Human Values in Education

GA 310

18 July 1924, Arnheim

II. Descent into the Physical Body, Goethe and Schiller

In this course of lectures I want in the first place to speak about the way in which the art of education can be furthered and enriched by an understanding of man. I shall therefore approach the subject in the way I indicated in my introductory lecture, when I tried to show how anthroposophy can be a practical help in gaining a true knowledge of man, not merely a knowledge of the child, but a knowledge of the whole human being. I showed how anthroposophy, just because it has an all-embracing knowledge of the whole human being—that is to say a knowledge of the whole of human life from birth to death, in so far as this takes place on earth—how just because of this it can point out in a right way what is essential for the education and instruction of the child.

It is very easy to think that a child can be educated and taught if one observes only what takes place in childhood and youth; but this is not enough. On the contrary, just as with the plant, if you introduce some substance into the growing shoot its effect will be shown in the blossom or the fruit, so it is with human life. The effect of what is implanted into the child in his earliest years, or is drawn out of him during those years, will sometimes appear in the latest years of life; and often it is not realised that, when at about the age of 50 someone develops an illness or infirmity, the cause lies in a wrong education or a wrong method of teaching in the 7th or 8th year. What one usually does today is to study the child—even if this is done in a less external way than I described yesterday—in order to discover how best to help him. This is not enough. So today I should like to lay certain foundations, on the basis of which I shall proceed to show how the whole of human life can be observed by means of spiritual science.

I said yesterday that man should be observed as a being consisting of body, soul and spirit, and in yesterday's public lecture I gave some indication of how it is the super-sensible in man, the higher man within man, that is enduring, that continues from birth until death, while the substances of the external physical body are always changing. It is therefore essential to learn to know human life in such a way that one perceives what is taking place on earth as a development of the pre-earthly life. We have not only those soul qualities within us that had their beginning at birth or at conception, but we bear within us pre-earthly qualities of soul, indeed, we bear within us the results of past earthly lives. All this lives and works and weaves within us, and during earthly life we have to prepare what will then pass through the gate of death and live again after death beyond the earth, in the world of soul and spirit. We must therefore understand how the super-earthly works into earthly life, for it is also present between birth and death. It works, only in a hidden way, in what is of a bodily nature, and one does not understand the body if one has no understanding of the spiritual forces active within it.

Let us now proceed to study further what I have just indicated. We can do so by taking concrete examples. An approach to the knowledge of man is contained in anthroposophical literature, for instance in my book Theosophy, in An Outline Of Occult Science or in Knowledge of the Higher Worlds. Let us start from what can lead to a real, concrete knowledge of man by taking as a foundation what anthroposophy has to say in general about man and the world. There are two examples which I should like to put before you, two personalities who are certainly well known to you all. I choose them because for many years I made an intensive study of both of them. I am taking two men of genius; later on we shall come down to less gifted personalities. We shall then see that anthroposophy does not only speak in a general, abstract way, but is able to penetrate deeply into real human beings and is able to get to know them in such a way that knowledge of man is shown to be something which has reality in practical life. In choosing these two examples, Goethe and Schiller, and so making an indirect approach, I hope to show how a knowledge of man is acquired under the influence of Spiritual Science.

Let us look at Goethe and Schiller from an outward point of view, as they appeared during the course of their lives, but let us in each case study the whole personality. In Goethe we have an individuality who entered life in a remarkable way. He was born black, or rather dark blue. This shows how extraordinarily difficult it was for his soul-spiritual being to enter into physical incarnation. But once this had taken place, once Goethe had overcome the resistance of this physical body, he was entirely within it. On the one hand it is hard to imagine a more healthy nature than Goethe had as a boy. He was amazingly healthy. He was so healthy that his teachers found him quite difficult; but children who give no trouble are seldom those who enjoy the best health in later life. On the other hand, children who are rather a nuisance to their teachers are those who accomplish more in later life because they have more active, energetic natures. The understanding teacher will therefore be quite glad when the children keep a sharp eye on him. Goethe from his earliest childhood was very much inclined to do this, even in the literal sense of the word. He peeped at the fingers of someone playing the piano and then named one finger “Thumbkin,” another “Pointerkin,” and so on. But it was not only in this sense that he kept a sharp eye on his teachers. Even in his boyhood he was bright and wide-awake; and this at times gave them trouble. Later on in Leipzig Goethe went through a severe illness, but here we must bear in mind that certain hard experiences and some sowing of wild oats were necessary in order to bring about a lowering of his health to the point at which he could be attacked by the illness which he suffered at Leipzig. After this illness we see that Goethe throughout this whole life is a man of robust health, but one who possesses at the same time an extraordinary sensitivity. He reacts strongly to impressions of all kinds, but does not allow them to take hold of him and enter deeply into his organism. He does not suffer from heart trouble when he is deeply moved by some experience, but he feels any such experience intensely; and this sensitivity of soul goes with him throughout life. He suffers, but his suffering does not find expression in physical illness. This shows that his bodily health was exceptionally sound. Moreover, Goethe felt called upon to exercise restraint in his way of looking at things. He did not sink into a sort of hazy mysticism and say, as is so often said: “O, it is not a question of paying heed to the external physical form; that is of small importance. We must turn our gaze to what is spiritual!” On the contrary, to a man with Goethe's healthy outlook the spiritual and the physical are one. And he alone can understand such a personality who is able to behold the spiritual through the image of the physical.

Goethe was tall when he sat, and short when he stood. When he stood you could see that he had short legs. [The German has the word Sitzgrösse for this condition.] This is an especially important characteristic for the observer who is able to regard man as a whole. Why had Goethe short legs? Short legs are the cause of a certain kind of walk. Goethe took short steps because the upper part of his body was heavy—heavy and long—and he placed his foot firmly on the ground. As teachers we must observe such things, so that we can study them in the children. Why is it that a person has short legs and a particularly big upper part of the body? It is the outward sign that such a person is able to bring to harmonious expression in the present earth life what he experienced in a previous life on earth. In this respect also Goethe was extraordinarily harmonious, for right into extreme old age he was able to develop everything that lay in his karma. Indeed he lived to be so old because he was able to bring to fruition the potential gifts with which karma had endowed him. After Goethe had left the physical body, this body was still so beautiful that all who saw him in death were fulfilled with wonder. One has the impression that Goethe had experienced to the full his karmic potentialities; now nothing more is left, and he must begin afresh when again he enters into an earthly body under completely new conditions. All this is expressed in the particular formation of such a body as Goethe's, for the cause of what man brings with him as predisposition from an earlier incarnation is revealed for the most part in the formation of the head. Now Goethe from his youth up had a wonderfully beautiful Apollo head, from which only harmonious forces streamed down into his physical body. This body, however, burdened by the weight of its upper part and with too short legs was the cause of his special kind of walk which lasted throughout his life. The whole man was a wonderfully harmonious expression of karmic predisposition and karmic fulfilment. Every detail of Goethe's life illustrates this.

Such a personality, standing so harmoniously in life and becoming so old, must inevitably have outstanding experiences in his middle years. Goethe was born in 1749 and he died in 1832, so he lived to be 83 years old. He reached middle age, therefore, at about his 41st year in 1790. If we take these years between 1790 and 1800 we have the middle decade of his life. In this decade, before 1800, Goethe did indeed experience the most important events of his life. Before this time he was not able to bring his philosophical and scientific ideas, important as they were, to any very definite formulation. The Metamorphosis of the Plants was first published in 1790; everything connected with it belongs to this decade 1790-1800. In 1790 Goethe was so far from completing his Faust that he brought it out as a Fragment; he had no idea then that he would ever finish it. It was in this decade that under the influence of his friendship with Schiller he conceived the bold idea of continuing his Faust. The great scenes, the Prologue in Heaven among others, belong to this period. So in Goethe we have to do with an exceptionally harmonious life; with a life moreover that runs its quiet course, undisturbed by inner conflict, devoted freely and contemplatively to the outer world.

As a contrast let us look at the life of Schiller. From the outset Schiller is placed into a situation in life which shows a continual disharmony between his life of soul and spirit and his physical body. His head completely lacks the harmonious formation which we find in Goethe. He is even ugly, ugly in a way that does not hide his gifts, but nevertheless ugly. In spite of this a strong personality is shown in the way he holds himself, and this comes to expression in his features also, particularly in the formation of the nose. Schiller is not long-bodied; he has long legs. On the other hand everything that lies between the head and the limbs, in the region of the circulation and breathing is in his case definitely sick, poorly developed from birth, and he suffers throughout his life from cramps. To begin with there are long periods between the attacks, but later they become almost incessant. They become indeed so severe that he is unable to accept any invitation to a meal; but has to make it a condition—as for instance on one occasion when coming to Berlin—that he is invited for the whole day, so that he may be able to choose a time free from such pains. The cause of all this is an imperfect development of the circulatory and breathing systems.

