Karmic Relationships I

GA 235

1 March 1924, Dornach

Lecture V

Speaking in detail about karma, we must of course distinguish between those karmic events of life which come to a man more from outside, and those which arise, as it were, from within. A human being's destiny is composed of many and diverse factors. To begin with, it depends on his physical and etheric constitution. Then it depends on the sympathies and antipathies with which he is able to meet the outer world, according to his astral and his Ego-constitution; and on the sympathies and antipathies with which others in their turn are able to encounter him according to his nature. Moreover, it depends on the myriad complications and entanglements in which he finds himself involved on the path of life. All these things work together to determine—for a given moment, or for his life as a whole—the human being's karmic situation.

I shall now try to show how the total destiny of man is put together from these several factors. Today we shall take our start from certain inner factors in his nature. Let us observe, for once, what is in many respects of cardinal importance. I mean, his predisposition to health and illness; and, with this underlying basis, all that comes to expression in his life, in the physical strength—and strength of soul—with which he is able to confront his tasks, and so on ...

To judge these factors rightly, we must however be able to see beyond many a prejudice that is contained in the civilisation of today. We must be able to enter more into the true original being of man; we must gain insight, what it really signifies to say that man, as to his deeper being, descends from spiritual worlds into this physical and earthly life.

All that people refer to nowadays as heredity, has even found its way, as you are well aware, into the realms of poetry and art. If any one appears in the world with such and such qualities, people will always begin by asking how he inherited them. If, for example, he appears with a predisposition to illness, they will at once ask, what of the hereditary circumstances?

To begin with, the question is quite justifiable; but in their whole attitude to these things nowadays, people look past the real human being; they completely miss him. They do not observe what his true being is, how his true being unfolds. In the first place, they say, he is the child of his parents and the descendant of his forebears. Already in his physiognomy, and even more perhaps in his gestures, they fondly recognise a likeness to his ancestors emerging. Not only so; they see his whole physical organism as a product of what is given to him by his forefathers. He carries this physical organism with him. They emphasise this very strongly, but they fail to observe the following:

When he is born, to begin with undoubtedly man has his physical organism from his parents. But what is the physical organism which he receives from his parents? The thoughts of the civilisation of today upon this question are fundamentally in error. For in effect, when he is at the change of teeth, man not only exchanges the teeth he first received, for others, but this is also the moment in life when the entire human being—as organisation—is for the first time renewed. There is a thorough-going difference as between what the human being becomes in his eighth or ninth year of life, and what he was in his third or fourth year. It is a thorough-going difference. That which he was—as organisation—in his third or fourth year, that he undoubtedly received by heredity. His parents gave it to him. That which emerges first in the eighth or ninth year of his life is in the highest degree a product of what he himself has brought down from spiritual worlds.

To picture the real underlying facts, we may put it as follows—though I am well aware it will shock the man of today. Man, we must say, when he is born, receives something like a model of his human form. He gets this model from his forefathers; they give him the model to take with him into life. Then, working on the model, he himself develops what he afterwards becomes. What he develops, however, is the outcome of what he himself brings with him from the spiritual world.

Fantastic as it may seem to the man of today—to those who are completely immersed in modern culture—yet it is so. The first teeth which the human being receives are undoubtedly inherited; they are the products of heredity. They only serve him as the model, after which he elaborates his second teeth, and this he does according to the forces he brings with him from the spiritual world. Thus he elaborates his second teeth. And as it is with the teeth, so with the body as a whole.

A question may here arise: Why do we human beings need a model at all? Why can we not do as indeed we did in earlier phases of earth-evolution? Just as we descend and gather in our ether-body (which, as you know, we do with our own forces, and bring it with us from the spiritual world), why can we not likewise gather to ourselves the physical materials and form our own physical body without the help of physical inheritance?

For the modern man's way of thinking, it is no doubt an grotesquely foolish question—mad, I need hardly say. But with respect to madness—let us admit it—the Theory of Relativity holds good. To begin with, people only apply the Theory to movements. They say you cannot tell, from observation, whether you yourself—with the body on which you are—are moving, or whether it is the neighbouring body that is moving. This fact emerged very clearly when the old cosmic theory was exchanged for the Copernican. Though, as I said, they apply the Theory of Relativity only to movements, yet we may also apply it (for it certainly has its sphere of validity) to the aforesaid ‘madness.’ Here are two people, standing side by side: each one is mad as compared to the other ... The question only remains, which of the two is absolutely mad?

In relation to the real facts of the spiritual world, this question must none the less be raised: Why does the human being need a model? Ancient world-conceptions answered it in their way. Only in modern time, when morality is no longer included in the cosmic order but only recognised as human convention, these questions therefore are no longer asked. Ancient world-conceptions not only asked the question; they also answered it. Originally, they said, man was pre-destined to come to the earth in such a way that he could form his own physical body from the substances of earth, just as he gathers to himself his ether-body from the cosmic ether-substance. But he then fell a prey to the Luciferic and Ahrimanic influences, and he thereby lost the faculty, out of his own nature to build his physical body. Therefore he must take it from heredity. This way of obtaining the physical body is the result of inherited sin.

This is what ancient world-conceptions said—that this is the fundamental meaning of “inherited sin.” It signifies the having to enter into the laws and conditions of heredity.

We in our time must first discover and collect the necessary concepts so as to take these questions sincerely, in the first place; and in the second place, to find the answers. It is quite true: man in his earthly evolution has not remained as strong as he was pre-disposed to be before the onset of the Luciferic and Ahrimanic influences. Therefore he cannot form his physical body of his own accord when he comes down into the earthly conditions. He is dependent on the model, he needs the model which we see growing in the first seven years of human life. And, as he takes his direction from the model, it is but natural if more or less of the model also remains about him in his later life. If, in his working on himself, he is altogether dependent on the model, then he forgets—if I may put it so—what he himself brought with him. He takes his cue entirely from the model. Another human being, having stronger inner forces as a result of former lives on earth, takes his direction less from the model; and you will see how greatly such a human being changes in the second phase of life, between the change of teeth and puberty.

This is precisely the task of school. If it is a true school, it should bring to unfoldment in the human being what he has brought with him from spiritual worlds into this physical life on earth.

Thus, what the human being afterwards takes with him into life will contain more or less of inherited characteristics, according to the extent to which he can or cannot overcome them.

Now all things have their spiritual aspect. The body man has in the first seven years of life is simply the model from which he takes his direction. Either his spiritual forces are to some extent submerged in what is pressed upon him by the model; then he remains quite dependent on the model. Or else, in the first seven years, that which is striving to change the model works its way through successfully.

This striving also finds expression outwardly. It is not merely a question of man's working on the model. While he is doing so, the original model gradually loosens itself, peels off, so to speak—falls away. It all falls away, just as the first teeth fall away. Throughout this process, the forms and forces of the model are pressing on the one hand, while on the other hand the human being is trying to impress what he himself has brought with him to the earth ... There is a real conflict in the first seven years of life. Seen from the spiritual standpoint, this conflict is signified by that which finds expression—outwardly, symptomatically—in the illnesses of childhood. The typical diseases of childhood are an expression of this inward struggle.

Needless to say, similar forms of illness often occur later in life. In such a case—to take only one example—it may be that the patient did not succeed very well in overcoming the model in the first seven years of life. And at a later age an inner impulse arises, after all to rid himself of what has thus karmically remained in him. Thus in the 28th or 29th year of life, a human being may suddenly feel inwardly roused, all the more vigorously to beat against the model, and as a result, he or she will get some illness of childhood.

If you have an eye for it, you will soon see how remarkable it is in some children—how greatly they change in physiognomy or gesture after the 7th or 8th year of their life. Nobody knows where the change comes from. The prevailing views of heredity are so strong nowadays that they have passed into the everyday forms of speech. When, in the 8th or 9th year, some feature suddenly emerges in the child (which, in real fact, is deeply, organically rooted) the father will often say: “Anyhow, he hasn't got it from me.” To which the mother will answer: “Well, certainly not from me.” All this is only due to the prevailing belief which has found its way into the parental consciousness—I mean of course, the belief that the children must have got everything from their parents.

On the other hand, you may often observe how children grow even more like their parents in this second phase of life than they were before. That is quite true. But we must take in earnest what we know of the way man descends into the physical world.

Among the many dreadful flowers of the swamp which psycho-analysis has produced, there is the theory of which you can read on all hands nowadays, namely that in the hidden sub-conscious mind every son is in love with his mother and every daughter with her father; and they tell of the many conflicts of life which are supposed to arise from this, in the sub-conscious regions of the soul. All these are of course amateurish interpretations of life. The truth however is, that the human being is in love with his parents already before he comes down into earthly life. He comes down just because he likes them.

Of course, the judgment of life which people have on earth must differ in this respect from the judgment they have outside the earthly life between death and a new birth. On one occasion, in the early stages of our anthroposophical work, a lady appeared among us who said: “No,” when she heard of reincarnation. She liked the rest of Anthroposophy very well, but with reincarnation she would have nothing to do; one earthly life, she said, was quite enough for her. Now we had very well-meaning followers in those days, and they tried in every imaginable way to convince the good lady that the idea was true after all, that every human being must undergo repeated lives on earth. She could not be moved. One friend belaboured her from the left, and another from the right. After a time, she left; but two days later, she wrote me a post-card to the effect that, after all, she was not going to be born again on earth!

To such a person, one who wishes simply to tell the truth from spiritual knowledge can only say: No doubt, while you are here on earth, it is not at all to your liking that you should come down again for a future life. But it does not depend on that. Here on earth, to begin with, you will go through the gate of death into the spiritual world. That you are quite willing to do. Whether or no you want to come down again will depend on the judgment which will be yours when you no longer have the body about you. For you will then form quite a different judgment.

The judgments man has in physical life on earth are, in fact, different from the judgments he has between death and a new birth. For there the point of view is changed. And so it is, if you say to a human being here on earth—a young human being, perhaps-that he has chosen his father, it is not out of the question that he might make objection: “Do you mean to say that I have chosen the father who has given me so many thrashings?” Yes, certainly he has chosen him; for he had quite another point of view before he came down to earth. He had the point of view that the thrashings would do him a lot of good ... Truly, it is no laughing matter; I mean it in deep earnestness.

