The Cyclic Movement of Sleeping and Waking

GA 172

6 November 1916, Dornach

Translator Unknown

Let us now approach the problem which lies before us in these lectures once more from another starting-point. For in spiritual science it must be so: we must always seek to encompass a problem and approach it from many different aspects.

Broadly speaking, one thing especially must strike us when we consider such a life as Goethe's. It is a great riddle in human evolution, even when we take into account repeated earthly lives and their effect in moulding the life of man. How is it that isolated individuals like Goethe are able to produce such wonderful creations out of their inner life? We think especially of Goethe's Faust. How is it that a single human being' can have so great an influence on the remainder of mankind through his creations? How does it come about that single individuals are thus lifted out of the remainder of mankind, summoned, as it were, by universal destiny, to do such mighty works? We will compare the life and work of every man with these great lives and works, and ask ourselves: What can we tell by this difference between the life of any individual and the lives of great men so-called?

This is a question we can only answer if we consider life a little more' in detail by the means which spiritual science affords. All that a man can perceive to begin with, especially with the knowledge of our time, is calculated to conceal certain truths, keeping them far removed from the free and open vision of mankind. This too makes it necessary for us to begin to speak of many things in connection with spiritual science, which alone will enable us to understand them rightly.

In spiritual science, as you know, we describe the human being as follows. Man, we say, as he appears to us in life, consists of the physical body, the etheric body, the astral body and the Ego. We then characterise the alternating conditions of sleeping and waking. In waking life, we say, the Ego and astral body are inside the physical body and the etheric, in sleep they are outside.

For an initial understanding of the matter that is enough, and it is quite in accordance with the spiritual-scientific facts. But the point is that in thus describing it we are giving only a portion of the full reality. We can never comprehend the full reality in one description. Whatever we describe, it is always only part of the full reality, and we must look for light from other quarters, rightly to illumine the partial reality which we have thus described.

In general, it is so: sleeping and waking represent a kind of cyclic movement for the human being. Strictly speaking, it only applies to the head when we say that the Ego and astral body of man are outside the physical and etheric body during sleep. In actual fact, precisely because they are outside the physical and etheric head of man, the Ego and astral body in sleep are acting all the more vividly upon the rest of man's organisation. During sleep—when the Ego and astral body are working- upon man as it were from without—all that is not 'head' in man, but the remainder of his organisation, is subjected to a far stronger influence by the Ego and the astral body, than it is in waking life. Indeed, we may truly say, the influence which the Ego and astral body wield over the head of man in waking life,—this influence they wield over the remaining organism during sleep. In a certain sense we may compare, notably the Ego of man, to the Sun. When it is day with us, the Sun is shining on our regions of the Earth. When it is night, the Sun is not merely out yonder; it actually illumines the other side of the Earth, making it daytime there. So in a certain sense it is the 'day' in our remaining organism, when for our sense-perception, which is mainly bound to the head, ˃t is the night-time. And it is night for our remaining organism when it is day-time for our head. For when we are awake the remainder of our organism is more or less withdrawn from the Ego and from the astral body. This too must be added, to illumine the full reality and so to understand the human being in his totality.

To understand what I have just said, we must however also realise the connection of the soul and the physical being of man in the following respect. I have often emphasised that the nervous system of the physical body is a single organisation. It is mere nonsense, not even justified by external anatomy, to divide the nerves into 'motor' and 'sensory.' The nerves are all of one kind, and they all have one function. The so-called motor nerves differ from the so-called sensory nerves only in this respect: the sensory nerves are so arranged that they serve for our perception of the outer world, whereas the motor nerves, so-called., enable us to perceive our own body. A motor nerve is not there to enable me to move my hand. That is mere nonsense. It is there to enable me to perceive the movement of my hand, that is, inwardly to perceive, whereas the sensory nerves are there to help me perceive the outer world. That is the only difference.

Now our nervous system, as you know, has three distinct members: first there are the nerves whose chief centre is in the brain—nerves, therefore, which are centred in the head. Then there are the nerves which are centred in the spinal column, and lastly, there are the nerves which we include in the so-called sympathetic system. These, in the main, are the three kinds of nerves which man possesses. Now the point is for us to recognise the relation between the three kinds of nervous systems and the spiritual members of man's organisation. Which is the most advanced, as it were the most refined member of the nervous system, and which the least advanced?

It goes without saying—those that come from the ordinary scientific outlook of to-day will answer—the nervous system of the brain is of course the most refined, the highest; for it distinguishes man from the animals. But it is not so in reality. The nervous system of the brain is connected in the main with the organisation of our etheric body. Needless to say, there are more far-reaching relationships on every hand, and our brain system also has its relations to the astral body and the Ego. But these relations are secondary. The primary, the most original relations are those between our brain-nervous-system and our etheric body. This does not affect the other aspect which I once explained, namely that the whole nervous system has come into being with the help of the astral body. That is an altogether different matter and should be kept distinct. In its original plan and predisposition, it was brought about during the old Moon epoch. But it has gone on evolving, and other relationships have entered in since its prime formation. And so in fact, our brain-nervous-system has the most intimate and important relations with our etheric body. On the other hand, the nervous system of the spinal column has the most intimate and primary relations with the astral body, such as we have it in us now. Finally, the sympathetic nervous system is related to the Ego, the real Ego of man. These are the primary relationships, as we now have them.

Bearing this in mind, we shall readily conceive that there is a peculiarly vivid relationship in sleep between our Ego and our sympathetic nervous system. This system, as you know, is mainly spread out in the abdominal organism, and with its strands it envelopes the spinal column from without ... Now these relations between the Ego and the sympathetic system are loosened during our day-waking life. They are still there, but they are loosened. In sleep they are more intimate. Moreover, the relations between the astral body and nerves of the spinal column are more intimate in sleep than in our day-waking life. Thus we may say: during our sleep the most intimate relationships arise, between our astral body and the nerves of our spinal column, and at the same time between our Ego and our sympathetic nervous system. In sleep, with our Ego we live more or less intensely in connection with our sympathetic system. Once the mysterious world of dreams is more accurately studied, what I am now saying out of spiritual- scientific research will soon be recognised.

If you bear this in mind, you will find the way over to another most essential thought. Something deeply significant is given to our life inasmuch as there is this rhythmic alternation, for example, in the living-together of the Ego with the sympathetic and the astral body with the spinal nervous system—a rhythmic alternation which is really identical with that between sleeping and waking. It will not appear altogether surprising to you, if we now assert: Inasmuch as the Ego is well inside the sympathetic system and the astral body well inside the spinal system during sleep, man with respect to his sympathetic and his spinal nervous system is awake in his sleep and asleep in his waking life.

Only this question may perhaps be raised at this point: How is it that we know so little of this wide-awake activity which is said to be unfolded during our sleep? Well, you must bear in mind how man has come to be. It was only during the present Earth- evolution that the Ego took up its abode in man. The Ego is in fact the 'baby' among the members of our human being. If you bear this in mind you will be less surprised that this Ego, in its life, cannot yet bring to consciousness what it experiences in the sympathetic nervous system during sleep, while it can well bring to consciousness what it experiences when it dwells in the fully perfected head. For the head, as you know, is in the main the outcome of all the impulses that worked throughout the old Moon and Sun and so on. What the Ego can bring to consciousness depends on the instrument it is able to use. The instrument it uses in the night is still comparatively tender. In former lectures I have explained that the remainder of man's organism was not evolved until a later time. Only at a later time was it added to the more highly perfect head-organisation. It is in fact a mere appendage of the latter. We say that in his physical body man has gone through the long stages of evolution from old Saturn onward,—but in reality we can only say this of the head. What is attached to the head is to a large extent a subsequent creation—Moon-creation, nay, no more than Earth-creation. Hence we are scarcely conscious, to begin with, of the vivid life which is unfolded in our sleep, the organic source of which is chiefly in the spinal column and the sympathetic system. But this life is therefore no less vivid, nor is it any the less important to us. Just as we say, In waking life man must be able to rise into his senses and his brain- system, so we may say with equal truth, In sleep he must be enabled to descend into his sympathetic system. No doubt you may reply, How complicated this makes it,—how it confuses all that we have learned hitherto. But man is a complicated being. We cannot understand him unless we receive with open mind these complications of his nature.

And now imagine, happening- with any human being, what I described in Goethe's case. The etheric body is loosened. When the etheric body is loosened, quite a different relationship arises in waking life between the soul- and-spirit and the physical-organic nature of man. He is placed, as I showed in the last lecture, on a kind of insulating stool. But such an effect necessarily involves another. It is very important to bear this in mind. Such a relationship cannot take place one-sidedly. Broadly speaking, we may say: Through the loosening of the etheric body the entire waking life of man is influenced; but this cannot happen unless his sleeping life is influenced at the same time. In such a case as Goethe's the consequence is simply this: The human being comes! into a less close relation to the impressions on his brain, and thereby, even in his waking life, he comes into a stronger and more intimate relation to his spinal and his sympathetic nervous systems. This too was the effect of Goethe's illness. He developed, as it were, a looser relation to his brain, and at the same time a more intimate relation to his sympathetic and spinal nervous systems. Now we may ask, generally speaking, what will be the result of this? What does it signify for the human being to come into a more intimate relation to his sympathetic and spinal nervous systems?

