Karma of Untruthfulness I

GA 173c

30 January 1917, Dornach

Lecture XXV

Today it seems appropriate to mention certain thoughts on the meaning and nature of our spiritual Movement—anthroposophical spiritual science, as we call it. To do so will necessitate references to some events which have occurred over a period of time and which have contributed to the preparation and unfolding of this Movement. If, in the course of these remarks, one or another of them should seem somewhat more personal—it would, at any rate, only seem to be so—this will not be for personal reasons but because what is more personal can be a starting point for something more objective. The need for a spiritual movement which makes known to people the deeper sources of existence, especially human existence, can be easily recognized by the way in which today's civilization has developed along lines which are becoming increasingly absurd. No one, after serious thought, will describe today's events as anything other than an absurd exaggeration of what has been living in more recent evolution.

From what you have come to know in spiritual science, you will have gained the feeling that everything, even what is apparently only external, has its foundation in the thoughts of human beings. Deeds which are done, events which take place in material life—all these are the consequence of what human beings think and imagine. And the view of the external world, which is gaining ground among human beings today, gives us an indication of some very inadequate thought forces. I have already put into words the fact that events have grown beyond human beings, have got out of hand, because their thinking has become attenuated and is no longer strong enough to govern reality. Concepts such as that of maya, the external semblance which governs the things of the physical plane, ought to be taken far more seriously by those familiar with them than they, in fact, often are. They ought to be profoundly imprinted on current consciousness as a whole. This alone might lead to the healing of the damage which—with a certain amount of justification—has come upon mankind. Those who strive to understand the functioning of man's deeds—that is, the way the reflections of man's thoughts function—will recognize the inner need for a comprehension of the human soul which can be brought about by stronger, more realistic thoughts.

In fact, our whole Movement is founded on the task of giving human souls thoughts more appropriate to reality, thoughts more immersed in reality, than are the abstract concept patterns of today. It cannot be pointed out often enough how very much mankind today is in love with the abstract, having no desire to realize that shadowy concepts cannot, in reality, make any impact on the fabric of existence. This has been most clearly expressed in the fourteen-, fifteen-year history of our Anthroposophical Movement. Now it is becoming all the more important for our friends to take into themselves what specifically belongs to this Anthroposophical Movement. You know how often people stressed that they would so much like to give the beautiful word ‘theosophy’ the honour it deserves, and how much they resisted having to give it up as the key word of the Movement. But you also know the situation which made this necessary.

It is good to be thoroughly aware in one's soul about this. You know—indeed, many of you shared—the goodwill with which we linked our work with that of the Theosophical Movement in the way it had been founded by Blavatsky, and how this then continued with Besant's and Sinnett's efforts, and so on. It is indeed not unnecessary for our members, in face of all the ill-meant misrepresentations heaped upon us from outside, to persist in pointing out that our Anthroposophical Movement had an independent starting-point and that what now exists has grown out of the seeds of those lectures I gave in Berlin which were later published in the book on the mysticism of the Middle Ages. We must stress ever and again that in connection with this book it was the Theosophical Movement who approached us, not vice versa. This Theosophical Movement, in whose wake it was our destiny to ride during those early years, was not without its connections to other occult streams of the nineteenth century, and in lectures given here I have pointed to these connections. But we should look at what is characteristic for that Movement.

If I were asked to point factually to one rather characteristic feature, I would choose one I have mentioned a number of times, which is connected with the period when I was writing in the journal Lucifer-Gnosis what was later given the title Cosmic Memory. A representative of the Theosophical Society, who read this, asked me by what method these things were garnered from the spiritual world. Further conversation made it obvious that he wanted to know what more-or-less mediumistic methods were used for this. Members of those circles find it impossible to imagine any method other than that of people with mediumistic gifts, who lower their consciousness and write down what comes from the subconscious.

What underlies this attitude? Even though he is a very competent and exceptionally cultured representative of the Theosophical Movement, the man who spoke to me on this was incapable of imagining that it is possible to investigate such things in full consciousness. Many members of that Movement had the same problem because they shared something which is present to the highest degree in today's spiritual life, namely, a certain mistrust in the individual's capacity for knowledge. People do not trust the inherent capacity for knowledge, they do not believe that the individual can have the strength to penetrate truly to the essential core of things. They consider that the human capacity for knowledge is limited; they find that intellectual understanding gets in the way if one wants to penetrate to the core of things and that it is therefore better to damp it down and push forward to the core of things without bringing it into play. This is indeed what mediums do; for them, to mistrust human understanding is a basic impulse. They endeavour, purely experimentally, to let the spirit speak while excluding active understanding.

It can be said that this mood was particularly prevalent in the Theosophical Movement as it existed at the beginning of the century. It could be felt when one tried to penetrate certain things, certain opinions and views, which had come to live in the Theosophical Movement. You know that in the nineties of the nineteenth century and subsequently in the twentieth century, Mrs Besant played an important part in the Theosophical Movement. Her opinion counted. Her lectures formed the centrepiece of theosophical work both in London and in India. And yet it was strange to hear what people around Mrs Besant said about her. I noticed this strongly as early as 1902. In many ways, especially among the scholarly men around her, she was regarded as a quite unacademic woman. Yet, while on the one hand people stressed how unacademic she was, on the other hand they regarded the partly mediumistic method she was famous for, untrammelled as it was by scientific ideas, as a channel for achieving knowledge. I could say that these people did not themselves have the courage to aim for knowledge. Neither had they any confidence in Mrs Besant's waking consciousness. But because she had not been made fully awake as a result of any scientific training, they saw her to some extent as a means by which knowledge from the spiritual world could be brought into the physical world. This attitude was extraordinarily prevalent among those immediately surrounding her. People spoke about her at the beginning of the twentieth century as if she were some kind of modern sibyl. Those closest to her formed derogatory opinions about her academic aptitude and maintained that she had no critical ability to judge her inner experiences. This was certainly the mood around her, though it was carefully hidden—I will not say kept secret—from the wider circle of theosophical leaders.

In addition to what came to light in a sibylline way through Mrs Besant, and through Blavatsky's The Secret Doctrine, the Theosophical Movement at the end of the nineteenth century also had Sinnett's book or, rather, books. The manner in which people spoke about these in private was, equally, hardly an appeal to man's own power of knowledge. Much was made in private about the fact that in what Sinnett had published there was nothing which he had contributed out of his own experience. The value of a book such as his Esoteric Buddhism was seen to lie particularly in the fact that the whole of the content had come to him in the form of ‘magical letters’, precipitated—no one knew whence—into the physical plane—one could almost say, thrown down to the physical plane—which he then worked into the book Esoteric Buddhism.

All these things led to a mood among the wider circles of the theosophical leaders which was sentimental and devotional in the highest degree. They looked up, in a way, to a wisdom which had fallen from heaven, and—humanly, quite understandable—this devotion was transferred to individual personalities. However, this became the incentive for a high level of insincerity which was easy to discern in a number of phenomena.

Thus, for instance, even in 1902 I heard in the more private gatherings in London that Sinnett was, in fact, an inferior spirit. One of the leading personalities said to me at that time: Sinnett could be compared with a journalist—say, of the Frankfurter Zeitung—who has been dispatched to India; he is a journalistic spirit who simply had the good fortune to receive the ‘Master's letters’ and make use of them in his book in a journalistic way which is in keeping with modern mankind!

You know, though, that all this is only one aspect of a wide spectrum of literature. For in the final decades of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth, there appeared—if not a Biblical deluge, then certainly a flood of—written material which was intended to lead mankind in one way or another to the spiritual world. Some of this material harked back directly to ancient traditions which have been preserved by all kinds of secret brotherhoods. It is most interesting to follow the development of this tradition.

