, denn er würde fortwährend einen unsäglichen, nicht erträglichen, zerstörenden Schmerz aushalten müssen, wenn er diese vergeistigte Erdenmaterie seines Kopfes hineintragen wollte in die geistige Welt.

Die Vogelwelt, durch den Adler repräsentiert, kann das, so daß in der Tat dadurch ein Zusammenhang geschaffen wird zwischen dem, was irdisch ist, und dem, was außerirdisch ist. Die irdische Materie wird zunächst gewissermaßen langsam in den Geist übergeführt, und das Vogelgeschlecht hat die Aufgabe, diese vergeistigte irdische Materie dem Weltenall zu übergeben. Man wird schon sagen können, wenn einmal die Erde am Ende ihres Daseins angekommen ist: diese Erdenmaterie ist vergeistigt worden, und das Vogelgeschlecht war da innerhalb der ganzen Ökonomie des Erdendaseins, um die vergeistigte Erdenmaterie in das Geisterland zurückzutragen.

Mit den Schmetterlingen ist es noch etwas anderes. Der Schmetterling vergeistigt noch mehr die irdische Materie als der Vogel. Der Vogel kommt immerhin dazu, viel näher der Erde zu stehen als der Schmetterling. Ich werde das nachher ausführen. Aber der Schmetterling ist imstande, dadurch, daß er eben die Sonnenregion gar nicht verläßt, seine Materie so weit zu vergeistigen, daß er nun nicht erst bei seinem Tode, wie der Vogel, sondern schon während seines Lebens fortwährend vergeistigte Materie an die Erdenumgebung, an die kosmische Erdenumgebung abgibt.

Denken Sie einmal, wie das eigentlich ein Großartiges ist in der ganzen kosmischen Ökonomie, wenn wir uns vorstellen können: die Erde, durchflattert von der Schmetterlingswelt in der mannigfaltigsten Weise und fortwährend in den Weltenraum hinausströmend vergeistigte Erdenmaterie, die die Schmetterlingswelt an den Kosmos abgibt! So daß wir also diese Region der Schmetterlingswelt um die Erde herum durch eine solche Erkenntnis mit noch ganz anderen Gefühlen betrachten können.

Wir können hineinschauen in diese flatternde Welt und können uns sagen: Ihr Flattertiere, ihr strahlt sogar Besseres als das Sonnenlicht, ihr strahlet Geistlicht in den Kosmos hinaus! — Das Geistige wird ja von unserer materialistischen Wissenschaft wenig berücksichtigt. Und so hat eigentlich diese materialistische Wissenschaft gar keine Handhabe, um auf diese Dinge, die zum Ganzen der Weltökonomie gehören, auch nur irgendwie zu kommen. Aber sie sind ja da, wie die physischen Wirkungen da sind, und sie sind wesentlicher als die physischen Wirkungen. Denn das, was da hinausstrahlt in das Geisterland, das wird fortwirken, wenn die Erde längst zugrunde gegangen ist; das, was heute der Physiker, der Chemiker konstatiert, das wird seinen Abschluß finden mit dem Erdendasein. So daß also, wenn irgendein Beobachter draußen im Kosmos säße und eine lange Zeit zur Beobachtung hätte, er sehen würde, wie etwas wie eine kontinuierliche Ausstrahlung von Geistmaterie in das Geisterland, von geistig gewordener Materie in das Geisterland stattfindet, wie die Erde ihr eigenes Wesen hinaus in den Weltenraum, in den Kosmos ausstrahlt, und wie, sprühenden Funken gleich, immerfort aufleuchtenden Funken, das, was das Vogelgeschlecht, jeder Vogel nach seinem Tode, aufglänzen läßt, in dieses Weltenall nunmehr strahlenförmig hinausgeht: ein Glimmern von Schmetterlingsgeisteslicht und ein Sprühen von Vogelgeisteslicht!

Das sind die Dinge, die aber zu gleicher Zeit dahin die Aufmerksamkeit lenken könnten, daß, wenn man nun zur anderen Sternenwelt hinausschaut, man auch nicht glauben soll, daß da nur das herunterstrahlt, was das Spektroskop zeigt, oder vielmehr, was in das Spektroskop der Spektroskopiker hineinphantasiert, sondern das, was von den anderen Sternenwelten zur Erde herunterstrahlt, ist ebenso das Ergebnis von Lebewesen in anderen Welten, wie das, was von der Erde hinausstrahlt in den Weltenraum, das Ergebnis von Lebewesen ist. Wir schauen einen Stern an und stellen uns mit dem heutigen Physiker so etwas vor, wie eine entzündete unorganische Flamme - so ähnlich. Es ist natürlich völliger Unsinn. Denn, was da geschaut wird, das ist durchaus das Ergebnis von Belebtem, Beseeltem, Vergeistigtem.

Gehen wir nun herein von diesem Schmetterlingsgürtel, wenn ich so sagen darf, der dieErde umgürtet, noch einmal zu dem Vogelgeschlechte. Wenn wir uns das, was wir schon wissen, vorstellen, so haben wir drei aneinandergrenzende Regionen. Über demselben sind andere Regionen, unter demselben wieder andere Regionen. Wir haben den Lichtäther, wir haben den Wärmeäther, der aber eigentlich zwei Teile hat, zwei Schichten; die eine ist die irdische Wärmeschicht, die andere ist die kosmische Wärmeschicht, und die spielen fortwährend ineinander. Wir haben in der Tat nicht einerlei, sondern zweierlei Wärme, diejenige Wärme, die eigentlich irdischen, tellurischen Ursprungs ist, und solche, die kosmischen Ursprungs ist. Die spielen fortwährend ineinander. Dann haben wir angrenzend an den Wärmeäther die Luft. Dann kämen Wasser und Erde, und oben käme chemischer Äther, Lebensäther.

