Inner Impulses of Evolution, The Mexican Mysteries, The Knights Templar

GA 171

17 September 1916, Dornach

2. The Influence of Luciferic and Ahrimanic Beings on Historical Development. The clear Perception of the Sensory World and Free Imaginations as the Task of Our Time. Genghis Khan and the Discovery of America

Yesterday, we tried to characterize the forces that permeated Greece and Rome in order to obtain an idea of the influences that have been carried over from the fourth into the fifth post-Atlantean age, and we gave some indication of where we have to look today for signs of continued activity of the forces of the fourth post-Atlantean age. I want to ask you now to turn your attention once again to our description of the civilizations of Greece and Rome.

In the way it developed, the civilization of Greece was a source of great disappointment to the luciferic powers. One can, of course, only say these things out of imaginative cognition, and this will also be true of what is to be presented to you today. The development of Greek civilization was a great disappointment to the luciferic powers because they expected something quite different from it. Think what this means. They had expected the civilization of Greece, the fourth epoch of post-Atlantean times, to bring into being for them all they had striven for during Atlantean times. On Atlantis they had developed certain activities, certain influences and forces and they had expected to see the fruits of their labors appear in the fourth post-Atlantean epoch. What was it they were really looking for?

To speak of such a matter lets us look right into the luciferic soul. We come to know this luciferic life that continually strives, hoping that certain results may ensue, but that continually meets with fresh disappointment. A logician would naturally ask, “Why do not these luciferic powers stop trying? Why do they not see that they must be forever and repeatedly disappointed?” Such a conclusion would be human, not luciferic, wisdom. At any rate, the luciferic powers have yet to come to this conclusion. On the contrary, it is their practice to redouble their efforts whenever they experience disappointment.

What was it, then, that the luciferic powers expected from this fourth post-Atlantean age? They wanted to obtain mastery of all the soul forces of the Greek people, those soul forces that were, as we have seen, directed to carrying over the ancient imaginations of the Chaldean-Egyptian period, and to incorporate them into the creations of their own fantasy. The luciferic powers made it their endeavor to work so strongly on the human beings of the Greek civilization that their imaginations, refined and distilled to fantasy, should fill their whole being. The Greeks would then have lost themselves in a soul world, in an everyday thinking, feeling and willing that would have consisted entirely of those subtle imaginations that had become complete fantasy.

If the Greeks had developed nothing in their souls but these imaginations refined to fantasy, if these enticing imaginations had come to fill their souls completely, the luciferic powers would have been able to lift the Greeks and a great part of humanity out of human evolution to place them in their own luciferic world. This was the intention of the luciferic powers. From the Atlantean epoch on, it had been their hope to achieve in the fourth post-Atlantean age what they had failed to do in Atlantis. Humanity, at the stage it had then reached, would have been incorporated into the cosmos. They wanted nothing less than to create for themselves a separate world where earthly gravity did not exist, but where human beings would dwell with absolute super-sensible lightness, entirely given up to a life of fantasy. It was the hope of the luciferic beings to create a planetary body, which would contain those members of humanity who had reached this highest development of the fantasy life. They made every endeavor to lead the souls of the Greeks away from the earth. Had they succeeded, these souls would gradually have forsaken the earth. The bodies that still came to birth would have been degenerate. Egoless beings would have been born, the earth would have fallen into decadence and a special luciferic kingdom would have begun. This did not come to pass. Why?

This condition did not come about because, mingled with the “self-deifying madness” of Greek poetry, to quote Plato, was the genius and greatness of Greek philosophy and wisdom. The Greek philosophers—Heraclitus, Thales, Anaximenes, Anaximander, Parmenides, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle—saved Greek civilization from being completely spiritualized in a life of fantasy. They kept the Greeks on earth, providing the strongest forces that kept Greece within earthly evolution. In considering the course of history, we must always take into account the forces that lie behind physical reality and are the true causes of all that happens. It was, then, in this way that Greece was preserved for earthly evolution.

Now, the luciferic beings would have been unable to achieve anything at all without the help of the ahrimanic beings. In all their intentions and hope they reckoned on their support. Indeed, it must always be that two forces strive together in this kind of working. Just as the luciferic beings were disappointed in Greece, so were the ahrimanic beings disappointed in Rome and the way it developed. The luciferic beings wanted to lead Grecian souls away from the earth-planet and the ahrimanic beings wanted to contribute their efforts to the end that the Roman civilization would assume a particular form. The ahrimanic beings exerted their strongest efforts in Rome, just as the luciferic beings did in Greece. They calculated that a certain hardening would arise on earth brought about by an entirely blind obedience and subjection to Rome. What did the ahrimanic powers want to accomplish in Rome? They wanted to establish a Roman Empire that would extend over the whole of the then known world, embracing within it every human activity. It would be directed entirely from Rome with the strictest centralization and the utmost development of the rule of might. They sought to establish a widely flung state machinery that would include and make subject to it all religious and artistic life. Its goal would be to stamp out all individuality. Every people and human being would comprise merely some small part of this mighty state machine.

Thanks to the clarity of its philosophers, however, Greece was not lulled into the luciferic dream, nor could Rome be hardened as these ahrimanic powers desired, because in Rome, too, something was working against them. This was described in the last lecture as Roman ideals, but the legal, political and military ideals that were then developing could not have withstood Ahriman alone. Within the Roman civilization the ahrimanic powers gathered for a stupendous onslaught. That attempt was like a repetition of their attempt made in Atlantean times, and it developed infinitely strong powers and forces. It was only from another side that Ahriman's intention was hindered. It was, at first, prevented by something that, at first sight, might be regarded as a lower trait in the Roman character, but that was not the case. As a matter of fact, the Romans had need of what I may have seemed to describe in the last lecture with some antipathy. They needed their ruthlessness, stubborn egoism, that continuous stirring up of emotions, to be able to march against the ahrimanic powers. Roman history—I beg you expressly to note this—is not a revelation of the ahrimanic powers. Although they stand in the background, it is a fight against them. If it is all confused and self-seeking, seeming to tend more and more toward a politicalization of the whole world, it is because only in this way could Ahriman's mechanizing be resisted.

All this alone, however, would not have been of much avail. Rome had also received Christianity, which in Rome would have assumed a form that would have given Ahriman a splendid opportunity to achieve his aim since, through the spiritual decline of a Roman rule that had been transformed into a papacy, the mechanizing of culture could have been accomplished. So another external power had to be brought against Ahriman, who works with much more external means than Lucifer. Ahriman, as we have seen, diverted the forces of Christianity to his own service. Another power had to be brought against him. This was the onslaught of the Germanic tribes caused by the migration of peoples in Europe. Through this onslaught on Rome, the mechanizing of the world under a single, all-embracing Roman Empire was hindered. If you will study all that took place in the migration of these peoples, you will find that you can get a true insight into it when you see it from this point of view. Whenever the migration of peoples occurs in the Roman world, Roman history is not thereby brought to an end, but the ahrimanic powers, combated throughout their history by the Romans, are repelled.

Thus did Ahriman meet with his disappointment, as Lucifer had met with his. But they will take up their tasks again in the fifth post-Atlantean age with all the more determination. Here is the point at which we must gain an understanding of the forces that are operative in our age, insofar as such an understanding is possible today.

The fourth post-Atlantean age extends both backwards and forwards from its central point in 333 A.D. It ended about 1413 A.D. and it began about 747 B.C. These are of course, approximate dates. I have just told you that the disappointment of Lucifer and Ahriman in the forms the Greek and Roman civilizations had assumed, has led them to make still stronger efforts in our fifth post-Atlantean age. Their efforts are already at work in the human forces that have been active from the fifteenth century. It does not matter whether something occurs a few decades earlier or later. In outer physical reality, which takes on the form of the “great illusion,” things are sometimes misplaced.

The fact that the Roman civilization could be retained in the evolution of humanity as it was due to the events brought about by the migrations of the peoples. If Rome had developed in such a way that a great all-embracing mechanized empire had arisen, it would only have been habitable for egoless human beings who would have remained on earth after Lucifer had drawn out their souls on the path of Greek culture and art. You see how Ahriman and Lucifer work together. Lucifer wants to take men's souls away and found a planet with them of his own. Ahriman has to help him. While Lucifer sucks the juice out of the lemon, as it were, Ahriman presses it out, thereby hardening what remains. This is what he tried to do to the civilization of Rome. Here we have an important cosmic process going on—all due to the intention and resolve of luciferic and ahrimanic powers. As I have said, they were disappointed. They have continued their efforts, however, and our fifth post-Atlantean age has yet to learn how strong these attacks are. They are now only beginning but they will become stronger and stronger. This age must learn, too, that the necessity to understand these attacks will become ever greater. At the beginning of an age the backward beings cannot work strongly. As yet, we are only in the beginning, and even though it became manifest only later, the luciferic and ahrimanic powers began to exert their forces before the expiration of the fourth post-Atlantean age.

