The Redemption of Thinking

GA 74

22 May 1920, Dornach

Lecture I

During these three days, I would like to speak about a topic that one normally considers from a more formal aspect, and whose contents one normally only considers that the position of the philosophical worldview to Christianity was fixed as it were by the underlying philosophical movement of the Middle Ages. Because just this aspect of the matter was recently refreshed because Pope Leo XIII called on his clerics to do Thomism the official philosophy of the Catholic Church, our present topic has a certain significance from this side.

However, I would just like to look not only from this formal aspect at the matter that is connected as medieval philosophy with the central personalities of Albert the Great (1193-1280) and Thomas Aquinas (~1225-1274), but in the course of these days I would like to show the deeper historical background from which this philosophical movement arose which our time appreciates too little. One can say that Thomas Aquinas tried to grasp the problem of knowledge, of the complete worldview in a quite astute way in the thirteenth century, in a way that is hard to comprehend with our thinking today because conditions are part of reflection that the human beings of the present hardly fulfil, even if they are philosophers. It is necessary that you can completely project your thoughts in the way of thinking of Thomas Aquinas, his predecessors and successors that you know how you have to understand the concepts which lived in the souls of these medieval people about which, actually, the history of philosophy reports quite externally.

If you look now at the centre of our consideration, at Thomas Aquinas, he is a personality that disappears, compared with the main current of Christian philosophy in the Middle Ages, as a personality as it were who is, actually, only the exponent of that which lives in a broad worldview current and expresses a certain universality with him. So that Thomism is something exceptionally impersonal, something that only manifests by the personality of Thomas Aquinas. Against it, you recognise immediately that you look at a full, whole personality if you envisage Augustine (354-430) who is the most important predecessor of Thomism. With Augustine, we deal with a struggling person, with Thomas Aquinas with the medieval church that determines its position to heaven, earth, human beings, history et cetera. It expresses itself—indeed, with certain restrictions—as church by the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas.

A significant event takes place between both men, and without looking at this event, it is not possible to determine the position of both personalities to each other. This event took place in 553 when Emperor Justinian I (527-565) branded Origen (185-~254) as a heretic. The whole colouring of Augustine's worldview becomes clear only if you consider the historical background from which Augustine worked his way out. However, this historical background changes because that powerful influence on the West stops which had originated from the Greek academies in Athens and somewhere else. This influence lasted until the sixth century, and then it decreased, so that something remained in the western current that was quite different from that in which Augustine had still lived.

I ask you to take into consideration that I would like to give an introduction only today that I treat the real being of Thomism tomorrow, and that the purpose of my executions will completely appear, actually, only at the third day. Since I am in a special situation, also with reference to the Christian philosophy of the Middle Ages, in particular of Thomism,—you forgive for this personal remark. I have emphasised many a time what I experienced once when I reported that before a proletarian audience what I have to regard as truth in the course of western history. It caused that the students took kindly to that, however, the leaders of the proletarian movement believed that this was no real Marxism. Although I appealed to freedom of teaching, one answered to me in the decisive meeting that this party knows no freedom of teaching but only reasonable compulsion!—Hence, I had to finish my teaching, although I had many students of the proletariat who supported me.

I experienced something similar another time with that which I wanted to say about Thomism and the medieval philosophy twenty years ago. At that time, the materialist monism was on its climax. To the care of a free, independent worldview, but only to the care of this materialist monism, the Giordano Bruno Association was founded in Germany in those days. Because it was impossible for me to take part in all empty gossip and phrases that appeared as monism in the world, I held a talk on Thomism in the Berlin Giordano Bruno Association. I tried to prove in this talk that Thomism is a spiritual monism, which manifests by an astute thinking of which the modern philosophy—influenced by Kant and Protestantism—has no idea or has no strength for it. Thus, I fell out also with monism! Today it is exceptionally difficult to speak of the things in such a way that the spoken arises from the real thing and is not put into the service of any party. Hence, I would like to speak about the phenomena, which I have indicated, during these three days again.

Augustine positions himself as a struggling personality in the fourth and fifth centuries, as I have already said. The way in which Augustine struggles makes a deep impression if one is able to go into the special nature of this struggle. Two questions rose in Augustine's soul of which one has no idea today where the real cognitive and psychological questions have faded, actually. The first question is that which one can characterise possibly while one says, Augustine struggles for the being of that which the human being can acknowledge, actually, as truth fulfilling his soul. The second question is, how can one explain the evil in a world that has, nevertheless, sense only if at least the purpose of this world deals with the good? How can one explain that never the voice of the evil is silenced in the human nature also not if the human being strives honestly and sincerely for the good?

I do not believe that one approaches Augustine really, if one interprets these two questions in such a way, as the average human people of the present would like to understand them. One has to look for the special colouring that these questions had for this man of the fourth and fifth centuries. Augustine experiences an internally moved, excessive life at first. However, in this life both questions appear repeatedly in him. He is in a conflict. The father is a pagan; the mother is a devout Christ. The mother did her best to win the son over to Christianity. At first, the son attains a certain seriousness of life and turns to Manichaeism. We want to look at this worldview later that Augustine got to know when he changed from a dissolute life to a serious one. Then, however, he felt more and more rejected—indeed, only after years—by Manichaeism, and a certain scepticism seized him from the whole trend of the philosophical life in which at a certain time the Greek philosophy had ended, and which survived then until the time of Augustine.

However, now scepticism withdraws more and more. Scepticism is only something to Augustine that brings him together with Greek philosophy. This scepticism leads him to that which exerted a deep influence certainly on his subjectivity on his whole attitude for some time. Scepticism leads him to a quite different direction, to Neoplatonism. Neoplatonism influenced Augustine even more than one normally thinks. One can understand his whole personality and his struggle only if one recognises how much he is involved in the Neoplatonic worldview. If one goes objectively into his development, one hardly finds, actually, that the break, which in this personality took place with the transition from Manichaeism to Neoplatonism or Plotinism, recurred with the same strength, when Augustine turned from Neoplatonism to Christianity. Since one can say, actually, Augustine remained a Neoplatonist to a certain degree. That is why his destiny induced him to get to know Christianity. It is, actually, not at all a big leap, but it is a natural development from Neoplatonism to Christianity. One cannot judge the Christianity of Augustine if one does not look at Manichaeism, a peculiar way to overcome the old pagan worldview at the same time with the Old Testament, with Judaism.

At that time, Manichaeism had expanded over North Africa where Augustine grew up in which many people of the West already lived. In the third century, Manichaeism came into being by Mani, a Persian (216-277). History hands down exceptionally little of it. If one wants to characterise Manichaeism, one must say, it depends more on the attitude of this worldview than on the literal contents.

It is typical for Manichaeism above all that the separation of the human experience into spiritual and material does not yet make sense. The words or ideas “spirit” and “matter” have no sense for Manichaeism. Manichaeism sees in that what appears material to the senses something spiritual and does not tower above that which presents itself to the senses if it speaks of the spiritual. It applies to it much more than one normally thinks that it assumes spiritual phenomena, spiritual facts, indeed, in the stars and in their ways that it assumes that with the sun mystery something spiritual takes place here on earth at the same time. Something material manifests as something spiritual at the same time and vice versa. Hence, it is a given for Manichaeism that it speaks of astronomical phenomena, of world phenomena in such a way as it also speaks of moral and of events within the human evolution. Thus, the contrast of light and darkness which Manichaeism teaches—copying the ancient Persian worldview—is something naturally spiritual at the same time even more than one thinks. Manichaeism still speaks of that what moves there apparently as sun at the firmament, of something that is also concerned with the moral entities and impulses within the human evolution. It speaks of the relations of this moral-physical, which is there at the firmament, to the signs of the zodiac like to twelve beings by whom the primal being, the primal light being of the world, specifies its activities.

However, something else is still distinctive of Manichaeism. It considers the human being by no means as that which the human being is to us today. The human being appears to us as a kind of crown of the earth creation. Manichaeism does not concede this. It considers the human being, actually, only as a scanty rest of that which should have become a human being on earth by the divine light being. Something else should have become a human being than that which now walks around as a human being on earth. That which now walks around as a human being on earth originated because the original human being whom the light being had created for supporting him in his fight against the demons of darkness lost this fight against these demons and was moved by the good powers into the sun. However, the demons still managed it to snatch a part of this original human being as it were from the real human being escaping to the sun and to form the earthly human race from it, which walks about on earth like a worse issue of that what could not live on the earth here because it had to be carried away into the sun during the big spiritual fight. The Christ Being appeared to lead the human being who was like a worse edition of his original destiny on earth, and Its activity shall erase the effect of the demons from the earth.

I know very well that not everything that one can still put into words of this worldview by our word usage, actually, is sufficient; since all that just arises from the depths of the soul life that are substantially different from the present ones. However, the essentials are that what I have already emphasised. Since as fantastic it may appear what I tell you about the progress of the earth in the sense of Manichaeism, it did not imagine that as something that one can only behold spiritually, but that a sense-perceptible phenomenon happens at the same time as something spiritual.

That was the first to work powerfully on Augustine. We understand the problems that are connected with the personality of Augustine, actually, even by the fact that one envisages this mighty effect of Manichaeism, of its spiritual-material principle. One must ask himself, why did Augustine become dissatisfied with Manichaeism? Not, actually, because of its mystic contents but because of the whole attitude of Manichaeism.

First, Augustine was taken in by the sensory descriptiveness, the vividness of this view, in a way. Then, however, something stirred in him that could not be content just with the vividness with which one considered the material as spiritual and the spiritual as material. One really does not manage it differently, as if one goes over from that which one has often only as a formal consideration to reality if one looks at the fact that Augustine was just a person who resembled very much the people of the Middle Ages and maybe even modern people than those people who were the natural bearers of Manichaeism. Augustine already has something of a renewal of mental life.

