Practical Course for Teachers

GA 294

4 September 1919, Stuttgart

XIII. On Drawing up the Time-table

You will have seen from these lectures, which lay down methods of teaching, that we are gradually nearing the mental insight from which should spring the actual timetable. Now I have told you on different occasions already that we must agree, with regard to what we accept in our school and how we accept it, to compromise with conditions already existing. For we cannot, for the time being, create for the Waldorf School the entire social world to which it really belongs. Consequently, from this surrounding social world there will radiate influences which will continually frustrate the ultimate ideal time-table of the Waldorf School. But we shall only be good teachers of the Waldorf School if we know in what relation the ideal time-table stands to the time-table which we will have to use at first because of the ascendancy of the social world outside. This will result for us in the most vital difficulties which we must therefore mention before going on, and these will arise in connection with the pupils, with the children, immediately at the beginning of the elementary school period and then again at the end. At the very beginning of the elementary school course there will, of course, be difficulties, because there exist the time-tables of the outside world. In these time-tables all kinds of educational aim are required, and we cannot risk letting our children, after the first or second year at school, fall short of the learning shown by the children educated and taught outside our school. After nine years of age, of course, by our methods our children should have far surpassed them, but in the intermediate stage it might happen that our children were required to show in some way, let us say, at the end of the first year in school, before a board of external commissioners, what they can do. Now it is not a good thing for the children that they should be able to do just what is demanded to-day by an external commission. And our ideal time-table would really have to have other aims than those set by a commission of this kind. In this way the dictates of the outside world partially frustrate the ideal time-table. This is the case with the beginning of our course in the Waldorf School. In the upper classes 1Dr. Steiner refers to the beginning of the Waldorf School when the higher classes were from the ages of 12 to 14. of the Waldorf School, of course, we are concerned with children, with pupils who have come in from other educational institutions, and who have not been taught on the methods on which they should have been taught.

The chief mistake attendant to-day on the teaching of children between seven and twelve is, of course, the fact that they are taught far too intellectually. However much people may hold forth against intellectualism, the intellect is considered far too much. We shall consequently get children coming in with already far more pronounced characteristics of old age—even senility—than children between twelve and fourteen should show. That is why when, in these days, our youth itself appears in a reforming capacity, as with the Scouts (Pfadfinder) and similar movements, where it makes its own demands as to how it is to be educated and taught, it reveals the most appalling abstractness, that is, senility. And particularly when youth desires, as do the Wandervögel, to be taught really youthfully, it craves to be taught on senile principles. That is an actual fact to-day. We came up against it very sharply ourselves in a commission on culture, where a young Wandervögel, or member of some youth movement, got up to speak. He began to read off his very tedious abstract statements of how modern youth desires to be taught and educated. They were too boring for some people because they were nothing but platitudes; moreover, they were platitudes afflicted with senile decay. The audience grew restless, and the young orator hurled into its midst: “I declare that the old folks to-day do not understand youth.” The only fact in evidence, however, was that this half-child was too much of an old man because of a thwarted education and perverted teaching.

Now this will have to be taken most seriously into account with the children who come into the school at twelve to fourteen, and to whom, for the time being, we are to give, as it were, the finishing touch. The great problems for us arise at the beginning and end of the school years. We must do our utmost to do justice to our ideal time-table, and we must do our utmost not to estrange children too greatly from modern life.

But above all we must seek to include in the first school year a great deal of simple talking with the children. We read to them as little as possible, but prepare our lessons so well that we can tell them everything that we want to teach them. We aim at getting the children to tell again what they have heard us tell them. But we do not adapt reading-passages which do not fire the fantasy; we use, wherever possible, reading-passages which excite the imagination profoundly; that is, fairy tales. As many fairy tales as possible. And after practising for some time with the child this telling of stories and retelling of them, we encourage him a little to tell very shortly his own experiences. We let him tell us, for instance, about something which he himself likes to tell about. In all this telling of stories, and telling them over, and telling about personal experiences, we guide, quite un-pedantically, the dialect into the way of educated speech, by simply correcting the mistakes which the child makes—at first he will do nothing but make mistakes, of course; later on, fewer and fewer. We show him, by telling stories and having them retold, the way from dialect to educated conversation. We can do all this, and in spite of it the child will have reached the standard demanded of him at the end of the first school year.

Then, indeed, we must make room for something which would be best absent from the very first year of school and which is only a burden on the child's soul: we shall have to teach him what a vowel is, and what a consonant is. If we could follow the ideal time-table we would not do this in the first school year. But then some inspector might turn up at the end of the first year and ask the child what “i” is, what “l” is, and the child would not know that one is a vowel and the other a consonant. And we should be told: “Well, you see, this ignorance comes of Anthroposophy.” For this reason we must take care that the child can distinguish vowels from consonants. We must also teach him what a noun is, what an article is. And here we find ourselves in a real dilemma. For according to the prevailing time-table we ought to use German terms and not say artikel. We have to talk to the child, according to current regulations, of Geschlechtswort (gender-words) instead of artikel, and here, of course, we find ourselves in the dilemma. It would be better at this point not to be pedantic and to retain the word artikel. Now I have already indicated how a noun should be distinguished from an adjective by showing the child that a noun refers to objects in space around him, to self-contained objects. You must try here to say to him: “Now take a tree: a tree is a thing which goes on standing in space. But look at a tree in winter, look at a tree in spring, and look at a tree in summer. The tree is always there, but it looks different in winter, in summer, in spring. In winter we say: ‘It is brown.’ In spring we say: ‘It is green.’ In summer we say: ‘It is leafy.’ These are its attributes.” In this way we first show the child the difference between something which endures and its attributes, and say: “When we use a word for what persists, it is a noun; when we use a word for the changing quality of something that endures it is an adjective.” Then we give the child an idea of activity: “Just sit down on your chair. You are a good child. Good is an adjective. But now stand up and run. You are doing something. That is an action.” We describe this action by a verb. That is, we try to draw the child up to the thing, and then we go from the thing over to the words. In this way, without doing the child too much harm, we shall be able to teach him what a noun is, an article, an adjective, a verb. The hardest of all, of course, is to understand what an article is, because the child cannot yet properly understand the connection of the article with the noun. We shall flounder fairly badly in an abstraction when we try to teach him what an article is. But he has to learn it. And it is far better to flounder in abstractions over it because it is unnatural in any case, than to contrive all kinds of artificial devices for making clear to the child the significance and the nature of the article, which is, of course, impossible.

In short, it will be a good thing for us to teach with complete awareness that we are introducing something new into teaching. The first school year will afford us plenty of opportunity for this. Even in the second year a good deal of this awareness will invade our teaching. But the first year will include much that is of great benefit to the growing child. The first school year will include not only writing, but an elementary, primitive kind of painting-drawing, for this is, of course, our point of departure for teaching writing. The first school year will include not only singing, but also an elementary training in the playing of a musical instrument. From the first we shall not only let the child sing, but we shall take him to the instrument. This, again, will prove a great boon to the child. We teach him the elements of listening by means of sound-combinations. And we try to preserve the balance between the production of music from within by song, and the hearing of sounds from outside, or by making them on the instrument.

These elements, painting-drawing, drawing with colours, finding the way into music, will provide for us, particularly in the first school year, a wonderful element of that will-formation which is almost quite foreign to the school of to-day. And if we further transform the little mite's physical training into Eurhythmy we shall contribute in a quite exceptional degree to the formation of the will.

