Cosmic Workings In Earth and Man

GA 351

31 October 1923, Dornach

V. Cosmic Workings In Earth and Man

Causes Of Infantile Paralysis

(Dr. Steiner asks if anyone has a question.)

Questioner: Dr. Steiner has spoken about epidemics and how they are to be fought. At the present time an epidemic has broken out—Infantile Paralysis—which attacks adults as well as children. Could Dr. Steiner say something about this?

Second Question: Is it harmful for people to keep plants in their bedrooms?

DR. STEINER: As for the question about plants in bedrooms, it is like this. In a general way it is quite correct that the plants give off oxygen which men then breathe in and that man himself breathes out carbonic acid gas. Thus man breathes out what the plant needs, and the plant what man needs. Now, if plants are kept in a room, the following must be remembered:

When one has plants in a room by day, things happen roughly as I have said; during the night the plant does indeed need rather more oxygen. During the night things are rather different. The plant does not need as much oxygen as man, but it needs oxygen. Thus in the darkness it makes demands on that which otherwise it gives to man. Naturally, man is not deprived altogether of oxygen, but he gets too little and that is harmful. Things balance themselves out in nature: every being has something that others need. So it is with plants, if one observes carefully. If the plants are put outside the bedroom when one sleeps, then there is no unhealthy effect. So much for this question.

Now as to Infantile Paralysis which just recently has become so prevalent in Switzerland too. It is still rather difficult to speak about this illness, since it has only assumed its present form quite recently, and one must wait till it has taken on more definite symptoms. Still, from the picture one can form at present—we have had a serious case of Infantile Paralysis in the Stuttgart Clinic and one can only judge by the cases which have occurred so far—one can say now that Infantile Paralysis, like its origin, Influenza, which leads to so many other diseases, is an extraordinarily complicated thing and can only be fought if one deals with the whole body. Just recently there has been discussion in medical circles as to how Infantile Paralysis should be treated. There is great interest in this now, because every week there are fresh cases of the disease. It is called Infantile Paralysis because it is mostly children who are attacked. Yet just recently there was a case of a young doctor who certainly is no longer a child, who was, I believe, perfectly healthy on Saturday, on Sunday was taken with Infantile Paralysis and was dead on Monday. This Infantile Paralysis strikes sometimes in an extraordinarily sudden way and we may well be anxious lest it grow into a very serious epidemic.

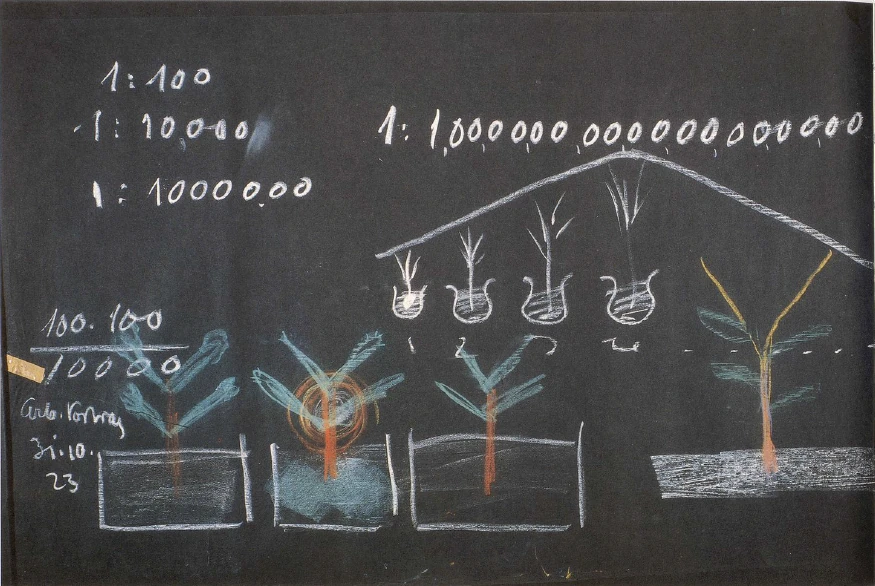

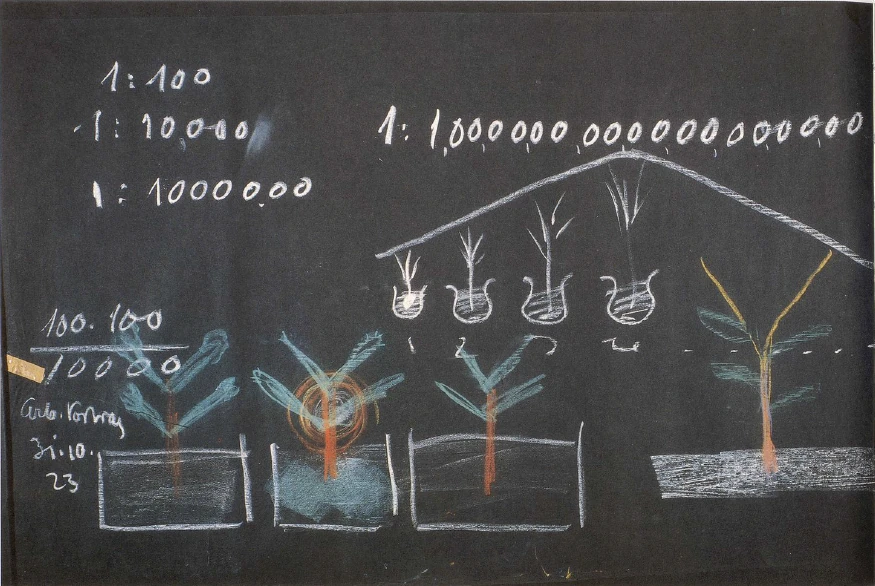

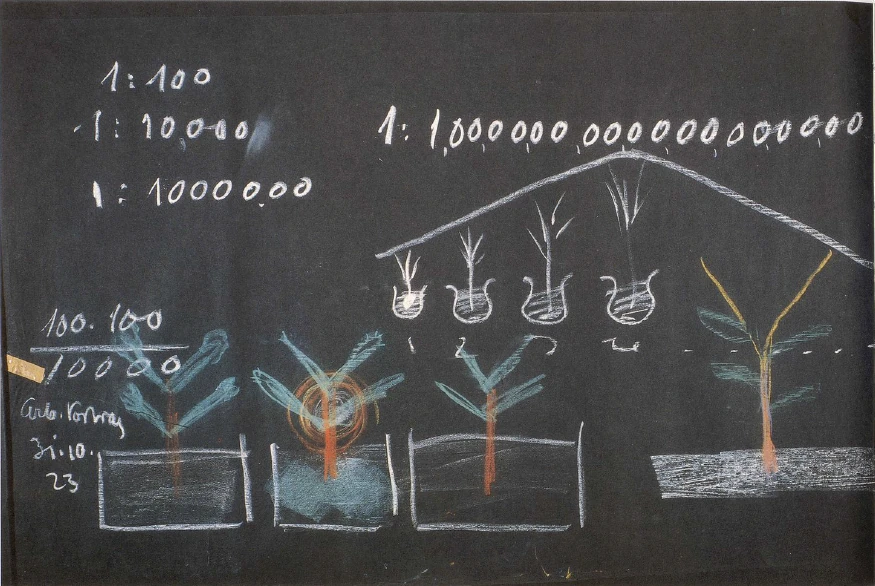

Now Infantile Paralysis is certainly connected, like Influenza itself, with the serious conditions of our time. Since we in our Biological Institute in Stuttgart succeeded in proving the effects of the minutest quantities of substance, one must speak about these things, even in public, in a quite different way than formerly. We have in Stuttgart simply shown that when one has any substance, dissolves it, dilutes it greatly, one has a tiny amount in a glass of water. One obtains, say, a 1 per cent solution. A drop of this is taken, diluted to a hundredth of its strength. It is now one ten-thousandth of its original strength. Again diluting this to one-hundredth of its strength, we have a solution one-millionth of the original strength. In Stuttgart we have succeeded in obtaining dilutions of one in a million, one in a billion—that is, with twelve zeros. You can imagine that there is now no more than a trace of the original substance left, and that it is a question, not of how much of the original substance is left, but of how the solution works: for it works quite differently from the original. These dilutions were made in Stuttgart and they are not so easily imitated. (Perhaps the German Exchange can do it, but nobody else!) This has been done with all sorts of substances. We then took a kind of flower pot, and poured into it in succession the various dilutions. First, ordinary water, then the 1 per cent dilution, then the .1 per cent, the .01 per cent and so on, up to one part in a trillion. Then we put a wheat seed in. This grows, and it grows better in the diluted liquid than in the non-diluted! And the higher the dilution the quicker the growth: one, two, three four, five dilutions—up to twelve. At the twelfth, the growth becomes slower again, then increases again, then decreases again. In this way one finds the effects of minute quantities of substances. It is very remarkable. The effect is rhythmic! If one dilutes, one comes to a certain dilution where the growth is greatest, then it gets less, then again greater—rhythmically. One sees, when the plant grows out of the ground, something works on it together with its substances, something which works rhythmically in its surroundings. The soil environment works into it. That is clearly to be seen.

Now when we are clear that very minute quantities of substance have an effect, we shall have no hesitation in recognising that in such times as the present, when so many men take incorrect nourishment and then rot as corpses in the ground, this works differently. Of course, for the earth as a whole, the effect is very diluted, but still it is different from what happens when men live healthily. And here again, the food which grows out of the earth is a factor.

Naturally, people with grossly materialistic scientific views do not understand this, because they say: What importance can the human corpse have for the whole earth? This effect is very diluted, naturally, but it works.

It will be well if we speak about the whole plant. The health of men is completely dependent on the growth of plants and therefore we must know what really is involved.

I have been greatly occupied with this point in connection with Infantile Paralysis, and it has turned out that one must really concern oneself with the whole man. Indications have appeared for all sorts of remedies for Infantile Paralysis. The subject is of great importance, since Infantile Paralysis may play a very grievous role in the future. It is naturally a question which occupies one greatly, and I have in fact given it a great deal of attention. There will probably have to be found a treatment made up of soda baths, iron arsenite (Fe As2 O3) and of yet another substance which will be obtained from the cerebellum, from the back part of the brain of animals. It will have to be a very complicated remedy. You see, the disease of Infantile Paralysis arises from very complicated and obscure causes and so requires a complicated remedy. These things have become of urgent importance to-day, and it is well that you should understand the whole question of the growth of plants.

