Man—Hieroglyph of the Universe

GA 201

23 April 1920, Dornach

Lecture Seven

The last lectures here described a path which, if followed in the right way, leads to a perception of the Universe and its organisation. As you have seen, this path compels a continuous search for the harmony existing between the process taking place in Man and the processes observed in the Universe. Tomorrow and the day after I shall have to treat our subject in such a way that the friends who have come to attend the General Meeting may be able to receive something from the two lectures at which they are present. To-morrow I shall go over again some of what has been said in order then to connect with it something fresh.

In perusing my Occult Science—an Outline, you will have seen that in the description it gives of the evolution of the known Universe a point is made of keeping everywhere in view the relationship of that evolution to the evolution of Man himself. Beginning with the Saturn period which was followed by the Sun and Moon periods preceding the Earth period, you will remember that the Saturn period was characterised by the laying of the first foundations of the human senses. And along this line of thought the book proceeds. Everywhere universal conditions are considered in a way that at the same time also describes the evolution of Man. In short, Man is not considered as standing in the Universe as modern science sees him—the outer Universe on the one hand, and Man on the other—two entities that do not rightly belong to each other. Here, on the contrary, the two are regarded as merged into each other, and the evolution of both is followed together. This conception must, of necessity, be applied also to the present attributes, forces and motions of the Universe. We cannot consider first the Universe abstractly in its purely spatial aspect, as is done in the Galileo-Copernican system, and then Man as existing beside it; we must allow both to merge into one another in our study.

This is only possible, when we have acquired an understanding of Man himself. I have already shown you how little modern natural science is in a position really to explain Man. What does science do, for instance, in that sphere where it is greatest, judging by modern methods of thought? It states in a grand manner that Man has evolved physically from other lower forms. It then shows how, during the embryonic period, Man passes again rapidly through these forms in recapitulation. This means that Man is looked upon as the highest of the animals. Science contemplates the animal kingdom and then builds up Man from what is found there; in other words, it examines everything non-human, and then says: ‘Here we come to a standstill; here Man begins’. Natural science does not feel called upon to study Man as Man, and consequently any real understanding of his nature is out of the question.

It is in truth very necessary today for people who claim to be experts in this domain of nature, to examine Goethe's investigations in natural science, particularly his Theory of Colours. Here a very different method of investigation is used from that to which we today are accustomed. At the very commencement mention is made of subjective, and of physiological colours, and the phenomena of the living experience of the human eye in connection with its environment are then carefully investigated. It is shown, for example, how these experiences or impressions do not merely last as long as the eye is exposed to its surroundings, but that an after-effect remains. You all know a very simple phenomenon connected with this. You gaze at a red surface, and then quickly turning to a white surface you will see the red in the green after-colour. This shows that the eye is, in a certain sense, still under the influence of the original impression. There is here no need to examine into the reason why the second colour seen should be green, we will only keep to the more general fact that the eye retains the after-effect of its experience.

We have here to do with an experience on the periphery of the human body, for the eye is on the periphery. When we contemplate this experience, we find that for a certain limited time the eye retains the after-effect of the impression; after that the experience ceases, and the eye can then expose itself to new impressions without interference from the last one.

Let us now consider quite objectively a phenomenon connected not with any single localised organ of the human organism, but with the whole human being. Provided our observations are unprejudiced, we cannot fail to recognise that this experience made by the whole human being is related to the experience with the localised eye. We expose ourselves to an impression, to an experience, with our whole being. In so doing, we absorb this experience just as the eye absorbs the impression of the colour to which it is exposed; and we find that after the lapse of months, or even years, the after-effect comes forth in the form of a thought-picture. The whole phenomenon is somewhat different, but you will not fail to recognise the relation of this memory picture to that after-picture of an experience which the eye retains for a short limited time.

This is the kind of question that man must face, for he can only gain some knowledge of the world when he learns to ask questions in the correct way. Let us therefore ask ourselves: What is the connection between these two phenomena—between the after-picture of the eye and the memory picture that rises up within us in relation with a certain experience? As soon as we put our question in this form and require a definite answer, we realise that the whole method of the present-day natural-scientific thought completely fails to supply the answer; and it fails because of its ignorance of one great fact—the fact of the universal significance of metamorphosis. This metamorphosis is something that is not completed in Man within the limits of one life, but only plays itself out in consecutive lives on Earth.

You will remember that in order to gain a true insight into the nature of Man, we divided him into three parts: head, rhythmic man and limbs. We may, for the present purpose, consider the last two as one, and we then have the head-organisation on the one hand and all that makes up the remaining parts on the other. As we try to comprehend this head-organisation, we must be able to understand how it is related to the whole evolution of Man. The head is a later metamorphosis, a transformation, of the rest of Man, considered in terms of its forces. Were you to imagine yourself without your head—and of course also without whatever is present in the rest of the organism but really belongs to the head—you would, in the first place, think of the remaining portion of your organism as substantial. But here we are not concerned with substance; it is the inter-relation of the forces of this substance which undergoes a complete transformation in the period between death and a new birth and becomes in the next incarnation the head-organisation. In other words, that which you now include in the lower part (the rhythmic man and the limbs) is an earlier metamorphosis of what is going to be head-organisation. But if you wish to understand how this metamorphosis proceeds, you will have to consider the following.

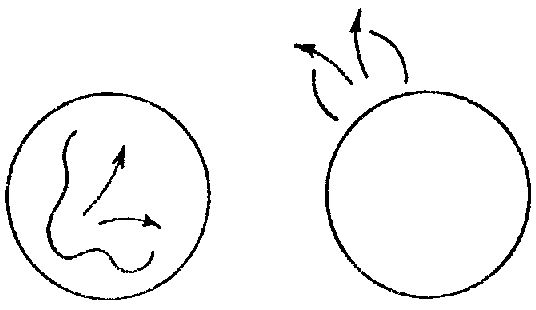

Take any one organ—liver or kidney—of your lower man, and compare it with your head-organisation. You will at once become aware of a fundamental, essential difference; namely, that all the activities of the lower parts of the body as distinct from the upper or head, are directed inwards, as instanced by the kidneys, whose whole activity is exercised interiorly. The activity of the kidneys is an activity of secretion. In comparing this organ with a characteristic organ of the head—the eye, for instance—you find the construction of the latter to be the exact opposite. It is directed entirely outwards, and the results of the changing impressions are transmitted inwardly to the reason, to the head. In any particular organ of the head you have the polar opposite of an organ belonging to the other part of the body. We might depict this fact diagrammatically.

Take the drawing on the left as the first metamorphosis, and the drawing on the right as the second; then you will have to imagine the first as the first life, and the second as the second life, and between the two is the life between death and a new birth. We have first an inner organ which is directed inward. Owing to the transformation taking place between two physical lives, the whole position and direction of this organ is entirely reversed—it now opens outwards. So that an organ which develops its activity inwardly in one incarnation, develops it outwardly in the succeeding life. You can now imagine that something has happened between the two incarnations that may be compared with putting on a glove, taking it off and turning it inside out; upon wearing the glove again, the surface which was previously turned inward comes outside, and vice versa. Thus it must be noted that this metamorphosis does not merely transform the organs, but turns them inside out; inner becomes outer. We can now say that the organs of the body (taking ‘body’ as the opposite to ‘head’) have been transformed. So that one or other of our abdominal organs, for instance, has now become our eyes in this incarnation. It has been reversed in its active forces, has become an eye, and has attained the ability to generate after-effects following upon impressions from without. Now this faculty must owe its origin to something.

Let us consider the eye and the mission of its life-activity, in an unbiased way. These after-effects only prove to us that the eye is a living thing. They prove that the eye, for a little while, retains impressions; and why? I will use as a simile something simpler. Suppose you touch silk; your organ of touch retains an after-effect of the smoothness of silk. If later on you again touch silk, you recognise it by what the first impression left behind with you. It is the same with the eye. The after-effect is somehow connected with recognition. The inner life which produces this after-effect, plays a part in the recognition. But the outer object, when recognised, remains outside. If I see any one of you now, and tomorrow meet you again and recognise you, you are physically present before me.

Now compare this with the inner organ of which the eye is a transformation in respect to its activity and forces. In this organ must reside something which in a certain sense corresponds to the eye's capacity for retaining pictures of impressions, something akin to the inner life of the eye; but it must be directed inward. And this must also have some connection with recognition. But to recognise an experience means to remember it. So when we look for the fundamental metamorphosis of the eye's activity in a former life, we must enquire into the activity of that organ which acts for the memory.