I have been presented with the usual time-table for the first school year. It consists of:

Religion—two hours a week.

The mother tongue—eleven hours a week.

Writing—there is no figure given for the number of hours, for it is included in the mother tongue.

Then:

Local geography—two hours 2The word hours is the translation of Schulstunden—50 minutes with intervals between. a week.

Arithmetic—four hours a week.

Singing and gymnastics together—one hour a week.

We shall not be guilty of this, for we should then sin too gravely against the well-being of the growing child. But we shall arrange, as far as ever it is in our power, for the singing and music and the gymnastics and Eurhythmy to be in the afternoon, and the rest in the morning, and we shall take, in moderation—until we think they have had enough—singing and music and gymnastics and Eurhythmy with the children in the afternoon. For to devote one hour a week to these subjects is quite ludicrous. That alone proves to you how the whole of teaching is now directed towards the intellect.

In the first year in the elementary school we are concerned, after all, with six-year-old children or with children at the most a few months over six. With such children you can quite well study the elements of painting and drawing, of music, and even of gymnastics and Eurhythmy; but if you take religion with them in the modern manner you do not teach them religion at all; you simply train their memory and that is the best that can be said about it. For it is absolutely senseless to talk to children of six to seven of ideas which play a part in religion. They can only be stamped on his memory. Memory training, of course, is quite good, but one must be aware that it here involves introducing the child to all kinds of things which have no meaning for the child at this age.

Another feature of the time-table for the first year will provoke us to an opinion different from the usual one, at least in practice. This feature reappears in the second year in a quite peculiar guise, even as a separate subject, as Schönschreiben (literally, pretty writing = calligraphy). In evolving writing from “painting-drawing” we shall obviously not need to cultivate “ugly writing” and “pretty writing” as separate subjects. We shall take pains to draw no distinction between ugly writing and pretty writing and to arrange all written work—and we shall be able to do this in spite of the outside time-table—so that the child always writes beautifully, as beautifully as he can, never suggesting to him the distinction between good writing and bad writing. And if we take pains to tell the child stories for a fairly long time, and to let him repeat them, and pay attention all the time to correct speaking on our part, we shall only need to take spelling at first from the point of view of correcting mistakes. That is, we shall not need to introduce correct writing, Rechtschreiben (spelling), and incorrect writing as two separate branches of the writing lesson.

You see in this connection we must naturally pay great attention to our own accuracy. This is especially difficult for us Austrians in teaching. For in Austria, besides the two languages, the dialect and the educated everyday speech, there was a third. This was the specific “Austrian School Language.” In this all long vowels were pronounced short and all short vowels long, and whereas the dialect quite correctly talked of “Die Sonne” (the sun), the Austrian school language did not say Die Sonne but Die Sohne, and this habit of talking becomes involuntary; one is constantly relapsing into it, as a cat lands on his paws. But it is very unsettling for the teacher too. The further one travels from north to south the more does one sink in the slough of this evil. It rages most virulently in Southern Austria. The dialect talks rightly of Der Suu; the school language teaches us to say Der Son. So that we say Der Son for a boy and Die Sohne for what shines in the sky. That is only the most extreme case. But if we take care, in telling stories, to keep all really long sounds long and all short ones short, all sharp ones sharp, all drawn-out ones prolonged, and all soft ones soft, and to take notice of the child's pronunciation, and to correct it constantly, so that he speaks correctly, we shall be laying the foundations for correct writing. In the first year we do not need to do much more than lay right foundations. Thus, in dealing with spelling, we do not yet need to let the child write lengthening or shortening signs, as even permitted in the usual school time-table—we can spend as long as we like over speaking, and only in the last instance introduce the various rules of spelling. This is the kind of thing to which we must pay heed when we are concerned with the right treatment of children at the beginning of their school life.

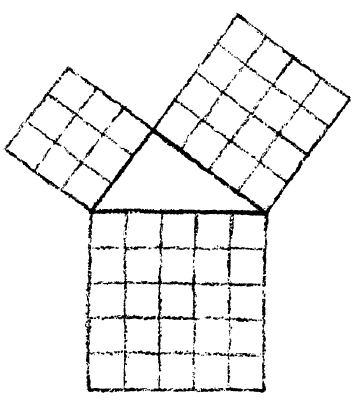

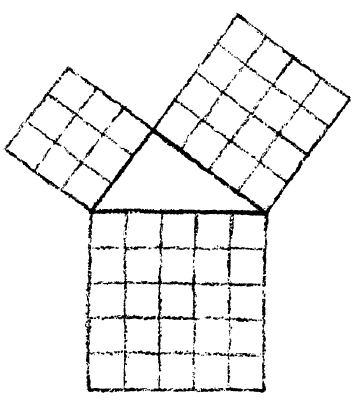

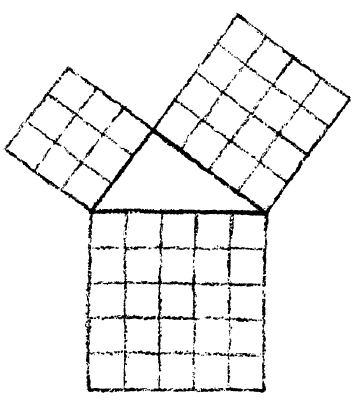

The children near the end of the school life, at the age of thirteen to fourteen, come to us maltreated by the intellectual process. The teaching they have received has been too much concerned with the intellect. They have experienced far too few of the benefits of will- and feeling-training. Consequently, we shall have to make up for lost ground, particularly in these last years. We shall have to attempt, whenever opportunity offers, to introduce will and feeling into the exclusively intellectual approach, by transforming much of what the children have absorbed purely intellectually into an appeal to the will and feelings. We can assume at any rate that the children whom we get at this age have learnt, for instance, the theorem of Pythagoras the wrong way, that they have not learnt it in the way we have discussed. The question is how to contrive in this case not only to give the child what he has missed but to give him over and above that, so that certain powers which are already dried up and withered are stimulated afresh as far as they can be revived. So we shall try, for instance, to recall to the child's mind the theorem of Pythagoras. We shall say: “You have learnt it. Can you tell me how it goes? Now you have said the theorem of Pythagoras to me. The square on the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares on the other two sides.”

But it is absolutely certain that the child has not had the experience which learning this should give his soul. So I do something more. I do not only demonstrate the theorem to him in a picture, but I show how it develops. I let him see it in a quite special way. I say: “Now three of you come out here. One of you is to cover this surface with chalk: all of you see that he only uses enough chalk to cover the surface. The next one is to cover this surface with chalk; he will have to take another piece of chalk. The third will cover this, again with another piece of chalk.” And now I say to the boy or girl who has covered the square on the hypotenuse: “You see, you have used just as much chalk as both the others together. You have spread just as much on your square as the other two together, because the square on the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares on the other two sides.” That is, I make it vivid for him by the use of chalk. It sinks deeper still into his soul when he reflects that some of the chalk has been ground down and is no longer on the piece of chalk but is on the board. And now I go on to say: “Look, I will divide the squares; one into sixteen, the other into nine, the other into twenty-five squares. Now I am going to put one of you into the middle of each square, and you are to think that it is a field and you have to dig it up. The children who have worked at the twenty-five little squares in this piece will then have done just as much work as the children who have turned over the piece with sixteen squares and the children who have turned over the piece with nine squares together. But the square on the hypotenuse has been dug up by your labour; you, by your work, have dug up the square on one of the two sides, and you, by your work, have dug up the square on the other side.” In this way I connect the child's will with the theorem of Pythagoras. I connect at least the idea with an exercise rooted significantly in his will in the outside world, and I again bring to life what his cranium had imbibed more or less dead.

