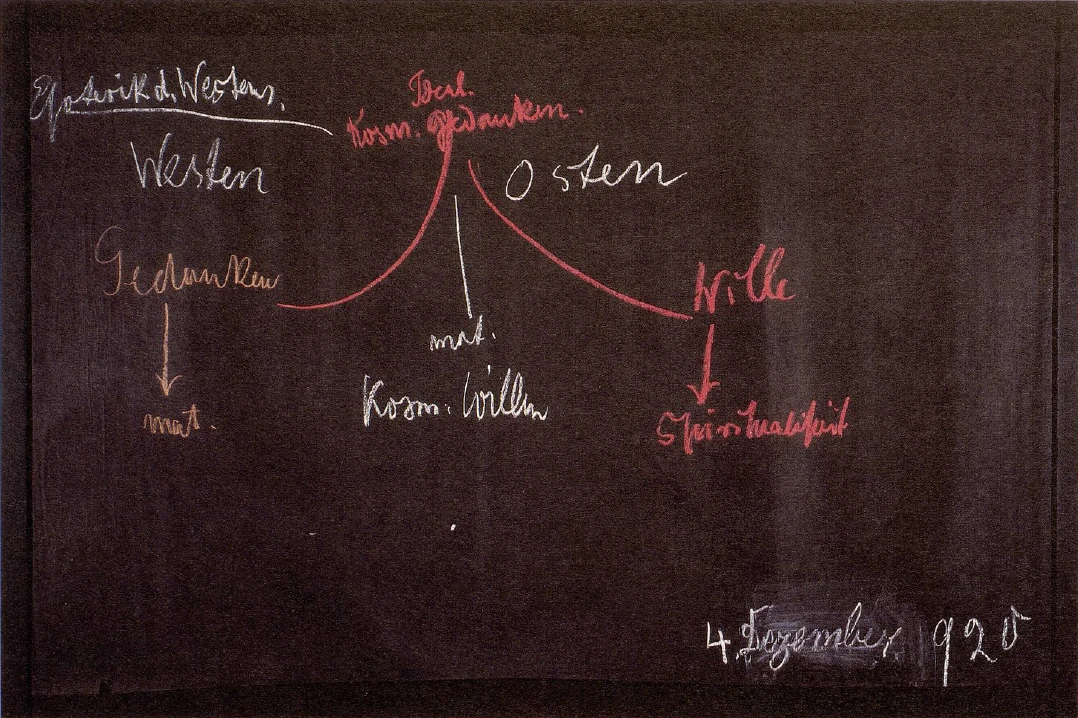

Hegel, Schopenhauer, Thought, Will

GA 202

4 December 1920, Dornach

Translated by Hanna von Maltitz

It is my intention now to bring several viewpoints to you regarding the relationship between human beings and the cosmic world on the one side and the spiritual development of human beings on the other. Our considerations will be supplementary to what we have already allowed to pass over our souls many times. Today I want to add a kind of introduction to our considerations of the next hours, which could appear to some as remotely relevant, the necessity of which will become clear in the next hour. I would like to remind you that in central European-German thought development, during the first half of the 19th century, besides events to which we have just referred, an additional, remarkable event took place. I have recently referred to the contrast which arises when considering Schiller's aesthetic letters on the one hand and Goethe's Fairy Tale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily on the other. Today I wish to point to a similar contrast, which appeared in the development of thought in the first half of the 19th century with Hegel on the one side and Schopenhauer on the other. With Goethe and Schiller we are dealing with two personalities who, at a certain time in their life, being surrounded by the constant contrasts of the central European thought development - a development of thought striving for equilibrium—managed to bring about an equilibrium in their deep friendship, whereas previously they had been repelled by one another.

Two other personality also represented polar opposites but with them it is impossible to say some kind of equilibrium was established: Hegel on the one side and Schopenhauer on the other. You only have to consider what I put forward in my “Riddles of Philosophy” to see the deep opposition between Schopenhauer and Hegel. It appears relevant that Schopenhauer really spared no swearwords in what he held as the truth in his characterization of his opponent Hegel. In many of Schopenhauer's work there is the wildest scolding of Hegel, Hegelianism and everything related to it. Hegel had less reason to scold Schopenhauer, because, before Hegel died, Schopenhauer would actually have remained without influence, not being established amongst remarkable philosophers. The contrast between these two personalities can be characterised by indicating how Hegel regarded the foundation of the world and the world development and everything pertaining to it, as consisting of real thought elements. Hegel firmly believed that thoughts were the foundation of everything. Hegel's philosophy fell into three parts: Firstly in logic, not subjective human logic but the system of thought that must form the foundation of the world. Secondly Hegel had his philosophy of nature, but nature for him was nothing other than an idea, not even an idea with a difference, but the idea which implies it exists out-of-itself. So also nature is an idea, but the idea in a different form, in a form which is sense-perceptible to people, ideas by contrast. The idea which reverts back to itself, this was to him the human being's spirit which had developed out of the simplest human-spiritual activities into the world's history and up to the beginning of the human subjective spirit in religion, art and science. When one wants to study Hegel's philosophy thus, you need to allow yourself entry into the development of world thoughts, just like Hegel let these world thoughts explain themselves.

Schopenhauer is the opposite. For Hegel thoughts, world thoughts were creative, actual reality in things; for Schopenhauer every thought was merely subjective, and as a subjective image only something unreal. For him the only real thing was will. Just as Hegel followed with human thought into everything mineral, animal or vegetative, for Schopenhauer it was all about “the will of nature”. So one can say Hegel is the thought philosopher and Schopenhauer the will philosopher.

In this way these two personalities stood opposite one another. So, what do we actually have here as thoughts on the one hand and will on the other? We would best introduce this polar opposite in the following lecture by allowing it to be brought before our souls when we observe human beings. We will for a moment divert our gaze from Hegelian philosophy and look at the reality of humanity. We already know: in people we predominantly have an intellectual, meaning a thought element, followed by a will element. The thought element is preferably assigned to the human head, the will element preferably to the human limb organism. With this we have already referred to the intellectual element as actually being that which permeated our bodies from a prenatal existence out of the spiritual worlds, flowing from us between death and a new birth, as well as out of the prenatal life and its remnants of an earlier earth life pouring into the essence of this earth life. The will element is however, I would like to say, the youth in contrast to the thought element in humanity; it goes through the portal of death and then enters the world between death and a new birth, gets converted, metamorphosed and builds the intellectual element in the next life. Essentially, we have in our soul organisation our intellectual as predominant, thought elements reaching back to antiquity; our will element reaching into the future. With this we have considered the polar opposites between thought and will.

Naturally we should never, in considering reality, schematize these things. It would be naturally schematized if one could say: every thought element directs us to earlier time and all will elements direct us towards our time past. It is not so, yet it is striking, I say, that which in people as the thought element reaches to earlier times while the will element goes into later times. Added to this human organisation it is striking that the backward aim in the thought element is a type of will element and included into the organisation becomes the will element, which rings right out through death and into the future, as a thought element. You may, when you enter with understanding into reality, never schematize, never merely list one idea beneath another, because you must be clear that in reality everything can be observed which at sometime or other appears striking, the remaining elements of reality existing within, and that above all, what may be in the background can at another point become a striking reality and then something else falls into the background.

When philosophers come to consider this or that from their particular point of view, you have your one-sided philosophers. Now that which I've characterized for you as thought elements in people, are not only in people bound to their head organization, but thoughts really spread out in the cosmos. The entire cosmos is threaded through with cosmic thoughts. Because Hegel was the stronger spirit, who, I want to say, felt the results of many past earthly lives, he directed his attention in particular to cosmic thoughts.

Schopenhauer experienced less events of his previous earth lives, thus directed his attention more towards cosmic will. Just as will and thought live in people, so will and thought live in the cosmos. What do thoughts mean for the cosmos as observed by Hegel in particular, and what does will mean for the cosmos in the way Schopenhauer observed it? Hegel didn't consider the kind of thoughts which took form within human beings. The entire world was for him basically only a revelation of thoughts. In fact, he had cosmic thought in mind. Observing the extraordinary formation of Hegel's spirit, one can say: this spirit shaping of Hegel refers to the West. Only Hegel manages to lift everything to an element of thought—everything pertaining to the West, for example materialistic developmental directives and materialistic thoughts in Western physics. One finds with Darwin a developmental teaching just as one finds a developmental teaching with Hegel. With Darwin it is a materialistic developmental philosophy, in which everything happens as if only mighty nature substances are involved and act creatively; with Hegel we see how everything which is in development is permeated through with thought, like thoughts in particular configurations, in their concrete expression—they are the actual development.

Henceforth we can say: in the West the world is approached from the standpoint of thought, but materialistic thought. Hegel idealized thought and as a result arrived at cosmic thought.

Hegel argued in his philosophy about thought but actually meant cosmic thought. Hegel said when we look into the outside world, be it observing a star in its orbit, an animal, plant or mineral, we actually see thoughts everywhere, only this kind of thought in the outer world is actually in a different form as in the thought-form being observed. One can't say in fact that Hegel was attempting to maintain these teachings of world thoughts as esoteric. They remained esoteric because Hegel's work is seldom read, but it wasn't his intention to keep the teaching of cosmic content of the world as esoteric. However, it is extraordinarily interesting that when it comes to western secret societies - this teaching relates in a certain way to the deepest esoteric teachings - that the world is actually created out of thoughts. One could say what Hegel so naively observed in the world, what western secret societies considered their observations, is what the Anglo-American peoples held as content of their secret teachings, while they had no intention of popularizing their secret teachings. As grotesquely as one might take it, one can say Hegel's philosophy is to a certain extent the basic nerve of the teachings of the West.

You see, here we have an important problem. You could really, when you become knowledgeable about all the esoteric teachings of Anglo-American secret societies, content-wise hardly find anything but Hegelian philosophy. However there is a difference which doesn't lie in the content, it lies in the handling. It is connected to this, that Hegel saw the things in a manner of a revelation, and the western secret societies keep a watchful eye over what Hegel presents to the world so it would not become generally known and remain as an esoteric secret teaching.

What actually lies at the basis of this? This is a very important question. If one has some kind of content which has originated out of the spirit and one considers it at a secret possession, then one gives it power, because when this content becomes popularised, it no longer has this power. Now I ask you to really for once focus completely: Any content containing knowledge becomes a force of power when held secret. To this is added that those who want to retain certain teachings as secrets, become quite unpleasant when these things are popularized. It is almost a universal law that whatever popularizes, gives insight. Power is given to that which is kept secret.

I have spoken to you over the last few years about various powers which emerged from the West. That these emerged out of the West did not come from knowledge which had been unknown in Central Europe, but this wisdom was treated in a different manner. Just imagine what kind of tragedy it predicted! It could even have seriously warded off events in world history from the power of western secret societies, if single individuals could have been studied in Central Europe, if this wasn't merely done in Central Europe but that it was thoroughly stated: In the (eighteen) eighties—I have mentioned this—Eduard von Hartmann openly printed that only two philosophers in the Central European faculties had been read by Hegel. Hegel was excessively discussed and lectures were held about him, but only two philosophy professors could be proved to have been shaped by Hegel. For those who have any kind of receptivity for such things could experience the following: when they read some volume of Hegel's out of some library they could only really state that the volume was not very well-thumbed! Sometimes one page to the next—I know this from experience—was most difficult to pry apart because the volume was still so new. And “Editions” Hegel has only experienced recently.

