Health and Illness I

GA 348

20 December 1922, Dornach

VII. Spiritual-Scientific Foundations for a True Physiology

Gentlemen, this time let us finish answering a question raised the other day.

By virtue of his skin, man is an entire sense organ. The skin of the human being is something extraordinarily complicated and truly marvellous. When we trace it from the outside inward, we find first a transparent and horny layer called the epidermis. It is transparent only in us white Europeans; in Africans, Indonesians and Malayans, it is saturated with coloured granules and thus tinged with colour. It is called “horny” because it consists of the same substance, arranged a little differently, from which the horns of animals and our nails and hair are fashioned. Our nails actually grow out of the uppermost layer of the skin. Under this layer lies the dermis, which consists of an upper and a lower layer. So we are in fact covered and enclothed with a three-layered skin: the outer epidermis, the middle layer of the dermis and the lower part of the dermis.

The lowest layer of the dermis nourishes the whole skin; it stores the nourishing substances for the skin. The middle layer is filled with all kinds of things, but in particular it is filled with muscle fibres. Everywhere in this layer are myriad tiny onion-like things, one next to the other; we have thousands upon thousands in our skin. We can call them “onions” because the distinguishing feature of an onion is its many peels, and these little corpuscles have such “onion peels”; the onion skin is on the surface, and the other, thinner part is on the inside. They were discovered by the Italian Pacini and are therefore called “Pacinian corpuscles.”

Around these microscopic corpuscles are from twenty to sixty such peels, so you can imagine how small they are.

Man is constituted in such a way that he has these microscopic little bulbs over the whole surface of his body. The largest number is found—in snakes as well as in men—on the tip of the tongue. Yes, it is almost comical, but most are found on the tip of the tongue! There are many on the tips of the fingers, on the palms of the hands and on other parts of the body, but most are on the tip of the tongue. For example, there are seven times more such little nerve bulbs on the tip of the tongue than there are on the finger tips.

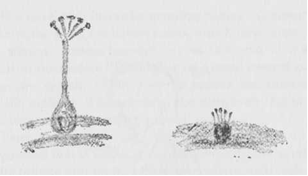

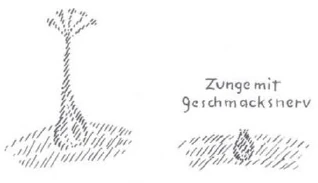

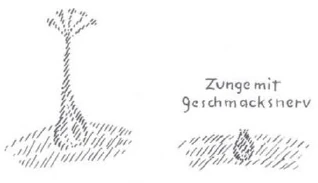

A nerve fibre originates from each of these corpuscles and finds its way into the brain via the spinal marrow. All these nerve fibres radiate from the brain, and everywhere in the body they form such nerve bulbs on its surface. So these nerve fibres in the brain go everywhere and eventually form the onions within the skin or dermis. It is interesting to realize that just as real onions grow in the ground and form onion blossoms above, so do these onions grow in the human body. There (pointing to his sketch) are the onions and the stem within. In those nerves of the tongue the stem is rather short, but in other nerves it is sometimes quite long. The nerve fibres going from the feet into the brain through the spinal marrow are extremely long. Everything that we have as onions in our skin actually has blossoms within our skull. You may imagine, then, that in regard to his skin man is a kind of soil; it is strangely formed, but it still is a kind of soil. On the surface is the epidermis, in which various crystal substances are deposited. Below are the solid masses of the body, and above is the layer of “humus.” Going from outside inward, beneath the hard, horny layer of the epidermis lies the dermis, which is the soil. From it grow all these onions that have blossoms in the brain. Their stems pass up into the brain and have blossoms there.

Well, gentlemen, in us older fellows things are such that only during sleep can we properly trace this network, but in a child it is still much in evidence. The child has a lively nerve bulb activity in the nerves as long as its intellect is unawakened; that is, throughout its first year, and just as the sun shines over the blossoms of the onions, so shines the light into the child that as yet does not translate with the intellect what it receives with its eyesight. This is indeed like the sun shedding its rays inside the head and opening up all the onion blossoms. In the nerves of the skin we carry a whole plant kingdom around within us. Later, however, when we enter grammar school this lively growing comes to an end, and then we use the forces from the nerves for thinking. We draw these forces out and use them for thinking. This is extremely interesting. Ordinarily, it is assumed that the nerves do the thinking, but the nerves do not think. We can employ the nerves for thinking only by stealing their light, so to speak. The human soul steals the light from the nerves, and it uses what it has taken away for thinking. It is really so. When we truly ponder the matter, we finally recognize at every point the independently active soul.

We have such inwardly growing onions in common with all animals. Even the lowest forms, which have slimy, primitive shapes, possess sensory nerves that end in a kind of onion on the surface. The higher we ascend toward man, the more are certain of these nerve onions transformed in a specific manner. The nerves of the taste buds, for example, are such transformed skin nerves.

Now, we possess these sensory bulbs at the tip of the tongue and that is why it is so sensitive. We taste on the back of the tongue and on the soft palate where such little onions are dispersed. Actually, they sit there in a little groove and within these grooves an onion penetrates into the nerves and pushes into the dermis as a nerve corpuscle. First, a tiny groove forms behind the tongue, and then an onion pushes itself into this groove. The root of the onion penetrates all the way to the surface of the tongue. On the base of the tongue are a tremendous number of tiny grooves, and in each little groove a “bulb” grows up from below. This accounts for our experience of taste.

We can be aware of everything with the sense of touch, or these onions located on our body's surface. Now, you know that what one feels one does not remember so well. I know with my feeling that a chair is hard because I feel its hardness with a certain number of nerve bulbs that constantly change, but my memory is not strained by this sensation. With the sense of taste it makes a little, though unconscious effort. Gourmets, however, always know beforehand what is good, not afterward when they have already tasted it, and that is why they order it.

So the nerve corpuscles pass through the spinal marrow directly into the brain and form blossoms there. Everything that we want to taste, however, must first be dissolved by the saliva in the mouth; we can taste nothing that hasn't first been transformed into fluid. But what is it that tastes? We would not be able to taste anything if we did not have fluid within us. Our solid human constitution, everything that is solid in the body, does not taste. Our inner fluid mixes with what is dissolved of the food. Thus, we can say that our own fluid mixes with the fluid from without. The solid part of the human organization does not taste anything. Our constitution is ninety percent water, and here, around the papillae of the tongue, it is in an especially fluid state. Just as water shoots out of a geyser, so do we have such a spurting forth of fluid on the tip of the tongue.

Saliva that has been spit out of the mouth is no longer part of me, but as long as that fluid is within the little gland of the tongue, it belongs to me as a human being, just as my muscles belong to me. I consist not only of solid muscles but also of water, and it is this fluid that actually does the tasting because it mixes with what comes as fluid from without. What does one do when one licks sugar? One drives saliva from within toward the taste buds. The dissolved sugar penetrates the fluid, and the “fluid man,” as it were, permeates himself with the sugar. The sugar is secreted delicately in the taste buds of the tongue and spreads out in one's own fluidity, giving him a feeling of well-being.

As human beings we can only taste, but why is this so? If we had fins and were fishes—which would be an interesting existence—every time we ate, the taste would penetrate right through our fins. But then we would have to swim in water, where we would find everything even the delicate substances well-dissolved. The fish tastes all the traces of substances that are in the water and follows the direction of its taste, which is constantly penetrating into the fins. If something pleasant flows in its direction, the fish will taste it, and its fins will immediately move toward it. We men cannot do what the fish can because we have no fins; in us they are completely lacking. But since we cannot use the sensation of taste to move around, we intensify it within. Fishes have a highly developed sense of taste, but they have no inward sense of it. We human beings have the taste within, we experience it; fishes exist in the totality of the water and experience taste together with the surrounding water. People have wondered why a fish swims far out into the ocean when it wants to lay its eggs. They swim far out, not only into the Atlantic Ocean, but also into other parts of the earth's oceans, and then the young slowly return to European waters. Why is this? Well, European fishes that swim around in our rivers are fresh-water fishes, but the eggs cannot mature in fresh water. Fishes sense by taste that a trace of salt flows toward the outlet of a river; they then swim out into the sea. If the sun shines differently on the other side of the earth, they taste that and by this sense swim halfway around the globe. Then the young taste their way back again to where the parent fishes have dwelt. So we see that fishes follow their taste in every way.

It is extremely interesting that the water that flows in the rivers and is contained in the seas is full of taste, and the fact that fishes swim around in them is really due to the water's taste. It is actually the taste of the water that makes them swim around; the taste of the water gives them their directions. Naturally, if the sun shines on a certain portion of water, everything that is in the water at that spot is thoroughly dissolved by the heat of the sun. It is changed into another taste, and that is why you see a lot of fishes swimming around there; it is the taste.

It is really a strange matter, gentlemen, because we would actually be swimming, too, if we went only by our taste. When I taste sugar the fluid man within me wants to swim toward it. The urge to swim is indeed there; we want to swim constantly according to our taste, but the solid body prevents us from doing so. From that element that continually would like to swim but cannot—we really have something like a fish within us that constantly wants to swim but is held back—we retain what our inner soul being makes out concerning taste. With taste we live completely within the etheric body, but the etheric body is held fast by the water in us, and that water in turn is held by our physical body. It is the most natural thing to say that man has an etheric body that is really not disposed to walking on the earth. It is suited only for swimming; it is in fact fish-like, but because man makes it stand erect it becomes something different. Man has within him this etheric body that is actually only in his fluid organization, and it is indeed so that he would constantly like to swim, swim in the elements of water that are contained even in the air. We would like to be always swimming there, but we transform this urge into the inner experience of taste.