It is impossible to explain these things in simple language such as is often desired at the present day, but we can direct our thoughts along a certain line which, if followed up, will lead us to this conception—namely that all our sense-organs which are directed outward have their correspondences in the inner organs, and that these latter are also the organs of memory. With the eye we see that which recurs as an impression from the outer world, while with those organs within the human body which correspond to the previous metamorphosis of the eye, we remember the pictures transmitted through the eye. We hear sound with the ear, and with the inner organ corresponding to the ear we remember that sound. Thereby the whole man as he directs or opens his organs inward, becomes an organ of memory. We confront the outer world, taking it into ourselves in the form of impressions. Materialistic natural science claims that we receive an impression, for instance, with the aid of the eye. The impression is transmitted to the optic nerve. But here the activity apparently ceases; as regards the process of cognition, the whole remaining organism is like the fifth wheel of a wagon! But this is far from being the truth. All that we perceive passes over into the rest of the organism. The nerves have no direct relation with memory. On the contrary the entire human body, the whole man, becomes a memory instrument, only specialised according to the particular organ that directs its activity inwards. Materialism is experiencing a tragic paradox—it fails to comprehend matter, because it sticks fast to its abstractions! It becomes more and more abstract, the spiritual is more and more filtered away; therefore it cannot penetrate to the essence of material phenomena, for it does not recognise the spiritual within the material. For instance materialism does not realise that our internal organs have very much more to do with our memory than has the brain, which merely prepares the idea or images so that they can be absorbed by the other organs of the whole body. In this connection our science is a perpetuation of a one-sided asceticism, which consists in unwillingness to understand the spirituality of the material world and a desire to overcome it. Our science has learnt sufficient asceticism to deprive itself of the capacity for understanding the world, when it claims that the eyes and other sense-organs receive the various impressions, pass them on to the nervous system and then to something else, which remains undefined. But this undefined “something” is the entire remaining organism! Here it is that memories originate through the transmutation of the organs.

This was very well known in the days when no spurious asceticism oppressed human perception. Therefore we find that the ancients, when speaking of ‘hypochondria’ for example, did not speak of it in the same way as does modern man and even the psycho-analyst when he maintains that hypochondria is merely psychic, is something rooted in the soul. No, hypochondria means a hardening of the abdominal and lower parts. The ancients knew well enough that this hardening of the abdominal system has as its result what we call hypochondria, and the English language which gives evidence of a less advanced stage than other European tongues, still contains a remnant of memory of this correspondence between the material and the spiritual. I can, at the moment, only remind you of one instance of this. In English, depression is called “spleen”. The word is the same as the name of the physical organ that has very much to do with this depression. For this condition of soul cannot be explained out of the nervous system, the explanation for it is to be found in the spleen. We might find a good many such correspondences, for the genius of language has preserved much; and even if words have become somewhat transformed for the purpose of applying them to the soul, yet they point to an insight Man once possessed in ancient times and that stood him in good stead.

To repeat—you, as entire Man, observe the surrounding world, and this world reacts upon your organs, which adapt themselves to these experiences according to their nature. In a medical school, when anatomy is being studied, the liver is just called liver, be it the liver of a man of 50 or of 25, of a musician or of one who understands as much of music as a cow does of Sunday after regaling itself upon grass for a week! It is simply liver. The fact is that a great difference exists between the liver of a musician and that of a non-musician, for the liver is very closely connected with all that may be summed up as the musical conceptions that live and resound in Man. It is of no use to look at the liver with the eye of an ascetic and see it as an inferior organ; for that apparently humble organ is the seat of all that lives in and expresses itself through the beautiful sequence of melody; it is closely concerned e.g. with the act of listening to a symphony. We must clearly understand that the liver also possesses etheric organs; it is these latter which, in the first place, have to do with music. But the outer physical liver is, in a certain sense, an externalisation of the etheric liver, and its form is like the form of the latter. In this way you see, you prepare your organs; and if it depended entirely upon yourself, the instruments of your senses, would, in the next incarnation, be a replica of the experiences you had made in the world in the present incarnation. But this is true only in measure, for in the interval between death and a new birth Beings of the higher Hierarchies come to our aid, and they do not always decide that injuries produced upon our organs by lack of knowledge or of self-control should be carried by us as our fate. We receive help between death and re-birth, and are therefore, in respect of this portion of our constitution, not dependent upon ourselves alone.

From all this you will see that a relation really exists between the head organisation and the rest of the body with its organs. The body becomes head, and we lose the head at death in so far as its formative forces are concerned. Therefore it is so essentially bony in its structure and is preserved longer on Earth than the rest of the organism, which fact is only the outer sign that it is lost to us for our following re-incarnation, in respect to all that we have to experience between death and re-birth. The ancient atavistic wisdom perceived these things plainly, and especially when that great relation between Man and Macrocosm was investigated, which we find expressed in the ancient description of the movements of the heavenly bodies. The genius of language has also here preserved a great deal. As I pointed out yesterday, physical Man adheres internally to the day-cycle. He demands breakfast every day, and not only on Sunday. Breakfast, dinner and supper are required every day, and not only breakfast on Sunday, dinner on Wednesday and supper on Saturday. Man is bound to the 24 hour cycle in respect to his metabolism—or the transmutation of matter from the outer world. This day-cycle in the interior of Man corresponds to the daily motion of the Earth upon its axis. These things were closely perceived by the ancient wisdom. Man did not feel that he was a creature apart from the Earth, for he knew that he conformed to its motions; he knew also the nature of that to which he conformed. Those who have an understanding for ancient works of art—though the examples still preserved today offer but little opportunity for studying these things—will be aware of a living sense, on the part of the ancients, of the connection of Man the Microcosm with the Macrocosm. It is proved by the position certain figures take up in their pictures, and the positions that certain others are beginning to assume etc.; in these, cosmic movements are constantly imitated.

But we shall find something of even greater significance in another consideration.

In almost all the peoples inhabiting this Earth, you find a recognised distinction or comparison existing between the week and the day. You have, on the one hand, the cycle of the transmutation of substances—or metabolism, which expresses itself in the taking of meals at regular intervals.. Man has however never reckoned according to this cycle alone; he has added to the day-cycle a week-cycle. He first distinguished this rising and setting of the Sun—corresponding to a day; then he added Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday, a cycle seven times that of the other, after which he came back once again to Sunday. (In a certain sense, after completing seven such cycles, we return also again to the starting-point.) We experience this in the contrast between day and week. But Man wished to express a great deal more by this contrast. He wished first to show the connection of the daily cycle with the motion of the Sun.

But there is a cycle seven times as great, which, whilst returning again to the Sun, includes all the planets—Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. This is the weekly cycle. This was intended to signify that, having one cycle corresponding to a day, and one seven times greater that included the planets, not only does the Earth revolve upon its axis (or the Sun go round), but the whole system has in itself also a movement. The movement can be seen in various other examples. If you take the course of the year's cycle, then you have in the year, as you know, 52 weeks, so that 7 weeks is about the seventh part—in point of number—of the year. This means, we imagine the week-cycle extended or stretched over the year, taking the beginning and end of the year as corresponding to the beginning and end of the week. And this necessitates the thought that all phenomena resulting from the weekly cycle must take place at a different speed from those events having their origin in the daily cycle.

And where are we to look for the origin of the feeling which impels us to reckon, now with the day-cycle, and now with the week-cycle? It arises from the sensation within us of the contrast between the human head-development, and that of the rest of the organism. We see the human head-organisation represented by a process to which I have already drawn your attention—the formation within about a year's cycle of the first teeth.

If you consider the first and second dentition you will see that the second takes place after a cycle that is seven times as long as the cycle of the first dentition. We may say that as the one year-cycle in respect to the first dentition stands to the cycle of human evolution that works up to the second dentition, so does the day stand to the week. The ancients felt this to be true, because they rightly understood another thing. They understood that the first dentition was primarily the result of heredity. You only need look at the embryo to realise that its development proceeds out of the head organisation; it annexes, as it were, the remainder of the organism later. You will then understand that the idea of the ancients was quite correct when they saw a connection of the formation of the first teeth with the head and of the second teeth with the whole human organism. And today we must arrive at the same result if we consider these phenomena objectively. The first teeth are connected with the forces of the human head, the second with the forces that work from out of the rest of the organism and penetrate into the head.

Through looking at the matter in this way, we have indicated an important difference between the head and the rest of the human body. The difference is one which can, in the first place, be considered as connected with time, for that which takes place in the human head has a seven times greater rapidity than that which takes place in the rest of the human organism. Let us translate this into rational language. Let us say, today you have eaten your usual number of meals in the proper sequence. Your organism demands a repetition of them tomorrow. Not so the head. This acts according to another measure of time; it must wait seven days before the food taken into the rest of the organism has proceeded far enough to enable the head to assimilate it. Supposing this to be Sunday, your head would have to wait until next Sunday before it would be in a position to benefit by the fruit of to-day's Sunday dinner. In the head organisation, a repetition takes place after a period of seven days, of what has been accomplished seven days before in the organism. All this the ancients knew intuitively and expressed by saying: a week is necessary to transmute what is physical and bodily into soul and spirit.

You will now see that metamorphosis also brings about a repetition in the succeeding incarnation in ‘single’ time of that which previously required a seven times longer period to accomplish. We are thus concerned with a metamorphosis which is spatial through the fact that our remaining organism—our body—is not merely transformed, but turned inside out, and is at the same time temporal, in that our head organisation has remained behind to the extent of a period seven times as long.

