The Responsibility of Man for World Evolution

GA 203

1 April 1921, Dornach

Lecture V

If we turn our attention to what we have often taken as the object of esoteric study, to what is described in my books, “Theosophy,” “Occult Science,” and others, as the principles of the human being, and if we consider this somewhat generally and. externally, we can look on the one hand towards all that can be called the forces, the faculties, of the human intellect. To be sure, what we comprise under the faculties of the intellect includes something entirely different from what we have described as the principles of man. But precisely through such studies as call our attention to various concepts and ideas from other points of view, we shall advance in our studies. Thus we see on the one hand activities of a more intellectual order of the human soul and spirit life, and we see on the other hand the activities of the soul and spirit life which are more applied to the appetitive faculties, to the will. Today we will turn our attention to these faculties with reference to mankind in general, that is, we will ask ourselves: what significance have the more intellectual forces, and what significance have the forces of a will nature in the life of humanity as a whole? If such a method of study is undertaken, it can only be fruitful if one does not dissociate man and mankind from the earth, but when one regards man as a member of the whole earth planet. The justification for this you will discover through statements which you find, for instance, in “Occult Science” concerning the Saturn, Sun and Moon evolutions of our Earth.

When you remember what has been said there about the Saturn, Sun and Moon evolutions you will see that the views there differ from those of the modern geologist and natural scientist, who consider the earth on the one hand geologically, as if man had no connection with it at all, and then again, mankind by itself in a kind of self-enclosed anthropology, as if this mankind walked about on a soil quite foreign to it. This is quite impossible as a really fruitful method of study. When you follow what was said about the Saturn, Sun and Moon evolution, you will see that in these evolutions the forces which worked in humanity itself and the forces which worked in the rest of the planet were not at all to be thought of as separate. The fact that humanity has reached a certain independence on the earth and walks about free of the planet, as it were upon its surface, is a phase of evolution, it must not be considered as a final standard. We must consider mankind in connection with the whole of earthly evolution. And, therefore, in the first place we must say to ourselves: if we turn our attention to the intellectual faculties and remember what has been said about the earlier metamorphoses, about the Saturn, Sun and Moon metamorphoses of the Earth's evolution then we arrive at the fact that this inner development of the intellect, which man has today, was not in existence in former stages of the Earth's development. What is today localised to some extent in our head as intellect was spread over the whole Earth planet as a universal intelligence, as an intelligence working according to law, penetrating everything. One could say that intelligence worked in the facts of the whole Earth evolution. The human being himself on the Moon, to say nothing of Saturn and Sun, had not yet, as we know, a reasoning consciousness, but instead a kind of dreamlike consciousness. This dreamlike consciousness looked out into the cosmic phenomena and man did not say to himself, “Out there the cosmic phenomena take place and I grasp them with my reason,” but man dreamed in pictures. What we find today localised in our head as intellect he saw as something which interpenetrated external facts and objects. We differentiate between the laws of nature and that which in us comprehends these laws of nature, and this latter we call our intelligence. The human being of earlier times, and that applies also to the earlier parts of our Earth evolution, lived in a soul-consciousness of pictures and he did not distinguish the laws of nature by his intelligence, but Nature herself had intelligence, Nature herself gave herself laws. There outside worked intelligence. It is an evolutionary phase of our humanity, now become independent, that we bear intelligence within us and there, outside, are the laws of nature. The sum total of these natural laws was the intelligence for the man of antiquity.

Now, as Earth humanity we have, as you know, already developed consciousness to a certain degree, so that intelligence is within us and outside exist natural laws which we only grasp with our intelligence. In pointing to these facts, we are touching upon an important evolutionary impulse of mankind. But we must be aware that this evolutionary impulse must be more and more laid hold of and perfected. Today indeed it is not yet fully perfected. We certainly say to ourselves that we have intellect within us, and there, without, the laws of nature hold sway, but we have not yet fully made intelligence our own. As humanity we have remained half-way as regards this receiving of intelligence, reason, natural law, into ourselves. And these facts which I have been touching upon are amongst those which above all must be examined from the standpoint of Spiritual Science precisely in our times. Nowadays we are still extraordinarily proud when we possess something of an intellectual nature, something pertaining to human knowledge in common with other people. Something still holds good today which is cutting very deeply into the whole development of human nature, namely, that science should be cultivated as something universal, hovering over humanity, as it were, and that when men devote themselves to science they should bring their individuality as a sacrifice, that they should think—well, as “everyone” thinks. It is an ideal, for instance, in our public educational institutions, to cultivate a science which is quite impersonal, quite un-individual, to make this science into something in respect of which one says “I” as little as possible, and says “one” as much as possible. “One” has discovered this or that, “one” must accept this or that as true. And the ideal of the official representative of science today would be just this—that one should not really be able to distinguish the separate professors very well—least of all as regards temperament—when one arrives at a college from another college far distant. It would be an ideal, if one—shall we say?—could listen to a lecture on botany somewhere in the north, then fly with a balloon towards the south and could there hear the continuation of this lecture, and if the continuation should correspond with what “one” really knows in Botany! Something quite impersonal, unindividual, it is this which people consider to be the right thing, and they have a horrible dread lest somehow or other anything personal should enter into this knowledge, into this working of the human intellect. It is just in this sphere that the levelling down of the whole of human culture is considered as of chief importance. It is a source of pride if one does not deviate from what has been formulated once and for all in a certain method. Thus, people would like to sunder science from man. It is separated from man also in still many other relations, as we know. Examples could be given of this. Just think how most men today who are connected in an official way with science write their dissertations, their professorial candidature treatises and so on. They put themselves into them as little as possible, and least of all they reckon with the fact that these books will be quite generally read. They are written; but they are scarcely read by those who have to test them in the college in question; at the most someone reads them who is obliged to do so, and then he tells the others what is contained in them. For science is something about which “one” thinks, not oneself personally. And then they are stored away in libraries. When someday someone or other writes a similar book he looks in the library catalogue and sees where he can find anything he must pay attention to and then that is stored away again, end enters least of all into the individual-personal. All of that is cut off. Yes, my dear friends, countless books abound in the libraries which have no personal interest at all. This is after all a dreadful situation. But what is worse, people have not the least idea of it, and feel quite satisfied, believing that they themselves do not need to know anything at all, for in the libraries you can find everything, if you only get the right catchword in the catalogue. There things rest. But men are withering away beside a science which is so unindividual. Science would have to be looked at differently if people wanted to keep it in their heads instead of on the library shelves.

This gives one through a few holes—so to say—for one could bring forward many things along these lines, an indication of how the ordinary intellectual culture in modern men is still unindividual, impersonal, how they would like to have it as something which carries on a sort of cloud existence above them. But what is brought about by man belongs not only to man, but to the cosmos. I have therefore said that in order to come to fruitful reflections, we must regard man in connection with the planet, and then again, the planet in connection with the whole universe.

What man brings about, therefore, by using his intellect he can deal with in two directions. He can exert it by developing sciences which all end in “one” thinks, “one” knows, “one” has attained these or those improvements. Then one writes it down in books and stores it away, then that is science, which the generations outgrow, and men can wither away with such a cultivation of the intellect. People can take the line of looking to many other things for their real interests but certainly not to what is an unreality, objective, with no personal touch, preserved in libraries—this they do not meddle with. One has known of learned assemblies who had a phrase, “one who is fond of talking shop” (Fachsimpeln). To gather in small circles and discuss scientific matters when there was an official assembly was considered as of far the least importance. Oh, no, one spoke there of all sorts of trivialities, lying far removed from anything that was really a matter of science. And those who had the weakness of being somewhat enthusiastic about their science and who then—shall we say?—when tea or black coffee was being drunk, began perhaps to speak of this or that philosophical subject, those were people who talked “shop,” whom one couldn't take quite seriously—who had not the mind of a man of the world.

I once encountered this lack of the personal in science in a very singular way. I attended an assembly where Helmholtz was giving a. lecture. At this lecture, which was read aloud word for word by Helmholtz and which had already been in print for some time, the audience listened to its being read—well, as one does listen to such a lecture. After the lecture, a journalist came up to me and said—“Why exactly that? One does not need that at all. Anyone can read such a lecture, who wants to, when it has been printed, why should it be read aloud to us as well? It would have been far more sensible if Helmholtz had simply walked about in the auditorium and given his hand to everyone. That would have done much more good.” That is a very true example of how estranged people are from what is flying about so impersonally as science. Naturally people are being dried up by it. This, then, is one way in which intellectual culture can be grasped.

The other method is this; to interest oneself in every single thing, so that one's mind catches fire and brings new life into science and the details are recast into living concepts, so to grasp everything that it is received from the first moment with the inner life of feeling. Thus, one can really imbue with an inner fire all that is given by science. By taking the various sciences one can gradually penetrate into the whole world existence, one can create something which becomes an innately personal concern of every human being who pursues it. That is the other method. On the one side impersonal, all that is carried on being cut off from humanity—in fact people would greatly prefer to find automatons for the pursuit of science. Then they would have nothing more to reflect upon with their own heads, for perhaps they would be productive without them. But all that happens in this way, or all that may happen from a fully heartfelt pursuit of science, is indeed not merely the concern of mankind, it is the concern of the whole planet and therewith of the whole universe. For what a man does, inasmuch as he cultivates something of an intellectual nature with his head, is just as much an event as when the water of a spring flows under the stream to the sea, or as when evaporation takes place, or it rains. What happens when plants sprout and so on, those are events of the one sort. What happens through the agency of man is an event of another sort. It is not merely a human concern, it is a concern of the whole planet. And this is precisely the task of man in his evolution on the earth—for the intelligence which formerly was poured out in common with the whole planet, to be drawn within by man, to be united with himself. Thus it is an evolutionary impulse of man to make knowledge his own personal concern, so that he can imbue it with enthusiasm, so that it can pass over into him and be seized by the fire of his heart. And if he does not do the latter, if he stores up knowledge in impersonal ways, then something does not happen which ought to happen in the sense of the Earth's evolution. The feeling nature of man is not seized by the culture of the intellect» The intellectual culture only develops in the head, as it were, and hovers too far away from the surface of the earth, merely in our heads. It makes no difference if many people are short, and their heads only reach about to the hearts of others, it develops only in the heads, and it ought to sink down to the hearts. But lying in wait for what is thus not taken in by the heart, what is not seized by the feeling nature of man, are the Luciferic spirits. And this for which the Luciferic spirits are thus waiting can be received by them when it hovers thus impersonally above the earth. For the only possibility of wresting the world of intellect away from the Luciferic spirits is to imbue it with feeling and make it a personal affair. And what is happening in our age, and what has happened for a long time and must become different, is that we are letting earthly existence become the prey of the Luciferic world, by our cold, empty, dried-up intellect. In this way the Earth is checked in her evolution, and is held back at an earlier stage. She will not arrive at her goal. And if man continues for a long time the impersonality of so-called science, the consequence will be the loss of the soul-nature altogether. This impersonal science is the murderer of the human soul and spirit nature. It dries men up, it withers them. Finally, it makes of the Earth something that one can call a dead planet with automatic men on it, who have lost their spirit and soul by these means. Here too one must say: things must even now be taken in earnest; we must not look on at this cosmic murder by the abstract impersonal pursuit of knowledge on earth. That is one thing.

