Colour

Part II

GA 228

29 July 1923, Dornach

3. Dimension, Number and Weight

Man in his earthly existence varies in his conditions of consciousness; he varies in the conditions of full wakefulness, of sleep, and of dreaming.

Let us first put the question to ourselves: is it an essential part of man to live as earthly being in these three conditions of consciousness?

We must clearly realize that of earthly beings only man lives in these three conditions. Animals live in an essentially different alternation. They do not have that deep, dreamless sleep which man has for the greater part of the time between falling asleep and awaking. On the other hand, animals do not have the complete wakefulness of man between awaking and going to sleep. Animal “wakefulness” is somewhat like human dream; but the experiences of the higher animals are more definite. On the other hand, animals are never so deeply unconscious as man is in deep sleep.

Therefore animals do not differentiate themselves from their surroundings so much as man. They have not got an outer and an inner world, as man has. The higher animals, (Dr. Steiner means by higher animals, the warm-blooded vertebrates, birds and mammals. – Ed.) subconsciously, feel themselves, with their whole inner being, like a part of the surrounding world.

When an animal sees a plant, his first feeling is not: that is outwardly a plant, and I am inwardly a separate being—but the animal gets a strong inner experience from the plant, a direct sympathy or antipathy. It feels as it were, the plant's nature inwardly. The circumstance that people of our time are not able to observe anything that is not obvious, prevents them from seeing in the impulses and behaviour of animals that it is as I have said.

Only man has the clear and sharp differentiation between his inner world and the outer world. Why does he recognize an outer world? How does he come at all to speak of an inner and an outer world? Because every time he sleeps, his ego and his astral body are outside his physical and etheric body: he abandons, so to speak, his physical and etheric bodies and is among those things which are outer world. During sleep we share the fate of outer things. As tables and benches, trees and clouds are during wakefulness outside our physical and etheric bodies and are therefore described as outer world, so, during sleep, our own astral bodies and our ego belong to the outer world. And here something happens.

In order to realize what happens here, let us first start from what happens when we face the world in a perfectly normal condition of wakefulness. There are the various objects outside us. And the scientific thought of man has gradually brought it to the point of recognizing such physical things as belonging certainly to the outer world as can be weighted, measured and counted. The content of our physical science without doubt is determined according to weight, dimension and number.

We reckon with the calculations which apply to earthly things, we weigh and measure them, and what we ascertain by weighing, measuring and counting really constitutes the physical. We would not describe a body as physical unless we could somehow put it to the proof by means of scales. But those things like colours, and sounds, the feeling even of warmth and cold, the real objects of sense-perceptions, these weave themselves about the things that are heavy, and measurable and countable. If we want to define any physical object, what constitutes its real physical nature is the part that can be weighed or counted, and with this alone the physicist really wants to be concerned. Of colour, sound and so on he says: Well, something occurs from outside with which weighing or counting is concerned—he says even of colour-phenomena: there are oscillating movements which make an impression on man from outside, and he describes this impression, when it concerns the eye, as colour, when it concerns the ear, as sound, and so on. One could really say that the modern physicist cannot make head or tail of all these things—sound, colour, warmth and cold. He regards them just as properties of something which can be ascertained with the scales or the measuring rod or arithmetic. Colours cling, as it were, to the physical; sound is wrung from the physical; warmth and cold surge up out of the physical. One says: that which has eight has redness, or, it is red.

You see, when a man is in the state between going to sleep and waking up, his ego and his astral body are in a different condition. Then the things of dimension, number and weight are not there at all, at any rate not according to earthly dimension, number and weight. When we sleep there are no things around us which can be weighed, however odd it appears, nor are there things around us which can be counted or measured. As an ego and an astral body one could not use a measuring rod in the state of sleep.

But what is there are—if I may so express it—the free-floating, free-moving sense-perceptions. Only in the present state of his development man is not capable of perceiving the free-floating redness, the waves of free-moving sound and so on.

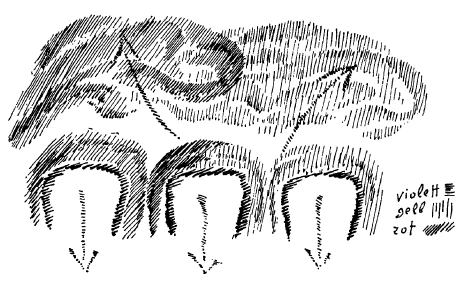

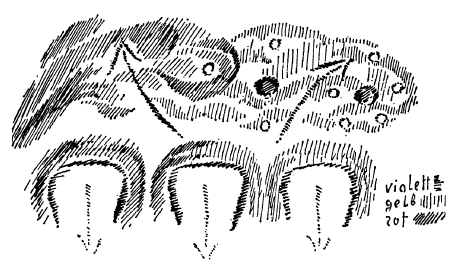

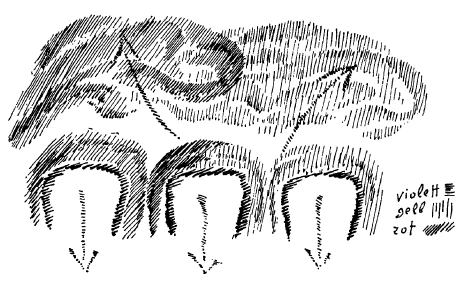

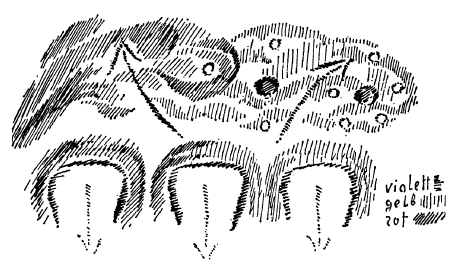

If we wish to draw the thing diagrammatically, we could do it like this. We could say: Here on earth we have solid weighable things (red) and to these are attached, as it were, the redness, the yellow, in other words, what the senses perceive in these things. When we sleep, the yellow is free and floating, and also the redness not clinging to such weight-conditions, but floating and weaving freely. It is the same with sound. It is not eh bell which rings, but the ringing floats in the air.

When we go about in our physical world and see something or other, we pick it up; only then is it really a thing, otherwise it might be an optical illusion. Weight must come in. Therefore, unless we feel its weight, we are apt to consider something that appears in the physical, as an optical illusion, like the colours of the rainbow.

If you open a book on Physics today you will see the explanation given—the rainbow is an optical illusion. Physicists look upon the raindrop as the reality; and then they draw lines which really have no meaning for what is there, but they seemingly imagine them there in space. They are then called rays. But the rays are not there at all, but one is told the eye projects them. Remarkable use indeed is made of this projection in modern Physics. Thus I assume we see a red object. In order to convince ourselves that it is no optical illusion, we lift it up—and it is heavy; thereby it guarantees its reality.

He who now becomes conscious in the ego and the astral body, outside the physical and etheric bodies, comes in the end to the conclusion that there is something like this in this free-floating, free-moving colour and sound; but it is different. In this free-floating coloured substance there is a tendency to scatter to the uttermost parts of the Earth. It has a contrary weight. (See Diagram 1) These things of the earth want to go down there to the earth's center (downward arrow); these (upward arrow) want to escape into universal space.

And there is something there similar to a measurement. You get it, for instance, if you have, let us say, a small reddish cloud, and this small reddish cloud is hemmed in by a mighty yellow structure; you then measure, not with a measuring-rule, but qualitatively, the stronger-shining red with the weaker-shining yellow. And as the measuring-rule tells you: that is five yards, the red tells you here: (see Diagram 1): if I were to spread myself out, I should go into the yellow five times. I must expand myself. I must become bigger, then I, too, should become yellow. Thus are measurements made in this case.

If it still more difficult to be clear about counting, because after all in earthly counting we mostly count only peas or apples, which lie side by side indifferently, and we always have the feeling that I we place as second one by the one, this one doesn't mind a bit that another one lies next to it. In human life it is of course different. There is sometimes the case that the one is directed to the other. But this is already verging on the spiritual.

In physical mathematics it is a matter of indifference to divisions what is added to them. But here it is not the case. When a one is of a definite kind, it demands—let us say—some three or five others, according to its kind. It has always an inner relationship to the others. Here number is a reality. And if a consciousness of it begins, as is the case when you are out there with your ego and your astral body, you also get to the point of ascertaining something like dimension, number and weight, but of an opposite kind.

And then, when sight and hearing out there are no longer a mere chaotic mingling of red and yellow and sounds, but you begin to feel things are ordered, then arises the perception of the spiritual beings, who realize themselves in these free-floating sense-experiences. Then we enter the positive spiritual world, and the life and doings of the spiritual beings. As here on earth we enter the life and doings of earthly things, ascertaining them with the scales and the rod and our calculations, so, by adapting ourselves to the purely qualitative, opposite weight-condition, i.e. by wanting to expand imponderably into the world-spaces and by measuring colour by colour, etc.—we come to the understanding of spiritual beings. Such spiritual beings also permeate all the realms of nature.

Man with his waking consciousness sees only the outside of minerals and plants and animal; but in sleep he is with all that is spiritual in all these beings of nature's realms. And when on awakening he returns again to himself, his ego and his astral body keep as it were the inclination and affinity towards the outward things and cause him to recognize an outer world. If man had an organization which was not designed for sleep, he could not recognize an outer world.

It is not a question of insomnia, for I did not way, “if a man does not sleep,” but “if man had an organization which was not designed for sleep.” The point is the being designed for something. Therefore, of course, man becomes ill if he suffers from insomnia, because his nature is not suited to it. But things are so arranged that man attains an outer world and to a vision of it, just because in sleep he passes the time in the outer world with the things he calls, when awake, the outer world.

