The Evolution of the Earth and Man

and the Influence of the Stars

GA 354

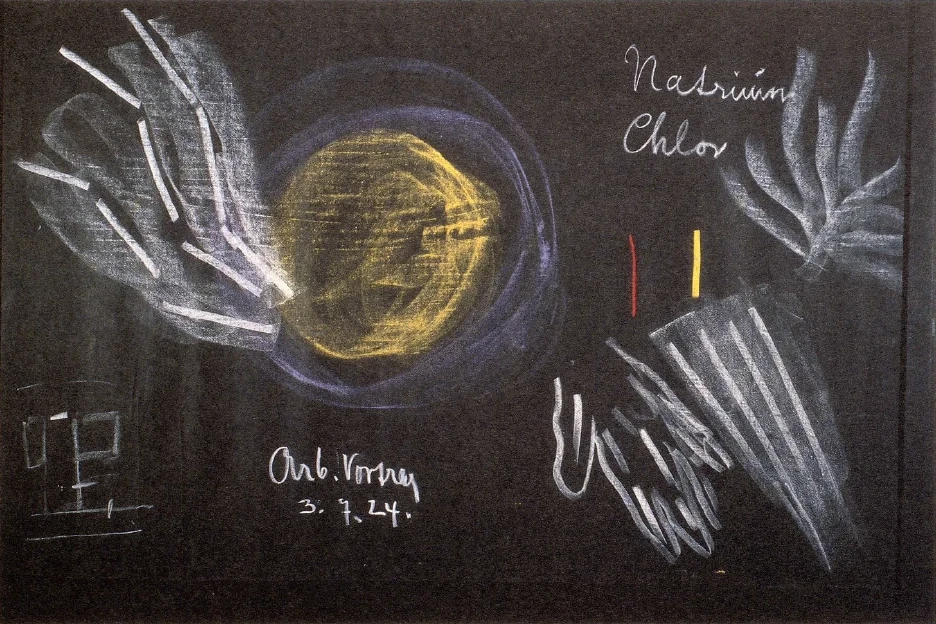

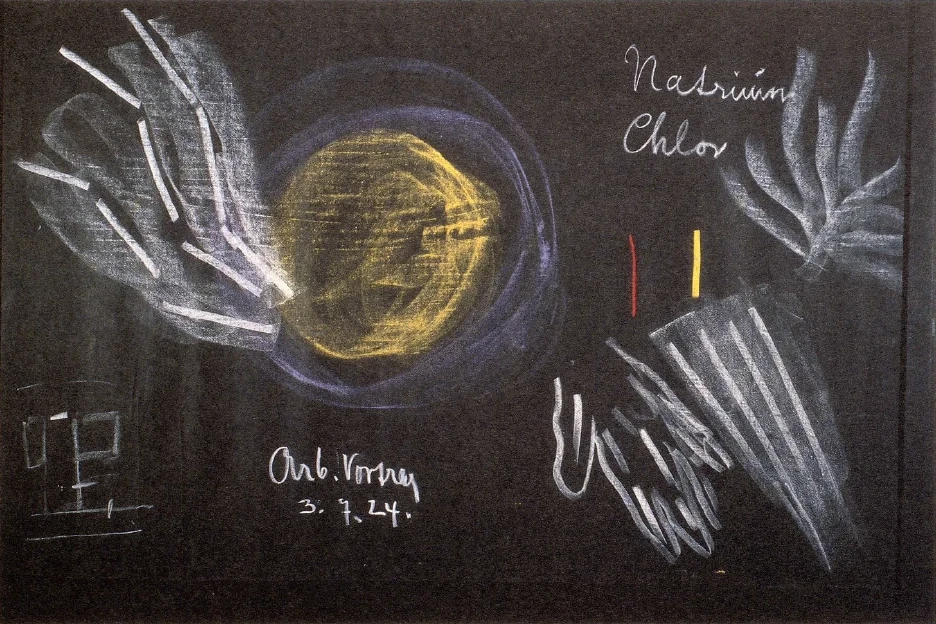

3 July 1924, Dornach

Lecture II

Rudolf Steiner: Good morning, gentlemen! Today I would like to speak further about the creation of the earth and the origin of man. It has surely become clear from what I have already said that the earth was originally not what it is today, but was a kind of living being.

I described the condition that existed before our actual Earth condition by saying that warmth, air, and water were there but as yet no really solid mineral structures. Now you must not imagine that the water existing at that time looked like the present water. Our present water has become what it is by the separation of certain substances which were formerly dissolved in it. If you take a glass of ordinary water and put some salt in it, the salt dissolves in the water and you get a fluid-a salt solution, as one calls it-which is denser than the original water. If you put your fingers in it, it feels much denser than water. Now dissolved salt is relatively thin; with certain other substances one gets quite a thickish liquid.

The fluid condition, the water condition which existed in earlier ages of our earth was therefore not that of today's water. That did not exist, for substances were dissolved in the water everywhere. All the substances that you have today-the Jura limestone mountains, for instance-were dissolved; harder rocks that you can't scratch with a knife (limestone can always be scratched) were also dissolved in the water. During this Old Moon stage, therefore, one has to do with a thickish fluid that contained in solution all the substances which today are solid.

The thin water of today, which consists essentially of hydrogen and oxygen, was separated off later; it has developed only during the earth period itself. Thus we have as an original condition of the earth a densified fluid, and round about it a kind of air. But this was not the air of today; just as the water was not like our present water, so the air was not the same as our present air. Our present air contains essentially oxygen and nitrogen; the other substances which it still contains are present to a very slight degree. There are even metals still present in the air, but in exceedingly small quantities. For instance, there is one metal, sodium, that is everywhere in the air. Just think what that means—that sodium is everywhere, that a substance which is in the salt on your table is present everywhere in tiny quantities.

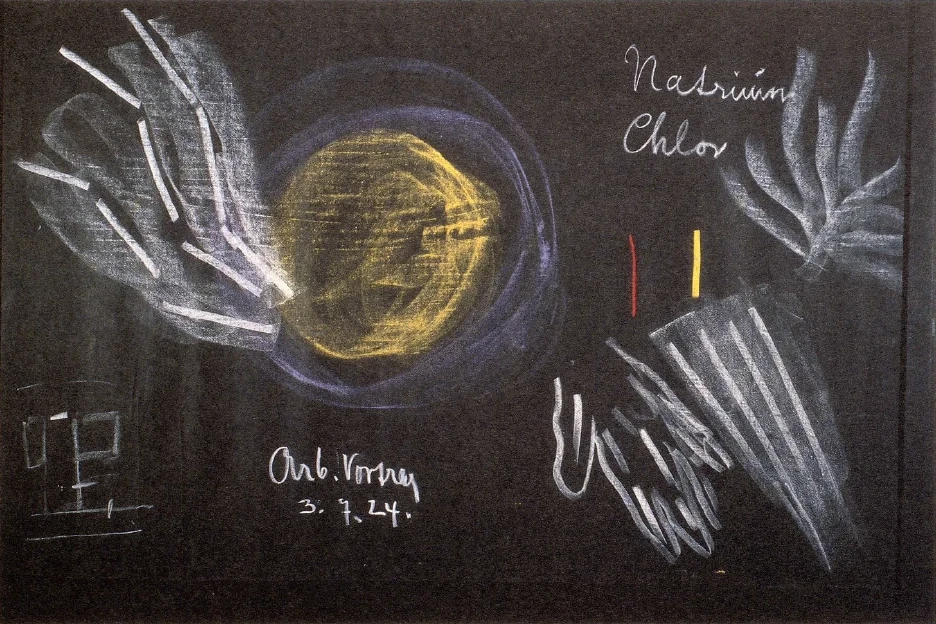

There are two substances—one is the sodium which I have just mentioned, which is present in small quantities in the air; then there is a substance of a gaseous nature which plays a great role when you bleach your laundry: chlorine. It causes the bleaching. Now the salt on your table is composed of sodium and chlorine, a combination of the two. Such things come about in nature.

You can ask how one knows that sodium is everywhere. It is possible today to tell from a flame what sort of substance is being burnt in it. For instance, you can get sodium in a metallic form and pulverize it and hold it in a flame. You can then find with an instrument called a spectroscope that there is a yellow line in it. There is another metal, for example, called lithium; if you hold that in the flame, you get a red line; the yellow is now not there, but there is a red line. One can prove with the spectroscope what substance is present.

But you get the yellow sodium line in almost every flame whenever you light one, without having put the sodium in yourself. Thus sodium is still in the air today. In earlier times immense quantities of metals and even of sulphur were present in the air. The air was quite saturated with sulphur. So there was a thickish water—if one had not been especially heavy one could have gone for a walk on it; it was like running tar—and there was a dense air, so dense that one could not have breathed in it with our present lungs. These were only formed later. The mode of life of the creatures that existed at that time was utterly different.

Now you must picture to yourselves that the earth once looked like this. (See drawing.) Had you found yourself there with your present eyes, you would not have discovered the stars and sun and moon out there, for you would have looked out into a vague ocean of air which reached an end eventually. If one could have lived then with the present sense organs, one would have seemed to be inside a world-egg beyond which one could see nothing. And you can imagine how different the earth looked at that time, like a kind of giant egg yolk, a thick fluid, and a thick air environment corresponding to the white of the present-day egg.

If you picture concretely what I have described, you will have to say: Well, beings such as we have today could not have lived at that time. Naturally, creatures like the elephant, and even human beings in their present form, would have sunk—nor could they have breathed. And because they could not have breathed, there were also no lungs as we know them now. Organs are formed entirely according to the function they are needed for. It is very interesting that an organ is simply not there if it is not needed. And so lungs only developed when the air was no longer so full of sulphur and metals as it had been in those ancient times.

Now to get an idea of what sort of creatures lived at that time, we must first look for those that lived in the thickish water. Creatures lived in that dense water that no longer exist today. Our present fish have their form because the water is thin. Even sea-water is comparatively thin; it contains much salt in solution, yet it is comparatively thin. But in that early time every possible substance was dissolved in the dense fluid, the dense ocean, of which, in fact, the whole earth, the Moon-sack consisted.

