World History in the Light of Anthroposophy

and as a Foundation for Knowledge of the Human Spirit

GA 233

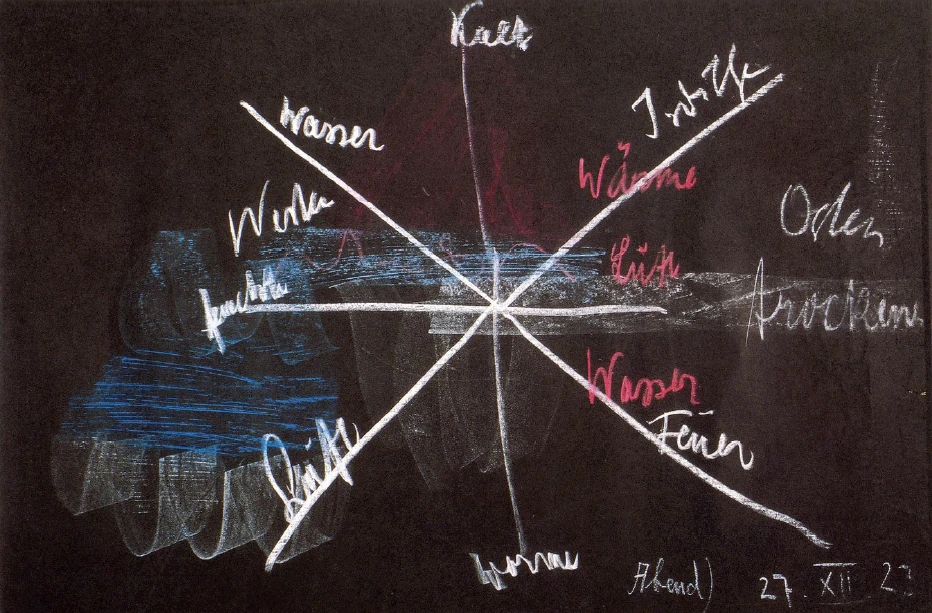

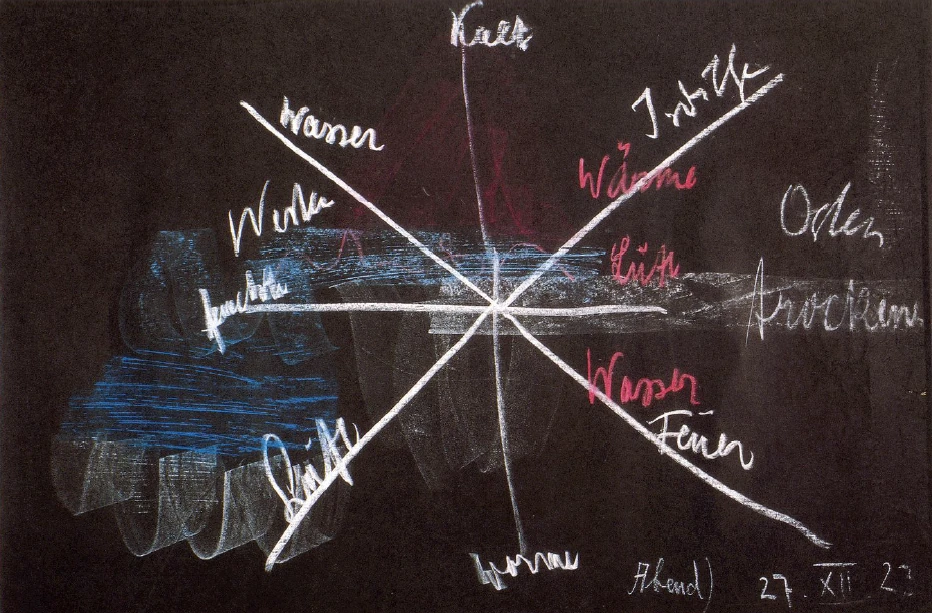

27 December 1923, Dornach

Lecture IV

It was my task yesterday to show from the example of individual personalities how the historical evolution of the world runs its course. If one seeks to come further in the direction of Spiritual Science, one cannot represent things otherwise than by showing the consequences of events as they reflect themselves in the human being. For not until our own epoch does man feel himself for reasons which we will discuss in the course of these lectures, shut off as an individual being from the rest of the world. In all previous epochs man felt—and, be it noted, in all subsequent epochs man will again feel himself as member of the whole Cosmos, as belonging to the entire world; even as a finger (as I have often expressed it) can have no independent existence for itself, but can only exist on a human being. For the moment a finger is separated from the human being, it is no longer a finger, it begins to decay, it is something quite different, subject to quite other laws than when attached to the human organism. And as a finger is only a finger in unison with the organism, so in the same way is man only a being having some form or other, whether in Earth-life or in the life between death and a new birth, in connection with the entire Cosmos. The consciousness of this was present in earlier epochs and will again be present in a later time; it is only darkened to-day because, as we shall hear, it was necessary for man that it should be darkened and clouded in order that he might develop to the full the experience of freedom. The farther we go back however into ancient times, the more do we find man possessing this consciousness of belonging to the whole Cosmos.

I have given you a picture of two personalities,—the one called Gilgamesh in the famous Epic and the other Eabani. I have shown you how these personalities lived in the ancient Egypto-Chaldean epoch in accordance with what was possible to men of that time, and how they afterwards experienced a deepening through the Mysteries of Ephesus. And I told you at the end of my lecture yesterday that these same human beings had their part later in the historical evolution of the world as Aristotle and Alexander.

In order now fully to understand the course of Earth evolution in the times when all these things were taking place, we must look more closely into what such souls were able to receive into themselves in these three successive periods.

I have told you how the personality who is concealed behind the name of Gilgamesh undertook a journey to the West and went through a kind of Western Post-Atlantean initiation.

Let us first form an idea of the nature of such an initiation, that we may the better understand what came later. We shall naturally turn to a place where echoes of the old Atlantean initiation remained on for a long time. This was the case with the Hibernian Mysteries,1See the 8th and 9th lectures in Mystery Knowledge and Mystery Centres. of which I have recently spoken to the friends who are here in Dornach. I must now repeat some of what I then said before we can come to a clear and full understanding of the subject we are treating.

The Mysteries of Hibernia, the Irish Mysteries, were in existence for a long time. They were still there at the time of the foundation of Christianity. And they are the Mysteries that in some respects preserved most faithfully the ancient wisdom-teaching of the Atlantean peoples. Let me give you a picture of the experiences of a person who was initiated into the Irish Mysteries in the Post-Atlantean epoch. Before he was able to receive the initiation he had to be strictly prepared; the preparation that had to be undergone before entering the Mysteries was always in those times of extraordinary strictness and rigour. The important thing in the Hibernian Mysteries was that the pupil should learn to become aware in powerful inward experience ofthat which is illusory in his environment,—in all the things, that is to say, to which man attributes being on the ground of his sense-perception. Then he was made aware of all the difficulties and obstacles which meet man when he searches after the truth, the real truth. And he was shown how, fundamentally, everything which surrounds us in the world of the senses is an illusion, that what the senses give is illusion, and that the truth conceals itself behind the illusion, so that in fact true being is not accessible to man through sense-perception.

Now, very likely you will say that this conviction you yourselves have held for a long time; you know this quite well. But all the knowledge a man can have in the present-day consciousness of the illusory character of the sense-world is as nothing compared with the inner shattering, the inner tragedy that men of that time suffered in their preparation for the Hibernian initiation. For when one says theoretically in this way: Everything is Maya, everything is illusion,—one takes it quite lightly! But the training of the Hibernian pupils was carried to such a point that they had to say to themselves: There is for man no possibility of penetrating the illusion and coming to real true Being.

The pupils were by this means trained to content themselves, as it were in desperation, with the illusion. They came into an attitude of despair: the illusory character, they felt, is so overpowering and so penetrating that one can never get beyond it. And in the life of these pupils we find always the feeling: Very well then, we must remain in the illusion. That means, however: we must lose the very ground from under our feet. For there is no standing firm on illusion! In truth, my dear friends, of the strictness and severity of the preparation in the ancient Mysteries, we to-day can scarcely form any idea. Men shrink in terror before what inner development actually demands.

Such was the experience that came to the pupils in regard to Being and its illusory character. And now there awaited them a similar experience regarding the search after Truth. They learned to know the hindrances man has in his emotions that hinder him from coming to truth, all the dark and overwhelming feelings that trouble the clear light of knowledge. And so once more they came to a great moment when they said to themselves: If Truth is not, well then we live—we must live—in error, in untruth. For a man to come thus to a time in his life when he despairs of Being and of Truth means, in short, that he tears out of him his own humanity.

All this was given in order that the human being, through experiencing the opposite of what he was finally to reach as his goal, might approach that goal with the right and deep human feeling. For unless one has learned what it means to live with error and illusion, then one cannot value Being and Truth. And the pupils of Hibernia had to learn to value Being and Truth.

And then, when they had gone through all this, when they had, as it were, experienced to the bitter end, the opposite pole of what they were eventually to reach, the pupils were led (and here I must describe what happened in the picture-language that can rightly represent what took place as reality in the Hibernian Mysteries)—they were led into a kind of sanctuary where were two pillar-statues of infinitely strong suggestive force, and of gigantic size. The one of these pillar-statues was inwardly hollow; the surface that surrounded the hollow space, the whole substance, that is, of which the statue consisted, was elastic throughout. Wherever one pressed, one could make an indentation into the statue; but the moment one ceased to press, the form restored itself.

The whole pillar-statue was made in such a way that the head was more particularly developed. When a man approached the statue, he had the feeling: Forces are streaming forth from the head into the colossal body. For of course he did not see the space within, he only became aware of it when he pressed. And the pupil was exhorted to press. He had the feeling that the forces of the head rayed out over the whole of the rest of the body, that in this statue the head does everything.

I willingly admit, my dear friends, that if a modern man in our present-day prosaic life were led before the statue, he would scarcely be able to experience anything but quite abstract ideas about it. That is certainly so. But it is a different matter, first to experience with one's whole inner being, with soul and spirit, yes, and with blood and nerves, the might of illusion and the might of error,—and then, after that, to experience the suggestive force of such a gigantic figure.

This statue had a male character.

By the side of it stood another, that had a female character. It was not hollow. It was composed of a substance that was not elastic, but plastic. When the pupil pressed this statue—and again he was exhorted to do so—he destroyed the form. He dug a hole in the body.