The other is the human desire-nature, which is connected with the will in man. What is connected with man's will-nature can again take two directions. The one path is for this will-nature to subordinate itself as much as possible to regulations or state decrees, and to unite itself with what is a kind of general law, so that this general law exists, and in addition there are only man's purely instinctive desires.

The other path is that what is reflected in man as desire, what is present as will should gradually raise itself to pure thought, expend itself in individual freedom so that it flows into the social life as love. It is the method of transmuting the forces of will and desire that I have described in the “Philosophy of Spiritual Activity.” There I have shown how the common law of humanity must proceed from each human individuality. I have described there how the social order arises through the harmony of men's acts, when what proceeds from the human individual is raised to pure thought. Men are afraid of a social order which is formed by every person giving himself his direction out of his own individuality. People like to organise what men should want. They like to establish categorical commands in the place of the love working out of each human being. Through the existence, however, of such abstract injunctions, whether they are commands on the pattern of the Decalogue, or laws of any individual State, then from out the individuality of man only instinctive desires have a value, those desires which we are seeing revive today especially, and which have become, as a matter of fact, the sole social ingredient of the present time. Again, that which happens in man when he does not make his will individual, does not raise it to pure thinking, that is not something affecting man alone, but it affects the whole planet and therewith the cosmos. And what occurs when the human will cannot become individual, this the Ahrimanic spirits are greedily awaiting. They make it their own, these Ahrimanic spirits, and they appropriate everything which lives in man of a will-nature, by way of desires not unfolded to love, and carry it over to individual demonic beings. Just as something of a more universal nature arises through that which is hovering over mankind as the intellectual faculty, so do quite individually formed demonic beings arise out of the human appetitive faculties not transformed into love.

And if there were no striving on the part of the individuals towards a community of freedom within the social order, the Earth would have to fulfil her purpose with these beings, who would then be individualised, but who would carry on an existence as Ahrimanic spirits, and who would take away from the Earth the possibility of evolving into the next planetary condition, the Jupiter metamorphosis. Stated shortly, that would mean that the abstract intellectuality of our planet would be perfected towards the one side, would not let it come to completion, and that which arises out of the will, not transmuted into love, would create on the other side sheer individual beings. No less than this is seen by one who sees into the beginnings of a civilisation which is undermining the true progressive development of the Earth. This is what such a seer sees being formed today if no impediment is put in the way of the impulses which on the one hand are now arising in the Western world with such strength, and on the other hand developing so forcibly in the Eastern world. What has proceeded purely out of human subjectivity over there and is lying at the base of the State culture, which has fallen into decadence, is something which will actually mould the Earth's evolution in the direction of individualised demons. And what is evolving in the West is something which will sail along into a universal standard of intellectuality and gradually make man into an automaton. These things can plainly be seen in the construction of these automatic machines, which are already here today—partially. I say “partially” consciously, for to be sure they are still to some extent very individual. In many respects, one can see their automatic nature, but there is something still left in these automatic machines which is at the same time very individual. Something which is to be noticed as an appendage to each of these separate automata, in which if things aren't exactly in the form of banknotes, there's at any rate a sound of gold and silver. But a universal automatism would also oblige the individual purse to become the general communistic purse.

All this is, however, something which must be regarded today not with mere sympathy and antipathy alone, but with that sight which looks through world events, which can observe what is happening among men in connection with cosmic events. When one sees things thus, one will say to oneself: it is given to man to bring forward the planet wisely in its evolution. The particular kind of existence which has been indicated today is threatening humanity if men do not try to convert knowledge into wisdom. And that can only come about if a man personally applies himself to knowledge, if he takes it personally into himself and binds it again to what, out of the desire nature transmuted by love, becomes the common concern of humanity. One can receive these things through Spiritual Science with a strong impulse of inner understanding.

As a matter of fact, it is shown in what has remained behind in the Moon as a cosmic symbol. When we sec the Moon in its first or last quarter, in what it shows us as its sickle form we have a. picture of what the Earth could become. In the dark part, it shows to one who can see the supersensible these little demoniacal forms moving about in ghastly fashion, where the curve of the sickle bends inwards. So that one is speaking quite correctly in saying: man must preserve the Earth from the Moon existence through all that I have now explained. The Moon shows in a cosmic picture placed before us what the Earth could become. And so we must accustom ourselves to penetrate in this way with inner feeling into that too which we see outside in the cosmos. We must so look upon the Moon that we can say: it shows us something set up through cosmic evolution as a caricature of the Earth existence, as what the Earth existence can become if man does not learn to understand how to make impersonal knowledge into his personal concern, if he does not learn how, through warmth, to change individual desires into love, through which they can develop into an associated social life that is a common concern of the whole of mankind. One can understand better what happens in the cosmos if one looks into what is being accomplished in man, and conversely one can see in the right way the tasks of mankind if one is able consciously to look into the conditions of the cosmos. For they are applicable also to that which should live in humanity as morality, as ethics.

The facts that are stated concerning Lucifer and Ahriman are not meant to be taken in such a way that one should theorise about them, that one should only say Ahriman is this, and Lucifer is that. But one should so take up these ideas into oneself that really one should see in all around the activity of the Luciferic spirits who want to hold back the Earth in earlier conditions. So too in all that is Ahriman one should see something which would hold back the Earth so that it does not advance to future stages. But one must penetrate those things in detail. One must be able to value the moral in relation to the laws of nature, and the laws of nature morally. When that happens then the great bridge will be thrown across between the moral world-concept and the theoretic world-concept, of which bridge I have, as you know, often spoken from this place.

Things which happen today must also he viewed from this standpoint. For only when the free-will of man invades these cosmic events can what has been indicated to you he turned to good service. The further evolution of the world is in fact entirely the task of man and of humanity. This must not be overlooked. And one who only wants to theorise, who, for instance, only wants to see and hears after so and so many centuries or millennia this or that will happen—does not consider that we are already living in a time when it is given over to mankind to co-operate in the metamorphosis of the earthly evolution; he does not consider that there must be received into man's soul that which is the general world-intelligence, nor that what lives individually in man as the forces of desire must flow out from mankind in the form of a universal love, which, however, is only attained through the pure freedom of thought.

Herewith I have set before your mind's eye two streams of culture, which are immensely important, and have sought in so doing to show again from a certain aspect what is the task of Spiritual Science when taken earnestly. The task lies in this direction. It does not really lie in a few persons having a feeling of well-being in the knowledge of this and that, but it lies in so grasping human evolution that world events come to pass in the true way out of humanity itself.

Achtzehnter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Wenn dasjenige, was wir oftmals als Gegenstand esoterischer Betrachtung angesehen haben, was wir in meiner «Theosophie», in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß», in anderen Büchern verzeichnet finden, als die Gliederung des Menschen, wenn wir das, und zwar etwas zusammenfassend, mehr von außen betrachten, so können wir hinblicken auf der einen Seite nach alledem, was wir im Menschen nennen können die Verstandeskräfte, die Verstandesfähigkeiten. Gewiß, was wir da unter Verstandesfähigkeiten zusammenfassen, umgreift das Verschiedenste von dem, was wir als die Glieder des Menschen bezeichnet haben. Allein gerade durch solche Betrachtungen, die die verschiedenen Begriffe und Ideen, die wir haben, unter anderen Gesichtspunkten ins Auge fassen, kommen wir ja in unseren Auseinandersetzungen weiter. Also wir sehen auf der einen Seite die mehr verstandesmäßigen Betätigungen des menschlichen Geist-Seelenlebens, und wir sehen auf der anderen Seite die mehr nach dem Begehrungsvermögen, nach dem Willensmäßigen hin gelegenen Betätigungen des menschlichen Geist- und Seelenlebens. Wir wollen heute diese Fähigkeiten einmal von dem Gesichtspunkte der ganzen Menschheit ins Auge fassen, das heißt, wir wollen uns fragen: Welche Bedeutung haben die mehr verstandesmäßigen Kräfte in dem Leben der Gesamtmenschheit und welche haben die mehr willensmäßigen Kräfte? Wenn man eine solche Betrachtungsweise unternimmt, dann kann sie nur fruchtbar sein, wenn man den Menschen und auch die Menschheit nicht isoliert betrachtet von dem gesamten Erdenplaneten, sondern als ein Glied des gesamten Erdenplaneten. Daß man dazu ein Recht hat, das ergibt sich Ihnen ja aus dem Verfolgen jener Auseinandersetzungen, die sich zum Beispiel in der «Geheimwissenschaft» finden über die Saturn-, Sonnen- und Mondenentwickelung unserer Erde.