And you see, this relationship of man to sleep gives the earthly concept of truth. How? Well, we call it truth when we can correctly reproduce inwardly something external, when we can accurately experience inwardly something external. But for this we require the arrangement of sleep. Without it we should have no concept of truth, so that we have to thank the state of sleep for truth. In order to surrender ourselves to the truth of things, we must pass our existence for a certain time with those tings. The things tell us something about themselves only because during sleep they are appreciated by us through our soul's presence with them.

It is different in the case of the dream-state. The dream is related, of course, with the memory, with the inner soul-life, with what preferably lives in the memory; when the dream is free-floating sound-colour world, it means we are still half outside our body. If we go completely down, the same forces which we unfold as moving and living in dream become forces of memory. Then we no longer differentiate ourselves in the same way from the outer world. Our inner being coincides with it. Then we live in it with our sympathies and antipathies so strong that we do not feel things as sympathetic or antipathetic, but that the sympathies and antipathies themselves show themselves pictorially.

If we had not the possibility of dreaming, nor the continuation of this dream-force in our inner life, we should have no beauty. That we have a disposition for beauty is due to the fact that we are able to dream. For prosaic existence we have to say: we have to thank the power of dreaming that we have a memory. For the art life of man we have to thank the power of dreaming that there is beauty. The manner in which we feel or create beauty is namely very similar to the weaving, creating power of dreaming.

We behave in the experience of beauty and to the creation of it—through the help of our physical body—as we behave outside our physical body or half bound to it, when we dream. There is really only a slight jump from dreaming to living in beauty. And only because in these materialistic times people are of such coarse temperament that they do not notice this jump, is so little consciousness to be found of the whole significance of beauty. Man must necessarily give himself up in dream in order to experience this free movement and life, whereas when one gives oneself up to freedom, to apparent inner compulsion, that is, if one experiences this jump one has no longer the feeling that it is the same as dreaming, that it is the same except that use is made of the powers of the physical body. This generation will long ponder what “chaos” meant in former times. There are most diverse definitions of “chaos.” Actually it can only be characterized by saying: when man reaches a state of consciousness in which the experience of weight, of earthly dimension just ceases, and things begin to become less heavy, but as yet with no tendency to escape into the universe, but maintain themselves still—let us say—horizontally, in equilibrium, when the fixed boundaries get blurred, when the swaying indefiniteness of the world is seen with the physical body still, but already also with the soul-constitution of dreaming, then you see chaos. And the dream is merely the shadowy approach of chaos towards man.

In Greece one still had the feeling that one cannot really make the physical world beautiful; it is half a necessity of nature; it is as it is. One cannot set up the Cosmos—which means the beautiful world—out of earthly things, but only out of chaos, by shaping the chaos. And what one makes with earthly things is merely an imitation in matter of the molded chaos.

This is always the case in Art; and in Greece, where the mystery-cults still had a certain influence, one had a very vivid image of this relation of chaos to Cosmos.

But when one looks round in all these worlds—the unconsciousness of sleep, the half-consciousness of dream—one does not find the Good. The beings who are in these worlds are predestined with all wisdom from the very beginning to run their life's course there. One finds in them controlling, constructive wisdom. One finds in them beauty. But there is no sense in speaking of goodness among these beings when as earth-man it is a question of our meeting them. We can only speak of goodness when there is a distinction between inner and outer world, so that the good can follow the spiritual world or not. As the state of sleep is apportioned to truth, the dream-state to beauty, so is the condition of wakefulness apportioned to goodness, to the Good.

| Sleep: | Truth | |

Dream:| | Beauty, Chaos | |

| Waking Consciousness: | Goodness |

This does not contradict what I have been saying during these days, that when one leaves earthly things and emerges into the Cosmos, one is induced to abandon also earthly concepts so as to speak of the moral world-order. For the moral world-order is necessarily as much foreordained in the spiritual world as causality is on this earth. Only there the predestination,—that which is appointed,—is spiritual; there is no contradiction.

But as regards human nature we must be clear: if we want to have the idea of truth, we must turn to the state of sleep; if we want to have the idea of beauty, we must turn to the state of dreaming, and if we want to have the idea of goodness, we must turn to the state of waking consciousness.

Man has thus, when awake, no vocation to his physical and etheric organization as regards truth, but as regards goodness. In this state we must most certainly arrive at the idea of goodness.

What does modern science achieve when it attempts to explain man? It refuses to rise from truth, through beauty to goodness; it wants to explain everything in accordance with an external causal necessity which corresponds only to the idea of truth. And here one entirely fails to reach that element in man which weaves and lives when he is awake. One reaches at the most only what man is when asleep. Therefore if you read anthropologists today with an alert eye, alert for the psychic peculiarities and forces of the world, you get the following impression. You say to yourself: Yes, that is all very nice, what we are told about man by modern science. But what sort of a fellow is this man really, about whom science tells us? He lies the whole time in bed ... he cannot apparently walk ... he cannot move. Movement, for example, is not in the least explained. He lies the whole time in bed.

It cannot be otherwise. Science explains man only when asleep. If you want to set him in motion, it would have to be done mechanically; wherefore, also, it is a scientific mechanism. One has to insert machinery into this sleeping man, to set this dummy in motion when he is to et up, and to put him to bed again in the evening.

Thus this science tells us absolutely nothing about the man who wanders about the world, who lives and moves and is awake; for what sets him in motion is contained in the idea of goodness, not in the idea of truth, which we gain chiefly from external things.

Now this is something which is not much thought about: one has the feeling, when a physiologist or anatomist of today describes man, that one would like to say: Wake u-p. Wake up! You are asleep, you are asleep! These people accustom themselves, under the influence of this way of looking at things, to the state of sleep. And as I have always said, people sleep through all sorts of things just because they are obsessed by science. Today, because the popular papers circulate everything everywhere, even the uneducated are also obsessed by science. There never were so many obsessed minds as today. It is remarkable with what words one must describe the real relationships of the present day. One must lapse into quite different epithets from those which are in common use today.

It is the same when the materialists try to place man in his surroundings. At the time of materialistic high-tide, people wrote books like one, for example, which stated in a certain chapter: Man is really of himself nothing. He is the product of the oxygen in the air, the product of the cold or warm temperature in which he is. He is really—so ends this materialistic description pathetically—a product of every air-current.

If one investigates such a description and imagines the man as he really is, as pictured thus by the materialist, he turns out to be a neurasthenic in the highest degree. The materialists have never described any other kind of man; if they did not notice that they described man when he is asleep, if they overdid their part and wanted to go further, they have never described him as anything but an extreme neurasthenic, who would die next day of his neurasthenia, who could not live at all, for this age of science has never grasped the idea of a living man.

Here lie the great tasks which must lead man out of present-day circumstances into such conditions in which the further life of world-history is alone possible. What is needed is a penetration into spirituality. The opposite pole must be found to that which has been attained. What was achieved during the nineteenth century7, so glorious for materialistic philosophy? What has been achieved?

In a wonderful way—we can say it sincerely and honestly—it succeeded in defining the outer world according to dimension, number and weight. In this, the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries achieved an extraordinary and mighty work. But finer feelings of the senses, colours, sounds, flutter about as it were in the indefinite. Physicists have entirely ceased to talk about colours and sounds. They talk of airwaves and ether waves. But those are after all not colours or sounds. Air-waves surely are not sounds, but at most the medium by which sounds are continued. There is no grasp of sense-qualities. We have to return to that. In fact one sees today only what can be determined by scales and measuring-rod and arithmetic. All else has escaped one.

And now when the theory of Relativity introduces a grand disorder into the measurable, the weighable, and the countable, everything is split asunder and falls to pieces. But ultimately this theory of Relativity founders at certain points. Not with regard to concepts: one does not get away from the theory of Relativity with earthly concepts, as I have had occasion to explain already in another place, but with reality one always gets away form the Relativity-concepts, for what can be measured or counted or weighed enters through measure, number and weight into quite definite relationships in outer sensible reality.

It is a question of seeing how colours, sounds, etc., are broken in Reality through consideration of weight, i.e. of that which really makes physical bodies. But with this tendency something extraordinarily important is overlooked. We forget namely Art. As we get more and more physical, Art departs further from us. No one will find a trace of Art in the books on Physics today. Nothing remains of Art—it must all go. It is ghastly studying a book on Physics at all today if one has an atom of feeling for beauty. Art is overlooked by man just because everything out of which colour and sound weave beauty, is, and is only recognized when it is attached to a weighty object. And the more physical people become, the more inartistic they become. Just think. We have a wonderful Physics; but it lives in denying Art; for it has reached the point of treating the world in such a manner that the artist takes no more heed of the physicist.

I do not think, for example that the musician lays much value on studying the physical theories of Acoustics. It is too wearisome, he doesn't bother. The painter will also not study this awful colour-theory which Physics contains. As a rule, if he bothers at all about colours, he turns still to Goethe's colour-theory. But that is false in the physicist's eyes. The physicists shut one eye and say: Well, well, it doesn't matter very much if a painter has a true or a false theory of colour.

It is a fact that Art must collapse under the physical philosophy of today. Now we must put the question to ourselves: Why did Art exist in older times?

If you go back to quite ancient times in which man still had an original clairvoyance, we find that they took less notice of dimension, number and weight in earthly things. They were not so important to them. They devoted themselves more to the colours and sounds of earthly things.

Remember that even Chemistry calculates in terms of weight only since Lavoisier; something more than a hundred years. Weight was first use din a world-philosophy at the end of the eighteenth century. Ancient mankind simply was not conscious that everything had to be defined according to earthly measure, number and weight. Man gave his heart and mind to the coloured carpet of the world, to the weaving the welling of sounds, not to the atmospheric vibrations.