In our intellectual time that is prone to the abstract, one considers that which goes forward historically in any century as result of the preceding century and so on. It is pure nonsense if one states that that which happens, for example, in the eighteenth year of a human being is a mere effect of that which has happened in the thirteenth, fourteenth years. Since in between something takes place which works its way up from the depths of human nature which is not a mere effect of the preceding in the sense as one speaks of effect and cause justifiably, but which is the sexual maturity which just emerges from the nature of humanity. One has to acknowledge such leaps also at other times of the individual human development, where something works up its way from depths to the surface; so that one cannot say, what happens is only the immediately straight effect of that which has preceded.

Such leaps also take place in the evolution of humanity, and you have to suppose that the spiritual condition of Manichaeism was before such leap and Augustine lived after the leap. He could not help ascending from that which a Manichaean considered as material-spiritual to the purely spiritual. Hence, he had to turn away from the vivid worldview of Manichaeism. That was the first to experience in his soul intensely, and we read his words: “the fact that I had to imagine bodily masses if I wanted to meditate on God and believed that nothing could exist but of that kind—this was the most substantial and almost the only reason of error which I could not avoid.”

Thus, he points back to that time in which Manichaeism lived in his soul; and thus he characterises this lifetime as an error. He wanted something at which he could look up as to something that forms the basis of the human being. He needed something that one cannot see as something material-spiritual immediately in the sensory universe, as the principles of Manichaeism did. As everything struggles intensely seriously and strongly to the surface of his soul, also this: “I asked the earth, and it spoke, I am not that. And what is on it, confessed the same.”

What does Augustine look for? He looks for the actual divine.—Manichaeism would have answered to him: I am that as earth, as far as the divine expresses itself by the earthly work.—Augustine continues: “I asked the sea and the abysses and what they entail as living: we are not your God, search Him above us.—I asked the blowing winds and the whole atmosphere with all its inhabitants: the philosophers who looked the being of the things in us were mistaken, we are not God.” Neither the sea, nor the atmosphere, nor everything that you can perceive with the senses. “I asked the sun, the moon, and the stars. They said: we are not God whom you search.”

Thus, he got free of Manichaeism, just of the element of Manichaeism that one has to characterise, actually, as the most significant. Augustine looks for a spiritual that is free of anything sense-perceptible. He lives just in that epoch of soul development when the soul had to break away from mere considering the sense-perceptible as something spiritual, the spiritual as something sense-perceptible; since one also misjudges the Greek philosophy in this respect absolutely. Hence, people have difficulties to understand the beginning of my Riddles of Philosophy because I tried to characterise it in such a way as it was.

If the Greek speaks of ideas, of concepts, the today's human beings believe that he means that with his ideas that we call thoughts or ideas today. This is not the case, but the Greek spoke of ideas as of something that he perceives in the outside world like colours and tones.

What appeared in Manichaeism with an oriental nuance exists in the entire Greek worldview. The Greek sees his idea as he sees a colour. He still has the sensory-spiritual, spiritual-sensory, that soul experience which does not at all ascend to that which we know as something spiritual that is free of anything sense-perceptible as we understand it now—whether as a mere abstraction or as real contents of our soul, this we do not yet want to decide at this moment. The soul experience that is free of anything sense-perceptible is not yet anything that the Greek envisages. He does not differentiate between thinking and sense perception.

One would have to correct the whole conception of the Platonic philosophy, actually, from this viewpoint, because only then it appears in the right light. So that one may say, Manichaeism is only a post-Christian elaboration of that what was in Hellenism. One also does not understand the great philosopher Aristotle who concludes the Greek philosophy if one does not know that—if he still speaks of concepts—he already stands, indeed, hard at the border of abstract understanding that he speaks, however, still in the sense of tradition seeing the concepts close to sense-perception.

Augustine was simply forced by the viewpoint, which people of his epoch had attained by real processes that took place in them among whom Augustine was an outstanding personality, no longer to experience in the soul as a Greek had experienced. He was forced to a thinking that still keeps its contents if it cannot talk of earth, air, sea, stars, sun and moon that does not have vivid contents. He has to push his way to a divine that should have such abstract contents. Only such worldviews spoke to him, actually, which had originated from another viewpoint that I have just characterised as that of the sensory-extrasensory. No wonder that these souls came to scepticism because they strove in uncertain way for something that was not yet there and because they could only find that which they could not take up.

However, on the other side the feeling to stand on a firm ground of truth and to get explanation about the question of the origin of the evil was so strong in Augustine that, nevertheless, Neo-Platonism influenced him equally considerably. Neo-Platonism or Plotinism in particular concludes Greek philosophy. Plotinus (~204-270) shows—what strictly speaking Plato's dialogues and in the least the Aristotelian philosophy cannot show—how the whole soul life proceeds if it searches a certain internalisation. Plotinus is the last latecomer of a kind of people who took quite different ways to knowledge than that which one later understood generally about which one developed an idea later. Plotinus appears to the modern human being, actually, as a daydreamer.

Plotinus appears just to those who have taken up more or less of the medieval scholasticism as an awful romanticist, even as a dangerous romanticist. I experienced that repeatedly. My old friend Vincenz Knauer (1828-1894), a Benedictine monk who wrote a history of philosophy and a book about the main problems of philosophy from Thales to Hamerling was the personified gentleness. This man scolded as never before if one discussed the philosophy of Neo-Platonism, in particular that of Plotinus. There he got very angry with Plotinus as with a dangerous romanticist. Franz Brentano (1838-1917), the brilliant Aristotelian, empiricist, and representative of the medieval philosophy wrote a booklet What a Philosopher Is Epoch-making Sometimes (1876). There, he got just angry with Plotinus, because Plotinus is the philosopher who was epoch-making as a dangerous romanticist at the end of the ancient Greek era. It is very difficult for the modern philosopher to understand Plotinus.

About this philosopher of the third century, we may say at first, that what we experience as our mind contents, as the sum of concepts that we form about the world is to him not at all, what it is to us. I would like to say if I may express myself figuratively (Steiner draws): We understand the world with sense perception, then we abstract concepts from the sense perception and end up in the concepts. We have the concepts as an inner soul experience and we are aware more or less that we have abstractions. The essentials are that we end up there; we turn our attention to the sensory experience and end up where we form the sum of our concepts, our ideas.

That was not the way for Plotinus. To Plotinus this whole world of sense perception hardly existed at first. However, that which was something for him about which he spoke as we speak about plants, minerals, animals and physical human beings, that was something that he saw now above the concepts, this was a spiritual world, and this spiritual world had a lower border for him. This lower border was the concepts. We get the concepts by turning to the sensory things, abstracting and forming the concepts and say, the concepts are the summaries, the essences of ideal nature from sense perception. Plotinus said who cared little about sense perception at first, we as human beings live in a spiritual world, and that which this spiritual world reveals as a last to us that we see as its lower border this are the concepts.

For us the sensory world is beneath the concepts; for Plotinus a spiritual world, the real intellectual world, is above the concepts. I could also use the following image: we imagine once, we would be immersed in the sea, and we looked up to the sea surface, the sea surface would be the upper border. We lived in the sea, and we would just have the feeling: this border surrounds the element in which we live.

For Plotinus this was different. He did not care about this sea around himself. However, for him this border which he saw there was the border of the world of concepts in which his soul lived, the lower border of that what was above it; so as if we interpreted the sea border as the border with the atmosphere. For Plotinus who was of the opinion that he continued the true view of Plato is that what is above the concepts at the same time that which Plato calls the world of ideas. This world of ideas is definitely something about which one speaks as a world in the sense of Plotinism.

It does not come into your mind, even if you are followers of modern subjective philosophy, if you look out at a meadow to say: I have my meadow, you have your meadow, the third one has his meadow, even if you are persuaded by the fact that you all have the mental picture of the meadow only, isn't that so? You talk about one meadow that is outdoors; in the same way, Plotinus speaks about one world of ideas, not of the world of ideas in the first head, or in the second head, or in the third head. The soul takes part in this world of ideas. So that we may say, the soul, the psyche, develops as it were from the world of ideas, experiencing this world of ideas. Just as the world of ideas creates the psyche, the soul, the soul for its part creates the matter in which it is embodied. Hence, that from which the psyche takes its body is a creation of this psyche.

There, however, is only the origin of individuation, there only the psyche divides, which, otherwise, participates in the uniform world of ideas, into the body A, into the body B and so on, and thereby the single souls originate only. The single souls originate from the fact that as it were the psyche is integrated into the single material bodies. Therefore, in the sense of Plotinism the human being can consider himself as a vessel at first. However, this is only that by which the soul manifests and is individualised. Then the human being has to experience his soul that rises to the world of ideas. Then there is a higher kind of experience. Talking about abstract concepts did not make sense to a Plotinist; since a Plotinist would have said, what should abstractions be? Concepts cannot be abstract, cannot be in limbo, they must be the concrete manifestations of the spiritual. One is wrong if one interprets in such a way that ideas are abstractions. This is the expression of an intellectual world, a world of spirituality. That also existed in the usual experience with those people out of whom Plotinus and his followers grew up. For them such talking about concepts generally did not make sense, because for them the spiritual world projected into their souls. At the border of this projection, this world of concepts originated. However, only if one became engrossed, if one developed the soul further, that resulted which now the usual human being could not know which just someone experienced who soared a higher experience. Then he experienced that which was still above the world of ideas which was the One if you want to call it this way, so he experiences the One what was for Plotinus that which no concept reaches if one could delve into it without concepts in the inside, and which one calls Imagination spiritual-scientifically. You can read up that in my book How Does One Attain Knowledge of Higher Worlds? What I called Imagination there delves into that which is above the world of ideas according to Plotinus.

Any cognition about the human soul also arose for Plotinus from this worldview. It is already contained in it. One can be an individualist only in the sense of Plotinus, while one is at the same time a human being who recognises that the human being rises to something that is above any individuality that he rises to something spiritual in which he rises upwards as it were, while we are more used today to submerging in the sensory. However, everything that is the expression of something that a right scholastic considers as a rave is nothing fictional for Plotinus, is not hypothetical. For Plotinus this was sure perception up to the One that could be experienced only in special cases, as for us minerals, plants, animals are percepts. He spoke only in the sense of something that the soul experiences immediately if he spoke about the soul, the Logos that participates in the Nous, in the world of ideas and in the One.

