Curative Education

GA 317

30 June 1924, Dornach

Lecture V

You will have been able to see how certain abnormalities in the life of the soul which we can recognise as symptoms of the oncoming of illness, show themselves in children in a rather undefined form, developing only later in a more definite manner. I was able to show you, for instance, how what later on becomes hysteria manifests in early childhood in a manner that is peculiar to that period, the abnormality remaining as yet quite undefined. In order however to be able to come to correct conclusions in regard to abnormalities that belong to childhood, we must also bear in mind the whole connection that exists between the pre-natal life (which may be said to carry into the physical life on earth the impulse of karma) and the gradual development of the child through the first two epochs—even perhaps also through the third.

Today we shall still continue to speak, by way of preparation, of general principles; then we shall be able afterwards to add what further needs to be said, with practical examples in front of us. For tomorrow morning Frau Dr. Wegman will put at our disposal a boy whom we have had here under treatment for some considerable time, and in whom we shall be able to demonstrate a condition that is strikingly typical.

And now in order to make clear to you something that you will need to know before seeing this boy, I should like to draw for you here a sketch of the human organism, in its totality.

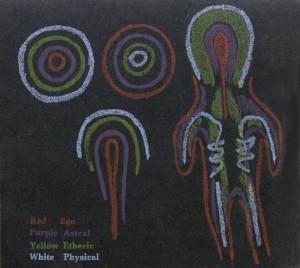

That there be no confusion, I will always draw the ego organisation red, then the astral organisation purple, the etheric organisation yellow, and lastly, the physical organisation white. And now let us be quite clear and exact in our thinking, and do our best to grasp the matter as accurately as possible. For the human organisation is not of such a nature that we can say: There is the ego organisation, there the astral organisation, there the etheric organisation, and so on. We must rather think of it in the following way. Picture to yourselves a being (see circles above, in the middle) organised in such a way that there is first of all, on the outside, the ego organisation (red); then, further inwards, the astral organisation (purple), then the etheric (yellow), and then the physical (white). You will have thus a being who shows his ego organisation outside, while he drives the astral organisation farther in, the etheric still farther in and the physical organisation farthest in of all.

And now, beside it, we will draw a different arrangement, where we have the ego organisation right inside (red), the astral organisation, as it were, raying outwards (purple); then, farther out, the etheric organisation (yellow), and still farther out, the physical organisation (white). We have now before us two beings that are the direct polar opposite of one another. Look at them carefully. As you see, the second being (on the left) will present, on the outside, a strong physical organisation, into which plays also the etheric organisation, whilst the astral and ego organisations tend to disappear within. But now, these conditions being given, a change can come about. The configuration of the being I have sketched here (on the left) may be modified in the following way (see Figure 1, left below). Here the physical organisation (white) may be fully developed above, while below it is unfinished, left open. Then we can have the etheric organisation (yellow), somewhat stronger here below than the physical, yet still unfinished. And we can have here the astral organisation (purple) coming down more in a sweeping curve; and, finally, the ego organisation (red) descending like a kind of thread. What we sketched before diagrammatically in the form of a sphere can quite well manifest also in this way.

To make the matter still clearer, I will draw this last figure here once again (see upper part of Figure 1, right)—the ego organisation (red), the astral organisation (purple), and ether organisation (yellow) and the physical organisation (white). And now we will add on to it below, the other being (figure in the middle, above) and we will do it in the following way. To begin with, for the ego organisation, which is outside, instead of describing a circle, as I did before, I will let the circle break and bend, so that we have this kind of form (red, on the lower part of Figure 1, on the right). As a matter of fact, this is what is continually happening with the sphere and the circle, wherever they occur in Nature—indeed, in the whole universe. Owing to the plasticity that is everywhere present, the sphere and the circle are perpetually undergoing modification in their form, being moulded and turned in various ways. Going inwards, I shall have to show next the astral organisation (purple); farther in, the ether organisation (yellow); and finally—pushed right inside, as it were—the physical organisation (white).

So now you have our second being changed into the head of man, and our first changed into the metabolism-and-limbs system. And in fact, this is how things really are in man. In the head organisation the ego hides itself right inside, the astral body is also comparatively hidden, while outside, showing form and shape, are the physical body and the ether body, giving form also to man's countenance. In the metabolism-and-limbs system, on the other hand, the ego is on the outside, vibrating all over the organism in its sensibility to warmth and to touch. Proceeding inwards from the ego, we have then the astral body vibrating in an inward direction; farther in, it all becomes etheric; and finally, inside the bones, it becomes physical.

We go therefore outwards from ego to physical body in the head organisation; the arrangement there is centrifugal. In the metabolism-and-limbs system, it is centripetal; we go here inwards from ego to physical. And the arrangement in the rhythmic system, in between the two, is in perpetual flow and interchange, so that one simply cannot say whether it is going from without inwards or from within outwards. For the rhythmic system is, in fact, half head system and half metabolism-and-limbs system. When we breathe in, it is more metabolism-and-limbs system; when we breathe out, it is more head system. The relationship between systole and diastole is expressed in the fact that the head system is to the limb system as outbreathing is to inbreathing. We carry therefore in us, you see, two directly opposite beings—mediated by the middle part of our organism, the rhythmic organism. What follows from this? A result, that is of no little importance.

Suppose we receive something through the medium of our head—as we do, for instance, when we listen to what another person is saying. Having been received by our head, it goes first into the ego, and into the astral body. But an interplay is always taking place in man's organism, and the moment something is caught and held fast, by means of an impression received in the one ego organisation (here in the head), it immediately vibrates right through into the other ego organisation (below). And then the same thing happens the moment something strikes home into the astral organisation; that too vibrates right through into the other astral organisation. If it were not so, we would have no memory. We owe our memory to the fact that all the impressions we receive from the external world have their reflections, their mirror-pictures, in the metabolism-and-limbs organisation. If I receive an impression from without, it disappears from the head organisation—which, as we have seen, is centripetally arranged, from physical on the outside to ego within. For the ego must maintain itself, it must hold its own. It cannot carry one single impression for hours on end; if it did, it would have to identify itself with the impression. No, it is down below that the impressions are preserved; and they have to make their way up again, for us to “remember” them.

But now, it may quite well happen that the whole of the lower system, which is, as we have seen, in direct polar contrast to the upper system, is constitutionally weak. In that case, when impressions occur, the impressions do not stamp themselves deeply enough into the lower system. The ego, let us say, receives an impression. If everything were normal, the stamp of the impression would be passed on to the lower system and only in the event of memory be fetched up again. If however the system down below, and in particular, the ego organisation—which covers there the whole periphery—is too weak, so that the impressions do not stamp themselves strongly enough, then the impressions that fail to sink down into the ego organisation of the lower system, keep streaming back again into the head.

We have with us a child who is constituted just in this way. One day we showed him, for the first time, a watch. It interested him. But his limb organisation is weak; consequently, the impression does not sink down, but rays back again. I sit down by this child, and begin to talk to him. All the time he is perpetually saying: “Lovely watch!” Hardly have I said a few more words than he says again: “A lovely watch!” The impression keeps coming back. In the education of children we must pay attention to such tendencies, of which there may sometimes be only very faint indications, but which are nevertheless quite important. For if we do not succeed in strengthening the too weak metabolism-and-limbs organisation, then this “streaming back” of impressions will go on happening with greater and greater intensity, and in later life the patient will suffer from the type of paranoia that is associated with fixed ideas. He will suffer from firmly fixed ideas. He will know that these ideas have no business to take up their abode, as it were, in his soul in this persistent way, but he will not be able to dismiss them. Why can he not dismiss them? Because while, up there above, there is the conscious soul-life, the unconscious, down below, is out of control; it keeps pushing certain ideas back into consciousness, which then become fixed ideas.

We said that the boy has a metabolism-and-limbs system that is too weakly developed. What does this mean? When metabolism and limbs are too weakly developed, the albumen substance in the human organism is prevented from containing the right amount of sulphur. We then have a metabolism-and-limbs system which produces albumen that is poor in sulphur. This can quite well happen; the proportion in which the constituents are combined in the albumen is, in such a case, different from what is usual. And, in consequence, we have in the patient what I have just been describing—fixed ideas, beginning to announce themselves in the organism in the years of childhood.

But now the opposite condition may also arise. The system of metabolism and limbs may be so constituted that it is too strongly attracted to sulphur. The albumen will then be too rich in sulphur. It will have in it carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, and—in proportion—too much sulphur. In a metabolism-and-limbs system of this kind—for the system is influenced in its manifestations by the particular combination of the substances within it—there will not be, as before, the urge to push everything back; but, on the contrary, in consequence of the albumen being too rich in sulphur, the impressions will be absorbed too powerfully, they will nest themselves in too strongly.

