The New Spirituality

and the Christ Experience of the Twentieth Century

GA 200

17 October 1920, Dornach

Lecture I

In the lectures given here during the course on history1 These were the lectures given by Dr Karl Heyer on 14, 15 and 16 October 1920, during the first course of the School of Anthroposophy at the Goetheanum with the theme: 'The Science of History and History from the Viewpoint of Anthroposophy' ('Anthroposophische Betrachtungen Ober die Geschichtswissenschaft und aus der Geschichte'). These are printed in Kultur und Erziehung (the third volume of the Courses of the School of Anthroposophy), Stuttgart, 1921. several things were mentioned which, particularly at the present time, it is especially important to consider. With regard to the historical course of humanity's development, the much-debated question mentioned to begin with was whether the outstanding and leading individual personalities are the principal driving forces in this development or whether the most important things are brought about by the masses. In many circles this has always been a point of contention and the conclusions have been drawn, more from sympathy and antipathy than from real knowledge. This is one fact which, in a certain sense, I should like to mention as being very important.

Another fact which, from a look at history, I should like to mention for its importance is the following. At the beginning of the nineteenth century Wilhelm von Humboldt2 See Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835): Über die Aufgabe des Geschiclztsschreibens (The Task of the Historian) in Volume IV of Humboldt's Works published by Leitzman, Berlin 1905 (see pages 35-56). Some relevant passages taken from these are as follows:

"The business of the historian, in the last but simplest analysis, is to portray the striving of an idea to attain existence in reality. For it is not always that it succeeds in this at the first attempt; and it is not so rare that the idea degenerates because it is unable to master in a pure way the matter counteracting it."

"The truth of everything that happens lies in the addition of the above-mentioned invisible part of every fact, and thus the history writer must add this to the events. Seen from this angle he is self-acting and even creative—not, indeed, by producing what does not already exist, but by forming out of his own inner strength that which, as it is in reality, he could not perceive through mere receptivity. In different ways, but just like the poet, he must in himself transform the scattered fragments into a whole."

"It may seem dubious to allow the realm of the history writer and that of the poet to meet, even at only one point. But the activity of both is undeniably related. For if the historian, like the poet, can achieve truth in his presentation of past events only by completing and linking the incomplete and disjointed elements of direct observation, then he does so, like the poet, only through imagination. Because, however, he places imagination subordinate to experience and the fathoming of reality, there is a difference here which cancels out all danger. Imagination does not work, at this lower position, as pure imagination, and is therefore more properly called an intuitive faculty and a talent for finding links."

"Of necessity, therefore, the historian too, must strive; not, like the poet, to give his material over to the dominion of the form of necessity but to hold steadily in consciousness the ideas which are its laws, because, permeated only by, these, he can then find their trace in the pure research of the real in its reality."

"The historian encompasses all the threads of earthly activity and all varieties of supersensible ideas; the sum-total of existence, more or less, is the object of his work and he must therefore also follow all avenues of the mind and spirit. Speculation, experience and poetry, however, are not separate, opposed and mutually-limiting activities of the mind, but different planes of its radiance."

"Apart from the fact that history, like every scientific activity, serves many subsidiary purposes, work on history is no less a free art, complete in itself, than philosophy and poetry."

"Just as philosophy strives for the first foundation of things, and art for the ideal of beauty, so history strives for a picture of human destiny in faithful truth, living abundance and pure clarity that are perceived by the warm inner-being [of the historian] in such a way that his personal views, feelings and demands are lost and dissolved away. It is the final purpose of the history-writer to awaken and nourish this mood, which, however, he only attains when he pursues for his fellow human beings the simple presentation of past events with conscientious faithfulness." appeared with a definite declaration, stipulating that history should be treated in such a way that one would not only consider the individual facts which can be outwardly observed in the physical world but, out of an encompassing, synthesizing force, would see what is at work in the unfolding of history—which can only be found by someone who knows how to get a total view of the facts in what in a sense is a poetic way, but in fact produces a true picture. Attention was also drawn to how in the course of the nineteenth century it was precisely the opposite historical mode of thought and approach which was then particularly developed, and that it was not the ideas in history that were pursued but only a sense that was developed for the external world of facts. Attention was also drawn to the fact that, with regard to this last question, one can only come to clarity through spiritual science, because spiritual science alone can uncover the real driving forces of the historical evolution of humanity.

A spiritual science of this kind was not yet accessible to Humboldt. He spoke of ideas, but ideas indeed have no driving force [of their own]. Ideas as such are abstractions, as I mentioned here yesterday3 See the final words of Rudolf Steiner, on 16 October 1920, after the close of the first course of the Anthroposophical School, in Die Kunst der Rezitation and Deklamation (First Edition) Dornach, 1928, page 118. And anyone who might wish to find ideas as the driving forces of history would never be able to prove that ideas really do anything because they are nothing of real substantiality, and only something of substantiality can do something. Spiritual science points to real spiritual forces that are behind the sensible-physical facts, and it is in real spiritual forces such as these that the propelling forces of history lie, even though these spiritual forces will have to be expressed for human beings through ideas.

But we come to clarity concerning these things only when, from a spiritual-scientific standpoint, we look more deeply into the historical development of humanity and we will do so today in such a way that, through our considerations, certain facts come to us which, precisely for a discerning judgement of the situation of modern humanity, will prove to be of importance.

I have often mentioned4 See i>Geschictliche Symptomatologie (GA 185), nine lectures given in Dornach in 1918, only two of which are translated in From Symptom to Reality in Modern History. that spiritual science, if it looks at history, would actually have to pursue a symptomatology; a symptomatology constituted from the fact that one is aware that behind what takes it course as the stream of physical-sensible facts lie the driving spiritual forces. But everywhere in historical development there are times when what has real being and essence (das eigentlich Wesenhafte) comes as a symptom to the surface and can be judged discerningly from the phenomena only if one has the possibility to penetrate more deeply from one's awareness of these phenomena into the depths of historical development.

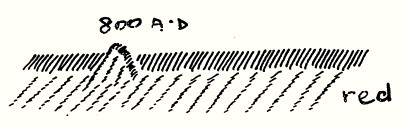

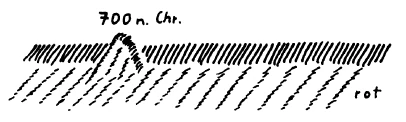

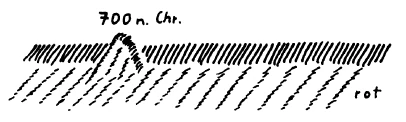

I would like to clarify this by a simple diagram. Let us suppose that this is a flow of historical facts (see diagram). The driving forces lie, for ordinary observation, below the flow of these facts. And if the eye of the soul observes the flow in this way, then the real activity of the driving forces would lie beneath it (red). But there are significant points in this flow of facts. And these significant points are distinguished by the fact that what is otherwise hidden comes here to the surface. Thus we can say: Here, in a particular phenomenon, which must only be properly evaluated, it was possible to become aware of something which otherwise is at work everywhere, but which does not show itself in such a significant manifestation.

Let us assume that this (see diagram) took place in some year of world history, let us say around 800 A.D. What was significant for Europe, let us say for Western Europe, was of course at work before this and worked on afterwards, but it did not manifest itself in such a significant way in the time before and after as it did here. If one points to a way of looking at history like this, a way which looks to significant moments, such a method would be in complete accord with Goetheanism. For Goethe wished in general that all perception of the world should be directed to significant points and then, from what could be seen from such points, the remaining content of world events be recognized. Goethe says of this5 See Bedeutende Fordnis durch ein einziges geistreiches Wort in Goethes Naturwissenschaftliche Schriften, edited and with a commentary by Rudolf Steiner in Kürschner's Deutsche National-Literatur, Volume II, page 34 (GA lb). Goethe says here:

"I do not rest until I find a significant point from which a great deal can be deduced or, rather, which of its own will brings forth a great deal and presents this to me, and which I then, with attention and receptivity, work on further faithfully and carefully. If, in my experience, I find some phenomenon which I cannot deduce, I simply let it lie as a problem; and I have found, in my long life, this way of doing things to be very beneficial. For when I was not able for a long time to unravel the origin or connection of some phenomenon but had to put it to one side, I found that, years later, it all suddenly became clear in the most beautiful way." that, within the abundance of facts, the important thing is to find a significant point from which the neighbouring areas can be viewed and from which much can be deciphered.

