Awakening to Community

GA 257

3 March 1923, Dornach

Lecture IX

Yesterday I undertook to give you a sort of report on the events that took place in Stuttgart. I went on to say that I would like to convey something of the substance of the lectures I delivered there. So I will do that today, and tomorrow try to add further comment supplementing yesterday's report.

The first lecture on Tuesday was conceived as a response to a quite definite need that had developed and made itself clearly felt during the discussions of Sunday, Monday and Tuesday; they have been described to you at least from the standpoint of the mood that prevailed there. The need I refer to was for a survey of the essentials of community building. Community building by human beings working in anthroposophy has recently played an important role in the Society. Young people in particular—but other, older ones as well—entered the Society with a keen longing to meet others in it with whom they could have a type of experience that life does not afford the single individual in today's social order. To say this is to call attention to a thoroughly understandable longing felt by many people of our time.

As a result of the dawning of the age of consciousness, old social ties have lost their purely human content and their purely human strength. People always used to grow into some particular community. They did not become hermits; they grew into some quite specific community or other. They grew into the community of a family, a profession, a certain rank. Recently they have been growing into the communities we call social classes, and so on.

These various communities have always carried certain responsibilities for the individual that he could not have carried for himself.

One of the strongest bonds felt by men of modern times has been that of class. The old social groupings: those of rank, of nationality, even of race—have given way to a sense of belonging to a certain class. This has recently developed to a point where the members of a given class—the so-called higher classes or aristocracy, the bourgeoisie, the proletariat—make common cause. Thus communities based on class have transcended national and even racial and other such loyalties, and a good many of the elements witnessed in modern international social life can be ascribed to these class communities.

But the age of the consciousness soul, which began early in the fifteenth century and has come increasingly to the fore, has recently been making itself felt in human souls with growing urgency and vehemence. This has made human beings feel that they can no longer find in class communities any elements that could carry them into something beyond merely individual existence. On the one hand, modern man has a strong sense of individuality and cannot tolerate any interference with his life of individual thought and feeling. He wants to be recognized as a personality. That goes back to certain primal causes. If I may again resort to the terminology I used yesterday, I would say that since the end of Kali Yuga—or, in other words, since this century began—something has been stirring in contemporary souls, no matter how unconsciously, that could be expressed in the words, “I want to be a distinct individual.” Of course, not everybody could formulate it thus. It shows itself in many kinds of discontent and psychic instability. But underlying them is the desire to be a distinct personality.

The truth is, however, that no one can get along on earth without other human beings. Historic ties and bonds like those that unite the proletariat in a sense of class belonging, for example, do not supply anything that on the one hand can satisfy the urge to be a distinct individual and on the other unite individuals with their fellowmen. Modern man wants the purely human element in himself to relate him to the purely human element in others. He does indeed want social ties, but he wants them to have an individual character like that experienced in personal friendships.

An endless amount of what goes on between human beings in contemporary life can be traced to a craving for such human communities. It was quite evident a while ago when a group of younger people came to me wanting to bring about a renewal of Christianity. It was their belief that such a renewal could be achieved only by making the Christ impulse very much alive in the sense that anthroposophy has demonstrated. This longing felt by younger theologians, some of whom were just completing their training and were therefore about to assume pastoral duties, others of whom were still studying, was the element that gave birth to the latest offshoot of our Society, the Movement for Religious Renewal.

Now quite a variety of things had to be done for this Movement for Religious Renewal. It was of first concern to bring the Christ impulse to life in a way suited to the present. To do this meant taking very seriously indeed the fact I have so often stressed: that the Christ not only spoke to human souls at the beginning of the Christian era but has carried out the promise that he made when he said, “I will be with you always, unto the very end of the earth.” This means that he can always be heard whenever a soul desires it, that a continuing Christ revelation is taking place. There had to be an ongoing evolution from the written Gospels to immediately living revelation of the Christ impulse. This was one aspect of the task of religious renewal.

The other was one that I had to characterize at once by saying that religious renewal must bring communities into being, that it must build religious communities. Once a community has equipped an individual with knowledge, he can do something with it by himself. But that direct experience of the spiritual world, which is not based on thought but rather on feeling and is religious by nature, this experience of the spiritual world as divine can only be found by forming communities. So a healthy building of community must, I said, go hand in hand with the healthy development of religious life.

The personalities who undertook the launching of this Movement for Religious Renewal were, at the outset, all Protestant theologians. Their attention could be called to the fact that it was just the Protestant denominations that had recently been tending to lay increasing emphasis on sermons, to the neglect of ritual. But preaching has an atomizing effect on communities. The sermon, which is intended to convey knowledge of the spiritual world, challenges the individual soul to form its own opinions. This fact is reflected in the particularly pronounced modern antagonism to the credo, the confession of beliefs, in an age when everyone wants to confess only to his own. This has led to an atomization, a blowing apart of the congregation, with a resultant focusing of the religious element on the individual.

This would gradually bring about the dissolution of the soul elements of the social order if there were not to be a renewed possibility of building true community. But true community building can only be the product of a cultus derived from fresh revelations of the spiritual world. So the cultus now in use in the Movement for Religious Renewal was introduced. It takes mankind's historical evolution fully into account, and thus represents in many of its single details as well as in its overall aspects a carrying forward of the historical element. But its every aspect also bears the imprint of fresh revelations, which the spiritual world can only now begin to make to man's higher consciousness.

The cultus unites those who come together at its celebration. It creates community, and Dr. Rittelmeyer said quite rightly, in the course of the Stuttgart deliberations, that in the community building power of the cultus the Movement for Religious Renewal presents a great danger—perhaps a very grave one—to the Anthroposophical Society. What was he pointing to when he said this? He was calling attention to the fact that many a person approaches the Society with the longing to find a link with others in a free community experience. Such communal life with the religious coloration that the cultus gives it can be attained, and people with such a longing for community life can satisfy it in the Movement for Religious Renewal. If the Society is not to be endangered, it must therefore also make a point of nurturing a community building element.

Now this called attention to a fact of the greatest importance in this most recent phase of the Society's development. It pointed out that anthroposophists must acquire an understanding of community building. An answer must be found to the question whether the community building that is being achieved in the Movement for Religious Renewal is the only kind there is at present, or whether there are other possibilities of attaining the same goal in the Anthroposophical Society.

This question can obviously only be answered by studying the nature of community building.

But that impulse to build community, which modern man feels and the cultus can satisfy, is not the only one that moves him, strong though it is; there is still another. Every human being of the present feels both kinds of longings, and it is most desirable that each and every one should have his need met by providing community building elements not only in the Movement for Religious Renewal but in the Anthroposophical Society as well.

When one is discussing something, one naturally has to clothe it in idea form. But what I am about to present in that form really lives at the feeling level in people of our time. Ideas are a device for making things clear. But what I want to talk about now is something that modern man experiences purely as feeling.

The first kind of community building that we encounter the moment we set out on earthly life is one that we take quite for granted and seldom think about or weigh in feeling. That is the community built by language. We learn to speak our mother-tongue as little children, and this mother-tongue provides us with an especially strong community building element because it comes into the child's experience and is absorbed by him at a time when his etheric body is still wholly integrated with the rest of his organism and as yet quite undifferentiated. This means that the mother-tongue grows completely at one with his entire being. But it is also an element that groups of human beings share in common. People feel united by a common language, and if you remember something I have often mentioned, the fact that a spiritual being is embodied in a language, that the genius of language is not the abstraction learned men consider it but a real spiritual being, you will sense how a community based on a shared language rests on the fact that its members feel the presence of a real genius of speech. They feel sheltered beneath the wings of a real spiritual being. That is the case wherever community is built.

All community building eventuates in a higher being descending from the world of the spirit to reign over and unite people who have come together in a common cause.

But there is another, individual element eminently capable of creating community that can make its appearance when a group foregathers. A common tongue unites people because what one is saying can live in those who are listening to him; they thus share a common content. But now let us imagine that a number of individuals who spent their childhood and early schooldays together find an occasion of the sort that could and indeed often does present itself to meet again some thirty years later. This little group of forty- or fifty-year-olds, every one of whom spent his childhood in the same school and the same region, begins to talk of common experiences as children and young people. Something special comes alive in them that makes for quite a different kind of community than that created by a common tongue. When members of a group speaking the same language come, in the course of meeting and talking, to feel that they understand one another, their sense of belonging together is relatively superficial compared with what one feels when one's soul-depths are stirred by entertaining common memories. Every word has a special coloring, a special flavor, because it takes one back to a shared youth and childhood. What unites people in such moments of communal experience reaches deeper levels of their soul life. One feels related in deeper layers of one's being to those with whom one comes together on this basis.

What is this basis of relationship? It consists of memories—memories of communal experiences of earlier days. One feels oneself transported to a vanished world where one once lived in company with these others with whom one is thus re-united.

This is to describe an earthly situation that aptly illustrates the nature of the cultus. For what is intended with the cultus? Whether its medium be words or actions, it projects into the physical world, in an entirely different sense than our natural surroundings do, an image of the super-sensible, the spiritual world. Every plant, every process in external nature is, of course, also an image of something spiritual, but not in the direct sense that a rightly presented verbal or ceremonial facet of the cultus is. The words and actions of the cultus convey the super-sensible world in all its immediacy. The cultus is based on speaking words in the physical world in a way that makes the super-sensible world immediately present in them, on performing actions in a way that conveys forces of the super-sensible world. A cultus ritual is one in which something happens that is not limited to what the eyes see when they look physically at ritualistic acts; the fact is rather that forces of a spiritual, super-sensible nature permeate ordinary physical forces. A super-sensible event takes place in the physical act that pictures it.

