The Tree of Life and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil

GA 162

24 July 1915, Dornach

1. The Tree of Life I

My dear friends,

When people encounter the world conception of Spiritual Science their chief desire is to have an answer to their questions, a solution of their problems. That is quite natural and understandable, one might even say justifiable. But something else must be added if the spiritual scientific-movement is really to become the living thing it must be, in accordance with the general course of evolution of earth and humanity. Above all, a certain feeling must be added, a certain perception that the more one strives to enter the spiritual world, the more the riddles increase. These riddles actually become more numerous for the human soul than they were before, and in a certain respect they become also more sacred. When we come into the spiritual scientific world concept, great life problems, the existence of which we hardly guessed before, first appear as the riddles they are.

Now, one of the greatest riddles connected with the evolution of the earth and mankind is the Christ-riddle, the riddle of Christ-Jesus. And with regard to this, we can only hope to advance slowly towards its actual depth and sanctity. That is to say, we can expect in our future incarnations gradually to have an enhanced feeling in what a lofty sense, in what an extraordinary sense this Christ-riddle is a riddle. We must not expect just that regarding this Christ-riddle much will be solved for us, but also that much of what we have hitherto found full of riddles concerning the entry of the Christ-Being into humanity's evolution, becomes still more difficult. Other things will emerge that bring new riddles into the question of the Mystery of Golgotha, or if one prefers, new aspects of this great riddle.

There is no question here of ever claiming to do more than throw some light from one or other aspect of this great problem. And I beg you to be entirely clear that only single rays of light can ever be thrown from the circuit of human conception upon this greatest riddle of man's earthly existence, nor do these rays attempt to exhaust the problem, but only to illumine it from various aspects. And so something shall here be added to what has already been said that may bring us again some understanding of one aspect of the Mystery of Golgotha.

You remember the pronouncement of the God Jahve, radiating from the far distance, which stands at the beginning of the Bible, after the Fall had come about. The words announced that now men had eaten of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil they must be banished from their present abode, so that they might not eat also of the Tree of Life. The Tree of Life was to be protected, as it were, from being partaken of by men who had already tasted of the Tree of Knowledge.

Now behind this primordial two-foldness of the eating of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil on the one hand and the eating of the Tree of Life on the other hand, there lies concealed something which cuts deep into life. Today we will turn our attention to one of the many applications to life of this pronouncement: we will bring to mind what we have long known: i.e., that the Mystery of Golgotha, in so far as it was accomplished within the evolution of earthly history, fell in the Fourth Post-Atlantean epoch, in the Graeco-Latin age.

We know indeed that the Mystery of Golgotha lies approximately at the conclusion of the first third of the Graeco-Latin age and that two-thirds of this age follow, having as their task the first incorporation of the secrets of the Mystery of Golgotha into human evolution.

Now we must distinguish two things in regard to the Mystery of Golgotha. The first is what took place as purely objective fact: in short, what happened as the entry of the Cosmic Being ‘Christus’ in the sphere of earthly evolution. It would be-hypothetically possible, one might say, it would be conceivable, for the Mystery of Golgotha, that is, the entry of the Impulse of Christ into earthly evolution, to have been enacted without any of the men on earth having understood or perhaps even known what had taken place there. It might quite well have happened that the Mystery of Golgotha had taken place, but had remained unknown to men, that no single person would have been able to think about solving the riddle of what had actually occurred there.

This was not to be. Earthly humanity was gradually to reach an understanding of what had happened through the Mystery of Golgotha. But none the less we must realise that there are two aspects: that which man receives as knowledge, as inner working in his soul, and that which has happened objectively within the human race, and which is independent of this human race—that is to say, of its knowledge. Now, men endeavoured to grasp what had taken place through the Mystery of Golgotha. We are aware that not only did the Evangelists, out of a certain clairvoyance, give those records of the Mystery of Golgotha which we find in the Gospels; an attempt was also made to grasp it by means of the knowledge which men had before the Mystery of Golgotha. We know that since the Mystery of Golgotha not only have its tidings been given out, but there has also arisen a New Testament theology, in its various branches. This New Testament theology, as is only natural, has made use of already existing ideas in asking itself: What has actually come about with the Mystery of Golgotha, what has been accomplished in it?

We have often considered how, in particular, Greek philosophy that which was developed for instance as Greek philosophy in the teachings of Plato and Aristotle—how the ideas of Greek philosophy endeavoured to grasp what had taken place in the Mystery of Golgotha, just as they took pains to understand Nature around them. And so we can say that on the one hand the Mystery of Golgotha entered as objective fact, and on the other hand, confronting it, are the different world-conceptions which had been developed since antiquity, and which reach a certain perfection at the time in which the Mystery of Golgotha took place, and then go on evolving.

Whence were these concepts derived? We know indeed that all these concepts, including those which live in Greek philosophy and which approached the Mystery of Golgotha from the earth, are derived from a primeval knowledge, from a knowledge which could not have been at man's disposal if, let us say, an original revelation had not taken place. For it is not only amaterialistic, but an entirely nonsensical idea that the attenuated philosophy which existed at the time of the Mystery of Golgotha could at its starting point have been formed by human beings themselves. It is primeval revelation, which as we know was founded in an age when men still had the remains of ancient clairvoyance; primeval revelation which in ancient times had been given to man for the most part in imaginative form and which had been attenuated to concepts in the age when the Mystery of Golgotha entered, the Graeco-Latin age. Thus one could see an intensive stream of primeval revelation arise in ancient times, which could be given to men because they still had the final relics of the old clairvoyance that spoke to their understanding and which then gradually dried up and withered into philosophy.

Thus a philosophy, a world-conception existed in many, many shades and nuances, and these sought in their own way to comprehend the Mystery of Golgotha. If we would find the last stragglers of what was diluted at that time to a world-concept of a more philosophic character; then we come to what lived in the old Roman age.

By this Roman age I mean the time that begins approximately with the Mystery of Golgotha, with the reign of the Emperor Augustus, and flows on through the time of the Roman Empire until the migration of nations that gave such a different countenance to the European world. And what we see flare up in this Roman age like a last great light from the stream flowing from revelation—that is the Latin-Roman poetry, which plays so great a role in the education of youth even up to our own day. It is all that developed as continuation of this Latin-Roman poetry till the decline of ancient Rome. Every possible shade of world-conception had taken refuge in Rome. This Roman element was no unity. It was extended over numberless sects, numberless religious opinions, and could only evolve a certain common ground from the multiplicity by withdrawing, as it were, into external abstractions.

Through this, however, we can recognise how something withered comes to expression in the far-spread Roman element in which Christianity was stirring as a new impulse. We see how Roman thought is at great pains to seize with its ideas what lay behind the Mystery of Golgotha. We see how endeavour was made in every possible way to draw ideas from the whole range of world conception in order to understand what hid behind this Mystery of Golgotha. And one can say, if one observes closely: it was a despairing struggle towards an understanding, a real understanding of the Mystery of Golgotha. And this struggle as a matter of fact continued in a certain current throughout the whole of the first millennium.

One should see, for instance, how Augustine first accepts all the elements of the old withered world-conception, and how he tries through all that he so accepts to grasp what was flowing in as living soul-blood, for he now feels Christianity flow like a living impulse into his soul. Augustine is a great and significant personality—but one sees in every page of his writings how he is struggling to bring into his understanding what is flowing to him from the Christ Impulse. And so it goes on, and this is the whole endeavour of Rome: to obtain in the western world of idea, in this world of world-conception, the living substance of what comes to expression in the Mystery of Golgotha.

What is it, then, that makes such efforts, that so struggles, that in the Roman-Latin element overflows the whole civilised world? What is it that struggles despairingly in the Latin impulse, in the concepts pulsating in the Latin language, to include the Mystery of Golgotha? What is that? That is also a part of what men have eaten in Paradise. It is a part of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. We can see in the primeval revelations when the old clairvoyant perceptions could still speak to men, how vividly alive concepts were in this ancient time, concepts which were still imaginations, and how they more and more dry up and die and become thin and poor. They are so thin that in the middle of the Middle Ages, when Scholasticism flourished, the greatest efforts of the soul were necessary to sharpen these attenuated concepts sufficiently to grasp in them the living life existing in the Mystery of Golgotha. What remained in these concepts was the most distilled form of the old Roman language with its marvellously structured logic, but with its almost entirely lost life-element. This Latin speech was preserved with its fixed and rigid logic, but with its inner life almost dead, as a realisation of the primeval divine utterance: Men shall not eat of the Tree of Life.

If it had been possible for what had evolved from the old Latin heritage to comprehend in full what had been accomplished in the Mystery of Golgotha, had it been possible for this Latin heritage, simply as if through a thrust, to gain an understanding of the Mystery of Golgotha, then this would have been an eating of the Tree of Life. But this was forbidden, after the expulsion from Paradise. The knowledge which had entered humanity in the sense of the ancient revelation was not to serve as a means of ever working in a living way. Hence it could only grasp the mystery of Golgotha with dead concepts.

‘Ye shall not eat of the Tree of Life’: this is a saying which also holds good through all aeons of earthly evolution with regard to certain phenomena. And one fulfilment of this saying was likewise the addition: ‘The Tree of Life will also draw near in its other form as the Cross erected on Golgotha—and life will stream out from it. But this older knowledge shall not eat of the Tree of Life.’