Wenn wir nun das Schmetterlingsgeschlecht nehmen, so gehört es vorzugsweise dem Lichtäther an, und der Lichtäther selber ist das Mittel, in dem die Leuchtekraft hervorholt aus dem Schmetterlingsei die Raupe; die Leuchtekraft im wesentlichen holt das hervor. Das ist schon nicht so beim Vogelgeschlecht. Die Vögel legen ihre Eier. Die müssen nun von Wärme ausgebrütet werden. Das Schmetterlingsei wird einfach der Sonnennatur überlassen; das Vogelei kommt in die Region der Wärme. In der Region des Wärmeäthers ist der Vogel vorhanden, und er überwindet eigentlich das, was bloße Luft ist.

Der Schmetterling fliegt auch in der Luft, aber er ist im Grunde genommen ganz ein Lichtgeschöpf. Und indem die Luft durchdrungen wird vom Lichte, wählt der Schmetterling innerhalb dieses Licht-Luftdaseins nicht das Luftdasein, sondern das Lichtdasein; die Luft ist ihm nur der Träger. Die Luft sind die Wogen, auf denen er gewissermaßen herumschwimmt, aber sein Element ist das Licht. Der Vogel fliegt in der Luft, aber sein Element ist eigentlich die Wärme, die verschiedenen Wärmedifferenzen in der Luft, und er überwindet in einem gewissen Grade die Luft. Der Vogel ist ja auch innerlich ein Luftwesen. Im hohen Grade ist er ein Luftwesen. Sehen Sie sich einmal die Knochen der Säugetiere, die Knochen des Menschen an: sie sind von Mark erfüllt. Wir werden davon noch sprechen, warum sie von Mark erfüllt sind. Die Vogelknochen sind hohl und nur mit Luft ausgefüllt. Wir bestehen also, insofern das in Betracht kommt, was innerhalb unserer Knochen ist, aus Markmäßigem, der Vogel besteht aus Luft, und sein Markmäßiges ist reine Luft. Wenn Sie die Vogellungen nehmen, so finden Sie in dieser Vogellunge eine ganze Menge von Säcken, die ausgehen von der Lunge; das sind Luftsäcke. Wenn der Vogel einatmet, dann atmet er nicht nur in die Lunge ein, sondern er atmet in diese Luftsäcke die Luft hinein, und von den Luftsäcken geht es in die hohlen Knochen. So daß, wenn man alles Fleisch und alle Federn von dem Vogel loslösen und die Knochen wegnehmen könnte, so würde man noch ein aus Luft bestehendes Tier bekommen, das die Form hätte der inneren Lungenausfüllung und auch der inneren Ausfüllung aller Knochen. Sie hätten, wenn man es in der Form vorstellt, ganz die Form des Vogels. Im Fleisch- und Beinadler sitzt ein Luftadler drinnen. Das ist nun nicht bloß aus dem Grunde, daß da noch ein Luftadler drinnen ist, sondern nun atmet der Vogel; durch die Atmung erzeugt er Wärme. Diese Wärme, die teilt er seiner Luft mit, die er nun in alle seine Gliedmaßen preßt. Da entsteht der Wärmeunterschied gegenüber der äußeren Umgebung. Da hat er seine Innenwärme, da hat er die äußere Wärme. In diesem Niveauunterschiede zwischen der äußeren Wärme der Luft und der Wärme, die er seiner eigenen Luft drinnen gibt, in diesem Niveauunterschiede, also in einem Niveauunterschiede innerhalb der Wärme, des Wärmeelementes lebt eigentlich der Vogel. Und wenn Sie den Vogel fragen würden in entsprechender Weise, wie es ihm eigentlich mit seinem Körper ist, dann würde er Ihnen - wenn Sie die Vogelsprache verstünden, würden Sie schon sehen, daß er das tut - so antworten, daß Sie erkennen würden, er redet von den fest substantiellen Knochen und von dem, was er sonst an sich trägt, etwa so, wie wenn Sie bepackt sind links und rechts und auf dem Rücken und auf dem Kopf mit lauter Koffern. Da sagen Sie auch nicht: Das ist mein Leib, der rechte Koffer, der linke Koffer und so weiter. - Geradesowenig wie Sie von diesen Dingen, mit denen Sie bepackt sind, als von Ihrem Leibe reden, sondern wie Sie das an sich tragen, so redet der Vogel, wenn er von sich redet, bloß von der von ihm erwärmten Luft, und von dem anderen als von dem Gepäck, das er mitträgt im irdischen Dasein. Diese Knochen, die diesen eigentlichen Vogelluftleib umhüllen: das ist sein Gepäck. So daß wir also durchaus sagen müssen: im Grunde genommen lebt der Vogel ganz und gar im Wärmeelemente, und der Schmetterling im Lichtelemente. Für den Schmetterling ist alles, was physische Substanz ist, die er vergeistigt, vor der Vergeistigung eigentlich erst recht, man möchte sagen nicht einmal Gepäck, sondern Hauseinrichtung. Noch ferner steht sie ihm.

