Fundamentals of the Science of Initiation

GA 191

17 October 1919, Dornach

To-day I wish to speak to you of some fundamental pieces of knowledge of the science of initiation, which will then supply to us a kind of foundation for that which we shall consider tomorrow and the day after tomorrow. To-day we shall first speak of something which lies in the consciousness of every human being, but is not grasped clearly enough in the ordinary course of life. When we speak of such things, we always speak of them from the standpoint of our present time, in the sense and meaning which I have often explained to you: namely, that knowledge is not in any way valid for all time and for every place, but that it is only valid for a certain definite time, indeed, only for a definite region of the earth. Thus, certain standpoints of knowledge would be valid, for instance, for the European civilisation, and other standpoints would be valid—let us say—for the knowledge of the East.

Everybody knows that we live, as it were, between two poles of our knowledge. Everyone feels that, on the one hand, we have the knowledge gained through our senses. A plain, unprejudiced person learns to know the world through his senses, and is even able to sum up what he sees and hears, and, in general, what he perceives through his senses. After all, that which science supplies to us, in the form in which science now exists in the Occident, is merely a summary of that which the senses convey to us.

But everyone can feel that there is also another kind of knowledge, and that it is not possible to be in the full sense of the word a real human being living in the ordinary world, unless another kind of knowledge is added to the one which has just been characterized. And this kind of knowledge is connected with our moral life. We do not only speak of ideas pertaining to the knowledge of Nature, and explaining this or that thing in Nature, we also speak of ethical ideas, ethical ideals. We feel that they are the motives of our actions, and that we allow them to guide us when we ourselves wish to be active in the ordinary world. And every man will undoubtedly feel that this knowledge of the senses, with the resulting intellectual knowledge (for, the intellectual knowledge is merely a result, an appendix of the knowledge transmitted by the senses) is a pole of our cognitive life which cannot reach as far as the ethical ideas. The ethical ideas are there, but when we pursue, for instance, natural science, we cannot find these ethical ideas by contemplating the plant-world, the mineral world, or by following any other branch of modern natural sciences. The tragic element of our time consists, for instance, in trying to discover, upon a natural-scientific basis, ideas which are to be applied to the social sphere. If sound common sense were adopted, this would never be possible. The ethical ideas exist as if on another side of life. And our life is indeed under the influence of these two streams: on the one hand, the knowledge of Nature, and on the other hand, the ethical knowledge.

From my The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity you will know that the highest ethical ideas required by us as human beings are given to us when we grasp moral intuitions, and that when we begin to gain possession of these ethical ideas, they are the foundation of our human freedom. On the other hand, you may perhaps also know that for certain thinkers there has always been a kind of abyss between that which is given, on the one hand, by the knowledge of Nature, and on the other hand, by ethical knowledge. The philosophy of Kant is based upon this abyss, which he is unable to bridge completely. For this reason, Kant has written a Critique of Theoretical Reason, of Pure Reason, as he calls it, where he grapples with natural science, and where he says all that he has to say about natural science, or the knowledge of Nature. On the other hand, he has also written a Critique of Practical Reason, where he speaks of ethical ideas. We might say: The whole human life is born for him out of two roots which are completely severed from one another, which he describes in his two chief critical studies.

Of course, it would be unfortunate for the human being if there were no connecting bridge between these two poles of our soul-life. Those who earnestly pursue, on the one hand, spiritual science, and on the other hand, earnestly consider the tasks of our present time, must eagerly ask themselves: Where is the bridge connecting ethical ideas and the ideas of Nature?

To-day we shall adopt the standpoint which I would like to characterize as a historical standpoint, in order to come to a knowledge of this bridge. You already know from the explanations which have recently been given here, that in past times man's soul-constitution was essentially different from that of a later time. The origin of Christianity really forms a deep incision in the whole evolution of humanity. And only if we understand what has really arisen in the evolution of humanity through the birth of Christianity we shall understand human reason.

That which lies behind the rise of Christianity—not to mention Jewish history—is the whole extent of pagan culture. Jewish culture was, after all, a preparation for Christianity. This whole extent of pagan culture is essentially different from our modern Christian culture. The more we go back into time, the more we shall find that this pagan culture had a uniform character. It was principally based upon human wisdom. I know that it is almost offending for a modern man to hear that, as far as wisdom is concerned, the ancients were far more advanced than modern man; nevertheless it was so. In ancient pagan times a wisdom extended over the earth, which was far nearer to the origin of things than our modern knowledge, particularly our modern natural sciences. This ancient, this primeval knowledge, was very concrete, it was a knowledge intensively connected with the spiritual reality of things. Something entered the human soul through man's knowledge of the reality of things. But the special characteristic of this ancient pagan wisdom was the fact that the human beings obtained it in such a way (you know that they obtained it from the Mysteries of the Initiates) that this wisdom contained both a knowledge of Nature, and an ethical knowledge. This extraordinarily significant truth in the history of human evolution, this truth which I have just explained to you, is ignored to-day only because people cannot go back to the truly characteristic times of the ancient pagan wisdom. A historical knowledge does not reach back so far as to enable us to grasp the times when the human beings who looked up to the stars really received from the stars, on the one hand, a wisdom explaining to them in their own way the course of the stars, but on the other hand, it also told them how they were to behave and act here upon the earth. Metaphorically speaking, (yet it is not entirely metaphorical, but quite objective up to a certain degree), we might say, that the ancient Egyptians and the ancient Chaldean civilisations were, for instance, of such a kind that men could read the laws of Nature in the course of the stars, but in the star's course they could also read the rules governing that which they were to do upon the earth.

The codices of the ancient Egyptian Pharaohs contain, for instance, rules concerning that which was to become law. It was so that for centuries ahead that which would later on become law was foretold prophetically. Everything contained in these codices was read from the course of the stars. In those ancient times there was no astronomy such as we have it now, merely containing mathematical laws of the movements of the stars or of the earth, but there was a knowledge of the cosmos which was at the same time moral knowledge, ethics.

The doubtful element of modern astrology, which does not go beyond the stage of dilettantism, is that people no longer feel that its contents can only be a complete whole if the laws discovered in it are at the same time moral laws for the human beings. This is something extraordinarily significant.

In the course of human evolution, the essence of that primeval science was lost. This lies at the foundation of the fact that certain Secret Schools—but the schools of an earnest character have really ceased to exist at the end of the 18th century—and even certain Secret Schools of the Occident, have again and again pointed back to this lost science, to the lost Word. As a rule, those who came later no longer knew what was meant by the expression “Word”. Nevertheless, this conceals a certain fact. In Saint-Martin's books we may still find an echo showing that up to the end of the 18th century it was very clearly felt that in ancient times men possessed a spiritual wisdom which they obtained simultaneously with their knowledge of Nature. Their spiritual wisdom also contained their moral and ethical wisdom; this had already disappeared in the eight centuries preceding the rise of Christianity. We may even say: Ancient Greek history is, essentially, the gradual loss of primeval wisdom.

If we study the philosophers before Socrates, namely Heraclitus, Thales, Anaximenes, Anaxagoras, the philosophers of the tragic epoch, as Nietzsche called them—I have dealt with them in my book Riddles of Philosophy, and have tried to give as good as possible a picture, from an external standpoint—if we study these philosophers (but the external writings tell us very little about them), we shall find again and again that the passages which have remained like oases in a desert, re-echo a great, encompassing wisdom and knowledge which existed in the remote past of human evolution. The words of Heraclitus, of Thales, Anaxagoras and Anaximenes, appear to us as if humanity had, as it were, forgotten its primeval wisdom and only remembered occasionally some fragmentary passages. The few passages of Thales, Anaxagoras, of the seven Greek sages, etc., which have been handed down to us traditionally, appear to us like fragmentary recollections.

In Plato we still encounter a kind of clear consciousness of this primeval wisdom; in Aristotle everything has been transformed into human wisdom.

And among the Stoics and Epicureans this gradually disappears. The ancient primeval knowledge only remains like an old legend. This is how matters stood with the Greeks.

The Romans—and they were by Nature a prosaic, matter-of-fact nation—even denied that this primeval knowledge had any meaning at all, and they transformed everything into abstractions. The course which I have just described to you in regard to the primeval knowledge, was necessary for the evolution of humanity. Man would never have reached freedom in the course of his development, had the primeval wisdom, which came to him indirectly through atavistic clairvoyance, remained in its original intensity and significance. Nevertheless, this primeval knowledge was connected with everything which could reach man from divine heights in the form, I might say, of moral impulses. This had to be rescued. The moral impulse had to be rescued for man.

Among the many things which we have already explained in regard to the Mystery of Golgotha we have also explained that the divine principle which descended to the earth trough the man, Jesus of Nazareth, contained the moral power which was little by little dispersed and cleft through the waning and gradual dying out of the ancient primeval wisdom. It is indeed so—although this may seem paradoxical to a modern man—that we can say: Once upon a time there was an old primeval wisdom. Man's moral power and moral wisdom were connected with primeval knowledge; this was contained in it as an integrant. The ancient primeval wisdom then lost its power, it could no longer be the bearer of a moral impulse

This moral impulse had, as it were, to be taken under the wing of the Mystery of Golgotha. And for the civilisation of the Occident, the further continuation was the Christ Impulse which has arisen from the Mystery of Golgotha containing that which had remained as a kind of moral extract from the ancient primeval wisdom.

