Spiritual Science as a Foundation for Social Forms

GA 199

6 August 1920, Dornach

Lecture I

I must begin with the gratifying observation that upon my return1 Reference to Rudolf Steiner's return from Stuttgart where, from July 24 until August 1, 1920, he had been giving lectures for the teachers of the Waldorf School, for the general public and the Anthroposophical Society. I encountered a great many friends who are here in Dornach for the first time. They have come to inform themselves about what goes on in Dornach and what is meant to proceed from here into our anthroposophical movement. I cordially welcome all the newly arrived friends and hope that because of their stay with us they can carry back with them many new inspirations. Among the friends we can greet once again are many we have not seen for years. This fact along with much else undoubtedly indicates the difficulties of the age in which we live. I have just returned from a visit in Stuttgart, which was filled with the manifold tasks generated within our anthroposophical sphere of work. Among other matters, it included the ending of the first academic year of the Waldorf School2 The Waldorf School: Founded by Emil Molt (1876–1936) in the year 1919 for the children of the workmen in the “Waldorf-Astoria” cigarette factory and the public as a coeducational elementary and high school under the leadership of Rudolf Steiner, who had also appointed the teachers and had given them preparatory courses. founded in Stuttgart. This Waldorf School belongs to those establishments which manifest most prominently the ideas of our anthroposophical spiritual movement. Even though one sets high standards for it, the completion of the first school year has demonstrated that there is cause for satisfaction. I can say this because it is possible to remain objective even if one is wholeheartedly involved in the project and even if, in a certain sense, one has been its instigator.

Above all it is gratifying to see how the Waldorf School teaching staff definitely understood how to proceed from a completely anthroposophical basis, as had always been the intention. Present-day conditions necessitated that this basis in anthroposophy should not produce a school that teaches a certain world view, a school in which anthroposophy would be taught. That was never the intention. With this in mind, therefore, we arranged the religious instruction so that children of Protestant parents, who wished them to have Protestant religious instruction, could be taught by a Protestant minister; Catholic children, by a priest. Only those who did not care to be numbered among the existing denominations were separately taught a form of anthroposophical religious instruction. Except for this, we certainly never considered the founding of an institution that teaches a specific world outlook. All efforts were directed toward the creation of a school in which the practical teaching impulses arising from the viewpoint and will of our spiritual science could for once be directly applied in the education and instruction of youth. It was our aim that the anthroposophic impetus should be expressed not in the content of the classes but in the way classes were taught, in the manner in which the whole school system was handled; that this impetus be manifested in the specific kind, and the different methods, of instruction. Once an anthroposophist has stimulated his classes through his anthroposophic will, the fertilization of the teaching process shows precisely what a vitalizing effect anthroposophy has when it is implemented in this way.

Throughout its first year, I always had the opportunity to observe the progress at the Waldorf School. Again and again, I was there for one or two weeks. I could supervise instruction and was able to watch the development of the different classes. I could see, for instance, how our friend, Dr. Stein,3 Dr. Walter Johannes Stein: 1891–1957, Dr. Caroline van Heydebrandt: 1866–1938; both teachers in the Waldorf School from 1919. succeeded in enlivening his history class for older students by bringing anthroposophic impulses into history. Anthropology, as taught by Fräulein Dr. von Heydebrandt in the fifth grade, was lifted from the tedium prevailing ordinarily in our schools by imbuing it truly with anthroposophic will. I could cite many other instances from which you could clearly see that without in any way teaching abstract anthroposophy the subject matter comes alive by the method and the way it is treated and fertilized by anthroposophy. This practical application of anthroposophic strength of purpose shows that anthroposophy need not remain an abstract, remote philosophy, but can definitely influence human activity, even though we unfortunately have little opportunity to penetrate human affairs, except in limited areas like the Waldorf School. Now, when we ended the first year something happened that seemed to be only an exterior matter, but, as I am about to explain, it was an event that had great inner significance. A complete innovation took place. It concerned the report cards.

The report card system is truly one of the most miserable aspects of our schools. In a superficial, groping manner, teachers must grade their students from 1, 2, 3, 4 to 5 and so on,T1In the German educational system, the grade of 1 is equivalent to an A; 4 is a D and 5 would indicate a failing grade. a procedure that stifles the very nature of schools in a most appalling way. Our report cards are based on actual educational psychology, on an absolutely practical application of human psychology. At the end of the first school year, the teachers were at the point where they were able to write a report card for every child corresponding to its own character and capabilities, individually indicating the possibility for continued growth and progress. No report card was like any other. There were no numbers indicating grades. Instead, through the teacher's individual insight into his pupil, the student received a characterization of his personality. Already in the course of the first school year, the teachers had so intimately sought to deepen their understanding of every child's soul that they were able to write into the report card an accompanying verse suited to each recipient's individual character.

These report cards are an innovation. Do not conclude, however, that it can be imitated or readily introduced somewhere else, because this change has been brought about by the whole spirit of the Waldorf School and is based on the fact that the most intensive educational psychology was practiced during the first school year. We carefully studied what was causing certain intimate manifestations in the faster or slower progress of a class, and already in the course of the first school year, we made a few discoveries that were in some ways surprising. We learned, for example, that the whole configuration of a class takes on a specific form if the number of boys and girls in that class is equal. The configuration is a quite different one if boys are in the majority and girls in the minority, and it changes again when there are more girls than boys in a class We have had all these examples in our classes. These imponderables, which elsewhere are not taken into consideration at all, are in many ways the essential element in a class.

When one attempts to express certain aspects of psychology, trying to define them in so many words, he is then already past the point that really matters. It is just the predominant and nonsensical custom of our time that one attempts to express things too rigidly in words. One cannot study matters thoroughly if one wants to express them in this constrictive word structure. One must be aware that by expressing things in this manner they can only be indicated approximately.

Of course, we always find ourselves in an odd position when we talk about the results of our anthroposophically oriented movement of spiritual science. The Waldorf School, whose teachers have proven themselves eminently suited to their tasks, could only justify itself because a group of human beings was gathered together who were most competent and pedagogically most qualified. It is unfortunate that in any effort to carry something out in a practical sense today, one encounters, much more than is generally realized, the one great obstacle, namely, a lack of qualified people. Today, the world has a paucity of people who are qualified for any real tasks in life. In our case the difficulty would be compounded should a second school be established. To find suitable, really proficient individuals capable of working in the spirit of anthroposophically oriented spiritual science would be much more difficult because the one existing school has, of course, already attracted all those who could seriously be considered. Yet there can be no doubt that, for once, something has been accomplished in a certain area. I must say, however, that this is like an island. There, in the course of the first school year, a spiritual system of education has become manifest which truly evolved from the fundamentals of anthroposophy. It is an island, however, enclosed within its shores. Beyond these shores, the financial and economic connections of the school are affected by the great decline in the economic and political life of the present. This is where the problems lie. We can see that our prospects are not what they should be; they are not as good as they should be considering the nature of our achievement. Yet does anyone have even a slight understanding of what the Waldorf School has created based on the spirit?

The Waldorf School was founded by our friend Molt4 See Preface and Introduction to Goethe's Naturwissenschaftliche Schriften, edited by Rudolf Steiner. Introductions to all the volumes written by Rudolf Steiner under the same title, Dornach, 1926. so that the children of the Waldorf Astoria Works could receive an education. Already in the first year, many children from the outside, who were unconnected to the factory, became students at the school; there must have been around 280 of them. Now, many new students have been registered, but from the Waldorf Astoria Works we have no more than were previously here, as well as the few who have meanwhile reached school age. If everything goes really well, and if economic and other problems can be solved, we shall, judging from the present applications, have more than four hundred students in our school. This means we shall have to build, hire more teachers, establish parallel classes. All this must happen! In a certain sense it will be a crucial test as to whether the financial understanding of our needs by those involved can keep pace with what induces so many people from the outside to bring us their children. It was somewhat ironical to me when the mother of one of our students was introduced to me in the school corridor as Frau Minister So and So. Even those connected with the present government are bringing their children to the Waldorf School now!

Some of these matters actually should be studied more closely in their social context as well. Then, perhaps, it would be possible to perceive the real needs of our society and how they are met by institutions such as the Waldorf School.

Now and then the Waldorf School was beset by a certain superficiality that is a characteristic of our times, as I have often pointed out. The leadership of the school was naturally confronted with people here and there who wanted to visit for a while, that is to snoop around a bit. Yet there is really not all that much to see. What does matter is the whole spirit at work in the school, and that is simply the anthroposophical spirit. People who can't make the effort to read anthroposophic books and who hope to set something from scouting round in the Waldorf School would be better served by deepening their knowledge of anthroposophy. For what bestows spirit on the Waldorf School and lies at its very foundation can only be seen in the spiritual impulses that are the Basis of anthroposophical spiritual life. I have often pointed out to those who have been attending my lectures for some time that today the anthroposophic spiritual life is not directed only toward the individual who seeks the way out of his soul's distress and life's afflictions in the spiritual forces of the world. Today, spiritual science must address itself to the need and decline of our time. Then, however, the comprehension of what spiritual science has to offer will be met by that special kind of understanding that a person today can generally bring to anything of a spiritual nature. When talking about spiritual science, it is often necessary to speak in an entirely different language than is customary. One could say that in a certain sense words acquire a new meaning through spiritual science. It is absolutely necessary to feel and to sense this.

Today I would like to acquaint you with some things that can illustrate how essential it is not only to be willing to hear a somewhat different world view expressed in customary terminology, but to learn to receive the words differently with one's feelings.