I have often pointed out how, in the second half of the eighteenth century, old traditions could be found in the circle led by Saint-Martin, the philosophe inconnu. In Saint-Martin's writings, especially Des erreurs et de la vérité, there is a very great deal of what came from ancient traditions, clothed in a more recent form. If we follow these traditions further back, we do indeed come to ideas which can conquer concrete situations, which can influence reality. By the time they had come down to Saint-Martin, these concepts had already become exceedingly shadowy, but they were nevertheless shadows of concepts which had once been very much alive; ancient traditions were living one last time in a shadowy form. So in Saint-Martin's work we find the healthiest concepts clothed in a form which is a final glimmer. It is particularly interesting to see how Saint-Martin fights against the concept of matter, which had already come to the fore. What did this concept of matter gradually become? It became a view in which the world is seen as a fog made up of atoms moving about and bumping into one another and forming configurations which are at the root of all things taking shape around us. In theory materialism reached its zenith at the point when the existence of everything except the atom was denied. Saint-Martin still maintained the view that the whole science of atoms, and indeed the whole belief that matter was something real, was nonsense; which indeed it is. If we delve into all that is around us, chemically, physically, we come in the final analysis not to atoms, not to anything material, but to spiritual beings. The concept of matter is an aid; but it corresponds to nothing that is real. Wherever—to use a phrase coined by du Bois-Reymond—‘matter floats about in space like a ghost’: there may be found the spirit. The only way to speak of an atom is to speak of a little thrust of spirit, albeit ahrimanic spirit. It was a healthy idea of Saint-Martin to do battle against the concept of matter.

Another immensely healthy idea of Saint-Martin was the living way in which he pointed to the fact that all separate, concrete human languages are founded on a single universal language. This was easier to do in his day than it is now, because in his time there was still a more living relationship to the Hebrew language which, among all modern languages, is the one closest to the archetypal universal language. It was still possible to feel at that time the way in which spirit flowed through the Hebrew language, giving the very words something genuinely ideal and spiritual. So we find in Saint-Martin's work an indication, concrete and spiritual, of the meaning of the word ‘the Hebrew’. In the whole way he conceived of this we find a living consciousness of a relationship of the human being with the spiritual world. This word ‘the Hebrew’ is connected with ‘to journey’. A Hebrew is one who makes a journey through life, one who gathers experiences as on a journey. Standing in the world in a living way—this is the foundation of this word and of all other words in the Hebrew language if they are sensed in their reality.

However, in his own time Saint-Martin was no longer able to find ideas which could point more precisely, more strongly, to what belonged to the archetypal language. These will have to be rediscovered by spiritual science. But he had before his soul a profound notion of what the archetypal language had been. Because of this his concept of the unity of the human race was more concrete and less abstract than that which the nineteenth century made for itself. This concrete concept of the unity of the human race made it possible for him, at least within his own circle, to bring fully to life certain spiritual truths, for instance, the truth that the human being, if only he so desires, really can enter into a relationship with spiritual beings of higher hierarchies. It is one of his cardinal principles, which states that every human being is capable of entering into a relationship with spiritual beings of higher hierarchies. Because of this there still lived in him something of that ancient, genuine mystic mood which knew that knowledge, if it is to be true knowledge, cannot be absorbed in a conceptual form only, but must be absorbed in a particular mood of soul—that is after a certain preparation of the soul. Then it becomes part of the soul's spiritual life.

Hand in hand with this, however, went a certain sum of expectations, of evolutionary expectations directed to those human souls who desired to claim a right to participate in some way in evolution. From this point of view it is most interesting to see how Saint-Martin makes the transition from what he has won through knowledge, through science—which is spiritual in his case—to politics, how he arrives at political concepts. For here he states a precise requirement, saying that every ruler ought to be a kind of Melchizedek, a kind of priest-king.

Just imagine if this requirement, put forward in a relatively small circle before the outbreak of the French Revolution, had been a dawn instead of a dusk; just imagine if this idea—that those whose concepts and forces were to influence human destiny must fundamentally have the characteristics of a Melchizedek—had been absorbed, even partially, into the consciousness of the time, how much would have been different in the nineteenth century! For the nineteenth century was, in truth, as distant as it could possibly be from this concept. The demand that politicians should first undertake to study at the school of Melchizedek would, of course, have been dismissed with a shrug.

Saint-Martin has to be pointed out because he bears within him something which is a last glimmer of the wisdom that has come down from ancient times. It has had to die away because mankind in the future must ascend to spiritual life in a new way. Mankind must ascend in a new way because a merely traditional continuation of old ideas never has been in keeping with the germinating forces of the human soul. These underdeveloped forces of the human soul will tend, during the course of the twentieth century, in a considerable number of individuals—this has been said often enough—to lead to true insight into etheric processes. The first third of the twentieth century can be seen as a critical period during which a goodly number of human beings ought to be made aware of the fact that events must be observed in the etheric world which lives all around us, just as much as does the air. We have pointed emphatically to one particular event which must be seen in the etheric world if mankind is not to fall into decadence, and that is the appearance of the Etheric Christ. This is a necessity. Mankind must definitely prepare not to let wither those forces which are already sprouting.

These forces must not be allowed to wither for, if they did, what would happen? In the forties and fifties of the twentieth century the human soul would assume exceedingly odd characteristics in the widest circles. Concepts would arise in the human soul which would have an oppressive effect. If materialism were the only thing to continue, concepts which exist in the human soul would arise, but they would rise up out of the unconscious in a way which people would not understand. A waking nightmare, a kind of general state of neurasthenia, would afflict a huge number of people. They would find themselves having to think things without understanding why they were thinking them.

The only antidote to this is to plant, in human souls, concepts which stem from spiritual science. Without these, the forces of insight into those concepts which will rise up, into those ideas which will make their appearance, will be paralysed. Then, not the Christ alone, but also other phenomena in the etheric world, which human beings ought to see, will withdraw from man, will go past unnoticed. Not only will this be a great loss, but human beings will also have to develop pathological substitute forces for those which ought to have developed in a healthy way.

It was out of an instinctive need in wide circles of mankind that the endeavours arose which expressed themselves in that flood of literature and written material mentioned earlier. Now, because of a peculiar phenomenon, the Anthroposophical Movement of Central Europe was in a peculiar position relative to the Theosophical Movement—particularly to the Theosophical Society—as well as to that other flood of written material about spiritual matters. Because of the evolutionary situation in the nineteenth century and at the beginning of the twentieth century, it was possible for a great number of people to find spiritual nourishment in all this literature; and it was also possible for a great number of people to be utterly astounded by what came to light through Sinnett and Blavatsky. However, all this was not quite in harmony with Central European consciousness. Those who are familiar with Central European literature are in no doubt that it is not necessarily possible to live in the element of this Central European literature while at the same time taking up the attitude of so many others to that flood. This is because Central European literature encompasses immeasurably much of what the seeker for the spirit longs for—only it is hidden behind the peculiar language which so many people would rather have nothing to do with.

We have often spoken about one of those spirits who prove that spiritual life works and weaves in artistic literature, in belletristic literature: Novalis. For more prosaic moods we might equally well have mentioned Friedrich Schlegel, who wrote about the wisdom of ancient India in a way which did not merely reproduce that wisdom but brought it to a fresh birth out of the western cultural spirit. There is much we could have pointed to that has nothing to do with that flood of written material, but which I have sketched historically in my book Vom Menschenrätsel. People like Steffens, like Schubert, like Troxler, wrote about all these things far more precisely and at a much more modern level than anything found in that flood of literature which welled up during the last decades of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century. You have to admit that, compared with the profundity of Goethe, Schlegel, Schelling, those things which are held to be so marvellously wise are nothing more than trivia, utter trivia. Someone who has absorbed the spirit of Goethe can regard even a work like such as Light on the Path as no more than commonplace. This ought not to be forgotten. To those who have absorbed the inspiration of Novalis or Friedrich Schlegel, or enjoyed Schelling's Bruno, all this theosophical literature can seem no more than vulgar and ordinary. Hence the peculiar phenomenon that there were many people who had the earnest, honest desire to reach a spiritual life but who, because of their mental make-up were, in the end, to some degree satisfied with the superficial literature described.

On the other hand, the nineteenth century had developed in such a way that those who were scientifically educated had become—for reasons I have often discussed—materialistic thinkers about whom nothing could be done. However, in order to work one's way competently through what came to light at the turn of the eighteenth to the nineteenth century through Schelling, Schlegel, Fichte, one does need at least some scientific concepts. There is no way of proceeding without them. The consequence was this peculiar phenomenon: It was not possible to bring about a situation—which would have been desirable—in which a number of scientifically educated people, however small, could have worked out their scientific concepts in such a way that they could have made a bridge to spiritual science. No such people were to be found. This is a difficulty that still exists and of which we must be very much aware.

