Health and Illness I

GA 348

29 November 1922, Dornach

III. The Formation of the Human Ear; Eagle, Lion, Bull and Man

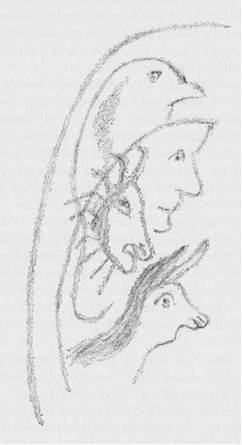

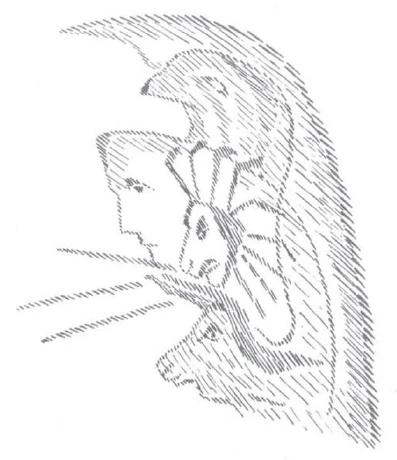

A question was asked about the design that appeared on the cover of the Austrian journal, Anthroposophy, showing the heads of an eagle, a lion, a bull and a man.

Dr. Steiner. Gentlemen, I think we should first bring to a conclusion our explanation of the human being, and then next time consider the aspects of man that these four symbols—the eagle, lion, bull and man—represent. Before we can say anything about them we must build a foundation, and this is something I shall try to do before the end of today's lecture. These four creatures, including man, spring from an ancient knowledge of the human being. They cannot be explained as the ancient Egyptians, for instance, would have done, but today they must be explained differently. One can interpret them correctly, of course, but nowadays one must begin from slightly different suppositions.

I would like now to direct your attention again to the way the human being evolves from his embryonic stage. I would like you to look once more at the very first stage, the earliest period. Conception has occurred, and the embryo is developing in the mother's womb. At first, it is just one microscopic cell containing proteinaceous substance and a nucleus. This single cell, the fertilized egg, actually marks the beginning of man's physical life.

Let us look then at the processes that immediately follow. What does this tiny egg, placed within the body of the mother, do? It divides. The one cell becomes two, and each of these cells divides in turn, thus creating more and more cells like the first. Eventually, our whole body is made up of such cells. They do not remain completely round but assume all manner of shapes and forms.

We must now take into account something I have mentioned before, which is the fact that the whole universe acts upon this minute cell in the mother's body. Nowadays, of course, such matters generally cannot be met with the necessary understanding, but it is nonetheless true that the whole cosmos works upon this cell. It is not at all the same if the ovum divides when, say, the moon stands in front of, or at a distance from, the sun. The whole starry heavens shed an influence on this cell, whose interior forms itself accordingly.

I have said before that during the first few months only the head of the unborn child is developed. (Referring to a drawing.) The head is already formed to this extent, and the rest of the body is really only an appendage. There are tiny little stubs, the hands, and other small protrusions, the legs. As it develops, the human being will transform its little appendages into hands, arms and feet.

How does this come about? How does it occur? The reason lies in the fact that in the earlier embryonic stages the influence of the starry heavens is greater. As the embryo develops and grows during those months in the mother's womb, it becomes increasingly subject to the gravity of the earth. When the world of the stars acts upon man, the emphasis is always on the head. It is gravity that, in time, draws out the other parts. The farther back we go, examining the second or first months of pregnancy, the more do we find these cells exposed to the influence of the stars. As more and more cells appear and millions gradually develop, they become increasingly subject to the forces of the earth.

Here is convincing evidence that the human body is magnificently organized. I would like to make this evident by considering one of the sense organs. I could just as easily take the example of the eye, but today I shall speak about the ear. You see, one of these cells develops into the ear. The ear is set into one of the cavities of the skull bones, and if you examine it properly, you will find that it is quite a remarkable structure. I shall explain the ear so that you can get some idea of it. You will see how such a cell moulds itself while it is still partially under the influence of the stars and partially under the influence of the earth. The ear is formed in such a marvellous way so that man can actually make use of it.

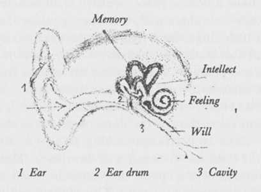

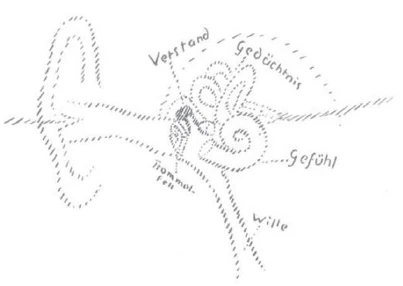

Let us proceed from the outside inward. To begin with, each of you can take hold of your auricle, the outer ear. We have sketched it as seen from the side (1). It consists of gristle and is covered with skin. It is designed to receive the maximum amount of sound. If we had only a hole there, the ear would capture much less sound. You can feel the passage into your ear; it goes into the interior of the so-called tympanic cavity, the interior of the head's bony system. This passage or canal is closed off inside by the eardrum, the tympanic membrane. There is really a thin, delicate, tiny skin attached to this canal, which might be likened to that of a drumhead. The ear, then, is closed off on the inside by the eardrum (2).

I'll continue by drawing the cavity that one observes in a skeleton (3). Here are the skull bones; here are the bones going to the jaw. Inside is a cavity into which this canal leads that is closed off by the eardrum. Behind the outer ear, the auricle, you have a hollow space, which I shall now tell you about. Not only does this canal, this outer passage that you can put your little finger into, lead into the head cavity, but another canal also leads into this cavity from the mouth. In other words, two passages lead into this cavity: one from the exterior that extends inward to the eardrum, and one from the mouth that enters behind the eardrum, which is called the Eustachian tube, though the name does not matter.

Now we come to a strange-looking thing—a veritable snail shell, the cochlea. It consists of two parts. Here is a membrane, and here is a space, the vestibule. Over here is another space, the tympanic cavity. The whole thing is filled with fluid, a living fluid, which I have described to you in another lecture. So within all this fluid is something made of skin that looks like a snail shell. Inside this snail shell, called the cochlea, are myriad little fibres that make up the basilar membrane. This is quite interesting. If you could penetrate the eardrum and look beyond it, you would find this soft snail shell, which is covered on the inside with minute, protruding hair-like fringes.

What, actually, is inside the cochlea? When one approaches the question truly scientifically, one notices that this is really a small piece of intestine that has somehow been placed within the ear. Just as we have the intestines within our abdomen, so do we have a tiny piece of intestine-like skin within our ear. The ear's configuration, then, is such that it contains a little intestine, just as in another part of the body we have a larger intestine. The cochlear duct, which is surrounded by a living fluid called the endolymph, is filled with another called the perilymph. All this is extremely interesting. The cochlea is closed off here by a tiny membrane shaped like an oval window, and here, again, by another little membrane that looks like a round window. Just as we can beat on a drum and make it vibrate, so do the sound waves, coming in from both sides, set into motion this little membrane, the oval window.

The oval window is a membrane set in the middle of the cochlea, and it closes off the inside of the little snail shell, which is filled with the slightly thicker fluid, the perilymph. The fluid on the outside is thinner. Below the oval window is another little membrane called the round window. Here we now approach something marvellous. Two tiny delicate bones sit on the membrane of the oval window. They look like a stirrup and are called the stapes. People also refer to them as the stirrup. So the stirrup sits on the little membrane, protruding in such a way as to resemble an upper and a lower arm on the membrane. Picture such an upper and lower arm of the stirrup and then here, strangely enough, another independent bone, the incus or anvil. The first two bones of the stirrup are connected by a joint; the incus is independent. These tiny bones are all in the ear, and since materialistic science looks at everything superficially, it calls the bone that sits directly on the eardrum, the hammer, this other bit of bone in the middle, the anvil, and this other, the stirrup—or malleus, incus and stapes.

Ordinary science, however, doesn't really know what these bones are. What is found here in the two arms of the stirrup is only a little different from an arm bent at the elbow. See, an elbow joint is the same as this joint of the stirrup above the membrane. And there is a kind of hand, on which sits an independent bone. We don't have such a bone in our hand, but it is comparable to our kneecap. So we can rightfully say that this is also like a leg, a foot; then that would be the thigh, that the knee (sketching), there the foot stands on the membrane, and there is the kneecap.

You see, it is most interesting that in the cavity of the ear we have first a kind of intestine and then a real hand, arm or foot. What is the purpose of all this? Well, imagine that a sound strikes the eardrum and everything in there begins to vibrate. Without being aware of it, the person is determining within the ear what kind of vibration it is. Now think of this, which you may have experienced at some time. You are standing somewhere on a street when something explodes behind you. You feel the explosion inwardly and may feel sick to your stomach from the shock. But this delicate shock that vibrates through the cochlea's “intestine” is felt by the fluid within, which conveys the vibrations that are imparted by the “touching” of the eardrum with a “hand,” as it were.