So let us take this year 800 A.D. We can point here to a fact in the history of Western European humanity which, from the point of view of the usual approach to history, might seem insignificant—which one would perhaps not find worthy of attention for what is usually called history—but which, nevertheless, for a deeper view of humanity's development, is indeed significant. Around this year there was a kind of learned theological argument between the man who was a sort of court philosopher of the Frankish realm, Alcuin,6 Alcuin (also Alhuin or Alchwin, i.e. 'Friend of the Temple') was rector of the monastery school at York around 735 to 804. In 782 he followed the summons of Charlemagne and took on the headship of the court school. He encouraged the sciences in the monasteries and raised to the central seat of the sciences the monastery school of St Martin at Tours, which he founded and whose Abbot he became in 796.

The debate with the Greek is described in Karl Werner's book Alcuin and sein Jahrhundert (Alcuin and His Century) Vienna 1881, Chapter 11. page 166, as follows:

Thus Charlemagne once wanted to know from Alcuin what should be made of the view of a Greek scholar, who presumably was a member of a Byzantine legation at Charlemagne's court, who had expressed the opinion to the emperor that Christ had paid the expiation for our sins to death. Alcuin found this manner of expression and the idea behind it to be inadmissible, for Christ was not—death's debtor and could not become so—the price of our redemption was paid by Christ to our divine Father, to whom, in dying, He commended His soul. Death [so Alcuin argued] is in no way a reality of being and substance but, to his way of thinking, was something purely negative, the mere absence or 'Carence' (Church Latin: the interval before benefits become available) of life; it is nothing existing in itself, and thus cannot receive anything, no payment can be paid to it. On the contrary, in the person of Christ, death itself, which God did not create, became the ransom for our debt and won life for us thereby, which He Himself gives us in His saviour power.' and a Greek also living at that time in the kingdom of the Franks. The Greek, who was naturally at home in the particular soul-constitution of the Greek peoples which he had inherited, had wanted to reach a discerning judgement of the principles of Christianity and had come to the concept of redemption. He put the question: To whom, in the redemption through Christ Jesus, was the ransom actually paid? He, the Greek thinker, came to the solution that the ransom had been paid to Death. Thus, in a certain sense, it was a sort of redemption theory that this Greek developed from his thoroughly Greek mode of thinking, which was now just becoming acquainted with Christianity. The ransom was paid to Death by the cosmic powers.

Alcuin, who stood at that time in that theological stream which then became the determining one for the development of the Roman Catholic Church of the West, debated in the following way about what the Greek had argued. He said: Ransom can only be paid to a being who really exists. But death has no reality, death is only the outer limit of reality, death itself is not real and, therefore, the ransom money could not have been paid to Death.

Now criticism of Alcuin's way of thinking is not what matters here. For to someone who, to a certain extent, can see through the interrelations of the facts, the view that death is not something real resembles the view which says: Cold is not something real, it is just a decrease in warmth, it is only a lesser warmth. Because the cold isn't real I won't wear a winter coat in winter because I'm not going to protect myself against something that isn't real. But we will leave that aside. We want rather to take the argument between Alcuin and the Greek purely positively and will ask what was really happening there. For it is indeed quite noticeable that it is not the concept of redemption itself that is discussed. It is not discussed in such a way that in a certain sense both personalities, the Greek and the Roman Catholic theologian, accept the same point of view, but in such a way that the Roman Catholic theologian shifts the standpoint entirely before he takes it up at all. He does not go on speaking in the way he had just done, but moves the whole problem into a completely different direction. He asks: Is death something real or not?—and objects that, indeed, death is not real.

This directs us at the outset to the fact that two views are clashing here which arise out of completely different constitutions of soul. And, indeed, this is the case. The Greek continued, as it were, the direction which, in the Greek culture, had basically faded away between Plato and Aristotle. In Plato there was still something alive of the ancient wisdom of humanity; that wisdom which takes us across to the ancient Orient where, indeed, in ancient times a primal wisdom had lived but which had then fallen more and more into decadence. In Plato, if we are able to understand him properly, we find the last offshoots, if I can so call them, of this primal oriental wisdom. And then, like a rapidly developing metamorphosis, Aristotelianism sets in which, fundamentally, presents a completely different constitution of soul from the Platonic one. Aristotelianism represents a completely different element in the development of humanity from Platonism. And, if we follow Aristotelianism further, it, too, takes on different forms, different metamorphoses, but all of which have a recognizable similarity. Thus we see how Platonism lives on like an ancient heritage in this Greek who has to contend against Alcuin, and how in Alcuin, on the other hand, Aristotelianism is already present. And we are directed, by looking at these two individuals, to that fluctuation which took place on European soil between two—one cannot really say world-views—but two human constitutions of soul, one of which has its origin in ancient times in the Orient, and another, which we do not find in the Orient but which, entering in later, arose in the central regions of civilization and was first grasped by Aristotle. In Aristotle, however, this only sounds a first quiet note, for much of Greek culture was still alive in him. It develops then with particular vehemence in the Roman culture within which it had been prepared long before Aristotle, and, indeed, before Plato. So that we see how, since the eighth century BC on the Italian peninsula a particular culture, or the first hints of it, was being prepared alongside that which lived on the Greek peninsula as a sort of last offshoot of the oriental constitution of soul. And when we go into the differences between these two modes of human thought we find important historical impulses. For what is expressed in these ways of thinking went over later into the feeling life of human beings; into the configuration of human actions and so on.

Now we can ask ourselves: So what was living in that which developed in ancient times as a world-view in the Orient, and which then, like a latecomer, found its [last] offshoots in Platonism—and, indeed, still in Neoplatonism? It was a highly spiritual culture which arose from an inner perception living pre-eminently in pictures, in imaginations; but pictures not permeated by full consciousness, not yet permeated by the full I-consciousness of human beings. In the spiritual life of the ancient Orient, of which the Veda and Vedanta are the last echoes, stupendous pictures opened up of what lives in the human being as the spiritual. But it existed in a—I beg you not to misunderstand the word and not to confuse it with usual dreaming—it existed in a dreamlike, dim way, so that this soul-life was not permeated (durchwellt) and irradiated (durchstrahlt) by what lives in the human being when he becomes clearly conscious of his 'I' and his own being. The oriental was well aware that his being existed before birth, that it returns through death to the spiritual world in which it existed before birth or conception. The oriental gazed on that which passed through births and deaths. But he did not see as such that inner feeling which lives in the `I am'. It was as if it were dull and hazy, as though poured out in a broad perception of the soul (Gesamtseelenanschauung) which did not concentrate to such a point as that of the I-experience. Into what, then, did the oriental actually gaze when he possessed his instinctive perception?

One can still feel how this oriental soul-constitution was completely different from that of later humanity when, for an understanding of this and perhaps prepared through spiritual science, one sinks meditatively into those remarkable writings which are ascribed to Dionysius the Areopagite.7 Rudolf Steiner drew attention at different times to the fact that the content of the writings of 533 A.D., attributed to Dionysius the Areopagite, do indeed stem from the person of this name mentioned in The Acts of the Apostles 17, 34. See the lectures on 17 and 25 March 1907 in Christianity Began as a Religion and Festivals of the Seasons respectively. I will not go into the question of the authorship now, I have already spoken about it on a number of occasions. 'Nothingness' (das Nichts) is still spoken of there as a reality, and the existence of the external world, in the way one views it in ordinary consciousness, is simply contrasted against this [nothingness] as a different reality. This talk of nothingness then continues. In Scotus Erigena,8 Johannes Scotus Erigena (c. 810–877) translator of the writings of Dionysius the Areopagite into Latin (see note 7). who lived at the court of Charles the Bald, one still finds echoes of it, and we find the last echo then in the fifteenth century in Nicolas of Cusa9 Nicolaus of Cusa (or Kures) (1401–1464), cardinal. But what was meant by the nothingness one finds in Dionysius the Areopagite and of that which the oriental spoke of as something self-evident to him? This fades then completely. What was this nothingness for the oriental? It was something real for him. He turned his gaze to the world of the senses around him, and said: This sense-world is spread out in space, flows in time, and in ordinary life world, is spread out in space, one says that what is extended in space and flows in time is something.

But what the oriental saw—that which was a reality for him, which passes through births and deaths—was not contained in the space in which the minerals are to be found, in which the plants unfold, the animals move and the human being as a physical being moves and acts. And it was also not contained in that time in which our thoughts, feelings and will-impulses occur. The oriental was fully aware that one must go beyond this space in which physical things are extended and move, and beyond this time in which our soul-forces of ordinary life are active. One must enter a completely different world; that world which, for the external existence of time and space, is a nothing but which, nevertheless, is something real. The oriental sensed something in contrast to the phenomena of the world which the European still senses at most in the realm of real numbers.

