Oswald Spengler, Prophet of World Chaos

GA 214

6 August 1922, Dornach

II. Oswald Spengler I

When some time ago the first volume of Spengler's Decline of the West appeared, there could be discerned in this literary production something like the will to tackle more intensively the elemental phenomena of decay and decline in our time. Here is a man who felt in much that is now active in the whole western world an impulse toward decline that must necessarily lead to a condition of utter chaos in western civilization, including America; and it could be seen that the man who had developed such a feeling—a very well-informed person, indeed, with mastery of many scientific ideas—was making the effort to present a sort of analysis of these phenomena.

It is clear, of course, that Spengler recognized this decline; and it is evident also that he had a feeling for everything of a declining nature exactly because all his thinking was itself involved in this decline; and because he felt this decadence in his very soul, I might say, he anticipated nothing but decadence as the outcome of all mass civilization. That is comprehensible. He believed that the West will become the prey of a kind of Caesarism, a sort of development of individual power, which will replace the differentiated, highly-organized cultures and civilizations with simple brute-force.

It is evident that Spengler, for one, had not the slightest perception of the fact that salvation for this western culture and civilization can come out of the will of mankind, if this will, in opposition to all that is moving headlong toward destruction, is directed toward the realization of something that can yet be brought forth out of the soul of man as a new force, if the human being of today wills it so. Of such a new force—naturally a spiritual force, based on spiritual activity—Oswald Spengler had not the slightest understanding.

Thus we can see that a very well-informed, brilliant man, with a certain penetrating insight, and able to coin such telling phrases, can actually arrive at nothing beyond a certain hope for the unfolding of a brute-power, which is remote from everything spiritual, from all inner human striving, and which depends entirely upon the development of external brutish force.

However, when the first volume appeared, it was possible to have at least a certain respect for the penetrating spirituality (I must use the expression again)—an abstract, intellectualistic spirituality—as opposed to the obtuseness of thinking which by no means is equal to the driving forces of history, but which so often gives the keynote to the literature of today.

Oswald Spengler's second volume has now appeared, and this indeed points out much more forcefully all that lives in a man of the present which can become his world-conception and philosophy, while he himself rejects, with a sort of brutality, everything genuinely spiritual. This second volume is likewise brilliant; yet in spite of his clever observations, Spengler shows nothing more than the dreadful sterility of an excessively abstract and intellectualistic mode of thought. The matter is extraordinarily noteworthy because it shows what a peculiar configuration of spirit can be attained by an undeniably notable personality of today.

In this second volume of Spengler's Decline of the West, it is primarily the beginning and the end that are of exceptional interest. But it is a melancholy interest which this beginning and end arouse; they really characterize the whole state of this man's soul. You need to read only a sentence or two at the beginning in order to estimate at once the soul-situation of Oswald Spengler, and likewise of many other people of the present time. What is to be said of it has not merely a German-literary significance, but an altogether international one.

Spengler begins with the following sentence: [The Decline of the West, by Oswald Spengler; Volume II: Perspectives of World History. Translated by Atkinson (Knopf). The above citation, however, and all others used herein are translated from the original of Spengler, Der Untergang des Abendlandes, by the translator of this lecture. Ed.] “Observe the flowers in the evening, when in the setting sun they close one after the other; something sinister oppresses you then, a feeling of puzzling anxiety in the presence of this blind, dreamlike existence bound to the earth. The mute forest, the silent meadows, yonder bush, and these tendrils, do not stir. It is the wind that plays with them. Only the little gnat is free. It still dances in the evening light; it moves whither it will,” and so on.

Notice the starting-point from the flowers, from the plants. Now when I have wished to point to what gives its significance to the thinking of the present, I have again and again found it necessary to begin with the kind of comprehension applied today to lifeless, inorganic, mineral nature. Perhaps some of you will remember that in order to characterize the striving of present-day thinking for clarity of view, I have often used the example of the impact of two resilient balls, where from the given condition of one ball you can deduce the condition of the other by pure calculation.

Of course, anyone of the Spenglerian soul-caliber can say that ordinary thinking does not discover how resilience works in these balls, nor what the relations are in a deeper sense. Anyone who thinks thus does not understand upon what clarity of thought depends at the present time. For such an objection would have neither greater validity nor less than would an assertion by someone that it is impossible for me to understand a sentence written down on paper without first having investigated the composition of the ink with which it is written. The important thing is always to discover the point at issue. In surveying inorganic nature, the matter of concern is not what may eventually be discovered behind it as force-impulse, just as the composition of the ink is not the important thing for the understanding of a sentence written with it; but the matter of importance is whether clear thinking is employed.

This definite kind of thinking is what humanity has achieved since the time of Galileo and Copernicus. It shows first that man can grasp by means of it only lifeless, inorganic nature; but that, on the other hand, only by yielding himself to it, as to the simplest and most primitive kind of pure thinking, can he develop freedom of the human soul, or any kind of freedom for man. Only one who understands the character of clear, objective thinking, as it holds sway in lifeless nature, can later rise to the other processes of thinking and of seeing—to that which permeates thought with vision, with inspiration, with imagination, with intuition.

Therefore, the first task confronting one who wishes to speak today with any authority on the ultimate configuration of our cultural life is to observe what it is that the power of present-day thinking rests upon. And those who have become aware of this power in the thinking of our time know that this thinking is active in the machine, that it has brought us modern technical sciences, in which by means of this thinking we construct external, lifeless, inorganic sequences, all of whose pseudo-intelligence is intended to contribute to the outer activities of man.

Only one who understands this begins to realize that the moment we start to deal with plant-life, this kind of thinking, grasped at first in its abstractness, leads to utter nonsense. Anyone who uses this kind of crystal-clear thinking—appropriate in its abstractness to the mineral world alone—not as a mere starting point for the development of human freedom, but instead employs it in thinking about the plant-world, will have before him in the plant-world something nebulous, obscure, mystical, which he cannot comprehend. For as soon as we look up to the plant-world we must understand that here—at least to the degree intended by Goethe with his primordial-plant (Urpflanze), and with the principle by means of which he traced the metamorphosis of this primordial-plant through all plant-forms—here at least in this Goethean sense, everyone who approaches the plant-world with a recognition of the real force of the thought holding sway in the inorganic world must perceive that the plant-world remains obscure and mystical in the worst sense of our time, unless it is approached with imagination—at least in the sense in which Goethe established his botanical views.

When anyone like Oswald Spengler rejects imaginative cognition and yet starts describing the plant-world in this way, he reaches nothing that will give clarity and force, but only a kind of confused thinking, a mysticism in the very worst sense of the word, namely materialistic mysticism. And if this has to be said about the beginning of the book, the end of it is in turn characterized by the beginning. The end of this book deals with the machine, with that which has given the very signature to modern civilization—the machine, which on the one hand is foreign to man's nature, yet is on the other precisely the means by which he has developed his clear thinking.

Some time ago—directly after the appearance of Oswald Spengler's book, and under the impression of the effect it was having—I gave a lecture at the College of Technical Sciences in Stuttgart on Anthroposophy and, the Technical Sciences, in order to show that precisely by submersion in technical science the human being develops that configuration of his soul-life which makes him free. I showed that, because in the mechanical world he experiences the obliteration of all spirituality, he receives in this same mechanical world the impulse to bring forth spirituality out of his own being through inner effort. Anyone, therefore, who comprehends the significance of the machine for our whole present civilization can only say to himself: This machine, with its impertinent pseudo-intelligence, with its dreadful, brutal, demonic spiritlessness, compels the human being, when he rightly understands himself, to bring forth from within those germs of spirituality that are in him. By means of the contrast the machine compels the human being to develop spiritual life.

But as a matter of fact, what I wished to bring out in that lecture was understood by no one, as I was able to learn from the after-effects.

Oswald Spengler places at the conclusion of his work some observations about the machine. Well, what you read there about the machine finally leads to a sort of glorification of the fear of it. We feel that what is said is positively the apex of modern superstition regarding the machine, which people feel as something demonic, as certain superstitious people sense the presence of demons. Spengler describes the inventor of the machine, tells how it has gradually gained ground, and little by little has laid hold of civilization. He describes the people in whose age the machine appeared.

“But for all of them there also existed the really Faustian danger that the devil might have a hand in the game, in order to lead them in spirit to that mountain where he promised them all earthly power. That is what is meant by the dream of those strange Dominicans, like Peter Peregrinus, about the perpetual motion device, through which God would have been robbed of His omnipotence. They succumbed to this ambition again and again; they extorted his secret from the Divinity in order to be God themselves.”

So Oswald Spengler understands the matter thus: that because man can now control machines, he can through this very act of controlling, imagine himself to be a God, can learn to be a God, because, according to his opinion, the God of the cosmic machine controls the machine. How could a man help feeling exalted to godhood when he controls a microcosm!

“They hearkened to the laws of the cosmic time-beat in order to do them violence, and then they created the idea of the machine as a little cosmos which yields obedience only to the will of man. But in doing so they overstepped that subtle boundary where, according to the adoring piety of others, sin began; and that was their undoing, from Bacon to Giordano Bruno. True faith has always held that the machine is of the devil.” Now he evidently intends at this point to be merely ironic; but that he intends to be not only ironic becomes apparent when in his brilliant way he uses words which sound somewhat antiquated. The following passage shows this:

“Then follows, however, contemporaneously with Rationalism, the invention of the steam-engine, which overturns everything and transforms the economic picture from the ground up. Till then nature had given service; now it is harnessed in the yoke as a slave, and its work measured, as in derision, in terms of horse-power. We passed over from the muscular strength of the negro, employed in organized enterprise, to the organic forces of the earth's crust, where the life-force of thousands of years lies stored as coal, and we now direct our attention to inorganic nature, whose waterpower has already been harnessed in support of the coal. Along with the millions and billions of horse-power the population increases as no other civilization would have considered possible. This growth is a product of the machine, which demands service and control, in return for which it increases the power of each individual a hundredfold. Human life becomes precious for the sake of the machine. Work becomes the great word in ethical thinking. During the eighteenth century it lost its derogatory significance in all languages. The machine works and compels man to work with it. All civilization has come into a degree of activity under which the earth quivers.

