Materialism and the Task of Anthroposophy

GA 204

23 April 1921, Dornach

Lecture VIII

Today, I shall have to turn to a seemingly more remote topic that will fit in, however, with yesterday's and tomorrow's subjects. I have frequently mentioned that when the evolution of humanity is surveyed, people proceed too much from the premise that the general condition of human soul life has basically remained the same ever since any human development can be traced historically or in prehistory. However, this assumption simply does not correspond to the facts. It is difficult, of course, to ascertain what the successive metamorphoses of human soul evolution were like if one is merely in a position to study the facts recorded in historical documents. If, on the other hand, one is able to look back further than these facts allow, then even the historical traditions present themselves in a different light. It then becomes evident that the human soul condition was not always what it is today or what it was in the ages still discernible by external means.

Above all, people believe the following: Human beings utilize something like geometry, like arithmetic, which, as we know, is mainly the theory of counting. Furthermore, they master the art of weighing, of determining weights of given objects. People then consider what measuring and measures represent and contemplate the way one counts and weighs things today. Then people think: Surely, in the age when, according to modern, prevalent opinion, human beings were still completely childlike, they were incapable of measuring, counting, and calculating anything. But ever since human beings were capable of that, these matters have been carried out approximately in the same way we execute them nowadays.

This is not the case at all, and even though it will lead us into a more remote subject, as I said, we must acquire a more exact idea of measures, numbers, and weights before we go into the historical considerations about mankind. Even according to external historical tradition the views concerning numbers prevailing in the Pythagorean School differed somewhat from those of today. As all of you realize, the Pythagoreans connected certain ideas with the numbers one, two, three, four, and so no. They linked quite definite conceptions with an even and an odd number. In short, they spoke about numbers in a certain qualitative sense, not merely in a quantitative one.

When the underlying reason for this is considered from the standpoint of spiritual science, we arrive at the realization that the Pythagorean School, which as yet was still a kind of esoteric school, represented basically only the last vestige of a much more ancient wisdom of numbers, going back to primordial times of which only the traditions have been preserved. And what is handed down to us concerning a science of numbers by Pythagoras is in fact already a decline from a much older teaching of numbers. When these matters are pursued further with the methods of spiritual science, we arrive by way of measure, number, and weight at concepts essentially different from those we possess today. As I said, even though it might create difficulties for some of you, we must make it somewhat clear to ourselves how these concepts of measuring, counting, and weighing are constituted today.

Measuring—how do we measure? We can only have one measure and it must be assumed in some manner. We cannot claim that this measure on which we base everything, such as the metric measure today, is somehow determined absolutely. It is determined as a certain segment of the northern quadrant of the earth's meridian that passes through Paris, and this segment, the ten millionth part, is not even exactly contained in that original prototype meter located in Paris. It is assumed, however, and we say that we proceed from a certain measure. With it, we then measure other lengths or surface areas by forming a square measure out of the unit of length. Yet, the figures arrived at concerning the object being measured refer to something completely arbitrary that was at one time assumed. It is important to make it clear to ourselves that we actually take an arbitrary measure as the basis, hence, that we always arrive only at a relation of some object to this arbitrarily assumed measure when we measure an object.

It is somewhat different in the case of numbers. In the abstract manner of our life today, we count, 1, 2, 3; we do this when counting apples or people, horses or chairs. To the object that is to be determined by the number it matters not what we designate as 1. We apply our peculiar way of counting to all things we count off, which, as a unit, represent an integrated totality.

Please note that in measuring we proceed from an arbitrary measure and we then relate everything to this arbitrary unit of measure. This unit of measure is something, so to speak; it exists. It is even conceivable, as it were, almost like a thing, an object. The unit of numbers cannot be pictured in this way. The unit of number is a completely abstract concept applicable to anything. No matter whether we count years or people or stars, we are led into total abstraction, into something that cannot stand for any particular reality since it could stand for all realities. When we take the arithmetic unit as the basis, the minute objective element still retained in measuring is lost to us.

When weighing something, we do not see the whole extent of what we take as the basis of weighing. There, the whole matter escapes us even more than in the case of numbers. When we count chairs, for example, and we say, “one,” “two,” “three,” we are at least finished when we come to the third chair that stands before us as a unit. In the case of a scale, on the other hand, we place a weight on one side of the scales—a weight in itself is nothing if it is not subject to earth's gravity, as we say—and the object we weigh is equal to the weight of the weights. Here, however, we are no longer by ourselves; basically, the whole earth is involved. Our point of reference here lies somehow completely beyond the realm we oversee. We enter into a complete abstraction when we say that something weighs five kilograms. Just think what you actually picture when you say that something weighs five kilograms. You place a five kilogram weight on a scale, but this weight by itself is really nothing! We are not dealing with a property of the thing itself. When I say, “one chair,” this one is at least integrated in the chair. The five kilograms, on the other hand, must relate themselves to the earth. You merely deal with something that relates to something else the whole extent of which you do not see at all, namely, the whole body of the earth. And when weighing the other object on the scale, which is to weigh five kilograms, again, you have something that escapes you completely, belonging again to a totality that is even less than an abstraction.

Let us proceed from numbers. In former times, and here we actually go back as far as the second post-Atlantean epoch, all thinking concerning numbers was dealt with in a significantly different manner from the way we treat it today in the outside world. People then really had concepts of 1, 2, and 3. For us, 2 is nothing but the presence of two units of 1; 3 is the presence of three, 4 that of four units of 1. Thus we continue counting by always adding 1 more. hence repeating the same act of thinking. We can repeat it indefinitely.

This was not the case in the second post-Atlantean epoch. Back then, people sensed the same difference between, let's say, two and three that we today feel only between different objects. In the number 3, one sensed a significantly different element from that in the number 2. Not only was it the addition of one unit; rather, one sensed something integrated in the 3, something where three things relate to one another. The 2 had an open element, something where two things lie indifferently side by side. People recalled this indifference in lying side by side when they said “two.” They did not sense this in the number 3, but only something that belongs together, where each thing relates to all the others. Concerning 2, a person could imagine that one thing escapes to the left, the other to the right. The 3 could not be pictured that way; instead, it was felt that if one unit would disappear, the remaining two would no longer be what they had been, for then, they would exist indifferently beside each other. The 3 combined the 2 in a totality, so to speak; it made them a whole. The form of arithmetic we have today, our elementary counting, this repetition of the same act, did not exist at all in those former times. Only now, through spiritual science, we are once again directed in a certain sense to the qualitative element of numbers.

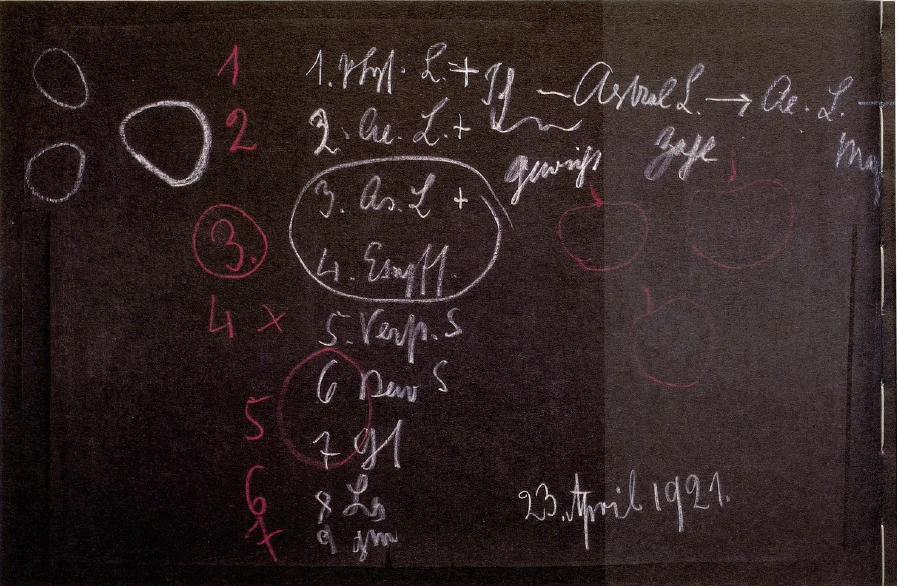

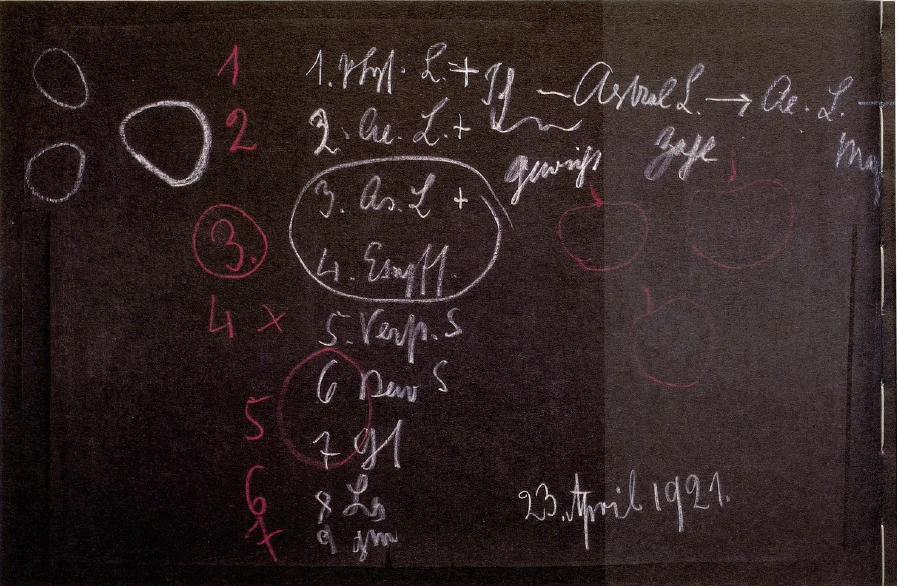

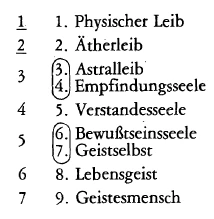

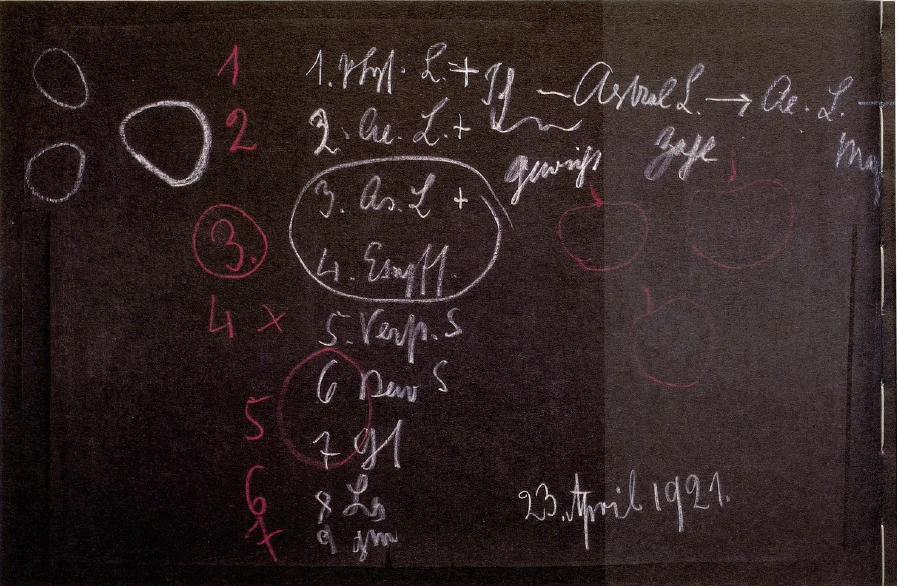

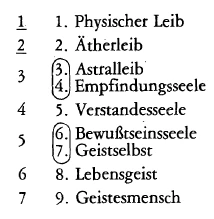

I can illustrate this with an example long since familiar to you so that you will realize that it is necessary to add not only 1 to 1, and so on, but to delve into the reality of existence with the numbers. In order to give you at least a very elementary idea of this matter, let me outline the following. In my book, Theosophy,1 Rudolf Steiner: Theosophy: An Introduction to the Supersensible Knowledge of the World and the Destination of Man. Rudolf Steiner Press, London, 1973. RSE 592. the individual members of the human being are described:

1. Physical Body

2. Ether Body

3. Astral Body

4. Sentient Soul

5. Intellectual or Mind Soul

6. Consciousness Soul

7. Spirit Self

8. Life Spirit

9. Spirit Man

To list the members of the human being side by side like this, however, signifies counting them off abstractly one after the other; it means that we do not delve into reality. Because these nine do not exist, we cannot count them like that at all: “1. physical body, 2. ether body, 3. astral body, 4. sentient soul.” You cannot count like that when you wish to comprehend the human organization and observe human beings today in their reality. In fact, it must be put like this: The physical body is delimited as an integrated whole, so is the etheric body. Pass on to the third member, on the other hand, it is not something self-enclosed. In the case of the actual human being, we cannot just add the sentient soul to the astral body. Instead, these two, the astral body and the sentient soul, must definitely be combined and thereby, passing from one to two to three in reality, we can, as it were, count off realistically, not merely finding in the 3 the simple addition of 1.

What develops in us as the “astral body” and the “sentient soul,” which interact with each other, is simply a third element, abstractly speaking, but by passing in reality to this third element, a third unit can no longer merely be added to the first two. Instead, we must realize that this third element is in itself different from the first two.

Then, the fourth member is counted off, which is actually the fifth, and again, in the modern human being, we must basically add together the sixth and seventh. Thus, we arrive at the way they are actually listed in my Theosophy: 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. We have seven actual components, which, when they are abstractly counted off, are nine:

Based on reality, we learn to say: By proceeding according to their inherent rules, one thing is not indifferent to the others. Just because this is the third member (see above, 3), it is something different. Certainly, due to our customary abstract thinking about numbers, we have to illustrate this a little, for this older way of thinking about numbers is foreign to ordinary consciousness. In ancient times, on the other hand, in the first and second period of the post-Atlantean epoch, it would not have occurred to anybody to imagine an indifferent addition in progressing from one number to the next. Instead, people experienced something when they passed from, say, 2 to 3, just as we experience something here when we pass from 2 to 3 (see above list). Today you can barely sense it in this example, but not yet in the number itself. In those former times people could sense it in the numbers themselves. They spoke of numbers in reference to their mutual relationships. Anything that existed in twos, for example, was felt to have a quality of openness towards the world, of not being closed off. Something existing in threes, as an actual three, was something closed off. You might now say that depending on what is counted a distinction has to be made. When you count, one man, one woman, one child, man and woman are equal to a duality, hence not closed off to the world; the child closes this duality off, forms a totality. When you count apples, on the other hand, we can indeed not say that three apples are more closed off than two. It was true that external matters were merely sensed in this way, but the number itself was experienced quite differently.

You might recall that certain aboriginal tribes still use their ten fingers to count, comparing to them the amount of objects present in their surroundings. So we could say that if we have three apples here, this is equal to three fingers.

For 1, 2, 3, however, these primitive people would not have said—naturally in the words of their own language—“thumb,” “index finger,” and “middle finger.” Although the objects they counted off in the outside world remained undefined, what represented those objects inwardly was very clearly defined, for the three fingers differ from one another. Well, mankind has now advanced so splendidly in the fifth period of the post-Atlantean epoch—basically, it was already like this in the fourth period—that we no longer need to count by means of our fingers. Instead, we say, “one, two, three.” The genius of language is not taken into consideration anymore. For if you would listen to what is contained in the words, purely based on feeling you would say: “Eins, entzwei” (“one, in two—cut in two.”)T1Translator's note: In the original German, Rudolf Steiner's example is quite clear. This is the reason the German words were retained and the English translation given in parenthesis. It is still retained in the language, and when you say: “Drei” (“three”), and you are sensitive to the sounds, you have something closed off. Three: when pictured correctly, three things can only be imagined as lying in a circle, connected to each other; two: into two (entzwei); three: self-enclosed, the genius of language still retains that.

Well, as I said, we have “advanced so far” that we can abstractly add one unit to another. Then we feel that this is 2, that is 1; in case of 3, one more has been added, and so on. Yet, why is it that we can count in the first place? In reality, we don't accomplish it any differently from primitive peoples. Only they did it with their five physical fingers. We, too, count with the fingers, but with those of our etheric body, and we no longer know it. It takes place in our subconscious, and we leave that out of consideration. We actually count by means of the etheric body; in reality, a number is still nothing but a comparison with what is contained within us. The whole of arithmetic is in us; we brought it to birth within us through our astral body. It actually emerges from our astral body, our ten fingers being merely replicas of the astral and etheric. These two are only utilized by the external finger, whereas, when we do sums, we express in the etheric body what brings about the inspiration of numbers in the astral body; then we count by means of the etheric body, with which we think in the first place.

Therefore, we can say that, outwardly, counting is something quite abstract for us today; inwardly, the reason we count is connected with the fact that we are counted in the first place, for we are counted out of universal being and are structured according to numbers. It is most interesting to trace the various methods of counting among the different folk groups in the world—according to the number 10, the decimal system, or the number 12—and how this relates to their different etheric and astral constitutions. Numbers are inborn into us, woven into us out of the cosmic totality. Outwardly, numbers are gradually becoming a matter of indifference to us; within us, this is not the case. Within ourselves, each number has its own definite quality. Just try and imagine that you could eliminate numbers from the universe and then see what things formed in numbers would look like if one thing were merely added to the other. Imagine the appearance of your hand, if the thumb were here, and the next finger would be added as the same unit and then the next, and so on. You would have five thumbs on your hand and five on the other! This would then correspond to abstract counting.

The spirits of the universe do not count like that. They create forms according to numbers, and they do it in the manner formerly connected with numbers during the first and even the second period of the post-Atlantean epoch. The development of abstract numbers out of the quite concrete concept of the element and quality of numbers is something that only evolved in the course of humanity's evolution. We have to realize that it has profound significance that the tradition handed down to us from the ancient mysteries relates that the gods fashioned man according to numbers. The saying that the world abounds in numbers implies that everything is fashioned according to numbers and that the human being, too, is formed on the basis of numbers. Hence, the modern way of counting did not exist in those ancient times; on the other hand, an imaginative thinking in the qualities of numbers did exist.

As I said, this leads us back to an age of long ago, namely, the first and second post-Atlantean periods, the ancient Indian and Persian eras, in which our present form of counting was not at all possible. In those times people connected something entirely different from two times one with the number 2. And likewise they associated something other than two plus one with three. As you can see, the human soul constitution has indeed changed considerably in the course of time.