Let us begin with a specific case. When speaking about any ideology today, it is designated by an abstract name: materialism, idealism, spiritualism, and so forth, and people are quite sure that they can say which is correct, and which is incorrect. A materialist comes to a spiritualist, for example, and explains to him his way of thinking, how he sees man's thoughts and feelings as products of the brain. The spiritualist answers, “You think incorrectly. I can refute that logically!” Or, perhaps, “That is contradicted by the facts!” In short, the crux of the matter is that today, when people talk about issues concerning world views, one ideology is said to be right and the other one wrong. The spiritualist presumes that only he has the correct philosophy, and wishes to prove the materialist wrong and convince him that he would be better off if he became a spiritualist.

Spiritual science has nothing to do with such a way of proceeding. It does not wish to lead to a different logical insight from that of other world views. Spiritual science, if it really fulfills its task, must become action based on insight. In spiritual science, knowledge must turn into action, action in the whole cosmic world context. I will explain this by using a few definite examples. Today, when people look at the world naively but with a slight materialist tendency, when they direct their eyes and ears outward, hear sounds, notice colors, experience warmth and similar sensations, they perceive the external material world. Should they become scientists, or merely absorb through popular means what science wishes to represent, they will then form or simply accept certain concepts that have originated through the combination of all the color, sound and warmth elements and others that are to be observed in the external world. Now, there are people who maintain that everything one sees is, in the first place, only an external phenomenon. Yet this idea is generally not gone into thoroughly enough. People see a rainbow, for example. As a result of their education, when they look at the rainbow, they are already convinced that the rainbow is only an apparition, that they cannot go to the place where the rainbow is, neatly put a foot on it and march along the rainbow bridge as if it were a solid object. People are sure that it cannot be done, that the rainbow is merely an apparition, a phenomenon that arises and then disappears again. They are convinced that they deal only with apparitions because they cannot come into contact with this aspect of the external world through their sense of touch and feeling. According to their view, as soon as something can be grasped or touched, it is no longer a phenomenon to the same degree, even though recent philosophy may in some instances claim that it is. In any case, the impressions of the sense of touch, for instance, are intuitively taken as something that guarantees a different external reality than the phenomenal realities of the rainbow.

This notwithstanding, all that our external senses perceive comprises merely a world of phenomena, modified perhaps in respect to the apparition of the rainbow, but a world of phenomena nevertheless. Regardless of how far we direct our gaze, how far we can hear, in whatever is seen, heard or otherwise perceived, we deal only with phenomena. I have attempted to explain this in the introduction to the third volume of Goethe's scientific writings.5 Rudolf Steiner: “The Portal of Initiation” contained in Four Mystery Play, GA 14 (Toronto, Steiner Book Centre, 1973). We deal with a tapestry of phenomena. Whoever makes an effort through experimentation or any combination of pure reasoning to find matter in the realm of appearances is pursuing a dead end.T2The “dead end” alluded to here is the translation of the German expression “Holzweg,” literally, “wooden path.” Like all such expressions in a language, it springs from real experience. The “Holzweg” is a rough timber road, or a system of such roads, proceeding into the forest and used by woodcutters. It leads nowhere and may dead-end suddenly. Hence, it would be easy to get lost on it. There is no matter out there. One deals only with a world of phenomena.

This is precisely what the whole spirit of spiritual science reveals: In the external world, one deals only with a world of appearances. An exponent of a current world outlook will therefore conclude that it is wrong to look for matter at all in the realm of phenomena. Anthroposophy cannot agree with this attitude; it must put it differently by saying: Because of the whole configuration of man's mind, he comes to the point where he wants to seek for matter in the moving tapestry of phenomena, to seek out there for atoms, molecules and so on, which are resting points in the phenomenon. Some picture these as tiny, miniature pellets, others imagine them to be points of energy and are proud of the fact; others, prouder still, think of them as mathematical fiction.

What is important, however, is not whether one thinks of them as small pellets, sources of energy, or mathematical fiction, but whether one thinks of the external world in atomistic terms. This is what is important. For a spiritual scientist, however, it is not merely wrong to think atomistically. The kind of concept determining rightness or wrongness may be sound logic, but it is abstract, and spiritual science has to do with realities. I urge you to take it very seriously when I say that spiritual science has to do with realities!

This is why certain concepts that have become merely logical categories for today's abstract world-view must be replaced by something real. This is why, in spiritual science, we not only say that one who seeks atoms or molecules in the external world thinks in the wrong way; we must consider this manner of thinking an unhealthy, sick thinking. We must replace the merely logical concept of wrongness with the realistic concept of sickness, of unhealthiness. We must point to a definite sickness of soul—regardless of how many people it has seized—which expresses itself in atomistic thinking. This condition is one of feeblemindedness. It is not merely logically wrong for us, it is an expression of feeblemindedness to think atomistically; in other words, it is feebleminded to seek in the external world something other than phenomena which, when it comes right down to it, are an a par with the phenomenon of the rainbow. It is relatively easy for people with other world outlooks to set things straight: they do it by refutation. To have been able to refute something is considered an accomplishment. Yet, in a spiritual-scientific sense, no final conclusion has been reached by refutation; it is important to refer to the healthy or unhealthy soul life, to actual processes expressed in man's whole physical, soul and spiritual being. To think atomistically is to think unhealthily, not merely erroneously. An actual unhealthy process takes place in the human organism when we think atomistically. This is one thing we must become clear about regarding the phenomena of the external world and its character of appearance.

We must also become clear about our inner life. Many people seek the spirit inwardly. To begin with, the spiritual cannot be found in the inner realm of man. Truly objective evaluation of every abstract form of mysticism bears this out. What today is sometimes—nay, often—called mysticism consists of brooding over one's inner self, attempting to seek self-knowledge by introverted brooding. What is discovered by practicing such one-sided mysticism? One certainly finds interesting things. When we look into the human being and find all those inwardly pleasant experiences arising which we call mystical—what are they really? They are just the very things that point us toward material existence. We do not discover matter in the external world where the sense phenomena are found; we come upon matter in our inner being. This brings us to the point where we can characterize these things correctly. Regarded from the most comprehensive point of view, it is the body's metabolism that seethes and boils there within the human interior and which flames up into consciousness as one-sided mysticism, mistaken by many to be the spirit that can be found in the inner self. It is not the spirit, it is the flame of metabolism within man. We find matter not in the external world, we find it in ourselves. We find it precisely through one-sided mysticism. That is why a great many people who do not want to be materialists deceive themselves. They excuse their not wanting to be materialists by saying, “Out there is base matter; I shall rise above it and turn to my inner being, for there I will find the spirit.”

Actually, spirit is neither without nor within. Outside are the interweaving phenomena; within ourselves is matter, constantly seething and boiling substance. This metabolic processing of matter kindles the flames that leap into consciousness and form the mystic impressions. Mysticism is the inwardly perceived corporeal matter of the metabolism. That is something that cannot be logically refuted, but must be traced back to actual processes when man yields in a one-sided way to the metabolism.

Just as the belief that it is possible to find traces of matter in the external world indicates feeblemindedness—that is, a real illness of the spirit, soul and bodily being of man—so does one-sided preoccupation with mysticism indicate a corporeal indisposition. It points toward something that sounds somewhat insulting if put bluntly. Yet we must use an expression that is, as it were, spoken from yonder side of the Guardian of the Threshold and means, “Childishness.” In the same way that one incurs feeblemindedness through atomistic thinking concerning the outer world, one becomes childish when yielding to a mysticism that wants to feel the spirit in the seething of the inner metabolism.

Childishness, of course, has a good side, too. When we observe the child we see a lot of spirit in it, and geniality in many instances consists in man's preserving the childlike spirit all the way into advanced age. When we look at the world from the other side of the threshold we can see that it is the spirit which, for instance, forms the child's brain, that spirit which accompanies us from the spiritual world when we enter the physical world through conception or birth. This spirit is most active in the child. Later, it is lost. Therefore, the word childishness is not meant as an insult in this instance, it merely denotes that spirit which forms the brain out of a more or less chaotic mass. Later on, however, if this spirit, which actually shapes the child's brain, does not pour itself sufficiently into logicality, into experience, into what life presents; if, instead, it acts in a one-sided manner and excludes the individual physical experiences; if it goes on working in the way it did during the first seven years, then instead of becoming intellectually mature one becomes childish. Childishness is frequently found to be a characteristic of a great many mystics, particularly arrogant ones. They wish to weave and live in that spirit which is really what should be active in the child's organism. They have retained this spirit, however, and, greatly impressed by their own accomplishment, they gaze at it in wonder in their consciousness, believing, in their one-sided, abstract mysticism, that they are perceiving a higher spirituality, when it is only the matter of their own metabolism.

Again, we do not need merely to refute the one-sided mystic if we are really well grounded in an anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. We must show that it is the sign of an ailing constitution of the spirit, soul and body when man broods one-sidedly within his inner being, thereby attempting to find the spirit.

I have drawn these two examples, familiar to you from anthroposophical literature, in order to point out to you how serious from a certain viewpoint matters can become when, leaving the ordinary spiritual life of today, one immerses oneself in anthroposphical spiritual life. There, one no longer deals with something as insignificant as “right” or “wrong.” It now becomes a question of “healthy” or “sick” conditions in the organic functions. Thus, on a higher level, something that goes in one direction must be considered healthy, while something going in another direction must be considered sick. I would like you to understand from these implications how spiritual science is an active knowledge; how it cannot stand still on the level of the nature of ordinary knowledge but becomes something real. The process of knowledge, insofar as it expresses itself in spiritual science, is something that actually takes place in the human organism.

In a similar manner we must define the element that lives in the realm of will. When we talk of the realm of will in our age—an age permeated by that grandiose decline we have often discussed—when we speak of what develops into human will impulses and try to define their character, then we say: Man is good or evil. Again, we are dealing with ethical categories—good and evil—which are just as necessary, of course, as logical categories. Yet, from what arises out of the impulses of spiritual science, it is not merely a question of what is meant when one action of man is designated as good and another as evil. When one calls a human action good, even in a karmic connection, it is a question of balancing in some way or other the good with the evil. We refer to something that pertains to an ethical judgment of man.

