Karma of Untruthfulness I

GA 173c

21 January 1917, Dornach

Lecture XXII

Let me start by drawing your attention to a number of things which might be of interest to you, beginning with an article in yesterday's issue of Schweizerische Bauzeitung, reporting on the Johannesbau in Dornach, near Basel. This is the result of a recent visit of a group of Swiss engineers and architects. The article is most gratifying and fair. Indeed, it is like an oasis in the midst of other things which have recently appeared in print about our efforts which had their source in our very midst. It is most satisfying to find such a fair discussion that gives the building its due, especially since it comes from specialist, objective quarters outside our own circle. Do read it. Herr Englert, who acted as guide for that group of Swiss engineers and architects who showed such genuine interest in our building from the technical and also the aesthetic point of view, has just reported that the article is also due to be published in French in the Geneva journal Bulletin de technique.

Further, I should like to draw your attention to a book—you will excuse my inability to tell you the title in the original language—just published by our friend Bugaev under his pen-name of Andrei Belyi. The book is in Russian and gives a very detailed account in great depth of the relationship between spiritual science and Goethe's view of the world. In particular it goes into the connections between Goethe's views and what I said in Berlin in the lecture cycle Human and Cosmic Thought about various world views, but it also discusses a good deal that is contained in spiritual science. Its connections to Goethe's views are discussed in depth and in detail and it is much appreciated that our friend Bugaev has published a revelation of our spiritual-scientific view in Russian.

Herr Meebold, too, has just published a book in Munich to which I should also like to draw your attention. The title is The Path to the Spirit. Biography of a Soul. You will find it interesting because Herr Meebold describes in it a number of experiences he had in connection with the Theosophical Society.

These are the oases in the desert of attacks. It seems that another has just appeared, written by one of our long-standing older members. It is said to be particularly scandalous, but I have not yet seen it. These attacks from among our members are particularly unwelcome because we realize that it is precisely these long-standing older members who ought to know better.

Yesterday we spoke about aspects of the human being's connections with the super-sensible world, particularly with regard to the fact that our dead, and indeed all those who have left their bodies and gone through the gate of death, must be thought of as being in that world. In our present context it is particularly important to understand that in the world through which man passes between death and a new birth an evolution, a development is taking place just as much as is the case here on the physical plane.

Here on the physical plane, taking a shorter span to start with, such as the post-Atlantean time, we speak of the Indian, the Persian, the Egypto-Chaldean, the Greco-Latin, the modern period, and so on. And we consider that during the course of these periods an evolutionary process takes place—in other words, that human souls and the manner in which these souls manifest in the world during this sequence of periods differ in characteristic ways.

Similarly, if only one can find sufficiently graphic concepts, one can speak of an evolution that takes place for these periods of time in the sphere through which the dead pass. There, too, an evolution takes place. On all kinds of occasions, where this has been possible, this evolution has been discussed in different ways. But relatively easy though it is to speak of evolution on the physical plane—and as you know it is not all that easy in this materialistic age—it is naturally less easy to do so with regard to the spiritual world, since for that world we lack sufficiently graphic concepts. Our language was created for the physical plane, and we are forced to use all kinds of paraphrases and graphic substitutes in order to describe the spiritual sphere in which the dead are living, especially with regard to evolution.

Naturally, of particular interest now is the fact that life between death and a new birth in our fifth post-Atlantean period is suitably different from what it was in earlier times. While the materialistic cultural period is running its course here on earth, a great deal is also taking place in the spiritual world. Since the dead have a far more intense experience of everything connected with evolution than is the case for people living on the physical plane, their destiny is most intensely dependent on the manner in which a certain evolution takes place in definite periods. The dead react far more intimately, far more subtly, to what lives in evolution than do the living—if we may use these expressions—and this is perhaps more noticeable in our materialistic age than has ever been the case before.

Now, to assist our understanding of a number of things we shall be discussing, I want to introduce into these lectures something that has emerged in relation to this, as a result of careful observation of the actual situation. To do this I shall have to widen our scope somewhat and speak today about various aspects in preparation for the statements towards which our train of thought is leading.

I have already pointed out that the right way to look at the human being in relation to the universe is to consider the individual parts of his being separately. From the spiritual point of view, what exists here on the physical plane is more a kind of image, a manifestation. Thus we may regard as fourfold the physical human being we see before us.

First we see the head. As you know from earlier discussions, the head as it appears in a particular incarnation is supposed to have reached its final stage in that incarnation. The head is the part most strongly exposed to death. For the way our head is formed is, for the most part, the consequence of our life in our previous incarnation. On the other hand, the formation of our next head in our next incarnation is the consequence of the life of our present body. A while ago I expressed this briefly by saying: Our body, apart from our head, metamorphoses itself into our head in our next incarnation, while our next body is growing towards us; whereas our present head is the metamorphosed body of our previous incarnation, the rest of our body has grown towards us more or less—there are varying degrees—out of what we have inherited.

This is how the metamorphosis takes place. Our head, as it were, falls away in one incarnation, having been the outcome of our body in our previous incarnation. And our body transforms itself, metamorphoses itself—as does leaf to petal in Goethe's theory of metamorphosis—into our head in our next incarnation. Now because our head is formed from the earthly body of our previous incarnation, the spiritual world has a great amount of work to do on this head between death and our new birth, for its archetypal form must be fashioned by the spiritual world in accordance with karma. That is why, even in the embryo, the head appears before anything else in its complete form, for more than any other part it has been influenced by the cosmos. The body, on the other hand, is influenced for the most part by the human organism. So this appears later than the head in the embryo. Apart from its physical substance, which has of course been gathered through heredity, our head, in its form, its archetypal form, is indeed shaped by the cosmos, by the sphere of the cosmos. It is not for nothing that your head is more or less spherical in shape, for it is an image of the sphere of the universe; the whole sphere of the universe works to form your head. Thus we can say that our head is formed from the sphere.

Just as here on earth people busily work to construct machines and build up trade and commerce, so in the spiritual world human beings are busy, though not exclusively, developing all the technical requirements, the spiritual technical requirements for building the head for their next incarnation from out of the sphere of the universe, the whole cosmos, in accordance with the karma of their earlier incarnations. We glimpse here a profound mystery of evolution.

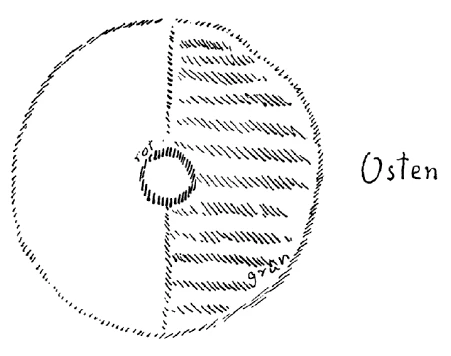

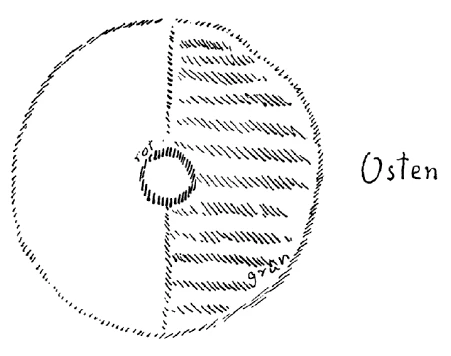

The second aspect we must consider, if we want to view man as a revelation of the whole universe, comprises all the organs of his breast, centred around lung and heart. Let us look at them without the head. The head is an image of the whole spherical cosmos. Not so, the organs of the breast. These are a revelation of all that comes from the East. They are formed out of what might be called the hemisphere. (See diagram).

Imagine the cosmos like this. Then you can see the head as an image of the cosmos. And the organs of the breast can be seen as an image of what streams in from the East—the hemisphere I am shading green. This hemisphere alone works on the organs of the breast. Or, expressed as a paradox: The breast organs are half a head.

This is the basic form. The head is based on the sphere, the breast organs on part of a circle, a kind of semicircle, only it is bent in various ways so that you can no longer recognize it exactly. You would be able to see that your head really is a sphere had luciferic and ahrimanic forces never worked on man. And you would see that the organs of the breast are really a hemisphere, had these forces never exercised their influence. The direction in relation to the centre—one would have to say for ordinary earthly geometry, the infinitely distant centre—is eastwards. An eastward-facing hemisphere.

Now we come to the third part of the human being, excluding head and breast organs: the abdominal organs and the limbs attached to the abdomen. Although this is not an exact term, I shall call all this the abdominal organs. Everything I comprehensively call the abdominal organs can also be related, like the other parts, to forces which work and organize from without. In this realm they work, of course, on man from the outside via embryological development in the way they do because during pregnancy the mother is dependent on the forces which have to be gathered together to form the abdomen, just as forces have to be collected from the sphere to form the head and from the East, the hemisphere, to form the organs of the breast.

The forces that work on the organs of the abdomen must be imagined as coming from the centre of the earth, but differentiated, with all that this entails, according to the region inhabited by the parents or ancestors. The forces all come from the centre of the earth, but with differentiations depending on whether a person is born in North America, Australia, Asia or Europe. The organs of the abdomen are determined by forces from the centre of the earth with differentiations according to region.

