An Occult Physiology

GA 128

26 March 1911, Prague

6. The Blood as Manifestation and Instrument of the Human Ego

From the last lecture we were able to gather that man, as a physical organisation, separates himself from the outside world, to a certain extent, by means of his skin. When we conceive the human organism entirely in the light in which we have had to do during the preceding lectures, it becomes necessary to say that it is this human organism itself, with its various force-systems, which provides itself with a definite external boundary by means of the skin. In other words, we must understand clearly that the human organism is a system of forces of a nature so self-determined that it gives itself the exact outline of form which appears in the contours of our skin. We shall have to say, therefore, that in connection with the life-process of man there is the interesting fact that in the outer border of the form we have, expressed in a picture, as it were, the combined activity of all the force-systems of the organism. If, on the other hand, the skin itself is to be such an expression for the organism, then we should have to presuppose that it must actually be possible in some way to find the whole man, in a certain sense, in the skin. For, if man as he exists is so to construct himself that the outer skin, as the boundary of his form, expresses what he is, it must in that case be possible to find in the skin everything belonging to his total organisation. As a matter of fact, if we look into what belongs to this total organisation of man, we shall find out how true it is that everything is present in the skin, inside the skin itself, which is present as a tendency in the force-systems of the entire organism.

In all the preceding we have seen that the whole man, in his appearance as earth-man, has in his blood-system the instrument of the ego, so that he actually is man by reason of the fact that he harbours within himself an ego, and that this ego can create an expression of itself as far as the physical system, can work with the blood as its instrument. And now, if the surface of the body, the boundary of the form, is an essential member of the whole organisation, we must conclude that this whole organisation must be active by means of the blood as far as the skin, in order that an expression of the whole human being in so far as he is physical can exist. If we observe the skin—and we must understand it as consisting of several layers stretched over the entire surface of the body—we find that, as a matter of fact, fine blood vessels do extend into this skin, and we are therefore obliged to conclude that it is by means of these fine blood vessels which extend into the skin that the ego is able to send out its forces and create for itself, through the blood, an expression of the human being extending as far as the skin. We know, furthermore, that the nervous system is the physical instrument for everything which we may characterise as consciousness. And, inasmuch as the boundary of the bodily surface is an expression of the plan of the human being as a whole, the nerves must also reach out into the skin-boundary in order that man may express himself adequately in this skin-boundary. We see, therefore, spreading out close to the fine blood vessels lying within the layers of the skin, the nerve-terminations, commonly although not quite correctly called tactile corpuscles, because it is believed that with the help of these man perceives the external world through the sense of touch, just as he perceives light and sound through the eye and the ear. Such is not the case, however, and we shall see later what the facts really are.

Thus we find present in the skin what constitutes the expression, or the bodily organ, of the human ego; and we find also what constitutes the expression of human consciousness reaching out into the skin in the form of fine nerves and their projections. Then we must look around for the expression of what we may consider as the instrument of the life-process. We have already in our last lecture directed attention to this instrument of the life-process, in our discussion of the function of secretion. In this function, in which we have seen that a sort of hindering takes place, as it were, we may recognise the expression of the life-process, to the extent that a living being which wills to exist in the world is compelled to shut itself off from the outside world. This self-enclosing can take place only by its experiencing a hindering within itself. This living through a hindrance in itself is brought about by means of the organs of secretion, which may be described in the broadest sense as glands. Glands are organs of secretion; and, in so far as they are such, there takes place in them that sort of hindrance which calls forth inner resistance, in order that a being may shut itself off within itself. We must presuppose, therefore, that such organs of secretion, similar to those we have everywhere else in the organism, belong also to the skin. And they do belong to the skin; for we find, in the skin organs of secretion, glands of the greatest possible variety, which carry on this function of secretion, in other words, a life-process, within the skin.

Now, if we ask finally what underlies this life-process, we shall find there something we may call a purely material process, that is, the conveying of substances from one organ to another. At this point we must differentiate carefully between a process such as has to do with life and is a process of secretion, which creates an inner hindrance, and that process which transports substances quite externally, which causes a transference of substances from one organ to another. These are not the same. To a materialistic conception it might seem as if they were, but to a living grasp of reality they are not so. As long as we are alive we are not dealing, in a single member of the human organisation, with a mere transportation of substances from one organ to another. In the very moment, rather, when the substances of nutrition are taken in by the life-process, we have to do with occurrences such as those of the inner secretive processes. Thus we come down a step from the real life-process to the process of the physical body when we say that this process of secretion, looked at physically, is such that the substances of nutrition which are taken in are transported to all the different parts of the physical body; whereas in its other aspect it is a living activity, a becoming aware of itself, as it were, on the part of the organism in its own inner being, through the setting up of hindrances. Through the life-processes there takes place at the same time a transporting of substances, and we find this in the skin just as in the other parts of the organism. The nutritive substances are continually being secreted, carried outwards in the skin, and there also excreted through the process of perspiration, so that here also what we may call a transporting in the physical sense, a changing of the substances in the organism, is physically present.

We have thus set forth in its essence the fact that even in the external organ of the skin are present both the blood-system, as the expression of the ego, and the nervous system as the expression of the consciousness. And now I wish little by little to direct you to the fact that we have a right to bring together all phenomena of consciousness under the expression “astral body,” that is, to conceive the nervous system comprehensively as an expression of the astral body; that we have what we may call the glandular system as an expression of the ether-body, or life-body; and the actual process of nutrition and depositing of substances as an expression of the physical body. To this extent all the separate members of the human organism are actually present in the skin-system, through which man shuts himself off from the outside world. Now, we must take into account the fact that all such divisions of the human organisation as the blood-system, the nervous system, the nutritive system, etc., form in their mutual relations a whole; and that when we observe these four systems of the human organisation and have them before us in the physical body, we are viewing the human organism in two aspects, as it were. We actually have it before us in two aspects and in such a way, indeed, that we may say that the human organism has meaning within our earth-existence only if, as an entire organism, it is the instrument of the ego. It can be this, however, only if the most immediate instrument which the human ego can employ, the blood-system, is present in it.

We can state thus that the blood-system is the most immediate instrument of the human ego. Yet the blood-system is possible only if all the other systems are first existent. The blood is not only, according to the meaning of the poet's words, “a very special fluid”; it is also obvious that it cannot exist as it is except by finding a place for itself in the entire remaining organism; its existence must necessarily be prepared for by all the rest of the human organism. The blood, as it exists in man, cannot be found anywhere else than in the human organism. We shall refer, further on, to the relation of the human blood to the blood of the animal; and this will be a very important consideration, since external science to-day takes little notice of it. To-day we are dealing with blood as the expression of the human ego, taking account, at the same time, of a remark which was made in the first lecture: namely, that what is here said concerning man cannot, without further thought, be applied to any other kind of earth-being whatever. We may say then that, when once the entire remaining organism of man is constructed as it is, it is then capable of receiving into itself the circulatory course of the blood, is capable, that is, of carrying the blood, of having within itself that instrument which is the tool of our ego. The whole human organism, however, must first be built up for this purpose.

As you know, there are other beings on the earth which seem to have a certain kinship with man, but which are not in a position to bring to expression a human ego. In their case it is obvious that what appears similar in these other systems to human potentialities is built up otherwise than in the human being. To put it somewhat differently: in all of these systems which precede the blood-system there must first be present everything, in a preparatory plan, which is capable of receiving the blood. This means that we must have a nervous system exactly fitted to receive a blood-system such as that of man; we must have a glandular system which is perfectly prepared for the circulation of human blood; and the system of nutrition must likewise be thoroughly prepared for the human blood-system. This signifies in turn, however, that even from the other aspect of man's organism, for example, the whole nutritional system, which we have described as expressing the actual physical body of man, there must be present the potentiality of the ego. The entire process of nutrition must, as it were, be so directed and guided through the organism that the blood can finally move in the courses which are right for it. What does that mean?

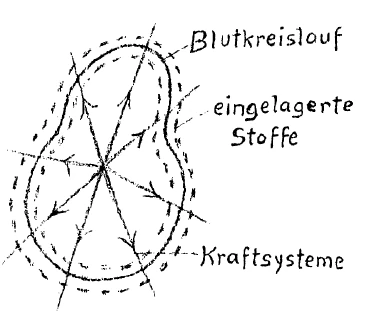

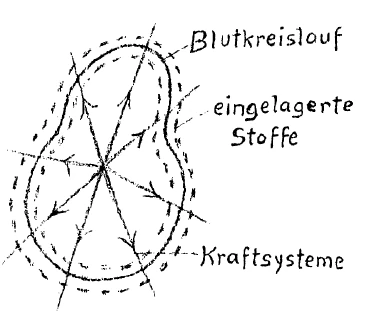

Let us assume, since everything is absolutely determined in its formation and its particular kind of activity by the quality of man's being, that we had to draw the course of the blood (in a mere diagram, of course) in this fashion. We should then have to say that this circulation of the blood must now be received by the rest of the organism, which must fit itself into this. This means that all the other systems of organs must be directed to the very place, or to the neighbourhood, where the blood has to be. We could not have the whole texture of the blood-vessels, as this exists in our head for example, or in some other part of our organism, if what is necessary to it were not in each case directed just where the blood is to circulate. That is, the force-systems (which I here indicate by a second line) must act in the human organism, beginning with the nutritive system, in such a way that they carry all the nutritive matter to the proper places, and at the same time so form it beforehand that in these places, by means of such preparation of the nutritive matter, the blood-system can hold exactly to the form of the course it now takes, and thereby be an expression of the ego. There must, accordingly, be contained in all the impulses of our nutritive apparatus, that is, our lowest organ-system, just that thing which makes of man an ego. In other words, the entire form which man finally presents to us must be incorporated in what we call the various methods of nutrition. Here we are looking down from the blood into the organ-systems which prepare the circulatory course of the blood, far, far down, from our ego to those processes which go on in the darkness of our organism. Although our blood is the expression of our ego-activity, the most conscious activity in us, it is at the same time necessary to look down into the obscure depths of our organism and say that the way in which our organism down there is built up and formed through other processes, concerning which we do not know at all how the different substances are carried to those places where they ought to be, in order that our organism may be constructed by the several force-systems just as the ego desires to have it—this shows us that, beginning with the nutritive processes, there are present in man's organism all the laws which lead ultimately to the formation of the course of the blood.

