Nine Lectures on Bees

GA 351

26 November 1923, Dornach

Lecture II

[In connection with a paper read to the work-people by Herr Müller]

Good morning, gentlemen! I will add just a few remarks to the statements made by Herr Müller—remarks which may perhaps be of interest to you, though naturally, as far as the present day is concerned, the time has not yet come when one could really apply these things in practical bee-keeping. For the moment, on this side of practical bee-keeping, very little, or perhaps not even anything much can be said, since Herr Müller has already given you a beautiful account of the way things are managed nowadays.

If you listened to him attentively it must have occurred the to you that this whole question of bee-keeping has something of the nature of a riddle. Obviously, the bee-keeper is first of all interested in what he has to do. Everyone must, in reality, take the greatest interest in bee-keeping, for in fact, more in human life depends on it than one usually thinks.

Let us look at it in a wider sense. As you have heard in the lectures Herr Müller has given you here, the bees are able to gather what is already present as nectar in the plants. They really only gather the nectar, and then we men take away as honey a portion of what was collected for the hive—on the whole it is not a very large portion. We might say that what man takes away is somewhere about 20%—roughly speaking.

But in addition to this the bee, by means of its bodily structure and organisation, can also take pollen from the plants. Thus the bee gathers from the plant something that exists there in very minute quantities and is difficult to procure. Pollen is collected by the bees, with the help of the minute brushes attached to their bodies, bees in the very, very small quantities in which, relatively speaking, it is available; this pollen is then stored away, or consumed in the hive.

In the bee we therefore have a creature before us that collects a substance extremely delicately prepared by Nature, and having done so, makes use of it in his own household.

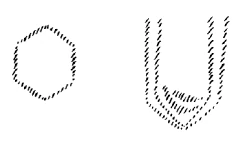

Now we will go a step further, to something very seldom noticed because one does not stop to think about it. Having transformed the food by means of its own bodily substances into wax—this the bee produces out of itself—the bees now makes a special little container in which to deposit its egg or in which to store up food supplies. This special little vessel is, I should like to say, a really great marvel, It appears to be hexagonal when we look at it from above; looked at from the side it is closed in this way. (Diagram 1 and Diagram 2.) Eggs can be deposited there, or food can be stored. Each vessel lies next to another; they fit extremely well together, so that this “surface” by which one cell, (for so it is called), is joined to another in the honey-comb, is exceedingly well made use of—the space is well used.

When the question is raised how can the bee instinctively build so skilfully formed a cell, people generally answer: “It is done that the space may be thoroughly well used.” That is true. If you try to imagine any other form of cell there would always be spaces, everything is joined together so that every part of the surface of the comb is completely made use of.

This certainly is one reason, but you see it is not the only reason. We must consider how the little larva which lies within it is entirely isolated, and one must not by any means believe that anything exists in Nature that is without forces. This six-angled, six-surfaced dwelling has certain forces within it; it would be quite another matter if the larva were to occupy a round one. In Nature it signifies something quite definite that it lies within this six-surfaced little dwelling-place. The larva receives the forces of the form later it feels in its body that it was once in this hexagonally-formed cell, in its youth when it was quite soft.

The bee is afterwards able to build similar cells out of the same forces which it thus absorbed. There lie the forces through which the bee afterwards works, for what the bee makes externally lies in its environment.

This is the first thing we must notice. Now there is another very remarkable fact that has been described to you. In the hive there is a variety of cells. I think every bee-keeper can well distinguish between the cells of the worker-bees and those of the drones. This is not a difficult matter, is it? It is still easier to distinguish between the cells of worker-bees and drones and those of the Queens, for the latter have not at all this form, they are more like a sack. The Queen cells have no such shape, they are more like a kind of sack; also there are very few of them in the hive. So we must say: The worker-bees and the drones (the males) develop-in hexagonal cells, but the Queen is developed in a “sack.” She is not at all concerned to have hexagonal surroundings. (Diagram 3 and Diagram 4).

Then we must consider something else. You see, the Queen for her development, i.e. until she is a complete full-grown insect, needs only sixteen days. She is then fully matured. A worker bee requires about twenty-one days to mature, which is a longer period. One might say that Nature bestows much more care on the development of the worker-bee than on that of the Queen.

But we shall soon see that quite another reason comes in question. The worker-bee then, needs twenty-one days, and the drone, the male—which will finish its task soonest of all—needs twenty-three to twenty-four days. The males are killed when they have fulfilled their task.

We have quite a new situation here. The different kinds of bees—Queens, workers and drones—all need a different number of days for their development.

Well, let us consider these twenty-one days needed by the worker-bees. There is something very special about this. A period of twenty-one days is not without meaning for what happens on the earth. Twenty-one days are equal to the period of time during which the Sun, approximately speaking, revolves once upon its own axis.

Now think, the worker-bee takes just that period of time for its development which the Sun takes to turn upon its axis. The worker-bee experiences one revolution of the Sun, and because it has experienced one complete revolution it enters into all the Sun can give.

If it wished to go further it would always meet only with the same Sun-influences, for if you picture to yourselves here the worker-bee, [Dr. Steiner draws on the blackboard.] (Diagram 5) and here the Sun at the moment when the egg is laid, then here we shall have the point exactly opposite the Sun. The Sun revolves upon its own axis once in twenty-one days; then it returns again and the first point is again here. If this were to continue, only such Sun-workings would be there as had once been there already. So the worker-bee by the time it is fully developed has experienced all that the Sun can give. Should the worker-bee continue to develop it must leave the Sun and enter the earth development; it will then no longer be having a Sun-influence in its development because it already had this, and has tasted it to the full. Now it passes into the earth development, but only as a perfect insect, as a matured creature. I might say—the worker-bee occupies herself only momentarily with this earth-development, and has then finished with her Sun-development, is entirely a creature of the Sun.

Now let us look at the drone. The drone, I might say, considers the matter a little longer. It does not think itself quite ready after twenty-one days, so before it is fully matured it enters the earth-development. The drone is thus an earthly being, whereas the worker-bee is entirely a child of the Sun.

How is it with the Queen? The Queen-bee does not even go through the whole of the Sun-revolution, but stays behind and remains always a creature of the Sun. For this reason the Queen is much nearer to her larval state than the others; the drones (the males) are the farthest removed from the larval state. The Queen is thereby able to lay eggs. In the bees it is clearly to be seen what it signifies to be exposed to the earth-influence or to the Sun-influence. As you know, it depends entirely on whether the bee completes, or does not complete its Sun-development, that it becomes either a Queen, a worker or a drone. The Queen lays eggs, and it is because she remains always under the influence of the Sun and receives nothing from the earth that she is enabled to do so. The worker-bee goes a little further and develops for another four or five days; it tastes the Sun to the full. But then, just when its body becomes firm enough it goes over, just for a moment, as I said, into the earth-development. Thus the worker-bee cannot return again to the Sun, for it has already thoroughly absorbed its influences. Consequently the worker-bee cannot lay eggs.

The drones are the males; they can fertilise; this power of fertilisation comes from the earth; the drones acquire it in the few days during which they continue their growth within the earth-evolution and before they reach maturity. So we can now say: in the bees it is clearly to be seen that fertilisation (male fecundation) comes from the earthly forces, and the female capacity to develop the egg comes from the forces of the Sun. So you see, you can easily imagine how significant is the length of time during which a creature develops. This is very important for, naturally, something happens within a definite time which could not occur in either a shorter or a longer time, for then quite other things would happen.

But there is something further to be considered. You see, the Queen develops in sixteen days. Then the point which stood opposite to her in the Sun is perhaps only here; [Drawing on the blackboard.] (Diagram 5) the Queen remains within the Sun-development. The remaining part of the Sun's course is gone through by the worker-bees, but they too remain within the Sun-development; they do not really pass out of it to the earth. And so, you see, they feel themselves entirely akin to the Queen because they belong to the same Sun-influence; the whole host of the worker-bees feel themselves related to the Queen. They say:—“The drones are betrayers; they have fallen to the earth. They no longer belong to us; we suffer them only because we need them.”

For what are they needed?

As you know, it sometimes happens that the Queen is not fertilised; nevertheless she lays eggs. The Queen need not necessarily be fertilised to lay eggs. Then we have what is called “virgin-brood.” This also happens with other insects; the scientific name for it is parthenogenesis. But only drones can emerge from these unfertilised eggs; no workers and no Queens. Thus when a Queen is unfertilised, worker-bees and Queens do not hatch out, only drones; such a colony is naturally useless.

You see, in “virgin-brood” only the opposite sex is produced, not the same sex. This is a very interesting fact, and an important one in the whole household of Nature—namely, that fertilisation is necessary if the same sex is to come into being (this applies to the lower animals of course, not to the higher ones). With the bees it is the case that only drones emerge where fertilisation has not taken place.

This fecundation of the bee is indeed a very special affair; there is nothing like a marriage-bed to which one retires, it all takes an entirely different course. It takes place openly, in the full sun-light and, though this may seem very strange at first, as high as possible in the air. The Queen-bee flies as far as possible towards the Sun to which she belongs. (I have already described this to you), and that drone alone which can overcome the earthly forces—for the drones have united themselves with the earthly forces—only that drone which can fly the highest is able to fecundate the Queen up there in the air.

The Queen returns and lays her eggs. So you see, the bees have no marriage-bed, they have a marriage flight; they must strive as far as they are able, towards the Sun. One must have, is it not so, fine weather for this marriage flight which really needs the Sun? In bad weather it cannot take place.