Seen from the occult point of view, the complete human being also has a fourth aspect. You will say that we have already dealt with the whole human being, and this is so, but from the occult point of view a fourth aspect must be considered. We have examined three parts, so now all that is left is the total human being. This totality, too, is a part. Head, chest and abdomen all together form the fourth aspect, the totality, and this totality is in turn formed by certain forces. This totality is formed by forces that come from the whole circumference of the earth. They are not differentiated according to region. The total human being is formed by the total circumference of the earth.

Herewith I have described to you the physical human being as an image of the cosmos, an image of the forces of the cosmos working together. Other aspects, too, might be considered in connection with the cosmos. For this we would have to think of the spiritual cosmos in relation to the human being, not only the physical cosmos. We have just been examining the physical human being, so we were able to remain with the physical cosmos. Once we start to consider the discarnate human being between death and a new birth we cannot remain with the elements of space, for the three-dimensional space that we have—though it determines the measure of the physical human being living between birth and death—does not determine the measure of the spiritual human being living between death and a new birth. We have to realize that those who are dead have at their disposal a world that is different from the one which lives in three dimensions.

To turn now to the discarnate human being, the one we call a dead human being, perhaps we need a different kind of consideration. Our method of consideration must remain more mobile. Also there are various points of view from which we could conduct our considerations, for life between death and a new birth is just as complicated as life between birth and death. So let us start with the relationship between the human being here on earth and the human being who has entered the spiritual world through death.

Once again we have the first part, but it is temporal rather than spatial. We could call it the first phase of a development. The dead human being goes, you might say, out into the spiritual world in a certain way; he leaves the physical world but, especially during the first few days, is still very much connected with it. It is very significant that the dead person leaves the physical world in close connection with the constellation arising for his life from the positions of the planets. For as long as the dead person is still connected with his etheric body, the constellation of planetary forces resounds and vibrates in a wonderful way through this etheric body. Just as the territorial forces of the earth vibrate very strongly with the waters of the womb that contains a growing physical human being, so in a most marked way do the forces of the starry constellations vibrate in the dead person who is still in his etheric body at the moment—which is, of course, karmically determined—when he has just left the physical world.

Investigations are often made—unfortunately not always with the necessary respect and dignity, but out of egoistic reasons—into the starry constellation prevailing at birth. Much less selfish and much more beautiful would be a horoscope, a planetary horoscope made for the moment of death. This is most revealing for the whole soul of the human being, for the entry into death at a particular moment is most revealing in connection with karma.

Those who decide to conduct such investigations—the rules are the same as those applied to the birth horoscope—will make all kinds of interesting discoveries, especially if they have known the people for whom they do this fairly well in life. For several days the dead person bears within himself, in the etheric body he has not yet discarded, an echoing vibration of what comes from the planetary constellation. So the first phase is that of the direction in the starry constellation. It is meaningful as long as the human being remains connected with his etheric body.

The second phase in the relationship of the human being to the cosmos is the direction in which he leaves the physical world when he becomes truly spiritual, after discarding his etheric body. This is the last phase to which terms can be applied in their usual, rather than in a pictorial, meaning to describe what the dead person does, terms which are taken from the physical world. After this phase the terms used must be seen more or less as pictures.

So, in the second phase the human being goes in the direction of whatever is the East as seen from his starting point—here, direction is still used in a physical sense, even though it is away from the physical world. Through whatever is for him an easterly direction the dead person journeys at a certain moment into the purely spiritual world. The direction is to the East. It is important to be aware of this. Indeed, an old saying found in various secret brotherhoods, preserved from the better days of mankind's occult knowledge, still points to this. Various brotherhoods speak of one who has died as having ‘entered into the eternal East’. Such things, when they are not foolish trappings added later, correspond to ancient truths. Just as we had to say that the organs of the breast are formed out of the East, so must we imagine the departure of the dead as going through the East. By stepping out of the physical world through the East into the spiritual world, the dead person achieves the possibility of participating in the forces which operate, not centrifugally as here on earth, but centripetally towards the centre of the earth. He enters into the sphere out of which it is possible to work towards the earth.

The third phase may be described as the transition into the spiritual world; and the fourth as working or having an effect out of the spiritual world, working with the forces from the spiritual world.

Such ideas bring us intimately close to what here binds the human being to the spiritual worlds. The table below shows that the conclusion of number 4 meets up with the beginning of number 1, namely working on the head out of the realm of the sphere. This work is done by the human being himself after he has entered into the spiritual world by way of the East.

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| Head: |

Breast organs: |

Abdominal organs: |

The totality: |

| from the sphere |

from the East |

from the centre of the earth, differentiated according to territory |

by the circumference of the earth |

| First Phase: Direction in the starry constellation |

Second Phase: Towards the East |

Third Phase: Transition into the spiritual world |

Fourth Phase: Working out of the spiritual world |

In our dealings with the dead we can perceive strongly that those who have died have to leave the physical world in an easterly direction. They are to be found in the world which they reach via the door of the East. They are beyond the door of the East. And in this connection the experiences we undergo now, in the fifth post-Atlantean period, in the sphere of development of materialism are very significant.

For you see, in this fifth post-Atlantean period, the dead now lack a great deal because of the materialistic culture prevalent in the world. Some aspects of this will be clear to you from what we said yesterday. When, by suitable means, we come to know the life of the dead today, we discover that they have a very strong urge to intervene in what human beings do here on earth. But in earlier times, when there was less materialism on the earth than there is today, it was easier for the dead to intervene in what took place on the earth. It was easier for them to influence the sphere of the earth through what those on earth felt and sensed of the after-effects of the dead.

Today it can be experienced very frequently—and this is always surprising in the actual case—that people who have been intensely involved in certain events during their life are unable, in their life after death, to have any interest in the events which take place after their death, because they lack any kind of link. Amongst us, too, there are souls who showed great interest for events on earth while they were here but who now, having gone to the spiritual world, find the events taking place since their death quite foreign to them. This is frequently the case, even with distinguished souls who here on earth were greatly gifted and filled with the liveliest interest.

This has been going on for a long time, indeed it has been on the increase during the whole of the fifth post-Atlantean period, ever since the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Expressed in commonplace terms—which are unfortunately all we have in our language—our experience is that, because they are less and less able to intervene in what human beings do, the dead have instead to intervene in the way people manifest as individual personalities. So we see that since the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the interest and the work of the dead has been concentrated increasingly on individual personalites rather than on the wider contexts concerning mankind. Since I have occupied myself closely with this very aspect, I have reached the conviction that it is connected with a certain phenomenon of modern times that is very noticeable to those who are interested in such things.

In recent history, unlike former times, we have the remarkable phenomenon of people being born with outstanding capacities. In general they work with tremendous idealism and distinguished endeavour but are incapable of gaining a broader view of life or of widening their horizons. In the whole of literature this has been expressing itself for some time. Individual ideas, concepts, and feelings, expressed either in literature or art, or even science, sometimes display strong promise. But an overall view is not achieved. This is also the reason why people find it so difficult to achieve the broader view needed in spiritual science. It happens chiefly because the dead approach individuals and work in them on capacities for which the foundations are laid during childhood and youth. The faculties which enable individuals to gain a broader view when they reach maturity are more or less untouched by the activities of the dead in this materialistic age. Incomplete talents, unfinished torsos—not only in the wide world, but also in individual situations—are therefore very prevalent because the dead can more readily approach individual souls rather than what lives socially in human evolution today. The dead have a strong urge to reach what lives socially in human evolution, but in our fifth post-Atlantean period this is exceedingly difficult for them.

There is another phenomenon today of which it is most important to become aware. There exist today many concepts and ideas which have to be very definite if they are to be of any use. Modern, more mercantile, life demands clearly defined concepts based on calculations. Science has become accustomed to this, but so has art. Think of the development art has undergone in this connection! It is not so long ago that art was concerned with great ideals on a wide scale, when, thank goodness, concepts were insufficient for an easy interpretation of great works which were full of meaning. This is no longer the case to the same extent. Today, art strives for naturalism, and concepts can easily encompass works of art because now they have often arisen merely from concepts instead of from an elemental, all-embracing world of feeling. Mankind is today filled to the brim with commonplace, naturalistic concepts which are determined by the fact that they have been conceived entirely in relation to the physical plane where it is in the nature of things to be sharply defined and individualized.

Now it is significant that the so-called dead do not appreciate such concepts. They do not appreciate sharply-defined concepts which are immobile and lifeless. One can learn some extraordinary things, some very interesting things in this connection—if I may be permitted to use such commonplace and banal expressions for these venerable circumstances. As you know, for we have gone through all this together here, I have recently been endeavouring to discuss, using lantern slides, all kinds of considerations about periods in the history of art. I have been endeavouring to find concepts for all kinds of artistic phenomena. To communicate through speech one has to find concepts. Yet I have constantly felt the need to avoid firm, clearly-defined concepts for artistic matters. Of course, for the lectures I had to attempt to define the concepts as far as possible, for they have to be defined if they are to be put into words. But while I was preparing the lectures and formulating the concepts I must say I had a certain aversion, if I may use this word, to expressing what had to be said in such meagre concepts as have to be used if things are to be expressed in words. Indeed, we shall only understand one another in these realms if you translate what has been expressed in close-textured concepts back into concepts of which the texture is less clearly defined.

