Awareness - Life - Form

GA 89

9 November 1904, Berlin

Planetary Evolution XI

We often talk about principles as if they were of the same kind and only differed in degree. Yet if we want to understand how things are connected, we need to get to know the principles themselves in their nature.

We need to distinguish three things in the world; three kinds of effects. Only things that take effect can be considered by a perceptive entity, and we therefore focus our attention on the effects. There are therefore three ways in which something may take effect—first, actually in the spirit; secondly in the soul, thirdly at the physical level. Effects in the spirit, anything that can in some way take effect in spirit, is called budhi; anything that can take effect at soul level is called kama; everything that can have a physical effect is called prana. Budhi, kama and prana are the three ways of taking effect. They are of the same kind but at different levels.

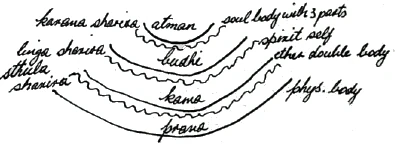

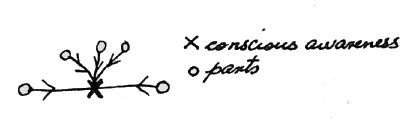

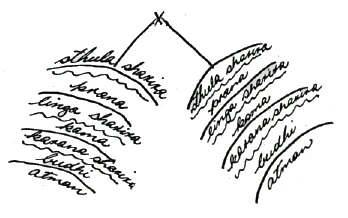

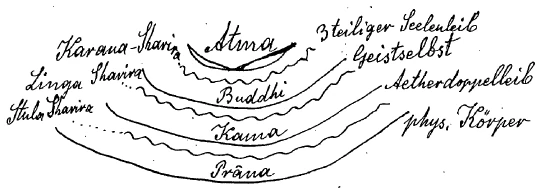

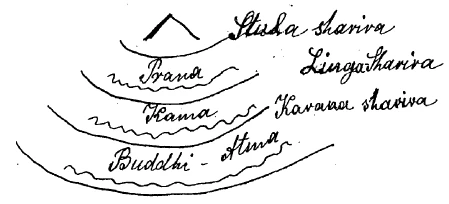

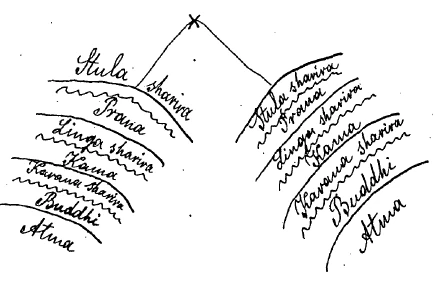

Now we have to realize that effects would always be fluid, indefinite, if they did not define themselves. If kama is to happen in a particular way, for instance, it must set itself limits. Budhi, kama and prana must therefore set themselves limits if they are to be defined influences or effects. In the theosophical literature these boundaries are called ‘sharira’, meaning ‘vessel, shell, sheath’. If budhi sets itself a boundary, this is called ‘karana sharira’; if kama does, it is ‘linga sharira’, and with prana it is ‘sthula sharira’. These sharira are thus the limits, the outer forms, which the three kinds of effects set for themselves. Now the following may happen (Fig. 10, starting from below).

First of all we have prana in action; then prana sets itself a limit on the outside—sthula sharira. Prana thus sets itself a boundary in one direction but remains billowing and open in the other. Prana is now joined by kama, setting itself a boundary here—linga sharira. Then prana is no longer billowing and open on this side either, for kama with its boundary has pushed its way in. Kama in turn remains open on the other side. Then budhi comes and limits itself off from kama, and you get karana sharira. The three principles thus have intermediate layers. If this is a spirit, a self-awareness must also live in these three principles and their interfaces—this is known as ‘atman’.

The human being consists of the three principles, the interfaces and self-awareness or atman. Each may have its own subdivisions. If we take it like this, we have the composition of the human being as such.

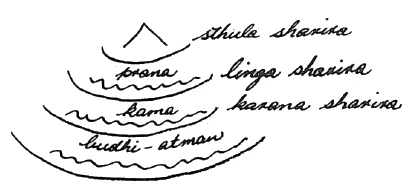

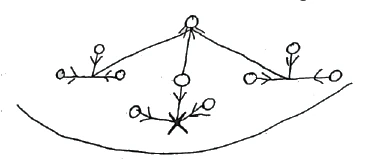

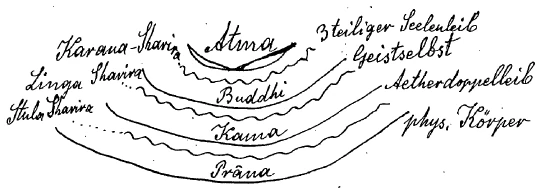

Here, in the human being (Fig. 10), the physical body is the outer shell, and atman rests inside. The arrangement can of course also be very different. [For the planetary spirit,] the situation is, for example, that prana shows itself initially as active, setting itself a limit, in an inward direction. (Fig. 11)

