Chance, Providence and Necessity

GA 163

28 August 1915, Dornach

3. Necessity and Chance in Historical Events

I want, as I've said, to use these days to lay the foundation we will need to bring the right light to bear on the concepts chance, necessity, and providence. But today that will require me to introduce certain preparatory concepts, abstract counterparts, as it were, of the beautiful concrete images we have been considering.1This lecture was preceded by a eurythmy performance of the final scenes of Goethe's Faust, II. And to do the job as thoroughly as we must, a lecture will have to be added on Monday. That will give us today, tomorrow (after the eurythmy performance), and Monday at seven. The performance tomorrow will be at three o'clock, and a further lecture will follow immediately.

For contemporary consciousness as it has come into being and gradually evolved up to the present under the influence of materialistic thought the concepts necessity and chance are indistinguishable. What I am saying is that many a person whose consciousness and mentality have been affected by a materialistic outlook can no longer tell necessity and chance apart.

Now there are a number of facts in relation to which even minds muddled by materialism can still accept the concept of necessity, in a somewhat narrow sense at least. Even individuals limited by materialism still agree that the sun will rise tomorrow out of a certain necessity. In their view, the probability that the sun will rise tomorrow is great enough to be tantamount to necessity. Facts of this kind occurring in the relatively great expanse of nature and natural happenings on our planet are allowed by such people to pass as valid cases of Necessity. Conversely, their concepts of necessity narrow when they are confronted with what may be called historical events. And an outstanding example is Fritz Mauthner, whose name has often been mentioned here; he is the author of Critique of Language, written for the purpose of out-Kanting Kant, as well as of a Philosophical Dictionary. An article on history appears in the latter. It is extremely interesting to see how he tries there to figure out what history is. He says, “When the sun rises, I am confronted with a fact.” To take an example, we have been able today, the 28th of August 1915, to witness the fact that the sun has risen. That is a fact. And now he concludes that we can ascribe this rising of the sun to a law, to necessity, only because it happened yesterday and the day before yesterday, and so on, as long as people have been observing the sun. It was not just a case of a single fact, but of a whole sequence of identical or similar facts in outer nature that brought about this recognition of necessity.

But when it comes to history, says Mauthner, Caesar, for example, was here only once, so we can't speak of necessity in his case. It would be possible to speak of necessity in his existence only if such a fact were to be repeated. But historical facts are not repeated, so we can't talk of necessity in relation to them. In other words, all of history has to be looked upon as chance. And Mauthner, as I've said, is an honest man, a really honest man. Unlike other less honest individuals, he is a man who draws the conclusions of his assumptions. So he says of historical “necessity,” for example, “That Napoleon outdid himself and marched to Russia or that I smoked one cigar more than usual in the past hour are two facts that really happened, both necessary, both—as we rightly expect in the case of the most grandiose as well as the most absurdly insignificant historical facts—not without consequences.” To his honest feeling, something that may be termed historical fact, like Napoleon's campaign against Russia (though it could equally well be some other happening) and the reported fact that he smoked an extra cigar, are both necessary facts if we apply the term “necessity” to historical facts at all.

You will be amazed at my citing this particular sentence from Mauthner's article on history. I cite it because we have here an honest man straightforwardly admitting something that his less honest fellows with a modern scientific background refuse to admit. He is admitting that the fact that Caesar lived cannot be distinguished from the fact of Mauthner himself having smoked an extra cigar by calling upon the means available to us and considered valid by contemporary science. No difference can be ascertained by the methods modern science recognizes! Now he takes a positive stand, declaring his refusal to recognize a valid difference, to be so foolish as to represent history as science, when, according to the hypotheses of present-day science, history cannot qualify as a science.

He is really honest; he says with some justification, for example, that Wundt set up a systematic arrangement of the sciences.2Wilhelm Wundt, 1832–1907, German philosopher and philologist. See also Mauthner's article “History” in his Dictionary of Philosophy. History was, of course, listed among them. But no more objective reason for Wundt's doing this can really be discovered than that it had become customary, or, in other words, it happens to be a fact that universities set up history faculties. If a regular faculty were provided to teach the art of riding, asserts Mauthner—and from his standpoint rightly—professors like Wundt would include the art of riding in their system of the sciences, not from any necessity recognized by current scientific insight, but for quite other reasons.

We really have to say that the present has parted ways to a very considerable extent with what we encounter in Goethe's Faust: this can be quite shattering if we take it seriously enough.3Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1749–1832, German poet, playwright, and novelist. Faust, dramatic poem. The quotations from Faust in this book are all taken from the translation by Bayard Taylor. There is much, very much in Faust that points to the profoundest riddles in the human soul. We simply don't take things sufficiently seriously these days. What does Faust say right at the beginning, after he has spoken of how little philosophy, jurisprudence, medicine, and theology were able to give him as a student, after expressing himself about these four fields of learning? What science and life in general have given him as nourishment for his soul has brought him to the following conviction:

No dog would endure such a curst existence!

Wherefore, from Magic I seek assistance,

That many a secret perchance I reach

Through spirit-power and spirit-speech,

And thus the bitter task forego

Of saying things I do not know,—

That I may detect the inmost force

Which binds the world and guides its course;

Its germs, productive powers explore,

And rummage in empty words no more

(Bayard Taylor translation)

What is it Faust wants to know, then? “Germs and productive powers”! Here, the human heart too senses in its depths a questioning about chance and necessity in life.

Necessity! Let us picture a person like Faust confronting the question of necessity in the history of the human race. Such an individual asks, Why am I present at this point in evolution? What brought me here? What necessity, running its course through what we call history, introduced me into historical evolution at just this moment? Faust asks these questions out of the very depths of his soul. And he believes that they can be answered only if he understands “productive powers and germs,” understands, in other words, how outer experience contains a hidden clue to the way the thread of necessity runs through everything that happens.

Now let us imagine a personality like Faust's having, for some reason or other, to make an admission similar to Fritz Mauthner's. Mauthner is, of course, not sufficiently Faustian to sense the consequences Faust would experience if he had to admit one day that he could distinguish no difference between the fact that Caesar occupied his place in history and the fact of having smoked an extra cigar in the past hour. Just imagine transferring into the mind of Faust the reflection on the nature of historical evolution voiced by Mauthner from his particular standpoint. Faust would have had to say, I am as necessary in ongoing world evolution as smoking an extra cigar once was to Fritz Mauthner. Things are simply not given their due weight. If they were, we would realize how significant it is for human life that an individual who embraces the entire scientific conscience of the present admits the impossibility of distinguishing, with the means currently available to science, between the fact that Caesar lived and the fact that Mauthner smoked an extra cigar, in other words, admits that the necessity in the one case is indistinguishable from the necessity in the other.

When the time comes that people sense this with a truly Faustian intensity, they will be mature enough to understand how essential it is to grasp the element of necessity in historical facts, in the way we have tried to do with the aid of spiritual science in the case of many a historical fact. For spiritual science has shown us how the facts relative to the successive historical epochs have been injected, as it were, into the sphere of external reality by advancing spiritual evolution. And what we might state about the necessity of this or that happening at some particular time differs very sharply indeed from the fact of Fritz Mauthner smoking his extra cigar. We have stressed the connection between the Old and the New Testaments, between the time preceding and the time following the Mystery of Golgotha, and stressed too how the various cultures succeeded one another in the post-Atlantean epoch and how the various facts occurring during these cultural periods sprang from spiritual causes.

The angle from which we view things is tremendously important. We should be aware of the consequences of the assumptions presently held to have sole scientific validity.

Days like yesterday, which was Hegel's birthday, and today, which is Goethe's, should be festive occasions for realizing how necessary it is to recall the great will-impulses of earlier times, to recall Hegel's and Goethe's impulses of will, in order to perceive how deeply humanity has become implicated in materialism. There have always been superficial people. The difference between our time and Goethe's and Hegel's is not that there were no superficial people then, but rather that in those days the superficial people could not manage to get their outlook recognized as the only valid one. There was that slight difference in the situation.

Yesterday was Hegel's birthday; he was born in Stuttgart on August 27, 1770. Since it was impossible for him, living at that time, to penetrate into truly spiritual life as we do today with the aid of spiritual science, he sought in his way to lay hold on the spiritual element in ideas and concepts; he made these his spiritual foothold. When we look at the phenomena surrounding us, we seek the spiritual life, the truly living life of the spirit that underlies them, whereas Hegel, since he could go no further, sought the invisible idea, the fabric of ideas, first the fabric of ideas in pure logic, then that behind nature, and finally that underlying everything that happens as a spiritual element. And he approached history too in such a way that he really accomplished much of significance in his historical studies, even if in the abstract form of ideas rather than in the concrete form of the spiritual.

