Universe, Earth and Man

GA 105

16 Aug 1908, Stuttgart

Lecture XI

In the previous lectures wide reaches, both of human evolution and also of world evolution, were brought before our souls. We saw how mysterious connections in the evolution of the world are reflected in the civilizations of the different nations belonging to the post-Atlantean period. We saw how the first epoch of earthly development is reflected in the civilization of ancient India; the second, during which the separation of the sun from the earth took place, is reflected in the Persian civilization; and we have endeavoured, as far as time permitted, to sketch the various events of the Lemurian epoch—the third in the course of the earth's development—in which man received the foundations of his ego, which is reflected in the civilization of Egypt. It was pointed out that the initiation wisdom of ancient Egypt was a kind of remembrance of this, which was the first period of earthly evolution in which man participated. Then, coming to the fourth age, that in which the true union between body and spirit is so beautifully presented in the art of Greece, we showed it to be a reflection of what man experienced with the ancient gods, the beings we have described as Angels. Nothing remained that could be reflected in our age—the fifth—the age now running its course. Secret connections do, however, exist between the different periods of post Atlantean civilization; these we have already touched on in the first of these lectures.

You may recall how it was stated that the confinement of the people of the present day to their own immediate surroundings, that is, to the materialistic belief that reality is only to be found between life and death, can be traced to the circumstance of the Egyptians having bestowed so much care on the preservation of the bodies of the dead. They tried at that time to preserve the physical form of man, and this has not been without an effect on souls after death. When the bodily form is thus preserved the soul after death is still connected in a certain way with the form it bore during life. Thought-forms are called up in the soul, these cling to the sensible form, and when the person incarnates again and again and the soul enters into new bodies these thought-forms endure.

All that the human soul experienced when it looked down from spiritual heights upon its corpse is firmly rooted within it, hence it has not been able to unlearn this, nor to turn away from the vision which bound it to the flesh. The result has been that countless souls who were incorporated in ancient Egypt are born again with the fruits of this vision, and can only believe in the reality of the physical body. This was firmly implanted in souls at that time. Things that take place in one age of culture are by no means unconnected with the ages that follow.

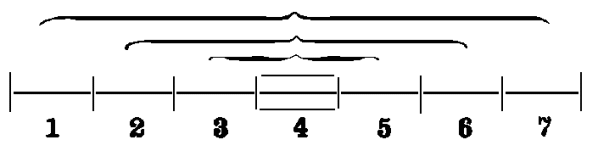

Suppose that we represent here the seven consecutive cultural periods of post-Atlantean civilization by a line. The fourth age, which is exactly in the middle, occupies an exceptional position.

We have only to consider this age exoterically to see that in it the most wonderful physical things have been produced, things by which man has conquered the physical world in a unique and harmonious way. Looking back to the Egyptian pyramids we observe a type of geometric form which demonstrates certain things symbolically. The close union of spirit—the formative human spirit—and the physical form had not yet been completed. We see this with special clearness in the Sphinx, the origin of which is to be traced to a remembrance of the Atlantean etheric human form. In its physical form the Sphinx gives us no direct conviction of this union, although it is a great human conception; in it we see the thought embodied that man is still animal-like below and only attains to what is human in the etheric head.

What confronts us on the physical plane is ennobled in the fourth age in the forms of Greek plastic art; and the moral life, the destiny of man, we find depicted in the Greek tragedies. In them we see the inner life of the spirit played out upon the physical plane in a very wonderful way; we see the meaning of earthly evolution in so far as the gods are connected with it.

So long as the earth was a part of the sun, high Sun-Spirits were united with the human race. By the end of the Atlantean epoch these exalted Beings had gradually faded, step by step, along with the sun, from the consciousness of man. Human consciousness was no longer capable of reaching up after death to the high realms where vision of the Sun-Spirits was possible. Assuming that we are at the standpoint of these Beings (which we can be in spirit), we can picture them saying: We were once united with humanity but had to withdraw from them for a time. The divine world had to disappear from human consciousness so as to re-appear in a newer, higher form through the Christ-Impulse.

A man who belonged to Grecian civilization was incapable as yet of understanding what was to come to earth through the Christ; but an Initiate, one who, as we have seen, knew the Christ aforetime, could say: That spiritual form which was preserved in men's minds as Osiris had to disappear for a time from the sight of man, the horizon of the Gods had to be darkened, but within us dwells the sure consciousness that the glory of God will appear again on earth. This certainty was the result of the cosmic consciousness which men possessed and the consciousness of the withdrawal of the glory of God and of its return is reflected in Greek tragedy.

We see man here represented as the image of the Gods, we see how he lives, strives, and has a tragic end. At the same time the tragedy holds within it the idea that man will yet conquer through his spiritual power. The drama was intended as a presentation of living and dying humanity, and at the same time it reflected man's whole relationship to the universe. In every realm of Greek culture we see this union between things of the spirit and things of the senses. It was a unique age in post-Atlantean civilization.

It is remarkable how certain phenomena of the third age are connected as by underground channels with our own, the fifth age. Certain things which were sown as seed during the Egyptian age are re-appearing in our own; others which were sown as seed during the Persian age will appear in the sixth; and things belonging to the first epoch will return in the seventh. Everything has a deep and law-filled connection, the past pointing always to the future. This connection will best be realized if we explain it by referring to the two extremes, those things connecting the first and the seventh age. Let us turn back to the first age and consider, not what history tells us, but what really existed in ancient pre-Vedic times.

Everything that appeared later had been first prepared for; this was especially the case with the division of mankind into castes. Europeans may feel strong objections to the caste system, but it was justified in the civilization of that time, and is profoundly connected with human karma. The souls coming over from Atlantis were really of very different values, and in some respects it was suitable for these souls, of whom some were at a more advanced stage than others, to be divided in accordance with the karma they had previously stored up for themselves. In that far off age humanity was not left to itself as it is now, but was really led and guided in its development in a much higher way than is generally supposed. At that time highly advanced individuals, whom we call the Rishis, understood the value of souls, and the difference there is between the various categories of souls. At the bottom of the division into castes lies a well-founded cosmic law. Though to a later age this may seem harsh, in that far-off time, when the guidance of humanity was spiritual, the caste principle was entirely suited to human nature.

It is true that in the normal evolution of man those who lived over into a new age with a particular karma came also into a particular caste, and it is also true that a man could only rise above any special caste if he underwent a process of initiation. Only when he attained a stage where he was able to strip off that which was the cause of his karma, only when he lived in Yoga, could the difference in caste, under certain circumstances, be overcome. Let us keep in mind the Anthroposophical principle which lays down that we must put aside all criticism of the facts of evolution and strive only to understand them. However had the impression this division into castes makes on us at the present time, there was every justification for it, and it has to be taken in connection with a far-reaching and just arrangement regarding the human race.

When a person speaks of races today he speaks of something that is no longer quite correct; even in Theosophical handbooks great mistakes are made on this subject. In them it is said that our evolution runs its course in Rounds, that in each Round there are Globes, and in each Globe, Races which develop one after the other—so that we have races in each epoch of the earth's evolution.

But this is not the case. Even in regard to present humanity there is no justification for speaking of a mere development of races. In the true sense of the word we can only speak of race development during the Atlantean epoch. People were so different in external physiognomy throughout the seven periods that one might speak rather of different forms than races. While it is true that the races have arisen through this, it is [in]correct to speak of races in the far back Lemurian epoch; and in our own epoch the idea of race will gradually disappear along with all the differences that are a relic of earlier times. We still speak of races, but all that remains of these today are relics of differences that existed in Atlantean times, and the idea of race has now lost its original meaning. What new idea is to arise in place of the present idea of race?

Humanity will be differentiated in the future even more than in the past; it will be divided into categories, but not in an arbitrary way; from their own spiritual inner capacities men will come to know that they must work together for the whole body corporate.

There will be categories and classes however fiercely class-war may rage today, among those who do not develop egoism but accept the spiritual life and evolve toward what is good a time will come when men will organize themselves voluntarily. They will say: One must do this, the other must do that. Division of work even to the smallest detail will take place; work will be so organized that a holder of this or that position will not find it necessary to impose his authority on others. All authority will be voluntarily recognized, so that in a small portion of humanity we shall again have divisions in the seventh age, which will recall the principle of castes, but in such a way that no one will feel forced into any caste, but each will say: I must undertake a part of the work of humanity, and leave another part to another—both will be equally recognized.

Humanity will be divided according to differences in intellect and morals; on this basis a spiritualized caste system will again appear. Led, as it were, through a secret channel, the seventh age will repeat that which arose prophetically in the first. The third, the Egyptian age, is connected in the same way with our own. Little as it may appear to a superficial view, all that was laid down during the Egyptian age re-appears in the present one. Most of the people living on the earth today were incarnated formerly in Egyptian bodies and experienced an Egyptian environment; having lived through other intermediate incarnations, they are now again on earth, and, in accordance with the laws we have indicated, they unconsciously remember what they experienced in Egypt.

