Pastoral Medicine

GA 318

17 September 1924, Dornach

Lecture X

Dear friends,

There is something that is always overlooked in this present age, something that has to do with the working, and the wanting to work, of the spiritual world. It is this: that total spiritual activity must include the creative activity to be found in human thought and feeling. What really lies at their foundation has been completely forgotten in this age of materialistic thought; today humankind is fundamentally entirely unaware of it. That is why in this very field a kind of evil mischief is perpetrated throughout our present civilization. You surely know that from every possible center, whatever it may be called, all kinds of instructions go out to people telling how they can enhance their thought power, how their thoughts can become powerful. In this way seeds are strewn in every direction of something that in earlier spiritual life was called—and still is called—“black magic.” Such things are the cause of both soul illnesses and bodily illnesses, and the physician and priest must be aware of them in the course of their work. If one is alert to these things, one already has a clearer perception of the illnesses and symptoms of human soul-life. Moreover one can work to prevent them. This is all of great importance. The intent of instruction about thought power is to give people a power they would otherwise not possess, and this is often used for pernicious reasons. There is every possible kind of instruction today with this intent—for instance, how business executives can be successful in their financial transactions. In this area a tremendous amount of mischief is perpetrated.

And what is at the bottom of it all? These things will simply become worse unless clear knowledge of them is sought precisely in the field of medicine and in the field of theology. For human thinking in recent times, particularly scientific thinking, has come enormously under the influence of materialism. Often today people express their satisfaction over the fact that materialism in science is on the decline, that the tendency everywhere is to try to reach out beyond materialism. But truly this is slight satisfaction for those who see through these things. In the eyes of such people, the scientists or the theologians who want to overcome materialism in a modern manner are much worse than the hard-shell materialists whose assertions gradually become untenable through their very absurdity. And those who talk so glibly about spiritualism, idealism, and the like are strewing sand in people's eyes—and it's going into their own eyes as well.

For what do Driesch13Hans Driesch (1867–1941). Scientist and philosopher. and others do, for instance, when they want to present something that is beyond physical-material events? They use exactly the same thoughts that have been used for hundreds of years to think about the material world alone, thoughts that indeed have no other capacity than to think about the material world alone. These are the thoughts they use to think about something that is supposed to be spiritual. But such thoughts do not have that capacity. For that, one has to go to true spiritual science. That is why such strange things appear and today it is not even noticed that they are strange. A person like Driesch, for instance, recognized officially by the outer world but in reality a dilettante, holds forth to the effect that one must accept the term “psychoid.” Well, if you want to ascribe to something a similarity to something else, that something else must itself be around somewhere. You can't speak of apelike creatures if there are no apes to start with. You can't speak of the “psychoid” if you say there's no such thing as a soul! And this silly nonsense is accepted today as science, honest science, science that is really striving to reach a higher level. These things must be realized. And the individuals in the anthroposophical movement who have had scientific training will be of some value in the evolution of our civilization if they don't allow themselves to be blinded by the flaring-up of will-o'-the-wisps but persist in observing carefully what is now essential to combat materialism.

Therefore the question must be asked: How is it possible for active, creative thinking to arise out of today's passive thinking? How must priests and physicians work so that creative impulses can now flow into the activity of individuals who are led and who want to be led by the spirit? Thoughts that evolve in connection with material processes leave the creative impulse outside in matter itself; the thoughts remain totally passive. That is the peculiar characteristic of our modern thought world, that the thoughts pervading the whole of science are quite passive, inactive, idle. This lack of creative power in our thinking is connected with our education, which has been completely submerged in the current passive science. Today human beings are educated in such a way that they simply are not allowed to think a creative thought—for fear that if they should actually entertain a creative thought they wouldn't be able to keep it objective but would add some subjective quirk to it! These are things that must be faced. But how can we come to creative thoughts? This can only happen if we really develop our knowledge of the human being. Humans cannot be known by uncreative thoughts, because by their very nature they themselves are creative. One must re-create if one wants knowledge. With today's passive thinking one can only understand the periphery of the human being; one has to ignore the inner being.

It is important that we really understand the place humanity has been given in this world. Today therefore, let us put something before our souls as a kind of goal that lies at the end of a long perspective, but that can make our thoughts creative—for it holds the secret for making human thought creative.

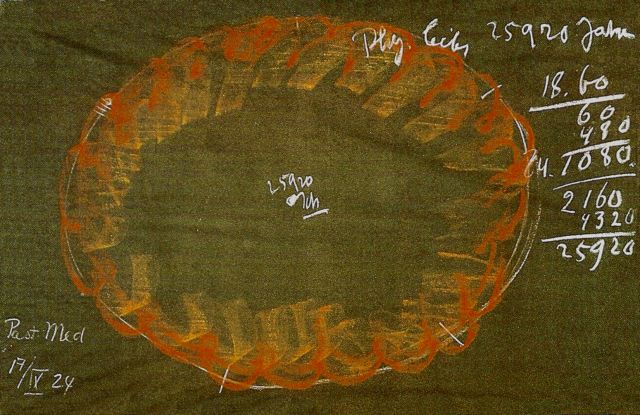

Let us think of the universe in its changing and becoming—say in the form of a circle. (Plate VII) We may picture it like this because actually the universe as it evolves through time presents a kind of rhythmic repetition, upward and downward, with respect to many phenomena. Everywhere in the universe we find rhythms like that of day and night: other, greater rhythms that extend from one Ice Age to another, and so forth. If first we confine our inquiry to the rhythm that has the largest intervals for human perception, it will be the so-called Platonic year, which has always played an important role in human thoughts and ideas about the world when these were filled with more wisdom than they are now.

We can come to the Platonic year if we begin by observing the place where the sun rises on the first day of spring, the twenty-first of March of each year. At that moment of time the sun rises at a definite spot in the sky. We can find this spot in some constellation; attention has been given to it through all the ages, for it moves slightly from year to year. If, for instance, in 1923 we had observed this point of spring, its place in the sky in relation to the other stars, and now in 1924 observe it again, we find it is not in the same place; it lies farther back on a line that can be drawn between the constellation of Taurus and the constellation of Pisces. Every year the place where spring begins moves back in the zodiac a little bit in that direction. This means that in the course of time there is a gradual shift through all the constellations of the starry world; it can be seen and recorded. If we now inquire what the sum of all these shifts amounts to, we can see what the distance is from year to year. One year it is here, the next year there, and so on—finally it has come back to the same spot. That means after a certain period of time the place of spring's beginning must again be in the very same spot of the heavens, and for the place of its rising the sun has traveled once around the entire zodiac. When we reckon that up, it happens approximately every 25,920 years. There we have found a rhythm that contains the largest time-interval possible for a human being to perceive—the Platonic cosmic year, which stretches through approximately 25,920 of our ordinary years.

There we have looked out into the distances of the cosmos. In a certain sense we have pushed our thoughts against something from which the numbers we use bounce back. We are pushing with our thoughts against a wall. Thinking can't go any further. Clairvoyance must then come to our aid; that can go further. The whole of evolution takes place in what is encircled by those 25,920 years. And we can very well conceive of this circumference, if you will—which obviously is not a thing of space, but of space-time—we can conceive of it as a kind of cosmic uterine wall. We can think of it as that which surrounds us in farthest cosmic space. (Plate VII, red-yellow)

Now let us go from what envelops us in farthest cosmic space, from the rhythm that has the largest interval of time that we possess, to what appears to us first of all as a small interval, that is, the rhythm of our breathing. Now we find—again, of course, we must use approximate numbers—we find eighteen breaths a minute. If we reckon how many breaths a human being takes in a day, we come to 25,920 breaths a day. We find the same rhythm in the smallest interval, in the human being the microcosm, as in the largest interval, the macrocosm.

Thus the human being lives in a universe whose rhythm is the same as that of the universe itself. But only the human being, not the animal; in just these finer details of knowledge one finally sees the difference between the human and the animal. The essential nature of the human physical body can only be realized if it is related to the Platonic cosmic year; 25,920 years: in that span of time the nature of our physical body is rooted. Take a look in An Outline of Esoteric Science at the tremendous time periods, at first determined otherwise than by time and space as we know them, through the metamorphosis of sun, moon, and earth. Look at all the things that had to be brought together, but not in any quantitative way; then you can begin to understand the present human physical body with all its elements.

And now let us go to the center of the circle, (Plate VII) where we have the 25,920 breaths that, so to speak, place humanity in the center of the cosmic uterus. Now we have reached the ego. For in the breathing—and remember what I said about the breathing, that in the upper human it becomes a finer breathing for our so-called spiritual life—we find the expression of the individual human life on earth. Here, then, we have the ego. Just as we must grasp the connection of our physical body to the large time interval, the Platonic cosmic year, so we must grasp the connection of our ego—which we can feel in every breathing irregularity—to the rhythm of our breathing.

So you see, our life on earth lies between these two things—our own breathing and the cosmic year. Everything that is of any importance for the human ego is ruled by the breath. And the life of our physical body lies within those colossal processes that are ruled by the rhythm of 25,920 years. The activity that takes place in our physical body in accordance with its laws is connected with the large rhythm of the Platonic year in the same way that our ego activity is connected with the rhythm of our breathing. Human life lies in between those two rhythms. Our human life is also enclosed within physical-etheric body and astral body-ego. From a certain point of view we can say that human life on earth lies between physical body-etheric body and astral body-ego; from another point of view, from the divine, cosmic aspect, we can say human life on earth lies between a day's breathing and the Platonic year. A day's breathing is in this sense a totality; it relates to our whole human life.