And so we see a dying knowledge struggling with life, we see how desperately it strives to incorporate the life of Golgotha in its concepts.1See ‘The Christmas Thought and the Mystery of the Ego. The Tree of the Cross and the Golden Legend’—Rudolf Steiner.

Now there is a peculiar fact, a fact which indicates that in Europe, confronting as it were the starting point of the East, a kind of primordial opposition was made. There is something like a sort of archetypal opposition set against the primeval-revelation2See Genesis 3:3—The creation of man decreed to mankind. Here, to be sure, we touch upon the outer rim of a very deep-lying secret, and one can really only speak in pictures of much that is to

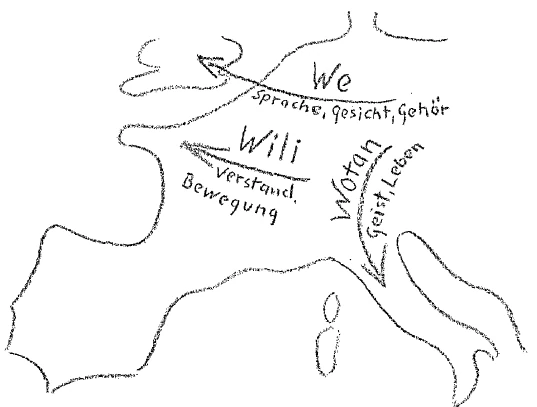

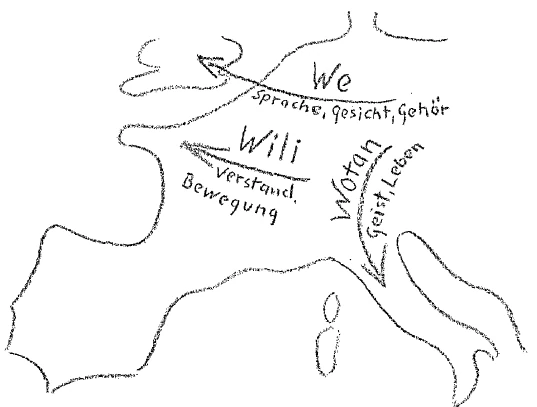

There exists in Europe a legend concerning the origin of man which is quite different from the one contained in the Bible. It has gone through later transformations no doubt, but its essentials are still to be recognised. Now the characteristic feature is not that this legend exists, but that it has been preserved longer in Europe than in other parts of the earth. But the important thing is that even while over in the Orient the Mystery of Golgotha had been accomplished, this different legend was still alive in the feelings of the inhabitants of Europe. Here, too, we are led to a tree, or rather to trees, which were found on the shore of the sea by the gods Wotan, Wile and We. And men were formed from two trees, the Ash and the Elm. Thus men were created by the trinity of the gods, (although this was Christianised later, it yet points to the European original revelation) by fashioning the two trees into men: Wotan gives men spirit and life; Wile gives men movement and intelligence, and We gives them the outer figure, speech, the power of sight and of hearing.

The very great difference that exists between this story of creation and that of the Bible is not usually observed—but you need only read the Bible—which is always a useful thing to do—and already in the first chapters you will remark the very great difference that exists between the two Creation legends. I should like but to point to one thing, and that is, according to the saga, a threefold divine nature flowed into man. It must be something of a soul-nature that the Gods have laid within him, which expresses itself in his form and which in fact is derived from the Gods. In Europe, therefore, man was conscious that inasmuch as one moves about on earth, one bears something divine within; in the Orient, on the contrary, one is conscious that one bears something Luciferic within one. Something is bound up with the eating of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil which has even brought men death, something that has turned all men away from the Gods and for which they have earned divine punishment. In Europe man is aware that in the human soul a threefold nature lives, that the Gods have sunk a force into the human soul. That is very significant.

One touches with this, as I have said, the edge of a great secret, a deep mystery. But it will be readily understood: it looks as if in this ancient Europe a number of human beings had been preserved who had not been taken away from sharing in the Tree of Life, in whom there lived on, so to say, the tree or the trees of Life; ash and elm. And with this the following fact stands in intimate harmony. European humanity (and if one goes back to the original European peoples this would be seen with great clarity in all details) actually had nothing of the higher, more far-reaching knowledge that men possessed in the Orient and in the Graeco-Latin world.

One should imagine for once the immense, the incisive contrast between the naive conceptions of European humanity, who still saw everything in pictures, and the highly evolved, refined philosophical ideas of the Graeco-Latin world. In Europe all was ‘Life’; over there all was ‘Knowledge of Good and Evil.’ In Europe something was left over, as it were, like a treasured remnant of the original forces of life; but it could only remain if this humanity were, in a way, protected from understanding anything that was contained in such marvellously finely wrought Latin concepts. To speak of a science of the ancient European population would be nonsense. One can only speak of them as living with all that germinated in their inner soul nature, that filled it through and through with life. What they believed they knew was something that was direct experience. This soul nature was destined to be radically different from the mood that was transmitted in the Latin influence. And it belongs to the great, the wonderful secrets of historical evolution, that the Mystery of Golgotha was to arise out from the perfected culture of wisdom and knowledge, but that the depths of the Mystery of Golgotha should not be grasped through wisdom; they were to be grasped through direct life.

It was therefore like a predetermined karma that—while in Europe up to a definite point life was grasped—the ego-culture appeared purely naively, vitally and full of life where the deepest darkness was; whereas over there where was the profoundest wisdom, the Mystery of Golgotha arose. That is like a predestined harmony. Out of the civilisation based on knowledge which was beginning to dry up and wither ascends this Mystery of Golgotha: but it is to be understood by those who, through their whole nature and being, have not been able to attain to the fine crystallisation of the Latin knowledge. And so we see in the history of human evolution the meeting between a nearly lifeless, more and more dying knowledge, and a life still devoid of knowledge, a life unfilled with knowledge, but one which inwardly feels the continued working of the divinity animating the world.

These two streams had to meet, had to work upon one another in the evolving humanity. What would have happened if only the Latin knowledge had developed further? Well, this Latin knowledge would have been able to pour itself out over the successors of the primitive European population: up to a certain time it has even done so. It is hypothetically conceivable, but it could not really have happened, that the original European population should have experienced the after-working of the dried up, fading knowledge.

For then, what these souls would have received through this knowledge would gradually have led to men's becoming more and more decadent; this drying, parching knowledge would not have been able to unite with the forces which kept mankind living. It would have dried men up. Under the influence of the after effects of Latin culture, European humanity would in a sense have been parched and withered. People would have come to have increasingly refined concepts, to have reasoned more subtly and have given themselves up more and more to thought, but the human heart, the whole human life would have remained cold under these fine spun, refined concepts and ideas.

I say that that would be hypothetically conceivable, but it could not really have taken place. What really happened is something very different. What really happened is that the part of humanity that had life but not knowledge streamed in among those people who were, so to say, threatened with receiving only the remains of the Latin heritage. Let us envisage the question from another side. At a definite period we find distributed over Europe, in the Italian peninsula, in the Spanish peninsula, in the region of present France, in the region of the present British Isles, certain remains of an original European population; in the North the descendants of the old Celtic peoples, in the South the descendants of the Etruscan and ancient Roman peoples. We meet with these there, and in the first place there flows into them what we have now characterised as the Latin stream. Then at a definite time, distributed over various territories of Europe, we meet with the Ostrogoths, the Visigoths, the Lombardi, the Suevi, the Vandals, etc. There is an age when we find the Ostrogoths in the south of present Russia, the Visigoths in eastern Hungary, the Langobardi or Lombard's where today the Elbe has its lower course, the Suevi in the region where today Silesia and Moravia lie, etc. There we meet with various of those tribes of whom one can say: they have ‘life’ but no ’knowledge.’

Now we can put the question: Where have these peoples gone to? We know that for the most part they have disappeared from the actual evolution of European humanity. Where have the Ostrogoths, the Visigoths, the Langobardi, etc. gone? We can ask this. In a certain respect they no longer exist as nations, but what they possessed as life exists, exists somewhat in the following way. My dear friends, let us consider first the Italian peninsula, let us consider it still occupied by the descendants of the old Roman population. Let us further imagine that on this old Italian peninsula there had been spread abroad what I have designated Latin knowledge, Latin culture; then the whole population would have dried up.

If exact research were made, it would be impossible not to admit that only incredible dilettantism could believe that anything still persists today of a blood relationship with the ancient Romans. Ostrogoths, Visigoths, Lombardi, marched in, and over these there streamed the Latin heritage—though merely mentally as seed of knowledge—it streamed over-the life-without-knowledge, and this gave it substance for continuing. Into the more southern regions there came a more Norman-Germanic element. Thus there streamed into the Italian peninsula from the European centre and the East a life-bearing population. Into Spain there streamed the Visigoths and the Suevi in order later to unite with the purely intellectual element of the Arabs, the Moors. Into the region of France there streamed the Franks and into the region of the British Isles, the Anglo-Saxon element.