Now I haven't established this as the basis for the facts I've particularly stipulated in the foregoing, but I want to show how this idealism living within Hegel nonetheless points towards the West, because on the one hand it appears again in the clumsy materialistic thoughts of Darwinism, of Spencerism and so on, and on the other in the esotericism of secret societies.

Now let's consider Schopenhauer. Schopenhauer is, I might say, the admirer of the will. That he has cosmic will in mind appears everywhere in Schopenhauer's work, in particular in the delightful treatise “Regarding the Will in Nature” where everything which exists and lives in nature is taken from a basis of will, expressed in the elemental power of nature.

Towards what does the entire soul constitution of Schopenhauer point if Hegel's soul state points to the West? You can see this in Schopenhauer himself because you soon find, in your studies, his deep leaning towards the Orient. It rose from his mood, it's not clear how. This preference of Schopenhauer's for Nirvana and for all that is oriental, this inclination towards everything Indian is irrational like his entire will philosophy; it arose to some extent from his subjective inclination. However in this lies a certain necessity. What Schopenhauer presented as a philosophy is a philosophy of will. This philosophy, as it belongs in Central Europe, he presented dialectically in thoughts; he rationalized about will but he actually spoke about will through the medium of thought. While he spoke thus about will, actually cosmic will materialized, entered deeply into his soul and rose in his consciousness as a preference for the East. He enthused about everything Indian. Just as we saw how Hegel pointed more to the West, so we see how Schopenhauer pointed towards the East. In the East however we don't find anything which is an element of will and what Schopenhauer really felt as the actual element of the East, was materialised and pressed into thinking and thus intellectualized. The entire form of the representation of cosmic will, which lies at the basis of eastern soul-life, does not appear as originating from the intellect, it is partly a poetic, partly a section derived directly from the observation of the relevant representation. Schopenhauer took what the oriental image form wanted to convey and intellectualized it in the Central European way; however that which he refers to, the cosmic will, this was after all the element at which he was pointing; from this he had formulated his soul orientation. This element is what lived in the world view of the Orient. When the oriental world view is permeated with love in particular, this element of love becomes nothing other than some aspect of cosmic will, and is not just raised from the intellect. So we may say: here the will is spiritualized. Like thoughts are materialised in the West, so in the East will becomes spiritualized.

In Central European elements we see within idealized cosmic thought, within materialized cosmic will, treated through the medium of thought, these two worlds creating an interplay; with reference to Hegelianism we have in western secret societies something similar to a deep relationship between Hegelian cosmic thought systems in the West, and if we penetrate this, in the subjectivity of Schopenhauer's penetration with the Orient, it brings to expression Schopenhauer's relationship with eastern esotericism.

It is quite extraordinary when you allow Schopenhauer's philosophy to work on you, the thought-element appears somewhat flat; Schopenhauer's philosophy is really not deep, but it has at the same time something intoxicating, something wilful which throbs within. Schopenhauer becomes most attractive and charming when shallow thoughts are penetrated with his will element - then traces of the warmth of will are found to some extent in his sentences. As a result he basically has become a shallow salon philosopher of his age. As the thought provoking age, which the first half of the nineteenth century was, passed and people suffered from thought deprivation, the time came for Schopenhauer to become the salon philosopher. Not much effort was needed to think, while the thrill of thought throbbing with will was allowed its influence particularly when something like “Parerga and Paralipomena” (“Appendices and Omissions”—philosophical reflections published 1851) came through, where these thrilling thoughts could work their craftiness.

Thus we have two opposing poles in the Hegel-Schopenhauer antitheses in the central regions of our civilization's development; the one a particular shaping from the West, and the other a particular formation from the East. In Central Europe they stood up to the time they balanced out, imperiously side by side, being incomparable to the alliance between Schiller and Goethe which was harmonious, as opposed to Hegel and Schopenhauer in their disharmonious relationship. Schopenhauer then became outside lecturer at the Berlin University at the same time as Hegel represented his own philosophy. Schopenhauer could hardly find an audience, his auditorium remained empty. Probably, when Hegel was idly asked about the Schopenhauer type philosophy - which he could manage because he was at the time an impressive, respected philosopher—then he merely shrugged his shoulders. When anybody spoke from the basis of this will element and stressed it in particular like (Friedrich) Schleiermacher, then compared with Hegel it still indicated something, Hegel would become uncomfortable. Therefore when Schleiermacher wanted to explain Christianity from this thoughtless element and said: Christianity cannot be understood through the thought element when one includes worldwide thoughts, to some extent the divine thoughts, grasped differently than through feeling oneself dependant on God, through which one develops a feeling of dependency on the universe - to this Hegel replied: Then the dog is the best Christian, because it has the best knowledge of the feeling of dependency! Obviously Hegel gave Schopenhauer a piece of his mind as he gave Schleiermacher, when he took the trouble. Hegel had to forever connect and convince everyone who didn't change towards understanding the reality of thought. For Schopenhauer these thoughts were nothing more than foam rising from the breaking of waves of cosmic will. Schopenhauer, who certainly from the characterised position had more occasion, insulted Hegel like a washerwoman in his work.

Within life's riddles, contributing to the centre of civilization, we thus see the contradictions which do not come to a harmonious closure. Both however, Schopenhauer as much as Hegel, felt a lack of what really constituted the understanding of mankind. Hegel lived in cosmic thought, and this was exactly that which made him so unpopular—because in daily life people are not going to soar up to cosmic thoughts. They have a particular feeling which they eagerly enter for comfort—a feeling which says: why should we split our heads with cosmic thoughts? That is done for us by the gods, or God. Being an Evangelist one says: a God does this, why should we especially bother with it? In particular that which appeared in the publications on thought was extraordinarily impersonal. History, for instance, which we discover through Hegel, has something thoroughly impersonal. Thus we have actually from the beginning of earth evolution right to the end of earth development, self enfolding thoughts.