If one comes up against this experience at a time when one is also concerned with the world of discarnate souls, the following can happen. One may be attempting to comprehend a phenomenon which gives one the feeling of being far too unintelligent to grasp it in concepts. One looks at the phenomenon but has insufficient understanding with which to bind it properly into concepts. This experience, which is particularly likely when one is contemplating a work of art, can bring one into especially intimate contact with discarnate souls, with the souls of the dead. For these souls prefer concepts which are not sharply defined, concepts which are more mobile and can mingle with the phenomena. Sharply defined concepts, concepts similar to those formed here on the physical plane under the influence of the physical conditions of the sense-perceptible world, give the dead the feeling of being nailed to one particular spot, whereas what they need for their life in the spiritual world is freedom of movement.

Therefore it is important that we occupy ourselves with spiritual science so that we may enter those intimate spheres of experience where, as was said yesterday, the living can encounter the dead; because the concepts of spiritual science cannot be as closely defined as can those of the physical plane. That is why malevolent or narrow-minded people can easily discover contradictions in the concepts of spiritual science. The concepts are alive, and what is alive is mobile, though it does not, in fact, harbour contradictions. We can achieve this by concerning ourselves with spiritual matters, and to do so we have to approach things from various sides. And approaching things from various sides really does bring us close to the spiritual world. That is why the dead feel comfortable when they enter a realm of human concepts which are mobile and not pedantically defined.

Indeed, the dead feel most ill at ease of all when they enter the realm of the most pedantic concepts. These are the ones that have recently come to be defined in relation to the spiritual world for those people who do not want to live in anything spiritual, but who want the concepts for sense-perceptible things to apply to the spiritual world as well. These people conduct spiritualistic experiments in order to imprison spiritual concepts in the world perceptible to the senses. They are, in fact, more materialistic than any others. They seek rigid concepts in order to hold commerce with the dead. Thus they torture the dead most of all, for if they want to approach they force them to enter the very realm most disliked by them. The dead love mobile concepts, not rigid ones.

These are experiences to which the fifth post-Atlantean period seems to be particularly prone, given the two circumstances of materialism here on earth and the peculiar situation of the dead as described. One and the same thing determines materialism here on earth and a certain kind of life in the spiritual world. In the Greco-Latin period the dead most definitely approached the living in a manner which differed from that of today. Nowadays, in the fifth post-Atlantean period, there is what I would like to call a more earthly element—but you must imagine this of course in a more pictorial sense—a more earthly composition in the substantiality of the dead than there used to be. The dead appear in a form that is much more like those of earthly conditions than used to be the case. They are more like human beings, if I may put it this way, than formerly. Because of this they have a somewhat paralysing effect on the living. It is nowadays so difficult to approach the dead because they bring about a numbness in us. Here on earth materialistic thoughts reign supreme. In the spiritual world, as a karmic result, the materialistic consequence reigns supreme, for there the spiritual corporeality of the dead has assumed earthly qualities. It is because the dead are super-strong, if I may put it thus, that they numb us. To overcome this numbness it is necessary to develop the strongest possible feelings for spiritual science. This is the difficulty today, or one of the difficulties, standing in the way of our relationship with the spiritual world.

For the earthly realm seen spiritually—indeed the earthly realm can be seen spiritually—things appear different from what might be assumed when they are not seen spiritually. It is correct to say, as we have done many a time, that we live in the age of materialism. Why? It is because human beings in this materialistic age—human beings in general, rather than those who understand these things—are too spiritual—paradoxical though this may sound. That is why they can be so easily approached by purely spiritual influences such as those of Lucifer and Ahriman. Human beings are too spiritual. Just because of this spirituality they easily become materialistic. It is so, is it not, that what the human being believes and thinks is something quite different from what he is. Those very people who are most spiritual are the ones most open to the whisperings of Ahriman, as a result of which they grow materialistic.

Strongly though one must combat materialistic views and materialistic ways of life, nevertheless one may not maintain that the most unspiritual people belong to the circles of materialists. I have personally met many spiritual people, that is, people who are themselves spiritual, not just in their views, among the monists and suchlike, and equally many coarse materialists especially among the spiritualists. Here, though they may speak of the spirit, are to be found the most coarsely materialistic characters. Haeckel, for instance, is a most spiritual person, regardless of what he often says. He is most spiritual, and just because of this can be approached by an ahrimanic world view. He is a most spiritual person, entirely permeated by the spirit. This once became clearly apparent to me in a cafe in Weimar. I have told this story before, perhaps more than once. Haeckel was sitting at the other end of the table with his beautiful, spiritual blue eyes and his marvellous head. Nearer to me sat the well-known bookseller Herz, a man who has done great service to the German book trade and who knew quite a bit about Haeckel in general. But he did not know that that was Haeckel sitting at the other end of the table. At one point Haeckel laughed heartily. Herz asked: Who is that man laughing so much down there? When I told him it was Haeckel he said: It can't be, evil people can't laugh like that!

Thus the concepts entertained by present-day materialists are so bare of spirituality that they are unable to discern the revelations of the spirit in the material world. So spiritual and material worlds fall apart and the spiritual world becomes no more than a set of concepts. Anyway, the biggest materialistic blockheads are often found today in societies and associations that call themselves spiritualistic. Here are the materialistic blockheads who on occasion have even succeeded in tracing mankind's descent from the apes, even from a particular ape, to the greater glory of the human race. These people were not satisfied with the descent of man from the apes in general, they even traced the lines back to particular apes. For those of you have not heard about this, let me explain. A few years ago a book appeared in which Mrs Besant and Mr Leadbeater described exactly which apes of ancient days they were descended from. They traced their family trees back to particular apes and you can read all about this. Such things are possible, even in much-read books today.

We need the concepts I have elaborated today in order to penetrate more deeply into certain aspects of the theme we are discussing. For our world is definitely dependent on the spiritual world in which the dead live; it is connected with the spiritual world. That is why I have endeavoured to unfold for you certain concepts which relate directly to observations of the immediate present. Everything that takes place here in the physical world has certain effects in the spiritual world. Conversely, the spiritual world with the deeds of the dead shows itself either in what the dead can do for the physical world or in what they cannot do because of the present materialistic age. I also described this present materialistic age in so far as it has been made excessively materialistic by certain secret brotherhoods, as I showed yesterday. The type of materialism that underlies all world events to a high degree today is what we might call the mercantile type.

I ask you to take good note for tomorrow of the concepts I have put before your souls today, concerning the life of the dead. But also please note how little the present age takes certain things for granted which were taken much more for granted in earlier times. We shall see tomorrow how all these things are linked. However, it is characteristic for our time that certain conceptual views are extended to mercantile life which would escape someone who fails to pay attention to such features of our time. We ought not to let them escape us. Mercantilism is all very well as long as it is put in the right light in the way it stands within social life. For this to happen it is necessary for us to have certain yardsticks for everything. Today, however, much conceptual chaos reigns. Yet within this conceptual chaos, concepts are given quite clear definitions, as is our way in the age of materialism in which concepts are fixed to ideas based on what the senses can experience. And when a chaos of concepts then results, as happens in today's materialism, this really does draw the sharpest possible line between the physical world in which human beings live between birth and death, and the super-sensible world in which they live between death and a new birth.

Only consider in this connection the fact that in Central Europe—in contrast to other regions where the inclination to philosophize is less pronounced—there is a tendency to philosophize about the mercantile system even though this is not at home in Central Europe. In Central Europe there is a tendency to make a philosophy of everything. Thus people also philosophize about what aspects of materialism are typical for our time. An interesting book by Jaroslav was published long before the war: Ideal and Business. Certain chapters interested me particularly because of their significance with regard to cultural history. It was not the content that interested me but their relation to cultural history; so, for instance, the chapter entitled ‘Plato and Retail Trade’. This deals with everything to do with commerce, with the mercantile system. Another interesting chapter is ‘The Astrological System Applied to the Price of Pepper’. Not uninteresting is also ‘Wholesale Trade as Described by Cicero’. Another chapter is entitled ‘Holbein's and Liebermann's Portraits of Merchants’. Not uninteresting, too, is the chapter ‘Jakob Böhme and the Problem of Quality’. Very interesting is ‘The Goddess Freya in Germanic Mythology in Relation to Free Competition’. And finally, especially interesting is ‘The Spirit of Commerce as Taught by Jesus’.

As you see, everything is thrown in the pot together. But by this very fact things gain that characteristic which makes for materialism. Let us take all this as a preparation for our considerations tomorrow.

Zweiundzwanzigster Vortrag

Ich darf Sie vielleicht zuerst auf einiges aufmerksam machen, das für Sie doch interessant sein könnte, zunächst auf einen Artikel in der «Schweizerischen Bauzeitung» vom 20. Januar 1917, wo über den Johannesbau in Dornach bei Basel gesprochen wird, und zwar auf Grundlage des Besuches, den vor kurzem die Schweizerischen Ingenieure und Architekten diesem Bau gemacht haben. Der Artikel ist sehr erfreulich und schön geschrieben, und es ist wirklich eine Oase, könnte man sagen, gegenüber manchem, was in der letzten Zeit gedruckt worden ist, auch jetzt wiederum gedruckt wird sonst über unsere Bestrebungen, gerade auch aus unserem Kreise heraus gedruckt wird. Es ist eine sehr erfreuliche Tatsache, daß von außenstehender, objektiver und namentlich fachmännischer Seite eine so erfreuliche und den Bau würdigende Auseinandersetzung erschienen ist. Also, der Artikel ist erschienen in der «Schweizerischen Bauzeitung» vom 20. Januar 1917; ich rate Ihnen, die Sache zu lesen. Eben wird mir von Herrn Englert, der dazumal die Führung mit übernommen hat der Schweizerischen Ingenieure und Architekten, die sich in so erfreulicher Weise für unseren Bau vom fachmännischen Standpunkte aus und vom allgemein ästhetischen Standpunkte aus interessiert haben, mitgeteilt, daß der Artikel auch im «Bulletin de technique», das in Genf in französischer Sprache erscheint, veröffentlicht werden wird.