All this is re-appearing now in a mysterious way, and if you are willing to recognize such secret connection of the great laws of the universe working from one civilization to another, you must make yourselves acquainted with the truth, not with all those legendary and fantastic ideas which are given out concerning the facts of human evolution.

People think too superficially about the spiritual progress of humanity. For example, someone remarks about Copernicus that a man with such ideas as his was possible, because in the age in which he lived a change in thought had arisen regarding the solar system. Anyone holding such an opinion has never studied, even exoterically, how Copernicus arrived at his ideas concerning the relationship of the heavenly bodies. One who has done this, and who more especially has followed the grand ideas of Kepler, knows differently, and he will be strengthened even more in these ideas by what occultism has to say about it.

Let us consider this so that we may see the matter clearly, and try to enter into the soul of Copernicus. This soul had lived in the age of ancient Egypt, and had then occupied an important position in the cult of Osiris; it knew that Osiris was held to be the same as the high Sun-Being.

The sun, in a spiritual sense, was at the centre of Egyptian thought and feeling; I do not mean the outwardly visible sun; it was regarded only as the bodily expression of the spiritual sun. Just as the eye is the expression for the power of sight, so to the Egyptian the Sun was the eye of Osiris, the embodiment of the Spirit of the Sun. All this had been experienced at one time by the soul of Copernicus, and it was the unconscious memory of it that impelled him to renew, in a form possible to a materialistic age, this ancient idea of Osiris, which at that time had been entirely spiritual. When humanity had sunk more deeply within the physical plane, this idea confronts us again in its materialistic form, as the Copernican theory.

The Egyptians possessed the spiritual conception and it was the world-karma of Copernicus to retain a memory of such conceptions, and this conjured forth that “combination of bearings” that led to his theory of the solar system. The case was similar with Kepler, who, in his three laws, presented the movement of the planets round the sun in a much more comprehensive way; however abstract they may appear to us, they were the result of a most profound conception. A striking fact in connection with this highly gifted being is contained in a passage written by himself and which fills us with awe when we read it. Kepler writes: “I have thought deeply upon the Solar System. It has revealed to me its secrets; I will carry over the sacred ceremonial vessels of the Egyptians into the modern world.”

Thoughts implanted in the souls of the ancient Egyptians meet us again, and our modern truths are the re-born myths of Egypt. Were it desired, we could follow this up in many details; we could follow it up to the very beginnings of humanity. Let us think once more of the Sphinx, that wondrous, enigmatic form which later became the Sphinx of Oedipus, who put its well-known riddle to man. We have learnt already that the Sphinx is built up from that human form which on the physical plane still resembled that of animals, although the etheric part had already assumed human form. In the Egyptian age man could only see the Sphinx in an etheric form after he had passed through certain stages of initiation. Then it appeared to him. But the important thing is that when a man had true clairvoyant perception it did not appear to him merely as a lump of wood does, but certain feelings were necessarily associated with the vision.

Under certain circumstances a callous person may pass by a highly important work of art and remain unmoved by it; clairvoyant consciousness is not like this; when really developed the fitting emotion is already aroused. The Greek legend of the Sphinx expresses the right feeling, experienced by the clairvoyant during the ancient Egyptian period and also in the Grecian Mysteries, when he had progressed so far that the Sphinx appeared to him. What was it that then appeared before his eyes? He beheld something incomplete something that was in course of development. The form he saw was in a certain way related to that of animals, and in the etheric head we saw what was to work within the physical form in order to shape it more like man. What man was to become, what his task was in evolution, this was the question that rose vividly before him when he saw the Sphinx—a question full of longing, of expectation, and of future development.

The Greeks say that all investigation and philosophy have originated from longing; this is also a saying of clairvoyants. A form appears to man which he can only perceive with his astral consciousness; it worries him, it propounds a riddle, the riddle of man's future. Further, this etheric form, which was present in the Atlantean epoch and lived on as a memory into the Egyptian age, is embodied more and more in man, and re-appears on the other side in the nature of man. It reappears in all the religious doubts, in the impotence of our age of civilization when faced with the question: What is man? In all unanswered questions, in all statements that revolve round “Ignorabimus,” we have to see the Sphinx. In ages that were still spiritual man could rise to heights where the Sphinx was actually before him—today it dwells within him in countless unanswered questions.

It is therefore very difficult for man at the present time to arrive at conviction with regard to the spiritual world. The Sphinx, which formerly was outside him, is now in his inner being, for a Being has appeared in the central epoch of post-Atlantean evolution Who has cast the Sphinx into the abyss—into the individual inner being of every man.

When the Greco-Latin age, with its after-effects, had continued into the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries we come to the fifth post-Atlantean age. Up to the present new doubts have arisen more and more in place of the old certainty. We meet with such things more and more, and if desired we could discover many more instances of Egyptian ideas, transformed into their materialistic counterpart in the new evolution. We might ask what has really happened in the present age, for this is no ordinary passing over of ideas; things are not met with directly, but they are as if modified. Everything is presented in a more materialistic form; even man's connection with animal nature re-appears, but changed into a materialistic conception. The fact that man knew in earlier times that he could not shape his body otherwise than in the semblance of animals, and that on this account in his Egyptian remembrances he pictured even his gods in animal forms, confronts us today in the generally held materialistic opinion that man has descended from animals. Darwinism is nothing but an heirloom of ancient Egypt in a materialistic form.

From this we see that the path of evolution has by no means been a straightforward one, but that something like a division has taken place, one branch becoming more materialistic and one more spiritual. That which had formerly progressed in one line now split into two lines of development, namely, science and belief.

Going back into earlier times, to the Egyptian, Persian, and ancient Indian civilizations, one does not find a science apart from faith. What was known regarding the spiritual origin of the world passed in a direct line to knowledge of particular things; men were able to rise from knowledge of the material world to the most exalted heights; there was no contradiction between knowledge and faith. An ancient Indian sage or a Chaldean priest would not have understood this difference; even the Egyptians knew no difference between what was simply a matter of belief or a fact of knowledge. This difference became apparent when man had sunk more deeply into matter, and had gained more material culture; but in order to gain this another organization was necessary.

Let us suppose that this descent of man into matter had not taken place; what would have happened? We considered a like descent in the last lecture, but it was of a different nature; this is a new descent in another realm, by which something like an independent science entered alongside the comprehension of what was spiritual. This occurred first in Greece. Up till then opposition between science and religion did not exist; and would have had no meaning to a priest of Egypt. Take, for instance, what Pythagoras learnt from the Egyptians, the teaching regarding numbers. This was not merely abstract mathematics to him; it gave him the musical secrets of the world in the harmony of numbers. Mathematics, which is only something abstract to the man of the present day, was to him a sacred wisdom with a religious foundation.

Man had, however, to sink more and more within the material, physical plane, and it can be seen how the spiritual wisdom of Egypt reappears—but transformed into a materialistic, mythical conception of the universe. In the future, the theories of today will be held to have had only temporal value, just as ancient theories have only a temporal value to the man of today. Perhaps men will then be so sensible that they will not fall into the mistake of some of our contemporaries who say: “Until the nineteenth century man was absolutely stupid as regards science; it was only then he became sensible all that was taught previously about anatomy was nonsense, only the last century has produced what is true.” In the future men will be wiser, and will not give tit for tat; they will not reject our myths of anatomy, philosophy, and Darwinism so disdainfully as present-day man rejects ancient truths. For it is the case that things which today are regarded as firmly established are but transitory forms of truth.

The Copernican system is but a transitory form, it has been brought about through the plunge into materialism, and will be replaced by something different. The forms of truth continually change. In order that all connection with what is spiritual should not be lost, an even stronger spiritual impulse had to enter human evolution. This was described yesterday as the Christ-Impulse. For a time mankind had to be left to itself, as it were, as regards scientific progress, and the religious side had to develop separately; it had to be saved from the progressive onslaught of science.

Thus we see how science, which devoted itself to material things, was separated for a while from things spiritual, which now followed a special course and the two movements—belief in what was spiritual, and the knowledge of external things—proceeded side by side. We even see in one particular period of development in the Middle Ages, a period immediately preceding our own, that science and belief consciously oppose each other, but still seek union.

Consider the Scholastics. They said: Faith was given to man by Christ, this we may not deny; it was a direct gift; and all the science which has been produced since the division took place, can only serve to prove this gift. We see in scholasticism the tendency to employ all science to prove revealed truth. At its prime it said: Men can gaze upwards to the blessedness of faith and to a certain degree human science can enter into it, but to do this men must devote themselves to it.

In the course of time all relationship between science and belief was, however, lost, and there was no longer any hope that they could advance side by side. The extremity of this divergence is found in the philosophy of Kant, where science and belief are completely sundered. In it, on the one hand, the categorical imperative is put forward with its practical postulates of reason; on the other hand, purely theoretical reason which has lost all connection with spiritual truths and declares that from the standpoint of science these cannot be found.

Another powerful impulse was, however, already making itself felt, which also represented a memory of ancient Egyptian thought. Minds appeared that were seeking a union between science and belief, minds that were endeavouring, through entering profoundly into science, to recognize the things of God with such certainty and clarity that they would be accessible to scientific thought. Goethe is typical of such a thinker and of such a point of view. To him religion, art, and science were one; he felt the works of Greek art to be connected with religion, as he felt the great thoughts of Divinity to be reflected in the countless plant formations he investigated.

