Karmic Relationships III

GA 237

11 July 1924, Dornach

V. Spiritual Conditions of Evolution Leading Up to the Anthroposophical Movement

The members of the Anthroposophical Society come into the Society, as indeed is obvious, for reasons that lie in their inner life, in the inner condition of their souls. And as we are now speaking of the karma of the Anthroposophical Society, nay of the Anthroposophical Movement altogether, showing how it arises out of the karmic evolution of members and groups of members, we shall need to perceive the foundations of this karma above all in the state of soul of those human beings who seek for Anthroposophy. This we have already begun to do, and we will now acquaint ourselves with certain other facts in this direction, so that we may enter still further into the karma of the Anthroposophical Movement.

Most important in the soul-condition of anthroposophists, as I have already said, are the experiences which they underwent in their incarnations during the first centuries of the founding of Christianity. As I said, there may have been other intervening incarnations; but that incarnation is above all important, which we find, approximately, in the fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, or eighth century A.D. In considering this incarnation we found that we must distinguish two groups among the human beings who come to the Anthroposophical Movement. These two groups we have already characterised. We are now going to consider something which they have in common. We shall consider a significant common element, lying at the foundation of the souls who have undergone such lines of evolution as I described in the last lecture.

Looking at the first Christian centuries, we find ourselves in an age when men were very different from what they are today. When the man of today awakens from sleep, he slips down into his physical body with great rapidity, though with the reservation which I mentioned here not long ago, when I said that this entry and expansion into the physical body really lasts the whole day long. Be that as it may, the perception that the Ego and the astral body are approaching takes place very quickly. For the awakening human being in the present age, there is, so to speak, no intervening time between the becoming-aware of the etheric body and the becoming-aware of the physical. Man passes rapidly through the perception of the etheric body—simply does not notice the etheric body,—and dives down at once into the physical. This is a peculiarity of the man of the present time.

The nature of the human beings who lived in those early Christian centuries was different. When they awoke from sleep they had a distinct perception: “I am entering a twofold entity: the etheric body and the physical.” They knew that man first passes through the perception of the etheric body, and then only enters into the physical. Thus indeed, in their moment of awakening they had before them—though not a complete tableau of life—still very many pictures of their past earthly life. And they had before them another thing, which I shall describe directly. For if man enters thus, stage by stage, into that which remains lying on the couch, into the etheric and physical bodies,—the result is that the whole period of waking life becomes very different from the experiences which we have in our waking life today.

Again, when we consider the moment of falling asleep nowadays, the peculiar thing is this:—when the Ego and astral body leave the physical and etheric, the Ego very quickly absorbs the astral body. And as the Ego confronts the cosmos without any kind of support, being unable at its present stage to perceive anything at all, man as he falls asleep ceases to have perceptions. For the little that emerges in his dreams is quite sporadic.

This again was not so in the times of which I am now speaking. The Ego did not at once absorb the astral body; the astral body continued to exist, independently in its own substance, even after the human being had fallen asleep. And to a certain extent, it remained so through the whole night. Thus in the morning the human being awakened not from utter darkness of unconsciousness, but with the feeling:—“I have been living in a world filled with light, in which all manner of things were happening.” Albeit they were only pictures, something was taking place there. It was so indeed: the man of that time had an intermediate feeling, an intermediate sensation between sleeping and waking. It was delicate, it was light and intimate, but it was there. It was only with the beginning of the 14th century that this condition ceased completely in civilised mankind.

Now this means that all the souls, of whose life I was speaking the other day, experienced the world differently from the man of the present time. Let us try to understand, my dear friends, how those human beings—that is to say you yourselves, all of you, during that time—experienced the world.

The diving down into the etheric and physical body took place in distinct stages. And the effect of this was that throughout his waking life man looked out upon Nature differently. He saw not the bare, prosaic, matter-of-fact world of the senses, seen by the man of modern times, who—if he would make any more of it—can only do so by his fancy or imagination. No, when the man of that time looked out, upon the world of plants, for instance, he saw the flowering meadow land as though there were spread over it a slight and gentle bluish-red cloud-halo. Especially at the time of day when the sun was shining less brightly (not at the height of noon-tide), it was as though a bluish-red light, like a luminous mist with manifold and moving waves and colours, were spread over the flowering meadow. What we see today, when a slight mist hangs over the meadow (which comes of course from evaporated water),—such a thing was seen at that time in the spiritual, in the astral. Indeed every tree-top was seen enveloped in a cloud, and when man saw the fields of corn, it was as though bluey-red rays were descending from the cosmos, springing forth in clouds of mist, descending into the soil of the earth.

And when man looked at the animals, he had not merely an impression of the physical shape, but the physical was enveloped in an astral aura. Slightly, delicately, and only intimately, this aura was seen. Nay, it was only seen when the sunshine light was working in a rather gentle way;—but seen it was. Thus everywhere in outer Nature man still perceived the spiritual, working and weaving.

Then, when he died, the experience he had in the first days after passing through the gate of death—gazing back upon the whole of his past earthly life—was in reality not unfamiliar to him. As he looked back upon his earthly life directly after death, he had a distinct feeling. He said to himself: Now I am letting go that quality, that aura from my own organism, which goes out into all that I have seen of the aura in external Nature. My etheric body goes to its own home. Such was man's feeling.

Naturally all these feelings had been much stronger in more ancient times. But they still existed—though in a slight and delicate form—in the time of which I am now speaking. And when man beheld these things directly after passing through the gate of death, he had the feeling: “In all the spiritual life and movement which I have seen hovering over the things and processes of Nature, the Word of the Father-God is speaking. My etheric body is going to the Father.”

And if man thus saw the outer world of Nature differently owing to the different mode of his awakening, so too he saw his own outer form differently than in subsequent ages. When he fell asleep the astral body was not immediately absorbed by the Ego. Now under such conditions the astral body itself is filled with sound. Thus from spiritual worlds there sounded into the sleeping human Ego,—though no longer so distinctly as in ancient times, still in a gentle and intimate way,—all manner of things which cannot be heard in the waking state. And on awakening man had the very real feeling: It was a language of spiritual Beings in the light-filled spaces of the cosmos in which I partook between my falling asleep and my awakening.

And when man had laid aside the etheric body a few days after passing through the gate of death, to live henceforth in his astral body, he had once more this feeling: “In my astral body I now experience in a returning course all that I thought and did on earth. In this astral body in which I lived every night during my sleep,-herein I am experiencing all that I thought and did on earth.” Moreover, while he had carried into his awakening moments only a vague and undetermined feeling, he now had a far clearer feeling. Now in the time between death and a new birth, as in his astral body he returned through his past earthly life, he had the feeling: “Behold in this my astral body lives the Christ I only did not notice it, but in reality every night my astral body dwelt in the essence and being of the Christ.” Now man knew, that for as long as he would have to go thus backward through his earthly life Christ would not desert him, for Christ was with his astral body.

My dear friends, it is so indeed, whatever may have been one's attitude to Christianity in those first Christian centuries, whether it was like the first group of whom I spoke or like the second, whether one had still lived as it were with the more Pagan strength, or with the weariness of Paganism, one was sure to experience—if not on earth, then after death—the great fact of the Mystery of Golgotha; Christ who had been the ruling Being of the Sun, had united Himself with what lives as humanity on earth. Such was the experience of all who had come in any way near to Christianity in the first centuries of Christian evolution. For the others, these experiences after their death remained more or less unintelligible.

Such were the fundamental differences in the experience of souls in the first Christian centuries, and afterwards. Now all this had another effect as well. For when man looked out upon the world of Nature in his waking life, he felt this world of Nature as the essential domain of the Father God. All the spiritual that he beheld living and moving there, was for him the expression, the manifestation and the glory of the Father God. And he felt: This world, in the time when Christ appeared on earth, stood verily in need of something. It was the need that Christ should be received into the substance of the earth for mankind. In relation to all the processes of Nature and the whole realm of Nature, man still had the feeling of a living principle of Christ. For indeed, his perception of Nature, inasmuch as he beheld a spiritual living and moving and holding sway there, involved something else as well. All this which he felt as a spiritual living and moving and holding sway,—hovering in ever-changing spirit-shapes over all plant and animal existence,—all this he felt so that with simple and unbiased human feeling he would describe it in the words: It is the innocence of Nature's being. Yes, my dear friends, what he could thus spiritually see was called in truth: the innocence in the kingdom of Nature. He spoke of the pure and innocent spirituality in all the working of Nature.

But the other thing, which he felt inwardly—feeling when he awakened that in his sleep he had been in a world of light and sounding spiritual being—of this he felt that good, and evil too, might there prevail. In this he felt, as it sounded forth from the depths of spiritual being, good spirits and evil spirits too were speaking. Of the good spirits he felt that they only wanted to raise to a higher level the innocence of Nature and to preserve it; but the evil spirits wanted to adulterate with guilt this guiltlessness of Nature. Wherever such Christians lived as I am now describing, the powers of good and evil were felt through the very fact that as man slept the Ego was not drawn in and absorbed into the astral body.

