Realism and Nominalism

GA 220

27 January 1923, Dornach

Translator Unknown

The spiritual life of the Middle Ages, from which the modern one derives, is essentially contained—as far as Europe is concerned—in what we call Scholasticism, that Scholasticism of which I have repeatedly spoken. At the height of the scholastic age two directions can be distinguished: Realism and Nominalism.

If we take the meaning of the word Realism, as it is often understood today, we do not grasp at once what was meant by medieval scholastic Realism. It was not called Realism because it approved only of the outer sense-reality and considered everything else an illusion; quite the contrary was the case—it was called Realism because it considered man's ideas on the things and processes of the world as something real, whereas Nominalism considered these ideas as mere names which signified nothing real.

Let us look at this matter quite clearly. In earlier days I explained the conceptions of Realism, by using the arguments of my old friend, Vincenz Knauer. Vincenz Knauer held that people who consider only the outer sense-reality, or that which can be found in the world as material substance, will not be able to understand what takes place, for instance, in the case of a caged wolf, which is fed exclusively on lamb's flesh for a long time. After a certain time the wolf has changed his old substance; this would consist entirely of lamb's flesh and in reality the wolf should turn into a lamb, if its substance is now lamb's substance! But this does not happen, for the wolf remains a wolf—that is, the material aspect does not matter; what matters is the form, which consists of the same substance in the lamb's case and in the wolf's case. We discover the difference between lamb and wolf because we gain a conception of the lamb and a conception of the wolf. But when someone says that ideas and conceptions are nothing at all, and that the material aspect of things is the only one that matters, then there should be no difference between lamb and wolf as far as the material substance is concerned, for this has passed over from the lamb into the wolf! If an idea really means nothing at all, the wolf should become a lamb if it keeps on eating lamb's flesh.

This induced Vincenz Knauer, who was a Realist in the medieval scholastic sense, to form the following conception:—What matters, is the form in which the substance is coordinated; this is the idea, or the concept. Also the medieval scholastic Realists were of this opinion. They said that ideas and concepts were something real, and that is why they called themselves Realists.

Their radical opponents were the Nominalists. They argued that there is nothing outside sense-reality, and that ideas and concepts are mere names through which we grasp the outer things of sense-reality.

We might adopt the following argument:—Let us take Nominalism and then Realism, such as we find it, for instance, in Thomas Aquinas, or in other scholastic philosophers; if we contemplate these two spiritual currents in quite an abstract way, their contrast will not be very evident. We might look upon them as two different human aspects. In the present day we are satisfied with such things because we are no longer kindled and warmed by what is expressed in these spiritual currents. But these things contain something very important. Let us take the Realists who argued that ideas and conceptions—that is, forms taken up by the sensory substance—are realities. The scholastic philosophers already considered ideas and thoughts as something abstract, but they called these abstractions a reality, because they were the result of earlier conceptions, far more concrete and essential.

In earlier ages, people did not merely look at the idea “wolf”, but at the real group-soul “wolf”, living in the spiritual world. This was a real being. But scholastic philosophers had subtilized this real being of an earlier age into the abstract idea. Nevertheless, the realistic scholastic philosophers still felt that, the idea does not contain a nothingness, but a reality. This reality indeed descended from earlier quite real beings, but people were then still aware of this descendancy or progeny. In the same way the ideas of Plato (which were far more alive and essentially endowed with Being than the medieval scholastic ideas) were the descendants of the ancient Persian Archangeloi-Beings, who lived and operated in the universe as Anschaspans. They were very real beings. For Plato they had grown more dim, and for the medieval scholastic philosophers they had grown abstract. This was the last stage of the old clairvoyance. Of course, medieval realistic scholasticism was no longer based upon clairvoyance, but what it had preserved traditionally, as its real ideas and conceptions, living in the stones, in the plants, in animals and in physical man, was still considered as something spiritual, although this spirituality was very thin indeed. When the age of abstraction or of intellectualism approached, the Nominalists discovered that they were not able to connect anything real with thoughts and ideas. For them these were mere names, coined for the convenience of man.

Medieval scholastic Realism, let us say, of a Thomas Aquinas, has not found a continuation in the more modern world conception, for man no longer considers ideas and thoughts as something real. If we were to ask people whether they considered thoughts and ideas as something real, we would only obtain an answer by placing the question somewhat differently. For instance, by asking someone who is firmly rooted in modern culture:—“Would you be satisfied if, after your death, you were to continue living merely as a thought or an idea?” In this case he would surely feel very unreal after death! This was not so for the realistic scholastic philosophers. For them, thoughts and ideas were real to such an extent, that they could not conceive that, as a mere thought or idea, they might lose themselves in the universe, after death. But as stated, this medieval scholastic Realism was not continued. In a modern world conception, everything consists of Nominalism. Nominalism has gained the upper hand more and more. And modern man (he does not know this, because he does not concern himself any more about such ideas) is a Nominalist in the widest meaning.

This has a certain deeper significance. One might say that the very passage from Realism to Nominalism—or better, the victory of Nominalism in our modern civilization—signifies that humanity has become completely powerless in regard to the grasping of the spiritual. For, naturally, just as the name “Smith” has nothing to do with the person standing before us, who is somehow called “Smith”, so have the ideas “wolf”, “lion”, conceived as mere names, no meaning whatever as far as reality is concerned. The passage from Realism to Nominalism expresses the entire process of the loss of spirit in our modern civilization. Take the following instance, and you will see that the entire meaning is lost as soon as Realism loses its meaning.

If I still find real ideas in the stone, in the plant, in the animals, and in physical man—or better still, if I find in them the ideas as realities—I can place the following question:—Is it possible that the thoughts that live in stones and plants, were once the thoughts of the Divine Being who created stones and plants? But if I see in thoughts and ideas mere names which man gives to stones and plants, I cut myself off from the Divine Being, and can no longer take it for granted that during the act of cognition I somehow enter in connection with the Divine Being.

If I am a scholastic Realist, I argue as follows:—I plunge into the mineral world, into the vegetable world and into the animal world; I form thoughts on quartz, sulphide of mercury and malachite. I form thoughts on the wolf, the hyena and the lion. I derive these from what I perceive through my senses. If these thoughts are something which a god originally placed into the stones and plants and animals, then my thoughts follow the divine thoughts. That is, in my thinking I create a link with the divinity.

If I stand on the earth as a forlorn human being, and perhaps imitate to some extent the lion's roar in the word “lion”, I myself give the lion this name; then, however, my knowledge contains no connection whatever with the divine spiritual creator of the beings. This implies that modern humanity has lost the capacity of finding something spiritual in Nature; the last trace of this was lost with scholastic Realism.

If we go back to the days in which men still had an insight into the true nature of such things through atavistic clairvoyance, we will find that the ancient Mysteries consisted more or less in the following conception: the Mysteries saw in all things a creative productive principle, which was looked upon as the “Father-principle”. When a human being proceeded from what his senses could perceive to the super-sensible, he really felt that he was proceeding to the divine Father-principle.

Only when scholastic Realism lost its meaning, it became possible to speak of atheism within the European civilization. For it was impossible to speak of atheism as long as people still found real thoughts in the things around them. There were already atheists among the Greeks; but they were not real atheists like the modern ones. Their atheism was not clearly defined. But it must also be said that in Greece we often find the first flashes of lightning, as if from an elementary human emotion, precursory of things which found their real justification during a later stage of human evolution. The actual theoretical atheism only arose when Realism, scholastic Realism, decayed.

However, this scholastic Realism continued to live in the divine, Father-principle, although the Mystery of Golgotha was enacted thirteen or fourteen centuries ago.

But the Mystery of Golgotha—I have often spoken of this—could really be grasped only through the knowledge of an older age. For this reason, those who wished to grasp the Mystery of Golgotha through what remained from the ancient Mystery wisdom of God the Father, looked upon the Christ merely as the Son of the Father.

Please consider carefully the thought which we shall form now. Imagine that someone tells you something concerning a person called Miller; you are only told that he is the son of the old Miller. Hence, the only thing you know about him is that he is the son of Miller. You wish to know more about him from the person who has told you this. But he keeps on telling you:—The old Miller is such and such a person, and he describes all kinds of qualities and concludes by saying—and the young Miller is his son. It was more or less the same when people spoke of the Mystery of Golgotha according to the ancient Father-principle. Nature was characterized in such a way that people said—the divine creative Father-principle lives in Nature, and Christ is the Son. Essentially, even the strongest Realists could not characterize the Christ otherwise than by saying that he was the Son of the Father. This is an essential point.

Then came a kind of reaction to all these forms of thought adhering to the stream which came from the Mystery of Golgotha, but which grasped it according to the Father-principle. As a kind of counter-stream, came all that which asserted itself as the evangelic principle, as protestantism, etc., during the passage from medieval life to modern life. A chief quality among all the qualities of this evangelization, or protestantism, is this that more importance was given to the fact that people wished to see the Christ in his own being. They did not base themselves on the old theology which considered the Christ only as the Son of the Father, according to the Father-principle, but they searched the Gospels in order to know the Christ as an independent Being, from the description of his deeds and the communication of the words of Christ. Really, this is what lies at the foundation of the Wycliffe and Comenius currents in German protestantism:—to consider the Christ as an independent Being.

