The Fall of the Spirits of Darkness

GA 177

20 October 1917, Dornach

10. The Influence of the Backward Angels

It cannot be said that our present age has no ideals. On the contrary, it has a great many ideals which, however, are not viable. Why is this so? Well, imagine—please forgive the somewhat bizarre image, but it does meet the case—a hen is about to hatch a chick and we take the egg away and hatch it out in a warm place, letting the chick emerge from the egg. So far so good; but if we were to do the same thing under the receiving part of an air pump and therefore in a vacuum, do you think the chick emerging from the egg would thrive? We would have all the developmental factors which evolution has given except for one thing—somewhere to put the chick for it to have the necessary conditions for life.

This is more or less how it is with the beautiful ideals people talk about so much today. Not only do they sound beautiful, but they are indeed ideals of great value. But the people of today are not inclined to face the realities of evolution, though the present age demands this. And so it happens that the oddest kinds of societies may evolve, representing and demanding all kinds of ideals, and yet nothing comes of it. There were certainly plenty of societies with ideals at the beginning of the twentieth century, but it cannot be said that the last three years have brought those ideals to realization. People should learn something from this, however—as I have said a number of times in these lectures.

Last Sunday (14 October) I sketched a diagram to show the spiritual development of the last decades. I asked you to take into account that anything which happens in the physical world has been in preparation for some time in the spiritual world. I was speaking of something quite concrete, namely the battle which began in the 1840s in the spiritual world lying immediately above our own. This was a metamorphosis of the battles which are always given the ancient symbol of the battle fought by St Michael against the dragon. I told you that this battle continued until November 1879, and after this Michael gained the victory—and the dragon, that is the ahrimanic powers, were cast down into the human sphere. Where are they now?

Now consider this carefully—the powers from the school of Ahriman which fought a decisive battle in the spiritual world between 1841 and 1879 were cast down into the human realm in 1879. Since then their fortress, their field of activity, is in the thinking, the inner responses and the will impulses of human beings, and this is specifically the case in the epoch in which we now are.

You must realize that infinitely many of the thoughts in human minds today are full of ahrimanic powers, as are their will impulses and inner responses. Events like these which play between the spiritual and the physical worlds are part of the great scheme of things; they are concrete facts which have to be reckoned with. What good is it to get bogged down in abstractions over and over again and to say something as abstract as: ‘Human beings must fight Ahriman.’ Such an abstract formula will get us nowhere. At the present time some people have not the least idea of the fact that they are in an atmosphere full of spirits. This is something which has to be considered in all its significance.

If you consider just this—that as a member of the Anthroposophical Society you are in a position to hear of these things and to occupy your thoughts and feelings with them—you will be aware of the full seriousness of the matter and that you have a task today, depending on your particular place in this present time, which is so full of riddles, so much open to question and so confused. You have to bring to this the best kinds of feelings and inner responses of which you are capable. Let us take the following example. Suppose a handful of people who have naturally come together and become friends, know of the spiritual situation I have described and of other, similar ones, whilst many other people do not know of them. You can be sure that if this hypothetical group of people were to decide to use the power they are able to gain from such knowledge for a particular purpose, the group—and its followers, though these would tend to be unaware of this—would be extremely powerful compared to people who have no idea of this and do not want to know of such things.

Precisely such a group existed in the eighteenth century and still continues today. A certain group of people knew of the facts of which I have spoken; they knew that the events I have described as happening in the nineteenth and on into the twentieth century would happen. In the eighteenth century this group decided to pursue certain aims which were in their own interests and to work towards certain impulses. This was done quite systematically.

The masses of humanity go through life as if asleep, without thought; they are completely unaware of what is going on in groups, some of them quite large, which may be right next door. Today, more than ever, people are much given up to illusion. Just consider the way in which many people keep saying today: ‘lt is amazing how effective modern communications are and how this brings people together! Everybody hears about everybody else! This is totally different from the way it was in earlier times.’ You will recall all the things people tend to say on the subject. But we only need to take a cool, rational view of some specific instances to find some very odd things going on in modern times. Who would believe, for example—I am merely giving an illustration—that the Press, which understands everything and goes into everything, would ever fail to make new literary works widely known? You would not think, would you, that profound, significant, epochmaking literary works would remain unknown? Surely we must hear of them in some way or other? Well, in the second half of the nineteenth century, ‘the Press’, as we call it today—with due respect—was in the early stages of becoming what it is today. A new literary work appeared at that time which was more epoch-making and of more radical importance than all the well-known authors taken together, people like Spielhagen,1Friedrich Spielhagen (1829–1911), German novelist. Gustav Freytag,2Gustav Freytag (1816–1895), German novelist and playwright. Works translated into English are Soll und Haben (1855; Debit and Credit 1858), Die Verlorne Handschrift (1864; The Lost Manuscript 1865) and Reminiscences (English translation in 1890). Paul Heyse3Paul Johann von Heyse (1830–1914), German writer, Nobel Prize and ennoblement in 1910. Wrote novels, plays, epic poems and translations of Italian poems but was especially famed as a writer of short stories. and many others whose works went through numerous editions. The work in question was Dreizehnlinden by Wilhelm Weber,4Friedrich Wilhelm Weber (1813–1894), Westphalian poet. Dreizehnlinden, an epic work on the time when the Saxons were converted to Christianity, was published in 1878. and it really was more widely read in the last third of the nineteenth century than any other work. But I ask you, how many people in this room do not know of the existence of Wilhelm Weber's Dreizehnlinden? You see how people live alongside each other, in spite of the Press. Profoundly radical ideas are presented in beautiful, poetic language in Dreizehnlinden, and these are alive today in the hearts and minds of thousands of people.

I have spoken of this to show that it is entirely possible today for the mass of people to know nothing of radically new developments which are right on their doorstep. You may be sure, if there is anyone here who has not read Dreizehnlinden—and I assume there must be some among our friends—that these individuals must nevertheless know three or four people who have read it. The barriers separating people are such that some of the most important things simply are not discussed among friends. People do not talk to each other. The instance I have given concerns only a minor matter in terms of world history, but the same applies to major matters. Things are going on in the world which many people fail to see clearly.

Thus it also happened that in the eighteenth century a society spread certain views and ideas which were taking root in people's minds and became effective in achieving the aims of such societies. The ideas entered into the social sphere and determined people's attitudes to others. People do not know the sources of many things that live in their emotions, inner responses and will impulses. Those who understand the processes of evolution do know, however, how impulses and emotions are produced. This was the case with a book published by such a society in the eighteenth century—perhaps not the book itself, but the ideas on which it was based; the book shows the way in which Ahriman is involved in different animals. The ahrimanic Spirit was, of course, called the devil then, and it was shown how the devil principle comes to expression in different ways in individual animal species. The Age of Enlightenment was at its height in the eighteenth century, and, of course, enlightenment still flourishes today. Really clever people, many of them to be found as members of the Press, managed to turn it into a joke and say, ‘Once again, some ...—I'm putting dot dot dot here—has written a book to say that animals are devils!’ Ah, but to spread ideas like these in such a way in the eighteenth century that they would take root in the minds of many people, and in doing so take account of the true laws of human evolution—that really had an effect. For it was important that the idea that animals were devils should exist in many minds by the time Darwinism came along and the idea would then arise in many nineteenth-century minds that people had gradually evolved from animals. At the same time, large numbers of other people had the idea that animals were devils. A strange accord was thus produced. As this really happened, it was perfectly real. People write histories about all kinds of things, but the forces which are really at work are not to be found in them.

We need to consider the following: animals can only thrive if they have air—not in the vacuum to be found under the receiver of an air pump. In the same way, ideas and ideals can only thrive if human beings enter into the real atmosphere of spiritual life. This means, however, that spiritual life must be encountered as a reality. Today, people like generalities better than most other things. And they easily fail to notice that since 1879 ahrimanic powers have been forced to descend from the spiritual world into the human realm—this is a fact. They had to penetrate human intellectuality, human thinking, responses and perceptions. And we will not find the right attitude to those powers by simply using the abstract formula: ‘Those powers must be fought.’ Well, what are people doing to fight them? What they are doing is no different from asking the stove to be nice and warm, yet failing to put in wood and light the fire. The first thing we must know is that, seeing that these powers have come down to earth, we must live with them; they exist and we cannot close our eyes to them, for they will be more powerful than ever if we do this. This is indeed the point: The ahrimanic powers which have taken hold of the human intellect become extremely powerful if we do not want to know them or learn about them.

The ideal of many people is to study science and then apply the laws of science to the social sphere. They only want to consider anything which is ‘real’, meaning anything which can be perceived by the senses, and never give a thought to the things of the spirit. If this ideal were to be achieved by a large section of humanity the ahrimanic powers would have gained their purpose, for people would then not know they existed. A monistic religion similar to Haeckel's materialistic monism5The German naturalist Ernst Heinrich Haeckel was Professor of Zoology at Jena and one of the first to outline the tree of animal evolution. His theory was one of materialistic monism. Works translated into English are Creation, 4th edn. 1892 (Natuerliche Schoepfungsgeschichte, 1868) and Evolution of Man, 1879 (Anthropogenie 1874). (See also Note 1 of lecture 2.) would be established and prove to be the perfect field for the work of these powers. It would suit them very well if people did not know they existed, for they could then work in the subconscious.