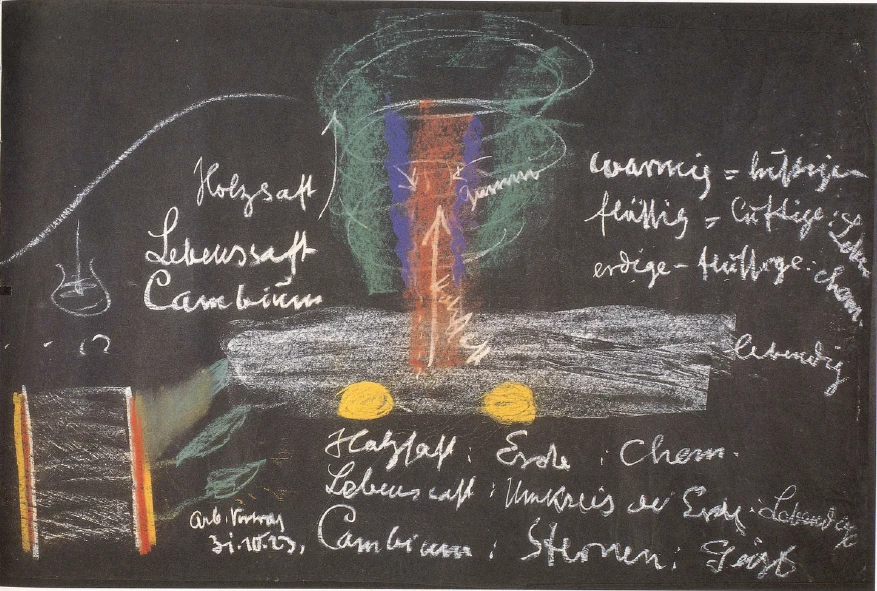

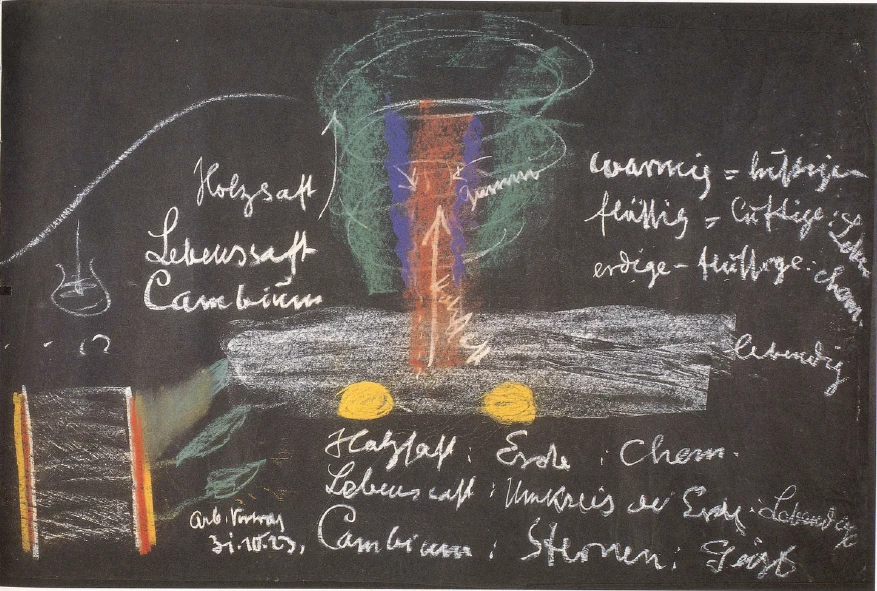

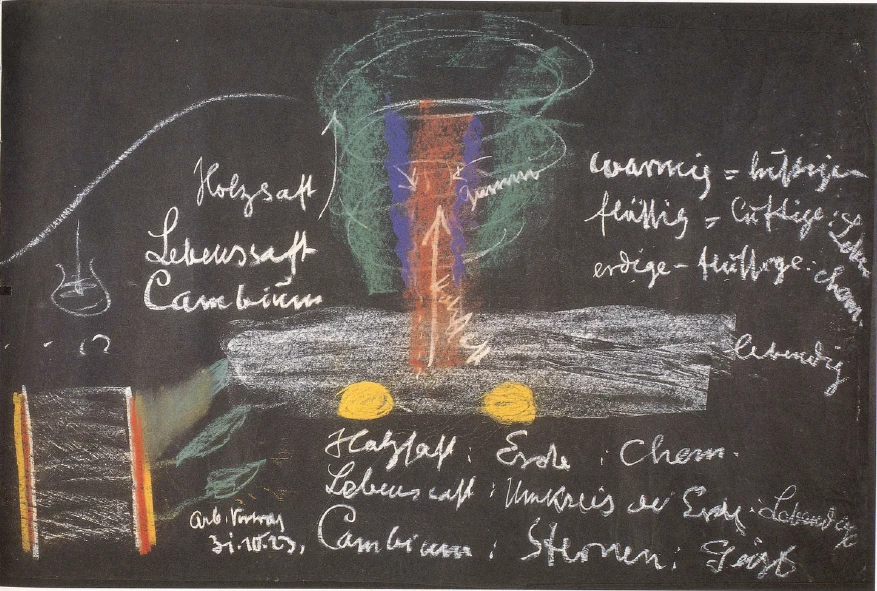

The plant grows out of the ground—I will represent it to-day with reference to the question which has been put. (Dr. Steiner makes a sketch on the blackboard.) The root grows out of the seed. Let us first take a tree; we can then pass to the ordinary plants. We take a tree: the stem grows up. This growth is very remarkable. This stem which grows there, is really only formed because it lets sap mount from the earth, and this sap in mounting carries up with it all kinds of salts and particles of earth; and so the stem becomes hard. When you look at the wood from the stem of a tree, you have a mounting sap, and this sap carries with it fine particles of earth, and all sorts of salts too, for instance, carbonate of soda, iron, etc., into the plants and this makes hard wood. The essential thing is that the sap mounts.

What happens, in reality? The earthy, the solid, becomes fluid! And we have an earthy-fluid substance mounting there. Then the fluid evaporates and the solid remains behind: that is the wood.

You see, this sap which mounts up in the tree—let us call it wood-sap—is not created there but is already contained everywhere in the earth, so that the earth in this respect is really a great living Being. This sap which mounts in the tree, is really present in the whole earth: only in the earth it is something special. It becomes in the tree what we see there. In the earth it is in fact the sap which actually gives it life. For the earth is really a living Being; and that which mounts in the tree is in the whole earth and through it the earth lives. In the tree it loses its life-giving quality; it becomes merely a chemical; it has only chemical qualities.

So when you look at a tree, you must say to yourself: the earthy-fluidic in the tree—that has become chemical; underneath in the earth it was still alive. So the wood-sap has partly died, as it mounted up in the tree. Were this all, never would a plant come into existence, but only stumps, dying at the top, in which chemical processes are at work. But the stem, formed from this sap, rises into the air, and the air always contains moisture. It comes into the moist air, it comes with the sap which has created it, from the earthy-fluidic into the fluidic-airy and life springs up in it anew so that around it green leaves appear and finally flowers. ... Again there is life. You see, in the foliage, in the leaf, in the bud, in the blossom, there is once more the sap of life; the wood-sap is dead life-sap. In the stem, life is always dying; in the leaf it is always being resurrected. So that we must say: We have wood-sap, which mounts; then we have life-sap. And what does this do! It travels all round and brings forth the leaves everywhere: so that you can see the spirals in which the leaves are arranged. The living sap really circles round. It arises from the fluid-airy element into which the plant comes when it has grown out of the earthy-fluidic element.

The stem, the woody stem, is dead and only that which sprouts forth around the plant is alive. This you can easily prove in the following very simple way. Go to a tree: you have the stem, then the bark, and in the bark the leaves grow. Now cut the bark away at that point; the leaves come away too. At this point leave the leaves with the bark. The result is that there the tree remains fresh and living, and here it begins to die. The wood alone with its sap cannot keep the tree alive; what comes with the leaves must come from outside and that again contains life. We see in this way that the earth can certainly put forth the tree, but she would have to let it die if it did not get life from the damp air: for in the tree the sap is only a chemical, no giver of life. The living sap that circulates, that gives it life. And one can really say: When the sap rises in the spring, the tree is created anew; when the living sap again circulates in the spring, every year the tree's life is renewed. The earth produces the sap from the earthy-fluidic; the fluidic-airy produces the living sap.

But that is not all. While this is happening, between the bark, still full of living sap, and the woody stem, there is formed a new layer. Now I cannot say that a sap is formed. I have already spoken of wood-sap, living sap, but I cannot again say that a sap is formed: for what is formed is quite solid: it is called cambium. It is formed between the bark which still belongs to the leaves, and the wood. When I cut here (see sketch) no cambium is formed. But the plant needs cambium too, in a certain way. You see, the wood sap is formed in the earthy-fluidic, the life sap in the fluidic-airy, and the cambium in the warm air, in the warm damp, or the airy-warmth. The plant develops warmth while it takes up life from outside. This warmth goes inward and develops the cambium inside. Or if the cambium does not yet develop—the plant needs cambium and you will shortly hear why—before the cambium forms, there is first of all developed a thicker substance: the plant gum. Plants form this plant gum in their inner warmth, and this, under certain conditions, is a powerful means of healing. Thus the sap carries the plant upwards, the leaves give the plant life, then the leaves by their warmth produce the gum which reacts on the warmth. And in old plants, this gum, running down to the ground, has become transparent. When the earth was less dense and damper, the gum became transparent and turned to Amber. You see, then, when you take up a piece of Amber, what from prehistoric plants ran down to the ground as resin and pitch. This the plant gives back to the earth: Pitch, Resin, Amber. And if the plant retains it, it becomes cambium. Through the sap the plant is connected with the earth; the life-sap brings the plant into connection with what circulates round the earth—with the airy-moist circumference of the earth. But the cambium brings the plant into connection with the stars, with what is above, and in such a way that within this cambium the form of the next plant develops. [See: Man as Symphony of the Creative Word, Twelve lectures given by Rudolf Steiner in Dornach, 19th October to 11th November, 1923, Rudolf Steiner Publishing Company.] This passes over to the seeds and in this way the next plant is born, so that the stars indirectly through the cambium create the next plant! So that the plant is not merely created from the seed—that is to say, naturally it is created from the seed, but the seed must first be worked on by the cambium, that is: by the whole heavens.

