The Foundations of Esotericism

GA 93a

24 October 1905, Berlin

Lecture XXII

As a continuation of the lecture on Karma and Reincarnation, let us select for special consideration the problem of death in its connection with the whole subject.

The question: Why does man die? continually claims the attention of mankind. But it is not quite easy to answer, for what we today call dying is directly connected with the fact that we stand at a quite definite stage of our development. We know that we live in three worlds, in the physical, astral and mental worlds and that our existence changes between these three worlds. We have within us an inner kernel of being which we call the Monad. We retain this kernel throughout the three worlds. It lives within us in the physical world, but also in the astral and devachanic worlds. This inner kernel, however, is always clad in a different garment. In the physical, astral and devachanic worlds the garment of our kernel-of-being is different.

Now we will first look away from death and picture the human being in the physical world clothed with a particular kind of matter. He then enters the astral and devachanic worlds always with a different garment. Let us now assume that the human being were conscious in all three worlds, so that he could perceive the things around him. Without senses and perception he would be unable to live consciously even in the physical world. If man today were equally conscious in all three worlds there would be no death, then there would only be transformation. Then he would pass over consciously from one world into the other. This passing over would be no death for him, and for those left behind at most something like a journey. At present things are so that man only gradually gains continuity of consciousness in these three worlds. At first he experiences it to be a darkening of his consciousness when he enters the other worlds from the physical world. The beings who retain consciousness do not know death. Let us now come to an understanding of the way in which man has reached the stage of having his present day physical consciousness and of how he will attain another consciousness.

We must learn to know man as a duality: as the Monad and what clothes the Monad. We ask: How has the one and how has the other arisen? Where did the astral man live before he became what he is today and where did the Monad live? Both have gone through different stages of development, both have gradually reached the point of being able to unite.

In considering the physical-astral human being we are taken back into very distant times, when he was only present as an astral archetype, as an astral form. The astral man who was originally present was a formation unlike the present astral body, a much more comprehensive being. We can picture the astral body of those times by thinking of the earth as a great astral ball made up of astral human beings. All the Nature forces and beings which surround us today were at that time still within man, who lived dissolved in astral existence. All plants, animals and so on, the animal instincts and passions, were still within him. What the lion, and all the mammals, have within them today, was at that time completely intermingled with the human astral body, which then contained within it all the beings at present spread over the earth. The astral earth consisted of human astral bodies joined together like a great blackberry and enclosed by a spiritual atmosphere in which there lived devachanic beings.

This atmosphere—astral air one might call it—which at that time surrounded the astral earth was composed of a somewhat thinner substance than the astral bodies of human beings. In this astral air lived spiritual beings—both lower and higher—among others the human Monads also, completely separated from the human astral bodies. This was the condition of the earth at that time. The Monads, which were already present in the astral air, could not unite with the astral bodies, for these were still too wild. The instincts and passions had first to be ejected. Thus through the throwing off of certain substances and forces possessed by the astral body, the latter gradually developed in a purer form. What had been thrown off however remained as separated astral forms, beings with a much denser astral body, with wilder instincts, impulses and passions.

Thus there now existed two astral bodies: a less wild human astral body and an astral body that was very wild and opaque. Let us keep these strictly apart, the human astral body and what lived around it. The human astral body becomes ever finer and nobler, always throwing off those parts of itself it needed to expel, and these became ever denser and denser. In this way, when they eventually reached physical density, the other kingdoms arose: the animal, plant and mineral kingdoms. Certain instincts and forces expelled in this way appeared as the different animal species.

So a continual purification of the astral body took place and this brought about on earth a necessary result. For through the fact that in consequence of this purification, what man once had within him he now had outside him, he entered into relationship with these beings, and what formerly he had had within him, now worked into him from outside. That is an eternal process which holds good also for the separation of the sexes, which from that time on affect each other from outside. To begin with, the whole world was interwoven with us; only later did it work upon us from outside. The original symbol for this coming back into oneself from the other side is the snake biting its tail.

In the purified astral body pictures arise now of the world surrounding it. Let us assume that a human being had perhaps separated off ten different forms, which are now around him. Previously they were within him and later he is surrounded by them. Now mirrored pictures arise in the purified astral body of the forms existing in the outer world. These mirrored pictures become a new force within him, they are active within him, transforming the nobler, purified astral body. For instance, it has rejected from itself the wilder instincts; these are now outside it as pictures and work upon it as formative force. The astral body is built up by means of the pictures of the world it has thrown off and which were earlier within it. They build up in it a new body. Formerly man had had the macrocosm within him, he then separated it off and now this formed within him the microcosm, a portion torn off from himself.

Thus at a certain stage we find the human being in a form which is given him by his surroundings. The mirrored pictures work on his astral body in such a way that they bring about in it differentiation and division. Through the mirrored pictures his astral body divided itself and he re-assembled it again out of the parts, so that he is now a membered organism. The undifferentiated astral mass has become differentiated into the different organs, the heart and so on. To begin with everything was astral and this was then enclosed by the physical human body. Thereby the human forms became more and more adapted to densification and to becoming a more complicated and comprehensive organism, which is an image of the entire environment.

What has become densest of all is the physical body; the etheric body is less dense and the astral body is the finest. They are in reality mirrored images of the outer-world, microcosm in the macrocosm. Meanwhile the astral body has become ever finer and finer, so that at a certain point of earth evolution the human being has a developed astral body. Through the fact that the astral body has become increasingly finer, it has attracted to itself the finer astral substance around it.

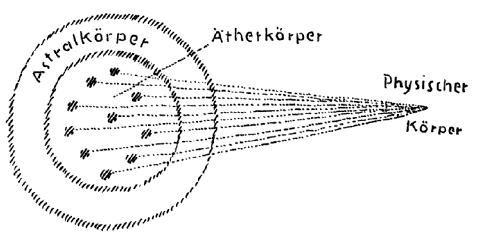

Meanwhile in the upper region the opposite evolutionary processes have taken place. The Monad has descended from the highest regions of Devachan into the astral region and in the course of this descent has become denser. Now the two parts approach each other. From the one side man ascends as far as the astral body, from the other side it is met by the Monad on its descent into the astral world. This was in the Lemurian Age. Thus they could mutually fructify each other. The Monad had clothed itself with devachanic substance, then again with astral airy substance. From below upwards we have the physical substance, then the etheric substance, then again astral substance. So both astral substances fructify one another and, as it were, melt into one another. What comes from above has the Monad within it. As though into a bed, it sinks itself into the astral substance.

