Karmic Relationships II

GA 236

27 May 1924, Dornach

Lecture V

We have now studied a number of examples showing how destiny unfolds, examples which can explain and illumine the life and history of mankind. The purpose of these studies has been to show that individuals themselves carry into later epochs of earthly existence what they have experienced and assimilated in earlier times. Connections have come to light which enable us to understand how certain decisive actions of men have their roots in moral causes created by themselves in the course of the ages.

It is not this kind of causal connection only that the study of karma can disclose to us. Many other things, too, become intelligible, which to external observation seem at first obscure and incomprehensible. But if we are to participate in the great change in thinking and perception that is essential in the near future if civilisation is to progress and not fall into decline, it is incumbent upon us to develop, in the first place, a sense for what in ordinary circumstances is beyond our grasp and the understanding of which requires insight into the deeper relationships of existence. A man who finds everything comprehensible may, of course, see no need to know anything of more deeply lying causes. But to find everything in the world comprehensible is a sign of illusion and merely indicates superficiality. In point of fact the vast majority of things in the world are incomprehensible to the ordinary consciousness. To be able to stand in wonder before so much that is incomprehensible in everyday life—that is really the beginning of a true striving for knowledge.

A call that has so often gone out from this platform is that anthroposophists shall have enthusiasm in their seeking, enthusiasm for what is implicit in Anthroposophy. And this enthusiasm must take its start from a realisation of the wonders confronting us in everyday life. Only then shall we be led to reach out to the causes, to the deeper forces underlying existence around us.

This attitude of wonder towards the surrounding world can spring both from contemplation of history and from observation of what is immediately present. How often our attention is arrested by events in history which seem to indicate that human life here and there has lost all rhyme and reason. And human life does indeed lose meaning if we focus our attention upon a single event in history and omit to ask: How do certain types of character emerge from this event? What form will they take in a later incarnation? ... If such questions remain unasked, certain events in history seem to be entirely meaningless, irrelevant, pointless. They lose meaning if they cannot become impulses of soul in a subsequent life on earth, find their balance and then work on into the future.

Now there is certainly something that really does not make sense in the phenomenon of a personality such as the Roman Emperor Nero. No reference has yet been made to Nero in lectures in the Anthroposophical Movement.

Think of all that history recounts of Nero. In face of such a personality it seems as if life could be mocked and scorned with impunity, as if the utterly flippant disregard for life displayed by one in a position of great power and authority, brought no consequences. Anyone hearing of Nero's deeds must be dull-witted if he is not driven to ask: What becomes of a soul such as this, who scorns the whole world, who regards the life of other men, nay even the existence of a whole city, as something he can play with? “What an artist is lost in me!” is a saying attributed to Nero, and it seems to be in line with his whole attitude and tenor of mind. Utmost flippancy, an intense desire and urge for destruction, acknowledged even by himself—and the soul actually taking pleasure in it all!

One can only be repelled by the story, for here is a personality who literally radiates destruction. And the question forces itself upon us: What becomes of such a soul?

Now we must be quite clear on this point: Whatever is discharged, as it were, upon the world, is reflected in the life between death and a new birth, and discharged in turn upon the soul who has been responsible for the destruction. A few centuries later, that is to say, a comparatively short time afterwards, Nero appeared again in the world in an unimportant form of existence. During this incarnation a certain balance was brought about in respect of the mania for destruction, the enthusiasm for destruction in which he had indulged as a ruler, simply out of an inner urge. In that next life on earth something of this was balanced out, for the same individuality was now in a position where he was obliged to destroy; he was in a subordinate position, acting under orders. The soul had now to realise what it is like when such acts are not committed out of free will while in a position of supreme power.

Matters of this kind must be studied quite objectively and all emotion avoided—that is absolutely essential. In a certain respect, such a destiny calls for pity—for to be as cruel as Nero, to have a mania for destruction as great as his, is, after all, a destiny. There is no need for hatred or censure; moreover such an attitude would prevent one from experiencing all that is required in order to understand the further developments. Insight into the things that have been spoken of here is possible only when they are looked at objectively, when no hostile judgment is passed but when human destiny is really understood. Things disclose themselves quite clearly, provided one has the faculty for understanding them ... That this Nero-destiny came vividly before me on one occasion was attributable to what seemed to be chance—but it was only seemingly chance.

One day, when a terrible event had occurred, an event of which I shall speak in a moment and which had a shattering effect throughout the region concerned, I happened to be visiting a person frequently mentioned in my autobiography: Karl Julius Schröer. When I arrived I found him profoundly shocked, as numbers were, by what had happened. And the word “Nero” fell from his lips—apparently without reason—as though it burst from dark depths of the spirit. To all appearances the word came entirely out of the blue. But later on it became quite clear that in reality the Akashic Record was here being voiced through human lips. The event referred to was the following.—

The Austrian Crown Prince had always been acclaimed as a brilliant personality, and great hopes were entertained for the time when he would ascend the Throne. Although all kinds of things were known about the behaviour of the Crown Prince Rudolf, they were accepted as almost inevitable in the case of one of such high rank; nobody dreamt for a moment that the things told about him might lead to any serious, tragic conflicts. It was therefore an overwhelming shock when it became known in Vienna that the Crown Prince Rudolf had met his death in mysterious circumstances near the Convent of the Holy Cross, outside Baden, near Vienna. Details gradually came to light and at first there was talk of a “fatal accident”—indeed this was officially announced. Then, after the official announcement, it became known that the Crown Prince had gone to his hunting lodge accompanied by the Baroness Vetsera and that there they had both met their death.

The details are so well-known that there is no need to recount them here. All that followed made it impossible for anyone acquainted with the circumstances to doubt that this was a case of suicide. For what happened first of all was that after the issue of the official announcement of the fatal accident, the Prime Minister of Hungary, Koloman Tisza, took exception to this version, and obtained from the then Emperor of Austria the promise that this incorrect statement should not be allowed to stand. The Hungarian Prime Minister refused to be responsible for making this announcement to his people, and he was very emphatic in his refusal. Besides this, there was a man on the medical staff who was one of the most courageous doctors in Vienna at the time and who was to assist at the post-mortem examination; and this man said that he would sign nothing that was not corroborated by the objective facts.

Well, the objective facts were a clear indication of suicide; this was officially admitted and the earlier announcement corrected. And if there were no other circumstances than the admission of suicide by a family as fervently Catholic as that of the Austrian Emperor, that alone would have precluded the slightest shadow of doubt.

Nobody who can judge the facts objectively will think of doubting it, but there is one very obvious question: How was it possible that anyone with such a brilliant future should turn to suicide when faced with circumstances which, in his position, could easily have remained concealed? Obviously, there was no objective reason why a Crown Prince should commit suicide on account of a love affair—I mean that there was no objective reason attributable to external circumstances.

There was no objective reason for such an action, but the fact was that this heir to a Throne found life utterly worthless—a state of mind which had, of course, a psychopathological basis. This itself needs to be understood, for a pathological condition of the soul is also connected with destiny. And the fundamental fact here is that one to whom a brilliant future was beckoning, found life utterly worthless.

This, my dear friends, is one of those phenomena in life which seem to be wholly inexplicable. And in spite of all that has been written or said about the whole affair, a true judgment can be formed only by one who says to himself: This single human life, this life of Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria, gives no clue to the suicide or to the causes of the preceding pathological state of mind; something else must be at the bottom of it all.

And now, if you picture to yourself the Nero soul, having subsequently experienced what I described and passing at length into that heir to a Throne who does away with himself, who forces the consequences by means of suicide ... then the whole setting is altered. Within the soul there is a tendency which originates in preceding earthly lives; in the time between death and rebirth the soul perceives in direct vision that nothing but forces of destruction have issued from it—and now the ‘grand reversal’, as I will call it, has to be experienced.

And how is it experienced?—A life abounding in things of external value reflects itself inwardly in such a way that its bearer considers it utterly worthless, and commits suicide. The soul becomes sick, half demented, seeking an external entanglement in the love affair, and so forth. But these things are merely the consequences of the soul's endeavour as it were to direct against itself all the arrows which in the past had been directed to the world. And then, when we have insight into these relationships, we perceive the unfolding of an overwhelming tragedy, but for all that a righteous, just tragedy. The two pictures are co-ordinated.

As I have said so often, it is the underlying details that make real investigation possible in such domains. Many factors in life must work together here.

I told you that when this shattering event had just occurred, I was on my way to Schröer. The event itself was not the reason for my visit—I happened to be on the way to him and he was the first person to whom I spoke about the matter. He said: “Nero! ...”—quite out of the blue, and I could not help asking myself: Why does he think of Nero just at this moment? He actually introduced the conversation with the mention of Nero. This amazed me at the time. But the shattering effect was all the greater in view of the particular circumstances in which the word “Nero” was uttered. Two days previously—all this was public knowledge—a Soirée had been held at the house of Prince Reuss, then German Ambassador in Vienna. The Austrian Crown Prince was present, and Schröer too, and the latter saw how the Crown Prince was behaving on that occasion—two days before the catastrophe. The strange behaviour at the Soirée, the suicide two days later, all of it described so dramatically by Schröer—this, in connection with the utterance of the name “Nero”, made one realise that there was good reason for further investigation.

Now why did I often follow up things that happened to fall from Schröer's lips? It was not that I simply took anything he said as a pointer, for he, of course, knew nothing of such matters. But many things he said, especially those which seemed to shoot out of the blue, were significant for me because of something that once came to light in a curious way.