Taking the whole of modern culture, we have to see in it a memory of Egyptian culture; Egyptian thought is reflected in it from its beginning.

The division in modern culture between science and belief did not arise without long preparation,—and if we are to understand how this came about we must glance briefly at the way post-Atlantean culture was prepared for during the Atlantean epoch.

We have seen how a handful of people who dwelt in the neighbourhood of Ireland had progressed the furthest; they had acquired those qualities which had to appear gradually in the succeeding epochs of civilization. The rudiments of the ego had been developing as we know since the Lemurian epoch, but each stage of selfhood in this small group of people, by whom the stream of culture was carried from West to East, consisted in a tendency to logical thought and the power of judgment. Up to this time these did not exist; if a thought arose it was already substantiated. The beginning of thought that was capable of judgment was implanted in these people, and they bore the rudiments of this with them from West to East in their colonizing migrations, one of which went southwards towards India. Here the first foundations of constructive thinking were laid. Later, this constructive thinking passed into the Persian civilization. In the third cultural period, that of Chaldea, it grew stronger and with the Greeks it developed so far that they have left behind them the glorious monument of Aristotelian philosophy.

Constructive thought continued to develop more and more, but always returned to a central point, where it received reinforcement. We must picture it as follows: When civilization came from the West into Asia one group, that having the smallest amount of purely logical thinking capacity, went toward India; the second group, which traveled towards Persia, had a little more; and the group that went towards Egypt had still more. From within this group were separated off the people of the Old Testament, who had exactly that combination of faculties which had to be developed in order that another forward step might be taken in this purely logical form of human cognition.

With this is associated the other thing we have been considering, namely, the descent to the physical plane. The further we descend the more does thought become merely logical, and the more it tends to a merely external faculty of judgment. Pure logical thought, mere human logic, that which proceeds from one idea to another, requires the human brain as its instrument; the cultivated brain makes logical thought possible. Hence external thinking, even when it has reached an astonishing height, can never of itself comprehend reincarnation, because it is in the first place only applicable to the things of the external sense world that surrounds us.

Logic may indeed be applied to all worlds, but can only be applied directly to the physical world; hence when it appears as human logic it is bound unconditionally to its instrument, the physical brain. Abstract thought could never have entered the world without a further descent into the world of the senses. This development of logical thought is bound up with the loss of ancient clairvoyant vision, and was bought at the cost of this loss. The task of man is to re-conquer clairvoyant vision, adding logical thought to it. In time to come he will obtain imagination as well, but logical thinking will be retained.

The human head had in the first place to be created similar to the etheric head before man could have a brain. It was then first possible for man to descend to the physical plane. In order that all spirituality should not be lost a point of time had to be chosen for the saving of this, when the last impulse to purely mechanical thought had not yet been given. If the Christ had appeared a few centuries later He would have come, as it were, too late, for humanity would have descended too far, would have been too much entangled in thought, and would not have been able to understand Christ. Christ had to come before this last impulse had been received, when the spiritually religious tendency could still be saved as a tendency leading to belief. Then came the last impulse, which plunged human thought to the lowest point, where it was banished and completely chained to physical life. This arose through the Arabs and Mohammedans. Moslem thought is a peculiar episode in Arabian life and thought, which in its passage over to Europe gave the final impulse to logical thinking—to that which is incapable of rising to what is spiritual.

To begin with, man was so led by what may be called Providence or a spiritual guidance that spiritual life was saved in Christendom; later, Arabism approached Europe from the south and provided the field for external culture. It is only capable of comprehending what is external. Do we not see this in the Arabesque, which is incapable of rising to what is living, but has to remain formal? We can also see in the Mosque how the spirit is, as it were, sucked out.

Humanity had first to be led down into matter, then in a roundabout way by means of Arabism, and the invasion of the Arab, we are shown how modern science first arose in the sharp contact of Arabism with Europeanism which had already accepted Christianity. The ancient Egyptian memories had come to life again; but what made them materialistic? What made them into thought-forms of the dead? We can show this clearly. If the path of progress had been smooth the memory of what had taken place previously would have re-appeared in our age. That which is spiritual has been saved as a whole, but one wing of European culture has been gripped by materialism. We also see how the remembrance of those who recalled the ancient Egyptian age was so changed by its passage through Arabism that it reappeared in a materialistic form. The fact that Copernicus comprehended the modern way of regarding the solar system was the outcome of his Egyptian memory. The reason why he presented it in a materialistic form, making of it a dead mechanical rotation, is because the Arabian mentality, encountering this memory from the other side, forced it into materialism.

From all that has been said you can see how secret channels connect the third and the fifth age. This can be seen even in the principle of initiation, and as modern life is to receive a principle of initiation in Rosicrucianism let us ask what this is.

In modern science we have to see a union between Egyptian remembrances and Arabism, which tends towards that which is dead. On the other side we see another union consummated, that between what Egyptian initiates imparted to their pupils and things spiritual. We see a union between wisdom and that which had been rescued as the truths of belief. This wondrous harmony between the Egyptian remembrance in wisdom and the Christian impulse of power is found in Rosicrucian spiritual teaching. So the ancient seed laid down in the Egyptian period re-appears, not merely as a repetition, but differentiated and upon a higher level.

These are thoughts which should not only instruct with regard to the universe, earth, and man, but they should enter as well into our feeling and our impulses of will and give us wings; for they show us the path we have to travel. They point the path to that which is spiritual, and also show how we may carry over into the future what, in a good sense, we have gained here on the purely material plane.

We have seen how paths separate and again unite; the time will come when not the remembrances only of Egypt will unite with spiritual truths to produce a Rosicrucian science, but science and Rosicrucianism will also unite. Rosicrucianism is both a religion and at the same time a science that is firmly bound to what is material. When we turn to the Babylonian period we find this is shown in myth of the third period of civilization; here we are told of the God Maradu, who meets with the evil principle, the serpent of the Old Testament, and splits his head in two, so that in a certain sense the earlier adversary is divided into two parts. This was in fact what actually happened; a partition of that which arose in the primeval, watery earth-substance, as symbolized by the serpent. In the upper part we have to see the truths upheld by faith, in the lower the purely material acceptance of the world. These two must be united—science and that which is spiritual—and they will be united in the future. This will come to pass when, through Rosicrucian wisdom, spirituality is intensified, and itself becomes a science, when it once more coincides with the investigations made by science. Then a mighty harmonious unity will again arise; the various currents of civilization will unite and flow together through the channels of humanity. Do we not see in recent times how this unity is being striven for?

When we consider the ancient Egyptian mysteries we see that religion, science, and art were then one. The course of the world evolution is shown in the descent of the Gods into matter; this is presented to us in a grand dramatic symbolism. Anyone who can appreciate this symbolism has science before him, for he sees there vividly portrayed the descent of man and his entrance into the world. He is also confronted with something else, namely, art, for the picture presented to him is an artistic reflection of science. But he does not see only these two, science and art, in the mysteries of ancient Egypt; they are for him at the same time religion, for what is presented to him pictorially is filled with religious feeling.

These three were later divided; religion, science, and art went separate ways, but already in our age men feel that they must again come together.

What else was the great effort of Richard Wagner than a spiritual striving, a mighty longing towards a cultural impulse? The Egyptians saw visible pictures because the external eye had need of them. In our age what they saw will be repeated; once more the separate streams of culture will unite, a whole will be constructed, this time preferably in a work of art whose elements will be the sequence of sound. On every side we find connections between what appertained to Egypt and modern times; everywhere this reflection can be seen. As time goes on our souls will realize more and more that each age is not merely a repetition but an ascent; that a progressive development is taking place in humanity. Then the most intimate strivings of humanity—the striving for initiation—must find fulfillment.

The principle of initiation suited to the first age cannot be the principle of initiation for the changed humanity of today. It is of no value to us to be told that the Egyptians had already found primeval wisdom and truth in ancient times; that these are contained in the old Oriental religions and philosophies, and that everything that has appeared since exists only to enable us to experience the same over again if we are to rise to the highest initiation. No! This is useless talk. Each age has need of its own particular force within the depths of the human soul.

When it is asserted in certain Theosophical quarters that there is a western initiation for our stage of civilization, but that it is a late product, that true initiation comes only from the East, we must answer that this cannot be determined without knowing something further. The matter must be gone into more deeply than is usually done. There may be some who say that in Buddha the highest summit was reached, that Christ has brought nothing new since Buddha; but only in that which meets us positively can we recognize what really is the question here. If we ask those who stand on the ground of Western initiation whether they deny anything in Eastern initiation, whether they make any different statements regarding Buddha than those in the East, they answer, “No.” They value all; they agree with all; but they understand progressive development. They can be distinguished from those who deny the Western principle of initiation by the fact that they know how to accept what Orientalism has to give, and in addition they know the advanced forms which the course of time has made necessary. They deny nothing in the realm of Eastern initiation.