The question therefore arises: What lies karmically, coming from a previous earthly life, in the case of a man who has to suffer in this way from cramping pains? Such pains, when they gain a hold in human life, point quite directly to a man's karma. If, with a sense of earnest scientific responsibility, one attempts to investigate these cramp phenomena from the standpoint of spiritual science, one always finds a definite karmic cause underlying them, the results of deeds, thoughts and feelings coming from an earlier life on earth. Now we have the man before us, and one of two things can happen. Either everything goes as harmoniously as with Goethe, so that one says to oneself: Here we have to do with Karma; here everything appears as the result of Karma. Or the opposite can also happen. Through special conditions which arise when a man descends out of the spiritual world into the physical, he comes into a situation in which he is not able fully to work through the burden of his karma.

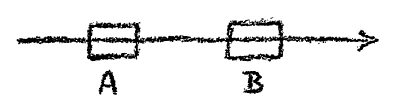

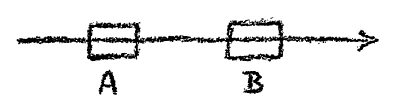

Man comes down from the spiritual world with definite karmic predispositions; he bears these within him. Let us assume that A in the diagram represents a place, a definite point of time in the life of a man when he should be able in some way to realise, to fulfil his karma, but for some reason this does not happen. Then the fulfilment of his karma is interrupted and a certain time must pass when, as it were, his karma makes a pause; it has to be postponed until the next life on earth. And so it goes on. Again, at B there comes a place when he should be able to fulfil something of his karma; but once more he has to pause and again postpone this part of his karma until his next incarnation. Now when someone is obliged to interrupt his karma in this way pains of a cramping nature always make their appearance in the course of life. Such a person is unable fully to fashion and shape into his life what he always bears within him. Here we have something which shows the true character of spiritual science. It does not indulge in fantasy, neither does it talk in vague, general terms about the four members of man's being; physical body, etheric body, astral body and ego. On the contrary, it penetrates into real life, and is able to point out where the real spiritual causes lie for certain external occurrences. It knows how man represents himself in outer life. This knowledge is what true spiritual science must be able to achieve.

I was now faced with the question: In a life such as Schiller's, how does karma work as the shaper of the whole of life if, as in his case, conditions are such that karma cannot properly operate, so that he has to make continual efforts to achieve what he has the will to achieve? For Goethe it was really comparatively easy to complete his great works. For Schiller the act of creation is always very difficult. He has, as it were, to attack his karma, and the way in which he goes to the attack will only show its results in the following earthly life. So one day I had to put to myself the following question: What is the connection between such a life as Schiller's and the more general conditions of life? If one sets about answering such a question in a superficial way nothing of any significance emerges, even with the help of the investigations of spiritual science. Here one may not spin a web of fantasy; one must observe. Nevertheless if one approaches straight away the first object that presents itself for observation, one will somehow go off on a side track. So I considered the question in the following way: How does a life take its course when karmic hindrances or other pre-earthly conditions are present?

I then proceeded to study certain individuals in whom something of this kind had already happened, and I will now give such an example. I could give many similar examples, but I will take one which I can describe quite exactly. I had an acquaintance, a personality whom I knew very well indeed in his present earthly life. I was able to establish that there were no hindrances in his life connected with the fulfilment of karma, but there were hindrances resulting from what had taken place in his existence between death and a new birth, that is in his super-sensible life between the last earthly life and the one in which I learned to know him. So in this case there were not, as with Schiller, hindrances preventing the fulfilment of karma, but hindrances in the way of bringing down into the physical body what he had experienced between death and a new birth in the super-sensible world. In observing this man one could see that he had experienced much of real significance between death and a new birth, but was not able to give expression to this in life. He had entered into karmic relationships with other people and had incarnated at a time when it was not possible fully to realise on earth what he had, as it were, piled up as the content of his inner soul experience between death and conception. And what were the physical manifestations which appeared as the result of his not being able to realise what had been present in him in the super-sensible world? These showed themselves through the fact that this personality was a stutterer; he had an impediment in his speech. And if one now takes a further step and investigates the causes at work in the soul which result in speech disturbances, then one always finds that there is some hindrance preventing what was experienced between death and a new birth in the super-sensible world from being brought down through the body into the physical world. Now the question arises: How do matters stand in the case of such a personality who has very much in him brought about through his previous karma, but who has it all stored up in the existence between death and a new birth and, because he cannot bring it down becomes a stutterer? What sort of things are bound up with such a personality in his life here on earth?

Again and again one could say to oneself: This man has in him many great qualities that he has gained in pre-earthly life, but he cannot bring them down to earth. He was quite able to bring down what can be developed in the formation of the physical body up to the time of the change of teeth; he could even develop extremely well what takes place between the change of teeth and puberty. He then became a personality with outstanding literary and artistic ability, for he was able to form and fashion what can be developed between puberty and the 30th year of life. Now, however, there arose a deep concern in one versed in a true knowledge of man, a concern which may be expressed in the following question: How will it be with this personality when he enters his thirties and should then develop to an ever increasing degree the spiritual or consciousness soul in addition to the intellectual or mind soul? Anyone who has knowledge of these things feels the deepest concern in such a case, for he cannot think that the consciousness soul—which needs for its unfolding everything that arises in the head, perfect and complete—will be able to come to its full development. For with this personality the fact that he stuttered showed that not everything in the region of his head was in proper order. Now apart from stuttering this man was as sound as a bell, except that in addition to the stutter, (which showed that not everything was in order in the head system) he suffered from a squint. This again was a sign that he had not been able to bring down into the present earthly life all that he had absorbed in the super-sensible life between death and a new birth. Now one day this man came to me and said: “I have made up my mind to be operated on for my squint.” I was not in a position to do more than say, “If I were you, I should not have it done.” I did all I could to dissuade him. I did not at that time see the whole situation as clearly as I do today, for what I am telling you happened more than 20 years ago. But I was greatly concerned about this operation. Well, he did not follow my advice and the operation took place. Now note what happened. Very soon after the operation, which was extremely successful, as such operations often are, he came to me in jubilant mood and said, “Now I shall not squint any more.” He was just a little vain, as many distinguished people often are. But I was very troubled; and only a few days later the man died, having just completed his 30th year. The doctors diagnosed typhoid, but it was not typhoid, he died of meningitis.

There is no need for the spiritual investigator to become heartless when he considers such a life; on the contrary his human sympathy is deepened thereby. But at the same time he sees through life and comprehends it in its manifold aspects and relationships. He perceives that what was experienced spiritually between death and a new birth cannot be brought down into the present life and that this comes to expression in physical defects. Unless the right kind of education can intervene, which was not possible in this case, life cannot be extended beyond certain definite limits. Please do not believe that I am asserting that anybody who squints must die at 30. Negative instances are never intended and it may well be that something else enters karmically into life which enables the person in question to live to a ripe old age. But in the case we are considering there was cause for anxiety because of the demands made on the head, which resulted in squinting and stuttering, and the question arose: How can a man with an organisation of this kind live beyond the 35th year? It is at this point of time that one must look back on a person's karma, and then you will see immediately that it in no way followed that because somebody had a squint he must die at 30. For if we take a man who has so prepared himself in pre-earthly life that he has been able to absorb a great deal between death and a new birth, but is unable to bring down what he has received into physical life, and if we consider every aspect of his karma, we find that this particular personality might quite well have lived beyond the 35th year; but then, besides all other conditions, he would have had to bear within him the impulse leading to a spiritual conception of man and of the world. For this man had a natural disposition for spiritual things which one rarely meets; but in spite of this, because strong spiritual impulses inherent in him from previous earth lives were too one-sided, he could not approach the spiritual.

I assure you that I am in a position to speak about such a matter. I was very friendly with this man and was therefore well aware of the deep cleft that existed between my own conception of the world and his. From the intellectual standpoint we could understand one another very well; we could be on excellent terms in other ways, but it was not possible to speak to him about the things of the spirit. Thus because with his 35th year it would have been necessary for him to find his way to a spiritual life, if his potential gifts up to this age were to be realised on earth, and because he was not able to come to a spiritual life, he died when he did. It is of course perfectly possible to stutter and have a squint and yet continue one's life as an ordinary mortal. There is no need to be afraid of things which must be stated at times if one wishes to describe realities, and not waste one's breath in mere phrases. Moreover from this example you can see how observation, sharpened by spiritual insight, enables one to look deeply into human life.