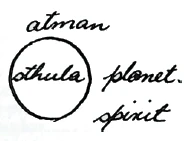

Prana is then limited on the inside by sthula sharira, kama by linga sharira, and budhi by karana sharira. We would thus have an entity where atman was on the outside, then budhi, then kama and last of all prana. Atman would then appear as wholly expanded in the periphery [an orb] and sthula sharira would be a point at the centre. (Fig. 12)

Such a spirit would be a dhyan chohan, a planetary spirit that must present in a way which is the reverse of the human way. In the human being, sthula sharira is on the outside, in dhyan chohans atman; then comes budhi, and so on.

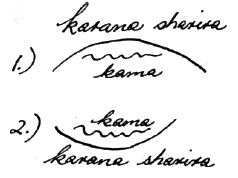

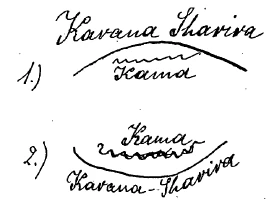

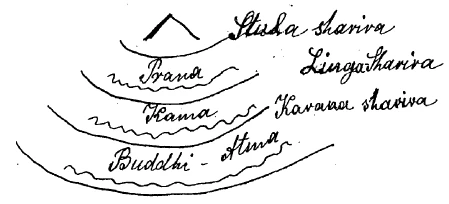

We can get a clear idea of this if we take the following example. If we close our eyes, it is dark for the time being; once we open them again, we see the light. We only see the light, however, because we have an inner feeling for it and are therefore able to receive it. It must first be there, however, if we are to receive it. And just as we have to be there to sense the light, so there must be an entity out there which reveals light. We are light receivers; out there must be light givers, light revealers. And just as we are only able to sense light because we have kama, the astral body, in us, so a planetary spirit must have a kama that lets light shine out. Kama is thus active towards the centre here, and in the radius of the circle there. (Fig. 13)

The circle which is convex towards the top is for us, for our sentience, for the one which receives, the principle moving towards the giver. The circle which is convex towards the bottom is the kama of the dhyanic spirit. The kama of revelation thus acts downwards—karana sharira. Whereas the human being has a kama that seeks to move towards the centre, so the planetary spirit has a kama that seeks to move outwards, to the periphery, revealing light, whilst the kama of the human being receives light. Two kinds of spirits, natures that complement one another, always go together. A spirit must have the desire—receiving; another must be able to give—giving. Human desirous kama presupposes that there is a giving kama, the kama of love.

Human budhi mediates insight. Such insight as we gain into things comes through our budhi. The planetary spirit must thus be a giver of thoughts, and human budhi a receiver. The planetary spirit thus acts in entirely the opposite way, complementing the human spirit.

Every single thing in the world exists only in the context of the whole; it is part of the whole. As a part it belongs to the whole planetary Earth spirit. Thus this table here consists of matter, which makes it an object we encounter in space; secondly it has energy, for it offers resistance, otherwise it would not exist for us; thirdly this energy does not come to expression at random but according to specific laws (natural laws).

What is energy? What is it that makes life possible in us? It is an energy which takes things in, maintaining life. Human vital energy serves to hold together the matter which is in the human being. Because of this, the matter and its energy in the human being is directed inwards, building the human being up from inside. Without this, we could not be perceived as living human beings. The table on the other hand has matter which is directed outwards, and this functions according to law. Matter as such cannot be perceived, only its properties and qualities such as colours, sounds, and so on. Matter itself is completely beyond sensory perception. A prana in matter withdraws completely from sensory perception but gives itself in order to reveal itself. We also have insight into the law which lies in matter, and the thought which comes to expression in it.

Budhi comes to outer expression in the natural world. Every body which gives outward expression to the planetary spirit is continually radiating outwards; its budhi is thus directed outwards. It becomes light which the senses perceive. Budhi lies in the properties and qualities of things, in the aspect which is on the outside. The law must reveal itself through karana sharira. Manas revealed is law. In being luminous, a body sends us budhi. The thought, expressing spirit, through which it sends us budhi, is karana sharira. The planetary spirit keeps kama to itself, withdrawing it from sensory perception. Its matter ... [Marie Steiner-von Sivers’ notes indicate a gap here.] On the other hand it reveals the cosmic thoughts which human beings must fathom deep down inside. The principle which the planetary spirit revealed wholly on the surface is its budhi. In the Bible, it says that the planetary spirit first of all revealed itself as light. The spirit thus reveals budhi qualities (light) at the first level. Budhi qualities (light) are revealed by the spirit at the first level. These ancient sacred teachings of the polarity between human being and planetary spirit are brought out most beautifully in esoteric Christian teaching. In cabbalistic terms the budhi qualities which come to revelation are called ‘powers’. It is thus the powers of light and darkness which revealed themselves first. Once again we can take Genesis literally.

