World History in the Light of Anthroposophy

and as a Foundation for Knowledge of the Human Spirit

GA 233

29 December 1923, Dornach

Lecture VI

Of peculiar importance for the understanding of the history of the West in its relation to the East is the period that lies between three or four hundred years before, and three or four hundred years after, the Mystery of Golgotha. The real significance of the events we have been considering, events that culminated in the rise of Aristotelianism and in the expeditions of Alexander to Asia, is contained in the fact that they form, as it were, the last Act in that civilisation of the East which was still immersed in the impulses derived from the Mysteries.

A final end was put to the genuine and pure Mystery impulse of the East by the criminal burning of Ephesus. After that we find only traditions of the Mysteries, traditions and shadow-pictures,—the remains, so to speak, that were left over for Europe and especially for Greece, of the old divinely-inspired civilisation. And four hundred years after the Mystery of Golgotha another great event took place, which serves to show what was still left of the ruins—for so we might call them—of the Mysteries.

Let us look at the figure of Julian the Apostate.1Flavius Claudius Julianus, called the Apostate by the Christians, was Roman Emperor from 361–363. Julian the Apostate, Emperor of Rome, was initiated, in the 4th century, as far as initiation was then possible, by one of the last of the hierophants of the Eleusinian Mysteries. This means that he entered into an experience of the old Divine secrets of the East, in so far as such an experience could still be gained in the Eleusinian Mysteries.

At the beginning of the period we are considering, stands the burning of Ephesus; and the day of the burning of Ephesus is also the day on which Alexander the Great was born. At the end of the period, in 363, we have the day of the death—the terrible and significant death—of Julian the Apostate far away in Asia. Midway between these two days stands the Mystery of Golgotha.

And now let us examine a little this period of time as it appears in the setting of the whole history of human evolution. If we want to look back beyond this period into the earlier evolution of mankind, we have first to bring about a change in our power of vision and perception, a change that is very similar to one of which we hear in another connection. Only we do not often bring the things together in thought.

You will remember how in my book Theosophy I had to describe the different worlds that come under consideration for man. I described them as the physical world; a transition world bordering on it, namely, the Soul-world; and then the world into which only the highest part of our nature can find entrance, the Spirit-land. Leaving out of account the special qualities of this Spirit-land, through which present-day man passes between death and a new birth, and looking only at its more general qualities and characteristics, we find that we have to give a new orientation to our whole thought and feeling, before we can comprehend the Land of the Spirits. And the remarkable thing is that we have to change and re-orientate our inner life of thought and feeling in just the same way when we want to comprehend what lies beyond the period I have defined. We shall do wrong to imagine that we can understand what came before the burning of Ephesus with the conceptions and ideas that suffice for the world of to-day. We need to form other concepts and other ideas to enable us to look across the years to human beings who still knew that as surely as man is united through breathing with the air outside him, so surely is he in constant union through his soul with the Gods.

Starting then from this world, the world that is a kind of earthly Devachan, earthly Spirit-land,—for the physical world fails us when we want to picture it,—we came into the interim period, lasting from about 356 B.C. to 363 A.D. And now what follows? Over in Europe we find the world from out of which present-day humanity is on the point of emerging into something new, even as the humanity of olden times came forth from the Oriental world, passed through the Greek world, and then into the realm of Rome.

Setting aside for the moment what went on in the inner places of the Mysteries, we have to see in the civilisation that has grown up through the centuries of the Middle Ages and developed on into our own time, a civilisation that has been formed on the basis of what the human being himself can produce with the help of his own conceptions and ideas. We may see a beginning in this direction in Greece, from the time of Herodotus onward. Herodotus describes the facts of history in an external way, he makes no allusion, or at most very slight allusion, to the spiritual. And others after him go further in the same direction. Nevertheless in Greece we always feel a last breath, as it were, from those shadow-pictures that were there to remind man of the spiritual life. With Rome on the other hand begins the period to which man to-day may still feel himself related, the period that has an altogether new way of thought and feeling, different even from what we have observed in Greece. Only here and there in the Roman world do we find a personality such as Julian the Apostate who feels something like an irresistible longing after the old world, and evinces a certain honesty in getting himself initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries.

What Julian, however, is able to receive in these Mysteries has no longer the force of knowledge. And what is more, he belongs to a world where men are no longer able to grasp in their soul the traditions from the Mysteries of the East.

Present-day mankind would never have come into being if Asia had not been followed first by Greece and then by Rome. Present-day mankind is built up upon personality, upon the personality of the individual. Eastern mankind was not so built up. The individual of the East felt himself part of a continuous divine process. The Gods had their purposes in Earth evolution. The Gods willed this or that, and this or that came to pass on the Earth below. The Gods worked on the will of men, inspiring them. Those powerful and great personalities in the East of whom I spoke to you—all that they did was inspired from the Gods. Gods willed: men carried it into effect. And the Mysteries were ordered and arranged in olden times to this end,—to bring Divine will and human action into line.

In Ephesus we first find a difference. There the pupils in the Mysteries, as I have told you, had to be watchful for their own condition of ripeness and no longer to observe seasons and times of year. There the first sign of personality makes its appearance. There in earlier incarnations Aristotle and Alexander the Great had received the impulse towards personality.

But now comes a new period. It is in the early dawn of this new period when Julian the Apostate experiences as it were the last longing of man to partake, even in that late age, in the Mysteries of the East. Now the soul of man begins to grow different again from what it was in Greece.

Picture to yourselves once more a man who has received some training in the Ephesian Mysteries. His constitution of soul is not derived from these Mysteries: he owes it to the simple fact that he is living in that age. When to-day a man recollects, when, as we say, he bethinks himself, what can he call to mind? He can call to mind something that he himself experienced in person during his present life, perhaps something that he experienced 20 or 30 years ago. This inward recollection in thought does not of course go further back than his own personal life. With the man who belonged, for instance, to the Ephesian civilisation it was otherwise. If he had received, even in a small degree, the training that could be had in Ephesus, then it was so with him that when he bethought himself in recollection, there emerged in his soul, instead of the memories that are limited to personal life, events of pre-earthly existence, events that preceded the Earth period of evolution. He beheld the Moon evolution, the Sun evolution, beholding them in the several kingdoms of Nature. He was able, too, to look within himself, and see the union of man with the Cosmic All; he saw how man depends on and is linked with the Cosmos. And all this that lived in his soul was true, ‘own’ memory, it was the cosmic memory of man.

We may therefore say that we are here dealing with a period when in Ephesus man was able to experience the secrets of the Universe. The human soul had memory of the far-past ages of the Cosmos.

This remembering was preceded in evolution by something else: it was preceded by an actual living within those earlier times. What remained was a looking back. In the time, however, of which the Gilgamesh Epic relates, we cannot speak of a memory of past ages in the Cosmos, we must speak of a present experience of what is past.

After the time of cosmic memory came what I have called the interim time between Alexander and Julian the Apostate. For the moment we will pass by this period. Then follows the age that gave birth to the western civilisation of the Middle Ages and of modern times. Here there is no longer a memory of the cosmic past, still less an experience in the present of the past; nothing is left but tradition.

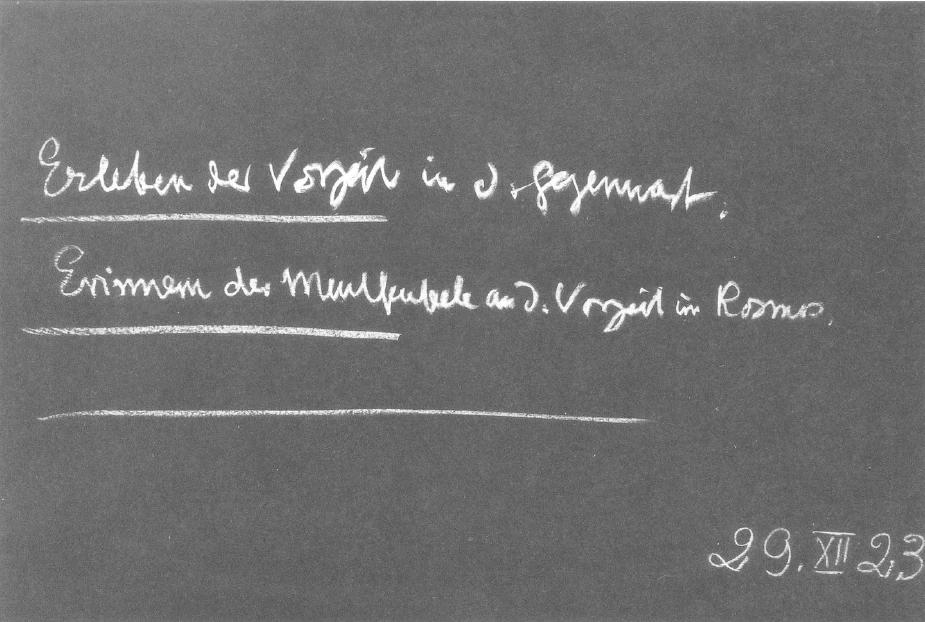

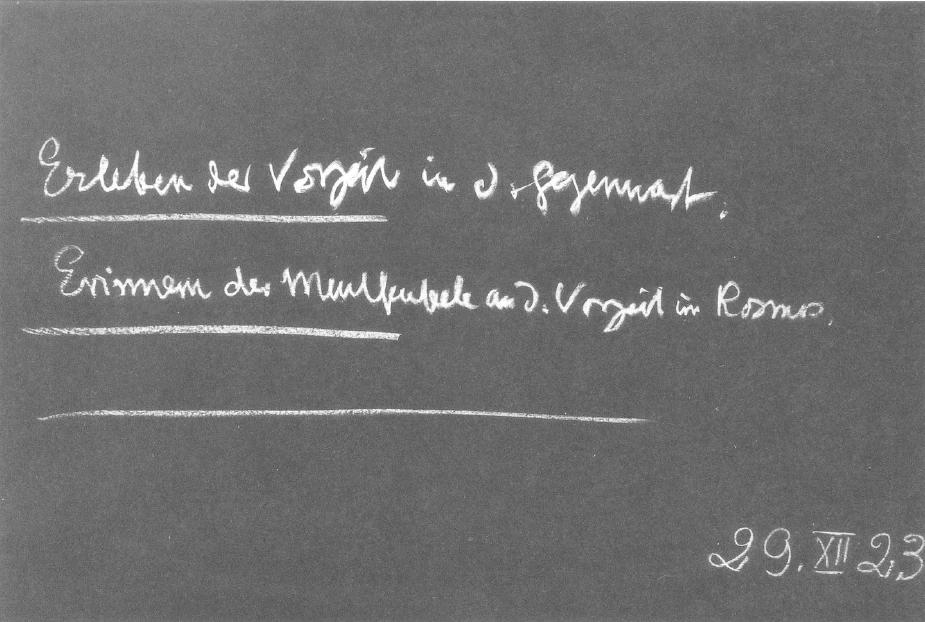

Present Experience of the Past.