The creatures that were in it could not swim in our sense, because the water was too thick; nor could they walk, for one needs firm ground for walking. You can imagine that these creatures had a bodily structure somewhere between what one needs for swimming-fins—and what one needs for walking—feet. You know, of course, what a fin looks like—it has quite fine, spiky bones and the flesh in between is dried-up. So that we have a fin with practically no flesh on it and prickly bones transformed to spikes: that is a fin. Limbs that are suitable for moving forward on firm ground, that is, for walking or crawling, have their bones set into the interior and the outer bulk of flesh covers them. We can conceive of such limbs that have the flesh outside and the bones inside; there the bulk of flesh is the main thing. That belongs to walking, or swimming.

But at that time there was neither walking nor swimming, but something in between. These creatures therefore had limbs in which there was something of a thorn-like, nature, but also something like joints. They were really quite ingenious joints, and in between, the flesh mass was stretched out like an umbrella. You still see many swimming creatures today with a “swim skin”—a web—between the bones, and they are the last relics of what once existed in vast numbers. Creatures existed which stretched out their limbs so that the spreading flesh mass was supported by the dense fluid. And they had joints in their limbs—the fishes today have none—and with these they could direct their half-swimming, half-walking.

So we are made aware of animals which particularly needed such limbs. Today the limbs would look immensely coarse and clumsy; they were not fins, not feet, not hands, but clumsy appendages on the body, thoroughly appropriate for living in that thick fluid. This was one kind of animal. If we want to describe them further, we must say: They were especially organized in the parts of the body where these immense limbs could arise. All the rest of them was poorly developed. If you look at the toads and similar creatures existing today which sort of swim in the thick fluid of boggy marshes, then you have a feeble, shrunken reminder of the gigantic animals which lived once upon a time, which were heavy and clumsy but had diminutive heads like turtles.

Other creatures lived in the dense air. Our present birds have had to acquire what they need to live in our thin air; they have had to develop something of a lung nature. But the creatures that lived at that time in the air had no lungs; in that dense sulphurous air it would not have been possible to breathe with lungs. They absorbed the air as a kind of food. They could not have eaten in the present way, for it would all have remained lying in the stomach. Nor was there anything solid there to eat. All that they took in as food they took in out of the densified air. Into what did they take it? Well, they took it into what developed in them especially.

Now the flesh masses that existed in those so to say, gliding creatures (for they were not really walking and not really swimming), could not be used by the air-creatures, for these had to support themselves in the air, not swim in the dense fluid. It came about then that the flesh masses which had developed in the gliding, half-swimming creatures became adapted to the sulphurous condition of the air. The sulphur dried up these flesh masses and made them into what you see today as the birds' feathers. With this flesh mass or dried-up tissue the creatures could form the limbs they needed. They were not wings in the present sense, but they supported them in the air, and were something similar to the wings of today. They were very, very different in one respect: there is only one thing remaining from these wing-like structures, and that is moulting, when our present birds lose their feathers. These former creatures supported themselves in the dense air with the structures that were not yet feathers but rather dried-up tissue.

Moreover, these structures were actually half for breathing and half for taking in nourishment. What existed in the air environment was absorbed. These organs were not used for flying; these rudimentary “wings” were for absorbing the air and pushing it away. Today only moulting is left of this process. At that time, these structures served for taking in nourishment, that is, the bird puffed up its tissue with what it absorbed from the air and then gave out again what it did not need. So such a bird had a very remarkable structure indeed!

And so at that time there lived those terribly clumsy creatures below in the water-element—our present turtles are indeed fine princes by comparison! And above were these remarkable creatures. And whereas our present birds sometimes behave in the air unmannerly (which we take very much amiss), these bird-like creatures in the air of that time excreted continuously. What came from them rained down, and rained down especially at certain times. The creatures below did not yet have the attitude which we have. We are indignant if sometimes a bird behaves in an unseemly way. But those creatures below in the fluid element were not displeased; they sucked up into their own bodies what fell down from above. That was the fructifying process at that time. That was the only way in which these creatures which had originated there could continue to live. In those ages there was no definite coming forth of one animal from another, as we have now. One might say that actually these creatures lived a long time; they kept renewing themselves. One could call it a sort of world-moulting; the animals down below kept rejuvenating themselves again and again.

On the other hand, to the creatures above came what was developed by those below and this again was a fructification. Reproduction was at that time of a very different nature; it went on in the whole earth-body. The upper world fructified the lower, the lower world fructified the upper. The whole earth-body was alive. One could say that the creatures below and the creatures above were like maggots in a body-where the whole body is alive and the maggots in it are alive too. It was one life, and the various beings lived in a completely living body.

But later something occurred of very special importance. The condition I have described could have gone on for a long time; all could have remained as it was without becoming our present earth. The heavy, clumsy creatures could have continued to inhabit the living earth together with the creatures able to live in the air. But one day something happened. It happened that one day from this living earth, let me say, a young one, an offspring, was formed and went out into cosmic space. It came about in this way: a small protuberance developed, which wore away (see drawing) and at last split off. And a body was now out in the universe which had, instead of the earlier conditions, the surrounding air inside and the thick fluid outside. Thus an inverted body was separated off. Whereas the Moon-earth remained with thick fluid for its inner nucleus and thickish air outside, a body split off which now had the thicker substance outside and the thinner inside. And if one investigates the matter without prejudice, in honest research, one can recognize in this body the present moon. Today just as one can find sodium in the air, one can also learn the exact constituents of the moon, and so one can know that the moon was once in the earth. What circles round us out there was formerly within the earth, then separated off and went out into the cosmos.

With this a complete change took place, not only in what separated itself off but also in the earth itself. Above all, the earth lost certain substances, and for the first time the mineral element could be formed in the earth. If the moon-substances had remained in the earth, minerals could never have been formed, and there would always have been a state of moving fluid. The departure of the moon brought death for the first time to the earth and with it the dead mineral kingdom. But with this came also the possibility for the present plants, present animals and man in his present form to develop.

We can say, therefore, that out of the Old Moon arose the present earth together with the mineral kingdom. And now all forms had to alter. For with the departure of the moon the air became less sulphurous, approaching nearer to the present condition, and what had been dissolved in the fluid was now thrown out, forming mountain-like masses. The water grew more and more like our present water. On the other hand the moon, which has around it what we have in the interior of the earth, produced a thickish, horny mass on the outside. This is what we see when we look up. It is not like our mineral kingdom, but it is as if our mineral kingdom had become horn-like and turned into glass. It is extraordinarily hard, harder than anything horn-like that we have on earth, but it is not quite mineral. Hence the peculiar shape of the moon mountains; they actually all look like horns that have been fastened on. They are formed in such a way that one can even perceive what had been organic in them, what had once been a part of life.

Beginning with the separation of the moon, our present minerals were gradually deposited from the former dense fluid. Particularly active was a substance that in those ancient times existed in great amounts and consisted of silica and oxygen—we call it silicic acid. One has the idea that an acid must be fluid, because that is the form in which it is used today. But the acid which I mean here and which is a genuine acid is extremely hard and firm. It is, in fact, quartz! The quartz which you find in the high mountains is silicic acid. And when it is whitish and like glass it is pure silicic acid. If it contains other substances you get the quartz—or flint—that looks violet, and so on. That comes from the substances contained in it.

