The Evolution of the Earth and Man

and the Influence of the Stars

GA 354

12 July 1924, Dornach

Lecture V

Rudolf Steiner: Gentlemen! I mentioned our wish to look further into the history that is connected with our present study of the world. You have seen how the human race gradually built itself up out of the rest of mighty Nature. It was only when conditions on the earth were such that men were able to live upon it—when the earth had died, when it no longer had its own life—that human and animal life could develop in the way I have pictured.

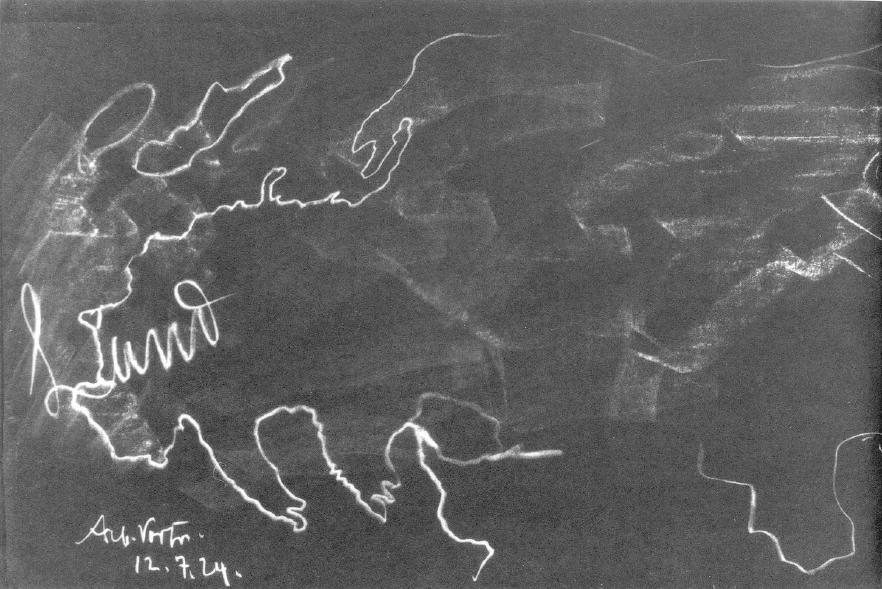

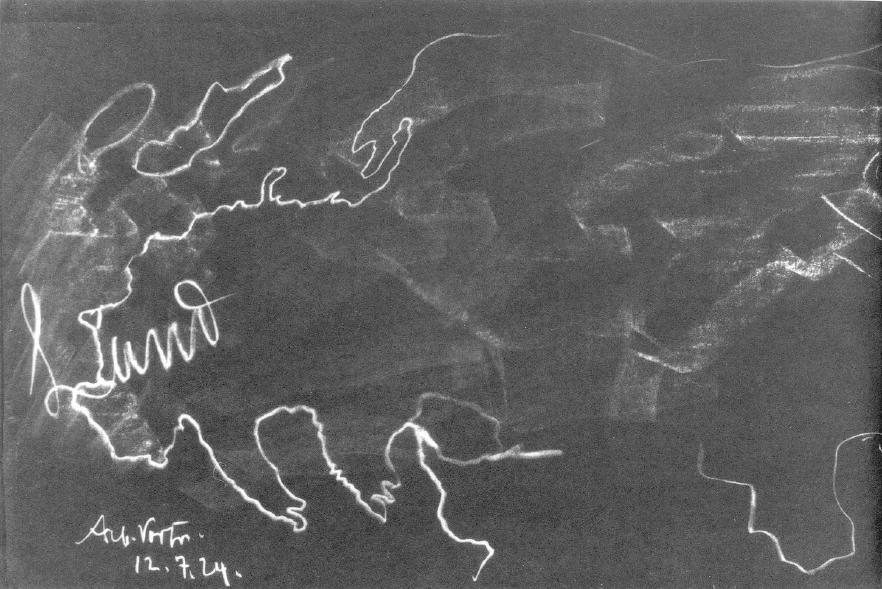

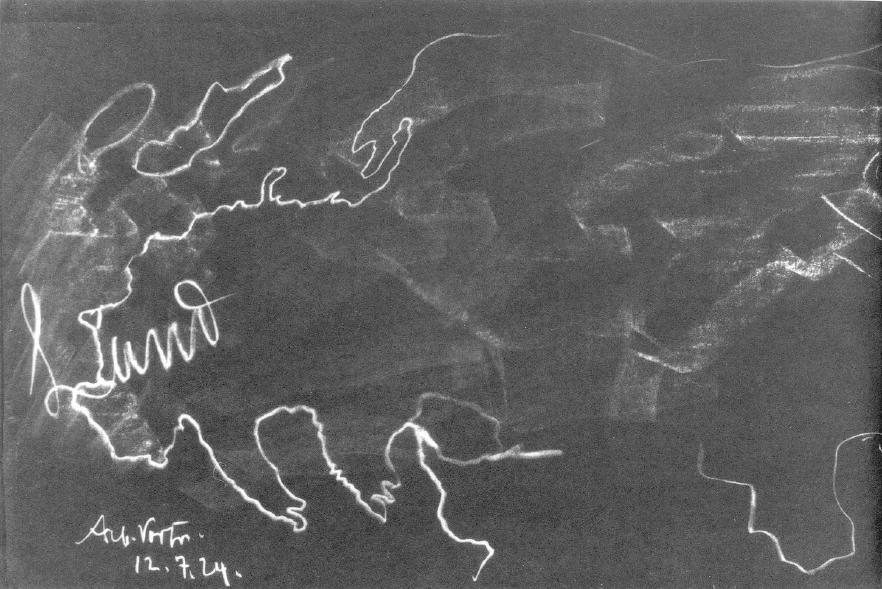

Now we have also seen that in the beginning, human life was actually quite different from what it is today, and had its field of action where the Atlantic Ocean is now. We have to imagine that where the Atlantic Ocean is today, there was formerly solid ground. Today we have Asia on the one hand; there is the Black Sea, below it is Africa, then there is Russia and also Asia. On the other hand, there is England, Ireland, and over there also America. Formerly all this in between was land, and here very little land; over here in Europe at that time there was actually a really huge sea. These countries were all in the sea, and when we come up to the north, Siberia was sea too; it was still all sea. Below where India is today, the land was appearing a little above the sea. Thus we actually have some land there, and on the other side again land. Where today we find the Asian peoples, the inhabitants of the Near East and those of Europe, there was sea—the land only rising up later. The land, however, went much farther, continuing right on to the Pacific Ocean where today there are so many islands, Java, Sumatra, and so on; they were all part of the continent formerly there—all this archipelago. Thus, where now the Pacific Ocean is, there was a great deal of land with sea between the two land masses.

Now the first peoples we are able to investigate have remained in this region, here, where the land has been preserved. When we took around us in Europe we can really say: Ten, twelve or fifteen thousand years ago the earth, the ground, became sufficiently firm for men to dwell upon it. Before that, only marine animals were there which developed out of the sea, and so on. If at that time you had looked for man, he would have been where the Atlantic Ocean is today. But over there in Asia, in eastern Asia, there were also men earlier than ten thousand years ago. These men naturally left descendants, and the descendants are very interesting on account of their culture, the most ancient on earth. Today these are the peoples called the Japanese and Chinese. They are very interesting because they are the last traces, so to say, of the oldest inhabitants of the earth.

As you have heard, there was, of course, a much older population on earth that was entirely wiped out. That was the humanity who lived in ancient Atlantis, of whom nothing remains. For even if remains did exist, we would have to dig down into the bed of the Atlantic Ocean to find them. We would have to get down to that bed—a more difficult procedure than people think—and dig there, and in all probability find nothing. For, as I have said, those people had soft bodies. The culture which they created with gestures was something that one cannot dig out of the ground-because there was nothing that endured! Thus, what was there long before the Japanese and Chinese is not accessible to ordinary science; one must have some knowledge of spiritual science if one wants to make such discoveries.

However, what has remained of the Chinese and Japanese peoples is very interesting. You see, the Chinese and the older Japanese—not those of today (about whom I am just going to speak)—the Chinese and Japanese had a culture quite different from ours. We would have a much better idea of it if our good Europeans had not in recent centuries extended their domination over those spheres, bringing about a complete change. In the case of Japan this change has been very effective. Although Japan has kept its name, it has been entirely Europeanized. Its people have gradually absorbed everything from the Europeans, and what remains of their ancient culture is merely its outward form. The Chinese have preserved their identity better, but now they can no longer hold out. It is true that the European dominion is not actively established there, but in those regions what the Europeans think is becoming all-prevailing, and what once existed there has disappeared. This is no cause for regret; it is in the nature of human evolution. It must, however, be mentioned.

Now if we observe the Chinese—among them, things can be seen in a less adulterated form—we find a culture distinct from all others, for the Chinese in their old culture did not include anything that can be called religion. The Chinese culture was devoid of religion.

You must picture to yourselves, gentlemen, what is meant by a “culture without religion”. When you consider the cultures that have religion you find everywhere—in the old Indian culture, for instance—veneration for beings who are invisible but who seem to resemble human beings on earth. It is the peculiar feature of all later religions that they represent their invisible beings as manlike.

Anthroposophy does not do this. Anthroposophy does not represent the super-sensible world anthropomorphically but as it actually is. Further, it sees in the stars the expression of the super-sensible. The remarkable thing is that the Chinese have had something of the same kind. The Chinese do not venerate invisible gods. They say: What is here on earth differs according to climate, according to the nature of the soil where one lives. You see, China in the most ancient times was already a large country and is still today larger than Europe; it is a gigantic country, has always been gigantic, and has had a tremendously large, vigorous population. Now, the idea that the population of the earth increases is just superstition on the part of modern science, which always makes its calculations from data to suit itself. The truth is that even in the most ancient times there was a vast population in China, also in South America and North America. There too in those ancient times the land reached out to the Pacific Ocean. If that is taken into account the population of the earth cannot be said to have grown.

So, gentlemen, we find a culture there that is quite ancient, and today this culture can still be observed as it actually existed ten thousand, eight thousand years ago. The Chinese said: Above in the north the climate is different, the soil is different, from what they are farther south; everything is different there. The growth of the plants is different and human beings have to live in a different way. But the sun is all-pervading. The sun shines in the north and in the south; it goes on its way and moves from warm regions to cold regions. They said: On earth diversity prevails, but the sun makes everything equal. They saw in the sun a fructifying, leveling force. They went on to say, therefore: If we are to have a ruler, our ruler must be like that; individual men differ, but he must rule over them like the sun. For this reason they gave him the name “Son of the Sun.” His task was to rule on earth as the sun rules in the universe. The individual planets, Venus, Jupiter, and so on, act in their various ways; the sun as ruler over the planets makes everything equal. Thus the Chinese pictured their ruler as a son of the Sun. For they took the word “son” essentially to imply “belonging to something.”