This is how the descent of the soul takes place. But in order that it can happen the Monad must develop a thirst to know the lower regions. This thirst must be taken for granted. As Monad one can only learn to know the lower regions by incarnating in the human body and by its means looking out into the surrounding world. Man now consists of four members. Firstly he has a physical body, secondly an etheric body, thirdly an astral body and within this as fourth member of the ego, the Monad. After the four-fold organism has come into being the Monad can look through it into the environment and a relationship is established between the Monad and everything that is in the surroundings. Through this the thirst of the Monad is partially assuaged.

We have seen that the entire human body is put together, has been put together, out of parts which arose through the fact that the originally undifferentiated mass divided itself into organs, after the original astral body had thrown off various portions of itself which were then reflected back, causing images to arise within it.60Text of this portion is very incomplete and cannot be considered as literal. These reflected images became forces within the astral body and these built up the etheric body, that is to say, through these manifold images the etheric body developed separate members. This etheric body now consisted of different parts and, as a further process, each of these parts densified within itself and so the differentiated physical body developed. Every such physical kernel, out of which the organs later develop, forms at the same time a kind of central point in the ether.

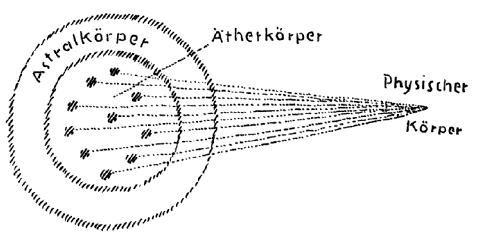

The intervening spaces between the centres are filled with the main etheric mass. We must think of the body as put together out of ten parts. These ten parts (shown in the diagram) hold the body together through their relationship; they are images of the whole of the rest of Nature and everything depends on how strongly they are connected. Different degrees of relationship exist between the separate parts. As long as these are retained the body is held together; when the various relationships cease, the parts fall away; the body disintegrates. Because during Earth evolution we have manifold forms, the parts in the etheric body only hold together to a certain degree. Human nature is an image of the beings which have been thrown off. In so far as these beings lead a separate existence, the parts of the physical body also lead a separate existence. When the relationship of forces has become so slight as to be non-existent, our life comes to an end. The length of our life is conditioned by the way in which the beings around us get on with each other.

The development of the higher man proceeds in such a way that, to begin with, man works upon his astral body. He works ideals into it, enthusiasm and so on. He fights against his instincts. As soon as he replaces passions with ideals, instincts with duties, and develops enthusiasm in the place of desires, he creates harmony between the parts of his astral body. This peace-making work begins with the entrance of the Monad, and the astral body gradually approaches immortality. From that time on, the astral body no longer dies but retains continuity to the degree in which it has induced peace in itself and established peace in the face of the destructive forces. From the time when the Monad enters, it brings about peace, to begin with in the astral body. Now the instincts begin to come into mutual relationship. Harmony comes about in the former chaos and an astral form arises which survives, remains living. In the physical and etheric bodies peace is as yet not established, and only partly so in the astral body. The latter retains its form for a short time only, but the more peace is established, so much the longer is the time in Devachan.

When someone has become a Chela he begins to establish peace in the etheric body. Then the etheric body too survives. The Masters also establish peace in the physical body; thus in their case the physical body also survives. The important thing is to bring into harmony the different bodies, which consist of separate warring parts, and transmute them into bodies having immortality.

Man has formed his physical body by putting out from himself the kingdoms of Nature, which then reflected themselves back into him. Through this, the single parts came into existence within him. Now he performs actions; through these he again has intercourse with his surroundings. What he now puts out are the effects of his deeds. He projects his actions into the surrounding world and gradually becomes a reflection of these actions. The Monad has been drawn into the human body; man begins to perform actions. These actions are incorporated into the surrounding world and are reflected back. To the same degree in which the Monad begins to establish peace, it also begins to take up the reflected images of its own actions.

Here we have come to a point where we continually create a new kingdom around us—the effects of our own actions. This again builds up something within us. As previously we fashioned the undifferentiated etheric body into separate members, we build into the monadic existence the effects of our actions. We call this the creation of our Karma. Thereby we can give permanence to everything in the Monad. Earlier the astral body had purified itself by casting off everything that was in it. Now man created for himself a new kingdom of deeds, as it were out of nothing, in regard to relationships, a ‘creation out of nothing’. That which previously had no existence, the new relationship, reflects itself in the Monad as something new, something having a pictorial character, and a new inner kernel of being is formed in the Monad, arising out of the reflected image of deeds, the reflection of Karma. As the work of the Monad progresses, the kernel of being becomes more and more enlarged. Let us observe the Monad after a period of time. On the one hand it will have established harmony out of the warring forces, and on the other hand out of the effects of deeds. Both unite and a unified formation arises.

Let us suppose that someone's earthly garment has been laid aside and the Monad remains. It retains the results of its deeds. The question is, how the results of the deeds are brought about. If these results have been so brought about that in the worlds in which the Monad now finds itself they can continue to be fruitful, then the human being can sojourn there for a long time; if not, for a short time only. In this case they must fall back again into the thirst of the Monad (for the physical plane) and once again inhabit a physical body.

Human life is a continual process of being enveloped in what surrounds us: Involution—Evolution. We take up image forms and according to these, shape our own body. What the Monad has brought about is again taken up by man as his Karma. Man will always be the result of his Karma. The Vedanta teaches that the different parts of the human being are dissolved and cast to the winds; what still remains of him, that is his Karma. This is the eternal which man has created out of himself, something which he himself had first to take up as image out of his environment. Man is immortal; he only needs to exert his will, he only needs to form his actions in such a way that they have a lasting existence. That part of us is immortal which we gain for ourselves from the outside world. We have come into being through the world and are beginning, through fructification with the Monad, to build up in ourselves the mirror of a new world. The Monad has quickened the mirrored images in us. Now these images can work outwards, and the effects of these images reflect themselves anew. A new inner life arises. With our actions we are continually changing our environment. Through this, new reflected images come about; these now become karma. This is a new life which springs up from within. The result of this is that in order to develop further from a definite point of time we must go out of ourselves and work selflessly in our surroundings. We must make possible this going out from ourselves in order selflessly to bring about harmonious relationships in our surroundings. This necessitates a harmonising of the reflected images in ourselves. It is our task to make the world around us a harmonious one. If we are a destructive element in the world, what is reflected into us is devastation: if we bring about harmony in the world, harmonies are reflected into us.