But what was the possibility that came from living in this—I might say—imponderable sensible perception? By it one had the possibility, when for instance, one approached a man, of seeing him not as we se him today, but one regarded him as a product of the whole universe. Man was more a confluence of the Cosmos. He was more a microcosm than the thing inside his skin that stands where man stands, on this tiny spot of earth. He thought of man more as an image of the world. Then, colours flowed together, as it were, from all sides, and gave man colours. There was world-harmony, and man in tune with it, receiving his shape from it.

Moreover, mankind today can scarcely understand anything of the way in which ancient mystery-teachers spoke to their pupils. For when a man today wants to explain the human heart, he takes an embryo and sees how the blood-vessels expand, a utricle or bag appears and the heart is gradually formed. Well, that is not what the ancient mystery-teachers told their pupils. That would have appeared to them no more important than knitting a stocking, because after all the process looks much the same. On the contrary they emphasized something else as of paramount importance. They said: the human heart is a product of gold, which lives everywhere in light, and which streams in from the universe and shapes the human heart. You have had the representation. Light quivers through the universe, and the light carries gold. Everywhere in light there is gold. Gold lives and moves in light. And when man lives on earth—you know already that it changes after seven years—his heart is not composed of the cucumber and the salad and the roast veal the man has in the meantime eaten, but these old teachers knew that the heart is built of light's gold, and the cucumbers and the salad are only the stimulus for the gold weaving in the light to build up the heart out of the whole universe.

Yes, those people talked differently and you must be aware of this difference, for one must relearn to talk thus, only on another plane of consciousness. In painting, what once was there, but then disappeared, when one still painted by cosmic inspiration, because weight did not yet exist,—this painting has left its last trace in, let me say, Cimabue, and the Russian Icon-painting. The Icon was still painted out of the macrocosm, the whole outer world. It was so to speak a slice out of the macrocosm. But then one began in a blind alley, one could not get further, for the simple reason that this world-philosophy no longer existed among mankind. If one had wanted to paint the Icon with inner sympathy, not merely by tradition and prayer, one would have to have known how to handle gold. The treatment of gold on the picture was one of the greatest secrets of ancient painting. It consisted in bringing out the human figure from the gold background.

There is a vast abyss between Cimabue and Giotto. Giotto began what Raphael later brought to perfection. Cimabue had it still from tradition. Giotto became already half a naturalist. He noticed that tradition was no longer alive inwardly in the soul. Now one must take the physical man, now one has no longer the universe. One can paint no longer out of the gold; one is compelled to paint from the flesh.

This has gone so far that painting has practically reverted to what it had so much of in the nineteenth century. Icons have no weight at all; they were snowed in out of the world; they are weightless. The only thing is, one cannot paint them any more today. But if they were to e painted in their original form, they would have no weight at all.

Giotto was the first to begin painting objects so that they have weight. From which it arose that everything one paints has weight, even in the picture, and then one paints it from the outside, so that the colours have a relation to what is painted, as the physicist explains it, that the colour appears there on the surface by means of some special wave-vibration. Art has finally also had to be reckoned with weight, which Giotto began in an aesthetic-artistic way and Raphael brought to its highest point.

Thus we may say: there the universal slipped out of man, and heavy man became what one can now see. But because the feelings of the ancient times were still there, the flesh became, so to speak, heavy only to a minimum degree, but still it became heavy. And then arose the Madonna as counter to the Icon—the Icon which ahs no weight, the Madonna which has weight, even if she is beautiful—beauty has survived. But Icons are no longer paintable at all, because man does not feel them. If men today think they can feel Icons, it is an untruth. Therefore also the Icon-cult was steeped in a certain sentimental untruth. It is a blind-alley in Art. It becomes dependent on a scheme, on tradition.

Raphael's painting, built as it is on Giotto's development fro Cimabue, can remain Art only so long as the light of beauty streams upon it. To a certain extent it was the sunny Renaissance painters who still sensed something of the gold weaving in the light, and at least gave their pictures the luster of gold, making it irradiate them from outside.

But that came to an end. And thus naturalism came into being, and in Art mankind sits between two stools on the ground, between the Icon and the Madonna and is called upon to discover what pure vibrating colour and pure vibrating sound are, with their opposite weight, opposed to measurableness, and ponderable countability. We must learn to paint out of colour itself. However elementary and bad and tentative, it is our job to paint out of colour, to experience colour itself; freed from weight, to experience colour itself. In these things one must be able to proceed consciously, even with artistic consciousness.

And if you look at the simple attempts of our programs, you will see that there a beginning is made, if only a beginning, to release colours from weight, to experience colour as an element per se, to cause colours to speak.

If that succeeds, then, as against the inartistic physical world-philosophy which lets all Art die out, an Art will be created out of the free element of colour, of sound, which once more is free from weight.

We also sit between two stools, between the Icon and the Madonna, but we must get up. Physical Science does not help us to do it. I have told you, one must stay on the ground if one applies only physical science of man. But we have to get up now; and for this we need Spiritual Science. That contains the life-element which carries us from weight to imponderable colour, to the reality of colour, fro bondage even in musical naturalism to free musical Art.

We see how in all provinces it is a question of making an effort, of mankind waking up. It is this we ought to take up—this impulse to awake, to look round and see what is and what is not, and to advance ever onwards wherever the summons calls.

These things already touch the nerve of our time.

I have described how the modern philosopher comes to admit to himself: where does this intellectualism lead? To build a gigantic machine, and place it in the centre of the earth, in order to blow up the earth into all corners of the universe—he admitted it is so. The others do not admit it!

And so I have tried in different places to show how the ideas of only thirty or forty years ago are dissolved through the theory of Relativity—simply melted away like snow in the sun—so I have tried to show you how the summons is to be found everywhere really to strive towards Anthroposophy. For the philosopher, Eduard von Hartmann says: if the world really is as we imagine it—i.e. as he imagined it in the sense of the nineteenth century—then we really must blow it up into space, because we cannot endure any longer on it; and it is only a question of progressing far enough till we are able to do it. We must sigh for this future time when we can blow the world into universal space.

But the Relativists, before that, will see to it that mankind has no concepts left. Space, Time, Movement are abolished. Even apart from this, one can reach such profound despair, that in certain circumstances one sees the highest satisfaction in that explosion into the whole universe.

One must, however, make oneself clearly acquainted with the meaning of certain impulses in our time.

Mass, Zahl Und Gewicht - Die Schwerelose Farbe als Forderung der Neuen Malentwickelung

Der Mensch wechselt während seines irdischen Daseins in den Bewußtseinszuständen, die wir ja auch in diesen Tagen schon von manchen Gesichtspunkten aus betrachtet haben, zwischen den Zuständen des völligen Wachens, des Schlafens und des Träumens. Und ich habe ja gerade bei dem kleinen Vortragszyklus während der Delegiertenversammlung die ganze Bedeutung des Träumens auseinanderzusetzen versucht. Wir wollen uns heute einmal zunächst die Frage vorlegen: Gehört es zum Wesentlichen des Menschen, als irdisches Wesen in diesen drei Bewußtseinszuständen zu leben?

Wir müssen uns klar sein darüber, daß innerhalb des irdischen Daseins nur der Mensch in diesen drei Bewußtseinszuständen lebt. Das Tier lebt ja in einem wesentlich anderen Wechsel. Jenen tiefen traumlosen Schlaf, den der Mensch die größte Zeit hindurch hat zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen, hat das Tier nicht, dagegen hat auch das Tier nicht das vollständige Wachsein, das der Mensch hat zwischen dem Aufwachen und Einschlafen. Der tierische Wachzustand ist eigentlich dem menschlichen Träumen etwas ähnlich. Nur sind die Bewußtseinserlebnisse der höheren Tiere bestimmter, gesättigter, möchte ich sagen, als die flüchtigen menschlichen Träume. Aber auf der anderen Seite ist das Tier niemals in jenem hohen Grade bewußtseinslos, wie der Mensch das im tiefen Schlafe ist.

Das Tier unterscheidet sich daher nicht in demselben Maße von seiner Umgebung wie der Mensch. Das Tier hat nicht in dieser Weise eine Außenwelt und Innenwelt, wie der Mensch sie hat. Das Tier rechnet sich eigentlich, wenn wir in menschliche Sprache übersetzen, was als ein dumpfes Bewußtsein in den höheren Tieren lebt, mit seinem ganzen Innenwesen zur Außenwelt mit.

Wenn das Tier eine Pflanze sieht, dann ist nicht zunächst für das Tier die Empfindung da: es ist außen eine Pflanze, und ich bin im Inneren ein geschlossenes Wesen, sondern für das Tier ist ein starkes inneres Erlebnis von der Pflanze da, eine unmittelbar sprechende Sympathie oder Antipathie. Das Tier empfindet gewissermaßen dasjenige, was die Pflanze äußert, in seinem Inneren mit. Daß in unserem heutigen Zeitalter die Menschen so wenig beobachten können, was sich nicht in ganz grober Weise der Beobachtung ergibt, dieser Umstand nur ist es ja, der sie verhindert, einfach an dem Getriebe, an dem Gehaben des Tieres schon zu sehen, daß das so ist, wie ich es gesagt habe.