When a European has fifty francs he has something. If he spends twenty-five francs of this he still has twenty-five francs; if he then spends fifteen francs he still has ten; if he spends this he has nothing. If now he continues to spend he has five, ten, fifteen, twenty-five francs in debts. He still has nothing; but, indeed, he has something very real when, instead of simply an empty wallet, he has twenty-five or fifty francs in debts. In the real world it also signifies something very real if one has debts. There is a great difference in one's whole situation in life between having nothing and having fifty francs' worth of debts. These debts of fifty francs are forces just as influential on one's situation in life as, on the other side and in an opposite sense, are fifty francs of credit. In this area the European will probably admit to the reality of debts for, in the real world, there always has to be something there when one has debts. The debts that one has oneself may still seem a very negative amount, but for the person to whom they are owed they are a very positive amount!

So, when it is not just a matter of the individual but of the world, the opposite side of zero from the credit side is truly something very real. The oriental felt—not because he somehow speculated about it but because his perception necessitated it he felt: Here, on the one side, I experience that which cannot be observed in space or in time; something which, for the things and events of space and time, is nothing but which, nevertheless, is a reality—but a different reality.

It was only through misunderstanding that there then arose what occidental civilization gave itself up to under the leadership of Rome—the creation of the world out of nothing with `nothing' seen as absolute `zero'. In the Orient, where these things were originally conceived, the world does not arise out of nothing but out of the reality I have just indicated. And an echo of what vibrates through all the oriental way of thinking right down to Plato—the impulse of eternity of an ancient world-view—lived in the Greek who, at the court of Charlemagne, had to debate with Alcuin. And in this theologian Alcuin there lived a rejection of the spiritual life for which, in the Orient, this `nothing' was the outer form. And thus, when the Greek spoke of death, whose causes lie in the spiritual world, as something real, Alcuin could only answer: But death is nothing and therefore cannot receive ransom.

You see, the whole polarity between the ancient oriental way of thinking, reaching to Plato, and what followed later is expressed in this [one] significant moment when Alcuin debated at the court of Charlemagne with the Greek. For, what was it that had meanwhile entered in to European civilization since Plato, particularly through the spread of Romanism? There had entered that way of thinking which one has to comprehend through the fact that it is directed primarily to what the human being experiences between birth and death. And the constitution of soul which occupies itself primarily with the human being's experiences between birth and death is the logical, legal one—the logical-dialectical-legal one. The Orient had nothing of a logical, dialectical nature and, least of all, a legal one. The Occident brought logical, legal thinking so strongly into the oriental way of thinking that we ourselves find religious feeling permeated with a legalistic element. In the Sistine Chapel in Rome, painted by the master-hand of Michelangelo, we see looming towards us, Christ as judge giving judgment on the good and the evil.

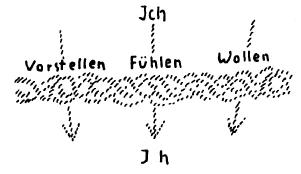

A legal, dialectical element has entered into the thoughts concerning the course of the world. This was completely alien to the oriental way of thinking. There was nothing there like guilt and atonement or redemptinn. For [in this oriental way of thinking] was precisely that view of the metamorphosis through which the eternal element [in the human being] transforms itself through births and deaths. There was that which lives in the concept of karma. Later, however, everything was fixed into a way of looking at things which is actually only valid for, and can only encompass, life between birth and death. But this life between birth and death was just what had evaded the oriental. He looked far more to the core of man's being. He had little understanding for what took place between birth and death. And now, within this occidental culture, the way of thinking which comprehends primarily what takes place within the span between birth and death increased [and did so] through those forces possessed by the human being by virtue of having clothed his soul-and-spirit nature with a physical and etheric body. In this constitution, in the inner experience of the soul-and-spirit element and in the nature of this experience, which arises through the fact that one is submerged with one's soul-and-spirit nature in a physical body, comes the inner comprehension of the 'I'. This is why it happens in the Occident that the human being feels an inner urge to lay hold of his 'I' as something divine. We see this urge, to comprehend the 'I' as something divine, arise in the medieval mystics; in Eckhart, in Tauler and in others. The comprehension of the 'I' crystallizes out with full force in the Middle (or Central) culture. Thus we can distinguish between the Eastern culture—the time in which the 'I' is first experienced, but dimly—and the Middle (or Central) culture—primarily that in which the 'I' is experienced. And we see how this 'I' is experienced in the most manifold metamorphoses. First of all in that dim, dawning way in which it arises in Eckhart, Tauler and other mystics, and then more and more distinctly during the development of all that can originate out of this I-culture.

We then see how, within the I-culture of the Centre, another aspect arises. At the end of the eighteenth century something comes to the fore in Kant10Immanuel Kant (1724–1804): Critique of Pure Reason, 1781; Prolegemena, 1783. which, fundamentally, cannot be explained out of the onward flow of this I-culture. For what is it that arises through Kant? Kant looks at our perception, our apprehension (Erkennen), of nature and cannot come to terms with it. Knowledge of nature, for him, breaks down into subjective views ( Subjektivitäten); he does not penetrate as far as the 'I' despite the fact that he continually speaks of it and even, in some categories, in his perceptions of time and space, would like to encompass all nature through the 'I'. Yet he does not push through to a true experience of the 'I'. He also constructs a practical philosophy with the categorical imperative which is supposed to manifest itself out of unfathomable regions of the human soul. Here again the 'I' does not appear.

In Kant's philosophy it is strange. The full weight of dialectics, of logical-dialectical-legal thinking is there, in which everything is tending towards the 'I', but he cannot reach the point of really understanding the 'I' philosophically. There must be something preventing him here. Then comes Fichte, a pupil of Kant's, who with full force wishes his whole philosophy to well up out of the 'I' and who, through its simplicity, presents as the highest tenet of his philosophy the sentence: `I am'. And everything that is truly scientific must follow from this `I am'. One should be able, as it were, to deduce, to read from this 'I am' an entire picture of the world. Kant cannot reach the 'I am'. Fichte immediately afterwards, while still a pupil of Kant's, hurls the `I am' at him. And everyone is amazed—this is a pupil of Kant's speaking like this! And Fichte says:11Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814) Erste und zweite Einleitung in die Wissenschaftslehre und Verstwh einer neuen Darstellung der Wiyenschaftslehre (First and Second Introduction into the Doctrine of Knowledge and an Attempt at a New Presentation of the doctrine of Knowledge). As far as he can understand it, Kant, if he could really think to the end, would have to think the same as me. It is so inexplicable to Fichte that Kant thinks differently from him, that he says: If Kant would only take things to their full conclusion, he would have to think [as I do]; he too, would have to come to the 'I am'. And Fichte expresses this even more clearly by saying: I would rather take the whole of Kant's critique for a random game of ideas haphazardly thrown together than to consider it the work of a human mind, if my philosophy did not logically follow from Kant's. Kant, of course, rejects this. He wants nothing to do with the conclusions drawn by Fichte.

We now see how there follows on from Fichte what then flowered as German idealistic philosophy in Schelling and Hegel, and which provoked all the battles of which I spoke, in part, in my lectures on the limits to a knowledge of nature.12Grenzen der Naturerkenntnis (Limits to a Knowledge of Nature (GA 322)—eight lectures given during the first course (Hochschulkurs) of the School of Spiritual Science in Dornach, 27 September to 3 October 1920 (GA 322). But we find something curious. We see how Hegel lives in a crystal-clear [mental] framework of the logical-dialectical-legal element and draws from it a world-view—but a world-view that is interested only in what occurs between birth and death. You can go through the whole of Hegel's philosophy and you will find nothing that goes beyond birth and death. It confines everything in world history, religion, art and science solely to experiences occurring between birth and death.

What then is the strange thing that happened here? Now, what came out in Fichte, Schelling and Hegel—this strongest development of the Central culture in which the 'I' came to full consciousness, to an inner experience—was still only a reaction, a last reaction to something else. For one can understand Kant only when one bears the following properly in mind. (I am coming now to yet another significant point to which a great deal can be traced). You see, Kant was still—this is clearly evident from his earlier writings—a pupil of the rationalism of the eighteenth century, which lived with genius in Leibnitz and pedantically in Wolff. One can see that for this rationalism the important thing was not to come truly to a spiritual reality. Kant therefore rejected it—this `thing in itself' as he called it—but the important thing for him was to prove. Sure proof! Kant's writings are remarkable also in this respect. He wrote his Critique of Pure Reason in which he is actually asking: `How must the world be so that things can be proved in it?' Not 'What are the realities in it?' But he actually asks: 'How must I imagine the world so that logically, dialectically, I can give proofs in it?' This is the only point he is concerned with and thus he tries in his Prologomena to give every future metaphysics which has a claim to being truly scientific, a metaphysics for what in his way of thinking can be proven: `Away with everything else! The devil take the reality of the world—just let me have the art of proving! What's it to me what reality is; if I can't prove it I shan't trouble myself over it!'