The spirit thus reveals budhi qualities on the first level. On the second it reveals its karana sharira; it orders things according to laws. Something which is convex in the macrocosm is thus concave in the microcosm. Something which the human being perceives last, comes first in the macrocosm; the microcosm finally comes to perceive and understand the sentient experience in the macrocosm.

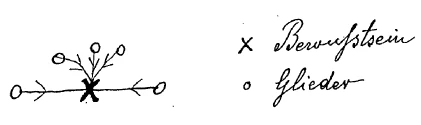

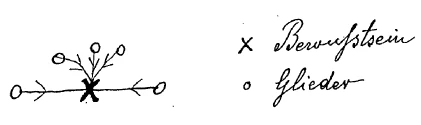

The question arises if there is a transitional stage between the two—between human being and planetary spirit. Think of an entity with one conscious awareness. That is the human being. He has different parts, but these share a common awareness. (Struggle between patricians and plebeians.)77Plebeians could not be priests or hold political office. From the 4th century BC onwards, the privileges of patricians grew less and less, and in 287 the plebeians were given equal rights politically. We might show it more or less like this (Fig. 14).

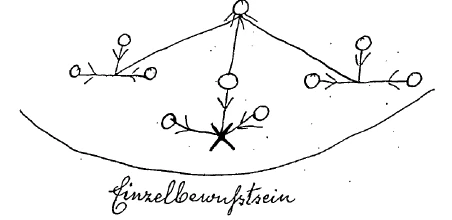

Individual parts all radiate towards the common awareness. If we take the latter to be energy, and the parts, too, we can say that the common awareness is predominant, influencing all the others. Now think of numerous entities functioning in this way (Fig. 15)

Each has its own existence. Through [the common ideal] it can connect its own with those of others. The different conscious minds create a common focus; they seek to gain a specific common ideal. This then lives in the different conscious minds as a common spiritual ideal. If they reach the point where their spiritual ideal is of greater value to them than they themselves, they will be drawn to it just as before they drew the parts of their conscious awareness to themselves. Where before they had been the focus or centre for those different spheres, the common ideal will then be the central focus for the large sphere. Individual entities then become parts of a common entity, giving up their separate existences and living in the common ideal. They cease to be centre and give themselves a common centre. A brotherhood lodge then develops from individual people. If the common ideal is so powerful that it draws all the individual conscious minds to it, these people make up a body that has a soul of a higher kind. A brotherhood lodge then develops with a perfectly communal spirit. This is a new entity. The soul could never have come down into the human being if he had not become a house for it with different parts. It is never possible for a higher principle to come down unless individual minds become vital parts, the form for a higher kind of house, so that the common awareness may come to expression in it.

This gives us the transition. Another centre is created. Human development is an inversion, the reversal of all principles. As human beings express themselves in seven ways, we get not one but seven centres. These will be the seven elohim, the pitris for the next planet.

Man thus progresses from a spirit which takes in the surrounding world to a spirit which reveals itself. The two completely opposite natures—human being and elohim or dhyan—are merely forms of one essential nature. At a future time, the human being will no longer be as he is now; he will be a dhyan chohanic spirit. In esoteric terms this is called the ‘secret of man becoming god’.

When individual conscious minds all turn to one centre, with everything outside becoming atman, there will be just a single core of sthula sharira inside, which is unity at its highest level.

Such oneness cannot be achieved on Earth; it needed seven sublime spirits to create it. This, then, is the Logos, with atman in the periphery. In the cabbala, the ‘realm’, union, crowns all. This is also the principle on which the Church is founded, with all human beings having part in one conscious awareness. The law of form is birth and death. The law of life is rebirth. The law of the spirit is karma. Life goes through birth and death, appearing in new forms all the time. Form is transient by nature, life repeats itself, the spirit does not perish, it is eternal.

Elfter Vortrag

Man redet oft von den Prinzipien, als ob sie gleichartig wären und nur verschiedene Grade hätten. Aber will man die Zusammenhänge verstehen, so müssen wir die Prinzipien selbst ihrer Natur nach kennenlernen.