Now all this shows you how closely the Queen remains related to the Sun. When fertilisation has taken place, then worker-bees emerge from the worker-cells; first the little larva appear, as Herr Müller has so well described, and then after twenty-one days develop into worker-bees. In the sack-like cells a Queen develops.

Now if we are to go further, I must tell you something you may naturally receive with some doubt, for it needs exact study. Nevertheless, it really is so. I will link this further matter to the following:—The worker-bee now mature and ready, sets out on its flight, visiting the flowers and trees to which it attaches itself by the minute hooks on its feet. (Diagram 6) It gathers both nectar and pollen. The pollen is carried on the body where there is a special contrivance for depositing it; the nectar it sucks up with its tongue. A part of the nectar is used for its own food, but the greater part is retained and this, on its return to the hive, the bee spits out. Actually, when we eat honey we eat the spittle of the bee; we must be quite clear as to this, but it is a very clean and sweet spittle.

Thus the bee gathers all it needs for food, for storing, and for further elaboration into wax, etc. Now we must ask ourselves, how does the bee find its way to the flowers? It finds its way to the flowers with absolute certainty, but one is quite unable to explain this by merely observing the eyes of the bee. The worker-bee (the drone has somewhat larger eyes), has only two small eyes, one at each side, and three quite minute ones on the forehead (Diagram 7). The drones have rather larger eyes. But when one studies these two eyes of the bee, one discovers that it sees very little with them, and that with the three minute frontal eyes it sees, to begin with, nothing at all. That is the strange thing that the bee does not find the flowers by sight, but by a sense more like the sense of smell. It finds its way to the flowers by a sense which is between taste and smell, on its flight it already, as it were, tastes the pollen and the nectar. From far away it tastes them, so the bee has no need to use its eyes at all.

Now make for yourself a clear picture of the following.

Think of a Queen-bee born in the realm of the Sun, and not having tasted the Sun's working to the full, has remained, so to speak, entirely under the influence of the Sun. The whole host of the worker-bees, though it has completed the course of the Sun's revolution, has not actually passed over to the earth development. These worker-bees feel themselves united with the Queen, not because they were under the same Sun, but because they remained within the Sun-development; this is why they feel themselves so united with the Queen. In their development they did not sever themselves from that of the Queen. The drones do not belong to them; they have separated themselves.

But now the following happens. In order that a new Queen can come into being, the marriage flight must have taken place. The Queen goes out into the Sun. A new Queen comes into being. At that moment a most remarkable thing happens to the whole host of the workers who feel themselves so united with the old Queen. Their tiny little eyes begin to see when the new Queen is born. This they cannot endure; they cannot endure that that which they themselves are, should come from elsewhere. The three minute frontal eyes, these three very small eyes of the worker-bees, are built up from within; they are permeated with the inner blood and so on, of the bee; they were never exposed to the external working of the Sun. But now the new Queen is born from out of the Sun, and brings Sun-light with her own body into the hive; now the bees become—I should like to say—clairvoyant with their little eyes. They cannot endure this light of the new Queen. The whole host of them prepares to swarm. It is like fear of the new Queen, as though they were dazzled. It is as though we were to look at the Sun itself.

That is why the bees swarm. And now one has once more to re-establish the colony on the basis of the majority of the worker-bees which still belong to the hive—that is, to the old Queen. The new Queen must find a new people. A part of the population of the hive has of course, remained behind, but these are those born under different circumstances. The reason why the bees swarm lies in the fact that the workers cannot endure the new Queen who brings in a new Sun-influence.

Now you might ask, “Why should the bees feel so sensitive towards this new Sun-influence?” This is indeed a very strange thing. No doubt you know that it is sometimes not at all pleasant to meet a bee; it may sting one. If one is so large an animal as man at the worst one gets an inflamed skin; all the same it is rather unpleasant. Smaller animals may even die from the sting of a bee. This is due to the fact that the sting is really a tube in which a kind of piston moves up and down, which is connected with a poison bag. This poison (very disagreeable to one who has to experience it) is however, of great value to the bees. It is by no means pleasant for the bee to have to part with its poison, and in reality it only does so because it cannot bear that any influence from outside should approach. The bee wants always to remain within itself, to stay within the sphere of its own substance. Every external influence is felt as disturbing, as something to be warded off by its poison. But this poison has at the same time quite another significance, for in the minutest quantities it continually passes over into the whole body of the bee; without it the bee could not exist at all.

One must understand in studying the worker-bee that it is unable to see with its small frontal eyes, and that this is due to the fact that the poison continually permeates these frontal eyes. The moment the new Queen appears with her new Sun-influence, this poison is harmfully affected. It ceases to be active, and the small eyes suddenly begin to see, for the fact that the bee lives its life in a perpetual twilight is due to the poison.

If I were to describe to you in a pictorial form what the bee experiences when a new Queen slips out of her sack-like cell, I should have to say: “The bee lives always in the twilight, and finds its way about by means of a sense between taste and smell; it lives in a twilight congenial to it. But when the new Queen appears it is exactly like when we walk in the twilight of a June evening, and the little glow-worms are shining.” Even so does the new Queen shine for the swarm, because the poison does not work strongly enough to keep the bees in their twilight seclusion from the world. It keeps within it even when it flies out, because it is then able with its poison to keep within itself. It needs the poison when it fears something from outside may disturb it. The whole colony desires to be entirely within itself.

Indeed, in order that the Queen may remain in the sphere of the Sun she may not dwell in an angular cell, but within a circular one. There she remains within the Sun-influence.

Here we touch upon something that makes bee-keeping so extremely interesting for everyone. For you see, in reality, things go on in the hive in exactly the same way as in the human head, only with a slight difference. In our head, for instance, the substances do not grow to such dimensions. In the human head we have nerves, blood-vessels, and the separately situated round-shaped cells which are always to be found. We have these three varieties of cells in the human head. The nerves consist of separate cells which only do not grow into independent beings because Nature encloses them on all sides; in reality, however, these nerves would like to become little animals. If the nerve-cells of the human head could develop in all directions, under the same conditions as those of the hive, then the nerve-cells would become drones.

The blood-cells which flow in the veins would become worker bees; and the single free cells which are, above all, in the centre of the head and go through the shortest period of development, may be compared with the Queen bees.

So in the human head we have the same three forces (Diagram 8) as in the hive.

Now the workers bring home what they gather from the plants, and work it up in their own bodies into wax, of which they then build the wonderful structure of the combs. The blood-cells of the human head however, do the same thing. From the head they pass into the whole body. When you look for instance, at a bone, at a piece of bone, you will find hexagonal cells everywhere. The blood that circulates through the whole body carries out the same work that is done in the hive by the bees. It is similar with the cells of our muscles which, once more, correspond to the wax-cells of the bees, but these cells being softer, dissolve more quickly, so it is here less noticeable. A study of the bones shows it very well. Thus, the blood has the same forces as those of the worker-bee.

One can even follow their development through the course of time. The cells which you find first developed in the human embryo, and which subsequently remain unchanged, are those that already exist in the early stages of embryonic life. The others, the blood-cells, come into existence somewhat later, and finally the nerve-cells are developed—just as with the bee-hive. Only man builds up a body which obviously belongs to him; the bee also builds up a body, but for the worker-bees, this body is the honey-comb—the cells. This building of the comb corresponds to what happens within our bodies,—namely, that the blood-cells in reality do this out of a kind of wax—but here it is not so easy to prove.

We ourselves are made of a kind of wax, just as the honey-comb forms the marvellous structure we find in the skep or hive.

So this is how it is. Man has a head, and this head works upon his great body which is actually a “bee-hive” and contains in its relationship between the albuminous cells (which remain round) and the blood, the same connection that exists in the bee-hive between the Queen and the worker-bees. Our nerves are continually destroyed; we continually use up our nervous system. We do not immediately kill our nerves—as the bees kill the drones—for in this case we should die every year, but, none the less, our nerves get weaker every year, and it is through this gradual weakening of the nerves, that man really dies. We are then no longer able to experience our body rightly; a man is actually always dying from the wearing out of his nerves.

When you look at the head—which represents the hive—you find that here all is well protected. If one injures one's head, it is a serious matter; the head cannot bear it. Equally, what happens through the presence of the new Queen—who is there by reason of the marriage flight—is something the bees cannot endure; they prefer to go away rather than remain with her.

This is why bee-keeping has always been regarded as profoundly significant. Man takes away from the bees—perhaps 20% of their honey—and one can justly say that this honey is extremely valuable to man, for with his ordinary food he gets very little honey because honey is distributed in such very small quantities in the plant-world. We get only minute quantities of honey into our bodies in this way.

We also have “bees” within us, namely, our blood, which carries the honey to the various parts of our body. It is honey that the bee needs for producing wax, out of which it then makes the “body” of the colony.

As we grow older, honey has an extremely favourable effect upon us. With children, it is milk that has a similar effect; honey helps us to build our bodies and is thus strongly to be recommended for people who are growing old. It is an exceedingly wholesome food; only one must not eat too much of it! If one eats too much of it, using it not merely as a condiment, one can make the formative forces too strongly active. The form may then get too rigid, and one may develop all kinds of illnesses. A healthy man feels just how much honey should take. Honey is particularly good for older people because it gives the body the right firmness.