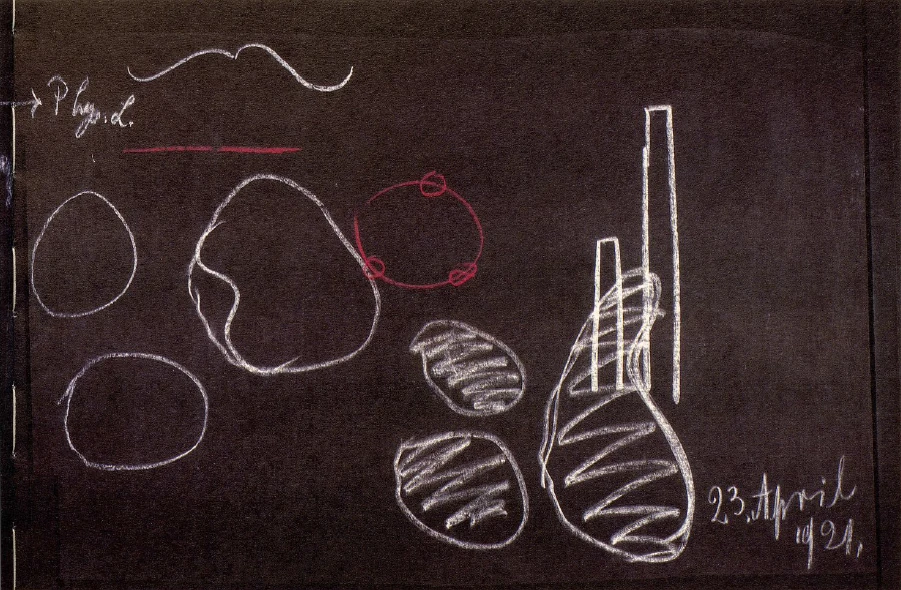

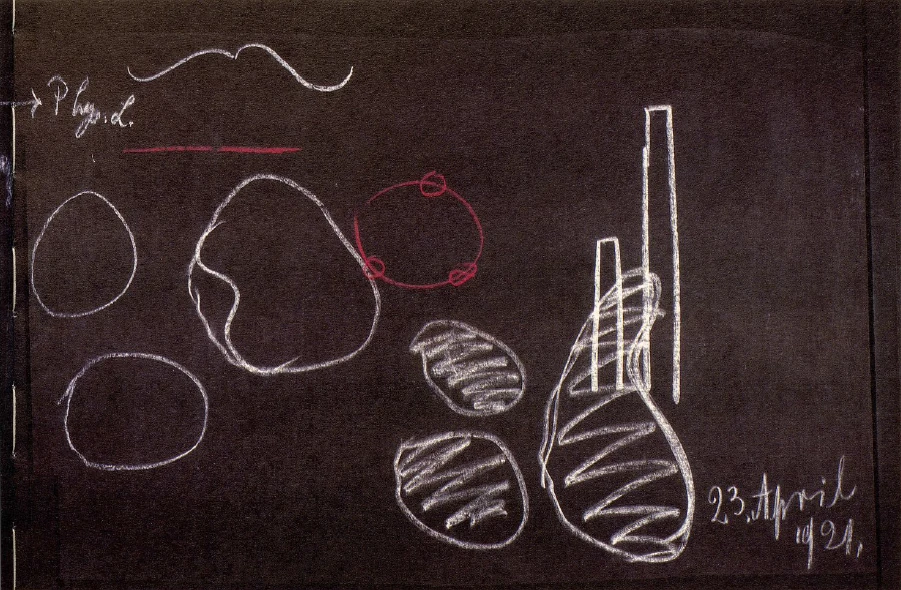

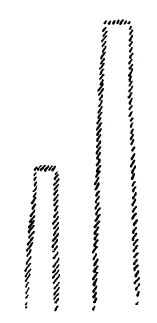

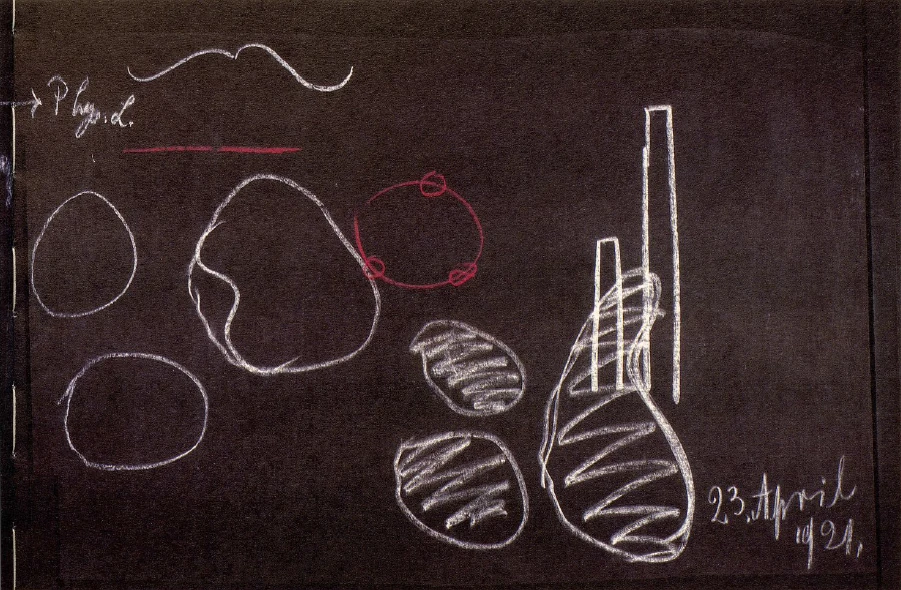

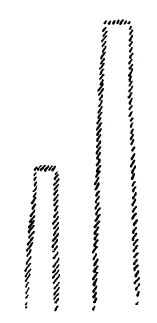

Turning now to the somewhat later period of time, the third period of the post-Atlantean epoch, we find that the measure was something quite different. Today, we measure on the basis of an assumed and arbitrary unit of measurement. Even in the third post-Atlantean period, for example, people did not really refer to such an arbitrary unit of measure. In measuring, they had in mind something quite pictorial. What they focused on may perhaps become clear to you from the following. Here, for instance, we see one column, there is another one (see sketch below); we look at these two columns. If we experience things abstractly, we say that the second column is twice as high as the first one; we measure it by the first one.

That, however, is a very abstract conception. Picturing it concretely, we can interpret it in approximately the following manner: When we evoke a feeling for the column on the left, we experience it to be weak in comparison to the one on the right. We feel that it must grow, and when it grows and grows and reaches this point up here (pointing to the taller column), it has become something special. It has put so much energy into this growth that it now possesses a strength such that its two parts are both equally strong. You can sense something qualitative there. You can go further and say: I have a structure here; I measure it against the other one and thus arrive at the symmetry; the concept of the measure expands for me, entering into the picture.

In this way, we gradually come to the idea that measure actually has to do with something that is still sensed dimly when we speak of moderationT2Translator's note: In German, this example is immediately clear. Mass means “measure;” maessig and massvoll mean “moderate.” in which case we are not thinking of measuring something. For example, when a person consumes only a certain quantity of some food, we might designate that as being moderate (maessig) without having measured the amount. We classify something else as immoderate (unmaessig). We are not measuring anything here, we make no comparison, measuring the stomach with what enters it, and so on. We don't measure the piece of meat and then eat it; we do not measure it against the size of the person. Instead, we refer to a quality when we speak of a moderate or immoderate intake of food. We arrive at something that is not so very different from what we term a measure today but it does show us that we refer to something abstract today when we speak of measure, namely, “the unit of measure contained in a certain quantity,” whereas formerly people defined it as something that was qualitatively connected with objects.

Above all, people sensed the measured symmetry of each member of man in relation to the totality of the human being without thinking at that point of a unit. One thing has remained from this, namely, that it seems abhorrent to us if, as artists, we are supposed to measure anything; for, if an artist actually has to take measurements so that the nose, for example, does not turn out to be too long or too short, this is not considered artistic. But we consider the work artistic when we see that the thing has the proper size for an organism. Therefore, we do not deal with an abstract process here but with something related to the pictorial element.

Finally, consider the unit of measure that still plays a certain role today, namely the so-called golden mean or golden section. It is not connected with measurements but only with a qualitative element. The smaller element is to the medium-sized one as the medium-sized one is to the whole. The smaller element may be any size, but it must always be to the medium-sized one as the medium-sized one is to the whole. We do not have a measurement in mind but something that reveals a certain interrelationship when we look at it. Yet, we speak of the harmonious measure that comes to expression in the golden mean. We cannot base the golden mean on any kind of unit of measure in the abstract sense as we do otherwise. Therefore, as we examine the various periods of humanity's evolution in regard to measuring, we find that in the fourth post-Atlantean period, the Greco-Roman age, this vivid awareness of measure and symmetry gradually transformed itself into abstract measuring. This was actually not the case until the fourth post-Atlantean period. In the third period people experienced the relationships of measure, the proportions, much more the way we only experience the golden mean. Likewise, as we go back into ancient times, our abstract counting can be traced back to an experience of the inner quality of numbers.

In the case of weight, human beings are already far removed from what existed in the first post-Atlantean period as an experience of weight. You need only recall a well-known phenomenon that most of you have experienced in observing an athlete who lifts a heavy weight with the inscription, “200 kilograms”; he tries and tries to lift it, sweating all the while, and you almost perspire with him. Then, when he's let you sweat long enough, he suddenly lifts it up and carries it off. The whole thing really has no absolute weight; that has only been feigned. You feel the weight because of the abstract inscription “200 kilograms.” The experience of weight is something we are deprived of nowadays. Therefore, it is one of the most profound experiences when, in regard to natural phenomena, the experience of absolute weight appears in clairvoyant consciousness, as is indeed the case.

It is really true that in the first post-Atlantean epoch, designated as the ancient Indian epoch, a human being still experienced something of weight relationships within himself. I have pointed out many times that our brain actually floats in the cerebral fluid and therefore—according to the well known law whereby a floating body seemingly becomes lighter by the amount of the weight of water it displaces—loses a considerable amount of its weight. Otherwise, the brain would crush the blood vessels lying underneath. The brain floats in the cerebral fluid, but people in their abstract awareness no longer notice this today; neither are they aware of any other relationships within themselves. We no longer experience weight, pay it no attention. There is a major difference between experiencing one's weight at age twelve, and when one is, say five times that age. Most people have forgotten, however, how heavy they appeared to themselves at age twelve, and therefore they cannot very well make the comparison. But let's assume that according to the scales you have the same weight at two ages. Yet this does not matter; what matters is the experience of the weight. This experience of weight that for people today is present only in regard to the earth, was something absolute during the first postAtlantean epoch.

Today, we experience only a remnant of that in art but there in a very pronounced manner. I need only call your attention to the following. Let us assume that I draw two figures. According to my view, this is really something unclear and unresolved, something that should not be. Two objects like that side by side induce me to draw a third one. But I can shape the third object only in such a way that it appears larger, in a sense, holding the other two together. Then I have the feeling that the three are floating in air and can mutually support each other.

When a painter nowadays draws three angels who are, after all, not viewed in connection with gravity, and he is concerned with composition, he distributes them in space in such a manner that they support each other, that one is borne by the other. Artistically, it would be the worst thing simply to draw three angels side by side on a canvas; such a painter would have no true artistic feeling. One must have a feeling for the weight of each one, how one thing carries the other. In artistic feelings, a slight touch has remained of what was mainly experienced inwardly by people in the post-Atlantean age as producing weight, as giving him weight.

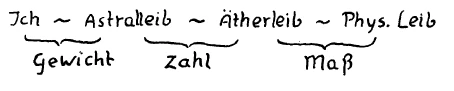

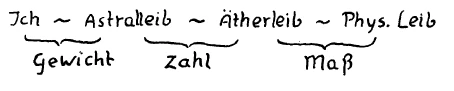

The experience of weight, number, and measure developed during the first three post-Atlantean periods according to the way human beings experienced themselves within the cosmos. And based on what had shaped them from out of the cosmos, the other matters were judged, namely, what they produced. When people observed what their astral body pushed into the etheric body, they had to tell themselves that the astral body counts, counts in a differentiating way thus forming the etheric body. Numbers are found between astral and etheric body and they are something alive and active within us.

Something else is located between etheric body and physical body. Through the inner relationships something is formed out of the etheric body that we can then behold. Basically, even our organism is structured according to the golden mean: the forehead is to a certain other part of the head as that in turn is to the whole length of the head, and so on. All this is imprinted by the etheric body into our physical body out of the cosmos and its relationships. Contained within us, measure and symmetry represent the transition from the etheric to the physical body. Finally, in the transition from the ego to the astral body lives what can be inwardly experienced as weight. I have often pointed out that the ego was actually born in the course of human evolution. The people of the ancient Indian period did not yet experience such an ego. They did, however, experience within themselves something causing weight, the condition of possessing form; hence, they sensed this heaviness, this downward pull, as well as their buoyancy, their ascent. They sensed within themselves what is overcome when the child changes from a being that crawls on all fours to one that walks. The people in ancient India did not experience their ego, but they did sense that they were fettered by the Ahrimanic forces to the earth, that they were weighted down by them, and that, on the other hand, they were borne upwards, lifted up by the Luciferic forces. All this, they experienced as their position of equilibrium. If we were to study the ancient terms for the ego we would find that the above experience was contained in the formulation of the words themselves. Just as the words were fitted together in the verbs according to their inner configuration, so the ancient words for the ego contained the balance between floating and falling.

|

I |

— |

Astral Body |

— |

Etheric Body |

— |

Physical Body |

|

Weight |

Number |

Measure |

Weight, which isn't abstract anymore, for we confront something completely unknown; number, something quite abstract, for it is totally unrelated to what is being counted; measure, which has become increasingly abstract for us—these abstract conceptions of ours are actually projected from our inner being to the outside. Something that has very real significance within the human being since he is fashioned according to measure, number, and weight is transferred by him to the indifferent external things. In this process of abstraction the human being dehumanizes himself. It is therefore possible to say that mankind's evolution tends in the direction of losing the inner experiences of weight, number, and measure, retaining only a slight touch of them in the artistic realm. We no longer experience them in such a manner that we sense ourselves as having been formed out of the cosmos according to weight, number, and measure.