Now, the blood presents to us the most mobile, the most active, of all our systems. We know, indeed, that even if we interfere only very slightly with the course of the blood, it follows at once another direction from the one it takes in the normal course. We need only prick ourselves and the blood at once takes another direction from its usual one. This is of infinite importance; for we can see from it that the blood is the most easily controlled element in the human body; that it has a good foundation in the other organic systems while at the same time it is the most controllable of them all, has the least stability within itself, and is more determined than any other system by the experiences of the conscious ego. I shall not now go into the fantastic theories of external science concerning blushing or turning pale from feelings of shame or anxiety; I shall merely point to the purely external fact that, underlying such experiences as fear or anxiety, or the feeling of shame, are ego-experiences which are recognisable in their effect upon the blood. With the feeling of fear or anxiety it is as if we wanted to guard ourselves, so to speak, against something which we believe will have an influence upon us: we draw back with our ego. With the feeling of shame we would best of all like to hide ourselves, to obliterate our ego. In both cases, referring only to the external facts, the blood, as an external physical instrument, follows physically what the ego lives through in itself. In the case of feelings of fear and anxiety, where a man would like to draw back into himself completely, from something which he feels to be threatening him, he becomes pale; the blood draws back to its centre, draws inward. When a man would like to hide himself because of his sense of shame, would like to obliterate his ego, or best of all not to exist, or to slink away somewhere, the blood, under the influence of what the ego may here live through, spreads out as far as the periphery. And so you see from this that the blood is the most easily controllable system in man, and that it can follow in a definite way the experiences of the ego.

Now, the further we go down into the organic systems, the less are they regulated so as to follow our ego in this way, the less inclined to adapt themselves wholly to the inner experiences of the ego. Whatever especially affects the nervous system is regulated as we know along certain definite nerve-courses, and these nerve-courses show us something relatively fixed, in their functioning, in contrast to the blood. Whereas the blood is mobile, and can be guided under the influence of ego-experiences from one part of the body to another, as happens in the case of shame and fear, we must say, with regard to the nerve- courses, that the forces which are active here must be the forces of consciousness, and that these forces cannot carry the nerve-substance from one place to another as can be done with the blood-substance. This substance of the nervous system is, indeed, more fixed than the substance of the blood.

And this is still more true in the case of the glandular system, which shows us glands that have certain definite tasks to perform in definite places within the organism. If a gland has to be brought into activity by some means or other to some definite purpose, it cannot be aroused by means of some such cord as the nerve-cord; rather it must be stimulated at the very place where it is situated. That which is contained in the glandular system, therefore, is even more fixed than the nerves; we must excite the glands where they are. Whereas we can guide the activity of the nerves along the nerve-cords (we have in this system connecting fibres also, which unite the separate ganglions), the gland must be looked for where it is located.

Still more striking, however, is this process of fixation, this process of being inwardly determined (not “being determinable”) in everything that has to do with the system of nutrition, by means of which man incorporates substances directly into himself in order to be a physical, sensuous being. For this incorporating of substances there must, nevertheless, be available a thorough preparation for the instrument of the ego as well as for the other instruments.

Thus, when we observe the human organism primarily with reference to its lowest system, the nutritive system, in its broadest sense, by means of which the substances within the organism are conveyed to all its various members, we may say that these substances must be so regulated that the formation, the external structure, of the man may proceed in a manner which finally renders possible the manifestation of the ego within this human organisation. To this end much is necessary. It is necessary not only that the substances of nutrition be conveyed in the most diverse ways, that they be deposited in all the different parts of the organism; but also that all possible provision be made to determine the outer form of the human organism.

Now, it is important that we should be clear as regards the following: in what we have called the skin are represented indeed, as we have found, all the systems of the human organism, so that we have been able to come even to the lowest system itself, the nutritive system, and to say that everything which in the strictest sense belongs to the physical system of man, considered as the system of nutrition, is poured into the skin. Yet you can easily understand that this skin as such, in spite of the fact that it has all these other systems in it, has one great defect. It does, to be sure, correspond to the form of the human organism; yet, of itself alone, it would not have this form. In spite of the fact that it has all the organ-systems in itself, it would not of itself be capable of giving to man the outline of his form. If that alone were present which is present in the skin, man would collapse, through it alone he could not maintain his upright form. From this we see that not only are there necessary those nutritive processes which make the skin a physical system, but that there must also be possible other manifold nutritive processes which determine the form of the human organism as a whole. At this point, therefore, it will not be difficult to grasp the fact that we must consider those nutritive processes which go on in the cartilage and the bones as such transformed nutritive processes. What sort of processes are they?

When the matter contained in our nutritive substances is conducted to a cartilage or a bone, it is really transported only as physical matter; and what we ultimately find in the cartilage or the bone is nothing else than the transformed nutritive substances. Here, however, they are transformed otherwise than in the skin. We must, therefore, conclude that we have, in the skin, transformed nutritive substances which are deposited in the outermost boundary of our body, following the outline of its form, for the purpose of making us into physical man; yet, on the other hand, through the way in which the nutritive matter is deposited in the bones, we must also see that there we have to do with a nutritive process which rounds out the human form but which, in comparison with that expressed in the skin, is a different transformation of the nutritive process. And now, if we follow the method of observation we used earlier in connection with the nervous system, it will not any longer be hard for us also to understand that this entire nutritive process is our transportation system for the supply of food.

When we look at the skin, which finally shuts man off from the outside world, and when we observe the nutritive substances that bring about that external enclosure which in itself certainly provides man with his surface structure, but which could not of itself produce the human form, it then becomes clear that this sort of nutritive process which is active in the skin is the most recent one in the human organism. In the manner of providing nourishment to the bones we see a process which bears a similar relation to the process of nourishment in the skin to that which we attributed to the process of the formation of the brain, as compared with that of the formation of the spinal cord. Just as the brain appeared to us to be the older organ, and the spinal cord the younger, and the brain appeared to be a metamorphosed spinal cord, so here we have a right to say: if that same thing which we see as the latest, external process of skin-formation is imagined at a maturer stage metamorphosed, we can then recognise this in the firmer, self-solidifying process of nourishment which appears in the building up of the cartilage and the shaping of the bones.

This observation of the human organism might, therefore, point us to the following conception, namely, that what to-day appears before us as the bony system, in which the process of nourishment shows us a quality of inner stability, an earthy quality, so to speak, this bony system actually did, at an earlier stage, also develop in a softer substance; and only later did it become hard and take on the form of the firm bony system. This can be indicated even by external science, which teaches us that certain forms which in later life are quite clearly bones in the human organism are in the early years of childhood still soft, have the quality of cartilage. This means, therefore, that out of a softer, cartilaginous mass the bones are formed, as a result of the depositing of a different sort of nutritive matter from that which is deposited in the mass of cartilage. Here we have, indeed, a transition from a softer to a firmer form, as this process still goes on to-day in the individual human life. If we see, then, in the cartilage an earlier stage of the bone, we may say that the whole depositing of the bony system in the organism appears to us as something representing a last result, as it were, of those processes appearing in the nourishing of the skin. First, the substances must in the simplest way be metamorphosed to the softest possible substance and driven toward the organs of the body; and, when this preparation has taken place, the nutritive process then can go on, and certain parts can be hardened into bony matter, in order that the form of the human organism as a whole may be the final result.

The nature of the bones as we see them, on the other hand, gives us the right to conclude from direct evidence that really we can find no further progress in the nutritive process beyond that in the bony formation, in so far as the human being, up to the present stage of his evolution, is concerned. Whereas we have in the content of the blood the most determinable substance in man, we have in the bony substance, in that which appears before us in the form of the bones, something which is not determinable, which has arrived at a stage of maximum fixity of form. Indeed, if we continue our previous observations, that the blood is man's most easily controlled instrument whereas the nerves are less subject to his influence, we must then consider that in the bony system, which is the foundation of the entire human organization, we have something that has arrived at the ultimate stage in its evolution so far as man of to-day is concerned, something which represents the product of a final metamorphosis. For this reason, moreover, everything which has to do with forming the bony system, in spite of the fact that this must be wholly directed toward the ego, must take place in such a way that the bones may be ultimately the carriers and supporters of an organism like this, in order that the courses of the blood may take such directions as they should, and this in turn in order that in these courses of the blood the human ego may have a proper instrument.