Now let us suppose the child has already learnt Latin or Greek. I try to make the children not only speak Latin and Greek but listen to one another as well, listen to each systematically when one speaks Latin, another Greek. And I try to make the difference live vividly for them which exists between the nature of the Greek and Latin languages. I should not need to do this in the ordinary course of teaching, for this realization would result of itself with the ideal time-table. But we need it with the children from outside, because the child must feel: when he speaks Greek he really only speaks with the larynx and chest; when he speaks Latin there is something of the whole being accompanying the sound of the language. I must draw the child's attention to this. Then I will point out to him the living quality of French when he speaks that, and how it resembles Latin very closely. When he talks English he almost spits the sounds out. The chest is less active in English than in French. In English a tremendous amount is thrown away and sacrificed. In fact, many syllables are literally spat out before they work. You need not say “spat out” to the children, but make them understand how, in the English language particularly, the word is dying towards its end. You will try like this to emphasize the introduction of the element of articulation into your language teaching with those children of twelve to fourteen whom you have taken over from the schools of to-day.

Dreizehnter Vortrag

Sie haben gesehen, daß wir uns in diesen Vorträgen, die methodischdidaktischer Natur sind, allmählich der Einsicht genähert haben, die uns den eigentlichen Lehrplan geben soll. Nun habe ich Ihnen schon verschiedentlich erzählt, daß wir ja mit Bezug auf dasjenige, was wir in unserer Schule aufnehmen und wie wir es aufnehmen, Kompromisse schließen müssen mit dem, was heute schon einmal da ist. Denn wir können ja vorläufig nicht zu der Waldorfschule hinzu auch die übrige soziale Welt schaffen, in welche diese Waldorfschule eigentlich hineingehört. Und so wird aus dieser umliegenden sozialen Welt heraus dasjenige strahlen, was uns auch den eventuellen Ideallehrplan der Waldorfschule immerfort durchkreuzen wird. Aber wir werden doch nur dann gute Lehrer in der Waldorfschule sein, wenn wir die Beziehungen kennen zwischen dem Ideallehrplan und dem, was unser Lehrplan zunächst noch sein muß wegen des Einflusses der äußeren sozialen Welt. Da werden sich uns gleich im Anfang der Volksschulzeit die bedeutsamsten Schwierigkeiten bei den Schülern, den Kindern ergeben, auf die wir daher zuerst hinweisen müssen, bei den Schülern, den Kindern gleich im Anfang der Volksschulzeit und dann wiederum am Ende. Gleich am Anfang der Volksschulzeit werden sich ja die Schwierigkeiten ergeben, weil Lehrpläne der Außenwelt vorliegen. In diesen Lehrplänen werden allerlei Lehrziele verlangt, und wir werden es nicht riskieren können, daß unsere Kinder, wenn sie das 1., das 2. Schuljahr absolviert haben, noch nicht so dastehen wie die draußen erzogenen und unterrichteten Kinder. Wenn das 9. Lebensjahr erreicht ist, dann werden ja nach unserer Methode unsere Kinder viel besser dastehen, aber in den Zwischenzeiten könnte es sein, daß verlangt würde, sagen wir, unsere Kinder sollen am Ende des 1. Schuljahres irgendwie vor einer Kommission der Außenwelt zeigen, was sie können. Nun ist es für die Kinder nicht gut, daß sie gerade dasjenige können, was heute eine Kommission in der Außenwelt verlangt. Und unser Ideallehrplan müßte eigentlich auf anderes hinarbeiten, als von einer solchen Kommission verlangt wird. So macht uns dasjenige, was von der Außenwelt diktiert ist, den Ideallehrplan zum Teil zunichte. So ist es am Anfang unseres Unterrichts in der Waldorfschule; in den oberen Klassen der Waldorfschule haben wir es ja mit Kindern, mit Schülern zu tun, welche schon aus den äußeren Unterrichtsanstalten hereinkommen, welche also schon methodisch und didaktisch nicht so unterrichtet worden sind, wie sie unterrichtet werden sollten.

Der hauptsächlichste Fehler, der dem Unterricht zwischen dem 7. und 12. Jahr heute anhaftet, ist ja der, daß viel zu sehr intellektuell unterrichtet wird. Wenn auch immer gepredigt wird gegen das Intellektuelle, es wird viel zu sehr nach dem Intellekt hingearbeitet. Wir werden daher Kinder hereinbekommen, welche schon einen stark greisenhaften Zug in sich haben, welche viel mehr Greisenhaftes in sich haben, als Kinder im 13., 14. Jahr haben sollten. Daher kommt es ja auch, daß — wenn heute unsere Jugend selber reformatorisch auftritt, wie bei den Pfadfindern und ähnlichen Bewegungen, wo sie selber verlangt, wie sie erzogen und unterrichtet werden soll - sie dann die greulichsten Abstraktionen, das heißt Greisenhaftes zutage bringt. Und gerade indem unsere Jugend immer fordert, wie es die Wandervögel fordern, recht jugendlich unterrichtet zu werden, verlangt sie, nach greisenhaften Grundsätzen unterrichtet zu werden. Das erleben wir ja wirklich. Wir haben es selbst bei einer Kulturratssitzung recht anschaulich erlebt, wo solch ein junger Wandervogel oder Angehöriger einer Jugendbewegung aufgetreten ist. Er fing an, seine ganz langweiligen Abstraktionen abzulesen, wie nun die Jugend verlange, unterrichtet und erzogen zu werden. Das war einigen zu langweilig, weil es lauter Selbstverständlichkeiten waren, aber Selbstverständlichkeiten, die etwas an Altersschwäche litten. Da wurden die Zuhörer unruhig, und der junge Redner schleuderte in die Menge hinein: Ich konstatiere, daß heute das Alter die Jugend nicht versteht. — Bloß das lag aber vor, daß dieses halbe Kind zu stark greisenhaft war wegen einer quergegangenen Erziehung und eines quergegangenen Unterrichtes.

Das ist es, was besonders wiederum stark berücksichtigt werden muß bei den Kindern, die wir mit 12 bis 14 Jahren in die Schule bekommen und denen wir sozusagen vorläufig den letzten Schliff geben sollten. Am Anfang und am Ende der Schuljahre entstehen für uns die großen Fragen. Wir müssen so viel als möglich tun, um unserem Ideallehrplan gerecht zu werden, und wir müssen so viel als möglich tun, um die Kinder nicht dem heutigen Leben zu stark zu entfremden.