“What has been developed in the course of scarcely a century is a spectacle of such magnitude that to human beings of a future culture, with different souls and different emotions, it must seem that at that time nature reeled. In previous ages, politics has passed over cities and peoples; human economy has interfered greatly with the destinies of the animal and plant world—but that merely touches life and is effaced again. This technical science, however, will leave behind it the mark of its age when everything else shall have been submerged and forgotten. This Faustian passion has altered the picture of the earth's surface.

“And these machines are ever more dehumanized in their formation; they become ever more ascetic, more mystical and esoteric. They wrap the earth about with an endless web of delicate forces, currents, and tensions. Their bodies become ever more immaterial, even more silent. These wheels, cylinders and levers no longer speak. All the crucial parts have withdrawn to the inside. Man senses the machine as something devilish, and rightly so. For a believer it indicates the deposition of God. It hands over sacred causality to man, and becomes silent, irresistible, with a sort of prophetic omniscience set in motion by him.

“Never has the microcosm felt more superior toward the macrocosm. Here are little living beings who, through their spiritual force, have made the unliving dependent upon them. There seems to be nothing to equal this triumph, achieved by only one culture, and, perhaps, for only a few centuries. But precisely because of it the Faustian man has become the slave of his own creation.”

We see here the thinker's complete helplessness with regard to the machine. It never dawns on him that there is nothing in the machine that could possibly be mystical for anyone who conceives the very nature of the unliving as lacking any mystical element.

And thus we see Oswald Spengler beginning with a hazy recital about plants, because he really has no conception at all of the nature and character of present-day cognition—which is closely related to the evolution of the mechanical life—because to him thinking remains only an abstraction, and on this account he is also unable to perceive the function of thinking in anything mechanical. In reality, thinking here becomes an entirely unsubstantial image, so that the human being in the mechanical age may become all the more real, may call forth his soul, his spirit, out of himself by resisting the mechanical. That is the significance of the machine-age for the human being, as well as for world-evolution.

When anyone intending to begin with metaphysical clarity starts out instead with a hazy recital about plants, he does so because in this mood he is in opposition to the machine. That is to say, Oswald Spengler has grasped the function of modern thinking only in its abstractness, and he sets to work on something that remains dark to him, namely, the plant-world.

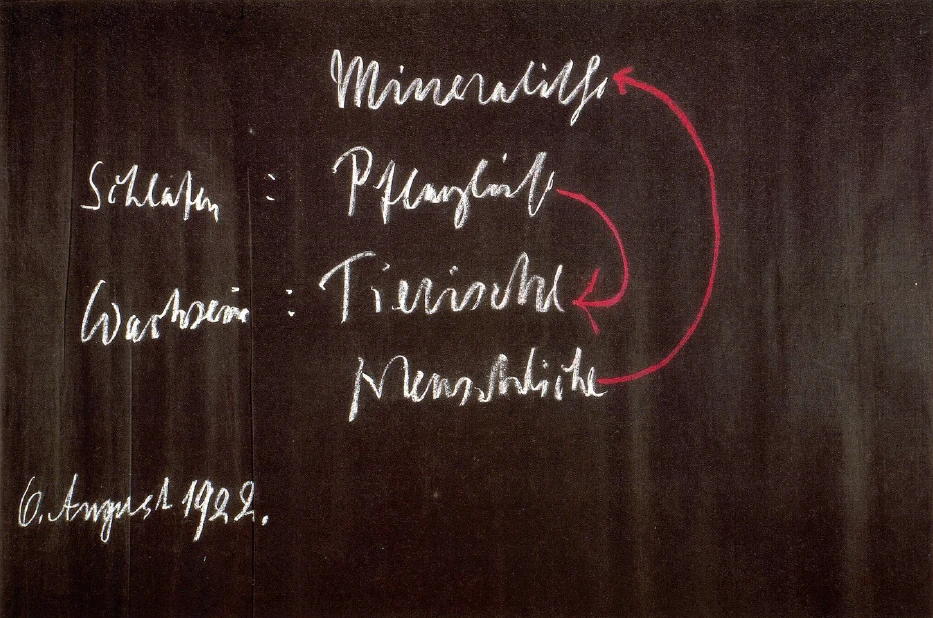

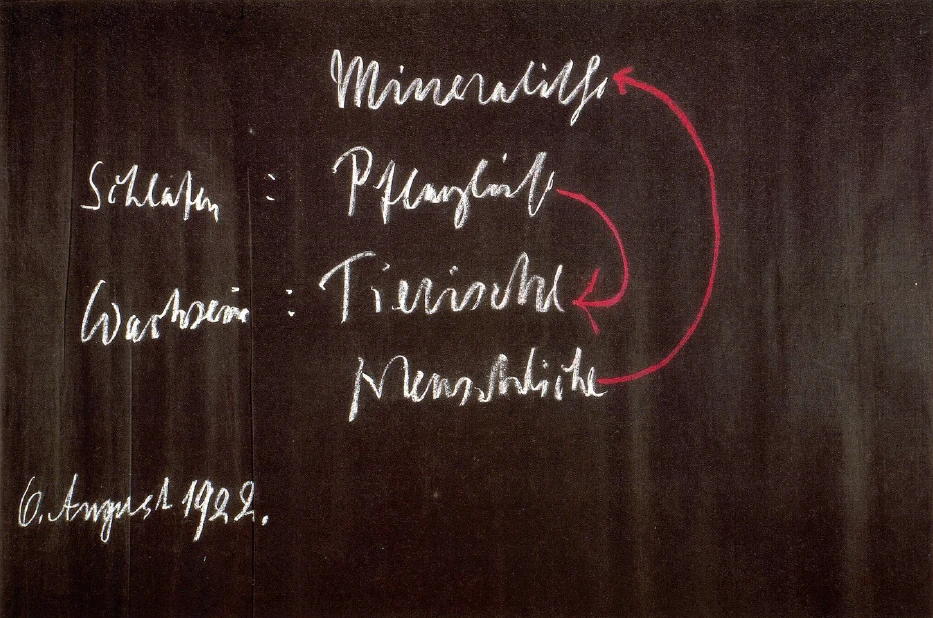

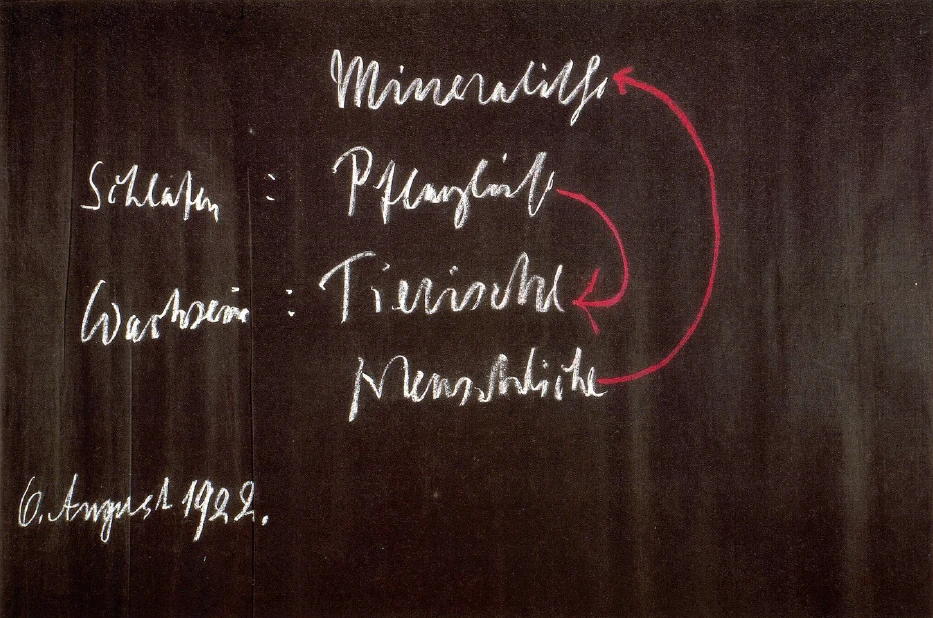

Now taking the mineral, the plant, the animal, and the human kingdoms, the last-named may be characterized for the present time by saying that since the middle of the fifteenth century we have advanced to the thinking that makes the mineral kingdom transparent to us. So that when we look at the human being of our time, as he is inwardly, as observer of the outer world, we must say that as human being he has at this precise time developed the conception of the mineral kingdom. But then we must characterize the significance of this mineral-thinking in the way I have just now characterized it.

But when someone who knows nothing of the real nature of the mineral kingdom takes his start from the plant kingdom, he gets no farther than the animal kingdom. For the animal bears in itself the plant-nature in the same form we today bear the mineral nature. It is characteristic of Oswald Spengler, first, that he begins with the plant, and in his concepts in no way gets beyond the animal (he deals with man only in so far as man is an animal) ; and second, that thinking really seems to him to be extraordinarily comprehensible, whereas, in reality, as I have just explained, it has been understood in its true significance only since the fourteenth century. He thus lets his thinking slide down just as far as possible into the animal world. We see him discovering, for example, that he has sense-perception, just as has the animal, and that this sense-perception, even in the animal, becomes a sort of judgment. In this way he tries to represent thinking merely as something like an intensification of the perceptive life of the animal.

Actually no one has proved in such a radical way as this same Oswald Spengler that the man of today with his abstract thinking reaches only the extra-human world, and no longer comprehends the human. And the essential characteristic of the human being, namely, that he can think, Oswald Spengler regards only as a sort of adjunct, which is inexplicable and really superfluous. For, according to Spengler, this thinking is really something highly superfluous in man.

“Understanding emancipated from feeling is called thinking. Thinking has forever brought disunion into the human waking state. It has always regarded the intellect and the perceptive faculty as the high and the low soul-forces. It has created the fatal contrast between the light-world of the eye, which is designated as a world of semblance and sense-delusion, and a literally-imagined world, in which concepts with slight but ever-present accent of light pursue their existence.”