After the pupil had found how in the one statue, owing to its elasticity, the form was always re-established, and how in the other he defaced the statue by pressing it, and after something else too had taken place, of which I shall speak presently, he left the place, and was only led back there again when all the deformations he had caused in the plastic non-elastic female figure had been restored, and the statue was intact. Thanks to all the preparations which the pupil had undergone—and I can only give them here in outline—he was able to receive in connection with the statue having a female character a deep inner experience in the whole of his being—body, soul and spirit.

This inner experience had of course been already prepared in him earlier, but it was established and confirmed in full measure through the suggestive influence of the statue. He received into him a feeling of inward numbness, of hard and frozen numbness. This so worked in him that he saw his soul filled with Imaginations. And these Imaginations were pictures of the Earth's winter, pictures that represented the winter of the Earth. Thus was the pupil led to perceive Reality, in the spirit, from within.

With the other, the male statue, he had a different experience. He felt as though all the life in him, which was generally spread out over the whole body, went into his blood, as if his blood were permeated with forces and pressing against his skin. Whereas before the one statue he had to feel that he was becoming a frozen skeleton, he had now to feel before the other that all the life in him was being consumed in heat, and he was living in a tightly-stretched skin. And this experience of the whole inner man pressing against the surface enabled the pupil to receive a new insight. He was able to say to himself: You have now a feeling and experience of what you would be if, of all the things in the Cosmos, the Sun alone worked upon you. In this way he learned to recognise the working of the Sun in the Cosmos, and how its working is distributed in the Cosmos. He learned to know man's relation to the Sun. And he learned that the reason why man is not in reality what he now felt himself to be under the suggestive influence of the Sun-statue, is because other forces, working in from other corners of the Cosmos, ‘mummify’ this working of the Sun. In such manner did the pupil learn to find his bearings in the Cosmos, to be, as it were, at home in the Cosmos.

And when the pupil felt the suggestive influence of the Moon-statue, when he had in him the hard frost of numbness and experienced a winter landscape within him (in the case of the Sun-statue, he experienced a summer landscape in the spirit), then he felt what he would be like if the Moon influences alone were present.

What does man really know about the world in the present-day? He knows, let us say, that the chicory flower is blue, that the rose is red, the sky blue, and so forth. But these facts make no violent or overwhelming impression upon him. They merely tell him of what is nearest at hand, of what is in his immediate environment. If man would know the secrets of the Cosmos, then he must become in his whole being a sense-organ,—and, to an intense degree.

Through the suggestive influence of the Sun-statue, the whole of the pupil's being was concentrated in the circulation of the blood. He learned to know himself as a Sun-being, as he experienced within him this suggestive influence. And he learned to know himself as Moon-being, by experiencing the suggestive influence of the female statue. And then he was able to tell from out of these inner experiences he had received, how Sun and Moon work upon the human being; even as we to-day can say, from the experience of our eyes, how the rose affects us, or from the experience of our ears can tell the working of the sound of C sharp, and so on.

Thus the pupils of these Mysteries experienced still, even in Post-Atlantean times, how man is placed, as it were, in the Cosmos. It was for them an immediate and direct experience.

Now what I have related to you to-day is but a brief sketch of the sublime experience that came to men in the Mysteries of Hibernia, and continued so to come until the first centuries of the Christian Era. It was a cosmic experience—this Sun-experience and Moon-experience.

In the Mysteries of Ephesus in Asia Minor the pupil had to undergo experiences of quite a different character. Here he experienced in a particularly intense manner, with the whole of his being, that which later found such perfect expression in the opening words of the John-Gospel: ‘In the beginning was the Word. And the Word was with God. And a God was the Word.’ In Ephesus, the pupil was led, not before two statues, but before one,—the statue that is known as the Artemis (Diana) of Ephesus. Identifying himself—as I said yesterday—with this statue which was fullness of life, which abounded everywhere in life, the pupil lived his way into the Cosmic Ether. With the whole of his inner feeling and experience he raised himself out of mere earthly life, raised himself up into the experience of the Cosmic Ether. And now he was guided, to a new knowledge. First of all, the real nature of human speech was communicated to him. And then from human speech, from the human image, that is, of the Cosmic Logos, from the humanly-imaged Logos, it was shown to the pupil how the Cosmic Word works and weaves creatively throughout the Universe.

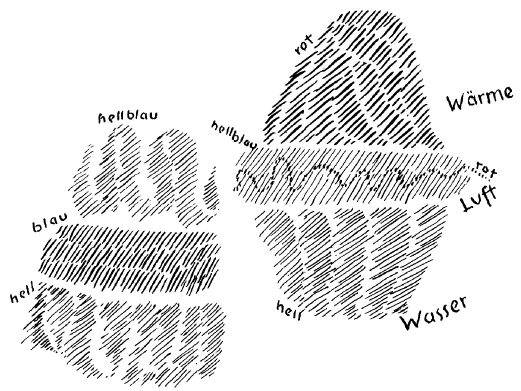

Once more, I can only describe these things in bare outline. The process was such that the attention of the pupil was especially drawn to what happens when the human being speaks, when he impresses the mark of his word on the outgoing breath. He was led to experience what happens with that which, through his own inner deed, man leads over into life,—to feel how his “word” looks in the element of air; and moreover, how two further processes are united with what takes place in the element of air.

Imagine that we have here the expired air, on which are impressed certain words that the human being speaks. Whilst this breath, formed into words, streams outwards from the breast, the rhythmic vibration goes downwards and passes over into the whole watery element that permeates the human organism. Thus at the level of his throat, his speech-organs, man has the air-rhythms when he speaks. But along with his speaking goes a wave-like surging and seething of the whole fluid-body in the human being. The fluid in man, that is below the region of speech, comes into vibration and vibrates in harmony. This is what it really means when we say that our speech is accompanied by feelings. If the watery element in the human being did not vibrate in harmony in this way, man's speech would go forth from him neutrally, indifferently; he would not be able to permeate what he says with feeling. And upwards in the direction of the head, goes the element of warmth, and accompanying the words that we impress upon the air are upward-streaming waves of warmth, which permeate the head and there make it possible for our words to be accompanied by thought.

Thus, when we speak, we have to do with three things: air, warmth and water. This process, which alone presents a complete picture of what lives and weaves in human speech was taken as the starting-point for the pupil of Ephesus.

It was then made clear to him that that which thus takes place in the human being is a cosmic process made human, and that in a certain far-off time the Earth itself worked in that way; only it was not then the air element, but the watery element, the fluid element—which I described yesterday as a volatile, fluid albumen—that had this wavelike moving and surging. Like the air in man, in the microcosm, when he speaks on the outgoing breath, so was once the volatile, fluid element, the albumen which surrounded the Earth like an atmosphere. And as to-day the air passes over into the warmth-element, so the albumen went upwards into a kind of air-element, and downwards into a kind of earthly element. And as with us feelings arise in our body through the fluid element, so in the Earth the Earth-formations, the Earth-forces sprang into existence, all the forces that work and seethe within the Earth. And above, in the airy element the cosmic thoughts were born, the soaring cosmic thoughts that work creatively in the earthly substance.

Majestic and powerful was the impression that the human being received at Ephesus, when he was shown how in his own speech lived the microcosmic echo of what had once been macrocosmic. And the pupil of Ephesus, when he spoke, felt an insight come to him through the experience of speech into the working of the Cosmic Word. He could perceive how the Cosmic Word set in motion the volatile fluid element, giving it movement full of meaning and import; he saw too how it went upward to the creative cosmic thought, and downward to the Earth-forces coming into being.

Thus did the pupil live his way into the Cosmos, by learning to understand aright what was in his own being. ‘Within thee is the human Logos. The human Logos works from out of thee during thy time on Earth. Thou, as man, art the human Logos.’ (For in very deed through that which streams downwards in the fluid element we are ourselves formed and moulded out of speech, whilst through that which streams upwards, we have our human thoughts during our time on Earth.) ‘And even as in thee the essence of humanity is the microcosmic Logos, so once in the far-off beginning of things was the Logos, and It was with God and Itself was a God.’

In Ephesus men had a profound understanding of this for they understood it in and through the human being.

In considering such a personality as is concealed behind the name of Gilgamesh, you must remember how he led his life in the whole milieu and environment that radiated out from the Mysteries. For all culture, all civilisation, was in earlier times a radiation from the Mysteries; so that when I name Gilgamesh to you, you must think of him—as long as he was living in Erech—not indeed as himself initiated into the Mysteries of Erech, but as living in a civilisation that was permeated with the feeling and experience man could have from his relation to the Cosmos.

An experience then came to this personality during his journey to the West, which made him directly acquainted, not with the Hibernian Mysteries themselves—he did not travel so far afield—but with what was cultivated in a colony of the Hibernian Mysteries, situated, as I told you, where the Burgenland now is. What he experienced there lived in his soul and then developed further in the life between death and new birth; and in the next earthly life he underwent at Ephesus a deepening of the soul in connection with this same experience.

The deepening of the soul took place for both the individuals of whom we have been speaking. Verily it was as though a torrent surged up from the depth of the civilisation of that time and broke like a great wave on the souls of these two. They experienced in vivid and intense reality what survived in Greece after the Homeric period only as a beautiful semblance, as the glory of something that is gone.

In Ephesus one could still have a feeling of the whole Reality in which man had once upon a time been living, in the days when he still had an immediate relation to the Divine-Spiritual; when Asia was for him only the lowest of the heavens, when he still had connection with the higher heavens bordering upon it. In those far-off times man had experienced in ‘Asia’ the presence of the Nature Spirits, and above, the presence of the Angels, Archangels, etc., and above them again, the Exusiai and the rest of the Hierarchies. Of all this one could still have as it were an after-feeling in Ephesus, in the place, that is, where Heraclitus also lived and where so much of the old Reality was still experienced even in later Grecian times, down to the 6th and 5th centuries B.C.

It was indeed characteristic of the Greek that he took what had once been experienced by man in connection with the Cosmos and steeped it in the myth, in beauty, in the element of art, turning it into images that man felt more human and more near to him.

Now we must turn our thoughts to a time when on the one hand the Greek civilisation had reached its zenith, when it had proudly pushed back, in the Persian wars, the last thrust as it were of the old Asiatic Reality, a time when however on the other hand Greece itself was already beginning to decline; and we must picture to ourselves what a man of such a time would experience if he still bore in his soul the unmistakable echoes of what had once been the Divine-Spiritual earthly Reality in body, soul, and spirit of mankind.