And now let us return to Schiller. When we consider the life of Schiller two things strike us above all others, for they are quite remarkable. There exists an unfinished drama by Schiller, a mere sketch, called the Malteser. We see from the concept underlying this sketch that if Schiller had wished to complete this drama, he could only have done so as an initiate, as one who had experienced initiation. It could not have been done otherwise. Up to a certain degree at least he possessed the inner qualities necessary for initiation, but owing to other conditions of his karma these qualities could not get through; they were suppressed, cramped. There was a cramping of his soul life too which can be seen in the sketch of the Malteser. There are long powerful sentences which never manage to get to the full stop. What is in him cannot find its way out. Now it is interesting to observe that with Goethe, too, we have such unfinished sketches, but we see that in his case, whenever he left something unfinished, he did so because he was too easy-going to carry it further. He could have finished it. Only in extreme old age, when a certain condition of sclerosis had set in would this have been impossible for him. With Schiller however we have another picture. An iron will is present in him when he makes the effort to develop the Malteser but he cannot do it. He only gets as far as a slight sketch. For this drama, seen in its reality, contains what, since the time of the Crusades, has been preserved in the way of all kinds of occultism, mysticism, and initiation science. And Schiller sets to work on such a drama, for the completion of which he would have had to bear within him the experience of initiation. Truly a life's destiny which is deeply moving for one who is able to see behind these things and look into the real being of this man. And from the time it became known that Schiller had in mind to write a drama such as the Malteser there was a tremendous increase in the opposition to him in Germany. He was feared. People were afraid that in his drama he might betray all kinds of occult secrets.

The second work about which I wish to speak is the following. Schiller is unable to finish the Malteser; he cannot get on with it. He lets some time go by and writes all manner of things which are certainly worthy of admiration, but which can also be admired by so-called philistines. If he could have completed the Malteser, it would have been a drama calling for the attention of men with the most powerful and vigorous minds. But he had to put it aside.

After a while he gets a new impulse which inspires his later work. He cannot think any more about the Malteser, but he begins to compose his Demetrius. This portrays a remarkable problem of destiny, the story of the false Demetrius who takes the place of another man. All the conflicting destinies which enter into the story as though emerging out of the most hidden causes, all the human emotions thereby aroused, would have had to be brought into this drama, if it were to be completed. Schiller sets to work on it with feverish activity. It became generally known—and people were still more afraid that things would be brought into the open which it was to their interest to keep hidden from the rest of mankind for some time yet.

And now certain things take place in the life of Schiller which, for anyone who understands them, cannot be accounted for on the grounds of a normal illness. We have a remarkable picture of this illness of Schiller's. Something tremendous happens—tremendous not only in regard to its greatness, but in regard to its shattering force. Schiller is taken ill while writing his Demetrius. On his sick bed in raging fever he continually repeats almost the whole of Demetrius. It seems as though some alien power is at work in Schiller, expressing itself through his body. There is of course no ground for accusing anyone. But, in spite of everything that has been written in this connection, one cannot do otherwise than come to the conclusion, from the whole picture of the illness, that in some way or another, even if in a quite occult way, something contributed to the rapid termination of Schiller's illness in his death. That people had some suspicion of this may be gathered from the fact that

Goethe, who could do nothing, but suspected much, dared not participate personally in any way during the last days of Schiller's life, not even after his death, although he felt this deeply. He dared not venture to make known the thoughts he bore within him.

With these remarks I only want to point out that for anyone able to see through such things Schiller was undoubtedly pre-destined to create works of a high spiritual order, but on account of inner and outer causes, inner and outer karmic reasons, it was all held back, dammed up, as it were, within him. I venture to say that for the spiritual investigator there is nothing of greater interest than to set himself the problem of studying what Schiller achieved in the last ten years of his life, from the Aesthetic Letters onwards, and then to follow the course of his life after death. A deep penetration into Schiller's soul after death reveals manifold inspirations coming to him from the spiritual world. Here we have the reason why Schiller had to die in his middle forties. His condition of cramp and his whole build, especially the ugly formation of his head, made it impossible for him to bring down into the physical body the content of his soul and spirit, deeply rooted as this was in spiritual existence.

When we bear such things in mind we must admit that the study of human life is deepened if we make use of what anthroposophy can give. We learn to look right into human life. In bringing these examples before you my sole purpose was to show how through anthroposophy one learns to contemplate the life of human beings. But let us now look at the matter as a whole. Can we not deepen our feeling and understanding for everything that is human simply by looking at a single human life in the way that we have done? If at a certain definite moment of life one can say to oneself: Thus it was with Schiller, thus with Goethe; thus it was with another young man—as I have told you—then, will not something be stirred in our souls which will teach us to look upon every child in a deeper way? Will not every human life become a sacred riddle to us? Shall we not learn to contemplate every human life, every human being, with much greater, much more inward attention? And can we not, just because a knowledge of man has been inscribed in this way into our souls, deepen within us a love of mankind? Can we not with this human love, deepened by a study of man which gives such profundity to the most inward, sacred riddle of life—can we not, with this love, enter rightly upon the task of education when life itself has become so sacred to us? Will not the teacher's task be transformed from mere ideological phrases or dream-like mysticism into a truly priestly calling ready for its task when Divine Grace sends human beings down into earthly life?

Everything depends on the development of such feelings. The essential thing about anthroposophy is not mere theoretical teaching, so that we know that man consists of physical body, etheric body, astral body and ego; that there is a law of karma, of reincarnation and so on. People can be very clever, they can know everything; but they are not anthroposophists in the true sense of the word when they only know these things in an ordinary way, as they might know the content of a cookery book. What matters is that the life of human souls is quickened and deepened by the anthroposophical world conception and that one then learns to work and act out of a soul-life thus deepened and quickened.

This then is the first task to be undertaken in furthering an education based on anthroposophy. From the outset one should work in such a way that teachers and educators may become in the deepest sense “knowers of men,” so that out of their own conviction, as a result of observing human beings in the right way, they approach the child with the love born out of this kind of thinking. It follows therefore that in a training course for teachers wishing to work in an anthroposophical sense the first approach is not to say: you should do it like this or like that, you should employ this or that educational knack, but the first thing is to awaken a true educational sense born out of a knowledge of man. If one has been successful in bringing this to the point of awakening in the teacher a real love of education then one can say that he is now ready to begin his work as an educator.

In education based on a knowledge of man, such for instance as the Waldorf School education, the first thing to be considered is not the imparting of rules, not the giving advice as to how one should educate, but the first thing is to hold Training Courses for Teachers in such a way that one finds the hearts of the teachers and so deepens these hearts that love for the child grows out of them. It is quite natural that every teacher believes that he can, as it were, impose this love on himself, but such an imposed human love can achieve nothing. Much good will may be behind it, but it can achieve nothing. The only human love which can achieve something is that which arises out of a deepened observation of individual cases.

If someone really wishes to develop an understanding of the essential principles of education based on a knowledge of man—whether he has already acquired a knowledge of spiritual science or whether, as can also happen, he has an instinctive understanding of these things—he will observe the child in such a way that he is faced with this question: What is the main trend of a child's development up to the time of the change of teeth? An intimate study of man will show that up to the change of teeth the child is a completely different being from what he becomes later on. A tremendous inner transformation takes place at this time, and there is another tremendous transformation at puberty. Just think what the change of teeth signifies for the growing child. It is only the outer sign for deep changes which are taking place in the whole human being, changes which occur only once, for only once do we get our second teeth, not every seven years. With the change of teeth the formative process taking place in the teeth comes to an end. From now on we have to keep our teeth for the rest of our lives. The most we can do is to have them stopped, or replaced by false ones, for we get no others out of our organism. Why is this? It is because with the change of teeth the organisation of the head is brought to a certain conclusion. If we are aware of this, if in each single case we ask ourselves: What actually is it that is brought to a conclusion with the change of teeth?—we are led, just at this point, to a comprehension of the whole human organisation, body, soul and spirit. And if—with our gaze deepened by a love gained through a knowledge of man such as I have described—we observe the child up to the change of teeth, we shall see that during these years he learns to walk, to speak and to think. These are the three most outstanding faculties to be developed up to the change of teeth.

Walking entails more than just learning to walk. Walking is only one manifestation of what is actually taking place, for it involves learning to adapt oneself to the world through acquiring a sense of balance. Walking is only the crudest expression of this process. Before learning to walk the child is not exposed to the necessity of finding his equilibrium in the world: now he learns to do this. How does it come about? It comes about through the fact that man is born with a head which requires a quite definite position in regard to the forces of balance. The secret of the human head is shown very clearly in the physical body. You must bear in mind that an average human brain weighs between 1,200 and 1,500 grammes. Now if such a weight as this were to press on the delicate veins which lie at the base of the brain they would be crushed immediately. This is prevented by the fact that this heavy brain floats in the cerebral fluid that fills our head. You will doubtless remember from your studies in physics that when a body floats in a fluid it loses as much of its weight as the weight of the fluid it displaces. If you apply this to the brain you will discover that our brain presses on its base with a weight of about 20 grammes only; the rest of the weight is lost in the cerebral fluid. Thus at birth man's brain has to be so placed that its weight can be brought into proper proportion in regard to the displaced cerebral fluid. This adjustment is made when we raise ourselves from the crawling to the upright posture. The position of the head must now be brought into relationship with the rest of the organism. Walking and using the hands make it necessary for the head to be brought into a definite position. Man's sense of balance proceeds from the head.