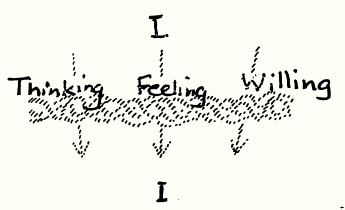

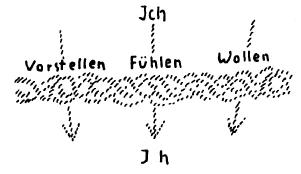

Those individuals did not, of course, think in this way who wrote books like, for example, Christian Wolff's13Baron Christian von Wolff, philosopher and mathematician, Vernünftige Gedanken von Gott, der Welt und der Seele des Menschen, auch allen Dingen überhaupt, 1719. Vernünftige Gedanken von Gott, der Welt und der Seele des Menschen, auch allen Dingen überhaupt (Reasoned Thoughts an God, the World, and the Soul of Man, and All Things Generally). What mattered for them was to have a clean, self-contained system of proof, in the way that they see proof. Kant lived in this sphere, but there was still something there which, although an excrescence squeezed out of the world-view of the Centre, nevertheless fitted into it. But Kant had something else which makes it inexplicable how he could become Fichte's teacher. And yet he gives Fichte a stimulus, and Fichte comes back at him with the strong emphasis of the 'I am'; comes back, indeed, not with proofs—one would not look for these in Fichte—but with a fully developed inner life of soul. In Fichte there emerges, with all the force of the inner life of soul, that which, in the Wolffians and Leibnitzites, can seem insipid. Fichte constructs his philosophy, in a wealth of pure concepts, out of the 'I am'; but in him they are filled with life. So, too, are they in Schelling and in Hegel. So what then had happened with Kant who was the bridge? Now, one comes to the significant point when one traces how Kant developed. Something else became of this pupil of Wolff by virtue of the fact that the English philosopher, David Hume,14David Hume (1711–1776), philosopher. awoke him, as Kant himself says, out of his dull dogmatic slumber. What is it that entered Kant here, which Fichte could no longer understand? There entered into Kant here—it fitted badly in his case because he was too involved with the culture of Central Europe—that which is now the culture of the West. This came to meet him in the person of David Hume and it was here that the culture of the West entered Kant. And in what does the peculiarity [of this culture] lie? In the oriental culture we find that the 'I' still lives below, dimly, in a dream-like state in the soul-experiences which express themselves, spread out, in imaginative pictures. In the Western culture we find that, in a certain sense, the 'I' is smothered (erdrückt) by the purely external phenomena (Tatsachen). The 'I' is indeed present, and is present not dimly, but bores itself into the phenomena. And here, for example, people develop a strange psychology. They do not talk here about the soul-life in the way Fichte did, who wanted to work out everything from the one point of the 'I', but they talk about thoughts which come together by association. People talk about feelings, mental pictures and sensations, and say these associate—and also will-impulses associate. One talks about the inner soul-life in terms of thoughts which associate.

Fichte speaks of the 'I'; this radiates out thoughts. In the West the 'I' is completely omitted because it is absorbed—soaked up by the thoughts and feelings which one treats as though they were independent of it, associating and separating again. And one follows the life of the soul as though mental pictures linked up and separated. Read Spencer,15Herbert Spencer (1820–1903), philosopher. read John Stuart Mill16John Stuart Mill (1806–1873), philosopher. read the American philosophers. When they come to talk of psychology there is this curious view that does not exclude the 'I' as in the Orient, because it is developed dimly there, but which makes full demand of the 'I'; letting it, however, sink down into the thinking, feeling and willing life of the soul. One could say: In the oriental the 'I' is still above thinking, feeling and willing; it has not yet descended to the level of thinking, feeling and willing. In the human being of the Western culture the 'I' is already below this sphere. It is below the surface of thinking, feeling and willing so that it is no longer noticed, and thinking, feeling and willing are then spoken of as independent forces.

This is what came to Kant in the form of the philosophy of David Hume. Then the Central region of the earth's culture still set itself against this with all force in Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel. After them the culture of the West overwhelms everything that is there, with Darwinism and Spencerism.

One will only be able to come to an understanding of what is living in humanity's development if one investigates these deeper forces. One then finds that something developed in a natural way in the Orient which actually was purely a spiritual life. In the Central areas something developed which was dialectical-legal, which actually brought forth the idea of the State, because it is to this that it can be applied. It is such thinkers as Fichte, Schelling and Hegel who, with enormous sympathy, construct a unified image (Gebilde) of the State. But then a culture emerges in the West which proceeds from a constitution of soul in which the 'I' is absorbed, takes its course below the level of thinking, feeling and willing; and where, in the mental and feeling life, people speak of associations. If only one would apply this thinking to the economic life! That is its proper place. People went completely amiss when they started applying [this thinking] to something other than the economic life. There it is great, is of genius. And had Spencer, John Stuart Mill and David Hume applied to the institutions of the economic life what they wasted on philosophy it would have been magnificent. If the human beings living in Central Europe had limited to the State what is given them as their natural endowment, and if they had not, at the same time, also wanted thereby to include the spiritual life and the economic life, something magnificent could have come out of it. For, with what Hegel was able to think, with what Fichte was able to think, one would have been able—had one remained within the legal-political configuration which, in the threefold organism, we wish to separate out as the structure of the State17Towards Social Renewal, 1919, (GA 23).—to attain something truly great. But, because there hovered before these minds the idea that they had to create a structure for the State which included the economic life and the spiritual life, there arose only caricatures in the place of a true form for the State. And the spiritual life was anyway only a heritage of the ancient Orient. It was just that people did not know that they were still living from this heritage of the ancient East. The useful statements, for example, of Christian theology—indeed, the useful statements still within our materialistic sciences—are either the heritage of the ancient East, or a changeling of dialectical-legal thinking, or are already adopted, as was done by Spencer and Mill, from the Western culture which is particularly suited for the economic life.

Thus the spiritual thinking of the ancient Orient had been distributed over the earth, but in an instinctive way that is no longer of any use today. Because today it is decadent, it is dialectical-political thinking which was rendered obsolete by the world catastrophe [World War I]. For there was no one less suited to thinking economically than the pupils of Fichte, Schelling and Hegel. When they began to create a State which, above all, was to become great through its economy, they had of necessity (selbstverständlich) to fail, for this was not what, by nature, was, endowed to them. In accordance with the historical development of humanity, spiritual thinking, political thinking and economic thinking were apportioned to the East, the Centre, and the West respectively. But we have arrived at a point of humanity's development when understanding, a common understanding, must spread equally over all humanity. How can this come about?

This can only happen out of the initiation-culture, out of the new spiritual science, which does not develop one-sidedly, but considers everything that appears in all areas as a three-foldness that has evolved of its own accord. This science must really consider the threefold aspect also in social life; in this case (as a three-foldness) encompassing the whole earth. Spiritual science, however, cannot be extended through natural abilities; it can only be spread by people accepting those who see into these things, who can really experience the spiritual sphere, the political sphere and the economic sphere as three separate areas. The unity of human beings all over the earth is due to the fact that they combine in themselves what was divided between three spheres. They themselves organize it in the social organism in such a way that it can exist in harmony before their eyes. This, however, can only follow from spiritual-scientific training. And we stand here at a point where we must say: In ancient times we see individual personalities, we see them expressing in their words what was the spirit of the time. But when we examine it closely—in the oriental culture, for example—we find that, fundamentally, there lives instinctively in the masses a constitution of soul which in a remarkable; quite natural way was in accord with what these individuals spoke.