It is very strange to follow, for instance, that which Occidental civilisation contains in the form of true science, true wisdom, up to the 8th or 9th century after Christ. Try to read the description of Occidental wisdom up to the 8th and 9th century, as contained in my book, Riddles of Philosophy, and you will see that, after all, this course of development contains nothing of what may be designated as knowledge, in our modern meaning. For this arises towards the middle of the 15th century, at the time of Galilei. Until that time, knowledge has really been handed down traditionally from the primeval wisdom of the past. It is no longer a wisdom gained through inner intuition, no longer a primeval wisdom experienced inwardly, but an external wisdom handed down traditionally. I have often told you the story of Galilei, the story which is not an anecdote, namely, how Galilei had to make a great effort in order to convince a friend of the truth of his statements. Like all the other people of the Middle Ages who pursued wisdom, this friend was accustomed to accept what was contained in the books of Aristotle, or in the other traditional works. Everything which was taught at that time was traditional. That which was contained in the books of Aristotle was handed down traditionally. And the learned friend of Galilei agreed with Aristotle that the nerves go out from the heart. Galilei endeavoured to explain to him that according to the knowledge he had gained by studying a corpse, he was obliged to say something else: namely, that in the human being the nerves go out from the head, or the brain. This Aristotelian thinker could not believe it. Galilei then led him to the corpse, showed him that the nerves in fact go out from the brain and not from the heart, and felt sure that his friend would now have to believe what he saw with his own eyes. But his friend said: “Indeed, this appears to be true; I can see with my own eyes that the nerves proceed from the brain. But Aristotle says the opposite, namely that the nerves proceed from the heart. If I have to choose between the evidence of the senses in Nature and Aristotle's statements, I prefer to believe in Aristotle, and not in Nature!” This is not an anecdote, but a true occurrence. After all, in our time we simply experience the same thing, only the other way round.

You see, at that time all knowledge was traditional. A new knowledge only began with the time of Galilei, Copernicus, and so forth. But throughout these centuries the moral impulse was borne by the Christian impulse. It was essentially connected with the religious element. This was not the case in pagan times. The pagans realised that when they obtained cosmic wisdom, they obtained at the same time a moral impulse.

A new impulse arose towards the middle of the 15th century, an impulse which completely severed the connection with everything that existed in the form of ancient wisdom, even though this merely existed traditionally. It is very interesting to see the passion with which those who brought to the surface this new science—for instance, Giordano Bruno—abuse everything which existed in the form of old traditional wisdom. Bruno almost begins to rave when he rails against the recollections of ancient wisdom. Something entirely new arises. In fact, we shall be far from understanding human evolution if we are unable to look upon this new element which thus arises, as a beginning.

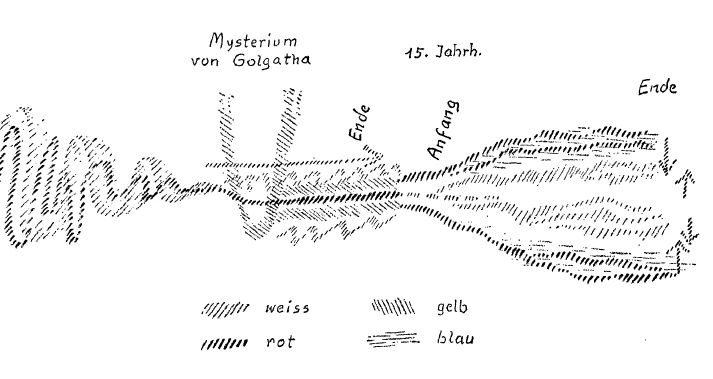

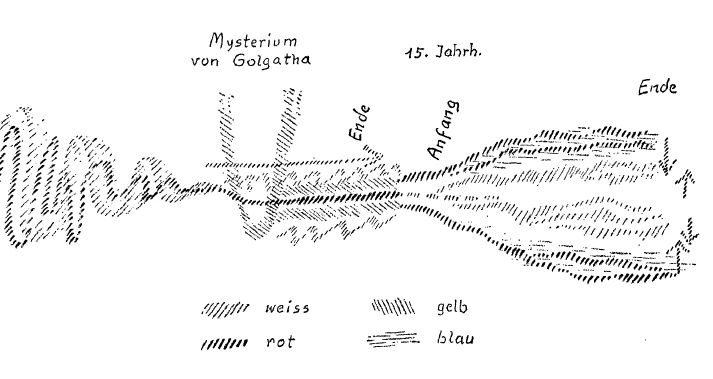

We may say (a drawing is made on the blackboard): If we indicate, here, the Mystery of Golgotha ... the moral impulse will continue from there, but what was that which the Mystery of Golgotha carried from an older into a more recent time? What was it, in reality, while it was being borne in that direction? It was an end. The more we progress, the more the ancient wisdom disappears, even in its traditional form. We may say that it continues to drip like water, in the form of traditional knowledge; but a new element, a beginning, arises with the 15th century.

Indeed, we have not advanced very far in this new direction. The few centuries which have elapsed since the middle of the 15th century have brought us some natural science, but we have not progressed far since that beginning.

What is this new wisdom? You see, it is a wisdom which, to begin with, in the form in which it has appeared, has this peculiarity: Contrary to the ancient pagan wisdom, it does not contain a moral impulse. You may study as much as possible of this new wisdom, of this Galilei wisdom—mineralogy, geology, physics, chemistry, biology, etc. etc.,—but you will never be able to draw a moral impulse out of this knowledge of Nature.

If modern people think that they can establish sociology upon the foundation of natural sciences, this is a tremendous illusion. For it is impossible to squeeze out of natural science, such as it exists to-day, that kind of knowledge which can be an ideal for human actions. For natural science is altogether in an elementary stage, and we can only hope that by developing more and more, it will again come to the point of containing, as natural science, moral impulses.

If the knowledge of Nature were to continue only in accordance with its own form, it would not be able to produce moral impulses out of its own nature. A new super-sensible knowledge will have to develop by the side of this knowledge of Nature. This super-sensible knowledge will then contain once more the rays of a moral will. And when the beginning which was made towards the middle of the 15th century will have reached its end at the conclusion of the evolution of the earth, then super-sensible knowledge will flow together with the knowledge of the senses, and a unity will arise out of this.

When the old pagan sage, or the follower of pagan wisdom received pagan wisdom from his initiate in the Mysteries, he received at one and the same time a knowledge of Nature, a cosmic knowledge, an anthropogenesis and a moral science, and this was simultaneously a moral impulse. All this was one.

To-day it is necessary to admit that we obtain on the one hand, a knowledge of Nature, and on the other hand, super-sensible knowledge. This knowledge of Nature is, as such, devoid of moral impulses. Moral impulses must be gained through a super-sensible knowledge. Since the social impulses must, after all, be moral impulses, no true social knowledge, and not even a sum of social impulses can be imagined, unless man rises to super-sensible knowledge.

It is important that modern man should realise that he must strike out a new course in regard to social science; he must tread a different path than that of natural science. But I am at the same time obliged to draw your attention to a strange paradox:—I have often explained to you here that the deepest truths of the science of initiation appear strange to the ordinary every-day consciousness, may even appear crazy to an extreme materialist, but in our time it is necessary to grow acquainted with this wisdom which appears so paradoxical to-day. For in our time many things which appear foolish to men are wisdom before God. It would be a good thing if this bible passage were to be considered a little by those who brush aside Anthroposophy with a supercilious smile, or who criticize it in a vile way. They should consider that what they look upon as foolishness may be “wisdom before the Gods”. It would be a very good thing if several people—and by “several” I mean many—particularly those who go to church with their prayer book and revile Anthroposophy, were to insist less upon their proud faith and look more closely into that which is really contained in the Christian faith. In our time it is necessary to become acquainted with several things which appear paradoxical. You see, two things are possible to-day. Someone may become acquainted with the natural science of to-day (I shall now characterize these two things rather sharply), he may, for instance, take up the facts supplied by the science of chemistry, physics, biology, etc. He may study diligently and eagerly the Theory of Evolution which has arisen from the so-called Darwinism. If he studies all this he may become a materialist, as far as his world conception based on knowledge is concerned. Indeed, he will become a materialist; this cannot be denied. Since men, as it were, so quickly arrive at an opinion, they become materialists if they give themselves up wholly to the external knowledge of Nature, according to the intentions of some of their contemporaries. But it is also possible to do something else. In addition to that which physics, chemistry, mineralogy, botany, geology, biology, offer, in addition to that which these sciences teach, we may also direct our attention to what we do in the physical laboratory, to our behaviour during an experiment; we may watch carefully how we behave in the chemical laboratory and what we do there; we may watch the way in which we investigate plants, animals, and their evolution.

Goethe's knowledge of Nature is chiefly based upon the fact that he has deeply studied the way in which others have come to their knowledge. The greatness of Goethe depends upon this very fact, namely, that he has deeply occupied himself with the way in which others have attained to their knowledge. And it is very, very significant to penetrate really into the essence and spirit of an essay by Goethe, such as “The Experiment as Mediator between Object and Subject”. Here we may see how Goethe carefully follows the way in which phenomena of Nature are handled. What we may call the method of investigation, this is something which he has studied with the greatest attention. If you read my Introduction to Goethe's Natural-Scientific Writings you will find what great results Goethe has reached by thus pursuing the natural-scientific method.

In a certain way, that which Goethe has done can be developed further for the achievements of the 19th century and up to the 20th century ... but Goethe was no longer able to do this.