Let us go further. At birth man's head is relatively highly organised, for up to a point it is already formed in the embryo, although it is not fully developed until the change of teeth. What however is first established during the time up to the change of teeth, what then receives its special outer organisation, is the rhythmic system of man. If people would only observe physical physiological processes more closely they would see how important the establishing of the circulatory and breathing systems is for the first seven years. They would recognise how here above all great damage can be done if the bodily life of the child does not develop in the right way. One must therefore reckon with the fact that in these first years of life something is at work which is only now establishing its own laws in the circulatory and breathing systems. The child feels unconsciously how his life forces are working in his circulation and breathing. And just as a physical organ, the brain, must bring about a state of balance, so must the soul in the first years of life play its part in the development of the breathing and circulatory systems. The physical body must be active in bringing about a state of balance proceeding from the head. The soul, in that it is rightly organised for this purpose, must be active in the changes that take place in the circulation and breathing. And just as the upright carriage and learning to use the hands and arms are connected with what comes to expression in the brain, so the way in which speech develops in man is connected with the systems of circulation and breathing. Through learning to speak man establishes a relationship with his circulation and breathing, just as he establishes a relationship between walking and grasping and the forces of the head by learning to hold the latter in such a way that the brain loses the right amount of weight. If you train yourself to perceive these relationships and then you meet someone with a clear, high-pitched voice particularly well-suited to the recitation of hymns or odes, or even to declamatory moral harangues, you may be sure that this is connected with special conditions of the circulatory system. Or again if you meet someone with a rough, harsh voice, with a voice like the beating together of sheets of brass and tin, you may be sure that this too is connected with the breathing or circulatory systems. But there is more to it than this. When one learns to listen to a child's voice, whether it be harmonious and pleasant, or harsh and discordant, and when one knows that this is connected with movements of the lungs and the circulation of the blood, movements inwardly vibrating through the whole man, right into the fingers and toes, then one knows that what is expressed through speech is imbued with qualities of soul. And now something in the nature of a higher man, so to say, makes its appearance, something which finds its expression in this picture relating speech with the physical processes of circulation and breathing. Taking our start from this point it is possible to look up and see into the pre-natal life of man which is subject to those conditions which we have made our own between death and a new birth. What a man has experienced in pre-earthly conditions plays in here, and so we learn that if we are to comprehend the being of man by means of true human understanding and knowledge we must train our ear to a spiritual hearing and listen to the voices of children. We can then know how to help a child whose strident voice betrays the fact that there is some kind of obstruction in his karma and we can do something to free him from such karmic hindrances.

From all this we can see what is necessary for education. It is nothing less than a knowledge of man; not merely the sort of knowledge that says: “This is a gifted personality, this is a good fellow, this is a bad one,” but the kind of knowledge that follows up what lies in the human being, follows up for instance what is spiritually present in speech and traces this right down into the physical body, so that one is not faced with an abstract spirituality but with a spirituality which comes to expression in the physical image of man. Then, as a teacher, you can set to work in such a way that you take into consideration both spirit and body and are thus able to help the physical provide a right foundation for the spirit. And further, if you observe a child from behind and see that he has short legs, so that the upper part of the body is too heavy a burden and his tread is consequently also heavy, you will know, if you have acquired the right way of looking at these things, that here the former earthly life is speaking, here karma is speaking. Or, for instance if you observe someone who walks in the same way as the German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte, who always walked with his heels well down first, and even when he spoke did so in such a way that the words came out, as it were “heels first,” then you will see in such a man another expression of karma.

In this way we learn to recognise karma in the child through observation based on spiritual science. This is something of the greatest importance which we must look into and understand. Our one and only help as teachers is that we learn to observe human beings, to observe the bodies of the children, the souls of the children and the spirits of the children. In this way a knowledge of man must make itself felt in the sphere of education, but it must be a knowledge which is deepened in soul and spirit.

With this lecture I wanted to call up a picture, to give an idea of what we are trying to achieve in education, and what can arise in the way of practical educational results from what many people consider to be highly unpractical, what they look upon as being merely fantastic day-dreaming.

Zweiter Vortrag

Über die Befruchtung der pädagogischen Kunst durch Menschenerkenntnis möchte ich in diesem Kursus zunächst sprechen, und so möchte ich die Sache gestalten — ich habe es gestern im einleitenden Vortrage schon angedeutet -, daß ich zunächst zeigen möchte, wie Anthroposophie praktisch werden kann in wirklicher Menschenerkenntnis, jetzt nicht etwa bloß in der Erkenntnis des Kindes, sondern in der Erkenntnis des ganzen Menschen; wie Anthroposophie dann gerade dadurch, daß sie den ganzen Menschen, das heißt das ganze menschliche Leben von der Geburt bis zum Tode, insofern es sich auf der Erde abspielt, kennenlernt, wie sie gerade dadurch auch in richtiger Art auf jene Notwendigkeiten hinweisen kann, die für die Erziehung und den Unterricht des Kindes bestehen.

Man denkt ja sehr leicht, daß man das Kind unterrichten und erziehen könne, wenn man nur dasjenige Leben zunächst beobachtet, das im kindlichen oder jugendlichen Alter abläuft. Aber das genügt nicht. Sondern geradeso wie bei der Pflanze, wenn Sie dem Keim irgendwie eine Substanz einpflanzen, dies sich in der Blütenbildung oder in der Frucht zeigt, so ist es auch im menschlichen Leben. Was in frühester Kindheit dem menschlichen Leben eingepflanzt wird, aus dem kindlichen Leben herausgeholt wird, das zeigt sich zuweilen im spätesten Lebensalter erst; und man weiß oftmals nicht, wenn der Mensch fünfzigjährig irgendwie in Krankheit, in Bresthaftigkeit verfällt, daß dies seine Ursache hat in einer falschen Erziehung oder in einem falschen Unterricht im 7., 8. Lebensjahr. Man geht ja heute so vor, daß man das Kind studiert - wenn auch nicht in so äußerlicher Weise, wie es gestern gesagt worden ist —, um das herauszufinden, was man um das Kind herum helfend macht. Das genügt nicht. Und so möchte ich heute Grundlagen schaffen, um darauf hinzuweisen, wie das ganze menschliche Leben geisteswissenschaftlich beobachtet werden kann.

Der Mensch solle beobachtet werden nach Leib, Seele und Geist, sagte ich schon gestern. Und in dem öffentlichen Vortrage deutete ich gestern an, wie erst das erste Übersinnliche im Menschen, ein höherer Mensch im Menschen, das Dauernde ist, das von der Geburt bis zum Tode geht, während der äußere physische Leib fortwährend ausgewechselt wird. Nun handelt es sich eben darum, dieses menschliche Leben auch so kennenzulernen, daß man sieht: auf der Erde spielt sich das ab, was sich aus dem vorirdischen Leben heraus entwickelt. Wir haben ja in uns nicht bloß dasjenige Seelische, das mit der Geburt oder mit der Empfängnis begonnen hat, wir tragen in uns das vorirdische Seelische, ja, wir tragen in uns die Ergebnisse längst verlaufener Erdenleben. Das alles wirkt und lebt und webt in uns, und wir müssen während des irdischen Lebens das vorbereiten, was dann durch die Pforte des Todes geht und nach dem Tode wieder draußen leben wird in der geistig-seelischen Welt. Wir müssen also begreifen, wie in dem irdischen Leben das Überirdische arbeitet. Denn das ist ja zwischen Geburt und Tod doch auch vorhanden; es arbeitet nur verborgen in dem Leiblichen drinnen, und man versteht das Leibliche nicht, wenn man nicht das im Leiblichen wirkende Geistige versteht.

Gehen wir nun einmal davon aus, das, was ich jetzt angedeutet habe, an konkreten Beispielen zu studieren: Menschenkenntnis, wie sie sich ergibt aus der Betrachtungsart, die in der anthroposophischen Literatur niedergelegt ist, wie zum Beispiel in meinem Buche «Theosophie», in der «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß» oder in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?». Gehen wir aus von dem, was man für eine wirkliche, konkrete Menschenerkenntnis gewinnen kann, wenn man das zugrunde legt, was eben Anthroposophie im allgemeinen über den Menschen und die Welt erkennen läßt. — Zwei Beispiele möchte ich da einmal voranstellen, die auch hier jedem wohlbekannt sein werden. Ich stelle sie aus dem Grunde voraus, weil für mich das Studium dieser zwei Persönlichkeiten, von denen ich ausgehen will, durch viele Jahre hindurch eine eingehende Beschäftigung gebildet hat. Ich nehme zwei geniale Persönlichkeiten; wir werden dann zu weniger genialen heruntersteigen. Wir werden daran sehen, wie Anthroposophie nicht nur im allgemeinen abstrakt herumredet, sondern imstande ist, auf konkrete Menschenwesen einzugehen und sie kennenzulernen, so daß Menschenerkenntnis sich zeigt als etwas, was wirklich im praktischen Leben drinnensteht. Ich wähle die beiden Beispiele: Goethe, Schiller, und möchte auf dem Umwege durch Goethe und Schiller zeigen, wie sich unter dem Einfluß von Geisteswissenschaft Menschenerkenntnis ergibt.