For Plotinus the whole world was a spiritual being as it were; again it has a nuance of worldview different from that of Manichaeism and that of Augustine. Manichaeism recognises a sensory-extrasensory; for it, the words and concepts “matter” and “spirit” do not yet make sense. From his sensory view, Augustine strives for attaining a spiritual experience that is free of the sense-perceptible. For Plotinus the whole world is spirit, for him sensory things do not exist. Since that which seems material is only the lowest manifestation of the spirit. Everything is spirit, and if we penetrate deeply enough into the things, everything manifests as spirit.

This is something with which Augustine could not completely go along. Why? Because he did not have the view. Because Augustine just lived already as a forerunner in his epoch—as I would like to call Plotinus a latecomer, Augustine was just a forerunner of those human beings who do no longer feel that in the world of ideas a spiritual world manifests. He did not behold this world. He could learn it only from others. He could only find out it that one said this, and he could still develop a feeling of the fact that something of a human way to truth is contained in it. This was the conflict, in which Augustine faced Plotinism. However, actually, he was never completely hostile to an inner understanding of Plotinism, even if he could not behold. He only suspected that in this world something must be which he could not reach.

In this mood, Augustine withdrew into loneliness in which he got to know the Bible and Christianity, and later the sermons of Aurelius Ambrosius (St. Ambrose, ~340-397, Bishop of Milan) and the Epistles of Paul. This mood persuaded him finally to say, what Plotinus sought as the being of the world in the being of the world of ideas, of the Nous, or in the One that one reaches only in special preferential soul states this appeared on earth in the person of Christ Jesus.—This arose to him as a conviction from the Bible: you do not need to soar the One; you need only to look at the historical tradition of Christ Jesus. There the One descended and became a human being.

Augustine swaps the philosophy of Plotinus for the church. He pronounces it clearly when he says: “Who could be so blinded to say that the church of the apostles deserves no faith which is so loyal and is supported by the accordance of so many brothers that it handed its scriptures conscientiously down to the descendants that it also maintained their chairs up to the present bishops with apostolic succession.” Augustine now places much value on the fact that one can prove, in the end,—if one only goes back through the centuries—that there lived human beings who still knew the disciples of the Lord, and an ongoing tradition of plausible kind exists that on earth that appeared which Plotinus tried to gain in the mentioned way.

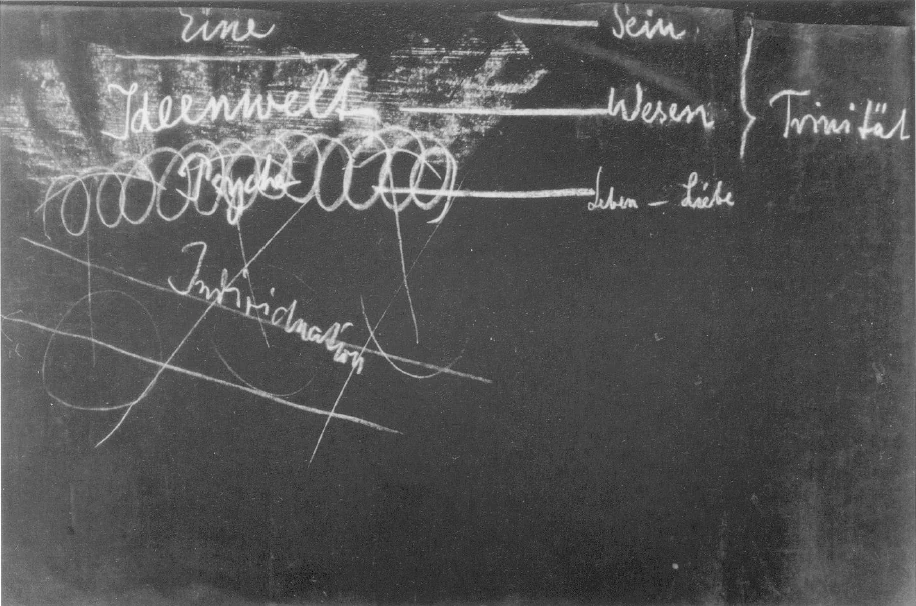

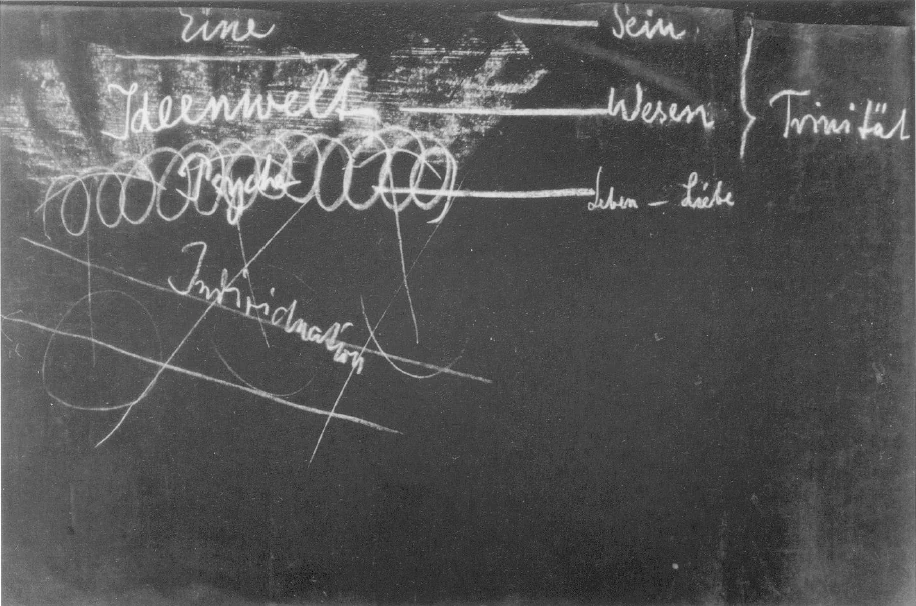

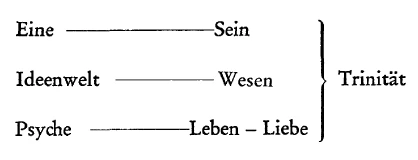

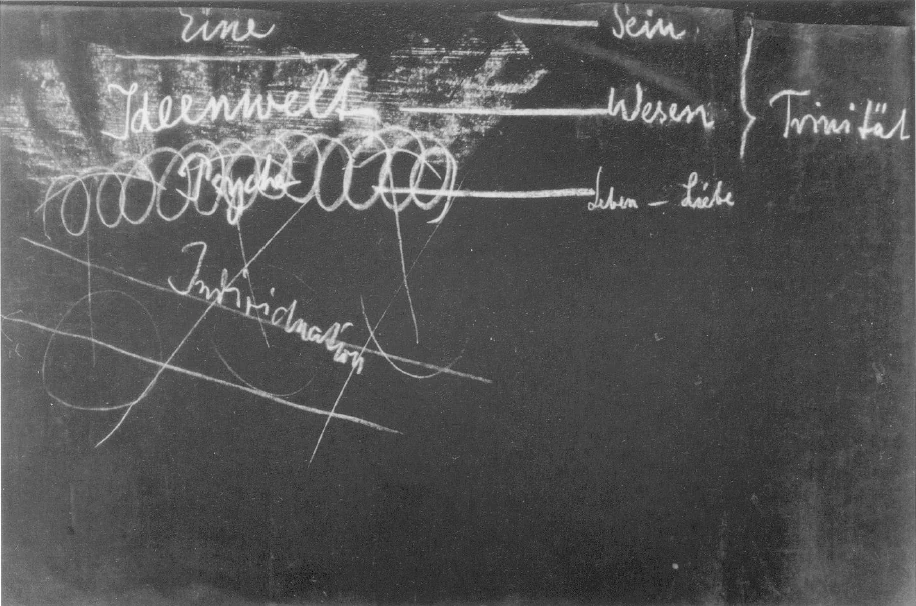

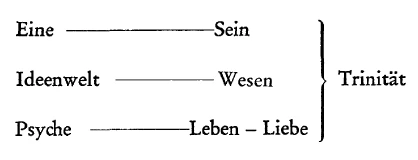

Augustine was now eager to use Plotinism, as far as he could penetrate into it to the understanding of that which had become accessible to his feeling by Christianity. He really applied that which he had received from Plotinism to understand Christianity and its contents. Thus, he transformed, for example, the concept of the One. For Plotinus this One was an experience; for Augustine who could not penetrate to this experience the One became something that he called with the abstract term “being,” the world of ideas was something that he called with the abstraction of “essence,” psyche something that he named with the abstraction “life” or also with the concept “love.” The fact that Augustine proceeded in such a way characterises best of all that he tried to grasp the spiritual world from which Christ Jesus had come with Neoplatonic, with Plotinist, he thought that there is a spiritual world above the human beings from which Christ comes. The tripartition was something that had become clear to Augustine from Plotinism. The three personalities of trinity—Father, Son, and Spirit—became clear to Augustine from Plotinism.

If one asks, what filled the soul of Augustine if he spoke of the three persons? One has to answer, that filled him, which he had learnt from Plotinus. He also brought that which he had learnt from Plotinus into his Bible understanding. One realises how this works on, because this trinity comes alive again, for example, with Scotus Eriugena (John Scotus Eriugena, ~815- ~877, Irish theologian, philosopher) who lived at the court of Charles the Bald in the ninth century. He wrote a book about the division of nature (De divisione naturae, original title: Periphyseon) in which we still find a similar trinity. Christianity interprets its contents with the help of Plotinism.

Augustine kept some basic essentials of Plotinism. Imagine that, actually, the human being is an earthly individual only, because the psyche projects down to the material like into a vessel. If we ascend a little bit to the higher essential, we ascend from the human to the divine or spiritual where the trinity is rooted, then we do no longer deal with the single human beings but with the species, with humanity.