But now let us consider from the cosmic standpoint what lies between human breathing, that is, the weaving life of the ego, and the course of a Platonic year, that is, the living force out in the macrocosm. As we maintain our rhythm of breathing through an entire day of twenty-four hours, we meet regularly another rhythm, the day-and-night rhythm, which is connected with how the sun stands in relation to the earth. The daily sunrise and sunset as the sun travels over the arch of heaven, the darkening of the sun by the earth, this daily circuit of the sun is what we meet with our breathing rhythm. This is what we encounter in our human day of twenty-four hours.

So let us do some more arithmetic to see how we relate to the world with our breathing, how we relate to the course of a macrocosmic day. We can figure it out in this way: Start from one day; in a year there are 360 days. (It can be approximate.) Now take a human life (again approximate) of seventy-two years, the so-called human life span. And we get 25,920 days. So we have a life of seventy-two years as the normal rhythm into which a human being is placed in this world, and we find it is the same rhythm as that of the Platonic sun year.

So our breathing rhythm is placed into our entire life in the rhythm of 25,920. One day of our life relates to the length of our entire life in the same rhythm as one of our breaths relates to the total number of our breaths during one day. What is it, then, that appears within the seventy-two years, the 25,920 days in the same way that a breath, one inhalation-exhalation, appears within the whole breathing process? What do we find there? First of all we have inbreathing-outbreathing, the first form of the rhythm. Second, as we live our normal human life there is something that we experience 25,920 times. What is that? Sleeping and waking. Sleeping and waking are repeated 25,920 times in the course of a human life, just as inbreathing and outbreathing are repeated 25,920 times in the course of a human day. But now we must ask, what is this rhythm of sleeping and waking? Every time we go to sleep we not only breathe carbon dioxide out, but as physical human beings we breathe our astral body and ego out. When we wake, we breathe them in again. That is a longer inbreathing-outbreathing: it takes twenty-four hours, a whole day. That is a second form of breathing that has the same rhythm. So we have a small breath, our ordinary inhalation-exhalation; and we have a larger breath by which we go out into the world and back, the breath of sleeping-waking.

But let us go further. Let us see how the average human life of seventy-two years fits into the Platonic cosmic year. Let us count the seventy-two years as belonging to one great year, a year consisting of days that are human lives. Let us reckon this great cosmic year in which each single day is a whole human life. Then count the cosmic year also as having 360 days, which would mean 360 human lives. Then we would get 360 human lives x 72 years = 25,920 years: the Platonic year.

What does this figure show us? We begin a life and die. What do we do when we die? When we die, we breathe out more than our astral body and ego from our earthly organism. We also breathe our etheric body out into the universe. I have often indicated how the etheric body is breathed out, spread out into the universe. When we come back to earth again, we breathe our etheric body in again. That is a giant breath. An etheric inbreathing-outbreathing. Mornings we breathe in the astral element, while with our physical breath we breathe in oxygen. With each earth-death we breathe the etheric element out; with each earth-life we breathe the etheric element in.

So there we have the third form of breathing: life and death. If we count life to be our life on earth, and death to be our life between death and a new birth, then we have the largest form of breathing in the cosmic year:

- Inhalation-exhalation, the smallest breath.

- Sleeping-waking, a larger breath.

- Life-death, the largest breath.

Thus we stand first and foremost in the world of the stars. Inwardly, we relate to our ordinary breathing; outwardly, we relate to the Platonic year. In between, we live our human life, and exactly the same rhythm is revealed in this human life itself.

But what comes into this space between the Platonic year and our breathing rhythm? Like a painter who prepares a canvas and then paints on it, let us try painting on the base we have prepared, that is, the rhythms we have found in numbers. With the Platonic year as with smaller time rhythms, especially with the rhythm of the year, we find that continual change goes on in the outer world. Also it is change that we perceive; we perceive it most easily in temperatures: warmth and cold. We need only to think of cold winter and warm summer—here again we could present numbers, but let us take the qualitative aspect of warmth and cold. Human beings live life within this alternation between warmth and cold. In the outer world the alternation is within the element of time; and for so-called nature, changing in a time sequence from one to the other is quite healthful. But human beings cannot do this. We have, in a certain sense, to maintain a normal warmth—or a normal coldness, if you will—within ourselves. We have to develop inner forces by which we save some summer warmth for winter and some winter cold for summer. In other words, we must keep a proper balance within; we must be so continually active in our organism that it maintains a balance between warmth and cold no matter what is happening outside.

There are activities within the human organism of which we are quite unaware. We carry summer within us in winter and winter within us in summer. When it is summer, we carry within us what our organism experienced in the previous winter. We carry winter within us through the beginning of spring until St. John's Day; then the change comes. As autumn approaches, we begin to carry the summer within us, and we keep it until Christmas, until December 21, when the balance shifts again. So we carry in us this continual alternation of warmth and cold. But what are we doing in all this?

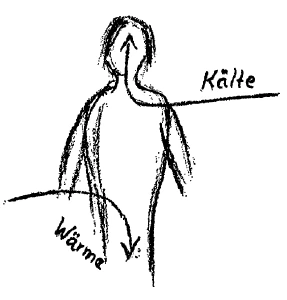

When we examine what we are doing, we find something extraordinarily interesting. Let this be the human being (see drawing below).

We realize from simple superficial observation that everything that enters the human being as cold shows the tendency to go to the nerve-sense system. And today we can point out that everything that works as cold, everything of a winter nature, works in the building up of our head, of our nerve-sense organization. Everything of a summer nature, everything that contains warmth, is given over to our metabolic-limb system. If we look at our metabolic-limb system, we can see that we carry within it everything summery. If we look at our nerve-sense functions, we can see that we carry in them everything we receive out of the universe that is wintry. So in our head we always have winter; in our metabolic-limb system we always have summer. And our rhythmic system maintains the balance between the one and the other. Warmth-cold, warmth-cold, metabolic system-head system, with a third system keeping them in balance. Material warmth is only a result of warmth processes, and material cold the result of cold processes. So we find a play of cosmic rhythm in the human organism. We can say that winter in the macrocosm is the creative force in the human nerve-sense system centered in the head. Summer in the macrocosm is the creative force in the human metabolic-limb system.

This way of looking into the human organism is another example of the initiatic medicine of which I spoke when I said it has a beginning in the book14Rudolf Steiner and Ita Wegman, Extending Practical Medicine (London: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1996). that Dr. Wegman worked out with me. The beginning is there for what must more and more become a part of science.

If we climb the rocks where the soil is so constituted that winter plants will grow in it, we come to that part of the outer world that is related to the organization of the human head. Let us suppose that we collect medicinal substances out in the world. We want to make sure that the spiritual forces appearing in an illness that originates in the nerve-sense system will be healed by the spirit in outer nature, so we climb very high in the mountains to find minerals and plants and bring them down for medicines for head illnesses. We are acting out of our creative thinking. It starts our legs moving toward things we must find in the earth that correspond to our medical needs. The right thoughts—and they come out of the cosmos—must impel us all the way to concrete deeds. These thoughts can stir us without our knowledge. People, say, who work in an office—they also have thoughts, at least they sometimes have them—now they are impelled by some instinct to go off on all sorts of hikes. Only they don't know the real reason—but that doesn't matter. It only becomes important if one observes such people from a physician's or a priest's standpoint. But a true view of the world also gives one inspiration for what one has to do in detail.

Now again, if we have to do with illnesses in the metabolic-limb system, we look for low-growing plants and for minerals in the soil. We look for what occurs as sediment, not for what grows above the earth in crystal form. Then we get the kind of mineral and plant remedies we need. That is how observation of the connection between processes in the macrocosm and processes in man lead one from pathology to therapy.

These connections must again be clearly understood. In olden times people knew them well. Hippocrates was really a latecomer as far as ancient medicine is concerned. But if you read a little of what he is supposed to have written, of what at any rate still preserved his spirit, you will find this viewpoint throughout. All through his writings you will find that the concrete details relate to broad knowledge and observation such as we have been presenting. In later times, such things were no longer of any interest. People came more and more to mere abstract, intellectual thinking and to an external observation of nature that led to mere experimentation. We must find the way back again to what was once vision of the relation between the human being and the world.

We live as human beings on the earth between our ego and our physical body, between breathing and the Platonic year. With our breathing we have a direct relation to the day. What do we relate to with our physical body? How do we relate physically to the Platonic year? There we relate to totally external conditions in the evolution of large natural processes—for instance, to climatic changes. In the course of the large natural processes human beings change their form, so that, for instance, successive racial forms appear, and so forth. We relate qualitatively to what happens in the shorter external changes, to what successive years and days bring us. In short, we evolve as human beings between these two farthest boundaries. But in between we can be free, because in between, even in the macrocosm, a remarkable element intervenes.