One should also adopt the plan of giving just the right quantity of honey to children suffering from rickets when they are nine to ten months of age, and continue this honey diet till the age of three or four years. Rickets would then not be as bad as it is, for this illness consists in the body being too soft, and collapsing. Of course, in the very first weeks children ought only to be given milk; honey would at that age have no affect. Honey contains the forces that give man's body firmness. These things should be understood.

So one can say that much more attention should be given to the keeping of bees than is usual.

The following is also possible. In Nature everything is wonderfully inter-related. In Nature the laws which man is unable to penetrate with his ordinary intelligence are the most important. These laws work—do they not?—always with a perfect freedom. This holds good for instance, with the proportion of the sexes on earth. This is not always the same, the number of men and women is not always, but only more or less an equal one; it is approximately equal over the whole earth. This is brought about in the wisdom of Nature. If it should ever come about—I believe I have already told you this—that men were ultimately able to determine the whole matter arbitrarily, then everything would fall into confusion. If in any country the population has been decimated by wars it will afterwards become more numerous. In Nature, every need calls forth the working of opposite forces.

Now, when the bees seek nectar from the plants, they naturally take this from plants which have also other uses—which give us fruits and so on. But the remarkable thing is that fruit-trees thrive much better in places where bees are kept, than in places where there are no bees.

When the bees take the nectar from the plants Nature does not remain idle, but produces more fruitful plants. So man not only benefits by the honey the bees make, but receives more from the plants visited by the bees. This is a law of great importance, and one we can well understand.

Observing things in this way, one is able to say—in the whole inter-relationship of the bee-colony—of this organism—Nature reveals something very wonderful to us. The bees are subject to forces of Nature which are truly wonderful and of great significance. One cannot but feel shy of fumbling among these forces of Nature. It is becoming increasingly obvious today that wherever man clumsily interferes with these forces he makes matters not better, but worse. He does not make them worse all at once, for it is really so that Nature is everywhere hindered, though notwithstanding these hindrances Nature works as best she may. Certain of these hindrances man can remove, and by doing away with them can make things easier for Nature. For example, he seems actually to be helping Nature when he makes use of bee-hives which are conveniently arranged, instead of using the old straw skeps.

But here we come to the whole question of artificial bee-keeping. You must not think that I am unable to see—even from a non-anthroposophical point of view—that modern bee-keeping methods seem at first very attractive, for certainly, it makes many things much easier. But the strong holding together—I should like to say—of one bee-generation, of one bee-family, will be impaired in the long run.

Speaking generally today, one cannot but praise modern bee-keeping; so long as we see all such precautions observed of which Herr Müller has told us, we must admire them in a certain sense. But we must wait and see how things will be in fifty to eighty years time, for by then certain forces which have hitherto been organic in the hive will be mechanised, will become mechanical. It is not possible to bring about that intimate relationship between the colony and a Queen that has been bought, which results naturally when a Queen comes into being in the natural way. Only, at first these things are not observed.

Of course, I by no means wish that a fanatical campaign in opposition to modern bee-keeping should be started, for one cannot do such things in practical life. To do so would be rather like something I will now tell you. It is possible to calculate approximately the time when there will be no more coal in the earth. The coal supply of the earth is exhaustible; one day it will come to an end. Now it would be quite possible to limit the amount of coal taken out of the earth, so that the supply would last as long as the earth itself. One cannot say that we ought to do so, for we should have a little faith for the future. One says “Well, of course we rob the earth of its coal, that is we rob our descendants of coal, but they will be able to invent something else so that they will not need coal any longer.” Naturally, one can say the same about the disadvantages of modern bee-keeping!

Still, it is well to be aware of the fact that by working mechanically we destroy what Nature has elaborated in so wonderful a way. You see bee-keeping has at all times been highly valued; in olden times especially, the bee was held to be a sacred animal. Why? It was so considered because in their whole activity, processes reveal themselves which also take place in man himself. If you take a piece of bees-wax in your hand you are in reality holding something between blood, muscle and bone, which in man's inner organisation passes through the stage of being wax. The wax does not however become solid, but remains fluidic till it is transformed into blood, or muscles, or into the cells of the bones. In the wax we have before us what we bear within us as forces, not as substance.

When men in olden times made candles of the bees-wax and lighted them, they knew that they performed a wonderful and sacred action: “This wax which we now burn we took from the hive; there it was hardened. When the fire melts it and it evaporates, then the wax passes into the same condition in which it is within our own bodies.”

In the melting wax of the candle men once apprehended something that rises up to the heavens, something that was also within their own bodies. This awoke a devotional mood in them, and this mood in its turn led them to look upon a bee as a specially sacred creature, because it prepares something which man must continually work out within himself. For this reason, the further back we go the more we find how men approached the bees with reverence. Of course, this was when they were still in their wild state; men found it so, and they looked upon these things as a revelation. Later they brought the bees into their household.

Quite wonderful riddles lie concealed in all that happens with the bees, and by much studying of them one can learn to know what happens between the head and the body in man.

I have now told you a few of those things I wished to speak of. On Wednesday we shall have our next meeting, and perhaps many questions will have arisen. Something may occur also to Herr Müller.

Today I only wished to make these remarks which, after all, are beyond doubt, for they are founded on real knowledge. But, there may still be much that can be made clearer.

Achter Vortrag

Guten Morgen, meine Herren! Ich habe vorgehabt, zu den Ausführungen von Herrn Müller einige Bemerkungen zu machen, die Ihnen vielleicht doch interessant sein können, obwohl heute natürlich in der Gegenwart nicht die Zeit dazu ist, solche Dinge schon wirklich anzuwenden in der praktischen Bienenzucht. Es ist ja auch über das Praktische der Bienenzucht sehr wenig noch zu sagen oder gar nichts eigentlich, da Herr Müller ja alles so, wie man es eben heute macht, durchaus in einer sehr schönen Weise vor Ihnen ausgeführt hat.

Es ist Ihnen aber an diesem, ich möchte sagen, Rätselwelt-Sein, wenn Sie aufmerksam zugehört haben, in bezug auf die ganze Natur der Bienenzucht etwas aufgegangen. Der Bienenzüchter, das ist ja selbstverständlich, interessiert sich zunächst für dasjenige, was er zu tun hat. Für die Bienenzucht muß eigentlich jeder Mensch das allergrößte Interesse haben, weil von der Bienenzucht wirklich mehr, als man denkt, im menschlichen Leben abhängt.

Betrachten wir die Sache einmal in einem etwas weiteren Umfange. Sehen Sie, die Bienen sind imstande - das haben Sie ja aus den Vorträgen, die Ihnen von Herrn Müller gehalten worden sind, gesehen -, dasjenige zu sammeln, was in den Pflanzen eigentlich schon als der Honig enthalten ist. Sie sammeln ja eigentlich bloß den Honig, und wir Menschen nehmen ihnen dann von dem, was sie in ihrem Bienenstocke sammeln, nur einen Teil weg, nicht einmal einen so sehr großen Teil. Denn man kann vielleicht sagen, daß dasjenige, was der Mensch wegnimmt, etwa 20 Prozent beträgt. So viel ungefähr beträgt dasjenige, was der Mensch den Bienen wegnimmt.

Außerdem aber kann die Biene durch ihre ganze Körperlichkeit, durch ihre ganze Organisation den Pflanzen auch noch Blütenstaub wegnehmen. So daß also die Biene gerade dasjenige von den Pflanzen sammelt, was eigentlich sehr wenig in ihnen enthalten ist und was sehr schwer zu haben ist. Blütenstaub wird ja in der winzigen Menge, in der er im Verhältnis vorhanden ist, von den Bienen gesammelt durch die Bürstchen, die sie an ihren Hinterbeinen haben, und wird ja auch aufgespeichert beziehungsweise verzehrt im Bienenstock. So daß wir also in der Biene zunächst dasjenige Tier haben, das außerordentlich fein von der Natur zubereiteten Stoff aufsaugt und für seinen eigenen Haushalt gebraucht.

Dann aber weiter: Nachdem die Biene - und das ist vielleicht das zunächst wenigst Auffällige, weil gar nicht darüber nachgedacht wird - erst ihre Nahrung durch ihren eigenen Verdauungsapparat umgewandelt hat in Wachs - das erzeugt sie ja durch sich selber, das Wachs -, macht sie, um Eier abzulegen, aber auch um ihre Vorräte aufzubewahren, ein eigenes kleines Gefäß. Und dieses eigene kleine Gefäß, das ist eine große Merkwürdigkeit, möchte ich sagen. Dieses Gefäß schaut ja so aus, daß es von oben angesehen sechseckig ist, von der Seite angesehen also so (siehe Zeichnung), und auf der einen Seite ist es ja so abgeschlossen. Dahinein können die Eier gelegt werden oder auch die Vorräte. Da ist eines an dem anderen. Die Dinge passen sehr gut zusammen, so daß bei den Bienenwaben durch diese Platte, mit der eine solche Zelle- so nennt man das- an die andere gefügt ist, der Raum außerordentlich gut ausgenützt ist.

Wenn man die Frage aufwirft: Wie kommt es, daß die Biene aus ihrem Instinkt heraus just eine so künstlich geformte Zelle baut? - so sagen die Leute gewöhnlich: Das ist, damit der Raum gut ausgenützt wird. - Das ist ja auch wahr. Wenn Sie sich irgendeine andere Form der Zelle denken würden, so würde immer ein Zwischenraum entstehen. Bei dieser Form entsteht kein Zwischenraum, sondern alles legt sich aneinander, so daß der Raum dieser Wabenplatte ganz ausgenützt ist.