Take a description of Buddha by one who accepts the standpoint of Western esotericism. This will not differ from that of a follower of Eastern esotericism; but the man with the Western standpoint holds that in Christ there is something which goes beyond Buddha. The Eastern standpoint does not allow this. If it is said that Buddha is greater than Christ that does not decide anything, for this depends on something positive. Here the Western standpoint is the same as the Eastern. The West does not deny what the East says, but it asserts something further.

The life of Buddha is not rightly understood when we read that Buddha perished through the enjoyment of too much pork; this must not be taken literally. It is rightly objected from the standpoint of Christian esotericism that people who understand something trivial from this understand nothing about it at all; this is only an image, and shows the position in which Buddha stood to his contemporaries. He had imparted too many of' the sacred Brahmanical secrets to the outer world. He was ruined through having given out that which was hidden, as is everyone else who imparts what is hidden.

This is what is expressed in this peculiar symbol. Allow me to emphasize strongly that we disagree in no way with Oriental conceptions, but people must understand the esotericism of such things. If it is said that this is of little importance: it is not the case. They might as well think it of little importance when we are told that the writer of the Apocalypse wrote it amid thunder and lightning, and if anyone found occasion to mock at the Apocalypse because of this we should reply: “What a pity he does not know what it means when we are told that the Apocalypse was imparted to the earth 'mid lightning and thunder!”

We must keep in mind the fact that no negation has passed the lips of Western esotericists, and that much that was puzzling at the beginning of the Anthroposophical movement has been explained by them. The followers of Western esotericism never find in it anything out of harmony with the mighty truths given to the world by H. P. Blavatsky. When we are told, for example, that we have to distinguish in the Buddha the Dhyani-Buddha, the Adi-Buddha, and the human Buddha, this is first fully explained by the Western esotericist. For we know that what is regarded as the Dhyani-Buddha is nothing but the etheric body of the historic Buddha that had been taken possession of by a God; that this etheric body had been laid hold of by the being whom we call Wotan. This was already contained in Eastern esotericism, but was only first understood in the right way through Western esotericism.

The Anthroposophical movement should be especially careful that the feeling which rises in our souls from such thoughts as these should stimulate in us the desire for further development, that we should not stand still for a moment. The value of our movement does not consist in the ancient dogmas it contains (if these are but fifteen years old), but in comprehending its true purpose, which is the opening up of fresh springs of spiritual knowledge. It will then become a living movement and will help to bring about that future which, if only very briefly, has been presented to your mental sight today, by drawing upon what we are able to observe of the past.

We are not concerned with the imparting of theoretic truths, but that our feeling, our perception, and our actions may be full of power.

We have considered the evolution of Universe, Earth, and Man; we desire so to grasp what we have gathered from these studies that we may be ready at any time to enter upon development.

What we call “future” must always be rooted in the past; knowledge has no value if not changed into motive power for the future. The purpose for the future must be in accordance with the knowledge of the past, but this knowledge is of little value unless changed into propelling force for the future.

What we have heard has presented to us a picture of' such mighty motive powers that not only our will and our enthusiasm have been stimulated, but our feelings of joy and of security in life have also been deeply moved. When we note the interplay of so many currents we are constrained to say: Many are the seeds within the womb of Time. Through an ever deepening knowledge man must learn how better to foster all these seeds. Knowledge in order to work, in order to gain certainty in life, must be the feeling that pervades all Anthroposophical study.

In conclusion I would like to point out that the so-called theories of Spiritual Science only attain final truth when they are changed into something living—into impulses of feeling and of certainty as regards life; so that our studies may not merely be theoretical, but may play a real part in evolution.

Elfter Vortrag

Wir haben weite Strecken der Menschheitsentwickelung und im Zusammenhang damit auch der Weltentwickelung vor dem Blicke unserer Seele vorüberziehen lassen. Wir haben gesehen, wie geheimnisvolle Zusammenhänge in der Weltentwickelung sich widerspiegelten in der eigentlichen menschlichen Kulturentwickelung, in der sogenannten nachatlantischen Zeit. Wir haben gesehen, wie die erste Periode unserer Erdentwickelung sich in der indischen Kultur spiegelte; wie die zweite, die der Trennung der Sonne von der Erde, sich in der persischen Kultur spiegelte; und dann haben wir versucht, soweit die Zeit es uns erlaubte, ganz besonders zu schildern und zu zeichnen, wie die mannigfachsten Geschehnisse und Ereignisse der lemurischen Zeit, die die dritte Epoche unserer Erdentwickelung bildet und wo der Mensch die erste Anlage zum Ich erhielt, wie alle diese Geschehnisse sich in der ägyptischen Kultur widerspiegelten. Wir haben gesehen, wie die Einweihungsweisheit der alten Ägypter eine Art Erinnerung an diese Zeit ist, die die Menschheit erst während der Erdentwickelung durchgemacht hat. Und dann haben wir gesehen, wie der vierte Zeitraum, die Zeit der eigentlichen Ehe zwischen Geist und Leib, die uns so schön in den Kunstwerken der Griechen entgegentritt, eine Spiegelung der Erlebnisse ist, die der Mensch mit den alten Göttern hatte, jenen Wesenheiten, die wir als Engel bezeichnen. Und wir sahen: nichts ist zurückgeblieben, was sich spiegeln könnte für unsere Zeit, für den fünften Zeitraum, der sich jetzt bei uns abspielt. Aber es bestehen geheimnisvolle Zusammenhänge zwischen den einzelnen Kulturepochen der nachatlantischen Zeit, Zusammenhänge, auf die wir schon im ersten Vortrage hindeuteten. Sie erinnern sich, daß wir darauf hinwiesen, wie das Gebanntsein des gegenwärtigen Menschen an die unmittelbar sinnliche Umgebung, wie dieser, man möchte sagen, materialistische Glaube, daß nur das wirklich ist, was Geschehnis zwischen Geburt und Tod ist, was im Fleisch verkörpert ist, wie das darauf zurückzuführen ist, daß die alten Ägypter solche besondere Sorgfalt auf die Konservierung ihrer Leichname verwandt haben. Damals hat man versucht, das, was physische Form ist vom Menschen, zu bewahren. Und das ist nach dem Tode nicht ohne Wirkung auf die Seele geblieben. Wenn die Form in dieser Weise konserviert wird, so ist in der Tat die Seele nach dem Tode in einer gewissen Beziehung noch mit der menschlichen Form verbunden, die sie während des Lebens hatte. Es bilden sich dann in der Seele Gedankenformen, die festhalten an dieser sinnlichen Form; und da der Mensch sich immer wieder und wieder verkörpert, die Seele in immer neuen Leibern auftritt, so bleiben diese Gedankenformen. Es hat sich fest eingewurzelt in der menschlichen Seele alles das, was sie erleben mußte, wenn sie aus geistigen Höhen hinunterschaute auf ihren als Mumie konservierten Leichnam. Daher hat die Seele es verlernt, den Blick abzuwenden von dem, was in das physische Fleisch eingebannt ist, und das hat es gemacht, daß zahlreiche Seelen, die im alten Ägypten verkörpert waren, heute mit der Frucht der Anschauung des sinnlichen Leibes wiederum verkörpert sind, sie können nur glauben, daß dieser sinnliche Leib das Wirkliche ist. Das wurde damals der Seele eingepflanzt. Denn all solche Dinge, die sich in einer Kulturepoche abspielen, sind durchaus nicht ohne Zusammenhang mit anderen Kulturepochen.

Wenn wir die sieben aufeinanderfolgenden Kulturepochen der nachatlantischen Zeit betrachten, so nimmt der vierte Zeitraum, der gerade in der Mitte ist, eigentlich eine gewisse Ausnahmestellung ein. Man braucht diesen Zeitraum nur exoterisch zu betrachten, und man wird gewahr werden, daß da im exoterischen Leben die wunderbarsten äußeren physischen Dinge geschaffen werden, durch die der Mensch sozusagen in einer ganz einzigartigen harmonischen Weise die physische Welt erobert. Wer zurückblickt auf die ägyptischen Pyramiden, der wird sich sagen: In diesen Pyramiden sehen wir noch eine Art geometrischer Form herrschen, die uns symbolisch zeigt, wie die Dinge etwas bedeuten. Es hat sich noch nicht jene tiefe Ehe vollzogen zwischen dem Geiste, dem formenden Menschengeiste, und der physischen Form. Insbesondere sehen wir das deutlich an der Sphinx, deren Ursprung wir ja aus einer Erinnerung an die atlantische ätherische Menschengestalt hergeleitet haben. Wir sehen, daß diese Sphinx im physischen Leibe uns unmöglich eine unmittelbare Überzeugung geben kann, trotzdem es eine große Menschheitskonzeption ist; wir sehen in ihr den Gedanken verkörpert, daß der Mensch unten noch tierisch ist und erst im Atherkopfe sich der Mensch bildet. Aber was uns auf dem physischen Plane entgegentreten kann, das sehen wir in den griechischen plastischen Gestalten veredelt, und was uns im moralischen Leben, im Schicksale der Menschen entgegentreten kann, das sehen wir in der tragischen Kunst der Griechen. In einer ganz wunderbaren Weise sehen wir da hinausgetragen auf den physischen Plan das innere Geistesleben; wir sehen den Sinn der Erdentwickelung, soweit die Götter damit verknüpft waren.