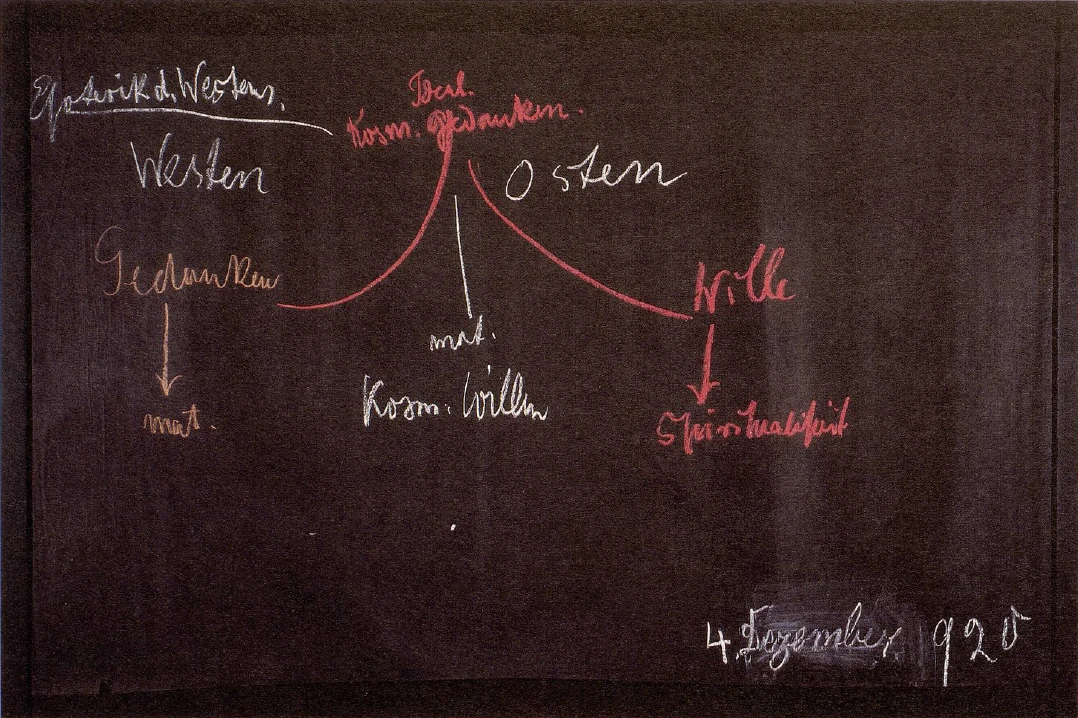

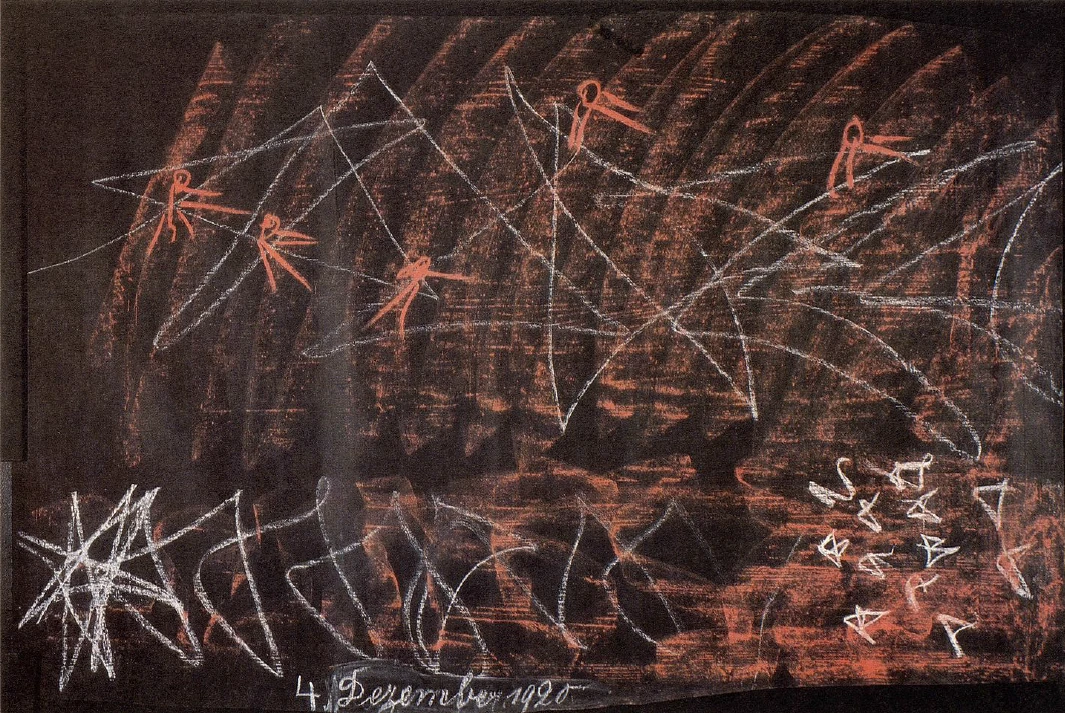

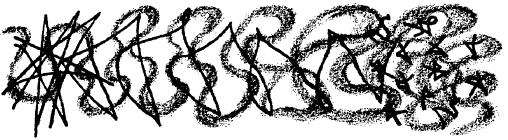

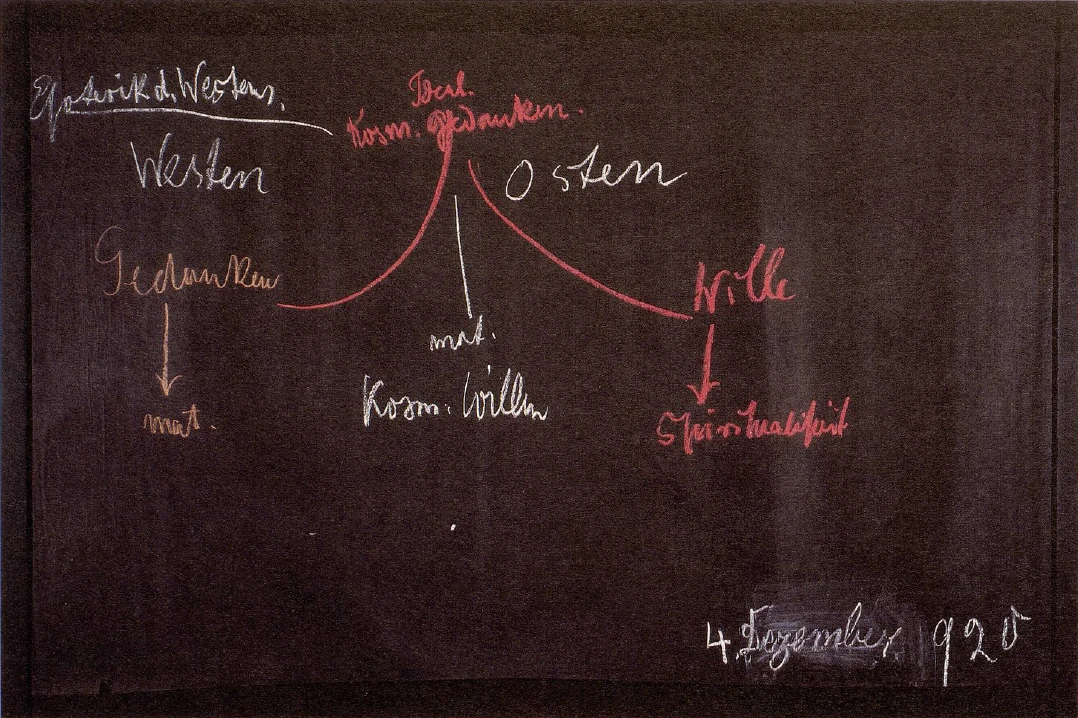

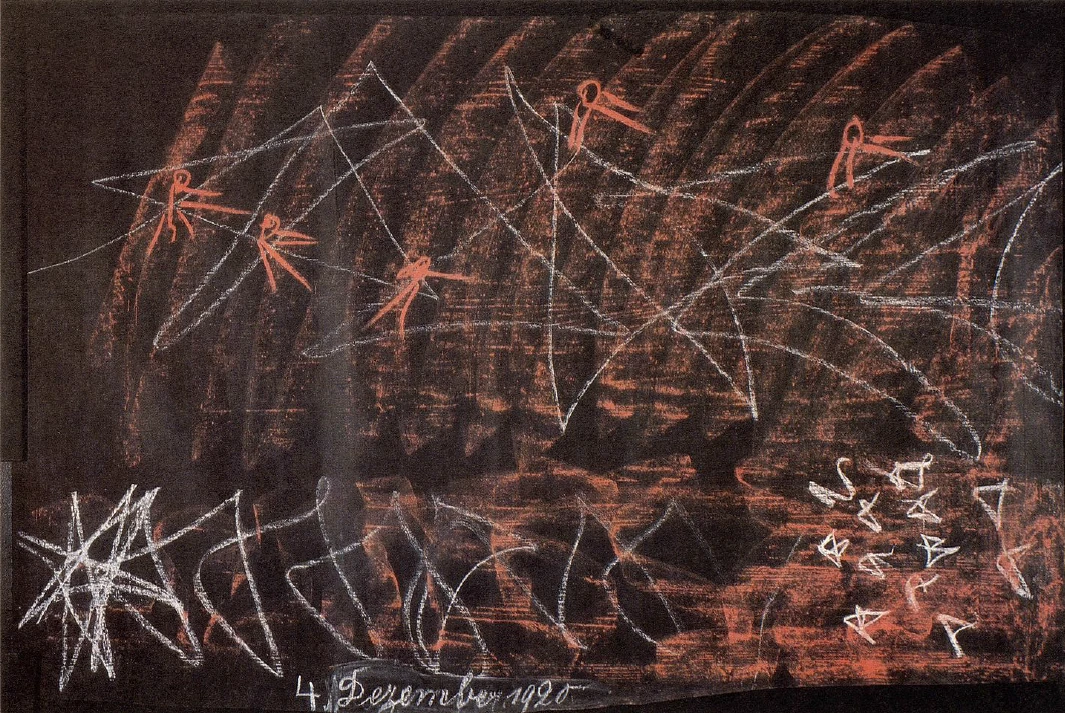

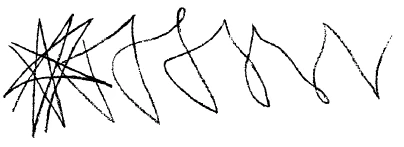

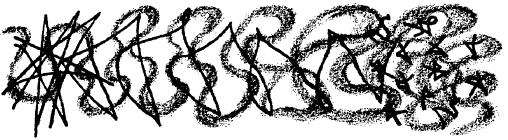

Should you want to schematically draw this Hegelian historical philosophy, here thoughts would rise up (a drawing is made), rise up, distort each other mutually and thus go through the historic development and in this web of thoughts people are spun in and are swept away by the thoughts. Thus actually for Hegel the historical development of these coalescing, corrupt thoughts harness people as automatons, out of these webs of world historic thought this thought system had to develop. For Schopenhauer of course thoughts were nothing more than froth. He directed his gaze to cosmic will, or in other words, to this sea of cosmic will. The human being is actually only a reservoir where merely a little of this cosmic will is collected. The Schopenhauer philosophy contains nothing of this developmental reasoning or progressive thinking, but is the unclear, irrational, the unreasonable element of will which flows from it. Within the human beings rises up, reflects in him as if it was reason but which he or she actually continually develops as foolishness. For Hegel the world is the revelation of reason. For Schopenhauer—what does the world mean to him? It is a remarkable thing, if one wants to answer the question: What is the world to Schopenhauer? It struck me particularly clearly once in a sentence of Eduard von Harman, where Schopenhauer was considered and discussed because Eduard von Hartman had Hegel on the one side and Schopenhauer on the other, Schopenhauer's side being predominant. I want to with this article, which was a purely philosophic article of Eduard von Harman, indicate, that for him the solution to the world riddle has to be expressed as follows: “The world is God's big foolishness.”—I had written this because I believe it's the truth. The editor of the newspaper, which appeared in Austria, answered me that this had to be deleted because the entire edition would be confiscated if this was printed in an Austrian newspaper; he simply couldn't write that the world was God's stupidity. Now, I didn't insist further but wrote to the editor of these “German Words”: Delete the “God's foolishness” but just remember another case: When I edited the German Weekly (Deutsche Wochenschrift) you didn't write about the world as God's foolishness, but that the Austrian school system is a stupidity of the teaching administration and I allowed it. - For sure, that weekly newspaper was confiscated at the time. I wanted to remind the man at least, that something similar had happened to him as was happening to me, only me with the loving God, and with him the Austrian the minister of education, Baron von Gautsch.

When one looks back over the most important world riddles, it is clear how Hegel and Schopenhauer represent two opposing poles, and they appear actually in their greatness, in their admirable, dignified greatness. I know for certain that some people find it extraordinary that a Hegel admirer like me can likewise produce such a draft, because some people can't imagine that when something in contrast to them is great, humour can also be retained about it, because people imagine one must unconditionally show a long face when one confesses to experiencing something great in a well known person.

Thus two opposite poles present themselves, but in this case not like with Schiller and Goethe which came to a harmonious equilibrium. We could find some solution to this disharmony if we consider that for Hegel the human being was evolving within a web spun with concepts of world history and for Schopenhauer the human being actually was nothing other than a little lamb, a small container where a portion of world-will had been poured in, basically only an extract of the cosmic world will. Both failed to perceive the actual individuality and personality of human beings. They also could not perceive what the actual being was which they sensed in the cosmos.

Hegel looked into the cosmos and saw this web of concepts within history, Schopenhauer looked into the cosmos and didn't see this web of concepts—that was only a mirror image for him—but he saw it as a sea of ruling will, to some extent tapped into these vessels in which human beings swam in this irrational, unreasonable sea of will (drawing is made). Human beings were only being fooled by what reflected in their unreasonable will as actual reason, imagination and thought. Yet these two elements are present in the cosmos. What Hegel saw was already in the cosmos. Cosmic thoughts exist. Hegel and the West viewed the cosmos and perceived world thoughts. Schopenhauer and the East looked at the cosmos and saw world will. Both are within. A useful cosmic world view could c0me into existence if the paradox could have been entered, resulting in Schopenhauer's scolding bringing him so far as to him leaving his skin behind, and despite Hegel's soul remaining in Hegel, that Schopenhauer entered Hegel so that Schopenhauer was actually inside Hegel. Then he would have seen the world-thoughts and world-will fusing! This is the deed which is within the world: world thoughts and world will. They exist in very different forms.

