Three Streams of Human Evolution

GA 184

6 October 1918, Dornach

Lecture Three

Yesterday I made two observations drawn from the science that we must call the science of Initiation, and I should like to remind you of them, for we shall need them as a connecting link. First, I said that the truths, the deepest truths, relating to the Mystery of Golgotha must by their nature be of the kind that cannot be substantiated through external historical evidence perceptible to the senses. Anyone who sets out by an external historical route to find a proof of the facts concerned with the Mystery of Golgotha, in the same way as historical evidence is sought for other facts, will be unable to discover it, for the Mystery of Golgotha is meant to relate itself to mankind in such a way that access to its truths is finally possible only by a supersensible path. If I may put it rather briefly—where the most important event in earthly existence is concerned, men are intended to accustom themselves to approaching it by supersensible means, not through the senses.

The second thing I said yesterday is that man, with the understanding he possesses according to his development as an earthly being, is never able, right up to his death, to comprehend the Mystery of Golgotha through his own understanding developed within the sense-world. I went on to say: It is only after his death, during the time he spends in the supersensible world, that there develops in man the understanding, and the forces for that understanding, which can fully make clear the Mystery of Golgotha. Hence I stated yesterday something which will quite naturally be held up by the external world as an absurdity, a paradox. I said that even the contemporaries of Christ were unable to reach such an understanding until the second or third century after the Mystery of Golgotha, during their life beyond the threshold; and that what has been written about the Mystery of Golgotha in those centuries was inspired by men who had been contemporaries of it and, from the spiritual world, from the supersensible world, had an inspiring influence on the writers of that period.

Now there is an apparent contradiction to this in the fact that the Gospels are inspired writings (as you may gather from my book, Christianity as Mystical Fact; they are inspired writings of Christianity. The inspired Gospels, therefore, could give expression to the truth about Christianity only because—as I have often emphasised—they were not written out of the primal nature and being of man, but with the remnants of atavistically clairvoyant wisdom.

What I have said here about the relation of mankind to the Mystery of Golgotha is drawn from the science of Initiation. If in this way something has been given out of supersensible knowledge, the question may well be asked: How does it appear when compared with the facts of external historical life? Hence at the beginning of this lecture to-day I want to put forward, as a particularly characteristic case—at first only as a question which should receive an answer by the end of our studies to-day—a typical ecclesiastical author of the second century. I might just as well—but then naturally I should have to give the whole treatment a different form—choose some other writer of the Church, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, or any other. But I am choosing one who is often mentioned—Tertullian. With regard to the personality of Tertullian I should like to ask how the external course of Christian life is related to the supersensible facts of which I was speaking yesterday, and have repeated in essence to-day.

Tertullian is a very remarkable personality. Anyone who hears the ordinary things said about Tertullian—well, he will hardly get beyond the knowledge of Tertullian that is generally current. He is said to have been the man who justified belief in the being of Christ, in the sacrificial death and the resurrection, by saying, Credo quia absurdum est—“I believe because it is absurd,” because no light is thrown upon all this by human reason. The words, Credo quia absurdum est, are not to be found in any of the other Fathers of the Church; they are pure invention, but they are the source of the later opinion about Tertullian that has been held, often dogmatically, right up to the present day.

When, on the other hand, we come to the real Tertullian—there is no need to be an actual follower of his—then the more exactly we get to know his personality, the more we respect this remarkable man. Above all we learn to respect Tertullian's use of the Latin language, the language which expresses the most abstract way of human thinking, and had come in other writers of his time to exemplify the thoroughly prosaic character of the Romans—Tertullian makes use of it with a true fieriness of spirit. Into his style of treatment he brings temperament, brings movement; he brings feeling and holy passion. Although he is a typical Roman who expresses himself as abstractly as any other Roman about what is often called reality—and although in the opinion of people versed in the Greek culture of that time he was not a particularly well educated man—he writes with impressiveness, with inner force, and in such a way that while using the abstract, Roman language, he became the creator of a Christian style. And the way in which Tertullian himself speaks is impressive enough. In a kind of apologia for the Christians he writes in such a way that one seems to be listening directly to the speech of a man in the grip of a holy passion.

There are certain passages where Tertullian is defending the Christians who, when they are accused under a procedure very like torture, do not deny but testify that they are Christians—testify to what they believe. And Tertullian says of them: In all other cases those who are tortured are accused of denying the truth; in the case of the Christians it is the reverse; they are declared infamous when they testify to what is in their souls. The aim of torturing is not to force them to speak the truth, which would be the only sense in torture; the aim is to force them to say what is untrue, while they continue to speak the truth. And when out of their souls they testify to the truth, they are looked upon as malefactors.

In short, Tertullian was a man with a fine sense of the absurd in life. He was a subtle observer who had already identified himself with what had developed as Christian consciousness and Christian wisdom. So it is really significant when he makes such a statement as: You have familiar sayings; very often you say out of immediate feeling in your soul: “God be with you,” “It is God's will,” and so on. But that is the belief of the Christians: the soul—if only unconsciously—is confessing itself to be Christian.

Tertullian is also a man of independent spirit. He says to the Romans, to whom he himself belongs: Consider the Christians' God and then reflect upon what you are able to feel about true piety. I ask you whether what you as Romans have introduced into the world is in keeping with true piety, or whether true piety is what the Christians desire? Into the world you have brought war, murder, killing (said Tertullian to his fellow-Romans); that is precisely what the Christians do not want. Your sanctuaries are blasphemies (so said Tertullian to the Romans) because they are trophies of victory, and trophies of victory are signs of the desecration of sanctuaries. ... Thus spoke Tertullian to the Romans. He was a man of independent feeling. And turning to the ways of Rome he said: Do men pray when they instinctively look up to the sky, or when they look up to the Capitol? Thus Tertullian was in no way a man entirely merged in the abstractions of Rome, for he was permeated with a lively sense of the presence in the world of the supersensible.

Anyone who speaks on the one hand with the independence and freedom of Tertullian, and at the same time out of the supersensible—such a man is very rare, even in those days when the supersensible was nearer than it later came to be. And Tertullian was more than merely rational. To declare that “when the Christians say what is true, you claim them to be malefactors, whereas men should be claimed as malefactors only if when tortured they say what is untrue ...” certainly that was rational, but it was also courageous. And Tertullian said other things, too, for instance: When you Romans look up to your Gods, who are demonic beings, and really put questions to them, you will receive the truth. But you do not want to receive the truth from these demonic beings. If an accused Christian is confronted by someone who is possessed by a demon, and out of whom the demon speaks, and if the Christian is allowed to question it in the right way, the demon will admit that it is a demon. And of the God whom the Christian acknowledges the demon will say—though with fear: “That is the God who now belongs to the world!” Tertullian does not call on the evidence of Christians alone, but also on that of demonic beings, saying that they will confess themselves to be demons if they are simply questioned, questioned fearlessly; and that, just as it is described in the Gospels, they will acknowledge Christ-Jesus to be the true Christ-Jesus.

At all events we have here a remarkable personality who, as a Roman, confronts his fellow-Romans in the second century. This personality strikes us especially when we consider his relation to the Mystery of Golgotha. The words spoken by Tertullian concerning the Mystery of Golgotha are approximately these: The Son of God is crucified. Because this is shameful, we are not ashamed. The Son of God has died; this is easy to believe because it is foolish. Tertullian's words are: Prorsus credibile est, quia ineptum est. It is credible, perfectly credible, because it is foolish. Thus: God's Son has died; this is perfectly credible because it is foolish. And He has been buried, He has risen again; this is certain, because it is impossible. From the words, Prorsus credibile est, quia ineptum est, the other untrue words have originated: Credo quia absurdum est.

Let us rightly understand what Tertullian says here about the Mystery of Golgotha. He says: The Son of God is crucified. If we men contemplate this crucifixion, because it is shameful we are not ashamed. What does he mean? He means that the best that can happen on earth is bound to be shameful, because it is the way of man to do what is shameful and not what is excellent. Were anything declared to be a most splendid deed, says Tertullian, a most splendid deed brought about by man, it could not be the most excellent event for the earth. For the earth the most excellent deed will indeed be one that brings shame to men, not fame—this is Tertullian's meaning.

To continue: “The Son of God has died. This is perfectly credible because it is foolish.” The Son of God has died; it is quite credible because human reason finds it foolish. Were human reason to pronounce it sensible it would not be credible, for what is found sensible by human reason cannot be the highest; it can never be the highest thing possible on earth. For human reason with its cleverness is not so high that it can arrive at what is highest; it arrives at the highest when it is foolish.

“He has been buried and has risen again. It is certain because it is impossible.” As a natural phenomenon it is impossible that the dead should rise again; but according to Tertullian the Mystery of Golgotha has nothing to do with natural phenomena. Were anything to be counted as a natural phenomenon, it would not be the most valuable thing on earth. What has most value for the earth can be no natural phenomenon and must, therefore, be impossible in the kingdom of nature. It is just on this account that He has been buried and has risen again, and it is therefore certain because it is impossible.

I should like to put Tertullian before you, with these words of his just quoted from his book, De Carne Christi, as a question. I have tried to describe him, first as a free, independent spirit, secondly as one who in man's immediate surroundings perceives the demonically supersensible. But at the same time I quoted three propositions of Tertullian's on account of which all clever people must look upon him really as a simpleton.