The highest degree of perfection which we have put out from ourselves, which we have established around us, this we shall take with us. Therefore the Rosicrucians said: Form the world in such a way that it contains within itself Wisdom, Beauty and Strength; then Wisdom, Beauty and Strength will be reflected into us. Wisdom is the reflection of Manas; Beauty, Piety, Goodness are the reflection of Buddhi; Strength is the reflection of Atma.

To begin with we develop around us a domain of Wisdom through ourselves fostering Wisdom. Then we develop a domain of Beauty in all regions. Then Wisdom becomes visible and reflects itself in us: Buddhi. Finally we bestow on the whole physical existence, Wisdom within, Beauty without.

If our will enables us to carry this through, then we have strength: Atma, the power to transpose all this into reality. Thus we establish the three kingdoms within us: Manas, Buddhi, Atma.

Not through laborious research does man progress further on the earth, but by embodying into the earth Wisdom, Beauty and Strength. Through the work of our higher Ego we transform the transient body given us by the Gods and create for ourselves immortal bodies. The Chela, who ennobles his etheric body (so that it remains in existence), gradually renounces the Maharajas. The Master, whose physical body also remains in existence, can renounce the Lipikas. He stands above Karma. This we must describe as the progress of man in his inner life. What is higher, outside ourselves, we must seek to approach. Therefore our Higher Self is not to be sought within us, but in the individualities who have ascended into loftier regions.

XXII

Als Fortsetzung der Besprechung von Karma und Reinkarnation wollen wir als besondere Frage im Zusammenhang des Ganzen das Problem des Todes behandeln.

Die Frage: Warum stirbt der Mensch? — beschäftigt fortwährend die Menschheit. Aber sie ist nicht so ganz leicht zu beantworten, denn was wir heute sterben nennen, hängt zusammen damit, daß wir auf einer ganz bestimmten Stufe unserer Entwickelung stehen. Wir wissen, daß wir zunächst in drei Welten leben, in der physischen, astralen und der mentalen Welt, und daß unser Dasein wechselt zwischen diesen drei Welten. In uns haben wir einen inneren Wesenskern, den wir die Monade nennen. Diesen Wesenskern erhalten wir uns durch die drei Welten hindurch. Er lebt in der physischen Welt in uns, aber auch in der astralen und devachanischen Welt lebt er in uns. Der innere Wesenskern ist da nur immer mit einem verschiedenen Gewande umkleidet. In der physischen, astralen und devachanischen Welt ist das Gewand unseres Wesenskernes verschieden.

Wir sehen nun zunächst ab von dem Tode und stellen uns den Menschen in der physischen Welt mit einer gewissen Materie bekleidet vor. Dann tritt er in die astrale und devachanische Welt jedesmal mit einem anderen Gewande. Nehmen wir nun an, der Mensch wäre in allen drei Welten bewußt, so daß er die Dinge ringsherum wahrnehmen könnte. Ohne Sinne und Wahrnehmung würde der Mensch auch in der physischen Welt nicht bewußt leben. Wäre der Mensch heute gleichmäßig in allen drei Welten bewußt, dann gäbe es keinen Tod, dann gäbe es nur Verwandlung. Dann würde der Mensch aus einer Welt in die andere bewußt hinübergehen. Dieses Hinübergehen wäre dann für ihn kein Sterben und für die Zurückbleibenden höchstens wie ein Verreisen. Nun ist es so, daß der Mensch erst nach und nach sich die Kontinuität des Bewußtseins in diesen drei Welten erwirbt. Er empfindet es zunächst als eine Verdunkelung seines Bewußtseins, wenn er aus der physischen in die anderen Welten hineingeht. Er wird sich erst wieder klar bewußt, wenn er in die physische Welt zurückkehrt. Die Wesen, die das Bewußtsein behalten, kennen den Tod nicht. Verständigen wir uns nun darüber, wie der Mensch dazu gekommen ist, das gegenwärtige physische Bewußtsein zu haben, und wie er ein anderes Bewußtsein erwerben wird.

Wir müssen den Menschen durchaus als eine Zweiheit, als aus zwei Wesen zusammengesetzt, erkennen: aus der Monade und der Umkleidung der Monade. Wir fragen: Wie ist das eine und wie ist das andere entstanden? Wo lebte der astralische Mensch, bevor er das geworden ist, was er heute ist, und wo lebte die Monade? — Beide haben verschiedene Entwickelungsstadien durchgemacht, beide sind nach und nach erst dazugekommen, sich vereinigen zu können.

Bei der Betrachtung des physisch-astralischen Menschen werden wir in sehr ferne Zeiten zurückgewiesen, wo er nur als ein astrales Urbild, als eine astrale Form vorhanden war. Der astrale Mensch, der da ursprünglich vorhanden war, der war ein Gebilde, das nicht so war wie der heutige Astralkörper, sondern eine viel umfassendere Wesenheit. Diesen einstigen Astralkörper kann man sich so vorstellen, daß die Erde damals wie ein großer Astralball war, zusammengesetzt aus den astralen Menschen. Alle Naturkräfte und Wesenheiten, die uns heute umgeben, waren damals noch im Menschen darinnen; der Mensch lebte aufgelöst im astralen Dasein. Alle Pflanzen, Tiere und so weiter, die tierischen Instinkte und Leidenschaften lebten damals noch im astralischen Menschen. Was heute der Löwe, was die sämtlichen Säugetiere in sich haben, war damals mit dem Astralkörper des Menschen durch und durch vermischt. Der Astralkörper des Menschen hatte damals sämtliche auf dieser Erde verteilten Wesenheiten in sich. Die astrale Erde war aus lauter astralen Menschenkörpern zusammengefügt wie eine große Brombeerkugel und eingeschlossen in eine geistige Atmosphäre, in der devachanische Wesenheiten lebten.