Note that this is a different condition from the one I described in an earlier lecture, where there is a congestion at the surface of an organ. That condition gives rise, as we saw, to fits. It is not congestion that we have now, but a kind of absorption of the impressions: the impressions are, as it were, sucked in—and consequently disappear. We bring it about that the child has impressions, but to no purpose; impressions of a particular nature simply disappear into the oversulphurous albumen. And only if we can succeed in getting these impressions back, in drawing them out again from the sulphurous albumen—only then shall we be able to establish a certain balance in the whole organism of spirit, soul and body. For the disappearance of the impressions in the sulphurousness of the metabolism-and-limbs system induces a highly unsatisfactory condition of soul; it has a disturbing, exciting effect. The whole organism is a little agitated, a slight tremor runs through it.

As you know, I have often said that Psycho-Analysis is dilettantism “squared”, because the Psycho-Analyst has no real knowledge of soul or spirit or body—nor of ether body; he does not know what it is that is taking place, all he can do is to describe. And since this is all he can do, he is quite content simply to say: “The things have disappeared down below; we must fetch them up again.” The strange thing is, you see, that materialism is quite unable to probe thoroughly into the qualities even of matter! Otherwise it would be known that the disappearance of the impressions is due to the fact that the albumen-substance in the will organism contains too much sulphur. Only by following the path of Spiritual Science can the nature and character of physical substance be discovered.

It would be good if those who have to educate abnormal children would learn to have an eye for whether a child is rich or poor in sulphur. We shall, I hope, be able to speak together of many different forms of soul abnormalities, but you ought really to come to the point where certain symptoms indicate of themselves the main direction in which you have to look for the cause of the trouble. Suppose I have a child to educate, in whom I observe that impressions make difficulties for him. This may, of course, be due to conditions described in the previous lectures. But if I am right in attributing it to the condition we have been describing today, then how am I to proceed?

To begin with, I look at the child. (The first thing is, of course, to know the child, to make oneself thoroughly acquainted with him; that is the first essential.) I look at him, and notice one of the most superficial of symptoms, namely, the colour of his hair. If the child has black hair, I shall not take the trouble to investigate whether he be rich in sulphur, for a child who has black hair certainly cannot be rich in sulphur, though it is possible he may be poor in sulphur. If, therefore, abnormal symptoms are present, I shall have to look for their cause in some other sphere. Even if recurring ideas show themselves, I shall nevertheless, in the case of a child with black hair, have to look for the cause elsewhere than in richness of sulphur. If however I have to do with a fair-haired or red-haired child, I shall look for signs of overmuch sulphur in the albumen. Fair hair is the result of overmuch sulphur, black hair comes from the iron in the human organism. It is indeed the case that so-called abnormalities of soul and spirit can be followed right into the physical substance of the organism.

Now, let us take a little volcano of this kind, a sulphurous child, who sucks down impressions into the region of the will, where they stiffen and cannot get out. We shall very quickly be able to detect this in the child. He will be subject to states of depression and melancholy. The hidden impressions that he carries inside him are a torment to him. We must raise them to the surface, and we must go about it, not with psycho-analysis as it is understood today, but with a true and right psycho-analysis. We must observe the child and find out what kind of thing it is that is inclined to disappear in him. In the case of a child who confronts us on the one hand with inner excitement and on the other hand outwardly with a certain apathy, we shall have to watch carefully until we can ascertain quite exactly what things he remembers easily and what things he lets disappear within him. Things that do not come back to him, we should bring before him repeatedly, again and again, and as far as possible in rhythmic sequence. A great deal can be done in this direction, and often in a far simpler way than people imagine. Healing and education—and the two are, as you know, nearly related—do not depend so much on concocting all kinds of mixtures—be they physical or psychical!—but on knowing exactly what can really help.

What is important, then, is to be able to know in any particular case what particular substance is required; we must really succeed in following the path that brings us to that knowledge.

In my experience in the Waldorf School I have often come across children who seem, in a way, quite apathetic, but at the same time show signs also of being inwardly in a state of excitement. We had, for instance, in Herr K's Class, a particularly odd little person. He was at once excited and apathetic. He has by now improved considerably. When he was in the third class—he is now in the fifth—his apathy showed itself in the fact that it was not easy to teach him anything; he never took anything in, he learned only very slowly and with difficulty. But scarcely had Herr K. turned away from him and begun to bend over another child in front, than up would jump this little spark and hit him smack on the back! The boy was, you see, at one and the same time—inwardly, in his will, like quicksilver and intellectually an apathetic child.

There are, in fact, quite a number of children who have this kind of disposition, in greater or less degree; and it is important to note that in such children the capacity for absorption of external impressions is as a rule limited to impressions of a particular kind or type. If we have the right inspiration—and it will come, once we have the right disposition of mind and soul—we shall find for the child a certain sentence, for example, and bring it before him, suggest it to him. This can work wonders. It is only a question of guiding the whole activity and exertions of the child, of turning them in a certain direction. But this the teacher must achieve; and he can easily do so, provided he does not try to be too clever, but rather to live in such a way that the world, as it were, lies open to his view; he should not ponder overmuch about the world, but “behold” it, as it shows itself to him.

Think how boring it is—and what I am about to say is something you need to take seriously if you want to educate abnormal children—only think how tedious it is to have to go through life with no more than a handful of concepts! The soul-life of many people today is terribly barren and tedious, just because they are forced to get along with a very few concepts. With so small a range of concepts mankind slides all too easily into decadence. How hard it is for a poet today to find rhymes; all the rhymes have been used before! It is the same in the other arts; on every hand we have echoes and reminders of the past, or there is nothing new left to be done. Look at Richard Strauss, who is now so famous—and at the same time so severely criticised. He has made all kinds of innovations in orchestral music, merely in order to avoid repeating eternally the same old things.

But now think, on the other hand, what an interesting time you could have if you set out to study, let us say, every possible form of nose! Each person has a different nose; and if you were to learn to be observant and to have a quick perception for all the various forms of nose, you would soon begin to have variety in your mental content, and it would then be possible also for your concepts to become inwardly alive, you would be continually moving from one to another. I have taken the nose merely as an example, of course. Through developing an intelligent feeling for form as such, for all the variety of form that lies open to our perception, we shall actually be cultivating a disposition of soul that will enable us to receive inspiration when the occasion requires.

As you live your way into this beholding of the world—not a thinking about, but a real beholding of the world—you will find that, if you have a child who is inwardly sulphurous, alert and active, but outwardly apathetic, then, through your being able to behold him, something will suggest itself to you in connection with him and his special constitution, that provides you with the right idea. You will perhaps feel: I must say to him every morning: “The sun is shining on the hill”—or it can be some other sentence; it can be quite a simple, everyday sentence. What matters is that it comes to him rhythmically. When something of this kind is brought to the child rhythmically, approaching him as it were from outside, then all the sulphurous element in him is unburdened, it becomes freer. So, with these children—who should indeed be protected in the tender years of childhood, lest later on they become the pet victims of Psycho-Analysts—with these children we shall achieve a great deal if we reckon especially with their rhythmic nature, and let some such sentence be imparted to them so that it comes to them from outside again and again, rhythmically.

It is, in fact, very good to make a regular practice of this with all children. It works beneficially. In the Waldorf School we have arranged that school begins with a verse which, as it were, saturates the life of thought, day after day, in rhythmic sequence. And where you have a case of overabsorption in the organism, this practice will definitely help to bring relief.

We shall be doing the right thing for abnormal children, if we bring them together in groups every morning. If we have only a small number of children, we can of course, at any rate to begin with, take them all together. Something quite wonderful can come out of this. Let the children repeat a verse that is in the nature of a prayer, even though there may be some among them who cannot say a word; you will find this repeating in chorus has a wonderful balancing influence. And particularly in the case of a child in whom impressions tend to disappear, will it be important to induce certain impressions by means of such rhythmical repetition. You can change the impressions, say every three or four weeks, but you must continue bringing them to the child again and again. This will have the result of relieving the internal condition; it can indeed happen that the albumen gradually ceases to have an excess of sulphur-content. How is one to explain this? The trouble is, as we have seen, that the internal parts of the child are not giving back the impressions; that is to say, the movement from below upwards is too weak, it is even negative. If now we bring in a strong impulse from above, we rouse the movement from below (that is weak) to a stronger activity.

Suppose, however, we have the opposite state of affairs. Suppose we have children who already begin to show a tendency to fixed ideas. The raying back of impressions is in these children too strong; there is too little sulphur in the plasma. Here we shall have to do the contrary of what we did before. When we observe that the same sentence, the same impression is perpetually coming again and again to the child, it will be helpful if we ourselves fabricate for him a new impression (one which our instinct tells us may be right for this child) and then bring it to him in a gentle whisper, murmuring it softly in his ear.

