The Evolution of Consciousness

GA 227

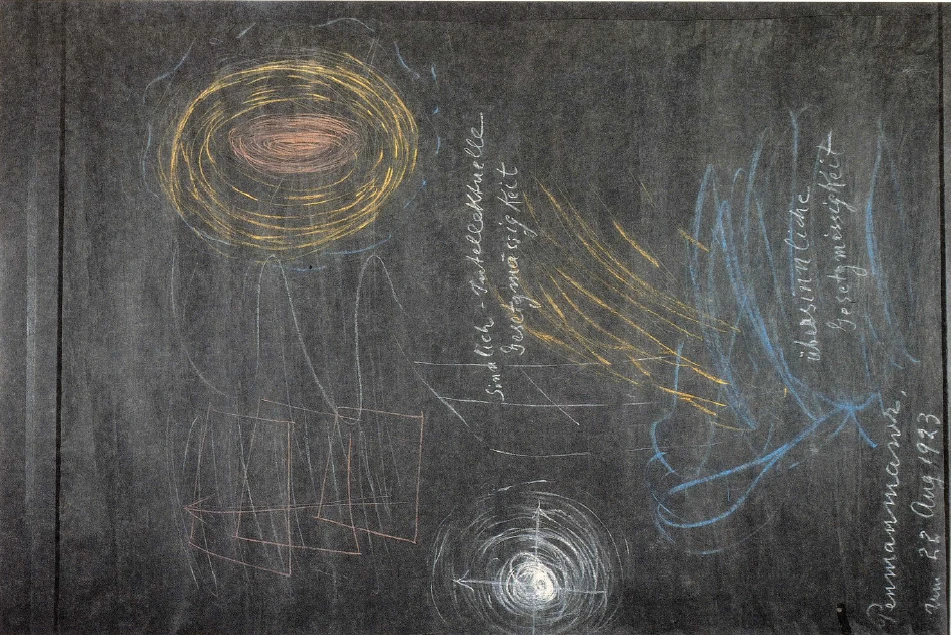

22 August 1923, Penmaenmawr

4. Dream Life

Between a man's waking life and his life in sleep—which yesterday I was able to picture for you at least in outline—there comes his dream life. It may have little significance for the immediate actualities of daily existence, but it has the greatest imaginable significance for a deeper knowledge of both world and man. This is not only because what a dream signifies must, in the Spiritual Science spoken of here, be fully recognised, so that the study of it may lead on to many other matters, but also because of the particular importance of dream life as a chink, shall we say, through which certain other worlds, different from the one experienced by human beings when awake, shine into this ordinary world. So it is that the puzzling elements in dream pictures often call attention both to other worlds, below or above the one normally accessible, and also give some indication of the nature of these worlds.

On the other hand it is extraordinarily difficult, from the standpoint of higher consciousness, to go deeply into the enigmas of dream life, for dreams have power to lead people into the greatest imaginable illusions. It is precisely when dreams are in question that people are inclined to go wrong over the relation of something illusory to the reality behind it. In this connection let us consider what I have said about sleep life and repeated lives on Earth.

An example of dream life, constantly recurring in one form or another, is this. We dream we have made something that, when awake, we never would have thought of making—something indeed outside the scope of anything we could have achieved in real life. We go on to dream that we cannot find this article we think we have made, and start frantically hunting for it.

Let us look at this example more closely. In the form I have described it figures in the dream life of everyone, with variations. But let us take a concrete instance. Let us say that a tailor, though a tailor only in a small way, dreams that he has made a ceremonial coat for a Minister of State. He feels quite satisfied with his work on the coat, which should now be lying ready. Suddenly, however, the mood of the dream changes and when he looks all round for the coat that has to be delivered, it is nowhere to be found.

Here you have a dream of something that could never happen to the dreamer, but of something he can very well imagine as highly desirable. He is only a small tailor for lowly folk, who never could order such a coat. But occasionally, in his ambitious day-dreams, he may have had the wish to make some high-rank garment; though perhaps incapable of it, he might still have cherished it as an ambition.

But what underlies all this? Something very real. When in sleep a man is out of his physical and etheric bodies with his Ego and astral body, he finds himself within the being who goes through repeated lives on Earth. What gives inner strength to the sleeping man, what above all is inwardly active in his being, is the Ego together with the astral body. These need not be limited to memories of experience in the life just over, but can go back to other lives on Earth. I am not theorising, but telling you of something rooted in reality, when I say: It may be that our dreamer once had something to do—let us say in an earlier, Roman incarnation—with an order for a certain ceremonial toga. He need not have been the tailor in this case; he may have been the servant, or perhaps even the friend, of a Roman statesman. And because at that time he had such a lively desire for his lord to appear before the world in the most dignified possible guise, destiny may have brought him to his present-day calling. For in human life generally, wishes, thoughts, have an extraordinary significance; and it is possible for the memory of what has been lived through in a former life on Earth to play into a man's soul and spirit, his Ego and astral body. Then, in the morning, when he dives down with his Ego and astral body into his etheric and physical bodies, a lingering memory of the splendid ceremonial toga comes up against the conceptions possible for the tailor in his present life—conceptions always there in his etheric body. Then what remains of the old Roman experience is checked; it has to accommodate itself to ideas which are limited to making garments for quite lowly people. Now the soul that sinks down in this way may find it very difficult to transpose into another key the feeling it has had about the splendid toga; it is hard to relate this to a picture of the terrible clothes the tailor is obliged to make. So the picture of the toga, encountering this obstacle, changes into a picture of a present-day official uniform; and only later, when the man is well down into his etheric and physical bodies is this picture lost.

So between falling asleep and waking we have our whole human life. We have to bring to bear on it all that as earthly beings we can conceive and think, and by this means try to unravel the strange forms taken by dreams. The great difficulty is to distinguish the immediate content of the dream, which may be sheer illusion, from the reality which lies behind it, for the reality may be something quite different. But anyone who gradually gets accustomed to finding his way among all the intricacies of dream life will finally see that we need not pay much attention to the pictures conjured up before the soul, for these pictures are shaped by the etheric body left behind in bed. This etheric body is the bearer of our thoughts and conceptions and these are absent from our real being during sleep. We have to separate the content of these conceptions from what I would call the dramatic course of the dream, and learn so to fix our attention on the dramatic element that it prompts questions such as: If I had this experience in waking life, would it give me immense pleasure? And, if I felt pleasure and had a sense of relief in this dream, was I heading in the dream for a catastrophe? Was I leaving some kind of exhibition and suddenly everything got into confusion—there was a crash and a disaster? Such questions must be given first place in the study of dreams—not the thought-content but the dramatic incidents.

Someone may dream he is climbing a mountain, and the going is becoming more and more arduous. Finally, he reaches a point where he can go no further; huge obstructions tower up in front of him. He feels as though they were something important hanging over his life. That is certainly a dream a man could have; one could enlarge on it. But either he or someone else may have another dream: he is entering a cave leading to some kind of mountain cavern. After passing the entrance, there is still a certain amount of light, but it gradually becomes darker, until he arrives at a place where he is not only in complete darkness but meets with such appalling conditions, including cold, that he can penetrate no further into the cave.

Here, you see, we have two dreams quite different from one another in content. From the dramatic standpoint both deal with an undertaking that begins well, and then runs into great difficulties, ending in an insurmountable obstacle. The pictures are quite different, the dramatic course is much the same. In the super-sensible world, as it were behind the scenes of life, both dreams can have the same basis. In both dreams the same thing can have affected the soul; the same thing can symbolise itself in a wide variety of picture-forms.

All this shows how we have to look for the key to a dream not—as is often done—by considering its content in an external way, but by studying its dramatic course and the effect it has on the dreamer's soul and spirit. Then, when our conceptual faculty has been strengthened by the exercises referred to in the past few days, we shall gradually progress from the illusory picture-world of the dream and be able to grasp through the dramatic element the true basis of all that we experience as super-sensible reality between going to sleep and waking.

Before speaking in detail—as I shall be doing—of the dream and its relation to the physical body of man and to his spiritual element, I should like to-day to describe how, through the dream world, he is found to belong to the Cosmos as a whole. We can see how in dreams the connection between single events in life is quite different from anything we experience when we are awake. We have just seen in the example given that in waking life things appear in a certain connection according to the laws holding good in the sense-world—a later event always follows an earlier one. The dream takes events that could happen in the sense-world and makes them chaotic. Everything becomes different; everything is broken up. All that is normally bound to the Earth by gravity, like man himself, is suddenly—in a dream—able to fly. A man will perform skilful flying feats without an aeroplane. And a mathematical problem, for instance, such as we may strain every nerve to solve in ordinary life, appears in a dream to be mere child’s play. The solution is probably forgotten on waking—well, that is a personal misfortune—but at any rate one gets the idea that the obstacles which hamper our thinking in daily life have disappeared. In effect, everything in daily life with definite connections loses them to a certain extent in dreams. If we want to picture what actually happens—or appears to happen—in a dream, we can imagine the following. Into a glass of water we put some kind of soluble salt in crystalline form, and watch it dissolve. We see how its clear-cut forms melt away, how they take on fantastic shapes, until all the salt is dissolved, and we are left with a glass of more or less homogenous fluid.

This is very like the kind of experience we have inwardly in dreams. The dream we have as we go to sleep and the dream we have just before waking both draw on the experiences of the day, break them up and give them all sorts of fantastic forms—at least we call them fantastic from the point of view of ordinary consciousness. The dissolving of a salt in a liquid is a good simile for the kind of thing that happens inwardly in a dream.