The following statement expresses the truth. If the southern regions had remained populated by descendants of the old Romans, and the Latin culture had gone on working in them, they would have faced the danger of completely losing the power of developing an ego-consciousness. Hence the descendants of ancient Rome were displaced and there was poured into this region where Latinism was to spread, what came from the element of the Ostrogoths and Lombardi. The blood of Ostrogoths and Lombardi as well as Norman blood absorbed the withering Latin culture. If the population had remained Romans they would have faced the danger of never being able to develop the element of the Consciousness-soul. Thus there went to the south in the Langobardi and the Ostrogoths what we can call the Wotan-Element, Spirit and Life. The Wotan-Element was, so to say, carried in the blood of the Langobardi and Ostrogoths and this made the further evolution and unfoldment of this southern civilisation possible.

With the Franks towards the West went the Wile-element, Intelligence and Movement, which again would have been lost if the descendants of the primitive European population who had settled in these regions had merely developed further under the influence of Rome. Towards the British Isles went We, what one can call: Configuration and Speech, and in particular the faculty to see and to hear. This has later experienced in English empiricism its later development as: Physiognomics, Speech, Sight, Hearing.

So we see that while in the new Italian element we have the expression of the Folk Soul in the Sentient-soul, we could express this differently by saying: The Wotan-element streams into the Italian peninsula. And we can speak of the journeying of the Franks to the West by saying: the Wile-element streams West, towards France. And so in respect of the British Isles we can express it by saying: the We-element streams in there.

In the Italian peninsula, therefore, nothing at all is left of the blood of the original European peoples, it has been entirely replaced. In the West, in the region of modern France, somewhat more of the original population exists, approximately there is a balance between the Frankish element and the original peoples. The greatest part of the original population is still in the British Isles.

But all this that I am now saying is fundamentally only another way of pointing to the understanding of what came out of the South through Europe, pointing to the fact that the Mystery of Golgotha was ensheathed in a dying wisdom and was absorbed through a living element still devoid of wisdom.

One cannot understand Europe if one does not bear this connection in mind; one can, however, understand Europe in all details if one grasps European life as a continuous process. For much of what I have said is still fulfilling itself in our own times. So, for instance, it would be interesting to consider the philosophy of Kant, from these two original polarities of European life, and show how Kant on the one hand desires to dethrone Knowledge, take all power from Knowledge, in order on the other hand to give place to Faith. That is only a continuation of the dim hidden consciousness that one can really do nothing with knowledge that has come up from below—one can only do something with what comes down from above as original life-without-knowledge. The whole contrast in pure and practical reason lies in this: I had to discard knowledge to make way for Faith. Faith, for which protestant theology fights, is a last relic of the life-without-knowledge, for life will have nothing to do with an analysed abstract wisdom.3Gap left between these sentences

But one can also consider older phenomena. One can observe how an endeavour appears among the most important leading personalities to create a harmony, as it were, between the two streams to which we have referred. For the modern physiognomy of Europe shows that up to our own day there is an after-working of the Latin knowledge in the European life, and that one can immediately envisage the map of Europe with the Latin knowledge raying out to south and west, and the Life still preserved in the centre. One can then see, for instance, how pains were taken at one time to overcome this dying knowledge. I should like to give an example. To be sure, this dying knowledge appears in the different spheres of life in different degrees, but already in the 8th-9th Century European evolution had so progressed that those who were the descendants of the European peoples with the Life could get no further with certain designations for cosmic or earthly relations which had been created in old Roman times. So even in the 8th-9th Centuries one could see that it had no special meaning for the original life of the soul when one said: January, February, March, April, May, etc. The Romans could make something of it, but the Northern European peoples could not do much with it; poured itself over these peoples in such a way as not to enter the soul, but rather to flow merely into the language, and it was therefore dying and withering. So an endeavour was made, especially towards Middle and Western Europe (over the whole stretch from the Elbe to the Atlantic Ocean and to the Apennines) to find designations for the months which could enter the feelings of European humanity. Such month-names were to be:

- Wintarmanoth

- Hornung

- Lenzinmanoth

- Ostarmanoth

- Winnemanoth (also Nannamanoth)

- Brachmanoth

- Henimanoth (using the word Hay)

- Aranmanoth (Aran = harvest)

- Widumanoth (Wide = what is left when one has gone over the field)

- Windumemanoth (vintage)

- Herbistmanoth

- Heiligmanoth

He who was at pains to make these names general was Charlemagne.

It shows how significant was the spirit of Charlemagne, for he sought to introduce something which has not up to now found entrance. We still have in the names of the months the last relics of the drying-up Latin cultural knowledge. Charlemagne was altogether a personality who aimed at many things which went beyond the possibility of being realised. Directly after his time, in the 9th Century, the wave of Latinism drew completely over Europe. It would be interesting to consider what Charlemagne desired to do in wishing to bring the radiation of the Wile-element towards the West. For the Latinising only appeared there later on.

Thus we can say that the part of mankind which has been race, which, as race, was the successor of the old Europe,—of the Europe from which the Roman influence proceeded and which itself became the successor of Rome, wholly for the south, largely for the north—has simply died out. Their blood no longer persists. Into the empty space left, there has poured in what came from Central Europe and the European East. One can therefore say: the racial element both of the European South and West is the Germanic element which is present in various shadings in the British Isles, in France, in Spain and in the Italian peninsula, though in this last completely inundated by the Latin influence.

The racial element therefore moves from East to the West and South, whereas the knowledge-element moves from South to North. It is the race-element which moves from the East to the West and South and along the West of Europe to the North, and gradually flows away towards the North. If one would speak correctly, one can talk of a Germanic race-element,-but not a Latin race. To speak of a Latin race is just as sensible as to speak of wooden iron; because Latinism is nothing that belongs to race, but something that has poured itself as bloodless knowledge over a part of the original European people. Only materialism can speak of a Latin race, for Latinism has nothing to do with race.

So we see how, as it were, the Bible saying works on in this part of European history, how the destiny of Latinism is the fulfilment of the words: ‘Ye shall not eat of the Tree of Life.’ We see how the Life given to the earth with the Mystery of Golgotha cannot come to full harmony with the old knowledge; but rather how into what remained of the ebbing original wisdom, new life had to enter. If we are to give a concrete answer to the question: Where does that remain, which from such new life has not been preserved in its own special character, but has disappeared in history, the element of the Visigoths, the Suevi, the Langobardi, the Ostrogoths, etc.? we must give as answer: It lives on as life within the Latin culture. That is the true state of affairs. That is what must be known regarding the primeval Bible two-fold utterance and its working in early times in the development of Europe, if we are to understand this European evolution.

I had to give you this historical analysis today because I shall have things to say which assume that one does not hold the false ideas of modern materialism and formalism with regard to historical evolution.

Achter Vortrag

Im Grunde streben die Menschen zunächst, indem sie an die geisteswissenschaftliche Weltanschauung herankommen, nach der Beantwortung von Fragen, nach der Lösung von Rätseln. Das ist ganz begreiflich und natürlich, und man kann auch sagen, gerechtfertigt. Aber ein anderes muß noch hinzukommen, wenn die geisteswissenschaftliche Bewegung wirklich das Lebendige werden soll, das sie nach dem allgemeinen Gang der Erden- und Menschheitsentwickelung eigentlich werden muß. Es muß hinzukommen vor allen Dingen ein gewisses Gefühl, eine gewisse Empfindung, daß sich, je mehr man strebt in die geistige Welt hineinzukommen, um so mehr die Rätsel häufen; daß die Rätsel geradezu mehr werden, als sie vorher für die menschliche Seele gewesen sind, und daß sie in gewisser Beziehung heiliger werden, diese großen Lebensrätsel, deren Vorhandensein wir ja vorher schon ahnen, die uns aber, so wie sie sind, selbst erst aufgehen, auch als Rätsel, wenn wir in die geisteswissenschaftliche Weltanschauung hineinkommen.

Nun ist ja eines der größten Rätsel, die mit der Erden- und Menschheitsentwickelung zusammenhängen, das Christus-Rätsel, das Rätsel des Christus Jesus. Und in bezug auf dieses Rätsel können wir allerdings ja nur hoffen, gewissermaßen langsam vorwärts zu dringen zu seiner eigentlichen Tiefe und Heiligkeit. Das heißt, wir können hoffen, nach und nach, in unseren zukünftigen Inkarnationen immer mehr und mehr zu empfinden, in welch hohem Sinne, in welch außerordentlichem Sinne dieses Christus-Rätsel ein Rätsel ist. Wir müssen nicht nur hoffen, daß uns manches in bezug auf das Christus-Rätsel gelöst werde, sondern wir müssen auch hoffen, daß manches von dem, was wir bisher als rätselhaft empfunden haben gegenüber dem Eintreten der Christus-Wesenheit in die Menschheitsentwickelung, noch schwieriger wird, daß sich zu dem noch manches andere hinzu ergibt, was uns in bezug auf das Mysterium von Golgatha neue Rätsel oder, wenn man lieber will, neue Seiten dieses großen Rätsels bringt.

Nun kann auch hier immer nur darauf Anspruch gemacht werden, gewissermaßen von da oder dort her dieses große Rätsel zu beleuchten, und ich bitte Sie durchaus, sich klar zu sein darüber, daß das nur immer, ich möchte sagen, einzelne Lichtströmungen sind, die aus dem Umkreise menschlicher Anschauung auf dieses größte Rätsel des menschlichen Erdendaseins geworfen werden, und daß sie wirklich nicht dieses Rätsel erschöpfen wollen, sondern es nur von verschiedenen Seiten her beleuchten sollen. Und so sei zu dem, was schon gesagt worden ist, auch hier noch einiges hinzugefügt, das uns wiederum eine Seite des Rätsels vom Mysterium von Golgatha nahelegen kann.