We shall have to see how Alexander the Great and Aristotle lived in a world that was not altogether adapted to them, in a world indeed that held great tragedy for them. The fact is, Alexander and Aristotle stood in an altogether different relation to the Spiritual from the men around them; for although they cannot be said to have concerned themselves very much with the Samothracian Mysteries, they had nevertheless a strong affinity in their souls to what went on with the Kabiri in those Mysteries. And right on into the Middle Ages there were those who understood what this meant. Men of the present day build up altogether false ideas of the Middle Ages: they do not realise that there were individuals of all classes in life, on into the 13th and 14th centuries, who possessed a clear spiritual vision, at any rate in that realm which in the ancient East was designated as ‘Asia.’ The Song of Alexander2Composed about 1125 by the Franconian priest Lamprecht; the first German secular epic poem. that was composed by a certain priest in the early Middle Ages is a very significant document; in comparison with the account history gives to-day of the doings of Alexander and Aristotle, the poem of the Priest Lamprecht is a sublime and grand conception, still akin to the old understanding of all that had come to pass through Alexander the Great.

Take for instance a passage in the poem where a wonderful description is given after the following style. When Springtime comes, you go out into the woods. You come to the edge of the wood. Flowers are blooming there, and the sun stands where it lets the shadow fall from the trees on to the flowers. And there you may see how in the shadow of the trees in Spring spiritual flower-children come forth from the calices of the flowers and dance in chorus at the edge of the wood.

In this description of Lamprecht the Priest we can perceive distinctly shining through, an old and real experience which was still accessible to men of that time. They did not go out into the woods, saying prosaically: Here is grass, and here are flowers, and here the trees begin; but when they approached the wood while the sun stood behind it and the shadow fell across the flowers, then in the shadow of the trees there came towards them from the flowers a whole world of flower-beings—beings that were actually present to them before they entered into the wood. For when they came in the wood itself they perceived quite other elemental spirits. This dance of the flower-spirits appeared to Lamprecht the Priest and he delighted especially in picturing it. It is indeed significant, my dear friends; Lamprecht, even as late as the 12th or beginning of the 13th century wishing to describe the campaigns of Alexander, permeates them everywhere with descriptions of Nature that still contain the manifestations of the elemental kingdoms. Underlying his Song of Alexander, there was this consciousness: ‘To describe what took place once upon a time in Macedonia when Alexander began his journeys into Asia, when Alexander was taught by Aristotle, we cannot merely describe the prosaic Earth as the environment of these events; no, to describe them worthily we must include with the prosaic Earth the kingdoms of the elemental beings.’ How different from a modern book of history, which is, of course, quite justified for present times. There you will read how Alexander, against the counsel of his teacher Aristotle whom he disobeyed, conceived himself to have the mission to reconcile the barbarians with civilised mankind, creating so to speak an average of culture; the civilised Greeks, the Hellenes, the Macedonians and the barbarians.

That, no doubt, is right enough for modern time. And yet how puerile, compared to the real truth! On the other hand we have a wonderful impression when we look at the picture Lamprecht gives us of the campaigns of Alexander, attributing to them quite a different goal. We feel as though what I have just described—the entry of the Nature-elemental kingdoms, of the Spiritual into the Physical in Nature,—were intended merely as an introduction. For what is the aim of Alexander's campaigns in the Alexanderlied of Lamprecht?

Alexander comes to the very gates of Paradise. Translated as it is into the Christian language of his time, this corresponds in a high degree, as I shall presently explain, to the real truth. For the campaigns of Alexander were not undertaken for the mere sake of conquest, still less against the advice of Aristotle to reconcile the barbarians with the Greeks. No, they were permeated by a real and lofty spiritual aim. Their impulse came out of the spirit. Let us read of it in Lamprecht's poem, who in his own way with great devotion, albeit 15 centuries after the life of Alexander, tells the heroic story. He tells us how Alexander came up to the gates of Paradise, but could not enter in, for, as Lamprecht says, he alone can enter Paradise who has the true humility, and Alexander, living in pre-Christian time, could not yet have that. Only Christianity could bring to mankind the true humility.

Nevertheless, if we conceive the thing not in a narrow but in a broad-minded way, we shall see how Lamprecht, the Christian priest, still feels something of the tragedy of Alexander's campaigns.

It is not without purpose that I have spoken of this ‘Song of Alexander.’ For now you will not be surprised if we take our start from the campaigns of Alexander in order to describe what went before and what went after in the history of Western mankind, in its connection with the East. For the real underlying feeling of these things was still widely present, as we have seen, at a comparatively late period in the Middle Ages. Not only so; it was present in so concrete a form that the ‘Song of Alexander’ could arise, describing as it does with wonderful dramatic power the events that were enacted through the two souls whom I have characterised.

The significance of this moment in the history of Macedonia reaches on the one hand far back into the past, and on the other hand far on into the future. And it is essential to bear in mind how something of a world-tragedy hangs over all that has to do with Aristotle and Alexander. Even externally the tragedy comes to light. It shows itself in this, my dear friends. Owing to peculiar circumstances—circumstances that were fateful for the history of the world—only the smallest part of the writings of Aristotle have come into Western Europe, and there been further studied and preserved by the Church. In point of fact it is only the writings that deal with logic or are clothed in logical form.

A serious study, however, of the little that is preserved of Aristotle's scientific writings will show what a powerful vision he still had of the connection of the whole Cosmos with the human being. Let me draw your attention to a single passage.

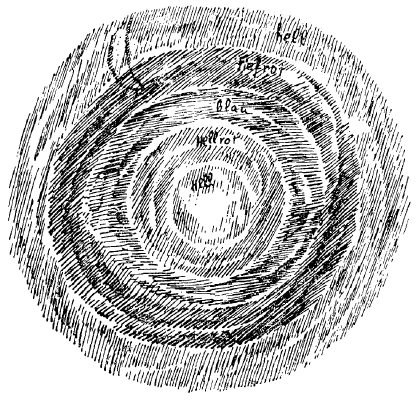

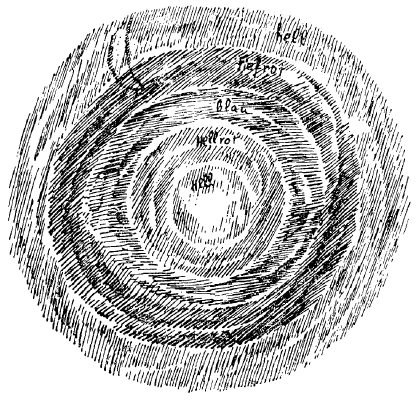

We speak to-day of the earth-element, the water-element, the air-element, the fire- or warmth-element, and then of the Ether. How does Aristotle represent all this? He shows the Earth, the hard firm Earth; the fluid Earth, the Water; then the Air; and the whole permeated and surrounded with Fire. But for Aristotle the ‘Earth’ in this sense teaches up as far as the Moon. And from the Cosmos, reaching from the stars to the Moon, not, that is to say, into the Earth-realm, but only as far as the Moon, coming towards us, as it were, from the Zodiac, from the stars—is the Ether, filling cosmic space. The Ether reaches downwards as far as the Moon.

All this may still be read by scholars in the books that have been written about Aristotle. Aristotle himself, however, used continually to say to his pupil Alexander: That Ether that is away there beyond the realm of earthly warmth—the light-ether, the chemical ether and the life-ether—was once upon a time united with the Earth. It came in as far as to the Earth. And when the Moon withdrew in the ancient epoch of evolution, then the Ether withdrew from the Earth. And so all that is around us in space as dead world—so ran Aristotle's teaching to his pupil Alexander—is not permeated by Ether. When however, Springtime approaches, and plants, animals and human beings come forth to new life on the Earth, then the elementary spirits bring down again the Ether from out of the realm of the Moon, bring it down into these newborn beings. Thus is the Moon the shaper and moulder of beings.

Standing before that great female figure in the Hibernian Mysteries, the pupil of the Mysteries had a most vivid experience of how the Ether does not really belong to the Earth, but is brought down thither by the elementary spirits, every year, in so far as it is needed for the up-springing into life.

And this was so for Aristotle. He, too, had a deep insight into the connection of the human being with the Cosmos. His pupil Theophrastus did not let the writings come westwards that treat of these things. Some of them, however, went to the East, where there was still an understanding for such truths. Thence they were brought by Jews and Arabs through North Africa and Spain to the West of Europe, and there met, in a manner that I shall have yet to describe, with the radiation of the Hibernian Mysteries, as these expressed themselves in the civilisation and culture of the peoples.

But now all that I have been describing to you was no more than the starting-point for the teaching that Aristotle gave to Alexander. It was a teaching that belonged entirely to inner experience. I might describe it in outline somewhat as follows. Alexander learned from Aristotle to understand how the earthy, watery, airy and fiery elements that live outside the human being in the world around him live also within the human being himself, and how he is in this connection a true microcosm. He learned how in the bones of the human being lives the earthy element, and how in his circulation and in all the fluids and humours in him lives the watery element. The airy element works in all that has to do with the breathing, and the fiery element lives in the thoughts of man. Alexander had still the conscious knowledge of living in the elements.

And with this experience of living in the elements of the world went also the experience of a near and intimate relationship with the Earth. In these days we travel East, West, North, South, but have no feeling for what streams into our being the while; we only see what our external senses perceive, we only see what the earthly substances in us, not what the elements in us perceive.