Ferner möchte ich auf das eben erschienene Buch - Sie verzeihen, wenn ich in der Ursprache den Titel Ihnen nicht vorlesen kann - aufmerksam machen, das Buch, das eben erschienen ist von unserem Freunde Andrej Bjely, der in der bürgerlichen Sprache, in der er Ihnen bekannt ist, Bugajew heißt. Das Buch ist in russischer Sprache erschienen und setzt in sehr ausführlicher Weise und in sehr eingehender Weise viele Beziehungen der Geisteswissenschaft zur Goetheschen Weltanschauung auseinander. Insbesondere werden die Beziehungen der Goetheschen Weltanschauung zu demjenigen, was einmal in dem Berliner Vortragszyklus über die verschiedenen Weltanschauungsstandpunkte gesagt worden ist — der Vortragszyklus hieß «Der kosmische und der menschliche Gedanke» -, aber auch sonst über dasjenige auseinandergesetzt, was in der Geisteswissenschaft enthalten ist. Die Beziehungen zur Goetheschen Weltanschauung werden in eindringlicher und ausführlicher Weise auseinandergesetzt, und daher ist es sehr erfreulich, daß wie eine Manifestation unserer geisteswissenschaftlichen Weltanschauung dieses Buch in russischer Sprache von unserem Freunde Bugajew erschienen ist.

Herr Meebold hat vor kurzem ein Buch erscheinen lassen, auf das ich auch hinweisen möchte, bei Piper&Co. in München ist das Buch erschienen. Es heißt: «Der Weg zum Geiste», eine Seelenbiographie, und es wird immerhin interessant sein für Sie aus dem Grunde, weil mancherlei Erfahrungen, die Herr Meebold machte mit der Theosophical Society, in diesem Buche beschrieben werden.

Das sind die Oasen in der Wüste der Angriffe, von denen einer, der mir noch nicht zugekommen ist, der aber besonders unerhört sein soll, jetzt eben wiederum von einem unserer langjährigen älteren Mitglieder erschienen ist; aber ich habe den gedruckten Artikel noch nicht gelesen, nur Mitteilungen darüber.

Es sind ja diejenigen Angriffe, die gerade aus dem Kreise der Mitglieder, namentlich älterer, langjähriger Mitglieder kommen, die sind ja besonders «erfreulich», weil man weiß, daß diese Mitglieder es anders wissen könnten. Aber wie gesagt, den Artikel selber habe ich noch nicht zu Gesicht bekommen, sondern nur Mitteilungen darüber.

Wir haben gestern einiges besprochen in Anknüpfung an die Beziehungen des Menschen zur übersinnlichen Welt, insoferne in dieser übersinnlichen Welt auch unsere Toten, überhaupt die entkörperten, die durch die Pforte des Todes gegangenen Menschen gedacht werden müssen. Es ist in unserem jetzigen Zusammenhang von ganz besonderer Bedeutung, daß man sich klarmacht, wie innerhalb jener Welt, die der Mensch durchmacht zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, ebenso eine Entwickelung, eine Evolution stattfindet wie hier auf dem physischen Plane.

Wir sprechen hier auf dem physischen Plan, wenn wir zunächst einen kurzen Zeitraum ins Auge fassen, zum Beispiel den der nachatlantischen Zeit, von der indischen, der persischen, der ägyptisch-chaldäischen, der griechisch-lateinischen Periode, Gegenwartsperiode und so weiter, und meinen, indem wir auf solche Perioden hinweisen, daß eine Evolution stattfindet, daß sich gewissermaßen die Seelen der Menschen und die Offenbarungen der Menschenseelen in diesen aufeinanderfolgenden Zeiträumen in charakteristischer Weise unterscheiden.

Ebenso könnte man, wenn man zugleich anschauliche Begriffe bekommen könnte dafür, von einer Evolution sprechen, die für solche Zeiträume stattfindet in dem Bereiche, welchen die Toten durchmachen; denn da findet auch eine Evolution statt. Und an den verschiedensten Stellen, wo das sein konnte, wurde ja auch auf diese Evolution hingewiesen, verschiedene Ausführungen wurden darüber gemacht. Allein, so leicht wie es ist, über die Evolution auf dem physischen Plane zu sprechen — und Sie wissen ja, das ist schon nicht so ganz leicht in unserer materialistischen Zeit -, so leicht dieses also ist für den physischen Plan, ist es natürlich für die geistige Welt nicht, denn für die geistige Welt haben wir keine ordentlich geprägten Begriffe. Die Sprache ist für den physischen Plan geschaffen, und es müssen allerlei Verbildlichungen, allerlei Umschreibungen stattfinden, wenn man auf die geistige Sphäre, in der die Toten sind, hinweisen will gerade mit Rücksicht auf die Evolution.

Insbesondere für uns bedeutsam ist natürlich, daß das Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt in unserem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum auch entsprechend anders ist als vorher. Während auf der Erde hier die materialistische Kulturepoche sich abspielt, spielt sich auch allerlei in der geistigen Welt ab. Und da die Toten noch viel intensiver solche Dinge erleben, die zusammenhängen mit der Evolution, als die hier auf dem physischen Plane lebenden Menschen, so hängt schon in intensivster Weise das Schicksal der Toten von der Art und Weise ab, wie eine bestimmte Evolution in bestimmten Perioden abläuft. Die Toten reagieren noch viel intimer, noch viel feiner auf dasjenige, was in der Evolution lebt, als die Lebendigen — wenn wir diese Ausdrücke gebrauchen wollen -, und vielleicht sogar mehr als zu irgendeiner andern Zeit ist das bemerkbar in unserer materialistischen Zeit.

Nun möchte ich in diese Vorträge zum weiteren Verständnis von mancherlei, das wir besprechen wollen, gerade dieses einfügen, was sich einer sorgfältigen Beobachtung des Tatbestandes in bezug darauf ergeben hat. Ich muß allerdings mit Bezug darauf etwas weiter ausgreifen und heute allerlei Betrachtungen anstellen, die erst vorbereiten sollen zu dem, was eigentlich zu sagen ist. Ich habe ja schon darauf hingewiesen, daß der Mensch richtig betrachtet wird im Verhältnisse zum Weltenall, wenn wir seine einzelnen Wesensglieder getrennt betrachten. Für die geistige Betrachtung ist ja dasjenige, was hier auf dem physischen Plane ist, mehr eine Abbildung, eine Offenbarung. Und so können wir in Anlehnung an manches, was wir schon besprochen haben, den Menschen, so wie er uns als physisches Wesen zunächst entgegentritt, viergliedrig auffassen.

Zunächst haben wir das Haupt. Dieses ist, wie Sie aus früheren Betrachtungen wissen, in der Form, wie es auftritt in irgendeiner Inkarnation, eigentlich dazu bestimmt, in dieser Inkarnation seinen Abschluß zu finden. Das Haupt ist am meisten dem Tode ausgesetzt. Denn wie unser Haupt gebildet ist — erinnern Sie sich an frühere Betrachtungen -, wie unser Haupt organisiert ist, ist es im wesentlichen das Ergebnis unseres Lebens in der früheren Inkarnation. Wie dagegen unser nächstes Haupt, unser nächster Kopf gebildet sein wird in der folgenden Inkarnation, das ist ein Ergebnis unseres jetzigen Leibeslebens. Kurz habe ich das ausgedrückt vor einiger Zeit, indem ich sagte: Der Leib des Menschen, außer dem Haupte, wandelt sich um zum Haupt in der nächsten Inkarnation, und der nächste Leib wächst zu, während das jetzige Haupt, das wir tragen, der umgewandelte Leib der vorhergehenden Inkarnation ist, und uns unser übriger Leib jetzt aus den Vererbungsverhältnissen mehr oder weniger — das alles ist gradweise verschieden — zugewachsen ist.

Das ist die Metamorphose. Das Haupt fällt gleichsam ab in einer Inkarnation, es ist das Ergebnis des Leibes der vorhergehenden Inkarnation. Und der Leib gestaltet sich um, metamorphosiert sich, wie in der Goetheschen Metamorphosenlehre das Blatt zur Blüte, zum Haupte in der nächsten Inkarnation. Dadurch aber, daß das Haupt, der Kopf gebildet wird aus dem Erdenleib der vorhergehenden Inkarnation, hat die geistige Welt mit diesem Haupte zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt besonders viel zu tun, denn es muß die Urform, das Urbild des Hauptes aus der geistigen Welt gemäß dem Karma herausgearbeitet werden. Daher erscheint auch im Embryo das Haupt zuerst vollkommen ausgebildet, weil es aus dem Kosmos heraus am meisten beeinflußt ist. Durch die menschliche Organisation wird der übrige Leib eigentlich am meisten beeinflußt. Daher erscheint diese übrige Organisation im Embryo später ausgebildet als das Haupt. Das Haupt ist schon — natürlich nicht seiner physischen Gestaltung nach, der physische Stoff ist gewiß der Vererbung entnommen, aber in bezug auf seine Formung, in bezug auf sein Urbild — aus dem Kosmos herausgebildet, ist, wie man sagen kann, aus der Sphäre. Ihr Haupt ist nicht umsonst mehr oder weniger kugelförmig; es ist das Haupt ein Abbild der ganzen Weltensphäre, und die ganze Weltensphäre arbeitet mit an der Bildung des Hauptes. So daß wir sagen können: das Haupt ist aus der Sphäre gebildet.