Everything was then so arranged that the people said: The Son of the Sun is our most important man. The others are his helpers, just as the planets are the helpers of the sun. They organized everything on the earth in accordance with what appeared above in the stars. All this was done without prayer, for they did not know the meaning of prayer. It was actually all done without their having what later would constitute a cult. What might be called their kingdom was organized so as to be an image of the heavens. It could not yet be called a state. (That is a mischief that modern men perpetrate.) But they arranged their earthly affairs to be an image of what appeared to them in the stars above.

Now something came about through this circumstance that was naturally quite different from what happened later: a man became the citizen of a kingdom. He had no creed to profess; he simply felt himself to be a member of a kingdom. Originally the Chinese had no gods of any kind; when later they did have them, they were gods taken over from the Indians. Originally they had no gods, but their connection with the super-sensible worlds was expressed by the essential nature of their kingdom and its institutions. Their institutions had a family quality. The Son of the Sun was at the same time father to all the other Chinese and these served him. Although it was a kingdom, it partook of the nature of a family.

All this was only possible for men whose thinking had as yet no resemblance to that of later humanity. The thinking of the Chinese at that time was not at all like that of later men. What we think today would have been quite foreign to the Chinese. We think, for example, “animal”; we think “man”; we think “vase” or “table”. The Chinese did not think in this way, but they knew: there is a lion, there a tiger, a dog, there's a bear—not, there is an animal. They knew: my neighbor has a table with corners; someone else has a table that is rounder. They gave names to single things, but what “a table” is, never entered their head; “table” as such—of that they had no knowledge. They were aware: there stands a man with a bigger head and longer legs, there one with a smaller head, with shorter legs, and so on; there is a smaller man, here a bigger man, but “man” in general was to them an unknown factor. They thought in quite a different way, in a way impossible for man today. They had need, therefore, of other concepts. Now if you think “table,” “man,” “animal,” you can extend this to legal matters, for Jurisprudence consists solely of such concepts. But the Chinese were unable to think out any legal system; with them everything was organized as in a family. Within a family, when a son or daughter wants to do something, there is no thought of such a thing as a legal contract. But today, if someone here in Switzerland wants to do something, he consults liability laws, marriage laws, and so on. There one finds all that is needed, and the laws then have to be applied to individual cases.

Inasmuch as human beings still retain something of the Chinese in them—and there always remains a little—they don't really feel comfortable about laws and must always have recourse to a lawyer. They are even at sea sometimes with general concepts. As for the Chinese, they never had a legal code; they had nothing at all of what later took on the nature of a state. All they had was what each individual could judge in his individual situation.

So, to continue. The whole Chinese language was influenced by this fact. When we say “table,” we at once picture a flat surface with one, two or three legs, and so on, but it must be something that can stand up like a table. If anyone were to tell me a chair is a table, I would say: A table? You stupid! that's not a table, that's a chair. And if someone else came along and called the blackboard a table, I'd call him something even stronger, for it's not a table at all but a blackboard. With our language we have to call each thing by its own special name.

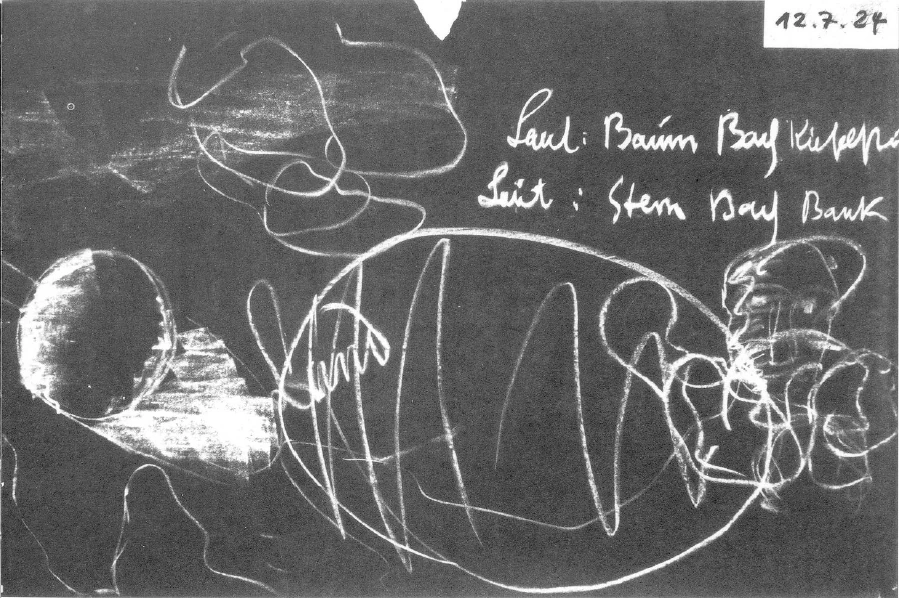

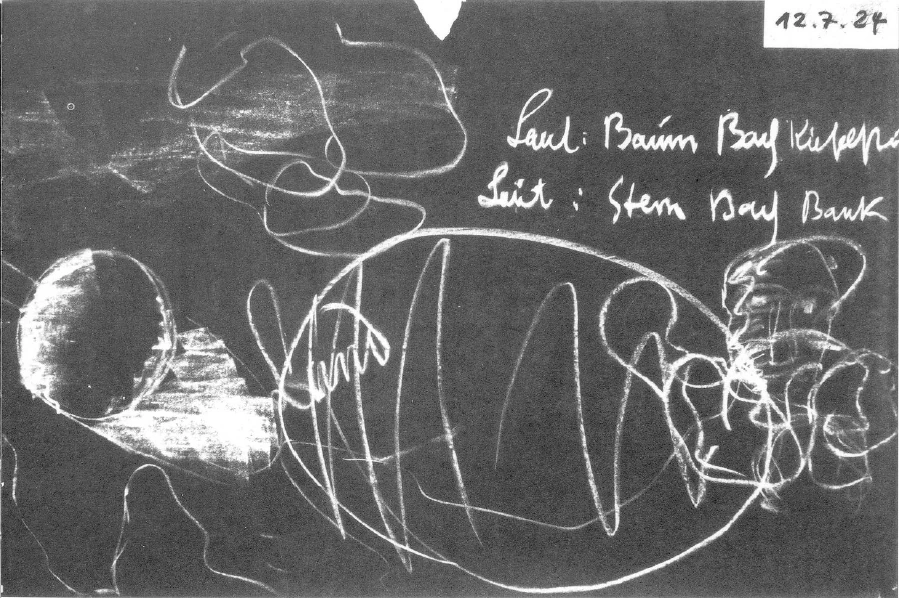

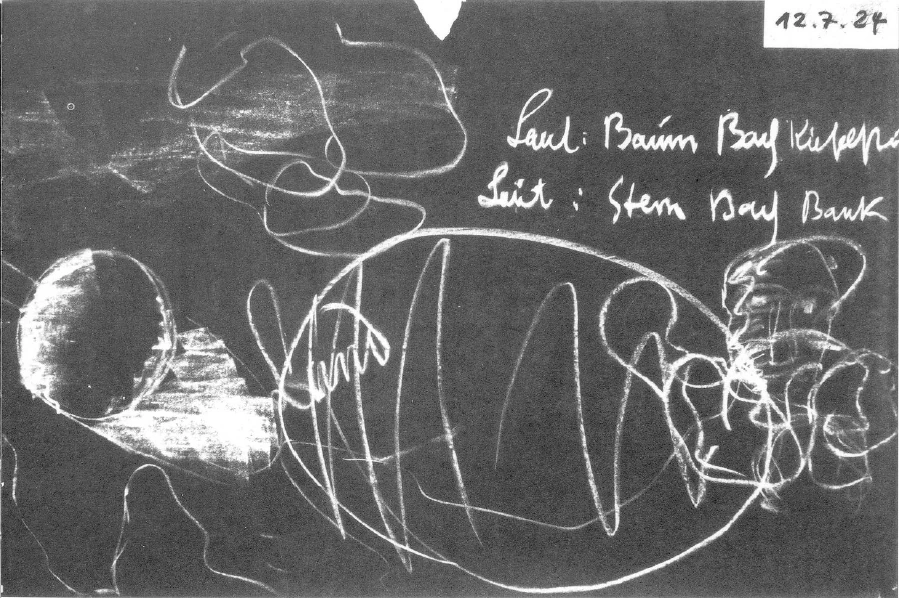

That is not so with Chinese. I will put this to you hypothetically; it will not be a precise picture, but you will get the idea from it. Say, then, that Chinese has the sounds OA, IOA, TAO, for instance.

It has then a certain sound for table, but this same sound signifies many other things too. Thus, let us say, such a sound might mean tree, brook, also perhaps pebble. Then it has another sound, let's say, that can mean star, as well as blackboard, and—for instance—bench. (These meanings may not be correct in detail; I mean only to show the way the Chinese language is built up.) And now the Chinese person knows: there are two sounds here, say LAO and BAO, each meaning things that are quite different but also both meaning brook. So he puts them together: BAOLAO. In this way he builds up his language. He does not build it up from names given to single things, but according to the various meanings of the various sounds. A sound may mean tree but it may also mean brook. When, therefore, he combines two sounds, both of which—beside many other things—mean brook, the other man knows that he means brook. But when he utters only one sound, no one knows what he means. In writing there are the same complications. So the Chinese have an extraordinarily complicated language and an extraordinarily complicated script.

And indeed, gentlemen, a great deal follows from this. It follows that for them it is not so easy to learn to read and write as it is for us-nor even to speak. With us, reading and writing can really be called simple; indeed, we are unhappy when our children don't learn quickly to read and write—we think it is “mere child's play.” With the Chinese this is not so; in China one grows quite old before one can write or in any way master the language. So you can easily imagine that the ordinary people are not at all able to do it, that only those who can go on learning up to a great age can at last become proficient. In China, therefore, noble rank is conferred as a matter of course from a spiritual basis on those who are cultured, and this spiritually high rank is called into being by the nature of the language and script. Here again it is not the same as in the West, where various degrees of nobility can be conferred and then passed on from one generation to another. In China rank can be attained only through education and scholarship.