Nur der Mensch hat dieses scharfe, deutliche Unterscheiden zwischen seiner Innenwelt und der äußeren Welt. Warum anerkennt der Mensch eine äußere Welt? Wodurch kommt der Mensch dazu, überhaupt von einer Innenwelt und von einer Außenwelt zu sprechen? Er kommt dadurch dazu, daß er mit seinem Ich und mit seinem astralischen Leibe jedesmal im Schlafzustand außerhalb seines physischen und seines Atherleibes ist, daß er sozusagen seinen physischen und Ätherleib sich selbst überläßt im Schlaf, und bei denjenigen Dingen ist, die Außenwelt sind. Wir teilen ja während unseres Schlafzustandes das Schicksal der äußeren Dinge. So wie Tische und Bänke, Bäume und Wolken während des Wachzustandes außerhalb unseres physischen und Ätherleibes sind, und wir sie deshalb als Außenwelt bezeichnen, so sind unser eigener astralischer Körper und unser eigenes Ich während des Schlafes der Außenwelt angehörig. Und wenn wir mit unserem Ich und mit unserem astralischen Leibe während des Schlafes der Außenwelt angehören, da geschieht etwas.

Um einzusehen, was da geschieht, wollen wir zunächst einmal von dem ausgehen, was eigentlich geschieht, wenn wir in einem ganz normalen Wachzustande der Welt gegenüberstehen. Da sind die Gegenstände außer uns. Und es hat ja allmählich das wissenschaftliche Denken der Menschen es dahin gebracht, als sicher für diese physischen Dinge der Außenwelt nur das anzuerkennen, was man messen, wägen und zählen kann. Der Inhalt unserer physischen Wissenschaft wird ja bestimmt nach Gewicht, nach Maß, nach Zahl.

Wir rechnen mit den Rechnungsoperationen, die einmal für die irdischen Dinge gelten, wir wägen die Dinge, wir messen sie. Und was wir durch Gewicht, Maß und Zahl bestimmen, das gibt eigentlich das Physische, Wir würden einen Körper nicht als einen physischen bezeichnen, wenn wir ihn nicht irgendwie mit der Waage in seiner Realität nachweisen könnten. Dasjenige aber, was zum Beispiel Farben sind, was Töne sind, was selbst Wärme- und Kälteempfindungen sind, was also die eigentlichen Sinneswahrnehmungen sind, das webt so hin über den schweren, meßbaren, zählbaren Dingen. Wenn wir irgendein physisches Ding bestimmen wollen, so ist das, was seine eigentliche physische Wesenheit ausmacht, eben dasjenige, was sich wägen, zählen läßt, womit der Physiker eigentlich bloß zu tun haben will. Von Farbe, von Ton und so weiter sagt er: Ja, da geschieht eben draußen etwas, was auch mit Wägen oder Zählen zu tun hat. — Er sagt ja selbst von den Farbenerscheinungen: Da draußen sind schwingende Bewegungen, die machen einen Eindruck auf den Menschen, und diesen Eindruck, den bezeichnet der Mensch, wenn das Auge ihn bestimmt, als Farbe, wenn das Ohr ihn bestimmt, als Ton und so weiter. — Eigentlich könnte man sagen: Mit allen diesen Dingen — Ton, Farbe, Wärme und Kälte — weiß der Physiker heute nichts anzufangen. Er betrachtet sie eben als Eigenschaften dessen, was sich mit der Waage, mit dem Maßstab oder durch die Rechnung bestimmen läßt. Es haften gewissermaßen die Farben an dem Physischen, es entringt sich dem Physischen der Ton, es wellt heraus aus dem Physischen die Wärme oder Kälte. Man sagt: Dasjenige, was ein Gewicht hat, das hat die Röte, oder es ist rot.

Wenn der Mensch nun in dem Zustand zwischen Einschlafen und Aufwachen ist, da ist es mit dem Ich und mit dem astralischen Leibe anders. Da sind die Dinge nach Maß, Zahl und Gewicht zunächst überhaupt nicht da. Nach dem irdischen Maß, Zahl und Gewicht sind die Dinge nicht da. Da haben wir nicht Dinge um uns herum, wenn wir schlafen, die man abwiegen kann, so sonderbar es erscheint, wir haben auch nicht Dinge um uns herum, die man zählen kann, oder die man messen kann unmittelbar. Einen Maßstab könnte man nicht anwenden als Ich und als astralischer Leib im Schlafzustande.

Aber was da ist, das sind, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, die frei schwebenden, frei webenden Sinnesempfindungen. Nur daß der Mensch im gegenwärtigen Zustand seiner Entwickelung nicht die Fähigkeit hat, die frei schwebende Röte, die Wellen des frei webenden Tones und so weiter wahrzunehmen.

Will man schematisch die Sache zeichnen, so könnte man das so machen. Man könnte sagen: Hier auf Erden haben wir wägbare feste Dinge [violette Bogen], und an diesen wägbaren festen Dingen haftet gewissermaßen die Röte, die Gelbe, also dasjenige, was die Sinne an den Körpern wahrnehmen. Wenn wir schlafen, dann ist die Gelbe frei schwebendes Wesen, die Röte ist frei schwebendes Wesen, nicht haftend an solchen Schwerebedingungen, sondern frei webend und schwebend. Ebenso ist es mit dem Ton: nicht die Glocke klingt, sondern das Klingen webt.

Und nicht wahr, wenn wir in unserer physischen Welt herumgehen, irgend etwas sehen, so heben wir es auf; dann ist es eigentlich erst ein Ding, sonst könnte es auch eine Augentäuschung sein. Das Gewicht muß hinzukommen. Daher ist man so geneigt, etwas, was im Physischen erscheint, ohne daß man es als schwer empfindet — wie die Farben des Regenbogens -, als eine Augentäuschung zu betrachten. Wenn Sie heute ein Physikbuch aufschlagen, so ist es so, daß man da erklärt: Das ist eine Augentäuschung. — Als das eigentlich Reale sieht man den Regentropfen an. Und da zeichnet man Linien hinein, die eigentlich gar nichts bedeuten für das, was da ist, aber die man sich so durch den Raum hin denkt; man nennt sie dann Strahlen. Aber die Strahlen sind gar nicht da. Dann sagt man: Das Auge projiziert sich das hinaus. — Dieses ProjJizieren ist ja überhaupt etwas, was in einer sehr sonderbaren Weise heute in der Physik angewendet wird. Also ich greife die Vorstellung auf: Wir sehen einen roten Gegenstand. Um uns zu überzeugen, daß es keine Augentäuschung ist, heben wir ihn, und er ist schwer: dadurch verbürgt er seine Realität.

Derjenige, der sich nun im Ich und im astralischen Leibe außerhalb des physischen und des Ätherleibes bewußt wird, der kommt auch endlich darauf, daß so etwas da drinnen schon ist in diesem frei schwebenden und frei webenden Farbigen, Tönenden; aber es ist anders. Es ist in einem so frei schwebenden Farbigen die Tendenz, in die Weiten der Welt hinaus sich zu entfernen; es hat eine entgegengesetzte Schwere. Diese Dinge der Erde, die wollen da herunter nach dem Mittelpunkt der Erde [siehe Zeichnung Seite 200, Pfeile abwärts], jene [Pfeile aufwärts] wollen frei hinaus in den Weltenraum.

Und es ist auch schon so etwas Ähnliches da wie ein Maß. Man kommt nämlich darauf, wenn man irgendwo, sagen wir, eine kleine rötliche Wolke hat, und diese kleine rötliche Wolke ist meinetwillen eingesäumt von einem mächtigen gelben Gebilde: Dann mißt man, aber nicht mit dem Maßstab, sondern qualitativ mißt man mit dem Roten, mit dem stärker Scheinenden das schwächer scheinende Gelbe. Und so wie Ihnen der Maßstab sagt: Das sind fünf Meter -, so sagt Ihnen hier das Rote [siehe Zeichnung]: Wenn ich mich ausbreiten würde, gehe ich fünfmal in das Gelbe hinein. Ich muß mich weiten, ich muß mächtiger werden, dann werde ich auch gelb. — So geschehen die Messungen hier.

Noch schwieriger ist das Zählen hier klarzumachen, weil wir beim irdischen Zählen ja doch zumeist nur Erbsen oder Apfel zählen, die gleichgültig nebeneinander liegen. Und wir haben immer das Gefühl, wenn wir aus der Eins zweie machen, so ist es dieser Eins eigentlich ganz gleichgültig, daß noch eine Zwei neben ihr ist. Im menschlichen Leben wird es ja schon anders; da ist es zuweilen so, daß Eins auf das Zwei angewiesen ist. Doch das geht ja auch schon in das Geistige hinein. Aber bei der eigentlichen physischen Mathematik ist es immer den Einteilungen gleichgültig, was sich zu ihnen gesellt. Das ist hier nicht der Fall.

Wenn hier irgendwo eine Eins [siehe Zeichnung] ist von einer bestimmten Art, so fordert das irgendwelche, sagen wir, drei oder fünf andere, je nachdem es ist. Das hat immer inneren Bezug zu den anderen, da ist die Zahl eine Realität. Und wenn ein Bewußtsein anfängt darüber, wie es ist, wenn man mit dem Ich und mit dem astralischen Leib da draußen ist, dann kommt man schon auch dahin, etwas wie Maß, Zahl und Gewicht zu bestimmen, aber nach entgegengesetzter Art.

Und dann, wenn einem das Schauen und Hören da draußen nicht mehr ein bloßes Schwimmeln und Schwummeln von Rot und Gelb und Tönen ist, sondern wenn man anfängt, auch da drinnen die Dinge so geordnet zu empfinden, dann beginnt das Wahrnehmen der geistigen Wesenheiten, die sich in diesen frei schwebenden Sinnesempfindungen verwirklichen, realisieren. Dann kommen wir hinein in die positive geistige Welt, in das Leben und Treiben der geistigen Wesenheiten. Wie wir hier auf Erden hineinkommen ins Leben und Treiben der irdischen Dinge, indem wir sie mit der Waage, mit dem Maßstab, mit unserer Rechnerei bestimmen, so kommen wir dadurch, daß wir uns aneignen das bloß qualitative, entgegengesetzte Schwersein, das heißt, mit Leichtigkeit sich ausdehnen wollen im Weltenraum, das Messen von Farbe durch Farbe und so weiter, hinein in das Erfassen von geistigen Wesenheiten. Solche geistigen Wesenheiten durchsetzen nun auch alles das, was draußen in den Reichen der Natur ist.

