The Tree of Life and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil

GA 162

31 July 1915, Dornach

3. The Power of Thought

My dear friends,

My dear friends, it is really difficult in our time to meet with full understanding when one speaks out of the sources of what we call Spiritual Science.

I have not in mind so much the difficulty of being understood among the individuals whom we encounter in life, but much more of being comprehensible to the cultural streams, the various world-conceptions and feelings which confront us at the present time.

When we consider European life we find in the first place a great difficulty which has sprung from the following cause. European life at the moment of passing over from mere sense perceptions to thinking about percepts—and this is effected by every individual in every moment of his waking life—does not feel how intimately connected is the thought-content with what we are as human beings.

People think thoughts, they form concepts, and they have the consciousness that through these thoughts and concepts they are, as it were, learning something of the world, that the images in fact reproduce something of the world. This is the consciousness people have. Each one who walks along the street has the feeling that because he sees the trees etc. concepts come to life, and that the concepts are inner presentations of what he perceives, and that he thus in some way takes the world of external percepts into himself and then lives them over again.

In the rarest cases, one can say practically never, is it brought to consciousness in the European world-conception that the thought, the act of thinking, is an actuality in our inner self as man, that we do something by thinking, that thinking is an inner activity, an inner work.

I called your attention here once to the fact that every thought is essentially different from what people usually believe it to be. People take it to be a reproduction of something perceptible. But it is not recognised as a form-builder, a moulder. Every thought that arises in us seizes, as it were, upon our inner life and shares (above all so long as we are growing) in our whole human construction. It already takes part in our structure before we are born and belongs to the forming forces of our nature. It goes on working continually and again and again replaces what dies away in us. So it is not only the case that we perceive our concepts externally, but we are always working upon our being through our thoughts, we work the whole time anew upon our forming and fashioning through what we conceive in ideas.

Seen with the eyes of spiritual science every thought appears like a head with a sort of continuation downwards, so that with every thought we actually insert in us something like a shadowy outline, a phantom, of ourselves; not exactly like us, but as similar as a shadow-picture. This phantom of ourselves must be inserted, for we are continuously losing something, something is being destroyed, is actually crumbling away. And what the thought inserts into our human form, preserves us, generally speaking, until our death. Thought is thus at the same time a definite inner activity, a working on our own construction.

The western world-concept has practically no knowledge of this at all. People do not notice, they have no inner feeling of how the thought grips them, how it really spreads itself out in them. Now and again a man will feel in breathing—though for the most part it is no longer noticed—that the breath spreads out in him, and that breathing has something to do with his re-building and regeneration. This applies also to thoughts, but the European scarcely feels any longer that the thought is actually striving all the time to become man, or, better said, to form the human shape.

But unless we come to a feeling of such forces within us we can hardly reach a right understanding, based on inner feeling and life, of what spiritual science really desires. For spiritual science is actually not active at all in what thought yields us inasmuch as it reproduces something external; it works in the life element of thought, in this continuous shaping process of the thought.

Therefore it has been very difficult for many centuries to speak of spiritual science or to be understood when it was spoken of, because this last characterised consciousness became increasingly lost to European humanity. In the Oriental world-conception this feeling about thought which I have just expressed exists in a high degree. At least the consciousness exists in a high degree that one must seek for this feeling of an inner experience of thought. Hence comes the inclination of the Oriental for meditation; for meditation should be a familiarising oneself with the shaping forces of thought, a becoming aware of the living feeling of the thought. That the thought accomplishes something in us should become known to us during meditating. Therefore we find in the Orient such expressions as: A becoming one, in meditation, with Brahma, with the fashioning process of the world. What is sought in the Oriental world-conception is the consciousness that when one rightly lives into the thought, one not only has something in oneself, not only thinks, but one becomes at home in the fashioning forces of the world. But it is rigidified, because the Oriental world-conception has neglected to acquire an understanding for the Mystery of Golgotha. To be sure, the Oriental world-conception of which we have yet to speak—is eminently fitted to become at home in the forming forces of thought life, but nevertheless in so doing, it comes into a dying element, into a network of abstract, unliving conceptions. So that one could say: whereas the right way is to experience the life of the thought-world, the Oriental world-conception becomes at home in a reflection of the life of thought. One should become at home in the thought-world as if one were transposing oneself into a living being; but there is a difference between a living being and a reproduction of a living being, let us say a paper mache copy. The oriental world-conception, whether Brahmanism, Buddhism, the Chinese and Japanese religions, does not become at home in the living being, but in something which may be described as a copy of the thought-world, which is related to the living thought-world, as the papier-mache organism is related to the living organism.

This then is the difficulty, as well in the West as in the East. One is less understood in the West, since in general not much consciousness exists there of these living, forming forces of thought; in the East one is not understood aright, since there people have not a genuine consciousness of the living nature of thought, but only of the dead reproduction, of the stiff, abstract weaving of thoughts.

Now you must be clear whence all that I have just analysed actually comes. You will all remember the account of the Moon evolution given in my book Occult Science. Man in his own evolution has taken his proper share in all that has taken place as Saturn, Sun and Moon evolutions, and he then further shares in what comes about as Earth evolution. When you call to mind the Moon evolution as described in my Occult Science you find that during that time the separation of the moon planet from the sun took place; that it proceeded for the first time in a distinct, definite way. Thus such a separation actually took place. We can say that whereas before there had been a kind of interconnected condition of the planetary world, at the separation of the moon from the sun there now took their course side by side the Moon evolution and the Sun evolution. This separate state was of great significance, as you can gather from Occult Science. Man as he now is could not have arisen if this separation had not taken place. But on the other hand, with every such event is intimately connected the emergence of a certain one-sidedness. It came about that certain beings of the Hierarchy of the Angeloi, who were at the human stage during the Moon evolution, at that time rebelled against, showed themselves in antipathy to, uniting again with the Sun. Thus the Moon broke away, and at the later reunion with the Sun they refused to take this step, and be reunited with the Sun.

All Luciferic staying behind rests upon an unwillingness to take part in later phases of evolution. And hence, on the one hand, the Luciferic element originated in the fact that certain beings from the Hierarchy of the Angeloi, who were human at that time, were not willing to reunite with the Sun in the last part of the Old Moon time. To be sure, they were obliged to descend again, but in their feeling, in their inner nature, they preserved a longing for the Moon existence. They were out of place, they were not at home in the existing evolution; they felt themselves to be actually Moon-beings. Their remaining behind consisted in this. The host of Luciferic beings who then in their further development descended upon our Earth naturally contained in their ranks this kind of being. They also live in us in the manner I have indicated in one of the last lectures. And it is they who will not let the consciousness arise, in our Western thinking, that thinking is inwardly alive. They want to keep it of a Moon-nature, cut off from the inner life element that is connected with the Sun, they want to keep it in the condition of separation. And their activity produces the result that man does not get a conscious feeling: thinking is connected with inner fashioning, but feels instead that thinking is only connected with the external, precisely with that which is separated. Thus in respect of thinking they evoke a feeling that it can only reproduce the external; that one cannot grasp the inner formative living element with it, but can only grasp the external. Thus they falsify our thinking.

It was in fact the karma of Western humanity to make acquaintance with these spirits, who falsify thinking in this manner, alter it, externalise it, who endeavour to give it the stamp of only being of service in reproducing outer things and not grasping the inner living element. It was apportioned to the karma of the Oriental peoples to be preserved from this kind of Luciferic element. Hence they retained more the consciousness that in thinking one must seek for the inwardly forming, shaping of the human being, for what unites him inwardly with the living thought-world of the universe. It was allotted to the Greeks to form the transition between the one and the other.

Since the Orientals have made little acquaintance with that Luciferic element I have just characterised, they have no real idea that one can also come into connection with the living element of thinking about the external. What they get hold of in this connection always seems made of paper mache they have little understanding of applying thinking to outer things. Lucifer must of course cooperate in the activity which I have just described, by which man feels the inclination to meditate on the outer world. But then it is like the swing of the pendulum to one side, man goes too far in this activity—towards the external. That is the common peculiarity of all life; it swings out sometimes to the one side, sometimes to the other. There must be the swinging out, but one must find the way back from the one to the other, from the Oriental to the Occidental. The Greeks were to find the transition from Oriental to Occidental. The Oriental would have fallen completely into rigid abstractions—has, indeed, partly done so, abstractions which are pleasing to many people—if Greece had not influenced the world. If we base our judgment simply on what we have now considered, we shall find in Greece the tendency to make thoughts inwardly formative and alive.

Now if you examine both Greek literature and Grecian art you will everywhere find how the Greek strove to produce the human form from his own inner experiencing; this is so in sculpture as well as in poetry, in fact in philosophy too. If you acquaint yourself with the manner in which Plato still sought, not to found an abstract philosophy, but to collect a group of men who talk with one another and exchange their views, so that in Plato we find no world-concept (we have only discussions) but men who converse, in whom thought works humanly, thoughts externalise, you will find this corroborated. Thus even in philosophy we do not have the thought expressing itself so abstractly, but it clothes itself as it were in the human being representing it.