I therefore state: Two things are possible. Let us keep to this, to begin with. We remain by the results which natural science supplies, or else we investigate the attitude needed in order to arrive at these natural scientific results. Let us keep to what we have said in regard to the knowledge of Nature; let us now observe the human striving after knowledge from another standpoint.

You know that beside natural science there is also a spiritual knowledge; in the form of Anthroposophy, the knowledge of man, we may pursue cosmology, anthropology, etc., in such a way that they lead to the kind of results described, for instance, in my Occult Science. There, we may find positive knowledge pointing to the spiritual world. Just as we obtain positive knowledge in natural science, in mineralogy, geology, etc., so we have, here, a positive knowledge referring to the spiritual world. In our anthroposophical movement it was particularly important for me to spread also this kind of positive knowledge concerning the spiritual world in the various books which I have written. Now we may also tackle things in such a way that we observe chiefly the way in which these things are done, and do not merely aim at obtaining knowledge. We observe how a person describes something, how he rises from external observation to inner observation; how he arrives to a higher spiritual conception, not through scientific investigations in the laboratory, in the clinic, in the astronomical observatory, but through his inner soul-development, along a mystical path. This would be parallel to the observation of the natural-scientific method, of the handling, of the way in which things are done. Also here we have this twofold element: to watch the results, and to watch the way in which our soul comes to these results.

Let us take hypothetically something which may seem rather paradoxical. Let us suppose that someone were to pursue the natural-scientific methods, like Goethe: he will certainly not become a materialist, but will undoubtedly accept a spiritual world-conception. An infallible way of overcoming materialism in our modern time is to have an insight into the natural-scientific methods of investigation. In the natural-scientific sphere, men become materialists only because they do not observe, because they insufficiently observe the way in which they carry on their investigations. They are satisfied with results, with what the clinic, the laboratory, the observatory supply. They do not progress as far as Goetheanism, i.e. the observation of their manner of research; for those who allow themselves to be influenced by the natural-scientific manner of contemplating the world and of handling things in order to reach knowledge, will at least become idealists, and probably spiritualists, if they only proceed far enough.

If we now try to avoid reaching the positive results of spiritual science, if we find it boring to enter into the details of spiritual science, and only like to hear again and again how man's soul becomes mystical, if we concentrate our chief attention upon the methods leading to the spiritual sphere, this will be the greatest temptation for really becoming materialists. The greatest temptation for becoming materialists is to ignore the concrete results of spiritual science and to emphasize continually the importance of mystical research, mystical soul-concentration, and the methods of entering the spiritual world.

You see this is a paradox. Those who observe natural science, natural research, become spiritualists; those who disdain to reach a real spiritual knowledge and who always speak of mysticism and of how spiritual knowledge is gained, are exposed to the great temptation of becoming more than ever materialistic. This should be known to-day. We cannot do without the knowledge of such things.

To-day we have monistic societies. Those who give themselves the air of leaders in these monistic societies spread a very superficial world-conception. They condense the external materialistic results of natural science to a superficial world-conception. This is so easy for modern men who do not wish to make a great effort, who prefer to go to the “movies” rather than to other places, and consequently prefer to accept a kind of cinema-science—for materialism is nothing else—they prefer this to something which must be worked out inwardly. These leaders of monistic societies therefore supply a superficial materialism. Undoubtedly they are, at least for a time, temporarily noxious creatures, for they spread errors. It is not good if they flourish, for of course they turn the heads of people in a materialistic way. Nevertheless they are the less dangerous elements, for to begin with they are generally honest people, but this honesty does not protect them against this spreading of errors; however, they are for the most part frankly honest and their errors will be overcome. They will only have a temporary significance.

But there are other people who systematically, knowingly, refuse to lead man towards the concrete positive results of spiritual-science. Indeed, they nourish the aversion which exists to-day through a certain love of ease, the aversion of penetrating into the positive concrete results of spiritual science. You know that the things described in my Occult Science must be studied several years if we wish to understand them, they are not comfortable for a modern man, who may indeed send his son to the university, if he is to become a chemical scientist; nevertheless, if he is to recognize and grasp heaven and earth in a spiritual way, he expects him to do this in a twinkle, at least in one evening, and from every lecture on the super-sensible worlds he expects to have the whole sum of cosmic wisdom. Concrete results of a positive spiritual research are uncomfortable for most men, and this aversion is made use of by certain personalities of the present time who persuade men that they do not need these things, that it is not necessary to pursue the positive concrete details of spiritual facts. “What is this talk of the higher hierarchies which must first be known? What is this talk of Saturn, Sun, Moon, Earth, Jupiter, Venus, Vulcan etc.? All this is unnecessary.” They will tell you: “If you concentrate deeply, if your soul becomes quite mystical, you shall reach the God within you”. They will tell you these things, give general indications on the connection of the material and the super-sensible world. They nourish man's aversion to penetrate into the concrete spiritual world. Why do they do this? Because apparently, apparently they wish to spread a spiritual mentality, but in reality they aim at something else: Along this path, more than ever, they seek to produce materialism. For this reason the leaders of the monistic societies are less harmful. But the others who so often spread mysticism to-day, and who always speak of all kinds of mystical things, they are those who truly foster materialism, who foster it in a most refined way. They put into the heads of men that one or the other way leads into the spiritual world, and they avoid speaking about it concretely. They chiefly speak in general phrases and if they remain victorious they will undoubtedly succeed in making the third generation entirely materialistic. To-day, the more certain and also more refined way leading into materialism is to transmit mysticism traditionally, a mysticism which despises to penetrate into positive spiritual-scientific results. Many things which appear to form part of the spiritual literature of to-day foster materialism far more strongly than, for instance, the books of Ernst Haeckel.

You see, these things are uncomfortable to hear, because in setting them before men we strongly appeal to their power of discernment, but men do not wish to listen to this appeal to their power of discernment. They are much more satisfied if every kind of mystical nonsense stimulates an inner lust of the soul. This is why there are so many opponents, particularly of those efforts which to-day honestly pursue spiritual life by disdaining to approach men with a shallow mysticism of a general nature. True spiritual science arouses opposition. In the present time there are numerous people and communities who do not in any way wish that a true spiritual regeneration and elevation should take hold of humanity, and who make use of the fact that materialism is undoubtedly fostered if they speak to men of mysticism in general terms. They make use of this fact. For this reason they wage war to the knife where they encounter honest paths which are meant to lead into spiritual science.

I have thus characterized an extensive literature which exists to-day. In reality everyone who takes up a mystical book, no matter of what kind, should appeal strongly to his own judgment. This is strictly necessary. For this reason we should not be led astray by the fact that the many pseudo-mystical scribbles of our present time seem to be so easily accessible. Of course, people will easily understand us if we tell them, for instance: “You only need to penetrate deeply into your inner being and God will be within you; your God whom you only find by treading your own path; no one can show you this path because every other man speaks of another God”, or similar stuff. To-day you will find this in many books, and it is described in a most tempting and misleading manner.

I would like you to take to heart these things very deeply. For that which is to be reached through our anthroposophical movement can only be reached through the fact that you are at least a small number of people who strive to cultivate the characterized power of discernment; it would be fatal for humanity if no effort were made to develop this power of discernment. To-day we must try to stand firmly on our feet, if we do not wish to lose our foothold in the midst of the confusion and chaos of the present. We may often ask to-day after the cause of so much confusion in humanity. But we can almost touch these causes. We may find them in insignificant facts, but we must be able to judge these little facts on the right way.

It is uncomfortable to see this immediately, in the many forms in which it exists on all sides. Many grotesque paradoxes can be found not only in rather loathsome places, but also in the modern life of humanity. They undoubtedly exist also in the modern life of humanity. And it is necessary to-day to strive to obtain a clear understanding, an understanding as sharp as a blade, if we wish to gain a firm foothold. This is the essential thing.

Siebenter Vortrag

Ich möchte Ihnen heute von einigen grundlegenden Erkenntnissen der Initiationswissenschaft sprechen, die uns dann eine Art Unterlage bieten sollen für das, was wir morgen und übermorgen betrachten wollen. Wir werden heute zunächst hinweisen auf etwas, was im Bewußtsein eines jeden Menschen liegt, was nur gewöhnlich nicht klar genug erfaßt wird. Wir reden, indem wir solche Dinge besprechen, immer vom Gesichtspunkt unserer Gegenwart, in dem Stil und Sinn, wie ich das ja öfter hier auseinandergesetzt habe: daß auch Erkenntnisse durchaus nicht gelten für immer und überall, sondern für eine bestimmte Zeit, ja sogar für eine bestimmte Räumlichkeit der Erde. So gelten gewisse Erkenntnis-Gesichtspunkte zum Beispiel für die europäische Zivilisation; andere Gesichtspunkte gelten für, sagen wir, die Erkenntnisse des Orients. Nun weiß wohl jeder Mensch, daß wir uns mit unserer Erkenntnis gewissermaßen zwischen zwei Polen befinden. Es fühlt jeder Mensch, wie auf der einen Seite diejenigen Erkenntnisse stehen, die wir gewinnen durch Sinnesanschauung. Der einfache, naive Mensch lernt durch seine Sinne die Welt kennen, kommt auch bis zu einem gewissen zusammenfassenden Punkt dessen, was er sieht, was er hört, was er überhaupt durch seine Sinne wahrnimmt. Und im Grunde genommen ist dasjenige, was die Wissenschaft bietet, so wie wit diese Wissenschaft jetzt im Abendlande haben, ja auch nichts anderes als eine Zusammenfassung dessen, was sinnlich den Menschen sich darbietet.