In matters of this kind it is certainly remarkable how one-sidedly people judge. When they put forward a proposition as false as Credo quia absurdum est, they are pronouncing judgment on the whole man in accordance with it. It is, however, necessary to take the three propositions—which certainly are not at first glance intelligible, for Tertullian is not to be easily understood—to take them first together with his complete awareness of the inter-working of the supersensible world into the human environment.

And now we want to bring before our souls something which in some measure is suited to spread light over the Mystery of Golgotha from another point of view. I have in mind two phenomena about which I said a few words during our studies of the day before yesterday. These two phenomena in the life of mankind are, first, the phenomenon of death, and secondly the phenomenon of heredity—death which is connected with the end of life, and heredity with birth. Where these are concerned it is important to have a clear insight into human life and the being of man. From all that I have been describing to you for some weeks you will be able to gather the following.

When man looks around with his senses at his environment and wishes to grasp the world of the senses with his understanding, then among the phenomena of the senses he encounter? also the phenomena of inheritance, for to a certain extent the characteristics of forefathers can be traced in their descendants, who are subject to the unconscious working of these inherited forces. Things connected with the mystery of birth, all the various inherited characteristics, are often studied without our knowing it. When, for example, we are learning about folklore, we are always speaking about inherited characteristics without noticing it. We cannot study a people without seeing all that we are studying in the light of inherited characteristics. When you speak of a particular people—of Russians, for example, of Englishmen, of Germans—you are speaking of qualities belonging to the realm of heredity, qualities the son acquires from the father, the father from the grandfather, and so on. The realm of heredity, connected as it is with the mysteries of birth, is indeed a wide realm, and when talking about external life we are often speaking of the facts and forces of heredity without being aware of it.

The fact that the mystery of death plays into the life of the senses is indeed constantly before us at the present time; it needs no reiteration. But if we look back over the human faculty for knowledge, something different becomes apparent. We see that this facility is adapted for grasping a great deal in the natural order, but it regards itself as sovereign and wants to grasp in terms of the natural order everything found therein.

Now this human faculty for knowledge is never adapted for grasping either the fact of heredity, which is connected with birth, or the fact of death. And so it turns out that the whole of man's outlook is permeated by false concepts, because it assigns to the sense-world phenomena which indeed are manifest in the sense-world but in their whole being are of a spiritual nature.

We count human death—it is different with animals and plants, as I have shown—we count human death among the phenomena taking place in the sense-world, because that is what it appears to be. But with this we get nowhere in learning about human death. It would never be possible for a natural science to say anything about the death of human beings; for on those lines we arrive merely at exchanging our whole human outlook for a delusion, with the facts of death mixed into it everywhere. We learn something about the truth of nature only when we omit death, and omit also inherited characteristics. A typical feature of human knowledge lies in its becoming corrupted, becoming mere appearance, because it claims to be able to deal with the entire world of the senses, including death and birth. And because it mixes death and birth into its whole outlook, its outlook concerning the world of the senses is falsified. We shall never perceive what man is as a sense-being if we ascribe to the sense-world the inherited qualities, which are indeed connected with death. We corrupt the whole picture of man developing along his normal straight line—I have told you of three streams, the normal straight line and the Luciferic and Ahrimanic side-streams—we corrupt the whole picture of mans development if we ascribe birth and death to his essential being in so far as he belongs to the world of the senses.

That is the strange situation in which we find the human faculty for knowledge! Under the guidance of nature itself this faculty is driven to thinking falsely because, were it able to think in accordance with truth, it would have to separate off from nature a picture of human life in which there was no heredity and no death. We should have to rule out death and heredity, paying no attention to death and birth, making our picture without them—then we should have a picture of nature. Inherited characteristics and death have no place in Goethe's world-outlook. They do not come into it and are not in keeping there. It is indeed the special characteristic of Goethe's world-outlook that you are unable to fit death and heredity into it. It is so good just because death and heredity have no place there, and that is why we can accept it as a true picture of the reality of nature.

Now up to the time of the Mystery of Golgotha people still thought about death and heredity out of certain spiritual depths, and more in conformity with nature. The Semitic peoples looked upon inherited characteristics as a direct continuance of the working of the God Jahve. They eliminated everything connected with heredity from nature, seeing it as the direct working of Jahve—for as long, at least, as the Jahve-outlook was properly understood. The God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, the God of Jacob, signified the continued working of inherited characteristics.

On the other hand, the Greek outlook—though in its decadence it had little success—sought to grasp something in the nature of man that lived in him between birth and death but had nothing to do with death. The Greeks sought to raise out of the sum-total of phenomena something with which death had no power to interfere. They had a certain horror of the very idea of death. Just because they concentrated on the realm of the senses, they had no wish to understand death; for they instinctively felt that when the human gaze is directed purely to the world of the senses—as it was with Goethe—death becomes a stranger. It is not in keeping with the sense-world; it is foreign to it.

But now there arose other outlooks, and the alteration in certain ancient outlooks appeared most typically among the leading peoples and individuals at the time when the Mystery of Golgotha was approaching. Men increasingly lost all ability to look into the spiritual world in the atavistic way; and so they came more and more to believe that birth and death, or heredity and death, belong to the world of the senses. Heredity and death—they do indeed play their part, very palpably, in the world of the senses, and men came more and more to the view that heredity and death belong there. This view wormed its way into the whole of man's outlook. For centuries prior to the Mystery of Golgotha the whole human outlook was permeated by the belief that heredity and death have to do with the world of the senses. Thereby something very, very remarkable came into being. You will understand it only if you allow the spirit of what I have been telling you in the last few days to work upon you in the right way.

Now the fact of heredity was easily seen by observing how it figured among the phenomena of nature, and it was thought to be a natural phenomenon. Increasingly the belief gained ground that heredity is a natural phenomenon. Every fact of this kind, however, evokes its polar opposite: in human life you can never cultivate a fact without that fact evoking its opposite. Man's life runs its course in the balancing of opposites. A basic condition of all knowledge is the recognition that life runs its course in opposites, and a state of balance between opposites is all we can strive for. What, therefore, was the consequence of this belief that heredity has its place among natural phenomena and belongs to them? The consequence was the bringing of the human will into terrible discredit; and this took the form—because its opposite developed—of bringing into the human will a fact belonging to the past, a fact we know in Spiritual Science as the influence of Luciferic and Ahrimanic spirits. And the effect on the soul of looking for heredity among the phenomena of nature was so potent that it led irresistibly to a moralistic world-outlook. For out of this misunderstanding of heredity its opposite came into being—the belief that once through the human will something had happened which went on to permeate the world as “original sin.” It was precisely through the introduction of heredity into the phenomena of nature that this great evil originated—the placing of “original sin” into the moral realm.

In this way human thinking wasted astray; it was unable to see that the way original sin is generally represented is blasphemy, terrible blasphemy. A God as conceived by the majority of people, a God who permits out of pure ambition, one might say, what happens in Paradise—according to the usual telling of the story—a God who does not do this with intentions of the kind described in the book Occult Science, but in the way usually described, would be no God of the heights. And to attribute this ambition to God is blasphemy. Only when we come to the point of not setting inherited characteristics in a moral light, but seeing them as a physically perceptible fact in a supersensible light; only when we relate them to the supersensible without any of this moral interpretation; when in the supersensible light we decline to fit them into a moral world-picture in the manner of rabbinical theology—only then do we come properly to terms with this matter.

Rabbinical theology will always give an elaborate intellectual interpretation of what are manifest in the world of the senses as the forces of heredity; but we should school ourselves through a spiritual outlook to discern the spirit in the inherited characteristics found in the sense-world. That is what it really comes to. And the essential thing is for you to see that, but for the Mystery of Golgotha, mankind would by then have reacted to the point of denying the spirit because people would have ceased to recognise the spirit in the inherited characteristics within the sense-world; for men have increasingly replaced the conception of the spirit by rabbinical and socialistic interpretations.

A tremendous amount is involved when a man is constrained to say: You understand nothing about the sense-world if you are not prepared for those phenomena which, because of their spiritual connections, do not really belong there. We must point to the connections of heredity with spiritual perception, supersensible perception. When the intellect takes hold of the realm of the senses, which is itself permeated with a spiritual, supersensible element, and turns it into a realm of morality, intellectually measurable—that is the spirit to which the spirit of Christ, the spirit of the Mystery of Golgotha, stands opposed. I mean this with reference to heredity and to death.

Certainly the Church Fathers were able to verify that even among the heathen there were many who were convinced of immortality. But what was involved in this? Only in ancient times had it been truly recognised that in the world of the senses death is indeed a supersensible phenomenon. By the time of the Mystery of Golgotha the prevailing outlook had been corrupted by an acceptance of death as an experience of the sense-world; and thereby the forces of death were extended over the rest of that world. Death has to be looked upon as a stranger in the sense-world. Only then can a genuine science of the natural order arise.