It will not be easy for those who have grown up in the world of present-day ideas to grasp without prejudice facts of this kind; for people to-day—especially those who regard themselves as scientific—know remarkably little about certain things. In truth I am not saying this because I like picking holes in science. That is not at all my intention. I value the scientific approach and should certainly never wish to see it replaced by the work of amateurs or dilettanti. Even from the standpoint of Spiritual Science the great progress, the strict truthfulness and trustworthiness, of science to-day, must be given full recognition. That is an understood thing. Nevertheless, the following has to be said.

When people to-day wish to know something, they turn to earthly objects and processes. They observe these and from their observations they work out laws of nature. They also make experiments to bring to light the secrets of nature, and the results of their experiments are further laws. Thus they come to laws of a certain type, and this they call science. Then they turn their gaze to the vastness of the heavens; they see—let us say—the wonderful spiral nebulae, where they see individual cosmic bodies emerging, and so on. To-day we photograph such things and see much more detail than telescopic observation can give. Now how do astronomers proceed to learn what is going on in those far celestial spaces? They turn to the laws of nature, laws founded on earthly conditions and earthly experiments, and then start speculating as to how, in conformity with those laws, a spiral nebula could have taken form in distant space. They form hypotheses and theories about the arising and passing away of worlds by treating facts discovered in their laboratories about manganese, oxygen, hydrogen, as laws that still hold good in heavenly spheres. When by such means a new substance is discovered, unconscious indications are sometimes given that science here is not on firm ground. Hydrogen has been found everywhere in the vastness of space, and helium, for example; and another substance that has been given a curious name, curious because it points to the confused thinking that comes in. It has been called nebulium. Thinking itself becomes nebulous here, for we find nebulium in company with helium and hydrogen. When people are so simple that they apply as laws of nature knowledge acquired in earthly laboratories, and indulge in speculation about what goes on outside in the wide realms of space, after the manner of the Swedish thinker Arrhenius [Svante August Arrhenius, a pioneer of modern physical chemistry; gained Nobel prize for his work on electrical conduction in dilute solutions. In one of his books, Das Werden der Welten, 1907 (English translation, Worlds in the Making, 1908), he suggested the name “nebulium” for a hypothetical gas represented by certain then unidentified lines in the spectra of gaseous nebulae. In 1927 it was shown that the lines are due to singly and doubly ionised atoms of oxygen.]—who has done untold harm in this connection—they are bound to fall from one error into another, if they are unable to consider without prejudice the following.

Again I should like to start with a comparison. From the history of science you will know that Newton, the English physicist and natural philosopher, established the theory of what is called gravitation—the effect of weight in universal space. He extended this law, illustrated in the ordinary falling of a stone attracted by the Earth, to the reciprocal relation between all bodies in the Cosmos. He stated also that the strength of gravity diminishes with distance. For any physicists who may be present I will remind you of the law—gravity decreases with the square of the distance. Thus if the distance doubles, gravity becomes four times weaker, and so on.

For such a force it is quite right to set up a law of this kind. But while we are bound to purely physical existence, it is impossible to think out this law far enough for universal application. Just imagine in the case of a cosmic body how the force of gravity must diminish with distance. It is strong at first and then grows weaker, still weaker, always weaker and weaker.

It is the same with the spreading out of light. As it spreads out from a given source, it becomes always weaker and weaker. This is recognised by scientists today. But they fail to recognise something else—that when they establish laws of nature in a laboratory, and then clothe them in ideas, the truth and content of these laws diminish as distance from the earth increases. When, therefore, a law is established on Earth for the combining of elements—oxygen, hydrogen or any others—and if a law of gravity is set up for the earth, then, as one goes out into cosmic space, the efficacy of this law will also decrease. If here in my laboratory I set up a law of nature and then apply it to a spiral nebula in far-off cosmic space, I am doing just the same as if I were to light a candle and then believe that if I could project its rays through cosmic space on to the spiral nebula, the candle would give the same amount of light out there. I am making precisely the same mistake if I believe that a finding I establish in my laboratory is valid in the far reaches of the Cosmos. So arises the widely prevalent mistaken idea that what is discovered quite rightly to be a natural law in a laboratory down here on earth can be applied also throughout the vast spaces of the heavens.

Now man himself is not exempt from the laws we encounter when earthly laws, such as those of gravity or of light, no longer hold good. If anyone wished to discover a set of laws other than our laws of nature, he would have to journey further and further away from the Earth; and to find such laws in a more intimate, human way, he goes to sleep. When awake, we are in the sphere where the laws of nature hold sway and in all that we do we are subject to them. For example, we decide to lift a hand or arm, and the chemico-physical processes taking place in the muscles, the mechanical play of the bony structure, are governed by the laws discovered in earthly laboratories, or by other means of observation. But our soul goes out in sleep from our physical and etheric bodies, and enters a world not subject to the laws of nature. That is why dreams are a mockery of those laws. We enter an entirely different world—a world to which we grow accustomed in sleep, just as when, awake in our physical body, we accustom ourselves to the world of the senses. This different world is not governed by our laws of nature; it has laws of its own. We dive into this world every night on going out of our physical and etheric bodies. Dreams are a power which forcibly opposes nature's laws.

While I am dreaming, the dream itself shows me that I am living in a world opposed to these laws, a world which refuses to be subject to them. While going to sleep in the evening and moving out of my physical and etheric bodies, I am still living half under the laws of nature, although I am already entering the world where they cease to be valid. Hence arises the confusion in the dream between natural laws and super-sensible laws; and it is the same while we are waking up again.

Thus we can say that each time we go to sleep we sink into, a world where the laws of nature are not valid; and each time we wake we leave that world to re-enter a world subject to those laws. If we are to imagine the actual process, it is like this. Picture the dream-world as a sea in which you are living, and assume that in the morning you wake out of the waves of dream-life—it is as if you arose out of the surge of those waves. You move from the realm of super-sensible law into the realm of intellectual, material law. And it seems to you as though everything you see in sharp outlines on waking were born out of the fluid and the volatile. Suppose you are looking, say, at a window. If you first dream of the window, it will indeed appear as though born out of something flowing, something indefinite perhaps, imbued with all manner of fiery flames. So the window rises up, and if you had been dreaming vividly you would realise how the whole sharply outlined world of our ordinary consciousness is born out of this amorphous background—as if out of the sea arose waves which then took on the forms of the everyday world.

Here we come to a point where—if as present-day men we are investigating these things anew—we feel reverent wonder at the dreamlike imaginations of earlier humanity. As I have said during these days, if we look back to the imaginations experienced even in waking life by the souls of those early peoples, imaginations embodied in their myths, legends and sayings of the gods, which all passed before them in so hazy a way compared with our clear perception of nature—when we look back on all this with the help of what can now be discovered quite independently of those old dreamy imaginations, we are filled with veneration and wonder. And if in this sphere we search again for truth, it echoes down from ancient Greece in a word which shows that the Greeks still retained some knowledge of these things. They said to themselves: “Something underlies the shaping of the world, something out of which all definite forms arise, but it is accessible only when we leave behind the world of the senses while we are asleep and dreaming.” The Greeks called this something, “Chaos”. All speculation, all abstract inquiry into the nature of this chaos, has been fruitless, but men to-day come near to it when it plays into their dreams. Yet in mediaeval times there was still some knowledge of a super-sensible, scarcely material substance lying behind all material substance, for a so-called quintessence, a fifth mode of being, was spoken of together with the four elements: earth, water, air, fire—and quintessence.

Or we find something that recalls the mediaeval vision when the poet with his intuitive perception says that the world is woven out of dreams. The Greeks would have said: The world is woven out of the chaos you experience when you leave the sense-world and are free of the body. Hence, to understand what the Greeks meant by “chaos” we must turn not to the material but to the super-sensible world.

When from the point of view of what is revealed to us on the path I have been describing here—the path leading through Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition, to higher knowledge and super-sensible worlds—when we follow all that goes on during our dreaming, sleeping and re-awaking, then we see that a man sleeps himself out of his daytime state into his life of sleep, out of which dreams may arise in a way that is chaotically vague, but also inwardly consistent. Behind, in bed, the physical body is left with the etheric body which is interwoven with the physical, giving it life, form, and power of growth. This twofold entity is left in the bed.

But another twofold entity goes out during sleep into a form of super-sensible existence which I might also describe to you in relation still to dream existence. For the higher knowledge given by Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition, it presents itself in the following way.

When a man goes out from his physical body and etheric body, his individuality resides in his astral body. As I said before, there is no need to be held up by words. We must have words, but we could just as well call the astral body something else. I am about to describe something concerning the astral body, and we shall see that the name is not important but rather the concepts that can be attached to it. Now, this astral body is made up of processes. Something happens in a man which develops out of his physical and etheric bodies, and it is these happenings which represent the astral body; whereas our concepts, our thoughts, are left behind in the etheric body.

Within the astral body there is spiritualised light, and cosmic warmth permeated by the force of the capacity for love. All this is present in the astral body, and at the time of waking it dives down into the etheric body. There it is held up and appears as the weaving, the action, of the dream. It may also appear in this way when, freeing itself from the physical and etheric bodies, it leaves the world of concepts. Thus it belongs to the nature of the astral body to carry us out from our physical and etheric bodies.

As I have already said, the astral body is that part of our being which actually opposes the laws of nature. From morning to night, from waking till going to sleep, we are subject to these laws—laws which in relation to space and time we can grasp through mathematics. When we sleep, however, we extricate ourselves both from the laws of nature and from the laws of mathematics—from the latter laws because our astral body has nothing to do with the abstractions of three-dimensional space. It has its own mathematics, following a straight line in one dimension only. I shall have to speak again about this question of dimensions. It is truly the astral body that releases us from the laws of nature, by which we are fettered between waking and sleeping; it is also the astral body that bears us into a completely different world, the super-sensible world.