Now I would like to point out something else to you. What is the purpose of this Eustachian tube leading from the mouth to the inner ear? If sounds simply passed into the ear from the auricle, we would not need it, but to comprehend another's speech we must first have learned to speak ourselves. When we listen to someone else and wish to comprehend him, the sounds we have learned to speak pass through the Eustachian tube. When another person is speaking to us, the sounds come in through the auricle and make the fluid vibrate. Because the air passes into the ear from the outside, and since we know how to set this air in motion with our own speech, we can understand the other person. In the ear, the element of our own speech that we are accustomed to meets the element of what the other person says; there the two meet.

You see, when I say, “house,” I am accustomed to having certain vibrations occur in my Eustachian tube; when I say, “powder,” I experience other vibrations. I am familiar with these vibrations. When I hear the word “house,” the vibration comes from outside, and because I am used to identifying this vibration when I say the word myself, and since my comprehension and the vibration from outside encounter each other in the ear, I am able to recognize its meaning. The tube that leads from the mouth into the ear was there when as a child I learned to speak. Thus, we learned to understand the other person simultaneously as we learned to talk. These matters are most interesting.

Now, things are really like this. Imagine that nothing but what I have just sketched here existed in the ear. Then you could at least understand another person's words and also listen to a piece of music, but you would not be able to remember what you had heard. You would have no memory for speech and sound if the ear had nothing more than these parts. There is another amazing structure in the ear that enables you to retain what you have heard. These are three hollow arches, which look like this (sketching). The second is vertical to the first, and the third, vertical to the second. Thus, they are vertical to each other in three dimensions. These so-called semi-circular canals are hollow and are also filled with a living, delicate fluid. The remarkable thing about it is that infinitely small crystals are constantly forming from it. If you hear the word, “house,” for example, or the tone C, tiny crystals are formed in there as a result. If you hear a different word—“man,” for instance—slightly different crystals are formed. In these three little canals, microscopically small crystals take shape, and these minute crystals enable us not only to understand but also to retain in our memory what we have comprehended. For what does the human being do unconsciously?

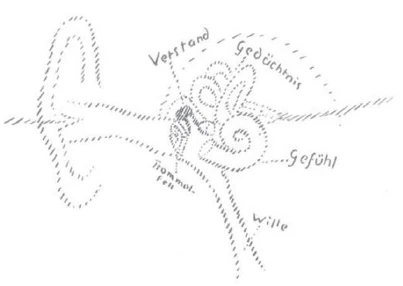

Imagine that you have heard someone say, “Five francs.” You want to remember what has been said, so with a pencil you write it into your notebook. What you have written with lead in your notebook has nothing to do with live francs except as a means of remembering them. Likewise, what one hears is inscribed into these delicate canals with the minute crystals that do, in fact, resemble letters, and a subconscious intelligence in us reads them whenever we need to recall something. So, indeed, we can say that the memory for tone and sound is located within these three semi-circular canals. Here where this arm is located is comprehension, intelligence. Here, within the cochlea is a portion of man's feeling. We feel the sounds in this part of the labyrinth, in the fluid within the little snail shell; there we feel the sounds. When we speak and produce the sounds ourselves, our will passes through the Eustachian tube. The whole configuration of the human soul is contained in the ear. In the Eustachian tube lives the will; here in the cochlea is feeling; intelligence is in the auditory ossicles, those little bones that look like an arm or leg; memory resides in the semi-circular canals. So that man can become aware of the complete process, a nerve passes from here (drawing) through this cavity and spreads out everywhere, penetrates everywhere. Through this auditory nerve, all these processes are brought to consciousness in our brain.

You see, gentlemen, this is something quite remarkable. Here in our skull we have a cavity. One enters the inner ear cavity by passing from the auricle through the auditory canal and eardrum. Everything I have described to you is contained therein. First, we stretch out the “hand” and touch the incoming tones to comprehend them. Then we transfer this sensation to the living fluid of the cochlea, where we feel the tone. We penetrate the Eustachian tube with our will, and because of the tiny crystal letters formed in the semi-circular canals, we can recall what has been said or sung, or whatever else has come to us as sound.

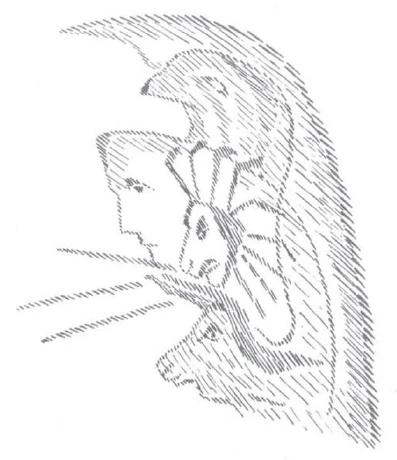

So we can say that within the ear we bear something like a little human being, because this little being has will, comprehension, feeling and memory. In this small cavity we carry a tiny man around with us. We really consist of many such minute human beings. The large human being is actually the sum of many little human beings. Later, I'll show you that the eye is also such a miniature man. The nose, too, is a little human being. All these “little men” that make up the total human being are held together by the nervous system.

These miniature men are created while man is still an embryo in the mother's body. All that is being formed and developed there is still under the influence of the stars. After all, these marvellous configurations—the canals that produce the crystals, the little auditory bones—cannot be moulded by the gravity and forces of the earth. They are organized in the womb of the mother by forces that descend from the stars. The cochlea and Eustachian tube are parts that belong to man as a being of earth and are developed later. They are shaped by the forces that originate from the earth, from the gravity that gives us our form and that enables the child to stand upright long after it is born.

You see, if initially one knows how the whole human being originates from one small cell, and how one cell is transformed into an eye while another becomes an ear and a third the nose, one understands how man is gradually built up. Actually, there are ten groups of cells that transform themselves, not just one, but we may still imagine there to be one cell in the beginning. So, at first, just one cell exists. This produces a second, which by being placed in a slightly different position comes under a different influence and develops into the ear. Another develops into the nose, a third into the eye, and so on. None of this proceeds from any influence of the earth. The forces of the earth can mould only those parts that are mostly round, just as in the abdomen the earth organizes the intestinal system. Everything else is formed by the influence of the stars.

We know of these matters today because we have microscopes. After all, the auditory bones are minute. Remarkably enough, these things were also known by men in ancient times, though the source of their knowledge was completely different from that of today. For example, 3,000 years ago the ancient Egyptians were also occupied with a knowledge of man's organization and knew in their way just how remarkable the inner functions of the human ear are. They said to themselves that man has ears, eyes and other organs belonging to the head. If we wish to explain them, we must ask how the ear, for instance, was moulded so differently from the other organs. The ancients said that those organs that are part of the head developed primarily from what comes down to the earth from above. They said, “High up in the air the eagle develops and matures. One must look up into that region if one wishes to observe the forces that form the organs in the human head.” So, these ancient people drew an eagle in place of the head when they were depicting the human being.

When we observe the heart or lungs, we find that they look completely different from the ear or eye. When we look at the lungs, we cannot turn to the stars, nor can we do so in the case of the heart. The force of the stars works strongly in the heart, but we cannot deduce the heart's configuration solely from the stars. The ancient Egyptians knew this; they knew that these organs could not be as closely linked to the stars as those of the head. They pondered these aspects and asked themselves which animal's constitution emphasized the organs similar to the human heart and lungs. The eagle particularly develops those organs that man has in his head.

The ancients thought that the animal that primarily develops the heart, that is all heart and therefore the most courageous, is the lion. So they named the section of man that contains the heart and lungs “lion.” For the head, they said “eagle,” and for the midsection, “lion.”

They realized that man's intestines were again organs of a different kind. You see, the lion has quite short intestines; their development is curtailed. The minute “intestine” in the human ear is formed most delicately, but man's abdominal intestines are by no means shaped so finely. In observing the intestines, you can compare their formation only with the nature of those animals that are mainly under their influence. The lion is under the influence of the heart, and the eagle is under the sway of the upper forces. When you observe cows after they have been grazing, you can sense how they and their kind are completely governed by their intestines. When they are digesting, they experience great well-being, so the ancients called the section of man that constitutes the digestive system, “bull.” That gives us the three members of human nature: Eagle—head; lion—breast; bull—abdomen.

Of course, the ancients knew when they studied the head that it was not an actual eagle, nor the midsection a lion, nor the lower part a bull. They knew that, and they said that if there were no other influence, we would all go about with something like an eagle for our head above, a lion in our chest region and a bull down below; we would all walk around like that. But something else comes into play that transforms what is above and moulds it into a human head, and likewise with the other parts. This agent is man himself; man combines these three aspects.

It is most remarkable how these ancient people expressed, in such symbols, certain truths that we acknowledge again today. Of course, they could form these images easier than we because, though we modern people may learn many things, the thoughts we normally acquire in school do not touch our hearts too deeply. It was quite different in the case of these ancient people. They were seized by the feeling emanating from thoughts and therefore dreamed of them. These people dreamed true dreams. The whole human being appeared as an image to them, and from his forehead they saw an eagle looking out, from the heart, a lion, and from the abdomen, a bull. They combined this into the beautiful image of the whole human being. One can truly say that long-ago people composed their concept of the human being from the elements of man, bull, eagle and lion.