A conversation I had with Schröer on one occasion led to the subject of phrenology. Not humorously, but with the seriousness with which he was wont to speak—of such things, employing a certain solemnity of language even in everyday matters, Schröer said to me: “I too was once examined by a phrenologist. He felt my head all over and discovered up there the bump of which he said: ‘There's the theosophist in you’.”—Remember that this was in the eighties of last century when there was as yet no talk of Anthroposophy. It was Schröer, not I, who was examined by the phrenologist who said: “There's the theosophist in you.” Now Schröer, outwardly, was far from being a theosophist—my autobiography makes that abundantly clear. But it was just when he spoke of things without apparent motive that his utterances were sometimes profoundly significant. And so there seemed to be a certain connection between the utterance of the word ‘Nero’ and the outer confirmation of his theosophical trend. This was what made him a personality to whose spontaneous utterances one paid heed.

And so investigation into the Nero destiny shed light on the subsequent Meyerling destiny and it was found that in the personality of the Austrian Crown Prince Rudolf one actually had to do with the Nero soul.

This investigation—which has taken a long time, for in matters of this kind one must be extremely cautious—presented special difficulties to me because I was continually being diverted by the fact that all kinds of people—you may believe it or not—were claiming with fanatical insistence that they themselves had been Nero! So it was a matter, first of all, of combating the subjective force emanating from these alleged reborn Neroes. One had to get through a kind of thicket.

But what I am telling you now, my dear friends, is much more important because it has to do with an historical phenomenon, namely, Nero himself. And to understand the further development is much more important than to understand, let us say, the actual catastrophe at Meyerling. For now we see how things which, to begin with, arouse horror and indignation—as does the life of Nero—live themselves out according to a perfect world-justice; we see how this world-justice is fulfilled and how the wrong returns, but in such a way that the individuality is himself involved in creating the balance.—That is what is so stupendous about karma.

Still more can become clear when such wrong is balanced out in the course of particular earthly lives. In this case the balance will be almost complete, for you will realise how closely the fulfilment is bound up with the compensatory deed. Just think of it ... a life which considers itself worthless, so worthless that a whole Empire (Austria was then a great Empire) and the rulership of it are abandoned! The suicide in such circumstances bears the consequence that after death it all has to be lived through in direct spiritual vision. This is the fulfilment, albeit the terrible fulfilment, of what may be called the righteous justice of destiny, the balancing out of the wrong.

But on the other hand, leaving all this aside, there was a tremendous force in Nero—a force which must not be lost for humanity. This force must of course be purified and we have spoken of the purification. If this has been accomplished, such a soul will carry its forces into later epochs of the earth's existence with salutary effects. When we apprehend karma as righteous compensation, we shall never fail to see how it tests the human being, puts him to the test even when he takes his place in life in a way that horrifies us. The just compensation is brought about, but the human forces are not lost. What has been committed in one life may, under certain circumstances, and provided the righteous justice has taken effect, even be transformed into a power for good. That is why a destiny such as the one described to-day is so profoundly moving.

This brings us to the consideration of good and evil, viewed in the light of karma: good and evil, fortune and misfortune, happiness and sorrow—as man experiences them breaking into, shining into, his individual life.

In regard to perception of a man's moral situation there was far greater sensitivity in earlier epochs of history than is to be found in modern humanity. Men of the present age are not really sensitive at all to the problem of destiny. Now and again, of course, one comes across someone who has an inkling of the onset of destiny; but real understanding of its problems is shrouded in darkness and bewilderment in our modern civilisation, which regards the single earthly life as something complete in itself. Things happen—and that is that. A disaster that befalls a man is commented on but not really pursued in thought. This is pre-eminently the case when through something that seems to be pure chance, a man who to all appearances is thoroughly good and who has committed no wrong, either perishes, or perhaps does not actually perish but has to endure terrible suffering on account of some injury, or other cause. No thought is given to why such a fate should cut in this way into a so-called innocent life.

Humanity was not always so obtuse and insensitive with regard to the problem of destiny. We need not go very far back in time to find that blows of destiny were felt to strike in from other worlds—even the destiny a man has brought upon himself.

What is the explanation of this? The explanation is that in earlier times men were not only endowed with instinctive clairvoyance but even when this had faded, its fruits were still preserved in traditions; moreover external conditions and customs did not conduce to such a superficial, commonplace view of the world as prevails to-day, in the age of materialism. There is much talk nowadays of the harmfulness of purely materialistic-naturalistic thinking which has become so universal and has even crept into the various creeds—for the religions too have become materialistic. In no single domain is outer civilisation sincerely desirous of knowing anything about the spiritual world and although men talk in theory of the need to fight this trend, a theoretical battle against materialistic ideas achieves very little. The point of salient importance is that by reason of the conception of the world which has led men to freedom, which will do so still more, and which constitutes a transitional period in the history of human evolution—by reason of this conception of the world, a certain means of healing that was available in earlier epochs for outer sense-observation has been lost.

In the early centuries of Greek civilisation—in fact it was so for a considerable time—men saw in nature around them the outer, phenomenal world. The Greek, as well as modern man, looked out at nature. True, the Greek saw nature in a rather different aspect, for the senses themselves have evolved—but that is not the point here. The Greek had a remedy wherewith to counteract the organic harm that is caused in man when he merely gazes out into nature.

We do not only become physiologically long-sighted with age as the result of having gazed constantly at nature, but this gives our soul a certain configuration. As it gazes at nature, the soul realises inwardly that not all the demands of vision are being satisfied. Unsatisfied demands of vision remain. And this holds good for the process of perception in general—hearing, feeling, and so forth. Certain elements in the perceptive process remain unsatisfied when we gaze out into nature. It is more or less the same as if a man in physical existence wished to spend his whole life without taking adequate food. Such a man deteriorates physically. But when he merely gazes at nature, the perceptive faculty in his life of soul deteriorates. He gets a kind of ‘consumption’ of soul in his sense-world. This was known in the old Mystery-wisdom.

But it was also known how this ‘consumption’ in the life of soul can be counteracted. It was known that the Temple Architecture, where men beheld the equipose between downbearing weight and upbearing support, or when, as in the East, they beheld forms that were really plastic representations of moral forces, when they looked at the architectural forms confronting the eye and the whole of the perceptive process, or experienced the musical element in these forms—it was known that here was the remedy against the consumption which befalls the senses when they merely gaze out into nature. And when the Greek was led into his temple where he beheld the pillars, above them the architrave, the inner composition and dynamic of it all, then his gaze was bounded and completed. When a man looks at nature his gaze is really no more than a stare, going on into infinity, never reaching an end. In natural science too, every problem leads on and on, in this way, without coming to finality. But the gaze is bounded and completed when one faces a work of great architecture created with the aim of intercepting the vision, rescuing it from the pull of nature. There you have one feature of life in olden times: this capturing of the outward gaze.

And again, when a man turns his gaze inwards to-day, it does not penetrate to the innermost core of his being. If he practises self-knowledge, what he perceives is a surging medley of all kinds of emotions and outer impressions, without clarity or definition. He cannot lay hold of himself inwardly; he lacks the strength to grasp this inner reality in imaginations, in pictures—as he must do before he can make any real approach to the inmost kernel of his being.

It is here that cult and ritual enacted reverently before men take effect. Everything of the nature of cult and ritual, not the external rites only but comprehension of the world expressed in imagery and pictures, leads man towards his innermost being. As long as he strives for self-knowledge with abstract ideas and concepts, nothing is achieved. But when he penetrates into his inmost being with pictures that give concrete definition to experiences of soul, then he achieves his aim. The inmost kernel of his being comes within his grasp.

How often have I not said that man must meditate in pictures, in images. This has been dealt with at ample length, even in public lectures.

And so, looking at man in the past, we find on the one side that his gaze and perception, when directed outwards, are as it were bounded, intercepted, by architectonic forms; on the other side, his inward-turned gaze is bounded and held firm by picturing his soul-life; and this can also be presented to him through the imagery of cult and ritual.

On the one side, therefore, there is the descent into the inmost being; on the other, the outward gaze lights upon the forms displayed in sacred architecture. A certain union is thereby achieved. Between what comes alive within and that upon which the gaze falls, there is an intermediate domain, imperceptible to man in his everyday consciousness because his outward gaze is not captured by forms of architecture born of deep, inner knowledge, nor is his inward gaze given definition by pictures and imaginations. But there is this intermediate domain ... if you let that work in your life, if you go about with inner self-knowledge deepened through imagination, and with sense-perceptions made whole and complete through forms created and inspired by a real understanding of man's nature ... then your feeling in regard to strokes of destiny will be the same as it was in olden times. By cultivating the domain that lies between the experience of true architectonic form and the experience of true, symbolic imagery along the path inwards, a man becomes sensitive to the strokes of destiny. He feels that what befalls him comes from earlier lives on earth.

This again is an introduction to the studies which we shall be pursuing and which will include consideration of the good and the evil in connection with karma.

But what is of salient importance is that within the Anthroposophical Movement there shall be right thinking. The architecture that would have fulfilled the needs of modern man, that would have been able to capture his gaze in the right way and to have led naturalistic perception, which veils and obscures the vision of karma, gradually into real vision—this architecture did once exist, in a certain form. And the fact that anthroposophical thoughts were uttered in the setting of those forms, kindled the inner vision. Among its other aspects the Goetheanum Building, together with the way in which Anthroposophy would have been cultivated in it, was in itself an education for the vision of karma. And that is what must be introduced into modern civilisation: education for the vision of karma.

But needless to say, it was in the interests of those who are opposed to what ought now to enter civilisation, that such a Building should fall a prey to the flames ... There, too, it is possible to look into the deeper connections. But let us hope that, before very long, forms that awaken a vision of karma will again stand before us, at the same place.

This is what I wanted to say in conclusion to-day, when so many friends from abroad are still with us after our Easter Meeting.