One can be lost in wonder in pondering over this rhythm of 25,920 years. One is awed by what happens between the universe and the human being. And as one contemplates all this, one realizes that the whole world—including the human being—is ordered according to measure, number, and weight. Everything is wonderfully ordered—but it all happens to be human calculation! And at important moments when we are explaining a calculation—even though it is correct—we always have to add that curious word “approximately.” For our human calculation never comes out exactly right. It is all absolutely logical; order and reason are in everything, they are alive and active, everything “works,” as we say. And yet there is something in all of it, something in the universe that is completely irrational. Something is there so that however profound our awe may be, even as initiates, when we go for an afternoon walk we still take an umbrella along. We take an umbrella because something could happen that is irrational. Something can appear in the life of the universe that simply “doesn't come out right” when numbers are applied to it. And so one has had to invent leap years, intercalary months, all kinds of things. Such things have always had to be used for the fixing of time. What is offered by a well-developed astronomy that has deepened into astrology and astrosophy (for one can think of it in that way) is all destroyed for immediate use by meteorology. This latter has not attained the rank of a rational science; [This lecture was given in 1924.] it is more or less permeated by vision, and will be, more and more. It takes an entirely different path; it consists of what is left over by the other sciences. Modern astronomy itself lives only in names; it is really nothing more than a system for giving names to stars. That is why even Serenissimus came to the end of his knowledge when newly found stars had to have names. He would visit the observatories in his country and let them show him various stars through the telescope, then after seeing everything he would say, “Yes, I know all that—but how you know what that star's name is, that very distant star, that's what I don't understand.” Yes, of course it's obvious, the standpoint you've adopted at this moment when you laugh at Serenissimus. But there's another standpoint: one could laugh at the astronomers. I'd rather you'd laugh at the astronomers, because there's something very strange going on in the world as it evolves.

If you want to inquire into the old way of naming things, Saturn and so forth, you should think back to our speech course,15Rudolf Steiner, Speech and Drama (Hudson, N.Y.: Anthroposophic Press, 1986). and recall that in olden times names were given from the feeling the astrologers and astrosophers had for the sound of some particular star. All the old star names were God-given, spirit-given. The stars were asked what their names were, because the tone of the star was always perceived and its name was then given accordingly. Now, indeed, you come to a certain boundary line in the development of astrosophy and astrology. Earlier they had to get the names from heaven. When you come to more recent times when the great discoveries were made, for instance, of the “little fellows” (Sternwichten), then everything is mixed up. One is called Andromeda, another has another Greek name. Everything is mixed up in high-handed fashion. One can't think that Neptune and Uranus are as truly characterized by their names as Saturn was. Now there is only human arbitrariness. And Serenissimus made one mistake. He believed the astronomers were carrying on their work similarly to the ancient astrosophers. But this was not so. They possessed only a narrow human knowledge, while the knowledge of the astrosophers of olden times, and astrologers of still older times, came directly out of humanity's intercourse with the gods. However, if today one would return from astronomy to astrology or astrosophy, and thereby have a macrocosm to live in that is rational throughout, then one would reach Sophia. Then one would find too that within this rationality and Sophia-wisdom meteoronomy, meteorology, and meteorosophy are the things that “don't come out right” by our human calculation, and one can only question them at their pleasure! That's another variety of Lady! In ordinary everyday life, one calls a lady capricious. And the meteorological Lady is capricious all the way from rainshowers to comets. But as one gradually advances from meteorology to meteorosophy one discovers the finer attributes of this world queen, attributes that do not come merely from caprice or cosmic emotion, but from the Lady's warm heart. But nothing will be accomplished unless in contrast to all the arithmetic, all the thinking, all that can be calculated rationally one acquires a direct acquaintance with the beings of the cosmos and learns to know them as they are. They are there; they do show themselves—shyly perhaps at first, for they are not obtrusive. With calculations one can go further and further, but then one is getting further and further away from the true nature of the world. For one is only reaching deeds from the past.

If one advances from ordinary calculation to the calculating of rhythms as it was in astrology for the harmony of the spheres, one goes on from the calculating of rhythms to a view of the organization of the world in numbers, as we find them in astrosophy. On the other hand one finds that the ruling world beings are rather shy. They do not appear at once. First they only present a kind of Akasha photography, and one is not sure of its source. One has the whole world to look at, but only in photographs displayed in various parts of the cosmic ether. And one does not know where they come from.

Then inspiration begins. Beings come out of the pictures and make themselves known. We move out of “-nomy” - but just to “-logy.” Only when we push through all the way to intuition does the being itself follow from inspiration and we come to Sophia. But this is a path of personal development that requires the effort of the whole human being. The whole human being must become acquainted with such a Lady, who hides behind meteorology—in wind and weather, moon and sun insofar as they intervene in the elements. Not just the head can be engaged as in “-logy,” but the whole human being is needed.

Already there is a possibility of taking the wrong path in this endeavor. You can even come to Anthroposophy through the head—by coming from anthroponomy, which is today the supreme ruling science, to anthropology. There you just have rationality, nothing more. But rationality is not alive. It describes only the traces, the footprints, of life and it gives one no impulse to investigate details. Yet life really consists of details and of the irrational element. What your head has grasped, you have to take down into the whole human being, and then with the whole human being progress from “-nomy” to “-logy,” finally to “-sophy,” which is Sophia.

We must have a feeling for all this if we want to enliven theology on the one side and medicine on the other through what can truly enliven them both—pastoral medicine. But the essential thing is that first of all, at the very outset of our approach to pastoral medicine, we learn to know the direction it should take in its observation of the world.

Zehnter Vortrag

Meine lieben Freunde! Was in unserer heutigen Zeit beim wirklichen Wirken und Wirkenwollen aus der geistigen Welt heraus immer übersehen wird, ist das, daß zu allem geistigen Wirken gehört, daß in den Gedanken, die der Mensch hat, und in den Gefühlen Aktivität, Schöpferisches sein kann. Was da eigentlich zugrunde liegt, das ist in der Zeit der materialistischen Denkungsweise völlig vergessen worden und ist heute im Grunde genommen der Menschheit ganz unbewußt. Daher wird so vielfach gerade auf diesem Gebiet eine Art Unfug getrieben, ein Unfug, der heute unter uns in der Menschheitszivilisation sogar ziemlich umfangreich waltet. Sie werden ja wissen, daß von allen möglichen zentralen Stellen oder dergleichen, wie man es nennt, allerlei Anweisungen an den Menschen ausgehen, wie man Gedankenkraft entwickeln kann, wie die Gedanken mächtig werden können. Man möchte sagen: Keime von dem, was man früher im Geistesleben genannt hat «schwarze Magie» und auch fortdauernd so nennt, werden dadurch überallhin ausgestreut. Gerade auf solche Dinge, die zu gleicher Zeit seelische und leibliche Krankheitsursachen sind, hat sowohl der Arzt wie der Priester bei ihrer in die Kultur, in die Zivilisationsentwickelung hineingehenden Wirkung zu achten. Denn wenn man gerade auf solche Dinge achtet, leistet man ja dasjenige, was sowohl zur Verhütung als auch zum besseren Erkennen der Krankheit und der Krankheitserscheinungen des menschlichen Seelenlebens bedeutsam ist. Man will mit solchen Anweisungen ja dem Menschen eine in ihm sonst nicht vorhandene Kraft geben, und verwendet das oftmals zu den unlautersten Dingen. Es gibt nach dieser Richtung ja alle möglichen Anweisungen heute schon, wie Handelsagenten dazu kommen können, Geschäfte zu machen und dergleichen. Auf diesem Gebiete wird heute ungeheuer viel an Unfug erarbeiter.

Aber sehen Sie, was liegt denn dem zugrunde? Diese Dinge müssen immer schlimmer werden, wenn gar nicht eine wirkliche Erkenntnis gerade auf dem Gebiete der Medizin und auf dem Gebiete der Theologie Platz greift nach dieser Richtung. Denn das Denken der Menschen der neueren Zeit, namentlich das wissenschaftliche Denken hat sich ganz ungeheuer ausgebildet unter dem Einfluß des Materialismus. Wenn heute schon vielfach eine Befriedigung darüber ausgesprochen wird, daß der Materialismus im Abnehmen begriffen sei in der Wissenschaft, daß man überall will über den Materialismus Hinausgehendes gestalten, ja, meine lieben Freunde, das macht gerade auf den, der die Dinge durchschaut, einen viel unangenehmeren Eindruck. Diese Wissenschafter, die auf heutige Art den Materialismus überwinden wollen, auch diejenigen Theologen, die auf heutige Art den Materialismus überwinden wollen, die sind vor den Augen dessen, der diese Dinge durchschaut, eigentlich viel schlimmer als die starren Materialisten, die nach und nach durch die Absurdität ihrer eigenen Sache die Sache unmöglich machen. Aber diese Schwätzer über Spiritualismus, über Idealismus und dergleichen streuen den Leuten Sand in die Augen und sich selber auch.