Sie erinnern sich an den weithin leuchtenden Ausspruch des Jahve-Gottes, der im Beginne der biblischen Urkunde steht, nachdem der Sündenfall geschehen war. Da wird gesagt, daß nunmehr die Menschen genossen haben von dem Baume der Erkenntnis des Guten und des Bösen, und daß sie aus ihrem bisherigen Aufenthaltsorte deshalb entfernt werden müssen, damit sie nicht auch von dem Baume des Lebens essen. Der Baum des Lebens muß geschützt werden gewissermaßen vor dem Angefressenwerden von den Menschen, die schon von dem Baume der Erkenntnis genossen haben.

Nun verbirgt sich hinter diesem Doppelursprung von dem Genusse des Baumes der Erkenntnis des Guten und Bösen einerseits, und von dem Genusse des Baumes des Lebens andererseits, etwas tief in das Leben Einschneidendes. Wir wollen heute einmal eine der vielen Anwendungen dieses Ausspruches auf das Leben ins Auge fassen, wir wollen uns einmal vor die Seele führen, was wir längst wissen: daß? das Mysterium von Golgatha, so wie es sich innerhalb der irdischen Geschichtsentwickelung vollzogen hat, in den vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum hineingefallen ist, hineingefallen ist in die griechisch- lateinische Zeit.

Wir wissen ja, dieses Mysterium von Golgatha liegt so ungefähr nach der Vollendung des ersten Drittels der griechisch-lateinischen Zeit, und zwei Drittel dieser griechisch-lateinischen Zeit folgen hinterher, um der ersten Einverleibung des Geheimnisses des Mysteriums von Golgatha in die Menschheitsentwickelung zu dienen.

Nun müssen wir zweierlei in bezug auf dieses Mysterium von Golgatha unterscheiden. Das eine ist dasjenige, was geschehen ist an reinen Tatsächlichkeiten; kurz, dasjenige, was geschehen ist als der Eintritt des kosmischen Wesens Christus in das Gebiet der Erdenentwickelung. Es wäre hypothetisch möglich, können wir sagen, es wäre denkbar, daß sich dieses Mysterium von Golgatha, das heißt der Eintritt des Impulses des Christus in die Erdenentwickelung, abgespielt hätte, ohne daß irgend jemand von den Menschen auf der Erde verstanden hätte oder vielleicht sogar nur gewußt hätte, was da geschehen ist. Es hätte ganz gut sein können, daß das Mysterium von Golgatha geschehen wäre, aber den Menschen unbewußt geblieben wäre, daß kein Mensch hätte daran denken können, sich zu enträtseln, was da eigentlich geschehen ist.

So sollte es ja eben nicht sein. Es sollte allmählich der Erdenmenschheit auch das Verständnis für dasjenige aufgehen, was durch das Mysterium von Golgatha geschehen ist. Aber daraus müssen wir doch ersehen, daß es zweierlei ist: dasjenige, was der Mensch als Wissen, als innere Verarbeitung in seine Seele aufnimmt, und das, was objektiv im Menschengeschlechte geschehen ist und was sich von diesem Menschengeschlechte, insofern es dem Wissen dieses Menschengeschlechtes angehört, unabhängig weiß. Nun, es versuchten die Menschen dasjenige, was da geschehen war durch das Mysterium von Golgatha, zu begreifen.

Wir wissen ja, daß die Evangelisten nicht nur aus einer gewissen Hellsichtigkeit die Aufzeichnungen über das Mysterium von Golgatha gemacht haben, die wir in den Evangelien finden, wir sollten wissen, daß auch versucht worden ist, mit den Mitteln der Erkenntnis, die die Menschen vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha gehabt haben, dieses Mysterium von Golgatha zu begreifen. Wir wissen, daß seit dem Mysterium von Golgatha nicht nur die Mitteilungen über die Sache unter die Menschen gekommen sind, sondern auch eine neutestamentliche Theologie in ihren verschiedenen Verzweigungen. Diese neutestamentliche Theologie hat, wie das selbstverständlich ist, die Begriffe, die die Menschen gehabt haben, verwendet, um sich zu fragen: was ist da eigentlich geschehen mit dem Mysterium von Golgatha, was hat sich da vollzogen?

Wir haben es öfter betrachtet, wie insbesondere die griechische Philosophie, dasjenige, was als griechische Philosophie sich ausgebildet hat, namentlich in Plato und Aristoteles, wie die Vorstellungen der griechischen Philosophie bemüht waren - ebenso, wie sie bemüht waren, die Natur um sich herum zu begreifen -, auch das zu begreifen, was durch das Mysterium von Golgatha geschehen ist. Und so, können wir sagen, tritt auf der einen Seite objektiv das Mysterium von Golgatha ein, und auf der anderen Seite, ihm entgegenkommend, sind die verschiedenen Weltanschauungen, die man seit Urzeiten ausgebildet hatte und die bis zu der Zeit, in der das Mysterium von Golgatha stattfand, eine gewisse Ausbildung erfahren haben und sich dann weiterentwickeln.

Woher waren diese Vorstellungen denn gekommen? Wir wissen ja, daß alle diese Vorstellungen, auch noch diejenigen, die in der griechischen Philosophie lebten und von der Erde aus dem Mysterium von Golgatha entgegengingen, von uralten Wissenschaften herrühren, von jenen Wissenschaften, welche sich den Menschen nicht hätten bieten können, wenn nicht, sagen wir, eine Uroffenbarung vorhanden gewesen wäre. Denn es ist nicht nur eine materialistische, sondern geradezu eine unsinnige Vorstellung, daß das, was in der Zeit des Mysteriums von Golgatha zur Philosophie verdünnt vorhanden war, an seiner Ausgangsstelle von den Menschen selber hätte gebildet werden können. Es ist Uroffenbarung, welche, wie wir wissen, gebildet worden ist in einer Zeit, in welcher die Menschen noch die Reste des uralten Hellsehens hatten; Uroffenbarung, welche zum großen Teile in alten Zeiten in bildhafter, in imaginativer Form den Menschen gegeben worden war, und welche sich eben zu Begriffen verdünnt hatte in der Zeit, in der das Mysterium von Golgatha eintrat, in der griechisch-lateinischen Zeit. Da konnte man entstehen sehen in uralten Zeiten einen intensiven Strom von Uroffenbarung, der den Menschen gegeben werden konnte aus dem Grunde, weil diese Menschen noch die letzten Reste des alten Hellsehens hatten, das zu dem alten Verständnisse der Menschen sprach, und das dann allmählich verstrohte, das heißt vertrocknete in der Philosophie.

So war also eine Philosophie eben da, eine Weltanschauung war da in vielen, vielen Schattierungen und Nuancen, und diese Schattierungen und Nuancen versuchten in ihrer Art, das Mysterium von Golgatha zu verstehen. Wenn wir die letzten Ausläufer ins Auge fassen wollen, sehen wollen, was dazumal also zu einer Weltanschauung sich verdünnte, die mehr philosophisch war, wenn wir die letzten Ausläufer davon betrachten wollen, so kommen wir etwa auf dasjenige, was im alten Römertum, in der römischen Zeit gelebt hat.

Mit dieser römischen Zeit meine ich diejenige Zeit, die etwa mit dem Mysterium von Golgatha, also mit der Regierung des Kaisers Augustus beginnt und die allmählich über die römische Kaiserzeit hin abflutet, bis die Völkerwanderung und dasjenige, was als Wirkung der Völkerwanderung eintritt, der europäischen Welt ein anderes Antlitz gegeben hat. Was wir in dieser Zeit aufflackern sehen wie ein letztes großes Licht der von der Uroffenbarung herkommenden Strömung, das ist die bis in unsere Zeit im Jugendunterricht eine so große Rolle spielende lateinisch-römische Poesie; das ist alles dasjenige, was sich als Fortsetzung dieser lateinisch-römischen Poesie bis zum Untergange des alten Römertums entwickelt hat. In dieses Römertum hinein hatten sich alle möglichen Nuancen von Weltanschauungen geflüchtet. Dieses Römertum war keine Einheit. Es breitete sich aus über zahlreiche Sekten, über zahlreiche religiöse Anschauungen und konnte eine gewisse Gemeinsamkeit dieser Vielheit nur dadurch entwickeln, daß sich das eigentliche Römertum gewissermaßen bis in die äußerlichen Abstraktionen zurückzog.

Das aber ist es auch, was uns erkennen läßt, wie sich in diesem Römertum, in das sich das Christentum hineinbewegte als ein neuer Impuls, wie sich in diesem sich hinziehenden Römertum eben etwas Verstrohendes zum Ausdrucke bringt. Wir sehen, wie dieses Römertum bemüht ist, intensiv bemüht ist, hereinzubekommen in seine Begriffe dasjenige, was hinter dem Mysterium von Golgatha steht, wie man versucht, auf jede mögliche Art heranzuholen von dem ganzen, breiten Gebiete der Weltanschauung, das man überschauen kann, alle möglichen Begriffe, um zu verstehen, was hinter diesem Mysterium von Golgatha steckt. Und man kann sagen, wenn man genau zusieht: es war wie ein verzweifeltes Ringen nach einem Verständnisse, nach einem eigentlichen Verständnisse des Mysteriums von Golgatha. Und dieses Ringen setzt sich im Grunde genommen in einer gewissen Strömung das ganze erste Jahrtausend noch fort.