Man is thus directly united with the spiritual world by means of the physically perceptible words and actions of the cultus. Rightly presented, its words and actions bring to our experience on the physical plane a world that corresponds to the pre-earthly one from which we human beings have descended. In just the same sense in which forty- or fifty-year-olds who have met again feel themselves transported back into the world they shared in childhood does a person who joins others at the celebration of a genuine cultus feel himself transported back into a world he shared with them before they descended to the earth. He is not aware of this; it remains a subconscious experience, but it penetrates his feeling life all the more deeply for that very reason. The cultus is designed with this intent. It is designed with a view to giving man a real experience of something that is a memory, an image of his pre-earthly life, of his existence before he descended to the earth. The members of congregations based on a cultus feel especially keenly what, for purposes of illustration, I have just described as taking place when a group comes together in later life and exchanges memories of childhood: They feel transported into a world where they lived together in the super-sensible. This accounts for the binding ties created by a cultus-based community, and it has always been the reason why it did so. Where it is a matter of a religious life that does not have an atomizing effect because of its stress on preaching but instead emphasizes the cultus, the cultus will lead to the forming of a true community or congregation. No religious life can be maintained without the community building element. Thus a community based in this sense on common memories of the super-sensible is a community of sacraments as well.

But no form of sacrament- or cultus-based community that remains standing where it is today can meet the needs of modern human beings. To be sure, it may be acceptable to many people. But cultus-based congregations would not achieve their full potential or—more important still—reach their real goal if they were to remain nothing more than communities united by common memories of super-sensible experience. This has created an increasing need for introducing sermons into the cultus. The trouble is that the atomizing tendency of sermons as these are presently conceived by the Protestant denominations has become very marked, because the real needs arising from the consciousness soul development of this Fifth Post-Atlantean epoch have not been taken into account. The concept of preaching in the older confessions is still based on the needs of the Fourth Post-Atlantean period. In these older churches, sermons conform to the world view that prevailed during the period of intellectual soul development. They are no longer suited to the modern consciousness. That is why the Protestant churches have gone over to a form of presentation that makes its appeal more to human opinion, to conscious human understanding.

There is every good reason for doing this, of course. On the other hand, no really right way of doing it has yet been found. A sermon contained within the cultus is a misfit; it leads away from the cultus in a cognitive direction. But this problem has not been well recognized in the form preaching has taken in the course of man's ongoing evolution. You will see this immediately when I remind you of a certain fact. You will see how little there is left when we omit sermons of more recent times that do not take a Biblical text. In most cases, Sunday sermons as well as those delivered on special occasions take some quotation from the Bible for their text because fresh, living revelation such as is also available in the present is rejected. Historical tradition remains the only source resorted to. In other words, a more individual form of sermon is being sought, but the key to it has not been found. Thus sermons eventuate in mere opinion, personal opinion, with atomizing effect.

Now if the recently established Movement for Religious Renewal, built as it is in all essentials on an anthroposophical foundation, reckons with fresh, ongoing revelation, with a living spiritual experience of the super-sensible world, then it will be just the sermon factor that will bring it to recognize its need for something further. This something is the same thing that makes fresh, ongoing, living knowledge of the spiritual world possible, namely, anthroposophical spiritual science. I might express it by saying that sermons will always be the windows through which the Movement for Religious Renewal will have to receive what an ongoing, living Anthroposophical Society must give it. But as I said when I spoke of the Movement for Religious Renewal at the last lecture I gave over there in the still intact Goetheanum, if the Movement for Religious Renewal is to grow, the Anthroposophical Society will have to stand by it in the liveliest possible way, with all the living life of anthroposophy flowing to it from a number of human beings as the channel. The Movement for Religious Renewal would soon go dry if it were not to have at least some people standing by it in whom anthroposophical cognition is a really living element.

But as I said, many individuals are presently entering the Society, seeking anthroposophy not just in the abstract but in the community belonging that satisfies a yearning of the age of consciousness. It might be suggested that the Society too should adopt a cultus. It could do this, of course, but that would take it outside its proper sphere. I will therefore now go on to discuss the specifically anthroposophical way of building community.

Modern life definitely has other community building elements to offer besides that based on common memories of pre-natal experience of the super-sensible world. The element I have in mind is one that is needed by the present in a form especially adapted to the age of consciousness.

In this connection I must point out something that goes entirely unnoticed by most human beings of our time.

There has, to be sure, always been talk of idealism. But when idealism is mentioned nowadays, such talk amounts to little more than hollow phrases, even in the mouths of the well-meaning. For ours is a time when intellectual elements and forces have come especially strongly to the fore throughout the entire civilized world, with the result that there is no understanding for what a whole human being is. The longing for that understanding is indeed there, particularly in the case of modern youth. But the very indefiniteness of the form in which youth conceives it shows that something lives in human souls today that has not declared itself at all distinctly; it is still undifferentiated, and it will not become the less naive for being differentiated.

Now please note the following. Imagine yourselves back in times when religious streams were rising and inundating humankind. You will find that in those bygone periods of human evolution this and that proclamation from the spiritual world was being greeted by many people with enormous enthusiasm. Indeed, it would have been completely impossible for the confessions extant today to find the strength to carry people if, at the time of these proclamations, souls had not felt a much greater affinity for revelations from the spiritual world than is felt today. Observing people nowadays, one simply cannot imagine them being carried away by anything in the nature of a proclamation of religious truths such as used to take place in earlier ages. Of course, sects do form, but there is a philistine quality about them in great contrast to the fiery response of human souls to earlier proclamations. One no longer finds the same inner warmth of soul toward things of the spirit. It suffered a rapid diminution in the last third of the nineteenth century. Granted, discontent still drives people to listen to this or that, and to join one or another church. But the positive warmth that used to live in human souls and was solely responsible for enabling individuals to put their whole selves at the service of the spirit has been replaced by a certain cool or even cold attitude. This coolness is manifest in human souls today when they speak of ideals and idealism. For nowadays the matter of chief concern is something that still has a long way to go to its fulfillment, that still has a long waiting period before it, but that as expectation is already very much alive in many human souls today. I can characterize it for you in the following way.

Let us take two states of consciousness familiar to everybody, and imagine a dreaming person and someone in a state of ordinary waking consciousness.

What is the situation of the dreamer? It is the same as that of a sleeping person. For though we may speak of dreamless sleep, the fact is that sleepers are always dreaming, though their dreams may be so faint as to go unnoticed.

What, I repeat, is the dreamer's situation? He is living in his own dream-picture world. As he lives in it he frequently finds it a good deal more vivid and gripping—this much can certainly be said—than his everyday waking experience. But he is experiencing it in complete isolation. It is his purely personal experience. Two people may be sleeping in one and the same room, yet be experiencing two wholly different worlds in their dream consciousness. They cannot share each other's experience. Each has his own, and the most they can do is tell one another about it afterwards.

When a person wakes and exchanges his dream consciousness for that of everyday, he has the same sense perception of his surroundings that those about him have. They begin to share a communal scene. A person wakes to a shared world when he leaves dreams behind and enters a day-waking state of consciousness. What wakes him out of the one consciousness into the other? It is light and sound and the natural environment that rouse him to the ordinary day-waking state, and other people are in the same category for him. One wakes up from dreams by the natural aspects of one's fellowmen, by what they are saying, by the way they clothe their thoughts and feelings in the language they use. One is awakened by the way other people naturally behave. Everything in one's natural environment wakes one to normal day consciousness. In all previous ages people woke up from the dream state to day-waking consciousness. And these same surroundings provided a person with the gate through which, if he was so minded, he entered spiritual realms.

Then a new element made its appearance in human life with the awakening and development of the consciousness soul. This calls for a second kind of awakening, one for which the human race will feel a growing need: an awakening at hand of the souls and spirits of other human beings. In ordinary waking life one awakens only in meeting another's natural aspects. But a person who has become an independent, distinct individual in the age of consciousness wants to wake up in the encounter with the soul and spirit of his fellowman. He wants to awaken to his soul and spirit, to approach him in a way that startles his own soul awake in the same sense that light and sound and other such environmental elements startle one out of dreaming.

This has been felt as an absolutely basic need since the beginning of the twentieth century, and it will grow increasingly urgent. It is a need that will be apparent throughout the twentieth century, despite the time's chaotic, tumultuous nature, which will affect every phase of life and civilization. Human beings will feel this need—the need to be brought to wake up more fully in the encounter with the other person than one can wake up in regard to the merely natural surroundings. Dream life wakes up into wakeful day consciousness in the encounter with the natural environment. Wakeful day consciousness wakes up to a higher consciousness in the encounter with the soul and spirit of our fellowman. Man must become more to his fellowman than he used to be: he must become his awakener. People must come closer to one another than they used to do, each becoming an awakener of everyone he meets. Modern human beings entering life today have stored up far too much karma not to feel a destined connection with every individual they encounter. In earlier ages, souls were younger and had not formed so many karmic ties. Now it has become necessary to be awakened not just by nature but by the human beings with whom we are karmically connected and whom we want to seek.