Now what does a person who honestly adopts Fritz Mauthner's standpoint do if, let us say, he sets about describing the evolution of art from Egyptian and Grecian times up to the present? He examines the documented findings, registers them, and then considers himself the more genuinely scientific the less ideas play into the proceedings and the more he keeps—objectively, as he thinks—to the purely external, factual evidence. Hegel based his attempt to write the history of art on a different approach. And he said something, among other things, that we are of course able to express more spiritually today: If we conceive, behind the outer development of art, the flowing, evolving world of the ideal, then and then only will the idea that has, so to speak, been hiding itself, try to issue forth in the material element, to reveal itself mysteriously in the material medium. In other words, the idea will not at first have wholly mastered matter, but expresses itself symbolically in it, a sphinx to be deciphered, as Hegel sees it. Then, in its further development, the idea gains a further mastery over matter, and harmony then exists between the mastering idea and its external, material expression. That is its classic form. When, finally, the idea has worked its way through the material and mastered it completely, the time will come when the overflowing fullness of the world of ideas will run over out of matter, so to speak; the ideal will be paramount.

At the merely symbolic level, the idea cannot as yet wholly take over the material. At the classic stage, it has reached the point of union with matter. When it has achieved romantic expression, it is as though the idea overflowed in its fullness. And now Hegel says that we should look in the surrounding world to see where these concepts are exemplified: the symbolic, sphinx-like form of art in Egypt, the classic form in Greece, the romantic form in modern times. Hegel thus bases his approach on the unity of the human spirit with the spirit of the world. The world spirit must allow us thoughts about the course of art's evolution. Then we must rediscover in the outer world what the world spirit first gave to us in thought form.

This, says Hegel, is the way external history too is “constructed.” He looks first for the progressive evolution of ideas, and then confirms it at hand of external events. That is what the Philistines, the superficial people, have never been able to grasp, and it is their reason for reproaching Hegel so bitterly. A person who is superficial despite his belonging to a spiritual scientific movement wants above all to know about his own incarnation, and there were of course people in Hegel's time too who were superficial in their own way. You can see from one of Hegel's remarks that there was one such. As you've seen, Hegel followed the principle of first lifting himself into the world of ideas and then rediscovering in the world around him what he had come to know in the ideal world.

Now the superficial critics had of course risen up in arms against this, and Hegel had to make the following comment: “In his many-sided naivete Herr Krug has challenged natural philosophy to perform the sleight of hand of deducing his pen only.” “Deducing” was the term used to denote a rediscovering in the outer world of everything that had first been discovered in the inner world. The person referred to in this remark was Wilhelm Traugott Krug, who was teaching at Leipzig at that time.4Wilhelm Traugott Krug, 1770–1842, German philosopher, influenced by Kant. Oddly enough, Krug was the predecessor of Mauthner in having written a philosophical dictionary, though he did not succeed in becoming a leading authority in his day. But he said, “If individuals like Hegel search for reality in ideas and then want to show, from the idea's necessity, how external reality coincides with it, then someone like Hegel had better come and demonstrate that he first encountered my pen as an idea.” Krug remarks that Hegel with his “idea” is not convincing in his assertions about the development of art from Egyptian to Greek to modern times, but if Hegel could “deduce” Krug's pen from his idea of it, that would impress him.

Hegel comments in the passage mentioned above, “It would have been possible to give him the hope of seeing this deed accomplished and his pen glorified if science had progressed so far and so cleared up everything of importance in heaven and on earth in the past and present as to leave nothing of greater importance in doubt” than Herr Krug's pen. But in today's world the mentality characteristic of superficial people is really dominant. And Fritz Mauthner would have to say honestly that there is no possibility of distinguishing between the necessity of Greek art coming into being at a certain time and the necessity involving Herr Krug's pen or his own extra cigar.

Now I have already called your attention to the prime importance of finding the proper angle from which to illuminate these lofty concepts of human life. We need to find the right angles from which to study necessity, chance, and providence.

I suggested that you picture Faust in such relation to the world that he would have to despair of the possibility of discovering any element of necessity. But now let's imagine just the opposite and picture Faust conceiving of himself in relation to a world where nothing but necessity exists, a world where he would have to regard every least thing he did as conditioned by necessity. Then he would indeed have to say that if there were no chance happenings, if everything had to be ruled by necessity, “no dog would endure such a curst existence,” and this not because of what he had been learning but because of the way the world had been arranged. And what would a person amount to if there were truth in Spinoza's dictum that everything we do and experience is every bit as necessitated as the path of a billiard ball which, struck by another, has no choice but to move in a way determined by the particular laws involved?5Baruch Spinoza, 1632–1677, Dutch philosopher. If that were true, nobody could endure such a world order, and it would be even less bearable for natures aware of “productive powers and germs!”

Necessity and chance exist in the universe in such a way that they correspond to a certain human yearning. We feel that we couldn't get along without both of them. But they have to be properly understood, to be judged from the right angle. To do that in the case of the concept of chance naturally requires abandoning any prejudices or preconceptions we may have on the subject. We will have to examine the concept very closely so that we can replace the cliche that this or that “chanced” to happen—as we are often forced to say—with something more suitable. We will have to search out the fitting angle. And we will find it only if we go a bit further in the study we began yesterday.

You are familiar with the alternating states of sleeping and waking. But we recognize that waking consciousness too has its nuances, and that it is possible to distinguish between varying degrees of awakeness. But we can go further in a study of that state. It is basically true that from the moment we awaken until we fall asleep again, our waking consciousness takes in nothing but objects in the world around us, senses their action, and produces our own images, concepts, and ideas. Sleeping consciousness, which has remained at the level of plant consciousness, then lets us behold ourselves as described yesterday, and, since our consciousness in this state is plantlike, this is a pleasurable absorption in ourselves.

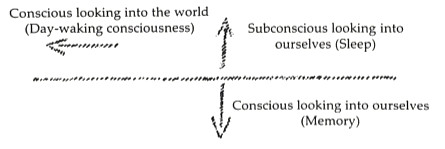

Now if we penetrate fully into the nature of human soul life, we come upon something that fits neither day nor night consciousness. I am referring to distinct memories of past experiences. Consider the fact that sleeping consciousness doesn't involve remembering anything. If you were to sleep continuously, you wouldn't need to remember previous experiences; there would be no such necessity, in any case. We do remember to some extent when we are dreaming, but in the plant consciousness of sleep we remember nothing of the past. It is certainly clear that memory plays no special part in sleep. In the case of ordinary day-waking consciousness we must say that we experience what is around us, but experiencing what we have gone through in the past represents a heightening of waking consciousness. In addition to experience of our present surroundings we experience the past, but now in its reflection in ourselves. So if I draw a horizontal line (see drawing) to represent the level of human consciousness, we may say that we look into ourselves in sleep.

I will write “Looking into ourselves” here; we can call it a subconscious looking. Day-waking consciousness can be set down as “Looking out consciously into the world.” Then a third kind of inner experiencing that doesn't coincide with looking into the world is the conscious “Looking into ourselves in memory.” So we have

“Conscious looking into ourselves” = memory“Consciousness looking into the world around us” = day-waking consciousness

“Subconsciousness looking into ourselves” = sleep

The fact is, then, that we have not just two sharply different states of consciousness, but three of them. Remembering is actually a deepened and more concentrated form of waking consciousness. The important thing about remembering is more than just being aware of something; we recapitulate awareness of it. Remembering makes sense only if we are aware of something all over again. Think a moment: if I encounter one of you whom I have seen before, but merely see him without recognizing him, memory isn't really involved. Memory, then, is recognition. And spiritual science teaches us too that whereas our ordinary day-waking consciousness, our consciousness of the world outside us, has reached the very peak of perfection, our remembering is actually only just beginning its evolution; it must go on and on developing. Metaphorically speaking, memory is still a very sleepy attribute of human consciousness. When it has undergone further evolution, another element of experience will be added to our present capacity, namely, the inner experiencing of past incarnations. That experiencing rests upon a heightening of our ability to remember, for no matter what else is involved, we are dealing here with recognition, and it must first travel the path of interiorization. Memory is a soul force just beginning its development./

Now let us ask, “What is the nature of this soul-force, this capacity to remember? What really happens in the remembering process?” Another question must be answered first, and that is, “How do we arrive, at this point in time, at correct concepts?”

You get an idea of what a correct concept is if you are not satisfied with a meager picturing of it; in most cases people have their own opinion of things rather than genuine concepts. Most individuals think they know what a circle is. If someone asks, Well, what is it? they answer, Something like this, and draw a circle. That may be a representation of a circle, but that is not what matters. A person who only knows that this drawing approximates a circle and remains satisfied with that has no concept of what a circle is. Only someone who knows enough to say that a circle is a curved line every point of which is equidistant from the center has a correct concept of a circle. An endless number of points is of course involved, but the circle is inwardly present in conceptual form. That is what Hegel was pointing out: that we must get down to the concept underlying external facts, and then recognize what we are dealing with in outer reality on the basis of our familiarity with the concept.

Let us explore what the difference is between the “half-asleep” status of the mere mental images with which most people are satisfied and the active possession of a concept. A concept is always in a process of inner growth, of inner activity. To have nothing more than the mental image of a table is not to have a concept of it. We have the concept “table” if we can say that it is a supported surface upon which other objects can be supported. Concepts are a form of inner liveliness and activity that can be translated into outer reality.