A further element came in with the reflections of various ancient philosophers on immortality. They turned to the immortal in man. They were right in doing so, for they said: Death is there in the world of the senses. But they said it out of a corrupted world-outlook; for otherwise they would have been impelled to say: Death is not there in the world of the senses; only in appearance does it enter there. Out of their corrupted world-outlook they said that death is in the sense-world. ... And they gradually pictured the sense-world in such a way that death had a place there. In consequence, all other things are corrupted ... it goes without saying that everything else goes wrong when death is given a place in the sense-world. When this was said out of a corrupted world-outlook, other things too had to be said, for instance: We must turn to something in opposition to death, to something of a supersensible nature that opposes death. And indeed, because in the last days of antiquity and out of a corrupted world-outlook people turned to an impersonal spirituality, this world of spiritual immortality—even when called by some other name—was the Luciferic world. What people call something is unimportant; what matters is the active reality behind the picture in their minds. And in this case the reality was the Luciferic world. Even if the words sounded different, these philosophers of late antiquity had in all their interpretations said nothing but: “As souls approaching death we want to take flight to Lucifer, who will receive us, so that immortality will be ours. We die into the kingdom of Lucifer.” That was the true meaning of their words.

I have told you about the forces that prevail in human knowledge, as a result of all the conditions I have described—well, these forces have remnants which can be seen still active to-day. For what must you admit if you take in earnest the words I have spoken to-day out of Initiation-wisdom? You will have to say: Man has his origin and his end. Neither may be understood with the human intellect that serves to understand nature; for by introducing birth and death into the sense-world, where they do not belong because they are strangers, we arrive at a false outlook about both the supersensible and the sensible. Both are corrupted—the comprehension of the spirit and the comprehension of nature. And what is the consequence? One consequence for example, is this: there is an anthropology which traces the origin of man to very primitive ancestors, and it does so quite scientifically and very cleverly. Go through these anthropological writings which trace men back to primitive ancestors, who are portrayed as though the characteristics which still belong to savage peoples were the starting-point of the human race. Scientifically, this opinion is quite in order, but the conclusion which should be drawn from it is the following: Just because it is scientifically in order to believe that birth and death belong to the world of the senses—on that very account it is false; on that account the real origin of man was different. When Kant and Laplace thought out their theory, they built it up from natural science. On the surface there is nothing to be said against it—but things were different for the very reason that the Kant-Laplace theory is correct from the standpoint of natural science. You arrive at the truth if, both for man's beginning and his end and for the origin and end of the earth, you acknowledge the opposite of what holds good for natural science in its present-day form. What Anthroposophy has to say about the origin of the earth will be all the more in accordance with the truth, the more it contradicts what can be said by a natural science that is correct in the sense of to-day.

Hence Anthroposophy does not contradict the natural science of to-day. It allows validity to natural science, but, instead of extending it beyond its boundaries, it shows the points where supersensible perception must come in. The more logical Anthroposophy is, the more correct will it be in respect of the present natural order, which is necessary for man and inherent in him, and all the more will it refrain from saying what is not true concerning the origins of man's existence and of the earth. And the less natural science divines what death really is, the more will it indulge in fantasy where death is concerned. But without the Mystery of Golgotha it would have been human destiny to think unavoidably out of a corrupted world-outlook about the most important things. For this did not depend at all on human will or human guilt; it depended entirely on human evolution.

In the course of his evolution man simply came to regard as his real being the combination of flesh, blood and bones in which he found himself. An Egyptian of ancient days, in the older and better period of Egypt, would have thought it terribly comic had anyone maintained that what walked around on two legs, and consisted of blood, flesh and bones, was really man. These things, however, do not depend upon theoretical considerations; they cannot be spun out of rumination. Gradually it came to seem natural for a man to accept as himself a form consisting of flesh, blood and bones—a form which in truth is a reflection of all the Hierarchies. So much error was spread abroad on these matters that, curiously enough, those very individuals who were led to see the error blundered into a still greater one.

Certainly there were some who arrived at the idea—but in an Ahrimanic-Luciferic way—that man is not just flesh and blood and bones. They now said: “Well, if we are something better than this combination of flesh, blood and bones, we will despise the flesh; we will look upon the human being as something higher and rise above this man of the senses.” But this image of flesh, blood and bones, together with the etheric and astral bodies, as seen by man is an illusion; in reality it is the purest likeness of the Godhead. As I have explained, the error we have been talking about is not an error because we ought to be seeing the devil in the world; but it is an error to identify ourselves with physical nature because in our own world we

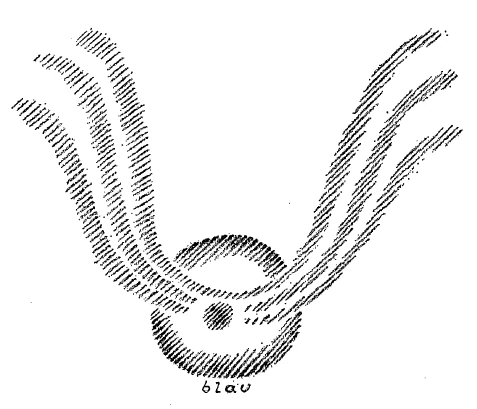

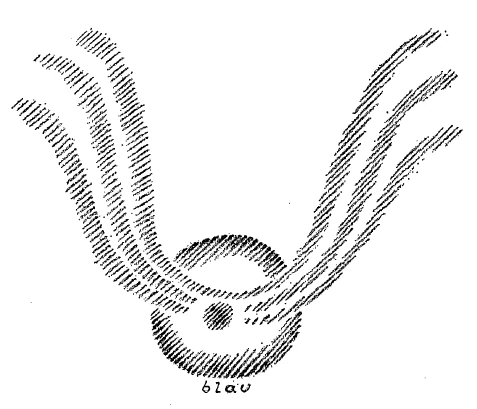

should be seeing God in us. It is also false to say: I am a quite high being, a tremendously high being, a tremendously lofty soul ... and everything around me is inferior and ugly (see blue in diagram, I). It is not like that. This is how the matter really is: There are the kingdoms of the higher Hierarchies, all divine Beings (diagram, II); they have considered it to be their divinely-appointed aim to give shape to a form that is in their image (blue circle). This form presents itself outwardly as the visible human body. And into this form, which is a copy of the Godhead and is shamefully belittled when looked upon as something inferior, the Spirits of Form have planted the human ego, the present soul—the youngest of man's members, as I have often said (the point in the blue circle.)

If the Mystery of Golgotha had not come about, man would have been able to gain only false conceptions about heredity and about death. And these false conceptions would have become ever more exaggerated. At present they appear at times in an atavistic way (as in many socialistic groups to-day an atavistic world-outlook prevails), so that death and birth are reckoned as phenomena of the senses. It would have been a necessity in man's further evolution for the door of the supersensible to be altogether closed to him. And what he could find of the supersensible within the sense-world—heredity and death—would have betrayed him, coming in a treacherous way to say: “We are of the senses” ... whereas they are not. Only by refusing to believe in a nature that shows us death and birth in a false light shall we reach the truth—such is the paradoxical way in which man is placed into the world.

There had to be planted into man something to bring equilibrium into his evolution—something able to lead him away from the belief that heredity and death are phenomena of the senses. Something had to be put before him to show clearly that death and heredity are not phenomena of the senses, but are supersensible. For this reason the event that gives man the truth about these things must not be accessible to his ordinary forces, for these are on the road to corruption and have to be set right by a powerful counter-shock. This counter-shock was the Mystery of Golgotha, for it entered human evolution as something supersensible, and so it gave men the choice—either to believe in this supersensible event, approaching it in a supersensible way but now consciously, or to succumb to those views which must result from regarding death and inherited characteristics as belonging to the world of the senses.

Hence two facts that are inseparable from a true view of the Mystery of Golgotha are those which form, as it were, its boundaries: namely, the Resurrection, which cannot be understood independently of the Virgin Birth—born not in the way that makes birth a delusive fact few mankind, but born in a supersensible way and going through death in a supersensible way. These are the two basic facts that have to act as boundaries to the life of Christ Jesus. No-one understands the Resurrection, which is meant to stand in opposition to the false idea that death belongs to the world of the senses—no-one understands this truth who does not accept its correlate, the Virgin Birth, the birth that is a supersensible fact.

Men wish to understand these truths, and modern Protestant theologians want to understand them in terms of theology, with the ordinary human intellect. But the ordinary human intellect is but a pupil of the sense-world, and, moreover, of a corrupted view of the sense-world which has arisen since the Mystery of Golgotha. And when they cannot understand these truths they become followers of Harnack, or something of the sort; they deny the Resurrection, while talking round and about it in all sorts of ways. And as for the Virgin Birth—well, they look upon that as something no reasonable being can even discuss.

Nevertheless, with the Mystery of Golgotha is intimately connected the metamorphosis of death—in other words, the metamorphosis of death from a fact of the sense-world into a supersensible fact; and the metamorphosis of heredity means that what the sense-world reflects in an illusory way as heredity, connected with the mystery of birth, is changed in the supersensible into the Virgin Birth.