In the same way, man also chooses his parents as to form and figure. He himself has a picture before him—the picture that he will become like them. He does not become like them by heredity, but by his own inner forces of soul-and-spirit—the forces he brings with him from the spiritual world. Therefore you need to judge in an all-round way out of both spiritual and physical science. If you do so, it will become utterly impossible to judge as people do when they say, with the air of making an objection: “I have seen children who became all the more like their parents in their second phase of life.” No doubt; but then the fact is, that these children themselves have set themselves the ideal of taking on the form of their parents.

Man really works, throughout the time between death and a new birth, in union with other departed souls, and with the beings of the Higher Worlds; he works upon what will then make it possible for him to build his body.

You see, we very much under-estimate the importance of what man has in his sub-consciousness. As earthly man, he is far wiser in the sub-conscious than in the surface-consciousness. It is indeed out of a far reaching, universal, cosmic wisdom that he elaborates within the model that afterwards emerges in the second phase of life—what he then bears as his own human being, the human form that properly belongs to him. In time to come, people will know how little they really receive—as far as the substance of the body is concerned—from the food they eat. Man receives far more from the air and the light, from all that he absorbs in a very finely-divided state from air and light, and so on. When this is realised, people will more readily believe that man builds up his second body quite independently of any inherited conditions. For he builds it entirely from his world-environment. The first body is actually only a model and that which comes from the parents—not only substantially, but as regards the outer bodily forces—is no longer there in the second period of life. The child's relation to his parents then becomes an ethical, a soul-relationship. Only in the first period of life—that is until the seventh year—is it a physical, hereditary relationship.

Now there are human beings who, in this earthly life, take a keen interest in all that surrounds them in the visible cosmos. They observe the world of plants, of animals; they take interest in this thing and that in the visible world around them. They take an interest in the majestic picture of the starlit sky. They are awake, so to speak, with their soul, in the entire physical cosmos. The inner life of a human being who has this warm interest in the cosmos differs from the inner life of one who goes past the world with a phlegmatic, indifferent soul.

In this respect, the whole scale of human characters is represented. There, for example, is a man who has been quite a short journey. When you afterwards talk to him, he will describe with infinite love the town where he has been, down to the tiniest detail. Through his keen interest, you yourself will get a complete picture of what it was like in the town he visited.

From this extreme we can pass to the opposite. On one occasion, for instance, I met two elderly ladies; they had just traveled from Vienna to Presburg, which is a beautiful city. I asked them what it was like in Presburg, what had pleased them there. They could tell me nothing except that they had seen two pretty little dachshunds down by the river-side! Well, they need not have gone to Presburg to see the dachshunds; they might just as well have seen them in Vienna. However, they had seen nothing else at all.

So do some people go through the world. And, as you know between these outermost ends of the scale, there are those who take every kind and degree of interest in the physical world around them.

Suppose a man has little interest in the physical world around him. Perhaps he just manages to interest himself in the things that immediately concern his bodily life—whether, for instance, one can eat more or less well in this or that district. Beyond that, his interests do not go; his soul remains poor. He does not imprint the world into himself. He carries very little in his inner life, very little of what has radiated into him from the phenomena of the world, through the gate of death into the spiritual realms. Thereby he finds the working with the spiritual beings, with whom he is then together, very difficult. And as a consequence, in the next life he does not bring with him, for the up-building of his physical body, strength and energy of soul, but weakness—a kind of faintness of soul. The model works into him strongly enough. The conflict with the model finds expression in manifold illnesses of childhood; but the weakness persists. He forms, so to speak, a frail or sickly body, prone to all manner of illnesses. Thus, karmically, our interest of soul-and-spirit in the one earthly life is transformed into our constitution as to health in the next life. Human beings who are “bursting with health” certainly had a keen interest in the visible world in a former incarnation. The detailed facts of life work very strongly in this respect.

No doubt it is more or less “risqué” nowadays to speak of these things, but you will only understand the inner connections of karma if you are ready to learn about the karmic details. Thus, for example, in the age when the human souls who are here today were living in a former life on earth, there was already an art of painting; and there were some human beings even then who had no interest in it at all. Even today, you will admit, there are people who do not care whether they have some atrocity hanging on the walls of their room or a picture beautifully painted. And there were also such people in the time when the souls who are here today were living in their former lives on earth. Now, I can assure you, I have never found a man or a woman with a pleasant face—a sympathetic expression—who did not take delight in beautiful paintings in a former life on earth. The people with an unsympathetic expression (which, after all, also plays its part in karma, and signifies something for destiny) were always the ones who passed by the works of art of painting with obtuse and phlegmatic indifference.

These things go even farther. There are human beings (and so there were in former epochs of the earth) who never look up to the stars their whole life long, who do not know where Leo is, or Aries or Taurus; they have no interest in anything in this connection. Such people are born, in a next life on earth, with a body that is somehow limp and flabby. Or if, by the vigour of their parents, they get a model that carries them over this, they become limp, lacking in energy and vigour, through the body which they then build for themselves.

And so it is with the entire constitution which a man bears with him in a given life on earth. In every detail we might refer it to the interests he had in the visible world—in an all-embracing sense—in his preceding life on earth.

People, for instance, who in our time take absolutely no interest in music—people to whom music is a matter of indifference—will certainly be born again in a next life on earth either with asthmatic trouble, or with some disease of the lung. At any rate, they will be born with a tendency to asthma or lung disease. And so it is in all respects; the quality of soul which develops in our earthly life through the interest we take in the visible world, comes to expression in our next life in the general tone of our bodily health or illness.

Here again, some one might say: To know of such things may well take away one's taste for a next life on earth. That again, is judged from the earthly standpoint, which is certainly not the only possible standpoint; for, after all, the life between death and a new birth lasts far longer than the earthly life. If a man is obtuse and indifferent with regard to anything in his visible environment, he takes with him an inability to work in certain realms between death and a new birth. He passes through the gate of death with the consequences of his lack of interest. After death he goes on his way. He cannot get near certain Beings; certain Beings hold themselves away from him; he cannot get near them. Other human souls with whom he was on earth, remain as strangers to him. This would go on for ever, like an eternal punishment of Hell, if it could not be modified. The only cure, the only compensation, lies in his resolving—between death and a new birth—to come down again into earthly life and experience in the sick body what his inability has signified in the spiritual world. Between death and a new birth he longs for this cure, for he is then filled with the consciousness that there is something he cannot do. Moreover, he feels it in such a way that in the further course, when he dies once again and passes through the time between death and new birth, that which was pain on earth becomes the impulse and power to enter into what he missed last time.

Thus we may truly say: in all essentials, man carries health and illness with him with his karma, from the spiritual world into the physical. Of course we must bear in mind that it is not always a fulfilment of karma, for there is also karma in process of becoming. Therefore we shall not relate to his former life on earth, everything the human being has to suffer in his physical life as regards health and illness. None the less we may know: in all essentials, that which emerges—notably from within outward—with respect to health and illness, is karmically determined as I have just described.

Here again, the world becomes intelligible only when we can look beyond this earthly life. In no other way can we explain it; the world cannot be explained out of the earthly life.

If we now pass from the inner conditions of karma which follow from a man's organisation, to the more outward aspect, here once again—only to strike the chords of karma, so to speak—we may take our start from a realm of facts which touches man very closely. Take, for example, our relation to other human beings, which is psychologically very much connected with the conditions of our health and illness, at any rate as regards the general mood and attunement of our soul.

Assume, for example, that someone finds a close friend in his youth. An intimate friendship arises between them; the two are devoted to one another. Afterwards life takes them apart—both of them, perhaps, or one especially—they look back with a certain sadness on their friendship in youth. But they cannot renew it. However often they meet in life, their friendship of youth does not arise again. How very much in destiny can sometimes depend on broken friendships of youth. You will admit, after all, a person's destiny can be profoundly influenced by a broken friendship of youth.

Now one investigates the matter ... I may add that one should speak as little as possible about these things out of mere theory. To speak out of theory is of very little value. In fact, you should only speak of such things either out of direct spiritual perception, or on the basis of what you have heard or read of the communications of those who are able to have direct spiritual vision, provided you yourselves find the communications convincing, and understand them well. There is no value in theorising about these things. Therefore I say, when you endeavour with spiritual vision to get behind such an event as a broken friendship of youth, as you go back into a former life on earth, this is what you generally find. The two people, who in a subsequent earthly life, had a friendship in their youth which was afterwards broken—in an earlier incarnation they were friends in later life.

Let us assume, for instance: two young people—boys or girls—are friends until their twentieth year. Then the friendship of their youth is broken. Go back with spiritual cognition into a former life on earth, and you will find that again they were friends. This time, however, it was a friendship that began about the twentieth year and continued into their later life. It is a very interesting case, and you will often find it so when you pursue things with spiritual science.

Examine such cases more closely and to begin with, this is what you find: If you enjoyed a friendship with a person in the later years of life, you have an inner impulse also to learn to know what he may be like in youth. The impulse leads you in a later life actually to learn to know him as a friend in youth. In a former incarnation you knew him in maturer years. This brought the impulse into your soul to learn to know him now also in youth. You could no longer do so in that life, therefore you do it in the next.

It has a great influence when this impulse arises—in one of the two or in both of them—and passes through death and lives itself out in the spiritual world between death and a new birth. For in the spiritual world, in such a case, there is something like a “staring fixedly” at the period of youth. You have an especial longing to fix your gaze on the time of youth, and you do not develop the impulse to learn to know your friend once more in maturer years. And so, in your next life on earth, the friendship of youth—pre-determined between you by the life you lived through before you came down to earth—is broken.

This is a case out of real life, for what I am now relating is absolutely real. One question, however, here arises: What was the older friendship like in the former life, what was it like, that rouses the impulse in you to have your friend with you only in youth in a new life on earth? The answer is this: for the desire to have the other being beside you in your youth and yet not to develop into a desire to keep him as your intimate friend in later life as well, something else must also have occurred. In all the instances of which I am aware, it has invariably been so: If the two human beings had remained united in their later life, if their friendship of youth had not been broken they would have grown tired and bored with one another: because, in effect, their friendship in maturer years in a former life took a too selfish direction. The selfishness of friendships in one earthly life avenges itself karmically in the loss of the same friendships in other lives.