We do no longer direct our ideas so strongly to the whole humanity from our concepts as Augustine did this from Plotinism. I would like to say, seen from below the human beings appear as individuals; seen from above—if one may say it hypothetically—the whole humanity appears as a unity. For Plotinus now from this viewpoint the whole humanity grew together, seen from the front, in Adam. Adam was the whole humanity. While Adam originated from the spiritual world, he was a being, connected with the earth, that had free will, and that was unable to sin because in it that lived which was still up there—not that which originates from the aberration of the matter. The human being who was Adam at first could not sin, he could not be unfree, and with it, he could not die. There the effect of that came which Augustine felt as the counter-spirit, as Satan. He seduced the human being who became material and with it the whole humanity.

You realise that in this respect Augustine lives with his knowledge completely in Plotinism. The whole humanity is one to him. The single human being does not sin, with Adam the whole humanity sins. If one dwells on that which often lives between the lines in particular of the last writings of Augustine, one realises how exceptionally difficult it was for Augustine to consider the whole humanity as sinful. In him, the individual human being lived who had a sensation of the fact that the single human being becomes responsible more and more for that which he does and learns. It appeared almost as something impossible to Augustine at certain moments to feel that the single human being is only a member of the whole humanity. However, Neo-Platonism, Plotinism was so firm in him that he was able to look at the whole humanity only. Thus, this state of all human beings—the state of sin and death—transitioned into the state of the inability to be free and immortal.

The whole humanity had fallen with it, had turned away from its origin. Now God would simply have rejected humanity if he were only fair. However, He is not only fair; He is also merciful. Augustine felt this way. Hence, God decided to save a part of humanity—please note: to save a part of humanity—God decided that a part of humanity receives His grace by which this part of humanity is led back to the state of freedom and immortality which can be realised, however, completely only after death. The other part of humanity—they are the not selected—remains in the state of sin. Hence, humanity disintegrates into two parts: in those who are selected, and in those who are rejected. If one looks in the sense of Augustine at humanity, it simply disintegrates into these two parts, into those who are without merit destined to bliss only because the divine plan has wisely arranged it this way, and in those who cannot get the divine grace whatever they do, they are doomed. This view, which one also calls the doctrine of predestination, arose for Augustine from his view of the whole humanity. If the whole humanity sinned, the whole humanity would deserve to be condemned.

Which dreadful spiritual fights did arise from this doctrine of predestination? Tomorrow I would like to speak how Pelagianism, Semipelagianism grew out of it. However, today I would still like to add something in the end: we realise now how Augustine as a vividly struggling personality stands between that view which goes up to the spiritual and for which humanity becomes one. He interprets this to himself in the sense of the doctrine of predestination. However, he felt compelled to ascend from the human individuality to something spiritual that is free of any sense-perceptible and can arise again only from the individuality. The characteristic feature of the age whose forerunner Augustine was is that this age became aware of that of which in antiquity the human being did not became aware: the individual experience.

Today one takes many things as phrases. Klopstock (1724-1803, German poet) was still serious, he did not use commonplace phrases when he began his Messiah with the words: “Sing, immortal soul, on the sinful men's redemption.”—Homer began honestly and sincerely: “Sing, o goddess, to me about the rage ...” or: “Sing, o muse, to me of the man, the widely wandered Odysseus.”—These men did not speak of that which lived in the individuality; they spoke of that which speaks as a general humanity, as a type soul, as a psyche through them. This is no commonplace phrase if Homer lets the muse sing instead of himself. The fact that one can regard himself as an individuality arises only gradually. Augustine is one of the first to feel the individual existence of the human being with individual responsibility. Hence, he lived in this conflict. However, there just originated in his experience the individual pursuit for the non-sensory spiritual. In him was a personal, subjective struggle.

In the subsequent time, that understanding was also buried which Augustine could still have for Plotinism. After the Greek philosophers, the latecomers of Plato and Plotinus, had to emigrate to Persia, after these last philosophers had found their successors in the Academy of Gondishapur, in the West this view to the spiritual disappeared, and only that remained which the philistine Aristotle delivered as filtered Greek philosophy to future generations, but also only in single fragments. This propagated and came via the Arabs to Europe. This was that which had no consciousness of the real world of ideas. Thus, the big question was left; the human being has to create the spiritual from himself. He must bear the spiritual as an abstraction. If he sees lions, he thinks the concept of the “lion” if he sees wolves, he thinks the concept “wolf” if he sees the human being, he thinks the concept of the human being, these concepts live only in him, they emerge from the individuality.

The whole question would not yet have had any sense for Plotinus; now this question still gets a deep different sense. Augustine could still grasp the mystery of Christ Jesus with that which shone from Plotinism in his soul. Plotinism was buried; with the closing of the Neoplatonic Academy in Athens by Emperor Justinian in 529, the living coherence with such views ended. Different people felt deeply, what it means: the scriptures and tradition give us account of a spiritual world, we experience supersensible concepts from our individuality, concepts which are abstracted from the sensory. How do we relate to existence with these concepts? How do we relate to the being of the world with these concepts? Do our concepts live only as something arbitrary in us, or does it have anything to do with the outer world?

In this form, the questions appeared in extreme abstraction, but in an abstraction that were very serious human and medieval-ecclesiastical problems. In this abstraction, in this intimacy the questions emerged in Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas. Then the quarrel between realists and nominalists took place. How does one relate to a world about which those concepts give account that can be born only in ourselves by our individuality? The medieval scholastics presented this big question to themselves. If you think which form Plotinism accepted in the doctrine of predestination, then you can feel the whole depth of this scholastic question: only a part of humanity could be blessed with the divine grace, can attain salvation; the other part was destined to the everlasting damnation from the start whatever it does. However, that which the human being could gain as knowledge to himself did just not arise from that into which Augustine could not yet transform his dreadful concept of predestination; this arose from the human individuality. For Augustine humanity was a whole, for Thomas every single human being was an individuality.

How is this big world process of predestination associated with that which the single human being experiences? How is that associated which Augustine had completely neglected, actually, with that which the single human being can gain to himself? Imagine that Augustine took the doctrine of predestination because he did not want to assert but to extinguish the human individuality for the sake of humanity; Thomas Aquinas only faced the single human being with his quest for knowledge. In that which Augustine excluded from his consideration of humanity, Thomas had to look for the human knowledge and its relation to the world.

It is not enough that one puts such a question in the abstract, intellectually and rationalistically. It is necessary that you grasp such a question with your whole heart, with your whole personality. Then you can estimate how this question weighed heavily on those persons who were its bearers in the thirteenth century.

1. Thomas und Augustinus

In diesen drei Tagen möchte ich über ein Thema sprechen, das gewöhnlich von einer mehr formalen Seite her betrachtet wird, und dessen Inhalt gewöhnlich nur darinnen gesehen wird, daß durch die zugrunde liegende philosophische Bewegung des Mittelalters die Stellung der philosophischen Weltanschauung zum Christentum gewissermaßen festgelegt worden sei. Da gerade diese Seite der Sache in der neueren Zeit eine Art Wiederauffrischung gefunden hat durch die Aufforderung des Papstes Leo XIII. an seine Kleriker, den Thomismus zur offiziellen Philosophie der katholischen Kirche zu machen, so hat von dieser Seite her gewiß unser gegenwärtiges "Thema eine gewisse Bedeutung.

Allein, ich möchte eben nicht bloß von dieser formalen Seite her die Sache betrachten, die sich als mittelalterliche Philosophie gewissermaßen herumkristallisiert um die Persönlichkeit des Albertus Magnus und des Thomas von Aquino, sondern ich möchte im Laufe dieser Tage dazu kommen, den tieferen historischen Hintergrund aufzuzeigen, aus dem diese von der Gegenwart trotz alledem viel zu wenig gewürdigte philosophische Bewegung sich erhoben hat. Man kann sagen: In einer ganz scharfen Weise versucht Thomas von Aquino im 13. Jahrhundert das Problem der Erkenntnis, der Gesamtweltanschauung zu fassen, in einer Weise, die, man muß es ihr zugestehen, heute eigentlich schwer nachzudenken ist, weil zu dem Nachdenken Voraussetzungen gehören, die bei den Menschen der Gegenwart kaum erfüllt sind, auch wenn sie Philosophen sind. Es ist notwendig, daß man sich ganz hineinversetzen könne in die Art des Denkens des Thomas von Aquino, seiner Vorgänger und Nachfolger, daß man zu wissen vermag, wie die Begriffe zu nehmen sind, wie die Begriffe in den Seelen dieser mittelalterlichen Menschen lebten, von denen eigentlich die Geschichte der Philosophie in ziemlich äußerlicher Weise berichtet.

Sieht man nun auf der einen Seite hin auf den Mittelpunkt dieser Betrachtung, auf Thomas von Aquino, so möchte man sagen, in ihm hat man eine Persönlichkeit, die gegenüber der Hauptströmung der christlichen Philosophie des Mittelalters eigentlich als Persönlichkeit verschwindet, die, man möchte sagen, eigentlich nur der Koeffizient oder der Exponent ist für dasjenige, was in einer breiten Weltanschauungsströmung lebt und nur mit einer gewissen Universalität eben gerade durch diese eine Persönlichkeit zum Ausdrucke kommt. So daß man, wenn man von dem Thomismus spricht, sein Auge richten kann auf etwas außerordentlich Unpersönliches, auf etwas, das sich eigentlich nur offenbart durch die Persönlichkeit des Thomas von Aquino. Dagegen erblickt man sofort, daß man eine volle, ganze Persönlichkeit mit alledem, was eben in einer Persönlichkeit sich darlebt, in den Mittelpunkt der Betrachtung stellen muß, wenn man denjenigen ins Auge faßt, auf den zunächst als hauptsächlichsten Vorgänger der Thomismus zurückgeht, wenn man Augustinus ins Auge faßt: bei Augustinus alles persönlich, bei Thomas von Aquino alles eigentlich ganz unpersönlich. Bei Augustinus haben wir es zu tun mit einem ringenden Menschen, bei Thomas von Aquino mit der ihre Stellung zum Himmel, zur Erde, zu den Menschen, zu der Geschichte und so weiter feststellenden mittelalterlichen Kirche, die sich eigentlich sogar, könnte man, allerdings mit gewissen Einschränkungen, sagen, als Kirche ausdrückt durch die Philosophie des Thomas von Aquino.