Also indem wir in diese Region hinaufkommen, zu dem Getier in diesen Regionen, kommen wir zu etwas, was wir gar nicht auf physische Art beurteilen dürfen. Wenn wir es auf physische Art beurteilen, so ist es etwa so, wie wenn wir einen Menschen so zeichnen wollten, daß wir seine Haare hineingewachsen malen würden in das, was er auf dem Kopfe tragen würde, seine Koffer zusammengewachsen mit den Armen, seinen Rücken mit irgend etwas, was er als Rucksack trägt, so daß wir ihn ganz buckelig machen würden, als ob der Rucksack hinten hinausgewachsen wäre. Wenn wir den Menschen so zeichnen würden, so würde das entsprechen der Vorstellung, die man sich als Materialist über den Vogel eigentlich macht. Das ist gar nicht der Vogel, das ist das Gepäck des Vogels. Der Vogel fühlt sich eigentlich auch so, als ob er furchtbar schleppt an diesem seinem Gepäck, denn er möchte am liebsten frank und frei, gar nicht belastet, als ein warmes Luftgetier durch die Welt seine Wanderung vollführen. Das andere ist ihm eine Last. Und er bringt den Tribut dem Weltendasein, indem er ihm diese Last vergeistigt und ins Geisterland hinausschickt, wenn er stirbt; der Schmetterling noch während seiner Lebenszeit.

Sehen Sie, der Vogel atmet und verwendet die Luft auf die Weise, wie ich es Ihnen gesagt habe. Beim Schmetterling ist es noch anders. Der Schmetterling atmet überhaupt nicht durch solche Vorrichtungen, wie sie die sogenannten höheren Tiere haben; es sind ja nur die voluminöseren Tiere, es sind nicht die höheren Tiere in Wirklichkeit. Der Schmetterling atmet eigentlich nur durch Röhren, die von seiner äußeren Umhüllung nach innen hineingehen, und die etwas aufgeblasen sind, so daß er die Luft aufspeichern kann, wenn er fliegt, so daß ihn das nicht stört, daß er da nicht immer zu atmen braucht. Er atmet eigentlich immer nur durch Röhren, die in sein Inneres hineingehen. Dadurch, daß er durch Röhren atmet, die in sein Inneres hineingehen, hat er die Möglichkeit, mit der Luft, die er einatmet, zugleich das Licht, das in der Luft ist, in seinen ganzen Körper aufzunehmen. Da ist auch ein großer Unterschied vorhanden.

Schematisch dargestellt: Stellen Sie sich ein höheres Tier vor; das hat die Lunge. In die Lunge kommt der Sauerstoff hinein und verbindet sich da mit dem Blute auf dem Umweg durch das Herz. Das Blut muß in Herz und Lunge einfließen, um mit dem Sauerstoff in Berührung zu kommen bei diesen voluminöseren Tieren und auch beim Menschen. Beim Schmetterling muß ich ganz anders zeichnen. Da muß ich so zeichnen: Wenn das der Schmetterling ist, gehen da überall die Röhren herein; diese Röhren verästeln sich weiter. Und der Sauerstoff geht nun da überall hinein, verästelt sich selber mit; die Luft dringt überall in den Körper ein.

Bei uns und bei den sogenannten höheren Tieren kommt die Luft nur als Luft bis in die Lungen; bei dem Schmetterling breitet sich die äußere Luft mit ihrem Inhalte an Licht im ganzen inneren Leib aus. Der Vogel breitet die Luft bis in seine hohlen Knochen hinein aus; der Schmetterling ist nicht nur nach außen hin das Lichttier, sondern er breiter das Licht, das von der Luft getragen wird, in seinem ganzen Körper überallhin aus, so daß er auch innerlich Licht ist. Wenn ich Ihnen schildern konnte, daß der Vogel eigentlich innerlich erwärmte Luft ist, so ist der Schmetterling eigentlich ganz Licht. Es besteht auch sein Körper aus Licht, und die Wärme ist für den Schmetterling eigentlich Last, Gepäck. Er flattert ganz und gar im Lichte und baut seinen Leib eigentlich ganz aus dem Lichte herein auf. Und wir müßten, wenn wir den Schmetterling in der Luft flattern sehen, eigentlich bloße Lichtwesen flattern sehen, über ihre Farben, ihr Farbenspiel sich freuende Lichtwesen. Das andere ist Bekleidung und Gepäck. Man muß erst darauf kommen, aus was eigentlich die Wesen der Erdenumgebung bestehen, denn der äußere Schein täuscht.

Diejenigen, die heute so oberflächlich dies oder jenes gelernt haben, sagen wir aus morgenländischer Weisheit, die sprechen davon, daß die Welt Maja ist. Aber das ist nun wirklich nichts, wenn man sagt: die Welt ist Maja. Man muß in den Einzelheiten sehen, wie sie Maja ist. Maja versteht man, wenn man weiß, der Vogel schaut eigentlich gar nicht in seiner Wesenheit so aus, wie er außen erscheint, sondern er ist ein warmes Luftwesen. Der Schmetterling schaut gar nicht so aus, wie er da erscheint, sondern er ist ein Lichtwesen, das da herumflattert, und das im wesentlichen eigentlich aus der Freude an dem Farbenspiel besteht, an jenem Farbenspiel, das an dem Schmetterlingsflügel entsteht, indem die irdische Staubmaterie vom Farbigen durchdrungen wird und dadurch auf der ersten Stufe der Vergeistigung hinaus ins geistige Weltenall, in den geistigen Kosmos ist.