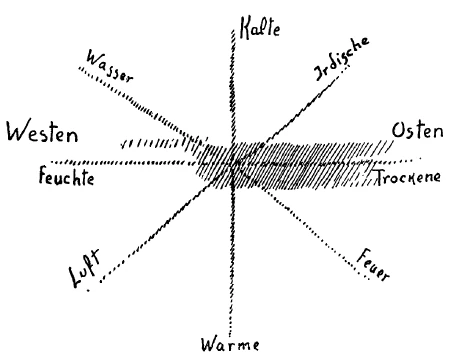

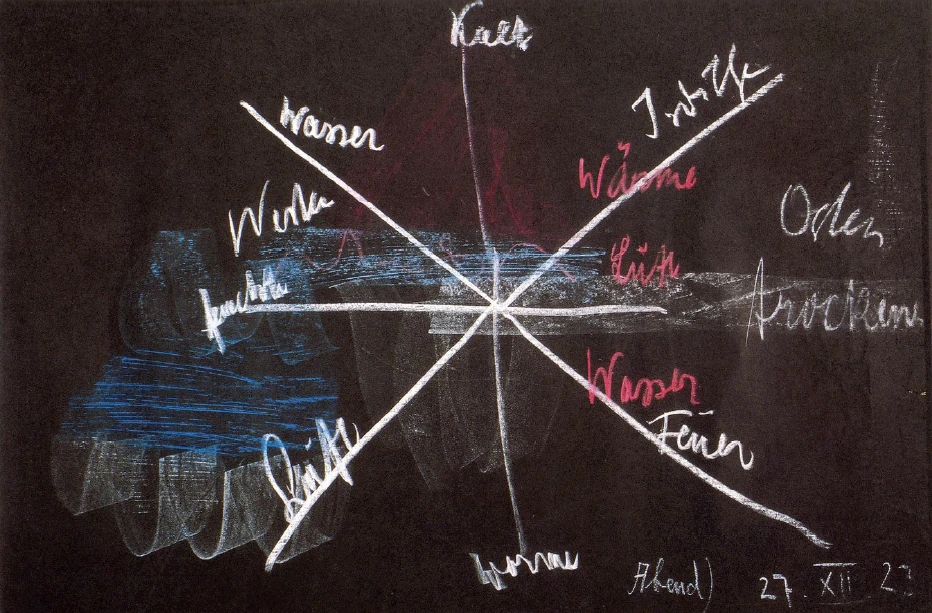

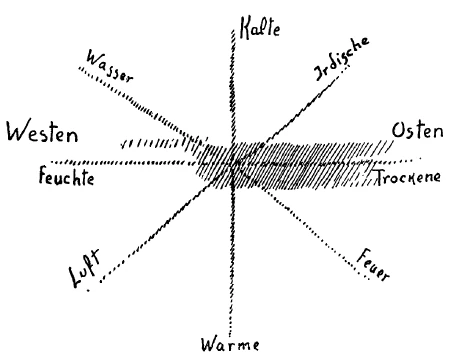

Aristotle, however, was able to teach Alexander: When you go eastwards over the Earth, you pass more and more into an element that dries you up. You pass into the Dry.

You must not imagine this to mean that when one travels to Asia one is completely dried up. We have here, of course, to do with fine and delicate workings, that Alexander was perfectly able to feel in himself after he had received the guidance and instruction of Aristotle. When he was in Macedonia he could feel: I have a certain measure of dampness or moistness in me, that diminishes as I go eastward. In this way, as he wandered over the Earth he felt its configuration, as you may feel a human being by touching him, let us say by drawing your hand caressingly over some part of his body, feeling the difference between nose and eye and mouth. So was a personality such as I have described to you able to perceive a difference between the experience he had when he came more and more into the Dry, and the experience that was his on the other hand in going westward and coming more and more into the Moist.

The other differentiations man still experiences to-day, though crudely. In the direction of the North he experiences the Cold; in the direction of the South the Warm, the Fire element. But the interplay of Moist and Cold, when one goes North-West—that is no longer experienced.

Aristotle awakened in Alexander all that Gilgamesh had passed through when he undertook the journey over to the West. And the result of it was that his pupil could perceive in direct inner experience what is felt in the direction of North-West, in the intermediate zone between Moist and Cold:—Water. A man like Alexander not merely could, but did actually speak in such a manner as not to say: There goes the road to the North-West—but instead: There goes the road to where the element of Water holds dominion. In the intermediate zone between Moist and Warm lies the element where the Air holds dominion.

Such was the teaching in the ancient Greek Chthonian Mysteries, and in the ancient Samothracian Mysteries; and thus did Aristotle teach his own immediate pupil.

And in the zone between Cold and Dry—that it to say, looking from Macedonia, towards Siberia—men had the experience of a region of the Earth where Earth itself, the earthy, holds dominion—the element Earth, the hard and the firm. In the intermediate zone between Warm and Dry, that is, towards India, was experienced a region of the Earth where the Fire element ruled.

And so it was that the pupil of Aristotle pointed Northwest and said: There I feel the Water-Spirits working upon the Earth; pointed South-West and said: There I feel the Air-Spirits; pointed North-East and there beheld hover especially the Spirits of the Earth; pointed South-East towards India, and saw the Spirits of Fire hover over the Earth, saw them there in their element.

And in conclusion, my dear friends, you will be able to feel the deep and close relation both to the natural and to the moral, when I tell you how Alexander began to speak in this way: I must leave the Cold-Moist element and throw myself into the Fire—I must undertake a journey to India. That was a manner of speaking that was as closely bound up with the natural as it was with the moral. I shall have more to say about this tomorrow.

I wanted to-day to give you a picture of what was living in those times; for in all that took place between Alexander and Aristotle we may see at the same time a reflection of the great and mighty change that was taking place in the world's history.. In those days it was still possible to speak in an intimate way to pupils, of the great Mysteries of the past. But then mankind began to receive in increasing measure logic, abstract knowledge, categories, and to push back the other.

We have therefore to see in these events the working of a tremendous and deep change in the historical evolution of mankind, and at the same time an all-important moment in the whole progress of European civilisation in its connection with the East.

Vierter Vortrag

Es war gestern meine Aufgabe, an einzelnen Persönlichkeiten zu zeigen, wie die weltgeschichtliche Entwickelung sich abspielt. Man kann, wenn man in geisteswissenschaftlicher Richtung vorwärtsschreiten will, auch gar nicht anders darstellen als so, daß man die Folge der Ereignisse in ihrer Spiegelung in dem Menschen zeigt. Denn bedenken Sie, daß nur unser Zeitalter aus Gründen, die wir noch im Verlauf dieser Vorträge besprechen werden, so geartet ist, daß der Mensch sich abgeschlossen von der übrigen Welt als ein einzelnes Wesen fühlt. Alle vorangehenden Zeitalter und auch alle folgenden Zeitalter, das muß ausdrücklich betont werden, sind so, daß die Menschen sich fühlten und fühlen werden als Glied der ganzen Welt, als hineingehörig in die ganze Welt. Wie ich oftmals gesagt habe: So wie ein Finger an einem Menschen kein für sich bestehendes Wesen sein kann, sondern nur am Menschen, während er vom Menschen abgetrennt eben nicht mehr der Finger ist, sondern zugrunde geht, etwas ganz anderes ist, ganz anderen Gesetzen unterliegt als am Organismus, geradeso wie der Finger nur Finger ist in Verbindung mit dem Organismus, so ist der Mensch nur Wesen in irgendeiner Form, sei es in der Form des Erdenlebens, sei es in der Form des Lebens zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, im Zusammenhange mit der ganzen Welt. - Aber das Bewußtsein davon war eben in früheren Zeiten vorhanden, wird später wieder vorhanden sein, ist nur heute getrübt, verdunkelt, weil, wie wit hören werden, der Mensch diese Vertrübung, Verdunkelung brauchte, um das Erlebnis der Freiheit in vollem Maße in sich ausbilden zu können. Und in je ältere Zeiten wir zurückkommen, um so mehr finden wir, wie die Menschen ein Bewußtsein ihrer Zusammengehörigkeit mit dem Kosmos haben.

Nun habe ich Ihnen zwei Persönlichkeiten dargestellt, die eine Gilgamesch genannt in dem bekannten Epos, die andere Eabani in demselben Epos, und ich habe Ihnen gezeigt, wie diese Persönlichkeiten im alten chaldäisch-ägyptischen Zeitraum auf die Art leben, wie man eben damals leben konnte, wie sie dann eine Vertiefung erfahren durch die ephesischen Mysterien. Und ich habe schon gestern darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie dieselben Menschenwesen dann in die weltgeschichtliche Entwickelung hineingestellt sind in Aristoteles und Alexander. Aber damit wir völlig verstehen können, wie in jenen Zeiten, in denen sich das für diese Persönlichkeiten abspielte, was ich beschrieben habe, der Gang der Erdenentwickelung überhaupt war, müssen wir noch genauer hineinschauen in dasjenige, was solche Seelen in diesen drei aufeinanderfolgenden Zeitpunkten in sich aufnehmen konnten.

Ich habe Sie ja darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie die hinter dem Namen Gilgamesch sich verbergende Persönlichkeit einen Zug nach dem Westen unternimmt und immerhin eine Art westlicher nachatlantischer Initiation durchmacht. Nun wollen wir uns, um das Spätere zu verstehen, eine Vorstellung davon bilden, wie eine solche späte Initiation war. Wir müssen da allerdings diese Initiation aufsuchen an derjenigen Stätte, wo Nachklänge der alten atlantischen Initiation lange Zeit bestehen blieben. Und das war der Fall bei den Mystetien von Hybernia, von denen ich ja zu den Freunden, die hier in Dornach sind, in der letzten Zeit schon gesprochen habe. Ich muß aber einiges von dem Besprochenen nachholen, damit wir das zum vollen Verständnis bringen, was hier in Betracht kommt.

Die Mysterien von Hybernia, die irischen Mysterien, haben ja lange Zeit bestanden. Sie haben bestanden noch zur Zeit der Begründung des Christentums, und sie sind diejenigen, welche von einer gewissen Seite her die alten Weisheitslehren der atlantischen Bevölkerung am treuesten bewahrt haben. Nun möchte ich Ihnen ein Bild geben zunächst über die Erlebnisse, die jemand hatte, der in die irischen Mysterien in der nachatlantischen Zeit eingeweiht worden ist. Derjenige, der diese Weihe, diese Initiation empfangen sollte, mußte dazumal in einer strengen Art vorbereitet werden, wie überhaupt die Vorbereitungen in die Mysterien in alten Zeiten von einer außerordentlichen Strenge waren. Der Mensch mußte eigentlich innerlich in seiner Seelenverfassung, in seiner ganzen menschheitlichen Verfassung umgestaltet werden. Dann handelte es sich darum, daß bei den Mysterien von Hybernia der Mensch zunächst so vorbereitet wurde, daß er aufmerksam wurde, in starken inneren Erlebnissen aufmerksam wurde auf dasjenige, was trügerisch ist in dem den Menschen umgebenden Sein, in allen den Dingen, die den Menschen so umgeben, daß er ihnen zunächst der Sinneswahrnehmung nach das Sein zuschreibt. Und der Mensch wurde ferner aufmerksam gemacht auf all die Schwierigkeiten und Hemmnisse, die sich ihm gegenüberstellen, wenn er nach der Wahrheit, nach der wirklichen Wahrheit strebt. Der Mensch wurde aufmerksam gemacht, daß im Grunde genommen alles, was uns in der Sinneswelt umgibt, eine Illusion ist, daß die Sinne ein Illusionäres geben und daß sich die Wahrheit verbirgt hinter der Illusion, daß also eigentlich das wahre Sein vom Menschen dutch die Sinneswahrnehmung nicht zu erreichen ist.