Denn was wird denn da, sagen wir in Drieschscher Weise oder in anderer Weise getan, um irgend etwas über materielles Geschehen hinaus vertreten zu können? Es werden genau dieselben Gedanken, die jahrhundertelang verwendet worden sind, um bloß das Materielle zu denken, die auch gar keine andere Möglichkeit haben, als das Materielle zu denken, verwendet, um ein angeblich Geistiges zu denken. Das können diese Gedanken gar nicht! Das kann man nur, wenn man in wirkliche Geisteswissenschaft eingeht. Daher kommen solche sonderbaren Dinge heraus, die heute gar nicht bemerkt werden. Es spricht zum Beispiel ein von der Außenwelt offiziell anerkannter, in Wirklichkeit furchtbar dilettantischer Driesch davon, daß man annehmen müsse: «Psychoide». Ja, meine lieben Freunde, wenn Sie irgendeinem Ding eine Ähnlichkeit zuschreiben wollen, muß das Ding irgendwo da sein. Sie können doch nicht sprechen von affenähnlichen Wesen, wenn nie ein Affe da ist. Sie können nie von Psychoiden sprechen, wenn nie eine Seele anerkannt wird im Menschen! Derlei Geschwätz gilt heute als echte, sogar ins Bessere hineinstrebende Wissenschaft. Das muß durchschaut werden. Und dann sind diejenigen, welche mit wissenschaftlicher Bildung drinnenstehen in der anthroposophischen Bewegung, für die Zivilisationsentwickelung etwas wert, wenn sie sich nicht blenden lassen von dem aufflackernden Irrlicht, sondern wenn sie ganz exakt hineinschauen in das, was nun wirklich notwendig ist und gegenüber dem Materialismus gebraucht wird.

Daher muß schon gefragt werden: Wie ist es möglich, daß aus der heutigen Passivität des Denkens wieder Aktivität, Schöpferisches wird? Wie muß gewirkt werden von Priesterschaft und Ärzteschaft, daß Schöpferisches in die vom Geist geleiteten, geleitet sein wollenden Arbeiten der Menschen hereinfließt? Die Gedanken, namentlich die sich an den materiellen Vorgängen entwickeln, lassen das Schöpferische draußen in der Materie, bleiben selber ganz passiv. Das ist das Eigentümliche der heutigen Gedankenwelt, wie sie überall in der Wissenschaft angewendet wird, daß sie ganz passiv, untätig, inaktiv ist. Daß gar kein Schöpferisches in den Gedanken ist, das hängt mit unserer ganz in die heute passive Wissenschaft eingetauchten Erziehung zusammen. Der Mensch wird schon so gebildet, so erzogen, daß er nur ja nicht zu einem schöpferischen Gedanken kommt, denn man hat gleich Angst, käme er zu einem schöpferischen Gedanken, so würde er nicht die objektive Wirklichkeit feststellen, sondern irgend etwas dazu tun. Das sind die Dinge, die erfaßt werden müssen. Nun aber, wie kann man zu schöpferischen Gedanken kommen? Sehen Sie, zu schöpferischen Gedanken kann man nur dann kommen, wenn man wirklich Menschenerkenntnis entwickelt; denn der Mensch läßt sich nicht unschöpferisch erkennen, weil er dem Wesen nach schöpferisch ist. Man muß nachschaffen, wenn man erkennen will. Man kann mit dem passiven Denken heute nur die Peripherie des Menschen erfassen, muß sein Inneres liegen lassen. Man muß das Hineingestelltsein des Menschen in die Welt wirklich erfassen. Deshalb wollen wir uns heute gewissermaßen etwas wie ein Ziel, das am Ende einer weiten Perspektive liegt, das uns aber die Gedanken schöpferisch machen kann, und wirklich auch das Geheimnis in sich schließt, die Gedanken schöpferisch zu machen, das wollen wir uns einmal vor die Seele hinstellen und dabei manches in unsere Betrachtungen aufnehmen, das Sie schon aus den allgemeinen anthroposophischen Vorträgen wissen.

Denken wir uns einmal schematisch, meine lieben Freunde, das im Werden wandelnde Weltenall in Form, nun ja, eines Umkreises (Ta- Tafel ii fel 11). Wir dürfen das schematisch aus dem Grunde, weil ja tatsächlich das werdende Weltenall in der Zeit eine Art rhythmischer Wiederh-Ölung darstellt, allerdings in aufsteigender Linie, in absteigender Linie in bezug auf manche Erscheinungen, aber überall finden wir im Weltenall etwas wie Tag- und Nachtrhythmus, sonstige Rhythmen, größere Rhythmen, die da verlaufen zwischen Eiszeit und Eiszeit und so weiter. Wenn wir uns zunächst an denjenigen Rhythmus halten, der für die menschliche Wahrnehmung derjenige mit den größten Intervallen ist, dann kommen wir auf das sogenannte platonische Jahr, das ja immer, als die Weltenbetrachtungen noch besser waren, eine große Rolle in diesen Anschauungen und menschlichen Weltbetrachtungen spielte.

Dieses platonische Jahr, man kommt zu ihm dadurch, daß man beobachtet den Aufgangspunkt der Sonne am Morgen an dem Tage, wo der Frühling seinen Anfang nimmt, am 21. März des Jahres. Da geht die Sonne an einem bestimmten Punkt des Himmels auf. Man kann diesen Punkt im Sternbild sehen, man notiert ja diesen Punkt durch alle Zeiten hindurch, denn er ändert sich um ein kleines Stück jedes Jahr. Wenn man, sagen wir, im vorigen Jahr beobachtet hat den Frühlingspunkt genau an seinem Orte am Himmel nach den anderen Sternen, also 1923 beobachtet hat, ihn 1924 wieder beobachtet hat, so liegt der diesjährige Aufgangspunkt der Sonne nicht an derselben Stelle, sondern er liegt verschoben in der Richtung, die man sich ziehen kann eben dadurch, daß man das Sternbild des Stieres mit dem Sternbild der Fische durch eine Linie verbindet. In dieser Richtung des Zodiakus verschiebt sich der Frühlingspunkt. So ist er jedes Jahr um ein Stückchen verschoben. Das weist hin darauf, daß in der ganzen Konstellation der Sternenwelt mit jedem Jahr eine Verschiebung stattfindet, die in dieser Weise registriert werden kann. Wenn man nun prüft, wie sich die Summe dieser Verschiebungen ausnimmt — Sie können es ja sehen, wenn eine Verschiebung stattfindet -, ist er in dem Jahre da, in dem Jahre da und so weiter. Einmal kommt die Verschiebung bis hierher, einmal bis hierher, bis sie auf denselben Punkt zurückkommt. Das heißt, es muß nach einem gewissen Zeitraum der Frühlingspunkt wieder an demselben Himmelsorte stehen. Es ist also eine einmalige Umdrehung des ganzen Sonnenweges in bezug auf den Morgenaufgang eingetreten. Wenn man das berechnet, so geschieht es alle 25 920 Jahre im Durchschnitt. So haben wir einen Rhythmus erfaßt, der das größte Intervall enthält, das dem Menschen zunächst in der Wahrnehmung zugänglich ist: das platonische Weltenjahr, das 25920 unserer Jahre ungefähr dauert.

Da haben wir hinausgeblickt in die Weltenweiten, und wir stoßen da gewissermaßen mit unseren Gedanken an etwas, woran die Zahlen, die wir entwickeln, abprallen. Wir stoßen an etwas, wie an eine Wand, mit unserem Denken. Darüber hinaus geht das Denken zunächst nicht. Da muß dann das Hellsehen kommen, das da hinausgeht. Aber es geht zunächst nicht hinaus das Denken. Alle Entwickelung läuft innerhalb dessen ab, was da umschlossen wird von diesen 25920 Jahren, und wir können ganz gut, wenn wir wollen, diesen Umfang, der allerdings nicht durch Raum, sondern durch Raum-Zeit abgeschlossen ist, wir können ihn vorstellen als eine Art kosmische Uteruswand. Wir stellen ihn also vor als dasjenige, was uns im weitesten Weltenraum umgibt (Tafel 11, rot-gelb). Und jetzt gehen wir von diesem, was uns da im weitesten Weltenraum umgibt als den Rhythmus, der in sich trägt die größten Intervalle, die wir haben, zu demjenigen, was uns zunächst im Menschen als ein kleineres Intervall erscheint, zum Atemzug.

Sehen Sie, da müssen wir natürlich wiederum approximative Zahlen annehmen, wenn wir den Atemzug nehmen: Achtzehn Atemzüge in der Minute; und rechnen aus, wieviel das im Tage Atemzüge sind, bekommen wir ja 25920 Atemzüge pro Tag beim Menschen.

Wir haben denselben Rhythmus, den wir draußen haben, mit den großen Intervallen, im Menschen, im Mikrokosmos mit kleinsten Intervallen. Da lebt also der Mensch in einem Weltenall, das er nachbildet in dem Rhythmus, der der Rhythmus des Weltenalls selber ist. Nur für den Menschen, nicht für das Tier, denn gerade in diesen feineren Erkenntnissen sieht man erst recht den Unterschied zwischen Mensch und Tier. Für den Menschen ist es ja so, daß die Kompaktheit, das Wesenhafte seines physischen Leibes nur erkannt werden kann, wenn man es zurückführt auf das platonische Weltenjahr. 25920 Jahre, darinnen wurzelt das Wesen unseres physischen Leibes. Sehen Sie einmal nach in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß», welche großen Zeiträume, zunächst durch anderes als durch Zeit-Raum bestimmt, durch die Metamorphose Sonne, Mond, Erde, welche Dinge zusammengetragen werden mußten, nicht in quantitativ zahlenmäßiger Weise, um den menschlichen physischen Leib, so wie er heute ist, zu verstehen aus seinen Elementen heraus.