To describe this process schematically we must say: When we are awake we carry on our life in the sphere where the laws of nature hold good; but on going to sleep we go out from there with our astral body. While we are living here in our physical and etheric bodies, our astral body, as a member of our being, is subject to the laws of nature, and in all its movements and functions lives entirely under those laws. On leaving the physical and etheric bodies, the astral body enters the super-sensible world and is subject to super-sensible laws, which are completely different. The astral body, too, is changed. While we are awake it is, as it were, in the straitjacket of nature's laws. Then it goes to sleep, which means that it leaves the physical and etheric bodies and moves in a world whose laws are in tune with its own freedom. Now what is this world? It is a world giving freedom of movement to the Ego-organisation which, together with the astral body, is then outside the physical and etheric bodies. Every night the Ego becomes free in the world to which the astral body carries it—free to carry out its own will in this world where the laws of nature no longer prevail.

In the time between going to sleep and waking, when our astral body is no longer subject to these laws, and we are in a world where the force of gravity, the law of energy, in fact all laws of that kind have ceased to be valid, the way is clear for those moral impulses which down here, during waking life, can find expression only under the constraint of the world of the senses and its ordering. Between sleeping and waking the Ego lives in a world where the moral law has the same force and power as the laws of nature have down here. And in that world where in sleep it is set free from laws of nature, the Ego can prepare itself for what it will have to be doing after death. In coming lectures we shall be speaking about this road from death to a new birth.

Between going to sleep and waking, the Ego can prepare in picture form, in Imaginations—which are not concepts, but strong impulses—for what it will have to strive for in the later reality of the spirit. When the Ego has gone through the gate of death, moral laws take the place that the laws of nature hold in the physical world of the senses.

Thus we can say that the Ego, even as a quite small spiritual seed, works upon what it has to carry through after death in the world of the spirit. Here, in what the Ego works upon in picture form during sleep, are indications of what we shall be able to carry over—not through any laws of nature but by reason of the spiritual world—from this life on Earth to the next. The causal effects of the moral impulses we have absorbed can be followed up here only when we have disposed ourselves in inward obedience to them. Just as the Ego during sleep works upon the moral impulses, and continues its work between death and a new birth, so these impulses acquire the force that otherwise the laws of nature possess, and in the next human body, which we shall bear in our following life on earth, they clothe themselves in our moral disposition, in our temperament, in the whole trend of our character—all wrongly ascribed to heredity. This has to be worked upon during sleep by the Ego when, freed by the astral body from the world of nature, it enters a purely spiritual world. Thus we see how in sleep a man prepares and grows familiar with his own future.

What, then, do the dreams show us? I would put it like this. During sleep too the Ego is active, but what it does is shown us by dreams in illusory pictures. In earthly life we are unable to take in what is already being woven during sleep for our next life on Earth. At the beginning of this lecture I explained how the dream, in the same confused way in which it presents the experiences of a past incarnation, also shows, in a chaotic form, what is prepared as a seed for humanity in future times.

Hence the right interpretation of dreams leads us to recognise that they are like a window through which we have only to look in the right way—a window into the super-sensible world. Behind this window the Ego is actively weaving, and this weaving goes on from one earthly life to the next. When we can interpret a dream rightly, then, through this window from the transitory world in which we live as earthly men, we already perceive that everlasting world, that eternity, to which in our true inner being we belong.

Das Traumleben

Zwischen das Wachleben des Menschen und das Schlafleben, von denen ich Ihnen wenigstens einiges skizzenhaft in der letzten Betrachtung habe schildern können, stellt sich hinein das Traumleben. Dieses Traumleben, das so wenig Bedeutung für die unmittelbare Wirklichkeit des Alltags haben kann, hat aber für die tiefere Erkenntnis sowohl der Welt wie auch des Menschen die denkbar größte Bedeutung. Nicht nur dadurch, daß in der Geisteswissenschaft, von der hier die Rede ist, die Bedeutung dieses Traumes voll gewürdigt werden muß, damit man von der Betrachtung des Traumes zu manchem anderen übergehen kann, sondern auch deshalb hat dieses Traumleben eine so besondere Bedeutung, weil es sozusagen die Ecke darstellt, durch welche gewisse andere Welten, als diejenige ist, die der Mensch wachend erlebt, in diese gewöhnliche Welt hereinscheinen. So daß der Mensch oftmals gerade durch das Rätselvolle der Traumesgebilde aufmerksam wird nicht nur darauf, daß es in den Untergründen oder auch Obergründen der ihm zugänglichen Welt noch andere Welten gibt, sondern auch darauf, wie etwa das Wesen dieser Welten sein könne.

Aber auf der anderen Seite ist es außerordentlich schwierig, in dieses ganze rätselhafte Traumleben vom Standpunkt des höheren Bewußtseins aus einzudringen, denn der Traum ist im Leben eine Macht, die den Menschen in die denkbar größte Illusion hineinversetzen kann. Und man wird leicht gerade gegenüber dem Traume geneigt, dasjenige, was sich illusionär hineinstellt in das Leben, in einer falschen Weise auf seine Wirklichkeit zu beziehen. Gehen wir einmal auf diese Weise vor, indem wir uns dabei durchaus auf dasjenige beziehen, was ich schon über das Schlafesleben und auch über die wiederholten Erdenleben gesagt habe.

Ein Beispiel, das in der einen oder anderen Art im Traumleben sich immer wiederholt, ist das, daß man im Traume irgend etwas gemacht hat, woran man im Wachleben gar nicht denken könnte, es irgendwie schon gemacht zu haben, was eben ganz außerhalb des Bereiches der Möglichkeit lag, es zu machen im bisherigen Erdenleben. Dann träumt man, daß man dieses, was man nun verfertigt hat, nicht finden könne, und man sucht wie ein Verrückter nach diesem abhanden gekommenen Dinge, das man gemacht zu haben glaubt.

Betrachten wir das Beispiel konkreter. In dieser Form, wie ich es geschildert habe, variiert in der einen oder anderen Art, kommt das ja im Traumleben eines jeden Menschen vor. Betrachten wir es konkret. Sagen wir, ein Schneider habe geträumt, obwohl er nur ein ganz kleiner Schneider ist für kleinbürgerliche Leute, daß er für einen Minister einen Staatsrock gemacht habe. Nun fühlt er sich schon ganz wohl in diesem Verfertigen des Staatsrockes, der nun schon da sein soll. Aber gleich darauf verwandelt sich der Traum in die Stimmung, daß er nun überall diesen Rock sucht, als er ihn dem Minister abliefern soll, und er kann ihn nirgends finden.

Hier haben Sie einen Traum, der ganz und gar in den Formen verläuft, die der Betreffende zwar nicht im Leben ausführen kann, die er sich aber namentlich wunschhaft recht gut noch vorstellen kann in dem Leben, das er eben auf der Erde führt. Ausführen kann er die Sache nicht, weil er eben nur ein kleiner Schneider für kleinbürgerliche Leute ist, und man kann den Rock nicht bei ihm bestellen. Aber manchmal mag durch seine kühnen Tagträume der Wunsch gegangen sein, einen solchen Staatsrock zu verfertigen. Vielleicht kann er das gar nicht, aber es wird der Wunsch seiner Tagträume.

Aber was liegt dem zugrunde? Dem liegt tatsächlich eine Wirklichkeit zugrunde. Wenn der Mensch mit seinem Ich und seinem astralischen Leib schlafend außerhalb des physischen Leibes und des ätherischen Leibes ist, dann befindet er sich ja in derjenigen Wesenheit, die durch die wiederholten Erdenleben durchgeht.

Dasjenige, was innerlich kraftet, was eigentlich innerlich tätig ist zunächst an seinem eigenen Wesen, während der Mensch schläft, das ist Ich und ist astralischer Leib: Das braucht in seinen Erlebnissen nicht etwa bloß Erinnerung zu haben an das eben jetzt verlebte Erdenleben, sondern das kann Erinnerungen haben an andere Erdenleben. Und ich erzähle Ihnen nicht irgend etwas hypothetisch Angenommenes, sondern etwas, was durchaus dem Gebiete der Wirklichkeit entstammt, von der ich spreche. Es kann also sein, daß der Betreffende allerdings einmal beteiligt war - sagen wir in alter römischer Zeit in einem früheren Erdenleben - an dem Bestellen einer besonders stattlichen Toga. Er braucht dazumal nicht einmal Schneider gewesen zu sein, aber er kann irgendwie der Diener oder vielleicht sogar der Freund eines römischen Staatsmannes gewesen sein. Sein Schicksal kann ihn vielleicht gerade dadurch, daß er dazumal einen so lebendigen Wunsch hatte, seinen Herrn in einer möglichst würdigen Weise vor die Welt hinzustellen, in dieser Inkarnation zu seinem Berufe gebracht haben. Denn für das gesamtmenschliche Leben sind eben gerade Wünsche, Gedanken von einer außerordentlich großen Bedeutung. Und so kann die Erinnerung an das in dieser Weise in einem früheren Erdenleben Durchlebte die Seele und den Geist des Menschen, Ich und astralischen Leib, durchziehen. Dann am Morgen, wenn der Mensch nun untertaucht, so wie ich das gestern nur skizzenhaft aufgezeichnet habe, mit seinem Ich und astralischen Leib in den ätherischen Leib und den physischen Leib, dann taucht diese Seele, die noch eben gesteckt hat in dem erinnernden Erleben von der Schönheit der Staatstoga, nun unter in diejenigen Vorstellungen, die der betreffende Kleidermacher im jetzigen Erdenleben haben kann; die stekken in seinem ätherischen Leibe. Da staut sich dasjenige, was eben noch als auf die alte Römerzeit bezüglich erlebt worden ist, das staut sich. Es soll hinein in die Vorstellungen, die er bei Tag haben kann. Aber bei Tag hat er nur dasjenige an Vorstellungen, daß er für die kleinbürgerlichen Leute Kleider macht. Nun kann die Seele, wenn sie da untertaucht, nur außerordentlich schwer umsetzen dasjenige, was sie eben an der schönen Staatstoga empfunden hat; das kann sie schwer vorstellen an den schrecklichen Kleidern, die der Kleidermacher zu machen hat. Da verwandelt es sich beim Übergehen, bei der Stauung, von der Vorstellung der Toga zu dem gegenwärtigen ministeriellen Staatsrock, und erst später, wenn der Betreffende ganz untergetaucht ist in seinen ätherischen und physischen Leib, dann vertilgt das, was er nun vorstellen muß, dasjenige, was er kurz vor dem Aufwachen erlebt hat.