This outlook continued in the description of the Gospels. One frequently proceeded from this point of view. One said that in the Gospel of Matthew the humanity of Jesus is truly described; hence, its author was called “man.” Then take the case of John, who depicts Jesus as if He hovered or flew over the earth. John actually describes what happens in the region of the head; he is the “eagle.” When one examines the Gospel of Mark, one will find that he presents Jesus as a fighter, the valiant one; hence, the “lion.” Mark writes like one who represents primarily those organs of man situated in the chest. How does Luke write? Luke is presented as a physician, as a man whose main goal is therapeutic, and the healing element can be recognized in his Gospel. Healing is accomplished by bringing remedial forces into the digestive organs. Consequently, Luke describes Jesus as the one who brings a healing element into the lower nature of man. Luke, then, is the “bull.” So one can picture the four Gospels like this: Matthew—man; Mark—lion; Luke—bull; John—eagle.

As for the journal whose cover depicts the four figures that you asked about, its purpose is to present something of value that can be communicated from one human spirit to another. So the true human being should be depicted in it. In rendering this drawing, the eagle is represented above, then the lion and bull, with man encompassing them all. This was done to show that the journal represents a serious concern with man. This is its aim. Not much of the human element is present in the bulk of what newspapers print these days. Here attention was to be drawn to the fact that this newspaper or journal could afford man the opportunity to express himself fully. What he says must not be stupid: the eagle. He must not be a coward: the lion. Nor should he lose himself in fanciful flights of thought but rather stand firmly on earth and be practical: the bull. The final result should be “man,” and it should speak to man. This is what one would like to see happen, that everything passed on from man to man be conducted on a human level.

Well, I did have time after all to get to your question after looking at those subjects I started with. I hope my answer was comprehensible. Were you interested in the description of the ear? One should know these things; one should be familiar with what is contained in the various organs that one carries around within the body.

Question: Is there time to say something about the “lotus flowers” that are sometimes mentioned?

Dr. Steiner: I'll get to that when I describe the individual organs to you.

Dritter Vortrag

Es wird gefragt wegen des Motives auf der Zeitschrift «Anthroposophie, Österreichischer Bote von Menschengeist zu Menschengeist»: Adler, Löwe, Stierkopf und Menschenkopf.

Dr. Steiner: Ich glaube, meine Herren, ich werde das am besten so machen, daß ich Ihnen den Menschen erst noch ganz fertig erkläre, soweit es notwendig ist, und daß ich dann den Menschen als in diesen vier Symbolen sich darstellend, das nächste Mal gebe. Nicht wahr, es ist nicht möglich, immer alles ohne Voraussetzungen zu sagen. Ich werde versuchen, heute noch diese Voraussetzungen zu schaffen. Denn sehen Sie, diese vier Tiere, wovon eigentlich das eine der Mensch ist, die gehen auf eine sehr frühe in der Menschheit vorhandene Menschenerkenntnis zurück. Heute könnte man nicht mehr so, wie das zum Beispiel die alten Ägypter gemacht haben, diese vier Tiere erklären, sondern heute muß man sie etwas anders erklären. Natürlich muß man sie richtig erklären, aber man muß heute von etwas anderen Voraussetzungen ausgehen.

Nun möchte ich Sie noch einmal aufmerksam machen, wie ich Sie immer wieder und wieder darauf hingewiesen habe, wie der Mensch ja hervorgeht aus dem Menschenkeim, der zunächst im Leibe der Mutter sich entwickelt. Ich habe Ihnen auch schon manches von diesem Menschenkeim gesagt. Nun möchte ich heute noch einmal zurückkehren zum allerersten Stadium, zu der allerersten Zeit, in der der Menschenkeim nach der Befruchtung im Leibe der Mutter sich entwickelt. Sehen Sie, da ist der Menschenkeim eben eine einzige Zelle, also eine Zelle, die im Innern Eiweißstoff hat und einen Kern (es wird gezeichnet). Das ist so klein, daß man es nur im Mikroskop erkennen kann. Und der Mensch nimmt eigentlich im physischen Leben seinen Anfang von einer einzigen solchen Eizelle, die befruchtet worden ist.

Nun müssen wir die nächsten Vorgänge ins Auge fassen. Sehen Sie, die nächsten Dinge, die sich mit diesem kleinen Ei, das im Leib der Mutter ist, abspielen, das sind diese, daß sich solch ein Ei teilt; es entstehen aus einem zwei, und aus jedem solchen wiederum zwei, die so nebeneinander sind, und so entstehen durch Teilung immer mehr und mehr solche Zellen. Unser ganzer Körper ist ja später aus solchen Zellen zusammengesetzt. Aber sie bleiben nicht so rund, sondern sie nehmen verschiedenste Formen an. Diese Zellen bekommen die verschiedensten Gestalten.

Nun müssen wir da etwas berücksichtigen, was ich Ihnen schon einmal gesagt habe, nämlich: Wenn diese kleine Zelle im Leibe der Mutter ist, dann wirkt eigentlich die ganze Welt auf diese Zelle ein - die ganze Welt. Heute kann man natürlich auf diese Dinge noch nicht mit dem nötigen Verständnis eingehen. Aber dennoch: Es wirkt die ganze Welt auf eine solche Zelle ein. Es ist nicht einerlei, ob, sagen wir, dieses Ei sich teilt, wenn da oben der Mond vor der Sonne steht; da ist es anders, als wenn der Mond abseits von der Sonne steht und so weiter. Also der ganze Sternenhimmel hat auf diese Zelle einen Einfluß. Und unter dem Einfluß dieses Sternenhimmels bildet sich auch das Innere der Zelle aus.

Nun, sehen Sie, wenn das Kind in den ersten Monaten ist - ich habe es Ihnen schon gesagt —, da ist ja eigentlich vom Kind nur der Kopf ausgebildet (es wird gezeichnet). Der Kopf ist ausgebildet, und der übrige Körper ist eigentlich nur solch ein Anhängsel; da sind dann kleine Stummel, die Hände, und andere kleine Stummel, die Beine. Und immer mehr und mehr wird dieses kleine Wesen eben so, daß es seine Hände und Arme umbildet, und diese Stummel da zu Füßen umbildet und so weiter.

Woher kommt das? Das müssen wir uns fragen: Woher kommt das? Das kommt davon her, daß der Mensch, je früher er im Keimzustand ist, desto mehr noch der Sternenwelt ausgesetzt ist, und je mehr er sich entwickelt, je längere Monate er im Mutterleibe ist, desto mehr der Schwerkraft der Erde ausgesetzt wird. Solange der Sternenhimmel auf den Menschen wirkt, ordnet er alles so an, daß die Hauptsache der Kopf ist. Erst die Schwerkraft treibt das andere da heraus. Und es ist so, daß eigentlich, je weiter wir zurückgehen in den ersten, zweiten Monat der Schwangerschaft, wir da um so mehr finden, daß alle diese Zellen, die da entstehen - Millionen von solchen Zellen bilden sich nach und nach —, dem Sterneneinfluß ausgesetzt sind und dann immer mehr und mehr von der Erde abhängig werden.

Sehen Sie, in dieser Beziehung kann man sich überzeugen, wie wunderbar eigentlich der menschliche Körper eingerichtet ist. Und das möchte ich Ihnen anschaulich machen an einem Sinnesorgan. Ich könnte es Ihnen ebensogut am Auge anschaulich machen; ich will es Ihnen heute am Ohr anschaulich machen. Denn, sehen Sie, eine von diesen Zellen, die wird das Ohr. Das Ohr ist da drinnen eingesetzt in einer Höhle der Kopfknochen. Eine solche Zelle wird also Ohr. Aber wenn Sie dieses Ohr, dieses menschliche Ohr richtig betrachten, dann ist das eigentlich ein ganz merkwürdiges Gebilde. Ich will es Ihnen einmal, damit Sie einen Begriff davon bekommen, darstellen, damit Sie auch sehen, wie eine solche Zelle allmählich sich gestaltet, teilweise noch unter dem Sterneneinfluß, teilweise unter dem irdischen Einfluß, in einer so merkwürdigen Weise, daß der Mensch dann die Sache brauchen kann.

Gehen wir zunächst einmal von außen nach innen. Da können Sie ja ein jeder sich beim Ohrwaschel anfassen; da haben wir also zunächst einmal das äußere Ohr. Das äußere Ohr, von der Seite gezeichnet, besteht aus Knorpel und ist mit einer Haut überzogen. Es ist eigentlich dazu da, daß recht viel von dem Ton, von dem Schall, der da ankommt, aufgefangen wird. Wenn wir bloß ein Loch da hätten, dann würde weniger von dem Schall aufgefangen werden können. Sie können hineingreifen ins Ohr; da geht dann ein Kanal ins Innere der sogenannten Paukenhöhle, ins Innere des Kopfknochensystems. Sehen Sie, dieser Kanal, der ist nun nach innen abgeschlossen von dem sogenannten Trommelfell. Da ist richtig an diesem Kanal angesetzt so etwas wie ein dünnes Häutchen, so daß man sagen kann: Es ist wie ein Trommelfell. Sie brauchen nur an eine Trommel zu denken, wo eine Haut oben ist, auf die man klopft; so ist das Ohr nach innen durch dieses Trommelfell abgeschlossen.