Man sehe, wie zum Beispiel Augustinus zuerst aufnimmt alle Elemente der alten verstrohenden Weltanschauung, und wie er versucht durch das, was er so aufnimmt, zu begreifen dasjenige, was als lebendiges Seelenblut hereinfließt, da er jetzt das Christentum wie einen lebendigen Impuls in seine Seele hineinfließen fühlt. Augustinus ist eine große und bedeutende Persönlichkeit; aber man sieht es jeder Seite seiner Schriften an, wie er ringt, um in sein Verständnis hineinzubringen, was aus dem Christus-Impulse heranflutet. So geht es fort, und so ist das ganze romanische Bemühen: hineinzubekommen in die abendländische Begriffswelt, in diese Weltanschauungswelt, die lebendige Substanz desjenigen, was in dem Mysterium von Golgatha zum Ausdruck kommt.

Was ist denn das, was sich da so bemüht, was da so ringt, was in dem Römertum, in dem Lateinertum die ganze gebildete Welt überflutet, was im Lateinertum verzweifelt ringt, in die Begriffe, die in der lateinischen Sprache pulsieren, hineinzubringen das Mysterium von Golgatha? Was ist denn das? Das ist auch ein Teil desjenigen, was gegessen haben die Menschen im Paradiese. Das ist ein Teil des Baumes der Erkenntnis des Guten und Bösen. Und ich möchte sagen, wir können sehen, wie ursprünglich in den Uroffenbarungen, als noch zu den Menschen alte, hellseherische menschliche Wahrnehmungen sprechen konnten, lebendig in dieser alten Zeit die Begriffe leben, die noch Imaginationen sind, und wie sie immer mehr und mehr vertrocknen und ersterben, dünner werden. Sie sind so dünn, daß um die Mitte des Mittelalters, als die Scholastik blühte, die größte Seelenanstrengung dazu gehörte, um die Begriffe, die schon so dünn geworden waren, so weit noch in sich zuzuspitzen, daß man in diese Begriffe dasjenige hereinbekam, was als lebendiges Leben im Mysterium von Golgatha vorhanden ist. Diesen Begriffen war geblieben die destillierteste Form der alten römischen Sprache mit ihrer so außerordentlich schön in sich gefügten Logik, aber mit ihrem fast ganz verlorenen Leben. Diese lateinische Sprache wird erhalten mit ihrer strammgeschürzten Logik, aber mit ihrem innerlich fast ganz erstorbenen Leben, wie eine Erfüllung des Urgötterspruches: Die Menschen sollen nicht essen vom Baume des Lebens.

Wenn es möglich gewesen wäre, daß dasjenige, was sich aus dem alten Lateinertum ausgebildet hat, voll hätte begreifen können, was mit dem Mysterium von Golgatha sich vollzogen hat, wäre es möglich gewesen, daß das Lateinertum, einfach wie durch einen Stoß, das Verständnis hätte gewinnen können von dem Mysterium von Golgatha, dann wäre dies gewesen ein Essen vom Baume des Lebens. Das aber war verboten, nach dem Ausschluß aus dem Paradiese. Diejenige Erkenntnis, die in die Menschheit gekommen war im Sinne der alten Uroffenbarung, die sollte nicht dazu dienen, jemals lebendig zu wirken. Daher konnte sie nur mit toten Begriffen das Mysterium von Golgatha erfassen.

«Ihr sollt nicht essen vom Baume des Lebens», das ist auch ein Ausspruch, der durch alle Äonen der Erdenentwickelung gilt mit Bezug auf gewisse Erscheinungen, und eine Erfüllung dieses Ausspruches war auch die, daß mit ihm gesagt war: Es wird herantreten der Baum des Lebens in seiner anderen Form als das auf Golgatha errichtete Kreuz, und es wird ausströmen von ihm das Leben. Aber diese alte Erkenntnis soll nicht essen von dem Baume des Lebens.

Und so sehen wir denn eine hinsterbende Erkenntnis sich abmühen mit dem Leben, sehen, wie sie verzweifelt ringt, das Leben von Golgatha hereinzubekommen in ihre Begriffe.

Nun gibt es eine eigentümliche Tatsache, eine Tatsache, welche hinweist darauf, daß gewissermaßen dem Ausgangspunkte, dem Orient gegenüber in Europa eine Art Uropposition gemacht war. Es gibt so etwas wie eine Art Uropposition gegen dasjenige, was verhängt war über die Menschheit in bezug auf die Uroffenbarung. Damit berührt man allerdings, ich möchte sagen, den Rand eines ungeheuer tief liegenden Geheimnisses, und man kann manches von dem, was darüber zu sagen ist, wirklich nur in Bildern sagen. Aber ich glaube, die Bilder können verstanden werden.

In Europa gibt es ja eine ganz andere Sage, die allerdings später Umgestaltungen erfahren hat; aber trotzdem ist auch in den Umgestaltungen ihr Wesentliches noch zu erkennen. Es gibt eine andere Sage von der Entstehung des Menschen als die in der Bibel enthaltene. Nun ist nicht das das Charakteristische, daß es diese Sage gibt, sondern daß diese Sage sich in Europa länger erhalten hat als in anderen Gegenden der Erde. Aber das Bedeutsame ist, daß auch als im Orient drüben sich das Mysterium von Golgatha vollzogen hatte, in den Gemütern der Europäer noch lebendig war diese andersartige Sage. Da werden wir auch an einen Baum geführt, oder wenigstens an Bäume geführt, die von den Göttern Wotan, Wili, We gefunden werden am Strande des Meeres. Und aus zwei Bäumen werden die Menschen geschaffen: aus der Esche und aus der Ulme. Es werden also von der Dreiheit der Götter - wenn das auch später verchristianisiert worden ist, so deutet es doch auf die europäische Uroffenbarung hin -, es werden von der Dreiheit der Götter die Menschen geschaffen, indem die beiden Bäume umgestaltet werden zu Menschen: Wotan gibt den Menschen Geist und Leben, Wili gibt den Menschen Bewegung und Verstand, und We gibt den Menschen die äuBere Gestalt, die Sprache, die Kraft des Sehens, die Kraft des Hörens.

Man beachtet gewöhnlich nicht den ganz großen Unterschied, der zwischen dieser Schöpfungssage des Menschen vorhanden ist und der biblischen. Aber Sie brauchen ja nur die Bibel zu lesen - und das ist immer nützlich, die Bibel zu lesen -, schon wenn Sie die ersten Kapitel lesen, merken Sie den ganz grandiosen Unterschied, der zwischen der Schöpfungssage des Menschen hier und dort besteht. Ich möchte nur auf das eine hinweisen, und das ist: daß in die Menschen, nach der Sage, einfließt ein dreigliedriges Göttliches. Das muß ein Seelenhaftes sein, das sich in seiner äußeren Gestalt ausdrückt und das im Grunde genommen von den Göttern herrührt, das die Götter in ihn gelegt haben. Man ist sich also in Europa dessen bewußt, daß indem man auf der Erde herumgeht, man ein Göttliches in sich trägt. Man ist sich dagegen im Orient bewußt, daß man ein Luziferisches in sich trägt. Mit dem Essen vom Baume der Erkenntnis des Guten und Bösen ist etwas verbunden, das den Menschen sogar den Tod gebracht hat, etwas, das alle von den Göttern abgebracht hat, und wofür man eine göttliche Strafe verdient hat. In Europa ist man sich bewußt, daß in der Menschenseele ein Dreifaches lebt, daß die Götter eine Kraft hineingesenkt haben in die Menschenseele. Das ist sehr bedeutsam.

Wie gesagt, man berührt damit den Rand eines großen Geheimnisses, eines tiefen Mysteriums. Aber es wird wohl verstanden werden: Es sieht ja so aus, als ob in diesem alten Europa eine Anzahl von Menschen aufbewahrt worden wären, die nicht so abgebracht “ worden sind von der Teilnahme am Baume des Lebens, in denen fortlebte sozusagen der Baum oder die Bäume des Lebens: Esche und Ulme. Und damit steht in innigem Einklang: daß diese europäische Menschheit - und würde man zurückgehen zur europäischen Urbevölkerung, so würde sich das mit einer großen Klarheit in allen Einzelheiten zeigen - eigentlich nichts gehabt hat von der höheren, weitgehenderen Erkenntnis, die man im Oriente und in der griechisch-lateinischen Welt hatte.