Mit dem wachen Bewußtsein sieht der Mensch nur die Außenseite der Mineralien, der Pflanzen, der Tiere. Aber bei dem, was in allen diesen Wesen der Naturreiche lebt als Geistiges, bei dem ist der Mensch, wenn er schläft. Und wenn er dann beim Aufwachen wiederum in sich zurückgeht, dann behalten sein Ich und sein astralischer Leib gewissermaßen die Neigung, die Affinität zu den äußeren Dingen und veranlassen den Menschen, daß er eine Außenwelt anerkennt. Wenn der Mensch eine Organisation hätte, die nicht zum Schlaf eingerichtet wäre, so würde er nicht eine Außenwelt anerkennen. Es kommt natürlich nicht darauf an, daß einer an Schlaflosigkeit leidet. Denn ich sage nicht, wenn der Mensch nicht schläft, sondern wenn der Mensch nicht eine Organisation hätte, die zum Schlafen eingerichtet wäre. Es handelt sich um das Eingerichtetsein zu etwas. Daher wird ja auch der Mensch krank, wenn er an Schlaflosigkeit leidet, weil das eben seiner Wesenheit nicht angepaßt ist. Aber die Dinge sind eben so: Gerade dadurch, daß der Mensch schlafend verweilt bei dem, was in der Außenwelt ist, bei dem, was er dann wachend seine Außenwelt nennt, dadurch kommt er auch zu einer Außenwelt, zu einer Anschauung von der Außenwelt.

Dieses Verhältnis des Menschen zum Schlaf, das gibt den irdischen Wahrheitsbegriff. Inwiefern? Nun, wir nennen es Wahrheit, wenn wir im Inneren ein Äußeres richtig nachbilden können, wenn wir ein Äußeres richtig im Inneren erleben. Dazu aber bedürfen wir der Einrichtung des Schlafes. Wir würden gar keinen Wahrheitsbegriff haben, wenn wir nicht die Einrichtung des Schlafens hätten. So daß wir sagen können: Dem Schlafzustand verdanken wir die Wahrheit. Wir müssen, um uns der Wahrheit der Dinge hinzugeben, mit den Dingen auch unser Dasein in einer gewissen Zeit verbringen. Die Dinge sagen uns von sich nur dadurch etwas, daß wir während des Schlafens mit unserer Seele bei ihnen sind.

Anders ist es mit dem Traumzustand. Der Traum ist ja, wie ich Ihnen in dem kleinen Zyklus während der Delegiertenversammlung ausgeführt habe, verwandt mit der Erinnerung, mit dem inneren Seelenleben, mit dem, was ja vorzugsweise in der Erinnerung lebt. Wenn der Traum frei schwebende Ton-Farbenwelt ist, so sind wir noch halb draußen aus unserem Leibe. Wenn wir ganz untertauchen, dann werden dieselben. Kräfte, die wir webend-lebend im Traume entfalten, Erinnerungskräfte. Da unterscheiden wir uns nicht mehr in derselben Weise von der Außenwelt. Da fällt unser Inneres zusammen mit der Außenwelt, da leben wir mit unseren Sympathien und Antipathien so stark in der Außenwelt, daß wir nicht die Dinge als sympathisch oder antipathisch empfinden, sondern daß die Sympathien und Antipathien selber sich bildhaftig zeigen.

Hätten wir nicht die Möglichkeit zu träumen und die Fortsetzung dieser Traumeskraft in unserem Inneren, so hätten wir keine Schönheit. Daß wir überhaupt Anlagen für die Schönheit haben, das beruht darauf, daß wir träumen können. Für das prosaische Dasein müssen wir sagen: Wir verdanken es der Traumeskraft, daß wir eine Erinnerung haben; für das künstlerische Dasein des Menschen verdanken wir der Traumeskraft die Schönheit. Also: Traumzustand hängt zusammen mit der Schönheit. Die Art, wie wir ein Schönes empfinden und ein Schönes schaffen, ist nämlich sehr ähnlich der webenden wirkenden Kraft des Träumens.

Wir verhalten uns beim Erleben des Schönen, beim Schaffen des Schönen — nur eben unter Anwendung unseres physischen Leibes - ähnlich, wie wir uns verhalten außer unserem physischen Leibe, oder halb verbunden mit unserem physischen Leibe, beim Träumen. Es ist eigentlich zwischen dem Träumen und dem Leben in Schönheit nur ein kleiner Ruck. Und nur weil in der heutigen materialistischen Zeit die Menschen so grob veranlagt sind, daß sie diesen Ruck nicht bemerken, ist so wenig Bewußtsein vorhanden von der ganzen Bedeutung der Schönheit. Man muß im Traume sich dem notwendig hingeben, um dieses Freischweben und -weben zu erleben. Während dann, wenn man sich der Freiheit, dem inneren Willkürgebaren hingibt, also nach dem Ruck lebt, man nicht mehr die Empfindung hat, daß es dasselbe ist wie das Träumen, da es nur unter Anwendung der Kräfte des physischen Leibes eben dasselbe ist.

Die heutigen Menschen werden lange nachdenken, was man in älteren Zeiten gemeint hat, wenn man «Chaos» gesagt hat. Es gibt die mannigfaltigsten Definitionen von Chaos. In Wirklichkeit kann das Chaos nur so charakterisiert werden, daß man sagt: Wenn der Mensch in einen Bewußtseinszustand kommt, wo das Erleben der Schwere, des irdischen Maßes, gerade aufhört, und die Dinge anfangen, halb leicht zu werden, aber noch nicht hinaus wollen in das Weltenall, sondern noch sich in der Horizontale, im Gleichgewicht erhalten, wenn die festen Grenzen verschweben, wenn also noch mit dem physischen Leib, aber schon mit der Seelenkonstitution des Träumens das webende Unbestimmte der Welt geschaut wird, dann schaut man das Chaos. Und der Traum ist bloß das schattenhafte Heranschweben des Chaos an den Menschen.

In Griechenland noch hatte man die Empfindung: Schön machen kann man eigentlich die physische Welt nicht. Die physische Welt ist halt Naturnotwendigkeit, sie ist, wie sie ist. Schön machen kann man nur dasjenige, was chaotisch ist. Wenn man das Chaos in den Kosmos wandelt, dann entsteht die Schönheit. Daher sind Chaos und Kosmos Wechselbegriffe. Man kann den Kosmos — das bedeutet eigentlich die schöne Welt — nicht aus den irdischen Dingen herstellen, sondern nur aus dem Chaos, indem man das Chaos formt. Und dasjenige, was man mit irdischen Dingen macht, ist bloß ein Nachahmen im Stoffe des geformten Chaos.

Das ist so bei allem Künstlerischen der Fall. Von diesem Verhältnis des Chaos zum Kosmos hatte man in Griechenland, wo die Mysterienkultur noch einen gewissen Einfluß hatte, noch eine sehr lebhafte Vorstellung.

Wenn man aber in allen diesen Welten herumkommt - in der Welt, in welcher der Mensch unbewußt ist, wenn er im Schlafzustande ist, in der Welt, in welcher der Mensch halbbewußt ist, wenn er im Traumzustand ist —, wenn man da überall herumwandelt: das Gute findet man nicht. Diese Wesenheiten, die da drinnen sind, sie sind vom Urbeginne ihres Lebenslaufes weisheitsvoll vorherbestimmt. Man findet in ihnen waltende, webende Weisheit, man findet in ihnen Schönheit. Aber es hat keinen Sinn, wenn es sich darum handelt, diese Wesenheiten, die wir als Erdenmensch erreichen, kennenzulernen, von Güte bei ihnen zu sprechen. Von Güte können wir erst sprechen, wenn der Unterschied da ist zwischen Innen- und Außenwelt, so daß das Gute der geistigen Welt folgen kann oder nicht folgen kann.

So wie der Schlafzustand der Wahrheit, der Traumzustand der Schönheit, so ist der Wachzustand der Güte, dem Guten zugeteilt.

Schlafzustand: Wahrheit

Traumzustand: Schönheit, Chaos

Wachzustand: Güte

Das aber widerspricht nicht dem, was ich in diesen Tagen gesagt habe, daß, wenn man das Irdische verläßt und hinauskommt in den Kosmos, man veranlaßt ist, auch die irdischen Begriffe fallenzulassen, um von moralischer Weltenordnung zu sprechen. Denn die moralische Weltenordnung, die ist im Geistigen ebenso vorherbestimmt, notwendig vorherbestimmt, wie hier auf Erden die Kausalität. Nur ist sie eben dort geistig: die Vorbestimmung, das In-sich-bestimmt-Sein. Also da ist kein Widerspruch.

Aber für die menschliche Natur müssen wir uns klar sein: Wollen wir die Idee der Wahrheit haben, dann müssen wir uns an den Schlafzustand wenden; wollen wir die Idee der Schönheit haben, dann müssen wir uns an den Traumzustand wenden; wollen wir die Idee der Güte haben, dann müssen wir uns an den Wachzustand wenden.

Der Mensch hat also, wenn er wach ist, nicht eine Bestimmung zu seinem physischen und ätherischen Organismus nach der Wahrheit, sondern die Bestimmung nach der Güte. Da müssen wir also erst recht auf die Idee der Güte kommen.