Nun fühlt wohl ein jeder, daß es andere Erkenntnisse gibt, daß man unmöglich ein Vollmensch sein kann im gewöhnlichen Sinne des Wortes für die alltägliche Welt, wenn man nicht eine andere Art von Erkenntnissen zu dieser eben charakterisierten hinzufügt. Und das ist die Art von Erkenntnissen, die es mit unserem moralischen Leben zu tun hat. Wir reden nicht nur von den Ideen der Naturerkenntnis, durch die wir uns das eine oder andere in der Natur erklären; wir reden von sittlichen Ideen, von sittlichen Idealen, die wir als Antriebe unseres Handelns empfinden, von denen wir uns beherrschen lassen, wenn wir selbst in unserer gewöhnlichen Welt auftreten wollen. Und es fühlt wohl auch jeder Mensch, daß wir mit dem einen Pol unseres erkennenden Lebens, der Sinneserkenntnis und ihrem Anhang, der Verstandeserkenntnis — denn die Verstandeserkenntnis ist nur ein Anhang der Sinneserkenntnis -, gewöhnlich nicht heraufreichen können bis zu den sittlichen Ideen. Die sittlichen Ideen sind da; aber wir können nicht, indem wir zum Beispiel Naturwissenschaft treiben, aus der Betrachtung der Pflanzenwelt, aus der Betrachtung der mineralischen Welt oder sonst irgendwie mit unserer gegenwärtigen Naturwissenschaft sittliche Ideen finden. Darin besteht ja gerade das Tragische unserer Zeit, daß man zum Beispiel auf sozialem Gebiete Ideen für das Handeln finden will nach naturwissenschaftlicher Methode. Niemals wird man das können, wenn man wirklich sich dem gesunden Menschenverstand hingibt. Wie auf einer anderen Seite des Lebens sind die sittlichen Ideen da. Wirklich steht unser Leben unter dem Einfluß dieser zwei Strömungen: des Naturerkennens auf der einen Seite, des sittlichen Erkennens auf der anderen Seite.

Sie wissen aus meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit», daß in der Erfassung der moralischen Intuitionen uns die höchsten sittlichen Ideen, die wir als Menschen brauchen, gegeben sind, und daß diese sittlichen Ideen, wenn wir in ihren Besitz kommen, unsere menschliche Freiheit begründen. Auf der anderen Seite wissen Sie vielleicht auch, daß sich für gewisse Denker immer eine Art von Kluft gezeigt hat zwischen dem, was Naturerkenntnis auf der einen Seite ist, was sittliche Erkenntnis auf der anderen Seite ist. Die Kantsche Philosophie beruht ja auf dieser Kluft, auf diesem Abgrunde, den sie nicht ganz überbrücken kann. Daher gibt es von Kant eine «Kritik» der theoretischen Vernunft, der «reinen Vernunft», wie er sagt, worin er sich nur mit der Naturerkenntnis auseinandersetzt, worin er alles dasjenige sagt, was er zu sagen hat über die Naturerkenntnis. Und auf der anderen Seite gibt es von ihm eine «Kritik der praktischen Vernunft», in welcher er spricht von den sittlichen Ideen. Man möchte sagen: Für ihn entspringt das gesamte menschliche Leben aus zwei voneinander ganz getrennten Wurzeln, die er in seinen zwei Haupt-«Kritiken» beschreibt.

Nun würde es natürlich mißlich um den Menschen stehen, wenn es keine Verbindungsbrücke gäbe zwischen diesen zwei Polen unseres Seelenlebens. Und derjenige, der sich ernstlich mit Geisteswissenschaft beschäftigt auf der einen Seite und andererseits es ernst nimmt mit den Aufgaben gerade unserer Zeit, der muß intensiv fragen: Wo ist die Brücke zwischen den sittlichen Ideen und den Naturideen?

Wir werden heute zur Erkenntnis dieser Brücke den Standpunkt wählen, den ich als den historischen bezeichnen möchte. Sie wissen ja aus den verschiedenen Betrachtungen, die wir hier angestellt haben, daß die Seelenverfassung der Menschen in älterer Zeit eine wesentlich andere war, als sie in späterer Zeit geworden ist. Die Entstehung des Christentums bildet wirklich einen tiefen Einschnitt in die ganze Entwickelung der Menschheit. Und nur wenn man versteht, was eigentlich mit dem Entstehen des Christentums sich herausgebildet hat in der Entwickelung der Menschheit, kommt man mit dem Verstehen des Menschen überhaupt zurecht.

Dasjenige, was zeitlich zurückliegt hinter der Entstehung des Christentums, ist, wenn wir von dem Judentum absehen — wir haben es vor kurzem hier erst wiederum erwähnt -, der ganze Umfang der heidnischen Kultur. Das Judentum war ja nur eine Vorbereitung für das Christentum. Dieser ganze Umfang der heidnischen Kultur unterscheidet sich ganz wesenhaft von unserer gegenwärtigen christlichen Kultur. Diese heidnische Kultur war, je weiter wir zurückgehen, eine einheitliche Kultur. Sie war eine Kultur, die vorzugsweise begründet war auf menschliche Weisheit. Ich weiß, dem Menschen der Gegenwart ist es beleidigend, wenn man ihm davon spricht, daß mit Bezug auf die Weisheit die alten Zeiten weiter waren als dieser Mensch der Gegenwart; aber es war so. Es gab über die Erde hin in der alten heidnischen Zeit eine Weisheit, die näher, viel näher war den Urgründen der Dinge als unser heutiges Wissen, namentlich als unsere heutige Naturwissenschaft. Und dieses alte, dieses uralte Wissen, es war ein sehr konkretes Wissen, es war ein Wissen, welches intensiv verbunden war mit der geistigen Wirklichkeit der Dinge. Der Mensch bekam etwas herein in seine Seele, indem er wußte von der Wirklichkeit der Dinge. Aber das besonders Eigentümliche war bei dieser alten heidnischen Weisheit, daß die Menschen, die sie empfingen — Sie wissen, die Menschen empfingen sie aus den Mysterien von den Initiierten -, sie so empfingen, daß in dieser Weisheit zu gleicher Zeit enthalten war Naturerkenntnis und Moralerkenntnis. Man verkennt heute diese für die Entwickelungsgeschichte der Menschheit außerordentlich bedeutungsvolle Wahrheit, die ich eben ausgesprochen habe, nur deswegen, weil man in der äußeren Geschichte nicht zurückgehen kann bis zu den eigentlich charakteristischen Zeiten der alten heidnischen Weisheit. Das historische Wissen reicht nicht so weit zurück, daß man mit ihm die Zeiten erfassen könnte, in denen die Menschen, indem sie zu den Sternen hinaufgeschaut haben, aus den Sternen empfingen diejenige Weisheit, die ihnen in ihrer Art auf der einen Seite erklärte den Sternenlauf, auf der anderen Seite aber auch sagte, wie sich die Menschen verhalten sollen in ihrem Handeln hier auf Erden. Etwas bildlich, aber im Grunde nicht ganz bildlich, sondern bis zu einem gewissen Grade doch gegenständlich gesprochen, könnte man sagen, daß noch die alte ägyptische, die alte chaldäische Kultur so waren, daß die Menschen Naturgesetze lasen im Sternenlaufe, aber auch lasen aus dem Sternenlauf die Vorschriften für dasjenige, was sie auf der Erde tun sollten. Die Kodizes der alten ägyptischen Pharaonen zum Beispiel enthalten Vorschriften über dasjenige, was Gesetz werden sollte. Es war so, daß über weite Jahrhunderte hin prophetisch vorausgesagt war, was in späterer Zeit Gesetz werden sollte. Aber das alles, was da in diesen Kodizes stand, war abgelesen von den Sternenläufen. Also es gab in jenen alten Zeiten nicht eine Astronomie, wie wir sie jetzt haben, die nur mathematische Gesetze der Sternenbewegung oder der Erdenbewegung enthält, sondern es gab eine Wissenschaft vom Kosmos, die zu gleicher Zeit Moralwissenschaft, Ethik war.

Das Bedenkliche der ja nunmehr bis zum Dilettantismus hinreichenden neueren Astrologie besteht darin, daß man in ihr nicht mehr fühlt, daß das, was in ihr gegeben ist, nur dann ein Ganzes ist, wenn mit den Gesetzen, die man in ihr verzeichnet, zugleich Moralgesetze für die Menschen gegeben sind. Das ist etwas sehr Bedeutsames, außerordentlich Bedeutsames. |

Nun war es im Menschheitsverlaufe so, daß jene Urwissenschaft der Menschen, jene Urweisheit der Menschen im wesentlichen verlorenging. Und es liegt ja das der Tatsache zugrunde, daß gewisse Geheimschulen, die aber in ihrer ernsten Form eigentlich schon aufgehört haben mit dem Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts, auch gewisse Geheimschulen des Abendlandes immer wieder und wiederum auf die verlorene Wissenschaft, das «verlorene Wort» zurückwiesen. Gewöhnlich wußten die Späteren gar nicht mehr, was sie unter dem Wort «Wort» dabei verstehen sollten. Aber es liegt dem eine gewisse Tatsache zugrunde. Und bei Saint-Martin kann man noch die Nachklänge davon lesen, wie man bis ins 18. Jahrhundert sehr genau gefühlt hat, daß in alten Zeiten die Menschen ein ihnen mit dem Naturwissen zugleich zukommendes Geisteswissen besessen haben, das auch ihre Moralwissenschaft enthielt und das verlorengegangen ist, verlorengegangen im Grunde schon in den acht Jahrhunderten, die der Entstehung des Christentums vorangegangen sind. Man kann sogar sagen: Die ältere griechische Geschichte ist im wesentlichen das allmähliche Verlieren der Urweisheit.