You see, such aspects really lead one to comprehend the human being. You cannot find this in any modern scientific book because people examine not the living human being but only the corpse, which no longer wants to swim. Nor does it participate any longer in life. We participate in life because actually we are the sum of everything existing in the world. We are fishes, and the water vapor that is similar to us is something in which we would like to be constantly swimming about. The fact that we cannot do so results in our pouring it into us and tasting it. The fishes are really cold creatures. They could taste things marvellously well that are dissolved in the water, but they do not do so because they immediately move their fins. If the fins would disappear from the fishes, they would become higher animals and would begin to have sensations of taste.

The nerve bulbs that I told you about last time are differently transformed “onions.” They penetrate into the mucous membrane of the nose, but they do not sit within a groove from which fluid seeps out; they reach all the way to the surface. That is why these nerve bulbs can perceive only what comes close to them. This means that we have to let the fragrance of the rose come up to the nerve bulb of our nose before we can smell it. Thus, one part of the human body has the function of fashioning in a special way these nerve bulbs, which are spread out over the whole skin, in order to sense smells permeating the air.

Not only does the outer air waft toward man, but also the breath streams out from within him. The breath constantly passes through the nose, and within this breath lives the air being of man. We are water, and as I told you earlier, we are also air. We do not have the air within us just for the fun of it. Like the water within me, my breath is not solid. Just as when I reach out my hand and feel that I have stretched out something solid, so I stretch what I contain in my air organism into my nose. There I grasp the fragrance of the rose or carnation. Indeed, I am not only a solid being but continually a being of water and air as well. We are the air as long as it is within us and is alive. When we stretch our “air hands” through the nose and grasp the fragrance of a rose or carnation—bad odors, too, of course—we do not touch it with our hand but rather grasp it with the nerve bulbs, which attract the breath from within so that it can take hold of the fragrance.

This is something that is manifest also in the dog. I have told you that as soon as the nose smells, the tail wags. Just as with fishes the fins start to move about, so, too, with dogs the tail starts to move. But what does this tail that can only wag really want to do? This is most interesting. The tail can only wag, but what does it really want to do? You see, gentlemen, the dog would really like to do something quite different. If it were not a dog but a bird it would fly under the influence of smell. Just as fishes swim, a dog would fly if it were a bird. Well, of course, a dog has no wings, and so he uses the substituted organ and just wags his tail. It isn't enough for flying, but it involves the same expenditure of energy. In human beings it is the same. Because we always have delicate sensations of smell that we do not even notice, we would constantly like to fly.

Think now of the swallows that live here in summer. What arises as scents from the flowers is pleasing to them, and because it is pleasing to their organ of smell they remain here. But when autumn comes or is just approaching, the swallows, if they could communicate among themselves, would say, “Oh, it's beginning to smell bad!” The swallow has an extraordinarily delicate sense of smell. You remember that I told you that people are perceptible to savage tribes all the way to Arlesheim. Well, for swallows the odour arising in the south is perceptible when fall is approaching; it actually spreads out all the way to the north. While in the south it smells good, up north it begins to smell of decay. The swallows are attracted to the good odour and fly south.

Whole libraries have been written about the flight of birds, but the truth is that even during the great migrations in spring and autumn the birds follow the extremely delicate dispersion of odours in the whole atmosphere of the earth. The organ of smell in the swallows guides them to the south and then back again to the north. When spring arrives here in our lands, it starts to smell bad for the swallows down south. When the delicate fragrances of spring flow southward to them, they fly back north. It is really true that the whole earth is one living being and that the other beings belong to it.

In our body, things are so organized that the blood flows to the head and then away from it. On the earth, things are so arranged that the migratory birds fly to the equator and then back to their point of departure. We, too, are influenced by the air because the air we breathe drives the blood to the head. Insofar as we are beings of air, we are completely permeated with smell. For example, a person who walks across a field that has just been fertilized with manure is really going there together with his airy being. The solid man and the fluid man do not notice the manure, but the man of air does, and then there arises in him, understandably enough, the urge to fly away. When the manure's stinking odour rises from the field, he would actually like to fly off into the air. He cannot do so because he lacks the wings and thus reacts inwardly to what he cannot fly away from; it becomes an internal process of the soul. As a result, man inwardly becomes permeated with the manure odour, with the evaporations that have become gaseous and vapor-like. He becomes suffused with the bad odour and says that he loathes it. His loathing is a reaction of the soul.

In the fluid man there exists the more delicate airy form that, in a way, he takes from the fluid organization of himself. It is through this that he can taste. Likewise, something lives in this airy form that we constantly renew in us through inhaling and exhaling. Each moment it is expelled and reborn; it is born eighteen times a minute and dies eighteen times a minute. It takes years for the solid form to die, but the airy form dies during exhalation eighteen times a minute and is born during inhalation. It is a continuous process of dying and being born. What is extracted within is the astral body. As I told you the other day, it is the astral body that reverses the forces of tail-wagging that should really be down below. Because these forces are pushed up and against the sense of smell, we are able to think. The brain grows to meet the nose under the influence of the astral body, and no one can really understand the brain who does not look at the whole matter in the way I have just done. This understanding results from a correct observation of our senses.

On account of our sense of smell we would always like to be flying. The bird can fly but we cannot; at best we have these solid shoulder blades. Why can the bird fly? Gentlemen, the bird has something peculiar that enables it to fly; it has hollow bones. Air is inside them and the air that the bird absorbs through its organ of smell comes into contact with the air that it has in its bones. Indeed, the bird is primarily a being of air. Its most important aspect consists of air; the rest is merely grown on to it. The many feathers a bird may have are actually all dried up. The most significant thing, even in the ostrich, is that a bit of air is still contained in each downy feather and all this air is connected with the air outside. The ostrich walks because it is too heavy to fly but, of course, the other birds do.

We human beings have only our shoulder blades attached to our back, which are clumsy and solidly shaped. Although we would constantly like to fly with them, we cannot. Instead, we push the whole spinal marrow into the brain and begin to think. Birds do not think. We have only to observe them properly to realize that everything goes into their flight. It looks clever, but it is really the result of what is in the air. Birds do not think, but we do because we cannot fly. Our thoughts are actually the transformed forces of flying. It is interesting that in human beings the sense of taste changes into forces of feeling. When I say, “I feel well,” I would really like to swim. Since I cannot, this impulse changes into an inner feeling of well-being. When I say, “The odour of the manure repulses me,” I would really like to fly away. But I cannot, and so I have the thought, “This is disgusting; this odour is repulsive!” All our thoughts are transformed smells. Man is such an accomplished thinker because he experiences in the brain, with that part I described earlier, everything that the dog experiences in the nose.

As human beings, we owe a lot to our nose. You see, people who have no sense of smell, whose mucous membrane is stunted, also lack a certain sense of creativity. They can think only through what they have inherited from their parents. It is always good that we inherit at least something; otherwise, if all our senses were not rudimentarily developed, we could not live at all. A person born blind also has inherited the interior of what the eye possesses. He has this primarily because he is not only a compact man but also a man of fluid and air.

We have now seen how strange all this is. We perceive solid substances with our sense of touch through the nerve bulbs that penetrate the skin everywhere; we become aware of watery substances with our sense of taste; what is of air, the vaporous, is recognized by us through the nerve bulbs that penetrate into the mucous membrane of the nose. We also sense something else around us, though in a more general way; that is, heat and cold. So, as human beings we are partly solid, water, air, and warmth, since we are usually warmer than the surrounding world.

You see, science does not really know that the aspect of tasting concerns the man of water and that the element of smell pertains to the man of air. Because the nerves of taste come into the taste buds, it is the scientific opinion that these nerves actually taste. But this is nonsense. In the mouth, it is the fluid of the watery organization of man that tastes, and in the nose, it is the element of air that smells. Furthermore, the part of us that is warmth perceives heat and cold. The internal warmth in us directly perceives the external warmth, and this is the difference between the sense of warmth and all the other senses. Warmth is produced by all the organs, and as human beings we harbour a world of warmth within us. This element of warmth perceives the other world of warmth around us. When we touch something that is hot or cold, we naturally perceive it just on the spot where we have touched it. But when it is cold in winter or hot in summer, we perceive this coldness or heat in our surroundings; we become a complete sense organ.

We can see how science errs in this regard. According to scientific books, the human being is some kind of compactly shaped form. All the bones are drawn on the paper; the muscles and nerves are all there. But this is utter nonsense because it represents no more than one tenth of the human being. The rest is up to ninety percent water, and then we must account for the air and the warmth within. In fact, three more persons—of water, air and warmth—should be sketched into the figures drawn up by materialistic science. Man cannot be comprehended in any other way. Only because we are warmer than our surroundings and are also a portion of a world of warmth do we experience ourselves as being independent in the world. If we were as cold as a fish or a turtle, we would have no ego; we could not speak of ourselves as “I.” We could never think if we had not transformed the sense of smell within us, or, in other words, if we had no astral body. Likewise, we would have no ego if we did not possess a portion of warmth within us.