Nowadays one is tempted to resort to some lively movement to explain matters of this sort to one's contemporaries. One really has an impulse to jump about for the sake of demonstrating how a true concept differs from the sleepy holding onto a mental image. One is strongly prompted to go chasing after concepts as a means of bringing people slightly into motion and enlivening the dreadfully lazy modern holding of mental images that now prevails; one wants to devote one's energies to clarifying the distinction between entertaining ordinary mental images and working one's way into the real heart of a matter. And why is one thus prompted? Because we know from spiritual science that the moment something reaches the level of the concept, the etheric body has to carry out this movement; it is involved in this movement. So we really must not shy away from rousing the etheric body if we intend to construct concepts.

What, then, is memory? What is remembering? If I have learned that a circle is a curved line every point of which is equidistant from the center, and am now to recall this concept, I must again carry out this movement in my etheric body. From the aspect of the etheric body, something becomes a memory when carrying out the movement in question has become habitual there. Memory is habit in the etheric body; we remember a thing when our etheric body has become used to carrying out the corresponding movement. We remember nothing except what the etheric body has taken on in the form of habits. Our etheric bodies must take it upon themselves, under the stimulus of re-approaching an object, being repeatedly brought into motion by us and thus given the opportunity of remembering, to repeat the motion they carried out in first approaching that object. And the more often the experience is repeated, the firmer and more ingrained does the habit become, so that memory gradually strengthens.

Now if we are really thinking instead of merely forming mental images, our etheric bodies take on all sorts of habits. But these etheric bodies are what the physical body is based on. You will notice that a person who wants to clarify a concept often tries to make illustrative gestures, even as he is talking about it. Of course we all have our own individual gestures anyway. Differences between people are seen in their characteristic gestures, that is, if we conceive the term “gesture” broadly enough. A person with a feeling for gesture learns a good deal about others from observing their gestures and seeing, for example, how they set their feet down as they walk. And the way we think when remembering something is thus really a habit of the etheric body. This etheric body is a lifelong trainer of the physical body—or perhaps I had better say that it tries to train the latter, but not entirely successfully. We can say, then, that the physical body, for example, the hand, is here:

When we think, we constantly try to send into the etheric body what then becomes habit there. But the physical body presents a barrier. Our etheric bodies can't manage to get everything into the physical body, and they therefore save up the forces thus prevented from entering the physical body. They are saved up and carried through the entire period of life between death and rebirth. The way we think and the way we imprint our memories upon the etheric body then comes to the fore in our next incarnation as our instinctive play of gesture. And when we see a person exhibiting habitual gestures from childhood on, we can attribute them to the fact that in his previous incarnation his thinking imprinted certain quite distinct mannerisms on his etheric body. If, in other words, I study a person's inborn gestures, they can become clues to the way he managed his thinking in past incarnations. But just think what this means! It means that thoughts so impress themselves upon us that they resurface as the next incarnation's gestures. We get an insight here into the way the thinking element evolves into external manifestation: what began as the inwardness of thought becomes the outwardness of gesture.

Modern science, in its ignorance of what distinguishes necessity from chance, looks upon history as happenstance. In a list of words dating back to 1482, which Mauthner refers to, we read the words, “geschicht oder geschehcn ding, historia res gesta.” “Res gesta” is what history used to be called. All that is left of this today is the abstract remnant “regeste.” When notes are taken on some happening, they are called the “register.” Why is this? The word is based on the same root as “gesture.” The genius of speech responsible for the creation of these words was still aware that we have to see something brought over from the past in historical events. If what we observe in individual gesture is to be understood as the residue of past lives on earth, born with the individual into an incarnation, surely it is not complete nonsense to assume something like gestures in what we encounter in the facts of history. A series of facts surfaces in the way we walk, and these are the gestures of our thinking in past incarnations.

Where, then, must we look for the facts underlying history? That is the question now confronting us. In the case of individual lives we have to look for the thoughts underlying gesture. If we regard historical events as gestures, where must we look for the thoughts behind them? We will take up the study of this matter tomorrow.

Dritter Vortrag

Ich will, wie ich schon erwähnt habe, in diesen Tagen zusammentragen dasjenige, was wir brauchen, um die Vorstellungen von Vorsehung, Notwendigkeit, Zufall in das richtige Licht zu setzen. Ich werde aber nötig haben, gerade heute gewissermaßen wie ein abstraktes Gegenbild der eben gesehenen, schönen, konkreten Bilder einige Vorbegriffe vorzubringen. Und wenn wir, wie das ja sein muß, gründlich zu Werke gehen wollen, so können wir die Betrachtung nicht anders anstellen, als wenn wir auch diesmal dann am Montag noch einen Vortrag anschließen, so daß ich also heute noch, dann morgen nach der eurythmischen Aufführung, und am Montag um sieben Uhr sprechen werde. Morgen wird um drei Uhr die Eurythmieaufführung sein, und daran werden wir einen weiteren Vortrag anschließen.

Die Begriffe «Notwendigkeit» und «Zufall» fallen für jenes Bewußtsein, das sich bis zu unserer Zeit allmählich herausgebildet hat, und das unter dem Einfluß materialistischer Vorstellungen entstanden ist, in einer gewissen Weise zusammen. Ich meine das so, daß viele Menschen, deren Bewußtseinsverfassung unter dem Einflusse der materialistischen Vorstellungen entstanden ist, heute schon nicht mehr unterscheiden können den Begriff der Notwendigkeit und den Begriff des Zufalls.

Nun gibt es eine Anzahl von Tatsachen, denen gegenüber selbst materialistisch verwirrte Köpfe den Begriff der Notwendigkeit, wenigstens in einem gewissen eingeschränkten Sinne, noch gelten lassen. Auch materialistisch eingeschränkte Leute lassen heute noch gelten, daß mit einer gewissen Notwendigkeit die Sonne morgen wiederum aufgehen werde. Die Wahrscheinlichkeit, daß die Sonne morgen aufgehen werde, ist eine so große nach Ansicht dieser Leute, daß man diese große Wahrscheinlichkeit schon wie eine Notwendigkeit bezeichnen kann. Solche Tatsachen, die sich draußen in der weiteren Natur, in der relativ weiteren Natur unseres Erdgeschehens abspielen, lassen solche Köpfe als Notwendigkeit gelten. Dagegen finden sie sich schon gewissermaßen beengt mit ihren Begriffen von Notwendigkeit, wenn sie an dasjenige herantreten, was in der Geschichte sich zugetragen hat, was sich, wie man sagt, historisch abgespielt hat. Und sehr bezeichnend ist da gerade ein Geist, wie der schon öfter jetzt vor Ihnen genannte Fritz Mauthner, der nicht nur seine «Kritik der Sprache» geschrieben hat, um Kant zu «überkanten», sondern der auch ein philosophisches Wörterbuch geschrieben hat. In diesem philosophischen Wörterbuch hat er auch einen Artikel «Geschichte». Und wie er da versucht, mit dem, was Geschichte ist, zurechtzukommen, das ist recht interessant. Er sagt sich: Wenn die Sonne aufgeht, da sehe ich eine Tatsache. Nehmen wir zum Beispiel an, heute am 28. August 1915 habe man die Tatsache sehen können, daß die Sonne aufgegangen ist. Dieses ist eine Tatsache. Daß diesem Aufgehen der Sonne ein Gesetz, eine gewisse Notwendigkeit zugrunde liegt, das kann man nur dadurch einsehen, meint Fritz Mauthner, daß gestern auch die Sonne aufgegangen ist, vorgestern auch und überhaupt, solange Menschen dies beobachten, ist die Sonne aufgegangen. Man hat es nicht mit einer Tatsache zu tun, sondern man kann von der einen Tatsache zu den gleichen oder ähnlichen Tatsachen gehen in der Natur draußen und kommt dadurch zur Einsicht in die Notwendigkeit. Aber nun in bezug auf Geschichte sagt sich Fritz Mauthner: Cäsar zum Beispiel ist doch nur einmal dagewesen, da kann man nicht von einer Notwendigkeit sprechen. Denn man könnte von einer Notwendigkeit, daß Cäsar hat kommen müssen, nur dann sprechen, wenn ein solches Faktum sich wiederholen würde. Nun wiederholen sich aber die geschichtlichen Tatsachen nicht. Also kann man da nicht von einer Notwendigkeit sprechen. Das heißt, die ganze Geschichte muß man dann ansehen als eine Art Zufall. - Und Mauthner ist ein ehrlicher Mann — das habe ich Ihnen schon gesagt -, er ist wirklich ein ehrlicher Mensch. Im Gegensatz zu anderen, die weniger ehrlich sind, ist er ein Mensch, der eben die Konsequenzen aus gewissen Voraussetzungen zieht. Und so sagt er zum Beispiel mit Bezug auf die geschichtliche Notwendigkeit: «Daß Napoleon sich übernahm und auch noch nach Rußland marschierte, daß ich in dieser Stunde eine Zigarre mehr rauchte als sonst, sind zwei wirklich geschehene Tatsachen, beide notwendig, beide — was man für die größten und für die lächerlich kleinsten Tatsachen der Geschichte mit Recht fordert — nicht ohne Folgen.» Aus seiner Ehrlichkeit heraus sind ihm etwas, das man eine Geschichtstatsache nennt, etwa Napoleons Zug nach Rußland - es könnte ebensogut etwas anderes sein —, und die Tatsache, daß er, wie er sagt, in dieser Stunde eine Zigarre mehr rauchte als sonst, beides notwendige Tatsachen, wenn man das Geschichtliche überhaupt als «notwendig» bezeichnet.