Memory of the Cosmic Past.

Tradition.

Men can now write down what has happened. History begins. History makes its first appearance in the Roman period. Think, my dear friends, what a tremendous change we have here! Think how the pupils in the Ephesian Mysteries lived with time. They needed no history books. To write down what happened would have been to them laughable. One only needed to ponder and meditate deeply enough, and what had happened would rise up before one from out of the depths of consciousness. Here was no demonstration of psycho-analysis such as a modern doctor might make: the human soul took the greatest delight in fetching up in this way out of a living memory that which had been in the past. In the time that followed, however, mankind as such had forgotten, and the necessity arose of writing down what happened. But all the while that man had to let his ancient power of cosmic memory crumble away, and begin in a clumsy manner to write down the great events of the world,—all this time personal memory, personal recollection was evolving in his inner being. For every age has its own mission, every age its own task.

Here you have the other side of that which I set before you in the very first lectures of this course, when I described the rise of what we designated ‘memory in time.’ This memory in time, or temporal memory, had, so to say, its cradle in Greece, grew up through the Roman culture into the Middle Ages and on into modern times. In the time of Julian the Apostate the seed was already sown for the civilisation based on personality, as is testified by the fact that Julian the Apostate found it, after all, of no avail to let himself be initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries.

We have now come to the period when the man of the West, beginning from the 3rd or 4th century after Christ and continuing down to our own time, lives his life on Earth entirely outside the spiritual world, lives in concepts and ideas, in mere abstractions. In Rome the very Gods themselves became abstractions. We have reached a time when mankind has no longer any knowledge of a living connection with the spiritual world. The Earth is no longer Asia, the lowest of the Heavens, the Earth is a world for itself, and the Heavens are far away, dim and darkened for man's view. Now is the time when man evolves personality, under the influence of the Roman culture that is spread abroad over the lands of the West. As we had to speak of a soul-world bordering on the spiritual world, on the land of the Spirits that is above,—so, bordering on this spiritual oriental world is the civilisation of the West; we may call it a kind of soul-world in time. This is the world that reaches right down to our own day. And now, in our time, although most men are not at all alive to the fact, another stupendous change is again taking place.

Some of you who often listen to my lectures will know that I do not readily call any period a period of transition, for in truth every period is such,—every period marks a transition from what comes earlier to what comes later. The point is that we should recognise for each period the nature of the transition.

What I have said will already have suggested that in this case it is as though, having passed from the Spirit-land into the Soul-world one were to come thence into the physical world. In modern civilisation as it has evolved up till now, we have been able to catch again and again echoes of the spiritual. Materialism itself has not been without its echoes of the spirit. True and genuine materialism in all domains has only been with us since the middle of the 19th century, and is still understood by very few in its full significance. It is there, however, with gigantic force, and to-day we are going through a transition to a third world, that is in reality as different from the preceding Roman world as this latter was different from the oriental.

Now there is one period of time that has had to be left out in tracing this evolution: the period between Alexander and Julian. In the middle of this period fell the Mystery of Golgotha. Those to whom the Mystery of Golgotha was brought did not receive it as men who understood the Mysteries, otherwise they would have had quite different ideas of the Christ Who lived in the man Jesus of Nazareth. A few there were, a few contemporaries of the Mystery of Golgotha, who had been initiated in the Mysteries, and these were still able to have such ideas of Him. But by far the greater part of Western humanity had no ideas with which to comprehend spiritually the Mystery of Golgotha. Hence the first way by which the Mystery of Golgotha found place on Earth was the way of external tradition. Only in the very earliest centuries were there those who were able to comprehend spiritually, from their connection with the Mysteries, what took place at the Mystery of Golgotha.

Nor is this all. There is something else, of which I have told you in recent lectures,2See the 8th and 9th lectures in Mystery Knowledge and Mystery Centres. and we must return to it here. Over in Hibernia, in Ireland, were still the echoes of the ancient Atlantean wisdom. In the Mysteries of Hibernia, of which I have given you a brief description, were two Statues that worked suggestively on men, making it possible for them to behold the world exactly as the men of ancient Atlantis had seen it. Strictly guarded were these Mysteries of Hibernia, hidden in an atmosphere of intense earnestness. There they stood in the centuries before the Mystery of Golgotha, and there they remained at the time of the Mystery of Golgotha. Over in Asia the Mystery of Golgotha took place; in Jerusalem the events came to pass that were later made known to men in the Gospels by the way of tradition. But in the moment when the tragedy of the Mystery of Golgotha was being enacted in Palestine, in that very moment it was known and beheld clairvoyantly in the Mysteries of Hibernia. No report was brought by word of mouth, no communication whatever was possible; but in the Mysteries of Hibernia the event was fulfilled in a symbol, in a picture, at the same time that it was fulfilled in actual fact in Jerusalem. Men came to know of it, not through tradition but by a spiritual path. Whilst in Palestine that most majestic and sublime event was being enacted in concrete physical reality,—over in Hibernia, in the Mysteries, the way had been so prepared through the performance of certain rites that at the very time when the Mystery of Golgotha was fulfilled, a living picture of it was present in the astral light.

The events in human evolution are closely linked together; there is, as it were, a kind of valley or chasm moving at this time over the world, into which man's old nearness with the Gods gradually disappears.

In the East the ancient vision of the Gods fell into decay after the burning of Ephesus. In Hibernia it remained on until some centuries after Christ, but even there too the time came when it had to depart. Tradition developed in its stead, the Mystery of Golgotha was transmitted by the way of oral tradition; and we find growing up in the West a civilisation that rests wholly on oral tradition. Later it comes to rely rather on external observation of Nature, on an investigation of Nature with the senses; but this after all is only what corresponds in the realm of Nature to tradition, written or oral, in the realm of history.

Here then we have the civilisation of personality. And in that civilisation the Mystery of Golgotha, with all that pertains to the spirit, is no longer perceived by man, it is merely handed down as history.

We must place this picture in all clearness before us, the picture of a civilisation from which the spiritual is excluded. It begins from the time that followed Julian the Apostate, and not until towards the end of the 19th century, beginning from the end of the seventies, did there come, as it were, a new call to humanity from the spiritual heights. Then began the age that I have often described as the Age of Michael. To-day I want to characterise it as the age when man, if he wishes to remain at the old materialism—and a great part of mankind does wish so to remain—will inevitably fall into a terrible abyss; he has absolutely no alternative but to go under and become sub-human, he simply cannot maintain himself on the human level. If man would keep on the human level, he must open his senses to the spiritual revelations that have again been made accessible since the end of the 19th century. That is now an absolute necessity.

For you must know that great spiritual forces were at work in Herostratus. He was, so to speak, the last dagger stretched out by certain spiritual powers from Asia. When he flung the burning torch into the Temple of Ephesus, demonic beings were behind him, holding him as one holds a sword,—or as it might be, a torch; he was but the sword or torch in their hands. For these demonic beings had determined to let nothing of the Spirit go over into the coming European civilisation; the spiritual was to be absolutely debarred entry there.

Aristotle and Alexander the Great placed themselves in direct opposition to the working of these beings. For what was it they accomplished in history? Through the expeditions of Alexander, the Nature knowledge of Aristotle was carried over into Asia; a pure knowledge of Nature was spread abroad. Not in Egypt alone, but all over Asia Alexander founded academies, and in these academies made a home for the ancient wisdom, where the study of it could still continue. Here too, the wise men of Greece were ever and again able to find a refuge. Alexander brought it about that a true understanding of Nature was carried into Asia.

Into Europe it could not find entrance in the same way. Europe could not in all honesty receive it. She wanted only external knowledge, external culture, external civilisation. Therefore did Aristotle's pupil Theophrastus take out of Aristotelianism what the West could accept and bring that over. It was the more logical writings that the West received. But that meant a great deal. For Aristotle's works have a character all their own; they read differently from the works of other authors, and his more abstract and logical writings are no exception. Do but make the experiment of reading first Plato and then Aristotle with inner concentration and in a meditative spirit, and you will find that each gives you quite a different experience.

When a modern man reads Plato with true spiritual feeling and in an attitude of meditation, after a time he begins to feel as though his head were a littler higher than his physical head actually is, as though he had, so to speak, grown out beyond his physical organism. That is absolutely the experience of anyone who reads Plato, provided he does not read him in an altogether dry manner.

With Aristotle it is different. With Aristotle you never have the feeling that you are coming out of your body. When you read Aristotle after having prepared yourself by meditation, you will find that he works right into the physical man. Your physical man makes a step forward through the reading of Aristotle. His logic works; it is not a logic that one merely observes and considers, it is a logic that works in the inner being. Aristotle himself is a stage higher than all the pedants who came after him, and who developed logic from him. In a certain sense we may say with truth that Aristotle's works are only rightly comprehended when they are taken as books for meditation. Think what would have happened if the Natural Scientific writings of Aristotle had gone over to the West as they were and come into Middle and Southern Europe. Men would, no doubt, have received a great deal from them, but in a way that did them harm. For the Natural Science that Aristotle was able to pass on to Alexander needed for its comprehension souls that were still touched with the spirit of the Ephesian age, the time that preceded the burning of Ephesus. Such souls could only be found over in Asia or in Egypt; and it was into these parts that this knowledge of Nature and insight into the Being of Nature were brought, by means of the expeditions of Alexander. Only later in a diluted form did they come over into Europe by many and diverse ways—especially, for example, by way of Spain,—but always in a very diluted or, as we might say, sifted form.

The writings of Aristotle that came over into Europe direct were his writings on logic and philosophy. These lived on, and found fresh life again in medieval scholasticism.