Und wenn wir da dann weitergehen, da will ich Ihnen die Höhlung zeichnen, die man am Skelett sieht. Sehen Sie, da sind überall die Kopfknochen, hier gehen die Knochen nach dem Kiefer hin; da ist eine Höhle drin, und in diese Höhle der Kopfknochen führt dieser Kanal, der durch das Trommelfell abgeschlossen ist, hinein. Hinter Ihrem Ohrwaschel haben Sie da drinnen eine Höhle; was da alles drinnen ist, will ich Ihnen nun sagen. Aber es geht nicht nur dieser äußere Kanal, in den Sie mit Ihrem kleinen Finger hineingreifen können, in diese Höhle hinein, sondern vom Mund geht auch wiederum ein solcher Kanal in diese Höhle hinein. Wenn da also der Mund ist (siehe Zeichnung), so geht auch wieder ein solcher Kanal da hinein. So daß also in diese Höhle zwei Kanäle hineingehen: einer von außen, einer vom Mund. Diesen Kanal, der vom Mund hineingeht, den nennt man die Eustachische Röhre, dieOhrtrompete. Nun, es kommt ja nicht auf dieNamen an.

Nun, sehen Sie, jetzt ist hier ein merkwürdiges Ding. Da würde man dann wiederum auf Knochen kommen. Es ist nun ein Loch, das in den Kopf hineingeht, im Knochen. Das ganze Ohr ist hier in einer Knochenhöhle drinnen. Aber hier ist ein merkwürdiges Ding, so ein richtiges Schneckenhaus (siehe Zeichnung). Und das Ganze besteht aus zwei Teilen; da hier ist eine Haut (das Spiralblatt), und da ist ein Raum (die Vorhoftreppe) und da ist der andere Raum (die Trommelhöhlentreppe). Das Ganze ist ausgefüllt mit Wasser, mit lebendigem Wasser, wie ich es Ihnen beschrieben habe. Und da drinnen ist so etwas wie ein Schneckenhaus, aber aus Haut. Und in dem Schneckenhaus drinnen, da sind lauter Fransen, lauter solche Fransen. Das ist außerordentlich interessant. Wenn Sie da das Trommelfell durchstoßen und weiter hineingehen würden, so würden Sie da drinnen ein Schneckenhaus finden, dieses weiche Schneckenhaus, und das ist innerlich mit solchen hautartigen Fransen besetzt. Was ist denn das eigentlich, dieses Schnekkenhaus da drinnen? Ja, meine Herren, wenn man mit wirklicher Wissenschaft an diese Sache herangeht, dann merkt man, was das ist. Das ist nämlich nichts anderes als ein Stückchen kleiner Darm, der sich ins Ohr verirrt hat. Geradeso wie wir im Bauch unsere Gedärme haben, so haben wir im Ohr ein Stückchen kleinen Darm. Das Ohr ist also so gestaltet, daß es, wie der Mensch selber seinen großen Darm hat, da einen kleinen Darm hat. Und der ist sowohl im Innern ausgefüllt mit solchem lebendigen Wasser, wie auch äußerlich umgeben von solchem lebendigen Wasser. Das ist außerordentlich interessant. Und dieses ganze Schneckenhaus, das ist hier abgeschlossen (siehe Zeichnung) - es ist alles mit Wasser gefüllt - durch ein Häutchen (ovales Fenster). Hier ist wiederum so ein Häutchen darauf (rundes Fenster). Ebenso wie, wenn man auf die Trommel klopft, das Trommelfell der Trommel in Bewegung kommt, so kann, wenn der Schall von beiden Seiten kommt, dieses Häutchen in Schwingung kommen.

Da in der Mitte, sagte ich Ihnen, ist eine Haut. Diese Haut schließt ab das, was mit dickerem lebendigen Wasser durchsetzt ist, und da ist dünneres Wasser; und da ist wiederum solch ein Häutchen zwischen den beiden Räumen. Da kommt nun etwas ganz besonders Interessantes. Da ist nämlich etwas, ich möchte sagen, ganz Wunderbares drinnen. Auf diesem Häutchen (des ovalen Fensters), da sitzt nämlich solch eine Sache darauf: Da sind zwei ganz feine, winzige Knochen; die sitzen so darauf und schauen aus wie ein Steigbügel. Daher haben die Leute das auch einen Steigbügel genannt. Das ist etwas ganz anderes; ich werde es Ihnen nachher sagen, was es ist. Wenn da dieses Häutchen ist, so sitzt da drauf dieser Steigbügel, und der hat richtig hier einen Knochenfortsatz. Und dieser Knochenfortsatz, der ist hier so wie der Oberarm und der Unterarm. Das sitzt dann hier auf diesem Ding drauf, auf diesem Häutchen. Also wenn Sie sich vorstellen würden, da wäre ein solcher Arm, der Oberarm da, der Unterarm da, so ist hier noch kurioserweise ein Knochen, der frei aufsitzt. Die sind im Gelenk miteinander verbunden, der sitzt hier frei auf. Das sind kleine, winzige Knochen. Nun, die materialistische Denkweise, die alles äußerlich betrachtet, die nennt diesen Knochen hier, der unmittelbar am Trommelfell aufsitzt und da aufschlägt, den Hammer, und das da hier, das Stückchen Knochen nennt sie den Amboß. Und das nennt sie den Steigbügel. Diese drei kleinen Knöchelchen werden also von der gewöhnlichen Wissenschaft genannt: Hammer, Amboß und Steigbügel.

Aber die gewöhnliche Wissenschaft weiß eigentlich nicht, was das ist. Dasjenige, was da ist in Steigbügelform, das ist nämlich, nur ein bißchen anders gestaltet, dasselbe, was hier im Oberarm ist. Sehen Sie, wie da das Gelenk ansitzt, so sitzt auf diesem Häutchen drauf das Gelenk. Und hier ist der Ellbogen; das ist also eine Art von Hand. Und da drauf, da sitzt ein freier Knochen. Den haben wir zwar nicht an der Hand, aber da an der Kniescheibe. Wir könnten ebensogut sagen: Das ist ein Bein, ein Fuß; dann wäre das ein Oberschenkel, das wäre das Knie (Zeichnung), da säße der Fuß darauf, und da ist die Kniescheibe.

Es ist sehr interessant, sehen Sie: Wir haben da in unserer Ohrhöhle drinnen zuerst eine Art von Eingeweide, und nachher eine richtige Hand oder Arm oder einen richtigen Fuß. Wozu ist denn das Ganze da? Nun, denken Sie sich, es kommt ein Schall. Der Schall, der schlägt da ans Trommelfell an. Das Ganze, was da ist, kommt in Erschütterung. So probiert der Mensch, ganz ohne daß er es weiß, im Innern des Ohres, was da für Erschütterungen anschlagen. Und denken Sie einmal nach, Sie werden das schon einmal gespürt haben, wenn Sie irgendwo auf der Straße stehen, und da hinten explodiert etwas - ich meine, Sie haben es schon bemerkt -: das spüren Sie in Ihren Eingeweiden! Ja, es kann sogar sein, daß man in den Eingeweiden krank wird von einer solchen Erschütterung. Die feinste Erschütterung aber, die da durch diesen Arm zieht, die verspürt das Wasser in diesem Schneckenhaus. Dieses Wasser im Schneckenhaus, das macht die Schwingungen mit, die der Mensch dadurch kennenlernt, daß er mit dieser Hand das Trommelfell angreift. Können Sie das verstehen? (Ja!)

Nun will ich Ihnen aber noch etwas sagen. Wozu ist denn diese Trompete da, die da vom Mund in das Ohr hineingeht? Ja, wenn da hier ein gewöhnlicher Schall hineingeht, da braucht man eigentlich diese Trompete nicht. Aber wenn wir einer dem andern zuhören, wenn einer redet zu dem andern und wir wollen ihn verstehen, denn wir haben ja reden gelernt - wenn wir selber nicht reden gelernt haben, können wir den andern nicht gut verstehen; dadurch, daß wir reden gelernt haben, dadurch gehen die Töne der Sprache durch die Eustachische Röhre, die Ohrtrompete so hinüber; und wenn der andere so her redet, dann geht das so her, erschüttert da; das geht über in diese Flüssigkeit. Und dadurch, daß die Luft durchgeht, durch die Eustachische Trompete ins Ohr hineingeht, und ich gewohnt worden bin, diese Luft selber zu bewegen durch meine eigene Sprache, kann ich den andern verstehen. Da drinnen in dem Ohr, da trifft sich dasjenige, was ich gewohnt bin, von meiner eigenen Sprache zu haben, und dasjenige, was von der Sprache des andern kommt. Das trifft sich hier.

Sie wissen, wenn ich spreche: Haus — da bin ich gewohnt, daß da drinnen in meiner Eustachischen Trompete gewisse Erschütterungen vorgehen; wenn ich sage: Pulver — eine andere Erschütterung. Diese Erschütterungen kenne ich. Wenn ich sage: Haus — so kommt die Erschütterung von außen, und ich bin gewohnt, wenn ich sage: Haus — dies wahrzunehmen. Und da treffen die beiden zusammen, meine Erkenntnis und die Erschütterung von außen, und ich verstehe, was «das Haus» heißt. Nicht wahr, das ist doch zu verstehen? Meine Trompete, die vom Mund ins Ohr hineingeht, die ist da, wenn wir selber als Kind reden lernen, damit wir zugleich den andern verstehen. Die Dinge sind außerordentlich interessant.