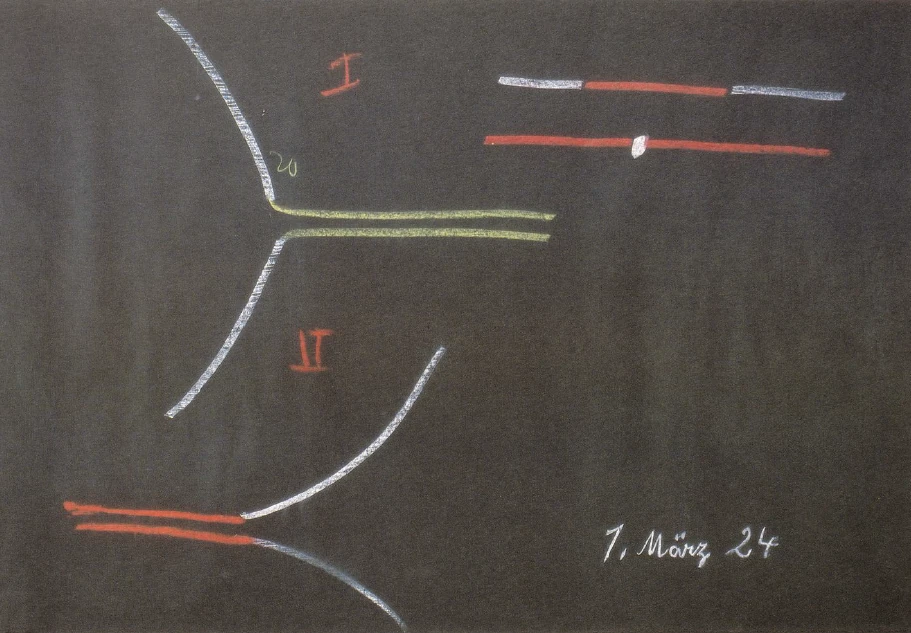

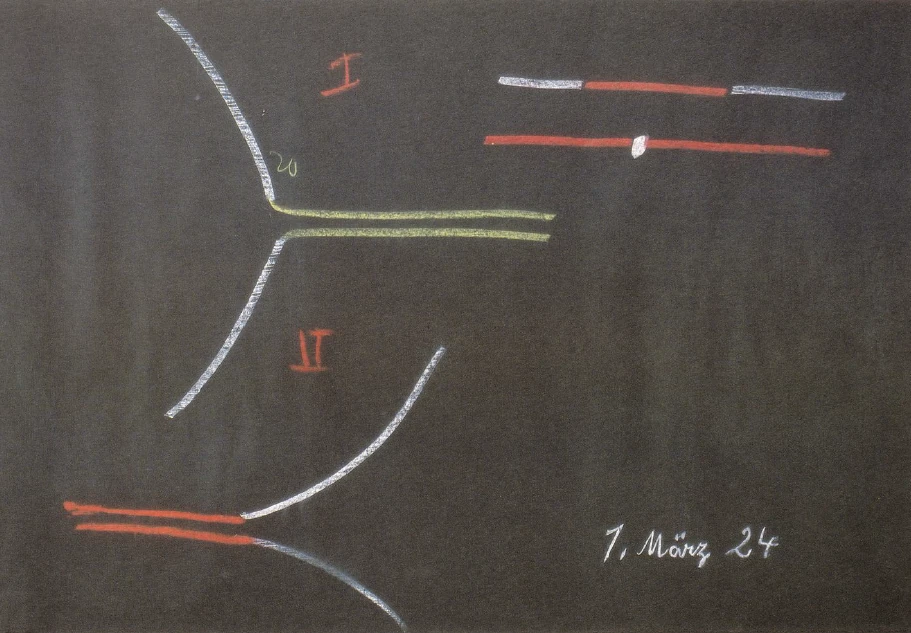

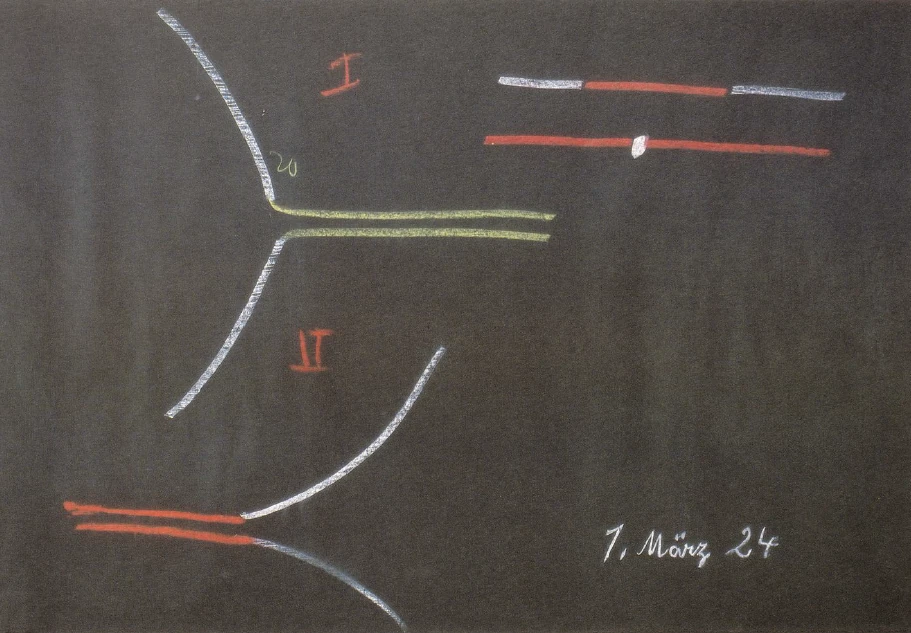

These things are complicated indeed; but you can always get a guiding line if you see this, for it is so in many cases: Two human beings go their way, each of them apart, say, till their twentieth year; thenceforward they go along in friendship (I). Then in the next earthly life, correspondingly, we generally get this second picture (II)—the picture of friendship in youth, after which their lives go apart.

This too you will find very often: If, in your middle period of life in one incarnation, you meet a human being who has a strong influence on your destiny (these things, of course, only hold good as a general rule—not in all cases), it is very likely that you had him beside you by forces of destiny at the beginning and at the end of your life in a previous incarnation. Then the picture is so: In the one incarnation you live through the beginning and ending of life together; in the other incarnation you are not with him at the beginning or at the end, but you encounter him in the middle period of life.

Or again it may be that in your childhood you are united by destiny with another human being; in a former life you were united with him precisely in the time before you approached your death. Such inverse reflections often occur in the relationships of karma.

Fünfter Vortrag

Wenn man über das Karma im einzelnen spricht, so muß man ja zunächst natürlich zwischen den karmischen Ereignissen, die im Menschenleben mehr von außen an den Menschen herantreten, und denjenigen, die von innen im Menschen gewissermaßen aufsteigen, unterscheiden.

Das Schicksal des Menschen setzt sich ja aus den allerverschiedensten Faktoren zusammen. Das Schicksal des Menschen ist von seiner physischen und ätherischen Konstitution abhängig, das Schicksal des Menschen ist abhängig von dem, was der Mensch nach seiner astralischen und Ich-Beschaffenheit an Sympathie und Antipathie der Außenwelt entgegenbringen kann, was man ihm wiederum nach seiner Beschaffenheit an Sympathie und Antipathie entgegenbringen kann; das Schicksal des Menschen ist wiederum abhängig von den allerallermannigfaltigsten Verwicklungen, Verstrickungen, in die der Mensch auf seinem Lebenswege verwoben wird. Das alles ergibt für irgendeinen Zeitpunkt oder in Summa für das ganze Leben eben die Schicksalslage des Menschen.

Nun werde ich versuchen, das Gesamtschicksal des Menschen aus den einzelnen Faktoren zusammenzusetzen. Dazu wollen wir heute einmal den Ausgangspunkt von gewissen inneren Faktoren im Menschen nehmen, wollen einmal auf jenen Faktor sehen, der da wirklich in vieler Beziehung in erster Linie ausschlaggebend ist, die Gesundheits- oder Krankheitslage des Menschen, und dasjenige, was als Unterlage für die Gesundheits- und Krankheitslage des Menschen dann zur Wirkung kommt in seiner physischen, in seiner seelischen Stärke, mit der er seine Aufgaben erfüllen kann und so weiter.

Will man aber diese Faktoren in der rechten Weise beurteilen, dann muß man ja über vieles, was in den heutigen Zivilisationsvorurteilen enthalten ist, hinwegsehen können. Man muß mehr auf die ursprüngliche Wesenheit des Menschen eingehen können, muß wirklich Einsicht gewinnen, was es denn eigentlich heißt, daß der Mensch seiner tieferen Wesenheit nach aus geistigen Welten zum physischen Erdendasein heruntersteigt.

Nun wissen Sie, daß heute auch schon in die Kunst, in die Dichtung zum Beispiel dasjenige eingezogen ist, was man unter den Begriff der Vererbung zuammenfaßt. Und wenn irgend jemand mit bestimmten Eigenschaften in der Welt auftritt, frägt man ja zuerst nach der Vererbung. Wenn jemand mit Krankheitsanlagen auftritt, frägt man: Wie steht es mit den Vererbungsverhältnissen?

Es ist gewiß zunächst eine durchaus berechtigte Frage. Aber so, wie man sich heute zu diesen Dingen verhält, so sieht man eigentlich an dem Menschen vorbei. Man sieht völlig an dem Menschen vorbei. Man sieht nicht auf dasjenige, was eigentlich des Menschen wahre Wesenheit ist, und wie sich diese Wesenheit entfaltet. Man sagt natürlich, der Mensch ist zunächst das Kind seiner Eltern, ist der Nachkomme seiner Vorfahren. Gewiß, man sieht das auch. Man sieht es auftreten schon in der äußeren Physiognomie, noch mehr in den Gebärden vielleicht, man sieht die Ähnlichkeit mit den Vorfahren auftreten. Aber nicht nur das. Man sieht ja auch, wie der Mensch seinen physischen Organismus eben als Produkt dessen hat, was ihm die Vorfahren geben. Er trägt diesen physischen Organismus an sich. Und man weist heute stark, sehr stark darauf hin, daß der Mensch diesen physischen Organismus an sich trägt.