Now, someone might say that the higher animals have their own body temperature, too. Yes, gentlemen, but they are burdened by their warmth. The higher animals would like to become an “I” but cannot. Just as we cannot swim or fly, the higher animals would like to become an “I” but cannot do it. You can discern that in their forms; they would really like to become an “I,” and because they cannot they assume their various shapes.

So, as human beings we have four parts in us: the solid man, which is the physical, material part; the fluid man, which carries the more delicate body—the life body or etheric body—within itself; the air being, the man of air who constantly dies and is renewed in the physical realm but who contains the astral body, which remains throughout life; the portion of warmth, the ego man.

The sense of warmth is distributed delicately over the whole human being. Here science does something peculiar.

When we examine the human being from a purely materialistic standpoint, we discover these nerve bulbs that I have described to you. Now, people say to themselves, “If I touch this box, I feel it and its solidness because of the nerve bulbs. If the box were cold, I would also feel the cold through such a nerve bulb.” They constantly look for these nerve bulbs of warmth and these nerve bulbs of feeling, but they never find them. Someone will examine a piece of skin, and because some of these nerve bulbs for feeling look a little different he thinks that they belong to something else. But it is all nonsense. There are no nerve bulbs sensitive to warmth because the whole human being is perceptive to warmth. These nerve bulbs are used only for sensing solid, water and vaporous substances. Where the sense of warmth begins, we become extremely “light-sensed” beings, that is, no more than a bit of warmth that perceives exterior heat. When we are surrounded by an amount of heat that enables us properly to say “I” to ourselves, we feel well, but when we are surrounded by freezing cold that takes away from us the amount of warmth that we are, we are in danger of losing our ego. The fear in our ego makes the cold outside perceptible to us. When somebody is freezing he is actually always afraid for his ego, and with good reason, because he pushes the ego out of himself faster than he actually should.

These are the aspects that will gradually lead us from the observation of the physical to the observation of the nonphysical, the non-material. Only in this way can we begin to comprehend man. Having mentioned all this, we shall be able to continue with quite interesting observations next time.

Siebenter Vortrag

Meine Herren, wir wollen heute die Frage von neulich fertig beantworten.

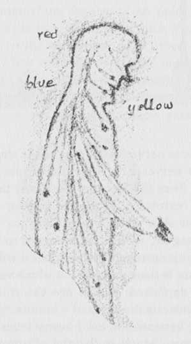

Sehen Sie, durch seine Haut ist eigentlich der Mensch im ganzen ein Sinnesorgan. Schon die Haut des Menschen ist etwas außerordentlich Kompliziertes, etwas ganz Wunderbares. Wenn man die Haut von außen nach innen verfolgt, so hat man ganz außen zunächst eine durchsichtige Schichte, die sogenannte Hornschicht der Oberhaut. Durchsichtig ist sie nur bei uns weißen Europäern, während die Oberhaut bei Negern und Indonesiern, Malaien, eben mit Farbkörnchen durchsetzt und dadurch gefärbt ist. Bei uns Europäern ist es aber eine durchsichtige Haut, die Hornschicht der Oberhaut. Hornschicht heißt sie, weil sie tatsächlich aus demselben Stoff besteht, nur ist er etwas anders angeordnet, aus dem die Hörner der Tiere und aus dem auch unsere Nägel und Haare bestehen, denn unsere Nägel wachsen eigentlich aus dieser äußeren Hornschichte der Haut heraus. Unter dieser Hornschicht liegt die sogenannte Lederhaut, die eigentlich wiederum aus zwei Schichten besteht, einer oberen Schichte (siehe Zeichnung, rot) und einer unteren Schichte, die ich hier vielleicht grünlich machen will. So sind wir also als Menschen eigentlich zugedeckt und umkleidet mit einer dreifachen Haut, mit einer äußeren Hornschicht, mit der mittleren Lederhaut und mit der inwendigen unteren Lederhaut.

Nun, sehen Sie, diese unterste, hier grün gezeichnete Lederhaut, die ist eigentlich zur Ernährung der ganzen Haut da. Da drinnen werden die Nahrungsstoffe der Haut abgelagert. Aber die mittlere, die ich hier rot gezeichnet habe, die ist mit allerlei Zeug ausgefüllt; vor allen Dingen aber ist sie mit Muskelfasern ausgefüllt. Aber was für uns ganz besonders wichtig ist: es sind da drinnen in dieser Haut lauter kleine Zwiebelchen, eines neben dem andern; so daß man da überall kleine Zwiebelchen (gelb), eines neben dem andern; so daß man da überall kleine Zwiebelchen hat. Solche haben wir Tausende und Tausende in unserer Haut drinnen, solche kleinen, ich kann sie Zwiebelchen nennen; denn eine Zwiebel, die ist ja besonders ausgezeichnet dadurch, daß sie Schalen hat, die äußere Schale, die zweite Schale, dritte Schale und so weiter, viele Schalen. Und diese kleinen Körperchen hier, die ein Italiener, Pacini, entdeckt hat, und die daher Pacinische Körperchen heißen, diese kleinen Körperchen, die haben solche Zwiebelschalen, bestehen aus solchen richtig so, daß die Zwiebelhaut nach außen ist, und der andere, der dünnere Teil,geht nach innen zu, wie ich es auch außen gezeichnet habe.

Nun, sehen Sie, um solche winzigkleinen Körperchen - sie sind ja winzig, man sieht sie ja nur durch die Mikroskope - sind zwanzig bis sechzig solche Schalen! Sie können sich denken, wie kleinwinzig das ist. Also der Mensch ist eigentlich so, daß er an seiner ganzen Körperoberfläche lauter solche kleinwinzigen Zwiebeln ausstreut. Am meisten, nicht nur bei den Schlangen, sondern auch beim Menschen, sind an der Zungenspitze. Das ist nämlich geradezu komisch: am meisten sind an der Zungenspitze! Viele sind auch an den Fingerspitzen, an der Hohlhand im Innern, an anderen Körperteilen; aber eben, wie gesagt, am meisten sind an der Zungenspitze. Wenn man zum Beispiel die vielen kleinen Zwiebelchen an der Zungenspitze und diejenigen, die man in den Fingerspitzen hat, vergleicht, so sind in den Fingerspitzen ungefähr siebenmal weniger als an der Zungenspitze.

Sehen Sie, von jedem solchen Zwiebelchen geht ein Nervenfaden aus. Der Nervenfaden, der geht zunächst auf irgendeinem Weg — er sucht sich schon seinen Weg - ins Rückenmark hinein, und vom Rückenmark ins Gehirn. Und Sie können sich vorstellen: Vom Gehirn gehen lauter solche Nervenfäden aus, überall in den Körper hin, und bilden da an der Körperoberfläche solche Zwiebeln, also auch zu der Zunge her solche Zwiebeln - überallhin. So daß ich den Menschen auch so zeichnen kann, daß im Gehirn alle diese Nervenfäden anfangen und überall hingehen, und am Ende in der Haut drinnen, in der Lederhaut, solche Zwiebeln bilden.

Das ist deshalb sehr interessant, weil man sich das wirklich vorstellen kann — und man stellt sich etwas Richtiges vor, wenn man sich das wirklich vorstellen kann -: Nehmen Sie an, da ist der Erdboden (siehe Zeichnung links); da drinnen haben wir eine wirkliche richtige Zwiebel; die wächst heraus aus dem Erdboden und bildet da oben die Zwiebelblüte. Ja, meine Herren, so ähnlich ist es nämlich im menschlichen Körper.

Da (siehe Zeichnung rechts) sind die Zwiebeln drinnen, und der Stengel, der ist nur innen — in den Nerven (der Zunge) ist er ja auch kurz, aber bei den anderen Nerven ist er manchmal furchtbar lang; die Zwiebelfädennerven, die von den Füßen gehen durch das Rückenmark ins Gehirn, sind furchtbar lang. Und von alldem, wovon wir in der Haut die Zwiebeln haben, haben wir eigentlich die Blüte in unserem Gehirnschädel drinnen. So daß Sie sich vorstellen können: Der ganze Mensch ist in seiner Haut eigentlich eine Art Erdboden, nur kurios gestaltet, aber er ist eine Art Erdboden. Außen hat er die Hornschichte, in der sogar allerlei Kristalle und so weiter eingelagert sind. Das sind unten die festen Körpermassen, darüber die «Humus»-Schichte. Beim Menschen liegt nur von außen nach innen unter der harten Hornhaut die Lederhaut. Das ist der Erdboden. Und aus dem Erdboden wachsen alle diese Zwiebeln heraus und haben im Gehirn ihre Blüte. Sie haben ihren Stiel bis ins Gehirn hinein und haben im Gehirn ihre Blüte.