Man sollte sich nur einmal den ungeheuer einschneidenden Gegensatz vorstellen zwischen den naiven Vorstellungen der europäischen Menschheit, die noch zur Zeit des Mysteriums von Golgatha alles in Bildern hatte, und den hochentwickelten, feinen philosophischen Begriffen der griechisch-lateinischen Welt. In Europa war alles «Leben», dort war alles «Erkenntnis des Guten und Bösen». In Europa war gleichsam etwas übrig geblieben, wie ein aufbewahrter Rest von den ursprünglichen Kräften des Lebens; aber es konnte nur übrig bleiben dadurch, daß diese Menschheit gewissermaßen bewahrt war, irgend etwas zu verstehen von dem, was in so wunderbar fein geschürzten Begriffen im Lateinertum enthalten war. Von einer Wissenschaft der alten europäischen Bevölkerung zu sprechen, wäre ein Unding. Man kann nur sprechen davon, daß diese Leute lebten mit alledem, was in ihrem Inneren, in ihrer Seele sprießte, sie durchvitalisierte. Was sie glaubten zu wissen, war etwas, was unmittelbares Erleben war. Radikal verschieden war diese Art, in der Seele gestimmt zu sein, von jener Stimmung, die sich fortpflanzte im Lateinertum. Und das gehört eben zu den großen, zu den wunderbaren Geheimnissen des geschichtlichen Werdens: daß, ich möchte sagen, aus der Vollendung der Wissenskultur, der Weisheitskultur, hervorgehen sollte das Mysterium von Golgatha; allein die Tiefen dieses Mysteriums von Golgatha sollten nicht begriffen werden durch die Weisheit, sie sollten begriffen werden durch das unmittelbare Leben.

Daher war es wie ein vorbestimmtes Karma, daß, als in Europa bis zu einem bestimmten Punkte erstarkt war das Leben, ich möchte sagen, die Ich-Kultur rein naiv, rein lebendig, rein vitalistisch auftrat da, wo die tiefste Finsternis war; während dort, wo die tiefste Weisheit war, das Mysterium von Golgatha aufstieg. Das ist wie eine prästabilierte Harmonie. Aus der Wissenskultur, die da begann strohern zu werden, steigt dieses Mysterium von Golgatha auf; verstanden aber soll dieses Mysterium von Golgatha werden von denjenigen, die durch ihr ganzes Wesen und ihr ganzes Sein nicht haben kommen können bis zu dieser feinen Auskristallisierung des lateinischen Wissens. Und so sehen wir in der Geschichte der Menschheitsentwickelung sich begegnen ein lebenloses, immer mehr und mehr ersterbendes Wissen und ein noch wissenloses Leben, ein wissenloses Leben, das aber innerlich, ich möchte sagen, das Fortwirken des die Welt belebenden Göttlichen erfühlt.

Diese zwei Strömungen mußten sich begegnen, mußten aufeinander wirken in der sich fortentwickelnden Menschheit. Was wäre geschehen, wenn nur das lateinische Wissen sich fortentwickelt hätte? Nun, dieses lateinische Wissen würde sich haben ergießen können über die Nachkommen der europäischen Urbevölkerung. Das hat es auch sogar bis zu einer gewissen Zeit getan. Hypothetisch denkbar ist es, aber nicht wirklich hätte es werden können, daß die europäische Urbevölkerung die Nachwirkung des sich verstrohenden Wissens erlebt hätte. Denn dann würde dasjenige, was diese Seelen durch dieses Wissen aufgenommen hätten, allmählich dazu geführt haben, daß die Menschen immer dekadenter und dekadenter geworden wären. Mit den die Menschheit lebendig erhaltenden Kräften hätte dieses vertrocknende, dieses verstrohende Wissen sich nicht vereinigen können. Es hätte dies die Menschen ausgedörrt. Gewissermaßen würde unter dem Einflusse der nachwirkenden |lateinischen Kultur die europäische Menschheit ausgedörrt sein, vertrocknet sein. Man würde immer mehr dazu gekommen sein, raffinierte Begriffe zu haben, immer mehr würde man spintisiert haben, immer mehr und mehr würde man gedacht haben; aber es würde das Menschenherz, das ganze menschliche Leben kalt geblieben sein unter diesen verfeinerten, raffinierten Begriffen.

Ich sage, hypothetisch wäre das denkbar, aber es hat nicht wirklich werden können. Wirklich geworden ist vielmehr ein anderes. Wirklich geworden ist dasjenige, daß der Teil der Menschheit, der ein wissenloses Leben hatte, einströmte in jene Menschen, welche sozusagen davon bedroht waren, nur die Überreste des Lateinertums zu empfangen.

Fassen wir die Frage von einer anderen Seite an. Wir treffen ja zu einer bestimmten Zeit über Europa verteilt, man kann sagen, auf der italienischen Halbinsel, auf der spanischen Halbinsel, in der Gegend des heutigen Frankreich, in der Gegend der heutigen britischen Inseln, gewisse Überreste einer europäischen Urbevölkerung an: im Norden die Nachkommen der alten keltischen Bevölkerung, im Süden die Nachkommen der alten römischen Bevölkerung. Die treffen wir dort an, in die fließt zunächst dasjenige hinein, was wir jetzt charakterisiert haben als lateinische Strömung. Dann treffen wir an, zu einer bestimmten Zeit, über verschiedene Territorien Europas verteilt: die Ostgoten, die Westgoten, die Langobarden, die Sueven, die Vandalen und so weiter. Es gibt eine Zeit, wo wir die Ostgoten finden im Süden des heutigen Rußland, die Westgoten im östlichen Ungarn, die Langobarden da, wo heute die Elbe ihren unteren Lauf hat; die Sueven in der Gegend, wo heute Mähren und Schlesien liegen und so weiter. Wir treffen da verschiedene von denjenigen Völkerschaften, von denen man sagen kann: sie haben wissenloses Leben.

Nun können wir die Frage aufwerfen: Wohin sind diese Völkerschaften gekommen? Wir wissen, sie sind verschwunden zum großen Teile aus der tatsächlichen Entwickelung der europäischen Menschheit. Wohin sind die Ostgoten, wohin die Westgoten, wohin die Langobarden gekommen? Das können wir fragen. In gewisser Beziehung sind sie als Völker nicht mehr vorhanden; aber dasjenige, was sie als Leben gehabt haben, ist vorhanden, ist etwa in der folgenden Weise vorhanden. Betrachten wir die italienische Halbinsel, betrachten wir sie noch besetzt von den Nachkommen der alten römischen Bevölkerung, denken wir uns, es hätte sich auf dieser alten italienischen Halbinsel dasjenige ausgebreitet, was ich als lateinisches Wissen, als lateinische Kultur gekennzeichnet habe: es wäre die ganze Bevölkerung vertrocknert.

Wenn man genau untersuchen würde, so würde man es als unglaublichen Dilettantismus ansehen müssen, zu glauben, daß heute irgend etwas von Blutsverwandtschaft mit dem alten Römertum noch vorhanden ist. Eingezogen sind Ostgoten, Westgoten, Langobarden, und über diese strömte hinüber dasjenige, was das Lateinertum war - aber bloß geistig als Wissenskeim -, über das wissenlose Leben, und das wissenlose Leben gab weiterhin die Substanz dazu. In den südlicheren Gegenden war es ein normannisch-germanisches Element. So strömte in die italienische Halbinsel das ein, was an lebentragender Bevölkerung vorhanden war, aus dem europäischen Mittelland und dem Osten. In Spanien strömte ein, um sich später mit dem rein verstandesmäßigen Elemente des Arabertums, des Maurentums zu verbinden, das Westgoten- und das Sueventum; in der Gegend von Frankreich strömte ein das Frankentum, und in der Gegend der britischen Inseln das Angelsachsentum.

Man trifft das Richtige, wenn man das Folgende sagt: Insbesondere waren die Gegenden des Südens vor der Gefahr, vollständig zu verlieren - wenn sie Nachkommen der alten Römer geblieben wären und die lateinische Kultur in ihnen fortgewirkt hätte - die Möglichkeit, ein Ich-Bewußtsein auszubilden. Daher wurde hinweggenommen die Nachkommenschaft des alten Römertums, und es wurde hineingeströmt in dieses Gebiet, wo sich ausbreiten sollte das Lateinertum, dasjenige, was von dem ostgotischen, von dem langobardischen Elemente kam. Ostgotisches, langobardisches Blut und auch Normannenblut nahm auf dasjenige, was verstrohende lateinische Kultur wurde. Vor der Gefahr wäre nämlich die Bevölkerung gewesen, wenn sie römisch geblieben wäre, nicht entwickeln zu können jemals das Element der Bewußitseinsseele.

So ging in den Langobarden und in den Ostgoten nach dem Süden dasjenige, was wir nennen können: das Wotan-Element, Geist und Leben. Da wurde sozusagen getragen im Blute der Langobarden, im Blute der Ostgoten, das Wotan-Element, und das machte die weitere Entwickelung, die weitere Entfaltung dieser südlichen Kultur möglich.

Nach Westen ging mit den Franken das Wili-Element, Verstand und Bewegung, was wiederum abhanden gekommen wäre, wenn die Nachkommenschaft der europäischen Urbevölkerung, die in diesen Gegenden gesessen hatte, sich bloß weiter entwickelt hätte unter dem Einfluß des Römertums.

Nach den britischen Inseln ging dasjenige, was man nennen kann: Gestaltung und Sprache, und namentlich die Fähigkeit, zu sehen und zu hören, was dann im englischen Empirismus seine spätere Ausbildung erfahren hat: in Physiognomik, Sprache, Gesicht, Gehör.