Man beachtet dabei das Folgende nicht. Wenn der Mensch geboren wird, so hat er gewiß zunächst seinen physischen Organismus von seinen Eltern. Aber was ist dieser physische Organismus, den er von seinen Eltern hat? Darüber denkt man in der heutigen Zivilisation im Grunde genommen ganz falsch.

Wenn der Mensch im Zahnwechsel steht, tauscht er ja nicht nur seine zuerst bekommenen Zähne gegen andere aus, sondern es ist das der Zeitpunkt im menschlichen Leben, in dem sich zum erstenmal die ganze menschliche Wesenheit als Organisation erneuert.

Nun ist es wirklich ein durchgreifender Unterschied zwischen dem, was dann der Mensch in seinem achten, neunten Jahre wird, und demjenigen, was er zum Beispiel im dritten, vierten Jahre war. Es ist ein durchgreifender Unterschied. Dasjenige, was er im dritten, vierten Jahre als Organisation war, hat er vererbt bekommen, das haben ihm die Eltern gegeben. Dasjenige, was da wird und zuerst auftritt im achten, neunten Lebensjahre, das geht im höchsten Grade hervor aus dem, was der Mensch heruntergetragen hat aus der geistigen Welt.

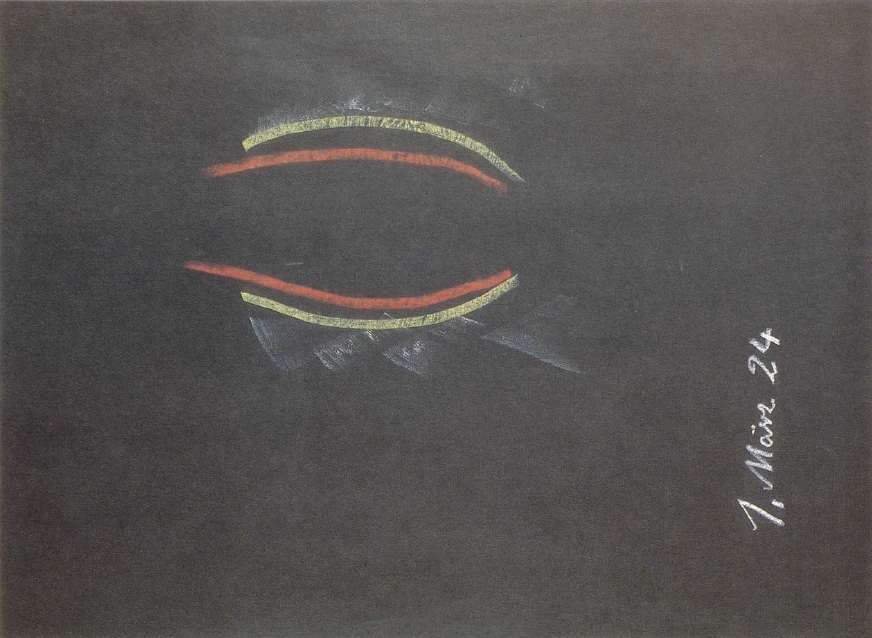

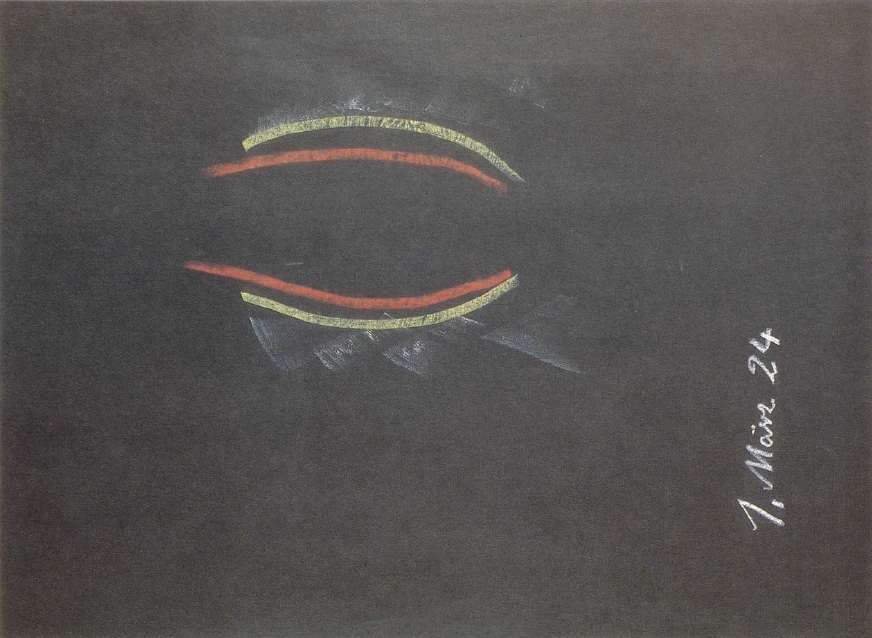

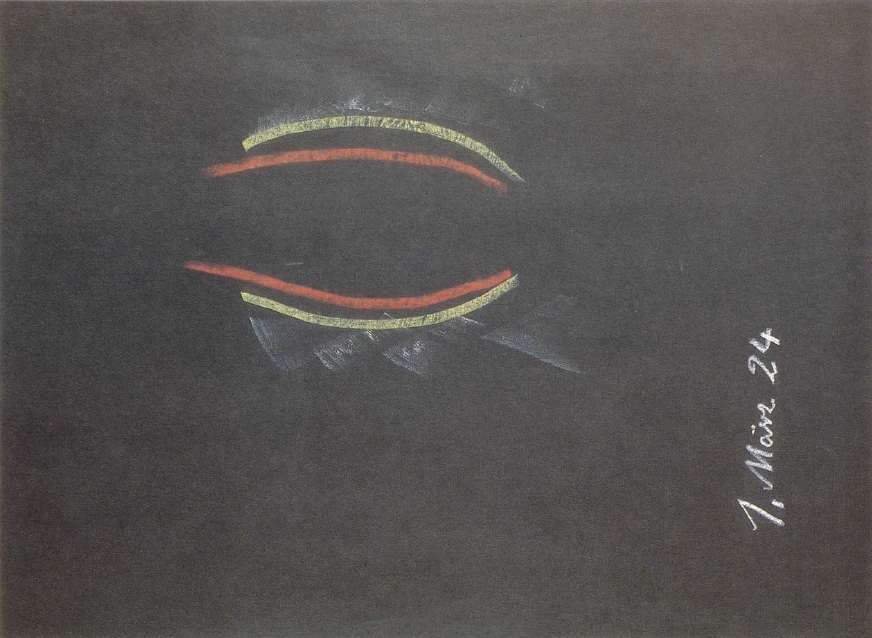

Will man das, was da eigentlich zugrunde liegt, schematisch zeichnen, so muß man es in der folgenden, die heutige Menschheit gewiß schockierenden Art tun. Man muß sagen: Der Mensch bekommt, indem er geboren wird, etwas mit wie ein Modell zu seiner Menschenform (siehe Zeichnung Seite 87, grün). Dieses Modell, das bekommt er von seinen Vorfahren. Sie geben ihm ein Modell mit. Und an diesem Modell entwickelt der Mensch dasjenige, was er später wird (rot). Das aber, was er da entwickelt, ist das Ergebnis dessen, was er aus geistigen Welten herunterträgt.

So schockierend es für einen heutigen Menschen auch sein kann, wenn er ganz in der Bildung der Gegenwart drinnensteckt, so muß man doch sagen: Die ersten Zähne, die der Mensch bekommt, sind ganz und gar vererbt, sind Vererbungsprodukte. Sie dienen ihm als Modell, nach dem er ausarbeitet — aber jetzt nach Maßgabe der Kräfte, die er sich herunterträgt aus der geistigen Welt — die zweiten Zähne; die arbeitet er sich aus.

So wie es mit den Zähnen ist, so ist es mit dem ganzen Organismus. Und die Frage könnte nur entstehen: Ja, warum brauchen wir als Menschen ein Modell? Warum können wir nicht einfach, wie es in älteren Phasen der Erdenentwickelung auch der Fall war, warum können wir nicht einfach, indem wir heruntersteigen und unseren Ätherleib an uns heranziehen — den ziehen wir ja durch unsere eigenen Kräfte heran, die wir heruntertragen aus der geistigen Welt -, warum können wir so nicht auch die physische Materie heranziehen und ohne physische Abstammung unseren physischen Leib formen?

Das ist natürlich für das Denken eines heutigen Menschen eine kolossal törichte Frage, eine verrückte Frage selbstverständlich. Aber nicht wahr, da muß man schon sagen: In bezug auf die Verrücktheit gilt schon einmal die Relativitätstheorie, wenn man auch die Relativitätstheorie zunächst heute nur auf Bewegungen anwendet und sagt, man kann für den Anblick nicht unterscheiden, ob man sich selber mit dem Körper, auf dem man sich befindet, bewegt, oder ob der Körper sich bewegt, der in der Nähe ist. Das ist deutlich hervorgetreten bei dem Übergang von der alten Welttheorie zur Kopernikanischen. Aber wenn man heute auch nur die Relativitätstheorie auf Bewegungen anwendet, so gilt sie - sie hat ja einen gewissen Geltungsbereich -, sie gilt schon in bezug auf diese angedeutete Verrücktheit: nämlich, da stehen zwei voneinander ab, der eine ist gegen den anderen verrückt. Es kommt nur darauf an, nicht wahr, wer absolut verrückt ist.