Diese Atmosphäre — Astralluft könnte man sie nennen -, die die damalige astrale Erde umgab, war aus einer etwas dünneren Substanz als der Astralkörper des Menschen. In dieser Astralluft lebten geistige Wesenheiten, niedere und höhere, unter anderem auch die menschlichen Monaden, ganz abgetrennt von dem menschlichen Astralkörper. Das war der damalige Zustand der Erde. Die Monaden, die schon vorhanden waren in der astralen Luft, die konnten sich nicht verbinden mit dem Astralkörper, denn die Astralkörper der Menschen waren damals noch zu wild. Die Instinkte und Leidenschaften mußten erst aus demselben herausgesetzt werden. So entstand durch Ausscheidung gewisser Substanzen und Kräfte, die der Astralkörper hatte, der menschliche Astralkörper allmählich in einer reineren Form. Die Ausscheidungen aber blieben gesonderte astrale Gebilde, Wesenheiten mit noch viel dichterem Astralleib, mit wilderen Einzelinstinkten, Trieben, Leidenschaften.

Jetzt waren also zwei Astralkörper da: ein weniger wilder menschlicher Astralkörper und ein sehr dichter wilder Astralleib. Halten wir diese beiden streng auseinander: den menschlichen Astralkörper und alles das, was da um ihn herum lebte. Der menschliche Astralkörper wird immer feiner, edler und treibt immer weitere Ausscheidungen heraus, welche immer dichter und dichter wurden. Daraus entstanden - als sie bis zur physischen Dichtigkeit kamen - die anderen Reiche: das Tier-, das Pflanzen- und das Mineralreich. Gewisse ausgeschiedene Instinkte und Kräfte traten durch diesen Verdichtungsprozeß als die verschiedenen Tierklassen hervor.

So fand eine fortwährende Reinigung der Astralkörper statt und das hatte auf der Erde eine notwendige Folge. Denn dadurch, daß der Mensch infolge der Reinigung das, was er früher in sich hatte, nun neben sich hatte, trat er in Verkehr mit diesen Wesen, und was er so früher in sich gehabt hatte, das wirkte jetzt von außen in den Menschen hinein. Das ist ein ewiger Prozeß, auch beim Absondern der beiden Geschlechter, die darnach auch von außen aufeinander einwirken. Die ganze Welt war zuerst mit uns verwoben; dann erst wirkte sie von außen auf uns ein. Das Ursymbol für dieses Zurückkommen in sich selbst von der anderen Seite ist die Schlange, die sich in den Schwanz beißt.

In dem geläuterten Astralkörper entstehen nun Bilder der ihn umgebenden Welt. Nehmen wir an, der Mensch hätte vielleicht zehn verschiedene Formen ausgesondert, die ihn nun umgeben. Früher waren sie in ihm und jetzt sind sie um ihn herum. Nun entstehen in dem geläuterten Astralleibe Spiegelbilder der ihn umgebenden Welt, der außer ihm sich befindenden Formen. Diese Spiegelbilder werden in ihm zu einer neuen Kraft, sie wirken in ihm, gestalten den edleren Astralkörper um, der sich geläutert hat. Er hat zum Beispiel die Wildheit aus sich herausgesetzt; sie ist jetzt außer ihm als ein Bild und wirkt nun auf ihn als gestaltende Kraft. Der Astralleib wird aufgebaut durch die Bilder der ausgeschiedenen Welt, die früher in ihm war. Sie bauen in ihm einen neuen Körper auf. Der Mensch hatte früher den Makrokosmos in sich gehabt, ihn dann herausgesetzt, und das formte nun in ihm den Mikrokosmos, einen Abriß seiner selbst.

So treffen wir den Menschen auf einer bestimmten Stufe an in einer Gestalt, die ihm verliehen wird von seiner ganzen Umgebung. Die Spiegelbilder wirken so auf seinen Astralleib, daß sie ihn differenzieten und spalten. Durch die Spiegelbilder spaltete sich sein Astralkörper und er setzte ihn wieder neu zusammen aus den Teilen, so daß er dann ein gegliederter Organismus ist. Die gemeinsame Astralmasse ist differenziert worden zu den verschiedenen Organen, zum Herzen und so weiter. Zuerst war alles astral, und dann hat sich der Physische Mensch herumgelagert. Die menschlichen Bildungen wurden dadurch immer mehr geeignet, sich zu verdichten und ein komplizierterer und mannigfaltigerer Organismus zu werden, der ein Abbild der ganzen Umgebung ist.

Was am allerdichtesten geworden ist, ist der physische Körper; weniger dicht ist der Ätherkörper, und am feinsten ist der Astralkörper. Sie sind im wesentlichen Spiegelbilder der Außenwelt, Mikrokosmos im Makrokosmos. Dabei ist der Astralkörper immer feiner und feiner geworden, so daß der Mensch an einem bestimmten Punkte der Erdenentwickelung einen entwickelten Astralkörper hat. Dadurch, daß der Astralkörper immer feiner geworden ist, hat er sich der feinen Astralmaterie um ihn herum angenähert.

In der oberen Region haben sich unterdessen die entgegengesetzten Entwickelungsvorgänge vollzogen. Die Monade ist von oben, aus den höchsten Devachanregionen bis in die Astralregion heruntergestiegen und hat sich bei diesem Abstieg verdichtet. Da kommen sich die beiden Teile entgegen. Von der einen Seite steigt der Mensch herauf bis in den Astralkörper, von der anderen Seite begegnet ihm die Monade auf ihrem Abstieg in der astralischen Welt. Das war in der lemurischen Zeit. Da konnten sich beide befruchten. Die Monade hat sich umkleidet mit devachanischer Materie, dann mit der astralen Luftmaterie. Von unten herauf haben wir die physische Materie, dann Äthermaterie, dann wieder Astralmaterie. So befruchten sich die beiden Astralmaterien und verschmelzen miteinander. Das was von oben kommt, hat die Monade in sich. Wie in ein Bett bettet sie sich in die Astralmaterie ein.