Now in setting forth these things Spengler develops an extraordinarily curious idea; namely, that in reality the whole spiritual civilization of man depends upon the eye, that it is really only distilled from the light-world, and concepts are only somewhat refined, somewhat distilled, visions in the light, which are transmitted through the eye. Oswald Spengler simply has no idea that thinking, when it is pure thought, not only receives the light-world of the eye, but unites this light-world with the whole man. It is an entirely different matter whether we think of an entity which is connected with the perception of the eye, or speak of conceptions or mental pictures. Spengler has something to say also about conceptions, or mental pictures (Vorstellen); but at this very point he tries to prove that thinking is only a sort of brain-dream and rarified light-world in man.

Now I should like to know whether with any kind of thinking that is not abstract, but is sound common sense, the word “stellen” (to put or place), when it is experienced correctly, can ever be associated with anything belonging to the light-world. A man “places” himself with his legs; the whole man is included. When we say “vorstellen” (to place before, to represent), we dynamically unite the light-entity with what we experience within as something dynamic, as a force-effect, as something that plunges down into reality. With realistic thinking, we absolutely dive down into reality. Consider the most important thoughts. Aside from mathematical ones, thoughts always lead to the realization that in them we have not merely a light-air-organism, but also something which man has as soul-experience when he causes a thought to be illuminated at the same time that he places both feet on the earth.

Therefore, all that Oswald Spengler has developed here about this light-world transformed into thinking is really nothing but exceedingly clever talk. It is absolutely necessary that this should be stated: the introduction to this second volume is brilliant twaddle, which then rises to such assertions as the following:

“This impoverishment of the sense-faculties involves at the same time an immeasurable deepening. The human waking existence is no longer mere tension between the body and the surrounding world. It is now life in a closed, surrounding light-world. The body moves in observable space. The experience of depth is a mighty penetration into visible distances from a light-center. This is the point which we call ‘I’, ‘I’ is a light-concept.”

Anyone who asserts that “I” is a light-concept has no idea, for example, how intimately connected is the experience of the I with the experience of gravity in the human organism; he has no notion at all of the experience of the mechanical that can arise in the human organism. But when it does arise consciously, then the leap is made from abstract thinking to the realistic, concrete thinking that leads to reality.

It might be said that Oswald Spengler is a perfect example of the fact that abstract thinking has become airy, and also light, and has carried the whole human being away from reality, so that he reels about somewhere in the light and has no suspicion that there is also gravity; for example—that there is also something that can be experienced, not merely looked at. The onlooker standpoint of John Stuart Mill, for instance, is here carried to the extreme. Therefore, the book is exceedingly characteristic of our time.

One sentence on page 13 [Der Untergang des Abendlandes, Vol. II.] appears terribly clever, but it is really only light and airy: “One fashions conception upon conception and finally achieves a thought-architecture in great style, whose edifices stand there in an inner light, as it were, in complete distinctness.”

So Oswald Spengler starts out with mere phraseology. He finds the plant-world “sleeping”; that represents first of all the world around us, which is thoroughly asleep. He finds that the world “wakes up” in the animal kingdom, and that the animal develops in itself a kind of microcosm. He gets no farther than the animal, but develops only the relation between the plant-world and the animal-world, and finds the former in the sleeping state and the latter in the waking state.

|

|

|

Mineral |

|

Sleeping: |

_ |

Plant |

|

Waking: |

|

Animal |

|

|

|

Human |

But everything that happens in the world really comes about under the influence of what is sleeping. The animal—therefore, for Oswald Spengler, man also—has sleep in himself. That is true. But all that has significance for the world proceeds from sleep, for sleep contains movement. The waking state contains only tensions—tensions which beget all sorts of discrepancies within, but still only tensions which are, as it were, just one more external item in the universe. Actually, an independent reality is one which arises from sleep.

And in this broth float all sorts of more or less superfluous, or savory and unsavory blobs of grease—which is the animal element; but there could be broth without these blobs of grease, except that these bring something into reality. In sleep the Where and the How are not to be found, but only the When and the Why. So that we find the following in the human being, who contains the plantlike as well—of the role played by the mineral element in the human being Oswald Spengler has no notion—so that in man we find the following: in as far as he is plantlike, he lives in time; he takes his stand in the “When” and the “Why,” the earlier being the Why of the later. That is the causal factor. And by living on thus through history man really expresses the plantlike in history. The animal-element—and therefore the human as well—which inquires as to the “Where” and the “How,” these (the animal and human elements) are just the blobs of grease that are added to it. (This is quite interesting as far as the inner tensions are concerned, but these really have nothing to do with what takes place in the world.) So we can say: Through cosmic relationships the “When” and the “Why” are implanted in the world for succeeding ages.

And in this on-flowing broth the grease-blobs float with their “Where” and “How.” And when a man—just one such drop of grease—floats in this broth, the “Where” and the “How” really concern only him and his inner tensions, his waking existence. What he does as a historical being proceeds from sleep.

Long ago it was said as a sort of religious imagination: The Lord giveth to his beloved in sleep. To the Spenglerian man it is nature that gives in sleep. Such is the thinking of one of the most prominent personalities of the present time, who, however—in order to avoid coming to terms with himself—plunges into the plant kingdom, thence to emerge no farther than the animal kingdom, into which the human also is stirred.

Now one would suppose that this concoction with its cleverness would avoid the worst blunders that thinking has made in the past; that is, that it would somehow be consistent. If the plant-existence is to be poured out over the history of humanity, then let the concoction be confined to the plant kingdom. It would be difficult, however, to enter upon a historical discussion concerning the man of the plant kingdom. Yet Oswald Spengler does discuss historically, even very cleverly, the plantlike activity of humanity during sleep. But in order that he may have something to say about this sleep of humanity, he makes use of the worst possible kind of thinking, namely, that of anthropomorphism, artificially distorting everything, imagining human qualities into everything. Hence, he speaks—as early as on page 9—of the plant, which has no waking-existence, because he wants to learn from it how he is to write history, and also give a description of the activity of man that arises from sleep.

But let us read the first sentences on page 9: “A plant leads an existence with no waking state”—Good. He means: “In sleep all beings become plants,” that is, man as well as animal—All right.—“the tension with the surrounding world is released, the measure of life moves on.” And now comes a great sentence: “A plant knows only the relation to When and Why.” Now the plant begins not only to dream, but to “know” in its blessed sleep. Thus one faces the conjecture that this sleep, destined to spread perpetually as history in human evolution, might now begin to wake up. For then Oswald Spengler could just as well write a history as to attribute to the plants a knowledge of When and Why. Indeed this sleep-nature of the plant has even some highly interesting qualities:

“The thrusting of the first green spears out of the winter-earth, the swelling of the buds, the whole force of blossoming, of fragrance, of glowing, of ripening—this is all desire for the fulfilment of a destiny and a constantly yearning query as to the Why.”

Of course history can very easily be described as plantlike, if the writer first prepares himself to that end through anthropomorphisms. And because all this is so, Oswald Spengler says further:

“The Where can have no meaning for the plantlike existence. That is the question with which the awakening human being daily recalls his world. For only the pulse-beat of existence persists through all the generations. The waking existence begins anew with each microcosm. That is the distinction between procreation and birth. The one is guarantee for permanence, the other is a beginning. And therefore, a plant is procreated but not born. It exists, but no awakening, no first day, spreads a sense-world around it ...”

If anyone wishes to follow Spenglerian thoughts, he must really, like a tumbler, first stand on his head and then turn over, in order mentally to reverse what is thought of in the human sense as right side up. But you see by concocting such

metaphysics, such a philosophy, Spengler arrives at the following: This sleeping state in man, that which is plantlike in him, this makes history. What is this in man? The blood—the blood which flows through the generations.

Well, in this way Spengler prepares a method for himself, so that he can say: The most important events developed in human history occur through the blood. To do this he must of course cut some more thought-capers:

“The waking existence is synonymous with ‘ascertaining’ (Feststellen), no matter whether the point in question is the sense of touch in one of the infusoria or human thinking of the highest order.”

Certainly when anyone thinks in such an abstract way, he simply fails to discover the difference between the sense of touch in one of the infusoria and human thinking of the highest order. He comes then to all sorts of extraordinarily strange assertions, such as: that this thinking is really a mere adjunct to the whole human life, that deeds originate in the blood, and that out of the blood history is made. And if there are still a few people who ponder about this, they do so with purely abstract thinking that has nothing whatever to do with actuality.

“That we not only live, but know about life, is the result of that observation of our corporeal being in the light. But the animal knows only life, not death.”

And so he explains that the thing of importance must come forth out of obscurity, darkness, out of the plantlike, out of the blood; and he claims that those people who have achieved anything in history have done so not at all as the result of an idea, of thinking—but that thoughts, even those of thinkers, are merely a by-product. About what thinking accomplishes, Oswald Spengler has no words disparaging enough.

And then he contrasts with thinkers all those who really act, because they let thinking be thinking; that is, let it be the business of others.

“Some people are born as men of destiny and others as men of causality. The man who is really alive, the peasant and warrior, the statesman, general, man of the world, merchant, everyone who wishes to become rich, to command, to rule, to fight, to take risks, the organizer, the contractor, the adventurer, the fencer, the gambler, is a world apart from the ‘spiritual’ man” (Spengler puts ‘spiritual’ in quotation marks), “from the saint, the priest, the scholar, idealist, ideologist, regardless of whether he is destined thereto by the power of his thinking or through lack of blood. Existence and being awake, measure and tension, instincts and concepts, the organs of circulation and those of touch—there will seldom be a man of eminence in whom the one side does not unquestionably surpass the other in significance.

“... the active person is a complete human being. In the contemplative person a single organ would like to act without the body or against it. For only the active man, the man of destiny” (that is, one whom thoughts do not concern)—“for only the active man, the man of destiny, lives, in the last analysis, in the real world, the world of political, military, and economic crises, in which concepts and theories count for nothing. Here a good blow is worth more than a good conclusion, and there is sense in the contempt with which the soldiers and statesmen of all times have looked down on the scribbler and the book-worm, who has the idea that world-history exists for the sake of the spirit, of science, or even of art.”