Nun tritt ja gerade im 1. Schuljahr im Lehrplan etwas sehr Verhängnisvolles zutage. Da wird verlangt, daß die Kinder schon das Ziel erreichen, möglichst viel lesen zu können, woneben sie wenig schreiben lernen. Das Schreiben wird gewissermaßen im Anfang erhalten, und das Lesen soll schon im 1. Schuljahr so weit gebracht werden, daß die Kinder wenigstens solche Lesestücke sowohl in deutscher wie in lateinischer Schrift lesen können, die schon mit ihnen zusammen gelesen oder vorgelesen worden sind. Aber immerhin in deutscher und lateinischer Schrift, während im Schreiben verhältnismäßig wenig verlangt wird. Wir würden, wenn wir idealiter erziehen könnten, selbstverständlich von den Formen, so wie wir das besprochen haben, ausgehen, und die Formen, die wir aber aus sich selbst entwickeln, die würden wir allmählich von dem Kinde in die Schreibbuchstaben umwandeln lassen. Wir werden das tun; wir werden uns nicht abhalten lassen, mit einem Zeichen- und Malunterricht zu beginnen und die Schreibbuchstaben aus diesem Zeichen- und Malunterricht herauszuholen, und wir werden erst dann zur Druckschrift übergehen. Wir werden, wenn das Kind gelernt hat, die geschriebenen Buchstaben zu erkennen, zur Druckschrift übergehen. Da werden wir einen Fehler machen, weil wir ja im 1. Schuljahr nicht die Zeit haben werden, beide Schriftarten, deutsche und lateinische Schrift, fertig herauszugestalten und dann noch deutsche und lateinische Schrift lesen zu lehren. Das würde das 1. Schuljahr zu sehr belasten. Daher werden wir den Weg vom malenden Zeichnen zum Deutschschreiben machen müssen, werden dann übergehen müssen von den deutschgeschriebenen Buchstaben zu deutschgedruckten Buchstaben im einfachen Lesen. Wir werden dann, ohne daß wir erst die lateinischen Buchstaben auch zeichnerisch erreicht haben, von der deutschen zur lateinischen Druckschrift übergehen. Das werden wir also als ein Kompromiß gestalten: Damit wir der wirklichen Pädagogik Rechnung tragen, werden wir das Schreiben aus dem Zeichnen entwickeln, aber, damit wir auf der andern Seite das Kind wiederum so weit bringen, wie es der Lehrplan verlangt, werden wir es auch zum elementaren Lesen der lateinischen Druckschrift bringen. Das wird also unsere Aufgabe bezüglich des Schreibens und Lesens sein.

Ich habe in diesen didaktischen Vorträgen schon darauf hingewiesen, daß, wenn wir die Formen der Buchstaben bis zu einem gewissen Grade entwickelt haben, wir schneller vorgehen müssen.

Dann müssen wir aber vor allen Dingen suchen, daß im 1. Schuljahr viel von dem getrieben wird, was einfaches Sprechen mit den Kindern ist. Wir lesen ihnen womöglich wenig vor, sondern bereiten uns so gut vor, daß wir ihnen alles, was wir an sie heranbringen wollen, erzählen können. Wir versuchen dann zu erreichen, daß die Kinder nach dem von uns Erzählten, Gehörten nacherzählen können. Wir verwenden aber nicht Lesestücke, die die Phantasie nicht anregen, sondern wir verwenden möglichst Lesestücke, die recht stark die Phantasie anregen, namentlich Märchenerzählungen. Möglichst viel Märchenerzählungen. Und wir versuchen, indem wir lange mit dem Kinde dieses Erzählen und Nacherzählen getrieben haben, es dann ein wenig dahin zu bringen, in kurzer Art Selbsterlebtes nachzuerzählen. Wir lassen uns zum Beispiel irgend etwas, was das Kind gern selbst erzählt, von dem Kinde erzählen. Bei all diesem Erzählen, Nacherzählen, Erzählen von Selbsterlebtem entwickeln wir ohne Pedanterie die Überleitung des Dialekts in die gebildete Umgangssprache, indem wir einfach die Fehler, die das Kind macht - zuerst macht es ja lauter Fehler, nachher wohl immer weniger —, korrigieren. Wir entwickeln beim Kind im Erzählen und im Nacherzählen den Übergang von dem Sprechen des Dialektes zur gebildeten Umgangssprache. Das können wir machen, und trotzdem wird das Kind am Ende des 1. Schuljahres das Lehrziel erreicht haben, das heute von ihm verlangt wird.

Dann müssen wir allerdings etwas einfügen, was im allerersten Schuljahre am besten doch wegbliebe und was etwas das kindliche Gemüt Belastendes ist: wir müssen dem Kinde beibringen, was ein Selbstlaut und was ein Mitlaut ist. Wenn wir dem idealen Lehrplan folgen könnten, würden wir das im 1. Schuljahre noch nicht tun. Aber dann könnte irgendein Inspektor am Ende des 1. Schuljahres kommen und das Kind fragen, was ein i ist und was ein l ist und das Kind wüßte nicht, daß das eine ein Selbstlauter, das andere ein Mitlauter ist. Und man würde uns sagen: Nun ja, dies Nichtwissen ist das Ergebnis der Anthroposophie. - Deshalb müssen wir dafür sorgen, daß das Kind Selbstlaute von Mitlauten unterscheiden kann. Wir müssen auch dem Kinde beibringen, was ein Hauptwort ist, was ein Artikel ist. Und nun kommen wir in eine rechte Kalamität hinein. Denn wir sollten nach dem hiesigen Lehrplan die deutschen Ausdrücke gebrauchen und nicht Artikel sagen. Da müssen wir zu dem Kinde nach der hiesigen Vorschrift statt Artikel Geschlechtswort sagen, und da kommt man ja natürlich in eine Kalamität hinein. Besser wäre es, wenn man da nicht pedantisch wäre und das Wort Artikel beibehalten könnte. Nun habe ich Ihnen ja schon Andeutungen darüber gemacht, wie man für das Kind Hauptwort von Eigenschaftswort unterscheidet, indem man das Kind anleitet zu sehen, wie das Hauptwort sich bezieht auf das, was draußen im Raum steht, für sich steht. Man muß da versuchen, dem Kinde zu sagen: Sieh einmal — Baum! Baum ist etwas, was im Raume stehen bleibt. Aber schau dir einen Baum im Winter an, schau dir einen Baum im Frühling an, und schau dir ihn im Sommer an. Der Baum ist immer da, aber er schaut anders aus im Winter, anders im Sommer, anders im Frühling. Wir sagen im Winter: Er ist braun. Wir sagen im Frühling: Er ist grün. Wir sagen im Sommer: Er ist bunt. Das sind seine Eigenschaften. — So bringen wir dem Kinde zuerst den Unterschied zwischen dem Bestehenbleibenden und den wechselnden Eigenschaften bei und sagen ihm dann: Wenn wir ein Wort brauchen für das Bestehenbleibende, ist es ein Hauptwort, wenn wir ein Wort brauchen für das, was an dem Bestehenbleibenden wechselt, ist es ein Eigenschaftswort. — Dann bringen wir dem Kinde den Begriff der Tätigkeit bei. Setz dich einmal auf deinen Stuhl. Du bist ein braves Kind. Brav ist ein Eigenschaftswort. Aber jetzt steh auf und laufe. Da tust du etwas. Das ist eine Tätigkeit. Diese Tätigkeit bezeichnen wir durch ein Tätigkeitswort. — Wir versuchen also, das Kind an die Sache heranzubringen, und dann gehen wir von der Sache zu den Worten über. Auf diese Weise werden wir, ohne zuviel Schaden anzurichten, dem Kinde beibringen können, was ein Hauptwort, ein Artikel, ein Eigenschaftswort, ein Zeitwort ist. Zu verstehen, was ein Artikel ist, das ist ja am allerschwierigsten, weil das Kind noch nicht recht die Beziehung des Artikels zum Hauptwort einsehen kann. Da werden wir ziemlich im Abstrakten herumplätschern, wenn wir dem Kinde beibringen wollen, was ein Artikel ist. Aber es muß es eben lernen. Und es ist viel besser, da im Abstrakten herumzuplätschern, weil es ohnedies etwas Unnatürliches ist, als allerlei künstliche Methoden auszusinnen, um auch den Artikel in seiner Bedeutung und Wesenheit dem Kinde klarzumachen, was ja unmöglich ist.