[ 2 ] Wenn Sie sich erinnern, was da gesagt ist über Saturn-, Sonnen- und Mondenentwickelung, dann werden Sie sehen, wie da die Sache nicht so betrachtet wird, wie es etwa die heutigen Geologen und Naturforscher machen, daß sie auf der einen Seite geologisch die Erde betrachten, als wenn der Mensch gar nicht dazu gehörte, und dann wiederum die Menschheit für sich in einer Art abgeschlossener Anthropologie, wie wenn diese Menschheit auf einem ihr ganz fremden Boden herumspazierte. Darum kann es sich für eine wirklich fruchtbare Betrachtungsweise nicht handeln. Wenn Sie verfolgen, was gesagt ist über die Saturn-, Sonnen- und Mondenentwickelung, so werden Sie sehen, daß in dieser Entwickelung gar nicht getrennt gedacht werden können die Kräfte, die in der Menschheit selber spielen, und die Kräfte, die im übrigen Planeten spielen. Daß auf der Erde die Menschheit eine gewisse Selbständigkeit erlangt hat und gewissermaßen unabhängig von dem Planeten auf dem Boden desselben herumspaziert, das ist ein Entwickelungszustand; er darf für die Betrachtungsweise nicht ausschließlich maßgebend sein. Wir müssen die Menschheit im Zusammenhange mit der ganzen Erdenentwickelung betrachten. Und da müssen wir zunächst sagen: Wenn wir die Verstandesfähigkeiten ins Auge fassen und uns erinnern an dasjenige, was über frühere Metamorphosen, über die Saturn-, Sonnen- und Mondenmetamorphose der Erdenentwickelung gesagt ist, dann werden wir darauf kommen, daß diese Innerlichkeit, die wir heute in dem Menschen der Verstandesentwickelung haben, vorher, also auf den vorigen Metamorphosen der Erdenentwickelung, nicht vorhanden war. Was heute in unserem Kopfe gewissermaßen als Verstand lokalisiert ist, das war als allgemeine Verständigkeit wie eine durchgreifende gesetzmäßige Verständigkeit über den ganzen Erdenplaneten verteilt. Man könnte sagen: Verstand wirkte in den Tatsachen der ganzen Erdenentwickelung. Der Mensch selber hatte ja — von Saturn und Sonne gar nicht zu sprechen — auf dem Monde noch nicht das Verstandesbewußtsein, sondern eine Art träumerischen Bewußtseins. Dieses träumerische Bewußtsein, das sah hinaus in die Weltenerscheinungen, und der Mensch sagte sich nicht, während er dieses träumerische Bewußtsein hatte: Da draußen spielen sich die Welterscheinungen ab, und ich begreife sie mit meinem Verstande -, sondern der Mensch träumte in Bildern. Er sah aber dasjenige, was wir heute wie in unserem Kopfe lokalisiert als Verstand empfinden, als die Dinge und Tatsachen draußen durchsetzend. Wir unterscheiden zwischen den Naturgesetzen und zwischen dem, was in uns diese Naturgesetze auffaßt und nennen das letztere unseren Verstand. Der Mensch der Vorzeit lebte seelisch bewußt nur in Bildern, und das war ja für die älteren Partien unserer Erdenentwickelung auch noch der Fall, und er unterschied nicht die Naturgesetze draußen von seinem Verstande, sondern die Natur selber hatte Verstand, die Natur selber gab sich ihre Gesetze. Da draußen wirkte der Verstand. Es ist ein Entwickelungsstadium unserer selbständig gewordenen Menschheit, daß wir sagen: Wir tragen in uns den Verstand und draußen sind die Naturgesetze. - Die Summe dieser Naturgesetze war für den Menschen der Vorzeit der Verstand.

[ 3 ] Nun haben wir ja als Erdenmenschheit bis zu einem gewissen Grade das Bewußtsein schon entwickelt, daß der Verstand in uns vorhanden ist und daß draußen eben die Naturgesetze vorhanden sind, die wir mit unserem Verstande nur auffassen. Wir berühren, indem wir auf diese Tatsache hinweisen, einen wichtigen Entwickelungsimpuls der Menschheit. Aber wir müssen uns bewußt sein, daß dieser wichtige Entwickelungsimpuls der Menschheit immer mehr und mehr aufgegriffen und noch immer mehr und mehr ausgebildet werden muß. Er ist ja im Grunde genommen heute noch nicht voll ausgebildet. Wir sagen uns zwar, wir hätten in uns den Verstand und draußen walteten die Naturgesetze; aber wir machen uns den Verstand noch nicht völlig zu eigen. Wir sind als Menschheit auf dem halben Wege stehengeblieben mit Bezug auf dieses In-uns-Aufnehmen des Verstandes, der Vernunft, der Naturgesetzlichkeit. Und gerade in unserer Zeit gehört zu denjenigen Dingen, auf die man am meisten hinsehen muß gerade vom geisteswissenschaftlichen Standpunkte aus, diese Tatsache, die ich eben berührt habe. Wir sind heute noch außerordentlich stolz darauf, wenn wir mit Bezug auf alles das, was dem Verstande angehört, was wir als menschliches Wissen anerkennen, etwas dem Menschen Gemeinsames haben. Es gilt heute immer noch als etwas, was außerordentlich einschneidend in die ganze menschliche Naturentwickelung ist, daß die Wissenschaft gewissermaßen wie ein allgemein über der Menschheit Schwebendes ausgebildet werden soll, und daß die Menschen, indem sie sich der Wissenschaft widmen, gewissermaßen ihre Individualität zum Opfer bringen sollen, daß sie denken sollen, wie halt «jedermann» denkt. Das ist ein Ideal namentlich unserer öffentlichen Lehranstalten, eine Wissenschaft, die ganz unpersönlich, die ganz unindividuell ist, auszubilden, diese Wissenschaft zu etwas zu machen, demgegenüber man möglichst wenig «Ich» sagt und möglichst viel «man» sagt: man hat dieses oder jenes gefunden, man muß dieses oder jenes für wahr halten! — Und das Ideal gerade der offiziellen Vertreter der Wissenschaft heute wäre ja wohl dieses, daß man die einzelnen Dozenten eigentlich nicht sehr unterscheiden könnte — höchstens in bezug auf das Temperament -, wenn man von einer Hochschule an eine sehr entfernte andere Hochschule hinkommt. Es würde geradezu als ein Ideal gelten, wenn man, sagen wir, einen Botanikvortrag irgendwo im Norden anhören könnte, dann mit einem raschen Ballon nach dem Süden fliegen könnte, dort die Fortsetzung dieses Vortrages hören könnte und er ganz dem entsprechen würde, was «man» eben in der Botanik weiß! Etwas ganz Unpersönliches, Unindividuelles, das ist dasjenige, was man auf diesem Gebiete als das Richtige betrachtet, und man hat eine greuliche Angst davor, daß irgendwie etwas Persönliches in dieses Wissen, in dieses Werk des menschlichen Verstandes hineinziehen könnte. Gerade auf diesem Gebiete gilt das Nivellieren der ganzen menschlichen Kultur am allermeisten. Man ist stolz darauf, nur ja nicht abzuweichen von dem, was ein für allemal in einer gewissen Weise formuliert ist. Also man möchte dasjenige, was Wissenschaft ist, vom Menschen absondern. Man sondert es ja auch noch in mancher anderen Beziehung vom Menschen ab. Dafür können Beispiele angeführt werden. Denken Sie sich nur einmal, wie heute die meisten Menschen, die sich in offizieller Weise am wissenschaftlichen Leben beteiligen, ihre Dissertationen, ihre Privatdozentenbücher, ihre Professoren-Kandidaturbücher und so weiter schreiben. Sie sind ja möglichst wenig dabei und sie rechnen möglichst wenig damit, daß diese Bücher nun etwa ganz allgemein gelesen würden. Sie werden geschrieben; aber kaum lesen sie diejenigen, die sie in dem betreffenden Kollegium zu prüfen haben, sondern höchstens einer liest sie notdürftig und sagt dann den anderen, was sie davon zu halten haben. Denn die Wissenschaft ist ja etwas, worüber «man» denkt, nicht einer persönlich, und dann werden sie in den Bibliotheken aufgespeichert. Wenn irgend jemand wieder einmal etwas Ähnliches schreibt, sieht er sich die Bibliothekkataloge an und sieht nach, wo er irgendwie etwas findet, was er berücksichtigen muß, und dann wird das wieder aufgespeichert, geht möglichst wenig an das IndividuellPersönliche heran. Es ist ja das alles abgesondert. In den Bibliotheken wuchert Unzähliges, was gar nicht irgendwie persönlich interessiert. Das ist im Grunde genommen ein schrecklicher Zustand. Aber das noch Schrecklichere ist, daß die Menschen das eigentlich gar nicht spüren, sich völlig beruhigt dabei fühlen, daß sie selber gar nichts zu wissen brauchen, denn in den Bibliotheken kann man ja alles finden, wenn man nur das betreffende Schlagwort in den Katalogen aufsuchen kann. Da ruhen die Dinge. Die Menschen gehen aber neben der Wissenschaft, die so etwas Allgemeines ist, einher. Es würde allerdings diese Wissenschaft anders ausschauen müssen, wenn die Menschen sie in ihren Köpfen und nicht in den Stellagen der Bibliotheken aufbewahren würden.

[ 4 ] Das ist dasjenige, was einem, ich möchte sagen, wie durch ein paar Löcher hindurch — denn man könnte vieles nach dieser Richtung hin anführen — einen Hinweis gibt, wie die allgemeine Verstandeskultur in der heutigen Menschheit noch unindividuell, unpersönlich ist, wie die Menschen sie als etwas, was ein Wolkendasein über einem führt, haben möchten. Dasjenige aber, was Menschen hervorbringen, das gehört nicht nur den Menschen, das gehört dem Weltall an. Deshalb habe ich gesagt, wir müssen, um zu einer fruchtbaren Betrachtung zu kommen, den Menschen im Zusammenhange mit seinem Planeten und dann ja auch wiederum den Planeten im Zusammenhange mit dem ganzen Weltenall betrachten.