Supposing we were to approach those who have undergone a scientific education, with the intention of introducing them to Anthroposophy: lawyers, doctors, philologists—not to mention theologians—when they have finished their academic education and reached a certain stage in life at which it is necessary for them, in accordance with life's demands, to make use of what they have absorbed, not to say, have learnt. They then no longer have either the inclination or the mobility to extricate themselves from their concepts and to seek for others. That is why scientifically-educated people are the most inclined to reject Anthroposophy, although it would only be a small step for a modern scientist to build a bridge. But he does not want to do so. It confuses him. What does he need it for? He has learnt what life demands of him and, so he believes, he does not want things which only serve to confuse him and undermine his confidence. It is going to take some considerable time before these people who have gone through the education of their day start to build bridges in any great numbers. We shall have to be patient. It will not come about easily, especially in certain fields. And when the building of bridges is seriously tackled in a particular field, great obstacles and hindrances will be encountered. It will be necessary above all to build bridges in the fields encompassed by the various faculties, with the exception of theology.

In the field of law the concepts being worked out are becoming more and more stereotyped and quite unsuitable for the regulation of real life. But they do regulate it because life on the physical plane is maya; if it were not maya, they would be incapable of regulating it. As it is, their application is bringing more and more confusion into the world. The application of today's jurisprudence, especially in civil law, does nothing but bring confusion into the situation. But this is not clearly seen. Indeed, how should it be seen? No one follows up the consequences of applying stereotyped concepts to reality. People study law, they become solicitors or judges, they absorb the concepts and apply them. What happens as a consequence of their application is of no interest. Or life is seen as it is—despite the existence of the law, which is a very difficult subject to study for many reasons, not least because law students tend to waste the first few terms—life is seen as it is; we see that everything is in a muddle and do no more than complain.

In the field of medicine the situation is more serious. If medicine continues to develop in the wake of materialism as it has been doing since the second third of the nineteenth century, it will eventually reach an utterly nonsensical situation, for it will end up in absurd medical specializations. The situation is more serious here because this tendency was, in fact, necessary and a good thing. But now it is time for it to be overcome. The materialistic tendency in medicine meant that surgery has reached a high degree of specialization, which was only possible because of this one-sided tendency. But medicine as such has suffered as a result. So now it needs to turn around completely and look towards a real spirituality—but the resistance to this is enormous.

Education is the field which, more than any other, needs to be permeated with spirituality, as we have said often enough. Bridges need to be built everywhere.

In technology—although it may appear to be furthest away from the spirit—it is above all necessary that bridges should be built to the life of the spirit, out of direct practical life. The fifth post-Atlantean period is the one which is concerned with the development of the material world, and if the human being is not to degenerate totally into a mere accomplice of machines—which would make him into nothing more than an animal—then a path must be found which leads from these very machines to the life of the spirit. The priority for those working practically with machines is that they take spiritual impulses into their own soul. This will come about the moment students of technology are taught to think just a little more than is the case at present; the moment they are taught to think in such a way that they see the connections between the different things they learn. As yet they are unable to do this. They attend lectures on mathematics, on descriptive geometry, even on topology sometimes; on pure mechanics, analytical mechanics, industrial mechanics, and also all the various more practical subjects. But it does not even occur to them to look for a connection between all these different things. As soon as people are obliged to apply their own common sense to things, they will be forced—simply on account of the stage of development these various subjects have reached—to push forward into the nature of these things and then on into the spiritual realm. From machines, in particular, a path will truly have to be found into the spiritual world.

I am saying all this in order to point out what difficulties today face the spiritual-scientific Movement, because so far there are no individuals to be found who might be capable of generating an atmosphere of taking things seriously. This Movement suffers most of all from a lack of being taken seriously. It is remarkable how this comes to the fore in all kinds of details. Much of what we have published would have been taken seriously, would have been seen in quite a different light, if it had not been made known that it stemmed from someone belonging to the Theosophical Movement. Simply because the person concerned was in the Theosophical Movement, his work was stamped as something not to be taken seriously. It is most important to realize this, and it is just these trifling details which make it plain. Not out of any foolish vanity but just so that you know what I mean, let me give you an example of one of these trifles which I came across only the other day.

In my book Vom Menschenrätsel I wrote about Karl Christian Planck as one of those spirits who, out of certain inner foundations, worked towards the spiritual realm, even though only in an abstract way. I have not only written about him in this book, but also—over the past few winters—spoken about him in some detail in a number of cities, showing how he went unrecognized, or was misunderstood, and referring especially to ane particular circumstance. This was the fact that, in the eighties, seventies, sixties, fifties, this man had ideas and thoughts in connection with industrial and social life which ought to have been put into practice. If only there had been someone at that time with the capacity of employing in social life the great ideas this man had, ideas truly compatible with reality, then—and I am not exaggerating—mankind would probably not now be suffering all that is going on today which, for the greater part, is a consequence of the totally wrong social structure in which we are living.

I have told you that it is a real duty not to let human beings come to a pass such as that reached by Karl Christian Planck, who finally came to be utterly devoid of any love for the world of external physical reality. He was a Swabian living in Stuttgart. He was refused a place in the philosophy department of Tübingen University, where he would have had the opportunity to put forward some of his ideas. I entirely intentionally mentioned the fact that, when he wrote the foreword to his book Testament of a German, he felt moved to say, ‘Not even my bones shall rest in the soil of my ungrateful fatherland’. Hard words. Words such as people today can be driven to utter when faced with the stupidity of their fellow human beings, who refuse to see the point about what is really compatible with reality. In Stuttgart I purposely quoted these words about his bones, for Stuttgart is Planck's fatherland in the narrower sense. There was little reaction, despite the fact that events had already reached a stage when there would have been every reason to understand the things he had said.

Now, however, a year-and-a-half later, the following notice may be found in the Swabian newspapers:

‘Karl Christian Planck. More than one far-seeing spirit foretold the present World War. But none anticipated its scale nor understood its causes and effects as clearly as did our Swabian countryman Planck.’

I said in my lecture that Karl Christian Planck had foreseen the present World War, and that he even expressly stated that Italy would not be on the side of the Central Powers, even though he was speaking at the time when the alliance had not yet been concluded, but was only in the making.

‘To him this war seemed to be the unavoidable goal toward which political and economic developments had been inexorably moving for the last fifty years.’

This is indeed the case!

‘Just as he revealed the damage being done in his day, so he also pointed the way which can lead us to other situations.’

This is the important point. But nobody listened!

‘By him we are told the deeper reasons underlying war profiteering and other black marks which mar so many good and pleasing aspects of the life of the nation today. He knows where the deeper, more inward forces of the nation lie and can tell us how to release them so that the moral and social renewal longed for by the best amongst us can come about. Despite all the painful disappointments meted out to him by his contemporaries, he continued to believe in these forces and their triumphant emergence.’

Nevertheless, he was driven to utter the words I have quoted!

‘The news will therefore be widely welcomed that the philosopher's daughter is about to give an introduction to Planck's social and political thinking in a number of public lectures.’

It is interesting that a year-and-a-half later his daughter should be putting in an appearance. This notice appeared in a Stuttgart newspaper. But a year-and-a-half ago, when I drew attention as plainly as possible in Stuttgart to the the philosopher Karl Christian Planck, no one took the slightest notice, and no one felt moved to make known what I had said. Now his daughter puts in an appearance. Her father died in 1880, and presumably she had been born by then. Yet she has waited all this time before standing up for him by giving public lectures.

This example could be multiplied not tenfold, but a hundredfold. It shows once again how difficult it is to bring together the all-embracing aspect of spiritual science with everyday practical details, despite the fact that it is absolutely essential that this should be done. Only through the all-embracing nature of spiritual science—this must be understood—can healing come about for what lives in the culture of today.

That is why it has been essential to keep steering what we call anthroposophical spiritual science, in whatever way possible, along the more serious channels which have been increasingly deserted by the Theosophical Movement. The spirit that was even known to the ancient Greek philosophers had to be allowed to come through, although this has led to the opinion that what is written in consequence is difficult to read. It has often not been easy. Especially within the Movement it met with the greatest difficulties. And one of the greatest difficulties has been the fact that it really has taken well over a decade to overcome one fundamental abstraction. Laborious and patient work has been necessary to overcome this fundamental abstraction which has been one of the most damaging things for our Movement. This basic abstraction consisted simply in the insistence on clinging to the word ‘theosophy’, regardless of whether whatever was said to be ‘theosophical’ referred to something filled with the spirituality of modern life, or to no more than some rubbish published by Rohm or anyone else. Anything ‘theosophical’ had equal justification, for this prompted ‘theosophical tolerance’.