This correspondence, however, became less and less. In our times we see the development of the opposite extreme. We see instincts arising in the masses which are the opposite of what is beneficial for humanity. We see things arising that absolutely call for the qualities that may arise in individuals who are able to penetrate the depths of spiritual science. No good will come from instincts, but only from the understanding (that Dr. Unger also spoke of here)18In the third week of the first course (of the School of Spiritual Science), Dr Carl Unger (1822–1929) gave lectures under the title of 'Rudolf Steiner's Works'. These six lectures, edited by Unger, can be found in Volume I of Carl Unger's Writings, Stuttgart, 1964. which, as is often stressed, every human being can bring towards the spiritual investigator if he really opens himself to healthy human reason. Thus there will come a culture in which the single individual, with his ever-deeper penetration into the depths of the spiritual world, will be of particular importance, and in which die one who penetrates in this way will be valued, just as someone who works in some craft is valued. One does not go to the tailor to have boots made or to the shoemaker to be shaved, so why should people go to someone else for what one needs as a world-view other than to the person who is initiated into it? And it is, indeed, just this that, particularly today and in the most intense sense, is necessary for the good of human beings even though there is a reaction against it, which shows how humanity still resists what is beneficial for it. This is the terrible battle—the grave situation—in which we find ourselves.

At no other time has there been a greater need to listen carefully to what individuals know concerning one thing or another. Nor has there been a greater need for people with knowledge of specific subject areas to be active in social life—not from a belief in authority but out of common sense and out of agreement based on common sense. But, to begin with, the instincts oppose this and people believe that some sort of good can be achieved from levelling everything. This is the serious battle in which we stand. Sympathy and antipathy are of no help here, nor is living in slogans. Only a clear observation of the facts can help. For today great questions are being decided—the questions as to whether the individual or the masses have significance. In other times this was not important because the masses and the individual were in accord with one another; individuals were, in a certain sense, simply speaking for the masses. We are approaching more and more that time when the individual must find completely within himself the source of what he has to find and which he has then to put into the social life; and [what we are now seeing] is only the last resistance against this validity of the individual and an ever larger and larger number of individuals. One can see plainly how that which spiritual science shows is also proved everywhere in these significant points. We talk of associations which are necessary in the economic life, and use a particular thinking for this. This has developed in the culture of the West from letting thoughts associate. If one could take what John Stuart Mill does with logic, if one could remove those thoughts from that sphere and apply them to the economic life, they would fit there. The associations which would then come in there would be exactly those which do not fit into psychology. Even in what appears in the area of human development, spiritual science follows reality.

Thus spiritual science, if fully aware of the seriousness of the present world situation, knows what a great battle is taking place between the threefold social impulse that can come from spiritual science and that which throws itself against this threefoldness as the wave of Bolshevism, which would lead to great harm (Unheil) amongst humanity. And there is no third element other than these two. The battle has to take place between these two. People must see this! Everything else is already decadent. Whoever looks with an open mind at the conditions in which we are placed, must conclude that it is essential today to gather all our forces together so that this whole terrible Ahrimanic affair can be repulsed.

This building stands here,19The first Goetheanum building, begun in 1913, was already put into use in 1920, although still under construction supervised by Rudolf Steiner and with the interior not yet finished. On New Year's Eve 1922–3 it was destroyed by fire. incomplete though it is for the time being. Today we cannot get from the Central countries that which for the most part, and in addition to what has come to us from the neutral states, has brought this building to this stage. We must have contributions from the countries of the former Entente. Understanding must be developed here for what is to become a unified culture containing spirit, politics and economics. For people must get away from a one:sided tendency and must follow those who also understand something of politics and economics, who do not work only in dialectics, but, also being engaged with economic impulses, have insight into the spiritual, and do not want to create states in which the State itself can run the economy. The Western peoples will have to realize that something else must evolve in addition to the special gift they will have in the future with regard to forming economic associations. The skill in forming associations has so far been applied at the wrong end, i.e. in the field of Psychology. What must evolve is understanding of the political-state element, which has other sources than the economic life, and also of the spiritual element. But at present the Central countries lie powerless, so people in the Western regions—one could not expect this of the Orient—will have to see what the Purpose of this building is! It is necessary for us to consider What must be done so that real provision is made for a new culture that should be presented everywhere in the university education of the future—here we have to show the way. In the foundation of the Waldorf Schools the culture has proved to be capable of bringing light into primary education. But for this we need the understanding support of the widest circles.

Above all we need the means. For everything which, in a higher or lower sense, is called a school, we need the frame of mind I have already tried to awaken at the opening of the Waldorf School in Stuttgart.20The Free Waldorf School was founded in Stuttgart in the spring of 1919 by Dr Emil Molt for the children, to begin with, of the employees of the Waldorf-Astoria cigarette factory. The school was under the supervision of Rudolf Steiner who appointed the teachers and gave the preparatory seminar courses. I said in my opening speech there: `This is one Waldorf school. It is well and good that we have it, but for itself it is nothing; it is only something if, in the next quarter of a year, we build ten such Waldorf schools and then others'. The world did not understand this, it had no money for such a thing. For it rests on the standpoint: Oh, the ideals are too lofty, too pure for us to bring dirty money to them; better to keep it in our pockets; that's the proper place for dirty money. The ideals, oh, they're too pure, one can't contaminate them with money! Of course, with purity of this kind the embodiment of ideals cannot be attained, if dirty money is not brought to them. And thus we have to consider that, up to now, we have stopped at one Waldorf school which cannot progress properly because in the autumn we found ourselves in great money difficulties. These have been obviated for the time being, but at Easter we shall be faced with them again. And then, after a comparatively short time, we will ask: Should we give up? And we shall have to give up if, before then, an understanding is not forthcoming which dips vigorously into its pockets.

It is thus a matter of awakening understanding in this respect. I don't believe that much understanding would arise if we were to say that we wanted something for the building in Dornach, or some such thing—as has been shown already. But—and one still finds understanding for this today—if one wants to create sanatoria or the like, one gets money, and as much as one wants! This is not exactly what we want—we don't want to build a host of sanatoria—we agree fully with creating them as far as they are necessary; but here it is a matter, above all, of nurturing that spiritual culture whose necessity will indeed prove itself through what this course21The first anthroposophical course of the Free School for Spiritual Science took place at the Goetheanum from 26 September to 16 October 1920. See also notes 1,3,12, and 18. I has attempted to accomplish. This is what I tried to suggest, to give a stimulus to what I expressed here a few days ago, in the words 'World Fellowship of Schools' (Weltschulverein).22i.e., a form of international support body for Waldorf Schools. Rudolf Steiner suggested the founding of a World Fellowship of Schools during an assembly of teachers on 16 October 1920. There is no available transcript of this talk.

Our German friends have departed but it is not a question of depending on them for this 'World Fellowship'. It depends on those who, as friends, have come here, for the most part from all possible regions of the non-German world—and who are still sitting here now—that they understand these words 'World Fellowship of Schools' because it is vital that we found school upon school in all areas of the world out of the pedagogical spirit which rules in the Waldorf School. We have to be able to extend this school until we are able to move into higher education of the kind we are hoping for here. For this, however, we have to be in a position to complete this building and everything that belongs to it, and be constantly able to support that which is necessary in order to work here; to be productive, to work on the further extension of all the separate sciences in the spirit of spiritual science.

People ask one how much money one needs for all this. One cannot say how much, because there never is an uppermost limit. And, of course, we will not be able to found a World Fellowship of Schools simply by creating a committee of twelve or fifteen or thirty people who work out nice statutes as to how a World Fellowship of Schools of this kind should work. That is all pointless. I attach no value to programmes or to statutes but only to the work of active people who work with understanding. It will be possible to establish this World Fellowship—well, we shall not be able to go to London for some time—in the Hague or some such place, if a basis can be created, and by other means if the friends who are about to go to Norway or Sweden or Holland, or any other country—England, France, America and so on—awaken in every human being whom they can reach the well-founded conviction that there has to be a World Fellowship of Schools. It ought to go through the world like wildfire that a World Fellowship must arise to provide the material means for the spiritual culture that is intended here.

If one is able in other matters, as a single individual, to convince possibly hundreds and hundreds of people, why should one not be able in a short time—for the decline is happening so quickly that we only have a short time—to have an effect on many people as a single individual, so that if one came to the Hague a few weeks later one would see how widespread was the thought that: 'The creation of a World Fellowship of Schools is necessary, it is just that there are no means for it.' What we are trying to do from Dornach is an historical necessity. One will only be able to talk of the inauguration of this World Fellowship of Schools when the idea of it already exists. It is simply utopian to set up committees and found a World Fellowship—this is pointless! But to work from person to person, and to spread quickly the realization, the well-founded realization, that it is so necessary—this is what must precede the founding. Spiritual science lives in realities. This is why it does not get involved with proposals of schemes for a founding but points to what has to happen in reality—and human beings are indeed realities—so that such a thing has some prospects.