However, the time for a spiritual way of looking at things had passed. Nominalism took hold of all minds and people were no longer able to find in the Gospels the divine spiritual being of the Christ. Modern theology lost this divine spiritual more and more. As I have often said, theologians looked upon the Christ as the “meek man of Nazareth”. Indeed, if you take Harnach's book—“The Essence of Christianity”, you will find that it contains a relapse; for in this book a modern theologian again describes the Christ very much after the Father-principle. In Harnach's book, the “Essence of Christianity”, we could substitute the word “Christ” wherever we read the word “God-Father”—this would make no great difference.

As long as the “wisdom of the Father” considered the Christ as the Son of God, people possessed in a certain sense a way of thinking which had a direct bearing on reality. However, when they wished to understand the Christ himself, in his divine spiritual being, the spiritual conception was already lost. They did not approach the Christ at all. For instance, the following case is very interesting (I do not know if many of you have noted it):—when one of those who wished at first to take part in the movement for a religious renewal,—but he did not take part in the end—, when the chief pastor of Nuremberg, Geyer, once held a lecture in Basle, he confessed openly that modern protestant theologians did not possess Christ—but only a universal God. This is what Geyer said, because he honestly confessed that people indeed spoke of the Christ, but the Father-principle was in reality the only thing that remained to them. This is connected with the fact that the human being who still looks at Nature spiritually (for he brings the spirit with him at birth) can only find the Father-principle in Nature. But since the decay of scholastic Realism he cannot even find this. Not even the Father-principle can be found, and atheistic opinions arose.

If we do not wish to remain by the description of the Christ, as being merely the Son of God, and wish instead to grasp this Son in his own nature, then we must not consider ourselves merely such as we are through birth; we must instead experience, during earthly life itself, a kind of inner awakening, no matter how weak this may be. We must pass through the following facts of consciousness and say to ourselves:—if you remain such as you were through birth, and see Nature merely through your eyes and your other senses and then consider Nature with your intellect, you are not a full human being, you cannot feel yourself fully as a human being. First you must awaken something in you which lies deeper still. You cannot be content with what you bring with you at birth. You must instead bring forth again in full consciousness what lies buried in greater depths.

One might say, that if we educate a human being only according to his innate capacities, we do not really educate him to be a complete human being. A child will grow into a full human being only if we teach him to look for something in the depths of his being, something he brings to the surface as an inner light, which is kindled during life on earth. Why is it so? Because the Christ who has gone through the Mystery of Golgotha, and is connected with earthly life, dwells in the depths of man. If we undertake this new awakening, we find the living Christ, who does not enter the usual consciousness which we bring with us at birth, and the consciousness that develops out of this innate consciousness. The Christ must be raised out of the depths` of the soul. The consciousness of Christ must arise in the life of the soul, then we shall really be able to say what I have often mentioned:—If we do not find the Father, we are not healthy, but are born with certain deficiencies. If we are atheists, this implies to a certain extent, that our bodies are ill. All atheists are physically ill to a certain extent. If we do not find the Christ, this is destiny and not illness, because it is an experience to find the Christ, not a mere observation. We find the Father-principle by observing what we ought to see in Nature. But we find the Christ, when we experience resurrection. The Christ enters this experience of resurrection as an independent Being, not merely as the Son of the Father. Then we learn to know that if we keep merely to the Father, in our quality of modern human beings, we cannot feel ourselves as complete human beings. The Father sent the Son to the earth in order that the Son might fulfill his works on earth. Can you not feel how the Christ becomes an independent being in the fulfillment of the Father's works?

In the present time, Spiritual Science alone enables us to understand the entire process of resurrection—to understand it practically, as an experience. Spiritual Science wishes to bring these very experiences to conscious knowledge out of the depths of the soul; they bring light into the Christ-experience.

Thus we may say, that with the end of scholastic Realism, it was no longer possible to grasp the principle of the Father-wisdom. Anthroposophical Realism, or that kind of Realism which again considers the spirit as something real, will at last be able to see the Son as an independent Being and to look upon the Christ as a Being perfect in itself. This will enable us to find in Christ the divine spiritual, in an independent way.

You see, this Father-principle really played the greatest imaginable part in older times. The theology which developed out of the ancient Mystery-wisdom was really interested only in the Father-principle. What kind of thoughts were predominant in the past?—Whether the Son is at one with the Father from all eternity, or whether he arose in Time and was born into Time. People thought about his descent from the Father. Consider the old history of dogmas; you will find throughout that the greatest value is placed on the question of Christ's descent. When the Third Person of the Trinity, the Spirit, was considered, people asked themselves whether the Spirit proceeded from the Father, with the Son or through the Son, etc. The problem was always connected with the genealogy of these three Godly Persons—that is, with what is connected with descent, and can be comprised in the Father-principle. During the strife between scholastic Realism and scholastic Nominalism, these old ideas of the Spirit's descent from the Father and from the Son were no longer understood. For you see, now they were three Persons. These three Persons who represent Godly Persons, were supposed to form one Godhead. The Realists comprised these three Godly Persons in one idea. For them, the idea was something real, hence the one God was something real for their knowledge. The Nominalists could not very well understand the Three Persons of the one God—consisting of Father, Son and Holy Ghost. When they summarized this Godhead, they obtained a mere word, or name. Thus the three Godly Persons became separate Persons for them, and the time in which scholastic Realism strove against scholastic Nominalism was also the time in which no real idea could be formed concerning this Godly Trinity. A living conception of the Godly Trinity was lost.

When Nominalism gained the upper hand, people understood nothing more of similar ideas, and took up the old ideas according to this or to that traditional belief; they were unable to form any real thought. And when the Christ came more to the fore in the protestant faith—although his divine spiritual being could no longer be grasped, because Nominalism prevailed—it was quite impossible to have any idea at all concerning the Three Persons. The old dogma of the Trinity was scattered.

The things had a great significance for mankind in the age when spiritual feelings were predominant, and played a great part in the human souls for their happiness and unhappiness. These things were pushed completely in the background during the age of modern narrow-mindedness. Are modern people interested in the connection between Father, Son and Holy Spirit, unless the problem happens to enter into theological quarrels? Modern man thinks that he is a good Christian, yet he does not worry about the relationships of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. He cannot understand at all that once this was one of mankind's burning soul-problems. He has grown narrow-minded, and for this reason we can term the age of Nominalism the narrow-minded age of European civilization, for narrow-minded people have no real feeling for the spiritual, that continually rouses the soul. These kinds of people live only in their habits. It is not possible to live entirely without spirit, yet the narrow-minded people would like to live without any spirit at all—get up without the spirit—breakfast without the spirit—go to the office without the spirit—lunch without the spirit—play billiards in the afternoon without the spirit—in fact they would like to do everything without the spirit! Nevertheless the spirit permeates the whole of life, but narrow-minded people do not bother about this—it does not interest them.

Hence we may argue: Anthroposophy should therefore strive to maintain the Universal-Divine. But it does not do this. It finds the divine-spiritual in God the Father; it also finds this divine-spiritual in God the Son. If we compare the conceptions of Anthroposophy with the earlier wisdom of the Father we will find more or less the following situation:—Please do not mind my using a somewhat trivial expression, but I should like to say, that, as far as Christ was concerned, the wisdom of the Father asked above all—”Who was his Father? Let us find out who his Father was and then we shall know him.” Anthroposophy is, of course, placed into modern life, and in working out natural sciences it should of course continue the wisdom of the Father. But Anthroposophy works out the wisdom of the Christ and begins with the Christ. Anthroposophy studies, if I may use this expression, history, and finds in history a descending evolution. It finds the Mystery of Golgotha and from thence an ascending evolution. In the Mystery of Golgotha it finds the central point and meaning of the entire history of man on earth. When Anthroposophy studies Nature it calls the old Father-principle into new life, but when it studies history it finds the Christ. Now it has learned two things. It is just as if I were to travel into a city where I make the acquaintance of an older man; then I travel into another city and I learn to know a younger man. I become acquainted with the older and with the younger, each one for himself. At first they interest me, each one for himself. Afterwards I discover a certain likeness between them. I follow this up and find that the younger man is the son of the older one. In Anthroposophy it is just the same—it learns to know the Father, and later on it learns to know the connection between the two; whereas the ancient wisdom of the Father proceeded from the Father and learned to know the connection between Father and Son at the very outset.

You see, in regard to all things, Anthroposophy must really find a new way, and if we really wish to enter into Anthroposophy, it is necessary to change the way of thinking and of feeling in respect to most things. In Anthroposophy, it is not enough if anthroposophists consider on the one hand a more or less materialistic world conception, or a world conception based more or less on ancient traditional beliefs, and then pass on to Anthroposophy, because this appeals to them more than other teachings. But they are mistaken. We must not only go from one conception to the other—from the materialistic monistic conception to the anthroposophical one—and then say that the latter is the best. Instead we must realize that what enables us to understand the monistic materialistic conception does not enable us to understand the anthroposophical conception. You see, theosophists believed that the understanding of the materialistic monistic conception enabled them also to understand the spiritual. For this reason we have the peculiar phenomenon that in the monistic materialistic world conception people argue as follows:—everything is matter; man consists only of matter—the material substance of the blood, of the nerves, etc.

Everything is matter. Theosophists—I mean the members of the Theosophical Society—say instead:—No, this is a materialistic view; there is the spirit. Now they begin to describe man according to the spirit:—the physical body which is dense, then the etheric body somewhat thinner, a kind of mist, a thin mist—these are in reality quite materialistic ideas! Now comes the astral body, again somewhat thinner, yet this is only a somewhat thin material substance, etc. This leads them up a ladder, yet they obtain merely a material substance that grows thinner and thinner. This too is a materialistic view. For the result is always “matter”, even though this grows thinner and thinner. This is materialism, but people call it “spirit”. Materialism at least is honest, and calls the matter “matter”, whereas, in the other case, spiritual names are given to what people conceive materialistically.