Only very gradually has it been possible to work against these things. They could not be pointed out directly at the beginning, because that would have seemed arrogant. Only gradually has it been possible to awaken a feeling for the fact that differences do exist, and that tolerance used in this connection is nothing more than an expression of a total lack of character on which to base judgements. What matters now is to work towards knowledge of a kind which can cope with reality, which can tackle the demands of reality. Only a spiritual science that works with the concepts of our time can tackle the demands of reality. Not living in comfortable theosophical ideas but wrestling for spiritual reality—this must be the direction of our endeavour.

Some people still have no idea what is meant by wrestling for reality, for they are fighting shy of understanding clearly how threadbare are the concepts with which they work today. Let me give you a small example, from a seemingly unrelated subject, of what it means to wrestle for reality in concepts. I shall be brief, so please be patient while I explain something that might seem rather far-fetched.

There were always isolated individuals in the nineteenth century who were prepared to take up the question of reality. For reality was then supposed to burst in on mankind with entirely fresh ideas about life, not only the unimportant aspects but especially the basic practical aspects of life. Thus at a certain point in the nineteenth century Euclid's postulate of parallels was challenged. When are two lines parallel? Who could have failed to agree that two lines are parallel if they never meet, however long they are! For that is the definition: That two straight lines are parallel if they never meet, whatever the distance to which they are extended. In the nineteenth century there were individuals who devoted their whole life to achieving clarity about this concept, for it does not stand up to exact thinking. In order to show you what it means to wrestle for concepts, let me read you a letter written by Wolfgang Bolyai. The mathematician Gauss had begun to realize that the definition of two straight lines being parallel if they meet at infinity, or not at all, was no more than empty words and meant nothing. The older Bolyai, the father, was a friend and pupil of Gauss, who also stimulated the younger Bolyai, the son. And the father wrote to the son:

‘Do not look for the parallels in that direction. I have trodden that path to its end; I have traversed bottomless night in which every light, every joy of my life has been extinguished. By God I implore you to leave the postulate of the parallels alone! Shun it as you would a dissolute association, for it can rob you of all your leisure, your health, your peace of mind and every pleasure in life. It will never grow light on earth and the unfortunate human race will never gain anything perfectly pure, not even geometry itself. In my soul there is a deep and eternal wound. May God save you from being eaten away by another such. It robs me of my delight in geometry, and indeed of life on earth. I had resolved to sacrifice myself for the truth. I would have been prepared for martyrdom if only I could have handed geometry back to mankind purified of this blemish. I have accomplished awful, gigantic works, have achieved far more than ever before, but never found total satisfaction. Si paullum a summo discessit, vergit ad imum. When I saw that the foundation of this night cannot be reached from the earth I returned, comfortless, sorrowing for my self and the human race. Learn from my example. Desiring to know the parallels, I have remained without knowledge. And they have robbed me of all the flowers of my life and time. They have become the root of all my subsequent failures, and much rain has fallen on them from our lowering domestic clouds. If I could have discovered the parallels I would have become an angel, even if none had ever known of my discovery.

... Do not attempt it ... It is a labyrinth that forever blocks your path. If you enter you will grow poor, like a treasure hunter, and your ignorance will not cease. Should you arrive at whatever absurd discovery, it will be for naught, untenable as an axiom ...

... The pillars of Hercules are situated in this region. Go not a step further, or you will be lost.’

Nevertheless, the younger Bolyai did go further, even more so than his father, and devoted his whole life to the search for a concrete concept in a field where such a concept seemed to exist, but which was, however, empty words. He wanted to discover whether there really was such a thing as two straight lines which did not meet, even in infinity. No one has ever paced out this infinite distance, for that would take an infinite time, but this time has not yet run its course. It is nothing more than words. Such empty words, such conceptual shadows, are to be found behind all kinds of concepts. I simply wanted to point out to you how even the most thorough spirits of the nineteenth century suffered because of the abstractness of these concepts! It is interesting to see that while children are taught in every school that parallel lines are those which never meet, however long they are, there have been individual spirits for whom working with such concepts became a hell, because they were seeking to push through to a real concept instead of a stereotyped concept.

Wrestling with reality—this is what matters, yet this is the very thing our contemporaries shun, more or less, because they ‘realize’, or imagine they realize, that they have ‘high ideals’! It is not ideals that matter, but impulses which work with reality. Imagine someone were to make a beautiful statement such as: At long last a time must come when those who are most capable are accorded the consideration due to them. What a lovely programme! Whole societies could be established in accordance with this programme. Even political sciences could be founded on this basis. But it is not the statement that counts. What counts is the degree to which it is permeated by reality. For what is the use—however valid the statement, and however many societies choose it for the prime point in their programmes—if those in power happen to see only their nephews as being the most capable? It is not a matter of establishing the validity of the statement that the most capable should be given their due. The important thing is to have the capacity to find those who are the most capable, whether they are one's nephews or not! We must learn to understand that abstract concepts always fall through the cracks of life, and that they never mean anything, and that all our time is wasted on all these beautiful concepts. I have no objection to their beauty, but what matters is our grasp and knowledge of reality.

Suppose the lion were to found a social order for the animals, dividing up the kingdom of the earth in a just way. What would he do? I do not believe it would occur to him to push for a situation in which the small animals of the desert, usually eaten by the lion, would have the possibility of not being eaten by the lion! He would consider it his lion's right to eat the small animals he meets in the desert. It is conceivable, though, that for the ocean he would find it just and proper to forbid the sharks to eat the little fishes. This might very well happen. The lion might establish a tremendously just social order in the oceans, at the North Pole or wherever else he himself is not at home, giving all the animals their freedom. But whether he would be pleased to establish such an order in his own region is a question indeed. He knows very well what justice is in the social order, and he will put it into practice efficiently in the kingdom of the sharks.

Let us now turn from lions to Hungaricus. I told you two days ago about his small pamphlet Conditions de Paix de l'Allemagne. This pamphlet swims entirely with the stream of that map of Europe which was first mentioned in the famous note from the Entente to Wilson about the partition of Austria. We have spoken about it. With the exception of Switzerland, Hungaricus is quite satisfied with this map. He begins by talking very wisely—just as most people today talk very wisely—about the rights of nations, even the rights of small nations, and about the right of the state to be coincident with the power of the nation, and so on. This is all very nice, in the same way that the statement, about the most capable being given his due, is nice. As long as the concepts remain shadowy we can, if we are idealists, be delighted when we read Hungaricus. For the Swiss, the pamphlet is even nicer than the map, for rather than wiping Switzerland off the map, Hungaricus adds the Vorarlberg and the Tyrol. So I recommend the Swiss to read the pamphlet rather than look at the map. But now Hungaricus proceeds to divide up the rest of the world. In his own way he accords to every nation, even the smallest, the absolute right to develop freely—as long as he considers he is not causing offence to the Entente. He trims his words a little, of course, saying ‘independence’ when referring to Bohemia, and obviously ‘autonomy’ with regard to Ireland. Well, this is the done thing, is it not! It is quite acceptable to dress things up a little. He divides up the world of Europe quite nicely, so that apart from the things I have mentioned—which are to avoid causing offence—he really endeavours to apportion the smallest nations to those states to which the representatives of the Entente believe they belong. It is not so much a question of whether these small territories are really inhabited by those nationalities, but of whether the Entente actually believes this to be the case. He makes every effort to divide up the world nicely, with the exception of the desert—oh, pardon me—with the exception of Hungary, which is where he practises his lion's right! Perfect freedom is laid down for the kingdom of the sharks. But the Magyar nation is his nation, and this is to comprise not only what it comprises today—though without it only a minority of the population would be Magyar, the majority being others—but other territories as well. Here he well and truly acts the part of the lion.

Here we see how concepts are formulated nowadays and how people think nowadays. It gives us an opportunity to study how urgent it is to find the transition to a thinking which is permeated with reality. For this, concepts such as those I have been giving you are necessary. I want to show you—indeed, I must show you—how spiritual thinking leads to ideas which are compatible with reality. One must always combine the correct thought with the object; then one can recognize whether that object corresponds to reality or not.