To understand how these powers work in the fifth post-Atlantean age, we must turn our attention for a moment to what is intended for man in the right and normal course of his evolution. It is rightfully intended that he shall take a further step forward. The step taken by humanity in the fourth post-Atlantean age is revealed in the culture of the Greeks and in the political development of the Romans, and it was through the battle with Lucifer and Ahriman that what was intended actually came about. These opposing forces are always such that they fit into the progressive plan of the world. They belong to it and are needed there as opposing forces. But what special qualities are the men of the fifth post-Atlantean age, our own, to develop?

We know that this is the age of the development of the consciousness soul and that, to accomplish this, a number of forces—soul and bodily forces—must be active. First, a clear perception of the sense world is necessary. This did not exist in earlier times because, as you know, a visionary, imaginative element continuously played into the human soul. The Greeks still possessed fantasy but, as we have seen, after fantasy and imagination had taken possession of humanity, as it did of the Greeks, it then became necessary for men to develop the faculty to see the world of external nature without the illumination of a vision standing behind it. We need not imagine that such a vision has to be a materialistic one. That point of view is itself an ahrimanically perverted perception of sense reality. As indicated before, observation of sense reality is one task incumbent upon the human soul in our fifth post-Atlantean age.

The other task is to unfold free imaginations side by side with the clear view of reality—in a way, a kind of repetition of the Egypto-Chaldean age. To date, humanity has not progressed too far in this task. Free imaginations as sought through spiritual science means imaginations not as they were in the third post-Atlantean age, but unfettered and undistilled into fantasy. It means imaginations in which man moves as freely as he does only in his intellect. That, then, is the other task of the fifth post-Atlantean age. The unfoldment of these two faculties will lead to a right development of the consciousness soul in our present epoch.

Goethe had a beautiful understanding of this clear perception, which, contrary to the materialistic point of view, he described as his “primal phenomenon” (Urphänomen). You will find that this has been dealt with at length in Goethe's writings, and I have spoken of it in my explanation of the primal phenomenon. His is a clear, pure perception of reality and of his primal phenomenon. Goethe not only gave the first impulse for perceptions free of any visions but also for free imaginations.1This distinction between pure perception free of memory pictures and visions on the one hand and an objective imagination which begins with brain-free thinking on the other is developed in Boundaries of Natural Science, Anthroposophic Press, 1983 What he has given us in his Faust, even though it has not yet gone far in the direction of spiritual science, and in comparison with spiritual science is still more or less instinctive, is nevertheless the first impulse to a free imaginative life. It is no mere world of fantasy, yet we have seen how deep this world of fantasy really is that develops in free imaginations in the wonderful drama, Faust.

So, over against this primal phenomenon, we have what Goethe calls typical intellectual perception. You will find it described in detail in my book, The Riddle of Man. This mode of thought must continue to develop. The men of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch, however, must not merely behold reality. They must be able to live with reality. They must get busy, like Goethe, and, working in quite a different way from that of the materialistic physicists, really make such use of their laboratory apparatus that it produces the primal phenomenon for them. They will then have to devise some way of getting the primal phenomenon into practical life. As you know, it is at home in, and holds sway throughout, nature. The intentions of humanity that come from free imaginations will have to be included in this primal phenomenon of nature. On the one hand, men will have to direct their gaze quite selflessly to the outer world to work in it and to gain knowledge of it. On the other, by powerful application of their personalities, they will have to bring it all into inner movement in order to find the imaginations for outer activity and outer knowledge. Gradually, the consciousness soul and its culture will achieve this transformation.

There will certainly be one-sidedness in this cultural epoch. That goes without saying. Our cognition will direct its efforts only outwards, as in Bacon, or only inwards, as in Berkeley. We have already spoken of this. The imaginative life welling up from within will not unfold without all manner of disturbing influences. But even now we can point to moments in this development when someone feels this free imaginative life springing up in his soul. In these beginnings it is still in great measure unfree, but we may see how so significant a man as Jacob Boehme, quite soon after the fifth post-Atlantean age began, felt how it was trying to develop in his soul. He brought this to expression in his Aurora, and we can feel as we read it how imaginative life was working within him. It must become free; Boehme still feels it to be a little unfree. Nevertheless, he knew it was a divine creative thing that was working in him. So Boehme was, in a sense, at the opposite pole to Bacon, whose endeavor always directed his attention to the external world. Jacob Boehme, however, was entirely engrossed in the world within, and described this world beautifully in the Aurora:

“I declare before God,” he says because he is speaking of his inner soul, “that I do not know how it comes to pass in me.” He means by this how the imaginations arise in him. “Without feeling the impulse of the will, I also don't know what I have to write.”

This is how Boehme speaks of the uprising of imaginations in himself. He detects the beginning of forces that must grow continually stronger in the men of the fifth post-Atlantean age.

“I declare before God that I do not know how it comes to pass in me. Without feeling the impulse of the will, I also don't know what I have to write. The spirit dictates to me in a great and marvelous knowledge what I write, so that often I do not know whether I am in this world with my spirit, and I rejoice exceedingly that sure and continuous knowledge is thus vouchsafed to me.”

Boehme describes the instreaming of the imaginative world. We can see that he feels harmony and rest in his soul, and he describes how men's souls shall, in the normal and right progress of their evolution, let themselves be taken hold of by these inner forces, which are to grow stronger in them in the fifth post-Atlantean age. But one must take possession of them in the pure inner being of the spirit and thereby avoid devious paths. In the seventeenth century one had to speak of these forces much in the way that Boehme, who spoke as a man completely and utterly devoted to divine righteousness, did.

The entire aim in the work of the luciferic and ahrimanic powers in the fifth post-Atlantean age, concerning both the perception of the primal phenomenon and the development of free imaginations, is to hinder these forces from arising in man. The luciferic and ahrimanic powers are working in this fifth post-Atlantean age to disturb these forces in the human soul, to employ them to a wrong end, thus bringing men's souls out of the earth sphere to establish a new sphere of their own. Many things must work together to disturb the right, quiet and slow unfolding of these forces. Note well that I say the quiet and slow unfolding because the entire period of 2,160 years, starting in 1413 A.D., should be used for the gradual unfoldment of the forces I have named, that is, free imaginations and the gradual development of working with primal phenomena. At intervals—by fits and starts, as it were—the luciferic and ahrimanic powers throw the whole weight of their opposition against this right evolution. When we bear in mind that everything is prepared for by the world beyond the earth long before it happens, we shall then not be surprised to find preparations being made to bring the strongest possible forces of opposition against the normal evolution of humanity.

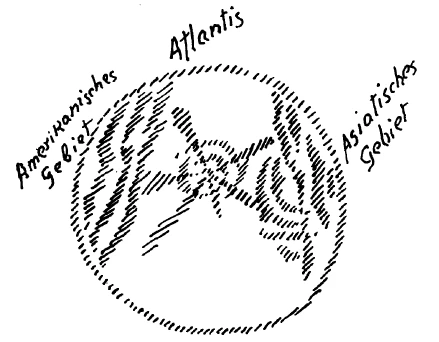

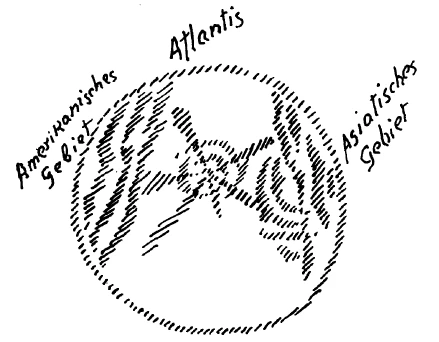

We have already seen how the luciferic and ahrimanic powers poured what they had developed in Atlantean times into Greece and Rome. Now, in an altered form, they have tried to repeat these efforts before the arrival of the fifth post-Atlantean age. You will not be surprised when I say that for this fifth post-Atlantean age, too, a powerful impetus had to be present bearing along with it the after workings, in a luciferic and ahrimanic sense, from Atlantis. We know that the Atlantean influences spread out from a region that was called Atlantis even by Plato. Let us make a diagram and imagine Atlantis here, then over here on the right would be Europe and Asia, and here on the left would be America. The old Atlantean forces, including the old luciferic and ahrimanic forces, spread out from Atlantis. Some part of these Atlantean forces, however, was held

back, and it came to work in our fifth post-Atlantean age as luciferic and ahrimanic forces. That is, some part of the good forces, which were good and right in Atlantean times, have been carried over to our time to become luciferic and ahrimanic forces. Only the center was transferred to another region.

Atlantis, as we know, is gone and the center transposed to Asia. You must imagine it on the reverse side of my drawing and the effects of the old Atlantean culture spreading out from it as a preparation for the fifth post-Atlantean age.