Ja, meine Herren, bei uns mehr alten Kerlen, bei denen ist das so, daß man eigentlich die ganze Geschichte nicht mehr richtig verfolgen kann, nur beim Schlaf; aber beim Kind ist das noch sehr viel mehr der Fall. Da ist es so, daß tatsächlich das Kind, solange sein Verstand nicht aufgeweckt ist, also im ganzen ersten Jahre, eine sehr lebhafte Zwiebeltätigkeit in sich, in den Nerven hat. Und geradeso wie die Sonne hinscheint über die Blüten bei den Zwiebeln, so scheint beim Kind, das noch nicht das Außenlicht, das es aufnimmt, in den Verstand umsetzt, das Licht hinein, und das ist allerdings so, wie wenn die Sonne im Kopfe sich verbreiten würde und alle diese Zwiebelblüten entfalten würde. Es wächst in der Tat in den Nerven ein ganzes Pflanzenleben in uns. Wir tragen da tatsächlich in den Hautnerven ein ganzes Pflanzenreich in uns. Nur hört später, wenn wir in die Volksschule kommen, eigentlich dieses lebhafte Wachsen auf. Da verwenden wir die Kräfte, die vorher aus den Nerven geworden sind, zum Denken - die ziehen wir heraus, verwenden sie zum Denken. Das ist sehr interessant. Denn man glaubt gewöhnlich, die Nerven denken. Die Nerven denken nicht. Die Nerven kann man nur so zum Denken verwenden, daß man ihnen gewissermaßen ihr Licht abstiehlt. Die menschliche Seele stiehlt den Nerven das Licht ab, und was sie abstiehlt, das verwendet sie zum Denken. Es ist schon so. Derjenige, der wirklich über diese Sache nachdenkt, der kommt in jedem Punkt dazu, einfach die selbständig wirkende Seele anzuerkennen.

Nun, sehen Sie, solche im Innern wachsende Zwiebelpflanzen, die haben wir eigentlich so ziemlich mit allen Tieren gemeinschaftlich. Alle Tiere, selbst die niedersten, die eigentlich nur, sagen wir, aus Schleimmasse bestehen, die etwas gestaltet sind, sehen und so weiter, alle diese Tiere haben eigentlich solche Gefühlsnerven, die in einer Art von Zwiebeln an der Oberfläche auslaufen. Je weiter wir nun zum Menschen heraufkommen, desto mehr werden einzelne von diesen Nervenzwiebeln dann besonders umgestaltet. Und solche umgestaltete Hautnerven sind zum Beispiel unsere Geschmacksnerven.

Also vorne an der Zunge — das habe ich schon das letzte Mal erwähnt —, da haben wir diese Gefühlsdrüsen. Daher ist die Zunge vorne so stark empfindlich. Aber hinten an der Zunge, da schmecken wir, und am weichen Gaumen schmecken wir und so weiter; also an Gaumen und Zunge hinten, da sind auch solche Zwiebelchen eingestreut. Aber die sitzen nämlich in einem Grübchen darinnen. Und in diesen Grübchen darinnen, da ist es diese Zwiebel, die in die Nerven hineingeht; die schiebt sich einfach als eine Zwiebel in die Lederhaut herein. Im hinteren Teil der Zunge bildet sich erst so ein kleines Grübchen; da schiebt sich dann in dieses Grübchen hinein, bis an die Oberfläche heraus, diese Zwiebel, so daß man die Wurzeln da durchschauen sieht. Da sind also an der Zungenwurzel furchtbar viele solche kleine Gruben, und in jeder Grube wächst auch von unten herauf solch eine Zwiebel, und dadurch können wir schmecken.

Und mit dem Gefühl, also mit diesen Zwiebeln, die an unserer Körperoberfläche sind, können wir überall alles wahrnehmen. Aber Sie werden ja selber wissen, daß man sich an das nicht viel erinnert. Wenn ich einen rauhen Stuhl habe, so weiß ich mit meinem Gefühl, daß er rauh ist, weil ich mit so und so viel Zwiebeln, die immer sich verändern, fühle, daß er rauh ist. Ich kann das, aber unser Gedächtnis strengt sich nicht viel an durch dieses Gefühl, strengt sich auch nicht sehr beim Geschmack an - wohl ein bißchen besser, aber unbewußt. Die Menschen, die Feinschmecker sind, wissen ja schon immer vorher, was gut ist, nicht erst, wenn sie es kosten; deshalb verschaffen sie sich es auch.

Nun, diese Zwiebeln gehen durch das Rückenmark, gehen direkt zum Gehirn und bilden dort ihre Blüte. Alles, was wir schmecken wollen, muß aber zuerst durch den Mundschleim aufgelöst werden. Nichts können wir schmecken, was nicht erst in Wasser verwandelt worden ist. Dann können wir aber fragen: Was schmeckt denn da eigentlich? Wir würden überhaupt nicht schmecken können, wenn wir nicht selber Wasser in uns hätten. Unser fester Mensch, das, was fest an uns ist, das schmeckt nämlich nicht. Es ist so, daß wenn da hier die Zungenzwiebel ist, da geht erst das Wasser um die Zungenzwiebel; das innere Wasser, aus dem der Mensch besteht, vermischt sich mit demjenigen, was in der Speise aufgelöst wird, und wir können sagen: unser eigenes Wasser vermischt sich mit dem Wasser von außen. Es ist also gar nicht der feste Mensch, der schmeckt, sondern wir bestehen doch, wie ich Ihnen schon gesagt habe, etwa zu neunzig Prozent aus Wasser. Das Wasser machen wir besonders flüssig hier um die Zungenwärzchen. Wie aus einem Geysir, wie aus einer solchen Erdgrube das Wasser aufspritzt, so haben wir wirklich solches Wasseraufspritzen an unserer Zungenwurzel.

Wenn ich Wasser, das Schleim des Mundes ist, ausspucke, dann ist es nicht mehr zum Menschen gehörig, es hat sich abgetrennt; aber solange das Wasser in meinen Zungengrübchen drinnen ist, da gehört es zu mir als Mensch, geradeso wie meine Muskeln zu mir gehören. Ich bestehe nicht bloß aus festen Muskeln, sondern ich bestehe aus Wasser. Und dieses Wasser ist es, was eigentlich schmeckt, weil es sich vermischt mit dem, was als Wasser von außen kommt.

Schleckt man Zucker — wie ist denn das? Wenn man Zucker schleckt, so treibt man Wasser von innen in die Zungengrübchen (Geschmackswärzchen), und in dieses Wasser fällt der aufgelöste Zucker herein, und der flüssige Mensch durchzieht sich mit dem Zucker, und da ist es ihm halt wohl, während der Zucker sich in seiner eigenen Flüssigkeit ausbreitet, weil der Zucker sich erst fein in diesen Zungengrübchen absondert.

Nun, sehen Sie, wir Menschen, wir können nur schmecken. Aber warum können wir nur schmecken? Hätten wir Flossen und wären wir Fische — es wäre auch ein interessantes Dasein —, dann würde jedesmal, wenn wir schmecken, der Geschmack auch durch die Flossen wirken. Aber wir müßten im Wasser schwimmen, damit wir recht gut immer alles aufgelöst hätten, auch die feinen Stoffe, denn der Fisch schmeckt alle die feinen Stoffe, die im Wasser sind, und nach seinem Geschmack richtet er sich; das geht immer gleich in die Flossen herein, und er schwimmt weiter mit den Flossen. Wenn ihm also von irgendeiner Seite etwas Angenehmes zuschwimmt, so schmeckt er das, und seine Flossen bewegen sich gleich dahin.

Wir Menschen können das nicht, was die Fische können. Wir haben keine Flossen. Die sind ganz verkümmert bei uns. Jetzt können wir den Geschmack nicht dazu verwenden, um uns zu bewegen; und deshalb verinnerlichen wir ihn. Die Fische haben einen feinen Geschmackssinn, aber keinen innerlichen Geschmack. Wir Menschen verinnerlichen den Geschmack; den erleben wir, währenddem die Fische eigentlich in dem ganzen Wasser drinnen leben, mit dem Wasser zusammen den Geschmack erleben. Daher ist es bei den Fischen auch so — die Leute haben sich darüber gewundert —, daß sie weit ins Meer hinausschwimmen, wenn sie ihre Eier absetzen wollen. Sie schwimmen sogar in den Atlantischen Ozean, an ganz andere Erdflächen. Und die Jungen kommen dann langsam wieder zurück in die europäischen Flüsse. Warum ist das so? Nun, die europäischen Flüsse, in denen die alle herumschwimmen, die sind Süßwasser. In dem süßen Wasser können die Eier nicht ausreifen. Die Fische schmecken, wie ein bißchen Salz herankommt gegen die Mündung zu; das schmecken diese Fische und schwimmen ins Meer hinaus. Und wenn auf der anderen Seite die Sonne anders auf die Erde scheint, schmecken sie das, und nach dem Geschmack schwimmen sie über die halbe Erde hinüber. Und die Jungen erst wiederum schmecken sich zurück, dahin, wo die Alten gelebt haben. Die richten sich also überhaupt nach dem Geschmack.

Das ist eine außerordentlich interessante Sache: das Wasser, das auf der Erde in Flüssen fließt und im Meer ist, das ist eigentlich voller Geschmack. Und wie die Fische da drinnen herumschwimmen, das ist eigentlich fortwährend dasjenige, was der Geschmack des Wassers tut. Der Geschmack des Wassers ist es eigentlich, der die Fische zum Schwimmen bringt, der ihnen auch die Richtungen gibt. Natürlich, wenn auf irgendein Stückchen Wasser die Sonne drauf scheint, so wird durch diese Sonnenwärme dort gleich alles das, was im Wasser drinnen ist, fein aufgelöst. Das wird in einen andern Geschmack verwandelt. Und deshalb sieht man die Fische da drinnen zappeln. Das ist alles der Geschmack.