So haben wir eben zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen unser gesamtmenschliches Leben da. In unserem Innern müssen wir uns mit unserem gesamtmenschlichen Leben entgegenstellen demjenigen, was wir in diesem Erdenleben vorstellen, denken können nach unseren Erfahrungen, und bekommen dadurch die sonderbaren Gestaltungen des Traumes heraus. Daher ist es gerade beim Traum so schwierig, seinen Inhalt, den er zunächst darbietet, und der ein vollständiges Gaukelbild sein kann, zu unterscheiden von der wahren Wirklichkeit, die eigentlich immer dahintersteckt. Diese wahre Wirklichkeit kann etwas ganz anderes sein. Aber derjenige gewöhnt sich nach und nach, in das ganze verwickelte Geschehen des Traumlebens sich hineinzufinden, der eben darauf aufmerksam wird, daß man beim Traume weniger dasjenige zu beachten hat, was einem in Bildern vor die Seele gezaubert wird, denn diese Bilder werden geformt von dem ja eigentlich im Bette zurückgelassenen ätherischen Leib, der die Gedanken, die Vorstellungen eben in sich trägt. Diese Vorstellungen hat man ja nicht in seinem eigentlichen inneren Wesen während des Schlafes. Man muß diesen Inhalt der Vorstellungen unterscheiden von etwas anderem, und dieses andere möchte ich nennen den dramatischen Verlauf des Traumes. Man muß sich allmählich gewöhnen, an den dramatischen Verlauf des Traumes so seine Aufmerksamkeit zu wenden, daß man sich frägt: Verläuft dieser Traum so, daß er, wenn die betreffenden Tatsachen im Tagesleben erfahren würden, ungeheure Freude machen würde? Hat man auch im Traume diese Freude, diese Befreiung erlebt, oder segelt man hinein im Traume in eine Katastrophe? Geht man von einer gewissen Exposition, wo sich Dinge zeigen können, dann verwickeln und dann ein Absturz kommt, über zu irgendeiner Katastrophe? Diese Fragen sollte man in erster Linie beachten, wenn das Traumleben in Betracht kommt, also nicht den gedanklichen Inhalt, sondern das dramatische Geschehen.

Es kann jemand träumen, er steigt auf einen Berg hinauf; die Bergwanderung wird immer schwieriger und schwieriger. Er kommt endlich an einen Punkt, wo er nicht weiter kann, wo sich ihm ungeheure Hindernisse entgegentürmen. Er empfindet diese Hindernisse wie etwas, was in sein Leben bedeutsam hineinragt. Gut, es kann jemand diesen Traum haben. Man könnte ihn weiter ausmalen. Aber er oder ein anderer kann einen anderen Traum haben: er bewegt sich durch den Eingang einer Höhle, die irgendwo meinetwillen in einen Bergkeller hineinführt. Er hat, nachdem er den Eingang durchschritten hat, noch etwas Helligkeit. Dann wird es immer finsterer und finsterer. Aber endlich kommt er an eine Stelle, wo es nicht nur völlig finster ist, sondern wo ihm auch entgegenkommen die furchtbarsten Kältewirkungen und dergleichen, so daß er von dieser Stelle aus nicht weiter in die Berghöhle hineindringen kann.

Sehen Sie, da haben Sie zwei dem Inhalte nach ganz verschiedene Träume; dramatisch stellen sie beide dar ein Unternehmen, das anfangs geht, dann Schwierigkeiten bietet, dann an ein unüberwindliches Hindernis kommt. Die Bilder sind ganz verschieden, der dramatische Verlauf ist der gleiche. Beiden Träumen kann nun dasselbe Ereignis in der übersinnlichen Welt, gewissermaßen hinter der Szene des Lebens, zugrunde liegen. Es kann bei beiden Träumen ganz dasselbe in der Seele vorgegangen sein, und ganz dasselbe kann sich in den verschiedensten Bildern nach außen hin zum Abbilde bringen.

Das will eben darauf aufmerksam machen, daß man nicht in äußerlicher Weise, wie es so häufig vorkommt, aus dem Inhalt der Träume zu schließen habe, sondern aus dem dramatischen Verlauf zunächst sich zu unterrichten habe, durch was des Menschen Seele und Geist da durchgegangen sein kann. Dann wird man, wenn man außerdem noch sein Vorstellungsvermögen dabei unterstützt durch solche Übungen, von denen ich in diesen Tagen gesprochen habe, dann wird man allmählich immer mehr und mehr hineinkommen, aus der illusionären Bilderwelt des Traumes heraus dasjenige durch die Dramatik hindurch erfassen zu können, was eigentlich als eine übersinnliche, zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen erlebte Wirklichkeit dem Traume zugrunde liegt.

Bevor ich über Einzelheiten des Traumes, seiner Beziehung zu dem physischen Körper des Menschen und zu dem Geistigen des Menschen spreche, was in den nächsten Tagen noch geschehen soll, möchte ich heute charakterisieren, wie der Mensch durch die Traumeswelt sich in den ganzen Kosmos, in das ganze Universum hineingestellt zeigt. Man kann ja sehen, wie im Traume beginnt ein ganz anderer Zusammenhang der einzelnen Ereignisse des Lebens, als derjenige ist, den wir im Wachleben durchmachen. Im Wachleben - das haben wir ja gerade an den eben erwähnten Beispielen gesehen - stellen sich nach den Gesetzen, in denen wir in der sinnlichen Welt einmal drinnen sind, die Dinge in einem gewissen Zusammenhang dar. Ein Folgendes muß immer auf ein Früheres kommen. Der Traum zeigt dasjenige, was in der gewöhnlichen Sinneswelt geschehen kann, in vollständiger Auflösung. Es wird alles anders; es löst sich alles auf. Dasjenige, was, wie der Mensch selbst, als sinnliches Wesen an den Erdboden durch die Schwere gebunden ist, kann im Traume plötzlich fliegen. Der Mensch macht Kunstflüge ohne Flugzeug im Traume. Woran man sich sonst die Zähne ausbeißt, an einem mathematischen Problem zum Beispiel, das erlebt man im Traume so, als ob man es kinderleicht gelöst habe. Man erinnert sich dann vielleicht an die Lösung im Wachen nicht mehr — nun, das ist ja ein persönliches Unglück -, aber jedenfalls hat man die Vorstellung, daß die Hemmnisse, die Hindernisse im Vorstellen, die im Tagesleben da sind, nicht da seien. Und so wird alles, was im Tagesleben einen festen Zusammenhang hat, in einer gewissen Weise im Traume aufgelöst. Wollen wir uns ein sinnliches Bild machen von dem, was da im Traume eigentlich geschieht - für unser Vorstellen natürlich nur geschieht -, so können wir sagen: Wir stellen meinetwillen ein Glas mit einer Flüssigkeit, mit Wasser hin, geben irgendein Salz, das sich auflösen kann, in das Wasser hinein und schauen nun dem Auflösen zu. Das Salz, nehmen wir an, wäre sogar kristallisiert und hätte bestimmte Formen. Das Salz zeigt uns zunächst, wenn wir es hineinwerfen, die bestimmtesten Formen. Dann aber sehen wir, wie sich die Formen auflösen, die phantastischsten Formen annehmen, bis sich endlich das ganze Salz im Wasser aufgelöst hat und wiederum eine mehr oder weniger homogene Flüssigkeit erscheint.

So ähnlich geht es im Vorstellen, im seelischen Erleben mit dem Traum. Sowohl der Einschlafetraum wie der Aufwachetraum nehmen sich heraus die gewöhnlichen Tageserlebnisse, lösen sie auf, geben ihnen alle möglichen phantastischen Formen, allen möglichen phantastischen Sinn; phantastisch nennen wir es vom Standpunkt des gewöhnlichen Bewußtseins aus. Es ist das ein ganz gutes Bild, die Auflösung irgendwelcher Salze in einer Flüssigkeit, für dasjenige, was seelisch-geistig eben eigentlich im Traume geschieht.

Nun wird man, wenn man so recht hineingewachsen ist in die heutige Vorstellungswelt, nicht leicht zu einem unbefangenen Begreifen dieser Tatsache kommen, denn die heutige, insbesondere die heutige sich wissenschaftlich nennende Menschheit weiß von gewissen Dingen tatsächlich außerordentlich wenig.

Wirklich, diese Dinge, die ich jetzt sage, sage ich nicht aus dem Grunde, weil ich gerne auch der Wissenschaft etwas am Zeuge flikken möchte. Das ist gar nicht meine Absicht. Ich schätze die Wissenschaftlichkeit und möchte nirgends Laientum oder Dilettantentum an die Stelle des wissenschaftlichen Betriebes gesetzt wissen. Man muß auch gerade vom Standpunkt der Geisteswissenschaft aus die großen Fortschritte und auch die begrenzte Wahrheit und Sicherheit der gegenwärtigen Wissenschaftlichkeit durchaus anerkennen. Das also durchaus vorausgesetzt. Dennoch muß das Folgende gesagt werden.