Gehen wir dann in die Mitte herein, wo wir die 25 920 Atemzüge haben (Tafel 11), die sozusagen den Menschen hineinstellen in die Mitte des Weltenuterus, dann kommen wir an das Ich heran. Denn in diesen Atemzügen zusammen mit dem, was ich gesagt habe über die Atmung, die nach dem oberen Menschen geht und sich zu dem sogenannten Geistesleben verfeinert, in der Atmung liegt ja die Ausprägung des individuellen Menschenlebens auf Erden. Hier haben wir also das Ich. Wie wir den Zusammenhang erfassen müssen unseres physischen Leibes mit den großen Zeiträumen, mit dem platonischen Weltenjahr, so müssen wir den Zusammenhang unseres Ichs, das wir ja spüren können in jeder Unregelmäßigkeit des Atems, mit unserem Atmungsrhythmus ins Auge fassen.

Sehen Sie, zwischen diesen beiden Dingen liegt des Menschen Leben auf Erden, zwischen Atemzug und Weltenjahr liegt das Menschenleben. Durch die Atemzüge wird geregelt alles dasjenige, was für das Ich bedeutsam ist. In jenen kolossalen Vorgängen, welche durch den Rhythmus von 25920 Jahren geregelt werden, liegt das Leben unseres physischen Leibes. Was im physischen Leib vorgeht an Gesetzmäßigkeit, hängt so zusammen mit dem großen Rhythmus des platonischen Weltenjahres, wie unsere Ich-Tätigkeit zusammenhängt mit dem Rhythmus unseres Atmens. Zwischen beiden drinnen liegt das Menschenleben, das wieder für uns eingeschlossen ist zwischen physischem Leib, Ätherleib - astralischem Leib und Ich. Wir können von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus sagen, das Menschenleben auf Erden liegt zwischen physischem Leib, Ätherleib - astralischem Leib und Ich, und von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte aus sagen, das Menschenleben vom göttlich-kosmischen Aspekte angesehen, liegt zwischen dem Atmen eines Tages und zwischen dem platonischen Weltenjahr. Das Atmen eines Tages ist ein Ganzes dadurch. Das Atmen eines Tages gehört dadurch zusammen mit dem, was Menschenleben ist.

Nun betrachten wir aber von diesem kosmischen Standpunkte aus, was zwischen dem menschlichen Atmen, also zwischen dem Weben und Wesen des Ich und dem Geschehen eines platonischen Weltenjahres, also dem Leben und Treiben draußen im Makrokosmos, was da dazwischen liegt. Sehen Sie, mit dem, was in unserem Atmungsorganismus wirken will, ist es so, daß mit der vierundzwanzigstündigen Atmung des Tages, mit dem, was da drinnen liegt zwischen diesem Atmen und dem, was wir in dieser Atmung als einen ganzen Atmungsrhythmus haben, wir jedesmal begegnen jenem Rhythmus, der als Tag- und Nachtrhythmus da ist und zusammenhängt mit dem Sonnenwesen, wie es im Verhältnis zum Erdenwesen steht. Im täglichen Aufund Untergehen der Sonne, im Hingehen der Sonne über das Himmelsgewölbe, im Verdunkeln der Sonne durch die Erde, in diesem täglichen Herumgehen der Sonne liegt dasjenige, dem wir begegnen mit unserem Atmungsrhythmus.

Aber damit kommen wir beim Tag an, beim Tag von vierundzwanzig Stunden, beim menschlichen Tag von vierundzwanzig Stunden kommen wir da an. Und jetzt rechnen wir da weiter, wie wir uns da gewissermaßen aus dem Atmen heraus in die Welt hineinarbeiten. Rechnen wir das einmal aus, wie wir uns da hineinarbeiten in dasjenige, was wir begegnen jetzt im Tageslauf des Makrokosmos, wie wir zunächst in ihm drinnenstehen. Sehen Sie, da können wir rechnen: Wir haben einen Tag, nehmen das Jahr meinetwegen zu dreihundertsechzig Tagen — die Dinge können ja approximativ sein —, dann haben wir dreihundertsechzig Tage. Jetzt rechnen wir ungefähr das Menschenleben zu zweiundsiebzig Jahren, das patriarchalische Alter, das angenommen worden ist, und wir bekommen 25920 Tage. Wir haben ein Menschenleben, das wieder ein Ganzes darstellt in zweiundsiebzig Jahren, das einen Rhythmus darstellt, in dem es sich in die Welt hineinstellt, der der gleiche Rhythmus des platonischen Sonnenjahres ist.

Wir stellen uns mit unserem Atmungsrhythmus in unser ganzes Menschenleben so hinein, daß wir es regeln nach dem Rhythmus 25 920. Wir kommen an bei demjenigen, was nun so in diesem Menschenleben drinnensteht, wie der Atmungszug im Tage steht. Nun, was steht denn in den zweiundsiebzig Jahren, in den 25 920 Tagen so drinnen, wie der Atmungszug, die Ein- und Ausatmung im Atmungszug drinnensteht? Was steht da so drinnen? Wir haben erstens Ein- und Ausatmung. Die erste Phase des Rhythmus. Wir haben zweitens: während des Tages, da stellen wir uns hinein in das Leben, erleben im Leben auch etwas 25 920 mal. Was denn? Schlafen und Wachen. Wir kommen zum zweiten: Schlafen und Wachen. Das wiederholt sich, der Wechselzustand von Schlafen und Wachen im Laufe des Menschenlebens 25 920 mal, ebenso wie sich das Einatmen und Ausatmen 25 920 mal im Laufe eines Tages, während eines Sonnenumganges wiederholt. Aber bedenken Sie, was ist denn dann Einschlafen und Aufwachen, Einschlafen-Aufwachen, Einschlafen-Aufwachen? Jedesmal, wenn wir einschlafen, atmen wir nicht bloß Kohlensäure aus, sondern wir atmen aus als physischer Mensch unseren astralischen Leib und unser Ich. Beim Aufwachen atmen wir es wieder ein. Das ist ein längerer Atemzug, der vierundzwanzig Stunden, ein Tag dauert. Das ist ein zweites Atmen, das sich in demselben Rhythmus bewegt. Wir haben also das kleinste Atmen, das im gewöhnlichen Ein- und Ausatmen besteht. Wir haben das größere Atmen, wo der Mensch schon in die Welt hinauswächst, dasjenige, was sich im Schlafen und Wachen auslebt.

Gehen wir weiter. Probieren wir jetzt einmal, wie so ein Menschenleben von zweiundsiebzig Jahren im Durchschnitt sich in das platonische Weltenjahr hineinstellt. Diese zweiundsiebzig Jahre, rechnen wir sie so, als ob sie auch einem Jahre angehören, einem ganzen Jahre, das aus solchen Tagen besteht, die ein Menschenleben sind. Rechnen wir also ein großes Weltenjahr, dessen einzelne Tage ein Menschenleben sind und rechnen wir dieses Weltenjahr auch zu 360 Tagen, das heißt zu 360 Menschenleben; wir bekommen: 72 mal 360 Menschenleben = 25920 Jahre, just das platonische Jahr.

Was tun wir aber denn da, wenn wir dieses platonische Jahr absolvieren? Wir fangen das Leben an und sterben. Was tun wir im Sterben? Im Sterben atmen wir mehr aus als unseren astralischen Leib und Ich mit Bezug auf unsere Erdenorganisation. Wir atmen den Ätherleib heraus ins Weltenall. Ich habe das oft dargestellt, wie der Ätherleib ausgeatmet wird ins Weltenall, wie er sich verbreitet im Weltenall. Wenn wir wieder zurückkommen, atmen wir wieder einen Ätherleib ein. Das ist ein Riesenatmen. Ein Äther Ein- und Ausatmen. Am Morgen atmen wir Astralisches ein. Mit jedem Atemzug atmen wir Sauerstoff ein, aber mit jedem Erdensterben atmen wir den Äther aus, und mit jedem Erdenleben atmen wir den Äther ein.

Da haben wir also das dritte: Leben und Tod. Wenn wir das Leben so auffassen, daß wir das Leben als das Leben in der Erde auffassen, und den Tod als das Leben zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt, kommen wir an beim platonischen Weltenjahr, indem wir zum kleinsten Atmen zunächst das größere Atmen, und dann zum größeren Atmen das größte Atmen hinzufügen.

1. Ein- und Ausatmung kleinstes Atmen

2. Schlafen und Wachen größeres Atmen

3. Leben, Tod größtes Atmen

Und so stehen wir zunächst, ich möchte sagen, in der Sternenwelt. Auf der einen Seite ruhen wir nach innen auf unserer Atmung, auf der anderen Seite ruhen wir nach außen auf dem platonischen Weltenjahr. Dazwischen spielt sich unser Menschenleben ab, aber in diesem Menschenleben selber offenbart sich wieder der gleiche Rhythmus.