Ja, meine Herren, diese Geschichte ist eigentlich sehr merkwürdig. Wir Menschen sollten eigentlich auch schwimmen, wenn wir uns bloß nach dem Geschmack richten würden. Wenn ich den Zucker schmecke, so will eigentlich etwas in mir, nämlich der wässerige Mensch, dorthin schwimmen. Der Drang zum Schwimmen ist schon da. Der Mensch will eigentlich fortwährend nach dem Geschmack schwimmen. Nur der feste Körper, der hält ihn wieder zurück. Und von dem, was da schwimmen will und nicht kann — wir haben eigentlich fortwährend einen Fisch in uns, der schwimmen will und nicht kann -, von dem, was nicht schwimmen kann, behalten wir das zurück, was unser innerlich Seelisches von dem Geschmack ausmacht. Denn mit dem Geschmack leben wir eigentlich ganz im Ätherleib drinnen, nur daß der Ätherleib festgehalten wird durch das Wasser, das wir haben, und das Wasser wird wieder festgehalten. Und es ist das Natürlichste, sich zu sagen: Der Mensch hat einen Ätherleib, der eigentlich gar nicht zum Gehen auf der Erde veranlagt ist, der nur zum Schwimmen veranlagt ist, der eigentlich ein Fisch ist, nur daß ihn der Mensch aufstellt, und dadurch wird er etwas anderes. Aber der Mensch hat diesen Ätherleib in sich, der eigentlich nur in seinem flüssigen Menschen drinnen ist. Und es ist schon so, daß eigentlich der Mensch fortwährend gern schwimmen möchte, schwimmen in dem feinen Wasser, das ja auch immer in der Luft ist. Da möchten wir eigentlich fortwährend schwimmen. Aber wir verwandeln dieses Schwimmen in das innere Geschmackserlebnis.

Sehen Sie, solche Sachen, die führen einen erst dahin, den Menschen zu begreifen. Das können Sie in keinem heutigen wissenschaftlichen Buch finden, weil die Menschen eigentlich nur den Leichnam des Menschen beobachten, nicht den lebenden Menschen. Wenn wir natürlich den Leichnam vor uns haben, so will der nicht mehr schwimmen. Aber der beteiligt sich auch nicht am Leben. Wir beteiligen uns deshalb am Leben, weil wir eigentlich alles zusammen, was in der Welt ist, sind. Wir sind Fische, und der Dunst, der Wasserdunst, der da eigentlich ist, der ist uns ja ähnlich. Aber in dem wollen wir fortwährend schwimmen, und daß wir es nicht können, das bewirkt, daß wir das alles nach innen gießen und schmecken. Die Fische sind ja eigentlich sehr kalte Wesen. Sie könnten wunderbar schmecken, was alles im Wasser aufgelöst ist. Sie tun es nicht, weil sie gleich ihre Flossen bewegen. Würden die Flossen der Fische weggenommen, dann würden die Fische höhere Tiere werden; sie würden anfangen zu schmecken.

Nun, wieder anders umgewandelte Zwiebeln, Nervenzwiebeln, sind die, von denen ich Ihnen das letzte Mal, am Samstag, geredet habe. Die gehen in die Nasenschleimhaut hinein. Aber diese Zwiebeln, die sind nun nicht in einem Grübchen, wo immer das Wasser sprudelt, sondern die gehen ganz an die Oberfläche heraus. Daher können diese Zwiebeln nur dasjenige wahrnehmen, was an sie herangeht, das heißt, wir müssen den Rosenduft herankommen lassen an die Nervenzwiebeln unserer Nase; nachher riechen wir ihn. So ist ein Stückchen vom menschlichen Leib dazu verwendet, daß es diese Zwiebeln, die aber über unsere ganze Haut ausgebreitet sind, besonders dazu ausbildet, dasjenige, was in der Luft liegt, aufzunehmen.

Aber, meine Herren, trotzdem, wenn Sie in der Nase des Menschen solch eine Zwiebel nehmen, die da in die Nase hereingeht, ja, da ist sie von der äußeren Luft umweht, die weht heran; aber außerdem weht von innen heraus die Atemluft. Es geht ja fortwährend der Atem durch die Nase. In diesem Atem drinnen lebt der Luftmensch. Wie ich Ihnen früher gesagt habe, wir sind Wasser, so sind wir auch Luft. Wir haben wirklich nicht bloß die Luft zum Spaß in uns. Geradeso wie ich Wasser in mir habe, so habe ich Atem in mir; der ist nicht fest. Und wie wenn ich meine Hand ausstrecke und fühle, ich habe etwas Festes ausgestreckt, so strecke ich, was ich in meinem Luftorganismus habe, in die Nase hinein. Das ist eine luftförmige Hand. Und da erfasse ich den Rosenduft oder den Nelkenduft. Ich bin nämlich nicht bloß ein fester Mensch, sogar nur zu zehn Prozent fester Mensch; ich bin eine Wassersäule, und fortwährend ein Luftmensch. Solange die Luft in uns ist, sind wir sie nämlich selber. Da lebt sie, die Luft. Und wir strecken diese Lufthände durch unsere Nase, strecken sie entgegen dem Rosenduft und Nelkenduft, natürlich auch dem Mistduft. Das greifen wir an; aber nicht mit der Hand greifen wir das an, sondern durch die Zwiebeln, die von innen den Atem anziehen, so daß der Atem den Rosenduft angreifen kann.

Das ist also so, daß es sich sogar beim Hund zeigt: Da riecht die Nase, und gleich wedelt der Schwanz, habe ich Ihnen gesagt. Geradeso wie beim Fisch die Flosse in Bewegung kommt, so kommt beim Hund der Schwanz in Bewegung. Aber was will denn der Schwanz tun, der nur wedeln kann? Es ist nämlich interessant: der Hundeschwanz kann nur wedeln. Aber was will er denn eigentlich tun? Sehen Sie, meine Herren, der Hund würde nämlich etwas ganz anderes tun; wenn er nicht ein Hund, sondern ein Vogel wäre, würde er nämlich fliegen unter dem Einfluß des Geruches! Geradeso wie der Fisch schwimmt, so würde der Hund fliegen, wenn er ein Vogel wäre. Nun, der Hund, der hat keine Flügel, und so benutzt er das Ersatzorgan und kann bloß wedeln. Es reicht ihm nicht; aber es ist dieselbe Kraftentfaltung. Und bei uns Menschen ist es auch so. Weil wir fortwährend fein riechen — wir bemerken es gar nicht —, wollen wir eigentlich immer fliegen. Geradeso wie wir fortwährend schwimmen wollen, wollen wir fortwährend fliegen.

Denken Sie sich nur einmal die Schwalben. Die Schwalben leben bei uns im Sommer. Da gefällt ihnen dasjenige, was aufsteigt als Düfte aus den Blumen und so weiter. Das gefällt ihnen eben im Geruchsorgan, und da bleiben sie da. Wenn aber bei uns der Herbst kommt, oder der Herbst nur herannaht, näher herankommt, ja, wenn da die Schwalben untereinander sich verständigen könnten, dann würden sie sagen: Da fängt es an, übel zu riechen! Der Geruchssinn der Schwalbe, der ist furchtbar fein. Und wie ich Ihnen gesagt habe, daß die Menschen bis Arlesheim wahrnehmbar sind, so ist der Geruch, der dem Süden entströmt, für die Schwalben wahrnehmbar, wenn der Herbst herankommt; der breitet sich aus bis nach dem Norden. Da unten riecht es gut; da oben fängt es an, mistig zu riechen! — Da fangen die Schwalben an, dahin zu fliegen, wo der gute Geruch sie anzieht, denn der kommt herauf vom Süden nach dem Norden.

Meine Herren, es sind ganze Bibliotheken geschrieben worden über den Vogelflug. Aber die Wahrheit ist, daß die Vögel selbst bei diesen großen Wanderungen im Herbst und Frühling sich nach der furchtbar feinen Verteilung der Gerüche in der ganzen Luftschichte unserer Erde richten. Durch ihre Geruchsorgane werden die Schwalben nach dem Süden geführt, und dann wiederum nach dem Norden. Wenn bei uns der Frühling kommt, da fängt es wiederum da unten an, mistig zu riechen für die Schwalben. Die feinen Frühlingsdüfte kommen zu ihnen nach dem Süden, und da fliegen sie herauf nach dem Norden. Es ist wirklich so, daß die Erde eigentlich ein ganzes lebendiges Wesen ist, und die anderen Wesen gehören dazu.

Sehen Sie, in unserem Leibe ist es so eingerichtet, daß das Blut zum Kopfe fließt und wiederum wegfließt. Auf der Erde ist es so eingerichtet, daß gewisse Vögel, die Zugvögel, nach dem Aquator hinfliegen und wieder zurückfliegen. Die Luft, die wir atmen, die treibt das Blut zum Kopfe. Wir sind ganz durchsetzt von Geruch, insofern wir ein Luftmensch sind. Und derjenige, der zum Beispiel, sagen wir, über den Acker geht, der gerade gemistet worden ist, der geht eigentlich mit seinem Luftmenschen dahin; denn der feste Mensch und der flüssige Mensch, die merken nichts von dem Miste. Aber der luftförmige Mensch, der merkt das, und da entsteht in ihm — aus dem, was ich gesagt habe, werden Sie es schon begreifen —, da entsteht in ihm begreiflicherweise eigentlich der Drang, er möchte fortfliegen. Eigentlich möchte der Mensch fortwährend wegfliegen in die Luft hinauf, wenn über dem Acker der Mist stinkt. Das kann er nicht, weil er keine Flügel hat. Und deshalb verinnerlicht der Mensch dasjenige, wovon er nicht fortfliegen kann. Er verinnerlicht es. Es wird seelisch. Und die Folge davon ist, daß der Mensch, insofern er Luftmensch ist, ganz innerlich erfüllt wird von dem Mistgeruch, von den gasförmig, dunstförmig gewordenen Ausdünstungen des Mistes. Er wird selber ganz mistig. Und da sagt er: das ekelt ihn. Seelisch ist das der Ekel.