Sie werden es erstaunlich finden, daß ich Ihnen gerade diesen Satz aus dem Artikel «Geschichte» von Fritz Mauthner anführe. Ich führe ihn an, weil in diesem Satz ein ehrlicher Mensch sich ehrlicherweise etwas gestanden hat, was die anderen, die weniger ehrlich sind, aus dem Untergrunde der heutigen wissenschaftlichen Gesinnung heraus sich eben nicht gestehen. Er hat sich gestanden: Mit den Mitteln, die wir haben, und die heute in der Wissenschaft gelten, kann man nicht unterscheiden die Tatsache, daß Cäsar gelebt hat, von der Tatsache, daß ich «in dieser Stunde eine Zigarre mehr rauchte als sonst». Man findet keinen Unterschied durch die Mittel, die die Wissenschaft heute gelten läßt! Nun stellt er sich positiv auf den Boden, keinen Unterschied gelten zu lassen, nicht so töricht zu sein, eine Geschichte aufzustellen als Wissenschaft, da es eine Geschichte als Wissenschaft nach den heutigen Voraussetzungen der Wissenschaft gar nicht geben kann. Er ist wirklich ehrlich; denn er sagt zum Beispiel, und zwar mit einem gewissen Recht, etwa das Folgende: Wundt hat ein Schema für die «Gliederung der Einzelwissenschaften» aufgestellt. Darin ist natürlich auch die Geschichte. Aber man findet eigentlich keinen objektiveren Grund, daß Wundt in seinem Schema der Wissenschaften auch die Geschichte angeführt hat, als daß es üblich geworden ist, das heißt, daß die zufällige Tatsache da ist, an den Universitäten für Geschichte eine ordentliche Professur zu haben. Würde man die Reitlehre zur ordentlichen Professur machen — so meint Fritz Mauthner von seinem Standpunkte aus mit Recht -, so würden Professoren wie Wundt auch das Thema der Reitkunst in einem Schema als «Wissenschaft» aufführen, nicht aus irgendeiner Notwendigkeit des heutigen wissenschaftlichen Begreifens heraus, sondern aus ganz etwas anderem heraus.

Man muß sagen: Die gegenwärtige Zeit ist weit, weit schon abgekommen von dem, was einem so entgegentritt aus dem Goetheschen «Faust», daß es, wenn man die Sache ganz ernst nimmt, einen doch eben recht tief erschüttern kann. Vieles, vieles ist ja in diesem Goetheschen «Faust», das uns auf tiefste Rätsel in der Menschenbrust hinweist. Man nimmt die Dinge heute nur nicht mehr ernst genug. Was sagt doch Faust gleich im Anfang, nachdem er sich zu der Nichtigkeit dessen bekannt hat, was ihm Philosophie, Juristerei, Medizin und auch Theologie seinerzeit haben geben können, nachdem er gegenüber diesen vier Fakultäten sich ausgesprochen hat? Er sagt: Das, was ihm aus dieser Wissenschaft heraus und auch sonst das Leben gebracht hat für seine Seele, das hätte ihn zu dem Bewußtsein gebracht:

Es möchte kein Hund so länger leben!

Und tu nicht mehr in Worten kramen.

Drum hab ich mich der Magie ergeben,

Ob mir durch Geistes Kraft und Mund<

Nicht manch Geheimnis würde kund,

Daß ich nicht mehr mit saurem Schweiß,

Zu sagen brauche, was ich nicht weiß,

Daß ich erkenne, was die Welt<

Im Innersten zusammenhält.

Schau alle Wirkenskraft und Samen,

Also, was will Faust erkennen? «Wirkenskraft und Samen»! Damit ist nämlich aus der Tiefe des menschlichen Herzens heraus hingedeutet auch auf die Frage nach «Notwendigkeit» und «Zufall» im Leben.

Notwendigkeit! Man denke sich nur eine solche Menschenwesenheit wie Faust vor die Frage der Notwendigkeit in dem geschichtlichen Leben der Menschheit hingestellt. Warum bin ich da - fragt sie -, an diesem Zeitpunkt des menschlichen Werdens? Was hat mich hereingestellt in diese Welt? Welche Notwendigkeit, die da läuft durch das, was wir Geschichte nennen, hat mich hereingestellt gerade in diesem Augenblicke in das geschichtliche Werden? — Aus der ganzen Tiefe der Seele heraus stellt Faust diese Frage. Und er glaubt, sie nur dann beantworten zu können, wenn er einsieht, wie «Wirkenskraft und Samen» sind, wie also dasjenige, was uns entgegentritt äußerlich, in sich verbirgt dasjenige, an dem man erkennt, wie der Faden notwendigen Werdens durch alles hindurchgeht.

Man denke sich nur, daß eine Natur wie Faust aus irgendwelchen Untergründen heraus kommen müßte zu einem ähnlichen Bekenntnisse wie Fritz Mauthner. Fritz Mauthner ist selbstverständlich nicht faustisch genug, um jene Konsequenz zu empfinden, die Faust empfinden würde, wenn er sich eines Tages gestehen müßte: Ich kann keinen Unterschied erkennen zwischen der Tatsache, daß Cäsar an seinen Platz in der Geschichte hingestellt worden ist, und der Tatsache, daß ich «in einer Stunde eine Zigarre mehr rauchte als sonst». — Denken Sie sich nur einmal in das Faust-Gemüt hinein die Frage gestellt von dem Gesichtspunkte aus, der hier durch Fritz Mauthner geltend gemacht worden ist gerade fürs geschichtliche Werden. Ich bin so notwendig im Gang der Entwickelung der Welt - hätte sich Faust sagen müssen -, wie es notwendig ist, daß Fritz Mauthner einmal in einer Stunde eine Zigarre mehr raucht. Man nimmt eben die Dinge gewöhnlich nicht ernst genug, sonst würde man einsehen, was das für das menschliche Leben für eine Bedeutung hat, daß einer, der alles wissenschaftliche Gewissen der Gegenwart zusammennimmt, sagt: Man kann heute mit den Mitteln der gegenwärtigen Wissenschaft nicht unterscheiden zwischen der Tatsache, daß Cäsar gelebt hat, und der Tatsache, daß Mauthner in einer Stunde eine Zigarre mehr als sonst geraucht hat; man kann nicht den Notwendigkeitswert des einen von dem Notwendigkeitswert des anderen unterscheiden.

Wenn die Menschen einmal dahin gekommen sein werden, dieses mit aller faustischen Intensität zu empfinden, dann werden sie reif sein zu verstehen, wie notwendig es ist, daß man geschichtliche Tatsachen in ihrer Notwendigkeit so begreift, wie wir es versucht haben für mancherlei geschichtliche Tatsachen durch die Geisteswissenschaft.

Denn diese hat uns gezeigt, wie gewissermaßen die Tatsache der aufeinanderfolgenden Epochen durch den großen Werdegang des Geistigen, ich möchte sagen, hineingespritzt sind in die Welt der äusseren Wirklichkeit. Und das, was wir sagen könnten über die Notwendigkeit, daß zu irgendeinem Zeitpunkt dies oder jenes geschieht, das unterscheidet sich ganz beträchtlich von der Tatsache, daß Fritz Mauthner «in einer Stunde eine Zigarre mehr rauchte». Wir haben erwähnt den Zusammenhang zwischen dem Alten und Neuen Testament oder zwischen der Zeit vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha und nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha, und dann wiederum haben wir erwähnt, wie sich in der nachatlantischen Zeit die einzelnen Kulturperioden folgen, wie in den Kulturperioden die einzelnen Tatsachen geschehen aus geistigen Untergründen heraus. Das erst gibt die Möglichkeit einer geschichtlichen Betrachtung.

Wie man die Dinge nimmt, darauf kommt unendlich viel an. Darauf kommt es an, daß man einsieht, wozu die Voraussetzungen führen, die man gegenwärtig allein als wissenschaftlich gelten läßt.