The fact is that he thereby comes into a quite different relation to the outer world. We are indeed always in a very intimate relation to the outer world,—we only do not observe how intimate it is. How often, for example, have I drawn your attention to this: The air which you carry within you at one moment, is outside you in the next moment, and another air is then inside you. What is now outside you, will, in the very next moment, have the form of your body; will have united itself with your body. The human organism is only apparently separated from the outer world. In reality it belongs to the whole outer world. When therefore such a change arises in its relation to the outer world, this will soon make itself felt very strongly in the whole life of man.

Here you may say: 'Surely the result would be that the lower nature of a man like Goethe would come into play with unusual intensity. For that which is connected with the spinal column and the sympathetic nervous system, is generally thought of as man's lower nature, and in this case the forces have withdrawn from the head and come more closely into connection with the sympathetic and the spinal nervous system.'

But we only begin to understand the matter when we fill ourselves with the perception that what we call 'understanding' or 'Intelligence' is not so closely bound to our individuality as we are wont to assume. These are things of which our present time has the most incorrect ideas,—naturally enough, according to its fundamental notions. These are the things which it is least able to tackle—a fact which emerged recently in the somewhat dense and idiotic way in which even the great scholars of our time received the alleged sensational discoveries and experiences with learned animals: dogs, monkeys, horses and the like. You know how suddenly the news went out into the world, about the learned horses, who were able to speak and to do all kinds of other things besides. Or of the learned dog which made such a sensation in Mannheim. Or of the learned monkey in the Frankfort Zoo, which was taught arithmetic and other arts, the details of which one would rather not explain in polite society. For by contrast to the remaining members of his tribe, the Frankfort chimpanzee learned to behave, with respect to certain human functions, not in the way monkeys generally behave, but like a human being. I will not pursue the matter any further.

Now all these things gave rise to great astonishment, not only among the ordinary public, but in the most learned circles. Even the most learned folk were quite enraptured when they heard, for instance, how the Mannheim dog had written a letter, after the death of a dear relative, of how the dear relative (the offspring of the dog) would now be with the archetypal soul, and what sort of a time it would be having, and so on ... It was really a most intelligent letter which the dear dog had written. Well, we need not concern. ourselves with the peculiarly complicated intelligence which was shewn in other matters. Let it suffice that all these animals performed sums of arithmetic. People afterwards spent much time investigating what such animals could do. In the case of the Frankfort monkey a strange discovery was made. When a sum was laid before him, which he was expected to work out to a certain number as the answer, he would point to, the required number. A series of numbers being placed side by side before him, he would point to the correct answer, for instance, of an addition sum. Alas, eventually they discovered that the learned monkey had simply grown accustomed to follow the direction of his trainer's look. Some who had formerly been astonished now declared: There is not a trace of intellect; it is all in the training. Indeed, it was only a more complicated instance, as when a dog fetches a stone you throw. So did the monkey pick out of a series of numbers the one to which—not the line of throw this time, but the line of vision of his trainer was directed.

Undoubtedly, on a closer investigation similar results would emerge in the other cases too. There is only one thing which must surprise us, namely, the fact that people are so astonished when animals occasionally perform these seemingly human feats. For after all, how much more spirit, how much more intelligence—taking intelligence objectively—is needed to achieve what is already so well known to us in the animal kingdom! I mean what the creatures do out of their so-called instinct. Things of untold significance are done in this way. Deep and profound relationships are here contained, which truly make us marvel at the Wisdom which everywhere holds sway, wherever the world's phenomena appear before us. We have Wisdom not only in our heads. Wisdom surrounds us everywhere, like light. Wisdom is working everywhere, and through the animal creatures also.

Incidentally, these unusual phenomena can only astonish those who have not entered seriously enough into the developments of modern learning. As to the men who write such learned dissertations nowadays about the Mannheim dog or other dogs, or about the horses or the Frankfort monkeys or the like,—I should like to read them a passage from Comparative Anatomy, by Carus, published as early as 1866. Nor is this by any means an isolated instance. And since they will not listen to me, I will read the passage to you now. Carus says, on page 231: "When a clog for instance has long been treated with tenderness and consideration by its master, these human qualities are impressed upon the animal, objectively, although it has no sense for the concept of goodness as such. These qualities become amalgamated with the sensible image of the human being, whom the dog sees so often. They cause the dog to recognise the man as the one who has shown it kindness in the past; even without the sense of sight, merely by smell or hearing it will know him. If therefore some injury is now done to the man, or if he is only made unable to show the dog further kindness, the creature feels it as an evil done to itself and is moved to wrath and vengeance. All this takes place therefore without any abstract thinking, merely by the sequence of one sense picture on another.' (It is undoubtedly true that for the dog one sense picture follows another in this way, but at the same time, intelligence and wisdom hold sway in the whole process.) 'It is, however, wonderful how near this interweaving, separating and re- associating of images of the inner sense can come to actual thought, and how like it can be in its effects! Thus I once saw a well-trained white poodle' (not the Mannheim dog,—the passage was written in 1866!) 'which rightly selected and put together the letters of the words which were recited to it. Or again, the animal seemed to solve simple sums of arithmetic by carrying the several figures, written (like the letters of the alphabet) on separate sheets of paper. Or again, it seemed able to count how many ladies there were in the room, and so on. Had it been a question of any real understanding of number as a mathematical concept, all this would have been impossible without true thought and reflection. But in the end it was found that the dog had been trained to perceive a very slight sign made by its master, and accordingly to pick out of the row of papers, along which it went up and down, the leaf with the right letter or number. Then, at another equally silent signal (like the flicking of the thumb nail with the nail of the fourth finger), it would lay the paper down again in another row and thus achieve the apparent miracle.'

So you see, not only has the phenomenon itself long been known, but even the solution, which the learned folk are rediscovering to-day, because they do not concern themselves with what has already been achieved in the development of science. Only so can these things come about, and they bear witness to the advancement not of our science but of our ignorance. On the other hand, the following comment has quite rightly been made. Such explanations as are given nowadays are certainly naïve, for, as Hermann Bahr has rightly said, Here comes Herr Pfungst and proves how these horses will react to the slightest signs, which the men who train them are quite unable to perceive—signs which they make unconsciously and which he himself was only able to perceive when he had spent a long time in his psychological laboratory, constructing the1 apparatus to perceive the minutest play of features. And as Hermann Bahr goes on to say, it is a strange conclusion. Only the horses are clever enough to observe such play of features, while a University lecturer needs many years—I think it was ten years or even more—to contrive the apparatus to perceive them.

There is of course a fragment of truth in all these things. But we must only consider them in the right way. Then we shall see that they can only be explained if we imagine objective Wisdom, objective Intelligence, implanted in the things of the world, just as it is in the instinctive actions of animals. We must imagine the animal included in the whole 'circuit' of objective Wisdom-relationships flowing through the World. We must not have the limited idea that Wisdom came into the World merely through man. We must think of Wisdom holding sway throughout the World, while man is only called upon through his peculiar organisation to perceive more of the Wisdom than the other creatures do. That is the difference between man and the other creatures. He, by virtue of his organisation, can perceive more of the Wisdom than they can. Nevertheless, the other creatures, through the Wisdom that is implanted in them, can perform functions as wise as men,—only that they are filled with Wisdom in another way. For one who studies the world in real earnest, the abnormal phenomena of Wisdom's working are indeed far less important than those that are constantly spread out before our eyes. These are far more significant. If you bear this in mind, you will no longer find the following so unintelligible. The animal is harnessed into the universal Wisdom so as to be connected with it quite instinctively,—far more so than the human being. The animal's route is, as it were, mapped out for it far more exactly than man's; man has been left far more free play. By this very means it is made possible for man to save up certain forces for his conscious knowledge of the world's relationships.

The most important thing is this: In the animal—especially the higher animal—the physical body is harnessed in the same World-connections, in which man is only harnessed with his etheric. Therefore, while man knows more about the World-relationships, the animal lives within them more closely, more intimately,—is more deeply contained in their circuit.

Think, therefore, of this objectively prevailing Intelligence, and say to yourself: All around us is not only light and air, but the prevailing Intelligence is everywhere. We move not only through the space of light, but through the space of Wisdom, filled with the all-prevailing Intelligence. Now you will estimate what it may mean for a man to be connected with the Universe—not in the ordinary way but in another way, with respect to the finer conditions of his organs. In normal life man is connected with the spiritual relationships of the Universe in such a way that the connection between the Ego and the sympathetic nervous system, and that between the astral body and the spinal nervous system, is to a large extent broken in his day-waking life. Because the connection is thus weakened, man in his ordinary normal life pays little heed to what takes place around him—what he would only be able to perceive if he actually perceived with his sympathetic nervous system just as he ordinarily perceives through his head.