It will be clear to you now that this human organisation is not, after all, quite so simple as our modern, comfort-loving science would like to believe. We must make up our mind to regard Man's organisation as much more complicated; for if we do not understand Man rightly, we are also prevented from realising the cosmic movements in which he takes part. The descriptions of the Universe circulated since the beginning of modern times are mere abstractions, for they are described without a knowledge of Man.

This is the reform that is necessary, above all, in Astronomy—a reform demanding the re-inclusion of Man in the scheme of things, when cosmic movements are being studied. Such studies will then naturally be somewhat more difficult.

Goethe felt intuitively the metamorphosis of the skull from the vertebrae, when, in a Venetian Jewish burial ground, he found a sheep's skull which had fallen apart into its various small sections; these enabled him to study the transformation of the vertebrae, and he then pursued his discovery in detail. Modern science has also touched upon this line of research. You will find some interesting observations relating to the matter, and some hypotheses built up upon it, by the comparative anatomist Karl Gegenbaur; but in reality Gegenbaur created obstacles for the Goethean intuitional research, for he failed to find sufficient reason to declare himself in favour of the parallel between the vertebrae and the single sections of the skull. Why did he fail? Because so long as people think only of a transformation and disregard the reversal inside out, so long will they gain only an approximate idea of the similarity of the two kinds of bones. For in reality the bones of the skull result from those forces which act upon Man between death and rebirth, and they are therefore bound to be essentially different in appearance from merely transformed bone. They are turned inside out; it is this reversal which is the important point.

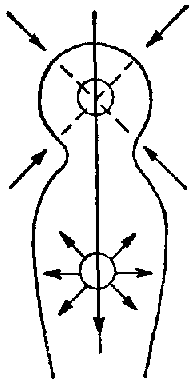

Imagine we have here (diagram) the upper or head-man. All influences or impressions proceed inward from without. Here below would be the rest of the human body. Here everything works from within outwards, but so as to remain within the organism. Let me put it in another way. With his head man stands in relation to his outer environment, while with his lower organism he is related to the processes taking place within himself. The abstract mystic says: “Look within to find the reality of the outer world.” But this is merely abstract thought, it does not accord with the actual path. The reality of the outer world is not found through inner contemplation of all that acts upon us from outside; we must go deeper and consider ourselves as a duality, and allow the world to take form in quite a different part of our being. That is why abstract mysticism yields so little fruit, and why it is necessary to think here too of an inner process.

I do not expect any of you to allow your dinner to stand before you untouched, depending upon the attractive appearance of it to appease your hunger! Life could not be supported in this way. No! We must induce that process which runs its course in the 24-hour cycle, and which, if we consider the whole man, including the upper or head organisation, only finishes its course after seven days. But that which is assimilated spiritually—for it has really to be assimilated and not merely contemplated!—also requires for this process a period seven times as long. Therefore it becomes necessary first intellectually to assimilate all we absorb. But to see it reborn again within us, we must wait seven years. Only then has it developed into that which it was intended to be. That is why after the founding of the Anthroposophical Society in 1901 we had to wait patiently, seven, and even fourteen years for the result!

Siebenter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Die letzten Betrachtungen hier waren gewidmet einem Wege, der entsprechend begangen dazu führt, eine Anschauung zu gewinnen über unser Weltenall und seine Organisation. Sie haben gesehen, daß dieser Weg notwendig macht, immerfort den Einklang aufzusuchen zwischen dem, was im Menschen selbst vor sich geht, und dem, was im großen Weltenall vor sich geht. Ich werde die folgenden Betrachtungen morgen und übermorgen so anzulegen haben, daß auch unsere von auswärts zur Generalversammlung gekommenen Freunde einiges von diesen Dingen werden haben können. Daher werde ich morgen von dem, was gesagt worden ist, kurz einiges zu wiederholen haben, das Wesentliche, um daran dann anderes anzuknüpfen. Heute will ich aber in den Gang unserer Betrachtungen einiges einfügen, das gerade geeignet sein kann, des Näheren auf den wahren Weg, das Weltall kennen zu lernen, hinzuweisen.

[ 2 ] Wenn Sie meine «Geheimwissenschaft» durchgehen, so werden Sie sehen, daß bei dieser skizzenhaften Darstellung der Entwickelung des uns bekannten Weltenalls, wie sie gegeben ist in dieser «Geheimwissenschaft», überall die Beziehung zum Menschen festgehalten ist. Wenn Sie ausgehen von der Saturnentwickelung, um dann bis zu unserer Erdenentwickelung fortzuschreiten durch die Sonnen- und Mondenentwickelung, so wissen Sie ja, daß diese Saturnentwickelung dadurch charakterisiert wird, mitcharakterisiert wird, daß durch diese Saturnentwickelung die erste Anlage gemacht worden ist für die menschliche Sinnenhaftigkeit. Und so geht es dann weiter. Überall werden die Zustände des Weltenalls so verfolgt, daß man zu gleicher Zeit damit die Entwickelung des Menschen hat. Also, der Mensch wird nicht so gedacht im Weltenall stehend, wie das in der äußeren Naturwissenschaft heute geschieht, daß man das Weltenall auf der einen Seite betrachtet, und dann den Menschen auf der andern Seite, wie zwei nicht recht zueinander gehörige Wesenheiten, sondern beides wird ineinander gedacht, wird in seiner Entwickelung miteinander verfolgt. Dies muß auch durchaus berücksichtigt werden, wenn man von dem spricht, was gegenwärtig Eigenschaften, Kräfte, Bewegungen und so weiter des Weltenalls sind. Man kann nicht auf der einen Seite im kopernikanisch-galileischen Sinne das Weltenall rein räumlich abstrakt betrachten und daneben gewissermaßen dann den Menschen, sondern man muß beide ineinanderfließen lassen während der Betrachtung.

[ 3 ] Das ist aber nur dann möglich, wenn man eine gehörige Vorstellung von dem Menschen selbst erst gewonnen hat. Ich habe Sie schon darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie wenig eingentlich die gegenwärtige naturwissenschaftliche Anschauung geeignet ist, Aufschlüsse über den Menschen selbst zu geben. Was tut sie denn eigentlich gerade da, wo sie aus ihren heutigen Voraussetzungen heraus am größten ist, diese Naturwissenschaft? Betrachten Sie sie nur. Sie stellt in einer Großartigkeit dar, wie der Mensch aus anderen Formen körperlich nach und nach sich entwickelt hat. Sie verfolgt, wie dann während der Embryonalzeit diese Formen wie in einer kurzen Wiederholung noch einmal durchgemacht werden. Das heißt, sie betrachtet den Menschen als das oberste der Tiere. Sie betrachtet die Tierheit, und dann setzt sie den Menschen zusammen aus alledem, was sie an der Tierheit gefunden hat. Das heißt, sie betrachtet alles Außermenschliche, um dann gewissermaßen zu sagen: So, hier Schlußpunkt, da endet das Außermenschliche, da kommt es beim Menschen an. — Es wird nicht der Mensch selbst als solcher betrachtet. Das ist dasjenige, was der heutigen Naturwissenschaft gar nicht gelegen ist, den Menschen als solchen zu betrachten, und daher gewinnt sie gar keine Anschauung von der menschlichen Wirklichkeit.

[ 4 ] Sehen Sie, ich möchte hier ausgehen von etwas, was ich gestern an ganz anderem Orte und in ganz anderem Zusammenhange vor anderem Publikum entwickelt habe, was aber auch hier aufklärend in unserem jetzigen Zusammenhange wirken kann. Es wäre wirklich heute sehr vonnöten, daß die Menschen, die sachverständig auf diesem Gebiete sein wollen, zur Goetheschen naturwissenschaftlichen Betrachtung, insbesondere zur Betrachtung seiner Farbenlehre ein wenig ihre Zuflucht nehmen würden. In dieser Farbenlehre ist eigentlich eine ganz andere Methode der naturwissenschaftlichen Betrachtung eingeschlagen, als man sie heute gewohnt ist. Gleich im Beginne ist die Rede von den sogenannten subjektiven Farben, von den physiologischen Farben, und da wird sehr sorgfältig untersucht, wie das menschliche Auge als ein Lebendiges Erlebnisse hat an der Umgebung, wie diese Erlebnisse durchaus nicht einfach nur so lange dauern, als das Auge der Außenwelt exponiert ist, ausgesetzt Ist, sondern wie eine Nachwirkung da ist. Sie kennen ja alle die einfachste Erscheinung auf diesem Gebiete: Sie sehen auf eine begrenzte, sagen wir zum Beispiel rote Fläche (Tafel 13, Rhombus links, Pfirsichblüt), wenden dann das Auge rasch ab und sehen auf eine weiße Fläche: Sie sehen das Rot in der grünen Nachfarbe. Das heißt, das Auge steht noch in einem gewissen Sinne unter dem Eindrucke desjenigen, was es erlebt hat. Nun, wir wollen jetzt nicht die Gründe untersuchen, warum gerade eine grüne Nachfarbe erscheint, sondern wir wollen nur an der mehr allgemeinen Tatsache festhalten, daß das Auge nachher das Erlebnis noch nachklingen läßt.