Betrachten wir einmal Goethe und Schiller äußerlich, ihrem Lebenslaufe nach, aber gehen wir auf die ganze Persönlichkeit aus. Wir haben Goethe in merkwürdiger Weise ins Leben hereintretend: er wurde ganz schwarz geboren, das heißt dunkelblau. Also er zeigte zunächst, daß er mit seinem Geistig-Seelischen außerordentlich schwer untertauchen konnte in das Physisch-Leibliche. Aber wiederum, als Goethe einmal untergetaucht war, als er dieses spröde physisch-leibliche Material in Anspruch genommen hatte, da war er auch ganz drinnen. Man kann sich eigentlich auf der einen Seite kaum eine gesündere Natur denken als die des Goethe-Knaben. Goethe ist unglaublich gesund. Er ist so gesund, daß seine Erzieher schon mit ihm einige Schwierigkeiten haben. Denn Kinder, mit denen man keine Schwierigkeiten hat, die sind in der Regel nicht die allergesündesten im späteren Alter. Kinder dagegen, die den Erziehern etwas unbequem werden, das sind die, welche dann später im Leben die mehr brauchbaren, weil die energischeren Naturen sind. Daher wird der verständige Erzieher es schon ganz gern haben, wenn ihm die Kinder auch etwas auf die Finger schauen. Und Goethe war von frühester Kindheit an durchaus geneigt, seinen Erziehern auf die Finger zu schauen, sogar bis zur Wörtlichkeit hin: er guckte beim Klavierspiel die Finger des Spielers ab und nannte dann den einen Finger den «Däumerling», den andern «Deuterling» und so weiter. Aber nicht nur in diesem äußerlichen Sinne schaute er seinen Erziehern auf die Finger, sondern er war eigentlich schon «hell» als Knabe, und die Erzieher hatten es daher manchmal schwierig. Später hat er ja in Leipzig eine schwere Krankheit durchgemacht. Aber mit Bezug darauf muß man sagen, es war dazu schon einiges von Strapazen, man kann auch sagen von kleinen Lumpereien notwendig, um die Gesundheit, die Goethe in sich trug, bis zu dem Grade ins Kranke hinüberzugestalten, wie dies gerade damals in Leipzig der Fall war. Dann aber sehen wir wieder, wie Goethe stramm sein ganzes Leben hindurch ein gesunder, aber ein außerordentlich sensitiver Mensch ist, wie er alles einzelne, was da ist, intensiv auf sich wirken lassen kann, wie es aber nicht sehr tief in den Organismus heruntergreift; er wird nicht gleich herzkrank, wenn er ein erschütterndes Ereignis verspürt, aber er verspürt dieses erschütternde Ereignis mit aller denkbaren Seelenschärfe. Und so sein ganzes Leben hindurch. Er leidet seelisch, ohne daß das seelische Leid ihn gleich in eine äußere Krankheit bringt. Das heißt, seine äußere Gesundheit ist außerordentlich fest.

Dann weiter, Goethe muß schon geradezu herausfordern, eine Betrachtungsweise anzuwenden, die nicht gleich ins Mystische geistig verschwimmt, weil man immer nur sagt: Ach, es kommt nicht darauf an, die äußere physische Gestalt ins Auge zu fassen; das ist niedrig, man muß das Geistige ins Auge fassen! — Sondern bei einem so gesunden Menschen wie Goethe, ist das Geistige und das Physische eines; das Geistige wirkt durch das Physische. Und nur der erkennt eine solche Persönlichkeit, der imstande ist, das Geistige durch das Bild des Physischen hindurch zu schauen.

Goethe war eine sogenannte Sitzgröße. Wenn er saß, kam er einem groß vor; wenn er stand, sah man, daß er kurze Beine hatte, Das ist etwas Eigentümliches, was für den, der nun den Menschen nach seiner Einheitlichkeit beobachten kann, besonders wichtig ist. Warum hatte Goethe kurze Beine? Die kurzen Beine bedingen einen besonderen Gang; er ging in kurzen Schritten, die, weil der Oberkörper schwer war-er war schwer und lang-, allerdings fest auf die Erde gesetzt wurden. Wir müssen das beobachten, damit wir es als Erzieher bei Kindern gut studieren können. — Was heißt das, es hat ein Mensch kurze Beine und einen übergroßen Oberkörper? Das heißt: Wir haben bei einem solchen Menschen in der äußeren Erscheinung gegeben, daß er das, was er in einem vorigen Erdenleben durchlebt hat, auf eine harmonische Weise karmisch in dem gegenwärtigen Erdenleben, das heißt in dem, von dem man spricht, zur Darstellung bringen kann.

Goethe war auch in dieser Beziehung außerordentlich harmonisch, daß er alles, was in seinem Karma lag, ausgestalten konnte bis ins höchste Lebensalter hin. Er wurde ja so alt, weil er alles, was in ihm karmisch veranlagt war, wirklich herausbringen konnte. Man hat bei Goethe, der, nachdem er den Leib verlassen hatte, eben diesem Leibe nach noch so wunderschön war, daß ihn alle im Tode bewunderten, man hat bei ihm den Eindruck: Da hat sich eigentlich alles ausgelebt, was karmisch veranlagt war; da ist eigentlich nichts geblieben, und Goethe muß neu anfangen, wenn er wieder in einem Erdenleben erscheint, unter ganz neuen Bedingungen. Das alles drückt sich gerade in einem so gestalteten Körper aus, wie ihn Goethe hatte. Denn das, was der Mensch aus einem vorigen Erdenleben veranlagt hat, kommt zunächst als Ursache in der Kopfbildung zum Vorschein. Nun hatte Goethe von Jugend auf diesen wunderschönen Apollo-Kopf, der nur die harmonischen Kräfte in die Körperlichkeit hineingoß. Er hatte aber diesen von der Last des Oberleibes beeindruckten Körper mit den zu kurzen Beinen, so daß er diesen Gang wieder hatte, der in seinem ganzen Lebenswandel zum Vorschein kommen konnte. Dieser ganze Mensch war karmische Voraussetzung und karmische Erfüllung im wunderbar Harmonischen. Alles einzelne, was man im Goethe-Leben hat, spricht ja das aus.

Bei einem solchen Menschen, der so harmonisch im Leben drinnensteht und so alt wird, muß ja nun die Mitte des Erdenlebens ganz besonders hervorragende Erlebnisse aufweisen. Goethe ist 1749 geboren, 1832 gestorben; er ist also etwa 83 Jahre alt geworden. Wir haben also sein mittleres Lebensalter etwa im 41. Jahre, das heißt um das Jahr 1790. Nehmen Sie nun die Zeit von 1790 bis 1800, so ist dies das mittelste Jahrzehnt, das Goethe erlebt hat. In diesem Jahrzehnt, vor 1800, hat Goethe tatsächlich die wichtigsten Lebensereignisse durchgemacht. Vorher konnte er in den wichtigen Lebens- und wissenschaftlichen Anschauungen nicht irgendwie zu einem Abschluß kommen. Die «Metamorphose der Pflanzen» wird 1790 erst veröffentlicht; alles was sich daran anschließt, schließt sich in diesem Jahrzehnt, von 1790 bis 1800, daran an. Goethe war 1790 mit seinem «Faust» so wenig fertig, daß er ihn als Fragment herausgab; er glaubte überhaupt nicht, mit ihm fertigzuwerden. In diesem Jahrzehnt faßt er unter dem Einfluß von Schillers Freundschaft die kühne Idee, diesen «Faust» weiterzuführen. Die großen Szenen, der Prolog im Himmel und so weiter kommen hier zum Ausdruck. — Also wir haben es bei ihm zu tun mit einem außerordentlich harmonischen Leben, und mit einem Leben, das in Ruhe verläuft, das durch nichts gestört wird von innen heraus, sondern das sich frei und sinnig der Außenwelt hingeben kann.

Betrachten wir dagegen Schillers Leben. Schiller wird von vornherein in einen Lebenszusammenhang hineingestellt, der eine fortwährende Disharmonie zeigt zwischen seinem Seelisch-Geistigen und seinem Körperlich-Physischen. Schiller hat durchaus nicht die harmonische Kopfbildung wie Goethe. Er ist eigentlich häßlich, nur geistvoll häßlich, aber doch eigentlich häßlich. Aber es liegt eine starke, persönlichkraftvolle Haltung auch in seiner Physiognomie, was ja insbesondere in der Nasenbildung zum Ausdruck kommt. Schiller ist nicht eine Sitzgröße, sondern er hat lange Beine. Alles dagegen, was zwischen Kopf und Gliedmaßen liegt, worin die Ursachen der Zirkulation und der Atmung liegen, ist bei ihm wirklich krank, kümmerlich von Anfang an ausgebildet, und er leidet sein ganzes Leben hindurch, zuerst mit größeren Pausen, dann aber fast unaufhörlich an Krämpfen. Diese Krämpfe werden später so stark, daß er sich nicht zu irgendeiner Mahlzeit einladen lassen kann, sondern daß er, als er zum Beispiel einmal nach Berlin kommt, sich ausbedingt, man solle ihn für den ganzen Tag einladen, so daß er sich die Zeit aussuchen könne, in der er dann frei von Krämpfen sei. Das alles rührt her von einem mangelhaft ausgebildeten Zirkulations- und Atmungsgebiet.