Ein bedeutsames Ereignis liegt zwischen den beiden, und ohne daß man den Blick auf dieses Ereignis richtet, ist es nicht möglich, die Stellung dieser beiden mittelalterlichen Persönlichkeiten zueinander festzustellen. Das Ereignis, das ich meine, das ist die durch den Kaiser Justinian betriebene Verketzerung des Origenes. Die ganze Färbung der Weltanschauung des Augustinus wird erst verständlich, wenn man den ganzen historischen Hintergrund, aus dem sich Augustinus herausarbeitet, ins Auge faßt. Dieser historische Hintergrund wird aber in der Tat ein ganz anderer dadurch, daß jener mächtige Einfluß — es war in der Tat ein mächtiger Einfluß trotz vielem, was in der Geschichte der Philosophie gesagt wird - auf das Abendland aufhört, der ausgegangen ist von den Philosophenschulen in Athen, ein Einfluß, der im wesentlichen bis ins sechste Jahrhundert hinein dauerte, dann abflutete, so daß etwas zurückbleibt, was tatsächlich in der weiteren philosophischen Strömung des Abendlandes etwas ganz anderes ist als das war, in dem Augustinus noch lebendig drinnengestanden hat.

Ich werde Sie bitten müssen zu berücksichtigen, daß heute mehr eine Einleitung gegeben wird, daß morgen das eigentliche Wesen des Thomismus hier behandelt werden soll, und daß mein Ziel, dasjenige, warum ich all das vorbringe, was ich in diesen Tagen sagen will, eigentlich erst am dritten Tage ganz zum Vorschein kommen wird. Denn sehen Sie, auch mit Bezug auf die christliche Philosophie des Mittelalters, namentlich des Thomismus, bin ich ja — verzeihen Sie einleitend diese persönliche Bemerkung - in einer ganz besonderen Lage. Ich habe öfter hervorgehoben, auch in öffentlichen Vorträgen, wie es mir einmal gegangen ist, als ich vor einer proletarischen Bevölkerung dasjenige vorgetragen hatte, was ich als die Wahrheit in dem Verlauf der abendländischen Geschichte ansehen muß. Es hat dazu geführt, daß zwar unter den Schülern eine gute Anhängerschaft da war, daß aber die Führer der proletarischen Bewegung um die Wende des 19. zum 20. Jahrhundert darauf gekommen sind, es würde da nicht echter Marxismus vorgetragen. Und obschon man sich berufen konnte darauf, daß eine Zukunftsmenschheit eigentlich doch etwas wie Lehrfreiheit anerkennen müsse, wurde mir in der maßgebenden Versammlung dazumal erwidert, diese Partei kenne keine Lehrfreiheit, sondern nur einen vernünftigen Zwang! - Und meine Lehrtätigkeit mußte, obwohl dazumal eine große Anzahl von Schülern herangezogen waren im Proletariat, damit beschlossen werden.

In einer ähnlichen Weise ging es mir an anderer Stätte mit demjenigen, was ich vor etwa jetzt neunzehn bis zwanzig Jahren sagen wollte über den Thomismus und alles dasjenige, was sich als mittelalterliche Philosophie daranschließt. Es war das die Zeit, in welcher eben um die Wende des 19. zum 20. Jahrhundert zu ganz besonderer Hochflut gekommen war dasjenige, was man gewohnt worden ist, den Monismus zu nennen. Als eine besondere Färbung des Monismus, nämlich als materialistischer Monismus, scheinbar zur Pflege einer freien, unabhängigen Weltanschauung, aber im Grunde genommen doch nur zur Pflege dieser materialistischen Färbung des Monismus, war dazumal in Deutschland der «Giordano-Bruno-Bund» begründet worden. Weil es mir unmöglich war, all das leere Phrasengerede mitzumachen, das dazumal als Monismus in die Welt ging, hielt ich im Berliner «Giordano-Bruno-Bund» einen Vortrag über den Thomismus. In diesem Vortrage suchte ich den Nachweis zu führen, daß in dem Thomismus ein wirklicher spiritueller Monismus gegeben sei, daß dieser spirituelle Monismus gegeben sei außerdem in der Weise, daß er sich offenbart durch das denkbar scharfsinnigste Denken, durch ein scharfsinniges Denken, von dem die neuere, unter Kantschem Einfluß stehende und aus dem Protestantismus hervorgegangene Philosophie im Grunde genommen keine Ahnung hat, zu dem sie aber jedenfalls keine Kraft mehr hat. Und so hatte ich es denn auch mit dem Monismus verdorben! Es ist tatsächlich heute außerordentlich schwierig, von den Dingen so zu sprechen, daß das Gesprochene aus der wirklichen Sache herausklingt und nicht in den Dienst irgendeiner Parteifärbung sich stellt. So zu sprechen über die Erscheinungen, die ich angedeutet habe, möchte ich mich in diesen drei Tagen wiederum bestreben.

Die Persönlichkeit des Augustinus stellt sich hinein in das vierte und fünfte Jahrhundert als, wie ich schon sagte, eine im eminenten Sinne ringende Persönlichkeit. Die Art und Weise, wie Augustinus ringt, das ist dasjenige, was sich einem tief in die Seele gräbt, wenn man auf die besondere Natur dieses Ringens einzugehen vermag. Zwei Fragen sind es, die sich in einer Intensität vor des Augustinus Seele stellen, von der man heute, wo die eigentlichen Erkenntnis- und Seelenfragen verblaßt sind, wiederum eigentlich keine Ahnung hat. Die erste Frage ist die, die man etwa dadurch charakterisieren kann, daß man sagt: Augustinus ringt nach dem Wesen desjenigen, was der Mensch eigentlich als Wahrheit, als eine ihn stützende, als seine Seele erfüllende Wahrheit anerkennen könne, Die zweite Frage ist diese: Wie ist zu erklären in einer Welt, die doch nur einen Sinn hat, wenn wenigstens das Ziel dieser Welt mit dem Guten irgend etwas zu tun hat, wie ist zu erklären in dieser Welt die Anwesenheit des Bösen? Wie ist zu erklären in der menschlichen Natur namentlich der Stachel des Bösen, der eigentlich — wenigstens nach des Augustinus Ansicht - niemals zum Schweigen kommt, die Stimme des Bösen, die niemals zum Schweigen kommt, auch dann nicht, wenn der Mensch ein ehrliches und aufrichtiges Streben nach dem Guten entwickelt?

Ich glaube nicht, daß man an Augustinus wirklich herankommt, wenn man diese zwei Fragen in dem Sinne nimmt, wie sie der Durchschnittsmensch der Gegenwart, auch wenn er Philosoph ist, zu nehmen geneigt ist. Man muß nach der besonderen Färbung suchen, die für diesen Menschen des vierten und fünften Jahrhunderts diese beiden Fragen hatten. Augustinus geht ja zunächst durch ein innerlich bewegtes, man möchte sagen ausschweifendes Leben. Aber aus diesem ausschweifenden und bewegten Leben heraus tauchen ihm doch immer wieder diese beiden Fragen auf. Persönlich ist er in einen Zwiespalt hineingestellt. Der Vater ist Heide, die Mutter ist fromme Christin. Die Mutter gibt sich alle Mühe, den Sohn für das Christentum zu gewinnen. Zunächst ist der Sohn nur für einen gewissen Ernst zu gewinnnen, und dieser Ernst richtet sich zunächst nach dem Manichäismus. Wir wollen nachher einige Blicke nach dieser Weltanschauung werfen, die zunächst in den Gesichtskreis des Augustinus hereintrat, als er von einem etwas lotterigen Leben zu einem vollen Lebensernst überging. Dann fühlte er sich aber immer mehr und mehr, allerdings erst nach Jahren, abgestoßen von dem Manichäismus, und es bemächtigte sich seiner nun wiederum, nicht etwa nur aus den Tiefen der Seele heraus oder aus irgendwelchen abstrakten Höhen her, sondern aus der ganzen Zeitströmung des philosophischen Lebens heraus ein gewisser Skeptizismus, der Skeptizismus, in den zu einer gewissen Zeit die griechische Philosophie ausgelaufen war, und der sich dann erhalten hat bis in die Zeit des Augustinus.

Aber nun tritt immer mehr und mehr der Skeptizismus zurück. Es ist der Skeptizismus für Augustinus gewissermaßen nur etwas, was ihn mit der griechischen Philosophie zusammenbringt. Und dieser Skeptizismus trägt ihm zu dasjenige, was zweifellos auf seine Subjektivität, auf die ganze Haltung seiner Seele für einige Zeit einen ganz außerordentlich tiefen Einfluß ausgeübt hat. Der Skeptizismus führt ihm eine ganz andere Richtung zu, dasjenige, was man in der Geschichte der Philosophie gewöhnlich den Neuplatonismus nennt. Und Augustinus ist viel mehr, als man gewöhnlich denkt, von diesem Neuplatonismus zugeführt worden. Die ganze Persönlichkeit und alles Ringen des Augustinus ist nur begreiflich, wenn man versteht, wie viel von neuplatonischer Weltanschauung hineingezogen ist in die Seele dieser Persönlichkeit. Und wenn man objektiv auf die Entwickelung des Augustinus eingeht, dann findet man eigentlich kaum, daß der Bruch, der in dieser Persönlichkeit war beim Übergang vom Manichäismus zum Plotinismus, sich in derselben Stärke wiederholt hat dann, als Augustinus vom Neuplatonismus zum Christentum überging. Denn man kann eigentlich sagen: Neuplatoniker in einem gewissen Sinne ist Augustinus geblieben; soweit er Neuplatoniker werden konnte, ist er es geblieben. Nur, daß er es eben nur bis zu einem gewissen Grade werden konnte. Und weil er es nur bis zu einem gewissen Grade werden konnte, trug ihn dann sein Schicksal dazu, bekannt zu werden mit der Erscheinung des Christus Jesus. Und eigentlich ist da gar kein enormer Sprung, sondern es ist in Augustinus eine naturgemäße Fortentwickelung vorhanden vom Neuplatonismus zum Christentum. $o, wie in Augustinus dieses Christentum lebt, kann man dieses augustinische Christentum nicht beurteilen, wenn man nicht zunächst hinschaut auf den Manichäismus, eine eigentümliche Form, die alte heidnische Weltanschauung zu überwinden zu gleicher Zeit mit dem Alten Testament, mit dem Judentum.