We have therefore these two streams. On the one hand we have always there a stream of wisdom that spreads far and wide, unobtrusively, among simple folk,—the secret source of much of medieval thought and insight. Long ago, through the expeditions of Alexander, it had made its way into Asia, and now it came back again into Europe by diverse channels, through Arabia, for instance, and later on following the path of the returning Crusaders. We find it in every corner of Europe,—inconspicuous, flowing silently in hidden places. To these places came men like Jacob Boehme,3(1575–1624), mystic. See Eleven European Mystics by Rudolf Steiner, Rudolf Steiner Publications, New York, 1971. Paracelsus4Theophrastus Paracelsus (1493–1541), physician. See Eleven European Mystics. and a number more, to receive that which had come thither by many a roundabout path and was preserved in these scattered primitive circles of European life. We have had amongst us in Europe far more folk-wisdom than is generally supposed. The stream continues even now. It has poured its flood of wisdom into reservoirs like Valentine Wiegel5(1533–1588), mystic. See Eleven European Mystics. or Paracelsus or Jacob Boehme,—and many more, whose names are less known. And sometimes it met there,—as for example, in Basil Valentine6Alchemist and Benedictine monk, lived from 1413 onwards in the Monastery of St. Peter in Erfurt. His writings were not discovered or printed till the beginning of the seventeenth century. See Eleven European Mystics.—new in-pourings that came over later into Europe. In the Cloisters of the Middle Ages lived a true alchemistic wisdom, not an alchemy that demonstrates changes in matter merely, but an alchemy that demonstrates the inner nature of the changes in the human being himself in the Universe. The recognised scholars meanwhile were occupying themselves with the other Aristotle, with a misstated, sifted, ‘logicised’ Aristotle. This Aristotelian philosophy, however, which the scholiasts and subsequently the scientists studied, brought none the less a blessing to the West. For only in the 19th century, when men could no longer understand Aristotle and simply studied him as if he were a book to be read like any other and not a book whereon to exercise oneself in meditation—only in the 19th century has it come about that men no longer receive anything from Aristotle because he no longer lives and works in them. Until the 19th century Aristotle was a book for the exercise of meditation; but in the 19th century the whole tendency has been to change what was once exercise, work, active power into abstract knowledge,—to change ‘do’ and ‘can’ into ‘know.’

Let us look now at the line of development, that leads from Greece through Rome to the West. It will illustrate for us from another angle the great change we are considering. In Greece there was still the confident assurance that insight and understanding proceed from the whole human being. The teacher is the gymnast.7Rudolf Steiner spoke in detail about this for instance in A Modern Art of Education by Rudolf Steiner, Rudolf Steiner Press, London, 1972 and Human Values in Education by Rudolf Steiner, Rudolf Steiner Press, London, 1971. From out of the whole human being in movement—for the Gods themselves work in the bodily movements of man—something is born that then comes forth and shows itself as human understanding. The gymnast is the teacher.

In Rome the rhetorician.8Rudolf Steiner spoke in detail about this for instance in A Modern Art of Education by Rudolf Steiner, Rudolf Steiner Press, London, 1972 and Human Values in Education by Rudolf Steiner, Rudolf Steiner Press, London, 1971. steps into the place of the gymnast. Already something has been taken away from the human being in his entirety; nevertheless we have at least still a connection with a deed that is done by the human being in a part of his organism. What movement there is in our whole being when we speak! We speak with our heart and with our lungs, we speak right down to our diaphragm and below it! We cannot say that speaking lives as intensely in the whole human being as do the movements of the gymnast, but it lives in a great part of him. (As for thoughts, they of course are but an extract of what lives in speech). The rhetorician steps into the place of the gymnast. The gymnast has to do with the whole human being. The rhetorician shuts off the limbs, and has only to do with a part of the human being and with that which is sent up from this part into the head, and there becomes insight and understanding.

The third stage appears only in modern times and that is the stage of the professor.9Rudolf Steiner spoke in detail about this for instance in A Modern Art of Education by Rudolf Steiner, Rudolf Steiner Press, London, 1972 and Human Values in Education by Rudolf Steiner, Rudolf Steiner Press, London, 1971. who trains nothing but the head of his pupils, who cares for nothing but thoughts. Professors of Eloquence were still appointed in some universities even as late as the 19th century, but these universities had no use for them, because it was no longer the custom to set any store by the art of speaking; thinking was all that mattered. The rhetorician died out. The doctors and professors, who looked after the least part of the human being, namely his head,—these became the leaders in education.

As long as the genuine Aristotle was still there, it was training, discipline, exercise that men gained from their study of him. The two streams remained side by side. And those of us who are not very young and who shared in the development of thought during the later decades of the 19th century, know well, if we have gone about among the country folk in the way that Paracelsus did, that a last remains of the medieval folk-knowledge, from which Jacob Boehme and Paracelsus drew, was still to be found in Europe even as late as the sixties and seventies of the last century. Moreover, it is also true that within certain orders and in the life of a certain narrow circle a kind of inner discipline in Aristotle was cultivated right up to the last decades of the 19th century. So that it has been possible in recent years still to meet here and there the last ramifications, as it were, of the Aristotelian wisdom that Alexander carried over into Asia and that returned to Europe through Asia Minor, Africa and Spain. It was the same wisdom that had come to new life in such men as Basil Valentine and those who came after him, and from which Jacob Boehme, Paracelsus and countless others had drawn. It was brought back to Europe also by yet another path, namely through the Crusaders. This Aristotelian wisdom lived on, scattered far and wide among the common people. In the later decades of the 19th century, one is thankful to say, the last echoes of the ancient Nature knowledge carried over into Asia by the expeditions of Alexander were still to be heard, even if sadly diminished and scarcely recognisable. In the old alchemy, in the old knowledge of the connections between the forces and substances of Nature that persisted so remarkably among simple country folk, we may discover again its last lingering echoes. To-day they have died away; to-day they are gone, they are no longer to be heard.

Similarly in these years one could still find isolated individuals who gave evidence of Aristotelian spiritual training; though to-day they too are gone. And thus what was carried east as well as what was carried west was preserved,—for that which was carried east came back again to the west. And it was possible in the seventies and eighties of the 19th century for one who could do so with new direct spiritual perception, to make contact with what was still living in these last and youngest children of the great events we have been describing.

There is, in truth, a wonderful interworking in all these things. For we can see how the expeditions of Alexander and the teachings of Aristotle had this end in view, to keep unbroken the threads that unite man with the ancient spirituality, to weave them as it were into the material civilisation that was to come, that so they might endure until such time as new spiritual revelations should be given.

From this point of view, we may gain a true understanding of the events of history, for it is often so that seemingly fruitless undertakings are fraught with deep significance for the historical evolution of mankind. It is easy enough to say that the expeditions of Alexander to Asia and to Egypt have been swept away and submerged. It is not so. It is easy to say that Aristotle ceased to be in the 19th century. But he did not. Both streams have lasted up to the very moment when it is possible to begin a renewed life of the Spirit.

I have told you on many occasions how the new life of the Spirit was able to begin at the end of the seventies, and how from the turn of the century onwards, it has been able to grow more and more. It is our task to receive in all its fullness the stream of spiritual life that is poured down to us from the heights.

And so to-day we find ourselves in a period that marks a genuine transition in the spiritual unfolding of man. And if we are not conscious of these wonderful connections and of how deeply the present is linked with the past, then we are in very truth asleep to important events that are taking place in the spiritual life of our time. And numbers of people are fast asleep to-day in regard to the most important events of all. But Anthroposophy is there for that very purpose,—to awaken man from sleep.

You who have come here for this Christmas Meeting,—I believe that all of you have felt an impulse that calls you to awaken. We are nearing the day—as this Meeting goes on, we shall have to pass the actual hour of the anniversary—we are coming to the day when the terrible flames burst forth that destroyed the Goetheanum. Let the world think what it will of the destruction by fire of the Goetheanum, in the evolution of the Anthroposophical movement the event of the fire has a tremendous significance.

We shall not however be able to judge of its full significance until we look beyond it to something more. We behold again the physical flames of fire flaring up on that night, we see the marvellous way in which the fusing metal of the organ-pipes and other metallic parts sent up a glow that caused that wonderful play of colour in the flames. And then we carry our memory over the year that has intervened. But in this memory must live the fact that the physical is Maya, that we have to seek the truth of the burning flames in the spiritual fire that it is ours now to kindle in our hearts and souls. In the midst of the physically burning Goetheanum shall arise for us a spiritually living Goetheanum.

I do not believe, my dear friends, that this can come to pass in the full, world-historic sense unless we can on the one hand look upon the flames mounting up in terrible tongues of fire from the Goetheanum that we have grown to love so dearly, and behold at the same time in the background that other treacherous burning of Ephesus, when Herostratus, guided by demonic powers, flung the flaming brand into the Temple. When we bring these two events together, setting one in the background and one in the foreground of our thought, we shall then have a picture that will perhaps have power to write deeply enough in our hearts what we have lost and what we must strive our utmost to build again.

Sechster Vortrag

Die Zeit drei bis vier Jahrhunderte vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha, drei bis vier Jahrhunderte nachher, was einen Zeitraum von sechs bis acht Jahrhunderten gibt, diese Zeit ist für das Verständnis der Geschichte des Abendlandes in ihrem Anschlusse an das Morgenland ganz besonders wichtig. Das Wesentliche der Ereignisse, von denen ich in den vergangenen Tagen gesprochen habe und die da gipfelten im Auftreten des Aristotelismus und in den Alexanderzügen von Makedonien nach Asien hinüber, das Wesentliche dieser Ereignisse ist, daß sie eine Art von Abschluß bilden für jene Zivilisation des Orients, die noch ganz und gar getaucht war in die Impulse des Mysterienwesens.

Der letzte Abschluß sozusagen dieser noch echten, reinen Mysterienimpulse des Orients war ja der frevlerische Brand von Ephesus. Und wir haben es dann zu tun mit demjenigen, was sozusagen für Europa, für Griechenland, dann übrigbleibt an Mysterientradition, an Schattenbildern, möchte ich sagen, der alten gottdurchdrungenen Zivilisation. Und vier Jahrhunderte nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha können wir sozusagen sehen durch ein anderes Ereignis, was noch vorhanden war von den Trümmern des Mysterienwesens. Wir können es sehen an Julianus Apostata. Julianus Apostata, der römische Kaiser, wird im 4. Jahrhundert in dasjenige eingeweiht, in das man eben eingeweiht werden konnte, von einem der letzten Hierophanten der eleusinischen Mysterien. Das heißt, Julianus Apostata erfuhr ebensoviel von dem, was die älteren Göttergeheimnisse des Orients waren, als im 4. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert in den Eleusinien noch zu erfahren war.