Wir müssen dreierlei in der Welt unterscheiden, dreierlei Arten von Wirkungen. Weil für ein wahrnehmendes Wesen nur das, was zur Wirkung kommt, in Betracht kommen kann, richten wir unsere Aufmerksamkeit auf die Wirkungen. Es gibt also dreierlei Arten, wie etwas wirken kann: erstens die eigentlich geistige, zweitens die seelische, drittens die körperliche Art von Wirkung. Die geistige Wirkung, alles, was irgendwie als Geist wirken kann, nennt man Budhi; alles, was seelisch wirken kann, nennt man Kama; alles, was körperlich wirken kann, nennt man Prana. Das sind die drei Wirkungsformen: Budhi, Kama, Prana. Als Wirkungsformen sind sie gleichartig, nur auf verschiedenen Stufen.

Nun muß man sich vorstellen, daß die Wirkungen fortwährend flüssig, unbestimmt wären, wenn sie sich nicht begrenzen würden. Soll zum Beispiel Kama in einer bestimmten Weise auftreten, so muß es sich eine Grenze geben. Also um zu begrenzten Wirkungen zu werden, müssen sich Budhi, Kama und Prana Grenzen geben. Diese Grenzen nennt man in der theosophischen Literatur «Shariras», das heißt Schalen, Hüllen, Scheiden. Und zwar bezeichnet man, wenn sich Budhi begrenzt, diese Grenze als Karana Sharira; gibt sich Kama eine Grenze, so nennt man diese Linga Sharira; gibt sich Prana eine Grenze, nennt man sie Sthula Sharira. Diese Shariras sind also die Grenzen, die Hüllen, die sich die drei Wirkungsarten setzen.

Es kann nun folgendes eintreten [es wird nun das Schema I an der Tafel entwickelt und zwar von unten nach oben angeschrieben]

Wir haben zuerst Prana in Wirksamkeit; dann gibt sich Prana eine Grenze nach außen: Sthula Sharira. Prana begrenzt sich also nach einer Seite und bleibt nach der anderen wogend offen. Zu Prana tritt nun Kama hinzu und gibt sich hier eine Grenze: Linga Sharira. Dadurch bleibt Prana auch auf dieser Seite nicht mehr wogend offen, weil sich Kama mit seiner Grenze hineinschiebt; aber Kama bleibt wieder offen nach der anderen Seite. Nun tritt Budh:i hinzu und gibt sich die Grenze gegen Kama und es entsteht Karana Sharira. Die drei Prinzipien haben also Zwischenlagen. Wenn dies ein Wesen ist, muß in diesen drei Prinzipien und ihren Zwischenlagen noch ein Ich-Bewußstsein leben: das bezeichnet man als Atma.

Aus den drei Prinzipien und den Zwischenlagen und dem IchBewußtsein oder Atma besteht der Mensch. Jedes einzelne kann Unterabteilungen haben. Wenn wir dies so fassen, haben wir die Zusammensetzung des Menschen als solchen gegeben.

Hier, beim Menschen [Schema I], bildet der physische Körper die äußere Hülle, und Atma ruht im Innern. Nun kann die Anordnung auch ganz anders sein. [Beim Planetengeist ist es] nämlich so, daß sich Prana zunächst nach innen wirksam zeigt und sich eine Grenze setzt. Dann würde folgendes entstehen [Schema folgende Seite]:

Prana ist dann nach innen begrenzt durch Sthula Sharira, Kama durch Linga Sharira, Budhi durch Karana Sharira und wir hätten nun ein Wesen, bei dem zuerst außen Atma liegt, dann Budhi, dann Kama und zuletzt Prana. Dann [folgendes Schema] würde Atma ganz im Umkreis ausgespannt erscheinen [eine Kugel], und Sthula Sharira wäre ein Punkt in der Mitte.

Ein solches Wesen ist ein Dhyan-Chohan, ein Planetengeist und muß umgekehrt wirken wie ein Mensch. Beim Menschen liegt Sthula Sharira nach außen, bei den Dhyan-Chohans Atma, dann kommt Budhi und so weiter.

Man kann sich davon eine klare Vorstellung machen durch folgendes Beispiel. Wenn wir unsere Augen schließen, ist es zuerst dunkel und wenn wir sie dann wieder aufmachen, dann sehen wir das Licht. Wir sehen das Licht aber nur, weil wir eine Empfindung dafür haben und es dadurch empfangen können. Es muß aber erst da sein, bevor wir es empfangen können. Und ebenso, wie wir da sein müssen, um Licht zu empfinden, so muß ein Wesen draußen sein, das Licht offenbart. Wir sind Lichtempfänger, draußen müssen Lichtgeber, Lichtoffenbarer sein. Und so wie wir das Licht nur dadurch empfinden können, daß wir in uns Kama, den Astralkörper haben, so muß ein planetarisches Wesen ein Kama haben, das Licht ausstrahlt. So daß also Kama hier gegen den Mittelpunkt hin wirkt und dort im Radius des Kreises.