Ich möchte sagen, jeder solcher Tag, wie der gestrige oder der heutige ist, der Geburtstag Jegels, der Geburtstag Goethes, sollte einem in einer festlichen Weise zu Gemüte führen, wie notwendig es ist, sich an die großen Willensimpulse der älteren Zeiten zu erinnern, sich Goethes und der Hegelschen Willensimpulse zu erinnern, um zu sehen, wie weit in das materialistische Fahrwasser die Menschheit seit jener Zeit hineingezogen ist. Sehen Sie, Flachlinge — wenn ich das Wort bilden darf - hat es ja immer gegeben. Und der Unterschied zwischen, sagen wir zum Beispiel, der Goethe-Zeit und unserer Zeit besteht nicht darin, daß es zu Goethes Zeit oder zu Hegels Zeit keine Flachlinge gegeben hätte, sondern nur darin besteht der Unterschied, daß dazumal die Flachlinge nicht ihre Gesinnung als die allein maßgebliche angeben konnten. Dazumal war die Sache doch noch etwas anders.

Gestern war Hegels Geburtstag, der 1770 am 27. August in Stuttgart geboren ist. Dieser Hegel versuchte, da er in seiner Zeit noch nicht eindringen konnte in das wirkliche spirituelle Leben, wie wir es heute versuchen durch die Geisteswissenschaft, in seiner Art das Geistige in der Idee, im Begriff zu haben, er versuchte von der Idee, von dem Begriff auszugehen. Wie wir suchen hinter den Erscheinungen des äußeren Lebens das spirituelle Leben, das lebendige Leben im Geiste, so suchte Hegel, weil er nur bis dahin kommen konnte, hinter allem Äußeren die unsichtbare Idee, ein Ideengewebe, zunächst das Ideengewebe der reinen Logik, dann das Ideengewebe, das hinter der Natur ist, und dann das, was hinter allem Geschehen als Geistiges ist. So suchte Hegel auch hinter der Geschichte, so daß er wirklich, wenn auch in der abstrakten Form des Ideellen, nicht in der konkreten Form des Spirituellen, doch manches Bedeutsame geleistet hat in bezug auf historische Betrachtungen.

Was tut ein Mensch, der heute ehrlich auf dem Standpunkte steht, den auch Fritz Mauthner einnimmt, und der, sagen wir, die Entwickelung der Kunst von den alten Ägyptern durch die Griechen bis herauf in unsere Zeit schildert? Er nimmt dasjenige, was die Urkunden gebracht haben, registriert diese Dinge und wird dann glauben, um so wissenschaftlicher zu sein, je weniger Ideen ihm bei dieser Sache aufgehen, je mehr er sich nach seiner Art objektiv an das rein äußere Tatsachenmaterial hält. Hegel hat doch anders versucht, etwa Kunstgeschichte zu schreiben, und er sagte zum Beispiel schon, was wir heute selbstverständlich viel spiritueller ausdrücken können: Wenn man sich hinter der äußeren Kunstentwickelung denkt die fließende, die werdende Welt des Ideellen, dann wird die Idee zuerst gleichsam versuchen, wie noch sich verbergend, hervorzukommen durch das äußere Material hindurch, sich geheimnisvoll zu offenbaren aus dem äußeren Material. Das heißt, die Idee wird sich zuerst noch nicht das Material ganz erobert haben, sie wird symbolisch sich durch das Material ausdrücken; sie wird sich noch erraten lassen, sphinxmäßig, meint Hegel. Dann wird die Idee, wenn sie weiterschreitet, sich das Material mehr erobern. Es wird eine Harmonie bestehen zwischen dem äußeren Ausdruck im Material und der Idee, die sich das Material erobert: Die klassische Ausdrucksform! Dann wird, wenn die Idee sich durchgearbeitet hat, das Material sich erobert hat, eine Zeit kommen, wo man gleichsam die Überfülle der Ideenwelt heraustropfen sieht aus dem Material, wo die Idee dann überwiegt. Beim Symbolischen kann die Idee noch nicht recht durch durchs Material. Beim Klassischen kommt sie durch, so daß sie sich mit ihm vereint. Bei der romantischen Ausdrucksform dringt, tropft sie gleichsam heraus, da ist die Idee in Überfülle. - Und nun sagt Hegel, jetzt suche man in der Außenwelt, wo sich diese Begriffe verwirklichen: Symbolische, sphinxartige Kunst im Ägyptertum, klassische Kunst im Griechentum, romantische Kunst in der Neuzeit. So geht Hegel davon aus: Wir sind im menschlichen Geiste beim Geiste der Welt. Der Geist der Welt muß uns gestatten, uns Gedanken zu machen, wie der Gang der Kunstentwickelung ist. Und dann müssen wir in der äußeren Welt das wiederfinden, was uns der Geist zuerst an Gedanken eingegeben hat.

So aber «konstruiert», wie man sagt, Hegel auch die äußere Geschichte. Er sucht zuerst den Werdegang der Ideen und läßt ihn dann bestätigen durch das, was äußerlich geschehen ist. Das ist etwas, was die Philister gar nicht haben begreifen können - ich meine die Flachlinge -, was sie ihm ganz furchtbar vorgeworfen haben. Denn so wie derjenige, der innerhalb einer geisteswissenschaftlichen Bewegung ein Flachling ist, vor allen Dingen wird wissen wollen, welches seine eigene Inkarnation ist, so gab es natürlich in ihrer Art diese Flachlinge auch in der Zeit, als Hegel gelebt hat. Und daß ein solcher Flachling existiert hat, sehen Sie zum Beispiel aus einer Anmerkung, die Hegel gemacht hat. Also Sie sehen, bei Hegel liegt zugrunde das Prinzip, zuerst sich in die Welt der Ideen aufzuschwingen, und dann das, was in der Idee erkannt ist, wiederzufinden da draußen. - Nun, gegen diese Sache haben sich natürlich die kritischen Flachlinge gefunden, und Hegel mußte folgendes anmerken: «Herr Krug hat in diesem und zugleich nach anderer Seite hin ganz naiven Sinne einst die Naturphilosophie aufgefordert, das Kunststück zu machen, nur seine Schreibfeder zu deduzieren.» Deduzieren nannte man das Wiederfinden in der Außenwelt all desjenigen, was man in der Ideenwelt gefunden hatte. Diese Anmerkung bezieht sich nämlich auf den dazumal in Leipzig lehrenden Wilhelm Traugott Krug. Komischerweise hat allerdings Wilhelm Traugott Krug auch ein «Philosophisches Wörterbuch» geschrieben wie Fritz Mauthner, war also der Vorgänger von Fritz Mauthner. Aber tonangebend konnte Wilhelm Traugott Krug eben doch nicht gerade werden in der damaligen Zeit! Aber er hat gesagt: Wenn solche Menschen wie Hegel zuerst in der Idee das Wirkliche finden wollen und dann aus der Notwendigkeit der Idee zeigen wollen, wie sich das, was da draußen ist, einreiht in die Idee, dann soll mal so einer kommen wie der Hegel und soll zeigen, wie er zuerst in seiner Idee meine Schreibfeder hat. Hegel mit seiner Idee — so meint Krug -, überzeugt mich gar nicht, wie er aufzeigt, wie sich die ägyptische Kunst zur griechischen und zur neueren Kunst entwickelt hat. Wenn er aber aus seiner Idee heraus meine Schreibfeder deduzieren kann, dann imponiert er mir! — Nun sagt Hegel dazu in der genannten Anmerkung: «Man hätte ihm etwa zu dieser Leistung und respektiven Verherrlichung seizer Schreibfeder Hoffnung machen können, wenn dereinst die Wissenschaft so weit vorgeschritten und mit allem Wichtigen im Himmel und auf Erden in der Gegenwart und Vergangenheit im Reinen sei, daß es nichts Wichtigeres mehr zu bezweifeln gebe» - als die Schreibfeder des Herrn Krug. — Aber wirklich, in der heutigen Gesinnung ist ja dasjenige, was Gesinnung der Flachlinge ist, tonangebend. Und Fritz Mauthner müßte ehrlicherweise sagen: Es gibt keine Möglichkeit, zu unterscheiden zwischen der Notwendigkeit, daß in irgendeinem Zeitpunkt die griechische Kunst entstanden ist, und der Notwendigkeit der Schreibfeder des Herrn Krug, oder der Notwendigkeit, daß Fritz Mauthner «in einer Stunde eine Zigarre mehr rauchte als sonst».

Nun habe ich Sie schon aufmerksam gemacht darauf, daß es gegenüber diesen hohen Begriffen des Menschenlebens noch zuvor darauf ankommt, die richtigen Ausgangspunkte, die richtigen Gesichtspunkte zu finden, um diese Begriffe zu beleuchten. Es wird sich also darum handeln, daß wir gegenüber den Begriffen Notwendigkeit, Zufall und Vorsehung die richtigen Gesichtspunkte finden.