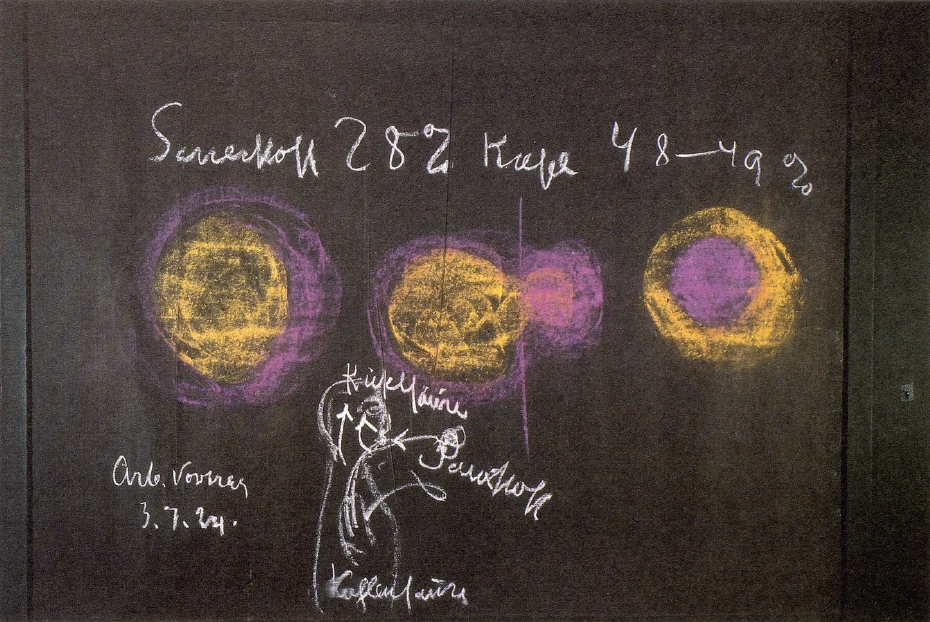

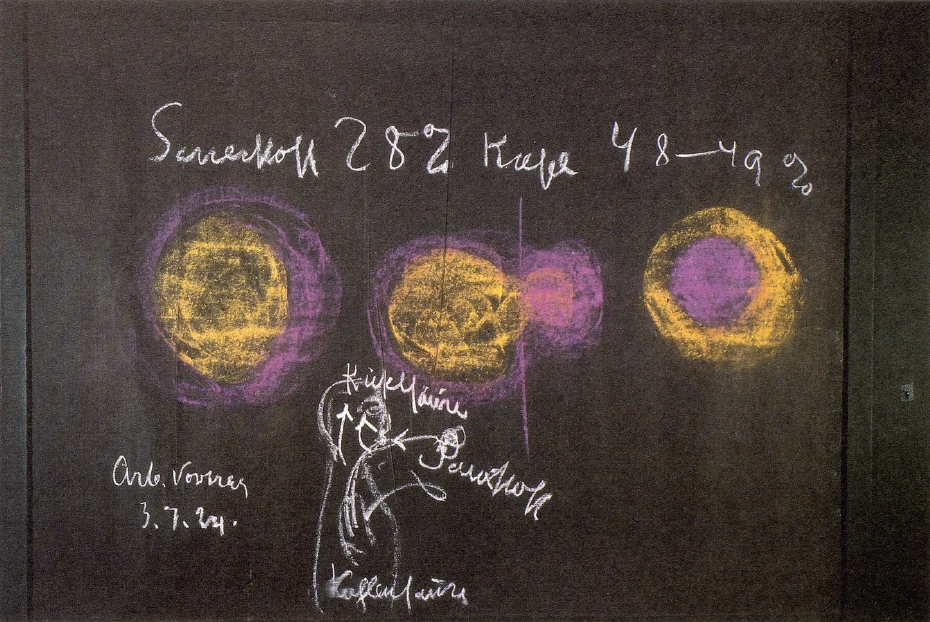

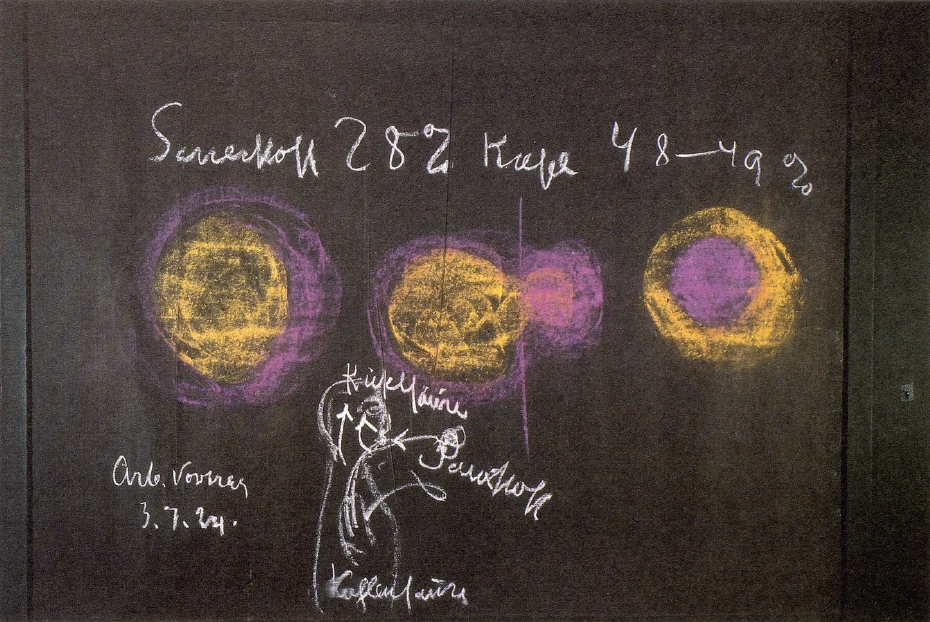

But the quartz which is so hard today that you can't scratch it with a knife, and if you hit your head on it, it would make a real hole in your head—this same quartz was dissolved in those ancient times, either in the thick fluid or in the finer surroundings of dense air. In addition to the sulphur there was an immense amount of dissolved quartz in the thick air around the earth. You can get an idea of the strong influence this dissolved silicic acid had at that time if you reflect on the composition of the earth today just here where we live. Of course you can say: There must be a great deal of oxygen, because we need it for breathing. Yes, there is a good deal of oxygen: 28 to 29% of the whole mass of the earth. But you must count everything. Oxygen is in the air and in many solid substances on the earth too; it is in the plants and animals. And if you put all this together it is 28% of the whole.

But silica, which when united with oxygen in the quartz gives silicic acid, is 48 to 49%! Think what that means: half of all that surrounds us and that we need, almost half of that is silica! When everything was fluid, when the air was almost fluid before it thickened—yes, then this silica played an enormous role, it was very important in that original condition. Nowadays these things are not understood rightly because concerning man's finer organization, people no longer have the right idea. They think today in a casual, crude way: Well, we're humans and we have to breathe. We breathe oxygen in and we breathe carbon dioxide out. We can't live if we don't breathe like this. But silica is still always contained in the air we inhale, genuine silica, tiny quantities of silica. Plenty is available, for 48 to 49% of our surroundings are made up of silica.

When we breathe, the oxygen goes down to the metabolism and unites with carbon, but at the same time it also goes up to the senses and the brain, to the nervous system: it goes everywhere. There it unites with the silica and forms silicic acid in us. If we look at a human being we see he has lungs and is inhaling air, that means, he is taking in oxygen. Below, the oxygen unites with carbon and forms carbon dioxide which he then exhales. But above, the silica is united in us with the oxygen and goes up into our head, as silicic acid—however, it does not become as solid up there as quartz. That, of course, would be a bad business if pure quartz crystals showed up inside your head—then instead of hair you would have quartz crystals, which perhaps would be quite beautiful and amusing! Still, that is not entirely fantasy—for there is a good deal of silicic acid in our hair, only it is still fluid, not crystallized. In fact, not only hair but practically everything in the nerves and senses contains silicic acid.

One discovers this when one first gets to know the beneficial, healing effects of silicic acid; it is tremendously helpful as a remedy. You must realize that the food received through the mouth into the stomach must pass through all manner of intermediate things before it comes up into the head, the eye, the ear, and so forth. That is a long way for the nourishment to go, and it needs helping forces to enable it to come up at all. It might be—in fact, it happens often—that a person has not enough helping forces and the foods do not work up properly into the head; then one must prescribe silicic acid which assists the nourishment to rise to the head and the senses. As soon as one sees that a patient is normal as regards stomach and intestines, but that the digestion does not go all the way to the sense organs, the head, or the skin, one must administer a silicic acid preparation as remedy. There one sees, in fact, what a very great role silicic acid still plays today in the human organism.

In that ancient condition of the earth, the silicic acid was not yet inhaled but was absorbed. The bird-like creatures in particular took it in. They absorbed it as they absorbed the sulphur, with the consequence that they became almost entirely sense organs. Just as we have silicic acid to thank for our sense organs, so at that time the earth as a whole owed its bird-like species to the working of the silicic acid that was present everywhere. Since, however, this did not come in the same way to those other creatures with the clumsy limbs, since the silicic acid reached those creatures less as they glided along in the dense fluid, they became in the main stomach- and digestion-creatures. There above in those days were terribly nervous creatures, aware of everything with a fine nervous sensitivity. On the other hand, those below in the thick fluid were of immense sagacity, but also of immense phlegmatism. They felt nothing of it; they were mere feeding-creatures, were really only an abdomen with clumsy limbs. The birds above were finely organized, were almost entirely sense organs. And indeed they were sense organs for the earth itself, so that it was not only filled with life but it perceived everything through these sense organs that were in the air, the fore-runners of our birds.

I tell you all this so that you may see how different everything once looked on the earth. All that was dissolved at that time became deposits later in the solid mineral mountains, the rock masses, and formed a kind of bony scaffolding. Only then was it possible for man and animal to form solid bones. For when externally the bony framework of the earth was formed, then bones began to form also inside the higher animals and man. What I have spoken of before was not yet firm, hard bone as we have today, but flexible, horn-like cartilage as it has still remained in the fish. All these things have in a certain way remained behind and atrophied, for in the earlier ages which I have described the life-conditions for them were there, but today the necessary life-conditions are no longer present.

We can say, therefore: In our modern birds we have the successors of the bird-like species which existed above in the dense air full of sulphur and silicic acid but now transformed and adapted to the present air. And in the amphibians of today, the crawling creatures, in the frogs and toads, but also in the chameleon, the snake, and so forth, we have the successors of the creatures that were swimming at that time in the dense fluid. The higher mammals and man in his present form came later.

Now this makes an apparent contradiction: I said to you last time that man was there first. But he lived in the warmth purely as soul and spirit; he was indeed already present in all that I have described, but not as a physical being. He was there in a very fine body in which he could support himself equally in the air and in the dense fluid. And neither he nor the higher mammals were visible as yet; only the heavy creatures and the bird-like air-creatures were visible. That is what must be distinguished when one says that man was already there. He was first of all, before even the air was there, but he was invisible, and he was still in an invisible state when the earth looked as I have now described. The moon had first to separate from the earth, then man could deposit mineral elements in himself, could form a mineral bony system, could develop such substances as protein, and so forth, in his muscles. At that time such substances did not as yet exist. Nevertheless, man has completely preserved in his present corporeal nature the legacy of those earlier times.

For the human being cannot now come into existence without the moon influence, coming now only from outside. Reproduction is connected with the moon, though no longer directly. It can therefore be seen that what is connected with reproduction—the woman's monthly periods—take their course in the same rhythmical periods as the phases of the moon, only they no longer coincide; they have freed themselves. But the moon influence has remained active in human reproduction.

We have found reproduction accomplished between the beings of the dense air and those of the dense fluid, between the bird-like race and the ancient giant amphibians. They mutually fructified one another because the moon was still within the earth. As soon as the moon was outside, fructification had to come from outside, because the fructifying principle lies in the moon.

We will continue from this point on Saturday3This lecture was postponed to Monday, July 7th at nine o'clock—if we can have that hour. The question put by Herr Dollinger is one that must be answered in detail, and if you have patience you will see how present-day life emerges from all the gradual preparatory conditions. The whole subject is indeed difficult to understand. But I believe one can understand if one looks at things in the way we have been looking.

Zweiter Vortrag

Guten Morgen, meine Herren! Nun will ich heute weiterreden über Erdenschöpfung, Menschenentstehung und so weiter. Es ist Ihnen ja wohl klargeworden aus dem, was ich Ihnen gesagt habe, daß unsere ganze Erde ursprünglich nicht so war, wie sie sich heute darstellt, wie sie heute ist, sondern sie war eine Art von Lebewesen. Und wir haben ja den vorletzten Zustand vor dem eigentlich irdischen Zustand, den wir besprochen haben, dadurch kennengelernt, daß wir sagen mußten: Wärme war da, Luft war da, Wasser war auch da; aber es war noch nicht eigentliche feste mineralische Erdenmasse da. Nur müssen Sie sich nicht vorstellen, daß das Wasser, das dazumal da war, schon so aussah wie das heutige Wasser. Das heutige Wasser ist ja erst so geworden dadurch, daß diejenigen Stoffe, die vorher im Wasser aufgelöst waren, sich aus dem Wasser heraus abgeschieden haben. Wenn Sie heute nur ein ganz gewöhnliches Glas Wasser nehmen, etwas Salz hineingeben, so löst sich das Salz im Wasser auf; Sie bekommen eine Flüssigkeit, eine Salzlösung, wie man sagt, die viel dicker ist als das Wasser. Wenn Sie hineingreifen, spüren Sie die Salzlösung viel dichter als das Wasser. Nun ist aufgelöstes Salz verhältnismäßig noch dünn. Es können auch andere Stoffe aufgelöst werden; dann kriegt man eine ganz dickliche Flüssigkeit. So daß also dieser Flüssigkeits-, dieser Wasserzustand, der einmal auf unserer Erde in früheren Zeiten da war, nicht heutiges Wasser darstellt. Das gab es überhaupt dazumal nicht, da in allen Wassern Stoffe aufgelöst waren. Denken Sie doch: Alles dasjenige, was Sie in heutigen Stoffen drinnen haben, das Jurakalkgebirge zum Beispiel, das war aufgelöst dadrinnen; alles dasjenige, was Sie in härteren Gesteinen haben, die Sie nicht mit dem Messer ritzen können — Kalk können Sie immer noch ritzen mit dem Stahlmesser -, das war auch aufgelöst im Wasser. Man hat es also während dieser alten Mondenzeit mit einer dicklichen Flüssigkeit zu tun, in der alle Stoffe, die heute fest sind, aufgelöst enthalten waren.