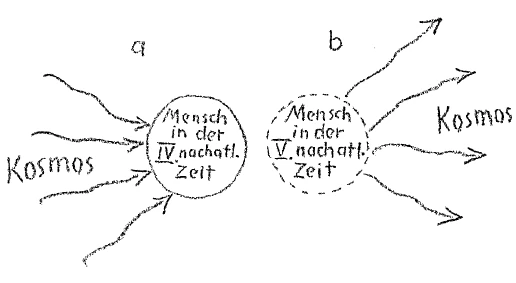

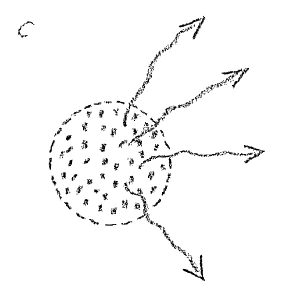

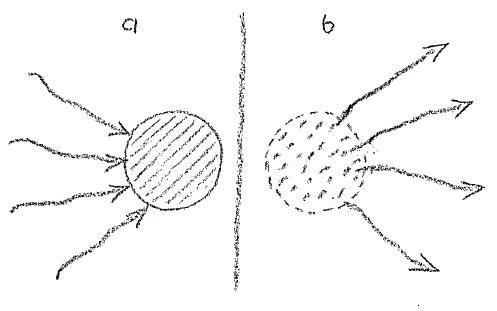

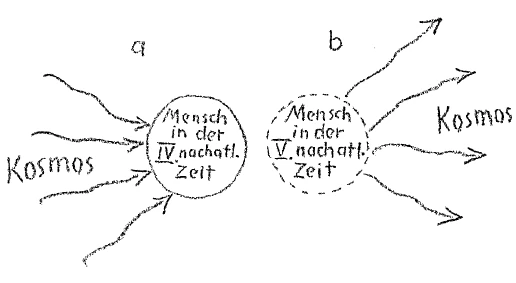

When in this way one sees Socrates converse, one cannot speak of Socrates on the one hand and of a Socratic world-conception on the other. It is a unity, one complete whole. One could not imagine in ancient Greece that someone—let us say, like a modern philosopher—came forward who had founded an abstract philosophy, and who placed himself before people and said: this is not the correct philosophy. That would have been impossible—it would only be possible in the case of a modern philosopher, (for this rests secretly in the mind of them each). The Greek Plato, however, depicts Socrates as the embodied world-conception, and one must imagine that the thoughts have no desire to be expressed by Socrates merely to impart knowledge of the world, but that they go about in the figure of Socrates and are related to people in the same way as he is. And to pour, as it were, this element of making thought human into the external form and figure, constitutes the greatness in the works of Homer and Sophocles, and in all the figures of sculpture and poetry which Greece has created. The reason why the sculptured gods of Grecian statuary are so human is that what I have just expressed was poured into them. This is at the same time a proof of how humanity's evolution in a spiritual respect strove as it were to grasp the living element of man from the thought-element of the cosmos and then to give it form. Hence the Grecian works of art appear to us (to Goethe they appeared so in the most eminent sense) as something which of its kind is hardly to be enhanced, to be brought to greater perfection, because all that was left of the ancient revelation of actively working and weaving thoughts had been gathered up and poured into the form. It was like a striving to draw together into the human form all that could be found as thoughts passing from within outwards, and this became in Greece philosophy, art, sculpture. (See Diagram (a) p.8a)

A more modern age has another mission, the present time has an entirely different task. We now have the task of giving back to the universe that which there is in man. (Diagram (b)). The whole pre-Grecian evolution led to man's taking from the universe all that he could discover of the living element of the human form in order to epitomise it. That is the unending greatness of Greek art—that the whole preceding world is actually epitomised and given form in it. Now we have the task reversed—the human being, who has been immeasurably deepened through the Mystery of Golgotha, who has been inwardly seized in his cosmic significance, is now to be given back again to the universe.

You must, however, inscribe in your souls that the Greeks had not, of course, the Christian view of the Mystery of Golgotha; for them everything flowed together out of the cosmic wisdom:

And now picture the immense, the immeasurable advance in the evolution of humanity when the Being who had formerly worked from the cosmos and who could only be known from the cosmos, and whom man could express in the earthly stage in the element of Form:—when this Being passed out of the cosmos into the earth, became man, and lives on in human evolution.

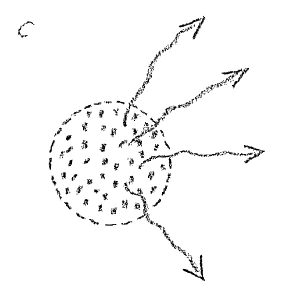

That which was sought out in the cosmos in pre-Grecian times now came into the earth, and that which had been poured out into form, was now itself in human evolution. (c) Naturally (I have therefore indicated it with dots) it is not yet rightly known—it is not yet rightly experienced, but it lives in man, and men have the task of giving it back gradually to the cosmos. We can picture this quite concretely, this giving back to the cosmos of what we have received through Christ. We must only not struggle against this giving back. One can really cling closely to the wonderful words: ‘I am with you all the days until the end of the Earth period.’

This means: what Christ has to reveal to us is not exhausted with what stands in the Gospel. He is not among us as one who is dead, who once upon a time permitted to be poured into the Gospels what he wished to bring upon earth, but he is in earthly evolution as a living Being. We can work through to him with our souls, and he then reveals himself to us as he revealed himself to the Evangelists. The gospel is therefore not something that was once there and then came to an end, the gospel is a continuous revelation. One stands as it were ever confronting the Christ, and looking up to Him, one waits again for revelation.

Assuredly he—whoever he may have been—who said: ‘I should still have much to write but all the books in the world could not contain it’—assuredly he, John, was entirely right. For if he had written all that he could write, he would have had to write all that would gradually in the course of human evolution result from the Christ event. He wished to indicate: Wait! Only wait! What all the books in the world could not contain will come to pass. We have heard the Christ, but our descendants will also hear Him, and so we continuously, perpetually, receive the Christ revelation. To receive the Christ revelation means: to acquire light upon the world from Him. And we must give back the truths to the cosmos from the centre of our heart and soul.

Hence we may understand as living Christ-revelation what we have received as Spiritual Science. He it is who tells us how the earth has originated, the nature of the human being, what conditions the earth passed through before it became earth. All that we have as cosmology, and give back to the universe, all this is revealed to us by Him. It is the continuous revelation of Christ to feel such a mood as this: that one receives the cosmos from the Christ in an inward spiritual way, drawn together as it were, and as one has received it to relate it to the world with understanding, so that one no longer looks up to the moon and stares at it as a great skittles-ball with which mechanical forces have moved skittles in the cosmos and which from these irregularities has acquired wrinkles, and so on—but recognises what the moon indicates, how it is connected with the Christ-nature and the Jahve-nature. It is a continuous revelation of the Christ to allot again to the outer world what we have received from Him. It is at first a process of knowledge. It begins with an intellectual process, later it will be other processes. Processes of inner feeling will result which arise from ourselves and pour themselves into the cosmos, such processes as these will arise.

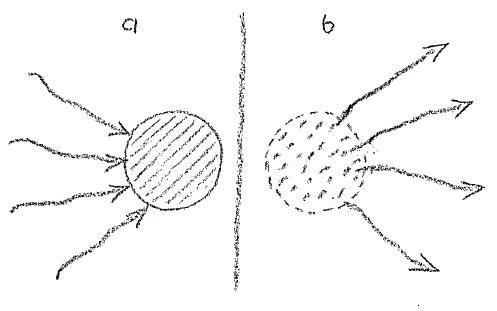

But you gather something else from what I have just explained. When you observe this motion- (Diagram (a) p.10a) where one has gathered up out of the cosmos, as it were, the component parts of the human being, which have in the Greek world-concepts, in Greek art, then flowed together to the whole human being, then you will understand: In Greece the evolution of humanity strove towards the plastic form, sculptured-form, and what they have reached in such form, we cannot as a matter of fact succeed in copying. If we imitate it nothing true or genuine results. That is therefore a certain apex in human evolution. One can in fact say this stream of humanity strives in Greece in sculpture towards a concentration of the entire human evolution preceding Greece.

When, on the contrary, one takes what has to happen here (b) it is what could be called a distribution of the component parts of man into the cosmos. You can follow this in its details. We assign our physical body to Saturn, the etheric body to the Sun, the astral body to the Moon, our Ego-organisation to the Earth. We really distribute man into the universe, and it can be said that the whole construction of Spiritual Science is based upon a distribution, a bringing again into movement, of what is concentrated in the human being. The fundamental key of this new world-conception (diagram (b)) is a musical one; of the old world (a) is a plastic one. The fundamental key of the new age is truly musical, the world will become more and more musical. And to know how man is rightly placed in the direction towards which human evolution is striving, means to know that we must strive towards a musical element, that we dare not recapitulate the old plastic element, but must strive towards a musical one.

I have frequently mentioned that on an important site in our Building there will be set up the figure of archetypal man, which one can also speak of as the Christ, and which will have Lucifer on the one side and Ahriman on the other. What is concentrated in the Christ we take out and distribute again in Lucifer and Ahriman, in so far as it is to be distributed. What was welded together plastically in the one figure we make musical, inasmuch as we make it a kind of melody: Christus-Lucifer-Ahriman.

Our Building is really formed on this principle. Our whole Building bears the special imprint in it: to bring plastic forms into musical movement. That is its fundamental character. If you do not forget that, in mentioning something like this, one is never to be arrogant, but to remain properly humble, and if you remember that in all that concerns our work on this Building only the first most imperfect steps have been taken, you will not misunderstand what is meant when I speak about it. It is of course not meant that anything at all of what floats before us as distant ideal is also only attained in the farthest future; but a beginning can be sought in that direction,—this one can say. More shall not be said than, that a beginning is desired.