Nun werden Sie sagen, das ist eine Überzeugung, die Sie in Ihrer langen anthroposophischen Zeit ja schon immer hatten. Das wissen Sie ganz gut, werden Sie sagen. Aber jenes Wissen, das überhaupt in dem gegenwärtigen Bewußtsein ein Mensch haben kann von dem illusionären Charakter der sinnlichen Außenwelt, das ist eben gar nichts gegen die inneren Erschütterungen, gegen die innere Tragik, die durchgemacht wurde von den Menschen, die damals vorbereitet wurden für die hybernische Einweihung. Denn wenn man so theoretisch sich sagt: Alles ist Maja, alles ist Illusion -, so nimmt man das eigentlich sehr leicht. Aber die Vorbereitung der hybernischen Schüler wurde so weit getrieben, daß sie sich sagten: Es gibt keine Menschenmöglichkeit, durch die Illusion dutchzudringen und zu dem wirklichen, wahrhaftigen Sein zu kommen.

Die Schüler wurden dadurch vorbereitet, daß sie sich, gewissermaßen zunächst aus Verzweiflung, innerlich seelisch zufriedenstellten mit der Illusion. Sie kamen in die verzweiflungsvolle Stimmung hinein, daß der illusionäre Charakter ein so aufdringlicher, ein so gewaltiger ist, daß man über die Illusion überhaupt nicht hinauskommen kann. Und es gab im Leben dieser Schüler immer wieder die Stimmung: Nun, dann muß man eben in der Illusion bleiben -, das heißt aber: Dann muß man den Boden unter den Füßen verlieren, denn auf der Illusion ist nicht festzustehen. — Ja, von der Strenge der Vorbereitung in den alten Mysterien, von der macht man sich heute im Grunde kaum eine Vorstellung. Die Menschen schrecken eben zurück vor demjenigen, was innere Entwickelung wirklich fordert.

Und ebenso, wie es mit dem Sein und seinem illusionären Charakter war, so war es für diese Schüler mit dem Streben nach Wahrheit. Und alles lernten sie kennen, was den Menschen verhindert in seinen Emotionen, in seinen dunklen, ihn überwältigenden Empfindungen und Gefühlen, zur Wahrheit zu kommen, was trübt das klare Licht der Erkenntnis. So daß sie auch da wiederum in einen Zeitpunkt hineinkamen, in dem sie sich sagten: Wenn wir also nicht in der Wahrheit leben können, dann müssen wir eben im Irrtum, in der Unwahrheit leben! - Es heißt ja geradezu, seine Menschheit aus sich selber herausreißen, wenn man eine Zeit seines Lebens dazu kommt, zu verzweifeln an Sein und Wahrheit.

Das alles war dazu da, damit der Mensch durch das Erleben des Gegenteiles von dem, was er zuletzt als das Ziel erreichen soll, diesem Ziele die richtig tiefe menschliche Empfindung entgegenbringt. Denn wer nicht kennengelernt hat, was es heißt, mit Irrtum und Illusion zu leben, der weiß eben das Sein und die Wahrheit nicht zu schätzen. Und schätzen lernen sollten die Schüler von Hybernia die Wahrheit und das Sein.

Und dann, wenn die Schüler solches durchgemacht hatten, wenn sie gewissermaßen den Gegenpol absolviert hatten von dem, wozu sie zuletzt kommen mußten, dann wurden sie - und ich muß das, was nun geschah, in solcher Bildlichkeit darstellen, wie sie dazumal in der Tat in den hybernischen Mysterien real war - in eine Art Heiligtum geführt, in dem zwei Bildsäulen waren, Bildsäulen von einer ungeheuer starken suggestiven Gewalt. Und die eine dieser Bildsäulen von gigantischer Größe, sie war so, daß sie innerlich hohl war; die Außenfläche, die den Hohlraum umgab, also die Gesamtsubstanz, aus der die Bildsäule bestand, war ein durchaus elastischer Stoff, so daß überall, wo man drückte, man hineindrücken konnte in die Bildsäule. Aber in dem Augenblicke, wo man mit dem Drücken nachließ, da stellte sich die Form wieder her. Die ganze Bildsäule war so gemacht, daß vorzugsweise das Haupt ausgebildet war und daß man, indem man ihr entgegentrat, das Gefühl hatte: vom Haupte aus strahlen die Kräfte in den übrigen kolossalen Körper, denn den hohlen Innenraum sah man natürlich nicht, nahm ihn nicht wahr, merkte ihn nur, wenn man drückte. Und man wurde angehalten zu drücken. Man hatte das Gefühl, daß der ganze übrige Körper außer dem Kopfe von den Kräften des Kopfes ausgestrahlt wird, daß der Kopf alles tut an dieser Bildsäule.

Ich gebe Ihnen gern zu, daß wenn ein heutiger Mensch in der gegenwärtigen Prosa des Lebens vor die Bildsäule hingeführt würde, er ja auch kaum etwas anderes als Abstraktes empfinden würde. Gewiß, aber es ist eben etwas anderes, mit seinem ganzen Inneren, mit seinem Geist, mit seiner Seele, mit seinem Blute, mit seinen Nerven erlebt zu haben die Macht der Illusion und die Macht des Irrtums und dann die suggestive Gewalt einer solchen gigantischen Gestalt zu erleben.

Diese Bildsäule hatte einen männlichen Charakter. Neben ihr stand eine andere, die einen weiblichen Charakter hatte. Sie war nicht hohl. Sie war aus einem nicht elastischen, aber plastischen Stoff. Wenn man an ihr drückte - und man wurde wieder angehalten, an ihr zu drücken -, zerstörte man die Form. Man grub ein Loch ein in den Körper.

Aber nachdem der Schüler an der einen Bildsäule erfahren hatte, daß dutch Elastizität sich alles wieder herstellte in der Form, nachdem er an der anderen Bildsäule erfahren hatte, daß er sie deformiert hatte mit seinem Drücken, verließ er nach einigem anderen, von dem ich gleich sprechen werde, den Raum, und er wurde erst wiederum in diesen Raum geführt, wenn alle die Fehler, die Deformationen, die er vollbracht hatte an der plastischen, nicht elastischen Bildsäule, die einen weiblichen Charakter hatte, wieder ausgeglichen waren. Er wurde erst wiederum hineingeführt, wenn die Bildsäule intakt war. Und durch alle diese Vorbereitungen - ich kann die Sache nur skizzenhaft schildern -, die der Schüler durchgemach hatte, bekam er bei der Bildsäule, die einen weiblichen Charakter hatte, in seinem ganzen Menschenwesen nach Geist, Seele und Leib ein inneres Erlebnis. Dieses innere Erlebnis war ja auch schon früher bei ihm vorbereitet, aber es stellte sich in vollstem Maße ein durch die suggestive Wirkung der Bildsäule selber. Er bekam in sich ein Gefühl einer inneren Erstarrung, einer inneren frostigen Erstartung. Und diese frostige Erstarrung wirkte so in ihm, daß er seine Seele mit Imaginationen aufgefüllt sah, und diese Imaginationen waren Bilder des Erdenwinters, Bilder, die darstellten den Erdenwinter. Also der Schüler wurde dazu geführt, von innen heraus das Winterliche zu schauen im Geiste.

Bei der anderen Bildsäule, der männlichen, war es so, daß der Schüler etwas empfand, wie wenn all sein Leben, das er sonst in seinem ganzen Leibe hatte, in sein Blut ginge, wie wenn das Blut durchdrungen würde von Kräften und an die Haut drückte. Während er also vor der einen Bildsäule glauben mußte, zum frostigen Skelett zu werden, mußte er vor der anderen Bildsäule glauben, daß sein ganzes inneres Leben in Hitze zugrunde gehe und er lebe in seiner ausgespannten Haut. Und dieses Erleben des ganzen Menschen, an dessen Oberfläche gedrückt, das führte den Schüler dazu, die Einsicht zu bekommen, sich zu sagen: Du verspürst dich, du empfindest dich, du erlebst dich so, wie du wärest, wenn von allem im Kosmos allein die Sonne auf dich wirkte. - Und der Schüler lernte auf diese Weise die kosmische Sonnenwirkung in ihrer Verteilung erkennen. Er lernte erkennen die Beziehung des Menschen zur Sonne. Und er lernte erkennen, daß der Mensch nur deshalb in Wirklichkeit nicht so ist, wie er sich jetzt unter der suggestiven Wirkung der Sonnenstatue vorkam, weil andere Kräfte von anderen Weltenecken aus diese Wirkung modifizieren. In solcher Art lernte sich der Schüler einleben in den Kosmos. Und wenn der Schüler die suggestive Wirkung der Mondenstatue empfand, wenn er also innerlich das Frostige hatte der Erstarrung, die winterliche Landschaft erlebte - bei der Sonnenstatue erlebte er sommerliche Landschaft im Geiste, wie aus sich selbst erzeugt -, dann fühlte der Mensch, wie er wäre, wenn nur die Mondenwitrkungen da wären.

Sehen Sie, in der Gegenwart, was weiß man denn eigentlich da von der Welt? Man weiß von der Welt, daß die Zichorie blau ist, daß die Rose rot ist, der Himmel blau ist und so weiter. Aber das sind ja keine erschütternden Eindrücke. Die berichten nur von dem Allernächsten, das in der menschlichen Umgebung ist. Der Mensch muß in einem intensiveren Maße mit seiner ganzen Wesenheit zum Sinnesorgan werden, wenn er die Geheimnisse des Weltenalls kennenlernen will. Und es wurde eben durch die suggestive Wirkung der Sonnenstatue sein Wesen in seinem ganzen Blutumlauf konzentriert. Der Mensch lernte sich als Sonnenwesen kennen, indem er diese suggestive Wirkung in sich erlebte. Und der Mensch lernte sich als Mondenwesen kennen, indem er die suggestive Wirkung der weiblichen Statue erlebte. Und dann konnte er aus diesen seinen inneren Erlebnissen heraus sagen, wie Sonne und Mond auf den Menschen wirken, so wie heute der Mensch nach dem Erlebnis seines Auges sagen kann, wie die Rose wirkt, nach dem Erlebnis seines Ohres, wie der Ton cis wirkt und so weiter. Und so erlebten die Schüler dieser Mysterien noch in den nachatlantischen Zeiten das Eingegliedertsein des Menschen in den Kosmos. Das wurde für sie eine unmittelbare Erfahrung.