However much that is erroneous and inadequate may be said about these things, man's task is not to accept them without understanding them. His task is to acquire supersensible knowledge, so that through the supersensible he can learn to grasp these things, which cannot be understood in the sense-world. If you think of the various lecture-courses in which these things have been spoken of, if you think particularly of the content of what I have given as the Fifth Gospel, [ Seven lectures given in Christiania (Oslo) from October 1st to 6th, 1913.] you will discover a whole series of ways by which these things may be understood, but understood supersensibly only. For it is right that, as long as the intellect of the student keeps to the realm of the senses, in accordance with the outlook of to-day, these facts cannot be understood. It is just when the most sublime facts of earthly life are such that they are unintelligible to the intellect of the student of the sense-world—it is just then that they are true. Hence it is not surprising that the science of Initiation is opposed by ordinary science, for it speaks of things which—just because they do not contradict true natural science—must contradict a natural order derived from a corrupted view of nature. Theology, too, has largely fallen a victim to this corrupted view of nature, though in a different direction.

When you take the other matter of which I was speaking yesterday, that only after death is man able to come to a right conception of the Mystery of Golgotha, then, if you reflect a little, you will no longer find it inconceivable that through the gate of death man enters a world where he cannot be tricked into thinking that death belongs to the world of the senses, for he sees death from the other side—I have often described this—and from this other side he learns increasingly to study death. And by this means he becomes ever more fitted to contemplate the Mystery of Golgotha in its true form. Thus we have to admit that had the Mystery of Golgotha not come about (but what is said in this connection can be understood only through supersensible knowledge), death would have taken possession of man. Evil also would be in the world, and wisdom also. But since men through their evolution had to fall into a corrupted view of nature, they were bound to have a false view of death. In wishing for immortality they turn to Lucifer, and in wishing to turn to the spirit they fall victim to Lucifer. If they do not turn to the spirit they become like dumb animals, and if they do turn to the spirit, they fall into Lucifer's grip. Looking to the future implies a wish to be immortal in Lucifer; looking towards the past means interpreting the world in such a way that inherited characteristics, which are supersensible, are viewed in terms of morality, thereby inventing the medieval blasphemy of original sin.

A real devotion to the Mystery of Golgotha is a protection against all these things. It brings into the world a true conception of birth and death, gained on a supersensible path. By a true conception of this kind men should be healed from the effects of the corrupted conception. Thus Christ Jesus is the Healer, the Saviour. And therefore—because men have not chosen to follow a corrupted conception of the world because they are good for nothing, but have come to it through their evolution, through their nature—therefore the Christ works healingly; therefore He is not only the Teacher but the Physician of mankind.

These things must be pondered—as I have said and must always repeat, they can be discerned only through supersensible knowledge—but if we are to ask ourselves: What kinds of knowledge could be reached by the souls who inspired such a spirit as Tertullian in the second century?—we must look to the dead who were perhaps contemporaries of Christ Jesus and have thus inspired Tertullian. Certainly, since there was much corrupted knowledge in the world, many things came through in distorted, clouded colourings. If, however, through the words of a Tertullian we hear the inspiring voices of the contemporaries of Christ, we shall understand how Tertullian was able to say such words as: “God's Son has been crucified. Because it is shameful, we are not ashamed of it.” Through a corrupted outlook men were bound to fall into shame; that which gives greatest meaning to the earth is manifest in human life as a shameful deed. “God's Son has gone through death. It is perfectly credible because it is foolish”—Prorsus credibile est, quia ineptum est. Precisely because it is foolishness by any criterion that man can reach with his ordinary intelligence up to the end of his physical life—for that very reason it is true in the sense of what I have been telling you to-day. “He is laid in the grave and has risen again; this is certain because it is impossible”—because within the corrupted phenomena of nature it does not happen.

When in the supersensible sense you take Tertullian's words as being inspired by Christ's contemporaries, who by that time had long been dead, you may say: Certainly Tertullian has absorbed all this, just in the way he could do in accordance with the constitution of his soul! ... But you will be able to divine how he came to be so inspired. Indeed, such a source was accessible only to a man who with his inner knowledge was so firmly grounded in the supersensible that he referred to demons being witness to the Divine, just as he spoke of human witnesses. For Tertullian spoke of how the demons themselves say they are demons and recognise the Christ. That was the preliminary condition for Tertullian being able to lay hold of what was given him through inspiration.

For those who incline to be Christians in a false way, there is something very disconcerting, thoroughly disconcerting, here. For just think, if even demons tell the truth and point to the true Christ, the demons might ultimately be questioned by a Jesuit—someone or other whom the Jesuit maintained was possessed by demons might be impelled by these demons to speak about the real origin of the Jesuits' Christ, and the demon might then say to the Jesuit: “Yours is not the Christ; the Christ of that other is the true one.”—You can understand the Jesuitical fear of the spiritual world! You can see how alarming it is to be exposed to the possible danger of being disowned in some corner of the spiritual world! Then someone might call Tertullian as witness for the Crown and might say: “Now see here, my dear Jesuit, the demon says himself that your God is a false God—and Tertullian, whom you have to recognise as a bona fide Church Father, says that demons tell the truth about themselves and about the Christ, just as the Bible states.” In short, the matter becomes very ticklish as soon as it is admitted by the supersensible world—even though in an unorthodox form—that demons witness to the truth. For even were we to cite Lucifer, he would not say what is untrue about the Christ! But it might leak out that something else is untrue about the Christ.

Now the truths of Initiation often sound different from what human beings find it convenient to acknowledge. Certainly this leads to things going rather criss-cross when to-day an endeavour is made to introduce Initiation truths to the external world—especially when they have to be introduced into the midst of immediate reality. Yes, as soon as the field is open for statements coming from the supersensible, some very remarkable conflicts may arise—when these statements are opposed by others which owe nothing to the supersensible!

This can often be applied to ordinary life. It has brought me a certain satisfaction that a suggestion I made really to myself during my lectures—and things I say during lectures I give out as my own conviction, with no intention of compelling others to accept them—this suggestion has been followed up, and our Building, out of all the conditions experienced at the present time, has been called the “Goetheanum.” And even if this has been with the assistance of certain supersensible impulses, it seems to me to be both right and good. But if I am asked by anyone for the reasons from an intellectual standpoint—as though I ought to count them all up on my fingers—if I am asked to give all the reasons for this, I should appear to myself a prodigious Philistine if I were to count up all the reasons for what has been felt out of a deep necessity—all the reasons for and against would seem to me like sheer hair-splitting.

One is often in this situation precisely when ascribing supersensible impulses to the will. People often say: “I don't understand this, I can't grasp what it means.” But is it terribly important whether you or anyone else grasps what a thing means? For what does this grasping (begreifen) mean? It really means putting a matter in the light where repose the thoughts which for decades a person has found comfortably suitable for himself. Otherwise its meaning is no different from what people call “understanding.” What people themselves call understanding often signifies very little where truths revealed from the spiritual world are concerned. Just in the most supersensible spheres—where truths are not mere theory but are meant to seize upon the will, to strike into the world of deeds—just here there is always something rather questionable when people ask intellectually: Why, why, why is this so? Or: How is this or that to be understood? In this connection we ought to accustom ourselves to finding for certain things belonging to the supersensible world an analogy—but only an analogy—with recognised facts of nature. If you leave here and a dog bites you and you have never before had a dog bite you, I don't know whether you will ask, Why has it bitten me? Or, How am I to understand it?—For what sort of connection has it with the intellect! You will simply relate the facts. So it is with certain supersensible things—we simply relate the facts. And there are many such things, as you can gather from what I have told you to-day—that in the sense-world there are two apparent events which conceal their real meaning: human death and human birth, which bring the supersensible into the world of the senses and are strangers in that world. They disguise themselves as sense-phenomena and in that way they extend their disguise over the rest of nature, so that the rest of nature also is bound to be seen in a false light by human beings to-day.

Thoroughly to understand these things, to absorb them thoroughly into our own approach to knowledge, is one of the future demands that will be made on human life. The Time Spirits will make this demand especially on those who are seeking knowledge for the future and wish to bring active will-impulses into some particular sphere. Particularly must the spiritual branches of culture be taken in hand—theology, medicine, jurisprudence, philosophy, natural science, even technics and social life, even politics—yes, truly, politics, even that strange creature! Into all this, those who understand the times ought to introduce the fruits of Spiritual Science.