Damit haben wir an einem Punkt, dem Ausgangspunkt eines gewissen Zeitalters, den Brand von Ephesus stehen. An dem Tage des Brandes von Ephesus ist der Geburtstag Alexanders des Großen. Wir haben am Ende dieser Epoche stehen, 363, den Todestag, den gewaltsamen Tod Julianus Apostatas drüben in Asien. Man möchte sagen: Mitten drinnen in diesem Zeitraume steht das Mysterium von Golgatha. Und nun sehen wir uns einmal an, wie sich dieser Zeitraum, den ich eben begrenzt habe, eigentlich ausnimmt in der ganzen Entwickelungsgeschichte der Menschheit. Wir haben ja jetzt die merkwürdige Tatsache vor uns liegen, daß, wenn wir zurückschauen wollen jenseits dieses Zeitraumes in die Entwickelung der Menschheit hinein, wir etwas tun müssen in unserem Anschauen, das sehr ähnlich ist einem anderen. Nur bringen wir die beiden Dinge oftmals nicht zusammen,

Erinnern Sie sich, wie ich genötigt war darzustellen in meiner «Theosophie» die Welten, die für uns in Betracht kommen: die physische Welt, daran grenzend eine Übergangswelt, die Seelenwelt, und dann als die Welt, in die nur Eintritt gewinnen kann der höchste Teil des Menschen, das Geisterland. Und wenn man absieht von den besonderen Eigentümlichkeiten dieses Geisterlandes, das gegenwärtig der Mensch durchmacht zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, wenn man so auf die allgemeinen Eigentümlichkeiten des Geisterlandes sieht, dann ist es so, daß wir in ganz ähnlicher Weise, wie wir umorientieren müssen unsere Seelenverfassung, um dieses Geisterland zu begreifen, umorientieren müssen unsere Seelenverfassung, um dasjenige zu begreifen, was jenseits dieses Zeitpunktes liegt. Mit den Begriffen und Vorstellungen, die auf die heutige Welt anwendbar sind, sollen wir nur ja nicht glauben, dasjenige verstehen zu können, was hinter dem Brande von Ephesus liegt. Da muß man andere Begriffe und Vorstellungen ausbilden, die einem eben gestatten, hinzuschauen auf Menschen, die noch wußten, daß sie, so wie der Mensch im Atmungsprozesse mit der äußeren Luft, sie durch ihre Seele fortdauernd mit den Göttern zusammenhängen.

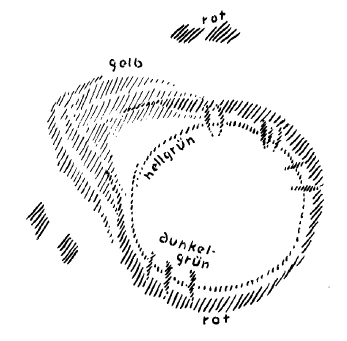

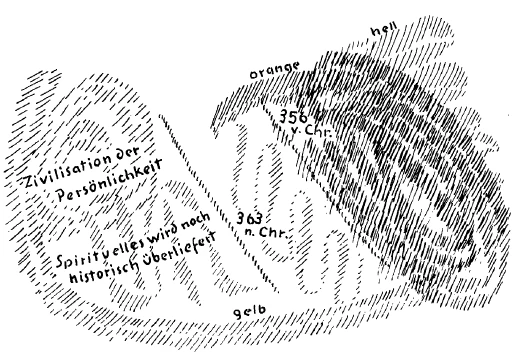

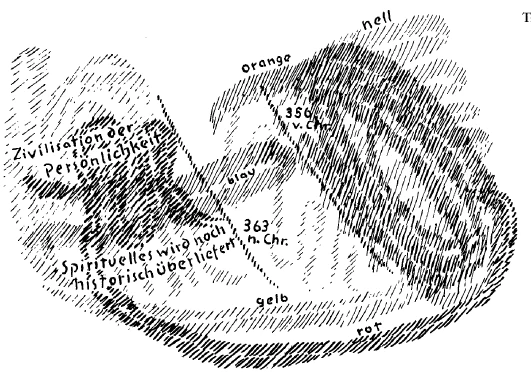

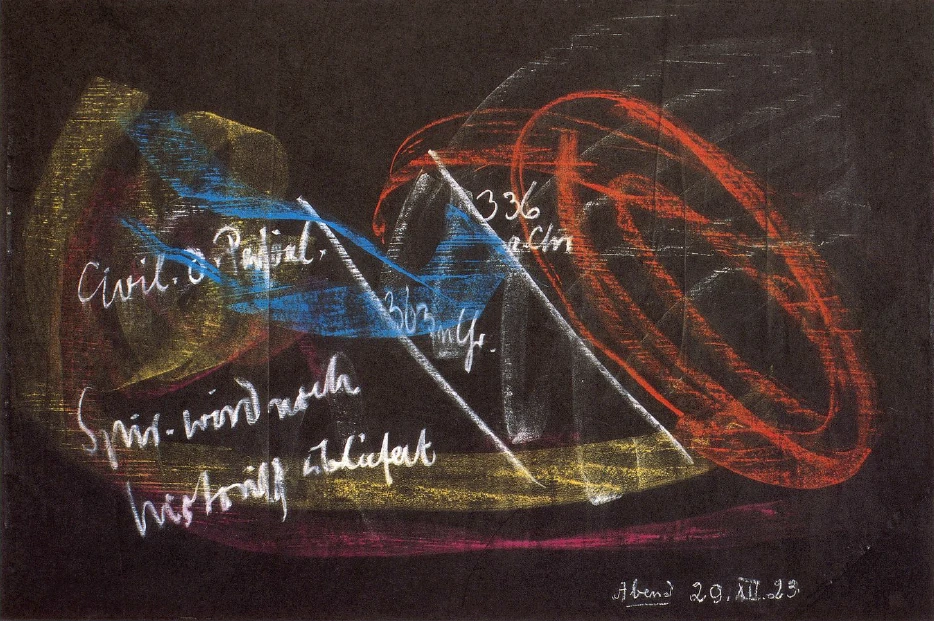

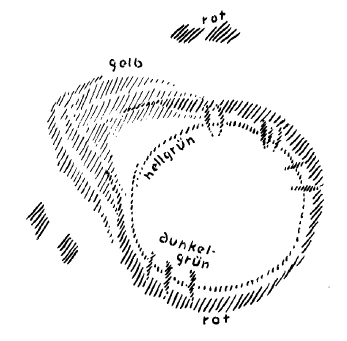

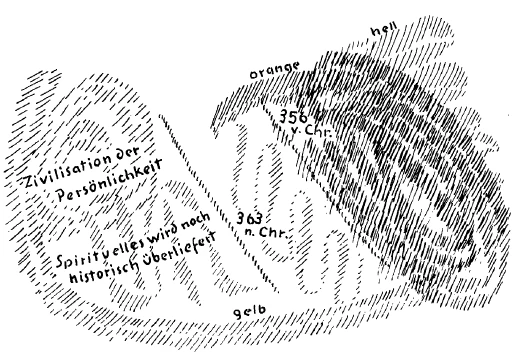

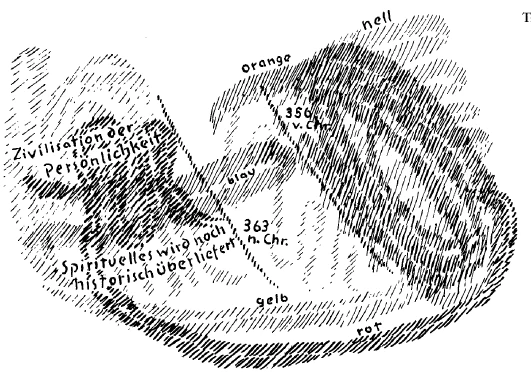

Und nun, sehen wir uns an diese Welt, die gewissermaßen ein irdisches Devachan, ein irdisches Geisterland ist, denn die physische Welt nützt nichts für diese Welt. Dann haben wir jene Zwischenzeit von meinetwillen 356 vor Christus bis 363 nach Christus. Und was liegt nun jenseits davon? Jenseits davon gegen Asien hin, jenseits gegen Europa zu liegt die Welt, aus der die gegenwärtige Menschheit eben im Begriffe ist ebenso herauszukommen, wie die alte Menschheit aus der orientalischen Welt über die griechische ins Römerreich hineingekommen ist (siehe Zeichnung). Denn dasjenige, was durch die Jahrhunderte des Mittelalters bis in unsere Zeiten herein sich als Zivilisation entwickelt hat, das ist eine Zivilisation, welche sich gebildet, entfaltet hat, abgesehen von dem eigentlichen Inneren des Mysterienwesens, welche sich entwickelt hat auf der Grundlage dessen, was der Mensch mit seinen Begriffen und Vorstellungen ausbilden kann. In Griechenland hatte es sich schon vorbereitet seit Herodot, der in äußerlicher Weise die Tatsachen der Geschichte beschrieben hat und nicht mehr an das Geistige oder wenigstens nur höchst mangelhaft an das Geistige herangetreten ist. Dann bildet sich das immer mehr und mehr aus. Aber in Griechenland bleibt immer noch etwas von dem Hauche jener Schattenbilder, die an das geistige Leben erinnern sollten. In Rom dagegen beginnt jenes Zeitalter, dem die Menschheit der Gegenwart noch verwandt ist, jenes Zeitalter, das in einer ganz anderen Weise eine Seelenverfassung hat, als selbst diejenige Griechenlandes noch war. Nur solch eine Persönlichkeit wie Julianus Apostata empfindet etwas wie eine unbesiegliche Sehnsucht nach der alten Welt, und er läßt sich mit einer gewissen Ehrlichkeit in die eleusinischen Mysterien einweihen. Aber es hat keine Erkenntniskraft mehr, was er da bekommt. Und vor allen Dingen, er entstammt einer Welt, die mit dem Inneren der Seele nicht mehr voll ergreifen kann, was da an Traditionen aus dem Mysterienwesen des Orients vorhanden war.

Die heutige Menschheit wäre nimmermehr entstanden, wenn eben nicht auf Asien Griechenland, Rom gefolgt wäre. Die heutige Menschheit ist jene Menschheit, die auf Persönlichkeit, auf die individuelle Persönlichkeit des Einzelnen gebaut ist. Die orientalische Persönlichkeit, die orientalische Menschheit war nicht auf die individuelle Persönlichkeit des Einzelnen gebaut. Der einzelne fühlte sich als ein Glied des fortlaufenden göttlichen Prozesses. Die Götter hatten ihre Absichten mit der Erdenentwickelung, die Götter wollten dies oder jenes; daher geschah dies oder jenes hier unten auf der Erde. Im Willen der Menschen wirkten inspirierend die Götter. Alles dasjenige, was die machtvollen Persönlichkeiten, auf die ich Ihnen hingedeutet habe, im Orient getan haben, war Götterinspiration. Die Götter wollten, und die Menschen taten. Und die Mysterien waren gerade dazu angetan in den älteren Zeiten, dieses Götterwollen und Menschentun in die richtigen Geleise zu bringen.