That is a plain statement; in fact, plain enough for anyone to recognize who said it: that it is definitely written by none other than a “scribbler and book-worm,” who merely puts on airs at the expense of others. Only a “scribbler and bookworm” could write:

“Some people are born as men of destiny and some as men of causality. The man who is really alive, the peasant and warrior, the statesman, general, man of the world, merchant, everyone who wishes to become rich, to command, to rule, to fight, to take risks, the organizer, the contractor, the adventurer, the fencer, the gambler, is a world apart from the ‘spiritual’ man, from the saint, the priest, the scholar, idealist, ideologist” ... As if there had never been confessionals and father confessors! Indeed, there are still other beings from whom all those classes of men glean their thoughts. In the society of all such people as have been mentioned—statesmen, generals, men of the world, merchants, fencers, gamblers, and so on—there have even been found soothsayers and fortune-tellers. So that actually the “world” that is supposed to separate the statesman, politician, etc., from the “spiritual” man is in reality not such an enormous distance. Anyone who can observe life will find that this sort of thing is written with utter disregard of all life-observation. And Oswald Spengler, who is a brilliant man and an eminent personality, makes a thorough job of it. After saying that in the realm of real events a blow is worth more than a logical conclusion, he continues thus:

“Here a good blow is worth more than a good conclusion, and there is sense in the contempt with which the soldiers and statesmen of all times have looked down on the scribbler and the book-worm, who has the idea that world-history exists for the sake of the spirit, of science, or even of art. Let us speak unequivocally: Understanding liberated from feeling is only one side of life, and not the decisive side. In the history of western thought, the name of Napoleon may be omitted, but in actual history Archimedes, with all his scientific discoveries, has perhaps been less influential than that soldier who slew him at the storming of Syracuse.”

Now if a brick had fallen on the head of Archimedes, then, according to this theory, this brick would be more important, in the sense of real logical history, than all that originated with Archimedes. And mind you, this was not written by an ordinary journalist, but by one of the most clever people of the present time. That is exactly the significant point, that one of the cleverest men of the present writes in this way.

And now exactly what is effective? Thinking? That just floats on top. What is effective is the blood. Anyone who speaks about the blood from the spiritual viewpoint, that is, speaks scientifically, will ask first of all how the blood originates, how the blood is related to man's nourishment. In the bowels blood does not yet exist; it is first created inside the human being himself. The flow of the blood down through the generations—well, if any kind of poor mystical idea can be formed, this is it. Nothing that nebulous mystics have ever said more or less distinctly about the inner soul-life was such poor mysticism as this Spenglerian mysticism of the blood. It refers to something that precludes all possibility, not only of thinking about it—of course that would make no difference to Oswald Spengler, because no one really needs to think, it is just one of the luxuries of life—but one should cease to speak about anything so difficult to approach as the blood, if one pretends to be an intelligent person, or even an intelligent higher animal.

From this point of view, it is perfectly possible, then, to inaugurate a consideration of history with the following sentence:

“All great historical events are sustained by such beings of a cosmic nature, as dwell in peoples, parties, armies, classes; while the history of the spirit runs its course in loose associations and circles, schools, educational classes, tendencies—in ‘isms.’ And here it is again a matter of destiny whether such a group finds a leader at the decisive moment of its greatest efficiency, or is blindly driven forward, whether the chance leaders are men of high caliber or totally insignificant personalities raised to the summit by the surge of events, like Pompey or Robespierre. It is the mark of the statesman that he comprehends with complete clarity the strength and permanence, direction and purpose of all these soul-masses which form and dissolve in the stream of time; nevertheless, here also it is a question of chance as to whether he will be able to rule them, or is dragged along by them.” In this way a consideration of history is inaugurated which lets the blood be the conqueror of everything that enters historical evolution through the spirit! Now:

“One power may be overthrown only by another power, not by a principle, and against money, there is no other” (but blood, he means). “Money is vanquished and deposed only by blood. Life is the first and last, the illimitable cosmic flux in microcosmic form. It is the fact in the world as history. Before the irresistible rhythm of successive generations, everything that the waking life has built up in its worlds of spirit finally disappears. The fact of importance in history is life, always only life, the race, the triumph of the will to power, and not the victory of truths, discoveries, or money. World-history is world-judgment. It has always decided in favor of life that was more vigorous, fuller, more sure of itself, in favor, that is, of the right to live, whether it was just or not in the waking life; and it has always sacrificed truth and righteousness to power, to race, and has condemned to death men and whole peoples to whom truth was more precious than deeds, and justice more essential than power. Thus another drama of lofty culture, this whole wonderful world of divinities, arts, thoughts, battles, cities, closes with the primeval facts of the eternal blood, which is one and the same with the eternally circling, cosmic, undulating flood. The clear, form-filled waking existence plunges again into the silent service of life, as demonstrated by the Chinese epoch and by the Roman Empire. Time conquers space, and time it is whose inexorable passage imbeds on this planet the fleeting incident—culture, in the incident—man, a form in which the incident—life, flows along for a time, while behind it in the light-world of our eyes appear the flowing horizons of earth-history and star-history.

“For us, however, whom destiny has placed in this culture at this moment of its evolution when money celebrates its last victories, and its successor, Caesarism, stealthily and irresistibly approaches, the direction is given within narrow limits which willing and compulsion must follow, if life is to be worth living.”

Thus does Oswald Spengler point to the coming Caesarism, to that which is to come before the complete collapse of the cultures of the West, and into which the present culture will be transformed.

I have put this before you today because truly the man who is awake—he matters little to Oswald Spengler—the man who is awake, even though he be an Anthroposophist, should take some account of what is happening. And so I wished from this point of view to draw your attention to a particular problem of the time. But it would be a poor conclusion if I were to say only this to you concerning this problem of our time. Therefore, before we must have a longer interval for my trip to Oxford, I will give another lecture next week Wednesday.

Sechster Vortrag

[ 1 ] Als vor einiger Zeit der erste Band von Spenglers «Der Untergang des Abendlandes» erschien, da konnte man in dieser literarischen Erscheinung etwas sehen, was den Willen in sich barg, eindringlicher sich zu beschäftigen mit den elementaren Verfalls- und Niedergangserscheinungen in unserer Zeit. Man konnte sehen, wie jemand in vielem, das in unserer gegenwärtigen Zeit im gesamten Abendlande wirkt, ein Gefühl dafür entwickelt, daß diese Impulse eigentlich nach und nach führen müssen zu einem völligen Chaoswerden der abendländischen Zivilisation mit ihrem amerikanischen Anhange; und daß jemand, der ein Gefühl dafür entwickelte, auch sehr kenntnisreich mit Beherrschung vieler wissenschaftlicher Ideen eine Art von Beurteilungen dieser Erscheinungen abzugeben sich bemühte.

[ 2 ] Man sah ja allerdings, daß Oswald Spengler das Niedergehende sieht. Man konnte auch dazumal schon finden, wie er, weil er in seinem ganzen Denken in diesem Niedergehen selber drinnensteckte, gerade deshalb auch eine Empfindung für alles Niedergehende hatte, und daß er, weil er, ich möchte sagen, in seiner eigenen Seelenverfassung die Dekadenz fühlte, sich nichts mehr versprach — das konnte man begreifen - von alledem, was aus der Massenzivilisation noch hervorgehen kann. Er glaubte, das Abendland werde eben einer gewissen Art von Cäsarismus verfallen, einer gewissen Art von Machtentfaltung einzelner, welche anstelle der differenzierten, vielfach gegliederten Kulturen und Zivilisationen ein einfaches Brutales setzen werden.

[ 3 ] Man konnte sehen, daß ein Mann wie Spengler nicht die geringste Empfindung dafür hatte, daß aus dem Willen der Menschheit heraus eine Rettung für diese Kultur und Zivilisation des Abendlandes kommen kann, wenn dieser Wille dahin geht, gegenüber alldem, was in den Niedergang mit voller Wucht hineinsegelt, geltend zu machen, was immerhin, wenn der Mensch heute will, aus dem Inneren des Menschen als eine neue Kraft hervorgeholt werden kann. Für solch eine neue Kraft, die natürlich eine geistige Kraft sein muß, die beruhen muß auf einem Herausarbeiten aus einem Spirituellen, hatte Oswald Spengler nicht die allergeringste Empfindung.

[ 4 ] So konnte man sehen, wie ein sehr kenntnisreicher, geistreicher Mensch, der so gute Aperçus prägen kann aus einem gewissen eindringlichen Sehen, eigentlich zu gar nichts anderem kommen kann als zu einer gewissen Hoffnung auf eine brutale Machtentfaltung, die abseits liegt von allem Geistigen, die abseits liegt von allem innerlichen Menschheitsstreben, die nur beruht auf einer Entfaltung eben der äußeren brutalen Kraft.

[ 5 ] Dennoch konnte man, als der erste Band erschienen war, wenigstens eine gewisse Achtung haben vor der - ich muß das Wort noch einmal gebrauchen — eindringlichen Geistigkeit, abstrakten, intellektualistischen Geistigkeit gegenüber dem Stumpfen, das den treibenden Gewalten der Geschichte so gar nicht gewachsen ist und das heute so vielfach gerade im Literarischen den Ton angibt.

[ 6 ] Nun ist vor kurzer Zeit der zweite Band Oswald Spenglers erschienen, und der zeigt nun allerdings in einer viel stärkeren Weise alles dasjenige, was in einem Menschen der Gegenwart lebt, der nun selber mit einer gewissen Brutalität alles wirklich Geistige zurückstößt, was als Weltanschauung und Lebensauffassung entstehen kann.

[ 7 ] Geistreich ist ja auch dieser zweite Band. Aber trotz dieser geistreichen Aperçus, die darinnen sind, zeigt er eigentlich nichts anderes als eine furchtbare Sterilität eines bis zum Exzeß abstrakten und intellektualistischen Denkens. Die Sache ist deshalb so außerordentlich bemerkenswert, weil man daraus sieht, zu welch einer besonderen Geistesformung eine immerhin bedeutende Persönlichkeit der Gegenwart kommt.

