Therapeutic Insights: Earthly and Cosmic Laws

GA 205

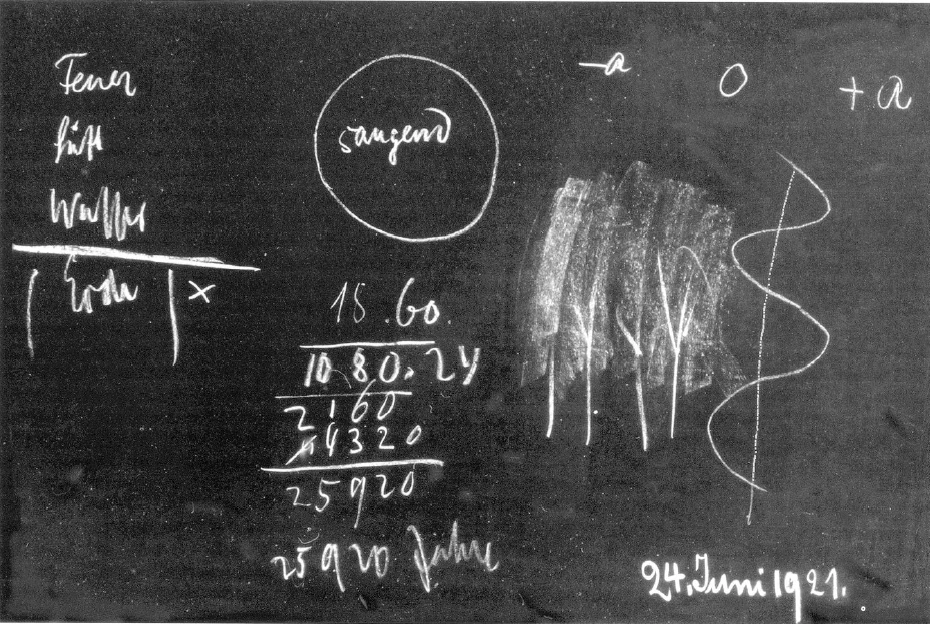

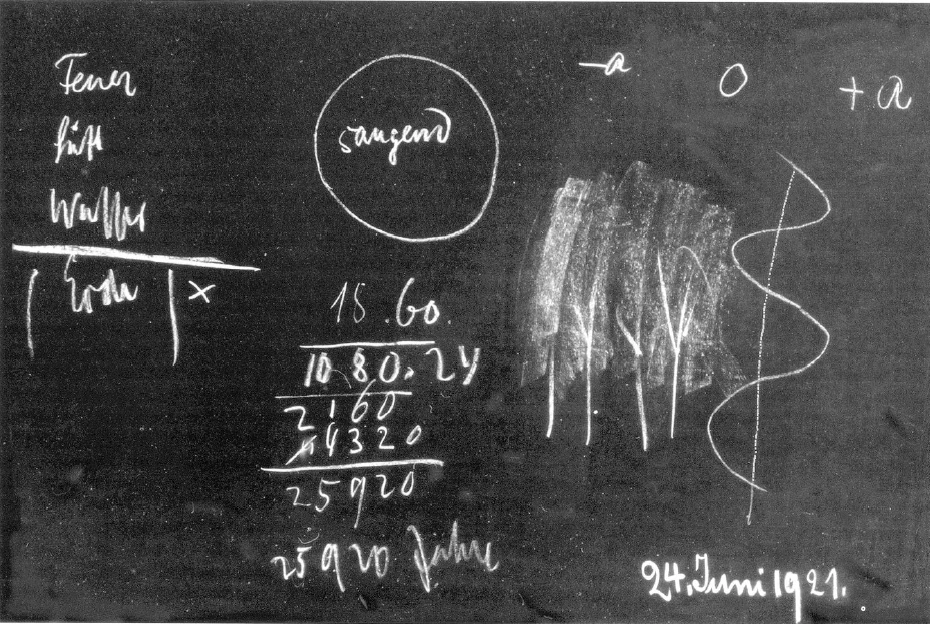

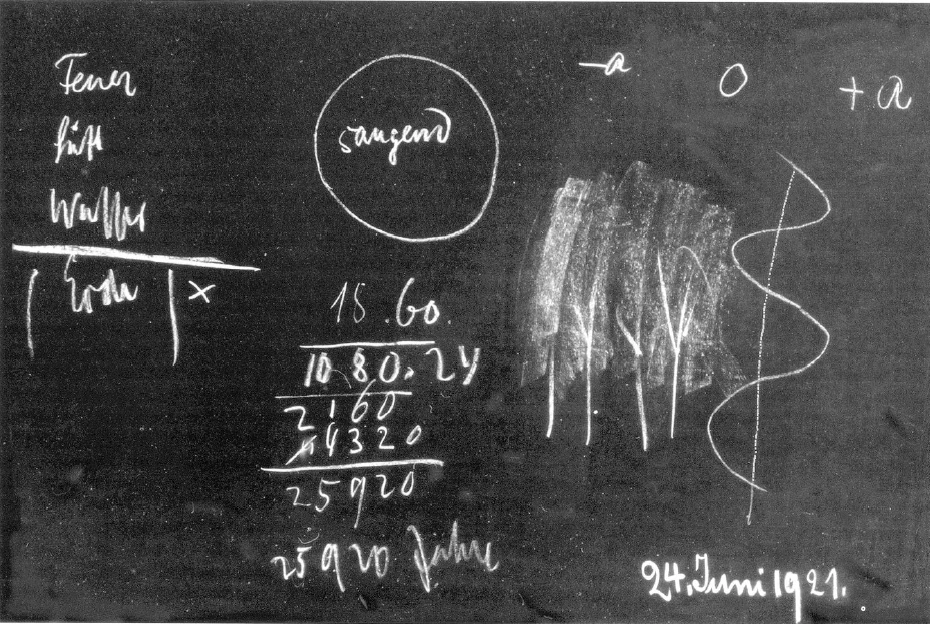

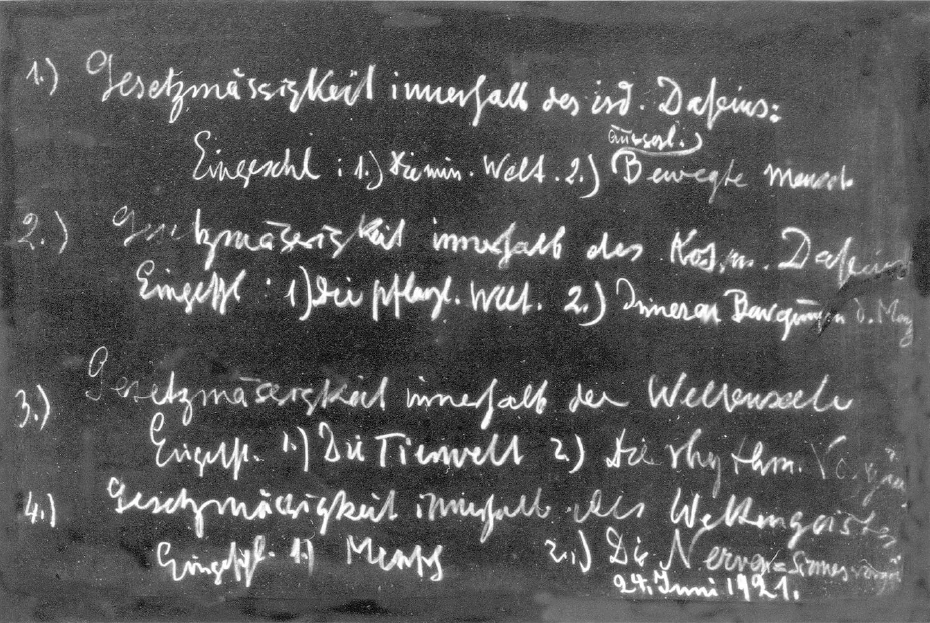

24 June 1921, Dornach

Lecture I

After the historical considerations we have undertaken, we shall explore today a few things about contemporary man. This will provide us with the possibility of observing more accurately the place of contemporary man in the whole course of time. We should be clear that in the way the human being stands before us as spiritual, soul, and bodily being, he is differently oriented in three directions. We see this already when we look at the human being purely outwardly. In his spirit, man goes through the world independently of outer phenomena, while in his soul he is not as independent of these outer phenomena. One need only consider certain relationships that are visible throughout life in order to discover how the real soul life has certain connections with the outer world. One can be depressed or uplifted in one's soul. Recall how you have often felt depressed in a dream, and how the root of this mood of depression had to be traced back to the irregularity of the breathing rhythm. One could say that this is merely an elementary example, and yet all soul life is never without a similar connection with the rhythmic life that we go through in the rhythm of our breathing, of our blood circulation, and the outer rhythmic life of the entire cosmos. Everything that takes place in the soul is connected with the world rhythm.

Whereas as spiritual beings we can feel highly independent of our environment, we cannot do the same regarding our soul life, for our soul life lies imbedded within the whole world rhythm.

Furthermore, we stand within universal world phenomena as bodily beings. Again, at first we may proceed from merely elementary examples. Man, as a bodily being, is heavy, that is to say, he has weight. Other merely mineral beings also have weight. Mineral beings, plant beings, animal beings, and the human being as a bodily being all partake in this universal weightiness, and we must actually lift ourselves above this universal weightiness when we wish to make the body a physical tool of the spiritual life. We have often mentioned that if it were only the physical weight of the brain that mattered, the weight would be so great (1300 to 1500 grams) that all the blood vessels lying underneath the brain would be crushed. The brain, however, is subject to the Archimedean principle, since it floats in the cerebrospinal fluid. It loses so much weight by floating in the cerebral fluid that it actually weighs only 20 grams and therefore presses on the vessels at the base of the brain with only these 20 grams. You can see from this that the brain actually strives much more upward than downward. It counteracts heaviness. It tears itself free of the universal gravity and thereby acts like any other body that is placed in water and loses as much of its weight as the weight of the displaced water.

You thus can see an interplay between our whole bodily being and the outer world. With our soul weavings we are not only integrated in a rhythm but are fully enmeshed in the outer physical life. If we stand on a given point of the earth, we press down upon that place; when we move to another point, we press down upon that new place. In our human body, we are as much physical beings as the physical beings of the other kingdoms of nature.