Der Manichäismus war in der Zeit, als Augustinus aufwuchs, schon eine Weltanschauungsströmung, die durchaus über Nordafrika, wo ja Augustinus aufwuchs, sich ausgedehnt hatte, in der viele Leute des Abendlandes schon lebten. Im dritten Jahrhundert etwa entstanden in Asien drüben durch Mani, einen Perser, ist vom Manichäismus historisch außerordentlich wenig auf die Nachwelt gekommen. Will man diesen Manichäismus charakterisieren, so muß man sagen: Mehr kommt es dabei an auf die ganze Haltung dieser Weltanschauung als auf dasjenige, was man heute wortwörtlich als Inhalt bezeichnen kann.

Dem Manichäismus ist vor allen Dingen eigentümlich, daß für ihn die Zweiteilung des menschlichen Erlebens als geistige Seite und als materielle Seite noch gar keinen Sinn hat. Die Worte oder Ideen «Geist» und «Materie» haben für den Manichäismus keinen Sinn. Der Manichäismus sieht in dem, was den Sinnen materiell erscheint, Geistiges und erhebt sich nicht über dasjenige, was sich den Sinnen darbietet, wenn er vom Geistigen spricht. Es ist in einem viel intensiveren Maße, als man gewöhnlich denkt, wo die Welt so abstrakt und intellektualistisch geworden ist, für den Manichäismus das der Fall, daß er in der Tat in den Sternen und in ihrem Gange geistige Erscheinungen, geistige Tatsachen sieht, daß er in dem Sonnengeheimnis zugleich dasjenige sieht, was als Geistiges, als Spirituelles hier auf der Erde sich vollzieht. Einerseits von Materie, andererseits von Geist zu sprechen, das hat für den Manichäismus keinen Sinn. Für ihn ist das, was geistig ist, zugleich materiell sich offenbarend, und dasjenige, was sich materiell offenbart, ist für ihn das Geistige. Daher ist es für den Manichäismus ganz selbstverständlich, daß er von Astronomischem, von Welterscheinungen so spricht, wie er auch von Moralischem und von Geschehnissen innerhalb der Menschheitsentwickelung spricht. So ist für den Manichäismus viel mehr als man denkt jener Gegensatz, den er in die Weltanschauung hineinsetzt — Licht und Finsternis, etwas Altpersisches nachahmend -, er ist für ihn zugleich durchaus ein selbstverständliches Geistiges. Und ein Selbstverständliches ist es, daß dieser Manichäismus noch spricht von dem, was da als Sonne scheinbar am Himmelsgewölbe sich bewegt, als von etwas, das auch mit den moralischen Entitäten und moralischen Impulsen innerhalb der Menschheitsentwickelung etwas zu tun hat, und daß er von den Beziehungen dieses Moralisch-Physischen, das da am Himmelsgewölbe dahingeht, zu den Zeichen des Tierkreises spricht wie zu zwölf Wesenheiten, durch die das Urwesen, das Urlichtwesen der Welt, seine Tätigkeiten spezifiziert.

Aber etwas anderes ist noch diesem Manichäismus eigen. Er sieht auf den Menschen hin, und dieser Mensch erscheint ihm keineswegs schon als dasjenige, als was uns heute der Mensch erscheint. Uns erscheint der Mensch wie eine Art Krone der Erdenschöpfung. Mag man nun mehr oder weniger materialistisch oder spiritualistisch denken, es erscheint dem Menschen heute der Mensch wie eine Art Krone der Erdenschöpfung, das Menschenreich wie das höchste Reich, oder wenigstens wie die Krönung des Tierreiches. Das kann der Manichäismus nicht zugeben. Für ihn ist das, was als Mensch auf der Erde gewandelt hat und eigentlich zu seiner Zeit noch wandelte, eigentlich nur ein spärlicher Rest desjenigen, was auf der Erde durch das göttliche Lichtwesen hätte Mensch werden sollen. Etwas ganz anderes hätte Mensch werden sollen als das, was jetzt als Mensch auf der Erde herumwandelt. Dasjenige, was jetzt als Mensch auf der Erde herumwandelt, ist dadurch entstanden, daß der ursprüngliche Mensch, den sich das Lichtwesen zur Verstärkung seines Kampfes gegen die Dämonen der Finsternis geschaffen hat, diesen Kampf gegen die Dämonen der Finsternis verloren hat, aber durch die guten Mächte in die Sonne versetzt worden ist, also aufgenommen worden ist von dem Lichtreiche selbst. Aber die Dämonen haben es doch zuwege gebracht, gewissermaßen ein Stück dieses Urmenschen dem in die Sonne entfliehenden wirklichen Menschen zu entreißen und daraus zu bilden, was das Menschen-Erdengeschlecht ist, dieses Menschen-Erdengeschlecht, das also herumwandelt wie eine schlechtere Ausgabe hier auf Erden desjenigen, was auf der Erde hier gar nicht leben könnte, weil es im großen Geisteskampfe in die Sonne entrückt werden mußte. Um wieder zurückzuführen den Menschen, der in dieser Weise wie eine schlechtere Auflage auf der Erde erschien, zu seiner ursprünglichen Bestimmung, ist dann die Christus-Wesenheit erschienen, und durch ihre Tätigkeit soll die Wirkung des Dämonischen von der Erde weggenommen werden.

Ich weiß sehr gut, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, daß alles das, was man im heutigen Sprachgebrauche von dieser Weltanschauung noch in Worte fassen kann, eigentlich kaum genügend sein kann; denn das ganze geht eben aus Untergründen des seelischen Erlebens hervor, die von den jetzigen wesentlich verschieden sind. Aber das Wesentliche, worauf es heute ankommen muß, das ist dasjenige, was ich schon hervorgehoben habe. Denn wie phantastisch es auch erscheinen mag, was ich Ihnen so erzähle über den Fortgang der Erdenentwickelung im Sinne der Manichäer, der Manichäismus stellte das durchaus vor nicht wie etwas, das man etwa nur im Geiste erschauen müßte, sondern wie etwas, das sich wie eine heute sinnlich genannte Erscheinung vor den physischen Augen zugleich als Geistiges abspielt.

Das war das erste, was mächtig auf Augustinus wirkte. Und die Probleme, die sich an die Persönlichkeit des Augustinus anknüpfen, gehen einem eigentlich auch nur dadurch auf, daß man diese mächtige Wirkung des Manichäismus, seines geistig-materiellen Prinzips, ins Auge faßt. Fragen muß man sich: Woraus gingen denn die Unbefriedigtheiten des Augustinus mit dem Manichäismus hervor? Nicht eigentlich aus dem, was man den mystischen Inhalt, wie ich ihn Ihnen jetzt charakterisiert habe, nennen könnte, sondern die Unbefriedigtheit ging aus der ganzen Haltung dieses Manichäismus hervor.

Zuerst war es für Augustinus so, daß er in gewissem Sinne eingenommen war, sympathisch berührt war von der sinnlichen Anschaulichkeit, von der Bildhaftigkeit, mit der diese Anschauung vor ihn hintrat. Dann aber regte sich in ihm etwas, was gerade mit dieser Bildhaftigkeit, mit der das Materielle geistig und das Geistige materiell angeschaut wurde, nicht zufrieden sein konnte. Und man kommt wirklich nicht anders zurecht, als wenn man hier von dem, was man eigentlich oftmals bloß als eine formelle Betrachtung vor sich hat, zu der Realität übergeht, wenn man also den Blick darauf wirft, daß der Augustinus eben ein Mensch war, der im Grunde genommen den Menschen des Mittelalters und vielleicht selbst den Menschen der neueren Zeit schon ähnlicher war, als er irgendwie sein konnte denjenigen Menschen, die durch ihre Seelenstimmung die naturgemäßen Träger des Manichäismus waren. Augustinus hat bereits etwas von dem, was ich eine Erneuerung des seelischen Lebens nennen möchte.

Bei anderen Gelegenheiten mußte auch in öffentlichen Vorträgen auf das, was hier in Betracht kommt, öfters hingewiesen werden. In unserer heutigen intellektuellen, zum Abstrakten hingeneigten Zeit, da sieht man eigentlich immer in dem, was geschichtlich wird für irgendein Jahrhundert, die Wirkung, die hervorgehen soll aus dem, was das vorige Jahrhundert gebracht hat und so weiter. Beim individuellen Menschen ist es ja ein reiner Unsinn zu sagen, dasjenige, was sich zum Beispiel im achtzehnten Lebensjahre abspielt, sei in ihm eine bloße Wirkung von dem, was sich im dreizehnten, vierzehnten Jahre abgespielt habe; denn dazwischen liegt etwas, was aus den tiefsten Tiefen der Menschennatur sich heraufarbeitet, was nicht bloß Wirkung ist des Vorhergehenden in dem Sinne, wie man von Wirkung als hervorgehend aus einer Ursache berechtigt sprechen kann, sondern was eben sich hineinstellt in das menschliche Leben als aus dem Wesen der Menschheit herauskommende Geschlechtsreife. Und auch zu andern Zeiten der individuellen Menschheitsentwickelung müssen solche Sprünge in der Entwickelung anerkannt werden, wo sich etwas emporringt aus Tiefen heraus an die Oberfläche; so daß man nicht sagen kann: Was geschieht, ist nur die unmittelbar gradlinige Wirkung desjenigen, was vorangegangen ist.