Not all who called themselves Christians in that time, or who were in any way near to Christianity, were in this state of soul. Nevertheless there were many people living in the southern and middle regions of Europe, who said: “Verily, my inner being that lives its independent life from the time I fall asleep till I awaken, belongs to the region of a good and to the region of an evil world.” Again and again men thought and pondered about the depth of the forces that bring forth the good and the evil in the human soul. Heavily they felt the fact that the human soul is placed into a world where good and evil powers battle with one another. In the very first centuries of Christianity, such feelings were not yet present in the southern and middle regions of Europe, but in the fifth and sixth centuries they became more and more frequent. Especially among those who received knowledge and teachings from the East (and as we know such teachings from the East came over in manifold ways), this mood of soul arose. It was especially widespread in those regions to which the name Bulgaria afterwards came to be applied. (In a strange way the name persisted even though quite different peoples inhabited these regions). Thus in later centuries, and indeed for a very long time in Europe, those in whom this mood of soul was most strongly developed were called ‘Bulgars.’ ‘Bulgars’—for the people of Western and Middle Europe in the later Christian centuries of the first half of the Middle Ages—Bulgars were human beings who were most strongly touched by this opposition of the good and evil cosmic spiritual powers.

Throughout Europe we find the name ‘Bulgar’ applied to human beings such as I have characterised. Now the souls of whom I am here speaking, had been to a greater or lesser degree in this very mood of soul. I mean the souls who in the further course of their development beheld those mighty pictures in the super-sensible ceremony, in which they themselves actively took part,—all of which happened in the spiritual world in the first half of the 19th century. All that they had lived through when they had known themselves immersed in the battle between good and evil, was carried by them through their life between death and a new birth. And this gave a certain shade and colouring to these souls as they stood before the mighty cosmic pictures.

To all this yet another thing was added. These souls were indeed the last in European civilisation to preserve a little of that distinct perception of the etheric and the astral body in waking and sleeping. Recognising one another by these common peculiarities of their inner life, they had generally lived in communities. And among the other Christians, who became more and more attached to Rome, they were regarded as heretics. Heretics were not yet condemned as harshly as in later centuries. Still, they were regarded as heretics. Indeed the others always had a certain uncanny feeling about them. They had the impression that these people saw more than other folk. It was as though they were related to the Divine in a different way through the fact that they perceived the sleeping state differently than the others among whom they dwelt. For the others had long lost this faculty and had approached more nearly to the condition of soul which became general in Europe in the 14th century.

Now when these human beings—who had the distinct perception of the astral and the etheric body—passed through the gate of death, then also they were different from the others. Nor must we imagine, my dear friends, that man between death and a new birth is altogether without share in what is taking place through human beings on the earth. Just as we look up from here into the spiritual world of heaven, so between death and a new birth man looks down from that world on to the earth. Just as we here partake with interest in the life of spiritual beings, so from the spiritual world one partakes in the experiences of earthly beings upon the earth. After the age which I have hitherto been describing there came the time when Christendom in Europe was arranging its existence under the assumption that man has no longer any knowledge of his astral or his etheric body. Christianity was now preparing to speak about the spiritual worlds without being able to presume any such knowledge or consciousness among men. For you must think, my dear friends, when the early Christian teachers, in the first few centuries, spoke to their Christians—though they already found a large number who were only able to accept the truth of their words by external authority—nevertheless the simpler, more child-like feeling of that time enabled men to accept such words, when spoken from a warm and enthusiastic heart. And of the warmth and enthusiasm of heart with which the men of those first Christian centuries could preach, people today, where so much has gone into the mere preaching-of-words, have no conception. Those however who were still able to speak to souls such as I have described today,—what kind of words could they speak? They, my dear friends, could say: “Behold what shows itself in the rainbow-shining glory over the plants, what shows itself as the desire-nature about the animals,—lo, this is the reflection, this is the manifestation of the spiritual world from which the Christ has come.” Speaking to such men about the truths of spiritual wisdom, they could speak, not as of a thing unknown, but in such a way as to remind their hearers of what they could still behold under certain conditions in the gently luminous light of the sun: The Spirit in the world of Nature. Again when they spoke to them of the Gospels which tell of spiritual worlds and spiritual Mysteries or of the secrets of the Old Testament, then again they spoke to them not as of a thing unknown, but they could say: “Here is the Word of the Testament. It has been written down by human beings, who heard, more fully and clearly than you, the whispered language of that spiritual world in which your souls are dwelling from the time you fall asleep till you awaken. But you too know something of this language, for you remember it when you awaken in the morning.” Thus it was possible to speak to them of the spiritual as of something known to them. In the conversation of the priests or preachers of that time with these men, something was contained of what was already going on in their own souls. So in that time the Word was still alive and could be cultivated in a living way.

Then when these souls, to whom one had still been able to speak in the living Word, had passed through the gate of death, they looked down again upon the earth, and beheld the evening twilight of the living Word below. And they had the feeling that it was the twilight of the Logos. “The Logos is darkening”—such was the underlying feeling in their souls. After their life in the 7th, 8th or 9th century (or somewhat earlier) when they had passed through the gate of death again and looked down upon the earth, they felt: “Down there upon the earth is the evening twilight of the living Logos.” Well may there have lived in these souls the Word: “And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us. But human beings are less and less able to afford a home, a dwelling place for the Word that is to live within the flesh, that is to live on upon the earth.” This, I say again, was an underlying mood, it was indeed the dominant feeling among these souls, as they lived in the spiritual world between the 7th or 8th and the 19th or 20th century, no matter whether their sojourn there was interrupted by another life on earth. It remained their fundamental underlying feeling: “Christ lives indeed for the earth, since for the earth He died; but the earth cannot receive Him. Somehow there must arise on earth the power for souls to be able to receive the Christ.”

Beside all the other things I have described, this feeling became more and more living in the souls who had been stigmatised during their earthly time as heretics. This feeling grew in them between their death and the coming of a renewed revelation of the Christ—a new declaration of His Being.

In this condition of their souls, these human beings—disembodied as they were—witnessed what was happening on earth. It was something hitherto unknown to them, nevertheless they learned to understand what was going on, on earth below. They saw how souls on earth were less and less taken hold of by the spirit, till there were no more human beings left, to whom it was possible to speak such words as these: ‘We tell you of the Spirit whom you yourselves can still behold hovering over the world of plants, gleaming around the animals. We instruct you in the Testament that was written out of the spiritual sounds whose whispering you still can hear when you feel the echo of your experiences of the night.’ This was no more.

Looking down from above they saw how different these things were now becoming. For in the development of Christendom a substitute was being introduced for the old way of speaking. For a long time, though the vast majority to whom the preachers spoke had no longer any direct consciousness of the Spiritual in their earthly life, still the whole tradition, the whole custom of their speech came down to them from the older times,—I mean, from the time when one knew, as one spoke to men about the Spirit, that they themselves still had some feeling of what it was. It was only about the 9th, 10th or 11th century that these things vanished altogether. Then there arose quite a different condition, even in the listener. Until that time, when a man listened to another, who, filled with a divine enthusiasm, spoke out of the Spirit, he had the feeling as he listened that he was going a little out of himself. He was going out a little, into his etheric body. He was leaving the physical body to a slight extent. He was approaching the astral body more nearly. It was literally true, men still had a slight feeling of being ‘transported’ as they listened. Nor did they care so very much in those times for the mere hearing of words. What they valued most was the inward experience, however slight, of being transported—carried away. Men experienced with living sympathy the words that were spoken by a God-inspired man.

But from the 9th, 10th, or 11th, and towards the 14th century, this vanished altogether. The mere listening became more and more common. Therefore the need arose to make one's appeal to something different, when one spoke of spiritual things. The need arose somehow to draw forth from the listener what one wanted him to have as a conception of the spiritual world. The need arose as it were to work upon him, until at length he should feel impelled even out of his hardened body to say something about the spiritual world. Thus there arose the need to give instruction about spiritual things in the play of question and answer. There is always a suggestive element in questions. And when one asked: What is baptism? Having prepared the human being so that he would give a certain answer; or when one asked: What is Confirmation? What is the Holy Spirit? What are the seven deadly sins?—when one trained them in this play of question and answer, one provided a substitute for the simple elemental listening. To begin with this was done with those who entered the Schools where this was first made possible. Through question and answer, what they had to say about the spiritual worlds was thoroughly brought home to them. In this way the Catechism arose.

We must indeed look at such events as this. For these things were really witnessed by the souls who were up there in the spiritual world and who now looked down to the earth. They said to themselves: something must now approach man which it was quite impossible for us to know in our lives, for it did not lie near to us at all.

It was a mighty impression when the Catechism was arising down upon the earth. Very little is given when historians outwardly describe the rise of the Catechism, but much is given, my dear friends, when we behold it as it appeared from the super-sensible: “Down there upon the earth men are having to undergo things altogether new in the very depths of their souls; they are having to learn by way of Catechism what they are to believe.” Herewith I have described a certain feeling, but there is another which I must describe to you as follows:—We must go back once more into the first centuries of Christendom. In those times it was not yet possible for a Christian simply to go into a church, to sit down or to kneel, and then to hear the Mass right through from the beginning—from the “Introitus”—to the prayers which follow the Holy Communion. It was not possible for all Christians to attend the whole Mass through. Those who became Christians were divided into two groups. There were the Catechumenoi who were allowed to attend the Mass till the reading of the Gospel was over. After the Gospel the Offertory was prepared, and then they had to leave. Only those who had been prepared for a considerable time for the holy inner feeling in which one was allowed to behold the Mystery of Transubstantiation, only these—the Transubstantii as they were called—were allowed to remain and hear the Mass through to the end.

