Pastoral Medicine

GA 318

9 September 1924, Dornach

Lecture II

Dear friends,

If we are going to consider the mutual concerns of priest and physician, we should look first at certain phenomena in human life that easily slide over into the pathological field. These phenomena require a physician's understanding, since they reach into profound depths, even into the esoteric realm of religious life. We have to realize that all branches of human knowledge must be liberated from a certain coarse attitude that has come into them in this materialistic epoch. We need only recall how certain phenomena that had been grouped together for some time under the heading “genius and insanity” have recently been given a crass interpretation by Lombroso1 Cesare Lombroso (1836–1909), Italian anthropologist. Wrote Genius and Insanity (1864) and The Criminal: Anthropological, Medical and Legal Aspects (1876). and his school and also by others. I am not pointing to the research itself—that has its uses—but rather to their way of looking at things, to what they brought out as “criminal anthropology,” from studying the skulls of criminals. The opinions they voiced were not only coarse but extraordinarily commonplace. Obviously the philistines all got together and decided what the normal type of human being is. And it was as near as could possibly be to a philistine! And whatever deviated from this type was pathological, genius on one side, insanity on the other; each in its own way was pathological. Since it is quite obvious to anyone with insight that every pathological characteristic also expresses itself bodily, it is also obvious that symptoms can be found in bodily characteristics pointing in one or the other direction. It is a matter of regarding the symptoms in the proper way. Even an earlobe can under certain conditions clearly reveal some psychological peculiarity, because such psychological peculiarities are connected with the karma that works over from earlier incarnations.

The forces that build the physical organism in the first seven years of human life are the same forces by which we think later. So it is important to consider certain phenomena, not in the customary manner but in a really appropriate way. We will not be regarding them as pathological (although they will lead us into aspects of pathology) but rather will be using them to obtain a view of human life itself.

Let us for a moment review the picture of a human being that Anthroposophy gives us. The human being stands before us in a physical body, which has a long evolution behind it, three preparatory stages before it became an earthly body—as is described in my book An Outline of Esoteric Science.2 Rudolf Steiner, An Outline of Esoteric Science (Hudson, N.Y.: Anthroposophic Press, 1985). This earthly body needs to be understood much more than it is by today's anatomy and physiology. For the human physical body as it is today is a true image of the etheric body, which is in its third stage of development, and of the astral body, which is in its second stage, and even to a certain degree of the ego organization that humans first received on earth, which therefore is in its first stage of development. All of this is stamped like the stamp of a seal upon the physical body—which makes the physical body extraordinarily complicated. Only its purely mineral and physical nature can be understood with the methods of knowledge that are brought to it today. What the etheric body impresses upon it is not to be reached at all by those methods. It has to be observed with the eye of a sculptor so that one obtains pictorial images of cosmic forces, images that can then be recognized again in the form of the entire human being and in the forms of the single organs.

The physical human being is also an image of the breathing and blood circulation. But the entire dynamic activity that works and weaves through the blood circulation and breathing system can only be understood if one thinks of it in musical forms. For instance, there is a musical character to the formative forces that were poured into the skeletal system and then became active in a finer capacity in the breathing and circulation. We can perceive in eurythmy how the octave goes out from the shoulder blade and proceeds along the bones of the arm. This bone formation of the arm cannot be understood from a mechanical view of dynamics, but only from musical insight. We find the interval of the prime extending from the shoulder blade to the bone of the upper arm, the humerus, the interval of the second in the humerus, the third from the elbow to the wrist. We find two bones there because there are two thirds in music, a larger and a smaller. And so on. In short, if we want to find the impression of the astral body upon the physical body, upon the breathing and blood circulation, we are obliged to bring a musical understanding to it.

Still more difficult to understand is the ego organization. For this one needs to grasp the meaning of the first verse of the Gospel of St. John: “In the beginning was the Word.” “The Word” is meant there to be understood in a concrete sense, not abstractly, as commentators of the Gospels usually present it. If this is applied concretely to the real human being, it provides an explanation of how the ego organization penetrates the human physical body. You can see that we ought to add much more to our studies if they are to lead to a true understanding of the human being. However, I am convinced that a tremendous amount of material could be eliminated not only from medical courses but from theological courses too. If one would only assemble the really essential material, the number of years medical students, for instance, must spend in their course would not be lengthened but shortened. Naturally it is thought in materialistic fashion today that if there's something new to be included, you must tack another half-year onto the course!

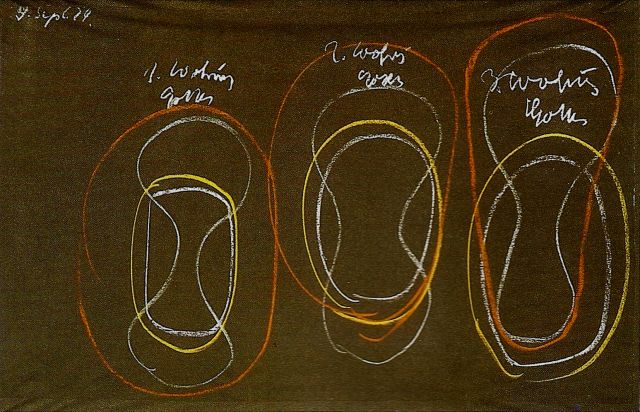

Out of the knowledge that Anthroposophy gives us, we can say that the human being stands before us in physical, etheric and astral bodies, and an ego organization. In waking life these four members of the human organization are in close connection. In sleep the physical body and etheric body are together on one side, and the ego organization and astral body on the other side. With knowledge of this fact we are then able to say that the greatest variety of irregularities can appear in the connection of ego organization and astral body with etheric body and physical body. For instance, we can have: physical body, etheric body, astral body, ego organization. (Plate I, 1) Then, in the waking state, the so-called normal relation prevails among these four members of the human organization.

But it can also happen that the physical body and etheric body are in some kind of normal connection and that the astral body sits within them comparatively normally, but that the ego organization is somehow not properly sitting within the astral body. (Plate I, 2) Then we have an irregularity that in the first place confronts us in the waking condition. Such people are unable to come with their ego organization properly into their astral body; therefore their feeling life is very much disturbed. They can even form quite lively thoughts. For thoughts depend, in the main, upon a normal connection of the astral body with the other bodies. But whether the sense impressions will be grasped appropriately by the thoughts depends upon whether the ego organization is united with the other parts in a normal fashion. If not, the sense impressions become dim. And in the same measure that the sense impressions fade, the thoughts become livelier. Sense impressions can appear almost ghostly, not clear as we normally have them. The soul-life of such people is flowing away; their sense impressions have something misty about them, they seem to be continually vanishing. At the same time their thoughts have a lively quality and tend to become more intense, more colored, almost as if they were sense impressions themselves.

When such people sleep, their ego organization is not properly within the astral body, so that now they have extraordinarily strong experiences, in fine detail, of the external world around them. They have experiences, with their ego and astral body both outside their physical and etheric bodies, of that part of the world in which they live—for instance, the finer details of the plants or an orchard around their house. Not what they see during the day, but the delicate flavor of the apples, and so forth. That is really what they experience. And in addition, pale thoughts that are after-effects in the astral body from their waking life.

You see, it is difficult if you have such a person before you. And you may encounter such people in all variations in the most manifold circumstances of life. You may meet them in your vocation as physician or as priest—or the whole congregation may encounter them. You can find them in endless variety, for instance, in a town. Today the physician who finds such a person in an early stage of life makes the diagnosis: psychopathological impairment. To modern physicians that person is a psychopathological impairment case who is at the borderline between health and illness; whose nervous system, for instance, can be considered to be on a pathological level. Priests, if they are well-schooled (let us say a Benedictine or Jesuit or Barnabite or the like; ordinary parish priests are sometimes not so well-schooled), will know from their esoteric background that the things such a person tells them can, if properly interpreted, give genuine revelations from the spiritual world, just as one can have from a really insane person. But the insane person is not able to interpret them; only someone who comprehends the whole situation can do so. Thus you can encounter such a person if you are a physician, and we will see how to regard this person medically from an anthroposophical point of view. Thus you can also encounter such a person if you are a priest—and even the entire congregation can have such an encounter.

But now perhaps the person develops further; then something quite special appears. The physical and etheric bodies still have their normal connection. But now there begins to be a stronger pull of the ego organization, drawing the astral body to itself, so that the ego organization and astral body are now more closely bound together. And neither of them enters properly into the physical and etheric bodies. (Plate I, 3) Then the following can take place: the person becomes unable to control the physical and etheric bodies properly from the astral body and ego. The person is unable to push the astral body and ego organization properly into the external senses, and therefore, every now and then, becomes “senseless.” Sense impressions in general fade away and the person falls into a kind of dizzy dream state. But then in the most varied way moral impulses can appear with special strength. The person can be confused and also extremely argumentative if the rest of the organism is as just described.