[ 8 ] Es ist in diesem Buche, in diesem zweiten Band von Spenglers «Untergang des Abendlandes», vor allen Dingen schon der Anfang und das Ende außerordentlich interessant. Aber traurig interessant ist dieser Anfang und das Ende; sie charakterisieren eigentlich die ganze Seelenverfassung dieses Menschen. Man braucht vom Anfange an nur ein paar Sätze zu lesen, um sogleich drinnenzustehen in der Seelensituation Oswald Spenglers ebenso wie in der Seelensituation vieler Menschen der Gegenwart.

[ 9 ] Das, was darüber zu sagen ist, hat nicht bloß eine deutsch-literarische Bedeutung, sondern eine durchaus internationale Bedeutung. Spengler beginnt mit dem folgenden Satze: «Betrachte die Blumen am Abend, wenn in der sinkenden Sonne eine nach der andern sich schließt: etwas Unheimliches dringt dann auf dich ein, ein Gefühl von rätselhafter Angst vor diesem blinden, traumhaften, der Erde verbundenen Dasein. Der stumme Wald, die schweigenden Wiesen, jener Busch und diese Ranke regen sich nicht. Der Wind ist es, der mit ihnen spielt. Nur die kleine Mücke ist frei. Sie tanzt noch im Abendlichte; sie bewegt sich, wohin sie will» und so weiter.

[ 10 ] Der Ausgangspunkt von den Blumen, von den Pflanzen — nun, ich fand mich immer wieder und wieder genötigt, wenn ich auf dasjenige hinweisen wollte, was gerade dem Denken der Gegenwart seine Signatur gibt, anzufangen von jener Art des Begreifens, die der Mensch zuwendet heute der leblosen, der mineralischen, der unorganischen Natur. Vielleicht werden sich manche von Ihnen erinnern, wie ich immer wieder und wieder gebraucht habe, um das Streben des heutigen Denkens nach Durchsichtigkeit des Anschauens zu charakterisieren, das Beispiel von dem Stoß zweier elastischer Kugeln, bei denen man aus dem gegebenen Zustand der einen Kugel durchsichtig rechnerisch den Zustand der anderen Kugel ableiten kann.

[ 11 ] Es kann natürlich jemand von Oswald Spenglerischem Seelenkaliber sagen: Man durchschaut ja mit dem gewöhnlichen Denken auch nicht, wie die Elastizitätskraft da drinnen wirkt, wie da drinnen die Zusammenhänge im tieferen Sinne sind. Ja, derjenige, der so denkt, weiß eben nicht, worauf es bei der Durchsichtigkeit des Denkensgegenwärtig ankommt. Denn ein solcher Einwand wäre nicht mehr wert und auch nicht weniger wert als der, den jemand machte, wenn ich sage: Ich verstehe einen Satz, der auf Papier niedergeschrieben ist — und er antwortet mir: Du verstehst ihn doch nicht, denn du hast nicht untersucht die Beschaffenheit der Tinte, mit der der Satz aufgeschrieben ist! - Es kommt eben immer darauf an, daß man das herausfindet, um was es sich handelt. Bei dem Überblicken der unorganischen Natur handelt es sich nicht um dasjenige, was man eventuell als Kraftimpulse dahinter noch finden kann, wie es hinter dem Aufgeschriebenen sich auch nicht um die Tinte handeln kann, sondern um das, was man durchsichtig in seinem Gedankenprozesse drinnen hat.

[ 12 ] Das ist dasjenige, was sich die Menschheit seit der Galilei-Kopernikus-Zeit errungen hat als eine bestimmte Art des Denkens, die erstens darstellt, daß man mit ihr nur die leblose, die unorganische Natur begreifen kann, daß man auf der anderen Seite aber, indem man sich diesem Denken zunächst als dem einfachsten und primitivsten reinen Denken hingibt, in ihr zuerst entfalten kann die Freiheit der menschlichen Seele, die Freiheit des Menschen überhaupt. Erst wer die Natur des gegenständlichen Denkens mit seiner Durchsichtigkeit, wie sie in der leblosen Natur waltet, durchschaut, kann dann aufsteigen zu den anderen Prozessen des Denkens und Anschauens, zu demjenigen, was das Denken durchsetzt mit Anschauen: mit Imagination, mit Inspiration, mit Intuition.

[ 13 ] Es ist also die erste Aufgabe desjenigen, der heute im intimsten Sinne mitreden will in bezug auf die äußere Konfiguration unseres Kulturlebens, daß er merkt, worauf eigentlich die Kraft gerade des heutigen Denkens beruht.

[ 14 ] Und derjenige, der so diese Kraft des heutigen Denkens verspürt hat, weiß, wie dieses Denken in der Maschine wirkt, wie dieses Denken uns die moderne Technik heraufgebracht hat, in der wir aus diesem Denken heraus äußere, unorganische leblose Zusammenhänge konstruieren, die alles an Durchsichtigkeit haben, was sie zum Behuf der äußeren Betätigung des Menschen haben sollen.

[ 15 ] Erst wer das versteht, rückt dann weiter ein in die Erkenntnis, daß in dem Augenblicke, wo wir die Pflanzen überschauen, wir mit diesem zunächst in seiner Abstraktion ergriffenen Denken in die reine Wuselei hineinkommen. Wer dieses kristallisch durchsichtige Denken für die mineralische Welt allein in seiner Abstraktheit haben will, nicht bloß als Durchgangspunkt für die Entwickelung der Freiheit des Menschen, sondern wer nun allein im Denken, mit diesem Denken seine Blicke auf die Pflanzenwelt richtet, der hat in der Pflanzenwelt ein Nebuloses, Dunkles, Mystisches vor sich, das er nicht durchblicken kann. Denn in dem Augenblicke, wo wir zur Pflanzenwelt hinaufschauen, müssen wir uns klar sein, daß hier, wenigstens in dem Grade, wie das Goethe gewollt hat mit seiner Urpflanze und mit dem Prinzip, durch das er die Urpflanze metamorphosiert durch alle Pflanzenformen hindurch — wenigstens in diesem Goetheschen Sinne muß einer, der aufrückt von einem Erkennen der wirklichen Kräfte des im Unorganischen waltenden Denkens, in der Pflanzenwelt verspüren, daß sie dunkel und mystisch im schlechtesten Sinne unserer Zeit bleibt, wenn man nicht aufrückt zu einer imaginativen Betrachtung — wenigstens eben in dem Sinne, in dem Goethe seine botanischen Anschauungen begründet hat.

[ 16 ] Wenn jemand wie Oswald Spengler die imaginative Erkenntnis abweist und dennoch beginnt mit der Pflanzenwelt, sie zu schildern beginnt, dann kommt er nicht zu irgend etwas, das Klarheit und Kraft gibt, dann kommt er zu einer Gedankenwuselei, zur Mystik im allerschlimmsten Sinne des Wortes, nämlich zur materialistischen Mystik. Und wenn man das vom Anfange sagen muß, so ist gerade durch diesen Anfang wiederum das Ende dieses Buches charakterisiert.

[ 17 ] Das Ende dieses Buches handelt von der Maschine, von demjenigen, das der neueren Zivilisation gerade die Signatur gegeben hat, der Maschine, die auf der anderen Seite dem Menschen gegenübersteht als dasjenige, was allerdings als Ding zunächst seiner Natur fremd ist, an dem er aber gerade das durchsichtige Denken entwickelt hat.

[ 18 ] Ich habe vor einiger Zeit — unmittelbar nach dem Erscheinen von Oswald Spenglers Buch - unter dem Eindruck der Wirkung, die Spenglers Buch gemacht hat, an der Technischen Hochschule in Stuttgart einen Vortrag gehalten über Anthroposophie und die technischen Wissenschaften, um da zu zeigen, wie gerade im Untertauchen in die Technik der Mensch diejenige Konfiguration seines Seelenlebens entwickelt, die ihn dann frei macht. So daß er dadurch, daß er in der maschinellen Welt alle Geistigkeit ausgelöscht erlebt, den Antrieb erhält — gerade innerhalb der maschinellen Welt -, durch inneres Aufraffen die Geistigkeit aus seinem Inneren zu holen; so daß derjenige, der heute das Darinnenstehen der Maschine in unserer ganzen Zivilisation begreift, sich eben sagen muß: Diese Maschine mit ihrer impertinenten Durchsichtigkeit, mit ihrer brutalen, schauderhaften, dämonischen Geistlosigkeit, zwingt den Menschen, wenn er sich nur selber versteht, aus seinem Inneren herauszuholen diejenigen Keime von Spiritualität, die in ihm sind. Durch den Gegensatz zwingt die Maschine den Menschen, spirituelles Leben zu entwickeln.

[ 19 ] Dasjenige, was ich damals habe sagen wollen, ist allerdings, wie ich aus den Nachwirkungen habe sehen können, von niemandem verstanden worden.

[ 20 ] Spengler stellt am Schlusse seines Werkes eine Betrachtung an über die Maschine. Nun, das, was Sie da lesen über die Maschine, das klingt zuletzt aus in einer Art Verherrlichung der Furcht vor der Maschine. Dasjenige, was über die Maschine gesagt wird, ist geradezu etwas, was man empfinden kann als den Gipfelpunkt des Aberglaubens des modernen Menschen gegenüber der Maschine, die er dämonisch empfindet, wie gewisse Menschen abergläubischer Art die Dämonen empfinden. Er schildert die Erfinder der Maschine; er schildert, wie nach und nach die Maschine heraufgekommen ist, wie nach und nach die Maschine die Zivilisation ergriffen hat. Er schildert die Menschen, in deren Zeitalter die Maschine eingetreten ist: «Aber für sie alle bestand auch die eigentlich faustische Gefahr, daß der Teufel seine Hand im Spiele hatte, um sie im Geist auf jenen Berg zu führen, wo er ihnen alle Macht der Erde versprach. Das bedeutet der Traum jener seltsamen Dominikaner wie Petrus Peregrinus vom perpetuum mobile, mit dem Gott seine Allmacht entrissen gewesen wäre. Sie erlagen diesem Ehrgeiz immer wieder; sie zwangen der Gottheit ihr Geheimnis ab, um selber Gott zu sein.»