Take Wilson's note to the Senate. As a sample it could even have certain effects in some respects. But this is not what matters. What matters is that it contains ‘shadowy concepts’. If it nevertheless has an effect, this is due to the vexatious nature of our time which can be influenced by vexatious means. Look at this matter objectively and try to form a concept against which you can measure the reality, the real content with which this shadowy concept could be linked. You need only ask one question: Could this note not just as well have been written in 1913? The idealistic nothings it contains could just as easily have been expressed in 1913! You see, a thinking which believes in the absolute is not based on reality. It is unrealistic to think that something ‘absolute’ will result every time. The present age has no talent for seeing through the lack of reality in thinking because it is always out for what is ‘right’ rather than for what is in keeping with reality.

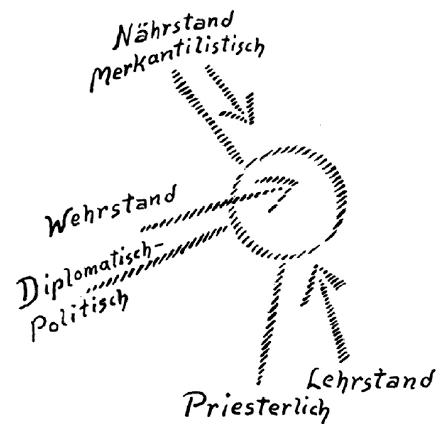

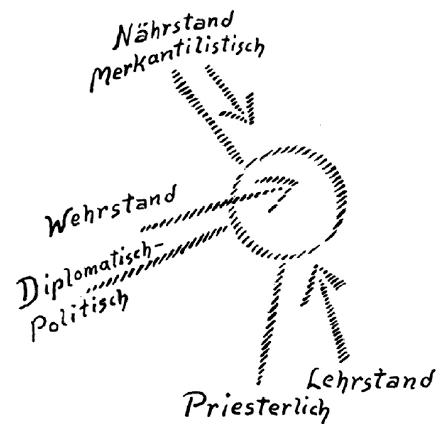

That is why in my book Vom Menschenrätsel I emphasized so heavily the importance not only of what is logical but also of what is in keeping with reality. A single decision that took account of the facts as they are at this precise moment would be worth more than all the empty phrases put together. Historical documents are perhaps the best means of showing that what I am saying has to do with reality, for as time has gone on the only people to come to the surface are those who want to rule the world with abstractions, and this is what has led to the plight of the world today. Proper thinking, which takes account of things as they are, will discover the realities wherever they are. Indeed, they are so close at hand! Take the real concept which I introduced from another point of view the other day: Out of what later became Italy in the South there arose the priestly cultic element which created as its opposition the Protestantism of Central Europe; from the West was formed the diplomatic, political element which also created an opposition for itself; and from the North-west was formed the mercantile element which again created for itself an opposition; and in Central Europe an opposition coming out of the general, human element will of necessity arise. Let us look once more at the way these things stream outwards. (See diagram.)

Even for the fourth post-Atlantean period—proceeding on from the old fourfold classification in which one spoke of castes—we can begin to describe this structure in a somewhat different way: Plato spoke of ‘guardian-rulers’; this is the realm for which Rome—priestly, papal Rome—seized the monopoly, achieving a situation in which she alone was allowed to establish doctrinal truths. She was to be the only source of all doctrine, even the highest.

In a different realm, the political, diplomatic element is nothing other than Plato's ‘guardian-auxiliaries’. I have shown you that, regardless of what people call Prussian militarism, the real military element was formed with France as its starting point, after the first foundations had been laid in Switzerland. That is where the military element began, but of course it created an opposition for itself by withholding from others what it considered to be its own prerogative. It wants to dominate the world in a soldierly way, so that when something soldierly comes to meet it from elsewhere it finds this quite unjustified, just as Rome finds it unjustified if something comes towards her which is to do with the great truths of the universe.

And here, instead of mercantilism, we might just as well write ‘the industrial and agricultural class’. Think on this, meditate on it, and you will come to understand that this third factor corresponds to the provision of material needs. So what is being withheld? Foodstuffs, of course!

If you apply Plato's concepts appropriately, in accordance with reality, then you will find reality everywhere, for with these concepts you will be able fully to enter into reality. Starting from the concept, you must find the way to reality, and the concept will be able to plunge down into the most concrete parts of reality. Shadowy concepts, on the other hand, never find reality, but they do lend themselves exceptionally well to idealistic chatter. With real concepts, though, you can work you way through to an understanding of reality in every detail. Here lies the task of spiritual science. Spiritual science leads to concepts through which you can really discover life, which of course is created by the spirit, and through which you will be able to join in a constructive way at working on the formation of this life.

One concept, in particular, requires realistic thinking, owing to the terrible destiny at present weighing down on mankind, for the corresponding unreal concept is especially persistent in this connection. Those who speak in the most unrealistic way of all, these days, are the clergymen. What they express about Christianity or the awareness of God, apropos of the war, is enough to send anyone up the wall, as they say. They distort things so frightfully. Of course things in other connections are distorted too, but in this realm the degree of absurdity is even greater.

Look at the sermons or tracts at present stemming from that source; apply your good common sense to them. Of course it is understandable that they should ask: Does mankind have to be subjected to this terrible, painful destiny? Could not the divine forces of God intervene on behalf of mankind to bring about salvation? The justification for speaking in this way does indeed seem absolute. But there is no real concept behind it. It does not apply to the reality of the situation. Let me use a comparison to show you what I mean.

Human beings have a certain physical constitution. They take in food which is of a kind which enables them to go on living. If they were to refuse food, they would grow thin, become ill, and finally starve to death. Now is it natural to complain that if human beings refuse to eat it is a weakness or malevolence on the part of God to let them starve? Indeed it is not a weakness on the part of God. He created the food; human beings only need to eat it. The wisdom of God is revealed in the way the food maintains the human beings. If they refuse to eat it, they cannot turn round and accuse God of letting them starve.

Now apply this to what I was saying. Mankind must regard spiritual life as a food. It is given by the gods, but it has to be taken in by man. To say that the gods ought to intervene directly is tantamount to saying that if I refuse to eat God ought to satisfy my hunger in some other way. The wisdom-filled order of the universe ensures that what is needed for salvation is always available, but it is up to human beings to make a relationship with it. So the spiritual life necessary for the twentieth century will not enter human beings of itself. They must strive for it and take it into themselves. If they fail to take it in, times will grow more and more dismal. What takes place on the surface is only maya. What is happening inwardly, is that an older age is wrestling with a new one. The general, human element is rising up everywhere in opposition to the specialized elements. It is maya to believe that nation is fighting against nation—and I have spoken about this maya in other connections too. The battle of nation with nation only comes about because things group themselves in certain ways but, in reality, the inward forces opposing one another are something quite different. The opposition is between the old and the new. The laws now fighting to come into play are quite different from those which have traditionally ruled over the world.

And again it was maya—that is, something appearing under a false guise—to say that those other laws were rising up on behalf of socialism. Socialism is not something connected with truth; above all it is not connected with spiritual life, for what it wants is to connect itself with materialism. What really wants to wrestle its way into existence is the many-sided, harmonious element of mankind, in opposition to the one-sided priestly, political or mercantile elements. This battle will rage for a long time, but it can be conducted in all kinds of different ways. If a healthy way of leading life, such as that described by Planck in the nineteenth century, had been adopted, then the bloody conduct of the first third of the twentieth century would, at least, have been ameliorated. Idealisms do not lead to amelioration, but realistic thinking does, and realistic thinking also always means spiritual thinking.

Equally, we can say that whatever has to happen will happen. Whatever it is that is wrestling its way out, must needs go through all these experiences in order to reach a stage at which spirituality can be united with the soul, so that man can grow up spiritually. Today's tragic destiny of mankind is that in striving upwards today, human beings are endeavouring to do so not under the sign of spirituality but under the sign of materialism. This in the first instance is what brought them into conflict with those brotherhoods who want to develop the impulses of the mercantile element, commerce and industry, in a materialistic way on a grand scale. This is today's main conflict. All other things are side issues, often terrible side issues. This shows us how terrible maya can be. But it is possible to strive for things in different ways. If others had been in power instead of the agents of those brotherhoods, then we would, today, be busy with peace negotiations, and the Christmas call for peace would not have been shouted down!

It is going to be immensely difficult to find clear and realistic concepts and ideas in respect of certain things; but we must all seek to find them in our own areas. Those who enter a little into the meaning of spiritual science, and compare this spiritual science with other things making an appearance just now, will see that this spiritual science is the only path that can lead to concepts which are filled with reality.