When we look at spiritual images, we must realize that we cannot contemplate these in the same way as we contemplate physical images; a new way of thinking must be found.

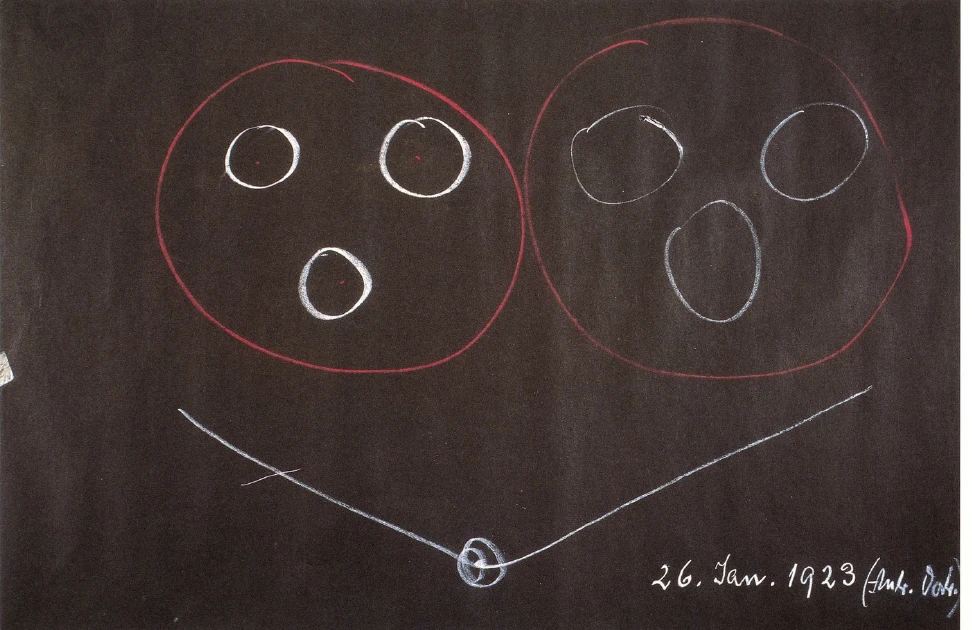

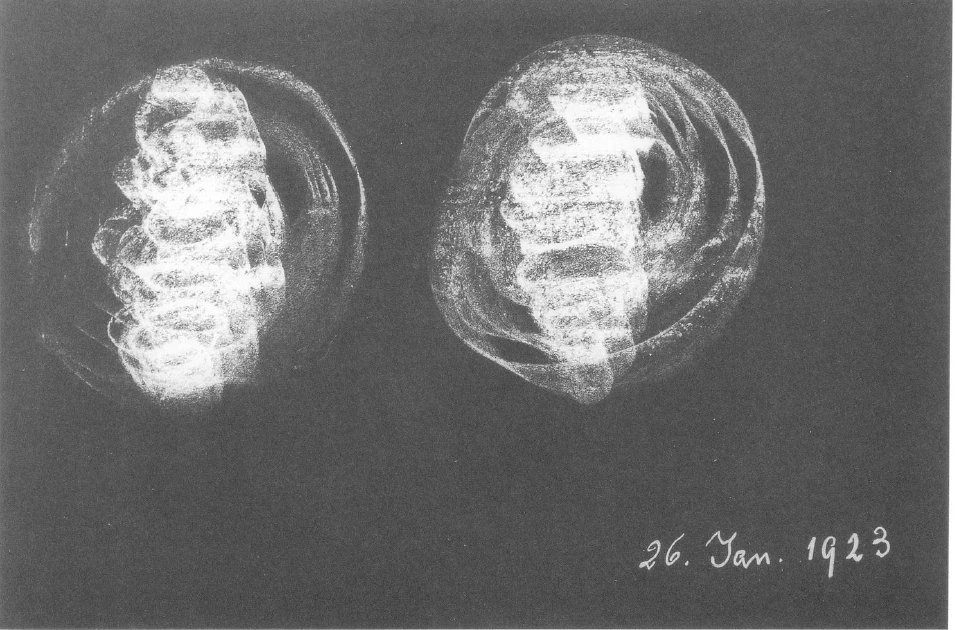

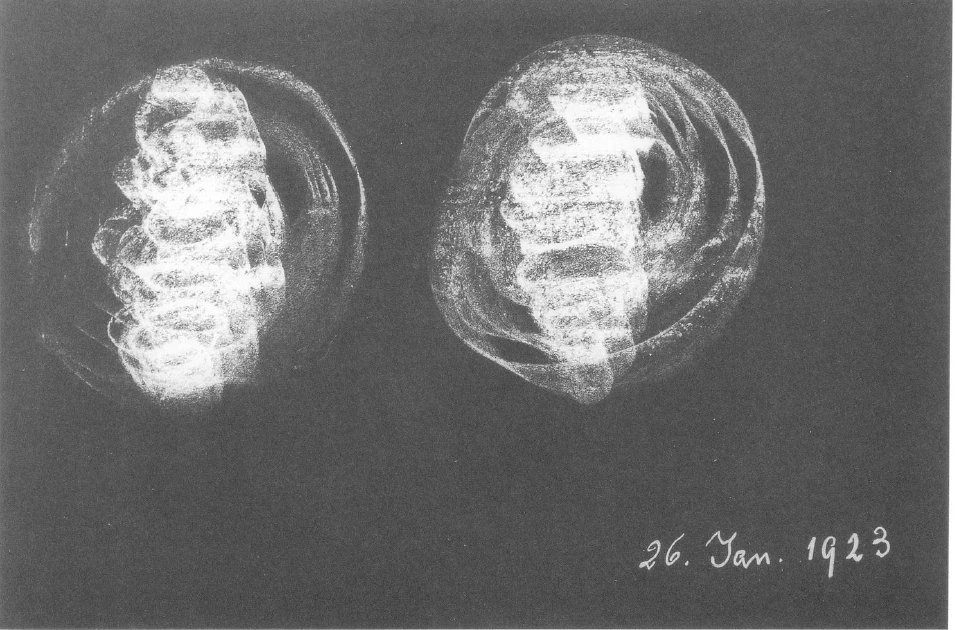

Things become very interesting at a special point in the history of the Theosophical Society. Materialism speaks of atoms. These atoms were imagined in many ways and strong materialists, who took into consideration the material quality of the body, formed all kinds of ideas about these atoms. One of these materialists built up a Theory of Atoms and imagined the atom in a kind of oscillating condition, as if some fine material substance were spinning round in spirals.

If you study Leadbeater's ideas on atoms, you will find a great resemblance with this theory.

An essay which appeared recently in an English periodical discussed the question of whether Leadbeater's atom was actually “seen”, or whether Leadbeater contented himself with reading the book on the Theory of Atoms and translating it into a “spiritual” language.

These things must be taken seriously. It matters very much that we should examine ourselves, in order to see if we still have materialistic tendencies and merely call them by all kinds of spiritual names. The essential point is to change our ways of thinking and of feeling—otherwise we cannot reach a really spiritual way of looking at things. This gives us an outlook, a perspective, that will help us to achieve the rise from sin as opposed to the fall into sin.

Elfter Vortrag

Das mittelalterliche Geistesleben, in dem das neuzeitliche seinen Ursprung genommen hat, ist für Europa im wesentlichen in dem enthalten, was man die Scholastik nennt, die Scholastik, von der ich ja auch hier schon wiederholt gesprochen habe. Nun gab es in der Hochblüte der Scholastik zwei Richtungen, die man unterscheidet, indem man die eine bezeichnet als Realismus und die andere als Nominalismus.

Wenn man die Bedeutung des Wortes Realismus nimmt, so wie man es heute oftmals versteht, so kommt man nicht gleich auf dasjenige, was mit dem mittelalterlichen scholastischen Realismus gemeint ist. Dieser Realismus trug seinen Namen nicht aus dem Grunde, weil er etwa bloß das äußerlich-sinnliche Reale gelten ließ und alles andere für Schein hielt, sondern ganz im Gegenteil. Dieser mittelalterliche Realismus hatte diese Bezeichnung, weil er die Begriffe, die sich der Mensch von den Dingen und Vorgängen in der Welt machte, für etwas Reales hielt, wahrend der Nominalismus diese Begriffe bloß für Namen hielt, die eigentlich nichts Reales bedeuten.

Machen wir uns diesen Unterschied einmal klar. Ich habe in früheren Zeiten mit einer Ausführung meines alten Freundes Vincenz Knauer auf die Anschauung des Realismus hingewiesen. Derjenige, der nur das Äußerlich-Sinnliche gelten läßt, das, was als Materielles in der Welt gefunden werden kann, wird nicht zurechtkommen damit, so meinte Vincenz Knauer, sich vorzustellen, wie es eigentlich mit einem Wolf wird, wenn er abgesperrt wird und lange Zeit nur Lammfleisch zu fressen bekommt. Da wird ja nach einer angemessenen Zeit der Wolf, nachdem er seine alte Materie ausgetauscht hat, der Materie nach nur aus Lammfleisch bestehen, und man müßte eigentlich dann erwarten, wenn der Wolf nur in seiner Materie bestünde, daß er ganz ein Lamm würde. Man wird das aber nicht erleben, sondern er bleibt eben ein Wolf. Das heißt, es kommt auf das Materielle nicht an, es kommt auf die Gestaltung an, die dasselbe Materielle einmal im Lamm, das andere Mal in dem Wolf hat. Aber wir Menschen kommen zu dem Unterschiede zwischen dem Lamm und dem Wolf eben dadurch, daß wir uns von dem Lamm einen Begriff, eine Idee machen, und auch von dem Wolf einen Begriff, eine Idee machen.