One way to help the ahrimanic powers, therefore, is to establish an entirely naturalistic religion. If David Friedrich Strauss6David Friedrich Strauss (1808–1874), German theologian. His Leben Jesu (1835/36) was designed to show the Gospels to be a collection of myths with perhaps just a little historical truth to them. His second Life of Jesus, composed for the German people (1864; translated 1865) sought to create a positive life of Christ. In Der alte und der neue Glaube (translates as ‘Old and New Religious Belief, 1872) he aimed to show that religious belief was dead and a new faith had to be created on the basis of modern science and of art. had fully achieved his ideal, which was to establish the narrow-minded religion which prompted Nietzsche to write an essay about him,7‘David Friedrich Strauss, der Bekenner und Schriftsteller’ (translates as ‘David Friedrich Strauss, Confessor and Writer’) is part one of Nietzsche's volume of essays Unzeitgemaesse Betrachtungen (translates as ‘Untimely Thoughts’), Leipzig 1873. the ahrimanic powers would feel even more at ease today than they do already. This is only one way, however. The ahrimanic powers will also thrive if people nurture the elements which they desire to spread among people today: prejudice, ignorance and fear of the life of the spirit. There is no better way of encouraging them.

Just think how many people there are today who actually make it their business to foster prejudice, ignorance and fear of the spiritual powers. As I said in yesterday's public lecture,8Lecture given in Basle on 19 October 1917. Not translated. Published in German in GA 72, Freiheit—Unsterblichkeit—Soziales Leben (1990). the decrees against Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler and others were not lifted until 1835. This means that until then Catholics were forbidden to study anything relating to the Copernican view, and so on. Ignorance in this respect was actively promoted, and gave an enormous boost to the ahrimanic powers. This was a real service given to those powers, for it gave them the opportunity to make thorough preparations for the campaign they would start in 1841.

A second statement should really follow the one I have just made to render it complete. However, this second statement cannot yet be made public by anyone who is truly initiated into these things. But if you get a feeling of what lies behind the words I have spoken, you may perhaps gain an idea of what is implied.

The scientific view is entirely ahrimanic. We do not fight it by refusing to know about it, however, but by being as conscious of it as possible and really getting to know it. You can do no better service for Ahriman than to ignore the scientific view or to fight it out of ignorance. Uninformed criticism of scientific views does not go against Ahriman, but helps him to spread illusion and confusion in a field which should really be shown in a clear light.

People must gradually come to the realization that everything has two sides. Modern people are so clever, are they not?—infinitely clever; and these clever modern people say the following: In the fourth post-Atlantean age, in the time of ancient Greece and Rome, people superstitiously believed that the future could be told from the way birds would be flying, from the entrails of animals and all kinds of other things. They were silly old fools, of course. The fact is that none of these scornful modern people actually know how the predictions were made. And everybody still talks just like the individual whom I gave as an example the other day,9See lecture 6. who had to admit that the prophesy given in a dream had come true, but went on to say: Well, it was as chance would have it.

Yet conditions were such in the fourth post-Atlantean age that there really was a science which considered the future. Then, people would not have been able to think that the kind of principles which are applied today would achieve anything in a developing social life. They could not have gained the great perspectives of a social nature, which went far beyond their own time, if they had not had a ‘science’, as it were, of the future. Believe me, everything people achieve today in the field of social life and politics is actually still based on the fruits of that old science of the future. This, however, cannot be gained by observing the things that present themselves to the senses. It can never be gained by using the modern scientific approach; for anything we observe in the outside world with the senses makes a science of the past. Let me tell you a most important law of the universe: If you merely consider the world as it presents itself to the senses, which is the modern scientific approach, you observe past laws which are still continuing. You are really only observing the corpse of a past world. Science is looking at life that has died.

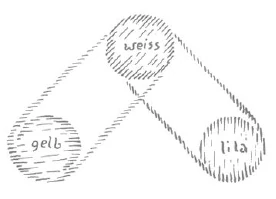

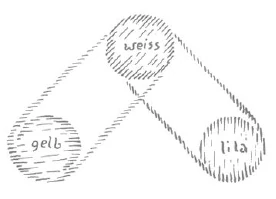

Imagine this is our field of observation (Fig. 10a, white circle), shown in diagrammatic form; this is what we have before our eyes, our ears and our other senses. Imagine this (yellow circle) to be all the scientific laws capable of being discovered. These laws do not relate to what is in there now, but to what has been there, what has been and gone and remains only in a hardened form. You need to find the things that are outside those laws, things which eyes cannot see and physical ears cannot hear: a second world with different laws (mauve circle). This is present inside reality, but it points to the future.

The situation with the world is just like the situation you get with a plant. The true plant is not the plant we see today; something is mysteriously inside it which cannot yet be seen and will only be visible to the eyes in the following year—the primitive germ. It is present in the plant, but it is invisible. In the same way the world which presents itself to our eyes holds the whole future in it, though this is not visible. It also holds the past, but this has withered and dried up and is now a corpse. Everything naturalists look at is merely the image of a ‘corpse, of something past and gone. It is also true, of course, that this past aspect would be missing if we considered the spiritual aspect only. However, the invisible element must be included if we are to have the complete reality. How can it be that people on the one hand set up Laplace's theory and on the other hand talk about the end of the world in the way Professor Dewar10Sir James Dewar (1842–1923), Professor of Physics at Cambridge. (Earlier editions referred to Professor Drews (1865–1935) in error.) does—I spoke of this in yesterday's public lecture. He construes that when the world comes to an end, people will read their newspapers at several hundred degrees below zero in the light of luminous protein painted on the walls; milk will be solid. I would love to know how people are going to milk such solid milk! Those are completely untenable ideas, as is the whole of Laplace's theory. All these theories come to nothing as soon as one goes beyond the field of immediate observation, and this is because they are theories of corpses, of things which are dead.

Clever people will say today that the priests of ancient Greece and Rome were either scoundrels and swindlers or that they were superstitious, for no one in their right mind can believe it is possible to discover anything about the future from the flight of birds and the entrails of animals. In time to come, people will be able to look down on the ideas of which people are so proud today; they will feel just as clever then as the present generation does now in looking down on the Roman priests conducting their sacrifices. Speaking of Laplace's theory and of Dewar they will say: Those were strange superstitions. People in the past observed a few millennia in earth evolution and drew conclusions from this as to the initial and final states of the earth. How foolish those superstitions were! Imagine the way in which those peculiar, superstitious people spoke of the sun and the planets separating out from a nebula and everything beginning to rotate. The things they will be saying about Laplace's theory and Dewar's ideas concerning the end of the world will be much worse than anything people are saying today about finding out about the future from sacrificial animals, the flight of birds and so on.

They are so high and mighty, these people who have entered fully into the Spirit and attitudes of scientific thinking and look down on the old myths and tales. ‘Humanity was childish then, with people taking dreams seriously! Just think how far we have come since then: today we know that everything is governed by a law of causality; we've certainly come a long way.’ Everyone who thinks like this fails to realize one thing: The whole of modern science would not exist, especially where it has its justification, if people had not earlier thought in myths. You cannot have modern science unless it is preceded by myth; it has grown out of the myths of old and you could no more have it today than you could have a plant with only stems, leaves and flowers and no root down below. People who talk of modern science as an absolute, complete in itself, might as well talk of a plant which is alive only in its upper part. Everything connected with modern science has grown from myth; myth is its root. There are elemental spirits which observe these things from the other worlds and they howl with hell's own derision when today's mighty clever professors look down on the mythologies of old, and on all the media of ancient superstition, having not the least idea that they and all their cleverness have grown from those myths and that not a single justifiable idea they hold today would be tenable if it were not for those myths. Something else, too, causes those elemental spirits to howl with hell's own derision—and we can say hell's own, for it suits the ahrimanic powers very well to have occasion for such derision—and this is to see scientists believe that they now have the theories of Copernicus, they have Galileo's ideas, they have this splendiferous law of the conservation of energy and this will never change and will be the same for ever and ever. A shortsighted view! Myth relates to our ideas just as the scientific ideas of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries relate to what will be a few centuries later. They will be overcome just as myth has been overcome. Do you think people will think about the solar system in 2900 in the way people think about it today? It may be the academics' superstition, but it should never be a superstition held among anthroposophists.

The justifiable ideas people have today, ideas which do indeed have some degree of greatness in the present time, arose from the mythology which evolved in the time of ancient Greece. Of course, nothing could possibly delight modern people more than to think: Ah, if only the ancient Greeks had been so fortunate as to have our modern science! But if the Greeks had had our modern science, then there could have been no knowledge of the Greek gods, no world of Homer, Sophocles, Aeschylus, Plato or Aristotle. Dr Faust's servant Wagner would be a veritable Dr Faust himself compared to the Wagners we would have today!11Wagner, Faust's narrow-minded, pedantic servant and pupil in Goethe's Faust. Human thinking would be dry as dust, empty and corrupt, for the vitality in our thinking has its roots in Greek and altogether fourth post-Atlantean mythology. Anyone who considers mythology to have been wrong and modern thinking to be right, is like someone who cannot see the need for roses to grow on bushes, making it necessary for us to cut them if we want to have a bouquet. Why should they not come into existence entirely on their own?