Solange die Erde mit der Sonne verbunden war, waren auch die hohen Sonnengeister mit dem menschlichen Geschlecht verbunden. Aber nach und nach mit der Sonne verschwanden auch die hohen Götter aus dem Bewußtsein der Menschen, stufenweise bis in die letzte atlantische Zeit hinein. Es war das Bewußtsein der Menschen selbst nach dem Tode nicht mehr fähig, sich in die hohen Regionen hinaufzubegeben, wo eine unmittelbare Anschauung der Sonnengötter möglich gewesen wäre. Wenn wir uns — und vergleichsweise darf das ja geschehen — auf den Standpunkt der Sonnengötter stellen, so können wir sagen: Ich war verbunden mit der Menschheit, aber ich mußte mich zurückziehen eine Zeitlang. Sozusagen verschwinden im menschlichen Bewußtsein mußte die göttliche Welt, um dann in einer erneuerten, höheren Gestalt durch den Christus-Impuls wieder aufzugehen. — Ein Mensch, der in der griechischen Welt stand, konnte noch nicht wissen, was der Erde durch den Christus kommen würde, aber der Eingeweihte, der, wie wir ja sahen, den Christus schon vorher kannte, er konnte sich sagen: Diese geistige Gestalt, die als Osiris festgehalten wurde, mußte für eine Weile untergehen für den Blick des Menschen, verfinstern mußte sich der Götterhorizont; aber das sichere Bewußtsein ist in uns, daß sie wiedererscheinen wird, die Gottesherrlichkeit auf Erden. - Das war das kosmische Bewußtsein, das man hatte, und dieses Bewußtsein von einem Heruntersinken der Gottesherrlichkeit und von dem Wiederaufgehen, das spiegelte sich im griechischen tragischen Kunstwerke ab, wo wir sehen, wie der Mensch selbst als Abbild der Götter hingestellt wird, wie er lebt und strebt und einen tragischen Untergang findet, Aber diese Tragik schließt zu gleicher Zeit in sich, daß der Mensch doch durch seine geistige Kraft siegen könne. So sollte das Drama, das Anschauen des lebenden und sterbenden Menschen, im Grunde auch ein Abbild des großen Zusammenhanges sein. Überall sehen wir so in Griechenland, auf allen Gebieten, diese Ehe zwischen dem Geist und dem Sinnlichen. Das war ein einzigartiger Zeitpunkt in der nachatlantischen Zeit.

Nun ist es merkwürdig, wie gewisse Erscheinungen der dritten Epoche wie durch unterirdische Kanäle mit unserem fünften Zeitraum in Verbindung stehen; gewisse Dinge, die wie Keime gelegt worden sind während der ägyptischen Periode, erscheinen wieder während unserer Zeit; andere, die während der persischen Zeit als Keime gelegt wurden, werden in der sechsten Epoche wieder erscheinen, und Dinge der ersten Epoche werden im siebenten Zeitraum wiederkehren. Alles hat einen tiefen gesetzmäßigen Zusammenhang, und das Vorhergehende deutet auf Zukünftiges hin. Am besten wird uns dieser Zusammenhang dadurch klar, daß wir es an dem extremsten Falle darstellen, an dem, was den ersten Zeitraum mit dem siebenten verbindet. Wir blicken zurück auf diesen ersten Zeitraum, und wir müssen da nicht auf das, was die Geschichte berichtet, Rücksicht nehmen, sondern auf das, was in den uralten vorvedischen Zeiten da war. Vorbereitet hat sich alles das, was später hervorgetreten ist; vorbereitet hat sich vor allen Dingen das, was wir als die Einteilung der Menschen in Kasten kennen. Gegen diese Kasten mag der Europäer viel einzuwenden haben, aber in jener Kulturrichtung, die damals vorhanden war, haben diese Kasten ihre Berechtigung gehabt, denn sie hingen im tiefsten Sinne mit dem Menschheitskarma zusammen. Die Seelen, die aus der Atlantis herüberrückten, waren wirklich von ganz verschiedenem Wert, und es paßte in einer gewissen Weise auf diese Seelen, von denen die einen vorgeschrittener als die anderen waren, das Gliedern in solche Kasten nach ihrem vorher in sie gelegten Karma. Und da in jener alten Zeit die Menschheit sich nicht so überlassen war wie in unserer heutigen Zeit, sondern wirklich in einem weit höheren Sinne, als wir uns heute vorstellen können, gelenkt und geleitet wurde in ihrer Entwickelung — da vorangeschrittene Individualitäten, die wir die Rishis nennen, ein Verständnis dafür hatten, was eine Seele wert ist, welcher Unterschied zwischen den einzelnen Kategorien von Seelen besteht -, so liegt dieser Kasteneinteilung ein wohlbegründetes kosmisches Gesetz zugrunde. Mag es in einer späteren Zeit noch so sehr als Härte erschienen sein, in jenen alten Zeiten, wo die Lenkung eine spirituelle war, war dieses Kastenwesen ein wirklich der Menschennatur Angepaßtes. Und ebenso wie es wahr ist, daß im allgemeinen in der normalen Entwickelung des Menschen derjenige, der mit einem bestimmten Karma in die neue Epoche hinüberlebte, auch in eine bestimmte Kaste kam, ebenso wahr ist es, daß man nur dann über die Bestimmungen dieser Kaste hinauskommen konnte, wenn man eine Einweihungsentwickelung durchmachte. Nur wenn man zu den Stufen kam, wo man abstreifte das, wohin einen das Karma hineingestellt hatte, nur wenn man in Joga lebte, dann konnten unter Umständen diese Kastenunterschiede überwunden werden. Wir wollen uns des geisteswissenschaftlichen Grundsatzes bewußt sein, daß jede Kritik der Evolution uns fernliegen muß, daß wir nur danach streben müssen, die Dinge zu verstehen. Mag diese Kasteneinteilung einen noch so schlimmen Eindruck machen, sie war im vollsten Sinne begründet, nur müssen wir sie im Zusammenhang mit einer umfassenden, gesetzmäßigen Bestimmung in bezug auf das Menschengeschlecht betrachten.

Wenn man heute von Rassen spricht, bezeichnet man etwas, was nicht mehr ganz richtig ist; auch in theosophischen Handbüchern werden hier große Fehler gemacht. Man spricht davon, daß unsere Entwickelung sich so vollzieht, daß Runden, und in jeder Runde Globen, und in jedem Globus Rassen sich hintereinander entwickeln, so daß wir also in allen Epochen der Erdevolution Rassen haben würden. Das ist aber nicht so. Es hat zum Beispiel schon gegenüber der heutigen Menschheit keinen rechten Sinn mehr, von einer bloßen Rassenentwikkelung zu sprechen. Von einer solchen Rassenentwickelung im wahren Sinne des Wortes können wir nur während der atlantischen Entwickelung sprechen. Da waren wirklich in den sieben entsprechenden Perioden die Menschen nach äußeren Physiognomien so sehr voneinander verschieden, daß man von anderen Gestalten sprechen konnte. Aber während es richtig ist, daß sich daraus die Rassen herausgebildet haben, ist esschon für die rückliegende lemurische Zeit nicht mehr richtig, von Rassen zu sprechen; und in unserer Zeit wird der Rassenbegriff in einer gewissen Weise verschwinden, da wird aller von früher her gebliebene Unterschied nach und nach verwischt. So daß alles, was in bezug auf Menschenrassen heute existiert, Überbleibsel aus der Differenzierung sind, die sich in der atlantischen Zeit herausgebildet hat. Wir können noch von Rassen sprechen, aber nur in einem solchen Sinne, daß der eigentliche Rassenbegriff seine Bedeutung verliert. Was aber wird dann für ein Begriff an die Stelle des heutigen Rassenbegriffs treten?