[ 5 ] Was der Mensch also hervorbringt, worauf er seinen Verstand anwendet, damit kann er in zweifacher Weise verfahren. Er kann auf der einen Seite diesen Verstand anstrengen, Wissenschaften auszubilden, die dann alle ins «man denkt», «man weiß», «man ist zu diesen und jenen Fortschritten gekommen» einmünden; dann schreibt man das in Bücher, dann speichert man das auf, dann ist das die Wissenschaft, über die so die Generationen hinwegwachsen; und die Menschen können bei einem solchen Betrieb des Verstandes vertrocknen. Sie können es so machen, daß sie dasjenige, was sie eigentlich interessant finden, in manchem anderen suchen, nur ja nicht in dem, was ja ohnedies Unwahrheit ist, objektiv von Persönlichem unberührte Unwahrheit, die objektiv in Bibliotheken aufbewahrt wird; sie können es so machen, daß sie das nun ja nicht berühren, Man hat ja Gelehrtenversammlungen gekannt, welche in ihrer Terminologie das Wort hatten vom Fachsimpeln. Es galt als etwas Minderwertiges, wenn man nach den offiziellen Reden sich über die einzelnen Dinge der Wissenschaft unterhielt etwa in kleinen Zirkeln und dergleichen. Da sprach man allerlei andere Allotria, die jedenfalls ganz fernlagen demjenigen, was eigentlich die wissenschaftlichen Angelegenheiten waren. Und diejenigen, die die Schwäche hatten, von ihrer Wissenschaft etwas begeistert zu sein, und die dann etwa anfingen, sagen wir, beim Tee oder beim schwarzen Kaffee von dem oder jenem philologischen oder sonstigen Thema zu sprechen, waren eben die Leute, die «Fachsimpelei» trieben, das waren diejenigen, die man nicht ganz ernst nahm, die keinen weltmännischen Geist hatten.

[ 6 ] Es trat mir einmal in einer ganz eigenartigen Weise entgegen, dieses Unpersönliche gegenüber der Wissenschaft. Ich war einmal bei einer Versammlung, bei welcher Helmholtz einen Vortrag hielt. Bei diesem Vortrag, der wörtlich abgelesen war von Helmholtz und der bereits längst im Drucke war, als er abgelesen wurde, hörten die Leute so zu, wie man eben bei einem solchen Vortrag, nun, zuhört. Nach dem Vortrag kam zu mir ein Journalist, der sagte: Wozu eigentlich das? Das brauchte man ja gar nicht. Wer das will, kann ja einen solchen Vortrag dann lesen, wenn er gedruckt wird; warum soll er einem auch noch vorgelesen werden? Es wäre doch viel gescheiter, wenn Helmholtz einfach im Auditorium herumginge und jedem die Hand reichte; das wäre ja doch viel mehr, da wäre doch viel mehr damit getan. — Das ist so richtig ein Beispiel für das Fremdsein gegenüber demjenigen, was da eigentlich als Wissenschaft so unpersönlich «herumfliegt». Dabei vertrocknen selbstverständlich die Leute. Das ist die eine Art, wie man die Verstandeskultur erfassen kann.

[ 7 ] Die andere Art ist diese, daß man sich für alle Einzelheiten interessiert, daß das Gemüt Feuer fängt und die Wissenschaft belebt, daß es sie umschmelzt in lebendige Begriffe, daß alles dasjenige, was wir begreifen, erfassen, geradezu in Empfang genommen wird von innerlichem Gemütsleben. So kann man alles das, was die Wissenschaft gibt, wirklich mit innerem Feuer durchdringen, so kann man, indem man die einzelnen Wissenschaften erfaßt, allmählich eindringen in das ganze Weltendasein, so kann man etwas gestalten, was jedes Menschen, der es betreibt, ureigenste persönliche Angelegenheit wird. Das ist das andere. Und das alles, was da getrieben wird auf der einen Seite, ist unpersönlich, abgesondert vom Menschen im Grunde genommen. Am liebsten möchten da die Menschen Automaten für den wissenschaftlichen Betrieb erfinden, so daß sie nichts mehr mit ihren eigenen Köpfen zu bedenken hätten, dann wären sie vielleicht produzierend ohne sie. Das aber, was geschieht aus vollem, herzhaftem Betreiben der Wissenschaft heraus, das sind ja nicht nur Angelegenheiten der Menschheit, das sind Angelegenheiten des ganzen Planeten und damit des ganzen Weltenalls. Denn dasjenige, was der Mensch tut, indem er denkt, indem er irgend etwas in seinem Kopfe verstandesmäßig ausbildet, das ist ein Geschehnis genau ebenso, wie wenn ein Wasser aus einer Quelle den Strom hinunter zum Meere fließt, oder wie wenn es verdunstet oder wenn es regnet. Was da äußerlich materiell geschieht im Regen, was geschieht, wenn die Pflanze sprießt und so weiter, das sind Ereignisse der einen Art. Was durch den Menschen geschieht, sind Ereignisse der anderen Art. Es ist nicht bloß eine menschliche Angelegenheit, es ist eine Angelegenheit des ganzen Planeten. Und das ist gerade die Aufgabe des Menschen in seiner Entwickelung auf der Erde, daß er den Verstand, der früher allgemein über das Planetarische ausgegossen war, daß er diesen Verstand in sich hereinnimmt, daß er ihn mit sich vereinigt. Also, es ist ein Entwickelungsimpuls des Menschen, daß er das Wissen zu seiner persönlichen Angelegenheit macht, daß er es durchziehen kann mit Enthusiasmus, daß es in ihn übergehen kann, so daß es ergriffen wird von seinem herzhaften Feuer. Und wenn das letztere nicht geschieht, wenn er das Wissen [nur] in unpersönlicher Weise aufspeichert, so geschieht etwas nicht, was im Sinne der Erdenentwickelung geschehen soll. Es wird nicht das Gemüt der Menschheit ergriffen von der Verstandeskultur. Die Verstandeskultur entwickelt sich gewissermaßen nur in dem Kopf und schwebt zu weit ab von der Oberfläche der Erde bloß in den Köpfen; sie entwickelt sich nur in den Köpfen und sollte heruntersinken bis in die Herzen. Aber es warten auf dasjenige, was also von den Herzen nicht erfangen wird, was also von dem Gemüte des Menschen nicht ergriffen wird, es warten auf das die luziferischen Geister. Und dasjenige, auf das so warten die luziferischen Geister, das können sie in Empfang nehmen, wenn es in dieser Weise unpersönlich über die Erde hinschwebt. Denn die einzige Möglichkeit, dasjenige, was Verstandeswelt ist, den luziferischen Geistern zu entreißen, ist, es mit dem Gemüte zu durchdringen, es zur persönlichen Angelegenheit zu machen. Und was in unserer Zeit geschieht, was seit langem geschieht und was anders werden muß, das ist eben, daß wir das irdische Dasein auf dem Umwege durch die kalte, nüchterne Verstandestrockenheit zur Beute werden lassen der luziferischen Welt. Dadurch wird die Erde aufgehalten in ihrer Entwickelung, dadurch wird die Erde zurückgehalten auf einem früheren Standpunkte. Sie kommt nicht zu ihrem Ende. Und wenn die Menschen lange, lange fortbetreiben das Unpersönliche der sogenannten Wissenschaft, dann wird die Folge diese sein, daß die Menschen ihre Seelenhaftigkeit überhaupt verlieren. Diese unpersönliche Wissenschaft ist die Mörderin des menschlichen Seelenhaften und Geisteshaften; sie vertrocknet den Menschen, sie dörrt ihn aus. Sie macht zuletzt aus der Erde dasjenige, was man nennen kann einen toten Planeten mit automatenhaften Menschen darauf, die ihr GeistigSeelisches auf diesem Wege verlieren. Auch da muß man sagen: Die Dinge müssen schon ernst betrachtet werden. Es darf nicht zugeschaut werden diesem kosmischen Mord durch den abstrakten Betrieb, den unpersönlichen Betrieb des Wissens auf der Erde. Das ist das eine.

[ 8 ] Das andere ist das menschliche Begehrensvermögen. Das ist dasjenige, was mit dem Willensmäßigen im Menschen zusammenhängt. Was mit dem Willensmäßigen im Menschen zusammenhängt, kann wiederum zwei Wege gehen. Der eine Weg ist der, daß dieses Willensmäßige sich möglichst unter Gebote oder Staatsgesetze und dergleichen unterordnet und sich fügt dem, was die allgemeinere Gesetzmäßigkeit ist, so daß die allgemeine Gesetzmäßigkeit da ist und daneben nur das rein instinktmäßige Begehren der Menschen.