Erst in Ephesus war das anders geworden. Da waren, wie ich Ihnen sagte, die Mysterienschüler auf ihre eigene Reife, nicht mehr auf Jahreszeitenlauf angewiesen. Da war zuerst die erste Spur von Persönlichkeit aufgetreten. Da hatten auch Aristoteles und Alexander der Große in früheren Inkarnationen den Impuls der Persönlichkeit empfangen. Aber nun kam die Zeit, die ihre Morgendämmerung da hat, wo Julianus Apostata die letzte Sehnsucht bekommt, ein Mensch des Mysterienwesens des Orients zu sein. Nun kommt die Zeit, in der es in der menschlichen Seele ganz anders wird, als es selbst in Griechenland war.

Stellen Sie sich noch solch einen Menschen vor, der in den ephesischen Mysterien etwa seine Schulung erlangt hat. Nicht durch die ephesischen Mysterien, sondern dadurch, daß er in jener Zeit lebte, war es so in seiner Seele. Sehen Sie, wenn heute ein Mensch sich besinnt, wie man sagt, auf was kann er sich besinnen? Er kann sich besinnen auf irgend etwas, was er persönlich seit seiner Geburt erlebt hat. Da ist ein Mensch von einem bestimmten Alter; er besinnt sich auf dasjenige, was er vor zwanzig, dreißig Jahren erlebt hat. Die innere Gedankenbesinnung führt nicht weiter als in das persönliche Leben. $o war es nicht bei den Menschen, die zum Beispiel noch die ephesische Zivilisation mitmachten. Wenn diese nur eine Spur jener Schulung hatten, die in Ephesus zu erlangen war, dann kam es, indem sie sich besannen, daß auftauchten in ihrer Seele, wie heute die Erinnerungen an das persönliche Leben auftauchen, die Ereignisse des vorirdischen Daseins und auch die Ereignisse, die der Erdenentwickelung in den einzelnen Reichen der Natur vorangegangen sind: Mondenentwickelung, Sonnenentwickelung. Da konnte man in sich hineinschauen, und man schaute Kosmisches, Verbindung des Menschen mit Kosmischem, gleichsam das Hängen des Menschen an dem Kosmischen. Das, was in der menschlichen Seele lebte, war Selbsterinnerung.

Wir können also sagen: Wir haben da ein Zeitalter, jenes Zeitalter, in dem man in Ephesus erleben konnte die Weltgeheimnisse. Da war ein Erinnern der Menschenseele an die Vorzeit im Kosmos. Diesem Erinnern ging voran ein wirkliches Drinnenleben in der Vorzeit. Es blieb davon einfach ein Hineinschauen in die Vorzeit. In der Zeit, von der das Gilgamesch-Epos erzählt, da können wir nicht sagen: Erinnern der Menschenseele an die Vorzeit im Kosmos; da müssen wir sagen: ein Erleben der Vorzeit in der Gegenwart. - Nun kommt jener Zeitraum von Alexander bis Julianus Apostata. Wir wollen ihn zunächst auslassen. Und dann kommen wir zu dem Zeitalter, aus dem die abendländische Zivilisation des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit herausgewachsen ist. Da gab es nicht mehr ein Etinnern der Menschenseele an die Vorzeit im Kosmos, nicht mehr ein Erleben der Vorzeit in der Gegenwart, sondern da gab es nur noch Tradition.

Erstens: Erleben der Vorzeit in der Gegenwart.

Zweitens: Erinnern der Menschenseele an die Vorzeit im Kosmos.

Drittens: Tradition.

Man konnte dasjenige aufschreiben, was geschehen ist. Geschichte entstand. Diese Geschichte beginnt mit dem römischen Zeitalter. Denken Sie sich den gewaltigen Unterschied! Denken Sie sich die Zeit, die mitgemacht wurde von den älteren ephesischen Schülern. Die brauchten keine Geschichtsbücher. Aufschreiben dasjenige, was geschehen ist, wäre ihnen lächerlich erschienen. Denn man mußte nachdenken, genügend tief nachdenken, dann kam herauf aus dem Untergrunde des Bewußtseins dasjenige, was geschehen ist. Und kein moderner Medikus war da, der das als Psychoanalyse darstellte, sondern es war gerade das Entzücken der Menschenseele, in dieser Weise heraufzuholen aus einem lebendigen Erinnern dasjenige, was einstmals da war.

Dann kam die Zeit, in der die Menschheit als solche vergessen hatte und notdürftig aufschreiben mußte dasjenige, was geschehen ist. Aber während die Menschheit das verkümmern lassen mußte, was früher in der Menschenseele kosmische Erinnerungskraft war, während die Menschheit stümperhaft anfangen mußte aufzuschreiben die Weltereignisse, Geschichte zu schreiben und so weiter, während der Zeit entwickelte sich im menschlichen Inneren das persönliche Gedächtnis, die persönliche Erinnerung. - Jedes Zeitalter hat seine besondere Mission, seine besondere Aufgabe. - Sie haben hier die andere Seite desjenigen, was ich schon in den allerersten Vorträgen so dargelegt habe, daß das Zeitengedächtnis auftrat. Dieses Zeitengedächtnis hatte seine erste Wiege in Griechenland, entwickelte sich aber dann eben durch die römisch-romanische Kultur in das Mittelalter herein bis in die Neuzeit herauf. Und daß zur Zeit des Julianus Apostata schon durchaus die Keime gelegt waren zu dieser Persönlichkeitskultur, dafür ist eben ein Beweis, daß es Julianus Apostata im Grunde genommen nichts mehr genützt hat, daß er sich in die eleusinischen Mysterien einweihen ließ.

Nun kommt also die Zeit, in der der Mensch im Abendlande vom 3., 4. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert an bis in unsere Zeit herein während seines Erdenlebens ganz außerhalb der geistigen Welt lebt, die Zeit, in der er in bloßen Begriffen und Ideen, in Abstraktionen lebt. In Rom werden selbst die Götter zu Abstraktionen. Es kommt die Zeit, in der die Menschheit nichts mehr weiß von dem lebendigen Zusammenleben mit der geistigen Welt. Die Erde ist nicht mehr Asia, das unterste Gebiet der Himmel, die Erde ist eine Welt für sich, und die Himmel sind ferne, sind abgedämpft im menschlichen Anschauen. So daß man sagen kann: Die Persönlichkeit entwickelt der Mensch unter dem Einflusse desjenigen, was als römische Kultur über das Abendland gekommen ist.

Geradeso wie an die Geisteswelt, das Geisterland, das oben ist, unten eine Seelenwelt angrenzt, so grenzt nun auch der Zeit nach dasjenige an diese geistige orientalische Welt an, was die Zivilisation des Abendlandes ist: eine Art Seelenwelt. Und diese Seelenwelt zeigt sich eigentlich direkt bis in unsere Tage herein. Aber die Menschheit merkt heute in ihren meisten Exemplaren noch nicht, daß tatsächlich ein mächtiger Umschwung im Gange ist. Einzelne der Freunde, die mich öfter hören, werden wissen, daß ich nicht gern davon spreche, daß ein Zeitalter ein Übergangszeitalter ist, denn es ist eben jedes Zeitalter ein Übergangszeitalter, nämlich vom Früheren zum Späteren. Es kommt nur darauf an, von was zu was der Übergang stattfindet. Aber gerade mit dem, was ich Ihnen gesagt habe, ist hingedeutet darauf, daß dieser Übergang so ist, wie wenn man vom Geisterland in die Seelenwelt und von da erst in die physische Welt kommt. Oh, es gab noch immer in der Zivilisation, die bisher sich entwickelt hat, gewisse geistige Anklänge! Selbst im Materialismus verrieten sich gewisse geistige Anklänge. Der eigentliche Materialismus auf allen Gebieten, er ist erst seit der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts da, und er wird noch von den wenigsten Menschen in seiner vollen Bedeutung verstanden. Aber er ist da mit einer riesigen Kraft, und es ist heute eine Übergangszeit zu einer dritten Welt, die wirklich von der vorhergehenden so verschieden ist, wie diese vorhergehende römische von der orientalischen verschieden ist.

Nun, ich möchte sagen, es ist gewissermaßen ein Zeitraum ausgespart worden zwischen Alexander und Julianus, und in die Mitte dieses Zeitraumes hinein fällt das Mysterium von Golgatha. Dieses Mysterium von Golgatha wird von der Menschheit nicht mehr so empfangen wie zur Zeit, da die Menschen die Mysterien begriffen haben, sonst würde man ja ganz andere Vorstellungen von dem Christus gehabt haben, der in dem Menschen Jesus von Nazareth gelebt hat. Aber nur wenige Menschen, die in die Mysterien eingeweihten Zeitgenossen des Mysteriums von Golgatha, hatten noch solche Vorstellungen. Die weitaus größte Zahl der abendländischen Menschheit hatte keine Vorstellungen, um spirituell das Mysterium von Golgatha zu begreifen. Daher war die erste Art, wie das Mysterium von Golgatha auf Erden Platz gegriffen hat, die durch äußere Tradition, durch die äußere Überlieferung. Nur in Eingeweihtenkreisen in den allerersten Jahrhunderten war es so, daß man auch spirituell begreifen konnte, was mit dem Mysterium von Golgatha geschehen war.

Aber etwas anderes war noch da, wovon ich schon zu einigen von Ihnen in kurz vorangegangenen Vorträgen gesprochen habe. Drüben in Hybernia, in Irland, waren die Nachklänge der alten atlantischen Weisheit. In den Mysterien von Hybernia, die ich Ihnen vorgestern skizziert habe, waren für den Schüler in den zwei suggestiven Gestalten die Möglichkeiten vorhanden, scharf so die Welt zu sehen, wie sie die alten Atlantier gesehen haben. Und streng in sich abgeschlossen, in eine Atmosphäre von ungeheurem Ernst gehüllt, waren diese Mysterien von Hybernia. Sie waren da in den Jahrhunderten vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha, sie waren auch da zur Zeit des Mysteriums von Golgatha. Drüben in Asien ging vor sich das Mysterium von Golgatha, in Jerusalem spielte sich dasjenige ab, was dann traditionell historisch mitgeteilt wird in den Evangelien. Aber ohne daß irgendein menschlicher Mund eine Nachricht überbracht hätte, ohne daß irgendeine andere Verbindung dagewesen wäre, wußte man hellsichtig in den Mysterien von Hybernia in dem Momente, als das Mysterium von Golgatha sich tragisch vollzog, daß in Palästina das reale Mysterium von Golgatha vor sich ging. In den Mysterienstätten von Hybernia vollzog sich das symbolische Bild gleichzeitig. Man lernte dort nicht durch Tradition, man lernte dort kennen das Mysterium von Golgatha auf spirituelle Art. Und während sich das großartigste, majestätischste Ereignis in Palästina in äußerer physischer Tatsächlichkeit zugetragen hat, hatten sich in den Mysterien von Hybernia jene Kulthandlungen vollzogen, durch die dort im Astrallichte ein lebendes Bild des Mysteriums von Golgatha da war.