Auch in der Zukunft, und mehr noch als in der Vergangenheit, wird die Menschheit sich sozusagen differenzieren, sich gliedern in gewisse Kategorien, aber nicht in aufgezwungene Kategorien, sondern die Menschen werden aus ihrer eigenen inneren geistigen Fähigkeit heraus dazu kommen, daß sie wissen, daß die Menschen zusammenarbeiten müssen zum gesamten sozialen Körper. Kategorien, Klassen wird es geben, aber wenn auch heute der Klassenkampf noch so sehr wütet, in denjenigen Menschen, die nicht den Egoismus ausbilden, sondern das spirituelle Leben in sich aufnehmen, in denen, die sich nach dem Guten hin entwickeln, wird es so kommen, daß sie sich freiwillig eingliedern in die Menschheit. Sie werden sich sagen: der eine muß dies, der andere jenes tun. Teilung der Arbeit, Teilung sogar bis in die feinsten Impulse hinein muß eintreten; und es wird sich so gestalten, daß derjenige, der Träger für das eine oder das andere ist, nicht nötig haben wird, seine Autorität den anderen aufzuzwingen. Alle Autorität wird immer mehr freiwillig anerkannt werden, so daß wir im siebenten Zeitraum bei einem kleinen Teile der Menschheit wiederum eine Einteilung haben werden, welche das Kastenwesen wiederholt, aber so, daß keiner sich in die Kaste hineingezwungen fühlt, sondern daß jeder sich sagt: Ich muß einen Teil der Menschheitsarbeit übernehmen und einem anderen einen anderen Teil überlassen — und beide werden gleich anerkannt werden. Die Menschheit wird sich nach moralischen und intellektuellen Differenzierungen gliedern und auf solcher Grundlage wird eine wiederum vergeistigte Kastenbildung eintreten. So wird, wie durch einen geheimnisvollen Kanal hinübergeleitet, sich in der siebenten Epoche wiederholen, was in der ersten sich prophetisch gezeigt hat. Und so hängt auch die dritte, die ägyptische Kulturentwickelung zusammen mit der unsrigen. So wenig es auch einem oberflächlichen Blicke erscheinen könnte, so treten doch all diejenigen Dinge in unserer Zeitepoche hervor, die während der ägyptischen Periode sozusagen veranlagt worden sind. Denken Sie sich einmal, daß die Seelen, die heute leben, zum großen Teile in ägyptischen Leibern verkörpert waren, die ägyptische Umwelt erlebt haben, dann nach anderen Zwischeninkarnationen jetzt wieder verkörpert sind und sich nun nach den angedeuteten Gesetzen unbewußt alles dessen erinnern, was sie in der ägyptischen Zeit durchlebt haben. In geheimnisvoller Weise tritt das nun wieder auf, und wenn Sie solche geheimnisvolle Beziehungen der großen Weltengesetze von einer Kultur zur anderen erkennen wollen, dann müssen Sie sich mit der Wahrheit bekanntmachen, nicht mit all den legendenhaften und phantastischen Darstellungen, die uns von den Tatsachen der menschlichen Entwickelung gegeben werden.

So wird zum Beispiel über den geistigen Fortschritt der Menschheit ziemlich oberflächlich gedacht. Man sieht, daß in einem bestimmten Zeitalter Kopernikus aufgetreten ist. Man sagt sich: Nun ja, er tritt auf, weil die Beobachtung in dieser Zeit gerade dahin geführt hat, daß man das Sonnensystem in Gedanken geändert hat. Wer eine solche Anschauung hat, der hat nicht einmal exoterisch studiert, wie Kopernikus zu seinen Ideen über den Zusammenhang am Himmel gekommen ist. Wer das studiert, und namentlich wer die großen, gewaltigen Ideen des Kepler verfolgt hat, der weiß etwas anderes darüber zu sagen, und er wird noch bestärkt durch das, was der Okkultismus dazu zu sagen hat. Nehmen wir das einmal, um es uns klar vorzustellen, recht handgreiflich. Wir versetzen uns in die Seele des Kopernikus. Diese war da in der alten ägyptischen Zeit; sie hat damals an einer besonders hervorragenden Stelle den Osiriskultus erlebt und hat gesehen, wie Osiris als ein Wesen betrachtet worden ist, das dem hohen Sonnenwesen gleichkommt. Die Sonne stand in geistig-spiritueller Beziehung in dem Mittelpunkte des ägyptischen Denkens und Fühlens, aber nicht die äußerliche sinnliche Sonne, die nur als der körperliche Ausdruck des Geistigen angesehen wurde. So wie das Auge der Ausdruck der Schkraft ist, so war für den Ägypter die Sonne das Auge des Osiris, der Ausdruck, die Verkörperung dessen, was der Geist der Sonne war. Das alles hatte die Seele des Kopernikus einst durchlebt, und die unbewußte Erinnerung daran war es, die ihn dazu bewog, in der Gestalt, wie es in einem materialistischen Zeitalter sein konnte, diese Idee wieder zu erneuern, diese alte Osirisidee, die damals spirituell war. Sie tritt uns da, wo die Menschheit tiefer heruntergestiegen ist auf den physischen Plan, in der materialistischen Ausgestaltung als Kopernikanismus entgegen. Die Ägypter haben das spirituell gehabt; sich an diesen Gedanken zu erinnern, war das Weltenkarma des Kopernikus, und das hat herausgezaubert jene Richtungskombination, die zu seinem Sonnensystem geführt hat. Und ähnlich war es bei Kepler, der in noch viel umfassenderem Sinne in seinen allerdings uns sehr abstrakt erscheinenden drei Gesetzen den Wandel der Planeten um die Sonne dargestellt hat. Er hat es aber herausgeholt aus einer tiefen Konzeption. Was aber auffallend ist bei diesem genialen Geiste, das ist die Stelle, die er selbst geschrieben hat, die uns mit Schauern erfüllt, wenn wir sie lesen und wo uns das eben Gesagte handgreiflich entgegentritt. Schrieb doch Kepler die Worte nieder: Ich habe mich hineinvertieft in dieses Sonnensystem, es hat sich mir enträtselt; ich will die heiligen Zeremoniengefäße der Ägypter in die moderne Welt hereinbringen.

Die Gedanken, die im alten Ägypten den Seelen eingepflanzt worden sind, treten uns wieder entgegen, und unsere modernen Wahrheiten sind wiedergeborene ägyptische Mythen. In viele Einzelheiten hinein könnten wir das verfolgen, wenn wir wollten. Wir können es verfolgen bis in die Anlagen der Menschen hinein. Wir gedenken noch einmal der Sphinx, jener wunderbaren rätselhaften Gestalt, die dann in der griechischen Kultur die Odipus-Sphinx geworden ist, die den Menschen das bekannte Rätsel aufgibt. Wir wissen aber auch schon, daß sie zusammengesetzt ist aus derjenigen menschlichen Gestalt, die auf dem physischen Plane noch der Tierform analog war, während ihr Ätherisches schon menschliche Gestaltangenommen hatte. In derägyptischen Zeit war der Mensch nur imstande, die Sphinx wirklich als ätherische Gestalt zu sehen, wenn er gewisse Einweihungsstufen durchgemacht hatte. Dann aber stand sie vor ihm. Und nun ist das Wichtige, daß, wenn man eine wirklich hellseherische Anschauung hat, man sie nicht nur wie einen Holzklotz vor sich hat, sondern daß sich gewisse Gefühle notwendig mit dieser Anschauung verknüpfen. Ein kalter Mensch kann unter Umständen an einer noch so bedeutsamen künstlerischen Erscheinung vorübergehen, ein kalter Mensch kann ungerührt bleiben; das hellseherische Bewußtsein ist nicht in dieser Lage: wenn es wirklich ausgebildet ist, wird das entsprechende Gefühl in ihm angeregt. Es ist in der griechischen Sage das richtige Gefühl ausgedrückt, das der Hellseher noch während der alten ägyptischen Zeit und in den griechischen Mysterien hatte, wenn er so weit war, daß ihm die Sphinx vor das Auge trat. Was war es denn, was ihm da vor das Auge trat? Etwas Unfertiges, etwas, was werden sollte. Er sah diese Gestalt, die in gewisser Beziehung noch tierische Formen hatte, im Ätherkopf sah er, was hineinwirken sollte in die physische Form, um diese menschenähnlicher zu gestalten. Wie dieser Mensch werden sollte, welch eine Aufgabe die Menschheit in der Entwickelung hatte, diese Frage stand lebendig vor ihm als eine Frage der Erwartung, der Sehnsucht, der Entfaltung des Kommenden, wenn er die Sphinx sah. Daß alle menschliche Forschung und Philosophie aus der Sehnsucht heraus entsteht, ist ein griechischer Ausspruch, aber zugleich auch ein hellseherischer. Man hat vor sich eine Gestalt, die nur mit astralischem Bewußtsein wahrgenommen wird, aber sie quält einen, sie gibt einem ein Rätsel auf: das Rätsel, wie man werden soll. Nunmehr hat sich diese Athergestalt, die in der atlantischen Zeit da war und in der ägyptischen Zeit in der Erinnerung lebte, mehr und mehr dem menschlichen Wesen einverleibt, und sie erscheint auf der anderen Seite in der Menschennatur wieder, sie erscheint in all den religiösen Zweifeln, in dem Unvermögen unserer Kulturepoche gegenüber der Frage: Was ist der Mensch? - In all den unbeantworteten Fragen, in all den Aussprüchen, die sich um das «Ignorabimus» drehen, erscheint die Sphinx wieder. In den Zeiten, die noch spirituell waren, konnte der Mensch sich aufschwingen, die Sphinx wirklich vor sich zu haben; heute lebt sie in seinem Inneren als die zahlreichen Fragen, die ohne Antwort sind. Daher kann der Mensch so schwer zu einer Überzeugung von der geistigen Welt kommen, weil die Sphinx, die früher außen war, nachdem gerade in dem mittleren Zeitraum sich der gefunden hat, der das Rätsel gelöst, der sie in den Abgrund, in das eigene Innere des Menschen gestürzt hat, weil diese Sphinx jetzt im Inneren des Menschen erscheint.