Aber was kommt denn nun in diesen Zwischenraum hinein, zwischen dem platonischen Weltenjahr und zwischen unserem Atemzug? Versuchen wir einmal dasjenige, was wir auf Grundlage des Rhythmus gewissermaßen zahlenmäßig so gefunden haben, wie ein Maler, der den Grund macht, um dann darauf zu malen, versuchen wir, nachdem wir diesen Grund gemacht haben, darauf zu malen. Da finden wir, daß sich sowohl mit dem platonischen Weltenjahr, wie auch mit kleineren Zeitenrhythmen, aber ganz offenbar mit dem Jahresrhythmus, abspielt ein fortwährender Wechsel in der äußeren Welt, den wir auch wahrnehmen, und den wir am leichtesten wahrnehmen, wenn wir ihn betrachten zunächst in den Qualitäten von warm und kalt. Wir brauchen nur daran zu denken, daß der Winter kalt ist, der Sommer warm ist, so haben wir das, was sich im Hintergrund als Zahlen ausnimmt, das haben wir qualitativ in Wärme und Kälte; und der Mensch steht mit seinem Leben drinnen in diesem Wechsel von Wärme und Kälte. Ja, sehen Sie, draußen darf es den Zeitenwechsel geben zwischen Wärme und Kälte, gibt ihn auch, und der sogenannten Natur, wenn sie zwischen Wärme und Kälte abwechselt, ist dieser Zeitenwechsel auch ganz heilsam. Das darf der Mensch nicht machen. Der muß gewissermaßen eine normale Wärme, eine normale Kälte - je nachdem man es relativ betrachtet - in sich bewahren. Er muß also innerliche Kräfte entwickeln, durch die er die Sommerwärme für den Winter aufspart und die Winterkälte für den Sommer aufspart. Er muß ausgleichen im Inneren, richtig im Inneren ausgleichen, fortwährend in der menschlichen Organisation so tätig sein, daß sie zwischen Wärme und Kälte, auch wie sie draußen in der Natur sich abspielt, ausgleicht.

Es sind Wirkungen im menschlichen Organismus, die man gar nicht beachtet. Er trägt innerlich den Sommer in den Winter, den Winter in den Sommer hinein. Wenn es Sommer ist, tragen wir in uns hinein das, was unser Organismus erlebt hat im Winter. Wir tragen durch den Frühlingspunkt hindurch bis nach Johanni hinein den Winter mit, dann gleicht sich das aus. Geht es gegen den Herbst zu, fangen wir an, den Sommer weiter mitzutragen, tragen ihn bis zu Weihnachten, bis zum 21. Dezember, dann gleicht es sich wieder aus. So daß wir diesen Wechsel von Wärme und Kälte fortwährend ausgleichend in uns tragen. Aber was machen wir da?

Sehen Sie, wenn man jetzt untersucht, was man damit macht, so kommt man zu einem außerordentlich interessanten Resultat. Wenn man den Menschen so auffaßt (Zeichnung $. 144), dann kommt man dazu, anzuerkennen schon durch eine oberflächliche Anschauung, daß sich alles dasjenige, was als Kälte auftritt im Inneren des Menschen, mit der Tendenz zeigt, nach dem Nerven-Sinnesmenschen hinzugehen. So daß man heute nachweisen kann: alles, was als Kälte wirkt, Winterliches, ist beteiligt an der Kopfbildung des Menschen, an der SinnesNervenorganisation. Alles, was sommerlich ist, alles, was Wärme enthält, ist beteiligt am Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßensystem des Menschen. Schauen wir auf unseren Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenmenschen hin, so tragen wir eigentlich in unserer Organisation alles Sommerliche. Schauen wir auf unsere Nerven-Sinnesfunktionen hin, so tragen wir in ihnen eigentlich alles dasjenige, was wir an Winterlichem aus dem Weltenall in uns aufnehmen. So leben wir mit unserem Kopf alle Winter, mit unserem Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganismus alle Sommer, und schaffen im Inneren durch den rhythmischen Organismus den Ausgleich, schöpfen hin und her Wärme und Kälte, Wärme und Kälte zwischen Stoffwechselsystem und Kopfsystem und kommen zu dem, was das übrige erst regelt. Die Wärme des Stoffes ist ja erst eine Folge der Wärmevorgänge, und die Kälte der Stoffe ist erst eine Folge der Kältevorgänge. Wir kommen auf ein Spiel des Weltenrhythmus in der menschlichen Organisation. Wir kommen dazu, uns zu sagen: Winter im Makrokosmos ist das Schöpferische in der menschlichen Kopfesbeziehungsweise Nerven-Sinnesorganisation. Sommer im Makrokosmos ist das Schöpferische im Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßensystem des Menschen.

Sehen Sie, schaut man so hinein in die menschliche Organisation, dann hat man wieder einen Anhaltspunkt für jene Initiatenmedizin, von der ich geredet habe, daß sie zunächst einen Anfang nimmt mit dem Buch, das Frau Dr. Wegman mit mir ausgearbeitet hat. Man hat einen Anfang von dem, was immer mehr und mehr wirklich eingreifen muß in die Wissenschaft.

Kriechen wir jetzt hinauf auf die Felsen, wo die Winterpflanzen wachsen, wo der Boden so ist, daß die Winterpflanzen wachsen, wir kommen an dasjenige in der Außenwelt, was mit der Organisation des menschlichen Kopfes zusammenhängt. Nehmen wir an, wir seien jetzt ein Heilmittelsammler in der Welt und wir wollen dafür sorgen, daß jene Geisteskräfte, die bei einer in der Nerven-Sinnesorganisation wurzelnden Krankheit auftreten, geheilt werden durch den Geist in der Außenwelt, kriechen wir hinauf in die hohen Berge, sammeln dort die Mineralien und Pflanzen und bringen von dort die Heilmittel für die Kopfkrankheiten. Wir verfahren aus unserem schöpferischen Denken heraus. Es bringt unsere Beine in Schwung zu jenen Dingen in der Erde, wo wir das Entsprechende finden müssen. Die richtigen Gedanken, die aus dem Kosmos stammen, müssen beschwingen das menschliche Handeln bis in das Konkrete hinein. Unbewußt tun sie das ja dadurch, daß der im Büro arbeitende Mensch, der ja auch Gedanken hat, wenigstens manchmal, daß der nun durch seinen Instinkt getrieben wird, da nun allerlei Wanderungen zu machen. Nur weiß man nicht den Zusammenhang dafür. Es ist ja auch nicht so wichtig. Das wird erst wichtig, wenn man es in medizinischer oder priesterlicher Beobachtung sieht. Aber ein genaues Betrachten der Welt gibt auch eine Beflügelung zu dem, was man im einzelnen zu tun hat.

Und wieder, merken wir Krankheiten im Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßensystem, da dringen wir mehr an das Irdisch-Pflanzenhafte und an das Irdisch-Mineralische vor, sehen wir nach dem, was sedimentiert, nicht nach dem, was in kristallinischer Weise oben wächst, und bekommen da das mineralische und pflanzliche Heilmittel. Und so ist es schon so, daß das Zusammenschauen von Vorgängen im Makrokosmos mit demjenigen, was im Menschen ist, wirklich hinüberführt von der Pathologie in die Therapie.

Sehen Sie, diese Dinge müssen eben wieder ganz klar durchschaut werden. Die alten Zeiten haben solche Zusammenhänge gut erkannt. Hippokrates ist eigentlich schon eine Art Spätling mit Bezug auf alte Medizin. Aber lesen Sie etwas nach in seinen angeblichen Schriften, die aber wenigstens noch in seinem Geiste gehalten sind, Sie werden diese Auffassung durchaus überall spüren. Da ist überall etwas von dem dariinnen, was im Einzelnen, Konkreten anknüpft an diese große Überschau, die man durch so etwas haben kann. Dann kommen die späteren Zeiten, wo für das menschliche Anschauen solche Dinge nicht mehr da waren, wo die Menschen immer mehr und mehr hineingekommen sind in das bloß abstrakte intellektualistische Denken und in das äußerliche Naturbeobachten, das dann zum bloßen Experiment geführt hat. Es muß wieder der Weg zurück gefunden werden zu demjenigen, was einmal Schauen des Zusammenhanges war zwischen Mensch und Welt.

So sehen Sie, leben wir als Menschen auf der Erde, indem wir zwischen unserem Ich und unserem physischen Leib leben; zwischen Atemzug und Weltenjahr, platonischem Weltenjahr — da leben wir drinnen und grenzen mit unserem Atemzug an den Tag an. Woran grenzen wir mit unserem physischen Leib? Mit dem platonischen Weltenjahr? — Da grenzen wir an die äußersten Verkettungen und Zusammenhänge im Klimawechsel in den großen Naturvorgängen, verändern in diesen großen Naturvorgängen unsere Gestalt, die menschliche Gestalt, so daß aufeinanderfolgende Rassenbildungen erscheinen und so weiter. Wir grenzen aber auch an alles dasjenige, was in kürzerem äußerem qualitativen Wechsel geschieht, wir grenzen an dasjenige, was die aufeinanderfolgenden Jahre uns bringen, die Tage uns bringen, kurz, wir entwickeln uns als Mensch zwischen diesen beiden äußersten Grenzen, emanzipieren uns aber in der Mitte, weil in der Mitte auch im Makrokosmos ein merkwürdiges Element eingreift.