Whenever we rise into the realm of the spiritual scientific, it is much more a question of recognizing that what is at work there is a certain manner of thinking, feeling and willing for human beings which leads upward to a fruitful development, to progress in evolution. On the one hand, we have abstract goodness. It is of outstanding moral value, but even that is ethically abstract. When it is a matter of spiritual-scientific impulses, however, man must not only do good, or only do the good which lets him appear as an ethically good person. He can do, think or feel only that which advances the world in its development in the external sense world; or he can do something that is not merely evil, leading to an ethical condemnation, but has a destructive effect on the world forces. This was already meant to be indicated in the Portal of Initiation,6 “Stimmen der Zeit,” Freiburg i. Br., 1918–1920, Otto Zimmermann SJ, Josef Kreitmaier SJ, Konstantin Nopels SJ. where Strader and Capesius are speaking and the following is pointed out: Everything that is done here in the sense world and is subject to ethical judgments of good and evil turns into phenomena behind the curtains of existence, having either a progressive, constructive effect or a destructive one, leading to decline. Just try to experience this entire scene that is permeated with thunder and lightning, where things are happening in a most realistic manner in the soul world while Capesius and Strader are discussing one or the other matter. Try to re-experience this scene and you will see how what we experience as the ethical sphere here on the physical plane is in reality very different there.

All this is to show you how serious world aspects become in that instance when, upon leaving today's customary way of judging by logical or outward human categories only, one ascends to the realities that confront us when we view the world from the spiritual scientific standpoint. Things become serious, yet they must be mentioned today because the world now demands a new kind of spiritual life. Things are happening in the world today that everyone sees but that nobody wishes to comprehend in their actual significance because one cannot take the step from external abstraction to reality. I want to give you a few other examples.

You find today that you live in a world where, among much else, there exist, for example in the social field, a great many party organizations—liberal, conservative and many other parties. Human beings are unaware of the actual nature of these parties. When they have to vote, they decide on one or the other party. They do not give much thought to what it really is that exists as party policy, pulsating through all of public life. They are incapable of taking these things seriously. There are quite a number of people who, in the nicest superficial manner, repeat all sorts of Orientalisms about the external world as Maya, but when it really comes to doing something in this external world they do not stick to what they repeat so abstractly. Otherwise, they would ask, “Maya? Then these parties must be Maya too. Then what is the reality to which this Maya points?”

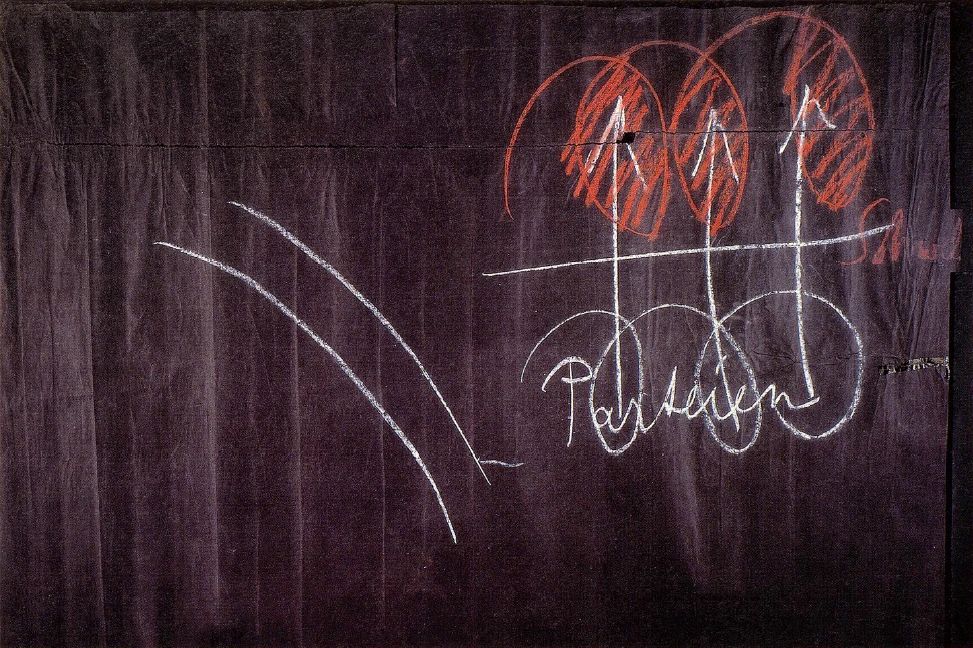

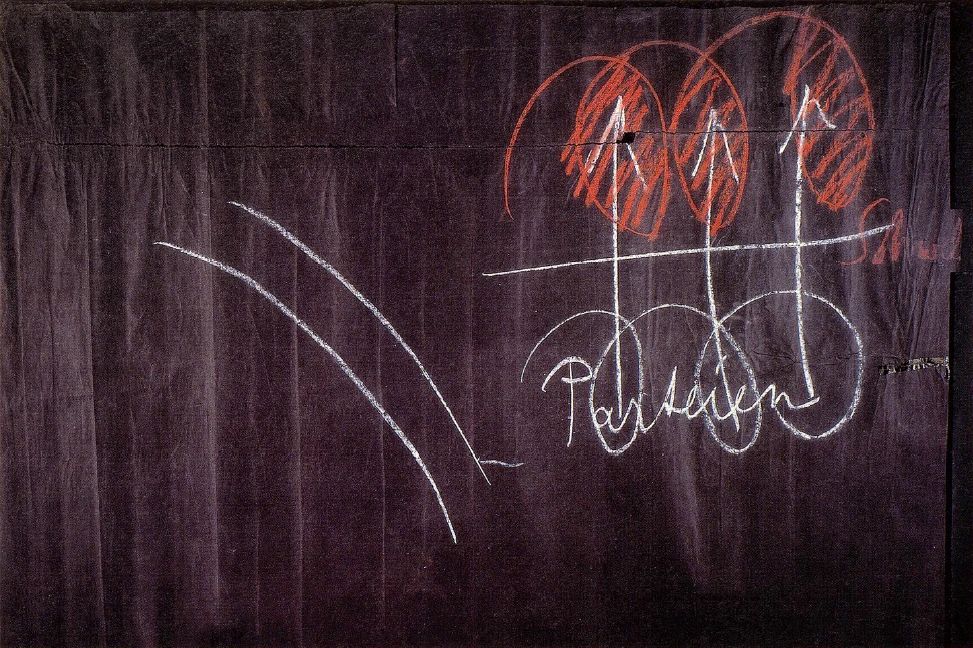

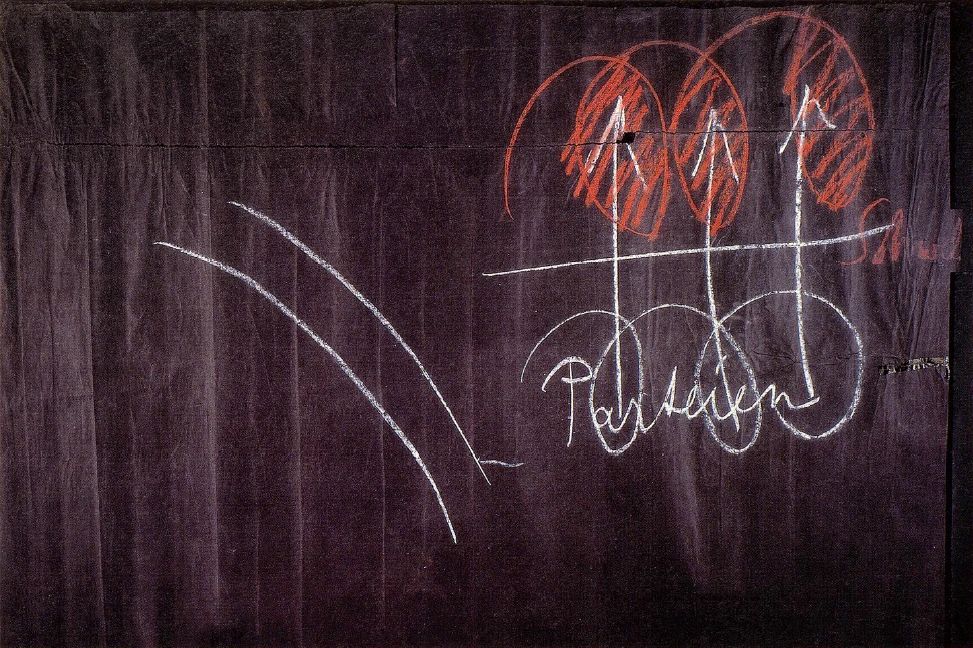

If this matter is pursued in a spiritual-scientific way in more detail—and tomorrow we shall go deeper into this topic—one finds that these parties exist in the external world by having programs and principles, that is, they pursue abstract ideas. Everything that lives in the external physical world, however, is always the replica, the reflection of what is present as a reality in a much more intense form in the spiritual world. Here is the physical world (see drawing, red), but everything in it points toward the spiritual, and only above, in the spiritual world, can the actual reality of these physical things be found (red). Down here, for instance, you find the parties (white). On the earth, they oppose each other, seeking to gather a great number of people under the umbrella of an abstract program. Then what are these parties a reflection of? What is up there in the spiritual world if these parties down here are Maya? No abstractions exist in the spiritual world above, only beings. Yet, political parties are rooted in abstraction. Above, one cannot profess adherence to a party program; there one can only be a follower of this or that being or hierarchy. There one cannot just subscribe to a program on the basis of the intellect; that cannot happen there. One must belong with one's whole being to another entity. What is abstract down here is being above; that is, the abstract below is only the shadow of beingness above. If you consider the two main categories of parties, the liberal and conservative, you know that each has its own program. When you look above to see what each is a reflection of, then you discover that ahrimanic being is projected here (see drawing, lower part) into the conservative views, luciferic being in the liberal thoughts. Down here, one follows a liberal or conservative program; up there, one is a follower of an ahrimanic or a luciferic being of some hierarchy.