So you see, the people who consider themselves to be the most enlightened today are living with entirely unrealistic ideas. The ideas evolved in the fourth post-Atlantean age seem like dreams rather than clearly defined ideas to the people of our present age; yet that particular way of thinking has provided the basis for what we are today. The thoughts we are able to evolve today will in turn provide the basis for the next age. They can only do so, however, if they evolve not only in the one direction, where they wither and dry up, but also in the direction of life. The breath of life comes into our thinking when we try and bring the things which exist to consciousness and also when we perceive the element which gives us a wideawake mind and makes us into people who are awake.

Since 1879 the situation is like this: people go to school and acquire scientific attitudes and thinking; their philosophy of life is then based on this scientific approach and they believe only the things which can be perceived in the world around us to be real, whilst everything else is purely imaginary. When people think like this, and infinitely many people do so today, Ahriman has the upper hand in the game and the ahrimanic powers are doing well. Who are these ahrimanic powers which have established their fortresses in human minds since 1879? They are certainly not human. They are angels, but they are backward angels, angels who are not following their proper course of evolution and therefore no longer know how to perform their proper function in the spiritual world that is next to our own. If they still knew how to do it, they would not have been cast down in 1879. They now want to perform their function with the aid of human brains. They are one level lower in human brains than they should be. ‘Monistic’ thinking, as it is called today, is not really done by humans. People often speak of the science of economics today, a science in which it was said at the time when the war started that it would be over in four months—I mentioned this again yesterday. When these things are said by scientists—it does not matter so much if people merely repeat them—they are the thoughts of angels who have made themselves at home in human heads. Yes, the human intellect is to be taken over more and more by such powers; they want to use it to bring their own lives to fruition. We cannot stand up to this by putting our heads in the sand like ostriches, but only by consciously entering into the experience. We cannot deal with this by not knowing what monists think, for example, but only by knowing it; we must also know that it is Ahriman science, the science of backward angels who infest human heads, and we must know about the truth and the reality.

Of course, it can be said like this here, using the appropriate terms—ahrimanic powers—because we take these things seriously. You know that you cannot speak like this to people outside, for they are totally unprepared. This is one of the barriers which divide us from others; but it is, of course, possible to find ways and means of speaking to them in such a way that the truth comes into what we say. If there were not a place where the truth can be said, this would also deprive us of the possibility of letting it enter into the profane science outside these walls. There must be at least some places where the truth can be presented in an honest, straightforward way. Yet we must never forget that even people who have made a connection with the science of the spirit often have almost insuperable difficulties in building the bridge to the realm of ahrimanic science. I have met a number of people who were extremely well informed in a particular field of ahrimanic science, being good scientists, orientalists, etc., and had also made the connection with our spiritual research. I have gone to a great deal of trouble to encourage them to build bridges. Think of what could have been achieved if a physiologist or a biologist who had all the specialized knowledge which it is possible to gain in such fields today had reconsidered physiology or biology in the light of the spirit, not exactly using our terminology, but considering those individual sciences in our spirit! I have tried it with orientalists. You see, people may be good followers of anthroposophy, and on the other hand they are orientalists and work in the way orientalists do. They are not prepared, however, to build the bridge from one to the other. This, however, is the urgent need in our time. For, as I said, the ahrimanic powers are doing well if people believe that science gives a true image of the world around us. If, on the other hand, we use spiritual science and the inner attitude which arises from it, the ahrimanic powers do not do so well. This spiritual science takes hold of the whole human being. It makes you into another person; you come to feel differently, to have different will impulses, and to relate to the world in a different way.

It is indeed true, and initiates have always said so: ‘When human beings are filled with spiritual wisdom, these are great horrors of darkness for the ahrimanic powers and a consuming fire. It feels good to the ahrimanic angels to dwell in heads filled with ahrimanic science; but heads filled with spiritual wisdom are like a consuming fire and the horrors of darkness to them.’ If we consider this in all seriousness we can feel: filled with spiritual wisdom we go through the world in a way which allows us to establish the right relationship with the ahrimanic powers; doing the things we do in the light of this, we build a place for the consuming fire of sacrifice for the salvation of the world, the place where the terror of darkness radiates out over the harmful ahrimanic element.

Let those ideas and feelings enter into you! You will then be awake and see the things that go on in the world. The eighteenth century really saw the last remnants of the old atavistic science die. The adherents of Saint-Martin, the ‘unknown philosopher,’ who was a student of Jacob Boehme, had some of the old atavistic wisdom and also considerable foreknowledge of what then was to come, and in our day has come. In those circles it was often said that from the last third of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century a kind of knowledge would radiate out which had its roots in the same sources, the same soil, where certain human diseases have their roots—I spoke of this last Sunday (14 October); people's views would then be rooted in falsehood, and their inner feelings would come from selfishness.

Let your eyes become seeing eyes in the light of the inner feelings of which we have spoken today and let them see what is alive and active in the present time! It may well be that your hearts grow sore with some of the things you find. This does no harm, however, for clear perception, even if painful, will bear good fruit today, fruit which is needed if we are to get out of the Chaos into which humanity has entered.

The first thing, or one of the first things, will have to be a science of education. And one of the first principles to be applied in this field is one which is much sinned against today. More important than anything you can teach and consciously give to boys and girls, or to young men and women, are the things that enter unconsciously into their souls whilst they are being educated. In a recent public lecture I spoke of the way in which our memory develops as though in the subconscious, and parallel to our conscious inner life. This is something especiaily to be taken into account in education. Educators must provide the soul not only with what children understand but also with ideas they do not yet understand, which enter mysteriously into their souls and—this is important—are brought out again later in life. We are coming closer and closer to a time when people will need more and more memories of their youth throughout the whole of their lives, memories they like, memories which make them happy. Education must learn to provide systematically for this. It will be poison in the education of the future if later on in life people look back on the toil and trouble of their schooldays, on the years of education, and do not like to think back to those days. It will be poison if the years of education have not provided a source to which they can return again and again to learn new things. On the other hand, if one has learned everything there is to be learned on a subject, nothing will be left for later on.

If you think on this, you will see that principles of great consequence will have to be the future guidelines for life, and this in a very different way from what is considered to be right today. It would be good for humanity if the hard lessons to be learned in the present time were not slept through by so many, and people would use them instead to become really familiar with the thought that a great many things will have to change. People have grown much too complacent in recent times and this prevents them from comprehending this thought in its full depth and, above all, also in its full intensity.

Zehnter Vortrag

Man kann nicht sagen, daß die Gegenwart keine Ideale hätte. Im Gegenteil, sie hat sehr, sehr viele Ideale. Aber diese Ideale sind nicht wirksam. Warum sind sie nicht wirksam? Denken Sie sich einmal verzeihen Sie das etwas merkwürdige Bild, aber es entspricht doch der Sache -, denken Sie sich einmal, ein Huhn wäre bereit, ein Ei auszubrüten, man würde dieses Ei aber nehmen und durch Wärme ausbrüten lassen, das Kückelchen aus dem Ei herauskommen lassen. All das wäre ja denkbar, aber wenn man das zum Beispiel unter dem Rezipienten einer Luftpumpe machen würde, im luftleeren Raume, meinen Sie, daß das Huhn, das aus dem Ei ausschlüpft, gedeihen würde? Da sind gewissermaßen alle in der Evolution gegebenen Entwickelungsmomente da, aber eines ist nicht da: wo hinein man das betreffende Kückelchen setzen soll, damit es seine Lebensbedingungen habe.

So ungefähr geht es mit all den schönen Idealen, von denen man in der Gegenwart so sehr häufig spricht. Sie klingen nicht nur schön, sie sind in der Tat wertvolle Ideale. Aber die Gegenwart läßt sich nicht angelegen sein, die wirklichen, die realen Bedingungen der Evolution kennenzulernen, so wie man sie einmal nach den Bedingungen der Gegenwart erkennen muß. Und so kommt es, daß man in den merkwürdigsten Gesellschaften alle möglichen Ideale prägen, vertreten, fordern kann, und es kommt nichts dabei heraus. Denn schließlich, Gesellschaften mit Idealen hat es wahrhaftig im Beginne des 20. Jahrhunderts genügend gegeben. Daß aber die letzten drei Jahre just eine Erfüllung dieser Ideale waren, das kann man nicht sagen. Nur müßte man aus einer solchen Tatsache etwas lernen, wie es ja gerade in diesen Betrachtungen öfter erwähnt worden ist.

Ich habe Ihnen nun vorigen Sonntag hier mit einigen Strichen ein Bild gegeben der geistigen Entwickelung der letzten Jahrzehnte. Ich habe Sie gebeten, darauf Rücksicht zu nehmen, daß dasjenige, was auf dem physischen Plane geschieht, längere Zeit vorbereitet ist in der geistigen Welt. Ich habe da auf ganz Konkretes hingewiesen. Ich habe darauf hingewiesen, wie in den vierziger Jahren in der unmittelbar an die unsrige nach oben angrenzenden geistigen Welt ein Kampf begonnen hat, eine Metamorphose jener Kämpfe, die man mit dem alten Symbolum bezeichnet als den Kampf des heiligen Michael mit dem Drachen. Und ich habe Ihnen angeführt, wie dieser Kampf in der geistigen Welt sich bis zum November 1879 abgespielt hat, wie man es also da in der geistigen Welt mit einem Kampf zu tun hatte, mit einem Kampf Michaels mit dem Drachen - wir wissen ja, was unter diesem Bilde zu verstehen ist -, wie dann nach dem November 1879 in der geistigen Welt der Sieg erfochten worden ist von seiten Michaels, und der Drache, das heißt die ahrimanischen Gewalten, heruntergestoßen worden sind in die Sphäre der Menschen. Wo sind sie jetzt?