That was a very different way of partaking in the Mass. Now the human beings of whom we have been speaking (who in their souls underwent the conditions I described, who looked down on to the earth and perceived this strange Catechism-teaching, which would have been so impossible for them)—they, in their religious worship too, had more or less preserved the old Christian custom of not allowing a man to take part in the whole Mass till he had undergone a longer preparation. They were still conscious of an exoteric and an esoteric portion in the Mass. They regarded as esoteric all that was done from the Transubstantiation onward.

Now once more they looked down and beheld what was going on in the outer ritual of Christendom. They saw that the whole Mass had become exoteric. The whole Mass was being enacted even before those who had not entered into any special mood of soul by special preparation. “Can a man on earth really approach the Mystery of Golgotha, if in unconsecrated mood he witnesses the Transubstantiation?” Such was their feeling as they looked down from the life that takes its course between death and a new birth: “Christ is no longer being recognised in His true being; the sacred ceremony is no longer understood.”

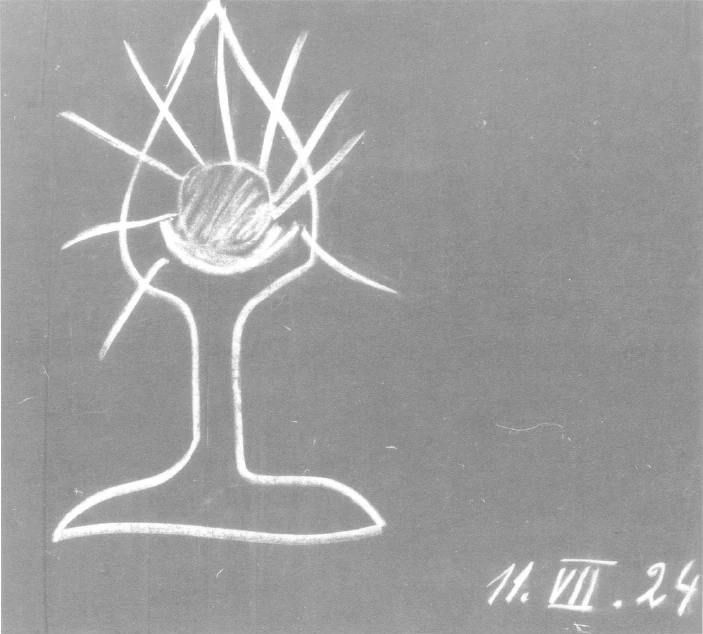

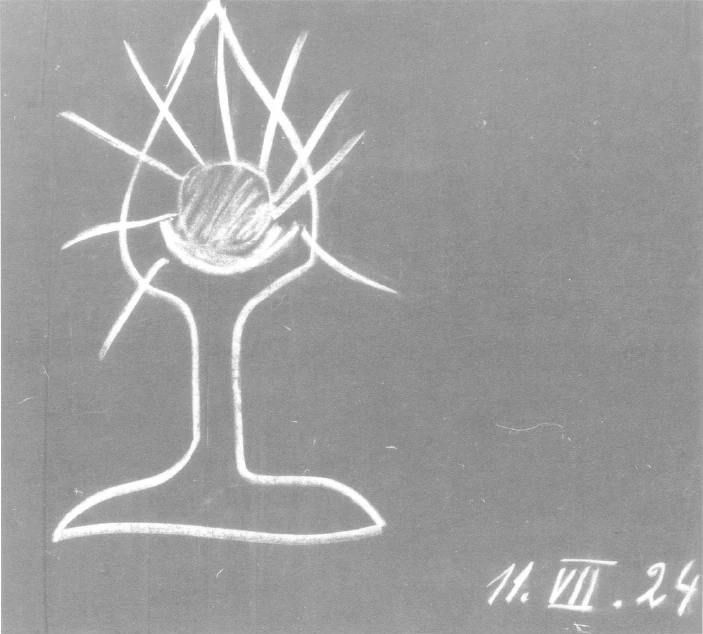

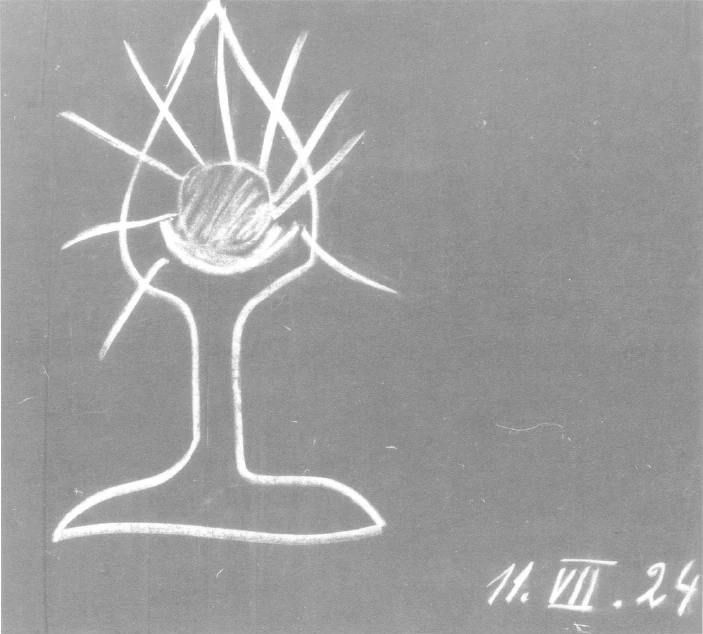

Such feelings poured themselves out within the souls whom I have now been describing. Moreover they looked down upon that which became a sacred symbol in the reading of the Mass, the so-called Sanctissimum wherein the Host is carried on a crescent cup. It is a living symbol of the fact that once upon a time the great Sun-Being was looked for in the Christ. For the very rays of the Sun are represented on every Sanctissimum, on every Monstrance. But the connection of the Christ with the Sun had been lost. Only in the symbol was it preserved; and in the symbol it has remained until this day. Yet even in the symbol it was not understood, nor is it understood today. This was the second feeling that sprang forth in their souls, intensifying their sense of the need for a new Christ-experience that was to come.

In the next lecture, the day after tomorrow, we will continue to speak of the karma of the Anthroposophical Society.

Fünfter Vortrag

Die Mitglieder der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft kommen zu dieser Gesellschaft, wie es ja durchaus selbstverständlich ist, aus Gründen der inneren Seelenverfassung. Wenn also über das Karma der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft gesprochen wird, wie wir es jetzt tun, über das Karma der anthroposophischen Bewegung überhaupt, aus der karmischen Entwickelung von Mitgliedern und Mitgliedergruppen heraus, dann muß es sich natürlich auch darum handeln, die Grundlagen zu diesem Karma in der Seelenverfassung der Menschen, die Anthroposophie suchen, zu sehen. Und das haben wir ja bereits begonnen. Wir wollen noch einiges zu dieser Seelenverfassung kennenlernen, um dann auch auf das weitere im Karma der anthroposophischen Bewegung eingehen zu können.

Sie haben ja gesehen, ich habe als auf das Wichtigste in der Seelenverfassung der Anthroposophen auf dasjenige hingewiesen, was diese in jenen Inkarnationen erlebt haben, die sie etwa in den ersten Jahrhunderten der Begründung des Christentums durchmachten, erlebt haben. Ich sagte, es können Inkarnationen dazwischen liegen, wichtig ist aber diejenige Inkarnation, die so in das 4. bis 8. nachchristliche Jahrhundert fällt. Diese Inkarnation hat uns durch ihre Betrachtung ergeben, daß wir zwei Gruppen von Persönlichkeiten zu unterscheiden haben, die zur anthroposophischen Bewegung kommen. Diese zwei Gruppen haben wir charakterisiert. Wir wollen aber jetzt etwas Gemeinsames ins Auge fassen, etwas, was sozusagen als wichtiges Gemeinsames auf dem Grunde der Seelen liegt, die eine solche Entwickelung durchgemacht haben, wie ich sie im letzten Mitgliedervortrag charakterisiert habe.

Wir stehen da durchaus, wenn wir auf diese ersten christlichen Jahrhunderte hinschauen, in einer Zeit, in der die Menschen noch ganz anders waren als jetzt. Wir können sagen: Wenn der heutige Mensch aufwacht, so geschieht das so, daß er eigentlich mit großer Schnelligkeit hineinschlüpft in seinen physischen Leib, natürlich mit der Reserve, die ich hier besprochen habe. Ich sagte schon, das Hineinschlüpfen und das Sich-Ausdehnen darinnen dauert ja den ganzen Tag; aber die Wahrnehmung, daß das Ich und der astralische Leib herankommen, das geschieht außerordentlich schnell. Es ist heute für den aufwachenden Menschen sozusagen keine Zwischenzeit vorhanden zwischen dem Gewahrwerden des ätherischen Leibes und dem Gewahrwerden des physischen Leibes. Man geht schnell durch die Wahrnehmung des ätherischen Leibes hindurch, bemerkt den ätherischen Leib gar nicht und taucht sogleich in den physischen Leib hinein beim Aufwachen. Das ist die Eigentümlichkeit des heutigen Menschen.