Geradeso wie in dem flüssigen Menschen dieser feinere Mensch lebt, den man eigentlich dem flüssigen Menschen abstiehlt, durch den man schmeckt, so lebt er in diesem luftförmigen Menschen, den wir in uns fortwährend erneuern, weil wir einatmen, ausatmen, den wir wieder abstoßen, der eigentlich in jedem Augenblick geboren wird, achtzehnmal geboren wird in einer Minute, wiederum stirbt, achtzehnmal in einer Minute, Sonst, nicht wahr, werden wir geboren, werden unter Umständen alte Kerle; es dauert jahrelang für den festen Menschen, bis er stirbt. Beim luftförmigen Menschen ist es so: der wird achtzehnmal in der Minute geboren beim Einatmen, und stirbt wieder beim Ausatmen. Es ist ein fortwährendes Geborenwerden und Sterben. Es ist geradeso. Und das, was da drinnen nun herausgenommen wird, das nennen wir den Astralleib, damit wir ein Wort haben. Aber es ist eben da. Und wie ich Ihnen das letzte Mal gesagt habe, daß dasjenige, was eigentlich da unten sein müßte, hinaufgeschoben, hinaufgeschoppt wird und dem Geruchssinn entgegenwächst, was uns da zum Denken bewegt, ist eben unser Astralleib, der das da hinaufschoppt. Kein Mensch kann das Gehirn richtig verstehen, das der Nase entgegenwächst durch den Astralleib, der eben nicht die ganze Sache so betrachtet, wie ich sie jetzt betrachtet habe. Das ist das, was aus einer richtigen Betrachtung unserer Sinne gerade hervorgeht.

Wir Menschen möchten eigentlich fortwährend fliegen durch unsern Geruch. Aber wir können nicht fliegen, weil wir höchstens diese festen Schulterblätter haben. Aber der Vogel kann fliegen. Warum kann der Vogel fliegen? Meine Herren, der Vogel hat etwas ganz Eigentümliches, wodurch er fliegen kann; der Vogel hat nämlich hohle Knochen. Da ist Luft drinnen. Und die Luft, die er durch sein Geruchsorgan aufnimmt, die kommt als Luft in Verbindung mit der Luft, die er in seinen Knochen drinnen hat. Der Vogel ist also wirklich hauptsächlich ein Luftwesen. Das Hauptsächlichste am Vogel ist eigentlich das, was aus Luft besteht. Das andere, das wächst nur an. Und wenn Sie einen Vogel anschauen, der viel Federn hat, werden Sie sehen, daß eigentlich alles abgedorrt ist. Aber das Wichtigste in ihm ist, selbst beim Strauß, daß in jeder solcher Flaumfeder noch etwas Luft drinnen ist, und mit dieser ganzen Luft, aus der er selber besteht, steht die äußere Luft selber in Verbindung. Der Strauß geht ja noch, weil er sonst zu schwer ist, um zu fliegen; aber die anderen Vögel fliegen eben.

Wir Menschen haben nur diese Schulterblätter, die noch dazu höchst ungeschickt, ganz festgefügt sind, an unserem Rücken. Mit denen möchten wir zwar fortwährend fliegen, aber wir können nicht, und so schieben wir das ganze Rückenmark ins Gehirn hinein und fangen an zu denken. Die Vögel denken eben nicht. Man braucht nur richtig die Vögel zu betrachten, so wird man sehen, daß alles bei ihnen in den Flug hineingeht. Es schaut sehr gescheit aus; aber das macht es eigentlich, was in der Luft ist. Die Vögel denken nicht. Wir denken, weil wir nicht fliegen können. Unsere Gedanken sind eigentlich die umgewandelten Flugkräfte. Das ist das Interessante am Menschen, daß sein Geschmack sich in die Gefühlskräfte verwandelt. Wenn ich sage: Ich fühle mich wohl -, so möchte ich eigentlich schwimmen. Aber ich kann nicht schwimmen, und da verwandelt sich das in das innere Wohlgefühl. Wenn ich sage: Mich ekelt -, so möchte ich eigentlich fliegen. Ich kann aber nicht fliegen; so verwandelt sich das in den Gedanken: Mich ekelt, der Mistgeruch ist ekelhaft. - Und so sind alle unsere Gedanken eigentlich im Grunde genommen umgewandelte Gerüche. Und der Mensch ist deshalb ein so vollkommener Denker, weil er all das, was der Hund in der Nase erlebt, im Gehirn erlebt mit dem, was ich da vorstelle. Wir verdanken als Menschen eigentlich unserer Nase außerordentlich viel. Sehen Sie, wenn Menschen keinen Geruch haben, wenn ihre Nasenschleimhaut also verkümmert ist — es gibt solche Menschen, die keinen Geruch haben -, fehlt ihnen eigentlich auch ein gewisses Erfindungsvermögen. Die können nur durch dasjenige denken, was sie vererbt haben von ihren Eltern. Es ist ja immer gut, daß wir auch etwas ererben, sonst könnten wir überhaupt nicht leben, wenn wir nicht alle Sinne ausgebildet hätten. Der Blindgeborene hat auch das Innere, was das Auge hat, ererbt, und hat es überhaupt dadurch, daß er nicht bloß ein fester Mensch ist, sondern auch ein flüssiger und ein luftförmiger Mensch ist.

Wir haben aber jetzt gesehen, wie merkwürdig das ist: Das Feste, das nehmen wir mit unserem Gefühl wahr durch die Zwiebeln, die überall nach der Haut hingehen; und das Flüssige, das Wässerige, das nehmen wir mit unserem Geschmackssinn wahr. Das Luftförmige, das Gasförmige, das nehmen wir wahr durch unsere Zwiebeln, die in die Nasenschleimhaut gehen. Wir spüren auch noch etwas anderes um uns herum, aber so im ganzen mehr: das ist Wärme und Kälte. So wie wir eigentlich als Mensch ein Stückchen fester Mensch sind, ein Stückchen Wasser als Mensch, ein Stückchen Luft als Mensch, so sind wir auch ein Stückchen Wärme. Wir sind ja auch wärmer als die äußere Welt.

Aber sehen Sie, die Wissenschaft weiß wirklich nicht richtig, daß das Schmeckende eigentlich der wässerige Mensch ist, und das Riechende der luftförmige Mensch ist. Die Wissenschaft denkt immer nach darüber: Da kommen die Geschmacksnerven in die Zungenwärzchen hinein, und eigentlich ist alles so, als wenn der Nerv schmecken oder riechen würde. Das ist aber ein Unsinn. Im Munde schmeckt das Wasser vom Wassermenschen, und in der Nase schmeckt die Luft oder riecht die Luft vom Luftmenschen. Und wenn wir Kälte oder Wärme wahrnehmen, so wird diese durch das Stückchen Wärme wahrgenommen, das wir selber sind. Direkt die Wärme in uns nimmt die äußere Wärme wahr. Und das ist eben beim Wärmesinn der Unterschied von den anderen Sinnen, daß es die Wärme selber ist, die von allen Organen abgesondert wird. Wir haben da als Menschen ein Stückchen Wärmewelt in uns, und diese Wärmewelt nimmt die andere Welt um sich herum wahr. Nur, wenn wir etwas angreifen, das heiß oder kalt ist, nehmen wir es natürlich nur an der Stelle wahr, wo wir es angreifen. Aber wenn es im Winter kalt ist, nehmen wir die ganze Kälte um uns herum wahr als Mensch, sind ein ganzes Sinnesorgan, und ebenso im Sommer die Hitze.

So sehen wir schon, wie falsch die Wissenschaft eigentlich auf diesem Gebiete ist. Wenn Sie irgendwo ein wissenschaftliches Buch aufschlagen, so ist es so, als wenn der ganze Mensch so irgendein festgestaltetes Gebilde wäre. Es werden eben hineingezeichnet die Knochen, die Muskeln, die Nerven. Aber das ist ja alles Unsinn. Das ist ja nur ein Zehntel von dem Menschen überhaupt. Das andere ist ja zu neunzig Prozent Wasser, und auch Luft ist da drinnen, und sogar ein Stückchen Wärme. Also eigentlich müßte in die Figuren, die da gezeichnet werden durch die materialistische Wissenschaft ein zweiter Mensch hineingezeichnet werden, der Wassermensch, und ein dritter Mensch, der Luftmensch, und ein vierter Mensch, der Wärmemensch. Anders ist der Mensch gar nicht zu begreifen. Und nur dadurch, daß wir auch ein Stückchen Weltenwärme sind, wärmer als unsere Umgebung, fühlen wir uns selbständig in der Welt. Wären wir so kalt wie ein Fisch oder eine Schildkröte, so hätten wir kein Ich, würden wir gar nicht zu uns «Ich» sagen. Geradeso wie wir niemals denken könnten, wenn wir nicht den Geruch in uns umgewandelt hätten, also keinen Astralleib hätten, so hätten wir kein Ich, wenn wir nicht ein Stückchen Wärme in uns hätten.