Nun frage ich Sie: Was erstrebt denn die Wissenschaft der Gegenwart, wenn sie den Menschen erklären will? Sie will ja nicht aufsteigen, indem sie den wachen Menschen erklären will, von der Wahrheit durch die Schönheit zur Güte, sie will ja alles nach einer äußeren kausalen Notwendigkeit, die nur der Idee der Wahrheit entspricht, erklären. Da kommt man gar nicht zu dem, was im Menschen wachend webt und lebt, da kommt man nur zu dem, was der schlafende Mensch höchstens ist. Wenn Sie daher heute Anthropologien lesen und es mit wachem Auge tun, wach für die Seeleneigentümlichkeiten und Kräfte der Welt, dann bekommen Sie folgenden Eindruck. Sie sagen sich: Das ist ja alles recht schön, was uns da erzählt wird von der heutigen Wissenschaft über den Menschen. Aber wie ist denn dieser Mensch eigentlich, von dem uns diese Wissenschaft erzählt? Er liegt fortwährend im Bett. Er kann nämlich nicht gehen. Bewegen kann er sich nicht. Die Bewegung zum Beispiel wird absolut gar nicht erklärt. Er liegt fortwährend im Bett.

Der Mensch, den die Wissenschaft erklärt, der kann nur als ein im Bett liegender Mensch erklärt werden. Es geht gar nicht anders. Die Wissenschaft erklärt nur den schlafenden Menschen. Wenn man ihn in Bewegung bringen will, dann müßte man das mechanisch tun. Deshalb ist sie auch ein wissenschaftlicher Mechanismus. Da muß man in diesen schlafenden Menschen eine Maschinerie hineinbringen, die diesen Plumpsack, wenn er aufstehen soll, in Schwung bringt und abends wiederum in das Bett legt.

Also diese Wissenschaft sagt uns überhaupt nichts vom Menschen, der da herumgeht in der Welt, der da webt und lebt, der da wacht. Denn was ihn in Bewegung setzt, das ist enthalten in der Idee der Güte, nicht in der Idee der Wahrheit, die wir von den äußeren Dingen zunächst gewinnen. Das ist etwas, was ziemlich wenig bedacht wird. Man hat das Gefühl, wenn einem der heutige Physiologe oder der heutige Anatom den Menschen beschreibt, daß man gerne sagen möchte: Wach auf, wach auf, du schläfst ja, du schläfst! Die Leute gewöhnen sich unter dem Einfluß dieser Weltanschauung eben den Schlafzustand an. Und was ich immer charakterisieren mußte: daß eigentlich die Menschen alles Mögliche verschlafen, das ist, weil sie von der Wissenschaft besessen sind. Heute ist ja — weil die populären Zeitschriften alles überall hinaustragen — auch schon der Ungebildete von der Wissenschaft besessen. Es hat nie so viel Besessene gegeben als heute, sie sind von der Wissenschaft besessen. Es ist ganz eigentümlich, wie man reden muß, wenn man die realen Verhältnisse der heutigen Zeit zu schildern hat. Man muß in ganz andere Töne verfallen als in diejenigen, die heute gang und gäbe sind.

So ist es ja auch, wenn nun der Mensch ein wenig von den Materialisten in die Umgebung hineingestellt wird. Als die materialistische Hochflut war, da haben die Leute solche Bücher geschrieben, wie zum Beispiel eines, das austönte in einem bestimmten Kapitel, in dem es heißt: Der Mensch ist eigentlich an sich nichts. Er ist das Ergebnis des Sauerstoffes der Luft, er ist das Ergebnis des Kältegrades oder des Wärmegrades, unter dem er ist. Er ist eigentlich — so endet pathetisch diese materialistische Schilderung — ein Ergebnis jedes Zuges der Luft.

Geht man auf eine solche Beschreibung ein und stellt man sich den Menschen vor, der das wirklich ist, was der materialistische Forscher da beschreibt, dann ist es nämlich im höchsten Grade ein Neurastheniker. Die Materialisten haben nie andere Menschen beschrieben. Wenn sie schon nicht bemerkten, daß sie eigentlich den Menschen schlafend schilderten, wenn sie sozusagen aus der Rolle gefallen sind und weitergehen wollten, haben sie nie andere Menschen beschrieben als hochgradige Neurastheniker, die schon am nächsten Tag sterben müssen vor lauter Neurasthenie, die gar nicht leben können. Denn den lebendigen Menschen hat eben diese Epoche der Wissenschaft niemals ergriffen.

Da liegen die großen Aufgaben, welche die Menschen aus den Zuständen der Gegenwart wiederum herausführen müssen in solche Zustände, unter denen das weitere Leben der Weltgeschichte einzig und allein möglich ist. Was gebraucht wird, das ist ein Eindringen in die Geistigkeit. Es muß der andere Pol gefunden werden zu dem, was erlangt worden ist. Was ist denn eigentlich erlangt worden gerade im Laufe des für die materialistische Weltanschauung gloriosen 19. Jahrhunderts? Was ist denn erlangt worden?

In einer wunderbaren Weise — es kann ganz aufrichtig und ehrlich gesagt werden - ist es gelungen, die äußere Welt nach Maß, Zahl und Gewicht zu bestimmen als irdische Welt. Darin hat das 19. Jahrhundert und der Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts Großartiges, Gewaltiges geleistet. Aber die Sinnesempfindungen, die Farben, die Töne, die flattern so herum im Unbestimmten. Die Physiker haben ja ganz aufgehört, von Farben und Tönen zu reden; sie reden von Luftschwingungen und Atherschwingungen, die sind ja nicht Farben und auch nicht Töne. Die Luftschwingungen sind doch keine Töne, sondern sie sind höchstens das Medium, auf dem die Töne sich fortpflanzen. Und es ist gar keine Erfassung da von dem, was die Sinnesqualitäten sind. Dazu muß man erst wiederum kommen. Eigentlich sieht man heute nur, was mit der Waage, mit dem Maßstab, mit der Rechnung sich bestimmten läßt. Das andere ist einem entschwebt.

Und wenn nun die Relativitätstheorie auch die Ihnen gestern beschriebene grandiose Unordnung hineinbringt in das, was sich messen, wägen, zählen läßt, dann zerklüftet sich alles, dann geht alles auseinander. Aber schließlich, an gewissen Grenzen scheitert schon diese Relativitätstheorie. Nicht gegenüber den Begriffen — mit den irdischen Begriffen entkommt man der Relativitätstheorie nicht; das habe ich an einem anderen Orte schon einmal auseinandergesetzt —, aber mit der Realität entkommt man immer den Relativitätsbegriffen. Denn was sich messen, zählen, wägen läßt, das geht durch Maß, Zahl und Gewicht ganz bestimmte Beziehungen ein in der äußeren sinnlichen Wirklichkeit.

Es war in Stuttgart, da hat einmal ein Physiker, oder eine Reihe von Physikern Anstoß genommen an der Behandlung der Relativitätstheorie von seiten der Anthroposophen. Dann hat er in einer Diskussion das einfache Experiment vorgeführt, daß es eigentlich ganz gleichgültig ist, ob ich hier die Zündholzschachtel habe und mit dem Zündholz darüber streiche: es brennt; oder ob ich das Zündholz festhalte und mit der Schachtel darüber streiche: dann brennt es auch. Es ist relativ.

Gewiß, hier ist es noch relativ. Und in bezug auf alles, was auf einen Newtonschen Raum bezogen wird, oder auf einen Euklidischen Raum, ist das alles relativ. Aber sobald jene Realität in Betracht kommt, die als Schwere, als Gewicht auftritt, da geht es nicht mehr so leicht, wie der Einstein es sich vorgestellt hat, denn da treten dann reale Verhältnisse auf. Man muß da wirklich wiederum paradox reden. Die Relativität läßt sich eben dann geltend machen, wenn man die ganze Wirklichkeit mit Mathematik und Geometrie und Mechanik verwechselt. Aber wenn man auf die wahre Wirklichkeit eingeht, dann geht das nicht mehr. Denn es ist ja schließlich doch nicht bloß relativ, ob man den Kalbsbraten ißt, oder ob der Kalbsbraten einen ißt! Mit der Zündholzschachtel läßt sich das machen, hin- und herzufahren, aber den Kalbsbraten muß man essen, man kann sich nicht von dem Kalbsbraten aufessen lassen. Es sind eben da Dinge, die diesen Relativitätsbegriffen Grenzen setzen. Diese Dinge sind so, daß wenn sie nun nach außen erzählt werden, man sagen wird: Da ist nicht das geringste Verständnis für diese ernste Theorie. — Aber die Logik ist doch schon so, wie ich sie sage: Es ist nicht anders, ich kann es nicht anders machen.