It is interesting, gentlemen, is it not, that if we judge superficially we would surely say: then we don't want to be Chinese. But please don't assume that I am saying we ought to become Chinese, or even particularly to admire China. That is what some people may easily say about it. Two years ago when we had a Congress in Vienna,6The Second International Congress, Vienna, June 1–12, 1922. See The Tension Between East and West. someone spoke of how some things in China were managed even today more wisely than we manage them—and immediately the newspapers reported that we wanted Chinese culture in Europe! That is not what was meant. In describing the Chinese culture, praise must be given in a certain way—but only in a certain way—for what it has of spiritual content. But it is a primitive culture, of a kind that can no longer be adopted by us. So you must not think I am agitating for another China in Europe! I simply wish to describe this most ancient of human cultures as it actually existed.

Now—to continue. What I have been saying is related to the whole manner of Chinese thinking and feeling. Indeed, the Chinese (and also the Japanese of more ancient times) occupied themselves a great deal, a very great deal, with art—with their kind of art. They painted, for instance. Now when we paint, it is quite a different affair from the Chinese painting. You see, when we paint (I will make this as simple as possible), when we paint a ball, for example, if the light falls on it, then the ball is bright in one part and dark over in the other, for it is in shadow; the light is falling beyond it. There again, on the light side, the ball is rather bright because there the light is reflected. Then we say: that side is in shadow, for the light is reflected on the other side; and then we have to paint also the shadow the ball throws on the ground. This is one of the characteristics of our painting: we must have light and shade on the objects. When we paint a face, we paint it bright where the light falls, and on the other side we make it dark. When we paint the whole man, if we paint properly, we put shadow in the same way falling on the ground.

But beside this we must pay attention to something else in our picture. Suppose I am standing here and want to paint. I see Herr Aisenpreis sitting in front; there behind, I see Herr Meier, and the two gentlemen at the back quite small. Were I to photograph them, in the photograph also they would come out quite small. When I paint, I paint in such a way that the gentlemen sitting in the front row are quite big, the next behind smaller, the next again still smaller and the one sitting right at the back has a really small head, a really small face. You see, when we paint we take perspective into account. We have to do it that way. We have to show light and shade and also perspective. This is inherent in the way we think.

Now the Chinese in their painting did not recognize light and shade, nor did they allow for perspective, because they did not see as we see. They took no notice of light and shade and no notice of perspective. This is what they would have said: Aisenpreis is certainly not a giant, any more than Meier is a dwarf. We can't put them together in a picture as if one were a giant and the other a dwarf, for that would be a lie, it is not the truth! That's the way they thought about things, and they painted as they thought. When the Chinese and the Japanese learn painting in their way, they do not look at objects from the outside, they think themselves right into the objects. They paint everything from within outwards as they imagine things for themselves. This, gentlemen, constitutes the very nature of Chinese and Japanese painting.

You will realize, therefore, that learning to see came only later to mankind. Human beings in that early China thought only in pictures, they did not form general concepts like “table” and so on, but what they saw they apprehended inwardly. This is not to be wondered at, for the Chinese descended from a culture during which seeing was different. Today we see as we do because there is air between us and the object. This air was simply not there in the regions where the Chinese were first established. In the times from which the Chinese have come down, people did not see in our way. In those ancient times it would have been nonsense to speak of light and shade, for there was not yet any such thing in the density the air then had. And so the Chinese still have no light and shade in their painting, and still no perspective. That came only later. From this you can see the Chinese think in quite a different way; they do not think as men do who came later.

However, this did not in the least hinder the Chinese from going very far in outer cleverness. When I was young—it is rather different now—we learned in school that Berthold Schwarz7Berthold Schwarz, Franciscan monk, Freiburg, around 1300. invented gunpowder, and this was told us as if there had never been gunpowder before. So Berthold Schwarz, while he was doing alchemistic experiments, produced gunpowder out of sulphur, nitre and carbon. But—the Chinese had made gunpowder thousands of years earlier!

Also we learned in school that Gutenberg8Johann Gutenberg, 1394–1468. invented the art of printing. We did learn many things that were correct, but in this case it looked to us as if there had formerly been no knowledge of printing. Actually, the Chinese already possessed this knowledge thousands of years earlier. They also had the art of woodcarving; they could cut the most wonderful things out of wood. In such external things the Chinese have had an advanced culture. This was in its turn the last remnant of a former culture still more advanced, for one recognizes that this Chinese art goes back to something even higher.

Thus it is characteristic of the Chinese to think not in concepts but in pictures, and to project themselves right into things. They have been able to make all those things which depend upon outer invention (except when it's a matter of steam-engines or something similar). So the present condition of the Chinese, which we may say is degenerate and uncultivated, has actually come about from centuries of ill-treatment at the hands of the Europeans.

You see that here is a culture that is really spiritual in a certain sense—and really ancient, that goes back to ten thousand years before our time. Much later, in the millennium preceding Christianity, individuals like Lao Tse9Lao Tse, Chinese philosopher, 6th century B.C. and Confucius10Confucius, 531–478 BC., Chinese ethical teacher. made the first written record of the knowledge possessed by the Chinese. Those masters simply wrote down what had arisen out of the intercourse among families in this old kingdom. They were not conscious of inventing rules of a moral or ethical nature; they were simply recording their experience of Chinese conduct. Previously, this had been done by word of mouth. Thus everything at that time was basically different. That is what can still be perceived today in the Chinese.

In contrast to this, it is hardly possible to see any longer the old culture of the Japanese people, because they have been entirely Europeanized. They follow European culture in everything. That they did not develop this culture out of themselves can be seen from their inability to discover on their own initiative what is purely European. The following, for example, really happened. The Japanese were to have steamships and saw no reason why they should not be able to manage them perfectly well themselves. They watched how to turn the ship, for instance, how to open the screw, and so on. Their instructors, the Europeans, worked with them for a time, and finally one day the Japanese said proudly: Now we can manage by ourselves, and we will appoint our own captain! So the European instructors were put ashore and off steamed the Japanese to the high seas. When they were ready to turn back, they turned the screw, and the ship turned round beautifully—but no one knew how to close the screw, and there was the ship whirling round and round on the sea, just turning and turning! The European instructors watching from the shore had to take a boat and bring the revolving ship to a standstill.

Perhaps you remember Goethe's poem, “The Magician's Apprentice” where the apprentice watches the spells of the old master-magician? And then, to save himself the trouble of fetching water, he learns a magic verse by which he will be able to make a broom into a water-carrier. One day when the old magician is out, the apprentice begins to put this magic into practice, and recites the words to start the broom working. The broom gets really down to business, and fetches water, and more water, and always more water. But the apprentice forgets how to stop it. Just imagine if you had your room flooded, and your broom went on fetching more and more water. In his desperation the apprentice chops the broom in two—then there are two water-carriers! When everything is drowned in water, the old master returns and says the right words for the broom to become a broom again.

As you know, the poem has been done in eurythmy recently, and the audience enjoyed it immensely. Well, the same kind of thing happened with the Japanese: they didn't know how to turn back the screw, and so the ship continued to go round and round. A regular ship's dance went on out there until the instructors on land could get a boat and come to the rescue.

Surely it is clear from all this that the European sort of invention is impossible for either the Chinese or the Japanese. But as to older inventions such as gunpowder, printing and so forth, they had already gone that far in much more ancient times than the Europeans. You see, the Chinese are much more interested in the world at large, in the world of the stars, in the universe as a whole.

Another people who point back to ancient days are the Indians. They do not go so far back as the Chinese, but they too have an old culture. Their culture may be said to have arisen from the sea later than the Chinese. The people who were the later Indian people came more from the north, settling down in what is now India as the land became free of water.

Now whereas the Chinese were more interested in the world outside, could project themselves into anything, the Indian people brooded more within themselves. The Chinese reflected more about the world—in their own way, but about the world; the Indians reflected chiefly about themselves, about man himself. Hence the culture that arose in India was more spiritualized. In the most remote times Indian culture was still free of religion; only later did religion enter into it. Man was their principal object of study, but their study was of an inward kind.

This too I can best make clear by describing the way the Indians used to draw and paint. The Chinese, looking at a man, painted him simply by entering into him with their thinking—without light and shade or perspective. That is really the way they painted him. Thus, if a Chinese had wanted to paint Herr Burle, he would have thought his way into him; he would not have made him dark there and light here, as we would do today, he would not have painted light and shadow, for they did not yet exist for the Chinese. Nor would he have made the hands bigger by comparison because of their being in front. But if the Chinese had painted Herr Burle, then Herr Burle would really have been there in the picture!

It was quite different with the Indians. Now just imagine the Indians were going to paint a picture: they would have started by painting a head. They too had no such thing as perspective. But they would at once have had the idea that a head could often be different, so they would make another, then a third again different, and a fourth, a fifth would have occurred to them. In this way they would gradually have had twenty or thirty heads side-by-side! These would all have been suggested to them by the one head. Or if they were painting a plant, they imagined at once that this could be different, and then there arose a number of young plants growing out of the older one. This is how it was in the case of the Indians in those very ancient times. They had tremendous powers of imagination. The Chinese had none at all and drew only the single thing, but made their way into this in thought. The Indians had a powerful imagination.

Now you see, gentlemen, those heads are not there. Really, if you look at Herr Burle, you see only one head. If you're drawing him here on the board, you can draw only one head. You are therefore not painting what is outwardly real if you paint twenty or thirty heads; you are painting something thought-out in your mind. The whole Indian culture took on that character; it was an inner culture of the mind, of the spirit. Hence when you see spiritual beings as the Indians thought of them, you see them represented with numbers of heads, numbers of arms, or in such a way that the animal nature of the body is made manifest.

You see, the Indians are quite different people from the Chinese. The Chinese lack imagination whereas the Indians have been full of it from the beginning. Hence the Indians were predisposed to turn their culture gradually into a religious one—which up to this day the Chinese have never done: there is no religion in China. Europeans, who are not given to making fine distinctions, speak of a Chinese religion, but the Chinese themselves do not acknowledge such a thing. They say: you people in Europe have a religion, the Indians have a religion, but we have nothing resembling a religion. This predisposition to religion was possible in the Indians only because they had a particular knowledge of something of which the Chinese were ignorant, namely, of the human body. The Chinese knew very well how to put themselves into something external to them. Now when there are vinegar and salt and pepper on our dinner table and we want to know how they taste, we first have to sample them on our tongue. For the Chinese in ancient times this was not necessary. They already tasted things that were still outside them. They could really feel their way into things and were quite familiar with what was external. Hence they had certain expressions showing that they took part in the outside world. We no longer have such expressions, or they signify at most something of a figurative nature. For the Chinese they signified reality. When I am becoming acquainted with someone and say of him: What a sour fellow he is!—I mean it figuratively; we do not imagine him to be really sour as vinegar is sour. But for the Chinese this meant that the man actually evoked in them a sour taste.