Solche Sprünge vollziehen sich auch mit der Gesamtmenschheit, und man muß annehmen, daß vor einem solchen Sprung dasjenige lag, was Manichäismus war, nach einem solchen Sprung diejenige Seelenverfassung, diejenige Seelenhaltung, in der sich auch Augustinus befand. Augustinus konnte einfach nicht auskommen in seinem Seelenleben, ohne daß er aufstieg von dem, was ein Manichäer materiell-geistig vor sich hatte, zu einem reinen Geistigen, zu einem bloß im Geiste Erkonstruierten, Eranschauten. Zu etwas viel Sinnlichkeitsfreierem mußte Augustinus aufsteigen als ein Manichäer aufstieg. Deshalb mußte er sich abwenden von der bildhaften, von der anschaulichen Weltanschauung des Manichäismus. Das war das erste, was sich in seiner Seele so intensiv auslebte, und wir lesen es etwa aus seinen Worten: Daß ich mir, wenn ich Gott denken wollte, Körpermassen vorstellen mußte und glaubte, es könne nichts existieren als derartiges — das war der gewichtigste und fast der einzige Grund des Irrtums, den ich nicht vermeiden konnte.

So weist er auf diejenige Zeit zurück, in der der Manichäismus mit seiner Sinnlichgeistigkeit, Geistigsinnlichkeit in seiner Seele lebte; so weist er auf diese Zeit hin, und so charakterisiert er diese Zeit seines Lebens als einen Irrtum. Er brauchte etwas, zu dem er aufblickte als zu etwas, das der Menschenwesenheit zugrunde liegt. Er brauchte etwas, das nicht so, wie die Prinzipien des Manichäismus, in dem sinnlichen Weltenall als Geistig-Sinnliches unmittelbar zu schauen ist. Wie bei ihm alles intensiv ernst und stark sich an die Oberfläche der Seele ringt, so auch dieses: «Ich fragte die Erde, und sie sprach: Ich bin es nicht. Und was auf ihr ist, bekannte das gleiche.»

Wonach fragt Augustinus? Er fragt, was das eigentlich Göttliche sei, und er fragt die Erde, und die sagt ihm: Ich bin es nicht. — Im Manichäismus wäre ihm geantwortet worden: Ich bin es als Erde, insofern das Göttliche durch das irdische Wirken sich ausspricht. — Und weiter sagt Augustinus: «Ich fragte das Meer und die Abgründe und was vom Lebendigen sie bergen: Wir sind dein Gott nicht, suche droben über uns. — Ich fragte die wehenden Lüfte, und es sprach der ganze Dunstkreis samt allen seinen Bewohnern: Die Philosophen, die in uns das Wesen der Dinge suchten, täuschten sich, wir sind nicht Gott.» Also auch nicht das Meer und auch nicht der Dunstkreis, alles dasjenige nicht, was sinnlich angeschaut werden kann. «Ich fragte Sonne, Mond und Sterne. Sie sprachen: Wir sind nicht Gott, den du suchst.»

So ringt er sich heraus aus dem Manichäismus, gerade aus dem Element des Manichäismus, das eigentlich als das Bedeutsamste, wenigstens in diesem Zusammenhange, charakterisiert werden muß. Nach einem sinnlichkeitsfreien Geistigen sucht Augustinus. Er steht gerade in demjenigen Zeitalter der menschlichen Seelenentwickelung drinnen, in dem die Seele sich losringen muß von dem bloßen Anschauen des Sinnlichen als eines Geistigen, des Geistigen als eines Sinnlichen; denn man verkennt auch in dieser Beziehung durchaus die griechische Philosophie. Und deshalb wird der Anfang meiner «Rätsel der Philosophie» so schwer verstanden, weil ich versuchte, einmal diese griechische Philosophie so zu charakterisieren, wie sie war.

Wenn der Grieche spricht von Ideen, von Begriffen, wenn Plato so spricht, so glauben die heutigen Menschen, Plato oder der Grieche überhaupt meine mit seinen Ideen dasjenige, was wir heute als Gedanken oder Ideen bezeichnen. Das ist nicht so, sondern der Grieche sprach von Ideen als von etwas, das er in der Außenwelt wahrnimmt, geradeso, wie er von der Farbe oder von Tönen als Wahrnehmungen in der Außenwelt sprach. Was nur im Manichäismus umgestaltet war mit einer, ich möchte sagen, orientalischen Nuance, das ist im Grunde in der ganzen griechischen Weltanschauung vorhanden. Der Grieche sieht seine Idee, wie er die Farbe sieht. Und er hat noch das Sinnlichgeistige, Geistigsinnliche, jenes Erleben der Seele, das gar nicht aufsteigt zu dem, was wir als sinnlichkeitsfreies Geistiges kennen; wie wir es nun auffassen, ob als eine bloße Abstraktion oder als einen realen Inhalt unserer Seele, das wollen wir in diesem Augenblick noch nicht entscheiden. Das ganze, was wir sinnlichkeitsfreies Erleben der Seele nennen, das ist ja noch nicht etwas, womit der Grieche rechnet. Er unterscheidet nicht in dem Sinne wie wir zwischen Denken und äußerem sinnlichen Wahrnehmen.

Die ganze Auffassung der Platonischen Philosophie müßte eigentlich von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus korrigiert werden, denn erst dann gewinnt sie ihr rechtes Antlitz. So daß man sagen kann: Der Manichäismus ist nur eine nachchristliche Ausgestaltung — wie ich schon sagte, mit orientalischer Nuance — desjenigen, was im Griechentum war. Man versteht auch nicht jenen großen Genialen, aber Erzphilister, der die griechische Philosophie abschließt, Aristoteles, wenn man nicht weiß, daß, wenn er noch spricht von den Begriffen, er zwar hart an der Grenze schon steht vom Erfassen von etwas sinnlichkeitsfreiem Abstrakten, daß er aber im Grunde genommen doch noch im Sinne der gefühlten Tradition desjenigen spricht, was auch die Begriffe noch im Umkreise der sinnlichen Welt gesehen hat wie die Wahrnehmungen.

Augustinus war einfach durch den Gesichtspunkt, zu dem sich die Menschenseelen durchgerungen hatten in seinem Zeitalter, durch reale Vorgänge, die sich in den Menschenseelen abspielten, in deren Reihen Augustinus stand als eine besonders hervorragende Persönlichkeit, Augustinus war einfach gezwungen, nicht mehr so bloß in der Seele zu erleben, wie ein Grieche erlebt hat; sondern er war gezwungen, zu sinnlichkeitsfreiem Denken aufzusteigen, zu einem Denken, das noch einen Inhalt behält, wenn es nicht reden kann von der Erde, von der Luft, vom Meer, von den Sternen, von Sonne und Mond, das einen unanschaulichen Inhalt hat. Und nach einem Göttlichen rang Augustinus, das einen solchen unanschaulichen Inhalt haben sollte. Und nun sprachen zu ihm nur Philosophien, Weltanschauungen, die eigentlich das, was sie ihm zu sagen hatten, von einem ganz anderen Gesichtspunkte aus sagten, nämlich von dem eben charakterisierten des Sinnlich-Übersinnlichen. Kein Wunder, daß, weil diese Seelen in unbestimmter Art strebten nach etwas, was noch nicht da war, und, wenn sie hinlangten wie mit geistigen Armen nach dem, was da war, sie nur finden konnten dasjenige, was sie nicht aufnehmen konnten, kein Wunder, daß diese Seelen zum Skeptizismus kamen!

Aber auf der anderen Seite war das Gefühl, auf einem sicheren Wahrheitsboden zu stehen und Aufschluß zu bekommen über die Frage nach dem Ursprung des Bösen, so stark in Augustinus, daß doch in seine Seele noch ebenso beträchtlich diejenige Weltanschauung hereingeleuchtet hat, die als Neuplatonismus am letzten Ausgange der griechischen philosophischen Entwickelung steht, namentlich in der Person des Plotin, und die uns auch historisch verrät — was im Grunde genommen nicht die Dialoge des Platon und am wenigsten die Aristotelische Philosophie verraten können -, wie das ganze Seelenleben dann verlief, wenn es eine gewisse Verinnerlichung, ein Hinausgehen über das Normale suchte. Plotin ist wie ein letzter Nachzügler einer Menschenart, die ganz andere Wege zur Erkenntnis, zum inneren Leben der Seele einschlug als dasjenige, was überhaupt nachher verstanden worden ist, wovon man nachher eine Ahnung entwickelt hat. Plotin steht so da, daß er dem heutigen Menschen eigentlich als Phantast erscheint.

Plotin erscheint gerade denjenigen, die mehr oder weniger in sich aufgenommen haben von der mittelalterlichen Scholastik, wie ein schrecklicher Schwärmer, ja, wie ein gefährlicher Schwärmer. Ich habe das wiederholt erleben können. Mein alter Freund Vincenz Knauer, der Benediktinermönch, der eine Geschichte der Philosophie geschrieben hat, und der auch ein Buch geschrieben hat über die Hauptprobleme der Philosophie von 'Thales bis Hamerling, war die Sanftmut selber. Dieser Mann schimpfte eigentlich nie zu andern Zeiten, als wenn man mit ihm über die Philosophie des Neuplatonismus, namentlich des Plotin, zu verhandeln hatte. Da wurde er bös und schimpfte sehr, fürchterlich über Plotin wie über einen gefährlichen Schwärmer. Und Brentano, der geistvolle Aristoteliker und Empiriker Franz Brentano, der aber auch die Philosophie des Mittelalters in einer außerordentlich tiefen und intensiven Weise in seiner Seele trug, er schrieb sein Büchelchen «Was für ein Philosoph manchmal Epoche macht», und da schimpft er eigentlich geradeso über Plotin, denn Plotin ist der Philosoph, der Mann, der nach seiner Meinung als ein gefährlicher Schwärmer am Ausgange des griechischen Altertums Epoche gemacht hat. Plotin zu verstehen, wird für den heutigen Philosophen tatsächlich außerordentlich schwer.