Geradeso wie hier im Leben eine rege Tätigkeit ist, um Maschinen zu bauen, um merkantiles Wesen zu besorgen und dergleichen, so ist in der geistigen Welt der Mensch unter anderem, nicht ausschließlich, aber unter anderem damit beschäftigt, all die Technizismen zu entwickeln, die jetzt spirituelle Technizismen sind, um für die nächste Inkarnation aus der Sphäre, aus der ganzen Welt, aus dem ganzen Kosmos heraus sein Haupt zu bilden gemäß seinem Karma in früheren Inkarnationen. Da schauen wir in tiefe Mysterien des Werdens hinein.

Das zweite, was ins Auge gefaßt werden muß, wenn der Mensch wie eine Offenbarung des ganzen Weltenalls in Betracht kommt, ist alles das, was die Brustorgane betrifft mit Mittelpunkt Lunge und Herz. Wir betrachten sie am besten getrennt von dem Haupte. Das Haupt ist ein Abbild des ganzen kugelförmigen Kosmos. Nicht so die Brustorgane. Sie sind eine Offenbarung derjenigen Kräfte, welche von Osten herkommen. Sie sind herausgebildet aus der, wie man sagen könnte, Halbsphäre. Wenn Sie sich den Kosmos so vorstellen (siehe Zeichnung Seite 206), so können Sie sich das Haupt als ein Abbild des Kosmos vorstellen. Wenn Sie sich hier den Osten vorstellen, so können Sie sich die Brustorgane als ein Abbild desjenigen vorstellen, was von Osten hereinstrahlt, also der Halbsphäre, die ich hier grün schraffiere. An den Brustorganen arbeitet nur die Halbsphäre. Man könnte, wenn man paradox sprechen wollte halber Kopf.

Das ist auch die Grundform. Dem Kopfe liegt die Kugelform zugrunde, den Brustorganen liegt zugrunde der Kreisteil, gewissermaßen der Halbkreis. Nur ist er verschiedentlich gebogen, und man kann es nicht mehr genau sehen. Sehen könnten Sie, daß Ihr Kopf wirklich eine Kugel ist, wenn auf den Menschen nie luziferische und ahrimanische Kräfte gewirkt hätten. Sehen würden Sie, daß die Brustorgane wirklich eine Halbsphäre sind, wenn eben diese Kräfte nicht gewirkt hätten. Und gewissermaßen die Richtung nach dem Mittelpunkte — aber man könnte sagen: für gewöhnliche irdische geometrische Verhältnisse nach dem unendlich fernen Mittelpunkte - ist nach dem Osten. Also Halbsphäre: nach dem Osten.

Jetzt haben wir als drittes Glied alles dasjenige, was sich im Menschen findet als Teilorgane außer Kopf und Brustorganen: Unterleibsorgane mit den daranhängenden Gliedmaßen. Alles das will ich, obwohl die Benennung nicht besonders genau ist, Unterleibsorgane nennen. Dieses, was wir so als Unterleibsorgane zusammenfassen, können wir nun auch ebenso beziehen auf äußerlich organisierende Kräfte, die natürlich hier auf diesem Gebiete hauptsächlich auf dem Umwege durch die Embryologie auf den Menschen wirken, aber eben auf diesem Umwege doch so wirken, weil während der Schwangerschaft die Mutter abhängig ist von den Kräften, die da aufgesucht werden müssen zu der Gestaltung des Unterleibes, ebenso wie die Sphäre aufgesucht werden muß zur Gestaltung des Kopfes, der Osten, die Halbsphäre aufgesucht werden muß zur Gestaltung der Brustorgane.

Was auf solche Weise auf die Organe des Unterleibes als Kräfte wirkt, das müssen Sie sich vorstellen so, daß es vom Mittelpunkte der Erde kommt, aber differenziert wird durch das Territorium, auf dem sich die Eltern beziehungsweise Voreltern aufhalten, durch das Territorium und alles, was damit zusammenhängt. Also wohlgemerkt, es kommen die Kräfte vom Mittelpunkte der Erde; aber ob ein Mensch in Nordamerika oder Australien oder Asien oder Europa zur Welt gekommen ist, es kommt aus dem Mittelpunkte der Erde, aber immer differenziert, einmal wie die Kraft wirkt durch das europäische Territorium differenziert, einmal durch das amerikanische Territorium differenziert, einmal durch das asiatische Territorium differenziert und so weiter. Also ich kann sagen: Die Unterleibsorgane werden bestimmt aus dem Mittelpunkte der Erde, in Differenzierung durch das Territorium.

Nun, wenn wir okkultistisch vollständig den Menschen betrachten wollen, so müssen wir noch ein Viertes betrachten. Da werden Sie sagen: Wir haben ja jetzt schon den ganzen Menschen. Gewiß, aber im Okkultismus kommt immer noch ein Viertes in Betracht, Jetzt haben wir drei Glieder des Menschen betrachtet; jetzt können wir noch den ganzen Menschen für sich betrachten. Das Ganze ist eben auch ein Glied. Also Kopf, Rumpf, Unterleib, aber jetzt alles zusammen, so daß wir als viertes Glied das Ganze haben, und dieses Ganze ist jetzt wiederum durch Kräfte gebildet. Aber es ist dieses Ganze gebildet durch Kräfte des ganzen Erdenumkreises. Also jetzt nicht differenziert durch das Territorium, sondern das Ganze des Menschen ist gebildet durch den ganzen Umkreis, also durch den Erdenumkreis.

Jetzt habe ich Ihnen den physischen Menschen als ein Abbild dargestellt des Kosmos, wie er gewissermaßen Bild ist der aus dem Kosmos zusammenwirkenden Kräfte. Wir können auch andere Verhältnisse im Zusammenhange mit dem Kosmos betrachten. Da müssen wir dann den geistigen Kosmos in Beziehung zum Menschen denken, nicht bloß den physischen Kosmos. Was wir jetzt betrachtet haben, war der physische Mensch. Daher konnten wir auch stehenbleiben bei dem physischen Kosmos. Betrachten wir den Menschen als entkörpertes Wesen zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt, dann können wir nicht stehenbleiben bei dem, was sich im Raume erschöpft, denn der dreidimensionale Raum, wie wir ihn haben, ist allerdings maßgebend für den physischen Menschen, der zwischen Geburt und Tod lebt, er ist aber nicht maßgebend für den geistigen Menschen, der zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt lebt. Man muß sich dann klar sein, daß der Tote eine andere Welt noch zur Verfügung hat als diejenige, die in drei Dimensionen lebt.

Nun muß man, wenn man den entkörperten Menschen, den sogenannten toten Menschen ins Auge faßt, vielleicht eine etwas andere Betrachtungsweise anstellen. Man muß eine Betrachtungsweise anstellen, die mehr in dem Beweglichen lebt. Und gewiß, man kann da von verschiedenen Gesichtspunkten Betrachtungen anstellen, denn das Leben zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt ist ebenso kompliziert wie das Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod. Aber legen wir zunächst zugrunde die Beziehung des Menschen, der auf der Erde hier ist, zu dem Menschen, der in die geistige Welt durch den Tod eingetreten ist.

Da haben wir wiederum ein erstes Glied — aber es ist das jetzt mehr zeitlich zu fassen -, ein erstes Entwickelungsstadium, könnten wir auch sagen. Der Tote geht, so könnte ich mich ausdrücken, in einer gewissen Weise in die geistige Welt hinaus; aber er geht aus der physischen Welt in die geistige Welt hinaus, er verläßt die physische Welt und ist Ja insbesondere in den ersten Tagen noch mit der physischen Welt zusammenhängend. Und da ist es sehr bedeutungsvoll, daß der Tote aus der physischen Welt hinausgeht gar sehr angepaßt an die Konstellation, die sich für sein Leben aus der Stellung der Planeten ergibt. Solange namentlich der Tote noch mit seinem Ätherleib zusammenhängt, klingen und schwingen wunderbar nach die Planetenkräfte, die Konstellation der Planetenkräfte durch diesen Ätherleib. So wie im Embryowasser beim Entstehen des physischen Menschen außerordentlich stark mitschwingen die Erdenterritorialkräfte, so schwingen bei dem Toten, der noch in:seinem Ätherleib ist, in einer ganz auffälligen Weise die Kräfte mit, die mit den Sternkonstellationen zusammenhängen in dem Augenblicke, wo — das Ganze ist ja natürlich karmisch bedingt - der Tote die physische Welt verlassen hat. Und man könnte, wenn man nur mit der nötigen Ehrfurcht und Würde vorgeht, interessante Entdeckungen machen, wenn man eben solche Sorgfalt anwenden würde, wie man leider oftmals sogar aus egoistischen Gründen anwendet, um eine Untersuchung zu machen für die Sternkonstellation der Geburt. Viel selbstlosere, viel schönere Resultate würde man bekommen, wenn man gewissermaßen das Horoskop stellte, namentlich das planetarische Horoskop, die Stellung der Planeten für den Moment des Todes. Das ist außerordentlich aufschlußreich für das ganze Wesen des seelischen Menschen, und außerordentlich aufschlußreich für den Zusammenhang des Karma mit dem Eintreten des Todes gerade in einem gewissen Momente.