Die Eigentümlichkeit jener Menschen, die noch in diesen ersten christlichen Jahrhunderten gelebt haben, die ich charakterisiert habe, bestand darin, daß sie im Aufwachen deutlich wahrnahmen: Ich komme in ein Zweifaches hinein, in den ätherischen Leib und in den physischen Leib. Und sie wußten: Man geht durch die Wahrnehmung des ätherischen Leibes durch und gelangt dann erst in den physischen Leib hinein. Und es war so, daß die Leute eigentlich in diesem Augenblicke, wo sie aufwachten, vor sich hatten, wenn auch nicht ein ganzes Lebenstableau, so doch viele Bilder aus ihrem bisherigen Erdenleben. Und noch etwas anderes hatten sie vor sich, was ich gleich nachher charakterisieren werde. Denn daß man so, ich möchte sagen, etappenweise in dasjenige hineingelangt, was im Bette liegenbleibt, in den ätherischen und in den physischen Leib, das bewirkte für die ganze Zeit des Wachseins etwas anderes, als was heute unsere Erlebnisse während des Wachseins sind.

Wiederum, wenn wir das Einschlafen heute betrachten, so ist das Eigentümliche, daß wenn das Ich und der astralische Leib aus dem physischen Leib und AÄtherleib herausgehen, so saugt das Ich sehr schnell den astralischen Leib auf. Und da das Ich ganz haltlos ist gegenüber dem Kosmos, noch gar nichts wahrnehmen kann, so hört der Mensch beim Einschlafen auf, wahrzunehmen. Was da herausdringt als Träume, ist ja nur sporadisch.

Wiederum war das nicht so in jenen Zeiten, von denen ich gesprochen habe. Da sog das Ich nicht sogleich den astralischen Leib auf, sondern der astralische Leib blieb in seiner eigenen Substanz selbständig bestehen, nachdem die Menschen eingeschlafen waren. Und er blieb eigentlich bis zu einem gewissen Grade die ganze Nacht hindurch bestehen. So daß der Mensch am Morgen nicht so aufwachte, daß er aus der Bewußtseinsfinsternis aufwachte, sondern er wachte so auf, daß er die Empfindung hatte: Du hast ja da in einer lichtvollen Welt gelebt, in der allerlei vorgegangen ist; Bilder waren es zwar, aber es ist allerlei vorgegangen. — Es war also durchaus so, daß der Mensch in der damaligen Zeit eine Zwischenempfindung hatte zwischen dem Wachen und Schlafen. Sie war leise, sie war intim, aber sie war da. Das hörte bei der eigentlich zivilisierten Menschheit erst vollständig auf mit dem Beginn des 14. Jahrhunderts. Dadurch aber erlebten ja alle die Seelen, von denen ich neulich gesprochen habe, die Welt anders, als sie die heutigen Menschen erleben. Stellen wir uns einmal vor das Auge, wie die Menschen, also Sie alle, meine lieben Freunde, dazumal die Welt erlebten.

Dadurch, daß eine Etappe war im Untertauchen in den ätherischen und physischen Leib, dadurch schaute der Mensch während seines ganzen Wachseins nicht so in die Natur hinaus, daß er nur die nüchterne prosaische Sinneswelt sah, die der Mensch heute sieht und die er, wenn er sie sich ergänzen will, nur durch seine Phantasie ergänzen kann. Sondern er schaute hinaus, sagen wir in die Welt der Pflanzen, zum Beispiel auf ein blumiges Wiesengebiet so, als ob ein leiser, bläulich-rötlicher Wolkenschein —- namentlich dann, wenn die Sonne milder schien am Tag, wenn es nicht gerade Mittagszeit war —, wie wenn ein bläulich-rötlicher, mannigfaltig gewellter und gewolkter Schein, Nebelschein, sich ausbreitete über der blumigen Wiese. Was man etwa heute sieht, wenn leichter Nebel über der Wiese ist, was dann aber herrührt von dem verdunsteten Wasser, das sah man im Geistig-Astralischen dazumal. Und so sah man eigentlich jede Baumkrone gehüllt in eine solche Wolke, so sah man Saatfelder so, wie wenn rötlich-bläuliche Strahlungen, nebelhaft sprießend, aus dem Kosmos in den Erdboden sich heruntersenkten.

Und schaute man die Tiere an, dann hatte man den Eindruck, daß diese Tiere nicht nur ihre physische Gestalt haben, sondern daß diese physische Gestalt in einer astralischen Aura sich befindet. Leise, intim nahm man diese Aura wahr, eigentlich aber nur, wenn die Lichtverhältnisse des Sonnenscheins in einer bestimmten milden Weise tätig waren. Aber man nahm sie eben wahr. Man sah also überall in der äußeren Natur Geistiges walten und weben.

Und starb man, dann war einem dasjenige, was man in den ersten Tagen, nachdem man durch die Pforte des Todes geschritten war, als eine Rückschau auf das Erdenleben hatte, etwas, was einem im Grunde vertraut war; denn man hatte eine ganz bestimmte Empfindung gegenüber dieser nach dem Tode auftretenden Rückschau auf das Erdenleben. Man hatte die Empfindung, daß man sich sagte: Jetzt entlasse ich aus meinem Organismus dasjenige Aurische, das hingeht zu dem, was ich in der Natur an Aurischem gesehen habe. In seine eigene Heimat geht mein Ätherleib — so empfand man.

Alle diese Empfindungen waren in noch älteren Zeiten natürlich wesentlich stärker. Aber sie waren auch noch, wenn auch in leiser Art, vorhanden in der Zeit, von der ich hier spreche. Und man empfand dann, wenn man dies sah, nachdem man durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen war: In all dem geistigen Weben und Leben, das ich geschaut habe über den natürlichen Dingen und natürlichen Vorgängen, spricht das Wort des Vatergottes, und zum Vater gehet mein Ätherleib.

Wenn der Mensch so durch die andere Art des Aufwachens die äußere Natur sah, so sah er auch sein eigenes Äußeres anders, als das später der Fall war. Wenn der Mensch einschlief, wurde der astralische Leib nicht gleich aufgesogen von dem Ich. In einem solchen Verhältnisse «tönt» der astralische Leib. Und es tönte aus geistigen Welten in das schlafende Menschen-Ich herein — wenn auch nicht mehr so deutlich wie in uralten Zeiten, so doch eben in leiser, intimer Form - allerlei, was man nicht hören kann im wachenden Zustande. Und der Mensch hatte beim Aufwachen durchaus die Empfindung: einer Geistersprache in lichten kosmischen Räumen war ich teilhaftig vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen.

Und wenn dann der Mensch, einige Tage nachdem er durch die Pforte des Todes geschritten war, den Ätherleib abgelegt hatte und nun in seinem astralischen Leibe lebte, dann hatte er wiederum das Gefühl: In diesem astralischen Leibe erlebe ich alles das im Rücklauf, was ich auf der Erde gedacht, getan habe. Aber ich erlebe in diesem astralischen Leibe, in dem ich jede Nacht im Schlafe gelebt habe, dasjenige, was ich auf Erden gedacht und getan habe. - Und während der Mensch nur Unbestimmtes mitnahm in das Aufwachen hinein, fühlte er jetzt, indem er in der Zeit zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt in seinem Astralleib sein Erdenleben zurücklebte: In diesem meinem astralischen Leibe lebt der Christus. Ich habe es nur nicht bemerkt, aber jede Nacht lebte mein astralischer Leib in der Wesenhaftigkeit des Christus. Jetzt wußte der Mensch: Solange er zu erleben hat dieses rücklaufende Erdenleben, verläßt ihn, weil er bei seinem astralischen Leibe ist, der Christus nicht.

Sehen Sie, wie man auch zum Christentum gestanden haben mag in diesen ersten christlichen Jahrhunderten, ob so wie die erste Gruppe der Menschen, die ich besprochen habe, ob so wie die zweite Gruppe, ob man gewissermaßen noch mit mehr heidnischer Kraft oder mit Heidentumsmüdigkeit lebte, man erlebte ganz gewiß — wenn auch nicht auf der Erde- nach dem Tode die große Tatsache des Mysteriums von Golgatha: daß sich der Christus, das früher dirigierende Wesen der Sonne, vereinigt hat mit dem, was als Menschen auf der Erde lebt. Das haben alle diejenigen erlebt, welche in den ersten Jahrhunderten der christlichen Entwickelung dem Christentum nahegetreten waren. Für die anderen ist es mehr oder weniger unverständlich geblieben, was sie da nach dem Tode erlebten. Das aber waren die Grundunterschiede im Erleben der Seelen in den ersten christlichen Jahrhunderten und später.