Fünfter Vortrag

Wir haben nun eine Reihe zusammenhängender Schicksalsentwickelungen betrachtet, welche aufklärend und erhellend für die Erfassung des geschichtlichen Lebens der Menschheit sein können. Die Betrachtungen, die wir gepflogen haben, sollten zeigen, wie aus vorhergehenden Erdenperioden das, was die Menschen in diesen vorhergehenden Erdenperioden erleben, erarbeiten, aufnehmen, hinübergetragen wird durch die Menschen selbst in spätere Erdenepochen. Und Zusammenhänge haben sich uns ergeben, so daß wir dasjenige, was durch Menschen, ich möchte sagen, tonangebend getan wird, begreifen aus im moralischen Sinne gemeinten Ursachen, die durch die Menschen selber gelegt worden sind im Laufe der Zeiten.

Aber nicht nur dieser, ich möchte sagen, ursächliche Zusammenhang kann uns durch solche auf das Karma gerichtete Betrachtungen vor die Seele treten, sondern auch manches kann sich lichtvoll aufklären, was eigentlich zunächst für eine äußerliche Weltenbetrachtung unklar, unbegreiflich erscheint.

Will man aber in dieser Beziehung mit der großen Umwandlung mitgehen, die in bezug auf die Empfindung und das Denken des Menschengemütes in der nächsten Zukunft notwendig ist, wenn die Zivilisation aufwärts-, nicht abwärtsgehen soll, dann ist es eben notwendig, daß man zunächst sozusagen einen Sinn für dasjenige entwickelt, was unter gewöhnlichen Umständen unbegreiflich ist und zu dessen Begreifen eben ein Einblick in tiefere menschliche und weltgesetzmäRige Verhältnisse gehört. Wer alles begreiflich findet, der braucht natürlich nichts zu begreifen von den oder jenen tieferen Ursachen. Aber dieses Begreiflichfinden ist ja nur scheinbar, denn alles begreiflich finden in der Welt, heißt eigentlich nur, allem gegenüber oberflächlich sein. Denn für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein sind in der Tat die meisten Dinge in Wirklichkeit unbegreiflich. Und verwundert stehenbleiben können vor den Unbegreiflichkeiten selbst des alleralltäglichsten Daseins, das ist im Grunde genommen erst der Anfang für wirkliches Erkenntnisstreben.

Das ist es ja, wonach von diesem Rednerpulte aus so oft der Seufzer ertönt ist: Man möge innerhalb anthroposophischer Kreise Enthusiasmus haben für das Suchen, Enthusiasmus haben für das, was eben in anthroposophischem Streben drinnenliegt. Und dieser Enthusiasmus muß wirklich damit beginnen, das Wunderbare in der Alltäglichkeit wirklich als etwas Wunderbares zu ergreifen. Dann wird man eben, wie gesagt, erst versucht sein, zu den Ursachen, zu den tiefer liegenden Kräften zu greifen, die dem uns umgebenden Dasein zugrunde liegen. Es können für den Menschen diese Verwunderungszustände gegenüber der alltäglichen Umgebung aus geschichtlichen Betrachtungen hervorgehen, aber auch aus dem, was in der Gegenwart beobachtet werden kann. Bei geschichtlichen Betrachtungen müssen wir ja oftmals stehenbleiben vor geschichtlichen Ereignissen, die uns aus der Vergangenheit berichtet werden und die erscheinen, als wenn da oder dort das Menschenleben wirklich in das Unsinnige ausliefe.

Nun, es bleibt das Menschenleben sinnlos, wenn wir es nur so betrachten, daß wir den Blick auf ein geschichtliches Ereignis lenken und nicht fragen: Wie gehen aus diesem geschichtlichen Ereignisgewisse Menschencharaktere hervor, wie nehmen sie sich aus, wenn sie in ihrer späteren Wiederverkörperung auftreten? -— Wenn wir darnach nicht fragen, so erscheinen auch gewisse geschichtliche Ereignisse völlig sinnlos, deshalb sinnlos, weil sie sich nicht erfüllen, weil sie ihren Sinn verlieren, wenn sie nicht ausgelebt werden können, wenn sie nicht weitere Seelenimpulse in einem folgenden Erdenleben werden, wenn sie nicht Ausgleich finden und dann weiterwirken in weiter folgenden Erdenleben.

So ist ganz gewiß eine historische Sinnlosigkeit gelegen in dem Auftreten einer solchen Persönlichkeit, wie sie der Nero war, der römische Cäsar Nero. Von ihm ist innerhalb der anthroposophischen Bewegung ja noch nicht gesprochen worden.

Nehmen Sie nur alles das in die Seele auf, was von dem römischen Cäsar Nero historisch berichtet wird. Gegenüber einer Persönlichkeit, wie es der Nero war, erscheint das Leben wie etwas, dem man ganz ungestraft einfach Hohn sprechen könnte, wie wenn man es verhöhnen könnte, wie wenn das gar keine Folgen hätte, wenn jemand mit einer restlosen Frivolität in einer an sich autoritativen Stellung auftritt.

Nicht wahr, man müßte eigentlich stumpf sein, wenn man so sieht, was der Nero macht, und wenn man gar nicht irgendwie dazu kommen könnte, sich zu fragen: Was wird denn nun eigentlich aus einer solchen Seele, die, wie der Nero, der ganzen Welt Hohn spricht, das Leben anderer Menschen, das Dasein fast einer ganzen Stadt als etwas betrachtet, womit er spielen kann? — Welch ein Künstler geht mit mir verloren! - Das ist ja bekanntlich der Ausspruch, der Nero in den Mund gelegt wird, und der wenigstens seiner Gesinnung entspricht. Also bis in ein Selbstbekenntnis hinein die alleräußerste Frivolität, der alleräußerste Zerstörungswille und Zerstörungstrieb, aber so, daß dieser Seele diese Sache gefällt.

Nun, da wird ja alles zurückgestoßen, was Eindruck auf den Menschen machen kann. Da gehen nur sozusagen weltzerstörende Strahlen von der Persönlichkeit aus. Und wir fragen uns: Was wird aus einer solchen Seele?

Man muß sich klar darüber sein: Alles das, was da sozusagen auf die Welt abgeladen wird, das strahlt ja nun zurück in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Das muß gewissermaßen auf die Seele selber wiederum sich abladen; denn alles dasjenige, was zerstört worden ist durch eine solche Seele, das ist nun da in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Nun kam Nero zunächst wenige Jahrhunderte oder verhältnismäßig kurze Zeit darnach in unbedeutetem Dasein wiederum auf die Welt, wo sich zunächst nur dasjenige ausgeglichen hat, was Zerstörungswut war, die er auf die Souveränität hin ausgeübt hatte, ausgeübt aus sich heraus, weil er es so wollte; dabei wirkte die Rage, man möchte sagen, der Enthusiasmus für die Zerstörungswut. In einem nächsten Erdenleben erfüllte sich ausgleichend schon etwas von dieser Sache und dieselbe Seelenindividualität war jetzt in einer Stellung, wo sie auch zerstören mußte, aber zerstören mußte in untergeordneter Stellung, wo sie Befehlen unterlag. Und da hatte diese Seele die Notwendigkeit, nun zu fühlen, wie das ist, wenn man es nicht aus freiem Willen heraus tut, nicht in Souveränität vollbringt.

Nun handelt es sich bei solchen Dingen wirklich darum, sie ohne Emotionen zu betrachten, sie ganz objektiv zu betrachten. Solch ein Schicksal, möchte ich sagen — denn auch so grausam zu sein wie Nero, so zerstörungswütig wie Nero zu sein, ist ja ein Schicksal -, ist im Grunde genommen ein erbarmungswürdiges Schicksal nach einer gewissen Seite hin. Man braucht gar nicht Rankünen zu haben, nicht irgendwie scharfe Kritik zu üben; dann würde man ohnedies nicht diejenigen Dinge erleben, die notwendig sind, um die Sache im weiteren Verlauf zu begreifen, denn in all die Dinge, von denen hier gesprochen worden ist, ist ja nur möglich hineinzuschauen, wenn man objektiv hineinschaut, wenn man nicht anklagt, sondern wenn man eben Menschenschicksale versteht. Aber die Dinge sprechen sich doch, wenn man nur den Sinn hat, sie zu verstehen, in einer deutlichen Weise aus. Und daß mir das Nero-Schicksal vor die Seele getreten ist, das war wirklich einem scheinbaren Zufall zuzuschreiben. Aber eben nur ein scheinbarer Zufall war es, daß mir dieses Nero-Schicksal einmal ganz besonders stark vor die Seele getreten ist.

Denn sehen Sie, als sich einmal ein erschütterndes Ereignis vollzogen hatte, ein Ereignis, von dem ich gleich sprechen werde, das in der Gegend, um die es sich handelt, weithin erschütternd wirkte, da kam ich gerade zu Besuch zu der in meinem Lebensabriß öfters genannten Persönlichkeit Karl Julius Schröer. Und als ich dahin kam, war auch er, wie viele Leute, ungeheuer erschüttert durch das, was geschehen war. Und er sprach - eigentlich so, daß es zunächst unmotiviert war — wie aus dunklen Geistestiefen heraus das Wort «Nero». Man hätte glauben können, es wäre ganz unmotiviert gewesen. Es war aber später durchaus zu sehen, daß da eigentlich nur durch einen Menschenmund etwas wie aus der Akasha-Chronik heraus gesprochen worden war. Es handelte sich um folgendes.