But when you compare this beginning with that which has undergone a certain completion in Greece, with the infinite perfection of the plastic principle in, for instance, the Greek you find polaric difference. In Greece everything strives for form. An Acropolis figure of Athena, or in the architecture of the Acropolis, or a Greek Temple, they stand there in order to remain eternally rigid in this form, in order to preserve for man a picture of what beauty in form can be.

Such a work as our Building, even when one day it becomes more perfect, will always stand there in such a way that one must actually say: this Building always stimulates one to overcome it as such, in order to come out through its form into the infinite. These columns and in particular the forms connected with the columns, and even what is painted and moulded, is all there in order, so to say, to break through the walls, in order to protest against the walls standing there and in order to dissolve the forms, dissolve them into a sort of etheric eye, so that they may lead one out into the far spaces of the Cosmic thought-world.

One will experience this building in the right way if one has the feeling in observing it that it dissolves, it overcomes its own boundaries; all that forms walls really wants to escape into cosmic distances. Then one has the right feeling. With a Greek temple one feels as if, one would like best to be united for ever with what is firmly enclosed by the walls and with what can only come in through the walls. Here, with our Building, one will particularly feel: If only these walls were not so tiresomely there—for wherever they stand they really want to be broken through, and lead out further into world of the cosmos. This is indeed how this Building should be formed, according to the tasks of our age, really out of the tasks of our age.

Since we have not only spoken for years, my dear friends, on the subjects of Spiritual Science, but have discussed with one another the right attitude of mind towards what is brought to expression through Spiritual Science, it can also be understood that when something in the world is criticised, one does not mean it at all as absolute depreciation, absolute blame, but that one uses phrases of apparent condemnation in order to characterise facts in the right connection.

When, therefore, one reproaches a world-historical personality, this does not imply that one would like to declare at the same time one's desire—at least in the criticism of this person—to be an executioner who cuts off his head—figuratively spoken—by expressing a judgment. This is the case with modern critics, but not with someone imbued with the attitude of mind of Spiritual Science. Please also take what I have now to say in the sense indicated through these words.

An incision had at some time to be made in mankind's evolution; it had at some time to be said: This is now the end of all that has been handed down from old times to the present: something new must being (diagram Page 109 (a)). This incision was not made all at once, it was in fact made in various stages, but it meets us in history quite clearly. Take, for instance, such an historical personality as the Roman Emperor Augustus, whose rule in Rome coincided with the birth of the current which we trace from the Mystery of Golgotha. It is very difficult today to make people fully clear wherein lay the quite essentially new element which entered Western evolution through the Emperor Augustus, as compared with what had already existed in Western civilisation till then, under the influence of the Roman Republic. One must in fact make use of concepts to which people are little accustomed today, if one wishes to analyse something of this sort. When one reads history books presenting the time of the Roman Republic as far as the Empire, one has the feeling that the historians wrote as if they imagined that the Roman Consuls and Roman Tribunes acted more or less in the manner of a President of a modern republic. Not much difference prevails whether Niebuhr or Mommsen speaks of the Roman Republic or of a modern republic, because nowadays people see everything through the spectacles of what they see directly in their own environment. People cannot imagine that what a man in earlier times felt and thought, felt too as regards public life, was something essentially different from what the present-day man feels. It was however radically different, and one does not really understand the age of the Roman Republic if one does not furnish oneself with a certain idea which was active in the conception of the old republican Roman, and which he took over into the age which is called the Roman Empire.

The ancient kings, from Romulus to Tarquinius Superbus, were to the ancient Romans actual beings, who were intimately connected with the divine, with the divinely spiritual world rulership. And the ancient Roman of the time of the kings could not grasp the significance of his kings otherwise than by thinking: In all that takes place there is something of the nature of what happened in the time of Numa Pompilius, who visited the nymph Egeria in order to know how he should act. From the gods, or from spirit-land one received the inspirations for what had to be done upon earth. That was a living consciousness. The kings were the bridges between what happened on earth and what the gods out of the spiritual world wished to come about.

Thus a feeling extended over public life which was derived from the old world conception—namely, that what a man does in the world is connected with what forms him from the cosmos, so that currents continually stream in from the cosmos. Nor was this idea confined to the government of mankind. Think of Plato: he did not chisel things out in his soul as ideas, but received them as outflow of the divine being. So too in ancient Rome they did not say to themselves: One man rules other men, but they said: The gods rule men, and he who in human form is governing, is only the vessel into which the impulses of the gods flow. This feeling lasted into the time of the Roman Republic when it was related to the Consular office. The Consular dignity in ancient times was not that genuine so-called bourgeois-element, as it were, which a state- government increasingly feels itself to be today, but the Romans really had the thought, the feeling, the living experience: Only he can be Consul whose senses are still open to receive what the gods wish to let flow into human evolution.

As the Republic went on and great discrepancies and quarrels arose, it was less and less possible to hold such sentiments, and this finally led to the end of the Roman Republic. The matter stood somewhat thus: People thought to themselves: if the Republic is said to have a significance in the world, the Consuls must be divinely inspired men, they must bring down what comes from the gods. But if one looks at the later Consuls of the Republic one can say to oneself: The gentlemen are no longer the proper instruments for the gods. And with this is linked the fact that it was no longer possible to have such a vital feeling for the significance of the Republic. The development of such a feeling lay of course behind men's ordinary consciousness. It lay very deep in the subconscious, and was only present in the consciousness of the so-called initiates. The initiates were fully cognisant of these things. Whoever therefore in the later Roman Republic was no ordinary materialistically thinking average citizen said to himself: 'Oh, this Consul, he doesn't please me—he's certainly not a divine instrument!' The initiate would never have admitted that, he would have said: He is, nevertheless, a divine instrument—Only ... with advancing evolution this divine inspiration could enter mankind less and less. Human evolution took on such a form that the divine could enter less and less, and so it came about that when an initiate, a real initiate appeared who saw through all this, he would have to say to himself: We cannot go on any further like this! We must now call upon another divine element which is more withdrawn from man. Men had developed outwardly, morally, etc., in such a way that one could no longer have confidence in those who were Consuls. One could not be sure that where the man's own development was in opposition to the divine, that the divine still entered. Hence the decision was reached to draw down, as it were, the instreaming of the divine into a sphere which was more withdrawn from men. Augustus, who was an initiate to a certain degree in these mysteries, was well aware of this. Therefore it was his endeavour to withdraw the divine world rulership from what men had hitherto, and to work in the direction of introducing the principle of heredity in the appointment to the office of Consul. He was anxious that the Consuls should no longer be chosen as they had been up to then, but that the office should be transmitted through the blood, so that what the Gods willed might be transmitted in this way. The continuance of the divine element in man was pressed down to a stage lying beneath the threshold of consciousness because men had reached a stage where they were no longer willing to accept the divine. You only arrive at a real understanding of this extraordinarily remarkable figure of Augustus, if you assume that he was fully conscious of these things, and that out of full consciousness, under the influence of the Athenian initiates in particular who came to him, he did all the things that are recorded of him. His limitation only lay in the fact that he could reach no understanding of the Mystery of Golgotha, that he only saw how human beings come down into matter, but could not conceive how the divine element should take anchor in the material of the blood. He had no understanding of the fact that something entirely new had now arisen in the Mystery of Golgotha. He was in a high sense an initiate of the old Mysteries, but he had no understanding for what was then emerging in the human race as a new element.

The point is, however, that what Augustus had accomplished was an impossibility. The divine cannot anchor in the pure material of the blood in earthly evolution, unless this earthly evolution is to fall into the Luciferic. Men would never be able to evolve if they could only do so as the blood willed, that is, developing from generation to generation what was already there before. However, something infinitely significant is connected with the accomplishment of this fact. You must remember that in early times when the ancient Mysteries were in force people possessed in the Mysteries a constant and powerfully active spiritual element, although that cannot be significant to us in the same way today. They knew, nevertheless, of the spiritual worlds; they came quite substantially into the human mind. And on the other hand people ceased in the time of Augustus to know anything of the spiritual element of the world; they no longer knew of it in consequence of man's necessary evolution. The Augustus-initiation actually consisted in his knowledge that men would become less and less fitted to take in the Spiritual element in the old way. There is an immense tragedy in what was taking place round the figure of Augustus. The ancient Mysteries were still in existence at that time, but the feeling continually arose: Something is not right in these ancient Mysteries. What was received from them was of immeasurable significance, a sublime spiritual knowledge. But it was also felt that something of immeasurable significance was approaching; the Mystery of Golgotha, which cannot be grasped with the old Mystery knowledge, with which the old Mystery knowledge was not in keeping. What could, however, be known to men through the Mystery of Golgotha itself was still very little. As a matter of fact even with our spiritual science we are today only at the beginning of understanding what has flowed into humanity with the Mystery of Golgotha. Thus there was something like a breaking away from the old elements, and we can understand that more and more there were men who said: We can do nothing with what comes to us from the Mystery of Golgotha. These were men who stood at a certain spiritual eminence in the old sense, the sense of the pre-Christian, the pre-Golgotha time.