Zwölfter Vortrag

Ich habe gestern aus der Wissenschaft heraus, die man nennen muß die Wissenschaft der Initiation, zwei Bemerkungen gemacht, an die ich Sie erinnern will, weil wir daran anknüpfen müssen. Zunächst sagte ich mit Bezug auf das Mysterium von Golgatha: Die tiefsten Wahrheiten, die sich auf dieses Mysterium von Golgatha beziehen, müssen nach der Natur der Sache solche sein, welche nicht durch äußere sinnenfällige, historische Zeugnisse belegt werden können. Wer einen Beweis für die Tatsachen, die sich mit dem Mysterium von Golgatha abgespielt haben, auf äußerem historischem Wege sucht, so wie man nach historischen Zeugnissen für andere Tatsachen sucht, der wird solche Zeugnisse nicht finden können, weil das Mysterium von Golgatha sich so in die Menschheit hineinstellen soll, daß der Zugang zu seinen Wahrheiten sich zuletzt auf übersinnlichem Wege vermittelt. Die Menschen sollen sich gewissermaßen gewöhnen, wenn ich mich trivial ausdrücken darf, das Wichtigste im Erdendasein so zu haben, daß sie sich ihm nicht auf sinnlichem, sondern nur auf übersinnlichem Wege nähern können. Das zweite, was ich gestern gesagt habe, ist dieses, daß der Mensch mit jenem Verständnisse, das ihm nach seiner Entwickelung zugeteilt ist als Erdenwesen, eigentlich bis zu seinem Tode - also wohlgemerkt: selbst bis zu seinem Tode - nicht so weit kommt, daß er aus seinem eigenen, innerhalb der Sinnenwelt sich entwickelnden Verständnisse zu einem Begreifen des Mysteriums von Golgatha kommen könnte. Ich habe gesagt: Erst nach dem Tode, erst post mortem entwickelt sich im Menschen, also im Menschen während seines Aufenthaltes in der übersinnlichen Welt, dasjenige Verständnis beziehungsweise die Kräfte zu demjenigen Verständnis, welches den vollen Aufschluß geben kann über das Mysterium von Golgatha. Deshalb sagte ich gestern etwas, was ganz selbstverständlich von der äußeren Welt als eine Absurdität hingestellt werden wird, als eine paradoxe Sache hingestellt werden wird. Ich sagte, daß eigentlich selbst die Zeitgenossen Christi erst im 2. und 3. Jahrhundert, nachdem das Mysterium von Golgatha abgelaufen war, zum Verständnisse kommen konnten - also erst in ihrem jenseitigen Leben -, und daß dann dasjenige, was geschrieben worden ist in diesen Jahrhunderten über das Mysterium von Golgatha, unter der Inspiration derjenigen Menschen geschrieben worden ist, die Zeitgenossen gewesen waren und aus der geistigen Welt, aus der übersinnlichen Welt heraus inspirierend auf die richtigen Schriftsteller des 2. und 3. Jahrhunderts gewirkt haben.

Nur in scheinbarem Widerspruch damit steht, daß die Evangelien, die ja Inspirationsbücher sind, wie Sie aus meiner Darstellung im «Christentum als mystische Tatsache» entnehmen können, Inspirationsschriften vom Christentum sind. Die inspirierten Evangelien konnten nur deshalb die Wahrheit über das Christentum äußern, weil sie, wie ich ja auch schon öfter betont habe, nicht aus der ureigenen Wesenheit vom Menschen heraus geschrieben worden sind, sondern noch mit dem letzten Reste der atavistisch-hellseherischen Weisheit über das Mysterium von Golgatha handelten.

Das, was ich so über die Beziehung der Menschheit zu dem Mysterium von Golgatha sagte, ist herausgeschöpft aus der Wissenschaft der Initiation selbst. Wenn man so etwas dann aus dieser übersinnlichen Erkenntnis heraus erkundet hat, dann kann man ja wohl fragen: Wie nimmt sich so etwas aus, wenn man damit vergleicht die Tatsachen des äußeren geschichtlichen Lebens? - Daher will ich im Beginne unserer heutigen Betrachtungen, als den besonders charakteristischen Fall - zunächst nur wie eine Frage, deren Antwort sich uns ergeben soll am Ende der heutigen Betrachtungen -, einen typischen Kirchenschriftsteller des 2. Jahrhunderts hervorheben. Ich könnte ebensogut, müßte aber dann die ganze Betrachtung selbstverständlich in anderer Form hier vor Ihnen vorbringen, Clemens von Alexandrien, könnte Origenes, ich könnte irgendeinen anderen Kirchenschriftsteller wählen. Ich wähle einen, der oft genannt wird: Tertullian. Ich möchte an der Persönlichkeit des Tertullianus die Frage aufwerfen: Wie verhielt sich der äußere Verlauf des christlichen Lebens zu diesen übersinnlichen Tatsachen, von denen ich gestern gesprochen habe, deren wesentlichsten Inhalt ich Ihnen heute wiederholt habe?

Tertullian ist eine sehr merkwürdige Persönlichkeit. Derjenige, der so die Dinge hört über Tertullianus, die gewöhnlich gesagt werden ja, der kommt zu nicht viel mehr als zu einem Wissen, welches davon beherrscht wird, daß Tertullianus derjenige gewesen sein soll, der den Glauben an die Wesenheit des Christus, an den Opfertod, an die Auferstehung, dadurch gerechtfertigt habe, daß er gesagt haben soll: Credo, quia absurdum est - Ich glaube, gerade weil es absurd ist, weil es der Vernunft nicht einleuchtet. - Die Worte: Credo, quia absurdum est - finden sich im ganzen Tertullianus nicht. Sie finden sich ebenso nicht im ganzen Schrifttum der übrigen Kirchenväter; sie sind rein erfunden, aber sie sind dasjenige, wodurch sich die Meinung der späteren Zeit über Tertullian bis heute oftmals zum Dogma gemacht hat. Wenn man dagegen an Tertullianus selbst herantritt - man braucht wahrhaftig nicht sein Anhänger zu werden -, dann bekommt man, je genauer man die Persönlichkeit des Tertullianus kennenlernt, immer mehr und mehr Respekt vor diesem merkwürdigen Mann. Vor allen Dingen bekommt man Respekt davor, wie Tertullianus die lateinische Sprache, diese lateinische Sprache, die ja ein Ausdruck der abstraktesten menschlichen Denkweise ist, diese lateinische Sprache, die auch schon zu seiner Zeit bei den andern Schriftstellern geworden ist der Ausdruck für das durch und durch prosaische Römertum, mit einem wahren Feuergeist handhabt: er bringt Temperament, er bringt Beweglichkeit, er bringt Empfindung und eine heilige Leidenschaft in die Art seiner Darstellung hinein. Und obzwar er ein typischer Römer ist, der sich so abstrakt ausdrückt wie nur irgendein Römer gegenüber dem, was man oftmals wirklich nennt, obzwar er nach der Anschauung der griechisch gebildeten Leute der damaligen Zeit nicht einmal ein besonders gebildeter Mensch ist, schreibt er mit Eindringlichkeit, mit innerer Kraft, schreibt er so, daß er aus der abstrakten römischen Sprache heraus geradezu der Schöpfer der christlichen Sprechweise geworden ist. Und die Art und Weise, wie er spricht, dieser Tertullianus, die ist wahrhaftig eindringlich genug. In einer Art Schutzschrift für die Christen redet er, man darf sagen, so, daß das geschriebene Wort wirkt, wie wenn man es unmittelbar von einem von heiliger Leidenschaft ergriffenen Menschen gesprochen hörte. Es gibt solche Stellen, wo Tertullian Verteidiger der Christen wird, die, wenn sie angeschuldigt werden, unter einer Prozedur, die dem Foltern sehr ähnlich ist, nicht leugnen, sondern gestehen, daß sie Christen sind und woran sie glauben. Da sagt Tertullian: Überall sonst beschuldigt man diejenigen, die gefoltert werden, daß sie leugnen; bei den Christen macht man es umgekehrt: man erklärt sie für verrucht, wenn sie gestehen, was in ihrer Seele ist. Man will sie durch das Foltern nicht dazu zwingen, daß sie die Wahrheit sagen, was allein einen Sinn hätte; man will sie dazu zwingen, daß sie die Unwahrheit sagen, während sie die Wahrheit sagen. Und wenn sie die Wahrheit gestehen aus ihrer Seele heraus, so betrachtet man sie als Bösewichter.

Kurz, Tertullian war schon ein Mann, welcher einen feinen Sinn hatte für das Absurde im Leben. Und Tertullian war bereits ein Geist, der zusammengewachsen war mit dem, was sich entwickelt hatte als christliches Bewußtsein und christliche Weisheit, ein feiner Beobachter des Lebens. So ist es wirklich etwas Bedeutsames, wenn er solch ein Wort hinwirft: Ihr habt Sprichwörter, ihr sagt im Leben sehr häufig aus unmittelbarstem Empfinden der Seele heraus: Gott befohlen, Gott will es - und so weiter. Das aber ist Christenglaube: die Seele bekennt sich, wenn sie gerade unbewußt sich ausspricht, als eine Christin. — Tertullian ist auch ein Mann mit unabhängigem Geist. Tertullian ist ein Mann, welcher den Römern, zu welchen er selber gehört, sagt: Betrachtet den Christen-Gott und überlegt euch dann, was ihr empfinden könnt über wahre Religiosität. Und ich frage euch, ob dasjenige, was ihr als Römer in die Welt einführt, wahrer Religiosität entspricht, oder ob dasjenige wahrer Religiosität entspricht, was die Christen wollen. Ihr führt Krieg und Mord und Totschlag in die Welt ein; das wollen die Christen gerade nicht. Eure Heiligtümer sind Gotteslästerungen, weil sie Siegeszeichen sind, und Siegeszeichen sind keine Heiligtümer, sondern Zeichen der Heiligtumschändung. - Das sagte Tertullian seinen Römern! Er war ein Mann mit Unabhängigkeitsgefühl, und hinblickend auf das Treiben Roms sagte er: Betet man vielleicht, indem man naturgemäß zum Himmel schaut, oder indem man zum Kapitol schaut? - Dabei war Tertullian keineswegs ein Mann, der aufging im abstrakten Römertum, denn er war tief durchdrungen von der Anwesenheit des Übersinnlich-Wesenhaften in der Welt. Jemanden, der auf der einen Seite so unabhängig und frei und zugleich so aus dem Übersinnlichen heraus spricht wie Tertullian, den soll man suchen, selbst innerhalb der damaligen Zeit, wo das Übersinnliche den Menschen noch näher lag als später! Und Tertullian sagte nicht nur in rationalistischer Weise: Die Christen sagen die Wahrheit, ihr erklärt sie als Bösewichter -, während man doch nur dafür, daß die Menschen das Unwahre sagen unter der Folter, sie als Bösewichter erklären sollte. - Gewiß, das war rationalistisch, wenn auch mutig, aber Tertullian sagte noch andere Dinge; Tertullian sagte zum Beispiel: Wenn ihr nur wirklich hinschaut, ihr Römer, auf eure Götter, welche Dämonen sind, und diese Dämonen wirklich befragt, da werdet ihr die Wahrheit erfahren. Aber ihr wollt nicht von den Dämonen die Wahrheit erfahren. Stellt man einen von einem Dämon Besessenen, aus dem der Dämon redet, einem angeklagten Christen gegenüber und läßt ihn von dem Christen in der richtigen Weise befragen: der Dämon läßt sich als Dämon erkennen; und wenn auch mit Furcht, so wird er auch von dem Gotte, den der Christ anerkennt, sagen: Das ist der Gott, der nun in die Welt gehört! Tertullian ruft nicht nur das Zeugnis der Christen, sondern auch das Zeugnis der Dämonen an, indem er sagt, daß die Dämonen sich auch als Dämonen bekennen werden, wenn man sie nur befragt, angstlos befragt, und daß sie gerade so, wie es auch in den Evangelien beschrieben ist, den Christus Jesus als den wirklichen Christus Jesus anerkennen.