Der österreichische Kronprinz Rudolf war ja als eine glänzende Persönlichkeit gefeiert worden und galt als eine Persönlichkeit, die große Hoffnungen erregte für die Zeit, wenn er einmal auf den Thron kommen sollte. Wenn man auch allerlei über jenen Kronprinzen Rudolf wußte, so war alles das, was man wußte, doch so, daß man es eben als Dinge auffaßte, nun ja, die sich eigentlich fast so gehörten für einen «Grandseigneur». Jedenfalls dachte niemand daran, daß das zu bedeutsamen, tragischen Konflikten führen könnte. Und es war daher eine ungeheuer große Überraschung, eine furchtbar große Überraschung, als in Wien bekannt wurde: der Kronprinz Rudolf ist in den Tod gegangen auf eine ganz mysteriöse Weise, in der Nähe des Stiftes Heiligenkreuz, in der Nähe von Baden bei Wien. Immer mehr und mehr Details kamen da zutage, und zunächst sprach man von einem Unglücksfall; ja, der «Unglücksfall» wurde sogar offiziell berichtet.

Dann, als der Unglücksfall schon ganz offiziell berichtet war, wurde bekannt, daß der Kronprinz Rudolf in Begleitung der Baronesse Vetsera hinausgefahren war zu seinem Jagdgute dort, und daß er mit ihr gemeinsam dann den Tod gefunden hatte.

Die Details sind so bekanntgeworden, daß sie wohl hier nicht erzählt zu werden brauchen. Alles Folgende hat sich so vollzogen, daß kein Mensch, der die Verhältnisse kannte, daran zweifeln konnte, als die Dinge bekannt wurden, daß ein Selbstmord des Kronprinzen Rudolf vorlag. Denn erstens waren die Umstände so, daß ja in der Tat, nachdem das offizielle Bulletin herausgegeben war, daß ein Unglücksfall vorläge, sich zunächst der ungarische Ministerpräsident Koloman Tisza gegen diese Version wendete und von dem damaligen österreichischen Kaiser selbst die Zusage erlangte, daß man nicht stehenbleiben werde bei einer unrichtigen Angabe. Denn dieser Koloman Tisza wollte vor seiner ungarischen Nation diese Angabe nicht vertreten und machte das energisch geltend. Dann aber fand sich in dem Ärztekollegium ein Mann, der damals eigentlich zu den mutigsten Wiener Ärzten gehörte und der auch mit die Leichenbeschau führen sollte, und der sagte, er unterschriebe nichts, was nicht durch die objektiven Tatsachen belegt wäre.

Nun, die objektiven Tatsachen wiesen eben auf den Selbstmord hin. Der Selbstmord wurde ja dann auch offiziell, das Frühere verifizierend, zugegeben, und wenn nichts anderes vorläge als die Tatsache, daß in einer so außerordentlich katholisch gesinnten Familie, wie es die österreichische Kaiserfamilie war, der Selbstmord zugegeben worden ist, so würde schon einzig und allein diese Tatsache bedeuten, daß man eigentlich nicht daran zweifeln kann. Also jeder, der die Tatsache da objektiv beurteilen kann, wird nicht daran zweifeln.

Aber das muß man fragen: Wie ist es möglich gewesen, daß überhaupt jemand, dem so Glänzendes in Aussicht stand, zum Selbstmord griff, gegenüber Verhältnissen, die sich ja zweifellos mit leichter Hand in solcher Lebenslage hätten kaschieren lassen? — Es ist ja gar kein Zweifel, daß ein objektiver Grund, daß ein Kronprinz wegen einer Liebesaffäre sich erschießt —, ich meine, ein objektiver Grund, für die äußeren Verhältnisse objektiv notwendiger Grund, natürlich nicht vorliegt.

Es lag auch kein äußerer objektiver Grund vor, sondern es war die Tatsache vorliegend, daß hier einmal eine Persönlichkeit, welcher der Thron unmittelbar in Aussicht stand, das Leben ganz wertlos fand, und das bereitete sich natürlich auf psychopathologische Weise vor. Aber die Psychopathologie muß ja auch in diesem Falle erst begriffen werden; denn die Psychopathologie ist schließlich auch etwas, was mit dem Schicksalsmäßigen zusammenhängt. Und die Grundtatsache, die da in der Seele wirkte, ist dennoch die, daß jemand, dem also das Allerglänzendste scheinbar winkte, das Leben ganz wertlos fand.

Das ist etwas, meine lieben Freunde, das einfach unter diejenigen Tatsachen gehört, die man unbegreiflich finden muß im Leben. Und soviel auch geschrieben worden ist, soviel auch über diese Dinge gesprochen worden ist, nur der kann eigentlich vernünftig urteilen über eine solche Sache, der sich sagt: Aus diesem einzelnen Menschenleben, aus diesem Leben des Kronprinzen Rudolf von Österreich ist der Selbstmord, und auch die vorhergehende Psychopathologie in ihrer Ursächlichkeit für den Selbstmord, nicht erklärlich. Da muß, wenn man verstehen will, etwas anderes zugrunde liegen.

Und nun denken Sie sich die Nero-Seele — nachdem sie noch durch das andere durchgegangen ist, wovon ich gesprochen habe — herübergekommen gerade in diesen sich selbst vernichtenden Thronfolger, der die Konsequenz zieht durch seinen Selbstmord: dann kehren sich die Verhältnisse einfach um. Dann haben Sie in der Seele die Tendenz liegend, die aus früheren Erdenleben stammt, die beim Durchgang durch die Zeit zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt im unmittelbaren Anblicke sieht, daß von ihr eigentlich nur zerstörende Kräfte ausgegangen sind, und die auch auf eine splendide Weise, möchte ich sagen, die Umkehrung erleben muß.

Diese Umkehrung, wie wird sie erlebt? Sie wird eben dadurch erlebt, daß ein Leben, das äußerlich alles, was wertvoll ist, enthält, nach innen sich so spiegelt, daß der Träger dieses Lebens es für so wertlos hält, daß er sich selber entleibt. Dazu wird die Seele krank, wird halb wahnsinnig. Dazu sucht sich die Seele die äußere Verwickelung mit der entsprechenden Liebesaffäre und so weiter. Aber das alles sind ja nur die Folgen des Strebens der Seele, ich möchte sagen, alle die Pfeile auf sich selbst zu richten, die früher diese Seele nach der Welt hin gewandt hat. Und wir sehen dann, wenn wir in das Innere solcher Verhältnisse hineinsehen, eine ungeheure Tragik sich entwickeln, aber eine gerechte Tragik, eine außerordentlich gerechte Tragik. Und die beiden Bilder ordnen sich uns zusammen.

Ich sagte oftmals: Kleinigkeiten sind es, welche den Dingen zugrunde liegen, die in Wahrheit, im vollen Ernste Untersuchungen auf solchen Gebieten möglich machen. Da muß mancherlei im Leben mitwirken.

Wie gesagt, als dieses Ereignis, das so erschütternd dazumal gewirkt hat, sich eben vollzogen hatte, war ich auf dem Wege zu Schröer. Ich bin nicht wegen dieses Ereignisses hingegangen, sondern ich war auf dem Wege zu Schröer. Es war sozusagen der nächste Mensch, mit dem ich über diese Sache sprach. Der sprach ganz unmotiviert: «Nero» — so daß ich mich eigentlich fragen mußte: Warum denkt der jetzt gerade an Nero? - Er leitete das Gespräch gleich ein mit «Nero». Es erschütterte mich das Wort «Nero» dazumal. Aber es erschütterte mich um so mehr, als dieses Wort «Nero» unter einem besonderen Eindrucke gesprochen war, denn zwei Tage vorher war ja, das ist auch öffentlich ganz bekannt geworden, eine Soiree bei dem damaligen deutschen Botschafter in Wien, bei dem Prinzen Reuß. Da war der österreichische Kronprinz auch anwesend. und Schröer auch, und er hatte dazumal gesehen, wie der Kronprinz sich verhalten hat, zwei Tage vor der Katastrophe. Und dieses merkwürdige Verhalten zwei Tage vor der Katastrophe bei jener Soir&e, was Schröer sehr dramatisch schilderte, und dann der nachfolgende Selbstmord zwei Tage darnach: dieses im Zusammenhange damit, daß da das Wort «Nero» ausgesprochen wurde, das war etwas, was schon so wirkte, daß man sich sagen konnte: Jetzt liegt eine Veranlassung vor, den Dingen nachzugehen. — Aber warum bin ich denn überhaupt vielen Dingen nachgegangen, die aus Schröers Mund kamen? Nicht als ob irgend etwas von Schröer, der ja solche Dinge natürlich nicht wissen konnte, einfach von mir aufgenommen worden wäre wie ein Omen oder so etwas. Aber manche Dinge, gerade die, welche scheinbar unmotiviert kamen, waren mir wichtig, wichtig durch etwas, was einmal merkwürdig zutage trat.

Ich kam mit Schröer in ein Gespräch über Phrenologie, und Schröer erzählte, nicht eigentlich humoristisch, sondern mit einem gewissen inneren Ernst, mit dem er solche Dinge aussprach — man erkannte den Ernst eben an der gehobenen Sprache, die er auch in dem täglichen Umgang sprach, wenn er etwas mit vollem Ernst sagen wollte -, Schröer sagte: Mich hat auch einmal ein Phrenologe untersucht, hat mir den Kopf abgegriffen und hat da oben jene Erhöhung gefunden, von der er dann gesagt hat: Da sitzt ja in Ihnen der Theosoph! - Von Anthroposophie sprach man dazumal nicht, denn das war in den achtziger Jahren; es bezieht sich also nicht auf mich, es bezieht sich auf Schröer. Den hat er untersucht und gesagt: Da sitzt der Theosoph.