Wer einmal Untersuchungen anstellen wird nach dieser Richtung — die Regeln sind ja dieselben wie für das Geburtshoroskop -, der wird zu allerlei interessanten Resultaten kommen, besonders wenn er die Menschen, für die er die Sache anstellt, im Leben mehr oder weniger gut gekannt hat. Denn der Tote trägt durch Tage hindurch mit seinem noch nicht abgegliederten Ätherleib etwas in sich, was Nachschwingen ist, namentlich aus der planetarischen Sternkonstellation. So daß wir sagen können: Erstes Entwickelungsstadium: Richtung in der Sternkonstellation. Das ist bedeutsam eben so lange, als der Mensch mit seinem Ätherleibe verbunden bleibt.

Das zweite, was nun im Verhältnis des Menschen zum Kosmos in Betracht kommt, das ist, daß der Mensch wirklich in einer gewissen Richtung, könnte man sagen, die physische Welt verläßt, wenn er selbst geistig wird nach Ablegung des Ätherleibes. Da ist es, wo man zuletzt noch im richtigen Sinne, nicht bloß im bildlichen Sinne auf dasjenige, was der Tote tut, Begriffe anwenden kann, die der physischen Welt entnommen sind; denn nach diesem Stadium werden die Begriffe mehr oder weniger Bilder.

Nun kann man sagen: Im zweiten Stadium wird — und jetzt gilt eben die Richtung noch physisch, obwohl es aus dem Physischen hinausgeht — die Richtung nach dem jeweiligen Osten eingeschlagen. Und durch den jeweiligen Osten wandelt in einem gewissen Zeitpunkte der Tote in die rein geistige Welt hinein. Das ist also die Richtung nach dem Osten. Es ist wichtig, dieses sich einmal zu vergegenwärtigen, weil ein altes Wort verschiedener Brüderschaften, das aus besseren Zeiten der okkulten Menschheitserkenntnis sich bewahrt hat, heute noch darauf aufmerksam macht. In allerlei Brüderschaften wird von demjenigen, der gestorben ist, so gesprochen, daß er «eingegangen ist in den ewigen Osten». Solche Dinge, insofern sie nicht später zugesetzter Firlefanz sind, entsprechen alten Wahrheiten. Geradeso wie wir hier davon sprechen mußten, daß die Brustorgane ihre Gliederung aus dem Osten haben, so müssen wir das Hingehen, den Hingang des Toten durch den Osten uns vorstellen. Indem aber der Tote durch den Osten gewissermaßen austritt aus der physischen Welt in die geistige hinein, gelangt er schon in das Gebiet der Sphäre, das heißt, er erlangt die Möglichkeit, an den Sphärenkräften teilzunehmen, die nun nicht, wie hier der Mensch, zentrifugal, sondern zentripetal nach dem Mittelpunkte der Erde hin wirken; er gelangt in die Sphäre hinein, in die Möglichkeit, nach der Erde zu wirken.

So daß wir also als drittes Stadium: Übergang in die geistige Welt setzen können, und als viertes Stadium: Wirkungen oder arbeiten aus der geistigen Welt, arbeiten mit den Kräften aus der geistigen Welt.

Mit solchen Ideen treten wir intim heran an dasjenige, was den Menschen hier bindet an die geistigen Welten. Sie können sogar, wenn Sie dieses Schema in der richtigen Weise betrachten, ersehen, daß Nummer 4 schließt mit dem, was Nummer 1 hier beginnt, das ist: die Arbeit an dem Haupte aus der Sphäre heraus. Sie wird von dem Menschen selbst verrichtet, wenn er durch den Osten eingezogen ist in die geistige Welt.

| Haupt: | Brustorgane: | Unterleibsorgane: | Das Ganze: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aus der Sphäre | Aus dem Osten | Aus dem Mittelpunkteder Durch den Erde, in Differenzierung Erdenumkreis durch das Territorium | FirstRowSecondColumn |

| Erstes Entwickelungsstadium: | Zweites Entwickelungsstadium: | Drittes Stadium: | Viertes Stadium: |

| Richtung in der Sternkonstellation | Richtung nach dem Osten | Übergang in die geistige Welt | Wirkungen aus der geistigen Welt |

Daß der Tote in der Richtung nach dem Osten die physische Welt verlassen muß, das ist beim Verkehren mit den Toten sehr stark wahrzunehmen. Sie befinden sich gewissermaßen in der Welt, die sie erreichen durch das Tor des Ostens. Sie sind jenseits des Tores des Ostens. Und mit Bezug auf solche Dinge sind gerade die Erfahrungen, die man jetzt im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum in der Entwickelungssphäre des Materialismus macht, bedeutsam.

Sehen Sie, in diesem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum entbehren gewissermaßen die Toten durch die materialistische Erdenkultur sehr viel. Manches wird Ihnen schon aus dem gestern Gesagten klar sein. Lernt man das Leben der Toten in der Gegenwart mit den entsprechenden Mitteln kennen, dann ergibt sich, daß sie sehr starke Triebe haben, einzugreifen in die Dinge, welche die Menschen hier auf Erden tun. Aber in früheren Zeiten, in denen weniger Materialismus auf der Erde gelebt hat als jetzt, konnten die Toten leichter eingreifen in das, was auf der Erde geschah. Sie konnten leichter durch die Erdenmenschen, durch das, was die Erdenmenschen als Nachwirkungen der Toten fühlten und empfanden, hereinwirken in die Erdensphäre. Heute ist es sehr, sehr häufig zu erleben, und ich habe gesehen, daß es immer wieder überraschend gewirkt hat im konkreten Falle, daß Menschen, welche hier intensiv an gewissen Zeitereignissen beteiligt waren und gestorben sind und dann weiterleben nach dem Tode, kein Interesse haben können für die Zeitereignisse, die sich hier abspielen nach ihrem Tode, weil die Verbindung fehlt. Auch unter uns sind solche Seelen, die, während sie hier waren auf dem physischen Plane, großes Interesse hatten für die Zeitereignisse, drüben in der geistigen Welt aber den Zeitereignissen, die sich jetzt nach ihrem Tode abspielen, fremd gegenüberstehen. Das ist gerade oftmals bei vorzüglichen Seelen, die hier rege Interessen und große Begabungen hatten, der Fall. Das ist aber schon lange so. Es ist so, nur immer mehr zunehmend, für die ganze Zeit des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums, es ist so seit dem 15., 16. Jahrhundert schon, nur zunehmend. Man kann da die Erfahrung machen, daß die Toten, da sie weniger eingreifen können in dasjenige, was die Menschen tun, sich mehr beschäftigen — es tut einem so leid, daß man so triviale Begriffe gebrauchen muß, aber man muß eben die Begriffe gebrauchen, die man in der Sprache hat -, also daß die Toten mehr eingreifen müssen in dasjenige, was die Menschen als einzelne Persönlichkeiten sind. Und das sieht man, daß das Interesse der Toten und die Arbeit der Toten seit dem 15., 16. Jahrhundert mehr auf die einzelnen Persönlichkeiten geht als auf die großen Zusammenhänge unter den Menschen. Und nachdem ich viel mich gerade in dieser Richtung befaßt habe mit diesem Problem, konnte ich mir die Überzeugung verschaffen, daß damit, mit dem, was ich jetzt gesagt habe, eine ganz bestimmte Zeiterscheinung zusammenhängt, die dem, der sich für solche Dinge interessiert, besonders stark auffallen muß in unserer neueren Geschichte. Wir haben in der neueren Geschichte im Gegensatz zu früheren Zeiten die merkwürdige Erscheinung, daß Menschen geboren werden mit sehr bedeutenden Anlagen, die so im allgemeinen wirken mit großem Idealismus, mit vorzüglichem Streben, daß aber diese Menschen es nicht dazu bringen können, Überschau über das Leben zu gewinnen, große Horizonte zu gewinnen. Das drückt sich im Grunde genommen im ganzen Schrifttum seit langer Zeit schon aus. In einzelnen Ideen, Begriffen, Vorstellungen, Empfindungen, die die Leute zum Ausdruck bringen, sei es in der Literatur, in der Kunst, sogar in der Wissenschaft, finden sich manchmal starke Ansätze. Aber — und deshalb ist es ja gerade für die Leute so schwer, sich zu der Überschau, die man haben muß in der Geisteswissenschaft, aufzuschwingen — zu einer großen Überschau bringen es die Leute nicht. Das kommt zum großen Teil davon her, daß die Toten mehr an den einzelnen Menschen herankommen und bei ihm das ausarbeiten, was mehr in der Kindheitsperiode, in der Jugendperiode des Daseins veranlagt wird, während dasjenige, was dem Menschen Überschau verschafft in den Reifezeiten des Daseins, in unserer materialistischen Zeit mehr oder weniger getrennt ist von der Tätigkeit der Toten. Unvollendete, Torso bleibende Talente, nicht bloß in der großen Welt, sondern auch im einzelnen, sind heute aus diesem Grunde sehr häufig, weil die Toten mehr an die einzelnen Seelen heran können als an dasjenige, was so in der Menschheitsentwickelung heute sozial lebt. Die Toten haben einen starken Trieb, an dasjenige heranzukommen, was in der Menschheitsentwickelung sozial lebt, aber es ist eben in unserem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum außerordentlich schwierig für sie.