Nun, die Frage muß aber trotzdem aufgeworfen werden gegenüber den Tatsachen der geistigen Welt: Warum braucht der Mensch ein Modell? — Ältere Weltanschauungen haben in ihrer Art die Antwort darauf gegeben. Nur in der heutigen Zeit, wo man überhaupt die Moralität nicht mehr in die Weltenordnung einbezieht, sondern nur als menschliche Konvention gelten lassen will, da stellt man solche Fragen nicht. Ältere Weltanschauungen haben wohl diese Fragen gestellt und haben sie für sich sogar beantwortet. Ältere Weltanschauungen haben gesagt: Ursprünglich war der Mensch dazu veranlagt, sich in der Weise auf die Erde hereinzustellen, daß er ebenso wie er seinen Ätherleib aus der allgemeinen kosmischen Äthersubstanz heranzieht, so auch seinen physischen Leib sich bildet aus den Substanzen der Erde. Nur ist der Mensch den luziferischen und ahrimanischen Einflüssen verfallen, und dadurch hat er die Fähigkeit verloren, sich aus seiner Wesenheit heraus seinen physischen Leib aufzubauen, und muß ihn aus der Abstammung entnehmen.

Diese Art, zu einem physischen Leib zu kommen, ist für den Menschen das Ergebnis der Erbsünde. Das haben ältere Weltanschauungen gesagt, das ist die eigentliche Grundbedeutung der Erbsünde: hinein sich versetzen zu müssen in die Erbverhältnisse.

Für unsere Zeit müssen ja erst wieder die Begriffe herbeigeschafft werden, um erstens solche Fragen ernst zu nehmen, zweitens, um Antworten darauf zu finden. Es ist eben tatsächlich der Mensch innerhalb seiner Erdenentwickelung nicht so stark geblieben, als er veranlagt war, bevor die luziferischen und ahrimanischen Einflüsse da waren. Und so ist der Mensch darauf angewiesen, nicht sogleich beim Hereintreten in die Erdenverhältnisse sich seinen physischen Leib von sich aus zu bilden, sondern er braucht eben ein Modell, jenes Modell, welches heranwächst in den ersten sieben Lebensjahren. Da er sich nach diesem Modell richtet, so ist es natürlich, daß von diesem Modell auch im späteren Leben etwas an ihm bleibt, mehr oder weniger. Derjenige, der als Mensch, welcher an sich selber wirkt, ganz und gar vom Modell abhängig ist, der wird, wenn ich so sagen darf, vergessen, was er eigentlich heruntergebracht hat, und wird sich ganz nach dem Modell richten. Derjenige, der stärkere innere Kraft hat, durch seine früheren Erdenleben erworben, er wird sich weniger nach dem Modell richten, und man wird dann sehen können, wie er sich sehr bedeutend verändert gerade im zweiten Lebensalter zwischen dem Zahnwechsel und der Geschlechtsreife.

Die Schule wird sogar die Aufgabe haben, wenn sie eine rechte Schule ist, dasjenige im Menschen zur Entfaltung zu bringen, was er heruntergetragen hat aus den geistigen Welten in das physische Erdendasein. So daß also dasjenige, was der Mensch dann weiter im Leben mit sich trägt, mehr oder weniger die Vererbungsmerkmale enthält, je nachdem er sie überwinden kann oder nicht überwinden kann.

Nun, sehen Sie, meine lieben Freunde, alle Dinge habe ihre geistige Seite. Was der Mensch da hat als seinen Körper in den ersten sieben Lebensjahren, das ist eben einfach ein Modell, nach dem er sich richtet. Entweder es gehen seine geistigen Kräfte in einem gewissen Grade in dem unter, was ihm da durch das Modell aufgedrängt wird, und er bleibt ganz vom Modell abhängig, oder er arbeitet in den ersten sieben Lebensjahren durch das Modell dasjenige durch, was das Modell verändern will. Dieses Arbeiten, dieses Durcharbeiten findet seinen äußeren Ausdruck. Denn es handelt sich ja nicht bloß darum, daß da gearbeitet wird und daß dieses hier das ursprüngliche Modell ist; sondern das ursprüngliche Modell löst sich ja los, schuppt sich ab sozusagen, fällt ab, wie die ersten Zähne abfallen; alles fällt ab. (Siehe Zeichnung, hell.) Es handelt sich da wirklich darum, daß von der einen Seite die Formen, die Kräfte das Modell drücken; auf der anderen Seite will der Mensch ausprägen, was er heruntergebracht hat. Das gibt einen Kampf in den ersten sieben Lebensjahren. Vom geistigen Gesichtspunkte aus gesehen, bedeutet dieser Kampf dasjenige, was dann äußerlich symptomatisch in den Kinderkrankheiten zum Ausdrucke kommt. Kinderkrankheiten sind der Ausdruck dieses inneren Kampfes.

Es treten natürlich bei den Menschen ähnliche Formen des Erkranktseins auch später auf. Das ist dann der Fall, wenn die Sache zum Beispiel so ist, daß jemand in den ersten sieben Lebensjahren es nicht sehr gut dazu gebracht hat, das Modell zu überwinden. Dann kann in einem späteren Lebensalter ein innerer Drang auftauchen, nun doch das, was da karmisch in ihm geblieben ist, herauszubekommen. Er kann in seinem achtundzwanzigsten, neunundzwanzigsten Lebensjahre plötzlich innerlich aufgerüttelt werden, gegen das Modell nun erst recht anstoßen, und bekommt dann eine Kinderkrankheit.

Nun kann man schon, wenn man einen Blick dafür hat, sehen, wie bei manchen Menschenkindern das stark auftritt, daß sie sich nach dem siebenten, achten Jahre wesentlich ändern, ändern in der Physiognomie, ändern in den Gesten. Man weiß nicht, woher gewisse Dinge kommen. Heute, wo man in der allgemeinen Zivilisationsansicht so außerordentlich an der Vererbung hängt, ist das schon sogar in die Redensarten übergegangen. Plötzlich tritt im achten, neunten LebensJahre bei einem Kinde etwas auf, was sehr organisch begründet ist. Der Vater sagt: Na, von mir hat er das nicht. - Die Mutter sagt: Nun, von mir erst recht nicht! — Das rührt natürlich von dem allgemeinen Glauben heute her, der in das elterliche Bewußtsein übergegangen ist, daß die Kinder alles von den Eitern haben müßten.

Auf der anderen Seite ist ja auch das, daß dann auch gesehen werden kann, wie Kinder unter Umständen in diesem zweiten Lebensalter sogar ähnlicher werden ihren Eltern, als sie früher waren. Ja, aber da müssen Sie nur in ganz vollem Ernste nehmen, wie der Mensch herunterkommt in die physische Welt.

Sehen Sie, die Psychoanalyse hat manche wirklich schreckliche Sumpfblüte getrieben; unter anderem zum Beispiel auch das — Sie können es ja heute überall lesen —, daß im Geheimen, im Unterbewußten jeder Sohn in seine Mutter verliebt ist, oder jede Tochter in den Vater verliebt ist, und daß das Lebenskonflikte gäbe in den unterbewußten Provinzen der Seele.

Nun, das alles sind natürlich dilettantische Lebensinterpretationen. Was aber wahr ist, das ist, daß der Mensch, schon bevor er heruntersteigt zum irdischen Dasein, in seine Eltern verliebt ist, daß er heruntersteigt, weil sie ihm gefallen. Nur muß man natürlich das Urteil, das die Menschen hier auf Erden haben über das Leben, unterscheiden von dem Urteil, das die Menschen haben außer dem irdischen Leben, zwischen dem Tod und einer neuer Geburt, über das Leben.

Im Anfange des anthroposophischen Wirkens kam es einmal vor, daß eine Dame auftrat, die hörte von den wiederholten Erdenleben und erklärte: Nein, das andere an der Anthroposophie gefiele ihr zwar, aber die wiederholten Erdenleben wollte sie nicht mitmachen, sie habe genug an dem einen; die wiederholten Erdenleben, die wolle sie nicht mitmachen. — Nun, es waren ja dazumal auch schon sehr wohlmeinende Anhänger da, die haben sich auf alle mögliche Weise bemüht, der Dame klarzumachen, daß das doch eine richtige Idee ist, und daß jeder Mensch die wiederholten Erdenleben eben mitmachen muß. Sie konnte sich nicht dazu bereitfinden. Der eine hat links, der andere rechts in sie hineingeredet. Sie ist dann abgereist. Mir aber hat sie eine Postkarte geschrieben nach zwei Tagen, sie wolle nun doch nicht noch einmal auf der Erde geboren werden!

In einem solchen Falle muß derjenige, der eben einfach die Wahrheit aus der geistigen Erkenntnis heraus sagen will, das Folgende zu den Leuten sagen: Gewiß, es mag sein, daß Sie, während Sie hier auf Erden sind, gar keinen Geschmack daran finden, wiederum zur Erde herunterzusteigen in einem zukünftigen Leben. Aber das ist ja nicht maßgebend. Hier auf Erden gehen Sie zunächst durch die Pforte des Todes in die geistige Welt hinein. Das wollen Sie. Ob Sie wieder heruntersteigen wollen, das hängt von Ihrem Urteile dann ab, wenn Sie keinen Leib mehr an sich tragen. Da werden Sie schon ein anderes Urteil dann sich bilden. - Die Urteile sind eben durchaus verschieden, die der Mensch hier im physischen Dasein hat, und diejenigen, die er hat zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Es ändert sich da jeder Gesichtspunkt.

Und so ist es auch. Wenn Sie jetzt einem Menschen, einem jungen Menschen hier auf der Erde sagen, er habe sich seinen Vater gewählt, so könnte er ja unter Umständen immerhin einwenden: Wie aber, einen Vater, der mich so geprügelt hat, den soll ich mir gewählt haben? — Er hat sich ihn wirklich gewählt, weil er einen anderen Gesichtspunkt hatte, bevor er zur Erde heruntergestiegen ist. Da hatte er nämlich den Gesichtspunkt, daß die Prügel ihm sehr gut tun werden. Es ist das tatsächlich gar keine lächerliche Sache, es ist absolut tiefernst gemeint. Und so wählt sich der Mensch auch seine Eltern nach der Gestalt. Er hat das Bild für sich selbst vor sich, seinen Eltern ähnlich zu werden. Er wird dann nicht durch Vererbung ähnlich, sondern durch seine inneren geistig-seelischen Kräfte, die er sich gerade aus der geistigen Welt herunterbringt. Deshalb sind in dem Augenblicke, wo man allseitig, aus der geistigen und aus der physischen Wissenschaft heraus urteilt, solche Urteile in Bausch und Bogen nicht mehr möglich, daß man sagt: Ich habe auch schon Kinder gesehen, die wurden erst in ihrem zweiten Lebensalter ihren Eltern ähnlicher. Gewiß, da liegt eben dann der andere Fall vor, daß diese Kinder sich als Ideal vorgesetzt haben, die Gestalt ihrer Eltern anzunehmen.