Its intent was to lucifericize and ahrimanicize it. It was actually the descendants of the old Atlantean teachers who were now working from a place in Asia. A priest there had been educated to behold—to have a belated vision, as it were, of what the Atlanteans called the “Great Spirit,” and to receive his commands. These the priest communicated to a young man of remarkable energy and strength who, by virtue of this authority, received the name “The Great Ruler of the Earth” from his community. This was Genghis Khan. The Great Spirit, through his follower and through that priest, gave to Genghis Khan the command to summon all the powers of Asia to spread the influence that would lead the fifth post-Atlantean age back into a luciferic form. These forces—and they were far more powerful than the forces established in Greek culture—were all employed to this end. Free imaginations were to be changed into old, visionary imaginations. Every effort was to be made to lull the soul of man to sleep in a dim and dreamy experience of imaginations instead of a free experience filled through and through with clear understanding.

With the help of the special forces that had been preserved from Atlantis, it was the intended purpose to carry an influence into the West that would make its culture visionary. Then it would have become possible to separate the souls of men from the earth and to form a new continent, a new planetary body with them. All the unrest and disturbance that came into the evolution of modern man through the Mongolian invasions, everything connected with them that has gone on working into the fifth post-Atlantean epoch—all this unrest, which was prepared long ago, is nothing more than the great attempt that is being made from Asia to bring about a visionary European culture. It would cut it off from the conditions of its further evolution and lead it altogether away from the earth, just as the East has experienced again and again this feeling of being filled with vision and of wanting to be estranged from the earth.

Something was needed to counterbalance this tendency. An opposite trend had to be created as a counterforce that moves in the direction of the normal evolution of mankind. The influence of Genghis Khan's priest was intended to bring about a kind of buoyancy and lightness in the human race that would draw man away from the earth. Over against this, a corresponding heaviness had to come to man from the weight of the earth; this was provided through the discovery of the western world. America, with all that it holds, was discovered and thereby earth heaviness, the desire to remain on earth, was given to man. The discovery of America and everything connected with it, and the way man carried his life into the many new places of the earth, all this, when seen in wider connections, shows itself as a counterbalancing force to the activity of Genghis Khan. America had to be discovered so that man might be brought to grow closer to the earth, to grow more and more materialistic. Man needed weight and heaviness to counterbalance the spiritualization that was the aim of the descendants of the “Great Spirit.”

Along with this normal process whereby the scene of action of man's life was extended to America, we find the other forces, the ahrimanic powers of the “Great Spirit,” intervening again. An influence came from America to Europe, and another came to permeate America from Asia. Thus, normal forces developed through the discovery of America and also powerful ahrimanic onslaughts. They worked less strongly at first, but will continue to work in our time and on into the future. We must learn to recognize these ahrimanic forces.

What Rome had achieved in the Church and in the ecclesiastical state was grasped by the ahrimanic influence. While it is comparatively easy to see how the luciferic influence worked on Genghis Khan—we have exact knowledge of the fact that a priest was initiated by the follower of the “Great Spirit”—it is much more difficult to say how the ahrimanic spirit worked. This is because the ahrimanic influence is dispersed and scattered. But you need only study how Spain, strictly Roman Catholic as it was, was fascinated by all the treasures of gold that were discovered in America. What a hold it had upon her! You can observe how strong the specter-like working of the old Romanism still was in such a ruler as Ferdinand of Castile or Charles V, the ruler of the kingdom over which the “sun never set.” Study the reaction of Europe to the gradual discovery and opening up of America and you will see what temptations came from that direction. Taken all in all, it is a history of temptation woven in with a history that runs a normal course.

Please do not go about saying that I have presented the discovery of America as an ahrimanic deed. In reality, I have said the very opposite. I have said that America had to be discovered and that the entire event was necessary to the progress of the world. Ahrimanic forces entered, however, and set themselves in violent opposition to what was happening quite rightly in the normal course of progress. Things are not so simple that we can say, “There is Lucifer, and there is Ahriman; they act and behave in such and such a way, and divide the world between them.” Things are by no means so simple as that.

We find, therefore, many forces working together when we set out to listen to them in their field of action behind the physical plane. These forces take possession of other forces. They try to seize the forces in man that have continued on from the fourth post-Atlantean epoch in order to distort them and make them serve their ends. Look at a man like Machiavelli. You will find in him the symbol for the politicizing of thought that begins in the Renaissance. He is a veritable revelation of the whole process. He was a great and powerful spirit but one who, under the onslaught of the forces of which I have told you, brings to a new life again the complete attitude of thought and mind that has its source in the heathen Rome of ancient times. You have a true picture of Machiavelli when you study the history of his time and see him, not as a single personality, but as the outstanding expression of many who think in the same way. In him you can observe these forces trying to charge forward with all speed, bringing to their assistance the atavistic—and thus luciferic—forces that have been left behind. Had things gone as Machiavelli intended, all of Europe would have become nothing but a political machine. Opposing the violent onslaught of such forces are the forces that work in the normal direction. Over against a figure like Machiavelli, who was purely political and turned all man's thought into political thinking, we can place another great figure, Thomas à Kempis, who was also Machiavelli's contemporary. He stands entirely within the slow and gradual evolution, working slowly and gradually. He was anything but a man of politics.

So we can follow the several streams in history. We shall find normal streams, and we shall also find currents that flow from earlier times and are made use of by the forces of which I have told you. Many forces work together in history and it is important to observe and study their connections. A man like Jacob Boehme felt free imaginations rising within him. We can say of such a man that he fortified himself against the attacks of Lucifer and Ahriman through the whole character of his life of soul and succeeded in going undisturbed along the straight path of evolution.

East of Europe, however, in all the culture of the East, we find an untold number of people who suffer greatly under the disturbing influence of Lucifer. His influence is, as we know, to draw man again and again away from the earth, to draw him right out of his physical body so that he shall perpetually fall into a state where he becomes no more than a vision of himself and is completely soul. That is the tendency that has been grafted onto Eastern Europe.

The feeling of being drawn in the other direction was given to the West. The world of imagination was pulled down into the heavy physical body so that what should rightly be free imagination working merely in the soul becomes instead something that rams the soul down into the organism, thereby causing the organism also to live on imaginations. You can hardly find a more telling description of what I mean than in the words of Alfred de Musset in which he attempts to give us a picture of the condition of his soul. De Musset is one who feels the presence of the imaginative life in himself, but he also feels the onslaught upon this life of imagination that seeks to thrust it right down into the bodily nature. This life of imagination, which does not belong in the bodily nature but should develop freely, hovering in and existing purely as a thing of the soul, is there taken hold of by earthly gravity and by what belongs to the body. In his book, Elle et Lui, which he was led to write from his relation with Georges Sand, you will find a fine description of his soul life. I would like to quote here a passage that will serve to show how he feels himself to be placed within an imaginative life that is the scene of conflict and dispute. He says:

Creation disturbs and bewilders me; it sets me trembling. Execution, always too slow for my desire, starts my heart beating wildly. Weeping, and restraining myself with difficulty from crying out, I give birth to an idea. In the moment of its birth it intoxicates me, but next morning it fills me with loathing. If I try to modify and change it, it only gets worse and escapes me altogether. It would be better for me to forget it and wait for another. But now this other comes upon me in such bewilderment and in such boundless dimensions that my poor being cannot grasp it. It oppress me, tortures me, until it can be realized. Then come the other sufferings, the birth throes, really physical pains that I am quite unable to define. Such is my life when I let myself be ruled by this giant artist who is in me.

Note the contrast with Boehme, who feels the God in him. With de Musset it is a giant artist.

It were better that I live as I have resolved, committing excesses of every kind in order to kill this gnawing worm, which others modestly call inspiration and I quite often openly call illness.

Almost every single sentence of this quote can be matched with a sentence in our quotation from Boehme. How singularly typical! Remember what I said just now, that normal evolution seeks to progress slowly. We shall have more to say about this tomorrow. Here, as described by de Musset, it is a Wild charge; it cannot be fast enough. The picture he gives us as he surveys himself is marvelous. “Creation disturbs and bewilders me; it sets me atremble,” he says, because this to will go faster and faster and comes storming in upon him from the ahrimanic side, disturbing what is still trying to progress slowly.

“Execution, always too slow for my desire, starts my heart beating wildly.” Here you have the whole psychology of the man who wants to live in free imaginations and is distressed and vexed by the onslaught of ahrimanic forces.

“Weeping and restraining myself with difficult from crying out...” Think of it! The imaginations work so physically in him that he feels like crying out when they find expression in him.

“I give birth to an idea. In the moment of its birth it intoxicates me, but next morning it fills me with loathing.” This because it comes from his organism and not from his soul!

“If I try to modify and change it, it only gets worse and escapes me altogether. Better I forget it and wait for another.” Here he wants perpetually to go faster, faster than normal evolution can go.