Da entsteht die Frage: Was liegt karmisch bei einem Menschen aus früheren Erdenleben her vor, der in dieser Weise an Krämpfen leiden muß? - Krämpfe sind, wenn sie ins menschliche Leben eingreifen, ungemein stark hinweisend auf das menschliche Karma. Wenn man vom geisteswissenschaftlichen Standpunkte aus mit ernster,verantwortlicher wissenschaftlicher Untersuchung an Krampferscheinungen herangeht, so findet man immer, da liegt beim Menschen ein bestimmtes Karma vor, Ergebnisse von Taten, Gedanken und Gefühlen früherer Erdenleben. Jetzt hat man den Menschen im gegenwärtigen Leben vor sich. Nun kann zweierlei eintreten. Entweder es geht so harmonisch zu wie bei Goethe, daß man sich sagt: Da ist das Karma, da kommt alles zum Vorschein, was karmisches Ergebnis ist. — Es kann aber auch das andere eintreten, es kann der Mensch durch besondere Bedingungen, die sich für ihn beim Herabsteigen aus der geistigen Welt in die physische ergeben, in die Lage kommen, daß er das, was karmisch auf ihm lastet, nicht immer ganz ausleben kann. Der Mensch kommt aus der geistigen Welt mit bestimmten karmischen Voraussetzungen herunter; er trägt sie in sich. Nehmen wir an, bei A wäre für einen Menschen eine Stelle, wo er in einem bestimmten Zeitpunkte seines Lebens sein Karma irgendwie verwirklichen sollte; aber durch irgend etwas geht es nicht. Dann setzt er sozusagen mit Bezug auf die Verwirklichung seines Karma aus, und es muß eine kürzere Zeit verfließen, wo sein Karma aussetzt; er muß dies dann für das nächste Erdenleben verschieben. Dann geht es so weiter. Wieder kommt eine Stelle, bei B, wo er etwas von seinem Karma verwirklichen sollte; aber er muß wiederum aussetzen, muß wiederum etwas von seinem Karma auf das nächste Erdenleben verschieben. Immer nun, wenn man nötig hat, so sein Karma auszusetzen, entstehen krampfartige Erscheinungen im Leben. Man kann etwas, was man im Inneren trägt, nicht ganz herausbilden in sein Leben. - Das ist eben die Eigentümlichkeit der Geisteswissenschaft, daß sie nicht im Phantastischen herumschwimmt, nur so im Allgemeinen herumredet, der Mensch habe die vier Wesensglieder: physischer Leib, ätherischer Leib, astralischer Leib und Ich, sondern daß sie eingeht auf das wirkliche Leben und hinweisen kann auf etwas im physischen Leben, wo die wirklichen geistigen Ursachen für irgendwelche äußeren Ereignisse liegen, so daß sie weiß, wie der Mensch im äußeren Leben sich darlebt. Das ist das, was wirkliche Geisteswissenschaft eben können muß.

Es entstand nun für mich die Frage: Wie wirkt Karma in einem solchen Leben wie dem Schillerschen als der Ausgestalter des ganzen Lebens, wenn eben solche Bedingungen vorliegen wie bei ihm, daß das Karma nicht heraus kann, daß er fortwährend Anstrengungen machen muß, um das zu erreichen, was er erreichen will? Goethe hat es im Grunde genommen leicht, seine großen Schöpfungen zu vollbringen; denn die sind das Ergebnis seines Karma. Schiller hat es immer schwer, seine großen Schöpfungen zustande zu bringen; er muß gegen das Karma anstürmen, und die Art, wie er anstürmt, wird sich erst wieder im folgenden Erdenleben ausleben. Da mußte ich mir eines Tages die Frage vorlegen: Wie hängt gerade ein solches Leben, wie das Schillersche, mit den allgemeinen Lebensbedingungen zusammen? — Wenn man leichtfertig an die Beantwortung einer solchen Frage geht, kommt auch bei ernster geisteswissenschaftlicher Untersuchung nichts Besonderes heraus; spintisieren darf man da nicht, man muß beobachten. Aber wenn man gleich an das erste Objekt der Beobachtung herangeht, wird man irgendwie daneben vorbeigehen. Daher legte ich mir die Frage folgendermaßen vor: Wie spielt sich ein Leben ab, wenn Hindernisse für das Karma oder für andere, vorirdische Bedingungen da sind?

Nun studierte ich Menschen daraufhin, wie sich so etwas verwirklicht, und ich will dafür jetzt ein Beispiel anführen. Ich könnte viele solcher Beispiele anführen, will aber jetzt eines nehmen, das ich ganz genau beschreiben kann. Ich hatte einen Bekannten, eine Persönlichkeit, die ich ganz genau ihrem gegenwärtigen Erdenleben nach kannte. Ich konnte konstatieren, wie in seinem Leben Hindernisse nicht vorhanden waren mit Bezug auf die Auslebung des Karma, sondern mit Bezug auf das, was sich abspielt im Dasein zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt, was sich also für diese Persönlichkeit im übersinnlichen Leben abgespielt hat zwischen dem letzten Erdenleben und diesem, in welchem ich sie kennenlernen konnte. Es waren also in diesem Falle nicht so, wie bei Schiller, Hindernisse da für das Ausleben des Karma, sondern Hindernisse für das richtige In-den-Körper-Hineinbringen dessen, was er durchlebt hatte zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt, das heißt in der übersinnlichen Welt. Man sah diesem Menschen an, er hat Bedeutsames erlebt zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt, aber er kann es nicht herausbringen. Er hatte sich hineingestellt in karmische Menschenzusammenhänge, hatte sich hineingestellt in ein Zeitalter, wo das nicht herauskommen kann, was er zwischen Tod und Empfängnis sozusagen angehäuft hatte an innerer Seelenhaftigkeit. Und worin zeigten sich die physischen Begleiterscheinungen für dieses Nicht-herausbringenKönnen des im Menschen vorhandenen Übersinnlichen? Sie zeigten sich darin, daß diese Persönlichkeit ein Stotterer war, daß sie Sprachstörungen hatte. Wenn man nun weitergeht und die seelisch-organischen Ursachen für Sprachstörungen untersucht, dann findet man immer, daß ein Hindernis da ist, das zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt erlebte Übersinnliche in die physische Welt durch die Körperlichkeit herunterzutragen. Nun muß man sich fragen: Was liegt bei einer solchen Persönlichkeit vor, die also sehr viel in sich hat, allerdings auch durch ihr vorheriges Karma, aber - aufgespeichert ist es worden im Dasein zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt — die das Aufgespeicherte nicht herunterbringen kann, und bei der sich dieses Nicht-herunterbringenKönnen im Stottern zeigt? Was sind mit einer solchen Persönlichkeit hier im Leben für Dinge verknüpft?

Man konnte sich immer wieder sagen: Dieser Mann hat in sich allerlei Großes, das er im vorirdischen Leben erworben hat, aber er kann es nicht herunterbringen. — Er konnte gut das herunterbringen, was man herausbringen kann in der Gestaltung des physischen Leibes bis zum Zahnwechsel, konnte sogar außerordentlich gut das aus sich herausbringen, was man dann vom Zahnwechsel bis zur Geschlechtsreife herausbringt; er wurde dann eine ausgezeichnete literarisch-künstlerische Persönlichkeit, indem er dasjenige herausgestaltete, was man herausgestalten kann zwischen der Geschlechtsreife und dem 30. Lebensjahr. Aber nun kam für den, der nun wirkliche Menschenerkenntnis erwerben kann, die große Sorge: Wie soll es mit dieser Persönlichkeit werden, wenn sie nun in die Dreißigerjahre kommt und dann immer mehr und mehr zu der Verstandes- oder Gemütsseele die Bewußtseinsseele herausbilden soll? Wer in dieser Richtung Erkenntnisse hat, bekommt in solchem Falle die größte Sorge, denn er kann sich nicht denken, daß die Bewußtseinsseele, zu deren Ausbildung man alles, was im Kopfe entspringt, vollständig intakt haben muß, voll herauskommen kann. Denn, daß bei dieser Persönlichkeit nicht alles im Kopfe gerade intakt war, das zeigte sich im Stottern. Und dieser Mann war zunächst äußerlich, mit Ausnahme seines Stotterns, kerngesund. Aber daß außer dem Stottern im Kopfe nicht alles intakt war, das zeigte sich darin, daß er außer Stottern noch Schielen hatte - wiederum ein Anzeichen dafür, daß man nicht alles, was man zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt im Überirdischen aufgenommen hat, im gegenwärtigen Erdenleben herausbringen kann. Eines Tages kam nun dieser Mann zu mir und sagte: Ich habe mir vorgenommen, mein Schielen operieren zu lassen. — Ich war nicht befugt, etwas anderes zu sagen als: Ich würde es nicht tun, wenn ich an seiner Stelle wäre. — Ich tat alles, um ihm abzureden. So genau wie heute sah ich damals in die Verhältnisse nicht hinein; denn das, was ich jetzt erzähle, liegt mehr als 20 Jahre zurück. Aber ich hatte große Sorge wegen dieser Operation. Nun, er ließ sich doch operieren, er folgte eben nicht. Und siehe da, schnell nach der Operation, die an sich, wie man es bei Operationen sehr häufig hat, außerordentlich gut verlief, kam er in voller Freude zu mir und sagte: Jetzt werde ich nicht mehr schielen! Ein bißchen eitel war er ja auch, wie manche bedeutende Persönlichkeit. Aber ich hatte meine große Sorge. Und nur nach Tagen starb der Mann, nachdem er das 30. Lebensjahr vollendet hatte. Die Ärzte diagnostizierten Typhus, aber es war gar nichts von Typhus vorhanden, sondern er starb an einer Hirnhautentzündung.