Kurz, es wird für uns schon gut sein, wenn wir mit vollem Bewußtsein unterrichten, daß wir etwas Neues in den Unterricht hineinbringen. Dazu wird sich uns im 1. Schuljahr reichlich Gelegenheit bieten. Noch in das 2. Schuljahr wird vieles in dieser Beziehung hineinspuken. Wir werden aber im 1. Schuljahr viel darin haben, was eine große Wohltat für das heranwachsende Kind ist. Wir werden im 1. Schuljahr nicht nur das Schreiben darin haben, sondern ein elementares, primitives Malen und Zeichnen, denn davon gehen wir ja behufs des Schreibunterrichts aus. Wir werden im 1. Schuljahr nicht bloß das Singen drin haben, sondern auch ein elementares Erlernen des Musikalischen am Instrument. Wir werden das Kind von Anfang an nicht nur singen lassen, sondern es zum Instrument hinführen. Das wird wiederum eine große Wohltat für das Kind sein. Wir werden ihm die ersten Elemente des Hörens von Tonzusammenhängen beibringen. Und wir werden versuchen, das Gleichgewicht zu halten zwischen dem Hervorbringen des Musikalischen durch den Gesang von innen und dem Hören des Tonlichen von außen oder dem Erzeugen des Tonlichen durch das Instrument.

Diese Dinge, das malende Zeichnen, das zeichnende Malen, das Sich-Hineinfinden in das Musikalische, das wird uns besonders für das 1. Schuljahr ein wunderbares Element der Willensbildung abgeben können, jener Willensbildung, die der heutigen Schule fast ganz fernliegt. Und führen wir dann für die Knirpse auch noch das gewöhnliche Turnen über in die Eurythmie, dann werden wir die Willensbildung ganz besonders fördern.

Es ist mir hier ein Lehrplan für das 1. Schuljahr vorgelegt worden. Der enthält:

Religion in 2 Stunden

Deutsch in 11 Stunden

Schreiben, da ist keine Stundenzahl angegeben, aber das

Schreiben wird eben im Deutschunterricht ausführlich

gelehrt, dann

Heimatkunde 2 Stunden

Rechnen 4 Stunden

Singen und Turnen zusammen 1 Stunde wöchentlich.

Das werden wir nicht tun, denn da würden wir zu stark gegen das Wohl des heranwachsenden Kindes sündigen. Sondern wir werden, so gut wir nur können, das Gesanglich-Musikalische und das TurnerischEurythmische auf den Nachmittag verlegen, das andere auf den Vormittag verlegen, und wir werden - in mäßiger Weise allerdings, bis wir fühlen sollten, es ist zuviel — das Gesanglich-Musikalische und Turnerisch-Eurythmische mit den Kindern nachmittags üben. Denn 1 Stunde wöchentlich dazu zu verwenden, ist geradezu eine Lächerlichkeit. Das beweist Ihnen schon, daß der ganze Unterricht aufs Intellektuelle hin dressiert ist.

Man hat es ja heute im 1. Elementarschuljahr mit sechsjährigen Kindern zu tun oder mit solchen, die höchstens ein paar Monate nach dem 6. Jahr sind. Mit solchen Kindern kann man ganz gut die Elemente des Zeichnerisch-Malerischen, des Musikalischen treiben und auch ganz gut Turnen und Eurythmie treiben; aber wenn man mit ihnen im heutigen Stile Religion treibt, dann erteilt man ihnen überhaupt keinen Religionsunterricht, sondern lediglich einen Gedächtnisunterricht, und das ist noch das Gute dabei. Denn es ist einfach unsinnig, zu dem sechsbis siebenjährigen Kinde von den Begriffen zu sprechen, die in der Religion eine Rolle spielen. Das kann es nur seinem Gedächtnis einprägen. Das Gedächtnispflegen ist ja ganz gut, aber man muß sich dessen bewußt sein, daß man da eigentlich mit allerlei an das Kind herantritt, wofür es in dieser Zeit nicht das allergeringste Verständnis hat.

Ein anderes noch, was hier schon für das erste Schuljahr steht, wird uns veranlassen, mindestens im praktischen Unterricht eine andere Ansicht darüber zu gewinnen, als man gewöhnlich hat. Im 2. Schuljahr tritt es ja dann noch in einer besonderen Weise auf, sogar als ein besonderer Unterrichtsgegenstand: das ist das Schönschreiben. Wir werden, indem wir das Schreiben aus dem malenden Zeichnen herausholen, doch gar nicht nötig haben, bei dem Kinde extra zu pflegen das Häßlichschreiben und das Schönschreiben. Wir werden uns bemühen, zwischen dem Häßlichschreiben und dem Schönschreiben keinen Unterschied zu machen und allen Schreibunterricht so zu gestalten — und das werden wir trotz des äußeren Lehrplanes können -, daß das Kind immer schön schreibt, so schön, als es notwendig ist, daß es niemals den Unterschied macht zwischen Schönschreiben und Häßlichschreiben. Und wenn wir uns bemühen, dem Kinde ziemlich lange zu erzählen und es nacherzählen zu lassen und uns dabei auch bemühen, richtig zu sprechen, dann werden wir das Rechtschreiben auch nur korrigierend zunächst zu treiben brauchen. Wir werden also auch nicht das Rechtschreiben und Unrechtschreiben als zwei besondere Strömungen des Schreibenletnens anzuführen brauchen.

Sehen Sie, in dieser Beziehung müssen wir natürlich sehr auf uns selber achtgeben. Uns Österreichern ist das beim Unterricht eine ganz besondere Schwierigkeit. Denn in Osterreich gab es außer den zwei Sprachen, dem Dialekt und der gebildeten Umgangssprache, noch eine dritte. Das war die besondere österreichische Schulsprache. Da sprach man alle langen Vokale kurz und alle kurzen Vokale lang, und während man im Dialekt richtig sagt «d’Sun», sagt die österreichische Schulsprache nicht etwa die Sonne, sondern «die Sohne», und das gewöhnt man sich unwillkürlich an. Man fällt immer wieder zurück wie die Katze auf die Pfoten. Aber auch für den Lehrer hat es etwas sehr Störendes. Immer mehr gerät man in dieses Übel hinein, je weiter man von Nord nach Süd kommt. In Südösterreich grassiert das Übel am allerstärksten. Der Dialekt sagt ganz richtig «der Suu»; die Schulsprache lehrt uns sagen «der Son». So daß man sagt «der Son» für den Knaben und «die Sohne» für das, was am Himmel scheint. Das ist nur das alleräußerste Extrem. Aber wenn wir uns bemühen, im Erzählen alles wirklich Lange lang und alles Kurze kurz, alles Scharfe scharf, alles Gedehnte gedehnt, alles Weiche weich zu halten und beim Kinde wieder achtgeben und fortwährend korrigieren, daß es richtig spricht, dann werden wir ihm die Vorbedingungen auch für ein richtiges Schreiben schaffen. Im 1. Schuljahr brauchen wir uns nicht viel mehr als die richtigen Vorbedingungen dazu zu schaffen. So können wir wir brauchen das Kind noch nicht Dehnungen und Schärfungen schreiben zu lassen, weil das ja auch der Schulplan gestattet - in bezug auf die Rechtschreibung möglichst lange beim bloßen Sprechen bleiben und erst zu allerletzt das Schreiben in das Rechtschreiben einlaufen lassen. Das ist so etwas, was wir beachten müssen, wenn es sich darum handelt, die Kinder richtig zu behandeln, die im Anfang ihrer Schulzeit stehen.