“But now this other comes upon me in such bewilderment and in such boundless dimensions that my poor being cannot grasp it. It oppresses me, tortures me, until it can be realized. Then come the other sufferings, the birth throes, actual physical pains that I am quite unable to define.” Then, when he beholds this giant artist that works within him, he says he would rather follow the life he has marked out for himself; that is, have nothing to do with this whole imaginative world, because he calls it an illness.

Now take by way of contrast, the saying of Jacob Boehme, “I declare before God, I myself do not know how it comes to pass in me.” Here you have an expression of joy and bliss. Confusion and bewilderment, on the other hand, can be heard in the words of de Musset, “Creation disturbs and bewilders me; it sets me trembling. Execution, always too slow for my desire, starts my heart beating wildly.”

With Boehme all is of the soul and, when he wants to write, he does not feel as though a giant artist, who makes him unhappy, were dictating to him, but a spirit. He feels that he is transported into the world where the spirit dictates to him. He is in this world and he is supremely happy to be there because a continuous stream of knowledge is given him that flows slowly and steadily on. Boehme is inclined to receive this slow stream of knowledge. He does not find it too slow because he is not overwhelmed by the swift attacking force I have described to you. On the contrary, he is protected from it.

If time permitted, we could present many more instances of ways in which individual human beings are situated in the world process. The examples I have selected are from those whose names have been preserved in history but, in a sense, all of mankind is subject to these same conditions in one way or another. I have only chosen these particular examples in order to express what is really widespread, and by taking special cases I have been able to give you a description of it in words. If you will try to make a survey of what we have been saying, you will then be able to understand much of what has come about in the course of evolution.

It would be quite possible in this connection to study many other phenomena of life. If, however, we confine ourselves today to the spiritual life, and moreover to that special region of the spiritual life comprising knowledge and cognition, we shall be able to find in it qualities that are characteristic of modern man, the recognition of which will make many things in life comprehensible. Since it is not possible to say much about the external life of today, owing to the existing prejudices and because men's souls are so deeply bound up with the conditions of the times in which they live, you will readily understand that it is only in a limited way that I can speak of the things that are carrying their influence right into the immediate present. It cannot be otherwise, as I have frequently made clear to you. I would like, however, to indicate certain phenomena of our time that are less calculated to arouse passions and emotions. Let me describe some phenomena that I will select from the life of cognition and feeling. I think you will find them underlying all I have been saying about the forces at work in this fifth post-Atlantean epoch. We will first consider these phenomena in a purely historical way in order afterward to see their relation to these forces.

Let us take first a phenomenon in which we all necessarily feel the deepest interest. The kind of understanding men have of the nature and being of Christ is of great significance, and so we will select examples of various kinds of understanding of His nature and being that lie near at hand. We have first of all a modern instance in Ernest Renan's The Life of Jesus, which appeared in the 19th century and went rapidly through many editions. I believe the twentieth appeared in 1900 after his death. Then we have The Life of Jesus, which is really no life of Jesus at all, by David Friedrich Strauss. Then we have—we cannot say, a life of Jesus, but coming from the east of Europe it is a view and conception of Christ that is of deep significance. It is not a life of Jesus but an understanding of Christ that culminates in what Soloviev wrote about Him and His part in the evolution of the earth. How significant are these three expressions of the spiritual life of the nineteenth century: The Life of Jesus by Renan, The Life of Jesus by Strauss, which is no life of Jesus at all and we shall presently hear why, and Soloviev's conception of the meaning of the Christ event in the evolution of the earth, for it is true, at any rate, to say that all of his work culminates in the Christ idea.

What is the fundamental premise of Renan's description of Jesus' life? If you want to appreciate rightly Renan's book, to understand it as a document of the times, then you must compare it with the earlier presentations of Jesus' life. Nor do you need to read only the literary accounts of His life; you can also look at the paintings of artists. You will find that the representation of the life of Jesus always takes the same path. In the early centuries of Roman Christianity, it was not only Christianity that was taken over from the East but also the manner in which Jesus was presented. The Greek art of pictorial representation was there in the West, as we know, but the ability to portray the Christ remained with the East. The Jesus countenance that is characteristic of Byzantine art was found repeatedly in the West until, in the thirteenth century, national impulses and ideas began to arise—those national ideas and impulses that later work themselves out in the way I have indicated in these last lectures.

Owing to the national impulse, a gradual change came about in the traditional stereotyped Jesus countenance that had been portrayed so long. Each of several nations appropriated the Jesus type and represented Him in its own way, and so we must recognize many different impulses at work in the different representations. Study, for example, the head of Jesus as painted by Guido Reni, Murillo, and LeBrun, and you will see how strikingly the national point of view steals in. These are only three instances that one could select. In each case there is a strong desire to represent Jesus in a national way. One has the impression that in Guido Reni's, paintings, to a far greater degree than was the case with his predecessors, we can detect the Italian type in the countenance of Jesus; similarly, in Murillo's representations, the Spanish; in LeBrun's, the French. All three painters show evidence as well of the working of church tradition; behind every one of their paintings stands the power of the Church.

Contrarily, you will find a resistance to this far reaching power of the Church, which we recognize in the art of Murillo, Lebrun, and Reni, in the works of Rubens, van Dyck, and Rembrandt—a resistance to it and a working in freedom out of their own pure humanity. Considering art in respect of its representations of the Jesus countenance, you have here direct artistic rebellion. You will now see that there is no standing still in this progression in the representation of Jesus because the forces that are at work in the world work also right into this domain. We can see how the breath of Romanism hovers over the paintings of the nationally minded LeBrun, Murillo, and Reni, and how in Rubens, van Dyck, and especially Rembrandt, the opposition to Romanism comes to such clear expression in their paintings of faces, not of Jesus alone but also of other Biblical characters. So we see how all the spiritual activities of man gradually take form among the various impulses that make themselves felt in human evolution.

Similarly, you would find that in the times when painting and representative art have given place to the word, for since the sixteenth century the word has had the same significance in such matters as pictorial representation had in earlier times, you will find that the figure of Jesus, of the Christ, is again continually changing. It is never fixed and constant but is always conceived according to how the various forces flow together in writers. Standing there before us as the latest products, let us say, we have the Jesus of Renan, the Jesus of Strauss, who is no Jesus, and the Christ of Soloviev. These are the latest products and how vastly different they are!

The Jesus of Renan is entirely a Jesus who, as a man, lives in the land of Palestine as a human historical figure. Palestine itself is marvelously depicted. With the aid of the best of modern scholarship it is described in such a way that one has before one the complete Palestinian landscape with its people. Wandering about this realistically rendered landscape and among its people is the figure of Jesus. The attempt is made to explain this Jesus figure on the basis of this landscape and its inhabitants; to explain how he grows up and becomes a man, and to explain how it was possible for such a man to arise in this land. The outstanding character of Renan's description will only be revealed when we compare it with earlier accounts and representations. These take the inner course of the events described in the Gospels and place them in a landscape that is really nowhere in particular. The facts as they are described in the Gospels are simply related over and over again and the landscape in which they occurred is totally disregarded. It is depicted in such a way that it might be anywhere.

Renan, however, goes to work to portray the Holy Land in a realistic, detailed way so that Jesus becomes a true Palestinian in this Holy Land. Christ Jesus, who should belong to all of mankind, becomes a Jesus who lives and walks in Palestine as an historical figure who is to be understood in relation to the Palestine of the years 1 to 33 A.D., that is, understood from the customs, views, opinions and landscape of the country—a right proper, realistic description. For once, Jesus was to be shown as an historical person and was to be described as any other in history. For Renan, it would have been meaningless to portray an abstract Socrates who might have lived anywhere, anytime, and it would have been equally meaningless for him to portray an abstract Jesus who might have lived anywhere on earth. In complete accord with the science of the nineteenth century, he sets out to depict Jesus as an historical figure living between the years 1 and 33 A.D., and made absolutely comprehensible by the conditions prevailing in Palestine at that time. Jesus lived from the year 1 to 33 A.D. He died in 33 A.D., just as any other man might have died in this or that year. If He continues to work in the world, it is in the same way any other dead person might have continued to work. Fitted completely into the modern point of view, Jesus was an historical personality accounted for by the milieu in which He lived. That is what Ernest Renan gives us in his Life of Jesus.

Now let us turn to the Life of Jesus that is in reality no life of Jesus by David Friedrich Strauss. I have said it is no life of Jesus. Strauss also works as a highly cultured and learned man. When he sets out to investigate anything, he does so with thoroughness akin to that of Renan in his domain. Strauss, however, does not turn his attention to the historical Jesus. He is, for him, only the figure to which he attaches something quite different. Thus, Strauss investigates all that was said of Jesus insofar as He was the Christ. He examines what is said about His miraculous entry into the world, His wonderful and miraculous development, His expression of great and special teachings, and how He undergoes suffering, death and resurrection. These are the accounts in the Gospels that Strauss selects for investigation.