Wer Geistesforscher ist, der braucht, wenn er ein solches Leben betrachtet, gewiß nicht herzlos zu werden; im Gegenteil, die menschliche Anteilnahme wird noch mehr vertieft. Aber man durchschaut auch zugleich das Leben nach seinen großen Zusammenhängen. Man durchschaut, wie das, was von geistig Erlebtem zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt im gegenwärtigen Leben nicht herunterkommen kann, sich in körperlichen Mängeln zum Ausdruck bringt. Wenn nun nicht in der richtigen Weise, wie es ja in diesem Falle nicht sein konnte, eine Erziehung eingreift, kann natürlich ein bestimmter Lebenspunkt gar nicht überschritten werden. Glauben Sie aber nicht, daß ich etwa behaupte: Jeder der schielt, muß im 30. Jahre sterben — negative Instanzen sind nie gemeint, sondern es kann karmisch wieder etwas eintreten, was den Betreffenden bis ins höchste Alter leben läßt. Aber hier war es so, daß durch die Inanspruchnahme des Kopfes diese eigentümliche Organisation, die in Schielen und Stottern zum Ausdruck kam, Sorge machte: Wie kommt diese Organisation über das 35. Lebensjahr hinweg? - Und nun ist da der Zeitpunkt, wo man zurückschauen muß auf das Karma des Menschen und da werden Sie gleich sehen, daß es nicht nötig ist, daß jemand, der schielt, im 30. Jahre stirbt. Denn wenn wir einen Menschen haben, der sich im vorirdischen Leben so vorbereitet hat, daß er sehr viel aufgenommen hat zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt, aber das Aufgenommene nicht herunterbringen kann in das physische Leben, und betrachten wir bei ihm das Karma ganz, so finden wir, daß diese betreffende Persönlichkeit ganz gut hätte nach dem 35. Jahre fortleben können, aber sie hätte dann zu allen andern Bedingungen den Impuls in sich tragen müssen, zu einer spirituellen Lebens- und Weltanschauung zu kommen. Denn dieser Mann war wie selten einer veranlagt für Spirituelles; aber er konnte wiederum, weil die starken geistigen Impulse, die aus früheren Erdenleben da waren, doch einseitige waren, nicht zum Spirituellen kommen.

Sie können versichert sein, daß ich über eine solche Sache reden kann. Ich war mit diesem Manne sehr befreundet und wußte daher, welcher Abgrund zwischen meiner eigenen Weltanschauung und der seinigen bestand. Man konnte sich intellektuell sehr gut mit ihm verständigen, konnte sich auch gemütlich verständigen; aber man konnte nicht etwas an ihn heranbringen, was spirituell ist. Und weil er mit dem 35. Jahre hätte zu einem spirituellen Leben übergehen müssen, wenn das, was bis zum 35. Jahre veranlagt war, auf der Erde hätte möglich sein sollen, er aber zu einem spirituellen Leben nicht kam, so starb er da. Also man kann ganz gut schielen und stottern, und kann doch fortleben, wenn man also als ein gewöhnlicher Erdenmensch fortzuleben vermag. Man darf nicht erschrecken über die Dinge, die schon einmal gesagt werden müssen, wenn man nicht in Phrasen aufgehen, sondern Realitäten schildern will. Aber an diesem Beispiele können Sie sehen, wie einen der geistig geschärfte Blick hineinschauen läßt in das menschliche Leben.

Und jetzt gehen wir zu Schiller zurück. Wenn wir das Schillersche Leben betrachten, so stellen sich vor allen Dingen zwei Erscheinungen in dieses Leben hinein, die ganz merkwürdig sind. Es gibt von Schiller ein unvollendetes, bloß entworfenes Drama, die «Malteser». Man sieht dem Konzept, dem Entwurf, der da ist, an: hätte Schiller diese «Malteser» zur Ausführung bringen wollen, dann hätte er unbedingt dieses Drama nur als Eingeweihter, als Initiierter schreiben können. Es wäre gar nicht anders gegangen. Er trug, wenigstens bis zu einem gewissen Grade, die Bedingungen zur Initiation in sich. Aber was er so in sich trug, das konnte wegen seines andern Karma nicht herauskommen; es verkrampfte sich, verkrampfte sich auch seelisch. Denn dem «Malteser»-Entwurf ist schon das Krampfhafte anzusehen: große, gewaltige Sätze, die überall nicht bis zum Punkt führen. Es kann nicht heraus, was in ihm ist. — Es ist nun interessant, auch bei Goethe haben wir solche Entwürfe; aber man sieht überall, wo Goethe etwas liegen läßt, da ist er zu bequem, er könnte schon weiter. Nur im höchsten Alter, als schon die Sklerose etwas auftrat, konnte er es nicht. Bei Schiller aber haben wir ein anderes Bild: es ist der eiserne Wille vorhanden, als er die «Malteser» entwirft, vorwärtszukommen; aber er kann nicht. Er kommt nur bis zu einem flüchtigen Entwurf. Denn die «Malteser», in Wirklichkeit gesehen, enthalten ja das, was von den Kreuzzügen her bewahrt worden ist an allerlei Okkultem, an Mystischem und an Initiationswissenschaft. Und an ein solches Drama, zu dessen Fertigstellung man die Erlebnisse der Initiation hätte wirklich in sich tragen müssen, geht Schiller heran. Wahrhaftig, ein Lebensschicksal, das den, der die Sache durchschaut, ungemein tief berührt und in die ganze Wesenheit dieses Menschen hineinschauen läßt. Und seit bekanntgeworden war, daß Schiller so etwas im Sinne hatte wie die «Malteser», seit der Zeit vermehrte sich die Gegnerschaft in Deutschland gegen ihn außerordentlich. Man fürchtete sich vor ihm. Man fürchtete, daß er allerlei an okkulten Geheimnissen in seinen Dramen verraten könne.

Die zweite Erscheinung, von der ich sprechen will, ist die folgende. Die «Malteser» bekommt er nicht fertig, kann nicht mit ihnen zurechtkommen. Er läßt Zeit vergehen, dichtet an allerlei Dingen, die gewiß bewundernswert sind, aber die auch schon bewundert werden können vom Philisterium. Die «Malteser», wenn er sie hätte ausführen können, wären etwas geworden für Menschen von höchstem geistigem Schwung! Er muß sie liegen lassen. Nach einiger Zeit tritt in ihm wiederum das auf, was den Impuls zu dem Späteren gegeben hat. An die «Malteser» kann er nicht wieder denken. Aber er beginnt, an seinem «Demetrius» zu dichten: ein merkwürdiges Schicksalsproblem, das vom falschen Demetrius, der an die Stelle eines andern getreten ist. Alle die Schicksalskonflikte, die da eintreten, wie aus den verborgensten Ursachen heraus, mit allen menschlichen Emotionen, mußten in dieses Drama hineinkommen, wenn es fertig würde. Schiller schreibt daran in einer geradezu fieberhaften Art. Es wird bekannt — und noch größere Furcht haben die Menschen davor, daß nun Dinge zum Vorschein kommen könnten, an denen viele ein Interesse hatten, daß sie eine Weile noch der Menschheit verborgen bleiben.

Und nun treten im Leben Schillers Erscheinungen ein, die derjenige, der sich auf solche Dinge versteht, nicht als etwas auch im KrankhaftNormalen allein Begründetes ersehen kann. Man hat ein merkwürdiges Krankheitsbild bei Schiller. Es tritt das Gewaltige ein — gewaltig nicht im Sinne der Größe, sondern im Sinne des Erschütternden: Schiller wird über seinem «Demetrius» krank; er spricht auf seinem Krankenlager fortwährend fast den ganzen «Demetrius» im hochgradigen Fieber heraus. Es wirkt etwas in Schiller wie eine fremde Macht, die sich durch den Körper ausdrückt. Man braucht selbstverständlich niemanden anzuklagen. Aber man kann nicht anders - trotz alledem, was nach dieser Richtung geschrieben worden ist —, als aus dem Krankheitsbilde die Vorstellung zu haben, da ist auf irgendeine, wenn auch ganz. okkulte Weise mitgeholfen worden an dem schnellen Sterben Schillers! Und daß Menschen eine Ahnung haben konnten, daß da mitgeholfen worden ist, das geht daraus hervor, wie Goethe, der nichts machen konnte, aber manches ahnte, in den letzten Tagen gar nicht wagte, den unmittelbar persönlichen Anteil — auch nicht nach dem Tode - zu nehmen, den er an dem wirklichen Hingange Schillers seinem Herzen nach wahrhaftig genommen hat. Er getraute sich nicht herauszugehen mit dem, was er in sich trug.