Die Kinder, die am Ende ihrer Schulzeit stehen, die dreizehn- bis vierzehnjährigen, die bekommen wir intellektualistisch verbildet. Es ist zuviel bei dem Unterricht auf ihre Intellektualität Rücksicht genommen worden. Sie haben viel zu wenig die Wohltat der Willens- und Gemütsbildung erfahren. Daher werden wir, was sie zu wenig erfahren haben, gerade in diesen letzten Jahren nachholen müssen. Wir werden daher bei jeder Gelegenheit den Versuch machen müssen, Wille und Gemüt in das bloß Intellektuelle hineinzubringen, indem wir vieles, was die Kinder rein intellektuell aufgenommen haben, dann in dieser Zeit noch in ein solches umwandeln, das sich an den Willen und ans Gemüt richtet. Wir können unter allen Umständen annehmen, daß die Kinder, die wir da in diesem Jahre bekommen, zum Beispiel den pythagoräischen Lehrsatz falsch gelernt haben, daß sie ihn nicht in der richtigen Weise gelernt haben, wie wir das besprochen haben. Es fragt sich, wie wir uns da helfen, so daß wir gewissermaßen nicht nur das geben, was das Kind nicht erhalten hat, sondern daß wir ihm noch mehr geben, so daß gewisse Kräfte, die schon abgetrocknet und abgedorrt sind, wieder belebt werden, soweit sie wieder belebt werden können. Daher versuchen wir zum Beispiel dem Kinde noch einmal den pythagoräischen Lehrsatz ins Gedächtnis zurückzurufen. Wir sagen: Du hast ihn gelernt. Sage mir, wie heißt er? — Sieh einmal, du hast mir jetzt den pythagoräischen Lehrsatz gesagt: das Quadrat der Hypotenuse ist gleich der Summe der Quadrate über den zwei Katheten. Aber es ist ganz gewiß seelisch in dem Kinde das nicht darin, was von dem Erlernen dieses pythagoräischen Lehrsatzes darin sein sollte. Daher tue ich ein übriges. Ich mache ihm nicht nur die Sache anschaulich, sondern ich mache ihm die Anschauung auch noch genetisch. Ich lasse ihm die Anschauung auf eine ganz besondere Weise entstehen. Ich sage: Kommt einmal, drei von euch, heraus. Der erste überdeckt diese Fläche hier mit der Kreide: gebt acht, daß er nur so viel Kreide verwendet, als notwendig ist, um die Fläche mit Kreide zu bedecken. Der zweite bedeckt diese Fläche mit Kreide, er nimmt ein anderes Kreidestück; der dritte diese, wiederum mit einem andern Kreidestück. — Und jetzt sage ich dem Jungen oder dem Mädchen, welches das Hypotenusenquadrat bedeckt hat: Sieh einmal, du hast gerade so viel Kreide gebraucht wie die beiden andern zusammen. Du hast auf das Quadrat so viel draufgeschmiert, wie die beiden zusammen, weil das Quadrat der Hypotenuse gleich ist der Summe der Quadrate der Katheten. - Ich lasse ihm also die Anschauung entstehen durch den Kreideverbrauch, Da legt es sich mit der Seele noch tiefer hinein, wenn es auch noch daran denkt, daß da von der Kreide etwas abgeschunden ist, was nicht mehr an der Kreide ist, was jetzt da auf der Tafel ist. Und jetzt gehe ich noch dazu über, zu sagen: Sieh einmal, ich teile die Quadrate ab, das eine in 16 Quadrate, das andere in 9 Quadrate, das andere in 25. In die Mitte von jedem Quadrat stelle ich jetzt einen von euch hinein, und ihr denkt euch, das ist ein Acker und ihr müßt den Acker umgraben. — Die Kinder, welche die 25 kleinen Quadrate auf dieser Fläche bearbeitet haben, haben dann gerade so viel gearbeitet wie die in der Fläche mit 16 Quadraten und die in der Fläche mit 9 Quadraten zusammen. Aber durch eure Arbeit ist das Quadrat über der Hypotenuse umgegraben worden; durch eure Arbeit das über der einen Kathete, und durch eure Arbeit das über der andern Kathete. - So verbinde ich mit dem pythagoräischen Lehrsatz etwas, was wollend ist in dem Kinde, was wenigstens die Vorstellung hervorruft, daß es mit seinem Willen sinnvoll in der äußeren Welt drinnensteht, und ich belebe ihm das, was ziemlich unlebendig in seinen Schädel hineingekommen ist.

Nehmen wir nun an, das Kind habe schon Lateinisch, Griechisch gelernt. Jetzt versuche ich, die Kinder dahin zu bringen, daß sie nicht nur lateinisch und griechisch sprechen, sondern daß sie sich auch anhören, methodisch sich anhören, wenn der eine lateinisch, der andere griechisch spricht. Und ich versuche, ihnen anschaulich, lebendig zu machen, welches der Unterschied ist im Leben des Griechischen und im Leben des Lateinischen. Das würde ich bei dem gewöhnlichen Unterricht nicht brauchen, denn das ergibt sich von selbst im Ideallehrplan. Aber bei den Kindern, die wir bekommen, brauchen wir das, weil das Kind fühlen soll: Wenn es griechisch spricht, so spricht es eigentlich nur mit dem Kehlkopf und der Brust; wenn es lateinisch spricht, so tönt immer etwas mit vom ganzen Menschen. Darauf muß ich das Kind aufmerksam machen. Ich werde dann auch das Kind aufmerksam machen auf das Lebendige, wenn es französisch spricht, das dem Lateinischen sehr ähnlich ist. Wenn es englisch spricht, spuckt es die Buchstaben fast aus; da ist die Brust weniger daran beteiligt als beim Französischsprechen, da wird viel, viel abgeworfen. Es werden namentlich manche Silben geradezu ausgespuckt, bevor sie vollständig wirken. Sie brauchen den Kindern nicht zu sagen ausgespuckt, aber Sie werden ihm begreiflich machen, wie das Wort gegen sein Ende hin erstirbt gerade in der englischen Sprache. So werden Sie versuchen, das artikulierende Element besonders scharf hineinzubringen in den Sprachunterricht für die Kinder im 13., 14. Lebensjahr, die Sie übernommen haben aus der gegenwärtigen Schule.