Nachdem die griechisch-lateinische Zeit mit ihren Nachwirkungen bis in das 13. und 14. Jahrhundert sich ausgelebt hat, leben wir seither in dem fünften Zeitraum. Seither haben sich immer mehr und mehr anstelle der alten Gewißheit neue Zweifel gesetzt. Immer mehr treten solche Dinge uns entgegen, und wenn wir nur wollen, können wir in vielen, vielen Einzelheiten der neueren Entwickelung die nur ins Materialistische umgesetzten ägyptischen Vorstellungen wiederfinden. Nur müssen wir uns fragen, was da denn eigentlich geschehen ist; denn eine gewöhnliche Übertragung ist es nicht; es treten uns diese Dinge nicht unmittelbar entgegen, sondern so, daß sie modifiziert sind. Alles ist in mehr materialistischer Weise ausgebildet, sogar den Zusammenhang des Menschen mit der Tierheit sehen wir, in materialistische Anschauung umgesetzt, wieder auftauchen. Daß der Mensch wußte, daß er früher seinen äußeren Leib noch nicht anders als tierähnlich gestalten konnte, daß er deshalb in der ägyptischen Erinnerung selbst seine Göttergestalten noch in Tierformen abgebildet hat, das tritt uns in den Weltanschauungen entgegen, die in materialistischer Weise den Menschen vom Tier abstammen lassen. Auch der Darwinismus ist nichts anderes als altes ägyptisches Erbgut in materialistischer Form.

Wir sehen also: nicht bloß ein gerader Fortgang der Entwickelung ist es, der uns da entgegentritt, sondern etwas wie eine Spaltung der Entwickelung. Ein Zweig wurde mehr materiell, einer mehr geistig. Das, was früher mehr in einer Linie gelaufen ist, spaltet sich in zwei Zweige der Menschheitsentwickelung. Gehen Sie in die alten Zeiten zurück, in die ägyptische, in die persische, in die altindische Kultur: eine für sich bestehende Wissenschaft, einen für sich bestehenden Glauben gab es da nicht. Das, was man erfaßte über die geistigen Urgründe der Welt, geht in einer geraden Linie bis zu dem Wissen von den Einzelheiten herunter, und man kann aufsteigen von dem Wissen der materiellen Welt bis zum höchsten Gipfel, einen Widerspruch zwischen Wissen und Glauben gibt es da nicht. Was wir heute diesen Gegensatz nennen, das würde ein altindischer Weiser, ein chaldäischer Priester nicht verstanden haben; sie wußten noch nicht von einem Unterschied, und auch die Ägypter wußten noch keinen Unterschied zwischen dem, was man bloß glauben soll und was ein Wissen sein soll. Dieser Unterschied machte sich erst geltend, als der Mensch tiefer hineinsank in die Materie, als immer tiefer die materielle Kultur von der Menschheit erobert wurde. Dazu aber war noch eine andere Einrichtung notwendig.

Denken wir uns einmal, daß dieser Abfall des Menschen nicht stattgefunden hätte, was wäre dann geschehen? Wir haben einen ähnlichen Abfall schon gestern betrachtet, der aber anderer Natur war; dies ist ein erneuter Abfall auf anderem Gebiet, der etwa eintritt, als eine selbständige Wissenschaft neben der Erfassung des Geistigen auftritt. Das ist erst in der griechischen Welt der Fall, vorher gab es diesen Gegensatz zwischen Wissenschaft und Religion nicht; für den ägyptischen Priester hätte solche Trennung keinen Sinn gehabt. Versenken Sie sich in das, was Pythagoras von den Ägyptern gelernt hat: die Zahlenlehre. Sie war ihm nicht abstrakte Mathematik, sie war ihm das, was ihm die Musikgeheimnisse der Welt in der Harmonie der Zahlen gab; eine heilige, mit religiöser Grundstimmung verbundene Weisheit war ihm die Mathematik, die heute dem Menschen als etwas Abstraktes erscheint. Aber der Mensch mußte immer mehr heruntersteigen mit der Wissenschaft in die materielle, physische Welt hinein, und wir sehen ja, wie selbst das, was die spirituelle Weisheit der Ägypter war, uns entgegentritt — wie in der Erinnerung umgestaltet - in der materialistischen Weltanschauungsmythe. Für die Zukunft werden all die Theorien der heutigen Menschen ebenso als etwas, was nur zeitlichen Wert hat, empfunden werden, wie heute die alten 'Theorien von der Menschheit empfunden werden. Hoffentlich sind dann die Menschen so gescheit, daß sie nicht in den Fehler verfallen wie die heutigen Menschen, die da sagen: Bis in das 19. Jahrhundert hat der Mensch unbedingt dumm sein müssen in der Wissenschaft, da erst ist er gescheit geworden, denn alles, was früher über den Menschenleib, über Anatomie gesagt wurde, ist ja Unsinn, und wahr ist nur, was das letzte Jahrhundert gebracht hat. — Aber der Mensch in der Zukunft wird gescheiter sein, er wird nicht Gleiches mit Gleichem vergelten. Er wird auf unsere Mythen der Anatomie, der Philosophie, des Darwinismus nicht so wegwerfend herunterschauen, wie der heutige Mensch auf die alten Wahrheiten herunterschaut. Aber es ist doch so, daß auch das vergängliche Formen der Wahrheit sind, was man heute als so fest begründet ansieht: das Kopernikanische Weltensystem, es ist nur eine vorübergehende Form. Sie wird ersetzt werden durch etwas anderes. Die Formen der Wahrheit ändern sich fortwährend, das ist herbeigeführt worden durch das Untertauchen des Menschen in die Materialität. Dafür mußte aber, damit im Menschen nicht aller Zusammenhang verlorenginge, ein um so stärkerer geistiger Impuls kommen, ein Impuls nach der Spiritualität hin. Diesen starken Impuls haben wir gestern charakterisiert in dem Christus-Impuls. Es mußte sozusagen die Menschheit «wissenschaftlich» eine Weile allein gelassen werden, und das Religiöse mußte in eine andere Strömung gebracht werden, gerettet werden vor dem fortschreitenden Einfall der Wissenschaft. So sehen wir, wie sich da abspaltet eine Weile die Wissenschaft, die auf das äußere Materielle geht, und das Spirituelle, das in einer besonderen Strömung fortgeht. Wir sehen, wie die zwei Strömungen, der Glaube für das Spirituelle und das Wissen für das äußere Materielle, nebeneinander hergehen. Ja, wir sehen sogar, daß in einer ganz bestimmten Periode der mittelalterlichen Entwickelung, in einer Periode, die der unseren eben vorangegangen ist, Wissen und Glauben sich bewußt gegeneinander stellen, aber noch eine Verbindung suchend.

Sehen Sie sich die Scholastiker an. Sie sagen: Es ist dem Menschen durch Christus ein Glaubensgut gegeben, das dürfen wir nicht antasten, das ist unmittelbar gegeben; alle Wissenschaft aber, die die Zeit hat hervorbringen können, seitdem jene Spaltung geschehen ist, kann nur dazu verwendet werden, um dieses Glaubensgut zu beweisen. — So sehen wir, wie in der Scholastik die Tendenz herrscht, alle Wissenschaft dazu anzuwenden, um die geoffenbarte Wahrheit zu beweisen. Da wo die Scholastik in ihrer Blüte steht, da sagt man: Man kann sozusagen von unten hinaufblicken in das Glaubensgut, und bis zu einem gewissen Grade kann menschliche Wissenschaft es durchdringen. Aber dann muß man sich dem Geoffenbarten hingeben. - Dann aber verliert sich im weiteren Verlauf der Zeiten die Verwandtschaft zwischen Glauben und Wissenschaft, man hat keine Hoffnung mehr, daß sie zusammengehen können; und das äußerste Extrem sehen wir in der Kantschen Philosophie, wo Wissenschaft und Glauben ganz und gar auseinandergetrieben werden, wo auf der einen Seite der kategorische Imperativ mit seinen praktischen Vernunftspostulaten hingestellt wird, und auf der anderen Seite die rein theoretische Vernunft, die allen Zusammenhang verloren hat, die sich sogar eingesteht: Es gibt keine Möglichkeit, von dem Wissen aus einen Zusammenhang mit den spirituellen Wahrheiten zu finden.

Aber es ist auch schon ein starker Impuls wieder da, der wiederum eine Erinnerung alter ägyptischer Gedankeneinflüsse darstellt. Wir sehen, wie sich wiederum Geister finden, die nun einen Zusammenfluß von Glauben und Wissen suchen, die in einer wissenschaftlichen Vertiefung wiederum das Göttliche zu erkennen suchen, und die da suchen, in dem Gott alles so klar und sicher zu erfassen, daß es wieder wissenschaftlicher Gedankenform zugänglich ist. Ein Typus eines solchen Denkens und Anschauens ist Goethe, bei dem tatsächlich Religion, Kunst und Wissenschaft in eines zusammenfließen, der ebenso dem griechischen Kunstwerke gegenüber Religion empfindet, wie er eine Summe von Pflanzenformen durchforscht, um den großen Gedanken der Gottheit wieder manifestiert zu finden im äußeren Ausdruck.