I should like to ask who would not look upon the human organism with the greatest admiration, and say: “I have here before me that which must have gone through the greatest number of transformations, the greatest number of stages, which must have begun with the lowest stage of a process of nutrition and finally have ascended, through countless epochs, as far as the bony system, which at length has been so constructed that it can be the firm bearer, the firm supporter of the ego!” Once we become aware of how the tendency of the ego works even in the forming of the separate bones, so that man can ultimately become an ego-bearer, who of us would not be filled with admiration before this edifice of the human organism and say: “When we observe this human being we find we have two poles, as it were, of physical existence represented in the blood-system, which is the most subject to outside influence, and the bony system, which is in itself the most solid of all, the one which has gone farthest in the state of impermeability to influence.” In this bony system of man the physical organisation has found the final expression of itself, an ultimate conclusion, whereas in the blood-system the human physical organisation has, in a certain sense and at its present stage of existence, made a new beginning.

When we look at our bony system, we can truly say that we revere it as an ultimate conclusion of the human physical organisation. And, when we look at our blood-system, we can say that we see in it a beginning, something which could begin only after all the other systems of the organisation were there first. We may say with regard to the bony system: “Its first beginning must already have been present, as a soft substance, before the glands could be given a place; for the glands had, indeed, to be supported at their appropriate places by the bone-forces; and such was the case likewise with the courses of the nerves and the blood. The bony system is the oldest of the force-systems belonging to the human organism; consequently it is the foundation of our organisation.”

If, therefore, we observe these two extremes in the human organisation, we find we have in the blood-system the most mobile element, the element which is so active within us that to a certain extent it follows every inner stirring of the ego; and in the bony system we have something almost entirely withdrawn from that over which our ego still has any influence, we can no longer reach it with our ego; yet in spite of this, the whole organisation of the ego is contained within its form. Hence, even to purely external observation, the blood-system and the bony system in man are like a beginning and a conclusion in contrast to each other. And, if we thus look at ourselves, having a blood-system which continually obeys all the stirrings of the ego, we must conclude that human life really expresses itself in this active blood. And when we look at our bony system we say: “It really is somewhat isolated; it is that which draws aloof from our human life, and serves it only as a support.” Or, to express it differently: “Our pulsating blood is our life; our bony system is that which has already withdrawn from a direct connection with our life, because of its ancient origin; has already eliminated itself, and continues merely to serve as a support, to give us form.” Whereas in our blood we are alive, we are in truth already dead in our bony system. And I urge you to look upon this expression as a leitmotiv for the lectures which follow, for it will help us to certain important physiological conclusions: “Whereas in our blood we are alive, we are in our bony system, strictly speaking, already dead!” Our bony system is like a scaffolding, the thing in us that is least of all alive, only a scaffolding to support us.

We have seen in man from the first a duality. And here this duality confronts us in yet another form: we have, on the one hand, in our blood that which is the most vitally active, the most living thing in man; and, on the other, we have in our bony system something which draws aloof from this vital activity of ours, something which really already bears death in itself. Moreover it is, in a certain sense, our bony system which is least subordinated in its form to the life of the ego. For this reason the bony system has already arrived, in its form, at a certain final conclusion, even though it still continues to grow, at that stage in a human life when the ego-experiences first begin to stir inwardly. By the time of the change of teeth the bony system has taken its form in the main; it then merely continues to develop by growth those forms which it has produced. In the forming of the new teeth, somewhere about the seventh year, we have the last productive activity of which the bony system is capable. During that very time when we ourselves still remain withdrawn from our inner vital activity, the chief development of our bony system is proceeding.

It is then, moreover, that most mistakes are made in the giving of nutrition, when the bony system is building itself out of the dark foundations and forces of the organism. The way is prepared in these years for bone-diseases such as rickets and the like, if the processes of nourishment are not properly directed. Thus we see that what is withheld from the ego works into our bony system.

It is entirely different in the case of the blood-system, which follows in active response the life of the individual human being and is more dependent than any other system upon the processes of our conscious inner life. It is a fallacy on the part of external science to believe that the nervous system is more susceptible to inner experiences than is the blood-system. I shall here point only to the fact that in a phenomenon such as blushing, where a shifting of the blood takes place, we have the very simplest form of the influencing of the blood-system by way of the ego-experiences; likewise, when we become pale from anxiety and fear, we have transitory expressions of ego-experiences clearly manifested in the instrument of the ego. The way the ego feels in fear or shame is expressed through its instrument, the blood. You can understand, therefore, if such expressions occur even in the merely transitory processes, that the more lasting, habitual experiences of the ego must certainly manifest themselves in the easily excitable element of the blood. There is no passion, no instinct, no emotion, whether we experience these habitually or whether they come to expression in an explosive way, which does not pass over, as inner experience, to the blood as the instrument of the ego, which does not there express itself externally. All the unwholesome elements of the inner life of the ego express themselves primarily in the blood-system. And so, wherever we wish to understand anything that goes on in the blood-system, it is important not merely to inquire as to the nutritive process but even more to look into the soul-processes in so far as they are inner ego-experiences, such as moods, habitual passions, emotions and the like. Only the materialist will direct his attention chiefly to the nutrition in connection with disturbances in the blood-system. For the nourishment of the blood is dependent upon that of the physical system, the glandular system, the nervous system, and the rest; and, as a matter of fact, the nutritive matter is already thoroughly filtered when it comes into the blood. If therefore the blood is to be affected from without, the organism must be already in a seriously diseased state. On the other hand all soul-processes, all processes of the ego, react directly upon what is occurring in the circulation of the blood.

Thus our bony system is the one which most of all draws aloof from the processes of our ego, while our blood-system accommodates itself more than any other to these ego-processes. Indeed this bony system is by nature, we might say, quite independent of the human ego, and yet adapted to its purpose, with the exception of one single portion which, just because it presents an exception to the characteristic of the bony system of not being determinable by the ego, has given cause for all sorts of mischief.

You know that there is such a thing as “Phrenology,” an investigation of the skull. This bone-investigation, in spite of the fact that, from a certain materialistic point of view, it is looked upon as superstition, has gradually, even where loyally fostered, taken on a materialistic colouring in accordance with the general fashion of our time. If we were disposed to characterise it somewhat crudely we might say: Phrenology is carried on in general in such a way that the expression of the inner nature of the ego is sought for in the forms in which the skull is moulded. Thereby certain general principles are set up, that one prominence in the skull signifies this, another that, and so forth. The human qualities are sought for in the light of these prominences, so that phrenology seeks in the bony system of the skull for a kind of plastic expression of the ego. And yet, if it is carried on in this way, even though it seems to look for spiritual expressions in the structure pf the single bones, it is harmful. For anyone who is a truly keen observer knows that no single human skull is like another, and that no one could ever account for this or that by way of generic elevations or depressions. Every separate skull is so different from every other that in each we find different forms.

Now, we have stated that whereas the blood in its vital activity is the system that most of all follows the ego, the bony structure withdraws from it, follows it least of any. And yet, although the bones in general appear to be designed according to type, the skull-bones and also the bones of the face seem in a certain way to correspond to the human ego. Anyone who observes the structure of the skull knows, at the same time, that although man himself is an individual and his skull-structure is also individual, yet this wonderful configuration of the skull has been designed from the beginning in accordance with the particular human individuality and must develop just as the other bones do only in a different form for each man. How does this come about? It comes about for the same reason that underlies the development of the individual qualities of man in general; for the entire life of the individual human being does not run its course only from a birth to a death, but continues throughout many incarnations. Whereas our ego has no influence, therefore, over the skull-structure in our present incarnation, it has developed during the intervening period between the last death and the last birth in accordance with the experiences of the preceding incarnation, the forces which determine the skull-structure; and it is these forces which determine the form of the skull in this incarnation. What the ego was in the preceding incarnation determines the form of the skull in this one; so that in the structure of our skull we have an external plastic expression of the way in which we, every single one of us, again however as individuals, have lived and acted in the preceding incarnation. Whereas all the other bones we have in us express something which is common to man, the skull in its external form expresses that which we were in an earlier incarnation.

Thus the element of the blood, which is the most vitally active of all, can be determined by the ego in this incarnation; our bones, on the other hand, have already entirely withdrawn during this incarnation from the influence of the ego, with the exception of the last remaining case of the skull-bone which also, however, no longer follows the ego in this incarnation, except only as the ego carries over its own evolution from the one incarnation into the next, and so develops the formative forces in the interval between the two that it can manifest in these very bones what was our nature and character in the preceding incarnation. There is no such thing as a general phrenology; but, to sum up, we must judge every man according to what he himself is; and the structure of our skull we must look upon as a work of art. Of course we are compelled to recognise something individual in the skull-structure; yet at the same time an individual something that is an expression of the ego of a preceding incarnation.