Aber das alles bewirkte noch etwas anderes. Das alles bewirkte, daß der Mensch, wenn er im wachenden Zustande die Natur schaute, diese Natur durchaus als die Domäne des Vatergottes empfand. Denn all das Geistige, was er da webend und lebend bemerkte, war ihm der Ausdruck, die Offenbarung des Vatergottes. Und er empfand, daß eine Welt da ist, die in der Zeit, in der der Christus auf der Erde erschien, etwas brauchte: nämlich die Aufnahme des Christus in die Erdensubstanz für die Menschheit. Es empfand der Mensch noch etwas wie lebendiges Christus-Prinzip gegenüber dem Naturgeschehen und Naturwalten. Denn es war ja etwas verbunden mit diesem Anschauen der Natur, so daß man in ihr ein geistiges Weben und Walten schaute.

Was da empfunden wurde als geistiges Weben und Walten, was da gewissermaßen in sich wandelnden Geistgestalten über allem Pflanzlichen und um alles Tierische schwebte, das wurde so empfunden, daß der unbefangen fühlende Mensch diese Empfindung zusammenbrachte in die Worte: Das ist Unschuld des Naturdaseins. Ja, meine lieben Freunde, was da geistig zu schauen war, nannte man geradezu die Unschuld im Naturwalten, und man sprach von der unschuldigen Geistigkeit im Naturwalten. Dasjenige aber, was innerlich gefühlt wurde, wenn man aufwachte: daß man vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen in einer Welt heller, tönender Geistigkeit war, das empfand man so, daß darinnen das Gute und das Böse walten kann, daß in ihm, wenn es so heraustönt aus den Tiefen des Geistigen, gute Geister und böse Geister sprechen, daß die guten Geister die Unschuld der Natur nur höher bringen wollen, sie bewahren wollen, daß die bösen Geister aber der Unschuld der Natur die Schuld beigeben. Und man empfand überall, wo solche Christen lebten, wie ich sie hier schildere, das Walten des Guten und das Walten des Bösen gerade durch den Umstand, daß im schlafenden Zustande beim Menschen das Ich nicht in sich hineinsog den astralischen Leib.

Es waren nicht alle diejenigen, die sich damals Christen nannten, oder irgendwie dem Christentum nahestanden, von dieser Seelenverfassung. Aber es war eine große Anzahl von Menschen, die in den südlichen und mittleren Gegenden Europas lebten, die sagten: Ja, mein Inneres, das sich da selbständig auslebt zwischen Einschlafen und Aufwachen, das gehört der Region einer guten und der Region einer bösen Welt an. Und viel, viel wurde nachgedacht und nachgesonnen über die Tiefe der Kräfte, die das Gute und Böse in der Menschenseele auslösen. Schwer wurde empfunden das Hineingestelltsein der Menschenseele in eine Welt, in der die guten und die bösen Mächte miteinander kämpfen. In den allerersten Jahrhunderten waren diese Empfindungen in den südlichen und mittleren Gegenden Europas noch nicht vorhanden, aber im 5., 6. Jahrhundert wurden sie immer häufiger; und namentlich unter denjenigen Menschen, die mehr Kunde erhielten vom Osten herüber — in der mannigfaltigsten Weise kam ja diese Kunde vom Osten herüber -, entstand diese Seelenstimmung. Und weil sich diese Seelenstimmung besonders stark in denjenigen Gegenden ausbreitete, für die sich der Name «Bulgarien» dann herausbildete - auf eine merkwürdige Weise blieb ja der Name auch, als später ganz andere Völkerschaften diese Gegenden bewohnten -, nannte man in späteren Jahrhunderten die längste Zeit hindurch in Europa Menschen, welche diese Seelenstimmung besonders stark ausgebildet hatten, Bulgaren. Bulgaren waren in den späteren christlichen Jahrhunderten der ersten Hälfte des Mittelalters für die West- und Mitteleuropäer Menschen, welche besonders stark berührt wurden von dem Gegensatze der guten und der bösen kosmisch-geistigen Mächte. Man findet den Namen Bulgaren in ganz Europa für solche Menschen, wie ich sie charakterisiert habe.

Aber mehr oder weniger gerade in solcher Seelenverfassung waren die Seelen, von denen ich hier spreche: die Seelen, die dann in ihrer weiteren Entwickelung dazu kamen, jene mächtigen Bilder im überirdischen Kultus zu schauen, an ihrer Betätigung mitzumachen, die dann in die erste Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts fielen. All das, was die Seelen durchleben konnten in diesem Sich-drinnen-Wissen in dem Kampfe zwischen Gut und Böse, das wurde durch das Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt hindurchgetragen. Und das nuancierte, das färbte die Seelen, die dann vor den geschilderten mächtigen Bildern standen.

Dazu kam aber noch etwas anderes. Diese Seelen waren sozusagen die letzten, die innerhalb der europäischen Zivilisation sich noch etwas bewahrt hatten von diesem gesonderten Wahrnehmen des ätherischen und astralischen Leibes im Wachen und Schlafen. Sie lebten durchaus, indem sie sich an diesen Eigentümlichkeiten des Seelenlebens erkannten, in Gemeinschaften. Man sah sie innerhalb derjenigen Christen, die sich immer mehr und mehr an Rom anschlossen, als Ketzer an. Man war ja dazumal noch nicht so weit, daß man die Ketzer in derselben strengen Form verdammte wie später, aber man sah sie als Ketzer an. Man hatte überhaupt von ihnen einen unheimlichen Eindruck. Man hatte eben den Eindruck, daß sie mehr sahen als die anderen Leute, daß sie auch zu dem Göttlichen in einer anderen Weise standen durch das Wahrnehmen des Schlafzustandes. Denn die anderen Menschen, unter denen sie wohnten, die hatten eben längst dieses verloren, hatten sich längst mehr der Seelenverfassung genähert, die dann im 14. Jahrhundert in Europa allgemein wurde.

Aber wenn dann diese Menschen, von denen ich da spreche, diese Menschen mit der gesonderten Wahrnehmung des astralischen und des Ätherleibes, durch die Pforte des Todes gingen, dann unterschieden sie sich auch von denjenigen, die anders waren. Und man darf nicht glauben, daß der Mensch zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt ohne allen Anteil ist an dem, was auf der Erde durch Menschen geschieht. Wie wir gewissermaßen von hier aus in die himmlisch-geistige Welt hinaufschauen, schaut man zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt von der himmlisch-geistigen Welt auf die Erde herunter. Wie man von hier aus teilnimmt an den Geistwesen, nimmt man von der geistigen Welt aus teil an dem, was die Erdwesen auf Erden erleben.

Nun folgte auf die Zeit, die ich hier schildere, jene, in der hier in Europa das Christentum sich darauf einrichtete, etwas zu sein auch unter der Voraussetzung, daß der Mensch nichts mehr weiß von seinem astralischen Leib und von seinem ätherischen Leib. Es richtete sich das Christentum darauf ein, über die geistige Welt zu reden, ohne daß beim Menschen diese Voraussetzungen gemacht werden konnten. Denn bedenken Sie nur, meine lieben Freunde: Wenn die alten christlichen Lehrer in den ersten Jahrhunderten zu ihren Christen sprachen, so fanden sie in der Tat schon eine große Zahl von solchen, die nur auf die äußere Autorität hin die Worte als wahr hinnehmen konnten; aber die noch naivere Stimmung der damaligen Zeit ließ eben diese Worte hinnehmen, wenn sie aus warmem, enthusiastischem Herzen gesprochen waren. Und wie warm und enthusiastisch Herzen in den ersten Jahrhunderten das Christentum predigten, davon macht man sich heute, wo so vieles in eine bloße Wortpredigt übergegangen ist, keinen Begriff mehr.

Aber diejenigen, die sprechen konnten zu solchen Seelen, wie ich sie hier geschildert habe, was konnten die für Worte sprechen? Ja, meine lieben Freunde, die konnten sagen: Schaut hin auf dasjenige, was sich in regenbogenschillerndem Scheine über den Pflanzen, was sich an Begierdenhaftem an den Tieren zeigt, schaut hin: das ist der Abglanz, das ist die Offenbarung der geistigen Welt, von der auch wir sprechen, der geistigen Welt, aus der heraus der Christus stammt. Man sprach gewissermaßen, indem man zu solchen Menschen von den geistigen Weistümern sprach, nicht von etwas Unbekanntem; man sprach zu ihnen, indem man sie erinnern konnte an dasjenige, was sie unter gewissen Umständen in der milden Sonnenbeleuchtung schauen konnten als den Geist in der Natur.