Nun, das ist ganz gewiß ein Grund. Aber es ist nicht der einzige Grund, sondern Sie müssen bedenken: Wenn da die kleine Made, die Larve drinnenliegt, so ist sie ganz abgeschlossen, und man soll nur ja nicht glauben, daß dasjenige, was in der Natur irgendwo vorhanden ist, keine Kräfte hat. Dieses ganze sechseckige Gehäuse, sechsflächige Gehäuse hat ja Kräfte in sich, und es wäre etwas ganz anderes, wenn die Larve in einer Kugel drinnenliegen würde. Daß sie in einer solchen sechsflächigen Häuslichkeit drinnenliegt, das bedeutet in der Natur etwas ganz anderes. Die Larve selber bekommt in sich diese Formen, und in ihrem Körper, da spürt sie, daß sie in ihrer Jugend, wo sie am meisten weich war, in einer solchen sechseckigen Zelle drinnen war. Und aus derselben Kraft, die sie da aufsaugt, baut sie dann selber eine solche Zelle. Da drinnen liegen die Kräfte, aus denen heraus die Biene überhaupt arbeitet. Also das liegt in der Umgebung, was die Biene äußerlich macht. Das ist schon das erste, auf was wir aufmerksam sein müssen.

Nun aber ist Ihnen ja ausgeführt worden die weitere sehr, sehr merkwürdige Tatsache: In dem ganzen Bienenstock finden sich ja verschiedenartige Zellen. Ich glaube, ein Bienenzüchter kann sehr gut Arbeitsbienenzellen und Drohnenzellen voneinander unterscheiden. Nicht wahr, das ist ja nicht besonders schwer. Und noch leichter kann er die Zellen der Arbeiterinnen und der Drohnen von, den Königinnenzellen unterscheiden, denn die Königinnenzellen haben ja gar nicht diese Form; die sind eigentlich so wie ein Sack. Es finden sich auch sehr wenige in einem Bienenstock. So daß man also sagen muß: Die Arbeiterinnen und die Drohnen - also die Männchen, das sind die Drohnen -, die entwickeln sich in solchen sechsflächigen Zellen, die Königin entwickelt sich aber eigentlich in einem Sack. Die nimmt keine Rücksicht auf dasjenige, was solch eine flächige Umgebung ist.

Dazu kommt aber noch etwas anderes. Sehen Sie, meine Herren, die Königin braucht zu ihrer vollen Entwickelung, bis sie ganz fertig ist, eine ausgewachsene Königin ist, nur 16 Tage. Dann ist sie schon eine ausgewachsene Königin. Eine Arbeiterin, die braucht ungefähr 21 Tage, also länger. Man könnte also sagen: die Natur verwendet viel mehr Sorgfalt auf die Ausgestaltung der Arbeiterinnen als der Königinnen. Wir werden nachher gleich sehen, daß dazu noch ein anderer Grund kommt. Also die Arbeiterin, die braucht 21 Tage. Und die Drohne, das Männchen, die am frühesten abgenützt wird - die Männchen werden, nachdem sie ihre Aufgabe erfüllt haben, getötet -, die braucht sogar 23 bis 24 Tage.

Sehen Sie, das ist wiederum eine neue Sache. Die verschiedenen Bienenarten, Königin, Arbeitsbiene, Drohne, brauchen eine verschiedene Anzahl von Tagen.

Nun, meine Herren, sehen Sie, mit diesen 21 Tagen, die die Arbeitsbiene braucht, hat es nämlich eine ganz besondere Bewandtnis. 21 Tage sind keine gleichgültige Zeit in allem, was auf der Erde geschieht. Diese 21 Tage, das ist diejenige Zeit, in der sich die Sonne ungefähr einmal um sich selber herum dreht.

Denken Sie sich also, die Arbeitsbiene wird gerade just fertig in der Zeit, in der sich die Sonne einmal um sich selber herumgedreht hat. Dadurch, meine Herren, macht die Arbeitsbiene eine ganze Umdrehung der Sonne durch, kommt also dadurch, daß sie eine ganze Umdrehung der Sonne durchgemacht hat, in all das hinein, was die Sonne an ihr bewirken kann.

Und wenn sie nun weitergehen wollte, so würde sie von der Sonne aus nur immer auf dasselbe treffen. Denn wenn Sie sich da die Arbeitsbiene vorstellen (es wird gezeichnet), da die Sonne, wenn das Ei gelegt wird, so ist dieses der Punkt, der gerade der Sonne gegenüberliegt. Die Sonne dreht sich in 21 Tagen einmal um sich selber herum. Da kommt sie wieder da her, da ist der Punkt wieder da. Wenn es jetzt weitergeht, kommt lauter Wirkung von der Sonne, die schon einmal da war. So daß die Arbeitsbiene just alles dasjenige bis zu ihrer vollen Entwickelung genießt, was die Sonne leisten kann. Würde sich nun die Arbeitsbiene weiter entwickeln, dann würde sie aus der Sonne heraus in die Erdenentwickelung hereinkommen, würde nicht mehr Sonnenentwickelung haben, weil sie die schon gehabt hat, ganz ausgekostet hat. Jetzt: kommt sie in die Erdenentwickelung herein. Die macht sie aber als fertiges Insekt nur mit, als ganz fertiges Tier. Also, sie nimmt gerade noch, ich möchte sagen, einen Moment, einen Augenblick für sich in Anspruch, und nachher ist sie abgeschlossen nach der Sonnenentwickelung und ist ganz Sonnentier, die Arbeitsbiene.

Betrachten Sie jetzt die Drohne. Die, möchte ich sagen, überlegt sich die Geschichte noch ein Stückel weiter. Die erklärt sich noch nicht für abgeschlossen nach 21 Tagen. Die begibt sich, bevor sie ausgewachsen ist, noch in die Erdenentwickelung hinein. So daß also die Drohne ein Erdentier ist. Die Arbeitsbiene ist das fertige Sonnenkind.

Und wie ist es mit der Königin? Die Königin macht überhaupt die ganze Sonnenentwickelung nicht einmal fertig. Die bleibt zurück. Die bleibt immer Sonnentier. Also die Königin, die bleibt gewissermaßen immer ihrem Larvenzustand, ihrem Madenzustand näher als die anderen Tiere. Und am weitesten entfernt vom Madenzustand ist die Drohne, das Männchen. Die Königin ist dadurch, [daß sie dem Madenzustand näher bleibt, imstande, ihre Eier abzulegen. Und Sie können an der Biene richtig sehen, was das bedeutet, unter Erdeinfluß sein oder unter Sonneneinfluß sein. Denn ob eine Biene Königin oder Arbeitsbiene oder Drohne wird, das hängt bloß davon ab, ob sie abwartet einmal eine Sonnenentwickelung oder ob sie das nicht abwartet. Die Königin kann dadurch Eier legen, daß ihr die Sonnenwirkung immer bleibt, daß sie gar nichts von der Erdenentwickelung aufnimmt. Die Arbeitsbiene, die geht weiter, die entwickelt sich 4 bis 5 Tage weiter. Die kostet die Sonne noch ganz aus. Aber da geht sie, indem gerade ihr Körper fest genug wird, auch schon wiederum in die Erdenentwickelung ein bißchen, sagte ich, einen Augenblick über. Sie kann deshalb nicht wiederum in die Sonnenentwickelung zurück, weil sie sich ganz absorbiert hat. Dadurch kann sie keine Eier legen.

Die Drohnen sind Männchen; die können befruchten. Die Befruchtung, die kommt also von der Erde. Die Befruchtungskräfte erwerben sich die Drohnen durch die paar Tage, die sie noch länger im Entwickelungszustande, nicht im fertigen Zustand, der Erdenentwickelung [hingegeben] sind. So daß man sagen kann: An den Bienen sieht man ganz klar, Befruchtung, männliche Befruchtung kommt von den Erdenkräften; weibliche Fähigkeit, Eier zu entwickeln, kommt von den Sonnenkräften.

Sehen Sie, meine Herren, da können Sie einfach ermessen daran, was die Länge der Zeit bedeutet, in der sich ein Wesen entwickelt. Das ist von ganz großer Bedeutung, weil natürlich während irgendeiner Zeit etwas vor sich geht, was in einer anderen Zeit, kürzeren oder längeren Zeit, nicht vor sich geht, sondern da geht etwas anderes vor sich.

Aber es kommt noch etwas in Betracht. Sehen Sie, die Königin, die entwickelt sich also in 16 Tagen. Da ist der Punkt (es wird an die Tafel gezeichnet), der ihr gegenübergestanden hat in der Sonne, vielleicht erst da; sie bleibt in der Sonnenentwickelung drinnen. Die Arbeiterinnen machen auch noch den Rest des Sonnenumlaufes mit, aber sie bleiben in der Sonnenwirkung drinnen, sie gehen nicht heraus bis zu der Erdenentwickelung. Dadurch fühlen sie sich verwandt mit der Königin. Weil sie zur selben Sonnenentwickelung gehören, fühlt sich der ganze Arbeiterinnenschwarm verwandt mit der Königin. Sie fühlen sich an die Königin gebunden. Die Drohnen, sagen sie, die sind schon Verräter; die sind schon zur Erde abgefallen. Die gehören nicht mehr eigentlich zu uns. Die dulden wir nur, weil wir sie brauchen. Und wozu braucht man sie?