The geometry we have when we compare congruent and similar figures, when we say that an ellipse is generated by a point so moving that its distance from a fixed point divided by its distance from a fixed line is a positive constant, is something abstract. There, we basically measure the distances and find that their sum is always equal to the large axis of the ellipse. Even if it was not pictured in any way, the ellipse was nevertheless experienced by people in the third post-Atlantean period in this peculiar relationship of two different quantities. In the relationship of one to the other they already sensed the elliptic element, just as they sensed the circle during the same age. And in the same way the nature of numbers was experienced. Humanity evolved in this way from concrete experience to something abstract, developing geometry out of the ancient experience of measure, arithmetic out of the former experience of numbers, and having completely lost the ancient experience of weight and thus having utterly dehumanized themselves, human beings developed only external observation out of it.

All this slowly prepared the way for the increasing abstractness of inner human experience, a development that culminated in the nineteenth century. Thus, the human being became lost to his own conception. He can no longer comprehend himself; he no longer has any idea that he produces geometry because he has been formed according to measure out of the cosmos, that he counts through his very nature. He is surprised when the so-called savages use their fingers in order to compare external objects with them. He has forgotten that he has been fashioned according to numbers out of the cosmos. He does not know that in this regard he, too, always remains a “savage,” that his etheric body had imprinted the numbers into his astral body in accordance with the inner qualities of the numbers themselves so that he could later experience the numbers also outside himself. In the course of humanity's evolution, geometry, arithmetic, and the science of weight and weighing have all moved into the abstract domain and have contributed to the fact that the human being could henceforth only devote himself to a science and a form of scientific research that observes these matters externally.

What do we do when we are involved in scientific research today? We measure, count, and weigh. Nowadays, you can indeed read of strange definitions of existence. We already have thinkers who state that existence, being, is that which is measurable. Yet, they naturally refer only to measuring with an arbitrary unit of measure. It is odd that existence is traced back to something actually based on arbitrariness. Therefore, the human being dwells in something that has been completely detached, excluded from him and in regard to which he has utterly lost the connection with himself. Due to such influences, the human being has lost himself in modern knowledge; something I have emphasized from a number of viewpoints, particularly during this lecture course.

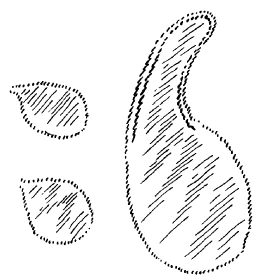

As I have often said, the human being has been lost in our perception of ourselves as merely the last step in the evolution of the animals. In society we have lost sight of the human being, for though we have invented extremely sophisticated machines, we are unable to integrate the significance of the people operating these machines into our social processes. We must learn to penetrate mankind's evolution; above all we must observe in this way how the process of man's intellectualization has come about. Just think how different people's frame of mind was in the first post-Atlantean period when they continuously experienced a changing equilibrium in placing one leg in front of the other. They always felt themselves become heavy, sensed a falling and floating. Picture how different it was when human beings felt that numbers permeate their own form, that they are built up according to measures. Think of how different that was from superficial measuring, counting, and weighing, leaving out the human being altogether. As I already indicated, at most it is possible for a person with a more sensitive awareness for language to gain some insight into the nature of numbers by means of what is in fact contained in the numerals, the words naming the numbers; or, from an artistic viewpoint, it is possible to sense that this, for example, in the sketch below is feasible:

but that this is impossible in this connection:

Such a person then has just a touch of the feeling for the inner condition of weight, the inner balance. If, by means of a line, I can follow some relationship in the other object, I have them balancing each other. However, if I sketch a protrusion over here, on the object on the right of second sketch, where there cannot be one, then I have no feeling for this balance. See how mankind has struggled to produce the external proportions out of its inner being, so to say, the outer appearance in contrast to the inward experience. Take a look at the painting by Raphael—it is actually true of all of Raphael's paintings but especially obvious in this one—depicting the “Marriage of Mary and Joseph,”2 “Il Sposalizio”, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milano. Raphael, 1483–1520, Italian painter. and see how the figures are positioned and painted in such a way that they support each other and that the viewer thus loses the feeling that anything exerts a downward pull. In particular, however, when ancient painters drew some flying creature, study how that was motivated, how you can clearly discern from this figure that it is not pulled down by weight but, rather, supports itself somehow by means of the relationship to other elements in the painting.

So, here we have the transition from the experience of the inner weighting to the external determination of weight: thus, here we have the course of mankind in the post-Atlantean epoch from inward experience to intellectualism, this struggling ascent to the intellect where everything experienced in our concepts is divorced from the human being; where we no longer experience the tearing in the word entzweien, (“to fall out with each other”; literally: “tearing in two”) when we say Zwei (“two”).

All this comes about slowly. When this term is employed further, when we say, zweifeln, “to doubt,” we sense the derivation from entzweien. After all, one who doubts something implies: Perhaps this is correct, perhaps it is not. It is open in both directions, the feeling of entzweien is inherent in the conceptual act. It is also already contained in the word for the number 2, zwei. Three—there you cannot experience this in the same manner when you apply it to something. Apply it to a judgment, where you have the major premise, the minor premise and the conclusion: a triad, a matter enclosed within itself. Take the syllogism about the most famous logical personality, the one about Gaius Julius Caesar:

All men are mortal;

Gaius is a man;

therefore Gaius is mortal

It all belongs together, the major and minor premise and the conclusion. However, if you take merely the first two, the matter remains open.

Hereby, I only wished to indicate to you what mankind's path to abstraction was like and how, in fact, by losing himself, man brought the intellect into his evolution.

We shall continue with this tomorrow. Today's subject was intended only as an episode, but you will see how it will fit in with further considerations.

Achter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Ich werde heute ein scheinbar entlegeneres Kapitel vorzubringen haben, das sich aber doch mit dem gestern Gesagten und morgen zu Sagenden zu einem Ganzen zusammenschließen wird. Ich habe öfters erwähnt, daß der Mensch, indem er die Entwickelung der Menschheit überblickt, zu sehr von der Anschauung ausgeht, daß eigentlich die Gesamtverfassung des menschlichen Seelenlebens, so lange es überhaupt eine menschliche Entwickelung gibt, die geschichtlich oder vorgeschichtlich zu verfolgen ist, im wesentlichen gleichgeblieben sei. Aber das, was da geglaubt wird, entspricht eben durchaus nicht den Tatsachen. Allerdings, es ist schwer zu konstatieren, wie die aufeinanderfolgenden Metamorphosen der menschlichen Seelenentwickelung gewesen sind, wenn man bloß in der Lage ist, auf die geschichtlich durch Dokumente überlieferten Tatsachen zu sehen. Wenn man jedoch weiter zurückschauen kann, als diese Tatsachen gehen, dann zeigt sich auch das geschichtlich Überlieferte in einem anderen Lichte, und dann zeigt sich, daß es mit der menschlichen Seelenbeschaffenheit nicht immer so gewesen ist, wie es heute ist, oder wie es in den Zeiten war, die gerade noch durch Äußerliches zu überschauen sind. Vor allen Dingen glaubt man: Nun ja, der Mensch hat zum Beispiel heute so etwas wie eine Geometrie, er hat so etwas wie eine Arithmetik, die ja im wesentlichen die Lehre vom Zählen ist, und er hat dann die Kunst des Wägens, des Gewichtbestimmens. Man macht sich Vorstellungen darüber, was messen ist, was ein Maß ist. Man macht sich Vorstellungen darüber, wie man heute zählt und wie man die Dinge abwiegt, und man denkt sich: Gewiß, in der Zeit, in der nach unserer nun einmal bestehenden Meinung die Menschen noch ganz kindlich waren, in der haben sie eben noch nicht messen, zählen und rechnen gekonnt. Aber seitdem man das kann, seitdem wird es eben ungefähr in derselben Weise ausgeübt, wie das heute ausgeübt wird.

[ 2 ] Das ist eben durchaus nicht der Fall, und wenn es auch, wie gesagt, in ein entlegeneres Gebiet führt, wir müssen uns schon einmal, bevor wir auf das Geschichtliche der Menschheit eingehen, etwas genauere Vorstellungen bilden über Maß, Zahl und Gewicht. Sie wissen ja, daß auch nach der äußeren Überlieferung in der pythagoräischen Schule über die Zahlen etwas andere Ansichten geherrscht haben als heute herrschen. Die Pythagoräer haben, wie Sie ja alle wissen, bestimmte Vorstellungen verknüpft mit der Zahl‘ - eins, zwei, drei, vier und so weiter -, sie haben ganz bestimmte Vorstellungen verbunden mit der geraden Zahl, mit der ungeraden Zahl. Kurz, sie haben in einer gewissen qualitativen Weise, nicht bloß in quantitativer Weise von der Zahl gesprochen.

[ 3 ] Wenn man dasjenige, was da zugrunde liegt, geisteswissenschaftlich betrachtet, so kommt man dazu, einzusehen, wie das, was in der pythagoräischen Schule vorhanden war, die ja immerhin noch eine Art Geheimschule war, im Grunde schon nur mehr der letzte Nachklang von einer viel älteren Zahlenweisheit war, die in uralte Zeiten zurückgeht, und von der sich nur Überlieferungen erhalten haben. Und das, was uns über Pythagoras gesagt wird, das ist im Grunde genommen schon etwas, was im Niedergange begriffen war von einer uralten Zahlenlehre. Man kommt eben, wenn man die Sachen geisteswissenschaftlich verfolgt, über Maß, Zahl und Gewicht zu wesentlich anderen Vorstellungen, als wir sie heute haben. Aber wie gesagt, wir müssen uns da ein wenig klarmachen können, wenn das auch manchen von Ihnen Schwierigkeiten bereiten mag, wie es heute um diese Begriffe Messen, Zählen, Wägen steht.