[ 21 ] Also Oswald Spengler faßt die Sache so auf, daß, weil der Mensch dazu gekommen ist, die Maschine zu dirigieren, er gerade durch dieses Dirigieren sich einbilden lernen kann, ein Gott zu sein, weil der Gott der Maschine des Weltenalls nach seiner Meinung die Maschine dirigiert. Wie sollte der Mensch nicht zum Gotte sich erhoben fühlen, wenn er nun einen Mikrokosmos dirigiert!

[ 22 ] «Sie belauschten die Gesetze des kosmischen Taktes, um sie zu vergewaltigen, und sie schufen so die /dee der Maschine als eines kleinen Kosmos, der nur noch dem Willen des Menschen gehorcht. Aber damit überschritten sie jene feine Grenze, wo für die anbetende Frömmigkeit der andern die Sünde begann, und daran gingen sie zugrunde, von Bacon bis Giordano Bruno. Die Maschine ist des Teufels: so hat der echte Glaube immer wieder empfunden.»

[ 23 ] Nun, selbstverständlich meint er es an dieser Stelle bloß ironisch. Aber daß er es nicht bloß ironisch meint, das sieht man dann, wenn er in seiner geistreichen Art Worte gebraucht, die etwas altertümlich klingen. Das zeigt die folgende Stelle: «Dann aber folgt zugleich mit dem Rationalismus die Erfindung der Dampfmaschine, die alles umstürzt und das Wirtschaftsbild von Grund aus verwandelt. Bis dahin hatte die Natur Dienste geleistet, jetzt wird sie als Sklavin ins Joch gespannt und ihre Arbeit wie zum Hohn nach Pferdekräften bemessen. Man ging von der Muskelkraft des Negers, die in organisierten Betrieben angesetzt wurde, zu den organischen Reserven der Erdrinde über, wo die Lebenskraft von Jahrtausenden als Kohle aufgespeichert liegt und richtet heute den Blick auf die anorganische Natur, deren Wasserkräfte schon zur Unterstützung der Kohle herangezogen sind. Mit den Millionen und Milliarden Pferdekräften steigt die Bevölkerungszahl in einem Grade, wie keine andre Kultur es je für möglich gehalten hätte. Dieses Wachstum ist ein Produkt der Maschine, die bedient und gelenkt sein will und dafür die Kräfte jedes einzelnen verhundertfacht. Um der Maschine willen wird das Menschenleben kostbar. Arbeit wird das große Wort des ethischen Nachdenkens. Es verliert im 18. Jahrhundert in allen Sprachen seine geringschätzige Bedeutung. Die Maschine arbeitet und zwingt den Menschen zur Mitarbeit. Die ganze Kultur ist in einen Grad von Tätigkeit geraten, unter dem die Erde bebt.»

[ 24 ] «Was sich nun im Laufe eines Jahrhunderts entfaltet, ist ein Schauspiel von solcher Größe, daß den Menschen einer künftigen Kultur mit andrer Seele und andern Leidenschaften das Gefühl überkommen muß, als sei damals die Natur ins Wanken geraten. Auch sonst ist die Politik über Städte und Völker hinweggeschritten; menschliche Wirtschaft hat tief in die Schicksale der Tier- und Pflanzenwelt eingegriffen, aber das rührt nur an das Leben und verwischt sich wieder. Diese Technik aber wird die Spur ihrer Tage hinterlassen, wenn alles andere verschollen und versunken ist. Diese faustische Leidenschaft hat das Bild der Erdoberfläche verändert.»

[ 25 ] «Und diese Maschinen werden in ihrer Gestalt immer mehr entmenschlicht, immer asketischer, mystischer, esoterischer. Sie umspinnen die Erde mit einem unendlichen Gewebe feiner Kräfte, Ströme und Spannungen. Ihr Körper wird immer geistiger, immer verschwiegener. Diese Räder, Walzen und Hebel reden nicht mehr. Alles was entscheidend ist, zieht sich ins Innere zurück. Man hat die Maschine als teuflisch empfunden, und mit Recht. Sie bedeutet in den Augen eines Gläubigen die Absetzung Gottes. Sie liefert die heilige Kausalität dem Menschen aus, und sie wird schweigend, unwiderstehlich, mit einer Art von vorausschauender Allwissenheit von ihm in Bewegung gesetzt.»

[ 26 ] «Niemals hat sich der Mikrokosmos dem Makrokosmos überlegener gefühlt. Hier gibt es kleine Lebewesen, die durch ihre geistige Kraft das Unlebendige von sich abhängig gemacht haben. Nichts erscheint diesem Triumph zu gleichen, der nur einer Kultur geglückt ist und vielleicht nur für eine kleine Zahl von Jahrhunderten.»

[ 27 ] «Aber gerade damit ist der faustische Mensch zum Sklaven seiner Schöpfung geworden.»

[ 28 ] Wir sehen, es taucht hier die völlige Ratlosigkeit des Denkers gegenüber der Maschine auf. Nichts ahnt dieser Denker davon, wie die Maschine dieses alles nicht ist, was irgendwie mystisch sein könnte, vor demjenigen, der gerade das Unlebendige in seiner mystikfreien Art erfaßt.

[ 29 ] Und so sehen wir, daß Oswald Spengler mit einer verwuselten Darstellung des Pflanzlichen beginnt, weil er eigentlich doch über die Art und den Charakter der gegenwärtigen Erkenntnis, die innig zusammenhängt mit der Entwickelung des maschinellen Lebens, gar keinen Begriff hat, weil ihm das Denken nur eine Abstraktion bleibt, und er deshalb auch die Funktion des Denkens im Maschinellen nicht verspüren kann. Das Denken wird da ganz und gar zum wesenlosen Bilde, damit der Mensch im maschinellen Zeitalter um so mehr zum Wesenhaften werden könne, seine Seele, seinen Geist durch den Widerstand gegen das Maschinelle aus sich selber hervorrufen könne. Das ist die menschliche Bedeutung, das ist die Weltentwickelungsbedeutung des maschinellen Lebens!

[ 30 ] Derjenige, der, indem er mit einer metaphysischen Klarheit beginnen will, mit einer verwuselten Darstellung des Pflanzlichen beginnt, der tut das aus dem Grunde, weil er in dieser Stimmung gegen die Maschine ist.

[ 31 ] Also Oswald Spengler hat die Funktion des neueren Denkens nur in seiner Abstraktheit begriffen, und er macht sich an das, was ihm dunkel bleibt, an das Pflanzenhafte.

[ 32 ] Nun, wenn man das Mineralische, das Pflanzliche, das Tierische, das Menschliche nimmt, so charakterisiert sich für die Gegenwart das Menschliche dadurch, daß wir seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts ganz zum mineralisch-durchsichtigen Denken vorgeschritten sind. So daß, wenn wir den Menschen der heutigen Zeit anschauen, wie er in seinem Inneren ist als Anschauer der Außenwelt, wir sagen müssen: Er hat als Menschliches gerade heute die Anschauung des Mineralischen entwikkelt. Dann muß man aber die Bedeutung dieses mineralischen Denkens so charakterisieren, wie ich das eben jetzt gemacht habe.

[ 33 ] Wenn aber jemand nichts vom Wesen des Mineralischen weiß, dann kommt er, wenn er beim Pflanzlichen anfängt, bloß bis zum Tierischen. Denn das Tierische trägt das Pflanzliche in derselben Form in sich, wie wir heute das Mineralische. Das ist das Charakteristische bei Oswald Spengler, daß er beim Pflanzlichen anfängt und in seinen Begriffen überhaupt nicht über das Tierische hinauskommt, den Menschen nur auffaßt, insofern der Mensch ein Tier ist, und daß ihm eigentlich das Denken, das in Wirklichkeit in seiner eigentlichen Bedeutung erst seit dem 14. Jahrhundert begriffen werden kann — das so begriffen werden kann, wie ich es jetzt dargestellt habe -, als etwas außerordentlich Unverständliches erscheint. Daher läßt er es, soweit als er es nur kann, hinunterkollern in das Tierische. So daß wir zum Beispiel ihn aufsuchen sehen, wie er gleich dem Tier auch ein Sinneswahrnehmen hat, wie dann dieses Sinneswahrnehmen im Tiere schon zu einer Art von Urteil wird. Und so versucht er, das Denken nur als etwas wie eine Steigerung des tierischen Wahrnehmungslebens hinzustellen.

[ 34 ] Im Grunde genommen hat keiner in so radikaler Weise wie gerade Oswald Spengler gezeigt, daß der Mensch heute mit dem abstrakten Denken überhaupt nur bis zu der außermenschlichen Welt kommt, die menschliche Welt nicht mehr begreift! Und das eigentlich Charakteristische des Menschen: daß der Mensch denken kann, das empfindet Oswald Spengler eigentlich nur als so eine Art Beigabe, die unerklärlich und im Grunde genommen eigentlich überflüssig ist für den Menschen. Denn im Grunde genommen ist — nach Spengler — dieses Denken doch etwas höchst Überflüssiges im Menschen: «Das vom Empfinden abgezogene Verstehen heißt Denken. Das Denken hat für immer einen Zwiespalt in das menschliche Wachsein getragen. Es hat von früh an Verstand und Sinnlichkeit als hohe und niedere Seelenkraft gewertet. Es hat den verhängnisvollen Gegensatz geschaffen zwischen der Lichtwelt des Auges, die als Scheinwelt und Sinnentrug bezeichnet wird, und einer im wörtlichen Sinne vor-gestellten Welt, in der die Begriffe mit ihrer nie abzustreifenden leisen Lichtbetonung ihr Wesen treiben.»