Es kommt ja zuweilen vor, daß eine Königin nicht befruchtet wird und sie legt doch entwickelungsfähige Eier. Die Königin braucht nicht unbedingt befruchtet zu werden, sie legt doch Eier. Das nennt man bei den Bienen - bei den anderen Insekten kommt es auch zum Teil vor eine Jungfernbrut, weil die Königin nicht befruchtet ist. Parthenogenesis nennt man es mit einem wissenschaftlichen Namen. Aber aus den Eiern, die jetzt gelegt werden, schlüpfen nur Drohnen aus! Da kommen keine Arbeitsbienen und keine Königinnen mehr heraus. Also wenn die Königin nicht befruchtet wird, dann können keine Arbeitsbienen und keine Königinnen mehr erzeugt werden, sondern nur Drohnen. Allein ein solcher Bienenstock ist natürlich nicht zu gebrauchen.

Sie sehen also, bei der Jungfernbrut entsteht nur das andere Geschlecht, nie dasselbe Geschlecht. Das ist eine sehr interessante Tatsache, und es ist überhaupt wichtig für den ganzen Haushalt der Natur, daß die Befruchtung notwendig ist, damit dasselbe Geschlecht entsteht - bei den niederen Tieren natürlich, nicht bei den höheren. Aber da ist es eben doch so, daß bei den Bieneneiern nur Drohnen entstehen, wenn keine Befruchtung eintritt.

Die Befruchtung ist überhaupt etwas ganz Besonderes bei den Bienen. Da geht das nicht so vor sich, daß eine Art von Hochzeitsbett vorhanden wäre und man sich zurückzöge während der Befruchtung, sondern das geht ganz anders vor sich. Da wird gerade mit der Befruchtung in die Öffentlichkeit gegangen, in die vollste Sonne, und zwar, was sehr merkwürdig erscheint, zunächst so hoch als möglich. Die Königin fliegt so hoch als möglich der Sonne entgegen, zu der sie gehört. Ich habe Ihnen das geschildert. Und die Drohne, die noch überwinden kann ihre Erdenkräfte denn die Drohnen haben sich mit den Erdenkräften vereinigt —, die noch am höchsten fliegen kann, die kann ganz oben in der Luft befruchten. Dann kommt die Königin wieder zurück und legt ihre Eier. Also Sie sehen, die Bienen haben kein Hochzeitsbett, sie haben einen Hochzeitsflug, und streben gerade, wenn sie die Befruchtung haben wollen, möglichst der Sonne entgegen. Es ist ja auch wohl so, daß man gutes Wetter braucht zum Hochzeitsflug, also die Sonne wirklich braucht, denn bei schlechtem Wetter geht das ja nicht vor sich.

Alles das zeigt Ihnen, wie verwandt die Königin mit der Sonne bleibt. Und wenn nun auf diese Weise die Befruchtung eintritt, dann werden Arbeiterinnen in den entsprechenden Arbeiterinnenzellen erzeugt; zunächst - wie Ihnen ja gut beschrieben worden ist durch Herrn Müller — entstehen die kleinen Maden und so weiter, und die entwickeln sich dann in einundzwanzig Tagen zu Arbeiterinnen. In diesen sackförmigen Zellen entwickelt sich dann eine Königin.

Um nun das Weitere einzusehen, muß ich Ihnen etwas sagen, was Sie ja natürlich zunächst etwas zweifelhaft aufnehmen werden, weil man dazu eben ein genaueres Studium braucht. Aber es ist doch so. Das weitere nämlich muß ich daran anknüpfen, daß ja nun die Arbeitsbiene, wenn sie reif geworden ist, fertig geworden ist, ausfliegt und an die Blumen, an die Bäume heranfliegt, mit ihren Fußkrallen sich ansetzen kann (es wird gezeichnet), und dann kann sie Honig aufsaugen und Blütenstaub sammeln. Den Blütenstaub, den trägt sie auf dem Körper, wo sie ihn absetzt. Das ist eine besondere Vorrichtung, die sogenannten Bürstchen an den Hinterbeinen, wo sie ihn absetzen kann. Aber den Honig saugt sie ein mit ihrem Saugrüssel. Ein Teil davon dient ihr zur eigenen Nahrung, aber den größten Teil behält sie in ihrem Honigmagen. Den speit sie wiederum aus, wenn sie zurückkommt. Also wenn wir Honig essen, dann essen wir ja in Wirklichkeit das Bienengespeie. Dessen müssen wir uns ja wirklich klar sein. Aber es ist ein sehr reinliches und süßes Gespei, was sonst das Gespei nicht ist, nicht wahr. Also sehen Sie, da sammelt die Biene dasjenige, was sie zum Fressen oder zu den Vorräten, zum Verarbeiten, zum Wachs und so weiter braucht.

Jetzt müssen wir uns fragen: Wodurch findet sich denn die Biene zu der Blume hin? - Sie geht mit einer ungeheuren Sicherheit an die Blume heran. Das kann man sich gar nicht erklären, wenn man auf die Augen der Biene sieht. Die Biene, die Arbeitsbiene - die Drohnen haben etwas gröRere Augen - hat zwei kleine Augen an den Seiten und drei ganz winzige Augen an der Stirn (es wird gezeichnet). Die Drohnen haben etwas gröRere Augen. Wenn man diese Augen bei der Arbeitsbiene prüft, dann kommt man darauf, daß sie sehr wenig sehen können, und die drei kleinen, winzigen Augen können zunächst überhaupt nichts sehen. Das ist das Merkwürdige, daß die Biene eigentlich nicht durch das Sehen an die Blume hinkommt, sondern durch etwas dem Geruch Ähnliches. Sie tastet sich nach dem Geruch fort und trifft dadurch auf die Blume auf. So daß eigentlich eine gewisse Empfindung, die so zwischen Geruch und Geschmack drinnensteht, die Biene zu der Blume hinführt. Die Biene schmeckt eigentlich schon Blütenstaub und Honig, wenn sie hinfliegt. Schon von der Ferne schmeckt sie es. Das ist dasjenige, was die Biene eigentlich dazu bewegt, die Augen gar nicht zu gebrauchen.

Jetzt stellen Sie sich recht klar einmal folgendes vor. Denken Sie sich also, eine Königin ist geboren worden, ist im Bereich der Sonne geboren worden, hat dann die Sonnenwirkung nicht ganz ausgekostet, sondern ist gewissermaßen bei der Sonnenwirkung geblieben. Ein ganzes Arbeitsbienenheer hat zwar die Sonnenwirkung noch weiter mitgemacht, aber ist nicht zur Erdenentwickelung übergegangen. Jetzt fühlen sich diese Arbeitsbienen mit der Königin verbunden; nicht deshalb, weil sie etwa unter derselben Sonne waren, sondern weil sie überhaupt in der Sonnenentwikkelung drinnengeblieben sind, fühlen sie sich mit ihr verbunden. Sie haben sich in ihrer Entwickelung nicht von der Entwickelung der Königin getrennt. Die Drohnen, die gehören nicht dazu. Die haben sich getrennt.

Aber nun tritt folgendes ein. Wenn eine neue Königin entsteht, muß der Hochzeitsflug stattgefunden haben. Das Tier, die Königin, ist in die Sonne herausgekommen. Eine neue Königin ist entstanden. Da tritt für die ganze Menge der Arbeitsbienen, die sich mit der alten Königin verbunden fühlen, etwas sehr Eigentümliches ein. Die kleinen, winzigen Augen werden sehend, wenn eine neue Königin geboren wird. Das können die Bienen nicht ertragen. Sie können nicht ertragen, daß dasselbe, was sie sind, von anderswo herkommt. Die drei kleinen Augen am Kopf, diese drei kleinen winzigen Augen, die sind bei den Arbeitsbienen ganz von innen heraus gebildet, sind von dem inneren Bienenblut und so weiter durchzogen. Sie sind nicht der äußeren Sonnenwirkung ausgesetzt gewesen. Dadurch, daß nun die neue Königin, die aus der Sonne herausgeboren ist, Sonnenlicht in den Bienenstock hineinbringt mit ihrem eigenen Körper, werden diese Bienen mit ihren kleinen Augen jetzt plötzlich, ich möchte sagen, hellsehend, können dieses Licht von der neuen Königin nicht vertragen. Jetzt fängt der ganze Schwarm an zu schwärmen. Es ist etwas wie Furcht vor der neuen Königin, wie wenn sie geblendet würden. Es ist geradeso, wie wenn man zur Sonne hinaufschaut. Daher schwärmen sie aus. Und man muß wiederum den Bienenstock begründen mit der alten Königin, wenigstens auf den Zusammenhalt von den meisten Arbeitsbienen, die noch mit der alten Königin zusammengehören. Die neue Königin muß sich neues Volk erwerben.

Es bleibt ja Volk zurück, aber das ist eben dasjenige, das unter anderen Bedingungen geboren ist. Aber der Grund, warum die Bienen ausschwärmen, der liegt eben darin, daß sie die neue Königin, die neue Sonnenwirkung hereinbringt, nicht ertragen.