It is really wonderful—a seed, a humble, modest little seed could only come into existence because the cambium—now not in liquid but in solid form—imitates the whole plant; and this form which arises there in the cambium—a new plant form—this carries the power to the seed to develop through the forces of the earth into a new plant.

Through mere speculation, when one simply puts the seed under a microscope, nothing is gained. We must be clear what parts the sap, the life sap, the cambium, play in the whole matter. The wood sap is a relatively thin sap: it is peculiarly fitted to allow chemical changes to take place in it. The life sap is certainly much thicker, it separates off its gum. If you make the gum rather thick, you can make wonderful figures with it. Thus the life sap, more pliable than the wood sap, clings more to the plant-form. And then it gives this up entirely to the cambium. That is still thicker, indeed quite sticky, but still fluid enough to take the forms which are given it by the stars.

So it is with trees, and so, too, with the ordinary plants. When the rootlet is in the earth, the sprout shoots upward. But it does not separate off the solid matter, does not make wood; it remains like a cabbage stalk. The leaves come out directly on the circumference, in spirals, the cambium is formed directly in the interior, and the cambium takes everything back to the earth with it. So that in the annual plants the whole process occurs much more quickly. In the tree, only the hard parts are separated out, and not everything is destroyed.

The same process occurs in ordinary plants too, but is not carried so far as in trees. In the tree it is a fairly complicated matter. When you look at the tree from above, you have first the pith inside: this gives the direction. Then layers of wood form round the pith. Towards the autumn the gum appears from the other side, and fastens the layers together. So we have the gummy wood of one year. In the next year this is repeated. Wood forms somewhere else, is again gummed together in the autumn, and so the yearly rings are formed. So you see everything clearly if only you understand that there are three things: wood sap, life sap, and cambium. The wood sap is the most fluid, it is really a chemical; the life sap is the giver of life; it is really, if I may so express myself, a living thing. And as for the cambium, there the whole plant is sketched out from the stars. It is really so. The wood sap rises and dies, then life again arises; and now comes the influence of the stars, so that from the thick, sticky cambium the new plant is sketched out. In the cambium one has a sketch, a sculptural activity. The stars model in it from the whole universe the complete plant form. So you see, we come from Life into the Spirit. What is modelled there is modelled from out of the World-Spirit. The earth first gives up her life to the plant, the plant dies, the air environment along with its light once more gives it life, and the World Spirit implants the new plant form. This is preserved in the seed and grows again in the same way. So that one sees in the growing plant how the plant world rises out of the earth, through death, to the living Spirit.

Now other investigations have been made in Stuttgart. These things are extraordinarily instructive. For instance, one can do the following, instead of merely investigating growth—which is very important, especially when one is dealing with the higher potencies, say of one in a trillion—one can do the following. We take metals or metallic compounds highly diluted in the manner previously described, for example, a copper compound solution, and put it into a flowerpot with some earth in it: we put it in as a kind of manure. In another similar flowerpot we put only earth, the same earth without the manure. Now we take two plants, as similar as possible, put one in the pot with the copper manured earth, and the other in the pot without the copper manure. And the remarkable thing is: if the copper is highly diluted, the leaves develop wrinkles on the edges—the others get no wrinkles, if they are smooth and had previously none. One must take the same earth, because many specimens previously contain copper. One dilutes it with copper; the same kind of plants must be taken so that comparisons can be made.

Now we take a third plant, put it into a third pot with earth, but instead of copper, we add lead. The leaves do not wrinkle but they become hard at the top and wither when lead is added. You have now a remarkable sight. These experiments were made in Stuttgart, and you plainly see, when you look at the pots in turn, how the substances of the earth work on plants.

You will no longer be surprised when you see plants with wrinkled leaves somewhere. If you dig in the earth there, you will find traces of copper. Or if you have leaves which are dry and withered at the edge, and dig in the earth, you will find traces of lead. Look at a common plant, say mare's tail, with which people clean pots; it grows just where the ground contains silicon; hence the little thorns. In this way you can understand the form of plants from the nature of the ground.

Now you can see of what importance it is when quite tiny amounts of any substance are mixed in the earth. Naturally, there is a churchyard somewhere outside, but the earth is everywhere permeated with wood sap, and the tiny quantities penetrate everywhere into the ground. And having investigated how these tiny quantities work, of which I have told you, we say: That which disappeared into the earth, we eat it again in our food. It is so strong that it lives in the plant form. And what happens then? Imagine I had thus a plant form from a lead-containing soil. To-day it is said that lead does not arise in soil. But lead does arise in soil, if one puts decaying living matter in it. It simply does arise in soil. A plant grows out of it: one may say, a lead-plant. Well, this lead plant when we eat it, has a quite different effect from a lead-less plant. Actually, when we eat a lead plant, our cerebellum, which lies at the back of the head, becomes drier than usual. It becomes drier.

Now you have the connection between the earth and the cerebellum. There are plants which simply through the constitution of the earth, through what men put into the earth and what then spreads everywhere, can dry up the cerebellum. As soon as our cerebellum is not in full working order, we become clumsy. When something happens to the cerebellum we become awkward and cannot properly control our feet and arms; and when the effect is much stronger, we become paralysed.

Thus, you see, is the connection between the soil and paralysis. A man eats a plant. If it has something dying at the edge of the leaves, as I have described to you, his cerebellum will be dried up somewhat. In ordinary life this is not noticed, but the man cannot any longer rightly direct his movements. If the effect is much stronger, paralysis sets in. When this drying up of the cerebellum happens in the head, so that man cannot control his muscles, at first this affects all those muscles which are dependent on a little gland in the head, the so-called pineal gland. If that happens, a man gets influenza. If the evil goes further, influenza changes to a complete paralysis. So that in every paralysis there is something that is inwardly connected with the soil. And so you see knowledge must be brought together from many sides if one is to do anything useful for men. It is useless to make a lot of statements—one must do so and so! For if one does not know how a man has taken into his organism something dying, one may have ever such good apparatus and the man will not recover. For everything that works in the plant and passes over from the plant to the man, is of great importance.

Wood sap develops in man as the ordinary colourless mucus. Wood sap in plants is, in man, mucus. The life sap of the plant which circulates from the leaves, corresponds to the human blood. And the cambium of the plant corresponds to the milk and the chyle in the human being. When a woman begins to nurse, certain glands in the breast cause a greater flow of milk. Here you have again something in human beings which is most strongly influenced by the stars, namely, milk. Milk is absolutely necessary for the development of the brain—the brain, one might almost say, is solidified milk. Decaying leaves create no proper cambium because they no longer have the power to work back into the proper warmth. They let the warmth escape outwards from the dying edges instead of sending it inwards. We eat these plants with an improperly developed cambium: they do not develop a proper milk; the women do not produce proper milk; the children get milk on which the stars cannot work strongly, and therefore they cannot develop properly.

Hence this Infantile Paralysis appears specially among children—but adults can also suffer from it, because men are all their lives influenced by the stars.

In these things Science and Medicine must work together: they must everywhere work together. But one should not isolate oneself in a single science. To-day there are men who specialise in animals—the zoologists; in men—the anthropologists; or in parts of men, with sick senses, or sick livers, or sick hearts—specialists of the inner organs. Then again there are the botanists, who study only plants; and the mineralogists, who study only stones; and the geologists who study the whole earth. Certainly this is very convenient. One has less to learn when one is merely a geologist or when one has only to learn about stones. Yes, but such knowledge is useless when one wants to do something for a man. When he is ill, one must understand the whole of Nature. It is useless merely to understand geology or botany or chemistry. One must understand chemistry and be able to follow its working right into the sap. It is really so. Students have a saying—there are in universities, as you perhaps know, both ordinary and extraordinary professors—and the students have a saying: the ordinary professors know nothing extraordinary, and the extraordinary professors know nothing ordinary! But one can go still further to-day. The geologist knows nothing of plants or animals or men; the anthropologist knows nothing of animals, or plants, or the earth. Neither knows really how the things upon which he works are connected. Just as man has specialised in work, he has specialised in knowledge. And that is much more dangerous. It is shocking when there are only geologists, botanists, etc., so that all knowledge is split up. This has been for men's convenience. People say to-day: a man can't know everything. Well, if one doesn't wish to take in all knowledge, one can despair of any really useful knowledge.

We live at a time when things have assumed a frightful aspect. It is as if a man who has to do with clocks wants to learn only how to file metals, another how to weld them. And there would be another, who knows how to put the clock together, but doesn't know how to work the single metals. Now one can get a certain distance in this way with machinery, although at the same time a certain amount of compulsion is necessary. But in Medicine nothing can be achieved if one does not take into account all branches of knowledge, even the knowledge of the earth. For in the tree trunk lives something which is carried up from the earth (which is the subject of geology) to the sap. There it dies. One must also know meteorology, the science of air, because from the surrounding air something is brought to the leaves which calls forth life in them again. And one must also know astrology, the science of the stars, if one wishes to understand the formation of cambium. And one must also know what enters with the cambium in the food. ... So that when one eats unsound cambium as a child, one gets an unsound brain. In this way diseases are caused by what is in the earth. This is what can be said about the causes of such apparently inexplicable diseases: the causes are in the soil.

Siebenter Vortrag

Guten Morgen! Ist Ihnen etwas eingefallen?

Fragesteller: Herr Doktor hat davon gesprochen, daß Volkskrankheiten ausbrechen könnten und wie sie eventuell zu bekämpfen wären. Nun ist eine Epidemie ausgebrochen, die Kinderlähmung, die auch die Erwachsenen ergriff. Könnte Herr Doktor etwas darüber sagen?

Ist es schädlich für den Menschen, wenn man Pflanzen im Zimmer hat?

Dr. Steiner: Was die Frage wegen der Pflanzen im Zimmer betrifft, so ist das so, sehen Sie: Dieses ist im Großen in der Natur absolut gültig, daß die Pflanzen Sauerstoff von sich geben, den der Mensch dann einatmet, und daß der Mensch selber die Kohlensäure ausatmer. Also dasjenige, was die Pflanze braucht, atmet der Mensch aus; dasjenige, was der Mensch braucht, strömt die Pflanze aus. Das ist im ganzen richtig. Nun, wenn man Pflanzen im Zimmer hat, muß man noch folgendes beachten. Wenn man Pflanzen bei Tag im Zimmer hat, dann geschieht ungefähr der Vorgang, von dem ich gesprochen habe. Wenn man Pflanzen in der Nacht im Zimmer hat, dann ist es so, daß die Pflanzen allerdings in der Nacht auch etwas Sauerstoff brauchen. Während der Nacht verhält sich die Pflanze etwas anders; sie braucht nicht in demselben Maße Sauerstoff wie der Mensch, aber sie braucht Sauerstoff. Also da macht sie, gerade wenn es finster ist, Anspruch auf dasjenige, was sie sonst dem Menschen gibt. Nun ist es natürlich nicht so, daß der Mensch den Sauerstoff vollständig zu entbehren hat, aber er kriegt zuwenig, und das wirkt dann giftig. Die Dinge gelten im großen und ganzen für das Naturdasein. Natürlich ist es wiederum so: Jedes Wesen hat etwas in sich, das etwas braucht, was die anderen auch brauchen. So ist es bei den Pflanzen, wenn man streng beobachten würde. Stellt man die Pflanzen, die man im Zimmer hat, in der Nacht, wenn man schläft, heraus, dann würde diese Giftigkeit nicht eintreten. Das in bezug auf diese Frage.