It was not so with the Indians; they could go much more deeply into their own bodies. If we go deeply into our own bodies, it is only when certain conditions are present—then we feel something there. Whenever we've had a meal and it remains in our stomach without being properly digested, we feel pain in our stomach. If our liver is out of order and cannot secrete sufficient bile, we feel pain on the right side of our body—then we are getting a liver complaint. When our lungs secrete too freely so that they are more full of mucus than they should be, then we feel there is something wrong with our lungs, that they are out of order. Today human beings are conscious of their bodies only in those organs that are sick. Those Indians of ancient times were conscious even of their healthy organs; they knew how the stomach, how the liver felt. When anyone wants to know this today, he has to take a corpse and dissect it; then he can examine the condition of the individual organs inside. No one today knows what a liver looks like unless they dissect it; it is only spiritual science that is able to describe it. The Indians could think of inner man; they would have been able to draw all his organs. With an Indian, however, if you had asked him to feel his liver and draw what he felt, he would have said: Liver?—well, here is one liver, here's another, and here's another, and he would have drawn twenty or thirty livers side-by-side.

So, gentlemen, you have there a different story. If I draw a complete man and give him twenty heads, I have a fanciful picture. But if I draw a human liver with twenty or thirty others beside it, I am drawing something not wholly fantastic; it would have been possible for these twenty or thirty livers really to have come into being! Every man has his distinctive form of liver, but there is no absolute necessity for that form; it could very well be different. This possibility of difference, this spiritual aspect of the matter, was far better understood by the Indians than by those who came later. The Indians said: When we draw a single object, it is not the whole truth; we have to conceive the matter spiritually. So the Indians have had a lofty spiritual culture. They have never set great store by the outer world but have had a spiritual conception of everything.

Now the Indians took it for granted that learning should be acquired in accordance with this attitude; therefore, to become an educated man was a lengthy affair. For, as you can imagine, with them it was not just a matter of going deeply into oneself and then being capable all at once of knowing everything. When we are responsible for the instruction of young people, we have first to teach them to read and write, imparting to them in this way something from outside. But this was not so in the case of the ancient Indians. When they wanted to teach someone, they showed him how to withdraw into his inner depths; he was to turn his attention away from the world entirely and to focus it upon his inner being.

Now if anyone sits and looks outwards, he sees you all sitting there and his attention is directed to the outer world. This would have been the way with the Chinese; they directed their attention outwards. The Indians taught otherwise. They said: You must learn to gaze at the tip of your nose. Then the student had to keep his eyes fixed so that he saw nothing but the tip of his nose, nothing else for hours at a time, without even moving his eyes.

Yes indeed, gentlemen, the European will say: How terrible to train people always to be contemplating the tip of their nose! True! for the European there is something terrible in it; it would be impossible for him to do such a thing. But in ancient India that was the custom. In order to learn anything an Indian did not have to write with his fingers, he had to look at the tip of his nose. But this sitting for hours gazing at the tip of his nose led him into his own inner being, led him to know his lungs, his liver, and so forth. For the tip of the nose is the same in the second hour as it is in the first; nothing special is to be seen there. From the tip of his nose, however, the student was able to behold more and more of what was within him; within him everything became brighter and brighter. That is why he had to carry out the exercise.

Now, as you know, when we walk about, we are accustomed to do so on our feet and this going about on our feet has an effect upon us. We experience ourselves as upright human beings when we walk on our feet. This was discouraged for those in India who had to learn something. While learning they had to have one leg like this and sit on it, while the other leg was in this position. Thus they sat, gazing fixedly at the tip of their nose, so that they became quite unused to standing; they had the feeling they were not upright men but crumpled up like an embryo in a mother's womb. You can see the Buddha portrayed in this way. It was thus that the Indians had to learn. Gradually they began to look within themselves, learned to know what is within man, came to have knowledge of the human physical body in an entirely spiritual way.

When we look within ourselves, we are conscious of our paltry thinking; we are slightly aware of our feeling but almost not at all of our willing. The Indians felt a whole world in the human being. You can imagine what different men they were from those who came later. They developed, as you know, a tremendous fantasy, expressed poetically in their books of wisdom—later in the Vedas and in the Vedantic philosophy, which still fill us with awe. It figured in their legends concerning super-sensible things, which still today amaze us.

And look at the contrast! Here were the Indians, there were the Chinese over there, and the Chinese were a prosaic people interested in the outer world, a people who did not live from within. The Indians were a people who looked entirely inward, contemplating within them the spiritual nature of the physical body.

So—I have begun to tell you about the most ancient inhabitants of the earth. Next time I will carry it further, so that we will finally arrive at the time we live in now.

Please continue to bring your questions. There may be details that you would like me to enlarge upon, and I can always at some following meeting answer the questions they have raised. But I can't tell you when the next session will be, because now I must go to Holland. I will send you word in ten days or so.

Fünfter Vortrag

Meine Herren! Ich habe Ihnen gesagt, daß wir noch etwas die Geschichte betrachten wollen, die sich anschließt an die Weltbetrachtung, die wir angestellt haben. Sie haben gesehen, wie sich so allmählich das Menschengeschlecht aus der übrigen großen Natur herausgebildet hat. Und erst als die Lebensverhältnisse für die Menschheit eben da waren auf der Erde, als sozusagen die Erde abgestorben war, die Erde nicht mehr ihr eigenes Leben hatte, konnte sich menschliches und auch tierisches Leben so entwickeln auf der Erde, wie ich es Ihnen dargestellt habe.

Und wir haben ja auch gesehen, daß sich das erste menschliche Leben noch ganz anders als das heutige eigentlich da abspielte, wo heute der Atlantische Ozean ist. In der Zeit müssen wir uns vorstellen, daß also die Erde da, wo heute der Atlantische Ozean ist, als fester Boden da war. Ich werde Ihnen also die Sache so ungefähr noch einmal aufzeichnen (es wird gezeichnet): Da kommt man jetzt nach Asien herüber. Das ist das Schwarze Meer. Da unten ist dann Afrika. Da ist dann Rußland, und da kommen wir nach Asien herüber. Da würde dann England, Irland sein. Da drüben ist Amerika. Hier war also überall früher Land, und nur ganz wenig Land hier überall; dahier, in Europa, hatten wir eigentlich damals ein ganz riesiges Meer. Diese Länder, die sind alle im Meer. Und wenn wir da hinüberkommen, so ist Sibirien auch noch Meer; das ist alles noch Meer. Und da unten, wo heute Indien ist — da ist dann Hinterindien -, dahier war es wiederum so, daß es etwas aus dem Meer herausgestiegen ist. Also wir haben eigentlich hier etwas Land; hier haben wir wieder Land. In dem Teil, wo heute die Asiaten, die Vorderasiaten und die Europäer leben, da war eigentlich Meer, und das Land ist erst später daraus emporgestiegen. Und dieses Land, das ging viel weiter, das ging noch bis in den Stillen Ozean hinein, wo heute die vielen Inseln sind; also die Inseln Java, Sumatra und so weiter, das sind Stücke von einem ehemaligen Land, der ganze Inselarchipel. Da also, wo heute der-Große Ozean ist, war wiederum viel Land; dazwischen war Meer.

Nun sind also die ersten Bevölkerungen, die wir verfolgen können, hier geblieben, wo etwas das Land sich erhalten hat. Wenn wir in Europa uns umschauen, so können wir eigentlich sagen: In Europa ist die Sache so, da ist vor heute etwa zehn-, zwölf-, fünfzehntausend Jahren erst die Erde soweit fest geworden, der Boden, daß Menschen da wohnen konnten. Vorher waren nur Seetiere da, die aus dem Meere sich herausentwickelten und so weiter. Wollte man dazumal nach den Menschen schauen, so müßte man da hinüber schauen, wo heute der Atlantische Ozean ist. Aber da drüben in Asien, in Ostasien, da waren eben auch schon Menschen in der Zeit vor zehntausend Jahren und so weiter. Diese Menschen, die haben natürlich Nachkommen hinterlassen; und die sind sehr interessant, meine Herren, diese Nachkommen gerade, denn das sind eigentlich diejenigen, die die älteste sogenannte Kultur haben auf der Erde. Das sind Völker, die wir heute als Mongolenvölker bezeichnen, das sind Japaner und Chinesen. Die sind eigentlich deshalb sehr interessant, weil sie Überreste sind sozusagen der ältesten Erdenbevölkerung, von der noch etwas geblieben ist.

Natürlich gibt es ja, wie Sie gesehen haben, eine viel ältere Erdenbevölkerung; die ist aber ganz zugrunde gegangen. Das ist die Bevölkerung, die hier in der alten Atlantis gelebt hat. Von der ist nichts mehr vorhanden. Denn da müßte man, selbst wenn Reste davon vorhanden wären, auf dem Boden des Atlantischen Ozeans graben. Man müßte erst herunterkommen auf den Boden — das ist schwerer als man denkt -, und dann müßte man da graben; dann würde man höchstwahrscheinlich nichts finden, weil die einen weichen Leib gehabt haben, wie ich Ihnen sagte. Und die Kultur, die sie mit den Gebärden gemacht haben, kann man auch nicht aus der Erde ausgraben, weil es nicht geblieben ist! Also das, was da viel älter ist als Japaner und Chinesen, das kann man nicht mit der äußeren Wissenschaft erreichen. Man muß Geisteswissenschaft treiben, wenn man solche Sachen erreichen will.

Aber interessant ist, was von Chinesen und Japanern geblieben ist. Sehen Sie, diese Chinesen und die älteren Japaner — nicht die heutigen; ich will gleich darüber einige Worte sagen —, die Chinesen und Japaner haben eigentlich eine Kultur, die ganz verschieden ist von der unsrigen. Man würde viel mehr richtig von der Sache denken, wenn nicht die braven Europäer in den letzten Jahrhunderten eben ihre Herrschaft ausgedehnt hätten über diese Gebiete und alles ganz anders gemacht hätten. Das ist ja zum Beispiel bei Japan vollständig gelungen. Wenn Japan auch dem Namen nach sich selber bewahrt — das sind ja ganz Europäer geworden; die haben ja alles von den Europäern nach und nach angenommen, und es ist ihnen nur als Äußerlichkeit geblieben, was ihnen von ihrer alten Kultur vorhanden war. Die Chinesen haben sich schon stärker bewahrt; aber jetzt können sie es ja auch nicht mehr. Denn die europäische Herrschaft hat sich zwar dort nicht als Herrschaft festgesetzt, aber dasjenige, was die Europäer denken, das gewinnt in diesen Gegenden die Oberhand. Denn es ist so, daß da alles verlorengeht, was einmal vorhanden war. Das ist ja nicht zu bedauern. Das ist einmal so in der Entwickelung der Menschheit. Aber sagen muß man es.