Now physicians find in such a case that physical and biochemical changes have taken place in the sense organs and the nerve substance. They will find, although they may take slight notice of them, great abnormalities in the ductless glands and their hormone secretion, in the adrenal glands, and the glands that are hidden in the neck as small glands within the thyroid gland. In such a case there are changes particularly in the pituitary gland and the pineal gland. These are more generally recognized than are the changes in the nervous system and in the general area of the senses.

And now the priest comes in contact with such a person. The person confesses to experiencing an especially strong feeling of sin, stronger than people normally have. The priest can learn very much from such individuals, and Catholic priests do. They learn what an extreme consciousness of sin can be like, something that is so weakly developed in most human beings. Also in such a person the love of one's neighbor can become tremendously intense, so much so that the person can get into great trouble because of it, which will then be confessed to the priest.

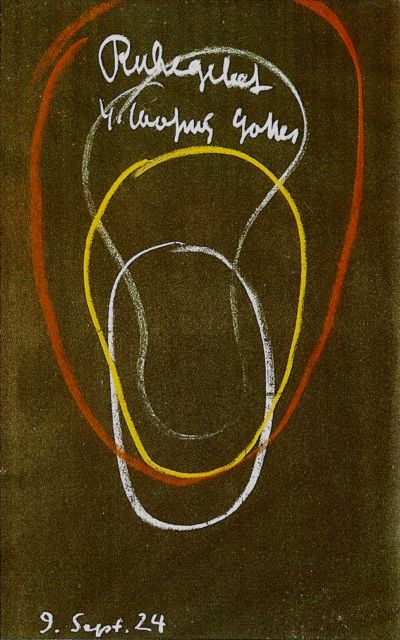

The situation can develop still further. The physical body can remain comparatively isolated because the etheric body—from time to time or even permanently—does not entirely penetrate it, so that now the astral and etheric bodies and the ego organization are closely united with one another and the physical organism is separate from them. (Plate II) To use the current materialistic terms (which we are going to outgrow as the present course of study progresses), such people are in most cases said to be severely mentally retarded individuals. They are unable from their soul-spiritual individuality to control their physical limbs in any direction, not even in the direction of their own will. Such people pull their physical organism along, as it were, after themselves. A person who is in this condition in early childhood, from birth, is also diagnosed as mentally retarded. In the present stage of earth evolution, when all three members—ego organization, astral organization, and etheric body—are separated from the physical, and the lone physical body is dragged along after them, the person cannot perceive, cannot be active, cannot be illumined by the ego organization, astral body, and etheric body. So experiences are dim and the person goes about in a physical body as if it were anesthetized. This is extreme mental retardation, and one has to think how at this stage one can bring the other bodies down into the physical organism. Here it can be a matter of educational measures, but also to a great extent of external therapeutic measures.

But now the priest can be quite amazed at what such a person will confess. Priests may consider themselves very clever, but even thoroughly educated priests—there really are such men in Catholicism; one must not underestimate it—they pay attention if a so-called sick person comes to them and says, “The things you pronounce from the pulpit aren't worth much. They don't add up to anything, they don't reach up to the dwelling place of God, they don't have any worth except external worth. One must really rest in God with one's whole being.” That's the kind of thing such people say. In every other area of their life they behave in such a way that one must consider them to be extremely retarded, but in conversation with their priest they come out with such speeches. They claim to know inner religious life more intimately than someone who speaks of it professionally; they feel contempt for the professional. They call their experience “rest in God.” And you can see that the priest must find ways and means to relate to what such a person—one can say patient, or one can use other terms—to what such a human being is experiencing within.

One has to have a sensitive understanding for the fact that pathological conditions can be found in all spheres of life, for the fact that some people may be quite unable at the present time to find their way in the physical-sense world, quite unable to be the sort of human being that external life now requires all of us to be. We are all necessarily to a certain degree philistines as regards external life. But such people as I am describing are not in condition to travel along our philistine paths; they have to travel other ways. Priests must be able to feel what they can give such a person, how to connect what they can give out of themselves with what that other human being is experiencing. Very often such a person is simply called “one of the queer ones.” This demands an understanding of the subtle transition from illness to spirituality.

Our study can go further. Think what happens when a person goes through this entire sequence in the course of life. At some period the person is in a condition (Plate I, 2) where only the ego organization has loosened itself from the other members of the organism. In a later period the person advances to a condition where neither ego nor astral enter the physical or etheric bodies. Still later, (Plate I, 3) the person enters a condition where the physical body separates from the other bodies. (Plate II) The person only goes through this sequence if the first condition, perhaps in childhood, which is still normal, already shows a tendency to lose the balance of the four members of the organism. If the physician comes upon such a person destined to go through all these four stages—the first very slightly abnormal, the others as I have pictured them—the physician will find there is tremendous instability and something must be done about it. Usually nothing can be done. Sometimes the physician prescribes intensive treatment; it accomplishes nothing. Perhaps later the physician is again in contact with this person and finds that the first unstable condition has advanced to the next, as I described it with the sense impressions becoming vague and the thoughts highly colored. Eventually the physician finds the excessively strong consciousness of sin; naturally a physician does not want to take any notice of that, for now the symptoms are beginning to play over into the soul realm. Usually it is at this time that the person finally gets in touch with a priest, particularly when the fourth stage becomes apparent.

Individuals who go through these stages—it is connected with their karma, their repeated earth lives—have purely out of their deep intuition developed a wonderful terminology for all this. Especially if they have gone through the stages in sequence, with the first stage almost normal, they are able to speak in a wonderful way about what they experience. They say, for instance, when they are still quite young, if the labile condition starts between seventeen and nineteen years: human beings must know themselves. And they demand complete knowledge of themselves. Now with their ego organization separated, they come of their own initiative to an active meditative life. Very often they call this “active prayer,” “active meditation,” and they are grateful when some well-schooled priest gives them instruction about prayer. Then they are entirely absorbed in prayer, and they are experiencing in it what they now begin to describe by a wonderful terminology. They look back at their first stage and call what they perceive “the first dwelling place of God,” because their ego has not entirely penetrated the other members of their organism, so to a certain extent they are seeing themselves from within, not merely from without. This perception from within increases; it becomes, as it were, a larger space: “the first dwelling place of God.”

What next appears, what I have described from another point of view, is richer; it is more inwardly detailed. They see much more from within: “the second dwelling place of God.” When the third stage is reached, the inner vision is extraordinarily beautiful, and such a person says, “I see the third dwelling place of God; it is tremendously magnificent, with spiritual beings moving within it.” This is inner vision, a powerful, glorious vision of a world woven by spirit: “the third dwelling place of God,” or “the House of God.” There are variations in the words used. When they reach the fourth stage, they no longer want advice about active meditation, for usually they have reached the view that everything will be given them through grace and they must wait. They talk about passive prayer, passive meditation, that they must not pray out of their own initiative, for it will come to them if God wants to give it to them. Here the priest must have a fine instinct for recognizing when this stage passes over into the next. For now these people speak of “rest-prayer,” during which they do nothing at all; they let God hold sway in them. That is how they experience “the fourth dwelling place of God.”

Sometimes from the descriptions they give at this stage, from what—if we speak medically—such “patients” say, priests can really learn a tremendous amount of esoteric theology. If they are good interpreters, the theological detail becomes clear to them—if they listen very carefully to what such “patients” tell them, to what they know. Much of what is taught in theology, particularly Catholic pastoral theology, is founded on what various enlightened, trained confessors have heard from certain penitents who have undergone this sequence of development.

At this point ordinary conceptions of health and illness cease to have any meaning. If such a man is hidden away in an office, or if such a woman becomes an housewife who must spend her days in the kitchen or something similar in bourgeois everyday life, these people become really insane, and behave outwardly in such a way that they can only be regarded as insane. If a priest notices at the right moment how things are developing and arranges for them to live in appropriate surroundings, they can develop the four stages in proper order. Through such patients, the enlightened confessor is able to look into the spiritual world in a modern way but similarly to the Greek priests, who learned about the spiritual world from the Pythians, who imparted all kinds of revelations concerning the spiritual world through earthly smoke and vapor.3 Pythians: priestesses of Apollo who delivered the oracles at Delphi. What sense would there be today in writing a thesis on the pathological aspect of the Greek Pythians? It could certainly be done and it would even be correct, but it would have no meaning in a higher sense. For as a matter of fact, very much of what flowed in a magnificent way from Greek theology into the entire cultural life of Greece originated in the revelations of the Pythians. As a rule, the Pythians were individuals who had come either to this third stage or even to the fourth stage.