Also bedenken wir wohl: Diejenigen Mächte von der Schule Ahrimans, die vom Jahre 1841 bis 1879 einen entscheidungsvollen Kampf ausgeführt haben in der geistigen Welt, sie sind 1879 gestürzt worden aus der geistigen Welt herunter in das Reich des Menschen. Und seit jener Zeit haben sie ihre Festung, haben sie das Feld ihres Wirkens - und zwar speziell in derjenigen Epoche, in der wir jetzt leben - in dem Denken, in dem Empfinden, in den Willensimpulsen der Menschen.

Vergegenwärtigen Sie sich daraus, wie unendlich viel in dem, was die Menschen denken, in dem, was die Menschen wollen und empfinden, in dieser unserer Zeit von ahrimanischen Mächten durchsetzt ist. Solche Ereignisse im Zusammenhange zwischen der geistigen und der physischen Welt liegen im Plane unserer ganzen Weltenordnung, und man muß mit diesen konkreten Tatsachen rechnen. Was nützt es, wenn man immerfort im Abstrakten stekkenbleibt und als ein richtiger Abstraktling sagt: Der Mensch muß Ahriman bekämpfen. — Es kommt ja nichts dabei heraus bei einer solchen abstrakten Formel. Die Menschen der Gegenwart ahnen zuweilen gar nicht, in welcher Geisteratmosphäre sie eigentlich stehen. Man muß diese Tatsache in ihrer ganzen schwerwiegenden Bedeutung ins Auge fassen.

Nehmen Sie nur einmal dieses: daß Sie als Mitglied der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft berufen sind, von diesen Dingen zu hören, sich in Ihren Gedanken, in Ihren Empfindungen mit diesen Dingen zu beschäftigen. Dann wird Ihnen der ganze Ernst der Sache vor die Seele treten, dann wird Ihnen schon vor die Seele treten, daß Sie mit dem Besten, was Sie fühlen und empfinden können, eine Aufgabe haben, je nach dem Platz, an dem Sie stehen in dieser so rätselvollen, so fragwürdigen, so verworrenen Gegenwart. Nehmen Sie etwa das folgende an: Irgendwo wären nur ein paar Menschen, die sich auf eine naturgemäße Weise zusammengetan hätten zu einer Art freundschaftlichem Verkehr, und dieser Kreis von Menschen, der wüßte von solchen und ähnlichen geistigen Zusammenhängen, wie ich sie Ihnen eben geschildert habe, und große Mengen von Menschen wüßten nichts davon. Seien Sie überzeugt, wenn dieser Kreis von Menschen, den ich jetzt hypothetisch vor Ihre Seele hingestellt habe, den Entschluß fassen würde, aus irgendwelchen Untergründen heraus, dasjenige, was er an Kraft gewinnen kann durch solches Wissen, in irgendeinen Dienst zu stellen, dann ist dieser geringe Kreis mit der Anhängerschaft, die er sich macht, oftmals ohne daß es dieser Anhängerschaft bewußt wird, sehr mächtig und am mächtigsten den Ahnungslosen gegenüber, die nichts wissen wollen von diesen Dingen.

Es war schon im 18. Jahrhundert ein gewisser Kreis von Menschen da, der ganz von dieser Art war. Der hat heute auch seine Fortsetzung. Ein gewisser Kreis von Menschen wußte von solchen Tatsachen, von denen ich Ihnen gesprochen habe, wußte davon, daß solches im 19. und bis ins 20. Jahrhundert hinein geschehen werde, wie ich es Ihnen geschildert habe. Dieser Kreis von Menschen nahm sich aber vor - schon im 18. Jahrhundert -, gewisse, man kann sagen für diesen Kreis selbstsüchtige Absichten zu vollziehen, gewisse Impulse anzustreben. Dazu hat er dann ganz systematisch gearbeitet.

Die Menschen leben ja heute in großen Massen wie schlafend, gedankenlos dahin, achten auch gar nicht darauf, was manchmal in ganz großen Kreisen, die neben ihnen leben, eigentlich vorgeht. In dieser Beziehung gibt man sich ja gerade heute vielen Illusionen hin. Denken Sie nur einmal, daß natürlich die Menschen heute sagen: Ach, wie wirkt doch unser Verkehr, wie bringt er die Menschen zueinander! Wie erfährt jeder vom andern! Wie ist das doch ganz anders als in früheren Zeiten! - Erinnern Sie sich an alles das, was nach dieser Richtung gesagt wird. Man braucht nur einzelne Tatsachen sinngemäß und vernunftgemäß zu betrachten, dann findet man, daß in dieser Beziehung die Gegenwart ganz merkwürdige Dinge aufweist. Wer glaubt zum Beispiel - ich will das alles nur zum Exempel, nur zum Beleg anführen -, daß literarische Erscheinungen heute nicht durch die Presse, die alles versteht und über alles sich ergeht, in weitesten Kreisen bekannt werden kann? Wer glaubt im Ernste, daß heute bedeutungsvolle, tief eingreifende, epochemachende literarische Erscheinungen unbekannt bleiben können? Man muß doch auf irgendeine Weise etwas davon erfahren. Das Merkwürdige ist, daß dasjenige, was man heute mit Respekt zu vermelden die Presse nennt, seinen Aufschwung erst im letzten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts begonnen hat; einen Ansatz dazu hat die Presse ja schon vorher gemacht, wenn sie auch noch nicht so war wie heute. Und trotzdem [die Presse nichts darüber geschrieben hat], konnte damals über ganz Mitteleuropa hin eine literarische Erscheinung epochemachend sein, epochemachender als all die bekannten Schriftsteller wie Spielhagen, Gustav Freytag, Paul Heyse und was ich noch für Leute mit vielen, vielen Auflagen nennen könnte, eine literarische Erscheinung, die weiter verbreitet war und viel stärker gewirkt hat als all das, wovon man etwas weiß: Denn kein Werk hat eigentlich einen so breiten Leserkreis gehabt in diesem letzten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts wie «Dreizehnlinden» von Wilhelm Weber. Nun frage ich Sie: Wieviele Menschen werden hier sitzen, die nicht einmal wissen, daß es ein «Dreizehnlinden» von Weber gibt? — So leben die Menschen heute nebeneinander, trotz der Presse. In diesen «Dreizehnlinden» sind, in einer schönen dichterischen Sprache, Ideen verkörpert, die tief einschneidend waren. Ja, die leben heute in Tausenden und Abertausenden von Gemütern.

Ich habe das angeführt, um zu exemplifizieren, daß es tatsächlich möglich ist, daß die Masse der Menschen nichts weiß von Dingen, die immerhin einschneidend sind und sich neben ihnen abspielen. Ja, Sie können sicher sein, wenn sich hier jemand finden sollte, der das Buch «Dreizehnlinden» nicht gelesen hat - und ich vermute, daß es solche unter den Freunden gibt -, Sie können ganz sicher sein: Sie waren schon in Ihrem Leben mit drei, vier Menschen zusammen, die «Dreizehnlinden» gelesen haben. Es sind eben solche Scheidewände zwischen den Menschen, daß oftmals über die wichtigsten Sachen zwischen Nahestehenden überhaupt nicht gesprochen wird. Man spricht sich nicht aus. Selbst Nahestehende sprechen sich über die wichtigsten Sachen nicht aus. Und so wie es in einer solchen Kleinigkeit ist - denn selbstverständlich ist das, was ich hier angeführt habe, für die weltgeschichtliche Entwickelung eine Kleinigkeit-, ist es ja dann im Großen. Es gehen eben in der Welt Dinge vor, die sich ein großer Teil der Menschheit nicht klarmacht.