Naturally, Renan, too, used the Gospels but he reduced them to what he, from his detailed and exact knowledge of Palestine, could conceive of the life of Jesus. This approach has no interest at all for Strauss. He tells himself that the Gospels relate this or that concerning Christ, who lived in Jesus. Then he sets out to investigate the extent to which what is related of the Christ has also been living as myth in other parts of the world, for instance, how the story that is told of a miraculous birth and the development of Jesus Christ is to be found in various other folk myths, as is also the Mystery of Golgotha, which is referred now the one god and then to another. Thus, Strauss sees in the figure of the historical Jesus only the opportunity for concentrating the myth forming activity of mankind into one personality. Jesus does not concern him at all. The only value He has for Strauss is that the myths, which are distributed all over the world, are concentrated in this single man Jesus. They are all hung on Him, as it were. These myths, however, all spring from a common impulse. All of them bear witness to the myth forming power that lives in mankind. Where does this myth forming power arise?

As Strauss sees it, in the course of mankind's earthly development, from the times of the first beginnings of the earth to its final end, mankind has and always will have a higher power in it than the merely external power that develops on the physical plane. A power runs right through mankind that will forever address itself to the super-earthly; this super-earthly finds expression in myths. We know that man bears something super-sensible within him that seeks to find expression in myth since it cannot be expressed in external physical science. Thus, Strauss does not see Jesus in the single individual, but rather the Christ in all men—the Christ who has lived in and through all men since their beginning, and who has brought it about that myths are told of Him. In the case of Jesus it is only that His personality gives occasion for the myth forming power to develop with extreme force and strength. In Him it is concentrated. Strauss, therefore, speaks of a Jesus that is in reality no Jesus, but he fastens upon Him the spiritual Christ force that lives in all humanity. For Strauss, mankind itself is the Christ, and He works always before and after Jesus. The true incarnation of the Christ is not the single Jesus, but the whole of humanity. Jesus is only the supreme representative for the representation of the Christ in mankind.

The main thing in all this is not Jesus as an historical figure, but an abstract mankind. Christ has become an idea, which incarnates in and through all mankind. That is the kind of highly distilled thought that a man of the nineteenth century is able to conceive! The element of life in the idea has become the Christ. He is conceived entirely as an idea and Jesus is passed by. This is a life of Jesus that is no more than a record of the fact that the idea, the divine, incarnates continually in all humanity. Christ is diluted down to an idea, is thought of merely as an idea.

So much for the second life of Jesus, The life of Jesus by David Friedrich Strauss. So we have Ernest Renan's Life of Jesus. which sets forth the historical figure of Jesus amidst the individuals around Him as well as by Himself. Then we have in Strauss's book the “idea of Christ,” which runs through all mankind. In this highly distilled form, however, it remains a mere abstraction.

When we come to Soloviev, behold, Jesus is no more, but only the Christ. Nevertheless, it is the Christ conceived as living. Not working in men as an idea, with the consequence that its power is transformed in him into a myth, but rather working as a living Being who has no body, is always and ever present among men, and is, in effect, positively responsible for the external organization of human life, the founder of the social order. Christ, who is forever present; a living Being who would never have needed a Jesus in order to come among men. Naturally, you will not find this so radically expressed in Soloviev, but that is of no account. It is the Christ as such Who stands always in the foreground—the Christ, moreover, as the living One who can only be comprehended in imagination, but by this means can be truly understood as a real and actual super-sensible Being working on earth.

There you have the three figures. The same Being meets us in the nineteenth century in a threefold description. The Life of Jesus by Ernest Renan, completely realistic; realistic history a fortiori; Jesus as an historical figure; a book that is written with all the learning of the nineteenth century. Then came David Friedrich Strauss with this idea of mankind, working on, running through all mankind, but remaining an idea, never awakening to life. Lastly, Soloviev's Christ; living power, living wisdom, altogether spiritual.

A realistic life of Jesus by Renan; an idealistic life of Jesus by Strauss that is also an idealistic presentation of the Christ impulse; a spiritual presentation of the Christ impulse by Soloviev.

Today, I want to place before you, side by side as three expressions of modern life, these three ways of cognizing the figure of Jesus Christ. Tomorrow we shall see how they take their place among the various impulses that we have recognized as working in mankind.

Zweiter Vortrag

Wir haben gestern versucht, gewissermaßen die Charakteristik zu geben der Kräfte, welche das Griechentum und das Römertum durchdrangen, um daraus eine Anschauung darüber zu gewinnen, was weiter wirksam geworden ist aus dem vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum herüber in den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum, und wir haben einiges angedeutet davon, wie dieses Herüberwirken, dieses Sich-Weiterergießen der Kräfte des vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraums in den fünften hinein sich zeigte. Ich möchte nun, daß Sie Ihre Aufmerksamkeit noch einmal zurücklenken auf die Art und Weise, wie wir das Griechentum, wie wir das Römertum charakterisieren konnten.

Das Griechentum, so wie es sich entwickelt hat, war eine große Enttäuschung für diejenigen Mächte, die man die luziferischen Mächte nennen kann. Es ist ja natürlich, daß man diese Dinge sozusagen nur aus der imaginativen Erkenntnis heraus geben kann, und so wollen wir es auch heute halten. Also eine große Enttäuschung war das Griechentum, wie es sich entwickelt hat, denn die luziferischen Mächte haben etwas ganz anderes erwartet vom Griechentum. Bedenken wir nur einmal, daß das Griechentum, als der vierte nachatlantische Zeitraum, in der nachatlantischen Zeit den luziferischen Mächten hätte gewissermaßen das bringen sollen, was sie für sich als luziferische Mächte angestrebt haben während der atlantischen Zeit. Die luziferischen Mächte haben gewisse Tätigkeiten, Kräfteeinwirkungen entfaltet während der atlantischen Zeit. Sie haben für sich die Früchte wiederholentlich erwartet in der vierten nachatlantischen Kulturepoche. Was haben sie denn eigentlich erwartet? Wenn man so etwas bespricht, kommt man zu einer Anschauung des Inneren der luziferischen Seele. Man lernt kennen dieses luziferische Leben, das besteht in fortwährenden Anstrengungen in gewissen Zeiträumen, in der Erwartung, daß diese Anstrengungen ihren Erfolg haben, und in immer neuen Enttäuschungen. Gewiß, ein sogenannter menschlicher Logiker könnte sich sagen: Warum geben die luziferischen Mächte ihr Streben nicht auf, da sie ja die Schlußfolgerung ziehen können, daß sie immer wieder enttäuscht werden müssen? — Ein solcher Schluß wäre eben auch menschliche Weisheit, nicht luziferische Weisheit. Es haben das eben die luziferischen Mächte bisher jedenfalls nicht getan, sondern sie vergrößern immer wieder ihre Anstrengungen, nachdem sie immer neue Enttäuschungen erlebt haben.

Was haben die luziferischen Mächte erwartet gerade von dem vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum? Sie haben erwartet, daß sie sich in diesem Zeitraum bemächtigen können all der Seelenkräfte des griechischen Volkes, welche darauf hinausliefen, die alten Imaginationen der chaldäisch-ägyptischen Zeit in die Phantasieschöpfung hereinzunehmen. Die luziferischen Mächte haben angestrebt, so stark auf die Menschen der griechischen Kultur zu wirken, daß diese verfeinerten, ich möchte sagen, bis zur Phantasie destillierten Imaginationen mächtig erfüllt hätten das ganze Wesen des Griechen, so daß der Grieche gewissermaßen ganz aufgegangen wäre in einer Seelenwelt, in einem alltäglichen Denken, Fühlen, Wollen, das ganz bestanden hätte in feinen, eben bis zur Phantasieanschauung verfeinerten Imaginationen. Wenn der Grieche nichts anderes in seiner Seele entwickelt hätte als diese verfeinerten Phantasieimaginationen, wenn er sich ganz erfüllt hätte mit diesen verfeinerten Gefühlsimaginationen, dann hätten die luziferischen Mächte den Menschen, diesen griechischen Menschen, und damit nachziehend einen großen Teil der Menschheit überhaupt, herausheben können aus der irdischen Evolution und in ihre luziferische Welt einfügen. Das war die Absicht der luziferischen Mächte. Es war auch die Hoffnung der luziferischen Mächte seit der alten atlantischen Zeit, das zu erreichen in diesem vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum, was während der Atlantis selber nicht gelungen war: die Einverleibung der Menschheit in den Kosmos auf der Stufe, die da die Menschheit erreicht hatte. Nichts Geringeres wollten die luziferischen Mächte, als für sich eine Welt schaffen, eine aparte, abgesonderte Welt, in welcher ohne die Erdenschwere, mit vollständiger übersinnlicher Leichtigkeit, die Menschenwesen wohnten, indem sie ganz aufgehen in dieser aparten luziferischen Welt in einem Phantasieleben.