[ 4 ] Messen - wie messen wir? Wir können nur ei» Maß haben, und dieses Maß, das muß in irgendeiner Weise angenommen sein. Wir können nicht sagen, daß dieses Maß, das wir zugrunde legen, nehmen wir also heute das Metermaß, irgendwie absolut bestimmt sei. Es ist angenommen, es ist bestimmt als ein bestimmter Teil des nördlichen Erdmeridianquadranten, der durch Paris geht, und es ist nicht einmal dieser Teil, der zehnmillionste Teil, genau enthalten in jenem gewissermaßen ehernen Grundmaßstab, der zu Paris sich befindet als der Urmeterstab. Aber es ist angenommen. Man sagt, man will von einem bestimmten Maß ausgehen, und dann mißt man andere Längen damit oder auch Flächen, indem man aus dem Längenmaß ein Quadratmaß bildet. Aber dasjenige, was man da herausbekommt über das zu Messende, ist zurückgeführt auf ein rein Willkürliches, auf ein einmal Angenommenes. Das ist wichtig, daß wir uns das klarmachen, daß wir eigentlich ein willkürliches Maß zugrunde legen, so daß wir immer nur das Verhältnis irgendeiner Größe zu diesem willkürlich angenommenen Maß haben, wenn wir messen. Mit der Zahl verhält es sich schon etwas anders.

[ 5 ] So wie wir heute einmal in unserem abstrakten Dasein leben, so zählen wir «eins», «zwei», «drei»; wir zählen «eins», «zwei», «drei», wenn wit Äpfel zählen, wenn wir Menschen zählen, wenn wir Pferde zählen, wenn wir Stühle zählen. Für das, was da durch die Zahl bestimmt werden soll, ist es gleichgültig, wofür wir «eins» sagen. Wir haben unsere besondere Art des Zählens für alle Dinge, die wir eben abzählen und die als Einheit etwas in sich Geschlossenes bilden.

[ 6 ] Merken Sie, wenn wit messen, so legen wir eine willkürliche Maßeinheit zugrunde; aber auf diese willkürliche Maßeinheit beziehen wir dann alles. Diese Maßeinheit ist gewissermaßen etwas, sie ist da; sie ist sogar vorstellbar, ich möchte sagen, in einer dingähnlichen Art, in einer sachähnlichen Art. Die Einheit als Zahl, die ist nicht vorstellbar in einer dinglichen Art. Was die Einheit als Zahl ist, das ist ein völliges Abstraktum, das ist etwas, was auf alles anwendbar ist. Es kommt nicht darauf an, ob wir Jahre zählen oder ob wir Menschen zählen oder ob wir Sterne zählen, wir werden ins völlig Abstrakte geführt, in dasjenige, mit dem gar keine Wirklichkeit gemeint werden kann, weil alle Wirklichkeiten damit gemeint sein können und keine Wirklichkeit gemeint sein kann. Wenn wit arithmetisch die Einheit zugrunde legen, da entfällt uns das bißchen Dinghafte, Sachhafte, was wir noch haben, wenn wir messen. Und gar beim Wägen, beim Wägen haben wir es zu tun damit, daß wir dasjenige gar nicht übersehen, was wir zugrunde legen. Da entfällt uns die Geschichte noch mehr als bei der Zahl. Bei der Zahl haben wir wenigstens, wenn wir etwa Stühle zählen und sagen «eins», «zwei», «drei, mit dem dritten Stuhle abgeschlossen und er steht als Einheit vor uns. Wenn wir aber eine Waage haben, da legen wir auf der einen Seite ein Gewicht auf - das Gewicht ist ja für sich nichts, wenn es nicht angezogen wird von der Erde, wie wir sagen -, und das wiederum, was wit abwägen, ist gleich dem Gewichte des Gewichtes. Aber wir stehen da gar nicht mehr allein; wir stehen im Grunde genommen mit der ganzen Erde da. Dasjenige, worauf wir uns beziehen, liegt völlig irgendwie außerhalb des Bereiches, den wir überschauen. Wir kommen in ein völliges Abstraktum hinein, wenn wir sagen: Irgend etwas wiegt fünf Kilo. - Denken Sie nur, was Sie da eigentlich in der Vorstellung haben, wenn Sie sagen, etwas wiegt fünf Kilo, Sie legen ein Fünfkilogewicht auf eine Waagschale, ja, aber ein Fünfkilogewicht, das ist ja nichts für sich! Es ist keine Eigenschaft des Dinges da. Wenn ich sage: Ein Stuhl - so ist wenigstens dieses «eins» geschlossen in dem Stuhl drinnen; aber diese fünf Kilo, die müssen sich auf die Erde beziehen. Da haben Sie nur irgend etwas, was eine Beziehung zu etwas ist, was Sie gar nicht überschauen: zum ganzen Erdenkörper. Und wenn Sie dann das andere auf der Waagschale, die fünf Kilo abwiegen sollen, so haben Sie wieder etwas, was Ihnen ganz entschlüpft, was wieder einem Ganzen angehört, was weniger ist als ein Abstraktum.

[ 7 ] Gehen wir von der Zahl aus. In früherer Zeit - und wir werden dabei zurückgeführt eigentlich bis in den zweiten nachatlantischen Zeitraum -, in dem zweiten nachatlantischen Zeitraum, da behandelte man das ganze Denken über die Zahl wesentlich anders, als es heute in der äußeren Welt behandelt wird. Da hatten wirklich die Menschen Vorstellungen über «eins», über «zwei», über «drei». Für uns ist «zwei» nichts anderes als das zweimalige Vorhandensein der Einheit; und «drei» ist das dreimalige Vorhandensein der Einheit ' und «vier» eben das viermalige Vorhandensein der Einheit. Und so zählen wir fort, indem wir immer nur «eins» dazugeben, also denselben Denkakt wiederholen. Wir können ihn ad infinitum, ins unendliche wiederholen.

[ 8 ] So war es nicht in dem zweiten nachatlantischen Zeitraum. Da fühlte man, sagen wir zwischen «zwei» und «drei», einen solchen Unterschied, wie man ihn heute nur zwischen Gegenständen fühlt. Man fühlte in der Drei etwas wesentlich anderes als in der Zwei, nicht bloß daß die Einheit dazugefügt ist, sondern man fühlte in der Drei etwas Geschlossenes, etwas, wo sich die drei Dinge aufeinander beziehen, in der Zwei etwas Offenes, etwas, wo die zwei Dinge gleichgültig nebeneinanderliegen. Diese Gleichgültigkeit desNebeneinanderliegens, an das dachte man, wenn man «zwei» sagte. In der Drei fühlte man nicht etwas gleichgültig Nebeneinanderliegendes, sondern man konnte sich unter Drei nur etwas vorstellen, was zusammengehört, wovon sich jedes auf das andere bezieht. Von der Zwei konnte man sich vorstellen, daß das eine links entwischt, das andere rechts entwischt. Von der Drei konnte man sich das nicht vorstellen. Von der Drei stellte man sich immer vor: Wenn das eine entwischt, dann sind die zwei anderen nicht mehr das, was sie gewesen sind, denn dann sind sie ein Gleichgültig-Daseiendes. Die Drei schloß gewissermaßen die Zwei zu einer Totalität, zu einem Ganzen zusammen. Ein solches Rechnen, wie wir es haben, das elementare Rechnen, das Wiederholen desselben Aktes, das gab es in jenen älteren Zeiten überhaupt nicht. Und erst heute werden wir dutch die Geisteswissenschaft wiederum in einer gewissen Weise in das Qualitative der Zahl hineingeführt.

[ 9 ] Ich kann Ihnen das an einem Beispiel, das Sie längst kennen, veranschaulichen, so daß Sie sehen werden: man ist genötigt, nicht bloß eins zu eins zu eins und so weiter hinzuzufügen, sondern mit der Zahl nun auch wirklichkeitsgemäß unterzutauchen in das Dasein. Damit Sie eine, es ist noch, ich möchte sagen, die elementarste, Vorstellung von der Sache bekommen, machen Sie mit mir das Folgende dutch. Sie finden in meiner «Theosophie» die einzelnen Glieder des Menschen beschrieben; diese Glieder des Menschen werden beschrieben:

1. Physischer Leib

2. Ätherleib

3. Astralleib

4. Empfindungsseele

5. Verstandes- oder Gemütsseele

6. Bewußtseinsseele

7. Geistselbst

8. Lebensgeist

9. Geistesmensch

[ 10 ] Aber diese Glieder der menschlichen Wesenheit so nebeneinanderzufügen, das heißt, sie nacheinander abstrakt aufzuzählen, das heißt nicht in die Wirklichkeit untertauchen. Denn diese Neun hier, die gibt es ja gar nicht; man kann gar nicht so zählen: 1. Physischer Leib, 2. Ätherleib, 3. Astralleib, 4. Empfindungsseele; man kann gar nicht so zählen, wenn man sich die menschliche Wesenheit klarmachen will, wenn man heute den Menschen seiner Wirklichkeit nach ansieht. Tatsächlich muß man so sagen: Physischer Leib, gut, der grenzt sich als ein in sich Geschlossenes ab, Ätherleib auch: aber der Astralleib, indem wir also zum Dritten übergehen, der ist nicht etwas in sich Abgeschlossenes, und wir können nicht einfach die Empfindungsseele zu ihm hinzuzählen beim wirklichen Menschen, sondern wir müssen diese zwei, Astralleib und Empfindungsseele, unbedingt zusammenfassen und dadurch, daß wir in der Wirklichkeit übergehen von eins zu zwei zu drei, können wir gewissermaßen real abzählen, können wir in der Drei nicht finden ein einfaches Hinzufügen.

[ 11 ] Dasjenige, was im Menschen sich bildet als «Astralleib» und «Empfindungsseele», die ineinanderwirken, ist abstrakt einfach ein Drittes; aber dadurch, daß wir in dieser Realität übergehen zum Dritten, können wir nicht mehr einfach zu den zwei Ersten ein Drittes hinzufügen, sondern müssen uns klar sein: dieses Dritte ist in sich etwas anderes als die beiden Ersten.