Jetzt können Sie fragen: Aber wie werden denn die Bienen so empfindlich gegen diese neue Sonnenwirkung? — Meine Herren, da ist etwas sehr Merkwürdiges vorhanden. Sie wissen ja vielleicht, daß es manchmal unangenehm werden kann, die Begegnung mit einer Biene zu machen. Sie sticht einen. Und wenn man ein so großes Wesen ist wie der Mensch, dann bekommt man höchstens eine entzündliche Hautstelle und so weiter, aber es bleibt immerhin unangenehm. Die kleinen Tiere, die sterben sogar daran. Das rührt davon her, daß die Biene einen Stachel hat, der eigentlich eine Röhre ist. In dieser Röhre bewegt sich so etwas wie ein Kolben auf und ab, und der geht zurück bis zur Giftblase, so daß Gift ausströmen kann.

Dieses Gift, das demjenigen, der ihm begegnet, recht unangenehm werden kann, ist für die Bienen außerordentlich wichtig. Der Biene ist es gar nicht einmal so stark angenehm, dieses Gift beim Stechen abgeben zu müssen; aber sie gibt es ab aus dem Grunde, weil sie überhaupt allen äußeren Einfluß nicht gut ertragen kann. Sie will in sich bleiben. Sie will beider Welt ihres Stockes bleiben, und jeden äußeren Einfluß empfindet sie als etwas Störendes. Den wehrt sie dann ab mit ihrem Gift. Aber das Gift hat fortwährend eine andere Bedeutung noch. Dieses Gift ist bei der Biene so, daß es immer in ganz kleinen, winzigen Mengen in den ganzen Bienenkörper übergeht. Und ohne dieses Gift könnte die Biene überhaupt nicht bestehen. Und wenn man die Arbeitsbiene betrachtet, so muß man sich sagen, daß sie mit ihren kleinen, winzigen Augen nicht sehen kann. Das beruht darauf, daß das Gift fortwährend in diese kleinen, winzigen Augen auch hineingeht. Dieses Gift, das wird nämlich in dem Augenblicke beeinträchtigt, wo die neue Königin, die neue Sonnenwirkung, da ist. Da bleibt das Gift nicht mehr wirksam. Da werden die Augen plötzlich sehend. So daß es die Biene eigentlich ihrem Gift verdankt, wie sie fortwährend ist, daß sie eigentlich fortwährend sozusagen in einer Dämmerung lebt.

Und wenn ich Ihnen das bildlich beschreiben soll, was die Bienen erleben, wenn eine neue Königin auskriecht aus einer solchen sackförmigen Zelle, da müßte ich sagen: So ein Bienlein, das lebt immer in der Dämmerung, tastet sich fort mit einem Geruchs-Geschmack, mit etwas, was zwischen Geruch und Geschmack in der Mitte drinnen ist, tastet sich fort, lebt in der Dämmerung, und die ist ihm angemessen. Wenn aber die neue Königin kommt, dann ist es geradeso, wie wenn wir im Juni im Finstern gehen und die Johanniskäferchen leuchten. So leuchtet die neue Königin dem Bienenschwarm, weil das Gift nicht mehr stark genug wirkt, um sie in sich zu erhalten. Die Biene braucht Abschluß von der Welt, Dämmerungsabschluß von der Welt. Den hat sie auch, wenn sie ausfliegt, weil sie eben mit ihrem Gift sich in sich halten kann. Sie braucht dann das Gift, wenn sie fürchtet, daß irgendwie von außen ein Einfluß kommt. Der Bienenstock will ganz in sich sein.

Damit die Königin im Sonnenbereich bleiben kann, darf sie auch nicht in einer solchen eckigen Zelle sein, sondern sie muß in einer rundlich geformten Zelle sein. Da bleibt sie eben unter dem Einfluß der Sonne.

Und sehen Sie, meine Herren, da kommen wir auf etwas, was tatsächlich macht, daß jeden Menschen die Bienenzucht außerordentlich interessieren muß. In dem Bienenstock drinnen geht es nämlich im Grunde genommen geradeso zu, nur mit ein bißchen Veränderung, wie im eigenen Menschenkopf. Nur daß im eigenen Menschenkopf die Substanzen nicht so auswachsen. Nicht wahr, im Menschenkopf drinnen haben wir Nerven, Blutgefäße und dann auch einzeln liegende sogenannte Eiweißzellen, die rundlich bleiben. Die sind auch immer irgendwo drinnen. Da haben wir auch dreierlei drinnen im Menschenkopfe. Die Nerven bestehen aber auch aus einzelnen Zellen, die nur, weil sie von allen Seiten von der Natur bedeckt sind, sich nicht ganz auswachsen zu Tieren; sie wollen aber eigentlich Tiere werden, diese Nerven, wollen auch kleine Tiere werden. Und wenn sich die Nervenzellen des menschlichen Kopfes nach allen Seiten würden entwickeln können unter denselben Bedingungen wie der Bienenstock, dann würden die Nervenzellen Drohnen werden. Die Blutzellen, die in den Adern fließen, würden Arbeitsbienen werden. Und die Eiweißzellen, die besonders im Mittelkopf vorhanden sind, die machen die kürzeste Entwickelung durch, die lassen sich der Königin vergleichen. So daß wir im Menschenkopf drinnen dieselben drei Kräfte haben.

Nun, die Arbeitsbienen, die bringen das, was sie an den Pflanzen sammeln, nach Hause, verarbeiten es in ihrem eigenen Körper zu Wachs und machen da diesen ganzen wunderbaren Zellenaufbau. Meine Herren, das machen die Blutzellen des menschlichen Kopfes auch! Die gehen vom Kopf in den ganzen Körper. Und wenn Sie sich zum Beispiel einen Knochen ansehen, ein Knochenstück ansehen, so sind da überall diese sechseckigen Zellen drinnen. Das Blut, das in dem Körper herumzirkuliert, das verrichtet dieselbe Arbeit, die die Bienen im Bienenstock verrichten. Nur, nicht wahr, bei den anderen Zellen, bei den Muskeln, wo es auch noch ähnlich ist - denn die Muskelzellen sind auch ähnlich den Wachszellen der Bienen -, da lösen sie sich zu bald auf, sind auch noch weich; da bemerkt man es nicht so. An den Knochen bemerkt man es sehr gut, wenn man es studiert. So daß das Blut auch die Kräfte hat, die eine Arbeitsbiene hat.

Ja, meine Herren, Sie können das sogar im Zusammenhang mit der Zeit studieren. Diejenigen Zellen, die Sie zuerst beim menschlichen Embryokeim entwickelt finden und die dann bleiben, die Eiweißzellen, das sind diejenigen Zellen, die schon in den frühesten Entwickelungszeiten des Embryo vorhanden sind. Die anderen, die Blutzellen, die entstehen etwas später, und zuletzt entstehen die Nervenzellen. Gerade so, wie es im Bienenstock drinnen geschieht! Nur daß der Mensch sich einen Leib aufbaut, der scheinbar zu ihm gehört, und die Biene baut auch einen Leib: das sind die Waben, die Zellen. Mit diesem Wachsbau geschieht dasselbe wie in unserem Körper drinnen, nur daß man da nicht mehr so leicht nachweisen kann, daß eigentlich die Blutzellen das aus einer Art von Wachs heraus machen. Aber wir sind selber aus einer Art von Wachs heraus gemacht, wie die Bienen die Waben im Korbe drinnen oder in der Kiste formen. So daß das so ist: Der Mensch hat einen Kopf, und der Kopf arbeitet an dem großen Leibe, der eigentlich der Bienenstock ist; und der Bienenstock, der enthält gerade in dem Zusammenhang zwischen der Königin und den Arbeitsbienen denselben Zusammenhang, den die Eiweißzellen, die rund bleiben, mit dem Blut haben. Und die Nerven, die werden fortwährend ruiniert. Die Nerven werden fortwährend abgenutzt, denn unser Nervensystem nutzen wir ab. Wir führen in unserem Inneren nicht sogleich eine Nervenschlacht aus - da würden wir ja jedes Jahr sterben -, wie die Bienen eine Drohnenschlacht; aber trotzdem werden unsere Nerven mit jedem Jahr schwächer. Und an den schwächer werdenden Nerven stirbt der Mensch eigentlich. Wir können dann den Körper nicht mehr so empfinden, und der Mensch stirbt eigentlich immer daran, daß er seine Nerven abnützt.

Wenn Sie jetzt den Kopf, der eigentlich den Bienenstock darstellt, anschauen, dann finden Sie, daß in diesem Menschenkopf alles geschützt ist. Und wenn man von außen etwas heranbringt, dann ist das eine furchtbare Verletzung. Das verträgt der Kopf nicht. Diesen Vorgang bei der Entstehung der neuen Königin verträgt auch der Bienenstock nicht, geht lieber fort, als daß er mit dieser neuen Königin zusammen sein muß.

Gerade aus diesem Grunde ist es, daß die Bienenzucht immer als etwas ungeheuer Bedeutsames angesehen worden ist. Nicht wahr, der Mensch nimmt 20 Prozent von dem Honig den Bienen weg, und man kann schon sagen: Dieser Honig ist den Menschen außerordentlich nützlich, denn der Mensch kriegt sonst mit seiner Nahrung sehr wenig Honig, weil der Honig sehr verteilt ist in kleinen Mengen bei den Pflanzen. Sonst kriegen wir winzige Honigmengen in uns. Wir haben ja auch «Bienen» in uns, nämlich unser Blut. Das trägt schon diesen Honig in die verschiedenen Teile des Körpers. Aber dieser Honig, der ist es ja, den die Biene braucht, um Wachs zu machen, aus dem sie den Körper, den Wabenbau des Bienenstockes machen kann.