Da sehen wir, wie das Ägyptertum sich an seinem Ausgangspunkte widerspiegelt. Wir können die ganze moderne Kultur durchnehmen: sie erscheint uns als eine Erinnerung des alten Ägyptertums. Aber diese Spaltung in der modernen Kultur ist nicht ohne weiteres zustande gekommen, sie hat sich langsam vorbereitet, und wenn wir verstehen wollen, wie das geschehen ist, dann müssen wir noch einen kurzen Blick darauf werfen, wie sich in der atlantischen Zeit die nachatlantische veranlagt hat.

Wir haben gesehen, daß ein kleines Häuflein von Menschen in der Gegend des heutigen Irland am meisten vorgeschritten war, wie sie diejenigen Fähigkeiten gehabt haben, die nach und nach in aufeinanderfolgenden Kulturepochen heraustraten. Die Ich-Anlage hat sich ja, wie wir wissen, seit der lemurischen Zeit her entwickelt, aber jene Stufe der Ichheit, die in diesem kleinen Häuflein Menschen lebte, das sozusagen die Kulturströmung von Westen nach Osten geschickt hat, bestand in der Anlage zum logischen Erwägen, zur Urteilskraft. Vorher gab es so etwas nicht; wenn ein Gedanke da war, war er auch schon bewiesen. Ein urteilendes Denken war bei diesem Völkchen veranlagt, und sie brachten diese Keimanlage hinüber vom Westen nach dem Osten, und bei jenen Kolonisationszügen, von denen einer nach Süden hinunterging, nach Indien, da wurde die erste Anlage zur Gedankenbildung gemacht. Dann wurde der persischen Kultur der kombinierende Gedanke eingeflößt, und in der dritten, in der chaldäischen, wurde dieser kombinierende Gedanke noch intensiver; die Griechen aber brachten es so weit, daß sie das herrliche Denkmal der aristotelischen Philosophie hinterließen. So geht es immer weiter, das kombinierende Denken entwickelt sich immer mehr und mehr, es geht aber immer auf einen Mittelpunkt zurück, und es finden Nachschübe statt. Wir müssen uns das so vorstellen: Als die Kultur von jenem Punkte hinübergezogen ist nach einem Punkte in Asien, da wandte sich ein Zug nach Indien, der noch am schwächsten durchtränkt war vom reinen logischen Denken. Der zweite Zug, der nach Persien ging, war schon mehr durchdrungen davon, der ägyptische noch mehr, und innerhalb dieses Zuges hat sich das Volk des Alten Testaments abgesondert, welches gerade diejenige Anlage zur Kombination hatte, die entwickelt werden mußte, um wiederum einen Schritt vorwärts zu machen in dieser reinen logischen Erkenntnisform des Menschen. Nun ist aber auch das andere damit verknüpft, was wir betrachtet haben: das Heruntersteigen auf den physischen Plan. Je mehr wir heruntersteigen, desto mehr wird der Gedanke bloß logisch und auf die äußere Urteilskraft angewiesen. Denn logisches Denken, reine bloße menschliche Logik, die von Begriff zu Begriff geht, die braucht zu ihrem Instrument das Gehirn; das ausgebildete Gehirn vermittelt bloß das logische Denken. Daher kann dies äußerliche Denken, selbst da, wo es eine erstaunliche Höhe erreicht, niemals zum Beispiel die Reinkarnation durch sich selbst erfassen, weil dieses logische Denken zunächst nur anwendbar ist auf das Äußerliche, Sinnliche um uns herum.

Die Logik ist zwar für alle Welten anwendbar, aber unmittelbar angewendet kann sie nur in bezug auf die physische Welt werden. Also an ihr Instrument, an das physische Gehirn ist die Logik unbedingt gebunden, wenn sie als menschliche Logik auftritt; nie hätte das rein begriffsmäßige Denken in die Welt kommen können ohne das Weiter-Heruntersteigen in die sinnliche Welt. Sie sehen, die Ausbildung des logischen Denkens ist verknüpft mit dem Verlust der alten hellseherischen Anschauung; wirklich hat der Mensch das logische Denken erkaufen müssen mit diesem Verlust. Er muß sich die hellseherische Anschauung wiederum hinzuerwerben zu dem logischen Denken. In späteren Zeiten wird der Mensch die Imagination dazu erhalten, aber das logische Denken wird ihm bleiben. Erst mußte das menschliche Gehirn erschaffen werden, heraustreten mußte der Mensch in die physische Welt. Der Kopf mußte erst ganz ausgestaltet werden, dem Ätherkopfe gleich, damit dieses Gehirn im Menschen sei. Da erst war es möglich, daß der Mensch in die physische Welt herabsteigen konnte. Zur Rettung des Spirituellen aber mußte der Zeitpunkt gewählt werden, wo noch nicht der letzte Impuls zum rein mechanischen, zum rein äußerlichen Denken gegeben war. Wenn der Christus einige Jahrhunderte später erschienen wäre, dann wäre er sozusagen zu spät gekommen, dann wäre die Menschheit zu weit heruntergestiegen gewesen, sie hätte sich mit dem Denken zu weit verstrickt gehabt, sie hätte den Christus nicht mehr verstehen können. Vor dem letzten Impulse mußte der Christus erscheinen, da noch konnte die religiös spirituelle Strömung als eine Glaubensströmung gerettet werden. Und dann konnte der letzte Impuls gegeben werden, der das Denken des Menschen herunterstieß in den tiefsten Punkt, so daß die Gedanken ganz gefesselt, gebannt wurden an das physische Leben. Das wurde durch die Araber und Mohammedaner gegeben. Der Mohammedanismus ist nichts anderes als eine besondere Episode in diesem Arabertum, denn in seinem Herüberziehen nach Europa gibt er den letzten Einfluß in das rein logische Denken, das sich nicht erheben kann zu Höherem, Geistigem.

Der Mensch wird durch das, was man eine geistige Weltenführung, eine Vorsehung nennen kann, so geführt: Erst wird das spirituelle Leben gerettet im Christentum, dann zieht um den Süden herum der Arabismus nach Europa, das der Schauplatz für die äußere Kultur werden soll. Der Arabismus ist nur imstande, das Äußere zu erfassen. Sehen wir nicht, wie die Arabeske selbst sich nicht zum Lebendigen erheben kann, wie sie bei der Form stehenbleibt? Wir können es an der Moschee sehen, wie der Geist sozusagen herausgesogen ist. Die Menschheit mußte erst herabgeführt werden in die Materie. Und auf dem Umwege durch die Araber, durch die Invasion der Araber, durch das, was man nennen kann den Zusammenstoß des Arabismus mit dem Europäertum, das aber schon in sich das Christentum aufgenommen hat, sehen wir, wie die moderne Wissenschaft erst veranlagt wird.

So sehen wir, daß auf der einen Seite die alte ägyptische Erinnerung wieder auflebt. Was aber macht sie materialistisch? Was macht sie zu der Gedankenform des Toten? Wir können es handgreiflich zeigen. Wäre der Weg glatt fortgegangen, dann wäre in unserem Zeitraum die Erinnerung von dem Früheren aufgetreten. So aber sehen wir, wie sich das Spirituelle in den Glauben hineinrettet, und wie der eine Flügel der europäischen Entwickelung von dem Materialistischen ergriffen wird; wie dem Menschen, der sich an die alte ägyptische Zeit erinnert, diese Erinnerung auf dem Wege durch den Arabismus so umgestaltet wird, daß sie ihm in materialistischer Form erscheint. Daß Kopernikus das moderne Sonnensystem überhaupt erfaßt hat, war eine ägyptische Erinnerung. Daß er es in materialistischer Weise gedeutet hat, daß er es zu einem Mechanischen, zu einem toten Rotieren gemacht hat, kommt davon her, daß von der anderen Seite her der Arabismus diese Erinnerung ins Materialistische herunterzog.

So sehen wir, wie geheimnisvolle Kanäle gehen von dem dritten zum fünften Zeitalter. Das sehen wir selbst in dem Einweihungsprinzip. Denn als das moderne Leben ein Einweihungsprinzip erhalten sollte in dem Rosenkreuzertum, was war es? Wir haben gesehen in der modernen Wissenschaft die Ehe zwischen der ägyptischen Erinnerung und dem Arabismus, der auf das Tote gerichtet ist. Auf der anderen Seite sehen wir eine andere Ehe sich vollziehen, eine Verbindung zwischen dem, was die ägyptischen Eingeweihten ihren Schülern eingepflanzt haben, und dem Spirituellen. Wir sehen eine Ehe zwischen der Weisheit und dem, was an Glaubenswahrheit gerettet worden ist. Jenen harmonischen Zusammenklang von ägyptischer Erinnerung in der Weisheit mit dem christlichen Kraftimpuls, wir sehen ihn in dem Rosenkreuzertum. So sehen wir den alten Samen, der in den ägyptischen Zeiten gelegt worden ist, wiederkehren, aber nicht als eine bloße Wiederholung, sondern differenziert, auf höherer Stufe angekommen.