Nun, wenn wir zunächst, weil es bei denen reiner erscheint, die Chinesen betrachten, so ist das so, daß sie eine Kultur haben, die sich schon deshalb von aller anderen Kultur unterscheidet, weil die Chinesen in ihrer alten Kultur eigentlich gar nicht dasjenige haben, was man Religion nennt. Die chinesische Kultur war noch eine religionslose Kultur.

Sie müssen sich darunter nur etwas vorstellen, meine Herren, unter «religionsloser Kultur». Nicht wahr, wenn man die Kulturen in Betracht zieht, die Religionen haben, so hat man überall, zum Beispiel in diesen altindischen Kulturen, die Verehrung von Wesenheiten, die unsichtbar sind, die aber doch so ähnlich ausschauen wie der Mensch auf der Erde. Das ist die Eigentümlichkeit aller späteren Religionen, daß sie sich die unsichtbaren Wesen so menschenähnlich vorstellen.

Nicht wahr, das tut die Anthroposophie nicht mehr. Die stellt sich die übersinnliche Welt nicht mehr menschenähnlich vor, sondern so wie sie eben ist, und geht auch dazu über, in den Sternen und so weiter den Ausdruck des Übersinnlichen zu sehen. Das Merkwürdige ist, daß etwas Ähnliches die Chinesen schon gehabt haben. Die Chinesen verehren nicht unsichtbare Götter, sondern die Chinesen sagen: Dasjenige, was hier auf der Erde ist, das ist verschieden, je nach dem Klima, je nach der Bodenbeschaffenheit, in der man ist. — Sehen Sie, China war ja schon in den allerältesten Zeiten ein großes Land, ist ja heute noch größer als Europa! Es ist ein Riesenland, ist immer ein Riesenland gewesen, hat eine ungeheuer große, starke Bevölkerung gehabt. Nicht wahr, daß die Bevölkerung auf der Erde zunimmt, das ist ja nur eine abergläubische Vorstellung der heutigen Wissenschaft, die immer nur . rechnet mit dem, womit sie rechnen will. In Wahrheit waren in ältesten Zeiten auch die Riesenbevölkerungen in China und auch drüben in Südamerika und auch in Nordamerika. In ältesten Zeiten ging ja auch dort das Land heraus gegen den Stillen Ozean. Nun, gegen das ist eigentlich unsere Erdenbevölkerung nicht gewachsen.

Also es ist da eine ganz alte Kultur, meine Herren. Diese Kultur kann man heute noch beobachten so, wie sie vor zehntausend, achttausend Jahren durchaus vorhanden war. Da hatten sich diese Chinesen gesagt: Ja, da oben, da ist ein anderes Klima, ein anderer Boden als da unten; da ist alles verschieden. Da ist das Pflanzenwachstum verschieden, da mußten die Menschen in verschiedener Weise leben. Aber die Sonne kommt überall hin: Die Sonne scheint da oben, die Sonne scheint da unten, die geht ihren Weg, die geht aus den wärmeren Gegenden zu den kälteren Gegenden und so weiter. — So sagten sich diese Leute: Auf der Erde herrscht Verschiedenheit; die Sonne macht alles gleich. - Und sie sahen daher in der Sonne dasjenige, was alles befruchtet, was alles gleich macht. Deshalb sagten sie: Wenn wir einen Herrscher haben, so muß der auch so sein. Die einzelnen Menschen sind verschieden, aber der muß wie die Sonne die Leute beherrschen. — Deshalb nannten sie ihn den Sohn der Sonne. Der war also verpflichtet, so zu regieren auf Erden, wie die Sonne in der Welt regiert. Die einzelnen Planeten: Venus, Jupiter und so weiter treiben Verschiedenes; die Sonne macht alles gleich als Herrscher über diese Planeten. Und so stellten sich die Chinesen vor, daß derjenige, der der Herrscher ist, der Sohn der Sonne ist. Nicht wahr: Unter «Sohn» verstand man eigentlich im wesentlichen dasjenige, was zu irgend etwas gehört.

Und nun war das ganze übrige Leben so eingerichtet, daß die Leute sich sagten: Nun ja, der Sohn der Sonne, das ist unser wichtigster Mensch; die anderen sind seine Helfer, so wie die Planeten und so weiter die Helfer der Sonne sind. — Und sie richteten auf Erden alles so ein, wie es ihnen oben bei den Sternen erschien. Und das alles machten sie, ohne daß sie beteten. Die Chinesen kannten das nicht, was man ein Gebet nennt. Das taten sie, ohne daß sie im Grunde so etwas hatten, was später ein Kultus war. Sie richteten sich dasjenige, was man ihr Reich nennen könnte, so ein, daß es ein Abbild des Himmels war. Man kann das noch nicht Staat nennen; das ist ein Unfug, den die heutigen Menschen treiben. Aber sie richteten sich dasjenige, was auf Erden war, so wie ein Abbild desjenigen ein, was ihnen am Sternenhimmel erschien.

Sehen Sie, dadurch kam etwas heraus, was natürlich ganz anders war als das Spätere; dadurch wurde man Bürger eines Reiches. Man gehörte nicht zu einem Religionsbekenntnis, man fühlte sich nur als zu einem Reich gehörig. Götter hatten die Chinesen ursprünglich schon gar nicht; wenn sie später Götter hatten, so waren die von den Indern übernommen. Ursprünglich hatten sie keine Götter, sondern sie drückten alles das, was sie als Beziehung zu den übersinnlichen Welten hatten, in ihrem Reichswesen aus, in dem sie ihre Einrichtungen hatten. Daher hatten diese Einrichtungen so etwas Familienhaftes. Der Sohn der Sonne war zugleich der Vater der übrigen Chinesen, und die dienten ihm. Wenn es auch ein Reich war, es hatte das Ganze etwas von Familienhaftem.

Das alles ist nur möglich, wenn die Menschen überhaupt noch gar kein solches Denken haben wie die späteren Menschen. Und die Chinesen hatten noch kein solches Denken wie die späteren Menschen. Was wir heute denken, war den Chinesen noch ganz fremd. Wir denken zum Beispiel Tier und denken Mensch; wir denken Vase, wir denken Tisch. So dachten die alten Chinesen nicht, sondern die Chinesen wußten: Es gibt einen Löwen, einen Tiger, einen Hund, einen Bären — aber nicht, daß es ein Tier gibt. Sie wußten: Der Nachbar hat einen eckigen Tisch; der andere hat einen etwas runderen Tisch. Die einzelnen Dinge nannten sie; aber das, was Tisch ist, das kam ihnen gar nicht in den Sinn. Den Tisch als solchen, den kannten sie nicht. Sie wußten: Da ist der eine Mensch mit einem etwas größeren Kopf, mit längeren Beinen, da ist der andere Mensch mit einem etwas kleineren Kopf, mit kürzeren Beinen und so weiter. Da ist ein kleiner Mensch, da ist ein großer Mensch; aber Mensch im allgemeinen kannten sie nicht. Sie dachten ganz anders. Der heutige Mensch kann sich nicht hineinversetzen in die Art und Weise, wie die Chinesen dachten. Daher brauchten sie auch andere Begriffe. Wenn man so denkt, sehen Sie: Tisch, Mensch, Tier — was ist dann? Das kann man juristisch ausbilden, denn die Juristerei besteht nur aus solchen Begriffen; aber die Chinesen konnten sich noch keine Juristerei ausdenken. Da war alles so eingerichtet wie in einer Familie. In der Familie sieht man nicht nach im Obligationenrecht, wenn der Sohn oder die Tochter etwas tun wollen. Wenn man heute etwas tun will in der Schweiz, schlägt man das Obligationenrecht, Eherecht und so weiter auf. Da ist dann alles drinnen. Das muß man dann auf das einzelne anwenden.

Insofern die Menschen noch ein bißchen etwas vom Chinesischen in sich haben - es bleibt ja immer ein bißchen was! -, da kennen sie sich noch nicht recht aus im Obligationenrecht; da müssen sie dann zum Advokaten gehen. Sie kennen sich auch noch nicht in allgemeinen Begriffen aus, die Leute. Die Chinesen, die hatten auch keine Juristerei. Sie hatten überhaupt eigentlich alles dasjenige noch nicht, was dann später zum Staatswesen wurde, Sie hatten nur dasjenige, was der einzelne Mensch wiederum im einzelnen sehen konnte.

Nun weiter. Davon ist zum Beispiel die ganze Sprache der Chinesen beeinflußt. Nicht wahr, wenn wir sagen: Tisch — so stellen wir uns darunter unbedingt etwas vor, was eine Platte hat und entweder eins, zwei oder drei Beine und so weiter, aber es muß etwas sein, was eben so wie ein Tisch stehen kann. Und wenn einer kommt und vom Stuhl sagt, das wäre ein Tisch, würden wir ihm sagen: Du bist ein Esel, das ist doch kein Tisch, das ist doch ein Stuhl. - Und wenn gar einer kommen würde und würde zu dem da (Wandtafel) Tisch sagen, da würden wir ihm sagen: Das ist ein doppelter Esel, denn das ist doch eine Tafel und kein Tisch! — Wir müssen eben nach dem, wie wir gerade unsere Sprache haben, jedes Ding mit einem Namen bezeichnen.

Das ist bei den Chinesen nicht der Fall, sondern sagen wir - ich will es nur hypothetisch anführen, es ist nicht genau so, aber Sie bekommen eine Vorstellung davon -, sagen wir, der Chinese hat einen Laut OA, IOA, TAO meinetwillen, er hat den Laut für Tisch zum Beispiel. Aber dieser selbe. Laut, der bedeutet dann noch vieles andere. Also, sagen wir, so ein Laut, der kann bedeuten: Baum, Bach, auch, sagen wir, Kieselstein und so weiter. Dann hat er einen anderen Laut, der kann bedeuten, sagen wir Stern, auch Tafel und zum Beispiel Bank. Ich meine nicht, daß das in der chinesischen Sprache so wirklich ist, aber es ist so aufgebaut. Jetzt weiß der Chinese: er hat zwei Laute, sagen wir zum Beispiel Lao und Bao, und beides bedeutet ganz Verschiedenes, nur Bach bedeuten sie beide; dann setzt er beides zusammen: Baolao. So baut er seine Sprache auf! Er baut seine Sprache nicht auf Namen auf, die dem einzelnen gegeben sind, sondern er setzt sie so zusammen, wie die verschiedenen Laute Verschiedenes bedeuten. Es kann Baum, aber auch Bach bedeuten. Wenn er dann einen Laut hat, der unter vielem anderem Baum, aber auch Bach bedeutet, so setzt er diesen mit einem anderen zusammen; dann weiß der andere, daß er den Bach meint; aber wenn er nur einen Laut ausspricht, dann weiß keiner, was gemeint ist. Und so kompliziert ist es auch mit dem Schreiben. So daß also die Chinesen eine außerordentlich komplizierte Sprache und eine außerordentlich komplizierte Schrift haben.