Wenn aber einer sagt: Begriffe und Ideen, die sind nichts, das Materielle ist allein etwas, dann unterscheidet sich das Materielle, das ganz aus dem Lamm hinübergegangen ist in den Wolf, beim Lamm und beim Wolf nicht; wenn der Begriff nichts ist, so muß der Wolf ein Lamm werden, wenn er immer nur Lammfleisch frißt. Daraus bildete dann Vincenz Knauer, der im mittelalterlich-scholastischen Sinne Realist war, eben die Anschauung heraus: Es kommt auf die Form an, in der die Materie angeordnet ist, und diese Form ist eben der Begriff, die Idee. Und solcher Ansicht waren die mittelalterlich-scholastischen Realisten. Sie sagten: Die Begriffe, die Ideen sind etwas Reales. Deshalb nannten sie sich Realisten. Dagegen waren die Nominalisten ihre radikalen Gegner. Die sagten: Es gibt nichts anderes als das äußerlich-sinnlich Wirkliche. Begriffe und Ideen sind bloße Namen, durch die wir die äußerlichsinnlichen wirklichen Dinge zusammenfassen. — Man kann sagen, wenn man den Nominalismus nimmt und dann den Realismus, so wie man ihn zum Beispiel bei Thomas Aguinas oder bei andern Scholastikern findet, und wenn man diese beiden geistigen Strömungen so ganz abstrakt hinstellt, dann hat man nicht viel von dem Unterschiede. Man kann sagen: Es sind zwei verschiedene menschliche Anschauungen.

In der heutigen Zeit ist man mit solchen Dingen zufrieden, weil man sich nicht besonders echauffiert für das, was in solchen geistigen Richtungen zum Ausdruck kommt. Aber es liegt ein ganz Wichtiges darinnen. Nehmen wir einmal die Realisten, die sagten: Ideen, Begriffe, Formen also, in denen das Sinnlich-Materielle angeordnet ist, sind Wirklichkeiten, - so waren für die Scholastiker diese Ideen und Begriffe allerdings schon Abstraktionen, aber sie nannten diese Abstraktionen ein Reales, weil diese ihre Abstraktionen die Abkömmlinge waren von früheren, viel konkreteren, wesentlicheren Anschauungen. In früherer Zeit sahen die Menschen nicht bloß auf den Begriff Wolf, sondern auf die reale, in der geistigen Welt vorhandene Gruppenseele Wolf. Das war eine reale Wesenheit. Diese reale Wesenheit einer früheren Zeit hatte sich bei den Scholastikern verflüchtigt zu dem abstrakten Begriff. Aber immerhin hatten die realistischen Scholastiker eben noch das Gefühl, im Begriff ist nicht ein Nichts enthalten, sondern es ist ein Reales enthalten.

Dieses Reale war allerdings der Nachkomme früherer ganz realer Wesenheiten, aber man spürte noch die Nachkommenschaft, geradeso wie die Ideen bei Platon — die ja wieder viel lebensvoller, wesenhafter sind als die mittelalterlichen scholastischen Ideen —- Nachkommen waren der alten, persischen Erzengelwesen, die als Amshaspands wirkten und lebten im Universum. Das waren sehr reale Wesenheiten. Bei Platon waren sie schon vernebelt und bei den mittelalterlichen Scholastikern verabstrahiert. Das war ein letztes Stadium, zu dem altes Hellsehen gekommen war. Gewiß, die mittelalterliche realistische Scholastik beruhte nicht mehr auf einem Hellsehen, aber dasjenige, was sie sich traditionell bewahrt . hatte als ihre realen Begriffe und Ideen, die überall in den Steinen, in den Pflanzen, in den Tieren, in den physischen Menschen lebten, wurden noch als ein Geistiges, wenn auch eben als ein sehr dünnflüssiges Geistiges angesehen. Die Nominalisten waren nun schon, weil ja die Zeit der Abstraktion, des Intellektualismus herannahte, gewahr geworden, daß sie nicht mehr fähig waren, mit der Idee, mit dem Begriff ein Wirkliches zu verbinden. Ein bloßer Name zur Bequemlichkeit der menschlichen Zusammenfassung war ihnen Begriff und Idee.

Der mittelalterlich-scholastische Realismus etwa eines Thomas Aquinas hat in der neueren Weltanschauung keine Fortsetzung gefunden, denn Begriffe und Ideen gelten den Menschen heute nicht mehr als etwas Reales. Würde man die Menschen fragen, ob ihnen Begriffe und Ideen als etwas Reales gelten, dann könnte man ja erst eine Antwort erhalten, wenn man die Frage etwas umwandelte, wenn man zum Beispiel einen so richtig in der modernen Bildung drinnensteckenden Menschen fragte: Wärst du zufrieden, wenn du nach deinem Tode bloß als Begriff, als Idee weiterleben würdest? — Da würde er sich höchst unreal vorkommen nach dem Tode. Das war noch nicht ganz so der Fall bei den realistischen Scholastikern. Bei denen war schon Begriff und Idee noch so weit real, daß sie sich gewissermaßen nicht ganz hätten verloren geglaubt im Weltenall, wenn sie nach dem Tode nur Begriff oder Idee gewesen wären. Dieser mittelalterlich-scholastische Realismus, wie gesagt, hat keine Fortsetzung erfahren. In der modernen Weltanschauung ist alles Nominalismus. Immer mehr und mehr ist alles Nominalismus geworden. Und der heutige Mensch - er weiß es zwar nicht, weil er sich nicht um solche Begriffe mehr bekümmert - ist im weitesten Umfange Nominalist.

Nun hat das aber eine gewisse, tiefere Bedeutung. Man kann sagen: Gerade der Übergang vom Realismus zum Nominalismus, ich möchte sagen, der Sieg des Nominalismus in der modernen Zivilisation bedeutet, daß die Menschheit völlig ohnmächtig geworden ist in bezug auf die Erfassung des Geistigen. Denn natürlich, geradesowenig wie der Name Schmidt etwas zu tun hat mit der Persönlichkeit, die vor uns steht und die einmal irgendwie den Namen Schmidt zugelegt bekommen hat, ebensowenig hat; wenn man sich einen Begriff, eine Idee - Wolf, Löwe - als bloße Namen vorstellt, das irgendeine Bedeutung für die Realität. Die ganze Entgeistigung der modernen Zivilisation drückt sich aus in dem Übergang vom Realismus zum Nominalismus. Denn sehen Sie, eine Frage hat ja ihren ganzen Sinn verloren, wenn der Realismus seinen Sinn verloren hat. Wenn ich in dem Stein, in den Pflanzen, in den Tieren, in den physischen Menschen noch reale Ideen finde — oder besser gesagt, Ideen als Realitäten finde -, dann kann ich die Frage aufwerfen, ob diese Gedanken, die in den Steinen leben, in den Pflanzen leben, ob diese einmal die Gedanken waren der göttlichen Wesenheit, welche der Urheber ist der Steine und der Pflanzen. Wenn ich aber in den Ideen und Begriffen nur Namen sehe, die der Mensch den Steinen und den Pflanzen gibt, dann bin ich abgeschnitten von einer Verbindung mit dem göttlichen Wesen, kann nicht mehr davon sprechen, daß ich irgendwie, indem ich erkenne, ein Verhältnis zu einem göttlichen Wesen eingehe.

Bin ich scholastischer Realist, so sage ich: Ich vertiefe mich in die Steinwelt, ich vertiefe mich in die Pflanzenwelt, ich vertiefe mich in die Tierwelt. Ich mache mir Gedanken von Quarz, von Zinnober, von Malachit; ich mache mir Gedanken von Lilien, von Tulpen; ich mache mir Gedanken von Wolf, von Hyäne, von Löwe. Diese Gedanken nehme ich aus dem, was ich sinnlich wahrnehme, auf. Sind diese Gedanken das, was ursprünglich eine Gottheit in die Steine, in die Pflanzen, in die Tiere hineingelegt hat, dann denke ich ja die Gedanken der Gottheit nach, das heißt, ich schaffe mir eine Verbindung in meinem Denken mit der Gottheit.

Wenn ich als verlorener Mensch auf der Erde stehe, und weil ich vielleicht, sagen wir, so ein bißchen nachahme das Gebrüll des Löwen mit dem Worte «Löwe», und diesen Namen dem Löwen selber gegeben habe, dann habe ich in meiner Erkenntnis nichts von einer Verbindung mit einem göttlich-geistigen Urheber der Wesenheiten. Das heißt, die moderne Menschheit hat die Fähigkeit verloren, in der Natur ein Geistiges zu finden, und die letzte Spur ist mit dem scholastischen Realismus verlorengegangen.

Wenn man nun zurückgeht in diejenigen Zeiten, die aus alter Hellsichtigkeit Einsicht hatten in die wahre Natur solcher Dinge, so wird man finden, daß die alte Mysterienanschauung etwa die folgende ist. Die alte Mysterienanschauung sah in allen Dingen ein schöpferisches, hervorbringendes Prinzip, das sie erkannte als das Vaterprinzip. Und indem man von dem sinnlich Wahrnehmbaren zu dem Übersinnlichen überging, fühlte man eigentlich: man ging zu dem göttlichen Vaterprinzip über. So daß die scholastischen realistischen Ideen und Begriffe das letzte waren, was die Menschheit in den Dingen der Natur als das Vaterprinzip suchte.