Die Menschen nehmen heute, wenn sie etwas wissen wollen, die irdischen Dinge und irdischen Vorgänge. Sie beobachten sie und schließen aus den Beobachtungen auf Naturgesetze. Sie machen wohl auch Experimente, um der Natur ihre Geheimnisse abzulauschen, und lassen sich aus dem, was die Experimente ergeben, wiederum ihre Naturgesetze offenbaren. Und so kommt man auf eine bestimmte Art von Gesetzen, die man dann seine Wissenschaft nennt. Und dann blickt man hinaus in die Himmelsweiten. Man sieht in den Himmelsweiten, sagen wir, die wunderbaren Spiralnebel, sieht in diesen Spiralnebeln einzelne Weltenkörper entstehen und dergleichen. Man nimmt diese Dinge heute selbst durch die photographische Methode auf, die noch viel genauer die Sachen zeigt als die gewöhnliche Beobachtung durch das Teleskop oder dergleichen. Und was tut man dann, um Erkenntnisse zu gewinnen über dasjenige, was da in den räumlichen Himmelsweiten vor sich geht? Man nimmt die Naturgesetze der Erde, dasjenige, was man von der Erde aus geschlossen hat, was man da erexperimentiert hat, das nimmt man, und dann spekuliert man darüber nach, wie nach denselben Naturgesetzen sich solch ein Spiralnebel in Raumesfernen gebildet haben könnte. Man macht Hypothesen und Theorien über Weltentstehung und Weltuntergang, um dasjenige, was man in seinem Laboratorium an dem Erdmangan, Erdensauerstoff, Wasserstoff entdeckt hat, als Naturgesetze anzuwenden auf die Himmelssphäre. Und wenn man dabei neue Stoffe entdeckt, so macht man ja zuweilen so unbewußte Andeutungen, daß man da in recht zweifelhaftes wissenschaftliches Getriebe hineinkommt. Man hat da überall Wasserstoff gefunden in den Raumesweiten, Helium zum Beispiel, aber man hat noch einen anderen Stoff gefunden, der hat einen sonderbaren Namen, sonderbar, weil er schon etwas hindeutet auf die Verwirrung des Denkens, die da eintritt. Er heißt nämlich Nebulium. Es wird das Denken da nebelhaft, daher dieses Nebulium neben dem Helium, neben dem Wasserstoff. Wenn man so einfach dasjenige, was man in seinem Erdenlaboratorium als Naturgesetze erkundet hat, anwendet, und nun auf die Art zum Beispiel des schwedischen Denkers Arrhenius, der in dieser Beziehung wirklich unendlich viel Unheil angerichtet hat, nachspekuliert, was da draußen in räumlichen Weiten vor sich gehen könne, dann muß man notwendigerweise in Irrtum über Irrtum hineinkommen, wenn man das Folgende nicht in unbefangener Art betrachten kann.

Sehen Sie, ich möchte wiederum von einem Vergleich ausgehen: Es ist Ihnen ja aus der Naturwissenschaft bekannt, wie Newton, der englische Physiker, Naturphilosoph, die Theorie aufgestellt hat der sogenannten Gravitation, der Schwerewirkung im ganzen Weltenraum. Er dehnte das Gesetz der Gravitation, das man am gewöhnlichen fallenden Stein sieht, den die Erde anzieht, auf die gegenseitigen Verhältnisse aller Weltenkörper aus. Er sprach auch aus, wie die Kraft dieser Gravitation, die Stärke, mit der Entfernung immer abnimmt.

Für Physiker, die in diesem Saale etwa sein könnten, kann man ja sagen, daß das Gesetz lautet, daß die Schwere mit dem Quadrat der Entfernung abnimmt, also in der Entfernung 2 viermal, in der Entfernung 3 neunmal schwächer ist; das heißt also mit dem Grade der Entfernung nimmt die Schwere ab.

Sehen Sie, für eine solche Kraft stellt man ein solches Gesetz auf. Das ist ganz richtig. Aber man hat nicht die Möglichkeit, wenn man bloß im rein physischen Dasein stehenbleibt, dieses Gesetz nun universell genug zu denken. Man denkt sich, wenn man hier einen Weltenkörper hat, dann nimmt seine Gravitationskraft mit der Entfernung ab; sie ist stark, sie wird schwächer, noch schwächer, noch schwächer und immer schwächer.

So ist es ja auch mit der Lichtausbreitung. Das Licht, das sich ausbreitet von einem bestimmten Lichtquell, wird immer schwächer und schwächer.

Das durchschaut der gegenwärtige Mensch mit seiner Wissenschaft. Aber er durchschaut nicht das andere, daß, wenn er Naturgesetze hier auf dem Erdenkörper aufstellt in seinem Laboratorium und diese Naturgesetze in Ideen bringt, daß die Wahrheit dieser Naturgesetze, der Inhalt dieser Naturgesetze auch aufhört, je weiter man sich von der Erde entfernt. Wenn man also auf der Erde ein Gesetz für die Verbindung von Elementen aufstellt, Sauerstoff und Wasserstoff oder irgendwelchen Elementen, wenn man auf der Erde das Gravitationsgesetz aufstellt, so nimmt die Wahrheit des Inhaltes dieses Gesetzes eben auch mit dem Hinausgehen in den Weltenraum ab. Und wenn ich hier in meinem Laboratorium ein gewisses Naturgesetz aufgestellt habe, und ich übertrage dieses Naturgesetz auf einen Spiralnebel im fernen Weltenraum, so habe ich genau dasselbe getan, als wenn ich glaube, wenn ich hier eine Kerze aufstelle, diese Kerze anzünde und nun durch den Weltenraum hinausstellen könnte in den Spiralnebel, so würde das Kerzenlicht da oben mit derselben Intensität scheinen wie hier. Gerade diesem selben Irrtum gebe ich mich hin, wenn ich glaube, daß das, was ich hier in meinem Laboratorium festgestellt habe, auch da draußen in dem fernen Weltenraum gilt. So daß gerade ein durchgreifender Irrtum dadurch entsteht, daß man das, was man in einem Erdenlaboratorium als ganz richtige Naturgesetze findet, nun übertragt auf die Weiten des Himmelsraumes.

Nun aber ist der Mensch nicht ausgeschlossen von jener Gesetzmäßigkeit, in die man hineinkommt, wenn eben die Erdengesetzmäßigkeit wie die Stärke der Gravitation oder des Lichtes nicht mehr gilt. Und wollte man eine Gesetzmäßigkeit, die anders ist als unsere Naturgesetze, finden im Raume, dann müßte man immer weiter und weiter von der Erde sich entfernen. Will man sie finden auf eine mehr innerlich menschliche Art, so geht man vom Wachen ins Schlafen über. Wenn wir wachen, stehen wir drinnen im Bereich dieser Naturgesetze. Wir tun alles, was wir tun, im Sinne dieser Naturgesetze. Wir nehmen uns vor, unsere Hand, unseren Arm zu erheben; die chemisch-physikalischen Vorgänge, die da in den Muskeln sich abspielen, die mechanischen Vorgänge, die sich im Knochengerüste abspielen, sie spielen sich ab nach den Gesetzen, die wir hier auf Erden in unserem Laboratorium oder durch Beobachtung erforschen. Dasjenige, was da drinnen als Seele lebt, das geht im Schlaf heraus aus dem physischen und aus dem Ätherleib. Und indem es herausgeht, dringt es in die Welt ein, die nun nicht unterworfen ist den Naturgesetzen. Deshalb beginnt der Traum ein solcher Spötter über die Naturgesetze zu werden. Wir dringen in eine ganz andere Welt hinein. Wir dringen in eine Welt hinein, in die wir uns ebenso schlafend hineinleben, wie wir wachend mit unserem physischen Körper uns in die Sinnenwelt hineinleben. Aber diese Welt ist eine andere. Diese Welt hat nicht unsere Naturgesetze, sondern diese Welt hat ganz andere Gesetze. Jede Nacht, indem wir aus unserem physischen und Ätherleib herausgehen, tauchen wir unter in eine Welt, in der unsere Naturgesetze nicht mehr gelten. Und der Traum ist diejenige Macht, welche die intensive Opposition den Naturgesetzen gegenüberstellt.

Indem ich träume, zeigt mir der Traum, daß ich in einer Welt lebe, die gegen die Naturgesetze protestiert, die den Naturgesetzen nicht unterworfen sein will. Wenn ich des Abends einschlafe und mich aus meinem physischen und Ätherleib herausbewege, dann lebe ich noch halb drinnen in den Naturgesetzen; aber ich trete schon ein in die Welt, die nun nicht von Naturgesetzen beherrscht wird. Da kommt dieses Durcheinander von Naturgesetzen und übersinnlichen Gesetzen im Traume zustande. Ebenso beim Aufwachen.