Auf uns Menschen, besonders wenn wir alt werden - beim Kind ist es die Milch, die so wirkt -, dann wirkt der Honig in einer außerordentlich günstigen Weise auf uns. Er fördert nämlich unsere körperliche Gestaltung. Daher ist Leuten, die alt geworden sind, der Honig außerordentlich zu empfehlen. Nur soll man sich daran nicht überessen. Überißt man sich daran, genießt man ihn nicht als eine Zutat nur, dann bildet man zuviel Gestaltung daraus. Dann wird die Gestaltung spröde und man bekommt allerlei Krankheiten. Nun, ein gesunder Mensch verspürt, wieviel er essen kann. Und dann ist insbesondere für Leute, die älter werden, der Honig ein außerordentlich gesundes Nahrungsmittel, weil er eigentlich unserem Körper Festigkeit gibt, richtig Festigkeit gibt.

Wenn man daher auch bei rachitischen Kindern diese Regel befolgen würde — nicht wahr, zuerst, in den allerersten Wochen, wo die Kinder eigentlich nur von Milch leben müßten, darf man das nicht tun, denn da wirkt der Honig noch nicht -, wenn man aber wirklich richtig dosiert, gerade dem rachitischen Kinde, wenn es so neun, zehn Monate alt geworden ist, Honig geben würde und es dann diese Honigdiät machen lassen würde bis zum dritten, vierten Jahre, dann würde die Rachitis, die englische Krankheit, nicht so schlimm sein können, als sie ist, weil die Rachitis darin besteht, daß der Körper zu weich bleibt, in sich zusammensinkt. Aber der Honig enthält in sich die Kraft, dem Menschen Gestalt zu geben, Festigkeit zu geben. Diese Zusammenhänge müssen eben durchaus eingesehen werden. So daß man sagen kann: Eigentlich müßte der Honig-, der Bienenzucht, noch viel, viel mehr Aufmerksamkeit zugewendet werden, als ihr zugewendet wird.

Es ist auch noch das Folgende möglich. In der Natur ist nämlich ein merkwürdiger Zusammenhang zwischen allem. Da sind diejenigen Gesetze, die der Mensch mit dem gewöhnlichen Verstande nicht durchschaut, eigentlich die allerwichtigsten. Nicht wahr, diese Gesetze wirken nur so, daß sie immer ein kleines bißchen Freiheit lassen. So ist es zum Beispiel bei den Geschlechtern auf der Erde. Es entstehen nicht ganz gleich viel Männer und Frauen auf der Erde, aber ungefähr gleich viele. Über die ganze Erde hin ist es ungefähr gleich. Das wird durch die Naturweisheit selber bewirkt. Wenn einmal die Geschichte kommen würde — ich glaube, ich habe es Ihnen schon gesagt -, daß die Menschen das Geschlecht willkürlich erzeugen könnten, dann würde die Sache gleich in Unordnung kommen. Nun, es ist ja auch so: Wenn zum Beispiel in irgendeiner Gegend durch wilde Kriege die Bevölkerung dezimiert ist, so wird sie nachher fruchtbarer. In der Natur also wirkt jeder Mangel in eine entgegengesetzte Kraft hinein.

Nun ist es auch so, daß, wenn irgendwo in einer Gegend die Bienen sich Honig suchen, sie dann ja natürlich den Honig von den Pflanzen wegnehmen. Aber sie nehmen den Honig weg von den Pflanzen, die man sonst auch braucht, die uns allerlei Früchte geben und dergleichen. Und das Eigentümliche ist, daß in Gegenden, wo Bienenzucht ist, auch die Obstbäume und Ähnliches besser gedeihen als in Gegenden, wo keine Bienenzucht ist. Also wenn die Bienen den Honig wegnehmen von den Pflanzen, wird die Natur nicht müßig, sondern sie erzeugt mehr solche fruchtbaren Pflanzen. So daß also der Mensch nicht nur vom Honig, den die Bienen geben, etwas hat, sondern daß ihm dann auch wiederum etwas von den Pflanzen gebracht wird, die von den Bienen besucht werden. Das ist ein Gesetz, in das man wirklich recht gut hineinschauen kann und das wichtig ist.

Nun, mit alledem hängt es aber zusammen, daß, wenn man so diese Sachen durchschaut, man sagen kann: In dem ganzen Wesen eines Bienenzusammenhanges, eines Organismus, ist schon etwas, in das von der Natur eine ganz wunderbare Weisheit hineingelegt ist. - Die Bienen stehen schon unter Naturkräften, die außerordentlich wichtig und wirklich wunderbar sind. Daher bekommt man eine gewisse Scheu davor, hineinzutapsen in diese Naturkräfte.

Die Dinge stellen sich nämlich heute noch immer so heraus, daß, wo der Mensch hineintapst in die Naturkräfte, er die Dinge nicht besser macht, sondern schlechter. Aber er macht es nicht gleich schlechter, sondern es ist schon so, daß die Natur überall Hindernisse hat. Trotz der Hindernisse wirkt sie in der besten Weise, wie sie kann. Gewisse Hindernisse, die kann der Mensch schon hinwegräumen, und damit kann er auch der Natur manches erleichtern. Und er erleichtert zum Beispiel der Natur ja wirklich in der Bienenzucht anscheinend dadurch sehr viel, daß er nicht die alten Bienenkörbe, sondern die neueren Bienenkisten benützt, die bequem eingerichtet sind und so weiter.

Aber nun kommt dieses Kapitel mit der künstlichen Bienenzucht. Sie dürfen nicht glauben, meine Herren, daß ich nicht einsehen würde, auch von gar nicht geisteswissenschaftlichem Standpunkte, daß natürlich die künstliche Bienenzucht zunächst im ersten Anhub etwas für sich hat, denn es wird natürlich manches erleichtert; aber dieses starke Zusammenhalten, ich möchte sagen, einer Bienengeneration, einer Bienenfamilie, das wird dadurch doch auf die Dauer beeinträchtigt werden. Man wird heute noch allgemein die künstliche Bienenzucht, wenn alle die Vorsichtsmaßregeln getroffen werden, die Herr Müller ausgeführt hat, natürlich in gewisser Beziehung nur loben können. Aber wie die Sachen in fünfzig oder achtzig Jahren sind, das muß abgewartet werden, denn da werden einfach gewisse Kräfte, die bisher im Bienenschwarm organisch wirkten, mechanisiert, die werden mechanisch gemacht. Es ist nicht mehr jene innige Verwandtschaft herzustellen zwischen der gekauften Bienenkönigin und den Arbeitsbienen, wie sie sich herstellt, wenn die Bienenkönigin von der Natur selber da ist. Aber in der allerersten Zeit macht sich so etwas noch nicht geltend.

Selbstverständlich würde ich durchaus nicht wollen, daß eine fanatische Bewegung gegen die künstliche Bienenzucht eingeleitet werden soll. Solche Sachen kann man eigentlich nicht machen im praktischen Leben. Denn das wäre ungefähr so wie etwas anderes, was ich Ihnen jetzt sagen will. Man kann ungefähr berechnen, wann einmal in der Erde keine Kohlen mehr sein werden. Der Kohlenvorrat der Erde ist ja erschöpfbar, geht einmal aus. Nun könnte man ja heute auch so wenig Kohlen aus der Erde herausfördern, daß das ungefähr so lange bliebe, bis die Erde selber zugrunde gegangen sein wird. Man kann nicht sagen, man soll es so machen, denn man muß da ein bißchen Vertrauen auf die Zukunft haben. Man muß sich sagen: Nun ja, gewiß, wir rauben der Erde alle Kohlen, das heißt, unseren Nachkommen rauben wir eigentlich die Kohlen; aber die werden schon etwas anderes dann erfinden, damit sie keine Kohlen brauchen. -So kann man natürlich auch sagen gegenüber den Nachteilen, die die künstliche Bienenzucht etwa hat.

Aber dabei bleibt es doch gut, wenn man sich bewußt ist, daß man dasjenige, was in der Natur in einer so wunderbaren Weise ausgebildet ist, eigentlich doch stört, wenn man etwas Mechanisches, Künstliches da hineinbringt. Denn die Bienenzucht hat zu allen Zeiten als etwas ganz Wunderbares gegolten. Die Biene galt gerade in ältesten Zeiten als ein heiliges Tier. Warum? Sie galt als ein heiliges Tier, weil sie eigentlich in ihrer ganzen Arbeit erkennen läßt, wie es im Menschen selber zugeht. Und wenn einer ein Stückchen Bienenwachs bekommt, so hat er eigentlich ein Zwischenprodukt zwischen Blut und Muskeln und Knochen. Das geht

innerlich im Menschen durch das Wachsstadium durch. Das Wachs wird dadurch noch nicht fest, sondern bleibt flüssig, bis es übergeführt werden kann in Blut oder Muskeln oder Knochenzellen. Man hat also eigentlich im Wachs dasjenige vor sich, was man als Kräfte. in sich hat.