So what is important here is that we finally learn from spiritual science how to stand in real life. I would never get involved with a simply utopian founding of the World Fellowship of Schools, but would always be of the opinion that this World Fellowship can only come about when a sufficiently large number of people are convinced of its necessity. It must be created so that what is necessary for humanity—it has already proved to be so from our course here—can happen. This World Fellowship of Schools must be created.

Please see what is meant by this Fellowship in all international life, in the right sense! I would like, in this request, to round off today what, in a very different way in our course, has spoken to humanity through those who were here and of whom we have the hope and the wish that they carry it out into the world. The World Fellowship of Schools can be the answer of the world to what was put before it like a question; a question taken from the real forces of human evolution, that is, human history. So let what can happen for the World Fellowship of Schools, in accordance with the conviction you have been able to gain here, happen! In this there rings out what I wanted to say today.

Erster Vortrag

Es ist in den Vorträgen, die hier während des Kursus über Geschichte gehalten worden sind, mehreres erwähnt worden, das zu betrachten gerade in der gegenwärtigen Zeit von einer ganz besonderen Wichtigkeit sein kann. Zunächst ist in bezug auf den geschichtlichen Verlauf der Menschheitsentwickelung die ja oftmals besprochene Frage erwähnt worden, ob die hauptsächlichsten treibenden Kräfte in dieser Entwickelung die einzelnen hervorragenden, tonangebenden Persönlichkeiten seien, oder ob das Wesentliche bewirkt werde nicht von diesen einzelnen Persönlichkeiten, sondern von den Massen. Es ist dieses in vielen Kreisen immer ein strittiger Punkt gewesen, und über ihn wurde wirklich mehr aus Sympathie und Antipathie heraus entschieden als aus wirklicher Erkenntnis. Das ist die eine Tatsache, die ich gewissermaßen als wichtig erwähnen möchte. Die andere Tatsache, die ich gerade aus den geschichtlichen Betrachtungen heraus als wichtig hier notieren möchte, ist die folgende: Mit einem deutlichen Kundgeben ist im Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts Wilhelm von Humboldt aufgetreten, indem er verlangt hat, die Geschichte solle so betrachtet werden, daß man nicht nur die einzelnen Tatsachen in Erwägung zieht, die äußerlich in der physischen Welt zu beobachten sind, sondern aus einer zusammenfassenden, synthetisierenden Kraft heraus dasjenige sieht, was im geschichtlichen Werden wirksam ist, was aber eigentlich nur gefunden werden kann von demjenigen, der in einem gewissen Sinne dichterisch, aber dann eigentlich die Wahrheit dichtend, die geschichtlichen Tatsachen zusammenzufassen weiß. Es ist auch darauf aufmerksam gemacht worden, wie im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts dann gerade die entgegengesetzte geschichtliche Denkweise und Gesinnung eine besondere Ausbildung erfahren hat, wie keineswegs Ideen in der Geschichte verfolgt worden sind, sondern eben nur der Sinn für die äußere Tatsachenwelt entwickelt worden ist. Und es ist darauf aufmerksam gemacht worden, daß gerade über die letztere Frage eigentlich erst zur Klarheit gekommen werden kann aus der Geisteswissenschaft heraus, weil ja erst die Geisteswissenschaft die wirklichen treibenden Kräfte des geschichtlichen Werdens der Menschheit enthüllen kann. Humboldt war eine solche Geisteswissenschaft noch nicht zugänglich. Er sprach von Ideen, aber Ideen haben doch keine treibende Kraft. Ideen als solche sind eben Abstraktionen, wie ich schon gestern hier erwähnte. Und derjenige, der auch Ideen als die treibenden Kräfte der Geschichte finden möchte, könnte niemals beweisen, daß diese Ideen wirklich etwas tun, denn sie sind nichts Wesenhaftes, und nur Wesenhaftes kann etwas tun. Die Geisteswissenschaft deutet auf wirkliche geistige Kräfte hin, die hinter den sinnlich-physischen Tatsachen sind, und in solchen wirklichen geistigen Kräften liegen die Motoren des Geschichtlichen, wenn auch diese geistigen Kräfte für den Menschen dann eben durch Ideen ausgedrückt werden müssen.

Aber über all diese Dinge kommen wir nur zur Klarheit, wenn wir einen tieferen Blick eben gerade vom geisteswissenschaftlichen Standpunkte aus in das geschichtliche Werden der Menschheit werfen, und wir wollen es heute einmal so tun, daß durch unsere Betrachtungen einige Tatsachen uns erfließen, die gerade für die Beurteilung der gegenwärtigen Menschheitssituation wichtig sein können. Ich habe schon öfter erwähnt, daß die Geisteswissenschaft, wenn sie geschichtliche Betrachtungen anstellt, dann eigentlich eine Symptomatologie betreiben müsse, eine Symptomatologie, die darin besteht, daß man sich bewußt ist: Hinter dem, was als physisch-sinnlicher Tatsachenstrom abläuft, liegen die treibenden geistigen Kräfte. Aber es gibt überall in dem geschichtlichen Werden Punkte, wo das eigentlich Wesenhafte symptomatisch an die Oberfläche tritt und wo man es beurteilen kann aus den Erscheinungen heraus, wenn man nur die Möglichkeit hat, in seiner Erkenntnis von diesen Erscheinungen aus mehr hineinzudringen in die Tiefen des geschichtlichen Werdens.

Ich möchte das durch eine einfache versinnlichende Zeichnung klarmachen. Nehmen wir einmal an, dies wäre ein Strom von geschichtlichen Tatsachen (siehe Zeichnung). Dasjenige, was treibende Kräfte sind, liegt eigentlich für die gewöhnliche Beobachtung unter dem Strom dieser Tatsachen. Wenn etwa ein Seelenauge diesen Strom der Tatsachen so beobachtet, dann würde unter dem Strom der Tatsachen das eigentliche Wirken der treibenden Kräfte liegen (rot). Aber es gibt bedeutsame Punkte innerhalb des Tatsachenstromes. Und diese bedeutsamen Punkte zeichnen sich eben dadurch aus, daß bei ihnen das sonst sich Verbergende an die Oberfläche tritt. So daß wir sagen können: Hier würde an einer besonderen Erscheinung, die man nur richtig abschätzen muß, klarwerden können, was auch sonst überall wirkt, was sich aber nicht an so prägnanten Erscheinungen zeigt. Nehmen wir an, das (siehe Zeichnung) wäre in irgendeinem Jahre der Weltgeschichte, was sich hier abspielt etwa 800 nach Christi Geburt. Dasjenige, was für Europa, sagen wir, für Westeuropa bedeutsam war, wirkte natürlich auch vorher, wirkte auch nachher; aber nicht in einer so prägnanten Art zeigte es sich in der vorhergehenden Zeit und in der nachfolgenden Zeit, wie gerade da. Wenn man auf eine solche Geschichtsbetrachtung weist, die hinschaut auf prägnante Punkte, so liegt eine solche durchaus im Sinne des Goetheanismus. Denn Goethe wollte überhaupt alle Weltbetrachtung so einrichten, daß auf gewisse prägnante Punkte hingeschaut werde und aus dem, was in solchen prägnanten Punkten erschaut werden kann, dann der übrige Gehalt des Weltgeschehens erkannt werden sollte. Goethe sagt geradezu, innerhalb der Fülle der Tatsachen komme es darauf an, überall einen prägnanten Punkt zu finden, von dem aus sich die Nachbargebiete überschauen lassen, von dem aus sich viel enträtseln läßt.

Nun, nehmen wir dieses Jahr 800 etwa. Da können wir auf eine Tatsache hinweisen in der westeuropäischen Menschheitsentwickelung, die gegenüber der gewöhnlichen Geschichtsbetrachtung unbedeutend erscheinen könnte, die man vielleicht gar nicht beachtenswert findet für das, was man sonst Geschichte nennt, die aber doch für eine tiefere Betrachtung des Menschheitswerdens eben ein prägnanter Punkt ist. Um dieses Jahr herum etwa war eine Art theologisch-gelehrter Streit zwischen dem Manne, der eine Art Hofphilosoph des Frankenreiches war, Alkuin, und einem damals im Frankenreiche lebenden Griechen. Der Grieche, der bewandert war gerade in der besonderen Seelenverfassung des Griechenvolkes, die sich auf ihn herüber vererbt hatte, hatte die Prinzipien des Christentums beurteilen wollen und kam auf den Begriff der Erlösung. Er stellte die Frage: Wem ist denn eigentlich bei dieser Erlösung durch den Christus Jesus das Lösegeld ausbezahlt worden? — Er, der griechische Denker, kam zu der Lösung, dem Tod sei das Lösegeld ausbezahlt worden. Also es war gewissermaßen eine Art Erlösungstheorie, die dieser Grieche aus dieser ganz griechischen Denkweise, die eben das Christentum kennenlernt, entwickelt hat. Dem Tod sei das Lösegeld durch die Weltenmächte ausbezahlt worden.