Such men said to themselves: Yes, we have been told of one, Christus, who has spread certain teachings. They did not yet feel the deeper nature of these teachings, but what they heard of them seemed to be like warmed-up ancient wisdom. It was told them that some person had been condemned, had died on the cross, had taught this and that. This generally seemed to them false and deceptive, whereas the ancient wisdom which was handed down to them seemed enormously grand and splendid. Out of this atmosphere we can understand Julian the Apostate, whose entire mood can be understood in this way. More and more, individuals came forward who said: That which is given by the old wisdom, the way it explains the cosmos, cannot be united with that which blossoms, as if from a new centre, through the Mystery of Golgotha.—One of the individuals who felt this way was the sixth century Byzantine emperor Justinian (who lived from 527–565,1According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, Justinian lived from 482–565, and ruled from 527–565. whose actions are to be understood from exactly this viewpoint. One must understand that he felt, through the whole manner in which he grew into his time, that something new was in the world ... at the same time there came into this new world that which was handed down from the old time. We will consider just three of these things which were thus handed down.

For a long time (five or six centuries) Rome had been ruled by emperors: The rank of consul, however, had existed for only a short time, and, like a shadow of the old times, these consuls were elected. If one looked at this election of consuls with the eyes of Justinian, one saw something which no longer made any sense, which had true meaning in the time of the Roman Republic, but was now without meaning: therefore he abolished the rank of consul. That was the first thing.

The second was that the Athenian-Greek schools were still in existence; in these was taught the old mystery-wisdom, which contained a much greater store of wisdom than that which was then being received under the influence of the Mystery of Golgotha. But this old mystery-wisdom contained nothing about the Mystery of Golgotha. For that reason Justinian closed the old Greek Philosophers' Schools.

Origenes, the Church Teacher, was well versed in what was connected with the Mystery of Golgotha, even though he still stood in the old wisdom, although not as strict initiate, yet as one having knowledge to a high degree. In his world-concept he had amalgamated the Christ-Event with the World-conception of the ancient, wisdom, he sought through this. to understand the Christ Event. That is just the interesting thing in the world concept of Origenes, that he was one of those who especially sought to grasp the Mystery of Golgotha in the sense of the old mystery wisdom. And the tragedy is that Origenes was condemned by the Catholic Church.

Augustus was the first stage. (see the lined diagram p.10a) Justinian in this sense was the second stage. Thus the earlier age is divided from the newer age, which- as regards the West—had no longer understanding for the Mystery wisdom. This wisdom had still lived on in the Grecian schools of philosophy, and had gradually to work towards the growth and prosperity of that current in mankind which proceeded from the Mystery of Golgotha. So it came about that the newer humanity, with the condemning of Origenes, with the closing of the Greek schools of philosophy, lost an infinite amount of the old spiritual treasure of wisdom. The later centuries of the Middle Ages worked for the most part with Aristotle, who sought to encompass the ancient wisdom through human intellect. Plato still received it from the ancient mysteries, Aristotle—he is, to be sure, infinitely deeper than modern philosophers—did not regard wisdom as a treasure of the Mysteries; he wished to grasp it with the human understanding. Thus what prevailed at that time in a noted degree was a thrusting back of the old Mystery Wisdom.

The remainder of the text is filled in here as it was cut off in the translation:

[Today, we are content with even less from Platonism. We see a certain leading away of our world of thoughts and ideas from our own inner being; and this has given rise to the feeling I characterized at the beginning of this lecture: that we have the feeling that thoughts are actually only representations of external objects and do not have any effect within us. In a certain sense, this stems from the fact that the old feeling of the preservation of living life and the weaving of thoughts in human beings was driven away with the closure of the philosophical schools by Justinian.

This is one reason why it is difficult to be understood when one speaks of spiritual science today: European humanity no longer has a proper relationship to its thoughts.

But there is something else in the human soul: the world of feelings and the world of the will. On the one hand, there is the conceptual and the intellectual; on the other, the emotional and the volitional. It is even more difficult to speak about this emotional and volitional aspect. People view thoughts as something that represent something out there. Modern people no longer have a proper sense of how this is connected to them in a living way. People today, especially Westerners, view the world of feelings and the world of the will as if they were acting entirely within their own souls, as if they were entirely contained within them. The world of feelings is the opposite of the world of thoughts: we become more aware of the world of thoughts as if it were meant to reflect something external; in the world of feelings, we no longer have the sensation that we are standing within it, where we could really stand if we grasped the reality, the being of the world of feelings. Namely, the cosmos also lives in this world of feelings. And while we as human beings in the European world have forgotten that the world of thoughts works within us, we have forgotten in the world of feelings that what we feel and want is also outside us. In our thoughts, we have lost the inner world; in the world of feelings, we have lost the outer world. We no longer notice any connection between our feelings and what is spreading out in the cosmos.

This came about because certain spirits, now from the hierarchy of the Archangels, did not want to participate in the separation of the moon; they remained with the ongoing development of the sun. Certain archangelic beings who had reached the human stage during the development of the Sun did not want to participate in the separation of the Moon from the Sun during the development of the Moon: they remained with the Sun, they did not go out with the Moon. As a result, these spirits entered into Luciferic paths of development. They now live in our feelings and prevent us from wanting to leave ourselves; they want to remain within us, they do not want to leave our feelings.

We will keep in mind the point I have now indicated here until tomorrow. What we have said today, we have said about the fact that we cannot find the right position in relation to the world of thoughts. Tomorrow we will show how we cannot find the right position in relation to the world of feelings, and how the mystery of Golgotha relates precisely to this world of feelings, and what our tasks are in relation to this world of feelings as we have it: that we must strive to make our worldview musical through the right understanding of what our thought life is.]

Zehnter Vortrag

Es ist in der Tat schwer in unserer Zeit, richtig verstanden zu werden, wenn man aus den Quellen desjenigen heraus spricht, was wir in unserem Zusammenhange Geisteswissenschaft nennen.

Weniger habe ich heute zunächst im Auge die Schwierigkeit des Verstandenwerdens bei den Einzelnen, denen wir im Leben begegnen, als vielmehr bei den Kulturen, bei den verschiedenen Weltanschauungs-Gedanken- und Gefühlsstrrömungen, denen wir in der heutigen Zeit gegenüberstehen.

Wenn wir das europäische Leben betrachten, so finden wir zunächst innerhalb desselben eine große Schwierigkeit dadurch erwachsen, daß dieses europäische Leben in dem Augenblicke, wo es aufrückt von dem bloßen Wahrnehmen durch die Sinne zum Denken über die Wahrnehmungen - und dieses Aufrücken muß ja jeder für sich in jedem Augenblicke des wachen Lebens besorgen -, daß, sage ich, dieses europäische Leben in seinem Gedankeninhalt selber im Grunde nicht fühlt, wie innig der Gedankeninhalt zusammenhängt mit demjenigen, was wir als Menschen sind.

Man denkt, man stellt vor, und man hat das Bewußtsein, daß man durch die Gedanken, die man sich bildet, durch die Vorstellungen, die man erlebt, etwas erfährt von der Welt, daß man gewissermaßen etwas wissen lernt von der Welt, daß eben die Vorstellungen etwas abbilden von der Welt. Dieses Bewußtsein hat man. Jeder, der über die Straße geht, hat ja das Gefühl, daß ihm dadurch, daß er die Bäume und so weiter anschaut, Vorstellungen aufleben, und daß diese Vorstellungen innere Repräsentanten sind desjenigen, was er wahrnimmt, daß er also durch die Vorstellungen gewissermaßen die Welt der äußeren Wahrnehmungen in sich aufnimmt und sie dann weiterlebt, diese Wahrnehmungen.

Daß daneben der Gedanke, das Denken überhaupt noch etwas Wesentliches ist in unserem inneren Selbst, in unserem inneren Selbst als Menschen, daß wir etwas tun, indem wir denken, daß das eine innere Tätigkeit ist, dieses Denken, eine innere Arbeit, das bringt man sich in den seltensten Fällen, man kann schon sagen, eigentlich gar nicht innerhalb der europäischen Weltanschauung so recht zum Bewußtsein.

Ich habe einmal hier darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß jeder Gedanke noch etwas wesentlich anderes ist als dasjenige, als was man ihn gewöhnlich anerkennt. Man erkennt ihn an als ein Abbild von etwas äußerlich Wahrnehmbarem. Aber man erkennt ihn nicht an als Formbildner, als Gestalter. Jeder Gedanke, der in uns auftaucht, ergreift gewissermaßen unser inneres Leben und hat Teil zunächst, so lange wir wachsen, an unserem ganzen Aufbauen als Menschen. Er hatte schon Anteil an unserem Aufbau, bevor wir überhaupt geboren worden sind, und gehört zu den bildenden Kräften unserer Natur. Er arbeitet immer weiter und er stellt immer wieder und wieder das her, was abstirbt in uns. Also es ist nicht nur so, daß wir außerhalb unsere Vorstellungen wahrnehmen, sondern wir arbeiten immer als denkende Wesen, wir arbeiten durch das, was wir vorstellen, immerfort neu an unserer Gestaltung und Bildung.

Geisteswissenschaftlich angesehen erscheint jeder Gedanke so ähnlich wie ein Kopf mit etwas wie einer Fortsetzung nach unten, so daß wir mit jedem Gedanken eigentlich in uns einschachteln etwas wie. ein Schattenbild von uns selber; nicht ganz ähnlich mit uns, aber so ähnlich wie ein Schattenbild. Dieses Schattenbild von uns selber muß in uns hineingeschachtelt werden, denn es geht fortwährend von uns etwas verloren, etwas zugrunde; es bröckelt ab in Wirklichkeit. Und das, was so da der Gedanke in uns als Menschengestalt hineinschachtelt, das erhält uns überhaupt bis zu unserem Tode hin. Also der Gedanke ist zugleich eine richtige innere Tätigkeit, ein Bauen an uns selber.