Wenn die Leute in alten Zeiten Bienenwachskerzen gemacht haben und die angezündet haben, so haben sie darinnen wirklich eine ganz merkwürdige heilige Handlung gesehen: Dieses Wachs, das da verbrennt, haben wir aus dem Bienenstock geholt. Da ist es fest gewesen. Wenn das Feuer dieses Wachs schmilzt und dieses Wachs da verdunstet, dann kommt das Wachs in denselben Zustand, in dem es in unserem eigenen Leibe ist. - Und im verbrennenden Wachs in der Kerze haben die Leute früher etwas geahnt, was da hinauffliegt zum Himmel, was in ihrem eigenen Leibe ist. Das war ihnen etwas, was sie zur besonderen Andacht gestimmt hat und was sie wiederum dazu geführt hat, die Biene als ein besonders heiliges Tier zu betrachten, weil die etwas bereitet, was eigentlich der Mensch fortwährend selber in sich bereiten muß. Und daher ist es schon so: In je ältere Zeiten wir kommen, desto mehr finden wir, daß die Leute Ehrfurcht dem ganzen Bienenwesen entgegengebracht haben. Nur war das ja natürlich wild; die Leute haben es gefunden, es als eine Offenbarung betrachtet. Später ist es in den Haushalt der Menschen genommen worden. Aber in alledem, was da bei den Bienen auftritt, liegen doch lauter ganz wunderbare Rätsel, und empfinden kann man die Bienen nur, wenn man viel studiert, was eigentlich zwischen dem Menschenhaupt und seinem Körper vor sich geht.

Nun habe ich Ihnen diese Bemerkungen gemacht. Am Mittwoch werden wir ja die nächste Stunde haben. Vielleicht wird sich manche Frage daran knüpfen. Vielleicht wird auch Herrn Müller selber das eine oder das andere einfallen. Ich wollte Ihnen nur diese Bemerkungen machen, die ja nicht anzuzweifeln sind, denn sie beruhen auf wirklicher Erkenntnis. Aber es handelt sich darum, daß vielleicht noch manches deutlicher gemacht werden kann.

Eighth Lecture

Good morning, gentlemen! I had intended to make a few comments on Mr. Müller's remarks that you might find interesting, although today is obviously not the time to actually apply such things in practical beekeeping. There is very little or nothing left to say about the practical aspects of beekeeping, as Mr. Müller has already explained everything in a very nice way, just as it is done today.

However, if you have listened carefully, you will have gained some insight into the mysterious world of beekeeping. Beekeepers are naturally interested first and foremost in what they have to do. Everyone should have a keen interest in beekeeping, because human life depends on beekeeping more than we think.

Let's look at the matter in a somewhat broader context. You see, bees are capable — as you have seen from the lectures given to you by Mr. Müller — of collecting what is actually already contained in plants as honey. They actually only collect the honey, and we humans then take only a part of what they collect in their hives, not even a very large part. For one could perhaps say that what humans take away amounts to about 20 percent. That is approximately how much humans take away from the bees.

In addition, however, bees can also take pollen from plants through their entire physicality, through their entire organization. So bees collect from plants precisely that which is actually very scarce in them and very difficult to obtain. Pollen, in the tiny amounts in which it is present in relation to other substances, is collected by bees using the brushes on their hind legs and is stored or consumed in the beehive. So, in bees, we have an animal that absorbs substances that have been prepared by nature in an extremely delicate way and uses them for its own household.

But then, after the bee has converted its food into wax through its own digestive system – which is perhaps the least noticeable thing at first, because no one thinks about it – it creates its own little vessel in order to lay eggs, but also to store its supplies. And this little container of its own is a great curiosity, I would say. This container looks like this: viewed from above, it is hexagonal, viewed from the side, it looks like this (see drawing), and on one side it is closed off. The eggs or the supplies can be placed inside. One is next to the other. The pieces fit together very well, so that in the honeycombs, thanks to this plate, which joins one cell—that's what it's called—to the next, the space is used extremely well.

When the question is raised: How is it that the bee, out of its instinct, builds such an artificially shaped cell? – people usually say: It is so that the space is well utilized. That is true. If you were to imagine any other shape for the cell, there would always be an empty space. With this shape, there is no empty space; everything fits together so that the space in this honeycomb plate is fully utilized.

Well, that is certainly one reason. But it is not the only reason. You must also consider the following: When the little maggot, the larva, lies inside, it is completely enclosed, and one should not think that what exists somewhere in nature has no power. This whole hexagonal casing, this six-sided casing, has power within it, and it would be quite different if the larva were to lie inside a sphere. The fact that it lies inside such a six-sided home means something completely different in nature. The larva itself takes on these forms, and in its body it feels that in its youth, when it was most soft, it was inside such a hexagonal cell. And from the same power that it absorbs there, it then builds such a cell itself. Inside it lie the forces from which the bee works. So what the bee does externally lies in its environment. That is the first thing we must be aware of.

Now, however, you have been told about another very, very strange fact: there are different types of cells in the entire beehive. I believe that a beekeeper can easily distinguish between worker bee cells and drone cells. That's not particularly difficult, is it? And it is even easier for him to distinguish the cells of the workers and drones from the queen cells, because the queen cells do not have this shape at all; they are actually like a sack. There are also very few of them in a beehive. So we have to say that the workers and the drones—the males, that is—develop in these six-sided cells, but the queen actually develops in a sack. She doesn't take into account what such a flat environment is like.

But there is something else. You see, gentlemen, the queen needs only 16 days to fully develop into a mature queen. Then she is already a mature queen. A worker bee needs about 21 days, which is longer. So you could say that nature takes much more care in the development of workers than queens. We will see later that there is another reason for this. So the worker takes 21 days. And the drone, the male, which is used up the earliest – the males are killed after they have fulfilled their task – takes as long as 23 to 24 days.

You see, this is another new thing. The different types of bees, queen, worker bee, drone, take a different number of days.

Now, gentlemen, you see, there is a very special reason for the 21 days that the worker bee needs. 21 days is not an insignificant period of time in everything that happens on earth. These 21 days are the time it takes for the sun to revolve around itself approximately once.

So imagine that the worker bee finishes just as the sun has revolved around itself once. As a result, gentlemen, the worker bee completes a whole revolution of the sun, and because it has completed a whole revolution of the sun, it experiences everything that the sun can do to it.

And if it wanted to continue, it would only ever encounter the same thing from the sun. Because if you imagine the worker bee (it is drawn), when the egg is laid, this is the point that is directly opposite the sun. The sun revolves around itself once every 21 days. Then it comes back there, and the point is there again. If it continues now, all the effects come from the sun that was already there. So that the worker bee enjoys everything the sun can do until it is fully developed. If the worker bee were to continue to develop, it would come out of the sun and into the earth's development, and would no longer have solar development, because it has already had it and enjoyed it to the full. Now it enters into earthly development. But it does so as a finished insect, as a completely finished animal. So it takes, I would say, just a moment, an instant for itself, and afterwards it is complete according to solar development and is a completely solar animal, the worker bee.

Now consider the drone. I would say that it takes the story a step further. It does not declare itself complete after 21 days. Before it is fully grown, it enters into the earth's development. So the drone is an earth animal. The worker bee is the finished child of the sun.

And what about the queen? The queen does not even complete the entire solar development. She remains behind. She always remains a sun animal. So the queen, in a sense, always remains closer to her larval state, her maggot state, than the other animals. And furthest removed from the maggot state is the drone, the male. The queen is thus able to lay her eggs because she remains closer to the maggot state. And you can really see in the bee what it means to be under the influence of the earth or under the influence of the sun. For whether a bee becomes a queen, a worker bee, or a drone depends solely on whether it waits for a sun development or whether it does not wait for it. The queen can lay eggs because she always remains under the influence of the sun and does not absorb anything from the earth's development. The worker bee goes further, developing for another 4 to 5 days. It still makes full use of the sun. But as soon as her body becomes firm enough, she enters into the earth's development again, just for a moment, I said. She cannot return to the sun's development because she has absorbed herself completely. As a result, she cannot lay eggs.

The drones are males; they can fertilize. Fertilization, therefore, comes from the earth. The drones acquire their fertilizing powers during the few days that they are still in a state of development, not in a finished state, devoted to earthly development. So one can say: In bees, one can see very clearly that fertilization, male fertilization, comes from the forces of the earth; the female ability to develop eggs comes from the forces of the sun.

You see, gentlemen, you can simply gauge this by the length of time it takes for a being to develop. This is of great importance, because of course something happens during a certain period of time that does not happen during another period of time, shorter or longer, but something else happens instead.

But there is something else to consider. You see, the queen develops in 16 days. There is the point (drawn on the board) that stood opposite her in the sun, perhaps only there; she remains inside the sun's development. The workers also complete the rest of the sun's orbit, but they remain within the sun's influence; they do not go out into the earth's development. This makes them feel related to the queen. Because they belong to the same sun development, the whole swarm of workers feels related to the queen. They feel bound to the queen. The drones, they say, are already traitors; they have already fallen to earth. They no longer really belong to us. We only tolerate them because we need them. And what do we need them for?

It sometimes happens that a queen is not fertilized and yet she lays eggs that are capable of developing. The queen does not necessarily need to be fertilized; she lays eggs anyway. In bees – and sometimes in other insects too – this is called virgin brood, because the queen is not fertilized. The scientific name for this is parthenogenesis. But only drones hatch from the eggs that are now laid! No more worker bees or queens come out. So if the queen is not fertilized, no more worker bees or queens can be produced, only drones. Of course, such a beehive alone is useless.

So you see, virgin brood only produces the opposite sex, never the same sex. This is a very interesting fact, and it is important for the entire household of nature that fertilization is necessary for the same sex to be produced – in lower animals, of course, not in higher ones. But in the case of bee eggs, only drones are produced if fertilization does not occur.