I wanted to say this very seriously to you at this time. Despite the fact that the task of spiritual science can only be comprehended out of the spirit itself, out of knowledge, and not out of what we have been discussing today, I wanted to show you the significance, the essential nature, of spiritual science for the present time. I wanted to show you how urgent it is for everything possible to be done to make spiritual science more widely known. It is so necessary in these difficult times for us to take spiritual science not only into our heads but really into our warm hearts. Only if we take it into the warmth of our hearts will we be capable of generating the strength needed by the present time.

None of us should allow ourselves to think that we are perhaps not in a suitable position, or not strong enough, to do what it is essential for us to do. Karma is sure to give every one of us, whatever our position, the opportunity to put the right questions to destiny at the right moment. Even if this right moment is neither today nor tomorrow, it is sure to come eventually. So once we have understood the impulses of this spiritual Movement we must stand firmly and steadfastly behind them. Today it is particularly necessary to set ourselves the aim of firmness and steadfastness. For either something important must come from one side or another—although this cannot be counted upon—in the very near future, or all conditions of life will become increasingly difficult. It would be utterly thoughtless to refuse to be clear about this. For two-and-a-half years it has been possible for what we now call war to carry on, while conditions remained as bearable as they now are. But this cannot go on for another year. Movements such as ours will be put te a severe test. There will be no question of asking when we shall next meet, or why do we not meet, or why this or that is not being published. No, indeed. It will be a question of bearing in our hearts, even through long periods of danger, a steadfast sense of belonging.

I wanted to say this to you today because it could be possible in the not too distant future that there will be no means of transport which will enable us to come together again; I am not speaking only of travel permits but of actual means of transport. In the long run, it will not be possible to keep the things going which constitute our modern civilization, if something breaks in on this civilization which, although it has arisen out of it, is nevertheless in absolute opposition to it. This is how absurd the situation is: Life itself is bringing forth things which are absolutely opposed to it.

So we must accept that difficult times may be in store for our Movement too. But we shall not be led astray if we have taken into ourselves the inner steadfastness, clarity and right feeling for the importance and nature of our Movement, and if in these serious times we can see beyond our petty differences. This, our Movement ought to be able to achieve; we ought to be able to look beyond our petty differences to the greater affairs of mankind, which are now at stake. The greatest of these is to reach an understanding of what it means to base thinking on reality. Wherever we look we are confronted with the impossibility of finding a thinking which accords with reality. We shall have to enter heart and soul into this search in order not to be led astray by all kinds of egoistic distractions.

This is what I wanted to say to you as my farewell today, since we are about to take leave of one another for some time. Make yourselves so strong—even if it should turn out to be unnecessary—that, even in loneliness of soul, your hearts will carry the pulse of spiritual science with which we are here concerned. Even the thought that we shall be steadfast will help a very great deal; for thoughts are realities. Many potential difficulties can still be swept away if we maintain an honest, serious quest in the direction we have here discussed so often.

Now that we have to depart for a while we shall not allow ourselves to flag, but shall make sure that we return if it is possible. But even if it should take a long time as a result of circumstances outside our control, we shall never lose the thought from our hearts and souls that this is the place—where our Movement has even brought forth a visible building—where the most intense requirement exists to bear this Movement so positively, so concretely, so energetically, that together we can carry it through, come what may. So wherever we are, let us stand together in thought, faithfully, energetically, cordially, and let us hear one another, even though this will not be possible with our physical ears. But we shall only hear one another if we listen with strong thoughts and without sentimentality, for the times are now unsuitable for sentimentality.

In this sense, I say farewell to you. My words are also a greeting, for in the days to come we shall meet again, though more in the spirit than on the physical plane. Let us hope that the latter, too, will be possible once more in the not too distant future.

Fünfundzwanzigster Vortrag

Es scheint mir richtig zu sein, heute einiges an Gedanken vorzubringen über die Bedeutung und das Wesen unserer geistigen Bewegung, der anthroposophisch orientierten Geisteswissenschaft, wie wir sagen. Nun wird es notwendig sein, anzuknüpfen an die eine oder die andere Erscheinung, die im Laufe der Zeit aufgetreten ist, in welcher sich diese Bewegung teils vorbereitet, teils entfaltet hat. Wenn dabei — was ja auch nur scheinbar sein soll — die eine oder die andere Bemerkung persönlicher Art fällt, so geschieht das nicht aus persönlichen Gründen, sondern darum, weil ja das Persönliche der Haltepunkt gleichsam sein soll für das, was sich objektiv ausspricht. Daß in einer geistigen Bewegung, welche gewissermaßen die Menschheit tiefer mit den Quellen des Seins, namentlich des menschlichen Seins selber bekanntmacht, eine gewisse Notwendigkeit liegt, dürfte ja einfach daraus für jeden ersichtlich sein, daß die Kultur der Gegenwart, wie sie sich entwickelt hat, in einer gewissen Weise sich eigentlich ad absurdum geführt hat. Denn es wird ja doch bei tieferem Nachdenken niemandem beifallen können, die Ereignisse, wie sie sich heute abspielen, als etwas anderes zu bezeichnen denn als eine Art Ad-absurdum-Führen desjenigen, was an Impulsen in der neueren Entwickelung gelebt hat.

Nun werden Sie aus dem, was Ihnen bekanntgeworden ist in der Geisteswissenschaft, wohl erfühlt haben, wie alles dasjenige, was sich auch scheinbar noch so äußerlich abspielt, zuletzt auf den Vorstellungen, auf den Gedanken der Menschen beruht. Was an Taten geschieht, was sich im materiellen Leben abwickelt, es ist ja durchaus, man kann sagen, ein Ergebnis desjenigen, was die Menschen vorstellen. Und die Anschauung der äußeren Welt, wie sie sich innerhalb der Menschheit heute gestaltet, gibt wohl ein Bild, das auf unzulängliche Gedankenkräfte ganz stark hinweist. Ich habe schon einmal das Wort gebraucht: Die Ereignisse sind eigentlich den Menschen über den Kopf gewachsen, weil das Denken dünn geworden ist und nicht mehr ausreicht, in die Wirklichkeit einzugreifen. Worte, wie das von der Maja, von dem äußeren Scheine, dem die Dinge auf dem physischen Plane unterliegen, die müßten viel ernster genommen werden von denjenigen, die sie schon kennen, als sie oftmals genommen werden. Und sie müßten sich tief, tief einprägen in das gesamte Zeitbewußtsein. Darinnen kann allein die Heilung von den Schäden liegen, die mit einer gewissen Notwendigkeit über die Menschen heraufgezogen sind. Wer versucht, verständig in das Triebwerk der Taten, also in das Triebwerk der Abbilder der Gedanken heute hineinzublicken, der wird schon die Notwendigkeit, die innere Notwendigkeit eines Erfassens der menschlichen Seele durch kräftigere, wirklichkeitsfreundlichere Gedanken erkennen.

Nun, im Grunde liegt unserer ganzen Bewegung dies zugrunde, den Menschenseelen wirklichkeitsfreundlichere Gedanken zu geben, von Wirklichkeit mehr durchtränkte Gedanken, als die abstrakten Begriffsschablonen der Gegenwart sind. Aber man kann nicht oft genug hinweisen darauf, wie sehr die Menschheit heute das Abstrakte liebt und gar kein Bewußtsein entwickeln will, daß das begreiflich Schattenhafte nicht wirklich in das Gewebe des Seins eingreifen kann. Das drückte sich ja insbesondere in der vierzehn-, fünfzehnjährigen Geschichte unserer anthroposophischen Bewegung aus. Es wird immer mehr notwendig sein, daß sich unsere Freunde durchdringen mit dem Spezifischen, was gerade diese anthroposophische Bewegung hatte. Sie wissen ja, wie oft betont worden ist, daß man es gern gehabt hätte, das schöne Wort «Theosophie» vollständig zu Ehren zu bringen, daß man sich lange gewehrt hat, dieses Wort als Kennwort der Bewegung aufzugeben. Aber Sie kennen ja auch alle die Verhältnisse, durch die dieses notwendig geworden ist. Und es ist schon gut, die Sache sich möglichst genau vor die Seele zu führen. Sie wissen ja, daß mit allem guten Willen — denn dieser gute Wille war ja in vielen von Ihnen selbst verankert - angeknüpft worden ist an die sogenannte ’Theosophische Bewegung, wie sie begründet worden ist durch die Blavatsky, wie sie dann ihre Fortsetzung gefunden hat in den Sinnettschen, Besantschen Bestrebungen und so weiter. Es ist wirklich nicht unnötig, daß gerade den vielen böswilligen Entstellungen gegenüber, die von auswärts kommen, unsere Mitglieder immer wieder betonen, daß die anthroposophisch gewordene Bewegung von einem selbständigen Zentrum ausgegangen ist, daß zunächst das, was wir jetzt haben, wirklich seine Keime hatte in den Vorträgen, die von mir in Berlin gehalten worden sind und die dann in der Schrift über die Mystik des Mittelalters niedergelegt sind. Und es muß immer wieder betont werden, daß durch diese Schrift die damals bestehende theosophische Bewegung sich uns, nicht wir ihr, genähert hat. Diese theosophische Bewegung nun, in deren Fahrwasser man die ersten Jahre zu sein hatte, sie steht ja, stand ja nicht ohne Zusammenhang mit andern okkulten Bestrebungen des 19. Jahrhunderts, und ich habe ja in Vorträgen, die hier gehalten worden sind, auf diesen Zusammenhang hingewiesen. Aber man muß auf das Charakteristische dieser Bewegung selbst sehen.