Wenn man die vorsokratischen Philosophen studiert, die Nietzsche die Philosophen des tragischen Zeitalters der Griechen genannt hat: Heraklit, Thales, Anaximenes, Anaxagoras — ich habe sie behandelt in meinen «Rätseln der Philosophie», so gut man sie für die Menschheit heute äußerlich behandeln kann, es ist ja nur wenig von ihnen in äußerer Schrift vorhanden -, dann findet man in diesen Sätzen, die da geblieben sind wie Oasen in einer Wüste, immer wieder, wie wenn nachklingen würde ein großes, umfassendes Wissen und Erkennen, das in der alten Menschheitszeit vorhanden war. Was Heraklit sagt, was Thales, Anaxagoras, Anaximenes sagen, das alles ist so, möchte man sagen, wie wenn die Menschheit vergessen hätte ihre Urweisheit und sich an einzelne fragmentarische Sätze da oder dort erinnert. Wie fragmentarische Erinnerungen kommen die paar Sätze heraus, die überliefert sind von Thales, Anaxagotas, von den sieben griechischen Weisen.

Und dann finden wir bei PJato noch eine Art deutlichen Bewußtseins von dieser Urweisheit, bei Aristoteles schon alles umgesetzt in äußere menschliche Weisheit. Bei den Stoikern und Epikureern verschwindet dann die Sache immer mehr und mehr. Es bleibt das alte Urwissen nur wie eine Sage zurück. So war es bei den Griechen.

Bei den Römern — die Römer waren ja von Naturanlage aus ein prosaisches, nüchternes Volk — war es gar so, daß sie jeden Sinn verleugneten für das Urwissen, daß sie alles in Abstraktionen umsetzten. Für die Entwickelung der Menschheit war es notwendig, daß der Gang ein solcher war, wie ich es Ihnen eben beschrieben habe mit Bezug auf die Urweisheit. Die Menschen hätten niemals zur Entwikkelung der Freiheit kommen können, wenn die Urweisheit, die ihnen ja auf dem Wege eines atavistischen Hellsehens zugekommen ist, in ihrer ursprünglichen Intensität und Bedeutung für den Menschen geblieben wäre. Aber mit dieser Urweisheit war doch verbunden alles, was an moralischen Impulsen, ich möchte sagen, von Götterhöhen herunter, den Menschen hat zukommen können. Das mußte gerettet werden. Es mußte den Menschen der moralische Impuls gerettet werden.

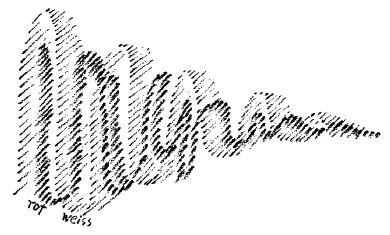

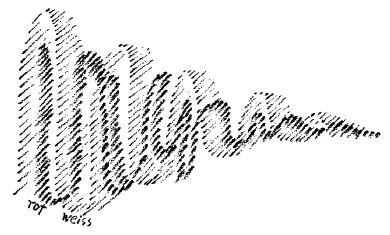

Und unter den mancherlei Dingen, die wir schon zu sagen hatten über das Mysterium von Golgatha, ist dieses, daß durch jenes göttliche Prinzip, das durch den Menschen Jesus von Nazareth auf die Erde hinuntergestiegen ist, getragen war die moralische Kraft, die allmählich natürlich auch zerstoben, zerklüftetr war mit dem Herabdämmern und allmählichen Ersterben der alten Urweisheit. Es ist wirklich so, wenn es auch dem heutigen Menschen paradox erscheint, daß man sagen kann: Es war eine alte Urweisheit vorhanden (siehe Zeichnung Seite 130, weiß). Mit dieser alten Urweisheit war verbunden die moralische Kraft, moralische Weisheit des Menschen. Die war als ein integrierender Bestandteil darin (rot). Nun ist die alte Urweisheit abgelähmt worden. Sie konnte nicht mehr der Träger sein des moralischen Impulses.

Dieser moralische Impuls mußte gewissermaßen in Schutz und Schirm genommen werden von dem Mysterium von Golgatha (siehe Zeichnung Seite 132, gelb), und seine weitere Fortpflanzung für die abendländische Zivilisation war dasjenige, was aus dem Mysterium von Golgatha entsprungen ist als Christus-Impuls, in den hineingetragen wurde dasjenige, was als moralischer Extrakt gewissermaßen von der alten Urweisheit geblieben ist.

Es ist sehr merkwürdig, wenn man verfolgt, sagen wir dasjenige, was in der abendländischen Zivilisation an eigentlicher Wissenschaft, an eigentlicher Weisheit lebt so bis in das 8., 9. nachchristliche Jahrhundert hinein. Lesen Sie einmal nach die Beschreibung des abendländischen Wissens in der Zeit bis in das 8., 9. nachchristliche Jahrhundert, wie ich es angedeutet habe in meinen «Rätseln der Philosophie». Sie werden sehen: es ist im Grunde genommen nichts da in dieser Entwickelung, was man in unserem heutigen Sinne als Wissen bezeichnen kann. Das kommt ja erst seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts herauf, seit der Galilei-Zeit. Was da vorhanden ist an Wissen, das ist eigentlich alles Überlieferung aus der alten Urweisheit, nicht mehr innerlich intuitierte Urweisheit, nicht mehr innerlich erlebte Urweisheit, aber äußerlich überlieferte Weisheit. Ich habe Ihnen ja oft jene Geschichte erzählt von Galei, die keine Anekdote ist, wie Galilei Mühe hatte, einen Freund zu überzeugen von der Wahrheit desjenigen, was er behauptete. Der Freund war gewöhnt, so wie die anderen Leute des Mittelalters, die sich der Pflege der Weisheit widmeten, zu nehmen, was in den Büchern des Aristoteles stand oder in den anderen überlieferten Büchern. Es war ja alles, was man so lernte in jener Zeit, Überlieferung. Man tradierte dasjenige, was in den Büchern des Aristoteles stand. Und dieser gelehrte Freund des Galilei sagte mit Aristoteles, daß die Nerven vom Herzen ausgehen. Galilei bemühte sich, ihm klarzumachen, daß er nach der Wissenschaft der Erfahrung an der Leiche etwas anderes sagen müsse: daß die Nerven vom Kopf, vom Gehirn ausgehen beim Menschen. Das glaubte der aristotelische Mann, dieser aristotelische Denker nicht. Da führte ihn Galilei an die Leiche, zeigte ihm die Tatsache, daß die Nerven vom Gehirn ausgehen und nicht vom Herzen und meinte, der müsse doch jetzt das glauben, was er mit seinen eigenen Augen sähe. Da sagte der Betreffende: Das scheint zwar so zu sein; der Augenschein lehrt, daß die Nerven vom Gehirn ausgehen, aber der Aristoteles sagt das Gegenteil. Wenn es sich für mich darum handelt, zu entscheiden zwischen dem Augenschein der Natur und dem, was Aristoteles sagt, dann glaube ich dem Aristoteles und nicht der Natur! - Es ist keine Anekdote, es ist eine wahre Begebenheit. Wir erleben im Grunde genommen das gleiche, nur umgekehrt auch in unserer Zeit.

Sehen Sie, es war alles Überlieferung, was an Wissen da war. Ein neues Wissen kam erst wiederum mit der Galilei-Zeit herauf, mit Kopernikus und so weiter. Aber es war durch den christlichen Impuls getragen der moralische Antrieb durch diese Jahrhunderte. Er war verbunden im wesentlichen mit dem religiösen Elemente. Das war nicht so in der heidnischen Kultur. In der heidnischen Kultur war eben der Mensch sich bewußt: Wenn er Weltenweisheit empfing, empfing er damit auch den moralischen Antrieb.

Nun kam mit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts ein neuer Antrieb herauf, welcher nun gründlich brach mit alledem, was alte Weisheit war, wenn sie auch jetzt nur noch durch Überlieferung vorhanden war. Es ist außerordentlich interessant zu sehen, mit welcher Rage diejenigen, die das neue Wissen herauftrugen, zum Beispiel Giordano Bruno, man darf schon sagen: schimpfen auf alles dasjenige, was alte Weisheitsüberlieferung war. Auch Bruno ist ja geradezu rasend, wenn er ins Schimpfen kommt über die alte Weisheitserinnerung. Es kommt eben etwas ganz Neues herauf. Und man geht wirklich weit weg von dem, was Verständnis der Menschheitsentwickelung ist, wenn man dieses Neue, das da heraufkommt, nicht anzusehen vermag als einen Anfang.

Sehen Sie, wir können sagen, wenn wir hier andeuten das Mysterium von Golgatha (siehe Zeichnung, gelb), daß sich der moralische Antrieb fortsetzt (rot). Was war es denn, was durch das Mysterium von Golgatha getragen wurde aus einer älteren Zeit in eine neuere Zeit, indem es in dieser Richtung (Pfeil nach rechts) getragen wurde? Es war ein Ende. Und je mehr wir immer weiter und weiter heraufkommen, desto mehr verschwindet die alte Weisheit, selbst in ihrer Überlieferung. Wir können sagen: sie perlt noch fort wie in Wellen als Überlieferung (weiß); aber mit dem 15. Jahrhundert kommt das Neue herauf, ein Anfang.