Der Kreis, der nach oben hin konvex ist, ist für uns, für die Empfindung, für das Empfangende, das dem Gebenden Entgegenstrebende. Der Kreis, der nach unten zu konvex ist, ist das Kama der dhyanischen Wesenheit. So wirkt das Kama der Offenbarung nach unten: Karana Sharira. So wie der Mensch ein Kama hat, das nach seinem Mittelpunkt hinstrebt, so hat der Planetengeist ein nach außen, nach dem Umkreis strebendes Kama, welches lichtoffenbarend ist, während das Kama des Menschen lichtempfangend ist. Es gehören immer zweierlei Wesenheiten von sich ergänzenden Naturen zusammen. Fine Wesenheit muß das Verlangen besitzen: die empfangende Wesenheit; eine andere muß geben können: die gebende Wesenheit. Menschliches verlangendes Kama setzt voraus, daß gebendes Kama da ist, Kama der Liebe.

Menschliche Budhi vermittelt das Erkennen. Dasjenige, was uns von den Dingen an Erkennen offenbart wird, wird empfangen durch unsere Budhi. Der planetarische Geist muß also gedankengebend, menschliche Budhi muß empfangend sein. Der planetarische Geist verhält sich somit ganz entgegengesetzt und ergänzend zum Menschengeist.

Ein jedes einzelne Ding in der Welt existiert nur im Weltenzusammenhang, es ist ein Glied im Ganzen. Als Glied gehört es dem ganzen planetarischen Erdgeist an. So hat zum Beispiel der Tisch erstens eine Materie, durch die er ein Wesen ist, das uns im Raume entgegentritt; zweitens hat er.Kraft, dadurch daß er Widerstand gibt, denn sonst würde er für uns nicht da sein; und zum dritten äußert sich die Kraft nicht beliebig, sondern nach bestimmten Gesetzen (Naturgesetzen).

Was ist die Kraft? Was ist das, was in uns das Leben möglich macht? Es ist eine Kraft, die einnehmend ist, das Leben erhaltend. Des Menschen Lebenskraft äußert sich dadurch, daß sie, was an Materie in ihm ist, zusammenhält. Daher ist die Materie und die ihr zukommende Kraft beim Menschen nach innen gerichtet, sie baut den Menschen von innen auf; er könnte sonst nicht als lebendes Wesen wahrgenommen werden. Der Tisch dagegen hat die nach außen gerichtete Materie, und diese äußert sich durch das Gesetz. Materie an sich kann nicht wahrgenommen werden, nur ihre Eigenschaften, wie Farben, Töne und so weiter. Die Materie selbst entzieht sich vollständig der Wahrnehmung. Es ist ein Prana in der Materie, welches sich ganz der Wahrnehmung entzieht, aber sich dahingibt, um sich zu offenbaren. Daneben erkennen wir das Gesetz in der Materie, den Gedanken, der sich darin ausdrückt.

Budhi äußert sich in der Natur nach außen. Jeder Körper, der der äußere Ausdruck des Planetengeistes ist, strahlt fortwährend nach außen, das heißt, er hat Budhi nach außen gekehrt. Es wird zum Licht, das wahrgenommen wird. Budhi ist in den Eigenschaften der Dinge, in dem, was nach außen liegt. Das Gesetz muß sich offenbaren durch Karana Sharira. Das sich offenbarende Manas ist das Gesetz. Indem ein Körper leuchtet, schickt er uns Budhi zu. Der Gedanke, die Geistesäußerung, durch die er es schickt, ist Karana Sharira. Kama dagegen behält der Planetengeist für sich; er entzieht es der Wahrnehmung. Seine Materie ... [in den Notizen von Marie Steiner-von Sivers ist hier eine Lücke markiert]. -— Dagegen offenbart er die kosmischen Gedanken, die der Mensch erst tief im Innern ergründen muß. Und was der planetarische Geist ganz an der Oberfläche äußert, hingibt, das ist sein Budhi.

In der Bibel ist dies zum Ausdruck gebracht. Es wird gesagt, daß der planetarische Geist in seiner ersten Äußerung eine Lichtäußerung war. Es sind Budhi-Eigenschaften (Licht), die der Geist auf der ersten Stufe offenbart. Diese uralte heilige Lehre von dem Gegensatz des Menschen und des Planetengeistes ist in der christlichen Esoterik schön zum Ausdruck gebracht. Man nennt die sich offenbarenden Budhi-Eigenschaften in der kabbalistischen Sprache «Gewalten». Daher offenbaren sich zunächst die Gewalten des Lichtes und der Finsternis. So kann man die Genesis wieder wörtlich nehmen.