The treatment could, for example, take the following form. The teacher says: “Look, there's red!” The child: “It's a lovely watch!” Teacher: “But you must look at the red.” Child: “A lovely watch!” And now we try repeating, each time a little more softly, a new impression which has the effect of paralysing the first. We say very softly: “Forget the watch!—Forget the watch!—Forget the watch!” Whispering to the child in this way, you will find that you gradually whisper away the fixed idea; as you whisper more and more softly, the fixed idea begins to yield, it too grows fainter and fainter. The remarkable thing is that when the idea is spoken—when the child hears it spoken—it is more weakly thought; it gradually quietens down, and at length the child gets the better of it. So we have this method too that we can use; and, as a matter of fact, very good results can be achieved with a treatment of this simple nature.

If only such things were known! Think how it is in an ordinary school. You have a class, and in this class are children who already have a tendency, though perhaps only slight, to fixed ideas. They are not transferred to special classes for backward children, they continue in their own class. And now perhaps there is a teacher who has a voice like thunder, who shouts loud enough to make the walls fall down. Later on, these children will turn into crazy men and women, suffering from fixed ideas. It would never have happened, had the teacher only known that he should at times speak more quietly, that he ought really to whisper certain things softly to the children. So very much depends on the manner in which we meet the children and deal with them!

Then, of course, in cases of this kind, the psychical treatment can be combined quite simply with ordinary therapy. If we have a child in whom impressions tend to disappear, it will be good to set out with the definite resolve to combat in this child the strong tendency he has to develop sulphur in the albumen. We can make good headway in this direction by seeing to it that the child has the right kind of nourishment. If, for instance, we were to give him a great deal of fruit, or food that is prepared from fruit, we should be nurturing and fostering his sulphurous nature. If, on the other hand, we give him a diet that is derived from roots, and contains substances that are rich, not in sugar, but in salt, then we shall be able to heal such a child. Naturally, this does not mean we are to sprinkle his food copiously with salt, but we should give him foods in which salt is contained—as it were, in already digested form. You will find that you can discover methods of this kind by learning to pay attention to things that are actually going on all the time in the world around you. (Here Dr. Steiner related a fact that he had himself observed, namely, that the population of a certain district instinctively preferred a particular diet, which worked counter to an illness that was prevalent in that district.) And so, in the case of these children, instead of leaving them to become subjects later on for the Psycho-Analyst, it would be far better if we were to give them in early childhood a diet that suits their need—a diet, that is, consisting of rather salty food.

Take now the opposite case—children who fail to absorb impressions, children in whom the impressions stream back. These children are poor in sulphur, and the best treatment for them is to give them as much fruit as possible; they will soon acquire a taste for it and enjoy eating it. If their condition has become decidedly pathological, we should try also to bring fragrance and aroma into their food; they should have fruits that smell sweetly. For aroma contains a strong sulphurous element. And for a very serious case, we shall have to administer sulphur direct. This can show you once again how from a spiritual study of the conditions, we are led straight on to the therapy that is required. But it must be spiritual study; it will never do to rest content with the mere description of phenomena; that will get us no further than symptomatology. What we have to do is to try to penetrate, in the way I have shown you, right into the inner structure and texture of the organism.

We have been considering irregularities which can occur in the human being when the lower part of him is not in right accordance with the upper part, so that the impressions which the head organisation receives above, fail to find the right resonance in the metabolism-and-limbs organisation. But now the condition is also possible where throughout the human being as a whole, ego organisation, astral organisation and etheric-physical organisation do not fit well together, do not harmonize. The physical organisation, let us say for example, is too dense. The child will then be absolutely incapable of sinking his astral body into this densified physical organisation. He will receive an impression in the astral body, and the astral body can stimulate the corresponding astrality of the metabolic system, but the stimulation is not passed on to the ether body, least of all to the physical. We can recognise this condition in a child by noticing how he reacts if we say to him: “Take a few steps forward.” He will not be able to do it. He does not rightly understand what he has to do. That is, he understands quite well the words we say, but he does not convey their meaning to his legs; it is as though the legs did not want to receive it. If we find this—that the child is in difficulties when we tell him to do something which involves the use of his legs, that he hesitates to bring his legs into movement at all—then that is for us a first sign that his physical body has become too hardened and is unwilling to receive thoughts; the child, in fact, shows indications of being feeble-minded. Since in such conditions the body bears too heavily on the soul, we shall find that moods of depression and melancholy also occur.

On the other hand, if a child's legs never wait for a command, but are perpetually wanting to run about, then we have in that child a tendency to a condition of mania. The tendency need only show itself very slightly, to begin with, but it is in the legs that we shall notice it first of all. It is accordingly most important that we should always include in our field of observation what a child does with his legs—and also with his fingers. A child who likes best to let his hands and legs—for you can notice the same thing in the hands—hang about anyhow, flop on to things, has the predisposition to be feeble-minded. A child who is perpetually moving his fingers, catching hold of everything, kicking out in all directions with his feet, is predisposed to become maniacal, and possibly violent.

But now these symptoms that are so marked in the limbs can be observed in all activities. In activities that are more connected with the spiritual and mental, they show themselves in a slighter form, and yet here too they are quite characteristic. In many children, for instance, you may be able to notice something like the following. A child acquires a knack of doing something with his hands. Let us say, he learns to draw a face in profile. And now, he simply cannot stop himself; whenever he sees anyone, he immediately wants to draw his profile. It becomes quite mechanical. This is a very bad sign in a child. Nothing will persuade him out of it. If he is just about to draw a profile, I can talk to him as much as ever I like, I can even offer him a sweet—he goes on just the same, the profile must be drawn! This is connected with the maniacal quality that develops when intellect runs to excess. The reverse of this—namely, the urge to do nothing, even when all the conditions are there ready, the urge not to let the thought go over into work and action—is connected with the feeble-mindedness that may be imminent.

All this goes to show that by learning to bring the limbs into proper control, we can do much to counteract on the one hand feeble-mindedness, and on the other hand the tendency to mania. And here the way is marked out for us at once to Curative Eurythmy.1For the relation of Curative Eurythmy to Eurythmy as Art see end of Lecture 12. In the case of a feebleminded child, what you have to do is to bring mobility into his metabolism-and-limbs system; this will stimulate also his whole spiritual nature. Let such a child do the movements for R, L, S, I (ee), and you will see what a good effect it will have. If, on the other hand, you have a child with a tendency to mania, then, knowing how it is with his metabolism-and limbs system, you will let him do the movements for M, N, B, P, A (as in Father), U (as in Ruth), and again you will see what an influence this will have on his maniacal tendency. We must always remember how intimate the connection still is in the young child between physical-etheric on the one hand, and soul-and-spirit on the other. If we bear this continually in mind, we shall find our way to the right methods of treatment.

Fünfter Vortrag

Sie konnten schon sehen, wie gewisse Abnormitäten in der Seele, im Seelenleben, die als Erkrankungssymptome auftreten, bei Kindern in einer unbestimmten Weise zutage treten, um sich dann später in bestimmterer Art auszubilden. Und sokonnte ich Sie aufmerksam machen darauf, wie dasjenige, was später hysterische Erscheinung wird, im kindlichen Alter in einer ganz eigenartigen, noch unbestimmten Weise auftritt. Um aber die eigentlichen Abnormitäten des kindlichen Alters richtig beurteilen zu können, muß man doch den ganzen Zusammenhang ins Auge fassen zwischen dem vorgeburtlichen Leben des Menschen, das sozusagen den Karmaimpuls hereinträgt ins physische Leben, und der allmählichen Entwickelung des Kindes durch die zwei ersten Lebensepochen, vielleicht sogar darüber hinaus durch die drei ersten Lebensepochen des Kindes.

Da werden wir heute zur Vorbereitung zunächst noch etwas mehr Theoretisches besprechen, dann werden wir an praktischen Beispielen alles weiter Nötige besprechen können. Und es wird ja Frau Dr. Wegman uns zunächst schon morgen früh einen Jungen hier zur Verfügung stellen, den wir schon längere Zeit hier in Behandlung des KlinischTherapeutischen Institutes sehen, und an dem wir dann demonstrieren können einiges ganz besonders Charakteristisches.

Um Ihnen das aber zu zeigen, was Sie noch vorher wissen müssen, möchte ich schematisch den menschlichen Organismus, die menschliche Totalorganisation vor Sie hinstellen (siehe Tafel 7). Ich möchte, damit das alles deutlich wird, in der folgenden Zeichnung die Ich-Organisation immer rot zeichnen. Ich möchte dann die astralische Organisation mit diesem Violett zeichnen, möchte dann die Ätherorganisation in diesem Gelb zeichnen, und möchte die physische Organisation in diesem Weiß zeichnen. Wollen wir also heute dasjenige, was für uns in Betracht kommt, ganz genau einmal festhalten, wollen wir uns bemühen, die Sache genau ins Auge zu fassen. Es ist nämlich nicht so in der menschlichen Organisation, daß wir sagen können: Da ist die IchOrganisation, da ist die astralische Organisation, da ist die Ätherorganisation und so weiter —, sondern die Sache ist so: Stellen Sie sich einmal vor eine Wesenheit, welche so organisiert ist, daß die IchOrganisation zunächst außen liegt; daß dann weiter nach innen die Astralorganisation liegt, dann die Ätherorganisation kommt, und dann die physische Organisation. So daß wir also gewissermaßen hier ein Wesen haben, das seine Ich-Organisation nach außen präsentiert, weiter nach innen drängt die Astralorganisation, weiter nach innen die Ätherorganisation und am weitesten nach innen drängt die physische Organisation (siehe Tafel 7, Mitte).