Now in a case like Goethe's, because the etheric body is withdrawn from the head, the astral body is brought into a more living relation to the spinal nervous system, and the Ego to the sympathetic system. Such a human being, therefore, comes into far more living intercourse with that which is always going on around him, which in normal human life is veiled from us inasmuch as we only enter into relation with our spiritual environment when we are asleep at night. In this way you will understand how such things as Goethe described were, for him, real perceptions. Of course they could not be so brutally clear and bright as the perceptions we receive from the outer world through our senses. Nevertheless, they were brighter than the perceptions a man ordinarily has of his environment where it is spiritual. What then did Goethe perceive most vividly in this way? Let us make it clear to ourselves by an example.

Goethe, by his peculiar Karma—by complications of Karma, as I have indicated—was destined to grow into the life of learning, not like an ordinary scholar, but in quite another way. What did he experience in this way?

For long centuries past, a man who grows into the life of scholarship and learning has had to experience a peculiar duality. It is more hidden today than it was in Goethe's time. But everyone experiences a certain split, inasmuch as in all our recorded learning we have before us an immense field wherein we find what has been preserved, more or less, from the fourth Post-Atlantean epoch. It is preserved in terminologies, word-systems which we are obliged to put up with. Far more than we imagine, we burrow in mere words. This has indeed become less flagrant in the 19th century, inasmuch as countless experiments have now been made. When we grow up into the life of knowledge we see far more than people used to see. And so, to some extent at least, such sciences as Jurisprudence have fallen from the very high throne they used to occupy. But when Jurisprudence and Theology still occupied their very lofty thrones, much that a man had to absorb as heritage from the fourth Post-Atlantean epoch was an immense system of words. That was what one had to enter into, to begin with. But alongside of it, what was emerging from the real needs of the 5th Post-Atlantean epoch was making itself felt increasingly,—the immediate life which springs from the great achievements of modern time. A youth who is merely driven forward from class to class may not feel it consciously, but one like Goethe felt it in the highest degree. I say again, one who is merely crammed from class to class does not feel it consciously, but he undergoes it none the less. Here we are touching on a real secret of modern life. Take the students who go through their University curriculum. Of course, we can fix our attention on what they actually go through, what they themselves know of it; but that is not all. Their inner life is something very different. They who thus experience the interwoven strata of the 4th and 5th Post- Atlantean epochs,—what if they only knew what a certain member of their being, all unawares, is doing within them? They would have quite a new understanding of what Goethe as a young man secreted into his Faust. For unconsciously, countless individuals who enter the modern life of education are undergoing this.

Through all that Goethe developed in himself by virtue of his special Karma, the human beings whom he came near during his youthful years were to him something quite different from what they would have been to him, had he not had this special Karma. He felt how the human beings, with whom he was growing up, must somehow be benumbed in order not to experience the Faustian life within them in its full reality. They must have it benumbed. This experience he had. For what was living so mysteriously in his fellow-men made an impression on him, such as is ordinarily only made by one human being on another when intimate relationships arise,—I mean when love arises between the one and the other. For when this happens, even in ordinary life the connection of the Ego with the sympathetic nervous system, and of the astral body with the spinal nervous system, is powerfully at work. However unconsciously, a peculiar activity here comes into play. In ordinary life, it only happens in this relationship of love. For Goethe it arose in a far wider circle. He had an immense sympathy and compassion, more or less subconscious, with these poor fellows who did not know what their inner life was passing through, while outwardly they were being driven from class to class, from examination to examination. All this became in him a rich experience. Now experiences become ideas. Ordinary experiences become the ideas of everyday life. These experiences became the ideas which Goethe thundered forth into his Faust. They are simply the experiences he underwent in wide circles around him, because the life of his sympathetic and spinal nervous systems was called, as it were, into greater wakefulness than usual. This was the other pole as against the damping-down of his head- life. But this tendency was already there in him from boyhood. We can see it from the descriptions he gives. He describes, for instance, how in his piano lessons not only the part of the human being which is otherwise concerned but his whole human being was brought into activity. Goethe, in fact, entered into communication with Reality far more intensely with his whole human being than others are wont to do. Therefore, we may truly say, Goethe was more awake by day than other men. So it was in the youthful time when he was working at his Faust. For this very reason he needed what I described in the last lecture as the period of sleep in the ten years at Weimar. This, too, was necessary—it was once more a 'damping-down. '

Thus Goethe was drawn into the Wisdom-filled working—the purely spiritual working—of the World around him, far more consciously than other men. He perceived what was living and weaving mysteriously in the human beings around him. Yet man is always standing in the midst of this. What is it in reality? Placed into the world as we are in the ordinary crude waking life, we are placed into it with our Ego; we are connected with it through our senses and our every-day ideas. But as you have seen, we are really connected with it far more intimately than this. For our Ego is in an intimate relation to our sympathetic system, and our astral body to our spinal system, and by virtue of this relation we have a far deeper and fuller connection with our environment than we have by virtue of our senses-system, our head. And now consider: Man needs this rhythmic alternation. His Ego and his astral body are in the head during his day-waking life and outside of it during his sleep. Inasmuch as they are outside the head during sleep, they develop a vivid inner life together with this other system, as I described before. The Ego and astral body need this alternation of diving down into the head, and going out of it. When man is outside the head with his Ego and his astral body, he develops not only the intimate relation to the rest of the body through the sympathetic and the spinal nervous system. For on the other side he also develops spiritual relations to the Spiritual World. Corresponding to this active living-together with the spinal and with the sympathetic nervous system, we have an active living-together in soul and spirit with the Spiritual World. At night the soul-and-spirit is outside the head, and consequently unfolds this vivid life in the remaining organism. Conversely we must say that in the day-waking life, when the Ego and astral body are more in the head, we are living together spiritually with our surrounding spiritual environment. We dive down, as it were, into a spiritual inner world in our sleep; but on awakening we plunge into a spiritual world around us.

In a man like Goethe this living- together with the spiritual environment i.s only more alive; he dreams it—he is like a man who, instead of 'sleeping like a log,' dreams in his sleep. It is rare for a man to dream thus consciously during his waking life. People like Goethe, however, do come into a kind of dreaming during their waking life. What for ordinary men remains unconscious, thus becomes for them, so to speak, the dream-woven forming of life.

Here then you have a more precise description of the matter. Of course you may now deduce from it a rather conceited notion, for you may say to yourselves: If that be so, we could all of us write Fausts, for we experience Faust inasmuch as in the daytime we penetrate into the surrounding world and live together with it. That is quite true; we do experience Faust. Only we experience it as we generally experience the other pole during the night, with our Ego and our astral body, when we are not dreaming. Only Goethe did not experience it thus unconsciously; he dreamt the experience, and was therefore able to express it in his Faust. Goethe dreamt the experience. What men like Goethe create is related to what ordinary men experience unconsciously, like dreaming and deep sleep are related on the other side of life. It is no different—this is the full reality! Like dreaming and deep sleep,—so are related the creations of the great spirits to the unconscious creations of other men.

Some things may still remain a riddle, even now. Nevertheless, you can here gain some insight into a fact which is deeply connected with the life of man,—which we may characterise somewhat as follows. Undoubtedly we could always tell a very great deal of the relation of our Being to the surrounding World if we were able to awaken, to- the level of a dream, our connection with the surrounding World. We need only awaken to the level of the dream; then we should experience immense things and be able to describe them, too. But this would have a peculiar effect. Think what would happen if—to put it tritely—all men were so conscious as to be able to describe what is in their World-environment. If, for example, all men could describe experiences expressible like those of Goethe which he expressed in his Faust, where should we get to? What would become of the World? Strange as it may sound, the World would come to a standstill! The World could not go on. The moment all human beings were to dream in the way a poet like Goethe dreamt his Faust,—the moment every one were to dream his connection with the outer World—human beings would spend in this way the forces they evolve out of their inner life, and human existence would in a certain sense consume itself. You can gain a feeble idea of what would happen if you consider the devastating effects which are already taking place because so many people—though they do not really dream—imagine that they dream, and go about parroting the reminiscences which they have picked up elsewhere. What I mean is that there are far too many 'poets.' Who does not believe himself to-day a poet or a painter or the like? The World could not exist if it were so, for all good things have their disadvantages, all good things cast their shadow.

Schiller, too, was a poet, and he dreamt many things in the way I just described. But what would happen if all men, who like Schiller were prepared in their youth to become doctors, hung up their medicine on a peg as Schiller did, and (since they would need support) were appointed Professors of History by wire-pulling from above, without ever having studied History in the proper way? What would happen, even if like Schiller they gave very stimulating lectures? After all, the students of Jena did not really learn what they needed to learn at Schiller's lectures. Indeed, by-and-bye Schiller let them drop and was very glad that he need no longer hold the lectures. Imagine that it happened so with every would-be Professor or Doctor! … All good things cast their shadow, that goes without saying. The World mu.st be preserved from coming to a standstill. Therefore, not all men can 'dream' in this way. It may sound trite to put it so, but it is a profound truth-—so deep that we may call it a truth of the Mysteries. For the forces with which ordinary human beings dream must still be used in the outer World to other ends,—namely to create the foundations for the further evolution of the Earth, which would indeed come to a standstill if all men were to dream in this way.