But we can think of a personality in a later epoch who went through these stages under the wise direction of her confessors, so that she could devote herself undisturbed to her inner visions. Something very wonderful developed for her, which indeed also remained to a certain degree pathological. Her life was not just a concern of the physician or of the priest but a concern of the entire Church. The Church pronounced her a saint after her death. This was St. Teresa.4 Teresa of Avila (1515–1582), Carmelite nun. Reformed the Carmelite Order in association with John of the Cross. Canonized by the Catholic Church. This was approximately her path.

You see, one must examine such things as this if one wants to discover what will give medicine and theology a real insight into human nature. One must be prepared to go far beyond the usual category of ideas, for they lose their value. Otherwise one can no longer differentiate between a saint and a fool, between a madman and a genius, and can no longer distinguish any of the others except a normal dyed-in-the-wool average citizen.

This is a view of the human being that must first be met with understanding; then it can really lead to fundamental esoteric knowledge. But it can also be tremendously enlightening in regard to psychological abnormalities as well as to physical abnormalities and physical illnesses. Certain conditions are necessary for these stages to appear. There has to be a certain consistency of the person's ego so that it does not completely penetrate the organism. Also there must be a certain consistency of the astral body: if it is not fine, as it was in St. Teresa, if it is coarse, the result will be different. With St. Teresa, because of the delicacy of her ego organization and astral body, certain physical organs in the lower body had been formed with the same fragile quality.

But it can happen that the ego organization and astral body are quite coarse and yet they have the same characteristic as above. Such an individual can be comparatively normal and show only the physical correlation: then it is only a physical illness. One could say, on the one hand there can be a St. Teresa constitution with its visions and poetic beauty, and on the other hand its physical counterimage in diseased abdominal organs, which in the course of this second person's life is not reflected in the ego and astral organization.

All these things must be spoken about and examined. For those who hold responsibility as physicians or priests are confronted by these things, and they must be equal to the challenge. Theological activity only begins to be effective if theologians are prepared to cope with such phenomena. And physicians only begin to be healers if they also are prepared to deal with such symptoms.

Zweiter Vortrag

Meine lieben Freunde! Wenn man von den gemeinsamen Angelegenheiten des Priesters und des Arztes spricht, so muß der Blick zunächst auf Erscheinungen kommen im menschlichen Leben, die in der Tat leicht ins Pathologische hinübergleiten, daher des Verständnisses des Arztes bedürfen, die aber auf der anderen Seite wiederum in einer außerordentlichen Weise in das Innere, ich möchte sagen, selbst in das Esoterische des religiösen Lebens hineinspielen. Wir müssen uns ja durchaus klar sein darüber, daß eigentlich alle Zweige der menschlichen Erkenntnis über etwas Grobes wiederum hinauskommen müssen, das in der materialistischen Epoche in sie hineingekommen ist. Wir brauchen uns nur zu erinnern, wie doch jetzt in einer gewissen Grobheit der Auffassung behandelt worden sind diejenigen Erscheinungen, die eine Zeitlang zusammengefaßt wurden unter «Genialität und Wahnsinn», grob behandelt worden sind von Lombroso und seiner Schule, aber auch von anderen. Wir können ebensogut aufmerksam machen nicht so sehr auf die Untersuchungen selbst — die haben ja ihre Verdienste —, aber auf die Anschauungsweise, die dadurch zutage trat, wir können ebenso aufmerksam machen auf dasjenige, was aufgetreten ist als Kriminalanthropologie und die Schädel untersuchte der Verbrecher. Die Gesinnungen, die dabei zutage traten, waren durchaus nicht nur grob, sondern trugen einen gewissen Stempel einer außerordentlich starken Philistrosität. Man kann schon sagen — und hier dürfen wir uns durchaus solcher Kategorien bedienen, denn es handelt sich um ein Grenzgebiet in der Pastoralmedizin —, man kann schon sagen, da taten sich im Grunde als Forscher und Denker die Philister zusammen, bildeten sich den Typus eines Normalmenschen heraus, der möglichst ein Philister war. Und was eben abliegt, das war pathologisch. Da das Genie nach der einen Seite, der Wahnsinn nach der anderen Seite abwich, so war eben beides in irgendeiner Weise pathologisch. Und da es für den Einsichtigen ganz selbstverständlich ist, daß jede pathologische Eigentümlichkeit sich auch körperlich ausdrückt, so ist es ganz selbstverständlich, daß in körperlichen Merkmalen nach der einen oder anderen Richtung hin Zeichen gefunden werden können. Es handelt sich ja darum, diese Zeichen in der richtigen Weise zu durchschauen. Gewiß ist ein Ohrläppchen unter Umständen außerordentlich charakteristisch für eine psychologische Eigentümlichkeit, weil solche psychologische Eigentümlichkeiten doch zusammenhängen mit dem Karma, das aber aus früheren Inkarnationen herüberwirkt.

Das, was die Kräfte des Aufbaues des physischen Organismus sind, namentlich in den ersten sieben Lebensjahren, das sind dieselben Kräfte, die später zutage treten. Wir wachsen ja in den ersten sieben Lebensjahren mit den Kräften, mit denen wir später denken; und so ist es schon wichtig und bedeutsam, daß man gerade, aber nun nicht in der hergebrachten, vor kurzem hergebrachten Weise, sondern in einer wirklich sachgemäßen Art an gewisse Erscheinungen zunächst herangeht. Weniger um sie als pathologisch anzusehen - ins Pathologische werden wir schon geführt werden, gerade von diesen Erscheinungen aus —, als um von diesen Erscheinungen aus das menschliche Leben einsehen zu können.

Stellen wir uns einmal ganz ernstlich, meine lieben Freunde, auf den Standpunkt, den uns Anthroposophie über den Menschen gibt. Der Mensch tritt uns entgegen in seinem physischen Leib, der eine lange Entwickelung hinter sich hat, der als physischer Leib durch drei vorbereitende Stadien, wie ich es beschrieben habe in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß» gegangen ist, bevor er der Erdenleib wurde, der zu seinem Verständnis wahrhaftig mehr braucht als dasjenige, was heute in Anatomie und Physiologie ihm entgegengebracht wird. Denn ich möchte auch hier darauf aufmerksam machen, daß ja dieser physische Leib des Menschen, so wie er heute ist, ein getreues Abbild ist des ätherischen Leibes, der in seiner dritten Epoche ist, des astralischen Leibes, der in seiner zweiten Epoche ist, und auch bis zu einem gewissen Grade der Ich-Organisation, die der Mensch erst auf der Erde aufgenommen hat, die also in ihrer ersten Epoche ist. Das alles prägt sich wie Siegelabdrücke in dem physischen Leib des Menschen aus. Das macht den physischen Leib dann außerordentlich kompliziert, so wie er uns heute entgegentritt. Er ist nur seiner rein mineralisch-physischen Beschaffenheit nach mit den Erkenntniskräften durchschaubar, mit denen man heute an ihn herantritt. Dasjenige, was der Ätherleib in ihn einprägt, das ist gar nicht mit diesen Erkenntniskräften durchschaubar. Es muß mit den Augen des plastischen Künstlers gesehen werden. Das muß gesehen werden so, daß man sich erwirbt Anschauungen, Bildgestaltungen, die aus den Kräften des Weltenalls heraus erfaßt werden und die man wiedererkennt in den Formen des ganzen Menschen, wiedererkennt in den Formen der einzelnen Organe.

Fernerhin ist dieser physische Mensch ein Abbild desjenigen, was in der Atmungs-Blutzirkulation ist. Die ganze Dynamik, die in der Blutzirkulation und Atmungszirkulation wirkend webt, die ist aber musikalisch orientiert, die kann man nur verstehen, wenn man sie in musikalischen Formen denkt. Man kann sie nur verstehen, wenn man zum Beispiel so denkt, daß man, sagen wir im Knochensystem sieht dasjenige, in das hineingeflossen sind die Bildekräfte, die dann im feineren in der Atmung und in der Zirkulation tätig sind, aber nach musikalischen Gestaltungskräften. Wir können geradezu wahrnehmen, wie die Oktave ausgeht rückwärts von den Schulterblättern und den Knochen entlang geht, und daß die Arme in ihrer Knochenformation nicht verstanden werden können aus einer mechanischen Dynamik heraus, sondern wenn man ihnen ein musikalisches Verständnis entgegenbringt. Da finden wir die Prim von den Schulterblättern bis zum Ansatz der Oberarmknochen, wir finden die Sekund im Oberarmknochen, die Terz vom Ellenbogen bis zum Handgelenk. Wir finden da zwei Knochen, weil es zwei Terzen gibt, eine große und eine kleine und so weiter. Kurz, wenn wir dasjenige, was in der Atmung und Blutzirkulation beherrscht ist vom astralischen Leib, im Abdruck im physischen Leibe wieder suchen, müssen wir musikalisches Verständnis entgegenbringen.