Dann ist es insbesondere für die Gegenwart von einer großen Bedeutung, sich mit einer andern Erscheinung bekanntzumachen. Sehen Sie, in unserer Zeit leben viele Begriffe, viele Vorstellungen, die außerordentlich bestimmt sein müssen, sonst kommt man mit diesen Vorstellungen nicht weiter. Insbesondere in dem modernen, mehr merkantilistischen Leben müssen rechnerisch stark umrissene Begriffe ausgebildet werden. Daran hat sich die Wissenschaft gewöhnt, daran hat sich aber auch die Kunst gewöhnt. Denken Sie nur, welche Entwickelung in dieser Beziehung die Kunst durchgemacht hat! Wir haben noch nicht lange jene Kunstperiode hinter uns, wo die Kunst auf die großen idealen Zusammenhänge gegangen ist, und — ich möchte sagen, Gott sei Dank — Begriffe nicht ausreichten, um in leichter Weise ein Kunstwerk zu interpretieren, wo die Kunstwerke vielsagend waren. Das ist heute nicht mehr in demselben Maße der Fall. Heute strebt man nach Naturalismus, und die Begriffe können leicht nachkommen, weil die Kunstwerke selber oftmals aus Begriffen nur hervorgegangen sind, nicht aus der elementar umspannenden Empfindung. Die Menschheit ist heute eben angefüllt mit bestimmten trivialisierten, naturalistischen Begriffen, welche dadurch bestimmt sind, daß sie ganz am physischen Plane ausgebildet sind, wo die Dinge eben auch bestimmt sind, individualisiert sind.

Nun ist es sehr bedeutsam, daß solche Begriffe von den sogenannten Toten nicht geliebt werden. Scharf umrissene Begriffe, die nicht beweglich sind, nicht leben, sie werden von den Toten nicht geliebt. Man kann da die merkwürdigsten Erfahrungen machen, Erfahrungen, die sehr interessant sind, wenn man eben solch einen trivial-banalen Ausdruck für diese ehrwürdigen Verhältnisse brauchen darf. Ich habe in der letzten Zeit mich hier bemüht, wie Sie wissen, denn wir haben ja das alles zusammen hier absolviert, auch allerlei Betrachtungen anzustellen über Kunstperioden in Anlehnung an unsere Lichtbilder. Ich habe mich bemüht, manche künstlerische Erscheinung in Begriffe zu bringen. Wenn man reden will, so muß man sie in Begriffe bringen. Allein ich hatte immer das Bedürfnis, die künstlerischen Zusammenhänge nicht in so stramme, festumrissene Begriffe zu kleiden. Wenn ich auch bei den Betrachtungen versucht habe, die Begriffe so weit als möglich zu schnüren: um sie in Worte zu prägen, muß man sie schon bestimmt fassen. Aber ich hatte während der Ausbildung der Begriffe in der Vorbereitung zu den Betrachtungen hier wirklich, ich möchte sagen, einen gewissen Widerwillen, wenn ich das Wort gebrauchen darf, die Zusammenhänge, auf die da hinzuweisen ist, mit so dürftigen Begriffen zu geben, wie sie eben gegeben werden müssen, wenn man sich aussprechen will. Und verstehen werden wir uns auf diesen Gebieten nur dann, wenn Sie gewissermaßen wieder zurückübersetzen dasjenige, was in engmaschigen Begriffen gesagt ist, in weitermaschige Begriffe.

Wenn man nun zu gleicher Zeit solches erlebt und, ich möchte sagen, zu tun hat mit den entkörperten Seelen, so findet man, daß gerade dann, wenn man eine Erscheinung überblicken will, der gegenüber man so recht die Empfindung hat: Du bist eigentlich viel zu wenig verständig, um diese Erscheinung in Verstandesbegriffe zu fassen, du schaust die Erscheinung, aber der Verstand reicht eigentlich nicht aus, um das, was geschaut wird, wirklich in Begriffe zu schnüren —, wenn man dieses Erlebnis hat, und man kann dieses Erlebnis gerade bei der Betrachtung künstlerischer Erscheinungen auch haben, dann kann man sich ganz besonders intim mit den entkörperten Seelen, mit den toten Seelen finden; denn diese lieben Begriffe, die nicht scharf umrissen sind, die sich mehr beweglich durch die Erscheinungen hindurchtragen lassen. Durch scharf umrissene Begriffe, durch solche Begriffe, die ähnlich sind denen, die hier auf dem physischen Plan unter der Einwirkung der physisch-sinnlichen Verhältnisse gebildet werden, fühlen sich die Toten wie angenagelt an bestimmte Orte, während sie ein freies Bewegen für ihr Leben in der geistigen Welt brauchen. Daher ist die Beschäftigung mit der Geisteswissenschaft auch aus diesem Grunde bedeutsam, um in jene intimen Erlebenssphären hineinzukommen, wo nach dem gestern Angedeuteten der lebende Mensch hier sich mit dem Toten begegnen kann, weil die geisteswissenschaftlichen Begriffe schon nicht so bestimmt gehalten werden können wie diejenigen, die für den physischen Plan ausgearbeitet werden.

Daher haben böswillige oder beschränkte Menschen es sehr leicht, in geisteswissenschaftlichen Begriffen Widersprüche zu entdecken, weil die Begriffe lebendig sind, und das Lebendige trägt in einem gewissen Sinne, wenn auch nicht den kontradiktorischen Widerspruch, so doch das Bewegliche in sich. Aber das kommt gerade durch die Beschäftigung mit dem Geistigen. Man muß da die Dinge von den verschiedensten Seiten beleuchten. Und dieses Beleuchten von den verschiedensten Seiten bringt einen nun wirklich der geistigen Welt nahe. Daher fühlen sich die Toten wohl, wenn sie hereinkommen können in die Sphäre von Menschenbegriffen, die nicht pedantisch umrissen sind, sondern die beweglich sind. Am unwohlsten fühlen sich die Toten, wenn sie hereinkommen sollen in die allerpedantischesten Begriffe, die für die übersinnliche Welt in der letzten Zeit geprägt worden sind für die Menschen, die nun ganz und gar nicht in der geistigen Welt leben wollen, sondern die auch für die geistige Welt Sinnliches haben wollen, die also spiritistische Experimente machen, um auch die geistigen Begriffe in die sinnliche Sphäre ganz fest hereinzubekommen. Das sind eigentlich die größten Materialisten. Diese Menschen suchen für den Verkehr mit den Toten gerade starre Begriffe auf. Daher martern sie die Toten am allermeisten, weil sie sie zwingen, wenn sie herankommen wollen, gerade in das Gebiet einzutreten, das der Tote seiner ganzen Organisation nach nicht lieben kann. Er liebt die beweglichen Begriffe, nicht die starren Begriffe.

Das sind, glaube ich, Erfahrungen, welche man ganz besonders machen kann in diesem Zeitalter der fünften nachatlantischen Periode, wo hier auf Erden der Materialismus herrscht und unter den Toten solche Eigentümlichkeiten, wie ich sie beschrieben habe. Denn es ist durchaus das gleiche, was hier auf der Erde den Materialismus bestimmt, und dafür ein ganz bestimmtes Leben auch in der geistigen Sphäre bestimmt. In der griechisch-lateinischen Zeit traten die Toten doch anders an die lebenden Menschen heran als in unserer Zeit. In der geistigen Sphäre ist, möchte ich sagen, heute in der fünften nachatlantischen Zeit mehr Irdisches — aber Sie müssen sich das natürlich imaginativ, bildlich vorstellen —, mehr irdische Zusammengesetztheit in der Substantialität der Toten als früher. Ein Toter erscheint einem heute in einer viel mehr den irdischen Verhältnissen nachgebildeten Gestalt als früher, menschenähnlicher, möchte ich sagen, ist der Tote heute, als er früher war. Und dadurch wirken die Toten heute auf die hier Lebenden mehr oder weniger paralysierend. Deshalb ist es so schwer heute, den Toten nahezukommen, weil man so sehr leicht betäubt wird durch sie. Hier auf der Erde herrschen die materialistischen Gedanken; in der geistigen Welt, als einem Karma daraus, herrscht gewissermaßen die materialistische Folge, die Verirdischung der spirituellen Leiblichkeit bei den Toten. Dadurch aber, daß die Toten, wenn ich den Ausdruck gebrauchen darf, überkräftig sind, dadurch wirken sie betäubend. Und man muß sich heute durch möglichst starke geisteswissenschaftliche Empfindungen erst die Kraft aneignen, um gegen diese Betäubung aufzukommen. Das ist die Schwierigkeit heute, eine der Schwierigkeiten, mit der geistigen Welt in Beziehung zu treten.

Nun, für die irdische Sphäre, die man ja auch geistig ansehen kann, nehmen sich die Dinge, wenn man sie geistig ansieht, anders aus, als man oftmals urteilt, wenn man die Dinge nicht geistig ansieht. Wir sagen selbstverständlich mit Recht, und wir haben es oft auseinandergesetzt: wir leben in dem materialistischen Zeitalter. Warum? Weil die Menschen in diesem materialistischen Zeitalter — nicht die Verständigen, aber die Menschen im allgemeinen -, so paradox es klingt, zu geistig sind. Daher sind sie so leicht zugänglich reinen Geistigkeiten wie ahrimanischen und luziferischen Einflüssen. Die Menschen sind zu geistig. Und gerade durch die Geistigkeit werden die Menschen heute leicht materialistisch. Nicht wahr, das, was der Mensch glaubt und denkt, ist ja etwas ganz anderes, als er ist. Gerade die geistigsten Menschen sind heute leicht zugänglich für ahrimanische Einflüsterungen und werden dadurch materialistisch.