Stellen wir daneben eine andere Anordnung, wo wir hätten die IchOrganisation ganz im Innern, nach außen gewissermaßen strahlend die Astralorganisation, noch weiter nach außen die Ätherorganisation, und noch weiter nach außen die physische Organisation (siehe Tafel 7, oben links). Sehen Sie, jetzt haben wir zwei polarisch sozusagen entgegengesetzte Wesenheiten. Wenn Sie ansehen diese zwei polarisch einander entgegengesetzten Wesenheiten, so können Sie sich sagen: Die zweite Wesenheit wird nach außen eine starke physische Organisation zeigen, in die noch die ätherische Organisation hineinspielt, dann wird mehr nach innen verschwinden die Astral- und Ich-Organisation. - Nun kann aber dadurch, daß das so ist, die Konfiguration etwas sich ändern. Die Konfiguration desjenigen, was ich hier an zweiter Stelle hergezeichnet habe, kann so sein: wir können die physische Organisation gewissermaßen nach oben voll ausgebildet haben und nach unten offen, verkümmert. Wir können dann die ätherische Organisation wiederum nach unten etwas stärker als die physische Organisation ausgebildet, aber doch noch verkümmert haben. Wir können die Astralorganisation schon mehr nach unten ausschweifend haben und die Ich-Organisation gewissermaßen wie eine Art von Faden nach unten gehend. Denn dasjenige, was schematisch hier in Kugelform angeordnet ist, kann nämlich durchaus so erscheinen (siehe Tafel 7, unten links).

Nun will ich aber die Sache noch etwas anschaulicher machen, indem ich diese Ich-Organisation hier Ihnen so zeichne, darauf die Astralorganisation, die Ätherorganisation und die physische Organisation. Und jetzt wollen wir anschließen das andere Wesen. Dieses andere Wesen wollen wir so anschließen, daß wir zunächst die Ich-Organisation, die hier außen ist, etwas konfiguriert sein lassen; also statt daß ich einen Kreis gezogen habe, habe ich den Kreis etwas konfiguriert sein lassen. So ist es ja immer in den Bildsamkeiten des Naturwesens, des Weltwesens überhaupt, daß dasjenige, was kugelig, was kreisig ist, sich in verschiedener Weise konfiguriert. Weiter nach innen habe ich jetzt an die Ich-Organisation anzuschließen die Astralorganisation, noch weiter nach innen die Ätherorganisation und endlich ganz nach innen geschlagen die physische Organisation (siehe Tafel 7, rechts). Und Sie haben das eine, erste Wesen, in den Kopf des Menschen verwandelt. Sie haben das zweite Wesen in das Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenwesen des Menschen verwandelt. Und, in der Tat, in Wirklichkeit ist es so, daß wir in der Kopforganisation des Menschen dasjenige haben, wo das Ich sich im Innern verbirgt, der Astralleib auch noch verhältnismäßig sich im Innern verbirgt, und nach außen konfiguriert der physische Leib und der Ätherleib auftreten und die Form geben des Antlitzes.

Dagegen im Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßensystem haben Sie die Sache so, daß eigentlich überall außen in der Wärme- und Drucksinnlichkeit des Organismus, überall außen vibriert das Ich, und vom Ich ausgehend vibriert nach innen der Astralleib, dann weiter drinnen wird es ätherisch, und in den Röhrenknochen wird es physisch nach innen.

So daß wir zentrifugal, vom Ich zum physischen Leibe nach außen, die Anordnung in der Kopforganisation haben, zentripetal, von außen nach innen, vom Ich bis zum Physischen, die Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganisation angeordnet haben. Und fortwährend durcheinanderflutend, so daß man gar nicht weiß: ist das von außen nach innen oder von innen nach außen, so ist die Anordnung im rhythmischen System dazwischen. Das rhythmische System ist halb Kopf, halb StoffwechselGliedmaßensystem. Wenn wir einatmen, ist es mehr StoffwechselGliedmaßensystem, wenn wir ausatmen ist es mehr Kopfsystem. So daß zwischen Systole und Diastole die Sache so verläuft, daß man sagen kann: Kopfsystem-Gliedmaßensystem = Ausatmung-Einatmung. Nun sehen Sie also, daß wir, vermittelt durch den mittleren Teil des rhythmischen Organismus, eigentlich zwei vollständig polarisch entgegengesetzte Wesenheiten in uns tragen. Was folgt daraus? Daraus folgt etwas außerordentlich wichtiges.

Denken Sie sich, wir nehmen etwas auf durch unseren Kopf, wie bei der Vermittlung durch die Sprache des andern, nehmen etwas auf mit dem Kopf, so geht das zunächst in das Ich hinein, in den Astralleib. Aber die Dinge stehen im Organismus in Wechselwirkung, und in dem Augenblicke, wo etwas hier angeschlagen wird, durch einen Eindruck in der einen Ich-Organisation, vibriert das auch in die andere IchOrganisation, und in dem Augenblick, wo etwas in die eine astralische Organisation einschlägt, vibriert das auch durch in die andere astralische Organisation. Wenn das nicht wäre, meine lieben Freunde, hätten wir kein Gedächtnis, denn alle Eindrücke, die wir von der Außenwelt bekommen, haben ihre Spiegelbilder in der StoffwechselGliedmaßenorganisation; und habe ich einen Eindruck von außen, so verschwindet er von der Kopforganisation, die vom Physischen nach dem Ich hinein zentripetal angeordnet ist. Das Ich muß sich aufrecht erhalten, das kann nicht einen einzigen Eindruck stundenlang haben, sonst würde es identisch werden mit dem Eindruck. Aber unten bleiben die Eindrücke, und da müssen sie wieder herauf, wenn erinnert wird.

Wenn Sie das aber bedenken, so bekommen Sie folgende Möglichkeit: Es kann das ganze untere System, das polarisch entgegengesetzt ist dem oberen System, im Menschen zu schwach veranlagt sein. Dann geschehen Eindrücke. Diese Eindrücke prägen sich nicht tief genug dem unteren System ein. Das Ich bekommt einen Eindruck. Ist alles normal, so prägt sich das dem unteren System ein, und es wird nur heraufgeholt in der Erinnerung. Ist das System unten, die Ich-Organisation, die ganz peripherisch herumliegt, zu schwach, prägen sich die Eindrücke nicht stark genug ein, so strahlt fortwährend das, was nicht untertaucht in die Ich-Organisation, nach oben zurück, strahlt in den Kopf hinein.

Wir haben ein Kind, das so organisiert ist. Wir haben ihm einmal, sagen wir, zum erstenmal eine Uhr gezeigt. Die hat es interessiert. Aber seine Gliedmaßenorganisation ist zu schwach. Dann taucht der Eindruck nicht unter, sondern strahlt zurück. Jetzt beschäftige ich mich mit dem Kinde, fortwährend sagt es: Die Uhr ist schön. -— Kaum bin ich ein paar Worte weitergegangen, so sagt es wieder: Die Uhr ist schön. — Es kommt zurück, Auf solche Anlagen, die manchmal nur ganz leise angedeutet sind, die aber außerordentlich wichtig sind, müssen wir die Aufmerksamkeit in der Erziehung des Kindes richten. Denn bringen wir es nicht zustande, die schwache Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganisation zu stärken, dann wird das auch immer stärker, dieses Zurückschlagen, und im späteren Leben tritt jene paranoische Erkrankung auf, die mit Zwangsvorstellungen verknüpft ist. Dann wird das zu festen, konsolidierten Zwangsvorstellungen. Es weiß, daß sie sich ganz unrichtig hineinstellen in sein Seelenleben, es kann sie aber nicht abweisen. Warum kann es sie nicht abweisen? Weil da oben das bewußte Seelenleben ist, aber das unbewußte unten ist unbeherrscht, es stößt zurück gewisse Vorstellungen, und es treten Zwangsvorstellungen auf.

Sie sehen, wir haben es da zu tun mit einem zu schwach ausgebildeten Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßensystem. Was heißt das? Ein zu schwach ausgebildetes Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßensystem ist dasjenige, welches verhindert, daß die Eiweißsubstanz im menschlichen Organismus die richtige Menge des Schwefels enthält. Also ein Stoffwechselsystem, das schwefelarmes Eiweiß entwickelt. Das kann nämlich da sein. Da gilt eine andere Stöchiomerrie als sonst. Dann tritt dieses ein, was ich jetzt beschrieben habe, daß diese sich im kindlichen Organismus ankündigenden Zwangsvorstellungen kommen.