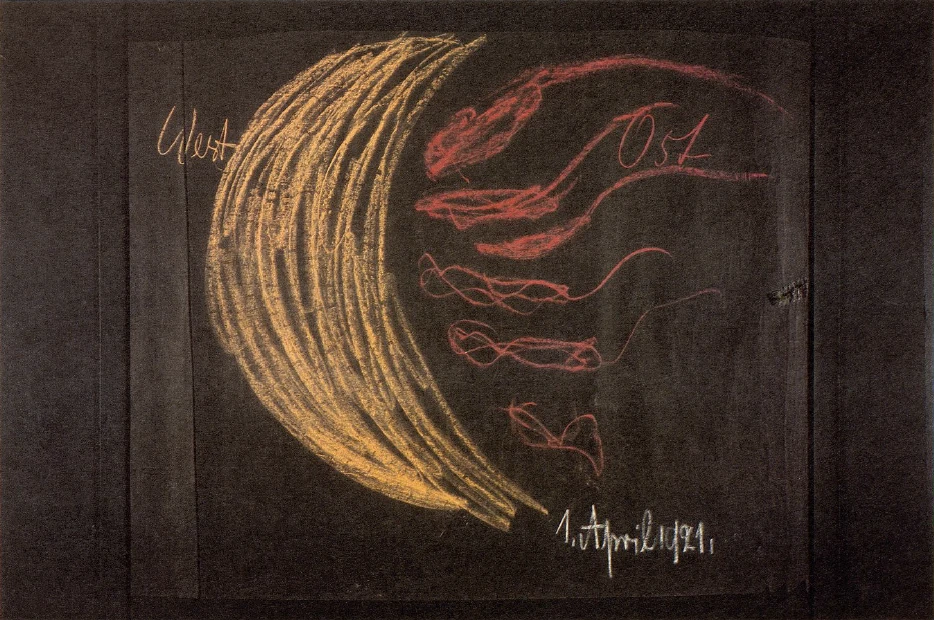

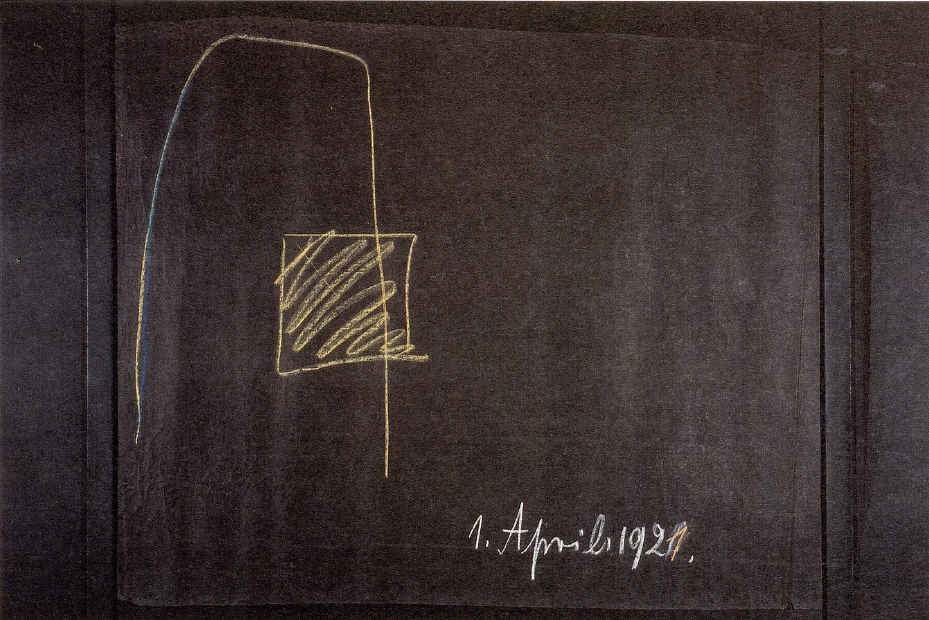

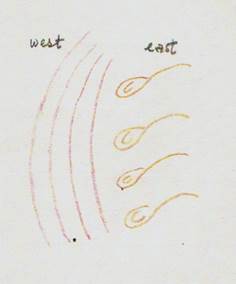

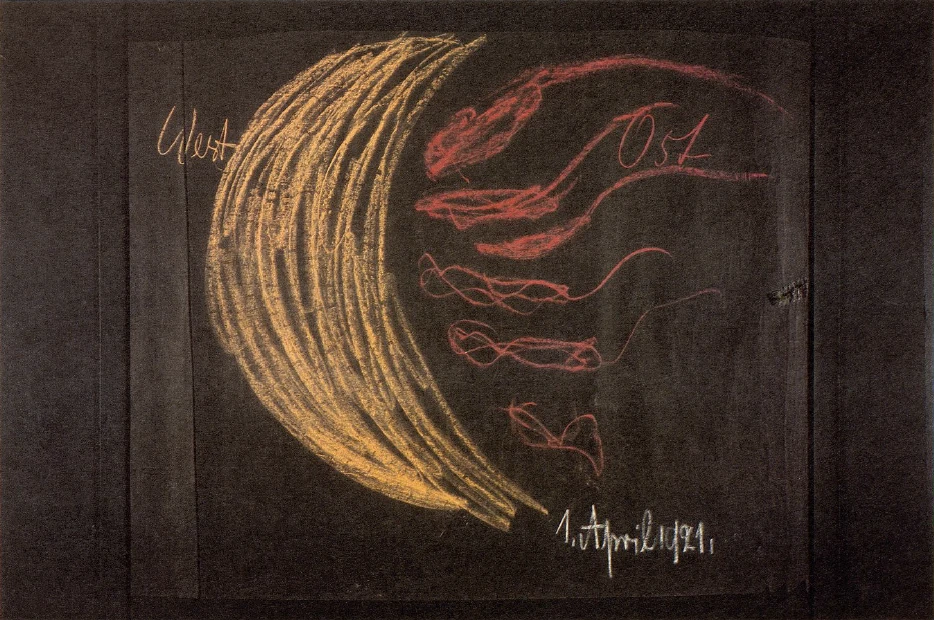

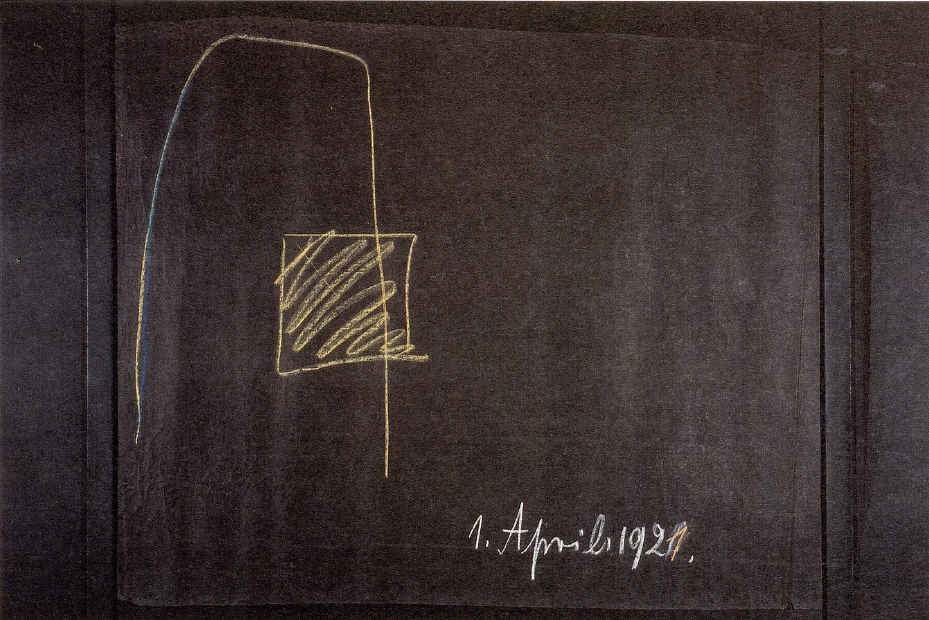

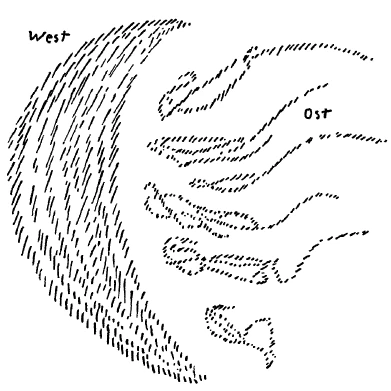

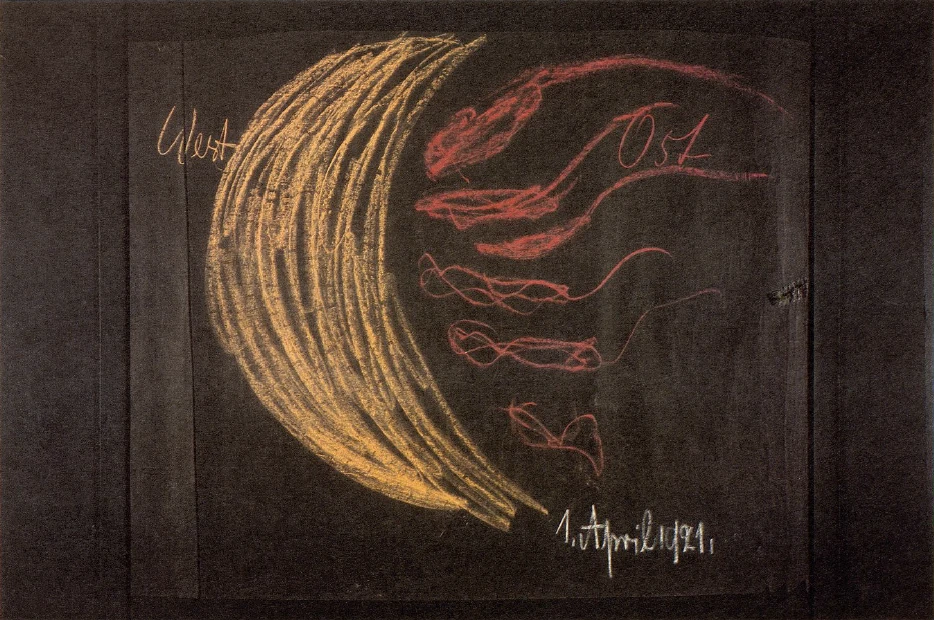

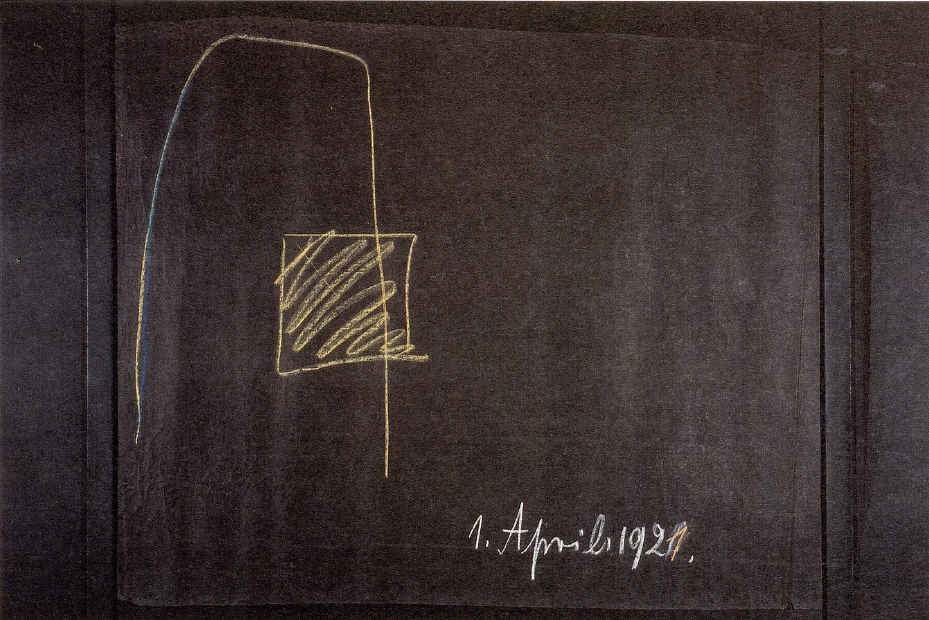

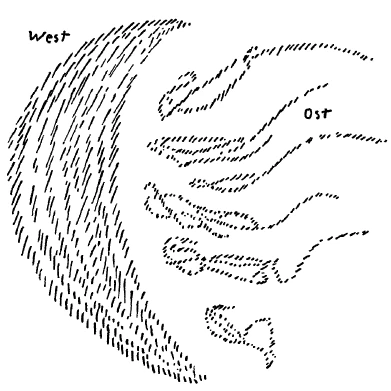

[ 9 ] Der andere Weg ist, daß sich dasjenige, was im Menschen als Begehrensvermögen sich spiegelt, was als Willensfähigkeit vorhanden ist, daß sich das allmählich heraufhebt zum reinen Denken, in Freiheit sich auslebt individuell, so daß es sich ins soziale Leben in Liebe ergießt. Es ist diejenige Art des Auslebens des Willens und des Begehrungsvermögens, wie ich sie geschildert habe in der «Philosophie der Freiheit». Da habe ich gezeigt, wie dasjenige, was allgemeine menschliche Gesetzmäßigkeit ist, hervorgehen muß aus jeder menschlichen Individualität und daß, wenn dasjenige, was aus der menschlichen Individualität hervorgeht, sich erhebt bis zum reinen Denken, daß dann durch das Zusammenstimmen dessen, was die Menschen tun, die soziale Ordnung entsteht. Die Menschen fürchten sich vor aller sozialen Ordnung, welche konstituiert wird dadurch, daß aus dem Individuellen heraus ein jeder Mensch sich [selbst] die Richtung gibt. Sie möchten organisieren, was die Menschen wollen sollen. Sie möchten «kategorische Imperative» an die Stelle der aus jedem Menschen heraus wirkenden Liebe setzen. Dadurch aber, daß solche abstrakten Gebote bestehen - seien sie nun Gebote nach dem Muster des Dekalog, seien sie Gesetze irgendwelcher Einheitsstaaten —, dadurch, daß solche Gebote bestehen, machen sich aus dem Individuellen des Menschen heraus nur geltend die instinktmäßigen Begierden, jene Begierden, die wir besonders heute aufleben sehen und die im Grunde genommen das einzige soziale Ingredienz der gegenwärtigen Zeit geworden sind. Wiederum ist das, was im Menschen dadurch geschieht, daß er seinen Willen nicht bis zum Individuellen gestaltet, ihn nicht erhebt zum reinen Denken, wiederum ist das nicht bloß etwas, was den Menschen allein angeht, sondern den ganzen Planeten und damit den Kosmos. Und auf das, was da geschieht, indem sich nicht der menschliche Wille individuell gestalten kann, auf das warten gierig die ahrimanischen Geister. Das eignen sie sich an, diese ahrimanischen Geister, und sie verwenden alles, was an nicht zur Liebe entfalteten Begierden im Menschen lebt, willensmäßig lebt, sie verwenden es so, daß sie es übertragen auf individuelle dämonische Wesenheiten. So wie mehr allgemeine Wesenheit entsteht durch dasjenige, was die über der Menschheit schwebende Verstandestätigkeit ist, so entstehen ganz individuell gestaltete dämonische Wesenheiten aus dem nicht in Liebe umgesetzten Begehrungsvermögen der einzelnen Individualitäten. Und es müßte, wenn nicht eine individuelle Gestaltung des freiheitlichen Zusammenlebens in der sozialen Ordnung angestrebt würde, sich die Erde erfüllen mit denjenigen Wesenheiten, die dann individuell wären, aber die ein ahrimanisch-geisterhaftes Dasein führen und die der Erde nehmen würden die Möglichkeit, sich in die nächste planetarische Metamorphose, in die Jupitermetamorphose hinein zu verwandeln. Schematisch gezeichnet würde das etwa so sein, daß die abstrakte Verstandesmäßigkeit ausbilden würde unseren Planeten (siehe Zeichnung links) nach der einen Seite, ihn nicht zur Vollendung kommen lassen würde, und dasjenige, was aus dem nicht in Liebe umgesetzten Willen entsteht, das würde auf der anderen Seite (rechts) lauter individuelle Wesenheiten gestalten. Schematisch ist damit gezeichnet, was heute jemand, der hineinsieht in die Anfänge einer den richtigen Entwickelungsvorgang des Erdenplaneten untergrabenden Zivilisation, sehen kann als dasjenige, was sich gestaltet, wenn diejenigen Impulse, die jetzt so stark ersprießen in der westlichen Welt, ihren ungehemmten Fortgang nehmen, und was sich so stark entwickelt in der östlichen Welt (siehe Zeichnung), was da liegt, als bloß aus der menschlichen Subjektivität hervorgehend, in der in die Dekadenz gekommenen Staatskultur; das ist eigentlich dasjenige, was nach individuellen Dämonen hin die Erdenentwickelung gestalten will. Was sich im Westen entwickelt, das ist das, was in ein allgemeines Verstandesmäßiges hineinsegeln und die Menschen allmählich zu Automaten machen will.