Es sind also Budhi-Eigenschaften, die der Geist auf der ersten Stufe offenbart. Auf der zweiten offenbart er sein Karana Sharira; er ordnet die Dinge nach Gesetzen. Was im Makrokosmos nun konvex angeordnet ist, ist im Mikrokosmos konkav. Was der Mensch zuletzt erkennt, kommt im Makrokosmos zuerst, der Mikrokosmos kommt zuletzt dazu, die Empfindung im Makrokosmos zu erkennen.

Nun frägt es sich, ob es einen Übergang gibt zwischen den beiden Wesenheiten, zwischen Mensch und Planetengeist. Man denke eine Wesenheit mit einem Bewußtsein: Das ist der Mensch; er hat verschiedene Glieder, aber mit einem gemeinsamen Bewußtsein. (Streit der Patrizier und Plebejer). Das wäre etwa so darzustellen:

Es sind einzelne Glieder, die alle hinstrahlen zu dem gemeinschaftlichen Bewußtsein. Wollen wir das gemeinschaftliche Bewußtsein als Kraft ansehen und die Glieder auch, so können wir sagen, das gemeinsame Bewußtsein ist das überwiegende, es wirkt auf die anderen alle. Man denke sich nun viele solcher Wesenheiten, die in dieser Weise wirksam sind:

Jede von den Wesenheiten hat ihre eigene Existenz. Durch [das gemeinsame Ideal] kann sie andere Existenzen mit ihrer verbinden. Diese verschiedenen Bewußtseine setzen sich selbst einen gemeinsamen Mittelpunkt, sie streben nach einem gemeinsamen bestimmten Ideal hin. Dieses lebt dann als gemeinschaftliches geistiges Ideal in den verschiedenen Bewußtseinen. Wenn diese dahin kommen, daß ihnen ihr geistiges Ideal wertvoller ist als sie selbst, dann werden sie von diesem Ideal genauso angezogen, wie sie selbst früher die Glieder ihres Bewußtseins zu sich herangezogen haben. Bildeten sie früher den Mittelpunkt für diese verschiedenen Sphären, so bildet das gemeinsame Ideal dann den Mittelpunkt für die große Sphäre. Die einzelnen Existenzen werden dann selbst Glieder der gemeinschaftlichen Existenz, geben ihr Sondersein auf und leben in dem gemeinschaftlichen Ideal. Sie hören auf, selbst Zentrum zu sein und geben sich ein gemeinschaftliches Zentrum. So entsteht aus einzelnen Menschen eine Bruderloge. Wenn ein so starkes gemeinschaftliches Ideal da ist, daß es die einzelnen Bewußtseinszentren alle anzieht, so bilden diese Menschen einen Körper, der eine Seele höherer Art hat. Dadurch entsteht eine Bruderloge mit einem vollständig gemeinschaftlichen Geist. Und so haben wir es mit einem neuen Wesen zu tun. Niemals hätte sich eine Seele in den Menschen senken können, wenn er nicht ein Gehäuse wäre aus Gliedern. Niemals kann sich ein Höheres herniedersenken, wenn nicht die einzelnen Bewußtseine zu Lebensgliedern werden, die Form für ein höheres Gehäuse, damit darin das gemeinschaftliche Bewußtsein zum Ausdruck kommt.

Damit haben wir den Übergang; es wird ein anderes Zentrum geschaffen. Eine Inversion, eine Umkehrung sämtlicher Prinzipien ist die menschliche Entwicklung. Da die Menschen sich in sieben Arten äußern, entsteht nicht ein Zentrum, sondern sieben Zentren. Dies werden die sieben Elohim, die Pitris für den nächsten Planeten sein.

So geht der Mensch von einem Wesen, das die Umgebung in sich aufnimmt, zu einem Wesen über, das sich offenbart. Die beiden ganz entgegengesetzten Wesenheiten, der Mensch und die Elohim oder Dhyani sind nur Formen einer Wesenheit. Was also der Mensch hier ist, wird er in Zukunft nicht mehr sein, sondern eine dhyan-chohanische Wesenheit. Das wird in der Esoterik das «Geheimnis der Gottwerdung des Menschen» genannt.

Wenn die Einzelbewußtseine sich alle einem Zentrum zuwenden und draußen alles Atma wird, wird im Innern nur ein einziger Kern von Sthula Sharira sein, also die Einheit im höchsten Grade.

Diese Einheit kann auf der Erde nicht erreicht werden; diese können erst sieben erhabene Geister bilden. Das ist dann der Logos, der Atma im Umkreis hat. In der Kabbala ist die Krone von allem das «Reich», die Vereinigung. Dieses Prinzip liegt auch der Kirche zugrunde, nämlich daß alle Menschen Glieder eines Bewußtseins werden.