We therefore can say that with our spiritual being we are to some extent independent of the outer world; with our soul being we are part of the rhythm of the world; and with our bodily being we are part of the rest of the world as though we were not also soul and spirit. We must consider this distinction carefully, for we do not attain an understanding of the higher being of man if we do not look at this threefold relationship of the human being to his entire environment. Now, let us look for a moment at man's environment. In man's environment (I am now summarizing what we have considered over the course of many months from different viewpoints) we first have all that is ruled by natural laws. Picture the whole universe ruled by natural laws and, included in these natural laws, the totality of this visible, sense-perceptible world.

Simple consideration shows that we are dealing here only with the actual earthly world. Only foolhardy and unjustified hypotheses of physicists can maintain that the same natural laws we observe on the earth around us are also applicable in the extraterrestrial cosmos. I have often pointed out to you how surprised the physicists would be if they were able to ascend to the place where the sun is. Physicists regard the sun as something comparable to a large gas oven without walls, more or less like a burning gas. If one arrived at the place in the cosmos where the sun is, one would not find such a burning gas. Instead one would find something totally unlike what the physicists imagine. If this (sketching) encloses the space that normally we picture as taken up by the sun, not only are there none of the substances found on earth, but there is even an absence of what we call empty space. Imagine, to begin with, filled space. On earth you always have a filled space around you. If it is not filled by solid or liquid substances, it is permeated by air, or at least by warmth, light, and so on. In short, we are always dealing with filled space. You also know, however, that it is possible, at least approximately, to create an empty space by extracting the air from a container with an air pump.

Imagine we have a filled space that we will designate with the letter A, preceded by a plus sign: +A. Now, as we make this space emptier and emptier, A will become smaller and smaller, but as the space is still filled we continue to use the + sign. We can imagine—although this is not actually possible under earthly conditions, for we can render space only approximately empty—that it would be possible to produce a completely empty space. Then, in this part of space that we have made empty, there would only be space. I will designate this with 0. It has 0 content. Now, we can do with this space the same thing that you do with your wallet: if your wallet is filled with money, you can take more and more out until finally there is nothing in it. If you want to spend more money, you cannot take anything more out of your wallet, as it is already empty. You can, however, go into debt. You have -0 in your wallet if you incur debts. You can think of this space in the same way: it is not only empty but you could say that it exerts suction because there is less than 0 in it: -A. It can be said of this space exerting suction—which is not just empty but has a content, which is the opposite of being filled by matter—that it is occupied by that space which one must imagine as filled out by the sun. The sun therefore has an inward suction; it does not exert pressure like a gas. The sun space is filled with negative materiality.

I only present this as an example in order for you to see that earthly lawfulness simply cannot be applied to the extraterrestrial cosmos. We must think of totally different relationships in the extraterrestrial cosmos from those we have learned to know in our environment on the earth. We must say that we are surrounded by lawfulness within earthly existence, and into this lawfulness is included the world of substances that is initially accessible to us. Now picture earthly existence. All you need to do is to picture the processes in the mineral world; place them before your soul, and you have that which, in so far as you see it, is completely encompassed by this lawfulness of earthly existence. Therefore we can say that the mineral world is encompassed by this lawfulness; yet something else is also encompassed by it. When we walk around, or even when we are carried around, in short when we act as objects in the physical world, we live in the same lawfulness as the mineral world. In relation to earthly lawfulness, it is immaterial whether we carry a stone around, whether it is moved, or whether a human being is carried around or moves himself; regarding this lawfulness, it is the same thing one way or the other. You need only consider that the only thing that comes into consideration regarding earthly lawfulness is a change in location of man's body, which he may, however, bring about himself. This is connected with other things. If you study only earthly lawfulness, what happens within the skin of man or what takes place in his soul can be quite irrelevant. Only the change in location within earthly space need be considered.

We thus can see that in addition to the mineral world there is the human being who has been moved (that is, outwardly moved). The only relationship of the outer world to man, in so far as that world is earthly and confronts our senses, is the relationship to the human being moved outwardly. If we seek any other relationship to man, we must at once refer to something else, and then we come to our extraterrestrial environment, for example, when we study the environment of the moon, that is, whatever emanates from the moon. It is a fact that many people are still aware of something of the effect of the moon on the earth. Many people believe in such effects of the moon on the earth, e.g., the connection of the phases of the moon with the quantity of rainfall. Learned people in our time consider this a superstition.

I have told you, some of you at least, of an amusing sequence of events that once took place in Leipzig. The unusual natural philosopher and aesthetician, Gustav Theodore Fechner, went so far as to write a book about the influence of the moon on weather conditions. He was a university colleague of the well-known botanist and natural scientist, Schleiden. Schleiden, as a modern materialist, was convinced, of course, that what his colleague Fechner was advancing about the influence of phases of the moon on the weather could only be based on superstition. In addition to the two scholars at the University of Leipzig there were also their wives, Frau Schleiden and Frau Fechner. At that time, the conditions were still so primitive that rain water needed to be collected for wash day. Frau Fechner said that she believed in what her husband had published concerning the influence of moon phases on the weather. She wanted to reach an agreement with Frau Professor Schleiden, who did not believe in what Fechner maintained, about when was the most efficient time to place out rain barrels in order to collect the most rain. Frau Fechner suggested that Frau Schleiden put out her barrels at different times, since according to Schleiden's opinion she should get just as much water as Frau Fechner. However, despite the fact that Frau Professor Schleiden considered the views of Professor Fechner to be exceedingly superstitious, she still chose to place her rain barrels out at the exact same times as Frau Fechner.

Now, the influence of the forces of other planetary bodies is less perceptible to our modern scientific consciousness. However, if one were to study more closely—as is to happen now in our scientific-physiological institute in Stuttgart—the line of growth followed on the stem by the leaves of plants, for example, one would find how each line is related to the movements of the planets, how these lines are, as it were, miniature pictures of the planetary movements. One thus would find that many things on the surface of the earth are comprehensible only when one knows the extraterrestrial and does not merely identify the extraterrestrial with the earthly, that is to say, when one presupposes that a lawfulness exists that is cosmic and not earthly.

We therefore can say that we have a second lawfulness within cosmic existence. Only when one begins to study these cosmic influences—and it is possible to do so quite empirically—will one have a true botany. Our plant world does not grow up out of the earth in the way conceived by a materialistic botany; rather it is pulled out by cosmic forces. What is pulled out in this way by cosmic forces in the process of growth is then permeated by the mineral forces that have saturated this cosmic plant structure so that it becomes visible to the senses. We thus can say firstly that the plant world is included in this cosmic lawfulness. Secondly, all that pertains to the inner movement of man—that is, a definitely physical movement, but within man—is included in this cosmic lawfulness (this is not as easy to establish as in the case of the plant world, because it achieves a certain independence from the rhythm of the outer processes; nevertheless, it imitates this rhythm inwardly). The outwardly moved human being, therefore, is included in the earthly lawfulness, but when you look upon your digestion, upon the movement of the nourishing substances in the digestive organs, when you look beyond merely the rhythm to the actual movement of the blood through the blood vessels—and there are many other things that move inwardly in man—you have a picture of what moves inside of the human being regardless of whether he is standing still or walking about. This cannot be integrated into the earthly lawfulness without further consideration but rather must be integrated into the cosmic lawfulness in the same way as are the forms and also the movements of the plants; in the human being, however, these forms and movements proceed much more slowly than they do in the plants. We therefore can say that the inner movements of man are also included in the cosmic lawfulness.

Now you could consider taking the cosmos into undefined distances; somehow in this way everything has an influence upon the life that develops on the earth's surface. Yet if these were the only two lawfulnesses that existed—that is, the earthly and cosmic lawfulnesses, in the way I have presented them to you—then nothing would exist on the earth but the mineral and plant kingdoms, for the human being, of course, would not be able to exist there. If the human being were present, he could move outwardly and the inner movements could take place, but this of course would not yet make up a human being. Neither would animals be able to be present on the earth under such conditions; in reality, only minerals and plants could exist. Cosmic lawfulness and cosmic content of being must be penetrated and permeated by something that is no longer a part of space, by something concerning which we cannot speak of space at all.

Naturally, everything that is included in the cosmic and earthly lawfulnesses must be thought of as existing in space; now, however, we must speak of something that cannot be thought of as existing in space, although it permeates the whole of cosmic lawfulness. Just imagine how in the human being the movements, that is his inner movements, are connected with his rhythm. To begin with, all that we call the movement of the nourishing substances within us merges into the movement of the blood. However, this movement doesn't take place in such a way that the blood simply flows through the veins as nutritive juice. Not only does the blood itself move rhythmically, but beyond that this rhythm has a definite relationship to the breathing rhythm through the consumption of oxygen by the blood. We have within us this dual rhythm. I pointed out once how the inner soul lawfulness is based upon the 4:1 ratio of the blood rhythm to the breathing rhythm in such a way that meter and verse measure are actually dependent upon it.

We thus see that what takes place as inner movement is related to rhythm, and rhythm, as we have said, is related to the soul life of the human being. In a similar way we must bring what we have in the movement of the stars into a relationship to the world soul. We therefore can speak of a third lawfulness within the world soul in which is encompassed: 1) the animal world, and 2) all the rhythmic processes related to the bodily human being. These rhythmic processes within man have a relationship to the whole world rhythm. We have already spoken about this, but I would like to bring it up again in relation to our further considerations here. You know that the human being takes approximately eighteen breaths per minute. Multiply that by sixty and you have the number of breaths per hour; multiply that total by twenty-four and you have the total for one day, approximately 25,920 breaths for the average human being in the course of a day. This number of breaths per day thus forms the day/night rhythm in the human being. We also know that the spring equinox moves through the constellations bit by bit each year, so that the point at which the sun rises in spring moves forward in the heavens. The length of time that it takes the sun to arrive again at its original point is 25,920 years. This is the rhythm of our universe, then, and our own breathing rhythm over twenty-four hours is a miniature picture of it. Hence, with our rhythm we are woven into the world rhythm, with our soul into the lawfulness of the world soul.

Now, there is a fourth lawfulness that lies at the basis of the entire universe as well as of the three previously mentioned lawfulnesses, namely, that within which we feel included when we become conscious of ourselves as spiritual human beings. In this process of becoming conscious of ourselves as spiritual human beings, we achieve clarity about these facts. At first we may not comprehend this or that about the world and, in fact, because of today's intellectualism, which has become a universal cultural force, very little indeed is comprehended. At a certain stage in our human evolution, we initially comprehend very little with our spirit. It is inherent, however, in the self-recognition of the spirit that it says to itself that as it evolves no boundaries can be imposed on its evolution. The spirit must be able to develop into the universe through knowing, feeling, and willing. By bearing the spirit within us, then, we must relate ourselves to a fourth lawfulness within the world spirit.