[ 10 ] Diese Dinge sind deutlich wahrzunehmen, wenn auch erst in den Anlagen jener Automaten, die heute schon teilweise — ich sage vollbewußt «teilweise», denn sie sind allerdings noch etwas sehr Individuelles - vorhanden sind. Mit Bezug auf vieles kann man ja den Automatismus schon sehen. Aber etwas ist in diesen Automaten noch immer in einer sehr individuellen Weise vorhanden, nämlich etwas, was da noch zu bemerken ist wie so ein Anhängsel an jedem dieser einzelnen Automaten, ein Anhängsel, in dem es, wenn die Dinge nicht gerade in Banknoten umgewandelt sind, nach Gold und Silber klingt. Aber der allgemeine Automatismus würde schon dahin wirken, daß auch die individuellen Geldtaschen zu allgemeinen kommunistischen Geldtaschen würden.

[ 11 ] Das ist aber dasjenige, was nicht allein betrachtet werden muß heute mit bloßen Sympathien und Antipathien, sondern mit jenem Blick, der das Weltgeschehen durchschaut, der das, was unter den Menschen geschieht, im Zusammenhange mit dem kosmischen Geschehen betrachten kann. Wenn man die Dinge so anschaut, wird man sich sagen: Es ist an die Menschen gegeben, den Planeten in seiner Entwickelung weise vorwärtszubringen. — Es droht diese besondere Art des Daseins, wie es hier schematisch angedeutet ist, der Menschheit, wenn die Menschheit nicht versucht, das Wissen zur Weisheit umzuwandeln, was nur dadurch geschehen kann, daß sich der Mensch für das Wissen persönlich einsetzt, daß er es persönlich in sich aufnimmt und daß er es wieder verbindet mit demjenigen, was auf dem Umwege der Liebe zur allgemeinen Menschheitsangelegenheit wird aus dem individuellen Begehrensvermögen heraus. Mit einem starken Einschlag von innerlichem Verständnis kann man diese Dinge aufnehmen durch die Geisteswissenschaft. Im Grunde genommen zeigt sich das heute ja so in dem, was, ich möchte sagen, als kosmisches Symbolum stehengeblieben istim Mond.

[ 12 ] Wenn wir den Mond in seinem ersten oder letzten Viertel haben, so haben wir in dem, was er uns in seiner Sichelform zeigt, ein Abbild desjenigen, was die Erde werden könnte; in der dunkleren Seite zeigt er ja demjenigen, der das Übersinnliche schauen kann, diese dämonischen Gestältlein, die in der nach einwärts gebildeten Biegung der Sichel sich in abscheulicher Weise bewegen. So daß man eigentlich sehr richtig spricht, wenn man sagt: Der Mensch muß durch das, was ich eben angeführt habe, die Erde bewahren vor dem Mondendasein. — Der Mond zeigt das, was die Erde werden kann, in einem kosmischen Bilde, das vor uns hingestellt ist. Und so müssen wir uns schon angewöhnen, das, was wir draußen im Kosmos sehen, auch in dieser Weise zu durchdringen mit einem innerlichen Sinn. Wir müssen den Mond so ansehen, daß wir sagen: Er weist uns etwas auf, was hingestellt ist durch die kosmische Entwickelung wie die Karikatur des Erdendaseins, wie das, was das Erdendasein werden kann, wenn der Mensch nicht verstehen lernt, das unpersönliche Wissen zu seiner persönlichen Angelegenheit zu machen, umzuglühen die individuellen Begehrungen in die Liebe, wodurch sie dasjenige werden, was im assoziativen sozialen Leben eine allgemeine Angelegenheit der ganzen Menschheit werden kann. Man kann das, was im Kosmos geschieht, besser verstehen, wenn man hinschaut auf das, was im Menschen sich vollzieht, und man kann umgekehrt dasjenige, was Menschenaufgabe ist, in der richtigen Weise sehen, wenn man die Bedingungen des Kosmos sinngemäß durchschauen kann. Dann wenden sie sich schon an auch auf dasjenige, was als Moralität, als Ethizismus in der Menschheit leben soll.