So, in addition to the need to recall one's super-sensible home, which the cultus meets, we have the further need to be awakened to the soul-spiritual element by other human beings, and the feeling impulse that can bring this about is that of the newer idealism. When the ideal ceases to be a mere abstraction and becomes livingly reunited with man's soul and spirit, it can be expressed in the words, “I want to wake up in the encounter with my fellowman.”

This is the feeling that, vague though it is, is developing in youth today, “I want to be awakened by my fellowman,” and this is the particular form in which community can be nurtured in the Anthroposophical Society. It is the most natural development imaginable for when people come together for a communal experience of what anthroposophy can reveal of the super-sensible, the experience is quite a different one from any that the individual could have alone. The fact that one wakes up in the encounter with the soul of the other during the time spent in his company creates an atmosphere that, while it may not lead one into the super-sensible world in exactly the way described in Knowledge of the Higher Worlds, furthers one's understanding of the ideas that anthroposophical spiritual science brings us from super-sensible realms.

There is a different understanding of things among people who share a common idealistic life based on mutual communication of an anthroposophical content, whether by reading aloud or in some other way. Through experiencing the super-sensible together, one human soul is awakened most intensively in the encounter with another human soul. It wakes the soul to higher insight, and this frame of mind creates a situation that causes a real communal being to descend in a group of people gathered for the purpose of mutually communicating and experiencing anthroposophical ideas. Just as the genius of a language lives in that language and spreads its wings over those who speak it, so do those who experience anthroposophical ideas together in the right, idealistic frame of mind live in the shelter of the wings of a higher being.

Now what takes place as a result?

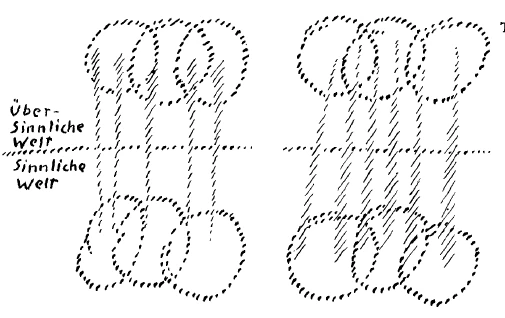

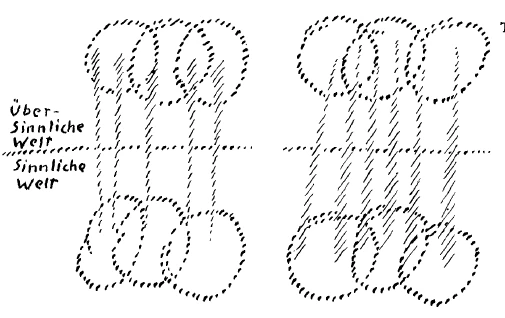

If this line (Dr. Steiner draws on the blackboard) represents the demarcation between the super-sensible and the sense world, we have, here above it, the processes and beings of the higher world experienced in the cultus; they are projected by the words and ritualistic acts of the cultus into the physical world here below the line. In the case of an anthroposophical group, experience on the physical plane is lifted by the strength of its genuine, spiritualized idealism into the spiritual world. The cultus brings the super-sensible down into the physical world with its words and actions. The anthroposophical group raises the thoughts and feelings of the assembled individuals into the super-sensible, and when an anthroposophical content is experienced in the right frame of mind by a group of human beings whose souls wake up in the encounter with each other, the soul is lifted in reality into a spirit community. It is only a question of this awareness really being present. Where it exists and groups of this kind make their appearance in the Anthroposophical Society, there we have in this reversed cultus, as I shall call it, in this polar opposite of the cultus, a most potent community building element. If I were to speak pictorially, I would put it thus: the community of the cultus seeks to draw the angels of heaven down to the place where the cultus is being celebrated, so that they may be present in the congregation, whereas the anthroposophical community seeks to lift human souls into super-sensible realms so that they may enter the company of angels. In both cases that is what creates community.

But if anthroposophy is to serve man as a real means of entering the spiritual world, it may not be mere theory and abstraction. We must do more than just talk about spiritual beings; we must look for the opportunities nearest at hand to enter their company. The work of an anthroposophical group does not consist in a number of people merely discussing anthroposophical ideas. Its members should feel so linked with one another that human soul wakes up in the encounter with human soul and all are lifted into the spiritual world, into the company of spiritual beings, though it need not be a question of beholding them. We do not have to see them to have this experience. This is the strength-giving element that can emerge from groups that have come into being within the Society through the right practice of community building. Some of the fine things that really do exist in the Society must become more common; that is what new members have been missing. They have looked for them, but have not found them. What they have encountered has instead been some such statement as, “If you want to be a real anthroposophist you must believe in reincarnation and the etheric body,” and so on.

I have often pointed out that there are two ways of reading a book like my Theosophy. One is to read, “Man consists of physical body, etheric body, astral body, etc., and lives repeated earth lives and has a karma, etc.” A reader of this kind is taking in concepts. They are, of course, rather different concepts than one finds elsewhere, but the mental process that is going on is in many respects identical with what takes place when one studies a cookbook. My point was exactly that the process is the important thing, not the absorption of ideas. It makes no difference whether you are reading, “Put butter into a frying pan, add flour, stir; add the beaten eggs, etc.,” or, “There is physical matter, etheric forces, astral forces, and they interpenetrate each other.” It is all one from the standpoint of the soul process involved whether butter, eggs and flour are being mixed at a stove or the human entelechy is conceived as a mixture of physical, etheric and astral bodies. But one can also read Theosophy in such a manner as to realize that it contains concepts that stand in the same relation to the world of ordinary physical concepts as the latter does to the dream world. They belong to a world to which one has to awaken out of the ordinary physical realm in just the way one wakes out of one's dream world into the physical. It is the attitude one has in reading that gives things the right coloring. That attitude can, of course, be brought to life in present-day human beings in a variety of ways. They are all described and there to choose from in Knowledge of the Higher Worlds. But modern man also needs to go through the transitional phase—one not to be confused with actually beholding higher worlds—of waking up in the encounter with the soul-spiritual aspect of his fellowman to the point of living into the spiritual world just as he awakes from dreams into the physical world through the stimulus of light and sound, etc.

We must rise to an understanding of this matter. We have to come to understand what anthroposophy ought to be within the Anthroposophical Society. It should be a path to the spirit. When it becomes that, community building will be the outcome.

But anthroposophy must really be applied to life. That is the essential thing, my dear friends. How essential it is can be illustrated by an example close at hand. After we had had many smaller meetings with a varying number of people there in Stuttgart and had debated what should be done to consolidate the Society, I came together with the young people. I am not referring to the meeting I reported on yesterday, which was held later; this was a prior meeting, but also one held at night. These particular young people were all students. Well, first there was some talk about the best way to arrange things so that the Society would function properly, and so on. But after awhile the conversation shifted to anthroposophy itself. We got right into its very essence because these young men and women felt the need to enquire into the form studies ought to take in future, how the problem of doctoral dissertations should be handled, and other such questions. It was not possible to answer them superficially; we had to plunge right into anthroposophy. In other words, we began with philistine considerations and immediately got into questions of anthroposophy and its application, such as, “How does one go about writing a doctoral dissertation as an anthroposophist? How does one pursue a subject like chemistry?” Anthroposophy proved itself life-oriented, for deliberations such as these led over into it quite of themselves.

The point is that anthroposophy should never remain abstract learning. Matters can, of course, be so arranged that people are summoned to a meeting called for the purpose of deciding how the Society should be set up, with a conversation about anthroposophy as a further item on the agenda. This would be a superficial approach. I am not suggesting it, but rather a much more inward one that would lead over quite of itself from a consideration of everyday problems to the insight that anthroposophy should be called upon to help solve them. One sees the quickening effect it has on life in just such a case as the one cited, where people were discussing the re-shaping of the Society only to end up, quite as a matter of organic necessity, in a discussion of how the anthroposophist and the scientific philistine must conceive the development of the embryo from their respective standpoints. We must make a practice of this rather than of a system of double-entry bookkeeping that sets down such philistine entries on one page as “Anthroposophical Society,” “Union for a Free Spiritual Life,” and so on. Real life should be going on without a lot of theory and abstractions and a dragging in of supposedly anthroposophical sayings such as “In anthroposophy man must find his way to man,” and so on. Abstractions of this kind must not be allowed to play a role. Instead, a concrete anthroposophical approach should lead straight to the core of every matter of concern. When that happens, one seldom hears the phrase, “That is anthroposophical, or un-anthroposophical.” Indeed, in such cases the word “anthroposophy” is seldom spoken. We need to guard against fanatical talk.

My dear friends, this is not a superficial matter, as you will see. At the last Congress in Vienna I had to give twelve lectures on a wide range of subjects, and I set myself the task of never once mentioning the word “anthroposophy.” And I succeeded! You will not discover the word “anthroposophy” or “anthroposophical” in a single one of the twelve lectures given last June in Vienna. The experiment was a success. Surely one can make a person's acquaintance without having any special interest in whether his name is Mueller and what his title is. One just takes him as he is. If we take anthroposophy livingly, just as it is, without paying much attention to what its name is, this will be a good course for us to adopt.