Thus we see that even this form of bone-structure, as it appears in the structure of the skull, is withdrawn from the blood to such an extent that the ego has no more influence over it excepting only during the passing between death and a new birth, when the ego receives, after death, still stronger forces with which to overcome and shape for itself those forces that have already completely withdrawn from the vital activity in the man. When, therefore, anyone speaks about the idea of reincarnation and says: “That is something which, speaking generally, is beyond our judgment or reason,” one may answer: “You can, if you will, convince yourself by tangible evidence that the human ego was present in a previous incarnation. When you take hold of a human head you have before you the tangible proof of reincarnation!” And anyone who does not admit this, who sees something paradoxical in the fact that, because of the way in which a thing is formed externally, the way a thing appears in its outward form, one is forced to infer something living that formed this exterior shape out of its own inner life, such a person has no right to deduce in any other case a living something when he comes across a plastic structure. He who cannot admit as strictly logical the conclusion that in the form of our individual skull is expressed the configuration of our ego of preceding incarnations has also no right, if he finds a shell, for example, to conclude from its form that at one time there was a living being in it! And anyone who does so conclude dare not dismiss the logical and absolutely equivalent conclusion that, in the individual plastic formation of a man's cranium, direct proof is given of the influence of an earlier life on the present one.

Thus you see that we have here one of the means by which to throw light by means of physiology upon the idea of reincarnation. We must only give ourselves time. If we are patient and wait, we shall discover where proofs may be procured, and how to procure them. And anyone who might be disposed to deny that there is logic in what has just been stated would have to disown all palaeontology; for it rests on the same inference. Thus we see how, by penetration into the forms of the human organisation, we can trace it back to its spiritual foundations.

Sechster Vortrag

Aus den letzten Vorträgen konnten wir ersehen, daß der Mensch als physische Organisation sich gewissermaßen durch seine Haut nach außen abgrenzt. Wenn wir den menschlichen Organismus ganz in dem Sinne auffassen, wie wir das nach den bisherigen Erörterungen tun müssen, dann ist es notwendig, daß wir uns sagen: Es ist der menschliche Organismus mit seinen verschiedenen Kraftsystemen selber, der sich in der Haut nach außen einen bestimmten Abschluß gibt. Mit anderen Worten: Uns muß klar sein, daß im menschlichen Organismus ein solches Gesamtsystem von Kräften ist, welche sich durch ihr Zusammenwirken so bestimmen, daß sie sich genau den Formumriß geben, der durch die Haut als äußere Begrenzung der Menschengestalt zum Vorschein kommt. So müssen wir eigentlich sagen, daß für den Lebensprozeß des Menschen die interessante Tatsache vorliegt, daß uns in der äußeren Formbegrenzung ein gleichsam bildhafter Ausdruck gegeben ist für die gesamte Wirksamkeit der Kraftsysteme im Organismus. Wenn nun in der Haut selber ein solcher Ausdruck des Organismus gegeben werden soll, so müssen wir voraussetzen, daß innerhalb der Haut eigentlich in einer gewissen Weise der ganze Mensch irgendwie zu finden sein muß. Denn, wenn der Mensch, so wie er ist, so gebildet sein soll, daß die äußere Haut als Formbegrenzung das ausdrückt, was er ist, so muß in der Haut alles das gefunden werden können, was im Menschen zur Gesamtorganisation gehört. Und in der Tat, wenn wir auf dasjenige eingehen, was zur Gesamtorganisation des Menschen gehört, so können wir finden, wie sehr eigentlich dasjenige innerhalb der Haut vorhanden ist, was in den Kraftsystemen des Gesamtorganismus veranlagt ist.

Da haben wir zunächst gesehen, daß der Gesamtmensch, wie er uns als Erdenmensch entgegentritt, das Werkzeug seines Ich in seinem Blutsystem hat, so daß der Mensch dadurch Mensch ist, daß er in sich ein Ich birgt, und dieses Ich sich bis zum physischen System herunter einen Ausdruck, ein Werkzeug schaffen kann im Blut. Ist nun unsere Körperoberfläche, unsere Formbegrenzung ein wesentliches Glied unserer Gesamtorganisation, so müssen wir sagen: Diese Gesamtorganisation muß durch das Blut bis in die Haut hinein wirken, damit in der Haut ein Ausdruck der ganzen menschlichen Wesenheit, insofern sie physisch ist, vorhanden sein kann. Betrachten wir die Haut, wie sie sich, aus mehreren Schichten bestehend, über die ganze Oberfläche des Leibes spannt, so finden wir, daß in der Tat in diese Haut feine Blutgefäße hineingehen. Durch diese feinen Blutgefäße kann das Ich seine Kräfte senden und sich bis in die Haut hinein einen Ausdruck der menschlichen Wesenheit schaffen. Wir wissen ferner, daß für alles, was wir als Bewußtsein zu bezeichnen haben, das Nervensystem das physische Werkzeug ist. Wenn nun die Körperoberflächenbegrenzung ein Ausdruck der Gesamtorganisation des Menschen ist, so müssen auch die Nerven bis in die Haut hinein sich erstrecken, damit das menschliche Bewußtsein bis in dieses Organ gehen kann. Wir sehen daher neben den feinen Blutgefäßen innerhalb der Hautschichten die mannigfaltigsten Nervenendungen verlaufen, die man ja gewöhnlich — obwohl nicht mit vollem Recht - die Tastkörperchen nennt, weil man annimmt, daß der Mensch mit Hilfe dieser Tastkörperchen die äußere Welt durch den Tastsiinn wahrnimmt, so wie er durch Augen und Ohren Licht und Schall wahrnimmt. Es ist das aber nicht eigentlich der Fall. Genauer betrachtet ist dieser Tastsinn der Ausdruck verschiedener Sinnestätigkeiten, zum Beispiel Wärmesinn und andere. Wir werden noch sehen, wie die Sache liegt. Wir finden also in der Haut dasjenige, was Ausdruck oder körperliches Organ des menschlichen Ich ist: das Blut. Wir sehen aber auch dasjenige, was Ausdruck des menschlichen Bewußtseins ist: das Nervensystem, das seine Ausläufer bis in die Haut hineinerstreckt.

Nun müssen wir uns umsehen nach dem Ausdruck dessen, was wir überhaupt betrachten können als das wesentliche Instrument des Lebensprozesses. Wir haben schon im letzten Vortrage auf dieses Instrument des Lebensprozesses aufmerksam gemacht bei der Besprechung der Absonderung. In der Absonderung, bei der, wie wir gesehen haben, gleichsam eine Art von Hemmnis auftritt, haben wir insofern den Ausdruck des Lebensprozesses zu sehen, als ein lebendiges Wesen, das in der Welt existieren will, notwendig hat, sich nach außen abzuschließen. Das kann nur dadurch geschehen, daß es in sich selber ein Hemmnis erlebt. Dieses Erleben eines Hemmnisses in sich selber wird vermittelt durch Absonderungsorgane, die man im weitesten Umfange als Drüsen bezeichnen kann. Drüsen sind Absonderungsorgane, und das Hemmnis tritt dadurch ein, daß sie den an sie herandrängenden Nahrungsstoffen sozusagen inneren Widerstand entgegensetzen. Wir müssen also voraussetzen, daß solche Absonderungsorgane, ebenso wie wir sie sonst im Organismus verteilt haben, auch der Haut angehören. Und sie gehören der Haut an; denn wir finden auch in der Haut Absonderungsorgane, Drüsen der verschiedensten Art, Schweißdrüsen, Talgdrüsen, welche dieses Absonderungsgeschäft — also einen Lebensprozeß — innerhalb der Haut betreiben.

Und wenn wir endlich nach dem fragen, was unterhalb des Lebensprozesses liegt, so werden wir da dasjenige finden, was wir nennen können den reinen Stoffprozeß, das Überleiten der Stoffe von einem Organ zum anderen. Ich möchte Sie jetzt an dieser Stelle bitten, genau zu unterscheiden zwischen einem solchen Absonderungsprozeß, der ein inneres Hemmnis schafft, der den Lebensprozessen angehört, und denjenigen Prozessen, die rein stoffliche Umlagerungen bewirken, also bloßes Transportieren der Stoffe von einem Orte zum anderen. Denn das ist nicht dasselbe. Für eine materialistische Anschauung könnte es so aussehen, aber für eine lebensvolle Erfassung der Wirklichkeit ist es nicht so. Wir haben es im menschlichen Organismus nicht bloß zu tun mit einer bloßen Transportierung der Stoffe. Allerdings findet überall ein Hinleiten der Stoffe, der Ernährungsprodukte, zu den einzelnen Organen statt. Aber in dem Augenblick, wo die Nahrungsstoffe aufgenommen werden, haben wir es mit einem Lebensprozesse zu tun, mit Absonderungsprozessen, die zugleich innere Hemmnisse schaffen. Es ist notwendig, dies zu unterscheiden von dem Prozeß der bloßen Stoffumlagerung. Wir steigen von dem Lebensprozeß hinunter zu den Prozessen des eigentlichen Physischen, wenn wir sagen, es sieht sich so an, wie wenn die aufgenommenen Nahrungsstoffe in die verschiedensten Teile des physischen Leibes transportiert würden. Es ist aber eine lebendige Tätigkeit, gleichsam ein Sichgewahrwerden des Organismus in seinem eigenen Innern, in dem durch die Absonderungsorgane innere Hemmnisse geschaffen werden.