[ 35 ] Nun, indem Spengler diese Dinge auseinandersetzt, entwickelt er eine außerordentlich kuriose Idee: nämlich die, daß im Grunde genommen die ganze geistige Zivilisation des Menschen vom Auge abhängt, eigentlich nur von der Lichtwelt abgezogen ist, und die Begriffe sind eigentlich nur etwas verfeinerte, etwas destillierte Anschauungen im Lichte, die durch das Auge vermittelt werden. Oswald Spengler hat eben keine Ahnung davon, daß das Denken, wenn es rein wirkt, nicht etwa bloß die Lichtwelt des Auges in sich aufnimmt, sondern daß das Denken diese Lichtwelt des Auges zusammenbringt mit dem ganzen Menschen. Es ist etwas durchaus anderes, ob wir an eine Entität denken, die mit der Wahrnehmung des Auges zusammenhängt, oder ob wir von Vorstellungen sprechen. Spengler redet auch vom Vorstellen, aber gerade damit will er den Beweis liefern, daß das Denken eigentlich nur so eine Art Hirntraum und verfeinerte Lichtwelt in dem Menschen ist.

[ 36 ] Nun möchte ich einmal wissen, ob man mit irgendeinem zwar nicht abstrakten Denken, aber gesunden Menschenverstand das Wort «stellen», wenn es richtig erlebt wird, jemals zusammenbringen kann mit irgend etwas, was der Lichtwelt angehört! — «Stellen» tut man sich mit seinen Beinen; man nimmt den ganzen Menschen dazu. Wenn einer sagt: «vorstellen», so verbindet er dynamisch das Lichtding mit demjenigen, was er in sich erlebt als Dynamisches, als Kraftwirkung, als etwas, was hineintaucht in die Wirklichkeit. Mit dem realistischen Denken tauchen wir durchaus in die Wirklichkeit hinein. Sehen Sie sich die wichtigsten Gedanken an — abgesehen von den mathematischen — überall führen sie, die Gedanken, zu so etwas hin, woraus Sie ersehen können, daß wir in den Gedanken nicht bloß einen Licht-, Luftorganismus haben, sondern auch dasjenige, was der Mensch als seelisches Erlebnis hat, indem er es vom Lichte beleuchtet sein läßt und zugleich auf die Erde beide Beine stellt.

[ 37 ] Daher ist alles das, was hier Oswald Spengler entwickelt über diese ins Denken umgewandelte Lichtwelt, im Grunde genommen nichts als ein außerordentlich geistreiches Geschwätz! Das ist dasjenige, was durchaus einmal ausgesprochen werden muß: die Einleitung zu diesem zweiten Bande ist geistreiches Geschwätz. Dieses geistreiche Geschwätz erhebt sich dann zu solchen Behauptungen, wie: «Diese Verarmung des Sinnlichen bedeutet zugleich eine unermeßliche Vertiefung. Menschliches Wachsein ist nicht mehr die bloße Spannung zwischen Leib und Umwelt. Es heißt jetzt: Leben in einer rings geschlossenen Lichtwelt. Der Leib bewegt sich im gesehenen Raume. Das Tiefenerlebnis ist ein gewaltiges Eindringen in sichtbare Fernen von einer Lichtmitte aus: es ist jener Punkt, den wir Ich nennen. «Ich» ist ein Lichtbegriff.»

[ 38 ] Derjenige, der behauptet, das Ich sei ein Lichtbegriff, der hat keine Ahnung davon, wie innig das Ich-Erlebnis verknüpft ist zum Beispiel mit dem Schwere-Erlebnis im menschlichen Organismus, der hat überhaupt keine Ahnung von der erlebten Mechanik, die schon im menschlichen Organismus auftreten kann! Dann aber, wenn sie auftritt, bewußt, dann ist auch der Sprung gemacht von dem abstrakten Denken zu dem konkreten, realen Denken, das in die Wirklichkeit hineinführt.

[ 39 ] Man möchte sagen: Oswald Spengler ist so richtig ein Beispiel dafür, daß das abstrakte Denken «luftig» geworden ist, sogar «lichtig» geworden ist und den ganzen Menschen wegträgt von der Wirklichkeit, so daß er da draußen irgendwo im Lichte herumtaumelt und nun keine Ahnung davon hat, daß es auch zum Beispiel eine Schwere gibt, daß es auch etwas gibt, was erlebt werden kann, nicht bloß angeschaut. Der Anschauerstandpunkt zum Beispiel des John Stuart Mill ist hier bis zum Extrem gebracht. Deshalb ist das Buch außerordentlich charakteristisch für unsere Zeit.

[ 40 ] Ein Satz. auf Seite 13 scheint ungeheuer geistreich zu sein, aber im Grunde genommen ist er «windig-lichtig»: «Man bildet Vorstellungen über Vorstellungen und gelangt endlich zu einer Gedankenarchitektur großen Stils, deren Bauten in voller Deutlichkeit gleichsam in einem inneren Lichte daliegen.»

[ 41 ] So geht denn Oswald Spengler aus von dem Phrasenhaften. Das Pflanzliche findet er «schlafend»; das stellt zunächst die Welt dar, die da um uns herum richtig schläft. Er findet, daß die Welt «wach» wird im Tierreiche, daß das Tier in sich eine Art Mikrokosmos entwickelt. Er kommt über das Tier nicht herauf; er entwickelt nur die Beziehung zwischen dem Pflanzlichen und dem Tierischen, findet das Pflanzliche in dem Schlafen, das Tierische in dem Wachsein.

Schlafen:

Mineralisches

PflanzlichesWachen:

Tierisches

Menschliches

[ 42 ] Aber alles dasjenige, was geschieht in der Welt, geschieht eigentlich unter dem Einfluß desjenigen, was schläft. Das Tier — damit für Oswald Spengler auch der Mensch — hat das Schlafen in sich. Das hat er auch. Aber alles dasjenige, was Bedeutung hat für die Welt, geht aus dem Schlafen hervor, denn das Schlafen hat die Bewegung in sich. Das Wachsein hat nur Spannungen in sich, Spannungen, die allerlei Diskrepanzen im Inneren erzeugen, aber eben nur Spannungen, die gewissermaßen als ein etwas Äußerliches zu dem Weltenall hinzukommen. Im Grunde genommen ist eine selbständige Wirklichkeit diejenige, die aus dem Schlafen kommt.

[ 43 ] Und in dieser Suppe schwimmen allerlei solche mehr oder weniger überflüssigen oder schmackhaften und unschmackhaften Fettaugen das ist das Tierische. Aber die Suppe könnte auch ohne diese Fettaugen bestehen. Nur bringen diese Fettaugen etwas in die Wirklichkeit hinein. Im Schlaf, da findet man nicht das Wo und Wie darinnen, da findet man nur das Wann und Warum. So daß wir auch beim Menschen, der ja als Tier noch das Pflanzliche in sich enthält - welche Rolle das Mineralische im Menschlichen spielt, davon hat Oswald Spengler keine Ahnung -, so daß wir beim Menschen folgendes finden: Insofern er pflanzlich ist, lebt er in der Zeit; er stellt sich hinein in das Wann und in das Warum, indem das Frühere das Warum des Späteren ist. Das ist das Kausale. Und indem der Mensch so in der Geschichte weiterlebt, lebt er eigentlich in der Geschichte das Pflanzliche aus. Das Tierische, und damit auch das Menschliche, das nach dem Wo und Wie frägt: das sind eben die Fettaugen; die kommen dazu. Das ist ja ganz interessant für die inneren Spannungen; aber sie haben nicht eigentlich etwas zu tun mit demjenigen, was in der Welt wirklich geschieht. So daß man sagen kann: durch die Weltenzusammenhänge ist der Welt eingepflanzt das Wann und Warum für die Zeitenfolge.

[ 44 ] Und in dieser fortströmenden Suppe, da schwimmen eben die Fettaugen mit ihrem Wo und Wie. Und wenn der Mensch - ein solches Fettauge — da schwimmt, so geht das Wo und Wie eigentlich nur ihn an und seine inneren Spannungen, sein Wachsein. Dasjenige, was er als geschichtliches Wesen tut, das kommt aus dem Schlaf.

[ 45 ] Früher hat man als eine Art Religionsphantasie gesagt: Den Seinen gibt's der Herr im Schlafe. - Dem Spenglerschen Menschen gibt es die Natur im Schlafe! So ist das Denken einer der bedeutendsten Persönlichkeiten der Gegenwart, das aber, um sich ja nicht über sich selber klar zu werden, zuerst in das Pflanzliche hinein verstrudelt, um aus dieser Strudelei nicht wiederum weiter herauszukommen als bis zum Tierischen, in das auch das Menschliche hineingestrudelt wird.

[ 46 ] Nun könnte man glauben, diese Strudelei vermeide in ihrer Geistreichigkeit die ärgsten Fehler, die das Denken in der Vergangenheit gemacht hat; sie sei sich also irgendwie treu darinnen. Wenn schon das Pflanzensein auch über die Geschichte der Menschheit ausgegossen werden soll, so bleibe sie beim Pflanzensein. Aber es ließe sich doch nicht gut mit dem Menschen des Pflanzenreiches eine geschichtliche Betrachtung anstellen. Nun, Oswald Spengler stellt, sogar sehr geistreich, geschichtliche Betrachtungen an über dasjenige, was die Menschheit in ihrer Entwickelung im Schlafe pflanzlich macht. Aber damit er doch über dieses Schlafen der Menschheit etwas zu sagen hat, bedient er sich der schlechtesten Art des Denkens, deren man sich nur bedienen kann: nämlich des Anthropomorphismus, alles in künstlicher Weise zu verzerren, überall das Menschliche hineinzuphantasieren. Er redet daher, schon auf Seite 9, von der Pflanze, die kein Wachsein hat, weil er an ihr erfahren will, wie er nun Geschichte schreiben soll, und nun auch eine Beschreibung dessen liefern soll, was aus dem Schlafe heraus die Menschen tun.

[ 47 ] Aber nun lese man die ersten Sätze auf Seite 9:

[ 48 ] «Eine Pflanze führt ein Dasein ohne Wachsein.» Gut.

[ 49 ] «Im Schlaf werden alle Wesen zu Pflanzen», meint er. Also der Mensch ebenso wie die Tiere! Schön. —

[ 50 ] «die Spannung zur Umwelt ist erloschen, der Takt des Lebens geht weiter.»