Alkuin, der damals in jener theologischen Strömung drinnenstand, welche dann maßgebend geworden ist für die Entwickelung der römisch-katholischen Kirche des Abendlandes, diskutierte in der folgenden Weise über das, was dieser Grieche vorgebracht hatte. Er sagte: Das Lösegeld kann doch nur einem Wesen ausbezahlt werden, das wirklich ist; aber der Tod hat doch keine Wirklichkeit, der Tod schließt nur die Wirklichkeit ab, der Tod ist nichts Wirkliches; also könne auch nicht das Lösegeld an den Tod bezahlt worden sein.

Nun, es kommt jetzt nicht darauf an, die Alkuinsche Denkweise zu kritisieren; denn für denjenigen, der die Tatsachenzusammenhänge etwas durchschauen kann, hat die ganze Anschauung, daß der Tod kein Wirkliches sei, etwas Ähnliches mit jener Anschauung, die sagt: Die Kälte ist doch nichts Wirkliches, sondern sie ist nur die Herabminderung der Wärme, ist nur eine geringere Wärme; da die Kälte nichts Wirkliches ist, ziehe ich mir keinen Winterrock im Winter an, denn ich werde mich doch nicht gegen etwas Unwirkliches schützen. — Aber davon wollen wir ganz absehen, wir wollen vielmehr den Streit zwischen Alkuin und dem Griechen rein positiv nehmen und wollen uns fragen, was da eigentlich geschehen ist; denn es ist schon etwas höchst Auffälliges, daß ja nicht diskutiert wird über den Begriff der Erlösung selber, nicht diskutiert wird so, daß gewissermaßen die beiden Persönlichkeiten, der Grieche und der römisch-katholische Theologe, denselben Gesichtspunkt einnehmen, sondern daß der römisch-katholische Theologe den Standpunkt ganz verschiebt, bevor er überhaupt darauf eingeht. Er redet nicht in der Richtung weiter, die er gerade eingeschlagen hat, sondern er bringt das ganze Problem in eine ganz andere Richtung. Er fragt: Ist der Tod etwas Wirkliches oder nicht? - und wendet ein, der Tod sei eben nichts Wirkliches.

Das weist uns von vorneherein darauf hin, daß da zwei Anschauungen zusammenstoßen, die aus ganz verschiedenen Seelenverfassungen herauskommen. Und so ist es auch. Der Grieche dachte gewissermaßen noch fort in der Richtung, die im Griechentum im Grunde genommen erst verglommen war zwischen Plato und Aristoteles. In Plato war noch etwas lebendig von der alten Weisheit der Menschheit, von jener Weisheit, die uns hinüberführt nach dem alten Orient, wo, allerdings in alten Zeiten, eine Urweisheit gelebt hat, die dann immer mehr und mehr in die Dekadenz gekommen ist. Die letzten Ausläufer, möchte ich sagen, dieser orientalischen Urweisheit, finden wir bei Plato, wenn wir ihn richtig verstehen können. Dann setzt, wie durch eine rasch sich entwickelnde Metamorphose, der Aristotelismus ein, der im Grunde genommen eine ganz andere Seelenverfassung darbietet, als es die platonische ist. Der Aristotelismus stellt ein ganz anderes Element dar in der Menschheitsentwickelung als der Platonismus. Und wenn wir den Aristotelismus dann weiter verfolgen, so nimmt er auch wiederum verschiedene Formen, verschiedene Metamorphosen an, aber sie lassen sich doch alle in ihrer Ähnlichkeit erkennen. Wir sehen dann, wie als altes Erbgut in dem Griechen, der gegen Alkuin zu kämpfen hat, der Platonismus weiter fortlebt, wie aber bei Alkuin bereits der Aristotelismus vorhanden ist. Und wir werden hingewiesen, indem diese beiden Menschen in unser Blickfeld treten, auf jenes Wechselspiel, das sich vollzogen hat auf europäischem Boden zwischen zwei, man kann nicht einmal gut sagen Weltanschauungen, sondern menschlichen Seelenverfassungen, derjenigen, die ihren Ursprung noch hat in alten Zeiten des Orients drüben und derjenigen, die sich dann später hineinstellt, die wir im Orient noch nicht finden, die auftauchte in den mittleren Gegenden der Zivilisation, die Aristoteles zuerst ergriffen hat. Sie klingt in Aristoteles aber erst leise an; denn in ihm lebt doch noch viel Griechentum, sie entwickelt sich aber dann mit besonderer Vehemenz in der römischen Kultur, innerhalb welcher sie sich schon lange vor Aristoteles, ja vor Plato vorbereitet hat. So daß wir auch sehen, wie auf der italienischen Halbinsel schon seit dem 8. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert sich eine besondere Kultur, nur nuanciert, vorbereitet neben dem, was auf der griechischen Halbinsel weiterlebt wie eine Art letzter Ausläufer der orientalischen Seelenverfassung. Und wenn wir auf die Unterschiede dieser beiden menschlichen Denkweisen eingehen, so finden wir wichtige historische Impulse. Denn dasjenige, was sich in diesen Denkweisen ausdrückt, ging dann über in das Gefühlsleben der Menschen, ging über in die Struktur der menschlichen Handlungen und so weiter.

Nun fragen wir uns einmal: Was lebte denn in dem, was in Urzeiten sich entwickelte im Oriente drüben als Weltanschauung, was dann im Platonismus, ja sogar noch im Neuplatonismus als in einem Spätling seine Ausläufer fand. Es ist eine hochgeistige Kultur, die aus einer inneren Anschauung kam, welche vorzugsweise in Bildern, in Imaginationen lebte, aber in Bildern, die nicht durchdrungen waren von dem Vollbewußtsein, noch nicht durchdrungen waren von dem vollen Ich-Bewußtsein der Menschen. In gewaltigen Bildern ging gerade im alten orientalischen Geistesleben, von dem Veda und Vedanta die Nachklänge sind, dasjenige auf, was eben im Menschen als das Geistige lebt. Aber es war in einer — ich bitte, das Wort nicht mißzuverstehen und es nicht mit dem gewöhnlichen Träumen zu verwechseln —, es war in einer traumhaften, in einer dumpfen Art vorhanden, so daß dieses Seelenleben nicht durchwellt und durchstrahlt war von dem, was im Menschen lebt, wenn er deutlich sich seines Ich und seiner eigenen Wesenheit bewußt wird. Der Orientale war sich wohl bewußt, daß seine Wesenheit vorhanden war vor der Geburt, daß sie durch den Tod wiederum in dieselbe geistige Welt zieht, in der sie vor der Geburt oder vor der Empfängnis vorhanden war. Der Orientale schaute auf dasjenige, was durch Geburten und Tode zog. Aber jenes innere Fühlen, das in dem «Ich bin» lebt, das schaute der Orientale als solches nicht an. Es war gewissermaßen dumpf, wie ausgeflossen in einer Gesamtseelenanschauung, die sich nicht bis zu einem solchen Punkte hin konzentriert, wie es das Ich-Erlebnis ist. In was schaute denn da der Orientale eigentlich hinein, wenn er sein instinktives Schauen hatte?

Man kann es noch fühlen, wie ganz anders diese orientalische Seelenverfassung war als die der späteren Menschheit, wenn man sich zu diesem Verständnis, vielleicht durch Geisteswissenschaft vorbereitet, in jene merkwürdigen Schriften vertieft, die zugeschrieben werden ich will jetzt die Autorfrage nicht weiter untersuchen, ich habe mich öfter darüber ausgesprochen - dem Dionysius vom Areopag, dem Areopagiten. Da wird noch gesprochen von dem «Nichts» als von einer Realität, der nur das Sein der äußeren Welt, wie man sie im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein überblickt, als etwas anderes Reales entgegengestellt wird. Dieses Sprechen von dem Nichts, das klingt dann noch weiter fort. Bei Scotus Erigena, der am Hofe Karls des Kahlen lebte, findet man noch Nachklänge, und den letzten Nachklang findet man dann im 15. Jahrhundert bei Nikolaus Cusanus. Aber dann verglimmt das vollständig, was gemeint war in dem Nichts, das man bei Dionysius dem Areopagiten findet, von dem aber der Orientale als von etwas ihm Selbstverständlichen sprach. Was war für den Orientalen dieses Nichts? Es war ein Wirkliches für ihn. Er richtete den Blick in die umgebende Sinneswelt, er sagte sich: Diese Sinneswelt ist ausgedehnt im Raum, verfließt in der Zeit, und man sagt im gewöhnlichen Leben zu dem, was im Raume ausgedehnt ist und in der Zeit verfließt, es sei ein Etwas.