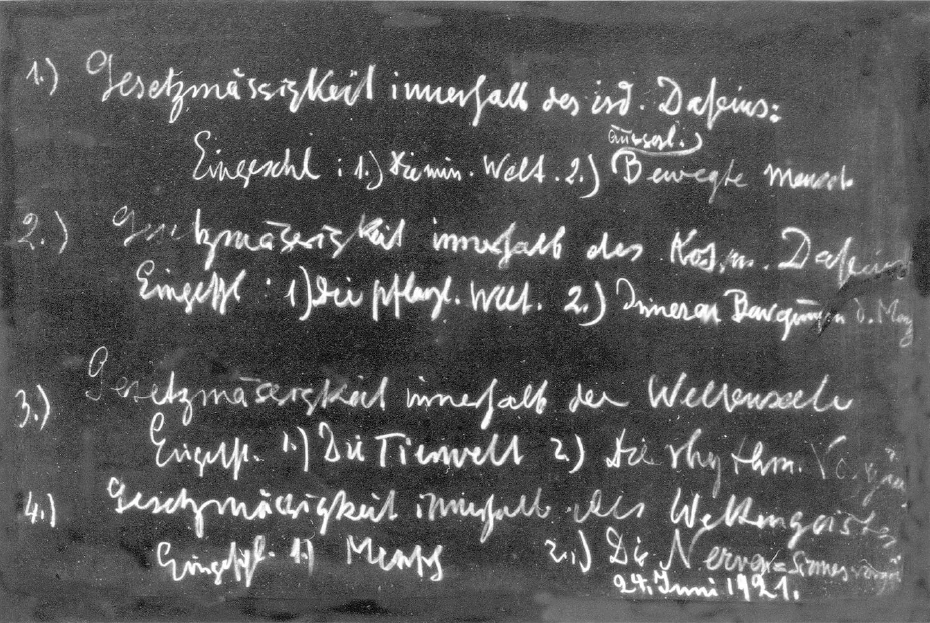

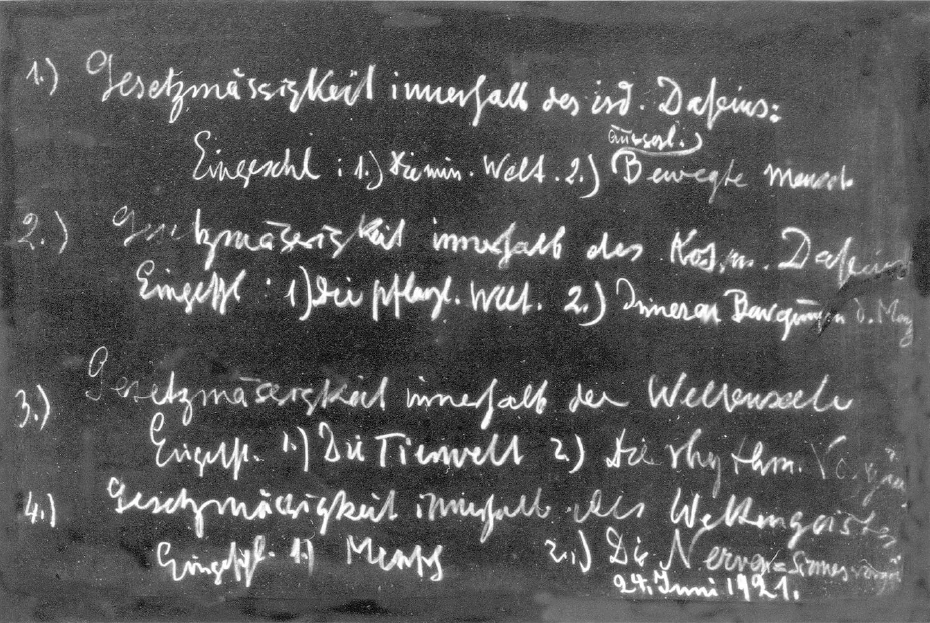

1.) Lawfulness within earthly existence

a) The mineral world b) The externally moved human being

2.) Lawfulness within cosmic existence

a) The plant world b) The inner movements of the human being

3.) Lawfulness within the world soul

a) The animal world b) The rhythmic processes

4.) Lawfulness within the world spirit

a) The human being b) The nerve-sense processes

Only now do we arrive at the real human being encompassed therein, for a human being could not really have existed merely within the other three lawfulnesses. Only now do we find the human being, but specifically that part of him that is his nerve-sense apparatus, all of what is, to begin with, the physical bearer of the spiritual life, the nerve-sense processes. When we look at the human being we consider first the entire human being in whom the head is the main bearer of the nerve-sense organs; then we consider the head itself. A human being is human, so to speak, by virtue of the fact that he has a head; the head is the most human part of man. In the human being as a whole and in the head, we already encounter the human being twice.

Now, when we consider what I have just described as a summary of what we have discussed in the last few weeks, it gives us to begin with a picture of the human being's connection with his environment; not merely the spatial environment, however, for the spatial world is related only to the first two lawfulnesses; we also have to do with the world that is non-spatial, which is related to the third and fourth lawfulnesses. It has become increasingly difficult for the contemporary human being to conceive that something could exist not within space or that sometimes it is not meaningful to speak in terms of space even when speaking of realities. Without such a conception, however, one can never rise to a spiritual science. If one wishes to remain within the confines of space, one cannot arrive at spiritual entities.

Last time I spoke here I told you about the world conception of the ancient Greeks in order to point out how in other eras the human being looked at the world differently from today. This picture of which I have just spoken to you can become evident to the human being in the present era; he arrives at it if, simply and without prejudice—that is undisturbed by the waste products sometimes offered by contemporary science—he observes the world.

I must add a few things to what I told you previously about the ancient Greek world conception so that we are able to see its connection with what I wished to present to you with this scheme. You see, if a human being is very clever he may say that the spatial world consists of some seventy-odd elements that have varying atomic weights and so on; those elements, he maintains, enter into syntheses; one can perform analyses on them, and so forth, and, based on chemical connections and chemical separations, one can explain what happens in the world regarding those seventy-odd elements. That they could be traced back to some earlier origin should not occupy us at the moment. In general, those seventy-odd elements are considered valid today in popular science.

A Greek—not in a contemporary incarnation, in which he would, of course, think like everyone else today if he were well educated—an ancient Greek, let us say, if he could appear in our present-day world, would be prompted to say, “Well, this is all very well and good, these seventy-odd elements, but one does not get very far with them; they actually tell us nothing about the world. We used to think quite differently about the world; we conceived of the world as consisting of fire, air, water, and earth.”

A contemporary person would reply, “That is a childish way to comprehend matters. We are far beyond that. We do, in fact, accept the aggregate states; in the gaseous aggregates we grant you the validity of the aeriform, in the fluid aggregates the watery, and in the solid aggregates the earthy. Warmth, however, does not mean at all the same thing to us as it does to you. We have moved beyond such childish notions. What constitutes the world for us we find in our seventy-odd elements.”

The ancient Greek would respond to this, “That is very nice, but fire—or warmth—air, water, earth are something entirely different from what you conceive. You do not understand in the least what we thought about it.”

At first our contemporary scholar would be curiously affected by such comments and would have the impression that he was encountering a human being from a more childlike stage of cultural development. The ancient Greek, because he would be immediately aware of what the modern scholar had in his head, would probably say, "What you call your seventy-two elements all belong to what we call earth; it is very nice that you differentiate it and analyze it further, but for us the properties that you recognize in your seventy-two elements belong to the earth. Of water, air, and fire you understand nothing; of those you have no conception.”

This Greek would continue—you can see that I do not choose an Oriental from an ancient cultural period but a knowledgeable Greek—“What ,you say about your seventy-two elements with their syntheses and analyses is all very nice, but to what do you believe it is related? It is all related merely to the physical human being once he has died and lies in the grave! There his substances, his entire physical body, undergo the processes that you learn to recognize in your physics and chemistry. What it is possible for you to learn within the structural relationships of your seventy-odd elements is not related at all to the living human being. You know nothing of the living human being because you know nothing of water, air, and fire. It is necessary first to know something about water, air, and fire in order then to know something about the living human being. With what is encompassed by your chemistry you know only what happens to man when he is dead and lying in the grave, the processes undergone by the corpse. That is all you come to know by means of your seventy-odd elements.”

If the ancient Greek went any further than this in this discussion he would not be a great success with our contemporary scholar, though he could go to the trouble of clarifying his views in the following way: “Your seventy-two elements are all what we consider earth. We may simply be regarding a general quality, but even if you analyze it further, you arrive merely at a more specific knowledge, and a more specific knowledge will not enable you to penetrate into the depths. If you acknowledged what we designate as water, however, you would have an element in which, as soon as it is weaving and living, earthly conditions are no longer active alone; water, in its entire activity, is subject to cosmic conditions.”

The ancient Greek's understanding of water was not limited merely to its physical characteristics but extended to everything that influences the earth as lawfulness from the cosmos, in which the movement of the water substance is encompassed. Within this movement of water substance lives the plant element. In distinguishing whatever is in the living and weaving water element from everything earthly, the ancient Greek saw in this living-weaving element the whole lawfulness of the life of vegetation, which is encompassed by this watery element. We thus can place this watery element schematically somewhere on the earth, but in such a way that it is determined from out of the cosmos. Then we can picture the mineral element, the actual earthly element, sprouting from below upward in a variety of ways, permeating the plants, infiltrating them, as it were, with earthly elements (see sketch).

What the ancient Greek thought about the watery element, however, was something essentially new, and it was for him a quite definite perception. The Greek did not view this conceptually; rather, he saw it in pictures, in imaginations. Of course we must go back to Platonic times (for Aristotle corrupted this way of viewing), even to pre- Platonic times, in order to find how the truly knowing Greek saw in imaginations what lives in the watery element and actually bears the vegetation, how he related everything to the cosmos. Now, however, the ancient Greek would continue, “What lies in the grave after a human being has died, what is lawfully penetrated by the structural laws that work in your seventy-odd elements, is inserted between birth—or let us say conception—and death into the etheric life working from the cosmos. This etheric life permeates you as a living human being; you will not understand any of this if you do not speak of water as a separate element, if you do not regard the plant world as being tethered in the watery element, if you do not see these pictures, these imaginations.”