Sie können jetzt sagen: Aber die höheren Tiere haben ja auch eine eigene Wärme. Ja, meine Herren, diese höheren Tiere, die tragen auch an dieser Wärme! Die höheren Tiere, die wollen nämlich ein Ich werden und können es nicht. So wie wir nicht schwimmen oder fliegen können, so möchten die höheren Tiere ein Ich werden und können es nicht. Und deshalb sind diese höheren Tiere so gebildet, wie sie eben sind. Man sieht ihnen an, sie möchten eigentlich ein Ich werden und können es nicht. Und dadurch haben sie ihre verschiedenen Gestalten.

Aber wir Menschen, wir haben einmal diese vier Teile in uns: den festen Menschen, der der eigentlich physische Mensch ist, der materielle Mensch; den wässerigen Menschen, der den Lebenskörper, den Ätherkörper, den feineren Körper in sich trägt; den luftförmigen Menschen, der den astralen Körper in sich trägt, der fortwährend stirbt und wieder erneuert wird im Physischen, aber als astralischer Mensch bleibt das ganze Leben hindurch; und das Stückchen Wärme, das wir in uns haben, das ist der Ich-Mensch.

Der Wärmesinn ist ja eigentlich auch auf den ganzen Menschen verteilt, aber er ist fein. Und die Wissenschaft, die macht da etwas Eigentümliches durch. Wenn man den Menschen rein materiell absucht, so findet man halt eben diese Gefühlszwiebeln, die ich Ihnen geschildert habe. Nun sagen sich die Leute: Wenn ich also die Schachtel hier angreife, da fühle ich durch diese Gefühlszwiebeln die Schachtel, das Feste. Wenn die Schachtel recht kalt ist, da müßte ich die Kälte ja auch durch eine solche Gefühlszwiebel fühlen. Ja, da suchen sie fortwährend diese Wärmezwiebeln und diese Gefühlszwiebeln und finden sie nicht! Alle Augenblicke kommt einer und untersucht ein Stückchen Haut. Da sehen manche von diesen Gefühlszwiebeln ein bißchen anders aus, und da meint man, die gehören nun zu etwas anderem. Aber das ist ein Unsinn. Wärmezwiebeln sind nicht da, weil der ganze Mensch eben diese Wärme wahrnimmt. Wir haben nur diese Zwiebeln, die für das Feste, für das Flüssige, also für den Geschmackssinn, und für das Luftförmige, also für den Geruchssinn da sind. Wo der Wärmesinn beginnt, da sind wir schon außerordentlich leicht-sinnige Wesen, nämlich bloß ein Stückchen Wärme, das eben die äußere Wärme wahrnimmt. Wenn wir von einer solchen Wärme umgeben sind, daß wir gerade recht zu uns «Ich» sagen können, dann fühlen wir uns wohl; wenn wir aber von Kälte umgeben sind, daß wir frieren, so nimmt uns die äußere Kälte dieses Stückchen Wärme, das wir sind, weg. Unser Ich will uns verloren gehen. Die Bangigkeit in unserem Ich, die macht uns dieses Stückchen Kälte wahrnehmbar. Wenn einer friert, so ist er eigentlich immer bange um sein Ich, und er hat einen Grund, bange zu sein, denn dann schiebt er das Ich schneller aus sich heraus, als er eigentlich soll.

Das sind eben die Dinge, die uns nach und nach immer mehr hinführen von den Betrachtungen des Physischen zu den Betrachtungen des Nichtphysischen, des Nichtmateriellen. Und auf diese Weise können wir erst den Menschen verstehen.

Wir werden nun, nachdem wir das vorausgeschickt haben, recht interessante Betrachtungen daran knüpfen können. Damit wollen wir das nächste Mal dann fortsetzen.

Seventh Lecture

Gentlemen, today we want to finish answering the question from the other day.

You see, through their skin, humans are actually sensory organs in their entirety. Human skin is something extraordinarily complex, something truly wonderful. If you examine the skin from the outside in, the outermost layer is a transparent layer called the stratum corneum. It is only transparent in white Europeans, while the stratum corneum of Negroes, Indonesians, and Malaysians is interspersed with pigment granules and therefore colored. For us Europeans, however, it is a transparent skin, the stratum corneum of the epidermis. It is called the stratum corneum because it is actually made of the same substance, only arranged slightly differently, as the horns of animals and our nails and hair, because our nails actually grow out of this outer stratum corneum of the skin. Underneath this horny layer is the so-called dermis, which actually consists of two layers, an upper layer (see drawing, red) and a lower layer, which I will perhaps color green here. So we humans are actually covered and clothed with a triple skin, with an outer horny layer, a middle dermis, and an inner lower dermis.

Now, you see, this lowest layer, the dermis, shown here in green, is actually there to nourish the entire skin. The nutrients for the skin are stored there. But the middle layer, which I have marked in red here, is filled with all kinds of stuff; above all, it is filled with muscle fibers. But what is particularly important for us is that inside this skin there are lots of little onions, one next to the other, so that everywhere you look there are little onions (yellow), one next to the other, so that everywhere you look there are little onions. We have thousands and thousands of these in our skin, these little things, which I can call bulbs; because a bulb is particularly distinguished by the fact that it has layers, the outer layer, the second layer, the third layer, and so on, many layers. And these little bodies here, which were discovered by an Italian, Pacini, and are therefore called Pacini bodies, these little bodies have such onion skins, consisting of such, so that the onion skin is on the outside, and the other, thinner part goes to the inside, as I have also drawn on the outside.

Now, you see, around such tiny little bodies—they are tiny, you can only see them through microscopes—there are twenty to sixty such layers! You can imagine how tiny that is. So humans are actually such that they have these tiny little bulbs scattered all over the surface of their bodies. Most of them, not only in snakes but also in humans, are on the tip of the tongue. It's really funny: most of them are on the tip of the tongue! Many are also found on the fingertips, on the inside of the palm, and on other parts of the body; but, as I said, most are found on the tip of the tongue. If you compare, for example, the many small bulbs on the tip of the tongue with those on the fingertips, there are about seven times fewer on the fingertips than on the tip of the tongue.

You see, a nerve fiber emanates from each of these bulbs. The nerve fiber first travels along some path — it finds its own way — into the spinal cord, and from the spinal cord to the brain. And you can imagine: all these nerve fibers emanate from the brain, going everywhere in the body, and forming these bulbs on the surface of the body, including on the tongue — everywhere. So I can also draw the human being in such a way that all these nerve fibers begin in the brain and go everywhere, and ultimately form these bulbs in the skin, in the cornea.

This is very interesting because you can really imagine it—and you imagine something correct when you can really imagine it—: Suppose there is the ground (see drawing on the left); inside it we have a real onion; it grows out of the ground and forms the onion flower above. Yes, gentlemen, it is similar in the human body.

There (see drawing on the right) are the bulbs inside, and the stem is only inside — in the nerves (of the tongue) it is also short, but in the other nerves it is sometimes terribly long; the bulbous nerves that go from the feet through the spinal cord to the brain are terribly long. And of all the things we have onions for in the skin, we actually have the blossom inside our skull. So you can imagine: the whole human being is actually a kind of soil in his skin, only curiously shaped, but he is a kind of soil. On the outside, he has the horny layer, in which all kinds of crystals and so on are stored. These are the solid body masses at the bottom, above which is the “humus” layer. In humans, only from the outside to the inside, under the hard cornea, is the dermis. That is the soil. And all these bulbs grow out of the soil and have their blossoms in the brain. They have their stems reaching into the brain and have their blossoms in the brain.

Yes, gentlemen, with us older folks, it is the case that one can no longer really follow the whole story, except when sleeping; but with children this is even more so. It is the case that as long as their minds are not awakened, that is, during their entire first year, children have a very lively onion activity within themselves, in their nerves. And just as the sun shines on the flowers of the bulbs, so the light shines into the child, who does not yet translate the external light it receives into the mind, and this is indeed as if the sun were spreading in the head and unfolding all these bulb flowers. In fact, a whole plant life grows in our nerves. We actually carry a whole plant kingdom within us in our skin nerves. But later, when we start elementary school, this lively growth actually stops. We then use the powers that previously came from the nerves for thinking — we draw them out and use them for thinking. This is very interesting. Because people usually believe that the nerves think. The nerves do not think. The nerves can only be used for thinking in such a way that their light is stolen from them, so to speak. The human soul steals the light from the nerves, and what it steals, it uses for thinking. That is how it is. Anyone who really thinks about this matter will come to recognize the independently acting soul in every respect.

Now, you see, we actually have these onion-like structures growing inside us in common with pretty much all animals. All animals, even the lowest ones, which actually consist only, let's say, of mucus, which are somewhat formed, can see, and so on, all these animals actually have sensory nerves that emerge on the surface in a kind of onion structure. The closer we get to humans, the more some of these nerve bulbs are specially transformed. And such transformed skin nerves are, for example, our taste buds.