Als der scholastische Realismus seinen Sinn verloren hatte, da begann eigentlich erst die Möglichkeit, innerhalb der europäischen Zivilisation von Atheismus zu sprechen. Denn solange man noch reale Gedanken in den Dingen fand, konnte man nicht von Atheismus sprechen. Daß unter den Griechen schon Atheisten waren, ist so aufzufassen, daß erstens dies keine rechten Atheisten waren wie die neueren; so ganz klare Atheisten waren sie doch nicht. Aber es ist ja auch das zu sagen, daß in Griechenland vielfach ein erstes Wetterleuchten wie aus einer elementaren, menschlichen Emotion heraus sich bildete für Dinge, die erst später ihre wirkliche Begründung in der Menschheitsentwickelung hatten. Und der richtige theoretische Atheismus kam eigentlich erst mit dem Verfall des Realismus, des scholastischen Realismus herauf.

Aber eigentlich lebte dieser scholastische Realismus noch immer bloß in dem göttlichen Vaterprinzip, trotzdem dreizehn, vierzehn Jahrhunderte vorher schon das Mysterium von Golgatha sich vollzogen hatte. Das Mysterium von Golgatha - ich habe es ja auch öfter ausgesprochen — wurde im Grunde genommen nur mit den Erkenntnissen einer alten Zeit verstanden. Und deshalb haben diejenigen, die dieses Mysterium von Golgatha mit den Resten der alten Mysterienweisheit von dem Vatergotte verstehen wollten, eigentlich in dem Christus bloß den Sohn des Vaters erkannt.

Bitte, wenden Sie viel Sorgfalt auf die Ideen, die wir jetzt entwikkeln wollen. Denken Sie: Ihnen wird irgend etwas erzählt von einer Persönlichkeit Müller, und es wird Ihnen im wesentlichen nur mitgeteilt: das ist der Sohn des alten Müller. Sie wissen nicht viel mehr von dem Müller, als daß er der Sohn des alten Müller ist. Sie wollen Näheres erfahren von dem, der Ihnen die Mitteilung macht. Der sagt Ihnen aber eigentlich immer nur: Ja, der alte Müller, das ist der und der. Und nun gibt er alle möglichen Eigenschaften an, und dann sagt er: Nun, und der junge Müller ist eben sein Sohn. So ungefähr war es in der Zeit, als man vom Mysterium von Golgatha noch nach dem alten Vaterprinzip sprach. Man charakterisierte die Natur so, daß man sagte: In ihr lebt das göttliche, schöpferische Vaterprinzip, und Christus ist der Sohn. — Im wesentlichen kamen auch die stärksten Realistiker zu keiner andern Charakteristik des Christus, als daß er der Sohn des Vaters ist. Das ist wesentlich.

Und dann kam als eine Art Reaktion auf alle diese Begriffsbildungen, die zwar treu hielten zu der Strömung, die vom Mysterium von Golgatha ausging, aber sie eben noch nach dem Vaterprinzipe auffaßten, es kam wie eine Art Gegenströmung alles das hinzu, was sich dann im Verlaufe des Überganges des mittelalterlichen Lebens zum neuen Leben als das evangelische Prinzip, als Protestantismus und so weiter geltend machte. Denn neben allen andern Eigenschaften, die diesem Evangelisieren, diesem Protestantismus eigen waren, ist ja eine hauptsächliche diese, daß man mehr Gewicht legte darauf, sich den Christus selber in seiner Wesenheit vor Augen zu stellen. Man griff nicht zu der alten Theologie, die nach dem Vaterprinzip in dem Christus nur den Sohn des Vaters sah, sondern man griff zu den Evangelien selber, um aus den Erzählungen der Taten und aus den Mitteilungen der Worte des Christus den Christus als eine selbständige Wesenheit kennenzulernen. Das liegt im Grunde dem Wiclifismus, das liegt der Strömung des Comenius, das liegt auch dem deutschen Protestantismus zugrunde: den Christus selbständig als abgeschlossene Wesenheit hinzustellen.

Allein es war jetzt die Zeit der geistigen Auffassung vorbei. Der Nominalismus hatte im Grunde genommen alle Gemüter ergriffen, und so fand man in den Evangelien nicht das Göttlich-Geistige in dem Christus. Und der neueren Theologie kam dann dieses Göttlich-Geistige immer mehr und mehr ganz abhanden. Der Christus wurde, wie ich öfter erwähnt habe, selbst für Theologen der schlichte Mann aus Nazareth.

Ja, wenn Sie das Harnacksche Buch «Das Wesen des Christentums» nehmen, so sehen sie sogar darinnen einen bedeutsamen Rückfall, denn da ist der Christus wiederum von einem modernen Theologen nun erst recht nach dem Vaterprinzip aufgefaßt. Und man könnte in dem Harnackschen Buche «Das Wesen des Christentums» überall, wo «Christus» steht, «Gottvater» setzen, es würde der Unterschied kein wesentlicher sein.

Also solange die Vaterweisheit den Christus als den Sohn des Gottes hingestellt hat, so lange hatte man eine im gewissen Sinne auf die Wirklichkeit lossteuernde Ansicht. Aber als man jetzt erfassen wollte den Christus selber in seiner göttlich-geistigen Wesenheit, da hatte man die geistige Auffassung schon verloren, man kam an den Christus nicht heran. Und es war zum Beispiel sehr interessant, ich weiß nicht, ob es viele bemerkt haben, als dann eine derjenigen Persönlichkeiten, die zunächst teilnehmen wollten an der Bewegung für religiöse Erneuerung, der aber dann nicht teilgenommen hat, der Nürnberger Hauptpastor Geyer, einmal in Basel einen Vortrag hielt, da hat er es offen eingestanden: Wir modernen evangelischen Theologen haben ja gar keinen Christus, wir haben ja nur den allgemeinen Gott. - So sagte Geyer, weil er eben redlich eingestand, daß zwar überall von Christus die Rede ist, daß aber eigentlich nur das Vaterprinzip geblieben ist. Das hängt damit zusammen, daß der Mensch, der noch mit Geist in die Natur hineinschaut, eben so wie er geboren wird - eigentlich in der Natur nur das Vaterprinzip finden kann; seit dem Verfall des scholastischen Realismus allerdings auch das nicht mehr. Daher wird eben das Vaterprinzip nicht gefunden, und atheistische Ansichten sind heraufgekommen.

Aber wenn man nicht stehenbleiben will bei der Charakteristik des Christus als des bloßen Sohnesgottes, sondern wenn man diesen Sohn in seiner eigenen Wesenheit erfassen will, dann muß man nicht bloß sich als Menschen nehmen, wie man geboren ist, sondern man muß im Erdenleben selber eine Art innerer, wenn auch noch so schwacher Erweckung erleben. Man muß einmal durchgehen durch folgende Bewußtseinstatsachen. Man muß sich sagen: Wenn du einfach als Mensch so bleibst, wie du geboren bist, wie deine Augen, deine übrigen Sinne dir die Natur zeigen, wenn du dann mit deinem Intellekt dieses Gesicht der Natur durchgehst, so bist du heute nicht völlig Mensch. Du kannst dich nicht ganz als Mensch fühlen, du mußt erst etwas in dir erwecken, was tiefer liegt. Du kannst nicht zufrieden sein mit dem, was in dir bloß geboren ist. Du mußt etwas, was tiefer in dir liegt, mit vollem Bewußtsein neuerdings aus dir herausgebären.

Man möchte sagen: Wenn man heute einen Menschen nur nach dem erzieht, was seine angeborenen Anlagen sind, so erzieht man ihn eigentlich nicht zum vollen Menschen; sondern nur, wenn man ihm beizubringen vermag, er müsse in den Tiefen seines Wesens etwas suchen, das er heraufholt aus diesen Tiefen, das wie ein inneres Licht ist, was angezündet wird während des Erdenlebens.

Warum ist das so? Weil der Christus durch das Mysterium von Golgatha gegangen ist und mit dem Erdenleben verbunden ist, in den Tiefen der Menschen lebt. Und wenn man diese Wiedererwekkung in sich vornimmt, dann findet man den lebendigen Christus, der in das sonstige Bewußtsein, in das angeborene und aus dem angeborenen heraus entwickelte Bewußtsein nicht einzieht, sondern der aus den Tiefen der Seele herausgeholt werden muß. Das Christus-Bewußtsein muß entstehen im Seelengeschehen. So daß man wirklich sagen kann, was ich ja öfter ausgesprochen habe: Wer den Vater nicht findet, der ist in irgendeiner Weise mit mangelnden Anlagen geboren, der ist nicht gesund. Atheist sein heißt, in einer gewissen Weise körperlich krank sein, und alle Atheisten sind in einer gewissen Weise körperlich krank. Den Christus nicht finden ist ein Schicksal, nicht eine Krankheit, weil den Christus finden eben ein Erlebnis ist, nicht ein bloßes Konstatieren. Das Vaterprinzip findet man, indem man konstatiert dasjenige, was man eigentlich sehen sollte in der Natur. Den Christus findet man nur, indem man ein Wiedergeburtserlebnis hat. Da tritt der Christus in diesem Wiedergeburtserlebnis als selbständiges Wesen, nicht bloß als Sohn des Vaters auf. Denn dann lernt man erkennen: Hält man sich als moderner Mensch bloß an den Vater, dann kann man sich nicht ganz als Mensch fühlen. Deshalb hat der Vater den Sohn gesandt, daß der Sohn sein Werk auf Erden vollende. Fühlen Sie, wie in der Vollendung des Vaterwerkes der Christus zur selbständigen Wesenheit wird?