We will speak further about these things tomorrow, and I will then give you something more in the way of a report.

Neunter Vortrag

Gestern habe ich mich bemüht, Ihnen eine Art Bericht zu’ geben über dasjenige, was in Stuttgart vorgefallen ist, und ich sagte dann, daß ich im wesentlichen den Inhalt der Vorträge andeuten möchte, die ich dort zu halten hatte. Ich werde also zunächst diesen Inhalt der Vorträge heute hier angeben und werde dann morgen versuchen, noch einiges in Anknüpfung an das gestern Ausgeführte zu sagen.

Der erste Vortrag am Dienstag hat sich ergeben aus einem ganz bestimmten Bedürfnisse heraus, das sich im Laufe der Ihnen ja, ich möchte sagen, wenigstens stimmungsgemäß geschilderten Diskussion am Sonntag, Montag und Dienstag, also aus einem Bedürfnis heraus, das sich aus diesen Diskussionen gebildet hatte, klar gezeigt hat. Es war das Bedürfnis, das Wesen der Gemeinschaftsbildung zu betrachten. Dieses Bilden von Menschengemeinschaften durch die anthroposophische Sache, das ist ja etwas, was in der letzten Zeit innerhalb unserer Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft eine große Rolle gespielt hat. Namentlich die Jugend, aber auch andere Menschen, ältere Menschen kamen in die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft herein mit der ausgesprochenen Sehnsucht, innerhalb dieser Gesellschaft andern Menschen zu begegnen, mit denen zusammen sie gewissermaßen dasjenige finden könnten, was in der heutigen sozialen Ordnung das Leben dem einzelnen nicht geben kann. Es ist damit ja hingewiesen auf eine durchaus begreifliche Sehnsucht vieler Menschen in unserer Zeit.

Durch das Heraufkommen des Bewußtseinszeitalters liegt ja die Sache so, daß die alten sozialen Bindungen den rein menschlichen Gehalt und die rein menschliche Kraft verloren haben. Der Mensch wuchs ja immer in eine gewisse Gemeinschaft hinein. Er wuchs nicht zum Lebenseinsiedler heran, sondern er wuchs in eine bestimmte Gemeinschaft hinein. Er wuchs in die Familiengemeinschaft, in die Berufsgemeinschaft, in die Standesgemeinschaft, in der letzten Zeit in dasjenige hinein, was man die Klassengemeinschaft nennt und so weiter. Diese Gemeinschaften haben immer etwas für den Menschen getragen, was er als einzelner nicht tragen kann. Eine der stärksten Bindungen von Menschen im sozialen Leben untereinander hat ja in der neuesten Zeit die Klassengemeinschaft abgegeben.

Es entstanden aus den alten gesellschaftlichen Formationen heraus, aus Standesgemeinschaften, Volksgemeinschaften, sogar aus Rassengemeinschaften, die Klassengemeinschaften. Und es ist in der letzten Zeit ja so geworden, daß ein gewisser Zusammenhalt da war in den sogenannten höheren Ständen, denen des Adels, in dem Bürgerstande und dann im Proletarierstande. So entstanden Klassengemeinschaften, die sich hinübererstreckt haben über Volkstümer, sogar über Rasseneigentümlichkeiten und so weiter. Und vieles von dem, was heute vorhanden ist im ganz internationalen sozialen Leben, ist zurückzuführen auf solche Klassengemeinschaften.

Nun aber ist ja das Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseele, das ja schon seit dem Beginn des 15. Jahrhunderts sich immer mehr und mehr angekündigt hat, in der neuesten Zeit mit einer gewissen Vehemenz, mit einer inneren Stärke aus den Menschenseelen heraus zur Offenbarung gekommen. Die Menschen fühlen doch: auch innerhalb von Klassengemeinschaften können sie nicht mehr zu dem kommen, was sie über das einzelne Individuelle hinaustragen soll. Der Mensch fühlt sich heute auf der einen Seite stark als eine Individualität, und er möchte zurückweisen dasjenige, was ihm sein individuelles Fühlen, Empfinden, sein individuelles Denken irgendwie beeinträchtigt. Er möchte eine Persönlichkeit sein. Und das rührt ja aus gewissen elementarischen Untergründen her. Es steckt in den Seelen der Menschen, wenn ich mich des Ausdruckes, dessen ich mich auch gestern bedient habe, noch einmal bedienen darf, seit dem Ablauf des Kali Yuga, also seit dem Beginne unseres Jahrhunderts, wenn auch noch so unklar, heute etwas, das sich ausdrückt in den Worten: Ich möchte eine in mir selbst geschlossene Persönlichkeit sein. - Gewiß, viele wissen sich das nicht zu formulieren. Es kündigt sich dann an in allerlei Unzufriedenheiten, in allerlei Haltlosigkeiten des Seelenlebens, aber es ist doch dieses: eine Persönlichkeit, eine geschlossene Persönlichkeit sein zu wollen.

Aber nun kann der Mensch einmal im irdischen Leben nicht ohne die andern Menschen auskommen. Die historischen Bindungen geben nicht das her, auch die proletarische Klassengemeinschaft zum Beispiel nicht, was zu gleicher Zeit dem Drang nach Persönlichkeit Rechnung trägt, und auf der andern Seite doch wiederum Menschen an Menschen schließt. Der Mensch möchte sich heute durch das rein Menschliche an das rein Menschliche des andern anschließen. Er möchte gewissermaßen zwar soziale Bindungen haben, aber sie sollen solchen individuellen Charakter tragen, wie etwa persönliche Freundschaften.

Und unendlich vieles, was heute im Leben zwischen Menschen spielt, ist ein Drängen nach solchen Menschengemeinschaften. Dieses Drängen nach solchen Menschengemeinschaften trat besonders stark zutage, als einige jüngere Persönlichkeiten vor einiger Zeit an mich herankamen mit der Tendenz, eine Art Erneuerung des Christentums herbeizuführen, wobei sie glaubten, daß diese Erneuerung des Christentums nur herbeigeführt werden könne durch das Verlebendigen des ChristusImpulses auf die Art, wie es aus der Anthroposophie heraus möglich ist. Aus dieser Sehnsucht von jüngeren Theologen, die zum Teil eben in der Vollendung ihres theologischen Studiums waren, also vor der Aufgabe standen, den Seelsorgerberuf zu übernehmen, oder die noch in dem theologischen Studium standen, aus dieser Sehnsucht heraus ist dann dasjenige entstanden, was, ich möchte sagen, eingetreten ist als die jüngste Begründung durch unsere Anthroposophische Gesellschaft, die «Bewegung für religiöse Erneuerung».

Nun war natürlich für diese Bewegung für religiöse Erneuerung so mancherlei zu tun. Vor allen Dingen handelte es sich darum, in der Weise, wie das heute sein kann, den Christus-Impuls zu verlebendigen. Dazu war notwendig, ganz ernst zu machen mit dem, was ich ja oftmals betont habe, daß der Christus nicht nur im Ausgangspunkt der christlichen Entwickelung zu den Menschenseelen gesprochen hat, sondern daß er wahr gemacht hat dasjenige, was in dem Worte liegt: «Ich bin bei euch alle Tage bis ans Ende der Erdenzeiten», das heißt, daß er jedesmal gehört werden kann, wenn eine Seele ihn hören will, daß also eine fortwährende Christus-Offenbarung stattfindet. Also von den aufgeschriebenen Evangelienoffenbarungen mußte zu den unmittelbar lebendigen Offenbarungen des Christus-Impulses geschritten werden. Das war ja die eine Seite der Aufgaben für die religiöse Erneuerung.

Die andere Seite war aber diejenige, die ich sogleich bezeichnen mußte dadurch, daß ich sagte: Aber eine religiöse Erneuerung muß herbeiführen Gemeindebildungen, religiöse Gemeindebildungen. Der Mensch kann seine Erkenntnis als einzelner pflegen, wenn er sie erst durch die Gemeinschaft erhalten hat. Aber jenes unmittelbare, nicht so sehr denkerische als empfindungsgemäße Erleben der geistigen Welt, das als Religiöses bezeichnet werden kann, das Erleben der geistigen Welt als einer göttlichen, das kann nur sich ausleben im Gemeinschaftbilden. Und so, sagte ich, muß eine Gesundung des religiösen Lebens durch eine gesunde Gemeinschaftsbildung entstehen.

Es waren ja zunächst evangelische theologische Persönlichkeiten, die diese Bewegung für religiöse Erneuerung unternahmen. Sie konnte man darauf hinweisen, wie gerade die evangelischen Bekenntnisse in der neueren Zeit immer mehr und mehr hingeneigt haben zur besonderen Betonung des Predigthaften und abgekommen waren von dem Kultusartigen. Aber die Predigt atomisiert die Gemeinschaften. Die Predigt, durch die ja die Erkenntnis von der göttlichen Welt durchdringen soll, fordert die einzelnen Seelen dazu auf, sich ihre eigene Meinung zu bilden, was sich ja ausgedrückt hat dadurch, daß das Credo, das Glaubensbekenntnis, am meisten angefochten worden ist in der neueren Zeit, daß gewissermaßen jeder sein eigenes Glaubensbekenntnis haben wollte. Ein Atomisieren, ein Zersprengen der Gemeinde und ein Hinlenken des Religiösen auf die einzelne Persönlichkeit ist eingetreten.