Sie sehen, wie die Dinge verkettet sind, wie tatsächlich, ich möchte sagen, eine Art Weltentales da ist, indem der alte Zusammenhang mit den Göttern schwindet.

Im Morgenlande korrumpiert diese alte Götteranschauung nach dem Brande von Ephesus. In Hybernia ist sie vorhanden, bleibt sie vorhanden, bis sie, aber da erst in der nachchristlichen Zeit, auch da verschwindet. Und es entwickelt sich alles, was vom Mysterium von Golgatha ausstrahlt, durch Tradition, durch mündliche Überlieferung. Es entwickelt sich überhaupt im Abendlande eine Zivilisation, die nur auf mündliche Überlieferung rechnet oder aber später auf eine äußere Naturforschung, auf eine rein sinnliche Naturforschung, was ja auf dem Gebiete der Natur entspricht der bloßen Überlieferung, der schriftlichen oder mündlichen Überlieferung auf geschichtlichem Gebiete.

So daß man sagen kann: Hier ist die Zivilisation der Persönlichkeit. Das Spiritualistische, das Mysterium von Golgatha wird noch historisch überliefert, nicht mehr geschaut (siehe Zeichnung, Seite 109). Man stelle sich das nur lebhaft vor, stelle sich vor, wie in der Zeit nach Julianus Apostata sich da eine Kultur mit Ausschluß des Spirituellen ausbreitet. Erst am Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts, vom Ende der siebziger Jahre an, kam sozusagen ein neuer Ruf aus geistigen Höhen an die Menschheit heran. Es begann jenes Zeitalter, das ich oftmals als das Michael-Zeitalter charakterisiert habe. Heute will ich es von dem Gesichtspunkte aus charakterisieren, daß ich sage: Es kam jenes Zeitalter, wo der Mensch, wenn er bleiben will beim alten Materialismus - und ein großer Teil der Menschheit will zunächst dabei bleiben -, dann aber in furchtbare Abgründe hineinkommen wird. Der Mensch, wenn er bleiben will beim alten Materialismus, kommt unbedingt ins Untermenschliche hinunter, kann sich nicht auf der menschlichen Höhe erhalten. Um sich aber auf der menschlichen Höhe zu erhalten, muß der Mensch seine Sinne eröffnen. Das ist unbedingte Notwendigkeit vom Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts ab, daß der Mensch eröffne seine Sinne den spirituellen Offenbarungen, die seither wiederum zu haben sind.

Es waren gewisse geistige Mächte am Werke, die in der Persönlichkeit des Herostrat, ich möchte sagen, nur ihren äußeren Ausdruck gefunden haben. Herostrat war sozusagen der letzte Degen, den vorstreckten gewisse geistige Mächte von Asien. Und als Herostrat die Brandfackel in den Tempel von Ephesus hineinschleuderte, waren hinter ihm, gewissermaßen ihn nur haltend als das Schwert oder als die Fortsetzung der Brandfackel, dämonische Wesenheiten, welche im Grunde genommen vorhatten, kein Spirituelles hinüberzulassen in diese europäische Zivilisation.

Dem, sehen Sie, widersetzen sich Aristoteles und Alexander der Große. Denn was geschah denn nun eigentlich? Durch die Alexanderzüge wurde nach Asien hinübergetragen dasjenige, was Naturwissen des Aristoteles war, und überall breitete sich aus ein gründliches Naturwissen. Alexander hatte überall, nicht nur in Alexandria, in Ägypten, sondern überall drüben in Asien Akademien gegründet, in denen er die alte Weisheit festsetzte, so daß diese alte Weisheit da war und lange Zeit gepflegt wurde. Immerzu konnten die griechischen Weisen kommen und fanden dort ihre Zufluchtstätte. Naturwissen wurde durch Alexander nach Asien getragen.

Europa konnte dieses tiefere Naturwissen zunächst in aller Ehrlichkeit nicht vertragen. Es wollte nur äußeres Wissen, äußere Kultur, äußere Zivilisation. Daher nahm von dem, was im Aristotelismus war, sein Schüler Theophrast dasjenige, was man dem Abendlande übergeben konnte. Aber in dem steckte noch immer außerordentlich viel. Die mehr logischen Schriften des Aristoteles bekam das Abendland. Aber das ist nun eben das Eigentümliche des Aristoteles, daß er sich doch anders liest, selbst da, wo er abstrakt und logisch ist, als andere Schriftsteller. Man versuche es nur einmal mit innerer, spiritueller, auf Meditation gegründeter Erfahrung, den Unterschied herauszufinden zwischen dem Lesen des Plato und dem Lesen des Aristoteles. Wenn ein moderner Mensch mit einer wirklichen, richtigen geistigen Empfindung und Grundlage einer gewissen Meditation Plato liest, dann fühlt er nach einiger Zeit so, wie wenn sein Kopf etwas höher als der physische Kopf wäre, wie wenn er etwas herausgekommen wäre aus seinem physischen Organismus. Es ist das unbedingt bei demjenigen, der nicht nur ganz grob Plato liest, durchaus der Fall.

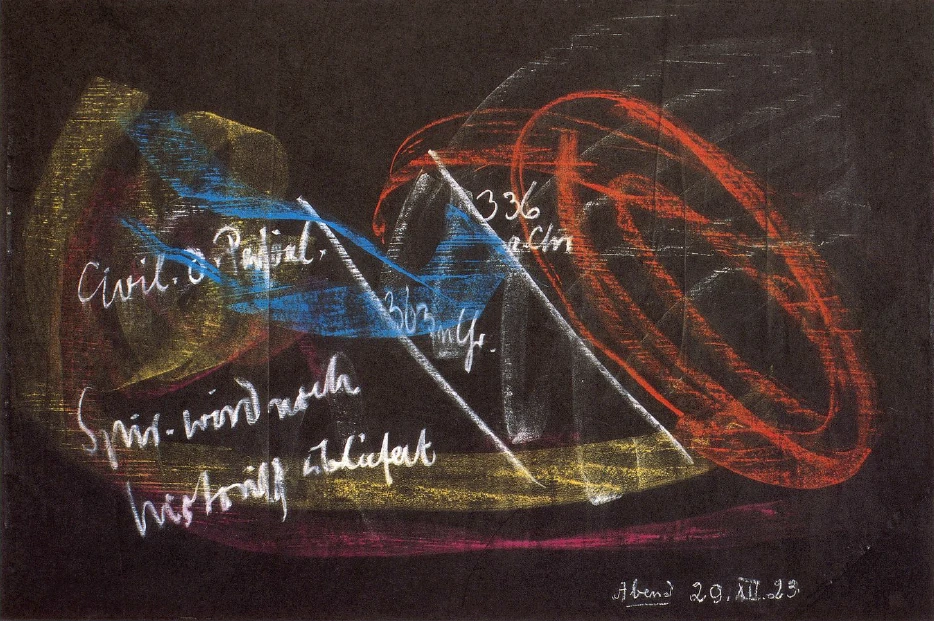

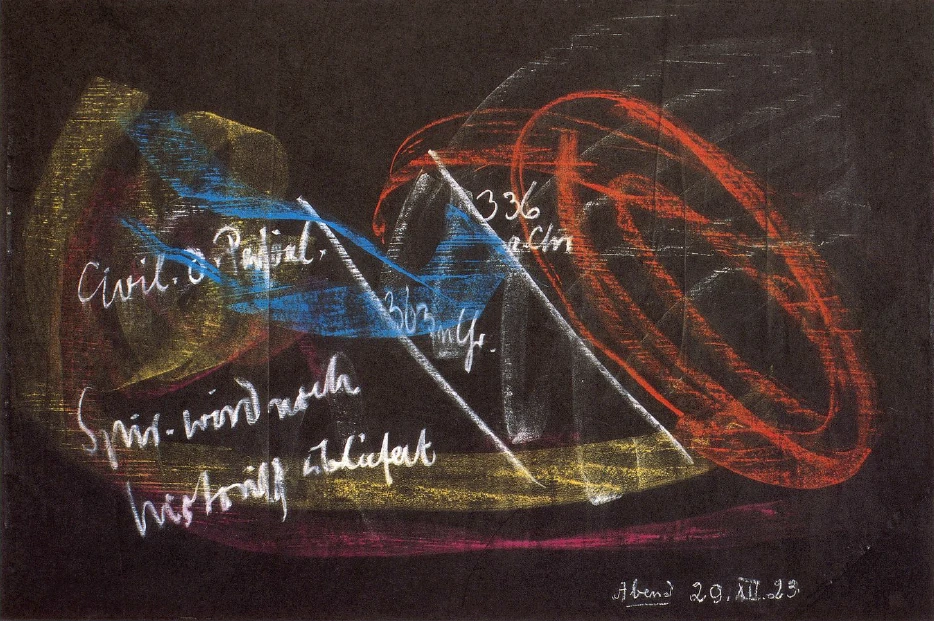

Bei Aristoteles ist das anders. Bei Aristoteles wird man niemals die Empfindung gewinnen können, daß man durch die Lektüre ausser den Körper kommt. Aber wenn man den Aristoteles auf Grundlage einer gewissen meditativen Vorbereitung liest, dann wird man das Gefühl haben: er arbeitet gerade in dem physischen Menschen. Der physische Mensch kommt gerade dutch Aristoteles vorwärts. Es arbeitet. Es ist nicht eine Logik, die man bloß betrachtet, sondern es ist eine Logik, die innerlich arbeitet. Aristoteles ist doch noch um ein Stück höher als alle die Pedanten, die hinterher gekommen sind und Logik aus dem Aristoteles gebildet haben. Aristoteles’ logische Werke sind in einer gewissen Beziehung nur dann richtig aufgefaßt, wenn sie als Meditationsbücher aufgefaßt werden. So daß ein Merkwürdiges vorliegt. Denken Sie sich einmal: Wenn auf das Abendland einfach übergegangen wären von Makedonien nach dem Westen, nach Mitteleuropa und Südeuropa, die naturwissenschaftlichen Schriften des Aristoteles, sie würden in einer Weise aufgenommen worden sein, die unheilvoll geworden wäre. Gewiß, die Menschen hätten manches aufgenommen, aber es wäre unheilvoll geworden. Denn dasjenige, was naturwissenschaftlich - ich habe eine Probe davon gegeben - Aristoteles zum Beispiel dem Alexander zu überliefern hatte, das mußte aufgefaßt werden mit Seelen, die doch noch berührt worden waren von dem Wesen der ephesischen Zeit, der vor dem Brande von Ephesus liegenden Zeit. Die konnte man nur drüben in Asien finden oder im ägyptischen Afrika. So daß durch die Alexanderzüge hinübergegangen war nach Asien die Naturwesenheits-Erkenntnis und -Einsicht (es wurde am Tafelbild - siehe Tafel IV - weitergezeichnet; orange nach rechts), und in abgeschwächter Gestalt kam sie später durch alle möglichen Züge über Spanien herüber nach Europa, aber in einem sehr durchgesiebten, abgeschwächten Zustande (gelb von rechts nach links).