Also es handelt sich darum, zu sehen, wie man durch die Berücksichtigung des Gewichtes — also dessen, was eigentlich die physischen Körper macht —, wie man da in der Wirklichkeit, möchte ich sagen, Farben, Töne und so weiter nirgendwo unterbringt. Aber mit dieser Tendenz entfällt einem etwas außerordentlich Wichtiges. Es entfällt einem nämlich das Künstlerische. Indem wir immer physikalischer und physikalischer werden, nimmt das Künstlerische von uns Abschied. Kein Mensch wird heute in dem, was die Physikbücher schildern, noch eine Spur von Kunst finden. Da ist nichts mehr von Kunst, da muß alles, alles heraus. Es ist ja schauderhaft, heute überhaupt ein Physikbuch zu studieren, wenn man noch eine Spur von Schönheitsgefühl hat. Dadurch, daß alles, woraus die Schönheit gewoben wird, aus Farbe und Ton, dadurch, daß das alles vogelfrei wird, daß es nur anerkannt wird, wenn es an den schweren Dingen haftet, gerade dadurch entfällt den Menschen die Kunst. Heute entfällt sie einem. Und je physischer die Menschen werden, desto unkünstlerischer werden sie! Denken Sie doch einmal: Wir haben eine großartige Physik. Dazu bedarf es wahrhaftig nicht des Zurechtweisens der Gegner, daß man auf anthroposophischem Felde sagt: Wir haben eine großartige Physik. — Aber die Physik lebt von der Verleugnung des Künstlerischen. Sie lebt in jedem einzelnen von der Verleugnung des Künstlerischen, denn sie ist angelangt bei einer Art, die Welt zu behandeln, bei der sich der Künstler gar nicht mehr kümmert um den Physiker.

Ich glaube zum Beispiel nicht, daß der Musiker heute großen Wert darauf legt, die physikalischen Theorien der Akustik zu studieren. Das ist ihm zu langweilig, es kümmert ihn nicht. Der Maler wird auch nicht gern diese schreckliche Farbenlehre, die in der Physik enthalten ist, studieren. Er wendet sich in der Regel, wenn er sich überhaupt um Farben kümmert, noch zur Goetheschen Farbenlehre. Aber die ist ja falsch nach der Ansicht der Physiker. Die Physiker drücken ein Auge zu und sagen: Nun ja, das ist ja nicht so wesentlich, ob der Maler eine richtige oder eine falsche Farbenlehre hat. - Es ist eben so, daß unter der physikalischen Weltanschauung von heute die Kunst zugrunde gehen muß. Nun müssen wir uns die Frage vorlegen: Warum war denn in älteren Zeiten eine Kunst da?

Wenn wir in ganz alte Zeiten zurückgehen, in die Zeiten, in denen die Menschen noch ein ursprüngliches Hellsehen hatten, da war es so, daß nämlich die Menschen nicht so viel merkten von Maß, Zahl und Gewicht in den irdischen Dingen. Es kam ihnen gar nicht so sehr auf Maß, Zahl und Gewicht an, sie gaben sich mehr den Farben, den Tönen der irdischen Dinge hin.

Denken Sie doch nur einmal, daß ja die Chemie erst seit Lavoisier mit dem Gewicht rechnet; das ist etwas mehr als hundert Jahre! Das Gewicht wurde ja erst angewendet auf eine Weltanschauung am Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts. Es war eben bei der älteren Menschheit das Bewußtsein nicht vorhanden, daß alles nach irdischem Maß, Zahl und Gewicht bestimmt werden muß. Man war mit seinem Gemüte hingegeben dem Farbenteppich der Welt, den Tonwebungen und -wellungen; nicht den Luftschwingungen, sondern den Tonwellungen und -webungen, denen war man hingegeben. Man lebte darin, auch indem man in der physischen Welt lebte.

Aber welche Möglichkeit hatte man denn dadurch, daß man in diesem schwerefreien sinnlichen Wahrnehmen lebte? Dadurch hatte man die Möglichkeit, wenn man zum Beispiel an den Menschen herankam, den Menschen gar nicht so zu sehen, wie man ihn heute sieht, sondern man sah sich den Menschen an wie ein Ergebnis des ganzen Weltenalls. Der Mensch war mehr ein Zusammenfluß des Kosmos. Er war mehr ein Mikrokosmos als dasjenige, was innerhalb seiner Haut da auf diesem kleinen Fleck Erde steht, wo der Mensch steht. Man dachte sich im Menschen mehr ein Abbild der Welt. Da flossen die Farben von allen Seiten so zusammen, gaben dem Menschen die Farben. Die Weltenharmonie war da, durchtönte den Menschen, gab dem Menschen die Gestalt.

Und von der Art und Weise, wie alte Mysterienlehrer zu ihren Schülern sprachen, kann ja die Menschheit heute kaum etwas verstehen. Denn wenn heute ein Mensch das menschliche Herz erklären will, so nimmt er einen Embryo und sieht, wie da die Blutgefäße sich aussacken, und wie da ein Schlauch zunächst entsteht und dann das Herz sich allmählich formt. Ja, so haben die alten Mysterienlehrer zu ihren Schülern nicht gesagt! Das hätte ihnen nicht viel wichtiger geschienen, als wenn man sich einen Strumpf strickt, weil ja schließlich der Vorgang so ganz ähnlich ausschaut. Dagegen haben sie etwas anderes als ein ungeheuer Wichtiges hervorgehoben. Sie haben gesagt: Das menschliche Herz ist ein Ergebnis des Goldes, das im Lichte überall lebt, und das von dem Weltenall hereinströmt und eigentlich das menschliche Herz bildet. Sie haben die Vorstellungen gehabt: Da webt durch das Weltenall das Licht, und das Licht trägt das Gold. Überall im Lichte ist das Gold, das Gold webt und lebt im Lichte. Und wenn der Mensch im irdischen Leben steht, dann ist sein Herz — Sie wissen ja, nach sieben Jahren ändert es sich — nicht aus den Gurken und aus dem Salat und aus dem Kalbsbraten aufgebaut, die der Mensch inzwischen gegessen hat, sondern da wußten diese alten Lehrer: das ist aus dem Golde des Lichtes aufgebaut. Und die Gurken und der Salat, die sind nur die Anregung dazu, daß das im Lichte webende Gold vom ganzen Weltenall das Herz aufbaut.

Ja, die Leute haben anders geredet, und man muß sich dieses Gegensatzes bewußt werden, denn man muß ja wieder lernen, so zu reden, nur eben auf einer anderen Bewußtseinsstufe. Dasjenige, was zum Beispiel auf dem Gebiete der Malerei einmal da war, was dann verschwunden ist, wo man noch aus dem Weltenall heraus gemalt hat, weil man noch nicht die Schwere hatte, das hat seine letzte Spur zurückgelassen — sagen wir zum Beispiel bei Cimabue und namentlich bei der Inkonenmalerei der Russen. Die Ikone ist noch aus der Außenwelt, aus dem Makrokosmos gemalt; sie ist gewissermaßen ein Ausschnitt aus dem Makrokosmos. Dann aber war man einmal bei der Sackgasse angelangt. Da konnte man nicht weiter, weil einfach für die Menschheit diese Anschauung nicht mehr da ist. Hätte man malen wollen die Ikone mit innerem Anteil, nicht bloß aus der Tradition und aus dem Gebet heraus, dann hätte man wissen müssen, wie man das Gold behandelt. Die Behandlung des Goldes auf dem Bilde, das war ja eines der größten Geheimnisse der alten Malerei. Heraufzubringen dasjenige, was am Menschen gestaltet ist, aus dem Hintergrunde des Goldes, das war die alte Malerei.

Es liegt ein ungeheurer Abgrund zwischen Cimabue und Giotto. Denn Giotto begann bereits mit dem, was dann Raffael auf besondere Höhe gebracht hat. Cimabue hatte es noch durch Tradition, Giotto wurde schon halber Naturalist. Er merkte: Die Tradition wird nicht mehr innerlich in der Seele lebendig. Jetzt muß man den physischen Menschen nehmen, jetzt hat man nicht mehr das Weltenall. Man kann nicht mehr aus dem Golde heraus malen, man muß aus dem Fleische heraus malen.

Das ist endlich so weit gekommen, daß ja schließlich die Malerei zu dem übergegangen ist, was sie im 19. Jahrhundert vielfach gehabt hart. Die Ikonen, die haben ja gar keine Schwere, die Ikonen sind «hereingescheint» aus der Welt; die haben ja keine Schwere. Man kann sie nur heute nicht mehr malen, aber wenn man sie in ursprünglicher Gestalt malte, hätten sie überhaupt kein Gewicht.

Giotto fing zuerst an, die Dinge so zu malen, daß sie Gewicht haben. Daraus wurde dann, daß alles, was man malt, auch auf dem Bilde Gewicht hat, und man streicht es dann von außen an; so daß sich die Farben zu dem verhalten, was gemalt ist, wie der Physiker erklärt, daß die Farbe da an der Oberfläche durch irgendeine besondere Wellenschwingung entsteht. Es hat die Kunst schließlich auch mit dem Gewichte gerechnet. Nur fing Giotto das in ästhetisch-künstlerischer Weise an, und Raffael brachte es dann auf die höchste Höhe.

So daß man sagen kann: Da ist das Weltenall gewichen aus dem Menschen, und der schwere Mensch wurde dasjenige, was man jetzt nur noch sehen konnte. Und weil noch die Gefühle der alten Zeit da waren, so wurde sozusagen das Fleisch möglichst wenig schwer, aber es wurde schwer. Und da entstand die Madonna als Gegensatz der Ikone: die Ikone, die kein Gewicht hat, die Madonna, die ja Gewicht hat, wenn sie auch schön ist. Die Schönheit hat sich noch erhalten. Aber Ikonen sind überhaupt nicht mehr malbar, weil der Mensch sie nicht erlebt. Und es ist eine Unwahrheit, wenn die Menschen heute glauben, daß sie Ikonen erleben. Daher auch die Ikonenkultur eben in eine gewisse sentimentale Unwahrheit eingetaucht war. Das ist eine Sackgasse in der Kunst, das wird schematisch, das wird traditionell.

Die Malerei Raffaels, die Malerei, die sich eigentlich auf dem aufbaut, was Giotto aus dem Cimabue gemacht hat, diese Malerei, die kann nur so lange Kunst bleiben, solange noch der alte Glanz der Schönheit auf sie strahlt. Gewissermaßen waren es die sonnigen Renaissancemaler, die noch etwas empfunden haben von dem im Lichte webenden Gold und wenigstens ihren Bildern den Glanz gaben, mit dem im Lichte webenden Gold sie von außen überstrahlen ließen.