Wir sind wahrhaftig in diesem Anfang noch nicht sehr weit drinnen. Die paar Jahrhunderte, die wir verlebt haben seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts, haben uns einige Naturwissenschaft gebracht; aber wir sind doch in diesem Anfange nicht sehr weit drinnen.

Doch, was ist das für eine Weisheit? Ja, sehen Sie, das ist eine Weisheit, die zunächst so, wie sie aufgetreten ist, gerade das Eigentümliche hat, daß sie entgegengesetzt der alten heidnischen Weisheit gar keinen moralischen Impuls in sich enthält. Wir können noch so viel im Sinne dieser neuen Weisheit, dieser Galilei-Weisheit Mineralogie, Geologie, Physik, Chemie, Biologie und so weiter studieren, wir werden niemals heraussaugen aus unserer Naturerkenntnis irgendeinen moralischen Antrieb.

Wenn die Leute heute glauben, Sozialwissenschaft auf Grundlage der Naturwissenschaft begründen zu können, so ist das eben eine gewaltige Illusion. Denn niemals läßt sich herauspressen aus dem Naturwissen dasjenige Wissen, das Ideal sein könnte für das menschliche Handeln so, wie wir dieses Naturwissen heute haben. Dieses Naturwissen steht eben durchaus im Anfange, und wir können nur hoffen, daß dieses Naturwissen, indem es sich immer weiter und weiter entwickelt, soweit kommt, daß es auch wiederum als solches moralische Impulse in sich enthalten kann. Aber wenn es sich in seiner Art nur weiterentwickeln würde, so würde es durch seine eigene Art nicht moralische Impulse aus sich hervortreiben können. Dazu ist notwendig, daß sich neben diesem Naturwissen nunmehr entwickelt ein neues übersinnliches Wissen (blau). Dann wird dieses übersinnliche Wissen auch wiederum die Strahlen moralischen Wollens in sich enthalten können (rot). Und wenn der Anfang, der mit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts gemacht ist, am Erdenende selbst an seinem Ende sein wird, dann wird zusammenfließen können dasjenige, was übersinnliches Wissen ist, mit dem sinnlichen Wissen (weiß), und es wird aus diesem eine Einheit entstehen können (Pfeile).

Sie sehen, wenn der alte heidnische Weise oder auch der Bekenner der alten heidnischen Weisheit von seinen Mysterien-Initiierten die heidnische Weisheit empfangen hat, so hat er in einem empfangen von diesen Initiierten: Naturwissen, kosmisches Wissen, Anthropogenesis und Moralwissenschaft, die ihm zu gleicher Zeit moralischer Antrieb war. Es war eins.

Heute ist notwendig, daß der Mensch sich zu dem Bekenntnis aufschwingt: Er bekommt auf der einen Seite das Naturwissen, auf der anderen Seite das übersinnliche Wissen. Das Naturwissen für sich wird bar sein der moralischen Antriebe. Die moralischen Antriebe werden durch ein übersinnliches Wissen gewonnen werden müssen. Und da schließlich auch die sozialen Antriebe letzten Endes moralische Antriebe sein müssen, so ist eine wirkliche Sozialerkenntnis, ja nicht einmal eine Summe von Sozialimpulsen denkbar, ohne daß sich die Menschen zu übersinnlicher Erkenntnis erheben.

Das ist wichtig für den gegenwärtigen Menschen, einzusehen, daß er einen anderen Weg einschlagen muß für das soziale Wissen, als ihm die Methode des Naturwissens geben kann. Aber indem ich dieses ausspreche, liegt zugleich die Notwendigkeit nahe, Sie auf ein merkwürdiges Paradoxon aufmerksam zu machen. Ich habe ja öfter gerade an diesem Orte hier es ausgesprochen, daß die tiefsten Wahrheiten der Initiationswissenschaft dem gewöhnlichen Alltagsbewußtsein paradox erscheinen, sonderbar erscheinen, dem groben Materialisten sogar hirnverbrannt erscheinen. Aber es ist notwendig in unserer Zeit, daß man sich bekanntmacht mit diesen vielfach heute paradox erscheinenden Weistümern. Denn auch für unsere Zeit gilt es, daß manches, was den Menschen als Torheit erscheint, Weisheit ist vor Gott. Es könnte nichts schaden, wenn dieses Bibelwort ein wenig berücksichtigt würde von denjenigen, die heute Anthroposophie entweder lächelnd in Hochmut aburteilen oder wüst kritisieren. Denn sie könnten bedenken, daß vielleicht dasjenige, was sie für Torheit anschauen, Weisheit sein könnte vor den Göttern. Es würde einigen Menschen - und das «einige» sind hier sehr viele — eigentlich recht gut tun, namentlich auch manchen, die mit ihrem Gebetbuch in die Kirche gehen und über Anthroposophie wettern, weniger auf ihr Hochmutsbekenntnis zu pochen, als mehr hineinzuschauen in dasjenige, was das Bekenntnis des Christentums wirklich enthält. In unserer Zeit ist es eben notwendig, sich mit einigem paradox Erscheinendem bekanntzumachen.

Es ist zum Beispiel zweierlei heute möglich. Es kann einer sich heute bekanntmachen mit der Naturwissenschaft unserer Zeit, ich will heute etwas schroff diese zwei Dinge hinstellen, die ich jetzt zu charakterisieren habe. Er kann zum Beispiel in sich aufnehmen, was heute die Wissenschaft der Chemie, der Physik bietet, was die Wissenschaft der Biologie bietet. Er kann fleißig und emsig studieren, was sich aus dem sogenannten Darwinismus heraus ergeben hat als Entwickelungsgeschichte. Er wird, indem er das alles studiert, Materialist werden können in bezug auf seine Erkenntnisanschauung. Er wird materialistisch werden können, gewiß, das ist nicht zu leugnen. Und weil die Menschen heute, ich möchte sagen, so schnell fertig sind mit dem Urteil, so werden sie eben materialistisch, wenn sie ganz aufgehen nach den Intentionen mancher ihrer Zeitgenossen in dem äußeren Naturwissen. Aber man kann auch noch etwas anderes tun. Man kann seine Aufmerksamkeit außer auf das, was Physik, Chemie, Mineralogie, Botanik, Zoologie, Biologie bieten, was diese Wissenschaften lehren, hinlenken auf das, was man im physikalischen Kabinett, im Experimentieren macht. Man kann achtgeben darauf, wie man sich im chemischen Laboratorium verhält, was man da tut; man kann achtgeben darauf, wie man Pflanzen untersucht, Tiere untersucht in ihrer Entwickelung.

Goethes Naturwissen beruht namentlich darauf, daß er sich viel damit beschäftigt hat, wie die anderen zu ihrem Wissen gekommen sind. Darauf beruht gerade die Größe Goethes, daß er sich viel mit der Art, wie die anderen zu ihrem Wissen kommen, beschäftigt hat. Und es ist sehr, sehr bedeutsam, einmal den wirklichen Geist einer solchen Abhandlung Goethes wie die vom «Versuch als Vermittler zwischen Objekt und Subjekt» wirklich zu studieren. Da sieht man, wie Goethe das Hantieren mit den Naturerscheinungen aufmerksam verfolgt hat. Was man Methode des Forschens nennen kann, das hat er aufmerksam, recht aufmerksam verfolgt. Wenn Sie nachlesen in meinen «Einleitungen zu Goethes Naturwissenschaftlichen Schriften», so werden Sie sehen, zu welch großartigen Resultaten Goethe durch dieses Verfolgen der naturwissenschaftlichen Methode gekommen ist. Man kann in einer gewissen Beziehung das, was Goethe getan hat, dann weiter fortsetzen für die Errungenschaften der Naturwissenschaft im 19. Jahrhundert und bis ins 20. Jahrhundert hinein, was Goethe ja nicht mehr tun konnte.

Also ich sage: zweierlei ist möglich. Halten wir das zunächst fest. Man bleibt stehen bei dem, was die Naturwissenschaften an Resultaten geben, oder aber man beschäftigt sich damit, nachzusehen, wie man sich verhält, um zu diesen naturwissenschaftlichen Resultaten zu kommen. Halten wir das fest, was wir so in bezug auf das Naturerkennen gesagt haben. Betrachten wir jetzt das menschliche Erkenntnisstreben von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte aus. Sie wissen, daß es außer der Naturwissenschaft noch ein geistiges Wissen gibt, daß man zum Beispiel Kosmologie, Anthropologie als Anthroposophie, Erkenntnis vom Menschen so betreiben kann, daß es zu Ergebnissen führt, wie ich sie verzeichnet habe, sagen wir in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß». Da hat man positive Erkenntnisse, die auf die geistige Welt hindeuten. So wie man in der Naturwissenschaft in Mineralogie, Geologie und so weiter positive Erkenntnisse erhält, so haben wir da positive Erkenntnisse, die sich auf die geistige Welt beziehen. Es war mir ganz besonders wichtig im Laufe unserer anthroposophischen Bewegung, in den verschiedenen von mir geschriebenen Büchern auch solche positiven Erkenntnisse der geistigen Welt zu verbreiten. Nun kann man es aber auch so machen, daß man auch da hauptsächlich darauf sieht, nicht zu diesen Erkenntnissen bloß zu kommen, sondern darauf zu sehen, auf welche Art der Mensch sie macht; in welcher Weise es der Mensch schildert, wie der Mensch von der äußeren Beobachtung zu der inneren Beobachtung kommt, wie er nicht nur naturforscherisch im Laboratorium, im physikalischen Kabinett, in der Klinik, auf der Sternwarte, sondern wie er durch seine innere Seelenentwickelung auf mystischem Wege zu höherer geistiger Anschauung kommt. Das würde parallel sein dem Hinschauen auf die naturwissenschaftliche Methode, auf das Hantieren, auf die Art, wie man es macht. Also auch da gibt es dieses Zwiefache: das Hinschauen auf die Ergebnisse und das Hinschauen auf die Art, wie man seelisch zu diesen Ergebnissen kommt.