[ 13 ] Die Dinge, die man spricht über Luzifer und Ahriman, sie sind wahrhaftig nicht so gemeint, daß man nur darüber theoretisieren soll, daß man nur so sprechen soll, daß eben Ahriman das ist und Luzifer das. Sondern man soll diese Begriffe nun auch so in sich aufnehmen, daß man im Grunde genommen in alledem, was um einen herum geschieht, die Wirksamkeiten der luziferischen Geister sieht, die das Erdenstadium in früheren Stadien zurückhalten möchten, und daß man in alledem, was Ahriman ist, dasjenige sieht, was das Erdenstadium zurückbehalten will, so daß es nicht weiterkommt in Zukunftsstadien hinein. Aber man muß in den Einzelheiten diese Dinge durchschauen. Man muß, ich möchte sagen, das Moralische naturgesetzlich, das Naturgesetzliche moralisch werten können. Wenn das geschieht, dann wird die große Brücke geschlagen werden zwischen der moralischen Weltanschauung und der theoretischen Weltanschauung, von welcher Brücke ich ja gerade an diesem Orte hier öfters gesprochen habe.

[ 14 ] Unter diesem Gesichtspunkte müssen auch die Dinge betrachtet werden, die heute geschehen. Denn nur, wenn der freie Wille des Menschen eingreift in dieses Weltgeschehen, kann dasjenige angewendet werden, was heute Ihnen skizzenhaft hier angedeutet worden ist. Die weitere Erdenentwickelung ist eben durchaus Aufgabe des Menschen und der Menschheit. Das darf nicht übersehen werden. Und derjenige, der nur theoretisieren will, der zum Beispiel nur sehen will, nur hören will: Nach so und so vielen Jahrhunderten oder Jahrtausenden geschieht das —, der berücksichtigt nicht, daß wir schon in einem Zeitalter leben, in dem es der Menschheit übergeben ist, mitzuwirken an den Metamorphosen der Erdenentwickelung, daß aufgenommen werden muß in das menschliche Gemüt das, was allgemeiner Weltverstand ist, und daß hinausfließen muß aus den Menschen in der Form der allgemeinen Menschenliebe, die aber nur in reinem, freiem Denken zu erreichen ist, dasjenige, was individuell im Menschen als Begehrungsvermögen lebt.

[ 15 ] Damit habe ich Ihnen zwei Kulturströmungen, die vor allen Dingen wichtig sind, vor das Seelenauge hingestellt und habe damit versucht zu zeigen, wiederum von einer gewissen Seite aus, welches die Aufgabe ernst gemeinter Geisteswissenschaft ist. In solchen Bahnen liegt diese Aufgabe. Sie liegt wirklich nicht darin, daß einige ein Wohlgefühl haben an dem Wissen von diesem oder jenem, sondern sie liegt schon darin — die Aufgabe dieser ernst gemeinten Geisteswissenschaft -, daß so in die Menschheitsentwickelung eingegriffen werde, daß in der richtigen Weise aus dem Menschentum heraus das Weltgeschehen sich formt.

Eighteenth Lecture

[ 1 ] If we take what we have often regarded as the subject of esoteric contemplation, what we find recorded in my “Theosophy,” in my “Outline of Secret Science,” in other books, as the structure of the human being, if we take that, in a somewhat summarized form, more from the outside, we can look, on the one hand, at everything we can call the intellectual powers, the intellectual abilities of the human being. Certainly, what we summarize here as intellectual abilities encompasses the most diverse aspects of what we have called the members of the human being. But it is precisely through such considerations, which view the various concepts and ideas we have from different perspectives, that we make progress in our investigations. So, on the one hand, we see the more intellectual activities of the human spirit-soul life, and on the other hand, we see the activities of the human spirit-soul life that are more oriented toward the desire faculty, toward the will. Today, we want to consider these faculties from the perspective of the whole of humanity, that is, we want to ask ourselves: What significance do the more intellectual forces have in the life of humanity as a whole, and what significance do the more volitional forces have? If we take this approach, it can only be fruitful if we do not view human beings and humanity in isolation from the entire planet Earth, but as a member of the entire planet Earth. That we have a right to do so is clear from following the discussions found, for example, in The Secret Science of the Earth's Evolution, concerning the Saturn, Sun, and Moon evolutions of our Earth.

[ 2 ] If you remember what is said there about the Saturn, Sun, and Moon evolutions, you will see that the matter is not viewed in the same way as it is by today's geologists and natural scientists, who, on the one hand, view the Earth geologically as if human beings did not belong to it at all, and then, on the other hand, view humanity as a kind of closed anthropology, as if humanity were walking around on soil that was completely foreign to it. This cannot be a truly fruitful way of looking at things. If you follow what has been said about the development of Saturn, the Sun, and the Moon, you will see that in this development the forces at work in humanity itself and the forces at work in the rest of the planet cannot be thought of separately. The fact that humanity has attained a certain independence on Earth and, in a sense, walks around on the surface of the planet independently of it, is a stage of development; it cannot be the sole criterion for our consideration. We must view humanity in connection with the entire development of the Earth. And here we must first say: When we consider the faculties of the intellect and remember what has been said about earlier metamorphoses, about the Saturn, Sun, and Moon metamorphoses of Earth's development, we come to the conclusion that this inner life, which we have today in the human being of intellectual development, did not exist previously, that is, in the earlier metamorphoses of Earth's development. What is today located in our heads as the intellect was distributed throughout the entire planet Earth as a general understanding, a pervasive, lawful understanding. One could say that the intellect was at work in the facts of the entire development of the Earth. The human being himself — not to mention Saturn and the Sun — did not yet have intellectual consciousness on the Moon, but rather a kind of dreamlike consciousness. This dreamlike consciousness looked out into the phenomena of the world, and while he had this dreamlike consciousness, the human being did not say to himself: “Out there, the phenomena of the world are taking place, and I understand them with my mind.” Instead, humans dreamed in images. But they saw what we today perceive as the mind, localized in our heads, as permeating the things and facts outside. We distinguish between the laws of nature and that which comprehends these laws of nature within us, and we call the latter our mind. The human beings of ancient times lived spiritually conscious only in images, and this was still the case for the earlier stages of our earth's development, and they did not distinguish between the laws of nature outside themselves and their mind, but nature itself had a mind, nature itself gave itself its laws. The mind was at work out there. It is a stage in the development of our humanity, which has become independent, that we say: We carry the mind within us and the laws of nature are outside. The sum of these laws of nature was the mind for the people of ancient times.

[ 3 ] Now, as human beings on earth, we have already developed to a certain degree the awareness that reason exists within us and that the laws of nature exist outside us, which we can only comprehend with our reason. By pointing out this fact, we touch upon an important impulse for the development of humanity. But we must be aware that this important impulse for the development of humanity must be taken up more and more and developed even further. After all, it is not yet fully developed today. We tell ourselves that we have reason within us and that the laws of nature reign outside, but we have not yet fully made reason our own. As humanity, we have stopped halfway in terms of taking in our intellect, our reason, and the laws of nature. And precisely in our time, one of the things that we must pay the most attention to, especially from the perspective of spiritual science, is this fact that I have just touched upon. Today, we are still extremely proud when we have something in common with other people in relation to everything that belongs to the intellect, to what we recognize as human knowledge. It is still considered today to be something extremely significant in the entire development of human nature that science should be developed as something hovering above humanity, and that people, by devoting themselves to science, should sacrifice their individuality and think as “everyone” thinks. This is an ideal, especially in our public educational institutions, to develop a science that is completely impersonal, completely non-individual, to make this science into something in relation to which one says as little as possible “I” and as much as possible “one”: one has found this or that, one must hold this or that to be true! — And the ideal of the official representatives of science today would probably be that one could not really distinguish between individual lecturers — except perhaps in terms of temperament — if one were to move from one university to another very distant university. It would be considered ideal if, say, one could listen to a lecture on botany somewhere in the north, then fly south in a fast balloon, listen to the continuation of this lecture there, and find that it corresponded exactly to what “one” knows in botany! Something completely impersonal, unindividual, is what is considered right in this field, and there is a terrible fear that something personal might somehow creep into this knowledge, into this work of the human mind. It is precisely in this field that the levelling of the whole of human culture is most prevalent. People are proud of not deviating from what has been formulated once and for all in a certain way. So they want to separate what science is from human beings. They also separate it from human beings in many other respects. Examples of this can be given. Just think of how most people who are officially involved in scientific life today write their dissertations, their private lecturers' books, their professorship candidacy books, and so on. They put as little effort into them as possible and expect as little as possible that these books will be read by the general public. They are written, but they are hardly ever read by those who have to examine them in the relevant department; at most, one person reads them perfunctorily and then tells the others what they should think of them. For science is something that “one” thinks about, not something that one thinks about personally, and then they are stored away in libraries. When someone writes something similar again, they look at the library catalogs and see where they can find something they need to take into account, and then that is stored away again, with as little reference to the individual or the personal as possible. It's all separate. Countless things that are of no personal interest whatsoever proliferate in libraries. That is basically a terrible state of affairs. But what is even more terrible is that people don't actually feel it, they feel completely reassured that they don't need to know anything themselves, because you can find everything in libraries if you can just look up the relevant keyword in the catalogs. That's where things rest. But people walk alongside science, which is something so general. However, this science would have to look different if people kept it in their heads and not on the shelves of libraries.

[ 4 ] This is what gives us, I would say, as if through a few holes—for one could cite many examples in this vein—an indication of how the general intellectual culture of humanity today is still unindividual, impersonal, how people want to have it as something that hovers above them like a cloud. But what human beings produce does not belong only to human beings; it belongs to the universe. That is why I said that in order to arrive at a fruitful consideration, we must view human beings in connection with their planet and then, in turn, view the planet in connection with the entire universe.

[ 5 ] So what humans produce, what they apply their intellect to, can be used in two ways. On the one hand, they can strain their intellect to develop sciences, which then all flow into “one thinks,” “one knows,” “one has made this or that progress”; then one writes this down in books, then one stores it, and then this is the science that generations grow up with; and human beings can wither away in such an operation of the intellect. They can do this by seeking what they actually find interesting in many other things, just not in what is in any case untrue, untrue in an objectively personal way, which is objectively stored in libraries; they can do this by not touching it, There have been gatherings of scholars who used the term “talking shop” in their terminology. It was considered inferior to discuss individual scientific matters after the official speeches, for example in small circles and the like. There, all sorts of nonsense was talked about, which was in any case far removed from what scientific matters actually were. And those who had the weakness of being enthusiastic about their science and who then began, say, over tea or black coffee, to talk about this or that philological or other topic, were precisely the people who were “talking shop,” those who were not taken entirely seriously, who lacked a sophisticated mind.