Das heutige dünne Wasser, das im wesentlichen aus Wasserstoff und Sauerstoff besteht, das hat sich erst später abgeschieden. Das ist erst entstanden während der Erdenzeit selber. So daß wir also einen ursprünglichen Zustand der Erde haben, der ein verdicklicht Flüssiges darstellt. Und ringsherum haben wir dann auch eine Art von Luft, aber wir haben keine solche Luft gehabt wie heute. Gerade wie das Wasser nicht so ausgeschaut hat wie unser heutiges Wasser, so war auch die Luft nicht so wie unsere heutige. Unsere heutige Luft enthält ja im wesentlichen Sauerstoff und Stickstoff. Die anderen Stoffe, die die Luft noch enthält, sind in sehr geringer Menge noch vorhanden. Es sind sogar Metalle als Metalle eigentlich noch in der Luft vorhanden, aber in furchtbar geringen Mengen. Sehen Sie, es ist zum Beispiel ein Metall, das Natrium heißt, in geringen Mengen in der Luft enthalten; überall, wo wir sind, ist das Natriummetall. Nun denken Sie aber doch, was das heißt, daß Natrium überall ist, das heißt, daß der eine Stoff, der in Ihrem Salz ist, wenn Sie auf dem Tisch Salz haben, in kleinen Mengen überall vorhanden ist.

Sehen Sie, es gibt zwei Stoffe — das eine ist dieser Stoff, den ich Ihnen jetzt angeführt habe, das Natrium, das in ganz kleiner Menge überall in der Luft vorhanden ist; und dann gibt es einen Stoff, der gasförmig ist, und der spielt besonders eine große Rolle, wenn Sie Ihre Wäsche bleichen: das ist das Chlor. Das bewirkt das Bleichen. Nun, sehen Sie, das Salz, das Sie auf dem Tisch haben, das besteht aus diesem Natrium und aus dem Chlor, ist aus diesen zusammengesetzt. So kommen die Dinge in der Natur zustande.

Sie können fragen: Ja, wie weiß man, daß Natrium überall ist? — Ja, sehen Sie, es gibt heute schon die Möglichkeit, wenn man irgendwo eine Flamme hat, nachzuweisen, was für ein Stoff in dieser Flamme verbrennt. Wenn Sie zum Beispiel, sagen wir, dieses Natrium, das man metallisch kriegen kann, pulverisieren und in eine Flamme hineinhalten, so können Sie dann mit einem Instrument, das man das Spektroskop nennt, eine gelbe Linie darinnen finden. Es gibt zum Beispiel ein anderes Metall, das heißt Lithium; wenn Sie das in die Flamme hineinhalten, so bekommen Sie eine rote Linie; da ist die gelbe nicht da, da ist die rote Linie da. Man kann also schon nachweisen mit dem Spektroskop, was für ein Stoff irgendwo vorhanden ist. Die gelbe Natriumlinie bekommen Sie fast aus jeder Flamme; das heißt, wenn Sie irgendwo, ohne daß Sie Natrium hineintun, eine Flamme anzünden, so kriegen Sie da die Natriumlinie in jeder Flamme. Also dieses Natrium ist heute noch in einer Flamme. Aber von allen diesen Metallen, namentlich aber vom Schwefel, waren früher riesige Mengen hier in der Luft vorhanden. So daß die Luft in jenem alten Zustand sozusagen höchst schwefelhaltig war, ganz ausgeschwefelt war. Wie wir also ein dickliches Wasser haben — wenn man nicht besonders schwer gewesen wäre, hätte man spazieren gehen können auf diesem Wasser; es ist so wie rinnender Teer zuweilen gewesen -, so ist die Luft auch dicker gewesen, so dick, daß man mit den heutigen Lungen darin nicht hätte atmen können. Die Lungen haben sich aber erst später gebildet. Die Lebensweise derjenigen Wesen, die dazumal da waren, war eine wesentlich andere.

Nun, so müssen Sie sich vorstellen, daß die Erde einmal ausgesehen hat. Hätten Sie sich mit heutigen Augen auf dieser Erde befunden, dann würden Sie auch nicht auf eine solche Ansicht gekommen sein, daß da draußen Sterne sind, Sonne und Mond sind; denn die Sterne hätten Sie nicht gesehen, sondern Sie hätten eben in ein unbestimmtes Luftmeer hineingeschaut, das aufgehört hätte nach einiger Zeit. Man wäre sozusagen, wenn man dazumal mit den heutigen Sinnesorganen hätte leben können, wie in einem Weltenei drinnen gewesen, über das man nicht hinausgesehen hätte. Wie in einem Weltenei drinnen wäre man gewesen! Und Sie können sich schon vorstellen, daß dann auch die Erde dazumal anders ausgesehen hat: ganz ausgefüllt mit einem riesigen Eidotter, einer dicklichen Flüssigkeit, und mit einer ganz dicklichen Luftumgebung — das ist das, was heute das Eiweiß im Ei darstellt.

Wenn Sie sich das ganz real vorstellen, was ich Ihnen da schildere, so werden Sie sich sagen müssen: Ja, dazumal konnten solche Wesen nicht leben, wie es die heutigen Wesen sind. Denn, natürlich, solche Wesen, wie die heutigen Elefanten und dergleichen, aber auch Menschen in der heutigen Gestalt, die wären da sozusagen versunken; außerdem hätten sie nicht atmen können. Und weil sie da nicht hätten atmen können, haben sie ja auch nicht Lungen in der heutigen Gestalt gehabt. Diese Organe bilden sich ganz in dem Sinne, wie sie gebraucht werden. Das ist das Interessante, daß ein Organ gar nicht da ist, wenn es nicht gebraucht wird. Also Lungen haben sich erst in dem Maße entwickelt, in dem die Luft nicht mehr so schwefelhaltig und metallreich war, wie sie in dieser alten Zeit war.

Nun, wenn wir uns eine Vorstellung bilden wollen, was für Wesen dazumal gelebt haben, dann müssen wir zuerst diejenigen Wesen aufsuchen, welche in dem dicklichen Wasser gelebt haben. In diesem dicklichen Wasser haben Wesen gelebt, die heute nicht mehr existieren. Nicht wahr, wenn wir heute von unserer gegenwärtigen Fischform reden, so ist diese Fischform da, weil das Wasser dünn ist. Auch das Meerwasser ist ja verhältnismäßig dünn; es enthält viel Salz aufgelöst, aber es ist doch verhältnismäßig dünn. Nun, dazumal war alles mögliche in dieser dicklichen Flüssigkeit, in diesem dicklichen Meere, aus dem eigentlich die ganze Erde, der Mondensack bestanden hat, aufgelöst. Die Wesen, die darinnen waren, die konnten nicht schwimmen, wie die heutigen Fische schwimmen, weil eben das Wasser zu dick war; aber sie konnten auch nicht gehen, denn gehen muß man auf einem festen Boden. Und so können Sie sich vorstellen, daß diese Wesen eine Organisation hatten, einen Körperbau hatten, der zwischen dem, was man braucht zum Schwimmen: Flossen, und dem, was man braucht zum Gehen: Füße, mitten drinnen liegt. Sehen Sie, wenn Sie Flossen haben - Sie wissen ja, wie Flossen ausschauen -, die haben solche stachelige, ganz dünne Knochen (es wird gezeichnet), und dasjenige, was dazwischen ist an Fleischmasse, das ist vertrocknet. So daß wir eine Flosse haben mit fast gar keiner Fleischmasse daran, mit stacheligen, zu Stacheln umgebildete Knochen - das ist eine Flosse. Gliedmaßen, die dazu dienen, auf Festem sich fortzubewegen, also zu gehen oder zu kriechen, die lassen die Knochen ins Innere zurücktreten und die Fleischmasse bedeckt sie äußerlich. So daß wir solche Gliedmaßen eben so auffassen können, daß sie Fleischmasse außen haben, die Knochen nur im Inneren; da ist die Fleischmasse das Hauptsächlichste. Das (es wird auf die Zeichnung verwiesen) gehört zum Gehen, das gehört zum Schwimmen. Aber weder Gehen noch Schwimmen gab es dazumal, sondern etwas, was dazwischen liegt. Daher hatten diese Tiere auch Gliedmaßen, in denen schon so etwas wie Stacheliges war, aber nicht der reine Stachel, sondern so, daß schon vorhanden war so etwas wie Gelenke. Es waren Gelenke, sogar ganz künstliche Gelenke; dazwischen war aber ausgespannt Fleischmasse wie ein Schirm. Wenn Sie heute noch manche Schwimmtiere anschauen, mit der Schwimmhaut zwischen den Knochen, dann ist das der letzte Rest dessen, was einstmals in höchstem Maße vorhanden war. Da waren Tiere vorhanden, welche ihre Gliedmaßen eben so ausstreckten, daß sie mit der Fleischmasse, die da ausgespannt war, getragen wurden von der dicklichen Flüssigkeit. Und sie hatten schon Gelenke an den Gliedern - nicht so wie die Fische heute, wo man keine Gelenke sieht -, sie hatten Gelenke. Dadurch konnten sie ihr halbes Schwimmen und ihr halbes Gehen dirigieren.