Es ist jedenfalls eine merkwürdige Persönlichkeit, die da im 2. Jahrhundert als ein Römer den Römern gegenübersteht. Auffallend wird uns diese Persönlichkeit, wenn wir nun sehen, wie sie sich zu dem Mysterium von Golgatha verhält. Die Worte, die Tertullianus über das Mysterium von Golgatha gesprochen hat, sie sind etwa die folgenden: Gekreuzigt ist Gottes Sohn. Wir schämen uns nicht, weil es schmählich ist. Gestorben ist Gottes Sohn; es ist völlig glaubhaft, weil es töricht ist. - Die Worte bei Tertullian heißen: Prorsus credibile est, quia ineptum est. Glaubhaft ist es, völlig glaubhaft ist es, weil es töricht ist. - Also: Gestorben ist Gottes Sohn; es ist völlig glaubhaft, weil es töricht ist. Und begraben ist er, auferstanden, es ist gewiß, weil es unmöglich ist. - Aus diesem Worte: Prorsus credibile est, quia ineptum est - aus diesem Worte ist das andere Unwahre geprägt worden: Credo, quia absurdum est.

Verstehen wir recht das Wort, das da Tertullianus ausspricht von dem Mysterium von Golgatha. Tertullianus sagt: Gekreuzigt ist Gottes Sohn. Wenn wir Menschen hinschauen auf diese Kreuzigung, so schämen wir uns dessen nicht, weil es schmählich ist. - Was meint er damit? Er meint damit, daß das Beste, was auf der Erde passieren konnte, schmählich sein muß, weil es die Art der Menschen ist, das Schmähliche zu tun, nicht das Vorzügliche zu tun. Würde irgend etwas, meint Tertullian, als eine schönste Tat hingestellt werden, von den Menschen getane schönste Tat, so könnte sie nicht die vorzüglichste für das Erdengeschehen sein. Die vorzüglichste Tat für das Erdengeschehen wird schon diejenige sein, die dem Menschen Schande macht, nicht Ruhm bringt; das meint er damit.

Weiter: Gestorben ist Gottes Sohn. Es ist völlig glaubhaft, weil es töricht ist. - Gestorben ist Gottes Sohn; es ist völlig glaubhaft, weil die menschliche Vernunft es töricht findet. Würde die menschliche Vernunft es gescheit finden, so würde es nicht glaubhaft sein, denn dasjenige, was die menschliche Vernunft gescheit findet, kann nicht das Höchste sein, kann nicht das Höchste der Erde sein. Denn die menschliche Vernunft ist nicht so hoch mit ihrer Gescheitheit, daß sie gerade an das Höchste gerät, sondern sie gerät an das Höchste, wenn sie töricht wird.

Begraben ist er, auferstanden. Es ist gewiß, weil es unmöglich ist. — Innerhalb der Naturerscheinungen ist es unmöglich, daß ein Toter aufersteht; aber das Mysterium von Golgatha hat nach des Tertullianus Meinung mit den Naturerscheinungen nichts zu tun. Würde man irgend etwas als Naturerscheinung bezeichnen müssen, so würde es nicht das Wertvollste der Erde sein. Dasjenige, was das Wertvollste der Erde ist, darf keine Naturerscheinung sein, muß also innerhalb des Reiches der Natur unmöglich sein. Gerade deshalb ist er begraben worden und auferstanden, und es ist deshalb gewiß, weil es unmöglich ist.

Zunächst möchte ich diesen Tertullianus insbesondere mit diesen in seinem Buche «De carne Christi» stehenden Worten, die ich eben angeführt habe, wie eine Frage hinstellen. Ich versuchte ihn zu charakterisieren, erstens als einen freien, unabhängigen Geist, zweitens als einen solchen Geist, der in unmittelbarer Umgebung der Menschen auch das Dämonisch-Übersinnliche sieht. Aber ich führte Ihnen zu gleicher Zeit drei seiner Sätze vor, wegen welcher Tertullianus von allen gescheiten Menschen als ein Tropf eigentlich angesehen werden müßte.

Es ist allerdings bei solchen Dingen immer merkwürdig, daß die Menschen einseitig urteilen; wenn sie so einen noch dazu falschen Satz aufbringen, wie Credo, quia absurdum est, dann beurteilen sie danach einen ganzen Menschen. Es ist aber eben nötig, daß man die drei Sätze, die ja allerdings nicht so ohne weiteres einleuchten Tertullianus will auch gar nicht so ohne weiteres einleuchten -, zusammenhält erstens mit der unabhängigen Geistigkeit des Tertullianus, dann zusammenhält mit seinem restlosen Bewußtsein von dem Mitwirken der übersinnlichen Welt innerhalb der menschlichen Umgebung.

Und jetzt wollen wir dasjenige vor unsere Seele hinstellen, was geeignet ist, einigermaßen wiederum von einem andern Gesichtspunkte aus Licht zu verbreiten über das Mysterium von Golgatha. Dasjenige, was über das Mysterium von Golgatha Licht zu verbreiten geeignet ist, sind zwei Erscheinungen im Leben der Menschheit, von denen ich schon einige Worte in der vorgestrigen Betrachtung gesprochen habe: die eine Erscheinung ist der Tod, die zweite Erscheinung die Vererbung. Der Tod, der mit dem Ende des Lebens zusammenhängt, die Vererbung, die mit der Geburt zusammenhängt. Hinsichtlich des Todes und der Vererbung ist es wichtig, daß man klar sieht mit Bezug auf das Menschenleben und auf die menschliche Wissenschaft. Aus alledem, was ich Ihnen nun seit Wochen darstelle, können Sie nämlich das Folgende entnehmen: Wenn der Mensch auf seine Umgebung hinblickt mit seinen Sinnen und das Sinnliche mit seinem Verstande sich begreiflich machen will, dann treten unter den Erscheinungen der Sinne ihm auch entgegen die Erscheinungen der Vererbung: daß gewissermaßen die Eigenschaften der Vorfahren in den Nachkommen spuken und der Mensch aus dem Unterbewußten dieser vererbten Kräfte heraus handelt. Dasjenige, was mit dem Mysterium der Geburt zusammenhängt, alle diese verschiedenen vererbten Merkmale, wir studieren sie oftmals, wenn wir nicht einmal an diese vererbten Merkmale denken: wenn wir zum Beispiel Völkerkunde treiben, reden wir ja, ohne daß wir darauf aufmerksam sind, immer von vererbten Merkmalen. Man kann nicht ein Volk studieren, ohne daß man eigentlich alles, was man studiert, im Kreise der vererbten Merkmale sieht. Wenn Sie von irgendeinem Volke, von den Russen, von den Engländern, von den Deutschen und so weiter reden, so reden Sie von denjenigen Eigenschaften, die in das Gebiet der Vererbung gehören, die der Sohn immer vom Vater, der Vater vom Großvater und so weiter erwirbt. Das Gebiet der Vererbung, das mit dem Mysterium der Geburt zusammenhängt, ist eben ein weites, und wir sprechen, indem wir von dem äußeren Leben, in das der Mensch hineingestellt ist, reden, vielfach von den Tatsachen, von den Kräften der Vererbung, ohne daß wir uns dessen immer bewußt sind. Daß das Mysterium des Todes sich hineinstellt in das Sinnenleben der Menschen, das ist ja jetzt eine immerdar vor Augen tretende Tatsache, so daß man nicht viele Worte darüber zu machen braucht. Aber wenn man nun, ich möchte sagen, rückwärts das menschliche Erkenntnisvermögen betrachtet, so zeigt sich ein anderes. Es zeigt sich nämlich, daß dieses menschliche Erkenntnisvermögen geeignet ist, vieles in der Naturordnung zu begreifen, aber es erklärt sich dieses menschliche Erkenntnisvermögen für souverän und will a/les begreifen, was in diese Naturordnung sich hineinstellt. Nun ist dieses menschliche Erkenntnisvermögen niemals geeignet, die Tatsache der Vererbung, die mit dem Mysterium der Geburt zusammenhängt, und die Tatsache des Todes zu begreifen. Und die eigentümliche Erscheinung tritt auf im Menschenleben, daß die ganze menschliche Anschauung durchsetzt ist von falschen Begriffen, weil diese Anschauung Erscheinungen zur Sinneswelt rechnet, die zwar in der Sinneswelt sich kundgeben, die aber ihrem ganzen Wesen nach geistiger Art sind. Wir zählen den Menschentod - mit dem Tod der Tiere und der Pflanzen ist es etwas anderes, ich habe vorgestern darauf aufmerksam gemacht - unter die Erscheinungen, die sich in der Sinneswelt abspielen, weil es so zu sein scheint. Aber dadurch erreichen wir nicht, daß wir etwas erfahren können über den Menschentod. Niemals würde eine Naturwissenschaft etwas sagen können über den Menschentod, sondern wir erreichen nur das, daß wir uns unsere ganze menschliche Anschauung in ein Scheinbild verwandeln, denn wir mischen überall die Tatsachen des Todes hinein. Und wir erfahren über die Natur in ihrer Wahrheit nur dann etwas, wenn wir den Tod auslassen und wenn wir die Vererbungsmerkmale auslassen. Das Eigentümliche der menschlichen Erkenntnis ist, daß sie verdorben wird - wenn ich mich des Ausdruckes bedienen darf -, zum Scheinbild gemacht wird, weil sie glaubt, sie könne sich über die ganze Sinneswelt auslassen, also auch über Tod und Geburt; und weil sie in ihre Auffassung der Natur Tod und Geburt hineinmischt, verdirbt sie sich ihre ganze Anschauung über die Sinneswelt. Man gelangt niemals zu einer Anschauung darüber, was der Mensch als Sinneswesen ist, wenn man die Eigenschaften der Vererbung, die ja mit der Geburt zusammenhängen, mit zu der Sinneswelt rechnet. Man verdirbt sich das ganze Bild des Menschen — ich habe drei Strömungen dargestellt, die gerade Linie, die normale Entwickelung, die seitliche luziferische und die seitliche ahrimanische -, die ganze Entwickelung des Menschen, die eben gerade fortläuft, wenn man Geburt und Tod zum Wesen des Menschen, insofern der Mensch der Sinneswelt zugehört, hinzurechnet.