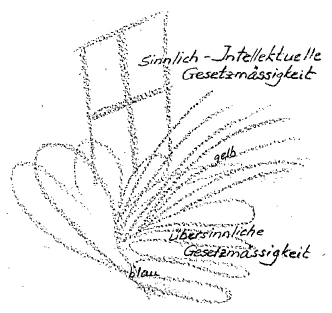

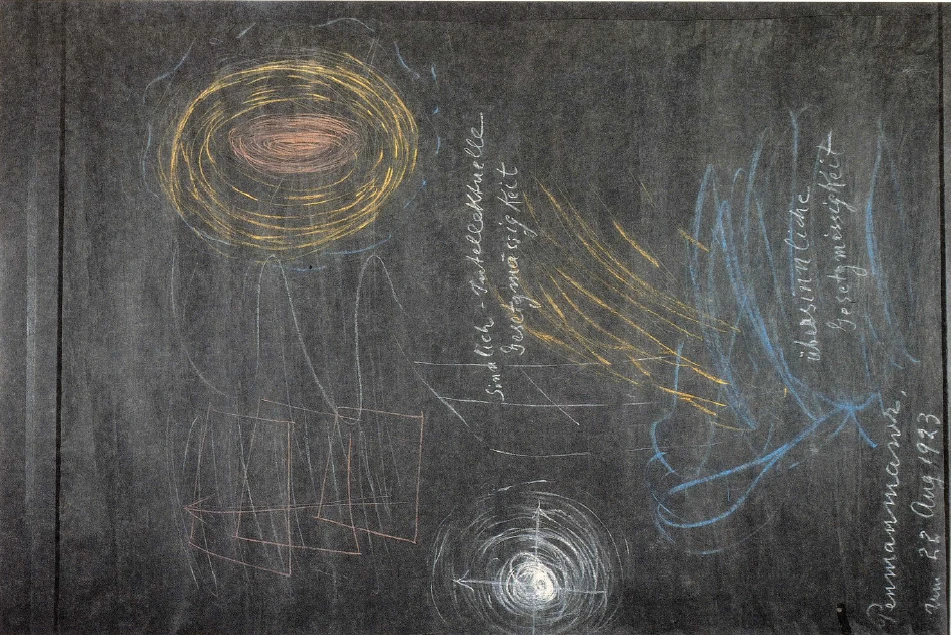

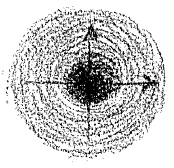

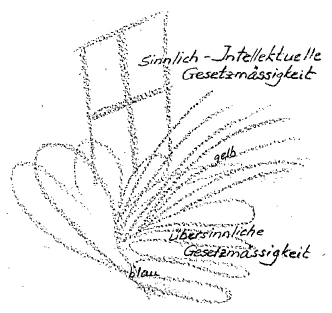

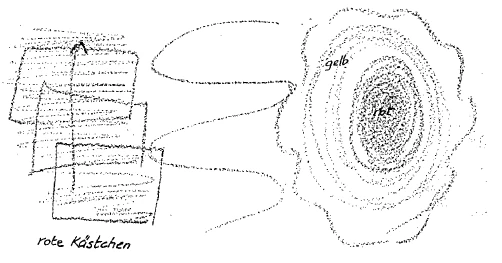

Man kann nun sagen, daß man mit jedem Einschlafen hineintaucht in eine Welt, in der unsere Naturgesetze nicht gelten, und mit jedem Aufwachen taucht man auf aus dieser Welt in die Welt, in der eben unsere Naturgesetze gelten. Wenn wir uns diesen Vorgang wirklich vorstellen, so ist es ja so: Denken Sie sich die Traumeswelt wie ein Meer, in dem Sie leben. Nehmen Sie an, Sie wachen auf aus dem flutenden Traumleben des Morgens. Es ist, wie wenn Sie sich herausbewegen würden aus dem flutenden Traumleben. Sie bewegen sich von einer übersinnlichen Gesetzmäßigkeit in die sinnlich-intellektuelle Gesetzmäßigkeit hinein. Und so ist es Ihnen, als wenn alles dasjenige, was Sie nach dem Aufwachen in scharfen Konturen sehen, herausgeboren würde aus dem Flüssigen, Flüchtigen. Sagen wir, Sie sehen meinetwillen hier Fenster; wenn Sie zuerst vom Fenster träumen, so wird Ihnen auch dieses Fenster herausgeboren erscheinen von etwas Verflossenem, von etwas Unbestimmtem vielleicht, das hier (gelb) allerlei Feuerflammen hat; da taucht das Fenster auf, und würden Sie ganz lebhaft träumen, so würden Sie sehen, wie die ganze, scharf konturierte bestimmte Tageswelt Ihres Bewußtseins auftaucht aus diesem Unbestimmten, wie wenn sich aus dem Meere heraus Wellen erheben würden (blau), diese Wellen sich aber dann zur Tageswelt formen würden.

Und hier ist einer derjenigen Punkte, wo man, wenn man als gegenwärtiger Mensch diese Dinge wieder erforscht, in jenes ehrfurchtsvolle Staunen hineinkommt, das man empfinden kann gegenüber den traumhaften Imaginationen einer früheren Menschheit, von denen ich auch in diesen Tagen gesprochen habe. Ich sagte, wenn wir zurückgehen zu demjenigen, was eine frühere Menschheit auch im Wachleben in traumhaften Imaginationen in der Seele erlebt hat, was sie dann in Mythen und Legenden in die Göttersagen geformt hat, was so unbestimmt vertfließt gegenüber demjenigen, was wir heute in fester Naturanschauung erfassen, wenn man zu dem zurückgeht mit dem, was man heute wieder entdecken kann, ganz selbständig, unabhängig von diesen alten traumhaften Imaginationen, dann kommt man aber doch zu einem ehrfürchtigen Erstaunen, zu einer ehrfürchtigen Bewunderung desjenigen, was in den Seelen dieser Menschen älterer Zeitepochen gelebt hat. Und aus dem alten Griechenland tönt uns noch ein Wort herüber, welches uns Zeugnis ist, wenn wir auf diesem Gebiete neuerdings dasjenige wieder erforschen, was die Wahrheit ist; es tönt uns aus dem alten Griechenland herüber ein Wort, welches uns bezeugt, daß die Griechen noch etwas gewußt haben von diesen Dingen, daß die Griechen sich vorgestellt haben: Es gibt etwas, was aller Weltgestaltung zugrunde liegt, aus dem sich alle bestimmten Gestalten erheben, das man aber nur erreichen kann, wenn man aus der Sinnenwelt heraus in den Schlafzustand, in einen traumhaften Zustand kommt. Das haben die Griechen genannt das Chaos. Und es war alle Spekulation, alle begriffliche Untersuchung, was das Chaos ist, vergeblich; denn das Chaos ist etwas, woran der heutige Mensch nahe kommt, wenn er ins Träumen hineinkommt. Nur noch ins Mittelalter ragt hinein irgend etwas von einer Kenntnis dessen, was so als übersinnliche, kaum schon Materie zu nennende äußere Substanz allen äußeren Substanzen zugrunde liegt, indem im Mittelalter gesprochen wird von der sogenannten Quintessenz, der fünften Wesenheit, neben den vier anderen Elementen: Erde, Wasser, Luft, Feuer — der Quintessenz.

Oder es dringt etwas noch in das mittelalterliche Schauen hinein, wenn der Dichter in einer so anschaulichen Art sagt: Die Welt ist aus den Träumen gewoben. Der Grieche würde gesagt haben: Die Welt ist aus dem gewoben, was du, wenn du aus dem Sinnlichen hinausdringst in die Welt, die du frei von deinem Körper erlebst, was du da erlebst als das Chaos. - So muß man schon, um zu verstehen, was die Griechen mit dem Chaos meinten, hinweisen auf dasjenige, was nicht in den sinnlichen, was in den übersinnlichen Welten liegt.

Wenn man nun die ganzen Vorgänge des Einschlafens, Träumens, Schlafens, Aufwachens verfolgt von jenen Gesichtspunkten aus, die sich ergeben, wenn man den Weg, den ich in diesen Tagen beschrieben habe, zu der höheren Erkenntnis durch Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition hinaufsteigt in die übersinnlichen Welten, wenn man also das Traum-, Schlaf-, Wachleben von dem Gesichtspunkt dieser Erkenntnis verfolgt, so stellt sich einem etwa das Folgende dar: Der Mensch schläft hinüber aus dem gewöhnlichen Tageszustand in sein Schlafesleben, aus dem die Träume in unbestimmt chaotischer, aber auch bewunderungswürdiger, innerlich einheitlicher Art heraussteigen können. Im Bette zurückgelassen wird der physische Körper und der Ätherleib, der als das eigentlich Belebende, Gestaltende, Wachstumbewirkende den physischen Körper durchzieht. Eine Zweiheit wird im Bette zurückgelassen.

Aber eine Zweiheit geht auch heraus und dringt ein in jenes übersinnliche Dasein zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen, das ich Ihnen also auch heute eben vom Gesichtspunkte des Traumerlebnisses aus beschreiben konnte.

Diese Zweiheit, sie stellt sich nun für die höhere Erkenntnis der Imagination, Inspiration und Intuition in der folgenden Weise dar: Da ist dasjenige, was dem Menschen eigen ist, wenn er herausdringt aus physischem und Ätherleib als sein astralischer Leib. Stoßen wir uns nicht, ich habe das schon gesagt, an Worten; man muß Worte haben, man könnte für astralischen Leib auch ein anderes Wort gebrauchen. Ich werde ja sogleich etwas charakterisieren, was den astralischen Leib betrifft, und wir werden sehen, daß es nicht auf Namen ankommt, sondern auf dasjenige, was man sich als Vorstellungen über sie aneignen kann. Dieser astralische Leib ist eine Summe von Vorgängen. Es geschieht etwas im Menschen, der aus seinem physischen und ätherischen Leib herauswächst. Eben dieses Geschehen, diese Vorgänge stellen den astralischen Leib dar. Im Ätherleib haben wir zurückgelassen die Vorstellungen, die Gedanken. Hier drinnen im astralischen Leib ist vergeistigtes Licht, von der Kraft der Liebefähigkeit durchzogene kosmische Wärme. Das alles ist im astralischen Leib vorhanden.

Dasjenige, was so im astralischen Leib vorhanden ist, das kann eben beim Aufwachen hineintauchen in den Ätherleib, sich stauen, und dann als das Gewebe, als das Spiel der Träume erscheinen, oder auch, indem es sich herausbewegt aus physischem und Ätherleib, indem es verläßt die Welt der Vorstellungen, wiederum als das Gewebe, das Spiel der einfachen Träume erscheinen. Es ist also im wesentlichen der astralische Leib, der uns herausträgt aus physischem und Ätherleib.