Wenn ich ein recht charakteristisches Merkmal, ich möchte sagen tatsachengemäß, hervorheben soll, so muß es dasjenige sein, auf das ich oftmals oder wenigstens öfters angespielt habe, als ich in der Zeitschrift «Lucifer-Gnosis» zunächst dasjenige veröffentlichte, was dann den Titel bekommen hat «Aus der Akasha-Chronik». Einer der Vertreter der Theosophischen Gesellschaft, der dieses las, fragte, auf welchem Wege die Dinge eigentlich aus der geistigen Welt herausgeholt werden. Und aus dem weiteren Gespräche mit ihm war es sehr ersichtlich, daß es sich darum handelte, zu erfahren, auf welchem mehr oder weniger medialen Wege diese Dinge gewonnen werden. Man konnte sich dort gar nicht denken, daß durch andere Mittel als dadurch, daß irgendein Mensch von medialer Veranlagung, der sein Bewußtsein herabgestimmt erhält und dann etwas aus der Unterbewußtheit heraus vorbringt, was dann aufgezeichnet wird, daß anders als auf diesem Wege diese Dinge zustande kommen. Was liegt denn da eigentlich zugrunde? Dem Manne, der so sprach, lag es völlig fern, sich vorzustellen, daß diese Dinge untersucht werden können bei völliger Aufrechterhaltung des wachen Bewußtseins, trotzdem er ein sehr geschulter und außerordentlich gebildeter Vertreter der theosophischen Bewegung ist. Es lag das vielen Mitgliedern dieser Bewegung aus dem Grunde fern, weil eben diesen vielen etwas eigen ist, was im modernen Geistesleben überhaupt im höchsten Maße vorhanden ist: ein gewisses Mißtrauen in die Eigenkraft des menschlichen Erkenntnisvermögens. Man traut dem menschlichen Erkenntnisvermögen nicht zu, daß es die Kraft in sich aufbringen könne, in das Innere der Dinge wirklich einzudringen. Man findet, das menschliche Erkenntnisvermögen sei doch begrenzt, eigentlich störe der Verstand nur - so findet man -—, wenn man mit ihm in das Wesen der Dinge eindringen will; daher muß man ihn abdämpfen. Man müsse, ohne daß der menschliche Verstand dabei tätig ist, in das Wesen der Dinge eindringen. — Beim Medium ist das ja der Fall, da wird das Mißtrauen in den menschlichen Verstand zu einem maßgebenden Impuls gemacht. Da wird wirklich mit Ausschluß der verständigen Erkenntnistätigkeit rein experimentell versucht, den Geist sprechen zu lassen.

Man kann sagen, daß in einer gewissen Art diese Stimmung die theosophische Bewegung, wie sie auch noch im Anfange unseres Jahrhunderts war, gar sehr durchsetzt hatte; diese Stimmung war da vielfach zu Hause. Und man konnte diese Stimmung empfinden, wenn man mit Einsicht gewisse Dinge verfolgte, die sich als Meinungen, als Anschauungen, als Ansichten in der theosophischen Bewegung abgesetzt hatten. Sie wissen ja, daß in den neunziger Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts und dann im 20. Jahrhundert Mrs. Besant eine große Rolle spielte in der theosophischen Bewegung. Auf dasjenige, was sie zu sagen hatte, hörte man. Ihre Vorträge standen im Mittelpunkte des theosophischen Wirkens in London und auch in Indien. Dennoch war es merkwürdig, die Persönlichkeiten aus der Umgebung von Mrs. Besant über Mrs. Besant sprechen zu hören. 1902 trat mir das schon sehr bedeutsam entgegen. Mrs. Besant galt in vieler Beziehung, namentlich den gelehrten Männern ihrer Umgebung, als eine durchaus ungelehrte Frau; aber während man auf der einen Seite das stark betonte, daß man es mit einer ungelehrten Frau zu tun hat, sah man doch auf der andern Seite in der, ich möchte sagen, nicht durch wissenschaftliche Vorstellungen getrübten, halb medialen Art des Wirkens, die man bei ihr rühmte, ein Hilfsmittel, zu Erkenntnissen zu kommen. Ich möchte sagen, die Leute trauten sich nicht zu, selbst zu Erkenntnissen zu kommen. Sie trauten natürlich auch dem wachen Bewußtsein von Mrs. Besant nicht zu, zu Erkenntnissen zu kommen. Aber weil sie nicht zur völligen Wachheit gekommen war durch eine wissenschaftliche Durchbildung, so betrachtete man sie gewissermaßen als ein Mittel, durch welches Kundgebungen aus der geistigen Welt ins Physische hereinkommen können. Das war doch bei der nächsten Umgebung außerordentlich ausgebildet. Und man kann schon sagen: Die Art, wie gesprochen wurde, die machte den Eindruck, als ob man Mrs. Besant am Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts ansah wie eine Art moderner Sibylle. Man konnte nach dieser Richtung gerade bei der nächsten Umgebung abfällige Urteile über die wissenschaftliche Begabung von Mrs. Besant hören, man konnte hören, wie man ihr gar keine Kritik über ihre inneren Erlebnisse zutraute. Das war durchaus die Stimmung, die ja natürlich sorgfältig verborgengehalten wurde - ich will nicht sagen, geheimgehalten wurde — vor dem größeren Kreise der theosophischen Leiter.

Außer diesem, was da durch das Sibyllenhafte von Mrs. Besant zutage trat, war ja Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts neben der «Geheimlehre» der Blavatsky insbesondere eine Art Bibel der theosophischen Bewegung das Buch von Sinnett, vielleicht besser gesagt die Bücher von Sinnett. Nun, wie man erst über die Bücher von Sinnett reden hörte im engeren Kreise, das war ebensowenig etwas, was man nennen könnte einen Appell an die eigene Erkenntniskraft des Menschen. Denn man legte einen großen Wert darauf im engsten Kreise, daß Sinnett ja nicht zu dem, was er veröffentlicht hat, irgend etwas aus seinen eigenen Erfahrungen hinzugebracht hat. Man sah den Wert eines solchen Buches wie des «Esoterischen Buddhismus» von Sinnett gerade darinnen, daß der Inhalt ganz und gar zustande gekommen ist durch «magische Briefe», durch Briefe, welche präzipitiert waren, die also von unbekannt woher in den physischen Plan hereingeschickt worden waren, man kann sagen, geworfen worden waren, und deren Inhalt dann einfach zu diesem Buche «Esoterischer Buddhismus» verarbeitet wurde.

Durch alle diese Dinge war zwar in den weiteren Kreisen der theosophischen Leiter eine Stimmung vorhanden, die sentimental-anbetend im höchsten Grade war. Man sah gewissermaßen zu einer Weisheit hinauf, die vom Himmel gefallen war, und übertrug, wie das ja menschlich begreiflich ist, die Verehrung auf Persönlichkeiten. Aber es lag darinnen der Antrieb zu einer starken Unaufrichtigkeit, die in den einzelnen Erscheinungen sehr gut verfolgt werden konnte.