[ 12 ] Dann kommen wir dazu, das Vierte zu zählen, was eigentlich das Fünfte ist, und dann müssen wir wiederum im Grunde genommen das Sechste und Siebente zusammenrechnen im heutigen Menschen, so daß wir eigentlich haben, wie Sie das auch in meiner«Theosophie» verzeichnet finden: drei, vier, fünf, sechs, sieben. Wir bekommen sieben wirkliche Glieder, die aber, wenn sie abstrakt aufgezählt werden, neun Glieder sind:

[ 13 ] Wir lernen aus der Wirklichkeit heraus zu sagen: Indem wir nach der Regel der Zahl vorgehen, ist nicht gleichgültig das eine dem anderen. Einfach dadurch, daß dies das Dritte ist (siehe Zusammenstellung, 3), ist es etwas anderes. Gewiß, wir müssen uns das heute, weil wir gewöhnt sind, über die Zahl abstrakt zu denken, ein wenig veranschaulichen, weil es dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein weit abliegt. Aber in alten Zeiten, also in der ersten und zweiten Periode nachatlantischer Zeit, da fiel es gar niemandem ein, in den Zahlen beim Vorrücken das gleichgültige Hinzufügen des einen zum anderen sich vorzustellen, sondern man erlebte etwas, wenn man überging, sagen wir von der Zwei zur Drei, so wie man hier etwas erlebt, wenn man übergeht von der Zwei zur Drei (siehe Zusammenstellung). Heute kann man es gerade erst fühlen an einem solchen Beispiel; man fühlt es noch nicht an der Zahl selber. In jenen alten Zeiten fühlte man es an den Zahlen selber. Man sprach von den Zahlen in ihren Verhältnissen zueinander. So empfand man zum Beispiel: Alles dasjenige, was als Zwei vorhanden ist, das hat etwas nach der Welt Offenes, das ist nichts Abgeschlossenes; dasjenige, was als Drei, als wirkliche Drei vorhanden ist, das ist etwas Abgeschlossenes. Nun werden Sie sagen, man muß da einen Unterschied machen, je nachdem, was man zählte. Wenn man zählte: Ein Mann, eine Frau, ein Kind, so ist Mann, Frau gleich Zweiheit, unabgeschlossen zur Welt; in dem Kinde schließt es sich ab, bildet eine Ganzheit. Wenn man Äpfel zählte, dann konnte man allerdings nicht sagen, daß drei Äpfel mehr abgeschlossen sind als zwei Äpfel. Ja, das Äußere empfand man nur so, aber die Zahl empfand man nicht so; die Zahl empfand man nämlich ganz anders.

[ 14 ] Sie werden sich erinnern, daß gewisse Stämme, die noch der Urbevölkerung angehören, nach ihren zehn Fingern zählen, indem sie die Anzahl des außen Vorhandenen mit ihren Fingern vergleichen, so daß man also sagen könnte, wenn drei Äpfel daliegen, das ist gleich drei Finger.

[ 15 ] Aber nun würde man nicht gesagt haben: Eins, zwei, drei natürlich in der entsprechenden Sprache: Daumen, Zeigefinger, Mittelfinger. -— Da hat man zwar draußen in der Welt nichts Bestimmtes; aber in dem, was einem innerlich repräsentierte das, was draußen ist, da hatte man etwas sehr Bestimmtes, denn die drei Finger, die sind voneinander verschieden. Nun, wir haben es so herrlich weit gebracht als Menschheit jetzt in der fünften Periode der nachatlantischen Zeit — es war schon in der vierten im wesentlichen so -, daß wir nicht mehr nötig haben, zu sagen: Daumen, Zeigefinger, Mittelfinger -, sondern wir sagen: Eins, zwei, drei. - Der Genius der Sprache wird nicht mehr berücksichtigt. Denn wenn Sie hinhören würden auf die Sprache, so würden Sie rein empfindungsgemäß sich sagen: Eins, entzwei -.das heißt auseinander. In der Sprache liegt es noch. Wenn Sie aber sagen: Drei - und haben ein Gefühl für die Laute, dann haben Sie das Geschlossene. Drei: sind nur zu denken eigentlich - wenn man sie richtig denkt - als zueinandergehörig im Kreise liegend. Zwei: entzwei; drei: in sich geschlossen. Der Genius der Sprache hat das noch.

[ 16 ] Ja, also wie gesagt, wir haben es «so herrlich weit gebracht», daß wir abstrakt eine Einheit an die andere herantragen können, und dann empfinden wir, nun ja: Das ist zwei, das ist eins; bei drei ist ja noch eins dabei und so weiter. Aber warum können wir denn überhaupt zählen? Ja, in Wirklichkeit machen wir es nämlich nicht anders als die Wilden, nur haben die Wilden das mit ihren fünf Fingern gemacht, mit ihren fünf physischen Fingern. Wir zählen auch, nur zählen wir mit den Fingern unseres Ätherleibes und wissen nichts mehr davon. Das spielt sich im Unterbewußtsein ab, da abstrahieren wit. Denn dasjenige, wodurch wir zählen, das ist eigentlich der Ätherleib, und eine Zahl ist noch immer nichts anderes in Wirklichkeit als ein Vergleichen mit demjenigen, was in uns ist. Die ganze Arithmetik ist in uns, und wir haben sie in uns hineingeboren durch unseren Astralleib, so daß sie eigentlich aus unserem Astralleib herauskommt, und unsere zehn Finger sind nur der Abdruck dieses. Astralischen und Ätherischen. Und dieser beiden bedient sich nur dieser äußere Finger, während wir, wenn wir rechnen, dasjenige, was durch den Astralleib bewirkt Inspiration von der Zahl, im Ätherleib ausdrücken und dann durch den Ätherleib, mit dem wir überhaupt denken, zählen. So daß wir sagen können: Äußerlich ist heute für uns das Zählen etwas recht Abstraktes, innerlich hängt es damit zusammen - und es ist sehr interessant, die verschiedenen Zählungsmethoden nach der Zehnzahl, nach dem Dezimalsystem oder nach der Zwölfzahl bei den verschiedenen Völkern zu verfolgen, wie das mit der verschiedenen Konstitution ihres Ätherischen und Astralischen zusammenhängt -, innerlich hängt es damit zusammen, daß wir zählen, weil wir selbst erst gezählt sind; wir sind aus der Weltenwesenheit heraus gezählt und nach der Zahl geordnet. Die Zahl ist uns eingeboren, einverwoben von dem Weltenganzen. Draußen werden uns nach und nach die Zahlen gleichgültig; in uns sind sie nicht gleichgültig, in uns hat jede Zahl ihre bestimmte Qualität. "Versuchen Sie es nur einmal, die Zahlen herauszuwerfen aus dem. Weltenall, und sehen Sie sich an, was der Zahl gemäß gestaltet wird, wenn einfach eins zu dem anderen hinzugesetzt würde; sehen Sie sich an, wie dann Ihre Hand ausschauen würde, wenn da der Daumen wäre, und nachher würde einfach das Nächste hinzugesetzt als die gleiche Einheit, dann wiederum, wiederum: Sie hätten fünf Daumen an der Hand, an der anderen Hand auch wiederum fünf Daumen! - Das würde dann entsprechen dem abstrakten Zählen.

[ 17 ] So zählen die Geister des Weltenalls nicht. Die Geister des Weltenalls gestalten nach der Zahl und sie gestalten in jenem Sinne nach der Zahl, den man früher mit der Zahl verband, wie gesagt, noch in der ersten, noch in der zweiten Periode der nachatlantischen Zeit. Das Herausentwickeln der abstrakten Zahl aus der ganz konkreten Vorstellung des Zahlenhaften, des Zahlenmäßigen, das hat sich erst im Laufe der Menschheitsentwickelung gebildet. Und darüber muß man sich klar sein, daß es eine tiefe Bedeutung hat, wenn aus den alten Mysterien heraus überliefert wird: Die Götter haben den Menschen nach der Zahl gebildet. - Die Welt ist voller Zahl, das heißt, alles wird nach der Zahl gebildet, und der Mensch ist nach der Zahl herausgestaltet, so daß unser Zählen in jenen alten Zeiten nicht vorhanden war; aber ein bildhaftes Denken in den Qualitäten der Zahl, das war vorhanden.

[ 18 ] Da kommen wir in alte Zeiten zurück, wie gesagt, bis in die erste, zweite nachatlantische Periode, in die urindische, in die urpersische Zeit, in denen ein Zählen in unserem Sinne durchaus nicht möglich war, wo man mit der Zwei etwas ganz anderes verbunden hat, als zweimal die Eins, mit der Drei etwas ganz anderes, als zwei und eins und dergleichen.

[ 19 ] Sie sehen, die menschliche Seelenverfassung hat sich schon im Laufe der Zeit ganz beträchtlich verändert. Und wenn wir nun den etwas späteren Zeitraum betrachten, der die dritte Periode der nachatlantischen Zeit ist, dann stellt sich das Maß als etwas ganz anderes heraus. Heute messen wit, indem wir eine willkürliche Maßeinheit annehmen. Aber an eine solche willkürliche Maßeinheit dachte man zum Beispiel noch im dritten nachatlantischen Zeitraum eigentlich nicht, sondern man hatte da auch in bezug auf das Messen etwas durchaus Bildhaftes im Auge. Man hatte dasjenige im Auge, was Ihnen vielleicht klarwerden kann, wenn wir uns sagen: Wir sehen zum Beispiel dieses als Säule und sehen dann das als Säule an (siehe Zeichnung); wir sehen nach diesen zwei Säulen hin. Wenn wir abstrakt empfinden, sagen wir, die zweite Säule ist zweimal so groß wie die erste; wir haben sie mit der ersten gemessen. — Aber das ist sehr abstrakt vorgestellt. Konkret vorgestellt ist das etwa in der folgenden Weise auszudeuten: Fühlen wir uns der ersten Säule gegenüber, so fühlen wir sie schwach gegenüber der zweiten; wir fühlen, daß sie wachsen muß, und wir fühlen, wenn sie wächst und wächst, daß, wenn sie bis hierher gewachsen ist, sie etwas Besonderes ist. Sie hat soviel Kraft aufgewendet auf dieses Wachsen, daß sie jetzt eine Stärke hat, wo durch sie etwa in ihren zwei Teilen sich so verhalten kann, daß die beiden gleich stark sind. Man kann da etwas Qualitatives empfinden. Man kann weitergehen. Man kann sagen: Ich habe hier ein Gebilde, ich messe es an dem anderen und bekomme so die Symmetrie heraus; es erweitert sich mir der Begriff des Maßes, er geht hinein in das Bild.