Nun, was die gerade jetzt auch in der Schweiz so stark auftretende Kinderlähmung betrifft. so ist es ja tatsächlich heute noch etwas schwierig, über diese Krankheit zu sprechen, aus dem Grunde, weil sie in der Form, wie sie jetzt auftritt, eigentlich erst seit einiger Zeit auftritt undman abwarten muß, was sie noch alles für besondere Symptome annimmt. Wir haben ja durchaus in der Stuttgarter Klinik zum Beispiel auch einen schweren Fall von Kinderlähmung gehabt; jedoch nach dem Bilde, das man heute schon haben kann - man kann ja immer nur nach den Fällen, die vorgekommen sind, urteilen -, nach den Fällen, die wir kennengelernt haben, die bei uns vorgekommen sind, muß man heute sagen, daß die Kinderlähmung, wie ja ihr Ausgangspunkt, die Grippe, die zu so sehr vielen Folgekrankheiten führt, auch eine außerordentlich komplizierte Sache ist. Und sie scheint nur zu bekämpfen zu sein, wenn man den ganzen Körper behandelt. Gerade neulich ist hier in ärztlichen Kreisen die Rede davon gewesen, wie man die Kinderlähmung bekämpfen soll. Es ist heute eben ein starkes Interesse dafür vorhanden, weil die Kinderlähmung im Grunde genommen mit jeder Woche sich mehr ausbreitet. Man nennt sie «Kinderlähmung», weil sie bei den Kindern am meisten auftritt. Aber es ist neulich ein Fall vorgekommen, wo ein junger Arzt - da ist man ja nicht mehr ganz Kind, wenn man ein junger Arzt ist- ich glaube am Samstag noch ganz frisch war, am Sonntag von der Kinderlähmung befallen wurde und am Montag tot war. Also die Kinderlähmung ergreift den Menschen unter Umständen in einer außerordentlich raschen Weise, und man könnte eigentlich besorgt sein, daß sie zu einer sehr schweren Epidemie sich ausbilden könnte.

Nun hängt sie ganz sicher zusammen, wie die Grippe selbst auch, mit unseren schwierigen Zeitereignissen. Es ist ja so: Seit es uns in Stuttgart in unserem Biologischen Institut gelungen ist, die Wirkungen kleinster Teile von Stoffen nachzuweisen, seit der Zeit muß über diese Dinge eigentlich ganz anders noch geredet werden; gerade auch in der Öffentlichkeit müßte anders noch geredet werden als sonst.

Wir haben in Stuttgart ja einfach gezeigt, daß man, wenn man irgendeinen Stoff nimmt, ihn auflöst, ihn ganz stark verdünnt, mit diesem verdünnten Stoff eine Wirkung erzielt. Man gibt von einem Stoff eine ganz kleine Menge in ein Wasserglas: man verdünnt ihn also so, daß man einen Teil von dem Stoff in neun Teile Wasser gibt, er also zehnmal verdünnt ist. Jetzt nimmt man von dem, was man da hat, was nur noch das Zehntel von der ursprünglichen Substanz enthält, wiederum einen Teil; den behandelt man wieder so, daß man ihn in ein Wasserglas gibt und ihn wiederum auf die Größe von 1:10 ausdehnen läßt. Jetzt hat man ihn schon 10 mal 10 verdünnt; das erste Mal 1:10, das zweite Mal, wenn man die Tropfenmenge verdünnt hat mit einer Verdünnung 10 mal 10, gibt das also zwei Nullen, 1:100. Wenn Sie die jetzt weiter verdünnen, wenn Sie also wiederum eine solche Menge nehmen und sie in neun Teile Wasser bringen, so müssen Sie wiederum eine Null anhängen, dann haben Sie 1:1000. Jetzt hat man nur noch das Tausendstel der Substanz drinnen. So haben wir in Stuttgart die Verdünnung gebracht bis zu eins zu einer Trillion - das ist mit 18 Nullen; so weit und sogar noch weiter haben wir verdünnt.

Also Sie können sich denken, daß da nur noch eine Spur drinnen ist von der ursprünglichen Substanz, und daß es eigentlich gar nicht mehr ankommt auf das, wieviel von der ursprünglichen Substanz drinnen ist, sondern wie diese Substanz als Verdünnungsmittel wirkt. Das Verdünnungsmittel wirkt ganz anders. Diese Verdünnungen also sind in Stuttgart gemacht worden. Dieses wird nicht so leicht jemand nachmachen. Höchstens die deutsche Valuta wird das nachmachen können, aber sonst nicht so leicht jemand. — Das ist mit den allerverschiedensten Stoffen gemacht worden. Wir haben es dann weiterhin so gemacht, daß wir eine kleine Art von Blumentöpfen genommen haben und da hinein dasjenige gegeben haben, was wir da bekommen haben. Also zunächst gewöhnliches Wasser, die gewöhnliche Lösung, dann dasjenige, wo das Zehntel drinnen war, dann das mit dem Hundertstel, dann das mit dem Tausendstel, dann das mit dem Zehntausendstel, mit dem Hunderttausendstel und so weiter bis zu einer Trillion. Also dies ist gemacht worden. Dann haben wir in die Blumentöpfchen Samen, Weizenkörner hineingesetzt. Das Weizenkorn wächst (es wird gezeichnet), und es wächst in der Verdünnung besser als in der Nichtverdünnung! Und so geht das fort. Sehen Sie, man bekam bei der weiteren Verdünnung also immer schnelleres Wachstum: eins, zwei, drei, vier, fünf und so weiter, bis man heraufkam zu der zwölften Verdünnung. Bei der zwölften Verdünnung ging es wiederum zurück, wurde wiederum kleiner. Dann stieg es wiederum hinauf und ging dann wiederum herunter.

Also auf diese Weise bekommt man die Wirkung von kleinsten Substanzen heraus. Die Wirkung von kleinsten Substanzen - das ist sehr merkwürdig, sehen Sie -, die ist rhythmisch! Verdünnt man, so bekommt man zuletzt bei einer gewissen Verdünnung das stärkste Wachstum, dann geht es wieder herunter, dann geht es wieder herauf; das geht rhythmisch. So daß man sieht: Wenn die Pflanze aus der Erde herauswächst, dann wirkt auf sie etwas, je nachdem sie belastet ist mit den Stoffen, was rhythmisch in der Umgebung wirkt. Da wirkt sozusagen die Erdenumgebung herein; das sieht man ganz deutlich.

Nun, wenn man sich darüber klar ist, daß kleinste Mengen etwas wirken, so wird man auch keine Bedenken mehr tragen, anzuerkennen, daß in solchen Zeiten wie jetzt, wo so viele Menschen unrichtige Nahrungsmittel zu sich nehmen und dann als Leichnam in der Erde verwesen, daß das anders wirkt! Das ist natürlich für die ganze Erde in starker Verdünnung, aber es wirkt eben anders, als wenn die Menschen gesund leben. Und das ist doch wieder in der Nahrung enthalten, die aus der Erde herauswächst. Das essen die Leute mit. So daß man sagen kann: Das ist etwas, was durch die Zeitverhältnisse mitbewirkt wird. Natürlich machen sich das die Leute mit der groben materialistischen Wissenschaft nicht klar, weil die sich sagen: Nun ja, was soll das, was man da in die Erde hereinlegt als Menschenleib, für die ganze Erde eine Bedeutung haben? - Es ist sehr verdünnt natürlich, was da vom Menschen hineinkommt, aber es wirkt.

Sehen Sie, meine Herren, da ist es dann gut, wenn wir überhaupt einmal über die ganze Pflanze sprechen. Die Gesundheitsverhältnisse der Menschen hängen ganz vom Pflanzenwachstum ab, und deshalb muß man kennen, was da im Pflanzenwachstum eigentlich alles mitwirkt.

Gerade das mit der Kinderlähmung hat mich ungeheuer stark beschäftigt, und es ist dabei herausgekommen, daß man eigentlich den ganzen Menschen behandeln muß. Es haben sich auch schon Anhaltspunkte für allerlei Heilmittel gerade für die Kinderlähmung ergeben. Dieses ist wahrscheinlich von einer großen Wichtigkeit, weil die Kinderlähmung in der Zukunft eine wirklich schmerzliche Rolle spielen könnte. Es ist natürlich eine Frage, die einen tief beschäftigt, und ich habe mich gerade damit beschäftigt. Es wird wahrscheinlich ein Arzneimittel hergestellt werden müssen, das da besteht aus Sodabädern, arseniksaurem Eisen und aus einer besonderen Substanz noch, die genommen wird aus dem Kleinhirn, aus dem hinteren Teil des Hirnes bei den Tieren. Also es wird ein sehr kompliziertes Heilmittel geben müssen gerade bei einer solchen Kinderlähmung. Sehen Sie, hier handelt es sich bei einer solchen Krankheit, die aus sehr verborgenen Ursachen kommt, darum, daß sie auch gerade kompliziert wieder wird geheilt werden müssen. Die Dinge sind eigentlich heute durchaus aktuell, und es ist gut, wenn Sie sich klarmachen, wie das ganze Pflanzenwachstum vor sich geht.