Noch komplizierter ist das Verständnis von der Ich-Organisation. Da ist es nötig zu begreifen, was angedeutet ist im ersten Vers des Johannes-Evangeliums: «Im Urbeginne war das Wort...» Was da als Verständnis des Wortes gemeint ist im Konkreten, nicht im Abstrakten, wie es die Evangelien-Interpreten gewöhnlich geben, das, wieder angewandt im Konkreten auf den wirklichen Menschen, gibt dann ein Verständnis von dem, wie die Ich-Organisation eingreift in den physisch-menschlichen Leib.

Sie sehen, wir müßten noch mancherlei in unsere Studien aufnehmen, wenn diese Studien wirklich zum Verständnis des Menschen führen sollten. Aber da es meine Überzeugung ist, daß sowohl vom Medizin- wie vom Theologiestudium außerordentlich viel ausgelassen werden könnte, so glaube ich, daß wenn man alles Wertvolle herausnehmen würde, die Zahl der Jahre, die heute zum Beispiel ein Medizinstudent braucht, nicht verlängert, sondern gekürzt werden könnte. Aber natürlich denkt man heute, wo man materialistisch denkt: wenn man etwas Neues aufnimmt, stückelt man ein halbes Jahr an die Kurse, die ohnehin schon vorhanden sind.

Wenn man sich ernsthaft auf den Standpunkt stellt, den wir in der Anthroposophie einnehmen müssen, so stellt der Mensch sich uns gegenüber in seinem physischen, ätherischen und astralischen Leibe und in seiner Ich-Organisation. Während des Wachens sind diese vier Glieder der menschlichen Organisation in inniger Verbindung. Während des Schlafens stellt sich auf die eine Seite der physische Leib und der Ätherleib, und entgegen auf die andere Seite die Ich-Organisation und der Astralleib. Wenn wir uns ernsthaft auf diesen Standpunkt stellen, dann werden wir uns ja sagen können, daß in der mannigfaltigsten Weise Unregelmäßigkeiten auftreten können in der Verbindung der Ich-Organisation, des astralischen Leibes mit dem ätherischen Leibe und dem physischen Leibe und so weiter. Sehen Sie, es kann zum Beispiel dieses eintreten, sagen wir, ich würde — schematisch selbstverständlich — hier den physischen Leib zeichnen, den Ätherleib, den Astralleib, die Ich-Organisation (Tafel 2, links): so kann im wachen Zustande immer die sogenannte normale Beziehung herrschen zwischen diesen vier Gliedern der menschlichen Organisation.

Es kann aber auch so sein, daß zunächst der physische Leib und der Ätherleib in einer Art normalem Zusammenhang sind, daß auch noch der astralische Leib verhältnismäßig drinnensitzt, daß aber die IchOrganisation in einer gewissen Weise nicht ordentlich im astralischen Leibe drinnensitzt (Tafel 2, Mitte). Wir haben dann eine Unregelmäßigkeit, die uns zunächst in der wachen Organisation entgegentreten kann. Der Mensch kommt mit seiner Ich-Organisation nicht gut in seinen astralischen Leib hinein. Dadurch ist sein Empfindungsleben durchaus gestört. Er kann sogar sehr lebhaft Gedanken bilden, denn die Gedanken überhaupt hängen von dem normalen Zusammenhang des astralischen Leibes mit den anderen Leibern ab. Aber ob mit diesen Gedanken auch die Sinnesempfindungen in der entsprechenden Weise erfaßt werden, das hängt davon ab, daß die Ich-Organisation normal mit den anderen Gliedern der menschlichen Wesenheit verbunden ist. Ist das nicht der Fall, hängt sozusagen die Ich-Organisation nicht ordentlich mit den anderen Gliedern der menschlichen Wesenheit zusammen, dann werden die Sinnesempfindungen verblassen. In demselben Maße, in dem die Sinnesempfindungen verblassen, in demselben Maße werden die Gedanken intensiver. Fast gespenstisch treten sie auf, nicht so rein, wie wir sie sonst haben. Das Seelenleben eines solchen Menschen verfließt so, daß seine Sinnesempfindungen etwas Verschwindendes, Nebelhaftes haben, dafür aber die Gedanken etwas Lebendiges, Intensiviertes, Koloriertes haben, das fast den Eindruck schwacher Sinnesempfindungen hervorruft.

Schläft dann ein solcher Mensch, dann ist auch während des Schlafes die Sache so, daß die Ich-Organisation nicht ordentlich im astralischen Leib drinnen ist. Die Folge davon ist, daß jetzt außerordentlich starke Erlebnisse mit den Feinheiten der äußerlichen Welt auftreten. Solch ein Mensch erlebt in demjenigen Teile der Welt, wo er eben ist, mit seinem Ich und seinem astralischen Leib, wenn er außer dem physischen und ätherischen Leib ist, die Feinheiten der Pflanzen, die Feinheiten des Obstgartens um sein Haus herum. Nicht das, was man bei Tage sieht, sondern die Feinheiten des Geschmacks der Apfel und dergleichen. Das ist schon so, daß das erlebt wird. Und dazu verblaßte Gedanken, die im astralischen Leibe nachwirkende Kräfte darstellen, aus dem wachen Leben nachwirkende Kräfte darstellen.

Sehen Sie, es ist jetzt schwer, wenn man einen solchen Menschen vor sich hat, und man kann ihn in irgendeiner Variante in den mannigfaltigsten Lagen des Lebens vor sich haben, man kann ihn als Arzt vor sich haben, man kann ihn als Priester vor sich haben, sogar als ganze Kirche ihn vor sich haben. Er tritt einem in irgendeiner Form, meinetwegen in einem Dorfe entgegen. Der Arzt sagt heute, namentlich wenn er ihn in irgendeinem Frühstadium des Lebens findet: Psychopathologische Minderwertigkeit. - Der Priester, namentlich wenn er ein gutgeschulter, sagen wir ein gutgeschulter Benediktiner ist — die Weltpriester in der katholischen Kirche sind zuweilen nicht so gut geschult —, aber wenn er ein gutgeschulter Benediktiner, Jesuit oder Barnabit oder dergleichen ist, dann weiß er auf esoterische Art, daß man aus den Dingen, die da erzählt werden von einem solchen Menschen — für den modernen Arzt ist es eine psychopathologische Minderwertigkeit -—, daß man aus diesen Dingen, die da erzählt werden, wenn man sie richtig interpretiert - trotzdem man einen Menschen vor sich hat, der hart an der Grenze steht zwischen Gesundheit und Krankheit, dessen Nervensystem zum Beispiel durchaus in pathologischem Sinne aufgefaßt werden kann -, wenn man einen solchen Menschen mit durchaus labilem Gleichgewicht in den zutage tretenden Seelenkräften vor sich hat, die ganz anders wirken als beim sogenannt normalen Menschen, dann weiß man, daß einem doch aus diesen Dingen, wenn man sie richtig interpretiert, echte Offenbarungen aus der geistigen Welt entgegenkommen können, wie schließlich von dem Wahnsinnigen selber - nur ist der Wahnsinnige nicht berufen dazu, sie zu interpretieren, sondern nur derjenige, der die ganze Sache durchschaut. Man kann ihn also als Arzt vor sich haben, und wir werden sehen, wie wir ihn in einem anthroposophischen Sinne ärztlich anzuschauen haben. Man kann ihn als Priester vor sich haben, man kann ihn auch als Kirche vor sich haben.

Nun kann es aber sein, daß er sich sogar weiterentwickelt und dann kommt etwas ganz Besonderes heraus. Nehmen wir an, er entwickelt sich weiter, dieser Mensch. In einem gewissen Lebensalter ist er so, wie ich ihn gezeichnet habe. Nehmen wir an, er entwickelt sich weiter, es entsteht eine stärkere Anziehung des nicht ganz im normalen Verhältnis zu den anderen Gliedern stehenden Ichs, so daß später dieses zustande kommt (Tafel 2, rechts). Wieder ist der physische und ätherische Leib sozusagen normal in Verbindung, aber die Ich-Organisation zieht den astralischen Leib an sich, und der will jetzt auch nicht ganz drinnen sein. Jetzt ist die Ich-Organisation und der astralische Leib mehr aneinandergebunden und alle beide zusammen kommen nicht ordentlich in den physischen und den Ätherleib hinein. Bei einem solchen Menschen kann das Folgende eintreten. Wir gewahren an ihm, daß er nicht imstande ist, seinen physischen Leib und Ätherleib ordentlich zu beherrschen vom astralischen Leib und Ich aus. Er kann den Astralleib und die Ich-Organisation nicht richtig vorschieben in die äußeren Sinne. So daß alle Augenblicke ihn die Sinne verlassen, überhaupt die Sinnesempfindungen verblassen und er in eine Art Taumel-Traumzustand kommt. Aber es können dann in der mannigfaltigsten Weise gerade die moralischen Impulse mit einer besonderen Stärke auftreten. Sie können konfus auftreten, aber sie können auch in einer außerordentlich kasuistisch großartigen Weise auftreten, wenn die Organisation so ist.