Das würde aber nach und nach überhaupt zur Auflösung der sozialen Ordnung nach dem Seelischen hin führen, wenn nicht die Möglichkeit einer wirklichen Gemeindebildung wieder da wäre. Aber die wirkliche Gemeindebildung, sagte ich, ist nur in einem Kultus gegeben, der nun wirklich aus den heutigen Offenbarungen der geistigen Welt heraus gewonnen wird. Und so ist denn jener Kultus auch eingezogen in die Bewegung für religiöse Erneuerung, der innerhalb derselben nun eben da ist. Dieser Kultus berücksichtigt durchaus die historische Entwickelung der Menschheit, trägt daher in vielen seiner Einzelheiten und auch in vielem, was in seiner Totalität auftritt, eine Fortführung des Historischen in sich. Aber er trägt überall auch die Einschläge desjenigen, was sich erst heute dem übersinnlichen Bewußtsein aus der geistigen Welt offenbaren kann.

Kultus bindet die Menschen, die im Kultus sich vereinigen, aneinander. Kultus schafft Gemeinden. Und Dr. Rittelmeyer hat im Verlaufe der Diskussionen ganz mit Recht gesagt: der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft erwächst in der Bewegung für religiöse Erneuerung gerade durch das gemeindebildende Element des Kultus eine gewisse starke, vielleicht die stärkste Gefahr. Auf was hat er damit hingedeutet? Er hat damit auf das hingedeutet, daß ja heute viele Menschen doch, wie ich schon vorhin sagte, an die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft herankommen mit der Tendenz, den Anschluß an andere Menschen im Sinne einer solchen freien Gemeinschaftsbildung zu finden, daß mit der religiösen Färbung durch den Kultus dieses Gemeinschaftsleben gefunden wird, daß daher diejenigen Menschen, welche diese Sehnsucht nach dem Gemeinschaftsleben haben, sie zunächst befriedigen werden innerhalb der Bewegung für religiöse Erneuerung. Und die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft müßte daher, wenn sie da nicht einer Gefahr entgegengehen will, danach trachten, auch ein gemeinschaftsbildendes Element zu pflegen.

Nun, damit warhingewiesen auf etwas, was gerade durch die neueste Phase unserer Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft von einer ganz besonderen Bedeutung ist. Es war hingewiesen darauf, daß erkannt werden muß von den Anthroposophen das Wesen der Gemeinschaftsbildung. Die Frage muß beantwortet werden: Ist diese Gemeinschaftsbildung, die in der religiösen Erneuerung auftritt, die einzig mögliche in der Gegenwart, oder findet sich auch eine andere Möglichkeit innerhalb der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft für die Gemeinschaftsbildung? Diese Frage kann natürlich nur beantwortet werden, wenn man das Wesen der Gemeinschaftsbildung etwas ins Auge faßt. Es ist aber im Menschen der Gegenwart nicht bloß jene Tendenz zur Gemeindebildung vorhanden - sie ist stark vorhanden, aber nicht bloß vorhanden -, die durch den Kultus befriedigt werden kann, sondern es ist noch eine andere Art von Sehnsucht nach Gemeinschaftsbildung vorhanden. Und so kann es ganz gut sein, daß diesen zwei Arten von Sehnsucht nach Gemeinschaftsbildung, die in jedem Menschen heute vorhanden sind, für jeden einzelnen Menschen Rechnung getragen werden kann, so daß nicht nur in der Bewegung für religiöse Erneuerung ein gemeinschaftsbildendes Element vorhanden ist, sondern auch in der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft.

Man muß natürlich, wenn man über solche Dinge spricht, diese in Ideen kleiden. Aber dasjenige, was ich nun in Ideen entwickeln werde, ist eigentlich im gefühlsmäßigen Erleben der heutigen Menschheit vorhanden. Man macht sich nur die Dinge dadurch klar, daß man sie in Ideen gibt; aber das, was ich jetzt ausdrücken will, ist etwas durchaus im heutigen Menschen eben gefühlsmäßig Vorhandenes.

Die erste Art der Gemeinschaftsbildung, die, ich möchte sagen, gleich bei unserer Lebensanfängerschaft auf der Erde an uns herantritt, die ja eine selbstverständliche ist, über die gewöhnlich nicht sehr nachgesonnen und nachempfunden wird, das ist jene Gemeinschaftsbildung, die durch die Sprache gegeben ist. Wir lernen als Kind die Sprache. Und ein besonders stark gemeinschaftsbildendes Element ist ja durch dieMuttersprache gegeben aus dem Grunde, weil die Muttersprache an das Kind herantritt und vom Kinde aufgenommen wird in der Zeit, in der der Ätherleib noch ganz und gar ungeschieden und undifferenziert in der übrigen Organisation darinnensteckt. Dadurch verwächst die Muttersprache ganz intensiv mit dem ganzen Wesen des Menschen. Diese Sprache ist aber etwas, was als ein Gemeinsames über Menschengruppen sich ausbreitet. Die Menschen finden sich zusammen in der gemeinschaftlichen Sprache. Und wenn Sie sich daran erinnern, was ich ja öfter hier ausgesprochen habe, daß in der Sprache tatsächlich ein Geistiges verkörpert ist, daß der Sprachgenius nicht bloß die Abstraktion der heutigen Gelehrten, sondern ein wirkliches geistiges Wesen ist, so werden Sie eben empfinden, wie die Gemeinschaft der Sprache darauf beruht, daß diejenigen, die in der gleichen Sprache sich verständigen, in ihrem Kreise, zu dem sie zusammengekommen sind, die Wirksamkeit des realen Sprachgenius fühlen. Sie fühlen sich gewissermaßen unter den Flügeln einer wirklichen geistigen Wesenheit. Und das ist bei aller Gemeinschaftsbildung der Fall.

Jede Gemeinschaftsbildung läuft darauf hinaus, daß unter denjenigen, die sich zur Gemeinschaft zusammenschließen, ein höheres GeistigWesenhaftes waltet, das gewissermaßen aus geistigen Welten heruntersteigt und die Menschen zusammenbindet. Aber wir können ja, ich möchte sagen singulär, im einzelnen noch anderes finden, was im eminentesten Sinne wie ein gemeinschaftsbildendes Element auftreten kann unter einer Anzahl von Menschen. Die gemeinsame Sprache, sie bindet die Menschen, weil, was der eine sagt, in dem andern leben kann, weil also gleichzeitig ein Gemeinsames in mehreren Menschen leben kann. Aber stellen wir uns einmal folgendes vor: Eine Anzahl von Menschen, die gemeinsam ihre Kindheit und erste Schulzeit verlebt haben, finden sich durch irgendwelche Veranlassung — so etwas könnte ja eintreten, ist auch oftmals eingetreten und herbeigeführt worden - nach dreißig Jahren wieder zusammen. Sie kommen dazu, nun als ein kleines Häuflein vierzig- bis fünfzigjähriger Menschen, innerhalb dessen jeder einzelne die Kindheit mit dem andern in der Schule, in derselben Gegend verlebt hat, von dem zu sprechen, was sie in ihrer Kindheit und Jugend miteinander erlebt haben. Da lebt in ihnen etwas ganz Besonderes auf, etwas, was noch in diesem Augenblicke eine ganz andere Gemeinschaft ist als bloß die durch die Sprache herbeigeführte. Wenn eine Menschengruppe, welche die gleiche Sprache spricht, nun während des Beisammenseins eben in dem durch die Sprache herbeigeführten Verständnis der Seelen sich zuammenfindet, so ist dieses Zusammenfinden doch etwas verhältnismäßig Oberflächliches gegenüber dem andern, das eintritt, wenn man tief innen im Seelenzentrum dadurch gepackt wird, daß man in gemeinsamen Erinnerungen lebt. Jedes Wort bekommt sein besonderes Kolorit, seine besondere Färbung dadurch, daß es hinweist auf gemeinsam verlebte Kindheit, gemeinsam verlebte Jugend. Es geht dasjenige, was da für die Augenblicke einer solchen Zusammengehörigkeit Mensch an Mensch bindet, tiefer in das Seelische hinein. Man fühlt sich mit tieferen Organen an dasjenige gebunden, mit dem man da zusammen ist.