So findet das Herabsteigen der Seele statt. Aber damit das geschehe, muß die Monade einen Durst nach Kenntnisnahme der unteren Regionen entwickeln. Diesen Durst muß man zunächst voraussetzen. Die unteren Regionen kann man als Monade nur kennenlernen, wenn man sich in dem Menschenkörper inkarniert und durch ihn in die Umgebung hinausschaut. Jetzt ist der Mensch viergliedrig: Er hat erstens einen physischen Körper, zweitens einen Ätherkörper, drittens einen Astralkörper und darinnen viertens das Ich, die Monade. Nachdem der viergliedrige Leib vorhanden ist, kann die Monade durch ihn hinausschauen in die Umgebung, und es tritt dann ein Verkehr ein zwischen der Monade und alledem, was in der Umgebung ist. Dadurch wird der Durst der Monade einigermaßen gestillt.

Wir haben gesehen, daß der ganze menschliche Leib sich zusammensetzt, zusammengesetzt hat aus Teilen, die dadurch entstanden sind, daß die ursprünglich ungegliederte Masse sich in Organe geteilt hat, nachdem der ursprüngliche Astralleib Verschiedenes ausgesondert hatte und durch diese um ihn herumstehenden Aussonderungen, die sich in ihm abspiegelten, in ihm Bilder entstanden sind. Diese Bilder wurden in ihm Kräfte und formten seinen Ätherleib; das heißt, durch diese mannigfaltigen Bilder wird sein Ätherleib gegliedert. In diesem nun aus Teilen bestehenden Ätherleib verdichtet sich wiederum jeder solche Ätherteil in sich und es entsteht der physische Gliedkörper. Jeder solche physische Kern, aus dem dann die Organe werden, bildet zu gleicher Zeit eine Art von Zentrum im Äther.

Die Zwischenräume zwischen den Zentren sind durch die bloße Äthermasse ausgefüllt. Wir denken uns den Körper so aus zehn Teilen zusammengesetzt. Diese zehn Teile, die wir als Schema nehmen, halten den Körper zusammen durch ihre Verwandtschaft; sie sind Abbilder der ganzen übrigen Natur und es hängt davon ab, wie stark sie zusammenhängen. Es bestehen in ihnen Grade der Verwandtschaft mit den einzelnen Teilen. Solange diese halten, bleibt der Körper zusammen, wenn die Verwandtschaftsgrade aufhören, fallen die Teile auseinander; der Körper zerfällt. Da wir während der irdischen Entwickelung die mannigfaltigsten Gebilde herausgesetzt haben, so halten die Teile im Ätherkörper nur in gewissem Grade zusammen. Die menschliche Natur ist ein Abbild der herausgesetzten Wesenheiten. Soweit die Wesen ein Sonderdasein führen, so weit führen auch die Teile des physischen Körpers ein Sonderdasein. Wenn die Verwandtschaft der Kräfte so gering geworden ist, daß sie aufhört, so leben wir nur bis dahin; das Maß unserer Lebenszeit ist dadurch bedingt, wie sich die Wesenheiten rund um uns herum vertragen.

Die Entwickelung des höheren Menschen geht so vor sich, daß der Mensch zunächst an seinem Astralleibe arbeitet. Da arbeitet er hinein Ideale, Enthusiasmus und so weiter. Die Instinkte bekämpft er. In dem Augenblicke, da der Mensch Ideale an die Stelle von Trieben, und Pflichten an die Stelle von Instinkten setzt, und Enthusiasmus statt Begierden entwickelt, schafft er Harmonie in die Teile seines Astralleibes hinein. Diese friedenstiftende Arbeit beginnt mit dem Eintritt der Monade und der Astralleib fängt an, immer mehr und mehr unsterblich zu werden. Von da an stirbt der Astralleib nicht mehr, sondern er überdauert in dem Maße, als er Frieden gestiftet hat, als der Friede gegenüber den zerstörenden Kräften standhalten kann. Von dem Augenblicke an, da die Monade hineinkommt, stiftet sie Frieden, zunächst im Astralleib. Da fangen die Instinkte an, sich zu vertragen. Harmonie entsteht in dem früheren Chaos und es entsteht ein astrales Gebilde, welches überdauert, leben bleibt. Im physischen Leib und im Ätherleib wird zunächst nicht Frieden gestiftet, sondern zum Teil nur im Astralleib. Er erhält sich in anderen Welten zunächst nur kurze Zeit, aber je mehr Frieden gestiftet worden ist, desto länger dauert die Devachanzeit.

Wenn dann der Mensch Chela geworden ist, fängt er auch an, im Ätherkörper Frieden zu stiften. Dann überdauert auch der Ätherkörper. Bei den Meistern wird auch Frieden im physischen Leib gestiftet; daher überdauert bei ihnen auch der physische Leib. Es handelt sich darum, die verschiedenen Körper, die aus einzelnen sich bekämpfenden Teilen bestehen, in Harmonie zu bringen und sie in ewige Körper zu verwandeln.

Der Mensch hat sich den physischen Körper geformt, indem er die Naturreiche aus sich herausgesetzt hat, die sich wieder in ihm spiegelten. Dadurch sind die einzelnen Teile in ihm entstanden. Nun vollbringt er Handlungen; durch diese tritt er wieder in Verkehr mit der Umgebung. Was er jetzt hinaussetzt, sind die Wirkungen seiner Taten. Jetzt gliedert er seine Taten in die Umwelt ein, und er wird nach und nach zu einem Spiegelbild dieser seiner Taten. Die Monade ist in den menschlichen Leib eingezogen; sie beginnt Taten zu tun. Ihre Taten sind es, die der Umwelt eingegliedert werden, und sie spiegeln sich wieder in ihm ab. In demselben Maße, in dem sie beginnt Frieden zu stiften, beginnt sie auch die Spiegelbilder ihrer eigenen Taten aufzunehmen.