Und dieser astralische Leib ist diejenige Wesenheit in uns, die, wie ich schon gesagt habe, die eigentliche Opposition macht gegen die Naturgesetze. Wir stecken vom Morgen bis zum Abend, vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen in dem Getriebe der Naturgesetze drinnen, in dem Getriebe der Naturgesetze, das wir auch durch die Mathematik erfassen können in bezug auf seine Räumlichkeit und Zeitlichkeit. Indem wir einschlafen, dringen wir heraus sowohl aus dem Gewebe der Naturgesetze, wie auch aus den mathematischen Gesetzen. Wir ziehen auch die Mathematik aus, denn unser astralischer Leib, der enthält nicht die tote, abstrakte Mathematik des dreidimensionalen Raumes, sondern eine in sich geschlossene, ich möchte sagen lebendige, aber geistig lebendige Mathematik, die nur in einer Dimension verläuft, die nur in der geraden Linie verläuft. Über diese Dimensionalität werde ich noch zu sprechen haben. Aber dieser astralische Leib ist es eigentlich, der uns frei macht von unserem Haften an den Naturgesetzen, welches vorhanden ist zwischen dem Aufwachen und Einschlafen. Wir werden durch unseren astralischen Leib in eine ganz andere Welt versetzt, in die übersinnliche Welt.

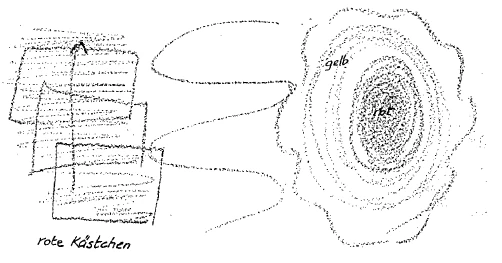

Wollte man diesen Vorgang etwa schematisch zeichnen, so müßte man sagen: Wir weben im Bereich der Naturgesetze, wenn wir wachen (weiß). Wir dringen aber mit unserem astralischen Leib, den wir ja auch in unserem physischen Leib drinnen haben, beim Einschlafen heraus (gelb). Hier im physischen und Ätherleib ist unser astralischer Leib ganz den Naturgesetzen unterworfen. Er ist ganz in allen seinen Bewegungen und Vorgängen so drinnen, daß er in den Naturgesetzen drinnen lebt, wie ich sie schematisch dargestellt habe in diesen Figuren (rote Kästchen).

Jetzt lebt sich der astralische Leib, indem er heraustritt aus dem physischen und Ätherleib, in die übersinnliche Welt hinein, und jetzt ist er in einer anderen, in einer übersinnlichen Gesetzmäßigkeit darinnen. Der astralische Leib ist etwas ganz anderes geworden. Er hat gewissermaßen die Zwangsjacke der Naturgesetze an vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen. Er schläft ein, das heißt, er dringt aus physischem und ätherischem Leib heraus, und er bewegt sich in der Welt freier Gesetzmäßigkeit, die seine ihm angemessene Gesetzmäßigkeit ist. Und in was kommt er da hinein? Er kommt nun hinein in eine Welt, das heißt, er bringt uns als Menschen in eine Welt hinein, die für das Ich, für die eigentliche Ich-Organisation, die nun im astralischen Leib drinnen ist und mit ihm aus dem physischen und Ätherleib herausgeht im Einschlafen, eine freie Beweglichkeit gibt; das Ich wird frei in der Welt, in die es der astralische Leib hineingetragen hat. Jede Nacht wird das Ich in einer Welt frei, in der die Naturgesetze nicht gelten, in der das Ich frei vom Zwang der Naturgesetze schalten und walten kann. Wenn wir zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen stehen und uns unser astralischer Leib befreit hat von den Naturgesetzen, wenn nicht mehr die Gravitation, nicht mehr das Gesetz der Energie, wenn gar nichts mehr von allen diesen Gesetzen gilt in der Welt, in die wir jetzt eingetreten sind, dann ist die Bahn freigegeben für jene sittlichen Impulse, die nur hier sich, ich möchte sagen, unter dem Zwang der sinnlichen Weltordnung in der Welt ausleben können, in der wir sind zwischen dem Aufwachen und Einschlafen. In einer Welt, in der das Sittengesetz nun dieselbe Kraft und Gewalt erlangt, wie hier die Naturgesetze haben, lebt das Ich vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen. Und in dieser Welt kann das Ich etwas vorbereiten. Das Ich kann in dieser Welt, in der es befreit ist im Schlafzustande von den Naturgesetzen, vorbereiten dasjenige, was es dann auszuführen hat, wenn es durch die Pforte des Todes geschritten ist. Über diesen Weg vom Tod bis zu einer neuen Geburt werden wir dann in den weiteren Vorträgen zu reden haben.

Das Ich kann nun vorbereiten zunächst in Bildformen, in Imaginationen, die aber nicht vorgestellt werden, sondern die Kraftimpulse sind, das Ich kann vorbereiten zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen die Bilder desjenigen, was es dann in der Geistwirklichkeit zu leisten hat. Wenn es durch die Pforte des Todes getreten ist, werden nämlich die Sittengesetze so sein, wie unsere Naturgesetze hier in der physisch-sinnlichen Welt sind. Hier zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen bereitet das durch den astralischen Leib befreite Ich schon in Bildern dasjenige vor, was in Geistwirklichkeit durchgemacht werden muß zwischen dem Tode und einem neuen Erdenleben. So daß wir sagen können: Das Ich arbeitet schon, wenn auch keimhaft, wie in einem ganz kleinen Geistkeim dasjenige aus, was es dann zu leisten hat im Geist-Universum nach dem Tode. Und in dem, was das Ich in diesem Schlafzustande schon hier ausarbeitet im Bilde, liegt schon angedeutet dasjenige, was wir durch keine Naturgesetze, sondern nur durch die geistige Welt von diesem Erdenleben in das nächste Erdenleben hinübernehmen können. Die Kausalitat desjenigen, was wir als sittlicher Mensch in uns aufgenommen haben, die sittlichen Impulse können wir hier nur dadurch verfolgen, daß wir uns gewissermaßen mit einem inneren Seelengehorsam unter sie stellen. So wie das Ich sie ausarbeitet im Schlafzustande und dann weiterarbeitet zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, so gewinnen diese sittlichen Impulse dieselben Kräfte, die sonst hier Naturgesetze haben, und kleiden sich hinein in den nächsten Menschenleib, den wir im folgenden Erdenleben tragen werden als unsere sittlich-natürliche Verfassung, als unser Temperament, als unsere Charakteranlage, die man nur mit Unrecht einer bloßen Vererbung zuschreibt, die so ausgearbeitet wird, daß das Ich schon daran zu arbeiten hat im Schlafzustande, wenn es durch den astralischen Leib befreit in einer nun nicht natürlichen, sondern in einer rein geistigen Welt zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen waltet. Und so können wir sehen, wie der Mensch durch den Schlafzustand schon seine Zukunft vorbereitet, wie er sich hineinlebt in seine Zukunft.

Und was zeigt uns der Traum? Ich möchte sagen: Da arbeitet das Ich während des Schlafens, aber der Traum zeigt uns diese Arbeit in illusionären Bildern. Wir können noch nicht in dieses Erdenleben hereinnehmen, was schon während des Schlafzustandes für das nächste Erdenleben gewoben wird. Der Traum - ich habe das im Anfang meines heutigen Vortrages erklärt - kann uns in seinen Bildern verworren dasjenige zeigen, was wir durchgemacht haben in früheren Erdenleben, so wie er in chaotischen Formen dasjenige zeigt, was keimhaft vorbereitet wird für die Menschheitszukunft in künftigen Zeiten.

So führt uns in der Tat die richtige Interpretation des Traumes dazu, anzuerkennen, daß der Traum doch etwas ist wie ein Fenster, durch das wir nur in der richtigen Weise durchschauen müssen, wie ein Fenster hinein in die übersinnliche Welt. Denn hinter diesem Fenster liegt dasjenige, was das Gewebe der Ich-Tätigkeit ist, die da dauert von früheren Erdenleben bis zu künftigen Erdenleben. Wir schauen schon in einer gewissen Weise, wenn wir den Traum in der richtigen Weise interpretieren können, durch das Fenster des Traumes von der Welt der Vergänglichkeit, in der wir als Erdenmensch leben, in die Welt der Dauer, der Ewigkeit, der wir mit unserer eigentlichen inneren Menschenwesenheit angehören.

Davon will ich dann morgen weitersprechen.

The dream life

Between the waking life of the human being and the sleeping life, of which I was able to give you at least a sketchy description in the last observation, is the dream life. This dream life, which can have so little significance for the immediate reality of everyday life, has the greatest conceivable significance for the deeper knowledge of both the world and the human being. Not only because in spiritual science, of which we are speaking here, the significance of this dream must be fully appreciated, so that one can pass from the contemplation of the dream to many other things, but also because this dream life has such a special significance because it represents, so to speak, the corner through which certain worlds other than that which man experiences waking, shine into this ordinary world. So that man often becomes aware, precisely through the mysteriousness of the dream formations, not only that there are other worlds in the subsoil or also the surface of the world accessible to him, but also of what the nature of these worlds might be.

But on the other hand it is extraordinarily difficult to penetrate this whole mysterious dream life from the standpoint of higher consciousness, for the dream is a power in life which can place man in the greatest conceivable illusion. And one is easily inclined, especially in the face of dreams, to relate that which presents itself illusionarily in life to its reality in a false way. Let us proceed in this way by referring to what I have already said about the life of sleep and also about repeated earth lives.

An example that is always repeated in one way or another in dream life is that one has done something in a dream that one could not even think of having done in waking life, something that was completely outside the realm of possibility to do in the previous earth life. Then you dream that you cannot find what you have now made, and you search like a madman for this lost thing that you think you have made.