Sehen Sie, da haben Sie, ich möchte sagen, zwei Stufen: den Schmetterling, den Bewohner des Lichtäthers in unserer Erdenumgebung; den Vogel, den Bewohner des Wärmeäthers in unserer Erdenumgebung. Und nun die dritte Sorte. Wenn wir herunterkommen in die Luft, da kommen wir dann zu jenen Wesen, welche in einer bestimmten Periode unserer Erdenevolution noch gar nicht da sein konnten, zum Beispiel in der Zeit, in der der Mond noch bei der Erde war, in der der Mond sich noch nicht von der Erde getrennt hatte. Da kommen wir zu Wesen, die zwar auch Luftwesen sind, das heißt, in der Luft leben, aber eigentlich schon durchaus hart berührt sind von dem, was der Erde eigentümlich ist, von der Erdenschwere. Der Schmetterling ist noch gar nicht von der Erdenschwere berührt. Der Schmetterling flattert freudig im Lichtäther und fühlt sich selber als ein Geschöpf, aus dem Lichtäther heraus geboren. Der Vogel überwindet die Schwere, indem er die Luft in seinem Inneren erwärmt, dadurch warme Luft ist, und warme Luft wird von der kalten Luft getragen. Er überwindet noch die Erdenschwere.

Diejenigen Tiere, welche zwar ihrer Abstammung gemäß noch in der Luft leben müssen, aber die Erdenschwere nicht überwinden können, weil sie nicht hohle Knochen haben, sondern markerfüllte Knochen, weil sie auch nicht solche Luftsäcke haben wie die Vögel, diese Tiere sind die Fledermäuse.

Die Fledermäuse sind ein ganz merkwürdiges Tiergeschlecht. Die Fledermäuse überwinden gar nicht durch das Innere ihres Körpers die Schwere der Erde. Sie sind nicht lichtleicht wie der Schmetterling, sie sind nicht wärmeleicht wie der Vogel, sie unterliegen schon der Schwere der Erde und fühlen sich auch schon in ihrem Fleisch und Bein. Daher ist den Fledermäusen dasjenige Element, aus dem zum Beispiel der Schmetterling besteht, in dem der Schmetterling ganz und gar lebt, dieses Element des Lichtes, unangenehm. Sie lieben die Dämmerung. Sie müssen die Luft benützen, aber sie haben die Luft am liebsten, wenn die Luft nicht das Licht trägt. Sie übergeben sich der Dämmerung. Sie sind eigentlich Dämmerungstiere. Die Fledermäuse können sich nur dadurch in der Luft halten, daß sie, ich möchte sagen, die etwas karikaturhaft aussehenden Fledermausflügel haben, die ja gar nicht wirkliche Flügel sind, sondern ausgespannte Häute, zwischen den verlängerten Fingern ausgespannte Häute, Fallschirme. Dadurch halten sie sich in der Luft. Dadurch überwinden sie, indem sie der Schwere selber etwas, was mit dieser Schwere zusammenhängt, als Gegengewicht entgegenstellen, die Schwere. Aber sie sind dadurch ganz in den Bereich der Erdenkräfte hereingespannt. Man kann niemals eigentlich nach den physikalisch-mechanischen Konstruktionen den Schmetterlingsflug so ohne weiteres konstruieren, auch den Vogelflug nicht. Es wird niemals vollständig stimmen. Man muß da etwas hineinbringen, das andere Konstruktionen noch enthält. Aber den Fledermausflug, den können Sie durchaus mit irdischer Dynamik und Mechanik konstruieren.

Die Fledermaus liebt nicht das Licht, die lichtdurchdrungene Luft, sondern höchstens die vom Lichte etwas durchspielte Dämmerungsluft. Die Fledermaus unterscheidet sich dadurch von dem Vogel, daß der Vogel, wenn er schaut, eigentlich immer das im Auge hat, was in der Luft ist. Selbst der Geier, wenn er das Lamm sieht, empfindet das so, daß das Lamm etwas ist, was am Ende des Luftkreises ist, wenn er von oben sieht, was wie an die Erde angemalt ist. Und außerdem ist es kein bloßes Sehen, es ist ein Begehren, was Sie wahrnehmen werden, wenn Sie den Geierflug, der auf das Lamm gerichtet ist, wirklich ansehen, der eine ausgesprochene Dynamik des Wollens, des Willens, des Begehrens ist. j