Und so etwas ging auch vor, als im 18. Jahrhundert eine Gesellschaft vorbereitete gewisse Gedanken, gewisse Anschauungen, welche sich einnisten in die Gemüter der Menschen und wirksame Kräfte werden, wirksame Kräfte im Gebiete dessen, was solche Gesellschaften wollen, und die dann ins soziale Leben übergehen, die dann bestimmen, wie die Menschen zueinander sich verhalten. Die Menschen wissen nicht, woher die Dinge kommen, die in ihren Emotionen, in ihren Empfindungen und in ihren Willensimpulsen leben. Aber diejenigen, die den Zusammenhang der Entwickelung kennen, wissen, wie man die Impulse, die Emotionen hervortreibt. So war es auch mit einem Buche - vielleicht nicht gerade mit dem Buch, aber mit dem, was an Ideen diesem Buch zugrundeliegt, das von einer solchen Gesellschaft im 18. Jahrhundert ausgegangen ist, wo dargestellt ist, welchen Anteil die ahrimanische Wesenheit an den verschiedenen Tieren hat. Natürlich nannte man die ahrimanische Wesenheit da Teufel, und man stellte dar, welche verschiedenen Ausprägungen des Teuflischen in den einzelnen Tierarten enthalten seien. Im 18. Jahrhundert hat ja das Zeitalter der Aufklärung besonders geblüht. Auch heute blüht noch die Aufklärung. Die ganz gescheiten Leute, die ja hauptsächlich auch den Stamm «Pressemenschen» stellen, die finden sich mit einem Witz ab, die sagen: Da hat wieder einmal so ein ... — jetzt mache ich Punkte - ein Buch geschrieben, daß die Tiere Teufel seien! — Ja, aber solche Ideen im 18. Jahrhundert so propagandieren, daß sie sich in vielen menschlichen Gemütern einnisten, derart propagandieren, daß man dabei die realen Entwickelungsgesetze der Menschheit beobachtet, das bewirkt etwas, das bewirkt wirklich etwas. Denn es ist wichtig, wenn im 19. Jahrhundert der Darwinismus auftaucht, wenn im 19. Jahrhundert bei einer großen Anzahl von Menschen die Idee auftaucht, daß die Menschen sich allmählich von den Tieren herauf entwickelt haben, und wenn dann bei einer andern großen Anzahl in den Gemütern die Idee sitzt, die Tiere seien Teufel. Das gibt einen merkwürdigen Zusammenklang. Das alles ist da, das alles ist real vorhanden! Aber die Menschen schreiben Geschichten, in diesen Geschichten ist alles mögliche enthalten; nur die wirklichen, wirksamen Kräfte sind nicht darin enthalten.

Was man berücksichtigen muß, das ist das folgende: Wie das Tier nur in der Luft gedeiht, nicht unter dem ausgepumpten Rezipienten der Luftpumpe, so können Ideen und Ideale nur gedeihen, wenn die Menschen eintauchen in die reale Atmosphäre des geistigen Lebens. Dazu muß aber dieses geistige Leben einem wirklich auch in seiner Realität entgegentreten. Heute jedoch liebt man Allgemeinheiten, richtige Allgemeinheiten; die liebt man ganz besonders. Und so wird man leicht unbeachtet lassen - was aber eine Tatsache ist -, daß ahrimanische Mächte seit dem Jahre 1879 heruntersteigen mußten von der geistigen Welt in das Reich der Menschen, daß sie durchsetzen mußten die menschliche Intellekrualität, das menschliche Denken und Empfinden und Anschauen. Und auch damit stellt man sich nicht in das rechte Verhältnis zu diesen Mächten, daß man einfach die abstrakte Formel hinstellt: Man muß diese Mächte bekämpfen. — Ja, was tun denn die Leute dazu, um sie zu bekämpfen? Sie tun eben nichts anderes als derjenige, der den Ofen ermahnt, er möge recht warm sein, ohne daß er Holz hineintut und Feuer macht. Man muß vor allen Dingen wissen, daß man jetzt, nachdem diese Mächte einmal auf die Erde heruntergegangen sind, mit ihnen leben muß, daß sie da sind, daß man nicht die Augen vor ihnen verschließen darf und daß sie am mächtigsten werden, wenn man die Augen vor ihnen verschließt. Das ist es gerade, daß diese ahrimanischen Gewalten, die den menschlichen Intellekt ergriffen haben, am mächtigsten werden, wenn man nichts von ihnen wissen, nichts von ihnen erfahren will.

Wenn das Ideal so mancher Menschen erreicht werden könnte, nur Naturwissenschaft zu studieren und aus den naturwissenschaftlichen Gesetzen auch soziale Gesetze zu machen, nur alles Reale, wie man sagt — wobei man aber das Sinnliche meint - ins Auge zu fassen, gar nicht daran zu denken, das Geistige zu pflegen, wenn dieses Ideal gelingen würde im weitesten Umkreise, dann hätten die ahrimanischen Mächte das allergewonnenste Spiel, denn dann wüßte man nichts von ihnen. Dann würde man eine monistische Religion im Haeckelschen Sinne gründen, und sie hätten das beste Arbeitsfeld. Denn das wäre ihnen gerade recht, wenn die Menschen nichts von ihnen wüßten und sie im Unterbewußtsein der Menschen arbeiten könnten.

Also Hilfe können die ahrimanischen Mächte dadurch erlangen, daß man eine ganz naturalistische Religion bringt. Hätte David Friedrich Strauß sein Ideal vollständig erreichen können, diese Philisterreligion zu begründen, um derentwillen Nietzsche das Buch geschrieben hat «David Friedrich Strauß, der Bekenner und Schriftsteller», dann würden sich die ahrimanischen Mächte heute noch viel wohler fühlen, als sie sich fühlen. Aber das ist nur das eine; die ahrimanischen Mächte können noch auf eine andere Weise sehr gut gedeihen. Sie können dadurch gedeihen, daß man diejenigen Elemente pflegt, die sie gerade so recht unter den Menschen der Gegenwart verbreiten möchten: Vorurteil, Unwissenheit und Furcht vor dem geistigen Leben. Durch nichts fördert man so sehr die ahrimanischen Mächte als durch Vorurteil, durch Unwissenheit und durch die Furcht vor dem geistigen Leben.

Nun aber überschauen Sie, wie viele Menschen es sich heute geradezu zur Aufgabe machen, Vorurteile, Unwissenheit und Furcht vor den geistigen Mächten zu pflegen. Ich habe gestern im öffentlichen Vortrage gesagt: 1835 wurden erst die Dekrete gegen Kopernikus, Galilei, Kepler und so weiter aufgehoben. Die Katholiken durften also bis 1835 nichts studieren von kopernikanischer Weltanschauung oder dergleichen. Die Unwissenheit in bezug darauf wurde geradezu gefördert. Das war eine mächtige Beförderung der ahrimanischen Gewalten. Es war ein guter Dienst, den man den ahrimanischen Gewalten geleistet hat; sie konnten sich gut vorbereiten für ihre Kampagne, die dann folgen sollte vom Jahre 1841 an.

Zu diesem Satze, den ich jetzt eben ausgesprochen habe, müßte ich eigentlich noch einen andern dazu sagen, damit er vollständig wäre. Allein diesen andern Satz kann heute noch keiner sagen, der in diese Dinge wirklich eingeweiht ist. Aber wenn Sie erfühlen, was in den Untergründen eines solchen Satzes enthalten ist, so werden Sie vielleicht selber eine Ahnung bekommen von dem, was ich meine.

Die naturwissenschaftliche Weltanschauung ist eine rein ahrimanische Sache; aber nicht dadurch bekämpft man sie, daß man nichts von ihr wissen will, sondern indem man sie - wo immer möglich in das Bewußtsein heraufbefördert, sie möglichst gut kennenlernt. Man kann Ahriman keinen größeren Dienst leisten, als die naturwissenschaftlichen Anschauungen zu ignorieren oder unverständig zu bekämpfen. Wer unverständige Kritik an den naturwissenschaftlichen Anschauungen übt, der bekämpft nicht, sondern der fördert Ahriman, weil er Täuschung, Trübnis ausbreitet über ein Feld, über das gerade Licht ausgebreitet werden sollte.

Die Menschen müssen sich nach und nach dazu erheben einzusehen, wie ein jegliches Ding schon einmal zwei Seiten hat. Die heutigen Menschen sind ja sehr gescheit, nicht wahr, grenzenlos gescheit, und so finden diese gescheiten Menschen der Gegenwart: In der vierten nachatlantischen Zeit, im griechisch-lateinischen Zeitalter, da hatte man noch den «Aberglauben», daß man aus dem Fluge der Vögel, aus den Eingeweiden der Tiere und mancherlei anderem die Zukunft erkennen könne. Nun, die Menschen, die das getan haben, waren natürlich «Dummköpfe». - Zwar weiß kein Mensch der Gegenwart, der heute die Sache abkanzelt, wie das eigentlich gemacht worden ist. Kein Mensch der Gegenwart redet auch anders als nach dem Beispiel, das ich Ihnen neulich einmal vorgeführt habe, wo der Betreffende zugeben mußte, daß eine Prophetie aus einem Traum heraus eingetroffen war, aber dann sagte: Nun ja, das hat eben der Zufall gewollt! — Aber nach den Grundbedingungen des vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraums gab es wirklich eine solche Wissenschaft, die etwas mit der Zukunft zu tun hatte. Man hat in dieser Zeit nicht den Glauben gehabt, daß man mit solchen Grundsätzen, wie man sie heute anwendet, im sozialen Werden etwas ausmachen kann. Sonst würde man ja auch dazumal nicht - man mag damit einverstanden sein oder nicht, darauf kommt es nicht an - weit über die Zeiten hinausgehende große Perspektiven sozialer Natur gefunden haben, wenn man nicht eine gewisse Wissenschaft der Zukunft gehabt hätte. Glauben Sie, heute zehren die Menschen in dem, was sie auf dem Felde des sozialen Lebens und der Politik zustandebringen, noch immer von dem, was aus der alten Zukunftswissenschaft hervorgegangen ist. Diese Zukunftswissenschaft kann man aber nie durch Beobachtung dessen gewinnen, was äußerlich vor den Sinnen da ist. Niemals kann man sie nach dem Muster der Naturwissenschaft gewinnen, denn was man äußerlich sinnlich beobachten kann, das ist Vergangenheitswissenschaft. Und jetzt verrate ich Ihnen ein sehr wichtiges, sehr wesenhaftes Gesetz des Weltenalls: Wenn Sie die Welt bloß sinnlich beobachten, so wie das moderne naturwissenschaftliche Anschauen die Welt beobachtet, dann beobachten Sie bloß vergangene Gesetze, die sich noch fortpflanzen; Sie beobachten eigentlich bloß den Weltenleichnam der Vergangenheit. Das gestorbene Leben betrachtet die Naturwissenschaft.