Nun, es war in der Tat so: Schröer war äußerlich alles eher als Theosoph; das geht ja aus meiner Lebensbeschreibung wohl hervor. Aber gerade da, wo er von Dingen sprach, welche eigentlich herausfielen aus dem Motivierten, das er sagte, gerade da waren seine Aussprüche manchmal außerordentlich tief bedeutend. So daß sich einem schon diese zwei Dinge zusammensetzen konnten: daß er da das Wort «Nero» aussprach und daß er auch durch dieses äußerliche Konstatieren seiner Theosophie einem gelten mußte als jemand, auf den man hinhorcht, bei dessen unmotivierten Dingen man sozusagen nachschaut.

Und so kam es denn wirklich, daß die Untersuchung in bezug auf das Nero-Schicksal dann aufklärend gewirkt hat für das weitere Schicksal, für das Mayerling-Schicksal, und gefunden werden konnte, daß man es wirklich mit der Nero-Seele in dem österreichischen Kronprinzen Rudolf zu tun hatte.

Es war mir diese Untersuchung, die lange gedauert hat — denn in solchen Dingen ist man sehr vorsichtig —, ganz besonders schwierig, weil ich ja natürlich immer beirrt worden bin durch alle möglichen Leute — ob Sie es nun glauben oder nicht, es ist so -—, die den Nero für sich in Anspruch nahmen und die das mit viel Fanatismus vertraten. So daß also, was an subjektiver Kraft ausging von solchen wiedergeborenen Neronen, natürlich zunächst bekämpft werden mußte. Man mußte durch das Gestrüpp da durch.

Aber man kann finden, meine lieben Freunde, daß das, was ich Ihnen jetzt hier sage, ja viel wichtiger ist, weil es eine historische Tatsache begreift - eben den Nero -, und daß das in dem weiteren Verlaufe viel wichtiger ist, als etwa die Katastrophe von Mayerling zu begreifen. Denn nun sieht man, wie solche Dinge, die eigentlich zunächst, man möchte sagen, empörend auftreten, wie das Dasein des Nero, sich mit voller Weltgerechtigkeit ausleben, wie sich die Weltgerechtigkeit wirklich erfüllt und wie zurückkommt das Unrecht, aber so, daß die Individualität hineingestellt ist in die Ausgleichung des Unrechtes. Und das ist das Ungeheure an dem Karma.

Und dann kann sich noch etwas anderes zeigen, wenn ein solches Unrecht ausgeglichen ist durch einzelne Erdenleben hindurch, wie es hier wohl fast schon ausgeglichen sein wird. Denn man muß nun wissen, daß ja zum Ausgleich dazugehört die ganze Erfüllung — denken Sie sich —, hervorgehend aus einem Leben, das sich wertlos hält, das so sehr sich wertlos hält, daß dieses Leben zunächst ein großes Reich und Österreich war ja dazumal noch ein großes Reich — und seine Herrschaft über ein großes Reich hingibt! Dieses Handanlegen an sich selbst in solchen Umständen, und hinterher, nachdem man durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen ist, weiterzuleben in der unmittelbar geistigen Anschauung, das erfüllt allerdings in einer furchtbaren Weise, was man Gerechtigkeit des Schicksals nennen kann: also Ausgleich des Unrechts.

Aber auf der anderen Seite, wenn wir jetzt von diesem Inhalte absehen, so ist ja wiederum eine ungeheure Kraft in diesem Nero gewesen. Diese Kraft darf nun auch nicht verlorengehen für die Menschheit; diese Kraft muß geläutert werden. Die Läuterung haben wir besprochen.

Ist nun eine solche Seele geläutert, dann wird sie die Kraft, die geläutert ist, eben auch in der Folgezeit in spätere Erdenepochen in einer heilsamen Weise hinübertragen. Und gerade dann, wenn wir das Karma als einen gerechten Ausgleich empfinden, werden wir auch niemals verfehlen können, zu sehen, wie das Karma prüfend auf den Menschen wirkt, prüfend wirkt selbst dann, wenn er sich in irgendeiner empörenden Weise in das Leben hereinstellt. Der gerechte Ausgleich geschieht, aber die Menschenkräfte gehen doch nicht verloren. Sondern es wird dann, wenn es durchlebt wird nach dem gerechten Ausgleich, dasjenige, was ein Menschenleben verübt hat, unter Umständen umgewandelt auch in Kraft zum Guten. Daher ist solch ein Schicksal, wie das heute geschilderte, schon auch durchaus erschütternd,

Damit aber sind wir unmittelbar herangelangt, meine lieben Freunde, an die Betrachtung dessen, was man Gut und Böse im Lichte des Karma nennen kann: Gut und Böse, Glück und Unglück, Freude und Leid, wie sie der Mensch in sein einzelnes individuelles Leben hereinblicken und hereinleuchten sieht.

In bezug auf die Empfindung der moralischen Lage eines Menschen waren frühere Erdenepochen, frühere geschichtliche Epochen viel empfänglicher als die heutige Menschheit. Die heutige Menschheit ist eigentlich gar nicht empfänglich für die Schicksalsfrage. Gewiß, man trifft ab und zu auf einen Menschen, der das Hereinspielen des Schicksals verspürt; aber das eigentliche Verständnis für die großen Schicksalsfragen, das ist für die heutige Zivilisation, welche das einzelne Erdenleben wie etwas Abgeschlossenes für sich betrachtet, doch etwas außerordentlich Dunkles und Unverständliches. Die Dinge geschehen halt. Es trifft einen ein Unglück, und man bespricht es, daß einen ein Unglück getroffen hat, aber man denkt nicht weiter nach. Man denkt namentlich auch darüber nicht weiter nach, wenn irgendein äußerlich scheinbar ganz guter Mensch, der gar nichts irgendwie verbrochen hat, durch irgend etwas, was von außen hereinwirkt wie ein Zufall, zugrunde geht, oder vielleicht nicht einmal zugrunde geht, sondern furchtbar viel leiden muß durch eine schreckliche Verletzung und dergleichen. Man denkt nicht nach, wie sich in ein sogenanntes unschuldiges Menschenleben so etwas hereinstellen kann.

Nun, so unempfänglich und unempfindlich für die Schicksalsfrage war die Menschheit nicht immer, Man braucht gar nicht sehr weit in der Zeitenwende zurückzugehen, dann finder man, daß die Menschen empfanden, daß die Schicksalsschläge aus anderen Welten hereinkommen, daß auch das, was man sich selber als Schicksal macht, aus anderen Welten hereinkommt.

Woher rührte denn das? Das rührte davon her, daß in früheren Epochen die Menschen nicht nur ein instinktives Hellsehen gehabt haben, und als das instinktive Hellsehen nicht mehr da war, Traditionen hatten über die Ergebnisse des instinktiven Hellsehens, nein, es waren auch die äußeren Einrichtungen so, daß die Menschen eigentlich die Welt nicht so oberflächlich, so banal anzusehen brauchten, wie heute im materialistischen Zeitalter die Welt angesehen wird. Man redet ja heute vielfach von der Schädlichkeit der bloßen äußerlich-materialistisch-naturalistischen Naturauffassung, die alle Kreise schließlich ergriffen hat, die auch die verschiedensten Bekenntnisse des religiösen Lebens ergriffen hat. Denn die Religionen sind ja auch materialistisch geworden. Von einer geistigen Welt will die äußere Zivilisation auf keinem Gebiete eigentlich mehr etwas wissen, und man redet davon, daß man so etwas theoretisch bekämpfen soll. Aber das ist nicht das Wichtigste; die theoretische Bekämpfung materialistischer Ansichten macht gar nicht so viel aus. Sondern das Wichtigste ist, daß durch die Anschauung, die allerdings den Menschen zur Freiheit gebracht hat und weiter zur Freiheit bringen will und die ja eine Durchgangsperiode bildet in der Entwickelungsgeschichte der Menschheit, auch das, was in früheren Epochen für die äußerliche sinnliche Anschauung des Menschen als ein Heilmittel da war, verloren worden ist.

Natürlich hat auch der Grieche in den ersten griechischen Jahrhunderten — es dauerte ja ziemlich lange - in der Natur ringsherum die äußere Erscheinungswelt gesehen. Er hat so wie die heutigen Menschen auf die Natur hingeschaut. Er hat die Natur etwas anders gesehen, denn auch die Sinne haben eine Entwickelung durchgemacht, aber darauf kommt es jetzt nicht an. Der Grieche hatte jedoch ein Heilmittel gegen die Schäden, die organisch in dem Menschen durch das bloße Hinausschauen in die Natur entstehen.

Wir werden ja wirklich nicht bloß physiologisch weitsichtig im Alter, wenn wir viel in die Natur hinausschauen, sondern durch das bloße Hinausschauen in die Natur bekommt unsere Seele eine gewisse Konfiguration. Sie schaut eigentlich in die Natur hinein und sieht in der Natur so, daß nicht alle Bedürfnisse des Sehens befriedigt werden. Es bleiben unbefriedigte Bedürfnisse des Sehens übrig. Und eigentlich gilt das überhaupt für das gesamte Wahrnehmen, Hören, Fühlen und so weiter; für die ist es dasselbe: es bleiben gewisse Reste unbefriedigt vom Wahrnehmen, wenn man bloß in die Natur hinausschaut. Und das Sehen bloß in die Natur hinaus ist ungefähr so, wie wenn ein Mensch im Physischen sein ganzes Leben hindurch leben wollte, ohne genügend zu essen. Wenn der Mensch leben wollte, ohne genügend zu essen, so würde er natürlich immer mehr und mehr herunterkommen im physischen Sinne. Aber wenn der Mensch immer nur in die Natur hinausschaut, kommt er seelisch in bezug auf das Wahrnehmen herunter. Er bekommt die Auszehrung, die seelische Auszehrung für seine Sinnenwelt. Das wußte man in früheren Mysterienweisheiten, daß man die Auszehrung für die Sinnenwelt bekommt.