Dasjenige aber, was direkt herübergekommen war, das waren die logischen Schriften des Aristoteles, war das Denkerische des Aristoteles. Und das lebte fort, lebte fort in der mittelalterlichen Scholastik.

Ja, und jetzt haben wir diese zwei Strömungen. Immer haben wir auf dem Grunde der mitteleuropäischen Einsichten dasjenige, was, ich möchte sagen, unansehnlich in weiten Kreisen von sogar etwas primitiven Menschen sich weiter fortpflanzt. Sehen Sie nur einmal, wie die Saat, die Alexander einstmals nach Asien hinübergetragen hat, die auf allen möglichen Wegen erst über Arabien und so weiter, dann aber auch auf den Landwegen durch die Kreuzfahrer nach Europa gekommen war, wie das überall lebt, aber unansehnlich, an verborgenen Stätten. Dahin kommen Leute wie Jakob Böhme, wie Paracelsus, wie zahlreiche andere, die das aufnehmen, was auf solchen Umwegen in die breiten primitiven Kreise Europas gekommen ist. Wir haben eine volkstümliche Weisheit hier übermittelt, viel mehr, als man gewöhnlich glaubt. Die lebt. Und sie rinnt manchmal in solche Reservoirs wie Valentin Weigel, wie Paracelsus, wie Jakob Böhme, wie viele andere, deren Namen viel weniger genannt wer Tafel 9 den; reichlich glänzt auf dasjenige, was da in Europa spät erst angekommener Alexandrinismus war oder ist, in Basilius Valentinus und so weiter. In Klöstern lebte eine wirkliche alchimistische Weisheit, die aber nicht bloß aufklärte über einige Verwandlungen der Stoffe, die aufklärte über innerste Eigentümlichkeiten der menschlichen Verwandlungen selber im Weltenall. Und die anerkannten Gelehrten beschäftigen sich mit einem allerdings entstellten, durchgesiebten, verlogisierten Aristoteles; aber dieser Aristoteles, mit dem sich die Scholastik und später die Wissenschaft beschäftigen als Philosophie, dieser Aristoteles wird doch dem Abendlande zum Segen. Denn erst im 19. Jahrhundert, als man nichts mehr verstand von Aristoteles, als man den Aristoteles nur noch studiert, als ob man ihn lesen sollte, als ob man nicht ihn üben sollte, als ob er nicht ein Meditationsbuch wäre, erst im 19. Jahrhundert kommt es dahin, daß die Menschen nichts mehr haben von Aristoteles, weil er nicht mehr in ihnen wirkt und lebt, sondern weil sie ihn bloß noch studieren, weil er nicht ein Übungsbuch ist, sondern ein Studienobjekt. Bis ins 19. Jahrhundert herein war er ein Übungsbuch. Aber sehen Sie, im 19. Jahrhundert geht ja alles so, daß dasjenige, was früher Übung war, was Können war, daß das sich umwandelt in abstraktes Wissen.

In Griechenland - nehmen wir diese andere Linie, dutch die sich die Sache auch charakterisiert -, in Griechenland hat man Vertrauen dazu, daß aus dem ganzen Menschen heraus noch das kommt, was der Mensch als Einsicht hat. Der Lehrer ist der Gymnast. Aus dem ganzen Menschen in seiner körperlichen Bewegung, in der die Götter wirken, kommt das zustande, was dann gewissermaßen heraufkommt und zu menschlicher Einsicht wird. Der Gymnast ist der Lehrer. In Rom tritt später an die Stelle des Gymnasten der Rhetor. Das ist schon etwas abstrahiert vom ganzen Menschen, aber es ist wenigstens noch etwas da, was zusammenhängt mit einem Tun des Menschen in einem Teil des Organismus. Was wird alles bewegt, wenn wir reden! Wie lebt das Reden in unserem Herzen, in unserer Lunge, wie in unserem Zwerchfell und weiter hinunter! Es lebt nicht mehr so intensiv im ganzen Menschen wie dasjenige, was der Gymnast getrieben hat, aber es lebt immerhin in einem großen Teil des Menschen. Und die Gedanken sind dann nur ein Extrakt aus dem, was im Reden lebt. Der Rhetor tritt an die Stelle des Gymnasten. Der Gymnast hat es mit dem ganzen Menschen zu tun. Der Rhetor hat es nur noch zu tun mit dem, was gewissermaßen die Gliedmaßen schon ausschließt und also aus einem Teil des Menschen herauf in den Kopf dasjenige schickt, was Einsicht ist. Und die dritte Stufe, die kommt erst in der Neuzeit herauf: das ist der Doktor, der nichts mehr abrichtet als den Kopf, der nur mehr auf die Gedanken sieht. Es ist ja so geworden, daß sozusagen noch im 19. Jahrhundert an einzelnen Hochschulen Professoren der Eloquenz ernannt worden sind, aber sie haben diese Professur nicht mehr ausüben können, weil es nicht mehr üblich war, etwas zu geben auf das Reden, weil alles nur noch denken wollte. Die Rhetoren starben aus. Diejenigen, die nur noch das Geringste am Menschen vertraten, die Doktoren, die nur noch den Kopf vertraten, die wurden die Führer der Bildung.

Und so war es wirklich, als der echte Aristoteles lebte, Übung, Askesis, Exerzitium, was aus dem Aristoteles folgte. Und diese zwei Strömungen verblieben sogar. Derjenige, der nicht ganz jung ist und der bewußt mitgemacht hat, was sich abspielte ab Mitte bis in die letzten Jahrzehnte des 19. Jahrhunderts, der weiß schon, wenn er etwas herumgekommen ist in der Art, wie etwa der Paracelsus unter dem Landvolke herumgegangen ist, der weiß schon, daß schließlich die letzten Überreste mittelalterlichen Volkswissens, aus dem Jakob Böhme, aus dem Paracelsus geschöpft hat, da waren bis in die siebziger, achtziger Jahre des 19. Jahrhunderts hinein. Und schließlich, auch das ist wahr: Namentlich innerhalb gewisser Orden und im Leben gewisser enger Kreise hat sich ein gewissser Aristotelismus der Praxis, der inneren Seelenpraxis auch noch erhalten bis in die letzten Jahrzehnte des 19. Jahrhunderts herein. Und man darf schon sagen: Man konnte noch kennenlernen auf der einen Seite die letzten Ausläufer desjenigen, was von Alexander vom Aristotelismus hinüber nach Asien getragen worden war, was auf der anderen Seite durch Vorderasien, Afrika, über Spanien herübergekommen ist und in solchen Leuten wie Basilius Valentinus und in Späteren auflebte als volkstümliche Weisheit, aus der ja auch Jakob Böhme, Paracelsus und zahlreiche andere geschöpft haben. Es ist auf anderem Wege auch wiederum zurückgekommen durch die Kreuzfahrer. Aber es war da in den breiten Massen des Volkes, und man konnte es noch finden. Man konnte noch in den letzten Jahrzehnten des 19. Jahrhunderts sagen: Gott sei Dank, daß da noch, wenn auch kaum erkennbar, wenn auch korrumpiert, die letzten Ausläufer desjenigen lebten, was als alte Naturwissenschaft durch die Alexanderzüge nach Asien hinübergetragen worden ist. Was da noch von alter Alchimie, von alter Erkenntnis und den Zusammenhängen der Natursubstanzen und Naturkräfte auf ganz merkwürdige Weise im primitiven Volkstume lebte, das waren die letzten Nachklänge. Heute sind sie erstorben, heute sind sie nicht mehr da, sind nicht mehr zu finden, ist in ihnen nichts mehr zu erkennen.

Ebenso war da bei gewissen einzelnen Leuten, die man kennenlernen konnte, aristotelische Geistesschulung. Heute ist sie nicht mehr da. Es war bewahrt dasjenige, was dazumal nach dem Osten hinübergetragen war (Fortsetzung der Tafelzeichnung; rot von rechts nach links), und dasjenige, was auf dem Umwege von Aristoteles’ Schüler Theophrastus nach dem Westen hinübergetragen war (blau von der Mitte nach links). Dasjenige aber, was nach dem Osten hinübergetragen war, das war wiederum zurückgekommen. Und man kann sagen: In den siebziger, achtziger Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts konnte angeknüpft werden mit neuem, unmittelbarem spirituellem Erkennen an dasjenige, was in den letzten Ausläufern anknüpfte an jene Ereignisse, die ich Ihnen geschildert habe. Das ist ein wunderbarer Zusammenhang, denn man sieht daraus, daß die Alexanderzüge und der Aristotelismus da waren, um den Faden mit dem alten Spirituellen aufrechtzuerhalten, um Einschläge zu haben in dasjenige, was materielle Kultur werden sollte, Einschläge zu haben, die gerade reichen, bis neue spirituelle Offenbarungen kommen sollten.

Sehen Sie, unter solchen Gesichtspunkten nimmt es sich ja wirklich so aus, und es ist dies wahr, daß scheinbare Unfruchtbarkeiten sich gerade als außerordentlich bedeutungsvoll im geschichtlichen Werden der Menschheit erweisen. Man kann leicht davon sprechen, daß die ganze Alexander-Expedition nach Asien und Ägypten hinüber dennoch verflutet wäre. Sie ist nicht verflutet. Man kann sagen, daß der Aristotelismus im 19. Jahrhundert aufgehört hat. Er hat nicht aufgehört. Beide Strömungen haben gereicht bis dahin, wo es möglich ist, ein neues spirituelles Leben zu beginnen.

Ich habe Ihnen ja an verschiedenen Orten öfter gesagt, daß dieses neue spirituelle Leben gerade am Ende der siebziger Jahre des 19. Jahrhunderts begonnen werden konnte in den ersten Andeutungen und dann mit dem Ende des Jahrhunderts immer mehr und mehr. Heute haben wir die Aufgabe, den vollen Strom des geistigen Lebens, der, ich möchte sagen, von den Höhen zu uns kommt, aufzufangen. Und so stehen wir heute drinnen in einem wirklichen Übergang der geistigen Menschheitsentfaltung. Und werden wir uns nicht bewußt dieser merkwürdigen Zusammenhänge und dieser Anknüpfung an Früheres, dann schlafen wir eigentlich gegenüber den wichtigsten Ereignissen, die sich um uns herum im geistigen Leben abspielen. Und wieviel wird eigentlich heute wirklich ge Tafel 9 schlafen gegenüber den allerwesentlichsten Ereignissen! Anthroposophie sollte aber dasein, um den Menschen zu erwecken.