So, sehen Sie, werden wir aufmerksam gemacht auf Tiere, welche in der Hauptsache solche Gliedmaßen brauchen. Uns würden sie heute riesig plump vorkommen, diese Gliedmaßen: sie sind nicht Flossen, nicht Füße, nicht Hände, sondern plumpe Ansätze an dem Leib, aber ganz geeignet, in dieser dicklichen Flüssigkeit zu leben. Das war die eine Art von Tieren. Wenn wir sie weiter beschreiben wollen, so müssen wir sagen: Diese Tiere waren ganz darauf veranlagt, den Körper so auszubilden, daß diese Riesengliedmaßen entstehen konnten. Alles übrige war schwach ausgebildet bei diesen Tieren. Sehen Sie, dasjenige, was heute noch vorhanden ist an Kröten oder an solchen Tieren, die im Sumpfigen, also Dicklich-Flüssigen schwimmen, wenn Sie das nehmen, so haben Sie eben schwache, verkümmerte zaghafte Nachbildungen von Riesentieren, die einmal gelebt haben, die plump waren, aber verkleinerte Köpfe hatten wie die Schildkröte.

Und in der verdicklichten Luft lebten andere Tiere. Unsere heutigen Vögel haben ja dasjenige annehmen müssen, was sie brauchen, weil sie eben in der dünnen Luft leben; daher mußten sie schon etwas von Lungen ausbilden. Aber die Tiere, die dazumal lebten in der Luft, die hatten keine Lungen, denn in dieser verdicklichten, schwefeligen Luft ging es nicht, mit Lungen zu atmen. Aber sie nahmen doch diese Luft auf, und sie nahmen sie so auf, daß es eine Art von Essen war. Diese Tiere konnten nicht in der heutigen Weise essen, denn es wäre ihnen alles im Magen liegengeblieben. Es war ja auch nichts Festes da zum Essen. Sie nahmen alles das, was sie aufnahmen an Nahrung, aus der verdicklichten Luft auf. Aber wo hinein nahmen sie es auf? Sehen Sie, sie nahmen es auf in dasjenige, was sich in ihnen wieder besonders ausgebildet hat.

Nun, diese Fleischmasse, die da vorhanden war an diesen Schwimmtieren dazumal, an diesen, ich möchte sagen, Gleittieren — denn es war ja nicht ein Gehen, war ja nicht ein Schwimmen -, diese Fleischmasse, die konnten wieder die damaligen Lufttiere nicht brauchen, weil sie ja nicht in der verdicklichten Flüssigkeit schwimmen, sondern in der Luft sich selber tragen sollten. Dieser Umstand, daß sie sich in der Luft selber tragen sollten, der bewirkte da bei diesen Tieren, daß diese Fleischmasse, die sich bei den gleitenden, halb schwimmenden Tieren entwickelte, sich anpaßte den Schwefelverhältnissen der Luft. Der Schwefel vertrocknete diese Fleischmasse und machte sie zu dem, was Sie heute an den Federn sehen. An den Federn ist diese vertrocknete Fleischmasse; es ist ja auch vertrocknetes Gewebe. Aber mit diesem vertrockneten Gewebe konnten diese Tiere wiederum diejenigen Gliedmaßen bilden, die sie brauchten. Es waren nun auch nicht im heutigen Sinne Flügel, aber die trugen sie in dieser Luft; sie waren schon flügelähnlich, aber nicht ganz so wie heutige Flügel. Vor allen Dingen waren sie in einem sehr, sehr voneinander verschieden. Sehen Sie, heute ist ja nur etwas noch zurückgeblieben von dem, was dazumal diese merkwürdigen, flügelähnlichen Gebilde hatten: heute ist nur zurückgeblieben das Mausern, wo die Vögel ihre Federn verlieren. Diese Gebilde also, die noch nicht Federn waren, aber die mehr die vertrockneten Gewebe ausbildeten, mit denen dann diese Tiere sich in der verdicklichten Luft erhielten — diese Gebilde waren eigentlich halb Atmungsorgane, halb Organe zur Aufnahme der Nahrungsmittel. Es wurde dasjenige, was in der Luftumgebung war, aufgenommen. Und so war ein jedes solches Organ, namentlich diejenigen Organe, die nicht zum Fliegen benutzt wurden, die aber auch da waren in ihren Ansätzen, wie der Vogel am ganzen Leib Federn hat. Diese Flügel waren zur Aufnahme der Luft und zum Abscheiden der Luft da. Heute ist davon nur das Mausern zurückgeblieben. Dazumal wurde aber damit genährt, das heißt der Vogel plusterte sein Gewebe auf mit dem, was er hereinsog von der Luft, und dann wiederum gab er das von sich, was er nicht mehr brauchte, so daß ein solcher Vogel schon ein sehr merkwürdiges Gebilde war.

Sehen Sie, in der damaligen Zeit lebten da unten diese furchtbar plumpen Wassertiere — die heutigen Schildkröten sind schon die reinsten Prinzen dagegen; diese Tiere da unten, die waren im flüssigen Element. Da oben waren diese merkwürdigen Tiere. Und während sich die heutigen Vögel da oben in der Luft manchmal unanständig benehmen — was wir ihnen schon übelnehmen, nicht wahr -, haben diese vogelartigen Tiere fortwährend abgeschieden. Und dasjenige, was von ihnen kam, regnete herunter. Besonders in gewissen Zeiten regnete es herunter. Aber die Tiere, die unten waren, die hatten ja noch nicht diese Gewohnheiten, die wir haben; wir sind gleich schrecklich ungehalten, wenn einmal ein Vogel sich etwas unanständig benimmt. So waren diese Tiere, die da unten in dem flüssigen Element waren, nicht; sondern die sogen wiederum auf - in ihren eigenen Körper sogen sie auf dasjenige, was da herunterfiel. Und das war aber zugleich die Befruchtung dazumal. Dadurch konnten diese Tiere, die da entstanden waren, überhaupt nur weiterleben, daß sie das aufnahmen; nur dadurch konnten sie weiterleben. Und wir haben dazumal nicht so ausgesprochen ein Hervorgehen des einen Tieres aus dem anderen gehabt wie jetzt, sondern man möchte sagen, dazumal war es noch so, daß eigentlich diese Tiere lange lebten; sie bildeten sich immer wiederum neu. Es war so ein Weltenmausern, möchte ich sagen; sie verjüngten sich immer wiederum, diese Tiere da unten. Dagegen die Tiere, die oben waren, die wiederum waren darauf angewiesen, daß zu ihnen dasjenige kam, was die Tiere unten entwickelten, und dadurch wurden diese wiederum befruchtet. So daß die Fortpflanzung dazumal etwas war, was im ganzen Erdenkörper vor sich ging. Die obere Welt befruchtete die untere, die untere Welt befruchtete die obere. Es war überhaupt ein ganzer belebter Körper. Und ich möchte sagen: Dasjenige, was da an solchen Tieren da unten und an Tieren da oben war, war wie die Maden in einem Körper drinnen, wo auch der ganze Körper lebendig ist und die Maden darinnen auch lebendig sind. Es war also ein Leben und die einzelnen Wesen, die drinnen lebten, lebten in einem ganzen lebendigen Körper drinnen.

Später aber ist einmal ein Zustand, ein Ereignis gekommen, das von ganz besonderer Wichtigkeit war. Diese Geschichte hätte nämlich lange fortgehen können; da wäre aber alles nicht so geworden, wie es jetzt auf der Erde ist. Da wäre alles so geblieben, daß plumpe Tiere mit luftfähigen Tieren zusammen einen lebendigen Erdenkörper bewohnt hätten. Aber es ist eines Tages eben etwas Besonderes eingetreten. Sehen Sie, wenn wir diese lebendige Bildung der Erde da nehmen (siehe Zeichnung), so trat das ein, daß sich eines Tages von dieser Erde wirklich, man kann schon sagen, ein Junges bildete, das in den Weltenraum herausging. Diese Sache geschah so, daß da ein kleiner Auswuchs entstand; das verkümmerte da und spaltete sich zum Schluß ab. Und es entstand statt dem da hier ein Körper draußen im Weltenraum, der das Luftförmige, das da in der Umgebung ist, innerlich hatte, und außen die dickliche Flüssigkeit hatte. Also ein umgekehrter Körper spaltete sich ab. Während die Mondenerde dabei blieb, ihren innerlichen Kern dickflüssig zu haben, außen dickliche Luft zu haben, spaltete sich ein Körper ab, der außen das Dickliche hat und innen das Dünne. Und in diesem Körper kann man, wenn man nicht mit Vorurteil, sondern mit richtiger Untersuchung an die Sache herangeht, den heutigen Mond erkennen. Heute kann man schon ganz genau wissen, so wie man zum Beispiel das Natrium in der Luft finden kann, aus was die Luft besteht. So kann man ganz genau wissen: Der Mond war einmal in der Erde drinnen! Was da draußen als Mond herumkreist, war in der Erde drinnen und hat sich von ihr abgetrennt, ist hinausgegangen in den Weltenraum.

Und damit ist dann aber eine ganze Veränderung eingetreten sowohl mit der Erde wie mit demjenigen, was hinausgegangen ist. Vor allen Dingen: Die Erde hat da gewisse Substanzen verloren, und jetzt erst konnte sich das Mineralische in der Erde bilden. Wenn die Mondensubstanzen in der Erde drinnen geblieben wären, so hätte sich niemals das Mineralische bilden können, sondern es wäre immer ein Flüssiges und Bewegtes gewesen. Erst der Mondenaustritt hat der Erde den Tod gebracht und damit das Mineralreich, das tot ist. Aber damit sind auch erst die heutigen Pflanzen, die heutigen Tiere und der Mensch in seiner heutigen Gestalt möglich geworden.

Nun können wir also sagen: Es ist aus dem alten Mondenzustand der Erde der heutige Erdenzustand entstanden. Damit ist das Mineralreich entstanden. Und jetzt haben sich alle Formen ändern müssen. Denn jetzt ist eben gerade dadurch, daß der Mond herausgetreten ist, die Luft weniger schwefelhaltig geworden, hat sich immer mehr und mehr genähert dem heutigen Zustand in der Erde selber. So hat sich auch abgesetzt dasjenige, was in der Flüssigkeit aufgelöst war, und gebirgsartige Einschlüsse gebildet, und das Wasser wurde immer mehr ähnlich unserem heutigen Wasser. Dagegen der Mond, der dasjenige in der Umgebung hat, was wir in der Erde im Inneren haben, der bildete nach außen eine ganz hornartig dickliche Masse; auf die schauen wir hinauf. Die ist nicht so wie unser Mineralreich, sondern die ist so, wie wenn unser Mineralreich hornartig geworden wäre und verglast wäre, außerordentlich hart, härter als alles Hornartige, was wir auf der Erde haben, aber doch nicht ganz mineralisch, sondern hornartig. Daher diese eigentümliche Gestalt der Mondberge. Diese Mondberge sehen eigentlich ja alle so aus wie Hörner, die angesetzt sind. Sie sind so gebildet, daß man das Organische darinnen, dasjenige, was einmal mit dem Leben zusammenhing, eigentlich an ihnen wahrnehmen kann.