Und wiederum, wenn man ihnen davon sprach, daß das Evangelium da ist, welches von der geistigen Welt, von den geistigen Geheimnissen verkündet, wenn man ihnen sprach von den Geheimnissen des Alten Testamentes, dann sprach man ihnen wieder nicht von etwas Unbekanntem, sondern man konnte ihnen sagen: Hier ist das Wort des Testamentes; dieses Wort des Testamentes ist von jenen Menschenwesen aufgeschrieben, die zwar deutlicher als ihr vernommen haben das Raunen jener Geistigkeit, in der eure Seelen zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen sind, aber ihr wißt von diesem Raunen, denn ihr erinnert euch daran, wenn ihr am Morgen aufgewacht seid. Und so konnte man davon zu diesen Menschen als von etwas Bekanntem sprechen. So war in gewisser Weise in dem Gespräche, das die Priester, das die Prediger der damaligen Zeit mit diesen Menschen führten, etwas darinnen von dem, was in den Seelen dieser Menschen selber sich abspielte. Und so war in dieser Zeit das Wort noch lebendig und konnte als Lebendiges gepflegt werden.

Und wenn dann diese Seelen, zu denen man im Worte sprechen konnte als in etwas Lebendigem, hinunterschauten auf die Erde, nachdem sie durch die Pforte des Todes geschritten waren, dann sahen sie auf die Abenddämmerung dieses lebendigen Wortes da unten, und sie hatten die Empfindung: der Logos dämmert. Das war die Grundempfindung solcher Seelen, wie ich sie geschildert habe, die nach dem 7., 8., 9. Jahrhundert oder schon etwas früher durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen sind, daß sie beim Hinunterschauen auf die Erde empfunden haben: Hier unten auf Erden ist die Abenddämmerung des lebendigen Logos. Und es lebte wohl in diesen Seelen das Wort: «Und das Wort ist Fleisch geworden und hat unter uns gewohnet», und sie empfanden: Aber die Menschen haben immer weniger ein Haus für das Wort, das im Fleische leben soll, fortleben soll auf der Erde.

Das gab wiederum eine Grundstimmung, die Grundstimmung bei den Seelen, die zwischen dem 7., 8. und dem 19., 20. Jahrhundert in der geistigen Welt lebten, auch wenn sie in irgendeinem Erdendasein eine Unterbrechung hatten, das gab die Grundstimmung ab: Der Christus lebt zwar für die Erde, denn er ist für die Erde gestorben, aber die Erde kann ihn nicht aufnehmen; und es muß werden die Kraft auf der Erde, daß Seelen den Christus aufnehmen können! Das lebte sich neben allem anderen, was ich geschildert habe, gerade in diese in ihrer Erdenzeit als ketzerisch angesehenen Seelen hinein zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt: Das Bedürfnis nach einer neuen, nach einer erneuerten Christus-Offenbarung, Christus-Verkündigung.

Unter solcher Seelenverfassung erlebten diese entkörperten Menschen, wie auf Erden dasjenige geschah, was ihnen auf der Erde eigentlich noch gänzlich unbekannt sein mußte. Sie lernten verstehen, was da unten auf Erden sich abspielte. Sie sahen, wie immer weniger und weniger die Seelen auf der Erde vom Geiste ergriffen waren, wie gar keine Menschen mehr da waren, denen man sagen konnte: Wir verkündigen euch den Geist, den ihr selber noch schwebend über der Pflanzenwelt, schimmernd an den Tieren schauen könnt. Wir lehren euch das Testament, das herausgeschrieben ist aus jenen Tönen, die ihr noch raunen hört, wenn ihr das Nachfühlen der nächtlichen Erlebnisse habt. — Alles das war nicht mehr da.

Sie sahen von oben, wo sich die Dinge ganz anders ausnahmen, wie in der christlichen Entwickelung ein Ersatz eintrat für die alte Sprache. Denn schließlich, wenn auch die Prediger zu den weitaus meisten Menschen schon so sprechen mußten, da diese kein Bewußtsein des Geistigen im Erdenleben hatten, es war die ganze Tradition, der ganze Gebrauch der Rede noch aus Zeiten heraus, in denen man voraussetzen konnte, daß, wenn man vom Geiste redete, die Menschen noch etwas fühlten vom Geiste.

Das alles verschwand eigentlich erst vollständig um das 9., 10., 11. Jahrhundert herum. Da entstand eine ganz andere Verfassung sogar im Anhören. Wenn man früher einen Menschen, der aus dem Geiste heraus sprach, der eben enthusiastisch-gotterfüllt war, reden hörte, da hatte man das Gefühl, beim Zuhören gehe man eigentlich etwas aus sich heraus, man gehe etwas in seinen ätherischen Leib hinein, den physischen Leib verlasse man etwas. Und wiederum hatte man das Gefühl, man nähere sich da dem astralischen Leibe. Man hatte wirklich immerhin noch ein leises Gefühl des Entrücktseins beim Zuhören. Man gab noch nicht so viel auf das bloße Nur-Hören, man gab viel mehr auf das, was man innerlich in einer leisen Entrücktheit erlebte. Man lebte mit die Worte, die gesprochen wurden von gottbegeisterten Menschen.

Das verschwand im 9., 10., 11. Jahrhundert gegen das 14. Jahrhundert hinüber vollständig. Das Nur-Hören wurde immer mehr gang und gäbe. Da entstand denn das Bedürfnis, an etwas anderes zu appellieren, wenn man von dem Geistigen sprach. Da entstand das Bedürfnis, aus dem, der zuhören sollte, herauszuziehen dasjenige, was er als Ansicht haben sollte über die geistige Welt. Es entstand das Bedürfnis, ihn gewissermaßen so zu bearbeiten, daß er sich aus diesem verhärteten Körper heraus doch noch gedrängt fühle, etwas über die geistige Welt zu sagen. Und daraus entstand das Bedürfnis, in Frage- und Antwortspiel die Unterweisung über die geistige Welt zu geben. Indem man fragt - Fragen haben immer etwas Suggestives -: Was ist die Taufe? — und den Menschen auf eine bestimmte Antwort präpariert, oder: Was ist die Firmung? Was ist der Heilige Geist? Was ist der Tod? Welches sind die sieben Hauptsünden? — indem man dieses Frage- und Antwortspiel präpariert, ersetzt man das selbstverständliche elementare Zuhören. Und es kam in dieser Zeit — zuerst an diejenigen Menschen, die in solche Schulen kamen, wo man das tun konnte - herauf, was ein Einlernen in Frage und Antwort war dessen, was über die geistige Welt zu sagen war: der Katechismus entstand.

Sehen Sie, man muß auf solche Ereignisse hinschauen. Das sahen die Seelen, die in besonders starker Weise da oben waren in der geistigen Welt und jetzt herunterschauten: Da muß etwas an die Menschen herankommen, was wir ja gar nicht kennen konnten, was uns gar nicht nahelag! Und das war ein mächtiger Eindruck, daß da unten auf der Erde der Katechismus entstand. Es ist nichts Besonderes damit gegeben, wenn die Historiker äußerlich die Entstehung des Katechismus zeigen; aber es ist viel gegeben, wenn man die Entstehung des Katechismus anschaut, wie sie sich von seiten der Übersinnlichkeit ausnahm: Da unten müssen die Menschen ganz Neues in dem Tiefsten ihrer Seele durchmachen, müssen auf Katechismusart lernen, was sie glauben sollen.

Damit schildere ich Ihnen eine Empfindung. Eine andere habe ich Ihnen in der folgenden Weise zu schildern. Wenn wir zurückgehen in die ersten Jahrhunderte des Christentums, so war noch nicht eine Möglichkeit vorhanden, daß man als Christ in eine Kirche ging, sich hinsetzte oder hinkniete und nun die Messe von Anfang an, vom Introitus bis zu den Gebeten, die da folgen auf die Kommunion, anhörte. Das war nicht möglich für alle, eine ganze Messe zu hören, sondern diejenigen, die Christen wurden, wurden in zwei Gruppen geteilt: die Katechumenen, welche bleiben durften bei der Messe, bis das Evangelium zu Ende gelesen war; nach dem Evangelium bereitet sich das Offertorium vor, da mußten sie hinausgehen. Und nur diejenigen, die schon längere Zeit für jene heilig-innige Gemütsstimmung vorbereitet waren, in der man das Mysterium der Transsubstantiation, die Wandlung wahrnehmen durfte: die Transsubstanten, die durften drinnenbleiben, die hörten die Messe zu Ende.

Das war ein ganz anderes Teilnehmen an der Messe. Die Menschen, von denen ich Ihnen da gesprochen habe, daß sie in ihren Seelen die Zustände durchmachten, die ich geschildert habe, die hinunterschauten und nun schon jenes merkwürdige, ihnen noch unmöglich erscheinende Ereignis des katechetischen Unterrichtes wahrnehmen, diese Menschen hatten sich mehr oder weniger für ihren Kultus die alte christliche Sitte bewahrt: den Menschen erst nach langer Vorbereitung die ganze Messe anhören zu lassen, mitmachen zu lassen. Diese Menschen, von denen ich da gesprochen habe, kannten durchaus ein Exoterisches und ein Esoterisches an der Messe. Als esoterisch wurde von ihnen angesehen, was von der Transsubstantiation, von der Wandlung ab geschieht.