So scharf man die materialistische Weltanschauung und die materialistischen Lebensgestaltungen bekämpfen muß, man darf nicht sagen, daß in den Kreisen dieser Materialisten die ungeistigsten Menschen sind. Wirklich, wenn ich da ein Persönliches einfügen darf: Ich habe viele geistige Menschen gefunden, nicht solche, die geistige Ansichten haben, sondern die geistige Menschen sind, in Monistenvereinen und dergleichen, dagegen grobe materialistische Naturen vorzugsweise in Spiritistenvereinen. Gerade da findet man, wenn auch dort vom Geiste geredet wird, die am gröbsten materialistischen Naturen. Und wirklich, abgesehen von dem, was er oftmals behauptet: Ein durchaus geistiger Mensch, der gerade aus Geistigkeit heraus zugänglich ist einer ahrimanischen Weltanschauung, ist zum Beispiel Haeckel. Haeckel ist ein geistiger Mensch, ein ganz durchgeistigter Mensch. Mir trat das einmal besonders deutlich vor Augen, als ich in Weimar in der dortigen alten «Künstlerschmiede» saß — ich habe die Sache schon einmal erzählt, vielleicht sogar mehrmals — und da war Haeckel am andern Ende des Tisches, mit seinen schönen geistigen blauen Augen und seinem schönen Kopfe. In meiner Nähe befand sich der berühmte Buchhändler Herz, der sehr viele Verdienste um den deutschen Buchhandel hat und der so im allgemeinen etwas von Haeckel wußte, aber nicht wußte, daß das der Haeckel ist, der da am andern Ende des Tisches saß. Als Haeckel einmal so herzlich lachte, fragte Herz: Wer ist denn der Mann, der da unten so lacht an dem Tische? — Da sagte ich: Das ist der Haeckel. — Das ist nicht möglich -, sagte er, böse Menschen können so nicht lachen!

Daher sind auch die Begriffe der Materialisten der Gegenwart so dünn, möchte ich sagen, so dünn von Geistigkeit, daß sie nicht herankommen an die Offenbarungen der Geistigkeit im Materiellen, und ihnen das Geistige und das Materielle auseinanderfällt, das Geistige zu bloßen Begriffen wird. Jedenfalls findet man die klotzigsten Materialisten heute in den vielfach spiritualistisch sich nennenden Gesellschaften, Vereinigungen und dergleichen. Klotzigen Materialismus findet man da, der es manchmal sogar dazu gebracht hat, zu seiner eigenen Verherrlichung seine eigene Affenabstammung — von einem bestimmten Affen noch dazu — für die Menschheit besonders zu registrieren. Nicht einmal mit der allgemeinen Affenabstammung des Menschen war man zufrieden, sondern man führte sich auf ganz bestimmte Affenvorfahren zurück. Man hat ja in dieser Beziehung manches Groteske erlebt. Für diejenigen, die es nicht wissen sollten, erkläre ich, daß ja vor ein paar Jahren ein Buch erschienen ist, in dem Mrs. Besant und Mr. Leadbeater genau angegeben haben, von welchen Affen sie abstammen in uralten Zeiten, und sie haben ihren Stammbaum bis auf bestimmte Affen zurückgeführt, so daß man dort diesen Stammbaum von den Affen her lesen kann. Das sind Dinge, die immerhin in vielgelesenen Büchern im heutigen Zeitalter auch möglich sind.

Und diese Begriffe, die ich heute entwickelt habe, die brauchen wir schon, um nun in manche Stellen unseres gegenwärtig zu besprechenden Themas tiefer einzudringen. Denn diese Welt hier ist durchaus abhängig von der geistigen Welt, in welcher die Toten sind, und hängt zusammen mit der geistigen Welt. Daher versuchte ich, Ihnen heute solche Begriffe zu entwickeln, die sich auf die Beobachtungen der unmittelbaren Gegenwart beziehen. Es ist wirklich alles dasjenige, was hier in der physischen Welt geschieht, von einer gewissen Wirkung hinauf in die geistige Welt. Aber auch die geistige Welt mit den Taten der Toten zeigt sich entweder in dem, was die Toten tun können für die physische Welt, oder auch in dem, was sie nicht tun können gerade in dem gegenwärtigen materialistischen Zeitalter. Und wir haben dieses materialistische Zeitalter charakterisiert, insofern es sogar übermaterialisiert worden ist durch gewisse okkulte Brüderschaften, wie ich Ihnen gestern auseinandergesetzt habe. Es ist heute im hohen Grade gerade der Typ des Materialismus allen Weltereignissen zugrunde liegend, welchen man den merkantilistischen Typ nennen kann. Und wie ich Sie bitte, auf der einen Seite sich für morgen gut zu merken die Begriffe, die ich in bezug auf das Leben der Toten heute vor Ihre Seele hingestellt habe, so bitte ich Sie, auf der andern Seite auch ins Auge zu fassen, wie wenig selbstverständlich heute vieles genommen wird, was in weniger materialistischen Zeitaltern viel selbstverständlicher genommen wurde. Der Zusammenhang mit diesen Erscheinungen wird uns erst morgen ganz klar werden. Allein, es ist doch ganz charakteristisch für unsere Zeit, daß man immerhin gerade auf das Merkantilistische gewisse Begriffsbetrachtungen ausdehnt, die dem, der keine Aufmerksamkeit hat für solche Zeiterscheinungen, entgehen. Aber sie sollten einem nicht entgehen. Merkantilismus auf der einen Seite, gut; aber er muß ins richtige Licht gestellt werden, in dem er im sozialen Leben drinnensteht. Dazu ist es notwendig, daß man gewisse Maßstäbe hat für alles. Aber heute lebt man vielfach im Chaos der Begriffe. Und wenn im Chaos der Begriffe die Begriffe ganz bestimmt gemacht werden, wie es im materialistischen Zeitalter der Fall ist, wo gerade an den sinnlichen Vorstellungen die Begriffe ganz bestimmt gemacht werden, und dann doch wiederum ein Begriffschaos herauskommt, wie es beim heutigen Materialismus der Fall ist, dann ist dieses wirklich so, daß es den schärfsten Strich zieht zwischen der physischen Welt, in der die Menschen zwischen Geburt und Tod sind, und der übersinnlichen Welt, in der die Menschen zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt sind.

Betrachten Sie in diesem Zusammenhange nur einmal die Tatsache, daß im Gegensatze zu andern Gebieten, wo man weniger philosophisch zu Werke geht, man gerade in Mitteleuropa auch mit dem merkantilistischen Wesen, trotzdem es in Mitteleuropa nicht so heimisch ist, gern philosophisch zu Werke geht. In Mitteleuropa macht man gern aus allem eine Philosophie. Man philosophiert auch über dasjenige, was im Materialismus unseres Zeitalters typisch ist. So gibt es ein interessantes Buch, interessant eben als Kulturerscheinung, das heißt: «Ideal und Geschäft», von Jaroslaw, lange vor dem Krieg erschienen. In diesem Buche sind einige Kapitel, die mich als kulturhistorisch bedeutsame besonders interessiert haben. Nicht das, was darin steht, hat mich interessiert, aber als kulturhistorisch interessant hat mich zum Beispiel besonders interessiert das Kapitel «Plato und das Detailgeschäft». Es ist also die Rede von allem, was den Kaufmannsstand, das Merkantilistische, betrifft. Da ist auch ein interessantes Kapitel «Das astrologische System der Pfefferpreise». Ein nicht uninteressantes Kapitel ist auch «Der Großhandel bei Cicero». Ein anderes Kapitel ist «Kaufmann-Porträts bei Holbein und bei Liebermann». Gar nicht uninteressant ist auch das Kapitel «Jakob Böhme und das Qualitätsproblem». Ganz interessant ist «Die Göttin Freia in der germanischen Mythologie und die freie Konkurrenz». Und besonders interessant «Der Wirtschaftsgeist, den Jesus lehrt».

Sie sehen, zusammengeworfen wird alles. Aber gerade dadurch, daß es so zusammengeworfen wird, gewinnen die Dinge denjenigen Charakter, der den Materialismus macht. Nehmen Sie dieses als eine Vorbereitung für andere Betrachtungen, die wir morgen anstellen werden,

Twenty-second Lecture

Perhaps I may first draw your attention to something that might be of interest to you, namely an article in the “Schweizerische Bauzeitung” of January 20, 1917, which discusses the Johannes Building in Dornach near Basel, based on a recent visit to the building by Swiss engineers and architects. The article is very pleasing and beautifully written, and it is truly an oasis, one might say, compared to some of what has been printed recently, and is now being printed again, about our efforts, especially from within our own circle. It is very gratifying that such a positive and appreciative review of the building has appeared from an outside, objective, and, in particular, expert source. The article appeared in the “Schweizerische Bauzeitung” on January 20, 1917; I recommend that you read it. Mr. Englert, who at the time was one of the leaders of the Swiss Engineers and Architects Association, which took such a keen interest in our building from a professional and general aesthetic point of view, has just informed me that the article will also be published in the Bulletin de technique, which appears in French in Geneva.