So sonderbar steht es mit dem menschlichen Erkenntnisvermögen. Dieses menschliche Erkenntnisvermögen wird unter der Anleitung der Natur selber dazu getrieben, Falsches zu denken, weil es, wenn es in Wahrheit denken könnte, sich aus der Natur ein Bild heraussondern müßte, in dem keine Vererbung und kein Tod im Menschenleben drinnen ist. Man müßte abstrahieren von Tod und Vererbung; man müßte auch nichts geben auf Tod und Geburt und müßte, abgesehen von diesen, sich ein Bild machen; dann würde man ein Naturbild bekommen. In der Goetheschen Weltanschauung haben die vererbten Merkmale und der Tod keinen Platz. Sie gehen nicht hinein, sie passen nicht hinein. Das ist das Eigentümliche gerade der Goetheschen Weltanschauung: Sie können nichts mit Tod und Vererbung innerhalb der Goetheschen Weltanschauung machen. Deshalb ist sie gerade so gut, und deshalb kann man sie als ein wahres Naturbild der Wirklichkeit annehmen, weil Tod und Vererbung darin keinen Platz haben.

Nun hat man bis in die Zeit des Mysteriums von Golgatha noch aus gewissen geistigen Untergründen heraus naturgemäßer über Tod und Vererbung gedacht. Die semitische Bevölkerung betrachtete die vererbten Merkmale als eine unmittelbare Fortwirkung des Gottes Jahve; man versteht die Jahve-Anschauung nur, wenn man dieses weiß. Sie stellte heraus das, was sich auf die Vererbung bezog - wenigstens da, wo man noch die Jahve-Anschauung gut verstanden hat -, aus der bloßen Natur, und sah darinnen unmittelbar ein Fortwirken Jahves. Der Gott Abrahams, der Gott Isaaks, der Gott Jakobs, das war nichts anderes als die fortwirkenden, vererbten Merkmale. Und die griechische Weltanschauung wiederum suchte, wenn ihr das auch in ihrer Dekadenz wenig gelang, etwas in der Menschennatur zu erfassen, was in dem Menschen auch zwischen Geburt und Tod lebt, was aber mit dem Tod nichts zu tun hat, suchte etwas herauszuheben aus der Summe der Erscheinungen, in das der Tod sich nicht hineinmischen kann. Die griechische Weltanschauung hatte einen gewissen Horror vor dem Begreifen des Todes; gerade weil sie auf das Sinnliche hingerichtet war, wollte sie den Tod nicht begreifen, da sie instinktiv spürte: Wenn man den Blick rein auf die Sinneswelt richtet — wie Goethe es wieder getan hat -, dann ist der Tod ein Fremdling. Er paßt nicht hinein in die Sinneswelt, er ist ein Fremdling.

Nun aber entstanden gewisse andere Anschauungen daraus, und dieses Anderswerden gewisser alter Anschauungen, das trat gerade ganz besonders charakteristisch hervor bei den tonangebenden Völkern und Menschen, als sich die Zeit dem Mysterium von Golgatha näherte. Die Menschen — wenn ich mich einmal populär ausdrücken will — verloren immer mehr die Möglichkeit, atavistisch hineinzuschauen in die geistige Welt; dadurch kamen sie immer mehr und mehr zu dem Glauben, daß Geburt und Tod oder Vererbung und Tod auch zu der Sinneswelt gehören. Sie gehen ja in der Sinneswelt herum, und zwar in sehr handgreiflicher Weise, möchte ich sagen, Vererbung und Tod. Die Menschen kamen immer mehr und mehr zu der Anschauung, daß Vererbung und Tod zu der Sinneswelt gehören. Und das nistete sich ein in die ganze menschliche Anschauung. Die ganze menschliche Anschauung wurde schon Jahrhunderte vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha durchdrungen von dem Glauben, daß Vererbung und Tod mit der Sinneswelt irgend etwas zu tun haben. Dadurch bildete sich etwas sehr, sehr Merkwürdiges aus. Sie werden es nur begreifen, wenn Sie den Geist von dem, was ich in diesen Tagen gesagt habe, in der richtigen Weise auf sich wirken lassen.

Die Tatsache der Vererbung, man sah sie, indem man sie in die Naturerscheinungen hereinrückte. Man glaubte, sie sei eine Naturerscheinung; immer mehr und mehr wurde der Glaube verbreitet, die Vererbung sei eine Naturerscheinung. Jede solche Tatsache, die auftritt im Leben, ruft ihren polarischen Gegensatz hervor; Sie können sich im menschlichen Leben gar nicht einer Tatsache hingeben, ohne daß diese Tatsache ihren Gegensatz hervorruft. Das Leben der Menschen verläuft eben im Gleichgewicht von Gegensätzen. Das ist eine Grundbedingung aller Erkenntnis, daß man anerkennt, daß das Leben in Gegensätzen verläuft, und nur der Gleichgewichtszustand zwischen Gegensätzen angestrebt werden kann. Was war deshalb die Folge dieses Glaubens, daß die Vererbung hereinfällt in die Naturerscheinungen, zu den Naturerscheinungen gehöre? Die Folge davon war eine furchtbare Verunglimpfung des menschlichen Willens. Diese Verunglimpfung des menschlichen Willens, sie besteht darinnen, daß man - weil der Gegensatz sich ausbildete - eine Tatsache der Vorzeit, die wir in der Geheimwissenschaft kennen als den Einfluß der luziferisch-ahrimanischen Geister, in den menschlichen Willen hereinrückte, und eine Tatsache, die man eigentlich auf dem Naturfeld suchte, so wirksam hat in der menschlichen Seele, daß es einen hineintrieb in eine moralische Weltanschauung. Weil man die Vererbung herausstellte in die Naturerscheinungen und sie auf diese Weise verkannte, bildete sich der Gegensatz heraus: Der Glaube, daß durch den menschlichen Willen einstmals das geschehen sei, was dann als Erbsünde durch die Welt geht. Es wurde gerade durch die falsche Einreihung der Vererbung in die Naturerscheinungen das Grundübel erzeugt, die Erbsünde auf das Moralfeld zu schieben.