[ 5 ] Da haben wir es zu tun mit einem Erlebnis an der Peripherie unseres menschlichen Leibes. Das Auge liegt an der Peripherie des menschlichen Leibes. Wir finden, wenn wir auf das Erlebnis des Auges hinschauen, daß durch eine gewisse begrenzte Zeit das Auge dieses Erlebnis noch ausklingen läßt. Dann ist das Erlebnis ganz abgeklungen. Dann kann das Auge unbeeinflußt durch das, was es erlebt hat, sich anderen Erlebnissen zuwenden. Betrachten wir rein anschauungsgemäß zunächst einmal eine Erscheinung, die nun nicht an ein einzelnes lokalisiertes Organ unseres Organismus gebunden ist, sondern an den ganzen Menschen gebunden ist, und wir werden, wenn wir uns unbefangener Beobachtung hingeben, nicht verkennen können, wie eben schon vor dieser Beobachtung dieses Erlebnis verwandt ist mit dem Erlebnis an dem lokalisierten Auge. Sie setzen sich einer Erscheinung, einem Erlebnis aus, Sie exponieren sich als ganzer Mensch diesem Erlebnis. Indem Sie sich als ganzer Mensch diesem Erlebnis exponieren, nehmen Sie es auf, so wie das Auge das Erlebnis der Farbe aufnimmt, gegenüber welcher es exponiert ist. Und jetzt können Sie erleben, daß noch nach Monaten, nach Jahren das Nacherlebnis, das Nachbild, in Form des Gedächtnisbildes aus Ihnen herauskommt. Es ist die ganze Erscheinung etwas anders, aber Sie werden das Verwandte des Erinnerungsbildes mit einem Nachbilde des Erlebnisses, das auf kurze, beschränkte Zeit das Auge hat, nicht verkennen können.

[ 6 ] So werden Fragen vor den Menschen in Richtigkeit hingestellt, und der Mensch kann ja nur etwas über die Welt erfahren, indem er in der richtigen Weise fragen lernt. Fragen wir uns einmal: Wie hängen diese beiden Erscheinungen zusammen, das Nachbild des Auges und das Erinnerungsbild an ein bestimmtes Erlebnis, das - wir wollen es ganz unbestimmt lassen woher — aus uns aufsteigt? — Sehen Sie, wenn man solche Fragen aufwirft und nach einer sachgemäßen Antwort sucht, so versagt sogleich die ganze Methode der gegenwärtigen naturwissenschaftlichen Betrachtung. Sie versagt aus dem Grunde, weil ja diese Betrachtung eines nicht weiß: sie weiß nicht die universelle Bedeutung der Metamorphose. Die ganze universelle Bedeutung der Metamorphose, die kennt die gegenwärtige Naturwissenschaft nicht. Diese Metamorphose ist etwas, was eben beim Menschen in dem einen Leben nicht abgeschlossen ist, was beim Menschen sich erst abschließt in den aufeinanderfolgenden Erdenleben.

[ 7 ] Sie wissen, wir unterscheiden zunächst einmal, um eine Ansicht gewinnen zu können über den ganzen Menschen — wenn wir von der Dreigliedrigkeit absehen, nur auf zwei Glieder sehen, wobei wir das zweite und dritte zusammenfassen -, wir unterscheiden zunächst die menschliche Kopforganisation und den übrigen Menschen. Wir müssen, wenn wir die menschliche Kopforganisation studieren wollen, verstehen können, wie diese Kopforganisation mit der ganzen Entwickelung des Menschen zusammenhängt. Sie ist eine spätere Metamorphose, sie ist die Umbildung des ganzen übrigen Menschen hinsichtlich seiner Kräfte. Was Sie, indem Sie sich kopflos denken natürlich mit alledem, was vom Kopf in den übrigen Organismus hineingehört und zum Kopf eigentlich gehört —, was Sie da im übrigen Menschen sind, das fassen Sie ja natürlich zunächst substantiell auf. Aber dieses Substantielle kommt nicht in Betracht, sondern der Kräftezusammenhang dieser Substanz metamorphosiert sich im All zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt und wird im nächsten Erdenleben Kopforganisation. Das heißt, was Sie jetzt in Ihrem außer dem Kopf befindlichen Menschen an sich tragen, ist eine frühere Metamorphose der späteren Kopforganisation. Wenn Sie aber verstehen wollen, wie diese Metamorphose zusammenhängt, dann müssen Sie das Folgende ins Auge fassen.

[ 8 ] Nehmen Sie einmal irgendein Organ — Leber oder Niere - Ihres übrigen Menschen und vergleichen Sie das mit Ihrer Kopforganisation, so finden Sie einen wesentlichen, durchgreifenden Unterschied. Sie finden nämlich den Unterschied, daß die ganze Tätigkeit der Organe Ihres außerkopflichen Menschen nach innen gerichtet ist. Wenn Sie zum Beispiel das Nierenorgan nehmen, so ist die ganze Tätigkeit nach dem Innern der Körperhöhle gerichtet. Dorthin ist die Tätigkeit des Nierensystems gerichtet. Und es ist diese Tätigkeit sogar auf Ausscheidung berechnet. Wenn Sie dieses Organ vergleichen mit irgendeinem Organ, das gerade für das Haupt, für den Kopf des Menschen charakteristisch ist, so können Sie das Auge nehmen. Das ist genau entgegengesetzt konstruiert, das ist ganz nach außen gerichtet. Und was es als Wechselbeziehung nach außen hat, das gibt es nach dem Innern des Menschen, nach dem Verständnis, nach dem Verstande ab. Sie haben in einem Organe des Hauptes das volle polarische Gegenbild eines Organes des übrigen Menschen. Der übrige Mensch hat seine Organe ganz nach dem Innern der Organisation des Organismus gerichtet. Das Haupt hat seine wesentlichen Organe nach außen geöffnet. Daher kann ich schematisch folgendes zeichnen (Tafel 13, oben):

[ 9 ] Nehmen wir einmal an, das wäre die eine Metamorphose, das wäre die andere Metamorphose, die hier in Betracht kommt, so müssen Sie sich vorstellen: erstes Leben, zweites Leben; dazwischen ist dann das Leben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. Wir haben ein inneres Organ. Dieses innere Organ ist nach innen geöffnet. Indem die Metamorphose wirksam ist zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, kehrt sich die ganze Stellung und alles, was an dieses Organ geknüpft wird, um. Das Organ wird nach außen geöffnet. Es ist also so, wie wenn dasjenige, was da nach innen seine Tätigkeit entfaltet, in der nächsten Inkarnation nach außen seine Tätigkeit entfaltet. Sie müssen sich also vorstellen, daß da etwas vorgegangen ist zwischen den zwei Inkarnationen, was man nur vergleichen kann damit, daß Sie sich denken, Sie haben hier einen Handschuh, den ziehen sie an; und nunmehr nehmen Sie ihn und drehen ihn um, so daß dasjenige, was an die Hand anliegt, nach außen kommt und das, was früher nach außen, nach der Luft zu lag, nach innen kommt. Also die Metamorphose hat sich nicht nur so vollzogen, daß dasjenige, was da die übrigen Organe sind, sich etwa bloß umgebildet hat, nein, es hat sich auch umgestülpt. Es ist das Innere, das nach innen Gewendete zum Äußeren, zum nach außen Gewendeten geworden. So daß wir sagen können: Die Organe - ich werde jetzt sprechen von Körper und Kopf als dem Gegensatze -, die Organe des Körpers metamorphosieren sich, indem sie sich umstülpen. Also unsere Augen wären in unserer vorhergehenden Inkarnation irgend etwas in unserem Bauche gewesen, wenn ich den Ausdruck eben gebrauchen darf. Das hat sich umgestülpt in seinen Kräften und ist jetzt Augen geworden, und die haben die Fähigkeit erlangt, Nachbilder zu erzeugen. Diese Fähigkeit, Nachbilder an der Außenwelt zu erzeugen, die muß auch von etwas herkommen. Wovon kommt diese Fähigkeit, Nachbilder zu erzeugen, her?