Aber im Grunde genommen sind wir ja in der Gegenwart nur durch Geisteswissenschaft imstande, den ganzen Vorgang der Wiedererweckung zu verstehen, praktisch zu verstehen, erlebensgemäß zu verstehen. Denn die Geisteswissenschaft will ja gerade solche Erlebnisse aus den Tiefen der Seele heraufholen in die bewußte Er kenntnis, welche Licht hineinbringen in das Christus-Erlebnis. Und so kann man sagen: Mit dem Verlauf des scholastischen Realismus hat sich die Möglichkeit des Prinzips der Vatererkenntnis erschöpft. Mit jenem Realismus, der den Geist wiederum als etwas Reales erkennt, und der der anthroposophische Realismus ist, mit diesem

Realismus wird nun der Sohn endlich in seiner selbständigen Wesenheit erkannt werden, wird der Christus erst eine abgeschlossene Wesenheit. Man wird dadurch das Göttlich-Geistige in selbständiger Weise in dem Christus wiederfinden.

Es hat wirklich in der älteren Zeit dieses Vaterprinzip die denkbar größte Rolle gespielt. Es interessierte eigentlich die aus der alten Mysterienweisheit heraus entwickelte Theologie nur das Vaterprinzip. Worüber dachte man denn nach? Ob der Sohn von Ewigkeit mit dem Vater zugleich ist, oder ob er in der Zeit entstanden ist, in der Zeit geboren ist. Man dachte eben über die Abstammung von dem Vater nach. Sehen Sie sich die ältere Dogmengeschichte an: überall ist hauptsächlich der Wert gelegt darauf, wie es sich mit der Abstammung des Christus verhält. Und als man die dritte Gestalt, den Geist hinzugenommen hat, dann hat man nachgedacht, ob der Geist zugleich mit dem Sohn von dem Vater ausgegangen ist oder durch den Sohn und so weiter. Immer handelt es sich eigentlich um die Genealogie dieser drei göttlichen Personen, also um dasjenige, was Abstammung ist, was also im Vaterprinzip zu begreifen ist.

In der Zeit, in welcher der Kampf war zwischen dem scholastischen Realismus und dem scholastischen Nominalismus, da kam man mit diesen alten Begriffen von der Abstammung des Sohnes vom Vater und des Geistes von Vater und Sohn nicht mehr zurecht. . Denn sehen Sie, jetzt waren drei Wesenheiten da. Diese drei Wesenheiten, die göttliche Personen darstellen, sollten eine Gottheit ‚bilden. Die Realisten faßten die drei göttlichen Personen in einer Idee zusammen, ihnen war die Idee ein Reales. Daher war der eine Gott für sie ein Reales für ihr Erkennen. Die Nominalisten kamen aber mit den drei Personen des einen Gottes nicht zurecht, denn nun hatten sie den Vater, den Sohn, den Geist, aber indem sie ihn zusammenfaßten, war das ein bloßes Wort, ein Nomen, und so fielen ihnen die drei göttlichen Personen auseinander. Und so war die Zeit, in welcher der scholastische Realismus mit dem scholastischen Nominalismus im Kampfe lag, auch die Zeit, in der man auch keinen rechten Begriff mehr zu verbinden wußte mit der göttlichen Dreifaltigkeit. Da verfiel eine lebensvolle Auffassung dieser göttlichen Dreifaltigkeit.

Als dann der Nominalismus siegte, da wußte man mit solchen Begriffen überhaupt nichts mehr anzufangen. Da nahm man eben, je nachdem man diesem oder jenem traditionellen Bekenntnisse zuneigte, die alten Begriffe auf, aber man konnte sich nichts Rechtes dabei denken. Und als dann in dem evangelischen Bekenntnis der Christus mehr in den Vordergrund gedrängt wurde, aber allerdings — weil man ja im Nominalismus drinnen war — seine göttlich-geistige Wesenheit nicht mehr erfaßt werden konnte, da wußte man eigentlich überhaupt nicht mehr irgendeinen Begriff von den drei Personen aufzufassen. Da zerflatterte das alte Dogma von der Dreifaltigkeit.

Diese Dinge, die in der Zeit, in der geistige Fühlungen noch eine große Bedeutung für die Menschen hatten, diese Dinge, die ja eine große Rolle spielten in bezug auf inneres Glück und Unglück der menschlichen Seele, diese Dinge hat die Zeit des modernen Philistertums vollständig in den Hintergrund gedrängt. Was interessiert schließlich den modernen Menschen, wenn er nicht gerade hineingetrieben wird in theologische Streitigkeiten, die Beziehung von Vater, Sohn und Geist? Er glaubt ja ein guter Christ zu sein, aber es wurmt ihn nicht weiter, wie es sich da verhält mit Vater, Sohn und Geist. Er kann sich gar nicht vorstellen, daß das einmal brennende Seelenfragen der Menschheit waren. Er ist eben Philister geworden. Deshalb kann man schon die Zeit des Nominalismus auch eben für die europäische Zivilisation die Zeit des Philisteriums nennen. Denn der Philister ist ja derjenige Mensch, der keine rechten Empfindungen hat für das immer weckende Geistige, der eigentlich in Gewohnheiten drinnen lebt. Ganz ohne Geist läßt es sich ja im Menschenleben nicht sein. Der Philister möchte am liebsten ganz ohne Geist sein, aufstehen ohne Geist, frühstücken ohne Geist, ins Büro gehen ohne Geist, Mittag essen ohne Geist, nachmittags Billard spielen ohne Geist und so weiter, er möchte alles ohne Geist machen. Aber unbewußt geht doch durch alles Leben der Geist hindurch. Nur kümmert sich der Philister nicht darum; es interessiert ihn nicht weiter.

So kann man sagen, daß Anthroposophie in dieser Beziehung das Ideal haben muß, nicht zu verlieren das Allgemein-Göttliche. Das tut sie nicht, denn sie findet in dem Vatergott das Göttlich-Geistige, abgetrennt in dem Sohnesgott das Göttlich-Geistige. Sie ist etwa in der folgenden Lage, wenn wir ihre Anschauungen vergleichen mit der früheren Vatererkenntnis: Ich möchte sagen - bitte, nehmen Sie mir den etwas trivialen Ausdruck nicht übel -, die Vatererkenntnis hat vor allen Dingen gefragt bei dem Christus: Wer ist sein Vater? — Weisen wir nach, wer sein Vater ist, dann haben wir Kenntnis von ihm. Kennen wir seinen Vater, dann haben wir Kenntnis von ihm. — Anthroposophie ist natürlich hingestellt in das moderne Leben. Indem sie Naturerkenntnis entwickelt, mußte sie ja natürlich die Vatererkenntnis weiterführen. Aber indem sie Christus-Erkenntnis entwickelt, geht sie zunächst nur vom Christus aus. Sie durchstudiert, wenn ich so sagen darf, die Geschichte, findet in der Geschichte eine absteigende Entwickelung, findet das Mysterium von Golgatha, von da an eine aufsteigende Entwickelung; findet in dem Mysterium von Golgatha den Mittelpunkt und den Sinn der ganzen menschheitlichen Erdengeschichte. Also indem Anthroposophie die Natur studiert, läßt sie auferstehen neu das alte Vaterprinzip. Indem sie aber Geschichte studiert, findet sie den Christus. Jetzt hat sie zweierlei kennengelernt. Und es ist so, wie wenn ich in die Stadt A reise und dort einen älteren Mann kennenlerne, dann in die Stadt B reise und da einen jüngeren Mann kennenlerne. Ich lerne den älteren Mann kennen, ich lerne den jüngeren Mann kennen, jeden für sich. Zunächst interessieren sie mich ganz für sich. Nachträglich fällt mir eine gewisse Ähnlichkeit auf. Ich gehe der Ähnlichkeit nach und komme darauf, daß der Jüngere der Sohn des Älteren ist. So ist es mit der Anthroposophie. Sie lernt den Christus kennen, sie lernt den Vater kennen, sie lernt die Beziehung zwischen beiden erst später kennen; während die alte Vaterweisheit eben ausgegangen ist vom Vater, und die Beziehung als das Ursprüngliche kennenlernte.

Sie sehen, in bezug auf alle Dinge eigentlich muß Anthroposophie einen neuen Weg einschlagen, und es ist schon notwendig, daß man in bezug auf die meisten Dinge umdenken und umfühlen lernt, wenn man wirklich ins Anthroposophische hineinkommen will. Das genügt eigentlich nicht für Anthroposophie, daß auf der einen Seite von den Anthroposophen die Weltanschauung gesehen wird mehr oder weniger materialistisch oder mehr oder weniger im Sinne von alten traditionellen Bekenntnissen lebend, und man nun zu etwas anderem geht — nämlich zur Anthroposophie, weil einem die gewissermaßen besser zusagt als eine andere Lehre. Aber so ist ja die Sache nicht. Man muß nicht nur von einem Bild zum anderen gehen, vom materialistischen, monistischen Bilde zum anthroposophischen Bilde und sich sagen: Nun, das anthroposophische Bild sagt mir besser zu. - Sondern man muß sich gestehen: Das, was dich befähigt, das monistisch-materialistische Bild anzuschauen, das befähigt dich nicht, das anthroposophische Bild anzuschauen.