Damit will ich nur andeuten, wie Schiller für den, der solche Dinge durchschauen kann, ganz zweifellos dazu prädestiniert war, Hochspirituelles aus sich heraus hervorzubringen, daß aber, wie durch innere und äußere Ursachen, karmisch innerlich und karmisch äußerlich die Sache zurückgestaut worden ist. Ich darf schon sagen, für den Geistesforscher bildet nichts ein so großes Interesse, als etwa folgendes Problem sich zu stellen: zu studieren, was Schiller geleistet hat in den letzten 10 Jahren seines Lebens, von den «Ästhetischen Briefen» an, und dann zu verfolgen, wie dieses Leben nach dem Tode abgelaufen ist. Da gibt es, wenn man sich vertieft in diese Seele Schillers nach dem Tode, geistige Inspirationen in Hülle und Fülle aus der geistigen Welt heraus. Da haben wir den Grund, warum Schiller in der Mitte der Vierzigerjahre sterben mußte. Er konnte einfach, wie sich das in seinen Krämpfen und in seiner ganzen Statur zeigte, namentlich aber in der häßlich geformten Kopforganisation zeigte, er konnte mit seinem Seelisch-Geistigen, das tief drinnenstand im spirituellen Dasein, nicht in seine Körperlichkeit hinein.

Wenn wir uns solche Dinge vorhalten, müssen wir uns doch sagen: Das Menschenleben wird schon in seiner Betrachtung vertieft, wenn man das anwendet, was Anthroposophie geben kann. — Man lernt hineinschauen in das Menschenleben. Nichts anderes wollte ich, als Ihnen durch die Beispiele, die ich gebracht habe, anführen, wie man durch die Anthroposophie lernt, das menschliche Leben anzuschauen. Nehmen Sie aber jetzt die ganze Sache. Kann man nicht in seiner Seele vertieft werden für alles, was menschlich ist, dadurch, daß man einfach in einer solchen Weise auf einzelne Menschenleben hinsieht? Wenn sich der Mensch in einem bestimmten Zeitpunkte seines Lebens sagen kann: So stand es um Schiller, so um Goethe, so stand es mit irgendeinem Menschen, der früh verstorben ist, wie ich es Ihnen angeführt habe, — ja, wird das nicht in der Seele des Menschen so wirken können, daß man lernt, jedes Kind auch vertieft anzuschauen? Daß einem jedes Menschenleben ein heiliges Rätsel wird? Lernt man denn nicht mit viel größerer, mit viel innigerer Aufmerksamkeit auf jedes Menschenleben und Menschenwesen hinschauen? Und kann man nicht gerade dadurch, daß auf diese Weise Menschenerkenntnis in die Seele sich einschreibt, Menschenliebe in sich vertiefen? Und kann man denn nicht mit dieser Menschenliebe, die an der Menschenbetrachtung, an der innigen, tiefen Menschenbetrachtung, an dem Miterleben der innerst heiligen Rätsel der Menschenseele sich vertieft, gerade an eine Erzieheraufgabe herantreten, wenn einem das Leben so heilig geworden ist? Wird sich nicht gerade dadurch der Erzieherberuf umwandeln lassen, nicht zum phrasenhaften, mystisch verträumten, wohl aber zum ganz wahrhaften Priesterberuf, der dasteht, wenn die göttliche Gnade die Menschen herunterschickt in das irdische Leben?

Auf die Entwickelung solcher Gefühle kommt es an! Das ist ja nicht das Wesentliche an der Anthroposophie, daß sie theoretisch lehrt: der Mensch besteht aus physischem Leib,Ätherleib, Astralleib und Ich, es gibt ein Karma, es gibt wiederholte Erdenleben und so weiter. Man kann sehr gescheit sein, kann das alles wissen; doch Anthroposoph im wahren Sinne des Wortes ist man dadurch nicht, wenn man diese Dinge auf die gewöhnliche Art, wie den Inhalt eines Kochbuches, weiß. Darauf kommt es an, daß das menschliche Seelenleben ergriffen und vertieft werde durch die anthroposophische Weltanschauung, und daß man dann wirken lernt aus einem solchen ergriffenen und vertieften Seelenleben.

Daher kann die erste Aufgabe, die für die Pädagogik auf der Grundlage der Anthroposophie erfüllt werden kann, diese sein, daß man zunächst darauf hinarbeitet, daß die Lehrer, die Erzieher im tiefsten Sinne Menschenerkenner seien, und daß sie, wenn sie diese Gesinnung nach rechter Menschenbeobachtung in sich aufgenommen haben, mit der Liebe, die aus dieser Gesinnung folgt, an das Kind herantreten. Daher ist das erste, was in einem Seminarkurs für im anthroposophischen Sinne wirken sollende Erzieher vorkommt, nicht, daß man sagt, du sollst es so oder so machen, sollst diesen oder jenen pädagogischen Handgriff anwenden, sondern das erste ist das Erwecken der pädagogischen Gesinnung aus Menschenerkenntnis heraus. Hat man diese pädagogische Gesinnung aus Menschenerkenntnis bis zur rechten Pädagogenliebe, bis zum Erwecken der Pädagogenliebe gebracht, dann kann man sagen, der Lehrer ist reif zum Erziehen, zum Unterrichten. Das erste, um was es sich bei einer auf Menschenerkenntnis begründeten Pädagogik handelt, wie es die Waldorfschul-Pädagogik zum Beispiel ist, das ist nicht, Regeln anzugeben, so oder so solle man erziehen, sondern das erste ist, die Seminarkurse so zu halten, daß man die Herzen der Lehrer findet, daß man diese Herzen so weit vertieft, daß aus ihnen heraus die Liebe zum Kinde erwächst. Die glaubt ja ein jeder natürlich sich andiktieren zu können. Aber diese andiktierte Menschenliebe kann ja nichts leisten; sie könnte vielen guten Willen haben, aber kann nichts leisten. Etwas leisten kann erst diejenige Menschenliebe, die aus einem vertieften Beobachten im Einzelfalle hervorgehen kann.

Wenn man das in sich trägt, das Erziehungswesen auf Menschenerkenntnis bauen zu wollen - sei es, daß man es jetzt durch wirkliche Geisteswissenschaft kennt, oder sei es instinktiv, wie man es auch kennen kann -, dann wird man das Kind daraufhin anschauen, daß man sich fragt: Was entwickelt sich beim Kinde vorzugsweise bis zum Zahnwechsel? — Denn bis zum Zahnwechsel ist das Kind ein ganz anderes Wesen als später, wenn man auf die Intimitäten des Menschen eingeht. Eine gewaltige innere Verwandlung macht das Menschenwesen mit dem Zahnwechsel durch, wieder eine gewaltige innere Verwandlung mit der Geschlechtsreife. Bedenken Sie nur, was der Zahnwechsel für den sich entwickelnden Menschen bedeutet. Der Zahnwechsel als solcher ist janur das äußere Zeichen für tiefe Veränderungen, die im ganzen menschlichen Wesen vor sich gehen, aber Veränderungen, die nur einmal vor sich gehen, denn man bekommt nur einmal zweite Zähne, man bekommt sie nicht alle 7 Jahre. Mit dem Zahnwechsel ist dann die Zahnbildung abgeschlossen. Man muß dann seine Zähne das ganze Leben hindurch behalten, kann sie sich höchstens plombieren lassen oder durch falsche ersetzen, aber man bekommt sie nicht wieder aus dem Organismus heraus. Warum ist das? Das ist deshalb, weil gerade mit dem Zahnwechsel die Kopforganisation einen gewissen Abschluß erlangt. Durchschaut man das, fragt man sich in jedem einzelnen Falle: Was erreicht denn da eigentlich mit dem Zahnwechsel seinen Abschluß? — so wird man, gerade von da ausgehend, dazu geführt, die ganze menschliche Organisation aufzufassen nach Leib, Seele und Geist. Und beobachtet man mit jenem in Liebe vertieften Blick, den man durch solche Menschenerkenntnis bekommt, wie ich es geschildert habe, das Kind bis zum Zahnwechsel hin, so sieht man: Dieses Kind bildet bis zum Zahnwechsel hin das Gehen aus, bildet das Sprechen aus und weiter das Denken. Das sind die drei Fähigkeiten, die bis zum Zahnwechsel als die hervorragendsten ausgebildet werden.