Aber man wußte auch, wodurch diese Auszehrung ausgeglichen wird. Man wußte, wenn man hinschaute bei der Tempelarchitektur auf das Ebenmaß des Tragenden und Lastenden oder wie im Orient auf die Formen, die eigentlich in äußerer Plastik Moralisches darstellten, wenn man hinschaute auf das, was in den Formen der Architektur sich dem Auge, dem Wahrnehmen überhaupt darbot, oder was dann eben wirklich an Architektur wiederum musikalisch sich darbot, daß darinnen das Heilmittel liegt gegen die Auszehrung der Sinne, wenn diese bloß in die Natur hinausschauen. Und wenn noch der Grieche in seinen Tempel geführt wurde, wo er das Tragende und Lastende sah, die Säulen, darüber den Architrav und so weiter, wenn er das wahrnahm, was da an innerer Mechanik und Dynamik ihm entgegentrat, dann wurde der Blick abgeschlossen. In der Natur dagegen stiert der Mensch hinaus, der Blick geht eigentlich ins Unendliche, und man kommt nie zu Ende. Man kann ja eigentlich Naturwissenschaft für jedes Problem ohne Ende treiben: es geht immer weiter, weiter. Aber es schließt sich der Blick ab, wenn man irgendeine wirkliche Archtitekturarbeit vor sich hat, die darauf ausgeht, diesen Blick zu fangen, zu entnaturalisieren. Sehen Sie, da haben Sie das eine, was da war in alten Zeiten: dieses Fangen des Blickes nach außen.

Und wiederum, die gegenwärtige Innenbeobachtung des Menschen, die kommt ja nicht dazu, wirklich in das menschliche Innere hineinzusteigen. Eigentlich sieht der Mensch, wenn er heute Selbsterkenntnis üben will, so ein Gebrodel von allen möglichen Empfindungen und äußeren Eindrücken. Es ist nichts irgendwie Klares da. Der Mensch kann sich im Inneren gewissermaßen nicht erfangen. Er kommt nicht an sein Inneres heran, weil er nicht die Kraft hat, so geistig bildhaft innerlich zu greifen, wie er greifen müßte, wenn er wirklich real an sein Inneres herankommen wollte.

Da wirkt der wirklich mit Inbrunst an den Menschen herankommende Kultus. Alles Kultusartige aber, nicht nur das äußerlich Kultusartige, sondern das Verstehen der Welt in Bildern, das wirkt so, daß der Mensch in sein Inneres hereinkommt. Solange man mit abstrakten Begriffen und Vorstellungen in sein Inneres zur Selbsterkenntnis kommen will, geht es nicht. Sobald man mit Bildern, die einem konkret machen die Seelenerlebnisse, in sein Inneres hinein sich versenkt, da kommt man in dieses Innere. Da erfängt man sich im Inneren.

Wie oft mußte ich daher sagen: Der Mensch muß meditieren in Bildern, damit er in sein Inneres wirklich hineinkommt. Das ist ja etwas, was sogar schon in öffentlichen Vorträgen jetzt hinlänglich besprochen wird.

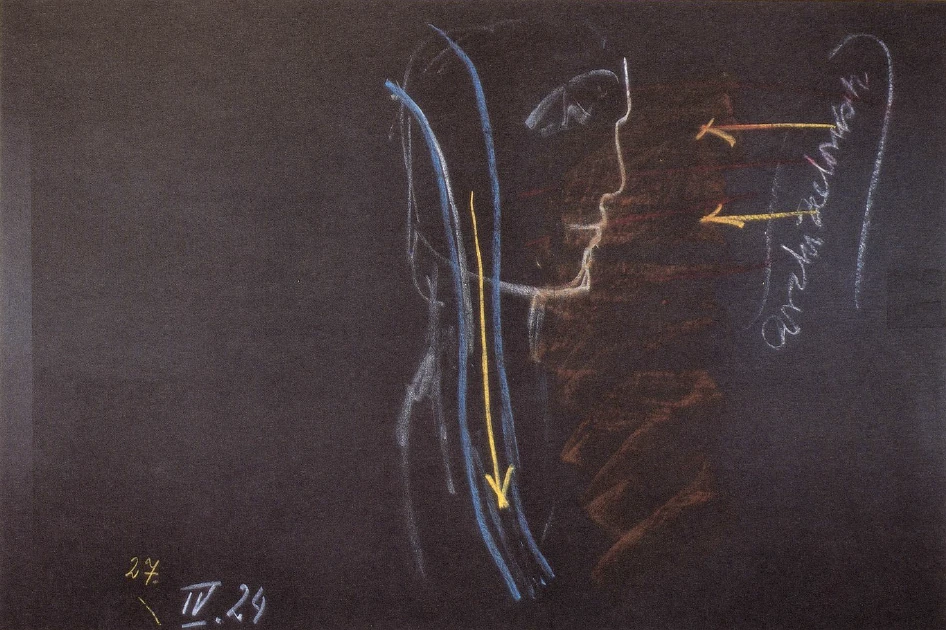

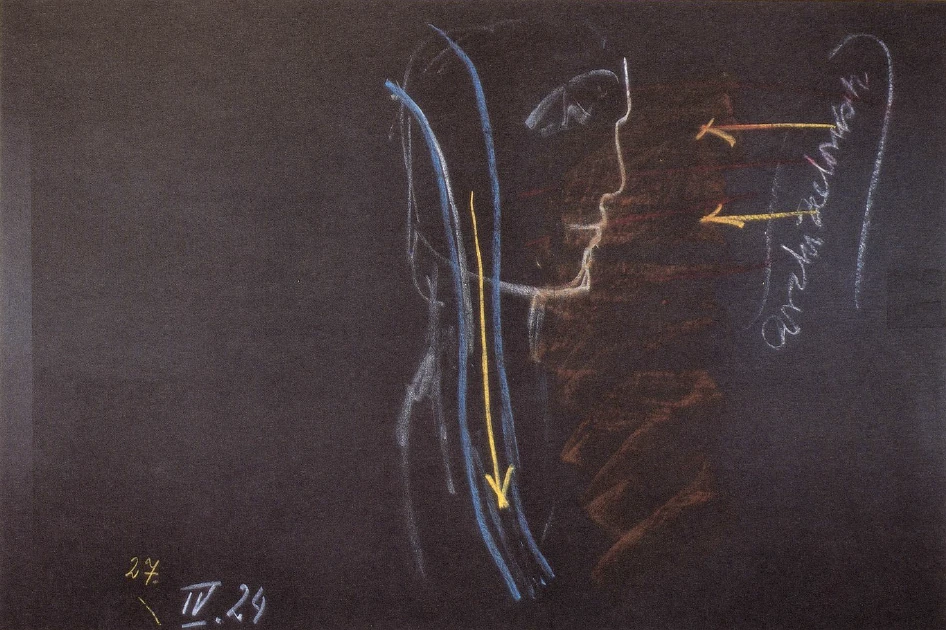

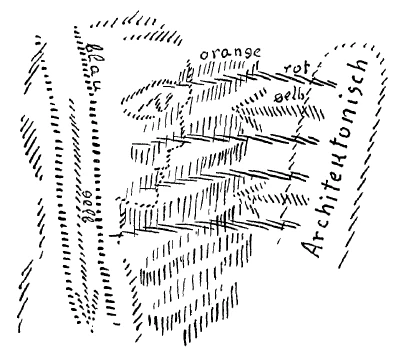

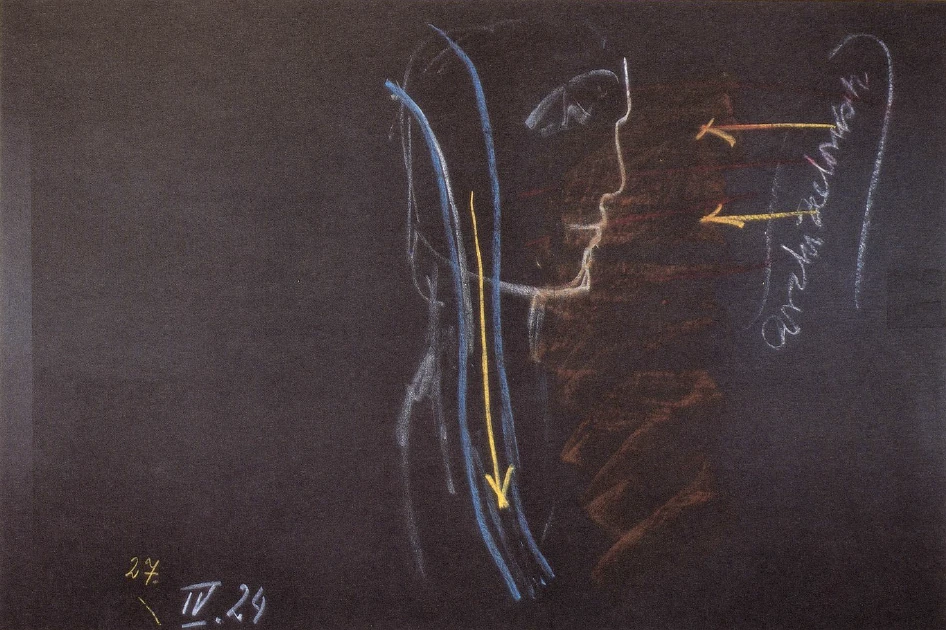

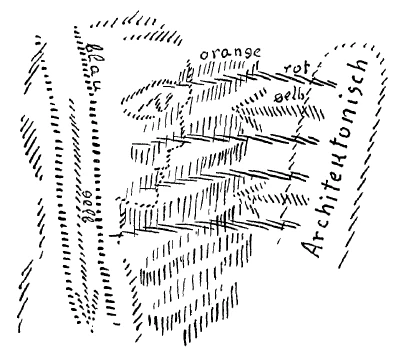

Und so hat man, wenn man auf den früheren Menschen zurückblickt, in diesem früheren Menschen dieses: Auf der einen Seite wird sein Blick und seine Empfindung nach außen durch das Architektonische gewissermaßen abgeschlossen, in sich abgefangen (siehe Zeichnung); nach innen wird der Blick dadurch abgefangen, daß der Mensch sich sein Seelenleben innerlich vorstellt, wie es ihm dann äußerlich in den Bildern des Kultus vorgestellt werden kann (blau).