Nun sahen sie wiederum herunter auf das, was sich im äußeren Kultus des Christentums zutrug. Sie sahen: Die ganze Messe ist exoterisch geworden, die ganze Messe spielt sich auch vor demjenigen ab, der noch nicht durch eine besondere Vorbereitung in eine besondere Seelenstimmung hineingekommen ist. Ja, kann denn da der Mensch auf der Erde wirklich zu dem Mysterium von Golgatha hinkommen, wenn er in unheiliger Stimmung die Transsubstantiation empfindet? — So empfanden diese Seelen von dem Leben aus, das zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt verfließt. Wer aber die Transsubstantiation nicht versteht, versteht nicht das Geheimnis von Golgatha. So dachten wiederum diese Seelen in ihrem Zustande zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt: Der Christus wird nicht mehr in seiner Wesenheit erkannt; der Kultus wird nicht mehr verstanden.

Das lud sich ab im Inneren der Seelen, die ich geschildert habe. Und wenn so diese Seelen auf dasjenige hinunterschauten, was sich ausbildete als ein Symbolum beim Messelesen — das sogenante Sanktissimum, worinnen die Hostie auf einem halbmondförmigen Untersatze ist -, dann empfanden sie: Das ist ja das lebendige Symbolum dafür, daß man einstmals in dem Christus das Sonnenwesen gesucht hat; denn auf jedem Sanktissimum, auf jeder Monstranz sind die Strahlen der Sonne darauf. Aber verlorengegangen ist der Zusammenhang des Christus mit der Sonne; nur noch im Symbolum ist er da. Er ist da geblieben bis zum heutigen Tage im Symbolum, aber das Symbolum selber wird nicht verstanden! - Das war die zweite Empfindung, aus der dann aufsprießte eine Verstärkung des Sinnes dafür, daß eine neue Christus-Empfindung kommen müsse.

Wir wollen dann übermorgen in dem nächsten Vortrag weitersprechen über das Karma der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft.

Fifth Lecture

The members of the Anthroposophical Society come to this Society, as is quite natural, for reasons of the inner constitution of the soul. So when we talk about the karma of the Anthroposophical Society, as we are doing now, about the karma of the anthroposophical movement in general, from the karmic development of members and groups of members, then of course it must also be a matter of seeing the foundations of this karma in the soul constitution of the people who seek anthroposophy. And we have already begun to do this. We want to get to know a few more things about this constitution of the soul in order to be able to go into the further karma of the anthroposophical movement.

You have seen that I referred to the most important thing in the soul constitution of anthroposophists as being what they experienced in the incarnations they went through in the first centuries of the foundation of Christianity. I said that there could be incarnations in between, but what is important is the incarnation that took place in the 4th to 8th century AD. This incarnation has shown us through its observation that we have to distinguish between two groups of personalities who come to the anthroposophical movement. We have characterized these two groups. But now we want to consider something in common, something that lies, so to speak, as an important commonality at the bottom of the souls that have undergone the kind of development I characterized in the last members' lecture.

When we look back at these first Christian centuries, we are standing in a time when people were still quite different from what they are now. We can say that when people today wake up, they actually slip into their physical body with great speed, naturally with the reserve that I have discussed here. I have already said that the slipping in and the stretching out in it takes the whole day; but the perception that the ego and the astral body are approaching happens extraordinarily quickly. For the awakening human being today there is, so to speak, no intermediate time between becoming aware of the etheric body and becoming aware of the physical body. One quickly passes through the perception of the etheric body, does not even notice the etheric body and immediately dives into the physical body when waking up. This is the peculiarity of the modern human being.

The peculiarity of those people who still lived in these first Christian centuries, whom I have characterized, consisted in the fact that they clearly perceived when they woke up: I enter a twofold body, the etheric body and the physical body. And they knew that one passes through the perception of the etheric body and only then enters the physical body. And it was so that the people actually had before them at that moment when they woke up, even if not a whole life tableau, at least many pictures from their previous life on earth. And they also had something else before them, which I will characterize later. For the fact that one thus, I would like to say, enters in stages into that which remains in the bed, into the etheric and physical body, brought about something different for the whole time of wakefulness than what our experiences are today during wakefulness.

Again, if we look at falling asleep today, the peculiar thing is that when the ego and the astral body leave the physical body and the etheric body, the ego very quickly absorbs the astral body. And since the ego is completely unstable in relation to the cosmos and cannot yet perceive anything, the human being ceases to perceive when he falls asleep. What comes out as dreams is only sporadic.

On the other hand, this was not the case in the times I have just mentioned. There the ego did not immediately absorb the astral body, but the astral body remained independent in its own substance after people had fallen asleep. And it actually remained in existence to a certain degree throughout the night. So that the human being did not wake up in the morning in such a way that he woke up from the darkness of consciousness, but he woke up in such a way that he had the feeling: You have lived in a world full of light, in which all kinds of things have taken place; they were indeed images, but all kinds of things have taken place. - So it was certainly the case that man at that time had an intermediate sensation between waking and sleeping. It was quiet, it was intimate, but it was there. This only completely ceased to exist in civilized mankind at the beginning of the 14th century. As a result, all the souls I spoke about the other day experienced the world differently than people do today. Let us imagine how people, that is, all of you, my dear friends, experienced the world at that time.

Because there was a stage of immersion in the etheric and physical body, man did not look out into nature during his entire waking life in such a way that he saw only the sober prosaic sensory world that man sees today and which, if he wants to supplement it, he can only supplement through his imagination. Rather, he looked out, let us say into the world of plants, for example at a flowery meadow, as if a soft, bluish-reddish glow of clouds -- especially when the sun shone more mildly during the day, when it was not exactly midday -, as if a bluish-reddish, variously wavy and cloudy glow, the glow of mist, spread out over the flowery meadow. What you see today, for example, when there is a light mist over the meadow, but which then comes from the evaporated water, that is what you saw in the spiritual-astral then. And so one actually saw every treetop shrouded in such a cloud, so one saw seed fields as if reddish-bluish radiations, sprouting like mist, descended from the cosmos into the ground.

And when one looked at the animals, one had the impression that these animals not only had their physical form, but that this physical form was in an astral aura. One perceived this aura quietly, intimately, but actually only when the light conditions of the sunshine were active in a certain mild way. But it was perceived. So you could see spiritual things weaving and moving everywhere in outer nature.

And when one died, then that what one had in the first days after one had passed through the gate of death as a review of earth life was something that was basically familiar to one; because one had a quite certain feeling towards this review of earth life occurring after death. One had the feeling that one said to oneself: "Now I release from my organism that auric which goes to what I have seen of the auric in nature. My etheric body is going to its own home - that is how one felt.

All these sensations were of course much stronger in even older times. But they were also still present, albeit in a quiet way, in the time I am talking about here. And one then felt, when one saw this after one had passed through the gate of death: In all the spiritual weaving and life, which I have seen above the natural things and natural processes, the word of God the Father speaks, and to the Father goes my etheric body.

When man thus saw external nature through the different way of waking up, he also saw his own external nature differently than was the case later. When the human being fell asleep, the astral body was not immediately absorbed by the ego. In such a state the astral body “sounds”. And all sorts of things that cannot be heard in the waking state sounded into the sleeping human ego from the spiritual worlds - although no longer as clearly as in ancient times, but still in a quiet, intimate form. And when he woke up, he had the feeling that he was partaking of a spirit language in light cosmic spaces from the moment he fell asleep until he woke up.

And when the human being, a few days after passing through the gate of death, had discarded the etheric body and now lived in his astral body, then he again had the feeling: In this astral body I experience everything in regression that I thought and did on earth. But in this astral body, in which I lived every night in sleep, I experience what I thought and did on earth. - And while the human being only took indeterminate things with him when he woke up, he now felt that he was reliving his earthly life in his astral body in the time between death and a new birth: The Christ lives in this astral body of mine. I just did not realize it, but every night my astral body lived in the beingness of the Christ. Now the person knew: As long as he has to experience this returning earthly life, the Christ will not leave him because he is with his astral body.

You see, however one may have stood towards Christianity in these first Christian centuries, whether like the first group of people I have discussed, whether like the second group, whether one lived to a certain extent with more pagan strength or with a weariness of paganism, one certainly experienced - even if not on earth - after death the great fact of the Mystery of Golgotha: That the Christ, the former directing Being of the Sun, united Himself with that which lives as men on earth. This was experienced by all those who came close to Christianity in the first centuries of its development. For the others it remained more or less incomprehensible what they experienced after death. But these were the basic differences in the experience of souls in the first Christian centuries and later.

But all this had another effect. All this had the effect that man, when he looked at nature in a waking state, perceived this nature as the domain of God the Father. For all the spiritual things he observed weaving and living there were for him the expression, the revelation of God the Father. And he felt that there was a world that needed something at the time when the Christ appeared on earth: namely, the incorporation of the Christ into the earthly substance for humanity. Man still felt something like a living Christ principle in relation to natural events and the forces of nature. For there was something connected with this contemplation of nature, so that one saw a spiritual weaving and working in it.