It can happen, however, that the moment you pass across the threshold it becomes necessary really to understand all this clearly, and neither be fooled by words nor succumb to illusions. It is quite easy to assume that one belongs to a certain good being. Just because you call a being good, however, does not make it so. Anyone can say, for instance, “I acknowledge Jesus, the Christ,” but in the spiritual world, one cannot follow a program. The whole manner in which the concepts and images of this Jesus, of Christ, fill such a person's soul indicates that it is merely the name of Jesus, the Christ, that he has in mind. Actually he is a follower of either Lucifer or Ahriman, but calls whichever it is by the name of Jesus or Christ.

I ask you: How many people today know that party opinions are shadows of realities in the spiritual world? Some do know and act according to their knowledge. I can point to some who know. The Jesuits, for instance, they know. Do not think that the Jesuits believe that when they write something6 “Stimmen der Zeit,” Freiburg i. Br., 1918–1920, Otto Zimmermann SJ, Josef Kreitmaier SJ, Konstantin Nopels SJ. against anthroposophy in their journals, for instance, they have hit upon something special and logically irrefutable. Refutations are not what counts there. The Jesuits know very well how their refutations could be countered. They are not concerned with a rational fighting for or against something, but with being followers of a certain spiritual being which I do not wish to name today, but which they call Jesus, their Leader, to whom they belong. Whoever this being may be, they call it Jesus. I do not wish to go into the facts more closely, but they call themselves soldiers and him their Leader. They do not fight to refute, they fight to recruit adherents for the companies, the army of Jesus—that is, the being they call Jesus. And they know very well that as soon as one Looks across the threshold, abstract categories, logical approval or disapproval no longer matter, only the hosts following one or the other being. Down on earth it is a matter of mere figures of speech. This is what mankind today is hardly willing to understand, namely, that if we wish to escape from the decline of our age it can no longer be a question of abstractions or merely of what one may think, but that we must deal with realities. We shall begin to ascend to realities when we stop talking about right or wrong and begin speaking about healthy or sick. We begin to rise to realities when we cease talking about programs of parties or world views, and instead speak about following real beings whom we encounter as soon as we become aware of what exists an yonder side of the threshold. It must be our concern today actually to take that serious step that leads from abstraction to reality, from merely logical knowledge to knowledge as deed. This alone can lead us out of the chaos now gripping the world.

The world situation, about which we shall speak tomorrow and the day after, can be judged in a sound way only by someone who examines it with the means that spiritual science is prepared to give him. Otherwise one will be unable to see in the right light the significant, existing contrasts between East and West. All that outwardly manifests itself in visible realities—what else is it but the inherently absurd expression of what lives as thoughts in people's heads? How, then, do these thoughts manifest themselves to us?

To answer this question and to conclude today's presentation, I would like again to call our attention to an obvious example. More than once, I have pointed out how Catholic clerical factions, especially here in Switzerland, are now resorting to a web of lies in order to destroy spiritual science. Those of you who have been here have witnessed a number of examples of what the Catholic Jesuits come up with in the attempt to destroy anthroposophy. Consider the attacks made by Jesuit seminarists with weapons that are certainly not nice. I need not characterize this; those who have not informed themselves can easily do so.

For Switzerland and Central Europe, where these things happen, are all part of the world. So, too, is America. I recently received a magazine published in America in which anthroposophically oriented spiritual science is characterized, while, at the same time, the Jesuits in Europe denounced spiritual science as a threat to the Catholic Church and to Christianity. You know by now that Reverend Kully7 Max Kully: 1878–1936, Catholic minister of Arlesheim near Basle. Reference to a calumnious article against Rudolf Steiner that he wrote in a Catholic Sunday paper, July 6, 1920. stated that there are three evils in the world. One is Judaism, the other Freemasonry, but the third—worse than all of them, even worse than Bolshevism—is what is taught here in Dornach. This originates from the Catholic side, and is how anthroposophy is characterized.

What about America? I want to read you a small paragraph from an American publication written at the same time Catholic journals over here printed their view of anthroposophy:

Just as the Catholic hierarchy has always insisted that the Roman church is the only one with any authority,

—Protestant sects do not come into consideration; according to the Roman church, these sects stand outside the gates; they are viewed merely as a great number of heretics?

so it is self-evident that the church which Steiner's glib tongue alludes to can be none other than the Roman Catholic church. This assumption is reinforced and indeed any doubt about the matter ceases, when one reads Steiner's other occult books. They all point to the same thing, namely, his writings are purely misleading; the sheepskin of a superficial occultism covering the wolf of Jesuitism.

So you see that in America anthroposophy is taken for Jesuitism, while in Europe the Jesuits strongly oppose anthroposophy as the biggest enemy of the Catholic church. That is how the world thinks today! That, however, is also how people think in Europe where they are living side by side; they are just not aware of it.

The American article concludes with several more nice sentences:

Steiner claims to be an initiate. That may be; but whether he is of the White Lodge or belongs to the Brothers of Shadow is something one can only decide when it is realized that he stood on the side of men of “blood and iron” ... and that a number of his students here (in America) were interned as German spies.

So you see, sometimes the wind blows from the Roman Catholic corner, sometimes from the American side! It just shows you how things are inside the heads of our contemporaries. Yet, from the thoughts hatched inside human heads, there developed what has led into the decline of the present, and the ascent must truly be sought in a different direction from the one where many seek it today.

Tomorrow, we shall continue with this subject.

Erster Vortrag

Ich habe auszugehen von der ja sehr erfreulichen Tatsache, daß ich bei meiner Ankunft hier eine große Anzahl von Freunden finden konnte, die neu hier angekommen sind, um sich zu informieren über das, was hier geschehen ist und was von hier aus beabsichtigt wird in unserer anthroposophischen Bewegung. Ich begrüße auf das herzlichste alle die angekommenen Freunde und hoffe, daß sie allerlei Anregungen von ihrem diesmaligen Aufenthalte mitnehmen werden. Es ist ja unter den Freunden, die wir hier wieder sehen können, eine Anzahl solcher, die wir seit Jahren nicht gesehen haben. Und das alles, daß wir seit Jahren manche Freunde nicht sehen konnten, das — mit vielem andern — weist ja hin auf die Schwierigkeiten der Zeit, in der wir leben. Ich selbst komme zurück von einem Stuttgarter Aufenthalte, der mit den mannigfaltigsten, innerhalb unserer anthroposophischen Bewegung gelegenen Aufgaben erfüllt war, der in sich geschlossen hat unter anderem auch den Schluß des ersten Schuljahres der in Stuttgart gegründeten «Waldorfschule». Diese Waldorfschule gehört ja zu denjenigen Einrichtungen, welche im eminentesten Sinne aus unserer anthroposophischen Geistesbewegung heraus gedacht sind. Und was der Abschluß des ersten Schuljahres gezeigt hat, das ist, wie ich glaube, auch dann, wenn man durchaus große Anforderungen stellt, immerhin als etwas Befriedigendes zu bezeichnen. Ich darf das hier aussprechen aus dem Grunde, weil man ja auch wohl solchen Dingen gegenüber objektiv sein kann, auch wenn man mit dem ganzen Herzen daran hängt, und auch dann, wenn man in einer gewissen Weise die Sache selber eingerichtet hat.

Als befriedigend ist vor allen Dingen mit Bezug auf diese Waldorfschule anzusehen, daß die Lehrerschaft es durchaus verstanden hat, erstens sich völlig, so wie es gewollt worden ist, auf anthroposophischen Boden zu stellen. Es sollte dieses Sich-auf-anthroposophischen-BodenStellen so sein, daß — und aus den gegenwärtigen Zeitverhältnissen heraus mußte das sein — die Waldorfschule ja nicht etwa eine Weltanschauungsschule sein sollte, nicht eine Schule, in der man etwa Anthroposophie lehrt. Das war ja nicht die Absicht. Wir haben deshalb absichtlich den Religionsunterricht so eingerichtet, daß diejenigen Kinder, deren Eltern wollten, daß sie den evangelischen Unterricht besuchen, von dem evangelischen Pfarrer unterrichtet werden konnten, die katholischen von dem katholischen Pfarrer und nur für diejenigen, welche sich keiner der bestehenden Konfessionen zuzählen wollten, wurde abgesondert von dem übrigen Unterricht eine Art anthroposophischer Religionsunterricht gegeben. Aber außer dem war es durchaus nicht die Absicht, eine Weltanschauungsschule zu begründen, sondern es war die Absicht, was sich an praktischen, pädagogisch-didaktischen Impulsen ergeben kann aus unserer geisteswissenschaftlichen Anschauung und aus unserem geisteswissenschaftlichen Wollen heraus, daß das einmal in Erziehung und im Unterricht der Jugend wirklich angewendet werde. Also in der Handhabung des Unterrichts, in der Handhabung des ganzen Schulwesens, nicht im Inhalte, sollte das Anthroposophische zum Ausdrucke kommen in der besonderen Artung der Pädagogik und Didaktik und der verschiedenen Unterrichtsmethoden. Allerdings, wenn dann der Anthroposoph aus seinem anthroposophischen Wollen heraus den Unterricht befruchter hat, dann zeigt es sich gerade bei dieser Befruchtung des Unterrichtes, wie belebend Anthroposophie wirkt, wenn sie eben wirklich Tat wird. Ich habe ja immer Gelegenheit gehabt, die Fortschritte während des ersten Schuljahres in der Waldorfschule zu beobachten; ich war ab und zu immer wiederum ein oder zwei Wochen da, konnte den Unterricht kontrollieren, konnte auch sehen, wie die einzelnen Klassen sich entwickeln. Ich konnte zum Beispiel bemerken, wie es unserem Freunde Dr. Stein gelungen war, den Geschichtsunterricht dadurch zu beleben, daß er anthroposophische Impulse in dasjenige hineingebracht hat, was eben schon Geschichtsunterricht für die älteren Schüler ist. Man konnte sehen, wie die Menschenkunde, der anthropologische Unterricht in der fünften Volksschulklasse befruchtet wurde von Fräulein Dr. von Heydebrand dadurch, daß sie nicht jene öde Menschenkunde den Kindern vorbrachte, wie das gewöhnlich in unseren Schulen der Fall ist, sondern daß sie wirklich diese Anthropologie befruchtete aus anthroposophischem Wollen. Und so könnte ich vieles im einzelnen anführen, aus dem Sie ersehen würden, wie, ohne daß man auch nur im entferntesten abstrakt Anthroposophie lehrt, gerade die Methodik, die Art der Behandlungsweise von Anthroposophie befruchtet werden kann und wie gerade diese praktische Anwendung anthroposophischen Wollens zeigt, daß tatsächlich Anthroposophie nicht eine abgezogene, abstrakte Weltanschauung bleiben muß, sondern daß sie unmittelbar eingreifen kann in das menschliche Tun, wenn es uns auch leider nur so wenig gestattet ist, in dieses menschliche Tun einzugreifen, sondern immer nur in so eingeschränkten Gebieten und auch eigentlich nur in solchen Gebieten, wie es eben die Waldorfschule ist. Und als wir dann das erste Schuljahr schlossen, da trat etwas auf, was, ich möchte sagen, zunächst auf scheinbar rein Äußerliches deutete, das aber in Wirklichkeit auf etwas sehr Innerliches deutet, wie ich gleich ausführen werde: eine völlige Neuerung trat auf, das waren die Zeugnisse.