Nun sind wir bei einem Punkte angekommen, wo wir fortwährend um uns herum ein neues Reich schaffen, die Wirkungen unserer eigenen Taten. Das baut in uns wiederum etwas auf. Wie wir früher den zurückgebliebenen Ätherkörper aus den Spiegelbildern herausgegliedert haben, so gliedern wir jetzt der monadischen Existenz die Wirkung unserer Taten ein. Das nennen wir die Begründung unseres Karmas. Dadurch können wir das alles in der Monade bleibend machen. Früher hat sich der Astralleib gereinigt, indem er alles abgeworfen hat, was in ihm war. Jetzt schafft der Mensch sich ein neues Tatenreich, gleichsam aus dem Nichts heraus, den Verhältnissen nach aus dem Nichts heraus. Das was vorher kein Dasein hat, das neue Verhältnis, es spiegelt sich als etwas Neues, das einen bildhaften Charakter hat, in der Monade ab, und es bildet sich in ihr ein neuer innerer Wesenskern, der aus dem Spiegelbild der Taten entsteht, das Spiegelbild des Karmas. Indem die Monade immer weiterarbeitet, vergrößert sich der Wesenskern mehr und mehr. Nach einiger Zeit schauen wir die Monade an: sie wird dann Harmonie herausgebildet haben aus den streitenden Kräften einerseits, und auf der anderen Seite aus den Wirkungen der Taten. Beide verbinden sich miteinander, es entsteht ein gemeinschaftliches Gebilde.

Nehmen wir an, von dem Menschen wird das irdische Kleid abgelöst und die Monade bleibt übrig. Sie behält die Wirkungen ihrer Taten zurück. Es fragt sich, wie die Wirkung der Taten beschaffen ist. Ist sie so beschaffen, daß sie in den Welten, in denen die Monade nun sich befindet, sich betätigen kann, dann werden die Menschen sich lange da aufhalten können, wenn nicht, dann kurz. Dann müssen sie wieder in den Durst der Monade [nach dem physischen Plan] zurückfallen und wieder einen physischen Körper beziehen.

Das menschliche Leben ist immerfort eine Einhüllung dessen, was uns umgibt: Involution - Evolution. Wir nehmen Bildformen auf und gestalten darnach unseren eigenen Körper. Was die Monade gewirkt hat, das nimmt der Mensch wieder auf als Karma. Der Mensch wird immerfort die Wirkung seines Karmas sein. - Im Vedanta wird gelehrt, daß die verschiedenen Teile des Menschen aufgelöst und in alle Windrichtungen verteilt werden; was dann noch von ihm vorhanden bleibt, das ist sein Karma. Das ist das Ewige, was der Mensch aus sich selbst gemacht hat, was er selbst zunächst als Bild aus seiner Umgebung aufgenommen hat. Der Mensch ist unsterblich; er braucht nur zu wollen, er braucht nur seine Taten so zu gestalten, daß sie ein bleibendes Dasein haben. Unsterblich ist an uns dasjenige, was wir uns von außen her erwerben. Wir sind geworden durch die Welt und fangen an, durch die Befruchtung mit der Monade in uns den Spiegel einer neuen Welt aufzubauen. Die Monade hat die Spiegelbilder in uns belebt. Jetzt können die Bilder hinauswirken, und nun spiegeln sich neuerdings die Wirkungen dieser Bilder. Es entsteht ein neues inneres Leben. Wir verändern mit unseren Taten fortwährend unsere Umgebung. Dadurch entstehen neue Spiegelbilder; die werden nun zum Karma. Das ist ein neues Leben, das dem Inneren entsprießt. Daraus geht hervor, daß wir, um uns höher zu entwickeln, von einem bestimmten Punkt an aus uns selbst herausgehen und selbstlos in die Umgebung wirken müssen. Dieses Herausgehen müssen wir möglich machen, um unsere Umgebung selbstlos in harmonische Verhältnisse zu versetzen. Das bedingt ein Harmonisieren der Spiegelbilder in uns. Unsere Aufgabe ist es, die Welt um uns herum zu einer harmonischen zu machen. Sind wir Zerstörer in der Welt, so spiegeln sich in uns die Verwüstungen; wirken wir Harmonie in der Welt, so spiegeln sich in uns die Harmonien.

Den letzten Grad von Vollkommenheit, den wir hinausgesetzt haben, den wir um uns gestiftet haben, werden wir mit uns nehmen. Daher sagten die Rosenkreuzer: Gestalte die Welt so, daß sie in sich enthält Weisheit, Schönheit und Stärke, dann spiegelt sich in uns Weisheit, Schönheit und Stärke. Hast du die Zeit dazu benutzt, dann ziehst du selbst aus dieser Erde hinaus mit dem Spiegelbild von Weisheit, Schönheit und Stärke. Weisheit ist das Spiegelbild des Manas; Schönheit, Frömmigkeit, Güte ist das Spiegelbild der Buddhi; Stärke ist das Spiegelbild des Atma.

Zuerst entwickeln wir um uns her ein Reich der Weisheit dadurch, daß wir die Weisheit fördern. Dann entwickeln wir ein Reich der Schönheit auf allen Gebieten. Dann tritt sichtbar Weisheit auf und es spiegelt sich in uns: Buddhi. Zuletzt verleihen wir dem Ganzen physisches Dasein, Weisheit im Inneren, Schönheit nach außen.

Wenn wir die Kraft haben, dies durchzusetzen, dann haben wir Stärke: Atma, die Kraft, alles das in Realität umzusetzen. So richten wir in uns die drei Reiche auf: Manas, Buddhi, Atma.

Nicht durch müßige Beschaulichkeit gelangt der Mensch auf der Erde weiter, sondern indem er der Erde Weisheit, Schönheit und Stärke einverleibt. Durch die Arbeit unseres höheren Ich gestalten wir die uns von den Göttern gegebenen vergänglichen Leiber um und schaffen uns selbst ewige Leiber. Der Chela, der seinen Ätherleib veredelt [so daß er erhalten bleibt], verzichtet allmählich auf die Maharajas. Der Meister, bei dem auch der physische Leib erhalten bleibt, kann auf die Lipikas verzichten. Er steht über Karma. Das müssen wir als den Fortschritt des Menschen in seinem Inneren bezeichnen. Was höher ist, außerhalb von uns, müssen wir suchen zu betreten. Daher ist unser höheres Selbst nicht in uns zu suchen, sondern in den höhergestiegenen Individualitäten.

XXII

Continuing our discussion of karma and reincarnation, we will now address the problem of death as a special question in connection with the whole.

The question: Why do humans die? — has always preoccupied humanity. But it is not so easy to answer, because what we call death today is connected with the fact that we are at a very specific stage of our development. We know that we live in three worlds, the physical, astral, and mental worlds, and that our existence alternates between these three worlds. Within us, we have an inner core of being that we call the monad. We retain this core being throughout the three worlds. It lives within us in the physical world, but it also lives within us in the astral and devachanic worlds. The inner core of our being is always clothed in a different garment. In the physical, astral, and devachanic worlds, the garment of our core being is different.