[ 10 ] Nun, betrachten wir einmal die Augen, die Aufgabe der Lebenstätigkeit des Auges, betrachten wir das einmal ganz unbefangen. Die Nachbilder beweisen uns ja nur, daß das Auge etwas Lebendiges ist, die Nachbilder beweisen uns ja nur, daß das Auge die Tätigkeit ein wenig festhält. Warum hält das Auge die Tätigkeit ein wenig fest? Lassen Sie uns von etwas Einfacherem ausgehen. Nehmen Sie einmal an, Sie greifen Seide an. Greife ich Seide an, so bleibt mir im Organ, im Gefühlsorgan eine Nachwirkung der Seidenglätte. Wenn ich wiederum an die Seide herankomme, so erkenne ich Seide wiederum an dem, was es in mir bewirkt hat. So ist es auch beim Auge. Das Nachbild hat etwas zu tun mit dem Wiedererkennen. Die innere Lebendigkeit, die da in Betracht kommt, damit das Nachbild entsteht, die hat etwas zu tun mit dem Wiedererkennen. Aber da draußen, wenn es sich um das Wiedererkennen handelt, da bleiben die Dinge. Sie bleiben draußen. Wenn ich jetzt jemanden von Ihnen sehe und ihn morgen wieder treffe und ihn wieder erkenne, da steht er leibhaftig da.

[ 11 ] Vergleichen wir das jetzt einmal mit dem, woraus das Auge als Metamorphose sich entwickelt hat in bezug auf die Tätigkeit. Sehen wir auf das Organ in unserem inneren Organismus, aus dem sich das Auge entwickelt hat. Da muß in einer gewissen Weise veranlagt sein dasjenige, was als die Fähigkeit des Nachbildens, als die Lebendigkeit des Auges erscheint, nur muß es nach innen gewendet sein. Da muß auch das etwas zu tun haben mit dem Wiedererkennen. Aber ein Erlebnis wiedererkennen heißt, sich daran erinnern. Suchen Sie also die ursprüngliche Metamorphose für die Tätigkeit des Auges in einem früheren Leben, so müssen Sie fragen nach der Tätigkeit des Organs, die wirkt für die Erinnerung. Diese Dinge lassen sich natürlich nicht so bequem und einfach darlegen, wie man es heute liebt; aber sie lassen sich eben dem Wege nach andeuten. Und verfolgen Sie den Weg, dann werden Sie finden: alle unsere Sinnesorgane, die nach außen gerichtet sind, haben ihre Gegenbilder in unseren inneren Organen. Und diese inneren Organe sind ja zu gleicher Zeit die Organe der Erinnerung. Mit dem Auge sehen Sie dasjenige, was im äußeren Leben wiederkehrt; mit dem, was in Ihrer Leibeshöhle entspricht der früheren Metamorphose des Auges, erinnern Sie sich an die Bilder, die Ihnen das Auge vermittelt. Mit dem Ohre hören Sie die Töne; mit demjenigen, was in Ihrer Leibeshöhle dem Ohr entspricht, erinnern Sie sich an die Töne. Und so wird der ganze Mensch, indem er seine Organe nach dem Innern öffnet, zum Erinnerungsorgan. Der ganze Mensch ist Erinnerungsorgan. Und wir stellen uns dem äußeren Leben gegenüber, wir nehmen dieses äußere Leben auf. Die materialistische Naturwissenschaft sagt, wir nehmen zum Beispiel Augenbilder auf; ihre Wirkungen übertragen sich auf den Augennerv. Damit ist es aber aus. Der ganze übrige Organismus ist für den Erkenntnisprozeß das fünfte Rad am Wagen. Das ist aber nicht wahr. Dasjenige, was wir wahrnehmen, geht in den übrigen Organismus über, und die Nerven haben mit der Erinnerung unmittelbar gar nichts zu tun, sondern die übrigen Organe, die Organe, welche ihre Tätigkeit nach innen öffnen. Der ganze Mensch ist Erinnerungswerkzeug, nur spezialisiert nach den verschiedenen Organen. Der Materialismus erlebt die furchtbare Tragik —- ich habe darauf schon aufmerksam gemacht -, daß er gerade das Materielle nicht erkennen kann, denn er bleibt in Abstraktionen stecken. Und der Materialismus wird immer abstrakter, das heißt filtrierter, geistiger, und er kann nicht in das Wesen der materiellen Erscheinungen eindringen. Er begreift nicht die Geistigkeit der materiellen Erscheinungen. Zum Beispiel begreift er nicht, daß mit unserem Gedächtnisse unsere inneren Leibesorgane viel mehr zu tun haben als das Gehirn, das nur die Vorstellungen vorbereitet, damit sie von den übrigen Leibesorganen aufgenommen werden. In dieser Beziehung ist unsere Wissenschaft - was denn eigentlich? - die fortgesetzte Askese, das fortgesetzte einseitige Asketentum. Worin besteht denn dieses einseitige Asketentum? Darinnen, daß man nicht die materielle Welt in ihrer Geistigkeit begreifen, sondern sie verachten, sie überwinden will, mit ihr nichts zu tun haben will. Unsere Wissenschaft hat schon von der Askese das gelernt, daß sie überhaupt nichts mehr begreift von der Welt; daß sie ausdenkt, die Augen und die übrigen Sinnesorgane nehmen die Wahrnehmungen auf, übertragen sie aufs Nervensystem und dann auf irgend etwas, was man im Unbestimmten läßt. Nein, dann geht das über in den übrigen Organismus. Da entstehen zunächst die Erinnerungen durch das Zurückschwingen der Organe.

[ 12 ] Das hat man in Zeiten, in denen eine falsche Askese nicht auf die Menschenanschauungen gedrückt hat, sehr wohl gewußt. Daher haben die Alten, wenn sie zum Beispiel von «Hypochondrie» gesprochen haben, nicht so gesprochen wie oftmals der moderne Mensch oder gar die Psychoanalytiker, daß die Hypochondrie nur etwas Seelisches sei, das da in der Seele wurzelt. Nein, Hypochondrie heißt ja Unterleibsknorpeligkeit. Die Alten haben ganz gut gewußt, daß das, was Hypochondrie ist, in einer Versteifung, in einer Verhärtung des Unterleibssystems seinen Grund hat. Und die englische Sprache, die noch auf einer Etappe steht, die gegenüber den andern europäischen Sprachen eine weniger vorgerückte Stufe darstellt, die hat in sich noch eine Erinnerung von diesem Zusammenklang des Materiellen mit dem Geistigen. Ich erinnere nur an das eine. Man nennt im Englischen seelisch etwas «spleen», aber es ist nicht bloß seelisch. Die Milz heißt auch «spleen». Und der «spleen» hat mit der Milz sehr viel zu tun. Das ist nämlich nicht etwas, was man bloß aus dem Nervensystem zu erklären hat, sondern was man aus der Milz zu erklären hat. Und so könnte sehr vieles gefunden werden. Der Genius der Sprache hat ja sehr vieles erhalten, und wenn auch die Worte etwas umgebildet sind für den seelischen Gebrauch, weisen sie doch auf dasjenige hin, was als eine Uranschauung der Menschheit gut funktioniert hat.

[ 13 ] Sie sehen sich also die Welt an, nehmen sie als ganzer Mensch wahr, und indem Sie sie als ganzer Mensch wahrnehmen, wirkt sie auf Ihre Organe. Diese Organe passen sich den Erlebnissen, der Erlebnisart an. Auf der Klinik, wenn man Anatomie treibt, ist Leber Leber; Leber eines Fünfzigjährigen, Leber eines Fünfundzwanzigjähtigen, Leber eines Musikers ist Leber; Leber eines, der von der Musik so viel versteht, wie der Ochs vom Sonntag, wenn er die ganze Woche Gras gefressen hat, ist auch Leber. Aber das Bedeutsame besteht darinnen, daß ein gewichtiger Unterschied ist zwischen der Leber eines Musikers und der Leber eines Nichtmusikers, weil die Leber sehr, sehr viel zu tun hat mit dem, was widerklingt im Menschen von musikalischen Vorstellungen. Ja, es nützt nichts, in asketischer Erkenntnis die Leber als ein geringes Organ zu betrachten. Diese Leber, die scheinbar ein so geringes Organ ist, ist der Sitz alles dessen, was in der schönen Folge der Melodien lebt, und die Leber hat sehr viel mit dem Anhören einer Symphonie zu tun. Nur muß man natürlich sich klar sein, daß diese Leber auch noch ein Ätherorgan hat und daß das in erster Linie damit zu tun hat. Aber die äußere physische Leber ist eben gewissermaßen das Exsudat der Ätherleber und ist so gestaltet, wie diese Ätherleber gestaltet ist. Ja, da bereiten Sie sich Ihre Organe zu, und wenn Sie nun ganz selbst sich überlassen wären, und insofern Sie sich selbst überlassen sind, würde ganz genau Ihr Sinnesapparat in der nächsten Inkarnation ein Abbild Ihrer Erlebnisse gegenüber der Umwelt sein. Er ist es in gewisser Beziehung, nur ist er es nicht ausschließlich, denn es kommen uns in dem Leben zwischen dem Tode und neuer Geburt Wesen der höheren Hierarchien zu Hilfe, welche bewirken, daß nicht immer alle jene Ungezogenheiten, die wir begehen gegenüber unseren Organen, auch wirklich von uns schicksalsmäßig getragen werden müssen. Es wird uns geholfen zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt. Wir sind in bezug auf diesen Teil unserer Organisation nicht auf uns allein angewiesen.