Auf der einen Seite kommt man in sein Inneres hinunter, auf der anderen Seite trifft man auf mit dem Blick nach außen auf das, was in der Architektur da ist, in der Tempelarchitektur, in der Kirchenarchitektur. Es schließt sich das merkwürdig zusammen. Zwischen dem, was im Inneren lebt, und dem, auf was der Blick hier zurückgeworfen wird, da ist ein Mittelfeld (orange), das ja der Mensch im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein gar nicht sieht, weil er seinen äußeren Blick heute nicht abfangen läßt von einer wirklichen, verinnerlichten Architektur, und weil er seine Innenschau nicht abfangen läßt von Imaginativem, von Bildhaftem. Aber was dazwischenliegt: Gehen Sie mit dem im Leben herum, gehen Sie herum mit einer durch Imagination vertieften Innenerkenntnis und mit einem durch äußere architektonische Formen, die nun wirklich aus dem Menschlichen heraus erbaut sind, geheilten Sinnesempfinden, dann bekommen Sie die Empfindung, wie sie die älteren Menschen gehabt haben für die Schicksalsschläge. Wenn man das ausbildet, was zwischen diesen beiden liegt, zwischen Empfindung des wahrhaft Architektonischen und Empfindung des wahrhaft symbolisch nach innen Gehenden, dann findet man die Empfänglichkeit für die Schicksalsschläge. Man empfindet das, was geschieht, als herüberkommend aus früheren Erdenleben Das ist nun wieder die Einleitung zu weiteren Karmabetrachtungen, die in der nächsten Zeit angestellt werden sollen und die dann auch das «Gut und Böse» in die Karmabetrachtungen einschließen. Aber sehen Sie, es handelt sich ja wirklich darum, daß in der anthroposophischen Bewegung real gedacht wird. Die dem heutigen modernen Menschen angemessene Architektur, die seinen Blick in der richtigen Weise abfangen könnte und die sein naturalistisches Schauen, das ihm das Karma verdeckt und verfinstert, allmählich in die Anschauung hätte hereinbringen können, die stand da draußen in einer gewissen Form da. Und daß innerhalb dieser Formen wiederum gesprochen wurde in anthroposophischen Auseinandersetzungen, das gab die Innenschau. Und unter allem anderen, was schon hervorgehoben worden ist, war gerade dieses Goetheanum, dieser Goetheanumbau mit der Art und Weise, wie in ihm immer mehr und mehr Anthroposophie getrieben worden wäre, die Erziehung zum karmischen Schauen. Diese Erziehung zum karmischen Schauen, sie muß in die moderne Zivilisation herein.

Aber den Feinden dessen, was herein muß in diese moderne Zivilisation, denen liegt natürlich daran, daß dasjenige, was im echten, wahren Sinne den Menschen heranerzieht, was notwendig ist für die Zivilisation, abbrennt. Und so ist es möglich, auch da in die tieferen Zusammenhänge hineinzuschauen. Aber hoffen wir, daß in Bälde an derselben Stelle wiederum Karmaschauen erweckende Formen vor uns stehen!

Das ist es, was ich heute, wo noch viele fremde, auswärtige Freunde zurückgeblieben sind von unserer Österveranstaltung her, was ich gerade heute als ein Schlußwort aussprechen wollte. Karmische Betrachtungen des individuellen menschlichen Lebens

Fifth Lecture

We have now looked at a series of interrelated developments of destiny which can be enlightening and illuminating for the understanding of the historical life of mankind. The observations we have made were intended to show how what people experience, develop and absorb in previous earth periods is carried over by people themselves into later earth epochs. And connections have arisen for us, so that we understand that which is done by people, I would like to say, setting the tone, from causes meant in the moral sense, which have been laid down by people themselves in the course of time.

But not only this, I would like to say, causal connection can come before our souls through such contemplations directed towards karma, but also many things can be clarified with light, which actually appear unclear, incomprehensible at first for an external observation of the world.

But if one wants to go along with the great transformation in this respect, which is necessary in the near future with regard to the feeling and thinking of the human mind, if civilization is to go upwards and not downwards, then it is necessary that one first develops, so to speak, a sense for that which is incomprehensible under ordinary circumstances and for the comprehension of which an insight into deeper human and world-law conditions is necessary. Anyone who finds everything comprehensible naturally does not need to understand anything about the deeper causes. But this finding of comprehension is only apparent, because finding everything comprehensible in the world actually only means being superficial about everything. For most things are in fact incomprehensible to the ordinary consciousness. And to be able to stand still in amazement before the incomprehensibility of even the most mundane existence is basically only the beginning of the real quest for knowledge.

That is what the sigh has so often sounded from this lectern: let there be enthusiasm for searching within anthroposophical circles, enthusiasm for what lies within anthroposophical striving. And this enthusiasm must really begin with truly grasping the miraculous in everyday life as something miraculous. Then, as I said, one will be tempted to reach for the causes, for the deeper forces that underlie the existence that surrounds us. These states of astonishment towards our everyday surroundings can arise from historical observations, but also from what can be observed in the present. In historical observations, we often have to stop in front of historical events that are reported to us from the past and which appear as if here or there human life is really turning into nonsense.

Well, human life remains meaningless if we only look at it in such a way that we direct our gaze to a historical event and do not ask: How do certain human characters emerge from this historical event, what do they look like when they appear in their later re-embodiment? -- If we do not ask about this, then certain historical events also appear completely meaningless, meaningless because they are not fulfilled, because they lose their meaning if they cannot be lived out, if they do not become further soul impulses in a subsequent earth life, if they do not find balance and then continue to have an effect in further subsequent earth lives.

So there is certainly a historical senselessness in the appearance of such a personality as Nero, the Roman Caesar Nero. He has not yet been spoken of within the anthroposophical movement.

Just take into your soul everything that is historically reported about the Roman Caesar Nero. Compared to a personality such as Nero, life seems like something that one could simply mock with impunity, as if one could mock it, as if there were no consequences at all when someone appears with complete frivolity in a position that is in itself authoritative.

Not true, one would actually have to be dull when one sees what Nero does, and if one could not somehow come to ask oneself: What becomes of such a soul who, like Nero, makes a mockery of the whole world, who regards the lives of other people, the existence of almost an entire city, as something he can play with? - What an artist is lost with me! - As is well known, this is the saying that is put into Nero's mouth and which at least corresponds to his attitude. So the utmost frivolity, the utmost destructive will and destructive instinct, right down to a self-confession, but in such a way that this soul likes it.

Well, everything that can make an impression on the human being is repelled. Only world-destroying rays, so to speak, emanate from the personality. And we ask ourselves: What becomes of such a soul?

You have to be clear about this: Everything that is unloaded onto the world, so to speak, now radiates back in the life between death and a new birth. It must, so to speak, be unloaded onto the soul itself; for everything that has been destroyed by such a soul is now there in the life between death and a new birth. Now Nero first came into the world again a few centuries or a relatively short time afterwards in an unmeaning existence, where at first only that which was destructive rage, which he had exercised towards sovereignty, exercised out of himself because he wanted it that way, was balanced out; in the process the rage, one might say the enthusiasm for the destructive rage, was at work. In the next life on earth something of this matter was already fulfilled in a balancing way and the same soul individuality was now in a position where it also had to destroy, but had to destroy in a subordinate position where it was subject to orders. And there this soul had the necessity to now feel what it is like when one does not do it out of free will, does not accomplish it in sovereignty.

Now it is really a matter of looking at such things without emotion, of looking at them quite objectively. Such a fate, I would say - because to be as cruel as Nero, to be as destructive as Nero, is also a fate - is basically a fate worthy of mercy from a certain point of view. There is no need to rankle, no need to be harshly critical in any way; then one would not experience those things that are necessary to understand the matter in its further course anyway, because it is only possible to look into all the things that have been spoken of here if one looks objectively, if one does not accuse, but if one understands human destinies. But things do express themselves in a clear way, if one only has the sense to understand them. And the fact that the fate of Nero came before my soul was really due to an apparent coincidence. But it was only an apparent coincidence that this fate of Nero once stood before my soul in a particularly strong way.

For you see, when a shocking event took place, an event that I will talk about in a moment, which had a far-reaching effect in the region in question, I came to visit Karl Julius Schröer, who is mentioned several times in my biography. And when I got there, he too, like many people, was tremendously shaken by what had happened. And he spoke the word “Nero” - actually in such a way that it was initially unmotivated - as if from the dark depths of his mind. One might have thought it was completely unmotivated. But later it was quite clear that something had actually been spoken through a human mouth, as if from the Akashic Records. It was the following:

The Austrian Crown Prince Rudolf had been celebrated as a brilliant personality and was regarded as a person who aroused great hopes for the time when he should come to the throne. Although all sorts of things were known about Crown Prince Rudolf, everything that was known was perceived as things that were almost appropriate for a “grand seigneur”. In any case, nobody thought that this could lead to significant, tragic conflicts. And it was therefore a tremendous surprise, a terribly big surprise, when it became known in Vienna that Crown Prince Rudolf had died in a very mysterious way, near Heiligenkreuz Abbey, near Baden near Vienna. More and more details came to light, and at first there was talk of an accident; indeed, the “accident” was even officially reported.