Thirteenth Lecture

You have seen that in these lectures, which are methodological and didactic in nature, we have gradually approached the insight that will give us the actual curriculum. I have already told you on several occasions that, with regard to what we take up in our school and how we take it up, we have to compromise with what already exists today. For the time being, we cannot create the rest of the social world to which this Waldorf school actually belongs. And so, from this surrounding social world, there will emanate that which will continually thwart the ideal curriculum of the Waldorf school. But we will only be good teachers in the Waldorf school if we understand the relationship between the ideal curriculum and what our curriculum must initially be due to the influence of the external social world. Right at the beginning of elementary school, we will encounter the most significant difficulties with the pupils, the children, which we must therefore point out first, with the pupils, the children, right at the beginning of elementary school and then again at the end. Right at the beginning of elementary school, difficulties will arise because of the curricula of the outside world. These curricula require all kinds of learning objectives, and we cannot risk our children, after completing the first and second grades, not being at the same level as children educated and taught outside. When they reach the age of nine, our children will be in a much better position according to our method, but in the meantime it could be that, say, our children are required to show a commission from the outside world what they can do at the end of the first school year. Now, it is not good for the children to be able to do exactly what a commission in the outside world demands today. And our ideal curriculum should actually work toward something other than what such a commission demands. Thus, what is dictated by the outside world partially destroys our ideal curriculum. This is how it is at the beginning of our teaching in the Waldorf school; in the upper grades of the Waldorf school, we are dealing with children, with students who have already come from external educational institutions, who have not been taught methodically and didactically as they should have been.

The main mistake that is inherent in teaching between the ages of 7 and 12 today is that teaching is far too intellectual. Even though there is always preaching against intellectualism, there is far too much emphasis on the intellect. We will therefore have children who already have a strong senile streak in them, who have much more senility in them than children of 13 or 14 should have. This is also why, when our youth today take a reformist stance, as in the case of the Boy Scouts and similar movements, where they themselves demand how they should be educated and taught, they then bring forth the most gruesome abstractions, that is, senility. And precisely because our youth always demands, as the Wandervögel demand, to be taught in a youthful manner, they demand to be taught according to senile principles. We are really experiencing this. We experienced it ourselves quite vividly at a cultural council meeting, where such a young Wandervogel or member of a youth movement appeared. He began to read out his very boring abstractions about how young people now demand to be taught and educated. Some found this too boring because it was all self-evident, but self-evident truths that suffered from senility. The audience became restless, and the young speaker hurled into the crowd: “I note that today, old age does not understand youth.” — But the fact was that this half-child was too senile because of a botched upbringing and botched education.

This is what must be taken into account, especially in the case of the children who come to school at the age of 12 to 14 and whom we should, so to speak, give the finishing touches to. At the beginning and end of the school year, we are faced with big questions. We must do as much as possible to live up to our ideal curriculum, and we must do as much as possible to prevent the children from becoming too alienated from today's life.

Now, something very disastrous comes to light in the curriculum, especially in the first year of school. Children are required to achieve the goal of being able to read as much as possible, while learning very little about writing. Writing is, in a sense, neglected at the beginning, and reading is to be brought to such a level in the first year of school that children can at least read passages in both German and Latin script that have already been read with them or read aloud to them. But at least in German and Latin script, while relatively little is required in writing. If we could educate ideally, we would of course start from the forms as we have discussed, and the forms that we develop ourselves, we would gradually have the child transform into written letters. We will do this; we will not be deterred from starting with drawing and painting lessons and extracting the letters from these drawing and painting lessons, and only then will we move on to block letters. Once the child has learned to recognize the written letters, we will move on to block letters. We will make a mistake here, because in the first year of school we will not have time to fully develop both types of writing, German and Latin script, and then also teach German and Latin script reading. That would place too much strain on the first year of school. Therefore, we will have to make the transition from drawing to writing German, and then move on from German handwriting to German print in simple reading. We will then move from German to Latin print without first having mastered Latin letters in drawing. We will therefore make a compromise: in order to take real pedagogy into account, we will develop writing from drawing, but in order to bring the child up to the level required by the curriculum, we will also teach them basic reading of Latin print. This will therefore be our task with regard to writing and reading.

I have already pointed out in these didactic lectures that once we have developed the forms of the letters to a certain degree, we must proceed more quickly.

But then, above all, we must ensure that in the first year of school, much of what is done is simply talking with the children. We read to them as little as possible, but prepare ourselves so well that we can tell them everything we want to teach them. We then try to get the children to retell what we have told them and what they have heard. However, we do not use reading material that does not stimulate the imagination, but rather reading material that strongly stimulates the imagination, namely fairy tales. As many fairy tales as possible. And by spending a long time telling and retelling stories with the children, we try to get them to briefly retell their own experiences. For example, we let the child tell us something that they like to talk about themselves. Through all this telling, retelling, and recounting of their own experiences, we develop the transition from dialect to educated colloquial language without pedantry, simply by correcting the mistakes the child makes — at first they make a lot of mistakes, but later fewer and fewer. Through storytelling and retelling, we help the child develop the transition from speaking dialect to educated colloquial language. We can do this, and the child will still have achieved the learning goal required of them at the end of the first school year.

Then, however, we have to add something that would be best left out in the very first years of school and that is somewhat stressful for the child's mind: we have to teach the child what a vowel and what a consonant is. If we could follow the ideal curriculum, we would not do this in the first year of school. But then some inspector might come at the end of the first school year and ask the child what an i is and what an l is, and the child would not know that one is a vowel and the other a consonant. And we would be told: Well, this ignorance is the result of anthroposophy. That is why we must ensure that the child can distinguish between vowels and consonants. We must also teach the child what a noun is, what an article is. And now we come to a real calamity. For according to the local curriculum, we should use the German expressions and not say “article.” According to the local regulations, we must say “gender word” to the child instead of “article,” and of course this leads to a calamity. It would be better not to be pedantic and to keep using the word “article.” I have already given you some hints on how to teach children to distinguish between nouns and adjectives by guiding them to see how nouns refer to things that stand alone in space. You have to try to say to the child: Look — a tree! A tree is something that remains in the room. But look at a tree in winter, look at a tree in spring, and look at it in summer. The tree is always there, but it looks different in winter, different in summer, different in spring. In winter we say: It is brown. In spring we say: It is green. In summer we say: It is colorful. These are its characteristics. — So we first teach the child the difference between permanent and changing characteristics and then tell them: if we need a word for what remains permanent, it is a noun; if we need a word for what changes in what remains permanent, it is an adjective. — Then we teach the child the concept of activity. Sit down on your chair. You are a good child. Good is an adjective. But now stand up and walk. You are doing something. That is an action. We describe this action with a verb. — So we try to introduce the child to the thing, and then we move from the thing to the words. In this way, without causing too much damage, we will be able to teach the child what a noun, an article, an adjective, and a verb are. Understanding what an article is is the most difficult thing, because the child cannot yet fully understand the relationship between the article and the noun. We will be dabbling in the abstract when we want to teach the child what an article is. But they have to learn it. And it is much better to dabble in the abstract, because it is something unnatural anyway, than to devise all kinds of artificial methods to make the meaning and essence of the article clear to the child, which is impossible.