Nun, dasjenige, was ich Ihnen erzählt habe, ist eine kurze Skizze dessen, was in ganz grandioser Weise bis in die ersten Jahrhunderte der christlichen Entwickelung herein an den Mysterien in Hybernia von den Schülern erlebt worden ist als kosmisches Erlebnis, indem man an das Sonnen- und an das Mondenerlebnis herangeführt wurde.

In ganz anderer Weise waren die Erlebnisse, welche die Schüler durchzumachen hatten in den ephesischen, den kleinasiatischen ephesischen Mysterien. In diesen ephesischen Mysterien erlebte man in ganz besonders intensiver Weise mit seinem ganzen Menschen dasjenige, was dann später einen paradigmatischen Ausdruck gefunden hat in den Anfangsworten des Johannes-Evangeliums: «Im Urbeginne war das Wort. Und das Wort war bei Gott. Und ein Gott war das Wort.»

In Ephesus wurde der Schüler nicht vor zwei Statuen geführt, sondern vor eine, vor die eine Statue, die ja bekannt ist als die Artemis von Ephesus. Und indem der Schüler sich identifizierte mit dieser Statue, die voller Leben war, die überall von Leben strotzte, lebte sich der Schüler in den Weltenäther ein. Er hob sich hinaus mit seinem ganzen inneren Erleben und Empfinden vom bloßen Erdenleben, er hob sich in das Erleben des Weltenäthers hinein. Und ihm wurde das Folgende klar. Ihm wurde zunächst vermittelt, was eigentlich die menschliche Sprache ist. Und an der menschlichen Sprache, also dem menschlichen Abbild, dem menschlichen abbildlichen Logos gegenüber dem Welten-, dem kosmischen Logos, an dem wurde ihm klargemacht, wie das Weltenwort schöpferisch durch den Kosmos webt und wallt.

Ich kann wiederum die Sache nur skizzieren. Sie ging so vor sich. Der Schüler wurde besonders aufmerksam darauf gemacht, wirklich zu erleben, was da geschieht, wenn der Mensch spricht, wenn er dem Atmungsaushauch das Wort einprägt. Der Schüler wurde zum Erleben dessen geführt, wie dasjenige, was er da dutch seine eigene innere Tat in Leben überführt, in dem luftigen Elemente geschieht, daß aber mit dem, was im luftigen Elemente geschieht, zwei andere Vorgänge verbunden sind.

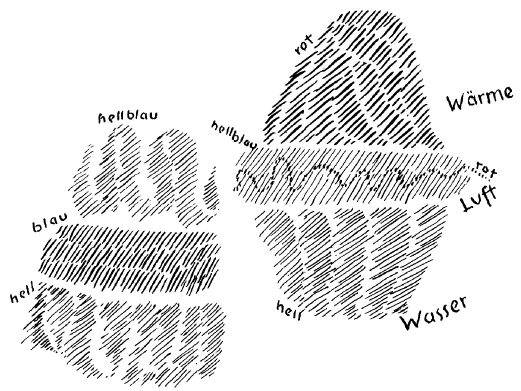

Stellen wir uns vor, dies sei der Aushauch (siehe Zeichnung, rechter Teil, hellblau mit roter Linie), dem eingeprägt würden gewisse Wortgebilde, die der Mensch spricht. Während dieser Aushauch, zu Worten geformt, aus unserer Brust nach außen strömt, geht nach unten die rhythmische Schwingung über in das ganze wäßtrige, in das flüssige Element, das den menschlichen Organismus durchzieht (hell; Wasser). So daß der Mensch beim Sprechen in der Höhe seines Kehlkopfes, seiner Sprachorgane, die Luftrhythmen hat; parallel aber geht mit diesem Sprechen ein Durchwellen und Durchwogen des Flüssigkeitsleibes in ihm. Die Flüssigkeit, die unterhalb der Sprachregion ist, kommt in Schwingungen, schwingt mit im Menschen. Und das ist es ja im wesentlichen, daß wir das, was wir sprechen, begleiten vom Fühlen. Und würde nicht mitschwingen das wäßrige Element im Menschen, die Sprache ginge neutral nach außen, gleichgültig nach außen; der Mensch würde nicht mitfühlen mit dem Gesprochenen. Nach oben aber, nach dem Kopf, geht das Wärmeelement (rot), und es begleiten die Worte, die wir dem Aushauche einprägen, die nach oben strömenden Wärmewellen, die unser Haupt durchdringen und die da bewirken, daß wir die Worte mit Gedanken begleiten. So daß, wenn wit sprechen, wir es zu tun haben mit dreierlei: mit Luft, Wärme, Wasser oder Flüssigkeit.

Dieser Vorgang, der erst ein Gesamtbild dessen gibt, was im menschlichen Sprechen webt und lebt, dieser Vorgang wurde zum Ausgangspunkt genommen bei dem Schüler von Ephesus. Und dann wurde ihm klargemacht, wie dieses, was da im Menschen sich abspielt, ein vermenschlichter Weltenvorgang ist, daß in einer gewissen älteren Zeit die Erde selber so gewirkt hat, daß in ihr nun nicht das luftförmige, aber das wäßrige, das flüssige Element (linker Teil der Zeichnung, blau), jenes flüssige Element, von dem ich gestern gesprochen habe als flüchtig-flüssiges Eiweiß, in einer solchen Wellenbewegung war. So wie dann im Menschen im Kleinen die Luft beim Aushauche ist, wenn er spricht, so war dereinst das die Erde als Atmosphäre umgebende flüchtig-flüssige Eiweiß. Und das ging dann über, so wie hier das Luftförmige in das Wärmeelement, in eine Art Luftelement (links, hellblau), und unten in eine Art erdigen Elementes (hell). So daß, wie bei uns in unserem Körper durch das flüssige Element die Gefühle entstehen, so entstanden in der Erde die Erdenbildungen, die Erdenkräfte, alles dasjenige, was in der Erde wirkt und wellt an Kräften. Und es entstand darüber im luftigen Element dasjenige, was webende kosmische Gedanken sind, die da schaffend wirken im Irdischen.

Das war ein majestätischer, gewaltiger Eindruck, den der Mensch in Ephesus bekam, wenn er aufmerksam darauf gemacht wurde, daß in seiner Sprache der mikrokosmische Nachklang dessen lebt, was einmal makrokosmisch war. Und der Schüler von Ephesus fühlte, indem er sprach, in dem Erlebnis des Sprechens eine Einsicht in das Wirken des Weltenwortes, wie es einstmals sinnvoll das flüssigflüchtige Element bewegte, wie es oben grenzte an die schaffenden Weltengedanken, unten an die entstehenden Erdenkräfte.

So lebte sich der Schüler ein in das Kosmische, indem er in richtiger Weise sein eigenes Sprechen verstehen lernte: In dir ist der menschliche Logos. Der menschliche Logos wirkt aus dir während deiner Erdenzeit, und du bist als Mensch der menschliche Logos. Denn in der Tat, durch dasjenige, was nach unten strömt im flüssigen Elemente, werden wir als Mensch geformt aus der Sprache heraus; durch dasjenige, was nach oben strömt, haben wir unsere menschlichen Gedanken während unserer Erdenzeit. - Aber ebenso, wie in dir das Menschlichste der mikrokosmische Logos ist, so war einstmals der Logos im Urbeginn und war bei Gott und war selber ein Gott.

Das wurde in Ephesus gründlich, weil durch den Menschen und am Menschen selber, verstanden.

Sehen Sie, wenn Sie sich nun solch eine Persönlichkeit anschauen wie diejenige, die sich hinter dem Namen Gilgamesch verbirgt, dann müssen Sie das Gefühl bekommen, daß diese ja lebte in dem ganzen Milieu, in der ganzen Umgebung, die ausstrahlte von den Mysterien. Denn alle Kultur, alle Zivilisation war in früheren Zeiten Ausstrahlung der Mysterien. Und wenn ich Ihnen Gilgamesch nenne, so war er, als er noch in seiner Heimat Erek war, zwar nicht in die Mysterien von Erek selber eingeweiht, wohl aber in einer Zivilisation drinnen, die substantiell durchsetzt war von dem, was man empfinden konnte durch diese Beziehung zum Kosmos. Und dann wurde von ihm etwas erlebt bei dem Zug nach dem Westen, was ihn direkt bekannt machte allerdings nicht mit den hybernischen Mystetien, soweit kam er nicht, aber gewissermaßen mit dem, was gepflegt wurde in einer Kolonie der hybernischen Mysterien, ich sagte Ihnen, im heutigen Burgenlande war diese Kolonie. Das lebte in der Seele dieses Gilgamesch. Das bildete sich weiter aus in dem Leben zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt, das nun folgte und für das dann beim nächsten Erdenleben in Ephesus selber die Vertiefung der Seele stattfand.

Nun, für beide Persönlichkeiten, von denen ich gesprochen habe, fand eine solche Vertiefung der Seele statt. Da brandete gewissermaßen aus der allgemeinen Zivilisation an die Menschenseelen dieser Persönlichkeiten etwas in Realität heran, in starker, intensiver Realität noch, was seit der homerischen Zeit in Griechenland im wesentlichen schon nur noch schöner Schein war.

Gerade in Ephesus drüben, an jener Stätte, an der ja auch Heraklit lebte und an der noch so viel von alter Realität empfunden wurde bis in die spätere griechische Zeit herein, bis ins 6., 5. Jahrhundert der vorchristlichen Zeit, gerade in Ephesus konnte man noch nachempfinden die ganze Realität, in der einstmals die Menschheit gelebt hat, als sie noch in unmittelbarer Beziehung zu dem Göttlich-Geistigen stand, als noch Asia nur der unterste der Himmel war, in dem man noch in Verbindung stand mit den oberen Himmeln, die daran grenzten, weil in Asia die Naturgeister erlebt wurden, darüber die Angeloi, Archangeloi und so weiter, darüber die Exusiai und so weiter. Und so kann man sagen: Während schon in Griechenland selbst die Nachklänge nur sich herausbildeten an dasjenige, was einstmals Realität war, während dasjenige, was Wirklichkeit war, sich umwandelte in die Bilder der Heroensagen, an denen noch deutlich zu merken ist, daß sie hinweisen auf ursprüngliche Realitäten, während in Griechenland das dramatische Element ursprünglicher Realitäten in Äschylos Leben gewann, war es eigentlich in Ephesus noch immer so, daß man, in das tiefe Dunkel der Mysterien getaucht, Nachklänge jener alten Realitäten empfand, in denen der Mensch in unmittelbarem Zusammenhange mit der göttlich-geistigen Welt lebte. Und das ist ja das Wesentliche des Griechentums, daß der Grieche in die dem Menschen näherliegenden Mythen und in die dem Menschen näherliegende Schönheit und Kunst getaucht hat, also ins Abbild getaucht hat dasjenige, was einstmals im Zusammenhange mit dem Kosmos eben vom Menschen erlebt werden konnte.