Let's look at the example more concretely. In this form, as I have described it, varied in one way or another, it occurs in every person's dream life. Let's look at it concretely. Let us say that a tailor has dreamed, although he is only a very small tailor for petty bourgeois people, that he has made a state coat for a minister. Now he feels quite at ease in making the state gown, which is now supposed to be there. But immediately afterwards the dream turns into the mood that he is now looking for this coat everywhere when he is supposed to deliver it to the minister, and he can't find it anywhere.

Here you have a dream that runs entirely in the forms that the person concerned cannot carry out in life, but which he can still imagine quite well in the life he is leading on earth. He cannot carry it out because he is only a small tailor for petty bourgeois people, and you cannot order a skirt from him. But sometimes his bold daydreams may have been driven by the desire to make such a state skirt. Maybe he can't do it at all, but it becomes the wish of his daydreams.

But what underlies this? It is actually based on a reality. When man is asleep with his ego and his astral body outside the physical body and the etheric body, then he is in that entity which passes through the repeated earth lives.

That which works inwardly, which is actually inwardly active in its own being while the human being is asleep, that is the ego and the astral body: In its experiences it need not merely have memories of the earthly life just now lived, but it can have memories of other earthly lives. And I am not telling you something hypothetically assumed, but something that definitely comes from the realm of reality I am talking about. It is therefore possible that the person concerned was once involved - let us say in ancient Roman times in an earlier earthly life - in the ordering of a particularly stately toga. He need not even have been a tailor at that time, but he may somehow have been the servant or perhaps even the friend of a Roman statesman. His fate may have brought him to his profession in this incarnation precisely because he then had such a lively desire to present his master to the world in the most dignified way possible. For it is precisely desires and thoughts that are of extraordinarily great importance for human life as a whole. And so the memory of what was experienced in this way in a previous life on earth can permeate the soul and spirit of the human being, ego and astral body. Then in the morning, when the human being now submerges, as I only sketched yesterday, with his ego and astral body into the etheric body and the physical body, then this soul, which has just been immersed in the reminiscent experience of the beauty of the state toga, now submerges into those ideas that the dressmaker in question can have in the present earthly life; they are in his etheric body. That which has just been experienced as relating to the old Roman times accumulates there. It should enter into the ideas that he can have during the day. But by day he has only those ideas that he makes clothes for the petty bourgeoisie. Now the soul, when it is immersed there, can only with extraordinary difficulty realize that which it has just felt in the beautiful state toga; it can hardly imagine it in the terrible clothes which the dressmaker has to make. During the transition, during the stasis, it transforms from the idea of the toga to the present ministerial state robe, and only later, when the person concerned is completely submerged in his etheric and physical body, does what he now has to imagine destroy what he experienced shortly before waking up.

So we have our whole human life there between falling asleep and waking up. In our inner being we have to confront our whole human life with what we can imagine in this earthly life, what we can think according to our experiences, and thus we get the strange forms of the dream. This is why it is so difficult to distinguish the content of a dream, which it initially presents and which can be a complete illusion, from the true reality that actually always lies behind it. This true reality can be something completely different. But the one who gradually becomes accustomed to the whole intricate process of dream life, who becomes aware of the fact that in dreams one has to pay less attention to what is conjured before the soul in images, for these images are formed by the etheric body actually left behind in bed, which carries the thoughts, the ideas within itself. One does not have these ideas in one's actual inner being during sleep. One must distinguish this content of the ideas from something else, and I would like to call this something else the dramatic course of the dream. One must gradually accustom oneself to pay attention to the dramatic course of the dream in such a way that one asks oneself: Does this dream proceed in such a way that, if the facts in question were experienced in daily life, it would give tremendous pleasure? Did one also experience this joy, this liberation in the dream, or did one sail into a catastrophe in the dream? Does one go from a certain exposure, where things can show themselves, then become entangled and then there is a crash, to some kind of catastrophe? These questions should be considered first and foremost when considering dream life, i.e. not the mental content, but the dramatic events.

Someone may dream that he is climbing a mountain; the mountain hike becomes more and more difficult. He finally reaches a point where he can go no further, where he is confronted by enormous obstacles. He perceives these obstacles as something that has a significant impact on his life. Well, someone can have this dream. You could go on to color it. But he or someone else can have a different dream: he moves through the entrance of a cave that leads into a mountain cellar somewhere for my sake. After passing through the entrance, there is still some light. Then it gets darker and darker. But finally he comes to a place where it is not only completely dark, but where he is also met by the most terrible cold effects and the like, so that he cannot penetrate any further into the mountain cave from this point.

You see, here you have two dreams that are quite different in content; dramatically they both depict an undertaking that goes well at first, then presents difficulties, then comes up against an insurmountable obstacle. The images are quite different, the dramatic course is the same. Both dreams can be based on the same event in the supersensible world, behind the scene of life, so to speak. Quite the same thing may have happened in the soul in both dreams, and quite the same thing may be represented outwardly in the most diverse images.

This is intended to draw attention to the fact that one should not draw conclusions from the content of dreams in an external way, as is so often the case, but should first learn from the dramatic course through which the human soul and spirit may have passed. Then, if you also support your imagination with the exercises I have been talking about these days, you will gradually become more and more able to grasp through the drama, out of the illusionary imagery of the dream, that which actually underlies the dream as a supersensible reality experienced between falling asleep and waking up.

Before I talk about details of the dream, its relationship to the physical body of man and to the spiritual of man, which will happen in the next few days, I would like to characterize today how man shows himself through the dream world into the whole cosmos, into the whole universe. You can see how in dreams a completely different context of the individual events of life begins than that which we go through in waking life. In waking life - as we have just seen from the examples just mentioned - things present themselves in a certain context according to the laws in which we are once immersed in the sensory world. A following must always come from an earlier. The dream shows that which can happen in the ordinary sense world in complete dissolution. Everything becomes different; everything dissolves. That which, like man himself, is bound to the earth by gravity as a sensual being, can suddenly fly in a dream. Man makes aerobatics without an airplane in a dream. What we usually grit our teeth over, a mathematical problem for example, we experience in a dream as if we had solved it child's play. One may then no longer remember the solution in waking life - well, that is a personal misfortune - but in any case one has the idea that the obstacles, the hindrances in the imagination that are there in daytime life are not there. And so everything that has a fixed connection in daily life is dissolved in a certain way in dreams. If we want to form a sensual picture of what actually happens in a dream - which of course only happens for our imagination - we can say: For my sake we place a glass with a liquid, with water, put some salt that can dissolve into the water and now watch it dissolve. The salt, we assume, would even be crystallized and have certain forms. The salt initially shows us the most definite forms when we throw it in. But then we see how the forms dissolve, taking on the most fantastic shapes, until finally all the salt has dissolved in the water and a more or less homogeneous liquid appears again.

It is similar in the imagination, in the mental experience of dreams. Both the dream of falling asleep and the dream of waking up take the ordinary experiences of the day, dissolve them, give them all kinds of fantastic forms, all kinds of fantastic meaning; we call it fantastic from the point of view of ordinary consciousness. This is a very good image, the dissolution of some salts in a liquid, for that which actually happens in dreams in the soul and spirit.

Now, if one has really grown into today's world of imagination, one will not easily come to an unbiased understanding of this fact, because today's humanity, especially today's humanity that calls itself scientific, actually knows extraordinarily little about certain things.

Really, I am not saying these things that I am saying now because I would like to flirt with science. That is not my intention at all. I value science and I don't want to see amateurism or dilettantism take the place of the scientific enterprise anywhere. From the point of view of spiritual science, the great progress and also the limited truth and certainty of present-day science must be recognized. This, then, is a prerequisite. Nevertheless, the following must be said.

Today, if people want to know something, they take earthly things and earthly processes. They observe them and deduce natural laws from their observations. They probably also carry out experiments in order to eavesdrop on nature's secrets, and from the results of these experiments, they in turn have the laws of nature revealed to them. And so you arrive at a certain type of law, which you then call your science. And then you look out into the vastness of the heavens. One sees in the expanse of the heavens, let us say, the wonderful spiral nebulae, sees individual world bodies arising in these spiral nebulae and the like. Today, we record these things ourselves using the photographic method, which shows things much more precisely than ordinary observation through a telescope or similar. And what do we then do to gain knowledge about what is going on in the spatial expanses of the heavens? You take the natural laws of the earth, what you have concluded from the earth, what you have experimented with there, and then you speculate about how such a spiral nebula could have formed at a distance in space according to the same natural laws. You make hypotheses and theories about the origin and end of the world in order to apply the laws of nature to the celestial sphere that you have discovered in your laboratory with earth manganese, earth oxygen and hydrogen. And when one discovers new substances in the process, one sometimes makes such unconscious allusions that one gets caught up in quite dubious scientific activity. Hydrogen has been found everywhere in the expanses of space, helium for example, but another substance has been found that has a strange name, strange because it already indicates something of the confusion of thought that occurs there. It is called nebulium. Thinking becomes nebulous, hence this nebulium next to helium, next to hydrogen. If you simply apply what you have discovered as natural laws in your earth laboratory and then speculate in the manner of the Swedish thinker Arrhenius, for example, who really did a great deal of mischief in this respect, as to what could be going on out there in spatial expanses, then you must necessarily fall into error upon error if you cannot consider the following in an unbiased manner.

You see, I would like to start again from a comparison: You know from natural science how Newton, the English physicist and natural philosopher, established the theory of so-called gravitation, the effect of gravity in the entire universe. He extended the law of gravitation, which can be seen in the ordinary falling stone that the earth attracts, to the mutual relations of all worldly bodies. He also explained how the force of this gravitation, the strength, always decreases with distance.