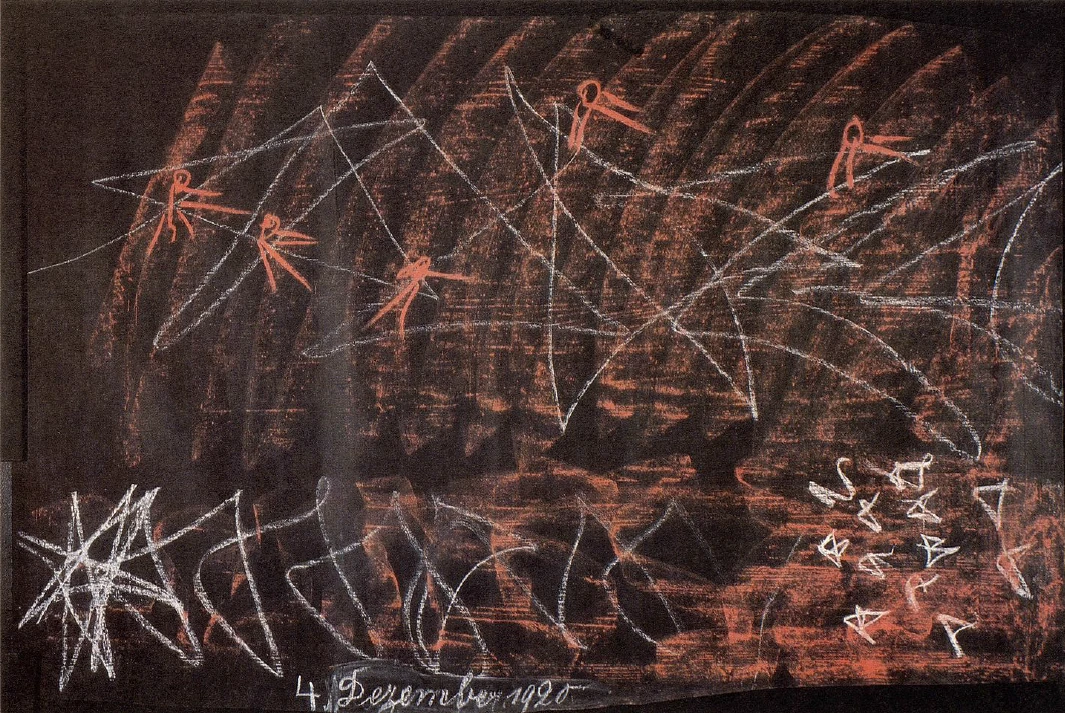

What is revealed to us through actual spiritual scientific research in relation to this cosmology? It tells us: when we look into the world and allow world thoughts to work on us, what do we see? We see, by letting world thoughts work on us, thoughts of the dim and distant past, everything which worked in the past up to the present moment. Thus we see, through our world-thought perception, that which is dying away when we look into the world. From this comes the hardened, the dead part of natural laws and we can practically only use mathematics to deal with what is dead when we consider nature's laws. However within that which speaks to our senses, which delights us in the light, what we hear in sound, what warms us and everything touching our senses, works out of world will. It is this, which rises out of the dead element of world thoughts and what basically gestures outwards to the future. Something chaotic, undifferentiated exists in the world thoughts, yet lives presently in world moments as a germ which progresses into the future. Submitting ourselves to the world's thought elements, we experience that which originated from the most horrible past, spilling into the present. However, in the human head is something different. In the human head thoughts are separated from outer world thoughts, and are bound into the human personality in an individual will element, which in this way may first only be looked at as that small reservoir, the little lamb of poured cosmic will-element. However, what one has intellectually, point backwards. We have basically developed this germ from a former life on earth. Will was involved there. Now it has become thought, is bound to our head organization, resurrected like a living copy of the cosmos in our head organization. We connect this to will, we rejuvenate it in our will. By rejuvenating it in will, we send it over to our next life on earth, our next earth incarnation.

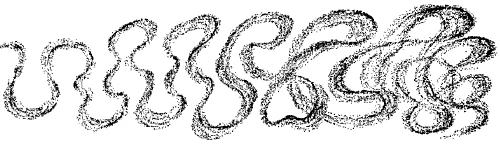

This world image must actually be drawn differently. We must draw it in such a way that the outer cosmic aspect of olden times is particularly rich in thought elements, but becomes ever more thinned out as we approach the present, allowing the thoughts, as they are in the cosmos, to gradually die out. The thought element we must consequently draw quite fine.

The further we go back, so the thoughts outweigh the Akashic images; the more we go forward, the ever denser the will element becomes. We should, if we want to look through this development, look at a light filled thought element in the most horrible time past, and on the most unreasonable element of will of the future.

But it doesn't remain like this, because we drag in thoughts which have been retained in our head. These thoughts are sent into the future. While cosmic thoughts die out more and more, germinate on human thoughts, from their point of origin they push through into the future as the cosmic element of will.

Thus we are the guardians of cosmic thoughts, thus the human being draws cosmic thought out of himself or herself into the world outside. Along the detour through the human being cosmic thoughts are propagated from ancient times into the future. The human being belongs to that which is the cosmos. However he doesn't belong like the materialist will think, that the human being is something which has developed out of the cosmos and is a piece of the cosmos, but that the human being also belongs to the creative element of the cosmos. He or she carries thoughts out of the past, into the future.

You see, here the human being enters into the tangible. If you really want to understand the human being you enter into what Schopenhauer and Hegel approached so one-sidedly. From this you realise that philosophic elements, being combined on a higher level, need to be threefold, just as the human being is to be understood in the cosmos.

Tomorrow we will consider the relationship between the human being and the cosmos in a concrete manner. I wanted to give you an introduction today, as promised; the necessity of it will be recognised in further lectures.

Vierter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Es wird in der nächsten Zeit hier meine Aufgabe sein, Ihnen einige Gesichtspunkte vorzubringen, die das Verhältnis betreffen zwischen dem Menschen und der kosmischen Welt auf der einen Seite, dem Menschen und der geschichtlichen Entwickelung der Menschheit auf der anderen Seite. Betrachtungen sollen das sein, welche vieles von dem, was wir schon vor unserer Seele haben vorüberziehen lassen, ergänzen können. Ich will heute zu den Betrachtungen der nächsten Stunden gewissermaßen eine Art Einleitung voranschicken, die vielleicht manchem etwas entlegen scheinen könnte, deren Notwendigkeit aber aus den folgenden Stunden schon wird eingesehen werden. Ich möchte Sie nämlich heute darauf aufmerksam machen, daß in der mitteleuropäisch-deutschen Gedankenentwickelung der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts außer den Tatsachen, auf die wir schon hingewiesen haben, noch eine andere, außerordentlich bezeichnende Tatsache vorliegt. Ich habe ja vor kurzer Zeit einmal hingewiesen auf jenen Gegensatz, der sich einem ergibt, wenn man einerseits Schillers Ästhetische Briefe und auf der anderen Seite Goethes Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der schönen Lilie betrachtet. Heute möchte ich hinweisen auf einen ähnlichen Gegensatz, der ja hervortrat in dieser Gedankenentwickelung aus der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts in Hegel auf der einen Seite, in Schopenhauer auf der anderen Seite. Wir haben es bei Goethe und Schiller mit zwei Persönlichkeiten zu tun, die in einer gewissen Zeit ihres Lebens dasjenige, was als ein, man kann sagen, bleibender Gegensatz gerade in der mitteleuropäischen Gedankenentwickelung vorhanden ist, was aber auch in dieser Gedankenentwickelung fortwährend nach Ausgleich strebt, in einer innigen Freundschaft zum Ausgleich gebracht haben, nachdem sie einander vorher abgestoßen hatten.

[ 2 ] Zwei andere Persönlichkeiten stellen die beiden polarischen Gegensätze auch dar, ohne daß man sagen kann, daß es bei ihnen zu irgendeinem Ausgleich gekommen ist: Hegel auf der einen Seite, Schopenhauer auf der anderen Seite. Man braucht nur ins Auge zu fassen, was ich selber in meinen «Rätseln der Philosophie» dargestellt habe, und man wird den tiefgehenden Gegensatz zwischen Schopenhauer und Hegel merken. Er tritt einem ja auch dadurch zutage, daß Schopenhauer wahrhaftig keine Schimpfworte gespart hat, um seinen Gegenpart Hegel in der Weise, wie er es für richtig gehalten hat, zu charakterisieren. Vieles in Schopenhauers Werken ist ja das wüsteste Geschimpfe auf Hegel, den Hegelianismus und alles, was irgendwie damit verwandt ist. Hegel hatte weniger Veranlassung, über Schopenhauer zu schimpfen, weil ja, ehe Hegel starb, Schopenhauer eigentlich ohne Einfluß geblieben war, also eigentlich nicht unter denjenigen Philosophen war, die bemerkt worden wären. Der Gegensatz zwischen diesen beiden Persönlichkeiten kann ja einfach dadurch charakterisiert werden, daß man hinweist darauf, wie Hegel den Urgrund der Welt und der Weltenentwickelung und alles dessen, was dazu gehört, in dem realen Gedankenelemente sieht. Hegel hält die Idee, den Gedanken für dasjenige, was allem zugrunde liegt. Und Hegels Philosophie zerfällt ja in drei Teile: Erstens in die Logik, die aber nicht die subjektive menschliche Logik ist, sondern die das System der Gedanken ist, die der Welt zugrunde liegen sollen. Dann verzeichnet Hegel als zweiten Teil seiner Philosophie die Natur. Aber die Natur ist ihm auch nichts anderes als Idee, nur eben die Idee in ihrem Anderssein, wie er sagt: die Idee in ihrem Außer-sich-Sein. Also auch die Natur ist Idee, aber die Idee in einer anderen Form, in der Form, in der man sie anschauen kann, mit den Sinnen betrachten kann, Idee in ihrem Anderssein. Die Idee, indem sie dann wiederum zurückkommt zu sich, sie ist ihm der Geist des Menschen, der sich entwickelt von den einfachsten menschlich-geistigen Betätigungen bis zur Weltgeschichte und bis zum Aufgang dieses menschlichen subjektiven Geistes in Religion, Kunst und Wissenschaft. Wenn man also Hegels Philosophie studieren will, so muß man sich einlassen in eine Entwickelung der Weltgedanken, so wie Hegel diese Weltgedanken eben für sich erklären konnte.

[ 3 ] Schopenhauer ist der Gegenpol. Während für Hegel die Gedanken, die Weltgedanken, das Schöpferische sind, also das eigentliche Reale in den Dingen, ist für Schopenhauer jedes Gedankenelement nur ein Subjektives, und auch als Subjektives nur ein Bild, nur etwas Unreales, während ihm das einzig Reale der Wille ist. Und ebenso wie Hegel im mineralischen, im tierischen, im pflanzlichen, im menschlichen Reiche den Gedanken verfolgt, so verfolgt Schopenhauer in allen diesen Reichen den Willen. Und die reizvollste Abhandlung Schopenhauers ist ja eigentlich diejenige «Über den Willen in der Natur». So daß man sagen kann: Hegel ist der Gedankenphilosoph, Schopenhauer ist der Willensphilosoph.

[ 4 ] Damit stehen in diesen beiden Persönlichkeiten zwei Elemente einander gegenüber. Denn, was haben wir eigentlich gegeben auf der einen Seite in dem Gedanken, auf der anderen Seite in dem Willen? Wir werden diesen polarischen Gegensatz zunächst einmal einleitend zu unserem nächsten Vortrage am besten vor unsere Seele treten lassen, wenn wir ihn am Menschen betrachten. Wir sehen jetzt für einen Augenblick ganz ab von Hegelischer Philosophie, von Schopenhauerscher Philosophie und sehen auf die Wirklichkeit des Menschen. Wir wissen ja schon: Im Menschen ist zunächst hervorstechend ein intellektuelles, das heißt, ein Gedankenelement vorhanden, und dann ein Willenselement. Das Gedankenelement ist vorzugsweise zugeordnet dem menschlichen Haupte, das Willenselement vorzugsweise dem menschlichen Gliedmaßenorganismus. Damit ist aber schon hingewiesen darauf, daß das intellektuelle Element eigentlich dasjenige ist, was aus unserem vorgeburtlichen Dasein aus geistigen Welten, die für uns zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt verfließen, sich einkörpert und aus dem vorgeburtlichen Leben sich herüberlebt in dieses Erdenleben, im wesentlichen. Das Willenselement aber ist dasjenige, das, ich möchte sagen, gegenüber dem Gedankenelement das Junge im Menschen ist, das, was durch die Pforte des Todes geht, dann eintritt in die Welt zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, sich da umwandelt, metamorphosiert und das intellektuelle Element des nächsten Lebens bildet. Im wesentlichsten, im hervorstechendsten haben wir in unserer seelischen Organisation unser intellektuelles, unser Gedankenelement, das in die Vorzeit verweist; wir haben unser Willenselement, das in die Zukunft verweist. Damit haben wir am Menschen diesen polarischen Gegensatz zwischen Gedanke und Wille betrachtet.