We have now arrived at a point where a very strange thing emerges. What are these forces in men really used for in the World? If, looking with the eyes of Spiritual Science, we ask what they are used for—these forces of which you might say at first, 'If only they were used for dreaming in every human being!'—what do we find that they are used for? (For in effect they are not spent in dreaming but in deep sleep.) They are used in all that is poured out, for the evolution of mankind, in the manifold work of human callings and professions. All this is poured into the multitudinous labour of our several callings.

Compared to such work as Goethe did in his Faust or Schiller in his Wallenstein, our work at our several callings in life is like deep sleep compared to dreaming. In our work at our particular calling we are asleep. This will sound strange to you, for you will say: That is just where you are wide awake. No, in this idea there is a great illusion. Man is not engaged with full waking consciousness in that which is actually brought about through his work at his life's calling. True, some of the effects of his calling upon his soul are brought home to his waking consciousness. Nevertheless, men know nothing of what is actually present in the whole texture of work, in craft and calling anfd profession, which they are constantly weaving about the Earth. It is indeed astonishing to find how these things hang together. Hans Sachs was a shoemaker and a poet; Jakob Boehme was a shoemaker and a mystical philosopher. In these cases, by a special constellation as it were—of which we may yet have opportunity to speak—we have 'sleeping' and 'dreaming' alternately, passing from one into the other.

What signifies—in such a man as Boehme—this interplay, this alternating life in the labour of his calling (for he really did make shoes for the brave men of Görlitz) and in his writings of a mystical and philosophic character?

Some people have strange views about these things. I have told you what we found on one occasion when we were at Görlitz. One evening before my lecture—I was about to lecture there on Boehme—I fell into conversation with a master of the local Grammar School. We spoke of the statue of Jakob Boehme, which we had just seen in the park. The people of Görlitz, as were told, called it, 'the cobbler in the park.' We remarked that the statue was beautiful. But the schoolmaster did not think so. Boehme, he said, is made to look like Shakespeare. One does not see that he is a cobbler. If you are going to make a statue to Jakob Boehme, he opined, you ought at least make him look like a cobbler.

Well, we need not concern ourselves with such an opinion. When a man like Jakob Boehme was writing down his great ideas in mystical philosophy, this was an outcome of something which can only have come into existence when Man was being gradually built up through the Saturn time, the Sun time, the Moon time and on into the Earth-epoch,—when, as we might say, a broad stream was flowing onward which in the last resort came to expression in this work of Jakob Boehme's. It is only by special karmic relationships that this broad stream can so express itself in an individual. Altogether, for the very existence of the human being upon Earth, all that has gone before, through the old Sun and Moon time, is necessary. So, too, needless to say, all this was necessary to create what was there in Jakob Boehme. (Only it was necessary here in a peculiar way.)

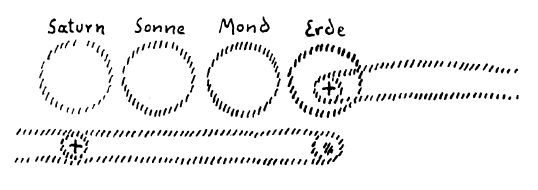

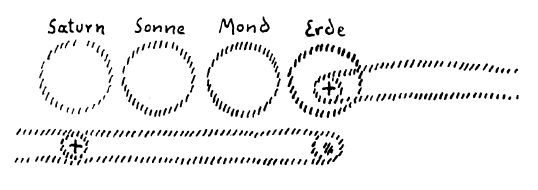

But then again, Boehme set to work and made boots and shoes for the worthy folk of Görlitz. How are these things connected? Undoubtedly, the fact that a man could acquire the skill for making boots and shoes is also connected with the same broad stream. But when the shoes are finished, they leave the man, and in the effects which they then have, they have no more to do with his skill and craftsmanship. Now they have to do with the protecting and warming of feet, and so forth. They go their way, independently, and here, too, they fulfil certain functions. They are loosed from the man, and what they now bring about out there in the world, will only have its effects at a later time. For it is only a beginning. The thing is now as follows:—[At this point in the argument the reader must imagine Dr. Steiner drawing on the blackboard as he speaks.]

Suppose I draw the initial cosmic activity which eventually led up to Jakob Boehme's mystical philosophy in this way. I out the very first beginning here. (See the drawing.) Then I must put the first beginning of his cobblery here. This streams on, and in the future Vulcan evolution will have reached the same perfection which has now been reached by what took place from Saturn evolution onward and flowed into his work as a mystical philosopher. This is an end; his mending of shoes is a beginning. We say, the Earth to-day is Earth,—and so of course it is. But if we could follow it back even beyond Saturn, then we should say: With respect to certain things the Earth is 'Vulcan.' We should then have to assume 'Saturn' at this point (in the drawing). Taken in this way, everything is relative. So we may also say: The Earth is Saturn, and Vulcan as it were is Earth. That which is done on Earth in Jakob Boehme's labour at his calling—not in his free production which goes beyond his 'job,' but what he does as his life's calling—that is the starting-point of something which on Vulcan will be as far advanced as that which was achieved on Saturn is now, on the present Earth. For Jakob Boehme to be able to write his mystical philosophy on Earth, something had to be done on Saturn, analogous to what he himself does in his cobbling. And this again he does, in order that in the future Vulcan evolution something may be done analogous to his writing of mystical philosophy on Earth.

A remarkable truth lies hidden here. That which on Earth we often value so little,—we value it little because it is the starting-point of what we shall only value in the future. It is natural for men to be far more intimately connected, in their inner being, with the past. They must first grow together with what is now in the beginning. Therefore, they are often far less fond of it than of what comes over to' them from the past. As to the whole range of those things into which we must yet be placed during this Earth-epoch in order that something of significance may come into being upon Vulcan, the full consciousness (which we have already upon Earth for such a thing as the philosophy of Jakob Boehme) will only arise when the Earth has evolved on through the Jupiter and Venus to the Vulcan time. Hence what is truly significant in man's external labour is wrapped in unconsciousness to-day, even as man was wrapped in unconsciousness on Saturn. For it was only on the Sun that he developed sleep-consciousness, and on the Moon dream-consciousness, and on the Earth waking-consciousness, with respect to his present conditions.

And go man really lives in deep sleep- consciousness with respect to all those things into which he enters when he places himself into any calling or profession. For it is just through his calling that he creates the future values. Not through what delights him in his calling, but through what unfolds without his being able to enter into it. If a man is making nails and he goes on and on, making nail after nail—well, my dear friends, naturally enough, to-day it gives him no great pleasure. But the nail goes on its way. It has its proper task. He concerns himself no longer with what happens to the nail; he does not follow up every nail that he manufactures. Nevertheless, all that is there veiled in the unconsciousness of deep sleep, is destined to come to life again in the future.

Thus, to begin with, we have been able to place side by side what the ordinary human being does—even the most insignificant labourer at his calling—side by side with what appears to us as the highest achievements. The highest achievements are an end; the least significant labour is always a beginning. I wanted to place these two conceptions side by side to start with. For we cannot understand the way man is connected with his calling through his Karma, if we do not know already in a wider way how a man's work in life (with which he is often connected quite externally) is related to the whole cosmic evolution in the midst of which the human being stands. So we shall presently go forward to work out the real Karmic question of a man's calling or profession. I had to give you these conceptions to begin with. For we must first gain, as it were, a universal concept of what flows from man into his calling.

Moreover, all these things are calculated very strongly to mould our moral feelings in the right direction. For our valuations are often incorrect because we do not envisage things in the true way. A grain of corn may often seem most insignificant when we see it lying there beside the beautiful unfolded flower. Nevertheless, the flower of a future evolution lies hidden in the grain of corn. And so I wanted to explain to you to-day, in connection with human work, how seed and flower are related in the evolution of all mankind.

Dritter Vortrag

Ich möchte jetzt von einem anderen Ausgangspunkt noch die Annäherung vollziehen an das Problem, an dem wir in diesen Betrachtungen arbeiten. Denn in der Geisteswissenschaft muß es so sein, daß man gewissermaßen das Problem von verschiedenen Punkten her einschließt und ihm sich von verschiedenen Punkten her auch nähert. Wenn wir einen solchen Lebenslauf betrachten wie denjenigen Goethes, so muß uns ja, ich möchte sagen, im groben eines auffallen, das einem überhaupt zum großen Rätsel in der Menschheitsentwickelung werden kann, auch dann noch, wenn man die wiederholten Erdenleben zunächst betrachtet und bei der Gestaltung des Lebens eines Menschen zu Rate zieht. Ich meine das Problem: Worin liegt es eigentlich, daß einzelne Menschen wie zum Beispiel Goethe in der Lage sind, aus ihrem Inneren heraus solch Bedeutsames zu schaffen, wie eben Goethe geschaffen hat, insbesondere durch seinen «Faust», durch solch Geschaffenes einen so bedeutenden Einfluß auf die übrige Menschheit zu haben? Wie kommt es, daß gewissermaßen einzelne Menschen herausgelöst werden aus der übrigen Menschheit und zu so Bedeutendem gewissermaßen von dem Weltengeschick berufen werden? - Wir vergleichen dann mit so bedeutendem Schaffen und Leben dasjenige jedes einzelnen Menschen und fragen uns: Was ergibt sich uns an dem Unterschiede jedes einzelnen Menschenlebens und dieser sogenannten hervorragenden Menschenleben?