Da wächst also die Pflanze aus dem Erdboden heraus. Ich will es heute sodarstellen, wie es geradederFrage entspricht, diederHerrDollinger gestellt hat (siehe Zeichnung). Nun wächst aus dem Keime die Wurzel heraus. Nehmen wir zunächst einen Baum; wir können dann zu der gewöhnlichen Pflanze übergehen. Wenn wir einen Baum nehmen, so wächst da der Stamm heraus. Ja, meine Herren, sehen Sie, schon dieses Wachsen des Stammes ist etwas außerordentlich Merkwürdiges. Dieser Stamm, der da wächst, der ist eigentlich nur dadurch gebildet, daß er Saft von der Erde nach oben gehen läßt, und dieser Saft, der aufsteigt - also das, was ich hier rot gezeichnet habe -, dieser aufsteigende Saft, der reißt mit sich alle möglichen Salze und Bestandteile der Erde; dadurch ist der Stamm überhaupt fest. Wenn Sie also Holz anschauen aus dem Stamm eines Baumes, so haben Sie einen aufsteigenden Saft, und dieser Saft reißt dann die festen Staubteile der Erde mit, allerlei Salze, also sagen wir kohlensaures Natrium, Eisensalzbestandteile in den Pflanzen. Alles das wird nun damitgerissen, und dadurch ist das Holz in sich fest. Nun, das Wesentliche ist, daß da der Saft aufsteigt.

Was geschieht denn da eigentlich? Sehen Sie, da kommt, wenn da das aufsteigt, das Feste, das Erdige, zum Flüssigen, und wir haben da aufsteigend Erdig-Flüssiges. Erdig-Flüssiges steigt da auf, es ist solch ein dicklicher, erdig-flüssiger Stoff. Das Flüssige verdunstet dann, und das Erdige bleibt zurück. Das, was da erdig zurückbleibt, das ist das Holz. Wenn der Saft nun da hinaufsteigt, so entsteht er nicht etwa da (es wird auf die Zeichnung hingewiesen), sondern dieser Saft, der da im Holz aufsteigt — nennen wir ihn Holzsaft -, der ist eigentlich in der ganzen Erde enthalten, so daß die Erde in dieser Beziehung ein einziges großes Lebewesen ist. Dieser Holzsaft, der im Baum nach aufwärts steigt, der ist im Grunde, wie gesagt, in der ganzen Erde vorhanden; nur, in der Erde ist dieser Saft eigentlich etwas ganz Besonderes. Er wird erst zu dem, was er im Baume darstellt, er wird erst dazu im Baume. In der Erde ist er nämlich der eigentlich erdenbelebende Saft. Die Erde ist wirklich ein Lebewesen. Und das, was dann in den Baum hinaufsteigt, das ist in der ganzen Erde; durch das lebt die Erde. Im Baum, da verliert nämlich dieser Saft seine Lebensfähigkeit, er wird ein Chemiker, da hat er nur noch chemische Kräfte.

Wenn Sie also einen Baum anschauen, so müssen Sie sich sagen: Das Erdig-Flüssige im Baum, das ist chemisch geworden, und in der Erde selber drunten, da war es noch lebendig. Es ist also der Holzsaft zum Teil gestorben, indem er in den Baum hinaufging.

Wenn nichts anderes wäre, dann würde überhaupt niemals eine Pflanze entstehen, sondern es würden nur Stümpfe entstehen, die nach oben absterben und in denen chemische Vorgänge sich abspielen. Aber da kommt ja das, was sich aus dem Holzsaft bildet, der Stamm, in die Luft heraus - und die Luft ist immer von Feuchtigkeit durchsetzt -, er kommt in die feuchte Luft heraus, in das Feuchte, in das Wäßrig-Luftige. Der Holzsaft- mit dem, was er erzeugt- kommt also aus dem Erdig-Flüssigen in das Flüssig-Luftige. Und im Flüssig-Luftigen, da bildet sich wiederum das Leben neu, so daß sich der Stamm ringsherum besetzt mit dem, was dann im grünen Laub lebt (es wird gezeichnet) und zuletzt in der Blüte und in allem, was da draußen ist. Das wird wiederum zum Leben erweckt. Im Laub, im Blatt, in der Blüte und in der Knospe, da lebt wiederum Lebenssaft; der Holzsaft ist abgestorbener Lebenssaft. Im Stamm stirbt fortwährend das Leben ab, im Blatte macht es sich neu. So daß wir sagen müssen: Wir haben Holzsaft, der steigt nach oben; dann haben wir Lebenssaft. - Was tut denn der? Sehen Sie, der Lebenssaft der kreist da herum und erzeugt überall die Blätter. Daher können Sie auch solche Spiralen, in denen die Blätter angeordnet sind, beobachten. Der Lebenssaft, der kreist also eigentlich herum. Und der rührt aus dem Flüssig-Luftigen her, in das die Pflanze kommt, wenn sie aus dem Erdig-Flüssigen herausgewachsen ist.

Sehen Sie, meine Herren, daß der Stamm, der Holzstamm tot ist und nur das da hier bei der Pflanze lebt, was sich ringsherum ansetzt, das können Sie auf eine sehr einfache Weise beweisen, nämlich folgendermaßen: Denken Sie einmal, Sie gehen an einen Baum heran, haben da den Holzstamm, dann haben Sie da die Rinde, und in der Rinde drinnen, da wachsen nun die Blätter darinnen (es wird gezeichnet). Jetzt gehe ich her Tafel! und schneide die Rinde weg - dadurch kommt das Blatt auch weg -, hier lasse ich aber die Blätter daran mit der Rinde. Und die Geschichte stellt sich so heraus, daß hier der Baum lebendig, frisch bleibt, und daß er da anfängt, abzusterben. Das Holz allein mit seinem Holzsaft kann den Baum nicht lebendig erhalten. Da muß von außen einfließen dasjenige, was mit den Blättern kommt; das enthält wieder das Leben. Wir sehen auf diese Weise: Die Erde kann zwar den Baum heraustreiben, aber sie müßte ihn sterben lassen, wenn er nicht von außen, von der feuchten Luft das Leben gekriegt hätte; denn im Baum drinnen ist der Holzsaft nur ein Chemiker, kein Lebenserreger. Das Leben, das herumkreist, das macht sein Leben aus. Und man kann eigentlich sagen: Wenn der Holzsaft im Frühling aufsteigt, so wird in der Erde der Baum neu. Wenn dann im Frühling der Lebenssaft wieder neu herumkreist, wird der Baum jedes Jahr neu lebendig. Die Erde wirkt auf den Holzsaft, das Erdig-Flüssige; das Flüssig-Luftige wirkt auf den Lebenssaft.

Das ist aber noch nicht zu Ende, sondern jetzt, während das geschieht, bildet sich zwischen der Rinde, die noch vom Lebenssaft durchzogen ist, und dem Holz eine neue Pflanzenschicht; da kann ich gar nicht mehr sagen, daß sich da ein Saft bildet. Hier habe ich gesagt: Holzsaft, Lebenssaft; aber hier kann ich nicht mehr sagen, daß sich ein Saft bildet, weil das, was sich da bildet, ganz dicklich ist. Es heißt das Kambium. Das bildet sich darinnen zwischen der Rinde, die noch zu den Blättern gehört, und dem Holz. Wenn ich also das da hier wegschneide (es wird gezeichnet), so bildet sich dadrinnen kein Kambium. Aber das Kambium, das braucht die Pflanze auch in einer gewissen Weise. Der Holzsaft bildet sich im ErdigFlüssigen, der Lebenssaft bildet sich im Flüssig-Luftförmigen, und das Kambium bildet sich in der warmen Luft, im Warmig-Luftigen oder im Luftig-Warmen. Die Pflanze entwickelt Wärme, indem sie von außen das Leben empfängt. Diese Wärme schickt sie in ihr eigenes Inneres, und aus dieser Wärme bildet sich da drinnen das Kambium. Oder, wenn sich noch nicht Kambium bildet - das Kambium braucht die Pflanze, Sie werden gleich noch hören wozu -, aber bevor das Kambium sich bildet, bildet sich schon etwas Dickliches: das ist der innere Pflanzengummi. In ihrer Wärme bilden die Pflanzen nach innen auch den Pflanzengummi, der unter Umständen ein wichtiges Heilmittel ist. Also der Holzsaft reißt die Pflanze nach aufwärts, die Blätter beleben die Pflanze; dann aber bilden wiederum die Blätter, indem sie die Wärme erregen, den Gummistoff, der wiederum zurück auf das Kambium wirkt. Und bei alten Pflanzen, bei ganz alten Pflanzen hat sich dieser Gummi, indem er zur Erde heruntergegangen ist, durchsichtig gemacht. Als die Erde noch weniger fest war, noch feucht-flüssig war, hat er sich durchsichtig gemacht, und da ist er zum Bernstein geworden. Also Sie sehen, wenn Sie ein Stück Bernstein nehmen, so ist das dasjenige, was bei einer uralten Pflanze der Erde aus dem Blatt wie Blut herausgeronnen ist, zur Erde herunter: Harz, Pech. Das alles fließt wieder nach unten, das gibt die Pflanze wieder der Erde zurück: Pech, Harz, Bernstein. Und wenn es die Pflanze selber behält, wird es eben das Kambium. Durch den Holzsaft steht die Pflanze mit der Erde in Verbindung; der Lebenssaft bringt die Pflanze in Verbindung mit dem, was um die Erde herumkreist, mit dem luftig-feuchtigen Umkreis der Erde. Aber das Kambium, das bringt die Pflanze in Verbindung mit den Sternen, mit dem, was oben ist. Und da ist es nun so, daß in diesem Kambium drinnen schon die Gestalt der nächsten Pflanze entsteht. Das geht dann auf den Samen über und dadurch wird die nächste Pflanze geboren; so daß die Sterne auf dem Umwege durch das Kambium die nächste Pflanze erzeugen. Also die Pflanze wird nicht aus dem Samen bloß erzeugt - das heißt, sie wird natürlich schon aus dem Samen erzeugt, aber der Samen muß zunächst die Einwirkung vom Kambium, das heißt, die Einwirkung vom ganzen Himmel haben.

Sehen Sie, das ist schon etwas Wunderbares: Wenn man einen Pflanzensamen in die Hand bekommt, so hat dieses anspruchslose, bescheidene kleine Staubkörnchen Samen nur dadurch entstehen können, daß das Kambium - jetzt nicht im Flüssigen, sondern in etwas Dicklichem - die ganze Pflanze nachmacht. Und diese Gestalt, die da drinnen im Kambium entsteht — eine neue Pflanzengestalt -, die überträgt die Kraft auf den Samen, und davon hat der Samen dann die Kraft, wiederum eine neue Pflanze unter der Einwirkung der Erde nach aufwärts wachsen zu lassen.