Dieses Zeugniswesen ist ja wirklich das Elendeste in unserem Schulwesen, dieses äußerliche Herumtappen der Lehrer, um da die Note i, 2, 3, 4, 5 und so weiter in die Zeugnisse hineinzuschreiben, das ist im Grunde genommen doch etwas, was in der fürchterlichsten Weise ertötend auf das Schulwesen wirkt. Unsere Zeugnisse sind hervorgegangen aus einer wirklichen Schulpsychologie, aus einer absoluten praktischen Anwendung der menschlichen Seelenkunde. Unsere Lehrer waren am Ende des ersten Schuljahres annähernd so weit, daß sie jedem Kinde ein den Charakterfähigkeiten entsprechendes, die Aussichten für das weitere Fortschreiten individuell bezeichnendes Zeugnis geben konnten. Kein Zeugnis glich dem andern. Keine Ziffernote war darin, sondern aus der individuellen Erkenntnis des Lehrers heraus gegenüber seinem Schüler wurde dem Schüler sein Wesen charakterisiert. Und so intim hatten sich bereits im Laufe des ersten Schuljahres die Lehrer in die Seele des Kindes zu vertiefen gesucht, daß sie jedem Kinde auf dem Zeugnis einen Geleitspruch mitgeben konnten, angemessen dem individuellen Charakter des einzelnen Kindes.

Diese Zeugnisse bilden eine Neuerung. Aber schließen Sie nicht daraus, daß man so etwas ohne weiteres irgendwo einführen kann, daß man es ohne weiteres irgendwo nachmachen kann, sondern das beruht tatsächlich auf dem ganzen Geiste der Waldorfschule, beruht darauf, daß in der Waldorfschule im ersten Schuljahr in der intensivsten Weise Schulpsychologie getrieben worden ist. Sorgfältig wurde von uns studiert, woher gewisse intime Erscheinungen in dem schnelleren oder langsameren Vorwärtskommen einer Klasse kommen. Und man kam schon im Laufe des ersten Schuljahres auf Dinge, die in gewisser Beziehung überraschend sind. So zum Beispiel stellte sich heraus, daß die ganze Konfiguration der Klasse eine ganz bestimmte ist, wenn der Zahl nach gleichviel Knaben und gleichviel Mädchen in der Klasse sind. Ganz anders stellt sich die Konfiguration, wenn die Majorität Knaben, die Minorität Mädchen sind, und umgekehrt wiederum, wenn die Majorität Mädchen, die Minorität Knaben sind. Wir haben alle Beispiele in unseren Klassen gehabt. Diese Imponderabilien, die man sonst gar nicht berücksichtigt, die sind in vieler Beziehung das Wesentliche.

Wenn man gewisse Dinge der Psychologie ausspricht, definieren will, dann sind sie im Grunde genommen schon gar nicht mehr das, um was es sich eigentlich handelt. Und das ist gerade ein großer Unfug in unserer Zeit, daß man die Dinge zu sehr in strammen Wortfolgen zum Ausdruck bringen will. Man kann die Dinge nicht ordentlich studieren, wenn man sie in strammen Wortfolgen zum Ausdruck bringen will. Man muß sich nur bewußt sein, daß dadurch, daß man die Dinge ausdrückt, sie eigentlich immer nur annäherungsweise bezeichnet werden.

Allerdings, wir sind ja immer in einer eigentümlichen Lage, wenn wir von den Ergebnissen unserer anthroposophisch orientierten geisteswissenschaftlichen Bewegung reden. Diese Waldorfschule, deren Lehrerschaft sich im eminentesten Sinne bewährt hat, konnte sich ja nur dadurch bewähren, daß wirklich zunächst die tüchtigsten, für die Pädagogik geeignetsten Menschen zusammengezogen worden sind. Man stößt ja heute leider, wenn man irgend etwas praktisch durchführen will, immer viel mehr als irgend jemand denkt, auf das eine große Hindernis, das ich nur so bezeichnen kann: die Welt ist heute arm an solchen Menschen, die für irgendwelche wirklichen Lebensaufgaben geeignet sind, und die Schwierigkeit würde wesentlich größer, wenn eine zweite Waldorfschule gegründet werden sollte. Da würde die Frage nach den geeigneten, wirklich tüchtigen Persönlichkeiten, die so aus dem Geiste anthroposophisch orientierter Geisteswissenschaft heraus wirken könnten,schon wesentlich schwieriger werden, weil man zu der einen [Schule] selbstverständlich alle diejenigen, die wirklich ernsthaft in Betracht kommen, zusammenziehen mußte. Dennoch, es ist einmal auf einem bestimmten Gebiete ganz zweifellos etwas erreicht worden. Aber ich möchte sagen, man sieht da eine Insel. Auf dieser Insel spielte sich ab im Laufe des ersten Schuljahres ein wirklich aus den Fundamenten der Anthroposophie herausgeholtes Unterrichts-Geisteswesen. Aber diese Insel hat Ufer, ist äußerlich begrenzt, und außerhalb dieser Ufer, da liegt die Finanzierung der Schule, da liegen die wirtschaftlichen Verhältnisse der Schule, die selbstverständlich drinnenstehen in dem niedergehenden wirtschaftlich-staatlichen Leben der Gegenwart. Und da beginnt bereits etwas, von dem man sagen muß: da sind die Aussichten nicht so, wie sie sein sollten, deshalb sein sollten, weil man doch solch einer Sache Verständnis entgegenbringen sollte. Aber steht man eigentlich dem, was schließlich die Waldorfschule aus dem Geiste heraus geleistet hat, in gewissem Grade verständnisvoll gegenüber? Zunächst ist von unserem Freunde Molt die Waldorfschule begründet worden, um den WaldorfKindern, den Kindern der Waldorf-Astoria-Fabrik, Unterricht zu geben. Nun waren schon im ersten Jahre viele fremde Kinder, die nicht der Waldorf-Astoria-Fabrik angehörten, in dieser Schule; so um zweihundertachtzig werden es gewesen sein. Jetzt sind bereits viele neue angemeldet; natürlich aus der Waldorf -Astoria - Fabrik nicht mehr als schon waren, höchstens diejenigen, die in dem entsprechenden Jahre geboren worden sind, und das sind nicht viele, also nur der Nachwuchs. Aber wenn alles wirklich gut geht, das heißt, wenn außer den andern auch die wirtschaftlichen Verhältnisse geordnet werden können, dann werden wir nach den jetzigen Anmeldungen schon über vierhundert Kinder in der Waldorfschule haben. Dazu muß gebaut werden, dazu müssen neue Lehrer angestellt werden, es müssen Parallelklassen begründet werden. All das muß geschehen, und es wird in gewissem Sinne eine Art von Kreuzprobe sein, ob das finanzielle Verständnis der Menschen nachkommen wird jenem Verständnisse, das immerhin schon dadurch bekundet worden ist, daß uns so viele Menschen von außen her ihre Kinder bringen. Ich darf wohl betonen, daß es mir immerhin niedlich vorkam, als auf dem Korridor mir eine Mutter eines in der Waldorfschule vorhandenen Kindes vorgestellt wurde als die Frau Minister Soundso. Also immerhin auch diejenigen, die mit dem gegenwärtigen Staatswesen so liiert sind, und ähnliche andere Leute, bringen uns ihre Kinder in die Waldorfschule.

Die Dinge sollte man eigentlich auch in sozialer Beziehung einmal eingehender studieren. Man würde vielleicht gerade an solchen Erscheinungen, wie die Waldorfschule eine ist, merken können, was wirklich unserer Zeit not tut.