[ 5 ] Natürlich dürfen wir, wenn wir an die Wirklichkeit herantreten, diese Dinge niemals so betrachten, daß wir schematisieren. Es wäre natürlich schematisiert, wenn man sagen würde: Alles gedankliche Element weist uns in unsere Vorzeit hin, und alles Willenselement weist uns in unsere Nachzeit hin. So ist es nicht; sondern hervorstechend, sagte ich, ist das im Menschen, daß das Gedankenelement in die Vorzeit, das Willenselement in die Nachzeit weist. Aber hinzuorganisiert wird bei dem Menschen an das hervorstechende, an das nach rückwärts weisende Gedankenelement ein willensmäßiges Element, und hinzuorganisiert wird wiederum zu dem Willenselement, das in uns braust, das durch den Tod hinaus in die Zukunft geht, ein Gedankenelement. Man darf, wenn man mit seinem Erkennen in die Wirklichkeit hineingehen will, niemals schematisieren, niemals die Ideen nur nebeneinander setzen, sondern man muß sich klar sein, daß in der Wirklichkeit alles nur so betrachtet werden kann, daß irgendwo etwas als das Hervorstechende erscheint, daß aber die übrigen Elemente der Wirklichkeit darinnen leben, und daß überall, was sonst im Hintergrunde sich hält, wiederum an einem anderen Orte der Wirklichkeit das Hervorstechendste ist und das andere sich im Hintergrunde hält.

[ 6 ] Wenn dann Philosophen kommen und von ihrem besonderen Gesichtspunkte aus das eine oder das andere betrachten, so kommen sie eben zu ihren einseitigen Philosophien. Nun ist aber das, was ich Ihnen eben charakterisiert habe als das Gedankenelement beim Menschen, nicht bloß im Menschen vorhanden und da an die Hauptesorganisation gebunden, sondern es ist der Gedanke wirklich im ganzen Kosmos ausgebreitet. Der ganze Kosmos ist durchzogen von kosmischen Gedanken. Indem Hegel ein starker Geist war, der, ich möchte sagen, das Ergebnis vieler verflossener Erdenleben fühlte, richtete er die Aufmerksamkeit besonders auf den kosmischen Gedanken.

[ 7 ] Schopenhauer fühlte in sich weniger das Ergebnis früherer Erdenleben, sondern richtete seine Aufmerksamkeit mehr auf den kosmischen Willen. Denn ebenso wie im Menschen Wille und Gedanke leben, so lebt auch im Kosmos Gedanke und Wille. Was bedeutet aber für den Kosmos der Gedanke, den Hegel besonders betrachtete, was bedeutet für den Kosmos der Wille, den Schopenhauer besonders betrachtete? Hegel hatte ja nicht den Gedanken im Auge, der sich im Menschen ausbildet. Die ganze Welt war ihm im Grunde genommen nur eine Offenbarung der Gedanken. Also er hatte den kosmischen Gedanken im Auge. Sieht man hin auf die besondere Geistesformierung Hegels, so muß man sagen: Diese Geistesformierung Hegels weist nach dem Erdenwesten hin. Nur daß Hegel das, was im Westen, zum Beispiel in der materialistischen Entwickelungslehre des Westens, in der materialistisch gedachten Physik des Westens zum Ausdrucke kommt, zum Element des Gedankens heraufhob. Man findet bei Darwin eine Entwickelungslehre, man findet bei Hegel eine Entwickelungslehre. Bei Darwin ist es eine materialistische Entwickelungslehre, indem alles sich so abspielt, als wenn nur grobe Natursubstanzen in die Entwickelung eintreten würden und diese vollführten; bei Hegel sehen wir, wie alles, was in Entwickelung ist, vom Gedanken durchpulst ist, wie der Gedanke in seinen besonderen Konfigurationen, in seinen konkreten Ausgestaltungen eigentlich das sich Entwickelnde ist.

[ 8 ] So daß wir sagen können: Im Westen betrachten die Geister die Welt vom Standpunkte des Gedankens, aber sie materialisieren den Gedanken. Hegel idealisiert den Gedanken, und er kommt daher zum kosmischen Gedanken.

[ 9 ] Hegel redet in seiner Philosophie vom Gedanken und meint eigentlich den kosmischen Gedanken. Hegel sagt: Wenn wir irgendwo hinsehen in der äußeren Welt, sei es, daß wir einen Stern in seiner Bahn, ein Tier, eine Pflanze, ein Mineral betrachten, sehen wir eigentlich überall Gedanken, nur daß diese Art Gedanken in der äußeren Welt eben in einer anderen Form als in der Gedankenform vorhanden sind. Man kann nicht sagen, daß Hegel gerade bestrebt war, diese Lehre von den Gedanken der Welt esoterisch zu halten. Sie ist esoterisch geblieben, denn Hegels Werke wurden wenig gelesen; aber es war nicht Hegels Absicht, die Lehre von dem kosmischen Inhalt der Welt esoterisch zu halten. Aber es ist doch außerordentlich interessant, daß, wenn man zu den Geheimgesellschaften des Westens kommt, dann in einer gewissen Beziehung es als eine Lehre der tiefsten Esoterik angesehen wird, daß die Welt eigentlich aus Gedanken gebildet wird. Man möchte sagen: Das, was Hegel so naiv hinsagte von der Welt, das betrachten die Geheimgesellschaften des Westens, der anglo-amerikanischen Menschheit nun als den Inhalt ihrer Geheimlehre, und sie sind der Ansicht, daß man eigentlich diese Geheimlehre nicht popularisieren solle. — So grotesk sich das auch zunächst ausnimmt, man könnte sagen: Hegels Philosophie ist in einer gewissen Weise der Grundnerv der Geheimlehre des Westens.

[ 10 ] Sehen Sie, hier liegt ein bedeutsames Problem vor. Sie können wirklich, wenn Sie bekannt werden mit den alleresoterischsten Lehren der Geheimgesellschaften der anglo-amerikanischen Bevölkerung, inhaltlich kaum etwas anderes finden als Hegelsche Philosophie. Aber es ist ein Unterschied, der liegt gar nicht im Inhalte, der liegt in der Behandlung. Der liegt darinnen, daß Hegel die Sache als etwas ganz Offenbares betrachtet, und die Geheimgesellschaften des Westens sorgsam darüber wachen, daß dasjenige, was Hegel vor die Welt hingestellt hat, ja nicht allgemein bekannt werde, daß das eine esoterische Geheimlehre bleibe.

[ 11 ] Was liegt da eigentlich zugrunde? Das ist ein sehr wichtiges Problem. Es liegt das zugrunde, daß wenn man irgendeinen solchen Inhalt, der aus dem Geiste heraus geboren ist, als Geheimbesitz betrachtet, dann gibt er Macht, während wenn er popularisiert wird, er nicht mehr diese Macht gibt. Und das bitte ich Sie nun wirklich einmal ganz gehörig ins Auge zu fassen: Irgendein Inhalt, den man als Erkenntnisinhalt hat, wird zu einer Machtkraft, wenn man ihn geheim hält. Daher sind diejenigen, die gewisse Lehren geheimhalten wollen, sehr unangenehm berührt, wenn die Dinge popularisiert werden. Das ist gegeradezu ein Weltgesetz, daß dasjenige, was popularisiert einfach Erkenntnis gibt, Macht gibt, wenn es sekretiert wird.

[ 12 ] Ich habe Ihnen im Verlauf der letzten Jahre verschiedentlich von jenen Kräften gesprochen, die vom Westen ausgegangen sind. Daß diese Kräfte vom Westen ausgegangen sind, rührte nicht davon her, daß da etwa ein Wissen vorhanden gewesen wäre, welches in Mitteleuropa nicht bekannt gewesen wäre; aber dieses Wissen wurde anders behandelt. Denken Sie sich nun, was für eine merkwürdige Tragik da vorliegt! Es hätte sogar in einer bedeutsamen Weise pariert werden können, was an weltgeschichtlichen Ereignissen aus der Macht westlicher Geheimgesellschaften hervorgegangen ist, wenn man in Mitteleuropa nur die eigenen Leute studiert hätte, wenn man in Mitteleuropa nicht gar so sehr das getan hätte, was man wirklich sehr gründlich konstatieren konnte: In den achtziger Jahren — ich habe das öfters erwähnt - hat Eduard von Hartmann öffentlich drucken lassen, daß es überhaupt an den sämtlichen mitteleuropäischen Fakultäten nur zwei Philosophen gab, welche Hegel gelesen hatten. Über Hegel geredet und Vorträge gehalten hatten natürlich sehr viele, aber nachweislich gab es nur zwei an Hegel gebildete Philosophieprofessoren. Und derjenige, der für solche Sachen einige Empfänglichkeit hatte, der konnte das Folgende erleben: Wenn er sich einen Band von Hegels Werken aus irgendeiner Bibliothek geben ließ, dann konnte er wirklich recht genau konstatieren, daß der nicht sehr zerlesen war! Da war manchmal eine Seite von der anderen — ich kenne das aus der eigenen Erfahrung — sehr schwer loszubringen, weil das Exemplar noch gar so neu war. Und «Auflagen» erlebt ja Hegel erst seit sehr kurzer Zeit.

[ 13 ] Nun, ich habe Ihnen das nicht aus dem Grunde hingestellt, weil ich auf diese Tatsachen besonders hinweisen möchte, die ich zuletzt charakterisiert habe, sondern weil ich zeigen wollte, wie das, was in Hegel idealistisch lebt, dennoch nach dem Westen hinüberweist, indem es auf der einen Seite wieder erscheint in den grobklotzigen materialistischen Gedanken des Darwinismus, des Spencerismus und so weiter, andererseits in der Esoterik der Geheimgesellschaften.

[ 14 ] Und nun nehmen wir Schopenhauer. Schopenhauer ist, ich möchte sagen, der Anbeter des Willens. Und daß er den kosmischen Willen im Auge hat, das geht ja eigentlich aus jeder Seite der Schopenhauerschen Werke hervor, insbesondere eben aus der reizvollen Abhandlung «Über den Willen in der Natur», wo er alles, was in der Natur leibt und lebt, als den zugrunde liegenden Willen, als die Urkraft der Natur darstellt. So daß wir sagen können: Schopenhauer materialisiert geradezu den kosmischen Willen.