Denken Sie sich einmal, dieses wäre, schematisch dargestellt, unser Beobachtungsfeld (siehe Zeichnung, weiß), dasjenige, was vor unseren Augen, unseren Ohren, vor den andern Sinnen sich ausbreitet. Denken Sie sich, das hier (siehe Zeichnung, gelb) wären die sämtlichen naturwissenschaftlichen Gesetze, die man finden kann. Dann geben diese sämtlichen naturwissenschaftlichen Gesetze gar nicht mehr das, was da drinnen ist, sondern das, was schon drinnen war, was darinnen vergangen ist und nur als ein Erstarrtes zurückgeblieben ist. Sie müssen außer diesen Gesetzen vielmehr dasjenige finden, was nicht Augen beobachten können, was nicht physische Ohren hören können: eine zweite Welt von Gesetzen (siehe Zeichnung, lila). In der Wirklichkeit ist sie drinnen, aber sie weist nach der Zukunft hin.

Es ist ja mit der Welt gerade so, wie wenn Sie eine Pflanze nehmen (es wird gezeichnet). So, wie heute eine Pflanze aussieht, ist sie ja nicht in Wahrheit; denn geheimnisvoll in ihr ist etwas, was Sie noch nicht sehen, was erst im nächsten Jahr so sein wird, daß es Augen sehen: die Keimanlage. Die ist aber schon drinnen, die ist unsichtbar drinnen. So ist in der Welt, die uns vorliegt, unsichtbar die Zukunft darinnen, die ganze Zukunft. Aber das Vergangene ist so darinnen, daß es schon verdorrt ist, vertrocknet, tot, Leichnam ist. Die ganze Naturbetrachtung gibt nur das Bild des Leichnams, nur Vergangenes. Gewiß, es fehlt einem dieses Vergangene, wenn man bloß auf das Geistige schaut; das ist wahr, aber zur totalen Wirklichkeit muß man das Unsichtbare dazu haben.

Wie kommt es, daß Leute auf der einen Seite eine Kant-Laplacesche Theorie aufstellen, auf der andern Seite über das Weltenende so reden wie der Professor Dewar — wie ich gestern im öffentlichen Vortrage erzählt habe -, der ein Erdenende konstruiert, wo die Leute Zeitungen lesen werden bei mehreren hundert Grad Kälte, mit Wänden, die mit leuchtendem Eiweiß angestrichen sind; Milch wird fest sein. Ich möchte bloß wissen, wie man sie melken wird, wenn sie fest wird! Das sind lauter unmögliche Vorstellungen, wie auch die ganze Kant-Laplacesche Theorie eine unmögliche Vorstellung ist. Sobald man mit diesen Theorien hinauskommt über das unmittelbare Beobachtungsfeld, versagen sie. Warum? Weil sie Theorien von Leichnamen, Theorien vom Toten sind.

Heute sagen die gescheiten Leute: Die griechischen, die römischen Opferpriester waren entweder Schurken und Schwindler oder Abergläubische, denn man kann ja natürlich als vernünftiger Mensch nicht glauben, daß man aus dem Flug der Vögel, aus den Opfertieren irgend etwas über die Zukunft herausfinden kann. — Die Menschen in der Zukunft, die werden aber auf die Vorstellungen der Gegenwart, auf die die Menschen heute so stolz sind, geradeso herabsehen können, wenn sie sich ebenso gescheit fühlen wie die heutige Generation gegenüber den römischen Opferpriestern. Und die werden sagen: Kant-Laplacesche Theorie! Dewar! Die haben merkwürdig abergläubische Vorstellungen gehabt! Die haben ein paar Jahrtausende der Erdenentwickelung beobachtet und dann Schlüsse gezogen auf Anfangs- und Endzustand der Erde. Welch törichter Aberglaube war das dazumal! Da hat es solche sonderbare, abergläubische Menschen gegeben, die geschildert haben, daß aus einem Urnebel sich Sonne und Planeten abgespalten haben, die dann ins Rotieren gekommen sind. Man wird noch viel schlimmere Dinge reden können über diese Vorstellungen der Kant-Laplacesche Theorie und über diese Vorstellungen vom Erdenende, als die heutigen Menschen reden über die Erforschung der Zukunft aus den Opfertieren oder aus dem Flug der Vögel und dergleichen.

Wie erhaben sind diese Menschen heute, die so recht den Geist und die Gesinnung des naturwissenschaftlichen Denkens aufgenommen haben, wie schauen sie herab auf die alten Mythen, auf die Märchen: kindliches Zeitalter der Menschheit, wo sich die Menschen Träume hingestellt haben! Wie weit sind wir dagegen gediehen: wir wissen heute, wie alles von einem gewissen Kausalgesetz beherrscht wird, wir haben es eben herrlich weit gebracht. — Aber alle, die so urteilen, wissen eines nicht: daß diese ganze Wissenschaft von heute nicht da wäre, gerade da, wo sie berechtigt ist, wenn das mythische Denken nicht vorangegangen wäre. Ja, die heutige Wissenschaft, ohne daß die Mythe vorangegangen ist, ohne daß sie aus der Mythe herausgewachsen ist, können Sie geradeso haben, wie Sie eine Pflanze haben können, die nur Stengel, Blätter und Blüten hat und da drunten keine Wurzel, die braucht man nicht.

Wer von der heutigen Wissenschaft als einem in sich selbst absolut Ruhenden spricht, der redet eben so, als wenn er die Pflanze bloß ihrem oberen Teile nach gedeihen lassen wollte. Alles, was heutige Wissenschaft ist, ist aus der Mythe herausgewachsen, die Mythe ist die Wurzel. Und es verursacht eben bei gewissen Elementargeistern, die solche Dinge von den andern Welten aus beobachten, ein wahres Hohngelächter der Hölle, wenn die ganz gescheiten Professorengemüter von heute heruntersehen auf die alten Mythologien, auf die alten Mythen, auf alle die Mittel des alten Aberglaubens, und keine Ahnung haben, daß sie mit all ihrer Gescheitheit herausgewachsen sind aus diesen Mythen, daß sie keinen einzigen berechtigten Gedanken der Gegenwart haben könnten, ohne daß diese Mythen dagewesen wären. Und ein anderes verursacht bei denselben Elementargeistern ein wahres Hohngelächter der Hölle - hier kann man sogar im eigentlichen Sinne sagen ein Hohngelächter der Hölle, denn den ahrimanischen Mächten ist das gerade recht, daß ihnen Gelegenheit zu einem solchen Hohngelächter gegeben wird -, nämlich wenn diese Leute glauben, nun haben sie die kopernikanische Theorie, nun haben sie den Galileismus, nun haben sie dieses gloriose Gesetz von der Erhaltung der Kraft. Das wird sich nie ändern, das wird nun in alle Zeiten hinein bleiben. — Ein kurzsichtiges Urteil! Geradeso, wie sich der Mythus zu unseren Vorstellungen verhält, so verhalten sich die Vorstellungen der Wissenschaft des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts zu dem, was wiederum ein paar Jahrhunderte später kommen wird. Das wird geradeso überwunden werden, wie der Mythus überwunden wurde. Glauben Sie, daß die Menschen im Jahre 2900 über das Sonnensystem ebenso denken werden, wie die heutigen Menschen denken? Das wäre Professorenaberglaube, das dürfte niemals Anthroposophenglaube sein.

Das, was die Menschen heute berechtigt denken können, was sie wirklich mit einer gewissen Größe hineinstellen in die gegenwärtige Zeit, das verdanken sie gerade dem Umstande, daß sich während der Griechenzeit so etwas ausgebildet hat wie die griechische Mythologie. Es würde ja natürlich nichts Entzückenderes geben für einen aufgeklärten Menschen der Gegenwart, als wenn er denken könnte: Ach, wären doch diese Griechen auch schon so glücklich gewesen, daß sie unsere heutige Wissenschaft gehabt hätten! - Aber hätten die Griechen unsere heutige Wissenschaft gehabt, wäre das nicht dagewesen, was gerade die Griechen gehabt haben, die Kunde von den griechischen Göttern, die Welt des Homer, Sophokles, Aischylos, Plato, Aristoteles, wäre das nicht dagewesen: Wagner wäre ein Faust gegen die Wagners, die dann heute herumgehen würden! Vertrocknet, verkommen wäre das menschliche Denken, öde wäre all unser Denken, denn was an Lebenskraft in unserem Denken ist, das kommt davon her, daß es wurzelt im griechischen Mythus, im Mythus der vierten nachatlantischen Zeit überhaupt. Und wer da glaubt, daß der Mythus eben falsch war und das heutige Denken richtig ist, der gleicht einem Menschen, der es unnötig findet, daß man Rosen erst vom Rosenstock abschneiden muß, wenn man ein Rosenbouquet haben will. Warum sollen denn die Rosen nicht direkt entstehen können?