Nun handelt es sich darum, daß der Mensch im Grunde genommen die ganze Zeit zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt im Vereine mit anderen verstorbenen Seelen und im Vereine mit den Wesenheiten der höheren Welten an demjenigen arbeitet, was ihm die Möglichkeit bringt, sich seinen Körper aufzubauen.

Sehen Sie, man unterschätzt das, was der Mensch im Unterbewußten trägt, gar sehr. Man ist im Unterbewußten viel weiser als im Oberbewußten als Erdenmensch. Man arbeitet schon aus einer weitgehenden universellen Weltenweisheit dasjenige aus, was sich innerhalb des Modells dann im zweiten Lebensalter zu dem ausgestaltet, was man nun als seinen eigentlichen, einem zugehörigen Menschen an sich trägt. Wird man einmal wissen, wie wenig der Mensch eigentlich in bezug auf seine Körpersubstanz aufnimmt aus dem, was er ißt — wie er viel mehr entnimmt dem, was er aus Luft und Licht und so weiter aufnimmt in außerordentlich fein verteiltem Zustande -, dann wird man auch eher glauben können, daß der Mensch sich ganz unabhängig von allen Vererbungsverhältnissen seinen zweiten Körper für das zweite Lebensalter ganz und gar aus der Umgebung aufbaut. Der erste Körper ist tatsächlich nur ein Modell, und dasjenige, was den Eltern entstammt, substantiell und auch den äußeren körperlichen Kräften nach, das ist nicht mehr da im zweiten Lebensalter.

Das Verhältnis zu den Eltern wird ein moralisch-seelisches im zweiten Lebensalter, und es ist ein physisches Vererbungsverhältnis nur im ersten Lebensalter bis zum siebenten Lebensjahre.

Nun, es gibt ja auch noch in diesem Erdenleben Menschen, die haben ein ganz reges Interesse für alles, was im sichtbaren Kosmos um sie herum ist. Es sind Menschen, die beobachten Pflanzen, beobachten die Tierwelt, sie haben Anteil, Interesse an dem und jenem, was in der sichtbaren Umwelt ist. Sie haben Interesse für die Erhabenheit des gestirnten Himmels. Sie sind sozusagen mit ihrer Seele beim ganzen physischen Kosmos dabei. Das Innere eines Menschen, der ein solches warmes Interesse für den physischen Kosmos hat, ist ja anders als das Innere eines Menschen, der mit einer gewissen Gleichgültigkeit, mit einem seelischen Phlegma an der Welt vorbeigeht.

Es gibt wirklich in dieser Beziehung die ganze Skala von Menschencharakteren. Auf der einen Seite, nicht wahr, hat einer eine ganz kurze Reise gemacht. Man redet nachher mit ihm. Er beschreibt einem die Stadt, in der er gewesen ist, mit einer unendlichen Liebe bis in die Kleinigkeiten hinein. Man bekommt unter Umständen deshalb, weil er so starkes Interesse gehabt hat, eine völlige Vorstellung von dem, wie es in der Stadt, wo er war, ausgesehen hat. Von diesem Extrem geht es bis zu dem anderen herunter, wie zum Beispiel jenem, wo ich einmal zwei ältere Damen getroffen habe, die von Wien nach Preßburg gereist waren. Preßburg ist eine schöne Stadt. Sie waren wiederum zurückgekommen. Ich fragte sie, wie es in Preßburg ausschaut, wie es ihnen gefallen hat. Nichts wußten sie zu erzählen, als daß sie am Strande zwei schöne Dackerln gesehen hätten! - Die hätten sie in Wien auch sehen können, sie hätten dazu nicht gebraucht nach Preßburg zu fahren. Aber sie haben eben nichts anderes gesehen.

So gehen manche Menschen durch die Welt. Zwischen diesen beiden äußersten Vertretern der Skala liegt ja jede Art von Interesse, die der Mensch für dasjenige haben kann, was die physisch sichtbare Welt ist.

Nehmen wir an, ein Mensch hat wenig Interesse für die umliegende physische Welt. Er interessiert sich meinetwillen gerade noch für das, was unmittelbar seine Körperlichkeit angeht, für die Art und Weise meinetwillen, ob man in irgendeiner Gegend gut oder schlecht ißt oder dergleichen, aber darüber hinaus gehen seine Interessen nicht. Seine Seele bleibt arm. Er trägt die Welt nicht in sich. Und er trägt wenig von dem, was die Erscheinungen der Welt ihm entgegengeleuchtet haben, durch die Pforte des Todes mit seinem Inneren hinüber in die geistige Welt. Dadurch wird ihm das Arbeiten drüben mit den geistigen Wesenheiten, mit denen er jetzt zusammen ist, schwer. Dadurch bringt er aber auch nicht Stärke, nicht Energie, sondern Schwäche, eine Art von Ohnmacht in seiner Seele mit für den Aufbau seines physischen Leibes. Das Modell wirkt schon stark auf ihn ein. Der Kampf mit dem Modell drückt sich in allerlei Kinderkrankheiten aus, aber dieSchwäche bleibt ihm. Er bildet gewissermaßen einen zerbrechlichen Leib, der allen möglichen Krankheiten ausgesetzt ist. So verwandelt sich karmisch seelisch-geistiges Interesse aus dem einen Erdenleben in die Gesundheitslage eines nächsten Erdenlebens. Diejenigen Menschen, die vor Gesundheit strotzen, die haben zunächst in einem früheren Erdenleben ein reges Interesse für die sichtbare Welt gehabt. Und in dieser Beziehung wirken wirklich die Einzeltatsachen des Lebens außerordentlich stark.

Gewiß, es ist ja, ich möchte sagen, mehr oder weniger riskiert heute, über diese Dinge zu sprechen; aber verstehen wird man die Zusammenhänge des Karma doch nur, wenn man geneigt ist, Einzelheiten über das Karma aufzunehmen. Es hat ja auch in der Zeit zum Beispiel, in der die Menschenseelen, die heute da sind, in einem früheren Erdenleben gelebt haben, schon Malerei gegeben, und es hat Menschen gegeben, welche an dieser Malerei kein Interesse hatten. Es gibt ja heute auch Menschen, denen es ganz gleichgültig ist, ob sie irgendeine malerische Scheußlichkeit an der Wand hängen haben oder irgendein sehr gut gemaltes Bild. So hat es auch in der Zeit, in der die Seelen, die heute leben, in früheren Erdenleben vorhanden waren, solche Menschen gegeben. Ja, sehen Sie, meine lieben Freunde, ich habe niemals einen Menschen gefunden, der ein sympathisches Gesicht hat, einen sympathischen Gesichtsausdruck hat, der nicht seine Freude an der Malerei in einem früheren Erdenleben gehabt hat. Menschen mit unsympathischem Gesichtsausdrucke - was ja auch im Karma des Menschen eine Rolle spielt, was für das Schicksal eine Bedeutung hat waren immer solche, die stumpf und gleichgültig, phlegmatisch an Bildwerken vorbeigegangen sind.

Aber es gehen die Dinge viel weiter. Es gibt Menschen, die ihr ganzes Leben hindurch — und das war auch schon in früheren Erdenaltern der Fall - niemals zu den Sternen aufsahen, die nicht wissen, wo der Löwe oder der Widder oder der Stier ist, die sich für gar nichts in dieser Richtung interessieren. Diese Menschen werden in einem nächsten Erdenleben mit einem irgendwie schlaffen Körper geboren, beziehungsweise wenn sie durch die Stärke ihrer Eltern noch das Modell bekommen, das sie darüber hinwegführt, werden sie an dem Körper, den sie sich dann selber aufbauen, schlaff, kraftlos.

Und so könnte man den ganzen Gesundheitszustand des Menschen, den er in irgendeinem Erdenleben trägt, zurückführen auf die Interessen, die er im früheren Erdenleben an der sichtbaren Welt in ihrem weitesten Umfange genommen hat.

Menschen, welche in unserer heutigen Zeit zum Beispiel absolut kein Interesse für Musikalisches haben, denen das Musikalische gleichgültig ist, die werden ganz sicher in einem nächsten Erdenleben entweder asthmatisch oder mit Lungenkrankheiten wiedergeboren werden, beziehungsweise für Lungenkrankheiten oder Asthma geeignet geboren werden. Es ist tatsächlich so, daß sich dasjenige Seelische, das sich ausbildet in einem Erdenleben durch das Interesse an der sichtbaren Welt, in der Gesundheits- oder Krankheitsstimmung des Körpers im nächsten Erdenleben zum Ausdrucke bringt.