So sehen wir, indem wir tatsächlich im neuen italienischen Elemente das Sprechen der Volksseele in der Empfindungsseele haben, wie wir das anders ausdrücken können dadurch, daß wir sagen: das Wotan-Element strömt in die italienische Halbinsel ein. So wie wir den Zug der Franken nach Westen ausdrücken können dadurch, daß wir sagen: das Wili-Element strömt nach dem Westen, nach Frankreich. Und wie wir das in bezug auf die britischen Inseln ausdrükken können dadurch, daß wir sagen: das We-Element strömt da hinein.

So ist auf der italienischen Halbinsel gar nichts mehr von dem Blute der europäischen Urbevölkerung vorhanden; das ist ganz ersetzt. Im Westen, in der Gegend des heutigen Frankreich, ist etwas mehr von der Urbevölkerung vorhanden, ungefähr so, daß sich die Waage halten das Frankenelement und die Urbevölkerung. Am meisten von der Urbevölkerung ist noch auf den britischen Inseln.

Das alles aber, was ich jetzt gesagt habe, ist im Grunde genommen nur eine andere Art, auf das Verständnis desjenigen hinzuweisen, was aus dem Süden kam durch Europa: hinzuweisen auf das Eingehülltsein des Mysteriums von Golgatha in eine untergehende Weisheit und auf dessen Aufgenommenwerden durch ein noch weisheitsloses Leben.

Man kann Europa nicht verstehen, wenn man diesen Zusammenhang nicht ins Auge faßt; man kann aber Europa in allen Einzelheiten verstehen, wenn man dieses europäische Leben erfaßt wie einen fortlaufenden Prozeß. Denn vieles von dem, was ich gesagt habe, vollzieht sich noch bis in unsere Tage herein. So zum Beispiel wäre es interessant, selbst so etwas wie die Philosophie Kants aus diesen zwei Urgegensätzen des europäischen Lebens heraus einmal ins Auge zu fassen und zu zeigen, wie Kant auf der einen Seite das Wissen absetzen will, dem Wissen alle Gewalt nehmen will, um auf der anderen Seite dem Glauben Platz zu machen. Das ist nur ein Fortwirken des dunklen, geheimen Bewußtseins: mit dem Wissen, das da von unten heraufgekommen ist, kann man ja eigentlich nichts anfangen; man kann nur etwas anfangen mit dem, was als ursprüngliches wissenloses Leben von oben herunter kommt. Der ganze Gegensatz der reinen und praktischen Vernunft liegt da darinnen: Ich mußte das Wissen wegräumen, um dem Glauben Platz zu machen. Der Glaube, für den die protestantische Theologie kämpft, ist ein letztes Überbleibsel des wissenlosen Lebens, denn das Leben will nichts wissen von einer auseinandergezogenen abstrakten Weisheit.

Aber auch ältere Erscheinungen kann man betrachten. Man kann zum Beispiel ins Auge fassen, wie gerade bei den geistig führenden Persönlichkeiten das Bemühen auftritt, gewissermaßen einen Einklang zu schaffen zwischen diesen zwei Strömungen, auf die aufmerksam gemacht worden ist. Denn das zeigt die heutige Physiognomie Europas, daß bis in unsere Tage nachwirkt das lateinische "Wissen in dem europäischen Leben, und daß man geradezu die Karte Europas mit dem nach Süden und Westen ausstrahlenden lateinischen Wissen und dem in der Mitte Europas noch sich bewahrenden Leben ins Auge fassen kann. Man kann sehen, wie man einmal sich Mühe gegeben hat - ich möchte ein Beispiel anführen -, dieses ersterbende Wissen zu überwinden. Gewiß, es tritt auf den verschiedenen Gebieten des Lebens in verschieden starker Weise auf, dies ersterbende Wissen; aber es war schon im 8. bis 9. Jahrhundert die europäische Entwickelung so weit, daß diejenigen, welche die Nachkommen waren der europäischen Bevölkerung, nichts Rechtes mehr machen konnten mit dem, was noch als gewisse Bezeichnungen für kosmische oder irdische Verhältnisse gebildet war aus alten römischen Zeiten. So konnte man schon im 8. bis 9. Jahrhundert einsehen, daß es dem ursprünglichen Leben der Seele nichts besonderes gibt, wenn man sagt: Januar, Februar, März, April, Mai. Damit konnten die Römer etwas anfangen, aber die nördlichere europäische Bevölkerung konnte nicht viel damit anfangen; es ergoß sich so über diese europäische Bevölkerung hin, daß es nicht in die Menschenseele, sondern vielfach nur in die Sprache hineinfloß und daher ersterbend, verstrohend war. Daher gab man sich Mühe, namentlich über Mittel- und Westeuropa hin...über den ganzen Strich, den man bezeichnen könnte als von der Elbe angefangen bis zum Atlantischen Ozean und bis zu den Apenninen gehend Bezeichnungen durchzubringen für die Monate, welche erfühlt werden können von der europäischen Menschheit. Solche Monatsbezeichnungen sollten sein:

1. Wintarmanoth.

2. Hornung.

3. Lenzinmanoth.

4. Ostarmanoth.

5. Winnemanoth (auch Nannamanoth).

6. Brachmanoth.

7. Heuimanoth (zusammengesetzt mit Heu).

8. Aranmanoth (Aran = die Ernte).

9. Widumanoth (Wide = das, was stehen geblieben ist, nachdem man über den Acker gegangen ist).

10. Windumemanoth (lateinisch = vindemia: Weinlese).

11. Herbistmanoth.

12. Heiligmanoth.

Derjenige, der sich bemüht hat, diese Bezeichnungen allgemein zu machen, ist Karl der Große.

Es ist bezeichnend dafür, wie bedeutsam der Geist Karls des Großen war, denn er versuchte damit etwas einzuführen, was bis heute kaum Eingang gefunden hat. Wir haben immer noch in den Monatsbezeichnungen die letzten Reste der verstrohenden lateinischen Wissenskultur. Karl der Große war überhaupt eine Persönlichkeit, welche vieles gewollt hat, das über die Möglichkeit des zu Verwirklichenden hinausgegangen ist. Es hat sich gerade nach ihm, im 9. Jahrhundert, die Welle des Lateinertums so recht hinübergezogen über Europa. Es wäre interessant, wenn ins Auge gefaßt würde, was Karl der Große gewollt hat, indem er die Ausstrahlungen des Wile-Elementes nach Westen bringen wollte. Denn die Latinisierung trat dort erst nachher auf.

So können wir sagen, daß derjenige Teil der Menschheit, der Rasse gewesen ist, der als Rasse die Nachfolgerschaft war des alten Europa, des Europa, aus dem das Römertum hervorgegangen ist, und der die Nachkommenschaft des Römertums selber gewesen ist, für den südlichen Teil ganz - und für den nördlicheren Teil zum großen Teile - einfach ausgestorben ist. Von dem ist im Blute nichts mehr vorhanden. Es hat sich in den leeren Raum, der da gelassen worden ist, hineinergossen, was von Mitteleuropa und dem europäischen Osten gekommen ist. So daß man sagen kann: das rassenhafte Element, auch des europäischen Südens und des europäischen Westens, ist das germanische Element, das nur in den verschiedenen Schattierungen in den britischen Inseln, in Frankreich, in Spanien und aber dort auch völlig überflossen vom Lateinertum - auf der italienischen Halbinsel vorhanden ist.

Das Rassenelement ist also dasjenige, was sich von Osten nach Westen und nach Süden hin bewegt, während das Wissenselement vom Süden nach Norden sich bewegt. Das Rassenelement ist es, welches sich von Osten nach Westen und Süden und längs des europäischen Westens nach Norden bewegt und allmählich abflutet nach dem Norden zu. So daß, wenn man richtig sprechen will, von einem germanischen Rassenelement, aber nicht von einer lateinischen Rasse gesprochen werden kann. Von einer lateinischen Rasse zu sprechen ist ebenso gescheit, wie von einem hölzernen Eisen zu sprechen; weil das Lateinertum, wie es geworden ist, nichts ist, was einer Rasse anhaftet, sondern etwas, was sich als blutloses Wissen über einen Teil der europäischen Urbevölkerung ergossen hat. Aber von einer lateinischen Rasse sprechen kann nur der Materialismus, denn Latinität hat nichts zu tun mit etwas Rassenhaftem.

So sehen wir, wie gewissermaßen der Bibelspruch fortwirkt in diesem Teile der europäischen Geschichte, wie das Schicksal der Latinität Erfüllung ist des Spruches: «Von dem Baume des Lebens sollt ihr nicht essen», und wie das Leben, das der Erde gegeben worden ist mit dem Mysterium von Golgatha, nicht völlig in Einklang kommen konnte mit dem alten Wissen; sondern wie in das, was geblieben ist von der Urweisheit und was versickert war, neues Leben hineinkommen mußte. Wenn wir sachlich die Frage beantworten sollen: Wo bleibt das, was aus solchem neuen Leben sich nicht erhalten hat in seiner besonderen Eigenart, sondern in der Geschichte verschwunden ist: das westgotische, das suevische, das langobardische, das ostgotische Element und so weiter? - so müssen wir zur Antwort geben: Es lebt als Leben fort innerhalb der lateinischen Kultur. Das ist der wahre Tatbestand, den man allerdings kennen muß mit Bezug auf dasjenige, was ausgeht von dem uralten Bibel-Doppelspruche und was in alten Zeiten mit Bezug auf die Entwickelung Europas wirkt, um diese Entwickelung Europas zu verstehen.