Man kann ja tatsächlich in Bewunderung versinken, wenn man diesen nach 25920 Jahren ungefähr geordneten Rhythmus auf sich wirken läßt. Es ergibt ja das wirklich bewundernde Versenken dasjenige, was zwischen Weltall und Mensch sich abspielt. Und wenn man sich da ganz hineinversenkt, dann erscheint einem einschließlich des Menschen die ganze Welt nach Maß, Zahl und Gewicht geordnet. Alles ist, möchte ich sagen, wunderbar geordnet, nur ist es trotzdem Menschenberechnung. Deshalb aber müssen wir an den entscheidenden Stellen, wenn wir sie etwas auseinandersetzen — trotzdem es gilt, trotzdem es drinnen ist —, müssen wir immer an die entscheidenden Stellen das merkwürdige Wort approximativ einfügen. Es geht immer nicht ganz auf. Es ist darinnen die Rationalität, sie ist darinnen, sie ist da, sie lebt, sie wirkt: es lebt alles das, was ich beschrieben habe. Nun stellt sich etwas hinein, etwas ganz Irrationales im Weltenall, was macht, daß, wenn wir uns noch so sehr vertiefen, bewundernd darin aufgehen - sogar als Initiat meinetwegen -, wenn wir irgendeinen Weg machen durch ein paar Stunden, wir doch einen Regenschirm mitnehmen, auch als Initiaten. Wir nehmen einen Regenschirm, weil nun etwas eintritt, was den Irrationalismus hat, wo dasjenige sich offenbart in der Realität, was in den Zahlen doch immer nicht aufgeht, daß man Schaltjahre, Schaltmonate, alles mögliche braucht. Man hat ja zur Zeitbestimmung das immer gebraucht. Dasjenige, was die ausgebildete Astronomie, die in Astrologie und Astrosophie hinein vertiefte Astronomie — denn man kann sich das so ausgebildet denken -, was die bietet, das wird alles wieder zerstört für das unmittelbare Leben durch die Meteorologie, die es nicht zum Rang einer rationalen Wissenschaft bringt, die vom Schauen schon etwas durchdrungen wird, von weiterem Schauen immer mehr durchdrungen wird, die aber einen ganz anderen Weg nimmt, die in dem darinnen lebt, was übrigbleibt von den anderen. Und gerade wenn wir die heutige Astronomie nehmen, die lebt ja wirklich in Namen, die ist wirklich eine Sternnamensgebung, sonst weiter nichts. Deshalb hat ja auch «Serenissimi» Verständnis aufgehört beim Namengeben der Sterne. Er besuchte die Sternwarte seines Landes, ließ sich verschiedenes zeigen, ferne Sterne durch die Teleskope, und dann sagte er, nachdem er das gesehen hatte: Das alles begreife ich. Aber wie Sie wissen, was dieser Stern, der da so weit draußen ist, was der für einen Namen hat, das begreife ich nicht. — Sehen Sie, es gibt ja den Standpunkt selbstverständlich, den Sie in diesem Augenblicke einnehmen, daß Sie über Serenissimus lachen. Es gibt auch einen anderen Standpunkt, daß man so auch über den Astronomen lacht. Ich möchte über den Astronomen mehr lachen, denn im Weltengange steht etwas sehr Merkwürdiges darinnen.

Wenn Sie nach den alten Benennungen Saturn und so weiter forschen, müssen Sie sich, um etwas zu begreifen, ein bißchen an unseren Sprachkurs erinnern, in dem die allermeisten von Ihnen drinnen sind, müssen sich erinnern, daß die alten Namen gegeben worden sind nach den Lautempfindungen, die die Astrologen und Astrosophen bei einem bestimmten Stern hatten. Und wir können überall bei den alten Sternennamen sagen: sie sind gottgegeben, sie sind geistgegeben. Sie wurden gefragt, wie sie heißen, die Sterne, weil man den Ton des Sternes wahrnahm und immer darnach den Namen gab. Ja, nun gehen Sie bis zu einer gewissen Grenze in der astrosophischen, astrologischen Entwickelung. Sie mußten die Namen vom Himmel herunterholen. Gehen Sie in die neuere Zeit hinein, wo die großen Entdeckungen gemacht worden sind mit den kleinen Sternwichten zum Beispiel, ja, da kollert alles durcheinander. Da heißt der eine Andromeda, der andere hat einen anderen griechischen Namen, da kollert alles willkürlich durcheinander. Man kann nicht den Neptun oder Uranus in derselben Weise mit seinem Namen belegt denken wie den Saturn. Das alles ist menschliche Willkür und Serenissimus hat nur den einen Fehler gemacht, daß er geglaubt hat, die Astronomen haben so fortgefahren wie die alten Astrosophen. Das haben sie nicht getan. Es ist eben nur menschliche Beschränktheit darinnen, während das Wissen der Astrosophen der alten Zeiten, der Astrologen der älteren Zeiten hervorgegangen ist aus dem Verkehr der Menschen mit den Göttern. Aber gerade wenn man heute wieder aufrückt von der Astronomie zur Astrologie, zur Astrosophie und dadurch lebt in etwas wie in einem Makrokosmos, der überall die Ratio hat, da reicht man hin bis zur Sophia. Dann findet man auf der anderen Seite, wie innerhalb dieser Ratio und Sophia in den Dingen, die nicht aufgehen in der Rechnung, darinnen lebt die Meteoronomie, Meteorologie und Meteorosophie, die man eigentlich immer nur nach ihrem eigenen freien Willen befragen kann. Das ist eine andere Dame. Außerlich, im gewöhnlichen physischen Leben, nennt man sie launisch. Aber das Meteorologische ist ziemlich launisch von den Tagesregen bis hinauf zu den Kometen. Aber indem man sich immer mehr hinauflebt von der Meteorologie zu der Meteorosophie, kommt man auch auf bessere Eigenschaften dieser Weltregiererin, auf diejenigen Eigenschaften, die nicht bloß aus der Laune, aus der kosmischen Emotion sind, ich möchte sagen, die aus der inneren Herzlichkeit dieser Dame kommen. Aber es geht eben nicht anders, meine lieben Freunde, als daß man dem Rechnen, dem Denken, alle dem, was sich rationell verfolgen läßt, auch gegenüberstellt die unmittelbare Bekanntschaft mit den Weltenwesen, sie kennenlernt, so wie sie sind. Da zeigen sie sich, sie sind da, zunächst sind sie etwas spröde, sie sind nicht aufdringlich. Beim Rechnen kommt man immer weiter und weiter heran, allerdings, aber man kommt von dem eigentlichen Weltenwesen immer mehr ab. Man kommt nur in zurückgebliebene Taten hinein.

Kommt man vom gewöhnlichen groben Berechnen zum rhythmischen Berechnen, wie es für die Sphärenharmonie war die Astrologie, so kommt man vom rhythmischen Berechnen zum Anschauen der Weltenorganisation in Figuren, Zahlen, die da sind in der Astrosophie. Aber man kommt nach der anderen Seite hin, ich möchte sagen so, daß sich schon die regierenden Weltenwesen etwas spröde erweisen. Sie sind nicht gleich da. Zuerst zeigen sie einem nur eine Art AkashaPhotographie, von der man aber nicht recht weiß, woher sie einem zugeworfen wird. Da hat man die Welt, aber eben nur überall im Weltenäther gezeichnete Photographien. Aber man weiß nicht, wo sie herkommen.

Dann tritt die Inspiration ein. Da fängt das Wesen an, durch das Bild heraus sich selber kundzugeben. Wir gehen zunächst aus der Nomie bloß zur Logie. Erst wenn wir ganz durchdringen zur Intuition, dann folgt der Inspiration das Wesen selber, wir kommen an die Sophia. Das ist aber ein persönlicher Entwickelungsweg, der den ganzen Menschen in Anspruch nimmt, der auch Bekanntschaft machen muß mit einer solchen Dame, die sich hinter der Meteorologie verbirgt, in Wind und Wetter, in Mond und Sonne, insoferne sie eingreifen in die Elemente. Da muß nicht nur der Kopf sich engagieren wie bei der Logie, sondern der ganze Mensch.

Nun können Sie aber daraus ersehen, daß schon auch eine Möglichkeit vorliegt, in dieser Beziehung, sich auf einen Irrweg zu begeben, denn Sie können auch in der Anthroposophie, indem Sie von der Anthroponomie, die eigentlich heute die allein herrschende Wissenschaft ist, zur Anthropologie kommen, können Sie zur Anthroposophie kommen mit dem Kopf. Da haben Sie dann lediglich die Ratio, aber die Ratio lebt nicht. Sie bezeichnet nur die Spuren des Lebens, wo es nicht darauf ankommt, daß man die Einzelheiten berücksichtigt. Das Leben lebt aber gerade in den Einzelheiten, in dem Irrationalen. Da müssen Sie hinunterleiten, was der Kopf erfaßt hat in den ganzen Menschen, und mit dem ganzen Menschen dann aufrücken von der Nomie zur Logie, zur Sophia.

Das ist dasjenige, was wir fühlen müssen, wenn wir beleben wollen Theologie auf der einen Seite, Medizin auf der anderen Seite durch dasjenige, was wirklich beides beleben kann, die Pastoralmedizin. Das ist dasjenige, was wir dann morgen durch einige Spezialbetrachtungen schließen wollen. Aber die Hauptsache ist diese, daß wir zuerst beim ersten Anhub des Hineingehens in die Pastoralmedizin die Wege kennenlernen, in denen sich in der Betrachtung der Welt die Pastoralmedizin bewegen muß.