Let us now disregard death for the moment and imagine human beings in the physical world clothed in a certain kind of matter. Then they enter the astral and devachanic worlds, each time wearing a different garment. Let us now assume that human beings were conscious in all three worlds, so that they could perceive the things around them. Without senses and perception, humans would not live consciously even in the physical world. If humans were equally conscious in all three worlds today, there would be no death, only transformation. Humans would then consciously pass from one world to another. This passing would not be dying for them, but at most like traveling for those left behind. Now it is the case that human beings only gradually acquire the continuity of consciousness in these three worlds. At first, they experience it as a darkening of their consciousness when they enter the other worlds from the physical world. They only become clearly conscious again when they return to the physical world. The beings who retain consciousness do not know death. Let us now agree on how human beings came to have their present physical consciousness and how they will acquire a different consciousness.

We must recognize human beings as a duality, composed of two beings: the monad and the envelope of the monad. We ask: How did one come into being and how did the other come into being? Where did the astral human being live before becoming what it is today, and where did the monad live? — Both have gone through different stages of development, both have gradually come to be able to unite.

When we consider the physical-astral human being, we are thrown back to very distant times, when he existed only as an astral archetype, as an astral form. The astral human being that originally existed there was a form that was not like today's astral body, but a much more comprehensive entity. This former astral body can be imagined as the Earth at that time being like a large astral ball, composed of astral human beings. All the forces of nature and beings that surround us today were still within human beings at that time; human beings lived dissolved in astral existence. All plants, animals, and so on, the animal instincts and passions still lived in astral human beings at that time. What lions and all mammals have within them today was thoroughly mixed with the astral body of human beings at that time. The astral body of human beings at that time contained all the beings distributed on this earth. The astral earth was composed entirely of astral human bodies, like a large blackberry ball, and enclosed in a spiritual atmosphere in which devachanic beings lived.

This atmosphere—which could be called astral air—that surrounded the astral earth at that time was made of a slightly thinner substance than the astral body of humans. Spiritual beings, both lower and higher, lived in this astral air, including human monads, completely separated from the human astral body. That was the state of the earth at that time. The monads that already existed in the astral air could not connect with the astral body, because the astral bodies of humans were still too wild at that time. The instincts and passions first had to be removed from them. Thus, through the elimination of certain substances and forces that the astral body possessed, the human astral body gradually emerged in a purer form. However, the eliminations remained separate astral formations, beings with an even denser astral body, with wilder individual instincts, drives, and passions.

So now there were two astral bodies: a less wild human astral body and a very dense, wild astral body. Let us keep these two strictly separate: the human astral body and everything that lived around it. The human astral body became increasingly refined and noble, expelling more and more secretions, which became denser and denser. When these reached physical density, they gave rise to the other kingdoms: the animal, plant, and mineral kingdoms. Certain expelled instincts and forces emerged through this process of densification as the various classes of animals.

Thus, a continuous purification of the astral bodies took place, and this had a necessary consequence on Earth. For as a result of the purification, human beings now had beside them what they had previously had within themselves, and they came into contact with these beings, and what they had previously had within themselves now worked into human beings from outside. This is an eternal process, also in the separation of the two sexes, which thereafter also influence each other from outside. The whole world was first interwoven with us; only then did it influence us from outside. The original symbol for this return to oneself from the other side is the snake biting its own tail.

Images of the world surrounding him now arise in the purified astral body. Let us assume that the human being has perhaps separated out ten different forms that now surround him. Previously they were within him, and now they are around him. Now mirror images of the world surrounding him, of the forms outside him, arise in the purified astral body. These mirror images become a new force within him; they work within him, reshaping the nobler astral body that has been purified. For example, he has cast out the wildness from within himself; it is now outside him as an image and now acts upon him as a formative force. The astral body is built up by the images of the separated world that used to be within him. They build a new body within him. The human being had previously had the macrocosm within him, then cast it out, and this now formed the microcosm within him, an outline of himself.

Thus we encounter the human being at a certain stage in a form that is bestowed upon him by his entire environment. The mirror images act on his astral body in such a way that they differentiate and divide it. Through the mirror images, his astral body split and he reassembled it from the parts, so that it then became a structured organism. The common astral mass has been differentiated into the various organs, the heart, and so on. At first, everything was astral, and then the physical human being formed around it. Human formations thus became increasingly capable of condensing and becoming a more complex and diverse organism that is a reflection of the entire environment.

What has become most dense is the physical body; less dense is the etheric body, and the finest is the astral body. They are essentially mirror images of the outside world, microcosms within the macrocosm. The astral body has become finer and finer, so that at a certain point in the Earth's development, human beings have a developed astral body. As the astral body has become finer and finer, it has approached the fine astral matter around it.

Meanwhile, the opposite developmental processes have taken place in the upper region. The monad has descended from above, from the highest Devachan regions to the astral region, and has become denser during this descent. Here the two parts meet. On one side, the human being ascends into the astral body; on the other side, the monad encounters him on its descent into the astral world. This was in the Lemurian epoch. There, both were able to fertilize each other. The monad clothed itself in devachanic matter, then in astral air matter. From below, we have physical matter, then etheric matter, then astral matter again. In this way, the two astral matters fertilize each other and merge together. What comes from above has the monad within it. Like a bed, it embeds itself in the astral matter.

This is how the descent of the soul takes place. But for this to happen, the monad must develop a thirst for knowledge of the lower regions. This thirst must first be presupposed. As a monad, one can only get to know the lower regions by incarnating in the human body and looking out into the environment through it. Now the human being is fourfold: First, they have a physical body; second, an etheric body; third, an astral body; and fourth, within it, the I, the monad. Once the fourfold body is in place, the monad can look out into the environment through it, and communication then takes place between the monad and everything in the environment. This satisfies the monad's thirst to some extent.

We have seen that the entire human body is composed of parts that came into being when the originally unstructured mass divided into organs after the original astral body had separated out various elements and, through these separations surrounding it, which were reflected in it, images arose within it. These images became forces within it and formed its etheric body; that is, its etheric body is structured by these manifold images. In this etheric body, now composed of parts, each such etheric part in turn condenses within itself and the physical limb body arises. Each such physical core, from which the organs then develop, simultaneously forms a kind of center in the ether.