[ 20 ] Auf diese Weise bekommt man allmählich eine Vorstellung, daß Maß tatsächlich etwas zu tun hat mit dem, was wir heute noch ganz dunkel empfinden, wenn wir von mäßig und maßvoll reden, wobei wir auch nicht an Abmessen denken. Wählen wir einmal dieses Beispiel: Wenn jemand eine bestimmte Speise in einem bestimmten Quantum zu sich nimmt, so finden wir das manchmal maßvoll, ohne daß wir es messen. Wir finden etwas anderes unmäßig. Aber wir messen da nicht irgend etwas ab, wir vergleichen nicht messend den Magen mit demjenigen, was hineinkommt und dergleichen. Wir messen auch nicht das Stück Fleisch ab und essen es dann, wit messen es nicht an der Größe des Menschen, sondern wir haben etwas Qualitatives, etwas Eigenschaftliches, wenn wir von maßvoll oder von maßlos und dergleichen sprechen. - Da kommen wir zu etwas, was zwar nicht so stark verschieden ist von dem, was wir heute das Maß nennen, was aber doch immerhin zeigt, daß wir heute unter dem Maß etwas Abstraktes, nämlich «das Enthaltensein der Maßeinheit in irgendeiner bestimmten Größe» verstehen, während man früher darunter etwas, was qualitativ mit den Dingen zusammenhing, verstand. So vor allen Dingen empfand man maßvoll jedes einzelne Glied des Menschen in bezug auf den Gesamtmenschen, ohne daß man dabei an eine Einheit dachte. Uns ist davon noch etwas zurückgeblieben, nämlich, daß es uns ekelhaft ist, wenn wit als Künstler irgend etwas abmessen sollen; wenn wir als Künstler messen sollen mit dem wirklichen Maßstabe, damit nun die Nase nicht zu lang oder zu kurz ist, so ist das eigentlich unkünstlerisch. Künstlerisch ist es nur, wenn im Anschauen eine Sache die Größe hat, die sie haben muß an einem Organismus. Also hier handelt es sich auch nicht um einen abstrakten Vorgang, sondern um etwas, was mit dem Bildhaften zusammenhängt. Und wenn Sie schließlich auf dasjenige Maßverhältnis, das heute noch eine gewisse Rolle spielt, sehen, auf den sogenannten Goldenen Schnitt, so hängt dieser ja nicht zusammen mit dem Messen, sondern er hängt zusammen mit etwas, was nur qualitativ ist: das Kleine verhält sich zum Mittleren, wie das Mittlere zum Großen. Das Kleine mag so groß sein, wie es will, es muß nur immer sich verhalten zu dem Mittleren wie das Mittlere zu dem Großen. Wir haben nicht eine Maßeinheit im Auge, sondern wir haben im Auge etwas, was sich im Anschauen aufeinander bezieht, und reden doch von dem Maß und dem Maßvollen, das sich im Goldenen Schnitt zum Ausdrucke bringt. Wir können gar nicht irgendwie beim Goldenen Schnitt dasjenige zugrunde legen, was Maßeinheit wäre im abstrakten Sinne, wie wir das sonst können. Wir können also sagen: Mit Bezug auf das Messen sehen wir in der Menschheitsentwickelung, indem wir die Zeiten durchgehen, daß im vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum, im griechisch-lateinischen, allmählich dieses anschauliche Empfinden des Maßes sich umwandelt in das abstrakte Messen. Das ist eigentlich erst im vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum der Fall. Im dritten empfand man viel mehr noch die Maßverhältnisse so, wie wir nur noch empfinden, wenn wir den Goldenen Schnitt empfinden. Und unser abstraktes Zählen geht zurück, indem wir in alte Zeiten kommen, auf ein Erleben der inneren Eigenschaft der Zahl.

[ 21 ] Nun, beim Gewicht, da ist der heutige Mensch schon ganz weit draußen, ganz furchtbar weit draußen aus dem, was im ersten nachatlantischen Zeitraum als Erleben des Gewichtes vorhanden war. Sie brauchen sich ja nur an eine sehr bekannte Erscheinung zu erinnern, die gewiß die meisten von Ihnen erlebt haben, wenn der Athlet kommt und seine furchtbar ‚schweren Gewichte. trägt, auf. denen «200 Kilo» steht; und er schleppt sie und schleppt- sie und er schwitzt, und Sie schwitzen schon fast mit ihm.:Und dann, wenn er Sie lange genug hat schwitzen lassen, dann hebt er sie plötzlich auf und läuft davon. Das Ganze hat gar kein Gewicht, sondern es ist Ihnen nur vorgetäuscht. Aber Sie empfinden eigentlich nach dem Abstraktum, was da daraufsteht: «200 Kilo.» Das Erleben des Gewichts ist uns eben heute durchaus entzogen. Daher gehört es auch zu den größten Erlebnissen, wenn beim hellseherischen Bewußtsein, wie es ja durchaus der Fall ist, gegenüber den Naturerscheinungen das Erlebnis des absoluten Gewichtes auftritt. Es ist durchaus so, daß in jenem ersten nachatlantischen Zeitraum, den wir den urindischen nennen, der Mensch in sich noch etwas empfand von Gewichtsverhältnissen. Ich habe Ihnen öfters davon gesprochen, daß eigentlich unser Gehirn im Gehirnwasser schwimmt und dadurch ja nach dem bekannten Gesetze, wonach ein schwimmender Körper scheinbar so viel leichter wird, als das Gewicht des verdrängten Wassers beträgt, das Gehirn wesentlich an seinem Gewichte verliert; sonst würde es uns ja die darunterliegenden Adern fortwährend zerdrücken. Das Gehirn schwimmt im Gehirnwasser; aber heute merkt der Mensch in seinem abstrakten Erleben nichts mehr davon. Er merkt auch von den anderen Verhältnissen nichts mehr in sich. Er erlebt nicht mehr das Gewicht, er gibt nicht acht auf dieses Erleben des Gewichtes. Es ist wesentlich verschieden, das Gewicht seines Körpers zu erleben, wenn man zwölf Jahre alt ist, oder wenn man, sagen wir, fünfmal so alt geworden ist; aber die meisten haben ja vergessen, wie sie sich selber schwer vorgekommen sind in ihrem zwölften Lebensjahre, und können es daher nicht gut vergleichen. Aber nehmen wir meinetwillen irgendwie zwei Lebensalter an, in denen man der Waage nach gleich schwer ist; dann kommt es nicht darauf an, sondern da kommt es auf das Erlebnis der Schwere an. Dieses Gewichtserlebnis, das heute also für den Menschen nur da ist in Beziehung zur Erde, dieses Gewichtserlebnis war ein Absolutes in dem ersten nachatlantischen Ä Zeitraum. E Heute empfinden wir nur noch einen Rest davon in der Kunst, in der Kunst allerdings sehr stark. Ich brauche Sie nur auf. folgendes aufmerksam zumachen. Nehmen Sie an, ich zeichne zwei’ Figuren: Da haben Sie für. meine Anschauung eigentlich etwas Ungeklärtes, | etwas Unaufgelöstes, ‚etwas, was nicht sein soll. So zwei Dinge nebeneinander, die fordern mich auf, ein Drittes dazuzumachen. Aber ‘ich kann das Dritte nur so machen, daß es größer i ist, die beiden : zusammenhält in einer gewissen Weise. Dann habe ich das Gefühl, die drei schweben in der Luft und können sich gegenseitig halten.

[ 22 ] Wenn der kompositionelle Maler heute drei Engel malt, die ja eine Schwereanschauung nicht haben, so verteilt er sie im Raume so, daß sie sich gegenseitig tragen, daß der eine von dem anderen getragen ist. Drei Engel einfach nebeneinander zu malen auf eine Fläche, das ist selbstverständlich das Schlechteste, was man künstlerisch leisten kann; da hat man kein wirkliches künstlerisches Gefühl für solche Dinge. Man muß ein Gefühl haben für das gegenseitige Gewicht, wie das eine das andere trägt, und im künstlerischen Empfinden ist noch ein leiser Anflug von dem vorhanden, was erlebt wurde vor allen Dingen innerlich im Menschen in der nachatlantischen Zeit als das Gewichtende. Das Erlebnis von Gewicht, Zahl und Maß, das entwickelt sich durch die drei ersten nachatlantischen Zeiträume so, wie es sich eben entwickeln mußte, indem der Mensch sich da drinnen fühlte im Kosmos. Und von dem, wonach er aus dem Kosmos heraus gebildet worden ist, wurden dann die anderen Dinge beurteilt, dasjenige, was er aus sich hervorbrachte. Schaute er auf das, was sein astralischer Leib in den Ätherleib hineinstieß, so mußte er sagen: Der Astralleib zählt, aber zählt differenzierend, zählt den Ätherleib. Er gestaltet ihn zählend. - Zwischen dem Astralleib und Ätherleib liegt die Zahl, und die Zahl ist ein Lebendes, ein in uns Wirksames. Zwischen dem Ätherleib und dem physischen Leib liegt etwas anderes. Aus dem Ätherleib heraus wird durch die inneren Verhältnisse dasjenige gebildet, was wir dann sehen; nach dem Goldenen Schnitt sind wir ja im Grunde genommen auch organisch aufgebaut: die Stirn zu einem gewissen Teil, und wiederum dieser andere Teil zu der ganzen Kopflänge und so weiter. Das alles prägt der Ätherleib aus dem Kosmos, aus kosmischen Verhältnissen unserem physischen Leib ein. Das Maß und das Maßvolle, das in uns ist, das ist der Übergang vom Ätherleib zum physischen Leib. Und endlich im Übergang vom Ich zum astralischen Leib liegt dasjenige, innerlich erlebbar, was Gewicht ist. Ich habe Ihnen öfters gesagt, das Ich wurde eigentlich erst geboren im Laufe der Menschheitsentwickelung. Der alte Inder der urindischen Zeit erlebte nicht ein solches Ich. Er erlebte aber innerlich das Gewichten, das Gestaltetsein, so daß er sowohl seine Schwere, sein Hinunterdrängen, wie seinen Auftrieb, sein Hinaufsteigen empfand. In sich empfand er dieses, was da überwunden wird, indem das Kind aus einem Kriecher ein Geher wird; das empfand er. Er empfand nicht «Ich», aber er empfand, wie er durch die ahrimanischen Mächte ani die Erde gefesselt wurde, «gewichtigt» wurde, wie er aufgetrieben wurde durch die luziferischen Mächte, hinaufgehoben wurde, und er empfand dies als seine Gleichgewichtslage. Würden wir die alten Worte, die für das Ich da waren, studieren, so würden wir finden, daß eben das in der Bildung der Worte selber drinnenliegt. So wie zusammengefügt wurden in den Verben die Worte ihrer inneren Konfiguration nach, so war da drinnenliegend das Gleichgewicht zwischen dem Schweben und dem Fallen.

[ 23 ] Unsere so abstrakten Vorstellungen: Gewicht, was ja überhaupt schon gar nicht mehr abstrakt ist, denn wir stehen einem ganz Unbekannten gegenüber; Zahl, was vollständig abstrakt ist, weil es dem, was gezählt wird, ganz gleichgültig ist; und Maß, was bei uns auch schon immer mehr abstrakt geworden ist —, das alles projiziert der Mensch eigentlich von seinem Inneren auf das Äußere. Er überträgt dasjenige, was in ihm eine reale Bedeutung hat, weil er nach Maß, Zahl und Gewicht konstruiert ist, aufgebaut ist, er überträgt das auf die gleichgültig äußeren Dinge, entmenscht sich in diesem Abstraktionsprozeß selber, so daß man sagen kann: Die Menschheitsentwickelung tendiert dahin, die inneren Erlebnisse von Gewicht, Zahl und Maß zu verlieren, nur einen letzten Anflug im Künstlerischen aufzubewahren, dann aber sie nicht mehr so zu erleben, daß der Mensch selber sich herausgestaltet fühlt aus dem Kosmos nach Gewicht, Zahl und Maß. Was wir heute als abstrakte Geometrie haben, wo wir kongruente und ähnliche Figuren vergleichen, wo wir sagen, daß eine Ellipse entsteht, wenn die Summe der Entfernung jedes ihrer Punkte von zwei bestimmten Punkten eine konstante Größe ist, das ist für uns etwas Abstraktes. Da messen wir im Grunde genommen die Entfernungen und finden ihre Summe immer gleich der großen Achse der Ellipse. Aber in diesem eigentümlichen Verhältnis von zwei voneinander verschiedenen Größen zueinander, in dem erlebte man noch im dritten nachatlantischen Zeitraum die Ellipse, auch wenn man sie gar nicht irgendwie vorstellte. Man fühlte in dem Maß des einen zu dem anderen schon das Elliptische, so wie man in der gleichen Zeit den Kreis fühlte. Und so fühlte man auch das Wesen der Zahl. So entwickelte sich die Menschheit vom konkreten Erleben zum Abstrakten hin und bildete aus dem alten Maßerleben die Geometrie aus, aus dem alten Zahlenerleben die Arithmetik und aus dem alten Gewichtserleben, indem der Mensch ganz und gar das Gewichtserlebnis verlor, sich ganz entmenschte, nur dasjenige, was äußerliches Beobachten ist.