[ 15 ] Wohin weist denn nun diese ganze Seelenverfassung Schopenhauers, wenn Hegels Seelenverfassung nach dem Westen weist? Das können Sie aus Schopenhauer selber sehen, denn Sie finden sehr bald, wenn Sie ihn studieren, welche tiefe Neigung Schopenhauer für den Orient hat. Das steigt aus seinem Gemüte herauf, man weiß eigentlich nicht wie. Diese Vorliebe Schopenhauers für das Nirwana und für alles das, was orientalisch ist, diese Hinneigung zum Indertum, sie ist irrational wie seine ganze Willensphilosophie, sie steigt gewissermaßen aus seinen subjektiven Neigungen herauf. Aber es liegt darinnen eine gewisse Notwendigkeit. Das, was Schopenhauer darstellt als seine Philosophie, ist eine Willensphilosophie. Er stellt allerdings diese Willensphilosophie, wie es sich für Mitteleuropa gehört, dialektisch dar, er stellt sie in Gedanken dar, er rationalisiert den Willen selber; er spricht eigentlich in Gedanken, aber er spricht vom Willen. Aber während er so spricht vom Willen, also eigentlich den kosmischen Willen materialisiert, geht ihm aus den Tiefen seiner Seele herauf in sein Bewußtsein die Hinneigung zum Orient. Er schwärmt geradezu für alles, was Indertum ist. Ebenso wie wir gesehen haben, daß Hegel mehr objektiv hinweist nach dem Westen, so sehen wir, wie Schopenhauer hinweist nach dem Osten. Im Osten finden wir aber nicht, daß das, was Willenselement ist und was Schopenhauer wirklich fühlt als das eigentliche Element des Ostens, materialisiert und in den Gedanken hereingepreßt, also intellektualisiert wird. Die ganze Form der Darstellung des kosmischen Willens, der ja dem östlichen Seelenleben zugrunde liegt, ist eine nicht nach dem Intellekt hin erscheinende, es ist eine zum Teil poetische, zum Teil aus der unmittelbaren Anschauung heraus sprechende Darstellung. Schopenhauer hat das, was der Orient in Bildform gesagt haben würde, in mitteleuropäischer Art intellektualisiert; aber dasjenige, auf das er hinweist: der kosmische Wille, der ist doch das Element, von dem der Orient her seine Seelenanschauung genommen hat. Er ist das Element, in dem die orientalische Weltanschauung lebte. Wenn die orientalische Weltanschauung die alldurchdringende Liebe besonders betont, so ist ja das Element der Liebe auch nichts anderes als ein gewisser Aspekt des kosmischen Willens, nur eben aus dem Intellekt herausgehoben. So daß wir sagen können: Hier wird der Wille spiritualisiert. Wie im Westen der Gedanke materialisiert wird, ist im Osten der Wille spiritualisiert gewesen.

[ 16 ] In dem mitteleuropäischen Elemente sehen wir, daß in dem idealisierten kosmischen Gedanken, in dem materialisierten kosmischen Willen, der aber auch gedankenhaft behandelt wird, diese zwei Welten auch in dieser Weise ineinanderspielen, daß wir in dem Hinweis des Hegelianismus auf die Geheimgesellschaften des Westens etwas haben wie eine tiefe Verwandtschaft des Hegelschen kosmischen Gedankensystems mit diesem Westen, daß wir in der Hinneigung, in der subjektiven Hinneigung Schopenhauers zum Orient etwas haben, was auch etwas wie eine Verwandtschaft Schopenhauers mit der Esoterik des Ostens zum Ausdruck bringt.

[ 17 ] Es ist ja merkwürdig, wenn man diese Schopenhauersche Philosophie auf sich wirken läßt, wie sie eigentlich in bezug auf das gedankliche Element etwas Plattes hat; die Schopenhauersche Philosophie ist ja nicht tief, aber sie hat zugleich etwas Trunkenes, etwas Willenhaftes, das in ihr pulst. Schopenhauer wird am anziehendsten und reizvollsten dann, wenn er eigentlich flache Gedanken mit seinem Willenselement durchdringt. Da sprüht dann gewissermaßen das Feuer des Willens durch seine Sätze. Dadurch ist er auch für ein im Grunde genommen flaches Zeitalter der Salonphilosoph geworden. Als ein gedankenvolles Zeitalter, wie es die erste Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts war, vorüberging, als die Menschen gedankenarm wurden, da wurde Schopenhauer der Salonphilosoph. Man brauchte nicht viel zu denken, man konnte aber das Prickelnde des durch die Gedanken pulsierenden Willens auf sich wirken lassen, insbesondere wenn man so etwas wie die «Parerga und Paralipomena» durchnahm, wo dieses Prickeln der Gedanken geradezu mit Raffinement wirkt.

[ 18 ] Und so hat man gerade in dem Gegensatze Hegel-Schopenhauer in dem mittleren Gebiete unserer Zivilisationsentwickelung die beiden entgegengesetzten Pole, von denen der eine seine besondere Ausbildung im Westen, der andere seine besondere Ausbildung im Osten erhalten hat. In Mitteleuropa stehen sie bis zu einem Ausgleich sich fördernd nebeneinander und haben in dem unvergleichlichen Freundschaftsbund zwischen Schiller und Goethe einen harmonischen, in dem Nebeneinanderstehen Hegels und Schopenhauers einen disharmonischen Ausgleich gefunden. Denn Schopenhauer wurde ja Privatdozent an der Universität zu Berlin in derselben Zeit, in der Hegel dort glanzvoll seine Philosophie vertrat. Schopenhauer konnte kaum Zuhörer finden, sein Auditorium blieb leer. Und wahrscheinlich, wenn Hegel irgendwie gefragt worden ist über die Schopenhauersche Philosophie — er konnte es sich damals leisten, denn er war ein eindrucksvoller, angesehener Philosoph -, dann hatte er dafür ein Achselzucken. Wenn irgendeiner mehr aus diesem Willenselement heraus sprach und dieses Element des Willens besonders betonte wie Schleiermacher, aber dann neben Hegel noch etwas bedeutete, dann wurde Hegel schon auch ungemütlicher. Und als Schleiermacher aus diesem gedankenlosen Elemente heraus das Christentum erklären wollte und sagte: Das Christentum würde nicht erfaßt in einem gedanklichen Elemente, wenn man die Gedanken des Weltenalls, gewissermaßen die göttlichen Gedanken anders umfaßte, als indem man sich abhängig fühlte von Gott, indem man ein Abhängigkeitsgefühl zum Universum entwickelte -, da erwiderte Hegel: Dann ist der Hund der beste Christ, denn der kennt das Abhängigkeitsgefühl am besten! — So würde selbstverständlich Hegel auch Schopenhauer heimgeleuchtet haben, wie er Schleiermacher heimgeleuchtet hat, wenn es sich gelohnt hätte. Denn Hegel hat überall zu Paaren getrieben jeden, der sich nicht hinaufschwang zum Begreifen der Realität der Gedanken. Für Schopenhauer waren aber die Gedanken gar nichts anderes als die Schaumblasen, die aufstiegen aus den Wellenschlägen des kosmischen Weltenwillens. Und Schopenhauer, der allerdings aus der eben gekennzeichneten Lage mehr Veranlassung dazu hatte, er schimpft ja in seinen Werken über Hegel wie ein Waschweib.

[ 19 ] Wir sehen also, da ist der Gegensatz, der geradezu die Lebensrätsel der Zivilisationsmitte ausmacht, nicht zu einem harmonischen Abschlusse gekommen. Beiden aber, Schopenhauer wie Hegel, fehlt ja eines, es fehlt ihnen das eigentliche Begreifen des Menschen. Hegel lebt in dem kosmischen Gedanken, und es hat etwas, was gerade Hegel unpopulär macht, daß er in diesem kosmischen Gedanken lebt. Denn im allgemeinen lieben es doch die Menschen nicht, sich zu kosmischen Gedanken aufzuschwingen. Sie haben ja ein gewisses Gefühl, dem sie sich aus Bequemlichkeit gerne hingeben, das Gefühl: Warum sollen wir uns die Köpfe zerbrechen mit kosmischen Gedanken? Das tun ja für uns die Götter, oder Gott. Wenn man ein Evangelischer ist, sagt man: der eine Gott tut das. Wenn sich schon die Götter um die kosmischen Gedanken bemühen, warum sollten wir uns noch besonders bemühen? — Und es hat wirklich das, was in Hegels Gedankenoffenbarungen zutage tritt, etwas außerordentlich Unpersönliches. Die Geschichte zum Beispiel, wie sie uns bei Hegel entgegentritt, hat etwas durch und durch Unpersönliches. Da haben wir eigentlich seit dem Beginn der Erdenentwickelung bis zum Ende der Erdenentwickelung den sich entfaltenden Gedanken.

[ 20 ] Wollte man diese Hegelsche Geschichtsphilosophie schematisch zeichnen, so müßte man sagen: Da steigen die Gedanken auf (es wird gezeichnet), steigen ab, verfilzen sich gegenseitig und gehen so durch die geschichtliche Entwickelung, und in diesen Gedankenspinnennetzen sind überall die Menschen eingespannt, werden von den Gedanken fortgerissen.So daß eigentlich für Hegel die geschichtliche Entwickelung diese hinfließenden, sich verfilzenden Gedanken sind, die den Menschen in sich einspannen wie einen Automaten, der da in diesen Spinnennetzen der weltgeschichtlichen Gedanken sich auch mit diesem Gedankensystem entwickeln muß. Für Schopenhauer ist ja der menschliche Gedanke nichts anderes als eine Schaumblase. Er richtet seinen Blick auf den kosmischen Willen, ich möchte sagen, auf dieses kosmische Willensmeer. Der Mensch ist eigentlich nur so ein Reservoir, wo auch ein bißchen von diesem kosmischen Willen drinnen aufgefangen ist. Die Schopenhauersche Philosophie hat nichts von dieser sich fortentwickelnden Vernunft oder dem sich fortentwickelnden Gedanken, sondern es ist das ungedankliche, das unrationale, das unvernünftige Willenselement, das fortfließt. Und da tauchen drinnen die Menschen auf, und in ihnen spiegelt sich, wie wenn es Vernunft wäre, das sich eigentlich fortdauernd entwickelnde Unvernünftige. Für Hegel ist die Welt die Offenbarung weisester Vernunft. Für Schopenhauer, ja, was ist die Welt für Schopenhauer? Es ist eine merkwürdige Sache, wenn man die Frage beantworten will: Was ist die Welt für Schopenhauer? — Sie trat mir einmal, diese merkwürdige Sache, besonders deutlich vor Augen, als ich einen Aufsatz über Eduard von Hartmann schrieb, wo man Schopenhauer berücksichtigen, besprechen muß, weil Eduard von Hartmann ja auf der einen Seite von Hegel, auf der anderen Seite von Schopenhauer ausgegangen ist, mehr aber von Schopenhauer. Ich wollte in diesem Aufsatze, der ein rein philosophischer Aufsatz über die Philosophie Eduard von Hartmanns war, andeuten, daß für Schopenhauer die Lösung des Welträtsels darinnen bestünde, daß man sagen müßte: Die Welt ist eine große Dummheit Gottes. — Ich habe das geschrieben, weil ich das für wahr hielt. Der Redakteur der Zeitschrift, die in Österreich erschien, antwortete mir, das müsse er herausstreichen, denn es würde ihm das ganze Heft konfisziert, wenn das in einer österreichischen Zeitschrift gedruckt würde; er könne einfach nicht schreiben, die Welt sei eine Dummheit Gottes. Nun, ich habe mich nicht weiter darauf versteift, sondern habe dem Manne, der dazumal der Redakteur dieser «Deutschen Worte» war, geschrieben: Streichen Sie die «Dummheit Gottes» heraus; aber ich erinnere Sie an einen anderen Fall: Als ich die «Deutsche Wochenschrift» redigierte, da schrieben Sie zwar nicht, daß die Welt eine Dummheit Gottes, aber daß das österreichische Schulwesen eine Dummheit der Unterrichtsverwaltung ist, und ich habe es stehen lassen. — Allerdings ist mir die Wochenschrift dazumal konfisziert worden. Ich wollte den Mann wenigstens daran erinnern, daß ihm etwas Ähnliches passiert ist wie mir, nur mir mit dem lieben Gott, ihm mit dem österreichischen Unterrichtsminister, dem Freiherrn von Gautsch.