Diese Frage kann man sich nur beantworten, wenn man sich das Leben mit den Mitteln, die uns die Geisteswissenschaft an die Hand gibt, etwas genauer betrachtet. Zunächst ist nämlich all das, was der Mensch erkennen kann, namentlich für unsere Zeit, dazu angelegt, gewisse Dinge zu kaschieren, zu maskieren und die unbefangene menschliche Betrachtung davon fernzuhalten. Das macht auch nötig, daß man vielfach zunächst sich anpassend an das, was zuerst verstanden werden kann, in der Geisteswissenschaft sprechen muß. Nun schildern wir ja in der Geisteswissenschaft gewöhnlich so, daß wir sagen: Der Mensch besteht, so wie er sich uns darstellt im Leben, aus seinem physischen Leibe, dem ätherischen Leibe, dem astralischen Leibe und dem Ich. - Und wir schildern dann, indem wir charakterisieren die Wechselzustände zwischen Wachen und Schlafen so, daß wir sagen: Während des Wachens sind Ich und astralischer Leib im physischen Leibe und im Ätherleib drinnen; während des Schlafens sind Ich und astralischer Leib draußen. — Das ist für ein Verständnis der Sache zunächst vollständig ausreichend und entspricht durchaus den geisteswissenschaftlichen Tatsachen. Aber es handelt sich darum, daß man dadurch, daß man so schildert, nur einen Teil der vollen Wirklichkeit gibt. Wir können niemals in einer Schilderung die volle Wirklichkeit umfassen; einen Teil der vollen Wirklichkeit geben wir eigentlich immer, wenn wir irgend etwas schildern, und wir müssen immer erst von einigen anderen Seiten wiederum Licht suchen, um die geschilderte Teilwirklichkeit in der richtigen Weise zu beleuchten. Und da muß gesagt werden: Es ist im allgemeinen so, daß Schlafen und Wachen wirklich eine Art zyklischer Bewegung für den Menschen darstellen. Strenge genommen sind nämlich Ich und astralischer Leib außer dem physischen und ätherischen Menschenleib im Schlafzustande nur außerhalb des Hauptes, während gerade dadurch, daß im Schlafe das Ich und der astralische Leib außerhalb des physischen und ätherischen Hauptes des Menschen sind, sie eine um so regere Tätigkeit und Wirksamkeit ausüben auf die andere menschliche Organisation. Alles das, was im Menschen nicht Haupt ist, sondern andere menschliche Organisation, steht gerade während des Schlafzustandes, in dem gewissermaßen Ich und astralischer Leib von außen auf den Menschen wirken, unter einem viel stärkeren Einflusse dieses Ich und dieses astralischen Leibes als während des wachen Zustandes. Und man kann schon sagen: Während des Schlafzustandes wird die Wirkung, die das Ich und der astralische Leib des Menschen im Wachzustande auf das Haupt ausüben, auf den übrigen Organismus ausgeübt. — Wir können daher mit Recht in einem gewissen Sinne vergleichen namentlich das Ich des Menschen mit der Sonne, die, wenn es bei uns Tag ist, unsere Gegend überleuchtet; wenn es bei uns Nacht ist, ist diese Sonne nicht bloß draußen, sondern sie beleuchtet auf der anderen Seite die Erde und macht dort Tag. So ist es in einem gewissen Sinne Tag in unserem übrigen Organismus, wenn es für unsere Sinneswahrnehmung, die ja vorzugsweise an das Haupt gebunden ist, Nacht ist, und Nacht ist es dafür auch für unseren übrigen Organismus, wenn es für unser Haupt Tag ist, das „heißt, unser übriger Organismus ist dem Ich mehr oder weniger ent5 zogen und auch dem astralischen Leib, wenn wir wachen. Das ist noch etwas, was zu der Beleuchtung der vollen Wirklichkeit dazukommen muß, wenn man den ganzen Menschen verstehen will.

Nun handelt es sich darum, daß man auch in diesem Sinne den Zusammenhang des Seelischen mit dem Physischen des Menschen richtig erfaßt, wenn man das, was ich eben angeführt habe, ordentlich verstehen will. Ich habe öfter betont, das Nervensystem des physischen Organismus ist eine einheitliche Organisation, und eigentlich ist es nichts weiter als ein bloßer Unsinn, der nicht einmal durch eine Anatomie gerechtfertigt wird, die Nerven zu teilen in sensitive und motorische Nerven. Die Nerven sind alle einheitlich organisiert, und sie haben alle eine Funktion. Die sogenannten motorischen Nerven unterscheiden sich nur dadurch von den sogenannten sensitiven Nerven, daß die sensitiven darauf eingerichtet sind, der Wahrnehmung der Außenwelt zu dienen, während die sogenannten motorischen Nerven der Wahrnehmung des eigenen Organismus dienen. Ein motorischer Nerv ist nicht dazu bestimmt, meine Hand zu bewegen - das ist ein bloßer Unsinn -, sondern der motorische Nerv, der sogenannte motorische Nerv, ist dazu bestimmt, die Bewegung der Hand wahrzunehmen, also innerlich wahrzunehmen, während der sensitive Nerv dazu bestimmt ist, bei der Wahrnehmung der Außenwelt zu dienen. Das ist der ganze Unterschied. Nun teilt sich unser Nervensystem, wie Sie ja wissen, in drei Glieder: in diejenigen Nerven, deren Hauptzentrum das Gehirn ist, also die im Haupte zentriert sind, dann in diejenigen Nerven, die im Rückenmark zentriert sind, und diejenigen Nerven, die wir zum sogenannten Gangliensystem rechnen. Das sind im wesentlichen die drei Arten von Nerven, die der Mensch hat. Nun handelt es sich darum, zu erkennen: Welche Beziehungen herrschen zwischen diesen drei Arten von Nervensystemen und den geistigen Gliedern unseres Organismus? Welches ist gewissermaßen das vorgerückteste, feinste Glied des Nervensystems und welches ist das am wenigsten vorgerückte Glied des Nervensystems?

Es ist ganz selbstverständlich, daß auf diese Frage diejenigen, die heute von der gewöhnlichen naturwissenschaftlichen Weltanschauung herkommen, antworten werden: Nun ja, das Nervensystem des Gehirnes ist natürlich das edelste, denn das ist dasjenige, das den Menschen von den Tieren unterscheidet. — Aber es ist nicht so. Dieses Nervensystem des Gehirnes hängt im wesentlichen zusammen mit der ganzen Organisation unseres Ätherleibes. Selbstverständlich sind überall weitere Beziehungen vorhanden, so daß natürlich unser ganzes Gehirnsystem auch Beziehungen zum astralischen Leib oder zum Ich hat, aber dies sind sekundäre Beziehungen. Die primären, die ursprünglichen Beziehungen sind zwischen unserem Gehirnnervensystem und zwischen unserem Ätherleib. Das hat nichts zu tun mit der Anschauungsweise, die ich einmal auseinandergesetzt habe, daß das ganze Nervensystem mit Hilfe des astralischen Leibes zustande gebracht worden ist; das ist etwas ganz anderes, das muß man durchaus unterscheiden. Das ist zustande gebracht worden in seiner ursprünglichen Veranlagung während der Mondenzeit, aber das hat sich weiterentwickelt und andere Beziehungen sind eingeleitet worden seit der ersten Bildung, so daß in der Tat unser Gehirnnervensystem innigste und bedeutsamste Beziehungen hat zu unserem Ätherleib. Das Rückenmarkssystem hat die innigsten und primärsten Beziehungen zu unserem Astralleib, so wie wir ihn jetzt als Menschen an uns tragen, und das Gangliensystem zu dem Ich, zu dem eigentlichen Ich. Das sind die primären Beziehungen, wie wir sie jetzt haben.

Wenn wir dies in Erwägung ziehen, so werden wir uns leicht vorstellen können, daß eine besonders rege Beziehung herrscht während unseres Schlafzustandes zwischen unserem Ich und unserem Gangliensystem, das vorzugsweise ausgebreitet ist in dem Rumpforganismus, das in Strängen das Rückenmark außen umkleidet und so weiter. Aber diese Beziehungen sind gelockert während des Tagwachens; sie sind vorhanden, aber sie sind gelockert während des Tagwachens. Sie sind inniger während des Schlafens. Und inniger als während des Tagwachens sind die Beziehungen zwischen dem astralischen Leib und den Rückenmarksnerven im Schlafzustande. So daß wir also sagen können: Während desSchlafzustandes treten ganz besonders innige Beziehungen auf zwischen unserem Astralleib und unseren Rückenmarksnerven und zwischen unserem Ich und unserem Gangliensystem. Wir leben mehr oder weniger während des Schlafes in unserem Ich stark zusammen mit unserem Gangliensystem. Wird man einmal die rätselvolle Traumwelt genauer studieren, so wird man dies schon erkennen, was ich so aus der geisteswissenschaftlichen Untersuchung heraus erwähne.