Das, was sich so handgreiflich in der Waldorfschule geltend machte, das war das Auftreten einer gewissen Oberflächlichkeit, die ja, wie ich oftmals hier ausgeführt habe, ein Charakteristikum gerade unserer Zeit ist. Auch an die Leitung der Waldorfschule ist es selbstverständlich herangetreten, daß da oder dort sich Leute fanden, die nun einmal ein bißchen hospitieren wollten, das heißt, etwas hineinriechen wollten in die Waldorfschule. Aber da kann man nicht viel sehen, denn auf die Einzelheiten kommt es dabei nicht an, sondern es kommt auf den ganzen Geist an, der in der Waldorfschule waltet, und der ist einfach der anthroposophische. Und statt daß die Leute, denen es zu langweilig ist, sich mit anthroposophischen Büchern zu befassen, hineingehen und sich einmal ansehen wollen, wie es in der Waldorfschule zugeht, sollten sie lieber sich in Anthroposophie vertiefen. Denn das, was der Waldorfschule den Geist gibt, die eigentliche Grundlage, das kann man lediglich an dem sehen, was an spirituellen Impulsen dem anthroposophischen Geistesleben zugrunde liegt. Dieses anthroposophische Geistesleben ist ja heute, wie ich für diejenigen, die länger hier sitzen, oftmals ausgeführt habe, eben nicht nur etwas, was sich an den einzelnen wendet, wenn er aus den Lebensnöten und aus den Seelennöten heraus den Aufblick zu den geistigen Kräften der Welt sucht, sondern diese Geisteswissenschaft ist etwas, was heute zu der Not unserer Zeit, zu dem ganzen Niedergang unserer Zeit sprechen muß. Da steht dann allerdings dem Verständnis dessen, was Geisteswissenschaft zu sprechen hat, die besondere Art des Verständnisses entgegen, die ein heutiger Mensch durchschnittlich allem entgegenbringen kann, was vor ihm in geistiger Beziehung auftritt. Es ist ja vielfach notwendig, daß, wenn geisteswissenschaftlich gesprochen wird, im Grunde genommen in einer ganz andern Sprache gesprochen werden muß als sonst. Man möchte sagen: Durch die Geisteswissenschaft erhalten die Worte in einer gewissen Beziehung eine neue Bedeutung.

Das zu fühlen, das zu empfinden, das ist durchaus notwendig. Und ich möchte Ihnen heute einiges von dem zeigen, welches Ihnen ersichtlich machen kann, wie notwendig es ist, nicht nur in alten Worten eine etwas andere Weltanschauung hören zu wollen, sondern mit dem Empfinden die Worte anders aufnehmen zu lernen.

Gehen wir von einem bestimmten Falle aus. Wenn heute geredet wird über irgendeine Weltanschauung, so bezeichnet man sie mit einem abstrakten Namen: Materialismus, Idealismus, Realismus, Spiritualismus und so weiter, und man ist einfach der Anschauung, daß man sagen kann: das eine oder das andere ist richtig oder unrichtig. Sagen wir, es ist heute einer Spiritualist. Ein Materialist kommt zu ihm und setzt ihm auseinander, wie er denkt, wie er zum Beispiel sich vorstellt, daß des Menschen Gedanken und Empfindungen ein Produkt des Gehirns sind. Dann wird der Spiritualist sagen: Du denkst unrichtig, ich werde dich logisch widerlegen, oder er wird sagen: Ich werde dich aus den Tatsachen heraus widerlegen. — Kurz, dasjenige, was in Frage kommt, wenn Menschen heute über Weltanschauungsfragen reden, das ist, daß sie das eine als richtig, das andere als unrichtig bezeichnen, daß also etwa der Spiritualist den Materialisten widerlegen will, das heißt, ihm beweisen will, daß er unrecht hat und daß es gut ist, wenn er die richtige Anschauung bekommt, so wie sie der Spiritualist zu haben vermeint.

In einer bloß solchen Lage ist Geisteswissenschaft nicht. Geisteswissenschaft will nicht nur zu einer andern logischen Erkenntnis führen als andere Weltanschauungen, Geisteswissenschaft muß werden, wenn sie ihre Aufgabe erfüllt, Taterkenntnis. Die Erkenntnis muß in ihr zur Tat werden, zur Tat im ganzen kosmischen Weltzusammenhange. Ich will Ihnen das an bestimmten Beispielen darlegen. Wenn die Menschen, die heute die Welt naiv, aber mit ein wenig materialistischer Empfindung betrachten, die Augen, die Ohren nach außen wenden, Töne hören, Farben wahrnehmen, Wärmeempfindungen haben und dergleichen, dann sehen sie die äußere Sinneswelt. Werden sie dann Wissenschafter oder nehmen sie auch nur in populärer Weise in sich auf, was Wissenschaft sein will, dann werden sie sich gewisse Vorstellungen, gewisse Begriffe ausbilden oder auch einfach nur aufnehmen, die durch die Kombination dieser in der Außenwelt gesehenen Farbenelemente, Tonelemente, Wärmeelemente und so weiter entstanden sind. Es gibt ja Leute, die sagen, daß alles, was man zunächst sieht, äußere Erscheinung ist. Aber diese Anschauung, daß alles äußere Erscheinung ist, nehmen die Menschen nicht tief genug. Sie sehen zum Beispiel den Regenbogen. Allerdings, wenn sie den Regenbogen betrachten, sind sie schon durch das, was sie nun einmal schulmäßig gelernt haben, davon überzeugt, daß der Regenbogen nur eine Erscheinung ist, daß man zum Beispiel nicht dahin gehen kann, wo der Regenbogen ist und hübsch das eine Bein zunächst auf die Brücke setzen und so über den Regenbogen als einen festen Gegenstand hinwegmarschieren kann. Die Menschen sind überzeugt, daß sie das nicht können, daß der Regenbogen nur eine Erscheinung, ein Phänomen ist, das aufsteigt und das wiederum abflutet. Aber nur so lange sind sie davon überzeugt, daß sie es da draußen in der Außenwelt mit Erscheinungen zu tun haben, solange sie mit dieser Außenwelt nicht durch ihren Tastsinn, durch ihren Gefühlssinn in Berührung kommen. Sobald sie etwas in der Außenwelt greifen können, dann ist es ihrer Empfindung gemäß nicht mehr in demselben Grade eine Erscheinung, wenn auch die neuere Philosophie das vielfach behauptet hat, aber es ist nicht für die Menschen der Empfindung gemäß eine Erscheinung. Mindestens gelten gefühlsmäßig die Eindrücke des Tastsinnes zum Beispiel als etwas, was eine andere äußere Wirklichkeit verbürgt als zum Beispiel die Erscheinungswirklichkeiten des Regenbogens.

Und dennoch, alles, was wir mit den äußeren Sinnen wahrnehmen, enthält nur Erscheinungswelt, modifiziert vielleicht gegenüber den Erscheinungen des Regenbogens, aber doch nur Erscheinungswelt: Wie weit wir auch den Blick richten, wie weit wir auch hören, was wir auch hören können, was wir auch sonst wahrnehmen können, in der Außenwelt haben wir es überall mit Erscheinungen zu tun, mit Phänomenen. Das habe ich ja schon in meiner Einleitung zum dritten Bande von Goethes naturwissenschaftlichen Schriften darzustellen versucht. In der Außenwelt haben wir es mit einem Gewebe von Erscheinungen zu tun. Und wer es versucht, sei es durch das Experiment, sei es durch irgendwelche Kombinationen verstandesmäßiger Art, da draußen im Reiche der Erscheinungen etwas von Materie zu finden, so wie man sich Materie vorstellt, der ist auf dem Holzwege. Es gibt da draußen nichts, was man als Materie auffinden könnte. Da hat man es mit Erscheinungswelt zu tun.

Das ist etwas, was ja, wenn ich den Ausdruck gebrauchen darf, aus dem ganzen Geiste der Geisteswissenschaft hervorgeht. Man hat es da draußen mit Erscheinungswelt zu tun. Nun wird derjenige, der heute auf dem Boden einer geläufigen Weltanschauung steht, kommen und sagen: Also ist es unrichtig, daß man die Materie draußen im Reiche der Erscheinungen suchen sollte. — Diese Redeweise kann Anthroposophie nicht teilen. Sie muß anders sagen. Sie muß sagen: Der Mensch kann durch das ganze Gefüge seines Geistes dazu kommen, in dem Gewebe, in dem Wogen der Phänomene, der Erscheinungen Materie suchen zu wollen, da draußen irgend etwas suchen zu wollen von Atomen, Molekülen und so weiter, welche Ruhepunkte sind in der Erscheinung. Die einen stellen sie wie kleine Schrotkörner vor, wenn auch nur ganz kleine, die andern stellen sie vor wie Kraftpunkte und sind sehr stolz darauf, sie so vorzustellen, wieder andere stellen sie vor als mathematische Fiktionen und sind noch stolzer darauf. Darauf kommt es nicht an, ob man sie sich als kleine Schrotkörner oder als Kraftpunkte oder als mathematische Fiktionen denkt, es kommt darauf an, ob man sich die Außenwelt atomistisch denkt. Darauf kommt es an. Es ist aber für den Geisteswissenschafter nicht bloß unrichtig, atomistisch zu denken. Ein solcher Begriff von richtig und unrichtig ist logisch, ist abstrakt, und Geisteswissenschaft hat es mit Realitäten zu tun. Ich bitte Sie, das sehr ernst aufzufassen, wenn ich sage: Geisteswissenschaft hat es mit Realitäten zu tun. - Daher müssen gewisse Begriffe, die für die gewöhnliche, heute so abstrakt gewordene Weltanschauung bloße logische Kategorien sind, durch Reales ersetzt werden. Daher sprechen wir in der Geisteswissenschaft nicht bloß davon, daß derjenige etwas Unrichtiges denkt, der in der Außenwelt Atome und Moleküle sucht, sondern wir müssen das Denken, das so vorgeht, als ein ungesundes, als ein krankes Denken auffassen. Den bloß logischen Begriff des Unrichtigen müssen wir ersetzen durch den realen Begriff des Kranken, des Ungesunden. Und wir müssen hindeuten auf eine ganz bestimmte Seelenerkrankung — wenn sie auch noch so viele Menschen ergriffen hat —,, die sich dadurch ausspricht, daß man atomistisch denkt. Und diese Seelenverfassung ist diejenige des Schwachsinns. Es ist für uns nicht bloß logisch unrichtig, atomistisch zu denken, es ist der Ausdruck eines schwachsinnigen Geistes, bloß atomistisch zu denken, das heißt, in der Außenwelt etwas anderes zu suchen als dasjenige, was Phänomene sind, was schließlich gleichwertig ist mit der Erscheinung des Regenbogens. Man hat es verhältnismäßig leicht in andern Weltanschauungen, die Dinge zurechtzurücken: man widerlegt. Man glaubt, etwas getan zu haben, wenn man widerlegt hat. Geisteswissenschaftlich ist damit nicht alles getan, wenn man widerlegt hat, sondern da kommt es darauf an, daß man auf das gesunde und kranke Seelenleben hinweist, auf reale Prozesse, die sich im ganzen Menschen, im Körperlichen, Seelischen und Geistigen darleben. Und atomistisch denken, ist krank denken, ist nicht bloß unrichtig denken. Es ist ein realer ungesunder Prozeß, der sich abspielt im menschlichen Organismus, wenn wir atomistisch denken. Das ist das eine, worüber wir uns klar werden müssen bezüglich der Phänomene der Außenwelt, bezüglich des Erscheinungscharakters der Außenwelt.