Und in was ist man zusammen? In Erinnerungen ist man zusammen, in demjenigen, was vor Zeiten gemeinschaftlich erlebt worden ist. In eine Welt fühlt man sich hineinversetzt, die jetzt nicht mehr da ist, in der man gemeinschaftlich gelebt hat mit jenen andern, mit denen man jetzt beisammen ist. Das gilt für irdische Verhältnisse, es soll nur veranschaulichen. Aber es veranschaulicht eben gerade das Wesen des Kultus, denn was wird denn angestrebt beim Kultus? Der Kultus, ob er nun durch Worte, ob er durch Handlungen sich offenbart, gibt in der sinnlich-physischen Welt etwas wieder, was in ganz anderem Sinne als dasjenige, was wir in der äußeren natürlichen Umgebung haben, unmittelbar Abbild der geistigen Welt, der übersinnlichen Welt ist. Gewiß, jede Pflanze, jeder Vorgang in der äußeren Natur ist Abbild eines Geistigen, aber nicht so unmittelbar wie dasjenige, was man in einer Kultzeremonie oder in einem Kultworte, das in der richtigen Weise ausgesprochen wird, offenbart. Da ist die übersinnliche Welt unmittelbar in Wort oder Handlung hineingelegt. Darin besteht ja der Kultus, daß in der sinnlichen Welt Worte so gesprochen werden, daß die übersinnliche Welt unmittelbar in ihrer Wesenhaftigkeit anwesend ist, Handlungen so vollzogen werden, daß in diesen Handlungen die Kräfte der übersinnlichen Welt anwesend sind. Eine Kultzeremonie ist ja eine solche, wo etwas geschieht, was nicht bloß das bedeutet, was da zelebriert wird, wenn man es äußerlich mit den Augen anschaut, sondern es geht durch die gewöhnlichen physischen Kräfte etwas, was eben geistige Kräfte, übersinnliche Kräfte sind. Ein übersinnliches Geschehen vollzieht sich im sinnlichen Abbilde.

Der Mensch ist also im sinnlichen Sprechen und im sinnlichen Handeln unmittelbar mit der geistigen Welt vereint. Es ist im richtigen Kultus so, daß die Welt, die gewissermaßen da in das Sinnliche hereingebracht wird in Wort und Handlung, derjenigen entspricht, aus der wir Menschen aus unserem vorirdischen Leben heruntergezogen sind. Wie sich, wenn drei, vier, fünf Menschen im vierzigsten, fünfzigsten Lebensjahre zusammenkommen, welche die Kindheit zusammen erlebt haben, diese versetzt fühlen in die Welt, in der sie als Kinder zusammen waren, so fühlt sich derjenige, der einen richtigen Kultus mit den andern zusammen mitmacht — er weiß es nicht, es bleibt im Unterbewußten, aber dadurch lebt es sich um so mehr in das Fühlen und Empfinden ein -, versetzt in die Welt, in der sie ja gemeinsam waren, bevor sie auf die Erde heruntergestiegen sind. Denn so wird der Kultus gebildet. Der Kultus wird so gebildet, daß der Mensch im Kultus richtig etwas erlebt, was durchaus Erinnerung ist, Bild von dem ist, was er im vorirdischen Dasein, also bevor er zur Erde heruntergestiegen ist, erlebt hat, Und so fühlen diejenigen, die zu einer Kultgemeinde gehören, in einem erhöhten Maße das, was ich vorhin nur zur Verdeutlichung beschrieben habe, wenn man in einem späteren Lebensalter zusammenkommt mit einer Gruppe und Kindheitserinnerungen austauscht: sie fühlen sich versetzt in eine Welt, die sie gemeinsam durchgemacht haben im Übersinnlichen. Das macht das Bindende in der Kultusgemeinde aus. Das hat immer das Bindende beim Kultus ausgemacht. Und wenn es sich um religiöses Leben handelt, das nicht atomisieren soll, das also nicht in die Predigt das Wesentlichste legen soll, sondern in den Kultus, dann führt der Kultus eben zur wirklichen Gemeinschaftsbildung, zur Gemeindebildung. Und religiöses Leben kann nicht ohne Gemeindebildung bestehen. Daher ist die Gemeinschaft, die auf diese Weise eine Erinnerungsgemeinschaft in bezug auf das Übersinnliche ist, auch eine Sakramentsgemeinschaft.

Nun ist es aber nicht möglich, daß diese Form der Sakramentengemeinschaft, also der Kultgemeinschaft, stehenbleibt für den modernen Menschen bei dem, was sie ist. Gewiß, für viele wird es heute noch so sein; aber die Kultgemeinschaft selber würde nicht ihren Wert, ihren rechten Wert haben, vor allen Dingen nicht ihr rechtes Ziel erreichen, wenn sie eben eine bloße Erinnerungsgemeinschaft an das übersinnliche Erleben bliebe. Daher ist ja auch immer mehr und mehr das Bedürfnis aufgetreten, hineinzubringen in den Kultus die Predigt. Nur ist bei der Ausbildung dieser Predigt, wie sie hervorgetreten ist in der neueren Zeit in den evangelischen Gemeinschaften, eben das Atomisierende so groß geworden, weil die wirklichen Bedürfnisse der Bewußtseinsseelenentwickelung im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum dabei eben nicht berücksichtigt worden sind. Die Predigt der älteren Kirchen ist durchaus aufgebaut auf den Bedürfnissen des vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraums. Die Predigt formt sich in den älteren Bekenntnissen aus der Weltanschauung des Verstandes- oder Gemütszeitalters heraus. Der moderne Mensch versteht das nicht mehr recht. Daher sind die evangelischen Bekenntnisse auch übergegangen zu der mehr auf die menschliche Meinung, auf die menschliche Bewußtseinserkenntnis gebauten Darstellung. Das ist auf der einen Seite etwas Vollberechtigtes. Auf der andern Seite ist wiederum die Form dafür noch gar nicht richtig gefunden. Die Predigt, die innerhalb des Kultus auftaucht, ist ja ein Herausfallen aus dem Kultus, ist ein Hinneigen vom Kultus aus zu der Erkenntnis. Aber wenig wird dem Rechnung getragen in der Form, welche die Predigt angenommen hat in der sich fortentwickelnden Menschheit. Ich brauche Sie nur an eines zu erinnern, so werden Sie das gleich einsehen. Rechnen Sie diejenigen Predigten der neueren Zeit ab, die nicht gebaut sind auf irgendein Bibeltextwort als Thema, so werden Sie sehen, wie wenig bleibt. Überall, bei Sonntagspredigten, bei Predigten für gewisse Anlässe, überall wird ein Bibeltextwort zugrunde gelegt, weil eben verleugnet wird die unmittelbare lebendige Offenbarung, die in der Gegenwart auch da sein kann. Aber es wird durchaus nur an das Historische angeknüpft. Also es wird zwar die individuelle Predigt gesucht, aber die Bedingung dafür ist nicht gefunden. Und so strömt eben die Predigt ein in die bloße menschliche Meinung, in die individuelle Meinung. Das aber atomisiert.

Wenn nun die neuerdings begründete Bewegung für religiöse Erneuerung, da sie ja im wesentlichen auf dem Boden steht, der aus der Anthroposophie kommt, mit der unmittelbar fortgehenden, sich fortbewegenden Offenbarung rechnet, also mit dem lebendigen GeistErleben aus der übersinnlichen Welt heraus, dann führt sie gerade ihre Predigt dazu, einzusehen, daß sie etwas anderes braucht, das nämlich, woraus unmittelbar diese fortdauernde lebendige Erkenntnis der geistigen Welt möglich ist. Sie braucht also anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft, Ich möchte sagen: die Predigt wird immer das Fenster sein, durch das die Bewegung für religiöse Erneuerung wird aufnehmen müssen dasjenige, was ihr eine fortwährende lebendige Anthroposophische Gesellschaft wird geben müssen. Dazu bedarf es aber, was ich Ihnen eben schon in dem letzten Vortrag drüben im noch bestehenden Goetheanum gesagt habe in bezug auf die religiöse Erneuerung, dazu bedarf es, daß, wenn wachsen soll diese Bewegung für religiöse Erneuerung, auch in aller Lebendigkeit die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft daneben sein muß, das heißt das lebendige Leben der Anthroposophie durch eine Anzahl von Menschen. Die Bewegung für religiöse Erneuerung würde sich bald das Wasser abgraben, wenn sie nicht eben wiederum neben sich hätte eine Anzahl von Menschen - es brauchen nicht gleich wiederum alle Menschen zu sein, aber immer eine Anzahl von Menschen -, in denen lebendig das anthroposophische Erkennen lebt.

Nun kommen aber eben viele Menschen, wie ich Ihnen gesagt habe, zur Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft und wollen nicht nur die anthroposophische Erkenntnis in abstracto, sondern sie wollen auch in ihr, eben aus einem Drang der Menschen unseres Bewußtseinszeitalters heraus, Gemeinschaftsbildungen haben. Man könnte nun sagen: die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft könne ja auch einen Kultus pflegen. Gewiß, das könnte sie auch; das gehört aber jetzt auf ein anderes Feld. Ich will jetzt die spezifisch anthroposophische Gemeinschaftsbildung einmal ins Auge fassen. Es gibt eben durchaus noch etwas anderes im heutigen Menschenleben als dasjenige, was beruhen kann in bezug auf die Menschengemeinschaft auf einer gemeinsamen Erinnerung an die vor dem Erdendasein durchlebte übersinnliche Welt. Es gibt das, was heute wiederum gebraucht wird gerade auf die Art und Weise, wie es nur im Bewußtseinszeitalter sein kann. Da ist man genötigt, über etwas zu sprechen, was mit Bezug auf den modernen Menschen von den meisten heute noch ganz übersehen wird. Gewiß, man hat zu allen Zeiten von Idealismus gesprochen, aber heute ist der Idealismus, wenn von ihm gesprochen wird, auch bei den Gutmeinenden zumeist nichts anderes als Phrase, richtige Phrase. Denn es fehlt heute, in jenem Zeitalter, wo in der ausgebreiteten Zivilisation besonders stark die intellektualistischen Kräfte und Elemente aufgetaucht sind, es fehlt das Weltverständnis des ganzen Menschen. Gewiß, als Sehnsucht ist es insbesondere in der heutigen Jugend vorhanden. Aber gerade jene Unbestimmtheit, mit der es auftritt in der heutigen Jugend, zeigt, daß eben etwas lebt in den heutigen Menschenseelen, was noch nicht klar geworden ist, was noch undifferenziert ist, was nicht unnaiver wird, wenn es differenziert wird.