Und wiederum findet der Arzt da in diesem Falle, daß eigentlich wesentliche organische Veränderungen schon da sind in der Konsistenz der Sinnesorgane und der Nervensubstanz. Die beachtet er weniger; aber namentlich wird er finden, daß starke Abnormitäten in den feineren Drüsen und in der Hormonbildung da sind, in denjenigen Drüsen, die wir als Nebennieren bezeichnen, und in den Drüsen, die hier am Halse als kleine Drüsen in der Schilddrüse versteckt sind. Namentlich sind in einem solchen Fall Veränderungen der Hypophysis cerebri und Epiphysis cerebri da. Das wird schon mehr beachtet als die Veränderungen, die im Nervensystem und im ganzen Sinnessystem vorhanden sind.

Der Priester kommt an einen solchen Menschen heran; dieser Mensch erzählt ihm von dem, was er unter einer solchen Konstitution erlebt. Er erlebt unter einer solchen Konstitution etwa ein besonders starkes Sündengefühl, ein verstärktes Sündengefühl, als sonst Menschen haben. Der Priester kann Mannigfaltiges lernen, und katholische Priester tun das. Sie lernen gerade von solchen Menschen die extreme Ausbildung dieses bei den anderen schwach entwickelten Sündengefühls. Die Nächstenliebe kann bei einem solchen Menschen bis zu ungeheurer Intensität anwachsen, so daß ein solcher Mensch gerade durch seine Nächstenliebe in mannigfaltige Nöte kommt, die er dem Priester dann beichtet.

Aber es kann noch weitergehen. Es kann jetzt dazu kommen, daß der physische Leib verhältnismäßig vereinsamt bleibt, daß der Ätherleib dauernd oder zeitweise nicht ganz hineingeht in den physischen Leib, daß dann der astralische Leib, der Ätherleib und die Ich-Organisation nahe miteinander verbunden sind und die physische Organisation draußen ist (Tafel 3). Man wird, wenn man sich heutiger materialistischer Ausdrücke bedient — aber wir werden aus diesen herauswachsen im Laufe der Stunde -, einen solchen Menschen in den häufigsten Fällen empfinden als einen hochgradig schwachsinnigen Menschen, der nach keiner Richtung hin, auch nicht nach der Willensrichtung vom Geistig-Seelischen aus, seine physischen Glieder beherrschen kann. Solch ein Mensch zieht gewissermaßen die physische Organisation nach. Ist von vornherein der Mensch so organisiert, dann empfindet man ihn auch wirklich als schwachsinnig, weil der Mensch im gegenwärtigen Stadium der Erdentwickelung, wenn das alles, die Ich-Organisation, die astralische Organisation und der Ätherleib, so isoliert ist, und einsam der physische Leib nachgeschleppt wird, dann nicht wahrnehmen kann, nicht tätig sein kann, sich nicht erleuchten kann an IchOrganisation, astralischem Leib und Ätherleib; so bleibt das dunkel, was er erlebt, und er geht wie betäubt in seinem physischen Leib herum. Es ist in hohem Grade Schwachsinn vorhanden, und man muß nachdenken, in diesem Stadium, wie man in die physische Organisation die anderen Leiber hineinbringen kann. Da kann es sich um pädagogische Maßregeln, aber auch durchaus um äußerlich therapeutische Maßnahmen handeln. Der Priester aber kann in den Fall kommen, daß er ganz überrascht sein kann von dem, was ihm gerade ein solcher Mensch beichtet. Der Priester kann sich sehr gescheit fühlen, aber durchgebildete Priester — es gibt solche wirklich im Katholizismus; man muß den Katholizismus nicht kleinlich beurteilen -, die passen schon auf, wenn ein solcher sogenannter Kranker zu ihnen kommt und zu ihnen sagt: Was du von der Kanzel verkündest, es will doch nicht viel besagen. Das alles macht nichts aus, das reicht eigentlich nicht bis zur Wohnung Gottes, das hat alles nur äußerlichen Wert. In Gott muß man wirklich mit seinem ganzen Menschen ruhen. — Das sagen solche Leute. In allem übrigen Leben benehmen sie sich so, daß man sie für hochgradig schwachsinnig halten kann, in der Unterredung mit den Priestern kommen sie zuweilen mit solchen Dingen. Sie prätendieren, das innere religiöse Leben intimer zu kennen als die, die berufsmäßig davon reden. Sie haben eine Verachtung für den, der berufsmäßig davon redet und sie nennen das, was sie erleben, die «Ruhe in Gott». Und sehen Sie, wieder muß es sich für den Priester darum handeln, Mittel und Wege zu finden, anzuknüpfen an dasjenige, was eigentlich ein solcher, man kann sagen Patient, man kann aber auch anders sagen, was ein solcher Mensch innerlich erlebt.

Man muß da ein feines Verständnis dafür haben, wie das Pathologische herüberspielt in allerlei Regionen, die den Menschen zunächst unfähig machen, in der physisch-sinnlichen Welt die rechten Wege zu finden, die ihn unfähig machen in einer Weise, wie es das äußere Leben von uns allen fordert, zu sein; und wir sind in einem gewissen Grade - es muß so sein — alle für das äußere Leben Philister. Aber solche Menschen sind nicht veranlagt dazu, auf Philisterwegen zu gedeihen, sie gehen immer andere Wege. Man muß als Priester anknüpfen können mit demjenigen, was man selber zu geben hat, an das, was der andere da erlebt; sehr häufig sind es «die da». Das ist schon dasjenige, was erfordert ein Verständnis für den feinen Übergang vom Kranken ins Geistige.

Aber die Sache kann viel weitergehen. Denken wir uns nun einmal folgendes: ein Mensch macht diesen ganzen Entwickelungsgang in verschiedenen Lebensaltern durch. In einem bestimmten Lebensalter ist er in diesem Zustand (Tafel 2, Mitte),wo die Ich-Organisation sich nur losgelöst hat von den anderen. In einem weiteren Lebensalter rückt er zu diesem Zustand vor (Tafel 2, rechts), in einem weiteren zu diesem (Tafel 3). Er macht so etwas nur durch, wenn schon der erste Zustand, der noch der normale ist, vielleicht während der Kindheit schon Anlagen zeigt, in ein labiles statt in ein stabiles Gleichgewicht der Glieder hineinzukommen. Wenn der Arzt nun über einen solchen Menschen kommt, der dazu berufen ist, diese ganzen vier Stadien durchzumachen - das erste hier etwas abnorm, die anderen aber in dem Sinne, wie ich sie schematisch aufgezeichnet habe -, wenn der Arzt über einen solchen Menschen kommt, wird er finden: da ist ein außerordentlich labiles Gleichgewicht vorhanden, da muß man etwas befestigen. Es läßt sich in der Regel nichts befestigen. Manchmal ist der Weg in einer außerordentlich intensiven Weise vorgezeichnet; es läßt sich nichts befestigen. Vielleicht, wenn der Arzt dann später wieder an denselben Menschen herankommt, findet er, daß sich der erste labile Zustand verwandelt hat in den anderen, wie ich ihn beschrieben habe mit dem Nebuloswerden der Sinnesempfindungen, den stark kolorierten Gedanken. Später findet er ein außerordentlich starkes Sündenbewußtsein wieder, wovon der Arzt natürlich, weil jetzt die Sache beginnt, stark ins Seelische hinüberzuspielen, nicht gerne Notiz nimmt. Jetzt geht dann in der Regel das Leben einer solchen Persönlichkeit erst recht an den Priester über, und namentlich, wenn es zum vierten Stadium kommt.