Von diesem Philosophen des dritten Jahrhunderts müssen wir zunächst sagen: Dasjenige, was wir als unseren Verstandesinhalt erleben, als unseren Vernunftinhalt erleben, was wir erleben als die Summe der Begriffe, die wir uns über die Welt machen, das ist für ihn durchaus nicht, was es für uns ist. Ich möchte sagen, wenn ich mich bildlich ausdrücken darf (es wird gezeichnet): Wir fassen die Welt auf durch Sinneswahrnehmungen, bringen dann durch Abstraktionen diese Sinneswahrnehmungen auf Begriffe und endigen so bei den Begriffen. Wir haben die Begriffe als inneres seelisches Erlebnis und sind uns, wenn wir Durchschnittsmenschen der Gegenwart sind, mehr oder weniger bewußt, daß wir ja Abstraktionen haben, etwas, was wir aus den Dingen wie herausgesogen haben. Das Wesentliche ist, wir endigen da; wir wenden unsere Aufmerksamkeit der Sinneserfahrung zu und endigen da, wo wir die Summe unserer Begriffe, unserer Ideen bilden.

Das war für Plotin nicht so. Für Plotin war diese ganze Welt der Sinneswahrnehmungen im Grunde genommen zunächst kaum vorhanden. Dasjenige aber, was für ihn etwas war, wovon er so sprach wie wir von Pflanzen, Mineralien, Tieren und physischen Menschen, das war etwas, was er nun über den Begriffen liegend sah, das war eine geistige Welt, und diese geistige Welt hatte für ihn eine untere Grenze. Diese untere Grenze waren die Begriffe. Während für uns die Begriffe dadurch gewonnen werden, daß wir zu den Sinnesdingen uns wenden, abstrahieren und die Begriffe uns bilden und sagen: Die Begriffe sind die Zusammenfassungen, die Extrakte ideeller Natur aus den Sinneswahrnehmungen -, sagte Plotin, der sich zunächst um die Sinneswahrnehmungen wenig kümmerte: Wir als Menschen leben in einer geistigen Welt, und dasjenige, was uns diese geistige Welt als ein Letztes offenbart, was wir wie ihre untere Grenze sehen, das sind die Begriffe.

Für uns liegt unter den Begriffen die sinnliche Welt; für Plotin liegt aber den Begriffen eine geistige Welt, die eigentliche intellektuelle Welt, die Welt des eigentlichen Geistesreiches. Ich könnte auch folgendes Bild gebrauchen: Denken wir uns einmal, wir wären in das Meer untergetaucht, und wir blicken hinauf bis zur Meeresoberfläche, sehen nichts als diese Meeresoberfläche, nichts über der Meeresoberfläche, so wäre die Meeresoberfläche die obere Grenze. Wir lebten im Meere, und wir hätten vielleicht eben in der Seele das Gefühl: Diese Grenze umschließt uns das Lebenselement, in dem wir sind —, wenn wir für das Meer organisierte Wesen wären.

Für Plotin war das anders. Er beachtete nicht dieses Meer um sich. Für ihn war aber seine Grenze, die er da sah, die Grenze der Begriffswelt, in der seine Seele lebte, die untere Grenze desjenigen, was über ihr war; also wie wenn wir die Meeresgrenze als die Grenze gegenüber dem Luftraum und der Wolkenwelt und so weiter auffassen würden. Für Plotin, der dabei durchaus für sich die Meinung hat, daß er die wahre, echte Anschauung des Plato fortsetzt, für Plotin ist dieses, was über den Begriffen liegt, zugleich dasjenige, was Plato die Ideenwelt nennt. Diese Ideenwelt ist zunächst durchaus etwas, wovon man als einer Welt spricht im i Sinne des Plotinismus.

Nicht wahr, es wird Ihnen allen nicht einfallen, selbst wenn Sie subjektivistisch oder Anhänger der modernen subjektivistischen Philosophie sind, wenn Sie hinaussehen auf die Wiese zu sagen: Ich habe meine, du hast deine Wiese, der dritte hat seine Wiese —, auch wenn Sie überzeugt sind davon, daß sie alle eben nur die Vorstellung der Wiese haben. Sie reden von der einheitlichen Wiese, von der einen Wiese, die draußen ist; so Plotin zunächst von der einen Ideenwelt, nicht von der Ideenwelt dieses Kopfes, oder eines zweiten Kopfes, oder der Ideenwelt im dritten Kopfe. An dieser Ideenwelt - und das merkt man ja schon aus der ganzen Art und Weise, wie man den Gedankengang zu charakterisieren hat, der zu dieser Ideenwelt führt -, an dieser Ideenwelt nimmt nun teil die Seele. So daß wir also sagen können: Gewissermaßen entfaltet sich aus der Ideenwelt heraus, diese Ideenwelt erlebend, die Seele, die Psyche. Und ebenso wie die Ideenwelt die Psyche, die Seele schafft, so schafft sich die Seele ihrerseits erst die Materie, in der sie verkörpert ist. So daß also dasjenige, woraus die Psyche ihren Leib nimmt, im wesentlichen ein Geschöpf dieser Psyche ist. |

Da aber ist erst der Ursprung der Individuation, da erst gliedert sich die Psyche, die sonst teilnimmt an der einheitlichen Ideenwelt, da gliedert sie sich in den Leib A, in den Leib B und so weiter ein, und dadurch entstehen erst die Einzelseelen. Die einzelnen Seelen entstehen dadurch, daß gewissermaßen die Psyche eingegliedert wird in die einzelnen materiellen Leiber. Geradeso, wie wenn ich eine große Menge Flüssigkeit hätte als eine Einheit, dann zwanzig Gläser nehmen und jedes mit dieser Flüssigkeit vollschütten würde, so daß ich überall diese Flüssigkeit, die als solche eine Einheit ist, nun drinnen hätte, geradeso habe ich überall die Psyche drinnen dadurch, daß die Psyche sich in Leibern, die sie sich aber selbst schafft, verkörpert. So daß im plotinischen Sinne der Mensch sich anschauen kann zunächst seiner Außenseite nach, seinem Gefäß nach. Das ist aber im Grunde genommen nur dasjenige, wodurch die Seele sich offenbart, wodurch die Seele sich auch individualisiert. Dann hat der Mensch innerlich zu erleben seine Seele selbst, die sich hinauferhebt zu der Ideenwelt. Dann gibt es eine höhere Art des Erlebens. Daß man von abstrakten Begriffen redet, das hätte für einen Plotinisten keinen Sinn; denn solche abstrakten Begriffe, ja, ein Plotinist würde gesagt haben: Was soll das sein, abstrakte Begriffe? Es können doch Begriffe nicht abstrakt sein, Begriffe können doch nicht in der Luft hängen, sie müssen doch irgendwie vom Geiste heruntergesenkt sein, sie müssen doch die konkreten Offenbarungen des Geistigen sein.

Man hat also unrecht, wenn man so interpretiert, daß das, was man als Ideen gegeben hat, irgendwelche Abstraktionen seien. Das ist der Ausdruck einer intellektuellen Welt, einer Welt der Geistigkeit. Es ist dasjenige, was auch im gewöhnlichen Erleben bei denjenigen Menschen vorhanden war, aus deren Verhältnissen Plotin und die Seinigen herauswuchsen. Für die hatte ein solches Reden über Begriffe, wie wir es heute entfalten, überhaupt keinen Sinn, denn für sie gab es nur ein Hereinragen der geistigen Welt in die Seelen. Und an der Grenze dieses Hereinragens, im Erleben, ergab sich diese Begriffswelt. Erst dann aber, wenn man sich vertiefte, wenn man weiterentwickelte die Seele, ergab sich das, was nun der gewöhnliche Mensch nicht wissen konnte, was eben ein solcher erlebte, der zu einem höheren Erleben sich aufschwang. Er erlebte dann dasjenige, was noch über der Ideenwelt war, das Eine, wenn man es etwa so nennen will, Erleben des Einen, was für Plotin dasjenige war, das für keine Begriffe zu erreichen war, weil es eben über der Begriffswelt war, das nur zu erreichen war, wenn man begriffslos ins Innere sich versenken konnte, und das charakterisiert ist durch das, was wir hier in unserer Geisteswissenschaft Imagination nennen. Sie können darüber nachlesen in meinem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?», nur daß dasjenige, was in diesem Buche gemeint ist, im Sinne der Gegenwart ausgebildet ist, während es bei Plotin im Sinne des alten ausgebildet war. Was da die Imagination genannt werden kann, das versenkt sich nach Plotin in dasjenige, was über der Ideenwelt steht.

Aus dieser Gesamtanschauung der Welt ergab sich für Plotin eigentlich auch alles Erkennen über die menschliche Seele. Es liegt ja eigentlich schon darinnen. Und man kann nur Individualist im Sinne Plotins sein, indem man zu gleicher Zeit ein Mensch ist, der anerkennt, wie der Mensch sich hinauflebt in etwas, das über alle Individualität erhaben ist, wie sich der Mensch hinauflebt in ein Geistiges, in das er sich gewissermaßen nach oben erhebt, während wir heute in unserem Zeitalter mehr die Gewohnheit haben, unterzutauchen in das Sinnliche. Das alles aber, was da der Ausdruck von etwas ist, was also selbst schon ein richtiger Scholastiker als Schwärmerei ansieht, das ist für Plotin nichts etwa Erdachtes, das sind für Plotin keine Hypothesen. Für Plotin war das so sichere Wahrnehmung, bis zu dem Einen hin, das eben nur in Ausnahmefällen erlebt werden konnte, für Plotin war es so sichere Wahrnehmung, so selbstverständliche Wahrnehmung, wie für uns eben heute Mineralien, Pflanzen, Tiere Wahrnehmungen sind. Er sprach nur im Sinne von etwas, das wirklich unmittelbar von der Seele erlebt wird, wenn er sprach von der Seele, dem Logos, der teilnimmt an dem Nous, an der Ideenwelt und an dem Einen.