Der Schmetterling sieht überhaupt, was auf der Erde ist, so wie im Spiegel; für den Schmetterling ist die Erde ein Spiegel. Er sieht das, was im Kosmos ist. Wenn Sie den Schmetterling flattern sehen, dann müssen Sie sich eigentlich vorstellen: die Erde, die beachtet er nicht, die ist ein Spiegel. Die Erde spiegelt ihm dasjenige, was im Kosmos ist. Der Vogel sieht nicht das Irdische, aber er sieht das, was in der Luft ist. Die Fledermaus erst fängt an, dasjenige wahrzunehmen, was sie durchfliegt, oder an dem sie vorbeifliegt. Und da sie das Licht nicht liebt, so ist sie eigentlich von all dem, was sie sieht, unangenehm berührt. Man kann schon sagen, der Schmetterling und der Vogel sehen auf eine sehr geistige Art. Das erste Tier von oben herunter, das auf irdische Art sehen muß, ist unangenehm von diesem Sehen berührt. Die Fledermaus hat das Sehen nicht gerne, und sie hat daher etwas, ich möchte sagen wie verkörperte Angst vor dem, was sie sieht und nicht sehen will. Sie möchte so vorbeihuschen an den Dingen: sehen müssen und nicht sehen wollen — da möchte sie sich so überall vorbeidrücken. Deshalb, weil sie sich so vorbeidrücken möchte, möchte sie auf alles so wunderbar hinhören. Die Fledermaus ist tatsächlich ein Tier, das dem eigenen Flug fortwährend zuhört, ob dieser Flug nicht irgendwie gefährdet wird.

Sehen Sie sich die Fledermausohren an. Sie können es den Fledermausohren ansehen, daß sie auf Weltenangst gestimmt sind. Das sind sie, diese Fledermausohren. Das sind ganz merkwürdige Gebilde, sie sind richtig aufs Hinschleichen durch die Welt, auf Weltenangst gestimmt. Das alles versteht man erst, wenn man die Fledermaus in diesem Zusammenhange betrachtet, in den wir sie jetzt hineinstellen.

Da müssen wir noch etwas sagen. Der Schmetterling gibt fortwährend vergeistigte Materie an den Kosmos ab, und er ist der Liebling der Saturnwirkungen. Nun erinnern Sie sich daran, wie ich hier ausgeführt habe, daß der Saturn der große Träger des Gedächtnisses unseres Planetensystems ist. Der Schmetterling hängt ganz zusammen mit dem Erinnerungsvermögen unseres Planeten. Das sind die Erinnerungsgedanken, die im Schmetterling leben. Der Vogel - ich habe Ihnen das auch schon ausgeführt — ist im Ganzen eigentlich ein Kopf, und in dieser durchwärmten Luft, die er durchfliegt durch den Weltenraum, ist er eigentlich der lebendig fliegende Gedanke. Was wir in uns als Gedanken haben, was ja auch zusammenhängt mit dem Wärmeäther, ist die Vogelnatur, die Adlernatur in uns. Der Vogel ist der fliegende Gedanke. Die Fledermaus aber ist der fliegende Traum, das fliegende Traumbild des Kosmos. So daß Sie sagen können: Die Erde ist umwoben von den Schmetterlingen: sie sind die kosmische Erinnerung; und von dem Vogelgeschlechte: es ist das kosmische Denken; und von der Fledermaus: sie ist der kosmische Traum, das kosmische Träumen. Es sind in der Tat die fliegenden Träume des Kosmos, die als Fledermäuse den Raum durchsausen. Wie der Traum das Dämmerlicht liebt, so liebt der Kosmos das Dämmerlicht, indem er die Fledermaus durch den Raum schickt. Die dauernden Gedanken der Erinnerung, sie sehen wir verkörpert in dem Schmetterlingsgürtel der Erde; die in der Gegenwart lebenden Gedanken in dem Vogelgürtel der Erde; die Träume in der Umgebung der Erde fliegen verkörpert als Fledermäuse herum. Fühlen Sie doch, wenn wir uns so recht in ihre Form vertiefen, wie verwandt dieses Anschauen einer Fledermaus mit dem Träumen ist! Eine Fledermaus kann man gar nicht anders ansehen, als daß einem der Gedanke kommt: du träumst doch; das ist doch eigentlich etwas, was nicht da sein sollte, was so heraus ist aus den übrigen Naturgeschöpfen, wie der Traum heraus ist aus der gewöhnlichen physischen Wirklichkeit.

Wir können also sagen: Der Schmetterling sendet die vergeistigte Substanz in das Geisterland hinein während seines Lebens; der Vogel sendet sie hinaus nach seinem Tode. Was macht nun die Fledermaus? Die Fledermaus sondert die vergeistigte Substanz, insbesondere jene vergeistigte Substanz, welche in den gespannten Häuten zwischen den einzelnen Fingern lebt, ab während ihrer Lebenszeit, übergibt sie aber nicht dem Weltenall, sondern sondert sie in der Erdenluft ab. Dadurch entstehen fortwährend, ich möchte sagen, Geistperlen in der Erdenluft. Und so haben wir umgeben die Erde mit diesem kontinuierlichen Glimmen der ausströmenden Geistmaterie des Schmetterlings, hineinsprühend dasjenige, was von den sterbenden Vögeln kommt, aber zurückstrahlend nach der Erde die eigentümlichen Einschlüsse der Luft, da wo die Fledermäuse absondern das, was sie vergeistigen. Das sind die Geistgebilde, die man immer schaut, wenn man eine Fledermaus fliegen sieht. Tatsächlich hat sie immer wie ein Komet etwas wie einen Schwanz hinter sich. Sie sondert Geistmaterie ab, schickt sie aber nicht fort, sondern stößt sie zurück in die physische Erdenmaterie. In die Luft hinein stößt sie sie zurück. Ebenso wie man mit dem physischen Auge die physische Fledermaus flattern sieht, so kann man flattern sehen durch die Luft diese entsprechenden Geistgebilde der Fledermäuse; die sausen durch den Luftraum. Und wenn wir wissen: die Luft besteht aus Sauerstoff, Stickstoff und anderen Bestandteilen, so ist das nicht alles; sie besteht außerdem aus dem Geisteinfluß der Fledermäuse.