[ 24 ] Ja, dutch alles dieses bereitete sich schon langsam vor, was sich dann im 19. Jahrhundert zu der vollständigen Kulmination entwickelt hat, es bereitete sich langsam vor das Abstraktwerden des inneren menschlichen Erlebens: der Mensch ging der menschlichen Auschauung verloren. Der Mensch kommt nicht mehr an sich heran; er ahnt nichts mehr davon, daß er Geometrie bildet, weil er nach dem Maß herausgebildet ist aus dem Kosmos, daß er zählt an sich, durch sich. Er ist überrascht, wenn die Wilden ihre Finger nehmen, um damit die äußeren Dinge zu vergleichen; aber er weiß nicht, daß er nach der Zahl herausgebildet ist aus dem Kosmos und daß er im Grunde genommen in dieser Beziehung immer ein Wilder bleibt und in seinem Ätherleib, der seinem astralischen Leib gemäß den inneren Eigenschaften der Zahlen selber die Zahlen eingebildet hat, daß er danach die Zahlen außen erlebt hat und so weiter. Geometrie, Arithmetik und die Gewichtslehre, das Wägen, das sind Dinge, die durchaus in die Sphäre des Abstrakten im Laufe der Menschheitsentwickelung eingezogen sind und die mitgewirkt haben, daß also der Mensch sich nurmehr überlassen konnte einer solchen Wissenschaft, einem solchen wissenschaftlichen Forschen, das diese Dinge im Äußeren anschaut.

[ 25 ] Was tun wir heute, wenn wir wissenschaftlich forschen? Wir messen, wir zählen, wir wägen. Sie können heute schon merkwürdige Definitionen des Seins lesen. Es gibt heute bereits Denker, die sagen: Seiend ist dasjenige, was man messen kann. - Aber dabei denkt man natürlich nur an das Messen mit einem willkürlichen Maßstab, und es ist merkwürdig, daß man nun das Sein zurückführt auf irgend etwas, dem eigentlich die Willkür zugrunde liegt. Man lebt also in etwas, was ganz und gar der Mensch aus sich herausgesetzt hat, bezüglich dessen er ganz und gar den Zusammenhang mit sich selber verloren hat. Unter solchen Einflüssen kam dann das zustande, was ich ja gerade während dieses Kurses von den verschiedensten Seiten her betont habe: daß in der neueren Erkenntnis der Mensch sich selber verloren hat. Er hat sich verloren, habe ich oft gesagt, in seiner Erkenntnis, indem er eigentlich nur dasteht wie der letzte Schlußpunkt der Tierreihe; er hat sich verloren in dem sozialen Leben, in dem wir zwar außerordentlich gute Maschinen ausgebildet haben, während wir aber nicht in unser soziales Leben einbeziehen können, was die Menschen bedeuten, die an den Maschinen stehen. Man muß lernen, hineinzuschauen in die Menschheitsentwickelung, man muß namentlich auf diese Weise beobachten, wie der Prozeß der Intellektualisierung des Menschen sich gebildet hat. Denken Sie nur einmal, was das für eine andere Seelenverfassung war, wenn in dem ersten nachatlantischen Zeitraum der Mensch fortwährend, indem er ein Bein vorstellte, die Gleichgewichtslage anders erlebte, fortwährend das Gewichtigwerden, das Fallen und Schweben erlebte, wenn er fühlte, wie die Zahl in seine eigene Gestalt hineingeschossen ist, wie er nach dem Maß aufgebaut ist. Denken Sie, wie das anders war, als wenn wir nur äußerlich messen, zählen, wägen und den Menschen dabei ganz aus dem Spiele lassen. Es ist schon so, daß heute höchstens, wie ich ja angedeutet habe, für denjenigen, der eine feinere Empfindung für die Sprache hat, noch etwas ersichtlich werden kann aus den Zahlworten über das Wesen der Zahl, denn in denen liegt schon etwas darinnen von dem Wesen der Zahl, oder aus dem künstlerischen Anschauen heraus, wenn jemand zum Beispiel empfindet, daß dies möglich ist:

ber dieses hier unmöglich ist in dieser Beziehung:

[ 26 ] Dann hat er einen Hauch von dem, was Empfinden der inneren Gewichtigkeit ist, des inneren Gleichgewichtes. Wenn ich folgen kann mit der Linie irgendeinem Verhältnis bei einem anderen, so habe ich ein gegenseitiges Sich-Halten. Wenn ich aber da ein Horn zeichne, wo keins sein kann, so habe ich für das gegenseitige Sich-Halten keine Empfindung. Sehen Sie sich nur einmal an, wie die Menschheit ringt, um, ich möchte sagen, aus dem Inneren herauszusetzen das äußere Maß, die äußere Anschauung gegenüber dem innerlichen Erleben. Sehen Sie sich an in dem Bilde von Raffael - eigentlich auf allen Bildern von Raffael, aber insbesondere in dem Bilde von Raffael, wo die «Vermählung von Maria und Joseph» gegeben wird -, sehen Sie sich da an, wie die Figuren dastehen, wie alles so ist, daß da die Dinge gegenseitig sich tragen, daß man verliert das Gefühl, es zieht auch nach unten. Sehen Sie sich insbesondere an, wenn wirklich ältere Maler irgendeine fliegende Gestalt malen, wie das motiviert ist, wie man dieser Gestalt ganz genau ansieht, daß das nicht heruntergewichtet, sondern daß sich das irgendwie dutch die anderen Verhältnisse selber trägt. Da haben Sie dieses Übergehen von dem innerlichen Gewichten zu dem äußerlichen Bestimmten des Gewichtes, und da haben Sie den Gang der Menschheit in der nachatlantischen Zeit vom inneren Erleben zum Intellektualismus, dieses Heraufringen zum Intellekt, wo alles, was vom Menschen in Vorstellung erlebt wird, vom Menschen losgelöst ist, wo der Mensch das Zerreißen, das «entzweien» gar nicht mehr erlebt, wenn er «zwei» sagt.

[ 27 ] Leise tritt das auf. Wenn man dann dieses Wort weiteranwendet, wenn man sagt: «zweifeln», da empfindet man den Anklang an «entzwei». Wer zweifelt, der sagt: Vielleicht ist das richtig, vielleicht ist das nicht richtig. - Das geht offen nach beiden Seiten hin; da ist das «entzweien» drinnen im Vorstellungsakt. Das liegt aber schon in der Zahl zwei.

[ 28 ] Drei - da können Sie nicht in derselben Weise empfinden, wenn Sie es auf etwas anwenden. Wenden Sie es auf das Urteil an, so haben Sie den Obersatz, den Untersatz, den Schlußsatz: eine Dreiheit, eine in sich geschlossene Sache. Nehmen Sie die berühmteste logische Persönlichkeit, den Cajus: «Alle Menschen sind sterblich; Cajus ist ein Mensch, also ist Cajus sterblich.» Die Sachen gehören zusammen: Obersatz, Untersatz, Schlußsatz. Aber nehmen Sie bloß Obersatz und Untersatz - und es bleibt offen.

[ 29 ] Also ich wollte Ihnen hierdurch andeuten, wie der Weg der Menschheit zur Abstraktion hin ist, wie tatsächlich die Menschheit, indem sie sich selber verloren, in ihre Entwickelung den Intellekt hereingeholt hat.

[ 30 ] Davon wollen wir dann morgen weiterreden. Das Heutige sollte eine Episode sein; aber Sie werden schon sehen, wie sich das mit den weitergehenden Betrachtungen zusammenschließt.

Eighth Lecture

[ 1 ] Today I will have to present a seemingly more remote chapter, but one that will nevertheless form a whole with what was said yesterday and what will be said tomorrow. I have often mentioned that when looking back over the development of humanity, people tend to assume that the overall constitution of the human soul has remained essentially the same throughout human history and prehistory. But what is believed here does not correspond to the facts at all. Admittedly, it is difficult to ascertain what the successive metamorphoses of human soul development have been like if one is only able to look at the facts handed down historically through documents. However, if we can look further back than these facts, then what has been handed down historically appears in a different light, and it becomes clear that the nature of the human soul has not always been as it is today, or as it was in times that can still be understood through external appearances. Above all, one believes: Well, today, for example, human beings have something like geometry, they have something like arithmetic, which is essentially the science of counting, and then they have the art of weighing, of determining weight. One forms ideas about what measuring is, what a measure is. People form ideas about how to count and weigh things today, and they think: Surely, in the time when, according to our current opinion, people were still quite childlike, they were not yet able to measure, count, and calculate. But since they have been able to do so, it has been practiced in much the same way as it is practiced today.

[ 2 ] That is certainly not the case, and even if, as I said, it leads us into a more remote area, we must first form a more precise idea of measure, number, and weight before we go into the history of mankind. You know that, according to external tradition, the Pythagorean school had somewhat different views on numbers than we do today. The Pythagoreans, as you all know, associated certain ideas with the numbers one, two, three, four, and so on. They had very specific ideas about even numbers and odd numbers. In short, they spoke about numbers in a certain qualitative way, not just in a quantitative way.

[ 3 ] If one considers the underlying principles from a spiritual scientific point of view, one comes to understand how what existed in the Pythagorean school, which was after all still a kind of secret school, was basically only the last echo of a much older wisdom of numbers which dates back to ancient times and of which only traditions have survived. And what we are told about Pythagoras is basically something that was already in decline from an ancient theory of numbers. When one pursues these matters from a spiritual-scientific perspective, one arrives at essentially different ideas about measure, number, and weight than we have today. But as I said, we need to be able to clarify for ourselves, even if this may be difficult for some of you, what these concepts of measuring, counting, and weighing mean today.