Damit war auch das Denken der Menschen verdorben; denn es kam dieses Denken nicht dazu, den richtigen Glauben anzunehmen, daß so, wie sich gewöhnlich die Menschen die Erbsünde vorstellen, die ganze Vorstellung eine Gotteslästerung ist, eine furchtbare Gotteslästerung. Ein Gott, der so, wie es sich die meisten Menschen vorstellen, man möchte sagen, rein aus Ambition heraus zuläßt, daß im Paradiese das geschieht, was gewöhnlich vom Paradiese erzählt wird, der das nicht aus solchen Intentionen heraus tut, wie es in der «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß» dargestellt wird, sondern so, wie das gewöhnlich dargestellt wird, der wäre wahrhaftig kein hoher Gott. Und dem Gotte diese Ambition beizulegen, ist eine Gotteslästerung. Nur dann, wenn man dazu kommt, die vererbten Merkmale, dasjenige, was sich von dem Vorfahren auf den Nachkommen vollzieht, nicht ins moralische Licht zu stellen, sondern selbst als sinnenfällige Tatsache schon im übersinnlichen Lichte zu sehen, nur wenn man hinschaut auf Übersinnliches und nicht erst eine moralische Deutung unternimmt, wenn man im übersinnlichen Lichte das schaut, was man nicht mit rabbinischer Theologie in eine moralische Weltinterpretation umsetzen soll, nur dann kommt man auf das, um was es sich auf diesem Gebiete handelt. Die rabbinische Theologie wird immer durch den Verstand uminterpretieren dasjenige, was sich als Vererbungskräfte in der Sinneswelt ausbreitet, und wofür man sich schulen sollte durch Geistanschauung, damit man schon in den vererbten Merkmalen in der Sinneswelt den Geist entdeckt. Das ist das, worauf es ankommt. Und den Hauptwert lege ich darauf, daß Sie einsehen: Ohne dieses Mysterium von Golgatha wäre die Menschheit in der Zeit des Mysteriums von Golgatha dazu gekommen, den Geist zu verleugnen, weil sie abgekommen wäre davon, für die Vererbungsmerkmale, die innerhalb der Sinneswelt sind, den Geist anzuerkennen, weil die Menschen dazu gekommen sind, immer mehr und mehr rabbinistische sowohl wie sozialistische Interpretationen an die Stelle der Geistanschauung zu setzen. Darauf beruht ungeheur viel, daß man sich genötigt sieht zu sagen: Du begreifst nichts in der Sinneswelt, wenn du dich nicht ausstattest für dasjenige, was in der Sinneswelt schon ein übersinnlicher Fremdling ist, weil es geistige Zusammenhänge hat. Auf die Vererbungszusammenhänge muß man mit der geistigen, mit der übersinnlichen Anschauung hinweisen. Der Verstand aber, der umgesetzt hat das Sinnliche, das schon ein Übersinnliches, ein Geistiges ist, in ein verstandesmäßig aufgefaßtes Moralisches, dieser Geist, der ist derjenige, dem der Geist Christi, der Geist des Mysteriums von Golgatha entgegensteht. Das mit Bezug auf die Vererbung und mit Bezug auf den Tod.

Gewiß, gerade die Kirchenväter konnten konstatieren, daß auch unter den Heiden die Menschen zahlreich waren, die von der Unsterblichkeit überzeugt waren. Aber um was handelt es sich denn dabei? Nun, in alten Zeiten hatte es sich dabei darum gehandelt, daß man erkannt hat: Der Tod ist in der Sinneswelt schon eine übersinnliche Erscheinung. Man hatte sich schon zur Zeit des Mysteriums von Golgatha die Weltanschauung dadurch verdorben, daß man den Tod als eine sinnliche Erscheinung genommen hat und dadurch die Todeskräfte auch ausbreitete über die übrige Sinneswelt. Der Tod muß als ein Fremdling innerhalb der Sinneswelt angesehen werden. Dann nur kann reine Wissenschaft von der Naturordnung entstehen.

Dazu ist gekommen dasjenige, was manche Philosophen des ausgehenden Altertums über die Unsterblichkeit ersonnen haben. Sie haben sich gewendet an das Unsterbliche im Menschen. Daran haben sie sich mit Recht gewendet, denn sie haben sich gesagt: Der Tod ist da in der Sinneswelt.- Das haben sie aber aus einer korrumpierten Weltanschauung heraus gesagt; denn aus einer nichtkorrumpierten Weltanschauung heraus hätten sie sagen müssen: Der Tod ist nicht da in der Sinneswelt, er tritt nur scheinbar in die Sinneswelt herein. - Und sie stellten allmählich die Sinneswelt so vor, daß der Tod darin Platz hat. Damit verdirbt man sich aber alle andern Dinge. Selbstverständlich verdirbt man sich alle andern Dinge, wenn man sie sich so vorstellt, daß der Tod einen Platz darin hat. Wenn sie sich aber aus einer korrumpierten Weltanschauung heraus das sagten, dann mußten sie sich noch etwas anderes sagen, dann mußten sie sich sagen: Wir müssen uns an irgend etwas wenden, das dem Tod widerspricht, an ein Übersinnliches, das dem Tod widerspricht. - Ja, dadurch, daß die Menschen im ausgehenden Altertum aus einer korrumpierten Weltanschauung heraus sich an das unpersönlich Geistige gewendet haben, war diese unsterbliche geistige Welt - wenn sie das auch anders genannt haben - die luziferische Welt. Wie der Mensch die Dinge benennt, darauf kommt es nicht an, sondern darauf kommt es an, was wirklich in seinen Vorstellungen kraftet: und so war es die luziferische Welt. Und wie auch die Worte anders lauteten, die Philosophen des ausgehenden Heidentums hatten eigentlich in allen ihren Interpretationen nichts anderes gesagt, als: Wir wollen als Seelen, indem wir dem Tod entgehen, zu Luzifer uns flüchten, der uns aufnimmt, so daß wir die Unsterblichkeit haben. Wir sterben ins Reich des Luzifer hinein. - Das war der wahre Sinn.

Die Nachzügler der Kräfte, welche in der menschlichen Erkenntnis aus all diesen Voraussetzungen heraus, die ich Ihnen heute gesagt habe, walten, die sieht man noch heute walten. Denn was müssen Sie sich denn eigentlich sagen, wenn Sie die Worte, die ich heute aus der Initiationsweisheit heraus wiederum zu Ihnen gesprochen habe, ernst nehmen? Sie müssen sagen: Es gibt des Menschen Ursprung und es gibt sein Ende. Beide dürfen nicht mit dem, was der Mensch als Verstand hat, der für die Natur taugt, ergriffen werden. Man kommt zu einer falschen Anschauung sowohl über das Übersinnliche wie auch über das Sinnliche, wenn man Geburt und Tod in das Sinnliche hineinmischt, wohinein sie nicht gehören, weil sie Fremdlinge sind. Man verdirbt sich beides: Man verdirbt sich die Geistauffassung und verdirbt sich die Naturauffassung. Was ist die Folge? Nun, eine der Folgen zum Beispiel ist diese: Es gibt eine Anthropologie, die den Ursprung des Menschen auf sehr niedrige Wesen zurückführt und ganz naturwissenschaftlich handelt, sehr gescheit dabei handelt. Gehen Sie durch alle diese Anthropologien, die den Menschenursprung zurückführen auf niedrige Wesen, die sie sich so vorstellen, als ob dasjenige, was heute unter den wilden Völkern noch heimisch ist, am Ausgange des Menschengeschlechts gewesen wäre! — Man urteilt naturwissenschaftlich ganz richtig, wenn man solch eine Vorstellung hat. Aber die Schlußfolgerung, die man daraus ziehen sollte, ist nämlich die folgende: Gerade weil das naturwissenschaftlich so richtig ist — vor der Naturwissenschaft richtig ist, die da glaubt, daß Geburt und Tod in die Sinneswelt gehören —, deshalb ist es falsch, deshalb war es anders am wirklichen Ursprung des Menschen. Und als Kant und Laplace ihre Theorie ausgedacht haben, haben sie aus der Narturwissenschaft heraus ihre Kant-Laplacesche Theorie gebildet. Man kann scheinbar nichts dagegen einwenden, aber gerade deshalb war es anders, weil die KantLaplacesche Theorie vom Standpunkt der heutigen Naturwissenschaft richtig ist. Sie kommen zu dem Richtigen, wenn Sie sowohl für den Menschenursprung und das Menschenziel, wie für den Erdenursprung und das Erdenziel als richtig anerkennen das Gegenteil von dem, was naturwissenschaftlich in dem heutigen Sinne richtig ist. Anthroposophie wird um so mehr das Richtige sagen über den Erdenursprung, je mehr sie im Widerspruche steht mit dem, was [darüber] aus einer im heutigen Sinne richtigen Naturwissenschaft gesagt werden kann. Daher steht Anthroposophie auch [wiederum] nicht im Widerspruch mit der heutigen Naturwissenschaft! Sie läßt die Naturwissenschaft gelten, aber sie erweitert sie nicht über ihre Grenzen hinaus, sondern sie zeigt gerade diejenigen Punkte auf, wo übersinnliche Anschauung eingreifen muß. Anthropologie wird, je logischer sie ist, je richtiger sie ist in bezug auf die heutige, dem Menschen notwendige und eingeborene Naturordnung, um so mehr das nicht sagen, was nicht war am Ausgangspunkte des Menschendaseins und der Erde! Und um so weniger wird die Naturwissenschaft das treffen, was den Tod betrifft, je mehr sie aus ihren Vorstellungen heraus über den Tod phantasiert.