Die Theosophen haben geglaubt, daß das Anschauen des materialistisch-monistischen Bildes sie schon befähige, das Geistige anzuschauen. Daher diese eigentümliche Erscheinung, daß man in der monistisch-materialistischen Weltanschauung davon redet: Alles ist Materie, der Mensch besteht auch nur aus der Materie; da ist Nervenmaterie, Blutmaterie und so weiter — alles Materie. Die Theosophen - ich meine die Mitglieder der Theosophischen Gesellschaft — sagen: Nein, das ist materialistische Anschauung; es gibt einen Geist. — Jetzt fangen sie aber an, den Menschen nach dem Geist zu beschreiben: den physischen Leib — dicht; jetzt den ätherischen Leib - dünner, aber Nebel, ein dünner Nebel, in Wirklichkeit doch ganz materielle Vorstellungen. Jetzt den astralischen Leib - der ist wieder dünner, aber er ist doch nur dünnere Materie und so weiter. Da kommt man auf einer Leiter hinauf, aber immer ist es dünnere Materie. Ja, das ist auch Materialismus, denn man kriegt ja doch immer nur Materie, wenn auch immer dünnere Materie. Es ist Materialismus, man nennt es nur Geist. Der Materialismus ist wenigstens ehrlich und nennt es Materie, während dort dasjenige, was materiell vorgestellt wird, mit dem Geistesnamen belegt wird. Man muß sich eben gestehen, daß man umdenken muß; man muß in anderer Art das Bild vom Geistigen anschauen lernen, als man das Bild vom Materiellen angeschaut hat. In der Theosophischen Gesellschaft wurde ja die Geschichte an einem Punkte ganz besonders interessant. Der Materialismus redet von Atomen. Diese Atome, die wurden in der verschiedensten Weise vorgestellt, und starke Materialisten, die Rücksicht genommen haben auf die materiellen Eigenschaften der Körper, haben sich zuletzt allerlei Vorstellungen von den Atomen gemacht. Unter anderem hat einer einmal eine Atomtheorie aufgestellt, da ist das Atom so wie in einer Art von Schwingungszustand dargestellt, wie wenn dadrinnen so dünnes Materielles in Spiralschwingungen wäre. Und wenn Sie bei ZLeadbeater die Atome nachschauen, da werden sie finden, das schaut geradeso aus. Neulich wurde überhaupt in einem Aufsatz einer englischen Zeitschrift die Frage aufgeworfen, ob nun dieses Leadbeatersche Atom «gesehen» ist, oder ob die Hellsichtigkeit des Leadbeater sich bloß darauf beschränkt hat, daß er dieses Buch gelesen hat und es ins Spiritualistische übersetzt hat.

Mit diesen Dingen muß eben durchaus Ernst gemacht werden. Es handelt sich durchaus darum, daß man sich selber prüfen muß, ob man nicht doch an dem Materialismus hängen bleibt und nur dem Materiellen allerlei geistige Namen anheftet. Ein Umdenken und Umfühlen, das ist dasjenige, worum es sich handelt, wenn man zu einer wirklich geistigen Weltanschauung kommen will. Damit ist dann erst ein Ausblick, eine Perspektive gewonnen in die Praxis dessen, was angestrebt werden muß in der Sündenerhebung gegenüber dem Sündenfall.

Eleventh Lecture

The intellectual life of the Middle Ages, in which the modern age originated, is essentially contained for Europe in what is called scholasticism, the scholasticism of which I have already repeatedly spoken here. Now, in the heyday of scholasticism, there were two directions, which are distinguished by calling one realism and the other nominalism.

If one takes the meaning of the word realism as it is often understood today, one does not immediately arrive at what is meant by medieval scholastic realism. This realism did not bear its name because it only accepted the external, sensual real and considered everything else to be illusory, but quite the opposite. This medieval realism had this name because it considered the concepts that man made of the things and processes in the world to be something real, whereas nominalism considered these concepts to be mere names that actually meant nothing real.

Let us make this difference clear to ourselves. In earlier times I referred to the view of realism in a statement by my old friend Vincenz Knauer. According to Vincenz Knauer, those who only accept the outwardly sensual, that which can be found as material in the world, will not be able to cope with the idea of what actually happens to a wolf when it is locked up and only gets lamb meat to eat for a long time. After a reasonable time, the wolf, having replaced its old matter, will consist only of lamb meat, and one would actually have to expect that if the wolf existed only in its matter, it would become entirely a lamb. But you will not experience this, it will remain a wolf. In other words, it is not the material that matters, it is the form that the same material has in the lamb at one time and in the wolf at another. But we humans arrive at the difference between the lamb and the wolf precisely because we form a concept, an idea, of the lamb and also form a concept, an idea, of the wolf.

\nBut if someone says: concepts and ideas are nothing, the material alone is something, then the material, which has passed completely from the lamb into the wolf, does not differ between the lamb and the wolf; if the concept is nothing, then the wolf must become a lamb if it always eats only lamb meat. From this Vincenz Knauer, who was a realist in the medieval scholastic sense, developed the view that what matters is the form in which matter is arranged, and this form is precisely the concept, the idea. And this was the view of the medieval scholastic realists. They said: concepts, ideas are something real. That is why they called themselves realists. The nominalists, on the other hand, were their radical opponents. They said: There is nothing other than the external-sensual real. Concepts and ideas are mere names by which we summarize the externally sensible real things. - You can say that if you take nominalism and then realism, as you find it in Thomas Aguinas, for example, or in other scholastics, and if you place these two intellectual currents in such an abstract way, then you don't have much of a difference. You could say that they are two different human views.

In this day and age, people are satisfied with such things, because they are not particularly enraged by what is expressed in such spiritual trends. But there is something very important in this. Let us take the realists, who said that ideas, concepts, forms in which the sensible-material is arranged, are realities, - for the scholastics these ideas and concepts were already abstractions, but they called these abstractions a real, because these abstractions of theirs were the descendants of earlier, much more concrete, more essential views. In earlier times people did not merely look at the concept of the wolf, but at the real group soul wolf that existed in the spiritual world. This was a real entity. This real entity of an earlier time had evaporated with the scholastics into an abstract concept. But at least the realist scholastics still had the feeling that the concept did not contain a nothing, but rather a real thing.

This real was, however, the descendant of earlier quite real entities, but one still sensed the descendants, just as the ideas of Plato - which are again much more alive, more substantial than the medieval scholastic ideas - were descendants of the ancient Persian archangel beings who worked and lived in the universe as Amshaspands. These were very real beings. With Plato they were already obscured and with the medieval scholastics they were abstracted. That was the last stage to which ancient clairvoyance had come. Certainly, medieval realist scholasticism was no longer based on clairvoyance, but that which it had traditionally preserved as its real concepts and ideas, which lived everywhere in the stones, in the plants, in the animals, in the physical human beings, was still regarded as a spiritual, albeit a very fluid spiritual. The Nominalists, because the time of abstraction, of intellectualism was approaching, had now realized that they were no longer able to connect a real thing with the idea, with the concept. A mere name for the convenience of human summarization was the concept and idea for them.

The medieval scholastic realism of Thomas Aquinas, for example, has found no continuation in the newer world view, because concepts and ideas are no longer regarded by people today as something real. If you were to ask people whether they regard concepts and ideas as something real, then you could only get an answer if you transformed the question a little, for example if you asked someone who is really immersed in modern education: Would you be satisfied if you lived on after your death merely as a concept, as an idea? - He would feel very unreal after death. This was not quite the case with the realist scholastics. For them, concept and idea were still real to such an extent that they would not have believed themselves to be completely lost in the universe if they had only been concepts or ideas after death. This medieval scholastic realism, as I said, has not been continued. In the modern world view, everything is nominalism. More and more, everything has become nominalism. And today's man - although he does not know it because he no longer cares about such concepts - is a nominalist to the greatest extent.

Now, however, this has a certain deeper meaning. One can say that the transition from realism to nominalism, I would say the victory of nominalism in modern civilization, means that mankind has become completely powerless to grasp the spiritual. For, of course, just as the name Schmidt has nothing to do with the personality that stands before us and that somehow once acquired the name Schmidt, neither does it have any meaning for reality if one imagines a concept, an idea - wolf, lion - as mere names. The entire de-spiritualization of modern civilization is expressed in the transition from realism to nominalism. For you see, a question has lost all its meaning when realism has lost its meaning. If I still find real ideas in the stone, in the plants, in the animals, in the physical human beings - or rather, if I find ideas as realities - then I can raise the question of whether these thoughts that live in the stones live in the plants, whether they were once the thoughts of the divine entity that is the originator of the stones and the plants. But if I see in the ideas and concepts only names that man gives to the stones and plants, then I am cut off from a connection with the divine being, can no longer speak of the fact that I somehow, by recognizing, enter into a relationship with a divine being.

If I am a scholastic realist, I say: I immerse myself in the stone world, I immerse myself in the plant world, I immerse myself in the animal world. I think about quartz, cinnabar, malachite; I think about lilies, tulips; I think about wolves, hyenas, lions. I take these thoughts from what I perceive through my senses. If these thoughts are what a deity originally placed in the stones, in the plants, in the animals, then I think the thoughts of the deity, that is, I create a connection in my thinking with the deity.