“We Greeks,” he would say, “certainly spoke about the etheric body of the human being, but we were not spinning the etheric body out of our fantasy. Rather we said: if one watches in spring the sprouting, greening plant world gradually and variously coloring itself, if one sees this plant world bearing fruit in summer and observes the leaves withering in autumn, if one follows this course of the year in the life of vegetation and has an inner understanding for it, what then appears before the eye of the soul connects with one just as strongly as one is connected with the mineral world by the bread and meat one eats. In a way analogous to eating one connects with what is outwardly visible in the plant world during the course of the year. Then if one penetrates oneself with the perception that everything happening in the course of twenty-four hours is like a miniature-image of this, repeating itself through one's entire life, then we have within us a miniature image of what constitutes the surrounding world out there from the watery, etheric element, from the cosmos. Whenever we regard this outer world with true understanding, we can say that what is out there also lives within us. We say that the spinach grows out there; I pick it, cook it, and eat it, and thereby have it in my stomach, that is, in my physical body; in the same way we can say, out there, in the course of the year, lives and weaves an etheric life, and that I have within myself.”

The Greek was not conceiving of the physical water; rather, what lay at the basis of his conception was what he grasped in his imagination and brought into living connection with the human being. Thus he would say further to our contemporary scholar, “You study the corpse that lies in the grave, because you study only the earth—your seventy-odd elements are only earth. We studied the living human being; in our time we studied the human being who is not yet dead, who grows and moves out of an inner activity. That is impossible without rising to the other elements.”

Thus it was with the ancient Greeks, and were we to go still further into the past, the airy element and then the fire or warmth element would meet us in full clarity. We will also consider these later. And that is what is so characteristic of our cultural evolution since the first third of the fifteenth century, that the understanding for these connections has simply been lost; thereby the understanding for the living human being was also lost. We study only the corpse in science today. We have often heard that this phase in the history of humanity's evolution had to come, had to come for other reasons, namely, so that humanity could undergo the phase of the evolution of freedom. However, in the process a certain understanding of nature and the human being has been lost since the first third of the fifteenth century. The understanding of natural science up to now has limited itself to this one element, earth, and now we must find the way back. We must find our way back through Imagination to the element of water, through Inspiration to the element of air, through Intuition to the element of fire.

What we have seen and interpreted as an ascent in higher cognition—the ascent from ordinary object cognition through Imagination, Inspiration, and Intuition—is fundamentally also an ascent to the elements. We will speak further about this in two days.

Dritter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Nach den historischen Betrachtungen, die wir angestellt haben, werden wir uns heute einiges vor die Seele führen über den gegenwärtigen Menschen, das uns dann die Möglichkeit bieten wird, das Hineingestelltsein dieses gegenwärtigen Menschen in die ganze Zeit, in den nächsten Tagen genauer zu betrachten. Wir müssen uns ja klar darüber sein, daß der Mensch, so wie er als geistiges, seelisches, leibliches Wesen vor uns steht, nach drei verschiedenen Richtungen verschieden in der Welt drinnensteht. Das ergibt sich ja schon, wenn wir den Menschen, ich möchte sagen, rein äußerlich betrachten. Seinem Geiste nach geht er unabhängig von den äußeren Erscheinungen durch die Welt; seiner Seele nach ist er nicht so unabhängig von den äußeren Erscheinungen. Man braucht nur gewisse Zusammenhänge, die durch das Leben hin sichtbar sind, zu betrachten, und man wird finden, wie das eigentlich seelische Leben gewisse Zusammenhänge hat mit der äußeren Welt. Man kann seelisch bedrückt sein, man kann seelisch erheitert sein. Erinnern Sie sich, wie oftmals Sie im Traume sich bedrückt fühlten, wie Sie dieses Bedrücktfühlen, wenn Sie aufwachen, zurückführen müssen auf eine Unregelmäßigkeit im Atmungsrhythmus. Das ist eine grobe Erscheinung, könnte man sagen, und dennoch, immer ist alles seelische Leben nicht ganz ohne einen ähnlichen Zusammenhang mit dem rhythmischen Leben, das wir durchmachen in unserem Atmungsrhythmus, in unserem Blutzirkulationsrhythmus und dem äußeren rhythmischen Leben des ganzen Kosmos. Alles, was in der Seele vorgeht, hängt zusammen mit dem Weltenrhythmus. Wenn wir also auf der einen Seite als geistige Wesen bis zu einem hohen Grade uns unabhängig fühlen von unserer Umwelt, können wir es nicht in bezug auf unser seelisches Leben, denn unser seelisches Leben steht im allgemeinen Weltenrhythmus darinnen.

[ 2 ] Noch mehr stehen wir in den allgemeinen Weltenerscheinungen darinnen als leibliches Wesen. Man braucht wiederum zunächst nur von groben Erscheinungen auszugehen. Man ist als leibliches Wesen schwer, man hat ein Gewicht. Andere bloß mineralische Wesenheiten haben auch ein Gewicht. Mineralische Wesen, pflanzliche Wesen, tierische Wesen und der Mensch als leibliches Wesen, sie alle gliedern sich ein in die allgemeine Schwere, und wir müssen sogar in einem gewissen Sinne uns erheben über diese allgemeine Schwere, wenn wir unseren Leib zum physischen Werkzeug des geistigen Lebens machen wollen. Wir haben das ja öfters erwähnt, wenn es auf das bloße physische Gewicht unseres Gehirnes ankäme, so wäre das ja so groß - eintausenddreihundert bis eintausendfünfhundert Gramm -, daß es uns alle Adern, die unter dem Gehirne sind, zerdrücken würde. Aber dieses Gehirn unterliegt dem Archimedischen Prinzip, indem es im Gehirnwasser schwimmt. Es verliert so viel von seinem Gewichte durch das Schwimmen im Gehirnwasser, daß es eigentlich nur zwanzig Gramm wiegt, also nur mit zwanzig Gramm auf die Adern der Gehirnbasis drückt. Sie sehen daraus, daß eigentlich das Gehirn viel mehr nach oben strebt als nach unten. Es widerstrebt der Schwere. Es reißt sich heraus aus der allgemeinen Schwere. Aber es macht dabei nichts anderes als irgendein anderer Körper, den Sie ins Wasser geben, und der ebensoviel von seinem Gewichte verliert, als das Gewicht des verdrängten Wasserkörpers ist.

[ 3 ] Sie sehen also ein Wechselspiel unseres ganzen leiblichen Wesens mit der äußeren Welt. Und zwar ist es so, daß wir hier nicht nur wie mit dem seelischen Weben in einen Rhythmus eingegliedert sind, sondern daß wir ganz drinnenstehen in diesem äußeren physischen Leben. Wenn wir an einer bestimmten Stelle des Erdbodens stehen, drücken wir auf diese Stelle des Erdbodens; wenn wir weggehen nach einer andern Stelle, drücken wir auf eine andere Stelle des Erdbodens. Wir sind also physische Wesen als leiblicher Mensch wie andere physische Wesen der andern Naturreiche auch.

[ 4 ] Wir können also sagen: Mit unserem geistigen Menschen sind wir in einer gewissen Weise von der Umwelt unabhängig, mit unserem seelischen Menschen sind wir in den Rhythmus der Welt eingegliedert, mit unserem leiblichen Menschen sind wir in die ganze übrige Welt so eingegliedert, wie wenn wir gar nicht Seele und Geist wären. Diese Unterscheidung müssen wir durchaus ins Auge fassen. Denn wir kommen auch nicht zu einem Verständnisse des höheren Wesens des Menschen, wenn wir nicht diese dreifache Stellung des Menschen zu seiner ganzen Umgebung ins Auge fassen. Wir wollen uns jetzt einmal die Umgebung des Menschen ansehen. In der Umgebung des Menschen haben wir zunächst - ich fasse verschiedenes, das wir seit vielen Monaten betrachtet haben, nur von andern Gesichtspunkten aus, jetzt zusammen - alles dasjenige, was von Naturgesetzen beherrscht wird. Stellen Sie sich einmal das Weltenall vor, von Naturgesetzen beherrscht, eingespannt in diese Naturgesetze die gesamte sichtbare oder sonst durch die Sinne wahrnehmbare Welt. Wir wollen dies zunächst als erste Umwelt des Menschen in Betracht ziehen.

[ 5 ] Wenn wir diese Welt in Betracht ziehen - eine einfache Überlegung zeigt, daß wir es ja dann nur mit der eigentlichen irdischen Welt zu tun haben. Nur waghalsige und unbegründete Hypothesen der Physiker können davon sprechen, daß denselben Naturgesetzen, die wir hier auf der Erde beobachten um uns herum, etwa auch der außerirdische Kosmos unterliegt. Ich habe Sie öfter darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie überrascht die Physiker sein würden, wenn sie an die Stelle hinaufkommen könnten, wo die Sonne ist. Die Physiker betrachten ja die Sonne als so etwas wie einen großen Gasofen, allerdings ohne Wände, so ungefähr wie ein brennendes Gas. Man würde dieses brennende Gas nicht finden, wenn man an die Stelle des Kosmos käme, wo die Sonne ist. Man würde an der Stelle des Kosmos, wo die Sonne ist, etwas finden, was allerdings sehr unähnlich ist der Vorstellung der Physiker. Wenn das hier (es wird gezeichnet) den Raum umschließt, den wir uns von der Sonne eingenommen denken, so ist an dieser Stelle nicht nur nichts vorhanden von all den Materien, die wir auf der Erde hier finden, sondern es ist nicht einmal dasjenige vorhanden an dieser Stelle, was wir den leeren Raum nennen. Denken Sie sich einmal zunächst den erfüllten Raum; Sie haben ja, indem Sie hier auf der Erde leben, immer den erfüllten Raum um sich. Ist er nicht von irgendwelchen festen oder flüssigen Substanzen durchsetzt, so ist er durchsetzt von Luft oder mindestens von Wärme, von Licht und so weiter. Kurz, wir haben es stets mit dem erfüllten Raum zu tun. Sie wissen aber, daß man ja auch, wenigstens annähernd, einen leeren Raum herstellen kann, wenn man aus dem Rezipienten der Luftpumpe die Luft auspumpt.