Ich habe Ihnen gesagt, man denke sich Faust so hineingestellt in die Welt, daß er verzweifeln müßte an der Möglichkeit, einen Notwendigkeitszusammenhang zu finden. Man denke sich aber jetzt das Umgekehrte: Man denke sich, daß Faust sich hineingestellt sehen müßte in eine Welt, in der es nur Notwendigkeit gibt, so daß er sich eines Tages sagen müßte: Ich bin hereingestellt in diese Welt, und alles, was ich tue, bis in das Kleinste hinein, ist Notwendigkeit. Da würde Faust erst recht sagen - jetzt nicht wegen seiner Erkenntnis, sondern wegen der Weltordnung: Es möchte kein Hund so länger leben, könnte es gar keinen Zufall geben, könnte nichts Zufälliges sein, könnte nichts so entstehen, daß es nicht notwendig ist! Und was wäre denn dieser ganze Mensch wirklich, wenn die Behauptung des Spinoza wahr wäre, daß alles dasjenige, was der Mensch tut und erlebt, so notwendig wäre, wie, wenn eine Billardkugel von einer anderen getroffen wird, diese andere, zweite, mit einer gewissen Notwendigkeit nach gewissen Gesetzen weiterfliegt. Wenn das so wäre, dann könnte der Mensch nimmermehr ertragen eine solche Weltordnung. Wie wenig sie zu ertragen wäre, das würden insbesondere diejenigen Naturen zu empfinden haben, die «alle Wirkenskraft und Samen» schauen!

Notwendigkeit und Zufälligkeit stehen so in der Welt drinnen, daß sie zugleich einer gewissen menschlichen Sehnsucht entsprechen. Der Mensch fühlt, daß er sie gewissermaßen nicht entbehren kann, weder Notwendigkeit noch Zufälligkeit. Aber man muß sie in einer richtigen Weise verstehen; man muß den richtigen Gesichtspunkt bekommen, um sie zu beurteilen. Natürlich muß man jetzt absehen beim Zufallsbegriff von all den Vorurteilen, die wir ihm gegenüber haben können. Wir werden uns den Begriff sehr genau ansehen müssen, damit wir vielleicht anstelle dieser Redensart, das oder jenes wäre Zufall - was wir ja oftmals genötigt sind zu sagen -, da, wo wir ernst leben wollen, etwas Besseres zu setzen vermögen. Aber wir werden den richtigen Gesichtspunkt zu suchen haben. Den werden wir nur finden, wenn wir die erst gestern begonnene Betrachtung etwas fortsetzen.

Sie kennen die Wechselzustände des Menschen zwischen Schlafen und Wachen. Aber wir haben schon gesagt, daß im Grunde genommen auch das Wachbewußtsein wiederum nuanciert ist, daß wir gewissermaßen verschiedene Stärken des Wachseins unterscheiden können. Aber wir können noch weiter gehen, wenn wir das Wachbewußtsein studieren. Im Grunde genommen führt uns ja das Wachbewußtsein vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen zunächst zu nichts anderem als dazu, die Dinge der Welt anzuschauen, ihr Wirken zu empfinden, uns Vorstellungen, Begriffe und Ideen zu bilden. Und dann führt uns das Schlafbewußtsein, dieses noch auf der Stufe des Pflanzenbewußtseins stehende Schlafbewußtsein, dazu, uns selbst anzuschauen in der Art, wie ich das gestern gesagt habe, und, weil es Pflanzenbewußtsein ist, uns eigentlich selbst zu genießen.

Wenn man nun recht gründlich eingeht auf die Natur des menschlichen Seelenlebens, so paßt etwas, was wir haben, weder in das Wesen des Tagesbewußtseins noch in das Wesen des Nachtbewußtseins hinein, das ist: die ganz deutliche Erinnerung an irgend etwas früher Erlebtes. Denken Sie doch: Schlafbewußtsein könnten Sie haben, ohne sich an irgend etwas zu erinnern. Wenn Sie immerfort schlafen würden, so würden Sie sich während des Schlafes nicht zu erinnern brauchen an dasjenige, was Sie vorher erlebt haben, es wäre wenigstens nicht notwendig. Im Traum erinnert man sich schon etwas, aber im tiefen Schlafe erinnert sich der Mensch in seinem Pflanzenbewußtsein an das Frühere nicht. Für das Schlafbewußtsein ist es ohnehin klar, daß die Erinnerung keine besondere Rolle spielt. Für das Tagesbewußtsein müssen wir aber auch sagen: Wir erleben durch das gewöhnliche Tagesbewußtsein das, was um uns herum ist, aber das Erleben desjenigen, was wir schon früher erlebt haben, das ist eigentlich eine Steigerung des gewöhnlichen Tagesbewußtseins. Da erleben wir nicht nur das, was um uns herum ist, sondern das, was war, aber in seiner Spiegelung in uns selber. - So daß Sie sagen können, wenn Sie hier gleichsam das Niveau des Menschenbewußtseins haben (siehe Zeichnung, waagerechte Linie), so schauen Sie während des Schlafes in sich selbst hinein: «In sich schauen». Aber wir können dieses In-sich-Schauen unterbewußt nennen. Das Tagesbewußtsein können wir dann so schematisieren, daß wir sagen: Wir sehen in die Welt hinaus: «Bewußt in die Welt schauen». Eine dritte Art des innerlichen Erlebens, die sich nicht deckt mit dem «In-die-Welt-Schauen», ist wirklich das bewußte «In-sich-Schauen» in der Erinnerung. Also «Bewußt in sich schauen» = Erinnerung. «Bewußt in die Welt schauen» = Tagesbewußtsein. «Unterbewußt in sich schauen» = Schlaf.

So daß wir eigentlich nicht bloß zwei scharf ausgeprägte Bewußtseinsunterschiede haben, sondern drei. Die Erinnerung ist wirklich ein vertieftes, ein verstärktes Tagesbewußtsein. Denn in der Erinnerung erkennen wir nicht bloß etwas, sondern wir erkennen etwas wieder, und das ist das Wichtige. Erinnerung hat ja nur einen Sinn, wenn wir etwas wiedererkennen. Denken Sie sich nur einmal: Wenn ich einen von Ihnen, den ich früher gesehen habe, heute wieder treffe, und ich sehe ihn nur, ich weiß aber nicht, daß er derselbe ist, den ich schon getroffen habe, dann ist es keine wirkliche Erinnerung. Erinnerung ist Wiedererkennen. Und die Geisteswissenschaft zeigt uns auch: Während unser gewöhnliches Tagesbewußtsein, also dieses Erkennen der Außenwelt, auf der höchsten Stufe der Vollkommenheit ist, ist unser Erinnern eigentlich gerade im Anfang seiner Entwickelung. Das Erinnern muß sich immer weiter und weiter ausbilden. Das Erinnern ist, wenn wir vergleichsweise sprechen dürfen, eine noch recht schläfrige Eigenschaft des menschlichen Bewußtseins, und wenn die Erinnerungskraft weiter ausgebildet sein wird, dann wird zu dem jetzigen Erleben etwas anderes hinzukommen, nämlich das Erleben, das innerliche Erleben früherer Inkarnationen. Das Erleben früherer Inkarnationen beruht auf einer Erhöhung des Erinnerungsvermögens, denn das muß unter allen Umständen ein Wiedererkennen sein. Es muß dieses Wiedererkennen unter allen Umständen den Weg durch das Innere durchmachen. Die Erinnerung ist eine Seelenkraft, die erst im Anfang ist.

Nun wollen wir einmal fragen: Welches ist denn die Natur dieser Seelenkraft, gerade dieser Erinnerungskraft? Wie geht denn eigentlich das Erinnern vor sich? — Da müssen Sie sich zuerst die Frage beantworten: Wie kommen wir denn überhaupt in der Gegenwart zu einem richtigen Begriff? — Sie bekommen eine Vorstellung, was ein richtiger Begriff ist, wenn Sie sich keine geringe Vorstellung machen von einem richtigen Begriff; denn die meisten Menschen haben ja nicht Begriffe, sondern haben nur Anschauungen. Die meisten Menschen glauben, sie wüßten, was ein Kreis ist. Wenn jemand frägt: Was ist ein Kreis? — so gibt man ihm zur Antwort: Ein Kreis ist eben so etwas. (Es wird ein Kreis gezeichnet.) Gewiß, das ist die Vorstellung des Kreises; aber darauf kommt es nicht an. Der hat noch keinen Begriff vom Kreis, der nur weiß, daß das hier ein Kreis ist, und dem nur das einfällt, was an der Tafel steht. Vom Kreis hat nur der einen Begriff, der zu sagen vermag: Ein Kreis ist eine krumme Linie, bei der jeder Punkt vom Mittelpunkt gleich weit entfernt ist. - Ich brauche allerdings eine Unendlichkeit von Punkten, aber ich kann den Kreis innerlich als Begriff finden. Das wollte Hegel sagen. Zunächst einmal den Begriff haben, auch für die äußere Tatsache, und dann die äußere Tatsache wiedererkennen aus dem Begriff.