If I stand on earth as a lost human being, and because I perhaps, let us say, imitate a little the roar of the lion with the word “lion”, and have given this name to the lion itself, then I have nothing in my cognition of a connection with a divine-spiritual originator of the entities. In other words, modern humanity has lost the ability to find a spiritual being in nature, and the last trace has been lost with scholastic realism.

If one now goes back to those times which had insight into the true nature of such things from ancient clairvoyance, one will find that the old mystery view is approximately the following. The old mystery view saw in all things a creative, generating principle, which it recognized as the Father principle. And by passing from the sensually perceptible to the supersensible, one actually felt that one was passing to the divine Father principle. So that the scholastic realist ideas and concepts were the last thing that mankind sought in the things of nature as the Father principle.

Once scholastic realism had lost its meaning, the possibility of speaking of atheism within European civilization really only began. For as long as one could still find real thoughts in things, one could not speak of atheism. The fact that there were already atheists among the Greeks is to be understood in such a way that, firstly, they were not real atheists like the newer ones; they were not quite clear atheists after all. But it must also be said that in Greece there was often a first glimmering of an elementary human emotion for things that only later had their real foundation in the development of mankind. And true theoretical atheism only really emerged with the decline of realism, scholastic realism.

But actually this scholastic realism still lived only in the divine father principle, although thirteen or fourteen centuries earlier the Mystery of Golgotha had already taken place. The Mystery of Golgotha - as I have often said - was basically only understood with the knowledge of an old time. And that is why those who wanted to understand this mystery of Golgotha with the remnants of the old mystery wisdom of the Father God actually recognized in the Christ only the Son of the Father.

Please take great care with the ideas that we now want to develop. Think: You are told something about a personality called Müller, and you are essentially only told that this is the son of the old Müller. You don't know much more about the miller than that he is the son of the old miller. You want to find out more from the person who is telling you. But he only ever tells you: Yes, the old miller, that's him and him. And now he gives you all kinds of characteristics and then he says: Well, and the young miller is his son. That's roughly how it was in the days when people still spoke of the Mystery of Golgotha according to the old father principle. Nature was characterized by saying that the divine, creative Father principle lives in it, and Christ is the Son. - Essentially, even the strongest realists came to no other characterization of Christ than that he is the Son of the Father. That is essential.

And then, as a kind of reaction to all these conceptualizations, which remained faithful to the current that emanated from the Mystery of Golgotha, but still understood it according to the Father principle, everything that then asserted itself in the course of the transition from medieval life to the new life as the evangelical principle, as Protestantism and so on, was added as a kind of counter-current. For apart from all the other characteristics that were peculiar to this evangelization, this Protestantism, one of the main ones was that more emphasis was placed on presenting Christ himself in his essence. They did not resort to the old theology, which, according to the father principle, saw in Christ only the Son of the Father, but they resorted to the Gospels themselves in order to get to know Christ as an independent being from the stories of his deeds and from the communication of his words. This is basically the basis of Wiclifism, this is the basis of Comenius' current, this is also the basis of German Protestantism: to present Christ as an independent, self-contained entity.

However, the time of spiritual conception was now over. Nominalism had basically gripped all minds, and so the divine-spiritual in Christ was not found in the Gospels. And in the newer theology, this divine-spirituality was more and more completely lost. As I have often mentioned, even for theologians the Christ became the simple man from Nazareth.

Yes, if you take Harnack's book “The Essence of Christianity”, you will even see a significant relapse in it, because there Christ is again understood by a modern theologian according to the Father principle. And in Harnack's book “The Essence of Christianity”, one could put “God the Father” wherever it says “Christ”, the difference would not be significant.

So as long as the wisdom of the Father presented Christ as the Son of God, one had a view that in a certain sense was based on reality. But when people wanted to grasp the Christ Himself in His divine-spiritual essence, they had already lost the spiritual view, they could not get close to the Christ. And it was very interesting, for example, I don't know if many people noticed, when one of the personalities who initially wanted to take part in the movement for religious renewal, but then didn't, the Nuremberg pastor Geyer, once gave a lecture in Basel, where he openly admitted it: We modern Protestant theologians have no Christ at all, we only have the universal God. - Geyer said this because he honestly admitted that although Christ is spoken of everywhere, only the Father principle has actually remained. This has to do with the fact that man, who still looks into nature with spirit, just as he is born, can actually only find the Father principle in nature; since the decline of scholastic realism, however, even this can no longer be found. That is why the father principle is not found, and atheistic views have arisen.

But if one does not want to stop at the characterization of Christ as the mere Son of God, but if one wants to grasp this Son in his own essence, then one must not merely take oneself as a human being as one is born, but one must experience a kind of inner awakening in earthly life itself, no matter how weak. One must go through the following facts of consciousness. You must say to yourself: If you simply remain as a human being as you were born, as your eyes, your other senses show you nature, if you then go through this face of nature with your intellect, then you are not completely human today. You cannot feel completely human, you must first awaken something deeper within you. You cannot be satisfied with what is merely born in you. You have to give birth to something that lies deeper within you with full consciousness.

One would like to say: If today a person is only educated according to what his innate dispositions are, then he is not actually being educated to become a full human being; but only if he is taught that he must seek something in the depths of his being, which he brings up from these depths, which is like an inner light that is kindled during his life on earth.

Why is this so? Because the Christ has passed through the Mystery of Golgotha and is connected with life on earth, living in the depths of human beings. And if one undertakes this reawakening within oneself, then one finds the living Christ, who does not enter into the other consciousness, into the innate consciousness and the consciousness developed out of the innate consciousness, but who must be drawn out of the depths of the soul. Christ-consciousness must arise in the soul. So that one can really say what I have often said: Anyone who does not find the Father is in some way born with deficient dispositions, he is not healthy. To be an atheist means to be physically ill in a certain way, and all atheists are physically ill in a certain way. Not finding the Christ is a fate, not an illness, because finding the Christ is an experience, not a mere statement. One finds the Father principle by stating what one should actually see in nature. The Christ can only be found by having a rebirth experience. In this rebirth experience the Christ appears as an independent being, not merely as the Son of the Father. For then one learns to recognize: If, as a modern human being, you merely cling to the Father, then you cannot feel fully human. That is why the Father sent the Son, so that the Son might complete his work on earth. Do you feel how, in the completion of the Father's work, Christ becomes an independent being?

But basically we are only able to understand the whole process of revival, to understand it practically, to understand it experientially, through spiritual science. For spiritual science wants to bring up precisely such experiences from the depths of the soul into conscious knowledge, which bring light into the Christ experience. And so one can say: with the course of scholastic realism, the possibility of the principle of the knowledge of the Father has been exhausted. With that realism, which in turn recognizes the spirit as something real, and which is anthroposophical realism, with this

Realism, the Son will finally be recognized in his independent being, the Christ will only become a completed being. The divine-spiritual will thus be found again in the Christ in an independent way.

This father principle really played the greatest conceivable role in the older times. The theology developed out of the old mystery wisdom was actually only interested in the Father principle. What were they thinking about? Whether the Son is from eternity with the Father, or whether he came into being in time, was born in time. They were thinking about descent from the Father. Take a look at the older history of dogma: everywhere the main emphasis is placed on the descent of Christ. And when the third figure, the Spirit, was added, it was considered whether the Spirit came forth from the Father at the same time as the Son or through the Son and so on. It is always really a question of the genealogy of these three divine persons, that is, of that which is descent, that which is to be understood in the Father principle.

In the time of the struggle between scholastic realism and scholastic nominalism, these old concepts of the descent of the Son from the Father and of the Spirit from the Father and Son were no longer acceptable. For you see, there were now three entities. These three entities, which represent divine persons, were to form a deity. The realists summarized the three divine persons in one idea, for them the idea was a real thing. Therefore, for them, the one God was a real thing for their cognition. The Nominalists, however, could not come to terms with the three persons of the one God, for now they had the Father, the Son and the Spirit, but by combining them they were a mere word, a noun, and so the three divine persons fell apart for them. And so the time in which scholastic realism was at war with scholastic nominalism was also the time in which people no longer knew how to connect a proper concept with the divine Trinity. A lively conception of this divine Trinity fell into disrepair.

When nominalism prevailed, people no longer knew what to do with such concepts. Depending on whether one was inclined towards this or that traditional confession, the old concepts were adopted, but nothing good could be thought of. And when in the Protestant confession Christ was pushed more to the fore, but - because one was in nominalism - his divine-spiritual essence could no longer be grasped, then one no longer really knew how to grasp any concept of the three persons. The old dogma of the Trinity fluttered away.

These things, which in the time when spiritual feelings still had a great significance for people, these things, which played a great role in relation to the inner happiness and unhappiness of the human soul, these things have been completely pushed into the background by the time of modern philistinism. After all, what is modern man interested in, if he is not driven into theological disputes, the relationship between Father, Son and Spirit? He believes he is a good Christian, but he is not bothered by the relationship between Father, Son and Spirit. He can't even imagine that these were once burning questions of the soul of mankind. He has become a Philistine. That is why the time of nominalism can also be called the time of Philistinism for European civilization. For the Philistine is the man who has no real feelings for the ever-awakening spiritual, who actually lives in habits. Human life cannot be entirely without spirit. The Philistine would prefer to be completely without spirit, to get up without spirit, have breakfast without spirit, go to the office without spirit, eat lunch without spirit, play billiards in the afternoon without spirit and so on, he would like to do everything without spirit. But unconsciously the spirit runs through all of life. It's just that the philistine doesn't care about it; it doesn't interest him any more.