[ 6 ] Nun stellen Sie sich vor, wir haben irgendeinen erfüllten Raum; wir wollen ihn mit dem Buchstaben A bezeichnen und ein Plus davorsetzen, + A. Jetzt können wir den Raum immer leerer und leerer machen, da wird das A immer kleiner und kleiner werden; aber der Raum ist erfüllt, deshalb bezeichnen wir das immer noch mit Plus. Wir können — obzwar wir das in der Tat nicht mit irdischen Verhältnissen durchführen können, denn wir können den Raum ja nur annähernd leer machen -, aber wir können uns denken, daß immerhin ein luftleerer Raum vollständig herstellbar wäre. Dann wäre eben in dem Teil des Raumes, der dann leer gemacht ist, nur Raum. Ich will ihn als Null bezeichnen. Er hat Null Inhalt. Nun können wir es aber so machen mit dem Raume, wie Sie es mit Ihrem Portemonnaie machen können. Wenn Sie Ihr Portemonnaie gefüllt haben, können Sie immer mehr und mehr herausnehmen; zuletzt ist einmal Null darinnen. Wenn Sie aber jetzt weiter Geld ausgeben wollen, können Sie aus dem Portemonnaie nichts mehr herausnehmen, wenn schon Null drinnen war, aber Sie können Schulden machen. Da ist noch weniger als Null dann im Portemonnaie drinnen, wenn Sie Schulden haben. So können Sie sich auch den Raum denken nicht nur leer, sondern ich möchte sagen saugend, weniger darinnen als Null, -A. Und von diesem Saugeraum, von diesem Raum, der nicht nur leer ist, sondern der einen Inhalt hat, der das Gegenteil von materieller Erfülltheit ist, von diesem Raum ist der Raum eingenommen, den man sich von der Sonne ausgefüllt zu denken hat. Also die Sonne ist innerlich saugend, nicht drückend wie ein Gas. Sie ist von negativer Materialität erfüllt.

[ 7 ] Das will ich nur als Beispiel anführen, damit Sie sehen, daß man nicht irdische Gesetzmäßigkeit so einfach auf den außerirdischen Kosmos übertragen kann. Da sind ganz andere Verhältnisse im außerirdischen Kosmos zu denken als diejenigen, die wir in unserer Umgebung auf der Erde kennenlernen. So daß wir, wenn wir zuerst sprechen von einer gewissen Gesetzmäßigkeit, wir sagen müssen: Wir sind von Gesetzmäßigkeit innerhalb des irdischen Daseins umgeben, und in diese Gesetzmäßigkeit ist die Welt des Stofflichen eingeschlossen, die uns zunächst zugänglich ist. — Stellen Sie sich diese Welt des irdischen Daseins vor: Sie brauchen sich nur die Vorgänge, die in der mineralischen Welt geschehen, vor Augen zu führen, vor die Seele zu rücken, so haben Sie dasjenige, was zunächst, insofern Sie es sehen, ganz eingeschlossen ist in diese Gesetzmäßigkeit des irdischen Daseins. Also wir können sagen: Da ist eingeschlossen erstens die mineralische Welt; zweitens aber ist noch etwas anderes eingeschlossen. Wenn wir herumgehen, oder auch wenn wir herumgetragen werden, kurz, wenn wir uns nur gewissermaßen, wenn ich mich grob ausdrücken darf, als Gegenstände benehmen in dieser physischen Welt, dann leben wir in derselben Gesetzmäßigkeit. Für die irdische Gesetzmäßigkeit ist es nämlich gleichgültig, ob ein Straßenstein herumgetragen wird, bewegt wird, oder ob der Mensch herumgetragen wird oder sich selber bewegt; das ist für die irdische Gesetzmäßigkeit ganz einerlei. Sie brauchen sich das nur zu überlegen. Für die irdische Gesetzmäßigkeit kommt nichts anderes in Betracht als die Ortsveränderung des Menschen, die er allerdings selber bewirken kann. Das hängt dann mit andern Dingen zusammen; aber wenn man bloß irdische Gesetzmäßigkeit studiert, dann kann es einem gleichgültig sein, was innerhalb der Haut des Menschen vorgeht, oder was in der Seele des Menschen vorgeht. Da kommt nur die Lageveränderung im irdischen Raume in Betracht.

[ 8 ] Wir können also sagen: Das zweite ist, außer der mineralischen Welt, der bewegte Mensch, und zwar der äußerlich bewegte Mensch (siehe Aufstellung Seite 62).- Wir finden keinen andern Bezug der äußeren Welt zum Menschen, insofern sie irdisch ist und vor unseren Sinnen auftritt, als lediglich den Bezug zum äußerlich bewegten Menschen. Wenn wir irgendeinen andern Bezug zum Menschen suchen wollen, dann müssen wir gleich zu etwas anderem unsere Zuflucht nehmen. Und da kommen wir allerdings zum Außerirdischen, zu unserer außerirdischen Umgebung, insofern wir zum Beispiel die Mondenumgebung studieren, dasjenige, was vom Monde ausgeht. Es tritt ja, wenigstens für das Bewußtsein vieler Menschen, noch etwas von der Wirkung des Mondes auf die Erde zutage. Die Menschen glauben in weitem Umkreise an solche Wirkungen des Mondes auf die Erde, zum Beispiel an den Zusammenhang der Mondesbewegungen mit den Regenphasen. Gelehrte Leute der Gegenwart betrachten das als Aberglaube. Ich habe Ihnen, wenigstens einigen von Ihnen, ja erzählt, daß das einmal in Leipzig einen niedlichen Tatsachenbestand gegeben hat.

[ 9 ] Der interessante Naturphilosoph und Ästhetiker, Gustav Theodor Fechner, hat sogar ein Buch verfaßt über den Einfluß des Mondes auf die Witterungsverhältnisse. Er war der Universitätskollege des bekannten Botanikers und Naturforschers Schleiden. Schleiden war selbstverständlich als moderner Materialist tief davon durchdrungen, daß sich so etwas nur auf Aberglauben stützen könne, was da sein Kollege Gustav Fechner über den Einfluß der Mondesphasen auf die Witterung geltend machte. Nun waren aber außer den beiden Gelehrten an der Universität Leipzig auch derer beiden Frauen, die Frau Schleiden und die Frau Fechner, und es waren dazumal noch so einfache Verhältnisse in Leipzig, daß man Regenwasser für die Wäsche sammelte. Nun behaupteten die Frauen, man könne bei gewissen Mondesphasen eben mehr Regenwasser auffangen und dadurch mehr Wasser zum Waschen bekommen als bei andern Mondesphasen. Und die Frau Professor Fechner sagte, sie glaube an das, was ihr Mann veröffentlicht habe über den Einfluß der Mondesphasen auf die Witterung; deshalb möchte sie mit der Frau Professor Schleiden, die nicht daran glaube, übereinkommen, daß diese ihre Tonnen hinstelle, wie es der Meinung des Professor Schleiden entspreche; sie würde ja nach dessen Meinung geradesoviel Regenwasser bekommen als sie, die Frau Professor Fechner, nach dem guten Rat ihres Mannes bekomme. Und siehe da, trotzdem der Professor Schleiden die Anschauung des Professor Fechner als außerordentlich abergläubisch angesehen hat, ging die Frau Professor Schleiden auf diesen Handel nicht ein, sondern wollte auch zu den andern Mondesphasen ihre Tonnen hinstellen, um das Regenwasser zu bekommen.

[ 10 ] Nun, weniger sichtbar ist zunächst für unser heutiges wissenschaftliches Bewußtsein der Einfluß von den Kräften anderer planetarischer Weltenkörper. Aber würde man — wie das nun geschehen soll inunserem wissenschaftlich-physiologischen Institut in Stuttgart - einmal genauer studieren zum Beispiel die Linie, nach der die Pflanzenblätter am Stengel wachsen, so würde man finden, wie jede einzelne Linie sich an die Bewegung der Planeten anschließt, wie diese Linien gewissermaßen Miniaturbilder der Planetenbewegungen darstellen. Und man würde finden, daß man manches auf der Oberfläche der Erde nur begreift, wenn man das Außerirdische kennt und dieses Außerirdische nicht einfach identifiziert mit dem Irdischen; wenn man voraussetzt, daß eine Gesetzmäßigkeit vorhanden ist, die kosmisch und nicht tellurisch ist.

[ 11 ] Also wir können sagen, wir haben eine zweite Gesetzmäßigkeit innerhalb des kosmischen Daseins. Wird man einmal studieren diese kosmischen Einflüsse - und man wird das ganz empirisch studieren können -, dann wird man erst eine wirkliche Botanik haben. Denn was als unsere Pflanzenwelt auf der Erde wächst, wächst nicht in der Weise aus der Erde heraus, wie es sich die materialistische Botanik vorstellt, sondern wird herausgezogen aus der Erde durch die kosmischen Kräfte. Und was durch die kosmischen Kräfte so im Pflanzenwachstum herausgezogen wird, durchsetzt wird es von den mineralischen Kräften, die gewissermaßen das kosmische Pflanzengerippe durchsetzen, so daß es sinnlich sichtbar wird. So daß wir sagen können, eingeschlossen ist in diese kosmische Gesetzmäßigkeit erstens die pflanzliche Welt; zweitens — aber allerdings so, daß es nicht so leicht zu konstatieren ist wie bei der pflanzlichen Welt, weil es sich eine gewisse Selbständigkeit erringt und unabhängig wird von dem Rhythmus der äußeren Vorgänge, dennoch aber den Rhythmus innerlich nachahmt — wird eingeschlossen in diese kosmische Gesetzmäßigkeit alles das, was innere Bewegung des Menschen ist, also durchaus physische, aber innere Bewegung des Menschen. In die irdische Gesetzmäßigkeit ist also erstens der äußerlich bewegte Mensch eingeschlossen; wenn Sie aber hinschauen auf Ihre Verdauung, auf die Bewegung der Nahrungsstoffe in den Verdauungsorganen, wenn Sie im weiteren schauen jetzt nicht auf den Rhythmus, sondern auf die Bewegung des Blutes durch die Blutgefäße — und es gibt noch vieles andere, was sich im Inneren des Menschen bewegt -, dann haben Sie ein Bild von dem, was im Inneren des Menschen sich bewegt, gleichgültig, ob er steht oder geht. Das kann nicht so ohne weiteres eingegliedert werden in die erste Gesetzmäßigkeit, sondern das muß eingegliedert werden in die kosmische Gesetzmäßigkeit, geradeso wie die Form und auch die Bewegungen der Pflanzen; nur gehen diese beim Menschen langsamer vor sich als die Formen und die Bewegungen der Pflanzen. So daß wir sagen können: Zweitens sind da eingegliedert die inneren Bewegungen des Menschen (siehe Aufstellung Seite 62).