So at the front of the tongue — I already mentioned this last time — we have these sensory glands. That is why the front of the tongue is so sensitive. But at the back of the tongue, we taste, and on the soft palate we taste, and so on; so on the palate and tongue at the back, there are also such bulbs scattered. But they sit in a dimple inside. And in these dimples inside, there is this bulb that goes into the nerves; it simply pushes itself into the dermis as a bulb. First, a small dimple forms at the back of the tongue; then this bulb pushes its way into this dimple, up to the surface, so that you can see the roots through it. So there are a tremendous number of such small pits at the root of the tongue, and in each pit such a bulb grows up from below, and that is how we can taste.

And with our sense of touch, with these bulbs on the surface of our body, we can perceive everything everywhere. But you yourself will know that we don't remember much of this. When I sit on a rough chair, I know with my sense of touch that it is rough, because I feel with so many bulbs, which are constantly changing, that it is rough. I can do that, but our memory doesn't exert itself much through this feeling, nor does it exert itself much when it comes to taste – perhaps a little better, but unconsciously. People who are gourmets always know in advance what is good, not only when they taste it; that is why they procure it for themselves.

Now, these onions go through the spinal cord, go directly to the brain, and form their blossom there. However, everything we want to taste must first be dissolved by the mucus in our mouths. We cannot taste anything that has not first been transformed into water. But then we can ask: What actually tastes good? We would not be able to taste anything at all if we did not have water in us ourselves. Our solid human being, that which is solid in us, does not taste anything. When the tongue bulb is there, the water first goes around the tongue bulb; the inner water that makes up the human being mixes with that which is dissolved in the food, and we can say that our own water mixes with the water from outside. So it is not the solid human being that tastes, but, as I have already told you, we consist of about ninety percent water. We make the water particularly liquid here around the papillae on the tongue. Just as water sprays out of a geyser, as if from a pit in the earth, so we really have such water spraying at the root of our tongue.

When I spit out water, which is mucus from the mouth, it no longer belongs to the human being; it has separated itself. But as long as the water is inside the pits of my tongue, it belongs to me as a human being, just as my muscles belong to me. I am not made up of solid muscles alone, but I am made up of water. And it is this water that actually tastes good, because it mixes with the water that comes from outside.

What happens when you lick sugar? When you lick sugar, you drive water from inside into the taste buds, and the dissolved sugar falls into this water, and the liquid human being permeates itself with the sugar, and it feels good to it while the sugar spreads in its own liquid, because the sugar first secretes itself finely into these taste buds.

Well, you see, we humans can only taste. But why can we only taste? If we had fins and were fish—which would also be an interesting existence—then every time we tasted something, the taste would also affect our fins. But we would have to swim in water so that we could always dissolve everything properly, even the fine substances, because fish taste all the fine substances that are in the water, and they orient themselves according to their taste; this always goes straight into their fins, and they swim on with their fins. So when something pleasant swims towards them from any direction, they taste it and their fins immediately move in that direction.

We humans cannot do what fish can do. We do not have fins. They are completely atrophied in us. Now we cannot use taste to move ourselves, and therefore we internalize it. Fish have a keen sense of taste, but no internal taste. We humans internalize taste; we experience it, while fish actually live in the water and experience taste together with the water. That is why fish swim far out into the sea when they want to lay their eggs, which has puzzled people. They even swim into the Atlantic Ocean, to completely different parts of the earth. And the young then slowly return to the European rivers. Why is that? Well, the European rivers in which they all swim are freshwater. The eggs cannot mature in the sweet water. The fish taste a little salt as they approach the mouth of the river; they taste it and swim out to sea. And when the sun shines differently on the other side of the earth, they taste it, and following the taste, they swim halfway around the world. And the young ones taste their way back to where the old ones lived. So they are guided entirely by taste.

This is an extremely interesting thing: the water that flows in rivers on earth and is in the sea is actually full of taste. And as the fish swim around in there, it is actually the taste of the water that is constantly at work. It is actually the taste of the water that makes the fish swim and also gives them direction. Of course, when the sun shines on any piece of water, the heat of the sun immediately dissolves everything that is in the water. It is transformed into a different taste. And that is why you see the fish wriggling around in there. It's all about taste.

Yes, gentlemen, this story is actually very strange. We humans should also swim if we were to follow our taste alone. When I taste sugar, something inside me, namely the watery human being, wants to swim there. The urge to swim is already there. Humans actually want to swim continuously according to their taste. Only the solid body holds them back. And from what wants to swim and cannot — we actually have a fish inside us that wants to swim and cannot — from what cannot swim, we retain what constitutes our inner soul from taste. For with taste we actually live entirely in the etheric body, only that the etheric body is held back by the water we have, and the water is held back again. And it is only natural to say to oneself: human beings have an etheric body that is not actually designed for walking on earth, but only for swimming; it is actually a fish, only that human beings stand it upright, and thereby it becomes something else. But human beings have this etheric body within them, which is actually only inside their liquid human being. And it is true that human beings actually want to swim all the time, to swim in the fine water that is always in the air. We actually want to swim all the time. But we transform this swimming into an inner taste experience.

You see, things like this are what lead us to understand human beings. You won't find this in any scientific book today, because people only observe the corpse of the human being, not the living human being. Of course, when we have the corpse in front of us, it no longer wants to swim. But it also no longer participates in life. We participate in life because we are actually everything that is in the world. We are fish, and the mist, the water mist that is actually there, is similar to us. But we want to swim in it all the time, and the fact that we cannot do so causes us to pour it all inside and taste it. Fish are actually very cold creatures. They could taste wonderfully everything that is dissolved in the water. They do not do so because they immediately move their fins. If the fins of the fish were taken away, the fish would become higher animals; they would begin to taste.

Now, another type of transformed bulb, the nerve bulb, is the one I talked to you about last time, on Saturday. These go into the nasal mucosa. But these bulbs are not in a dimple where water bubbles up, but rather they come right up to the surface. Therefore, these bulbs can only perceive what comes to them, which means we have to let the scent of roses reach the nerve bulbs in our nose; then we can smell it. So a small part of the human body is used to train these bulbs, which are spread over our entire skin, to absorb what is in the air.

But, gentlemen, nevertheless, when you take such a bulb in the human nose, which enters the nose, yes, it is blown by the outside air that blows in; but in addition, the breath air blows from within. Breath passes continuously through the nose. The air man lives inside this breath. As I told you earlier, we are water, and we are also air. We really don't just have air in us for fun. Just as I have water in me, I have breath in me; it is not solid. And just as when I stretch out my hand and feel that I have stretched out something solid, I stretch out what I have in my air organism into my nose. It is an air-shaped hand. And there I grasp the scent of roses or carnations. For I am not merely a solid human being, not even ten percent solid; I am a column of water and constantly an air-being. As long as the air is in us, we are it ourselves. That is where it lives, the air. And we stretch these air hands through our nose, stretch them toward the scent of roses and carnations, and of course also toward the scent of manure. We grasp it; but we do not grasp it with our hands, but through the bulbs that draw in the breath from within, so that the breath can grasp the scent of roses.

So this is how it is, even with dogs: the nose smells, and immediately the tail wags, as I told you. Just as the fish's fin moves, so the dog's tail moves. But what does the tail want to do, since it can only wag? It's interesting: the dog's tail can only wag. But what does it actually want to do? You see, gentlemen, the dog would do something completely different; if it were not a dog but a bird, it would fly under the influence of the smell! Just as the fish swims, the dog would fly if it were a bird. Well, the dog has no wings, so it uses its substitute organ and can only wag its tail. It is not enough for him, but it is the same display of power. And it is the same with us humans. Because we are constantly smelling things—we don't even notice it—we actually always want to fly. Just as we constantly want to swim, we constantly want to fly.

Just think of the swallows. The swallows live with us in the summer. They like the scents that rise from the flowers and so on. They like what they smell, and so they stay here. But when autumn comes, or when autumn is approaching, when it is getting closer, if the swallows could communicate with each other, they would say: It's starting to smell bad! The swallow's sense of smell is incredibly sensitive. And just as I told you that humans can be perceived as far as Arlesheim, so too can the smell that flows from the south be perceived by the swallows when autumn approaches; it spreads as far as the north. Down there it smells good; up there it starts to smell like manure! — That's when the swallows start flying to where the good smell attracts them, because it comes up from the south to the north.

Gentlemen, entire libraries have been written about bird flight. But the truth is that even during these great migrations in autumn and spring, the birds are guided by the incredibly subtle distribution of smells throughout the air layer of our earth. Their sense of smell guides the swallows south, and then back north again. When spring comes here, it starts to smell manure-like down there for the swallows. The delicate scents of spring come to them in the south, and so they fly up north. It is really true that the earth is actually a living being, and the other beings belong to it.You see, our bodies are designed so that blood flows to the head and then flows away again. The earth is designed so that certain birds, migratory birds, fly to the equator and then fly back again. The air we breathe drives the blood to the head. We are completely permeated by smell, insofar as we are air beings. And someone who, for example, walks across a field that has just been manured, is actually walking there as an air being; for the solid being and the liquid being notice nothing of the manure. But the air-like human being notices it, and then – as you will understand from what I have said – the urge to fly away arises in him. Actually, the human being would like to fly away continuously into the air when the manure stinks above the field. He cannot do so because he has no wings. And so the human being internalizes that which he cannot fly away from. He internalizes it. It becomes part of his soul. And the result is that the human being, insofar as he is an airy human being, becomes completely filled with the smell of manure, with the gaseous, vaporous exhalations of the manure. He himself becomes completely manure-like. And then they say: it disgusts them. Spiritually, that is disgust.