Aber es kann ja auch das Umgekehrte da sein. Das StoffwechselGliedmaßensystem kann so veranlagt sein, daß es eine zu starke Anziehung zum Schwefel hat: dann wird das Eiweiß zu schwefelreich. Dann haben wir im Eiweiß Kohlenstoff, Sauerstoff, Stickstoff, Wasserstoff, und im Verhältnis dazu zuviel Schwefel. Wir bekommen dann in dieser Stoffwechselorganisation, die ja namentlich von der Zusammensetzung der Substanzen, die darinnen sind, in ihrer Offenbarung beeinflußt ist, den Drang, nicht alles zurückzustoßen, sondern im Gegenteil: Durch den überreichlichen Schwefel werden die Eindrücke zu stark absorbiert, sie nisten sich da zu stark ein. Das ist noch etwas anderes als das Stauen an der Oberfläche der Organe, das ich das frühere Mal beschrieben habe. Das Stauen bewirkt Krampfzustände. Aber hier haben wir es zu tun nicht mit dem Stauen, sondern mit einem Einsaugen der Eindrücke. Und die Folge davon ist, daß die Eindrücke verschwinden. Wir verursachen, daß das Kind Eindrücke hat, aber wir können nichts machen: gewisse Eindrücke, nach ihrer besonderen Beschaffenheit, verschwinden hinein in die schwefelreiche Eiweißsubstanz. Und nur, wenn wir es dann dahin bringen, diese Eindrücke aus der schwefelhaltigen Eiweißsubstanz wieder herauszukriegen, dann bringen wir ein gewisses Gleichgewicht im geistig-seelisch-physischen Organismus hervor, Denn dieses Verschwinden der Eindrücke in die Schwefelhaltigkeit hinein bewirkt in der Tat einen höchst unbefriedigenden Seelenzustand, weil es innerlich aufregt. Fein, gelinde regt es auf, macht den ganzen Organismus innerlich fein erbeben.

Sehen Sie, ich habe öfters gesagt: Psychoanalyse ist Dilettantismus im Quadrat, weil der Psychoanalytiker weder die Seele, noch den Geist, noch den Körper, noch den Ätherleib kennt, er weiß überhaupt nicht, was da vorgeht, er beschreibt nur. Und weil er nicht mehr kann, als beschreiben, sagt er: Die Dinge sind unten verschwunden, man muß sie wieder heraufholen. - Das Merkwürdige ist, daß der Materialismus die Eigenschaften des Materiellen nicht erforschen kann. Sonst würde man wissen, daß dasjenige, was vorliegt, in der Eiweißsubstanz des Willensorganismus, die zu schwefelreich ist, seinen Grund hat. Die Eigentümlichkeit der physischen Substanz findet man erst auf geisteswissenschaftlichem Wege.

Und so wäre es schon gut, wenn derjenige, der abnorme Kinder zu erziehen hat, sich einen Blick dafür aneignet, ob ein Kind schwefelreich oder schwefelarm ist. Wir werden ja von den verschiedensten Formen der seelischen Abnormitäten sprechen können, aber wir sollten uns aneignen die Möglichkeit, wirklich nach bestimmten Symptomen in bestimmte Fährte hingetrieben zu werden. Wenn ich ein Kind zur Erziehung bekomme, bei dem ich sehe, daß Eindrücke zunächst Schwierigkeiten machen, so kann das natürlich zurückzuführen sein auf solche Zustände, wie ich sie in den letzten Tagen beschrieben habe. Es kann aber auch auf das heute Beschriebene zurückzuführen sein. Wie kann ich da vorgehen?

Zunächst sehe ich mir das Kind an. Man hat es zunächst kennengelernt; man muß es kennenlernen. Zunächst sehe ich es mir an und nehme eines der oberflächlichsten Symptome: die Färbung der Haare. Hat das Kind schwarze Haare, so werde ich nicht viel danach suchen, ob es schwefelreich sein könnte; denn wenn es schwarze Haare hat, kann es höchstens schwefelarm sein. Und ich werde dann, wenn abnorme Symptome da sind, sie in irgendeiner andern Sphäre suchen müssen als in einem Schwefelreichtum, höchstens in der Schwefelarmut bei schwarzhaarigen Kindern. Und wenn sich dann noch zeigen wiederkehrende Vorstellungen, so muß ich woanders suchen als im Schwefelreichtum. Habe ich aber ein blondes oder ein rothaariges Kind, so werde ich in der Richtung des Schwefelreichtums der Eiweißsubstanz suchen. Blonde Haare kommen von zu reichlichem Schwefel, schwarze Haare von Eisenhaltigkeit des menschlichen Organismus. So können wir bis in die physische Substantialität hinein die sogenannten geistig-seelischen Abnormitäten verfolgen.

Nun, nehmen wir einen solchen feuerspeienden Berg, ein schwefelhaltiges Kind, das also gewissermaßen in die Willensregion hineinsaugt die Eindrücke, so daß sie sich darin versteifen und nicht heraus können. Diese Erscheinung können wir beim Kinde sehr bald bemerken. Das Kind wird Depressionszuständen unterworfen sein, melancholischen Zuständen. Es quälen diese verborgenen Eindrücke, die da im Inneren sind. Wir müssen sie an die Oberfläche heben, müssen nicht psychoanalytisch im heutigen Sinne vorgehen, sondern im richtigen Sinne psychoanalytisch. Das können wir dadurch, daß wir uns nun bekanntmachen mit demjenigen, wovon wir merken, daß es beim Kinde mehr oder weniger verschwindet. Und so sollten wir das Kind, das uns entgegentritt auf der einen Seite mit innerlicher Aufgeregtheit, auf der andern Seite mit einer gewissen äußeren Apathie, so ins Auge fassen, daß wir uns genau bewußt werden: an was erinnert sich dieses Kind leicht, was läßt es in sein Inneres verschwinden? Dasjenige, was ihm nicht wieder auftritt, sollten wir möglichst in rhythmischer Folge immer wieder und wiederum vor das Kind bringen. In dieser Beziehung, meine lieben Freunde, läßt sich sehr viel tun. Manchmal auf eine viel einfachere Weise, als man denkt; denn Heilen und Erziehen — und beide sind ja miteinander verwandt — beruht ja nicht so sehr darauf, daß man allerlei Mixturen, seien es physische, seien es seelische, kompliziert hervorbringt, sondern daß man weiß, was eigentlich hilft.

Deshalb haben wir es ja auch mit unseren Heilmitteln etwas schwer. Mit Recht verlangt natürlich der Arzt von unseren Heilmitteln, daß wir ihm sagen, was es ist, weil er es wissen möchte. Aber da die Heilmittel in der Regel darauf beruhen, daß man weiß, was hilft, da es einfache Substanzen sind, so kann in dem Augenblick, wo man es gesagt hat, jeder sie nachmachen. Rechnet man zu gleicher Zeit auf ökonomische Arbeit, so ist man in einer Zwickmühle. Es handelt sich also darum, das, was angewendet werden soll, wirklich zu kennen, darauf wirklich zu kommen.

Ich habe es in der Waldorfschule öfters erlebt, daß Kinder da sind, die in einer gewissen Weise Apathie zeigen, aber auch wieder innere Aufgeregtheit zeigen. So hatten wir insbesondere in der Klasse, die Herr Killian hat, einen in dieser Richtung sehr sonderbaren Kauz. Er war aufgeregt und apathisch zugleich. Jetzt ist er schon besser geworden. Als er in der dritten Klasse war - jetzt ist er in der fünften -, aber als er noch in der dritten Klasse war, zeigte sich seine Apathie darin, daß man nicht leicht etwas an ihn heranbrachte. Er nahm nichts auf, lernte langsam und schwer. Aber kaum ging Herr Killian von der hinteren Bank weg und beugte sich vorn zu einem andern, flugs war der Feuerstein da und gab dem Herrn Killian eins hintendrauf. Und so war er zu gleicher Zeit innerlich willensmäßig ein Quecksilber, intellektuell ein apathisches Kind.

Ja sehen Sie, solche Kinder, mehr oder weniger mit solchen Anlagen, gibt es viele. Nun handelt es sich darum, daß bei solchen Kindern in der Regel das da ist, daß sich die Absorptionsfähigkeit für äußere Eindrücke auf ganz bestimmte Arten von Eindrücken beschränkt, die bestimmten, typischen Charakter haben. Wenn man nun einen richtigen Einfall hat - und das kommt einem, wenn die richtige Gesinnung da ist -, dann findet man zum Beispiel für das Kind einen bestimmten Satz, und man bringt das Kind gerade auf diesen Satz. Das kann Wunder wirken. Es handelt sich nur darum, daß man die ganze Strebensrichtung des Kindes in einer gewissen Weise orientiert. Dahin muß es aber eigentlich doch der Erzieher bringen. Er kann es leicht dahin bringen, wenn er nicht gar zu gescheit sein will, wenn er so leben will, daß ihm die Welt anschaulich wird, daß er nicht zuviel über die Welt nachdenkt, sondern sie anschaulich nimmt.