[ 12 ] Sie können nun den Kosmos nehmen, ich möchte sagen bis in unbestimmte Entfernungen, irgendwie hat alles in dieser Weise Einfluß auf das Leben, das sich auf der Erdoberfläche entwickelt. Aber wenn dieses beides nur vorhanden wäre, wenn nur vorhanden wäre irdische Gesetzmäßigkeit und kosmische Gesetzmäßigkeit in dem Sinne, wie ich sie jetzt vor Sie hingestellt habe, so würde nichts anderes auf der Erde vorhanden sein können als die mineralische Welt und die pflanzliche Welt, denn der Mensch könnte da natürlich nicht vorhanden sein. Bewegen könnte er sich, wenn er vorhanden sein könnte, und innerliche Bewegungen könnten vorhanden sein, aber das gibt natürlich noch nicht den Menschen. Auch nicht Tiere könnten auf der Erde vorhanden sein, real könnten nur vorhanden sein Mineralien und Pflanzen. Es muß dasjenige, was zunächst kosmische Gesetzmäßigkeit und kosmischer Seinsinhalt ist, durchsetzt und durchwebt sein von etwas, das wir überhaupt nicht mehr zum Raume rechnen können, demgegenüber wir nicht mehr vom Raume sprechen können.

[ 13 ] Natürlich ist alles, was unter eins und zwei fällt, im Raume zu denken, aber wir müssen von etwas sprechen, was nicht mehr im Raume als vorhanden gedacht werden kann, was aber zunächst durchsetzt alle kosmische Gesetzmäßigkeit. Sie brauchen nur daran zu denken, wie beim Menschen seine Bewegungen, seine inneren Bewegungen mit seinem Rhythmus zusammenhängen. Zunächst landet ja gewissermaßen dasjenige, was die Bewegung unserer Nahrungsstoffe in uns ist, in der Blutbewegung. Aber die Blutbewegung findet ja nicht so statt, daß das Blut einfach als der Nahrungssaft die Adern durchläuft. Das Blut bewegt sich rhythmisch, und außerdem steht dieser Rhythmus wiederum in einem bestimmten Verhältnis zum Atmungsrhythmus, indem Sauerstoff für die Blutbildung verbraucht wird. Wir haben diesen doppelten Rhythmus. Ich habe einmal darauf hingewiesen, wie auf diesem Verhältnis des Blutrhythmus zum Atmungsrhythmus, von vier zu eins, innere seelische Gesetzmäßigkeit so beruht, daß Metrik und Versmaß eigentlich davon abhängen.

[ 1 ] Wir sehen also, daß dasjenige, was sich da abspielt als innere Bewegung, mit dem Rhythmus zusammenhängt, und von dem Rhythmus haben wir gesagt, daß er in Beziehung steht zum Seelenleben des Menschen. Ebenso müssen wir das, was wir in den Bewegungen der Sterne haben, in Beziehung bringen zur Weltenseele. So daß wir zum dritten sprechen können von der Gesetzmäßigkeit innerhalb der Weltenseele (siehe Aufstellung Seite 62), und darinnen haben wir eingeschlossen erstens die Tierwelt und zweitens alles dasjenige, was zunächst mit Bezug auf den leiblichen Menschen seine rhythmischen Vorgänge sind. Diese rhythmischen Vorgänge innerhalb des Menschen stehen ja im Verhältnisse zum gesamten Weltenrhythmus. Wir haben auch davon schon gesprochen, wollen uns aber das jetzt für die nächsten Betrachtungen dieser Tage wieder vor die Seele führen.

[ 15 ] Sie wissen, achtzehn Atemzüge hat ungefähr der Mensch in der Minute. Rechnen Sie das sechzigmal, so bekommen Sie die Atemzüge in der Stunde. Nehmen Sie das vierundzwanzigmal, so bekommen Sie die Atemzüge des Tages: Sie bekommen ungefähr 25920 Atemzüge für den normalen Menschen im Laufe des Tages. Diese Zahl der Atemzüge bildet also den Tag- und Nachtrhythmus im Menschen. Wir wissen, daß der Frühlingsaufgangspunkt der Sonne mit jedem Jahr etwas weiterrückt, so daß gewissermaßen die Sonne um das Himmelsgewölbe ihren Frühlingsaufgangspunkt vorwärtsrückt. Und die Dauer der Zeit, nach welcher dieser Frühlingsaufgangspunkt wieder an seinen alten Ort zurückkommt, ist 25920 Jahre. Das ist der Rhythmus zunächst unseres Weltenalls, und unser Atemrhythmus in vierundzwanzig Stunden ist ein Miniaturabbild davon. Wir befinden uns also mit unserem Rhythmus eingesponnen in den Weltenrhythmus, durch unsere Seele in die Gesetzmäßigkeit der Weltenseele.

[ 16 ] Das vierte, das wir betrachten können, ist nun die Gesetzmäßigkeit, die dem ganzen Weltenall zugrunde liegt, wie auch alle drei früheren Gesetzmäßigkeiten, jene Gesetzmäßigkeiten, innerhalb welcher wir uns fühlen, wenn wir unserer selbst als geistige Menschen uns bewußt werden. Wenn wir unserer selbst als geistige Menschen uns bewußt werden, dann ist das ja so, daß wir uns klar darüber sein müssen: Wir können zunächst das oder jenes von der Welt nicht begreifen, denn mit dem heutigen Intellektualismus, der schon einmal die allgemeine geistige Kulturkraft ist, wird ja das wenigste begriffen; wir begreifen also mit unserem Geiste in einem bestimmten menschlichen Entwickelungszustande zunächst wenig. Aber es liegt in der Selbstauffassung des Geistes selber, daß er sich sagt: Wenn er sich entwickelt, so können ihm keine Grenzen gegeben sein. Er muß sich in das Weltenall hinein erkennend, fühlend, wollend entwickeln können. Und so müssen wir, indem wir unseren Geist in uns tragen, ihn beziehen auf eine vierte Gesetzmäßigkeit innerhalb des Weltengeistes (siehe Aufstellung Seite 62).

[ 17 ] Und nun erst kommen wir zu dem, was darinnen eingeschlossen ist als reales Wesen, denn der Mensch könnte ja innerhalb der andern Gesetzmäßigkeiten gar nicht da sein. Da kommen wir erst dazu, den Menschen zu finden, aber im Speziellen vom Menschen dasjenige, was sein Nerven-Sinnesapparat ist, alles das, was zunächst der physische Träger des geistigen Lebens ist, also die Nerven-Sinnesvorgänge. Es ist ja beim Menschen so, daß zunächst der ganze Mensch in Betracht kommt, der seinen Kopf, das heißt, den hauptsächlichsten Berger der Nerven-Sinnesorgane trägt, und dann dieser Kopf selber. Der Mensch ist gewissermaßen dadurch Mensch, daß er seinen Kopf hat, und das menschlichste am Menschen ist der Kopf, ist das Haupt.

1.) Gesetzmäßigkeit innerhalb des irdischen Daseins

Eingeschlossen: 1) Die mineralische Welt 2) Der äußerlich bewegte Mensch

2.) Geserzmäßigkeit innerhalb des kosmischen Daseins

Eingeschlossen: 1) Die pflanzliche Welt 2) Die inneren Bewegungen des Menschen

3.) Gesetzmäßigkeit innerhalb der Weltenseele

Eingeschlossen: 1) Die Tierwelt 2) Die rhythmischen Vorgänge

4.) Gesetzmäßigkeit innerhalb des Weltengeistes

Eingeschlossen: 1) Der Mensch 2) Die Nerven-Sinnesvorgänge

[ 8 ] So daß uns schon da der Mensch zweimal begegnen darf. Nun gibt uns das zunächst - wenn wir es als Zusammenfassung betrachten von dem, was wir in den letzten Wochen besprochen haben - ein Bild des Zusammenhanges der Menschen mit der Umwelt, aber mit jener Umwelt, die nicht bloß die räumliche ist, denn auf die räumliche Welt bezieht sich nur eins und zwei, sondern auch mit derjenigen Welt, die die nichträumliche ist. Darauf bezieht sich dann drei und vier. Das wird ja insbesondere den Menschen der Gegenwart schwer, zu denken, daß irgend etwas nicht im Raume sein könnte, oder daß es keinen Sinn hat, vom Raume zu reden, wenn man auch von Realitäten spricht. Ohne das kann man aber nicht zu einer geistigen Wissenschaft aufsteigen. Wer im Raume bleiben will, kann nicht zu geistigen Entitäten aufsteigen.

[ 19 ] Ich habe Ihnen das letzte Mal, als ich hier sprach, von der Weltanschauung der Griechen gesprochen, um Sie darauf hinzuweisen, wie zu andern Zeiten die Menschen die Welt anders angesehen haben, als das heute der Fall ist. Dieses Bild, von dem ich Ihnen eben gesprochen habe, ergibt sich dem Menschen der Gegenwart; es ergibt sich ihm, wenn er einfach vorurteilslos, ungehindert durch das, was an Schutt die heutige Wissenschaft aufwirft, die Welt betrachtet.

[ 20 ] Nun muß ich zu dem, was ich Ihnen über die griechische Anschauung gesagt habe, noch einiges hinzufügen, damit wir den Anschluß finden an dasjenige, was ich durch dieses Schema Ihnen habe sagen wollen. Wenn der Mensch ganz gescheit ist, dann sagt er: Die räumliche Welt besteht aus etlichen siebzig Elementen, die verschiedene Atomgewichte haben und so weiter, und diese Elemente gehen Synthesen ein, man kann Analysen mit ihnen vollführen und so weiter. Auf chemischen Verbindungen und chemischen Entbindungen beruht dasjenige, was in der Welt vorgeht in bezug auf diese etlichen siebzig Elemente. Daß sie weiter zurückgeführt werden können auf etwas Ursprünglicheres, darum wollen wir uns im gegenwärtigen Augenblicke weniger kümmern. Im allgemeinen gelten ja der populären Wissenschaft heute diese etlichen siebzig Elemente.

[ 21 ] Ein Grieche, nicht in seiner gegenwärtigen Verkörperung, da würde er ja natürlich auch so denken wie die gegenwärtigen Menschen, wenn er gelehrt wäre, aber sagen wir, wenn er als alter Grieche wiederum hereingeschneit kommen könnte in die gegenwärtige Welt, dann würde er sagen: Ja, das ist ja ganz schön, diese etlichen siebzig Elemente, aber mit dem kommt man nicht weit, die sagen eigentlich nichts über die Welt aus. Da haben wir ganz anders über die Welt gedacht. Wir haben gedacht, die Welt besteht aus Feuer, Luft, Wasser, Erde.