[ 21 ] Wenn man so hinblickt auf das Wesentlichste des Welträtsels, sieht man so recht wie in Hegel und Schopenhauer die beiden entgegengesetzten Pole dastehen, und sie erscheinen tatsächlich in ihrer Größe, in ihrer bewunderungswürdigen Größe. Ich weiß ja allerdings, daß manche Leute es sonderbar finden, daß, wenn jemand ein solcher Hegel-Verehrer ist wie ich, er auch eine solche Zeichnung hinsetzen kann, weil sich manche Leute nicht vorstellen können, daß gegenüber dem, was man als groß empfindet, man auch den Humor beibehalten kann, weil sich die Leute vorstellen, man müsse unbedingt, wenn man irgend etwas als groß empfindet, immer das lange Gesicht bekommen, das bekannte.

[ 22 ] Also die zwei entgegengesetzten Pole stehen da vor uns, die in diesem Falle nicht wie bei Schiller und Goethe zu einem harmonischen Ausgleich gekommen sind. Und wir werden etwas zur Erklärung dieser Disharmonie finden können, wenn wir sehen, daß für Hegel der Mensch eben solch ein im Spinnennetz der Begriffe der Weltgeschichte sich fortentwickelndes Wesen ist, und daß für Schopenhauer eigentlich der Mensch nichts anderes ist als ein kleines Schäffchen, also ein kleines Gefäß, wo ein Teil des Weltenwillens hineingeschüttet ist, also im Grunde genommen nur ein Ausschnitt aus dem kosmischen Weltenwillen. Beide können also nicht auf das eigentliche Individuelle, Persönliche des Menschen hinsehen. Aber sie können auch nicht hinsehen auf das eigentliche Wesen dessen, was sie im Kosmos sehen.

[ 23 ] Hegel schaut auf den Kosmos und sieht in der Geschichte dieses Spinnennetz von Begriffen. Schopenhauer schaut auf den Kosmos und sieht nicht dieses Spinnennetz von Begriffen — das ist bloß das Spiegelbild für ihn -, aber er sieht dafür das Meer des waltenden Willens, und da wird gewissermaßen abgezapft in diese Gefäße dasjenige, was als Menschen da fortschwimmt in diesem unrationalen, unvernünftigen Willensmeer (es wird gezeichnet). Die Menschen werden nur geäfft, indem sich in ihnen der unvernünftige Wille spiegelt, als wenn er Vernunft, Vorstellung, Gedanke wäre. Aber wir haben diese zwei Elemente im Kosmos drinnen. Was Hegel sieht, ist schon im Kosmos drinnen. Die Gedanken sind im Kosmos. Hegel und der Westen betrachten den Kosmos und sehen die Weltgedanken. Schopenhauer und der Osten betrachten den Kosmos und sehen den Weltenwillen. Beides ist drinnen. Und eine in bezug auf den Kosmos dienliche Weltanschauung wäre zustande gekommen, wenn das Paradoxon hätte eintreten können, daß das Geschimpfe des Schopenhauer ihn endlich so weit gebracht hätte, daß er aus seiner Haut gefahren wäre, und, trotzdem Hegels Seele in Hegel geblieben wäre, er in Hegel hineingefahren wäre, so daß Schopenhauer in Hegel drinnen gewesen wäre. Dann hätte der den Weltgedanken und den Weltenwillen gesehen, der da aus Schopenhauer und aus Hegel zusammengewachsen wäre! Das ist in der Tat dasjenige, was in der Welt ist: Weltgedanke und Weltenwille. Und sie sind in sehr verschiedenen Gestalten vorhanden.

[ 24 ] Was sagt uns nun die wirkliche geisteswissenschaftliche Untersuchung in bezug auf diese Kosmologie? Sie sagt uns: Blicken wir hinein in die Welt, um die Weltgedanken auf uns wirken zu lassen, was sehen wir? Wir sehen, indem wir die Weltgedanken auf uns wirken lassen, die Gedanken der Vorzeit, alles das, was gewirkt hat in der Vorzeit bis zu diesem gegenwärtigen Augenblicke. Das sehen wir, indem wir die Weltgedanken sehen, denn der Weltgedanke erscheint uns in seinem Absterben, wenn wir in die Welt hinausblicken. Daher kommt das Starre, Tote der Naturgesetze, und daß wir fast nur die Mathematik brauchen können, die vom Toten handelt, wenn wir die Natur gesetzmäßig überschauen wollen. In dem aber, was zu unseren Sinnen spricht, was uns entzückt im Lichte, was wir hören im Ton, in dem, was uns wärmt, in all dem, was an uns sinnlich herantritt, wirkt der Weltenwille. Das ist es, was aus dem toten Element der Weltgedanken aufgeht, und was im Grunde genommen in die Zukunft hinüberweist. Etwas von, ich möchte sagen, Chaotischem, Undifferenziertem hat der Weltenwille; aber er lebt im gegenwärtigen Weltenmomente doch als der Keim dessen, was in die Zukunft hinübergeht. Überlassen wir uns aber dem Gedankenelemente der Welt, so haben wir das, was aus der grauesten Vorzeit in die Gegenwart herüberspielt. Nur im menschlichen Haupte, da ist es anders. Im menschlichen Haupte ist der Gedanke, aber er ist abgesondert von dem äußeren Weltengedanken, und er ist innerhalb der menschlichen Persönlichkeit an ein individuelles Willenselement gebunden, das ja meinetwillen zunächst nur angesehen werden mag wie das in ein kleines Reservoir, in ein Schäffchen abgezapfte kosmische Willenselement. Aber das, was der Mensch in seiner Intellektualität hat, weist nach rückwärts. Wir haben es im Grunde genommen dem Keime nach entwickelt in dem vorigen Erdenleben. Da war es Wille. Jetzt ist es Gedanke geworden, ist gebunden an unsere Hauptesorganisation, ist herausgeboren wie ein lebendiges Nachbild des Kosmos in unserer Hauptesorganisation. Wir verbinden es mit dem Willen, wir verjüngen es in dem Willen. Und indem wir es verjüngen in dem Willen, schicken wir es hinüber in unser nächstes Erdenleben, in unsere nächste Erdeninkarnation.

[ 25 ] Dieses Weltenbild, wir müßten es eigentlich noch anders zeichnen. Wir müßten so zeichnen, daß das äußere Kosmische in alten Zeiten besonders reich an Gedankenelementen ist, daß es immer schütterer und schütterer wird, indem wir in die Gegenwart hereinkommen, daß der Gedanke, wie er im Kosmos ist, nach und nach erstirbt. Das Willens element müssen wir zunächst fein zeichnen. Je weiter wir zurückgehen, desto mehr überwiegt der Gedanke in den Akasha-Bildern; je mehr wir vorwärtsschreiten, wird das Willenselement dichter und immer dichter. Wir müßten, wenn wir diese Entwickelung durchblicken würden, auf ein lichtvolles Gedankenelement der grauesten Vorzeit hinschauen, und auf das unvernünftige Willenselement der Zukunft.

[ 26 ] Aber das bleibt nicht so, denn da hinein trägt der Mensch nun die Gedanken, die er in seinem Kopfe bewahrt hat. Die schickt er hinüber in die Zukunft. Und während die kosmischen Gedanken immer mehr und mehr absterben, keimen auf die menschlichen Gedanken; aus ihrem Quellpunkt heraus durchdringen sie in der Zukunft das kosmische Element des Willens.

[ 27 ] So ist der Mensch der Bewahrer des kosmischen Gedankens, so trägt der Mensch aus sich heraus den kosmischen Gedanken in die Welt hinaus. Auf dem Umwege durch den Menschen pflanzt sich der kosmische Gedanke von der Urzeit in die Zukunft hinein fort. Der Mensch gehört zu dem, was Kosmos ist. Aber er gehört nicht so dazu, wie ihn etwa der Materialist denkt, daß der Mensch auch so etwas ist, was sich aus dem Kosmos herausentwickelt hat und ein Stück des Kosmos ist, sondern der Mensch gehört auch zu dem schöpferischen Elemente des Kosmos. Er trägt den Gedanken hinüber aus der Vergangenheit in die Zukunft.

[ 28 ] Sehen Sie, da kommt man in das Konkrete hinein. Wenn man den Menschen wirklich versteht, kommt man hinein in das, was Schopenhauer und Hegel einseitig gebracht haben. Und Sie sehen daraus, wie auch im philosophischen Elemente auf einer höheren Stufe zusammengefaßt werden muß dasjenige, was dreigegliedert ist, wie der Mensch erfaßt werden muß im Kosmos.

[ 29 ] Nun, wir werden dann morgen in einer anschaulicheren Weise in diesen Zusammenhang des Menschen mit dem Kosmos hineinblicken. Ich wollte Ihnen heute dieses als eine Einleitung geben, wie gesagt, deren Notwendigkeit schon im weiteren Fortgange wird erkannt werden können.

Fourth lecture

[ 1 ] My task here in the coming days will be to present to you some points of view concerning the relationship between the human being and the cosmic world on the one hand, and the human being and the historical development of humanity on the other. These will be reflections that may supplement much of what we have already considered. Today, I would like to preface the reflections of the next few hours with a kind of introduction, which may seem somewhat remote to some, but whose necessity will become apparent in the following hours. For I would like to draw your attention today to the fact that in the development of thought in Central Europe and Germany in the first half of the 19th century, apart from the facts we have already pointed out, there is another extremely significant fact. I recently pointed out the contrast that arises when one considers Schiller's Aesthetic Letters on the one hand and Goethe's fairy tale of the green snake and the beautiful lily on the other. Today I would like to point out a similar contrast that emerged in this development of thought in the first half of the 19th century in Hegel on the one hand and Schopenhauer on the other. In Goethe and Schiller, we are dealing with two personalities who, at a certain point in their lives, brought into balance what can be described as a lasting contrast, particularly in the development of Central European thought, but which also continually strives for balance in this development, after they had previously repelled each other.