Diese letztere Erkenntnis hat man innerhalb der abendländischen Weltanschauung fast gar nicht. Man verspürt nicht, man fühlt nicht in seinem Gemüte, wie einen der Gedanke ergreift, wie er sich wirklich in uns ausbreitet. Ein Mensch, der atmet, fühlt noch ab und zu, obwohl er meist jetzt auch darauf nicht mehr achtet, daß der Atem sich in ihm ausbreitet, daß der Atem etwas zu tun hat mit seinem Wiederaufbau, mit seiner Regeneration. So ist es auch mit dem Gedanken. Aber da fühlt es der europäische Mensch schon kaum mehr, daß der Gedanke eigentlich bestrebt ist, fortwährend Mensch zu werden oder, besser gesagt, Menschengestalt zu bilden.

Ohne dies Erfühlen von solchen Kräften, die in uns sind, kommen wir aber kaum dazu, wirklich ein richtiges Verständnis, ein inneres Gefühls- und Lebensverständnis dessen zu gewinnen, was die Geisteswissenschaft will. Denn sie arbeitet eigentlich gar nicht in dem, was der Gedanke uns liefert, indem er ein Äußeres abbildet, sondern sie arbeitet in diesem Lebenselemente des Gedankens, in diesem fortwährenden Gestalten des Gedankens.

Es war schon seit Jahrhunderten deshalb, weil der europäischen Menschheit dieses zuletzt charakterisierte Bewußtsein immer mehr abhanden kam, recht schwierig, von Geisteswissenschaft zu sprechen, respektive verstanden zu werden, wenn man davon sprach. In der morgenländischen Weltanschauung ist dieses Gefühl, das ich eben ausgesprochen habe gegenüber dem Gedanken, in einem hohen Maße vorhanden. Es ist wirklich in einem hohen Maße vorhanden; mindestens ist das Bewußtsein vorhanden, daß man dieses Gefühl vom inneren Erleben des Gedankens suchen muß. Daher die Neigung der Morgenländer zum Meditieren; denn das Meditieren soll ja sein ein solches Sich-Hineinleben in die Gestaltungskräfte des Gedankens, soll werden ein Gewahrwerden des lebendigen Fühlens des Gedankens. Daß der Gedanke in uns etwas tut, sollte man gewahr werden während des Meditierens. Daher finden wir solche Aussprüche im Morgenlande wie: Im Meditieren Einswerden mit dem Brahma, mit dem Gestaltenden der Welt. Dieses Bewußtsein, daß man mit dem Gedanken, wenn man sich recht in ihn einlebt, nicht nur etwas in sich hat, nicht nur selber denkt, sondern sich einlebt in die Gestaltungskräfte der Welt, das wird in der morgenländischen Weltanschauung gesucht. Aber es ist erstarrt, erstarrt aus dem Grunde, weil die morgenländische Weltanschauung es versäumt hat, sich ein Verständnis anzueignen für das Mysterium von Golgatha.

Zwar ist die morgenländische Weltanschauung - und davon werden wir noch sprechen - in hohem Grade geneigt, sich hineinzuleben in die Gestaltungskräfte des Gedankenlebens, aber sie lebt sich doch dabei ein in ein ersterbendes Element, sie lebt sich ein in ein Gewebe von abstrakten, unlebendigen Vorstellungen. So daß man sagen könnte: Während das richtige Einleben darinnen besteht, daß man das Leben der Gedankenwelt erlebt, lebt sich die morgenländische Weltanschauung ein in eine Nachbildung des Lebens der Gedanken. Man sollte sich so einleben in die Gedankenwelt, wie wenn man sich hineinversetzt in ein lebendiges Wesen. Aber es ist ein Unterschied zwischen einem lebendigen Wesen und dem Nachgemachten eines lebendigen Wesens, nehmen wir an, einer Nachahmung aus Papiermaché. Die morgenländische Weltanschauung lebt sich nicht in das lebendige Wesen hinein, weder Brahmanismus, noch Buddhismus, noch das Chinesentum, noch das Japanertum; sondern sie leben sich hinein in etwas, was man bezeichnen kann wie eine Nachahmung der Gedankenwelt, wie in etwas, das sich so verhält zu der lebendigen Gedankenwelt, wie der aus Papiermaché nachgemachte Organismus zum lebendigen Organismus.

Das ist also das Schwierige sowohl im Abendlande auf der einen Seite, wie auf der anderen Seite im Morgenlande. Man wird im Abendlande weniger verstanden, weil man da überhaupt nicht viel Bewußtsein von diesen lebendigen Gestaltungskräften des Gedankens hat; im Morgenlande wird man nicht richtig verstanden, weil man da nicht so recht ein Bewußtsein hat von der Lebendigkeit der Gedanken, sondern nur von dem toten Nachgemachten, von dem steifen, im Abstrakten Webenden der Gedanken.

Nun brauchen Sie sich nur klarzumachen, woher das, was ich jetzt eben auseinandergesetzt habe, eigentlich kommt. Sie erinnern sich wohl alle an die Darstellung der Mondenentwickelung, die gegeben worden ist in meinem Buche «Geheimwissenschaft». Der Mensch hat ja in seiner eigenen Entwickelung richtig mitgemacht alles das, was sich zugetragen hat als Saturn-, Sonnen- und Mondentwickelung, und er macht weiter zurzeit das hier mit, was sich zuträgt als Erdenentwickelung. Wenn Sie sich erinnern an die Mondentwickelung, wie sie dargestellt ist in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft», so werden Sie darauf kommen, daß damals während der Mondentwickelung stattgefunden hat das Loslösen des Mondplaneten von der Sonne. Das trat dazum ersten Male in ausgesprochener Weise auf. So daß ein solches Loslösen wirklich stattfand. Wir können also sagen: Während vorher in gewissem Sinne da war ein Ineinander-Geschachteltsein der planetarischen Welt, war bei der Loslösung des Mondes von der Sonne der vorirdischen Zeit ein Nebeneinander-Laufen, ein zeitweiliges Nebeneinander-Laufen der Mondenentwickelung und der Sonnenentwickelung da. Ein solches Losgelöstsein war da.

Dieses Losgelöstsein hat, wie Sie ersehen können aus der «Geheimwissenschaft», eine große Bedeutung. Der Mensch hätte, so wie er jetzt ist, nicht entstehen können, wenn diese Loslösung nicht stattgefunden hätte. Aber auf der anderen Seite ist mit jedem solchen Vorgange das Hereinkommen einer Einseitigkeit in unsere Entwickelung innig verknüpft. Es ist so gekommen, daf gewisse Wesen aus der Hierarchie der Angeloi, die also während der Mondentwickelung Menschen waren, dazumal, man könnte sagen, sich geweigert haben, sich antipathisch gezeigt haben gegen das WiederZusammengehen mit der Sonne. Der Mond trennte sich also ab, und bei dem späteren Wieder-Zusammengehen mit der Sonne haben sie sich geweigert, diesen Schritt mitzumachen, wieder zusammenzugehen mit der Sonne.

Alles luziferische Zurückbleiben beruht ja auf einem solchen Nicht-Mitmachen späterer Entwickelungsphasen; und so ist ein Teil des Luziferischen darin begründet, daß solche Wesen aus der Hierarchie der Angeloi, die damals Menschen waren, nicht mitmachen wollten das Wieder-Zusammengehen mit der Sonne im letzten Teile der alten Mondenzeit. Gewiß, sie mußten ja wieder herunter, aber in ihrem Gemüte, in ihrem Inneren, haben sie sich die Sehnsucht für das Mondendasein erhalten. Sie waren dann deplaciert; sie waren nicht weiter zu Hause in der eigentlichen Entwickelung, sie fühlten sich eigentlich als Mondwesen. Darin bestand ihr Zurückgeblieben. sein. Diese Art von Wesen gehörte natürlich auch zu der Schar von luziferischen Wesen, die dann in ihrer weiteren Entwickelung gewissermaßen auf unsere Erde heruntergestiegen sind. Die leben auch in uns in der Art, wie ich es in einem der letzten Vorträge angedeutet habe. Und diese sind es, welche gewissermaßen in unserm Denken des Abendlandes nicht heraufkommen lassen das Bewußtsein, daß dieses Denken ein innerlich lebendiges ist. Sie wollen es mondenhaft erhalten, abgetrennt von dem inneren Lebenselemente, das mit dem Sonnenhaften zusammenhängt; sie wollen es in der Lostrennung erhalten. Und sie wirken dahin, daß man ins Bewußtsein hineinbekommt nicht ein Gefühl: das Denken hängt mit der inneren Gestaltung zusammen -, sondern ein Gefühl, wie wenn das Denken nur mit dem Äußeren zusammenhinge, eben mit dem, was losgetrennt ist. So daß sie für das Denken ein Gefühl hervorrufen: man kann nur abbilden mit dem Denken das Äußere, man kann nicht ergreifen das innerlich Gestaltende, Lebendige, man kann nur Äußeres ergreifen. Sie verfälschen also unser Denken.

Das war eben das Karma der abendländischen Menschheit, gerade Bekanntschaft zu machen mit diesen Geistern, die in dieser Form das Denken verfälschen, das Denken verändern, veräußerlichen, die bestrebt sind, ihm den Stempel aufzudrücken, als ob es nur dienen könnte, das Äußere abzubilden und nicht das innerlich Lebendige zu erfassen. Dem Karma der morgenländischen Bevölkerung war es beschieden, verschont zu bleiben von dieser Art luziferischer Elemente. Daher blieb ihr mehr das Bewußtsein, im Denken das innerlich Formende, Gestaltende des Menschen zu suchen, das ihn im Inneren Vereinigende mit der lebendigen Gedankenwelt des Universums. Den Griechen war es auferlegt, den Übergang zu bilden zwischen dem einen und dem anderen.