Dann aber, wenn Sie dies in Erwägung ziehen, werden Sie auch eine Brücke finden zu dem anderen wesentlichen, bedeutungsvollen Gedanken: daß für das Leben etwas sehr Wichtiges dadurch gegeben sein muß, daß ein rhythmischer Wechsel eintritt im Zusammenleben des Ichs zum Beispiel mit dem Gangliensystem und des astralischen Leibes mit dem Rückenmarkssystem, ein rhythmischer Wechsel, der identisch ist mit dem Wechsel des Schlafens und Wachens. Denn es wird Ihnen nicht allzu verwunderlich erscheinen, wenn man sagt: Dadurch, daß das Ich eigentlich so recht im Gangliensystem und der astralische Leib so recht im Rückenmarkssystem ist im Schlafe, dadurch wacht der Mensch mit Bezug auf Gangliensysteem und Rückenmarkssystem während des Schlafens und schläft er während des Wachens. - Man kann da nur die Frage aufwerfen: Wie kommt es denn, daß man von dem so regen Wachen, das ja eigentlich entwickelt werden muß während des Schlafens, so wenig weiß? Nun, wenn Sie in Erwägung ziehen, wie der Mensch geworden ist, daß ja das Ich des Menschen erst während des Erdendaseins in ihm Platz genommen hat, also eigentlich das Baby ist unter unseren menschheitlichen Gliedern, so wird es Ihnen nicht staunenswert sein, daß dieses Ich eben sich noch nicht zum Bewußtsein bringen kann dasjenige, was es erlebt im Gangliensystem während des Schlafens, während es sich wohl zum Bewußtsein bringen kann das, was es erlebt, wenn es in dem voll ausgebildeten Haupte ist, das ja hauptsächlich das Ergebnis ist aller derjenigen Impulse, die durch Mond, Sonne und so weiter gewirkt haben. Was das Ich sich zum Bewußtsein bringen kann, hängt von dem Instrument ab, dessen es sich bedienen kann. Das Instrument, dessen es sich in der Nacht bedient, ist verhältnismäßig noch zart. Denn ich habe Ihnen in früheren Vorträgen ausgeführt, daß der übrige Organismus eigentlich erst später entwickelt worden ist, daß der erst hinzugekommen ist zu dem mehr vollendeten Kopforganismus des Menschen, daß der ein Anhängsel ist des Kopforganismus. Wenn wir davon sprechen, daß der Mensch seinem physischen Leib nach mehr oder weniger lange Stadien vom Saturn aus durchgemacht hat, so können wir das nur mit Bezug auf das Haupt, auf den Kopf aussprechen. Dasjenige, was sich an den Kopf anhängt, ist vielfach spätere Bildung, Mondenbildung und sogar erst Erdenbildung. Daher kommt das rege Leben, das entwickelt wird während des Schlafens und das vielfach seinen organischen Sitz hat im Rückenmark und im Gangliensystem, zunächst wenig zum Bewußtsein, aber es ist deshalb ein nicht minder reges, bedeutsam reges Leben. Und man kann ebensogut sagen, im Schlafe soll dem Menschen die Möglichkeit geboten werden, hinunterzusteigen in sein Gangliensystem, wie ihm im Wachen die Möglichkeit gegeben ist, hinaufzusteigen zu seinen Sinnen und zu seinem Gehirnsystem. Gewiß, Sie werden sagen: Wie kompliziert sich — und vielleicht sogar: Wie verwirrt sich dadurch alles das, was wir uns angeeignet haben! - Aber der Mensch ist ein kompliziertes Wesen und man lernt ihn nicht verstehen, wenn man nicht diese Komplikation, diese Kompliziertheit wirklich einmal auf sich wirken läßt.

Nun denken Sie sich einmal, daß bei einem Menschen das eintritt, was ich Ihnen mit Bezug auf Goethe beschrieben habe: daß der ätherische Leib gelockert wird. Dann, wenn der ätherische Leib gelockert wird, dann tritt eine ganz andere Beziehung ein im Wachen zwischen dem Seelisch-Geistigen und dem Organischen, dem Physischen des Menschen. Der Mensch wird, so wie ich es gestern beschrieben habe, auf eine Art Isolierschemel gestellt. Aber es kann niemals eine solche Wirkung eintreten, ohne eine andere nach sich zu ziehen. Das ist sehr wichtig ins Auge zu fassen. Eine solche Beziehung tritt nicht einseitig ein, sondern sie zieht eine andere nach sich. Wenn man diese Beziehung, die ich gestern charakterisiert habe, etwas gröber ausspricht, so könnten wir auch sagen: Dadurch, daß der ätherische Leib gelockert ist, wird das ganze Wachleben des Menschen in einer gewissen Weise beeinträchtigt, beeinflußt. Aber das kann nicht sein, ohne daß zu gleicher Zeit das Schlafleben des Menschen beeinflußt wird. Die Folge davon ist einfach, daß der Mensch in losere Beziehungen tritt zu seinen Gehirneindrücken, wenn so etwas bei ihm auftritt wie bei Goethe. Dadurch tritt er auch in intimere, in stärkere Beziehungen während des Wachens zu seinen Rückenmarksnerven und zu dem Gangliensystem. Das ist damals, als Goethe krank wurde, zu gleicher Zeit eingetreten, daß er gewissermaßen eine losere Beziehung zu seinem Gehirn entwickelt hat, aber zugleich eine intimere Beziehung zu seinem Gangliensystem und zu seinem Rückenmarkssystem.

Was tritt denn dadurch aber überhaupt auf? Was soll das heißen, eine intimere Beziehung tritt zum Gangliensystem, zum Rückenmarkssystem ein? Dadurch tritt der Mensch nämlich in eine ganz andere Beziehung zur Außenwelt. Wir sind ja immer in inniger Beziehung zur ganzen Außenwelt; wir achten nur nicht darauf, in welch inniger Beziehung wir eigentlich zur Außenwelt stehen. Aber ich habe Sie öfter aufmerksam darauf gemacht: Die Luft, die Sie in einem Augenblick in Ihrem Innern tragen, ist im nächsten Augenblicke draußen und eine andere Luft ist drinnen; dasjenige, was jetzt draußen ist, hat im nächsten Augenblicke die Form des Leibes und vereinigt sich mit Ihrem Leib. Es ist ja nur scheinbar der Menschenorganismus geschieden von der Außenwelt; er ist ein Glied dieser Außenwelt, er gehört zu dieser ganzen Außenwelt dazu. Wenn also eine solche Änderung in der Beziehung zur Außenwelt eintritt wie die charakterisierte, so macht sich das schon mit Bezug auf das Leben des Menschen stark geltend. Nun kann man ja sagen: Dadurch müßte eigentlich die niedere Natur des Menschen bei einer solchen Persönlichkeit wie Goethe - denn man bezeichnet gewöhnlich dasjenige, was an Rückenmark und Gangliensystem gebunden ist, als die niedere Natur — nun besonders stark hervortreten. Vom Haupte ziehen sich die Kräfte zurück; das Gangliensystem und das Rückenmarkssystem nehmen sie mehr in Anspruch.