Das Gesetz der Form ist Geburt und Tod. Das Gesetz des Lebens ist die Wiedergeburt. Das Gesetz des Geistes ist Karma. Das Leben geht durch Geburt und Tod und erscheint in immer neuen Formen. Die Form ist vergänglich, das Leben wiederholt sich, der Geist ist unvergänglich, ewig.

Eleventh Lecture

People often talk about principles as if they were all the same and only differed in degree. But if we want to understand the connections, we must learn about the nature of the principles themselves.

We must distinguish between three things in the world, three kinds of effects. Because only that which has an effect can be considered by a perceiving being, we focus our attention on the effects. There are three ways in which something can have an effect: first, the spiritual effect; second, the soul effect; and third, the physical effect. The spiritual effect, everything that can act as spirit in some way, is called budhi; Everything that can have a psychic effect is called Kama; everything that can have a physical effect is called Prana. These are the three forms of effect: Budhi, Kama, Prana. As forms of effect, they are similar, only at different levels. For example, if Kama is to occur in a certain way, there must be a limit. So in order to become limited effects, Budhi, Kama, and Prana must set limits for themselves. In theosophical literature, these limits are called “Shariras,” meaning shells, envelopes, or sheaths. When Budhi sets a limit, this limit is called Karana Sharira; if Kama sets itself a limit, it is called Linga Sharira; if Prana sets itself a limit, it is called Sthula Sharira. These Shariras are therefore the limits, the shells, that the three modes of action set for themselves.

The following can now occur [scheme I is now developed on the board, written from bottom to top]

First we have Prana in action; then Prana sets itself a boundary to the outside: Sthula Sharira. Prana thus limits itself on one side and remains undulating and open on the other. Kama now joins Prana and sets itself a boundary: Linga Sharira. As a result, Prana no longer remains open on this side either, because Kama pushes in with its boundary; but Kama remains open on the other side. Now Budhi joins and sets itself a boundary against Kama, and Karana Sharira is created. The three principles therefore have intermediate layers. If this is a being, then an ego consciousness must also live in these three principles and their intermediate layers: this is called Atma.

Human beings consist of the three principles and the intermediate layers and the ego consciousness or Atma. Each individual principle can have subdivisions. If we understand this, we have the composition of the human being as such.

Here, in the human being [diagram I], the physical body forms the outer shell, and Atma rests within. Now, the arrangement can also be quite different. [In the case of the planetary spirit], prana first manifests itself inwardly and sets a boundary. Then the following would arise [diagram on the next page]:

Prana is then limited inwardly by Sthula Sharira, Kama by Linga Sharira, Budhi by Karana Sharira, and we would now have a being in which Atma lies first on the outside, then Budhi, then Kama, and finally Prana. Then [according to the following diagram] Atma would appear to be spread out completely around the circumference [a sphere], and Sthula Sharira would be a point in the center.

Such a being is a Dhyan-Chohan, a planetary spirit, and must act in the opposite way to a human being. In humans, Sthula Sharira is on the outside, in Dhyan-Chohans it is Atma, then comes Budhi and so on.

The following example gives a clear mental image of this. When we close our eyes, it is dark at first, and when we open them again, we see the light. But we only see the light because we have a sensation for it and can therefore receive it. However, it must be there before we can receive it. And just as we must be there to perceive light, so there must be a being outside that reveals light. We are light receivers; outside there must be light givers, light revealers. And just as we can only perceive light because we have Kama, the astral body, within us, so a planetary being must have a Kama that radiates light. So Kama acts here towards the center and there in the radius of the circle.

The circle that is convex at the top is for us, for feeling, for the receiver, the one striving toward the giver. The circle that is convex downward is the Kama of the dhyanic entity. Thus, the Kama of revelation acts downward: Karana Sharira. Just as man has a Kama that strives toward its center, so the planetary spirit has a Kama that strives outward, toward the circumference, which is light-revealing, while the Kama of man is light-receiving. Two beings of complementary natures always belong together. One being must possess desire: the receiving being; another must be able to give: the giving being. Human desiring Kama presupposes that there is giving Kama, Kama of love.

Human budhi conveys knowledge. That which is revealed to us by things in terms of knowledge is received through our budhi. The planetary spirit must therefore be thought-giving, while human budhi must be receptive. The planetary spirit thus behaves in a manner that is completely opposite to and complementary to the human spirit.Every single thing in the world exists only in the context of the world; it is a link in the whole. As a link, it belongs to the whole planetary Earth spirit. For example, the table first has a material substance through which it is a being that confronts us in space; secondly, it has power in that it offers resistance, for otherwise it would not be there for us; and thirdly, this power does not express itself arbitrarily, but according to certain laws (laws of nature).