Then, when the accident had already been officially reported, it became known that Crown Prince Rudolf had gone out to his hunting estate there accompanied by Baroness Vetsera, and that he had met his death together with her.

The details have become so well known that they need not be recounted here. Everything that followed took place in such a way that no one who knew the circumstances could doubt when it became known that Crown Prince Rudolf had committed suicide. Firstly, the circumstances were such that, after the official bulletin had been issued stating that there had been an accident, the Hungarian Prime Minister Koloman Tisza initially turned against this version and obtained a promise from the then Austrian Emperor himself that they would not stop at an incorrect statement. For this Koloman Tisza did not want to defend this statement before his Hungarian nation and vigorously asserted this. But then there was a man in the medical council who was actually one of the bravest Viennese doctors at the time and who was also supposed to conduct the coroner's inquest, and he said that he would not sign anything that was not supported by the objective facts.

Well, the objective facts pointed to suicide. The suicide was then also officially admitted, verifying the earlier facts, and if there were nothing other than the fact that suicide was admitted in such an extraordinarily Catholic-minded family as the Austrian imperial family, then this fact alone would mean that one could not really doubt it. So anyone who can judge the fact objectively will not doubt it.

But the question must be asked: how was it possible that someone who had such brilliant prospects could have resorted to suicide in the face of circumstances that could undoubtedly have been easily concealed in such a life situation? - There is no doubt that there was no objective reason for a crown prince to shoot himself because of a love affair - I mean, an objective reason, an objectively necessary reason for the external circumstances, of course.

There was also no external objective reason, but rather the fact that a personality who had an imminent prospect of the throne found life completely worthless, and that naturally prepared itself in a psychopathological way. But in this case, too, psychopathology must first be understood; for psychopathology is, after all, also something connected with fate. And the basic fact that was at work in the soul is nevertheless that someone for whom the most glamorous thing seemed to be beckoning found life completely worthless.

This is something, my dear friends, that simply belongs among those facts that one must find incomprehensible in life. And no matter how much has been written, no matter how much has been said about these things, only those who say to themselves: the suicide, and also the preceding psychopathology in its causality for the suicide, cannot be explained from this individual human life, from this life of Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria. If you want to understand, there must be something else underlying it.

And now imagine the soul of Nero - after it has gone through the other things I have spoken of - coming over into this self-destroying heir to the throne, who draws the consequence through his suicide: then the circumstances are simply reversed. Then you have the tendency lying in the soul that comes from earlier earthly lives, which, when passing through the time between death and a new birth, sees in the immediate sight that only destructive forces have actually emanated from it, and which must also experience the reversal in a splendid way, I would like to say.

How is this reversal experienced? It is experienced precisely by the fact that a life which outwardly contains everything that is valuable is reflected inwardly in such a way that the bearer of this life considers it so worthless that he empties himself. This causes the soul to become ill, to go half mad. In addition, the soul seeks outward involvement with the corresponding love affair and so on. But all these are only the consequences of the soul's striving, I would like to say, to direct all the arrows at itself which this soul formerly turned towards the world. And then, when we look into the interior of such conditions, we see a tremendous tragedy developing, but a just tragedy, an extraordinarily just tragedy. And the two images come together for us.

I have often said that it is the little things that underlie things that in truth, in all seriousness, make investigations in such areas possible. Many things in life must be involved.

As I said, when this event, which had such a shattering effect back then, had just taken place, I was on my way to Schröer. I didn't go there because of this event, but I was on my way to Schröer. It was, so to speak, the next person I spoke to about this matter. He spoke in a completely unmotivated way: “Nero” - so that I actually had to ask myself: Why is he thinking about Nero right now? - He started the conversation with “Nero”. The word “Nero” shook me at the time. But it shocked me all the more because this word “Nero” was spoken under a particular impression, because two days earlier there had been a soiree with the then German ambassador in Vienna, Prince Reuss, which became quite public. The Austrian crown prince was also present, as was Schröer, and he had seen how the crown prince had behaved two days before the catastrophe. And this strange behavior two days before the catastrophe at that soirée, which Schröer described very dramatically, and then the subsequent suicide two days after that: this in connection with the fact that the word “Nero” was pronounced, that was something that already had such an effect that one could say to oneself: Now there is a reason to look into things. - But why did I follow up so many things that came out of Schröer's mouth? Not as if something from Schröer, who of course couldn't know such things, had simply been taken up by me like an omen or something. But some things, especially those that seemed unmotivated, were important to me, important because of something that came to light in a strange way.

I got into a conversation with Schröer about phrenology, and Schröer told me, not actually humorously, but with a certain inner seriousness with which he said such things - you could tell how serious he was by the elevated language he used in his daily dealings when he wanted to say something with complete seriousness - Schröer said: "A phrenologist once examined me, tapped my head and found this elevation up there, of which he then said: That's the theosophist in you! - They didn't talk about anthroposophy back then, because that was in the eighties; so it wasn't referring to me, it was referring to Schröer. He examined him and said: That's where the Theosophist is sitting.

Well, it was indeed like that: Schröer was outwardly more of a theosophist than a theosophist; that is clear from my biography. But it was precisely where he spoke of things that actually fell outside of what he said in terms of motivation that his statements were sometimes extraordinarily profound. So that these two things could be put together: that he pronounced the word “Nero” and that he had to be regarded as someone to whom one listens, to whose unmotivated things one looks, so to speak, through this outward statement of his theosophy.

And so it really came about that the investigation into the fate of Nero had an enlightening effect on his further fate, the fate of Mayerling, and it was found that we were really dealing with the Nero soul in the Austrian Crown Prince Rudolf.

I found this investigation, which took a long time - because one is very careful in such matters - particularly difficult, because I was of course always misled by all kinds of people - whether you believe it or not, it is so - who claimed Nero for themselves and who advocated it with great fanaticism. So that whatever subjective power emanated from such reborn Nerons naturally had to be combated first. You had to get through the undergrowth.

But you may find, my dear friends, that what I am saying to you now is much more important because it grasps a historical fact - Nero - and that this is much more important in the further course of events than grasping the catastrophe of Mayerling, for example. For now one sees how such things, which actually appear at first, one might say, outrageous, like the existence of Nero, are lived out with full world justice, how world justice is really fulfilled and how injustice returns, but in such a way that individuality is placed in the equalization of injustice. And that is the monstrous thing about karma.

And then still something else can show itself when such an injustice is balanced through individual earth lives, as it will probably almost already be balanced here. For one must now know that the whole fulfillment - think of it - belongs to the balancing, arising from a life that considers itself worthless, that considers itself so worthless that this life first of all gives up a great empire - and Austria was then still a great empire - and its dominion over a great empire! This laying hands on oneself in such circumstances, and afterwards, after one has passed through the gate of death, continuing to live in the immediate spiritual view, that fulfills in a terrible way what one can call the justice of fate: that is, the compensation of injustice.

But on the other hand, if we now disregard this content, there was again a tremendous power in this Nero. This power must not be lost to humanity; this power must be purified. We have discussed the purification.

Once such a soul has been purified, it will transfer the purified power to later epochs on earth in a beneficial way. And precisely when we perceive karma as a just equalization, we can never fail to see how karma has a testing effect on man, a testing effect even when he enters into life in some outrageous way. The just balance happens, but the human powers are not lost. Rather, when it is lived through after the just compensation, that which a human life has perpetrated may also be transformed into power for good. That is why a fate such as the one described today is quite shocking,

But this brings us directly, my dear friends, to the consideration of what we can call good and evil in the light of karma: Good and evil, happiness and unhappiness, joy and sorrow, as man sees them peering and shining into his single individual life.

With regard to the perception of a person's moral situation, earlier eras on earth, earlier historical epochs were much more receptive than humanity today. Today's humanity is actually not at all receptive to the question of destiny. Certainly, every now and then you meet a person who senses the interplay of destiny; but the actual understanding of the great questions of destiny is something extraordinarily dark and incomprehensible for today's civilization, which regards the individual life on earth as something self-contained. Things just happen. A misfortune strikes you and you talk about the fact that a misfortune has struck you, but you don't think about it any further. In particular, you don't give it a second thought when some outwardly apparently quite good person, who has done nothing wrong at all, perishes through something that comes in from outside like a coincidence, or perhaps doesn't even perish, but has to suffer terribly through a terrible injury and the like. You don't think about how something like this can happen to a so-called innocent human life.

Well, mankind has not always been so insensitive and unresponsive to the question of fate. You don't have to go back very far in time to find that people felt that the blows of fate come from other worlds, that what you make yourself as fate also comes from other worlds.

Where did that come from? It came from the fact that in earlier epochs people not only had instinctive clairvoyance, and when instinctive clairvoyance was no longer there, they had traditions about the results of instinctive clairvoyance, no, the external institutions were also such that people did not actually need to view the world as superficially, as banally, as the world is viewed today in the materialistic age. There is much talk today of the harmfulness of the merely external, materialistic, naturalistic view of nature, which has finally taken hold of all circles, and which has also taken hold of the most diverse confessions of religious life. After all, religions have also become materialistic. Outer civilization no longer really wants to know anything about a spiritual world in any field, and there is talk of fighting such things theoretically. But that is not the most important thing; the theoretical fight against materialistic views does not matter so much. Rather, the most important thing is that through the view that has brought man to freedom and wants to continue to bring him to freedom, and which forms a transitional period in the developmental history of mankind, what was there in earlier epochs as a remedy for the external sensual view of man has also been lost.