Die Morgenländer haben, weil sie mit jenem luziferischen Elemente, das ich eben charakterisiert habe, wenig Bekanntschaft geschlossen haben, keine rechte Ahnung davon, daß man auch in Zusammenhang kommen kann mit dem Lebendigen des Denkens über das Äußere. Es ist bei ihnen immer wie aus Papiermaché dasjenige, mit dem sie da zusammenkommen; sie haben wenig Verständnis, das Denken auf das Äußere anzuwenden. Es muß schon Luzifer mitwirken in der Tätigkeit, die ich Ihnen eben charakterisiert habe, damit der Mensch die Neigung bekommt, auch über die äußere Welt nachzudenken. Dann ist es aber gleich so wie beim Pendelausschlag, der nach der einen Seite hingeht: er versteift sich auf diese Tätigkeit nach dem Äußeren. Das ist überhaupt die Eigentümlichkeit alles Lebens: daß es einmal nach der einen und einmal nach der anderen Seite ausschlägt. Ausschlagen muß sein, aber man muß wieder den Rückweg finden von dem einen zum anderen, von dem Morgenländischen zu dem Abendländischen. Die Griechen sollten finden den Übergang von dem Morgenländischen zu dem Abendländischen. Das Morgenländische würde ganz in steife Abstraktionen verfallen sein - ist es ja auch zum Teil -, die sogar von manchen Menschen geliebt werden, wenn das Griechentum nicht eingegriffen hätte in die Welt. Wenn wir rein auf dem aufbauen, was wir jetzt betrachtet haben, so werden wir im Griechentum die Tendenz finden, innerlich gestalthaft, lebendig zu machen den Gedanken.

Nun, verfolgen Sie sowohl die griechische Literatur wie die griechische Kunst, so werden Sie überall finden, wie der Grieche danach strebt, aus seinem inneren Erleben die menschlichen Formen herauszubringen, sowohl in der Plastik wie in der Dichtung, Ja sogar in der Philosophie. Wenn Sie sich bekanntmachen mit der Art und Weise, wie noch Plato versuchte, nicht eine abstrakte Philosophie zu begründen, sondern Menschen hinzustellen, die miteinander sprechen, die ihre Ansichten austauschen, so daß eben nicht eine Weltanschauung dasteht bei Plato - wir haben ja bei ihm nur Gespräche -, sondern Menschen, die sich aussprechen, die Gedanken äußern, in denen der Gedanke menschlich wirkt, so werden Sie das bestätigt finden. Also wir haben es bis in die Philosophie hinein so, daß der Gedanke sich nicht abstrakt ausspricht, sondern sich verkleidet gleichsam in dem ihn vertretenden Menschen.

Wenn man so Sokrates sprechen sieht, kann man nicht von Sokrates auf der einen Seite und von sokratischer Weltanschauung auf der anderen Seite sprechen. Das ist Eins, eine Einheit. Man könnte sich in Griechenland nicht denken, daß, meinetwillen wie ein moderner Philosoph, einer in Griechenland aufgetreten wäre, der eine abstrakte Philosophie begründet hätte, der sich hinstellt vor die Menschen und sagt: Das ist nun die richtige Philosophie. - Das wäre unmöglich, das wäre nur bei einem modernen Philosophen möglich, denn dies ruht ja im Geheimen bei jedem modernen Philosophen. Der Grieche Plato aber, der stellt den Sokrates hin als die verkörperte Weltanschauung, und man muß sich denken, daß die Gedanken von Sokrates nicht so ausgesprochen werden wollen, als ob man bloß die Welt erkennt, sondern daß sie in Gestalt des Sokrates herumgehen und sich so zu den Menschen verhalten, wie er sich eben verhält. Und dieses Element, die Gedanken zu vermenschlichen, gleichsam in das äußere Formenhafte, Gestaltenhafte zu gießen, das ist das gleiche bei den Homerischen, bei den Sophokleischen, bei allen dichterischen Figuren, und ist das gleiche bei allen plastischen Figuren, die das Griechentum geschaffen hat. Deshalb sind die plastischen Götter der griechischen Bildhauerei so menschlich, weil das hineingegossen ist, was ich eben ausgesprochen habe.

Das ist zu gleicher Zeit ein Hinweis darauf, wie die Entwickelung der Menschheit in geistiger Beziehung danach strebte, gleichsam aus dem Gedanklichen des Kosmos heraus zu erfassen das Lebendige des Menschen und es dann zu gestalten. Deshalb erscheinen uns diese griechischen Kunstwerke - Goethe haben sie ja in eminentem Sinne so geschienen - als etwas, was in seiner Art kaum mehr zu erhöhen, kaum zu vervollkommnen ist, weil man zusammengefaßt hat all das, was einem geblieben ist aus der alten Uroffenbarung an lebendig wirkenden und webenden Gedanken, die man da in die Form ausgegossen hat. Es war gleichsam das Bestreben, all das, was man als den Gedanken von innen heraus finden konnte, zusammenzuziehen zu der menschlichen Gestalt, die im Griechentum Philosophie, Kunst, Plastik geworden ist (Zeichnung a, Seite 198).

Eine andere Aufgabe hat die neuere Zeit, die Gegenwart, eine völlig andere Aufgabe. Jetzt hat man die Aufgabe, gewissermaßen das, was im Menschen ist, dem Weltall wieder zurückzugeben (Zeichnung b). Es hat alle vorgriechische Entwickelung dahin geführt, zusammenzunehmen das, was man aus der Welt heraus gewissermaßen über das Lebendige der Form des Menschen entdecken konnte, um das zusammenzufassen. Das ist das unendlich Große der griechischen Kunst, daß eigentlich die ganze Vorwelt in ihr zusammengefaßt und gestaltet ist. Jetzt haben wir die Aufgabe, umgekehrt den Menschen, der unendlich vertieft worden ist durch das Mysterium von Golgatha, der in seiner kosmischen Bedeutung innerlich erfaßt worden ist, wieder dem Universum zurückzugeben.

Sie müssen sich nur wirklich ganz in die Seele einschreiben, daß diese Griechen die christliche Anschauung von dem Mysterium von Golgatha eben nicht hatten, daß bei ihnen alles aus der kosmischen Weisheit heraus zusammenfloß. Und nun denken Sie sich diesen ungeheuren, wirklich unermeßlichen Fortschritt in der Entwickelung der Menschheit dadurch, daß die Wesenheit, die früher vom Kosmos draußen gewirkt hat, die man so aus dem Kosmos heraus erkennen mußte, und darnach auf dem irdischen Schauplatze in der Form ausdrücken konnte, daß die nun aus dem Kosmos heraus in die Erde hineingeht, selber Mensch wird, in der Menschenentwickelung weiterlebt.

Das, was man gesucht hat in der vorchristlichen Zeit draußen im Kosmos, das kam jetzt herein in die Erde, und das, was man in die Form ausgießen konnte, das ist jetzt in der Menschenentwickelung selber darinnen (Zeichnung c). Natürlich - ich habe es deshalb mit Punkten angedeutet: es wird noch nicht richtig erkannt, es wird noch nicht richtig erfühlt; aber es lebt in den Menschen, und die Menschen haben die Aufgabe, es nach und nach wiederum zurückzugeben dem Kosmos. Das können wir uns ganz konkret vorstellen, dieses Zurückgeben desjenigen an den Kosmos, was wir durch den Christus empfangen haben. Wir müssen uns nur nicht sträuben gegen dieses Zurückgeben.

Man kann wirklich eng sich anklammern an das wunderbare Christus-Wort: «Ich bin bei Euch alle Tage bis an das Ende der Erdenzeit.» Das heißt, was Christus uns zu offenbaren hat, ist nicht erschöpft mit dem, was im Evangelium steht. Er ist nicht als ein Toter unter uns, der einmal das, was er auf die Erde bringen wollte, in die Evangelien hinein hat ausgießen lassen, sondern er ist als ein Lebendiger darinnen in der Erdenentwickelung. Und wir können uns mit unserer Seele zu ihm durcharbeiten. Dann offenbart er sich uns gerade so, wie er sich den Evangelisten geoffenbart hat. Das Evangelium ist dann nicht etwas, was einmal dagewesen ist und dann versiegte, das Evangelium ist dann eine fortwährende Offenbarung. Man steht gewissermaßen immer dem Christus gegenüber und erwartet, zu ihm aufschauend, aufs Neue die Offenbarung.

Gewiß hat derjenige - sei er nun gewesen, wer auch immer -, der da gesagt hat: Noch vieles hätte ich zu schreiben, aber alle Bücher der Welt könnten es nicht fassen -, gewiß hat er unendlich Recht gehabt, denn hätte er alles schreiben wollen, was er hätte schreiben können, so hätte er schreiben müssen, was sich erst im Laufe der Menschheitsentwickelung aus dem Christus-Ereignisse nach und nach ergeben wird. Er wollte darauf hinweisen: Wartet nur, wartet nur! Es wird schon das kommen, was alle Bücher der Welt nicht fassen können. Wir haben den Christus gehört, aber die Nachgeborenen werden ihn auch weiter hören, und so empfangen wir fortdauernd, fortwährend diese Christus-Offenbarung. - Diese ChristusOffenbarung empfangen heißt: Von Ihm Aufschluß erlangen über die Welt. Und dies Empfangene müssen wir wiederum aus dem Zentrum des Gemüts dem Kosmos zurückgeben.