Mit den Lebensvorgängen findet zugleich ein Transport der Stoffe statt, und das ist in der Haut ebenso wie in den anderen Teilen des Organismus. Durch die Haut werden die Abfälle der Nahrungsstoffe ausgeschieden, abgesondert, nach außen getragen durch den Prozeß der Schweißabsonderung, des Schwitzens, so daß auch hier ein rein physisches Transportieren der Stoffe vorhanden ist.

Damit haben wir im wesentlichen charakterisiert, daß in dem äußeren Organ der Haut sich finden sowohl das Blutsystem als Ausdruck des Ich als auch das Nervensystem als Ausdruck des Bewußtseins. Ich will jetzt nach und nach dazu überleiten, daß wir ein Recht haben, alle Bewußtseinserscheinungen zusammenzufassen mit dem Ausdruck «Astralleib», daß wir also das Nervensystem bezeichnen können als einen Ausdruck des Astralleibes, das Drüsensystem als einen Ausdruck des Äther- oder Lebensleibes und daß wir den eigentlichen Ernährungs-Umlagerungsprozeß bezeichnen können als einen Ausdruck des physischen Leibes. Insofern sind alle einzelnen Gliederungen der menschlichen Organisation in dem Hautsystem, durch das sich der Mensch nach außen abschließt, tatsächlich vorhanden. Nun müssen wir allerdings berücksichtigen, daß alle Gliederungen der menschlichen Organisation, Blutsystem, Nervensystem, Ernährungssystem und so weiter, in ihren gegenseitigen Beziehungen ein Ganzes ausmachen und daß wir gleichsam, indem wir diese vier Systeme der menschlichen Organisation betrachten und sie am physischen Leibe uns vor Augen führen, den menschlichen Organismus von zwei Seiten vor uns haben. Wir haben ihn tatsächlich von zwei Seiten, und zwar zunächst so, daß wir sagen können: Der menschliche Organismus hat innerhalb des Erdendaseins nur einen Sinn, wenn er als Gesamtorganismus das Werkzeug unseres Ich ist. Das kann er aber nur sein, wenn das nächste Werkzeug, dessen sich das menschliche Ich bedienen kann, das Blutsystem, inihm vorhanden ist. Nun ist aber das Blutsystem nur möglich, wenn ihm die anderen Systeme in ihrer Bildung vorangehen. Das Blut ist nicht nur im Sinne des Dichterwortes «ein ganz besonderer Saft», sondern es ist leicht einzusehen, daß es so, wie es ist, überhaupt nicht existieren kann, ohne daß es sich einlagert dem ganzen übrigen Organismus des Menschen; es ist nötig, daß es in seiner Existenz vorbereitet ist durch den ganzen übrigen menschlichen Organismus. Das Blut, so wie der Mensch es hat, kann nirgends vorkommen als im menschlichen Organismus. Wir dürfen durchaus nicht das, was für das Blut des Menschen gesagt worden ist, ohne weiteres auf ein anderes Lebewesen der Erde übertragen. Ich werde vielleicht später noch Gelegenheit haben, über das Verhältnis von menschlichem Blut zu tierischem Blut zu sprechen. Das wird eine sehr wichtige Betrachtung sein, weil die äußere Wissenschaft auf diesen Unterschied wenig Rücksicht nimmt. Heute wollen wir nur hinweisen auf das Blut als Ausdruck des menschlichen Ich. Ist einmal der ganze übrige Organismus des Menschen aufgebaut, so ist er erst fähig, Blut zu tragen, den Blutkreislauf in sich aufzunehmen, erst dann kann er in sich das Instrument haben, welches als Werkzeug unserem Ich dient. Dazu muß aber der Gesamtorganismus des Menschen erst aufgebaut sein.

Sie wissen, daß es auch andere Wesenheiten neben dem Menschen auf der Erde gibt, die in einer gewissen Verwandtschaft mit dem Menschen augenscheinlich stehen, die aber nicht in der Lage sind, ein menschliches Ich zum Ausdruck zu bringen. Bei diesen ist offenbar dasjenige, was in den entsprechenden Systemen der menschlichen Anlage ähnlich sieht, doch anders aufgebaut als beim Menschen. In allen diesen Systemen, die dem Blutsystem vorausgehen, muß schon die Möglichkeit veranlagt sein, das Blut aufnehmen zu können. Das heißt, wir müssen erst ein solches Nervensystem haben, welches ein Blutsystem im Sinne des menschlichen Blutsystems aufnehmen kann; wir müssen ein solches Drüsensystem haben und ebenso ein solches Ernährungssystem, die vorgebildet sein müssen für die Aufnahme eines menschlichen Blutsystems. Das bedeutet, es muß zum Beispiel schon auf der Seite des menschlichen Organismus, die wir bezeichnet haben als den eigentlichen Ausdruck des physischen Leibes des Menschen, beim Ernährungssystem, das Ich veranlagt sein. Es muß gleichsam der Prozeß der Bildung des Ernährungssystems durch den Organismus so gelenkt und geleitet sein, daß zuletzt das Blut sich in den richtigen Bahnen bewegen kann. Was heißt das?

Das bedeutet, daß der Blutkreislauf in seiner Gestaltung, in der ganzen Art seiner Regsamkeit, bedingt ist durch die Ich-Wesenheit des Menschen. Denken wir uns den Blutkreislauf in dieser ovalen Linie völlig schematisch angedeutet (siehe Zeichnung), so müssen wir sagen, es muß ja der Blutkreislauf von dem übrigen Organismus aufgenommen werden, das heißt, alle Organsysteme müssen so angeordnet sein, daß der Blutkreislauf sich eingliedern kann. Wir könnten das ganze Gewebe unserer Blutgefäße — sei es am Kopfe oder an einem anderen Teil unseres Organismus — nicht so haben, wie es ist, wenn nicht überall dahin, wo das Blut kreisen soll, die entsprechenden Dinge geleitet werden, die da sein müssen. Das heißt, die Kraftsysteme müssen im menschlichen Organismus, vom Ernährungssystem angefangen, so wirken, daß sie an die betreffenden Orte das notwendige Ernährungsmaterial hintragen und es zugleich so gestalten, so vorbilden, daß an diesen Orten das Blut genau die Form seines Verlaufs einhalten kann, deren es bedarf, um ein Ausdruck des Ich werden zu können. Es muß daher in alle Impulse unseres Ernährungsapparates, also des untersten Systems unseres Organismus, schon dasjenige hineingelegt sein, was den Menschen zu einem IchWesen macht. Die ganze Form, die der Mensch zuletzt in seiner physischen Vollendung zeigt, muß schon hineingegliedert sein in die Organsysteme bis in das hinein, was die verschiedenen Ernährungsprozesse des Menschen sind. Da sehen wir von dem Blute hinunter in die den Blutkreislauf vorbereitenden Organsysteme zu den Prozessen, die weitab von unserem Ich im Dunkel unseres Organismus sich abspielen. Während das Blut der Ausdruck unserer Ich-Tätigkeit ist, also Ausdruck des Bewußtesten ist, was wir haben, sind wir nicht fähig, hinunterzusehen in die unbekannten Tiefen des physischen Leibes. Wir wissen nicht, wie die Stoffe hingeleitet, hingetragen werden zu den einzelnen Orten unseres Organismus, wo sie verwendet werden müssen, um ihn aufzubauen und zu formen, damit er Werkzeug unseres Ich sein kann. Das zeigt uns, daß schon von Anfang an bei der Ernährung alle Gesetze im Organismus des Menschen liegen, die zuletzt zur Gestaltung des Blutkreislaufes führen.

Das Blut als solches stellt sich uns nun dar als das beweglichste, als das regsamste aller unserer Systeme. Und wir wissen ja, wenn wir auch nur in geringem Maße irgendwie eingreifen in die Blutbahn, so nimmt das Blut sogleich andere Wege. Wir brauchen uns nur an irgendeiner Stelle zu stechen, so nimmt das Blut gleich einen anderen Weg als sonst. Das ist unendlich wichtig zu berücksichtigen, denn daraus können wir ersehen, daß das Blut das bestimmbarste Element im menschlichen Leibe ist. Es hat seine gute Unterlage an den anderen Örgansystemen, aber es ist zugleich das aller bestimmbarste, das die wenigste innere Stetigkeit hat. Das Blut kann ungeheuer bestimmt werden durch die Erlebnisse des bewußten Ich. Ich will dabei nicht eingehen auf die phantastischen Theorien, die von seiten der äußeren Wissenschaft über das Erröten oder Erbleichen bei Scham- oder Angstgefühlen aufgestellt werden, ich will nur hinweisen auf die rein äußere Tatsache, daß solchen Erlebnissen wie Furcht oder Angst und Schamgefühl Ich-Erlebnisse zugrunde liegen, die in ihrer Wirkung auf das Blut erkennbar sind. Beim Furcht- und Angstgefühl ist es so, daß wir uns gleichsam schützen wollen vor irgend etwas, von dem wir glauben, daß es gegen uns wirkt; wir zucken da gleichsam mit unserem Ich zurück. Beim Schamgefühl ist es so, daß wir uns am liebsten verstecken möchten, uns sozusagen hinter das Blut zurückziehen, unser Ich auslöschen möchten. Beide Male - ich will dabei nur auf die äußeren Tatsachen eingehen — folgt das Blut materiell, als äußeres materielles Werkzeug dem, was das Ich in sich erlebt. Beim Furchtund Angstgefühl, wo der Mensch sich so stark in sich zurückziehen möchte vor etwas, von dem er sich bedroht fühlt, da wird er bleich; das Blut zieht sich zurück von der Oberfläche zum Zentrum, nach innen. Wenn sich der Mensch beim Schamgefühl verstecken möchte, sich auslöschen möchte, wenn er am liebsten nicht wäre und irgendwo hineinschlüpfen möchte, da drängt sich das Blut unter dem Eindrucke dessen, was das Ich erlebt, bis zur Peripherie des Organismus, und der Mensch wird rot. So sehen wir, daß das Blut das am leichtesten bestimmbare System im menschlichen Organismus ist und den Erlebnissen des Ich am schnellsten folgen kann.