Verständnis für das, was da eigentlich geschieht, gewinnt man erst, wenn man sich durchdringt mit der Erkenntnis, daß, was wir Verstand, Vernunft nennen, nicht eigentlich so eng gebunden ist an unsere Individualität, wie man das gewöhnlich annimmt. Gerade über diese Dinge hat unsere Gegenwart nach allen ihren Grundvorstellungen selbstverständlich, könnte man sagen, die allerverkehrtesten Begriffe. Über diese Dinge kommt unsere Gegenwart am allerwenigsten zurecht. Das hat sich insbesondere gezeigt an der, man möchte sagen, «dalketen» Art - ich weiß nicht, ob der Ausdruck allgemein verstanden wird, er bezeichnet eine gewisse Art, sich zu den Dingen zu stellen, die Stumpfsinnigkeit mit Blödigkeit verbindet -, wie sich unsere Zeit bis in die gelehrtesten Kreise hinein verhalten hat zu dem, was da zum Vorscheir kommen sollte durch gewisse Erfahrungen, die man machte mit «gelehrten Tieren»: Hunden, Affen, Pferden und so weiter, Sie wissen ja, daß plötzlich durch die Welt gegangen ist die Kunde von den gelehrten Pferden, die rechnen können, die alle möglichen anderen Dinge noch können, von einem sehr gelehrten Hunde, der Aufsehen gemacht hat in Mannheim, von einem gelehrten Affen in einem Frankfurter Tiergarten, dem man das Rechnen neben anderen Dingen beigebracht hat, die man in Einzelheiten nicht gern in guter Gesellschaft schildert, die man nur andeuten kann. Der Frankfurter Schimpanse nämlich hat, im Gegensatz zu den anderen Mitgliedern des Affengeschlechts, sich mit Bezug auf gewisse Bedürfnisse dazu abrichten lassen, sich in der Weise zu benehmen, wie sich sonst nicht Affen, sondern wie sich Menschen benehmen; weiter will ich dieses Thema nicht ausführen. Aber das alles hat nicht nur Laienkreise, sondern auch Gelehrtenkreise in großes Erstaunen versetzt. Nicht nur Laien, sondern auch Gelehrte fielen in eine Art von Verzückung, als insbesondere der Mannheimer Hund einen Brief schrieb, nachdem ihm ein teurer Angehöriger gestorben war: wie dieser teure Angehörige, der Sprößling des Hundes, nun bei der Urseele sein werde, wie er es dort haben werde und so weiter. Es war ein sehr intelligenter Brief, den jener Hund schrieb. Nun, nicht wahr, auf die besonders komplizierten Intelligenzäußerungen braucht man dabei nicht einzugehen, aber immerhin: Rechnungsleistungen haben alle diese verschiedenen Tiere zustande gebracht. Man hat sich dann viel abgegeben mit der Untersuchung desjenigen, was solche Tiere leisten können. Beim Frankfurter Affen ist etwas ganz Besonderes herausgekommen. Man hat sich nämlich überzeugen können, daß er, wenn man ihm eine Rechnung vorlegte, die er zu einer bestimmten Zahl als Resultat führen sollte, diese Zahl in einer Reihe von Zahlen nebeneinander zeigte; auf die richtige Zahl zeigte er hin, und die Summe ergab sich zum Beispiel aus einzelnen Additionen. Da kam man darauf, daß dieser gelehrte Affe sich einfach angewöhnt hatte, genau sich zu richten nach der Blickrichtung seines Dresseurs. Einige, die früher erstaunt waren, sagten schon: Keine Spur von einem Geist, alles ist Dressur. — Es ist eigentlich nichts anderes als ein etwas kompliziertes Verfahren, wie wenn der Hund apportiert, wenn man ihm einen Stein hinwirft und er holt ihn; so holte der Affe aus einer Reihe von Zahlen diejenige heraus, auf die jetzt nicht die Wurfrichtung fiel, sondern einfach der Blick seines Erziehers.

Es werden gewiß bei genauerer Untersuchung ähnliche Resultate auch bei den übrigen Tieren erzielt werden. Erstaunt muß man eigentlich nur immer über das eine sein: daß die Menschen gar so frappiert sind, wenn solche Tiere einmal etwas scheinbar Menschenähnliches leisten. Denn wie viel mehr Geist, wie viel mehr Verstand - wenn man den Verstand objektiv nimmt — gehört selbstverständlich zu all dem dazu, was einem gut bekannt ist in dem Tierreiche, was aus dem sogenannten Instinkte heraus geleistet wird! Denn da wird in der Tat ungeheuer Bedeutungsvolles geleistet, und da liegen tief bedeutsame Zusammenhänge darinnen, die einen bewundern lassen die Weisheit, die da waltet überall, wo Erscheinungen zutage treten. Wir haben Weisheit nicht nur in unserem Kopf; Weisheit ist es, die uns wie das Licht überall umgibt, die überall wirkt und die auch durch die Tiere hindurch wirkt. Über solche extraordinäre Erscheinungen sind diejenigen bloß erstaunt, die überhaupt sich nicht ernsthaft mit wissenschaftlichen Entwickelungen befaßt haben. Ich möchte all denen, die heute so gelehrte Abhandlungen schreiben über den Mannheimer Hund und ähnliche Hunde, über die Pferde, über den Frankfurter Affen und so weiter, ich möchte denen — neben anderem kann man das, das ist nicht vereinzelt - nur eine Stelle aus dem schon 1866 erschienenen Buche «Vergleichende Psychologie» von Carus vorlesen; da die anderen mir nicht zuhören, so werde ich diese Stelle zunächst Ihnen vorlesen. Da heißt es bei Carus Seite 231: «Wenn also zum Beispiel der Hund lange von seinem Herrn mit Schonung und Neigung behandelt wird, so prägen sich die menschlichen Züge dem Tiere, obwohl es keinen Sinn hat für den Begriff der Güte an sich, doch gegenständlich ein, amalgamieren sich mit dem Sinnenbilde dieses Menschen, den der Hund oft erblickt, und lassen ihn diese Persönlichkeit, sogar ohne den Sinn des Gesichts, zum Beispiel bloß durch den Geruch oder durch das Gehör, als der kennen, von dem ihm Gutes einst zukam. Wird daher jetzt etwa diesem Menschen ein Leid zugefügt, ja ihm dadurch vielleicht sogar die Möglichkeit genommen, fernere Wohltaten den Hunde zuzuteilen, so empfindet das Tier dies wie ein ihm selbst zugefügtes Übel, und wird dadurch zu Zorn und Rache bewegt; alles dies somit ohne irgend ein abstraktes Denken, sondern immer nur, indem Sinnenbild an Sinnenbild sich anreiht.»

Das ist gewiß wahr, daß Sinnenbild an Sinnenbild sich beim Hunde anreiht; aber in der ganzen Begebenheit waltet Verstand und Weisheit.

«Merkwürdig bleibt es indes, wie sehr ein solches eigentümliches Verweben, Trennen und Wiederverbinden von Vorstellungen des innern Sinnes, doch dem wirklichen Denken nahe kommen und ihm in seinen Folgen gleichen kann! — So sah ich einst einen wohlabgerichteten weißen Pudel» — das war nicht der Mannheimer Hund, denn das ist 1866 geschrieben — «welcher zum Beispiel die Buchstaben ihm vorgesagter Worte richtig auswählte und zusammenlegte, welcher einfache Rechenexempel durch Zusammentragen einzelner, gleich den Buchstaben, auf besondre Blätter geschriebenen Zahlen zu lösen schien, welcher auszuzählen schien, wie viel Damen sich unter der anwesenden Gesellschaft befanden, und dergleichen mehr. — Natürlich wäre alles dies, sobald es sich um ein wirkliches Verstehen der Zahl — als mathematischen Begriff - gehandelt hätte, ohne ein eigentliches Nachdenken nicht möglich gewesen; es fand sich aber endlich, daß der Hund nur abgerichtet war, auf ein sehr leises Zeichen seines Herrn, das Blatt mit dem bestimmten Buchstaben, oder mit der passenden Zahl, aus der aufgelegten Reihe, an welcher er auf- und niederging, aufzunehmen, und auf den Wink eines andern eben so leisen Tons (etwa ein Knipsen mit dem Daumennagel und dem Nagel des vierten Fingers) das Blatt in einer andern Reihe wieder niederzulegen und dadurch solch scheinbares Wunder zu vollbringen.»

Sie sehen, nicht bloß die Erscheinung ist längst bekannt, sondern auch die Lösung, die heute erst wiederum mit vieler Mühe die Gelehrten feststellen, weil die Leute sich nicht kümmern um dasjenige, was geleistet worden ist in der wissenschaftlichen Entwickelung. Nur deshalb kommen solche Dinge zustande, die nicht von unserer vorgerückten Wissenschaft, sondern von unserer vorgerückten Ignoranz zeugen! Aber auf der anderen Seite hat man mit Recht etwas eingewendet. Wenn es sich nun wiederum bloß um solche Erklärungen handeln würde, wie sie heute vorgebracht werden, so kann man nicht minder solche Erklärungen naiv finden; denn Hermann Bahr hat mit Recht gesagt: Nun, da ist also der Herr Pfungst gekommen und hat gezeigt, wie die Pferde auf ganz leise Deutungen reagieren, die die Menschen, die da dressieren, nicht wahrnehmen, sondern unbewußt machen, die er selber erst wahrzunehmen in der Lage war, nachdem er sich lange in seinem physiologischen Laboratorium Apparate konstruiert hat, um diese winzigen Mienen wahrzunehmen. — Hermann Bahr hat mit Recht eingewendet, daß es doch eine eigentümliche Auslegung ist, daß nun die Pferde so gescheit sein sollen, solche Mienen zu beobachten, während ein Privatdozent erst lange Jahre — ich glaube, zehn oder noch mehr Jahre hat er dazu gebraucht - sich Apparate konstruieren muß, um sie wahrzunehmen! Es ist in allen solchen Dingen selbstverständlich ein Stückchen Richtigkeit; aber man muß die Dinge nur recht anschauen. Und recht angeschaut zeigt sich eben, daß die Dinge nur erklärlich sind, wenn man geradeso wie zu den Instinkthandlungen objektive Weisheit, objektive Vernunft in die Dinge hinein versetzt sich denkt, wenn man das Tier eingeschaltet denkt in ein ganzes System durch die Welt gehender objektiver Weisheitszusammenhänge; wenn man sich mit anderen Worten nicht darauf beschränkt, zu denken, daß Weisheit durch den Menschen bloß in die Welt gekommen ist, sondern erkennt, daß Weisheit durch die ganze Welt waltet und der Mensch nur dazu berufen ist, durch seine besondere Organisation mehr als die anderen Wesen von dieser Weisheit wahrzunehmen. Dadurch unterscheidet sich der Mensch von den übrigen Wesen, daß er durch seine Organisation mehr von der Weisheit wahrnehmen kann als die anderen Wesen. Verrichten aber können die anderen Wesen durch die ihnen eingepflanzte Weisheit ebenso Weisheitsvolles wie der Mensch, nur von anderer Art Weisheitsvolles. Und die außerordentlichen Erscheinungen des Weisheitswirkens sind eigentlich für denjenigen, der Ernst macht mit der Weltbetrachtung, die viel weniger wichtigen als diejenigen, die immer vor unseren Augen ausgebreitet sind. Die sind die viel wichtigeren. Wenn Sie dies in Erwägung ziehen, so werden Sie das Folgende nicht mehr unverständlich finden.