Also einen planetarischen Körper zu schaffen mit solchen Wesen, die aus der Menschheit heraus zu der höchsten Entwickelung des Phantasielebens gekommen sind, das war die Hoffnung der luziferischen Wesenheiten. Und die luziferischen Wesenheiten machten alle Anstrengungen, die Griechen dazu zu bringen, sie als Seelen hinwegzuführen von der Erde. Dann würden die Seelen nach und nach die Erde verlassen haben; die Körper, die noch entstanden wären, würden verfallen sein. Ich-lose Individuen würden entstanden sein. Die Erde wäre der Dekadenz entgegengegangen und ein besonderes luziferisches Reich wäre entstanden. Das ist nicht geschehen. Und wodurch ist es nicht geschehen? Es ist nicht geschehen dadurch, daß sich in den sich vergöttlichenden Wahnsinn der griechischen Dichter — um dies platonische Wort zu gebrauchen - hineinmischte die geniale Größe der griechischen Philosophie, der griechischen Weisheit. Seine Philosophen: Heraklit, Thales, Anaximander, Anaximenes, Parmenides, Sokrates, Plato, Aristoteles, sie haben das Griechentum gerettet vor der vollständigen Vergeistigung im Phantasieleben. Sie haben das Griechentum auf der Erde erhalten. Sie sind diejenige Macht, welche die stärksten Kräfte geliefert hat zur Erhaltung des Griechentums innerhalb der Erdenevolution.

So muß man im Zusammenhange betrachten die hinter der physischen Wirklichkeit liegenden Kräfte, welche die wahren Ursachen sind für das, was geschieht. Auf diese Weise ist also das Griechentum der Erdenevolution erhalten geblieben. Mit Bezug auf diese Aufgabe hätten die luziferischen Wesenheiten ohnehin nichts erreichen können, wenn sie nicht unterstützt worden wären von den ahrimanischen Wesenheiten. Es haben die luziferischen Wesenheiten bei dieser Absicht und bei dieser Hoffnung auch gerechnet auf die Unterstützung der ahrimanischen Wesenheiten. Dieses muß ja immer sein, daß in diesen Wirkungen zwei Kräfte zusammenstreben.

Ebenso wie die luziferischen Wesenheiten enttäuscht worden sind durch das Griechentum, so sind die ahrimanischen Wesenheiten enttäuscht worden durch das Römertum, wie es sich entwickelt hat. Denn wie ihrerseits die luziferischen Wesenheiten im Griechentum erreichen wollten das, was angedeutet worden ist: ein Hinwegführen der Menschenseelen von dem irdischen Planeten, so wollten auch die ahrimanischen Wesenheiten ihre Arbeit zu diesem Hinwegführen tun. Dazu sollte die römische Kultur eine ganz bestimmte Gestalt annehmen. Im Römertum haben die ahrimanischen Mächte ihre stärksten Kräfte eingesetzt, so wie im Griechentum die luziferischen. Denn die ahrimanischen Kräfte haben darauf gerechnet, daß durch das Römertum auf der Erde eine gewisse Erstarrung entstehe in einem ganz blinden Gehorsam und in einer blinden Unterwerfung unter das Römertum. Was die ahrimanischen Mächte mit dem Römertum wollten, bestand darin, daß sich über die ganze damals bekannte Erde hin ein römisches Reich erstreckte, ein römisches Reich, welches alle menschliche Betätigung in sich fassen sollte, welches mit strengstem Zentralismus und ärgster Machtentfaltung von Rom aus hätte dirigiert werden sollen: gewissermaßen von Europa ausgehend eine große, eine weitverbreitete Staatsmaschine, die zu gleicher Zeit alles religiöse und alles künstlerische Leben aufgenommen und sie sich unterworfen hätte. Eine große Staatsmaschine, ein Staatsmechanismus, in dem beabsichtigt war von seiten der ahrimanischen Mächte, alle Individualität ersterben zu lassen, so daß ein jeglicher Mensch, ein jegliches Volk nur ein Glied in diesem großen Staatsmechanismus gewesen wäre.

So wenig das Griechentum in den luziferischen Traum einzulullen war wegen der Helligkeit seiner Philosophen, so wenig war aber das Römertum so zum Erstarren zu bringen, wie es die ahrimanischen Mächte gewollt haben. Und den ahrimanischen Mächten wirkte gerade entgegen im Römertum das, was wir gestern angeführt haben als die römischen Ideale; gerade das wirkte zunächst entgegen. Aber das allein hätte gegen Ahriman nicht anstürmen können, was an juristischen, an politischen, an soldatischen Idealen sich entwickelte; denn gerade innerhalb dieser römischen Welt entwickelten die ahrimanischen Kräfte etwas wie einen bedeutsamen großen Versuch als Wiederholung ihres Versuches in der atlantischen Zeit, unendlich starke Kräfte und Mächte. Nur dadurch, daß von einer anderen Seite her das durchbrochen wurde, was die ahrimanischen Mächte mit dem Römertum vorhatten, nur dadurch ist der Ansturm Ahrimans verhindert worden; zuerst verhindert worden durch etwas, was vielleicht gerade so aussieht, als ob man es niedrig taxieren sollte. Das ist aber nicht der Fall. Die Römer brauchten gerade das, was vielleicht, indem es gestern geschildert worden ist, so ausgesehen hat, als ob man es mit Antipathie hätte schildern wollen, die Römer brauchten gerade diese Rücksichtslosigkeit, diesen starren Egoismus, dieses Immerfort-und-fort-Aufrürteln der Emotionalität, um gegen den Ansturm der ahrimanischen Mächte vorgehen zu können. Und die römische Geschichte ist nicht etwa - ich bitte Sie, das ausdrücklich zu beachten — eine Offenbarung ahrimanischer Mächte! Die stehen dahinter: die römische Geschichte ist ein Kampf gegen die ahrimanischen Mächte. Und wenn sie so verworren ist, wenn sie so selbstsüchtig ist, wenn sie so auf Verpolitisierung der Welt gerichtet ist, so ist das deshalb, weil nur auf diese Weise der Mechanisierung Ahrimans Widerstand geboten werden konnte.

Aber all das hätte nicht viel gefruchtet, aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil das Römertum auch aufgenommen hat das Christentum, und dadurch würde das Christentum im Römertum eine Form angenommen haben, durch die Ahriman erst recht sein Ziel hätte erreichen können, indem er gerade durch die geistige Abdämmerung des ins Papsttum verwandelten Römertums die Mechanisierung der Kultur der neueren Zeit hätte bewirken können. So mußte dem Ahriman, der ja mit viel äußerlicheren Mitteln wirkt als Luzifer, entgegengestellt werden eine andere Macht, auch eine äußerliche Macht. Ahriman hat die Kräfte des Christentums in seinen Dienst verkehrt, wie wir eben gesehen haben. Es mußte ihm eine andere Macht entgegengestellt werden, und die bestand in den anstürmenden Völkern der Völkerwanderung. Dadurch, daß dem Römertum entgegengetreten worden ist in den anstürmenden Völkern der Völkerwanderung, ist verhindert worden, daß jene starre Mechanisierung unter einem alles umfassenden Römerreich eingetreten ist. Studieren Sie die Vorgänge während der Völkerwanderung, so werden Sie sehen, daß Sie eine richtige Einsicht erst gewinnen, wenn Sie diese auffassen als Vorstöße gegen die Mechanisierung in einem allumfassenden römischen Reich. Überall schiebt sich das, was aus der Völkerwanderung kommt, in das Römerreich hinein, nicht um die römische Geschichte aus der Welt zu schaffen, sondern um die hinter der römischen Geschichte wirkende, ja von der römischen Geschichte selbst bekämpfte ahrimanische Macht zurückzudrängen.

Auf diese Weise ist Ahriman, ist Luzifer enttäuscht worden. Um so bedeutungsvoller wollen sie ihre Aufgabe für den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum wieder aufnehmen. Und hier ist der Punkt, wo man zu einem Verständnisse kommt der Kräfte, die in dem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum wirksam sind, soweit ein solches Verständnis heute möglich ist.