So sonderbar und paradox das klingt: dieses Traumgeschlecht der Fledermäuse sendet kleine Gespenster in die Luft herein, die sich dann vereinigen zu einer gemeinsamen Masse. Man nennt in der Geologie das, was unterhalb der Erde ist und noch eine Gesteinsmasse ist, die breiweich ist, Magma. Man könnte von einem Geistmagma in der Luft sprechen, das von den Ausflüssen der Fledermäuse herrührt.

Gegen dieses Geistmagma waren in alten Zeiten, in denen es instinktives Hellsehen gegeben hat, die Menschen sehr empfindlich, geradeso wie heute noch manche Leutegegen Materielleres, zum Beispiel schlechte Düfte, empfindlich sind; nur daß man das als etwas, ich möchte sagen, mehr Plebejisches ansehen könnte, während in der alten instinktiven Hellseherzeit die Menschen empfindlich waren für das, was als Fledermausrest in der Luft vorhanden ist.

Dagegen haben sie sich geschützt. Und in manchen Mysterien gab es ganz besondere Formeln, durch die sich die Menschen innerlich versperrten, damit dieser Fledermausrest keine Gewalt über sie habe. Denn als Menschen atmen wir mit der Luft nicht bloß den Sauerstoff und den Stickstoff ein, wir atmen auch diese Fledermausreste ein. Nur ist die heutige Menschheit nicht darauf aus, sich vor diesen Fledermausresten schützen zu lassen, sondern während sie unter Umständen recht empfindlich ist, ich will sagen für Gerüche, ist sie höchst unempfindlich für Fledermausreste. Die verschluckt sie, man kann schon sagen, ohne daß sie auch nur irgend etwas von Ekel dabei empfindet. Es ist ganz merkwürdig: Leute, die sonst recht zimperlich sind, verschlucken das, von dem ich hier spreche, was das Zeug hält. Aber das geht dann auch in den Menschen hinein. Es geht nicht in den physischen und in den Ätherleib, aber es geht in den Astralleib hinein.

Ja, Sie sehen, wir kommen da zu merkwürdigen Zusammenhängen. Initiationswissenschaft führt eben überall in das Innere der Zusammenhänge hinein: diese Fledermausreste sind die begehrteste Nahrung dessen, was ich Ihnen in den Vorträgen hier geschildert habe als den Drachen. Nur müssen sie zuerst in den Menschen hineingeatmet werden, diese Fledermausreste. Und der Drache hat seine besten Anhaltspunkte in der menschlichen Natur, wenn der Mensch seine Instinkte durchsetzt sein läßt von diesen Fledermausresten. Die wühlen da drinnen. Und die frißt der Drache und wird dadurch fett, natürlich geistig gesprochen, und bekommt Gewalt über den Menschen, bekommt Gewalt in der mannigfaltigsten Weise. Und da ist es so, daß auch der heutige Mensch sich wiederum schützen muß. Der Schutz soll kommen von dem, was hier geschildert worden ist als die neue Form des Streites des Michael mit dem Drachen. Was der Mensch an innerer Erkraftung gewinnt, wenn er den Michael-Impuls so aufnimmt, wie es hier geschildert worden ist, das schützt ihn gegen die Nahrung, die der Drache bekommen soll; dann schützt er sich gegen den ungerechtfertigten Fledermausrest innerhalb der Atmosphäre.

Man darf eben nicht zurückschrecken davor, die Wahrheiten aus dem inneren Weltenzusammenhang hervorzuholen, wenn man wirklich in diesen inneren Weltenzusammenhang eindringen will. Denn diejenige Form des Wahrheitssuchers, die heute die allgemein anerkannte ist, die führt eben zu gar nichts Wirklichem, sondern zumeist nur zu etwas nicht einmal Geträumtem, eben zur Maja. Die Wirklichkeit muß durchaus auf dem Gebiete gesucht werden, wo man auch alles physische Dasein durchspielt sieht von geistigem Dasein. Da kann man an die Wirklichkeit nur herandringen, wenn man sie so betrachtet, wie es nun in diesen Vorträgen geschieht.

Zu irgend etwas Gutem oder zu irgend etwas Bösem sind die Wesen vorhanden, die irgendwo vorhanden sind. Alles steht so im Weltenzusammenhang drinnen, daß man erkennen kann, wie es mit den anderen Wesen zusammenhängt. Für den materialistisch Gesinnten flattern die Schmetterlinge, fliegen die Vögel, flattern die Flattertiere, die Fledermäuse. Aber da ist es fast so, wie es manchmal bei einem nicht sehr kunstsinnigen Menschen ist, wenn er sich sein Zimmer voll hängt mit allem möglichen Bilderzeugs, das nicht zusammengehört, das keinen inneren Zusammenhang hat. So hat für den gewöhnlichen Weltenbetrachter das, was da durch die Welt fliegt, auch keinen inneren Zusammenhang, weil er keinen sieht. Aber alles im Kosmos steht an seiner Stelle, weil es von dieser Stelle aus eben einen inneren Zusammenhang mit der Totalität des Kosmos hat. Ob Schmetterling, ob Vogel, ob Fledermaus, alles steht mit irgendeinem Sinn in der Welt darinnen.