Und nun müssen wir uns vorstellen, wie, als nun schon auf der einen Seite diese griechische Zivilisation auf ihrem Höhepunkte angelangt war, als sie stolz zurückgewiesen hatte sogar dasjenige, was, wie in den Perserkriegen, noch nachstofen wollte von alter asiatischer Realität, als sie auf der einen Seite auf ihrem Höhepunkte angelangt war, aber auf der anderen Seite schon im Sturze war, wie das Persönlichkeiten erlebten, die in ihren Seelen deutlich die Nachklänge desjenigen trugen, was einstmals göttlich-geistige irdische Realität in Geist, Seele und Leib des Menschen war.

Und so müssen wir uns vorstellen, daß eigentlich Alexander der Große und Aristoteles in einer Welt lebten, die ihnen doch nicht ganz konform war, die eigentlich tragisch für sie war. Das Eigentümliche ist, daß in Alexander und in Aristoteles Menschen lebten, die eine andere Beziehung zum Geistigen hatten als ihre Umgebung, die, trotzdem sie sich nicht viel kümmerten um die samothrakischen Mysterien, dennoch in ihrer Seele eine große Verwandtschaft hatten mit dem, was in den samothrakischen Mysterien mit den Kabiren vorging. Das hat man lange Zeit gefühlt, im Mittelalter noch nachgefühlt. Und man muß schon sagen — darüber machen sich die Menschen heute ganz falsche Vorstellungen -, wie noch im Mittelalter, bis herein ins 13., 14. Jahrhundert, bei einzelnen Menschen aller Stände ein deutliches geistiges Anschauen wenigstens auf dem Gebiete war, das man einstmals im alten ÖOriente drüben Asia genannt hat. Und das im Mittelalter von einem Priester gedichtete «Alexanderlied» ist immerhin ein schr bedeutsames Dokument des späteren Mittelalters. Gegenüber dem, was heute in der Geschichte entstellt lebt von demjenigen, was sich abgespielt hat durch Alexander und Aristoteles, erscheint das, was der Priester Lamprecht als Alexanderlied etwa im 12. Jahrhundert gedichtet hat, noch als eine großartige, mit der alten verwandte Auffassung dessen, was durch Alexander den Großen geschehen ist.

Sie brauchen nur das Folgende sich vor die Seele zu stellen. Wir haben im Alexanderlied des Pfaffen Lamprecht ja eine wunderbare Schilderung, eine wunderbare Schilderung etwa der folgenden Art: Jedes Jahr, wenn der Frühling kommt und man geht nach einem Wald hinaus und kommt an den Waldestand, da wo an diesem Waldesrand Blumen wachsen und wo zu gleicher Zeit die Sonne so steht, daß von den Waldesbäumen der Schatten fällt auf die am Waldesrande wachsenden Blumen, da sieht man, wie im Schatten der Waldesbäume im Frühling aus den Blumenkelchen hervorkommen die geistigen Blumenkinder, die an den Waldesrändern Tänze und Reigen vollführen. - Und man erkennt ganz deutlich, daß in dieser Schilderung des Pfaffen Lamprecht durchschimmert etwas von einer wirklichen Erfahrung, von einer Erfahrung, die Menschen der damaligen Zeit noch machen konnten; daß sie nicht in die Wälder hinausgingen, um in prosaischer Weise zu sagen: Da ist Gras, da sind Blumen, da fangen die Bäume an -, sondern wenn sie sch dem Walde näherten, dann trat ihnen, wenn die Sonne hinter dem Walde stand und der Schatten über die Blumen her fiel, im Schatten der Waldesbäume von den Blumen aus entgegen die ganze Welt von Blumengeschöpfen, die da waren für sie, bevor sie den Wald betraten, wo sie ja dann im Walde die anderen Elementargeister wahrnahmen. Aber dieser Blumenreigen, der erschien dem Pfaffen Lamprecht als das, was er besonders gern schildern wollte. Und es ist immerhin bedeutsam, daß, als der Pfaffe Lamptecht die Alexanderzüge schildern wollte, er diese Schilderung durchsetzte und durchströmte — noch im 12. Jahrhundert, Anfang des 12. Jahrhunderts -, dutchsetzte und durchströmte mit Schilderungen der Natur, die überall das Sich-Offenbaren der Elementarreiche in sich schließen. Das Ganze ist getragen von dem Bewußtsein: Wenn man schildern will, was da vorging einstmals in Makedonien, als die Alexanderzüge nach Asien begannen und als Alexander von Aristoteles unterrichtet wurde, wenn man das schildern will, so kann man es nicht schildern, indem man die prosaische Erde ringsherum beschreibt, sondern man kann es allein schildern, wenn man hinzunimmt zu der prosaischen Erde die Reiche der elementarischen Wesenheiten.

Aber sehen Sie, wenn Sie heute ein Geschichtswerk lesen - es ist ja ganz berechtigt für die gegenwärtige Zeit -, nun ja, dann lesen Sie eben: Alexander hat gegen den Rat seines Lehrers Aristoteles, dem er ungehorsam war, die Mission sich eingebildet, er müsse die Barbaren mit den zivilisierten Menschen versöhnen und müsse eine Durchschnittskultur etwa hervorrufen, die bestehen sollte aus den zivilisierten Griechen, aus den Hellenen, aus den Makedoniern und den Barbaren. Das ist zwar für die heutige Zeit richtig, aber dennoch, gegenüber der Wahrheit, der wirklichen Wahrheit ist es eben läppisch. Und man empfängt den Eindruck des Großartigen, wenn man sieht, wie der Pfaffe Lamprecht, indem er die Alexanderzüge schildert, diesen Alexanderzügen ein ganz anderes Ziel setzt. Und es kommt einem vor, als ob dasjenige, was ich eben geschildert habe als das Hereinragen der Natur-Elementarreiche, des Geistigen der Natur in das Physische der Natur, als ob dies eben bloß die Introduktion sein sollte. Denn was ist das Ziel der Alexanderzüge im Alexanderlied des Pfaffen Lamprecht?

Alexander kommt bis an die Pforte des Paradieses! Das ist zwar ins Christliche der damaligen Zeit umgesetzt, aber es entspricht eigentlich in einem hohen Maße, wie ich weiter ausführen werde, der Wahrheit. Denn die Alexanderzüge waren nicht bloß gemacht, um Eroberungen zu vollziehen oder, gar gegen den Rat des Aristoteles, um die Barbaren mit den Hellenen zu versöhnen, sondern die Alexanderzüge waren durchsetzt von einem wirklichen hohen geistigen Ziel, und sie waren impulsiert aus dem Geiste heraus. Und wit lesen dann beim Pfaffen Lamprecht, der also, man kann sagen, fünfzehn Jahrhunderte, nachdem Alexander gelebt hat, in seiner Art mit großer Hingebung diese Alexanderzüge schildert, wir lesen, daß Alexander bis an die Pforte des Paradieses kommt, aber in das Paradies selber nicht hineinkommt, weil, wie der Pfaffe Lamprecht meint, nur derjenige in das Paradies hineinkommt, der die rechte Demut hat. Aber Alexander konnte in der vorchristlichen Zeit noch nicht die rechte Demut haben, denn die rechte Demut konnte erst das Christentum in die Menschheit hineinbringen. Immerhin, wenn man nicht in engherzigem, sondern in weitherzigem Sinn so etwas auffaßt, so sehen wir, wie der christliche Pfaffe Lamprecht etwas von dem Tragischen der Alexanderzüge empfindet.

Nun, ich wollte Sie mit dieser Schilderung des Alexanderliedes nur aufmerksam darauf machen, daß es nicht überraschend zu sein braucht, wenn man gerade an diesem Beispiel der Alexanderzüge einsetzt, um das Vorhergehende und Nachherige der Menschheitsgeschichte des Abendlandes in seiner Angliederung an das Morgenland zu schildern. Denn dasjenige, was dabei als Empfindung zugrunde liegt, war noch, wie Sie sehen, bis zu einer verhältnismäßig späten Zeit des Mittelalters nicht nur als eine allgemeine Empfindung vorhanden, sondern in so konkreter Weise vorhanden, daß dieses Alexanderlied entstehen konnte, das nun eigentlich wirklich in einer großartig dramatischen Weise schildert, was nun durch die beiden Seelen, die ich Ihnen charakterisiert habe, sich abgespielt hat. Durchaus weist dieser Punkt der makedonischen Geschichte auf der einen Seite weit in die Vergangenheit zurück, auf der anderen Seite weit in die Zukunft hinein. Und man muß vor allen Dingen dabei berücksichtigen, daß über all dem, was bei Aristoteles und Alexander vorhanden ist, weltgeschichtliche Tragik schwebt. Schon äußerlich verrät sich diese weltgeschichtliche Tragik. Sie verrät sich dadurch, daß ja durch die besonderen Verhältnisse, durch die besonderen weltgeschichtlichen Schicksalsverhältnisse von Aristoteles nur der kleinste Teil der Schriften in das europäische Abendland gekommen sind und dann von der Kirche weiter gepflegt worden sind. Es sind eigentlich im wesentlichen nur die logischen und die ins Logische gekleideten Schriften. Wer aber heute noch sich vertieft in das Wenige, was von den naturwissenschaftlichen Schriften des Aristoteles erhalten ist, der wird bei Aristoteles sehen, wie gewaltig seine Einsicht noch war in den Zusammenhang des Kosmos mit dem Menschen. Ich möchte Sie da nur auf eines aufmerksam machen.

Wir sprechen heute ja auch vom irdischen Elemente, vom wäßsrigen Elemente, vom luftigen Elemente, vom feurigen oder Wärmeelemente und dann von dem anderen, dem Äther. Wie stellt Aristoteles die Sache dar? Er stellt die Erde dar, die feste Erde (siehe Zeichnung, heller Kern), die flüssige Erde, Wasser (hellrot), die Luft (blau), das Ganze mit dem Feuer durchdrungen und vom Feuer umgeben (tiefrot). Aber so reicht für Aristoteles die Erde bis zum Monde hinauf. Und vom Kosmos herein, von den Sternen herein bis zum Monde - also nicht mehr in den irdischen Bereich, aber bis zum Monde, bis hierher -, vom Tierkreis, von den Sternen herein reicht räumlich-kosmisch der übrige Äther (hell außen). Der Äther reicht bis zum Monde herunter.