Versuchen Sie nun, was für ein Unterschied besteht zwischen dem «Halbschläfrigen» der bloßen Vorstellung, mit dem die meisten Menschen zufrieden sind, und dem aktiven Einen-Begriff-Haben. Ein Begriff ist immer ein innerliches Werden, eine innerliche Tätigkeit. Man hat nicht einen Begriff von einem 'Tisch, wenn man nur die Vorstellung hat, sondern man hat einen Begriff von einem Tisch, wenn man etwa zu sagen vermag: Ein Tisch ist ein auf einer bloßen Unterlage Aufgesetztes, das etwas anderes tragen kann. Der Begriff ist ein innerliches Rege- und Tätigsein, das man in die Realität umzusetzen vermag.

Man ist versucht, wenn man unseren heutigen Zeitgenossen so etwas erklären will, ich möchte sagen, schon herumzuspringen. Man möchte am liebsten herumspringen, damit man zeigen kann, wie ein wahrer Begriff sich unterscheidet von dem schläfrigen Haben der Vorstellung. Am liebsten möchte man, um die Menschen einmal ein wenig in Bewegung zu bringen, dies furchtbar träge Vorstellungsvermögen von heute in Regsamkeit bringen, möchte den Begriffen überall nachspringen, möchte sich der Unterscheidung hingeben zwischen der gewöhnlichen Vorstellung und dem, wo man wirklich herum muß um den Mittelpunkt. Nun ja, warum möchte man das? Weil man weiß aus der Geisteswissenschaft, daß, sobald etwas zum Begriff heraufkommt, der Ätherleib wirklich diese Bewegung machen muß. Der Ätherleib ist in dieser Bewegung drinnen, so daß man sich eben nicht scheuen darf, den Ätherleib in Schwung zu bringen, wenn man Begriffe konstruieren will. Das darf man nicht scheuen.

Was ist nun aber Erinnerung? Was ist erinnern? Wenn ich gelernt habe: Ein Kreis ist eine krumme Linie, bei der jeder Punkt vom Mittelpunkt gleich weit entfernt ist -, und wenn ich mich erinnern soll an diesen Begriff, so muß ich im Ätherleib wiederum diese Bewegung ausführen. Dann ist, vom Standpunkte des Ätherleibes aus gesprochen, etwas zur Erinnerung geworden, wenn die Ausführung der betreffenden Bewegung im Ätherleibe Gewohnheit geworden ist. Erinnerung ist Gewohnheit des Ätherleibes. Wir erinnern uns an irgendeine Sache, wenn unser Ätherleib gewöhnt worden ist, die der Sache entsprechende Bewegung auszuführen. An nichts erinnern Sie sich als an dasjenige, was Ihr Ätherleib an Gewohnheiten angenommen hat. Ihr Ätherleib muß, wenn Sie ihn häufig bewegen und ihn wieder erinnern lassen, aus sich heraus die Gewohnheit entwickeln, durch die Annäherung an den Gegenstand die Gewohnheit entwickeln, dieselben Bewegungen auszuführen, die er ausgeführt hat, veranlaßt durch die erste Annäherung an den Gegenstand. Und weil die Gewohnheit sich immer mehr und mehr einnistet, so wird die Erinnerung immer fester und fester, je öfter sich das Ereignis wiederholt.

Nun sagte ich aber: Wenn wir wirklich denken, nicht bloß vorstellen, so nimmt der Ätherleib allerlei Gewohnheiten an. Aber dieser Ätherleib ist ja dasjenige, was zugrunde liegt dem physischen Leibe. Sie werden finden, daß Menschen, die einen Begriff klarmachen wollen, manchmal versuchen, in ihren äußeren Gebärden den Begriff nachzuahmen, selbst die Sprache zu begleiten mit einer solchen Gebärde. Aber der Mensch hat überhaupt Gebärden, ihm eigene Gebärden. Dadurch unterscheiden sich die Menschen, daß sie ihnen eigene Gebärden haben, wenn Sie nur den Ausdruck Gebärde weit genug nehmen. — Die Menschen haben ihre eigenen Gesten - Gebärde oder Geste ist ja dasselbe. Wenn man etwas Sinn für Gebärden hat, dann erkennt man einen Menschen schon, wenn man hinter ihm geht, an der Art und Weise, wie seine Gebärden sind, zum Beispiel mit dem Absatz auf dem Boden aufzutreten. Die Art, wie Sie jetzt denken, die ist also eigentlich, wenn dieses Denken Erinnerung wird, Gewohnheit des Ätherleibes. Dieser Ätherleib dressiert sich nun das Leben hindurch den physischen Leib. Das heißt, vielleicht besser gesagt, er versucht ihn zu dressieren, aber es gelingt ihm nicht recht. So daß wir sagen können: Hier ist der physische Leib, nun, meinetwillen die Hand.

Wir versuchen nun, wenn wir denken, fortwährend in den Ätherleib hineinzusenden das, was dann Gewohnheit wird. Aber an dem physischen Leibe haben wir eine Grenze. Unser Ätherleib kann wirklich nicht alles in den physischen Leib hineinsenden. Daher spart er sich diese Kräfte auf, für die ihm der physische Leib ein Hindernis ist; und die trägt er hindurch durch das ganze Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Wie Sie jetzt denken, wie Sie dem Ätherleib die Erinnerungen aufprägen, so kommt das in der nächsten Inkarnation als Ihr verborgenes Gebärdenspiel, als Ihre angeborene Geste zum Vorschein. Und wenn wir jetzt finden: Ach, dieser Mensch nimmt seit der Kindheit diese bestimmte Geste an, dann ist das aus dem Grunde, weil er in dem vorigen Leben, in der vorigen Inkarnation. seinem Ätherleib eingeprägt hat ganz bestimmte Arten durch sein Denken. Das heißt, wenn ich eines Menschen Gesten, so weit ihm diese Gesten angeboten sind, studiere, so können mir diese zu einem Lesezeichen werden für die Art und Weise, wie er in früheren Leben mit dem Denken sich abgefunden hat. Denken Sie aber, was das heißt! Das heißt: Der Gedanke drückt sich gleichsam so in die menschliche Wesenheit ein, daß er als Geste wieder erscheint in der neuen Inkarnation. Wir schauen da hinein in dieses Werden und Weben des Gedanklichen zum Festen, zum Daseienden, zum äußerlich Daseienden. Was erst innerlich Gedanke ist, es wird äußerlich Geste.

Geschichte, Historie empfindet man heute als etwas Zufälliges in der Wissenschaft, die eben nichts weiß über Notwendigkeit und ihren Unterschied von Zufälligkeit. In einem Vokabular vom Jahre 1482, Mauthner selber registriert das, steht: «geschicht oder geschehen ding, historia res gesta». «Res gesta» hat man nämlich früher die Geschichte genannt! Jetzt ist nur noch zurückgeblieben das abstrakte Wort «Regeste». Wenn man sich Notizen anlegt für Geschehenes, nennt man das Regeste! «Res gestaa»! Warum denn? Das ist dasselbe Wort wie die «Geste». Der Sprachgenius, der diese Worte «res gesta» gebildet hat, er wußte noch, daß man auch in dem, was historisch sich darlebt, etwas zu sehen hat, was stehengeblieben ist. Wenn man in der Geste des einzelnen Menschen, die mit ihm geboren ist, das Residuum, das Rückgebliebene von Gedanken in vorigen Inkarnationen zu sehen hat, dann wird es nicht mehr ein völliges Unding sein, vorauszusetzen, daß man in dem, was einem in den Tatsachen der Geschichte entgegentritt, auch etwas wie Gesten sieht. Wenn ich gehe, so sind das eine Reihe von Tatsachen: das sind die Gesten für mein Denken in der früheren Inkarnation.

Wo haben wir denn die Gedanken für die Geschichte zu suchen? Das ist die Frage, die sich uns nun aufwirft. Für das einzelne menschliche Leben haben wir für die Geste die Gedanken in der vorigen Inkarnation zu suchen. Schauen wir das, was in der Geschichte geschieht, als Geste an, wo haben wir dafür die Gedanken zu suchen?

Mit diesen Betrachtungen wollen wir dann morgen beginnen.

Third Lecture

As I have already mentioned, I intend to gather together during these days what we need in order to place the concepts of providence, necessity, and chance in their proper light. However, I will need to introduce a few preliminary concepts, which will serve, as it were, as an abstract counterpoint to the beautiful, concrete images we have just seen. And if we want to proceed thoroughly, as we must, we cannot begin our consideration until we have given another lecture on Monday, so that I will speak today, then tomorrow after the eurythmy performance, and on Monday at seven o'clock. Tomorrow at three o'clock there will be the eurythmy performance, and we will follow it with another lecture.

The concepts of “necessity” and “chance” coincide in a certain way for the consciousness that has gradually developed up to our time and that has arisen under the influence of materialistic ideas. I mean that many people whose consciousness has been shaped by materialistic ideas are now no longer able to distinguish between the concepts of necessity and chance.