Vielleicht könnte jetzt jemand sagen: Das zu wissen, könnte einem schon den Geschmack an dem folgenden Erdenleben nehmen. — Aber das ist wiederum solch ein Urteil, das man vom Erdenstandpunkte aus fällt, der ja wirklich nicht der einzige ist, denn das Leben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt dauert länger als das Erdenleben. Wenn jemand stumpf ist für irgend etwas Sichtbares in seiner Umgebung, dann bleibt er in der Unfähigkeit, auf gewissen Gebieten zu arbeiten zwischen Tod und einer neuen Geburt, und er ist nun durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen, sagen wir, mit den Folgen der Interesselosigkeit. Er geht weiter nach dem Tode. Er kommt nicht heran an gewisse Wesenheiten. Gewisse Wesenheiten halten sich von ihm zurück, weil er nicht an sie heran kann. Andere Menschenseelen, mit denen er auf der Erde zusammen war, bleiben ihm fremd. Das würde ewig dauern, es würde eine Art Ewigkeit der Höllenstrafen geben, wenn es nicht abgeändert werden könnte. Daß der Mensch nun beschließt zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, ins irdische Leben herunterzusteigen und das, was ein Unvermögen ist in der geistigen Welt, nun auch zu fühlen an dem erkrankten Leibe, das ist der einzige Ausgleich, das ist die einzige Kur. Diese Kur wünscht man zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, denn zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt hat man nur das: Man kann etwas nicht; aber man fühlt es nicht. So daß dann im weiteren Verlauf, wenn man wieder stirbt und wiederum geht durch die Zeit zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, das, was irdischer Schmerz war, der Antrieb ist, nun hereinzukommen in dasjenige, was man versäumt hat. So kann man sagen, der Mensch trägt sich im wesentlichen Gesundheit und Krankheit mit seinem Karma aus der geistigen Welt in die physische Welt herunter.

Und wenn man dabei berücksichtigt, daß es nicht immer ein sich erfüllendes, sondern auch ein werdendes Karma gibt, daß gewisse Dinge auch zum ersten Mal auftreten können, dann wird man natürlich nicht alles, was der Mensch, sagen wir, von gesundheitlicher oder Krankheitsseite zu erleiden hat im physischen Leben, auf die früheren Erdenleben beziehen. Aber man wird wissen, daß durchaus dasjenige, was namentlich von innen heraus veranlagt auftritt in bezug auf Gesundheits- und Krankheitsverhältnisse, auf dem Umwege, den ich eben charakterisiert habe, karmisch bestimmt ist. Die Welt wird eben erst erklärlich, wenn man über das Erdenleben hinaus zu sehen vermag. Vorher ist sie nicht erklärlich. Aus dem Erdenleben ist die Welt nicht erklärlich.

Und wenn wir von diesen inneren Bedingungen des Karma, die aus der Organisation folgen, mehr nach dem Äußerlichen, nach dem Äußeren gehen, so können wir wiederum, ich möchte sagen, nur um zunächst das Thema anzuschlagen, ausgehen von einem den Menschen nahe berührenden Tatsachengebiet. Nehmen wir zum Beispiel dasjenige, was nun seelisch sehr stark mit der allgemeinen seelischen Gesundheits- und Krankheitsstimmung zusammenhängen kann im Verhältnis zu anderen Menschen.

Ich will den Fall setzen, jemand findet einen Jugendfreund. Es bildet sich eine innige Jugendfreundschaft heraus. Die Menschen hängen sehr aneinander. Das Leben führt sie auseinander, so daß vielleicht bei beiden, vielleicht bei einem besonders, mit einer gewissen Wehmut zurückgesehen wird auf die Jugendfreundschaft. Aber sie läßt sich nicht wieder herstellen, so oft man sich im Leben auch trifft, die Jugendfreundschaft stellt sich nicht wieder her. Wenn Sie bedenken, wieviel unter Umständen von solch einer zerbrochenen Jugendfreundschaft schicksalsmäßig abhängen kann, dann werden Sie doch sich sagen, das Schicksal des Menschen kann tiefgehend beeinflußt sein von solch einer zerbrochenen Jugendfreundschaft.

Man sollte eigentlich möglichst wenig über solche Dinge aus der Theorie heraus reden. Das aus der Theorie heraus Reden hat eigentlich keinen besonderen Wert. Man sollte über diese Dinge im Grunde genommen nur reden entweder aus der unmittelbaren Anschauung heraus oder auf Grundlage dessen, was man mündlich oder schriftlich vernommen hat von demjenigen, der eine solche unmittelbare Anschauung haben kann, und was einem plausibel erscheint, begreiflich ist. Das Theoretisieren über diese Dinge hat keinen Wert. Deshalb will ich sagen, wo man sich bemüht, mit geistiger Anschauung hinter so etwas zu kommen wie eine zerbrochene Jugendfreundschaft, da stellt sich das Folgende heraus.

Geht man in ein früheres Erdenleben zurück, so findet man in der Regel, daß die beiden Menschen, die Jugendfreundschaft in einem Leben hatten, welche dann zerbrochen ist, daß diese in einem früheren Erdenleben eine Freundschaft im späteren Leben hatten.

Also nehmen wir an, zwei Menschen sind Jugendfreunde oder Jugendfreundinnen bis zu ihrem zwanzigsten Lebensjahre, dann zerbricht die Jugendfreundschaft. Geht man nun mit Geisteserkenntnis zurück in ein früheres Erdenleben, so findet man, da war eine Freundschaft zwischen den beiden Leuten auch vorhanden, aber die hat etwa im zwanzigsten Jahre begonnen und ging ins spätere Leben hinauf. Das ist ein sehr interessanter Fall, den man oftmals findet, wenn man den Dingen geisteswissenschaftlich nachgeht.

Zunächst stellt sich dann, wenn man die Fälle genauer prüft, dieses ein, daß der Drang, den Menschen, mit dem man eine Freundschaft in älteren Jahren hatte, nun auch so kennenzulernen, wie er in der Jugend sein kann, einen im nächsten Leben dazu führt, ihn wirklich als Jugendfreund kennenzulernen. Man hat ihn als älteren Menschen in einem vorigen Erdenleben gekannt; das hat den Drang in die Seele gebracht, ihn nun auch in der Jugend kennenzulernen. Das kann man nicht mehr in diesem Leben, so macht man es im nächsten Leben.

Aber das hat einen großen Einfluß, wenn in einem von den beiden oder in den beiden dieser Drang entsteht, durch den Tod geht und dann zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt sich auslebt in der geistigen Welt. Denn dann ist in der geistigen Welt etwas da wie ein Hinstarren auf die Jugend. Man hat diese ganz besondere Sehnsucht, auf die Jugend hinzustarren, und man bildet nicht den Drang aus, den Menschen auch wiederum im Alter kennenzulernen. Und so zerbricht die Jugendfreundschaft, die vorbestimmt war aus dem Leben, das man durchlebt hat, bevor man auf die Erde herabgestiegen ist.

Nun, es ist das durchaus ein Fall, den ich Ihnen aus dem Leben erzähle. Das, was ich Ihnen erzähle, ist durchaus etwas, was real ist. Es entsteht nur jetzt die Frage: Ja, wie war denn eigentlich im vorigen Leben die ältere Freundschaft, so daß sie nun diesen Drang entstehen ließ, den Menschen in der Jugend wiederum zu haben in einem neuen Erdenleben?

Nun, damit sich dieser Trieb, den Menschen in der Jugend zu haben, nicht dennoch dazu auswächst, dann den Jugendfreund im Alter weiter zu haben, muß irgend etwas anderes im Leben eintreten. In all den Fällen, die mir bewußt sind, ist es dann immer so gewesen, daß, wären diese Menschen in einem späteren Leben vereinigt geblieben, wäre die Jugendfreundschaft nicht zerbrochen, so würden sie einander überdrüssig geworden sein, weil sie die Freundschaft in einem früheren Leben, die eine Altersfreundschaft war, zu egoistisch ausgebildet haben. Der Egoismus von Freundschaften in einem Erdenleben rächt sich karmisch in dem Verlust dieser Freundschaften in anderen Erdenleben. So sind die Dinge kompliziert. Aber man bekommt immer einen Leitfaden, wenn man eben sieht: Es ist in vielen Fällen dies vorhanden, daß zwei Menschen in einem Erdenleben, sagen wir, bis zu ihrem zwanzigsten Lebensjahr ihr Leben für sich und dann weiter in Freundschaft gehen (siehe Zeichnung I). In einem nächsten Erdenleben entspricht gewöhnlich diesem Bilde dann das andere (II), es entspricht diesem anderen die Jugendfreundschaft, und dann geht das Leben auseinander. Das ist sehr häufig der Fall. Wie denn überhaupt das gefunden wird, daß sich die einzelnen Erdenleben, ich möchte sagen, ihrer Konfiguration nach angesehen, gegenseitg ergänzen.

Besonders das wird häufig gefunden: Trifft man einen Menschen, der auf das Schicksal einen starken Einfluß hat — die Dinge gelten natürlich nur in der Regel, sind nicht für alle Fälle gültig --, aber trifft man einen Menschen im mittleren Lebensalter in einer Inkarnation, so hat man ihn unter Umständen am Anfange und am Ende des Lebens in einer vorigen Inkarnation schicksalsmäßig neben sich gehabt. Dann ist das Bild so: Man durchlebt Anfang und Ende in der einen Inkarnation mit dem anderen Menschen zusammen, und in einer anderen Inkarnation durchlebt man Anfang und Ende nicht, aber man trifft ihn gerade in der Mitte des Lebens.

Oder aber es stellt sich so heraus, daß man als Kind an irgendeinen Menschen gebunden ist schicksalsmäßig. In einem vorigen Erdenleben war man gerade, bevor man zu Tode ging, mit demselben Menschen verbunden. Solche Spiegelungen finden in den schicksalsmäßigen Zusammenhängen außerordentlich häufig statt.

Fifth Lecture

When one speaks of karma in detail, one must of course first distinguish between the karmic events that approach the human being more from the outside and those that rise from within the human being, so to speak.

A person's destiny is made up of the most diverse factors. Man's destiny depends on his physical and etheric constitution, man's destiny depends on the sympathy and antipathy he can show to the outside world according to his astral and ego constitution, on the sympathy and antipathy that can be shown to him according to his constitution; man's destiny depends in turn on the most varied entanglements and entanglements in which man becomes entangled on his path through life. All of this results in a person's fate at any given time or in sum for his entire life.

Now I will try to put together the overall destiny of man from the individual factors. To do this, let us take certain inner factors in the human being as our starting point today, let us look at the factor that is really decisive in many respects in the first place, the human being's state of health or illness, and that which then comes into effect as the basis for the human being's state of health and illness in his physical and spiritual strength, with which he can fulfill his tasks and so on.

But if one wants to judge these factors in the right way, then one must be able to overlook much of what is contained in today's prejudices of civilization. One must be able to look more closely at the original nature of man, must really gain insight into what it actually means that man descends from spiritual worlds to physical earthly existence according to his deeper nature.