Je weiter wir hinunterrücken in unseren Organsystemen, desto weniger folgen die Anordnungen der Systeme unserem Ich, desto weniger sind sie geneigt, sich den Erlebnissen des Ich anzupassen. Was das Nervensystem anbelangt, so wissen wir, daß es angeordnet ist in bestimmten Nervenbahnen und daß diese in ihrem Verlauf etwas verhältnismäßig Festes darstellen. Während das Blut regsam ist und je nach den inneren Erlebnissen des Ich von einem Körperteil zum anderen bis in die Peripherie geführt werden kann, ist es bei den Nerven so, daß den Nervenbahnen entlang diejenigen Kräfte verlaufen, welche wir als «Bewußtseinskräfte» zusammenfassen können, und daß diese nicht die Nervenmaterie von einem Orte zum anderen tragen können, wie das mit dem Blut in seinen Bahnen möglich ist. Das Nervensystem ist also schon weniger bestimmbar als das Blut; und noch weniger bestimmbar ist das Drüsensystem, das uns die Drüsen zeigt für ganz bestimmte Verrichtungen an ganz bestimmten Orten des Organismus. Wenn eine Drüse durch irgend etwas tätig gemacht werden soll zu einem bestimmten Zwecke, so kann sie nicht erregt werden durch einen Strang ähnlich dem Nervenstrang, sonmuß diese Drüse an dem Orte, wo sie eben ist, erregt werden. Es ist also das Drüsensystem noch weniger bestimmbar, wir müssen die Drüsen da erregen, wo sie sind. Während wir die Nerventätigkeit den Nervensträngen entlang leiten können — wir haben da noch Verbindungsfasern, welche die einzelnen Nervenknoten miteinander verbinden -, kann die Drüse nur an dem Ort zu einer Tätigkeit erregt werden, wo sie ist. Noch mehr aber ist dieser gleichsam Verfestigungsprozeß, dieser Prozeß des inneren Bestimmtseins, des NichtBestimmbarseins ausgesprochen in alle dem, was zum Ernährungssystem gehört, durch das der Mensch sich direkt die Stoffe eingliedert, um ein physisch-sinnliches Wesen zu sein. Dennoch muß in der Eigenart dieser Stoffeingliederung eine völlige Vorbereitung für das Werkzeug des Ich gegeben sein.

Betrachten wir nun einmal den menschlichen Organismus in bezug auf sein unterstes System, das Ernährungssystem im umfassendsten Sinne, durch das die Stoffe nach allen Gliedern des Organismus transportiert werden, so muß die Anordnung dieser Stoffe so geschehen, daß die Formung, der äußere Aufbau des Menschen so vor sich gehen kann, daß zuletzt der Ausdruck des Ich im menschlichen Organismus möglich ist. Dazu ist vieles notwendig. Nicht nur, daß die Ernährungsstoffe in der verschiedensten Weise transportiert und an die verschiedensten Orte des Organismus gelagert werden, sondern auch, daß alle möglichen Vorkehrungen getroffen werden, um die äußere Form des menschlichen Organismus zu bedingen.

Nun ist es wichtig, daß wir uns folgendes klarmachen. In dem, was wir die Haut genannt haben, sind zwar alle Systeme des menschlichen Organismus vertreten, bis zum untersten System, dem Ernährungssystem, und wir konnten sagen: In die Haut wird alles ergossen, was im eminentesten Sinne zum physischen System des Menschen gehört. Aber Sie können sich leicht denken, daß diese Haut — trotzdem sie alle diese Systeme in sich hat — für sich einen großen Fehler hat, so paradox das auch klingt. Sie hat zwar so wie sie am Menschen ist, die Form des menschlichen Organismus, diese Form würde sie aber durch sich selber nicht haben; durch sich selber würde sie nicht in der Lage sein, dem Menschen seine charakteristische Formbegrenzung zu geben. Ohne Unterstützung würde die Haut in sich selber zusammensinken; da würde der Mensch sich nicht aufrecht halten können. Daraus sehen wir, daß nicht bloß diejenigen Ernährungsprozesse stattfinden müssen, welche die Haut erhalten, sondern es müssen auch die mannigfaltigsten anderen Prozesse stattfinden und zusammenwirken, welche die Gesamtform des Menschenorganismus bilden. Da wird es uns nicht schwer sein zu begreifen, daß wir auch als solche umgewandelten Ernährungsprozesse diejenigen Prozesse anzusehen haben, die vor sich gehen in den Knorpeln und in den Knochen. Was sind das für Prozesse?

Wenn das Material unserer Nahrungsstoffe bis zu einem Knorpel oder Knochen geleitet wird, so ist im Grunde genommen auch nur physisches Material dahin transportiert. Was wir zuletzt im Knorpel oder Knochen finden, ist ja nichts anderes als die umgewandelten Nahrungsstoffe; aber sie sind in anderer Art umgewandelt als zum Beispiel in der Haut. Daher können wir sagen: Wir haben in der Haut zwar die umgewandelten Nahrungsstoffe zu sehen, die sich in der äußersten Formumgrenzung unseres Leibes ablagern. In der Art aber, wie im Knochen das Ernährungsmaterial abgelagert wird, haben wir einen solchen Ernährungsprozeß zu sehen, wo das Material sich rundet zur menschlichen Form. Es ist also ein umgekehrter Ernährungsprozeß wie derjenige in der menschlichen Haut. Nun wird es uns gar nicht mehr schwierig sein, gleichsam nach dem Muster der Betrachtungen, die wir für das Nervensystem angestellt haben, uns auch diesen gesamten Ernährungsprozeß, das Transportierungssystem der Nahrungsmittel zu denken.

Wenn wir die Haut anschauen und auf die Ernährungsstoffe sehen, welche sie zustande bringen, diesen äußeren Abschluß, der dem Menschen die Oberfläche gibt, aber niemals selber die menschliche Form hervorbringen könnte, so wird es uns klar sein, daß die Hauternährung die jüngste Art der Ernährung ist im Menschenorganismus; und wir erkennen, daß wir in der Art, wie die Knochen ernährt werden, einen analogen Prozeß zu sehen haben, der in einem ähnlichen Verhältnis zur Hauternährung steht, wie wir den Prozeß der Gehirnbildung in ein Verhältnis setzen konnten zum Prozeß der Rückenmarksbildung. Wir werden dasselbe Recht haben zu sagen: Dasjenige, was wir zunächst äußerlich im Hauternährungsprozeß auftreten sehen, können wir auf einer späteren, das heißt hier höheren Stufe umgewandelt sehen in der festen Form der Knochenbildung. - Es weist uns eine solche Betrachtung des menschlichen Organismus darauf hin, daß unser Knochensystem früher als weiche Substanz bestanden hat und sich erst im Laufe der Entwickelung verfestigt hat. Das kann auch durch die äußere Wissenschaft nachgewiesen werden, die uns lehren kann, wie gewisse Gebilde, die später deutlich Knochen sind, im kindlichen Alter noch weich, knorpelhaft auftreten und daß erst nach und nach aus einer weicheren, knorpelmäßigen Masse durch Einlagerung von Ernährungsmaterial sich die Knochenmasse bildet. Da haben wir ein Hinüberführen von einer weichen in eine festere Substanz, wie es auch beim einzelnen Menschen sich vollzieht. Wir haben also im Knorpel eine Vorstufe des Knochens zu sehen und können sagen, daß uns die ganze Einlagerung des Knochensystems in den Organismus als etwas erscheint, was sozusagen ein letztes Resultat derjenigen Prozesse darstellt, die uns in der Hauternährung vor Augen treten. Es werden also zuerst in einfachster Weise die Ernährungsstoffe umgewandelt zu einer weichen, biegsamen Substanz, und dann, wenn dies vorbereitet ist, kann der Ernährungsprozeß sich abspielen, durch den gewisse Teile sich erst verhärten zu Knochenmaterie, damit zuletzt die Form des menschlichen Gesamtorganismus zum Vorschein kommt. Die Art, wie uns die Knochen entgegentreten, gibt uns Anlaß zu sagen: Über die Knochenbildung hinaus haben wir eigentlich dann kein weiteres Fortschreiten der Ernährungsprozesse zur Verfestigung, soweit der Mensch der gegenwärtigen Entwickelungsstufe in Betracht kommt. Während wir auf der einen Seite im Blut die bestimmbarste, wandlungsfähigste Substanz im Menschen haben, können wir andererseits in der Knochensubstanz dasjenige erblicken, was völlig unbestimmbar ist, was bis zu einem letzten Punkte sich verhärtet, verfestigt hat, über den hinaus es keine weitere Umwandlung mehr gibt; sie hat es bis zur starrsten Form gebracht. Wenn wir nun die früheren Betrachtungen fortsetzen, dann müssen wir sagen: Das Blut ist das bestimmbarste Werkzeug des Ich im Menschen, die Nerven sind es schon weniger, die Drüsen noch weniger, und im Knochensystem haben wir das, was am letzten Punkte seiner Evolution angelangt ist, was ein letztes Umwandlungsprodukt darstellt in bezug auf die Bestimmbarkeit durch das Ich. Deshalb geschieht alles, was zur Formung des Knochensystems gehört, in der Weise, daß zuletzt die Knochen Träger und Stütze eines weicheren Organismus sein können, in welchem Lebens- und Ernährungsvorgänge so ablaufen, daß das Blut in seinen Bahnen in der rechten Weise verlaufen kann, damit das menschliche Ich in ihm ein Werkzeug haben kann.