[ 14 ] Aber Sie sehen daraus, daß ein solcher Zusammenhang besteht zwischen dem ganzen übrigen Menschen und seinen Organen und seiner Kopforganisation. Der Körper wird Kopf, und den Kopf verlieren wir in bezug auf seine Kräftebildung mit dem Tod. Daher ist er auch wesentlich knöcherig in seiner Form und erhält sich länger als der übrige Organismus hier auf der Erde. Das ist nur das äußere Zeichen dafür, daß er uns verlorengeht für unsere folgende Inkarnation, für alles das, was wir durchzumachen haben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt.

[ 15 ] Diese Dinge, die wurden von der alten atavistischen Weisheit wohl gefühlt, und sie wurden auch dann gefühlt, wenn jener große Zusammenhang des Menschen mit dem Makrokosmos gesucht wurde, der in den alten Beschreibungen über die Himmelsbewegungen zum Ausdrucke kam. Der Genius der Sprache hat auch in dieser Beziehung manches erhalten. Sehen Sie, der Mensch - ich habe es Ihnen das letzte Mal ausgeführt - macht innerlich den Tageskteislauf mit. Sie machen Anspruch darauf, jeden Tag zu frühstücken, nicht bloß am Sonntag. Sie machen Anspruch darauf, jeden Tag zu Mittag zu essen und Abendbrot zu essen, nicht bloß, daß Sie frühstücken am Sonntag, Mittagessen am Mittwoch und Abendessen am Sonnabend; das tun Sie nicht. Sie unterliegen in bezug auf dasjenige, was Stoffwechsel mit der Außenwelt ist, dem Tageskreislauf. Diesen macht der Mensch innerlich mit. Dieser Tageskreislauf des Inneren, der entspricht im Menschen dem Tageskreislauf der Erde um ihre Achse. Solche Dinge wurden lebendig gefühlt in der Urweisheit. Da hat der Mensch gewußt, er ist nicht abgesondert von der Erde, er macht das mit, was die Erde macht. Und er wußte auch hinzudeuten auf dasjenige, was er da mitmacht. Wer Sinn hat für alte Kunstwerke, obwohl wir in den erhaltenen Kunstwerken sehr wenig Gelegenheit haben, diese Dinge uns noch anzuschauen, der kann selbst aus den alten Kunstwerken noch herausfühlen, wie eine lebendige Empfindung da war bei den Alten vom Zusammenhange des Mikrokosmos, des Menschen, mit dem Makrokosmos, aus der Stellung gewisser Figuren, aus der beginnenden Bewegung gewisser Figuren und so weiter; in denen sind zumeist kosmische Bewegungen nachgeahmt. Aber in etwas anderem liegt noch mehr.

[ 16 ] Sehen Sie, bei allen oder bei den meisten Völkern finden Sie dem Tag die Woche gegenübergestellt. Sie haben auf der einen Seite, wenn ich so sagen darf, den Kreislauf des Stoffwechsels, was sich darin ausdrückt, daß Sie jeden Tag essen müssen zu denselben Mahlzeiten. Aber der Mensch war niemals so, daß er nur nach diesem Kreislauf des Stoffwechsels gerechnet hat. Er hat hinzugefügt zu dem Tageskteislauf den Wochenkteislauf. Er hat unterschieden erstens Sonne, Auf- und Untergang, dem Tageskreislauf entsprechend; aber er hat hinzugefügt: Sonntag, Montag, Dienstag, Mittwoch, Donnerstag, Freitag, Samstag - einen siebenfach so langen Zeitraum. Dann ist er wiederum zurückgekommen zum Sonntag. Gewissermaßen kommen wir nach 7 Kreisläufen wiederum zurück (Tafel 14, links). Das ist gefühlt in dem Gegensatze zwischen Tag und Woche. Aber mit diesem Gegensatz zwischen Tag und Woche wollte der Mensch noch viel mehr ausdrücken. Er wollte ausdrücken: der Tageskreislauf hängt mit der Sonne zusammen, mit dem Sonnenumgang. Wir nennen ihn heute scheinbar; das geht uns augenblicklich nichts an.

[ 17 ] Nun haben wir einen siebenmal so großen Zeitraum, der wiederum zur Sonne zurückkehrt, aber der alle Planeten in sich aufnimmt, . Sonne, Mond, Mars, Merkur, Jupiter, Venus und Saturn. Der Wochenumgang nimmt alle Planeten in sich auf. Dadurch sollte gesagt werden: Wir haben einen Kreislauf, der dem Tag entspricht, einen andern Kreislauf, der einem siebenmal so großen Zeitraum entspricht, und der die Planeten in sich aufnimmt. Es sollte darauf hingedeutet werden: Nicht bloß dreht sich die Erde um ihre Achse, oder die Sonne geht herum, sondern das ganze System hat in sich auch eine Bewegung. Diese Bewegung könnte noch in manchem anderen gesehen werden. Nehmen Sie einmal den Jahreskreislauf, so bekommen Sie im Jahr, wie Sie wissen, 52 Wochen. Das ist ungefähr das Siebentel der Zahl nach, der Tage im Jahreskreislauf. Das heißt, die Wochen, von dem Jahresanfangs- zum Jahresendpunkt gedacht, machen notwendig zu denken, daß dasjenige, was von den Wochen geschieht, in einer anderen Geschwindigkeit geschieht, als was vom Tageskreislauf geschieht.

[ 18 ] Woher rührte denn das Gefühl, das eine Mal zu rechnen mit einem Tageskreislauf, das andere Mal zu rechnen mit einem Wochenkreislauf? Woher rührte denn dieses Gefühl? Das rührte von der Empfindung des Gegensatzes zwischen der menschlichen Hauptesentwickelung und der Entwickelung des ganzen übrigen Menschen her. Die menschliche Hauptesentwickelung, wir sehen sie in etwas repräsentiert, worauf ich Sie auch schon aufmerksam gemacht habe, wir sehen sie repräsentiert in dem, was im Haupte sich herausbildet ungefähr in einem Jahreskreislauf: in der Zahnbildung, der ersten Zahnbildung, der Milchzahnbildung.

[ 19 ] Wenn Sie den Zahnwechsel ins Auge fassen, so tritt er nach einem siebenmal so großen Zeitraume ein, um das 7. Lebensjahr herum. Man kann sagen: wie sich der einzelne Jahreskreislauf in bezug auf die Zahnbildung verhält zu dem Kreislauf in der Menschenentwickelung, der bis zum Zahnwechsel hin wirkt, so verhält sich der Tag zur Woche. Das wurde gefühlt. Und es wurde deshalb gefühlt, weil man das andere richtig empfand: Zahnbildung, insofern die Milchzähne entstehen, ist vorzugsweise ein Ergebnis der Vererbung. Sie brauchen nur den Embryo anzuschauen, wie er sich eigentlich aus der Kopfbildung heraus entwickelt und das andere anschließt, so werden Sie auch verstehen, daß die Empfindung der Alten richtig war, die Milchzahnbildung mehr mit dem Kopf, die spätere Zahnbildung mehr mit dem ganzen menschlichen Organismus in Zusammenhang zu bringen. Das ist ein Ergebnis, das sich allerdings heute auch wiederum einstellt, wenn wir sachgemäß die Sache betrachten. Die Milchzähne sind an die Kräfte des menschlichen Hauptes gebunden. Die anderen Zähne sind an die Kräfte gebunden, die aus dem übrigen Organismus in das Haupt hereinschießen.

[ 20 ] Damit aber haben Sie an einem besonderen Falle hingedeutet auf einen wichtigen Gegensatz des Hauptes und des übrigen menschlichen Organismus. Dieser Gegensatz ist zunächst ein zeitlicher. Dasjenige, was im menschlichen Kopf vor sich geht, geht siebenmal so schnell vor sich wie das, was im übrigen menschlichen Organismus vor sich geht. Übersetzen wir uns das einmal in eine vernünftige Sprache — wir haben es eben in einer realen Sprache ausgedrückt -, jetzt übersetzen wir uns das in eine vernünftige Sprache. Denken Sie sich einmal, Sie essen heute, Sie haben heute die entsprechenden Mahlzeiten gegessen, ordnungsgemäß gegessen. Aber was Sie da gegessen haben - Ihr Organismus verlangt, daß Sie es morgen wiederholen. Aber Ihr Haupt, das hält ein anderes Tempo ein. Das Haupt muß 7 Tage lang warten, bis dasjenige, was heute von Ihrem übrigen Organismus aufgenommen worden ist, so weit ist, daß es vom Haupte verarbeitet werden kann. Wenn morgen Sonntag ist und Sie essen, dann muß Ihr Haupt bis zum nächsten Sonntag warten, um die Früchte dieses Essens zu haben. Da geschieht nach einer 7-tägigen Periode eine Wiederholung dessen, was Sie 7 Tage vorher in Ihrem Organismus vollbracht haben. Das fühlte man und drückte gleichsam das dadurch aus, daß man sagte: die Woche hindurch braucht man, bis das Physisch-Leibliche geistig-seelisch wird.