Das lesen ja auch heute noch die Gelehrten in den Büchern, die über Aristoteles geschrieben werden. Aristoteles selber aber sagte seinem Schüler Alexander immer wieder und wiederum: Jener Äther, der da außerhalb des Irdisch-Wärmehaften ist, also der Lichtäther, chemische Äther, Lebensäther, war auch einstmals mit der Erde verbunden. Das alles ging bis zur Erde herein. Als aber der Mond sich zurückzog in der alten Entwickelung, da zog sich der Äther von der Erde zurück. Und - so meinte Aristoteles zu seinem Schüler Alexander - so ist dasjenige, was äußerlich räumlich tote Welt ist, auf der Erde zunächst nicht vom Äther durchzogen. Aber wenn zum Beispiel der Frühling naht, dann bringen die Elementargeister von dem Monde für diejenigen Wesen, die entstehen — die Pflanzen, die Tiere, die Menschen -, den Äther aus dem Mondenbereiche gerade wiederum in diese Wesen hinein, so daß der Mond das Gestaltende ist.

Stand man vor der einen, der weiblichen Gestalt in Hybernia, so empfand man das ganz lebhaft, wie der Äther eigentlich nicht der Erde angehört, sondern von den Elementargeistern alljährlich, soweit er notwendig ist zur Entstehung der Wesen, auf die Erde heruntergebracht wird.

Es gab auch für Aristoteles tiefe Einsichten in den Zusammenhang des Menschen mit dem Kosmos. Die Schriften, die davon handelten, hat der Schüler Theophrast nicht nach dem Westen kommen lassen. Nach dem Orient ging einiges von diesen Schriften zurück, wo noch Verständnis für solche Dinge war. Und da kam es dann durch Nordafrika und Spanien, durch Juden und Araber kam es nach dem Westen von Europa und stieß in der Weise, wie ich das noch schildern will, mit den Ausstrahlungen, mit den Zivilisationsausstrahlungen der Mysterien von Hybernia zusammen.

Aber das, was ich Ihnen bis jetzt charakterisiert habe, war ja nur der Ausgangspunkt für die Lehren, die Aristoteles dem Alexander gab. Die bezogen sich durchaus auf inneres Erleben. Und wenn ich, ich möchte sagen, in etwas kohlezeichnender Darstellung die Sache gebe, so muß ich folgendes sagen: Alexander lernte durch Aristoteles gut kennen, daß dasjenige, was draußen in der Welt lebt als das irdische, das wäßtige, das luftige, das feurige Element, auch im Menschen drinnen lebt, daß der Mensch in dieser Beziehung ein wirklicher Mikrokosmos ist, daß in ihm, in seinen Knochen, das irdische Element lebt, daß in seiner Blutzirkulation und in alle dem, was Säfte in ihm sind, Lebenssäfte sind, das wäßrige Element lebt; daß in ihm das luftige Element in der Atmung und Atmungserregung wirkt, in der Sprache wirkt, daß das feurige Element in den Gedanken lebt. Alexander wußte sich noch in den Elementen der Welt lebend. Aber indem man sich in den Elementen der Welt lebend fühlte, fühlte man auch noch seine innige Verwandtschaft mit der Erde. Heute reist der Mensch nach Ost, nach West, nach Nord, nach Süd: er empfindet nicht, was da eigentlich alles auf ihn einstürmt, denn er sieht ja nur dasjenige, was seine äußeren Sinne wahrnehmen, und er sieht ja nur, was die irdischen Substanzen in ihm wahrnehmen, nicht was die Elemente in ihm wahrnehmen. Aber Aristoteles konnte den Alexander lehren: Wenn du auf der Erde nach dem Östen ziehst, ziehst du immer mehr und mehr hinein in ein dich austrocknendes Element. Du ziehst in das Trockene hinein (siehe Zeichnung).

Sie müssen sich das nicht so vorstellen, daß, wenn man nach Aisen hinüberzieht, man ganz austrocknet. Es ist natürlich das so, daß es feine Wirkungen sind, aber Wirkungen, die durchaus nach den Anleitungen des Aristoteles Alexander in sich empfand. Et konnte sich in Makedonien sagen: Ich habe einen gewissen Grad von Feuchtigkeit in mir; der vermindert seine Feuchtigkeit, indem ich nach Osten hinüberziehe. — So fühlte er mit der Wanderung auf der Erde die Konfiguration der Erde, wie man fühlt, sagen wir, wenn man einen Menschen berührt, über irgendeinen Teil seines Körpers streichelnd fährt, wie der Unterschied ist zwischen Nase und Augen und Mund. So nahm eine solche Persönlichkeit, wie die geschilderte, noch wahr, wie der Unterschied ist, wenn man sich erlebt, indem man immer mehr und mehr in das Trockene hineinkommt, und wie man sich erlebt, wenn man nach der anderen Seite, nach dem Westen, in das Feuchte hineinkommt.

Die anderen Differenzierungen, die erleben die Menschen, wenn auch grob, noch heute. Gegen Norden erleben sie ja das Kalte, gegen Süden das Warme, das Feurige. Aber jenes Zusammenspiel von feucht-kalt, wenn man nach dem Nordwesten hinüberkam, das fühlen die Menschen nicht mehr. Aristoteles machte rege in Alexander, was Gilgamesch erlebt hat, als er den Zug nach dem Westen hinüber unternommen hatte. Und die Folge davon war, daß im unmittelbaren inneren Erleben der Schüler das wahrnehmen konnte, was nun eben erlebt wird in der Zwischenzone zwischen feucht und kalt nach Nordwesten hin: Wasser. Und es war durchaus nicht nur eine mögliche, sondern eine sehr wirkliche Redensart für einen solchen Menschen wie Alexander, daß er nicht sagte: Dahin geht der Zug, nach Nordwesten -, sondern: Dahin geht der Zug, wo das Element des Wassers die Oberhertschaft führt. - In der Zwischenzone zwischen feucht und warm liegt das Element, wo die Luft die Oberhertschaft führt. So war es in den alten griechisch-chthonischen Mysterien gelehrt, so war es in den alten samothrakischen Mysterien gelehrt, so war es von Aristoteles seinem unmittelbaren Schüler gelehrt. Und in der Zwischenzone zwischen kalt und trocken, also gegen Sibirien zu von Makedonien aus, wurde die Region der Erde erlebt, wo die Erde selbst, das Irdische die Oberherrschaft führte, das Element Erde, das Feste. In der Zwischenzone zwischen warm und trocken, also gegen Indien hin, wurde jene Region der Erde erlebt, wo vorherrschte das Feuerelement. Und so war es, daß der Schüler des Aristoteles nach Nordwesten zeigte und sagte: Da empfinde ich herwirkend auf der Erde die Wassergeister. — Daß er nach Südwesten zeigte und sagte: Da her empfinde ich die Luftgeister. Daß er nach Nordosten zeigte, und da die Geister der Erde vorzugsweise heranschweben sah. Daß er nach Südosten zeigte, gegen Indien zu, und die Geister des Feuers heranschweben oder in ihrem Elemente sah.

Und Sie empfinden jene tiefe Verwandtschaft gegenüber dem Natürlichen und gegenüber dem Moralischen, wenn ich jetzt am Schlusse sage, es entstand in Alexander die Redensart: Ich muß aus dem kaltfeuchten Elemente heraus mich ins Feuer stürzen, den Zug nach Indien unternehmen! - Das war eine Redensart, die ebenso an Natürliches anknüpfte, wie sie anknüpfte an Moralisches, wovon wir dann morgen sprechen wollen. Aber ich wollte Sie hineinführen anschaulich in dasjenige, was da lebte. Denn in dem, was da verhandelt wurde zwischen Alexander und Aristoteles, sehen Sie zu gleicher Zeit sich spiegeln den ganzen Umschwung in der weltgeschichtlichen Entwickelung. Man konnte noch im intimen Unterricht in der damaligen Zeit sprechen von den großen Mysterien der vergangenen Zeit. Dann nahm die Menschheit nur mehr das Logische, das Abstrakte, die Kategorien auf, während sie das andere zutückstieß. Daher deuten wir damit zugleich auf einen ungeheuren Umschwung in der weltgeschichtlichen Entwickelung der Menschheit, auf einen allerwichtigsten Punkt in dem ganzen Hergang der europäischen Zivilisation in ihrem Zusammenhange mit dem Orient. Davon dann morgen weiter.

Fourth Lecture

Yesterday it was my task to show how world-historical development takes place in individual personalities. If one wants to advance in the direction of spiritual science, one cannot present it in any other way than by showing the sequence of events as they are mirrored in the human being. For consider that only our age, for reasons that we shall discuss in the course of these lectures, is such that man, cut off from the rest of the world, feels himself to be a single being. All preceding ages and also all following ages, this must be expressly emphasized, are such that men felt and will feel themselves to be a member of the whole world, belonging to the whole world. As I have often said: Just as a finger cannot be a being existing for itself on a human being, but only on the human being, while if it is separated from the human being it is no longer a finger, but perishes, is subject to completely different laws than on the organism, just as the finger is only a finger in connection with the organism, so man is only a being in some form, be it in the form of life on earth, or in the form of the life between death and a new birth, in connection with the whole world. But the awareness of this was present in earlier times, and will be present again later, it is only clouded, darkened today because, as we will hear, man needed this clouding, darkening, in order to be able to fully develop the experience of freedom within himself. And the further back in time we go, the more we find that people were aware of their connection to the cosmos.

Now I have presented to you two personalities, one called Gilgamesh in the well-known epic, the other Eabani in the same epic, and I have shown you how these personalities live in the ancient Chaldean-Egyptian period in the way one could live at that time, and how they then undergo a deepening through the Ephesian mysteries. And yesterday I already pointed out how these same human beings are then placed in the world-historical development in Aristotle and Alexander. But in order to understand fully how the course of earthly evolution was in those times in which the events I have described took place for these personalities, we must look even more closely at what such souls were able to absorb in themselves at these three successive points in time.

I have already drawn your attention to the fact that the personality hidden behind the name Gilgamesh undertakes a journey to the West and undergoes a kind of Western post-Atlantic initiation. Now, in order to understand what happened later, let us form an idea of what such a late initiation was like. We must seek out this initiation at the place where echoes of the old Atlantean initiation persisted for a long time. And that was the case with the mysteries of Hybernia, which I have already spoken about recently to the friends here in Dornach. However, I have to catch up on some of what was discussed so that we can fully understand what is at issue here.