Now you know that today that which is subsumed under the concept of heredity has already entered into art, into poetry for example. And when someone appears in the world with certain characteristics, one first asks about heredity. When someone appears with a predisposition to disease, one asks: What about the hereditary relationships?

It is certainly a perfectly legitimate question at first. But the way we look at these things today, we are actually looking past the person. We completely ignore the human being. We do not look at what man's true nature actually is and how this nature unfolds. One says, of course, that man is first of all the child of his parents, the descendant of his ancestors. Certainly, you can see that too. You can already see it in the outward physiognomy, perhaps even more in the gestures, you can see the resemblance to the ancestors. But not only that. You can also see how the human being's physical organism is the product of what the ancestors gave him. He carries this physical organism with him. And today it is strongly, very strongly pointed out that man carries this physical organism with him.

The following is not taken into account. When a human being is born, he certainly has his physical organism from his parents. But what is this physical organism that he has from his parents? In today's civilization, people basically think about this in the wrong way.

When a human being changes teeth, he not only exchanges the teeth he first got for others, but this is the time in human life when the whole human being renews itself as an organization for the first time.

Now there really is a profound difference between what man becomes in his eighth or ninth year and what he was, for example, in his third or fourth year. It is a profound difference. That which he was as an organization in his third or fourth year was inherited, it was given to him by his parents. That which becomes and first appears in the eighth, ninth year of life emerges to the highest degree from that which the human being has carried down from the spiritual world.

If you want to describe schematically what actually underlies this, you have to do it in the following way, which is certainly shocking to mankind today. It must be said that when man is born, he receives something like a model for his human form (see drawing on page 87, green). He gets this model from his ancestors. They give him a model. And it is from this model that man develops what he later becomes (red). But what he develops there is the result of what he carries down from spiritual worlds.

As shocking as it can be for a person today, when he is completely immersed in the education of the present, it must be said that the first teeth that a person gets are completely inherited, are products of heredity. They serve him as a model after which he works out - but now according to the forces that he carries down from the spiritual world - the second teeth; he works them out for himself.

As it is with the teeth, so it is with the whole organism. And the question could only arise: Yes, why do we as humans need a model? Why can we not simply, as was the case in older phases of earthly development, why can we not simply, by descending and drawing our etheric body to us - which we draw through our own forces that we carry down from the spiritual world - why can we not also draw physical matter and form our physical body without physical descent?

This is of course a colossally foolish question for the thinking of a modern human being, a crazy question of course. But isn't it true that the theory of relativity applies in relation to craziness, even if today the theory of relativity is initially only applied to movements and says that we cannot distinguish for sight whether we ourselves are moving with the body on which we are located or whether the body that is nearby is moving. This became clear during the transition from the old world theory to the Copernican theory. But even if you only apply the theory of relativity to movements today, it is valid - it does have a certain range of validity - it is already valid in relation to this implied madness: namely, two bodies stand apart from each other, one is mad in relation to the other. It only depends, doesn't it, on who is absolutely mad?

Now, the question must nevertheless be raised in relation to the facts of the spiritual world: Why does man need a model? - Older world views have given the answer in their own way. Only in the present day, where morality is no longer included in the world order at all, but is only accepted as a human convention, such questions are not asked. Older worldviews probably asked these questions and even answered them for themselves. Older world views have said: Originally, man was predisposed to place himself on earth in such a way that, just as he draws his etheric body from the general cosmic etheric substance, he also forms his physical body from the substances of the earth. But man has fallen prey to the Luciferic and Ahrimanic influences, and as a result he has lost the ability to build his physical body out of his essence and must take it from his ancestry.

This way of coming to a physical body is the result of original sin for man. This is what older worldviews said, this is the actual basic meaning of original sin: to have to put oneself into the hereditary relationships.

For our time, we first have to find the concepts again, firstly to take such questions seriously, and secondly to find answers to them. It is true that man has not remained as strong in his earthly development as he was before the Luciferic and Ahrimanic influences were present. And so the human being is not dependent on forming his physical body of his own accord as soon as he enters into earthly relationships, but he needs a model, the model that grows up in the first seven years of life. Since he orients himself according to this model, it is natural that something of this model remains with him in later life, more or less. The person who, as a person who works on himself, is entirely dependent on the model, will, if I may say so, forget what he has actually brought down and will orient himself entirely towards the model. He who has stronger inner strength, acquired through his earlier lives on earth, will be less dependent on the model, and you will then be able to see how he changes very significantly, especially in the second age between the change of teeth and sexual maturity.

The school will even have the task, if it is a real school, to bring to development in man that which he has carried down from the spiritual worlds into the physical earthly existence. So that what the human being then carries with him further in life contains more or less of the hereditary characteristics, depending on whether he can or cannot overcome them.

Now, you see, my dear friends, all things have their spiritual side. What man has as his body in the first seven years of his life is simply a model that he follows. Either his spiritual powers are submerged to a certain extent in what is imposed on him by the model, and he remains completely dependent on the model, or he works through the model in the first seven years of life to change what the model wants to change. This work, this working through, finds its external expression. For it is not merely a question of working and that this is the original model; but the original model detaches itself, flakes off, so to speak, falls off, as the first teeth fall off; everything falls off. (See drawing, light.) It is really a question of the forms, the forces pressing the model from one side; on the other side the human being wants to express what he has brought down. There is a struggle in the first seven years of life. Seen from the spiritual point of view, this struggle means that which then finds outward symptomatic expression in childhood illnesses. Childhood illnesses are the expression of this inner struggle.

Of course, similar forms of illness also occur in people later on. This is the case, for example, when someone has not managed to overcome the model very well in the first seven years of life. Then, at a later age, an inner urge may arise to get rid of what has remained in him karmically. In his twenty-eighth or twenty-ninth year, he can suddenly be shaken up inwardly, push against the model all the more, and then get a childhood illness.

Now, if you have an eye for it, you can already see how strongly this occurs in some human children, that they change considerably after the seventh, eighth year, change in physiognomy, change in gestures. One does not know where certain things come from. Today, when the general view of civilization is so strongly attached to heredity, this has even become part of the idiom. Suddenly, in the eighth or ninth year of a child's life, something occurs that is very organically based. The father says: Well, he didn't get it from me. - The mother says: Well, certainly not from me! - Of course, this stems from the general belief today, which has passed into the parental consciousness, that children should have everything from their parents.

On the other hand, it is also possible to see how children in this second age may even become more like their parents than they used to be. Yes, but you only have to take it very seriously how a person descends into the physical world.

You see, psychoanalysis has produced some really horrible quagmires; among other things, for example - you can read it everywhere today - that in secret, in the subconscious, every son is in love with his mother, or every daughter is in love with her father, and that this gives rise to life conflicts in the subconscious provinces of the soul.

Now, of course, these are all amateurish interpretations of life. But what is true is that man, even before he descends to earthly existence, is in love with his parents, that he descends because he likes them. Only, of course, one must distinguish the judgment that people have here on earth about life from the judgment that people have outside of earthly life, between death and a new birth, about life.

In the early days of anthroposophical work it once happened that a lady appeared who heard about the repeated earth lives and declared: No, she liked the other aspects of anthroposophy, but she did not want to take part in the repeated earth lives, she had had enough of the one; she did not want to take part in the repeated earth lives. - Well, at that time there were already very well-meaning followers who tried in every possible way to make the lady realize that this was a correct idea after all, and that every human being must take part in the repeated earth lives. She was not prepared to do so. One talked into her on the left, the other on the right. She then left. But after two days she wrote me a postcard saying that she didn't want to be born on earth again after all!

In such a case, the person who simply wants to tell the truth out of spiritual knowledge must say the following to the people: Certainly, it may be that while you are here on earth, you have no taste for descending to earth again in a future life. But that is not decisive. Here on earth you first go through the gate of death into the spiritual world. That is what you want. Whether you want to descend again depends on your judgment when you no longer have a body. You will form a different judgment then. - The judgments that man has here in physical existence and those that he has between death and a new birth are quite different. Every point of view changes.

And so it is. If you now tell a person, a young person here on earth, that he has chosen his father, he could possibly object: But how could I have chosen a father who beat me like that? - He really chose him because he had a different point of view before he descended to earth. He had the idea that the beating would do him a lot of good. It's actually not a ridiculous thing at all, it's meant to be absolutely serious. And so man also chooses his parents according to their image. He has the image before him of becoming like his parents. He does not become similar through heredity, but through his inner spiritual-soul forces, which he brings down from the spiritual world. Therefore, at the moment when one judges from all sides, from spiritual and physical science, it is no longer possible to make such sweeping judgments as to say: "I have also seen children who only became more like their parents in their second age. Of course, there is the other case where these children have set themselves the ideal of taking on the form of their parents.

Now it is a matter of the fact that man basically works the whole time between death and a new birth in union with other deceased souls and in union with the beings of the higher worlds on that which brings him the possibility of building up his body.

You see, people greatly underestimate what they carry in their subconscious. One is much wiser in the subconscious than in the superconscious as an earthling. One already works out from a far-reaching universal wisdom of the world that which then develops within the model in the second age into that which one now carries about oneself as one's actual human being. Once you know how little man actually takes in in terms of his bodily substance from what he eats - how much more he takes in from what he absorbs from air and light and so on in an extraordinarily finely distributed state - then you will also be able to believe more readily that man builds up his second body for the second age entirely from his surroundings, quite independently of all hereditary relationships. The first body is in fact only a model, and that which originates from the parents, both substantially and in terms of external physical forces, is no longer there in the second age.

The relationship to the parents becomes a moral-spiritual one in the second age, and it is a physical hereditary relationship only in the first age up to the seventh year of life.

Now, there are still people in this earthly life who have a very lively interest in everything that is around them in the visible cosmos. There are people who observe plants, observe the animal world, they have an interest in this and that which is in the visible environment. They are interested in the sublimity of the starry sky. They are, so to speak, involved with their soul in the entire physical cosmos. The inner being of a person who has such a warm interest in the physical cosmos is different from the inner being of a person who passes by the world with a certain indifference, with a spiritual phlegm.