Auch in bezug auf unser Inneres müssen wir uns klar werden. Viele Menschen suchen das Geistige im Innern. Zunächst findet man das Geistige im menschlichen Inneren nicht. Die wirklich objektive Betrachtung jeder abstrakten Mystik zeigt das. Was man manchmal Mystik nennt, ja vielleicht nicht manchmal, sondern was man in unserer Zeit sehr häufig Mystik nennt, besteht darin, daß man in sein Inneres hineinbrütet, daß man, wie man sagt, Selbsterkenntnis durch dieses In-seinInneres-Hineinbrüten sucht. Was findet man, wenn man solche einseitige Mystik treibt? Gewiß, man findet interessante Dinge. Aber wenn man in den Menschen hineinschaut und einem da jene innerlich so wohlgefälligen Erlebnisse aufsteigen, die man als mystischen Inhalt bezeichnet, was sind sie eigentlich? Nun, das sind gerade die Dinge, welche uns auf das materielle Dasein hinweisen. Materie finden wir nicht in der Außenwelt, wo die Erscheinungen der Sinne sind, Materie finden wir in unserem Inneren. Wir sind jetzt so weit, daß wir diese Dinge in der richtigen Weise charakterisieren können. Da brodelt und kocht im menschlichen Inneren der Stoffwechsel im weitesten Umfange; und die Flamme, die der Stoffwechsel schafft, wenn sie ins Bewußtsein heraufschlägt, das ist die einseitige Mystik, von der viele glauben, daß es der Geist ist, den man im Inneren finden kann. Es ist nicht der Geist, es sind die Flammen des Stoffwechsels im Inneren des Menschen. Nicht in der Außenwelt finden wir die Materie, in uns selbst finden wir sie, und gerade durch einseitige Mystik finden wir sie. Daher täuschen sich viele, die nicht materialistisch sein möchten und die aber dieses Nicht-materialistisch-sein-Wollen begleiten mit den Worten, die sie etwa so aussprechen: Da draußen ist die niedere Materie; über die erhebe ich mich und wende mich dem eigenen Inneren zu, da finde ich den Geist. — Nichts vom Geiste zunächst ist weder draußen noch innen. Draußen sind die Erscheinungen, die ineinanderwebenden Erscheinungen, und in unserem Inneren ist die Materie, da ist das Kochen und Brodeln der Materie. Und dieses Kochen und Brodeln der Materie läßt die Flammen aufflackern, die ins Bewußtsein hereinschlagen und die Mystik bilden. Mystik ist die innerlich wahrgenommene Körpermaterie des Stoffwechsels. Und diese Mystik ist wiederum nicht etwas, was man logisch widerlegen kann, sondern was man zurückführen muß auf reale Prozesse, wenn der Mensch sich dem Stoffwechsel in einseitiger Weise hingibt. So wie der Glaube, daß man in der äußeren Welt etwas von Materie finden kann, auf Schwachsinn hinweist, also auf eine reale Erkrankung des Geistig-Seelisch-Körperlichen des Menschen, so weist auf eine körperliche Ungesundheit das einseitige Weben in der Mystik hin. Es weist hin auf etwas, das sich ja ein bißchen beleidigend ausnimmt, wenn man es so einfach ausspricht. Aber es muß da ein Ausdruck angewendet werden, der gewissermaßen von jenseits des Hüters der Schwelle gesprochen ist, und dann heißt der Ausdruck «Kindsköpfigkeit». So wie man schwachsinnig wird durch atomistisches Denken über die Außenwelt, so wird man kindsköpfig, wenn man sich einer Mystik hingibt, die den Geist in dem Brodeln des inneren Stoffwechsels spüren will.

Kindsköpfigkeit hat natürlich auch eine gute Seite, denn wenn wir das Kind betrachten, so ist in dem Kinde sehr viel Geist, und Genialität besteht vielfach darin, daß sich der Mensch bis ins spätere Alter den kindlichen Geist bewahrt. Und wenn wir von jenseits der Schwelle die Welt betrachten, so sehen wir, wie der Geist es ist, der im Kinde zum Beispiel das Gehirn formt, jener Geist, der schon herauskommt aus der geistigen Welt, wenn wir durch die Konzeption oder Geburt in die physische Welt einziehen. Dieser Geist, der da aus der geistigen Welt herauskommt, der ist im Kinde am meisten tätig, verliert sich später. Und da ist dann kindsköpfig nicht etwa ein Schimpfwort, sondern da bedeutet es nur, daß es eben der Geist ist, der aus einem fast chaotischen Klumpen heraus das Gehirn formt, der heruntergestiegen ist durch die Tat des Geistes aus der geistigen Welt in die physische Welt. Aber wenn dieser Geist, der eigentlich das Gehirn des Kindes formen soll, später nicht so wirkt, daß er sich hineinergießt in die Logizität, in die Erfahrung, in die Erlebnisse, sondern wenn er dann einseitig wirkt und die einzelnen materiellen Erlebnisse ausschließt, wenn er so weiter wirken will, wie er in den ersten sieben Lebensjahren gewirkt hat, dann wird man statt genial kindsköpfig. Und Kindsköpfigkeit ist ein Charakteristikum einer großen Anzahl von oftmals sehr hochmütigen Mystikern. Sie wollen weben und leben in dem Geist, der eigentlich im kindlichen Organismus tätig sein sollte, der ihnen aber verblieben ist, und den sie nun im Bewußtsein, indem sie sich selber außerordentlich viel darauf zugute tun, anstaunen, und während sie die bloße Materie des Stoffwechsels wahrnehmen, glauben sie, eine höhere Geistigkeit in ihrer einseitigen abstrakten Mystik wahrzunehmen.

Wiederum wollen wir nicht bloß den einseitigen Mystiker widerlegen, wenn wir wirklich auf dem Boden einer anthroposophisch orientierten Geisteswissenschaft stehen, sondern wir müssen zeigen, daß es auf einer kranken Konstitution des Geistes, der Seele, des Leibes beruht, wenn der Mensch, einseitig in sein Inneres hineinbrütend, den Geist finden will.

Ich habe Ihnen diese beiden Beispiele, die Ihnen ja hinlänglich aus der anthroposophischen Literatur bekannt sind, hier von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte angeführt, um Ihnen zu zeigen, wie die Dinge ernst werden, wenn man aus dem gewöhnlichen heutigen Geistesleben hineintaucht in das anthroposophische. Da hat man es nicht zu tun mit etwas so Leichtwiegendem wie «falsch» oder «richtig», sondern um «gesund» oder «krank» in den organischen Funktionen. So muß man auf einer höheren Stufe das, was nach einer gewissen Richtung hin geht, als gesund, oder das, was nach einer andern Richtung geht, als krank bezeichnen. Und ich möchte, daß Sie aus diesen Andeutungen verstehen, wie Geisteswissenschaft Taterkenntnis ist, wie sie nicht stehenbleiben kann bei dem Charakter der gewöhnlichen Erkenntnis, sondern wie sie wird dasjenige, was Realität ist. Der Erkenntnisprozeß, insofern er sich in der Geisteswissenschaft ausspricht, ist etwas, was real sich vollzieht im menschlichen Organismus.