What is power? What is it that makes life possible within us? It is a force that is engaging, that sustains life. The life force of human beings manifests itself in that it holds together the matter within them. Therefore, matter and the force that belongs to it are directed inward in human beings; it builds them up from within; otherwise, they could not be perceived as living beings. The table, on the other hand, has matter that is directed outward, and this manifests itself through the law. Matter itself cannot be perceived, only its properties, such as colors, sounds, and so on. Matter itself completely eludes perception. There is a prana in matter that completely eludes perception, but gives itself over to revealing itself. In addition, we recognize the law in matter, the thought that expresses itself in it.

Budhi expresses itself outwardly in nature. Every body that is the outward expression of the planetary spirit radiates outwardly all the time, which means it has turned Budhi outward. It becomes the light that is perceived. Budhi is in the properties of things, in what lies outwardly. The law must reveal itself through Karana Sharira. The revealing Manas is the law. By shining, a body sends us budhi. The thought, the expression of spirit through which it sends it, is karana sharira. Kama, on the other hand, is kept by the planetary spirit for itself; it withdraws it from perception. Its matter ... [there is a gap marked here in Marie Steiner-von Sivers' notes]. — In contrast, it reveals the cosmic thoughts that human beings must first fathom deep within themselves. And what the planetary spirit expresses and gives on the very surface is its budhi.

This is expressed in the Bible. It is said that the planetary spirit's first expression was an expression of light. It is budhi qualities (light) that the spirit reveals at the first stage. This ancient sacred teaching about the contrast between human beings and the planetary spirit is beautifully expressed in Christian esotericism. In Kabbalistic language, the budhi qualities that reveal themselves are called “powers.” Therefore, the powers of light and darkness are revealed first. Thus, Genesis can be taken literally again.

It is therefore Budhi qualities that the spirit reveals at the first stage. At the second stage, it reveals its Karana Sharira; it orders things according to laws. What is now arranged convexly in the macrocosm is concave in the microcosm. What man recognizes last comes first in the macrocosm; the microcosm comes last in recognizing the sensation in the macrocosm.

Now the question arises whether there is a transition between the two entities, between man and planetary spirit. Consider an entity with a consciousness: that is the human being; he has different members, but with a common consciousness. (Conflict between patricians and plebeians). This could be represented as follows:

These are individual members, all of whom radiate toward the common consciousness. If we regard the common consciousness as a force and the members as well, we can say that the common consciousness is the predominant one; it acts upon all the others. Now imagine many such entities acting in this way:

Each of the beings has its own existence. Through [the common ideal], it can connect other existences with its own. These different consciousnesses set themselves a common center; they strive toward a common, specific ideal. This then lives as a communal spiritual ideal in the various consciousnesses. When they reach the point where their spiritual ideal is more valuable to them than themselves, they are attracted to this ideal in the same way that they previously attracted the members of their consciousness to themselves. Whereas they previously formed the center for these different spheres, the common ideal then forms the center for the greater sphere. The individual existences then become members of the communal existence themselves, give up their special nature, and live in the communal ideal. They cease to be centers themselves and give themselves a communal center. In this way, individual human beings form a brotherhood. When there is such a strong communal ideal that it attracts all the individual centers of consciousness, these people form a body that has a higher kind of soul. This creates a brotherhood with a completely communal spirit. And so we are dealing with a new being. A soul could never have descended into human beings if they were not a shell made of limbs. Nothing higher can ever descend unless the individual consciousnesses become limbs of life, the form for a higher shell, so that the communal consciousness can be expressed within it.

This brings us to the transition; another center is created. Human development is an inversion, a reversal of all principles. Since humans express themselves in seven ways, not one center arises, but seven centers. These will be the seven Elohim, the Pitris for the next planet.

Thus, humans transition from beings that absorb their surroundings to beings that reveal themselves. The two completely opposite entities, man and the Elohim or Dhyani, are only forms of one entity. What man is here, he will no longer be in the future, but rather a dhyan-chohanic entity. In esotericism, this is called the “secret of man's becoming God.”

When all individual consciousnesses turn toward a center and everything outside becomes Atma, there will be only a single core of Sthula Sharira within, that is, unity in the highest degree.

This unity cannot be achieved on earth; it can only be formed by seven exalted spirits. This is then the Logos, which has Atma in its orbit. In Kabbalah, the crown of everything is the “Kingdom,” the union. This principle also underlies the Church, namely that all people become members of one consciousness.

The law of form is birth and death. The law of life is rebirth. The law of the spirit is karma. Life goes through birth and death and appears in ever new forms. Form is transitory, life repeats itself, the spirit is imperishable, eternal.