Nun, sehen Sie, es setzte sich also von diesem Zeitpunkt an, wo der Mond hinausging, aus der damaligen dicklichen Flüssigkeit immer mehr und mehr das heutige Mineralreich ab. Da wirkte insbesondere ein Stoff, der in diesen alten Zeiten riesig stark vorhanden war, ein Stoff, der aus Kiesel und Sauerstoff besteht und den man Kieselsäure nennt. Sehen Sie, Sie haben die Vorstellung, eine Säure muß — weil das bei einer heutigen Säure, die man verwendet, eben so ist —, eine Säure muß etwas Flüssiges sein. Aber die Säure, die eine richtige Säure ist und die ich hier meine, die ist etwas ganz Festes! Das ist nämlich der Quarz, den Sie im Hochgebirge finden; denn der Quarz ist Kieselsäure. Und wenn er weißlich und glasartig ist, so ist er sogar reine Kieselsäure; wenn er irgendwelche andere Stoffe enthält, dann bekommen Sie diese Quarze, die violettlich und so weiter sind. Das ist von den Stoffen, die drinnen eingeschlossen sind.

Aber dieser Quarz, der heute so dick ist, daß Sie ihn nicht mit dem Stahlmesser ritzen können, daß Sie sich schon ordentliche Löcher schlagen, wenn Sie sich ihn an den Kopf schlagen, dieser Quarz war dazumal in jenen alten Zeiten ganz aufgelöst — entweder aufgelöst dadrinnen in der dicklichen Flüssigkeit oder in den halbfeinen Partien in der Umgebung, in der verdicklichten Luft aufgelöst. Und man kann schon sagen: Neben dem Schwefel waren riesige Mengen von solchem aufgelöstem Quarz in der verdicklichten Luft, welche die damalige Erde hatte. Sie können eine Vorstellung davon bekommen, wie stark dazumal der Einfluß dieser aufgelösten Kieselsäure gewesen ist, wenn Sie heute betrachten, wie eigentlich die Erde noch immer zusammengesetzt ist bloß da, wo wir leben. Sie können ja natürlich sagen: Da muß viel Sauerstoff da sein, denn den brauchen wir zum Atmen; viel Sauerstoff muß auf der Erde sein. — Es ist auch viel Sauerstoff auf der Erde, achtundzwanzig bis neunundzwanzig Prozent der gesamten Erdenmasse, die wir haben. Sie müssen dann nur alles nehmen. In der Luft ist der Sauerstoff, in vielen Substanzen, die fest sind auf der Erde, ist der Sauerstoff enthalten; der Sauerstoff ist in den Pflanzen, in den Tieren. Aber wenn man alles zusammennimmt, so sind es achtundzwanzig Prozent. Aber Kiesel, der im Quarz drinnen mit dem Sauerstoff verbunden Kieselsäure gibt, Kiesel sind achtundvierzig bis neunundvierzig Prozent vorhanden! Denken Sie sich, was das heißt: Die Hälfte von alldem, was uns umgibt und was wir brauchen, fast die Hälfte ist Kiesel! Natürlich, wie alles flüssig war, die Luft fast flüssig war, ehe sie sich verdickte - ja, da spielte dieser Kiesel eine Riesenrolle; der bedeutete sehr viel in diesem ursprünglichen Zustande.

Man respektiert diese Dinge nicht ordentlich, weil man da, wo der Mensch feiner organisiert ist, heute nicht mehr die richtige Vorstellung vom Menschen hat. Heute stellen sich die Menschen grobklotzig vor: Nun ja, wir atmen als Menschen; da atmen wir den Sauerstoff ein, der bildet sich in uns zur Kohlensäure um, wir atmen die Kohlensäure aus. Schön. Gewiß, wir atmen den Sauerstoff ein, wir atmen die Kohlensäure aus. Wir könnten nicht leben, wenn wir nicht diese Atmung hätten. Aber in der Luft, die wir doch einatmen, ist heute noch immer Kiesel enthalten, richtiger Kiesel, und wir atmen immer ganz kleine Mengen von Kiesel auch ein. Genug ist da vorhanden, denn achtundvierzig bis neunundvierzig Prozent Kiesel ist ja in unserer Umgebung. Während wir atmen, geht allerdings nach unten, nach dem Stoffwechsel, der Sauerstoff und verbindet sich mit dem Kohlenstoff; aber er geht zugleich nach aufwärts zu den Sinnen und zu dem Gehirn, zum Nervensystem — überall geht er hin. Da verbindet er sich mit dem Kiesel und bildet in uns Kieselsäure. So daß wir sagen können: Wenn wir da den Menschen haben (es wird gezeichnet), hier der Mensch seine Lungen hat, und er atmet nun Luft ein, so hat er hier Sauerstoff. Der geht in ihn hinein. Und nach unten verbindet sich der Sauerstoff mit dem Kohlenstoff und bildet Kohlensäure, die man dann wieder ausatmet; nach oben aber wird der Kiesel mit dem Sauerstoff verbunden in uns, und es geht da in unseren Kopf hinauf Kieselsäure, die da in unserem Kopf drinnen nicht gleich so dick wird wie der Quarz. Das wäre natürlich eine üble Geschichte, wenn da lauter Quarzkristalle darinnen entstehen würden; da würden Ihnen statt der Haare gleich Quarzkristalle herauswachsen — es könnte ja unter Umständen ganz schön und drollig sein! Aber sehen Sie, so ganz ohne ist das doch nicht, denn die Haare, die Ihnen herauswachsen, haben nämlich sehr viel Kieselsäure in sich; da ist sie nur noch nicht kristallisiert, da ist sie noch in einem flüssigen Zustand. Die Haare sind sehr kieselsäurehaltig. Überhaupt alles, was in den Nerven ist, was in den Sinnen ist, ist kieselsäurehaltig.

Daß das so ist, meine Herren, darauf kommt man ja erst, wenn man die wohltätige Heilwirkung der Kieselsäure kennenlernt. Die Kieselsäure ist ein ungeheuer wohltätiges Heilmittel. Sie müssen doch bedenken: Der Mensch muß die Nahrungsmittel, die er durch den Mund in seinen Magen aufnimmt, durch alle möglichen Zwischendinge führen, bis sie in den Kopf hinaufkommen, bis sie zum Beispiel ans Auge, ans Ohr herankommen. Das ist ein weiter Weg, den da die Nahrungsmittel nehmen müssen; da brauchen sie Hilfskräfte, daß sie da überhaupt heraufkommen. Es könnte durchaus sein, daß die Menschen diese Hilfskräfte zu wenig haben. Ja, viele Menschen haben zu wenig Hilfskräfte, so daß die Nahrungsmittel nicht ordentlich in den Kopf herauf arbeiten. Dann, sehen Sie, muß man ihnen Kieselsäure eingeben; die befördert dann die Nahrungsmittel hinauf zu den Sinnen und in den Kopf. Sobald man bemerkt, daß der Mensch zwar die Magen- und Darmverdauung ordentlich hat, daß aber diese Verdauung nicht bis zu den Sinnen hingeht, nicht bis in den Kopf, nicht bis in die Haut hineingeht, muß man Kieselsäurepräparate als Heilmittel nehmen. Da sieht man eben, was diese Kieselsäure heute noch für eine ungeheure Rolle im Menschen spielt.

Und diese Kieselsäure wurde ja dazumal, als die Erde in diesem alten Zustande war, noch nicht geatmet, sondern sie wurde aufgenommen, aufgesogen. Namentlich diese vogelartigen Tiere nahmen diese Kieselsäure auf. Neben dem Schwefel nahmen sie diese Kieselsäure auf. Und die Folge davon war, daß diese Tiere eigentlich fast ganz Sinnesorgan wurden. So wie wir unsere Sinnesorgane der Kieselsäure

verdanken, so verdankte dazumal überhaupt die Erde ihr vogelartiges Geschlecht dem Wirken der Kieselsäure, die überall war. Und weil die Kieselsäure an diese anderen Tiere mit den plumpen Gliedmaßen, während sie so hinglitten in der dicklichen Flüssigkeit, weniger herankam, wurden diese Tiere vorzugsweise Magen- und Verdauungstiere. Da oben waren also dazumal furchtbar nervöse Tiere, die alles wahrnehmen konnten, die eine feine, nervöse Empfindung hatten. Diese Urvögel waren ja furchtbar nervös. Dagegen was unten in der dicklichen Flüssigkeit war, das war von einer riesigen Klugheit, aber auch von einem riesigen Phlegmatismus; die spürten gar nichts davon. Das waren bloße Nahrungstiere, waren eigentlich nur ein Bauch mit plumpen Gliedmaßen. Die Vögel oben waren fein organisiert, waren fast ganz Sinnesorgan. Und wirklich Sinnesorgane, die es machten, daß die Erde selber nicht nur wie belebt war, sondern alles empfand durch diese Sinnesorgane, die herumflogen, die die damaligen Vorläufer der Vögel waren.

Ich erzähle Ihnen das, damit Sie sehen, wie ganz anders alles einmal auf der Erde ausgesehen hat. Also alles das, was da aufgelöst war, hat sich dann in dem festen mineralischen Gebirge, in den Felsmassen abgeschieden, bildete eine Art von Knochengerüst. Damit war aber auch für den Menschen und für die Tiere erst die Möglichkeit gegeben, feste Knochen zu bilden. Denn wenn sich draußen das Knochengerüst der Erde bildete, bildeten sich im Inneren der höheren Tiere und des Menschen die Knochen. Daher war alles dasjenige, was ich Ihnen hier eingezeichnet habe, noch nicht da; es gab noch nicht solche feste Knochen, wie wir sie heute haben, sondern das alles waren biegsame, hornartige, knorpelige Dinge, wie es heute beim Fisch nur noch zurückgeblieben ist. Alle diese Dinge sind schon in einer gewissen Weise zurückgeblieben, sind aber dann verkümmert, weil dazumal in alldem, was ich Ihnen beschrieben habe, die Lebensbedingungen dazu da waren. Heute sind für diese Dinge nicht mehr die Lebensbedingungen da. So daß wir sagen können: In unseren heutigen Vögeln haben wir die für die Luft umgewandelten Nachfolger dieses vogelartigen Geschlechtes, das da oben in der schwefelhaltigen und kieselsäurehaltigen dicklichen Luft war. Und in all demjenigen, was wir heute haben in den Amphibien, in den Kriechtieren, in alldem, was Frösche- und Krötengezücht ist, aber auch in alldem, was Chamäleons, Schlangen und so weiter sind, haben wir die Nachkommen desjenigen, was dazumal in der dicklichen Flüssigkeit schwamm. Und die höheren Säugetiere und der Mensch in seiner heutigen Gestalt, die kamen ja erst später dazu.