Now there are a number of facts which even materialistically confused minds still accept as necessary, at least in a certain limited sense. Even people with limited materialistic views still accept that the sun will rise again tomorrow with a certain degree of necessity. The probability that the sun will rise tomorrow is so great in the opinion of these people that this high probability can already be described as a necessity. Such facts, which take place outside in the wider nature, in the relatively wider nature of our earthly existence, are accepted as necessity by such minds. On the other hand, they find themselves somewhat constrained by their concepts of necessity when they approach what has happened in history, what has, as they say, taken place historically. And very characteristic here is a mind such as that of Fritz Mauthner, whom I have mentioned several times now, who not only wrote his “Critique of Language” in order to “out-Kant” Kant, but also wrote a philosophical dictionary. In this philosophical dictionary, he also has an article on “history.” And how he tries to come to terms with what history is is quite interesting. He says to himself: When the sun rises, I see a fact. Let us assume, for example, that today, on August 28, 1915, one could see the fact that the sun rose. This is a fact. The fact that this rising of the sun is based on a law, a certain necessity, can only be understood, according to Fritz Mauthner, by the fact that the sun also rose yesterday, and the day before yesterday, and in general, as long as people observe it, the sun has risen. We are not dealing with a fact, but we can move from one fact to the same or similar facts in nature and thereby gain an understanding of necessity. But now, with regard to history, Fritz Mauthner says: Caesar, for example, only existed once, so we cannot speak of necessity. For one could only speak of a necessity that Caesar had to come if such a fact were to repeat itself. But historical facts do not repeat themselves. So one cannot speak of necessity here. This means that the whole of history must then be regarded as a kind of coincidence. And Mauthner is an honest man—I have already told you that—he is truly an honest person. Unlike others who are less honest, he is a person who draws conclusions from certain premises. And so, for example, with reference to historical necessity, he says: “That Napoleon overreached himself and marched into Russia, that I smoked one more cigar than usual at that moment, are two facts that really happened, both necessary, both—as one rightly demands of the greatest and the most ridiculously small facts in history—not without consequences.” Out of his honesty, something that is called a historical fact, such as Napoleon's march to Russia—it could just as well be something else—and the fact that, as he says, he smoked one more cigar than usual at that hour, are both necessary facts, if one can call historical events “necessary” at all.

You will find it astonishing that I quote this particular sentence from Fritz Mauthner's article “History.” I quote it because in this sentence an honest man has honestly admitted something that others, who are less honest, do not admit to themselves from the depths of today's scientific mindset. He has admitted to himself: With the means we have, and which are accepted in science today, it is impossible to distinguish between the fact that Caesar lived and the fact that I smoked one more cigar than usual at this hour. No difference can be found by the means that science accepts today! Now he takes a positive stance, refusing to allow any distinction, not foolishly setting up history as science, since history as science cannot exist according to the present-day premises of science. He is truly honest, for he says, for example, and with a certain degree of justification, something like the following: Wundt has established a scheme for the “classification of the individual sciences.” This naturally includes history. But there is really no more objective reason why Wundt included history in his scheme of the sciences than that it has become customary, that is, that there happens to be a regular professorship of history at universities. If riding were to become a regular professorship—as Fritz Mauthner rightly argues from his point of view—then professors like Wundt would also include the subject of equestrian art in a scheme as a “science,” not out of any necessity of today's scientific understanding, but out of something else entirely.

It must be said that the present age has strayed far, far from what we encounter in Goethe's Faust, so much so that, if we take the matter seriously, it can shake us to the core. There is much, much in Goethe's Faust that points to the deepest mysteries of the human heart. People today simply do not take things seriously enough. What does Faust say right at the beginning, after he has acknowledged the futility of what philosophy, law, medicine, and even theology were able to offer him at the time, after he has spoken out against these four faculties? He says: What these sciences and life in general have brought him for his soul has made him realize:

No dog would want to live like this any longer!

That is why I have surrendered myself to magic,

Whether through the power of the mind and the mouth

Many a secret would be revealed,

That I would no longer have to sweat bitterly

To say what I do not know,

That I would recognize what holds the world together

holds together in its innermost being.

See all the power and seeds at work,

and do not rummage around in words any longer.

So what does Faust want to know? “Power and seeds”! This points from the depths of the human heart to the question of “necessity” and “chance” in life.

Necessity! Just imagine a human being like Faust faced with the question of necessity in the historical life of humanity. Why am I here, she asks, at this moment in human development? What brought me into this world? What necessity, running through what we call history, brought me into historical development at this very moment? Faust asks this question from the depths of his soul. And he believes he can only answer it if he understands how “force and seed” work, how that which confronts us externally conceals within itself that which reveals how the thread of necessary becoming runs through everything.

Just imagine that a nature like Faust's would have to emerge from some underground source to arrive at a confession similar to that of Fritz Mauthner. Fritz Mauthner is, of course, not Faustian enough to feel the same consequences that Faust would feel if he had to admit one day: I can see no difference between the fact that Caesar was placed in his place in history and the fact that I smoked one more cigar than usual in an hour. Just imagine yourself in Faust's mind, asking yourself the question from the point of view that Fritz Mauthner has just asserted here precisely for historical becoming. I am as necessary to the course of world development, Faust would have had to say to himself, as it is necessary for Fritz Mauthner to smoke one more cigar in an hour. People do not usually take things seriously enough, otherwise they would realize what significance it has for human life when someone who embodies all the scientific conscience of the present says: Today, with the means of present-day science, it is impossible to distinguish between the fact that Caesar lived and the fact that Mauthner smoked one more cigar than usual in an hour; it is impossible to distinguish the value of necessity of one from the value of necessity of the other.

Once people have come to feel this with all Faustian intensity, they will be ready to understand how necessary it is to understand historical facts in their necessity, as we have attempted to do for many historical facts through spiritual science.

For spiritual science has shown us how, in a sense, the fact of successive epochs has been injected into the world of external reality through the great development of the spiritual, I would say. And what we could say about the necessity that this or that happens at a certain point in time differs considerably from the fact that Fritz Mauthner “smoked one more cigar in an hour.” We have mentioned the connection between the Old and New Testaments, or between the time before the mystery of Golgotha and after the mystery of Golgotha, and then we mentioned how the individual cultural periods follow one another in the post-Atlantean era, how the individual facts occur in the cultural periods out of spiritual foundations. This is what makes a historical view possible.

How one takes things depends infinitely on many factors. What matters is that one understands where the conditions that are currently accepted as scientific alone lead.

I would like to say that every day like yesterday or today, the birthday of Hegel, the birthday of Goethe, should lead one in a festive way to realize how necessary it is to remember the great impulses of will from earlier times, to remember Goethe's and Hegel's impulses of will, in order to see how far humanity has been drawn into materialistic waters since that time. You see, shallow people — if I may coin the term — have always existed. And the difference between, say, Goethe's time and our time is not that there were no shallow people in Goethe's time or in Hegel's time, but only that at that time the shallow people could not claim that their views were the only ones that mattered. Things were somewhat different back then.

Yesterday was Hegel's birthday. He was born on August 27, 1770, in Stuttgart. Hegel, unable to penetrate the real spiritual life of his time, as we are trying to do today through spiritual science, attempted in his own way to grasp the spiritual in the idea, in the concept. He tried to start from the idea, from the concept. Just as we search behind the phenomena of outer life for spiritual life, for living life in the spirit, so Hegel, because he could only go so far, searched behind everything external for the invisible idea, a web of ideas, first the web of pure logic, then the web of ideas behind nature, and then that which is spiritual behind all events. Hegel also searched behind history, so that he really did achieve something significant in relation to historical considerations, albeit in the abstract form of the ideal, not in the concrete form of the spiritual.What does a person do today who honestly takes the position also taken by Fritz Mauthner and who, let us say, describes the development of art from the ancient Egyptians through the Greeks up to our time? He takes what the documents have brought, registers these things, and then believes that the fewer ideas occur to him in this matter, the more he sticks to the purely external factual material in his own objective way, the more scientific he is. Hegel tried to write art history differently, and he said, for example, what we can express much more spiritually today: if one thinks behind the external development of art the flowing, becoming world of ideas, then the idea will first try, as it were, still hidden, to emerge through the external material, to reveal itself mysteriously from the external material. This means that the idea will not yet have completely conquered the material; it will express itself symbolically through the material; it will still be possible to guess at it, like a sphinx, according to Hegel. Then, as the idea progresses, it will conquer the material more and more. There will be harmony between the external expression in the material and the idea that conquers the material: the classical form of expression! Then, when the idea has worked its way through, has conquered the material, a time will come when one sees, as it were, the superabundance of the world of ideas dripping out of the material, where the idea then prevails. In the symbolic, the idea cannot yet fully penetrate the material. In the classical, it penetrates so that it unites with it. In the romantic form of expression, it penetrates, drips out, as it were, and the idea is in abundance. And now Hegel says, look in the outside world to see where these concepts are realized: symbolic, sphinx-like art in Egypt, classical art in Greece, romantic art in modern times. Hegel thus proceeds from the assumption that we are in the human spirit with the spirit of the world. The spirit of the world must allow us to form ideas about the course of the development of art. And then we must find in the external world what the spirit first gave us in the form of ideas.