[ 21 ] Sie sehen, die Metamorphose besteht auch darinnen, daß dasjenige, was eine siebenmal so lange Zeit braucht, in der einfachen Zeit wiederholt wird, wenn das nächste Leben folgt auf dieses Leben. Wir haben es also zu tun mit einer räumlichen Metamorphose dadurch, daß unser übriger Organismus, unser Körper, nicht bloß sich umwandelt, sondern umstülpt; und wir haben es zu tun mit einer zeitlichen Metamorphose, indem unsere Hauptesorganisation um 7 zurückgeblieben ist.

[ 22 ] Es ist in der Tat diese menschliche Organisation nicht so einfach, als man es haben möchte im Sinne der heutigen bequemen Wissenschaft. Man muß sich schon darauf einlassen, diese Menschheitsorganisation komplizierter zu denken. Und studiert man den Menschen nicht, so kann man auch nicht studieren, an welchen Bewegungen des Weltenalls der Mensch teilnimmt. Deshalb sind die seit dem Beginn der Neuzeit beschriebenen Bewegungen des Weltenalls eben Abstraktionen, sind beschrieben mit Ausschluß von Menschenkenntnis.

[ 23 ] Das ist die Reform, die vor allen Dingen der Astronomie bevorsteht, daß wiederum der Mensch einbezogen werden muß, indem die Bewegungen des Weltenalls studiert werden. Natürlich werden dadurch die Studien etwas schwieriger als sie sonst sind.

[ 24 ] Sehen Sie, Goethe hat aus einer großartigen Intuition heraus die Metamorphose des Menschenschädels aus dem Rückgrat, aus dem Wirbelknochen des Rückgrats in sich gefühlt, als er einmal in Venedig am Juden-Kirchhof einen glücklich gespalteten Schöpsenschädel fand. Der war so schön in seine einzelnen Stücke auseinandergefallen, daß Goethe an diesem Schöpsenschädel die Umwandlung der menschlichen Rückgratswirbelknochen in Schädelknochen studieren konnte. Goethe hat dann das im einzelnen verfolgt. Die Wissenschaft hat sich auch in einer gewissen Weise dieser Sache angenommen. Sie finden interessante Beobachtungen, die der vergleichende Anatom Gar Gegenbaur darüber gemacht hat, und Hypothesen, die er darüber aufgestellt hat - sehr schöne Dinge; aber eigentlich konnte Gegenbaur der Goetheschen Intuition nur Schwierigkeiten machen. Er findet nicht, daß man den richtigen Parallelismus der Wirbelknochen des Rückgrates mit den einzelnen Gebilden am Schädel angeben könne.

[ 25 ] Ja, sehen Sie, warum das? Weil die Leute nicht ans Umstülpen denken, weil nicht bloß an ein Umwandeln zu denken ist, sondern an eine Umstülpung; daher kann nur annähernd eine Zusammenfassung von Schädelknochen ähnlich sein dem Rückgratwirbel. Denn in Wirklichkeit werden ja die Schädelknochen in ihrer Form gebildet als das Ergebnis jener Kräfte, die auf den Menschen wirken zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt und müssen daher wesentlich anders ausschauen, als bloß umgewandelte andere Knochen. Umgestülpt sind sie. Dieses Umstülpen, das ist dasjenige, was in Betracht kommt. Und jetzt werden Sie eines vor allen Dingen begreifen.

[ 26 ] Nehmen Sie einmal an, das wäre gewissermaßen schematisch der obere Mensch, der Kopfmensch. Alle Wirkungen gehen von außen nach innen. Das wäre der übrige Mensch (Tafel 14, rechts). Alle Wirkungen gehen von innen nach außen, aber sie bleiben in dem organischen Inneren des Menschen. So daß wir sagen können: Der Mensch steht durch seinen Kopf mit der Umwelt in Beziehung, durch seinen übrigen Organismus mit dem, was in ihm selbst vor sich geht. Der abstrakte Mystiker sagt: Schaue in dein Inneres, dann findest du das Wesen der Außenwelt. — Das ist aber nur sehr abstrakt gedacht, denn so stimmt es nicht. Das Wesen der Außenwelt finden wir nicht, wenn wir alles dasjenige innerlich betrachten, was von außen auf uns einwirkt, sondern erst dann, wenn wir tiefer gehen, wenn wir erst uns als eine Dualität betrachten und aus einem ganz anderen Teile unseres Wesens die Welt wieder erstehen lassen. Das ist der Grund, warum bei der abstrakten Mystik so wenig herauskommt und warum es notwendig ist, auch hier an einen inneren Prozeß zu denken, nicht bloß an ein abstraktes Umwandeln der äußeren Anschauung.

[ 27 ] Sehen Sie, ich möchte ja keinem von Ihnen zumuten, das Mittagessen vor sich stehen zu lassen und durch den schönen Anblick gesättigt sein zu sollen. Das geht nicht, nicht wahr. Es würde das Leben nicht unterhalten werden können. Wir müssen den Prozeß herbeiführen, der zunächst in 24 Stunden abläuft, und wenn wir den ganzen Menschen, den Hauptesmenschen dazugenommen, ins Auge fassen, nach 7 Tagen erst abläuft. Dasjenige aber, was geistig aufgenommen wird, das muß ebenso wirklich aufgenommen werden, kann nicht bloß angeschaut werden, muß innerlich verarbeitet werden, braucht auch eine siebenmal so lange Periode. Daher ist es notwendig, zunächst das, was aufgenommen wird, intellektuell zu verarbeiten. Aber damit es wiedergeboren werden kann, haben wir 7 Jahre verlaufen zu lassen. Dann taucht es erst wiederum auf. Dann wird es erst dasjenige, was es werden soll. Das war ja der Grund, warum, nachdem angefangen worden ist so um 1901 mit der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft, geduldig 7 Jahre, dann sogar 14 Jahre gewartet worden ist auf das, was da herauskommt.

[ 28 ] Nun, an diesem Punkte will ich heute lieber schließen! Wir werden morgen dann davon weiter reden.

Seventh Lecture

[ 1 ] The last considerations here were devoted to a path that, when followed accordingly, leads to gaining an insight into our universe and its organization. You have seen that this path makes it necessary to constantly seek harmony between what is happening within the human being and what is happening in the great universe. Tomorrow and the day after tomorrow, I will have to structure the following considerations in such a way that our friends who have come from outside to the General Assembly will also be able to gain some insight into these things. Therefore, tomorrow I will have to briefly repeat some of what has been said, the essentials, in order to then tie in other things. Today, however, I want to insert into the course of our reflections something that may be particularly suitable for pointing out in more detail the true path to knowing the universe.

[ 2 ] If you go through my “Secret Science,” you will see that in this sketchy presentation of the development of the universe known to us, as given in this “Secret Science,” the relationship to human beings is maintained throughout. If you start from the development of Saturn and then proceed to the development of our Earth through the development of the Sun and Moon, you know that this development of Saturn is characterized, co-characterized, by the fact that through this development of Saturn the first foundation was laid for human sense perception. And so it continues. Everywhere, the conditions of the universe are traced in such a way that one has the development of the human being at the same time. So, human beings are not thought of as standing in the universe, as is done in modern natural science, which views the universe on one side and human beings on the other, as two entities that do not really belong together. Rather, both are thought of as interrelated and their development is traced together. This must also be taken into account when speaking of what are currently considered to be the properties, forces, movements, and so on of the universe. One cannot, on the one hand, view the universe in a purely abstract, spatial sense in the Copernican-Galilean sense and then, as it were, place human beings alongside it; rather, one must allow both to flow into each other during the observation.

[ 3 ] But this is only possible if one has first gained a proper understanding of the human being itself. I have already pointed out to you how little the present scientific view is actually suited to providing insights into the human being itself. What does this natural science actually do where it is greatest, based on its present premises? Just consider it. It presents in a grandiose manner how human beings gradually developed physically from other forms. It traces how these forms are then repeated in a short cycle during the embryonic period. In other words, it regards human beings as the highest of the animals. It considers animal nature and then composes human beings from all that it has found in animal nature. That means it looks at everything outside of humans, and then says, like, “Okay, this is where it ends, this is where the non-human ends, and this is where humans start.” It doesn't look at humans themselves. That's what modern science doesn't want to do, look at humans as humans, and that's why it doesn't get a clue about what humans are really like.

[ 4 ] You see, I would like to start here from something I developed yesterday in a completely different place and in a completely different context before a different audience, but which can also have an enlightening effect here in our current context. It would really be very necessary today for people who want to be experts in this field to take refuge a little in Goethe's scientific observation, especially in his theory of colors. In this theory of colors, a completely different method of scientific observation is actually employed than one is accustomed to today. Right at the beginning, there is talk of so-called subjective colors, of physiological colors, and there is a very careful examination of how the human eye, as a living organism, experiences its surroundings, how these experiences do not simply last as long as the eye is exposed to the outside world, but how there is an aftereffect. You are all familiar with the simplest phenomenon in this field: you look at a limited area, say a red surface (plate 13, rhombus on the left, peach blossom), then quickly turn your eyes away and look at a white surface: you see the red in the green after-color. This means that the eye is still, in a certain sense, under the impression of what it has experienced. Now, we do not want to investigate the reasons why a green after-color appears, but we want to stick to the more general fact that the eye allows the experience to linger afterwards.