Ich möchte wissen, wer nicht mit höchster Bewunderung und Ehrfurcht erfüllt würde, wenn er hiineinblickt in den menschlichen Organismus und sich vorzustellen versucht: Im Knochensystem habe ich dasjenige vor mir, was die meisten Verwandlungen, die meisten Stufen durchgemacht haben muß, was von den untersten Stufen aufgestiegen ist durch viele, viele Epochen hindurch bis zum heutigen Knochensystem; es ist zuletzt so gestaltet worden, daß es der feste Träger, die feste Stütze des Ich sein kann. Wenn man gewahr wird, wie bis in die Bildungen der einzelnen Knochen hinein die Tendenz des Ich wirkt, wer könnte da nicht mit tiefster Bewunderung erfüllt werden gegenüber diesem Bau des menschlichen Organismus.

Sehen wir diesen Menschen an, so haben wir zwei Pole des physischen Daseins gegeben, einmal im Blutsystem, das das bestimmbarste Werkzeug des Ich ist, und dann im Knochensystem, das in äußerer Form und innerer Struktur am meisten fest ist, am unbestimmbarsten, am wenigsten wandlungsfähig, das in der Unbestimmbarkeit am weitesten vorgeschritten ist. Wir dürfen daher sagen: Im Knochensystem hat die physische Organisation des Menschen vorläufig ihren letzten Ausdruck, ihren Abschluß gefunden, während sie in dem Blutsystem in einem gewissen Sinne einen neuen Anfang genommen hat. Schauen wir auf unser Knochensystem hin, so können wir sagen: Wir verehren in diesem Knochensystem einen letzten Abschluß der menschlichen physischen Organisation. — Und schauen wir auf unser Blutsystem, so können wir sagen: Wir sehen in ihm einen Anfang, etwas, das erst anfangen konnte, nachdem alle anderen Systeme vorangegangen sind. -— Vom Knochensystem können wir sagen: Eine gewisse erste Anlage, die ersten Kräfte zur Bildung des Knochensystems mußten schon vorhanden gewesen sein, bevor Drüsen- und Nervensystem im Organismus zur Entwickelung kamen, denn diese mußten durch das Knochensystem ihre entsprechenden Orte angewiesen erhalten. Das älteste der Kraftsysteme des menschlichen Organismus haben wir im Knochensystem in uns.

Wenn wir nun das Blutsystem und das Knochensystem als zwei Pole bezeichnet haben, so wollten wir damit bildlich ausdrücken, daß in ihnen gleichsam die beiden äußersten Enden der menschlichen Organisation zu sehen sind. Im Blutsystem haben wir das beweglichste Element vor uns, das so regsam ist, daß es jeder Regung unseres Ich folgt. Und im Knochensystem haben wir dasjenige, was fast ganz dem Einfluß unseres Ich entzogen ist, wo wir nicht mehr hinunterreichen mit unserem Ich; dennoch aber liegt in seiner Form schon die ganze Organisation des Ich darinnen. Es stehen damit schon rein äußerlich betrachtet Blutsystem und Knochensystem im Menschen wie ein Anfang und ein Abschluß einander gegenüber. Und wenn wir so unser Blutsystem anschauen, das fortwährend allen Regungen des Ich folgt, so sagen wir uns: Im regsamen Blut drückt sich uns so recht das menschliche Leben aus. - Wenn wir auf unser Knochensystem schauen, sagen wir uns: Es symbolisiert alles das, was sich unserem Leben entzieht und dem Organismus nur als Stütze dient. — Unser pulsierendes Blut ist unser Leben; unser Knochensystem ist dasjenige, was sich dem unmittelbaren Leben schon entzogen hat - weil es ein so alter Herr ist -, was sich schon ausgeschaltet hat und nur noch als Stütze dienen will, nur noch Form geben will. Während wir in unserem Blute am meisten organisch leben, sind wir im Grunde genommen in unserem Knochensystem schon gestorben. Und ich bitte Sie, diesen Ausspruch wie ein Leitmotiv für die folgenden Vorträge zu betrachten, denn es werden sich wichtige physiologische Dinge daraus ergeben. Während wir in unserem Blute leben, sind wir in unserem Knochensystem eigentlich schon gestorben. Unser Knochensystem ist wie ein Gerüst, es ist das am wenigsten Lebendige, es ist nur das uns stützende Gerüst in uns.

Wir haben schon am Anfang dieser Vortragsreihe im Menschen eine Zweiheit gesehen; jetzt tritt uns diese Zweiheit noch einmal in einer anderen Weise entgegen. Auf der einen Seite das Regsamste, Lebendigste im Blut, auf der anderen Seite etwas wie ein sich der organischen Regsamkeit am meisten Entziehendes, den Tod eigentlich schon in sich Tragendes im Knochensystem. Unser Knochensystem hat einen gewissen Abschluß schon erhalten - in seiner Ausformung wenigstens, wenn es auch nachher noch wächst - bis zu der Lebenszeit des Menschen, wo die Ich-Erlebnisse beginnen regsam zu werden. Bis zum Zahnwechsel im siebten Lebensjahr hat das Knochensystem sich im wesentlichen seine Form gegeben. Gerade in der Zeit also findet die Hauptentwickelung unseres Knochensystems statt, wo wir selber noch der Regsamkeit unseres Ich in hohem Maße entzogen sind. In dieser Zeit, wo das Knochensystem sich aufbaut aus den dunklen Untergründen und Kräften unseres Organismus heraus, können auch die meisten Fehler in der Ernährung gemacht werden. Gerade in diesen ersten sieben Lebensjahren können in der Ernährung des Kindes besonders folgenschwere Fehler gemacht werden, die sich auf das Knochensystem übel auswirken, zum Beispiel in rachitischen Erkrankungen, die namentlich davon herrühren, daß die Ernährungsprozesse in diesen Jahren nicht in der richtigen Weise geleitet werden, zum Beispiel wenn man der Naschhaftigkeit der Kinder nachgibt und ihnen alles mögliche gibt, wonach sie Verlangen tragen. So sehen wir das, was dem Ich entzogen ist, in unser Knochensystem hineinwirken.

Ganz anders ist es beim Blutsystem, welches regsam folgt unserem einzelmenschlichen Leben und mehr als alles andere abhängig ist von den Prozessen unseres inneren Erlebens. Es ist nur eine Art von Kurzsichtigkeit seitens der äußeren Wissenschaft, zu glauben, daß von den inneren Erlebnissen das Nervensystem mehr abhängig wäre als das Blutsystem. Ich will nur darauf hinweisen, daß wir die ein fachste Art der Beeinflussung des Blutsystems durch die Ich-Erlebnisse in der Scham und in der Furcht haben, wo eine Umlagerung des Blutes stattfindet, die deutlich ausdrückt die Ich-Erlebnisse in dem Werkzeuge des Ich, dem Blut. Sie können sich also denken, wenn sich schon vorübergehende Prozesse so ausdrücken, wie sich dann dauernde oder gewohnheitsmäßige Erlebnisse des Ich ausdrücken müssen in dem erregsamen Elemente des Blutes. Es gibt keine Leidenschaft, keinen Trieb oder Affekt, ob wir sie gewohnheitsmäßig haben oder ob sie explosionsartig zum Ausdruck kommen, die nicht als innere Erlebnisse übertragen werden auf das Blut als Instrument des Ich. Alle ungesunden Elemente des Ich-Erlebens kommen im Blutsystem zum Ausdruck.