Also Sie sehen, meine Herren, mit dem bloßen Spekulieren, wenn man einfach das Samenkorn unter das Mikroskop legt, kommt nichts heraus. Da muß man sich klar sein darüber, wie das Ganze zusammenhängt mit dem Holzsaft, Lebenssaft und Kambium. Daher ist auch der Holzsaft ein verhältnismäßig dünnlicher Saft; er ist eigentlich darauf berechnet, daß in ihm leicht chemische Wirkungen sich bilden können. Der Lebenssaft der Pflanze, der ist schon viel mehr dicklich, er sondert ja auch den Gummi ab. Wenn Sie den Gummi ein bißchen dick machen, können Sie wunderbare Figuren daraus machen. Der Lebenssaft also, der hat schon etwas Dicklicheres gegenüber dem Holzsaft, der schmiegt sich schon mehr der Pflanzenform an. Und dann gibt er die ganze Form an das Kambium ab. Das ist noch dicklicher, schon ganz zäh, ist nur noch so weich, daß es die Formen annehmen kann, die ihm von den Sternen gegeben werden.

So ist es beim Baum, so aber auch bei der gewöhnlichen Pflanze. Wenn da die Erde ist und man da das Würzelchen hat, so wächst der Sproß nach oben; aber jetzt setzt es nicht gleich die festen Stoffe ab, es wird nicht zum Holz - es bleibt so wie eben ein Krautstengel ist -, das kommt nicht so weit; dann bilden sich gleich die Blätter daran im Umkreis, spiralig, und dann bildet sich auch da im Inneren gleich das Kambium aus, und das Kambium nimmt wiederum alles zur Erde mit zurück. So daß bei der einjährigen Pflanze der Prozeß, der ganze Vorgang viel schneller vor sich geht. Beim Baume, da sondern sich nur die festen Bestandteile ab, und es wird nicht gleich alles verwendet. Aber derselbe Vorgang findet auch bei der ganz gewöhnlichen Pflanze statt, nur kommt es nicht so weit wie beim Baume. Beim Baume ist es überhaupt ein ziemlich komplizierter Vorgang. Wenn Sie den Stamm von oben anschauen, haben Sie das so, daß zunächst das Mark darinnen ist - das ist also etwas, was die Richtung angibt; dann bildet sich um das Mark herum das, was Holzablagerungen sind. Geht es jetzt gegen den Herbst zu, da kommt der Gummi von der anderen Seite, und der klebt das Holz zusammen. Jetzt haben wir von einem Jahr das gummierte Holz. Im nächsten Jahr geschieht mit dem, was da aufsteigt, wiederum dasselbe, es muß jetzt nur mehr an einen anderen Ort gehen, wird wiederum zusammengummiert im Herbst, und dadurch, daß immer weiter zusammengummiert wird, entstehen die Jahresringe. Also Sie sehen, alle die Dinge werden sehr erklärlich, wenn man nur innerlich die Vorgänge richtig verstehen kann, wenn man nur weiß, daß da dreierlei Stoffe vorhanden sind: Holzsaft, Lebenssaft und Kambium. Der Holzsaft ist am flüssigsten, der ist also eigentlich ein Chemiker. Der Lebenssaft, der belebt; der ist also eigentlich, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, ein Lebendiger. Und dasjenige, was im Kambium geschieht - ja, da wird eigentlich aus den Sternen heraus die ganze Pflanze gezeichnet. Es ist wirklich so, meine Herren! Da geht der Holzsaft aufwärts, stirbt ab; da entsteht wieder das Leben, und jetzt kommt die Sternenwirkung: da entsteht das, daß aus dem Kambium, das schon zäh, dicklich geworden ist, aus dem Sterneneinflusse die neue Pflanze gezeichnet wird. So daß man im Kambium richtig eine Zeichnung, eine Bildhauerarbeit der neuen Pflanze hat; das wird da hinein gebildhauert. Da wird von den Sternen hineinmodelliert aus dem ganzen Weltenraum dasjenige, was dann die ganze Pflanzenform ist. Da, sehen Sie, kommen wir aus dem Leben in den Geist hinein. Denn was da modelliert wird, das wird aus dem Weltengeist heraus modelliert. Das ist sehr interessant, meine Herren: Die Erde gibt ihr Leben zunächst an die Pflanze ab, die Pflanze stirbt, die Luftumgebung gibt der Pflanze mit ihrem Licht zusammen wiederum das Leben, und der Weltengeist gibt die neue Pflanzenform herein. Die bewahrt sich dann im

Samen und wächst dann wieder auf die gleiche Weise. So daß man also in der aufsteigenden Pflanze einen Weg sieht, wie aus der Erde heraus durch den Tod zum lebendigen Geist die ganze Pflanzenwelt sich aufbaut.

Holzsaft: Erde: Chemisches

Lebenssaft: Umkreis der Erde: Lebendiges

Kambium: Sterne: Geist

Nun werden in Stuttgart noch andere Versuche gemacht. Diese Dinge hier sind außerordentlich lehrreich. Statt daß man bloß das Wachstum untersucht — was also schon wichtig ist, besonders wenn man in die höheren Verdünnungen hinaufkommt von eins zu einer Trillion, was also schon sehr interessant ist -, kann man nämlich noch folgendes machen. Man nimmt ganz verdünnte, auf die beschriebene Weise verdünnte Me- Tafel 10 talle oder Metallverbindungen, sagen wir zum Beispiel man nimmt Kupfe- """ riges, ganz verdünnt, so daß man es in einer Lösung hat. Jetzt gibtman das in einen Blumentopf. Da ist Erde drinnen. In diese Erde gibt man gewissermaßen als eine Art Dünger das Kupfer hinein. Daneben stellt man einen Topf auf, der bloße Erde hat, dieselbe Erde, die aber nicht durch das Kupfer gedüngt ist. Es muß dieselbe Erde sein, aber sie hat nicht das Kupfer. Nun nimmt man wiederum ganz dieselben Pflanzen - die Pflanzen müssen möglichst gleich weit im Wachstum sein -, setzt die eine Pflanze hinein in die mit Kupfer also gewissermaßen gedüngte Erde, und die andere Pflanze setzt man in die Erde hinein, in der keine Kupferdüngung enthalten ist. Und das Merkwürdige stellt sich heraus, gerade wenn man das Kupfer recht stark verdünnt hat, daß die Blätter hier am Rande Runzeln kriegen — die anderen kriegen keine Runzeln, wenn sie glatte Blätter haben, nicht schon von vornherein Runzeln haben. Deshalb muß man dieselbe Erde nehmen, weil viele Erden ja schon von früher das Kupfer enthalten. Man muß dieselbe Erde nehmen - das eine Mal verkupfert man sie- und man muß die gleiche Pflanze nehmen, damit man das genau vergleichen kann.

Nun nimmt man eine dritte Pflanze, gibt in ein drittes Gefäß wiederum dieselbe Erde hinein, gibt ihr aber jetzt statt Kupfer Blei hinein. Da fällt es den Blättern gar nicht ein, sich zu runzeln, sondern sie werden in der Spitze dürr und blättern ab, werden also welk am Ende und blättern ab, wenn man Blei hineintut. Jetzt haben Sie auf einmal ein ganz merkwürdiges Bild. Diese Untersuchungen werden in Stuttgart gemacht, und sie sehen sehr schön aus, diese Dinge, wenn man da hintereinander alle die Blumentöpfe stehen hat und nun sieht, wie die Stoffe der Erde auf die Pflanzen wirken.

Sie werden sich künftighin nun nicht mehr verwundern, wenn Sie irgendwo Pflanzenformen sehen mit runzeligen Blättern. Wenn man da in die Erde hineingräbt, so werden Sie Spuren von Kupfer finden. Oder wenn Sie Blätter haben, die am Rande leicht runzeln und dürr werden, und Sie graben dann in die Erde hinein, so werden Sie leicht Spuren von Blei finden. Sehen Sie zum Beispiel hin auf die bekannte Pflanze, die man Zinnkraut nennt, mit der man die Töpfe scheuert. Diese Pflanze wächst wiederum gerade an solchen Orten, wo der Boden Silizium enthält; daher bekommen sie diese steifen kieseligen Stengel. So können Sie aus dem Boden heraus die Pflanzenformen verstehen.

Nun können Sie aber auch verstehen, was es für eine Bedeutung hat, wenn ganz kleine Mengen von irgendeiner Substanz dem Grund und Boden beigemischt werden. Natürlich ist der Kirchhof irgendwo draußen, aber die Erde ist ja überall ganz durchzogen vom Holzsaft, und die kleinen Mengen gehen überall gerade in den Boden über. Und wenn man einmal die Versuche gemacht hat, wie diese kleinen Mengen wirken, von denen ich Ihnen jetzt erzählt habe, dann sagt man sich: Ja, dasjenige, was gerade in kleinen Mengen in den Boden hinein verflüchtigt war, das essen wir ja mit! Es ist so stark, daß es in der Pflanzenform lebt. Und was geschieht da weiter? Denken Sie sich, ich hätte also hier eine Pflanzenform gekriegt, die aus einem bleihaltigen Boden kommt. Heute, sagen die Leute, entsteht das Blei nicht. Aber im Boden entsteht eben Blei, wenn man gerade in den Boden hinein verwesendes Lebendiges bringt. Es entsteht eben einfach im Boden Blei. Da wächst nun die Pflanze heraus - wir können geradezu sagen: es wächst eine Blei-Pflanze heraus. - Nun schön. Wenn wir diese Pflanze, diese Blei-Pflanze essen, dann hat sie eine ganz andere Wirkung, als wenn Sie eine Pflanze essen, die keine Blei-Pflanze ist. Wenn wir eine Blei-Pflanze essen, so wirkt das so, daß unser Kleinhirn, das da hinten im Kopfe ist, trockener wird, als es sonst ist. Es wird trockener.

Jetzt haben Sie einen Zusammenhang zwischen dem Boden und dem Kleinhirn. Es kann also Pflanzen geben, die einfach durch die Beschaffenheit des Bodens, durch das, was man irgendwo in die Erde hineinbringt und was sich dann irgendwo verteilt, das Kleinhirn etwas austrocknen. Nun, meine Herren, in dem Augenblick, wo wir das Kleinhirn nicht in voller Kraft haben, werden wir ungeschickt. Wenn dem Kleinhirn irgend etwas passiert, werden wir ungeschickt, können die Füße und die Arme nicht mehr ordentlich bewegen; und wenn das dann etwas stärker wird, werden wir an den Gliedern gelähmt.