Und ich glaube, für alle diejenigen, die jetzt hier bei dieser Weihnachtstagung versammelt sind, gibt es einen Impuls einer möglichen Erweckung. Sehen Sie, wir stehen ja unmittelbar vor dem Tage und werden uns in dieser Tagung eben bis zu dem Jähren dieses traurigen Ereignisses hindurchfinden müssen, wir stehen vor jenem Tage, da die furchtbaren Feuergarben aufloderten, die das Goetheanum verzehrten. Und mag nun die Welt denken, wie sie will, über dieses Feuerverzehren des Goetheanum, in der Entwickelung der anthroposophischen Bewegung bedeutet dieser Brand etwas Ungeheures. Aber man beurteilt ihn doch nicht in seiner vollen Tiefe, wenn man nicht hinschaut auf der einen Seite, wie diese physischen Feuerflammen dazumal aufschlugen, als in merkwürdiger Art - ich werde davon noch sprechen in den nächsten Tagen - von den Orgelpfeifen, von anderem Metallischem das sengende Metallische in die Flammen hineinloderte, so daß diese merkwürdigen Färbungen der Flammen entstanden. Dann mußte man die Erinnerung mit hinübernehmen in das verflossene Jahr. Aber in dieser Erinnerung muß leben die Tatsache, daß Physisches Maja ist, daß wir die Wahrheit aus den Feuerflammen in dem geistigen Feuer zu suchen haben, das wir nunmehr anzufachen haben in unseren Herzen, in unseren Seelen. Aufgehen sollte uns in dem physisch brennenden Goetheanum das geistig wirksame Goetheanum.

Ich glaube nicht, daß das in vollem weltgeschichtlichem Sinne geschehen kann, wenn man nicht sieht auf der einen Seite das uns teuer gewordene Goetheanum in der furchtbaren gigantischen Flamme auflodern und im Hintergrunde den anderen frevelhaften Brand von Ephesus, wo Herostrat die Brandfackel hineinwarf, geleitet von dämonischen Mächten. In dem Zusammenempfinden desjenigen, was da im Vordergrunde, und desjenigen, was im Hintergrunde steht, wird man vielleicht doch ein Bild gewinnen können, das tief genug in unser Herz hineinschreiben kann, was wir vor einem Jahre verloren haben und was wir mit allen Kräften wieder erbauen müssen.

Sixth Lecture

The time three to four centuries before the Mystery of Golgotha, three to four centuries after, which gives a period of six to eight centuries, this time is particularly important for the understanding of the history of the West in its connection to the Orient. The essence of the events of which I have spoken in the past few days and which culminated in the emergence of Aristotelianism and in the Alexander campaigns from Macedonia to Asia, the essence of these events is that they form a kind of conclusion for that civilization of the Orient which was still completely immersed in the impulses of the Mysteries.

The last conclusion, so to speak, of these still genuine, pure mystery impulses of the Orient was the sacrilegious fire of Ephesus. And we then have to deal with what remains, so to speak, for Europe, for Greece, of the mystery tradition, of shadow images, I would say, of the old God-infused civilization. And four centuries after the Mystery of Golgotha we can see, so to speak, through another event, what was still left of the ruins of the mystery system. We can see it in Julianus Apostata. Julianus Apostata, the Roman emperor, is initiated in the 4th century into that into which one could just be initiated, by one of the last hierophants of the Eleusinian Mysteries. In other words, Julianus Apostata learned just as much about the older mysteries of the gods of the Orient as could still be learned in the Eleusinian mysteries in the 4th century AD.

This brings us to a point, the starting point of a certain age, the burning of Ephesus. The day of the burning of Ephesus is the birthday of Alexander the Great. We are at the end of this epoch, 363, the anniversary of the death, the violent death of Julianus Apostata over in Asia. One might say that the Mystery of Golgotha stands in the middle of this period. And now let us take a look at how this period, which I have just limited, actually stands out in the entire history of human development. We now have before us the curious fact that, if we want to look back beyond this period into the development of mankind, we must do something in our view that is very similar to another. Only we often do not bring the two things together,

Remember how I was compelled to describe in my “Theosophy” the worlds that come into consideration for us: the physical world, bordering on it a transitional world, the soul world, and then as the world into which only the highest part of man can gain entry, the spirit world. And if we disregard the particular peculiarities of this spirit-land, which man is presently passing through between death and a new birth, if we thus look at the general peculiarities of the spirit-land, then it is the case that in a very similar way to how we must reorient our soul constitution in order to comprehend this spirit-land, we must reorient our soul constitution in order to comprehend that which lies beyond this point in time. With the concepts and ideas that are applicable to today's world, we should not believe that we can understand what lies beyond the fire of Ephesus. We must develop other concepts and ideas that allow us to look at people who still knew that they, like man in the breathing process with the outer air, they are continuously connected with the gods through their souls.

And now, let us look at this world, which is, so to speak, an earthly devachan, an earthly spirit land, for the physical world is of no use to this world. Then we have that interim period from my will 356 before Christ to 363 after Christ. And what lies beyond that? Beyond that towards Asia, beyond that towards Europe, lies the world from which present-day humanity is just about to emerge, just as ancient humanity emerged from the Oriental world via the Greek into the Roman Empire (see drawing). For that which has developed as a civilization through the centuries of the Middle Ages up to our own times is a civilization which has formed and unfolded, apart from the actual interior of the Mystery Being, which has developed on the basis of what man can form with his concepts and ideas. In Greece it had already been prepared since Herodotus, who described the facts of history in an external way and no longer approached the spiritual, or at least only very inadequately. This then developed more and more. But in Greece there still remains something of the breath of those shadowy images that should remind us of the spiritual life. In Rome, on the other hand, begins that age to which mankind of the present is still related, that age which has a soul constitution quite different from that of Greece. Only such a personality as Julianus Apostata feels something like an invincible longing for the old world, and he allows himself to be initiated into the Eleusinian mysteries with a certain sincerity. But there is no more power of knowledge in what he receives. And above all, he comes from a world that can no longer fully grasp the traditions of the mysteries of the Orient with the inner soul.

Today's humanity would never have come into being if Asia had not been followed by Greece and Rome. Today's humanity is that humanity which is built on personality, on the individual personality of the individual. The oriental personality, the oriental humanity was not built on the individual personality of the individual. The individual felt himself to be a member of the ongoing divine process. The gods had their intentions with earthly development, the gods wanted this or that; therefore this or that happened down here on earth. The gods inspired the will of man. Everything that the powerful personalities I have pointed out to you did in the Orient was inspired by the gods. The gods wanted, and the people did. And in the older times, the mysteries were precisely designed to bring this will of the gods and the actions of men into the right channels.

It was only in Ephesus that things changed. There, as I told you, the students of the Mysteries were dependent on their own maturity, no longer on the course of the seasons. It was there that the first trace of personality appeared. Aristotle and Alexander the Great had also received the impulse of personality in earlier incarnations. But now came the time, which has its dawn there, where Julianus Apostata gets the last longing to be a man of the mystery being of the Orient. Now comes the time when the human soul becomes quite different from what it was even in Greece.

Imagine another such person who has received his training in the Ephesian Mysteries. It was not through the Ephesian Mysteries, but through the fact that he lived at that time that it was so in his soul. You see, when a man today reflects, as they say, what can he reflect on? He can reflect on something that he has personally experienced since his birth. There is a person of a certain age; he reflects on what he experienced twenty or thirty years ago. The inner reflection leads no further than his personal life. $This was not the case with people who, for example, were still part of the Ephesian civilization. If they had only a trace of the training that was to be acquired in Ephesus, then it came about, as they reflected, that memories of their personal life, the events of their pre-earthly existence and also the events that preceded the earthly development in the individual kingdoms of nature emerged in their souls, as they do today: Lunar evolution, solar evolution. There one could look into oneself and see the cosmic, the connection of the human being with the cosmic, as it were the attachment of the human being to the cosmic. What lived in the human soul was self-remembering.

We can therefore say that we have an age, the age in which the mysteries of the world could be experienced in Ephesus. There was a remembering of the human soul of the prehistoric times in the cosmos. This remembering was preceded by a real inner life in the past. What remained was simply a looking into the past. In the time of which the Epic of Gilgamesh tells, we cannot say that the human soul remembers the past in the cosmos; we must say that it experiences the past in the present. - Now comes the period from Alexander to Julianus Apostata. Let us leave it out for the moment. And then we come to the age from which the Western civilization of the Middle Ages and modern times grew. There was no longer a remembrance of the human soul of the past in the cosmos, no longer an experience of the past in the present, but only tradition.

Firstly: experiencing the past in the present.

Second: Remembering the human soul of the past in the cosmos.

Thirdly: tradition.

One could write down what had happened. History came into being. This history begins with the Roman age. Think of the enormous difference! Think of the time that was experienced by the older Ephesian disciples. They didn't need history books. Writing down what happened would have seemed ridiculous to them. For one had to think, think deeply enough, then what had happened came up from the depths of consciousness. And there was no modern medicus who presented this as psychoanalysis, but it was precisely the delight of the human soul to bring up in this way from a living memory what had once been there.

Then came the time when humanity as such had forgotten and had to make a makeshift record of what had happened. But while mankind had to let atrophy that which was formerly cosmic power of memory in the human soul, while mankind had to bunglingly begin to write down world events, to write history and so on, during this time the personal memory, the personal remembrance, developed within the human being. - Every age has its own special mission, its own special task. - Here you have the other side of what I have already explained in the very first lectures, that the memory of time emerged. This memory of time had its first cradle in Greece, but then developed through the Roman-Roman culture into the Middle Ages and up to modern times. And the fact that at the time of Julianus Apostata the seeds of this culture of personality had already been sown is proof of the fact that Julianus Apostata's initiation into the Eleusinian mysteries was basically of no further use.

So now comes the time in which man in the Occident, from the 3rd, 4th century AD right up to our own time, lives entirely outside the spiritual world during his life on earth, the time in which he lives in mere concepts and ideas, in abstractions. In Rome even the gods become abstractions. The time comes when mankind no longer knows anything about living together with the spiritual world. The earth is no longer Asia, the lowest region of the heavens, the earth is a world of its own, and the heavens are distant, dimmed in human vision. So that one can say: Man develops his personality under the influence of what has come over the Occident as Roman culture.