Denken Sie doch nur einmal - und das ist etwas, was Sie in die Gesinnung aufnehmen müssen, wenn Sie abnorme Kinder erziehen wollen —, wie langweilig es ist, immer wieder mit ein paar Begriffen, die der Mensch hat, operieren zu müssen. Es ist furchtbar langweilig und öde, das Seelenleben vieler Menschen, weil sie mit ein paar Begriffen operieren müssen. Die Menschheit kommt zu stark in die Dekadenz hinein mit diesen paar Begriffen. Wie schwer ist es heute schon für den Dichter, Reime zu finden, weil alles schon abgereimt ist. Ebenso ist es in den andern Künsten: überall Anklänge, weil eigentlich alles schon durchgemacht ist. Denken Sie sich nur, wie Richard Strauß, der jetzt so berühmte und berüchtigte, alles mögliche schon ins Orchester hineinsetzt, um nicht nur die ewigen alten Dinge zu bringen! Dagegen, wie interessant ist es, ich will sagen, nur einmal alle möglichen Nasenformen zu studieren — jeder Mensch hat eine andere Nase — und sich einen Blick anzueignen für alle möglichen Nasenformen! Da hat man Mannigfaltigkeit darinnen. Da hat man auch die Möglichkeit, die Begriffe innerlich lebendig zu machen, da geht man immer über von einem zum andern. Nun, nicht wahr, ich habe nur die Nasenformen herausgegriffen; wenn man für Formen, für Anschaubares Sinn entwickelt, dann lebt man sich allmählich in eine Seelenstimmung hinein, bei der einem etwas einfällt, wenn die Veranlassung dazu da ist.

Und Sie werden es eben erleben, meine lieben Freunde, daß, wenn Sie sich so in ein anschauliches, wenn ich so sagen soll, Anschauen der Welt hineinleben, nicht in ein denkendes, dann werden Sie es erleben, daß, wenn Sie so ein Kind haben, das innerlich schwefelig, regsam ist, äußerlich apathisch ist, Ihnen dann durch die Anschauung an seiner Konfiguration so etwas aufgeht an dem Kinde, das Ihnen die richtige Idee herbeiführt. Sie werden das Gefühl haben, diesem Kinde muß ich sagen jeden Morgen: Die Sonne bescheint den Berg — oder irgend etwas; es kann eine ganz gleichgültige Sache sein. Es handelt sich darum, daß so etwas rhythmisch an das Kind von außen dringt. Wenn es so rhythmisch von außen herandringt, wird alles in ihm befindliche Schweflige entlastet, wird freier. Und wir erreichen also bei solchen Kindern, welche behüter werden sollen in zarter Kindheit, daß sie nicht später die beliebten Objekte der Psychoanalytiker werden, wir erreichen bei solchen Kindern sehr viel, wenn wir gerade auf ihr rhythmisches Wesen rechnen, und wenn ihnen immer wieder von außen herein durch uns so etwas beigebracht wird.

Aber sehen Sie, es wirkt schon günstig, wenn man so etwas überhaupt zur allgemeinen Regel macht. Bei uns in der Waldorfschule werden die Stunden begonnen mit einem Spruch, der schon an sich in rhythmischer Folge jeden Tag das Vorstellungsleben in einer gewissen Weise durchsetzt. Dadurch wird schon manches gerade von dem zu starken Absorbieren im Organismus freigelegt.

Nun sollten abnorme Kinder, wenn man sie richtig behandeln will, doch eigentlich jeden Morgen in gewissen Gruppen vereinigt werden. Hat man eine geringe Anzahl von abnormen Kindern, so kann man ja zunächst alle einmal zusammennehmen. Und da kann etwas ganz Wunderbares herauskommen, wenn man einen gebetartigen Spruch die Kinder sagen läßt, selbst wenn solche darunter sind, die nichts sagen können. Es ist doch eine wunderbar ausgleichende Wirkung in dem, was da chormäßig zustande kommt. Es wird also sich vorzugsweise darum handeln, daß man für solche Kinder, bei denen Eindrücke verschwinden, durch rhythmische Wiederholung hervorruft bestimmte Eindrücke, die man etwa alle drei bis vier Wochen wechseln kann, daß man immer wieder von außen solche Eindrücke bringt und dadurch das Innere freilegt, so daß auch das Eiweiß sich allmählich seinen höheren Schwefelgehalt abgewöhnt. Worauf beruht da die Sache? Die Sache beruht darauf, daß das Innere die Eindrücke nicht zurückgibt, also es geht etwas zu Schwaches von unten herauf, das ist negativ. Bringen wir dagegen ein Starkes von oben heran, so regen wir das Schwache hier zu einer stärkeren Tätigkeit an (siehe Tafel 8).

Nehmen wir an, wir haben den umgekehrten Fall: wir haben es mit Kindern zu tun, die schon die erste Keimanlage zu Zwangsvorstellungen haben. Es strahlt zu stark zurück, es ist zu wenig Schwefel im Plasma. Da werden wir auch wirklich das Entgegengesetzte tun müssen. Und da ist von besonderer Wirkung, wenn wir merken, es kommt immer wiederum derselbe Satz, derselbe Eindruck an das Kind heran, wenn wir jetzt von außen wiederum einen Eindruck formen, von dem wir instinktiv glauben, daß er für dieses Kind passen kann, aber jetzt diesen Eindruck wie in ganz leisem Raunen ihm beibringen, lispelnd diesen Eindruck an das Kind heranbringen. Also die Behandlung kann die folgende sein: Sieh’ einmal, das ist rot! - Das Kind: Die Uhr ist schön. - Der Lehrer: Du mußt auf das Rote aufmerksam sein! — Das Kind: Die Uhr ist schön. — Jetzt versuche man immer leiser und leiser einen bestimmten Eindruck, der sogar einfach den ersten paralysierend ist, ganz leise zu wiederholen: Die Uhr vergiß! - Die Uhr vergiß! Die Uhr vergiß! — Also in dieser Weise raunen zum Kinde, und Sie werden sehen, nach und nach, durch dieses Raunen, durch dieses rhythmisch raunende Absprechen von der Zwangsvorstellung, wird die Zwangsvorstellung sich bequemen, auch immer leiser zu werden. Es ist das Merkwürdige, wenn sie ausgesprochen wird, wird sie schwächer gemacht, sie dämpft sich allmählich ab, und zuletzt kommt das Kind über die Sache hinaus, so daß wir auch das in der Hand haben und in der Tat durch unsere einfache seelische Behandlung außerordentlich viel bewirkt werden kann.

Ja, solche Dinge müssen nur gewußt werden. Denn stellen Sie sich nur vor, in der gewöhnlichen Schule: Sie haben eine Klasse, darin sind Kinder, die zunächst schon solche Anlagen zu Zwangsvorstellungen haben, aber noch leise. Sie werden nicht in Klassen für Minderbegabte versetzt, sondern sie gehen mit in der Klasse. Aber es ist ein donnernder Lehrer da, der alles so andonnert, daß die Wände einstürzen. Dann werden aus solchen Kindern richtige Verrückte, die an Zwangsvorstellungen leiden. Es wäre nicht eingetreten, wenn der Lehrer gewußt hätte, daß er unter Umständen auch seine Stimme dämpfen muß, und daß er den Kindern leise hätte etwas zuraunen müssen. Es kommt viel darauf an, daß wir uns in der richtigen Art zu den Kindern verhalten.

Dann kann natürlich gerade bei diesen Dingen sich die psychische Behandlung einfach mit dem gewöhnlichen Therapeutischen verbinden. Wir werden natürlich, wenn wir ein Kind haben, bei dem Eindrücke verschwinden, gut tun, uns zu sagen: Nun, wir wollen bei diesem Kinde vor allen Dingen einmal die starke Neigung zur Schwefelbildung im Eiweiß bekämpfen.- Das können wir schon dadurch, daß wir das Kind in der richtigen Weise ernähren. Geben wir ihm zum Beispiel viel Fruchtnahrung oder viel von derjenigen Art von Nahrung, die aus der Fruchtsubstanz kommt, so werden wir sein schwefliges Wesen fördern. Geben wir ihm eine Diät, die mit Wurzeligem zusammenhängt, die zusammenhängt mit alledem, was nicht zuckerreich, sondern salzreich ist — natürlich dürfen wir ihm nicht die Suppe versalzen, sondern wir müssen das geben, wo das Salz verarbeitet ist -, dann werden wir ein solches Kind heilen können. Und sehen Sie, man kommt auf solche Dinge dadurch, daß man sich einen Blick aneignet für das, was geschieht.