Tenth Lecture

My dear friends! What is always overlooked in our time when it comes to real action and the desire to act from the spiritual world is that all spiritual action requires activity and creativity in human thoughts and feelings. What actually underlies this has been completely forgotten in this age of materialistic thinking and is, in fact, completely unconscious to humanity today. That is why so much nonsense is being perpetrated in this area, nonsense that is even quite widespread among us in human civilization today. You will know that all kinds of instructions are issued to people from all kinds of central authorities or similar bodies, as they are called, on how to develop the power of thought, how thoughts can become powerful. One might say that seeds of what used to be called “black magic” in spiritual life, and is still called that today, are being scattered everywhere. Both doctors and priests must pay attention to such things, which are at the same time causes of mental and physical illness, in their effect on culture and the development of civilization. For when one pays attention to such things, one is doing what is important both for the prevention and for a better understanding of illness and the symptoms of illness in human soul life. Such instructions are intended to give people a power that they would not otherwise have, and are often used for the most dishonest purposes. There are already all kinds of instructions of this kind today, such as how sales agents can do business and the like. An enormous amount of mischief is being done in this area today.

But you see, what is the basis for this? These things must become worse and worse if real knowledge does not take hold in this area, particularly in the fields of medicine and theology. For the thinking of people in modern times, especially scientific thinking, has developed enormously under the influence of materialism. When today many people express satisfaction that materialism is on the decline in science, that everywhere people want to create something that goes beyond materialism, well, my dear friends, this makes a much more unpleasant impression on those who see through things. These scientists who want to overcome materialism in today's way, and also those theologians who want to overcome materialism in today's way, are actually much worse in the eyes of those who see through these things than the rigid materialists who gradually make the matter impossible through the absurdity of their own cause. But these chatterers about spiritualism, idealism, and the like are throwing sand in people's eyes, and in their own as well.

For what is being done, let us say in the Drieschian manner or in some other manner, in order to be able to represent anything beyond material events? Precisely the same thoughts that have been used for centuries to think only the material, and which have no other possibility than to think the material, are being used to think something supposedly spiritual. These thoughts cannot do that! You can only do that if you enter into real spiritual science. That is why such strange things come out that are not even noticed today. For example, Driesch, who is officially recognized by the outside world but is in reality terribly amateurish, says that one must assume the existence of “psychoids.” Yes, my dear friends, if you want to attribute a similarity to something, that something must be there somewhere. You cannot speak of monkey-like beings if there are never any monkeys there. You can never speak of psychoids if the soul is never recognized in human beings! Such talk is considered today to be genuine science, even striving for the better. This must be seen through. And then those who are involved in the anthroposophical movement with a scientific education are of value to the development of civilization if they do not allow themselves to be blinded by the flickering will-o'-the-wisp, but if they look very precisely at what is really necessary and needed in the face of materialism.

Therefore, we must ask: How is it possible for today's passivity of thought to become active and creative again? How must the clergy and the medical profession work to ensure that creativity flows into the work of people who are guided by the spirit and want to be guided? Thoughts, especially those that develop from material processes, leave creativity outside in the material world and remain completely passive themselves. This is the peculiarity of today's world of thought, as applied everywhere in science, that it is completely passive, inactive, and unproductive. The fact that there is no creativity in thought at all is related to our education, which is completely immersed in today's passive science. People are educated and brought up in such a way that they are prevented from arriving at creative thoughts, because there is a fear that if they did, they would not establish objective reality, but would do something about it. These are the things that need to be understood. But how can one arrive at creative thoughts? You see, one can only arrive at creative thoughts if one truly develops knowledge of human nature, for human beings cannot be understood in an uncreative way, because they are creative by nature. One must recreate if one wants to understand. With passive thinking today, one can only grasp the periphery of human beings; one must leave their inner being aside. One must truly grasp the place of human beings in the world. Therefore, today we want to set ourselves a kind of goal that lies at the end of a broad perspective, but which can make our thoughts creative and truly contains the secret of making thoughts creative. We want to place this before our souls and include in our considerations some things that you already know from the general anthroposophical lectures.

Let us imagine schematically, my dear friends, the universe in the process of becoming in the form of, well, a circle (Table ii fel 11). We can do this schematically because the universe in the making actually represents a kind of rhythmic repetition in time, albeit in an ascending line, in a descending line in relation to some phenomena, but everywhere in the universe we find something like a day and night rhythm, other rhythms, larger rhythms that run between ice ages and so on. If we first stick to the rhythm that has the longest intervals for human perception, we arrive at the so-called Platonic year, which always played a major role in these views and human perceptions of the world when observations of the world were still better.

This Platonic year is arrived at by observing the rising point of the sun in the morning on the day when spring begins, March 21 of the year. The sun rises at a specific point in the sky. This point can be seen in the constellation, and it is noted throughout the ages, because it changes slightly each year. If, say, last year the vernal equinox was observed exactly in its place in the sky relative to the other stars, that is, in 1923, and then observed it again in 1924, this year's point of sunrise is not in the same place, but is shifted in the direction that can be traced by connecting the constellation of Taurus with the constellation of Pisces with a line. The vernal equinox shifts in this direction of the zodiac. So it shifts a little bit every year. This indicates that a shift takes place every year in the entire constellation of the starry world, which can be recorded in this way. If you now check how the sum of these shifts looks — you can see it when a shift takes place — it is there in that year, there in that year, and so on. Once the shift reaches this point, once it reaches this point, until it returns to the same point. This means that after a certain period of time, the vernal equinox must be back in the same place in the sky. So a single rotation of the entire path of the sun in relation to the morning sunrise has occurred. If you calculate this, it happens every 25,920 years on average. Thus we have identified a rhythm that contains the largest interval that is initially accessible to human perception: the Platonic world year, which lasts approximately 25,920 of our years.

We have looked out into the vastness of the world, and our thoughts have, in a sense, come up against something that the numbers we develop bounce off. We come up against something like a wall with our thinking. Thinking cannot go beyond this for the time being. Then clairvoyance must come in, which goes beyond this. But thinking cannot go beyond this for the time being. All development takes place within what is enclosed by these 25,920 years, and if we want to, we can easily imagine this scope, which is not enclosed by space but by space-time, as a kind of cosmic uterine wall. So we imagine it as that which surrounds us in the widest space of the universe (plate 11, red-yellow). And now we move from that which surrounds us in the widest space of the universe as the rhythm that carries within itself the greatest intervals we have, to that which initially appears to us in human beings as a smaller interval, the breath.

You see, of course we have to use approximate figures again when we take the breath: eighteen breaths per minute; and if we calculate how many breaths that is per day, we get 25,920 breaths per day for humans.

We have the same rhythm that we have outside, with the large intervals, in humans, in the microcosm with the smallest intervals. So humans live in a universe that they replicate in the rhythm that is the rhythm of the universe itself. Only for humans, not for animals, because it is precisely in these finer insights that one can really see the difference between humans and animals. For humans, the compactness, the essence of their physical body can only be recognized when it is traced back to the Platonic world year. 25,920 years, in which the essence of our physical body is rooted. Take a look at my “Outline of Esoteric Science” to see what great periods of time, determined initially by something other than time-space, by the metamorphosis of sun, moon, and earth, had to be brought together, not in a quantitative, numerical way, in order to understand the human physical body as it is today from its elements.

Let us then go into the center, where we have the 25,920 breaths (Table 11), which, so to speak, place the human being in the center of the world womb, and then we come to the I. For in these breaths, together with what I have said about breathing, which goes to the higher human being and refines itself into the so-called spiritual life, breathing contains the expression of the individual human life on earth. So here we have the I. Just as we must grasp the connection between our physical body and the great periods of time, with the Platonic world year, so we must consider the connection between our I, which we can feel in every irregularity of the breath, and our breathing rhythm.

You see, human life on earth lies between these two things; human life lies between the breath and the world year. Everything that is significant for the I is regulated by the breaths. The life of our physical body lies in those colossal processes that are regulated by the rhythm of 25,920 years. What happens in the physical body in terms of regularity is connected to the great rhythm of the Platonic world year in the same way that our ego activity is connected to the rhythm of our breathing. Between the two lies human life, which for us is enclosed between the physical body, the etheric body, the astral body, and the ego. From a certain point of view, we can say that human life on earth lies between the physical body, the etheric body, the astral body, and the I, and from another point of view, we can say that human life, viewed from the divine-cosmic aspect, lies between the breathing of a day and the Platonic world year. The breathing of a day is a whole in this sense. The breathing of a day thus belongs together with what human life is.

Now, from this cosmic point of view, let us consider what lies between human breathing, that is, between the weaving and being of the I, and the events of a Platonic world year, that is, life and activity outside in the macrocosm. You see, with what wants to work in our respiratory organism, it is so that with the twenty-four-hour breathing of the day, with what lies within between this breathing and what we have in this breathing as a whole breathing rhythm, we encounter each time that rhythm which is there as the day and night rhythm and is connected with the sun being in relation to the earth being. In the daily rising and setting of the sun, in the sun's journey across the vault of heaven, in the darkening of the sun by the earth, in this daily going around of the sun lies that which we encounter with our breathing rhythm.