So konnte ich zum Beispiel schon 1902 hören, wie in den engsten Kreisen in London davon gesprochen wurde, daß Sinnett eigentlich ein untergeordneter Geist sei. Es sagte mir dazumal eine der führenden Persönlichkeiten: Ja, der Sinnett, man kann ihn vergleichen mit einem Journalisten etwa der «Frankfurter Zeitung», nach Indien versetzt, ein journalistischer Geist, der einfach das Glück gehabt hat, die Meisterbriefe zu empfangen und sie journalistisch in einer Weise, wie es für die Menschheit der neueren Zeit ansprechend ist, in dem Buche «Esoterischer Buddhismus» zu verwerten! — Sie wissen aber auch, daß all dieses doch in einer breiten Literatur drinnen stand, in einem breiten Schrifttum. Denn es ist ja wirklich, ich will nicht sagen eine Sündf£lut, aber eine Flut von Schriften erschienen in den letzten Jahrzehnten des 19. Jahrhunderts und in den ersten Jahrzehnten des 20. Jahrhunderts, welche bestimmt waren, irgendwie die Menschen hinzuführen zur spirituellen Welt. Unter diesen Schriften waren solche, die in unmittelbarer Anknüpfung standen an alte Traditionen, wie sie sich bewahrt haben in den verschiedensten okkulten Brüderschaften. Es ist im Grunde genommen interessant, die Entwickelung dieser Traditionen zu verfolgen.

Ich habe öfter schon darauf hingewiesen, wie in der zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts in dem Kreise, dessen Führer Saint-Martin, der «Unbekannte Philosoph» war, sich in entsprechender Weise alte Traditionen ausgelebt haben. Und wenn man die Schriften, namentlich «Wahrheit und Irrtümer» von Saint-Martin heute sich vornimmt, so findet man darinnen doch sehr, sehr viel von einer letzten Gestalt, die alte okkulte Traditionen angenommen haben. Verfolgt man diese Traditionen weiter zurück, dann gelangt man durchaus noch zu Vorstellungen, welche das Konkrete beherrschen, welche eingreifen in die Wirklichkeiten. Bei Saint-Martin sind die Begriffe schon sehr schattenhaft geworden, aber es sind doch die Schatten von Begriffen, die einstmals voll lebendig waren, es lebten eben zum letzten Mal in schattenhafter Weise alte Traditionen auf. Und so findet man bei Saint-Martin die gesündesten Begriffe, aber in einer Form, die ein letztes Aufflackern ist. Da ist es ja insbesondere interessant, zu sehen, wie Saint-Martin kämpft gegen den damals schon aufgekommenen Begriff der Materie. Wozu ist denn dieser Begriff der Materie nach und nach geworden? Dazu ist er geworden, daß man die ganze Welt ansieht als einen Nebel von Atomen, die in irgendeiner Weise sich bewegen und stoßen, und die durch ihre Konfiguration all das hervorrufen, was als Welt um den Menschen herum sich ausbildet. Theoretisch hat ja der eigentliche Materialismus seinen Höhepunkt dadurch erfahren, daß man dann alles übrige geleugnet hat außer dieser Atomwelt. Saint-Martin stand noch auf dem Standpunkt, daß die ganze Atomistik, überhaupt der Glaube, daß Materie etwas Wirkliches sei, ein Unsinn ist, wie es ja auch tatsächlich der Fall ist. Wenn man den Dingen zu Leibe geht, die uns umgeben chemisch, physisch, so kommt man zuletzt nicht auf Atome, nicht auf Materielles, sondern auf geistige Wesenkeiten. Der Begriff der Materie ist ein Hilfsbegriff; er entspricht nichts Wirklichem. Denn da, wo, um diesen Ausdruck Da Bois-Reymonds zu gebrauchen, «Materie im Raume spukt», da ist wirklich Geist vorhanden, und wenn man von einem Atom reden will, so könnte man höchstens so von dem Atom reden, daß es ein kleiner Stoß des Geistes ist, allerdings Ahrimans. Das war ein gesunder Begriff von Saint-Martin, sein Bekämpfen des Begriffes der Materie.

Ebenso war ein ungeheuer gesunder Begriff bei Saint-Martin, daß er noch hinwies in lebendiger Art auf die Tatsache, daß menschlichen, konkreten, einzelnen Sprachen eine Universalsprache zugrunde liegt. Und das konnte man in der damaligen Zeit aus dem Grunde besser als später, weil man derjenigen Sprache, welche unter den gegenwärtigen am ehesten nahesteht der ursprünglichen Universalsprache, der hebräischen Sprache, noch lebendiger gegenüberstand, weil man noch in den Worten der hebräischen Sprache etwas vom Fließen des Geistes und dadurch in den Worten selber etwas Geistig-Ideelles, etwas wirklich Geistiges verspüren konnte. Bei Saint-Martin finden Sie daher noch den konkret-spirituellen Hinweis auf das, was das Wort «Hebräer» selber bedeutet. Und in der ganzen Art und Weise, wie er das auffaßt, sieht man, wie noch das lebendige Bewußtsein vorhanden war von einer Beziehung des Menschen zur geistigen Welt. Denn das Wort «Hebräer» hängt zusammen mit «reisen»: wer ein Hebräer ist, ist derjenige, der eine Lebensreise macht, der auf einer Reise erfährt, erlebt. Dieses lebendige Drinnenstehen in der Welt liegt in diesem Wort, liegt aber allen andern Worten der hebräischen Sprache zugrunde, wenn sie real erfühlt werden.

Nun konnte jaSaint-Martin zu seiner Zeit nicht mehr Vorstellungen finden — diese müssen erst wiederum durch Geisteswissenschaft gewonnen werden -, welche präziser, stärker auf das Ursprachliche hinweisen. Aber als eine Ahnung stand die Ursprache vor seiner Seele. Damit aber hatte er nicht einen so abstrakten Begriff von der Einheitlichkeit des Menschengeschlechtes, wie ihn dann das 19. Jahrhundert ausbildete, sondern er hatte einen konkreten Begriff davon. Dieser konkrete Begriff von der Einheitlichkeit des Menschengeschlechtes führte ihn aber auch dahin, gewisse geistige Wahrheiten wenigstens in seinem Kreise noch voll lebendig zu machen, zum Beispiel die Wahrheit, daß der Mensch, wenn er nur will, wirklich mit geistigen Wesen höherer Hierarchien in Beziehungen treten kann. Das ist ein Kardinalsatz bei Saint-Martin, daß jeder Mensch mit geistigen Wesenheiten höherer Hierarchien in Beziehungen treten kann. Aber dadurch lebte in ihm gewissermaßen etwas noch von jener alten, echten mystischen Stimmung, welche wußte, daß das Wissen nicht bloß in Begriffen aufgenommen werden kann, wenn es wirkliches Wissen sein soll, sondern in einer gewissen Seelenverfassung aufgenommen werden muß, das heißt nach einer gewissen Vorbereitung der Seele. Dann wird es zum spirituellen Leben der Seele. Damit aber war verknüpft eine gewisse Summe von Forderungen, von Evolutionsforderungen an die menschlichen Seelen, die überhaupt Anspruch machen wollten, an der Evolution irgendwie teilzunehmen. Und von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus ist es so interessant, wenn dann Saint-Martin überleitet dasjenige, was er aus dem Erkennen, aus der Wissenschaft heraus — die aber spirituell bei ihm ist — gewinnt, zur Politik, wenn er also zu den politischen Begriffen kommt. Denn da hat er ja die präzise Forderung: Jeder Regierende müsse eine Art Melchisedek sein, eine Art Priesterregent.

Und denken Sie sich, wenn diese Forderung, die geltend gemacht worden ist in verhältnsmäßig kleinem Kreise, bevor die Französische Revolution hereinbrach, wenn diese Forderung nicht Abendröte, sondern Morgenröte geworden wäre, wenn etwas davon ins Zeitbewußtsein übergegangen wäre von dem melchisedekartigen Grundcharakter derjenigen, die mit ihren Vorstellungen und Kräften einzugreifen haben in die menschlichen Geschicke, was alles anders hätte werden müssen im 19. Jahrhundert, als es geworden ist! Denn das 19. Jahrhundert stand wahrhaftig dann so fern als möglich dieser Auffassung, die eben charakterisiert worden ist. Man hätte ja die Anforderung, daß Politiker durch die Schule Melchisedeks durchzugehen haben, selbstverständlich nur mit einem Lächeln abgefertigt.