Es sind eben alles unwirkliche Vorstellungen, in denen die Menschen leben, die gerade heute zu den Aufgeklärtesten zu gehören glauben. Dieser vierte nachatlantische Zeitraum mit seiner Ausbildung des Mythus, mit seiner Ausbildung von Vorstellungen, die für den heutigen Menschen eher Träumen ähnlich sind als den scharf umrissenen naturwissenschaftlichen Vorstellungen, diese ganze Denkweise des vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraums, die ist die Grundlage für das, was wir heute sind. Das aber, was wir heute denken, was wir heute ausbilden können, das wiederum muß die Grundlage sein für den nächsten Zeitraum. Das kann es aber nur sein, wenn es nicht bloß nach der Seite des Verdorrens sich entwikkelt, sondern wenn es sich nach der Seite des Lebens entwickeln will. Leben aber wird eingehaucht demjenigen, was heute ist, wenn man versucht, das, was einmal war, ins Bewußtsein heraufzuheben und das zu erkennen, was einem ein waches Bewußtsein gibt, was einen zu einer wachen Persönlichkeit macht.

Seit dem Jahre 1879 ist es so: Wenn einer in die Schule geht, dort naturwissenschaftliche Gesinnung und Denkart aufnimmt, sich dann eine Weltanschauung aneignet im Sinne dieser naturwissenschaftlichen Denkart und nun den Glauben hat, nur das, was sich in der Sinnenwelt ausbreitet, das kann man wirklich nennen, alles andere ist ja doch nur Phantasieprodukt -, wenn einer so denkt - und wie viele Leute denken heute so -, dann hat Ahriman sein gutes Spiel, dann geht es den ahrimanischen Mächten gut. Denn diese ahrimanischen Mächte, die sich seit dem Jahre 1879 in den menschlichen Gemütern sozusagen ihre Festungen begründet haben, was sind sie denn eigentlich? Menschen sind sie nicht; Engel sind sie, aber zurückgebliebene Engel - Engel, die aus ihrer Entwickelungsbahn herausgekommen sind, die es verlernt haben, in der nächstangrenzenden geistigen Welt ihre Aufgabe zu verrichten. Würden sie das können, dann wären sie nicht im Jahre 1879 gestürzt worden. Sie sind heruntergestürzt, weil sie oben ihre Aufgabe nicht erfüllen können. Jetzt wollen sie ihre Aufgabe mit Hilfe der Köpfe, der Gehirne der Menschen erfüllen. In den Gehirnen der Menschen sind sie um einen Plan tiefer, als wo sie eigentlich hingehören. Was man heute monistisch denken nennt, das tun ja gar nicht in Wirklichkeit die Menschen. Was man heute nationalökonomische Wissenschaft nennt, das ist vielfach von der Art, wie ich es gestern wiederum hingestellt habe. Wenn man das ausspricht, was daam Anfang des Krieges geschrieben wurde, der Krieg müsse in vier Monaten aus sein — ich meine als Wissenschafter ausspricht; wenn man es bloß nachspricht, kommt es nicht so darauf an -: Was geht denn da in den Köpfen der Menschen vor? All das sind ja Engelsgedanken, die in den Köpfen der Menschen nisten, Gedanken von zurückgebliebenen Engeln. Ja, der menschliche Verstand soll eben immer mehr und mehr in Anspruch genommen werden von solchen Mächten, die sich seiner bemächtigen wollen, damit sie ihr Leben ausleben können. Gegen das kommt man nicht auf, wenn man den Kopf in den Sand steckt und Vogel-Strauß-Politik spielt, sondern nur, wenn man bewußt mitlebt. Nicht, wenn man nicht weiß, was zum Beispiel die Monisten denken, kommt man dagegen auf, sondern wenn man es weiß, aber wenn man auch weiß, daß es Ahrimanwissenschaft ist, daß es die Wissenschaft von zurückgebliebenen Engeln ist, die in den Köpfen der Menschen nistet, wenn man Bescheid weiß von der Wahrheit, von der Wirklichkeit.

Natürlich, wir sprechen das hier so aus, daß wir uns der entsprechenden Ausdrücke bedienen - ahrimanische Mächte -, weil wir diese Dinge ernstnehmen. Sie wissen, so können Sie nicht sprechen, wenn Sie draußen zu den Menschen sprechen, die heute ganz unvorbereitet sind. Denn da ist eben eine der Scheidewände. Da kommt man nicht heran an die Menschen; aber man kann natürlich Mittel und Wege finden, um zu den andern Menschen so zu sprechen, daß dasjenige, was einmal Wahrheit ist, einfließt. Dahingegen, wenn es gar keine Stätte gäbe, wo die Wahrheit gesagt werden könnte, dann würde man ja auch keine Möglichkeit haben, sie einfließen zu lassen in die äußere, profane Wissenschaft. Es muß ja mindestens einzelne Stätten geben, wo die Wahrheit in einer ursprünglichen, echten Form ausgesprochen werden kann. Nur müssen wir niemals vergessen, daß es den heutigen Menschen oftmals unüberwindliche Schwierigkeiten macht, wenn sie selbst auch schon wirklich den Anschluß finden an die spirituelle Wissenschaft, die Brücke zu schlagen hinüber ins Reich der ahrimanischen Wissenschaft. Ich habe manche Menschen gefunden, die sehr gut Bescheid wußten auf diesem oder jenem Gebiet der ahrimanischen Wissenschaft, die entweder gute Naturwissenschafter oder gute Orientalisten waren und so weiter, die dann auch den Anschluß gefunden haben an unsere spirituelle Forschung. Oh, ich habe mir viele Mühe gegeben, um solche Menschen zu veranlassen, nun die Brücke zu schlagen. Was wäre geschehen, wenn ein Physiologe, ein Biologe mit all dem Spezialwissen, das man auf diesen Gebieten heute gewinnen kann, die Physiologie, die Biologie spirituell durchgearbeitet hätte, so daß man nicht gerade unsere Ausdrücke gebraucht hätte, aber in unserem Geist diese einzelnen Wissenschaften bearbeitet hätte! Ich habe es bei Orientalisten versucht. Gewiß, die Menschen können auf der einen Seite gute Anhänger der Anthroposophie sein, auf der andern Seite sind sie Orientalisten und machen die Sache so, wie es Orientalisten machen. Aber die Brücke von dem einen zu dem andern wollen sie nicht schlagen. Das ist es aber gerade, was die Gegenwart so notwendig braucht, was so intensiv notwendig ist, denn, wie gesagt, da befinden sich die ahrimanischen Mächte sehr wohl, wenn man Naturwissenschaft so betreibt, als ob das ein Abbild der äußeren Welt wäre. Aber wenn man mit spiritueller Wissenschaft und mit der Gesinnung kommt, die aus der spirituellen Wissenschaft fließt, da befinden sich die ahrimanischen Mächte weniger gut. Diese spirituelle Wissenschaft ergreift ja den ganzen Menschen. Man wird ein anderer Mensch dadurch, man lernt anders fühlen und anders wollen, man lernt, sich anders in die Welt hineinzustellen.

Es ist wahr, was immer von Eingeweihten gesagt wurde: Wenn das den Menschen durchströmt, was von spiritueller Weisheit kommt, dann ist es für die ahrimanischen Mächte ein großer Schrekken der Finsternis und ein verzehrend Feuer. Wohl ist es den ahrimanischen Engeln, in den Köpfen zu wohnen, die heute mit ahrimanischer Wissenschaft erfüllt sind; aber wie verzehrend Feuer, wie ein großer Schrecken der Finsternis werden diejenigen Köpfe von den ahrimanischen Engeln empfunden, die mit spiritueller Weisheit durchsetzt sind. Nehmen wir solch eine Sache in ihrem vollen Ernste, fühlen wir das: Wenn wir uns mit spiritueller Weisheit durchsetzen, dann gehen wir so durch die Welt, daß wir ein rechtes Verhältnis begründen zu den ahrimanischen Mächten, daß wir selber durch das, was wir tun, das aufrichten, was da sein muß, daß wir zum Heile der Welt aufrichten die Stätte des verzehrenden Opferfeuers, die Stätte, wo der Schrecken der Finsternis strahlt über das schädliche Ahrimanische.

Durchdringen Sie sich mit solchen Ideen, durchdringen Sie sich mit solchen Empfindungen! Dann werden Sie wach und schauen die Dinge an, die draußen in der Welt vorgehen, schauen an, was draußen in der Welt geschieht. Im 18. Jahrhundert sind eigentlich die letzten Reste der alten atavistischen Wissenschaft erstorben. Die Anhänger des «unbekannten Philosophen» Saint-Martin, des Schülers von Jakob Böhme, hatten manches von der alten atavistischen Weisheit, sie hatten dafür aber auch vieles von einem Vorauswissen dessen, was kommen werde, was in unserer Zeit aber schon gekommen ist. Und oftmals wurde in diesen Kreisen davon gesprochen, daß von dem letzten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts und von der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts ein Wissen ausstrahlen werde, das da wurzelt in denselben Quellen, in demselben Boden, wo bestimmte menschliche Krankheiten wurzeln - ich habe letzten Sonntag davon gesprochen -, wo Anschauungen herrschen werden, die da wurzeln in der Lüge, wo Empfindungen herrschen werden, die da wurzeln in der Selbstsucht.