Nun haben solche Menschen, die diese Stadien durchmachen — was mit ihrem Karma, mit ihren wiederholten Erdenleben zusammenhängt -, rein innerlich intuitiv ausgebildet eine wunderbare Terminologie. Sie können reden — namentlich wenn sie die Stadien hintereinander durchmachen, so daß das erste Stadium nahezu normal war -, sie können reden in einer wunderbaren Weise über das, was sie erleben. Sie sagen zum Beispiel als ganz junger Mensch, wenn das labile Stadium mit siebzehn oder neunzehn Jahren auftritt: Der Mensch muß sich selbst erkennen. — Und mit Intensität fordern sie nach allen Richtungen von sich selbst die Selbsterkenntnis. Hier, wo die Ich-Organisation heraustritt, kommen sie von selbst auf das aktive meditative Leben. Sie nennen es sehr häufig «das tätige Gebet», was ein aktives Meditieren ist, und sind sehr dankbar, wenn ihnen irgendein geschulter Priester Vorschriften gibt über das Gebet. Sie gehen dann ganz auf in dem Gebet, erleben aber zu gleicher Zeit in diesem Gebet dasjenige, was sie jetzt anfangen, mit einer wunderbaren Terminologie zu belegen. Sie blicken zurück auf ihr erstes Stadium und nennen das, was sie wahrnehmen: die erste Wohnung Gottes, weil sie dadurch, daß sie mit ihrem Ich nicht ganz untertauchen in die übrigen Glieder, sich gewissermaßen auch von innen beschauen, nicht bloß von außen. Das vergrößert sich, wenn man von innen beschaut, das wird wie ein weiter Raum: die erste Wohnung Gottes.

Das, was dann auftritt, was ich von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte beschrieben habe, das wird reicher, es wird innerlich gegliedert; der Mensch sieht viel mehr von seinem Inneren: die zweite Wohnung Gottes. Wenn das dritte Stadium eintritt, ist die innere Schau von einer außerordentlichen Schönheit, und solche Menschen sagen sich: Ich sehe die dritte Wohnung Gottes mit ungeheuren Herrlichkeiten, mit den darin wandelnden geistigen Wesenheiten. — Es ist Innenschau, aber es ist eine mächtige, grandiose Anschauung einer geistwebenden Welt. Die dritte Wohnung Gottes oder das Haus Gottes. Das ist in der Sprache verschieden. Kommen sie bei dem vierten Stadium an, dann wollen sie nicht mehr aufnehmen irgendwelche Ratschläge in bezug auf aktive Meditation, sondern sie bekommen gewöhnlich die Ansicht, alles muß ihnen durch Gnade selber gegeben werden. Sie müssen warten. Sie sprechen vom passiven Gebet, von der passiven Meditation, die man nicht unternehmen darf, die eintreten muß, wenn sie einem Gott geben will. Da muß der Priester einen feinen Spürsinn dafür haben, wenn das eine Stadium in das andere übergeht. Dann reden diese Menschen von dem «Ruhegebet», wobei der Mensch gar nichts mehr tut, wobei er Gott in sich walten läßt. So erlebt er es in der vierten Wohnung Gottes.

Der Priester kann unter Umständen aus den Beschreibungen, die nun gegeben werden, aus dem, was nun, wenn wir ärztlich reden, so ein «Patient» spricht, tatsächlich außerordentlich viel Esoterisch-Theologisches lernen. Und ist er ein guter Interpret, so wird ihm das Theologische ungeheuer konkret, wenn er hinhorcht auf dasjenige, was ihm solche «Patienten» sagen — ich sage das unter Gänsefüßchen -, zu sagen wissen. Vieles von dem, was namentlich in der katholischen Theologie gelehrt wird, in der pastoralen Theologie, es rührt her von dem Verkehr von aufgeklärten, geschulten Beichtvätern mit Beichtkindern, die sich in dieser Richtung entwickeln.

Die gewöhnlichen Begriffe, die man hat über Gesundsein und Kranksein, hören auf, ihre Geltung, ihre Bedeutung zu haben. Steckt man eine Persönlichkeit wie diese in ein Büro, oder macht man sie zur gewöhnlichen Ehefrau, wo sie das Kochen beaufsichtigen muß oder sonst etwas im bürgerlichen Leben, so wird sie richtig wahnsinnig, und führt sich eben so auf, äußerlich, daß sie gar nicht anders aufgefaßt werden kann als wahnsinnig. Bemerkt der Priester im rechten Moment, wohin der Weg geht, dirigiert er sie ins Nonnenhafte hinein; läßt er sie im entsprechenden Milieu leben, entwickeln sich die vier Stadien hintereinander, so daß in der Tat der geschulte Beichtvater durch eine solche Patientin in einer ähnlichen Weise im modernen Stil hineinschauen kann in die geistigen Welten wie der griechische Priester durch die Pythien, die ihm durch den Rauch, den Dunst der Erde allerlei über die geistige Welt kundgegeben haben, sich über die geistige Welt unterrichten ließen. Was hilft es viel, wenn heute einer eine Dissertation schreibt über das Pathologische der griechischen Pythien! Das kann man ganz gut, das wird richtig sein, auch exakt sein, aber es ist nichts damit getan in einem höheren Sinne. Denn im Grunde genommen ist doch ungeheuer vieles von dem, was aus der griechischen Theologie im eminenten Sinne hineingeflossen ist in das ganze griechische Kulturleben, entstanden unter den Offenbarungen der Pythien. Die Pythien waren in der Regel Persönlichkeiten, die entweder bis zu diesem dritten Stadium oder gar bis zum vierten Stadium gekommen sind. Aber denken wir uns in einer späteren Zeit, eine Persönlichkeit mache gerade unter der klugen Führung von Beichtvätern diese Stadien so durch, daß sie sich ungehindert hingeben kann ihren inneren Anschauungen, dann wird etwas außerordentlich Wunderbares aus ihr, das deshalb doch in einem gewissen Grade pathologisch bleibt. Dann hat es nicht nur der Arzt, nicht nur der Priester, dann hat es die ganze Kirche damit zu tun und beschäftigt sich damit, daß sie diese Persönlichkeit nach dem Tode heilig spricht; und das ist die heilige Theresia, die hat ungefähr diesen Weg durchgemacht.

Sehen Sie, meine lieben Freunde, an diesen Dingen muß man sich heranschulen, wenn man dasjenige, was in der Verständigung von Medizin und Theologie zur Einsicht in die menschliche Wesenheit führen muß, wenn man in dem wirken will. Dann muß man dazu kommen, über die gewöhnlichen Begriffskategorien hinauszukommen, die da ihren Sinn verlieren, denn sonst kann man nicht mehr einen Heiligen von einem Narren, einen Wahnsinnigen von einem Genie unterscheiden, und gar nichts mehr unterscheiden, als wenn einer ein normaler Durchschnittsbürger ist, von all den anderen.

Das ist die Anschauung der menschlichen Wesenheit, die nun zunächst mit Verständnis verfolgt werden muß, die wirklich ins gründlich Esoterische hineinführen kann, die aber ungeheuer aufklärend ist nicht nur über psychologische Abnormitäten, sondern die aufklärend wirken kann auch über physische Abnormitäten, über physisches Kranksein. Denn damit solche Stadien eintreten, meine lieben Freunde, sind ja gewisse Voraussetzungen nötig, Voraussetzungen, die in einer gewissen Konsistenz eines solchen Ichs, das nicht ganz hineingeht, und eines solchen Astralleibs liegen. Ist aber die Konsistenz nicht fein wie bei der heiligen Theresia, sondern grob, dann bildet sich folgendes. Bei der heiligen Theresia bildeten sich durch die Feinheit ihrer Ich-Organisation und die Feinheit ihres Astralleibes plastisch gewisse physische Organe, namentlich Unterleibsorgane, sehr an die Ich-Organisation und an den astralischen Leib.

Aber es kann so eintreten, daß die Ich-Organisation und der astralische Leib recht grob sind und dennoch diese Eigentümlichkeit haben. Dann tritt noch immer die Möglichkeit auf, weil die Ich-Organisation und der Astralleib grob sind, daß eine solche Persönlichkeit ziemlich normal sein kann. Aber dann können die physischen Korrelate auftreten, und es ist nur eine physische Erkrankung da. Man möchte sagen: man kann die Konstitution haben der heiligen Theresia mit all dem Poetischen ihrer Offenbarungen auf der einen Seite und das physische Gegenbild in kranken Unterleibsorganen, die sich dann nicht zeigen in ihrem Ausleben in der Ich-Organisation und astralischen Organisation.

Von all diesen Dingen muß gesprochen werden. Alle diese Dinge müssen durchschaut werden, denn sie treten demjenigen, der Arztaufgaben hat, und auch demjenigen, der Priesteraufgaben hat, durchaus entgegen, und er muß ihnen gewachsen sein. Erst dann beginnt Theologisch-Religiöses wirksam zu sein, wenn der Theologe solchen Erscheinungen gewachsen ist. Erst dann wird der Arzt zum Heiler der Menschen, wenn er auch solchen Erscheinungen gewachsen ist.