[ 22 ] Da würde der Mann der Gegenwart sagen: Das ist eben einer kindlichen Auffassungsweise eigen. Über das sind wir längst hinaus. Wir lassen ja in den Aggregatzuständen, in den gasigen Aggregatzuständen das Luftförmige gelten, im flüssigen Aggregatzustand das Wässerige und im festen Aggregatzustand lassen wir die Erde gelten. Aber Wärme gilt uns überhaupt nicht mehr als irgend etwas, das man so anspricht wie du. Wir sind eben über diese kindlichen Vorstellungen hinaus. Wir haben dasjenige, was die Welt für uns konstituiert, in unseren etlichen siebzig Elementen.

[ 23 ] Da würde der Grieche sagen: Ganz schön, aber Feuer oder Wärme, Luft, Wasser, Erde, das ist uns etwas ganz anderes, als was du dir darunter vorstellst. Und was wir uns darunter vorgestellt haben, davon verstehst du gar nichts. - Nun würde zuerst der heutige Gelehrte etwas sonderbar berührt sein davon, und er würde meinen, er stünde eben einem Menschen auf kindlicherer Kulturentwickelungsstufe gegenüber. Aber der Grieche würde vielleicht - denn er würde gleich überschauen, was der moderne Gelehrte eigentlich in seinem Kopfe hat -, er würde sich ganz gewiß nicht zurückhaltend verhalten, sondern er würde sagen: Ja, weißt du, was du deine zweiundsiebzig Elemente nennst, das gehört alles für uns zu der Erde dazu; es ist ja schön, daß du das differenzierst, daß du das weiter spezifizierst, aber die Eigenschaften, die du bei deinen zweiundsiebzig Elementen anerkennst, die gehören für uns zur Erde dazu. Von Wasser, Luft und Feuer verstehst du gar nichts, davon weißt du gar nichts.

[ 24 ] Und er würde weiter reden, der Grieche — Sie sehen, ich wähle nicht eine weit im Orient zurückgelegene Kulturepoche, sondern nur einen wissenden Griechen -, er würde sagen: Was du da von deinen zweiundsiebzig Elementen mit ihren Synthesen und Analysen sagst, ist ja alles ganz schön, aber was glaubst du, worauf sich das bezieht? Es bezieht sich ja alles lediglich auf den physischen Menschen, wenn er gestorben ist und im Grabe liegt. Da gehen seine Stoffe, da geht sein ganzer physischer Leib die Prozesse durch, die du kennenlernst in deiner Physik, in deiner Chemie. Das, was du innerhalb der Strukturverhältnisse deiner etlichen siebzig Elemente kennenlernen kannst, das bezieht sich ja gar nicht auf den lebenden Menschen. Du weißt gar nichts von dem lebenden Menschen, weil du nichts weißt von Wasser, Luft und Feuer. Man muß erst etwas wissen von Wasser, Luft und Feuer, dann weiß man etwas vom lebenden Menschen. Durch das, was du mit deiner Chemie umfassest, weißt du nur etwas von dem, was mit dem Menschen geschieht, wenn er gestorben ist und im Grabe liegt, von dem, was der Leichnam als seine Prozesse durchmacht. Von dem weißt du nur, wenn du mit deinen etlichen siebzig Elementen kommst.

[ 25 ] Er würde ja nun mit dem weiteren bei dem gegenwärtigen Gelehrten nicht sonderlich Glück haben, der Grieche, aber er würde sich vielleicht in der folgenden Weise bemühen, ihm noch etwas klarzumachen. Er würde ihm sagen: Sieh einmal, wenn du deine zweiundsiebzig Elemente betrachtest, so ist das für uns alles Erde. Wir betrachteten zwar nur das Allgemeine; aber wenn du das auch spezifizierst: es ist eben nur ein genaueres Kennen, und durch das genauere Kennen dringt man nicht in die Tiefen. Wenn du aber wüßtest, was wir als Wasser bezeichnen, so hättest du ein Element, an dem, sobald es überhaupt in sein Weben und Leben kommt, nicht mehr bloß die irdischen Verhältnisse tätig sind, sondern das Wasser in seiner ganzen Wirksamkeit unterliegt kosmischen Verhältnissen.

[ 26 ] Der Grieche verstand unter dem Wasser nicht das physische Wasser, sondern er verstand darunter all das, was an Gesetzmäßigkeit vom Kosmos auf die Erde hereinspielt, in das die Wasser - Stoffbewegung einbezogen ist. Und innerhalb dieser Wasser -Stoffbewegung lebt wiederum das pflanzliche Element. Der Grieche schaute - indem er von allem Erdigen dasjenige unterschied, was im lebend-webenden Wasserelement ist — in diesem lebend-webenden Elemente zu gleicher Zeit die ganze Gesetzmäßigkeit des vegetabilischen Lebens, das eingespannt ist in dieses wässerige Element. So daß wir sagen können: Dieses wässerige Element können wir schematisch irgendwohin auf die Erde in irgendeiner Weise hinstellen, aber vom Kosmos aus determiniert hinstellen. Und nun können wir von unten hinauf irgendwie sprossend, in allerlei Weise sprossend das mineralische Element denken, das eigentlich irdische Element, das dann die Pflanzen durchsetzt, gewissermaßen durchspritzt mit dem irdischen Elemente. Aber was der Grieche sich unter dem wässerigen Elemente dachte, war etwas wesentlich Neues, und es war das für ihn eine ganz positive Anschauung. Und er schaute das nicht in Begriffen an, er schaute das in Bildern an, in Imaginationen. Wir müssen allerdings bis in die platonische Zeit zurückgehen — denn durch Aristoteles ist diese Anschauungsweise verdorben worden -, wir müssen bis auf Plato, auf die vorplatonische Zeit zurückgehen, und finden dann, wie der wirklich wissende Grieche in Imagination dasjenige angeschaut, hat, was da im wässerigen Element lebte und die Vegetation eigentlich trug, und was er durchaus auf den Kosmos bezog.

[ 27 ] Nun würde er weiter sagen: Siehst du, das, was da im Grabe liegt, wenn der Mensch gestorben ist, und was gesetzmäßig durchzogen ist von den Strukturgesetzen, die in deinen etlichen siebzig Elementen wirken, das ist eingespannt zwischen der Geburt, oder sagen wir der Empfängnis und dem Tode, in das ätherische Leben, in das aus dem Kosmos hereinwirkende ätherische Leben. Von dem bist du durchsetzt, wenn du ein lebendiger Mensch bist, und von dem verstehst du nichts, wenn du nicht von Wasser als einem besonderen Elemente redest, und wenn du nicht hinausschaust in die Pflanzenwelt als eingespannt in das wässerige Element, wenn du nicht diese Bilder, diese Imaginationen siehst.

[ 28 ] Wir Griechen - würde er sagen -, wir redeten gewiß vom Ätherleib des Menschen, aber wir erdichteten nichts über den Ätherleib, sondern wir sagten: Was einem da erscheinen kann vor dem Seelenauge, wenn man im Frühling die aufsprießende, grünwerdende Pflanzenwelt sieht, wenn man die allmählich sich verschieden färbende Pflanzenwelt sieht, wenn man diese Pflanzenwelt zum Fruchten kommen sieht im Sommer und die Blätter welk werden sieht gegen den Herbst zu, was einem da erscheinen kann, wenn man einen solchen Jahreslauf in der Vegetation sieht und ein inneres Verständnis dafür hat, das setzt sich zu einem ebenso in Bezug, wie man sich durch Brot und Fleisch, die man ißt, zur mineralischen Welt in Bezug setzt; ebenso setzt man sich zu dem in Bezug, was im Jahreslauf draußen sichtbar ist in der vegetabilischen Welt. Und durchdringt man sich mit der Anschauung, daß überhaupt ja alles in uns im vierundzwanzigstündigen Lauf wie in einem Miniaturbild abläuft und dann sich durch das ganze Leben hindurch wiederholt, so haben wir in uns ein Miniaturbild dessen, was da draußen aus dem wässerigen, ätherischen Elemente heraus, aus dem Kosmos heraus die Umwelt konstituiert. Wir können, wenn wir mit Verständnis diese äußere Welt anschauen, sagen: Das, was da draußen ist, lebt in unserem Inneren. - Geradeso wie wir sagen: Der Spinat wächst da draußen, ich pflücke ihn, ich koche ihn und esse ihn und dadurch habe ich ihn im Magen, das heißt in meinem physischen Leibe -, so können wir sagen: Da draußen im Jahreslaufe webt und lebt ein ätherisches Leben, und das habe ich in mir.

[ 29 ] Nicht das physische Wasser ist es, an das der Grieche dachte, aber das, was er in diesen Imaginationen erfaßte und zum Menschen in lebendige Beziehung brachte, das lag seiner Anschauung zugrunde. Und so würde er weiter sagen zu seinem Unterredner: Du studierst den Leichnam, der im Grabe liegt, weil du nur Erde studierst, denn deine etlichen siebzig Elemente sind Erde. Wir studierten den lebenden Menschen. Wir studierten während unserer Zeit auch den Menschen, der noch nicht gestorben ist, der aus innerer Regsamkeit heraus wächst und sich bewegt. Das kann man nicht, wenn man nicht aufsteigt zu den andern Elementen.

[ 30 ] So war es bei den Griechen, und würden wir weiter zurückkommen, dann würde uns mit aller Deutlichkeit das Luftelement und das Feuer- oder Wärmeelement entgegentreten. Das wollen wir später auch noch betrachten; aber ich will zunächst heute darauf hinweisen, wie dieses, daß der Mensch in seinem Inneren nicht die richtigen Kräftezusammenhänge sieht, in der Tat davon abhängt, daß er diese Kräftezusammenhänge auch in der Außenwelt nicht finden kann, daß er verzichtet auf diese Kräftezusammenhänge. Und das ist das Charakteristische unserer Kulturentwickelung seit dem ersten Drittel des 15. Jahrhunderts, daß das Verständnis für diese Zusammenhänge der Elemente einfach verlorengegangen ist, damit aber auch verlorengegangen ist das Verständnis für den lebendigen Menschen. Wir studieren den Leichnam in der offiziellen Wissenschaft. Wir haben ja öfter gehört, daß diese Phase schon einmal in der Entwickelungsgeschichte der Menschheit kommen mußte, aus andern Gründen allerdings kommen mußte, nämlich damit die Menschheit durch die Phase der Freiheitsentwickelung durchgehen könne. Aber ein gewisses Verständnis für Natur und Mensch ist seit dem ersten Drittel des 15. Jahrhunderts verlorengegangen. Das Verständnis hat sich bisher beschränkt auf dieses bloße eine Element, die Erde. Und wir müssen wiederum den Rückweg antreten. Wir müssen uns wiederum zurückfinden durch die Imagination zu dem Elemente des Wassers, durch die Inspiration zu dem Elemente der Luft, durch die Intuition zu dem Elemente des Feuers. Im Grunde genommen ist es auch ein Aufstieg zu den Elementen, was wir als einen Aufstieg in der höheren Erkenntnis gesehen und gedeutet haben, den Aufstieg von dem gewöhnlichen gegenständlichen Erkennen durch die Imagination, Inspiration zur Intuition. Davon wollen wir dann übermorgen weiterreden.