Aber das, was der Orientale sah, was für ihn eine Realität war, die durch Geburten und Tode geht, das war nicht in diesem Raum enthalten, in dem sich die Mineralien befinden, die Pflanzen sich entwickeln, die Tiere sich bewegen, der Mensch als physisches Wesen sich bewegt und handelt, es war auch nicht in jener Zeit enthalten, in der sich unsere Vorstellungen, Gefühle und Willensimpulse abspielen. Der Orientale war sich ganz klar: Man muß aus diesem Raume herausgehen, in dem die physischen Dinge ausgedehnt sind, und sich bewegen, und man muß aus dieser Zeit herausgehen, in der unsere Seelenkräfte des gewöhnlichen Lebens sich betätigen. Man muß in eine ganz andere Welt eindringen, in die Welt, die für das äußere zeitlich-räumliche Dasein das Nichts ist, das aber doch ein Wirkliches ist. Der Orientale empfand eben gegenüber den Welterscheinungen etwas, was der Europäer höchstens noch auf dem Gebiete der realen Zahl empfindet. Wenn der Europäer fünfzig Franken hat, so hat er etwas. Wenn er fünfundzwanzig Franken davon ausgibt, so hat er nur noch fünfundzwanzig Franken; wenn er wieder fünfzehn Franken ausgibt, so hat er noch zehn; wenn er diese auch ausgibt, hat er nichts; wenn er jetzt mit Ausgeben weiterfährt, hat er fünf, zehn, fünfzehn, fünfundzwanzig Franken Schulden. Er hat immer nichts, aber er hat doch etwas sehr Reales, wenn er statt einfach leerem Portemonnaie fünfundzwanzig oder fünfzig Franken Schulden hat. Das bedeutet in der realen Welt auch etwas sehr Reales, wenn man diese Schulden hat. Es ist ein Unterschied in der ganzen Lebenssituation, ob man nichts hat oder ob man fünfzig Franken Schulden hat. Diese fünfzig Franken Schulden sind ebenso wirksame Kräfte für die Lebenssituation, wie auf der anderen Seite im entgegengesetzten Sinne fünfzig Franken Vermögen wirksame Kräfte sind. Auf diesem Gebiete läßt sich wahrscheinlich der Europäer auf die Realität der Schulden ein, denn es muß in der realen Welt immer etwas vorhanden sein, wenn man Schulden hat. Die Schulden, die man selber hat, mögen für einen eine noch so sehr negative Größe sein, für den anderen, dem man sie schuldet, sind sie aber eine recht positive Größe.

Also, wenn es nicht bloß auf das Individuum ankommt, sondern auf die Welt, dann ist dasjenige, was ja nach der einen Seite der Null liegt, die entgegengesetzt ist der Vermögensseite, doch etwas sehr Reales. Der Orientale empfand, aber nicht, weil er irgendwie spekulierte, sondern weil ihn seine Anschauung nötigte, so zu empfinden, er empfand: Da erlebe ich auf der einen Seite den Raum und die Zeit, und auf der anderen Seite erlebe ich dasjenige, was nicht im Raum und in der Zeit beobachtet werden kann, was für die Raum- und Zeitdinge und für das Raum- und Zeitgeschehen ein Nichts ist, aber eine Realität ist, eben nur eine andere Realität. Nur durch ein Mißverständnis ist dann dasjenige entstanden, dem sich die abendländische Zivilisation unter Roms Führung hingegeben hat: die Schöpfung der Welt aus dem Nichts, wobei man unter dem Nichts nur die Null gedacht hat. Im Oriente, wo diese Dinge ursprünglich konzipiert worden sind, entsteht die Welt nicht aus dem Nichts, sondern aus jenem Realen, auf das ich Sie eben hingewiesen habe. Und ein Nachklang desjenigen, das durch alle orientalische Denkweise und bis zu Plato herunter vibriert hat, was Ewigkeitsimpuls einer alten Weltanschauung war, ein Nachklang davon lebte in dem Griechen am Hofe Karls des Großen, der mit Alkuin zu diskutieren hatte. Und eine Abweisung des geistigen Lebens, für das dieses Nichts die äußere Form war im Oriente, lebte bei dem Theologen Alkuin, der daher, als der Grieche von dem Tod, der aus dem geistigen Leben heraus verursacht ist, als von etwas Realem sprach, nur erwidern konnte: Der Tod ist doch ein Nichts, also kann er kein Lösegeld erhalten.

Sehen Sie, all das, was Gegensatz ist zwischen alter orientalischer, bis zu Plato reichender Denkweise und dem, was später folgte, drückt sich aus in diesem prägnanten Punkte, wo Alkuin mit dem Griechen am Hofe Karls des Großen diskutierte. Denn, was war mittlerweile eingezogen in die europäische Zivilisation seit Plato, namentlich durch die Verbreitung des romanischen Wesens? Es war eingezogen diejenige Denkweise, welche man dadurch zu begreifen hat, daß sie vorzugsweise auf das geht, was der Mensch durchlebt zwischen Geburt und Tod. Die Seelenverfassung, die sich vorzugsweise beschäftigt mit dem, was der Mensch durchlebt zwischen Geburt und Tod, das ist die logisch-juristische, die logisch dialektisch-juristische. Das Morgenland hatte nichts Logisch-Dialektisches und am wenigsten etwas Juristisches. Das Abendland brachte in die morgenländische Denkweise das logisch-juristische Denken so stark hinein, daß wir selbst das religiöse Empfinden durchjuristet finden. Wir sehen in der Sixtinischen Kapelle in Rom uns entgegenragen von der Meisterhand Michelangelos den Weltenrichter Christus, der da richtet über die Guten und die Bösen.

In die Gedanken über den Weltverlauf ist Juristisch-Dialektisches hineingezogen. Ganz fremd war das der orientalischen Denkweise. Da gab es so etwas nicht, wie Schuld und Sühne, wie Erlösung überhaupt. Daher kann der Grieche fragen: Was ist denn diese Erlösung? — Da gab es eben die Anschauung jener Metamorphose, durch die sich das Ewige umgestaltet durch Geburten und Tode hin; da gab es dasjenige, was in dem Begriff des Karma lebte. Dann aber wurde alles hereingespannt in eine Anschauungsweise, welche eigentlich nur gültig ist für das Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod, welche nur umfassen kann dieses Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod. Das aber, dieses Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod, hatte sich gerade wieder dem Orientalen entzogen. Er blickte viel mehr auf des Menschen Wesenskern hin. Er hatte weniger Verständnis für das, was sich zwischen Geburt und Tod abspielte. Und innerhalb dieser abendländischen Kultur wurde nun groß jene Denkweise, die vorzugsweise das erfaßt, was innerhalb von Geburt und Tod sich abspielt durch jene Kräfte, die der Mensch dadurch hat, daß er sein Geistig-Seelisches mit einem Leib umkleider hat, mit einem physischen und ätherischen Leibe. In dieser Konstitution, in dem innerlichen Erleben des Geistig-Seelischen und in der Art dieses Erlebens, die davon herkommt, daß man eben eingetaucht ist mit dem Geistig-Seelischen in einen physischen Leib, kommt die klare, die volle Erfassung, die innerliche Erfassung des Ich. Daher geschieht es auch im Abendlande, daß der Mensch sich gedrängt fühlt, gerade sein Ich zu erfassen, sein Ich als Göttliches zu erfassen. Wir sehen diesen Drang, das Ich als ein Göttliches zu erfassen, auftreten bei den mittelalterlichen Mystikern, bei Eckart, bei Tauler, bei den anderen. Diese Erfassung des Ich kristallisiert sich mit aller Macht heraus in dem, was die mittlere Kultur ist. So daß wir unterscheiden können: die Ostkultur, die Zeit, in der das Ich erst dumpf erlebt wird; die Mittelkultur, sie ist vorzugsweise diejenige, in der das Ich erlebt wird. Und wir sehen, wie in den mannigfaltigsten Metamorphosen dieses Ich erlebt wird: erst, ich möchte sagen, in jener dämmerhaften Weise, in der es auftritt bei Eckart, bei Tauler, bei den anderen Mystikern; dann immer deutlicher und deutlicher, indem sich alles dasjenige herausentwickelt, was aus dieser Ich-Kultur stammen kann.