The spaces between the centers are filled with the mere etheric mass. We imagine the body to be composed of ten parts. These ten parts, which we take as a model, hold the body together through their kinship; they are images of the rest of nature, and it depends on how strongly they are connected. There are degrees of kinship between them and the individual parts. As long as these hold, the body remains together; when the degrees of kinship cease, the parts fall apart and the body disintegrates. Since we have projected the most diverse forms during our earthly development, the parts of the etheric body only hold together to a certain degree. Human nature is a reflection of the projected entities. To the extent that the entities lead a separate existence, the parts of the physical body also lead a separate existence. When the kinship of forces has become so small that it ceases, we live only until then; the length of our life is determined by how well the beings around us get along.

The development of the higher human being proceeds in such a way that the human being first works on his astral body. There he works in ideals, enthusiasm, and so on. He fights his instincts. The moment a person replaces drives with ideals, duties with instincts, and develops enthusiasm instead of desires, he creates harmony within the parts of his astral body. This peacemaking work begins with the entry of the monad, and the astral body begins to become more and more immortal. From then on, the astral body no longer dies, but survives to the extent that it has brought peace, that peace can withstand the destructive forces. From the moment the monad enters, it brings peace, first in the astral body. Then the instincts begin to get along. Harmony arises in the former chaos and an astral structure emerges which endures and remains alive. Peace is not initially established in the physical body and the etheric body, but only partly in the astral body. It initially lasts only a short time in other worlds, but the more peace has been established, the longer the devachan period lasts.

When a person has become a chela, they also begin to establish peace in the etheric body. Then the etheric body also endures. The masters also establish peace in the physical body; therefore, the physical body also endures for them. It is a matter of bringing the various bodies, which consist of individual parts that fight each other, into harmony and transforming them into eternal bodies.

Human beings have formed their physical bodies by projecting the natural kingdoms out of themselves, which were then reflected back into them. This is how the individual parts within them came into being. Now they perform actions; through these, they re-enter into communication with their surroundings. What they now project outwards are the effects of their deeds. Now they integrate their deeds into the environment, and gradually become a reflection of these deeds. The monad has entered the human body; it begins to perform deeds. It is these deeds that are integrated into the environment, and they are reflected back in it. To the same extent that it begins to make peace, it also begins to absorb the reflections of its own deeds.

Now we have arrived at a point where we are constantly creating a new realm around us, the effects of our own deeds. This in turn builds something within us. Just as we previously separated the residual etheric body from the reflections, we now integrate the effects of our actions into the monadic existence. We call this the foundation of our karma. This allows us to make everything permanent in the monad. Previously, the astral body purified itself by casting off everything that was within it. Now, human beings create a new realm of action, as it were out of nothing, out of nothing according to the circumstances. That which previously had no existence, the new relationship, is reflected in the monad as something new that has a pictorial character, and a new inner core of being is formed in it, arising from the mirror image of the deeds, the mirror image of karma. As the monad continues to work, the core of its being grows larger and larger. After some time, we look at the monad: it will then have developed harmony from the conflicting forces on the one hand, and on the other hand from the effects of the deeds. Both connect with each other, and a communal structure emerges.

Let us assume that the earthly garment is removed from the human being and the monad remains. It retains the effects of its deeds. The question arises as to the nature of the effects of the deeds. If they are such that they can be active in the worlds in which the monad now finds itself, then human beings will be able to remain there for a long time; if not, then only for a short time. Then they must fall back into the thirst of the monad [for the physical plane] and take on a physical body again.

Human life is constantly enveloped by what surrounds us: involution – evolution. We absorb images and shape our own bodies accordingly. What the monad has wrought, man takes up again as karma. Human beings will always be the effect of their karma. Vedanta teaches that the various parts of human beings are dissolved and scattered in all directions; what remains of them is their karma. This is the eternal, what human beings have made of themselves, what they themselves have initially absorbed as images from their surroundings. Human beings are immortal; they only need to want it, they only need to shape their deeds in such a way that they have a lasting existence. What is immortal in us is what we acquire from outside. We have become through the world and are beginning to build up the mirror of a new world through the fertilization with the monad within us. The monad has enlivened the mirror images within us. Now the images can have an effect, and now the effects of these images are reflected anew. A new inner life emerges. We are constantly changing our environment with our actions. This creates new mirror images, which now become karma. This is a new life that springs from within. It follows from this that, in order to develop ourselves further, we must, from a certain point on, go out from ourselves and act selflessly in our environment. We must make this stepping out possible in order to selflessly bring our environment into harmony. This requires harmonizing the mirror images within us. Our task is to make the world around us harmonious. If we are destroyers in the world, the devastation is reflected in us; if we bring harmony to the world, the harmonies are reflected in us.

We will take with us the final degree of perfection that we have set forth, that we have created around us. That is why the Rosicrucians said: Shape the world so that it contains wisdom, beauty, and strength, then wisdom, beauty, and strength will be reflected in us. If you have used your time for this, then you yourself will depart from this earth with the reflection of wisdom, beauty, and strength. Wisdom is the reflection of Manas; beauty, piety, and goodness are the reflection of Buddhi; strength is the reflection of Atma.

First, we develop a realm of wisdom around us by promoting wisdom. Then we develop a realm of beauty in all areas. Then wisdom becomes visible and is reflected in us: Buddhi. Finally, we give the whole physical existence, wisdom within, beauty without.

If we have the power to enforce this, then we have strength: Atma, the power to turn all this into reality. In this way we establish the three realms within ourselves: Manas, Buddhi, Atma.

It is not through idle contemplation that man progresses on earth, but by incorporating wisdom, beauty, and strength into the earth. Through the work of our higher self, we transform the transitory bodies given to us by the gods and create eternal bodies for ourselves. The chela who refines his etheric body [so that it is preserved] gradually renounces the maharajas. The master, whose physical body is also preserved, can renounce the Lipikas. He stands above karma. We must describe this as the progress of the human being within. We must seek to enter what is higher, outside of ourselves. Therefore, our higher self is not to be sought within us, but in the higher individualities.