In einer ähnlichen Weise muß charakterisiert werden dasjenige, was auf dem Gebiete des Willens lebt. Wenn wir vom Gebiete des Willens sprechen in unserem Zeitalter, das diesen grandiosen Niedergang enthält, über den wir oftmals gesprochen haben, wenn wir von dem sprechen, was sich als menschliche Willensimpulse ausbildet, und vom Charakter dieser Willensimpulse, dann sagen wir: Der Mensch ist gut oder böse. —- Und es sind uns wiederum gut und böse sittliche Kategorien, die selbstverständlich ebenso notwendig sind wie die logischen Kategorien. Aber für dasjenige, was als Impulse aus der Geisteswissenschaft herausfließt, handelt es sich nicht allein um das, was man meint, wenn man irgendeine Handlung des Menschen als gut, eine andere als böse bezeichnet. Da handelt es sich darum, daß man - selbst im karmischen Zusammenhange -, wenn man eine Handlung als gut bezeichnet, sagen will: Der Mensch muß das Gute mit dem Bösen in irgendeiner Weise ausgleichen. Man meint etwas, was zur sittlichen Beurteilung des Menschen gehört. In dem Augenblicke, wo wir in die Gebiete hineinsteigen, welche die geisteswissenschaftlichen sind, handelt es sich um mehr, da handelt es sich darum, daß es eine gewisse Art und Weise des Denkens, Fühlens und Wollens für die Menschen gibt, die zum Aufstieg führt, die zu einer fruchtbaren Entwickelung führt, zu einem Vorwärtskommen in der Entwickelung. Auf der einen Seite haben wir das abstrakte Gute, das sittlich-abstrakte, außerordentlich wertvolle, aber eben sittlich-abstrakte Gute; wenn es sich aber um die Impulse der Geisteswissenschaft handelt, hat der Mensch nicht nur das Gute zu tun, oder wird der Mensch nicht nur das Gute tun, das ihn als einen sittlich guten Menschen erscheinen läßt, sondern er kann dasjenige tun oder denken oder fühlen, was die Welt in ihrer Entwickelung bloß in der äußeren Sinneswelt weiterbringt, oder er kann etwas tun, was nicht bloß böse ist und zur sittlichen Beurteilung beiträgt, sondern was auf die Weltenkräfte zerstörerisch wirkt. Das sollte schon in der «Pforte der Einweihung» angedeutet werden, da wo Strader und Capesius sprechen und darauf hingedeutet wird: Was hier in der sinnlichen Welt getan wird, was hier der sittlichen Beurteilung von Gut und Böse unterliegt, das sind hinter den Kulissen des Daseins Erscheinungen, die vorwärtswirkend-aufbauend oder niedergehend-zerstörend sind. Versuchen Sie nur zu fühlen diese ganze Szene, wo es blitzt und donnert, wo es in der Seelenwelt in einer sehr realen Weise hergeht, während Capesius und Strader dieses oder jenes besprechen, versuchen Sie diese Szene nachzufühlen, dann werden Sie sehen, wie sich da zur Realität steigert, was wir als die sittliche Welt hier auf dem physischen Plane erleben.

Das alles soll Ihnen zeigen, wie es beginnt, mit der Welt ernst zu werden in dem Augenblicke, wo man von der bloßen heute gewohnten Beurteilung nach logischen oder nach bloß äußerlich-menschlichen Kategorien zu den Realitäten aufsteigt, die uns entgegentreten, wenn wir die Welt geisteswissenschaftlich betrachten. Die Dinge werden ernst, aber sie müssen heute ausgesprochen werden, denn die Welt fordert heute ein neues Geistesleben. Heute gehen die Dinge in der Welt vor, die ein jeder sieht, die aber niemand eigentlich in ihrer realen Bedeutung verstehen will, weil man den Schritt nicht machen kann von der äußerlichen Abstraktheit zur Realität. Ich will Sie auf noch andere Beispiele hinweisen.

Sie erleben es heute, daß Sie hineinwachsen in eine Welt, in der es unter vielem andern, auf sozialem Felde zum Beispiel, Parteien gibt, liberale, konservative und alle möglichen andern Parteien. Die Menschen schlafen gegenüber dem, was diese Parteien sind. Wenn sie Wahlzettel erhalten, so bekennen sie sich zu einer oder der andern Partei, denken nicht viel darüber nach, was eigentlich das ist, was im ganzen öffentlichen Leben, dieses Leben durchwühlend, als Parteimeinung existiert. Man kann eben die Dinge nicht ernst nehmen. Da ist eine ganze Menge von Leuten, die plappern in der schönsten Weise alle möglichen Orientalismen von Maja in der Außenwelt nach; aber sobald sie einen Schritt in dieser Außenwelt machen wollen, dann bleiben sie nicht bei dem, was sie abstrakt nachplappern. Denn sonst würden sie zum Beispiel fragen: Maja? Also sind auch die Parteien Maja? Was ist denn die Wirklichkeit, auf die diese Maja hinweist?

Geht man geisteswissenschaftlich — und wir werden uns morgen genauer über diese Sache aussprechen — genauer auf diese Sache ein, dann findet man, daß Parteien in der äußeren physischen Welt da sind, indem sie Programme haben, Grundsätze haben, das heißt, indem sie abstrakten Ideen nachjagen. Aber alles, was äußerlich in der physischen Welt lebt, ist immer das Abbild, der Abglanz dessen, was in der geistigen Welt eine Realität intensiverer Art ist. Da haben wir immer die physische Welt (siehe Zeichnung, waagrechte Linie). Aber alles hier in der physischen Welt weist hin auf Geistiges. Und da oben in der geistigen Welt sind für diese physischen Dinge erst die eigentlichen Realitäten (siehe Zeichnung, rot). Da unten sind zum Beispiel die Parteien (weiß); wovon sind sie Abglanz? Auf der Erde bekämpfen sich diese Parteien; da suchen sie eine Menge von Menschen unter einem abstrakten Programm zusammenzuhalten. Wovon sind denn diese Parteien der Abglanz? Was ist denn da oben in der geistigen Welt, wenn hier in der Maja die Parteien sind? In der geistigen Welt gibt es keine Abstraktionen, und die Parteien stehen unter Abstraktionen. Da oben gibt es nur Wesen. Da oben kann man sich nicht zu einem Parteiprogramm bekennen, sondern da kann man Anhänger dieses oder jenes Wesens, dieser oder jener Hierarchie sein. Man kann dort nicht bloß mit seinem Intellekt einem Programm anhängen, das gibt es da nicht; man muß mit seinem ganzen Menschen einem andern Wesen nachgehen. Was hier abstrakt ist, ist da oben wesenhaft, das heißt, das Abstrakte ist hier nur Schatten des Wesenhaften da oben. Und wenn Sie die beiden Hauptkategorien der Parteien, konservativ und liberal, nehmen, so ist es so, daß die konservative Partei ein Programm hat, die liberale Partei ein Programm hat; aber wenn man hinaufsieht, wovon das der Abglanz ist, dann zeigt sich: Ahrimanisches Wesen schattet sich hier (siehe Zeichnung, unterer Teil) im Konservativen ab, luziferisches Wesen schattet sich hier ab im Liberalen. Hier läuft man einem konservativen oder einem liberalen Programm nach, oben ist man Anhänger von einem ahrimanischen Wesen irgendeiner Hierarchie oder einem luziferischen Wesen irgendeiner Hierarchie.

Dabei kann es aber vorkommen, daß man in dem Augenblicke, wo man die Schwelle überschreitet (das Wort «Schwelle» wird an die Tafel geschrieben), nötig hat, sich wirklich klar darüber zu sein, daß man sich nicht durch Worte täuschen läßt, sich keinen Illusionen hingibt. Man kann sehr leicht glauben, man gehöre zu irgendeinem guten Wesen. Aber damit, daß man irgendein Wesen mit einem guten Namen bezeichnet, ist es noch nicht ein gutes. Es kann zum Beispiel irgend jemand sagen: Ich bekenne mich zu Jesus, dem Christus. — In der geistigen Welt kann man sich nicht zu einem Programm bekennen, aber nach der ganzen Art und Weise, wie die Vorstellungen, die Begriffe von diesem Jesus, dem Christus, in seiner Seele leben, ist es nur der Name des Jesus, des Christus, in Wirklichkeit hängt er dann Luzifer oder Ahriman an und ergibt nur Luzifer oder Ahriman den Namen Jesus oder Christus.

Aber ich frage Sie: Wie viele Menschen wissen heute davon, daß Parteimeinungen Abschattungen sind von Wesenhaftem in der geistigen Welt? Manche wissen es, und die richten dann das, was sie tun, nach diesem Wissen ein. Ich kann Sie hinweisen auf solche, die so etwas wissen. Nehmen Sie die Jesuiten, die wissen das. Glauben Sie nicht, daß die Jesuiten meinen, wenn sie zum Beispiel in ihren Blättern jetzt gegen Anthroposophie schreiben, daß sie mit ihren Gründen da irgend etwas besonders träfen, was nicht widerlegt werden könnte. Aber auf Widerlegungen kommt es dabei nicht an. Und was man schließlich einwenden kann gegen solche Widerlegungen, das wissen die Jesuiten sehr gut, denn den Jesuiten kommt es nicht darauf an, mit Gründen für oder wider zu fechten, sondern ihnen kommt es darauf an, Anhänger zu sein eines gewissen Wesens, das ich aber heute noch nicht bezeichnen will, das sie aber ihren Anführer Jesus nennen, dem sie zugehören. Mag dieses Wesen sein, was immer, sie nennen es Jesus. Ich will nicht auf den Tatbestand genauer hinweisen; aber sie bezeichnen sich als Soldaten, ihn als den Anführer, und sie kämpfen nicht, um zu widerlegen, sie kämpfen, um Anhänger zu werben für die Kompanien, für das Heer des Jesus, das heißt desjenigen Wesens, das sie Jesus nennen. Und sie wissen ganz genau, daß, sobald man über die Schwelle hinaufschaut, es nicht auf abstrakte Kategorien, nicht auf logische Zusagen oder Widerlegungen ankommt, sondern daß es da ankommt auf die Heerfolge des einen oder des andern Wesens, während es unten auf der Erde sich um Redensarten handelt. Das ist aber dasjenige, was die Menschen heute so schwer begreifen wollen, daß, wenn wir heraus wollen aus dem Niedergang der Zeit, es sich nicht mehr handeln darf um bloße Abstraktionen, nicht bloß um das, was man sich denken kann, sondern daß es sich um Realitäten handeln muß, Wir beginnen zu Realitäten aufzusteigen, wenn wir nicht mehr bloß von richtig oder unrichtig, sondern von gesund oder krank sprechen. Wir beginnen zu Realitäten aufzusteigen, wenn wir nicht von Parteiprogrammen oder Weltanschauungsprogrammen sprechen, sondern von der Gefolgschaft irgend welcher realer Wesenheiten, die uns sogleich begegnen, wenn wir auf die Dinge hindeuten, die jenseits der Schwelle liegen. Es handelt sich heute darum, wirklich jenen ernsten Schritt zu machen von der Abstraktion zur Realität, von der bloß logischen Erkenntnis zur Erkenntnis als Tat. Und nur das kann herausführen aus all der Verwirrung, in der die Welt heute steckt.