Dieser vierte nachatlantische Zeitraum dehnt sich nach hinten und vorn aus. Ungefähr ist sein Ende das Jahr 1413, seine Mitte das Jahr 333 nach Christi Geburt, und etwa 747 vor Christi Geburt ist sein Anfang. Das haben wir ja öfter besprochen. Das sind Zahlen, die ja natürlich heute nur approximativ gelten. Ich sagte nun: Das, was Luzifer und Ahriman nicht erreichen konnten im vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum, was ihre Enttäuschung war, eben die Gestalt, die das Griechentum und Römertum angenommen hatte, führte sie zum verstärkten Anstreben im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum, also vom 15. Jahrhundert an. Und in den menschlichen Kräften, die da wirken seit dem 15. Jahrhundert, sind diese Anstrengungen schon darinnen. Natürlich kommt es nicht darauf an, ob etwas ein paar Jahrzehnte früher oder später auftritt; in der äußeren physischen Wirklichkeit, wo man es ja mit der großen Täuschung zu tun hat, verschieben sich die Dinge zuweilen etwas. Daß das Römertum, so wie es erhalten worden ist, für die Entwickelung der Menschheit erhalten werden konnte, wird also verdankt den Ereignissen der Völkerwanderung. Denn hätte sich das Römertum so entwickelt, daß ein großes, umfassendes, mechanisiertes Weltenreich entstanden wäre, so wäre dieses Weltenreich nur möglich zu bewohnen gewesen von jenen Ich-losen Menschen, die auf der Erde hätten zurückbleiben sollen, nachdem die luziferischen Geister die Seelen auf dem Wege des Griechentums hinausgebracht hätten.

Sie sehen also, wie Ahriman und Luzifer zusammenarbeiten. Die Menschenseelen will Luzifer heraus haben und einen eigenen Planeten mit ihnen begründen; Ahriman mußte nun ihn unterstützen dadurch, daß, während Luzifer gewissermaßen den Saft aus der Zitrone heraussaugt, Ahriman ihn herausdrückt, indem er das, was zurückbleibt, verhärtet. Und das versuchte er im Römischen Reiche zu tun. Sie sehen da einen mächtigen, umfassenden kosmischen Prozeß, der sich entwickelt hat, der aber beabsichtigt war von den ahrimanischen und luziferischen Mächten. Wie gesagt, diese waren enttäuscht. Sie haben ihre Anstrengungen weiter fortgesetzt, und der fünfte nachatlantische Zeitraum wird schon noch merken und verstehen lernen, wie stark diese Anstürme sind, die ja erst ihren Anfang genommen haben, und die, weil immer im Anfang eines Zeitraumes die Anstürme, die von den zurückbleibenden Wesen ausgehen, am geringsten sind und dann immer mächtiger werden, und wie daher auch die Notwendigkeit, diese Anstürme zu verstehen, immer größer und größer wird. Schon vor Ablauf des vierten nachatlantischen Kulturzeitraumes haben die luziferischen und ahrimanischen Mächte begonnen, ihre Kräfte einzusetzen, wenn auch die Manifestation, die Offenbarung dieses Einsetzens erst später herausgekommen ist.

Will man verstehen, wie in dem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum diese Anstürme wirken, so muß man ein wenig das Augenmerk auf das richten, was in der gerecht fortlaufenden Menschheitsentwickelung mit dem Menschen selber beabsichtigt ist. Mit dem Menschen selber ist beabsichtigt, daß er wiederum ein Stück vorschreitet, als Menschengeschlecht vorschreitet in der Gesamtentwickelung. Wie die Menschheit als solche vorwärtsgekommen ist im vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum, das zeigt ja die Kulturentwickelung der Griechen, das zeigt die politische Entwickelung der Römer. Es ist gerade durch den Kampf gegen Luzifer und Ahriman das zustande gekommen, was hat zustande kommen sollen; denn immer werden die Kräfte dieser Mächte so gewendet, daß sie gewissermaßen in den fortgehenden Weltenplan hineinpassen, daß man sieht, sie gehören dazu. Man braucht sie als widerständige Kräfte. Also, welche Fähigkeiten sollten die Menschen des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums, unseres Zeitraums, besonders entwickeln? Wir wissen ja, daß es sich um die Entwickelung der Bewußtseinsseele handelt, allein diese muß sich wiederum zusammensetzen aus einer Reihe von Kräften, Seelenkräften, körperlichen Kräften. Das erste, was entwickelt werden muß, wenn der Mensch richtig auf der Erde bleiben soll, das ist ein wirkliches reines Anschauen der Sinnenwelt. Ein solches reines Anschauen der Sinnenwelt war in den früheren Zeiträumen nicht da, weil immer in das menschliche Seelenleben das Visionäre, das Imaginative hereinspielte, bei den Griechen noch die Phantasie. Aber nachdem die Phantasie die Menschheit soweit ergriffen hatte, wie sie im griechischen Leben eben sie ergriffen hat, da wurde notwendig, daß die Menschen die Fähigkeit entwickelten, unbehelligt durch eine dahinterstehende Vision die äußere Naturwirklichkeit anzuschauen. Wir brauchen uns dabei nicht vorzustellen, daß das materialistische Weltbild damit gemeint ist; dieses materialistische Weltenbild ist schon ein ahrimanisch verzerrtes Anschauen der Sinneswirklichkeit. Aber, wie gesagt, die Sinneswirklichkeit ordentlich zu beobachten, das war die eine Aufgabe des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums.

Die andere Aufgabe der Menschenseele ist diese: neben der reinen Anschauung der Wirklichkeit zu entwickeln freie Imagination, in einer Beziehung eine Art Wiederholung der ägyptisch-chaldäischen Zeit. Darinnen ist der fünfte nachatlantische Zeitraum noch nicht sehr weit. Freie Imaginationen müssen entwickelt werden, wie sie gesucht werden durch die Geisteswissenschaft, also nicht gebundene Imaginationen, wie sie der dritte nachatlantische Zeitraum hatte, nicht zur Phantasie destillierte Imaginationen, sondern freie Imaginationen, in denen man sich so frei bewegt, wie sich der Mensch sonst nur in seinem Verstande frei bewegt. Daraus, daß diese zwei Fähigkeiten entwickelt werden, wird sich ergeben das rechte Entwickeln der Bewußtseinsseele des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums.

Goethe hat sehr schön empfunden das reine Anschauen, das er im Gegensatz zum Materialismus bezeichnet hat mit seinem Urphänomen. Sie können in Goethes Schriften und in meinen Erklärungen dazu über dieses Urphänomen viel gesprochen finden. Es ist die reine Anschauung der Wirklichkeit, dieses Urphänomen. Aber Goethe hat nicht nur den ersten Anstoß gegeben zu einer visionsfreien sinnlichen Beobachtung im Urphänomen, sondern er hat auch den ersten Anstoß gegeben zur freien Imagination; denn gerade das, was wir in seinem «Faust» gefunden haben, wenn es auch noch nicht weit ist in geisteswissenschaftlicher Beziehung, wenn es auch noch in gewisser Weise instinktiv nur im Verhältnis zur Geisteswissenschaft ist, es ist doch der erste Anstoß des freien imaginativen Lebens, denn es ist nicht bloß eine Phantasiewelt. Wir haben gesehen, wie tief wirklich diese Phantasiewelt ist, die in freien Imaginationen in diesem wunderbaren Faust-Drama entwickelt wird. So allerdings haben wir dem Urphänomen gegenüber das, was Goethe das typische intellektuelle Anschauen nennt. Sie können in meinem Buche «Vom Menschenrätsel» darüber Genaueres lesen. Das muß sich immer weiter und weiter ausbilden. Auf der einen Seite muß der fünfte nachatlantische Zeitraum in der Wirklichkeit nicht nur anschauen, sondern mit der Wirklichkeit leben können, so daß er abseits von den materialistischen Physikern so wie Goethe etwa hantiert in seinem physikalischen Kabinette, um die Instrumente so zu gebrauchen, daß sie ihm die Urphänomene geben. So muß man sich eine Hantierung auch in bezug auf das praktische Leben denken, welche dieses praktische Leben mit dem Urphänomen durchdringt, welche also in der Natur so zu Hause ist, daß die Natur von dem Urphänomen aus beherrscht wird, und eingeschlossen in dieses Urphänomen der Natur müssen werden die Intentionen des Menschengeschlechtes, die aus der freien Imagination kommen. Auf der einen Seite gewissermaßen selbstlos den Blick auf die Außenwelt zur Erkenntnis und zur Arbeit zu richten, und auf der anderen Seite das Ganze selbst mit stärkster Einsetzung der Persönlichkeit in innerliche Regung und Bewegung zu bringen, um die Imaginationen zu finden für die äußere Tätigkeit und äußere Erkenntnis, das wird die Bewußtseinsseele und das Kulturleben der Bewußtseinsseele nach und nach in die Wirklichkeit verwandeln.