Third Lecture

[ 1 ] Following the historical considerations we have made, we will today reflect on the present human being, which will then enable us to take a closer look at the place of this present human being in the whole of time, in the days to come. We must be clear that human beings, as spiritual, soul, and physical beings, stand before us in three different directions within the world. This becomes apparent when we consider human beings from a purely external perspective. According to their spirit, they pass through the world independently of external appearances; according to their soul, they are not so independent of external appearances. One need only consider certain connections that are visible throughout life, and one will find how the soul life actually has certain connections with the external world. One can be depressed in the soul, one can be cheerful in the soul. Remember how often you have felt depressed in your dreams, how you have had to attribute this feeling of depression when you wake up to an irregularity in your breathing rhythm. This is a crude phenomenon, one might say, and yet all spiritual life is not entirely without a similar connection to the rhythmic life we experience in our breathing rhythm, in our blood circulation rhythm, and in the external rhythmic life of the entire cosmos. Everything that goes on in the soul is connected with the rhythm of the world. So while on the one hand, as spiritual beings, we feel to a high degree independent of our environment, we cannot say the same about our soul life, because our soul life is embedded in the general rhythm of the world.

[ 2 ] We are even more embedded in the general phenomena of the world as physical beings. Again, we need only start from gross phenomena. As physical beings, we are heavy; we have weight. Other purely mineral beings also have weight. Mineral beings, plant beings, animal beings, and human beings as physical beings are all part of the general heaviness, and we must even rise above this general heaviness in a certain sense if we want to make our bodies the physical tools of spiritual life. We have often mentioned that if it were merely a question of the physical weight of our brain, it would be so great—one thousand three hundred to one thousand five hundred grams—that it would crush all the veins below the brain. But this brain is subject to Archimedes' principle, in that it floats in the cerebral fluid. It loses so much of its weight by floating in the cerebral fluid that it actually weighs only twenty grams, and thus presses only twenty grams on the veins at the base of the brain. You can see from this that the brain actually strives much more upward than downward. It resists gravity. It tears itself out of the general gravity. But in doing so, it does nothing different from any other body that you put in water, which loses as much of its weight as the weight of the displaced water.

[ 3 ] So you see an interplay between our entire physical being and the external world. And it is so that we are not only integrated into a rhythm here, as with the weaving of the soul, but that we are completely immersed in this external physical life. When we stand at a certain point on the earth's surface, we exert pressure on that point; when we move to another point, we exert pressure on another point. As physical beings, we are therefore physical beings like other physical beings in other realms of nature.

[ 4 ] We can therefore say that with our spiritual human nature we are in a certain sense independent of the environment, with our soul nature we are integrated into the rhythm of the world, and with our physical nature we are integrated into the rest of the world as if we had no soul or spirit at all. We must keep this distinction clearly in mind. For we cannot come to an understanding of the higher nature of the human being unless we take into account this threefold position of the human being in relation to its entire environment. Let us now take a look at the environment of the human being. In the environment of human beings, we first have—I am now summarizing various things that we have been considering for many months, only from different points of view—everything that is governed by natural laws. Imagine the universe, governed by natural laws, and within these natural laws the entire visible world or the world that can be perceived by the senses. Let us consider this as the first environment of human beings.

[ 5 ] When we consider this world, a simple reflection shows that we are then only dealing with the actual earthly world. Only reckless and unfounded hypotheses by physicists can claim that the same natural laws that we observe around us here on Earth also apply to the extraterrestrial cosmos. I have often pointed out how surprised physicists would be if they could go up to where the sun is. Physicists regard the sun as something like a large gas furnace, but without walls, something like a burning gas. One would not find this burning gas if one were to go to the place in the cosmos where the sun is. One would find something at the place in the cosmos where the sun is, but it would be very different from what physicists imagine. If this (it is drawn) encloses the space that we imagine the sun occupies, then not only is there nothing at this point of all the matter that we find here on Earth, but there is not even what we call empty space. First, imagine the filled space; living here on Earth, you are always surrounded by filled space. If it is not filled with any solid or liquid substances, it is filled with air or at least with heat, light, and so on. In short, we are always dealing with filled space. But you know that it is possible to create empty space, at least approximately, by pumping the air out of the recipient of the air pump.

[ 6 ] Now imagine that we have some kind of filled space; let's call it A and put a plus sign in front of it, + A. Now we can make the space emptier and emptier, and A will become smaller and smaller; but the space is still filled, so we still call it plus. We can—although we cannot actually do this in earthly circumstances, because we can only make the space approximately empty—but we can imagine that a completely airless space could be created. Then there would only be space in the part of the space that has been emptied. I will call it zero. It has zero content. Now we can do the same with space as you can do with your wallet. When your wallet is full, you can take more and more out of it; eventually there will be nothing left. But if you want to continue spending money, you can't take anything else out of your wallet if it was already empty, but you can go into debt. Then there is even less than zero in your wallet if you have debts. In the same way, you can think of space as not just empty, but, I would say, sucking, containing less than zero, -A. And this sucking space, this space that is not only empty but has a content that is the opposite of material fullness, this space is occupied by the space that one must imagine to be filled by the sun. So the sun is internally sucking, not pressing like a gas. It is filled with negative materiality.

[ 7 ] I only want to give this as an example so that you can see that earthly laws cannot be simply transferred to the extraterrestrial cosmos. The conditions in the extraterrestrial cosmos are completely different from those we experience in our environment on Earth. So when we first speak of a certain lawfulness, we must say: We are surrounded by lawfulness within earthly existence, and this lawfulness encompasses the material world that is initially accessible to us. Imagine this world of earthly existence: you need only bring to mind the processes that take place in the mineral world, bring them before your soul, and you have that which, insofar as you see it, is initially completely enclosed in this lawfulness of earthly existence. So we can say: first, the mineral world is enclosed; but second, something else is also enclosed. When we walk around, or even when we are carried around, in short, when we behave, so to speak, as objects in this physical world, then we live in the same lawfulness. For earthly law, it is irrelevant whether a paving stone is carried around, moved, or whether a human being is carried around or moves himself; this is completely irrelevant for earthly law. You only need to think about it. For earthly law, nothing else matters except the change of location of the human being, which he can, of course, bring about himself. This is then connected with other things; but if one studies only earthly laws, then it is irrelevant what goes on inside the human skin or what goes on in the human soul. Only the change of position in earthly space is taken into consideration.

[ 8 ] We can therefore say: The second thing, apart from the mineral world, is the moving human being, namely the externally moving human being (see list on page 62). We find no other connection between the external world and the human being, insofar as it is earthly and appears before our senses, than the connection to the externally moving human being. If we want to find any other connection to human beings, we must immediately turn to something else. And this brings us to the extraterrestrial, to our extraterrestrial environment, insofar as we study, for example, the environment of the moon, that which emanates from the moon. At least for the consciousness of many people, something of the moon's effect on the earth is still apparent. People in many circles believe in such effects of the moon on the earth, for example, in the connection between the movements of the moon and the rainy seasons. Contemporary scholars consider this to be superstition. I have told you, at least some of you, that there was once a charming case of this in Leipzig.

[ 9 ] The interesting natural philosopher and aesthetician Gustav Theodor Fechner even wrote a book about the influence of the moon on weather conditions. He was a university colleague of the well-known botanist and natural scientist Schleiden. Schleiden, as a modern materialist, was of course deeply convinced that what his colleague Gustav Fechner claimed about the influence of the phases of the moon on the weather could only be based on superstition. However, in addition to the two scholars at the University of Leipzig, there were also their two wives, Mrs. Schleiden and Mrs. Fechner, and at that time, conditions in Leipzig were still so simple that rainwater was collected for washing. Now, the women claimed that during certain phases of the moon, more rainwater could be collected and thus more water was available for washing than during other phases of the moon. And Professor Fechner's wife said that she believed what her husband had published about the influence of the phases of the moon on the weather; therefore, she wanted to agree with Professor Schleiden's wife, who did not believe in this, that she would place her barrels where Professor Schleiden thought they should be; according to his opinion, she would get just as much rainwater as she would. Professor Fechner would get, according to her husband's good advice. And lo and behold, even though Professor Schleiden considered Professor Fechner's view to be extremely superstitious, Professor Schleiden did not agree to this deal, but wanted to place her barrels during the other phases of the moon as well in order to get the rainwater.

[ 10 ] Now, the influence of the forces of other planetary bodies is less visible to our scientific consciousness today. But if one were to study more closely, as is now to be done at our scientific-physiological institute in Stuttgart, for example, the line along which plant leaves grow on the stem, one would find that each individual line follows the movement of the planets, that these lines are, in a sense, miniature images of planetary movements. And one would find that many things on the surface of the earth can only be understood if one knows the extraterrestrial and does not simply identify the extraterrestrial with the terrestrial; if one assumes that there is a law that is cosmic and not telluric.

[ 11 ] So we can say that we have a second law within cosmic existence. Once we study these cosmic influences—and we will be able to study them empirically—then we will have a true botany. For what grows as our plant world on earth does not grow out of the earth in the way that materialistic botany imagines, but is drawn out of the earth by cosmic forces. And what is drawn out in this way by the cosmic forces in plant growth is permeated by the mineral forces, which in a sense permeate the cosmic plant skeleton, so that it becomes sensually visible. So we can say that this cosmic law includes, first, the plant world; second—but in a way that's not as easy to see as with the plant world, because it gains a certain independence and becomes separate from the rhythm of external processes, while still imitating that rhythm internally—this cosmic law includes everything that which is the inner movement of the human being, that is, the physical but inner movement of the human being. The earthly law therefore includes, first, the outwardly moving human being; but if you look at your digestion, at the movement of food substances in the digestive organs, if you look further, not at the rhythm, but at the movement of the blood through the blood vessels — and there is much else that moves within the human being — then you have a picture of what moves within the human being, regardless of whether he is standing or walking. This cannot be readily integrated into the first law, but must be integrated into the cosmic law, just like the form and movements of plants; only in humans these occur more slowly than the forms and movements of plants. So we can say: Secondly, the inner movements of the human being are integrated (see list on page 62).