Daher dürfen wir das, was wir als Geisteswissenschaft erhalten haben, auffassen als lebendige Christus-Offenbarung. Er ist es, der uns wiederum sagt, wie die Erde entstanden ist, wie es sich mit der Menschennatur verhält, was die Erde für Zustände durchgemacht hat, bevor sie Erde geworden ist. Alles das, was wir als Kosmologie haben, was wir der Welt wieder zurückgeben, all das offenbart Er uns. In dieser Stimmung sich fühlen, von dem Christus gleichsam innerlich geistig den zusammengezogenen Kosmos zu empfangen und ihn so wie man ihn empfängt, verständnisvoll der Welt zuzuweisen, so daß man nicht mehr hinaufschaut nach dem Monde und ihn anglotzt als eine große Kegelkugel, mit der mechanische Kräfte Kegel geschoben haben im Weltall und die von diesen UnregelmäRigkeiten Runzeln bekommen hat und dergleichen, sondern erkennt, was er anzeigt, wie er zusammenhängt mit der Christus- und JahveNatur und so weiter: das ist die fortwährende Offenbarung des Christus. Wir müssen wiederum an die Außenwelt zuteilen das, was wir von ihm empfangen. Es ist zunächst ein Erkenntnisprozeß. Mit einem Erkenntnisprozeß fängt es an, später werden es schon andere Prozesse sein. Es werden Gemütsprozesse, Gefühlsprozesse sich ergeben, die von uns ausgehen und sich hinaus ergießen in den Kosmos; die werden daraus entstehen.

Aber noch ein anderes ersehen Sie aus dem, was ich eben auseinandergesetzt habe. Wenn Sie diesen Gang betrachten (Zeichnung a, Seite 201), wo man aus dem Kosmos herein zusammengefaßt hat, ich möchte sagen, die Bestandstücke des Menschen, die dann in der griechischen Weltanschauung, in der griechischen Kunst zusammengeflossen sind zu dem ganzen Menschen, so werden Sie sehen: die Menschheitsentwickelung strebte im Griechentum nach plastischer Gestaltung, nach bildhafter Gestaltung; und das, was das Griechentum erlangt hat an bildhafter Gestaltung, können wir in der Tat nicht wiederum nachmachen. Wenn wir es nachahmen, so wird nichts Rechtes daraus. Das ist also ein gewisser Höhepunkt in der Menschheitsentwickelung. Man kann nämlich sagen: Die Menschheitsströmung strebt im Griechentum in der Plastik nach Konzentration aus der gesamten vorgriechischen Menschheitsentwickelung herein.

Wenn man dagegen das nimmt, was bier geschieht (Zeichnung b), was jetzt zu geschehen hat, so ist es, ich möchte sagen, ein Aufteilen der Bestandstücke des Menschen an den Kosmos. Sie können das bis in Einzelheiten verfolgen. Wir teilen unseren physischen Leib dem Saturn zu, den Ätherleib der Sonne, den Astralleib dem Monde, unsere Ich-Gestaltung der Erde. Also wir teilen wirklich auf, wir teilen den Menschen wiederum auf in die Welt; und so können Sie sehen: der ganzen Komposition der Geisteswissenschaft liegt ein Aufteilen, ein Wieder-in-Bewegung-Bringen dessen, was im Menschen konzentriert ist, zugrunde. Die Grundstimmung dieser neuen Weltanschauung (Zeichnung b) ist eine musikalische, die Grundstimmung der alten Welt (a) war eine plastische. Die Grundstimmung der neueren Zeit ist richtig musikalisch, die Welt wird auch immer musikalischer werden. Und wissen, wie man in der richtigen Art darinnen steht in dem, wonach die Menschheitsentwickelung strebt, heißt wissen, daß man nach einem musikalischen Elemente streben muß, daß man nicht wiederholen darf das alte plastische Element, sondern daß man nach einem musikalischen Elemente zu streben hat.

Ich habe öfter erwähnt, daß an einen wichtigen Platz unseres Baues hingestellt sein wird eine Urmenschen-Gestalt, die man auch als den Christus ansprechen kann, und die auf der einen Seite Luzifer, auf der anderen Seite Ahriman haben wird. Das, was im Christus konzentriert ist, nehmen wir heraus und teilen es in Luzifer und Ahriman wieder auf, insofern es aufzuteilen ist. Wir machen das, was plastisch zusammengeschweißt wurde in die einzige Gestalt, musikalisch, indem wir es gleichsam zu einer Melodie machen: Christus-Luzifer-Ahriman.

Nach diesem Prinzip ist wirklich unser ganzer Bau geformt. Unser ganzer Bau trägt das besondere Grundgepräge in sich: die plastischen Formen in musikalische Bewegung zu bringen. Das ist sein Grundcharakter. Wenn Sie nicht vergessen, daß, indem man so etwas andeutet, man niemals hochmütig werden soll, sondern hübsch demütig bleiben soll, und wenn Sie beachten, daß mit dem, was mit diesem Bau getan ist, die unvollkommensten ersten Schritte getan worden sind, so werden Sie nicht mißverstehen, was mit all den Aussprüchen, die ich über den Bau tue, gemeint ist. Selbstverständlich ist nicht gemeint, daß irgend etwas von dem, was uns als fernes Ideal vorschwebt, auch nur im Allerentferntesten erreicht ist; aber ein Anfang soll damit gewollt sein, könnte man sagen. Mehr will damit auch nicht gesagt sein, als daß ein Anfang gewollt sein soll.

Aber wenn Sie diesen Anfang vergleichen mit dem, was eine gewisse Vollendung im Griechentum erlebt hatte, mit der unendlichen Vervollkommnung des plastischen Prinzipes, ich will sagen, in den griechischen Gestalten der Athene und anderer, oder wie es sich in der Architektur auslebt in der Akropolis und dergleichen, wenn Sie diese Vollendung mit dem Anfang vergleichen, so werden Sie neben allem übrigen einen polarischen, einen radikalen Unterschied finden. Dort im Griechentum strebt alles nach dem Einfrieren in der Form, nach dem Festwerden in der Form. Solch eine Akropolis oder eine griechische Plastik, sie stehen da, um ewig eigentlich in dieser Form erstarrt stehen zu bleiben, um den Menschen ein Bild dessen zu bewahren, was die Schönheit der Form sein kann.

Solch ein Werk wie unser Bau ist, es wird, auch wenn es einmal vollkommener ausgestaltet sein wird, immer dastehen so, daß man eigentlich sagen kann: man wird dadurch eigentlich immer angeregt, diesen Bau als solchen zu überwinden, um durch seine Formen hinauszukommen ins Unendliche. Diese Säulen und namentlich die Formen, die sich an die Säulen anschließen, und selbst dasjenige, was gemalt und gebildet wird, es ist alles dazu da, um sozusagen die Wände zu durchbrechen, um zu protestieren dagegen, daß da Wände stehen, und um die Formen aufzulösen, ich möchte sagen, in einer ätherischen Lauge aufzulösen, so daß sie einen hinausführen können in die Weiten der kosmischen Gedankenwelt.

Man wird diesen Bau richtig empfinden, wenn man das Gefühl hat: dieser Bau, wenn man ihn betrachtet, löst sich auf, er überwindet seine eigenen Grenzen; alles, was da sich zu Wänden bildet, das will eigentlich hinaus in die Weiten der Welt. Dann hat man das richtige Gefühl. Mit einem griechischen Tempel fühlt man so, daß man am liebsten immer mehr eins werden möchte mit dem, was da fest durch die Wände umschlossen ist und mit dem, was nur durch die Wände herein kann. Hier bei unserem Bau wird man eigentlich das Gefühl haben: Wenn diese Wände doch nur nicht so genierlich da wären, denn sie wollen an jedem Platze, den sie darbieten, eigentlich durchbrochen werden und weiter hineinführen in die Welt des Kosmos. So sollte eben dieser Bau aus den Aufgaben unserer Zeit heraus gebildet werden, wirklich aus den Aufgaben unserer Zeit heraus.

Nachdem wir jahrelang gesprochen haben nicht nur über die Gegenstände der Geisteswissenschaft, sondern auch gesprochen haben miteinander so, wie man gesinnungsmäßig dasjenige meint, was durch die Geisteswissenschaft zum Ausdruck gebracht wird, so kann es auch verstanden werden, daß dann, wenn man über dieses oder jenes in der Welt etwas Abfälliges sagt, man es gar nicht absolut abfällig, absolut tadelnd meint, sondern daß man die scheinbar tadelnden Worte gebraucht, um Tatsachen zu charakterisieren in dem richtigen Zusammenhange.

Wenn man daher, ich will sagen, im Zusammenhang mit dem Gesprochenen einer welthistorischen Persönlichkeit Vorwürfe macht, so ist das nicht so gemeint, wie wenn man damit zugleich erklären wollte, daß man, wenigstens in seinem Urteil gegenüber dieser Persönlichkeit, so eine Art Scharfrichter sein möchte, der ihr, geistig gemeint, den Kopf abschlägt, indem man ein Urteil ausspricht. Moderne Kritiker sind so; aber derjenige, welcher von geisteswissenschaftlicher Gesinnung durchdrungen ist, ist nicht so. In dem Sinne, der durch diese Worte angedeutet ist, nehmen Sie, bitte, auch das, was ich jetzt zu sagen habe.