Jetzt ist die Sache aber so: Denken Sie sich, es wäre alles da im Ohr, was ich Ihnen aufgezeichnet habe, aber nichts anderes zunächst. Sie würden allenfalls, sagen wir, den anderen verstehen können, Sie würden auch ein Musikstück anhören können; aber Sie würden sich das, was Sie anhören, nicht merken können. Sie hätten kein Gedächtnis für Sprache oder Töne. Wenn das Ohr nur so wäre, so hätten Sie kein Gedächtnis für Sprache oder Töne. Damit Sie ein Gedächtnis haben, ist noch etwas anderes im Ohr. Damit Sie nun auch im Gedächtnis dasjenige, was Sie hören, behalten können, ist noch eine andere Einrichtung da. Da sind nämlich hier drei solche Bögen; die sind da oben (siehe Zeichnung). Sie müssen sich vorstellen also solche Bögen, die hohl sind. Da ist der zweite, der steht senkrecht drauf auf dem ersten; und da ist noch ein dritter, der steht wiederum senkrecht auf dem andern. Sie stehen in den drei Richtungen senkrecht aufeinander. Das ist also noch ein weiteres wunderbares Gebilde, das in diesem Ohr drinnen ist. Diese Kanäle da oben sind aber hohl — natürlich, weil es Kanäle sind. Und da drinnen ist wiederum ein feines, lebendiges Wasser. Das sitzt da drinnen.

Aber das Merkwürdige an diesem lebendigen Wasser ist das, daß sich fortwährend kleine Kristalle aus diesem Wasser heraus bilden, winzige kleine Kristalle. Wenn Sie zum Beispiel hören: Haus, oder ein C hören, so bilden sich da drinnen solche kleine Kristalle; wenn Sie hören: Mensch, bilden sich etwas andere Kristalle. In diesen drei winzigen Kanälen bilden sich winzige Kristalle, und diese winzigen Kristalle, die machen, daß wir nicht nur verstehen können, sondern auch das Verstandene im Gedächtnis behalten können. Denn was tut der Mensch unbewußt?

Sie brauchen sich nur vorzustellen, Sie hören, sagen wir: fünf Franken; Sie wollen das Gesprochene erinnern, schreiben sich das in Ihr Notizbuch. Das, was Sie da mit Blei in Ihr Notizbuch eingeschrieben haben, das hat nichts mit den fünf Franken zu tun, aber Sie erinnern sich daran durch die Notiz. Geradeso wird in diese feinen Kanäle durch die winzigen Kristalle, die eigentlich wie Buchstaben sind, eingeschrieben, was man hört. Und durch einen unbewußten Verstand wird das wiederum, wenn wir es brauchen, gelesen. So daß wir sagen können: Da drinnen (in den drei halbkreisförmigen Kanälen), da ist das Gedächtnis für die Töne und für die Laute. Da hier, bei diesem Arm oder Bein (Zeichnung, Gehörknöchelchen), da ist das Verständnis. Da drinnen in dieser Schnecke, da ist ein Stückchen Gemüt vom Menschen, ein Stückchen Gefühl. Da fühlen wir die Töne in diesem (Teil des) Labyrinth, in diesem Schneckenhauswasser drinnen. Da fühlen wir die Töne. Und wenn wir reden und selbst den Ton hervorbringen, so geht durch unsere Eustachische Trompete der Wille zum Sprechen. Da ist das ganze Seelische des Menschen drinnen im Ohr: In dieser Trompete hier, da lebt der Wille; da drinnen (in der Schnecke) lebt das Gefühl; da drinnen (bei diesem Arm oder Bein, den Gehörknöchelchen) lebt der Verstand; und da in diesem (in den drei kleinen halbkreisförmigen Kanälen) lebt das Gedächtnis. Und damit der Mensch sich das, wenn es fertig ist, zum Bewußtsein bringen kann, geht von hier aus durch diese Höhle hier (siehe Zeichnung), durch dieses Loch hier ein Nerv. Der Nerv breitet sich überall aus, kleidet alles aus, geht überall hin. Und durch diesen Nerv kommt uns das Ganze dann zum Bewußtsein hier im Gehirn.

Sehen Sie, meine Herren, etwas höchst Eigentümliches! Wir haben da in unserem Schädel, in unseren Schädelknochen, eine Höhle drinnen; es geht einfach eine solche Höhle hinein. In die Höhle kommt man hinein, wenn man vom äußeren Ohr durch den Gehörgang mit Durchstoßung vom Trommelfell hineingeht. In dieser Höhle ist all das drinnen, was ich Ihnen gezeigt habe. Zunächst streckt man die Hand aus, welche die Töne, die hereinkommen, berührt, so daß wir die Töne verstehen können. Dann übertragen wir das auf diese Schnecke, auf das lebendige Wasser; dadurch fühlen wir den Ton. Wir stoßen mit dem Willen hinein durch unsere Eustachische Trompete. Und durch die kleinen Kristallzeichen, die in diesen drei, wie man sie nennt, halbkreisförmigen Kanälen sind, erinnern wir uns an dasjenige, was gesprochen oder gesungen wird, oder was uns sonst als Klang kommt.

Wir können also sagen: Da drinnen tragen wir eigentlich wiederum einen kleinen Menschen, richtig einen kleinen Menschen. Denn der Mensch hat Wille, Gefühl, Verständnis, Verstand und Gedächtnis. In dieser kleinen Höhle tragen wir wieder einen kleinen Menschen drinnen. Wir bestehen halt nur aus lauter kleinen Menschen. Unser großer Mensch ist nur die Zusammenfassung von lauter kleinen Menschen. Ich werde Ihnen nächstens zeigen, daß das Auge auch ein kleiner Mensch ist. Die Nase ist auch ein kleiner Mensch. Und diese kleinen Menschen werden durch das Nervensystem zusammengehalten und geben dann den Gesamtmenschen. Und diese kleinen Menschen entstehen dadurch, daß eigentlich all dasjenige, was da drinnen sich bildet, solange der Mensch im Keimzustand im Leibe der Mutter ist, noch unter dem Gestirneinfluß steht. Denn all diese wunderbaren Gebilde da, also die Kanäle, die die Kristalle bilden, und dieser Arm, die kann die Schwerkraft der Erde und alles, was auf der Erde ist, nicht bilden. Die werden noch im Mutterleibe veranlagt durch die Kräfte, die von den Sternen hereinwirken. Und erst dasjenige, was zum Menschen gehört, also diese Partie dahier, die Schnecke und die Eustachische Trompete, das wird später ausgebildet. Die wird dazu gemacht durch dasjenige, was von der Erde ausgeht, geradeso wie wir als ganzer Mensch unsere ganze Gestalt durch die Erdenschwere kriegen, und wir uns ja erst aufrichten als Kind, das schon längst geboren ist.

Sehen Sie, wenn man zunächst weiß, wie der ganze Mensch ausgeht von einer kleinen Zelle, und die eine Zelle sich zum Auge umbildet, die andere Zelle - es sind eigentlich zehn Haufen, die sich umbilden, es ist nicht nur eine Zelle, aber das macht nicht viel Unterschied, wenn man sich vorstellt, daß das nur eine ist —, also die eine sich zum Auge umbildet, die andere zum Ohr, die dritte zur Nase, dann sieht man, wie sich der Mensch nach und nach aufbaut dadurch, daß er zuerst nur aus einer einzigen Zelle besteht, die eine zweite erzeugt, und dadurch, daß sie an einen andern Ort geht, unter einen andern Einfluß kommt, sie wird jetzt anders, wird zum Ohr, eine andere wird zur Nase, eine dritte zum Auge und so weiter. Aber das ist wahrhaftig nicht alles von den Erdenkräften ausgehend. Die Erdenkräfte könnten nur dasjenige bilden, was im ausgesprochenen Sinne rund ist, geradeso wie in unserem Bauch die Erde unser Gedärm bildet. Aber alles übrige wird noch von den Sternen herein gebildet.

Nun, nicht wahr, das alles wissen wir heute dadurch, daß wir eben Mikroskope haben, durch die wir diese Sachen beobachten können. Diese Knöchelchen sind ja ganz furchtbar klein. Nun aber, das Merkwürdige ist eben, daß man in älteren Zeiten so etwas auch gewußt hat, und daß man das aus einer ganz anderen Art von Erkenntnis heraus gewußt hat, als wir heute das wissen. Und nun haben, sagen wir zum Beispiel, die alten Ägypter vor dreitausend Jahren sich auch mit einer solchen Erkenntnis beschäftigt und haben auch schon in ihrer Art gewußt, wie wunderbar das in dem menschlichen Ohr drinnen ist. Und sie haben sich dann gesagt: Der Mensch hat an seinem Kopf Ohren, Augen und andere Organe. Wenn wir uns diese Organe erklären wollen, so können wir nur sagen: Wodurch ist das Ohr, das Auge — wie gesagt, das werde ich Ihnen nächstens einmal erklären — so geworden, ganz anders als die Organe sonst am Körper? Da haben sie gesagt: Diese Organe am Kopf, Ohr, Auge, die sind deshalb so geworden, weil vorzugsweise auf diese Organe das wirkt, was von außen zum Irdischen kommt, von oben herunter. - Dann haben sie hinaufgeschaut und haben gesagt: Da oben fliegt ein Adler zum Beispiel, der bildet sich aus hoch in den Lüften; da hinauf muß man schauen, wenn man auf die Kräfte schauen will, die im menschlichen Kopfe die Organe bilden. — Deshalb haben sie zunächst, wenn sie den Menschen aufgezeichnet haben, für den Kopf den Adler gezeichnet.