Bitte beachten Sie nur einmal folgendes: Versetzen Sie sich zurück in Zeiten, in denen religiöse Strömungen innerhalb der Menschheit sich ausgebreitet haben. Sie werden sehen, daß in abgelebten, in früheren Zeiten der geschichtlichen Entwickelung der Menschheit der oder jener Verkündigung aus der geistigen Welt von vielen Menschen mit ungeheurem Enthusiasmus begegnet worden ist. Ja, es wäre gar nicht möglich gewesen, daß die heute vorhandenen religiösen Bekenntnisse die Menschen tragen, wenn nicht bei ihrer Verkündigung eine viel stärkere Affinität der Seelen für etwas, was aus der geistigen Welt verkündet worden ist, vorhanden gewesen wäre, als das heute der Fall ist. Man kann sich gar nicht vorstellen, wenn man die heutigen Menschen betrachtet, daß sie von so etwas gefangen werden könnten, wie oftmals in früheren Zeiten die Verkündigung religiöser Wahrheiten war. Gewiß, es finden heute noch Sektenbildungen statt; aber gegenüber dem Feuer, mit denen Menschenseelen früheren Verkündigungen entgegengekommen sind, haben die heutigen Sektenbildungen etwas Philiströses. Es ist nicht die innere Wärme der Seelen vorhanden für das Aufnehmen von Geistigem. Das hat im letzten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts sogar in rapider Weise abgenommen. Aus der Unbefriedigtheit finden sich heute allerdings noch Menschen, die dem oder jenem zuhören, auch zu einem gewissen Bekenntnis von dem oder jenem kommen; aber jene positive Wärme, die früher da war in den Menschenseelen und die einzig und allein möglich gemacht hat, daß man um Geistiges sein ganzes Wesen, sein ganzes menschliches Wesen eingesetzt hat, das ist gewichen einer gewissen Kühle, ja Kälte. Und diese Kühle und diese Kälte, die ist ja auch in den Menschenseelen vorhanden, wenn sie heute von Idealen und Idealismus reden. Denn heute ist eigentlich etwas die Hauptsache, was im Grunde noch lange nicht Erfüllung ist, was im Grunde noch lange Erwartung sein wird, aber als Erwartung in ungeheuer vielen Menschen heute schon lebt. Das kann ich Ihnen auf die folgende Weise charakterisieren.

Nehmen Sie die zwei jedem Menschen ja gut bekannten Bewußtseinszustände, die vorhanden sind: den träumenden Menschen und den Menschen im gewöhnlichen wachen Tagesbewußtsein. Wie ist es beim träumenden Menschen? Beim schlafenden Menschen, der nicht träumt, ist es ja ebenso, denn traumlos schlafen heißt nur, daß die Träume so sehr herabgedämpft sind, daß man sie nicht merkt. Also wie ist es beim träumenden Menschen?

Er lebt in seiner Traumbilderwelt. Er lebt in derselben, indem sie oftmals für ihn viel anschaulicher, viel tiefer ins Herz gehend ist - das kann man schon sagen - als dasjenige, was man im Alltag beim wachen Tagesbewußtsein erlebt. Aber man erlebt es isoliert. Man erlebt es als die einzelne menschliche Persönlichkeit. In einem und demselben Zimmer können zwei Menschen schlafen, sie haben zwei ganz verschiedene Welten in ihrem Traumbewußtsein. Sie erleben diese Welten nicht miteinander. Jeder erlebt sie für sich; sie können sich höchstens hinterher den Inhalt erzählen.

Wacht der Mensch auf aus dem Traumbewußtsein in das gewöhnliche Tagesbewußtsein, so nimmt er durch seine Sinne dieselben Dinge wahr, die derjenige, der ihm zunächst steht, auch wahrnimmt. Eine gemeinschaftliche Welt tritt ein. Der Mensch erwacht zu einer gemeinschaftlichen Welt, indem er aus dem Traumbewußtsein in das wache Tagesbewußtsein übergeht. Ja, an was erwacht denn der Mensch aus dem Traumbewußtsein ins wache Tagesbewußtsein? Er erwacht am Licht, am Geräusch, an seiner natürlichen Umgebung - in dieser Beziehung machen auch die andern Menschen keine Ausnahme — zum wachen Tagesbewußtsein, zum gewöhnlichen wachen Tagesbewußtsein. Aus dem Traum heraus erwacht man an dem Natürlichen des andern Menschen, an seiner Sprache, an dem, was er einem sagt, und so weiter, an der Art und Weise, wie sich seine Gedanken und Empfindungen in die Sprache hineinkleiden. An dem, wodurch der gewöhnliche Mensch, der andere Mensch sich natürlich auslebt, erwacht man. Also man erwacht an der natürlichen Umgebung zum gewöhnlichen Tagesbewußtsein. In allen früheren Zeitaltern war es so, daß der Mensch aus dem Traumbewußtsein ins wache Tagesbewußtsein an der natürlichen Umgebung erwachte. Und dann hatte er an seiner natürlichen Umgebung zugleich das Tor, durch das er, wenn er es tat, in ein Übersinnliches hineindrang.

Mit dem Erwachen der Bewußtseinsseele, mit dem Entfalten der Bewußtseinsseele ist in dieser Beziehung ein neues Element hereingetreten ins Menschenleben. Da muß es nämlich noch ein zweites Erwachen geben, und dieses zweite Erwachen wird immer mehr und mehr als ein Bedürfnis der Menschheit auftreten: Das ist das Erwachen an Seele und Geist der andern Menschen. Im gewöhnlichen wachen Tagesleben erwacht man ja nur an der Natur des andern Menschen; aber an Seele und Geist des andern Menschen will der Mensch erwachen, der selbständig, der persönlich durch das Bewußtseinszeitalter geworden ist. Er will an Seele und Geist des andern Menschen erwachen, er will dem andern Menschen entgegentreten so, daß der andere Mensch in seiner eigenen Seele einen solchen Ruck hervorbringt, wie es gegenüber dem Traumleben das äußere Licht, das äußere Geräusch und so weiter hervorbringt.

Dieses Bedürfnis ist einmal ein ganz elementares seit dem Beginne des 20. Jahrhunderts und wird immer stärker werden. Das ganze 20. Jahrhundert hindurch wird, trotz allem seinem chaotischen, tumultuarischen Wesen, das die ganze Zivilisation durchsetzen wird, dieses als Bedürfnis aufzeigen: es wird sich einstellen das Bedürfnis, daß Menschen an dem andern Menschen in einem höheren Grade werden erwachen wollen, als man erwachen kann an der bloßen natürlichen Umgebung. Traumleben, es erwacht an der natürlichen Umgebung zum wachen Tagesleben. Waches Tagesleben, es erwacht am andern Menschen, an Seele und Geist des andern Menschen zu einem höheren Bewußtsein. Der Mensch muß mehr werden, als er dem Menschen immer war. Er muß ihm zu einem weckenden Wesen werden. Die Menschen müssen sich näherkommen, als sie sich bisher gestanden haben: zu einem weckenden Wesen muß jeder Mensch, der einem andern entgegentritt, werden. Dazu haben eben die modernen Menschen, die ins Leben jetzt hereingetreten sind, viel zu viel Karma aufgespeichert, als daß sie nicht ihr Schicksal verbunden fühlen würden, ein jeder mit dem, der ihm im Leben als anderer Mensch entgegentritt. Wenn man in frühere Zeitalter zurückgeht, da waren die Seelen jünger, da haben sie weniger karmische Zusammenhänge gehabt. Jetzt tritt eben die Notwendigkeit ein, daß man nicht nur durch die Natur erweckt wird, sondern durch die Menschen, die mit einem karmisch verbunden sind und die man suchen will.

Und so gibt es außer jenem Bedürfnis nach Erinnerung an die übersinnliche Heimat, die durch den Kultus befriedigt werden kann, das andere Bedürfnis, sich erwecken zu lassen zum Geistig-Seelischen durch den andern Menschen. Und der Gefühlsimpuls, der da wirksam sein kann, der ist der des neueren Idealismus. Wenn das Ideal aufhört, ein bloßes abstraktes zu sein, wenn es lebendig verwurzelt sein wird wiederum mit dem menschlich Seelisch-Geistigen, dann wird es eben die Form annehmen: Ich will erwachen an dem andern Menschen. - Das ist schließlich ganz im Unbestimmten das Gefühl, das durch die Jugend heute sich einstellt: Ich will erwachen an dem andern Menschen. Und das ist es, was als besonderes Gemeinschaftsleben in der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft gepflegt werden kann, was sich da auf die natürlichste Weise von der Welt einstellt. Denn, wenn eine Menschengruppe sich zusammenfindet, um gemeinsam zu erleben dasjenige, was aus der übersinnlichen Welt heraus durch die Anthroposophie geoffenbart werden kann, dann ist dieses Erleben in einer Menschengruppe eben etwas anderes als das einsame Erleben. Daß man erwacht an der Seele des andern in dem Momente, wo man zusammen ist, das gibt eine Atmosphäre ab, die nicht etwa in die übersinnliche Welt hineinführt so, wie es in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» beschrieben ist, die aber das Verständnis der Ideen fördert, welche durch anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft von der übersinnlichen Welt gegeben werden.