[ 51 ] Und jetzt kommt ein kapitaler Satz:

[ 52 ] «Eine Pflanze kennt nur die Beziehung zum Wann und Warum.»

[ 53 ] Nun fängt die Pflanze an, nicht nur zu träumen, sondern zu «kennen» in ihrem seligen Schlaf. Man steht also etwa vor der Vermutung: Dieser Schlaf, der sich da als Geschichte fortströmend verbreiten soll in der menschlichen Entwickelung, der könnte nun auch eigentlich anfangen zu wachen. Denn mit demselben Rechte könnte dann Oswald Spengler eine Geschichte schreiben, wie er der Pflanze ein Kennen von Wann und Warum andichtet. Ja, dieses Schlafeswesen der Pflanze hat sogar höchst interessante Eigenschaften:

[ 54 ] «Das Drängen der ersten grünen Spitzen aus der Wintererde, das Schwellen der Knospen, die ganze Gewalt des Blühens, Duftens, Leuchtens, Reifens: das alles ist Wunsch nach der Erfüllung eines Schicksals und eine beständige sehnsüchtige Frage nach dem Wann.»

[ 55 ] Ja, man kann sehr leicht die Geschichte als Pflanzenleben schildern, wenn man sich erst durch Anthropomorphismen dazu vorbereitet!

[ 56 ] Und weil das alles so ist, so sagt Oswald Spengler weiter: «Das Wo kann für ein pflanzenhaftes Dasein keinen Sinn haben. Es ist die Frage, mit welcher der erwachende Mensch sich täglich wieder auf seine Welt besinnt. Denn nur der Pulsschlag des Daseins dauert durch alle Geschlechter an. Das Wachsein beginnt für jeden Mikrokosmos von neuem: das ist der Unterschied von Zeugung und Geburt. Das eine ist Bürgschaft der Dauer, die andere ist ein Anfang. Und deshalb wird eine Pflanze erzeugt, aber nicht geboren. Sie ist da, aber kein Erwachen, kein erster Tag spannt eine Sinnenwelt um sie aus.»

[ 57 ] Man muß wirklich, wenn man die Spenglerschen Gedanken nachdenken will, wie ein Stehaufmännchen zuerst auf den Kopf sich stellen und dann umspringen, um dasjenige, was im menschlichen Sinn gerade gedacht ist, wieder umzudenken! Aber sehen Sie, dadurch, daß sich Oswald Spengler eine solche Metaphysik, eine solche Philosophie zurechtlegt, kommt er nun dazu, zu sagen: Dieses Schlafende im Menschen, das, was im Menschen wie eine Pflanze ist, das macht Geschichte. Was ist das im Menschen? Das Blut, das Blut, das durch die Geschlechter rinnt.

[ 58 ] Nun, so bereitet sich Oswald Spengler eine Methode vor, um sagen zu können: Die wichtigsten Ereignisse, die in der Menschengeschichte sich entwickeln, die geschehen durch das Blut. Dazu muß er allerdings noch einige Gedankenbocksprünge machen: «Insofern ist Wachsein gleichbedeutend mit «Feststellen», ob es sich nun um das Tasten eines Infusors oder um menschliches Denken vom höchsten Range handelt.»

[ 59 ] Ja, wenn man so abstrakt denkt, dann findet man eben den Unterschied nicht heraus zwischen dem Tasten eines Infusors und dem Denken eines Menschen von allerhöchstem Range! Und dann kommt man zu allerlei außerordentlich merkwürdigen Behauptungen; zu dem, daß eigentlich dieses Denken eine Beigabe des gesamten Menschenlebens ist: Aus dem Blut herauf geschehen die Taten, aus dem Blut herauf werde Geschichte gemacht. Und wenn dann auch noch einige da sind, die über das nachdenken, so ist es eben ein abstraktes Nachdenken und hat mit dem Geschehen nicht das geringste zu tun: «Daß wir nicht nur leben, sondern um «das Leben» wissen, ist das Ergebnis jener Betrachtung unseres leibhaften Wesens im Licht. Aber das Tier kennt nur das Leben, nicht den Tod.»

[ 60 ] Und so führt er aus, daß eigentlich dasjenige, worauf es ankommt, aus dem Dunkeln, Finstern, aus dem Pflanzenhaften, aus dem Blute hervorkommen muß, und daß alle diejenigen Menschen, die etwas in der Geschichte gemacht haben, nun ja nicht irgend etwas aus einer Idee, aus einem Denken heraus gemacht haben, sondern die Gedanken, auch die Gedanken der Denker, die gehen nur so nebenher. Über dasjenige, was das Denken leistet, hat Oswald Spengler nicht genug herabwürdigende Worte.

[ 61 ] Und dann stellt er dagegen alle diejenigen, die wirklich handeln, weil sie das Denken Denken sein lassen, das Denken das Geschäft der anderen sein lassen: «Es gibt geborene Schicksalsmenschen und Kausalitätsmenschen. Der eigentlich lebendige Mensch, der Bauer und Krieger, der Staatsmann, Heerführer, Weltmann, Kaufmann, jeder, der reich werden, befehlen, herrschen, kämpfen, wagen will, der Organisator und Unternehmer, der Abenteurer, Fechter und Spieler, ist durch eine ganze Welt von dem «geistigen» Menschen» — «geistigen» setzt Spengler in Anführungszeichen — «getrennt, dem Heiligen, Priester, Gelehrten, Idealisten und Ideologen, mag dieser nun durch die Gewalt seines Denkens oder den Mangel an Blut dazu bestimmt sein. Dasein und Wachsein, Takt und Spannung, Triebe und Begriffe, die Organe des Kreislaufs und die des Tastens — es wird selten einen Menschen von Rang geben, bei dem nicht unbedingt die eine Seite die andre an Bedeutung überragt.»

[ 62 ] «...der Tätige ist ein ganzer Mensch: im Betrachtenden möchte ein einzelnes Organ ohne und gegen den Leib wirken.»

[ 63 ] «Denn nur der Handelnde, der Mensch des Schicksals» — also derjenige, den die Gedanken nichts angehen - «lebt letzten Endes in der wirklichen Welt, der Welt der politischen, kriegerischen und wirtschaftlichen Entscheidungen, in der Begriffe und Systeme nicht mitzählen. Hier ist ein guter Hieb mehr wert als ein guter Schluß und es liegt Sinn in der Verachtung, mit welcher der Soldat und Staatsmann zu allen Zeiten auf die Tintenkleckser und Bücherwürmer herabgesehen hat, die der Meinung waren, daß die Weltgeschichte um des Geistes, der Wissenschaft oder gar der Kunst willen da sei.»

[ 64 ] Das ist deutlich gesprochen! Aber auch so deutlich, daß man erkennt, wer es gesprochen hat: daß es doch nun schließlich ein «Tintenkleckser und Bücherwurm» geschrieben hat, der sich nur aufspielt zu Händen anderer. Und ein «Tintenkleckser und Bücherwurm» muß es schon sein, der da schreibt: «Es gibt geborene Schicksalsmenschen und Kausalitätsmenschen. Der eigentlich lebendige Mensch, der Bauer und Krieger, der Staatsmann, Heerführer, Weltmann, Kaufmann, jeder, der reich werden, befehlen, herrschen, kämpfen, wagen will, der Organisator und Unternehmer, der Abenteurer, Fechter und Spieler, ist durch eine ganze Welt von dem «geistigen» Menschen getrennt, dem Heiligen, Priester, Gelehrten, Idealisten und Ideologen.» Als ob es niemals Beichtstühle gegeben hätte und Beichtväter gegeben hätte! Ja, es gibt sogar noch andere Wesen, bei denen alle diese Sorten von Menschen sich die Gedanken holen. Man hat sogar schon in der Gesellschaft von all solchen Leute, die da angeführt werden, Staatsmänner, Heerführer, Weltmänner, Kaufleute, Fechter, Spieler und so weiter sogar schon Wahrsagerinnen und Kartenschlägerinnen gefunden! So daß also durchaus die Welt, durch die der Staatsmann, der Politiker und so weiter getrennt sein soll von dem «geistigen» Menschen, eine so ungeheure Weite nicht hat in der Wirklichkeit. Derjenige, der das Leben betrachten kann, der wird eben finden, daß so etwas hingeschrieben wird mit Ausschluß jeder Lebensbetrachtung. Und Oswald Spengler, der ein geistreicher Mann und eine bedeutende Persönlichkeit ist, macht es gründlich. Nachdem er gesagt hat, daß im Reich des wirklichen Geschehens ein Hieb mehr wert ist als ein logischer Schluß, da fährt er fort also: «Hier ist ein guter Hieb mehr wert als ein guter Schluß und es liegt Sinn in der Verachtung, mit welcher der Soldat und Staatsmann zu allen Zeiten auf die Tintenkleckser und Bücherwürmer herabgesehen hat, die der Meinung waren, daß die Weltgeschichte um des Geistes, der Wissenschaft oder gar der Kunst willen da sei. Sprechen wir es unzweideutig aus: das vom Empfinden freigewordene Verstehen ist nur eine Seite des Lebens und nicht die entscheidende. In einer Geschichte des abendländischen Denkens darf der Name Napoleon fehlen, in der wirklichen Geschichte aber ist Archimedes mit all seinen wissenschaftlichen Entdeckungen vielleicht weniger wirksam gewesen als jener Soldat, der ihn bei der Erstürmung von Syrakus erschlug.»

[ 65 ] Nun, wenn dem Archimedes ein Ziegelstein auf den Kopf gefallen wäre, dann wäre nach dieser Theorie dieser Ziegelstein mehr wert als all dasjenige, was von Archimedes ausgegangen war, im Sinne der wirklichen, der logischen Geschichte! Aber so schreibt heute nicht etwa der gewöhnlichste Journalist, so schreibt einer der gescheitesten Menschen der Gegenwart. Das ist gerade das Bedeutsame, daß so etwas einer der gescheitesten Menschen der Gegenwart schreibt.

[ 66 ] Und nun, was ist also eigentlich das Wirksame? Das Denken, das schwimmt so obenauf. Was ist das Wirksame? Das Blur.