Wenn wir zum Beispiel Herz und Lunge anschauen, so schauen die ganz anders aus als Auge und Ohr. Wenn wir die Lunge anschauen, da können wir nicht viel zu den Sternen gehen, und beim Herz können wir auch nicht viel zu den Sternen gehen. Die Kraft der Sterne wirkt im Herzen ganz besonders, aber die Form, die Gestalt, die können wir nicht so auf die Sterne beziehen. Das wußten auch schon die alten Ägypter vor dreitausend Jahren: die können wir nicht so auf die Sterne beziehen wie die Kopforgane. Nun dachten sie nach: Wo gibt es ein Tier, welches besonders diejenigen Organe ausbildet, die ähnlich sind dem menschlichen Herzen und der menschlichen Lunge und so weiter? Der Adler bildet besonders diejenigen Organe aus, die ähnlich sind dem menschlichen Kopfe. Das Tier — haben die Alten gefunden -, das am meisten das Herz ausbildet, daher auch das mutigste Tier ist, ganz Herz ist, das ist der Löwe. Daher haben sie diese Organpartie, Lunge, Herz und so weiter, «Löwe» genannt. So haben sie also gesagt: Kopf = Adler. Dann der Löwe, der den mittleren Menschen ausmacht. Und dann haben sie gesagt: Aber noch ganz anders schauen des Menschen Gedärme aus. Sehen Sie, der Löwe hat nämlich sehr kurze Gedärme; bei dem sind die Gedärme zu kurz gekommen. Also die Gedärme schauen ganz anders aus. Im Ohr ist eigentlich nur das ganz kleine Gedärm; das ist zierlich gebildet. Unsere übrigen Gedärme sind gar nicht so zierlich gebildet. Wenn man auf die Gedärme hinschauen will, so muß man die Bildung der Gedärme vergleichen mit den Tieren, welche besonders unter dem Einfluß ihrer Gedärme stehen. Der Löwe steht unter dem Einfluß des Herzens; der Adler steht unter dem Einfluß der oberen Kräfte. Unter dem Einfluß der Gedärme — ja, wenn Sie hinschauen, wenn die Kühe gefressen haben, dann können Sie anmerken den Ochsen und Kühen: diese Tiere stehen ganz unter dem Einfluß ihrer Gedärme. Denen ist furchtbar wohl, wenn sie verdauen. Daher nannten die alten Menschen das, was beim Menschen zu den Gedärmen gehört, den Stier- oder Kuh-Menschen.

Und jetzt haben Sie die drei Glieder der menschlichen Natur:

Adler = Kopf

Löwe = Brust

Stier = dasjenige, was zum Verdauungssystem gehört.

Das wußten natürlich diese alten Menschen auch: Wenn ich nun einem Menschen begegne — der Kopf, der ist doch nicht eigentlich ein Adler, und der mittlere Mensch ist auch nicht ein Löwe, der untere ist auch nicht ein Stier oder ein Ochs. Das wußten sie schon. Daher sagten sie: Ja, wenn nichts anderes da wäre, so gingen wir alle so herum, daß wir oben einen Adlerkopf hätten, dann einen Löwen im Körper, und dann würden wir in den Stier auslaufen. So würden wir alle herumlaufen. Aber nun kommt noch etwas, was den Kopf da oben so umbildet und macht wie einen Menschenkopf, und das wiederum, was macht, daß wir nicht ein eigentlicher Löwe sind und so weiter, das ist der eigentliche Mensch. Der faßt dann alles zusammen. (Siehe Zeichnung S. 70.)

Und es ist wirklich eigentlich merkwürdig, wie diese alten Menschen gewisse Wahrheiten, die wir heute wieder erkennen, dadurch zum Ausdrucke gebracht haben, daß sie Bilder geformt haben. Allerdings, diese Bilder waren ihnen leichter zu formen als uns. Sehen Sie, wir heutigen Menschen, wir können ja manches lernen, aber man kann nicht sagen, daß uns diese Gedanken, die wir heute fürs gewöhnliche lernen, wenn wir sie draußen in der Schule lernen, so sehr zu Herzen gehen. Das war bei diesen alten Menschen doch ganz anders. Die wurden wirklich von Gefühl ergriffen von diesen Gedanken, und deshalb träumten sie auch davon. Und richtig träumten diese Menschen: sie sahen im Bilde den ganzen Menschen und gewissermaßen aus der Stirne heraus einen Adler blickend, aus dem Herzen einen Löwen und aus dem Bauch einen Stier. Das malten sie dann zum ganzen Menschen zusammen, ein sehr schönes Bild. So daß man sagen kann: Die Alten haben eben den Menschen zusammengesetzt aus Mensch, Stier, Adler, Löwe.

Das hat sich ja noch fortgesetzt in die Beschreibungen der Evangelien hinein. Man ist viel von diesen Dingen ausgegangen. So zum Beispiel sagte man: Nun, es gibt ein Evangelium nach Matthäus, das beschreibt eigentlich den Menschen Jesus geradeso wie einen Menschen, und deshalb wurde dieser Schreiber des Matthäus-Evangeliums der «Mensch» genannt. Aber nehmen wir den Johannes, sagten die Alten: Ja, der beschreibt den Jesus so, wie wenn er über der Erde schwebte, wie wenn er über die Erde flöge; er beschreibt eigentlich nur dasjenige, was im menschlichen Kopfe vorgeht. Das ist der «Adler». Wenn Sie das Evangelium des Markus lesen, so werden Sie sehen, da wird Jesus als der Kämpfer dargestellt, als der Streitbare, der «Löwe». Der beschreibt so wie einer, der vorzugsweise die Brustorgane darstellt. Und der Lukas, wie beschreibt denn der? Lukas ist ja sogar vorgestellt worden als ein Arzt, der vorzugsweise auf die Heilung ausgeht. Das sieht man dem Evangelium auch an. Heilen muß man, indem man nun in die Verdauungsorgane etwas hereinbringt. Daher beschreibt er den Jesus als «Stier», der vorzugsweise in die Verdauung etwas hereinbringt. Und so kann man die vier Evangelien zusammenfassen:

Matthäus = Mensch

Markus = Löwe

Lukas = Stier

Johannes = Adler

Nun, bei dieser Zeitung [an deren Kopf die vier Gestalten dargestellt sind, nach denen gefragt wurde] war ich ja vor die Aufgabe gestellt, daß darin gegeben werden sollte, was von Menschengeist zu Menschengeist geht, was ein Mensch dem andern Wertvolles sagen kann. So sollte man auch den Menschen darstellen. Es ist also in dieser Figur dargestellt oben der Adler, dann der Löwe, der Stier, die Kuh, und dann der Mensch selbst, der sie zusammenfaßt. Das ist also so, damit man sehen kann, diese Zeitung soll etwas recht Menschliches sein. Sie werden ja begreifen, meine Herren, daß man das heute gern den Menschen sagen möchte, daß man ihnen etwas Menschliches sagen möchte. Denn in dem, was heute vielfach auch durch die Zeitungen gegeben wird, ist ja nicht viel Menschliches enthalten. Also das sollte zum Ausdruck gebracht werden, daß in dieser Zeitung wirklich der Mensch so recht voll alle seine Organe ausleben soll. Es soll nicht dumm sein, was er redet, also: Adler; es soll auch nicht feige sein, also: Löwe. Aber es soll auch nicht in der Luft verfliegen, sondern praktisch auf der Erde stehen, also: Stier, Kuh. Und das Ganze soll dem Menschen etwas geben, soll zum Menschen sprechen. Das möchte man ja heute, daß alles, alles wirklich vom Menschen zum Menschen gehen könnte.

Nun bin ich doch noch dazu gekommen, von dem Ausgangspunkte aus mich dem zu nähern, was Sie gefragt haben, und ich hoffe, daß diese Frage verständlich werden konnte. Hat gerade die Ohrengeschichte Sie etwas interessiert? Man soll wissen, was man eigentlich in sich trägt!

Frage betreffs der Lotosblumen, von denen manchmal gesprochen werde, ob darüber etwas noch gesagt werden könne.

Dr. Steiner: Dazu werde ich dann kommen, wenn ich Ihnen die einzelnen Organe erkläre. Die nächste Vortragsstunde werden wir dann am Samstag um zehn Uhr haben.

Third Lecture

A question is asked about the motif on the magazine “Anthroposophy, Austrian Messenger from Human Spirit to Human Spirit”: eagle, lion, bull's head, and human head.

Dr. Steiner: Gentlemen, I believe the best way to proceed is to first explain the human being to you in full, as far as necessary, and then next time to present the human being as represented in these four symbols. It is not possible, after all, to say everything without any prerequisites. I will try to lay these foundations today. For you see, these four animals, one of which is actually the human being, go back to a very early understanding of humanity. Today, we can no longer explain these four animals in the same way as the ancient Egyptians did, for example, but must explain them somewhat differently. Of course, we must explain them correctly, but today we must start from somewhat different premises.