Nun nehmen wir einmal etwas, was schon durch seine Annahme etwas paradox wirkt, hypothetisch an. Nehmen wir einmal an, jemand würde sich in der Naturwissenschaft hauptsächlich wie Goethe beschäftigen mit der Verfolgung der naturwissenschaftlichen Methoden — der wird sicher nicht Materialist, der wird sicher zu einer spirituellen Weltanschauung sich bekennen. In der neueren Zeit ist es ein sicherer Weg, den Materialismus zu überwinden, die Art des Forschens in der Naturwissenschaft zu durchschauen. Und Materialisten auf naturwissenschaftlichem Gebiete werden die Menschen eben nur deshalb, weil sie sich entweder gar nicht oder zu wenig befassen mit der Art ihres Forschens. Sie bleiben bei den Ergebnissen stehen, bei dem, was die Klinik, das Kabinett, die Sternwarte bringt. Sie gehen nicht über zum Goetheanismus, zu der Betrachtung der Art des Forschens; denn wer die naturwissenschaftliche Art, die Welt anzuschauen, zu operieren mit den Dingen, um zu Erkenntnissen zu kommen, auf sich wirken läßt, der wird zum mindesten Idealist, aber wahrscheinlich Spiritualist, wenn er nur weit genug vordringt.

Wenn man nun versucht, es zu vermeiden, zu positiven Ergebnissen der Geisteswissenschaft zu kommen, wenn man langweilig findet, sich mit den Einzelheiten der Geisteswissenschaft abzugeben, und nur immer und immer beschrieben haben will, wie die Seele des Menschen mystisch wird, wenn man also da auf die Methoden, zum Geistigen zu kommen, sein Hauptaugenmerk richtet, so ist das in Wirklichkeit die größte Versuchung, materialistisch zu werden. Die größte Versuchung, materialistisch zu werden, ist, sich nicht befassen zu wollen mit den konkreten Ergebnissen der Geisteswissenschaft und nur immer und immer zu betonen das mystische Forschen, das mystische Seelenvertiefen, die Methode, in die geistige Welt hineinzukommen.

Sehen Sie, das ist eine paradoxe Sache. Wer das Naturwissen, das Naturforschen beobachtet, wird Spiritualist; wer verschmäht, zu wirklichen geistigen Erkenntnissen zu kommen und nur von Mystik redet, das heißt, wie man es macht, um zu geistigen Erkenntnissen zu kommen, der ist der großen Versuchung ausgesetzt, erst recht ein Materialist zu werden. Solche Dinge muß man heute wissen. Ohne das Wissen solcher Dinge kommt man nicht aus. Denn, schen Sie, heute gibt es Monistenbünde; da verbreiten die Menschen, die sich als Führer aufspielen in solchen Monistenbünden, eine oberflächliche Weltanschauung. Sie fassen zusammen die äußeren materialistischen Resultate der Naturwissenschaft zu einer oberflächlichen Weltanschauung. Die leuchten den Menschen der heutigen Zeit ein, die sich nicht viel anstrengen wollen, die lieber ins Kino gehen als zu irgend etwas anderem und daher lieber eine Art Kinowissenschaft — denn das ist ja der Materialismus — nehmen, als dasjenige, was innerlich erarbeitet werden muß. Diese Führer der Monistenbünde, die liefern also einen oberflächlichen Materialismus. Gewiß, sie sind Schädlinge, denn sie verbreiten Irrtümer. Es ist nicht gut, daß man sie hochkommen läßt, denn sie verdrehen den Leuten materialistisch die Köpfe. Aber sie sind die weniger Gefährlichen, denn sie sind zum großen Teil ehrlich. Diese Ehrlichkeit schützt sie zwar nicht davor, Irrtümer zu verbreiten, aber immerhin, sie sind meistens schlicht ehrlich, und ihre Irrtümer werden überwunden werden. Sie werden nur eine temporäre Bedeutung haben.

Aber es gibt andere Menschen, die lehnen es ab — systematisch, wissentlich —, zu den konkreten positiven Ergebnissen der Geisteswissenschaft die Menschen zu führen. Ja, sie schüren die heute bestehende, aus einer gewissen Bequemlichkeit heraus bestehende Abneigung der Menschen, sich einzulassen auf positive konkrete Ergebnisse der Geisteswissenschaft. Sie wissen, solche Dinge, wie sie in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft» stehen, die man ein paar Jahre lang studieren muß, wenn man sich hineinfinden will, die sind nicht bequem für den heutigen Menschen, der zwar seinen Sohn auf die Universität schickt oder auf die Hochschule, wenn dieser ein Chemiker werden soll, der aber voraussetzt, wenn er Himmel und Erde erkennen und geistig erobern soll, daß er das im Handumdrehen an einem Abend mindestens machen muß, und der von jedem Vortrag über die übersinnlichen Welten verlangt, daß er ihm die ganze Summe der Weltenweisheit gibt. Konkrete Ergebnisse positiver geistiger Forschung finden die Menschen unbequem. Und diese Neigung der Menschen benützen einzelne in der Gegenwart vorhandene Persönlichkeiten und reden dann den Menschen ein, daß man solche Dinge nicht braucht, daß es nicht nötig ist, sich mit positiven einzelnen konkreten geistigen Tatsachen zu befassen. Sie sagen: Ach, was reden da die Menschen von höheren Hierarchien, die man erst kennenlernen müsse? Was reden die Menschen von Saturn, Sonne, Mond, Erde, Jupiter, Venus, Vulkan und so weiter? Das alles braucht man nicht! — Man erzählt den Menschen: Wenn ihr nur recht euch innerlich vertieft, wenn ihr recht mystisch die Seele macht, dann dringt ihr zu dem Gotte in eurer eigenen Wesenheit vor. — Man erzählt das den Menschen, gibt ihnen so allgemeine Andeutungen über dasjenige, was Beziehung der materiellen Welt zur übersinnlichen Welt ist. Man schürt an die Abneigung der Menschen, in konkrete geistige Welten einzudringen. Und warum tut man das? Weil man scheinbar verbreiten will spirituelle Gesinnung; aber in Wirklichkeit will man etwas anderes: Man will erst recht auf diesem Wege den Materialismus erzeugen. Deshalb sind die Führer der Monistenbünde die am wenigsten schädlichen. Diejenigen, die heute Mystik verbreiten und den Menschen immer von allerlei Mystik reden, die sind oftmals die eigentlichen Pfleger, die raffinierten Pfleger des Materialismus. Sie reden auf die Menschen ein von irgendeinem Wege, der in die geistigen Welten führt, vermeiden es, im Konkreten zu sprechen, reden hauptsächlich in allgemeinen Redensarten und erreichen ganz sicher, daß in der dritten Generation die Welt durchmaterialisiert ist, wenn sie zum Siege gelangen. Der sicherere und raffiniertere Weg in den Materialismus hinein ist heute vielfach, Mystik zu tradieren den Leuten, die es verschmähen, auf positive, geisteswissenschaftliche Resultate einzugehen. Und manches, was heute erscheint auf dem Boden sogenannter geistiger Literatur, das ist viel stärker ein Pfleger des Materialismus als zum Beispiel die Ernst Haeckelschen Bücher.

Solche Dinge sind den Menschen heute unbequem zu hören, weil, indem man so etwas vor die Menschen hinstellt, man in starkem Maße appelliert an ihr Unterscheidungsvermögen. Aber die Menschen möchten heute nicht den Appell empfangen an ihr Unterscheidungsvermögen. Die Menschen möchten viel lieber innerliche seelische Wollust erregt haben mit allerlei mystischem Zeug. Deshalb ist es auch, daß so viel Gegnerschaft erwächst gerade denjenigen Bestrebungen, die es heute ehrlich meinen mit dem geistigen Leben, indem sie es verschmähen, in allgemeinem «Mysteln» an die Menschen heranzukommen. Wer wirkliche Geisteswissenschaft bringt, erfährt Gegnerschaften. Denn es gibt eben zahlreiche Menschen und Menschengemeinschaften in der Gegenwart, die auf keinen Fall möchten, daß wahre geistige Erhebung in die Menschheit kommt, und die die Tatsache benützen, daß, wenn man im allgemeinen dem Menschen mystisch herumredet, man den Materialismus ganz sicher pflegt. Diese Tatsache benützen sie. Deshalb bekämpfen sie bis aufs Messer die ehrlichen Wege, die in die Geisteswissenschaft hineinführen sollen.