Finden sich Menschen, die mit Idealismus in einer Menschengruppe zusammenleben, die sich, sei es durch Vorlesen, sei es durch etwas anderes, dasjenige gegenseitig mitteilen, was Inhalt der Anthroposophie ist, dann ist ein anderes Verständnis da. Durch das gemeinsame Erleben des Übersinnlichen wird eben gerade am intensivsten Menschenseele an Menschenseele erweckt, die Seele erwacht in ein höheres Verständnis hinein, und wenn diese Gesinnung da ist, bildet sich etwas heraus, das bewirkt, daß auf Menschen, die vereinigt sind im gegenseitigen SichMitteilen und im Miteinander-Erleben anthroposophischer Ideen, ein gemeinsames, wirkliches Wesen sich herniedersenkt. Wie in der Sprache der Sprachgenius lebt, in dessen Fittichen gleichsam die Menschen leben, so leben sie unter den Fittichen eines höheren Wesens, wenn sie mit der richtigen idealistischen Gesinnung miteinander erleben die anthroposophischen Ideen. Was tritt denn da ein?

Nun, wenn dies (es wird gezeichnet) das Niveau ist, wodurch übersinnliche Welt von sinnlicher Welt sich scheidet, so haben wir im Kultus die Vorgänge und Wesenhaftigkeiten der höheren Welt (oben); wir haben sie im Kultus, im Kultuswort und in der Kultushandlung auch in die physische Welt herunterprojiziert (unten). Wenn wir einen anthroposophischen Zweig haben, so haben wir dasjenige, was in der physischen Welt in der anthroposophischen Gruppe erlebt wird, durch die Kraft des wirklichen Idealismus, der spirituell wird, hinaufversetzt in die geistige Welt. Durch den Kultus wird das Übersinnliche in Wort und Handlung heruntergeholt in die physische Welt. Durch den anthroposophischen Zweig werden die Gedanken und Empfindungen der Anthroposophengruppe hinauferhoben in die übersinnliche Welt. Und wenn in der richtigen Gesinnung erlebt wird der anthroposophische Inhalt von einer Menschengruppe, wobei Menschenseele an Menschenseele erwacht, wird tatsächlich diese Menschenseele erhoben zur Geistgemeinschaft. Nur handelt es sich darum, daß dieses Bewußtsein wirklich vorhanden ist. Wenn dieses Bewußtsein vorhanden ist und solche Gruppen in der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft auftreten, dann ist in diesem, wenn ich so sagen darf, umgekehrten Kultus, in dem andern Pol des Kultus, etwas Gemeinschaftsbildendes im eminentesten Sinne vorhanden. Man möchte sagen, wenn man bildlich sprechen will: Die Kultgemeinde versucht die Engel des Himmels zu veranlassen, herunterzugehen in den Kultraum, damit sie unter den Menschen seien. Die anthroposophische Gemeinde versucht, die Menschenseelen zu erheben in die übersinnliche Welt, damit sie unter die Engel kommen. Das ist in beiden das gemeinschaftsbildende Element.

Aber wenn Anthroposophie dem Menschen etwas sein soll, was wirklich in die übersinnliche Welt führt, dann darf sie nicht Theorie, nicht Abstraktion sein. Dann darf man nicht bloß von geistigen Wesen reden, sondern man muß die nächsten, die unmittelbarsten Gelegenheiten aufsuchen, um mit geistigen Wesen zusammenzusein. Die Arbeit einer anthroposophischen Gruppe besteht nicht bloß darin, daß eine Anzahl von Menschen über anthroposophische Ideen reden, sondern daß sie sich als Menschen so vereinigt fühlen, daß Menschenseele an Menschenseele erwacht und die Menschen hinaufversetzt werden in die geistige Welt, so daß sie wirklich unter geistigen Wesen sind, wenn auch vielleicht ohne Schauen. Auch wenn das in der Anschauung nicht da ist, im Erleben kann es da sein. Und das ist dann das Stärkende, das Kräftigende, das aus den Gruppen hervorgehen kann, die mit richtiger Gemeinschaftsbildung eben entstanden sind innerhalb der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft. Es ist eben notwendig, daß das, was in vieler Beziehung doch vorhanden ist in der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft, allgemeiner werde; und das ist es, was die in den letzten Jahren Eintretenden dann nicht gefunden haben. Sie haben eigentlich das gesucht, haben es aber nicht gefunden. Sie haben höchstens gefunden: Ja, wenn du richtiger Anthroposoph sein willst, dann mußt du an den Atherleib und an die Wiederverkörperung glauben und so weiter.

Ich habe es oft betont: Man kann ein Buch wie zum Beispiel meine «Theosophie» auf zweifache Weise lesen. Man kann so lesen, daß man da liest: Der Mensch besteht aus physischem Leib, Ätherleib, Astralleib und so weiter, der Mensch hat wiederholte Erdenleben, Karma, das heißt, man nimmt Begriffe auf. Gewiß, das sind andere Begriffe als auf einem andern Felde, aber der geistige Prozeß, der sich abspielt, ist unter Umständen genau derselbe, wie wenn man ein Kochbuch liest. Denn gerade das habe ich ja oft gesagt, es handelt sich um den geistigen Prozeß, nicht um die Aufnahme von Ideen. Es ist ganz einerlei, ob Sie lesen, Sie sollen Butter in eine Pfanne gießen, Mehl hineintun, das durcheinanderrühren, Eier hineinschlagen, oder ob Sie lesen: Es gibt physischen Stoff, ätherische Kräfte, astralische Kräfte, die sind da durcheinandergemischt. Es ist ganz einerlei als Seelenprozeß, ganz einerlei, ob Sie Butter, Fett, Eier, Mehl auf irgendeinem Kochherde zusammengemischt haben oder ob Sie für die Menschenwesenheit physischen Leib, Atherleib, Astralleib zusammengemischt sich vorstellen. Man kann aber auch die «Theosophie» so lesen, daß man weiß: In ihr sind Begriffe enthalten, die sich zu der gewöhnlichen Begriffswelt des Physischen so verhalten wie die Begriffswelt des Physischen zur Traumwelt. Sie gehören einer Welt an, in die man ebenso aus der gewöhnlichen physischen hinein erwachen muß, wie man aus der Traumwelt in die physische Welt erwacht. Es ist die Gesinnung, mit der man liest, die dann das richtige Kolorit den Dingen gibt. Und diese Gesinnung wird eben für den Menschen der Gegenwart, durch verschiedene Mittel natürlich, lebendig. Die andern, die der Mensch für sich ausmachen kann, sind ja alle beschrieben in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?». Aber für den modernen Menschen ist eben auch noch die Durchgangsphase, ganz abgegrenzt von der Anschauung der höheren Welt, notwendig: daß er erwachen kann an dem SeelischGeistigen des andern Menschen zu dem Hineinleben in die geistige Welt, wie er erwacht aus dem Traumleben durch Licht und Geräusch und so weiter in die physische Welt herein.

Dafür muß man sich Verständnis erringen. Es ist notwendig, Verständnis zu erringen für das, was Anthroposophie in der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft sein soll: Ein Geistesweg soll sie sein. Dann findet sich auch die Gemeinschaftsbildung, wenn sie ein Geistesweg ist. Aber esmuß wirklich Anthroposophie ins Leben hinein. Das ist ein Bedürfnis, meine lieben Freunde. Daß es ein Bedürfnis ist, ich kann es Ihnen an einem ganz naheliegenden Beispiel veranschaulichen. Nachdem wir viele kleinere Versammlungen im kleinsten und im größeren Kreise in Stuttgart hatten, wo viel verhandelt worden ist über das, was man nun tun soll für die Konsolidierung der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft, war ich auch einmal - es war nicht jeneVersammlung, von der ich Ihnen gestern erzählte, die war erst später, sondern früher, es war aber auch in der Nacht - zusammen mit der Jugend. Es war akademische Jugend. Ja da redete man nun auch zunächst darüber, wie man es am besten macht, damit die Gesellschaft die richtige Form bekommt, damit alles richtig getan wird und so weiter. Aber nach einiger Zeit war das Gespräch abgeglitten zu dem Anthroposophischen selber. Man war mitten drinnen, weil die Studenten und Studentinnen das Bedürfnis hatten, zu fragen: Wie soll man in der Zukunft studieren, wie soll man seine Doktorarbeiten machen und so weiter? -— Das konnte man nicht äußerlich beantworten, sondern da mußte man durchaus in die Anthroposophie hineinsegeln. Das heißt, man fing an mit dem Philiströsen und kam gleich in das Anthroposophische hinein in seiner Anwendung: Wie macht man, wenn man Anthroposoph ist, eine Doktordissertation? Wie studiert man, wenn man Anthroposoph ist, Chemie und so weiter? Also es erwies sich die Anthroposophie dadurch als lebensfähig, daß ein Gespräch von selber in sie hineinlief.