Now I would like to draw your attention once again, as I have pointed out to you again and again, to how the human being emerges from the human germ, which first develops in the mother's body. I have already told you a few things about this human germ. Today I would like to return once again to the very first stage, to the very first moment in which the human germ develops in the mother's body after fertilization. You see, at this stage the human germ is just a single cell, a cell that contains protein and a nucleus (drawing is made). It is so small that it can only be seen under a microscope. And human life actually begins with a single egg cell that has been fertilized.

Now we must consider the next processes. You see, the next things that happen to this little egg in the mother's womb are that it divides; one becomes two, and each of these in turn becomes two more, which are next to each other, and so more and more of these cells are created through division. Our entire body is later composed of such cells. But they do not remain so round; instead, they take on a wide variety of shapes. These cells take on a wide variety of forms.

Now we must take into account something I have already told you, namely: when this little cell is in the mother's body, the whole world actually has an effect on this cell — the whole world. Today, of course, it is not yet possible to go into these things with the necessary understanding. But nevertheless: the whole world has an effect on such a cell. It is not the same whether, say, this egg divides when the moon is in front of the sun; it is different when the moon is away from the sun, and so on. So the whole starry sky has an influence on this cell. And under the influence of this starry sky, the interior of the cell also forms.

Now, you see, when the child is in its first months—I have already told you—only the head is actually formed (it is drawn). The head is formed, and the rest of the body is really just an appendage; there are little stumps, the hands, and other little stumps, the legs. And more and more, this little being becomes such that it transforms its hands and arms, and transforms these stubs at its feet, and so on.

Where does this come from? We must ask ourselves: Where does this come from? It comes from the fact that the earlier a human being is in the embryonic state, the more it is exposed to the starry world, and the more it develops, the longer it is in the womb, the more it is exposed to the Earth's gravity. As long as the starry sky has an effect on humans, it arranges everything so that the main thing is the head. Only gravity drives the other parts out. And it is actually the case that the further back we go into the first or second month of pregnancy, the more we find that all these cells that are developing there — millions of such cells are gradually forming — are exposed to the influence of the stars and then become more and more dependent on the earth.

You see, in this respect, one can convince oneself how wonderfully the human body is actually constructed. And I would like to illustrate this to you using a sensory organ. I could just as easily illustrate this with the eye, but today I want to illustrate it with the ear. For, you see, one of these cells becomes the ear. The ear is located inside a cavity in the skull. So one such cell becomes the ear. But if you look at this ear, this human ear, properly, it is actually a very strange structure. I want to describe it to you so that you can get an idea of it, so that you can also see how such a cell gradually forms, partly under the influence of the stars, partly under the influence of the earth, in such a strange way that humans can then use it.

Let's start from the outside and work our way in. You can all touch your earlobes; so first we have the outer ear. The outer ear, seen from the side, consists of cartilage and is covered with skin. Its purpose is to capture as much of the sound that reaches it as possible. If we only had a hole there, less of the sound would be captured. You can reach into the ear; there is a canal leading into the interior of the so-called tympanic cavity, into the interior of the skull. You see, this canal is closed off on the inside by the so-called eardrum. Attached to this canal is something like a thin membrane, so that one can say: It's like an eardrum. Just think of a drum, where there is a skin on top that you tap on; the ear is closed off on the inside by this eardrum.

And if we continue, I want to draw you the cavity that you can see on the skeleton. You see, there are the bones of the head everywhere, here the bones go towards the jaw; there is a cavity inside, and this canal, which is closed off by the eardrum, leads into this cavity of the head bones. Behind your earlobe, you have a cavity inside; I will now tell you what is inside it. But it's not just this outer canal, which you can reach into with your little finger, that leads into this cavity; there is also a canal leading into this cavity from the mouth. So where the mouth is (see drawing), there is also a canal leading into it. So there are two canals leading into this cavity: one from the outside and one from the mouth. This canal that goes in from the mouth is called the Eustachian tube, the auditory tube. Well, it doesn't matter what it's called.

Now, you see, here is a strange thing. Here you would come across bone again. It is now a hole that goes into the head, into the bone. The whole ear is inside a bone cavity here. But here is a strange thing, a real snail shell (see drawing). And the whole thing consists of two parts; there is a membrane (the spiral leaf), and there is a space (the vestibular staircase) and there is the other space (the tympanic cavity staircase). The whole thing is filled with water, with living water, as I have described to you. And inside there is something like a snail shell, but made of membrane. And inside the snail shell, there are lots of fringes, lots of fringes like this. That is extremely interesting. If you were to pierce the eardrum and go further in, you would find a snail shell inside, this soft snail shell, and it is lined with skin-like fringes. What exactly is this snail shell inside? Yes, gentlemen, if you approach this matter with real science, you will realize what it is. It is nothing more than a small piece of intestine that has strayed into the ear. Just as we have our intestines in our abdomen, we have a small piece of intestine in our ear. The ear is designed in such a way that, just as humans have a large intestine, it has a small intestine. And this is filled with living water on the inside and surrounded by living water on the outside. This is extremely interesting. And this whole snail shell, which is enclosed here (see drawing) – it is all filled with water – by a membrane (oval window). Here again is a membrane on top (round window). Just as when you tap on a drum, the drumhead starts to move, so when sound comes from both sides, this membrane can start to vibrate.

In the middle, as I told you, there is a membrane. This membrane separates what is filled with thicker living water from what is filled with thinner water, and there is another membrane between the two spaces. Now here comes something very interesting. There is something inside that I would describe as quite wonderful. On this membrane (of the oval window) there is something like this: There are two very fine, tiny bones; they sit on top of it and look like a stirrup. That is why people have also called it a stirrup. It is something completely different; I will tell you what it is later. When this membrane is there, this stirrup sits on top of it, and it has a bone protrusion right here. And this bony protrusion is like the upper arm and the forearm. It sits here on this thing, on this membrane. So if you imagine there is an arm like this, with the upper arm here and the forearm there, then curiously there is another bone here that sits freely on top. They are connected to each other at the joint, and it sits freely here. These are small, tiny bones. Well, the materialistic way of thinking, which looks at everything externally, calls this bone here, which sits directly on the eardrum and strikes it, the hammer, and that piece of bone here, it calls the anvil. And it calls this the stirrup. So these three small bones are called by conventional science: hammer, anvil, and stirrup.

But conventional science does not really know what this is. What is there in the shape of a stirrup is, in fact, only slightly differently shaped, the same as what is here in the upper arm. See how the joint sits there, the joint sits on this little membrane. And here is the elbow; so this is a kind of hand. And on top of that is a free bone. We don't have that in our hand, but we do have it in our kneecap. We could just as well say: that is a leg, a foot; then that would be a thigh, that would be the knee (drawing), the foot would sit on top of it, and there is the kneecap.

It's very interesting, you see: first we have a kind of intestine in our ear cavity, and then a real hand or arm or a real foot. What is the whole thing there for? Well, imagine a sound coming. The sound hits the eardrum. The whole thing that is there starts to vibrate. This is how humans, without even knowing it, test what kind of vibrations are hitting the inside of the ear. And think about it, you will have felt this before when you are standing somewhere on the street and something explodes behind you — I mean, you have noticed it — you feel it in your intestines! Yes, it may even be that such a vibration makes you sick in your gut. But the finest vibration that passes through this arm is felt by the water in this snail shell. This water in the snail shell participates in the vibrations, which humans become aware of when they touch the eardrum with this hand. Can you understand that? (Yes!)

Now I want to tell you something else. What is the purpose of this trumpet that goes from the mouth into the ear? Yes, if an ordinary sound enters here, this trumpet is not really necessary. But when we listen to each other, when one person speaks to another and we want to understand them, because we have learned to speak – if we have not learned to speak ourselves, we cannot understand the other person well; because we have learned to speak, the sounds of speech pass through the Eustachian tube, the auditory tube, and when the other person speaks like this, it goes like this, vibrates there; it passes into this fluid. And because the air passes through, enters the ear through the Eustachian tube, and I have become accustomed to moving this air myself through my own speech, I can understand the other person. Inside the ear, what I am accustomed to having from my own speech meets what comes from the other person's speech. That is where they meet.

You know, when I say “house,” I am used to certain vibrations occurring inside my Eustachian tube; when I say “powder,” another vibration occurs. I am familiar with these vibrations. When I say “house,” the vibration comes from outside, and I am used to perceiving this when I say “house.” And there the two come together, my knowledge and the vibration from outside, and I understand what “the house” means. Isn't that understandable? My tube, which goes from the mouth to the ear, is there when we ourselves learn to speak as children, so that we can understand others at the same time. Things are extremely interesting.

But now the thing is this: imagine that everything I have recorded for you was there in your ear, but nothing else at first. You would be able to understand others, let's say, and you would also be able to listen to a piece of music; but you would not be able to remember what you heard. You would have no memory for language or sounds. If the ear were only like that, you would have no memory for language or sounds. In order for you to have a memory, there is something else in the ear. In order for you to be able to remember what you hear, there is another mechanism. There are three such arches here; they are up there (see drawing). You have to imagine arches that are hollow. There is a second one, which stands vertically on top of the first; and there is a third one, which in turn stands vertically on top of the other. They stand vertically on top of each other in three directions. So this is another wonderful structure inside the ear. But these channels up there are hollow—naturally, because they are channels. And inside them is fine, living water. That is what is inside them.