Ja, aber daraus folgt vieles, meine Herren. Daraus folgt, daß man nicht so leicht wie bei uns lesen und schreiben lernen konnte, nicht einmal sprechen. Bei uns kann man wirklich sagen: Lesen und Schreiben ist kinderleicht, und wir sind sogar alle unglücklich, wenn unsere Kinder nicht lesen und schreiben lernen; es muß eben «kinderleicht» sein. Das ist bei den Chinesen nicht so; da wird man ein alter Bursche, bis man schreiben lernen kann oder die Sprache beherrscht. Daher kann man sich auch vorstellen, daß eigentlich das Volk das alles nicht kann, und daß nur diejenigen, die bis ins höchste Alter lernen, das alles beherrschen. Daher ist in China von selbst den Gebildeten ein geistiger Adel gegeben. Also in China ist dieser geistige Adel durch das, was in der Sprache und Schrift ist, hervorgerufen. Und wiederum ist es nicht so, wie es im Westen der Fall ist, wo der Adel einigermaßen ernannt ist und dann sich forterbt, sondern in China ist es nur möglich, eine solche Rangstellung sich zu erringen durch Bildung, durch Gelehrsamkeit.

Es ist sehr merkwürdig, meine Herren: Wir müssen natürlich, wenn wir äußerlich heute beurteilen wollen, immer betonen: Wir wollen nur ja keine Chinesen werden! — Also Sie müssen das nicht so auffassen, als ob ich sagen wollte, wir wollen Chinesen werden oder China besonders bewundern. Das ist etwas, was natürlich einige Leute einem leicht nachsagen können, und als wir in Wien vor zwei Jahren einen Kongreß hatten, da hat einer von uns davon geredet, daß die Chinesen heute noch verschiedene Einrichtungen haben, die weiser sind als die unsrigen. Flugs haben die Zeitungen geschrieben, wir wollten für Europa die chinesische Kultur haben! — Nicht wahr, das ist also nicht damit gemeint! Nur wird man, wenn man die chinesische Kultur beschreibt, so sprechen, daß man in eine Art, nur in eine Art von Lob hineinkommt, weil sie ja etwas Geistiges hat. Nur ist sie primitiv; sie ist so, daß man sich jetzt nicht mehr darauf einlassen kann. Also Sie müssen deshalb schon nicht glauben, daß ich wünsche, daß man China in Europa einführt! Aber ich will Ihnen doch beschreiben diese älteste Menschheitskultur, wie sie eben wirklich war.

Nun weiter: Das, was ich da sagte, hängt nun überhaupt zusammen mit der ganzen Art und Weise, wie diese Chinesen dachten und fühlten. Die Chinesen nämlich und auch die älteren Japaner beschäftigten sich auch sehr viel, außerordentlich viel mit ihrer Kunst, ihrer Art von Kunst; sie malten zum Beispiel. Ja, wenn wir malen, dann ist das etwas ganz anderes, als wenn diese Chinesen malen! Sehen Sie, wenn wir malen — ich will das Einfachste machen -, wenn wir zum Beispiel eine Kugel malen (es wird gezeichnet), sagen wir, wenn so das Licht kommt, dann ist diese Kugel hier hell, dahier ist sie dunkel, da ist sie im Schatten, da trifft das Licht vorbei; da ist sie wiederum auf der Lichtseite ein bißchen hell, weil da das zurückgeworfene Licht kommt -, dann sagen wir, das ist Selbstschatten, weil da das zurückgeworfene Licht kommt; und dann müßten wir hier noch extra aufmalen den Schatten, den sie auf den Boden wirft, den Überschatten. Das ist das eine, wie wir malen. Wir müssen Licht und Schatten auf unseren Dingen haben. Wenn wir ein Gesicht malen, dann malen wir hierher Helligkeit, wenn da das Licht kommt; dahier machen wir es dunkel. Ebenso sehen wir vom Menschen, wenn wir richtig malen, einen Schatten, der auf den Boden fällt.

Aber außerdem müssen wir bei unserem Malen noch etwas berücksichtigen. Nehmen wir an, ich stehe da und ich will malen. Da sehe ich da vorne den Herrn Aisenpreis sitzen, und da hinten sehe ich den Herrn Meier und die beiden Herren, die da hinten sind; die muß ich auch malen: Herrn Aisenpreis ganz groß, Herrn Meier und die beiden Herren da hinten ganz klein. So werden sie auch auf der Photographie, wenn ich photographiere, ganz klein. Wenn ich das male, mache ich das so, daß ich die Herren, die auf der vordersten Reihe sitzen, ganz groß male, die nächsten kleiner, die nächsten noch kleiner, und der da ganz hinten sitzt, der hat einen winzig kleinen Kopf, ein winzig kleines Gesicht. Da sehen Sie, man muß nach der Perspektive malen. Das muß man auch bei uns. Wir müssen nach Licht und Schatten malen, wir müssen nach der Perspektive malen. So ist es einmal in unserer Denkweise.

Ja, die Chinesen, meine Herren, die kannten weder Licht noch Schatten beim Malen, noch kannten sie eine Perspektive, weil sie überhaupt nicht so gesehen haben wie wir! Die haben gar nicht geachtet auf Licht und Schatten, auf die Perspektive; denn die haben so gesagt: Aisenpreis ist doch nicht ein Riese, und Meier ist doch nicht ein kleiner, winziger Zwerg! Die können wir doch nicht so durcheinanderstellen auf einem Bild, daß der eine ein Riese, der andere ein Zwerg wäre; das ist doch eine Lüge! Das ist doch gar nicht wahr! — Die haben sich so hineingedacht in alles und haben so gemalt, wie sie sich hineingedacht haben. Und die Chinesen und Japaner, wenn sie in ihrer Art malen lernen, lernen sie es nicht so, daß sie es von außen anschauen, sondern sich hineindenken in die Dinge; sie malen alles von innen heraus, wie sie sich es denken müssen. Das macht das Wesen der chinesischen und japanischen Malerei aus.

Also Sie sehen: Das Sehenlernen, das tritt erst später in der Menschheit auf. Die Menschen, die da im alten China waren, die haben nur in ihrer Art bildlich gedacht; sie haben nicht allgemeine Begriffe gebildet, wie Tisch und so weiter, aber das, was sie gesehen haben, haben sie innerlich erfaßt. Das ist auch gar nicht wunderbar, meine Herren, denn die Chinesen kamen ja von einer solchen Kultur her, bei der man nicht so gesehen hat. Wir sehen heute so, weil die Luft zwischen uns und dem Gegenstand ist. Aber diese Luft war ja nicht da in den Gegenden, aus denen die Chinesen herkamen. In den Zeiten, von denen die Chinesen herkamen, da sah man noch nicht so. In älteren Zeiten wäre es ein Unsinn gewesen, von Licht und Schatten zu reden, weil es das noch nicht gab in der Luftdichte. So hat sich das bei den Chinesen erhalten, daß sie Licht und Schatten nicht haben für die Dinge, die sie malen, und nicht haben irgendeine Perspektive. Das kommt erst später auf. Daraus sehen Sie schon, wie die Chinesen ganz anders innerlich denken. Sie denken nicht so wie die späteren Menschen.

Aber all das hinderte die Chinesen gar nicht, daß sie es in bezug auf äußere Geschicklichkeiten sehr weit brachten. Sehen Sie, in der Zeit, als ich noch jung war, jetzt ist es etwas anders geworden, da hat man halt in der Schule gelernt: Das Schießpulver hat Berthold Schwarz erfunden. Und es war so gemeint, als wenn es früher niemals ein Schießpulver gegeben hätte und der Berthold Schwarz aus Schwefel, Kalisalpeter und Kohle einmal, als er seine alchimistischen Versuche gemacht hat, das Schießpulver gefunden hätte. Nun, die Chinesen haben aber schon das Schießpulver vor Jahrtausenden gemacht!

Dann lernte man in der Schule: Gutenberg hat die Buchdruckerkunst erfunden. — Man lernte da vieles auch richtig, aber es schaut so aus, als ob es früher niemals einen Buchdrucker gegeben hätte. Die Chinesen hatten ihn schon vor Jahrtausenden! Ebenso hatten die Chinesen die Holzschneidekunst, konnten die wunderbarsten Sachen aus Holz herausschneiden. Also die Chinesen haben in diesen Außerlichkeiten eine hohe Kultur gehabt. Und diese Kultur war wiederum nur der letzte Überrest einer Kultur, die früher noch höher war; denn das sieht man dieser chinesischen Kunst an, daß sie herstammt von etwas, was noch höher war.

Nun, das Eigentümliche aber bei diesen Chinesen, das ist eben das, daß sie gar nicht in Begriffen denken können, sondern nur in Bildern; aber dann versetzen sie sich in das Innere der Gegenstände hinein. Und so können sie auch alle die Gegenstände machen, die durch äußere Erfindungen gemacht werden, wenn es nicht gerade Dampfmaschinen sind oder so etwas. Und so, wie die Chinesen heute, man kann schon sagen, verlottert und unkultiviert sind,* so sind sie eigentlich erst ge Siehe Hinweis auf $. 244. 85 worden, nachdem sie eigentlich wirklich jahrhundertelang malträtiert worden sind von den Europäern.

Da sehen Sie, meine Herren, daß es eine Kultur hier gab, die eigentlich in gewissem Sinne geistig ist, und die ganz alt ist, die auf zehntausend Jahre vor unsere Zeit schon zurückgeht. Und verhältnismäßig spät, erstin dem Jahrtausend, das vor dem Christentum liegt, da haben solche Leute wieder Lao-tse, der Konfuzius, dasjenige, was diese Chinesen gehabt haben an Kenntnissen, aufgeschrieben. Aber diese Herren haben nichts anderes aufgeschrieben als dasjenige, was sich so ergeben hat im Familienumgang des großen Reichs. Die haben gar nicht das Bewußtsein gehabt, daß sie etwas erfinden als Moral-, Sittlichkeitsregeln und so weiter, sondern dasjenige, was sie vorgefunden haben, wie sich die Chinesen benommen haben, das haben sie aufgeschrieben. Früher hat man es nur ausgesprochen. Also alles war im Grunde genommen anders dazumal. Nun, sehen Sie, das ist dasjenige, was sich gewissermaßen heute noch an den Chinesen beobachten läßt.