Es mußte einmal gewissermaßen ein Einschnitt in der Menschheitsentwickelung gemacht werden; es mußte gewissermaßen einmal gesagt werden: Nun hat es ein Ende mit dem, was da von alten Zeiten bis jetzt heraufgekommen ist; es muß etwas Neues beginnen. Er ist nicht auf einmal gemacht worden, dieser Einschnitt; er ist sogar in mehreren Etappen gemacht worden. Aber er tritt uns in der Geschichte ganz deutlich entgegen. Nehmen Sie einmal eine solche Persönlichkeit der Geschichte wie den römischen Kaiser Augustus, also denjenigen Herrscher Roms, dessen Herrschaft zusammenfiel mit dem Aufleben der Strömung, die wir herleiten von dem Mysterium von Golgatha. Es ist heute auch schon schwierig, den Menschen ganz klarzumachen, worin das ganz wesentlich Neue bestand, das durch den Kaiser Augustus in die abendländische Entwickelung hineinkam gegenüber dem, was bis dahin unter dem Einfluß der römischen Republik in dieser abendländischen Kultur drinnen war. Man muß eben doch zu Begriffen greifen, die heute den Menschen wenig geläufig sind, wenn man so etwas auseinandersetzen will.

Wenn man Geschichtsbücher liest, welche die Zeit der römischen Republik bis zur Kaiserzeit darstellen, da hat man so das Gefühl, daß die Geschichtsschreiber heute so schreiben, als wenn sie die Art, wie die römischen Konsuln und römischen Tribunen wirkten, ungefähr so sich dächten, wie das Wirken eines Präsidenten einer modernen Republik. Viel Unterschied herrscht ja nicht, wenn Niebuhr oder Mommsen über die römische Republik oder wenn sie über eine moderne Republik sprechen, weil man heute alles durch die Brille dessen sieht, was man eben unmittelbar in seiner eigenen Umgebung hat. Man kann sich nicht vorstellen, dafß dasjenige, was ein Mensch in weiter zurückliegenden Zeiten empfand und dachte, auch empfand gegenüber dem öffentlichen Leben, etwas ganz anderes war, als was der heutige Mensch empfindet. Es war aber etwas radikal anderes, und man versteht die römische republikanische Zeit wirklich nicht, wenn man sich nicht einen gewissen Begriff verschafft, der lebendig war in der Auffassung des alten republikanischen Römers, den er herübergenommen hat aus der Zeit, die man als die römische Königszeit bezeichnet.

Die alten Könige, von Romulus bis Tarquinius Superbus, die waren für den alten Römer wirklich Wesenheiten, die innig zusammenhingen mit dem Göttlichen, mit der göttlich-geistigen Weltregierung. Und nicht anders konnte der alte Römer der Königszeit die Bedeutung seines Königs begreifen als dadurch, daß er sich vorstellen konnte: bei jedem Geschehen liegt etwas Ähnliches vor wie bei Numa Pompilius, dem römischen König, der zur Nymphe FEgeria ging, um zu wissen, was er zu tun habe. Von den Göttern, respektive aus dem Geisterlande empfing man die Inspirationen für das, was man auf der Erde zu tun hatte. Das war ein lebendiges Bewußtsein. Die Könige waren die Brücke zwischen dem, was auf der Erde geschah, und dem, was die Götter aus der geistigen Welt heraus mit der Erde wollten.

So war auf das öffentliche Leben ausgedehnt dasjenige, was ein Gefühl in der alten Weltanschauung überhaupt war: das, was der Mensch in der Welt wirkt, hängt zusammen mit dem, was aus dem Kosmos herein ihn gestaltet, so daß fortwährend Einströmungen aus dem Kosmos geschehen. Man machte nicht Halt bei der Menschheitsregierung. So wie man, wenn man Plato war, sich sagte: Was der Mensch wissen kann, existiert nicht dadurch, daß er es in seiner Seele ausziseliert als Begriffe, sondern dadurch, daß er es als Ausfluß der göttlichen Wesenheiten bekommt. - So sagte man sich auch im alten Rom nicht, ein Mensch regiert die anderen Menschen, sondern man sagte: Die Götter regieren den Menschen, und derjenige, welcher da äußerlich in Menschengestalt regiert, der ist nur das Gefäß, in das die Impulse der Götter hineinfließen. - Das war aber noch übergegangen bis in die Zeiten der römischen Republik auf die Konsul-Würde. Die Konsul-Würde ist in der alten Zeit nicht etwa jenes, ich möchte sagen, bürgerliche Element, als das sich etwa eine heutige Staatsregierung immer mehr oder weniger bildet, sondern der Römer hatte wirklich den Gedanken, das Gefühl, die lebendige Empfindung: Der kann nur Konsul sein, der noch den Sinn offen hat für das, was die Götter in die Menschheitsentwickelung hineinfließen lassen wollen.

Daß man das immer weniger glauben konnte, als die Republik vorschritt und als die großen Diskrepanzen und Streitigkeiten in der Republik kamen, das führte gerade dazu, daß die römische Republik nicht weiter bestehen konnte. Es war das etwa so: Man dachte sich, wenn die Republik eine Bedeutung in der. Welt haben soll, so müssen die Konsuln gewissermaßen doch göttlich inspirierte Menschen sein; sie müssen das heruntertragen, was von den Göttern kommt.

Wenn man sich aber die späteren Konsuln der Republik ansah, so konnte man sich sagen: Die Kerle sind nicht mehr die richtigen Werkzeuge für die Götter. - Damit hängt aber auch zusammen, daß? man nicht mehr so fühlen, lebendig fühlen konnte für die Berechtigung der Republik. Nun lag natürlich die Entwickelung eines solchen Gefühls hinter dem offenbaren Bewußtsein der Menschen. Das lag sehr stark im Unterbewußten und war im Bewußtsein nur bei den sogenannten Eingeweihten. Die Eingeweihten wußten in diesen Dingen völlig Bescheid. Wer daher auch in der späteren römischen Republik meinetwillen noch ein gewöhnlicher, materialistisch denkender Durchschnittsbürger war, der sagte: Na, der Konsul, der gefällt mir nicht, der ist gewiß kein göttliches Instrument! - Der Eingeweihte würde das nie zugegeben haben, er würde gesagt haben: Er ist trotzdem ein göttliches Instrument; nur mit der fortschreitenden Entwickelung kann die göttliche Inspiration immer weniger in die Menschheit hinein. Die menschliche Entwickelung nimmt eine solche Gestalt an, daß immer weniger das Göttliche hereinkommen kann.

Und so kam es, daß, als ein Eingeweihter, ein wirklich Eingeweihter auftrat, der das alles durchschaute, er sich sagen mußte: So können wir es nicht mehr weiter machen! Wir müssen jetzt an ein anderes göttliches Element appellieren, das mehr den Menschen entzogen ist. - So, wie sich die Menschen äußerlich, moralisch und so weiter entwickelt hatten, so konnte man denen, die Konsuln wurden, nicht mehr zutrauen, daß nun wirklich da, wo der Mensch sich durch seine eigene Entwickelung entgegenstellt dem Göttlichen, das Göttliche noch hereinkam. Daher kam man dazu, gleichsam das Hereinströmen des Göttlichen herabzudrücken auf ein Gebiet, das mehr den Menschen entzogen war. Das sah Augustus, der bis zu einem gewissen Grade ein in diese Geheimnisse Eingeweihter war, wohl ein. Daher war es sein Bestreben, die göttliche Weltregierung zu entziehen dem, was die Menschen bisher hatten, und zurückzugehen auf das, wo die Götter noch unbewußster wirken, also darauf hinzuarbeiten, daß bei der Erteilung der Konsul-Würde das Erblichkeitsprinzip in Betracht gezogen würde. Er war bestrebt, die Konsuln nicht mehr so zu wählen, wie sie bis dahin gewählt wurden, sondern so, daß die Würde durch das Blut weitergepflanzt werde, so daß dadurch die Fähigkeit weitergepflanzt werde, im öffentlichen Leben das zum Ausdruck zu bringen, was die Götter wollen. Man drückte auf eine unter der Schwelle des Bewußtseins liegende Stufe herab den Fortgang des Göttlichen im Menschen, weil man sah, daß die Menschen auf einer Stufe angekommen waren, wo sie das Göttliche nicht mehr entgegennehmen konnten.

Sie kommen nur dann zu einem wirklichen Verständnis dieser außerordentlich merkwürdigen Gestalt des Augustus, wenn Sie überall voraussetzen, daß er diese Dinge voll gewußt hat und aus vollem Bewußtsein heraus, unter dem Einfluß der dazumal namentlich athenischen Eingeweihten, die zu ihm gekommen sind, alle die Dinge getan hat, die uns von ihm berichtet werden. Seine Grenze lag nur darinnen, daß er kein Verständnis gewinnen konnte für das Mysterium von Golgatha, daß er nur sah, wie die Menschen herunterkommen in die Materie, und daher nur einen Sinn haben konnte für das Versenken des Göttlichen im Materiellen des Blutes. Kein Verständnis hatte er dafür, daß etwas ganz Neues nun aufging in dem Mysterium von Golgatha. Er war ein in hohem Sinne Eingeweihter in die alten Mysterien, aber er hatte kein Verständnis für das, was sich jetzt in dem Menschengeschlecht als Neues heraufentwickelte.