Das Tier ist so in die Weltenweisheit eingespannt, daß es recht innig mit dieser Weltenweisheit verknüpft ist, viel stärker als der Mensch. Es ist dem Tier gewissermaßen eine viel gebundenere Marschroute mitgegeben als dem Menschen. Der Mensch ist viel freier gelassen als das Tier; dadurch ist es ihm auch möglich, Kräfte zu ersparen für das Erkennen der Zusammenhänge. Die Hauptsache ist diese, daß beim Tiere, namentlich also bei den höheren Tieren, der physische Leib in dieselben Weltenzusammenhänge eingespannt ist, in die beim Menschen erst der ätherische Leib eingespannt ist. Daher weiß der Mensch mehr von den Weltenzusammenhängen, aber das Tier steckt viel inniger, viel näher darinnen, ist viel mehr eingeschaltet in diese Weltenzusammenhänge. Wenn Sie also objektiv waltende Vernunft in Erwägung ziehen und sich sagen: Um uns herum ist nicht nur Luft und Licht, um uns herum ist auch waltende Vernunft überall; wenn wir gehen, gehen wir nicht nur durch den Lichtraum, sondern auch durch den Weisheitsraum, durch den waltenden Vernunftraum, — dann werden Sie ermessen, was es bedeutet, wenn der Mensch in bezug auf die feineren Verhältnisse seiner Organe in die Welt in anderer Weise eingespannt wird, als er gewöhnlich eingespannt ist. Nun ist der Mensch im normalen Leben in einer Weise in die geistigen Weltenverhältnisse eingespannt, daß stark beeinträchtigt ist der Zusammenhang zwischen dem Ich und dem Gangliensystem und dem astralischen Leib und dem Rückenmarkssystem für das tagwache Leben; dadurch, daß das stark beeinträchtigt ist, herabgedämpft ist, dadurch ist der Mensch im gewöhnlichen, normalen Leben wenig aufmerksam auf das, was sich um ihn herum abspielt und was er nur wahrnehmen könnte, wenn er wirklich mit seinem Gangliensystem ebenso wahrnehmen würde, wie er sonst durch seinen Kopf wahrnimmt.

Wenn aber nun in einem solch ausgezeichneten Falle, wie das bei Goethe der Fall ist, der astralische Leib, weil der Ätherleib aus dem Kopf herausgezogen ist, in ein regeres Verhältnis gebracht worden ist zum Rückenmarkssystem und das Ich zum Gangliensystem, so tritt auch ein viel regerer Verkehr ein mit dem, was uns immer umgibt und umspielt und was uns allein dadurch verhüllt ist, daß wir nur zu nachtschlafender Zeit im normalen Menschenleben mit unserer geistigen Umwelt in Beziehung treten. Dadurch aber kommen Sie darauf, zu verstehen, wie so etwas, wie Goethe es beschrieben hat, für ihn einfach wahrzunehmen war, wirkliche Wahrnehmung war, eine Wahrnehmung, die natürlich nicht so brutal hell sein konnte, wie die Wahrnehmungen sind, die wir durch unsere Sinne von der Außenwelt beziehen, aber die doch heller war als die Wahrnehmungen, die sonst ein Mensch von seiner Umgebung hat, insofern diese Umgebung geistig ist.

Nun, was nahm denn Goethe auf diese Art besonders rege wahr? Machen wir uns einmal klar, was Goethe besonders rege wahrnahm, an einem besonderen Falle. Goethe war durch sein besonderes Karma dazu verurteilt, ins Gelehrtenleben, ins Erkenntnisleben hineinzuwachsen — durch Komplikationen des Karmas, wie ich Ihnen angedeutet habe — wiederum nicht so wie ein Dutzendgelehrter. Was erlebt er auf diese Weise? Nun, sehen Sie, seit langen Jahrhunderten erlebt ein Mensch, der ins Gelehrtenleben hineinwächst, einen bedeutsamen Zwiespalt. Dieser Zwiespalt ist heute sogar mehr verborgen als zu Goethes Zeiten. Aber es erlebt jeder einen gewissen Zwiespalt dadurch, daß man in dem, was niedergelegte Wissenschaft ist, ein ungeheuer breites Feld hat, in dem das zu finden ist, was mehr oder weniger vom vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum aufbewahrt worden ist. Es wird aufbewahrt in den Terminologien, in den Wortsystemen, die man genötigt ist aufzunehmen. Man kramt viel mehr, als man meint, in Worten. Gemildert wurde es dadurch, daß im 19. Jahrhundert allmählich viel experimentiert worden ist und daß man dadurch so hineinwächst in das Wissen, daß man mehr gesehen hat, als früher gesehen worden ist, und daß wenigstens schon bis zu einem gewissen Grade solche Wissenschaften, wie die Jurisprudenz, von ihrem ganz besonders hohen Sitz heruntergesunken sind, auf dem sie vorher saßen. Aber als noch Jurisprudenz und Theologie die ganz besonders hohen Sitze einnahmen, da war wirklich ein umspannendes Wortsystem dasjenige, in das man sich zunächst einlebte, und so war vieles von dem, was man aufnehmen mußte als eine Erbschaft des vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraums. Daneben machte sich geltend immer mehr und mehr, was aus den Bedürfnissen des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums herkommt, das unmittelbare Leben, das aus den großen Errungenschaften der neueren Zeit stammt.

Das empfindet derjenige nicht, der so einfach geschoben wird von Klasse zu Klasse, aber ein Mensch wie Goethe, der empfand das im allerhöchsten Maße. Ich sage: Es empfindet der Mensch es nicht, der so geschoben wird von Klasse zu Klasse, aber er macht es nicht minder durch. Er macht es wirklich durch. Und da streifen wir schon ein gewisses Geheimnis des modernen Lebens. Studenten, die durch das Studium gehen, wir können sie überblicken nach dem, was sie durchmachen und was sie selbst davon wissen; aber was sie so durchmachen, ist nicht alles. Ihr Inneres ist etwas ganz anderes. Und würden diese Menschen, die diese ineinandergewobenen Schichten — vierter und fünfter nachatlantischer Zeitraum — durchmachen, wissen, was ein gewisses Glied ihres Wesens, ohne daß sie es wissen, mit ihnen durchmacht, dann würden sie noch ein ganz anderes Verständnis für dasjenige haben, was Goethe jugendlich schon in seinen «Faust» hineingeheimnißt hat, denn unbewußt machen das Unzählige mit, die sich hineinleben in den heutigen Bildungsweg. So daß man sagen muß: Durch alles das, was Goethe sich heranerzogen hat vermöge seines besonderen Karmas, waren ihm die Menschen, denen er nahetrat während seines noch jugendlichen Lebens, etwas ganz anderes, als sie ihm geworden wären, wenn er nicht dieses besondere Karma gehabt hätte. Denn er fühlte und empfand, wie eigentlich die Menschen, mit denen zusammen er da aufwuchs, betäubt werden mußten, um das Faustische Leben in sich eben betäubt zu haben, nicht in Wirklichkeit zu haben. Das konnte er dadurch empfinden, weil dasjenige, was auf geheimnisvolle Weise in seinen Mitmenschen lebte, auf ihn einen solchen Eindruck machte, wie sonst nur der Eindruck gemacht wird von einem Menschen auf den anderen Menschen, wenn besonders intime Verhältnisse auftreten, ich will sagen, wenn sich Liebe entwickelt zwischen dem einen und dem anderen Menschen. Wenn sich Liebe entwickelt zwischen dem einen und dem anderen Menschen, ist ja im gewöhnlichen Leben tätig im hohen Grade unbewußt auch der Zusammenhang des Ich mit dem Gangliensystem und des Astralleibs mit dem Rückenmarkssystem. Da kommt etwas ganz Besonderes in Wirksamkeit. Aber dasjenige, was sonst nur in diesem Liebeverhältnis tätig ist, das trat für Goethe auf in einem weiteren Kreise, indem er das ungeheure, mehr oder weniger unterbewußte Mitgefühl hatte mit den armen Kerlen - verzeihen Sie den Ausdruck -, die nicht wußten, was ihr Inneres durchmacht, während sie äußerlich gedrängt wurden von Klasse zu Klasse, von Prüfung zu Prüfung. Das fühlte er, das gab ihm eine reiche Erfahrung,