Sehen Sie, meine Herren, so ist der Weg von dem Boden zu der Menschenlähmung. Der Mensch ißt von einer Pflanze, und wenn diese an dem Rande der Blätter etwas Absterbendes hat, wenn sie so geworden ist, wie ich es Ihnen beschrieben habe, so wird jetzt sein Kleinhirn etwas vertrocknen. Im gewöhnlichen Leben merkt man es nicht gleich, aber der Mensch kann sich dann nicht mehr richtig orientieren; wird das stärker, so kommt die Lähmung. Nun ist es wiederum so, daß zuallererst, wenn man sich nicht orientieren kann, wenn dieses auftritt im Kopfe, daß man sich nicht orientieren kann - was vom Vertrocknen des Kleinhirns ausgeht -, so ergreift das zunächst alle die Muskeln, die da oben im Kopfe von einer kleinen Drüse versorgt werden, von der sogenannten Zirbeldrüse, und namentlich die Sehpartien. Geschieht das, dann kriegt man bloß die Grippe. Geht die Lähmung weiter, so bildet sich die Grippe um zum ganzen gelähmten Menschen. So daß also in allen Lähmungserscheinungen etwas steckt, was mit dem Boden der Erde innig zusammenhängt. Und daraus sehen Sie, daß man wirklich von vielen Seiten her die Kenntnisse nehmen muß, damit man etwas Gesundendes für den Menschen zustande bringt. Es genügt wirklich nicht, daß man allerlei Redensarten macht, so und so soll es sein! Denn wenn man nicht weiß, wodurch die Menschen zuerst ihren Organismus abgestorben bekommen, dann kann man noch so gute Einrichtungen haben: die Menschen werden halt eben doch nicht mehr tüchtig sein. Denn alles dasjenige, was in der Pflanze wirkt und von der Pflanze in den Menschen übergeht, das ist ja auch im Menschen wiederum von einer großen Bedeutung.

Sehen Sie, der Holzsaft, der entspricht eigentlich im Menschen dem ganz gewöhnlichen farblosen Zellsaft, dem Schleim. Der Holzsaft in der Pflanze ist beim Menschen der Lebensschleim. Der Lebenssaft der Pflanze, der da von den Blättern herumkreist, der entspricht dem menschlichen Blute. Und das Kambium der Pflanze, das entspricht im Menschen der Milch und dem Milchsaft. Wenn die Frau zum Stillen kommt, entwickelt sie nur den Milchsaft durch gewisse Drüsen in der Brust stärker. Da haben Sie wiederum das, was am stärksten beim Menschen von den Sternen beeinflußt wird: der Milchsaft. Dieser Milchsaft aber, der ist ganz besonders notwendig zur Bildung des Gehirns. Das Gehirn ist sozusagen eigentlich im Menschen verhärteter Milchsaft. Wenn man also solche Blätter hat, die absterben, dann erzeugen sie kein ordentliches Kambium, weil sie nicht mehr die Kraft haben, zurückzuwirken in der richtigen Wärme. Sie lassen die Wärme durch die absterbenden Teile nach außen wirken, nicht mehr richtig zurückwirken. Wir essen Pflanzen mit einem nicht ordentlich ausgebildeten Kambium: sie bilden in uns den Milchsaft nicht ordentlich aus; die Frauen bilden die Frauenmilch nicht ordentlich aus, die Kinder bekommen schon eine Milch, auf welche die Sterne nicht besonders stark wirken, die Kinder können sich nicht gut ausbilden. Daher tritt diese Lähmung natürlich auch besonders bei Kindern auf. Sie kann aber auch bei Großen auftreten, weil ja der Mensch das ganze Leben beeinflußt bleiben muß von der Sternenwelt, wie ich Ihnen schon auseinandergesetzt habe.

In diesen Dingen muß die Naturwissenschaft und die Heilmethode zusammenarbeiten. Das muß überall zusammenarbeiten. Aber man kann nicht in irgendeiner einzelnen Wissenschaft sich abschließen. Nicht wahr, heute gibt es überall Leute, die beschäftigen sich nur mit den Tieren; andere nur mit dem Menschen, das sind die Anthropologen. Dann wiederum andere mit einem Teil vom Menschen: mit kranken Sinnen, mit kranken Lebern, kranken Herzen; also auf Inneres spezialisieren sich diese Leute. Dann wieder studieren die Botaniker nur die Pflanzen, die Mineralogen die Steine, die Geologen das ganze Erdreich. Dadurch wird etwas sehr Bequemes geschaffen für die Wissenschaft. Man hat weniger zu lernen, wenn man bloß Geologe wird oder bloß von den Steinen zu lernen hat. Ja, aber solch ein Wissen nützt gar nichts! Es hat gar keinen Zweck,

solch ein Wissen; wenn man mit dem Menschen etwas anfangen will, wenn er krank ist, so muß man die ganze Natur zusammennehmen. Es hat keinen Nutzen, solch eine bloße Geologie oder eine bloße Botanik oder eine bloße Chemie zu verstehen. Nicht wahr, die Chemie muß man verfolgen können bis hinein in das Arbeiten des Holzsaftes! Es ist wirklich so. Die Studenten haben einen Spruch ersonnen - es gibt ja an der Universität, wie Sie vielleicht wissen, ordentliche Professoren und außerordentliche Professoren -, und die Studenten haben da den Spruch ersonnen: Die ordentlichen Professoren wissen nichts Außerordentliches, und die außerordentlichen Professoren wissen nichts Ordentliches. - Aber das kann man heute viel weiter ausdehnen: Der Geologe weiß nichts von der Pflanze, vom Tier, vom Menschen;der Anthropologe weiß nichts vom Tier, von der Pflanze, von der Erde. Keiner weiß eigentlich, wie die Dinge zusammenhängen, mit denen er sich beschäftigt. Geradeso wie man sich in der Arbeit spezialisiert hat, verspezialisiert man sich im Wissen. Und da ist es viel schädlicher. Es ist haarsträubend, wenn es nur Geologen, nur Botaniker und so weiter gibt, denn dadurch wird das ganze Wissen zersplittert, und es kommt nichts Ordentliches zustande. Es ist dieses zur Bequemlichkeit der Menschen geschehen. Die Leute sagen heute schon: Man kann nicht ein Mensch sein, der alles weiß. - Ja, wenn man eben nicht ein Mensch sein will, der alles Wissen zusammennehmen kann, dann muß man eben auch gleich sagen: Man muß überhaupt verzichten auf ein nützliches Wissen. Wir leben schon in einer Zeit, in der die Dinge im Grunde eine fürchterliche Gestalt angenommen haben. Es ist gerade so, wie wenn einer, der mit der Uhr zu tun hat, dazu bloß das Feilen von Metallen lernen will. Nicht wahr, dann muß eben natürlich das herauskommen, daß schließlich einer das Feilen der Metalle kennt, der andere das Schweißen der Metalle und so fort. Und dann käme wiederum einer, der das Zusammensetzen der Uhr kennt, aber wiederum nicht weiß, wie man die einzelnen Metalle bearbeitet. Nun, nicht wahr: beim Maschinellen, da geht es wiederum ein bißchen, obwohl es natürlich auch wiederum nicht geht, ohne daß man die Menschen zwingt. Aber im Medizinischen zum Beispiel wird überhaupt nichts erreicht, wenn man nicht alles Wissen, bis zum Wissen der Erde, zusammennehmen kann. Denn im Holzstamm drinnen lebt dasjenige, was von der Erde, also von dem Gegenstand der Geologie, aufwärtsgetragen wird bis zum Holzsaft. Da erstirbt es. Man muß nun auch die Meteorologie, die Luft kennen, weil von der Umgebung den Blättern dasjenige zugetragen wird, was wiederum Leben hervorruft. Und man muß auch Astronomie, Sternkunde kennen, wenn man die Gestaltung des Kambium verstehen will. Wiederum muß man das kennen, was mit dem Kambium in den Menschen hineinkommt, wenn er ihn verzehrt: den Milchsaft, der zum Gehirn sich umbildet; so daß man also, wenn man verdorbenes Kambium kriegt, als Erwachsener ein verdorbenes Gehirn bekommt. Und auf diese Weise erzeugen sich aus dem, was in der Erde drinnen ist, die Krankheiten.

Das ist dasjenige, was darüber zu sprechen ist, woher solche scheinbar unerklärlichen Krankheiten kommen. Sie liegen im Erdboden drinnen begründet.

Seventh Lecture

Good morning! Have you thought of anything?

Questioner: The doctor spoke about the possibility of widespread diseases breaking out and how they might be combated. Now an epidemic has broken out, polio, which has also affected adults. Could the doctor say something about this?

Is it harmful for humans to have plants in their rooms?

Dr. Steiner: As far as the question about plants in the room is concerned, it is like this: in nature, it is absolutely true that plants give off oxygen, which humans then breathe in, and that humans themselves breathe out carbon dioxide. So what the plant needs, humans breathe out; what humans need, plants give off. That is correct overall. Now, if you have plants in your room, you have to consider the following. If you have plants in your room during the day, then the process I have described takes place. If you have plants in your room at night, then the plants also need some oxygen at night. During the night, the plant behaves somewhat differently; it does not need oxygen to the same extent as humans, but it does need oxygen. So, especially when it is dark, it claims what it otherwise gives to humans. Now, of course, it is not the case that humans have to do without oxygen completely, but they get too little, and that then has a toxic effect. These things apply to nature in general. Of course, it is also true that every being has something within itself that needs something that others also need. This is the case with plants, if one observes them closely. If you put the plants you have in your room outside at night while you sleep, this toxicity would not occur. That is all I have to say on this question.

Now, as far as polio is concerned, which is currently so prevalent in Switzerland, it is still somewhat difficult to talk about this disease today, because it has only been occurring in its current form for a short time and we have to wait and see what other specific symptoms it will develop. We have had a severe case of polio at the Stuttgart clinic, for example; However, based on the picture we have today—we can only judge based on the cases that have occurred—based on the cases we have encountered, we must say today that polio, like its source, the flu, which leads to so many secondary diseases, is also an extremely complicated matter. And it seems that it can only be combated by treating the whole body. Just recently, there has been talk in medical circles here about how to combat polio. There is a great deal of interest in this today because polio is basically spreading more and more every week. It is called “polio” because it occurs most frequently in children. But recently there was a case where a young doctor—and you are no longer quite a child when you are a young doctor—I believe he was still fresh on Saturday, was struck by polio on Sunday, and was dead on Monday. So polio can strike people extremely quickly under certain circumstances, and there is cause for concern that it could develop into a very serious epidemic.