[ 6 ] This impersonal attitude toward science struck me in a very peculiar way once. I was once at a meeting where Helmholtz gave a lecture. During this lecture, which was read verbatim by Helmholtz and had already been in print for a long time when it was read, people listened as one does at such a lecture. After the lecture, a journalist came up to me and said: What was that all about? It wasn't necessary. Anyone who wants to can read a lecture like that when it's printed; why should it be read aloud? It would be much smarter if Helmholtz simply walked around the auditorium and shook everyone's hand; that would be much more meaningful, it would achieve much more. — That's a perfect example of the alienation from what is actually “floating around” so impersonally as science. Of course, people dry up. That's one way of understanding intellectual culture.

[ 7 ] The other way is to be interested in all the details, so that the mind catches fire and enlivens science, melting it into living concepts, so that everything we understand and grasp is received directly by our inner mental life. In this way, one can truly permeate everything that science has to offer with inner fire; in this way, by grasping the individual sciences, one can gradually penetrate the whole of world existence; in this way, one can create something that becomes the most personal matter of every human being who pursues it. That is the other thing. And everything that is done on the one hand is impersonal, fundamentally separate from human beings. People would prefer to invent automatons for scientific work so that they would no longer have to think with their own heads; then they might be productive without them. But what happens out of the full, heartfelt pursuit of science is not only a matter for humanity, it is a matter for the entire planet and thus for the entire universe. For what man does when he thinks, when he forms something in his mind through his intellect, is an event just as when water flows from a spring down a stream to the sea, or when it evaporates or when it rains. What happens externally and materially in the rain, what happens when a plant sprouts, and so on, are events of one kind. What happens through human beings are events of a different kind. It is not merely a human affair, it is an affair of the entire planet. And that is precisely the task of human beings in their development on Earth, that they take in the intellect that was previously poured out over the planetary sphere, that they unite it with themselves. So it is an impulse in human evolution that people make knowledge their own personal business, that they can pursue it with enthusiasm, that it can pass into them so that it is seized by their heart's fire. And if the latter does not happen, if they [only] store up knowledge in an impersonal way, then something does not happen that should happen in the sense of Earth's evolution. The mind of humanity is not seized by intellectual culture. Intellectual culture develops, so to speak, only in the head and hovers too far above the surface of the earth, merely in the minds; it develops only in the minds and should sink down into the hearts. But what is not received by the hearts, what is not grasped by the human mind, is awaited by the Luciferic spirits. And what the Luciferic spirits await in this way, they can receive when it floats impersonally over the earth in this manner. For the only way to wrest what belongs to the world of the intellect from the Luciferic spirits is to penetrate it with the heart, to make it a personal matter. And what is happening in our time, what has been happening for a long time and what must change, is precisely that we are allowing our earthly existence, by taking a detour through cold, sober intellectual dryness, to become the prey of the Luciferic world. This is holding back the Earth in its development, holding it back at an earlier stage. It cannot come to its end. And if people continue for a long, long time with the impersonality of so-called science, the result will be that people will lose their soul nature altogether. This impersonal science is the murderer of the human soul and spirit; it withers people, it dries them out. Ultimately, it turns the earth into what can be called a dead planet with automaton-like human beings on it who lose their spiritual soul life in this way. Here, too, it must be said: things must be taken seriously. We must not stand by and watch this cosmic murder through the abstract activity, the impersonal activity of knowledge on earth. That is one thing.

[ 8 ] The other is the human capacity for desire. This is what is connected with the will in human beings. What is connected with the will in human beings can in turn take two paths. One path is that this will submits as far as possible to commandments or state laws and the like and conforms to what is the more general law, so that the general law is there and alongside it only the purely instinctive desires of human beings.

[ 9 ] The other path is that what is reflected in human beings as the capacity for desire, what exists as the capacity for will, gradually rises to pure thinking, lives itself out freely and individually, so that it pours into social life in love. This is the way of living out the will and the capacity for desire as I have described it in The Philosophy of Freedom. There I showed how that which is general human law must emerge from every human individuality, and that when that which emerges from human individuality rises to pure thinking, then social order arises through the harmony of what people do. People fear all social order that is constituted by each individual giving [himself] direction out of his individuality. They want to organize what people should want. They want to replace the love that works out of each human being with “categorical imperatives.” But because such abstract commandments exist—whether they are commandments based on the model of the Decalogue or laws of some uniform state—because such commandments exist, only the instinctive desires of human beings assert themselves, those desires that we see reviving today and which have basically become the only social ingredient of the present age. Again, what happens in human beings as a result of their failure to shape their will to the point of individuality, of their failure to raise it to pure thinking, is not merely something that concerns human beings alone, but the entire planet and thus the cosmos. And what happens when the human will cannot shape itself individually is eagerly awaited by the Ahrimanic spirits. These Ahrimanic spirits appropriate this for themselves, and they use everything that lives in human beings as desires that have not developed into love, that live willfully, they use it in such a way that they transfer it to individual demonic beings. Just as more general beings arise through the intellectual activity that hovers above humanity, so too do individually formed demonic beings arise from the capacity for desire of individual beings that has not been transformed into love. And if we did not strive for an individualized form of free coexistence in the social order, the earth would be filled with beings that would then be individual, but would lead an Ahrimanic, spirit-like existence and would deprive the earth of the possibility of transforming itself into the next planetary metamorphosis, the Jupiter metamorphosis. Schematically drawn, this would be such that abstract intellectuality would form our planet (see drawing on the left) on one side, preventing it from reaching completion, and that which arises from the will not translated into love would form purely individual beings on the other side (right). This is a schematic representation of what someone today who looks into the beginnings of a civilization that is undermining the proper development process of the Earth planet can see as what will come into being if the impulses that are now sprouting so strongly in the Western world continue unchecked, and what is developing so strongly in the Eastern world (see drawing), which lies there merely as emerging from human subjectivity in the decadent state culture; this is actually what wants to shape the development of the Earth according to individual demons. What is developing in the West is what wants to sail into a general intellectual realm and gradually turn people into automatons.

[ 10 ] These things can be clearly perceived, albeit only in the predispositions of those automatons that already exist today — I say “partially” quite deliberately, because they are still very individual. With regard to many things, automatism can already be seen. But there is still something in these machines that is very individual, something that can be noticed as an appendage to each of these individual machines, an appendage that, when things are not converted into banknotes, sounds like gold and silver. But the general automatism would already have the effect that even individual money bags would become general communist money bags.

[ 11 ] But that is what must not be considered today with mere sympathies and antipathies, but with a view that sees through world events, that can see what is happening among human beings in connection with cosmic events. If you look at things in this way, you will say to yourself: it is up to human beings to bring the planet forward wisely in its development. — This particular kind of existence, as schematically indicated here, threatens humanity if humanity does not try to transform knowledge into wisdom, which can only happen if human beings personally commit themselves to knowledge, by taking it personally into themselves and reconnecting it with what, through the detour of love for the general human cause, arises from individual desire. With a strong sense of inner understanding, these things can be grasped through spiritual science. Basically, this is evident today in what I would call the cosmic symbol that has remained in the moon.

[ 12 ] When we have the moon in its first or last quarter, we have in its crescent shape a picture of what the earth could become; in its darker side, it shows those who can see the supersensible these demonic little figures moving in a hideous manner in the inward curve of the crescent. So it is actually very correct to say that through what I have just mentioned, human beings must preserve the earth from becoming like the moon. The moon shows us what the earth can become in a cosmic image that is set before us. And so we must accustom ourselves to penetrate what we see outside in the cosmos in this way with an inner sense. We must look at the moon in such a way that we say: It points to something that has been placed there by cosmic evolution as a caricature of earthly existence, as what earthly existence can become if human beings do not learn to make impersonal knowledge their personal concern, to transform individual desires into love, whereby they become what can become a general concern of the whole of humanity in associative social life. One can understand better what happens in the cosmos by looking at what takes place in human beings, and conversely, one can see what the task of human beings is in the right way if one can understand the conditions of the cosmos in their meaning. Then they will already turn to what should live as morality, as ethics, in humanity.

[ 13 ] The things that are said about Lucifer and Ahriman are truly not meant to be merely theoretical, to be spoken of in such a way that Ahriman is this and Lucifer is that. Rather, one should take these concepts into oneself in such a way that one sees in everything that happens around oneself the workings of the Luciferic spirits who want to hold back the earth stage in earlier stages, and that one sees in everything that Ahriman is, that which wants to hold back the earth stage so that it cannot progress into future stages. But one must see through these things in detail. One must, I would say, be able to evaluate the moral in terms of natural law, and the natural in terms of morality. When that happens, the great bridge will be built between the moral worldview and the theoretical worldview, a bridge I have often spoken of here.

[ 14 ] The things that are happening today must also be viewed from this perspective. For only when the free will of human beings intervenes in world events can what has been outlined here today be applied. The further development of the earth is precisely the task of man and humanity. This must not be overlooked. And those who only want to theorize, who, for example, only want to see, only want to hear: After so many centuries or millennia, this will happen — they do not take into account that we are already living in an age in which it is up to humanity to participate in the metamorphoses of the earth's development, that what is general world understanding must be taken into the human mind, and that what lives individually in human beings as the capacity for desire must flow out of human beings in the form of universal love, which, however, can only be achieved through pure, free thinking.

[ 15 ] I have thus presented to you two cultural currents that are of paramount importance, and have attempted to show, again from a certain point of view, what the task of serious spiritual science is. This task lies in such paths. It really does not lie in the fact that some people feel good about knowing this or that, but rather in the fact that the task of this serious spiritual science is to intervene in human development in such a way that world events are formed in the right way out of humanity itself.