An den Japanern läßt sich das kaum mehr beobachten, weil sie sich ganz europäisiert haben und sie alles der europäischen Kultur nachmachen. Daß sie nicht aus ihnen selber gewachsen ist, diese Kultur, das geht daraus hervor, daß sie das, was rein europäisch ist, nicht aus sich selber heraus finden können. Da passierte ja zum Beispiel einmal folgendes: Die Japaner sollten ein Dampfschiff verwenden; sie haben sich eingebildet, das könnten sie schon ganz wunderbar verwenden. Sie haben zum Beispiel abgeguckt, wie man umdreht mit einem Dampfschiff, was man da für eineSchraube aufmacht und so weiter. Nun, dann haben die Lehrer, die Europäer, das eine Zeitlang mit den Japanern durchgemacht; dann waren die Japaner schon stolz und haben gesagt: Das können wir jetzt selber machen, wir können selber einen Kapitän stellen. - Nun haben sich die europäischen Lehrer auf dem Lande aufgestellt, und die Japaner sind mit ihrem Dampfschiff aufs hohe Meer hinausgefahren. Nun wollten sie auch das Umdrehen probieren, machten die Schrauben auf, und siehe da, das Schiff drehte um - aber dann wußten sie nicht, wie man wieder zumacht; und nun drehte das Schiff fortwährend, tanzte auf dem Meer herum, und die europäischen Lehrer, die an der Küste standen, mußten in einem Boot auf das Meer fahren und das Schiff erst wiederum zum Stillstand bringen. — Sie wissen, daß es ein Gedicht von Goethe gibt: «Der Zauberlehrling», wo ein Junge von einem alten Zaubermeister sich die Sprüche abgelauscht hat. Nun hat er gelernt, damit er nicht selber das Wasser holen muß, durch Zauberspruch einen Besen zu verwandeln, daß der das Wasser herbeihole. Nun fängt er an, als der alte Meister einmal wegging, sich das Wasser vom Besen bringen zu lassen. Die Worte, die hatte er, daß er den Besen veranlassen konnte, das Wasser zu bringen. Und nun fängt der Besen an, immer Wasser und Wasser zu bringen — aber nun hat der Junge vergessen, wie er ihn wiederum zum Stillstand bringen kann! Nun denken Sie, wenn Sie Wasser hätten im Zimmer und der Besen immer wieder Wasser bringt, bis der Lehrling sogar den Besen zerhackt: da werden sogar zwei Besen daraus, die bringen beide jetzt Wasser! Als alles schon überschwemmt ist und immer mehr Wasser kommt, da ist der alte Meister gekommen, der das Wort sagte, so daß der Besen wieder zum Besen geworden ist.

Nicht wahr, das Gedicht ist neulich hier eurythmisiert worden, machte den Leuten riesigen Spaß. So erging es auch den Japanern: Die hatten auch nicht gewußt, wie die Schraube wieder zurückgedreht werden mußte, und das Schiff da draußen drehte und drehte sich. Da war da draußen so ein richtiger Schiffstanz, bis die auf dem Lande stehenden Lehrer mit dem Boot hinausfahren konnten und dem wieder abhalfen.

Daraus geht hervor: Europäische Sachen eigentlich erfinden können die Chinesen nicht — das können auch die Japaner nicht -, aber erfinden die eigentlich älteren Sachen, wie Schießpulver, Buchdruck und so weiter, darauf sind diese in viel, viel älteren Zeiten gekommen als die Europäer.

Nun, sehen Sie, der Chinese hat eben großes Interesse für die Umwelt, großes Interesse für die Sterne, wie überhaupt großes Interesse für die Außenwelt.

Ein anderes Volk, das nun auch weit zurückweist auf alte Zeiten, das ist dann das indische. Aber so weit wie das chinesische weist das indische nicht zurück. Das indische Volk hat auch eine alte Kultur. Aber diese alte Kultur, die ist, ich möchte sagen, erst später als die chinesische aus dem Meer aufgestiegen. Die Leute, die da im späteren Indien waren, die sind mehr vom Norden, als das dann hier vom Wasser frei wurde, heruntergekommen, haben sich dann da niedergelassen.

Nun, diese Inder haben, während die Chinesen sich mehr für das, was außen in der Welt ist, interessierten, in jedes Ding sich hineindenken konnten, mehr in sich hineingebrütet. Die Chinesen haben mehr über die Welt nachgedacht, in ihrer Art, aber eben über die Welt nachgedacht; die Inder dachten mehr über sich nach, über den Menschen selber. Daher entstand eine sehr verinnerlichte Kultur in Indien. In den ältesten Zeiten war nun die indische Kultur auch noch religionsfrei, denn auch in die indische Kultur ist die Religion erst später hereingekommen. Man hat hauptsächlich den Menschen betrachtet, aber man hat den Menschen innerlich betrachtet.

Sehen Sie, das kann ich Ihnen auch wiederum aus dem, wie diese Inder gezeichnet und gemalt haben, am besten erklären. Wenn die Chinesen einen Menschen gesehen haben, haben sie ihn einfach gemalt, indem sie sich in ihn hineingedacht haben, ohne Licht und Schatten, ohne Perspektive. Also wenn ein Chinese schon hätte Herrn Burle malen wollen, so hätte er sich hineingedacht in ihn; er hätte ihn da nicht schwarz gemacht, wie wir es heute machen, und da hell — Licht und Schatten hätte er nicht gemacht; er hätte auch nicht die Hände im Verhältnis, weil wir die Hände immer vorne haben, etwas größer gemacht. Aber wenn der Chinese den Herrn Burle nun gemalt hätte, dann wäre eben der Herr Burle da auf dem Bild.

Bei den Indern war das ganz anders. Denken Sie sich, die Inder hätten gemalt. Da hätten sie angefangen, hätten versucht, den Kopf zu malen — Perspektive hatten sie ja auch nicht. Aber dann wäre ihnen gleich eingefallen: Der Kopf könnte auch anders sein — da hätten sie gleich einen zweiten, einen dritten gemacht, noch anders, und dann wäre ihnen ein vierter und fünfter eingefallen. So hätten sie nach und nach zwanzig, dreißig Köpfe nebeneinander gehabt! So viel ist ihnen eingefallen bei dem einen Kopf. Oder bei einer Pflanze, wenn sie die gemalt hätten: gleich fiel ihnen ein, die könnte auch anders sein — und dann entstanden gleich viele, viele junge Pflanzen, die aus der älteren hervorwuchsen! So war es bei den ältesten Indern. Die haben diese riesige Phantasie gehabt. Die Chinesen haben gar keine Phantasie gehabt, die machten nur das einzelne, aber sie dachten sich in das einzelne hinein. Die Inder hatten diese riesenhafte Phantasie.

Nun, sehen Sie, meine Herren, das ist ja nicht da; wahrhaftig, wenn man Herrn Burle ansieht, da hat man nur einen Kopf, und wenn man ihn da hinmalt (an die Tafel), kann man auch nur einen Kopf malen. Also man malt nichts, was äußerlich wirklich ist, wenn man da zwanzig, dreißig Köpfe malt; da malt man etwas, was nur im Geiste gedacht ist. Und so wurde die ganze indische Kultur. Die wurde eine ganz innerlich geistige Kultur. Daher, wenn Sie indische geistige Wesen sehen, wie die Leute es sich gedacht haben, dann haben sie diese mit vielen Köpfen, mit vielen Armen gemalt oder so, daß anderes, Tierisches aus dem herausgeht, was also da im Körper ist und so weiter.

Sehen Sie, diese Inder, das sind ganz andere Menschen als die Chinesen. Die Chinesen sind phantasielos, die Inder sind ursprünglich voll Phantasie. Daher waren die Inder auch geeignet, nach und nach ihre Kultur ins Religiöse umzuwandeln. Die Chinesen haben nie ihre Kultur, bis heute nicht, ins Religiöse umgewandelt; in China gibt es keine Religion. Die Europäer, sehen Sie, die alles miteinander verwursteln, die reden von einer chinesischen Religion. Kein Chinese wird das zugeben! Der sagt: Ihr in Europa habt eine Religion, die Inder haben eine Religion; wir haben nicht das, was eurer Religion ähnlich ist -, sagen die Chinesen. Nun, aber das, wie diese Inder veranlagt waren, das war nur möglich dadurch, daß diese Inder eine ganz genaue Kenntnis hatten, was die Chinesen nicht so hatten, von dem menschlichen Körper. Der Chinese konnte sich in alles, was außen ist, sehr gut hineinversetzen. Deshalb malte er auch so, wie ich es Ihnen sagte. Wenn er aber auch andere Dinge wahrnahm, dann konnte er sich gut hineinversetzen. Sehen Sie, wenn wir auf unserem Tisch Essig stehen haben und Salz und Pfeffer und wollen wissen, wie diese Dinge schmecken, dann müssen wir Pfeffer und Salz und Essig erst auf die Zunge kriegen; dann wissen wir, wie es schmeckt. Das war beim alten Chinesen nicht so: Der schmeckte die Dinge schon, wenn sie draußen waren. Er konnte sich wirklich in sie hineinversetzen. Und mit dem Äußeren war der Chinese gut vertraut. Daher hatte er auch Ausdrücke, die zeigten, daß er teilnahm an der Außenwelt. Wir haben nicht mehr solche Ausdrücke — höchstens bedeuten sie bei uns etwas Bildliches. Beim Chinesen bedeuteten sie etwas Wirkliches. Wenn ich einen Menschen kennenlerne, und ich sage: Das ist ein säuerlicher Mensch -, dann werden Sie sich etwas Bildliches vorstellen. Daß er wirklich sauer ist wie Essig, das stellen Sie sich dann nicht vor. Aber beim Chinesen bedeutete das, daß dieser Mensch in ihm hervorgerufen hätte einen säuerlichen Geschmack.