Herr Dr. Steiner erzählt eine Beobachtung aus seinem Leben: Die Bevölkerung einer bestimmten Gegend bevorzugte instinktiv eine bestimmte Diät, die einem in der dortigen Gegend herrschenden Leiden entgegenwirkte.

Also durch eine entsprechende Diät gerade bei solchen Kindern, die später das Objekt für Psychoanalytiker werden, wäre es viel besser, statt sie dem Psychoanalytiker auszuliefern, sie mit etwas salzhaltiger Nahrung im kindlichen Alter zu behandeln.

Nehmen Sie den umgekehrten Fall: Kinder, die nicht absorbieren die Eindrücke, bei denen sie zurückströmen, die schwefelarm sind, die wird man physisch am besten so behandeln müssen, daß man ihnen möglichst viel Obstnahrung beibringt, daß man sie gewöhnt, gerne Obst zu essen. Und kommt das schon stark ins Pathologische herüber, dann versucht man, ihnen auch namentlich Aromatisches beizubringen, Früchte mit Aroma. Denn im Aroma liegt ein starkes schwefeliges Element. Und wenn es gar zu pathologisch wird, muß man direkt therapeutisch mit Sulfur vorgehen. Aber Sie sehen, gerade aus der geistigen Betrachtung der Sache kommt man auch auf die Therapie, die man in einem solchen Fall anzuwenden hat. Und das ist wichtig, daß man sich niemals zufrieden gibt mit der bloßen Beschreibung einer Erscheinung denn da hat man nur die Symptomatologie —, sondern daß man versucht, wie ich es dargestellt hatte, in das innere Gefüge des Organismus hineinzusteigen.

Nun sehen Sie, das sind Unregelmäßigkeiten, die dadurch hervorgerufen werden, daß sozusagen das Untere zum Oberen im Menschen nicht richtig paßt, daß die Eindrücke, die das Obere, die Kopforganisation bekommt, nicht die richtige Resonanz finden in der StoffwechselGliedmaßenorganisation. Nun kann es aber auch so sein, daß im ganzen die Ich-Organisation, die astralische und die ätherisch-physische Organisation nicht zusammenpassen, daß, sagen wir, die physische Organisation zu dicht ist. Ja, dann haben wir das vor uns, daß das Kind absolut nicht in die Lage kommt, seinen Astralleib in diese verdichtete physische Organisation unterzutauchen. Es bekommt also einen Eindruck in den Astralleib, der Astralleib kann die entsprechende Astralität des Stoffwechselsystems zwar anregen, aber diese Anregung geht nun nicht in den Ätherleib und namentlich nicht in den physischen Leib über. Wir können dieses beobachten, ob es so ist, wenn wir merken, daß das Kind es nicht recht zustande bringt,wenn wir sagen: Marschiere einmal, gehe einmal fünf, sechs Schritte! — Es versteht nicht recht, was es tun soll, das heißt, es versteht das Wort ganz gut, aber es bringt es nicht in die Beine hinein, es ist, als ob die Beine es nicht aufnehmen wollten. Daß der physische Körper zu verhärtet ist und auch Gedanken nicht aufnehmen will, das Kind schwachsinnig erscheint, das merken wir am ehesten, wenn wir Schwierigkeiten finden beim Kinde, wenn wir ihm etwas befehlen, was durch die Beine ausgeführt werden soll, und das Kind zögert, seine Beine überhaupt in Bewegung zu setzen. Solche Zustände werden dann, weil eben der Körper zu schwer wirkt, seelisch begleitet sein von depressiv-melancholischen Stimmungen. Dagegen, wenn die Beine gar nicht abwarten irgendeine Aufforderung, sondern immer laufen wollen, dann haben wir im Kinde die Anlage zum Maniakalischen. Es braucht sich zunächst nur ganz schwach zu zeigen, aber in den Beinen merkt man das alles zuallererst. Daher sollte es durchaus auch in den Bereich der Beobachtung fallen, was das Kind sonst mit seinen Beinen und mit seinen Fingern tut. Sehen Sie, ein Kind, welches am liebsten seine Hände und Beine — man kann es auch an den Händen beobachten - auf alles fallen läßt, überall aufliegen läßt, das hat die Anlage zum schwachsinnig werden. Ein Kind, das fortwährend seine Finger bewegt, das alles anfaßt, überall mit den Füßen herumschlägt, hat die Anlage, stark maniakalisch zu werden, tobend eventuell zu werden. Aber, was wir am stärksten an den Gliedmafßen bemerken, können wir an aller Tätigkeit bemerken; nur bei gewissen, mit Geistigem verknüpften Tätigkeiten tritt es schwächer, aber besonders charakteristisch hervor. Denken Sie nur einmal, wie stark bei manchem Kinde das Folgende der Fall ist: Es lernt irgendeinen Handgriff, sagen wir, es eignet sich an die Möglichkeit, ein Gesichtsprofil zu zeichnen. Es kann gar nicht mehr aufhören, überall, wenn es einen Menschen sieht, möchte es sein Gesichtsprofil zeichnen. Es wird ganz mechanisch. Das ist ein sehr schlechtes Zeichen für ein Kind. Und es läßt sich gar nicht davon abbringen. Wenn es dabei ist, ein Profil zu zeichnen, kann ich zu ihm reden, was ich will, ihm selbst eine Leckerei bringen, es bleibt dabei, das Gesichtsprofil muß aufgezeichnet werden. Das hängt zusammen mit dem maniakalischen Charakter des Ausschweifens des Intellektualistischen. Dagegen der Drang, selbst wenn alle Bedingungen dazu da sind, nichts zu tun, nicht überzugehen zur Arbeit, das hängt wiederum zusammen mit dem Schwachsinn, der im Anzuge sein kann.

Das alles weist uns doch eben darauf hin, wie nach beiden Richtungen hin, indem wir die Glieder in regelmäßiger Weise beherrschen lernen, wir dem Schwachsinn und dem Maniakalischen entgegenwirken können. Und da haben Sie den unmittelbaren Übergang gerade bei schwachsinnigen Kindern zur Heileurythmie. Wenn Sie ein schwachsinniges Kind vor sich haben, so haben Sie die Notwendigkeit, sein Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßensystem überzuführen in die Beweglichkeit. Dadurch wird angeregt sein Geistiges. Lassen Sie es RLSI machen, und Sie werden sehen, wie günstig Sie auf das Kind wirken. Haben Sie es mit einem maniakalischen Kinde zu tun, wissen Sie, wie es zusammenhängt mit dem Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselsystem, lassen Sie es MN BPAU machen, und Sie werden wiederum sehen, wie das auf seinen maniakalischen Charakter zurückwirkt. Wir müssen eben überall diesen innigen Zusammenhang, der beim Kinde noch da ist, zwischen dem Physisch-Ätherischen und dem Seelisch-Geistigen berücksichtigen. Dann kommen wir auch zu den entsprechenden Behandlungsmethoden.

Fifth Lecture

You have already seen how certain abnormalities in the soul, in the life of the soul, which manifest themselves as symptoms of illness, appear in children in an indefinite way, only to develop later in a more definite form. And so I was able to draw your attention to how what later becomes a hysterical manifestation appears in childhood in a very peculiar, as yet indefinite way. However, in order to be able to correctly assess the actual abnormalities of childhood, one must consider the entire context between the prenatal life of the human being, which, so to speak, carries the karmic impulse into physical life, and the gradual development of the child through the first two stages of life, perhaps even beyond that, through the first three stages of the child's life.

Today, in preparation, we will first discuss something more theoretical, and then we will be able to discuss everything else that is necessary using practical examples. And Dr. Wegman will provide us with a boy here tomorrow morning, whom we have been treating here at the Clinical Therapeutic Institute for some time, and on whom we will then be able to demonstrate some very characteristic features.

However, in order to show you what you need to know beforehand, I would like to present a schematic representation of the human organism, the total human organization (see plate 7). To make everything clear, I would like to draw the ego organization in red in the following diagram. I would then like to draw the astral organization in violet, the etheric organization in yellow, and the physical organization in white. So if we want to record exactly what is relevant to us today, let us try to look at the matter closely. For in the human organization, we cannot say: there is the ego organization, there is the astral organization, there is the etheric organization, and so on — rather, the situation is this: imagine a being that is organized in such a way that the ego organization is on the outside; then further inward is the astral organization, then comes the etheric organization, and then the physical organization. So we have, in a sense, a being that presents its ego organization outwardly, with the astral organization pressing inward, the etheric organization further inward, and the physical organization pressing furthest inward (see plate 7, center).

Let us place another arrangement next to it, where we would have the ego organization completely inside, the astral organization radiating outward, so to speak, the etheric organization further outward, and the physical organization even further outward (see plate 7, top left). You see, now we have two polar opposites, so to speak. If you look at these two polar opposites, you can say to yourself: the second entity will show a strong physical organization on the outside, into which the etheric organization still plays a part, while the astral and ego organizations will disappear more and more inward. But now, because this is the case, the configuration may change somewhat. The configuration of what I have drawn here in second place may be as follows: we may have the physical organization fully developed upwards, so to speak, and open and stunted downwards. We may then have the etheric organization somewhat more developed downwards than the physical organization, but still stunted. We can have the astral organization already more expansive downward and the ego organization, so to speak, like a kind of thread going downward. For what is schematically arranged here in spherical form can indeed appear like this (see plate 7, bottom left).