Nun kommt ein scheinbarer Widerspruch heraus, meine Herren. Das letzte Mal sagte ich Ihnen: Der Mensch war zuerst da; aber er war seelisch-geistig nur in der Wärme da. Der Mensch war schon auch bei alldem dabei, was ich Ihnen gezeigt habe, aber er war noch nicht als physisches Wesen da, war in einem ganz feinen Körper da, in dem er sich sowohl in der Luft wie in der dicklichen Flüssigkeit aufhalten konnte. Sichtbarlich war er noch nicht da. Sichtbarlich waren auch die höheren Säugetiere noch nicht da, sondern sichtbarlich waren eben diese plumpen Tiere da und waren diese luftigen, vogelartigen Tiere da. Und das muß man eben unterscheiden, wenn man sagt: Der Mensch war schon da. Er war zuallererst da, wie nicht einmal die Luft da war, aber er war in einem nicht sichtbaren Zustande da und war noch damals, als die Erde so ausgeschaut hat, in einem nicht sichtbaren Zustande da. Erst mußte sich der Mond von der Erde trennen, dann konnte der Mensch auch in sich Mineralisches ablagern, ein mineralisches Knochensystem bilden, konnte in den Muskeln solche Stoffe wie das Myosin und so weiter absondern. Die waren dazumal noch nicht da. Und es entstand der Mensch. Aber er hat eben doch heutzutage in seiner Körperlichkeit durchaus die Erbschaft von diesem Früheren erhalten.

Denn ohne Mondeneinfluß, der nur jetzt von außen ist, nicht mehr innere Erde, entsteht ja der Mensch nicht. Die Fortpflanzung hängt schon mit dem Monde zusammen, nur nicht mehr direkt. Daher können Sie auch sehen, daß das, was mit der Fortpflanzung beim Menschen zusammenhängt, die vierwöchentliche Periode der Frau, in derselben rhythmischen Periode verläuft wie die Mondenphasen, nur fallen sie nicht mehr zusammen, haben sich voneinander emanzipiert. Aber das ist geblieben, daß dieser Mondeneinfluß durchaus tätig ist in der menschlichen Fortpflanzung.

So können wir sagen: Wir haben die Fortpflanzung gefunden zwischen den Wesen der verdicklichten Luft und denen der verdicklichten Flüssigkeit, zwischen dem alten vogelähnlichen Geschlecht und den alten Riesenamphibien. Die befruchteten sich gegenseitig, weil der Mond noch drinnen war. Sofort, als der Mond draußen war, mußte die Außenbefruchtung eintreten. Denn im Monde liegt eben das Befruchtungsprinzip.

Nun, von diesen Gesichtspunkten aus wollen wir dann am nächsten Samstag, wo wir die Stunde hoffentlich um neun Uhr haben können, weiter fortsetzen. Die Frage von Herrn Dollinger ist eben eine, die ausführlich beantwortet werden muß; wir werden aber schon zurechtkommen, wenn Sie Geduld haben, bis Sie die Gegenwart herausspringen sehen aus demjenigen, was allmählich eigentlich geschieht. Es liegt in der Frage, die eben schwer verständlich ist. Aber ich glaube, man kann die Sache, wenn man sie so anschaut, wie wir es getan haben, schon verstehen.

Second Lecture

Good morning, gentlemen! Today I would like to continue talking about the creation of the Earth, the origin of humankind, and so on. From what I have told you, it has probably become clear to you that our entire Earth was not originally as it is today, but was a kind of living being. And we have learned about the penultimate state before the actual earthly state, which we have discussed, by saying that there was heat, there was air, there was also water; but there was not yet any actual solid mineral earth mass. However, you must not imagine that the water that was there at that time already looked like today's water. Today's water only became like this because the substances that were previously dissolved in the water separated from the water. If you take a normal glass of water today and add a little salt to it, the salt dissolves in the water; you get a liquid, a salt solution, as it is called, which is much thicker than water. If you reach into it, you will feel that the salt solution is much denser than the water. Now, dissolved salt is still relatively thin. Other substances can also be dissolved; then you get a very thick liquid. So this liquid, this state of water that once existed on our earth in earlier times, does not represent today's water. It did not exist at all back then, because substances were dissolved in all waters. Just think: everything that you have in today's substances, the Jurassic limestone mountains, for example, was dissolved in there; everything you find in harder rocks that you cannot scratch with a knife — you can still scratch limestone with a steel knife — was also dissolved in water. So during this ancient lunar period, we are dealing with a thick liquid in which all substances that are solid today were dissolved.

Today's thin water, which consists mainly of hydrogen and oxygen, only separated later. It only came into being during the Earth period itself. So we have an original state of the Earth that represents a thickened liquid. And all around us we also have a kind of air, but we did not have air like we have today. Just as the water did not look like our water today, the air was not like our air today. Our air today consists mainly of oxygen and nitrogen. The other substances that the air still contains are present in very small quantities. There are even metals still present in the air, but in terribly small quantities. You see, for example, there is a metal called sodium in small quantities in the air; wherever we are, there is sodium metal. Now think about what it means that sodium is everywhere, that is, that the substance that is in your salt, if you have salt on the table, is present in small quantities everywhere.

You see, there are two substances—one is the substance I have just mentioned, sodium, which is present in very small quantities everywhere in the air; and then there is a substance that is gaseous and plays a particularly important role when you bleach your laundry: that is chlorine. That is what causes the bleaching. Now, you see, the salt you have on your table consists of this sodium and chlorine; it is composed of these two elements. That is how things come about in nature.

You may ask: Yes, how do we know that sodium is everywhere? — Well, you see, today it is possible to detect what kind of substance is burning in a flame if you have a flame somewhere. For example, if you pulverize this sodium, which can be obtained in metallic form, and hold it in a flame, you can then find a yellow line in it using an instrument called a spectroscope. There is another metal, for example, called lithium; if you hold it in the flame, you get a red line; the yellow line is not there, but the red line is. So you can already use the spectroscope to detect what kind of substance is present somewhere. You get the yellow sodium line from almost any flame; that is, if you light a flame somewhere without putting sodium in it, you will get the sodium line in every flame. So this sodium is still in a flame today. But of all these metals, especially sulfur, huge quantities used to be present here in the air. So that the air in that ancient state was, so to speak, highly sulphurous, completely sulphurised. Just as we have thick water — if you weren't particularly heavy, you could walk on this water; it was sometimes like running tar — so the air was also thicker, so thick that you couldn't breathe in it with today's lungs. But lungs were only formed later. The way of life of the beings that were there at that time was very different.

Now, you must imagine what the Earth once looked like. If you had been on this Earth with today's eyes, you would not have come to the conclusion that there are stars, sun, and moon out there; for you would not have seen the stars, but would have looked into an indefinite sea of air that would have ceased after a while. If you had been able to live with today's sensory organs back then, you would have been inside a world egg, so to speak, beyond which you would not have been able to see. You would have been inside a world egg! And you can imagine that the Earth would have looked different back then: completely filled with a huge egg yolk, a thick liquid, and a very thick atmosphere — that is what the egg white in an egg represents today.

If you imagine what I am describing to you in a very real way, you will have to say to yourself: Yes, at that time, beings such as those we know today could not have lived. For, of course, beings such as today's elephants and the like, but also humans in their present form, would have sunk, so to speak; moreover, they would not have been able to breathe. And because they could not have breathed there, they did not have lungs in their present form. These organs develop entirely in accordance with their use. It is interesting to note that an organ does not exist if it is not needed. So lungs only developed to the extent that the air was no longer as sulfur-rich and metal-rich as it was in those ancient times.

Now, if we want to form an idea of what kind of creatures lived back then, we must first look for those creatures that lived in the thick water. Creatures that no longer exist today lived in this thick water. Isn't it true that when we talk about our current fish form today, this fish form exists because the water is thin? Seawater is also relatively thin; it contains a lot of dissolved salt, but it is still relatively thin. Now, back then, all kinds of things were dissolved in this thick liquid, in this thick sea, which actually consisted of the entire Earth, the lunar sac. The beings that were in it could not swim as today's fish swim, because the water was too thick; but they could not walk either, because walking requires solid ground. And so you can imagine that these beings had an organization, a physique that lay somewhere between what you need for swimming: fins, and what you need for walking: feet. You see, when you have fins – you know what fins look like – they have these spiky, very thin bones (drawing is made), and the flesh between them has dried up. So we have a fin with almost no flesh on it, with spiky bones that have been transformed into spines – that is a fin. Limbs that are used to move on solid ground, i.e., to walk or crawl, allow the bones to recede into the interior and the flesh covers them externally. So we can understand such limbs as having flesh on the outside and bones only on the inside; the flesh is the most important part. This (refer to the drawing) belongs to walking, this belongs to swimming. But neither walking nor swimming existed at that time, but something in between. Therefore, these animals also had limbs in which there was already something like spines, but not pure spines, but rather something like joints. They were joints, even completely artificial joints; but in between them was stretched flesh like an umbrella. If you look at some swimming animals today, with the webbing between their bones, that is the last remnant of what was once present to the highest degree. There were animals that stretched out their limbs in such a way that they were carried by the thick liquid with the mass of flesh stretched out between them. And they already had joints in their limbs – not like fish today, where you can't see any joints – they had joints. This enabled them to control half their swimming and half their walking.

So, you see, our attention is drawn to animals that mainly need such limbs. Today, these limbs would seem enormously clumsy to us: they are not fins, not feet, not hands, but clumsy appendages on the body, but quite suitable for living in this thick liquid. That was one type of animal. If we want to describe them further, we must say: these animals were entirely predisposed to develop their bodies in such a way that these giant limbs could develop. Everything else was poorly developed in these animals. You see, what still exists today in toads or animals that swim in swampy, thick, liquid environments are weak, stunted, timid replicas of giant animals that once lived, which were clumsy but had smaller heads like turtles.