Eine reiche Literatur, die es heute gibt, habe ich Ihnen damit gekennzeichnet. Eigentlich stehen heute die Dinge so, daß jeder, der ein mystisches Buch in die Hand nimmt, welcher Art immer es ist, stark an sein eigenes Unterscheidungsvermögen appellieren muß. Das ist sehr notwendig. Daher darf man sich auch nicht beirren lassen davon, daß vieles mystelnde Geschreibsel, das in der Gegenwart erscheint, leicht verständlich ist. Selbstverständlich ist es für den Menschen leicht verständlich, wenn man ihm zum Beispiel sagt: Du brauchst nur in dein Inneres ganz tief hineinzuschauen; dann lebt ein Gott in dir, dein Gott, den du nur findest, indem du deinen eigenen Weg gehst. Kein anderer kann dir diesen Weg vermitteln; denn jeder andere spricht von einem anderen Gotte. — Sie finden es heute in vielen Büchern außerordentlich versucherisch, verführerisch dargestellt. Diese Dinge, die bitte ich Sie, recht eindringlich sich zu Gemüte: zu führen. Denn dasjenige, was durch unsere anthroposophische Bewegung erreicht werden soll, erreichen Sie nur dadurch, daß Sie wenigstens eine kleine Schar sind, welche sich aufringen will zu dem charakterisierten Unterscheidungsvermögen. Es wäre schlimm für die Menschheit, wenn man sich nicht aufraffen würde zu diesem Unterscheidungsvermögen. Man muß schon heute sich stark auf die Füße stellen, wenn man in der heutigen Verwirrung und in dem heutigen Chaos feststehen will. Man kann heute sich oftmals fragen, worin denn eigentlich die Ursachen so vieler Verwirrung in der Menschheit bestehen. Aber man kann sie ja fast greifen, diese Ursachen. Sie liegen in kleinen Tatsachen. Man muß nur diese kleinen Tatsachen richtig beurteilen können.

Ich möchte Ihnen zum Schluß eine kleine Tatsache mitteilen, die mir gerade vor ein paar Stunden vor Augen getreten ist, und die ganz geeignet ist, auf die Seelenstimmung der Menschen in der Gegenwart einiges Licht zu werfen. Mein Leipziger Verleger, Altmann, schrieb mir — ich habe den Brief vor ein paar Stunden erhalten, ich weiß nicht, wie sich sonst die Sache verhält —, daß ein scharfer, angreifender Artikel — das ist ja sicher auch gestattet, nicht wahr! - in einer theosophischen Zeitschrift in Leipzig erschienen ist gegen meine Anthroposophie, ein vernichtender Artikel in demselben Heft, wo abgedruckt sind mein Seelenkalender und mein Aufruf an die Kulturmenschheit, so daß also nebeneinander stehen die Verse des Seelenkalenders «nach Rudolf Steiner», mein «Aufruf an das deutsche Volk und die Kulturwelt» und hinterher ein Angriffsartikel: «Rudolf Steiners Appell an den Instinkt der Mittelmäßigkeit» — zur Charakteristik der gegenwärtigen Anthroposophie.

Sehen Sie, in solchen Dingen zeigt sich immerhin einiges von der Konstitution einer gegenwärtigen Menschenseele. Da tritt es nur in grotesker Form zu Tage. Aber es ist unbequem, in den vielen Gestalten gleich zu sehen, wo es überall vorhanden ist. Mancherlei groteske Widersprüche, die sind nicht etwa nur an solchen etwas unreinlichen Orten vorhanden, sondern sie sind auch im heutigen Menschheitsleben durchaus vorhanden. Und es ist nötig heute, sich wirklich zur Klarheit, zur, ich möchte sagen, messerscharfen Klarheit durchzuringen, wenn man fest stehen will. Das ist es, worauf es ankommt.

Seventh Lecture

Today I would like to speak to you about some fundamental insights of the science of initiation, which will then serve as a kind of foundation for what we will consider tomorrow and the day after tomorrow. Today we will first point to something that lies in the consciousness of every human being, but which is usually not grasped clearly enough. When we discuss such things, we always speak from the standpoint of our present, in the style and sense that I have often explained here: that insights are by no means valid forever and everywhere, but only for a certain time, even for a certain place on earth. Certain points of view, for example, apply to European civilization; other points of view apply to, say, the insights of the Orient. Now, every human being knows that with our knowledge we are, in a sense, between two poles. Every human being feels how, on the one hand, there are the insights we gain through sensory perception. The simple, naive person learns about the world through their senses and also arrives at a certain summary of what they see, what they hear, what they perceive through their senses in general. And basically, what science offers us, as we now have it in the West, is nothing more than a summary of what presents itself to human beings through the senses.

Now everyone feels that there are other kinds of knowledge, that it is impossible to be a complete human being in the ordinary sense of the word for the everyday world unless one adds another kind of knowledge to that just characterized. And that is the kind of knowledge that has to do with our moral life. We are not just talking about the ideas of natural knowledge, through which we explain one thing or another in nature; we are talking about moral ideas, moral ideals, which we feel as the driving forces of our actions, which we allow to control us when we want to act in our ordinary world. And every human being probably feels that with one pole of our cognitive life, sensory knowledge and its appendage, intellectual knowledge—for intellectual knowledge is only an appendage of sensory knowledge—we cannot usually reach moral ideas. Moral ideas exist, but we cannot, for example, by studying natural science, by observing the plant world, the mineral world, or in any other way with our present natural science, find moral ideas. This is precisely the tragedy of our time, that we want to find ideas for action in the social sphere, for example, using scientific methods. This will never be possible if we truly surrender ourselves to common sense. Moral ideas exist on another side of life. Our lives are truly influenced by these two currents: the recognition of nature on the one hand, and moral recognition on the other.

You know from my Philosophy of Freedom that in the grasping of moral intuitions we are given the highest moral ideas we need as human beings, and that these moral ideas, when we come into possession of them, establish our human freedom. On the other hand, you may also know that for certain thinkers there has always been a kind of gulf between what is knowledge of nature on the one hand and what is moral knowledge on the other. Kant's philosophy is based on this gulf, on this abyss, which it cannot completely bridge. Hence Kant's “Critique” of theoretical reason, of “pure reason,” as he calls it, in which he deals only with knowledge of nature, in which he says everything he has to say about knowledge of nature. On the other hand, he wrote a “Critique of Practical Reason,” in which he speaks of moral ideas. One might say that, for him, all human life springs from two completely separate roots, which he describes in his two main “critiques.”

Now, of course, the human being would be in a difficult position if there were no connecting bridge between these two poles of our soul life. And anyone who is seriously engaged in spiritual science on the one hand and takes the tasks of our time seriously on the other, must ask intensively: Where is the bridge between moral ideas and natural ideas?

Today, in order to recognize this bridge, we will take what I would call the historical point of view. You know from the various considerations we have made here that the soul constitution of human beings in earlier times was essentially different from what it has become in later times. The emergence of Christianity really marks a deep cut in the entire development of humanity. And only when we understand what actually emerged in the development of humanity with the emergence of Christianity can we come to terms with the understanding of the human being in general.

What lies behind the emergence of Christianity, if we disregard Judaism — which we mentioned again here recently — is the entire scope of pagan culture. Judaism was only a preparation for Christianity. This entire scope of pagan culture differs fundamentally from our present Christian culture. The further back we go, the more we see that this pagan culture was a unified culture. It was a culture based primarily on human wisdom. I know that it is offensive to people today to hear that the ancients were more advanced than we are in terms of wisdom, but that is how it was. In the old pagan times, there was a wisdom throughout the earth that was closer, much closer to the fundamental principles of things than our present knowledge, especially our present natural science. And this ancient, this ancient knowledge was a very concrete knowledge, it was a knowledge that was intensely connected with the spiritual reality of things. Human beings received something into their souls by knowing the reality of things. But what was particularly peculiar about this ancient pagan wisdom was that the people who received it—you know, people received it from the mysteries of the initiates—received it in such a way that this wisdom contained both knowledge of nature and moral knowledge at the same time. Today, the truth I have just expressed, which is extraordinarily significant for the history of human development, is misunderstood simply because we cannot go back in external history to the truly characteristic times of ancient pagan wisdom. Historical knowledge does not go back far enough to enable us to grasp the times when people, looking up at the stars, received from them the wisdom that, on the one hand, explained the course of the stars to them in their own way and, on the other hand, also told them how they should behave in their actions here on earth. Somewhat figuratively, but not entirely figuratively, rather to a certain extent concretely, one could say that the ancient Egyptian and Chaldean cultures were such that people read the laws of nature in the course of the stars, but also read from the course of the stars the rules for what they should do on Earth. The codes of the ancient Egyptian pharaohs, for example, contain rules about what was to become law. It was the case that, over many centuries, it was prophesied what would become law in later times. But everything that was written in these codes was read from the movements of the stars. So in those ancient times there was not an astronomy as we have it now, which contains only mathematical laws of the movement of the stars or the movement of the earth, but there was a science of the cosmos, which was at the same time a science of morality, ethics.

The problem with modern astrology, which has now reached the level of amateurism, is that it no longer recognizes that what it presents is only a whole if the laws it records are also moral laws for human beings. This is something very important, extremely important. |

Now, in the course of human history, this original science of mankind, this original wisdom of mankind, was essentially lost. And this is based on the fact that certain secret schools, which in their serious form actually ceased to exist at the end of the 18th century, also repeatedly referred back to the lost science, the “lost word.” Usually, those who came later no longer knew what they were supposed to understand by the word “word.” But there is a certain fact underlying this. And in Saint-Martin one can still read echoes of how, until the 18th century, it was felt very strongly that in ancient times people possessed a spiritual knowledge that came to them together with their knowledge of nature, which also included their moral science and which was lost, lost basically already in the eight centuries that preceded the emergence of Christianity. One could even say that ancient Greek history is essentially the gradual loss of primordial wisdom.