What was perceived there as spiritual weaving and working, what hovered, as it were, in changing spiritual forms above all plant life and around all animal life, was perceived in such a way that the unbiased feeling human being summarized this feeling in the words: This is the innocence of nature's existence. Yes, my dear friends, what could be seen spiritually there was called the innocence of nature's being, and one spoke of the innocent spirituality of nature's being. But that which was felt inwardly when one woke up: that one was in a world of bright, resounding spirituality from the time one fell asleep until one woke up, that was felt in such a way that good and evil can reign in it, that good spirits and evil spirits speak in it when it sounds out like this from the depths of the spiritual, that the good spirits only want to bring the innocence of nature higher, want to preserve it, but that the evil spirits attribute guilt to the innocence of nature. And everywhere where such Christians lived as I am describing here, one felt the reign of good and the reign of evil precisely through the circumstance that in the sleeping state of man the ego did not draw the astral body into itself.

Not all those who called themselves Christians at that time, or were somehow close to Christianity, were of this soul constitution. But there were a large number of people who lived in the southern and central regions of Europe who said: "Yes, my inner being, which lives itself out independently between falling asleep and waking up, belongs to the region of a good and the region of an evil world. And much, much thought and contemplation was given to the depth of the forces that trigger good and evil in the human soul. The fact that the human soul is placed in a world in which good and evil forces fight with each other was felt to be difficult. In the very first centuries these feelings were not yet present in the southern and central regions of Europe, but in the 5th and 6th centuries they became more and more frequent; and especially among those people who received more news from the East - for this news came from the East in the most varied ways - this mood of the soul arose. And because this mood of the soul spread particularly strongly in those regions for which the name “Bulgaria” then developed - in a strange way the name remained even when later quite different peoples inhabited these regions - in later centuries people who had developed this mood of the soul particularly strongly were called Bulgarians for the longest time in Europe. In the later Christian centuries of the first half of the Middle Ages, Bulgarians were people for Western and Central Europeans who were particularly strongly affected by the opposition of good and evil cosmic-spiritual powers. The name Bulgarians is found throughout Europe for such people as I have characterized them.

But the souls I am talking about here were more or less in just such a state of mind: the souls who then, in their further development, came to see those powerful images in the supernatural cult, to participate in their activity, which then took place in the first half of the 19th century. All that the souls were able to experience in this inner knowing in the struggle between good and evil was carried through life between death and a new birth. And that nuanced, that colored the souls, which then stood before the powerful images described.

But there was something else too. These souls were, so to speak, the last ones within European civilization who had still retained something of this separate perception of the etheric and astral body in waking and sleeping. They lived in communities, recognizing themselves by these peculiarities of soul life. They were regarded as heretics among those Christians who increasingly aligned themselves with Rome. At that time, people had not yet reached the point of condemning heretics in the same strict manner as later, but they were regarded as heretics. People had a generally sinister impression of them. One had the impression that they saw more than the other people, that they also related to the divine in a different way by perceiving the state of sleep. Because the other people among whom they lived had long since lost this, had long since come closer to the state of mind that became common in Europe in the 14th century.

But when these people I am talking about, these people with the separate perception of the astral and the etheric body, passed through the gate of death, then they also differed from those who were different. And one must not believe that between death and a new birth man is without all share in what happens on earth through men. Just as we look up from here into the heavenly-spiritual world, so to speak, we look down from the heavenly-spiritual world to earth between death and a new birth. Just as one participates from here in the spirit beings, one participates from the spiritual world in what the earth beings experience on earth.

Now the time I am describing here was followed by the time when here in Europe Christianity set itself up to be something also on the condition that man no longer knows anything of his astral body and of his etheric body. Christianity prepared itself to talk about the spiritual world without being able to make these assumptions about man. For just consider, my dear friends: when the old Christian teachers spoke to their Christians in the first centuries, they did indeed find a large number of those who could only accept the words as true on the basis of external authority; but the even more naïve mood of the time allowed these very words to be accepted if they were spoken from a warm, enthusiastic heart. And how warmly and enthusiastically hearts preached Christianity in the first centuries is no longer understood today, when so much has turned into mere word preaching.

But those who could speak to such souls as I have described here, what words could they speak? Yes, my dear friends, they could say: "Look at that which appears in a rainbow of shimmering light above the plants, that which shows itself in desire in the animals, look: that is the reflection, that is the revelation of the spiritual world of which we also speak, the spiritual world from which the Christ comes. By speaking to such people of the spiritual wisdoms, one did not speak of something unknown; one spoke to them by reminding them of what they could see under certain circumstances in the mild sunlight as the spirit in nature.

And again, when one spoke to them that the Gospel is there, which proclaims of the spiritual world, of the spiritual secrets, when one spoke to them of the secrets of the Old Testament, then one did not speak to them again of something unknown, but one could say to them: Here is the word of the testament; this word of the testament is written down by those human beings who have indeed heard more clearly than you the murmur of that spirituality in which your souls are between falling asleep and waking up, but you know of this murmur, for you remember it when you have woken up in the morning. And so you could speak of it to these people as something familiar. In a certain way, the conversations that the priests and preachers of that time had with these people contained something of what was going on in the souls of these people themselves. And so the Word was still alive at that time and could be cultivated as a living thing.

And when then these souls, to whom one could speak in the word as in something living, looked down to earth after they had walked through the gate of death, then they looked at the twilight of this living word down there, and they had the feeling: the Logos dawns. That was the basic feeling of those souls, as I have described them, who passed through the gate of death after the 7th, 8th, 9th century or a little earlier, that they felt when they looked down to earth: Down here on earth is the twilight of the living Logos. And the word probably lived in these souls: “And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us”, and they felt: 'But men have less and less a house for the Word, which is to live in the flesh, to live on in the earth.

This in turn gave rise to a basic mood, the basic mood of the souls who lived in the spiritual world between the 7th, 8th and 19th, 20th century, even if they had an interruption in some earthly existence, this gave rise to the basic mood: The Christ indeed lives for the earth, for he died for the earth, but the earth cannot receive him; and there must become the power on earth that souls can receive the Christ! In addition to everything else I have described, this is what lived in these souls, who were regarded as heretical during their time on earth, between death and a new birth: the need for a new, a renewed revelation of Christ, a proclamation of Christ.

Under such a state of soul these disembodied people experienced how that happened on earth which actually still had to be completely unknown to them on earth. They learned to understand what was happening down there on earth. They saw how fewer and fewer souls on earth were seized by the spirit, how there were no longer any people left to whom one could say: We proclaim to you the spirit that you yourselves can still see hovering over the plant world, shimmering in the animals. We teach you the will that is written out of those sounds that you still hear whispering when you feel the nightly experiences. - All that was no longer there.

They saw from above, where things were quite different, how the old language was replaced in the Christian development. For after all, even if the preachers had to speak to the vast majority of people in this way, since they had no awareness of the spiritual in earthly life, the whole tradition, the whole use of speech was still from times when it could be assumed that when one spoke of the spirit, people still felt something of the spirit.

All that really only disappeared completely around the 9th, 10th and 11th centuries. Then a completely different constitution developed, even in listening. In earlier times, when you heard a person who spoke out of the spirit, who was enthusiastic and filled with gods, you had the feeling that you were actually going out of yourself when you listened, that you were going into your etheric body and leaving your physical body. And again you had the feeling that you were approaching the astral body. You really still had a slight feeling of being enraptured as you listened. One did not yet give so much to mere listening, one gave much more to what one experienced inwardly in a quiet rapture. You lived with the words that were spoken by people who were enthusiastic about God.

This disappeared completely in the 9th, 10th and 11th centuries towards the 14th century. Hearing alone became more and more commonplace. The need arose to appeal to something else when speaking of the spiritual. The need arose to draw out of the listener that which he should have as a view of the spiritual world. The need arose to work on him, so to speak, so that he would still feel compelled out of this hardened body to say something about the spiritual world. And from this arose the need to give instruction about the spiritual world in a game of questions and answers. By asking - questions always have something suggestive about them -: What is baptism? - and preparing the person for a certain answer, or: What is confirmation? What is the Holy Spirit? What is death? What are the seven capital sins? - By preparing this question and answer game, the natural elementary listening is replaced. And it was at this time - first to those people who came to such schools where one could do this - that there arose what was a learning in question and answer of what was to be said about the spiritual world: the catechism came into being.

You see, you have to look at such events. The souls who were up there in the spiritual world in a particularly strong way and now looked down saw this: Something must be approaching people that we could not even know, that was not even close to us! And it was a powerful impression that the catechism came into being down there on earth. There is nothing special about it when historians outwardly show the origin of the catechism; but much is given when one looks at the origin of the catechism as it took place from the side of the supersensible: Down there men have to go through quite new things in the depths of their souls, have to learn in the catechism way what they are to believe.

This is one of my feelings. I have another to describe to you in the following way. If we go back to the first centuries of Christianity, it was not yet possible for a Christian to go into a church, sit down or kneel down and listen to the Mass from the beginning, from the Introit to the prayers that followed Communion. It was not possible for everyone to listen to a whole Mass, but those who became Christians were divided into two groups: the catechumens, who were allowed to stay at Mass until the Gospel had been read to the end; after the Gospel, the offertory was prepared and they had to go out. And only those who had already been prepared for some time for that holy, inward mood in which the mystery of transubstantiation, the consecration, could be perceived: the transubstants, were allowed to stay inside, they heard the Mass to the end.