Ich mußte Ihnen heute gleichsam diese geschichtliche Auseinandersetzung geben, weil ich Ihnen Dinge zu sagen haben werde, welche voraussetzen, daß man über diese geschichtliche Entwickelung nicht die falschen Begriffe des heutigen Materialismus und Formalismus habe.

Eighth Lecture

Basically, by approaching the spiritual scientific worldview, people initially strive to find answers to questions and solutions to riddles. This is completely understandable and natural, and one could even say justified. But something else must be added if the spiritual scientific movement is to become truly alive, which it must become according to the general course of the development of the earth and of humanity. Above all, a certain feeling must be added, a certain sense that the more one strives to enter the spiritual world, the more the riddles accumulate; that the riddles actually become more than they were previously for the human soul, and that they become, in a certain sense, more sacred, these great mysteries of life, whose existence we already suspect, but which, as they are, only become apparent to us as mysteries when we enter into the spiritual scientific worldview.

Now, one of the greatest mysteries connected with the development of the earth and humanity is the mystery of Christ, the mystery of Jesus Christ. And with regard to this mystery, we can only hope, as it were, to slowly advance toward its true depth and holiness. That means we can hope that, little by little, in our future incarnations, we will feel more and more the high and extraordinary sense in which this Christ mystery is a mystery. We must not only hope that some things will be solved for us in relation to the Christ mystery, but we must also hope that some of what what we have hitherto found enigmatic about the entry of the Christ Being into human evolution will become even more difficult, that many other things will be added to it which will bring us new enigmas or, if you prefer, new aspects of this great mystery in relation to the mystery of Golgotha.

Now, here too, we can only claim to shed light on this great mystery from one angle or another, and I ask you to be clear that these are only, I would say, individual rays of light that are cast from the sphere of human perception onto this greatest mystery of human existence on earth, and that they do not really seek to exhaust this mystery, but only to illuminate it from different sides. And so, to what has already been said, let us add a few things here that may again suggest to us one side of the enigma of the mystery of Golgotha.

You will recall the widely quoted statement of the God Yahweh at the beginning of the biblical record, after the Fall had taken place. There it is said that now human beings have enjoyed the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and that they must therefore be removed from their previous dwelling place so that they do not also eat of the tree of life. The tree of life must be protected, as it were, from being eaten by people who have already enjoyed the tree of knowledge.

Now, behind this dual origin of the enjoyment of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil on the one hand, and the enjoyment of the tree of life on the other, lies something deeply incisive in life. Today, let us consider one of the many applications of this statement to life. Let us bring to mind what we have long known: that the mystery of Golgotha, as it unfolded within the course of earthly history, fell into the fourth post-Atlantean epoch, fell into the Greco-Latin period.

We know that this mystery of Golgotha lies roughly after the completion of the first third of the Greek-Latin period, and two thirds of this Greek-Latin period follow afterwards in order to serve the first incorporation of the secret of the mystery of Golgotha into human evolution.

Now we must distinguish between two things in relation to this mystery of Golgotha. One is what happened in pure facts; in short, what happened as the entry of the cosmic being Christ into the realm of Earth's evolution. It would be hypothetically possible, we might say, conceivable, that this mystery of Golgotha, that is, the entry of the Christ impulse into the evolution of the earth, could have taken place without anyone on earth understanding or perhaps even knowing what had happened. It could well have been that the mystery of Golgotha would have taken place, but remained unconscious to human beings, that no human being would have been able to think of unraveling what had actually happened.

But that was not how it was meant to be. Gradually, human beings on Earth were to gain an understanding of what happened through the Mystery of Golgotha. But we must see that there are two things here: that which human beings take into their souls as knowledge, as inner processing, and that which has happened objectively in the human race and which is independent of the human race insofar as it belongs to the knowledge of this human race. Now, people tried to understand what had happened through the mystery of Golgotha.

We know that the evangelists did not merely record the mystery of Golgotha, which we find in the Gospels, out of a certain clairvoyance; we should know that attempts were also made to understand this mystery of Golgotha with the means of knowledge available to people before the mystery of Golgotha. We know that since the Mystery of Golgotha, not only have the messages about the event come among human beings, but also a New Testament theology in its various branches. This New Testament theology has, as is only natural, used the concepts that people had in order to ask themselves: What actually happened in the Mystery of Golgotha? What took place there?

We have often considered how Greek philosophy in particular, what developed as Greek philosophy, especially in Plato and Aristotle, how the ideas of Greek philosophy endeavored—just as they endeavored to understand the nature around them—to understand what happened through the Mystery of Golgotha. And so, we can say that on the one hand, the mystery of Golgotha objectively enters the picture, and on the other hand, coming towards it are the various worldviews that had been developed since time immemorial and which, by the time the mystery of Golgotha took place, had undergone a certain development and were then continuing to evolve.

Where did these ideas come from? We know that all these ideas, even those that lived in Greek philosophy and approached the mystery of Golgotha from the earth, originate from ancient sciences, from those sciences that could not have been available to human beings if there had not been, so to speak, a primordial revelation. For it is not only a materialistic but downright nonsensical idea that what existed in the time of the mystery of Golgotha in a diluted form as philosophy could have been formed by human beings themselves at its point of origin. It is primal revelation which, as we know, was formed at a time when human beings still had the remnants of ancient clairvoyance; primal revelation which, in ancient times, was given to human beings largely in pictorial, imaginative form, and which had been diluted into concepts at the time when the mystery of Golgotha occurred, in the Greek-Latin period. In ancient times, an intense stream of primordial revelation could be seen emerging, which could be given to people because they still had the last remnants of the old clairvoyance that spoke to the old understanding of human beings and then gradually scattered, that is, dried up in philosophy.

So there was a philosophy, a worldview in many, many shades and nuances, and these shades and nuances tried in their own way to understand the mystery of Golgotha. If we want to consider the last remnants, to see what at that time was diluted into a worldview that was more philosophical, if we want to look at the last remnants of this, we come to what lived in ancient Rome, in Roman times.

By this Roman period, I mean the period that begins roughly with the mystery of Golgotha, that is, with the reign of Emperor Augustus, and gradually ebbs away through the Roman Empire until the migration of peoples and the effects of that migration have given the European world a different face. What we see flaring up in this period like a last great light from the stream originating in the original revelation is the Latin-Roman poetry that has played such an important role in youth education up to our time; it is everything that developed as a continuation of this Latin-Roman poetry until the decline of ancient Roman culture. All kinds of nuances of worldviews had taken refuge in this Roman culture. This Roman culture was not a unified whole. It spread across numerous sects and religious views and could only develop a certain commonality in this diversity by withdrawing, as it were, into external abstractions.

But this is also what allows us to recognize how, in this Romanism into which Christianity moved as a new impulse, how, in this protracted Romanism, something confusing comes to expression. We see how this Roman spirit is striving, intensely striving, to incorporate into its concepts that which lies behind the mystery of Golgotha, how it is trying in every possible way to draw from the whole broad field of worldview that can be surveyed, all possible concepts in order to understand what lies behind this mystery of Golgotha. And if you look closely, you can say that it was like a desperate struggle for understanding, for a real understanding of the mystery of Golgotha. And this struggle basically continued in a certain current throughout the entire first millennium.

Consider, for example, how Augustine first takes in all the elements of the old, decaying worldview, and how he tries, through what he takes in, to understand what flows in as living soul blood, since he now feels Christianity flowing into his soul as a living impulse. Augustine is a great and significant personality, but one can see on every page of his writings how he struggles to bring into his understanding what is flooding in from the Christ impulse. This is how it goes on, and this is the whole Romanesque endeavor: to bring into the Western world of concepts, into this worldview, the living substance of what is expressed in the mystery of Golgotha.

What is it that strives so hard, that struggles so hard, that floods the entire educated world in Roman culture, in Latin culture, that struggles desperately in Latin culture to bring the mystery of Golgotha into the concepts that pulsate in the Latin language? What is it? This is also part of what people ate in Paradise. It is part of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. And I would like to say that we can see how, in the original revelations, when ancient, clairvoyant human perceptions could still speak to people, the concepts that are still imaginations lived vividly in those ancient times, and how they are drying up and dying more and more, becoming thinner. They are so thin that by the middle of the Middle Ages, when scholasticism flourished, it took the greatest effort of the soul to sharpen the concepts that had already become so thin to such an extent that one could bring into these concepts what is present as living life in the mystery of Golgotha. These concepts retained the most distilled form of the ancient Roman language with its extraordinarily beautiful internal logic, but with its life almost completely lost. This Latin language is preserved with its rigid logic, but with its inner life almost completely dead, as a fulfillment of the original divine decree: “Men shall not eat of the tree of life.”

If it had been possible for what developed out of ancient Latin culture to fully comprehend what took place in the mystery of Golgotha, it would have been possible for Latin culture, simply as if by a blow, to gain understanding of the mystery of Golgotha, and this would have been like eating from the tree of life. But this was forbidden after the expulsion from Paradise. The knowledge that had come into humanity in the sense of the ancient revelation was not to serve to ever have a living effect. Therefore, it could only grasp the mystery of Golgotha with dead concepts.