And other animals lived in the thickened air. Our birds today have had to adapt to what they need because they live in thin air; therefore, they had to develop something like lungs. But the animals that lived in the air at that time did not have lungs, because it was not possible to breathe with lungs in this thickened, sulfurous air. But they still absorbed this air, and they absorbed it in such a way that it was a kind of food. These animals could not eat in the way we do today, because everything would have remained in their stomachs. There was nothing solid to eat. They absorbed all their food from the thickened air. But where did they absorb it? You see, they absorbed it into what had developed specially within them.

Now, this mass of flesh that was present in these swimming animals at that time, in these, I would say, gliding animals — for it was not walking, it was not swimming — this mass of flesh could not be used by the air animals of that time, because they did not swim in the thickened liquid, but had to carry themselves in the air. The fact that they had to carry themselves in the air caused these animals to adapt the flesh that had developed in the gliding, semi-swimming animals to the sulfur conditions in the air. The sulfur dried up this flesh and turned it into what you see today in the feathers. This dried-up flesh mass is found on the feathers; it is, in fact, dried-up tissue. But with this dried-up tissue, these animals were able to form the limbs they needed. They were not wings in the modern sense, but they carried them in the air; they were wing-like, but not quite like today's wings. Above all, they were very, very different from each other. You see, today only a little remains of what these strange, wing-like structures once had: today, only moulting remains, when birds lose their feathers. These structures, which were not yet feathers, but rather the dried tissue with which these animals supported themselves in the thickened air — these structures were actually half respiratory organs, half organs for absorbing food. They absorbed what was in the air around them. And so each of these organs, especially those that were not used for flying but were also present in their rudimentary form, just as birds have feathers all over their bodies. These wings were there to absorb air and to expel air. Today, only moulting remains of this. At that time, however, they were nourished by it, that is, the bird fluffed up its tissue with what it sucked in from the air, and then it exhaled what it no longer needed, so that such a bird was a very strange creature.

You see, in those days, there were these terribly clumsy aquatic animals living down there—today's turtles are pure princes in comparison; these animals down there were in the liquid element. Up there were these strange animals. And while today's birds sometimes behave indecently up there in the air — which we resent, don't we — these bird-like animals were constantly excreting. And what came from them rained down. Especially at certain times, it rained down. But the animals that were down below did not yet have the habits that we have; we are immediately terribly indignant when a bird behaves indecently. But these animals that were down there in the liquid element were not like that; instead, they sucked it up—they sucked up what fell down into their own bodies. And that was also the fertilization at that time. It was only by taking this in that these animals that had come into being could continue to live; only by doing so could they continue to live. And at that time, we did not have such a distinct emergence of one animal from another as we do now, but one might say that at that time, these animals actually lived for a long time; they were constantly renewing themselves. It was a kind of world renewal, I would say; these animals down below were constantly rejuvenating themselves. In contrast, the animals that were above depended on receiving what the animals below developed, and through this they were fertilized in turn. So that reproduction at that time was something that took place throughout the entire body of the Earth. The upper world fertilized the lower, the lower world fertilized the upper. It was a whole living body. And I would like to say: what was there in such animals down below and in animals up above was like maggots inside a body, where the whole body is alive and the maggots inside are also alive. So it was a life, and the individual beings that lived inside lived inside a whole living body.

Later, however, a state of affairs arose, an event that was of very special importance. This story could have gone on for a long time, but then everything would not have turned out as it is now on earth. Everything would have remained as it was, with clumsy animals living together with air-breathing animals on a living Earth. But one day something special happened. You see, if we take this living formation of the Earth (see drawing), what happened was that one day a young creature, so to speak, was formed from this Earth and went out into space. This happened in such a way that a small outgrowth developed; it withered there and finally split off. And instead of it, a body was formed out there in outer space, which had the airy substance that is in the environment on the inside and the thick liquid on the outside. So a reversed body split off. While the lunar Earth remained with its inner core being viscous and its exterior being thick air, a body split off that had the thick substance on the outside and the thin substance on the inside. And in this body, if one approaches the matter without prejudice but with proper investigation, one can recognize today's Moon. Today, just as we can find sodium in the air, we can know exactly what the air consists of. So we can know for sure: the moon was once inside the earth! What circles out there as the moon was inside the earth and separated from it, going out into space.

And with that, a whole change took place, both with the Earth and with that which went out. Above all, the Earth lost certain substances, and only now could the mineral realm form in the Earth. If the lunar substances had remained inside the Earth, the mineral realm could never have formed, but it would always have been fluid and in motion. It was only the departure of the Moon that brought death to the Earth and with it the mineral kingdom, which is dead. But this also made possible the plants, animals, and human beings of today in their present form.

So now we can say: The present state of the earth arose from the old lunar state of the earth. This gave rise to the mineral kingdom. And now all forms had to change. For now, precisely because the moon left, the air became less sulfuric and increasingly approached the present state of the earth itself. Thus, what was dissolved in the liquid settled and formed mountainous inclusions, and the water became more and more similar to our water today. In contrast, the moon, which has in its environment what we have inside the earth, formed a thick, horn-like mass on the outside; we look up at it. It is not like our mineral kingdom, but rather as if our mineral kingdom had become horn-like and vitrified, extremely hard, harder than anything horn-like that we have on Earth, but not entirely mineral, rather horn-like. Hence the peculiar shape of the lunar mountains. These lunar mountains actually all look like horns that have been attached. They are formed in such a way that one can actually perceive the organic matter within them, that which was once connected with life.

Now, you see, from the moment the moon went out, more and more of today's mineral kingdom separated from the thick liquid that existed at that time. A substance that was particularly abundant in those ancient times had a significant effect. This substance consists of silica and oxygen and is called silicic acid. You see, you have the idea that an acid must be something liquid, because that is the case with the acids we use today. But the acid that is a real acid, and which I mean here, is something very solid! It is quartz, which you find in the high mountains; for quartz is silicic acid. And when it is whitish and glassy, it is even pure silicic acid; when it contains any other substances, you get quartz that is violet and so on. This is due to the substances that are enclosed inside.

But this quartz, which today is so thick that you cannot scratch it with a steel knife, that you can make proper holes if you hit yourself on the head with it, this quartz was completely dissolved in those ancient times — either dissolved inside the thick liquid or dissolved in the semi-fine particles in the environment, in the thickened air. And one can already say: in addition to sulfur, there were huge amounts of such dissolved quartz in the thickened air that the Earth had at that time. You can get an idea of how strong the influence of this dissolved silicic acid was back then if you consider today how the Earth is still composed, at least where we live. Of course, you can say: There must be a lot of oxygen there, because we need it to breathe; there must be a lot of oxygen on Earth. There is also a lot of oxygen on Earth, twenty-eight to twenty-nine percent of the total mass of the Earth that we have. You just have to take everything. Oxygen is in the air, oxygen is contained in many substances that are solid on Earth; oxygen is in plants, in animals. But if you take everything together, it is twenty-eight percent. But silica, which is combined with oxygen in quartz to form silicic acid, accounts for forty-eight to forty-nine percent! Think about what that means: half of everything that surrounds us and that we need, almost half, is silica! Of course, when everything was liquid, when the air was almost liquid before it thickened – yes, then this silica played a huge role; it meant a great deal in this original state.

People do not respect these things properly because, in areas where humans are more finely organized, they no longer have the right idea about humans. Today, people imagine themselves as clumsy: Well, we breathe as humans; we inhale oxygen, which is converted into carbon dioxide in our bodies, and we exhale the carbon dioxide. Fine. Certainly, we inhale oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide. We could not live if we did not have this respiration. But the air we breathe still contains silica, real silica, and we also breathe in very small amounts of silica. There is enough of it, because forty-eight to forty-nine percent of our environment is silica. While we breathe, however, oxygen goes down to the metabolism and combines with carbon; but at the same time it goes upward to the senses and to the brain, to the nervous system — it goes everywhere. There it combines with the silica and forms silicic acid in us. So we can say: when we have the human being (it is drawn), here the human being has his lungs, and he now breathes in air, so he has oxygen here. It goes into him. And downwards, the oxygen combines with the carbon and forms carbonic acid, which is then exhaled again; but upwards, the silica combines with the oxygen in us, and silicic acid goes up into our head, where it does not immediately become as thick as quartz. That would of course be a bad thing if quartz crystals were to form in there; Instead of hair, quartz crystals would grow out of your head—which could be quite beautiful and funny under certain circumstances! But you see, it's not entirely without significance, because the hair that grows out of your head contains a lot of silicic acid; it just hasn't crystallized yet, it's still in a liquid state. Hair contains a lot of silicic acid. In fact, everything in the nerves and in the senses contains silicic acid.

Gentlemen, you only realize this when you learn about the beneficial healing properties of silicic acid. Silicic acid is an incredibly beneficial remedy. You must remember that the human being must pass the food he takes into his stomach through his mouth through all kinds of intermediate stages until it reaches the head, until it reaches the eye or the ear, for example. That is a long way that food has to travel; it needs help to get there at all. It could well be that people have too little of these aids. Yes, many people have too little of these aids, so that the food does not work its way up to the head properly. Then, you see, you have to give them silicic acid; that transports the food up to the senses and into the head. As soon as one notices that a person's stomach and intestinal digestion is working properly, but that this digestion does not reach the senses, does not reach the head, does not reach the skin, one must take silicic acid preparations as a remedy. This shows what an enormous role silicic acid still plays in humans today.

And this silicic acid was not yet breathed in when the earth was in its ancient state, but was absorbed and taken in. These bird-like animals in particular absorbed this silicic acid. In addition to sulfur, they absorbed this silicic acid. As a result, these animals actually became almost entirely sensory organs. Just as we owe our sensory organs to silicic acid,

the Earth at that time owed its bird-like species to the action of silicic acid, which was everywhere. And because the silicic acid was less accessible to these other animals with their clumsy limbs as they glided along in the thick liquid, these animals became primarily stomach and digestive animals. So up there at that time there were terribly nervous animals that could perceive everything and had a fine, nervous sensibility. These primeval birds were terribly nervous. In contrast, what was down in the thick liquid was of enormous intelligence, but also of enormous phlegmatism; they felt nothing of it. They were mere food animals, actually just a belly with clumsy limbs. The birds above were finely organized, almost entirely sensory organs. And they really were sensory organs, which meant that the earth itself was not only animated, but also felt everything through these sensory organs that flew around, which were the precursors of birds at that time.