But the remarkable thing about this living water is that tiny crystals are constantly forming out of it, tiny little crystals. For example, when you hear “house” or the letter C, such small crystals form inside; when you hear “human,” slightly different crystals form. Tiny crystals form in these three tiny channels, and these tiny crystals enable us not only to understand, but also to retain what we have understood in our memory. For what does a person do unconsciously?

Just imagine you hear, say, “five francs”; you want to remember what was said, so you write it down in your notebook. What you have written in your notebook with a pencil has nothing to do with the five francs, but you remember it because of the note. In the same way, what we hear is inscribed in these fine channels through the tiny crystals, which are actually like letters. And through an unconscious mind, this is read again when we need it. So we can say: in there (in the three semicircular channels) is the memory for sounds and noises. Here, in this arm or leg (drawing, ossicles), there is understanding. Inside this cochlea, there is a little piece of the human mind, a little piece of feeling. We feel the sounds in this (part of the) labyrinth, inside this snail shell water. We feel the sounds. And when we speak and produce the sound ourselves, the will to speak passes through our Eustachian tube. The whole soul of the human being is inside the ear: in this tube here, the will lives; in there (in the cochlea), feeling lives; there inside (in this arm or leg, the ossicles) lives the intellect; and there in this (in the three small semicircular canals) lives the memory. And so that the human being can become aware of this when it is finished, a nerve runs from here through this cavity here (see drawing), through this hole here. The nerve spreads everywhere, covers everything, goes everywhere. And through this nerve, the whole thing then comes to our consciousness here in the brain.

See, gentlemen, something most peculiar! We have a cavity inside our skull, in our skull bones; such a cavity simply goes in there. You can enter the cavity by going from the outer ear through the ear canal, piercing the eardrum. Everything I have shown you is inside this cavity. First, you stretch out your hand, which touches the sounds that come in, so that we can understand the sounds. Then we transfer this to the cochlea, to the living water; this is how we feel the sound. We push into it with our will through our Eustachian tube. And through the small crystal signs that are in these three, as they are called, semicircular canals, we remember what is spoken or sung, or whatever else comes to us as sound.

So we can say: inside there we actually carry a little human being, a real little human being. For the human being has will, feeling, understanding, intellect, and memory. In this little cave we carry a little human being inside us. We consist only of little human beings. Our big human being is only the sum of all the little human beings. I will show you next time that the eye is also a little human being. The nose is also a little human being. And these little human beings are held together by the nervous system and then form the whole human being. And these little human beings come into being because everything that forms inside while the human being is in the embryonic state in the mother's body is still under the influence of the stars. For all these wonderful structures there, that is, the channels that form the crystals, and this arm, cannot be formed by the gravity of the earth and everything that is on the earth. They are still formed in the womb by the forces that come in from the stars. And only that which belongs to the human being, that is, this part here, the cochlea and the Eustachian tube, is formed later. It is made by that which emanates from the earth, just as we as whole human beings get our whole form from the earth's gravity, and we only stand up as children who have long since been born.

You see, when you first know how the whole human being starts from a small cell, and one cell transforms into the eye, another cell—there are actually ten clusters that transform, it is not just one cell, but that does not make much difference when you imagine that it is only one— so one transforms into the eye, another into the ear, the third into the nose, then you see how the human being gradually builds itself up by first consisting of only a single cell, which produces a second, and by going to another place, coming under another influence, it now becomes different, becomes the ear, another becomes the nose, a third becomes the eye, and so on. But that is truly not all that comes from the forces of the earth. The forces of the earth could only form what is round in the strict sense, just as in our stomach the earth forms our intestines. But everything else is still formed by the stars.

Well, isn't it true that we know all this today because we have microscopes through which we can observe these things? These little bones are terribly small. But the remarkable thing is that people in earlier times also knew this, and that they knew it from a completely different kind of knowledge than we have today. And now, let's say, for example, that the ancient Egyptians three thousand years ago were also concerned with such knowledge and already knew in their own way how wonderful the human ear is. And then they said to themselves: Man has ears, eyes, and other organs on his head. If we want to explain these organs, we can only say: How did the ear, the eye — as I said, I will explain this to you next time — become so different from the other organs of the body? They said: These organs on the head, the ear, the eye, have become so because they are primarily affected by what comes to the earthly realm from outside, from above. Then they looked up and said: Up there, for example, an eagle is flying, forming itself high in the air; one must look up there if one wants to see the forces that form the organs in the human head. That is why, when they first drew the human being, they drew an eagle for the head.When we look at the heart and lungs, for example, they look very different from the eye and ear. When we look at the lungs, we cannot go very far to the stars, and when we look at the heart, we cannot go very far to the stars either. The power of the stars has a very special effect on the heart, but we cannot relate its form and shape to the stars in the same way. The ancient Egyptians already knew this three thousand years ago: we cannot relate it to the stars in the same way as the organs of the head. So they thought: Where is there an animal that particularly develops organs that are similar to the human heart and lungs and so on? The eagle particularly develops organs that are similar to the human head. The animal, the ancients found, that most closely resembles the heart, and is therefore also the bravest animal, is the lion. That is why they called this organ, the lungs, heart, and so on, “lion.” So they said: head = eagle. Then the lion, which represents the middle man. And then they said: But human intestines look completely different. You see, the lion has very short intestines; its intestines are too short. So the intestines look completely different. In the ear, there is actually only a very small intestine; it is delicately formed. Our other intestines are not so delicately formed. If you want to look at the intestines, you have to compare their formation with animals that are particularly influenced by their intestines. The lion is influenced by the heart; the eagle is influenced by the higher powers. Under the influence of the intestines — yes, if you look at cows after they have eaten, you can see that oxen and cows are completely under the influence of their intestines. They feel terribly good when they digest. That is why the ancients called what belongs to the intestines in humans the bull or cow man.

And now you have the three limbs of human nature:

Eagle = head

Lion = chest

Bull = that which belongs to the digestive system.

Of course, these ancient people also knew this: when I meet a human being, the head is not actually an eagle, and the middle part is not a lion, nor is the lower part a bull or an ox. They already knew that. So they said: Yes, if there were nothing else, we would all walk around with an eagle's head at the top, then a lion in the body, and then we would end up as a bull. That is how we would all walk around. But now there is something else that transforms the head up there and makes it like a human head, and that in turn is what makes us not actually lions and so on; that is the actual human being. That then brings everything together. (See drawing on p. 70.)

And it is really strange how these ancient people expressed certain truths that we recognize again today by forming images. Of course, these images were easier for them to form than for us. You see, we people today can learn many things, but it cannot be said that the ideas we learn today in school touch our hearts very deeply. It was quite different for these ancient people. They were truly moved by these ideas, and that is why they also dreamed about them. And these people truly dreamed: they saw the whole human being in the image, with an eagle looking out of the forehead, a lion out of the heart, and a bull out of the stomach. They then painted this together to form the whole human being, a very beautiful image. So one can say that the ancients composed the human being from man, bull, eagle, and lion.

This continued into the descriptions in the Gospels. A lot of these things were taken as a given. For example, they said: Well, there is a Gospel according to Matthew, which actually describes the man Jesus just like a human being, and that is why the writer of the Gospel of Matthew was called “the man.” But take John, said the ancients: Yes, he describes Jesus as if he were floating above the earth, as if he were flying above the earth; he actually only describes what goes on in the human mind. That is the “eagle.” If you read the Gospel of Mark, you will see that Jesus is portrayed as the fighter, the warrior, the “lion.” . He describes him as someone who primarily represents the chest organs. And Luke, how does he describe him? Luke has even been presented as a physician who is primarily concerned with healing. You can see that in the Gospel as well. Healing must be done by introducing something into the digestive organs. Therefore, he describes Jesus as a “bull,” who preferably introduces something into the digestion. And so the four Gospels can be summarized as follows:

Matthew = human

Mark = lion

Luke = bull

John = eagle

Now, with this newspaper [at the top of which the four figures mentioned above are depicted], I was faced with the task of conveying what passes from human spirit to human spirit, what one person can say to another that is valuable. This is also how people should be portrayed. So, in this figure, the eagle is depicted at the top, then the lion, the bull, the cow, and then the human being himself, who brings them all together. This is so that one can see that this newspaper is intended to be something quite human. You will understand, gentlemen, that today one would like to say this to people, that one would like to say something human to them. For in what is often presented in the newspapers today, there is not much that is human. So it should be expressed that in this newspaper, man should really be able to live out all his faculties to the full. What they say should not be stupid, i.e., eagle; nor should it be cowardly, i.e., lion. But it should not fly away into the air either, but stand practically on the ground, i.e., bull, cow. And the whole thing should give something to people, should speak to people. That is what we want today, that everything, everything could really go from people to people.

Now I have finally come to approach what you asked from the starting point, and I hope that this question has become understandable. Were you particularly interested in the story about the ears? One should know what one actually carries within oneself!

Question regarding the lotus flowers that are sometimes mentioned, whether anything more can be said about them.

Dr. Steiner: I will come to that when I explain the individual organs to you. The next lecture will be on Saturday at ten o'clock.