Aber das hörte auf. Und so ist der Naturalismus geworden. Und so sitzt heute die Menschheit künstlerisch zwischen zwei Stühlen auf der Erde, zwischen der Ikone und der Madonna, und ist darauf angewiesen, dasjenige zu entdecken, was die reine webende Farbe, der reine webende Ton ist, mit ihrem entgegengesetzten Gewicht, entgegengesetzt der Meßbarkeit, der wägbaren Zählbarkeit. Wir müssen lernen, aus der Farbe heraus zu malen. Treffen wir das heute versuchsweise auch noch so anfänglich und schlecht, es ist unsere Aufgabe, aus der Farbe heraus zu malen, die Farbe selber zu erleben, losgelöst von der Schwere die Farbe selber zu erleben. In diesen Dingen muß man bewußt, auch künstlerisch bewußt, vorgehen können.

Und wenn Sie sich ansehen, was erstrebt wurde in den einfachen Versuchen unserer Programme, dann werden Sie sehen: da ist, wenn es auch nur ein Anfang ist, eben doch der Anfang gemacht, die Farben loszubekommen von der Schwere, die Farbe als ein in sich selbst tragendes Element zu erleben, zum Sprechen zu bringen die Farben. Wenn das gelingt, dann wird gegenüber der unkünstlerischen physikalischen Weltanschauung, die alle Kunst ausdampfen läßt, aus dem freien Elemente der Farbe, des Tones eine Kunst geschaffen, die wiederum frei ist von Schwere.

Ja, wir sitzen auch zwischen zwei Stühlen, zwischen der Ikone und der Madonna, aber wir müssen aufstehen. Dazu hilft uns die physische Wissenschaft nicht. Ich habe Ihnen gesagt: Man muß ja immer liegenbleiben, wenn man nur die physische Wissenschaft anwendet auf den Menschen. Nun müssen wir aber aufstehen! Dazu brauchen wir wirklich Geisteswissenschaft. Die enthält das Lebenselement, das uns hinträgt von der Schwere zur schwerelosen Farbe, zur Realität der Farbe, von dem Gebundensein selbst schon im musikalischen Naturalismus zu der freien musikalischen Kunst und so weiter.

Auf allen Gebieten sehen wir, wie es sich handelt um ein Sich-Aufraffen, um ein Erwachen der Menschheit. Das ist es, daß wir aufnehmen sollten diesen Impuls zum Erwachen, zum Hinausschauen, zum Erblicken dessen, was ist und was nicht ist, und wo überall die Aufforderungen liegen, weiter vorzuschreiten. Deshalb war es, daß ich eigentlich jetzt vor dieser Sommerpause, die durch die englische Reise bedingt ist, wollen mußte, sowohl bei der Delegiertenversammlung wie jetzt in diesen Tagen, gerade mit solchen Betrachtungen abzuschließen, wie ich sie Ihnen gebracht habe. Diese Dinge gehen schon an den Nerv unserer Zeit. Und das ist notwendig, daß man das andere so hereinscheinen läßt in unsere Bewegung, wie ich versucht habe es anzudeuten.

Ich habe geschildert, wie der Philosoph der Neuzeit dazu gekommen ist, sich zu gestehen: Wozu führt denn dieser Intellektualismus? Eine Riesenmaschine zu bauen, die man in den Mittelpunkt der Erde versetzt, um von da aus die Erde in alle Räume des Weltenalls hinauszusprengen! Er gestand sich, daß das so ist. Die anderen gestehen es sich nicht!

Und so habe ich versucht an den verschiedensten Stellen — zum Beispiel als ich Ihnen gestern zeigte, wie die Begriffe, die noch vor dreißig, vierzig Jahren da waren, heute durch die Relativitätstheorie aufgelöst werden, einfach hinschmelzen wie der Schnee an der Sonne -, so habe ich versucht, Ihnen zu zeigen, wie überall die Aufforderungen liegen, zur Anthroposophie doch wirklich hinzustreben. Denn es sagt doch der Philosoph Eduard von Hartmann: Wenn die Welt so ist, wie wir uns sie vorstellen müssen — das heißt, wie er sie nach dem Sinn des 19. Jahrhunderts vorstellt -, dann müssen wir eigentlich, weil wir es nicht in ihr aushalten können, sie in den Weltenraum hinaussprengen, und es handelt sich nur darum, daß wir einmal so weit sind, daß wir es ausführen können. Diese Zeit müssen wir herbeisehnen, wo wir die Welt in alle Weiten des Universums versprengen können. — Vorher sorgen dann noch die Relativisten dafür, daß die Menschen keine Begriffe mehr haben! Raum, Zeit, Bewegung lösen sich auf, dann kann man ohnedies schon so in Verzweiflung kommen, daß man unter gewissen Voraussetzungen das höchste Befriedigende schon sieht in diesem Hinaussprengen in das ganze Universum. Aber man muß sich eben in klarer Weise bekanntmachen mit dem, was als gewisse Impulse in unserer Zeit liegt.

Mass, Number, and Weight—The Weightless Color as a Requirement of New Developments in Painting

During their earthly existence, human beings alternate between states of consciousness that we have already considered from various perspectives in recent days: between states of complete wakefulness, sleep, and dreaming. And I have just tried to explain the whole significance of dreaming in the short series of lectures during the delegates' meeting. Today, let us first ask ourselves the question: Is it part of the essence of human beings to live in these three states of consciousness as earthly beings?

We must be clear that within earthly existence, only human beings live in these three states of consciousness. Animals live in a fundamentally different cycle. Animals do not experience the deep, dreamless sleep that humans have for most of the time between falling asleep and waking up, but neither do they have the complete wakefulness that humans have between waking up and falling asleep. The animal state of wakefulness is actually somewhat similar to human dreaming. Only the conscious experiences of higher animals are more definite, more saturated, I would say, than the fleeting human dreams. But on the other hand, animals are never as unconscious as humans are in deep sleep.

Animals therefore do not differ from their environment to the same extent as humans. Animals do not have an external world and an internal world in the same way that humans do. If we translate what lives as a dull consciousness in higher animals into human language, animals actually relate to the outside world with their entire inner being.

When an animal sees a plant, it does not initially have the sensation: there is a plant outside, and I am a closed being inside. Instead, the animal has a strong inner experience of the plant, an immediate sympathy or antipathy. The animal senses, in a sense, what the plant expresses within itself. The fact that in our present age people are so incapable of observing anything that does not present itself in a very crude manner is precisely what prevents them from simply seeing in the behavior and actions of animals that this is indeed the case, as I have said.

Only humans have this sharp, clear distinction between their inner world and the outer world. Why do humans recognize an outer world? What causes humans to speak of an inner world and an outer world at all? They do so because, with their ego and astral body, they are outside their physical and etheric bodies every time they are asleep, leaving their physical and etheric bodies to themselves, so to speak, and being with those things that are the outer world. During our sleep, we share the fate of external things. Just as tables and benches, trees and clouds are outside our physical and etheric bodies when we are awake, and we therefore call them the external world, so our own astral body and our own ego belong to the external world during sleep. And when we belong to the outside world with our ego and our astral body during sleep, something happens.

In order to understand what happens there, let us first start with what actually happens when we face the world in a completely normal waking state. There are objects outside of us. And scientific thinking has gradually led people to recognize as certain only those physical things in the outside world that can be measured, weighed, and counted. The content of our physical science is determined by weight, measure, and number.

We calculate using the arithmetic operations that apply to earthly things, we weigh things, we measure them. And what we determine by weight, measure, and number is actually what constitutes the physical. We would not describe a body as physical if we could not somehow prove its reality with scales. But what colors are, for example, what sounds are, what even sensations of heat and cold are, what the actual sensory perceptions are, weaves its way through the heavy, measurable, countable things. If we want to determine any physical thing, what constitutes its actual physical essence is precisely that which can be weighed and counted, which is what physicists actually want to deal with. Of color, sound, and so on, he says: Yes, something is happening out there that also has to do with weighing or counting. He himself says of color phenomena: There are vibrating movements out there that make an impression on people, and this impression is described by people as color when it is determined by the eye, as sound when it is determined by the ear, and so on. — Actually, one could say: physicists today don't know what to do with all these things — sound, color, warmth, and cold. They regard them as properties of what can be determined with scales, with a measuring stick, or by calculation. Colors, so to speak, adhere to the physical; sound emanates from the physical; warmth or cold radiates from the physical. People say: that which has weight has a reddish hue, or is red.

When a person is in the state between falling asleep and waking up, things are different with the ego and the astral body. There, things do not exist at all in terms of measure, number, and weight. According to earthly measure, number, and weight, things are not there. When we sleep, we do not have things around us that can be weighed, strange as it may seem, nor do we have things around us that can be counted or measured directly. One could not apply a standard as an ego and as an astral body in the state of sleep.

But what is there, if I may express it this way, are the freely floating, freely weaving sensory impressions. It is just that in the present state of their development, human beings do not have the ability to perceive the freely floating redness, the waves of freely weaving sound, and so on.

If one wanted to draw a diagram of this, one could do so as follows. One could say: Here on earth we have weighable, solid things [violet arc], and attached to these weighable, solid things, in a sense, is the red, the yellow, that is, what the senses perceive in bodies. When we sleep, the yellow is a free-floating entity, the red is a free-floating entity, not attached to such conditions of heaviness, but freely weaving and floating. It is the same with sound: it is not the bell that rings, but the ringing that weaves.