[ 5 ] Here we are dealing with an experience at the periphery of our human body. The eye is located at the periphery of the human body. When we look at the experience of the eye, we find that for a certain limited time the eye allows this experience to linger. Then the experience has completely faded away. Then the eye, uninfluenced by what it has experienced, can turn to other experiences. Let us first consider, purely intuitively, a phenomenon that is not bound to a single localized organ of our organism, but is bound to the whole human being, and if we give ourselves over to unbiased observation, we will not be able to fail to recognize how, even before this observation, this experience is related to the experience at the localized eye. You expose yourself to a phenomenon, an experience; you expose yourself as a whole human being to this experience. By exposing yourself as a whole human being to this experience, you take it in, just as the eye takes in the experience of color to which it is exposed. And now you can experience that even after months, after years, the after-experience, the afterimage, emerges from you in the form of a memory image. The whole phenomenon is somewhat different, but you will not be able to fail to recognize the similarity between the memory image and an afterimage of the experience that the eye has for a short, limited time.

[ 6 ] In this way, questions are posed to people in the right way, and people can only learn about the world by learning to ask questions in the right way. Let us ask ourselves: How are these two phenomena connected, the afterimage of the eye and the memory image of a particular experience that arises within us—we will leave its origin completely undefined? You see, when one raises such questions and seeks a proper answer, the entire method of contemporary scientific observation immediately fails. It fails because this observation does not know one thing: it does not know the universal meaning of metamorphosis. The whole universal meaning of metamorphosis is unknown to contemporary natural science. This metamorphosis is something that is not completed in the one life of the human being, but is only completed in successive earthly lives.

[ 7 ] You know that in order to gain an understanding of the whole human being — if we disregard the threefold division and look only at two members, combining the second and third — we first distinguish between the human head organization and the rest of the human being. If we want to study the human head organization, we must be able to understand how this head organization is connected with the entire development of the human being. It is a later metamorphosis, it is the transformation of the entire rest of the human being in terms of its forces. When you think of yourself as headless, naturally including everything that belongs to the head in the rest of the organism and actually belongs to the head — what you are in the rest of the human being — you naturally conceive of this as something substantial. But this substance is not what is important here. Rather, the interrelationship of forces within this substance undergoes a metamorphosis in the universe between death and a new birth, and in the next earthly life becomes the head organization. This means that what you now carry within you in your human being outside your head is an earlier metamorphosis of the later head organization. But if you want to understand how this metamorphosis is connected, you must consider the following.

[ 8 ] Take any organ—the liver or kidney—of your remaining human being and compare it with your head organization, and you will find a significant, fundamental difference. You will find that the entire activity of the organs of your extra-head human being is directed inward. If you take the kidney organ, for example, all of its activity is directed toward the interior of the body cavity. That is where the activity of the renal system is directed. And this activity is even designed for excretion. If you compare this organ with any organ that is characteristic of the head, you can take the eye. It is constructed in exactly the opposite way, it is directed entirely outward. And what it has as an external interrelationship is transmitted to the inner part of the human being, to the understanding, to the mind. In one organ of the head, you have the complete polar counterpart of an organ of the rest of the human being. The rest of the human being has organs that are entirely directed toward the inner organization of the organism. The head has its essential organs open to the outside. Therefore, I can draw the following diagram (plate 13, above):

[ 9 ] Let us assume that this is one metamorphosis and that the other metamorphosis that comes into consideration here is the other one. Then you must imagine: first life, second life; in between is the life between death and a new birth. We have an inner organ. This inner organ is open inward. As the metamorphosis takes effect between death and a new birth, the whole position and everything connected with this organ is reversed. The organ is opened outward. It is therefore as if that which unfolds its activity inwardly in one incarnation unfolds its activity outwardly in the next incarnation. You must therefore imagine that something has happened between the two incarnations that can only be compared to the following: you have a glove here, which you put on; and now you take it and turn it inside out, so that what was touching your hand is now on the outside and what was previously on the outside, exposed to the air, is now on the inside. So the metamorphosis has not only taken place in such a way that the remaining organs have merely been transformed, no, they have also been turned inside out. It is the inner part, the part that was turned inward, that has become the outer part, the part that is turned outward. So we can say: the organs — I will now speak of the body and the head as opposites — the organs of the body undergo metamorphosis by turning themselves inside out. So our eyes would have been something in our abdomen in our previous incarnation, if I may use that expression. This has turned inside out in its powers and has now become eyes, and they have acquired the ability to produce afterimages. This ability to produce afterimages of the outside world must also come from somewhere. Where does this ability to produce afterimages come from?

[ 10 ] Now, let us consider the eyes, the function of the eye in life, and let us consider this quite impartially. The afterimages only prove to us that the eye is something alive; the afterimages only prove to us that the eye retains its activity to a certain extent. Why does the eye retain activity to a certain extent? Let's start with something simpler. Suppose you touch silk. When I touch silk, an aftereffect of the silk's smoothness remains in my sensory organ. When I touch silk again, I recognize it by the effect it has had on me. The same is true of the eye. The afterimage has something to do with recognition. The inner vitality that comes into play in the formation of the afterimage has something to do with recognition. But out there, when it comes to recognition, things remain where they are. They remain outside. If I see one of you now and meet you again tomorrow and recognize you, you are standing there in the flesh.

[ 11 ] Let us now compare this with what the eye has developed into as a metamorphosis in relation to activity. Let us look at the organ in our inner organism from which the eye has developed. What appears as the ability to reproduce images, as the liveliness of the eye, must be predisposed in a certain way, but it must be turned inward. This must also have something to do with recognition. But to recognize an experience means to remember it. So if you look for the original metamorphosis of the activity of the eye in a previous life, you must ask about the activity of the organ that is responsible for memory. Of course, these things cannot be explained as conveniently and simply as people like to do today, but they can be hinted at. And if you follow this path, you will find that all our sense organs that are directed outward have their counterparts in our inner organs. And these inner organs are at the same time the organs of memory. With the eye you see what recurs in outer life; with what corresponds in your body cavity to the earlier metamorphosis of the eye, you remember the images that the eye conveys to you. With the ear you hear sounds; with what corresponds in your body cavity to the ear, you remember the sounds. And so, by opening its organs to the inner world, the whole human being becomes an organ of memory. The whole human being is an organ of memory. And we face external life, we take in this external life. Materialistic natural science says that we take in, for example, images with our eyes; their effects are transmitted to the optic nerve. But that is all. The rest of the organism is the fifth wheel on the wagon for the process of cognition. But that is not true. What we perceive passes into the rest of the organism, and the nerves have nothing directly to do with memory, but rather the other organs, the organs that open their activity inward. The whole human being is a memory tool, only specialized according to the different organs. Materialism experiences the terrible tragedy—I have already pointed this out—that it cannot recognize the material, because it remains stuck in abstractions. And materialism becomes increasingly abstract, that is, filtered, more intellectual, and it cannot penetrate the essence of material phenomena. It does not understand the spirituality of material phenomena. For example, it does not understand that our inner bodily organs have much more to do with our memory than the brain, which only prepares the ideas so that they can be taken up by the other bodily organs. In this respect, what is our science? It is continued asceticism, continued one-sided asceticism. What does this one-sided asceticism consist of? It consists in not understanding the material world in its spirituality, but in despising it, wanting to overcome it, wanting to have nothing to do with it. Our science has already learned from asceticism that it understands nothing at all about the world; that it imagines that the eyes and the other sense organs take in perceptions, transmit them to the nervous system, and then to something that is left undefined. No, then it passes into the rest of the organism. There, memories arise through the recoil of the organs.

[ 12 ] This was well known in times when false asceticism did not weigh heavily on people's views. That is why the ancients, when they spoke of “hypochondria,” for example, did not speak as modern people or even psychoanalysts often do, that hypochondria is only something psychological, rooted in the soul. No, hypochondria means cartilage in the lower abdomen. The ancients knew very well that what hypochondria is has its cause in a stiffening, a hardening of the abdominal system. And the English language, which is still at a stage that is less advanced than other European languages, still has a memory of this harmony between the material and the spiritual. I will mention just one example. In English, something spiritual is called “spleen,” but it is not merely spiritual. The spleen is also called “spleen.” And the “spleen” has a lot to do with the spleen. This is not something that can be explained solely by the nervous system, but rather by the spleen. And many other examples could be found. The genius of language has preserved a great deal, and even if words have been somewhat modified for spiritual use, they still point to what has functioned well as a primordial view of humanity.