Einseitigkeiten werden sich selbstverständlich innerhalb dieses Kulturzeitraumes entwickeln. Die Erkenntnis wird nur nach der Außenwelt streben wie im Baconismus, oder sie wird nur nach dem Inneren streben wie im Berkeleyismus. Davon haben wir gesprochen. Dieses imaginative Leben, welches aus dem Inneren des Menschen hervorquellen will, wird sich unter allerlei Störungen entwickeln. Aber wir können doch schon hinweisen auf gewisse Punkte der Entwickelung, in denen dieser oder jener Mensch fühlt, wie aus der Seele gerade dieses imaginative Leben hervorkommt, dieses freie imaginative Leben. Anfangs ist es noch sehr wenig frei, sehr gebunden; aber beachten wir, wie ein in seiner Art so bedeutsamer Mensch wie Jakob Böhme, kurz nachdem der fünfte nachatlantische Zeitraum begonnen hat, schon fühlt, wie das imaginative Leben in seiner Seele sich herausentwickeln will. Er spricht es deutlich aus in seiner «Aurora», wie er fühlt, daß das imaginative Leben in ihm arbeitet. Frei muß es erst werden; er fühlt es noch etwas unfrei, aber er fühlt, daß da das Göttlich-Schöpferische in ihm wirkt. Und so ist er in gewissem Sinne der Gegenpol zu dem Baconismus, der da anstrebt, in einseitiger Weise nur auf die Außenwelt den Blick zu richten. Jakob Böhme ist ganz in der Innenwelt beschäftigt und beschreibt in der «Aurora» schön:

«Ich sage vor Gott» — weil er von seinem Innern spricht, sagt er so -, «daß ich selber nicht weiß, wie mir damit geschieht» - indem die Imaginationen in ihm aufgehen -; «ohne daß ich den treibenden Willen habe, weiß ich auch nichts, was ich schreiben soll.» So spricht er vom Aufgehen der Imaginationen; das ist der Anfang von Kräften, die immer mehr und mehr die Menschheit des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums überkommen müssen, die da Jakob Böhme spürt. «Ich sage vor Gott, daß ich selber nicht weiß, wie mir damit geschieht; ohne daß ich den treibenden Willen habe, weiß ich auch nichts, was ich schreiben soll. Denn so ich schreibe, diktiert es mir der Geist in großer wunderlicher Erkenntnis, daß ich oft nicht weiß, ob ich nach meinem Geist in dieser Welt bin und mich des hoch erfreue, da mir denn die stete und gewisse Erkenntnis wird mitgegeben.»

Das Hereinströmen der imaginativen Welt beschreibt er. Wir sehen, er fühlt sich harmonisch ruhig in seiner Seele und beschreibt, wie normalerweise im gerechten Fortgange der Entwickelung die Menschenseelen von diesen inneren Kräften sich sollen ergreifen lassen. Diese Kräfte sollen über die Menschenseele kommen im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum; aber sie sollen ergriffen werden im reinen geistigen Inneren. Sie sollen nicht irgendwelche irrtümliche Wege nehmen. Ungefähr so über diese Kräfte im 17. Jahrhundert müßte man reden, wie Jakob Böhme redet, dann redete man als ein ganz nur der göttlichen allgemeinen Gerechtigkeit hingegebener Mann von diesen Kräften. Daß weder die eine Art von Kräften, das reine Anschauen der Urphänomene, noch die andere Art von Kräften, die Entwickelung der freien Imaginationen, die nicht in Visionen bestehen, sondern die eben freie Imaginationen sind, aufkommen, daß diese Kräfte in der Menschenseele möglichst gestört werden, möglichst dazu verwendet werden, um nun wiederum die Menschheit als Seele hinauszubringen aus dem Erdenplan und mit ihnen einen besonderen Plan zu begründen, das ist nun die Wirkensart der luziferischen und ahrimanischen Mächte in dem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum.

Vieles muß ja zusammenwirken, damit die richtige Entfaltung, die ruhige und langsame Entfaltung gestört werde. Hören Sie wohl: ich sage nicht nur die ruhige, sondern die ruhige und langsame Entfaltung, denn es soll ja der ganze Zeitraum von 1413 an durch 2160 Jahre ungefähr dazu verwendet werden, um diese Kräfte, die ich angeführt habe, freie Imaginationen und Urphänomene beziehungsweise urphänomenale Arbeit, nach und nach zu entwickeln. Stoßweise, mit allen möglichen widerstrebenden Kräften, wirken nun die luziferischen und ahrimanischen Mächte dagegen. Wenn wir nur ins Auge fassen wollen, daß das, was geschieht, immer lange vorbereitet wird von der außerirdischen Welt, dann wird es uns nicht unverständlich sein, daß Vorbereitungen getroffen worden sind, um recht, recht starke Gegenwirkungen gegen die normale Evolution der Menschheit zu bewirken. Wir haben ja gesehen, daß schon ins Griechentum und Römertum die luziferischen und ahrimanischen Mächte das hineingegossen haben, was sie in der atlantischen Zeit entwickelt haben. In einer veränderten Form versuchten sie nun diese Anstrengungen zu wiederholen schon vor dem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum für diesen fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum. Sie werden es also jetzt nicht unbegreiflich finden, wenn ich sage, daß notwendig war ein starker Anstoß mit Nachwirkungen, luziferisch-ahrimanischen Nachwirkungen der Atlantis auch für diesen fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum. Wir wissen ja, daß die atlantischen Wirkungen ausgestrahlt sind von dem, was ja Plato bereits kennt als die Atlantis. Wir wollen es einmal schematisch so machen, daß wir etwa die Atlantis uns hier denken (siehe Zeichnung); dann würde hier das europäische, asiatische Gebiet sein, und hier würde das amerikanische Gebiet sein. Davon strahlten also aus die alten arlantischen Kräfte, auch die alten atlantischen luziferischen und ahrimanischen Kräfte.

Nun wurde von diesen etwas zurückbehalten, um als luziferische und ahrimanische Mächte zu wirken im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum, und zwar auch von den guten Kräften etwas zurückbehalten, von den in der atlantischen Zeit berechtigten Kräften etwas zurückbehalten, was jetzt auch luziferisch und ahrimanisch ist. Nur wurde der Mittelpunkt nach einem anderen Punkte der Erde verlegt. Die Atlantis ist ja fort. Der Mittelpunkt wurde nach Asien hinüber verlegt, so daß Sie also sich vorstellen würden auf der abgekehrten Seite desjenigen, was ich da schematisch gezeichnet habe, in Asien drüben, von da ausstrahlend Nachwirkungen der alten atlantischen Kultur als Vorbereitung für den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum, ihn zu luziferisieren und zu ahrimanisieren. Es waren im wesentlichen Nachkommen der alten atlantischen Lehrer, welche nun wirkten von einem Punkt in Asien drüben. Ein Priester war dazu erzogen worden, das, was man in der alten Atlantis gesehen hat, nachträglich zu schauen, zu schauen das, was der Atlantier nannte den Großen Geist, und von diesem Großen Geist Aufträge zu empfangen. Und diese Aufträge teilte der mit diesen Aufträgen initiierte Priester einem jungen, außerordentlich starken, tatkräftigen, tüchtigen Menschen mit, der durch diese Aufträge dann innerhalb seiner Gemeinschaft den Namen «Der große Beherrscher der Erde» erhielt, Dschingis-Khan. Und der Große Geist hatte durch seinen Nachfolger, auf dem Umwege durch diesen Priester, an Dschingis-Khan den Auftrag gegeben, alles, was aufzubringen war an Mächten in Asien, dazu zu verwenden, um auszubreiten das, was den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum zurückführen konnte in eine luziferische Gestaltung. Diese starken Kräfte, die noch viel stärker waren als die im Griechentum einsetzenden, die wurden aufgewendet von dieser Seite her. Von dieser Seite her sollten alle freien Imaginationen verwandelt werden in alte Imaginationen, in visionäre Imaginationen. Es sollte in der stärksten Weise gearbeitet werden, die Seele des Menschen ganz einzulullen in dämmerndes Erleben der Imaginationen, nicht in freies, von der Vernunft durchtränktes Erleben der Imaginationen. Die Absicht bestand, mit den besonderen Kräften, die da aus der Atlantis herein erhalten waren, so nach dem Westen zu wirken, daß die Kultur des Westens eine visionäre Kultur geworden wäre. Dann hätte man die Seelen abtrennen und einen besonderen Kontinent, einen besonderen planetarischen Körper mit ihnen bilden können. Alle Unruhen, welche durch die Mongolenstürme und alles das, was damit zusammenhängt, in die Entwickelung der neueren Menschheit gekommen sind und was fortgewirkt hat im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum, nachdem sie vorbereitet waren schon früher, alle diese Unruhen bedeuten den großen, von Asien ausgegangenen Versuch, die europäische Kultur zu «vervisionieren», um sie abzutrennen von den Bedingungen der fortlaufenden Evolution, um sie gewissermaßen hinwegzuführen von der Erde. Der Osten empfand sehr wohl immer wieder und wiederum dieses Durchvisionieren, dieses Entfremdenwollen von der Erde.