Verfolgen Sie mit sehendem Auge, mit dem Auge, das sehend wird durch die Empfindungen, von denen wir heute gesprochen haben, was durch die Gegenwart wallt und west! Vielleicht wird von manchem, was Sie erfahren, Ihr Herz wund werden. Das aber schadet nichts, denn klare Erkenntnis, auch wenn sie schmerzt, wird heute gute Früchte tragen von der Art, wie sie gebraucht werden, um herauszukommen aus dem Chaos, in das sich die Menschheit hineinbegeben hat.

Das erste oder eines von den ersten Dingen wird sein müssen die Erziehungswissenschaft. Und auf dem Gebiete der Erziehungswissenschaft wird wiederum einer der ersten Grundsätze ein solcher sein müssen, gegen den heute am allermeisten gesündigt wird. Wichtiger als alles, was Sie einem Knaben oder Mädchen oder einem jungen Mann oder einer Jungfrau lehren und bewußt anerziehen können, wichtiger ist dasjenige, was unbewußt während der Erziehungszeit in die Seelen der Menschen hineinfließt. Ich habe erst im vorigen öffentlichen Vortrage davon gesprochen, daß das Gedächtnis etwas ist, was sich wie im Unterbewußtsein als Parallelerscheinung des bewußten Seelenlebens ausbildet. Darauf muß gerade bei der Erziehung Rücksicht genommen werden. Nicht nur, was das Kind versteht, muß der Erzieher der Seele beibringen, sondern auch dasjenige, was das Kind noch nicht versteht, was sich in geheimnisvoller Weise hineinerstreckt in des Kindes Seele und was - das ist wichtig - dann im späteren Leben herausgeholt wird.

Wir nähern uns immer mehr der Zeit, in der die Menschen während ihres ganzen Lebens immer mehr und mehr Erinnerungen an ihre Jugendzeit brauchen werden, Erinnerungen, die sie gerne haben, Erinnerungen, die sie glücklich machen. Das muß die Erziehung lernen, systematisch zu leisten. Gift wird es sein für die Erziehung der Zukunft, wenn die Menschen im späteren Leben zurückdenken müssen, wie sie sich geplagt haben während der Schulzeit, während der Erziehungszeit, wenn sie sich ungern erinnern an ihre Schul- und Erziehungszeit, wenn ihnen die Schul- und Erziehungszeit nicht ein Quell ist, aus dem sie immer von neuem lernen, lernen, lernen können. Wenn man aber schon alles gelernt hat als Kind, was man vom Lehrstoff lernen kann, bleibt ja nichts mehr für später.

Wenn Sie dies wiederum bedenken, dann werden Sie sehen, wie anders ganz gewichtige Grundsätze in der Zukunft Lebensdirektiven werden müssen gegenüber dem, was man heute für das Richtige ansieht. Gut wäre es für die Menschheit, wenn die traurigen Erfahrungen der Gegenwart nicht von so vielen verschlafen würden, sondern wenn die Menschen diese traurigen Erfahrungen der Gegenwart benützen würden, um sich möglichst vertraut zu machen mit dem Gedanken: Vieles, vieles muß anders werden! Zu selbstgefällig ist die Menschheit der letzten Zeiten geworden, um diesen Gedanken in seiner vollen Tiefe und vor allen Dingen in seiner vollen Intensität zu ermessen.

Tenth Lecture

It cannot be said that the present has no ideals. On the contrary, it has very, very many ideals. But these ideals are not effective. Why are they not effective? Imagine—forgive me for using a somewhat strange image, but it does correspond to the situation—imagine that a hen is ready to hatch an egg, but someone takes this egg and incubates it, allowing the chick to hatch from the egg. All this is conceivable, but if you did this, for example, under an air pump, in a vacuum, do you think the chicken that hatches from the egg would thrive? In a sense, all the stages of development given in evolution are there, but one thing is missing: where to put the chick so that it has the conditions it needs to live.

This is roughly how it is with all the beautiful ideals that are so often talked about today. They not only sound beautiful, they are indeed valuable ideals. But the present does not allow us to get to know the real, actual conditions of evolution as they must be recognized according to the conditions of the present. And so it happens that in the strangest societies, all kinds of ideals can be coined, represented, and demanded, and nothing comes of it. After all, there were certainly enough societies with ideals at the beginning of the 20th century. But one cannot say that the last three years have been a fulfillment of these ideals. One should learn something from this fact, as has been mentioned several times in these reflections.

Last Sunday, I gave you a brief overview of the spiritual development of the last few decades. I asked you to bear in mind that what happens on the physical plane is prepared over a long period of time in the spiritual world. I pointed out some very concrete examples. I pointed out how, in the 1840s, a battle began in the spiritual world immediately above ours, a metamorphosis of those battles that are referred to in ancient symbolism as the battle of St. Michael with the dragon. And I explained to you how this battle in the spiritual world unfolded until November 1879, how there was a battle in the spiritual world, a battle between Michael and the dragon—we know what this image means—and how, after November 1879, Michael won the victory in the spiritual world and the dragon, that is, the Ahrimanic forces, were cast down into the sphere of human beings. Where are they now?

So let us consider: those powers of the Ahriman school, which waged a decisive battle in the spiritual world from 1841 to 1879, were cast down from the spiritual world into the realm of human beings in 1879. And since that time they have had their stronghold, their field of activity — especially in the epoch in which we now live — in the thinking, feeling, and will impulses of human beings.

Consider how infinitely much of what people think, want, and feel in our time is permeated by Ahrimanic forces. Such events in the connection between the spiritual and physical worlds are part of the plan of our entire world order, and we must reckon with these concrete facts. What good does it do to remain stuck in abstractions and say, like a true abstract thinker: Man must fight Ahriman. — Nothing comes of such an abstract formula. People today sometimes have no idea of the spiritual atmosphere in which they actually live. We must face this fact in all its seriousness.

Take this, for example: as a member of the Anthroposophical Society, you are called upon to hear about these things, to engage with them in your thoughts and feelings. Then the whole seriousness of the matter will dawn on you, then it will dawn on you that you have a task to fulfill with the best of what you can feel and sense, depending on your place in this so mysterious, so questionable, so confused present. Take the following example: Somewhere there were only a few people who had come together in a natural way to form a kind of friendly association, and this circle of people knew about such and similar spiritual connections as I have just described to you, and large numbers of people knew nothing about them. Be convinced that if this circle of people, which I have now hypothetically placed before your soul, were to decide, for whatever reason, to put the power they gained from such knowledge into some kind of service, then this small circle, with the followers it would attract, often without those followers being aware of it, would be very powerful, and most powerful of all against those who were unaware and wanted to know nothing about these things.

There was already a certain circle of people in the 18th century who were entirely of this kind. It continues today. A certain circle of people knew about the facts I have told you about, knew that such things would happen in the 19th and into the 20th century, as I have described to you. However, this circle of people decided – as early as the 18th century – to pursue certain goals that could be described as selfish for this circle, to strive for certain impulses. They then worked toward this goal in a very systematic manner.

People today live in large masses, as if asleep, thoughtlessly, paying no attention to what is actually going on in the large circles that exist alongside them. In this respect, people today are particularly prone to illusions. Just think how people today say: Oh, how wonderful our communication is, how it brings people together! How everyone learns about each other! How different it is from earlier times! Remember everything that is said along these lines. One need only consider individual facts in their context and in a reasonable manner to find that, in this respect, the present day exhibits some very strange things. Who believes, for example—I am only citing this as an example, as evidence—that literary phenomena today cannot become known in the widest circles through the press, which understands everything and reports on everything? Who seriously believes that significant, profound, epoch-making literary phenomena can remain unknown today? One must learn about them in some way. The strange thing is that what we respectfully refer to today as the press only began to flourish in the last third of the 19th century; the press had already made a start on this before, even if it was not yet what it is today. And yet [even though the press wrote nothing about it], a literary phenomenon could be epoch-making throughout Central Europe at that time, more epoch-making than all the well-known writers such as Spielhagen, Gustav Freytag, Paul Heyse, and many others I could name who had large print runs. It was a literary phenomenon that was more widespread and had a much greater impact than anything we know of: For no work has actually had such a wide readership in the last third of the 19th century as “Dreizehnlinden” by Wilhelm Weber. Now I ask you: How many people will be sitting here who do not even know that there is a “Dreizehnlinden” by Weber? — That is how people live side by side today, despite the press. In Dreizehnlinden, ideas that were deeply influential are embodied in beautiful poetic language. Yes, they live on today in thousands upon thousands of minds.

I have cited this to illustrate that it is indeed possible for the masses to know nothing about things that are nevertheless significant and happening right next to them. Yes, you can be sure that if there is anyone here who has not read the book “Dreizehnlinden” — and I suspect that there are some among your friends — you can be quite certain that you have already been with three or four people in your life who have read “Dreizehnlinden.” There are such dividing walls between people that often the most important things are not discussed at all between those who are close to each other. People don't talk about them. Even those who are close to each other don't talk about the most important things. And just as it is in such a small matter—because what I have mentioned here is, of course, a small matter in terms of world history—so it is in the big picture. There are things going on in the world that a large part of humanity does not understand.