Mögen diejenigen, die solches heute verspotten wollen, mögen sie es verspotten. Die Menschen haben sich in bezug auf das Verspotten schon anderes geleistet. Berühmte Akademien haben das Urteil abgegeben: es kann keine Meteorsteine geben, weil Eisen nicht vom Himmel fallen kann und so weiter. Warum sollen die Menschen nicht auch spotten über die Funktionen der Fledermäuse, von denen ich heute gesprochen habe? Das alles darf aber nicht beirren darin, tatsächlich unsere Zivilisation zu durchziehen mit der Erkenntnis des Geistigen.

Fifth Lecture

These lectures deal with the inner connection of world phenomena and world beings, and you have already seen that many things arise of which he who only considers the outer world of phenomena can at first have no idea. We have seen how basically every kind of being - we have shown this with a few examples - has its task in the whole context of cosmic existence. Now today we want to look once again, recapitulating as it were, at the kinds of beings we have already spoken of, and we want to consider what I have said in the last few days about the nature of butterflies. I have just developed this butterfly nature in contrast to the plant being, and we have been able to say to ourselves how the butterfly is actually a being that belongs to the light, to the light in so far as it is modified by the power of the outer planets, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn. So that actually, if we want to understand the butterfly in its essence, we must look up into the higher regions of the cosmos and say to ourselves: these higher regions of the cosmos endow the earth, endow the earth with the butterfly essence.

But now, I would like to say, this gracing of the earth actually goes much deeper. Let us remember how we had to say that the butterfly does not actually participate in direct earthly existence, but only indirectly, insofar as the sun with its warmth and luminous power is active in earthly existence. The butterfly even lays its eggs where they do not come out of the region of the sun's activity, where they remain in the region of the sun's activity, so that the butterfly does not hand over its egg to the earth, but actually only to the sun. Then the caterpillar crawls out, which is under the influence of the Mars effect; of course, the sun effect always remains present. The chrysalis is formed, which is under the influence of Jupiter. The butterfly crawls out of the chrysalis, which then reflects in its color iridescence that in the surroundings of the Earth which can be the solar luminous power of the Earth united with the Saturnian power.

So we actually see directly effective within the earthly existence, in the surroundings of the earthly existence, the Saturn effect in the manifold colors of the butterfly existence. But let us remember that the substances which come into consideration for world existence are of two kinds. We have to do with the purely material substances of the earth, and we have to do with the spiritual substances, and I have told you that the strange thing is that man has the spiritual substance underlying his metabolic limb-organism, while his head, his head, has the physical substance underlying it. In the lower nature of man the spiritual substance is permeated with physical force effects, with gravity effects, with the other earthly force effects. In the head the earthly substance, which is brought up into the head of man through the whole metabolism, the circulation, the nervous activity and so on, is permeated by supersensible spiritual forces, which are reflected in our thinking, in our imagination. So that in the head of man we have spiritualized physical matter, and in the metabolic system of limbs we have earthly - if I may use that word - earthly spiritual substantiality.

Well, we have this spiritualized matter above all in the butterfly being. By remaining in the realm of solar existence, the butterfly being takes possession of earthly matter, I would like to say - it is of course still metaphorically speaking - only as in the finest dust. The butterfly appropriates earthly matter only as in the finest dust. It also obtains its nourishment from those substances of the earth which have been worked through by the sun. It unites with its own essence only that which is sun-worked; it already extracts the finest, so to speak, from everything earthly and drives it to the most complete spiritualization. In fact, if you look at the butterfly's wing, you are basically looking at the most spiritualized earthly matter. Because the matter of the butterfly's wing is imbued with color, it is the most spiritualized matter on earth.

The butterfly is actually the being that lives entirely in spiritualized earth matter. You can even see it spiritually, how the butterfly despises its body, which it has in the midst of its colored wings, in a certain way, because its whole attention, its whole group soul actually rests in the joyful enjoyment of its wing colors.

Just as one can follow the butterfly in the admiration of its dazzling colors, one can follow it in the admiration of the fluttering joy of these colors. This is something that should basically already be cultivated in children, this joy in the spirituality that flutters around in the air, and which is actually fluttering joy, joy in the play of colors. In this respect, the painterly is nuanced in a quite wonderful way. And then something else underlies it all.

We could say of the bird, which we found represented in the eagle, that at its death it can carry the spiritualized earth substance into the spiritual world, that it thereby has its task in cosmic existence, that as a bird it spiritualizes the earth matter and can do that which man cannot do. Man has also spiritualized earth matter in his head to a certain degree, but he cannot take this earth matter into the world he lives through between death and a new birth, for he would have to endure an unspeakable, unbearable, destructive pain continually if he wanted to carry this spiritualized earth matter of his head into the spiritual world.

The bird world, represented by the eagle, can do this, so that in fact a connection is created between that which is earthly and that which is extraterrestrial. The earthly matter is first, so to speak, slowly transferred into the spirit, and the bird family has the task of handing over this spiritualized earthly matter to the universe. Once the earth has reached the end of its existence it will be possible to say: this earthly matter has been spiritualized, and the bird race was there within the whole economy of earthly existence to carry the spiritualized earthly matter back into the spirit land.

With the butterflies it is something else. The butterfly spiritualizes earthly matter even more than the bird. After all, the bird comes to stand much closer to the earth than the butterfly. I will explain this later. But the butterfly, by not leaving the solar region at all, is able to spiritualize its matter to such an extent that it now not only releases spiritualized matter to the earth environment, to the cosmic earth environment, at its death, like the bird, but already during its life.