Second Lecture

My dear friends! When speaking of the common concerns of the priest and the physician, we must first consider phenomena in human life that can easily slip into the pathological and therefore require the understanding of the physician, but which, on the other hand, also play an extraordinary role in the inner, I would even say esoteric, life of religion. We must be quite clear that all branches of human knowledge must actually transcend something coarse that has entered into them in the materialistic epoch. We need only remember how crudely those phenomena have been treated, phenomena that for a time were summarized under the heading of “genius and madness,” crudely treated by Lombroso and his school, but also by others. We can just as well draw attention not so much to the investigations themselves — which do have their merits — but to the way of thinking that came to light as a result; we can also draw attention to what emerged as criminal anthropology and the examination of criminals' skulls. The attitudes that came to light in this context were not only crude, but also bore the stamp of an extraordinarily strong philistinism. One can already say—and here we may well use such categories, for this is a borderline area in pastoral medicine— one can already say that, as researchers and thinkers, the philistines basically got together and developed the type of a normal person who was as philistine as possible. And whatever deviated from this was pathological. Since genius deviated in one direction and madness in the other, both were pathological in some way. And since it is quite natural for the discerning person to realize that every pathological peculiarity also expresses itself physically, it is quite natural that signs can be found in physical characteristics in one direction or the other. The point is to understand these signs in the right way. Certainly, an earlobe can, under certain circumstances, be extremely characteristic of a psychological peculiarity, because such psychological peculiarities are connected with karma, which has an effect from previous incarnations.The forces that build up the physical organism, especially in the first seven years of life, are the same forces that later come to the fore. During the first seven years of life, we grow with the forces with which we will later think; and so it is important and significant that we approach certain phenomena in a certain way, but not in the traditional, recently traditional way, but in a truly appropriate way. Less to regard them as pathological — we will already be led to the pathological, precisely from these phenomena — than to be able to understand human life from these phenomena.

Let us, my dear friends, take a very serious look at the perspective that anthroposophy gives us on human beings. Human beings come to us in their physical bodies, which have undergone a long development, which as physical bodies have gone through three preparatory stages, as I have described in my Outline of Esoteric Science, before becoming the earthly body, which truly requires more than what is offered today in anatomy and physiology to understand it. For I would like to point out here that the physical body of the human being, as it is today, is a faithful reflection of the etheric body, which is in its third epoch, of the astral body, which is in its second epoch, and also, to a certain extent, of the ego organization, which the human being has only taken on on earth and which is therefore in its first epoch. All of this is imprinted like seal impressions on the physical body of the human being. This makes the physical body extraordinarily complex, as we see it today. It can only be understood in terms of its purely mineral-physical nature with the powers of cognition with which we approach it today. What the etheric body imprints on it cannot be understood with these powers of cognition. It must be seen with the eyes of the sculptor. It must be seen in such a way that one acquires insights and images that are grasped from the forces of the universe and that one recognizes in the forms of the whole human being, recognizes in the forms of the individual organs.

Furthermore, this physical human being is a reflection of what is in the respiratory and blood circulation. The whole dynamic that weaves its way through the blood circulation and respiratory circulation is musically oriented, however, and can only be understood if one thinks of it in musical forms. One can only understand it if one thinks, for example, that in the skeletal system one sees that into which the formative forces have flowed, which then work in the finer aspects of respiration and circulation, but according to musical formative forces. We can actually perceive how the octave extends backwards from the shoulder blades and runs along the bones, and that the arms cannot be understood in terms of their bone formation from a mechanical dynamic, but rather when approached with a musical understanding. There we find the prime from the shoulder blades to the base of the upper arm bones, we find the second in the upper arm bone, the third from the elbow to the wrist. We find two bones there because there are two thirds, a major and a minor, and so on.

In short, if we seek what is governed by the astral body in breathing and blood circulation in the imprint in the physical body, we must approach it with musical understanding.“In the beginning was the Word...” What is meant here by understanding the Word in concrete terms, not in abstract terms, as is usually given by interpreters of the Gospels, when applied again in concrete terms to the real human being, then gives an understanding of how the ego organization intervenes in the physical human body.

You see, we would have to include many things in our studies if these studies were really to lead to an understanding of the human being. But since it is my conviction that a great deal could be omitted from both medical and theological studies, I believe that if everything of value were to be taken out, the number of years that a medical student needs today, for example, could be shortened rather than lengthened. But of course, today, with our materialistic thinking, we think that if we add something new, we have to add six months to the courses that already exist.

If we seriously adopt the standpoint that we must take in anthroposophy, we see the human being in his physical, etheric, and astral bodies and in his ego organization. During waking life, these four members of the human organization are in intimate connection with each other. During sleep, the physical body and the etheric body are on one side, and the ego organization and the astral body are on the other. If we seriously take this standpoint, then we can say that irregularities can occur in the most diverse ways in the connection between the ego organization, the astral body, the etheric body, and the physical body, and so on. You see, for example, this can happen: let's say I would draw — schematically, of course — the physical body, the etheric body, the astral body, and the ego organization (plate 2, left): in the waking state, the so-called normal relationship can always prevail between these four members of the human organization.

But it can also be the case that initially the physical body and the etheric body are in a kind of normal relationship, that the astral body is also relatively well integrated, but that the ego organization is in a certain way not properly integrated into the astral body (plate 2, center). We then have an irregularity that can initially confront us in the waking organization. The human being does not fit well into his astral body with his ego organization. This completely disrupts his sensory life. He can even form thoughts very vividly, because thoughts depend entirely on the normal connection of the astral body with the other bodies. But whether these thoughts are accompanied by corresponding sensory perceptions depends on the ego organization being normally connected with the other members of the human being. If this is not the case, if the ego organization is not properly connected with the other members of the human being, so to speak, then the sensory perceptions will fade. To the same extent that the sensory perceptions fade, thoughts become more intense. They appear almost ghostly, not as pure as we otherwise have them. The soul life of such a person flows in such a way that their sensory perceptions have something vanishing, misty about them, but their thoughts have something lively, intensified, colorful about them, which almost evokes the impression of weak sensory perceptions.

When such a person sleeps, the situation is such that even during sleep the ego organization is not properly inside the astral body. The result of this is that they now have extremely strong experiences with the subtleties of the outer world. Such a person experiences, in the part of the world where they are, with their ego and their astral body, when they are outside their physical and etheric bodies, the subtleties of the plants, the subtleties of the orchard around their house. Not what one sees during the day, but the subtleties of the taste of apples and the like. That is how it is experienced. And in addition, faded thoughts, which represent forces continuing to act in the astral body, represent forces continuing to act from waking life.

You see, it is difficult now when you have such a person in front of you, and you can have him in front of you in any variation in the most diverse situations in life, you can have him in front of you as a doctor, you can have him in front of you as a priest, you can even have him in front of you as an entire church. He encounters you in some form, for example in a village. Today, the doctor says, especially if he finds him in some early stage of life: psychopathological inferiority. The priest, especially if he is a well-trained, let's say a well-trained Benedictine — the secular priests in the Catholic Church are sometimes not so well trained — but if he is a well-trained Benedictine, Jesuit, Barnabite, or the like, then he knows in an esoteric way that from the things that are told by such a person — for the modern doctor it is psychopathological inferiority — that from these things that are told, if one interprets them correctly — even though one has before one a person who is on the borderline between health and illness, whose nervous system, for example, can certainly be understood in a pathological sense — if one has before one such a person with a thoroughly unstable balance in the soul forces that come to the fore, which have a completely different effect than in so-called normal people, then one knows that from these things, if one interprets them correctly, real revelations from the spiritual world, as ultimately from the madman himself — only the madman is not called upon to interpret them, but only the one who sees through the whole thing. So you can have him in front of you as a doctor, and we will see how we have to look at him medically in an anthroposophical sense. One can have him before one as a priest, one can also have him before one as a church.

Now it may be that he develops further and then something very special emerges. Let us assume that this person develops further. At a certain age, he is as I have described him. Let us assume that he develops further, that a stronger attraction arises from the ego, which is not quite in a normal relationship with the other members, so that later this comes about (plate 2, right). Again, the physical and etheric bodies are, so to speak, normally connected, but the ego organization draws the astral body to itself, and now it does not want to be completely inside either. Now the ego organization and the astral body are more closely connected, and both together do not fit properly into the physical and etheric bodies. The following can happen to such a person. We notice that he is unable to properly control his physical and etheric bodies from his astral body and ego. They cannot properly project the astral body and the ego organization into the outer senses. As a result, their senses abandon them at every moment, their sensory perceptions fade away, and they enter a kind of dizzying dream state. But then moral impulses can arise with particular strength in the most diverse ways. They may appear confused, but they may also appear in an extraordinarily casuistic and magnificent way, if the organization is such.