Now, like the flu itself, it is certainly related to the difficult times we are living in. The fact is that since we at the Biological Institute in Stuttgart succeeded in proving the effects of the smallest particles of substances, we have had to talk about these things in a completely different way; especially in public, we have had to talk about them differently than before.

In Stuttgart, we simply showed that if you take any substance, dissolve it, dilute it very strongly, you can achieve an effect with this diluted substance. You put a very small amount of a substance into a glass of water: you dilute it so that you put one part of the substance into nine parts of water, so it is diluted ten times. Now take a part of what you have, which now contains only a tenth of the original substance, and treat it again by adding it to a glass of water and allowing it to expand to a ratio of 1:10. Now you have diluted it 10 times 10; the first time 1:10, the second time, when you have diluted the amount of drops with a dilution of 10 times 10, that gives two zeros, 1:100. If you dilute it further, i.e., if you take another such amount and add it to nine parts water, you have to add another zero, then you have 1:1000. Now you only have one thousandth of the substance left. In Stuttgart, we diluted it to one in a trillion – that's 18 zeros; we diluted it that far and even further.

So you can imagine that there is only a trace of the original substance left, and that it no longer matters how much of the original substance is in there, but how this substance acts as a diluent. The diluent has a completely different effect. These dilutions were made in Stuttgart. It will not be easy for anyone to replicate this. At most, the German currency will be able to replicate this, but otherwise it will not be easy for anyone else to do so. — This was done with a wide variety of substances. We then continued by taking a small type of flower pot and putting what we had obtained into it. First, ordinary water, the ordinary solution, then the one with a tenth in it, then the one with a hundredth, then the one with a thousandth, then the one with a ten-thousandth, with a hundred-thousandth, and so on up to a trillion. So this was done. Then we put seeds, wheat grains, into the flower pots. The wheat grain grows (it is drawn), and it grows better in the dilution than in the non-dilution! And so it goes on. You see, with further dilution, you got faster and faster growth: one, two, three, four, five, and so on, until you came up to the twelfth dilution. At the twelfth dilution, it went back down again, becoming smaller again. Then it rose again and then went down again.

In this way, you get the effect of the smallest substances. The effect of the smallest substances — which is very strange, you see — is rhythmic! If you dilute, you finally get the strongest growth at a certain dilution, then it goes down again, then it goes up again; it goes rhythmically. So you can see that when the plant grows out of the earth, something affects it, depending on how it is burdened with substances that have a rhythmic effect in the environment. The earth's environment has an effect, so to speak; you can see that very clearly.

Now, if you are clear that the smallest amounts have an effect, then you will have no qualms about acknowledging that in times like these, when so many people eat the wrong foods and then decay as corpses in the earth, it has a different effect! Of course, this is greatly diluted for the whole earth, but it has a different effect than when people live healthily. And that is again contained in the food that grows out of the earth. People eat that too. So one can say: this is something that is influenced by the circumstances of the time. Of course, people with a crude materialistic science do not realize this, because they say to themselves: Well, what does what we put into the earth as a human body have to do with the whole earth? Of course, what comes from humans is very diluted, but it has an effect.

You see, gentlemen, it is good to talk about the whole plant. People's health depends entirely on plant growth, and that is why we need to know what actually contributes to plant growth.

Polio in particular has preoccupied me enormously, and the conclusion I have come to is that we actually need to treat the whole person. There are already indications for all kinds of remedies specifically for polio. This is probably of great importance because polio could play a truly painful role in the future. It is, of course, a question that deeply concerns us, and I have been working on it. It will probably be necessary to produce a medicine consisting of soda baths, ferric arsenate, and a special substance taken from the cerebellum, the rear part of the brain in animals. So a very complicated remedy will be needed, especially for polio. You see, with such a disease, which has very hidden causes, it is precisely because it is so complex that it will be difficult to cure. These things are actually very relevant today, and it is good to understand how the whole process of plant growth takes place.

So the plant grows out of the ground. Today I want to illustrate this in a way that corresponds to the question posed by Mr. Dollinger (see drawing). Now the root grows out of the seed. Let us first take a tree; we can then move on to the ordinary plant. When we take a tree, the trunk grows out of it. Yes, gentlemen, you see, even this growth of the trunk is something extraordinarily remarkable. This trunk that grows is actually only formed by allowing sap to rise from the earth, and this sap that rises—that is, what I have drawn here in red—this rising sap carries with it all kinds of salts and components of the earth; this is what makes the trunk solid. So when you look at wood from the trunk of a tree, you have a rising sap, and this sap then carries with it the solid dust particles of the earth, all kinds of salts, such as sodium carbonate and iron salt components in the plants. All of this is now carried along, and this is what makes the wood solid. Now, the essential thing is that the sap rises.

What actually happens there? You see, when it rises, the solid, the earthy, comes to the liquid, and we have earthy-liquid rising. Earthy-liquid rises there, it is such a thick, earthy-liquid substance. The liquid then evaporates, and the earthy remains behind. What remains behind as earthy substance is the wood. When the sap rises, it does not originate there (refer to the drawing), but this sap that rises in the wood — let's call it wood sap — is actually contained in the whole earth, so that in this respect the earth is a single large living being. This wood sap, which rises upwards in the tree, is basically, as I said, present throughout the earth; only, in the earth, this sap is actually something very special. It only becomes what it represents in the tree; it only becomes that in the tree. In the earth, it is actually the sap that animates the earth. The earth is truly a living being. And what then rises up into the tree is present throughout the earth; this is what gives life to the earth. In the tree, this sap loses its vitality; it becomes a chemist, possessing only chemical powers.

So when you look at a tree, you must say to yourself: the earthy-liquid in the tree has become chemical, and in the earth itself below, it was still alive. So the wood sap has died in part by rising up into the tree.

If nothing else were to happen, then no plants would ever develop, but only stumps that die off at the top and in which chemical processes take place. But then what is formed from the sap, the trunk, comes out into the air – and the air is always permeated with moisture – it comes out into the moist air, into the moisture, into the watery-airy. The sap – with what it produces – thus comes from the earthy-liquid into the liquid-airy. And in the liquid-airy, life is formed anew, so that the trunk is surrounded by what then lives in the green foliage (it is drawn) and finally in the blossom and in everything that is out there. This is brought back to life. In the foliage, in the leaf, in the blossom, and in the bud, the sap of life lives again; the sap of the wood is dead sap of life. In the trunk, life continually dies, in the leaf it is renewed. So we must say: we have sap of the wood, which rises upward; then we have sap of life. - What does it do? You see, the sap circulates around and produces leaves everywhere. That is why you can also observe spirals in which the leaves are arranged. The sap actually circulates around. And it comes from the liquid-airy element into which the plant enters when it has grown out of the earthy-liquid element.

You see, gentlemen, that the trunk, the wooden trunk, is dead and only what grows around it on the plant is alive. You can prove this in a very simple way, namely as follows: Imagine you walk up to a tree, you have the wooden trunk, then you have the bark, and inside the bark, the leaves grow (drawing is made). Now I go to the board and cut away the bark—which also removes the leaves—but here I leave the leaves on with the bark. And the result is that here the tree remains alive and fresh, and there it begins to die. The wood alone, with its sap, cannot keep the tree alive. What comes with the leaves must flow in from outside; that contains life again. In this way we see that although the earth can sprout the tree, it would have to let it die if it did not receive life from outside, from the moist air; for inside the tree, the sap is only a chemist, not a life-giver. The life that circulates around it is what makes it alive. And one can actually say that when the sap rises in spring, the tree is renewed in the earth. When the life sap circulates again in spring, the tree comes to life anew every year. The earth acts on the sap, the earthy-liquid; the liquid-airy acts on the life sap.

But that is not the end of it. Now, while this is happening, a new plant layer forms between the bark, which is still permeated by the life sap, and the wood; I can no longer say that a sap is forming there. Here I have said: wood sap, life sap; but here I can no longer say that a sap is forming, because what is forming there is very thick. It is called the cambium. It forms inside between the bark, which still belongs to the leaves, and the wood. So when I cut this away (it is drawn), no cambium forms inside. But the plant also needs the cambium in a certain way. The wood sap forms in the earthy-liquid, the life sap forms in the liquid-airy, and the cambium forms in the warm air, in the warm-airy or in the airy-warm. The plant develops warmth by receiving life from the outside. It sends this warmth into its own interior, and from this warmth the cambium forms inside. Or, if cambium has not yet formed – the plant needs cambium, you will hear why in a moment – but before the cambium forms, something thick already forms: this is the inner plant gum. In their warmth, plants also form plant gum inside, which can be an important remedy under certain circumstances. So the sap pulls the plant upwards, the leaves enliven the plant; but then the leaves, by generating warmth, form the gum substance, which in turn acts back on the cambium. And in old plants, in very old plants, this gum has become transparent as it has descended to the earth. When the earth was still less solid, still moist and liquid, it became transparent and turned into amber. So you see, when you take a piece of amber, it is what has flowed out of the leaf like blood from an ancient plant of the earth, down to the earth: resin, pitch. All of this flows down again, the plant gives it back to the earth: pitch, resin, amber. And when the plant keeps it for itself, it becomes the cambium. The plant is connected to the earth through the sap; the lifeblood connects the plant to what circles around the earth, to the airy, moist environment surrounding the earth. But the cambium connects the plant to the stars, to what is above. And it is in this cambium that the form of the next plant is already emerging. This then passes to the seed, and through this the next plant is born; so that the stars, via the cambium, produce the next plant. So the plant is not produced solely from the seed – that is, it is of course produced from the seed, but the seed must first be influenced by the cambium, that is, by the whole sky.

You see, this is something wonderful: when you hold a plant seed in your hand, this unassuming, modest little speck of dust could only have come into being because the cambium — now not in a liquid form, but in something thick — imitates the whole plant. And this form that arises inside the cambium — a new plant form — transfers its power to the seed, and from this the seed then has the power to grow a new plant upward under the influence of the earth.

So you see, gentlemen, mere speculation, simply placing the seed under a microscope, will get you nowhere. You have to be clear about how the whole thing is connected with the sap, the lifeblood, and the cambium. That is why the sap is a relatively thin juice; it is actually designed so that chemical reactions can easily take place in it. The plant's lifeblood is much thicker, as it also secretes gum. If you make the gum a little thicker, you can make wonderful figures out of it. The sap, then, is somewhat thicker than the wood sap and clings more closely to the shape of the plant. And then it transfers the entire shape to the cambium. This is even thicker, quite viscous, but still soft enough to take on the shapes given to it by the stars.