[ 2 ] Two other personalities also represent these polar opposites, without it being possible to say that any balance was ever achieved between them: Hegel on the one side, Schopenhauer on the other. One need only consider what I myself have presented in my “Riddles of Philosophy” to notice the profound contrast between Schopenhauer and Hegel. It is also evident in the fact that Schopenhauer truly spared no abusive words in characterizing his counterpart Hegel in the way he deemed appropriate. Much of Schopenhauer's work is the most vicious ranting against Hegel, Hegelianism, and everything related to it. Hegel had less reason to rant about Schopenhauer because, before Hegel died, Schopenhauer had remained largely influential, and was not really among the philosophers who had been noticed. The contrast between these two personalities can be characterized simply by pointing out how Hegel sees the origin of the world and the development of the world and everything that belongs to it in real elements of thought. Hegel considers the idea, the thought, to be the foundation of everything. And Hegel's philosophy is divided into three parts: First, logic, which is not subjective human logic, but the system of thoughts that are supposed to underlie the world. Then Hegel lists nature as the second part of his philosophy. But nature is nothing other than an idea to him, only the idea in its otherness, as he says: the idea in its being outside itself. So nature is also an idea, but an idea in a different form, in the form in which it can be seen, perceived with the senses, an idea in its otherness. The idea, in returning to itself, is for him the spirit of man, which develops from the simplest human-spiritual activities to world history and to the emergence of this human subjective spirit in religion, art, and science. So if one wants to study Hegel's philosophy, one must engage in a development of world thoughts, just as Hegel was able to explain these world thoughts for himself.

[ 3 ] Schopenhauer is the opposite. While for Hegel thoughts, world thoughts, are creative, i.e., the actual reality in things, for Schopenhauer every element of thought is only subjective, and even as subjective only an image, only something unreal, while for him the only reality is the will. And just as Hegel pursues thought in the mineral, animal, plant, and human realms, Schopenhauer pursues the will in all these realms. And Schopenhauer's most fascinating treatise is actually “On the Will in Nature.” So one can say that Hegel is the philosopher of thought, Schopenhauer is the philosopher of the will.

[ 4 ] Thus, two elements stand in opposition to each other in these two personalities. For what do we actually have on the one hand in thought and on the other in will? We will best introduce this polar opposition at the beginning of our next lecture by considering it in relation to human beings. Let us now turn our attention away from Hegelian philosophy and Schopenhauer's philosophy for a moment and look at the reality of human beings. We already know that there is, first of all, a striking intellectual element, that is, a thought element, and then a will element in human beings. The thought element is primarily associated with the human head, while the will element is primarily associated with the human limb organism. This already indicates that the intellectual element is actually that which, from our pre-birth existence in spiritual worlds that flow between death and a new birth, embodies itself and lives over from pre-birth life into this earthly life, in essence. The element of will, however, is that which, I would say, is the young element in the human being in relation to the element of thought, that which passes through the gate of death, then enters the world between death and a new birth, transforms itself there, undergoes a metamorphosis, and forms the intellectual element of the next life. In the most essential, most striking way, we have in our soul organization our intellectual, our thought element, which points to the past; we have our will element, which points to the future. With this, we have considered this polar opposition between thought and will in human beings.

[ 5 ] Of course, when we approach reality, we must never view these things in such a way that we schematize them. It would of course be schematized to say that all the element of thought points us to our past, and all the element of will points us to our future. That is not the case; rather, what is striking, I said, is that in human beings, the element of thought points to the past, and the element of will points to the future. But in human beings, a volitional element is added to the striking, backward-pointing element of thought, and in turn, a thought element is added to the element of will that rages within us and continues into the future through death. If one wants to enter into reality with one's knowledge, one must never schematize, never simply juxtapose ideas, but must be clear that in reality everything can only be viewed in such a way that something appears somewhere as the most prominent feature, but that the other elements of reality live within it, and that everywhere what remains in the background is, in turn, the most prominent in another place of reality, and the other remains in the background.

[ 6 ] When philosophers then come and look at one thing or another from their particular point of view, they arrive at their one-sided philosophies. Now, however, what I have just characterized as the element of thought in human beings is not only present in human beings and bound to the organization of the head, but thought is actually spread throughout the entire cosmos. The entire cosmos is permeated by cosmic thoughts. Because Hegel was a strong spirit who, I would say, felt the result of many past earthly lives, he focused his attention particularly on cosmic thought.

[ 7 ] Schopenhauer felt less the result of previous earthly lives within himself, but focused his attention more on the cosmic will. For just as will and thought live in man, so too do thought and will live in the cosmos. But what does the thought that Hegel particularly considered mean for the cosmos, and what does the will that Schopenhauer particularly considered mean for the cosmos? Hegel did not have in mind the thought that develops in humans. For him, the whole world was basically just a revelation of thoughts. So he had cosmic thought in mind. Looking at Hegel's particular form of thought, one must say that it points to the western part of the earth. Only that Hegel elevated to the element of thought that which is expressed in the West, for example in the materialistic theory of evolution of the West, in the materialistically conceived physics of the West. One finds a theory of evolution in Darwin, one finds a theory of evolution in Hegel. In Darwin, it is a materialistic theory of evolution, in which everything takes place as if only coarse natural substances entered into evolution and carried it out; in Hegel, we see how everything that is in evolution is pulsated by thought, how thought in its particular configurations, in its concrete forms, is actually that which is evolving.

[ 8 ] So we can say: In the West, minds view the world from the standpoint of thought, but they materialize thought. Hegel idealizes thought and thus arrives at the cosmic thought.

[ 9 ] In his philosophy, Hegel speaks of thought and actually means cosmic thought. Hegel says: When we look anywhere in the external world, whether we are looking at a star in its orbit, an animal, a plant, or a mineral, we actually see thoughts everywhere, only that this kind of thought exists in the external world in a different form than in the form of thought. It cannot be said that Hegel was particularly concerned with keeping this doctrine of the thoughts of the world esoteric. It remained esoteric because Hegel's works were little read; but it was not Hegel's intention to keep the doctrine of the cosmic content of the world esoteric. But it is nevertheless extremely interesting that when one comes to the secret societies of the West, it is regarded in a certain sense as a doctrine of the deepest esotericism that the world is actually formed out of thoughts. One might say that what Hegel so naively said about the world is now regarded by the secret societies of the West, by Anglo-American humanity, as the content of their secret doctrine, and they are of the opinion that this secret doctrine should not actually be popularized. As grotesque as this may seem at first, one could say that Hegel's philosophy is, in a certain sense, the nerve center of the secret teachings of the West.

[ 10 ] You see, there is a significant problem here. If you become familiar with the most esoteric teachings of the secret societies of the Anglo-American population, you will find that their content is virtually identical to Hegel's philosophy. But there is a difference, and it does not lie in the content, but in the treatment. It lies in the fact that Hegel regards the matter as something completely obvious, and the secret societies of the West carefully ensure that what Hegel has presented to the world does not become generally known, that it remains an esoteric secret doctrine.

[ 11 ] What is actually behind this? This is a very important problem. The underlying principle is that if you regard any content that is born out of the spirit as secret property, then it gives power, whereas if it is popularized, it no longer gives this power. And I ask you to really take this to heart: any content that one has as knowledge becomes a power when one keeps it secret. Therefore, those who want to keep certain teachings secret are very uncomfortable when things are popularized. It is a law of the world that what is popularized simply gives knowledge, and what is kept secret gives power.

[ 12 ] Over the past few years, I have spoken to you on several occasions about the forces that originated in the West. The fact that these forces originated in the West did not stem from the existence of knowledge that was unknown in Central Europe; rather, this knowledge was treated differently. Now think about what a strange tragedy this is! The world-historical events that emerged from the power of Western secret societies could have been prevented in a significant way if people in Central Europe had only studied their own people, if they had not done so much of what could be very thoroughly documented: In the 1880s—I have mentioned this often—Eduard von Hartmann had it publicly printed that there were only two philosophers in all of Central European universities who had read Hegel. Of course, many had talked about Hegel and given lectures on him, but there were only two philosophy professors who were educated in Hegel. And anyone who was receptive to such things could experience the following: if they borrowed a volume of Hegel's works from any library, they could see quite clearly that it had not been read very much! Sometimes it was very difficult to turn the pages—I know this from my own experience—because the copy was not very new. And Hegel has only been experiencing “print runs” for a very short time.

[ 13 ] Now, I have not mentioned this to you because I particularly want to draw attention to the facts I have just described, but because I wanted to show how what lives on in Hegel as idealism nevertheless points to the West, in that it reappears on the one hand in the crude materialistic ideas of Darwinism, Spencerism, and so on, and on the other hand in the esotericism of secret societies.

[ 14 ] And now let us take Schopenhauer. Schopenhauer is, I would say, the worshipper of the will. And that he has the cosmic will in mind is evident from every page of Schopenhauer's works, especially from his fascinating treatise “On the Will in Nature,” where he presents everything that lives and exists in nature as the underlying will, as the primal force of nature. So we can say that Schopenhauer virtually materializes the cosmic will.

[ 15 ] Where does Schopenhauer's entire state of mind point, if Hegel's state of mind points to the West? You can see this for yourself in Schopenhauer, because when you study him, you very quickly discover his deep inclination toward the Orient. It rises from his mind, and one does not really know how. Schopenhauer's preference for nirvana and for everything Oriental, this inclination toward the inner self, is irrational, like his entire philosophy of will; it arises, so to speak, from his subjective inclinations. But there is a certain necessity in this. What Schopenhauer presents as his philosophy is a philosophy of will. However, he presents this philosophy of will dialectically, as befits Central Europe; he presents it in thought, he rationalizes the will itself; he actually speaks in thought, but he speaks of the will. But while he speaks of the will in this way, that is, while he actually materializes the cosmic will, the inclination toward the Orient rises from the depths of his soul into his consciousness. He is downright enthusiastic about everything that is inner life. Just as we have seen that Hegel points more objectively toward the West, we see how Schopenhauer points toward the East. In the East, however, we do not find that what is the element of will and what Schopenhauer really feels as the actual element of the East is materialized and pressed into thought, that is, intellectualized. The entire form of representation of the cosmic will, which is the basis of Eastern spiritual life, is not intellectual in nature; it is partly poetic and partly based on direct observation. Schopenhauer intellectualized what the Orient would have expressed in pictorial form in a Central European manner; but what he points to, the cosmic will, is nevertheless the element from which the Orient derived its view of the soul. It is the element in which the Oriental worldview lived. If the Oriental worldview emphasizes all-pervading love in particular, then the element of love is nothing other than a certain aspect of the cosmic will, only lifted out of the intellect. So we can say: here the will is spiritualized. Just as thought is materialized in the West, so the will has been spiritualized in the East.

[ 16 ] In the Central European element, we see that in the idealized cosmic thought, in the materialized cosmic will, which is also treated conceptually, these two worlds also interact in this way, that in Hegelianism's reference to the secret societies of the West, we have something like a deep kinship between Hegel's cosmic system of thought and this West, that in Schopenhauer's inclination, his subjective inclination toward the East, we have something that also expresses something like a kinship between Schopenhauer and the esotericism of the East.