Think how great this actually is in the whole cosmic economy, if we can imagine: the earth, fluttered through by the butterfly world in the most manifold way and continuously flowing out into the world space spiritualized earth matter, which the butterfly world gives off to the cosmos! So that through such a realization we can look at this region of the butterfly world around the earth with quite different feelings.

We can look into this fluttering world and can say to ourselves: You fluttering animals, you radiate even better than the sunlight, you radiate spiritual light out into the cosmos! - Our materialistic science takes little account of the spiritual. And so this materialistic science actually has no means of even somehow coming to grips with these things that are part of the whole of the world economy. But they are there, just as the physical effects are there, and they are more essential than the physical effects. For that which radiates out into the spirit-land will continue to work when the earth has long since perished; that which the physicist, the chemist states today, will find its conclusion with earthly existence. So that if any observer were sitting outside in the cosmos and had a long time to observe, he would see how something like a continuous radiation of spirit-matter into the spirit-land, of matter that has become spiritual into the spirit-land, takes place, how the earth radiates its own being out into the universe, into the cosmos, and how, like sparkling sparks, constantly shining sparks, that which makes the bird race, every bird after its death, shine, now radiates out into this universe: a glimmering of butterfly spirit light and a spraying of bird spirit light!

These are the things, however, which at the same time could draw attention to the fact that when one now looks out to the other star world, one should also not believe that only what the spectroscope shows shines down there, or rather what the spectroscopist fantasizes into the spectroscope, but what shines down from the other star worlds to earth is just as much the result of living beings in other worlds as what shines out from earth into the universe is the result of living beings. We look at a star and imagine something like an ignited inorganic flame with today's physicist - something like that. Of course, this is complete nonsense. Because what we are looking at is definitely the result of animate, animated, spiritual things.

Let us now move on from this butterfly girdle, if I may say so, which encircles the earth, to the bird family once again. If we imagine what we already know, we have three adjacent regions. Above them are other regions, below them other regions again. We have the light ether, we have the heat ether, but it actually has two parts, two layers; one is the earthly heat layer, the other is the cosmic heat layer, and they constantly interact with each other. In fact, we do not have one kind of heat, but two kinds, the heat that is actually of earthly, telluric origin and the heat that is of cosmic origin. They constantly interact with each other. Then we have the air adjacent to the heat ether. Then would come water and earth, and on top would come chemical ether, life ether.

If we now take the butterfly, it belongs preferably to the light ether, and the light ether itself is the means by which the luminous force brings forth the caterpillar from the butterfly egg; the luminous force essentially brings this forth. This is not the case with birds. Birds lay their eggs. They now have to be hatched by heat. The butterfly's egg is simply left to the nature of the sun; the bird's egg comes into the region of warmth. The bird is present in the region of heat ether, and it actually overcomes what is mere air.

The butterfly also flies in the air, but it is essentially a creature of light. And because the air is permeated by light, the butterfly does not choose to be an air creature within this light-air existence, but a light creature; the air is only the carrier for it. The air is the waves on which it floats, so to speak, but its element is light. The bird flies in the air, but its element is actually the heat, the various heat differences in the air, and it overcomes the air to a certain degree. The bird is also inwardly an aerial being. To a high degree it is an aerial being. Take a look at the bones of mammals, the bones of man: they are filled with marrow. We will talk about why they are filled with marrow. Bird bones are hollow and filled only with air. So we are made of marrow as far as what is inside our bones is concerned, the bird is made of air, and its marrow is pure air. If you take the bird's lungs, you will find in them a whole series of sacs that emanate from the lungs; these are air sacs. When the bird breathes in, it not only breathes into the lungs, but it breathes the air into these air sacs, and from the air sacs it goes into the hollow bones. So that if you could detach all the flesh and feathers from the bird and take away the bones, you would still get an animal consisting of air, which would have the form of the inner filling of the lungs and also the inner filling of all the bones. If you imagine it in this form, you would have the shape of the bird. An aerial eagle sits inside the flesh and leg eagle. This is not merely for the reason that there is still an aerial eagle inside, but now the bird breathes; through breathing it produces warmth. It communicates this heat to its air, which it now presses into all its limbs. This creates the difference in warmth compared to the external environment. There he has his inner warmth, there he has the outer warmth. The bird actually lives in this difference in level between the external heat of the air and the heat that it gives to its own air inside, in this difference in level, that is, in a difference in level within the heat, the heat element. And if you were to ask the bird in a corresponding way how it actually feels about its body, then it would answer you - if you understood bird language, you would already see that it does so - in such a way that you would recognize that it is talking about the solid substantial bones and about what else it carries about itself, something like when you are packed left and right and on your back and on your head with a lot of suitcases. You don't say: This is my body, the right suitcase, the left suitcase and so on. - Just as you do not speak of these things with which you are packed as your body, but as you carry them on you, so the bird, when it speaks of itself, speaks only of the air warmed by it, and of the other as the baggage it carries with it in earthly existence. These bones that envelop this actual bird's body of air: that is its baggage. So that we must certainly say: basically, the bird lives entirely in the warmth element, and the butterfly in the light element. For the butterfly, everything that is physical substance, which it spiritualizes, is actually, before spiritualization, not even baggage, one might say, but home furnishings. It is even further away from it.