Now I want to make the matter even clearer by drawing this ego organization here for you, then the astral organization, the etheric organization, and the physical organization. And now let us connect the other being. We will connect this other being in such a way that we first allow the ego organization, which is on the outside here, to be somewhat configured; so instead of drawing a circle, I have allowed the circle to be somewhat configured. This is always the case in the pictorial representations of the nature of being, of the world in general, that what is spherical, what is circular, is configured in various ways. Further inward, I now have to connect the astral organization to the ego organization, and even further inward, the etheric organization, and finally, completely inward, the physical organization (see Plate 7, right). And you have transformed the first being into the human head. You have transformed the second being into the human metabolic-limb system. And, in fact, in reality, it is so that in the head organization of the human being we have that which the I hides within, the astral body also hides relatively within, and outwardly the physical body and the etheric body appear and give the form of the face.

In contrast, in the metabolic-limb system, the ego vibrates everywhere on the outside, in the warmth and pressure sensitivity of the organism, and from the ego, the astral body vibrates inward, then further inside it becomes etheric, and in the tubular bones it becomes physical inwardly.

So that we have a centrifugal arrangement in the head organization, from the I to the physical body outward, and a centripetal arrangement in the metabolic-limb organization, from the outside to the inside, from the I to the physical. And constantly flowing through each other, so that one does not know whether it is from the outside to the inside or from the inside to the outside, the arrangement in the rhythmic system is in between. The rhythmic system is half head, half metabolic-limb system. When we inhale, it is more metabolic-limb system, when we exhale, it is more head system. So that between systole and diastole, the situation is such that one can say: head system-limb system = exhalation-inhalation. Now you see that, mediated by the middle part of the rhythmic organism, we actually carry two completely polar opposites within us. What follows from this? Something extremely important follows from this.

Imagine that we take something in through our head, as when we communicate through the language of another, take something in with our head, then it first goes into the I, into the astral body. But things interact within the organism, and the moment something strikes here, through an impression in one ego organization, it also vibrates into the other ego organization, and the moment something strikes one astral organization, it also vibrates through into the other astral organization. If this were not the case, my dear friends, we would have no memory, for all the impressions we receive from the outside world have their mirror images in the metabolic-limb organization; and when I have an impression from outside, it disappears from the head organization, which is arranged centripetally from the physical to the I. The ego must maintain itself; it cannot have a single impression for hours on end, otherwise it would become identical with the impression. But the impressions remain below, and they must come back up when we remember.

But if you consider this, you arrive at the following possibility: The entire lower system, which is polar opposite to the upper system, may be too weak in humans. Then impressions occur. These impressions are not imprinted deeply enough in the lower system. The ego receives an impression. If everything is normal, this is imprinted in the lower system and is only brought up in memory. If the lower system, the ego organization, which lies completely peripherally, is too weak, the impressions are not imprinted strongly enough, so that what does not submerge into the ego organization constantly radiates back upwards, radiates into the head.

We have a child who is organized in this way. Let's say we showed him a watch for the first time. He was interested in it. But his limb organization is too weak. Then the impression does not submerge, but radiates back. Now I am busy with the child, and he keeps saying: The watch is beautiful. — As soon as I have gone a few words further, he says again: The watch is beautiful. — It comes back. We must focus our attention on such predispositions, which are sometimes only very faintly indicated but are extremely important, when educating the child. For if we do not succeed in strengthening the weak limb metabolism organization, then this backlash will become stronger and stronger, and in later life that paranoid illness associated with obsessive thoughts will appear. Then it becomes fixed, consolidated obsessive thoughts. They know that these thoughts are completely wrong in their soul life, but they cannot reject them. Why can't they reject them? Because the conscious soul life is up there, but the unconscious below is uncontrolled, it pushes back certain ideas, and obsessive thoughts arise.

You see, we are dealing here with an underdeveloped metabolic limb system. What does that mean? An underdeveloped metabolic limb system is one that prevents the protein substance in the human organism from containing the right amount of sulfur. In other words, a metabolic system that develops low-sulfur protein. That can happen. In this case, a different stoichiometry applies than usual. Then what I have just described occurs, namely that these obsessive thoughts appear in the child's organism.

But the opposite can also be the case. The metabolic limb system can be predisposed to have too strong an attraction to sulfur: then the protein becomes too rich in sulfur. Then we have carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, and, in relation to this, too much sulfur in the protein. In this metabolic organization, which is influenced in its manifestation by the composition of the substances it contains, we then feel the urge not to reject everything, but on the contrary: Due to the excess sulfur, impressions are absorbed too strongly and become too deeply ingrained. This is different from the congestion on the surface of the organs that I described earlier. Congestion causes cramps. But here we are not dealing with congestion, but with a suction of impressions. And the result of this is that the impressions disappear. We cause the child to have impressions, but there is nothing we can do: certain impressions, due to their special nature, disappear into the sulfur-rich protein substance. And only when we manage to get these impressions out of the sulfur-rich protein substance again do we bring about a certain balance in the mental, emotional, and physical organism. For this disappearance of impressions into the sulfur content does indeed cause a highly unsatisfactory state of mind, because it causes inner agitation. It causes a slight agitation, making the whole organism tremble internally.

You see, I have often said that psychoanalysis is amateurism squared, because the psychoanalyst knows neither the soul, nor the spirit, nor the body, nor the etheric body; he has no idea what is going on there, he only describes it. And because he can do no more than describe, he says: Things have disappeared down below, we must bring them back up again. The strange thing is that materialism cannot investigate the properties of the material. Otherwise, we would know that what is present has its cause in the protein substance of the will organism, which is too rich in sulfur. The peculiarity of physical substance can only be found through spiritual science.

And so it would be good if those who have to educate abnormal children could learn to recognize whether a child is rich or poor in sulfur. We will be able to talk about the most diverse forms of mental abnormalities, but we should acquire the ability to be guided by certain symptoms in a specific direction. If I am given a child to educate and I see that impressions initially cause difficulties, this can of course be attributed to conditions such as those I have described in recent days. But it may also be due to what has been described today. How can I proceed in this case?

First, I look at the child. You have just met them; you have to get to know them. First, I look at them and take one of the most superficial symptoms: the color of their hair. If the child has black hair, I will not look too closely to see if it could be rich in sulfur, because if it has black hair, it can at most be low in sulfur. And if there are abnormal symptoms, I will have to look for them in some sphere other than sulfur richness, at most in sulfur deficiency in black-haired children. And if recurring ideas then appear, I must look elsewhere than in sulfur richness. But if I have a blond or red-haired child, I will look in the direction of sulfur richness in the protein substance. Blond hair comes from too much sulfur, black hair from iron content in the human organism. In this way, we can trace so-called mental and emotional abnormalities back to their physical substance.

Now, let us take such a fire-breathing mountain, a sulfuric child, who, in a sense, sucks impressions into the region of the will, so that they become rigid there and cannot escape. We can notice this phenomenon in children very early on. The child will be subject to states of depression, melancholic states. These hidden impressions that are inside torment them. We must bring them to the surface, not in the psychoanalytical sense of today, but in the true psychoanalytical sense. We can do this by familiarizing ourselves with what we notice is more or less disappearing in the child. And so we should look at the child who comes to us with inner excitement on the one hand and a certain outer apathy on the other, in such a way that we become fully aware of what this child easily remembers and what it allows to disappear into its inner self. We should bring what does not reappear to the child again and again, in rhythmic succession if possible. In this regard, my dear friends, there is much that can be done. Sometimes in a much simpler way than one might think; for healing and education—and both are related—are not so much based on producing all kinds of complicated mixtures, whether physical or mental, but on knowing what actually helps.

That is why we have some difficulty with our remedies. Of course, the doctor rightly demands that we tell him what our remedies are, because he wants to know. But since the remedies are usually based on knowing what helps, because they are simple substances, anyone can imitate them the moment they are revealed. If you also want to work economically, you find yourself in a dilemma. So it is a matter of really knowing what is to be used, of really coming up with it.

I have often seen children at the Waldorf school who show a certain apathy, but also inner excitement. In Mr. Killian's class in particular, we had a very strange bird in this regard. He was excited and apathetic at the same time. He has improved now. When he was in third grade—he is now in fifth—his apathy manifested itself in the fact that it was not easy to get through to him. He took in nothing, learned slowly and with difficulty. But as soon as Mr. Killian left the back bench and leaned forward to another, Feuerstein was quickly there and gave Mr. Killian a slap on the back. And so he was at the same time internally volitional, mercurial, and intellectually an apathetic child.