And again, in this case, the doctor finds that there are already significant organic changes in the consistency of the sensory organs and the nervous substance. He pays less attention to these; but he will find, in particular, that there are strong abnormalities in the finer glands and in hormone production, in the glands we call the adrenal glands, and in the glands hidden here in the neck as small glands in the thyroid gland. In particular, in such a case, there are changes in the pituitary gland and the pineal gland. This is already more noticeable than the changes that are present in the nervous system and in the entire sensory system.

The priest approaches such a person; this person tells him about what he experiences with such a constitution. With such a constitution, he experiences, for example, a particularly strong sense of sin, a heightened sense of sin, than other people have. The priest can learn many things, and Catholic priests do so. They learn from such people the extreme development of this feeling of sin, which is weakly developed in others. Love for one's neighbor can grow to tremendous intensity in such a person, so that precisely because of his love for his neighbor, such a person encounters manifold difficulties, which he then confesses to the priest.

But it can go even further. It can now happen that the physical body remains relatively isolated, that the etheric body does not enter the physical body completely, either permanently or temporarily, so that the astral body, the etheric body, and the ego organization are closely connected with each other, and the physical organization is left outside (Plate 3). If we use today's materialistic terms — but we will outgrow these in the course of the hour — we will in most cases perceive such a person as a highly feeble-minded person who cannot control his physical limbs in any direction, not even in the direction of the will from the spiritual-soul. Such a person, in a sense, drags the physical organization behind them. If a person is organized in this way from the outset, then they are indeed perceived as feeble-minded, because at the present stage of Earth's development, when all of this — the ego organization, the astral organization, and the etheric body — is so isolated and the physical body is dragged along alone, then he cannot perceive, cannot be active, cannot enlighten himself in the ego organization, astral body, and etheric body; what he experiences remains dark, and he walks around as if numb in his physical body. There is a high degree of mental deficiency, and at this stage one must consider how to bring the other bodies into the physical organization. This may involve educational measures, but also external therapeutic measures. The priest, however, may find himself completely surprised by what such a person confesses to him. The priest may feel very clever, but well-educated priests — and there really are such priests in Catholicism; one should not judge Catholicism too harshly — are careful when such a so-called sick person comes to them and says: What you proclaim from the pulpit does not mean much. None of that matters; it doesn't really reach God's dwelling place; it all has only external value. In God, one must truly rest with one's whole being. — That is what such people say. In all other aspects of life, they behave in such a way that one might consider them to be highly feeble-minded, but in conversation with priests, they sometimes bring up such things. They pretend to know the inner religious life more intimately than those who speak about it professionally. They have contempt for those who talk about it professionally, and they call what they experience “rest in God.” And you see, once again, the priest must find ways and means to connect with what such a person, one might say a patient, but one could also say differently, what such a person experiences inwardly.

One must have a subtle understanding of how the pathological plays out in all kinds of areas that initially make people incapable of finding the right paths in the physical-sensual world, that make them incapable of being in the way that external life demands of us all; and to a certain extent—it must be so—we are all philistines when it comes to external life. But such people are not predisposed to thrive in philistine ways; they always go other ways. As a priest, one must be able to connect with what one has to give, with what the other person is experiencing; very often it is “those there.” That is what requires an understanding of the subtle transition from the sick to the spiritual.

But the matter can go much further. Let us now consider the following: a person goes through this entire process of development at different ages. At a certain age, he is in this state (plate 2, center), where the ego organization has only detached itself from the others. At another age, they advance to this state (plate 2, right), and at yet another to this one (plate 3). They only go through this if the first state, which is still the normal one, already shows signs during childhood of entering into an unstable rather than a stable equilibrium of the limbs. When the physician encounters such a person, who is destined to go through all four stages—the first one somewhat abnormal, but the others as I have schematically described them—when the physician encounters such a person, he will find that there is an extremely unstable equilibrium and that something must be stabilized. As a rule, nothing can be stabilized. Sometimes the path is marked out in an extremely intense way; nothing can be fixed. Perhaps when the doctor later approaches the same person again, he will find that the first unstable state has changed into the other one I described, with the nebulousness of the sensory perceptions and the strongly colored thoughts. Later, he finds an extremely strong sense of sin, which the doctor, of course, does not like to take note of, because now the matter is beginning to play strongly into the soul. Now, as a rule, the life of such a personality passes on to the priest, especially when it comes to the fourth stage.

Now, such people who go through these stages — which are related to their karma, to their repeated earthly lives — have developed a wonderful terminology purely intuitively within themselves. They can talk — especially when they go through the stages one after the other, so that the first stage was almost normal — they can talk in a wonderful way about what they are experiencing. For example, as very young people, when the unstable stage occurs at seventeen or nineteen, they say: Man must know himself. — And with intensity they demand self-knowledge from themselves in all directions. Here, where the ego organization emerges, they come to the active meditative life of their own accord. They very often call it “active prayer,” which is active meditation, and are very grateful when some trained priest gives them instructions on prayer. They then become completely absorbed in prayer, but at the same time experience in this prayer what they are now beginning to describe with wonderful terminology. They look back on their first stage and call what they perceive the first dwelling place of God, because by not completely submerging their ego in the other members, they also observe themselves from within, so to speak, and not just from without. This enlarges when one observes from within; it becomes like a wide space: the first dwelling place of God.

What then occurs, what I have described from a certain point of view, becomes richer, it becomes internally structured; the human being sees much more of his inner being: the second dwelling place of God. When the third stage occurs, the inner vision is of extraordinary beauty, and such people say to themselves: I see the third dwelling place of God with immense glories, with the spiritual beings walking within it. It is inner vision, but it is a powerful, grandiose view of a spirit-weaving world. The third dwelling place of God or the house of God. This varies in language. When they reach the fourth stage, they no longer want to accept any advice regarding active meditation, but usually come to the view that everything must be given to them by grace itself. They must wait. They speak of passive prayer, of passive meditation, which one must not undertake, which must come about if one wants to give oneself to God. The priest must have a keen sense of when one stage transitions into the next. Then these people speak of the “prayer of rest,” in which the person does nothing at all, allowing God to reign within them. This is how he experiences it in the fourth dwelling place of God.

Under certain circumstances, the priest can learn an extraordinary amount of esoteric theology from the descriptions that are now given, from what, in medical terms, such a “patient” says. And if he is a good interpreter, theology becomes tremendously concrete for him when he listens to what such “patients” — I say this in quotation marks — have to say. Much of what is taught in Catholic theology, in pastoral theology, stems from the interaction between enlightened, trained confessors and penitents who are developing in this direction.

The usual concepts we have about health and illness cease to have any validity or meaning. If you put a personality like this in an office, or make her an ordinary wife, where she has to supervise the cooking or do other things in bourgeois life, she will go completely mad and behave in such a way that she cannot be perceived as anything other than insane. If the priest notices at the right moment where this is leading, he directs her into a nun-like existence; he lets her live in the appropriate milieu, the four stages develop one after the other, so that in fact the trained confessor can look into the spiritual worlds in a similar way through such a patient in a modern style, just as the Greek priest was instructed about the spiritual world through the Pythias, who revealed all kinds of things about the spiritual world to him through the smoke, the mist of the earth. What good does it do today to write a dissertation on the pathology of the Greek Pythias? One can do that quite well, it will be correct, even accurate, but it accomplishes nothing in a higher sense. For, basically, an enormous amount of what flowed from Greek theology in the eminent sense into the whole of Greek cultural life arose from the revelations of the Pythias. The Pythias were usually personalities who had reached either this third stage or even the fourth stage. But let us imagine that in a later period, under the wise guidance of confessors, a personality goes through these stages in such a way that she can devote herself unhindered to her inner visions, then something extraordinarily wonderful emerges from her, which nevertheless remains pathological to a certain degree. Then it is not only the doctor, not only the priest, but the whole church that has to deal with it and is concerned with declaring this personality a saint after death; and that is Saint Teresa, who went through something like this.

You see, my dear friends, one must train oneself in these things if one wants to work in the field of medicine and theology, which must lead to an understanding of human nature. Then one must go beyond the usual categories of concepts, which lose their meaning there, because otherwise one can no longer distinguish a saint from a fool, a madman from a genius, and distinguish nothing at all, except whether someone is a normal average citizen from all the others.

This is the view of human nature that must first be pursued with understanding, which can truly lead into the thoroughly esoteric, but which is also tremendously enlightening, not only about psychological abnormalities, but which can also have an enlightening effect on physical abnormalities, on physical illness. For certain conditions are necessary for such stages to occur, my dear friends, conditions that lie in a certain consistency of such an ego that does not go in completely, and of such an astral body. But if the consistency is not fine, as in Saint Teresa, but coarse, then the following occurs. In Saint Teresa, the fineness of her ego organization and the fineness of her astral body formed certain physical organs, namely abdominal organs, very much like the ego organization and the astral body.