Nun, das war bei den Indern eben nicht so. Die Inder, die konnten sich vielmehr in den eigenen Körper vertiefen. Wenn wir uns in den Körper vertiefen, dann können wir nur unter gewissen Umständen etwas fühlen in unserem Körper. Wenn jedesmal, wenn wir eine Mahlzeit hinter uns haben, diese Mahlzeit im Magen liegen bleibt, der Magen nicht ordentlich verdauen kann, dann fühlen wir Schmerzen in unserem Magen; wenn unsere Leber nicht in Ordnung ist, nicht genügend Galle absondern kann, dann fühlen wir Schmerzen auf der rechten Seite des Körpers, dann werden wir leberkrank. Wenn unsere Lunge zu viel Exsudate, also Absonderungen, von sich gibt, so daß sie mit Schleim ausgefüllt wird, den sie nicht haben soll, so fühlen wir: Die Lunge, die ist nicht richtig in Ordnung, die ist krank. Der heutige Mensch fühlt den Körper nur in denjenigen Organen, wo er krank ist. In diesen älteren Zeiten fühlte der Inder auch die gesunden Organe; er wußte, wie der Magen, wie die Leber sich anfühlt. Wenn der Mensch das heute wissen will, muß er sich einen Leichnam nehmen, muß ihn zerschneiden; er schaut die einzelnen Organe, wie sie im Inneren sind, an. Kein Mensch wüßte heute, wie eine Leber ausschaut, wenn man sie nicht sezieren würde — außerdem: die Geisteswissenschaft ist in der Lage, sie zu beschreiben! Die Inder, die dachten den Menschen von innen her; sie hätten alle Organe zeichnen können. Nur beim Zeichnen wiederum, wenn Sie einem Inder die Aufgabe gegeben hätten, er soll seine Leber fühlen, und er soll das, was er fühlt, zeichnen, so hätte er gesagt: Leber — das ist eine Leber, das eine andere Leber, das ist wieder eine andere Leber, und er hätte zwanzig bis dreißig Lebern nacheinander aufgezeichnet.

Ja, meine Herren, da wird die Geschichte schon anders. Wenn ich einen fertigen Menschen habe und ihm zwanzig Köpfe mache, dann habe ich ein Phantasiegebilde. Wenn ich aber eine menschliche Leber aufzeichne und dabei zwanzig-, dreißigmal eine Leber mache, dann ist es wirklich so, daß ich eigentlich nicht etwas ganz Phantastisches aufzeichne, sondern diese zwanzig, dreißig Lebern hätten eigentlich entstehen können! Es hat ja jeder Mensch seine bestimmte Form der Leber, wie er sein Gesicht hat; aber das ist nicht so arg notwendig, sondern sie könnte der Form nach auch anders sein. Und dieses, daß etwas anders sein kann, dieses Geistige an der Sache, das haben die Inder viel besser verstanden als die Späteren. Die haben gesagt: Wenn man ein einzelnes Ding zeichnet, so ist das gar nicht wahr, sondern man muß sich die Dinge geistig vorstellen. - Daher haben die Inder eine hohe geistige Kultur gehabt, haben eigentlich allmählich nicht mehr viel gegeben auf die äußere Welt, sondern haben sich alles geistig vorgestellt.

Aber diese Inder, die hielten darauf, daß man tatsächlich auch in dieser Weise die Sache lernt. Und daher war es wiederum bei ihnen so, daß man, um ein gebildeter Mensch zu werden, lange lernen mußte. Denn nicht wahr, es war nicht so, daß sich auf einmal der Mensch hat in sich vertiefen und alles daher hat wissen können; er mußte dazu erst Anleitung haben. Wenn wir einen Jungen oder ein Mädchen unterrichten, so sind wir verpflichtet, es so zu tun, daß wir es lesen und schreiben lehren und so weiter, also ihm äußerlich etwas beibringen. Das war bei den alten Indern nicht der Fall. Die haben, wenn sie wirklich jemanden etwas lehren wollten, ihn hingesetzt: Er mußte sich innerlich in sich vertiefen, er mußte sogar möglichst die Aufmerksamkeit von der Welt ablenken und auf das Innere richten. Nun aber, wenn einer sitzt und so hinschaut, so sieht er Sie alle da sitzen, und er wird auf die Außenwelt gelenkt. Das hätten die Chinesen gemacht, die lenkten die Aufmerksamkeit auf die Außenwelt. Die Inder taten anderes. Die sagten: Du mußt lernen deine Nasenspitze anzuschauen. — Dann mußte er die Augen so halten, daß er nichts anderes sah als seine Nasenspitze, nichts anderes, stundenlang, und gar nicht mit den Augen wegschaute.

Ja, meine Herren, der Europäer sagt: Das ist etwas Schreckliches, wenn man die Leute anleitet, sie sollen immer auf ihre Nasenspitze schauen. — Gewiß, für den Europäer hat es etwas Schreckliches; er kann das nicht nachmachen. Aber im alten Indien war es eben Sitte. Derjenige, der etwas lernen sollte, sollte nicht mit den Fingern schreiben, sondern auf seine Nasenspitze sehen. Dadurch aber, daß er dasaß und stundenlang auf seine Nasenspitze sah, wurde er auf das Innere gelenkt, lernte Lunge, Leber und so weiter kennen; da wurde er wirklich auf das Innere gelenkt. Denn die Nasenspitze ist in der ersten Stunde wie in der zweiten; er sieht nichts Besonderes an der Nasenspitze. Aber von der Nasenspitze aus sieht er immer mehr und mehr in sein Inneres; da wird es im Inneren immer heller und heller.

Dazu mußten sie noch das Folgende ausüben. Nicht wahr, man ist gewöhnt, wenn man herumgeht, auf seinen Füßen zu gehen. Ja, meine Herren, dieses Auf-den-Füßen-Gehen, das übt einen Einfluß auf uns aus. Wir fühlen uns dann als aufrechte Menschen, wenn wir auf den Füßen gehen. Auch das wurde abgestellt bei denen, die etwas lernen sollten in Indien. Die mußten, während sie lernten, das eine Bein so haben und sich darauf setzen, das andere so; so daß sie also so saßen und immer auf die Nasenspitze schauten - daß sie sich ganz abgewöhnten zu stehen, sondern daß sie da das Gefühl hatten: sie sind nicht aufrechtstehende Menschen, sondern das ist verkrüppelt, das ist noch wie bei einem Embryo, wie wenn sie im Mutterleib noch wären. - So können Sie ja auch die Buddha-Figuren sehen. So mußten die Inder lernen. Und so schauten sie allmählich in ihr Inneres hinein und lernten das Innere des Menschen kennen, lernten den physischen Leib des Menschen ganz geistig kennen.

Wenn wir in uns hineinschauen, da fühlen wir das armselige Denken und ein bißchen das Fühlen, fast gar nicht mehr das Wollen. Die Inder fühlten eine ganze Welt in dem Menschen. Natürlich können Sie sich vorstellen, daß das ganz andere Menschen waren als die späteren. Und dann entwickelte sich diese ungeheure Phantasie; die haben sie in ihren dichterischen Weisheitsbüchern niedergelegt, später in den Veden oder in der Vedanta-Philosophie, die wir heute noch bewundern; sie haben sie niedergelegt in all den Legenden, die sie über die übersinnlichen Dinge haben, die wir heute noch bewundern. Sehen Sie, das ist der Gegensatz: Die Inder waren hier, die Chinesen da drüben, und die Chinesen waren ein Volk, welches nüchtern, äußerlich war, gar nicht von innen, vom Inneren lebte. Die Inder waren ein Volk, das ganz nach dem Inneren schaute, aber eigentlich den physischen Körper, der geistig ist, im Inneren anschaute.

Nun, da habe ich Ihnen zunächst etwas von den ältesten Bevölkerungen der Erde gesagt. Meine Herren, ich werde doch noch das nächste Mal fortsetzen, damit wir weiterkommen bis herauf, wo wir jetzt leben, und wir werden also die Geschichte weiter betrachten.

Setzen Sie sich aber doch Fragen zurecht. Es wird Sie jetzt immer mehr und mehr das Einzelne und Besondere interessieren, aber ich werde das nächste Mal immer auch wiederum berücksichtigen, was mir für Fragen gestellt werden, und so allmählich weiterschreiten. — Nur kann ich Ihnen nicht sagen, wann die nächste Stunde sein wird. Ich muß jetzt nach Holland fahren, und werde Ihnen sagen lassen, wann die nächste Stunde dann sein wird, in zehn bis vierzehn Tagen.

Fifth Lecture

Gentlemen! I have told you that we want to look a little more closely at history, which follows on from the view of the world that we have taken. You have seen how the human race gradually developed out of the rest of nature. And only when the conditions for human life were in place on Earth, when the Earth had, so to speak, died, when the Earth no longer had its own life, could human and animal life develop on Earth as I have described to you.

And we have also seen that the first human life was very different from today's, actually taking place where the Atlantic Ocean is today. At that time, we must imagine that the earth where the Atlantic Ocean is today was solid ground. So I will sketch the situation for you again (sketching): Here we come over to Asia. That is the Black Sea. Down there is Africa. Then there is Russia, and we come over to Asia. That would be England and Ireland. Over there is America. So, in the past, there was land everywhere, and only very little land here; here in Europe, we actually had a huge sea at that time. These countries are all in the sea. And when we cross over there, Siberia is also still sea; it's all still sea. And down there, where India is today—that's Hinterindien—here it was again the case that something rose out of the sea. So we actually have some land here; here we have land again. In the part where the Asians, the Near Easterners, and the Europeans live today, there was actually sea, and the land only rose up from it later. And this land went much further, it went all the way into the Pacific Ocean, where the many islands are today; so the islands of Java, Sumatra, and so on, are pieces of a former land, the whole island archipelago. So where the Great Ocean is today, there used to be a lot of land; in between was sea.

So the first populations that we can trace remained here, where some of the land remained intact. If we look around Europe, we can actually say: In Europe, the situation is such that it was only about ten, twelve, fifteen thousand years ago that the earth became solid enough for humans to live there. Before that, there were only sea creatures that evolved from the sea and so on. If you wanted to look for humans at that time, you would have to look over to where the Atlantic Ocean is today. But over there in Asia, in East Asia, there were already humans ten thousand years ago and so on. These humans naturally left descendants, and these descendants are very interesting, gentlemen, because they are actually the ones who have the oldest so-called culture on Earth. These are peoples that we today refer to as Mongolian peoples, namely the Japanese and Chinese. They are actually very interesting because they are remnants, so to speak, of the oldest population on Earth, of which something still remains.

Of course, as you have seen, there is a much older population on Earth, but it has been completely destroyed. This is the population that lived here in ancient Atlantis. Nothing remains of it. Even if there were any remains, one would have to dig on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. First you would have to descend to the bottom — which is harder than you might think — and then you would have to dig there; then you would most likely find nothing, because they had soft bodies, as I told you. And the culture they created with their gestures cannot be dug up from the earth either, because it has not remained! So what is much older than the Japanese and Chinese cannot be achieved with external science. One must pursue spiritual science if one wants to achieve such things.