Und überall, wo wir irgend etwas verstehen wollen, was im Blutsystem vorgeht, da ist es wichtig, nicht bloß zu fragen nach dem Ernährungsprozeß, sondern vielmehr nach den seelischen Prozessen zu suchen, insofern sie Ich-Erlebnisse sind, wie Stimmungen, dauernde Leidenschaften, Affekte und so weiter. Nur eine matenialistische Gesinnung wird bei Störungen im Blutsystem das Hauptaugenmerk auf die Ernährung lenken; denn die Bluternährung baut sich auf auf die Ernährung des physischen $ystems, des Drüsensystems, des Nervensystems und so weiter, und im Grunde genommen sind die Nahrungsstoffe schon sehr filtriert, wenn sie an das Blut herankommen. Wenn daher das Blut von dieser Seite her beeinträchtigt werden soll, muß schon eine ganz wesentliche Erkrankung des Organismus aufgetreten sein; dagegen wirken alle seelischen, alle Ich-Prozesse in unmittelbarer Weise auf das Blut zurück.

So entzieht sich unser Knochensystem am meisten den Vorgängen unseres Ich, und so fügt sich unser Blutsystem am allermeisten den Vorgängen unseres Ich. Ja, dieses Knochensystem ist am allerwenigsten veranlagt, dem Ich zu folgen, man möchte sagen, es ist ganz unabhängig vom Ich, aber doch ist es für das Ich organisiert.

Nur ein kleiner Teil des Knochensystems macht von der Unbestimmbarkeit durch das Ich eine Ausnahme und zeigt eine individuelle Prägung, nämlich die Schädelknochen, besonders der obere Teil des Schädels. Diese Tatsache hat zu verschiedenem Unfug Veranlassung gegeben.

Sie wissen, daß es eine Phrenologie, eine Schädelknochenuntersuchung, gibt. Diese hat nach und nach, trotzdem sie von materialistischer Seite als Aberglaube angesehen wird, nach den allgemeinen Gepflogenheiten unserer Zeit eine materialistische Nuance angenommen. Wenn wir grob charakterisieren wollen, können wir sagen: Im allgemeinen wird Phrenologie so beschrieben, daß in den Formen unserer Schädelbildung der Ausdruck gesucht wird für die innere Beschaffenheit unseres Ich, indem gleichsam allgemeine Gesichtspunkte aufgestellt werden und erklärt wird, der eine Höcker bedeute dies, der andere das und so weiter. Da will man die menschlichen Eigenschaften auffinden an den verschiedenen Höckern, die sich an unserem Schädel zeigen. In dem Knochensystem des Schädels wird also von der Phrenologie gesucht eine Art plastischer Ausdruck für unser Ich. Nun ist das aber, wenn es so getrieben wird, auch wenn scheinbar geistige Ausdrücke im Bau der einzelnen Knochen gesucht werden, doch ein Unfug. Denn wer wirklich ein feiner Beobachter ist, der weiß, daß kein einziger menschlicher Schädel dem anderen gleicht und daß man niemals Erhöhungen oder Vertiefungen angeben könnte, die für diese oder jene Eigenschaft allgemein typisch sind, sondern daß ein jeder Schädel sich unterscheidet von dem anderen, so daß wir bei jedem Menschenschädel andere Formen vor uns haben.

Nun haben wir gesagt, daß sich unserem Ich, dem das Blut in seiner Regsamkeit am meisten folgt, der Knochenbau entzieht, ihm am wenigsten folgt. Es ist merkwürdig, daß uns dennoch die Bildung des Schädels und der Gesichtsknochen dem Ich entsprechend gestaltet erscheinen, während der Knochenbau mehr allgemein typisch erscheint. Wer den Schädelbau betrachtet, der weiß: So wahr der Mensch selber individuell ist, so wahr ist auch sein Schädelbau individuell.

Wie kommt es, daß diese wunderbare Konfiguration des Schädels von Anfang an der einzelnen menschlichen Individualität entsprechend angelegt ist, wenn doch das Ich keinen Einfluß auf den Knochenbau hat? Woher kommt es, daß der Schädel, der sich so entwikkeln muß, wie die anderen Knochen auch, anders ist bei jedem Menschen? Woher kommt das? Das kommt einfach aus demselben Grunde, aus dem die individuellen Eigenschaften des Menschen sich überhaupt entwickeln, nämlich daher, daß das individuelle menschliche Gesamtleben nicht nur verläuft von der Geburt bis zum Tode, sondern verläuft in vielen Inkarnationen. Während unser Ich also in der gegenwärtigen Inkarnation keinen Einfluß hat auf den Schädelbau, hat es durch die Erlebnisse seiner vorangegangenen Inkarnation die Kräfte entwickelt, die in der Zeit zwischen dem Tode und der nächsten Geburt die Konfiguration des Schädelbaues, die Schädelform, in dieser Inkarnation bestimmen. Wie das Ich in der vorherigen Inkarnation war, das bestimmt die Schädelform in der jetzigen Inkarnation, so daß wir in dem Bau unseres Schädels einen äußeren plastischen Ausdruck haben für die Art und Weise, wie wir, jeder einzelne, als Individualität, in der vorhergehenden Inkarnation gelebt und gewirkt haben. Während alle anderen Knochen bei uns etwas Allgemein-Menschliches ausdrücken, drückt der Schädel in seiner äußeren Form das aus, was wir waren und was wir getan haben in der vorigen Inkarnation.

Das äußerst regsame Element des Blutes kann also bestimmt werden vom Ich in dieser Inkarnation. Unsere Knochen aber haben sich in dieser Inkarnation dem Einfluß des Ich schon ganz entzogen, bis auf den letzten Rest, den Schädelknochen, der aber dem Ich auch nicht mehr in dieser Inkarnation folgen kann. Der Schädelknochen, der aus der Weiche der Keimessubstanz heraus sich entwickelt hat, wo das Ich noch gestaltend einwirken konnte, gibt einen Ausdruck dafür, wie wir in der vorherigen Inkarnation waren. Eine allgemeine Phrenologie gibt es nicht. Wenn wir Phrenologie überhaupt in Betracht ziehen wollen, so darf sie keine schematisierende Wissenschaft sein, sondern sie sollte auf eine künstlerische Art und Weise die plastischen Eigentümlichkeiten des Schädelbaues betrachten. Wir müssen unseren Schädelbau beurteilen wie ein Kunstwerk. Wir müssen allerdings in dem Schädelbau etwas Individuelles sehen, aber etwas Individuelles, das ein Ausdruck der Geschichte des Ich ist in einer vorhergehenden Inkarnation. So sehen wir, daß selbst diese Form des Knochenbaus, wie sie uns im Schädelbau entgegenrritt, dem Ich soweit entzogen ist, daß es in der gegenwärtigen Inkarnation darauf keinen Einfluß mehr hat. Aber es hat noch Einfluß darauf beim Durchgang zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt, wo es in gewissem Sinne die Kräfte wieder aufnimmt, die sich ihm im vergangenen Leben schon entzogen hatten und welche unter seinem Einfluß für das nächste Leben das Knochensystem und besonders den Schädel aufbauen.

Wenn daher von der Wiederverkörperungsidee gesprochen und gesagt wird, das sei eine Sache, die sich im allgemeinen der Beurteilung durch unsere Vernunft entziehe, da müsse man eben das glauben, was der Geistesforscher sagt -, so ist das nicht richtig. Man kann darauf erwidern: Ihr könnt euch handgreiflich davon überzeugen, daß das menschliche Ich in einer vorhergehenden Inkarnation dagewesen sein muß; im menschlichen Schädel hat man handgreiflich den Beweis vor sich, wie der Mensch in der vorhergehenden Inkarnation war. Wer das nicht zugibt, wer darin etwas Paradoxes sieht, daß man aus der Art, wie etwas äußerlich geformt ist, schließen muß auf etwas früher Lebendiges, das aus seinem früheren Leben heraus das Äußere geformt hat, der hat auch kein Recht, sonstwie auf ein früher Lebendiges zu schließen, wenn ihm irgendwo eine plastische Gestalt entgegentritt. Wer nicht den Schluß zugibt als einen streng logischen, daß in der individuellen Schädelform, die wir haben, sich die Konfiguration des Ich aus früheren Inkarnationen ausdrückt, der hat auch kein Recht, wenn er zum Beispiel irgendwo auf der Erde eine leere Muschel findet, aus der äußeren Form dieser Muschel schließen zu wollen, daß da einmal ein Lebewesen drin war. Wer aus der toten Muschel schließen will auf ein Lebewesen, das einmal da drinnen war und die Muschel geformt hat, der darf den logisch ganz gleichwertigen Schluß nicht abweisen, daß in der individuellen Ausgestaltung unseres Schädels der unmittelbare Beweis gegeben ist für das Hereinwirken eines früheren Lebens in dieses Leben.

So sehen Sie, daß wir hier eines der Tore haben, durch die wir physiologisch hineinleuchten können in die Reinkarnationsidee. Solche Tore gibt es viele; man muß sich nur Zeit lassen. Wenn man geduldig ist und wartet, dann wird man die Stellen finden, wo die Beweise erbracht werden können und wie sie zu erbringen sind. Und wer leugnen wollte, daß in dem, was jetzt gesagt worden ist, Logik liegt, der müßte auch die gesamte Paläontologie leugnen, denn sie beruht auf denselben Schlußfolgerungen. So sehen wir, wie wir durch Eindringen in die Formen des menschlichen Organismus diesen auf seine geistigen Grundlagen zurückführen können.

Sixth Lecture