In short, it will be good for us if we teach with full awareness that we are introducing something new into the classroom. We will have ample opportunity to do so in the first school year. Much will still be introduced in this regard in the second school year. However, in the first school year we will have a lot that is very beneficial for the growing child. In the first school year we will not only have writing, but also elementary, primitive painting and drawing, because that is what we start with in order to teach writing. In the first school year we will not only have singing, but also elementary learning of music on an instrument. From the very beginning, we will not only let the child sing, but also introduce them to instruments. This will also be a great benefit for the child. We will teach them the first elements of hearing tonal relationships. And we will try to maintain a balance between producing music through singing from within and hearing sounds from outside or producing sounds through instruments.

These things, painting-like drawing, drawing-like painting, finding one's way into music, will provide us with a wonderful element of will formation, especially for the first year of school, a will formation that is almost completely absent from today's schools. And if we then transfer the usual gymnastics for the little ones to eurythmy, we will promote the development of will in a very special way.

I have been presented with a curriculum for the first school year. It contains:

Religion for 2 hours

German for 11 hours

Writing, no number of hours is specified, but

writing is taught in detail in German lessons

, then

local history for 2 hours

arithmetic for 4 hours

singing and gymnastics together for 1 hour per week.

We will not do that, because it would be too detrimental to the well-being of the growing child. Instead, we will do our best to move singing, music, and gymnastics/eurythmy to the afternoon and the other subjects to the morning, and we will practice singing, music, and gymnastics/eurythmy with the children in the afternoon, albeit in moderation, until we feel it is too much. Because spending one hour a week on this is downright ridiculous. This alone proves to you that the entire curriculum is geared toward the intellectual.

Today, in the first year of elementary school, we are dealing with six-year-old children or those who are at most a few months past the age of six. With such children, one can quite easily teach the elements of drawing and painting, music, and also gymnastics and eurythmy; but if one teaches them religion in the current style, then one is not teaching them religion at all, but merely teaching them to memorize, and that is still the best-case scenario. For it is simply nonsensical to talk to six- to seven-year-old children about the concepts that play a role in religion. They can only memorize them. Cultivating memory is all well and good, but one must be aware that one is actually approaching the child with all sorts of things for which it has not the slightest understanding at this age.

Another thing that is already present in the first year of school will cause us to gain a different view of it, at least in practical teaching, than is usually the case. In the second year of school, it then appears in a special way, even as a special subject: that is calligraphy. By removing writing from the realm of painting and drawing, we will not need to cultivate ugly writing and beautiful writing in children. We will endeavor not to make any distinction between ugly writing and beautiful writing and to organize all writing lessons in such a way—and we will be able to do this despite the external curriculum—that the child always writes beautifully, as beautifully as is necessary, and never makes a distinction between beautiful writing and ugly writing. And if we make an effort to tell the child stories for quite a long time and let them retell them, while also making an effort to speak correctly, then we will only need to correct their spelling at first. So we will not need to introduce correct and incorrect spelling as two separate trends in writing.

You see, in this regard, we must of course be very careful ourselves. For us Austrians, this is a particular difficulty when it comes to teaching. Because in Austria, in addition to the two languages, the dialect and the educated colloquial language, there was a third. That was the special Austrian school language. In this language, all long vowels were pronounced short and all short vowels long, and while in dialect you say “d'Sun” correctly, in Austrian school language you don't say “die Sonne” (the sun), but “die Sohne” (the sons), and you automatically get used to this. You always fall back on it like a cat falls on its feet. But it is also very disturbing for the teacher. The further you go from north to south, the more you get caught up in this evil. This problem is most prevalent in southern Austria. The dialect correctly says “der Suu”; the school language teaches us to say “der Son.” So you say “der Son” for the boy and “die Sohne” for what shines in the sky. That's just the extreme case. But if we make an effort to keep everything long really long and everything short really short, everything sharp really sharp, everything stretched really stretched, everything soft really soft when we speak, and if we pay attention to children and constantly correct them so that they speak correctly, then we will also create the preconditions for them to write correctly. In the first year of school, we don't need to do much more than create the right preconditions for this. So we don't need to have the child write elongations and sharpenings yet, because the school curriculum allows for that – in terms of spelling, we should stick to speaking for as long as possible and only introduce writing into spelling at the very end. This is something we need to bear in mind when it comes to treating children who are just starting school correctly.

The children who are at the end of their school years, the thirteen- to fourteen-year-olds, are intellectually overeducated. Too much attention has been paid to their intellectuality in the classroom. They have experienced far too little of the benefits of will and character building. Therefore, we will have to make up for what they have missed out on, especially in these last few years. We will therefore have to try at every opportunity to bring will and soul into the purely intellectual, by transforming much of what the children have absorbed purely intellectually into something that addresses the will and soul. We can assume under all circumstances that the children we are receiving this year have, for example, learned the Pythagorean theorem incorrectly, that they have not learned it in the right way, as we have discussed. The question is how we can help ourselves so that we not only give the child what it has not received, but give it even more, so that certain powers that have already dried up and withered away are revived, insofar as they can be revived. Therefore, we try, for example, to remind the child once again of the Pythagorean theorem. We say: You have learned it. Tell me, what is it called? — Look, you have now told me the Pythagorean theorem: the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the two cathetus. But it is quite certain that what should be in the child's soul from learning this Pythagorean theorem is not there. Therefore, I do something else. I not only make the matter clear to him, but I also make the insight genetic. I let the insight arise in a very special way. I say: Come out, three of you. The first one covers this area here with chalk: make sure that he uses only as much chalk as is necessary to cover the area with chalk. The second one covers this area with chalk, using another piece of chalk; the third one covers this area, again with another piece of chalk. — And now I say to the boy or girl who covered the hypotenuse square: Look, you used just as much chalk as the other two together. You have covered the square with as much chalk as the other two together, because the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the legs. So I let them grasp the concept through the use of chalk. They understand it even more deeply when they also remember that some of the chalk has been scraped off, that it is no longer on the chalk, that it is now on the blackboard. And now I go on to say: Look, I divide the squares, one into 16 squares, the other into 9 squares, the other into 25. I now place one of you in the middle of each square, and you think to yourselves, this is a field and you have to dig up the field. — The children who have worked on the 25 small squares on this area have then worked just as much as those in the area with 16 squares and those in the area with 9 squares combined. But through your work, the square above the hypotenuse has been dug up; through your work, the one above the one cathetus, and through your work, the one above the other cathetus. - In this way, I connect the Pythagorean theorem with something that is willing in the child, something that at least evokes the mental image that it is meaningfully present in the outside world with its will, and I enliven what has entered its skull in a rather lifeless state.

Let us now assume that the child has already learned Latin and Greek. Now I try to get the children to not only speak Latin and Greek, but also to listen, to listen methodically, when one speaks Latin and the other speaks Greek. And I try to make clear to them, vividly and vividly, what the difference is in the life of Greek and in the life of Latin. I wouldn't need to do this in ordinary lessons, because it comes naturally in the ideal curriculum. But with the children we get, we need to do this because the child should feel that when they speak Greek, they are actually only speaking with their larynx and chest; when they speak Latin, something from the whole person always resonates. I have to make the child aware of this. I will also draw the child's attention to the liveliness when they speak French, which is very similar to Latin. When they speak English, they almost spit out the letters; the chest is less involved than when speaking French, and much, much is discarded. Some syllables in particular are literally spat out before they have their full effect. You don't need to tell the children “spit out,” but you will make them understand how the word dies away towards the end, especially in the English language. In this way, you will try to bring the articulating element into the language teaching for the children aged 13 and 14 whom you have taken over from the current school.